User login

A survey of liability claims against obstetric providers highlights major areas of contention

An analysis of 882 obstetric claims closed between 2007 and 2014 highlighted 3 common patient allegations:

- a delay in treatment of fetal distress (22%). The term fetal distress remains a common allegation in malpractice claims. Cases in this category most often reflected a delay or failure to act in the face of Category II or III fetal heart-rate tracings.

- improper performance of vaginal delivery (20%). Almost half of the cases in this category involved brachial plexus injuries linked to shoulder dystocia. Patients alleged that improper maneuvers were used to resolve the dystocia. The remainder of cases in this category involved forceps and vacuum extraction deliveries.

- improper management of pregnancy (17%). Among the allegations were a failure to test for fetal abnormalities, failure to recognize complications of pregnancy, and failure to address abnormal findings.

Together, these 3 allegations accounted for 59% of claims. Other allegations included diagnosis-related claims, delay in delivery, improper performance of operative delivery, retained foreign bodies, and improper choice of delivery method.1

The Obstetrics Closed Claims Study findings were released earlier this spring by the Napa, California−based Doctors Company, the nation’s largest physician-owned medical malpractice insurer.1 Susan Mann, MD, a spokesperson for the company, provided expert commentary on the study at the 2015 Annual Clinical Meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists in San Francisco. (Listen to this accompanying audiocast featuring her comments.) Dr. Mann practices obstetrics and gynecology in Brookline, Massachusetts, and at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. She is president of the QualBridge Institute, a consulting firm focused on issues of quality and safety.

Top 7 factors contributing to patient injury

The Doctors Company identified specific factors that contributed to patient injury in the closed claims:

1. Selection and management of therapy (34%). Among the issues here were decisions involving augmentation of labor, route of delivery, and the timing of interventions. This factor also related to medications—for example, a failure to order antibiotics for Group A and Group B strep, a failure to order Rho(D) immune globulin for Rh-negative mothers, and a failure to provide magnesium sulfate for women with eclampsia.

2. Patient-assessment issues (32%). The Doctors Company reviewers found that physicians frequently failed to consider information that was available, or overlooked abnormal findings.

3. Technical performance (18%). This factor involved problems associated with known risks of various procedures, such as postpartum hemorrhage and brachial plexus injuries. It also included poor technique.

4. Communication among providers (17%)

5. Patient factors (16%). These factors included a failure to comply with therapy or to show up for appointments.

6. Insufficient or lack of documentation (14%)

7. Communication between patient/family and provider (14%).

“Studying obstetrical medical malpractice claims sheds light on the wide array of problems that may arise during pregnancy and in labor and delivery,” the study authors conclude. “Many of these cases reflect unusual maternal or neonatal conditions that can be diagnosed only with vigilance. Examples include protein deficiencies, clotting abnormalities, placental abruptions, infections, and genetic abnormalities. More common conditions should be identified with close attention to vital signs, laboratory studies, changes to maternal and neonatal conditions, and patient complaints.”

“Obstetric departments must plan for clinical emergencies by developing and maintaining physician and staff competencies through mock drills and simulations that reduce the likelihood of injuries to mothers and their infants,” the study authors conclude.

Tips for reducing malpractice claims in obstetrics

The Obstetrics Closed Claim Study identified a number of “underlying vulnerabilities” that place patients at risk and increase liability for clinicians. The Doctors Company offers the following tips to help reduce these claims:

• Require periodic training and certification for physicians and nurses to maintain competency and facilitate conversations about fetal heart-rate (FHR) tracing interpretation. Both parties should use the same terminology when discussing the strips.

• Use technology that allows physicians to review FHR patterns from remote locations so that physicians and nurses are able to see the same information when discussing next steps.

• When operative vaginal delivery is attempted in the face of a Category III FHR tracing, a contingency team should be available for possible emergent cesarean delivery.

• Foster a culture in which caregivers feel comfortable speaking up if they have a concern. Ensure that the organization has a well-defined escalation guideline.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Reference

- The Doctors Company. Obstetrics Closed Claim Study. http://www.thedoctors.com/KnowledgeCenter/PatientSafety/articles/CON_ID_011803. Published April 2015. Accessed May 6, 2015.

An analysis of 882 obstetric claims closed between 2007 and 2014 highlighted 3 common patient allegations:

- a delay in treatment of fetal distress (22%). The term fetal distress remains a common allegation in malpractice claims. Cases in this category most often reflected a delay or failure to act in the face of Category II or III fetal heart-rate tracings.

- improper performance of vaginal delivery (20%). Almost half of the cases in this category involved brachial plexus injuries linked to shoulder dystocia. Patients alleged that improper maneuvers were used to resolve the dystocia. The remainder of cases in this category involved forceps and vacuum extraction deliveries.

- improper management of pregnancy (17%). Among the allegations were a failure to test for fetal abnormalities, failure to recognize complications of pregnancy, and failure to address abnormal findings.

Together, these 3 allegations accounted for 59% of claims. Other allegations included diagnosis-related claims, delay in delivery, improper performance of operative delivery, retained foreign bodies, and improper choice of delivery method.1

The Obstetrics Closed Claims Study findings were released earlier this spring by the Napa, California−based Doctors Company, the nation’s largest physician-owned medical malpractice insurer.1 Susan Mann, MD, a spokesperson for the company, provided expert commentary on the study at the 2015 Annual Clinical Meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists in San Francisco. (Listen to this accompanying audiocast featuring her comments.) Dr. Mann practices obstetrics and gynecology in Brookline, Massachusetts, and at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. She is president of the QualBridge Institute, a consulting firm focused on issues of quality and safety.

Top 7 factors contributing to patient injury

The Doctors Company identified specific factors that contributed to patient injury in the closed claims:

1. Selection and management of therapy (34%). Among the issues here were decisions involving augmentation of labor, route of delivery, and the timing of interventions. This factor also related to medications—for example, a failure to order antibiotics for Group A and Group B strep, a failure to order Rho(D) immune globulin for Rh-negative mothers, and a failure to provide magnesium sulfate for women with eclampsia.

2. Patient-assessment issues (32%). The Doctors Company reviewers found that physicians frequently failed to consider information that was available, or overlooked abnormal findings.

3. Technical performance (18%). This factor involved problems associated with known risks of various procedures, such as postpartum hemorrhage and brachial plexus injuries. It also included poor technique.

4. Communication among providers (17%)

5. Patient factors (16%). These factors included a failure to comply with therapy or to show up for appointments.

6. Insufficient or lack of documentation (14%)

7. Communication between patient/family and provider (14%).

“Studying obstetrical medical malpractice claims sheds light on the wide array of problems that may arise during pregnancy and in labor and delivery,” the study authors conclude. “Many of these cases reflect unusual maternal or neonatal conditions that can be diagnosed only with vigilance. Examples include protein deficiencies, clotting abnormalities, placental abruptions, infections, and genetic abnormalities. More common conditions should be identified with close attention to vital signs, laboratory studies, changes to maternal and neonatal conditions, and patient complaints.”

“Obstetric departments must plan for clinical emergencies by developing and maintaining physician and staff competencies through mock drills and simulations that reduce the likelihood of injuries to mothers and their infants,” the study authors conclude.

Tips for reducing malpractice claims in obstetrics

The Obstetrics Closed Claim Study identified a number of “underlying vulnerabilities” that place patients at risk and increase liability for clinicians. The Doctors Company offers the following tips to help reduce these claims:

• Require periodic training and certification for physicians and nurses to maintain competency and facilitate conversations about fetal heart-rate (FHR) tracing interpretation. Both parties should use the same terminology when discussing the strips.

• Use technology that allows physicians to review FHR patterns from remote locations so that physicians and nurses are able to see the same information when discussing next steps.

• When operative vaginal delivery is attempted in the face of a Category III FHR tracing, a contingency team should be available for possible emergent cesarean delivery.

• Foster a culture in which caregivers feel comfortable speaking up if they have a concern. Ensure that the organization has a well-defined escalation guideline.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

An analysis of 882 obstetric claims closed between 2007 and 2014 highlighted 3 common patient allegations:

- a delay in treatment of fetal distress (22%). The term fetal distress remains a common allegation in malpractice claims. Cases in this category most often reflected a delay or failure to act in the face of Category II or III fetal heart-rate tracings.

- improper performance of vaginal delivery (20%). Almost half of the cases in this category involved brachial plexus injuries linked to shoulder dystocia. Patients alleged that improper maneuvers were used to resolve the dystocia. The remainder of cases in this category involved forceps and vacuum extraction deliveries.

- improper management of pregnancy (17%). Among the allegations were a failure to test for fetal abnormalities, failure to recognize complications of pregnancy, and failure to address abnormal findings.

Together, these 3 allegations accounted for 59% of claims. Other allegations included diagnosis-related claims, delay in delivery, improper performance of operative delivery, retained foreign bodies, and improper choice of delivery method.1

The Obstetrics Closed Claims Study findings were released earlier this spring by the Napa, California−based Doctors Company, the nation’s largest physician-owned medical malpractice insurer.1 Susan Mann, MD, a spokesperson for the company, provided expert commentary on the study at the 2015 Annual Clinical Meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists in San Francisco. (Listen to this accompanying audiocast featuring her comments.) Dr. Mann practices obstetrics and gynecology in Brookline, Massachusetts, and at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. She is president of the QualBridge Institute, a consulting firm focused on issues of quality and safety.

Top 7 factors contributing to patient injury

The Doctors Company identified specific factors that contributed to patient injury in the closed claims:

1. Selection and management of therapy (34%). Among the issues here were decisions involving augmentation of labor, route of delivery, and the timing of interventions. This factor also related to medications—for example, a failure to order antibiotics for Group A and Group B strep, a failure to order Rho(D) immune globulin for Rh-negative mothers, and a failure to provide magnesium sulfate for women with eclampsia.

2. Patient-assessment issues (32%). The Doctors Company reviewers found that physicians frequently failed to consider information that was available, or overlooked abnormal findings.

3. Technical performance (18%). This factor involved problems associated with known risks of various procedures, such as postpartum hemorrhage and brachial plexus injuries. It also included poor technique.

4. Communication among providers (17%)

5. Patient factors (16%). These factors included a failure to comply with therapy or to show up for appointments.

6. Insufficient or lack of documentation (14%)

7. Communication between patient/family and provider (14%).

“Studying obstetrical medical malpractice claims sheds light on the wide array of problems that may arise during pregnancy and in labor and delivery,” the study authors conclude. “Many of these cases reflect unusual maternal or neonatal conditions that can be diagnosed only with vigilance. Examples include protein deficiencies, clotting abnormalities, placental abruptions, infections, and genetic abnormalities. More common conditions should be identified with close attention to vital signs, laboratory studies, changes to maternal and neonatal conditions, and patient complaints.”

“Obstetric departments must plan for clinical emergencies by developing and maintaining physician and staff competencies through mock drills and simulations that reduce the likelihood of injuries to mothers and their infants,” the study authors conclude.

Tips for reducing malpractice claims in obstetrics

The Obstetrics Closed Claim Study identified a number of “underlying vulnerabilities” that place patients at risk and increase liability for clinicians. The Doctors Company offers the following tips to help reduce these claims:

• Require periodic training and certification for physicians and nurses to maintain competency and facilitate conversations about fetal heart-rate (FHR) tracing interpretation. Both parties should use the same terminology when discussing the strips.

• Use technology that allows physicians to review FHR patterns from remote locations so that physicians and nurses are able to see the same information when discussing next steps.

• When operative vaginal delivery is attempted in the face of a Category III FHR tracing, a contingency team should be available for possible emergent cesarean delivery.

• Foster a culture in which caregivers feel comfortable speaking up if they have a concern. Ensure that the organization has a well-defined escalation guideline.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Reference

- The Doctors Company. Obstetrics Closed Claim Study. http://www.thedoctors.com/KnowledgeCenter/PatientSafety/articles/CON_ID_011803. Published April 2015. Accessed May 6, 2015.

Reference

- The Doctors Company. Obstetrics Closed Claim Study. http://www.thedoctors.com/KnowledgeCenter/PatientSafety/articles/CON_ID_011803. Published April 2015. Accessed May 6, 2015.

Mammographic breast density is a strong risk factor for breast cancer

Breast density is a strong, prevalent, and potentially modifiable risk factor for breast cancer, which makes it of special interest to clinicians whose jobs involve breast cancer risk prediction. That was the theme of a talk by Karla Kerlikowske, MD, of the UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center in San Francisco. Dr. Kerlikowske delivered the John I. Brewer Memorial Lecture May 3 at the 2015 Annual Clinical Meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists in San Francisco.

Mammographic breast density is a radiologic term, Dr. Kerlikowske explained. “The only way to really know someone’s breast density is if they have a mammogram.” The whiter the mammogram, the denser the breast. The darker the mammogram, the fattier the breast.

According to the American College of Radiology, the following 4 categories of breast composition are defined by the “visually estimated” content of fibroglandular-density tissue within the breasts:

A. The breasts are almost entirely fatty.

B. There are scattered areas of fibroglandular density.

C. The breasts are heterogeneously dense, which may obscure small masses.

D. The breasts are extremely dense, which lowers the specificity of mammography.

Categories C and D signify dense breasts, which contain a high degree of collagen, epithelial cells, and stroma. In the United States, more than 25 million women are thought to have dense breasts.

Women who have a family history of breast cancer are more likely to have dense breasts. And women who have dense breasts have an elevated risk of breast cancer. They also have a higher risk of advanced disease, as well as a higher risk of large, high-grade, and lymph node-positive tumors, said Dr. Kerlikowske.

Breast-density legislation is increasing

Twenty-two states now have laws mandating that women found to have heterogeneously dense or extremely dense breasts be notified of their status, said Dr. Kerlikowske. That prompts the question: How should these patients be managed?

Breast density declines with age. Breast density also is influenced by body mass index (BMI). As BMI increases, density declines.

Breast density also can be affected by medications, such as hormone therapy and tamoxifen, Dr. Kerlikowske said.

For example, breast density declines about 1% to 2% per year in postmenopause. In postmenopausal women who take estrogen alone, breast density increases slightly. “But the real increase is for people who take estrogen plus progestin,” said Dr. Kerlikowske. “It’s thought that the progestin component is what increases breast density.” Estrogen-progestin therapy confers the same risk of breast cancer as that faced by a premenopausal woman with dense breasts.

As for tamoxifen, it reduces breast density by 2% to 3% per year in postmenopausal women, Dr. Kerlikowske said. “People who have a decrease of more than 10% in breast density are those who have a reduction in breast cancer.” If a woman doesn’t have that reduction with tamoxifen—about half of women don’t—there is no reduction in breast cancer mortality.

“There’s some thought that you should look at mammograms during the first year of tamoxifen use and, if you don’t see a change, consider switching to another medication,” said Dr. Kerlikowske.

More frequent mammograms and supplemental imaging are options for detecting cancers early. Among the modalities that have been studied in this regard are ultrasonography, tomosynthesis, and breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

“If you do more tests, such as ultrasound, you will definitely find additional lesions,” said Dr. Kerlikowske. “There’s no question. But what are the harms?”

The biopsy rate almost doubles after ultrasonography, compared with mammography. And the number needed to screen to detect cancer is fairly high. For mammography, that number is about 250. For ultrasonography, tomosynthesis, and breast MRI, it is higher.

Tomosynthesis is more cost-effective than supplemental ultrasonography because it decreases the number of false positives, Dr. Kerlikowske said.

What’s the bottom line?

Not every woman with dense breasts is at high risk for breast cancer, said Dr. Kerlikowske. And although breast density is prevalent, it is potentially modifiable.

Nevertheless, breast density confers an elevated risk of breast cancer and can also mask tumors. Women with dense breasts likely should avoid the use of postmenopausal hormone therapy. They also may be candidates for more frequent mammography and/or supplemental imaging.

The Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) Risk Calculator is the only tool that incorporates breast density. In the works is a new model that also incorporates benign breast disease.

Risk-prediction tool considers density and other factors

A risk-prediction tool from the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) is the only model to incorporate breast density. The BCSC Risk Calculator is available free of charge for the iPhone and iPad (an Android version is in the works). The tool takes 5 factors into consideration in estimating a woman’s 5-year risk of developing invasive breast cancer:

• age

• race/ethnicity

• breast density

• family history of breast cancer (first-degree relative)

• personal history of breast biopsy.

The tool is designed for use by health professionals. It is not appropriate for determining risk in women younger than 35 years or older than 79 years; women with a previous diagnosis of breast cancer, lobular carcinoma in situ, ductal carcinoma in situ, or atypical ductal hyperplasia; or women who have undergone breast augmentation. Other risk-prediction models are more appropriate for women with a BRCA mutation.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Breast density is a strong, prevalent, and potentially modifiable risk factor for breast cancer, which makes it of special interest to clinicians whose jobs involve breast cancer risk prediction. That was the theme of a talk by Karla Kerlikowske, MD, of the UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center in San Francisco. Dr. Kerlikowske delivered the John I. Brewer Memorial Lecture May 3 at the 2015 Annual Clinical Meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists in San Francisco.

Mammographic breast density is a radiologic term, Dr. Kerlikowske explained. “The only way to really know someone’s breast density is if they have a mammogram.” The whiter the mammogram, the denser the breast. The darker the mammogram, the fattier the breast.

According to the American College of Radiology, the following 4 categories of breast composition are defined by the “visually estimated” content of fibroglandular-density tissue within the breasts:

A. The breasts are almost entirely fatty.

B. There are scattered areas of fibroglandular density.

C. The breasts are heterogeneously dense, which may obscure small masses.

D. The breasts are extremely dense, which lowers the specificity of mammography.

Categories C and D signify dense breasts, which contain a high degree of collagen, epithelial cells, and stroma. In the United States, more than 25 million women are thought to have dense breasts.

Women who have a family history of breast cancer are more likely to have dense breasts. And women who have dense breasts have an elevated risk of breast cancer. They also have a higher risk of advanced disease, as well as a higher risk of large, high-grade, and lymph node-positive tumors, said Dr. Kerlikowske.

Breast-density legislation is increasing

Twenty-two states now have laws mandating that women found to have heterogeneously dense or extremely dense breasts be notified of their status, said Dr. Kerlikowske. That prompts the question: How should these patients be managed?

Breast density declines with age. Breast density also is influenced by body mass index (BMI). As BMI increases, density declines.

Breast density also can be affected by medications, such as hormone therapy and tamoxifen, Dr. Kerlikowske said.

For example, breast density declines about 1% to 2% per year in postmenopause. In postmenopausal women who take estrogen alone, breast density increases slightly. “But the real increase is for people who take estrogen plus progestin,” said Dr. Kerlikowske. “It’s thought that the progestin component is what increases breast density.” Estrogen-progestin therapy confers the same risk of breast cancer as that faced by a premenopausal woman with dense breasts.

As for tamoxifen, it reduces breast density by 2% to 3% per year in postmenopausal women, Dr. Kerlikowske said. “People who have a decrease of more than 10% in breast density are those who have a reduction in breast cancer.” If a woman doesn’t have that reduction with tamoxifen—about half of women don’t—there is no reduction in breast cancer mortality.

“There’s some thought that you should look at mammograms during the first year of tamoxifen use and, if you don’t see a change, consider switching to another medication,” said Dr. Kerlikowske.

More frequent mammograms and supplemental imaging are options for detecting cancers early. Among the modalities that have been studied in this regard are ultrasonography, tomosynthesis, and breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

“If you do more tests, such as ultrasound, you will definitely find additional lesions,” said Dr. Kerlikowske. “There’s no question. But what are the harms?”

The biopsy rate almost doubles after ultrasonography, compared with mammography. And the number needed to screen to detect cancer is fairly high. For mammography, that number is about 250. For ultrasonography, tomosynthesis, and breast MRI, it is higher.

Tomosynthesis is more cost-effective than supplemental ultrasonography because it decreases the number of false positives, Dr. Kerlikowske said.

What’s the bottom line?

Not every woman with dense breasts is at high risk for breast cancer, said Dr. Kerlikowske. And although breast density is prevalent, it is potentially modifiable.

Nevertheless, breast density confers an elevated risk of breast cancer and can also mask tumors. Women with dense breasts likely should avoid the use of postmenopausal hormone therapy. They also may be candidates for more frequent mammography and/or supplemental imaging.

The Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) Risk Calculator is the only tool that incorporates breast density. In the works is a new model that also incorporates benign breast disease.

Risk-prediction tool considers density and other factors

A risk-prediction tool from the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) is the only model to incorporate breast density. The BCSC Risk Calculator is available free of charge for the iPhone and iPad (an Android version is in the works). The tool takes 5 factors into consideration in estimating a woman’s 5-year risk of developing invasive breast cancer:

• age

• race/ethnicity

• breast density

• family history of breast cancer (first-degree relative)

• personal history of breast biopsy.

The tool is designed for use by health professionals. It is not appropriate for determining risk in women younger than 35 years or older than 79 years; women with a previous diagnosis of breast cancer, lobular carcinoma in situ, ductal carcinoma in situ, or atypical ductal hyperplasia; or women who have undergone breast augmentation. Other risk-prediction models are more appropriate for women with a BRCA mutation.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Breast density is a strong, prevalent, and potentially modifiable risk factor for breast cancer, which makes it of special interest to clinicians whose jobs involve breast cancer risk prediction. That was the theme of a talk by Karla Kerlikowske, MD, of the UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center in San Francisco. Dr. Kerlikowske delivered the John I. Brewer Memorial Lecture May 3 at the 2015 Annual Clinical Meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists in San Francisco.

Mammographic breast density is a radiologic term, Dr. Kerlikowske explained. “The only way to really know someone’s breast density is if they have a mammogram.” The whiter the mammogram, the denser the breast. The darker the mammogram, the fattier the breast.

According to the American College of Radiology, the following 4 categories of breast composition are defined by the “visually estimated” content of fibroglandular-density tissue within the breasts:

A. The breasts are almost entirely fatty.

B. There are scattered areas of fibroglandular density.

C. The breasts are heterogeneously dense, which may obscure small masses.

D. The breasts are extremely dense, which lowers the specificity of mammography.

Categories C and D signify dense breasts, which contain a high degree of collagen, epithelial cells, and stroma. In the United States, more than 25 million women are thought to have dense breasts.

Women who have a family history of breast cancer are more likely to have dense breasts. And women who have dense breasts have an elevated risk of breast cancer. They also have a higher risk of advanced disease, as well as a higher risk of large, high-grade, and lymph node-positive tumors, said Dr. Kerlikowske.

Breast-density legislation is increasing

Twenty-two states now have laws mandating that women found to have heterogeneously dense or extremely dense breasts be notified of their status, said Dr. Kerlikowske. That prompts the question: How should these patients be managed?

Breast density declines with age. Breast density also is influenced by body mass index (BMI). As BMI increases, density declines.

Breast density also can be affected by medications, such as hormone therapy and tamoxifen, Dr. Kerlikowske said.

For example, breast density declines about 1% to 2% per year in postmenopause. In postmenopausal women who take estrogen alone, breast density increases slightly. “But the real increase is for people who take estrogen plus progestin,” said Dr. Kerlikowske. “It’s thought that the progestin component is what increases breast density.” Estrogen-progestin therapy confers the same risk of breast cancer as that faced by a premenopausal woman with dense breasts.

As for tamoxifen, it reduces breast density by 2% to 3% per year in postmenopausal women, Dr. Kerlikowske said. “People who have a decrease of more than 10% in breast density are those who have a reduction in breast cancer.” If a woman doesn’t have that reduction with tamoxifen—about half of women don’t—there is no reduction in breast cancer mortality.

“There’s some thought that you should look at mammograms during the first year of tamoxifen use and, if you don’t see a change, consider switching to another medication,” said Dr. Kerlikowske.

More frequent mammograms and supplemental imaging are options for detecting cancers early. Among the modalities that have been studied in this regard are ultrasonography, tomosynthesis, and breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

“If you do more tests, such as ultrasound, you will definitely find additional lesions,” said Dr. Kerlikowske. “There’s no question. But what are the harms?”

The biopsy rate almost doubles after ultrasonography, compared with mammography. And the number needed to screen to detect cancer is fairly high. For mammography, that number is about 250. For ultrasonography, tomosynthesis, and breast MRI, it is higher.

Tomosynthesis is more cost-effective than supplemental ultrasonography because it decreases the number of false positives, Dr. Kerlikowske said.

What’s the bottom line?

Not every woman with dense breasts is at high risk for breast cancer, said Dr. Kerlikowske. And although breast density is prevalent, it is potentially modifiable.

Nevertheless, breast density confers an elevated risk of breast cancer and can also mask tumors. Women with dense breasts likely should avoid the use of postmenopausal hormone therapy. They also may be candidates for more frequent mammography and/or supplemental imaging.

The Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) Risk Calculator is the only tool that incorporates breast density. In the works is a new model that also incorporates benign breast disease.

Risk-prediction tool considers density and other factors

A risk-prediction tool from the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) is the only model to incorporate breast density. The BCSC Risk Calculator is available free of charge for the iPhone and iPad (an Android version is in the works). The tool takes 5 factors into consideration in estimating a woman’s 5-year risk of developing invasive breast cancer:

• age

• race/ethnicity

• breast density

• family history of breast cancer (first-degree relative)

• personal history of breast biopsy.

The tool is designed for use by health professionals. It is not appropriate for determining risk in women younger than 35 years or older than 79 years; women with a previous diagnosis of breast cancer, lobular carcinoma in situ, ductal carcinoma in situ, or atypical ductal hyperplasia; or women who have undergone breast augmentation. Other risk-prediction models are more appropriate for women with a BRCA mutation.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

ACOG, SMFM, and others address safety concerns in labor and delivery

At least half of all cases of maternal morbidity and mortality could be prevented, or so studies suggest.1,2

The main stumbling block?

Faulty communication.

That’s the word from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, the American College of Nurse-Midwives, and the Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses.3

In a joint “blueprint” to transform communication and enhance the safety culture in intrapartum care, these organizations, led by Audrey Lyndon, PhD, RN, FAAN, from the University of California, San Francisco, School of Nursing, describe the extent of the problem, steps that various team members can take to improve safety, notable success stories, and communication strategies.3 In this article, the joint blueprint is summarized, with a focus on steps obstetricians can take to improve the intrapartum safety culture.

Scope of the problem

A study of more than 3,282 physicians, midwives, and registered nurses produced a troubling statistic: More than 90% of respondents said that they had “witnessed shortcuts, missing competencies, disrespect, or performance problems” during the preceding year of practice.4 Few of these clinicians reported that they had discussed their concerns with the parties involved.

A second study of 1,932 clinicians found that 34% of physicians, 40% of midwives, and 56% of registered nurses had witnessed patients being put at risk within the preceding 2 years by other team members’ inattentiveness or lack of responsiveness.5

These findings suggest that health care providers often witness weak links in intrapartum safety but do not always address or report them. Among the reasons team members may be hesitant to speak up when they perceive a potential problem:

- feelings of resignation or inability to change the situation

- fear of retribution or ridicule

- fear of interpersonal or intrateam conflict.

Although Lyndon and colleagues acknowledge that it is impossible to eliminate adverse outcomes entirely or completely eradicate human error, they argue that significant improvements can be made by adopting a number of manageable strategies.

Recommended strategies

Lyndon and colleagues describe some of the challenges of effective communication in a health care setting:

Lyndon and colleagues go on to mention a number of strategies to improve communication, boost safety, and reduce medical errors.

1. Remember that the patient is part of the team

The patient and her family play a key role in identifying the potential for harm during labor and delivery, Lyndon and colleagues assert. They should be considered members of the intrapartum team, care should be patient-focused, and any communications from the patient should not only be heard but fully considered. In fact, explicit elicitation of her experience and concerns is recommended.

2. Consider that you might be part of the problem

It is human nature to attribute a communication problem to the other people involved, rather than take responsibility for it oneself. One potential solution to this mindset is team training, where all members are encouraged to communicate clearly and listen attentively. Organizations that have been successful at improving their culture of safety have implemented such training, as well as the use of checklists, training in fetal heart-rate monitoring, formation of a patient safety committee, external review of safety practices, and designation of a key clinician to lead the safety program and oversee team training.

3. Structure handoffs

The team should standardize handoffs so that they occur smoothly and all channels of communication remain open and clear.

“Having structured formats for debriefing and handoffs are steps in the right direction, but solving the problem of communication breakdowns is more complicated than standardizing the flow and format of information transfer,” Lyndon and colleagues assert. “Indeed, solving communication breakdowns is a matter of individual, group, organizational, and professional responsibility for creating and sustaining an environment of mutual respect, curiosity, and accountability for behavior and performance.”3

4. Learn to communicate responsibly

“Differences of opinion about clinical assessments, goals of care, and the pathway to optimal outcomes are bound to occur with some regularity in the dynamic environment of labor and delivery,” note Lyndon and colleagues. “Every person has the responsibility to contribute to improving how we relate to and communicate with each other. Collectively, we must create environments in which every team member (woman, family member, physician, midwife, nurse, unit clerk, patient care assistant, or scrub tech) is comfortable expressing and discussing concerns about safety or performance, is encouraged to do so, and has the support of the team to articulate the rationale for and urgency of the concern without fear of put-downs, retribution, or receiving poor-quality care.”3

5. Be persistent and proactive

When team members have differing expectations and communication styles, useful approaches include structured communication tools such as situation, background, assessment, recommendation (SBAR); structured handoffs; board rounds; huddles; attentive listening; and explicit elicitation of the patient’s concerns and desires.3

If someone fails to pay attention to a concern you raise, be persistent about restating that concern until you elicit a response.

If someone exhibits disruptive behavior, point to or establish a code of conduct that clearly describes professional behavior.

If there is a difference of opinion on patient management, such as fetal monitoring and interpretation, conduct regular case reviews and standardize a plan for notification of complications.

6. If you’re a team leader, set clear goals

Then ask team members what will be needed to achieve the outcomes desired.

“Team leaders need to develop outstanding skills for listening and eliciting feedback and cross-monitoring (being aware of each other’s actions and performance) from other team members,” note Lyndon and colleagues.

7. Increase public awareness of safety concepts

When these concepts and best practices are made known to the public, women and families become “empowered” to speak up when they have concerns about care.

And when they do speak up, it pays to listen.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Geller SE, Rosenberg D, Cox SM, et al. The continuum of maternal morbidity and mortality: factors associated with severity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(3):939–944.

2. Mitchell C, Lawton E, Morton C, McCain C, Holtby S, Main E. California Pregnancy-Associated Mortality Review: mixed methods approach for improved case identification, cause of death analyses and translation of findings. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18(3):518–526.

3. Lyndon A, Johnson MC, Bingham D, et al. Transforming communication and safety culture in intrapartum care: a multi-organization blueprint. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(5):1049–1055.

4. Maxfield DG, Lyndon A, Kennedy HP, O’Keeffe DF, Ziatnik MG. Confronting safety gaps across labor and delivery teams. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(5):402–408.e3.

5. Lyndon A, Zlatnik MG, Maxfield DG, Lewis A, McMillan C, Kennedy HP. Contributions of clinical disconnections and unresolved conflict to failures in intrapartum safety. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2014;43(1):2–12.

At least half of all cases of maternal morbidity and mortality could be prevented, or so studies suggest.1,2

The main stumbling block?

Faulty communication.

That’s the word from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, the American College of Nurse-Midwives, and the Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses.3

In a joint “blueprint” to transform communication and enhance the safety culture in intrapartum care, these organizations, led by Audrey Lyndon, PhD, RN, FAAN, from the University of California, San Francisco, School of Nursing, describe the extent of the problem, steps that various team members can take to improve safety, notable success stories, and communication strategies.3 In this article, the joint blueprint is summarized, with a focus on steps obstetricians can take to improve the intrapartum safety culture.

Scope of the problem

A study of more than 3,282 physicians, midwives, and registered nurses produced a troubling statistic: More than 90% of respondents said that they had “witnessed shortcuts, missing competencies, disrespect, or performance problems” during the preceding year of practice.4 Few of these clinicians reported that they had discussed their concerns with the parties involved.

A second study of 1,932 clinicians found that 34% of physicians, 40% of midwives, and 56% of registered nurses had witnessed patients being put at risk within the preceding 2 years by other team members’ inattentiveness or lack of responsiveness.5

These findings suggest that health care providers often witness weak links in intrapartum safety but do not always address or report them. Among the reasons team members may be hesitant to speak up when they perceive a potential problem:

- feelings of resignation or inability to change the situation

- fear of retribution or ridicule

- fear of interpersonal or intrateam conflict.

Although Lyndon and colleagues acknowledge that it is impossible to eliminate adverse outcomes entirely or completely eradicate human error, they argue that significant improvements can be made by adopting a number of manageable strategies.

Recommended strategies

Lyndon and colleagues describe some of the challenges of effective communication in a health care setting:

Lyndon and colleagues go on to mention a number of strategies to improve communication, boost safety, and reduce medical errors.

1. Remember that the patient is part of the team

The patient and her family play a key role in identifying the potential for harm during labor and delivery, Lyndon and colleagues assert. They should be considered members of the intrapartum team, care should be patient-focused, and any communications from the patient should not only be heard but fully considered. In fact, explicit elicitation of her experience and concerns is recommended.

2. Consider that you might be part of the problem

It is human nature to attribute a communication problem to the other people involved, rather than take responsibility for it oneself. One potential solution to this mindset is team training, where all members are encouraged to communicate clearly and listen attentively. Organizations that have been successful at improving their culture of safety have implemented such training, as well as the use of checklists, training in fetal heart-rate monitoring, formation of a patient safety committee, external review of safety practices, and designation of a key clinician to lead the safety program and oversee team training.

3. Structure handoffs

The team should standardize handoffs so that they occur smoothly and all channels of communication remain open and clear.

“Having structured formats for debriefing and handoffs are steps in the right direction, but solving the problem of communication breakdowns is more complicated than standardizing the flow and format of information transfer,” Lyndon and colleagues assert. “Indeed, solving communication breakdowns is a matter of individual, group, organizational, and professional responsibility for creating and sustaining an environment of mutual respect, curiosity, and accountability for behavior and performance.”3

4. Learn to communicate responsibly

“Differences of opinion about clinical assessments, goals of care, and the pathway to optimal outcomes are bound to occur with some regularity in the dynamic environment of labor and delivery,” note Lyndon and colleagues. “Every person has the responsibility to contribute to improving how we relate to and communicate with each other. Collectively, we must create environments in which every team member (woman, family member, physician, midwife, nurse, unit clerk, patient care assistant, or scrub tech) is comfortable expressing and discussing concerns about safety or performance, is encouraged to do so, and has the support of the team to articulate the rationale for and urgency of the concern without fear of put-downs, retribution, or receiving poor-quality care.”3

5. Be persistent and proactive

When team members have differing expectations and communication styles, useful approaches include structured communication tools such as situation, background, assessment, recommendation (SBAR); structured handoffs; board rounds; huddles; attentive listening; and explicit elicitation of the patient’s concerns and desires.3

If someone fails to pay attention to a concern you raise, be persistent about restating that concern until you elicit a response.

If someone exhibits disruptive behavior, point to or establish a code of conduct that clearly describes professional behavior.

If there is a difference of opinion on patient management, such as fetal monitoring and interpretation, conduct regular case reviews and standardize a plan for notification of complications.

6. If you’re a team leader, set clear goals

Then ask team members what will be needed to achieve the outcomes desired.

“Team leaders need to develop outstanding skills for listening and eliciting feedback and cross-monitoring (being aware of each other’s actions and performance) from other team members,” note Lyndon and colleagues.

7. Increase public awareness of safety concepts

When these concepts and best practices are made known to the public, women and families become “empowered” to speak up when they have concerns about care.

And when they do speak up, it pays to listen.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

At least half of all cases of maternal morbidity and mortality could be prevented, or so studies suggest.1,2

The main stumbling block?

Faulty communication.

That’s the word from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, the American College of Nurse-Midwives, and the Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses.3

In a joint “blueprint” to transform communication and enhance the safety culture in intrapartum care, these organizations, led by Audrey Lyndon, PhD, RN, FAAN, from the University of California, San Francisco, School of Nursing, describe the extent of the problem, steps that various team members can take to improve safety, notable success stories, and communication strategies.3 In this article, the joint blueprint is summarized, with a focus on steps obstetricians can take to improve the intrapartum safety culture.

Scope of the problem

A study of more than 3,282 physicians, midwives, and registered nurses produced a troubling statistic: More than 90% of respondents said that they had “witnessed shortcuts, missing competencies, disrespect, or performance problems” during the preceding year of practice.4 Few of these clinicians reported that they had discussed their concerns with the parties involved.

A second study of 1,932 clinicians found that 34% of physicians, 40% of midwives, and 56% of registered nurses had witnessed patients being put at risk within the preceding 2 years by other team members’ inattentiveness or lack of responsiveness.5

These findings suggest that health care providers often witness weak links in intrapartum safety but do not always address or report them. Among the reasons team members may be hesitant to speak up when they perceive a potential problem:

- feelings of resignation or inability to change the situation

- fear of retribution or ridicule

- fear of interpersonal or intrateam conflict.

Although Lyndon and colleagues acknowledge that it is impossible to eliminate adverse outcomes entirely or completely eradicate human error, they argue that significant improvements can be made by adopting a number of manageable strategies.

Recommended strategies

Lyndon and colleagues describe some of the challenges of effective communication in a health care setting:

Lyndon and colleagues go on to mention a number of strategies to improve communication, boost safety, and reduce medical errors.

1. Remember that the patient is part of the team

The patient and her family play a key role in identifying the potential for harm during labor and delivery, Lyndon and colleagues assert. They should be considered members of the intrapartum team, care should be patient-focused, and any communications from the patient should not only be heard but fully considered. In fact, explicit elicitation of her experience and concerns is recommended.

2. Consider that you might be part of the problem

It is human nature to attribute a communication problem to the other people involved, rather than take responsibility for it oneself. One potential solution to this mindset is team training, where all members are encouraged to communicate clearly and listen attentively. Organizations that have been successful at improving their culture of safety have implemented such training, as well as the use of checklists, training in fetal heart-rate monitoring, formation of a patient safety committee, external review of safety practices, and designation of a key clinician to lead the safety program and oversee team training.

3. Structure handoffs

The team should standardize handoffs so that they occur smoothly and all channels of communication remain open and clear.

“Having structured formats for debriefing and handoffs are steps in the right direction, but solving the problem of communication breakdowns is more complicated than standardizing the flow and format of information transfer,” Lyndon and colleagues assert. “Indeed, solving communication breakdowns is a matter of individual, group, organizational, and professional responsibility for creating and sustaining an environment of mutual respect, curiosity, and accountability for behavior and performance.”3

4. Learn to communicate responsibly

“Differences of opinion about clinical assessments, goals of care, and the pathway to optimal outcomes are bound to occur with some regularity in the dynamic environment of labor and delivery,” note Lyndon and colleagues. “Every person has the responsibility to contribute to improving how we relate to and communicate with each other. Collectively, we must create environments in which every team member (woman, family member, physician, midwife, nurse, unit clerk, patient care assistant, or scrub tech) is comfortable expressing and discussing concerns about safety or performance, is encouraged to do so, and has the support of the team to articulate the rationale for and urgency of the concern without fear of put-downs, retribution, or receiving poor-quality care.”3

5. Be persistent and proactive

When team members have differing expectations and communication styles, useful approaches include structured communication tools such as situation, background, assessment, recommendation (SBAR); structured handoffs; board rounds; huddles; attentive listening; and explicit elicitation of the patient’s concerns and desires.3

If someone fails to pay attention to a concern you raise, be persistent about restating that concern until you elicit a response.

If someone exhibits disruptive behavior, point to or establish a code of conduct that clearly describes professional behavior.

If there is a difference of opinion on patient management, such as fetal monitoring and interpretation, conduct regular case reviews and standardize a plan for notification of complications.

6. If you’re a team leader, set clear goals

Then ask team members what will be needed to achieve the outcomes desired.

“Team leaders need to develop outstanding skills for listening and eliciting feedback and cross-monitoring (being aware of each other’s actions and performance) from other team members,” note Lyndon and colleagues.

7. Increase public awareness of safety concepts

When these concepts and best practices are made known to the public, women and families become “empowered” to speak up when they have concerns about care.

And when they do speak up, it pays to listen.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Geller SE, Rosenberg D, Cox SM, et al. The continuum of maternal morbidity and mortality: factors associated with severity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(3):939–944.

2. Mitchell C, Lawton E, Morton C, McCain C, Holtby S, Main E. California Pregnancy-Associated Mortality Review: mixed methods approach for improved case identification, cause of death analyses and translation of findings. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18(3):518–526.

3. Lyndon A, Johnson MC, Bingham D, et al. Transforming communication and safety culture in intrapartum care: a multi-organization blueprint. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(5):1049–1055.

4. Maxfield DG, Lyndon A, Kennedy HP, O’Keeffe DF, Ziatnik MG. Confronting safety gaps across labor and delivery teams. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(5):402–408.e3.

5. Lyndon A, Zlatnik MG, Maxfield DG, Lewis A, McMillan C, Kennedy HP. Contributions of clinical disconnections and unresolved conflict to failures in intrapartum safety. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2014;43(1):2–12.

1. Geller SE, Rosenberg D, Cox SM, et al. The continuum of maternal morbidity and mortality: factors associated with severity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(3):939–944.

2. Mitchell C, Lawton E, Morton C, McCain C, Holtby S, Main E. California Pregnancy-Associated Mortality Review: mixed methods approach for improved case identification, cause of death analyses and translation of findings. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18(3):518–526.

3. Lyndon A, Johnson MC, Bingham D, et al. Transforming communication and safety culture in intrapartum care: a multi-organization blueprint. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(5):1049–1055.

4. Maxfield DG, Lyndon A, Kennedy HP, O’Keeffe DF, Ziatnik MG. Confronting safety gaps across labor and delivery teams. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(5):402–408.e3.

5. Lyndon A, Zlatnik MG, Maxfield DG, Lewis A, McMillan C, Kennedy HP. Contributions of clinical disconnections and unresolved conflict to failures in intrapartum safety. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2014;43(1):2–12.

Clinicians are adept at estimating uterine size prior to benign hysterectomy

In a poster presented at the 2015 ACOG Annual Clinical Meeting in San Francisco, Neal Marc Lonky, MD, and colleagues from the Southern California Permanente Group assessed the clinical acumen of physicians in estimating uterine size prior to elective hysterectomy for benign indications. They found that the correlation between estimates and actual uterine weight was 0.79 (P<.001), with a very low conversion rate for the surgery.1

Lonky and colleagues collected preoperative uterine estimates and actual specimen weights prospectively for 1,079 cases of benign hysterectomy. The surgeries were performed by 186 primary surgeons and assistant surgeons at 10 Kaiser Permanente Southern California medical centers. Surgeons based the route of hysterectomy on estimates of uterine size, which were calculated using bimanual examination, ultrasonography, or both. Linear regression was used to measure and compare the relationship between estimated uterine size and the pelvic specimen weight.

Uterine size estimates ranged from 4 cm to 40 cm, and specimen weights ranged from 2 g to 4,607 g. The mean (SD) estimate of uterine size was 11.7 (4.43) cm, and the mean actual specimen weight was 334.6 (401.42) g.

The mean age of women in the sample was 47.2 (8.35) years. Overall, 379 women (35.1%) were Hispanic, 325 (30.1%) were non-Hispanic white, 281 (26.0%) were non-Hispanic black, and 81 (7.5%) were Asian/Pacific Islander. The mean body mass index (BMI) was 30.0 (6.37) kg/m2, with a range of 16.8 to 67.9 kg/m2.

“This is real world research,” said Dr. Lonky. “It’s called comparative effectiveness research. Basically, all patients who are undergoing the procedure are entered in the registry, and the clinical acumen of the physician—either using or not using ultrasound—is assessed.”

“We looked at whether or not we had a bias toward one patient age group, race/ethnicity, BMI, or estimated uterine size. But there were no clusters, so this was truly a random distribution,” said Dr. Lonky.

“These findings may be population-specific to my group of doctors,” he added. “They should be replicated in other settings. It may be that residents are not going to be as linear.”

Reference

- Lonky NM, Chiu V, Mohan Y. Clinical utility of the estimation of uterine size in planning hysterectomy approach. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(5 suppl):19S.

In a poster presented at the 2015 ACOG Annual Clinical Meeting in San Francisco, Neal Marc Lonky, MD, and colleagues from the Southern California Permanente Group assessed the clinical acumen of physicians in estimating uterine size prior to elective hysterectomy for benign indications. They found that the correlation between estimates and actual uterine weight was 0.79 (P<.001), with a very low conversion rate for the surgery.1

Lonky and colleagues collected preoperative uterine estimates and actual specimen weights prospectively for 1,079 cases of benign hysterectomy. The surgeries were performed by 186 primary surgeons and assistant surgeons at 10 Kaiser Permanente Southern California medical centers. Surgeons based the route of hysterectomy on estimates of uterine size, which were calculated using bimanual examination, ultrasonography, or both. Linear regression was used to measure and compare the relationship between estimated uterine size and the pelvic specimen weight.

Uterine size estimates ranged from 4 cm to 40 cm, and specimen weights ranged from 2 g to 4,607 g. The mean (SD) estimate of uterine size was 11.7 (4.43) cm, and the mean actual specimen weight was 334.6 (401.42) g.

The mean age of women in the sample was 47.2 (8.35) years. Overall, 379 women (35.1%) were Hispanic, 325 (30.1%) were non-Hispanic white, 281 (26.0%) were non-Hispanic black, and 81 (7.5%) were Asian/Pacific Islander. The mean body mass index (BMI) was 30.0 (6.37) kg/m2, with a range of 16.8 to 67.9 kg/m2.

“This is real world research,” said Dr. Lonky. “It’s called comparative effectiveness research. Basically, all patients who are undergoing the procedure are entered in the registry, and the clinical acumen of the physician—either using or not using ultrasound—is assessed.”

“We looked at whether or not we had a bias toward one patient age group, race/ethnicity, BMI, or estimated uterine size. But there were no clusters, so this was truly a random distribution,” said Dr. Lonky.

“These findings may be population-specific to my group of doctors,” he added. “They should be replicated in other settings. It may be that residents are not going to be as linear.”

In a poster presented at the 2015 ACOG Annual Clinical Meeting in San Francisco, Neal Marc Lonky, MD, and colleagues from the Southern California Permanente Group assessed the clinical acumen of physicians in estimating uterine size prior to elective hysterectomy for benign indications. They found that the correlation between estimates and actual uterine weight was 0.79 (P<.001), with a very low conversion rate for the surgery.1

Lonky and colleagues collected preoperative uterine estimates and actual specimen weights prospectively for 1,079 cases of benign hysterectomy. The surgeries were performed by 186 primary surgeons and assistant surgeons at 10 Kaiser Permanente Southern California medical centers. Surgeons based the route of hysterectomy on estimates of uterine size, which were calculated using bimanual examination, ultrasonography, or both. Linear regression was used to measure and compare the relationship between estimated uterine size and the pelvic specimen weight.

Uterine size estimates ranged from 4 cm to 40 cm, and specimen weights ranged from 2 g to 4,607 g. The mean (SD) estimate of uterine size was 11.7 (4.43) cm, and the mean actual specimen weight was 334.6 (401.42) g.

The mean age of women in the sample was 47.2 (8.35) years. Overall, 379 women (35.1%) were Hispanic, 325 (30.1%) were non-Hispanic white, 281 (26.0%) were non-Hispanic black, and 81 (7.5%) were Asian/Pacific Islander. The mean body mass index (BMI) was 30.0 (6.37) kg/m2, with a range of 16.8 to 67.9 kg/m2.

“This is real world research,” said Dr. Lonky. “It’s called comparative effectiveness research. Basically, all patients who are undergoing the procedure are entered in the registry, and the clinical acumen of the physician—either using or not using ultrasound—is assessed.”

“We looked at whether or not we had a bias toward one patient age group, race/ethnicity, BMI, or estimated uterine size. But there were no clusters, so this was truly a random distribution,” said Dr. Lonky.

“These findings may be population-specific to my group of doctors,” he added. “They should be replicated in other settings. It may be that residents are not going to be as linear.”

Reference

- Lonky NM, Chiu V, Mohan Y. Clinical utility of the estimation of uterine size in planning hysterectomy approach. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(5 suppl):19S.

Reference

- Lonky NM, Chiu V, Mohan Y. Clinical utility of the estimation of uterine size in planning hysterectomy approach. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(5 suppl):19S.

Endometriosis and pain: Expert answers to 6 questions targeting your management options

Endometriosis has always posed a treatment challenge. Take the early 19th Century, for example, before the widespread advent of surgery, when the disease was managed by applying leeches to the cervix. In fact, as Nezhat and colleagues note in their comprehensive survey of the 4,000-year history of endometriosis, “leeches were considered a mainstay in treating any condition associated with menstruation.”1

Fast forward to the 21st Century, and the picture is a lot clearer, though still not crystal clear. The optimal approach to endometriosis depends on numerous factors, foremost among them the chief complaint of the patient—pain or infertility (or both).

In this article—Part 2 of a 3-part series on endometriosis—the focus is on medical and surgical management of pain. Six experts address such questions as when is laparoscopy indicated, who is best qualified to treat endometriosis, is excision or ablation of lesions preferred, what is the role of hysterectomy in eliminating pain, and what to do about the problem of recurrence.

In Part 3, to be published in the June 2015 issue of OBG Management, endometriosis-associated infertility will be the topic of discussion.

In Part 1, 7 experts answer crucial questions on the diagnosis of endometriosis.

For a detailed look at the pathophysiology of endometriosis-associated pain, see “Avoiding “shotgun” treatment: New thoughts on endometriosis-associated pelvic pain,” by Kenneth A. Levey, MD, MPH, in this issue.

1. What are the options for empiric therapy?

One reason for the diagnostic delay for endometriosis, which still averages about 6 years, is that definitive diagnosis is achieved only through laparoscopic investigation and histologic confirmation. For many women who experience pain thought to be associated with endometriosis, however, clinicians begin empiric treatment with medical agents as a way to avert the need for surgery, if at all possible.

“There is no cure for endometriosis,” says John R. Lue, MD, MPH, “but there are many ways that endometriosis can be treated” and the impact of the disease reduced in a patient’s life. Dr. Lue is Associate Professor and Chief of the Section of General Obstetrics and Gynecology and Medical Director of Women’s Ambulatory Services at the Medical College of Georgia and Georgia Regents University in Augusta, Georgia.

Among the medical and hormonal management options:

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), often used with combined oral contraceptives (OCs). NSAIDs are not a long-term treatment option because of their effect on cyclo-oxygenase (COX) 1 and 2 enzymes, says Dr. Lue. COX-1 protects the gastrointestinal (GI) system, and prolonged use of NSAIDs can cause adverse GI effects.

- Cyclic combined OCs “are recommended as first-line therapy in the absence of contraindications,” says Dr. Lue, and are often used in combination with NSAIDs. However, the failure rate may be as high as 20% to 25%.2 “If pain persists after a trial of 3 to 6 months of cyclic OCs, one can consider switching to continuous low-dose combined OCs for an additional 6 months,” says Dr. Lue. When combined OCs were compared with placebo in the treatment of dysmenorrhea, they reduced baseline pain scores by 45% to 52%, compared with 14% to 17% for placebo (P<.001).2 They also reduced the volume of endometriomas by 48%, compared with 32% for placebo (P = .04). According to Linda C. Giudice, MD, PhD, “In women with severe dysmenorrhea who have been treated with cyclic combined OCs, a switch to continuous combined OCs reduced pain scores by 58% within 6 months and by 75% at 2 years” (P<.001).2 Dr. Giudice is the Robert B. Jaffe, MD, Endowed Professor in the Reproductive Sciences and Chair of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Sciences at the University of California, San Francisco.

- Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) or the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS). These agents suppress the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis to different degrees. DMPA suppresses the HPO completely, preventing ovulation. The LNG-IUS does not fully suppress the HPO but acts directly on endometrial tissue, with antiproliferative effects on eutopic and endometriotic implants, says Dr. Lue. The LNG-IUS also is effective at suppressing disease after surgical treatment, says Dr. Giudice.2

- Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist therapy, with estrogen and/or progestin add-back therapy to temper the associated loss in bone mineral density, “may be effective—if only temporarily—as it inhibits the HPO axis and blocks ovarian function, thereby greatly reducing systemic estrogen levels and inducing artificial menopause,” says Dr. Lue.

- Norethindrone acetate, a synthetic progestational agent, is occasionally used as empiric therapy for endometriosis because of its ability to inhibit ovulation. It has antiandrogenic and antiestrogenic effects.

- Aromatase inhibitors. Dr. Lue points to considerable evidence that endometriotic implants are an autocrine source of estrogen.3 “This locally produced estrogen results from overexpression of the enzyme P450 aromatase by endometriotic tissue,” he says. Consequently, in postmenopausal women, “aromatase inhibitors may be used orally in a daily pill form to curtail endometriotic implant production of estrogen and subsequent implant growth.”4 In women of reproductive age, aromatase inhibitors are combined with an HPO-suppressive therapy, such as norethindrone acetate. These strategies represent off-label use of aromatase inhibitors.

- Danazol, a synthetic androgen, has been used in the past to treat dysmenorrhea and dyspareunia. Because of its severe androgenic effects, however, it is not widely used today.

“For those using medical approaches, endometriosis-related pain may be reduced by using hormonal treatments to modify reproductive tract events, thereby decreasing local peritoneal inflammation and cytokine production,” says Pamela Stratton, MD. Because endometriosis is a “central sensitivity syndrome,” multidisciplinary approaches may be beneficial to treat myofascial dysfunction and sensitization, such as physical therapy. “Chronic pain conditions that overlap with endometriosis-associated pain, such as migraines, irritable bowel syndrome, or painful bladder syndrome should be identified and treated. Mood changes of depression and anxiety common to women with endometriosis-associated pain also warrant treatment,” she says.

Dr. Stratton is Chief of the Gynecology Consult Service, Program in Reproductive and Adult Endocrinology, at the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development in Bethesda, Maryland.

2. When is laparoscopy indicated?

When medical and hormonal treatments fail to control a patient’s pain, laparoscopy is indicated to confirm the diagnosis of endometriosis. During that procedure, it is also advisable to treat any endometriosis that is present, provided the surgeon is highly experienced in such treatment.

Proper treatment is preferable—even if it requires expert consultation. “No treatment and referral to a more experienced surgeon are better than incomplete treatment by an inexperienced surgeon,” says Ceana Nezhat, MD. “Not all GYN surgeons have the expertise to treat advanced endometriosis.” Dr. Nezhat is Director of the Nezhat Medical Center and Medical Director of Training and Education at Northside Hospital, both in Atlanta, Georgia.

Dr. Stratton agrees about the importance of thorough treatment of endometriosis at the time of diagnostic laparoscopy. “At the laparoscopy, the patient benefits if all potential sources of pain are investigated and addressed.” At surgery, the surgeon should look for and treat any lesions suspicious for endometriosis, as well as any other finding that might contribute to pain, she says. “For example, routinely inspecting the appendix for endometriosis or other lesions, and removing affected appendices is reasonable; also, lysis and, where possible, excision of adhesions is an important strategy.”

If a medical approach fails for a patient, “then surgery is indicated to confirm the diagnosis and treat the disease,” agrees Tommaso Falcone, MD.

“Surgery is very effective in treating the pain associated with endometriosis,” Dr. Falcone continues. Randomized clinical trials have shown that up to 90% of patients who obtain pain relief from surgery will have an effect lasting 1 year.6 If patients do not get relief, then the association of the pain with endometriosis should be questioned and other causes searched.” Dr. Falcone is Professor and Chair of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the Cleveland Clinic in Cleveland, Ohio.

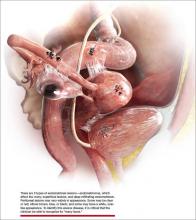

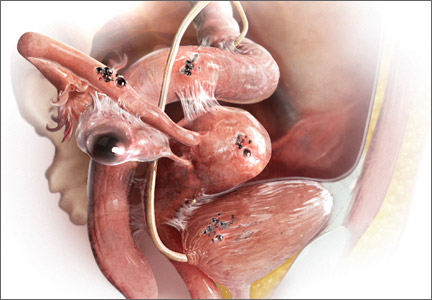

The most common anatomic sites of implants

“The most common accepted theory for pathogenesis of endometriosis suggests that implants develop when debris from retrograde menstruation attaches to the pelvic peritoneum,” says Dr. Stratton.7 “Thus, the vast majority of lesions occur in the dependent portions of the pelvis, which include the ovarian fossae (posterior broad ligament under the ovaries), cul de sac, and the uterosacral ligaments.8 The bladder peritoneum, ovarian surface, uterine peritoneal surface, fallopian tube, and pelvic sidewall are also frequent sites. The colon and appendix are less common sites, and small bowel lesions are rare.”

“However, pain location does not correlate with lesion location,” Dr. Stratton notes. “For this reason, the goal at surgery is to treat all lesions, even ones that are not in sites of pain.”

3. How should disease be staged?

Most surgeons with expertise in treating endometriosis attempt to stage the disease at the time of initial laparoscopy, even though a patient’s pain does not always correlate with the stage of disease.

“The staging system for endometriosis is a means to systematically catalogue where lesions are located,” says Dr. Stratton.

The most commonly used classification system was developed by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM). It takes into account such characteristics as how deep an implant lies, the extent to which it obliterates the posterior cul de sac, and the presence and extent of adhesions. Although the classification system is broken down into 4 stages ranging from minimal to severe disease, it is fairly complex. For example, it assigns a score for each lesion as well as the size and location of that lesion, notes Dr. Stratton. The presence of an endometrioma automatically renders the disease as stage III or IV, and an obliterated cul de sac means the endometriosis is graded as stage IV.

“This system enables us to communicate with each other about patients and may guide future surgeries for assessment of lesion recurrence or the planning of treatment for lesions the surgeon was unable to treat at an initial surgery,” says Dr. Stratton.

“Women with uterosacral nodularity, fixed pelvic organs, or severe pain with endometriomas may have deep infiltrating lesions. These lesions, in particular, are not captured well with the current staging system,” says Dr. Stratton. Because they appear to be innervated, “the greatest benefit to the patient is achieved by completely excising these lesions.” Preoperative imaging may help confirm the existence, location, and extent of these deep lesions and help the surgeon plan her approach “based on clinical and imaging findings.”

“Severity of pain or duration of surgical effect does not correlate with stage or extent of disease,” Dr. Stratton says.9 “In fact, patients with the least amount of disease noted at surgery experience pain sooner, suggesting that the central nervous system may have been remodeled prior to surgery or that the pain is in part due to some other cause.10 This observation underscores the principle that, while endometriosis may initiate pain, the pain experience is determined by engagement of the central nervous system.”

For more information on the ASRM revised classification of endometriosis, go to http://www.fertstert.org/article/S0015-0282(97)81391-X/pdf.

4. Which is preferable—excision or ablation?

In a prospective, randomized, double-blind study, Healey and colleagues compared pain levels following laparoscopic treatment of endometriosis with either excision or ablation. Preoperatively, women in the study completed a questionnaire rating various types of pain using visual analogue scales. They then were randomly assigned to treatment of endometriosis via excision or ablation. Postoperatively, they again completed a questionnaire about pain levels at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months. Investigators found no significant difference in pain scores at 12 months.11

Five-year follow-up of the same population yielded slightly different findings, however. Although there was a reduction in all pain scores at 5 years in both the excision and ablation groups, a significantly greater reduction in dyspareunia was observed in the excision group at 5 years.12

In an editorial accompanying the 5-year follow-up data, Dr. Falcone and a coauthor called excision versus ablation of ovarian, bowel, and peritoneal endometriosis one of the “great debates” in the surgical management of endometriosis.13

“When there is deep involvement of adjacent organs, there is general consensus that excision is best for optimal surgical outcome,” they write. “However, for disease involving the peritoneum alone, there are proponents for either option.”13

“This is a very controversial issue,” says Dr. Falcone, “and the debate can sometimes be somewhat inflammatory…. It is hard to understand how a comparative trial could even be accomplished between excision and ablation,” he adds. “In my experience, deep disease typically occurs on the pelvic sidewall over the ureter or in the cul de sac on the bowel or infiltrating the bladder peritoneum. Therefore, ablation would increase the risk of damaging any of these structures. With superficial disease away from critical structures, it should be fine to ablate. Everywhere else and with deep disease you need to excise or leave disease behind.”

“Endometriomas are a special situation,” Dr. Falcone says. “Excision of the cyst has been shown in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to be associated with less risk of recurrence.14 Therefore, it should be the treatment of choice. However, in patients interested in future fertility, we must take into consideration the potential damage to ovarian reserve associated with excision.”