User login

A Surgical Surge

Many or most specialties in medicine are adopting a hospitalist model, at least to a limited extent. In fact, hospital care of adult medical patients wasn’t even the first place the idea was adopted.

In talking with people from hundreds of institutions it seems clear the idea appeared earlier and grew more quickly in pediatrics than adult medicine. And in the past 10 to 15 years, fields like obstetrics (“laborists”), psychiatry, gastroenterology, and many others have slowly begun to adopt the hospitalist model.

One of the most recent disciplines to join the parade is general surgery. And when comparing the forces in play for hospitalists in the early 1990s to the current situation for surgical hospitalists, I think we may be close to a surge in surgical hospitalists similar to what we’ve seen with medical hospitalists in the past 10 years.

When I say surgical hospitalists, I’m referring to surgeons with a nearly exclusive inpatient practice. Other terms such as surgicalist, acute care surgeon, and traumatologist overlap to some degree but have ambiguous meanings.

Generalizations

For some months I have contacted all the surgical hospitalist practices I can find to learn what forces led to their creation and how they are structured. Several common themes are emerging:

Prevalence: There are probably no more than 20 to 40 surgical hospitalist practices, but many institutions are considering the idea. This is similar to the situation for medical hospitalists in the early to mid-1990s.

Driver to start program: In every program I’ve found, the main impetus to start it was to address the burden of emergency department (ED) call for existing general surgeons. Like primary care, ED call is regarded as unattractive because it is unpredictable (lots of night and weekend work), usually has a poor payer mix, and many general surgeons have seen the “center of gravity” of their practice move away from the hospital toward an ambulatory surgery center over the past 10 years or so. Additionally, many general surgeons are increasingly uncomfortable caring for trauma patients because of recent changes in that field. (For an excellent discussion of the changing nature of general surgery and trauma care see “The Acute Care Surgeon” in The Hospitalist, May 2006, p. 25.)

Case volume: General surgery case volume tends to go up at a hospital that puts a surgical hospitalist program in place. When existing surgeons are relieved of ED call they increase their volume of (mostly elective) surgery. The availability of surgical hospitalists may mean fewer emergency cases presenting to the ED are referred elsewhere (which may happen when non-hospitalist surgeons are required to take ED call). These changes in case volume and the timing of the operations (e.g., volume of night surgeries may go up) may require adjustments to operating room staffing and scheduling. Presumably this increased volume would not occur in an area oversupplied with surgeons.

Economics: Like nearly all medical hospitalist programs, surgical hospitalist practices are not viable without financial support in addition to collected professional fees. In all cases I am aware of, this support comes from the sponsoring hospital.

While the cost may be similar to what the hospital might have paid for existing surgeons to take ED call, hospitals seem to be getting a better return on that investment with surgical hospitalists. A small group of surgical hospitalists can handle the increased volume and all ED calls, improving clinical and service quality. Some institutions report that surgical hospitalists are much more attentive to billing for nonoperative work than their predecessors.

Structure: Programs should have an outpatient clinic where the surgical hospitalists can provide post-operative follow-up. In most cases, each surgeon spends only half a day a week in the clinic.

Scope of practice: All surgical hospitalist practices take most or all ED general surgery calls. In some institutions, the surgical hospitalist also leads the trauma team. Other duties at a few institutions include things like managing a wound-care clinic and being on-call to place lines.

Opinion of other surgeons: Community private practice surgeons tend to support these programs, but most institutions limit or prohibit surgical hospitalists from accepting elective referrals. Community surgeons are still offered the option of remaining on the ED call schedule—as might be the case for surgeons new to the community. At least one institution reported that the presence of surgical hospitalists improved recruitment of non-hospitalist general surgeons. However, I am also aware of one program put into place largely at the insistence of the existing surgeons. Those same surgeons later insisted it be dissolved because they saw it as unwanted competition.

Staff needs: Surgical hospitalist practices nearly always require fewer doctors than a medical hospitalist practice in the same institution. This can lead to a tension between having the right number of surgical hospitalists for the case volume (often just one or two doctors) and enough to provide for a reasonable call schedule. Existing groups have adopted a number of strategies.

Groups with only two doctors often have each work seven on/seven off. The doctor on-call for that week takes all night call him/herself. In some practices that have a medical hospitalist in-house all night, it could be reasonable to have routine calls on the surgical patients (e.g., sleeping pills, laxatives, low urine output, fever) first paged to the medical hospitalist, who refers the call to the surgical hospitalist only as needed.

At least one practice has hired enough surgeons so the call burden on each is reasonable. This might be more staff than required for the patient volume: Four surgical hospitalists each work 12-hour shifts in a seven on/seven off schedule. During the seven consecutive night shifts (worked by each surgeon one week in four), patient volume is low.

Some practices hire community surgeons as moonlighters or consider using nurse practitioners or physician’s assistants as first responders at night.

Demographics: Surgical hospitalists are usually midcareer doctors, not surgeons who have recently completed their training. Many say they have gotten burned out with the stress of operating a private practice and prefer hospital work to office work.

Where Will It All Lead?

In every institution I have made contact with, the medical and surgical hospitalists have a good working relationship. Each is available to the other for consults, and they work together so frequently that they can begin to build a greater sense of teamwork. It is important that both groups jointly develop guidelines, such as who admits which type of patients.

If, like primary care doctors, general surgeons and a handful of other specialties with significant hospital volume (such as obstetrics and gastroenterology) move largely to a hospitalist model, U.S. healthcare will have made a remarkable transformation. In the span of my career we will have gone from a system of most doctors seeing patients in and out of the hospital to a division of physician labor such that most doctors practice almost exclusively in only one setting or the other.

I can see how this could be a good thing for patients and medical professionals, but that isn’t a given. For it to turn out we must preserve the elements of the earlier system that worked well and mitigate new problems and complexities. We will need well-designed research to show the economic and quality effects of the hospitalist model on non-primary care fields such as general surgery. We face growing challenges in ensuring excellent communication between inpatient and outpatient caregivers—something that doesn’t work ideally in all medical hospitalist practices.

Let Me Hear From You

I’d like to hear about any surgical hospitalist program you know of so I can add it to my database of information about such programs. And if you’re thinking about becoming a surgical hospitalist or you’re an institution thinking about starting such a practice, feel free to contact me so we can compare notes. I can be reached at (425) 467-3316, or by e-mail: john@jnelson.net. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospitalist practice management-consulting firm. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

Many or most specialties in medicine are adopting a hospitalist model, at least to a limited extent. In fact, hospital care of adult medical patients wasn’t even the first place the idea was adopted.

In talking with people from hundreds of institutions it seems clear the idea appeared earlier and grew more quickly in pediatrics than adult medicine. And in the past 10 to 15 years, fields like obstetrics (“laborists”), psychiatry, gastroenterology, and many others have slowly begun to adopt the hospitalist model.

One of the most recent disciplines to join the parade is general surgery. And when comparing the forces in play for hospitalists in the early 1990s to the current situation for surgical hospitalists, I think we may be close to a surge in surgical hospitalists similar to what we’ve seen with medical hospitalists in the past 10 years.

When I say surgical hospitalists, I’m referring to surgeons with a nearly exclusive inpatient practice. Other terms such as surgicalist, acute care surgeon, and traumatologist overlap to some degree but have ambiguous meanings.

Generalizations

For some months I have contacted all the surgical hospitalist practices I can find to learn what forces led to their creation and how they are structured. Several common themes are emerging:

Prevalence: There are probably no more than 20 to 40 surgical hospitalist practices, but many institutions are considering the idea. This is similar to the situation for medical hospitalists in the early to mid-1990s.

Driver to start program: In every program I’ve found, the main impetus to start it was to address the burden of emergency department (ED) call for existing general surgeons. Like primary care, ED call is regarded as unattractive because it is unpredictable (lots of night and weekend work), usually has a poor payer mix, and many general surgeons have seen the “center of gravity” of their practice move away from the hospital toward an ambulatory surgery center over the past 10 years or so. Additionally, many general surgeons are increasingly uncomfortable caring for trauma patients because of recent changes in that field. (For an excellent discussion of the changing nature of general surgery and trauma care see “The Acute Care Surgeon” in The Hospitalist, May 2006, p. 25.)

Case volume: General surgery case volume tends to go up at a hospital that puts a surgical hospitalist program in place. When existing surgeons are relieved of ED call they increase their volume of (mostly elective) surgery. The availability of surgical hospitalists may mean fewer emergency cases presenting to the ED are referred elsewhere (which may happen when non-hospitalist surgeons are required to take ED call). These changes in case volume and the timing of the operations (e.g., volume of night surgeries may go up) may require adjustments to operating room staffing and scheduling. Presumably this increased volume would not occur in an area oversupplied with surgeons.

Economics: Like nearly all medical hospitalist programs, surgical hospitalist practices are not viable without financial support in addition to collected professional fees. In all cases I am aware of, this support comes from the sponsoring hospital.

While the cost may be similar to what the hospital might have paid for existing surgeons to take ED call, hospitals seem to be getting a better return on that investment with surgical hospitalists. A small group of surgical hospitalists can handle the increased volume and all ED calls, improving clinical and service quality. Some institutions report that surgical hospitalists are much more attentive to billing for nonoperative work than their predecessors.

Structure: Programs should have an outpatient clinic where the surgical hospitalists can provide post-operative follow-up. In most cases, each surgeon spends only half a day a week in the clinic.

Scope of practice: All surgical hospitalist practices take most or all ED general surgery calls. In some institutions, the surgical hospitalist also leads the trauma team. Other duties at a few institutions include things like managing a wound-care clinic and being on-call to place lines.

Opinion of other surgeons: Community private practice surgeons tend to support these programs, but most institutions limit or prohibit surgical hospitalists from accepting elective referrals. Community surgeons are still offered the option of remaining on the ED call schedule—as might be the case for surgeons new to the community. At least one institution reported that the presence of surgical hospitalists improved recruitment of non-hospitalist general surgeons. However, I am also aware of one program put into place largely at the insistence of the existing surgeons. Those same surgeons later insisted it be dissolved because they saw it as unwanted competition.

Staff needs: Surgical hospitalist practices nearly always require fewer doctors than a medical hospitalist practice in the same institution. This can lead to a tension between having the right number of surgical hospitalists for the case volume (often just one or two doctors) and enough to provide for a reasonable call schedule. Existing groups have adopted a number of strategies.

Groups with only two doctors often have each work seven on/seven off. The doctor on-call for that week takes all night call him/herself. In some practices that have a medical hospitalist in-house all night, it could be reasonable to have routine calls on the surgical patients (e.g., sleeping pills, laxatives, low urine output, fever) first paged to the medical hospitalist, who refers the call to the surgical hospitalist only as needed.

At least one practice has hired enough surgeons so the call burden on each is reasonable. This might be more staff than required for the patient volume: Four surgical hospitalists each work 12-hour shifts in a seven on/seven off schedule. During the seven consecutive night shifts (worked by each surgeon one week in four), patient volume is low.

Some practices hire community surgeons as moonlighters or consider using nurse practitioners or physician’s assistants as first responders at night.

Demographics: Surgical hospitalists are usually midcareer doctors, not surgeons who have recently completed their training. Many say they have gotten burned out with the stress of operating a private practice and prefer hospital work to office work.

Where Will It All Lead?

In every institution I have made contact with, the medical and surgical hospitalists have a good working relationship. Each is available to the other for consults, and they work together so frequently that they can begin to build a greater sense of teamwork. It is important that both groups jointly develop guidelines, such as who admits which type of patients.

If, like primary care doctors, general surgeons and a handful of other specialties with significant hospital volume (such as obstetrics and gastroenterology) move largely to a hospitalist model, U.S. healthcare will have made a remarkable transformation. In the span of my career we will have gone from a system of most doctors seeing patients in and out of the hospital to a division of physician labor such that most doctors practice almost exclusively in only one setting or the other.

I can see how this could be a good thing for patients and medical professionals, but that isn’t a given. For it to turn out we must preserve the elements of the earlier system that worked well and mitigate new problems and complexities. We will need well-designed research to show the economic and quality effects of the hospitalist model on non-primary care fields such as general surgery. We face growing challenges in ensuring excellent communication between inpatient and outpatient caregivers—something that doesn’t work ideally in all medical hospitalist practices.

Let Me Hear From You

I’d like to hear about any surgical hospitalist program you know of so I can add it to my database of information about such programs. And if you’re thinking about becoming a surgical hospitalist or you’re an institution thinking about starting such a practice, feel free to contact me so we can compare notes. I can be reached at (425) 467-3316, or by e-mail: john@jnelson.net. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospitalist practice management-consulting firm. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

Many or most specialties in medicine are adopting a hospitalist model, at least to a limited extent. In fact, hospital care of adult medical patients wasn’t even the first place the idea was adopted.

In talking with people from hundreds of institutions it seems clear the idea appeared earlier and grew more quickly in pediatrics than adult medicine. And in the past 10 to 15 years, fields like obstetrics (“laborists”), psychiatry, gastroenterology, and many others have slowly begun to adopt the hospitalist model.

One of the most recent disciplines to join the parade is general surgery. And when comparing the forces in play for hospitalists in the early 1990s to the current situation for surgical hospitalists, I think we may be close to a surge in surgical hospitalists similar to what we’ve seen with medical hospitalists in the past 10 years.

When I say surgical hospitalists, I’m referring to surgeons with a nearly exclusive inpatient practice. Other terms such as surgicalist, acute care surgeon, and traumatologist overlap to some degree but have ambiguous meanings.

Generalizations

For some months I have contacted all the surgical hospitalist practices I can find to learn what forces led to their creation and how they are structured. Several common themes are emerging:

Prevalence: There are probably no more than 20 to 40 surgical hospitalist practices, but many institutions are considering the idea. This is similar to the situation for medical hospitalists in the early to mid-1990s.

Driver to start program: In every program I’ve found, the main impetus to start it was to address the burden of emergency department (ED) call for existing general surgeons. Like primary care, ED call is regarded as unattractive because it is unpredictable (lots of night and weekend work), usually has a poor payer mix, and many general surgeons have seen the “center of gravity” of their practice move away from the hospital toward an ambulatory surgery center over the past 10 years or so. Additionally, many general surgeons are increasingly uncomfortable caring for trauma patients because of recent changes in that field. (For an excellent discussion of the changing nature of general surgery and trauma care see “The Acute Care Surgeon” in The Hospitalist, May 2006, p. 25.)

Case volume: General surgery case volume tends to go up at a hospital that puts a surgical hospitalist program in place. When existing surgeons are relieved of ED call they increase their volume of (mostly elective) surgery. The availability of surgical hospitalists may mean fewer emergency cases presenting to the ED are referred elsewhere (which may happen when non-hospitalist surgeons are required to take ED call). These changes in case volume and the timing of the operations (e.g., volume of night surgeries may go up) may require adjustments to operating room staffing and scheduling. Presumably this increased volume would not occur in an area oversupplied with surgeons.

Economics: Like nearly all medical hospitalist programs, surgical hospitalist practices are not viable without financial support in addition to collected professional fees. In all cases I am aware of, this support comes from the sponsoring hospital.

While the cost may be similar to what the hospital might have paid for existing surgeons to take ED call, hospitals seem to be getting a better return on that investment with surgical hospitalists. A small group of surgical hospitalists can handle the increased volume and all ED calls, improving clinical and service quality. Some institutions report that surgical hospitalists are much more attentive to billing for nonoperative work than their predecessors.

Structure: Programs should have an outpatient clinic where the surgical hospitalists can provide post-operative follow-up. In most cases, each surgeon spends only half a day a week in the clinic.

Scope of practice: All surgical hospitalist practices take most or all ED general surgery calls. In some institutions, the surgical hospitalist also leads the trauma team. Other duties at a few institutions include things like managing a wound-care clinic and being on-call to place lines.

Opinion of other surgeons: Community private practice surgeons tend to support these programs, but most institutions limit or prohibit surgical hospitalists from accepting elective referrals. Community surgeons are still offered the option of remaining on the ED call schedule—as might be the case for surgeons new to the community. At least one institution reported that the presence of surgical hospitalists improved recruitment of non-hospitalist general surgeons. However, I am also aware of one program put into place largely at the insistence of the existing surgeons. Those same surgeons later insisted it be dissolved because they saw it as unwanted competition.

Staff needs: Surgical hospitalist practices nearly always require fewer doctors than a medical hospitalist practice in the same institution. This can lead to a tension between having the right number of surgical hospitalists for the case volume (often just one or two doctors) and enough to provide for a reasonable call schedule. Existing groups have adopted a number of strategies.

Groups with only two doctors often have each work seven on/seven off. The doctor on-call for that week takes all night call him/herself. In some practices that have a medical hospitalist in-house all night, it could be reasonable to have routine calls on the surgical patients (e.g., sleeping pills, laxatives, low urine output, fever) first paged to the medical hospitalist, who refers the call to the surgical hospitalist only as needed.

At least one practice has hired enough surgeons so the call burden on each is reasonable. This might be more staff than required for the patient volume: Four surgical hospitalists each work 12-hour shifts in a seven on/seven off schedule. During the seven consecutive night shifts (worked by each surgeon one week in four), patient volume is low.

Some practices hire community surgeons as moonlighters or consider using nurse practitioners or physician’s assistants as first responders at night.

Demographics: Surgical hospitalists are usually midcareer doctors, not surgeons who have recently completed their training. Many say they have gotten burned out with the stress of operating a private practice and prefer hospital work to office work.

Where Will It All Lead?

In every institution I have made contact with, the medical and surgical hospitalists have a good working relationship. Each is available to the other for consults, and they work together so frequently that they can begin to build a greater sense of teamwork. It is important that both groups jointly develop guidelines, such as who admits which type of patients.

If, like primary care doctors, general surgeons and a handful of other specialties with significant hospital volume (such as obstetrics and gastroenterology) move largely to a hospitalist model, U.S. healthcare will have made a remarkable transformation. In the span of my career we will have gone from a system of most doctors seeing patients in and out of the hospital to a division of physician labor such that most doctors practice almost exclusively in only one setting or the other.

I can see how this could be a good thing for patients and medical professionals, but that isn’t a given. For it to turn out we must preserve the elements of the earlier system that worked well and mitigate new problems and complexities. We will need well-designed research to show the economic and quality effects of the hospitalist model on non-primary care fields such as general surgery. We face growing challenges in ensuring excellent communication between inpatient and outpatient caregivers—something that doesn’t work ideally in all medical hospitalist practices.

Let Me Hear From You

I’d like to hear about any surgical hospitalist program you know of so I can add it to my database of information about such programs. And if you’re thinking about becoming a surgical hospitalist or you’re an institution thinking about starting such a practice, feel free to contact me so we can compare notes. I can be reached at (425) 467-3316, or by e-mail: john@jnelson.net. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospitalist practice management-consulting firm. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

Haggle With the Hospital

Negotiating support from the hospital where you practice is one of the most critical skills you can learn. I am often asked, “How can our group prove our value to the hospital so we can get the support we need?” The best approach is the same whether you are a practice employed by the hospital or a separate legal entity that contracts with the hospital.

There are many valuable sources of guidance regarding the best way to negotiate any important agreement, including a book I recommend, Getting to Yes. I suggest you read such a book if you want to be a better negotiator. But here I want to highlight some features of negotiations between a hospital medicine practice and a hospital that such sources won’t specifically address.

Clearly this is complicated, and different situations call for different strategies. These are generalizations worth thinking about in any situation.

Know what is important to the hospital. I often hear hospitalists say, “We want to attend to the things that are important to the hospital, but we don’t know what those things are.” If that is really the case, the communication between the hospital and hospitalists must be awfully poor—and there is an opportunity for the hospitalists to improve it. It is worth the time and energy required to know what is on the mind of the hospital’s leadership. It may be as simple as having a person-to-person conversation with one or more hospital leaders about what they see as the institution’s most important goals—and how your practice could help achieve them. You need to be sure and understand the particulars at your hospital, but the topics below are on the mind of most executives.

Propose using additional funding to ensure adequate staffing, not raises for existing doctors. In the current environment of difficult recruiting, hospital executives are usually far more inclined to pay for increased staffing than worry about whether you need a raise just because you deserve it. So it is usually much more effective to tell the hospital, “Our practice needs more money so we can add doctors and more fully meet the demand for our services.” Much less effective is saying, “We [existing hospitalists] are working so hard that if we don’t get more money we’re going to quit.”

While the latter may be true, a hospital executive is much more likely to respond positively to paying for increased manpower so the existing doctors won’t have to continue working at unreasonably high workloads, rather than to providing money to support a raise for doctors already working unreasonably hard.

Propose additional resources to support quality improvement, and consider sharing some financial risk. Most hospital executives care about their hospital’s performance on quality measures and are willing to provide money to improve it. You might win more financial support if it is contingent on your group improving performance on quality measures.

You could propose that the hospital make additional money available to encourage and reward improved performance. You could even put existing financial support at risk and ask the hospital to match it. In other words, you could say you will contribute $5,000 or $10,000 of the money currently provided annually by the hospital per full-time equivalent hospitalist into a pool matched dollar for dollar (or some other ratio) by the hospital. Your group would get less total financial support (i.e., lose the funds put at risk) if quality doesn’t improve, but get more support if performance improved by an agreed-upon amount. A willingness to share financial risk demonstrates your commitment to success and can be compelling to the hospital.

Know your data. Hard data are far more effective than anecdotes when trying to convince the hospital of your practice’s value. Trumpet your successes, but remember that same executive will probably hear from 10 others in the same week that spending huge sums of money on their product or service will dramatically improve the hospital’s bottom line. If you’re trying to convince the hospital that every dollar spent to support your practice will provide an attractive return on investment, you need hard data to prove it.

It would be best if you could independently collect this data. But in most cases, you will have to rely on data the hospital has collected. It’s worthwhile to insist on routine reports (e.g., monthly, or no less than quarterly) from the hospital summarizing your group’s performance on quality and financial metrics (CMS core measures, patient satisfaction, cost per case). This data will be critical to you when you negotiate financial support from the hospital.

You should also have data about other hospitalist practices, such as results from the 2005-06 “SHM Survey of Hospitalist Productivity and Compensation” and other sources I discussed in a recent column (July 2007, p. 73). And if you’re able to get reliable data about other practices in your local marketplace (i.e., something more significant than just what you heard through the grapevine), be sure to share that information as well.

Agree to conditions carefully. Don’t agree to do things you would be unhappy doing just because it might help get more financial support from the hospital. Executives know it is bad business to pay people more money to get them to keep doing something they don’t want to do. Such an agreement usually leads to the hospitalists asking for more money each year to continue providing the service—and the quality of the service is often sub par if it’s something the hospitalists really don’t want to do (even if paid well to do it).

Stay focused on hospital performance—even in areas not specifically governed by your contractual relationship. Many or most hospitals that employ hospitalists assume all the financial risk for the practice. That is, the hospital agrees to make up the difference between collected professional fee revenue and the cost of operating the practice.

If the doctors underdocument and downcode, or are not compulsive about ensuring that their charges get to the billing agent, fee collections will suffer—and the hospital will end up having to pay more to support the practice.

If you are in such a situation, you should ensure that you’re helping to support optimal documentation, coding, billing, and collection practices—even if it won’t increase your paycheck but simply saves the hospital money. This will increase your chance of getting the hospital to increase financial support of your practice.

Remember your financial support isn’t a one-time negotiation; it is part of an ongoing relationship. In some negotiations, such as buying a car from a stranger, it seems reasonable to use any leverage most favorable for you. After all, you’re unlikely to ever interact with that person again. A hospitalist practice might compel the hospital to provide more support by threatening to quit suddenly. Yet it is usually a bad idea to do this because it can severely damage the long-term relationship.

Further, if you make it clear you’re going to quit unless you get more money, the hospital is in a tough spot. While the hospital may not want to lose you, any executive will realize that by making such a threat you probably aren’t committed to staying long even if you do get more financial support. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospitalist practice management-consulting firm. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

Negotiating support from the hospital where you practice is one of the most critical skills you can learn. I am often asked, “How can our group prove our value to the hospital so we can get the support we need?” The best approach is the same whether you are a practice employed by the hospital or a separate legal entity that contracts with the hospital.

There are many valuable sources of guidance regarding the best way to negotiate any important agreement, including a book I recommend, Getting to Yes. I suggest you read such a book if you want to be a better negotiator. But here I want to highlight some features of negotiations between a hospital medicine practice and a hospital that such sources won’t specifically address.

Clearly this is complicated, and different situations call for different strategies. These are generalizations worth thinking about in any situation.

Know what is important to the hospital. I often hear hospitalists say, “We want to attend to the things that are important to the hospital, but we don’t know what those things are.” If that is really the case, the communication between the hospital and hospitalists must be awfully poor—and there is an opportunity for the hospitalists to improve it. It is worth the time and energy required to know what is on the mind of the hospital’s leadership. It may be as simple as having a person-to-person conversation with one or more hospital leaders about what they see as the institution’s most important goals—and how your practice could help achieve them. You need to be sure and understand the particulars at your hospital, but the topics below are on the mind of most executives.

Propose using additional funding to ensure adequate staffing, not raises for existing doctors. In the current environment of difficult recruiting, hospital executives are usually far more inclined to pay for increased staffing than worry about whether you need a raise just because you deserve it. So it is usually much more effective to tell the hospital, “Our practice needs more money so we can add doctors and more fully meet the demand for our services.” Much less effective is saying, “We [existing hospitalists] are working so hard that if we don’t get more money we’re going to quit.”

While the latter may be true, a hospital executive is much more likely to respond positively to paying for increased manpower so the existing doctors won’t have to continue working at unreasonably high workloads, rather than to providing money to support a raise for doctors already working unreasonably hard.

Propose additional resources to support quality improvement, and consider sharing some financial risk. Most hospital executives care about their hospital’s performance on quality measures and are willing to provide money to improve it. You might win more financial support if it is contingent on your group improving performance on quality measures.

You could propose that the hospital make additional money available to encourage and reward improved performance. You could even put existing financial support at risk and ask the hospital to match it. In other words, you could say you will contribute $5,000 or $10,000 of the money currently provided annually by the hospital per full-time equivalent hospitalist into a pool matched dollar for dollar (or some other ratio) by the hospital. Your group would get less total financial support (i.e., lose the funds put at risk) if quality doesn’t improve, but get more support if performance improved by an agreed-upon amount. A willingness to share financial risk demonstrates your commitment to success and can be compelling to the hospital.

Know your data. Hard data are far more effective than anecdotes when trying to convince the hospital of your practice’s value. Trumpet your successes, but remember that same executive will probably hear from 10 others in the same week that spending huge sums of money on their product or service will dramatically improve the hospital’s bottom line. If you’re trying to convince the hospital that every dollar spent to support your practice will provide an attractive return on investment, you need hard data to prove it.

It would be best if you could independently collect this data. But in most cases, you will have to rely on data the hospital has collected. It’s worthwhile to insist on routine reports (e.g., monthly, or no less than quarterly) from the hospital summarizing your group’s performance on quality and financial metrics (CMS core measures, patient satisfaction, cost per case). This data will be critical to you when you negotiate financial support from the hospital.

You should also have data about other hospitalist practices, such as results from the 2005-06 “SHM Survey of Hospitalist Productivity and Compensation” and other sources I discussed in a recent column (July 2007, p. 73). And if you’re able to get reliable data about other practices in your local marketplace (i.e., something more significant than just what you heard through the grapevine), be sure to share that information as well.

Agree to conditions carefully. Don’t agree to do things you would be unhappy doing just because it might help get more financial support from the hospital. Executives know it is bad business to pay people more money to get them to keep doing something they don’t want to do. Such an agreement usually leads to the hospitalists asking for more money each year to continue providing the service—and the quality of the service is often sub par if it’s something the hospitalists really don’t want to do (even if paid well to do it).

Stay focused on hospital performance—even in areas not specifically governed by your contractual relationship. Many or most hospitals that employ hospitalists assume all the financial risk for the practice. That is, the hospital agrees to make up the difference between collected professional fee revenue and the cost of operating the practice.

If the doctors underdocument and downcode, or are not compulsive about ensuring that their charges get to the billing agent, fee collections will suffer—and the hospital will end up having to pay more to support the practice.

If you are in such a situation, you should ensure that you’re helping to support optimal documentation, coding, billing, and collection practices—even if it won’t increase your paycheck but simply saves the hospital money. This will increase your chance of getting the hospital to increase financial support of your practice.

Remember your financial support isn’t a one-time negotiation; it is part of an ongoing relationship. In some negotiations, such as buying a car from a stranger, it seems reasonable to use any leverage most favorable for you. After all, you’re unlikely to ever interact with that person again. A hospitalist practice might compel the hospital to provide more support by threatening to quit suddenly. Yet it is usually a bad idea to do this because it can severely damage the long-term relationship.

Further, if you make it clear you’re going to quit unless you get more money, the hospital is in a tough spot. While the hospital may not want to lose you, any executive will realize that by making such a threat you probably aren’t committed to staying long even if you do get more financial support. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospitalist practice management-consulting firm. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

Negotiating support from the hospital where you practice is one of the most critical skills you can learn. I am often asked, “How can our group prove our value to the hospital so we can get the support we need?” The best approach is the same whether you are a practice employed by the hospital or a separate legal entity that contracts with the hospital.

There are many valuable sources of guidance regarding the best way to negotiate any important agreement, including a book I recommend, Getting to Yes. I suggest you read such a book if you want to be a better negotiator. But here I want to highlight some features of negotiations between a hospital medicine practice and a hospital that such sources won’t specifically address.

Clearly this is complicated, and different situations call for different strategies. These are generalizations worth thinking about in any situation.

Know what is important to the hospital. I often hear hospitalists say, “We want to attend to the things that are important to the hospital, but we don’t know what those things are.” If that is really the case, the communication between the hospital and hospitalists must be awfully poor—and there is an opportunity for the hospitalists to improve it. It is worth the time and energy required to know what is on the mind of the hospital’s leadership. It may be as simple as having a person-to-person conversation with one or more hospital leaders about what they see as the institution’s most important goals—and how your practice could help achieve them. You need to be sure and understand the particulars at your hospital, but the topics below are on the mind of most executives.

Propose using additional funding to ensure adequate staffing, not raises for existing doctors. In the current environment of difficult recruiting, hospital executives are usually far more inclined to pay for increased staffing than worry about whether you need a raise just because you deserve it. So it is usually much more effective to tell the hospital, “Our practice needs more money so we can add doctors and more fully meet the demand for our services.” Much less effective is saying, “We [existing hospitalists] are working so hard that if we don’t get more money we’re going to quit.”

While the latter may be true, a hospital executive is much more likely to respond positively to paying for increased manpower so the existing doctors won’t have to continue working at unreasonably high workloads, rather than to providing money to support a raise for doctors already working unreasonably hard.

Propose additional resources to support quality improvement, and consider sharing some financial risk. Most hospital executives care about their hospital’s performance on quality measures and are willing to provide money to improve it. You might win more financial support if it is contingent on your group improving performance on quality measures.

You could propose that the hospital make additional money available to encourage and reward improved performance. You could even put existing financial support at risk and ask the hospital to match it. In other words, you could say you will contribute $5,000 or $10,000 of the money currently provided annually by the hospital per full-time equivalent hospitalist into a pool matched dollar for dollar (or some other ratio) by the hospital. Your group would get less total financial support (i.e., lose the funds put at risk) if quality doesn’t improve, but get more support if performance improved by an agreed-upon amount. A willingness to share financial risk demonstrates your commitment to success and can be compelling to the hospital.

Know your data. Hard data are far more effective than anecdotes when trying to convince the hospital of your practice’s value. Trumpet your successes, but remember that same executive will probably hear from 10 others in the same week that spending huge sums of money on their product or service will dramatically improve the hospital’s bottom line. If you’re trying to convince the hospital that every dollar spent to support your practice will provide an attractive return on investment, you need hard data to prove it.

It would be best if you could independently collect this data. But in most cases, you will have to rely on data the hospital has collected. It’s worthwhile to insist on routine reports (e.g., monthly, or no less than quarterly) from the hospital summarizing your group’s performance on quality and financial metrics (CMS core measures, patient satisfaction, cost per case). This data will be critical to you when you negotiate financial support from the hospital.

You should also have data about other hospitalist practices, such as results from the 2005-06 “SHM Survey of Hospitalist Productivity and Compensation” and other sources I discussed in a recent column (July 2007, p. 73). And if you’re able to get reliable data about other practices in your local marketplace (i.e., something more significant than just what you heard through the grapevine), be sure to share that information as well.

Agree to conditions carefully. Don’t agree to do things you would be unhappy doing just because it might help get more financial support from the hospital. Executives know it is bad business to pay people more money to get them to keep doing something they don’t want to do. Such an agreement usually leads to the hospitalists asking for more money each year to continue providing the service—and the quality of the service is often sub par if it’s something the hospitalists really don’t want to do (even if paid well to do it).

Stay focused on hospital performance—even in areas not specifically governed by your contractual relationship. Many or most hospitals that employ hospitalists assume all the financial risk for the practice. That is, the hospital agrees to make up the difference between collected professional fee revenue and the cost of operating the practice.

If the doctors underdocument and downcode, or are not compulsive about ensuring that their charges get to the billing agent, fee collections will suffer—and the hospital will end up having to pay more to support the practice.

If you are in such a situation, you should ensure that you’re helping to support optimal documentation, coding, billing, and collection practices—even if it won’t increase your paycheck but simply saves the hospital money. This will increase your chance of getting the hospital to increase financial support of your practice.

Remember your financial support isn’t a one-time negotiation; it is part of an ongoing relationship. In some negotiations, such as buying a car from a stranger, it seems reasonable to use any leverage most favorable for you. After all, you’re unlikely to ever interact with that person again. A hospitalist practice might compel the hospital to provide more support by threatening to quit suddenly. Yet it is usually a bad idea to do this because it can severely damage the long-term relationship.

Further, if you make it clear you’re going to quit unless you get more money, the hospital is in a tough spot. While the hospital may not want to lose you, any executive will realize that by making such a threat you probably aren’t committed to staying long even if you do get more financial support. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospitalist practice management-consulting firm. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

A Unit-Based Approach

Would you want all your patients on the same nursing unit? Think about it—no more walking all over the building to see a few patients on each floor.

Because you would be physically present on “your” unit nearly all day, you could develop close working relationships with the nurses and other caregivers, which might improve everyone’s satisfaction with work. Everyone could better anticipate your work flow and communicate this to patients and families. You likely would be paged much less often because the nursing staff could keep track of whether you’re with a patient or off the floor to attend a conference; they could hold non-urgent issues until you get back.

All these things might make you and others more efficient—able to see the same number of patients you see today in less time, while maintaining or improving quality and cost effectiveness.

Sound familiar? The idea that working at only one site leads to efficiency and quality improvement is one of the underpinnings of the hospitalist concept. Instead of covering the outpatient office and hospital every day, doctors can focus on only the hospital or only the office. But what if you extended that idea to focusing your practice on only one unit within the hospital rather than the whole building? Would that be a good idea and lead to the benefits described above, or would that be taking the idea of “focused practice” too far?

Before answering, I should describe the approaches some practices have taken to pursue the benefits of concentrating patients in one part of the hospital. I’ll refer to this idea as “unit-based hospitalists,” the term current SHM President Rusty Holman uses when talking about this idea.

Locate most hospitalist patients in one unit. This is the most common form of unit-based hospitalists. Most institutions find the closest they can get to unit-based hospitalists is to have all hospitalist admissions go to the same floor when that floor has a bed available and the patient doesn’t require placement elsewhere. In such cases, the hospitalist practice might have something like 50% of patients on that floor and 50% dispersed throughout the hospital (telemetry, ICU, surgery floor). So the whole hospitalist practice has a primary “home” within the hospital, while each hospitalist spends part of each day caring for patients elsewhere. This is not very difficult for most hospitals to implement—and many are because most hospitalist patients end up on the “general medical” floor. This lets the hospitalist spend more time on that unit than any other. She can get to know the staff on that floor better, which might lead to many benefits, including improved satisfaction and efficiency.

Locate individual hospitalists on different hospital units. A more pure, but uncommon, form of unit-based hospitalists involves changing the way hospitalists are placed through the institution rather than changing patient placement. Each hospitalist in the group is assigned to a different nursing unit—or perhaps more than one unit—and sees whichever hospitalist patients are placed there. This system has the advantage of the hospitalist working all or most of the day on the same nursing unit, which can foster excellent teamwork. Instead of the nurse having to figure out which hospitalist to page for a particular patient, he simply needs to know, “Who is our hospitalist today?” and can contact that doctor for issues on most patients. Additionally, because the hospitalist will spend nearly the whole day physically on that unit, paging can be reduced significantly.

Despite its advantages, basing an individual hospitalist on a particular unit of the hospital is uncommon because in its purest form it can lead to terrible hospitalist-patient continuity. And, it’s hard to be confident that the disruptions in continuity are worth the benefits of the unit-based system. For example, the practice may have a patient to admit in the ED but can’t know which hospitalist should see the patient until a room is assigned. The fifth-floor hospitalist might go admit the patient in the ED, only to have the patient end up on the third floor, in which case the third-floor hospitalist would take over the next day. And each time the patient transferred to a new unit, either because of medical needs such as telemetry or simply because the hospital is full and needs to move patients, he would get a new hospitalist.

In addition to problems with continuity for patients who occupy more than one unit during their stay, this system would mean individual hospitalist workloads might get far out of balance. One floor might be very busy, while another is slow or limited by nurse staff shortages, and the respective hospitalists would have a correspondingly out-of-balance workload. A group could decide to address these problems by, for example, having the fifth-floor hospitalist see patients in other parts of the hospital in an effort to provide better hospitalist-patient continuity and address out-of-balance patient loads. But if this happens with any regularity it would mean the group has essentially moved back to a non-unit-based system.

In nearly all hospitals it would be unnecessary and unreasonable to assign a hospitalist to each nursing unit because some units tend to have few hospitalist patients. Yet when patients end up in those units because of medical necessity or bed space needs, one of the hospitalists will have to leave his/her unit to see this patient. If this happens often enough, it begins to dilute or negate the benefit of basing a hospitalist in one or two units.

Although one of the potential benefits of the unit-based model is enhanced relationships and integration among hospitalists and other unit-based clinical staff, it would be difficult to ensure that the same one or two hospitalists always work in a particular unit, and would limit scheduling flexibility dramatically. For example, if Dr. Starsky and Dr. Hutch are the unit-based hospitalists for Unit A, what happens if Dr. Starsky and Dr. Hutch are both scheduled to be off for the same block of days? What happens if both are scheduled to work the same block of days? To obtain the benefits of enhanced relationships and better unit integration, the practice would need to ensure that this scheduling overlap rarely happens—and that’s hard to do.

Where is the sweet spot in grouping patients and hospitalists by nursing unit? There is a wide range of opinion about whether unit-based hospital medicine in any form is worth pursuing. Some hospitalists are convinced that grouping all of their patients on the same unit could decrease efficiency because the doctor is nearly always working within view of patients and families and may be regularly interrupted. I am convinced that assigning each hospitalist to a particular unit in the hospital yields the greatest benefits. But I also think most institutions will find that the complexity and costs of this system are simply too high to justify. In that case, the next best approach might be to locate most hospitalist patients on the same unit unless that unit is full or the patient must be placed elsewhere. There is a good chance this is happening in your hospital—even if it isn’t written in the policy manual. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospitalist practice management-consulting firm. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

Would you want all your patients on the same nursing unit? Think about it—no more walking all over the building to see a few patients on each floor.

Because you would be physically present on “your” unit nearly all day, you could develop close working relationships with the nurses and other caregivers, which might improve everyone’s satisfaction with work. Everyone could better anticipate your work flow and communicate this to patients and families. You likely would be paged much less often because the nursing staff could keep track of whether you’re with a patient or off the floor to attend a conference; they could hold non-urgent issues until you get back.

All these things might make you and others more efficient—able to see the same number of patients you see today in less time, while maintaining or improving quality and cost effectiveness.

Sound familiar? The idea that working at only one site leads to efficiency and quality improvement is one of the underpinnings of the hospitalist concept. Instead of covering the outpatient office and hospital every day, doctors can focus on only the hospital or only the office. But what if you extended that idea to focusing your practice on only one unit within the hospital rather than the whole building? Would that be a good idea and lead to the benefits described above, or would that be taking the idea of “focused practice” too far?

Before answering, I should describe the approaches some practices have taken to pursue the benefits of concentrating patients in one part of the hospital. I’ll refer to this idea as “unit-based hospitalists,” the term current SHM President Rusty Holman uses when talking about this idea.

Locate most hospitalist patients in one unit. This is the most common form of unit-based hospitalists. Most institutions find the closest they can get to unit-based hospitalists is to have all hospitalist admissions go to the same floor when that floor has a bed available and the patient doesn’t require placement elsewhere. In such cases, the hospitalist practice might have something like 50% of patients on that floor and 50% dispersed throughout the hospital (telemetry, ICU, surgery floor). So the whole hospitalist practice has a primary “home” within the hospital, while each hospitalist spends part of each day caring for patients elsewhere. This is not very difficult for most hospitals to implement—and many are because most hospitalist patients end up on the “general medical” floor. This lets the hospitalist spend more time on that unit than any other. She can get to know the staff on that floor better, which might lead to many benefits, including improved satisfaction and efficiency.

Locate individual hospitalists on different hospital units. A more pure, but uncommon, form of unit-based hospitalists involves changing the way hospitalists are placed through the institution rather than changing patient placement. Each hospitalist in the group is assigned to a different nursing unit—or perhaps more than one unit—and sees whichever hospitalist patients are placed there. This system has the advantage of the hospitalist working all or most of the day on the same nursing unit, which can foster excellent teamwork. Instead of the nurse having to figure out which hospitalist to page for a particular patient, he simply needs to know, “Who is our hospitalist today?” and can contact that doctor for issues on most patients. Additionally, because the hospitalist will spend nearly the whole day physically on that unit, paging can be reduced significantly.

Despite its advantages, basing an individual hospitalist on a particular unit of the hospital is uncommon because in its purest form it can lead to terrible hospitalist-patient continuity. And, it’s hard to be confident that the disruptions in continuity are worth the benefits of the unit-based system. For example, the practice may have a patient to admit in the ED but can’t know which hospitalist should see the patient until a room is assigned. The fifth-floor hospitalist might go admit the patient in the ED, only to have the patient end up on the third floor, in which case the third-floor hospitalist would take over the next day. And each time the patient transferred to a new unit, either because of medical needs such as telemetry or simply because the hospital is full and needs to move patients, he would get a new hospitalist.

In addition to problems with continuity for patients who occupy more than one unit during their stay, this system would mean individual hospitalist workloads might get far out of balance. One floor might be very busy, while another is slow or limited by nurse staff shortages, and the respective hospitalists would have a correspondingly out-of-balance workload. A group could decide to address these problems by, for example, having the fifth-floor hospitalist see patients in other parts of the hospital in an effort to provide better hospitalist-patient continuity and address out-of-balance patient loads. But if this happens with any regularity it would mean the group has essentially moved back to a non-unit-based system.

In nearly all hospitals it would be unnecessary and unreasonable to assign a hospitalist to each nursing unit because some units tend to have few hospitalist patients. Yet when patients end up in those units because of medical necessity or bed space needs, one of the hospitalists will have to leave his/her unit to see this patient. If this happens often enough, it begins to dilute or negate the benefit of basing a hospitalist in one or two units.

Although one of the potential benefits of the unit-based model is enhanced relationships and integration among hospitalists and other unit-based clinical staff, it would be difficult to ensure that the same one or two hospitalists always work in a particular unit, and would limit scheduling flexibility dramatically. For example, if Dr. Starsky and Dr. Hutch are the unit-based hospitalists for Unit A, what happens if Dr. Starsky and Dr. Hutch are both scheduled to be off for the same block of days? What happens if both are scheduled to work the same block of days? To obtain the benefits of enhanced relationships and better unit integration, the practice would need to ensure that this scheduling overlap rarely happens—and that’s hard to do.

Where is the sweet spot in grouping patients and hospitalists by nursing unit? There is a wide range of opinion about whether unit-based hospital medicine in any form is worth pursuing. Some hospitalists are convinced that grouping all of their patients on the same unit could decrease efficiency because the doctor is nearly always working within view of patients and families and may be regularly interrupted. I am convinced that assigning each hospitalist to a particular unit in the hospital yields the greatest benefits. But I also think most institutions will find that the complexity and costs of this system are simply too high to justify. In that case, the next best approach might be to locate most hospitalist patients on the same unit unless that unit is full or the patient must be placed elsewhere. There is a good chance this is happening in your hospital—even if it isn’t written in the policy manual. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospitalist practice management-consulting firm. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

Would you want all your patients on the same nursing unit? Think about it—no more walking all over the building to see a few patients on each floor.

Because you would be physically present on “your” unit nearly all day, you could develop close working relationships with the nurses and other caregivers, which might improve everyone’s satisfaction with work. Everyone could better anticipate your work flow and communicate this to patients and families. You likely would be paged much less often because the nursing staff could keep track of whether you’re with a patient or off the floor to attend a conference; they could hold non-urgent issues until you get back.

All these things might make you and others more efficient—able to see the same number of patients you see today in less time, while maintaining or improving quality and cost effectiveness.

Sound familiar? The idea that working at only one site leads to efficiency and quality improvement is one of the underpinnings of the hospitalist concept. Instead of covering the outpatient office and hospital every day, doctors can focus on only the hospital or only the office. But what if you extended that idea to focusing your practice on only one unit within the hospital rather than the whole building? Would that be a good idea and lead to the benefits described above, or would that be taking the idea of “focused practice” too far?

Before answering, I should describe the approaches some practices have taken to pursue the benefits of concentrating patients in one part of the hospital. I’ll refer to this idea as “unit-based hospitalists,” the term current SHM President Rusty Holman uses when talking about this idea.

Locate most hospitalist patients in one unit. This is the most common form of unit-based hospitalists. Most institutions find the closest they can get to unit-based hospitalists is to have all hospitalist admissions go to the same floor when that floor has a bed available and the patient doesn’t require placement elsewhere. In such cases, the hospitalist practice might have something like 50% of patients on that floor and 50% dispersed throughout the hospital (telemetry, ICU, surgery floor). So the whole hospitalist practice has a primary “home” within the hospital, while each hospitalist spends part of each day caring for patients elsewhere. This is not very difficult for most hospitals to implement—and many are because most hospitalist patients end up on the “general medical” floor. This lets the hospitalist spend more time on that unit than any other. She can get to know the staff on that floor better, which might lead to many benefits, including improved satisfaction and efficiency.

Locate individual hospitalists on different hospital units. A more pure, but uncommon, form of unit-based hospitalists involves changing the way hospitalists are placed through the institution rather than changing patient placement. Each hospitalist in the group is assigned to a different nursing unit—or perhaps more than one unit—and sees whichever hospitalist patients are placed there. This system has the advantage of the hospitalist working all or most of the day on the same nursing unit, which can foster excellent teamwork. Instead of the nurse having to figure out which hospitalist to page for a particular patient, he simply needs to know, “Who is our hospitalist today?” and can contact that doctor for issues on most patients. Additionally, because the hospitalist will spend nearly the whole day physically on that unit, paging can be reduced significantly.

Despite its advantages, basing an individual hospitalist on a particular unit of the hospital is uncommon because in its purest form it can lead to terrible hospitalist-patient continuity. And, it’s hard to be confident that the disruptions in continuity are worth the benefits of the unit-based system. For example, the practice may have a patient to admit in the ED but can’t know which hospitalist should see the patient until a room is assigned. The fifth-floor hospitalist might go admit the patient in the ED, only to have the patient end up on the third floor, in which case the third-floor hospitalist would take over the next day. And each time the patient transferred to a new unit, either because of medical needs such as telemetry or simply because the hospital is full and needs to move patients, he would get a new hospitalist.

In addition to problems with continuity for patients who occupy more than one unit during their stay, this system would mean individual hospitalist workloads might get far out of balance. One floor might be very busy, while another is slow or limited by nurse staff shortages, and the respective hospitalists would have a correspondingly out-of-balance workload. A group could decide to address these problems by, for example, having the fifth-floor hospitalist see patients in other parts of the hospital in an effort to provide better hospitalist-patient continuity and address out-of-balance patient loads. But if this happens with any regularity it would mean the group has essentially moved back to a non-unit-based system.

In nearly all hospitals it would be unnecessary and unreasonable to assign a hospitalist to each nursing unit because some units tend to have few hospitalist patients. Yet when patients end up in those units because of medical necessity or bed space needs, one of the hospitalists will have to leave his/her unit to see this patient. If this happens often enough, it begins to dilute or negate the benefit of basing a hospitalist in one or two units.

Although one of the potential benefits of the unit-based model is enhanced relationships and integration among hospitalists and other unit-based clinical staff, it would be difficult to ensure that the same one or two hospitalists always work in a particular unit, and would limit scheduling flexibility dramatically. For example, if Dr. Starsky and Dr. Hutch are the unit-based hospitalists for Unit A, what happens if Dr. Starsky and Dr. Hutch are both scheduled to be off for the same block of days? What happens if both are scheduled to work the same block of days? To obtain the benefits of enhanced relationships and better unit integration, the practice would need to ensure that this scheduling overlap rarely happens—and that’s hard to do.

Where is the sweet spot in grouping patients and hospitalists by nursing unit? There is a wide range of opinion about whether unit-based hospital medicine in any form is worth pursuing. Some hospitalists are convinced that grouping all of their patients on the same unit could decrease efficiency because the doctor is nearly always working within view of patients and families and may be regularly interrupted. I am convinced that assigning each hospitalist to a particular unit in the hospital yields the greatest benefits. But I also think most institutions will find that the complexity and costs of this system are simply too high to justify. In that case, the next best approach might be to locate most hospitalist patients on the same unit unless that unit is full or the patient must be placed elsewhere. There is a good chance this is happening in your hospital—even if it isn’t written in the policy manual. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospitalist practice management-consulting firm. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

Promote Proper CPT Coding

Code nearly all visits at the highest level” was the entire orientation I got to CPT coding when I first started practice as a hospitalist in the 1980s.

I couldn’t believe this advice, which came from another physician, was sound—and it isn’t. So I tried to learn a little more about the subject on my own. After a year or so of somewhat futile self-education in coding, I decided I could never learn the very confusing rules and chose to do nearly the opposite of the “code all visits high” strategy: I coded nearly all visits at very low levels.

While some hospitalists are experts at proper CPT coding, I think a lot (the majority?) feel uneasy and do what I tended to do years ago: They “downcode” many visits, believing this will provide a margin of safety against being audited and accused of “upcoding.” The problem with this approach is that it can cost your practice significant professional fee revenue. And according to the letter of the law, downcoding is just as illegal as upcoding. (Though I haven’t seen any newspaper headlines about Medicare creating teams of auditors to stamp out illegal downcoding.)

Strategies to Improve

If you’re like many hospitalists and feel uneasy about how accurately you’re choosing CPT codes, I have a few suggestions.

First, SHM has a new course on CPT coding designed specifically for hospitalists. The next meetings are Oct. 3 in San Francisco and April 3, 2008, in San Diego as a precourse to SHM’s Annual Meeting 2008. The previous versions of the course have received high praise.

There are also a number of strategies your hospitalist group can use to help ensure proper coding stays on each doctor’s mind. Some organizations have an internal coding expert who might regularly review each doctor’s coding and provide education to address problem areas. Whether you have such an internal expert or not, you should probably have an annual audit by an external certified coder—someone who has no financial connection to your institution.

In addition to external resources, I think every group should create a monthly or quarterly report that allows each doctor to see his or her own pattern of coding compared with that of everyone else in the group. This will be most valuable if everyone’s name remains visible to everyone else. It should then be easy for me to tell that I code discharges at the low level far more often than the group average. I should be able to see that my partner Jane codes half of initial consult visits at the highest level and I code most of them much lower.

It would be unusual that this information would lead to strife and dissent within the group. If it does, you probably have significant cultural and interpersonal problems within your group. It will usually lead to the doctors talking about their patterns of documenting and coding among themselves—which goes a long way to keep the issue on everyone’s mind.

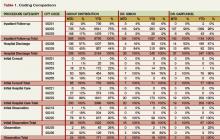

One format for such a report is on p. 61. CPT codes are grouped by category on the left side. The next set of columns is labeled “group distribution” and shows the month-to-date (MTD) and running 12-month (YTD) distribution of codes for all doctors in the group. Specific data for two doctors in the group is to the right of the group distribution. Note that there are more than 10 doctors in this hypothetical group, but I have shown only two of them because of space limitations.

When reviewing this table, Dr. Simon may get a little uncomfortable because she codes only 2% of follow-up visits at the highest level, but the group as a whole uses the highest code 17% of the time. And, she codes 88% of discharges at the high level, compared with 44% for the group as a whole. She is also out of step with her partners in highest initial consult and the middle initial observation codes. This information will probably make her receptive to peer-to-peer learning from her partners and may motivate her to review some of the coding rules.

Dr. Simon and Dr. Garfunkel are out of step with the group in how often they use the code for the middle level initial observation visit. This group needs to investigate whether these two doctors are coding these visits correctly, and everyone else is in error, or vice versa.

It is important to point out that the goal of the report isn’t to get each doctor to simply mirror the distribution of the group’s overall coding pattern. There might be cases in which the outlier doctor is coding correctly and everyone else is wrong. So the group average can’t be accepted as correct, and any significant discrepancies between one or two doctors and the group as a whole should be reviewed and discussed.

While a coding comparison table like this isn’t enough to ensure proper coding, it is a useful tool for highlighting the areas most in need of attention. I know of cases in which hospitalists who practiced together for several years had no idea their coding patterns were so dramatically different until they created a report like this. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

Code nearly all visits at the highest level” was the entire orientation I got to CPT coding when I first started practice as a hospitalist in the 1980s.

I couldn’t believe this advice, which came from another physician, was sound—and it isn’t. So I tried to learn a little more about the subject on my own. After a year or so of somewhat futile self-education in coding, I decided I could never learn the very confusing rules and chose to do nearly the opposite of the “code all visits high” strategy: I coded nearly all visits at very low levels.

While some hospitalists are experts at proper CPT coding, I think a lot (the majority?) feel uneasy and do what I tended to do years ago: They “downcode” many visits, believing this will provide a margin of safety against being audited and accused of “upcoding.” The problem with this approach is that it can cost your practice significant professional fee revenue. And according to the letter of the law, downcoding is just as illegal as upcoding. (Though I haven’t seen any newspaper headlines about Medicare creating teams of auditors to stamp out illegal downcoding.)

Strategies to Improve

If you’re like many hospitalists and feel uneasy about how accurately you’re choosing CPT codes, I have a few suggestions.

First, SHM has a new course on CPT coding designed specifically for hospitalists. The next meetings are Oct. 3 in San Francisco and April 3, 2008, in San Diego as a precourse to SHM’s Annual Meeting 2008. The previous versions of the course have received high praise.

There are also a number of strategies your hospitalist group can use to help ensure proper coding stays on each doctor’s mind. Some organizations have an internal coding expert who might regularly review each doctor’s coding and provide education to address problem areas. Whether you have such an internal expert or not, you should probably have an annual audit by an external certified coder—someone who has no financial connection to your institution.