User login

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has caused more than 1 million deaths in the United States and continues to be a major public health challenge. Cases can be asymptomatic, or symptoms can range from a mild respiratory tract infection to acute respiratory distress and multiorgan failure.

Three strategies can successfully contain the pandemic and its consequences:

- Public health measures, such as masking and social distancing

- Prophylactic vaccines to reduce transmission

- Safe and effective drugs for reducing morbidity and mortality among infected patients.

Optimal treatment strategies for patients in ambulatory and hospital settings continue to evolve as new studies are reported and new strains of the virus arise. Many medical and scientific organizations, including the National Institutes of Health (NIH) COVID-19 treatment panel,1 Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA),2 World Health Organization (WHO),3 and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,4 provide recommendations for managing patients with COVID-19. Their guidance is based on the strongest research available and is updated intermittently; nevertheless, a plethora of new data emerges weekly and controversies surround several treatments.

In this article, we

We encourage clinicians, in planning treatment, to consider:

- The availability of medications (ie, use the COVID-19 Public Therapeutic Locatora)

- The local COVID-19 situation

- Patient factors and preferences

- Evolving evidence regarding new and existing treatments.

Most evidence about the treatment of COVID-19 comes from studies conducted when the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2 was not the dominant variant, as it is today in the United States. As such, drugs authorized or approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat COVID-19 or used off-label for that purpose might not be as efficacious today as they were almost a year ago. Furthermore, many trials of potential therapies against new viral variants are ongoing; if your patient is interested in enrolling in a clinical trial of an investigational COVID-19 treatment, refer them to www.clinicaltrials.gov.

General managementof COVID-19

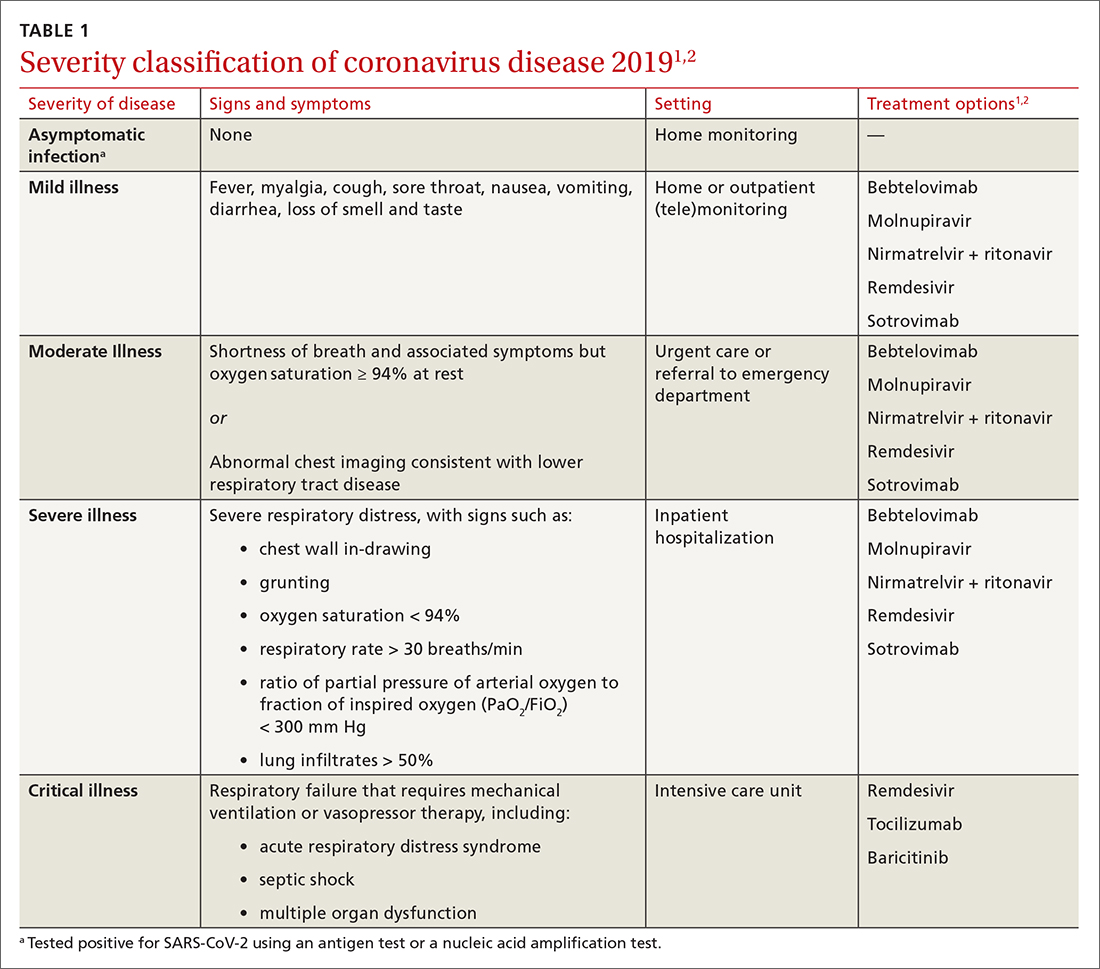

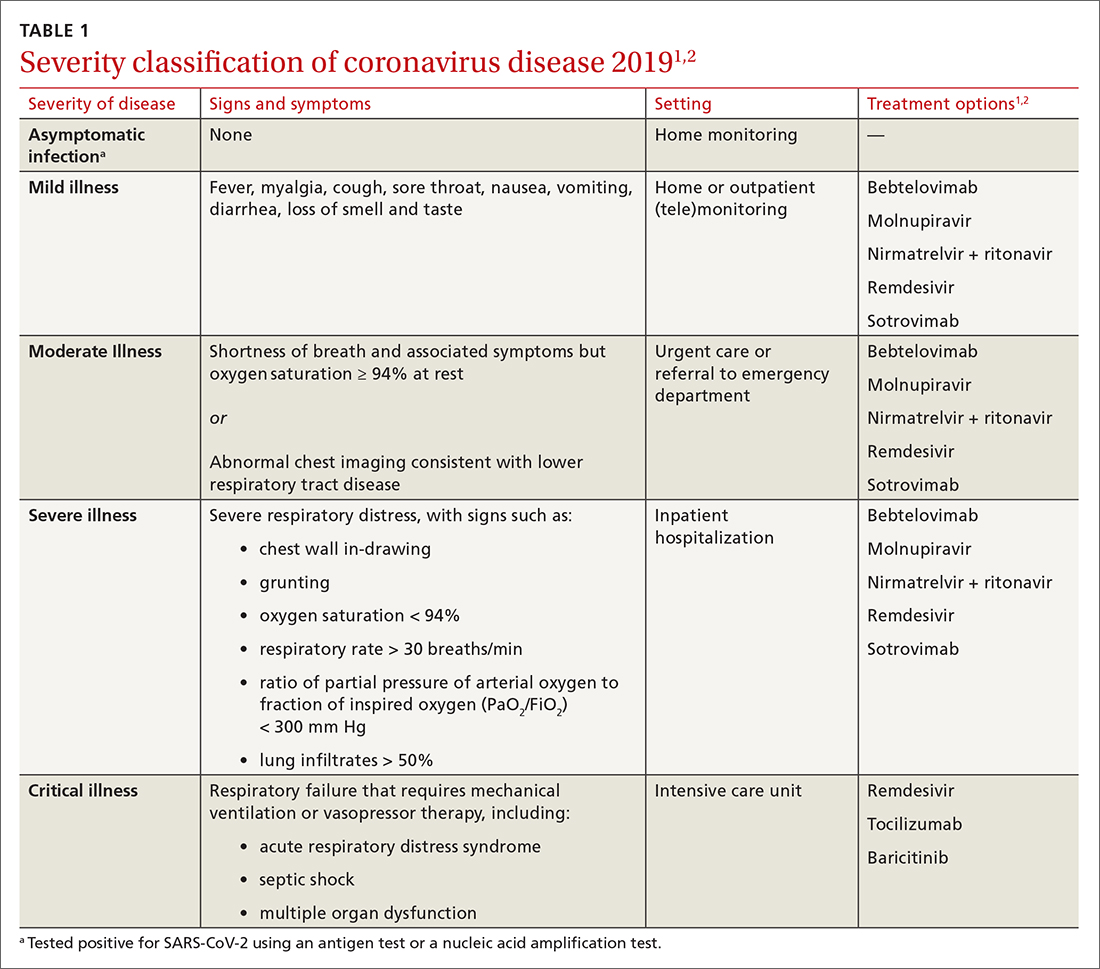

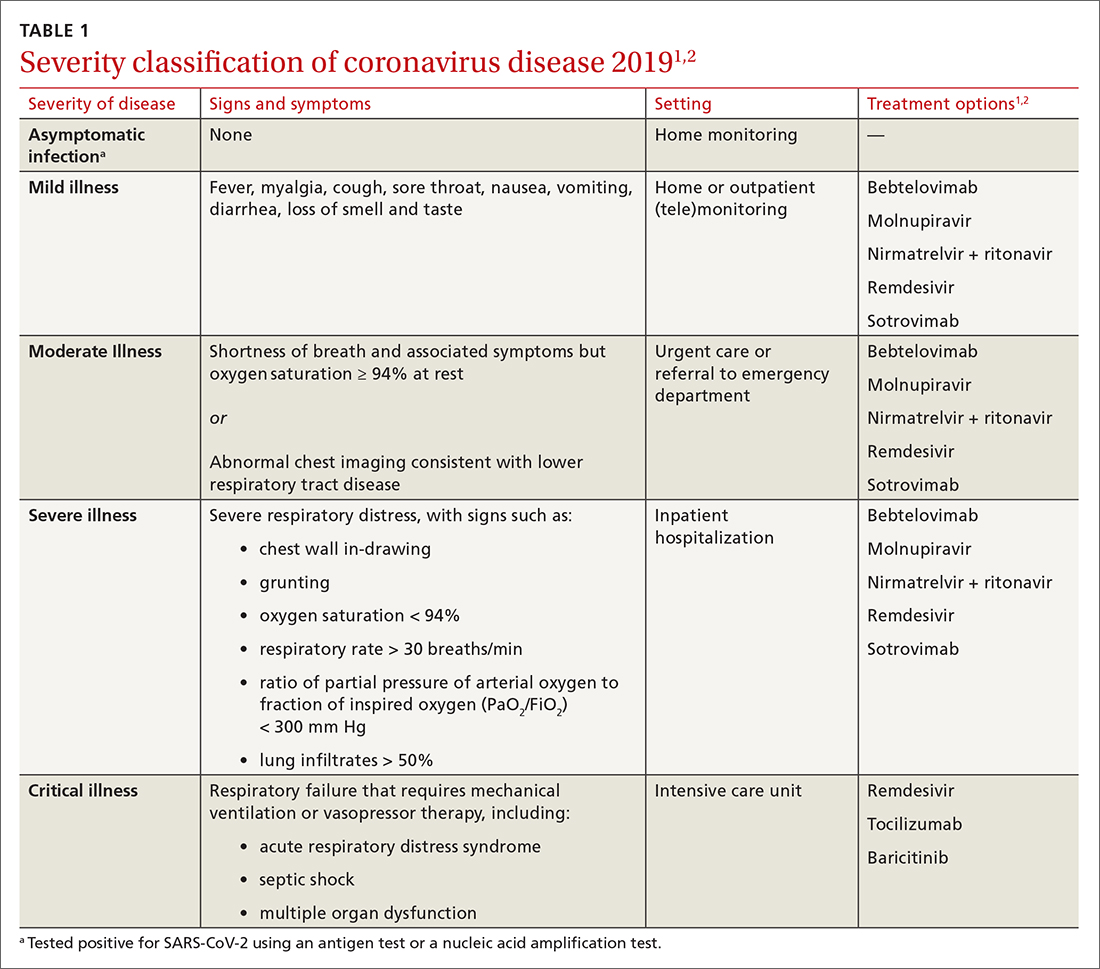

Patients with COVID-19 experience a range of illness severity—from asymptomatic to mild symptoms, such as fever and myalgia, to critical illness requiring intensive care (TABLE 11,2). Patients with COVID-19 should therefore be monitored for progression, remotely or in person, until full recovery is achieved. Key concepts of general management include:

Assess and monitor patients’ oxygenation status by pulse oximetry; identify those with low or declining oxygen saturation before further clinical deterioration.

Continue to: Consider the patient's age and general health

Consider the patient’s age and general health. Patients are at higher risk of severe disease if they are > 65 years or have an underlying comorbidity.4

Emphasize self-isolation and supportive care, including rest, hydration, and over-the-counter medications to relieve cough, reduce fever, and alleviate other symptoms.

Drugs: Few approved, some under study

The antiviral remdesivir is the only drug fully approved for clinical use by the FDA to treat COVID-19 in patients > 12 years.5,6

In addition, the FDA has issued an emergency use authorization (EUA) for several monoclonal antibodies as prophylaxis and treatment: tixagevimab packaged with cilgavimab (Evusheld) is the first antibody combination for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) against COVID-19; the separately packaged injectables are recommended for patients who have a history of severe allergy that prevents them from being vaccinated or those with moderate or severe immune-compromising disorders.7

In the pipeline. Several treatments are being tested in clinical trials to evaluate their effectiveness and safety in combating COVID-19, including:

- Antivirals, which prevent viruses from multiplying

- Immunomodulators, which reduce the body’s immune reaction to the virus

- Antibody therapies, which are manufactured antibodies against the virus

- Anti-inflammatory drugs, which reduce systemic inflammation and prevent organ dysfunction

- Cell therapies and gene therapies, which alter the expression of cells and genes.

Continue to: Outpatient treatment

Outpatient treatment

Several assessment tools that take into account patients’ age, respiratory status, and comorbidities are available for triage of patients infected with COVID-19.8

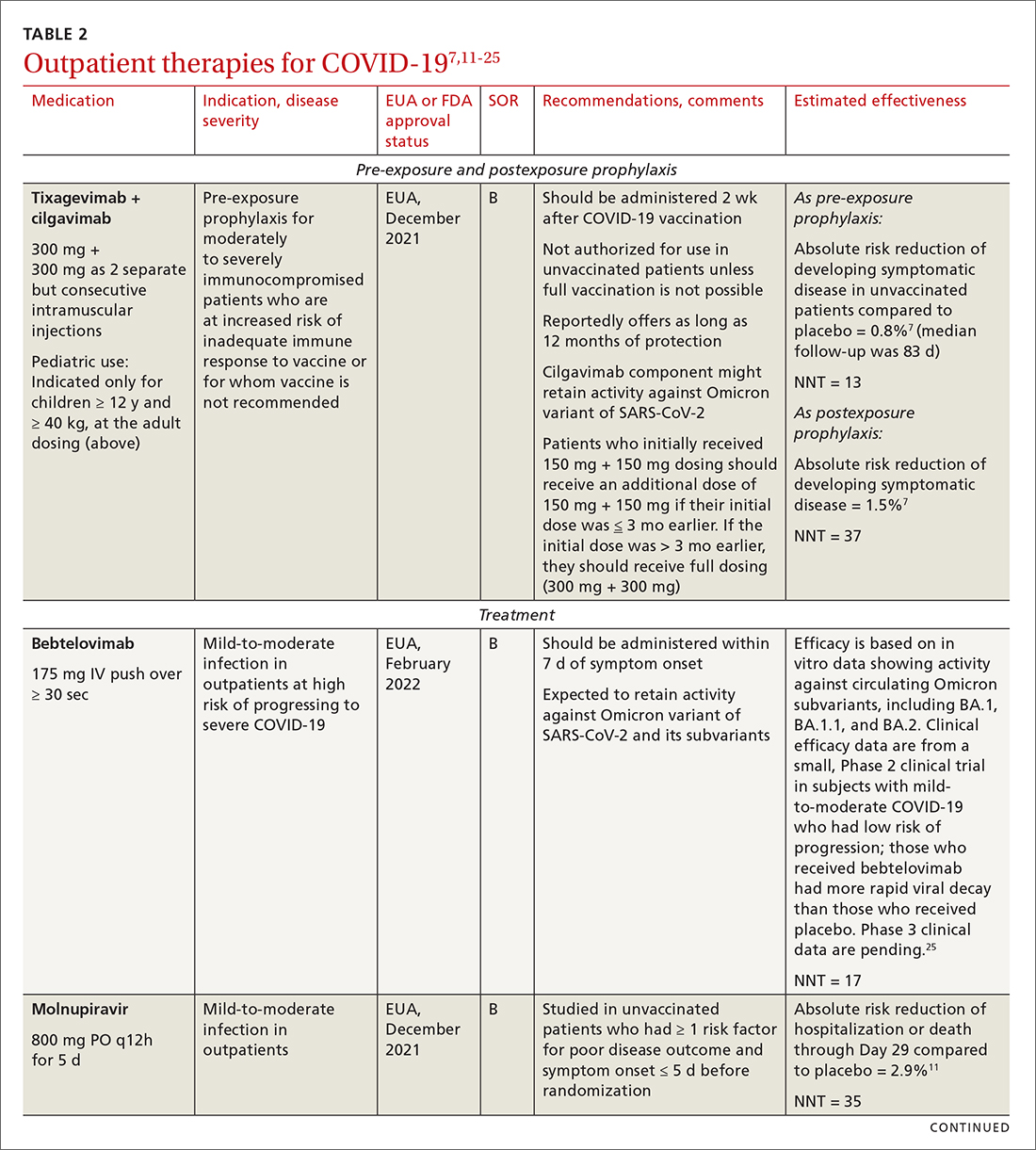

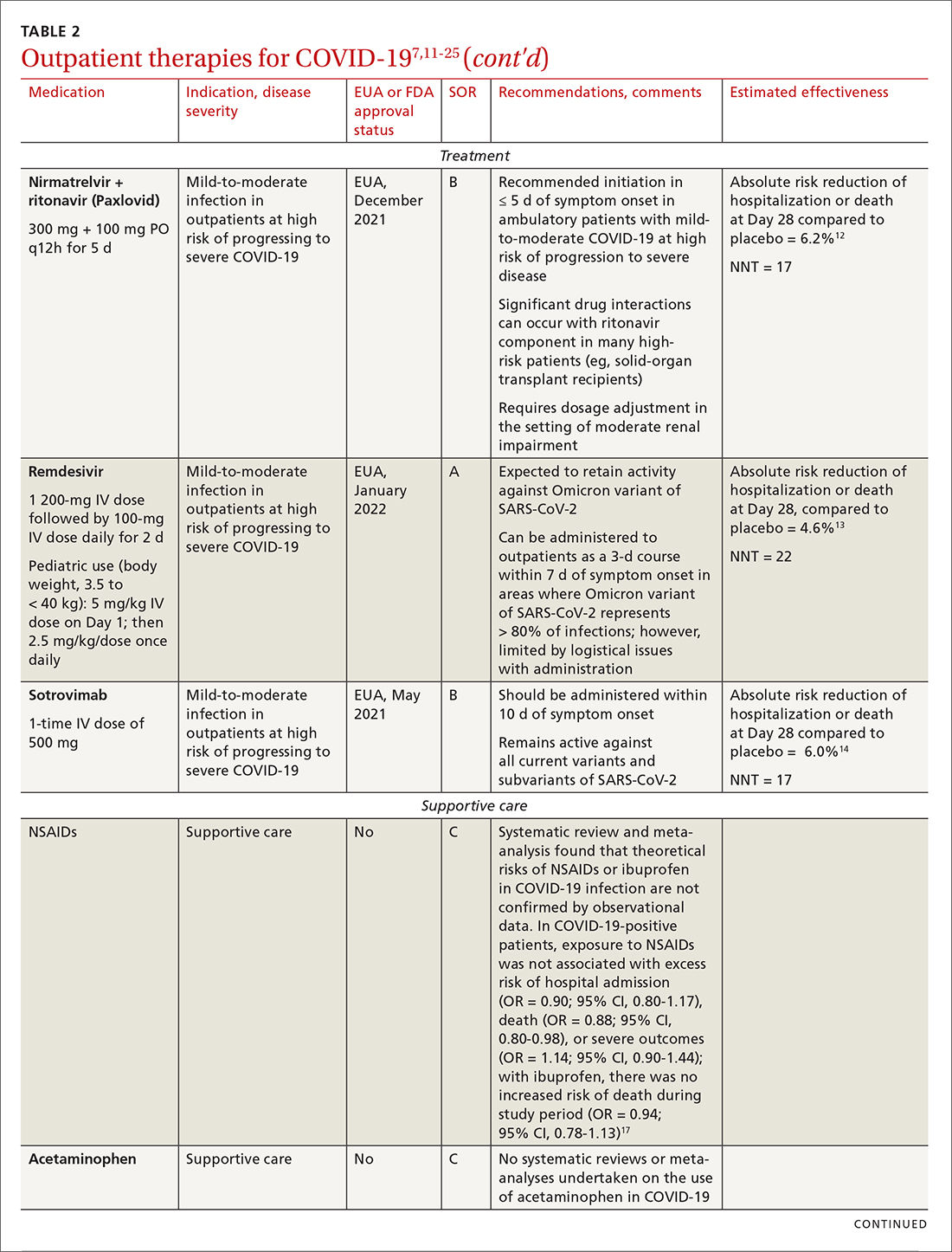

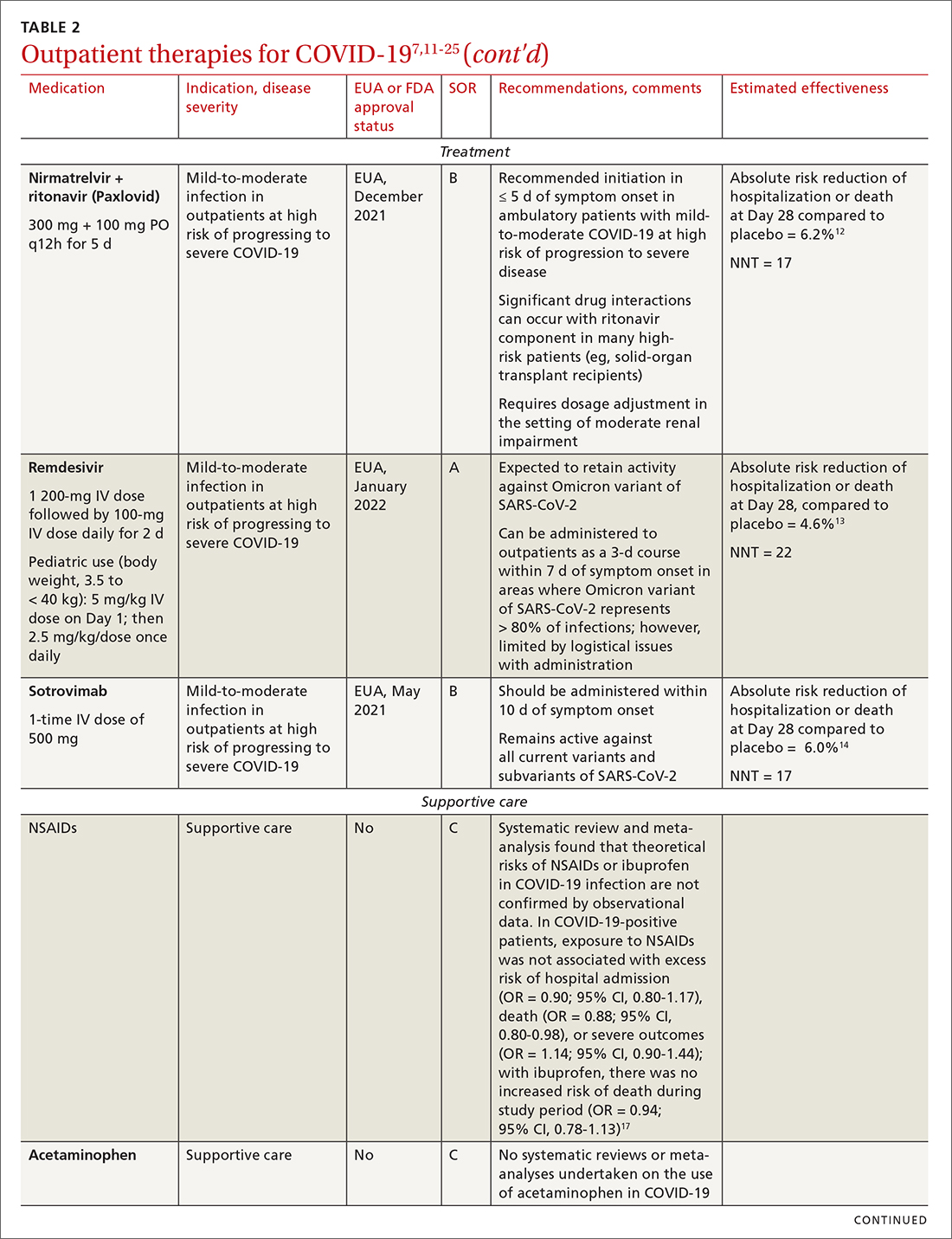

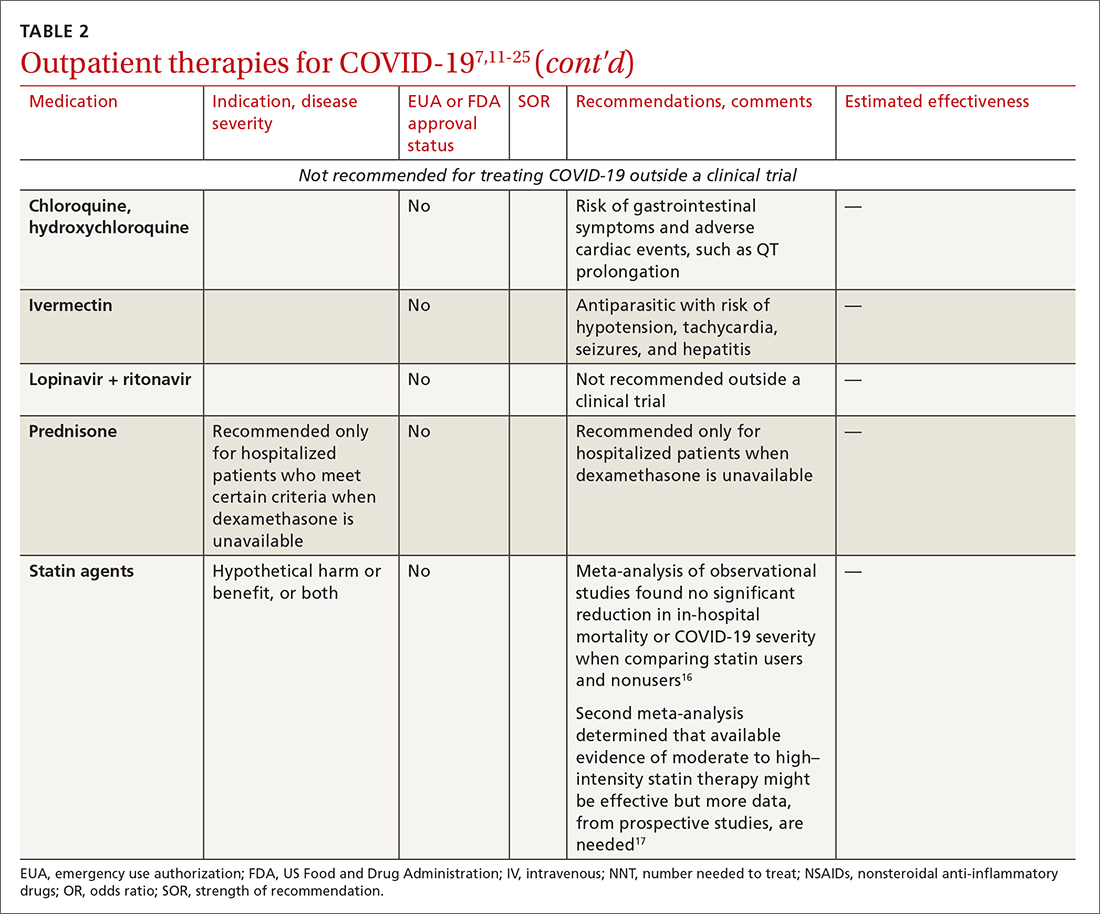

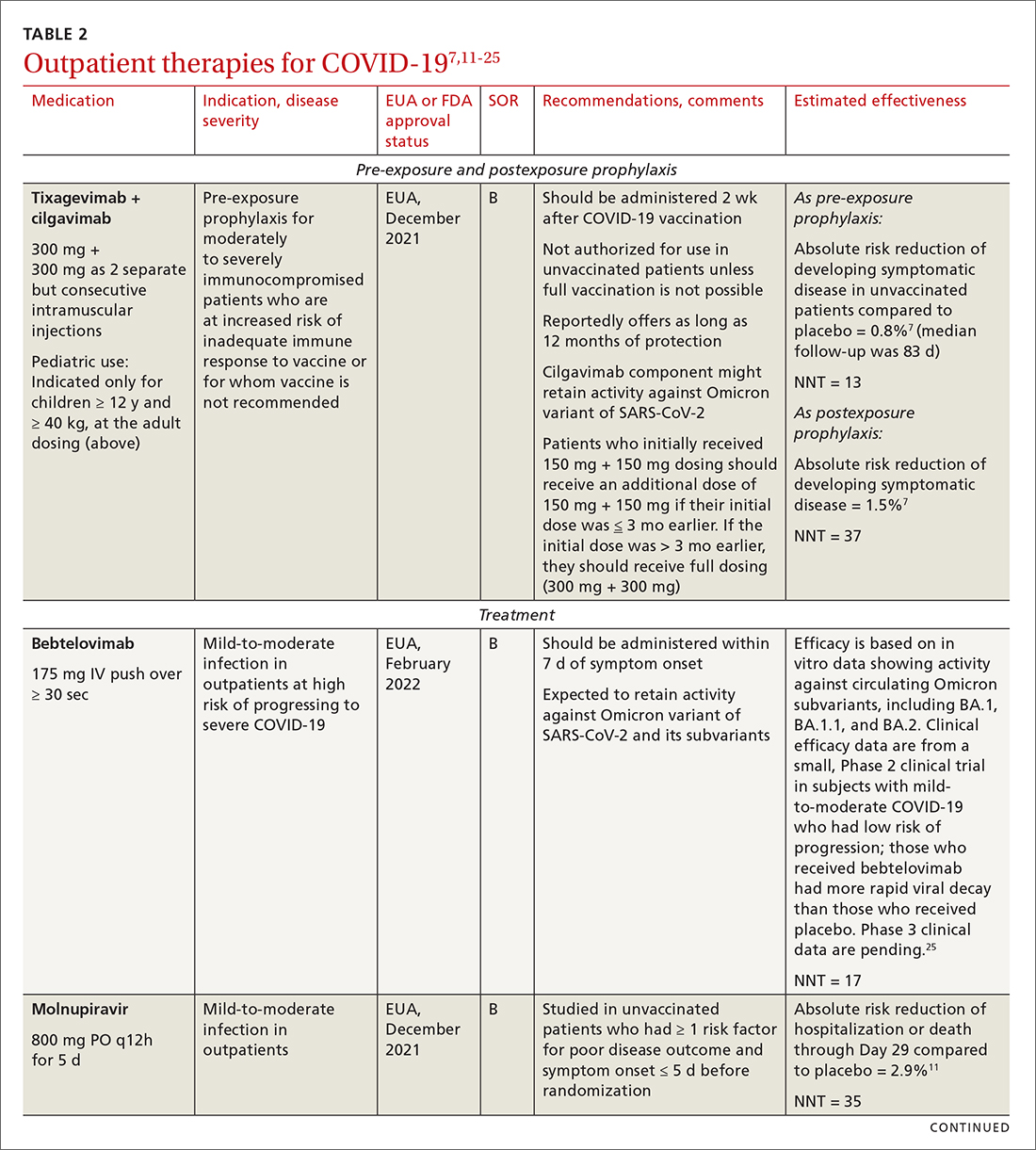

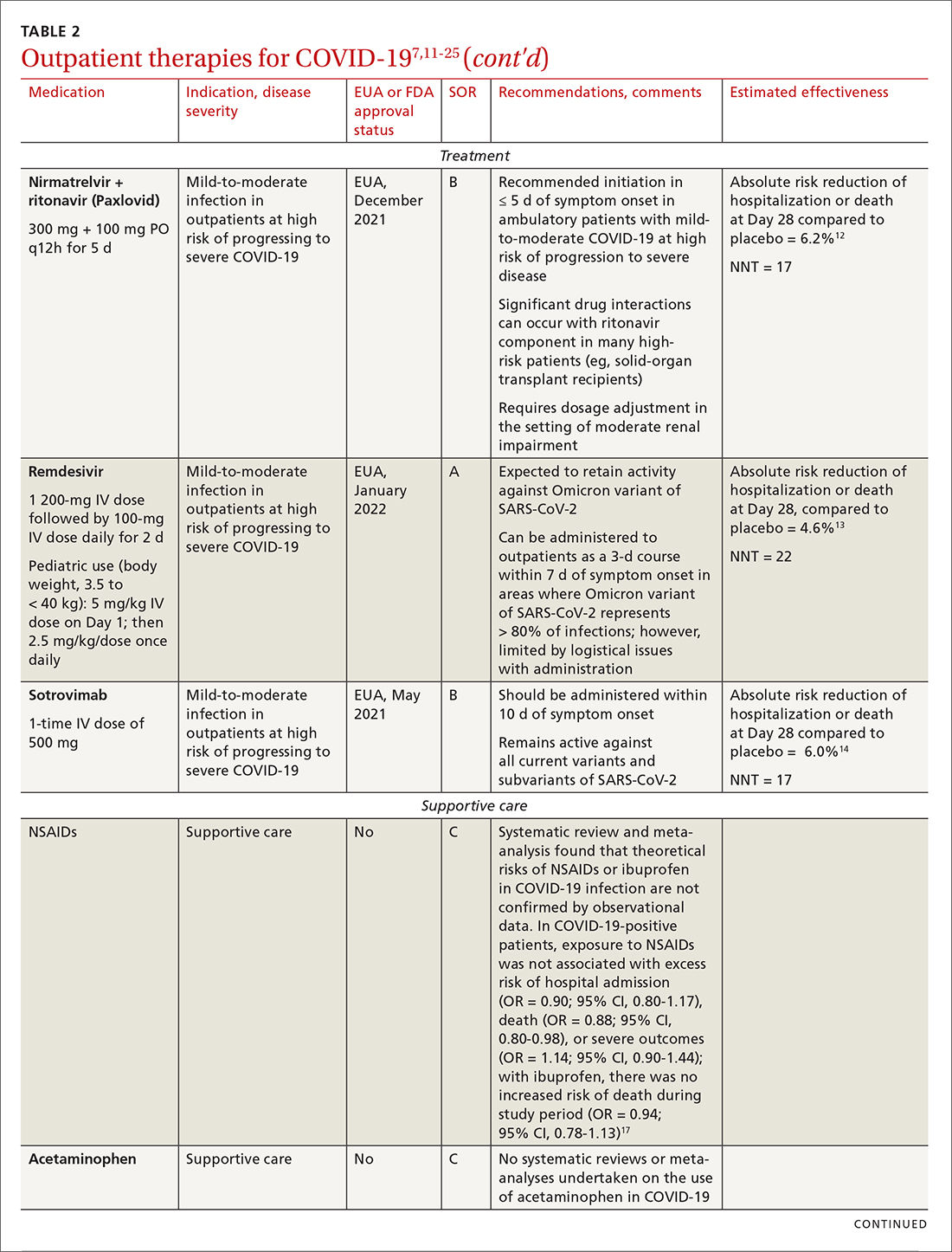

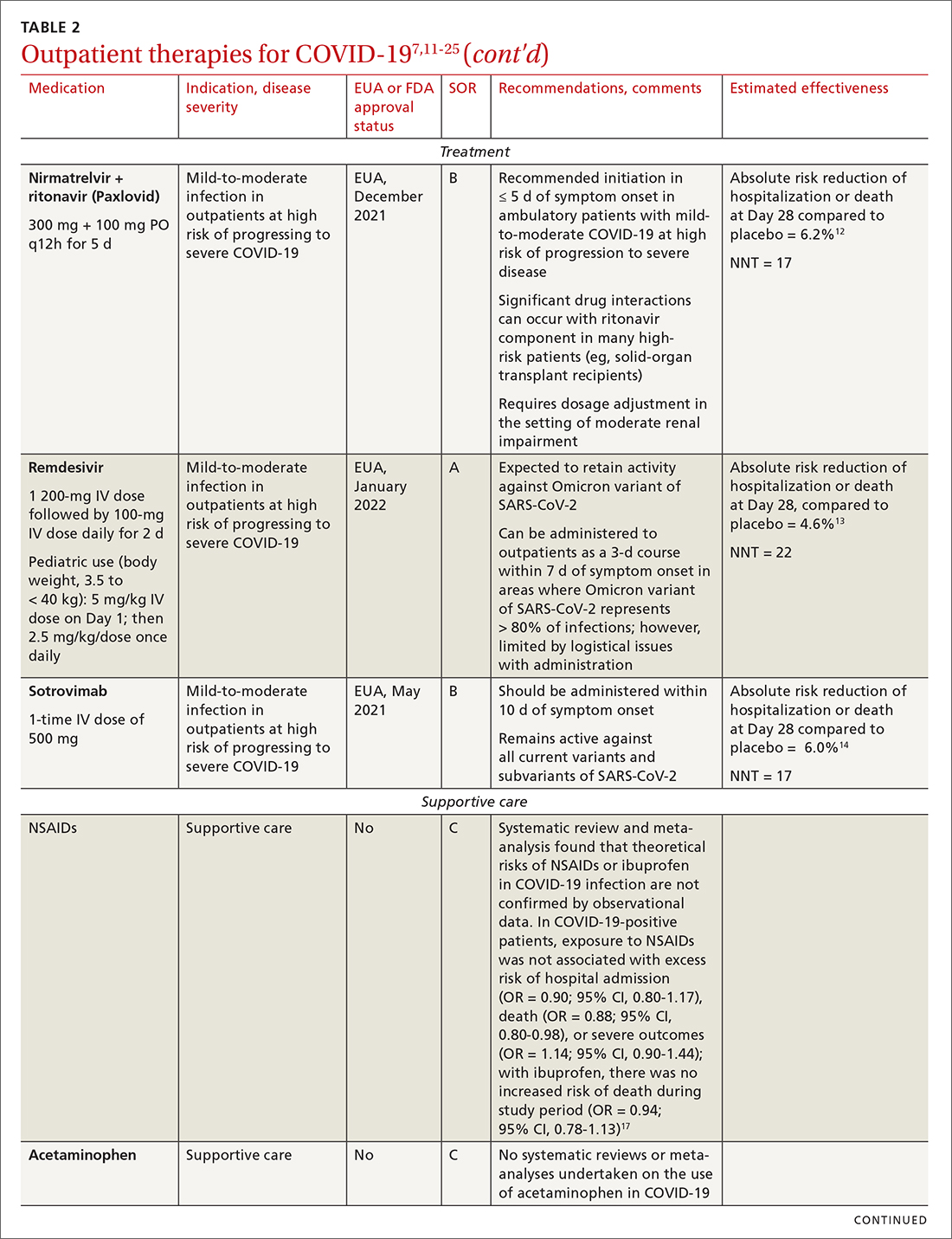

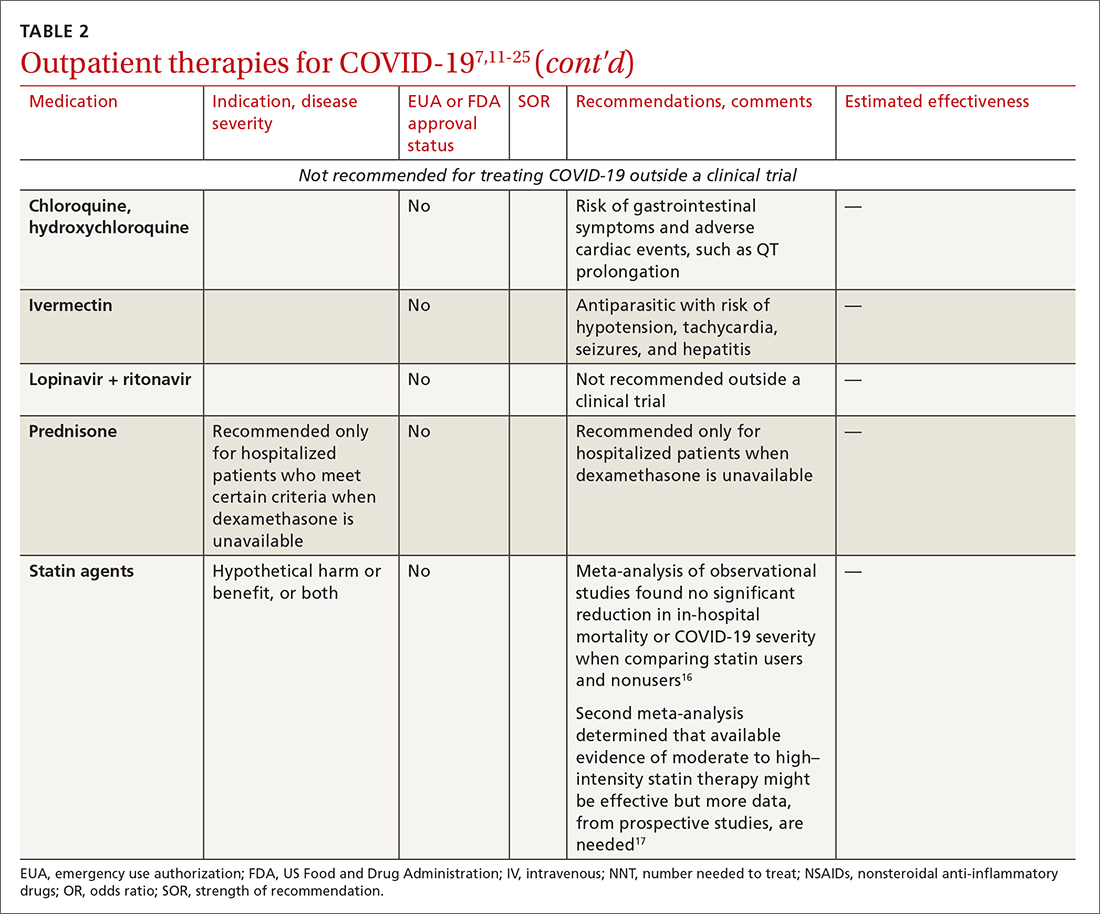

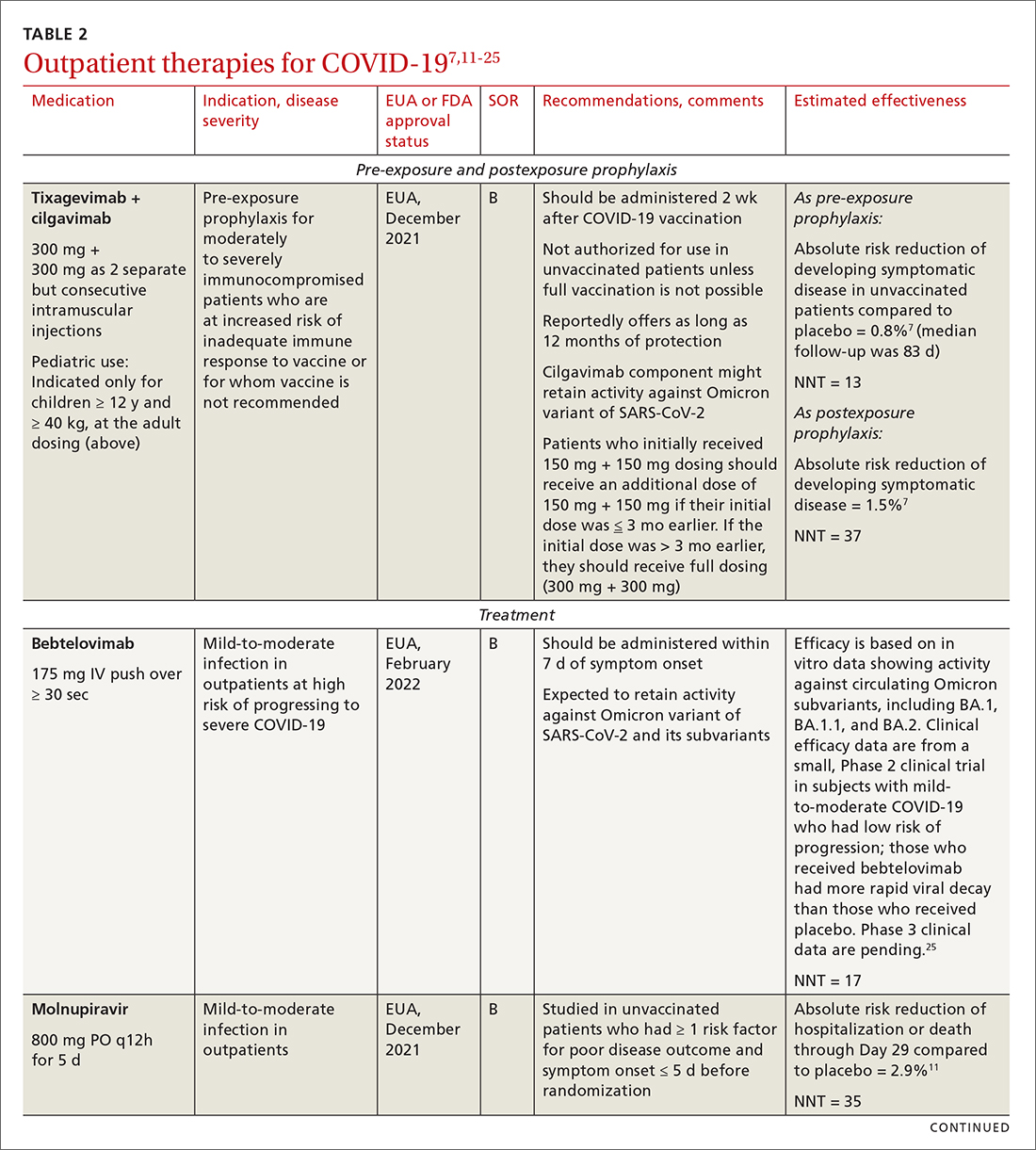

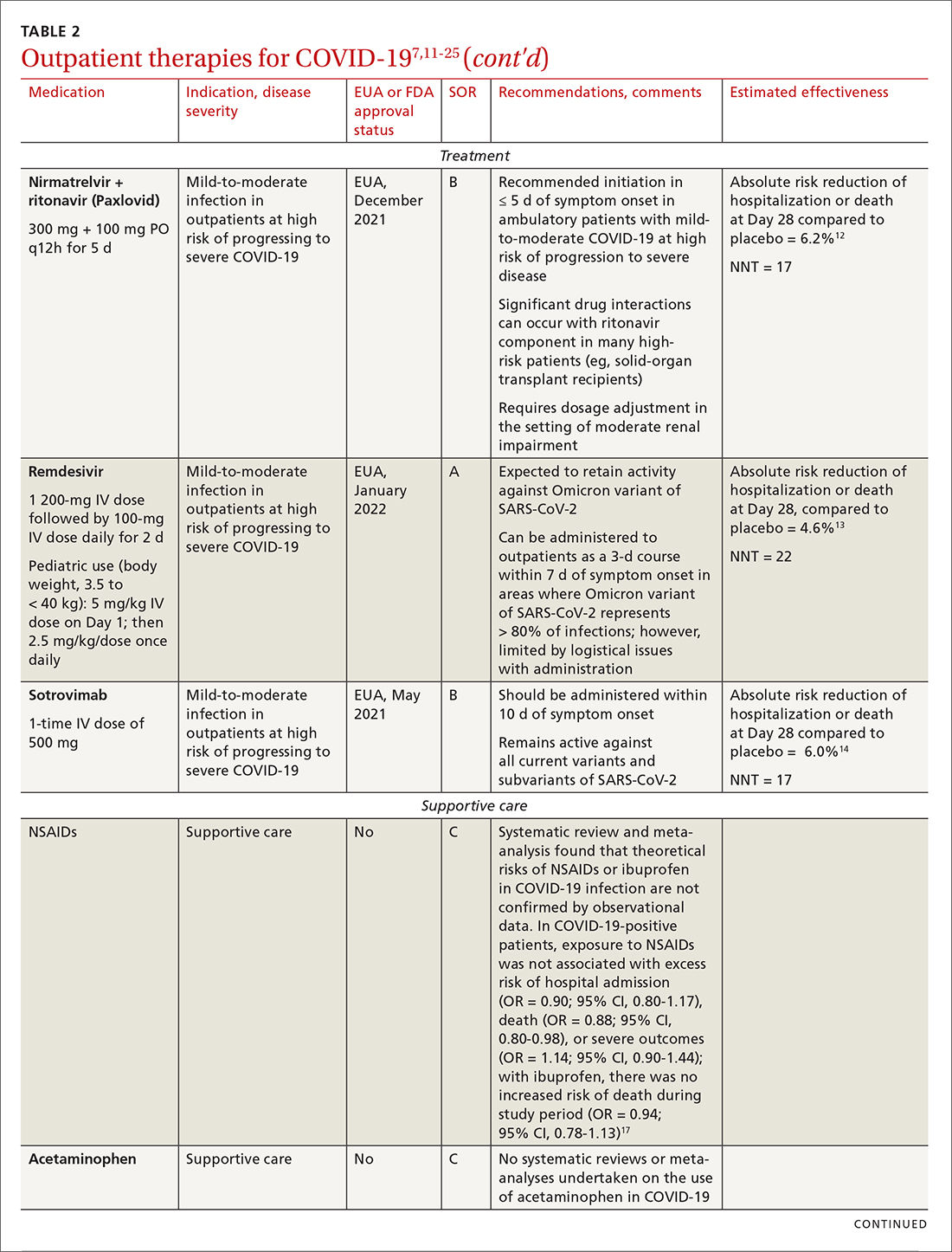

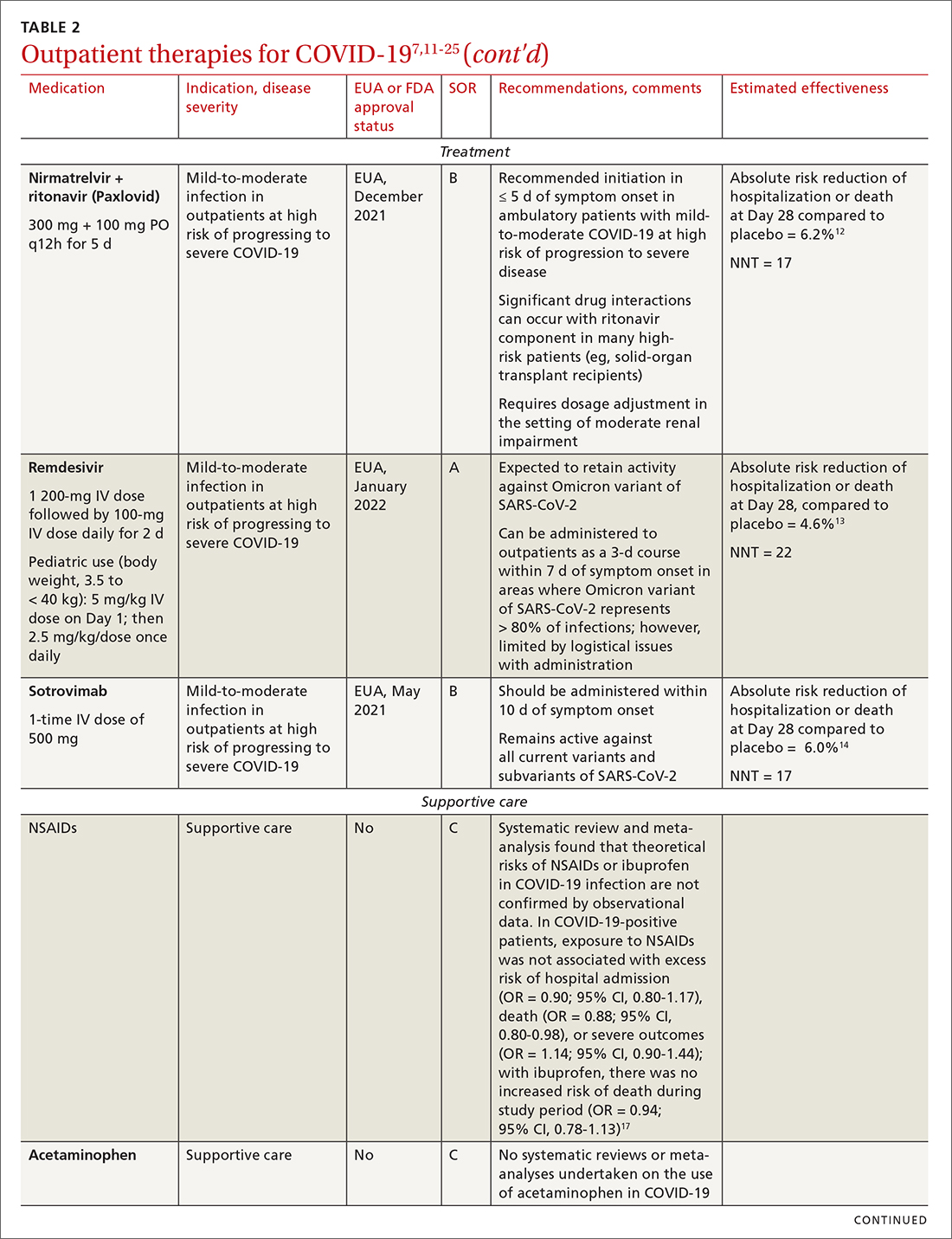

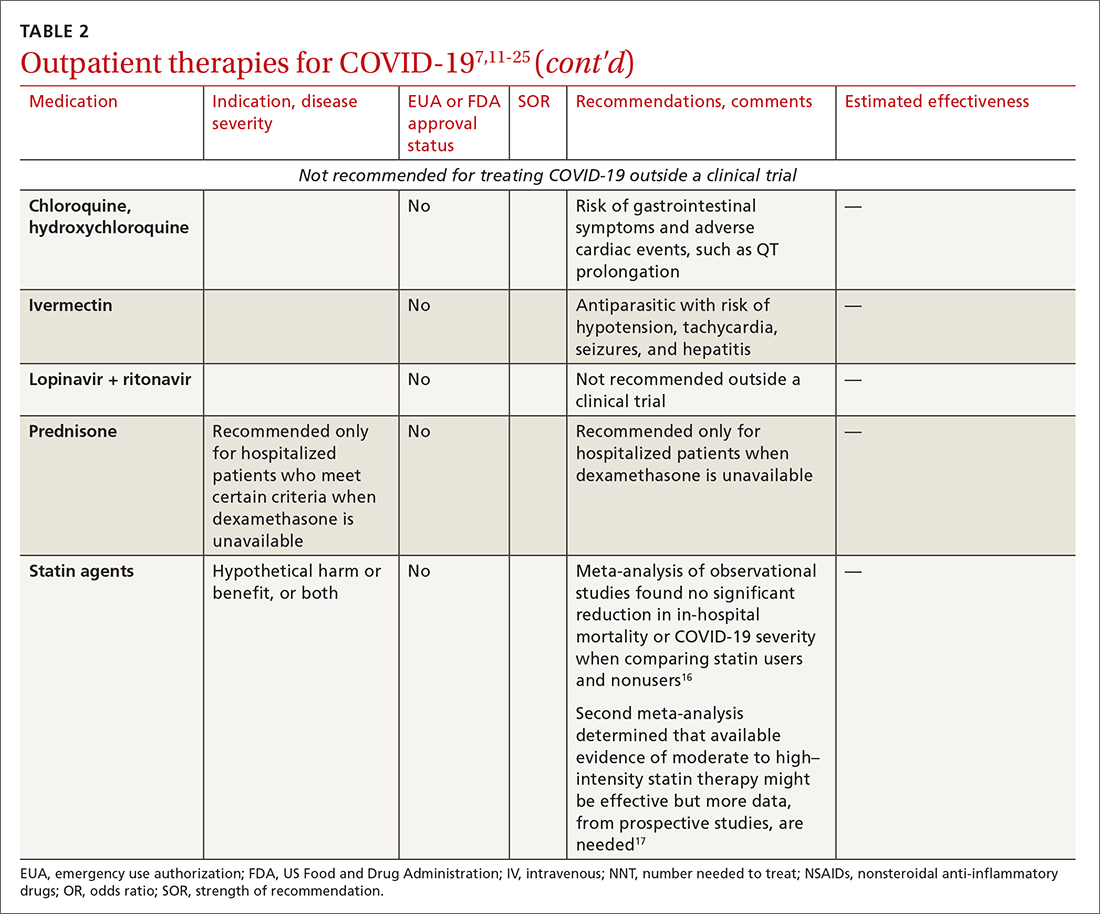

Most (> 80%) patients with COVID-19 have mild infection and are safely managed as outpatients or at home.9,10 For patients at high risk of severe disease, a few options are recommended for patients who do not require hospitalization or supplemental oxygen; guidelines on treatment of COVID-19 in outpatient settings that have been developed by various organizations are summarized in TABLE 2.7,11-25

Antiviral drugs target different stages of the SARS-CoV-2 replication cycle. They should be used early in the course of infection, particularly in patients at high risk of severe disease.

IDSA recommends antiviral therapy with molnupiravir, nirmatrelvir + ritonavir packaged together (Paxlovid), or remdesivir.11,12,26,27 Remdesivir requires intravenous (IV) infusion on 3 consecutive days, which can be difficult in some clinic settings.13,28 Nirmatrelvir + ritonavir should be initiated within 5 days after symptom onset. Overall, for most patients, nirmatrelvir + ritonavir is preferred because of oral dosing and higher efficacy in comparison to other antivirals. With nirmatrelvir + ritonavir, carefully consider drug–drug interactions and the need to adjust dosing in the presence of renal disease.28,29 There are no data on the efficacy of any combination treatments with these agents (other than co-packaged Paxlovid).

Monoclonal antibodies for COVID-19 are given primarily intravenously. They bind to the viral spike protein, thus preventing SARS-CoV-2 from attaching to and entering cells. Bamlanivimab + etesevimab and bebtelovimab are available under an EUA for outpatient treatment.14b Treatment should be initiated as early as possible in the course of infection—ideally, within 7 to 10 days after onset of symptoms.

Continue to: Bebtelovimab was recently given...

Bebtelovimab was recently given an EUA. It is a next-generation antibody that neutralizes all currently known variants and is the most potent monoclonal antibody against the Omicron variant, including its BA.2 subvariant.31 However, data about its activity against the BA.2 subvariant are based on laboratory testing and have not been confirmed in clinical trials. Clinical data were similar for this agent alone and for its use in combination with other monoclonal antibodies, but those trials were conducted before the emergence of Omicron.

In your decision-making about the most appropriate therapy, consider (1) the requirement that monoclonal antibodies be administered parenterally and (2) the susceptibility of the locally predominating viral variant.

Other monoclonal antibody agents are in the investigative pipeline; however, data about them have been largely presented through press releases or selectively reported in applications to the FDA for EUA. For example, preliminary reports show cilgavimab coverage against the Omicron variant14; so far, cilgavimab is not approved for treatment but is used in combination with tixagevimab for PreP—reportedly providing as long as 12 months of protection for patients who are less likely to respond to a vaccine.32

Corticosteroids. Guidelines recommend against dexamethasone and other systemic corticosteroids in outpatient settings. For patients with moderate-to-severe symptoms but for whom hospitalization is not possible (eg, beds are unavailable), the NIH panel recommends dexamethasone, 6 mg/d, for the duration of supplemental oxygen, not to exceed 10 days of treatment.1

Patients who were recently discharged after COVID-19 hospitalization should not continue remdesivir, dexamethasone, or baricitinib at home, even if they still require supplemental oxygen.

Continue to: Some treatments should not be in your COVID-19 toolbox

Some treatments should not be in your COVID-19 toolbox

High-quality studies are lacking for several other potential COVID-19 treatments. Some of these drugs are under investigation, with unclear benefit and with the potential risk of toxicity—and therefore should not be prescribed or used outside a clinical trial. See “Treatments not recommended for COVID-19,” page E14. 1-4,15-19,33-41

SIDEBAR

Treatments not recommended for COVID-191-4,15-19,33-41

Fluvoxamine. A few studies suggest that the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor fluvoxamine reduces progression to severe disease; however, those studies have methodologic challenges.33 The drug is not FDA approved for treating COVID.33

Convalescent plasma, given to high-risk outpatients early in the course of disease, can reduce progression to severe disease,34,35 but it remains investigational for COVID-19 because trials have yielded mixed results.34-36

Ivermectin. The effect of ivermectin in patients with COVID-19 is unclear because high-quality studies do not exist and cases of ivermectin toxicity have occurred with incorrect administration.39

Hydroxychloroquine showed potential in a few observational studies, but randomized clinical trials have not shown any benefit.15

Azithromycin likewise showed potential in a few observational studies; randomized clinical trials have not shown any benefit, however.15

Statins. A few meta-analyses, based on observational studies, reported benefit from statins, but recent studies have shown that this class of drugs does not provide clinical benefit in alleviating COVID-19 symptoms.16,17,37

Inhaled corticosteroids. A systematic review reported no benefit or harm from using an inhaled corticosteroid.18 More recent studies show that the inhaled corticosteroid budesonide used in early COVID-19 might reduce the need for urgent care38 and, in patients who are at higher risk of COVID-19-related complications, shorten time to recovery.19

Vitamins and minerals. Limited observational studies suggest an association between vitamin and mineral deficiency (eg, vitamin C, zinc, and vitamin D) and risk of severe disease, but high-quality data about this finding do not exist.40,41

Casirivimab + imdevimab [REGEN-COV2]. This unapproved investigational combination treatment was granted an EUA in 2020 for postexposure prophylaxis. The EUA was withdrawn in January 2022 because of the limited efficacy of casirivimab + imdevimab against the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2.

Postexposure prophylaxis. National guidelines1-4 recommend against postexposure prophylaxis with hydroxychloroquine, colchicine, inhaled corticosteroids, or azithromycin.

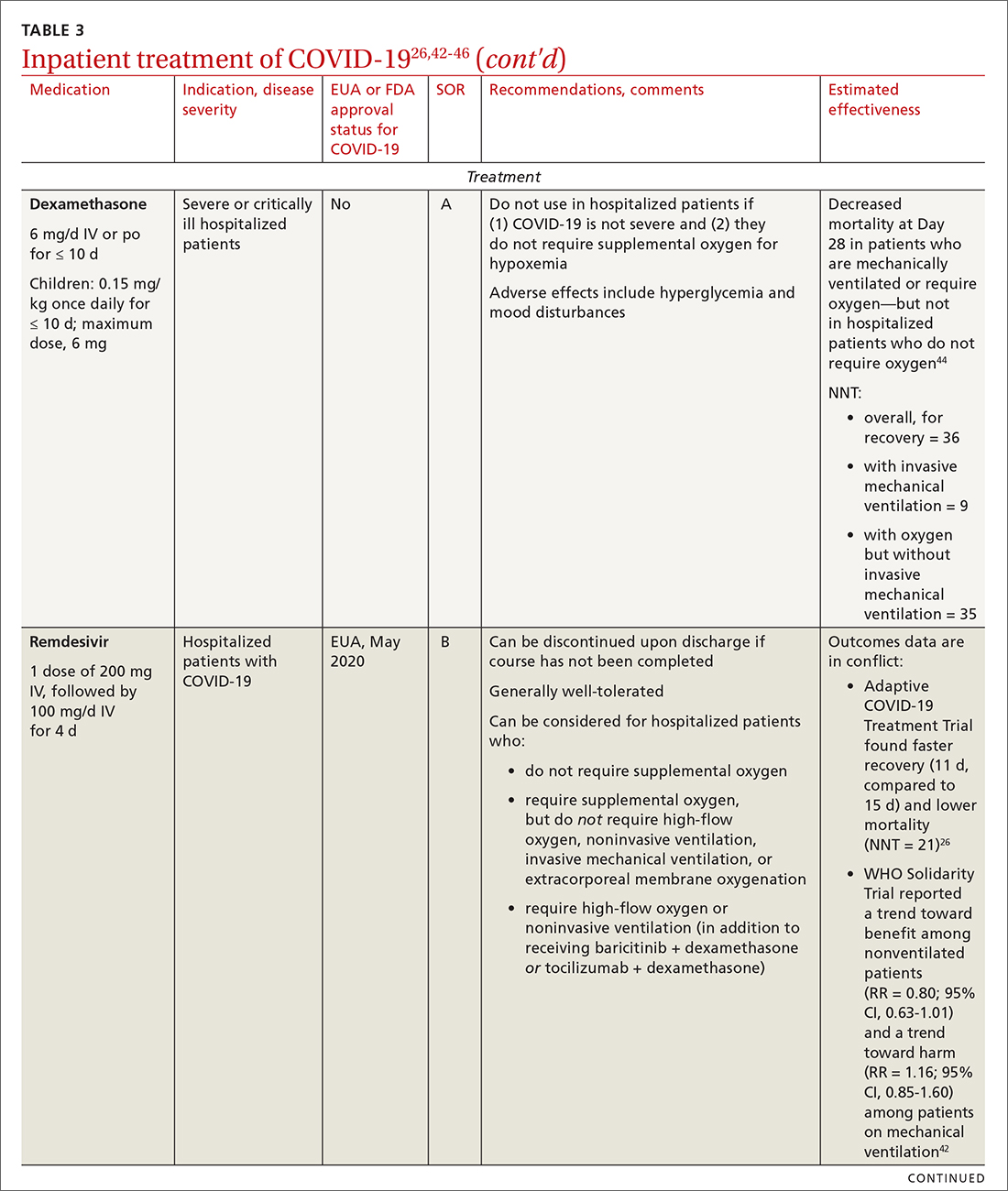

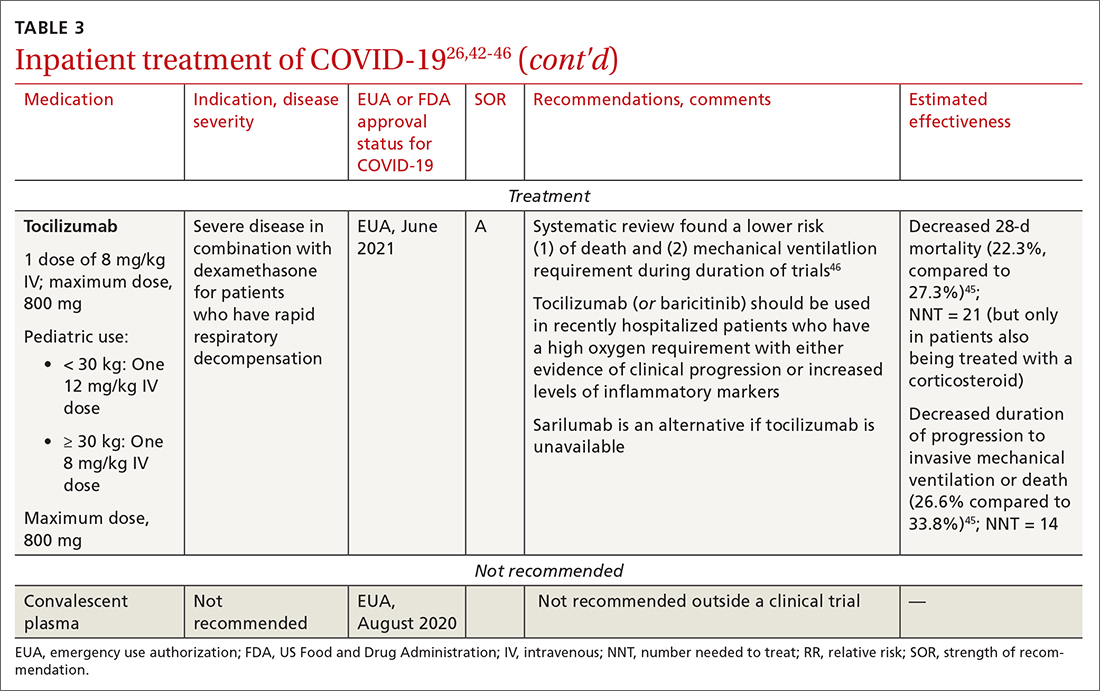

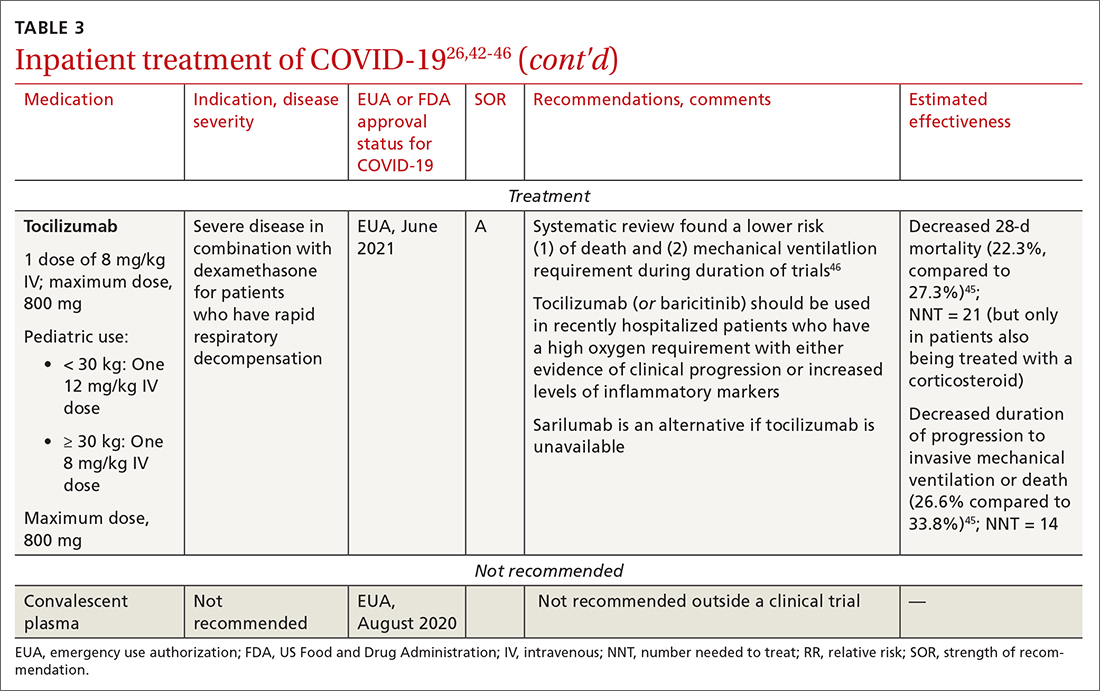

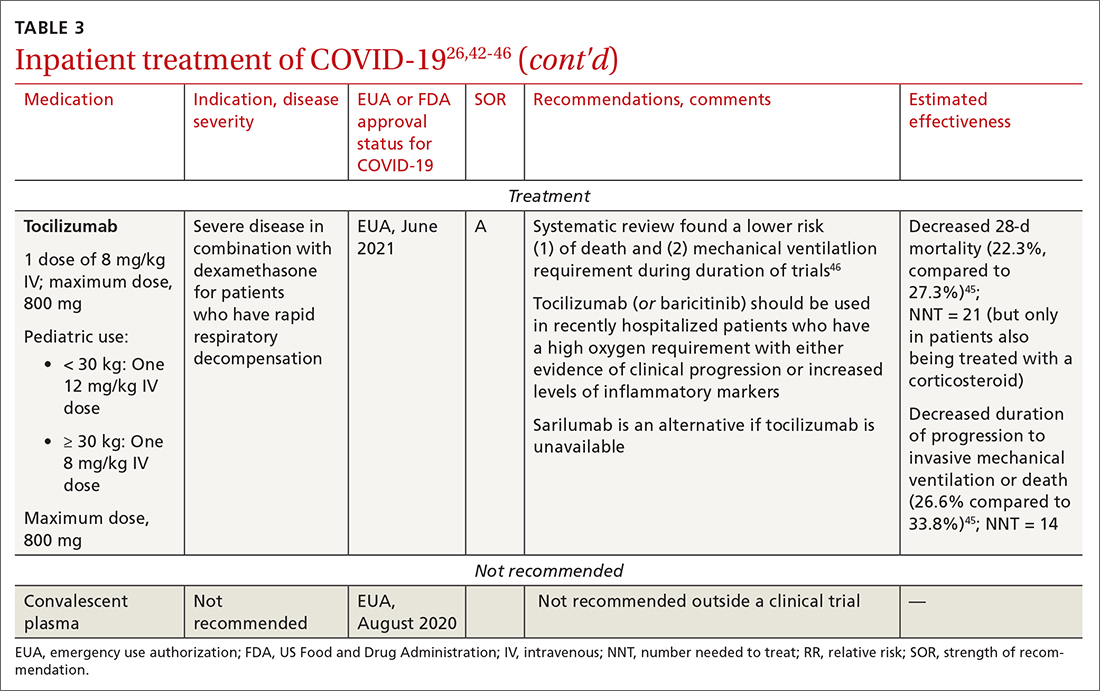

TABLE 27,11-25 and TABLE 326,42-46 provide additional information on treatments not recommended outside trials, or not recommended at all, for COVID-19.

Treatment during hospitalization

The NIH COVID-19 treatment panel recommends hospitalization for patients who have any of the following findings1:

- Oxygen saturation < 94% while breathing room air

- Respiratory rate > 30 breaths/min

- A ratio of partial pressure of arterial O2 to fraction of inspired O2 (PaO2/FiO2) < 300 mm Hg

- Lung infiltrates > 50%.

General guidance for the care of hospitalized patients:

- Treatments that target the virus have the greatest efficacy when given early in the course of disease.

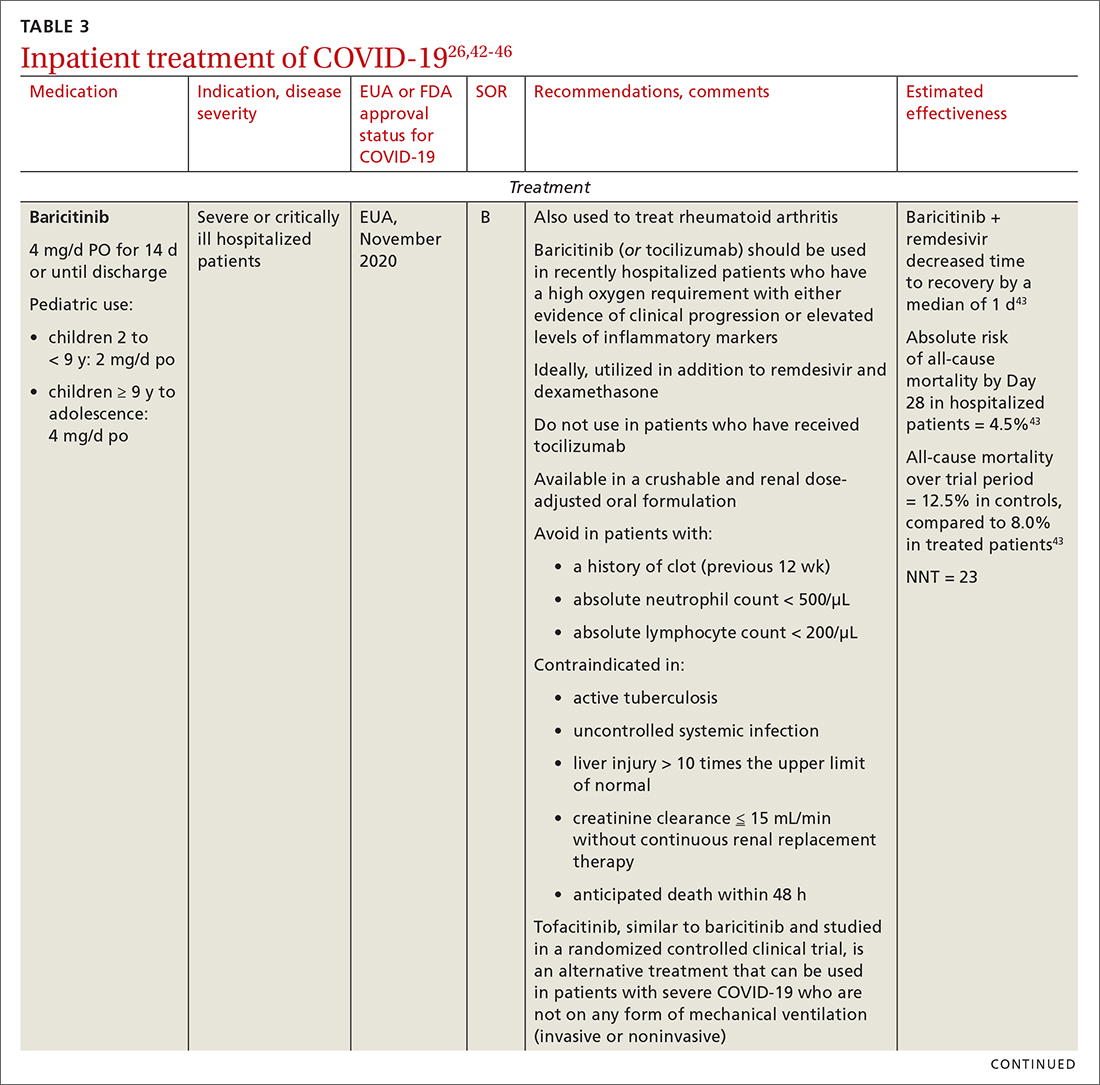

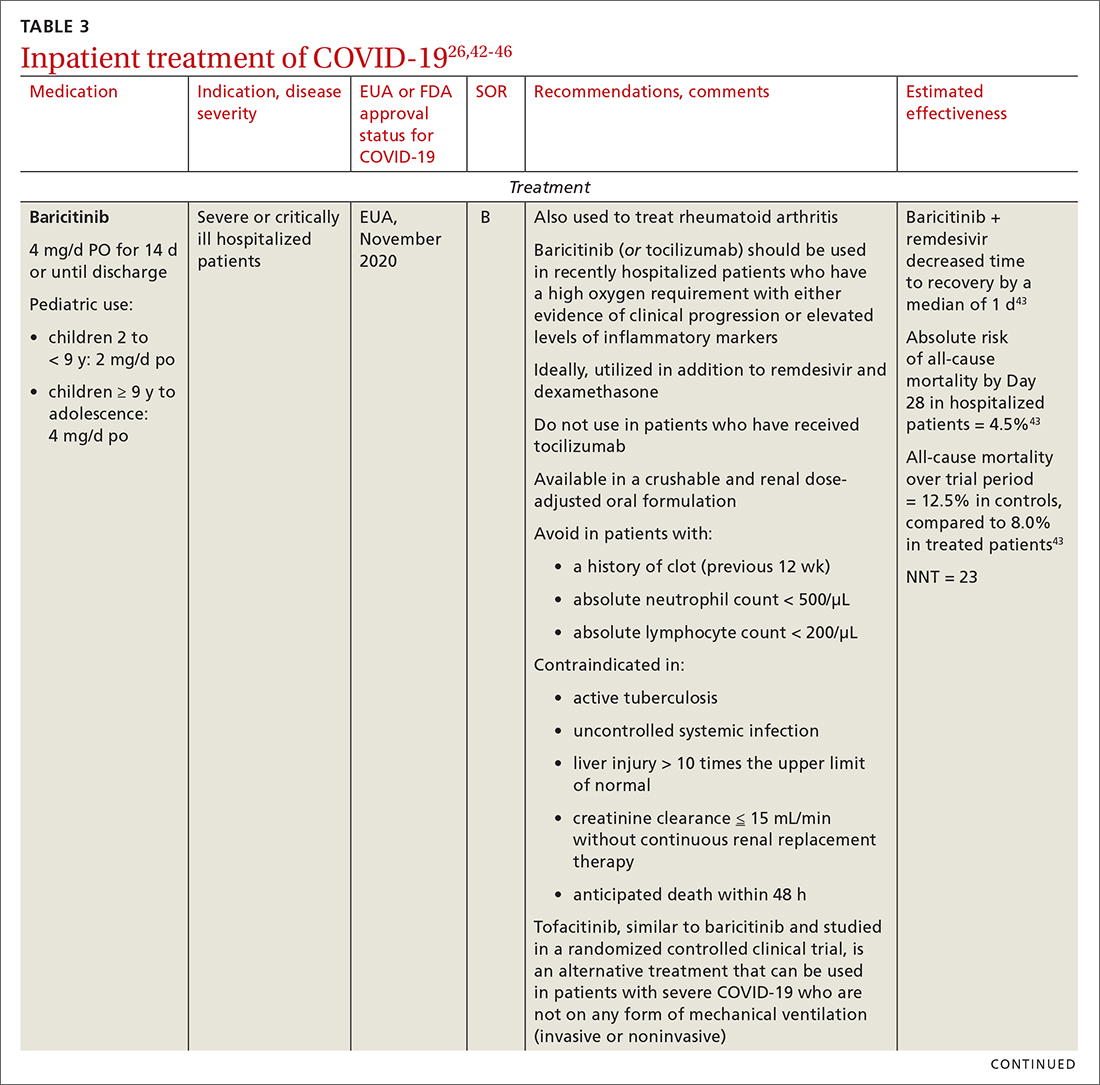

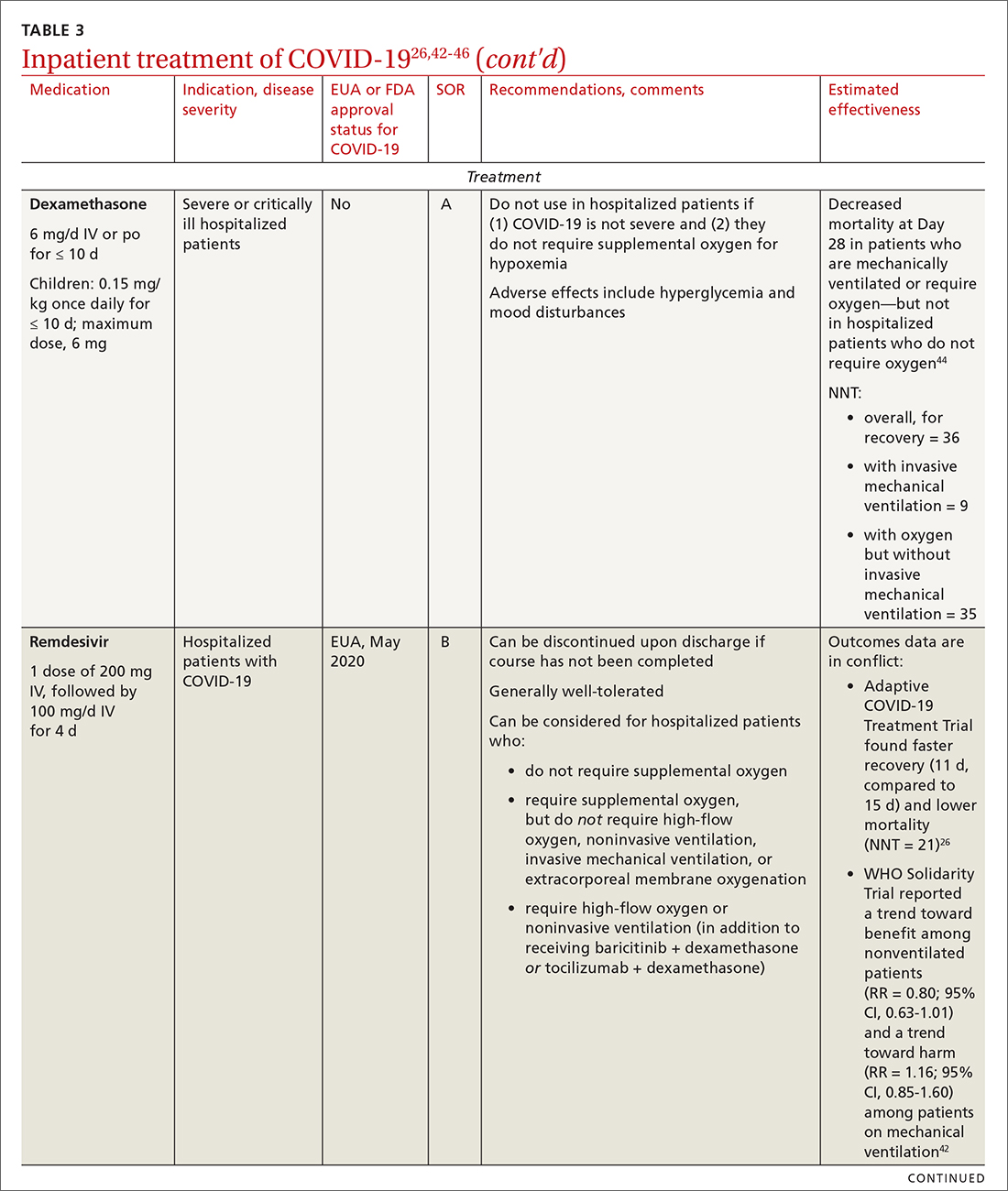

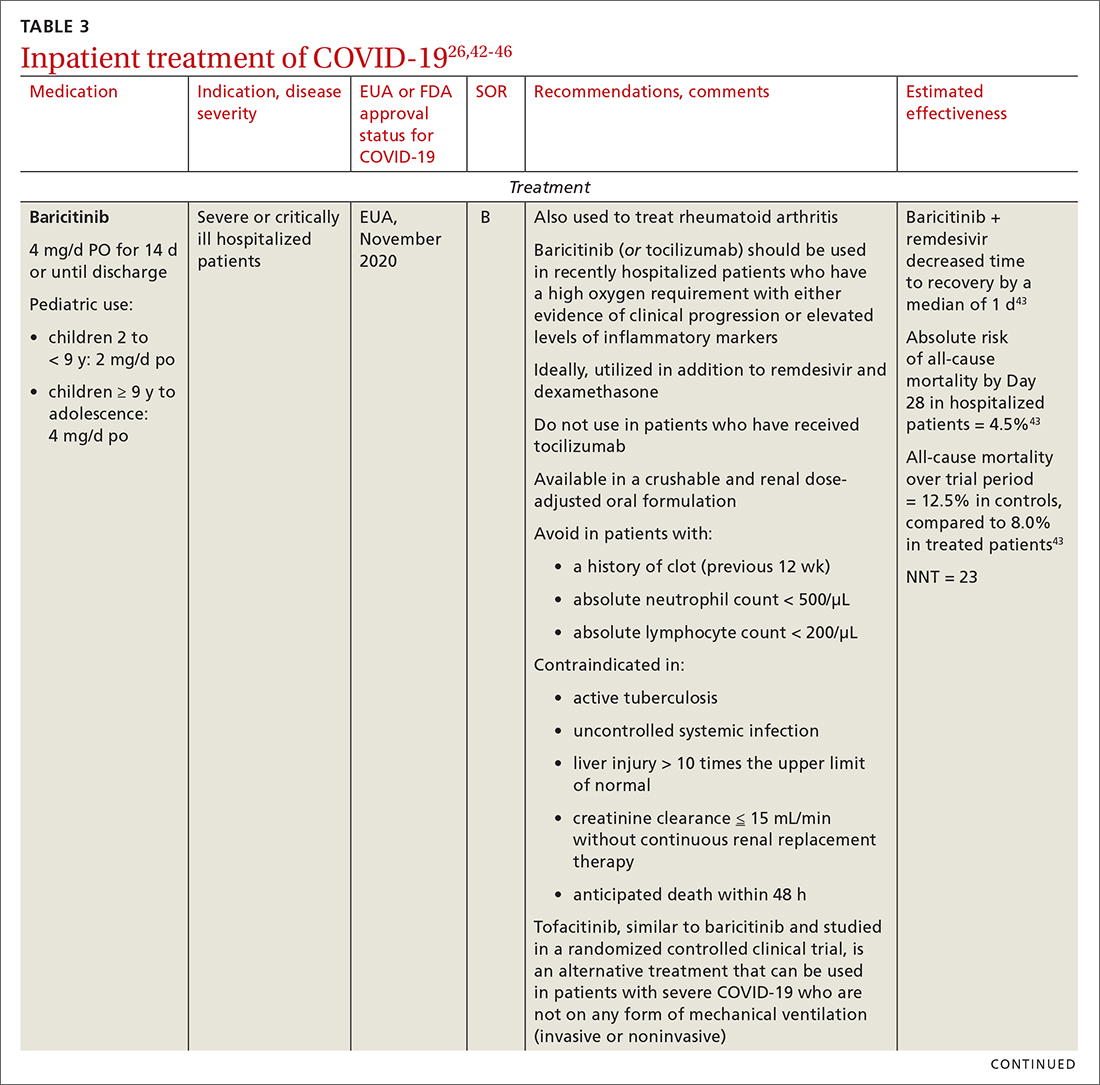

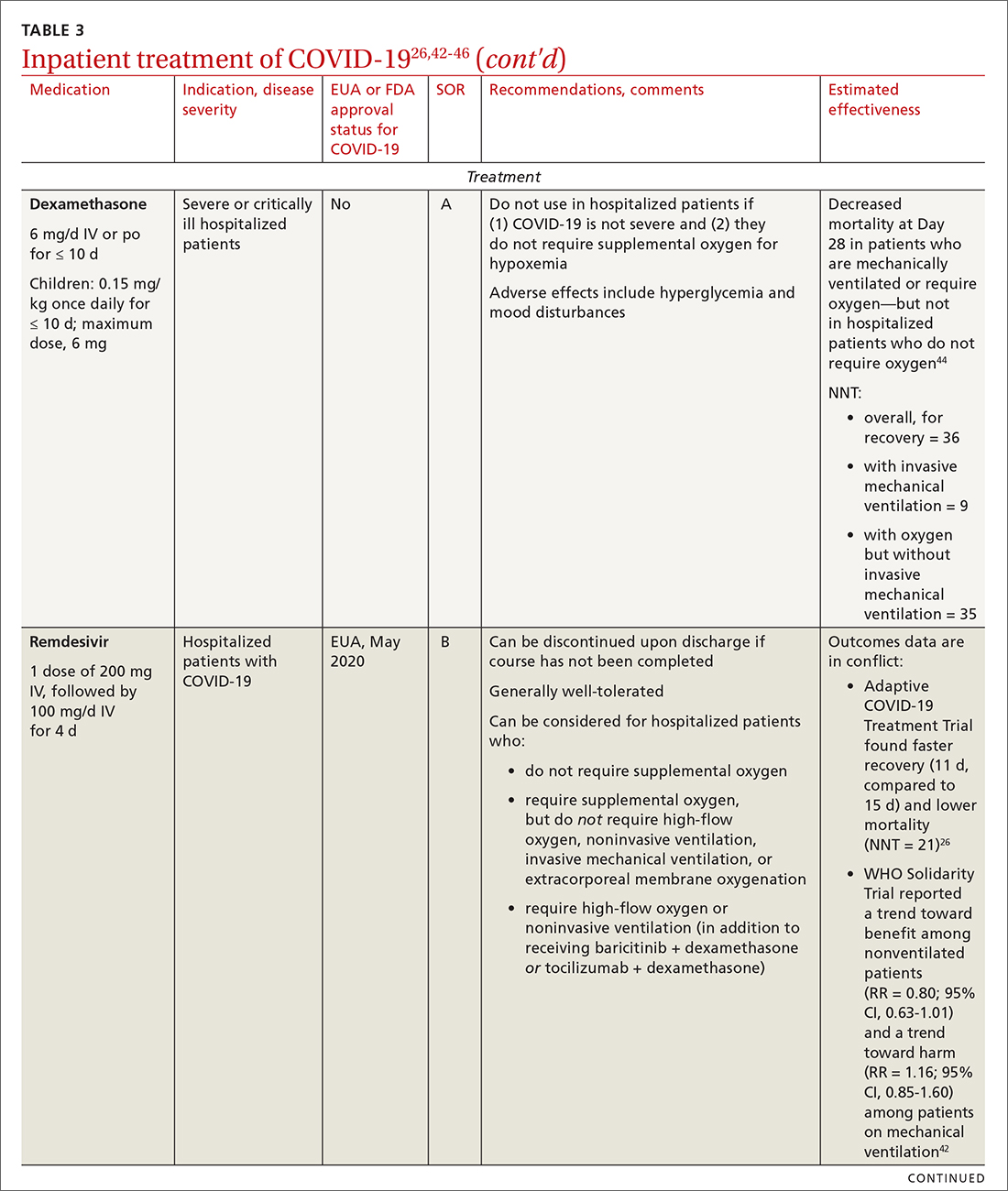

- Anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive agents help prevent tissue damage from a dysregulated immune system. (See TABLE 326,42-46)

- The NIH panel,1 IDSA,2 and WHO3 recommend against dexamethasone and other corticosteroids for hospitalized patients who do not require supplemental oxygen.

- Prone positioning distributes oxygen more evenly in the lungs and improves overall oxygenation, thus reducing the need for mechanical ventilation.

Remdesivir. Once a hospitalized patient does require supplemental oxygen, the NIH panel,1 IDSA,2 and WHO3 recommend remdesivir; however, remdesivir is not recommended in many other countries because WHO has noted its limited efficacy.42 Dexamethasone is recommended alone, or in combination with remdesivir for patients who require increasing supplemental oxygen and those on mechanical ventilation.

Baricitinib. For patients with rapidly increasing oxygen requirements, invasive mechanical ventilation, and systemic inflammation, baricitinib, a Janus kinase inhibitor, can be administered, in addition to dexamethasone, with or without remdesivir.47

Continue to: Tocilizumab

Tocilizumab. A monoclonal antibody and interleukin (IL)-6 inhibitor, tocilizumab is also recommended in addition to dexamethasone, with or without remdesivir.48 Tocilizumab should be given only in combination with dexamethasone.49 Patients should receive baricitinib or tocilizumab—not both. IDSA recommends tofacitinib, with a prophylactic dose of an anticoagulant, for patients who are hospitalized with severe COVID-19 but who are not on any form of ventilation.50

Care of special populations

Special patient populations often seek primary care. Although many questions remain regarding the appropriate care of these populations, it is useful to summarize existing evidence and recommendations from current guidelines.

Children. COVID-19 is generally milder in children than in adults; many infected children are asymptomatic. However, infants and children who have an underlying medical condition are at risk of severe disease, including multisystem inflammatory syndrome.51

The NIH panel recommends supportive care alone for most children with mild-to-moderate disease.1 Remdesivir is recommended for hospitalized children ≥ 12 years who weigh ≥ 40 kg, have risk factors for severe disease, and have an emergent or increasing need for supplemental oxygen. Dexamethasone is recommended for hospitalized children requiring high-flow oxygen, noninvasive ventilation, invasive mechanical ventilation, or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Molnupiravir is not authorized for patients < 18 years because it can impede bone and cartilage growth.

There is insufficient evidence for or against the use of monoclonal antibody products for children with COVID-19 in an ambulatory setting. For hospitalized children, there is insufficient evidence for or against use of baricitinib and tocilizumab.

Continue to: Patients who are pregnant

Patients who are pregnant are at increased risk of severe COVID-19.52,53 The NIH states that, in general, treatment and vaccination of pregnant patients with COVID-19 should be the same as for nonpregnant patients.1

Pregnant subjects were excluded from several trials of COVID-19 treatments.54 Because Janus kinase inhibitors, such as baricitinib, are associated with an increased risk of thromboembolism, they are not recommended in pregnant patients who are already at risk of thromboembolic complications. Molnupiravir is not recommended for pregnant patients because of its potential for teratogenic effects.

The Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine states that there are no absolute contraindications to the use of monoclonal antibodies in appropriate pregnant patients with COVID-19.55 Remdesivir has no known fetal toxicity and is recommended as a treatment that can be offered to pregnant patients. Dexamethasone can also be administered to pregnant patients who require oxygen; however, if dexamethasone is also being used to accelerate fetal lung maturity, more frequent initial dosing is needed.

Older people. COVID-19 treatments for older patients are the same as for the general adult population. However, because older people are more likely to have impaired renal function, renal function should be monitored when an older patient is being treated with COVID-19 medications that are eliminated renally (eg, remdesivir, baricitinib). Furthermore, drug–drug interactions have been reported in older patients treated with nirmatrelvir + ritonavir, primarily because of the effects of ritonavir. Review all of a patient’s medications, including over-the-counter drugs and herbal supplements, when prescribing treatment for COVID-19, and adjust the dosage by following guidance in FDA-approved prescribing information—ideally, in consultation with a pharmacist.

Immunocompromised patients. The combination product tixagevimab + cilgavimab [Evusheld] is FDA approved for COVID-19 PrEP, under an EUA, in patients who are not infected with SARS-CoV-2 who have an immune-compromising condition, who are unlikely to mount an adequate immune response to the COVID-19 vaccine, or those in whom vaccination is not recommended because of their history of a severe adverse reaction to a COVID-19 vaccine or one of its components.7

Continue to: Summing up

Summing up

With a growing need for effective and readily available COVID-19 treatments, there are an unprecedented number of clinical trials in process. Besides antivirals, immunomodulators, and antibody therapies, some novel mechanisms being tested include Janus kinase inhibitors, IL-6-receptor blockers, and drugs that target adult respiratory distress syndrome and cytokine release.

Once larger trials are completed, we can expect stronger evidence of potential treatment options and of safety and efficacy in children, pregnant women, and vulnerable populations. During the pandemic, the FDA’s EUA program has brought emerging treatments rapidly to clinicians; nevertheless, high-quality evidence, with thorough peer review, remains critical to inform COVID-19 treatment guidelines.

ahttps://healthdata.gov/Health/COVID-19-PublicTherapeutic-Locator/rxn6-qnx8/data

b Sotrovimab was effective against the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2—the dominant variant in early 2022— but is currently not FDA authorized in any region of the United States because of the prevalence of the Omicron BA.2 subvariant.30

CORRESPONDENCE

Ambar Kulshreshtha, MD, PhD, Department of Epidemiology, Emory Rollins School of Public Health, 4500 North Shallowford Road, Suite 134, Atlanta, GA 30338; akulshr@emory.edu

1. COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) treatment guidelines. National Institutes of Health. July 19, 2022. Accessed July 21, 2022. www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov

2. IDSA guidelines on the treatment and management of patients with COVID-19. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Updated June 29, 2022. Accessed July 21, 2022. www.idsociety.org/practice-guideline/covid-19-guideline-treatment-and-management/#toc-23

3. Therapeutics and COVID-19: living guideline. World Health Organization. July 14, 2022. Accessed July 21, 2022. https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1449398/retrieve

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinical care considerations. Updated May 27, 2022. Accessed July 21, 2022. www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-guidance-management-patients.html

5. Coronavirus (COVID-19) update: FDA approves first COVID-19 treatment for young children. Press release. US Food and Drug Administration. April 25, 2022. Accessed August 11, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-approves-first-covid-19-treatment-young-children

6. Know your treatment options for COVID-19. US Food and Drug Administration. Updated August 15, 2022. Accessed July 21, 2022. www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/know-your-treatment-options-covid-19

7. Tixagevimab and cilgavimab (Evusheld) for pre-exposure prophylaxis of COVID-19. JAMA. 2022;327:384-385. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.24931

8. Judson TJ, Odisho AY, Neinstein AB, et al. Rapid design and implementation of an integrated patient self-triage and self-scheduling tool for COVID-19. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020;27:860-866. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa051

9. Gandhi RT, Lynch JB, Del Rio C. Mild or moderate Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1757-1766. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp2009249

10. Greenhalgh T, Koh GCH, Car J. Covid-19: a remote assessment in primary care. BMJ. 2020;368:m1182. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1182

11. Jayk Bernal A, Gomes da Silva MM, Musungaie DB, et al; . Molnupiravir for oral treatment of Covid-19 in nonhospitalized patients. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:509-520. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2116044

12. Hammond J, Leister-Tebbe H, Gardner A, et al; . Oral nirmatrelvir for high-risk, nonhospitalized adults with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:1397-1408. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2118542

13. Gottlieb RL, Vaca CE, Paredes R, et al; . Early remdesivir to prevent progression to severe Covid-19 in outpatients. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:305-315. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2116846

14. Gupta A, Gonzalez-Rojas Y, Juarez E, et al; . Early treatment for Covid-19 with SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody sotrovimab. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1941-1950. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2107934

15. Skipper CP, Pastick KA, Engen NW, et al. Hydroxychloroquine in nonhospitalized adults with early COVID-19: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:623-631. doi: 10.7326/M20-4207

16. Scheen AJ. Statins and clinical outcomes with COVID-19: meta-analyses of observational studies. Diabetes Metab. 2021;47:101220. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2020.101220

17. Kow CS, Hasan SS. Meta-analysis of effect of statins in patients with COVID-19. Am J Cardiol. 2020;134:153-155. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2020.08.004

18. Halpin DMG, Singh D, Hadfield RM. Inhaled corticosteroids and COVID-19: a systematic review and clinical perspective. Eur Respir J. 2020;55:2001009. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01009-2020

19. Yu L-M, Bafadhel M, Dorward J, et al; . Inhaled budesonide for COVID-19 in people at high risk of complications in the community in the UK (PRINCIPLE): a randomised, controlled, open-label, adaptive platform trial. Lancet. 2021;398:843-855. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01744-X

20. Siemieniuk RA, Bartoszko JJ, JP, et al. Antibody and cellular therapies for treatment of covid-19: a living systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2021;374:n2231. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n2231

21. Siemieniuk RA, Bartoszko JJ, Zeraatkar D, et al. Drug treatments for covid-19: living systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;370:m2980. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2980

22. Agarwal A, Rochwerg B, Lamontagne F, et al. A living WHO guideline on drugs for covid-19. BMJ. 2020;370:m3379. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3379

23. Goldstein KM, Ghadimi K, Mystakelis H, et al. Risk of transmitting coronavirus disease 2019 during nebulizer treatment: a systematic review. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2021;34:155-170. doi: 10.1089/jamp.2020.1659

24. Schultze A, Walker AJ, MacKenna B, et al; . Risk of COVID-19-related death among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma prescribed inhaled corticosteroids: an observational cohort study using the OpenSAFELY platform. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:1106-1120. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30415-X

25. What are the safety and efficacy results of bebtelovimab from BLAZE-4? Lilly USA. January 12, 2022. Accessed August 17, 2022. www.lillymedical.com/en-us/answers/what-are-the-safety-and-efficacy-results-of-bebtelovimab-from-blaze-4-159290

26. Beigel JH, Tomashek KM, Dodd LE, et al; . Remdesivir for the treatment of Covid-19—final report. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1813-1826. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007764

27. Cao B, Wang Y, Wen D, et al. A trial of lopinavir–ritonavir in adults hospitalized with severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1787-1799. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001282

28. Gandhi RT, Malani PN, Del Rio C. COVID-19 therapeutics for nonhospitalized patients. JAMA. 2022;327:617-618. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.0335

29. Wen W, Chen C, Tang J, et al. Efficacy and safety of three new oral antiviral treatment (molnupiravir, fluvoxamine and Paxlovid) for COVID-19: a meta-analysis. Ann Med. 2022;54:516-523. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2022.2034936

30. Planas D, Saunders N, Maes P, et al. Considerable escape of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron to antibody neutralization. Nature. 2022:602:671-675. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04389-z

31. Emergency use authorization (EUA) for bebtelovimab (LY-CoV1404): Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) review. US Food and Drug Administration. Updated February 11, 2022. Accessed July 21, 2022. www.fda.gov/media/156396/download

32. Bartoszko JJ, Siemieniuk RAC, Kum E, et al. Prophylaxis against covid-19: living systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2021;373:n949. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n949

33. Reis G, Dos Santos Moreira-Silva EA, Silva DCM, et al; TOGETHER Investigators. Effect of early treatment with fluvoxamine on risk of emergency care and hospitalisation among patients with COVID-19: the TOGETHER randomised, platform clinical trial. Lancet Glob Health. 2022;10:e42-e51. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00448-4

34. RECOVERY Collaborative Group. Convalescent plasma in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 (RECOVERY): a randomised controlled, open-label, platform trial. Lancet. 2021;397:2049-2059. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00897-7

35. Simonovich VA, Burgos Pratx LD, Scibona P, et al; . A randomized trial of convalescent plasma in Covid-19 severe pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:619-629. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2031304

36. Joyner MJ, Carter RE, Senefeld JW, et al. Convalescent plasma antibody levels and the risk of death from Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1015-1027. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2031893

37. Ayeh SK, Abbey EJ, Khalifa BAA, et al. Statins use and COVID-19 outcomes in hospitalized patients. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0256899. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0256899

38. Ramakrishnan S, Nicolau DV Jr, Langford B, et al. Inhaled budesonide in the treatment of early COVID-19 (STOIC): a phase 2, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9:763-772. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00160-0

39. Temple C, Hoang R, Hendrickson RG. Toxic effects from ivermectin use associated with prevention and treatment of Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2197-2198. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2114907

40. Thomas S, Patel D, Bittel B, et al. Effect of high-dose zinc and ascorbic acid supplementation vs usual care on symptom length and reduction among ambulatory patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection: the COVID A to Z randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e210369. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0369

41. Adams KK, Baker WL, Sobieraj DM. Myth busters: dietary supplements and COVID-19. Ann Pharmacother. 2020;54:820-826. doi: 10.1177/1060028020928052

42. Pan H, Peto R, Henao-Restrepo A-M, et al. Repurposed antiviral drugs for Covid-19—interim WHO Solidarity trial results. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:497-511. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2023184

43. Kalil AC, Patterson TF, Mehta AK, et al; . Baricitinib plus remdesivir for hospitalized adults with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:795-807. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2031994

44. ; Sterne JAC, Murthy S, Diaz JV, et al. Association between administration of systemic corticosteroids and mortality among critically ill patients with COVID-19: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2020;324:1330-1341. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17023

45. ; Shankar-Hari M, Vale CL, Godolphin PJ, et al. Association between administration of IL-6 antagonists and mortality among patients hospitalized for COVID-19: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2021;326:499-518. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.11330

46. Wei QW, Lin H, Wei R-G, et al. Tocilizumab treatment for COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Dis Poverty. 2021;10:71. doi: 10.1186/s40249-021-00857-w

47. Zhang X, Shang L, Fan G, et al. The efficacy and safety of Janus kinase inhibitors for patients with COVID-19: a living systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:800492. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.800492

48. RECOVERY Collaborative Group. Tocilizumab in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 (RECOVERY): a randomised, controlled, open-label, platform trial. Lancet. 2021;397:1637-1645. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00676-0

49. Gordon AC, Mouncey PR, Al-Beidh F, et al. Interleukin-6 receptor antagonists in critically ill patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1491-1502. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2100433

50. Guimaraes PO, Quirk D, Furtado RH, et al; . Tofacitinib in patients hospitalized with Covid-19 pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:406-415. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2101643

51. Feldstein LR, Rose EB, Horwitz SM, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in U.S. children and adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:334-346. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021680

52. Allotey J, Stallings E, Bonet M, et al. Clinical manifestations, risk factors, and maternal and perinatal outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnancy: living systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;370:m3320. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3320

53. Villar J, Ariff S, Gunier RB, et al. Maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality among pregnant women with and without COVID-19 infection: the INTERCOVID multinational cohort study. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175:817-826. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.1050

54. Jorgensen SCJ, Davis MR, Lapinsky SE. A review of remdesivir for COVID-19 in pregnancy and lactation. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2021;77:24-30. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkab311

55. Management considerations for pregnant patients with COVID-19. Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Accessed July 21, 2022. https://s3.amazonaws.com/cdn.smfm.org/media/2336/SMFM_COVID_Management_of_COVID_pos_preg_patients_4-30-20_final.pdf

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has caused more than 1 million deaths in the United States and continues to be a major public health challenge. Cases can be asymptomatic, or symptoms can range from a mild respiratory tract infection to acute respiratory distress and multiorgan failure.

Three strategies can successfully contain the pandemic and its consequences:

- Public health measures, such as masking and social distancing

- Prophylactic vaccines to reduce transmission

- Safe and effective drugs for reducing morbidity and mortality among infected patients.

Optimal treatment strategies for patients in ambulatory and hospital settings continue to evolve as new studies are reported and new strains of the virus arise. Many medical and scientific organizations, including the National Institutes of Health (NIH) COVID-19 treatment panel,1 Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA),2 World Health Organization (WHO),3 and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,4 provide recommendations for managing patients with COVID-19. Their guidance is based on the strongest research available and is updated intermittently; nevertheless, a plethora of new data emerges weekly and controversies surround several treatments.

In this article, we

We encourage clinicians, in planning treatment, to consider:

- The availability of medications (ie, use the COVID-19 Public Therapeutic Locatora)

- The local COVID-19 situation

- Patient factors and preferences

- Evolving evidence regarding new and existing treatments.

Most evidence about the treatment of COVID-19 comes from studies conducted when the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2 was not the dominant variant, as it is today in the United States. As such, drugs authorized or approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat COVID-19 or used off-label for that purpose might not be as efficacious today as they were almost a year ago. Furthermore, many trials of potential therapies against new viral variants are ongoing; if your patient is interested in enrolling in a clinical trial of an investigational COVID-19 treatment, refer them to www.clinicaltrials.gov.

General managementof COVID-19

Patients with COVID-19 experience a range of illness severity—from asymptomatic to mild symptoms, such as fever and myalgia, to critical illness requiring intensive care (TABLE 11,2). Patients with COVID-19 should therefore be monitored for progression, remotely or in person, until full recovery is achieved. Key concepts of general management include:

Assess and monitor patients’ oxygenation status by pulse oximetry; identify those with low or declining oxygen saturation before further clinical deterioration.

Continue to: Consider the patient's age and general health

Consider the patient’s age and general health. Patients are at higher risk of severe disease if they are > 65 years or have an underlying comorbidity.4

Emphasize self-isolation and supportive care, including rest, hydration, and over-the-counter medications to relieve cough, reduce fever, and alleviate other symptoms.

Drugs: Few approved, some under study

The antiviral remdesivir is the only drug fully approved for clinical use by the FDA to treat COVID-19 in patients > 12 years.5,6

In addition, the FDA has issued an emergency use authorization (EUA) for several monoclonal antibodies as prophylaxis and treatment: tixagevimab packaged with cilgavimab (Evusheld) is the first antibody combination for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) against COVID-19; the separately packaged injectables are recommended for patients who have a history of severe allergy that prevents them from being vaccinated or those with moderate or severe immune-compromising disorders.7

In the pipeline. Several treatments are being tested in clinical trials to evaluate their effectiveness and safety in combating COVID-19, including:

- Antivirals, which prevent viruses from multiplying

- Immunomodulators, which reduce the body’s immune reaction to the virus

- Antibody therapies, which are manufactured antibodies against the virus

- Anti-inflammatory drugs, which reduce systemic inflammation and prevent organ dysfunction

- Cell therapies and gene therapies, which alter the expression of cells and genes.

Continue to: Outpatient treatment

Outpatient treatment

Several assessment tools that take into account patients’ age, respiratory status, and comorbidities are available for triage of patients infected with COVID-19.8

Most (> 80%) patients with COVID-19 have mild infection and are safely managed as outpatients or at home.9,10 For patients at high risk of severe disease, a few options are recommended for patients who do not require hospitalization or supplemental oxygen; guidelines on treatment of COVID-19 in outpatient settings that have been developed by various organizations are summarized in TABLE 2.7,11-25

Antiviral drugs target different stages of the SARS-CoV-2 replication cycle. They should be used early in the course of infection, particularly in patients at high risk of severe disease.

IDSA recommends antiviral therapy with molnupiravir, nirmatrelvir + ritonavir packaged together (Paxlovid), or remdesivir.11,12,26,27 Remdesivir requires intravenous (IV) infusion on 3 consecutive days, which can be difficult in some clinic settings.13,28 Nirmatrelvir + ritonavir should be initiated within 5 days after symptom onset. Overall, for most patients, nirmatrelvir + ritonavir is preferred because of oral dosing and higher efficacy in comparison to other antivirals. With nirmatrelvir + ritonavir, carefully consider drug–drug interactions and the need to adjust dosing in the presence of renal disease.28,29 There are no data on the efficacy of any combination treatments with these agents (other than co-packaged Paxlovid).

Monoclonal antibodies for COVID-19 are given primarily intravenously. They bind to the viral spike protein, thus preventing SARS-CoV-2 from attaching to and entering cells. Bamlanivimab + etesevimab and bebtelovimab are available under an EUA for outpatient treatment.14b Treatment should be initiated as early as possible in the course of infection—ideally, within 7 to 10 days after onset of symptoms.

Continue to: Bebtelovimab was recently given...

Bebtelovimab was recently given an EUA. It is a next-generation antibody that neutralizes all currently known variants and is the most potent monoclonal antibody against the Omicron variant, including its BA.2 subvariant.31 However, data about its activity against the BA.2 subvariant are based on laboratory testing and have not been confirmed in clinical trials. Clinical data were similar for this agent alone and for its use in combination with other monoclonal antibodies, but those trials were conducted before the emergence of Omicron.

In your decision-making about the most appropriate therapy, consider (1) the requirement that monoclonal antibodies be administered parenterally and (2) the susceptibility of the locally predominating viral variant.

Other monoclonal antibody agents are in the investigative pipeline; however, data about them have been largely presented through press releases or selectively reported in applications to the FDA for EUA. For example, preliminary reports show cilgavimab coverage against the Omicron variant14; so far, cilgavimab is not approved for treatment but is used in combination with tixagevimab for PreP—reportedly providing as long as 12 months of protection for patients who are less likely to respond to a vaccine.32

Corticosteroids. Guidelines recommend against dexamethasone and other systemic corticosteroids in outpatient settings. For patients with moderate-to-severe symptoms but for whom hospitalization is not possible (eg, beds are unavailable), the NIH panel recommends dexamethasone, 6 mg/d, for the duration of supplemental oxygen, not to exceed 10 days of treatment.1

Patients who were recently discharged after COVID-19 hospitalization should not continue remdesivir, dexamethasone, or baricitinib at home, even if they still require supplemental oxygen.

Continue to: Some treatments should not be in your COVID-19 toolbox

Some treatments should not be in your COVID-19 toolbox

High-quality studies are lacking for several other potential COVID-19 treatments. Some of these drugs are under investigation, with unclear benefit and with the potential risk of toxicity—and therefore should not be prescribed or used outside a clinical trial. See “Treatments not recommended for COVID-19,” page E14. 1-4,15-19,33-41

SIDEBAR

Treatments not recommended for COVID-191-4,15-19,33-41

Fluvoxamine. A few studies suggest that the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor fluvoxamine reduces progression to severe disease; however, those studies have methodologic challenges.33 The drug is not FDA approved for treating COVID.33

Convalescent plasma, given to high-risk outpatients early in the course of disease, can reduce progression to severe disease,34,35 but it remains investigational for COVID-19 because trials have yielded mixed results.34-36

Ivermectin. The effect of ivermectin in patients with COVID-19 is unclear because high-quality studies do not exist and cases of ivermectin toxicity have occurred with incorrect administration.39

Hydroxychloroquine showed potential in a few observational studies, but randomized clinical trials have not shown any benefit.15

Azithromycin likewise showed potential in a few observational studies; randomized clinical trials have not shown any benefit, however.15

Statins. A few meta-analyses, based on observational studies, reported benefit from statins, but recent studies have shown that this class of drugs does not provide clinical benefit in alleviating COVID-19 symptoms.16,17,37

Inhaled corticosteroids. A systematic review reported no benefit or harm from using an inhaled corticosteroid.18 More recent studies show that the inhaled corticosteroid budesonide used in early COVID-19 might reduce the need for urgent care38 and, in patients who are at higher risk of COVID-19-related complications, shorten time to recovery.19

Vitamins and minerals. Limited observational studies suggest an association between vitamin and mineral deficiency (eg, vitamin C, zinc, and vitamin D) and risk of severe disease, but high-quality data about this finding do not exist.40,41

Casirivimab + imdevimab [REGEN-COV2]. This unapproved investigational combination treatment was granted an EUA in 2020 for postexposure prophylaxis. The EUA was withdrawn in January 2022 because of the limited efficacy of casirivimab + imdevimab against the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2.

Postexposure prophylaxis. National guidelines1-4 recommend against postexposure prophylaxis with hydroxychloroquine, colchicine, inhaled corticosteroids, or azithromycin.

TABLE 27,11-25 and TABLE 326,42-46 provide additional information on treatments not recommended outside trials, or not recommended at all, for COVID-19.

Treatment during hospitalization

The NIH COVID-19 treatment panel recommends hospitalization for patients who have any of the following findings1:

- Oxygen saturation < 94% while breathing room air

- Respiratory rate > 30 breaths/min

- A ratio of partial pressure of arterial O2 to fraction of inspired O2 (PaO2/FiO2) < 300 mm Hg

- Lung infiltrates > 50%.

General guidance for the care of hospitalized patients:

- Treatments that target the virus have the greatest efficacy when given early in the course of disease.

- Anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive agents help prevent tissue damage from a dysregulated immune system. (See TABLE 326,42-46)

- The NIH panel,1 IDSA,2 and WHO3 recommend against dexamethasone and other corticosteroids for hospitalized patients who do not require supplemental oxygen.

- Prone positioning distributes oxygen more evenly in the lungs and improves overall oxygenation, thus reducing the need for mechanical ventilation.

Remdesivir. Once a hospitalized patient does require supplemental oxygen, the NIH panel,1 IDSA,2 and WHO3 recommend remdesivir; however, remdesivir is not recommended in many other countries because WHO has noted its limited efficacy.42 Dexamethasone is recommended alone, or in combination with remdesivir for patients who require increasing supplemental oxygen and those on mechanical ventilation.

Baricitinib. For patients with rapidly increasing oxygen requirements, invasive mechanical ventilation, and systemic inflammation, baricitinib, a Janus kinase inhibitor, can be administered, in addition to dexamethasone, with or without remdesivir.47

Continue to: Tocilizumab

Tocilizumab. A monoclonal antibody and interleukin (IL)-6 inhibitor, tocilizumab is also recommended in addition to dexamethasone, with or without remdesivir.48 Tocilizumab should be given only in combination with dexamethasone.49 Patients should receive baricitinib or tocilizumab—not both. IDSA recommends tofacitinib, with a prophylactic dose of an anticoagulant, for patients who are hospitalized with severe COVID-19 but who are not on any form of ventilation.50

Care of special populations

Special patient populations often seek primary care. Although many questions remain regarding the appropriate care of these populations, it is useful to summarize existing evidence and recommendations from current guidelines.

Children. COVID-19 is generally milder in children than in adults; many infected children are asymptomatic. However, infants and children who have an underlying medical condition are at risk of severe disease, including multisystem inflammatory syndrome.51

The NIH panel recommends supportive care alone for most children with mild-to-moderate disease.1 Remdesivir is recommended for hospitalized children ≥ 12 years who weigh ≥ 40 kg, have risk factors for severe disease, and have an emergent or increasing need for supplemental oxygen. Dexamethasone is recommended for hospitalized children requiring high-flow oxygen, noninvasive ventilation, invasive mechanical ventilation, or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Molnupiravir is not authorized for patients < 18 years because it can impede bone and cartilage growth.

There is insufficient evidence for or against the use of monoclonal antibody products for children with COVID-19 in an ambulatory setting. For hospitalized children, there is insufficient evidence for or against use of baricitinib and tocilizumab.

Continue to: Patients who are pregnant

Patients who are pregnant are at increased risk of severe COVID-19.52,53 The NIH states that, in general, treatment and vaccination of pregnant patients with COVID-19 should be the same as for nonpregnant patients.1

Pregnant subjects were excluded from several trials of COVID-19 treatments.54 Because Janus kinase inhibitors, such as baricitinib, are associated with an increased risk of thromboembolism, they are not recommended in pregnant patients who are already at risk of thromboembolic complications. Molnupiravir is not recommended for pregnant patients because of its potential for teratogenic effects.

The Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine states that there are no absolute contraindications to the use of monoclonal antibodies in appropriate pregnant patients with COVID-19.55 Remdesivir has no known fetal toxicity and is recommended as a treatment that can be offered to pregnant patients. Dexamethasone can also be administered to pregnant patients who require oxygen; however, if dexamethasone is also being used to accelerate fetal lung maturity, more frequent initial dosing is needed.

Older people. COVID-19 treatments for older patients are the same as for the general adult population. However, because older people are more likely to have impaired renal function, renal function should be monitored when an older patient is being treated with COVID-19 medications that are eliminated renally (eg, remdesivir, baricitinib). Furthermore, drug–drug interactions have been reported in older patients treated with nirmatrelvir + ritonavir, primarily because of the effects of ritonavir. Review all of a patient’s medications, including over-the-counter drugs and herbal supplements, when prescribing treatment for COVID-19, and adjust the dosage by following guidance in FDA-approved prescribing information—ideally, in consultation with a pharmacist.

Immunocompromised patients. The combination product tixagevimab + cilgavimab [Evusheld] is FDA approved for COVID-19 PrEP, under an EUA, in patients who are not infected with SARS-CoV-2 who have an immune-compromising condition, who are unlikely to mount an adequate immune response to the COVID-19 vaccine, or those in whom vaccination is not recommended because of their history of a severe adverse reaction to a COVID-19 vaccine or one of its components.7

Continue to: Summing up

Summing up

With a growing need for effective and readily available COVID-19 treatments, there are an unprecedented number of clinical trials in process. Besides antivirals, immunomodulators, and antibody therapies, some novel mechanisms being tested include Janus kinase inhibitors, IL-6-receptor blockers, and drugs that target adult respiratory distress syndrome and cytokine release.

Once larger trials are completed, we can expect stronger evidence of potential treatment options and of safety and efficacy in children, pregnant women, and vulnerable populations. During the pandemic, the FDA’s EUA program has brought emerging treatments rapidly to clinicians; nevertheless, high-quality evidence, with thorough peer review, remains critical to inform COVID-19 treatment guidelines.

ahttps://healthdata.gov/Health/COVID-19-PublicTherapeutic-Locator/rxn6-qnx8/data

b Sotrovimab was effective against the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2—the dominant variant in early 2022— but is currently not FDA authorized in any region of the United States because of the prevalence of the Omicron BA.2 subvariant.30

CORRESPONDENCE

Ambar Kulshreshtha, MD, PhD, Department of Epidemiology, Emory Rollins School of Public Health, 4500 North Shallowford Road, Suite 134, Atlanta, GA 30338; akulshr@emory.edu

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has caused more than 1 million deaths in the United States and continues to be a major public health challenge. Cases can be asymptomatic, or symptoms can range from a mild respiratory tract infection to acute respiratory distress and multiorgan failure.

Three strategies can successfully contain the pandemic and its consequences:

- Public health measures, such as masking and social distancing

- Prophylactic vaccines to reduce transmission

- Safe and effective drugs for reducing morbidity and mortality among infected patients.

Optimal treatment strategies for patients in ambulatory and hospital settings continue to evolve as new studies are reported and new strains of the virus arise. Many medical and scientific organizations, including the National Institutes of Health (NIH) COVID-19 treatment panel,1 Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA),2 World Health Organization (WHO),3 and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,4 provide recommendations for managing patients with COVID-19. Their guidance is based on the strongest research available and is updated intermittently; nevertheless, a plethora of new data emerges weekly and controversies surround several treatments.

In this article, we

We encourage clinicians, in planning treatment, to consider:

- The availability of medications (ie, use the COVID-19 Public Therapeutic Locatora)

- The local COVID-19 situation

- Patient factors and preferences

- Evolving evidence regarding new and existing treatments.

Most evidence about the treatment of COVID-19 comes from studies conducted when the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2 was not the dominant variant, as it is today in the United States. As such, drugs authorized or approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat COVID-19 or used off-label for that purpose might not be as efficacious today as they were almost a year ago. Furthermore, many trials of potential therapies against new viral variants are ongoing; if your patient is interested in enrolling in a clinical trial of an investigational COVID-19 treatment, refer them to www.clinicaltrials.gov.

General managementof COVID-19

Patients with COVID-19 experience a range of illness severity—from asymptomatic to mild symptoms, such as fever and myalgia, to critical illness requiring intensive care (TABLE 11,2). Patients with COVID-19 should therefore be monitored for progression, remotely or in person, until full recovery is achieved. Key concepts of general management include:

Assess and monitor patients’ oxygenation status by pulse oximetry; identify those with low or declining oxygen saturation before further clinical deterioration.

Continue to: Consider the patient's age and general health

Consider the patient’s age and general health. Patients are at higher risk of severe disease if they are > 65 years or have an underlying comorbidity.4

Emphasize self-isolation and supportive care, including rest, hydration, and over-the-counter medications to relieve cough, reduce fever, and alleviate other symptoms.

Drugs: Few approved, some under study

The antiviral remdesivir is the only drug fully approved for clinical use by the FDA to treat COVID-19 in patients > 12 years.5,6

In addition, the FDA has issued an emergency use authorization (EUA) for several monoclonal antibodies as prophylaxis and treatment: tixagevimab packaged with cilgavimab (Evusheld) is the first antibody combination for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) against COVID-19; the separately packaged injectables are recommended for patients who have a history of severe allergy that prevents them from being vaccinated or those with moderate or severe immune-compromising disorders.7

In the pipeline. Several treatments are being tested in clinical trials to evaluate their effectiveness and safety in combating COVID-19, including:

- Antivirals, which prevent viruses from multiplying

- Immunomodulators, which reduce the body’s immune reaction to the virus

- Antibody therapies, which are manufactured antibodies against the virus

- Anti-inflammatory drugs, which reduce systemic inflammation and prevent organ dysfunction

- Cell therapies and gene therapies, which alter the expression of cells and genes.

Continue to: Outpatient treatment

Outpatient treatment

Several assessment tools that take into account patients’ age, respiratory status, and comorbidities are available for triage of patients infected with COVID-19.8

Most (> 80%) patients with COVID-19 have mild infection and are safely managed as outpatients or at home.9,10 For patients at high risk of severe disease, a few options are recommended for patients who do not require hospitalization or supplemental oxygen; guidelines on treatment of COVID-19 in outpatient settings that have been developed by various organizations are summarized in TABLE 2.7,11-25

Antiviral drugs target different stages of the SARS-CoV-2 replication cycle. They should be used early in the course of infection, particularly in patients at high risk of severe disease.

IDSA recommends antiviral therapy with molnupiravir, nirmatrelvir + ritonavir packaged together (Paxlovid), or remdesivir.11,12,26,27 Remdesivir requires intravenous (IV) infusion on 3 consecutive days, which can be difficult in some clinic settings.13,28 Nirmatrelvir + ritonavir should be initiated within 5 days after symptom onset. Overall, for most patients, nirmatrelvir + ritonavir is preferred because of oral dosing and higher efficacy in comparison to other antivirals. With nirmatrelvir + ritonavir, carefully consider drug–drug interactions and the need to adjust dosing in the presence of renal disease.28,29 There are no data on the efficacy of any combination treatments with these agents (other than co-packaged Paxlovid).

Monoclonal antibodies for COVID-19 are given primarily intravenously. They bind to the viral spike protein, thus preventing SARS-CoV-2 from attaching to and entering cells. Bamlanivimab + etesevimab and bebtelovimab are available under an EUA for outpatient treatment.14b Treatment should be initiated as early as possible in the course of infection—ideally, within 7 to 10 days after onset of symptoms.

Continue to: Bebtelovimab was recently given...

Bebtelovimab was recently given an EUA. It is a next-generation antibody that neutralizes all currently known variants and is the most potent monoclonal antibody against the Omicron variant, including its BA.2 subvariant.31 However, data about its activity against the BA.2 subvariant are based on laboratory testing and have not been confirmed in clinical trials. Clinical data were similar for this agent alone and for its use in combination with other monoclonal antibodies, but those trials were conducted before the emergence of Omicron.

In your decision-making about the most appropriate therapy, consider (1) the requirement that monoclonal antibodies be administered parenterally and (2) the susceptibility of the locally predominating viral variant.

Other monoclonal antibody agents are in the investigative pipeline; however, data about them have been largely presented through press releases or selectively reported in applications to the FDA for EUA. For example, preliminary reports show cilgavimab coverage against the Omicron variant14; so far, cilgavimab is not approved for treatment but is used in combination with tixagevimab for PreP—reportedly providing as long as 12 months of protection for patients who are less likely to respond to a vaccine.32

Corticosteroids. Guidelines recommend against dexamethasone and other systemic corticosteroids in outpatient settings. For patients with moderate-to-severe symptoms but for whom hospitalization is not possible (eg, beds are unavailable), the NIH panel recommends dexamethasone, 6 mg/d, for the duration of supplemental oxygen, not to exceed 10 days of treatment.1

Patients who were recently discharged after COVID-19 hospitalization should not continue remdesivir, dexamethasone, or baricitinib at home, even if they still require supplemental oxygen.

Continue to: Some treatments should not be in your COVID-19 toolbox

Some treatments should not be in your COVID-19 toolbox

High-quality studies are lacking for several other potential COVID-19 treatments. Some of these drugs are under investigation, with unclear benefit and with the potential risk of toxicity—and therefore should not be prescribed or used outside a clinical trial. See “Treatments not recommended for COVID-19,” page E14. 1-4,15-19,33-41

SIDEBAR

Treatments not recommended for COVID-191-4,15-19,33-41

Fluvoxamine. A few studies suggest that the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor fluvoxamine reduces progression to severe disease; however, those studies have methodologic challenges.33 The drug is not FDA approved for treating COVID.33

Convalescent plasma, given to high-risk outpatients early in the course of disease, can reduce progression to severe disease,34,35 but it remains investigational for COVID-19 because trials have yielded mixed results.34-36

Ivermectin. The effect of ivermectin in patients with COVID-19 is unclear because high-quality studies do not exist and cases of ivermectin toxicity have occurred with incorrect administration.39

Hydroxychloroquine showed potential in a few observational studies, but randomized clinical trials have not shown any benefit.15

Azithromycin likewise showed potential in a few observational studies; randomized clinical trials have not shown any benefit, however.15

Statins. A few meta-analyses, based on observational studies, reported benefit from statins, but recent studies have shown that this class of drugs does not provide clinical benefit in alleviating COVID-19 symptoms.16,17,37

Inhaled corticosteroids. A systematic review reported no benefit or harm from using an inhaled corticosteroid.18 More recent studies show that the inhaled corticosteroid budesonide used in early COVID-19 might reduce the need for urgent care38 and, in patients who are at higher risk of COVID-19-related complications, shorten time to recovery.19

Vitamins and minerals. Limited observational studies suggest an association between vitamin and mineral deficiency (eg, vitamin C, zinc, and vitamin D) and risk of severe disease, but high-quality data about this finding do not exist.40,41

Casirivimab + imdevimab [REGEN-COV2]. This unapproved investigational combination treatment was granted an EUA in 2020 for postexposure prophylaxis. The EUA was withdrawn in January 2022 because of the limited efficacy of casirivimab + imdevimab against the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2.

Postexposure prophylaxis. National guidelines1-4 recommend against postexposure prophylaxis with hydroxychloroquine, colchicine, inhaled corticosteroids, or azithromycin.

TABLE 27,11-25 and TABLE 326,42-46 provide additional information on treatments not recommended outside trials, or not recommended at all, for COVID-19.

Treatment during hospitalization

The NIH COVID-19 treatment panel recommends hospitalization for patients who have any of the following findings1:

- Oxygen saturation < 94% while breathing room air

- Respiratory rate > 30 breaths/min

- A ratio of partial pressure of arterial O2 to fraction of inspired O2 (PaO2/FiO2) < 300 mm Hg

- Lung infiltrates > 50%.

General guidance for the care of hospitalized patients:

- Treatments that target the virus have the greatest efficacy when given early in the course of disease.

- Anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive agents help prevent tissue damage from a dysregulated immune system. (See TABLE 326,42-46)

- The NIH panel,1 IDSA,2 and WHO3 recommend against dexamethasone and other corticosteroids for hospitalized patients who do not require supplemental oxygen.

- Prone positioning distributes oxygen more evenly in the lungs and improves overall oxygenation, thus reducing the need for mechanical ventilation.

Remdesivir. Once a hospitalized patient does require supplemental oxygen, the NIH panel,1 IDSA,2 and WHO3 recommend remdesivir; however, remdesivir is not recommended in many other countries because WHO has noted its limited efficacy.42 Dexamethasone is recommended alone, or in combination with remdesivir for patients who require increasing supplemental oxygen and those on mechanical ventilation.

Baricitinib. For patients with rapidly increasing oxygen requirements, invasive mechanical ventilation, and systemic inflammation, baricitinib, a Janus kinase inhibitor, can be administered, in addition to dexamethasone, with or without remdesivir.47

Continue to: Tocilizumab

Tocilizumab. A monoclonal antibody and interleukin (IL)-6 inhibitor, tocilizumab is also recommended in addition to dexamethasone, with or without remdesivir.48 Tocilizumab should be given only in combination with dexamethasone.49 Patients should receive baricitinib or tocilizumab—not both. IDSA recommends tofacitinib, with a prophylactic dose of an anticoagulant, for patients who are hospitalized with severe COVID-19 but who are not on any form of ventilation.50

Care of special populations

Special patient populations often seek primary care. Although many questions remain regarding the appropriate care of these populations, it is useful to summarize existing evidence and recommendations from current guidelines.

Children. COVID-19 is generally milder in children than in adults; many infected children are asymptomatic. However, infants and children who have an underlying medical condition are at risk of severe disease, including multisystem inflammatory syndrome.51

The NIH panel recommends supportive care alone for most children with mild-to-moderate disease.1 Remdesivir is recommended for hospitalized children ≥ 12 years who weigh ≥ 40 kg, have risk factors for severe disease, and have an emergent or increasing need for supplemental oxygen. Dexamethasone is recommended for hospitalized children requiring high-flow oxygen, noninvasive ventilation, invasive mechanical ventilation, or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Molnupiravir is not authorized for patients < 18 years because it can impede bone and cartilage growth.

There is insufficient evidence for or against the use of monoclonal antibody products for children with COVID-19 in an ambulatory setting. For hospitalized children, there is insufficient evidence for or against use of baricitinib and tocilizumab.

Continue to: Patients who are pregnant

Patients who are pregnant are at increased risk of severe COVID-19.52,53 The NIH states that, in general, treatment and vaccination of pregnant patients with COVID-19 should be the same as for nonpregnant patients.1

Pregnant subjects were excluded from several trials of COVID-19 treatments.54 Because Janus kinase inhibitors, such as baricitinib, are associated with an increased risk of thromboembolism, they are not recommended in pregnant patients who are already at risk of thromboembolic complications. Molnupiravir is not recommended for pregnant patients because of its potential for teratogenic effects.

The Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine states that there are no absolute contraindications to the use of monoclonal antibodies in appropriate pregnant patients with COVID-19.55 Remdesivir has no known fetal toxicity and is recommended as a treatment that can be offered to pregnant patients. Dexamethasone can also be administered to pregnant patients who require oxygen; however, if dexamethasone is also being used to accelerate fetal lung maturity, more frequent initial dosing is needed.

Older people. COVID-19 treatments for older patients are the same as for the general adult population. However, because older people are more likely to have impaired renal function, renal function should be monitored when an older patient is being treated with COVID-19 medications that are eliminated renally (eg, remdesivir, baricitinib). Furthermore, drug–drug interactions have been reported in older patients treated with nirmatrelvir + ritonavir, primarily because of the effects of ritonavir. Review all of a patient’s medications, including over-the-counter drugs and herbal supplements, when prescribing treatment for COVID-19, and adjust the dosage by following guidance in FDA-approved prescribing information—ideally, in consultation with a pharmacist.

Immunocompromised patients. The combination product tixagevimab + cilgavimab [Evusheld] is FDA approved for COVID-19 PrEP, under an EUA, in patients who are not infected with SARS-CoV-2 who have an immune-compromising condition, who are unlikely to mount an adequate immune response to the COVID-19 vaccine, or those in whom vaccination is not recommended because of their history of a severe adverse reaction to a COVID-19 vaccine or one of its components.7

Continue to: Summing up

Summing up

With a growing need for effective and readily available COVID-19 treatments, there are an unprecedented number of clinical trials in process. Besides antivirals, immunomodulators, and antibody therapies, some novel mechanisms being tested include Janus kinase inhibitors, IL-6-receptor blockers, and drugs that target adult respiratory distress syndrome and cytokine release.

Once larger trials are completed, we can expect stronger evidence of potential treatment options and of safety and efficacy in children, pregnant women, and vulnerable populations. During the pandemic, the FDA’s EUA program has brought emerging treatments rapidly to clinicians; nevertheless, high-quality evidence, with thorough peer review, remains critical to inform COVID-19 treatment guidelines.

ahttps://healthdata.gov/Health/COVID-19-PublicTherapeutic-Locator/rxn6-qnx8/data

b Sotrovimab was effective against the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2—the dominant variant in early 2022— but is currently not FDA authorized in any region of the United States because of the prevalence of the Omicron BA.2 subvariant.30

CORRESPONDENCE

Ambar Kulshreshtha, MD, PhD, Department of Epidemiology, Emory Rollins School of Public Health, 4500 North Shallowford Road, Suite 134, Atlanta, GA 30338; akulshr@emory.edu

1. COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) treatment guidelines. National Institutes of Health. July 19, 2022. Accessed July 21, 2022. www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov

2. IDSA guidelines on the treatment and management of patients with COVID-19. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Updated June 29, 2022. Accessed July 21, 2022. www.idsociety.org/practice-guideline/covid-19-guideline-treatment-and-management/#toc-23

3. Therapeutics and COVID-19: living guideline. World Health Organization. July 14, 2022. Accessed July 21, 2022. https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1449398/retrieve

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinical care considerations. Updated May 27, 2022. Accessed July 21, 2022. www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-guidance-management-patients.html

5. Coronavirus (COVID-19) update: FDA approves first COVID-19 treatment for young children. Press release. US Food and Drug Administration. April 25, 2022. Accessed August 11, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-approves-first-covid-19-treatment-young-children

6. Know your treatment options for COVID-19. US Food and Drug Administration. Updated August 15, 2022. Accessed July 21, 2022. www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/know-your-treatment-options-covid-19

7. Tixagevimab and cilgavimab (Evusheld) for pre-exposure prophylaxis of COVID-19. JAMA. 2022;327:384-385. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.24931

8. Judson TJ, Odisho AY, Neinstein AB, et al. Rapid design and implementation of an integrated patient self-triage and self-scheduling tool for COVID-19. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020;27:860-866. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa051

9. Gandhi RT, Lynch JB, Del Rio C. Mild or moderate Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1757-1766. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp2009249

10. Greenhalgh T, Koh GCH, Car J. Covid-19: a remote assessment in primary care. BMJ. 2020;368:m1182. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1182

11. Jayk Bernal A, Gomes da Silva MM, Musungaie DB, et al; . Molnupiravir for oral treatment of Covid-19 in nonhospitalized patients. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:509-520. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2116044

12. Hammond J, Leister-Tebbe H, Gardner A, et al; . Oral nirmatrelvir for high-risk, nonhospitalized adults with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:1397-1408. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2118542

13. Gottlieb RL, Vaca CE, Paredes R, et al; . Early remdesivir to prevent progression to severe Covid-19 in outpatients. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:305-315. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2116846

14. Gupta A, Gonzalez-Rojas Y, Juarez E, et al; . Early treatment for Covid-19 with SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody sotrovimab. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1941-1950. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2107934

15. Skipper CP, Pastick KA, Engen NW, et al. Hydroxychloroquine in nonhospitalized adults with early COVID-19: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:623-631. doi: 10.7326/M20-4207

16. Scheen AJ. Statins and clinical outcomes with COVID-19: meta-analyses of observational studies. Diabetes Metab. 2021;47:101220. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2020.101220

17. Kow CS, Hasan SS. Meta-analysis of effect of statins in patients with COVID-19. Am J Cardiol. 2020;134:153-155. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2020.08.004

18. Halpin DMG, Singh D, Hadfield RM. Inhaled corticosteroids and COVID-19: a systematic review and clinical perspective. Eur Respir J. 2020;55:2001009. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01009-2020

19. Yu L-M, Bafadhel M, Dorward J, et al; . Inhaled budesonide for COVID-19 in people at high risk of complications in the community in the UK (PRINCIPLE): a randomised, controlled, open-label, adaptive platform trial. Lancet. 2021;398:843-855. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01744-X

20. Siemieniuk RA, Bartoszko JJ, JP, et al. Antibody and cellular therapies for treatment of covid-19: a living systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2021;374:n2231. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n2231

21. Siemieniuk RA, Bartoszko JJ, Zeraatkar D, et al. Drug treatments for covid-19: living systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;370:m2980. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2980

22. Agarwal A, Rochwerg B, Lamontagne F, et al. A living WHO guideline on drugs for covid-19. BMJ. 2020;370:m3379. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3379

23. Goldstein KM, Ghadimi K, Mystakelis H, et al. Risk of transmitting coronavirus disease 2019 during nebulizer treatment: a systematic review. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2021;34:155-170. doi: 10.1089/jamp.2020.1659

24. Schultze A, Walker AJ, MacKenna B, et al; . Risk of COVID-19-related death among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma prescribed inhaled corticosteroids: an observational cohort study using the OpenSAFELY platform. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:1106-1120. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30415-X

25. What are the safety and efficacy results of bebtelovimab from BLAZE-4? Lilly USA. January 12, 2022. Accessed August 17, 2022. www.lillymedical.com/en-us/answers/what-are-the-safety-and-efficacy-results-of-bebtelovimab-from-blaze-4-159290

26. Beigel JH, Tomashek KM, Dodd LE, et al; . Remdesivir for the treatment of Covid-19—final report. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1813-1826. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007764

27. Cao B, Wang Y, Wen D, et al. A trial of lopinavir–ritonavir in adults hospitalized with severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1787-1799. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001282

28. Gandhi RT, Malani PN, Del Rio C. COVID-19 therapeutics for nonhospitalized patients. JAMA. 2022;327:617-618. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.0335

29. Wen W, Chen C, Tang J, et al. Efficacy and safety of three new oral antiviral treatment (molnupiravir, fluvoxamine and Paxlovid) for COVID-19: a meta-analysis. Ann Med. 2022;54:516-523. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2022.2034936

30. Planas D, Saunders N, Maes P, et al. Considerable escape of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron to antibody neutralization. Nature. 2022:602:671-675. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04389-z

31. Emergency use authorization (EUA) for bebtelovimab (LY-CoV1404): Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) review. US Food and Drug Administration. Updated February 11, 2022. Accessed July 21, 2022. www.fda.gov/media/156396/download

32. Bartoszko JJ, Siemieniuk RAC, Kum E, et al. Prophylaxis against covid-19: living systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2021;373:n949. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n949

33. Reis G, Dos Santos Moreira-Silva EA, Silva DCM, et al; TOGETHER Investigators. Effect of early treatment with fluvoxamine on risk of emergency care and hospitalisation among patients with COVID-19: the TOGETHER randomised, platform clinical trial. Lancet Glob Health. 2022;10:e42-e51. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00448-4

34. RECOVERY Collaborative Group. Convalescent plasma in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 (RECOVERY): a randomised controlled, open-label, platform trial. Lancet. 2021;397:2049-2059. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00897-7

35. Simonovich VA, Burgos Pratx LD, Scibona P, et al; . A randomized trial of convalescent plasma in Covid-19 severe pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:619-629. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2031304

36. Joyner MJ, Carter RE, Senefeld JW, et al. Convalescent plasma antibody levels and the risk of death from Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1015-1027. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2031893

37. Ayeh SK, Abbey EJ, Khalifa BAA, et al. Statins use and COVID-19 outcomes in hospitalized patients. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0256899. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0256899

38. Ramakrishnan S, Nicolau DV Jr, Langford B, et al. Inhaled budesonide in the treatment of early COVID-19 (STOIC): a phase 2, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9:763-772. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00160-0

39. Temple C, Hoang R, Hendrickson RG. Toxic effects from ivermectin use associated with prevention and treatment of Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2197-2198. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2114907

40. Thomas S, Patel D, Bittel B, et al. Effect of high-dose zinc and ascorbic acid supplementation vs usual care on symptom length and reduction among ambulatory patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection: the COVID A to Z randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e210369. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0369

41. Adams KK, Baker WL, Sobieraj DM. Myth busters: dietary supplements and COVID-19. Ann Pharmacother. 2020;54:820-826. doi: 10.1177/1060028020928052

42. Pan H, Peto R, Henao-Restrepo A-M, et al. Repurposed antiviral drugs for Covid-19—interim WHO Solidarity trial results. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:497-511. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2023184

43. Kalil AC, Patterson TF, Mehta AK, et al; . Baricitinib plus remdesivir for hospitalized adults with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:795-807. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2031994

44. ; Sterne JAC, Murthy S, Diaz JV, et al. Association between administration of systemic corticosteroids and mortality among critically ill patients with COVID-19: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2020;324:1330-1341. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17023

45. ; Shankar-Hari M, Vale CL, Godolphin PJ, et al. Association between administration of IL-6 antagonists and mortality among patients hospitalized for COVID-19: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2021;326:499-518. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.11330

46. Wei QW, Lin H, Wei R-G, et al. Tocilizumab treatment for COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Dis Poverty. 2021;10:71. doi: 10.1186/s40249-021-00857-w

47. Zhang X, Shang L, Fan G, et al. The efficacy and safety of Janus kinase inhibitors for patients with COVID-19: a living systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:800492. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.800492

48. RECOVERY Collaborative Group. Tocilizumab in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 (RECOVERY): a randomised, controlled, open-label, platform trial. Lancet. 2021;397:1637-1645. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00676-0

49. Gordon AC, Mouncey PR, Al-Beidh F, et al. Interleukin-6 receptor antagonists in critically ill patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1491-1502. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2100433

50. Guimaraes PO, Quirk D, Furtado RH, et al; . Tofacitinib in patients hospitalized with Covid-19 pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:406-415. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2101643

51. Feldstein LR, Rose EB, Horwitz SM, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in U.S. children and adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:334-346. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021680

52. Allotey J, Stallings E, Bonet M, et al. Clinical manifestations, risk factors, and maternal and perinatal outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnancy: living systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;370:m3320. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3320

53. Villar J, Ariff S, Gunier RB, et al. Maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality among pregnant women with and without COVID-19 infection: the INTERCOVID multinational cohort study. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175:817-826. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.1050

54. Jorgensen SCJ, Davis MR, Lapinsky SE. A review of remdesivir for COVID-19 in pregnancy and lactation. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2021;77:24-30. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkab311

55. Management considerations for pregnant patients with COVID-19. Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Accessed July 21, 2022. https://s3.amazonaws.com/cdn.smfm.org/media/2336/SMFM_COVID_Management_of_COVID_pos_preg_patients_4-30-20_final.pdf

1. COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) treatment guidelines. National Institutes of Health. July 19, 2022. Accessed July 21, 2022. www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov

2. IDSA guidelines on the treatment and management of patients with COVID-19. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Updated June 29, 2022. Accessed July 21, 2022. www.idsociety.org/practice-guideline/covid-19-guideline-treatment-and-management/#toc-23

3. Therapeutics and COVID-19: living guideline. World Health Organization. July 14, 2022. Accessed July 21, 2022. https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1449398/retrieve

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinical care considerations. Updated May 27, 2022. Accessed July 21, 2022. www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-guidance-management-patients.html

5. Coronavirus (COVID-19) update: FDA approves first COVID-19 treatment for young children. Press release. US Food and Drug Administration. April 25, 2022. Accessed August 11, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-approves-first-covid-19-treatment-young-children

6. Know your treatment options for COVID-19. US Food and Drug Administration. Updated August 15, 2022. Accessed July 21, 2022. www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/know-your-treatment-options-covid-19