User login

Traditional mentorship models may not be adequate for academic hospitalists. The traditional dyadic mentorship model, in which a senior principal investigator and research mentee collaborate for career advancement, is well suited for basic science or clinical research. In contrast, areas of academic hospital medicine such as quality improvement, medical education, hospital operations, point-of-care ultrasound, and clinical expertise may be less suited to this traditional mentoring model. In addition, experienced mentors are limited and those available are often overcommitted or have inadequate time due to responsibilities with other leadership roles. Senior mentors may also be limited because of our specialty’s focus on clinical practice rather than longitudinal research or projects.9 There are other limitations of traditional mentorship that are applicable to all fields of academic medicine, including disparate goals, expectations, levels of commitment, and the inherent power differential between the mentor and mentee.10

In this perspective, we discuss our experience with implementing an alternative and complementary mentorship strategy called facilitated peer mentorship with junior faculty hospitalists in the Division of General Internal Medicine at New York–Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center.

In facilitated peer mentoring programs, faculty typically work collaboratively in groups of three to five with other faculty who are of similar rank, and a faculty member of a higher academic rank works with the group in meeting their scholarly goals.11 The role of the facilitator is to ensure a safe and respectful learning environment, foster peer collaboration, and redirect the group to draw upon their own experiences. Each junior faculty member serves as both a mentor and mentee for each other with bidirectional feedback, guidance, and support in a group setting. This model emphasizes collaboration, peer networking, empowerment, and the development of personal awareness.10 A number of academic medical centers have used peer mentoring as a response to the challenges encountered in the traditional dyad model.12 To our knowledge, the only published example of a peer mentoring model in academic hospital medicine is in the form of a research-in-progress conference.13 While this example addresses peer-mentored research, there is a gap in other areas of academic hospital medicine with mentoring needs—most of all in personal development and career satisfaction.

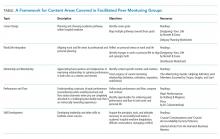

We piloted a 12-month facilitated peer mentoring program for new hospitalists. The goal of the program was for junior faculty hospitalists to develop a better understanding of their own identity and core values that would enable them to more confidently navigate career choices, enhance their work vitality and career satisfaction, and develop their potential for leadership roles in academic hospital medicine. Each year, a cohort of four to five incoming hospitalists from different backgrounds, interests, and experience were grouped with a more experienced colleague at an associate professor rank who expressed interest and was selected by our section chief to lead the program. The program was required for new hospitalists and consisted of six 90-minute sessions every two months. The attendance rate was 100% and was ensured by scheduling all sessions at the beginning of the academic year with dates agreed upon by all participants. An e-mail reminder was sent one week prior to each session. Each session had assigned readings and an agenda for discussions (see Table for details).

Our evaluation of the program after two years with two separate cohorts included qualitative feedback through an anonymous survey for participants; in addition, qualitative feedback was collected in a one-hour, in-person discussion and reflection with each cohort. We learned several lessons from the feedback we received from program participants. First, our impression was that the career experience of the junior faculty member had a significant impact on the perceived value of group meetings. For those who entered the hospitalist workforce immediately upon completing their terminal training in internal medicine, the exercise of considering different career versions of themselves had added value in promoting thinking outside-the-box for career opportunities within hospital medicine. Academic hospitalists and general internists more broadly, tend to have broad interests that fuel their passions but may also make it more difficult to define long-term goals. One junior faculty member paired her life interests in global medical education with building an international collaboration with other academic hospitalist programs; another faculty member gained confidence and expanded her network of collaborators by designing a research pilot study on hospitalist-initiated end-of-life discussions. In both cases, the junior faculty identified the facilitated peer mentoring program as a strong influence in finding these opportunities. Peer mentoring at the time of entry into the field of hospital medicine, when many have undefined career goals, can be helpful for navigating this issue at the start of a career. On the other hand, those who had already worked as a hospitalist for one or two years and joined the program found less value in career planning exercises.

Second, junior faculty differed in their desire for scope and depth of the curriculum. Some preferred more frequent sessions with more premeeting readings and self-assessments in fewer topics that were covered more longitudinally. A proposed example of a longitudinal topic was defining and refining existing mentoring relationships. Others found it useful to cover more ground with a potpourri of themes; they wanted to cover different knowledge, skills, and attitudes considered important for personal growth and career development, such as negotiation, leading teams, and managing conflict. We recommend the goals of the peer group be defined collaboratively at the beginning of new groups to respond to the needs of the group.

Third, junior faculty varied in how they viewed the goal of the program on a spectrum ranging from social support to mentorship. On one end of the spectrum, the program provided a safe venue for colleagues to convene periodically to discuss work challenges; this group found the support from peers to be helpful. On the other end, some found value in the coaching and mentoring from peers and the experienced facilitator that guided personal growth and career development.

Our pilot program has several limitations. This is a single-center program with a relatively small number of participants; thus, our experience may be unique to our institution and not representative of all academic hospital medicine programs. We also did not obtain any quantitative metrics of evaluation—mixed methods should be used in the future for more rigorous program evaluation. Finally, our peer mentoring model may not cover all domains of mentoring such as sponsorship for career advancement, provision of resources, and promotion of scholarship, though we mentioned an anecdote of scholarship that resulted from networking and redefining of goals that were facilitated through this program. Scholarship is certainly an important feature of academic medicine—other peer mentoring programs may consider forming groups based on research interests to address this gap. A tailored curriculum toward research and scholarship may garner more interest and benefit from participants interested in advancement of scholarship activities.

Overall, the field of hospital medicine is growing rapidly with junior faculty who need effective mentorship. Facilitated peer mentorship among small groups of junior faculty is a feasible and pragmatic mentorship model that can complement more traditional mentorship models. We discovered wide-ranging and contrasting experiences in our program, which suggests that peer mentorship is not a one-size-fits-all approach. However, facilitated peer mentorship can be a highly adaptable and alternative approach to mentorship for diverse groups of hospitalists, including general internal medicine, pediatrics, and other sub

1. Harrison R, Hunter AJ, Sharpe B, Auerbach AD. Survey of US academic hospitalist leaders about mentorship and academic activities in hospitalist groups. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(1):5-9. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.836.

2. Reid MB, Misky GJ, Harrison RA, Sharpe B, Auerbach A, Glasheen JJ. Mentorship, productivity, and promotion among academic hospitalists. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(1):23-27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-011-1892-5.

3. Cumbler E, Rendón P, Yirdaw E, et al. Keys to career success: resources and barriers identified by early career academic hospitalists. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(5):588-589. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4336-7.

4. Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marusić A. Mentoring in academic medicine: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296(9):1103-1115. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.296.9.1103.

5. Pololi LH, Evans AT, Civian JT, et al. Faculty vitality-surviving the challenges facing academic health centers: a national survey of medical faculty. Acad Med. 2015;90(7):930-936. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000674.

6. Nagarur A, O’Neill RM, Lawton D, Greenwald JL. Supporting faculty development in hospital medicine: design and implementation of a personalized structured mentoring program. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(2):96-99. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2854.

7. Wachter RM. The state of hospital medicine in 2008. Med Clin North Am. 2008;92(2):265-273, vii. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2007.10.008.

8. Wiese J, Centor R. The need for mentors in the odyssey of the academic hospitalist. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(1):1-2.

9. Rogers JC, Holloway RL, Miller SM. Academic mentoring and family medicine’s research productivity. Fam Med. 1990;22(3):186-190.

10. Pololi L, Knight S. Mentoring faculty in academic medicine. A new paradigm? J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(9):866-870.

11. Varkey P, Jatoi A, Williams A, et al. The positive impact of a facilitated peer mentoring program on academic skills of women faculty. BMC Med Educ. 2012;12:14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-12-14.

12. Pololi LH, Evans AT. Group peer mentoring: an answer to the faculty mentoring problem? A successful program at a large academic department of medicine. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2015;35(3):192-200. https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.21296.

13. Abougergi MS, Wright SM, Landis R, Howell EE. Research in progress conference for hospitalists provides valuable peer mentoring. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(1):43-46. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.865.

Traditional mentorship models may not be adequate for academic hospitalists. The traditional dyadic mentorship model, in which a senior principal investigator and research mentee collaborate for career advancement, is well suited for basic science or clinical research. In contrast, areas of academic hospital medicine such as quality improvement, medical education, hospital operations, point-of-care ultrasound, and clinical expertise may be less suited to this traditional mentoring model. In addition, experienced mentors are limited and those available are often overcommitted or have inadequate time due to responsibilities with other leadership roles. Senior mentors may also be limited because of our specialty’s focus on clinical practice rather than longitudinal research or projects.9 There are other limitations of traditional mentorship that are applicable to all fields of academic medicine, including disparate goals, expectations, levels of commitment, and the inherent power differential between the mentor and mentee.10

In this perspective, we discuss our experience with implementing an alternative and complementary mentorship strategy called facilitated peer mentorship with junior faculty hospitalists in the Division of General Internal Medicine at New York–Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center.

In facilitated peer mentoring programs, faculty typically work collaboratively in groups of three to five with other faculty who are of similar rank, and a faculty member of a higher academic rank works with the group in meeting their scholarly goals.11 The role of the facilitator is to ensure a safe and respectful learning environment, foster peer collaboration, and redirect the group to draw upon their own experiences. Each junior faculty member serves as both a mentor and mentee for each other with bidirectional feedback, guidance, and support in a group setting. This model emphasizes collaboration, peer networking, empowerment, and the development of personal awareness.10 A number of academic medical centers have used peer mentoring as a response to the challenges encountered in the traditional dyad model.12 To our knowledge, the only published example of a peer mentoring model in academic hospital medicine is in the form of a research-in-progress conference.13 While this example addresses peer-mentored research, there is a gap in other areas of academic hospital medicine with mentoring needs—most of all in personal development and career satisfaction.

We piloted a 12-month facilitated peer mentoring program for new hospitalists. The goal of the program was for junior faculty hospitalists to develop a better understanding of their own identity and core values that would enable them to more confidently navigate career choices, enhance their work vitality and career satisfaction, and develop their potential for leadership roles in academic hospital medicine. Each year, a cohort of four to five incoming hospitalists from different backgrounds, interests, and experience were grouped with a more experienced colleague at an associate professor rank who expressed interest and was selected by our section chief to lead the program. The program was required for new hospitalists and consisted of six 90-minute sessions every two months. The attendance rate was 100% and was ensured by scheduling all sessions at the beginning of the academic year with dates agreed upon by all participants. An e-mail reminder was sent one week prior to each session. Each session had assigned readings and an agenda for discussions (see Table for details).

Our evaluation of the program after two years with two separate cohorts included qualitative feedback through an anonymous survey for participants; in addition, qualitative feedback was collected in a one-hour, in-person discussion and reflection with each cohort. We learned several lessons from the feedback we received from program participants. First, our impression was that the career experience of the junior faculty member had a significant impact on the perceived value of group meetings. For those who entered the hospitalist workforce immediately upon completing their terminal training in internal medicine, the exercise of considering different career versions of themselves had added value in promoting thinking outside-the-box for career opportunities within hospital medicine. Academic hospitalists and general internists more broadly, tend to have broad interests that fuel their passions but may also make it more difficult to define long-term goals. One junior faculty member paired her life interests in global medical education with building an international collaboration with other academic hospitalist programs; another faculty member gained confidence and expanded her network of collaborators by designing a research pilot study on hospitalist-initiated end-of-life discussions. In both cases, the junior faculty identified the facilitated peer mentoring program as a strong influence in finding these opportunities. Peer mentoring at the time of entry into the field of hospital medicine, when many have undefined career goals, can be helpful for navigating this issue at the start of a career. On the other hand, those who had already worked as a hospitalist for one or two years and joined the program found less value in career planning exercises.

Second, junior faculty differed in their desire for scope and depth of the curriculum. Some preferred more frequent sessions with more premeeting readings and self-assessments in fewer topics that were covered more longitudinally. A proposed example of a longitudinal topic was defining and refining existing mentoring relationships. Others found it useful to cover more ground with a potpourri of themes; they wanted to cover different knowledge, skills, and attitudes considered important for personal growth and career development, such as negotiation, leading teams, and managing conflict. We recommend the goals of the peer group be defined collaboratively at the beginning of new groups to respond to the needs of the group.

Third, junior faculty varied in how they viewed the goal of the program on a spectrum ranging from social support to mentorship. On one end of the spectrum, the program provided a safe venue for colleagues to convene periodically to discuss work challenges; this group found the support from peers to be helpful. On the other end, some found value in the coaching and mentoring from peers and the experienced facilitator that guided personal growth and career development.

Our pilot program has several limitations. This is a single-center program with a relatively small number of participants; thus, our experience may be unique to our institution and not representative of all academic hospital medicine programs. We also did not obtain any quantitative metrics of evaluation—mixed methods should be used in the future for more rigorous program evaluation. Finally, our peer mentoring model may not cover all domains of mentoring such as sponsorship for career advancement, provision of resources, and promotion of scholarship, though we mentioned an anecdote of scholarship that resulted from networking and redefining of goals that were facilitated through this program. Scholarship is certainly an important feature of academic medicine—other peer mentoring programs may consider forming groups based on research interests to address this gap. A tailored curriculum toward research and scholarship may garner more interest and benefit from participants interested in advancement of scholarship activities.

Overall, the field of hospital medicine is growing rapidly with junior faculty who need effective mentorship. Facilitated peer mentorship among small groups of junior faculty is a feasible and pragmatic mentorship model that can complement more traditional mentorship models. We discovered wide-ranging and contrasting experiences in our program, which suggests that peer mentorship is not a one-size-fits-all approach. However, facilitated peer mentorship can be a highly adaptable and alternative approach to mentorship for diverse groups of hospitalists, including general internal medicine, pediatrics, and other sub

Traditional mentorship models may not be adequate for academic hospitalists. The traditional dyadic mentorship model, in which a senior principal investigator and research mentee collaborate for career advancement, is well suited for basic science or clinical research. In contrast, areas of academic hospital medicine such as quality improvement, medical education, hospital operations, point-of-care ultrasound, and clinical expertise may be less suited to this traditional mentoring model. In addition, experienced mentors are limited and those available are often overcommitted or have inadequate time due to responsibilities with other leadership roles. Senior mentors may also be limited because of our specialty’s focus on clinical practice rather than longitudinal research or projects.9 There are other limitations of traditional mentorship that are applicable to all fields of academic medicine, including disparate goals, expectations, levels of commitment, and the inherent power differential between the mentor and mentee.10

In this perspective, we discuss our experience with implementing an alternative and complementary mentorship strategy called facilitated peer mentorship with junior faculty hospitalists in the Division of General Internal Medicine at New York–Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center.

In facilitated peer mentoring programs, faculty typically work collaboratively in groups of three to five with other faculty who are of similar rank, and a faculty member of a higher academic rank works with the group in meeting their scholarly goals.11 The role of the facilitator is to ensure a safe and respectful learning environment, foster peer collaboration, and redirect the group to draw upon their own experiences. Each junior faculty member serves as both a mentor and mentee for each other with bidirectional feedback, guidance, and support in a group setting. This model emphasizes collaboration, peer networking, empowerment, and the development of personal awareness.10 A number of academic medical centers have used peer mentoring as a response to the challenges encountered in the traditional dyad model.12 To our knowledge, the only published example of a peer mentoring model in academic hospital medicine is in the form of a research-in-progress conference.13 While this example addresses peer-mentored research, there is a gap in other areas of academic hospital medicine with mentoring needs—most of all in personal development and career satisfaction.

We piloted a 12-month facilitated peer mentoring program for new hospitalists. The goal of the program was for junior faculty hospitalists to develop a better understanding of their own identity and core values that would enable them to more confidently navigate career choices, enhance their work vitality and career satisfaction, and develop their potential for leadership roles in academic hospital medicine. Each year, a cohort of four to five incoming hospitalists from different backgrounds, interests, and experience were grouped with a more experienced colleague at an associate professor rank who expressed interest and was selected by our section chief to lead the program. The program was required for new hospitalists and consisted of six 90-minute sessions every two months. The attendance rate was 100% and was ensured by scheduling all sessions at the beginning of the academic year with dates agreed upon by all participants. An e-mail reminder was sent one week prior to each session. Each session had assigned readings and an agenda for discussions (see Table for details).

Our evaluation of the program after two years with two separate cohorts included qualitative feedback through an anonymous survey for participants; in addition, qualitative feedback was collected in a one-hour, in-person discussion and reflection with each cohort. We learned several lessons from the feedback we received from program participants. First, our impression was that the career experience of the junior faculty member had a significant impact on the perceived value of group meetings. For those who entered the hospitalist workforce immediately upon completing their terminal training in internal medicine, the exercise of considering different career versions of themselves had added value in promoting thinking outside-the-box for career opportunities within hospital medicine. Academic hospitalists and general internists more broadly, tend to have broad interests that fuel their passions but may also make it more difficult to define long-term goals. One junior faculty member paired her life interests in global medical education with building an international collaboration with other academic hospitalist programs; another faculty member gained confidence and expanded her network of collaborators by designing a research pilot study on hospitalist-initiated end-of-life discussions. In both cases, the junior faculty identified the facilitated peer mentoring program as a strong influence in finding these opportunities. Peer mentoring at the time of entry into the field of hospital medicine, when many have undefined career goals, can be helpful for navigating this issue at the start of a career. On the other hand, those who had already worked as a hospitalist for one or two years and joined the program found less value in career planning exercises.

Second, junior faculty differed in their desire for scope and depth of the curriculum. Some preferred more frequent sessions with more premeeting readings and self-assessments in fewer topics that were covered more longitudinally. A proposed example of a longitudinal topic was defining and refining existing mentoring relationships. Others found it useful to cover more ground with a potpourri of themes; they wanted to cover different knowledge, skills, and attitudes considered important for personal growth and career development, such as negotiation, leading teams, and managing conflict. We recommend the goals of the peer group be defined collaboratively at the beginning of new groups to respond to the needs of the group.

Third, junior faculty varied in how they viewed the goal of the program on a spectrum ranging from social support to mentorship. On one end of the spectrum, the program provided a safe venue for colleagues to convene periodically to discuss work challenges; this group found the support from peers to be helpful. On the other end, some found value in the coaching and mentoring from peers and the experienced facilitator that guided personal growth and career development.

Our pilot program has several limitations. This is a single-center program with a relatively small number of participants; thus, our experience may be unique to our institution and not representative of all academic hospital medicine programs. We also did not obtain any quantitative metrics of evaluation—mixed methods should be used in the future for more rigorous program evaluation. Finally, our peer mentoring model may not cover all domains of mentoring such as sponsorship for career advancement, provision of resources, and promotion of scholarship, though we mentioned an anecdote of scholarship that resulted from networking and redefining of goals that were facilitated through this program. Scholarship is certainly an important feature of academic medicine—other peer mentoring programs may consider forming groups based on research interests to address this gap. A tailored curriculum toward research and scholarship may garner more interest and benefit from participants interested in advancement of scholarship activities.

Overall, the field of hospital medicine is growing rapidly with junior faculty who need effective mentorship. Facilitated peer mentorship among small groups of junior faculty is a feasible and pragmatic mentorship model that can complement more traditional mentorship models. We discovered wide-ranging and contrasting experiences in our program, which suggests that peer mentorship is not a one-size-fits-all approach. However, facilitated peer mentorship can be a highly adaptable and alternative approach to mentorship for diverse groups of hospitalists, including general internal medicine, pediatrics, and other sub

1. Harrison R, Hunter AJ, Sharpe B, Auerbach AD. Survey of US academic hospitalist leaders about mentorship and academic activities in hospitalist groups. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(1):5-9. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.836.

2. Reid MB, Misky GJ, Harrison RA, Sharpe B, Auerbach A, Glasheen JJ. Mentorship, productivity, and promotion among academic hospitalists. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(1):23-27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-011-1892-5.

3. Cumbler E, Rendón P, Yirdaw E, et al. Keys to career success: resources and barriers identified by early career academic hospitalists. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(5):588-589. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4336-7.

4. Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marusić A. Mentoring in academic medicine: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296(9):1103-1115. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.296.9.1103.

5. Pololi LH, Evans AT, Civian JT, et al. Faculty vitality-surviving the challenges facing academic health centers: a national survey of medical faculty. Acad Med. 2015;90(7):930-936. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000674.

6. Nagarur A, O’Neill RM, Lawton D, Greenwald JL. Supporting faculty development in hospital medicine: design and implementation of a personalized structured mentoring program. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(2):96-99. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2854.

7. Wachter RM. The state of hospital medicine in 2008. Med Clin North Am. 2008;92(2):265-273, vii. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2007.10.008.

8. Wiese J, Centor R. The need for mentors in the odyssey of the academic hospitalist. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(1):1-2.

9. Rogers JC, Holloway RL, Miller SM. Academic mentoring and family medicine’s research productivity. Fam Med. 1990;22(3):186-190.

10. Pololi L, Knight S. Mentoring faculty in academic medicine. A new paradigm? J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(9):866-870.

11. Varkey P, Jatoi A, Williams A, et al. The positive impact of a facilitated peer mentoring program on academic skills of women faculty. BMC Med Educ. 2012;12:14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-12-14.

12. Pololi LH, Evans AT. Group peer mentoring: an answer to the faculty mentoring problem? A successful program at a large academic department of medicine. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2015;35(3):192-200. https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.21296.

13. Abougergi MS, Wright SM, Landis R, Howell EE. Research in progress conference for hospitalists provides valuable peer mentoring. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(1):43-46. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.865.

1. Harrison R, Hunter AJ, Sharpe B, Auerbach AD. Survey of US academic hospitalist leaders about mentorship and academic activities in hospitalist groups. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(1):5-9. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.836.

2. Reid MB, Misky GJ, Harrison RA, Sharpe B, Auerbach A, Glasheen JJ. Mentorship, productivity, and promotion among academic hospitalists. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(1):23-27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-011-1892-5.

3. Cumbler E, Rendón P, Yirdaw E, et al. Keys to career success: resources and barriers identified by early career academic hospitalists. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(5):588-589. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4336-7.

4. Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marusić A. Mentoring in academic medicine: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296(9):1103-1115. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.296.9.1103.

5. Pololi LH, Evans AT, Civian JT, et al. Faculty vitality-surviving the challenges facing academic health centers: a national survey of medical faculty. Acad Med. 2015;90(7):930-936. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000674.

6. Nagarur A, O’Neill RM, Lawton D, Greenwald JL. Supporting faculty development in hospital medicine: design and implementation of a personalized structured mentoring program. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(2):96-99. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2854.

7. Wachter RM. The state of hospital medicine in 2008. Med Clin North Am. 2008;92(2):265-273, vii. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2007.10.008.

8. Wiese J, Centor R. The need for mentors in the odyssey of the academic hospitalist. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(1):1-2.

9. Rogers JC, Holloway RL, Miller SM. Academic mentoring and family medicine’s research productivity. Fam Med. 1990;22(3):186-190.

10. Pololi L, Knight S. Mentoring faculty in academic medicine. A new paradigm? J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(9):866-870.

11. Varkey P, Jatoi A, Williams A, et al. The positive impact of a facilitated peer mentoring program on academic skills of women faculty. BMC Med Educ. 2012;12:14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-12-14.

12. Pololi LH, Evans AT. Group peer mentoring: an answer to the faculty mentoring problem? A successful program at a large academic department of medicine. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2015;35(3):192-200. https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.21296.

13. Abougergi MS, Wright SM, Landis R, Howell EE. Research in progress conference for hospitalists provides valuable peer mentoring. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(1):43-46. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.865.

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine