User login

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries are common, and arthroscopic ACL reconstruction is a routine procedure. Successful ACL reconstruction requires correct placement of the graft within the anatomical insertion of the native ACL.1-3 Errors in surgical technique—specifically, improper femoral tunnel placement—are the most common cause of graft failure in patients who present with recurrent instability after ACL reconstruction.4 There has been much emphasis on placing the tunnel more centrally in the ACL footprint as well as in a more horizontal position, which is thought to provide better rotational control and anterior-to-posterior translational stability.5-7

Two common techniques for creating the femoral tunnel, transtibial and anteromedial drilling, have their unique limitations. Transtibial drilling can place the tunnel high in the notch, resulting in nonanatomical, vertical graft placement.8,9 This technique can be modified to obtain a more anatomical tunnel, but the risk is the tunnel will be short and close to the joint line.10 To avoid these difficulties, surgeons began using an anteromedial portal.11,12 Although anteromedial drilling places the tunnel in a more anatomical position, it too has drawbacks, including the need to hyperflex the knee, a short tunnel, damage to articular cartilage, proximity to neurovascular structures, and difficulty in visualization during drilling.13-16

Femoral tunnel drilling techniques using flexible guide pins and reamers have been developed to address the limitations of rigid instruments. When we first started using flexible instruments through anteromedial portals, there were multiple incidents of reamer breakage during drilling. We therefore developed a technique that uses a flexible guide pin with a rigid reamer to place the femoral tunnel in an anatomical position. The patient described in this article provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this report.

Technique

We begin with our standard arthroscopic portals, including superolateral outflow, lateral parapatellar, and medial parapatellar portals. The medial parapatellar portal is placed under direct visualization with insertion of an 18-gauge spinal needle, ensuring the trajectory reaches the anatomical location of the native ACL on the lateral femoral condyle (LFC). The ACL stump is débrided with a shaver and a radiofrequency ablator, leaving a remnant of tissue to assist with tunnel placement. We do not routinely perform a notchplasty unless there is a concern about possible graft impingement, or the notch is abnormally small. The anatomical footprint is marked with a small awl (Figure 1), and the arthroscope is moved into the anteromedial portal to confirm anatomical placement of the awl mark (Figure 2).

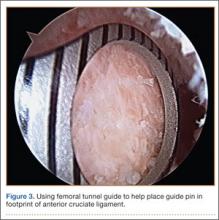

With the knee flexed to 100° to 110°, a flexible 2.7-mm nitonol guide pin (Smith & Nephew, Memphis, Tennessee) is placed freehand through the anteromedial portal into the anatomical footprint of the ACL, marked by the awl, and is passed through the femur before exiting the lateral skin. In most cases, we prefer freehand placement of the awl and pin; however, a femoral drill guide may be used to place the pin into the anatomical footprint of the ACL (Figure 3). The flexible pin allows for knee hyperflexion, clearance of the medial femoral condyle, central placement of the pin between the footprints of the anteromedial and posterolateral bundles for anatomical single-bundle reconstruction, and drilling of a long tunnel (average, 35-40 mm). The pin has a black laser marking that should be placed at the edge of the articular surface of the LFC to ensure appropriate depth of insertion (Figure 4).

A small incision is then made around the guide wire on the lateral thigh, and an outside-in depth gauge is used to obtain an accurate length for the femoral tunnel. The gauge must abut the femoral cortex for accurate assessment of tunnel length. We use an Endobutton (Smith & Nephew) for fixation of the graft in the tunnel. The measured length of the tunnel is used to select an Endobutton of appropriate size and the proper reaming depth for suspension. We routinely use a 10- or 15-mm Endobutton, which provides an average 20 to 25 mm of graft inside the bony tunnel. The knee may then be relaxed to a normal resting flexion angle off the side of the bed, and the arthroscope is inserted into a medial portal or an accessory anteromedial portal to ensure anatomical placement of the pin. Using a flexible guide pin allows the knee to be relatively extended, providing good visualization of overall positioning in relation to the posterior wall of the LFC, whereas keeping the knee in a flexed position (as with a rigid guide pin) can often compromise this visualization.

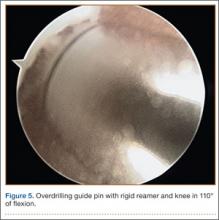

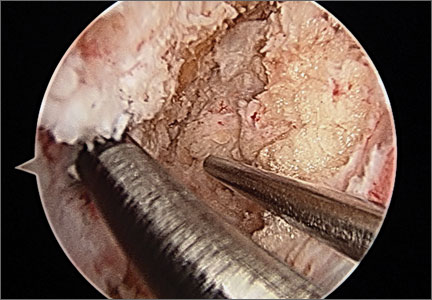

Using a solid reamer corresponding to the size of the graft, we drill over the guide pin to the appropriate depth, again with the knee hyperflexed (Figure 5), making sure not to breach the lateral femoral cortex, which would compromise fixation with the Endobutton. After drilling with the rigid reamer is completed, placement of the tunnel in an anatomical position is again confirmed with the knee in the normal resting flexion angle (Figure 6). Once the tibial tunnel is drilled at the anatomical footprint, the graft is passed with the proper-length Endobutton and is fixed on the tibial side with a bioabsorbable interference screw 1 to 2 mm larger than the soft-tissue graft and tibial tunnel size. The knee is flexed to 30° while the tibial screw is placed. Graft tension and impingement are then checked (Figure 7). Postoperative anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the knee may be obtained to confirm anatomical placement of the tunnels as well as proper positioning of the Endobutton (Figures 8A, 8B).

Discussion

Successful ACL reconstruction depends heavily on anatomical tunnel positioning. Failure to place the femoral tunnel in the anatomical footprint of the native ACL results in incomplete restoration of knee kinematics, rotational instability, and graft failure.1-7 Two common techniques for creating this tunnel, transtibial and anteromedial drilling, can reliably place it in an anatomical position. Each technique, however, has limitations. Transtibial drilling can place the tunnel too vertical and high in the notch, or produce a short tibial tunnel close to the joint line.8-10 Anteromedial drilling requires knee hyperflexion, risks damaging the articular cartilage and nearby neurovascular structures, and makes visualization difficult.13-16

One option for addressing some of the difficulties and limitations with anteromedial drilling is to use flexible guide pins and reamers, as first introduced by Cain and Clancy.1 In a cadaveric study, Silver and colleagues17 demonstrated that interosseous tunnels drilled with flexible guide pins were on average more than 6 mm longer than those drilled with rigid pins and consistently were 40 mm or longer. In addition, all tunnels drilled with flexible guide pins were on average 42.3 mm away from the peroneal nerve and 26.1 mm away from the femoral origin of the lateral collateral ligament—safe distances.

Steiner and Smart18 compared flexible and rigid instruments used to drill transtibial and anteromedial (without hyperflexion) anatomical femoral tunnels in ACL reconstruction in cadaveric knees. Although transtibial drilling with flexible pins produced anatomical tunnels, the tunnels were shorter, and the pins exited more posterior in comparison with anteromedial drilling with flexible pins. Transtibial tunnels drilled with rigid pins were nonanatomical and exited more superior and anterior on the femur, resulting in longer tunnels. Anteromedial tunnels drilled with rigid and flexible pins were placed anatomically, but flexible pins produced longer tunnels, did not require hyperflexion (120°), could easily be placed with the knee in 90° of flexion, and did not violate the posterior femoral cortex.

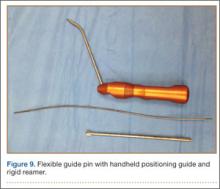

Five times in our early experience with flexible guide pins and reamers, the reamer broke when LFC reaming was initiated. In each case, the broken reamer was retrieved. However, these complications resulted in increased surgical time and cost. In addition, an unretrievable reamer could have caused further injury and suboptimal outcomes. We subsequently developed an anteromedial technique that uses a flexible guide pin with a rigid reamer to place the femoral tunnel in an anatomical position (Figure 9). The flexible pin provides consistent placement of anatomical tunnels averaging 35 to 40 mm in length. Use of the flexible pin does not require constant hyperflexion of the knee, and it allows for better visualization of the posterior wall of the LFC, ensures anatomical graft placement, and decreases the risk of damaging articular cartilage and causing neurovascular injury. Use of the rigid reamer negates the risks and additional costs associated with reamer breakage. It is unclear why 5 flexible reamers broke during our early use of flexible guide pins and reamers, but it is possible that, because of the patients’ anatomy, placement of the pin in the correct anatomical position in the ACL footprint put a significant amount of abnormal stress on the reamer during tunnel reaming, leading to breakage and failure.

A short femoral tunnel is a common complication of using an anteromedial portal for tunnel drilling.13-16 With the technique we have been using, tunnel lengths average 35 to 40 mm. To address the occasional shorter tunnel, we use Endobutton Direct (Smith & Nephew), which allows for direct fixation of the graft on the button, maximizing the amount of graft in the femoral tunnel and minimizing graft–tunnel length mismatch. In the event there is a lateral wall breach during overdrilling with the reamer, the femoral graft may be secured with screw and post, with interference screw, or with the larger Xtendobuton (Smith & Nephew).

We have successfully used this technique with bone–patellar tendon–bone (BPTB) and hamstring autografts, as well as allografts. Complications, such as graft–tunnel length mismatch, have been uncommon, but, when using BPTB grafts, passing the bone block into the femoral tunnel can be difficult because of the sharp turn required.

Conclusion

Successful ACL reconstruction depends heavily on placement of the graft within the anatomical insertion of the native ACL. With the development of techniques that use flexible guide pins and reamers, it has become possible to place longer anatomical femoral tunnels without the need for hyperflexion. Use of a flexible guide pin with a rigid reamer allows placement of longer anatomical tunnels through an anteromedial portal, reduces time spent with the knee in hyperflexion, provides better viewing, poses less risk of damage to the articular cartilage and neurovascular structures, and at a lower cost with less risk of reamer breakage. In addition, this technique can be used with a variety of graft options, including BPTB grafts, hamstring autografts, and allografts.

1. Cain EL Jr, Clancy WG Jr. Anatomic endoscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with patella tendon autograft. Orthop Clin North Am. 2002;33(4):717-725.

2. Chhabra A, Starman JS, Ferretti M, Vidal AF, Zantop T, Fu FH. Anatomic, radiographic, biomechanical, and kinematic evaluation of the anterior cruciate ligament and its two functional bundles. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(suppl 4):2-10.

3. Christel P, Sahasrabudhe A, Basdekis G. Anatomic double-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with anatomic aimers. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(10):1146-1151.

4. Allen CR, Giffin JR, Harner CD. Revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Orthop Clin North Am. 2003;34(1):79-98.

5. Miller CD, Gerdeman AC, Hart JM, et al. A comparison of 2 drilling techniques on the femoral tunnel for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(3):372-379.

6. Seon JK, Park SJ, Lee KB, Seo HY, Kim MS, Song EK. In vivo stability and clinical comparison of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using low or high femoral tunnel positions. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(1):127-133.

7. Steiner ME, Battaglia TC, Heming JF, Rand JD, Festa A, Baria M. Independent drilling outperforms conventional transtibial drilling in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(10):1912-1919.

8. Kopf S, Forsythe B, Wong AK, et al. Nonanatomic tunnel position in traditional transtibial single-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction evaluated by three-dimensional computed tomography. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(6):1427-1431.

9. Tompkins M, Milewski MD, Brockmeier SF, Gaskin CM, Hart JM, Miller MD. Anatomic femoral tunnel drilling in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: use of an accessory medial portal versus traditional transtibial drilling. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(6):1313-1321.

10. Heming JF, Rand J, Steiner ME. Anatomical limitations of transtibial drilling in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(10):1708-1715.

11. Harner CD, Honkamp NJ, Ranawat AS. Anteromedial portal technique for creating the anterior cruciate ligament femoral tunnel. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(1):113-115.

12. Lubowitz JH. Anteromedial portal technique for the anterior cruciate ligament femoral socket: pitfalls and solutions. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(1):95-101.

13. Basdekis G, Abisafi C, Christel P. Influence of knee flexion angle on femoral tunnel characteristics when drilled through the anteromedial portal during anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(4):459-464.

14. Zantop T, Haase AK, Fu FH, Petersen W. Potential risk of cartilage damage in double bundle ACL reconstruction: impact of knee flexion angle and portal location on the femoral PL bundle tunnel. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2008;128(5):509-513.

15. Farrow LD, Parker RD. The relationship of lateral anatomic structures to exiting guide pins during femoral tunnel preparation utilizing an accessory medial portal. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18(6):747-753.

16. Nakamura M, Deie M, Shibuya H, et al. Potential risks of femoral tunnel drilling through the far anteromedial portal: a cadaveric study. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(5):481-487.

17. Silver AG, Kaar SG, Grisell MK, Reagan JM, Farrow LD. Comparison between rigid and flexible systems for drilling the femoral tunnel through an anteromedial portal in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2010;26(6):790-795.

18. Steiner ME, Smart LR. Flexible instruments outperform rigid instruments to place anatomic anterior cruciate ligament femoral tunnels without hyperflexion. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(6):835-843.

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries are common, and arthroscopic ACL reconstruction is a routine procedure. Successful ACL reconstruction requires correct placement of the graft within the anatomical insertion of the native ACL.1-3 Errors in surgical technique—specifically, improper femoral tunnel placement—are the most common cause of graft failure in patients who present with recurrent instability after ACL reconstruction.4 There has been much emphasis on placing the tunnel more centrally in the ACL footprint as well as in a more horizontal position, which is thought to provide better rotational control and anterior-to-posterior translational stability.5-7

Two common techniques for creating the femoral tunnel, transtibial and anteromedial drilling, have their unique limitations. Transtibial drilling can place the tunnel high in the notch, resulting in nonanatomical, vertical graft placement.8,9 This technique can be modified to obtain a more anatomical tunnel, but the risk is the tunnel will be short and close to the joint line.10 To avoid these difficulties, surgeons began using an anteromedial portal.11,12 Although anteromedial drilling places the tunnel in a more anatomical position, it too has drawbacks, including the need to hyperflex the knee, a short tunnel, damage to articular cartilage, proximity to neurovascular structures, and difficulty in visualization during drilling.13-16

Femoral tunnel drilling techniques using flexible guide pins and reamers have been developed to address the limitations of rigid instruments. When we first started using flexible instruments through anteromedial portals, there were multiple incidents of reamer breakage during drilling. We therefore developed a technique that uses a flexible guide pin with a rigid reamer to place the femoral tunnel in an anatomical position. The patient described in this article provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this report.

Technique

We begin with our standard arthroscopic portals, including superolateral outflow, lateral parapatellar, and medial parapatellar portals. The medial parapatellar portal is placed under direct visualization with insertion of an 18-gauge spinal needle, ensuring the trajectory reaches the anatomical location of the native ACL on the lateral femoral condyle (LFC). The ACL stump is débrided with a shaver and a radiofrequency ablator, leaving a remnant of tissue to assist with tunnel placement. We do not routinely perform a notchplasty unless there is a concern about possible graft impingement, or the notch is abnormally small. The anatomical footprint is marked with a small awl (Figure 1), and the arthroscope is moved into the anteromedial portal to confirm anatomical placement of the awl mark (Figure 2).

With the knee flexed to 100° to 110°, a flexible 2.7-mm nitonol guide pin (Smith & Nephew, Memphis, Tennessee) is placed freehand through the anteromedial portal into the anatomical footprint of the ACL, marked by the awl, and is passed through the femur before exiting the lateral skin. In most cases, we prefer freehand placement of the awl and pin; however, a femoral drill guide may be used to place the pin into the anatomical footprint of the ACL (Figure 3). The flexible pin allows for knee hyperflexion, clearance of the medial femoral condyle, central placement of the pin between the footprints of the anteromedial and posterolateral bundles for anatomical single-bundle reconstruction, and drilling of a long tunnel (average, 35-40 mm). The pin has a black laser marking that should be placed at the edge of the articular surface of the LFC to ensure appropriate depth of insertion (Figure 4).

A small incision is then made around the guide wire on the lateral thigh, and an outside-in depth gauge is used to obtain an accurate length for the femoral tunnel. The gauge must abut the femoral cortex for accurate assessment of tunnel length. We use an Endobutton (Smith & Nephew) for fixation of the graft in the tunnel. The measured length of the tunnel is used to select an Endobutton of appropriate size and the proper reaming depth for suspension. We routinely use a 10- or 15-mm Endobutton, which provides an average 20 to 25 mm of graft inside the bony tunnel. The knee may then be relaxed to a normal resting flexion angle off the side of the bed, and the arthroscope is inserted into a medial portal or an accessory anteromedial portal to ensure anatomical placement of the pin. Using a flexible guide pin allows the knee to be relatively extended, providing good visualization of overall positioning in relation to the posterior wall of the LFC, whereas keeping the knee in a flexed position (as with a rigid guide pin) can often compromise this visualization.

Using a solid reamer corresponding to the size of the graft, we drill over the guide pin to the appropriate depth, again with the knee hyperflexed (Figure 5), making sure not to breach the lateral femoral cortex, which would compromise fixation with the Endobutton. After drilling with the rigid reamer is completed, placement of the tunnel in an anatomical position is again confirmed with the knee in the normal resting flexion angle (Figure 6). Once the tibial tunnel is drilled at the anatomical footprint, the graft is passed with the proper-length Endobutton and is fixed on the tibial side with a bioabsorbable interference screw 1 to 2 mm larger than the soft-tissue graft and tibial tunnel size. The knee is flexed to 30° while the tibial screw is placed. Graft tension and impingement are then checked (Figure 7). Postoperative anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the knee may be obtained to confirm anatomical placement of the tunnels as well as proper positioning of the Endobutton (Figures 8A, 8B).

Discussion

Successful ACL reconstruction depends heavily on anatomical tunnel positioning. Failure to place the femoral tunnel in the anatomical footprint of the native ACL results in incomplete restoration of knee kinematics, rotational instability, and graft failure.1-7 Two common techniques for creating this tunnel, transtibial and anteromedial drilling, can reliably place it in an anatomical position. Each technique, however, has limitations. Transtibial drilling can place the tunnel too vertical and high in the notch, or produce a short tibial tunnel close to the joint line.8-10 Anteromedial drilling requires knee hyperflexion, risks damaging the articular cartilage and nearby neurovascular structures, and makes visualization difficult.13-16

One option for addressing some of the difficulties and limitations with anteromedial drilling is to use flexible guide pins and reamers, as first introduced by Cain and Clancy.1 In a cadaveric study, Silver and colleagues17 demonstrated that interosseous tunnels drilled with flexible guide pins were on average more than 6 mm longer than those drilled with rigid pins and consistently were 40 mm or longer. In addition, all tunnels drilled with flexible guide pins were on average 42.3 mm away from the peroneal nerve and 26.1 mm away from the femoral origin of the lateral collateral ligament—safe distances.

Steiner and Smart18 compared flexible and rigid instruments used to drill transtibial and anteromedial (without hyperflexion) anatomical femoral tunnels in ACL reconstruction in cadaveric knees. Although transtibial drilling with flexible pins produced anatomical tunnels, the tunnels were shorter, and the pins exited more posterior in comparison with anteromedial drilling with flexible pins. Transtibial tunnels drilled with rigid pins were nonanatomical and exited more superior and anterior on the femur, resulting in longer tunnels. Anteromedial tunnels drilled with rigid and flexible pins were placed anatomically, but flexible pins produced longer tunnels, did not require hyperflexion (120°), could easily be placed with the knee in 90° of flexion, and did not violate the posterior femoral cortex.

Five times in our early experience with flexible guide pins and reamers, the reamer broke when LFC reaming was initiated. In each case, the broken reamer was retrieved. However, these complications resulted in increased surgical time and cost. In addition, an unretrievable reamer could have caused further injury and suboptimal outcomes. We subsequently developed an anteromedial technique that uses a flexible guide pin with a rigid reamer to place the femoral tunnel in an anatomical position (Figure 9). The flexible pin provides consistent placement of anatomical tunnels averaging 35 to 40 mm in length. Use of the flexible pin does not require constant hyperflexion of the knee, and it allows for better visualization of the posterior wall of the LFC, ensures anatomical graft placement, and decreases the risk of damaging articular cartilage and causing neurovascular injury. Use of the rigid reamer negates the risks and additional costs associated with reamer breakage. It is unclear why 5 flexible reamers broke during our early use of flexible guide pins and reamers, but it is possible that, because of the patients’ anatomy, placement of the pin in the correct anatomical position in the ACL footprint put a significant amount of abnormal stress on the reamer during tunnel reaming, leading to breakage and failure.

A short femoral tunnel is a common complication of using an anteromedial portal for tunnel drilling.13-16 With the technique we have been using, tunnel lengths average 35 to 40 mm. To address the occasional shorter tunnel, we use Endobutton Direct (Smith & Nephew), which allows for direct fixation of the graft on the button, maximizing the amount of graft in the femoral tunnel and minimizing graft–tunnel length mismatch. In the event there is a lateral wall breach during overdrilling with the reamer, the femoral graft may be secured with screw and post, with interference screw, or with the larger Xtendobuton (Smith & Nephew).

We have successfully used this technique with bone–patellar tendon–bone (BPTB) and hamstring autografts, as well as allografts. Complications, such as graft–tunnel length mismatch, have been uncommon, but, when using BPTB grafts, passing the bone block into the femoral tunnel can be difficult because of the sharp turn required.

Conclusion

Successful ACL reconstruction depends heavily on placement of the graft within the anatomical insertion of the native ACL. With the development of techniques that use flexible guide pins and reamers, it has become possible to place longer anatomical femoral tunnels without the need for hyperflexion. Use of a flexible guide pin with a rigid reamer allows placement of longer anatomical tunnels through an anteromedial portal, reduces time spent with the knee in hyperflexion, provides better viewing, poses less risk of damage to the articular cartilage and neurovascular structures, and at a lower cost with less risk of reamer breakage. In addition, this technique can be used with a variety of graft options, including BPTB grafts, hamstring autografts, and allografts.

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries are common, and arthroscopic ACL reconstruction is a routine procedure. Successful ACL reconstruction requires correct placement of the graft within the anatomical insertion of the native ACL.1-3 Errors in surgical technique—specifically, improper femoral tunnel placement—are the most common cause of graft failure in patients who present with recurrent instability after ACL reconstruction.4 There has been much emphasis on placing the tunnel more centrally in the ACL footprint as well as in a more horizontal position, which is thought to provide better rotational control and anterior-to-posterior translational stability.5-7

Two common techniques for creating the femoral tunnel, transtibial and anteromedial drilling, have their unique limitations. Transtibial drilling can place the tunnel high in the notch, resulting in nonanatomical, vertical graft placement.8,9 This technique can be modified to obtain a more anatomical tunnel, but the risk is the tunnel will be short and close to the joint line.10 To avoid these difficulties, surgeons began using an anteromedial portal.11,12 Although anteromedial drilling places the tunnel in a more anatomical position, it too has drawbacks, including the need to hyperflex the knee, a short tunnel, damage to articular cartilage, proximity to neurovascular structures, and difficulty in visualization during drilling.13-16

Femoral tunnel drilling techniques using flexible guide pins and reamers have been developed to address the limitations of rigid instruments. When we first started using flexible instruments through anteromedial portals, there were multiple incidents of reamer breakage during drilling. We therefore developed a technique that uses a flexible guide pin with a rigid reamer to place the femoral tunnel in an anatomical position. The patient described in this article provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this report.

Technique

We begin with our standard arthroscopic portals, including superolateral outflow, lateral parapatellar, and medial parapatellar portals. The medial parapatellar portal is placed under direct visualization with insertion of an 18-gauge spinal needle, ensuring the trajectory reaches the anatomical location of the native ACL on the lateral femoral condyle (LFC). The ACL stump is débrided with a shaver and a radiofrequency ablator, leaving a remnant of tissue to assist with tunnel placement. We do not routinely perform a notchplasty unless there is a concern about possible graft impingement, or the notch is abnormally small. The anatomical footprint is marked with a small awl (Figure 1), and the arthroscope is moved into the anteromedial portal to confirm anatomical placement of the awl mark (Figure 2).

With the knee flexed to 100° to 110°, a flexible 2.7-mm nitonol guide pin (Smith & Nephew, Memphis, Tennessee) is placed freehand through the anteromedial portal into the anatomical footprint of the ACL, marked by the awl, and is passed through the femur before exiting the lateral skin. In most cases, we prefer freehand placement of the awl and pin; however, a femoral drill guide may be used to place the pin into the anatomical footprint of the ACL (Figure 3). The flexible pin allows for knee hyperflexion, clearance of the medial femoral condyle, central placement of the pin between the footprints of the anteromedial and posterolateral bundles for anatomical single-bundle reconstruction, and drilling of a long tunnel (average, 35-40 mm). The pin has a black laser marking that should be placed at the edge of the articular surface of the LFC to ensure appropriate depth of insertion (Figure 4).

A small incision is then made around the guide wire on the lateral thigh, and an outside-in depth gauge is used to obtain an accurate length for the femoral tunnel. The gauge must abut the femoral cortex for accurate assessment of tunnel length. We use an Endobutton (Smith & Nephew) for fixation of the graft in the tunnel. The measured length of the tunnel is used to select an Endobutton of appropriate size and the proper reaming depth for suspension. We routinely use a 10- or 15-mm Endobutton, which provides an average 20 to 25 mm of graft inside the bony tunnel. The knee may then be relaxed to a normal resting flexion angle off the side of the bed, and the arthroscope is inserted into a medial portal or an accessory anteromedial portal to ensure anatomical placement of the pin. Using a flexible guide pin allows the knee to be relatively extended, providing good visualization of overall positioning in relation to the posterior wall of the LFC, whereas keeping the knee in a flexed position (as with a rigid guide pin) can often compromise this visualization.

Using a solid reamer corresponding to the size of the graft, we drill over the guide pin to the appropriate depth, again with the knee hyperflexed (Figure 5), making sure not to breach the lateral femoral cortex, which would compromise fixation with the Endobutton. After drilling with the rigid reamer is completed, placement of the tunnel in an anatomical position is again confirmed with the knee in the normal resting flexion angle (Figure 6). Once the tibial tunnel is drilled at the anatomical footprint, the graft is passed with the proper-length Endobutton and is fixed on the tibial side with a bioabsorbable interference screw 1 to 2 mm larger than the soft-tissue graft and tibial tunnel size. The knee is flexed to 30° while the tibial screw is placed. Graft tension and impingement are then checked (Figure 7). Postoperative anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the knee may be obtained to confirm anatomical placement of the tunnels as well as proper positioning of the Endobutton (Figures 8A, 8B).

Discussion

Successful ACL reconstruction depends heavily on anatomical tunnel positioning. Failure to place the femoral tunnel in the anatomical footprint of the native ACL results in incomplete restoration of knee kinematics, rotational instability, and graft failure.1-7 Two common techniques for creating this tunnel, transtibial and anteromedial drilling, can reliably place it in an anatomical position. Each technique, however, has limitations. Transtibial drilling can place the tunnel too vertical and high in the notch, or produce a short tibial tunnel close to the joint line.8-10 Anteromedial drilling requires knee hyperflexion, risks damaging the articular cartilage and nearby neurovascular structures, and makes visualization difficult.13-16

One option for addressing some of the difficulties and limitations with anteromedial drilling is to use flexible guide pins and reamers, as first introduced by Cain and Clancy.1 In a cadaveric study, Silver and colleagues17 demonstrated that interosseous tunnels drilled with flexible guide pins were on average more than 6 mm longer than those drilled with rigid pins and consistently were 40 mm or longer. In addition, all tunnels drilled with flexible guide pins were on average 42.3 mm away from the peroneal nerve and 26.1 mm away from the femoral origin of the lateral collateral ligament—safe distances.

Steiner and Smart18 compared flexible and rigid instruments used to drill transtibial and anteromedial (without hyperflexion) anatomical femoral tunnels in ACL reconstruction in cadaveric knees. Although transtibial drilling with flexible pins produced anatomical tunnels, the tunnels were shorter, and the pins exited more posterior in comparison with anteromedial drilling with flexible pins. Transtibial tunnels drilled with rigid pins were nonanatomical and exited more superior and anterior on the femur, resulting in longer tunnels. Anteromedial tunnels drilled with rigid and flexible pins were placed anatomically, but flexible pins produced longer tunnels, did not require hyperflexion (120°), could easily be placed with the knee in 90° of flexion, and did not violate the posterior femoral cortex.

Five times in our early experience with flexible guide pins and reamers, the reamer broke when LFC reaming was initiated. In each case, the broken reamer was retrieved. However, these complications resulted in increased surgical time and cost. In addition, an unretrievable reamer could have caused further injury and suboptimal outcomes. We subsequently developed an anteromedial technique that uses a flexible guide pin with a rigid reamer to place the femoral tunnel in an anatomical position (Figure 9). The flexible pin provides consistent placement of anatomical tunnels averaging 35 to 40 mm in length. Use of the flexible pin does not require constant hyperflexion of the knee, and it allows for better visualization of the posterior wall of the LFC, ensures anatomical graft placement, and decreases the risk of damaging articular cartilage and causing neurovascular injury. Use of the rigid reamer negates the risks and additional costs associated with reamer breakage. It is unclear why 5 flexible reamers broke during our early use of flexible guide pins and reamers, but it is possible that, because of the patients’ anatomy, placement of the pin in the correct anatomical position in the ACL footprint put a significant amount of abnormal stress on the reamer during tunnel reaming, leading to breakage and failure.

A short femoral tunnel is a common complication of using an anteromedial portal for tunnel drilling.13-16 With the technique we have been using, tunnel lengths average 35 to 40 mm. To address the occasional shorter tunnel, we use Endobutton Direct (Smith & Nephew), which allows for direct fixation of the graft on the button, maximizing the amount of graft in the femoral tunnel and minimizing graft–tunnel length mismatch. In the event there is a lateral wall breach during overdrilling with the reamer, the femoral graft may be secured with screw and post, with interference screw, or with the larger Xtendobuton (Smith & Nephew).

We have successfully used this technique with bone–patellar tendon–bone (BPTB) and hamstring autografts, as well as allografts. Complications, such as graft–tunnel length mismatch, have been uncommon, but, when using BPTB grafts, passing the bone block into the femoral tunnel can be difficult because of the sharp turn required.

Conclusion

Successful ACL reconstruction depends heavily on placement of the graft within the anatomical insertion of the native ACL. With the development of techniques that use flexible guide pins and reamers, it has become possible to place longer anatomical femoral tunnels without the need for hyperflexion. Use of a flexible guide pin with a rigid reamer allows placement of longer anatomical tunnels through an anteromedial portal, reduces time spent with the knee in hyperflexion, provides better viewing, poses less risk of damage to the articular cartilage and neurovascular structures, and at a lower cost with less risk of reamer breakage. In addition, this technique can be used with a variety of graft options, including BPTB grafts, hamstring autografts, and allografts.

1. Cain EL Jr, Clancy WG Jr. Anatomic endoscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with patella tendon autograft. Orthop Clin North Am. 2002;33(4):717-725.

2. Chhabra A, Starman JS, Ferretti M, Vidal AF, Zantop T, Fu FH. Anatomic, radiographic, biomechanical, and kinematic evaluation of the anterior cruciate ligament and its two functional bundles. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(suppl 4):2-10.

3. Christel P, Sahasrabudhe A, Basdekis G. Anatomic double-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with anatomic aimers. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(10):1146-1151.

4. Allen CR, Giffin JR, Harner CD. Revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Orthop Clin North Am. 2003;34(1):79-98.

5. Miller CD, Gerdeman AC, Hart JM, et al. A comparison of 2 drilling techniques on the femoral tunnel for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(3):372-379.

6. Seon JK, Park SJ, Lee KB, Seo HY, Kim MS, Song EK. In vivo stability and clinical comparison of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using low or high femoral tunnel positions. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(1):127-133.

7. Steiner ME, Battaglia TC, Heming JF, Rand JD, Festa A, Baria M. Independent drilling outperforms conventional transtibial drilling in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(10):1912-1919.

8. Kopf S, Forsythe B, Wong AK, et al. Nonanatomic tunnel position in traditional transtibial single-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction evaluated by three-dimensional computed tomography. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(6):1427-1431.

9. Tompkins M, Milewski MD, Brockmeier SF, Gaskin CM, Hart JM, Miller MD. Anatomic femoral tunnel drilling in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: use of an accessory medial portal versus traditional transtibial drilling. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(6):1313-1321.

10. Heming JF, Rand J, Steiner ME. Anatomical limitations of transtibial drilling in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(10):1708-1715.

11. Harner CD, Honkamp NJ, Ranawat AS. Anteromedial portal technique for creating the anterior cruciate ligament femoral tunnel. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(1):113-115.

12. Lubowitz JH. Anteromedial portal technique for the anterior cruciate ligament femoral socket: pitfalls and solutions. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(1):95-101.

13. Basdekis G, Abisafi C, Christel P. Influence of knee flexion angle on femoral tunnel characteristics when drilled through the anteromedial portal during anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(4):459-464.

14. Zantop T, Haase AK, Fu FH, Petersen W. Potential risk of cartilage damage in double bundle ACL reconstruction: impact of knee flexion angle and portal location on the femoral PL bundle tunnel. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2008;128(5):509-513.

15. Farrow LD, Parker RD. The relationship of lateral anatomic structures to exiting guide pins during femoral tunnel preparation utilizing an accessory medial portal. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18(6):747-753.

16. Nakamura M, Deie M, Shibuya H, et al. Potential risks of femoral tunnel drilling through the far anteromedial portal: a cadaveric study. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(5):481-487.

17. Silver AG, Kaar SG, Grisell MK, Reagan JM, Farrow LD. Comparison between rigid and flexible systems for drilling the femoral tunnel through an anteromedial portal in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2010;26(6):790-795.

18. Steiner ME, Smart LR. Flexible instruments outperform rigid instruments to place anatomic anterior cruciate ligament femoral tunnels without hyperflexion. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(6):835-843.

1. Cain EL Jr, Clancy WG Jr. Anatomic endoscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with patella tendon autograft. Orthop Clin North Am. 2002;33(4):717-725.

2. Chhabra A, Starman JS, Ferretti M, Vidal AF, Zantop T, Fu FH. Anatomic, radiographic, biomechanical, and kinematic evaluation of the anterior cruciate ligament and its two functional bundles. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(suppl 4):2-10.

3. Christel P, Sahasrabudhe A, Basdekis G. Anatomic double-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with anatomic aimers. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(10):1146-1151.

4. Allen CR, Giffin JR, Harner CD. Revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Orthop Clin North Am. 2003;34(1):79-98.

5. Miller CD, Gerdeman AC, Hart JM, et al. A comparison of 2 drilling techniques on the femoral tunnel for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(3):372-379.

6. Seon JK, Park SJ, Lee KB, Seo HY, Kim MS, Song EK. In vivo stability and clinical comparison of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using low or high femoral tunnel positions. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(1):127-133.

7. Steiner ME, Battaglia TC, Heming JF, Rand JD, Festa A, Baria M. Independent drilling outperforms conventional transtibial drilling in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(10):1912-1919.

8. Kopf S, Forsythe B, Wong AK, et al. Nonanatomic tunnel position in traditional transtibial single-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction evaluated by three-dimensional computed tomography. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(6):1427-1431.

9. Tompkins M, Milewski MD, Brockmeier SF, Gaskin CM, Hart JM, Miller MD. Anatomic femoral tunnel drilling in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: use of an accessory medial portal versus traditional transtibial drilling. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(6):1313-1321.

10. Heming JF, Rand J, Steiner ME. Anatomical limitations of transtibial drilling in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(10):1708-1715.

11. Harner CD, Honkamp NJ, Ranawat AS. Anteromedial portal technique for creating the anterior cruciate ligament femoral tunnel. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(1):113-115.

12. Lubowitz JH. Anteromedial portal technique for the anterior cruciate ligament femoral socket: pitfalls and solutions. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(1):95-101.

13. Basdekis G, Abisafi C, Christel P. Influence of knee flexion angle on femoral tunnel characteristics when drilled through the anteromedial portal during anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(4):459-464.

14. Zantop T, Haase AK, Fu FH, Petersen W. Potential risk of cartilage damage in double bundle ACL reconstruction: impact of knee flexion angle and portal location on the femoral PL bundle tunnel. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2008;128(5):509-513.

15. Farrow LD, Parker RD. The relationship of lateral anatomic structures to exiting guide pins during femoral tunnel preparation utilizing an accessory medial portal. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18(6):747-753.

16. Nakamura M, Deie M, Shibuya H, et al. Potential risks of femoral tunnel drilling through the far anteromedial portal: a cadaveric study. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(5):481-487.

17. Silver AG, Kaar SG, Grisell MK, Reagan JM, Farrow LD. Comparison between rigid and flexible systems for drilling the femoral tunnel through an anteromedial portal in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2010;26(6):790-795.

18. Steiner ME, Smart LR. Flexible instruments outperform rigid instruments to place anatomic anterior cruciate ligament femoral tunnels without hyperflexion. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(6):835-843.