User login

Anterior hip dislocations have been reported to account for approximately 5% to 10% of all hip dislocations.1 Epstein and Wiss2 originally divided anterior hip dislocations into superior (type I, including pubic or subspinous) and inferior (type II, including obturator and perineal) dislocations. This classification was further subdivided based on the presence of either no associated fracture (type A), fracture of the femoral head or neck (FNF; type B), or fracture of the acetabulum (type C).3 Of all anterior hip dislocations, it has been reported that the inferior or obturator type of dislocation is more common, constituting approximately 70% of all anterior dislocations.4 In 1943, Pringle5 described the mechanism of obturator dislocation as simultaneous abduction, flexion, and external rotation of the hip. Our literature search found only 2 case reports in non-English-language journals of a complete FNF associated with an attempted reduction of an anterior hip dislocation.6,7 Indentation fractures of the femoral head have been more commonly reported than FNFs, with a reported incidence of 35% to 55% after anterior dislocation.4,8 DeLee and colleagues8 also found that those patients with indentation fractures were at a higher risk for developing avascular necrosis of the femoral head in addition to being more likely to report poor or fair function of the hip 2 years after reduction.

There have been a number of different reduction maneuvers for anterior dislocation of hips published in the literature. Epstein and Harvey9 advocated reduction by traction in the line of the femur with the hip flexed and in gentle internal rotation and abduction while the patient was under general anesthesia. Toms and Williams,10 however, recommended adduction with gradual release of the longitudinal traction. Polesky and Polesky11 described a reduction method involving sharp internal rotation, which was found to be associated with FNF. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report, and approval was obtained from the Emory University Institutional Review Board.

Case Report

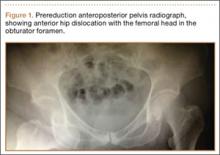

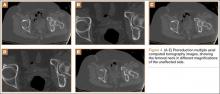

The patient was a 73-year-old woman, an independent ambulator with minimal antecedent hip pain, who, as a pedestrian, was struck by a heavy-duty pickup truck at low velocity. She was flown to our level I trauma center from an outside hospital. The patient arrived hemodynamically stable, with a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 15 and with major complaints of right shoulder and right hip pain. She had a positive Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma (FAST), and underwent a subsequent urgent chest, abdomen, and pelvis computed tomography (CT) scan for further investigation. CT showed a grade 1 liver laceration. Her anteroposterior (AP) pelvic radiograph and pelvic CT scan showed an anterior hip dislocation with the femoral head located adjacent to the obturator foramen (Figures 1, 2). The AP pelvic radiograph and pelvic CT scan were scrutinized extensively before reduction to rule out a possible FNF. Comparing the right and left femoral necks through multiple axial CT images showed no obvious differences between the 2 sides (Figures 3, 4). Her only other orthopedic injury was an inferior shoulder dislocation. It is not routine for the general surgery trauma team to obtain a pelvic CT scan prior to involvement of the orthopedic service and prompt reduction of a hip dislocation. Upon initial examination of her right hip, it was fixed in slight flexion and external rotation; she was neurovascularly intact.

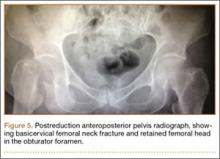

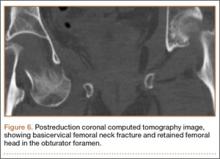

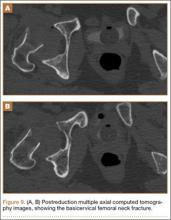

After being cleared by the trauma service, the patient provided informed consent for closed reduction of the hip and shoulder under conscious sedation, performed by the emergency department (ED) staff. She received intravenous fentanyl and midazolam, and the reduction was attempted. The reduction maneuver was performed with gentle inline traction, adduction, and internal rotation and extension. There was an audible clunk, and the hip was thought to be reduced and stable. The right leg lower extremity was placed into a knee immobilizer and she remained neurovascularly intact. The shoulder was reduced. After the procedure, the patient had an episode of hypoxia requiring oxygenation via a bag valve mask by the ED staff. Postreduction radiographs confirmed reduction of the right shoulder; however, they also showed a FNF with the femoral head retained near the obturator foramen (Figures 5, 6). The patient and her family were informed of the fracture, and a total hip arthroplasty (THA) was recommended, given her pre-injury mild symptomatic osteoarthritis in the hip and her age. The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit for cardiopulmonary monitoring and was found to have a troponin leak on hospital day 1. She was evaluated by the cardiology service; serial electrocardiograms and troponins ruled out acute myocardial infarction. The patient was cleared for surgery on hospital day 4.

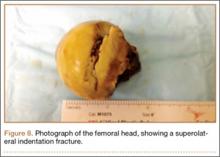

On hospital day 5, she underwent a right THA via a Kocher-Langenbeck approach. The patient’s femoral head was found to be anterior and laterally adjacent to her ischial tuberosity with an indentation fracture. The sciatic nerve was identified and found to be intact. A metal-on-polyethylene Stryker Accolade femoral component and Trident acetabular shell were implanted, and a posterior capsular repair was performed (Figure 7).

The patient tolerated the procedure well, and her postoperative course was uneventful. She was discharged to a subacute rehabilitation facility on postoperative day 3. The patient returned for her 2-week postoperative visit ambulating without assistance. At her last follow-up visit, approximately 6 weeks after surgery, she was a functionally independent community ambulator. Phone conversations with her private orthopedist at 6 months confirmed continued ambulation without problems.

Discussion

This case report of a complication that occurred in our institution has resulted in a change in our protocol for treatment of geriatric anterior hip dislocations. Our institution is a level I trauma center, and traumatic hip dislocations are relatively common, occurring usually in young patients with high-energy trauma. Although somewhat controversial, it is generally assumed that the incidence of avascular necrosis of the femoral head after dislocation of the hip is correlated with the time interval from dislocation to reduction of the hip. Therefore, our protocol for hip dislocations of the hip in young trauma patients is urgent reduction in the ED under appropriate analgesia and muscle relaxation.

In this case report, the patient was older than 65 years with radiographic evidence of possible impingement and postsurgical evidence of impingement of the femoral head in the obturator foremen (Figures 1, 2, 8). In addition, the patient was significantly osteopenic radiographically. An attempted reduction in the ED resulted in FNF requiring THA (Figures 5, 6, 9). After discussion of this complication in our institution’s morbidity and mortality conference, we have developed a protocol for the geriatric patient (older than 65 years) with a traumatic hip dislocation. These patients will undergo attempted reduction under controlled analgesia and muscle relaxation in the operating room (OR) with an attending surgeon present, ideally, an attending surgeon comfortable with arthroplasty in a terminally cleaned OR room. Our institution’s surgical site infection rate after total joint arthroplasty has significantly decreased with improved patient selection and the use of terminally cleaned OR rooms. Because our policy is to perform closed reduction of dislocated hips in an urgent manner, if there is not a terminally clean room or an arthroplasty-trained attending orthopedic surgeon available, then informed consent with discussion of the possibility of fracture requiring a subsequent arthroplasty should be obtained from the patient before the attempted reduction.

After review of the available literature, we believe that this case highlights some of the important treatment principles when treating anterior hip dislocations in the ED. The relatively high incidence of indentation fractures of the femoral head with obturator dislocations puts these fractures at higher risk for possible impingement around the obturator ring. This impingement, coupled with preexisting osteopenia, can predispose these dislocations to FNF, if appropriate analgesia and sedation are not obtained and gentle reduction is not performed. In addition, while it may not be time- or cost-effective to perform closed reduction on every hip dislocation, we bring geriatric patients with radiographic osteopenia to the OR for more controlled reductions. In the informed consent discussion, the possibility of FNF is mentioned, and the patient and family are told that an elective total hip replacement will be performed if this complication occurs.

We consider the following to be risk factors for closed reductions of anterior hip dislocations: (1) preexisting osteopenia on plain films, (2) age greater than 65 years, and (3) radiographic femoral head impingement on the surrounding bony pelvis. We continue to consider closed reduction of both anterior and posterior hip dislocations as urgent (within 6 hours from time of dislocation). This case adds to the existing literature on the risk of FNF with closed reduction of obturator hip dislocations, and we hope that it will encourage further study into the safest and most cost-effective reduction protocol.

1. Amihood, S. Anterior dislocation of the hip. Injury. 1975;7(2):107-110.

2. Epstein HC, Wiss DA. Traumatic anterior dislocation of the hip. Orthopedics. 1985;8(1):130, 132-134.

3. Epstein HC. Traumatic dislocations of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1973(92):116-142.

4. Erb RE, Steele JR, Nance EP Jr, Edwards JR. Traumatic anterior dislocation of the hip: spectrum of plain film and CT findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;165(5):1215-1219.

5. Pringle JH. Traumatic dislocation at the hip joint. An experimental study in the cadaver. Glasgow Med J. 1943;21:25-40.

6. Esenkaya I, Görgeç M. Traumatic anterior dislocation of the hip associated with ipsilateral femoral neck fracture: a case report. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2002;36(4):366-368.

7. Sadler AH, DiStefano M. Anterior dislocation of the hip with ipsilateral basicervical fracture. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985;67(2):326-329.

8. DeLee JC, Evans JA, Thomas J. Anterior dislocation of the hip and associated femoral-head fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62(6):960-964.

9. Epstein HC, Harvey JP Jr. Traumatic anterior dislocations of the hip: management and results. An analysis of fifty-five cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972;54(7):1561-1562.

10. Toms AD, Williams S, White SH. Obturator dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83(1):113-115.

11. Polesky RE, Polesky FA. Intrapelvic dislocation of the femoral head following anterior dislocation of the hip. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972;54(5):1097-1098.

Anterior hip dislocations have been reported to account for approximately 5% to 10% of all hip dislocations.1 Epstein and Wiss2 originally divided anterior hip dislocations into superior (type I, including pubic or subspinous) and inferior (type II, including obturator and perineal) dislocations. This classification was further subdivided based on the presence of either no associated fracture (type A), fracture of the femoral head or neck (FNF; type B), or fracture of the acetabulum (type C).3 Of all anterior hip dislocations, it has been reported that the inferior or obturator type of dislocation is more common, constituting approximately 70% of all anterior dislocations.4 In 1943, Pringle5 described the mechanism of obturator dislocation as simultaneous abduction, flexion, and external rotation of the hip. Our literature search found only 2 case reports in non-English-language journals of a complete FNF associated with an attempted reduction of an anterior hip dislocation.6,7 Indentation fractures of the femoral head have been more commonly reported than FNFs, with a reported incidence of 35% to 55% after anterior dislocation.4,8 DeLee and colleagues8 also found that those patients with indentation fractures were at a higher risk for developing avascular necrosis of the femoral head in addition to being more likely to report poor or fair function of the hip 2 years after reduction.

There have been a number of different reduction maneuvers for anterior dislocation of hips published in the literature. Epstein and Harvey9 advocated reduction by traction in the line of the femur with the hip flexed and in gentle internal rotation and abduction while the patient was under general anesthesia. Toms and Williams,10 however, recommended adduction with gradual release of the longitudinal traction. Polesky and Polesky11 described a reduction method involving sharp internal rotation, which was found to be associated with FNF. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report, and approval was obtained from the Emory University Institutional Review Board.

Case Report

The patient was a 73-year-old woman, an independent ambulator with minimal antecedent hip pain, who, as a pedestrian, was struck by a heavy-duty pickup truck at low velocity. She was flown to our level I trauma center from an outside hospital. The patient arrived hemodynamically stable, with a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 15 and with major complaints of right shoulder and right hip pain. She had a positive Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma (FAST), and underwent a subsequent urgent chest, abdomen, and pelvis computed tomography (CT) scan for further investigation. CT showed a grade 1 liver laceration. Her anteroposterior (AP) pelvic radiograph and pelvic CT scan showed an anterior hip dislocation with the femoral head located adjacent to the obturator foramen (Figures 1, 2). The AP pelvic radiograph and pelvic CT scan were scrutinized extensively before reduction to rule out a possible FNF. Comparing the right and left femoral necks through multiple axial CT images showed no obvious differences between the 2 sides (Figures 3, 4). Her only other orthopedic injury was an inferior shoulder dislocation. It is not routine for the general surgery trauma team to obtain a pelvic CT scan prior to involvement of the orthopedic service and prompt reduction of a hip dislocation. Upon initial examination of her right hip, it was fixed in slight flexion and external rotation; she was neurovascularly intact.

After being cleared by the trauma service, the patient provided informed consent for closed reduction of the hip and shoulder under conscious sedation, performed by the emergency department (ED) staff. She received intravenous fentanyl and midazolam, and the reduction was attempted. The reduction maneuver was performed with gentle inline traction, adduction, and internal rotation and extension. There was an audible clunk, and the hip was thought to be reduced and stable. The right leg lower extremity was placed into a knee immobilizer and she remained neurovascularly intact. The shoulder was reduced. After the procedure, the patient had an episode of hypoxia requiring oxygenation via a bag valve mask by the ED staff. Postreduction radiographs confirmed reduction of the right shoulder; however, they also showed a FNF with the femoral head retained near the obturator foramen (Figures 5, 6). The patient and her family were informed of the fracture, and a total hip arthroplasty (THA) was recommended, given her pre-injury mild symptomatic osteoarthritis in the hip and her age. The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit for cardiopulmonary monitoring and was found to have a troponin leak on hospital day 1. She was evaluated by the cardiology service; serial electrocardiograms and troponins ruled out acute myocardial infarction. The patient was cleared for surgery on hospital day 4.

On hospital day 5, she underwent a right THA via a Kocher-Langenbeck approach. The patient’s femoral head was found to be anterior and laterally adjacent to her ischial tuberosity with an indentation fracture. The sciatic nerve was identified and found to be intact. A metal-on-polyethylene Stryker Accolade femoral component and Trident acetabular shell were implanted, and a posterior capsular repair was performed (Figure 7).

The patient tolerated the procedure well, and her postoperative course was uneventful. She was discharged to a subacute rehabilitation facility on postoperative day 3. The patient returned for her 2-week postoperative visit ambulating without assistance. At her last follow-up visit, approximately 6 weeks after surgery, she was a functionally independent community ambulator. Phone conversations with her private orthopedist at 6 months confirmed continued ambulation without problems.

Discussion

This case report of a complication that occurred in our institution has resulted in a change in our protocol for treatment of geriatric anterior hip dislocations. Our institution is a level I trauma center, and traumatic hip dislocations are relatively common, occurring usually in young patients with high-energy trauma. Although somewhat controversial, it is generally assumed that the incidence of avascular necrosis of the femoral head after dislocation of the hip is correlated with the time interval from dislocation to reduction of the hip. Therefore, our protocol for hip dislocations of the hip in young trauma patients is urgent reduction in the ED under appropriate analgesia and muscle relaxation.

In this case report, the patient was older than 65 years with radiographic evidence of possible impingement and postsurgical evidence of impingement of the femoral head in the obturator foremen (Figures 1, 2, 8). In addition, the patient was significantly osteopenic radiographically. An attempted reduction in the ED resulted in FNF requiring THA (Figures 5, 6, 9). After discussion of this complication in our institution’s morbidity and mortality conference, we have developed a protocol for the geriatric patient (older than 65 years) with a traumatic hip dislocation. These patients will undergo attempted reduction under controlled analgesia and muscle relaxation in the operating room (OR) with an attending surgeon present, ideally, an attending surgeon comfortable with arthroplasty in a terminally cleaned OR room. Our institution’s surgical site infection rate after total joint arthroplasty has significantly decreased with improved patient selection and the use of terminally cleaned OR rooms. Because our policy is to perform closed reduction of dislocated hips in an urgent manner, if there is not a terminally clean room or an arthroplasty-trained attending orthopedic surgeon available, then informed consent with discussion of the possibility of fracture requiring a subsequent arthroplasty should be obtained from the patient before the attempted reduction.

After review of the available literature, we believe that this case highlights some of the important treatment principles when treating anterior hip dislocations in the ED. The relatively high incidence of indentation fractures of the femoral head with obturator dislocations puts these fractures at higher risk for possible impingement around the obturator ring. This impingement, coupled with preexisting osteopenia, can predispose these dislocations to FNF, if appropriate analgesia and sedation are not obtained and gentle reduction is not performed. In addition, while it may not be time- or cost-effective to perform closed reduction on every hip dislocation, we bring geriatric patients with radiographic osteopenia to the OR for more controlled reductions. In the informed consent discussion, the possibility of FNF is mentioned, and the patient and family are told that an elective total hip replacement will be performed if this complication occurs.

We consider the following to be risk factors for closed reductions of anterior hip dislocations: (1) preexisting osteopenia on plain films, (2) age greater than 65 years, and (3) radiographic femoral head impingement on the surrounding bony pelvis. We continue to consider closed reduction of both anterior and posterior hip dislocations as urgent (within 6 hours from time of dislocation). This case adds to the existing literature on the risk of FNF with closed reduction of obturator hip dislocations, and we hope that it will encourage further study into the safest and most cost-effective reduction protocol.

Anterior hip dislocations have been reported to account for approximately 5% to 10% of all hip dislocations.1 Epstein and Wiss2 originally divided anterior hip dislocations into superior (type I, including pubic or subspinous) and inferior (type II, including obturator and perineal) dislocations. This classification was further subdivided based on the presence of either no associated fracture (type A), fracture of the femoral head or neck (FNF; type B), or fracture of the acetabulum (type C).3 Of all anterior hip dislocations, it has been reported that the inferior or obturator type of dislocation is more common, constituting approximately 70% of all anterior dislocations.4 In 1943, Pringle5 described the mechanism of obturator dislocation as simultaneous abduction, flexion, and external rotation of the hip. Our literature search found only 2 case reports in non-English-language journals of a complete FNF associated with an attempted reduction of an anterior hip dislocation.6,7 Indentation fractures of the femoral head have been more commonly reported than FNFs, with a reported incidence of 35% to 55% after anterior dislocation.4,8 DeLee and colleagues8 also found that those patients with indentation fractures were at a higher risk for developing avascular necrosis of the femoral head in addition to being more likely to report poor or fair function of the hip 2 years after reduction.

There have been a number of different reduction maneuvers for anterior dislocation of hips published in the literature. Epstein and Harvey9 advocated reduction by traction in the line of the femur with the hip flexed and in gentle internal rotation and abduction while the patient was under general anesthesia. Toms and Williams,10 however, recommended adduction with gradual release of the longitudinal traction. Polesky and Polesky11 described a reduction method involving sharp internal rotation, which was found to be associated with FNF. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report, and approval was obtained from the Emory University Institutional Review Board.

Case Report

The patient was a 73-year-old woman, an independent ambulator with minimal antecedent hip pain, who, as a pedestrian, was struck by a heavy-duty pickup truck at low velocity. She was flown to our level I trauma center from an outside hospital. The patient arrived hemodynamically stable, with a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 15 and with major complaints of right shoulder and right hip pain. She had a positive Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma (FAST), and underwent a subsequent urgent chest, abdomen, and pelvis computed tomography (CT) scan for further investigation. CT showed a grade 1 liver laceration. Her anteroposterior (AP) pelvic radiograph and pelvic CT scan showed an anterior hip dislocation with the femoral head located adjacent to the obturator foramen (Figures 1, 2). The AP pelvic radiograph and pelvic CT scan were scrutinized extensively before reduction to rule out a possible FNF. Comparing the right and left femoral necks through multiple axial CT images showed no obvious differences between the 2 sides (Figures 3, 4). Her only other orthopedic injury was an inferior shoulder dislocation. It is not routine for the general surgery trauma team to obtain a pelvic CT scan prior to involvement of the orthopedic service and prompt reduction of a hip dislocation. Upon initial examination of her right hip, it was fixed in slight flexion and external rotation; she was neurovascularly intact.

After being cleared by the trauma service, the patient provided informed consent for closed reduction of the hip and shoulder under conscious sedation, performed by the emergency department (ED) staff. She received intravenous fentanyl and midazolam, and the reduction was attempted. The reduction maneuver was performed with gentle inline traction, adduction, and internal rotation and extension. There was an audible clunk, and the hip was thought to be reduced and stable. The right leg lower extremity was placed into a knee immobilizer and she remained neurovascularly intact. The shoulder was reduced. After the procedure, the patient had an episode of hypoxia requiring oxygenation via a bag valve mask by the ED staff. Postreduction radiographs confirmed reduction of the right shoulder; however, they also showed a FNF with the femoral head retained near the obturator foramen (Figures 5, 6). The patient and her family were informed of the fracture, and a total hip arthroplasty (THA) was recommended, given her pre-injury mild symptomatic osteoarthritis in the hip and her age. The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit for cardiopulmonary monitoring and was found to have a troponin leak on hospital day 1. She was evaluated by the cardiology service; serial electrocardiograms and troponins ruled out acute myocardial infarction. The patient was cleared for surgery on hospital day 4.

On hospital day 5, she underwent a right THA via a Kocher-Langenbeck approach. The patient’s femoral head was found to be anterior and laterally adjacent to her ischial tuberosity with an indentation fracture. The sciatic nerve was identified and found to be intact. A metal-on-polyethylene Stryker Accolade femoral component and Trident acetabular shell were implanted, and a posterior capsular repair was performed (Figure 7).

The patient tolerated the procedure well, and her postoperative course was uneventful. She was discharged to a subacute rehabilitation facility on postoperative day 3. The patient returned for her 2-week postoperative visit ambulating without assistance. At her last follow-up visit, approximately 6 weeks after surgery, she was a functionally independent community ambulator. Phone conversations with her private orthopedist at 6 months confirmed continued ambulation without problems.

Discussion

This case report of a complication that occurred in our institution has resulted in a change in our protocol for treatment of geriatric anterior hip dislocations. Our institution is a level I trauma center, and traumatic hip dislocations are relatively common, occurring usually in young patients with high-energy trauma. Although somewhat controversial, it is generally assumed that the incidence of avascular necrosis of the femoral head after dislocation of the hip is correlated with the time interval from dislocation to reduction of the hip. Therefore, our protocol for hip dislocations of the hip in young trauma patients is urgent reduction in the ED under appropriate analgesia and muscle relaxation.

In this case report, the patient was older than 65 years with radiographic evidence of possible impingement and postsurgical evidence of impingement of the femoral head in the obturator foremen (Figures 1, 2, 8). In addition, the patient was significantly osteopenic radiographically. An attempted reduction in the ED resulted in FNF requiring THA (Figures 5, 6, 9). After discussion of this complication in our institution’s morbidity and mortality conference, we have developed a protocol for the geriatric patient (older than 65 years) with a traumatic hip dislocation. These patients will undergo attempted reduction under controlled analgesia and muscle relaxation in the operating room (OR) with an attending surgeon present, ideally, an attending surgeon comfortable with arthroplasty in a terminally cleaned OR room. Our institution’s surgical site infection rate after total joint arthroplasty has significantly decreased with improved patient selection and the use of terminally cleaned OR rooms. Because our policy is to perform closed reduction of dislocated hips in an urgent manner, if there is not a terminally clean room or an arthroplasty-trained attending orthopedic surgeon available, then informed consent with discussion of the possibility of fracture requiring a subsequent arthroplasty should be obtained from the patient before the attempted reduction.

After review of the available literature, we believe that this case highlights some of the important treatment principles when treating anterior hip dislocations in the ED. The relatively high incidence of indentation fractures of the femoral head with obturator dislocations puts these fractures at higher risk for possible impingement around the obturator ring. This impingement, coupled with preexisting osteopenia, can predispose these dislocations to FNF, if appropriate analgesia and sedation are not obtained and gentle reduction is not performed. In addition, while it may not be time- or cost-effective to perform closed reduction on every hip dislocation, we bring geriatric patients with radiographic osteopenia to the OR for more controlled reductions. In the informed consent discussion, the possibility of FNF is mentioned, and the patient and family are told that an elective total hip replacement will be performed if this complication occurs.

We consider the following to be risk factors for closed reductions of anterior hip dislocations: (1) preexisting osteopenia on plain films, (2) age greater than 65 years, and (3) radiographic femoral head impingement on the surrounding bony pelvis. We continue to consider closed reduction of both anterior and posterior hip dislocations as urgent (within 6 hours from time of dislocation). This case adds to the existing literature on the risk of FNF with closed reduction of obturator hip dislocations, and we hope that it will encourage further study into the safest and most cost-effective reduction protocol.

1. Amihood, S. Anterior dislocation of the hip. Injury. 1975;7(2):107-110.

2. Epstein HC, Wiss DA. Traumatic anterior dislocation of the hip. Orthopedics. 1985;8(1):130, 132-134.

3. Epstein HC. Traumatic dislocations of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1973(92):116-142.

4. Erb RE, Steele JR, Nance EP Jr, Edwards JR. Traumatic anterior dislocation of the hip: spectrum of plain film and CT findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;165(5):1215-1219.

5. Pringle JH. Traumatic dislocation at the hip joint. An experimental study in the cadaver. Glasgow Med J. 1943;21:25-40.

6. Esenkaya I, Görgeç M. Traumatic anterior dislocation of the hip associated with ipsilateral femoral neck fracture: a case report. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2002;36(4):366-368.

7. Sadler AH, DiStefano M. Anterior dislocation of the hip with ipsilateral basicervical fracture. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985;67(2):326-329.

8. DeLee JC, Evans JA, Thomas J. Anterior dislocation of the hip and associated femoral-head fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62(6):960-964.

9. Epstein HC, Harvey JP Jr. Traumatic anterior dislocations of the hip: management and results. An analysis of fifty-five cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972;54(7):1561-1562.

10. Toms AD, Williams S, White SH. Obturator dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83(1):113-115.

11. Polesky RE, Polesky FA. Intrapelvic dislocation of the femoral head following anterior dislocation of the hip. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972;54(5):1097-1098.

1. Amihood, S. Anterior dislocation of the hip. Injury. 1975;7(2):107-110.

2. Epstein HC, Wiss DA. Traumatic anterior dislocation of the hip. Orthopedics. 1985;8(1):130, 132-134.

3. Epstein HC. Traumatic dislocations of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1973(92):116-142.

4. Erb RE, Steele JR, Nance EP Jr, Edwards JR. Traumatic anterior dislocation of the hip: spectrum of plain film and CT findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;165(5):1215-1219.

5. Pringle JH. Traumatic dislocation at the hip joint. An experimental study in the cadaver. Glasgow Med J. 1943;21:25-40.

6. Esenkaya I, Görgeç M. Traumatic anterior dislocation of the hip associated with ipsilateral femoral neck fracture: a case report. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2002;36(4):366-368.

7. Sadler AH, DiStefano M. Anterior dislocation of the hip with ipsilateral basicervical fracture. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985;67(2):326-329.

8. DeLee JC, Evans JA, Thomas J. Anterior dislocation of the hip and associated femoral-head fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62(6):960-964.

9. Epstein HC, Harvey JP Jr. Traumatic anterior dislocations of the hip: management and results. An analysis of fifty-five cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972;54(7):1561-1562.

10. Toms AD, Williams S, White SH. Obturator dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83(1):113-115.

11. Polesky RE, Polesky FA. Intrapelvic dislocation of the femoral head following anterior dislocation of the hip. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972;54(5):1097-1098.