User login

Intra-articular corticosteroid injections (CSIs) have been a common treatment for osteoarthritis since the 1950s and continue to be an option for patients who prefer nonoperative management.1 Although CSIs may improve pain secondary to osteoarthritis temporarily, they do not slow articular cartilage degradation, and many patients request multiple CSIs before total joint arthroplasty ultimately is required.1,2 Therefore, acute and chronic side effects of CSI must be considered when repeatedly administering corticosteroids.

A postinjection flare, the most common acute side effect of intra-articular CSI, is characterized by a localized inflammatory response that can last 2 to 3 days. The flare occurs in 2% to 25% of CSI cases.3-5 Symptoms can range from mild joint effusion to disabling pain.6 In the present case, a severe postinjection flare occurred after intra-articular administration of triamcinolone acetonide (Kenalog). This case is novel in that its acuity of onset, severity of symptoms, and synovial fluid analysis mimicked septic arthritis, which was ultimately ruled out with negative cultures and confirmation of triamcinolone acetonide crystals in the synovial aspirate, viewed by polarized light microscopy. To date, only one other case of an immediate (<2 hours) and severe postinjection flare in response to triamcinolone has been reported.7 As CSIs are often used in the nonoperative treatment of osteoarthritis, it is imperative for the treating physician to be aware of this potential side effect in order to appropriately inform the patient of this risk and guide treatment should the scenario arise. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 56-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, hypothyroidism, and moderate bilateral knee osteoarthritis presented with left knee pain. She had been receiving annual hylan injections for 5 years and had no adverse reactions, but the pain gradually worsened over the past 3 months. She was given an intra-articular injection of 2 mL of 1% lidocaine and 2 mL (40 mg) of triamcinolone acetonide in the left knee.

Two hours later, she experienced swelling and intense pain in the knee and was unable to ambulate. Physical examination revealed she was afebrile but was having severe pain in the knee through all range of motion. The knee had no appreciable erythema or warmth. Laboratory data were significant: White blood cell (WBC) count was 14,600, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 1 mm/h. The knee was aspirated with a return of 25 mL of “butterscotch”-colored fluid (Figure 1). The patient was admitted to rule out iatrogenic septic arthritis, or chronic, indolent septic arthritis acutely worsened by CSI, until synovial fluid analysis and cultures could be performed (Table 1).

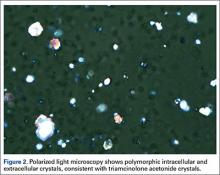

She was treated overnight with a compressive wrap, elevation, ice, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, which provided significant pain relief. Polarized light microscopy revealed polymorphic intracellular and extracellular crystals with crystal morphology consistent with the injection of triamcinolone ester (Figure 2). Gram stain showed many WBCs but no organisms. These findings were thought to represent an exogenous crystal-induced acute inflammatory response. Given the patient’s improving clinical course, she was discharged the next morning.

Twelve days later, at clinic follow-up, she was still experiencing pain above her baseline level. Given the continued effusion, 8 mL of synovial fluid was aspirated, which appeared clear and only slightly blood-tinged. Synovial analysis showed resolution of leukocytosis, confirming a severe postinjection flare in response to triamcinolone acetonide.

Discussion

Although rare, side effects from repeated intra-articular CSIs include hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysfunction and steroid-induced myopathy.8,9 Acute side effects are more common and include postinjection flare, iatrogenic septic arthritis, local tissue atrophy, cartilage damage, tendon rupture, nerve atrophy, increased blood glucose, and osteonecrosis.10,11 The present case report describes an extreme example of a postinjection flare in response to triamcinolone acetonide and summarizes the characteristics of injections that cause flares.

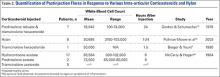

The physical properties of corticosteroids have a significant impact on their efficacy and on their potential for adverse events. Corticosteroid preparations can be water-soluble or water-insoluble. Most commonly, water-insoluble preparations that contain insoluble corticosteroid esters (eg, triamcinolone, methylprednisolone) are used in intra-articular injections. These form microcrystalline aggregates in solution, which require the patient’s own hydrolytic enzymes (esterases) to release the active moiety and thus have a longer duration of action. However, they are more commonly associated with postinjection flares compared with their more soluble and faster- acting counterparts (eg. dexamethasone, betamethasone).10 Microcrystalline aggregates, which are larger in size, induce a stronger inflammatory response, and in a dose-dependent manner.6A sterile inflammatory reaction to hydrocortisone, cortisone, dexamethasone, triamcinolone, and prednisolone crystals in normal joints has been previously described,6,12,13 and crystals of the various preparations have been demonstrated within leukocytes by both polarized light and electron microscopy.12,13 Table 2 summarizes previous synovial fluid analyses after intra-articular injections of various corticosteroid preparations in normal healthy joints and in patients experiencing a postinjection flare. To date, there have been no reports of an immediate (<2 hours) and severe postinjection flare in response to triamcinolone acetonide, though there was a report of a postinjection flare in response to triamcinolone hexacetonide (Aristospan),7 and here the synovial fluid WBC count (30,000) was much lower.

Although many cases of corticosteroid hypersensitivity have been reported, in rare cases intra-articular administration of triamcinolone has caused anaphylactic reactions and shock.14,15 Multiple case studies have determined that the specific excipient carboxymethylcellulose (found in many triamcinolone preparations), and not the corticosteroid itself, can cause an immunoglobulin E–mediated anaphylactic reaction.16-18 Therefore, performing skin-prick tests for potential corticosteroids and their excipients in patients with known postinjection flares might help prevent serious adverse reactions.18,19

The present case involved an extreme postinjection flare in response to intra-articular administration of triamcinolone acetonide. Postinjection flares are rare but significant events, and physicians using CSIs in the treatment of arthritis need to be aware of this potential reaction in order to appropriately inform patients of this risk and guide treatment should the scenario arise.

1. Hollander JL, Brown EM Jr, Jessar RA, Brown CY. Hydrocortisone and cortisone injected into arthritic joints; comparative effects of and use of hydrocortisone as a local antiarthritic agent. J Am Med Assoc. 1951;147(17):1629-1635.

2. Bellamy N, Campbell J, Robinson V, Gee T, Bourne R, Wells G. Intraarticular corticosteroid for treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;19(2):CD005328.

3. Friedman DM, Moore ME. The efficacy of intraarticular steroids in osteoarthritis: a double-blind study. J Rheumatol. 1980;7(6):850-856.

4. Brown EM Jr, Frain JB, Udell L, Hollander JL. Locally administered hydrocortisone in the rheumatic diseases; a summary of its use in 547 patients. Am J Med. 1953;15(5):656-665.

5. Hollander JL, Jessar RA, Brown EM Jr. Intra-synovial corticosteroid therapy: a decade of use. Bull Rheum Dis. 1961;11:239-240.

6. McCarty DJ Jr, Hogan JM. Inflammatory reaction after intrasynovial injection of microcrystalline adrenocorticosteroid esters. Arthritis Rheum. 1964;7(4):359-367.

7. Berger RG, Yount WJ. Immediate “steroid flare” from intraarticular triamcinolone hexacetonide injection: case report and review of the literature. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33(8):1284-1286.

8. Mader R, Lavi I, Luboshitzky R. Evaluation of the pituitary-adrenal axis function following single intraarticular injection of methylprednisolone. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(3):924-928.

9. Raynauld JP, Buckland-Wright C, Ward R, et al. Safety and efficacy of long-term intraarticular steroid injections in osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(2):370-377.

10. MacMahon PJ, Eustace SJ, Kavanagh EC. Injectable corticosteroid and local anesthetic preparations: a review for radiologists. Radiology. 2009;252(3):647-661.

11. Sparling M, Malleson P, Wood B, Petty R. Radiographic followup of joints injected with triamcinolone hexacetonide for the management of childhood arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33(6):821-826.

12. Eymontt MJ, Gordon GV, Schumacher HR, Hansell JR. The effects on synovial permeability and synovial fluid leukocyte counts in symptomatic osteoarthritis after intraarticular corticosteroid administration. J Rheumatol. 1982;9(2):198-203.

13. Gordon GV, Schumacher HR. Electron microscopic study of depot corticosteroid crystals with clinical studies after intra-articular injection. J Rheumatol. 1979;6(1):7-14.

14. Karsh J, Yang WH. An anaphylactic reaction to intra-articular triamcinolone: a case report and review of the literature. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;90(2):254-258.

15. Larsson LG. Anaphylactic shock after i.a. administration of triamcinolone acetonide in a 35-year-old female. Scand J Rheumatol. 1989;18(6):441-442.

16. García-Ortega P, Corominas M, Badia M. Carboxymethylcellulose allergy as a cause of suspected corticosteroid anaphylaxis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;91(4):421.

17. Patterson DL, Yunginger JW, Dunn WF, Jones RT, Hunt LW. Anaphylaxis induced by the carboxymethylcellulose component of injectable triamcinolone acetonide suspension (Kenalog). Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1995;74(2):163-166.

18. Steiner UC, Gentinetta T, Hausmann O, Pichler WJ. IgE-mediated anaphylaxis to intraarticular glucocorticoid preparations. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193(2):W156-W157.

19. Ijsselmuiden OE, Knegt-Junk KJ, van Wijk RG, van Joost T. Cutaneous adverse reactions after intra-articular injection of triamcinolone acetonide. Acta Derm Venereol. 1995;75(1):57-58.

20. Pullman-Mooar S, Mooar P, Sieck M, Clayburne G, Schumacher HR. Are there distinctive inflammatory flares after hylan g-f 20 intraarticular injections? J Rheumatol. 2002;29(12):2611-2614.

Intra-articular corticosteroid injections (CSIs) have been a common treatment for osteoarthritis since the 1950s and continue to be an option for patients who prefer nonoperative management.1 Although CSIs may improve pain secondary to osteoarthritis temporarily, they do not slow articular cartilage degradation, and many patients request multiple CSIs before total joint arthroplasty ultimately is required.1,2 Therefore, acute and chronic side effects of CSI must be considered when repeatedly administering corticosteroids.

A postinjection flare, the most common acute side effect of intra-articular CSI, is characterized by a localized inflammatory response that can last 2 to 3 days. The flare occurs in 2% to 25% of CSI cases.3-5 Symptoms can range from mild joint effusion to disabling pain.6 In the present case, a severe postinjection flare occurred after intra-articular administration of triamcinolone acetonide (Kenalog). This case is novel in that its acuity of onset, severity of symptoms, and synovial fluid analysis mimicked septic arthritis, which was ultimately ruled out with negative cultures and confirmation of triamcinolone acetonide crystals in the synovial aspirate, viewed by polarized light microscopy. To date, only one other case of an immediate (<2 hours) and severe postinjection flare in response to triamcinolone has been reported.7 As CSIs are often used in the nonoperative treatment of osteoarthritis, it is imperative for the treating physician to be aware of this potential side effect in order to appropriately inform the patient of this risk and guide treatment should the scenario arise. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 56-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, hypothyroidism, and moderate bilateral knee osteoarthritis presented with left knee pain. She had been receiving annual hylan injections for 5 years and had no adverse reactions, but the pain gradually worsened over the past 3 months. She was given an intra-articular injection of 2 mL of 1% lidocaine and 2 mL (40 mg) of triamcinolone acetonide in the left knee.

Two hours later, she experienced swelling and intense pain in the knee and was unable to ambulate. Physical examination revealed she was afebrile but was having severe pain in the knee through all range of motion. The knee had no appreciable erythema or warmth. Laboratory data were significant: White blood cell (WBC) count was 14,600, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 1 mm/h. The knee was aspirated with a return of 25 mL of “butterscotch”-colored fluid (Figure 1). The patient was admitted to rule out iatrogenic septic arthritis, or chronic, indolent septic arthritis acutely worsened by CSI, until synovial fluid analysis and cultures could be performed (Table 1).

She was treated overnight with a compressive wrap, elevation, ice, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, which provided significant pain relief. Polarized light microscopy revealed polymorphic intracellular and extracellular crystals with crystal morphology consistent with the injection of triamcinolone ester (Figure 2). Gram stain showed many WBCs but no organisms. These findings were thought to represent an exogenous crystal-induced acute inflammatory response. Given the patient’s improving clinical course, she was discharged the next morning.

Twelve days later, at clinic follow-up, she was still experiencing pain above her baseline level. Given the continued effusion, 8 mL of synovial fluid was aspirated, which appeared clear and only slightly blood-tinged. Synovial analysis showed resolution of leukocytosis, confirming a severe postinjection flare in response to triamcinolone acetonide.

Discussion

Although rare, side effects from repeated intra-articular CSIs include hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysfunction and steroid-induced myopathy.8,9 Acute side effects are more common and include postinjection flare, iatrogenic septic arthritis, local tissue atrophy, cartilage damage, tendon rupture, nerve atrophy, increased blood glucose, and osteonecrosis.10,11 The present case report describes an extreme example of a postinjection flare in response to triamcinolone acetonide and summarizes the characteristics of injections that cause flares.

The physical properties of corticosteroids have a significant impact on their efficacy and on their potential for adverse events. Corticosteroid preparations can be water-soluble or water-insoluble. Most commonly, water-insoluble preparations that contain insoluble corticosteroid esters (eg, triamcinolone, methylprednisolone) are used in intra-articular injections. These form microcrystalline aggregates in solution, which require the patient’s own hydrolytic enzymes (esterases) to release the active moiety and thus have a longer duration of action. However, they are more commonly associated with postinjection flares compared with their more soluble and faster- acting counterparts (eg. dexamethasone, betamethasone).10 Microcrystalline aggregates, which are larger in size, induce a stronger inflammatory response, and in a dose-dependent manner.6A sterile inflammatory reaction to hydrocortisone, cortisone, dexamethasone, triamcinolone, and prednisolone crystals in normal joints has been previously described,6,12,13 and crystals of the various preparations have been demonstrated within leukocytes by both polarized light and electron microscopy.12,13 Table 2 summarizes previous synovial fluid analyses after intra-articular injections of various corticosteroid preparations in normal healthy joints and in patients experiencing a postinjection flare. To date, there have been no reports of an immediate (<2 hours) and severe postinjection flare in response to triamcinolone acetonide, though there was a report of a postinjection flare in response to triamcinolone hexacetonide (Aristospan),7 and here the synovial fluid WBC count (30,000) was much lower.

Although many cases of corticosteroid hypersensitivity have been reported, in rare cases intra-articular administration of triamcinolone has caused anaphylactic reactions and shock.14,15 Multiple case studies have determined that the specific excipient carboxymethylcellulose (found in many triamcinolone preparations), and not the corticosteroid itself, can cause an immunoglobulin E–mediated anaphylactic reaction.16-18 Therefore, performing skin-prick tests for potential corticosteroids and their excipients in patients with known postinjection flares might help prevent serious adverse reactions.18,19

The present case involved an extreme postinjection flare in response to intra-articular administration of triamcinolone acetonide. Postinjection flares are rare but significant events, and physicians using CSIs in the treatment of arthritis need to be aware of this potential reaction in order to appropriately inform patients of this risk and guide treatment should the scenario arise.

Intra-articular corticosteroid injections (CSIs) have been a common treatment for osteoarthritis since the 1950s and continue to be an option for patients who prefer nonoperative management.1 Although CSIs may improve pain secondary to osteoarthritis temporarily, they do not slow articular cartilage degradation, and many patients request multiple CSIs before total joint arthroplasty ultimately is required.1,2 Therefore, acute and chronic side effects of CSI must be considered when repeatedly administering corticosteroids.

A postinjection flare, the most common acute side effect of intra-articular CSI, is characterized by a localized inflammatory response that can last 2 to 3 days. The flare occurs in 2% to 25% of CSI cases.3-5 Symptoms can range from mild joint effusion to disabling pain.6 In the present case, a severe postinjection flare occurred after intra-articular administration of triamcinolone acetonide (Kenalog). This case is novel in that its acuity of onset, severity of symptoms, and synovial fluid analysis mimicked septic arthritis, which was ultimately ruled out with negative cultures and confirmation of triamcinolone acetonide crystals in the synovial aspirate, viewed by polarized light microscopy. To date, only one other case of an immediate (<2 hours) and severe postinjection flare in response to triamcinolone has been reported.7 As CSIs are often used in the nonoperative treatment of osteoarthritis, it is imperative for the treating physician to be aware of this potential side effect in order to appropriately inform the patient of this risk and guide treatment should the scenario arise. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 56-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, hypothyroidism, and moderate bilateral knee osteoarthritis presented with left knee pain. She had been receiving annual hylan injections for 5 years and had no adverse reactions, but the pain gradually worsened over the past 3 months. She was given an intra-articular injection of 2 mL of 1% lidocaine and 2 mL (40 mg) of triamcinolone acetonide in the left knee.

Two hours later, she experienced swelling and intense pain in the knee and was unable to ambulate. Physical examination revealed she was afebrile but was having severe pain in the knee through all range of motion. The knee had no appreciable erythema or warmth. Laboratory data were significant: White blood cell (WBC) count was 14,600, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 1 mm/h. The knee was aspirated with a return of 25 mL of “butterscotch”-colored fluid (Figure 1). The patient was admitted to rule out iatrogenic septic arthritis, or chronic, indolent septic arthritis acutely worsened by CSI, until synovial fluid analysis and cultures could be performed (Table 1).

She was treated overnight with a compressive wrap, elevation, ice, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, which provided significant pain relief. Polarized light microscopy revealed polymorphic intracellular and extracellular crystals with crystal morphology consistent with the injection of triamcinolone ester (Figure 2). Gram stain showed many WBCs but no organisms. These findings were thought to represent an exogenous crystal-induced acute inflammatory response. Given the patient’s improving clinical course, she was discharged the next morning.

Twelve days later, at clinic follow-up, she was still experiencing pain above her baseline level. Given the continued effusion, 8 mL of synovial fluid was aspirated, which appeared clear and only slightly blood-tinged. Synovial analysis showed resolution of leukocytosis, confirming a severe postinjection flare in response to triamcinolone acetonide.

Discussion

Although rare, side effects from repeated intra-articular CSIs include hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysfunction and steroid-induced myopathy.8,9 Acute side effects are more common and include postinjection flare, iatrogenic septic arthritis, local tissue atrophy, cartilage damage, tendon rupture, nerve atrophy, increased blood glucose, and osteonecrosis.10,11 The present case report describes an extreme example of a postinjection flare in response to triamcinolone acetonide and summarizes the characteristics of injections that cause flares.

The physical properties of corticosteroids have a significant impact on their efficacy and on their potential for adverse events. Corticosteroid preparations can be water-soluble or water-insoluble. Most commonly, water-insoluble preparations that contain insoluble corticosteroid esters (eg, triamcinolone, methylprednisolone) are used in intra-articular injections. These form microcrystalline aggregates in solution, which require the patient’s own hydrolytic enzymes (esterases) to release the active moiety and thus have a longer duration of action. However, they are more commonly associated with postinjection flares compared with their more soluble and faster- acting counterparts (eg. dexamethasone, betamethasone).10 Microcrystalline aggregates, which are larger in size, induce a stronger inflammatory response, and in a dose-dependent manner.6A sterile inflammatory reaction to hydrocortisone, cortisone, dexamethasone, triamcinolone, and prednisolone crystals in normal joints has been previously described,6,12,13 and crystals of the various preparations have been demonstrated within leukocytes by both polarized light and electron microscopy.12,13 Table 2 summarizes previous synovial fluid analyses after intra-articular injections of various corticosteroid preparations in normal healthy joints and in patients experiencing a postinjection flare. To date, there have been no reports of an immediate (<2 hours) and severe postinjection flare in response to triamcinolone acetonide, though there was a report of a postinjection flare in response to triamcinolone hexacetonide (Aristospan),7 and here the synovial fluid WBC count (30,000) was much lower.

Although many cases of corticosteroid hypersensitivity have been reported, in rare cases intra-articular administration of triamcinolone has caused anaphylactic reactions and shock.14,15 Multiple case studies have determined that the specific excipient carboxymethylcellulose (found in many triamcinolone preparations), and not the corticosteroid itself, can cause an immunoglobulin E–mediated anaphylactic reaction.16-18 Therefore, performing skin-prick tests for potential corticosteroids and their excipients in patients with known postinjection flares might help prevent serious adverse reactions.18,19

The present case involved an extreme postinjection flare in response to intra-articular administration of triamcinolone acetonide. Postinjection flares are rare but significant events, and physicians using CSIs in the treatment of arthritis need to be aware of this potential reaction in order to appropriately inform patients of this risk and guide treatment should the scenario arise.

1. Hollander JL, Brown EM Jr, Jessar RA, Brown CY. Hydrocortisone and cortisone injected into arthritic joints; comparative effects of and use of hydrocortisone as a local antiarthritic agent. J Am Med Assoc. 1951;147(17):1629-1635.

2. Bellamy N, Campbell J, Robinson V, Gee T, Bourne R, Wells G. Intraarticular corticosteroid for treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;19(2):CD005328.

3. Friedman DM, Moore ME. The efficacy of intraarticular steroids in osteoarthritis: a double-blind study. J Rheumatol. 1980;7(6):850-856.

4. Brown EM Jr, Frain JB, Udell L, Hollander JL. Locally administered hydrocortisone in the rheumatic diseases; a summary of its use in 547 patients. Am J Med. 1953;15(5):656-665.

5. Hollander JL, Jessar RA, Brown EM Jr. Intra-synovial corticosteroid therapy: a decade of use. Bull Rheum Dis. 1961;11:239-240.

6. McCarty DJ Jr, Hogan JM. Inflammatory reaction after intrasynovial injection of microcrystalline adrenocorticosteroid esters. Arthritis Rheum. 1964;7(4):359-367.

7. Berger RG, Yount WJ. Immediate “steroid flare” from intraarticular triamcinolone hexacetonide injection: case report and review of the literature. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33(8):1284-1286.

8. Mader R, Lavi I, Luboshitzky R. Evaluation of the pituitary-adrenal axis function following single intraarticular injection of methylprednisolone. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(3):924-928.

9. Raynauld JP, Buckland-Wright C, Ward R, et al. Safety and efficacy of long-term intraarticular steroid injections in osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(2):370-377.

10. MacMahon PJ, Eustace SJ, Kavanagh EC. Injectable corticosteroid and local anesthetic preparations: a review for radiologists. Radiology. 2009;252(3):647-661.

11. Sparling M, Malleson P, Wood B, Petty R. Radiographic followup of joints injected with triamcinolone hexacetonide for the management of childhood arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33(6):821-826.

12. Eymontt MJ, Gordon GV, Schumacher HR, Hansell JR. The effects on synovial permeability and synovial fluid leukocyte counts in symptomatic osteoarthritis after intraarticular corticosteroid administration. J Rheumatol. 1982;9(2):198-203.

13. Gordon GV, Schumacher HR. Electron microscopic study of depot corticosteroid crystals with clinical studies after intra-articular injection. J Rheumatol. 1979;6(1):7-14.

14. Karsh J, Yang WH. An anaphylactic reaction to intra-articular triamcinolone: a case report and review of the literature. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;90(2):254-258.

15. Larsson LG. Anaphylactic shock after i.a. administration of triamcinolone acetonide in a 35-year-old female. Scand J Rheumatol. 1989;18(6):441-442.

16. García-Ortega P, Corominas M, Badia M. Carboxymethylcellulose allergy as a cause of suspected corticosteroid anaphylaxis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;91(4):421.

17. Patterson DL, Yunginger JW, Dunn WF, Jones RT, Hunt LW. Anaphylaxis induced by the carboxymethylcellulose component of injectable triamcinolone acetonide suspension (Kenalog). Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1995;74(2):163-166.

18. Steiner UC, Gentinetta T, Hausmann O, Pichler WJ. IgE-mediated anaphylaxis to intraarticular glucocorticoid preparations. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193(2):W156-W157.

19. Ijsselmuiden OE, Knegt-Junk KJ, van Wijk RG, van Joost T. Cutaneous adverse reactions after intra-articular injection of triamcinolone acetonide. Acta Derm Venereol. 1995;75(1):57-58.

20. Pullman-Mooar S, Mooar P, Sieck M, Clayburne G, Schumacher HR. Are there distinctive inflammatory flares after hylan g-f 20 intraarticular injections? J Rheumatol. 2002;29(12):2611-2614.

1. Hollander JL, Brown EM Jr, Jessar RA, Brown CY. Hydrocortisone and cortisone injected into arthritic joints; comparative effects of and use of hydrocortisone as a local antiarthritic agent. J Am Med Assoc. 1951;147(17):1629-1635.

2. Bellamy N, Campbell J, Robinson V, Gee T, Bourne R, Wells G. Intraarticular corticosteroid for treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;19(2):CD005328.

3. Friedman DM, Moore ME. The efficacy of intraarticular steroids in osteoarthritis: a double-blind study. J Rheumatol. 1980;7(6):850-856.

4. Brown EM Jr, Frain JB, Udell L, Hollander JL. Locally administered hydrocortisone in the rheumatic diseases; a summary of its use in 547 patients. Am J Med. 1953;15(5):656-665.

5. Hollander JL, Jessar RA, Brown EM Jr. Intra-synovial corticosteroid therapy: a decade of use. Bull Rheum Dis. 1961;11:239-240.

6. McCarty DJ Jr, Hogan JM. Inflammatory reaction after intrasynovial injection of microcrystalline adrenocorticosteroid esters. Arthritis Rheum. 1964;7(4):359-367.

7. Berger RG, Yount WJ. Immediate “steroid flare” from intraarticular triamcinolone hexacetonide injection: case report and review of the literature. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33(8):1284-1286.

8. Mader R, Lavi I, Luboshitzky R. Evaluation of the pituitary-adrenal axis function following single intraarticular injection of methylprednisolone. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(3):924-928.

9. Raynauld JP, Buckland-Wright C, Ward R, et al. Safety and efficacy of long-term intraarticular steroid injections in osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(2):370-377.

10. MacMahon PJ, Eustace SJ, Kavanagh EC. Injectable corticosteroid and local anesthetic preparations: a review for radiologists. Radiology. 2009;252(3):647-661.

11. Sparling M, Malleson P, Wood B, Petty R. Radiographic followup of joints injected with triamcinolone hexacetonide for the management of childhood arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33(6):821-826.

12. Eymontt MJ, Gordon GV, Schumacher HR, Hansell JR. The effects on synovial permeability and synovial fluid leukocyte counts in symptomatic osteoarthritis after intraarticular corticosteroid administration. J Rheumatol. 1982;9(2):198-203.

13. Gordon GV, Schumacher HR. Electron microscopic study of depot corticosteroid crystals with clinical studies after intra-articular injection. J Rheumatol. 1979;6(1):7-14.

14. Karsh J, Yang WH. An anaphylactic reaction to intra-articular triamcinolone: a case report and review of the literature. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;90(2):254-258.

15. Larsson LG. Anaphylactic shock after i.a. administration of triamcinolone acetonide in a 35-year-old female. Scand J Rheumatol. 1989;18(6):441-442.

16. García-Ortega P, Corominas M, Badia M. Carboxymethylcellulose allergy as a cause of suspected corticosteroid anaphylaxis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;91(4):421.

17. Patterson DL, Yunginger JW, Dunn WF, Jones RT, Hunt LW. Anaphylaxis induced by the carboxymethylcellulose component of injectable triamcinolone acetonide suspension (Kenalog). Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1995;74(2):163-166.

18. Steiner UC, Gentinetta T, Hausmann O, Pichler WJ. IgE-mediated anaphylaxis to intraarticular glucocorticoid preparations. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193(2):W156-W157.

19. Ijsselmuiden OE, Knegt-Junk KJ, van Wijk RG, van Joost T. Cutaneous adverse reactions after intra-articular injection of triamcinolone acetonide. Acta Derm Venereol. 1995;75(1):57-58.

20. Pullman-Mooar S, Mooar P, Sieck M, Clayburne G, Schumacher HR. Are there distinctive inflammatory flares after hylan g-f 20 intraarticular injections? J Rheumatol. 2002;29(12):2611-2614.