User login

Emergency departments are not primary care clinics, but some patients use them that way. This relatively small group of patients consumes a disproportionate share of healthcare at great cost, earning them the label of “high users.” Mostly poor and often burdened with mental illness and addiction, they are not necessarily sicker than other patients, and they do not enjoy better outcomes from the extra money spent on them. (Another subset of high users, those with end-stage chronic disease, is outside the scope of this review.)

Herein lies an opportunity. If—and this is a big if—we could manage their care in a systematic way instead of haphazardly, proactively instead of reactively, with continuity of care instead of episodically, and in a way that is convenient for the patient, we might be able to improve quality and save money.

A DISPROPORTIONATE SHARE OF COSTS

In the United States in 2012, the 5% of the population who were the highest users were responsible for 50% of healthcare costs.1 The mean cost per person in this group was more than $43,000 annually. The top 1% of users accounted for nearly 23% of all expenditures, averaging nearly $98,000 per patient per year—10 times more than the average yearly cost per patient.

CARE IS OFTEN INAPPROPRIATE AND UNNECESSARY

In addition to being disproportionately expensive, the care that these patients receive is often inappropriate and unnecessary for the severity of their disease.

A 2007–2009 study2 of 1,969 patients who had visited the emergency department 10 or more times in a year found they received more than twice as many computed tomography (CT) scans as a control group of infrequent users (< 3 visits/year). This occurred even though they were not as sick as infrequent users, based on significantly lower hospital admission rates (11.1% vs 17.9%; P < .001) and mortality rates (0.7% vs 1.5%; P < .002).2

This inverse relationship between emergency department use and illness severity was even more exaggerated at the upper extreme of the use curve. The highest users (> 29 visits to the emergency department in a year) had the lowest triage acuity and hospital admission rates but the highest number of CT scans. Charges per visit were lower among frequent users, but total charges rose steadily with increasing emergency department use, accounting for significantly more costs per year.2

We believe that one reason these patients receive more medical care than necessary is because their medical records are too large and complex for the average physician to distill effectively in a 20-minute physician-patient encounter. Physicians therefore simply order more tests, procedures, and admissions, which are often medically unnecessary and redundant.

WHAT DRIVES HIGH COST?

Mental illness and chemical dependence

Drug addiction, mental illness, and poverty frequently accompany (and influence) high-use behavior, particularly in patients without end-stage diseases.

Szekendi et al,3 in a study of 28,291 patients who had been admitted at least 5 times in a year in a Chicago health system, found that these high users were 2 to 3 times more likely to suffer from comorbid depression (40% vs 13%), psychosis (18% vs 5%), recreational drug dependence (20% vs 7%), and alcohol abuse (16% vs 7%) than non-high-use hospitalized patients.3

Mercer et al4 conducted a study at Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC, aimed at reducing emergency department visits and hospital admissions among 24 of its highest users. They found that 23 (96%) were either addicted to drugs or mentally ill, and 20 (83%) suffered from chronic pain.4

Drug abuse among high users is becoming even more relevant as the opioid epidemic worsens. Given that most patients requiring high levels of care suffer from chronic pain and many of them develop an opioid addiction while treating their pain, physicians have a moral imperative to reduce the prevalence of drug abuse in this population.

Low socioeconomic status

Low socioeconomic status is an important factor among high users, as it is highly associated with greater disease severity, which usually increases cost without any guarantee of an associated increase in quality. Data suggest that patients of low socioeconomic status are twice as likely to require urgent emergency department visits, 4 times as likely to require admission to the hospital, and, importantly, about half as likely to use ambulatory care compared with patients of higher socioeconomic status.5 While this pattern of low-quality, high-cost spending in acute care settings reflects spending in the healthcare system at large, the pattern is greatly exaggerated among high users.

Lost to follow-up

Low socioeconomic status also complicates communication and follow-up. In a 2013 study, physician researchers in St. Paul, MN, documented attempts to interview 64 recently discharged high users. They could not reach 47 (73%) of them, for reasons largely attributable to low socioeconomic status, such as disconnected phone lines and changes in address.6

Clearly, the usual contact methods for follow-up care after discharge, such as phone calls and mailings, are unlikely to be effective in coordinating the outpatient care of these individuals.

Additionally, we must find ways of making primary care more convenient, gaining our patients’ trust, and finding ways to engage patients in follow-up without relying on traditional means of communication.

Do high users have medical insurance?

Surprisingly, most high users of the emergency department have health insurance. The Chicago health system study3 found that most (72.4%) of their high users had either Medicare or private health insurance, while 27.6% had either Medicaid or no insurance (compared with 21.6% in the general population). Other studies also found that most of the frequent emergency department users are insured,7 although the overall percentage who rely on publicly paid insurance is greater than in the population at large.

Many prefer acute care over primary care

Although one might think that high users go to the emergency department because they have nowhere else to go for care, a report published in 2013 by Kangovi et al5 suggests another reason—they prefer the emergency department.5 They interviewed 40 urban patients of low socioeconomic status who consistently cited the 24-hour, no-appointment-necessary structure of the emergency department as an advantage over primary care. The flexibility of emergency access to healthcare makes sense if one reflects on how difficult it is for even high-functioning individuals to schedule and keep medical appointments.

Specific reasons for preferring the emergency department included the following:

Affordability. Even if their insurance fully paid for visits to their primary care physicians, the primary care physician was likely to refer them to specialists, whose visits required a copay, and which required taking another day off of work. The emergency department is cheaper for the patient and it is a “one-stop shop.” Patients appreciated the emergency department guarantee of seeing a physician regardless of proof of insurance, a policy not guaranteed in primary care and specialist offices.

Accessibility. For those without a car, public transportation and even patient transportation services are inconvenient and unreliable, whereas emergency medical services will take you to the emergency department.

Accommodations. Although medical centers may tout their same-day appointments, often same-day appointments are all that they have—and you have no choice about the time. You have to call first thing in the morning and stay on hold for a long time, and then when you finally get through, all the same-day appointments are gone.

Availability. Patients said they often had a hard time getting timely medical advice from their primary care physicians. When they could get through to their primary care physicians on the phone, they would be told to go to the emergency department.

Acceptability. Men, especially, feel they need to be very sick indeed to seek medical care, so going to the emergency department is more acceptable.

Trust in the provider. For reasons that were not entirely clear, patients felt that acute care providers were more trustworthy, competent, and compassionate than primary care physicians.5

None of these reasons for using the emergency department has anything to do with disease severity, which supports the findings that high users of the emergency department were not as sick as their normal-use peers.2

QUALITY IMPROVEMENT AND COST-REDUCTION STRATEGIES

Efforts are being made to reduce the cost of healthcare for high users while improving the quality of their care. Promising strategies focus on coordinating care management, creating individualized patient care plans, and improving the components and instructions of discharge summaries.

Care management organizations

A care management organization (CMO) model has emerged as a strategy for quality improvement and cost reduction in the high-use population. In this model, social workers, health coaches, nurses, mid-level providers, and physicians collaborate on designing individualized care plans to meet the specific needs of patients.

Teams typically work in stepwise fashion, first identifying and engaging patients at high risk of poor outcomes and unnecessary care, often using sophisticated quantitative, risk-prediction tools. Then, they perform health assessments and identify potential interventions aimed at preventing expensive acute-care medical interventions. Third, they work with patients to rapidly identify and effectively respond to changes in their conditions and direct them to the most appropriate medical setting, typically primary or urgent care.

Effective models

In 1998, the Camden (NJ) Coalition of Healthcare Providers established a model for CMO care plans. Starting with the first 36 patients enrolled in the program, hospital admissions and emergency department visits were cut by 47% (from 62 to 37 per month), and collective hospital costs were cut by 56% (from $1.2 million to about $500,000 per month).8 It should be noted that this was a small, nonrandomized study and these preliminary numbers did not take into account the cost of outpatient physician visits or new medications. Thus, how much money this program actually saves is not clear.

Similar programs have had similar results. A nurse-led care coordination program in Doylestown, PA, showed an impressive 25% reduction in annual mortality and a 36% reduction in overall costs during a 10-year period.9

A program in Atlantic City, NJ, combined the typical CMO model with a primary care clinic to provide high users with unlimited access, while paying its providers in a capitation model (as opposed to fee for service). It achieved a 40% reduction in yearly emergency department visits and hospital admissions.8

Patient care plans

Individualized patient care plans for high users are among the most promising tools for reducing costs and improving quality in this group. They are low-cost and relatively easy to implement. The goal of these care plans is to provide practitioners with a concise care summary to help them make rational and consistent medical decisions.

Typically, a care plan is written by an interdisciplinary committee composed of physicians, nurses, and social workers. It is based on the patient’s pertinent medical and psychiatric history, which may include recent imaging results or other relevant diagnostic tests. It provides suggestions for managing complex chronic issues, such as drug abuse, that lead to high use of healthcare resources.

These care plans provide a rational and prespecified approach to workup and management, typically including a narcotic prescription protocol, regardless of the setting or the number of providers who see the patient. Practitioners guided by effective care plans are much more likely to effectively navigate a complex patient encounter as opposed to looking through extensive medical notes and hoping to find relevant information.

Effective models

Data show these plans can be effective. For example, Regions Hospital in St. Paul, MN, implemented patient care plans in 2010. During the first 4 months, hospital admissions in the first 94 patients were reduced by 67%.10

A study of high users at Duke University Medical Center reported similar results. One year after starting care plans, inpatient admissions had decreased by 50.5%, readmissions had decreased by 51.5%, and variable direct costs per admission were reduced by 35.8%. Paradoxically, emergency department visits went up, but this anomaly was driven by 134 visits incurred by a single dialysis patient. After removing this patient from the data, emergency department visits were relatively stable.4

Better discharge summaries

Although improving discharge summaries is not a novel concept, changing the summary from a historical document to a proactive discharge plan has the potential to prevent readmissions and promote a durable de-escalation in care acuity.

For example, when moving a patient to a subacute care facility, providing a concise summary of which treatments worked and which did not, a list of comorbidities, and a list of medications and strategies to consider, can help the next providers to better target their plan of care. Studies have shown that nearly half of discharge statements lack important information on treatments and tests.11

Improvement can be as simple as encouraging practitioners to construct their summaries in an “if-then” format. Instead of noting for instance that “Mr. Smith was treated for pneumonia with antibiotics and discharged to a rehab facility,” the following would be more useful: “Family would like to see if Mr. Smith can get back to his functional baseline after his acute pneumonia. If he clinically does not do well over the next 1 to 2 weeks and has a poor quality of life, then family would like to pursue hospice.”

In addition to shifting the philosophy, we believe that providing timely discharge summaries is a fundamental, high-yield aspect of ensuring their effectiveness. As an example, patients being discharged to a skilled nursing facility should have a discharge summary completed and in hand before leaving the hospital.

Evidence suggests that timely writing of discharge summaries improves their quality. In a retrospective cohort study published in 2012, discharge summaries created more than 24 hours after discharge were less likely to include important plan-of-care components.12

FUTURE NEEDS

Randomized trials

Although initial results have been promising for the strategies outlined above, much of the apparent cost reduction of these interventions may be at least partially related to the study design as opposed to the interventions themselves.

For example, Hong et al13 examined 18 of the more promising CMOs that had reported initial cost savings. Of these, only 4 had conducted randomized controlled trials. When broken down further, the initial cost reduction reported by most of these randomized controlled trials was generated primarily by small subgroups.14

These results, however, do not necessarily reflect an inherent failure in the system. We contend that they merely demonstrate that CMOs and care plan administrators need to be more selective about whom they enroll, either by targeting patients at the extremes of the usage curve or by identifying patient characteristics and usage parameters amenable to cost reduction and quality improvement strategies.

Better social infrastructure

Although patient care plans and CMOs have been effective in managing high users, we believe that the most promising quality improvement and cost-reduction strategy involves redirecting much of the expensive healthcare spending to the social determinants of health (eg, homelessness, mental illness, low socioeconomic status).

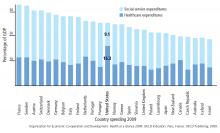

Among developed countries, the United States has the highest healthcare spending and the lowest social service spending as a percentage of its gross domestic product (Figure 1).15 Although seemingly discouraging, these data can actually be interpreted as hopeful, as they support the notion that the inefficiencies of our current system are not part of an inescapable reality, but rather reflect a system that has evolved uniquely in this country.

Using the available social programs

Exemplifying this medical and social services balance is a high user who visited her local emergency department 450 times in 1 year for reasons primarily related to homelessness.16 Each time, the medical system (as it is currently designed to do) applied a short-term medical solution to this patient’s problems and discharged her home, ie, back to the street.

But this patient’s high use was really a manifestation of a deeper social issue: homelessness. When the medical staff eventually noted how much this lack of stable shelter was contributing to her pattern of use, she was referred to appropriate social resources and provided with the housing she needed. Her hospital visits decreased from 450 to 12 in the subsequent year, amounting to a huge cost reduction and a clear improvement in her quality of life.

Similar encouraging results have resulted when available social programs are applied to the high-use population at large, which is particularly reassuring given this population’s preponderance of low socioeconomic status, mental illness, and homelessness. (The prevalence of homelessness is roughly 20%, depending on the definition of a high user).

New York Medicaid, for example, has a housing program that provides stable shelter outside of acute care medical settings for patients at a rate as low as $50 per day, compared with area hospital costs that often exceed $2,200 daily.17 A similar program in Westchester County, NY, reported a 45.9% reduction in inpatient costs and a 15.4% reduction in emergency department visits among 61 of its highest users after 2 years of enrollment.17

Need to reform privacy laws

Although legally daunting, reform of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and other privacy laws in favor of a more open model of information sharing, particularly for high-risk patients, holds great opportunity for quality improvement. For patients who obtain their care from several healthcare facilities, the documentation is often inscrutable. If some of the HIPAA regulations and other patient privacy laws were exchanged for rules more akin to the current model of narcotic prescription tracking, for example, physicians would be better equipped to provide safe, organized, and efficient medical care for high-use patients.

Need to reform the system

A fundamental flaw in our healthcare system, which is largely based on a fee-for-service model, is that it was not designed for patients who use the system at the highest frequency and greatest cost. Also, it does not account for the psychosocial factors that beset many high-use patients. As such, it is imperative for the safety of our patients as well as the viability of the healthcare system that we change our historical way of thinking and reform this system that provides high users with care that is high-cost, low-quality, and not patient-centered.

IMPROVING QUALITY, REDUCING COST

High users of emergency services are a medically and socially complex group, predominantly characterized by low socioeconomic status and high rates of mental illness and drug dependency. Despite their increased healthcare use, they do not have better outcomes even though they are not sicker. Improving those outcomes requires both medical and social efforts.

Among the effective medical efforts are strategies aimed at creating individualized patient care plans, using coordinated care teams, and improving discharge summaries. Addressing patients’ social factors, such as homelessness, is more difficult, but healthcare systems can help patients navigate the available social programs. These strategies are part of a comprehensive care plan that can help reduce the cost and improve the quality of healthcare for high users.

- Cohen SB; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Statistical Brief #359. The concentration of health care expenditures and related expenses for costly medical conditions, 2009. http://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_files/publications/st359/stat359.pdf. Accessed December 18, 2017.

- Oostema J, Troost J, Schurr K, Waller R. High and low frequency emergency department users: a comparative analysis of morbidity, diagnostic testing, and health care costs. Ann Emerg Med 2011; 58:S225. Abstract 142.

- Szekendi MK, Williams MV, Carrier D, Hensley L, Thomas S, Cerese J. The characteristics of patients frequently admitted to academic medical centers in the United States. J Hosp Med 2015; 10:563–568.

- Mercer T, Bae J, Kipnes J, Velazquez M, Thomas S, Setji N. The highest utilizers of care: individualized care plans to coordinate care, improve healthcare service utilization, and reduce costs at an academic tertiary care center. J Hosp Med 2015; 10:419–424.

- Kangovi S, Barg FK, Carter T, Long JA, Shannon R, Grande D. Understanding why patients of low socioeconomic status prefer hospitals over ambulatory care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013; 32:1196–1203.

- Melander I, Winkelman T, Hilger R. Analysis of high utilizers’ experience with specialized care plans. J Hosp Med 2014; 9(suppl 2):Abstract 229.

- LaCalle EJ, Rabin EJ, Genes NG. High-frequency users of emergency department care. J Emerg Med 2013; 44:1167–1173.

- Gawande A. The Hot Spotters. The New Yorker 2011. www.newyorker.com/magazine/2011/01/24/the-hot-spotters. Accessed December 18, 2017.

- Coburn KD, Marcantonio S, Lazansky R, Keller M, Davis N. Effect of a community-based nursing intervention on mortality in chronically ill older adults: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med 2012; 9:e1001265.

- Hilger R, Melander I, Winkelman T. Is specialized care plan work sustainable? A follow-up on healthpartners’ experience with patients who are high-utilizers. Society of Hospital Medicine Annual Meeting, Las Vegas, NV. March 24-27, 2014. www.shmabstracts.com/abstract/is-specialized-care-plan-work-sustainable-a-followup-on-healthpartners-experience-with-patients-who-are-highutilizers. Accessed December 18, 2017.

- Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA 2007; 297:831–841.

- Kind AJ, Thorpe CT, Sattin JA, Walz SE, Smith MA. Provider characteristics, clinical-work processes and their relationship to discharge summary quality for sub-acute care patients. J Gen Intern Med 2012; 27:78–84.

- Hong CS, Siegel AL, Ferris TG. Caring for high-need, high-cost patients: what makes for a successful care management program? Issue Brief (Commonwealth Fund) 2014; 19:1–19.

- Williams B. Limited effects of care management for high utilizers on total healthcare costs. Am J Managed Care 2015; 21:e244–e246.

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. Health at a Glance 2009: OECD Indicators. Paris, France: OECD Publishing; 2009.

- Emeche U. Is a strategy focused on super-utilizers equal to the task of health care system transformation? Yes. Ann Fam Med 2015; 13:6–7.

- Burns J. Do we overspend on healthcare, underspend on social needs? Managed Care. http://ghli.yale.edu/news/do-we-overspend-health-care-underspend-social-needs. Accessed December 18, 2017.

Emergency departments are not primary care clinics, but some patients use them that way. This relatively small group of patients consumes a disproportionate share of healthcare at great cost, earning them the label of “high users.” Mostly poor and often burdened with mental illness and addiction, they are not necessarily sicker than other patients, and they do not enjoy better outcomes from the extra money spent on them. (Another subset of high users, those with end-stage chronic disease, is outside the scope of this review.)

Herein lies an opportunity. If—and this is a big if—we could manage their care in a systematic way instead of haphazardly, proactively instead of reactively, with continuity of care instead of episodically, and in a way that is convenient for the patient, we might be able to improve quality and save money.

A DISPROPORTIONATE SHARE OF COSTS

In the United States in 2012, the 5% of the population who were the highest users were responsible for 50% of healthcare costs.1 The mean cost per person in this group was more than $43,000 annually. The top 1% of users accounted for nearly 23% of all expenditures, averaging nearly $98,000 per patient per year—10 times more than the average yearly cost per patient.

CARE IS OFTEN INAPPROPRIATE AND UNNECESSARY

In addition to being disproportionately expensive, the care that these patients receive is often inappropriate and unnecessary for the severity of their disease.

A 2007–2009 study2 of 1,969 patients who had visited the emergency department 10 or more times in a year found they received more than twice as many computed tomography (CT) scans as a control group of infrequent users (< 3 visits/year). This occurred even though they were not as sick as infrequent users, based on significantly lower hospital admission rates (11.1% vs 17.9%; P < .001) and mortality rates (0.7% vs 1.5%; P < .002).2

This inverse relationship between emergency department use and illness severity was even more exaggerated at the upper extreme of the use curve. The highest users (> 29 visits to the emergency department in a year) had the lowest triage acuity and hospital admission rates but the highest number of CT scans. Charges per visit were lower among frequent users, but total charges rose steadily with increasing emergency department use, accounting for significantly more costs per year.2

We believe that one reason these patients receive more medical care than necessary is because their medical records are too large and complex for the average physician to distill effectively in a 20-minute physician-patient encounter. Physicians therefore simply order more tests, procedures, and admissions, which are often medically unnecessary and redundant.

WHAT DRIVES HIGH COST?

Mental illness and chemical dependence

Drug addiction, mental illness, and poverty frequently accompany (and influence) high-use behavior, particularly in patients without end-stage diseases.

Szekendi et al,3 in a study of 28,291 patients who had been admitted at least 5 times in a year in a Chicago health system, found that these high users were 2 to 3 times more likely to suffer from comorbid depression (40% vs 13%), psychosis (18% vs 5%), recreational drug dependence (20% vs 7%), and alcohol abuse (16% vs 7%) than non-high-use hospitalized patients.3

Mercer et al4 conducted a study at Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC, aimed at reducing emergency department visits and hospital admissions among 24 of its highest users. They found that 23 (96%) were either addicted to drugs or mentally ill, and 20 (83%) suffered from chronic pain.4

Drug abuse among high users is becoming even more relevant as the opioid epidemic worsens. Given that most patients requiring high levels of care suffer from chronic pain and many of them develop an opioid addiction while treating their pain, physicians have a moral imperative to reduce the prevalence of drug abuse in this population.

Low socioeconomic status

Low socioeconomic status is an important factor among high users, as it is highly associated with greater disease severity, which usually increases cost without any guarantee of an associated increase in quality. Data suggest that patients of low socioeconomic status are twice as likely to require urgent emergency department visits, 4 times as likely to require admission to the hospital, and, importantly, about half as likely to use ambulatory care compared with patients of higher socioeconomic status.5 While this pattern of low-quality, high-cost spending in acute care settings reflects spending in the healthcare system at large, the pattern is greatly exaggerated among high users.

Lost to follow-up

Low socioeconomic status also complicates communication and follow-up. In a 2013 study, physician researchers in St. Paul, MN, documented attempts to interview 64 recently discharged high users. They could not reach 47 (73%) of them, for reasons largely attributable to low socioeconomic status, such as disconnected phone lines and changes in address.6

Clearly, the usual contact methods for follow-up care after discharge, such as phone calls and mailings, are unlikely to be effective in coordinating the outpatient care of these individuals.

Additionally, we must find ways of making primary care more convenient, gaining our patients’ trust, and finding ways to engage patients in follow-up without relying on traditional means of communication.

Do high users have medical insurance?

Surprisingly, most high users of the emergency department have health insurance. The Chicago health system study3 found that most (72.4%) of their high users had either Medicare or private health insurance, while 27.6% had either Medicaid or no insurance (compared with 21.6% in the general population). Other studies also found that most of the frequent emergency department users are insured,7 although the overall percentage who rely on publicly paid insurance is greater than in the population at large.

Many prefer acute care over primary care

Although one might think that high users go to the emergency department because they have nowhere else to go for care, a report published in 2013 by Kangovi et al5 suggests another reason—they prefer the emergency department.5 They interviewed 40 urban patients of low socioeconomic status who consistently cited the 24-hour, no-appointment-necessary structure of the emergency department as an advantage over primary care. The flexibility of emergency access to healthcare makes sense if one reflects on how difficult it is for even high-functioning individuals to schedule and keep medical appointments.

Specific reasons for preferring the emergency department included the following:

Affordability. Even if their insurance fully paid for visits to their primary care physicians, the primary care physician was likely to refer them to specialists, whose visits required a copay, and which required taking another day off of work. The emergency department is cheaper for the patient and it is a “one-stop shop.” Patients appreciated the emergency department guarantee of seeing a physician regardless of proof of insurance, a policy not guaranteed in primary care and specialist offices.

Accessibility. For those without a car, public transportation and even patient transportation services are inconvenient and unreliable, whereas emergency medical services will take you to the emergency department.

Accommodations. Although medical centers may tout their same-day appointments, often same-day appointments are all that they have—and you have no choice about the time. You have to call first thing in the morning and stay on hold for a long time, and then when you finally get through, all the same-day appointments are gone.

Availability. Patients said they often had a hard time getting timely medical advice from their primary care physicians. When they could get through to their primary care physicians on the phone, they would be told to go to the emergency department.

Acceptability. Men, especially, feel they need to be very sick indeed to seek medical care, so going to the emergency department is more acceptable.

Trust in the provider. For reasons that were not entirely clear, patients felt that acute care providers were more trustworthy, competent, and compassionate than primary care physicians.5

None of these reasons for using the emergency department has anything to do with disease severity, which supports the findings that high users of the emergency department were not as sick as their normal-use peers.2

QUALITY IMPROVEMENT AND COST-REDUCTION STRATEGIES

Efforts are being made to reduce the cost of healthcare for high users while improving the quality of their care. Promising strategies focus on coordinating care management, creating individualized patient care plans, and improving the components and instructions of discharge summaries.

Care management organizations

A care management organization (CMO) model has emerged as a strategy for quality improvement and cost reduction in the high-use population. In this model, social workers, health coaches, nurses, mid-level providers, and physicians collaborate on designing individualized care plans to meet the specific needs of patients.

Teams typically work in stepwise fashion, first identifying and engaging patients at high risk of poor outcomes and unnecessary care, often using sophisticated quantitative, risk-prediction tools. Then, they perform health assessments and identify potential interventions aimed at preventing expensive acute-care medical interventions. Third, they work with patients to rapidly identify and effectively respond to changes in their conditions and direct them to the most appropriate medical setting, typically primary or urgent care.

Effective models

In 1998, the Camden (NJ) Coalition of Healthcare Providers established a model for CMO care plans. Starting with the first 36 patients enrolled in the program, hospital admissions and emergency department visits were cut by 47% (from 62 to 37 per month), and collective hospital costs were cut by 56% (from $1.2 million to about $500,000 per month).8 It should be noted that this was a small, nonrandomized study and these preliminary numbers did not take into account the cost of outpatient physician visits or new medications. Thus, how much money this program actually saves is not clear.

Similar programs have had similar results. A nurse-led care coordination program in Doylestown, PA, showed an impressive 25% reduction in annual mortality and a 36% reduction in overall costs during a 10-year period.9

A program in Atlantic City, NJ, combined the typical CMO model with a primary care clinic to provide high users with unlimited access, while paying its providers in a capitation model (as opposed to fee for service). It achieved a 40% reduction in yearly emergency department visits and hospital admissions.8

Patient care plans

Individualized patient care plans for high users are among the most promising tools for reducing costs and improving quality in this group. They are low-cost and relatively easy to implement. The goal of these care plans is to provide practitioners with a concise care summary to help them make rational and consistent medical decisions.

Typically, a care plan is written by an interdisciplinary committee composed of physicians, nurses, and social workers. It is based on the patient’s pertinent medical and psychiatric history, which may include recent imaging results or other relevant diagnostic tests. It provides suggestions for managing complex chronic issues, such as drug abuse, that lead to high use of healthcare resources.

These care plans provide a rational and prespecified approach to workup and management, typically including a narcotic prescription protocol, regardless of the setting or the number of providers who see the patient. Practitioners guided by effective care plans are much more likely to effectively navigate a complex patient encounter as opposed to looking through extensive medical notes and hoping to find relevant information.

Effective models

Data show these plans can be effective. For example, Regions Hospital in St. Paul, MN, implemented patient care plans in 2010. During the first 4 months, hospital admissions in the first 94 patients were reduced by 67%.10

A study of high users at Duke University Medical Center reported similar results. One year after starting care plans, inpatient admissions had decreased by 50.5%, readmissions had decreased by 51.5%, and variable direct costs per admission were reduced by 35.8%. Paradoxically, emergency department visits went up, but this anomaly was driven by 134 visits incurred by a single dialysis patient. After removing this patient from the data, emergency department visits were relatively stable.4

Better discharge summaries

Although improving discharge summaries is not a novel concept, changing the summary from a historical document to a proactive discharge plan has the potential to prevent readmissions and promote a durable de-escalation in care acuity.

For example, when moving a patient to a subacute care facility, providing a concise summary of which treatments worked and which did not, a list of comorbidities, and a list of medications and strategies to consider, can help the next providers to better target their plan of care. Studies have shown that nearly half of discharge statements lack important information on treatments and tests.11

Improvement can be as simple as encouraging practitioners to construct their summaries in an “if-then” format. Instead of noting for instance that “Mr. Smith was treated for pneumonia with antibiotics and discharged to a rehab facility,” the following would be more useful: “Family would like to see if Mr. Smith can get back to his functional baseline after his acute pneumonia. If he clinically does not do well over the next 1 to 2 weeks and has a poor quality of life, then family would like to pursue hospice.”

In addition to shifting the philosophy, we believe that providing timely discharge summaries is a fundamental, high-yield aspect of ensuring their effectiveness. As an example, patients being discharged to a skilled nursing facility should have a discharge summary completed and in hand before leaving the hospital.

Evidence suggests that timely writing of discharge summaries improves their quality. In a retrospective cohort study published in 2012, discharge summaries created more than 24 hours after discharge were less likely to include important plan-of-care components.12

FUTURE NEEDS

Randomized trials

Although initial results have been promising for the strategies outlined above, much of the apparent cost reduction of these interventions may be at least partially related to the study design as opposed to the interventions themselves.

For example, Hong et al13 examined 18 of the more promising CMOs that had reported initial cost savings. Of these, only 4 had conducted randomized controlled trials. When broken down further, the initial cost reduction reported by most of these randomized controlled trials was generated primarily by small subgroups.14

These results, however, do not necessarily reflect an inherent failure in the system. We contend that they merely demonstrate that CMOs and care plan administrators need to be more selective about whom they enroll, either by targeting patients at the extremes of the usage curve or by identifying patient characteristics and usage parameters amenable to cost reduction and quality improvement strategies.

Better social infrastructure

Although patient care plans and CMOs have been effective in managing high users, we believe that the most promising quality improvement and cost-reduction strategy involves redirecting much of the expensive healthcare spending to the social determinants of health (eg, homelessness, mental illness, low socioeconomic status).

Among developed countries, the United States has the highest healthcare spending and the lowest social service spending as a percentage of its gross domestic product (Figure 1).15 Although seemingly discouraging, these data can actually be interpreted as hopeful, as they support the notion that the inefficiencies of our current system are not part of an inescapable reality, but rather reflect a system that has evolved uniquely in this country.

Using the available social programs

Exemplifying this medical and social services balance is a high user who visited her local emergency department 450 times in 1 year for reasons primarily related to homelessness.16 Each time, the medical system (as it is currently designed to do) applied a short-term medical solution to this patient’s problems and discharged her home, ie, back to the street.

But this patient’s high use was really a manifestation of a deeper social issue: homelessness. When the medical staff eventually noted how much this lack of stable shelter was contributing to her pattern of use, she was referred to appropriate social resources and provided with the housing she needed. Her hospital visits decreased from 450 to 12 in the subsequent year, amounting to a huge cost reduction and a clear improvement in her quality of life.

Similar encouraging results have resulted when available social programs are applied to the high-use population at large, which is particularly reassuring given this population’s preponderance of low socioeconomic status, mental illness, and homelessness. (The prevalence of homelessness is roughly 20%, depending on the definition of a high user).

New York Medicaid, for example, has a housing program that provides stable shelter outside of acute care medical settings for patients at a rate as low as $50 per day, compared with area hospital costs that often exceed $2,200 daily.17 A similar program in Westchester County, NY, reported a 45.9% reduction in inpatient costs and a 15.4% reduction in emergency department visits among 61 of its highest users after 2 years of enrollment.17

Need to reform privacy laws

Although legally daunting, reform of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and other privacy laws in favor of a more open model of information sharing, particularly for high-risk patients, holds great opportunity for quality improvement. For patients who obtain their care from several healthcare facilities, the documentation is often inscrutable. If some of the HIPAA regulations and other patient privacy laws were exchanged for rules more akin to the current model of narcotic prescription tracking, for example, physicians would be better equipped to provide safe, organized, and efficient medical care for high-use patients.

Need to reform the system

A fundamental flaw in our healthcare system, which is largely based on a fee-for-service model, is that it was not designed for patients who use the system at the highest frequency and greatest cost. Also, it does not account for the psychosocial factors that beset many high-use patients. As such, it is imperative for the safety of our patients as well as the viability of the healthcare system that we change our historical way of thinking and reform this system that provides high users with care that is high-cost, low-quality, and not patient-centered.

IMPROVING QUALITY, REDUCING COST

High users of emergency services are a medically and socially complex group, predominantly characterized by low socioeconomic status and high rates of mental illness and drug dependency. Despite their increased healthcare use, they do not have better outcomes even though they are not sicker. Improving those outcomes requires both medical and social efforts.

Among the effective medical efforts are strategies aimed at creating individualized patient care plans, using coordinated care teams, and improving discharge summaries. Addressing patients’ social factors, such as homelessness, is more difficult, but healthcare systems can help patients navigate the available social programs. These strategies are part of a comprehensive care plan that can help reduce the cost and improve the quality of healthcare for high users.

Emergency departments are not primary care clinics, but some patients use them that way. This relatively small group of patients consumes a disproportionate share of healthcare at great cost, earning them the label of “high users.” Mostly poor and often burdened with mental illness and addiction, they are not necessarily sicker than other patients, and they do not enjoy better outcomes from the extra money spent on them. (Another subset of high users, those with end-stage chronic disease, is outside the scope of this review.)

Herein lies an opportunity. If—and this is a big if—we could manage their care in a systematic way instead of haphazardly, proactively instead of reactively, with continuity of care instead of episodically, and in a way that is convenient for the patient, we might be able to improve quality and save money.

A DISPROPORTIONATE SHARE OF COSTS

In the United States in 2012, the 5% of the population who were the highest users were responsible for 50% of healthcare costs.1 The mean cost per person in this group was more than $43,000 annually. The top 1% of users accounted for nearly 23% of all expenditures, averaging nearly $98,000 per patient per year—10 times more than the average yearly cost per patient.

CARE IS OFTEN INAPPROPRIATE AND UNNECESSARY

In addition to being disproportionately expensive, the care that these patients receive is often inappropriate and unnecessary for the severity of their disease.

A 2007–2009 study2 of 1,969 patients who had visited the emergency department 10 or more times in a year found they received more than twice as many computed tomography (CT) scans as a control group of infrequent users (< 3 visits/year). This occurred even though they were not as sick as infrequent users, based on significantly lower hospital admission rates (11.1% vs 17.9%; P < .001) and mortality rates (0.7% vs 1.5%; P < .002).2

This inverse relationship between emergency department use and illness severity was even more exaggerated at the upper extreme of the use curve. The highest users (> 29 visits to the emergency department in a year) had the lowest triage acuity and hospital admission rates but the highest number of CT scans. Charges per visit were lower among frequent users, but total charges rose steadily with increasing emergency department use, accounting for significantly more costs per year.2

We believe that one reason these patients receive more medical care than necessary is because their medical records are too large and complex for the average physician to distill effectively in a 20-minute physician-patient encounter. Physicians therefore simply order more tests, procedures, and admissions, which are often medically unnecessary and redundant.

WHAT DRIVES HIGH COST?

Mental illness and chemical dependence

Drug addiction, mental illness, and poverty frequently accompany (and influence) high-use behavior, particularly in patients without end-stage diseases.

Szekendi et al,3 in a study of 28,291 patients who had been admitted at least 5 times in a year in a Chicago health system, found that these high users were 2 to 3 times more likely to suffer from comorbid depression (40% vs 13%), psychosis (18% vs 5%), recreational drug dependence (20% vs 7%), and alcohol abuse (16% vs 7%) than non-high-use hospitalized patients.3

Mercer et al4 conducted a study at Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC, aimed at reducing emergency department visits and hospital admissions among 24 of its highest users. They found that 23 (96%) were either addicted to drugs or mentally ill, and 20 (83%) suffered from chronic pain.4

Drug abuse among high users is becoming even more relevant as the opioid epidemic worsens. Given that most patients requiring high levels of care suffer from chronic pain and many of them develop an opioid addiction while treating their pain, physicians have a moral imperative to reduce the prevalence of drug abuse in this population.

Low socioeconomic status

Low socioeconomic status is an important factor among high users, as it is highly associated with greater disease severity, which usually increases cost without any guarantee of an associated increase in quality. Data suggest that patients of low socioeconomic status are twice as likely to require urgent emergency department visits, 4 times as likely to require admission to the hospital, and, importantly, about half as likely to use ambulatory care compared with patients of higher socioeconomic status.5 While this pattern of low-quality, high-cost spending in acute care settings reflects spending in the healthcare system at large, the pattern is greatly exaggerated among high users.

Lost to follow-up

Low socioeconomic status also complicates communication and follow-up. In a 2013 study, physician researchers in St. Paul, MN, documented attempts to interview 64 recently discharged high users. They could not reach 47 (73%) of them, for reasons largely attributable to low socioeconomic status, such as disconnected phone lines and changes in address.6

Clearly, the usual contact methods for follow-up care after discharge, such as phone calls and mailings, are unlikely to be effective in coordinating the outpatient care of these individuals.

Additionally, we must find ways of making primary care more convenient, gaining our patients’ trust, and finding ways to engage patients in follow-up without relying on traditional means of communication.

Do high users have medical insurance?

Surprisingly, most high users of the emergency department have health insurance. The Chicago health system study3 found that most (72.4%) of their high users had either Medicare or private health insurance, while 27.6% had either Medicaid or no insurance (compared with 21.6% in the general population). Other studies also found that most of the frequent emergency department users are insured,7 although the overall percentage who rely on publicly paid insurance is greater than in the population at large.

Many prefer acute care over primary care

Although one might think that high users go to the emergency department because they have nowhere else to go for care, a report published in 2013 by Kangovi et al5 suggests another reason—they prefer the emergency department.5 They interviewed 40 urban patients of low socioeconomic status who consistently cited the 24-hour, no-appointment-necessary structure of the emergency department as an advantage over primary care. The flexibility of emergency access to healthcare makes sense if one reflects on how difficult it is for even high-functioning individuals to schedule and keep medical appointments.

Specific reasons for preferring the emergency department included the following:

Affordability. Even if their insurance fully paid for visits to their primary care physicians, the primary care physician was likely to refer them to specialists, whose visits required a copay, and which required taking another day off of work. The emergency department is cheaper for the patient and it is a “one-stop shop.” Patients appreciated the emergency department guarantee of seeing a physician regardless of proof of insurance, a policy not guaranteed in primary care and specialist offices.

Accessibility. For those without a car, public transportation and even patient transportation services are inconvenient and unreliable, whereas emergency medical services will take you to the emergency department.

Accommodations. Although medical centers may tout their same-day appointments, often same-day appointments are all that they have—and you have no choice about the time. You have to call first thing in the morning and stay on hold for a long time, and then when you finally get through, all the same-day appointments are gone.

Availability. Patients said they often had a hard time getting timely medical advice from their primary care physicians. When they could get through to their primary care physicians on the phone, they would be told to go to the emergency department.

Acceptability. Men, especially, feel they need to be very sick indeed to seek medical care, so going to the emergency department is more acceptable.

Trust in the provider. For reasons that were not entirely clear, patients felt that acute care providers were more trustworthy, competent, and compassionate than primary care physicians.5

None of these reasons for using the emergency department has anything to do with disease severity, which supports the findings that high users of the emergency department were not as sick as their normal-use peers.2

QUALITY IMPROVEMENT AND COST-REDUCTION STRATEGIES

Efforts are being made to reduce the cost of healthcare for high users while improving the quality of their care. Promising strategies focus on coordinating care management, creating individualized patient care plans, and improving the components and instructions of discharge summaries.

Care management organizations

A care management organization (CMO) model has emerged as a strategy for quality improvement and cost reduction in the high-use population. In this model, social workers, health coaches, nurses, mid-level providers, and physicians collaborate on designing individualized care plans to meet the specific needs of patients.

Teams typically work in stepwise fashion, first identifying and engaging patients at high risk of poor outcomes and unnecessary care, often using sophisticated quantitative, risk-prediction tools. Then, they perform health assessments and identify potential interventions aimed at preventing expensive acute-care medical interventions. Third, they work with patients to rapidly identify and effectively respond to changes in their conditions and direct them to the most appropriate medical setting, typically primary or urgent care.

Effective models

In 1998, the Camden (NJ) Coalition of Healthcare Providers established a model for CMO care plans. Starting with the first 36 patients enrolled in the program, hospital admissions and emergency department visits were cut by 47% (from 62 to 37 per month), and collective hospital costs were cut by 56% (from $1.2 million to about $500,000 per month).8 It should be noted that this was a small, nonrandomized study and these preliminary numbers did not take into account the cost of outpatient physician visits or new medications. Thus, how much money this program actually saves is not clear.

Similar programs have had similar results. A nurse-led care coordination program in Doylestown, PA, showed an impressive 25% reduction in annual mortality and a 36% reduction in overall costs during a 10-year period.9

A program in Atlantic City, NJ, combined the typical CMO model with a primary care clinic to provide high users with unlimited access, while paying its providers in a capitation model (as opposed to fee for service). It achieved a 40% reduction in yearly emergency department visits and hospital admissions.8

Patient care plans

Individualized patient care plans for high users are among the most promising tools for reducing costs and improving quality in this group. They are low-cost and relatively easy to implement. The goal of these care plans is to provide practitioners with a concise care summary to help them make rational and consistent medical decisions.

Typically, a care plan is written by an interdisciplinary committee composed of physicians, nurses, and social workers. It is based on the patient’s pertinent medical and psychiatric history, which may include recent imaging results or other relevant diagnostic tests. It provides suggestions for managing complex chronic issues, such as drug abuse, that lead to high use of healthcare resources.

These care plans provide a rational and prespecified approach to workup and management, typically including a narcotic prescription protocol, regardless of the setting or the number of providers who see the patient. Practitioners guided by effective care plans are much more likely to effectively navigate a complex patient encounter as opposed to looking through extensive medical notes and hoping to find relevant information.

Effective models

Data show these plans can be effective. For example, Regions Hospital in St. Paul, MN, implemented patient care plans in 2010. During the first 4 months, hospital admissions in the first 94 patients were reduced by 67%.10

A study of high users at Duke University Medical Center reported similar results. One year after starting care plans, inpatient admissions had decreased by 50.5%, readmissions had decreased by 51.5%, and variable direct costs per admission were reduced by 35.8%. Paradoxically, emergency department visits went up, but this anomaly was driven by 134 visits incurred by a single dialysis patient. After removing this patient from the data, emergency department visits were relatively stable.4

Better discharge summaries

Although improving discharge summaries is not a novel concept, changing the summary from a historical document to a proactive discharge plan has the potential to prevent readmissions and promote a durable de-escalation in care acuity.

For example, when moving a patient to a subacute care facility, providing a concise summary of which treatments worked and which did not, a list of comorbidities, and a list of medications and strategies to consider, can help the next providers to better target their plan of care. Studies have shown that nearly half of discharge statements lack important information on treatments and tests.11

Improvement can be as simple as encouraging practitioners to construct their summaries in an “if-then” format. Instead of noting for instance that “Mr. Smith was treated for pneumonia with antibiotics and discharged to a rehab facility,” the following would be more useful: “Family would like to see if Mr. Smith can get back to his functional baseline after his acute pneumonia. If he clinically does not do well over the next 1 to 2 weeks and has a poor quality of life, then family would like to pursue hospice.”

In addition to shifting the philosophy, we believe that providing timely discharge summaries is a fundamental, high-yield aspect of ensuring their effectiveness. As an example, patients being discharged to a skilled nursing facility should have a discharge summary completed and in hand before leaving the hospital.

Evidence suggests that timely writing of discharge summaries improves their quality. In a retrospective cohort study published in 2012, discharge summaries created more than 24 hours after discharge were less likely to include important plan-of-care components.12

FUTURE NEEDS

Randomized trials

Although initial results have been promising for the strategies outlined above, much of the apparent cost reduction of these interventions may be at least partially related to the study design as opposed to the interventions themselves.

For example, Hong et al13 examined 18 of the more promising CMOs that had reported initial cost savings. Of these, only 4 had conducted randomized controlled trials. When broken down further, the initial cost reduction reported by most of these randomized controlled trials was generated primarily by small subgroups.14

These results, however, do not necessarily reflect an inherent failure in the system. We contend that they merely demonstrate that CMOs and care plan administrators need to be more selective about whom they enroll, either by targeting patients at the extremes of the usage curve or by identifying patient characteristics and usage parameters amenable to cost reduction and quality improvement strategies.

Better social infrastructure

Although patient care plans and CMOs have been effective in managing high users, we believe that the most promising quality improvement and cost-reduction strategy involves redirecting much of the expensive healthcare spending to the social determinants of health (eg, homelessness, mental illness, low socioeconomic status).

Among developed countries, the United States has the highest healthcare spending and the lowest social service spending as a percentage of its gross domestic product (Figure 1).15 Although seemingly discouraging, these data can actually be interpreted as hopeful, as they support the notion that the inefficiencies of our current system are not part of an inescapable reality, but rather reflect a system that has evolved uniquely in this country.

Using the available social programs

Exemplifying this medical and social services balance is a high user who visited her local emergency department 450 times in 1 year for reasons primarily related to homelessness.16 Each time, the medical system (as it is currently designed to do) applied a short-term medical solution to this patient’s problems and discharged her home, ie, back to the street.

But this patient’s high use was really a manifestation of a deeper social issue: homelessness. When the medical staff eventually noted how much this lack of stable shelter was contributing to her pattern of use, she was referred to appropriate social resources and provided with the housing she needed. Her hospital visits decreased from 450 to 12 in the subsequent year, amounting to a huge cost reduction and a clear improvement in her quality of life.

Similar encouraging results have resulted when available social programs are applied to the high-use population at large, which is particularly reassuring given this population’s preponderance of low socioeconomic status, mental illness, and homelessness. (The prevalence of homelessness is roughly 20%, depending on the definition of a high user).

New York Medicaid, for example, has a housing program that provides stable shelter outside of acute care medical settings for patients at a rate as low as $50 per day, compared with area hospital costs that often exceed $2,200 daily.17 A similar program in Westchester County, NY, reported a 45.9% reduction in inpatient costs and a 15.4% reduction in emergency department visits among 61 of its highest users after 2 years of enrollment.17

Need to reform privacy laws

Although legally daunting, reform of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and other privacy laws in favor of a more open model of information sharing, particularly for high-risk patients, holds great opportunity for quality improvement. For patients who obtain their care from several healthcare facilities, the documentation is often inscrutable. If some of the HIPAA regulations and other patient privacy laws were exchanged for rules more akin to the current model of narcotic prescription tracking, for example, physicians would be better equipped to provide safe, organized, and efficient medical care for high-use patients.

Need to reform the system

A fundamental flaw in our healthcare system, which is largely based on a fee-for-service model, is that it was not designed for patients who use the system at the highest frequency and greatest cost. Also, it does not account for the psychosocial factors that beset many high-use patients. As such, it is imperative for the safety of our patients as well as the viability of the healthcare system that we change our historical way of thinking and reform this system that provides high users with care that is high-cost, low-quality, and not patient-centered.

IMPROVING QUALITY, REDUCING COST

High users of emergency services are a medically and socially complex group, predominantly characterized by low socioeconomic status and high rates of mental illness and drug dependency. Despite their increased healthcare use, they do not have better outcomes even though they are not sicker. Improving those outcomes requires both medical and social efforts.

Among the effective medical efforts are strategies aimed at creating individualized patient care plans, using coordinated care teams, and improving discharge summaries. Addressing patients’ social factors, such as homelessness, is more difficult, but healthcare systems can help patients navigate the available social programs. These strategies are part of a comprehensive care plan that can help reduce the cost and improve the quality of healthcare for high users.

- Cohen SB; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Statistical Brief #359. The concentration of health care expenditures and related expenses for costly medical conditions, 2009. http://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_files/publications/st359/stat359.pdf. Accessed December 18, 2017.

- Oostema J, Troost J, Schurr K, Waller R. High and low frequency emergency department users: a comparative analysis of morbidity, diagnostic testing, and health care costs. Ann Emerg Med 2011; 58:S225. Abstract 142.

- Szekendi MK, Williams MV, Carrier D, Hensley L, Thomas S, Cerese J. The characteristics of patients frequently admitted to academic medical centers in the United States. J Hosp Med 2015; 10:563–568.

- Mercer T, Bae J, Kipnes J, Velazquez M, Thomas S, Setji N. The highest utilizers of care: individualized care plans to coordinate care, improve healthcare service utilization, and reduce costs at an academic tertiary care center. J Hosp Med 2015; 10:419–424.

- Kangovi S, Barg FK, Carter T, Long JA, Shannon R, Grande D. Understanding why patients of low socioeconomic status prefer hospitals over ambulatory care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013; 32:1196–1203.

- Melander I, Winkelman T, Hilger R. Analysis of high utilizers’ experience with specialized care plans. J Hosp Med 2014; 9(suppl 2):Abstract 229.

- LaCalle EJ, Rabin EJ, Genes NG. High-frequency users of emergency department care. J Emerg Med 2013; 44:1167–1173.

- Gawande A. The Hot Spotters. The New Yorker 2011. www.newyorker.com/magazine/2011/01/24/the-hot-spotters. Accessed December 18, 2017.

- Coburn KD, Marcantonio S, Lazansky R, Keller M, Davis N. Effect of a community-based nursing intervention on mortality in chronically ill older adults: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med 2012; 9:e1001265.

- Hilger R, Melander I, Winkelman T. Is specialized care plan work sustainable? A follow-up on healthpartners’ experience with patients who are high-utilizers. Society of Hospital Medicine Annual Meeting, Las Vegas, NV. March 24-27, 2014. www.shmabstracts.com/abstract/is-specialized-care-plan-work-sustainable-a-followup-on-healthpartners-experience-with-patients-who-are-highutilizers. Accessed December 18, 2017.

- Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA 2007; 297:831–841.

- Kind AJ, Thorpe CT, Sattin JA, Walz SE, Smith MA. Provider characteristics, clinical-work processes and their relationship to discharge summary quality for sub-acute care patients. J Gen Intern Med 2012; 27:78–84.

- Hong CS, Siegel AL, Ferris TG. Caring for high-need, high-cost patients: what makes for a successful care management program? Issue Brief (Commonwealth Fund) 2014; 19:1–19.

- Williams B. Limited effects of care management for high utilizers on total healthcare costs. Am J Managed Care 2015; 21:e244–e246.

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. Health at a Glance 2009: OECD Indicators. Paris, France: OECD Publishing; 2009.

- Emeche U. Is a strategy focused on super-utilizers equal to the task of health care system transformation? Yes. Ann Fam Med 2015; 13:6–7.

- Burns J. Do we overspend on healthcare, underspend on social needs? Managed Care. http://ghli.yale.edu/news/do-we-overspend-health-care-underspend-social-needs. Accessed December 18, 2017.

- Cohen SB; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Statistical Brief #359. The concentration of health care expenditures and related expenses for costly medical conditions, 2009. http://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_files/publications/st359/stat359.pdf. Accessed December 18, 2017.

- Oostema J, Troost J, Schurr K, Waller R. High and low frequency emergency department users: a comparative analysis of morbidity, diagnostic testing, and health care costs. Ann Emerg Med 2011; 58:S225. Abstract 142.

- Szekendi MK, Williams MV, Carrier D, Hensley L, Thomas S, Cerese J. The characteristics of patients frequently admitted to academic medical centers in the United States. J Hosp Med 2015; 10:563–568.

- Mercer T, Bae J, Kipnes J, Velazquez M, Thomas S, Setji N. The highest utilizers of care: individualized care plans to coordinate care, improve healthcare service utilization, and reduce costs at an academic tertiary care center. J Hosp Med 2015; 10:419–424.

- Kangovi S, Barg FK, Carter T, Long JA, Shannon R, Grande D. Understanding why patients of low socioeconomic status prefer hospitals over ambulatory care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013; 32:1196–1203.

- Melander I, Winkelman T, Hilger R. Analysis of high utilizers’ experience with specialized care plans. J Hosp Med 2014; 9(suppl 2):Abstract 229.

- LaCalle EJ, Rabin EJ, Genes NG. High-frequency users of emergency department care. J Emerg Med 2013; 44:1167–1173.

- Gawande A. The Hot Spotters. The New Yorker 2011. www.newyorker.com/magazine/2011/01/24/the-hot-spotters. Accessed December 18, 2017.

- Coburn KD, Marcantonio S, Lazansky R, Keller M, Davis N. Effect of a community-based nursing intervention on mortality in chronically ill older adults: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med 2012; 9:e1001265.

- Hilger R, Melander I, Winkelman T. Is specialized care plan work sustainable? A follow-up on healthpartners’ experience with patients who are high-utilizers. Society of Hospital Medicine Annual Meeting, Las Vegas, NV. March 24-27, 2014. www.shmabstracts.com/abstract/is-specialized-care-plan-work-sustainable-a-followup-on-healthpartners-experience-with-patients-who-are-highutilizers. Accessed December 18, 2017.

- Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA 2007; 297:831–841.

- Kind AJ, Thorpe CT, Sattin JA, Walz SE, Smith MA. Provider characteristics, clinical-work processes and their relationship to discharge summary quality for sub-acute care patients. J Gen Intern Med 2012; 27:78–84.

- Hong CS, Siegel AL, Ferris TG. Caring for high-need, high-cost patients: what makes for a successful care management program? Issue Brief (Commonwealth Fund) 2014; 19:1–19.

- Williams B. Limited effects of care management for high utilizers on total healthcare costs. Am J Managed Care 2015; 21:e244–e246.

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. Health at a Glance 2009: OECD Indicators. Paris, France: OECD Publishing; 2009.

- Emeche U. Is a strategy focused on super-utilizers equal to the task of health care system transformation? Yes. Ann Fam Med 2015; 13:6–7.

- Burns J. Do we overspend on healthcare, underspend on social needs? Managed Care. http://ghli.yale.edu/news/do-we-overspend-health-care-underspend-social-needs. Accessed December 18, 2017.

KEY POINTS

- The top 5% of the population in terms of healthcare use account for 50% of costs. The top 1% account for 23% of all expenditures and cost 10 times more per year than the average patient.

- Drug addiction, mental illness, and poverty often accompany and underlie high-use behavior, particularly in patients without end-stage medical conditions.

- Comprehensive patient care plans and care management organizations are among the most effective strategies for cost reduction and quality improvement.