User login

A 29-year-old woman with a history of frequent migraines presented to her primary care provider for a refill of medication. For the past two years she had been taking rizatriptan 10 mg, but with little relief. She stated that she had continued to experience discrete migraines several days per month, often clustered around menses. The severity of the headaches had negatively affected her work attendance, productivity, and social interactions. She wondered if she should be taking a different kind of medication.

The patient had been diagnosed with migraines at age 12, just prior to menarche. She described her headache as a unilateral, sharp throbbing pain associated with increased sensitivity to light and sound as well as nausea. She denied any history of head trauma. She had no allergies, and the only other medications she was taking at the time were an oral contraceptive (ethinyl estradiol/norgestimate 0.035 mg/0.18 mg with an oral triphasic 21/7 treatment cycle) and fluoxetine 20 mg for depression.

The patient worked daytime hours as a sales representative. She considered herself active, exercised regularly, ate a balanced diet, and slept well. She consumed no more than two to four alcoholic drinks per month and denied the use of herbals, dietary supplements, tobacco, or illegal drugs.

The patient stated that her mother had frequent headaches but had never sought a medical explanation or treatment. She was unaware of any other family history of headaches, and there was no family history of cardiovascular disease. Her sister had been diagnosed with a prolactinoma at age 25. At age 26, the patient had undergone a pituitary protocol MRI of the head with and without contrast, with negative results.

On examination, the patient was alert and oriented with normal vital signs. Her pupils were equal and reactive to light, and no papilledema was evident on fundoscopic examination. The cranial nerves were grossly intact and no other neurologic deficits were appreciated. No carotid bruits were present on cardiovascular exam.

Based on the patient’s history and physical exam, she met the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-II)1 diagnostic criteria for migraine without aura (1.1). When asked to recall the onset and frequency of attacks she had had in the previous four weeks, she noted that they regularly occurred during her menstrual cycle.

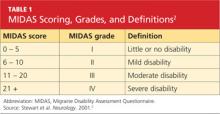

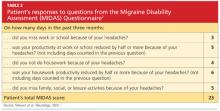

She was subsequently asked to begin a diary to record her headache characteristics, severity, and duration, with days of menstruation noted. The Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) questionnaire2 (see Tables 1 and 22) was performed to measure the migraine attacks’ impact on the patient’s life; her score indicated that the headaches were causing her severe disability.

The patient’s abortive migraine medication was changed from rizatriptan 10 mg to the combination sumatriptan/naproxen sodium 85 mg/500 mg. She was instructed to take the initial dose as soon as she noticed signs of an impending migraine and to repeat the dose in two hours if symptoms persisted. The possibility of starting a preventive medication was discussed, but the patient wanted to evaluate her response to the combination triptan/NSAID before considering migraine prophylaxis.

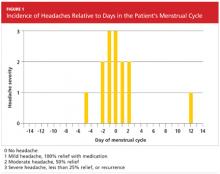

Three months later, the patient returned for follow-up, including a review of her headache diary. She stated that the frequency and intensity of attacks had not decreased; acute treatment with sumatriptan/naproxen sodium made her headaches more bearable but did not ameliorate symptoms. The patient had recorded a detailed account of each migraine which, based on the ICHD-II criteria,1 demonstrated a pattern of headache occurrences consistent with menstrually related migraine. She reported a total of 18 headaches in the previous three months, 12 of which had occurred within the five-day perimenstrual period (see Figure 1).

Based on this information and the fact that the patient’s headaches were resistant to previous treatments, it was decided to alter the approach to her migraine management once more. In an effort to limit estrogen fluctuations during her menstrual cycle, her oral contraceptive was changed from ethinyl estradiol/norgestimate to a 12-week placebo-free monophasic regimen of ethinyl estradiol/levonorgestrel 20 mg/90 mcg. For intermittent prophylaxis, she was instructed to take frovatriptan 2.5 mg twice daily, beginning two days prior to the start of menses and continuing through the last day of her cycle. For acute treatment of breakthrough migraines, she was prescribed sumatriptan 20-mg nasal spray to take at the first sign of migraine symptoms and instructed to repeat the dose if the pain persisted or returned.

The patient continued to track her headaches in the diary and was seen in the office after three months of following the revised menstrual migraine management plan. She reported fewer migraines associated with her menstrual cycle and noted that they were less severe and shorter in duration. When she repeated the MIDAS test, her score was reduced from 23 to 10. In the subsequent nine months she has reported a consistent decrease in migraine prevalence and now rarely needs the abortive therapy.

DISCUSSION

Migraine, though commonly encountered in clinical practice, is a complex disorder. For women, migraine headaches have been recognized by the World Health Organization as the 12th leading cause of “life lived with a disabling condition.”3 Pure menstrual migraine and menstrually related migraine will be the focus of discussion here.

Etiology

Menstrually related migraine (comparable to pure menstrual migraine, although the latter is distinguished by occurring only during the perimenstrual period1) is recognized as a distinct type of migraine associated with perimenstrual hormone fluctuations.4 Of women who experience migraine, 42% to 61% can associate their attacks with the perimenstrual period5; this is defined as two days before to three days after the start of menstruation.

It has also been determined that women are more likely to have migraine attacks during the late luteal and early follicular phases (when there is a natural drop in estrogen levels) than in other phases (when estrogen levels are higher).6 Despite clinical evidence to support this estrogen withdrawal theory, the pathophysiology is not completely understood. It is possible that affected women are more sensitive than other women to the decrease in estrogen levels that occurs with menstruation.7

History and Physical Findings of Menstrual Migraines

Almost every woman with perimenstrual migraines reports an absence of aura.7 In the evaluation of headache, the same criteria for migraine without aura pertain to the classifications of pure menstrual migraine (PMM) or menstrually related migraine (MRM).1 Correlation of migraine attacks to the onset of menses is the key finding in the patient history to differentiate menstrual migraine from migraine without aura in women.8 Furthermore, perimenstrual migraines are often of longer duration and more difficult to treat than migraines not associated with hormone fluctuations.9

In order to distinguish between PMM and MRM, it is important to understand that pure menstrual migraine attacks take place exclusively in the five-day perimenstrual window and at no other times of the cycle. The criteria for MRM allow for attacks at other times of the cycle.1

In addition to causing physical pain, menstrual migraines can impact work performance, household activities, and personal relationships. The MIDAS questionnaire is a disability assessment tool that can reveal to the practitioner how migraines have affected the patient’s life over the previous three months.10 This is a useful method to identify patients with disabling migraines, determine their need for treatment, and monitor treatment efficacy.

Diagnosis

Menstrual migraine is a clinical diagnosis made by findings from the patient’s history. The International Headache Society has established specific diagnostic criteria in the ICHD-II for both PMM and MRM.1 An accurate and detailed migraine history is invaluable for the diagnosis of menstrual migraine. Although a formal questionnaire can serve as a good screening tool, it relies on the patient’s ability to recall specific times and dates with accuracy.11 Recall bias can be misleading in any attempt to confirm a diagnosis. The patient’s conscientious use of a daily headache diary or calendar (see Figure 2, for example) can lead to a precise record of the characteristics and timing of migraines, overcoming these obstacles.

Brain imaging is necessary if the patient’s symptoms suggest a critical etiology that requires immediate diagnosis and management. Red flags include sudden onset of a severe headache, a headache characterized as “the worst headache of the patient’s life,” a change in headache pattern, altered mental status, an abnormal neurologic examination, or fever with neck stiffness.12

Treatment Options for Menstrual Migraine

There is no FDA-approved treatment specific for menstrual migraines; however, medications used for management of nonmenstrual migraines are also those most commonly prescribed for women with menstrual migraine headaches.13 Because these headaches are frequently more severe and of longer duration than nonmenstrual migraine headaches, a combination of intermittent preventive therapy, hormone manipulation, and acute treatment strategies is often necessary.4

Acute therapy is aimed to treat migraine pain quickly and effectively with minimal adverse effects or need for additional medication. Triptans have been the mainstay of menstrual migraine treatment and have been proven effective for both acute attacks and prevention.4 Sumatriptan has a rapid onset of action and may be given orally as a 50- or 100-mg tablet, as a 6-mg subcutaneous injection, or as a 20-mg nasal spray.14

Abortive therapies are most effective when taken at the first sign of an attack. Patients can repeat the dose in two hours if the headache persists or recurs, to a maximum of two doses in 24 hours.15 Rizatriptan is another triptan used for acute treatment of menstrual migraine headaches. Its initial 10-mg dose can be repeated every two hours, to a maximum of 30 mg per 24 hours. NSAIDs, such as naproxen sodium, have also been recommended in acute migraine attacks. They seem to work synergistically with triptans, inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis and blocking neurogenic inflammation.15

Clinical study results have demonstrated superior pain relief and decreased migraine recurrence when a triptan and NSAID are used in combination, compared with use of either medication alone.4 A single-tablet formulation of sumatriptan 85 mg and naproxen sodium 500 mg may be considered for initial therapy in hard-to-treat patients.14

Preventive therapy should be considered when responsiveness to acute treatment is inadequate.4 Nonhormonal intermittent prophylactic treatment is recommended two days prior to the beginning of menses, continuing for five days.16 Longer-acting triptans, such as frovatriptan 2.5 mg and naratriptan 1.0 mg, dosed twice daily, have been demonstrated as effective in clinical trials when used during the perimenstrual period.17,18

The advantage of short-term therapy over daily prophylaxis is the potential to avoid adverse effects seen with continuous exposure to the drug.3 However, successful therapy relies on consistency in menstruation, and therefore may not be ideal for women with irregular cycles or those with coexisting nonmenstrual migraines.16 Estrogen-based therapy is an option for these women and for those who have failed nonhormonal methods.19

The goal of hormone prophylaxis is to prevent or reduce the physiologic decline in estradiol that occurs in the late luteal phase.4 Clinical studies have been conducted using various hormonal strategies to maintain steady estradiol levels, all of which decreased migraine prevalence.19 Estrogen fluctuations can be minimized by eliminating the placebo week in traditional estrogen/progestin oral contraceptives to achieve an extended-cycle regimen, resembling that of the 12-week ethinyl estradiol/levonorgestrel formulation.19

Continuous use of combined oral contraceptives is also an option for relief of menstrual migraine. When cyclic or extended-cycle regimens allow for menses, supplemental estrogen (10- to 20-mg ethinyl estradiol) is recommended during the hormone-free week.14

CONCLUSION

Proper diagnosis of menstrual migraines, using screening tools and the MIDAS questionnaire, can help practitioners provide the most effective migraine management for their patients. The most important step toward a good prognosis is acknowledging menstrual migraine as a unique headache disorder and formulating a precise diagnosis in order to identify individually tailored treatment options. With proper identification and integrated acute and prophylactic treatment, women with menstrual migraines are able to lead a healthier, more satisfying life.

REFERENCES

1. International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders. 2nd ed. Cephalalgia. 2004;24(suppl 1):1-160.

2. Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Dowson AJ, Sawyer J. Development and testing of the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) Questionnaire to assess headache-related disability. Neurology. 2001;56(6 suppl 1):S20-S28.

3. MacGregor EA. Perimenstrual headaches: unmet needs. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2008;12(6):468-474.

4. Mannix LK. Menstrual-related pain conditions: dysmenorrhea and migraine. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2008;17(5):879-891.

5. Martin VT. New theories in the pathogenesis of menstrual migraine. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2008;12(6):453-462.

6. MacGregor EA. Migraine headache in perimenopausal and menopausal women. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2009;13(5):399-403.

7. Martin VT, Wernke S, Mandell K, et al. Symptoms of premenstrual syndrome and their association with migraine headache. Headache. 2006; 46(1):125-137.

8. Martin VT, Behbehani M. Ovarian hormones and migraine headache: understanding mechanisms and pathogenesis—part 2. Headache. 2006;46(3):365-386.

9. Granella F, Sances G, Allais G, et al. Characteristics of menstrual and nonmenstrual attacks in women with menstrually related migraine referred to headache centres. Cephalalgia. 2004;24(9):707-716.

10. Hutchinson SL, Silberstein SD. Menstrual migraine: case studies of women with estrogen-related headaches. Headache. 2008;48 suppl 3:S131-S141.

11. Tepper SJ, Zatochill M, Szeto M, et al. Development of a simple menstrual migraine screening tool for obstetric and gynecology clinics: the Menstrual Migraine Assessment Tool. Headache. 2008; 48(10):1419-1425.

12. Marcus DA. Focus on primary care diagnosis and management of headache in women. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1999;54(6):395-402.

13. Tepper SJ. Tailoring management strategies for the patient with menstrual migraine: focus on prevention and treatment. Headache. 2006;46(suppl 2):S61-S68.

14. Lay CL, Payne R. Recognition and treatment of menstrual migraine. Neurologist. 2007;13(4):197-204.

15. Henry KA, Cohen CI. Perimenstrual headache: treatment options. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2009;13(1):82-88.

16. Calhoun AH. Estrogen-associated migraine. www.uptodate.com/contents/estrogen-associated-migraine. Accessed May 4, 2011.

17. Silberstein SD, Elkind AH, Schreiber C, et al. A randomized trial of frovatriptan for the intermittent prevention of menstrual migraine. Neurology. 2004;63:261-269.

18. Mannix LK, Savani N, Landy S, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of naratriptan for short-term prevention of menstrually related migraine: data from two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies. Headache. 2007;47(7):1037-1049.

19. Calhoun AH, Hutchinson S. Hormonal therapies for menstrual migraine. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2009;13(5):381-385.

A 29-year-old woman with a history of frequent migraines presented to her primary care provider for a refill of medication. For the past two years she had been taking rizatriptan 10 mg, but with little relief. She stated that she had continued to experience discrete migraines several days per month, often clustered around menses. The severity of the headaches had negatively affected her work attendance, productivity, and social interactions. She wondered if she should be taking a different kind of medication.

The patient had been diagnosed with migraines at age 12, just prior to menarche. She described her headache as a unilateral, sharp throbbing pain associated with increased sensitivity to light and sound as well as nausea. She denied any history of head trauma. She had no allergies, and the only other medications she was taking at the time were an oral contraceptive (ethinyl estradiol/norgestimate 0.035 mg/0.18 mg with an oral triphasic 21/7 treatment cycle) and fluoxetine 20 mg for depression.

The patient worked daytime hours as a sales representative. She considered herself active, exercised regularly, ate a balanced diet, and slept well. She consumed no more than two to four alcoholic drinks per month and denied the use of herbals, dietary supplements, tobacco, or illegal drugs.

The patient stated that her mother had frequent headaches but had never sought a medical explanation or treatment. She was unaware of any other family history of headaches, and there was no family history of cardiovascular disease. Her sister had been diagnosed with a prolactinoma at age 25. At age 26, the patient had undergone a pituitary protocol MRI of the head with and without contrast, with negative results.

On examination, the patient was alert and oriented with normal vital signs. Her pupils were equal and reactive to light, and no papilledema was evident on fundoscopic examination. The cranial nerves were grossly intact and no other neurologic deficits were appreciated. No carotid bruits were present on cardiovascular exam.

Based on the patient’s history and physical exam, she met the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-II)1 diagnostic criteria for migraine without aura (1.1). When asked to recall the onset and frequency of attacks she had had in the previous four weeks, she noted that they regularly occurred during her menstrual cycle.

She was subsequently asked to begin a diary to record her headache characteristics, severity, and duration, with days of menstruation noted. The Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) questionnaire2 (see Tables 1 and 22) was performed to measure the migraine attacks’ impact on the patient’s life; her score indicated that the headaches were causing her severe disability.

The patient’s abortive migraine medication was changed from rizatriptan 10 mg to the combination sumatriptan/naproxen sodium 85 mg/500 mg. She was instructed to take the initial dose as soon as she noticed signs of an impending migraine and to repeat the dose in two hours if symptoms persisted. The possibility of starting a preventive medication was discussed, but the patient wanted to evaluate her response to the combination triptan/NSAID before considering migraine prophylaxis.

Three months later, the patient returned for follow-up, including a review of her headache diary. She stated that the frequency and intensity of attacks had not decreased; acute treatment with sumatriptan/naproxen sodium made her headaches more bearable but did not ameliorate symptoms. The patient had recorded a detailed account of each migraine which, based on the ICHD-II criteria,1 demonstrated a pattern of headache occurrences consistent with menstrually related migraine. She reported a total of 18 headaches in the previous three months, 12 of which had occurred within the five-day perimenstrual period (see Figure 1).

Based on this information and the fact that the patient’s headaches were resistant to previous treatments, it was decided to alter the approach to her migraine management once more. In an effort to limit estrogen fluctuations during her menstrual cycle, her oral contraceptive was changed from ethinyl estradiol/norgestimate to a 12-week placebo-free monophasic regimen of ethinyl estradiol/levonorgestrel 20 mg/90 mcg. For intermittent prophylaxis, she was instructed to take frovatriptan 2.5 mg twice daily, beginning two days prior to the start of menses and continuing through the last day of her cycle. For acute treatment of breakthrough migraines, she was prescribed sumatriptan 20-mg nasal spray to take at the first sign of migraine symptoms and instructed to repeat the dose if the pain persisted or returned.

The patient continued to track her headaches in the diary and was seen in the office after three months of following the revised menstrual migraine management plan. She reported fewer migraines associated with her menstrual cycle and noted that they were less severe and shorter in duration. When she repeated the MIDAS test, her score was reduced from 23 to 10. In the subsequent nine months she has reported a consistent decrease in migraine prevalence and now rarely needs the abortive therapy.

DISCUSSION

Migraine, though commonly encountered in clinical practice, is a complex disorder. For women, migraine headaches have been recognized by the World Health Organization as the 12th leading cause of “life lived with a disabling condition.”3 Pure menstrual migraine and menstrually related migraine will be the focus of discussion here.

Etiology

Menstrually related migraine (comparable to pure menstrual migraine, although the latter is distinguished by occurring only during the perimenstrual period1) is recognized as a distinct type of migraine associated with perimenstrual hormone fluctuations.4 Of women who experience migraine, 42% to 61% can associate their attacks with the perimenstrual period5; this is defined as two days before to three days after the start of menstruation.

It has also been determined that women are more likely to have migraine attacks during the late luteal and early follicular phases (when there is a natural drop in estrogen levels) than in other phases (when estrogen levels are higher).6 Despite clinical evidence to support this estrogen withdrawal theory, the pathophysiology is not completely understood. It is possible that affected women are more sensitive than other women to the decrease in estrogen levels that occurs with menstruation.7

History and Physical Findings of Menstrual Migraines

Almost every woman with perimenstrual migraines reports an absence of aura.7 In the evaluation of headache, the same criteria for migraine without aura pertain to the classifications of pure menstrual migraine (PMM) or menstrually related migraine (MRM).1 Correlation of migraine attacks to the onset of menses is the key finding in the patient history to differentiate menstrual migraine from migraine without aura in women.8 Furthermore, perimenstrual migraines are often of longer duration and more difficult to treat than migraines not associated with hormone fluctuations.9

In order to distinguish between PMM and MRM, it is important to understand that pure menstrual migraine attacks take place exclusively in the five-day perimenstrual window and at no other times of the cycle. The criteria for MRM allow for attacks at other times of the cycle.1

In addition to causing physical pain, menstrual migraines can impact work performance, household activities, and personal relationships. The MIDAS questionnaire is a disability assessment tool that can reveal to the practitioner how migraines have affected the patient’s life over the previous three months.10 This is a useful method to identify patients with disabling migraines, determine their need for treatment, and monitor treatment efficacy.

Diagnosis

Menstrual migraine is a clinical diagnosis made by findings from the patient’s history. The International Headache Society has established specific diagnostic criteria in the ICHD-II for both PMM and MRM.1 An accurate and detailed migraine history is invaluable for the diagnosis of menstrual migraine. Although a formal questionnaire can serve as a good screening tool, it relies on the patient’s ability to recall specific times and dates with accuracy.11 Recall bias can be misleading in any attempt to confirm a diagnosis. The patient’s conscientious use of a daily headache diary or calendar (see Figure 2, for example) can lead to a precise record of the characteristics and timing of migraines, overcoming these obstacles.

Brain imaging is necessary if the patient’s symptoms suggest a critical etiology that requires immediate diagnosis and management. Red flags include sudden onset of a severe headache, a headache characterized as “the worst headache of the patient’s life,” a change in headache pattern, altered mental status, an abnormal neurologic examination, or fever with neck stiffness.12

Treatment Options for Menstrual Migraine

There is no FDA-approved treatment specific for menstrual migraines; however, medications used for management of nonmenstrual migraines are also those most commonly prescribed for women with menstrual migraine headaches.13 Because these headaches are frequently more severe and of longer duration than nonmenstrual migraine headaches, a combination of intermittent preventive therapy, hormone manipulation, and acute treatment strategies is often necessary.4

Acute therapy is aimed to treat migraine pain quickly and effectively with minimal adverse effects or need for additional medication. Triptans have been the mainstay of menstrual migraine treatment and have been proven effective for both acute attacks and prevention.4 Sumatriptan has a rapid onset of action and may be given orally as a 50- or 100-mg tablet, as a 6-mg subcutaneous injection, or as a 20-mg nasal spray.14

Abortive therapies are most effective when taken at the first sign of an attack. Patients can repeat the dose in two hours if the headache persists or recurs, to a maximum of two doses in 24 hours.15 Rizatriptan is another triptan used for acute treatment of menstrual migraine headaches. Its initial 10-mg dose can be repeated every two hours, to a maximum of 30 mg per 24 hours. NSAIDs, such as naproxen sodium, have also been recommended in acute migraine attacks. They seem to work synergistically with triptans, inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis and blocking neurogenic inflammation.15

Clinical study results have demonstrated superior pain relief and decreased migraine recurrence when a triptan and NSAID are used in combination, compared with use of either medication alone.4 A single-tablet formulation of sumatriptan 85 mg and naproxen sodium 500 mg may be considered for initial therapy in hard-to-treat patients.14

Preventive therapy should be considered when responsiveness to acute treatment is inadequate.4 Nonhormonal intermittent prophylactic treatment is recommended two days prior to the beginning of menses, continuing for five days.16 Longer-acting triptans, such as frovatriptan 2.5 mg and naratriptan 1.0 mg, dosed twice daily, have been demonstrated as effective in clinical trials when used during the perimenstrual period.17,18

The advantage of short-term therapy over daily prophylaxis is the potential to avoid adverse effects seen with continuous exposure to the drug.3 However, successful therapy relies on consistency in menstruation, and therefore may not be ideal for women with irregular cycles or those with coexisting nonmenstrual migraines.16 Estrogen-based therapy is an option for these women and for those who have failed nonhormonal methods.19

The goal of hormone prophylaxis is to prevent or reduce the physiologic decline in estradiol that occurs in the late luteal phase.4 Clinical studies have been conducted using various hormonal strategies to maintain steady estradiol levels, all of which decreased migraine prevalence.19 Estrogen fluctuations can be minimized by eliminating the placebo week in traditional estrogen/progestin oral contraceptives to achieve an extended-cycle regimen, resembling that of the 12-week ethinyl estradiol/levonorgestrel formulation.19

Continuous use of combined oral contraceptives is also an option for relief of menstrual migraine. When cyclic or extended-cycle regimens allow for menses, supplemental estrogen (10- to 20-mg ethinyl estradiol) is recommended during the hormone-free week.14

CONCLUSION

Proper diagnosis of menstrual migraines, using screening tools and the MIDAS questionnaire, can help practitioners provide the most effective migraine management for their patients. The most important step toward a good prognosis is acknowledging menstrual migraine as a unique headache disorder and formulating a precise diagnosis in order to identify individually tailored treatment options. With proper identification and integrated acute and prophylactic treatment, women with menstrual migraines are able to lead a healthier, more satisfying life.

REFERENCES

1. International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders. 2nd ed. Cephalalgia. 2004;24(suppl 1):1-160.

2. Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Dowson AJ, Sawyer J. Development and testing of the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) Questionnaire to assess headache-related disability. Neurology. 2001;56(6 suppl 1):S20-S28.

3. MacGregor EA. Perimenstrual headaches: unmet needs. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2008;12(6):468-474.

4. Mannix LK. Menstrual-related pain conditions: dysmenorrhea and migraine. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2008;17(5):879-891.

5. Martin VT. New theories in the pathogenesis of menstrual migraine. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2008;12(6):453-462.

6. MacGregor EA. Migraine headache in perimenopausal and menopausal women. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2009;13(5):399-403.

7. Martin VT, Wernke S, Mandell K, et al. Symptoms of premenstrual syndrome and their association with migraine headache. Headache. 2006; 46(1):125-137.

8. Martin VT, Behbehani M. Ovarian hormones and migraine headache: understanding mechanisms and pathogenesis—part 2. Headache. 2006;46(3):365-386.

9. Granella F, Sances G, Allais G, et al. Characteristics of menstrual and nonmenstrual attacks in women with menstrually related migraine referred to headache centres. Cephalalgia. 2004;24(9):707-716.

10. Hutchinson SL, Silberstein SD. Menstrual migraine: case studies of women with estrogen-related headaches. Headache. 2008;48 suppl 3:S131-S141.

11. Tepper SJ, Zatochill M, Szeto M, et al. Development of a simple menstrual migraine screening tool for obstetric and gynecology clinics: the Menstrual Migraine Assessment Tool. Headache. 2008; 48(10):1419-1425.

12. Marcus DA. Focus on primary care diagnosis and management of headache in women. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1999;54(6):395-402.

13. Tepper SJ. Tailoring management strategies for the patient with menstrual migraine: focus on prevention and treatment. Headache. 2006;46(suppl 2):S61-S68.

14. Lay CL, Payne R. Recognition and treatment of menstrual migraine. Neurologist. 2007;13(4):197-204.

15. Henry KA, Cohen CI. Perimenstrual headache: treatment options. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2009;13(1):82-88.

16. Calhoun AH. Estrogen-associated migraine. www.uptodate.com/contents/estrogen-associated-migraine. Accessed May 4, 2011.

17. Silberstein SD, Elkind AH, Schreiber C, et al. A randomized trial of frovatriptan for the intermittent prevention of menstrual migraine. Neurology. 2004;63:261-269.

18. Mannix LK, Savani N, Landy S, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of naratriptan for short-term prevention of menstrually related migraine: data from two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies. Headache. 2007;47(7):1037-1049.

19. Calhoun AH, Hutchinson S. Hormonal therapies for menstrual migraine. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2009;13(5):381-385.

A 29-year-old woman with a history of frequent migraines presented to her primary care provider for a refill of medication. For the past two years she had been taking rizatriptan 10 mg, but with little relief. She stated that she had continued to experience discrete migraines several days per month, often clustered around menses. The severity of the headaches had negatively affected her work attendance, productivity, and social interactions. She wondered if she should be taking a different kind of medication.

The patient had been diagnosed with migraines at age 12, just prior to menarche. She described her headache as a unilateral, sharp throbbing pain associated with increased sensitivity to light and sound as well as nausea. She denied any history of head trauma. She had no allergies, and the only other medications she was taking at the time were an oral contraceptive (ethinyl estradiol/norgestimate 0.035 mg/0.18 mg with an oral triphasic 21/7 treatment cycle) and fluoxetine 20 mg for depression.

The patient worked daytime hours as a sales representative. She considered herself active, exercised regularly, ate a balanced diet, and slept well. She consumed no more than two to four alcoholic drinks per month and denied the use of herbals, dietary supplements, tobacco, or illegal drugs.

The patient stated that her mother had frequent headaches but had never sought a medical explanation or treatment. She was unaware of any other family history of headaches, and there was no family history of cardiovascular disease. Her sister had been diagnosed with a prolactinoma at age 25. At age 26, the patient had undergone a pituitary protocol MRI of the head with and without contrast, with negative results.

On examination, the patient was alert and oriented with normal vital signs. Her pupils were equal and reactive to light, and no papilledema was evident on fundoscopic examination. The cranial nerves were grossly intact and no other neurologic deficits were appreciated. No carotid bruits were present on cardiovascular exam.

Based on the patient’s history and physical exam, she met the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-II)1 diagnostic criteria for migraine without aura (1.1). When asked to recall the onset and frequency of attacks she had had in the previous four weeks, she noted that they regularly occurred during her menstrual cycle.

She was subsequently asked to begin a diary to record her headache characteristics, severity, and duration, with days of menstruation noted. The Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) questionnaire2 (see Tables 1 and 22) was performed to measure the migraine attacks’ impact on the patient’s life; her score indicated that the headaches were causing her severe disability.

The patient’s abortive migraine medication was changed from rizatriptan 10 mg to the combination sumatriptan/naproxen sodium 85 mg/500 mg. She was instructed to take the initial dose as soon as she noticed signs of an impending migraine and to repeat the dose in two hours if symptoms persisted. The possibility of starting a preventive medication was discussed, but the patient wanted to evaluate her response to the combination triptan/NSAID before considering migraine prophylaxis.

Three months later, the patient returned for follow-up, including a review of her headache diary. She stated that the frequency and intensity of attacks had not decreased; acute treatment with sumatriptan/naproxen sodium made her headaches more bearable but did not ameliorate symptoms. The patient had recorded a detailed account of each migraine which, based on the ICHD-II criteria,1 demonstrated a pattern of headache occurrences consistent with menstrually related migraine. She reported a total of 18 headaches in the previous three months, 12 of which had occurred within the five-day perimenstrual period (see Figure 1).

Based on this information and the fact that the patient’s headaches were resistant to previous treatments, it was decided to alter the approach to her migraine management once more. In an effort to limit estrogen fluctuations during her menstrual cycle, her oral contraceptive was changed from ethinyl estradiol/norgestimate to a 12-week placebo-free monophasic regimen of ethinyl estradiol/levonorgestrel 20 mg/90 mcg. For intermittent prophylaxis, she was instructed to take frovatriptan 2.5 mg twice daily, beginning two days prior to the start of menses and continuing through the last day of her cycle. For acute treatment of breakthrough migraines, she was prescribed sumatriptan 20-mg nasal spray to take at the first sign of migraine symptoms and instructed to repeat the dose if the pain persisted or returned.

The patient continued to track her headaches in the diary and was seen in the office after three months of following the revised menstrual migraine management plan. She reported fewer migraines associated with her menstrual cycle and noted that they were less severe and shorter in duration. When she repeated the MIDAS test, her score was reduced from 23 to 10. In the subsequent nine months she has reported a consistent decrease in migraine prevalence and now rarely needs the abortive therapy.

DISCUSSION

Migraine, though commonly encountered in clinical practice, is a complex disorder. For women, migraine headaches have been recognized by the World Health Organization as the 12th leading cause of “life lived with a disabling condition.”3 Pure menstrual migraine and menstrually related migraine will be the focus of discussion here.

Etiology

Menstrually related migraine (comparable to pure menstrual migraine, although the latter is distinguished by occurring only during the perimenstrual period1) is recognized as a distinct type of migraine associated with perimenstrual hormone fluctuations.4 Of women who experience migraine, 42% to 61% can associate their attacks with the perimenstrual period5; this is defined as two days before to three days after the start of menstruation.

It has also been determined that women are more likely to have migraine attacks during the late luteal and early follicular phases (when there is a natural drop in estrogen levels) than in other phases (when estrogen levels are higher).6 Despite clinical evidence to support this estrogen withdrawal theory, the pathophysiology is not completely understood. It is possible that affected women are more sensitive than other women to the decrease in estrogen levels that occurs with menstruation.7

History and Physical Findings of Menstrual Migraines

Almost every woman with perimenstrual migraines reports an absence of aura.7 In the evaluation of headache, the same criteria for migraine without aura pertain to the classifications of pure menstrual migraine (PMM) or menstrually related migraine (MRM).1 Correlation of migraine attacks to the onset of menses is the key finding in the patient history to differentiate menstrual migraine from migraine without aura in women.8 Furthermore, perimenstrual migraines are often of longer duration and more difficult to treat than migraines not associated with hormone fluctuations.9

In order to distinguish between PMM and MRM, it is important to understand that pure menstrual migraine attacks take place exclusively in the five-day perimenstrual window and at no other times of the cycle. The criteria for MRM allow for attacks at other times of the cycle.1

In addition to causing physical pain, menstrual migraines can impact work performance, household activities, and personal relationships. The MIDAS questionnaire is a disability assessment tool that can reveal to the practitioner how migraines have affected the patient’s life over the previous three months.10 This is a useful method to identify patients with disabling migraines, determine their need for treatment, and monitor treatment efficacy.

Diagnosis

Menstrual migraine is a clinical diagnosis made by findings from the patient’s history. The International Headache Society has established specific diagnostic criteria in the ICHD-II for both PMM and MRM.1 An accurate and detailed migraine history is invaluable for the diagnosis of menstrual migraine. Although a formal questionnaire can serve as a good screening tool, it relies on the patient’s ability to recall specific times and dates with accuracy.11 Recall bias can be misleading in any attempt to confirm a diagnosis. The patient’s conscientious use of a daily headache diary or calendar (see Figure 2, for example) can lead to a precise record of the characteristics and timing of migraines, overcoming these obstacles.

Brain imaging is necessary if the patient’s symptoms suggest a critical etiology that requires immediate diagnosis and management. Red flags include sudden onset of a severe headache, a headache characterized as “the worst headache of the patient’s life,” a change in headache pattern, altered mental status, an abnormal neurologic examination, or fever with neck stiffness.12

Treatment Options for Menstrual Migraine

There is no FDA-approved treatment specific for menstrual migraines; however, medications used for management of nonmenstrual migraines are also those most commonly prescribed for women with menstrual migraine headaches.13 Because these headaches are frequently more severe and of longer duration than nonmenstrual migraine headaches, a combination of intermittent preventive therapy, hormone manipulation, and acute treatment strategies is often necessary.4

Acute therapy is aimed to treat migraine pain quickly and effectively with minimal adverse effects or need for additional medication. Triptans have been the mainstay of menstrual migraine treatment and have been proven effective for both acute attacks and prevention.4 Sumatriptan has a rapid onset of action and may be given orally as a 50- or 100-mg tablet, as a 6-mg subcutaneous injection, or as a 20-mg nasal spray.14

Abortive therapies are most effective when taken at the first sign of an attack. Patients can repeat the dose in two hours if the headache persists or recurs, to a maximum of two doses in 24 hours.15 Rizatriptan is another triptan used for acute treatment of menstrual migraine headaches. Its initial 10-mg dose can be repeated every two hours, to a maximum of 30 mg per 24 hours. NSAIDs, such as naproxen sodium, have also been recommended in acute migraine attacks. They seem to work synergistically with triptans, inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis and blocking neurogenic inflammation.15

Clinical study results have demonstrated superior pain relief and decreased migraine recurrence when a triptan and NSAID are used in combination, compared with use of either medication alone.4 A single-tablet formulation of sumatriptan 85 mg and naproxen sodium 500 mg may be considered for initial therapy in hard-to-treat patients.14

Preventive therapy should be considered when responsiveness to acute treatment is inadequate.4 Nonhormonal intermittent prophylactic treatment is recommended two days prior to the beginning of menses, continuing for five days.16 Longer-acting triptans, such as frovatriptan 2.5 mg and naratriptan 1.0 mg, dosed twice daily, have been demonstrated as effective in clinical trials when used during the perimenstrual period.17,18

The advantage of short-term therapy over daily prophylaxis is the potential to avoid adverse effects seen with continuous exposure to the drug.3 However, successful therapy relies on consistency in menstruation, and therefore may not be ideal for women with irregular cycles or those with coexisting nonmenstrual migraines.16 Estrogen-based therapy is an option for these women and for those who have failed nonhormonal methods.19

The goal of hormone prophylaxis is to prevent or reduce the physiologic decline in estradiol that occurs in the late luteal phase.4 Clinical studies have been conducted using various hormonal strategies to maintain steady estradiol levels, all of which decreased migraine prevalence.19 Estrogen fluctuations can be minimized by eliminating the placebo week in traditional estrogen/progestin oral contraceptives to achieve an extended-cycle regimen, resembling that of the 12-week ethinyl estradiol/levonorgestrel formulation.19

Continuous use of combined oral contraceptives is also an option for relief of menstrual migraine. When cyclic or extended-cycle regimens allow for menses, supplemental estrogen (10- to 20-mg ethinyl estradiol) is recommended during the hormone-free week.14

CONCLUSION

Proper diagnosis of menstrual migraines, using screening tools and the MIDAS questionnaire, can help practitioners provide the most effective migraine management for their patients. The most important step toward a good prognosis is acknowledging menstrual migraine as a unique headache disorder and formulating a precise diagnosis in order to identify individually tailored treatment options. With proper identification and integrated acute and prophylactic treatment, women with menstrual migraines are able to lead a healthier, more satisfying life.

REFERENCES

1. International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders. 2nd ed. Cephalalgia. 2004;24(suppl 1):1-160.

2. Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Dowson AJ, Sawyer J. Development and testing of the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) Questionnaire to assess headache-related disability. Neurology. 2001;56(6 suppl 1):S20-S28.

3. MacGregor EA. Perimenstrual headaches: unmet needs. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2008;12(6):468-474.

4. Mannix LK. Menstrual-related pain conditions: dysmenorrhea and migraine. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2008;17(5):879-891.

5. Martin VT. New theories in the pathogenesis of menstrual migraine. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2008;12(6):453-462.

6. MacGregor EA. Migraine headache in perimenopausal and menopausal women. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2009;13(5):399-403.

7. Martin VT, Wernke S, Mandell K, et al. Symptoms of premenstrual syndrome and their association with migraine headache. Headache. 2006; 46(1):125-137.

8. Martin VT, Behbehani M. Ovarian hormones and migraine headache: understanding mechanisms and pathogenesis—part 2. Headache. 2006;46(3):365-386.

9. Granella F, Sances G, Allais G, et al. Characteristics of menstrual and nonmenstrual attacks in women with menstrually related migraine referred to headache centres. Cephalalgia. 2004;24(9):707-716.

10. Hutchinson SL, Silberstein SD. Menstrual migraine: case studies of women with estrogen-related headaches. Headache. 2008;48 suppl 3:S131-S141.

11. Tepper SJ, Zatochill M, Szeto M, et al. Development of a simple menstrual migraine screening tool for obstetric and gynecology clinics: the Menstrual Migraine Assessment Tool. Headache. 2008; 48(10):1419-1425.

12. Marcus DA. Focus on primary care diagnosis and management of headache in women. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1999;54(6):395-402.

13. Tepper SJ. Tailoring management strategies for the patient with menstrual migraine: focus on prevention and treatment. Headache. 2006;46(suppl 2):S61-S68.

14. Lay CL, Payne R. Recognition and treatment of menstrual migraine. Neurologist. 2007;13(4):197-204.

15. Henry KA, Cohen CI. Perimenstrual headache: treatment options. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2009;13(1):82-88.

16. Calhoun AH. Estrogen-associated migraine. www.uptodate.com/contents/estrogen-associated-migraine. Accessed May 4, 2011.

17. Silberstein SD, Elkind AH, Schreiber C, et al. A randomized trial of frovatriptan for the intermittent prevention of menstrual migraine. Neurology. 2004;63:261-269.

18. Mannix LK, Savani N, Landy S, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of naratriptan for short-term prevention of menstrually related migraine: data from two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies. Headache. 2007;47(7):1037-1049.

19. Calhoun AH, Hutchinson S. Hormonal therapies for menstrual migraine. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2009;13(5):381-385.