User login

THE CASE

Eric M,* a 36-year-old new patient, visits a primary care clinic for a check-up accompanied by his wife. A thorough history and physical exam reveal no concerns. He is active and a nonsmoker, drinks only socially, takes no medications, and reports no concerning symptoms. At the end of the visit, though, he says he has been experiencing erectile dysfunction for the past 6 months. What began as intermittent difficulty maintaining erections now “happens a lot.” He is distressed and says, “It just came out of the blue.” The patient’s wife then says she believes men cannot achieve erections if they are having an affair. When the chagrined patient simply asks for “those pills,” his wife says in a raised voice, “He’s a liar!”

●

*The patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity.

Some family physicians may feel ill-equipped to talk about sexual and relational problems and lack the skills to effectively counsel on these matters.1 Despite the fact that more than 70% of adult patients want to discuss sexual topics with their family physician, sexual problems are documented in as few as 2% of patient notes.2 One of the most commonly noted sexual health concerns is erectile dysfunction (ED), estimated to occur in 35% of men ages 40 to 70.3 Many ED cases have psychological antecedents including stress, depression, performance anxiety, pornography addiction, and relationship concerns.4,5

Assessing ED. The inability to achieve or maintain an erection needed for satisfactory sexual activity is typically diagnosed through symptom self-report and with thorough history taking and physical examination.6 However, more objective scales can be used. In particular, the International Index of Erectile Function, a 15-question scale, is useful for both diagnosis and treatment monitoring (www.baus.org.uk/_userfiles/pages/files/Patients/Leaflets/iief.pdf).7 Common contributors to ED can be vascular (eg, hypertension), neurologic (eg, multiple sclerosis), psychological (noted earlier), or hormonal (eg, thyroid imbalances).6 In this article, we focus on the relationship context in which ED exists. A review of medical evaluation and management can be found elsewhere.8

Key relational questions

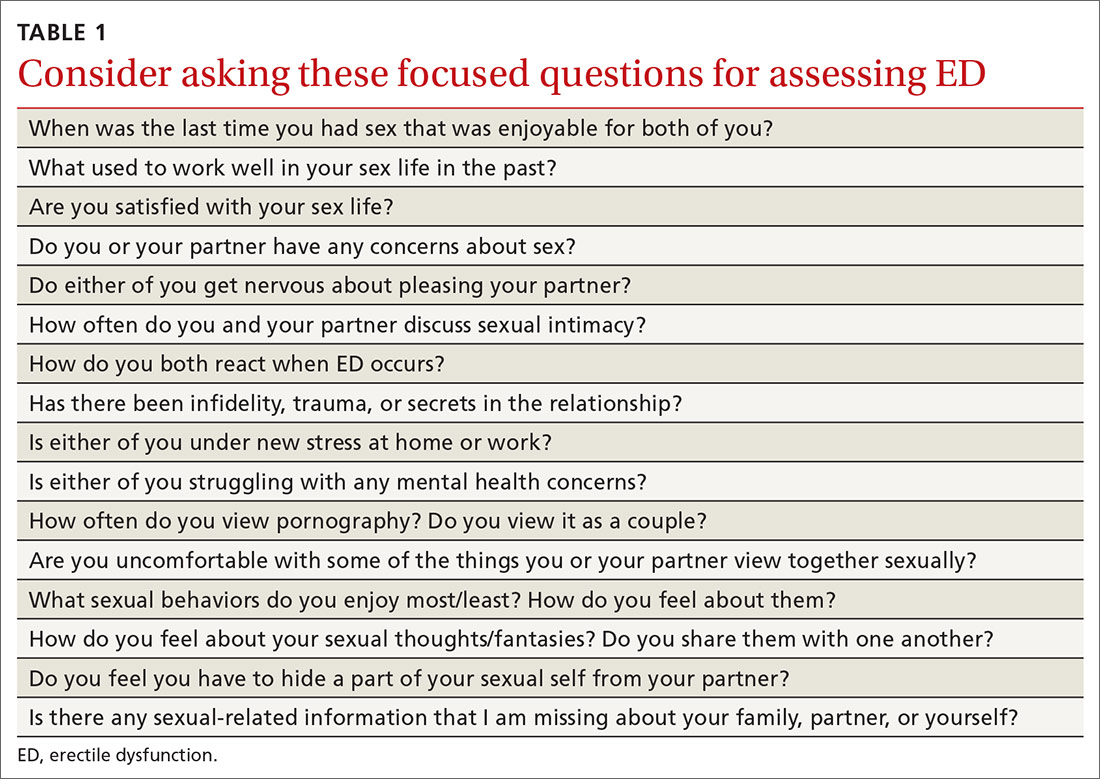

Identify norms that are specific to the couple. Patients from a variety of cultures prefer that their clinicians initiate the conversation about ED.11,12 We specifically recommend that clinicians, using relationally focused questions, inquire about sexual norms and desires that may be situated in culture, family of origin, or gender (TABLE 1).

Continue to: Treating ED within a relationship

Treating ED within a relationship

Once a couple’s sexual relationship has been fully assessed, you may confidently develop a treatment plan for managing sexual dysfunction relationally as well as medically, an approach to ED advised by the American Urological Association.13 We propose that primary care treatment for ED involve collaboration between the physician, the patient/couple (if the patient is partnered), and, as needed, a behavioral health specialist.

The physician’s role ...

Managing ED relationally is important on many fronts. If, for instance, a type-5 phosphodiesterase (PDE-5) inhibitor is needed, both the patient and partner should learn about best practices for optimizing success, such as avoiding excessive alcohol intake or high-fat meals immediately before and after taking a PDE-5.14

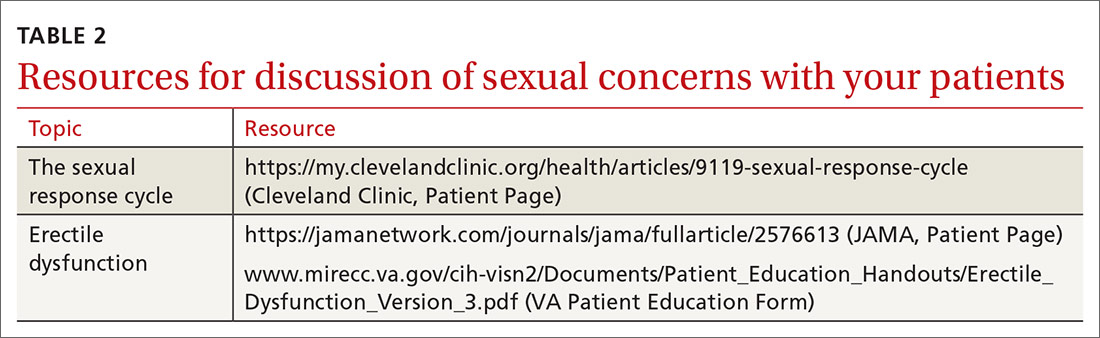

Sex ed. Regardless of the couple’s age, be prepared to offer high-quality sexual education. Either partner may have faulty knowledge (or even a lack of knowledge) of basic sexual functioning. Physicians have an opportunity to explain healthy erectile functioning, the sexual response cycle, and ways in which PDE-5 medications work (and do not work). (For a list of resources to facilitate these discussions, see TABLE 2.)

Avoid avoidance. Physicians can intervene on patterns of shame that may surround ED simply by discussing sexual functioning openly and honestly. ED often persists due to avoidance—ie, anxiety about sexual performance can lead couples to avoid sex, which perpetuates more anxiety and avoidance. Normalizing typical sexual functioning, encouraging couples to “avoid avoidance,” and providing referrals as needed are core elements of relational intervention for ED.

Setting the tone. Family physicians are not routinely trained in couples therapy. However, you can employ communication skills that allow each partner to be heard by using empathic/reflective listening, de-escalation, and reframing. Asking “What effect are the sexual concerns having on both of you?” and “What were the circumstances of the last sexual encounter that were pleasing to both of you?” can help promote intimacy and mutual satisfaction.

Continue to: The behavioral specialist's role

The behavioral specialist’s role

Behavioral health specialists may treat ED using methods such as cognitive behavioral therapy or evidence-based couple interventions.4 Cognitive methods for the treatment of ED include examination of maladaptive thoughts around pressure to perform and achieving sexual pleasure. Behavioral methods for treatment of ED are typically aimed at the de-coupling of anxiety and sexual activity. These treatments can include relaxation and desensitization, specifically sensate focus therapy.15

Sensate focus therapy involves a specific set of prescriptive rules for sexual activity, initially restricting touch to non-demand pleasurable touch (eg, holding hands) that allows couples to connect in a low-anxiety context focused on relaxation and connection. As couples are able to control anxiety while engaging in these activities, they engage in increasingly more intimate activities. Additionally, behavioral health specialists trained in couples therapy are vital to helping increase communication regarding sexual activity, sexual scripts, and the relationship in general.4

Identifying a treatment team

In coordinating couples care in the treatment of ED, enlist the help of a therapist who has specific knowledge and skills in the treatment of sexual disorders. While the number of qualified or certified sex therapists is limited, referring providers can visit the American Association of Sexuality Educators, Counselors, and Therapists Web site (www.aasect.org) for possible referral sources. Another option is the American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy Web site (www.aamft.org) under “Find a therapist.” Lastly, the Society for Sex Therapy and Research (www.sstarnet.org) is another professional association that provides information and local referral sources. For patients and partners located in rural areas where access is limited, telehealth options may need to be explored.

THE CASE

Mr. M and his wife were seen for a follow-up appointment by his primary care provider, who ruled out any additional causes of ED (eg, hormonal, vascular), discussed with both the patient and his wife basic sexual health and sexual functioning, dispelled several commonly held myths (ie, individuals cannot obtain an erection because of infidelity or lying), validated sexual concerns as a significant health issue, and prescribed a PDE-5 inhibitor.

Mr. M and his wife were referred to a behavioral health specialist in the clinic who had expertise in couples therapy. At several subsequent visits, the patient and his wife worked on improving the quality and quantity of communication regarding their sexual goals, mutual de-escalation of anxiety, increased emotional intimacy, and sensate focus techniques.

Continue to: As the result of the interventions...

As the result of these interventions, both the patient and his wife were able to engage in sex with less anxiety, and the patient increasingly was able to achieve more satisfactory erections without the use of the PDE-5 inhibitor. At the conclusion of therapy, the patient and his wife reported an increase in sexual satisfaction.

CORRESPONDENCE

Katherine Buck, PhD, Family Health Center, John Peter Smith Health Network, 1500 S. Main Street, Fort Worth, TX 76104; kbuck@jpshealth.org.

1. Macdowall W, Parker R, Nanchahal K, et al. ‘Talking of Sex’: developing and piloting a sexual health communication tool for use in primary care. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;81:332-337.

2. Sadovsky R. Asking the questions and offering solutions: the ongoing dialogue between the primary care physician and the patient with erectile dysfunction. Rev Urol. 2003;5(suppl 7):S35-S48.

3. Boston University School of Medicine. Sexual Medicine. Epidemiology of ED. 2019. www.bumc.bu.edu/sexualmedicine/physicianinformation/epidemiology-of-ed/. Accessed May 27, 2020.

4. Weeks GR, Gambescia N, Hertlein KM, eds. A Clinician’s Guide to Systemic Sex Therapy. 2nd ed. London, England: Routledge; 2016.

5. Colson MH, Cuzin A, Faix A, et al. Current epidemiology of erectile dysfunction, an update. Sexologies. 2018;27:e7-e13.

6. Rew KT, Heidelbaugh JJ. Erectile dysfunction. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94820-94827.

7. Rosen RC, Cappelleri JC, Smith MD, et al. Development and evaluation of an abridged, 5-item version of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) as a diagnostic tool for erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 1999;11:319-326.

8. Rew KT, Heidelbaugh JJ. Erectile dysfunction. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94:820-827.

9. Dean J, Rubio-Aurioles E, McCabe M, et al. Integrating partners into erectile dysfunction treatment: improving the sexual experience for the couple. Int J Clin Pract. 2008;62:127-133.

10. Shamloul R, Ghanem H. Erectile dysfunction. Lancet. 2013; 381:153-165.

11. Lo WH, Fu SN, Wong SN, et al. Prevalence, correlates, attitude and treatment seeking of erectile dysfunction among type 2 diabetic Chinese men attending primary care outpatient clinics. Asian J Androl. 2014;16:755-760.

12. Zweifler J, Padilla A, Schafer S. Barriers to recognition of erectile dysfunction among diabetic Mexican-American men. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1998;11:259-263.

13. American Urological Society. Erectile dysfunction: AUA guideline (2018). www.auanet.org/guidelines/erectile-dysfunction-(ed)-guideline. Accessed May 27, 2020.

14. Huang S, Lie J. Phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE5) inhibitors in the management of erectile dysfunction. P T. 2013;38;414-419.

15. Masters WH, Johnson VE. Human Sexual Inadequacy. Boston: Little Brown; 1970.

THE CASE

Eric M,* a 36-year-old new patient, visits a primary care clinic for a check-up accompanied by his wife. A thorough history and physical exam reveal no concerns. He is active and a nonsmoker, drinks only socially, takes no medications, and reports no concerning symptoms. At the end of the visit, though, he says he has been experiencing erectile dysfunction for the past 6 months. What began as intermittent difficulty maintaining erections now “happens a lot.” He is distressed and says, “It just came out of the blue.” The patient’s wife then says she believes men cannot achieve erections if they are having an affair. When the chagrined patient simply asks for “those pills,” his wife says in a raised voice, “He’s a liar!”

●

*The patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity.

Some family physicians may feel ill-equipped to talk about sexual and relational problems and lack the skills to effectively counsel on these matters.1 Despite the fact that more than 70% of adult patients want to discuss sexual topics with their family physician, sexual problems are documented in as few as 2% of patient notes.2 One of the most commonly noted sexual health concerns is erectile dysfunction (ED), estimated to occur in 35% of men ages 40 to 70.3 Many ED cases have psychological antecedents including stress, depression, performance anxiety, pornography addiction, and relationship concerns.4,5

Assessing ED. The inability to achieve or maintain an erection needed for satisfactory sexual activity is typically diagnosed through symptom self-report and with thorough history taking and physical examination.6 However, more objective scales can be used. In particular, the International Index of Erectile Function, a 15-question scale, is useful for both diagnosis and treatment monitoring (www.baus.org.uk/_userfiles/pages/files/Patients/Leaflets/iief.pdf).7 Common contributors to ED can be vascular (eg, hypertension), neurologic (eg, multiple sclerosis), psychological (noted earlier), or hormonal (eg, thyroid imbalances).6 In this article, we focus on the relationship context in which ED exists. A review of medical evaluation and management can be found elsewhere.8

Key relational questions

Identify norms that are specific to the couple. Patients from a variety of cultures prefer that their clinicians initiate the conversation about ED.11,12 We specifically recommend that clinicians, using relationally focused questions, inquire about sexual norms and desires that may be situated in culture, family of origin, or gender (TABLE 1).

Continue to: Treating ED within a relationship

Treating ED within a relationship

Once a couple’s sexual relationship has been fully assessed, you may confidently develop a treatment plan for managing sexual dysfunction relationally as well as medically, an approach to ED advised by the American Urological Association.13 We propose that primary care treatment for ED involve collaboration between the physician, the patient/couple (if the patient is partnered), and, as needed, a behavioral health specialist.

The physician’s role ...

Managing ED relationally is important on many fronts. If, for instance, a type-5 phosphodiesterase (PDE-5) inhibitor is needed, both the patient and partner should learn about best practices for optimizing success, such as avoiding excessive alcohol intake or high-fat meals immediately before and after taking a PDE-5.14

Sex ed. Regardless of the couple’s age, be prepared to offer high-quality sexual education. Either partner may have faulty knowledge (or even a lack of knowledge) of basic sexual functioning. Physicians have an opportunity to explain healthy erectile functioning, the sexual response cycle, and ways in which PDE-5 medications work (and do not work). (For a list of resources to facilitate these discussions, see TABLE 2.)

Avoid avoidance. Physicians can intervene on patterns of shame that may surround ED simply by discussing sexual functioning openly and honestly. ED often persists due to avoidance—ie, anxiety about sexual performance can lead couples to avoid sex, which perpetuates more anxiety and avoidance. Normalizing typical sexual functioning, encouraging couples to “avoid avoidance,” and providing referrals as needed are core elements of relational intervention for ED.

Setting the tone. Family physicians are not routinely trained in couples therapy. However, you can employ communication skills that allow each partner to be heard by using empathic/reflective listening, de-escalation, and reframing. Asking “What effect are the sexual concerns having on both of you?” and “What were the circumstances of the last sexual encounter that were pleasing to both of you?” can help promote intimacy and mutual satisfaction.

Continue to: The behavioral specialist's role

The behavioral specialist’s role

Behavioral health specialists may treat ED using methods such as cognitive behavioral therapy or evidence-based couple interventions.4 Cognitive methods for the treatment of ED include examination of maladaptive thoughts around pressure to perform and achieving sexual pleasure. Behavioral methods for treatment of ED are typically aimed at the de-coupling of anxiety and sexual activity. These treatments can include relaxation and desensitization, specifically sensate focus therapy.15

Sensate focus therapy involves a specific set of prescriptive rules for sexual activity, initially restricting touch to non-demand pleasurable touch (eg, holding hands) that allows couples to connect in a low-anxiety context focused on relaxation and connection. As couples are able to control anxiety while engaging in these activities, they engage in increasingly more intimate activities. Additionally, behavioral health specialists trained in couples therapy are vital to helping increase communication regarding sexual activity, sexual scripts, and the relationship in general.4

Identifying a treatment team

In coordinating couples care in the treatment of ED, enlist the help of a therapist who has specific knowledge and skills in the treatment of sexual disorders. While the number of qualified or certified sex therapists is limited, referring providers can visit the American Association of Sexuality Educators, Counselors, and Therapists Web site (www.aasect.org) for possible referral sources. Another option is the American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy Web site (www.aamft.org) under “Find a therapist.” Lastly, the Society for Sex Therapy and Research (www.sstarnet.org) is another professional association that provides information and local referral sources. For patients and partners located in rural areas where access is limited, telehealth options may need to be explored.

THE CASE

Mr. M and his wife were seen for a follow-up appointment by his primary care provider, who ruled out any additional causes of ED (eg, hormonal, vascular), discussed with both the patient and his wife basic sexual health and sexual functioning, dispelled several commonly held myths (ie, individuals cannot obtain an erection because of infidelity or lying), validated sexual concerns as a significant health issue, and prescribed a PDE-5 inhibitor.

Mr. M and his wife were referred to a behavioral health specialist in the clinic who had expertise in couples therapy. At several subsequent visits, the patient and his wife worked on improving the quality and quantity of communication regarding their sexual goals, mutual de-escalation of anxiety, increased emotional intimacy, and sensate focus techniques.

Continue to: As the result of the interventions...

As the result of these interventions, both the patient and his wife were able to engage in sex with less anxiety, and the patient increasingly was able to achieve more satisfactory erections without the use of the PDE-5 inhibitor. At the conclusion of therapy, the patient and his wife reported an increase in sexual satisfaction.

CORRESPONDENCE

Katherine Buck, PhD, Family Health Center, John Peter Smith Health Network, 1500 S. Main Street, Fort Worth, TX 76104; kbuck@jpshealth.org.

THE CASE

Eric M,* a 36-year-old new patient, visits a primary care clinic for a check-up accompanied by his wife. A thorough history and physical exam reveal no concerns. He is active and a nonsmoker, drinks only socially, takes no medications, and reports no concerning symptoms. At the end of the visit, though, he says he has been experiencing erectile dysfunction for the past 6 months. What began as intermittent difficulty maintaining erections now “happens a lot.” He is distressed and says, “It just came out of the blue.” The patient’s wife then says she believes men cannot achieve erections if they are having an affair. When the chagrined patient simply asks for “those pills,” his wife says in a raised voice, “He’s a liar!”

●

*The patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity.

Some family physicians may feel ill-equipped to talk about sexual and relational problems and lack the skills to effectively counsel on these matters.1 Despite the fact that more than 70% of adult patients want to discuss sexual topics with their family physician, sexual problems are documented in as few as 2% of patient notes.2 One of the most commonly noted sexual health concerns is erectile dysfunction (ED), estimated to occur in 35% of men ages 40 to 70.3 Many ED cases have psychological antecedents including stress, depression, performance anxiety, pornography addiction, and relationship concerns.4,5

Assessing ED. The inability to achieve or maintain an erection needed for satisfactory sexual activity is typically diagnosed through symptom self-report and with thorough history taking and physical examination.6 However, more objective scales can be used. In particular, the International Index of Erectile Function, a 15-question scale, is useful for both diagnosis and treatment monitoring (www.baus.org.uk/_userfiles/pages/files/Patients/Leaflets/iief.pdf).7 Common contributors to ED can be vascular (eg, hypertension), neurologic (eg, multiple sclerosis), psychological (noted earlier), or hormonal (eg, thyroid imbalances).6 In this article, we focus on the relationship context in which ED exists. A review of medical evaluation and management can be found elsewhere.8

Key relational questions

Identify norms that are specific to the couple. Patients from a variety of cultures prefer that their clinicians initiate the conversation about ED.11,12 We specifically recommend that clinicians, using relationally focused questions, inquire about sexual norms and desires that may be situated in culture, family of origin, or gender (TABLE 1).

Continue to: Treating ED within a relationship

Treating ED within a relationship

Once a couple’s sexual relationship has been fully assessed, you may confidently develop a treatment plan for managing sexual dysfunction relationally as well as medically, an approach to ED advised by the American Urological Association.13 We propose that primary care treatment for ED involve collaboration between the physician, the patient/couple (if the patient is partnered), and, as needed, a behavioral health specialist.

The physician’s role ...

Managing ED relationally is important on many fronts. If, for instance, a type-5 phosphodiesterase (PDE-5) inhibitor is needed, both the patient and partner should learn about best practices for optimizing success, such as avoiding excessive alcohol intake or high-fat meals immediately before and after taking a PDE-5.14

Sex ed. Regardless of the couple’s age, be prepared to offer high-quality sexual education. Either partner may have faulty knowledge (or even a lack of knowledge) of basic sexual functioning. Physicians have an opportunity to explain healthy erectile functioning, the sexual response cycle, and ways in which PDE-5 medications work (and do not work). (For a list of resources to facilitate these discussions, see TABLE 2.)

Avoid avoidance. Physicians can intervene on patterns of shame that may surround ED simply by discussing sexual functioning openly and honestly. ED often persists due to avoidance—ie, anxiety about sexual performance can lead couples to avoid sex, which perpetuates more anxiety and avoidance. Normalizing typical sexual functioning, encouraging couples to “avoid avoidance,” and providing referrals as needed are core elements of relational intervention for ED.

Setting the tone. Family physicians are not routinely trained in couples therapy. However, you can employ communication skills that allow each partner to be heard by using empathic/reflective listening, de-escalation, and reframing. Asking “What effect are the sexual concerns having on both of you?” and “What were the circumstances of the last sexual encounter that were pleasing to both of you?” can help promote intimacy and mutual satisfaction.

Continue to: The behavioral specialist's role

The behavioral specialist’s role

Behavioral health specialists may treat ED using methods such as cognitive behavioral therapy or evidence-based couple interventions.4 Cognitive methods for the treatment of ED include examination of maladaptive thoughts around pressure to perform and achieving sexual pleasure. Behavioral methods for treatment of ED are typically aimed at the de-coupling of anxiety and sexual activity. These treatments can include relaxation and desensitization, specifically sensate focus therapy.15

Sensate focus therapy involves a specific set of prescriptive rules for sexual activity, initially restricting touch to non-demand pleasurable touch (eg, holding hands) that allows couples to connect in a low-anxiety context focused on relaxation and connection. As couples are able to control anxiety while engaging in these activities, they engage in increasingly more intimate activities. Additionally, behavioral health specialists trained in couples therapy are vital to helping increase communication regarding sexual activity, sexual scripts, and the relationship in general.4

Identifying a treatment team

In coordinating couples care in the treatment of ED, enlist the help of a therapist who has specific knowledge and skills in the treatment of sexual disorders. While the number of qualified or certified sex therapists is limited, referring providers can visit the American Association of Sexuality Educators, Counselors, and Therapists Web site (www.aasect.org) for possible referral sources. Another option is the American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy Web site (www.aamft.org) under “Find a therapist.” Lastly, the Society for Sex Therapy and Research (www.sstarnet.org) is another professional association that provides information and local referral sources. For patients and partners located in rural areas where access is limited, telehealth options may need to be explored.

THE CASE

Mr. M and his wife were seen for a follow-up appointment by his primary care provider, who ruled out any additional causes of ED (eg, hormonal, vascular), discussed with both the patient and his wife basic sexual health and sexual functioning, dispelled several commonly held myths (ie, individuals cannot obtain an erection because of infidelity or lying), validated sexual concerns as a significant health issue, and prescribed a PDE-5 inhibitor.

Mr. M and his wife were referred to a behavioral health specialist in the clinic who had expertise in couples therapy. At several subsequent visits, the patient and his wife worked on improving the quality and quantity of communication regarding their sexual goals, mutual de-escalation of anxiety, increased emotional intimacy, and sensate focus techniques.

Continue to: As the result of the interventions...

As the result of these interventions, both the patient and his wife were able to engage in sex with less anxiety, and the patient increasingly was able to achieve more satisfactory erections without the use of the PDE-5 inhibitor. At the conclusion of therapy, the patient and his wife reported an increase in sexual satisfaction.

CORRESPONDENCE

Katherine Buck, PhD, Family Health Center, John Peter Smith Health Network, 1500 S. Main Street, Fort Worth, TX 76104; kbuck@jpshealth.org.

1. Macdowall W, Parker R, Nanchahal K, et al. ‘Talking of Sex’: developing and piloting a sexual health communication tool for use in primary care. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;81:332-337.

2. Sadovsky R. Asking the questions and offering solutions: the ongoing dialogue between the primary care physician and the patient with erectile dysfunction. Rev Urol. 2003;5(suppl 7):S35-S48.

3. Boston University School of Medicine. Sexual Medicine. Epidemiology of ED. 2019. www.bumc.bu.edu/sexualmedicine/physicianinformation/epidemiology-of-ed/. Accessed May 27, 2020.

4. Weeks GR, Gambescia N, Hertlein KM, eds. A Clinician’s Guide to Systemic Sex Therapy. 2nd ed. London, England: Routledge; 2016.

5. Colson MH, Cuzin A, Faix A, et al. Current epidemiology of erectile dysfunction, an update. Sexologies. 2018;27:e7-e13.

6. Rew KT, Heidelbaugh JJ. Erectile dysfunction. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94820-94827.

7. Rosen RC, Cappelleri JC, Smith MD, et al. Development and evaluation of an abridged, 5-item version of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) as a diagnostic tool for erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 1999;11:319-326.

8. Rew KT, Heidelbaugh JJ. Erectile dysfunction. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94:820-827.

9. Dean J, Rubio-Aurioles E, McCabe M, et al. Integrating partners into erectile dysfunction treatment: improving the sexual experience for the couple. Int J Clin Pract. 2008;62:127-133.

10. Shamloul R, Ghanem H. Erectile dysfunction. Lancet. 2013; 381:153-165.

11. Lo WH, Fu SN, Wong SN, et al. Prevalence, correlates, attitude and treatment seeking of erectile dysfunction among type 2 diabetic Chinese men attending primary care outpatient clinics. Asian J Androl. 2014;16:755-760.

12. Zweifler J, Padilla A, Schafer S. Barriers to recognition of erectile dysfunction among diabetic Mexican-American men. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1998;11:259-263.

13. American Urological Society. Erectile dysfunction: AUA guideline (2018). www.auanet.org/guidelines/erectile-dysfunction-(ed)-guideline. Accessed May 27, 2020.

14. Huang S, Lie J. Phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE5) inhibitors in the management of erectile dysfunction. P T. 2013;38;414-419.

15. Masters WH, Johnson VE. Human Sexual Inadequacy. Boston: Little Brown; 1970.

1. Macdowall W, Parker R, Nanchahal K, et al. ‘Talking of Sex’: developing and piloting a sexual health communication tool for use in primary care. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;81:332-337.

2. Sadovsky R. Asking the questions and offering solutions: the ongoing dialogue between the primary care physician and the patient with erectile dysfunction. Rev Urol. 2003;5(suppl 7):S35-S48.

3. Boston University School of Medicine. Sexual Medicine. Epidemiology of ED. 2019. www.bumc.bu.edu/sexualmedicine/physicianinformation/epidemiology-of-ed/. Accessed May 27, 2020.

4. Weeks GR, Gambescia N, Hertlein KM, eds. A Clinician’s Guide to Systemic Sex Therapy. 2nd ed. London, England: Routledge; 2016.

5. Colson MH, Cuzin A, Faix A, et al. Current epidemiology of erectile dysfunction, an update. Sexologies. 2018;27:e7-e13.

6. Rew KT, Heidelbaugh JJ. Erectile dysfunction. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94820-94827.

7. Rosen RC, Cappelleri JC, Smith MD, et al. Development and evaluation of an abridged, 5-item version of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) as a diagnostic tool for erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 1999;11:319-326.

8. Rew KT, Heidelbaugh JJ. Erectile dysfunction. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94:820-827.

9. Dean J, Rubio-Aurioles E, McCabe M, et al. Integrating partners into erectile dysfunction treatment: improving the sexual experience for the couple. Int J Clin Pract. 2008;62:127-133.

10. Shamloul R, Ghanem H. Erectile dysfunction. Lancet. 2013; 381:153-165.

11. Lo WH, Fu SN, Wong SN, et al. Prevalence, correlates, attitude and treatment seeking of erectile dysfunction among type 2 diabetic Chinese men attending primary care outpatient clinics. Asian J Androl. 2014;16:755-760.

12. Zweifler J, Padilla A, Schafer S. Barriers to recognition of erectile dysfunction among diabetic Mexican-American men. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1998;11:259-263.

13. American Urological Society. Erectile dysfunction: AUA guideline (2018). www.auanet.org/guidelines/erectile-dysfunction-(ed)-guideline. Accessed May 27, 2020.

14. Huang S, Lie J. Phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE5) inhibitors in the management of erectile dysfunction. P T. 2013;38;414-419.

15. Masters WH, Johnson VE. Human Sexual Inadequacy. Boston: Little Brown; 1970.