User login

Intermittent High-Dose Inhaled Corticosteroid Works for Wheezing Toddlers

SAN FRANCISCO – Intermittent courses of high-dose inhaled budesonide were as effective and as safe as daily low-dose inhaled budesonide in wheezing toddlers but exposed them to a lower cumulative dose of the corticosteroid in a year-long study of 278 children.

The two groups did not differ significantly in the frequency of exacerbations that required systemic corticosteroids, the frequency or severity of respiratory tract illness, the number of urgent or emergent visits for care, or other efficacy and safety measures, Dr. Leonard B. Bacharier and his associates reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

Children in the daily low-dose budesonide group, however, were exposed to more than three times the cumulative dose of budesonide, compared with the intermittent high-dose therapy group – 150 mg vs. 46 mg.

The multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, called the Maintenance Versus Intermittent Inhaled Steroids in Wheezing Toddlers (MIST) study, is the last of eight clinical trials performed by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Childhood Asthma Research and Education Network.

The NHLBI’s 2007 "Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management of Asthma" recommended using daily low-dose inhaled corticosteroids to treat children who have a positive modified Asthma Predictive Index.

The MIST study is the first to compare the currently recommended daily low-dose regimen with the intermittent high-dose regimen, said Dr. Bacharier of Washington University, St. Louis.

On the basis of the MIST results, Dr. Bacharier and his associates recommended instead that clinicians consider using intermittent high-dose inhaled corticosteroids in the subset of children identified in the MIST study, who were not the most severe asthma cases. They suggested starting a 7-day course of high-dose budesonide early during respiratory tract illnesses in wheezing children who have a positive modified Asthma Predictive Index, have had at least one exacerbation in the past year, use albuterol less than 3 days per week, and have had no more than one night awakening in the prior 2 weeks.

The study enrolled children 12-53 months of age, nearly half of whom were in the lower age range of 12-32 months. All children had a history of at least four wheezing episodes in the prior year (or at least three if they’d had 3 months or more of asthma controller therapy) and a positive modified Asthma Predictive Index. Each child also had at least one severe exacerbation that required systemic corticosteroids or an unscheduled urgent or emergent visit or hospitalization in the previous year.

The study excluded children who had more than two hospitalizations for wheezing or more than six courses of oral corticosteroids.

During a 2-week run-in period, all children used a nebulized placebo nightly and albuterol as needed. During this period, children who had persistent asthma symptoms or who did not follow the protocol for more than 25% of days also were excluded.

The children were then randomized for 52 weeks of therapy. The daily low-dose budesonide group used 0.5 mg of nebulized budesonide once daily at night except during respiratory tract illness, when they switched to "respiratory tract illness kits" that gave them nebulized placebo in the morning and 0.5 mg of budesonide at night for 7 days. The intermittent high-dose budesonide group used nebulized placebo once daily at night except during respiratory tract illness, when their kits gave them 1 mg of budesonide in the morning and at night for 7 days.

Previous studies have shown that daily inhaled corticosteroids have "a small but statistically significant class effect on reducing linear growth in preschool-aged children, which only partially reverses after discontinuation of study treatments," which was a main reason for studying the intermittent-therapy alternative, Dr. Bacharier said.

In the MIST study, children in the daily-therapy group grew an average of 7.76 cm, compared with 8.01 cm in the intermittent-therapy group, but the 0.25-cm greater growth with intermittent therapy was not statistically significant.

There were no significant differences between groups in baseline characteristics, adherence to therapy during the study, declines in levels of exhaled nitric oxide, time to first exacerbation, or time to treatment failure.

The NHLBI funded the study. AstraZeneca provided the budesonide and placebo for the study. Dr. Bacharier has been a consultant for AstraZeneca (which markets budesonide), Merck, and Novartis, and has received honoraria from GlaxoSmithKline.

SAN FRANCISCO – Intermittent courses of high-dose inhaled budesonide were as effective and as safe as daily low-dose inhaled budesonide in wheezing toddlers but exposed them to a lower cumulative dose of the corticosteroid in a year-long study of 278 children.

The two groups did not differ significantly in the frequency of exacerbations that required systemic corticosteroids, the frequency or severity of respiratory tract illness, the number of urgent or emergent visits for care, or other efficacy and safety measures, Dr. Leonard B. Bacharier and his associates reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

Children in the daily low-dose budesonide group, however, were exposed to more than three times the cumulative dose of budesonide, compared with the intermittent high-dose therapy group – 150 mg vs. 46 mg.

The multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, called the Maintenance Versus Intermittent Inhaled Steroids in Wheezing Toddlers (MIST) study, is the last of eight clinical trials performed by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Childhood Asthma Research and Education Network.

The NHLBI’s 2007 "Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management of Asthma" recommended using daily low-dose inhaled corticosteroids to treat children who have a positive modified Asthma Predictive Index.

The MIST study is the first to compare the currently recommended daily low-dose regimen with the intermittent high-dose regimen, said Dr. Bacharier of Washington University, St. Louis.

On the basis of the MIST results, Dr. Bacharier and his associates recommended instead that clinicians consider using intermittent high-dose inhaled corticosteroids in the subset of children identified in the MIST study, who were not the most severe asthma cases. They suggested starting a 7-day course of high-dose budesonide early during respiratory tract illnesses in wheezing children who have a positive modified Asthma Predictive Index, have had at least one exacerbation in the past year, use albuterol less than 3 days per week, and have had no more than one night awakening in the prior 2 weeks.

The study enrolled children 12-53 months of age, nearly half of whom were in the lower age range of 12-32 months. All children had a history of at least four wheezing episodes in the prior year (or at least three if they’d had 3 months or more of asthma controller therapy) and a positive modified Asthma Predictive Index. Each child also had at least one severe exacerbation that required systemic corticosteroids or an unscheduled urgent or emergent visit or hospitalization in the previous year.

The study excluded children who had more than two hospitalizations for wheezing or more than six courses of oral corticosteroids.

During a 2-week run-in period, all children used a nebulized placebo nightly and albuterol as needed. During this period, children who had persistent asthma symptoms or who did not follow the protocol for more than 25% of days also were excluded.

The children were then randomized for 52 weeks of therapy. The daily low-dose budesonide group used 0.5 mg of nebulized budesonide once daily at night except during respiratory tract illness, when they switched to "respiratory tract illness kits" that gave them nebulized placebo in the morning and 0.5 mg of budesonide at night for 7 days. The intermittent high-dose budesonide group used nebulized placebo once daily at night except during respiratory tract illness, when their kits gave them 1 mg of budesonide in the morning and at night for 7 days.

Previous studies have shown that daily inhaled corticosteroids have "a small but statistically significant class effect on reducing linear growth in preschool-aged children, which only partially reverses after discontinuation of study treatments," which was a main reason for studying the intermittent-therapy alternative, Dr. Bacharier said.

In the MIST study, children in the daily-therapy group grew an average of 7.76 cm, compared with 8.01 cm in the intermittent-therapy group, but the 0.25-cm greater growth with intermittent therapy was not statistically significant.

There were no significant differences between groups in baseline characteristics, adherence to therapy during the study, declines in levels of exhaled nitric oxide, time to first exacerbation, or time to treatment failure.

The NHLBI funded the study. AstraZeneca provided the budesonide and placebo for the study. Dr. Bacharier has been a consultant for AstraZeneca (which markets budesonide), Merck, and Novartis, and has received honoraria from GlaxoSmithKline.

SAN FRANCISCO – Intermittent courses of high-dose inhaled budesonide were as effective and as safe as daily low-dose inhaled budesonide in wheezing toddlers but exposed them to a lower cumulative dose of the corticosteroid in a year-long study of 278 children.

The two groups did not differ significantly in the frequency of exacerbations that required systemic corticosteroids, the frequency or severity of respiratory tract illness, the number of urgent or emergent visits for care, or other efficacy and safety measures, Dr. Leonard B. Bacharier and his associates reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

Children in the daily low-dose budesonide group, however, were exposed to more than three times the cumulative dose of budesonide, compared with the intermittent high-dose therapy group – 150 mg vs. 46 mg.

The multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, called the Maintenance Versus Intermittent Inhaled Steroids in Wheezing Toddlers (MIST) study, is the last of eight clinical trials performed by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Childhood Asthma Research and Education Network.

The NHLBI’s 2007 "Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management of Asthma" recommended using daily low-dose inhaled corticosteroids to treat children who have a positive modified Asthma Predictive Index.

The MIST study is the first to compare the currently recommended daily low-dose regimen with the intermittent high-dose regimen, said Dr. Bacharier of Washington University, St. Louis.

On the basis of the MIST results, Dr. Bacharier and his associates recommended instead that clinicians consider using intermittent high-dose inhaled corticosteroids in the subset of children identified in the MIST study, who were not the most severe asthma cases. They suggested starting a 7-day course of high-dose budesonide early during respiratory tract illnesses in wheezing children who have a positive modified Asthma Predictive Index, have had at least one exacerbation in the past year, use albuterol less than 3 days per week, and have had no more than one night awakening in the prior 2 weeks.

The study enrolled children 12-53 months of age, nearly half of whom were in the lower age range of 12-32 months. All children had a history of at least four wheezing episodes in the prior year (or at least three if they’d had 3 months or more of asthma controller therapy) and a positive modified Asthma Predictive Index. Each child also had at least one severe exacerbation that required systemic corticosteroids or an unscheduled urgent or emergent visit or hospitalization in the previous year.

The study excluded children who had more than two hospitalizations for wheezing or more than six courses of oral corticosteroids.

During a 2-week run-in period, all children used a nebulized placebo nightly and albuterol as needed. During this period, children who had persistent asthma symptoms or who did not follow the protocol for more than 25% of days also were excluded.

The children were then randomized for 52 weeks of therapy. The daily low-dose budesonide group used 0.5 mg of nebulized budesonide once daily at night except during respiratory tract illness, when they switched to "respiratory tract illness kits" that gave them nebulized placebo in the morning and 0.5 mg of budesonide at night for 7 days. The intermittent high-dose budesonide group used nebulized placebo once daily at night except during respiratory tract illness, when their kits gave them 1 mg of budesonide in the morning and at night for 7 days.

Previous studies have shown that daily inhaled corticosteroids have "a small but statistically significant class effect on reducing linear growth in preschool-aged children, which only partially reverses after discontinuation of study treatments," which was a main reason for studying the intermittent-therapy alternative, Dr. Bacharier said.

In the MIST study, children in the daily-therapy group grew an average of 7.76 cm, compared with 8.01 cm in the intermittent-therapy group, but the 0.25-cm greater growth with intermittent therapy was not statistically significant.

There were no significant differences between groups in baseline characteristics, adherence to therapy during the study, declines in levels of exhaled nitric oxide, time to first exacerbation, or time to treatment failure.

The NHLBI funded the study. AstraZeneca provided the budesonide and placebo for the study. Dr. Bacharier has been a consultant for AstraZeneca (which markets budesonide), Merck, and Novartis, and has received honoraria from GlaxoSmithKline.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF ALLERGY, ASTHMA, AND IMMUNOLOGY

Intermittent High-Dose Inhaled Corticosteroid Works for Wheezing Toddlers

SAN FRANCISCO – Intermittent courses of high-dose inhaled budesonide were as effective and as safe as daily low-dose inhaled budesonide in wheezing toddlers but exposed them to a lower cumulative dose of the corticosteroid in a year-long study of 278 children.

The two groups did not differ significantly in the frequency of exacerbations that required systemic corticosteroids, the frequency or severity of respiratory tract illness, the number of urgent or emergent visits for care, or other efficacy and safety measures, Dr. Leonard B. Bacharier and his associates reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

Children in the daily low-dose budesonide group, however, were exposed to more than three times the cumulative dose of budesonide, compared with the intermittent high-dose therapy group – 150 mg vs. 46 mg.

The multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, called the Maintenance Versus Intermittent Inhaled Steroids in Wheezing Toddlers (MIST) study, is the last of eight clinical trials performed by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Childhood Asthma Research and Education Network.

The NHLBI’s 2007 "Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management of Asthma" recommended using daily low-dose inhaled corticosteroids to treat children who have a positive modified Asthma Predictive Index.

The MIST study is the first to compare the currently recommended daily low-dose regimen with the intermittent high-dose regimen, said Dr. Bacharier of Washington University, St. Louis.

On the basis of the MIST results, Dr. Bacharier and his associates recommended instead that clinicians consider using intermittent high-dose inhaled corticosteroids in the subset of children identified in the MIST study, who were not the most severe asthma cases. They suggested starting a 7-day course of high-dose budesonide early during respiratory tract illnesses in wheezing children who have a positive modified Asthma Predictive Index, have had at least one exacerbation in the past year, use albuterol less than 3 days per week, and have had no more than one night awakening in the prior 2 weeks.

The study enrolled children 12-53 months of age, nearly half of whom were in the lower age range of 12-32 months. All children had a history of at least four wheezing episodes in the prior year (or at least three if they’d had 3 months or more of asthma controller therapy) and a positive modified Asthma Predictive Index. Each child also had at least one severe exacerbation that required systemic corticosteroids or an unscheduled urgent or emergent visit or hospitalization in the previous year.

The study excluded children who had more than two hospitalizations for wheezing or more than six courses of oral corticosteroids.

During a 2-week run-in period, all children used a nebulized placebo nightly and albuterol as needed. During this period, children who had persistent asthma symptoms or who did not follow the protocol for more than 25% of days also were excluded.

The children were then randomized for 52 weeks of therapy. The daily low-dose budesonide group used 0.5 mg of nebulized budesonide once daily at night except during respiratory tract illness, when they switched to "respiratory tract illness kits" that gave them nebulized placebo in the morning and 0.5 mg of budesonide at night for 7 days. The intermittent high-dose budesonide group used nebulized placebo once daily at night except during respiratory tract illness, when their kits gave them 1 mg of budesonide in the morning and at night for 7 days.

Previous studies have shown that daily inhaled corticosteroids have "a small but statistically significant class effect on reducing linear growth in preschool-aged children, which only partially reverses after discontinuation of study treatments," which was a main reason for studying the intermittent-therapy alternative, Dr. Bacharier said.

In the MIST study, children in the daily-therapy group grew an average of 7.76 cm, compared with 8.01 cm in the intermittent-therapy group, but the 0.25-cm greater growth with intermittent therapy was not statistically significant.

There were no significant differences between groups in baseline characteristics, adherence to therapy during the study, declines in levels of exhaled nitric oxide, time to first exacerbation, or time to treatment failure.

The NHLBI funded the study. AstraZeneca provided the budesonide and placebo for the study. Dr. Bacharier has been a consultant for AstraZeneca (which markets budesonide), Merck, and Novartis, and has received honoraria from GlaxoSmithKline.

SAN FRANCISCO – Intermittent courses of high-dose inhaled budesonide were as effective and as safe as daily low-dose inhaled budesonide in wheezing toddlers but exposed them to a lower cumulative dose of the corticosteroid in a year-long study of 278 children.

The two groups did not differ significantly in the frequency of exacerbations that required systemic corticosteroids, the frequency or severity of respiratory tract illness, the number of urgent or emergent visits for care, or other efficacy and safety measures, Dr. Leonard B. Bacharier and his associates reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

Children in the daily low-dose budesonide group, however, were exposed to more than three times the cumulative dose of budesonide, compared with the intermittent high-dose therapy group – 150 mg vs. 46 mg.

The multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, called the Maintenance Versus Intermittent Inhaled Steroids in Wheezing Toddlers (MIST) study, is the last of eight clinical trials performed by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Childhood Asthma Research and Education Network.

The NHLBI’s 2007 "Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management of Asthma" recommended using daily low-dose inhaled corticosteroids to treat children who have a positive modified Asthma Predictive Index.

The MIST study is the first to compare the currently recommended daily low-dose regimen with the intermittent high-dose regimen, said Dr. Bacharier of Washington University, St. Louis.

On the basis of the MIST results, Dr. Bacharier and his associates recommended instead that clinicians consider using intermittent high-dose inhaled corticosteroids in the subset of children identified in the MIST study, who were not the most severe asthma cases. They suggested starting a 7-day course of high-dose budesonide early during respiratory tract illnesses in wheezing children who have a positive modified Asthma Predictive Index, have had at least one exacerbation in the past year, use albuterol less than 3 days per week, and have had no more than one night awakening in the prior 2 weeks.

The study enrolled children 12-53 months of age, nearly half of whom were in the lower age range of 12-32 months. All children had a history of at least four wheezing episodes in the prior year (or at least three if they’d had 3 months or more of asthma controller therapy) and a positive modified Asthma Predictive Index. Each child also had at least one severe exacerbation that required systemic corticosteroids or an unscheduled urgent or emergent visit or hospitalization in the previous year.

The study excluded children who had more than two hospitalizations for wheezing or more than six courses of oral corticosteroids.

During a 2-week run-in period, all children used a nebulized placebo nightly and albuterol as needed. During this period, children who had persistent asthma symptoms or who did not follow the protocol for more than 25% of days also were excluded.

The children were then randomized for 52 weeks of therapy. The daily low-dose budesonide group used 0.5 mg of nebulized budesonide once daily at night except during respiratory tract illness, when they switched to "respiratory tract illness kits" that gave them nebulized placebo in the morning and 0.5 mg of budesonide at night for 7 days. The intermittent high-dose budesonide group used nebulized placebo once daily at night except during respiratory tract illness, when their kits gave them 1 mg of budesonide in the morning and at night for 7 days.

Previous studies have shown that daily inhaled corticosteroids have "a small but statistically significant class effect on reducing linear growth in preschool-aged children, which only partially reverses after discontinuation of study treatments," which was a main reason for studying the intermittent-therapy alternative, Dr. Bacharier said.

In the MIST study, children in the daily-therapy group grew an average of 7.76 cm, compared with 8.01 cm in the intermittent-therapy group, but the 0.25-cm greater growth with intermittent therapy was not statistically significant.

There were no significant differences between groups in baseline characteristics, adherence to therapy during the study, declines in levels of exhaled nitric oxide, time to first exacerbation, or time to treatment failure.

The NHLBI funded the study. AstraZeneca provided the budesonide and placebo for the study. Dr. Bacharier has been a consultant for AstraZeneca (which markets budesonide), Merck, and Novartis, and has received honoraria from GlaxoSmithKline.

SAN FRANCISCO – Intermittent courses of high-dose inhaled budesonide were as effective and as safe as daily low-dose inhaled budesonide in wheezing toddlers but exposed them to a lower cumulative dose of the corticosteroid in a year-long study of 278 children.

The two groups did not differ significantly in the frequency of exacerbations that required systemic corticosteroids, the frequency or severity of respiratory tract illness, the number of urgent or emergent visits for care, or other efficacy and safety measures, Dr. Leonard B. Bacharier and his associates reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

Children in the daily low-dose budesonide group, however, were exposed to more than three times the cumulative dose of budesonide, compared with the intermittent high-dose therapy group – 150 mg vs. 46 mg.

The multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, called the Maintenance Versus Intermittent Inhaled Steroids in Wheezing Toddlers (MIST) study, is the last of eight clinical trials performed by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Childhood Asthma Research and Education Network.

The NHLBI’s 2007 "Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management of Asthma" recommended using daily low-dose inhaled corticosteroids to treat children who have a positive modified Asthma Predictive Index.

The MIST study is the first to compare the currently recommended daily low-dose regimen with the intermittent high-dose regimen, said Dr. Bacharier of Washington University, St. Louis.

On the basis of the MIST results, Dr. Bacharier and his associates recommended instead that clinicians consider using intermittent high-dose inhaled corticosteroids in the subset of children identified in the MIST study, who were not the most severe asthma cases. They suggested starting a 7-day course of high-dose budesonide early during respiratory tract illnesses in wheezing children who have a positive modified Asthma Predictive Index, have had at least one exacerbation in the past year, use albuterol less than 3 days per week, and have had no more than one night awakening in the prior 2 weeks.

The study enrolled children 12-53 months of age, nearly half of whom were in the lower age range of 12-32 months. All children had a history of at least four wheezing episodes in the prior year (or at least three if they’d had 3 months or more of asthma controller therapy) and a positive modified Asthma Predictive Index. Each child also had at least one severe exacerbation that required systemic corticosteroids or an unscheduled urgent or emergent visit or hospitalization in the previous year.

The study excluded children who had more than two hospitalizations for wheezing or more than six courses of oral corticosteroids.

During a 2-week run-in period, all children used a nebulized placebo nightly and albuterol as needed. During this period, children who had persistent asthma symptoms or who did not follow the protocol for more than 25% of days also were excluded.

The children were then randomized for 52 weeks of therapy. The daily low-dose budesonide group used 0.5 mg of nebulized budesonide once daily at night except during respiratory tract illness, when they switched to "respiratory tract illness kits" that gave them nebulized placebo in the morning and 0.5 mg of budesonide at night for 7 days. The intermittent high-dose budesonide group used nebulized placebo once daily at night except during respiratory tract illness, when their kits gave them 1 mg of budesonide in the morning and at night for 7 days.

Previous studies have shown that daily inhaled corticosteroids have "a small but statistically significant class effect on reducing linear growth in preschool-aged children, which only partially reverses after discontinuation of study treatments," which was a main reason for studying the intermittent-therapy alternative, Dr. Bacharier said.

In the MIST study, children in the daily-therapy group grew an average of 7.76 cm, compared with 8.01 cm in the intermittent-therapy group, but the 0.25-cm greater growth with intermittent therapy was not statistically significant.

There were no significant differences between groups in baseline characteristics, adherence to therapy during the study, declines in levels of exhaled nitric oxide, time to first exacerbation, or time to treatment failure.

The NHLBI funded the study. AstraZeneca provided the budesonide and placebo for the study. Dr. Bacharier has been a consultant for AstraZeneca (which markets budesonide), Merck, and Novartis, and has received honoraria from GlaxoSmithKline.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF ALLERGY, ASTHMA, AND IMMUNOLOGY

Major Finding: Wheezing toddlers on intermittent high-dose budesonide or daily low-dose budesonide had similar results regarding frequency of exacerbations that required systemic corticosteroids, frequency or severity of respiratory tract illness, and number of urgent or emergent visits for care.

Data Source: Year-long multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 278 children.

Disclosures: The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute funded the study. AstraZeneca provided the budesonide and placebo for the study. Dr. Bacharier has been a consultant for AstraZeneca (which markets budesonide), Merck, and Novartis, and has received honoraria from GlaxoSmithKline.

Cerebral Microbleeds Common in Elderly

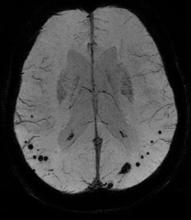

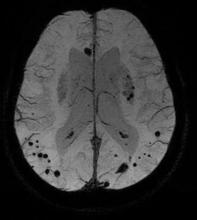

LOS ANGELES – The prevalence of cerebral microbleeds increased from 24% to 28%, and microbleeds rarely disappeared over a mean of 3 years, in a study of 831 older adults in the general Dutch population.

A subset of nondemented adults aged 60 years or older in the Rotterdam Study underwent brain MRI scans and other examinations in 2005-2006 and again in 2008-2010. Independent raters looked for microbleeds in side-by-side comparisons of the baseline and follow-up scans without knowing which was which and without access to other imaging or test results. The mean time between scans was 3.4 years.

People with microbleeds at baseline were five times more likely to develop new microbleeds. Among 203 people with microbleeds on the first scan, 25% had new microbleeds on the second scan compared with 5% of 628 people without microbleeds at baseline, Dr. Mariëlle M.F. Poels said at the International Stroke Conference.

The risk was even higher in people who had multiple microbleeds at baseline, who were seven times more likely to develop new microbleeds compared with people with no microbleeds on the initial scan, said Dr. Poels of Erasmus University, Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

The incidence of microbleeds increased with age, from 8% in people aged 60-69 years to 19% in people older than 80 years (Stroke 2011;42:656-61).

Previous longitudinal studies of cerebral microbleeds were smaller and focused on patients seen at memory clinics or patients with cerebral amyloid angiopathy instead of the general population.

The study used a three-dimensional T2*-weighted gradient-recalled echo sequence to detect microbleeds, defined as focal areas of very low signal intensity. The investigators used other MRI sequences to rate infarcts and used a validated tissue classification technique to assess white matter lesion volume. They collected DNA samples for apolipoprotein E genotyping.

Only six people (3%) had fewer microbleeds at follow-up compared with baseline. Four of these six had one microbleed on the initial scan and none at follow-up. The fifth person had two microbleeds at baseline and one at follow-up. The number of microbleeds in the sixth person decreased from 11 at baseline to 6 at follow-up, Dr. Poels said at the conference, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

In addition, another six people had some microbleeds on the initial scan that had disappeared at follow-up, but they also had new microbleeds, so their total number of microbleeds did not decrease over time. All but one of these six had more than five microbleeds at baseline and a higher number at follow-up.

In the entire cohort, 258 new microbleeds developed between the first and second scans, and only 18 microbleeds seemed to disappear. "Microbleeds rarely disappear," she said.

The location of microbleeds at baseline strongly predicted the location of new microbleeds. Of the new microbleeds, 60% were strictly lobar and 40% were either deep or infratentorial microbleeds.

Certain vascular risk factors for microbleeds were associated with the location of new microbleeds, suggesting that deep or infratentorial microbleeds are independent indicators of hypertensive vasculopathy, the investigators suggested.

High systolic blood pressure, high pulse pressure, and hypertension were associated with new deep or infratentorial microbleeds but not with new lobar microbleeds. Increasing serum total cholesterol was associated with a decreasing incidence of deep or infratentorial microbleeds on the follow-up scan.

The presence of lacunar infarcts at baseline was associated with a fourfold higher risk for new deep or infratentorial microbleeds at follow-up than in people without infarcts. A fourfold higher risk for new strictly lobar microbleeds was seen in people with the apolipoprotein E4 genotype. People with larger white matter lesion volume at baseline had double the likelihood of new microbleeds in any of the locations, compared with people with smaller white matter lesion volume at baseline.

"Microbleed assessment on T2*-weighted MRI may serve as a possible marker of both cerebral amyloid angiopathy and hypertensive vasculopathy progression," Dr. Poels said.

Controlling vascular risk factors in people who already have microbleeds may slow the progression of pathology and prevent symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage, she suggested.

The 831 participants who completed both MRI scans were younger and healthier than the 231 people who dropped out of the study after the first scan, either because they refused a second scan or were ineligible to continue. This may have resulted in underestimation of the true incidence of microbleeds in the general population and underestimation of associations between risk factors and incident cerebral microbleeds, the investigators noted.

Dr. Poels and her associates said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – The prevalence of cerebral microbleeds increased from 24% to 28%, and microbleeds rarely disappeared over a mean of 3 years, in a study of 831 older adults in the general Dutch population.

A subset of nondemented adults aged 60 years or older in the Rotterdam Study underwent brain MRI scans and other examinations in 2005-2006 and again in 2008-2010. Independent raters looked for microbleeds in side-by-side comparisons of the baseline and follow-up scans without knowing which was which and without access to other imaging or test results. The mean time between scans was 3.4 years.

People with microbleeds at baseline were five times more likely to develop new microbleeds. Among 203 people with microbleeds on the first scan, 25% had new microbleeds on the second scan compared with 5% of 628 people without microbleeds at baseline, Dr. Mariëlle M.F. Poels said at the International Stroke Conference.

The risk was even higher in people who had multiple microbleeds at baseline, who were seven times more likely to develop new microbleeds compared with people with no microbleeds on the initial scan, said Dr. Poels of Erasmus University, Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

The incidence of microbleeds increased with age, from 8% in people aged 60-69 years to 19% in people older than 80 years (Stroke 2011;42:656-61).

Previous longitudinal studies of cerebral microbleeds were smaller and focused on patients seen at memory clinics or patients with cerebral amyloid angiopathy instead of the general population.

The study used a three-dimensional T2*-weighted gradient-recalled echo sequence to detect microbleeds, defined as focal areas of very low signal intensity. The investigators used other MRI sequences to rate infarcts and used a validated tissue classification technique to assess white matter lesion volume. They collected DNA samples for apolipoprotein E genotyping.

Only six people (3%) had fewer microbleeds at follow-up compared with baseline. Four of these six had one microbleed on the initial scan and none at follow-up. The fifth person had two microbleeds at baseline and one at follow-up. The number of microbleeds in the sixth person decreased from 11 at baseline to 6 at follow-up, Dr. Poels said at the conference, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

In addition, another six people had some microbleeds on the initial scan that had disappeared at follow-up, but they also had new microbleeds, so their total number of microbleeds did not decrease over time. All but one of these six had more than five microbleeds at baseline and a higher number at follow-up.

In the entire cohort, 258 new microbleeds developed between the first and second scans, and only 18 microbleeds seemed to disappear. "Microbleeds rarely disappear," she said.

The location of microbleeds at baseline strongly predicted the location of new microbleeds. Of the new microbleeds, 60% were strictly lobar and 40% were either deep or infratentorial microbleeds.

Certain vascular risk factors for microbleeds were associated with the location of new microbleeds, suggesting that deep or infratentorial microbleeds are independent indicators of hypertensive vasculopathy, the investigators suggested.

High systolic blood pressure, high pulse pressure, and hypertension were associated with new deep or infratentorial microbleeds but not with new lobar microbleeds. Increasing serum total cholesterol was associated with a decreasing incidence of deep or infratentorial microbleeds on the follow-up scan.

The presence of lacunar infarcts at baseline was associated with a fourfold higher risk for new deep or infratentorial microbleeds at follow-up than in people without infarcts. A fourfold higher risk for new strictly lobar microbleeds was seen in people with the apolipoprotein E4 genotype. People with larger white matter lesion volume at baseline had double the likelihood of new microbleeds in any of the locations, compared with people with smaller white matter lesion volume at baseline.

"Microbleed assessment on T2*-weighted MRI may serve as a possible marker of both cerebral amyloid angiopathy and hypertensive vasculopathy progression," Dr. Poels said.

Controlling vascular risk factors in people who already have microbleeds may slow the progression of pathology and prevent symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage, she suggested.

The 831 participants who completed both MRI scans were younger and healthier than the 231 people who dropped out of the study after the first scan, either because they refused a second scan or were ineligible to continue. This may have resulted in underestimation of the true incidence of microbleeds in the general population and underestimation of associations between risk factors and incident cerebral microbleeds, the investigators noted.

Dr. Poels and her associates said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – The prevalence of cerebral microbleeds increased from 24% to 28%, and microbleeds rarely disappeared over a mean of 3 years, in a study of 831 older adults in the general Dutch population.

A subset of nondemented adults aged 60 years or older in the Rotterdam Study underwent brain MRI scans and other examinations in 2005-2006 and again in 2008-2010. Independent raters looked for microbleeds in side-by-side comparisons of the baseline and follow-up scans without knowing which was which and without access to other imaging or test results. The mean time between scans was 3.4 years.

People with microbleeds at baseline were five times more likely to develop new microbleeds. Among 203 people with microbleeds on the first scan, 25% had new microbleeds on the second scan compared with 5% of 628 people without microbleeds at baseline, Dr. Mariëlle M.F. Poels said at the International Stroke Conference.

The risk was even higher in people who had multiple microbleeds at baseline, who were seven times more likely to develop new microbleeds compared with people with no microbleeds on the initial scan, said Dr. Poels of Erasmus University, Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

The incidence of microbleeds increased with age, from 8% in people aged 60-69 years to 19% in people older than 80 years (Stroke 2011;42:656-61).

Previous longitudinal studies of cerebral microbleeds were smaller and focused on patients seen at memory clinics or patients with cerebral amyloid angiopathy instead of the general population.

The study used a three-dimensional T2*-weighted gradient-recalled echo sequence to detect microbleeds, defined as focal areas of very low signal intensity. The investigators used other MRI sequences to rate infarcts and used a validated tissue classification technique to assess white matter lesion volume. They collected DNA samples for apolipoprotein E genotyping.

Only six people (3%) had fewer microbleeds at follow-up compared with baseline. Four of these six had one microbleed on the initial scan and none at follow-up. The fifth person had two microbleeds at baseline and one at follow-up. The number of microbleeds in the sixth person decreased from 11 at baseline to 6 at follow-up, Dr. Poels said at the conference, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

In addition, another six people had some microbleeds on the initial scan that had disappeared at follow-up, but they also had new microbleeds, so their total number of microbleeds did not decrease over time. All but one of these six had more than five microbleeds at baseline and a higher number at follow-up.

In the entire cohort, 258 new microbleeds developed between the first and second scans, and only 18 microbleeds seemed to disappear. "Microbleeds rarely disappear," she said.

The location of microbleeds at baseline strongly predicted the location of new microbleeds. Of the new microbleeds, 60% were strictly lobar and 40% were either deep or infratentorial microbleeds.

Certain vascular risk factors for microbleeds were associated with the location of new microbleeds, suggesting that deep or infratentorial microbleeds are independent indicators of hypertensive vasculopathy, the investigators suggested.

High systolic blood pressure, high pulse pressure, and hypertension were associated with new deep or infratentorial microbleeds but not with new lobar microbleeds. Increasing serum total cholesterol was associated with a decreasing incidence of deep or infratentorial microbleeds on the follow-up scan.

The presence of lacunar infarcts at baseline was associated with a fourfold higher risk for new deep or infratentorial microbleeds at follow-up than in people without infarcts. A fourfold higher risk for new strictly lobar microbleeds was seen in people with the apolipoprotein E4 genotype. People with larger white matter lesion volume at baseline had double the likelihood of new microbleeds in any of the locations, compared with people with smaller white matter lesion volume at baseline.

"Microbleed assessment on T2*-weighted MRI may serve as a possible marker of both cerebral amyloid angiopathy and hypertensive vasculopathy progression," Dr. Poels said.

Controlling vascular risk factors in people who already have microbleeds may slow the progression of pathology and prevent symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage, she suggested.

The 831 participants who completed both MRI scans were younger and healthier than the 231 people who dropped out of the study after the first scan, either because they refused a second scan or were ineligible to continue. This may have resulted in underestimation of the true incidence of microbleeds in the general population and underestimation of associations between risk factors and incident cerebral microbleeds, the investigators noted.

Dr. Poels and her associates said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE INTERNATIONAL STROKE CONFERENCE

Major Finding: Cerebral microbleeds were present in 24% of elderly people in the general population, increased in number with age, and rarely disappeared over time.

Data Source: Repeat brain MRI scans a mean of 3 years apart in 831 elderly non-demented adults within the longitudinal Rotterdam Study.

Disclosures: Dr. Poels and her associates said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

Cerebral Microbleeds Common in Elderly

LOS ANGELES – The prevalence of cerebral microbleeds increased from 24% to 28%, and microbleeds rarely disappeared over a mean of 3 years, in a study of 831 older adults in the general Dutch population.

A subset of nondemented adults aged 60 years or older in the Rotterdam Study underwent brain MRI scans and other examinations in 2005-2006 and again in 2008-2010. Independent raters looked for microbleeds in side-by-side comparisons of the baseline and follow-up scans without knowing which was which and without access to other imaging or test results. The mean time between scans was 3.4 years.

People with microbleeds at baseline were five times more likely to develop new microbleeds. Among 203 people with microbleeds on the first scan, 25% had new microbleeds on the second scan compared with 5% of 628 people without microbleeds at baseline, Dr. Mariëlle M.F. Poels said at the International Stroke Conference.

The risk was even higher in people who had multiple microbleeds at baseline, who were seven times more likely to develop new microbleeds compared with people with no microbleeds on the initial scan, said Dr. Poels of Erasmus University, Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

The incidence of microbleeds increased with age, from 8% in people aged 60-69 years to 19% in people older than 80 years (Stroke 2011;42:656-61).

Previous longitudinal studies of cerebral microbleeds were smaller and focused on patients seen at memory clinics or patients with cerebral amyloid angiopathy instead of the general population.

The study used a three-dimensional T2*-weighted gradient-recalled echo sequence to detect microbleeds, defined as focal areas of very low signal intensity. The investigators used other MRI sequences to rate infarcts and used a validated tissue classification technique to assess white matter lesion volume. They collected DNA samples for apolipoprotein E genotyping.

Only six people (3%) had fewer microbleeds at follow-up compared with baseline. Four of these six had one microbleed on the initial scan and none at follow-up. The fifth person had two microbleeds at baseline and one at follow-up. The number of microbleeds in the sixth person decreased from 11 at baseline to 6 at follow-up, Dr. Poels said at the conference, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

In addition, another six people had some microbleeds on the initial scan that had disappeared at follow-up, but they also had new microbleeds, so their total number of microbleeds did not decrease over time. All but one of these six had more than five microbleeds at baseline and a higher number at follow-up.

In the entire cohort, 258 new microbleeds developed between the first and second scans, and only 18 microbleeds seemed to disappear. "Microbleeds rarely disappear," she said.

The location of microbleeds at baseline strongly predicted the location of new microbleeds. Of the new microbleeds, 60% were strictly lobar and 40% were either deep or infratentorial microbleeds.

Certain vascular risk factors for microbleeds were associated with the location of new microbleeds, suggesting that deep or infratentorial microbleeds are independent indicators of hypertensive vasculopathy, the investigators suggested.

High systolic blood pressure, high pulse pressure, and hypertension were associated with new deep or infratentorial microbleeds but not with new lobar microbleeds. Increasing serum total cholesterol was associated with a decreasing incidence of deep or infratentorial microbleeds on the follow-up scan.

The presence of lacunar infarcts at baseline was associated with a fourfold higher risk for new deep or infratentorial microbleeds at follow-up than in people without infarcts. A fourfold higher risk for new strictly lobar microbleeds was seen in people with the apolipoprotein E4 genotype. People with larger white matter lesion volume at baseline had double the likelihood of new microbleeds in any of the locations, compared with people with smaller white matter lesion volume at baseline.

"Microbleed assessment on T2*-weighted MRI may serve as a possible marker of both cerebral amyloid angiopathy and hypertensive vasculopathy progression," Dr. Poels said.

Controlling vascular risk factors in people who already have microbleeds may slow the progression of pathology and prevent symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage, she suggested.

The 831 participants who completed both MRI scans were younger and healthier than the 231 people who dropped out of the study after the first scan, either because they refused a second scan or were ineligible to continue. This may have resulted in underestimation of the true incidence of microbleeds in the general population and underestimation of associations between risk factors and incident cerebral microbleeds, the investigators noted.

Dr. Poels and her associates said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – The prevalence of cerebral microbleeds increased from 24% to 28%, and microbleeds rarely disappeared over a mean of 3 years, in a study of 831 older adults in the general Dutch population.

A subset of nondemented adults aged 60 years or older in the Rotterdam Study underwent brain MRI scans and other examinations in 2005-2006 and again in 2008-2010. Independent raters looked for microbleeds in side-by-side comparisons of the baseline and follow-up scans without knowing which was which and without access to other imaging or test results. The mean time between scans was 3.4 years.

People with microbleeds at baseline were five times more likely to develop new microbleeds. Among 203 people with microbleeds on the first scan, 25% had new microbleeds on the second scan compared with 5% of 628 people without microbleeds at baseline, Dr. Mariëlle M.F. Poels said at the International Stroke Conference.

The risk was even higher in people who had multiple microbleeds at baseline, who were seven times more likely to develop new microbleeds compared with people with no microbleeds on the initial scan, said Dr. Poels of Erasmus University, Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

The incidence of microbleeds increased with age, from 8% in people aged 60-69 years to 19% in people older than 80 years (Stroke 2011;42:656-61).

Previous longitudinal studies of cerebral microbleeds were smaller and focused on patients seen at memory clinics or patients with cerebral amyloid angiopathy instead of the general population.

The study used a three-dimensional T2*-weighted gradient-recalled echo sequence to detect microbleeds, defined as focal areas of very low signal intensity. The investigators used other MRI sequences to rate infarcts and used a validated tissue classification technique to assess white matter lesion volume. They collected DNA samples for apolipoprotein E genotyping.

Only six people (3%) had fewer microbleeds at follow-up compared with baseline. Four of these six had one microbleed on the initial scan and none at follow-up. The fifth person had two microbleeds at baseline and one at follow-up. The number of microbleeds in the sixth person decreased from 11 at baseline to 6 at follow-up, Dr. Poels said at the conference, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

In addition, another six people had some microbleeds on the initial scan that had disappeared at follow-up, but they also had new microbleeds, so their total number of microbleeds did not decrease over time. All but one of these six had more than five microbleeds at baseline and a higher number at follow-up.

In the entire cohort, 258 new microbleeds developed between the first and second scans, and only 18 microbleeds seemed to disappear. "Microbleeds rarely disappear," she said.

The location of microbleeds at baseline strongly predicted the location of new microbleeds. Of the new microbleeds, 60% were strictly lobar and 40% were either deep or infratentorial microbleeds.

Certain vascular risk factors for microbleeds were associated with the location of new microbleeds, suggesting that deep or infratentorial microbleeds are independent indicators of hypertensive vasculopathy, the investigators suggested.

High systolic blood pressure, high pulse pressure, and hypertension were associated with new deep or infratentorial microbleeds but not with new lobar microbleeds. Increasing serum total cholesterol was associated with a decreasing incidence of deep or infratentorial microbleeds on the follow-up scan.

The presence of lacunar infarcts at baseline was associated with a fourfold higher risk for new deep or infratentorial microbleeds at follow-up than in people without infarcts. A fourfold higher risk for new strictly lobar microbleeds was seen in people with the apolipoprotein E4 genotype. People with larger white matter lesion volume at baseline had double the likelihood of new microbleeds in any of the locations, compared with people with smaller white matter lesion volume at baseline.

"Microbleed assessment on T2*-weighted MRI may serve as a possible marker of both cerebral amyloid angiopathy and hypertensive vasculopathy progression," Dr. Poels said.

Controlling vascular risk factors in people who already have microbleeds may slow the progression of pathology and prevent symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage, she suggested.

The 831 participants who completed both MRI scans were younger and healthier than the 231 people who dropped out of the study after the first scan, either because they refused a second scan or were ineligible to continue. This may have resulted in underestimation of the true incidence of microbleeds in the general population and underestimation of associations between risk factors and incident cerebral microbleeds, the investigators noted.

Dr. Poels and her associates said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – The prevalence of cerebral microbleeds increased from 24% to 28%, and microbleeds rarely disappeared over a mean of 3 years, in a study of 831 older adults in the general Dutch population.

A subset of nondemented adults aged 60 years or older in the Rotterdam Study underwent brain MRI scans and other examinations in 2005-2006 and again in 2008-2010. Independent raters looked for microbleeds in side-by-side comparisons of the baseline and follow-up scans without knowing which was which and without access to other imaging or test results. The mean time between scans was 3.4 years.

People with microbleeds at baseline were five times more likely to develop new microbleeds. Among 203 people with microbleeds on the first scan, 25% had new microbleeds on the second scan compared with 5% of 628 people without microbleeds at baseline, Dr. Mariëlle M.F. Poels said at the International Stroke Conference.

The risk was even higher in people who had multiple microbleeds at baseline, who were seven times more likely to develop new microbleeds compared with people with no microbleeds on the initial scan, said Dr. Poels of Erasmus University, Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

The incidence of microbleeds increased with age, from 8% in people aged 60-69 years to 19% in people older than 80 years (Stroke 2011;42:656-61).

Previous longitudinal studies of cerebral microbleeds were smaller and focused on patients seen at memory clinics or patients with cerebral amyloid angiopathy instead of the general population.

The study used a three-dimensional T2*-weighted gradient-recalled echo sequence to detect microbleeds, defined as focal areas of very low signal intensity. The investigators used other MRI sequences to rate infarcts and used a validated tissue classification technique to assess white matter lesion volume. They collected DNA samples for apolipoprotein E genotyping.

Only six people (3%) had fewer microbleeds at follow-up compared with baseline. Four of these six had one microbleed on the initial scan and none at follow-up. The fifth person had two microbleeds at baseline and one at follow-up. The number of microbleeds in the sixth person decreased from 11 at baseline to 6 at follow-up, Dr. Poels said at the conference, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

In addition, another six people had some microbleeds on the initial scan that had disappeared at follow-up, but they also had new microbleeds, so their total number of microbleeds did not decrease over time. All but one of these six had more than five microbleeds at baseline and a higher number at follow-up.

In the entire cohort, 258 new microbleeds developed between the first and second scans, and only 18 microbleeds seemed to disappear. "Microbleeds rarely disappear," she said.

The location of microbleeds at baseline strongly predicted the location of new microbleeds. Of the new microbleeds, 60% were strictly lobar and 40% were either deep or infratentorial microbleeds.

Certain vascular risk factors for microbleeds were associated with the location of new microbleeds, suggesting that deep or infratentorial microbleeds are independent indicators of hypertensive vasculopathy, the investigators suggested.

High systolic blood pressure, high pulse pressure, and hypertension were associated with new deep or infratentorial microbleeds but not with new lobar microbleeds. Increasing serum total cholesterol was associated with a decreasing incidence of deep or infratentorial microbleeds on the follow-up scan.

The presence of lacunar infarcts at baseline was associated with a fourfold higher risk for new deep or infratentorial microbleeds at follow-up than in people without infarcts. A fourfold higher risk for new strictly lobar microbleeds was seen in people with the apolipoprotein E4 genotype. People with larger white matter lesion volume at baseline had double the likelihood of new microbleeds in any of the locations, compared with people with smaller white matter lesion volume at baseline.

"Microbleed assessment on T2*-weighted MRI may serve as a possible marker of both cerebral amyloid angiopathy and hypertensive vasculopathy progression," Dr. Poels said.

Controlling vascular risk factors in people who already have microbleeds may slow the progression of pathology and prevent symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage, she suggested.

The 831 participants who completed both MRI scans were younger and healthier than the 231 people who dropped out of the study after the first scan, either because they refused a second scan or were ineligible to continue. This may have resulted in underestimation of the true incidence of microbleeds in the general population and underestimation of associations between risk factors and incident cerebral microbleeds, the investigators noted.

Dr. Poels and her associates said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE INTERNATIONAL STROKE CONFERENCE

Major Finding: Cerebral microbleeds were present in 24% of elderly people in the general population, increased in number with age, and rarely disappeared over time.

Data Source: Repeat brain MRI scans a mean of 3 years apart in 831 elderly non-demented adults within the longitudinal Rotterdam Study.

Disclosures: Dr. Poels and her associates said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

Cerebral Microbleeds Common in Elderly

LOS ANGELES – The prevalence of cerebral microbleeds increased from 24% to 28%, and microbleeds rarely disappeared over a mean of 3 years, in a study of 831 older adults in the general Dutch population.

A subset of nondemented adults aged 60 years or older in the Rotterdam Study underwent brain MRI scans and other examinations in 2005-2006 and again in 2008-2010. Independent raters looked for microbleeds in side-by-side comparisons of the baseline and follow-up scans without knowing which was which and without access to other imaging or test results. The mean time between scans was 3.4 years.

People with microbleeds at baseline were five times more likely to develop new microbleeds. Among 203 people with microbleeds on the first scan, 25% had new microbleeds on the second scan compared with 5% of 628 people without microbleeds at baseline, Dr. Mariëlle M.F. Poels said at the International Stroke Conference.

The risk was even higher in people who had multiple microbleeds at baseline, who were seven times more likely to develop new microbleeds compared with people with no microbleeds on the initial scan, said Dr. Poels of Erasmus University, Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

The incidence of microbleeds increased with age, from 8% in people aged 60-69 years to 19% in people older than 80 years (Stroke 2011;42:656-61).

Previous longitudinal studies of cerebral microbleeds were smaller and focused on patients seen at memory clinics or patients with cerebral amyloid angiopathy instead of the general population.

The study used a three-dimensional T2*-weighted gradient-recalled echo sequence to detect microbleeds, defined as focal areas of very low signal intensity. The investigators used other MRI sequences to rate infarcts and used a validated tissue classification technique to assess white matter lesion volume. They collected DNA samples for apolipoprotein E genotyping.

Only six people (3%) had fewer microbleeds at follow-up compared with baseline. Four of these six had one microbleed on the initial scan and none at follow-up. The fifth person had two microbleeds at baseline and one at follow-up. The number of microbleeds in the sixth person decreased from 11 at baseline to 6 at follow-up, Dr. Poels said at the conference, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

In addition, another six people had some microbleeds on the initial scan that had disappeared at follow-up, but they also had new microbleeds, so their total number of microbleeds did not decrease over time. All but one of these six had more than five microbleeds at baseline and a higher number at follow-up.

In the entire cohort, 258 new microbleeds developed between the first and second scans, and only 18 microbleeds seemed to disappear. "Microbleeds rarely disappear," she said.

The location of microbleeds at baseline strongly predicted the location of new microbleeds. Of the new microbleeds, 60% were strictly lobar and 40% were either deep or infratentorial microbleeds.

Certain vascular risk factors for microbleeds were associated with the location of new microbleeds, suggesting that deep or infratentorial microbleeds are independent indicators of hypertensive vasculopathy, the investigators suggested.

High systolic blood pressure, high pulse pressure, and hypertension were associated with new deep or infratentorial microbleeds but not with new lobar microbleeds. Increasing serum total cholesterol was associated with a decreasing incidence of deep or infratentorial microbleeds on the follow-up scan.

The presence of lacunar infarcts at baseline was associated with a fourfold higher risk for new deep or infratentorial microbleeds at follow-up than in people without infarcts. A fourfold higher risk for new strictly lobar microbleeds was seen in people with the apolipoprotein E4 genotype. People with larger white matter lesion volume at baseline had double the likelihood of new microbleeds in any of the locations, compared with people with smaller white matter lesion volume at baseline.

"Microbleed assessment on T2*-weighted MRI may serve as a possible marker of both cerebral amyloid angiopathy and hypertensive vasculopathy progression," Dr. Poels said.

Controlling vascular risk factors in people who already have microbleeds may slow the progression of pathology and prevent symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage, she suggested.

The 831 participants who completed both MRI scans were younger and healthier than the 231 people who dropped out of the study after the first scan, either because they refused a second scan or were ineligible to continue. This may have resulted in underestimation of the true incidence of microbleeds in the general population and underestimation of associations between risk factors and incident cerebral microbleeds, the investigators noted.

Dr. Poels and her associates said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – The prevalence of cerebral microbleeds increased from 24% to 28%, and microbleeds rarely disappeared over a mean of 3 years, in a study of 831 older adults in the general Dutch population.

A subset of nondemented adults aged 60 years or older in the Rotterdam Study underwent brain MRI scans and other examinations in 2005-2006 and again in 2008-2010. Independent raters looked for microbleeds in side-by-side comparisons of the baseline and follow-up scans without knowing which was which and without access to other imaging or test results. The mean time between scans was 3.4 years.

People with microbleeds at baseline were five times more likely to develop new microbleeds. Among 203 people with microbleeds on the first scan, 25% had new microbleeds on the second scan compared with 5% of 628 people without microbleeds at baseline, Dr. Mariëlle M.F. Poels said at the International Stroke Conference.

The risk was even higher in people who had multiple microbleeds at baseline, who were seven times more likely to develop new microbleeds compared with people with no microbleeds on the initial scan, said Dr. Poels of Erasmus University, Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

The incidence of microbleeds increased with age, from 8% in people aged 60-69 years to 19% in people older than 80 years (Stroke 2011;42:656-61).

Previous longitudinal studies of cerebral microbleeds were smaller and focused on patients seen at memory clinics or patients with cerebral amyloid angiopathy instead of the general population.

The study used a three-dimensional T2*-weighted gradient-recalled echo sequence to detect microbleeds, defined as focal areas of very low signal intensity. The investigators used other MRI sequences to rate infarcts and used a validated tissue classification technique to assess white matter lesion volume. They collected DNA samples for apolipoprotein E genotyping.

Only six people (3%) had fewer microbleeds at follow-up compared with baseline. Four of these six had one microbleed on the initial scan and none at follow-up. The fifth person had two microbleeds at baseline and one at follow-up. The number of microbleeds in the sixth person decreased from 11 at baseline to 6 at follow-up, Dr. Poels said at the conference, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

In addition, another six people had some microbleeds on the initial scan that had disappeared at follow-up, but they also had new microbleeds, so their total number of microbleeds did not decrease over time. All but one of these six had more than five microbleeds at baseline and a higher number at follow-up.

In the entire cohort, 258 new microbleeds developed between the first and second scans, and only 18 microbleeds seemed to disappear. "Microbleeds rarely disappear," she said.

The location of microbleeds at baseline strongly predicted the location of new microbleeds. Of the new microbleeds, 60% were strictly lobar and 40% were either deep or infratentorial microbleeds.

Certain vascular risk factors for microbleeds were associated with the location of new microbleeds, suggesting that deep or infratentorial microbleeds are independent indicators of hypertensive vasculopathy, the investigators suggested.

High systolic blood pressure, high pulse pressure, and hypertension were associated with new deep or infratentorial microbleeds but not with new lobar microbleeds. Increasing serum total cholesterol was associated with a decreasing incidence of deep or infratentorial microbleeds on the follow-up scan.

The presence of lacunar infarcts at baseline was associated with a fourfold higher risk for new deep or infratentorial microbleeds at follow-up than in people without infarcts. A fourfold higher risk for new strictly lobar microbleeds was seen in people with the apolipoprotein E4 genotype. People with larger white matter lesion volume at baseline had double the likelihood of new microbleeds in any of the locations, compared with people with smaller white matter lesion volume at baseline.

"Microbleed assessment on T2*-weighted MRI may serve as a possible marker of both cerebral amyloid angiopathy and hypertensive vasculopathy progression," Dr. Poels said.

Controlling vascular risk factors in people who already have microbleeds may slow the progression of pathology and prevent symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage, she suggested.

The 831 participants who completed both MRI scans were younger and healthier than the 231 people who dropped out of the study after the first scan, either because they refused a second scan or were ineligible to continue. This may have resulted in underestimation of the true incidence of microbleeds in the general population and underestimation of associations between risk factors and incident cerebral microbleeds, the investigators noted.

Dr. Poels and her associates said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – The prevalence of cerebral microbleeds increased from 24% to 28%, and microbleeds rarely disappeared over a mean of 3 years, in a study of 831 older adults in the general Dutch population.

A subset of nondemented adults aged 60 years or older in the Rotterdam Study underwent brain MRI scans and other examinations in 2005-2006 and again in 2008-2010. Independent raters looked for microbleeds in side-by-side comparisons of the baseline and follow-up scans without knowing which was which and without access to other imaging or test results. The mean time between scans was 3.4 years.

People with microbleeds at baseline were five times more likely to develop new microbleeds. Among 203 people with microbleeds on the first scan, 25% had new microbleeds on the second scan compared with 5% of 628 people without microbleeds at baseline, Dr. Mariëlle M.F. Poels said at the International Stroke Conference.

The risk was even higher in people who had multiple microbleeds at baseline, who were seven times more likely to develop new microbleeds compared with people with no microbleeds on the initial scan, said Dr. Poels of Erasmus University, Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

The incidence of microbleeds increased with age, from 8% in people aged 60-69 years to 19% in people older than 80 years (Stroke 2011;42:656-61).

Previous longitudinal studies of cerebral microbleeds were smaller and focused on patients seen at memory clinics or patients with cerebral amyloid angiopathy instead of the general population.

The study used a three-dimensional T2*-weighted gradient-recalled echo sequence to detect microbleeds, defined as focal areas of very low signal intensity. The investigators used other MRI sequences to rate infarcts and used a validated tissue classification technique to assess white matter lesion volume. They collected DNA samples for apolipoprotein E genotyping.

Only six people (3%) had fewer microbleeds at follow-up compared with baseline. Four of these six had one microbleed on the initial scan and none at follow-up. The fifth person had two microbleeds at baseline and one at follow-up. The number of microbleeds in the sixth person decreased from 11 at baseline to 6 at follow-up, Dr. Poels said at the conference, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

In addition, another six people had some microbleeds on the initial scan that had disappeared at follow-up, but they also had new microbleeds, so their total number of microbleeds did not decrease over time. All but one of these six had more than five microbleeds at baseline and a higher number at follow-up.

In the entire cohort, 258 new microbleeds developed between the first and second scans, and only 18 microbleeds seemed to disappear. "Microbleeds rarely disappear," she said.

The location of microbleeds at baseline strongly predicted the location of new microbleeds. Of the new microbleeds, 60% were strictly lobar and 40% were either deep or infratentorial microbleeds.

Certain vascular risk factors for microbleeds were associated with the location of new microbleeds, suggesting that deep or infratentorial microbleeds are independent indicators of hypertensive vasculopathy, the investigators suggested.

High systolic blood pressure, high pulse pressure, and hypertension were associated with new deep or infratentorial microbleeds but not with new lobar microbleeds. Increasing serum total cholesterol was associated with a decreasing incidence of deep or infratentorial microbleeds on the follow-up scan.

The presence of lacunar infarcts at baseline was associated with a fourfold higher risk for new deep or infratentorial microbleeds at follow-up than in people without infarcts. A fourfold higher risk for new strictly lobar microbleeds was seen in people with the apolipoprotein E4 genotype. People with larger white matter lesion volume at baseline had double the likelihood of new microbleeds in any of the locations, compared with people with smaller white matter lesion volume at baseline.

"Microbleed assessment on T2*-weighted MRI may serve as a possible marker of both cerebral amyloid angiopathy and hypertensive vasculopathy progression," Dr. Poels said.

Controlling vascular risk factors in people who already have microbleeds may slow the progression of pathology and prevent symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage, she suggested.

The 831 participants who completed both MRI scans were younger and healthier than the 231 people who dropped out of the study after the first scan, either because they refused a second scan or were ineligible to continue. This may have resulted in underestimation of the true incidence of microbleeds in the general population and underestimation of associations between risk factors and incident cerebral microbleeds, the investigators noted.

Dr. Poels and her associates said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE INTERNATIONAL STROKE CONFERENCE

Major Finding: Cerebral microbleeds were present in 24% of elderly people in the general population, increased in number with age, and rarely disappeared over time.

Data Source: Repeat brain MRI scans a mean of 3 years apart in 831 elderly non-demented adults within the longitudinal Rotterdam Study.

Disclosures: Dr. Poels and her associates said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

Study Finds Icatibant Relieves Acute Angioedema

SAN FRANCISCO – The experimental drug icatibant relieved moderate or severe acute attacks of hereditary angioedema faster than placebo in the third randomized, double-blind, controlled trial of the experimental drug in 98 patients.

Among 88 patients with cutaneous and/or abdominal acute attacks, the 43 patients randomized to treatment with a single subcutaneous injection of 30 mg of icatibant reported that symptom relief started a median of 2 hours after treatment, compared with 20 hours for the 45 patients randomized to saline placebo injection. Symptom relief was defined as at least a 50% decrease in the combined Visual Analog Scale (VAS) symptom score, compared with baseline.

"I think this represents a very exciting, important advance in the treatment of an underserved population," Dr. William R. Lumry said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

A significant difference between groups was seen as early as 1 hour after treatment, but the 50% or greater reduction in VAS symptom scores was not achieved until 2 hours after treatment, Dr. Lumry and his associates reported.

The third For Angioedema Subcutaneous Treatment (FAST-3) trial followed two earlier phase III trials of the drug for acute attacks of hereditary angioedema, FAST-1 and FAST-2 (N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;363:532-41).

A "not approvable" letter from the Food and Drug Administration prompted Shire, the company developing icatibant, to provide more data to the FDA. The company’s response and results from FAST-3 are scheduled to be reviewed by the FDA in August 2011.

The FAST-3 study enrolled adults in 11 countries with moderate to very severe swelling from type I or type II hereditary angioedema that had been going on for no more than 12 hours and included at least one VAS score of 30 mm or greater. Patients were observed for 8 hours after injection, and their skin swelling, skin pain, abdominal pain, difficulty swallowing, and voice changes were assessed every 30 minutes for 4 hours after injection and at 5, 6, 8, and 12 hours. Rescue therapy was permitted but withheld if possible for 8-9 hours after injection.

Only the cutaneous and abdominal attacks were considered in the primary results, said Dr. Lumry, medical director of the Allergy and Asthma Research Associates Research Center, Dallas.

The 10 patients with laryngeal swelling attacks provided additional data. Five patients with severe laryngeal attacks immediately received open-label icatibant and reported onset of relief of symptoms a median of 2.3 hours later. Among five patients with mild to moderate laryngeal attacks, three patients who were randomized to icatibant treatment reported onset of symptom relief a median of 2.5 hours after treatment.

The two patients with mild to moderate attacks who were randomized to placebo both ended up getting icatibant, one whose attack was severe enough to warrant treatment, and the other a patient who received icatibant as rescue therapy 3.4 hours after randomization. Combined, the two patients with mild to moderate laryngeal attacks who were randomized to placebo reported onset of symptom relief a median of 3.2 hours after treatment.

Secondary outcomes in the nonlaryngeal cohort were significantly improved in the icatibant group, compared with the placebo group, Dr. Lumry said. The median time to initial symptom relief (assessed by the patients and the investigators) was less than 1 hour in the icatibant group and about 3.5 hours in the placebo group. The median time to onset of relief of the primary symptom (skin pain, skin swelling, or abdominal pain) was 1.5 hours in the icatibant group and 18.5 hours in the placebo group. The median time to almost complete symptom relief was less than 1 hour with icatibant and 36 hours with placebo.

Safety measures were recorded daily for 5 days and at a final 14-day safety visit.