User login

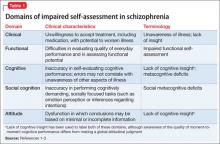

Lack of insight or “unawareness of illness” occurs within a set of self-assessment problems commonly seen in schizophrenia.1 In the clinical domain, people who do not realize they are ill typically are unwilling to accept treatment, including medication, with potential for worsened illness. They also may have difficulty self-assessing everyday function and functional potential, cognition, social cognition, and attitude, often to a variable degree across these domains (Table 1).1-3

Self-assessment of performance can be clinically helpful whether performance is objectively good or bad. Those with poor performance could be helped to attempt to match their aspirations to accomplishments and improve over time. Good performers could have their functioning bolstered by recognizing their competence. Thus, even a population whose performance often is poor could benefit from accurate self-assessment or experience additional challenges from inaccurate self-evaluation.

This article discusses patient characteristics associated with impairments in self-assessment and the most accurate sources of information for clinicians about patient functioning. Our research shows that an experienced psychiatrist is well positioned to make accurate judgments of functional potential and cognitive abilities for people with schizophrenia.

Patterns in patients with impaired self-assessment

Healthy individuals routinely overestimate their abilities and their attractiveness to others.4 Feedback that deflates these exaggerated estimates increases the accuracy of their self-assessments. Mildly depressed individuals typically are the most accurate judges of their true functioning; those with more severe levels of depression tend to underestimate their competence. Thus, simply being an inaccurate self-assessor is not “abnormal.” These response biases are consistent and predictable in healthy people.

People with severe mental illness pose a different challenge. As in the following cases, their reports manifest minimal correlation with other sources of information, including objective information about performance.

CASE 1

JR, age 28, is referred for occupational therapy because he has never worked since graduating from high school. He tells the therapist his cognitive abilities are average and intact, although his scores on a comprehensive cognitive assessment suggest performance at the first percentile of normal distribution or less. His self-reported Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) score is 4. He says he would like to work as a certified public accountant, because he believes he has an aptitude for math. He admits he has no idea what the job entails, but he is quite motivated to set up an interview as soon as possible.

CASE 2

LM, age 48, says his “best job” was managing an auto parts store for 18 months after he earned an associate’s degree and until his second psychotic episode. His most recent work was approximately 12 years ago at an oil-change facility. He agrees to discuss employment but feels his vocational skills are too deteriorated for him to succeed and requests an assessment for Alzheimer’s disease. His cognitive performance averages in the 10th percentile of the overall population, and his BDI score is 18. Tests of his ability to perform vocational skills suggest he is qualified for multiple jobs, including his previous technician position.

Individuals with schizophrenia who report no depression and no work history routinely overestimate their functional potential, whereas those with a history of unsuccessful vocational attempts often underestimate their functional potential. Inaccurate self-assessment can contribute to reduced functioning—in JR’s case because of unrealistic assessment of the match between skills and vocational potential, and in LM’s case because of overly pessimistic self-evaluation. For people with schizophrenia, inability to self-evaluate can have a bidirectional adverse impact on functioning: overestimation may lead to trying tasks that are too challenging, and underestimation may lead to reduced effort and motivation to take on functional tasks.

Metacognition and introspective accuracy

“Metacognition” refers to self-assessment of the quality and accuracy of performance on cognitive tests.5-7 Problem-solving tests— such as the Wisconsin Card Sorting test (WCST), in which the person being assessed needs to solve the test through performance feedback—are metacognition tests. When errors are made, the strategy in use needs to be discarded; when responses are correct, the strategy is retained. People with schizophrenia have disproportionate difficulties with the WCST, and deficits are especially salient when the test is modified to measure self-assessment of performance and ability to use feedback to change strategies.

“Introspective accuracy” is used to describe the wide-ranging self-assessment impairments in severe mental illness. Theories of metacognition implicate a broad spectrum, of which self-assessment is 1 component, whereas introspective accuracy more specifically indicates judgments of accuracy. Because self-assessment is focused on the self, and hence is introspective, this conceptualization can be applied to self-evaluations of:

• achievement in everyday functioning (“Did I complete that task well?”)

• potential for achievement in everyday functioning (“I could do that job”)

• cognitive performance (“Yes, I remembered all of those words”)

• social cognition (“He really is angry”).

Domains of impaired introspective accuracy

Everyday functioning. The 3 global domains of everyday functioning are social outcomes, productive/vocational outcomes, and everyday activities, including residential independence/support for people with severe mental illness. Two areas of inquiry are used in self-assessing everyday functioning: (1) what are you doing now and (2) what could you do in the future? For people with schizophrenia, a related question is how perceived impairments in everyday functioning are associated with subjective illness burden.

People with schizophrenia report illness burden consistent with their self-reported disability, suggesting their reports in these domains are not random.8 Studies have consistently found, however, that these patients report:

• less impairment on average in their everyday functioning than observed by clinicians

• less subjective illness burden compared with individuals with much less severe illnesses.

Their reports also fail to correlate with clinicians’ observations.9 Patients with schizophrenia who have never been employed may report greater vocational potential than those employed full-time. Interestingly, patients who were previously—but not currently—employed reported the least vocational potential.10 These data suggest that experience may be a factor: individuals who have never worked have no context for their self-assessments, whereas people who are persistently unemployed may have a perspective on the challenges associated with employment.

In our research,9 high-contact clinicians (ie, case manager, psychiatrist, therapist, or residential facility manager) were better able than family or friends to generate ratings from an assessment questionnaire that correlated with performance-based measures of patients’ ability to perform everyday functional skills. The ratings were generated across multiple functional status scales, suggesting that the rater was more important than the specific scale. We concluded that high-contact clinicians can generate ratings of everyday functioning that are convergent with patients’ abilities, even when they have no information about actual performance scores.

Cognitive performance. When self-reported cognitive abilities are correlated with the results of performance on neuropsychological assessments, the results are quite consistent. Patients provide reports that do not correlate with their objective performance.11 Interestingly, when clinicians were asked to use the same strategies as patients to generate ratings of cognitive impairment, clinician ratings had considerably greater evidence of validity. In several studies, patients’ ratings of their cognitive performance did not correlate with their neuropsychological test performance, even though they had just been tested on the assessment battery. Ratings by clinicians or other high-contact informants (who were unaware of patients’ test performance) were much more strongly related to patients’ objective test performance, compared with patient self-reports.12

The convergence of clinician ratings of cognitive performance with objective test data has been impressive. Correlation coefficients of at least r = 0.5, reflecting a moderate to large relationships between clinician ratings and objective performance, have been detected. Individual cognitive test domains, such as working memory and processing speed, often do not correlate with each other or with aspects of everyday functioning to that extent.13 These data suggest that a clinician assessment of cognitive performance, when focused on the correct aspects of cognitive functioning, can be a highly useful proxy for extensive neuropsychological testing.

Social cognitive performance. Introspective accuracy for social cognitive judgments can be assessed similarly to the strategies used to assess the domains of everyday functioning and cognitive performance. Patients are asked to complete a typical social cognitive task, such as determining emotions from facial stimuli or examining the eye region of the face, to determine the mental state of the depicted person. Immediately after responding to each stimulus, participants rate their confidence in the correctness of that response.

Consistent with the pattern of introspective accuracy for everyday functioning, patients with schizophrenia tend to make more high-confidence errors than healthy individuals on social cognitive tasks. That is, the patients are less likely to realize when they are wrong in their judgments of social stimuli. A similar pattern has been found for mental state attribution,14 recognition of facial emotion from the self,15 and recognition of facial emotion from others.16 These high-confidence errors also are more likely to occur for more difficult stimuli, such as faces that display only mildly emotional expressions. These difficulties appear to be specific to judgments in an immediate evaluation situation. When asked to determine if the behavior of another individual is socially appropriate, individuals with schizophrenia are as able as healthy individuals to recognize social mistakes.17 This work suggests that, at least within the domain of social cognition, introspective accuracy impairment is not caused by generalized poor judgment, just as self-assessments of disability and illness burden are generated at random.

Choosing a reliable informant

If a clinician has not had adequate time or exposure to a patient to make a cognitive or functional judgment, what should the strategy be? If asking the patient is uninformative, who should be asked? Our group has gathered information that may help clinicians identify informants who can provide ratings of cognitive performance and everyday functioning that are convergent with objective evidence.

In a systematic study of validity of reports of various informants, we compared correlations between reports of competence of everyday functioning with objective measures of cognitive test performance and ability to perform everyday functional skills. Our findings:

• Patient reports of everyday functioning were not correlated with performance-based measures for any of 6 rating scales.9

• Clinician reports of everyday functioning were correlated with objective performance across 4 of 6 rating scales.

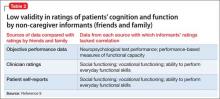

• Correlations between ratings generated by friend or relative informants and other information were almost shocking in their lack of validity (Table 2).9

We concluded that ratings generated by a generic informant—someone who simply knows the patient and is willing to provide ratings—are highly likely to be uninformative. If a friend or relative provides information of limited usefulness, the report could easily lead to clinical decisions with high potential for bad outcomes. For example, attempts could fail to transition someone with impaired everyday living skills to independent living, or a patient whose potential is underestimated might not be offered opportunities to achieve attainable functional goals.

We found that the closer the rater was to a full caregiver role, the better and more accurate the information obtained. Caregivers who had regular contact with patients had much more valid ratings when performance on functionally relevant objective measures was considered. Patients with caregivers had greater impairments in everyday outcomes, however, suggesting that this subset was more impaired than the overall sample. For patients without caregivers, other sources of information—including careful observation by high-contact clinicians—seem to be required to generate a valid assessment of functioning.

Direct functional implications of impaired introspective accuracy

Clinical effects of reduced awareness of illness include reduced adherence to medication, followed by relapse, disturbed behavior, leading to emergency room treatments or acute admissions, and—more rarely—disturbed behavior associated with violence or self-harm. Relapses such as these can adversely affect brain structure and function, with declines in cognitive functioning early in the illness.

Our recent study18 quantifies the direct impact of impairments in introspective accuracy on everyday functioning. We asked 214 individuals with schizophrenia to self-evaluate their cognitive ability with a systematic rating scale and to self-report their everyday functioning in social, vocational, and everyday activities domains. We used performance-based measures to assess their cognitive abilities and everyday functional skills. Concurrently, high-contact clinicians rated these same abilities with the same rating scales. We then predicted everyday functioning, as rated by the clinicians, with the discrepancies between self-assessed and clinician-assessed functioning, and patients’ scores on the performance-based measures.

Impaired introspective accuracy, as indexed by difference scores between clinician ratings and self-reports, was a more potent predictor of everyday functional deficits in social, vocational, and everyday activities domains than scores on performance-based measures of cognitive abilities and functional skills. Even when we analyzed only deficits in introspective accuracy for cognition as the predictor of everyday outcomes in these 3 real-world functional domains, the results were the same. Impaired introspective accuracy was the single best predictor of everyday functioning in all 3 domains, with actual abilities considerably less important.

Patient characteristics that predict introspective accuracy

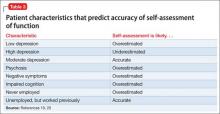

Patient characteristics associated with impairments in introspective accuracy (Table 3)19,20 are easy to identify and assess. Subjective reports of depression have a bell-shaped relationship with introspective accuracy. A self-reported score of 0 by a disabled schizophrenia patient suggests some unawareness of an unfortunate life situation; mild to moderate scores are associated with more accurate self-assessment; and more severe scores, as seen in other conditions, often predict overestimation of disability.19

Psychosis and negative symptoms are associated with reduced introspective accuracy and global over-reporting of functional competence.20 Patients who have never worked have no way to comprehend the specific challenges associated with obtaining and sustaining employment. Patients who had a job and have not been able to return work may perceive barriers as more substantial than they are.

Tips to manage impairments in introspective accuracy

Ensure that assessment information is valid. If a patient has limited ability to self-assess, seek other sources of data. If a patient has psychotic symptoms, denies being depressed, or has limited life experience, the clinician should adjust her (his) interpretation of the self-report accordingly, because these factors are known to adversely affect the accuracy of self-assessment. Consider informants’ level and quality of contact with the patient, as well as any motivation or bias that might influence the accuracy of their reports. Other professionals, such as occupational therapists, can provide useful information as reference points for treatment planning.

Consider treatments aimed at increasing introspective accuracy, such as structured training and exposure to self-assessment situations,6 and interventions aimed at increasing organization and skills performance. Cognitive remediation therapies, although not widely available, have potential to improve functioning, with excellent persistence over time.21

Related Resources

• Harvey PD, ed. Cognitive impairment in schizophrenia: characteristics, assessment and treatment. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2013.

• Gould F, McGuire LS, Durand D, et al. Self-assessment in schizophrenia: accuracy of assessment of cognition and everyday functioning [published online February 2, 2015]. Neuropsychology.

• Dunning D. Self-insight: detours and roadblocks on the path to knowing thyself. New York, NY: Psychology Press; 2012.

Acknowledgment

This paper was supported by Grants MH078775 to Dr. Harvey and MH093432 to Drs. Harvey and Pinkham from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Disclosures

Dr. Harvey has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Forum Pharmaceuticals, Genentech, Otsuka America Pharmaceuticals, Roche, Sanofi, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Pinkham has served as a consultant for Otsuka America Pharmaceuticals.

1. Amador XF, Flaum M, Andreasen NC, et al. Awareness of illness in schizophrenia and schizoaffective and mood disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(10):826-836.

2. Medalia A, Thysen J. A comparison of insight into clinical symptoms versus insight into neuro-cognitive symptoms in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2010;118(1-3):134-139.

3. Beck AT, Baruch E, Balter JM, et al. A new instrument for measuring insight: the Beck Cognitive Insight Scale. Schizophr Res. 2004;68(2-3):319-329.

4. Kruger J, Dunning D. Unskilled and unaware of it: how difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;77(6):1121-1134.

5. Lysaker P, Vohs J, Ballard R, et al. Metacognition, self-reflection and recovery in schizophrenia. Future Neurology. 2013;8(1):103-115.

6. Lysaker PH, Dimaggio G. Metacognitive capacities for reflection in schizophrenia: implications for developing treatments. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40(3):487-491.

7. Koren D, Seidman LJ, Goldsmith M, et al. Real-world cognitive—and metacognitive—dysfunction in schizophrenia: a new approach for measuring (and remediating) more “right stuff.” Schizophr Bull. 2006;32(2):310-326.

8. McKibbin C, Patterson TL, Jeste DV. Assessing disability in older patients with schizophrenia: results from the WHODAS-II. J Ner Men Dis. 2004;192(6):405-413.

9. Sabbag S, Twamley EW, Vella L, et al. Assessing everyday functioning in schizophrenia: not all informants seem equally informative. Schizophr Res. 2011;131(1-3):250-255.

10. Gould F, Sabbag S, Durand D, et al. Self-assessment of functional ability in schizophrenia: milestone achievement and its relationship to accuracy of self-evaluation. Psychiatry Res. 2013;207(1-2):19-24.

11. Keefe RS, Poe M, Walker TM, et al. The Schizophrenia Cognition Rating Scale: an interview-based assessment and its relationship to cognition, real-world functioning, and functional capacity. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(3):426-432.

12. Durand D, Strassnig M, Sabbag S, et al. Factors influencing self-assessment of cognition and functioning in schizophrenia: implications for treatment studies [published online July 25, 2014]. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2014.07.008.

13. McClure MM, Bowie CR, Patterson TL, et al. Correlations of functional capacity and neuropsychological performance in older patients with schizophrenia: evidence for specificity of relationships? Schizophr Res. 2007;89(1-3):330-338.

14. Köther U, Veckenstedt R, Vitzthum F, et al. “Don’t give me that look” - overconfidence in false mental state perception in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2012;196(1):1-8.

15. Demily C, Weiss T, Desmurget M, et al Recognition of self-generated facial emotions is impaired in schizophrenia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;23(2):189-193.

16. Moritz S, Woznica A, Andreou C, et al. Response confidence for emotion perception in schizophrenia using a Continuous Facial Sequence Task. Psychiatry Res. 2012;200(2-3):202-207.

17. Langdon R, Connors MH, Connaughton E. Social cognition and social judgment in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research: Cognition. 2014;1(4):171-174.

18. Gould F, McGuire LS, Durand D, et al. Self-assessment in schizophrenia: accuracy of evaluation of cognition and everyday functioning [published online February 2, 2015]. Neuropsychology.

19. Bowie CR, Twamley EW, Anderson H, et al. Self-assessment of functional status in schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res. 2007;41(12):1012-1018.

20. Sabbag S, Twamley EW, Vella L, et al. Predictors of the accuracy of self-assessment of everyday functioning in people with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2012;137(1- 3):190-195.

21. McGurk SR, Mueser KT, Feldman K, et al. Cognitive training for supported employment: 2-3 year outcomes of a randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(3):437-441.

Lack of insight or “unawareness of illness” occurs within a set of self-assessment problems commonly seen in schizophrenia.1 In the clinical domain, people who do not realize they are ill typically are unwilling to accept treatment, including medication, with potential for worsened illness. They also may have difficulty self-assessing everyday function and functional potential, cognition, social cognition, and attitude, often to a variable degree across these domains (Table 1).1-3

Self-assessment of performance can be clinically helpful whether performance is objectively good or bad. Those with poor performance could be helped to attempt to match their aspirations to accomplishments and improve over time. Good performers could have their functioning bolstered by recognizing their competence. Thus, even a population whose performance often is poor could benefit from accurate self-assessment or experience additional challenges from inaccurate self-evaluation.

This article discusses patient characteristics associated with impairments in self-assessment and the most accurate sources of information for clinicians about patient functioning. Our research shows that an experienced psychiatrist is well positioned to make accurate judgments of functional potential and cognitive abilities for people with schizophrenia.

Patterns in patients with impaired self-assessment

Healthy individuals routinely overestimate their abilities and their attractiveness to others.4 Feedback that deflates these exaggerated estimates increases the accuracy of their self-assessments. Mildly depressed individuals typically are the most accurate judges of their true functioning; those with more severe levels of depression tend to underestimate their competence. Thus, simply being an inaccurate self-assessor is not “abnormal.” These response biases are consistent and predictable in healthy people.

People with severe mental illness pose a different challenge. As in the following cases, their reports manifest minimal correlation with other sources of information, including objective information about performance.

CASE 1

JR, age 28, is referred for occupational therapy because he has never worked since graduating from high school. He tells the therapist his cognitive abilities are average and intact, although his scores on a comprehensive cognitive assessment suggest performance at the first percentile of normal distribution or less. His self-reported Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) score is 4. He says he would like to work as a certified public accountant, because he believes he has an aptitude for math. He admits he has no idea what the job entails, but he is quite motivated to set up an interview as soon as possible.

CASE 2

LM, age 48, says his “best job” was managing an auto parts store for 18 months after he earned an associate’s degree and until his second psychotic episode. His most recent work was approximately 12 years ago at an oil-change facility. He agrees to discuss employment but feels his vocational skills are too deteriorated for him to succeed and requests an assessment for Alzheimer’s disease. His cognitive performance averages in the 10th percentile of the overall population, and his BDI score is 18. Tests of his ability to perform vocational skills suggest he is qualified for multiple jobs, including his previous technician position.

Individuals with schizophrenia who report no depression and no work history routinely overestimate their functional potential, whereas those with a history of unsuccessful vocational attempts often underestimate their functional potential. Inaccurate self-assessment can contribute to reduced functioning—in JR’s case because of unrealistic assessment of the match between skills and vocational potential, and in LM’s case because of overly pessimistic self-evaluation. For people with schizophrenia, inability to self-evaluate can have a bidirectional adverse impact on functioning: overestimation may lead to trying tasks that are too challenging, and underestimation may lead to reduced effort and motivation to take on functional tasks.

Metacognition and introspective accuracy

“Metacognition” refers to self-assessment of the quality and accuracy of performance on cognitive tests.5-7 Problem-solving tests— such as the Wisconsin Card Sorting test (WCST), in which the person being assessed needs to solve the test through performance feedback—are metacognition tests. When errors are made, the strategy in use needs to be discarded; when responses are correct, the strategy is retained. People with schizophrenia have disproportionate difficulties with the WCST, and deficits are especially salient when the test is modified to measure self-assessment of performance and ability to use feedback to change strategies.

“Introspective accuracy” is used to describe the wide-ranging self-assessment impairments in severe mental illness. Theories of metacognition implicate a broad spectrum, of which self-assessment is 1 component, whereas introspective accuracy more specifically indicates judgments of accuracy. Because self-assessment is focused on the self, and hence is introspective, this conceptualization can be applied to self-evaluations of:

• achievement in everyday functioning (“Did I complete that task well?”)

• potential for achievement in everyday functioning (“I could do that job”)

• cognitive performance (“Yes, I remembered all of those words”)

• social cognition (“He really is angry”).

Domains of impaired introspective accuracy

Everyday functioning. The 3 global domains of everyday functioning are social outcomes, productive/vocational outcomes, and everyday activities, including residential independence/support for people with severe mental illness. Two areas of inquiry are used in self-assessing everyday functioning: (1) what are you doing now and (2) what could you do in the future? For people with schizophrenia, a related question is how perceived impairments in everyday functioning are associated with subjective illness burden.

People with schizophrenia report illness burden consistent with their self-reported disability, suggesting their reports in these domains are not random.8 Studies have consistently found, however, that these patients report:

• less impairment on average in their everyday functioning than observed by clinicians

• less subjective illness burden compared with individuals with much less severe illnesses.

Their reports also fail to correlate with clinicians’ observations.9 Patients with schizophrenia who have never been employed may report greater vocational potential than those employed full-time. Interestingly, patients who were previously—but not currently—employed reported the least vocational potential.10 These data suggest that experience may be a factor: individuals who have never worked have no context for their self-assessments, whereas people who are persistently unemployed may have a perspective on the challenges associated with employment.

In our research,9 high-contact clinicians (ie, case manager, psychiatrist, therapist, or residential facility manager) were better able than family or friends to generate ratings from an assessment questionnaire that correlated with performance-based measures of patients’ ability to perform everyday functional skills. The ratings were generated across multiple functional status scales, suggesting that the rater was more important than the specific scale. We concluded that high-contact clinicians can generate ratings of everyday functioning that are convergent with patients’ abilities, even when they have no information about actual performance scores.

Cognitive performance. When self-reported cognitive abilities are correlated with the results of performance on neuropsychological assessments, the results are quite consistent. Patients provide reports that do not correlate with their objective performance.11 Interestingly, when clinicians were asked to use the same strategies as patients to generate ratings of cognitive impairment, clinician ratings had considerably greater evidence of validity. In several studies, patients’ ratings of their cognitive performance did not correlate with their neuropsychological test performance, even though they had just been tested on the assessment battery. Ratings by clinicians or other high-contact informants (who were unaware of patients’ test performance) were much more strongly related to patients’ objective test performance, compared with patient self-reports.12

The convergence of clinician ratings of cognitive performance with objective test data has been impressive. Correlation coefficients of at least r = 0.5, reflecting a moderate to large relationships between clinician ratings and objective performance, have been detected. Individual cognitive test domains, such as working memory and processing speed, often do not correlate with each other or with aspects of everyday functioning to that extent.13 These data suggest that a clinician assessment of cognitive performance, when focused on the correct aspects of cognitive functioning, can be a highly useful proxy for extensive neuropsychological testing.

Social cognitive performance. Introspective accuracy for social cognitive judgments can be assessed similarly to the strategies used to assess the domains of everyday functioning and cognitive performance. Patients are asked to complete a typical social cognitive task, such as determining emotions from facial stimuli or examining the eye region of the face, to determine the mental state of the depicted person. Immediately after responding to each stimulus, participants rate their confidence in the correctness of that response.

Consistent with the pattern of introspective accuracy for everyday functioning, patients with schizophrenia tend to make more high-confidence errors than healthy individuals on social cognitive tasks. That is, the patients are less likely to realize when they are wrong in their judgments of social stimuli. A similar pattern has been found for mental state attribution,14 recognition of facial emotion from the self,15 and recognition of facial emotion from others.16 These high-confidence errors also are more likely to occur for more difficult stimuli, such as faces that display only mildly emotional expressions. These difficulties appear to be specific to judgments in an immediate evaluation situation. When asked to determine if the behavior of another individual is socially appropriate, individuals with schizophrenia are as able as healthy individuals to recognize social mistakes.17 This work suggests that, at least within the domain of social cognition, introspective accuracy impairment is not caused by generalized poor judgment, just as self-assessments of disability and illness burden are generated at random.

Choosing a reliable informant

If a clinician has not had adequate time or exposure to a patient to make a cognitive or functional judgment, what should the strategy be? If asking the patient is uninformative, who should be asked? Our group has gathered information that may help clinicians identify informants who can provide ratings of cognitive performance and everyday functioning that are convergent with objective evidence.

In a systematic study of validity of reports of various informants, we compared correlations between reports of competence of everyday functioning with objective measures of cognitive test performance and ability to perform everyday functional skills. Our findings:

• Patient reports of everyday functioning were not correlated with performance-based measures for any of 6 rating scales.9

• Clinician reports of everyday functioning were correlated with objective performance across 4 of 6 rating scales.

• Correlations between ratings generated by friend or relative informants and other information were almost shocking in their lack of validity (Table 2).9

We concluded that ratings generated by a generic informant—someone who simply knows the patient and is willing to provide ratings—are highly likely to be uninformative. If a friend or relative provides information of limited usefulness, the report could easily lead to clinical decisions with high potential for bad outcomes. For example, attempts could fail to transition someone with impaired everyday living skills to independent living, or a patient whose potential is underestimated might not be offered opportunities to achieve attainable functional goals.

We found that the closer the rater was to a full caregiver role, the better and more accurate the information obtained. Caregivers who had regular contact with patients had much more valid ratings when performance on functionally relevant objective measures was considered. Patients with caregivers had greater impairments in everyday outcomes, however, suggesting that this subset was more impaired than the overall sample. For patients without caregivers, other sources of information—including careful observation by high-contact clinicians—seem to be required to generate a valid assessment of functioning.

Direct functional implications of impaired introspective accuracy

Clinical effects of reduced awareness of illness include reduced adherence to medication, followed by relapse, disturbed behavior, leading to emergency room treatments or acute admissions, and—more rarely—disturbed behavior associated with violence or self-harm. Relapses such as these can adversely affect brain structure and function, with declines in cognitive functioning early in the illness.

Our recent study18 quantifies the direct impact of impairments in introspective accuracy on everyday functioning. We asked 214 individuals with schizophrenia to self-evaluate their cognitive ability with a systematic rating scale and to self-report their everyday functioning in social, vocational, and everyday activities domains. We used performance-based measures to assess their cognitive abilities and everyday functional skills. Concurrently, high-contact clinicians rated these same abilities with the same rating scales. We then predicted everyday functioning, as rated by the clinicians, with the discrepancies between self-assessed and clinician-assessed functioning, and patients’ scores on the performance-based measures.

Impaired introspective accuracy, as indexed by difference scores between clinician ratings and self-reports, was a more potent predictor of everyday functional deficits in social, vocational, and everyday activities domains than scores on performance-based measures of cognitive abilities and functional skills. Even when we analyzed only deficits in introspective accuracy for cognition as the predictor of everyday outcomes in these 3 real-world functional domains, the results were the same. Impaired introspective accuracy was the single best predictor of everyday functioning in all 3 domains, with actual abilities considerably less important.

Patient characteristics that predict introspective accuracy

Patient characteristics associated with impairments in introspective accuracy (Table 3)19,20 are easy to identify and assess. Subjective reports of depression have a bell-shaped relationship with introspective accuracy. A self-reported score of 0 by a disabled schizophrenia patient suggests some unawareness of an unfortunate life situation; mild to moderate scores are associated with more accurate self-assessment; and more severe scores, as seen in other conditions, often predict overestimation of disability.19

Psychosis and negative symptoms are associated with reduced introspective accuracy and global over-reporting of functional competence.20 Patients who have never worked have no way to comprehend the specific challenges associated with obtaining and sustaining employment. Patients who had a job and have not been able to return work may perceive barriers as more substantial than they are.

Tips to manage impairments in introspective accuracy

Ensure that assessment information is valid. If a patient has limited ability to self-assess, seek other sources of data. If a patient has psychotic symptoms, denies being depressed, or has limited life experience, the clinician should adjust her (his) interpretation of the self-report accordingly, because these factors are known to adversely affect the accuracy of self-assessment. Consider informants’ level and quality of contact with the patient, as well as any motivation or bias that might influence the accuracy of their reports. Other professionals, such as occupational therapists, can provide useful information as reference points for treatment planning.

Consider treatments aimed at increasing introspective accuracy, such as structured training and exposure to self-assessment situations,6 and interventions aimed at increasing organization and skills performance. Cognitive remediation therapies, although not widely available, have potential to improve functioning, with excellent persistence over time.21

Related Resources

• Harvey PD, ed. Cognitive impairment in schizophrenia: characteristics, assessment and treatment. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2013.

• Gould F, McGuire LS, Durand D, et al. Self-assessment in schizophrenia: accuracy of assessment of cognition and everyday functioning [published online February 2, 2015]. Neuropsychology.

• Dunning D. Self-insight: detours and roadblocks on the path to knowing thyself. New York, NY: Psychology Press; 2012.

Acknowledgment

This paper was supported by Grants MH078775 to Dr. Harvey and MH093432 to Drs. Harvey and Pinkham from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Disclosures

Dr. Harvey has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Forum Pharmaceuticals, Genentech, Otsuka America Pharmaceuticals, Roche, Sanofi, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Pinkham has served as a consultant for Otsuka America Pharmaceuticals.

Lack of insight or “unawareness of illness” occurs within a set of self-assessment problems commonly seen in schizophrenia.1 In the clinical domain, people who do not realize they are ill typically are unwilling to accept treatment, including medication, with potential for worsened illness. They also may have difficulty self-assessing everyday function and functional potential, cognition, social cognition, and attitude, often to a variable degree across these domains (Table 1).1-3

Self-assessment of performance can be clinically helpful whether performance is objectively good or bad. Those with poor performance could be helped to attempt to match their aspirations to accomplishments and improve over time. Good performers could have their functioning bolstered by recognizing their competence. Thus, even a population whose performance often is poor could benefit from accurate self-assessment or experience additional challenges from inaccurate self-evaluation.

This article discusses patient characteristics associated with impairments in self-assessment and the most accurate sources of information for clinicians about patient functioning. Our research shows that an experienced psychiatrist is well positioned to make accurate judgments of functional potential and cognitive abilities for people with schizophrenia.

Patterns in patients with impaired self-assessment

Healthy individuals routinely overestimate their abilities and their attractiveness to others.4 Feedback that deflates these exaggerated estimates increases the accuracy of their self-assessments. Mildly depressed individuals typically are the most accurate judges of their true functioning; those with more severe levels of depression tend to underestimate their competence. Thus, simply being an inaccurate self-assessor is not “abnormal.” These response biases are consistent and predictable in healthy people.

People with severe mental illness pose a different challenge. As in the following cases, their reports manifest minimal correlation with other sources of information, including objective information about performance.

CASE 1

JR, age 28, is referred for occupational therapy because he has never worked since graduating from high school. He tells the therapist his cognitive abilities are average and intact, although his scores on a comprehensive cognitive assessment suggest performance at the first percentile of normal distribution or less. His self-reported Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) score is 4. He says he would like to work as a certified public accountant, because he believes he has an aptitude for math. He admits he has no idea what the job entails, but he is quite motivated to set up an interview as soon as possible.

CASE 2

LM, age 48, says his “best job” was managing an auto parts store for 18 months after he earned an associate’s degree and until his second psychotic episode. His most recent work was approximately 12 years ago at an oil-change facility. He agrees to discuss employment but feels his vocational skills are too deteriorated for him to succeed and requests an assessment for Alzheimer’s disease. His cognitive performance averages in the 10th percentile of the overall population, and his BDI score is 18. Tests of his ability to perform vocational skills suggest he is qualified for multiple jobs, including his previous technician position.

Individuals with schizophrenia who report no depression and no work history routinely overestimate their functional potential, whereas those with a history of unsuccessful vocational attempts often underestimate their functional potential. Inaccurate self-assessment can contribute to reduced functioning—in JR’s case because of unrealistic assessment of the match between skills and vocational potential, and in LM’s case because of overly pessimistic self-evaluation. For people with schizophrenia, inability to self-evaluate can have a bidirectional adverse impact on functioning: overestimation may lead to trying tasks that are too challenging, and underestimation may lead to reduced effort and motivation to take on functional tasks.

Metacognition and introspective accuracy

“Metacognition” refers to self-assessment of the quality and accuracy of performance on cognitive tests.5-7 Problem-solving tests— such as the Wisconsin Card Sorting test (WCST), in which the person being assessed needs to solve the test through performance feedback—are metacognition tests. When errors are made, the strategy in use needs to be discarded; when responses are correct, the strategy is retained. People with schizophrenia have disproportionate difficulties with the WCST, and deficits are especially salient when the test is modified to measure self-assessment of performance and ability to use feedback to change strategies.

“Introspective accuracy” is used to describe the wide-ranging self-assessment impairments in severe mental illness. Theories of metacognition implicate a broad spectrum, of which self-assessment is 1 component, whereas introspective accuracy more specifically indicates judgments of accuracy. Because self-assessment is focused on the self, and hence is introspective, this conceptualization can be applied to self-evaluations of:

• achievement in everyday functioning (“Did I complete that task well?”)

• potential for achievement in everyday functioning (“I could do that job”)

• cognitive performance (“Yes, I remembered all of those words”)

• social cognition (“He really is angry”).

Domains of impaired introspective accuracy

Everyday functioning. The 3 global domains of everyday functioning are social outcomes, productive/vocational outcomes, and everyday activities, including residential independence/support for people with severe mental illness. Two areas of inquiry are used in self-assessing everyday functioning: (1) what are you doing now and (2) what could you do in the future? For people with schizophrenia, a related question is how perceived impairments in everyday functioning are associated with subjective illness burden.

People with schizophrenia report illness burden consistent with their self-reported disability, suggesting their reports in these domains are not random.8 Studies have consistently found, however, that these patients report:

• less impairment on average in their everyday functioning than observed by clinicians

• less subjective illness burden compared with individuals with much less severe illnesses.

Their reports also fail to correlate with clinicians’ observations.9 Patients with schizophrenia who have never been employed may report greater vocational potential than those employed full-time. Interestingly, patients who were previously—but not currently—employed reported the least vocational potential.10 These data suggest that experience may be a factor: individuals who have never worked have no context for their self-assessments, whereas people who are persistently unemployed may have a perspective on the challenges associated with employment.

In our research,9 high-contact clinicians (ie, case manager, psychiatrist, therapist, or residential facility manager) were better able than family or friends to generate ratings from an assessment questionnaire that correlated with performance-based measures of patients’ ability to perform everyday functional skills. The ratings were generated across multiple functional status scales, suggesting that the rater was more important than the specific scale. We concluded that high-contact clinicians can generate ratings of everyday functioning that are convergent with patients’ abilities, even when they have no information about actual performance scores.

Cognitive performance. When self-reported cognitive abilities are correlated with the results of performance on neuropsychological assessments, the results are quite consistent. Patients provide reports that do not correlate with their objective performance.11 Interestingly, when clinicians were asked to use the same strategies as patients to generate ratings of cognitive impairment, clinician ratings had considerably greater evidence of validity. In several studies, patients’ ratings of their cognitive performance did not correlate with their neuropsychological test performance, even though they had just been tested on the assessment battery. Ratings by clinicians or other high-contact informants (who were unaware of patients’ test performance) were much more strongly related to patients’ objective test performance, compared with patient self-reports.12

The convergence of clinician ratings of cognitive performance with objective test data has been impressive. Correlation coefficients of at least r = 0.5, reflecting a moderate to large relationships between clinician ratings and objective performance, have been detected. Individual cognitive test domains, such as working memory and processing speed, often do not correlate with each other or with aspects of everyday functioning to that extent.13 These data suggest that a clinician assessment of cognitive performance, when focused on the correct aspects of cognitive functioning, can be a highly useful proxy for extensive neuropsychological testing.

Social cognitive performance. Introspective accuracy for social cognitive judgments can be assessed similarly to the strategies used to assess the domains of everyday functioning and cognitive performance. Patients are asked to complete a typical social cognitive task, such as determining emotions from facial stimuli or examining the eye region of the face, to determine the mental state of the depicted person. Immediately after responding to each stimulus, participants rate their confidence in the correctness of that response.

Consistent with the pattern of introspective accuracy for everyday functioning, patients with schizophrenia tend to make more high-confidence errors than healthy individuals on social cognitive tasks. That is, the patients are less likely to realize when they are wrong in their judgments of social stimuli. A similar pattern has been found for mental state attribution,14 recognition of facial emotion from the self,15 and recognition of facial emotion from others.16 These high-confidence errors also are more likely to occur for more difficult stimuli, such as faces that display only mildly emotional expressions. These difficulties appear to be specific to judgments in an immediate evaluation situation. When asked to determine if the behavior of another individual is socially appropriate, individuals with schizophrenia are as able as healthy individuals to recognize social mistakes.17 This work suggests that, at least within the domain of social cognition, introspective accuracy impairment is not caused by generalized poor judgment, just as self-assessments of disability and illness burden are generated at random.

Choosing a reliable informant

If a clinician has not had adequate time or exposure to a patient to make a cognitive or functional judgment, what should the strategy be? If asking the patient is uninformative, who should be asked? Our group has gathered information that may help clinicians identify informants who can provide ratings of cognitive performance and everyday functioning that are convergent with objective evidence.

In a systematic study of validity of reports of various informants, we compared correlations between reports of competence of everyday functioning with objective measures of cognitive test performance and ability to perform everyday functional skills. Our findings:

• Patient reports of everyday functioning were not correlated with performance-based measures for any of 6 rating scales.9

• Clinician reports of everyday functioning were correlated with objective performance across 4 of 6 rating scales.

• Correlations between ratings generated by friend or relative informants and other information were almost shocking in their lack of validity (Table 2).9

We concluded that ratings generated by a generic informant—someone who simply knows the patient and is willing to provide ratings—are highly likely to be uninformative. If a friend or relative provides information of limited usefulness, the report could easily lead to clinical decisions with high potential for bad outcomes. For example, attempts could fail to transition someone with impaired everyday living skills to independent living, or a patient whose potential is underestimated might not be offered opportunities to achieve attainable functional goals.

We found that the closer the rater was to a full caregiver role, the better and more accurate the information obtained. Caregivers who had regular contact with patients had much more valid ratings when performance on functionally relevant objective measures was considered. Patients with caregivers had greater impairments in everyday outcomes, however, suggesting that this subset was more impaired than the overall sample. For patients without caregivers, other sources of information—including careful observation by high-contact clinicians—seem to be required to generate a valid assessment of functioning.

Direct functional implications of impaired introspective accuracy

Clinical effects of reduced awareness of illness include reduced adherence to medication, followed by relapse, disturbed behavior, leading to emergency room treatments or acute admissions, and—more rarely—disturbed behavior associated with violence or self-harm. Relapses such as these can adversely affect brain structure and function, with declines in cognitive functioning early in the illness.

Our recent study18 quantifies the direct impact of impairments in introspective accuracy on everyday functioning. We asked 214 individuals with schizophrenia to self-evaluate their cognitive ability with a systematic rating scale and to self-report their everyday functioning in social, vocational, and everyday activities domains. We used performance-based measures to assess their cognitive abilities and everyday functional skills. Concurrently, high-contact clinicians rated these same abilities with the same rating scales. We then predicted everyday functioning, as rated by the clinicians, with the discrepancies between self-assessed and clinician-assessed functioning, and patients’ scores on the performance-based measures.

Impaired introspective accuracy, as indexed by difference scores between clinician ratings and self-reports, was a more potent predictor of everyday functional deficits in social, vocational, and everyday activities domains than scores on performance-based measures of cognitive abilities and functional skills. Even when we analyzed only deficits in introspective accuracy for cognition as the predictor of everyday outcomes in these 3 real-world functional domains, the results were the same. Impaired introspective accuracy was the single best predictor of everyday functioning in all 3 domains, with actual abilities considerably less important.

Patient characteristics that predict introspective accuracy

Patient characteristics associated with impairments in introspective accuracy (Table 3)19,20 are easy to identify and assess. Subjective reports of depression have a bell-shaped relationship with introspective accuracy. A self-reported score of 0 by a disabled schizophrenia patient suggests some unawareness of an unfortunate life situation; mild to moderate scores are associated with more accurate self-assessment; and more severe scores, as seen in other conditions, often predict overestimation of disability.19

Psychosis and negative symptoms are associated with reduced introspective accuracy and global over-reporting of functional competence.20 Patients who have never worked have no way to comprehend the specific challenges associated with obtaining and sustaining employment. Patients who had a job and have not been able to return work may perceive barriers as more substantial than they are.

Tips to manage impairments in introspective accuracy

Ensure that assessment information is valid. If a patient has limited ability to self-assess, seek other sources of data. If a patient has psychotic symptoms, denies being depressed, or has limited life experience, the clinician should adjust her (his) interpretation of the self-report accordingly, because these factors are known to adversely affect the accuracy of self-assessment. Consider informants’ level and quality of contact with the patient, as well as any motivation or bias that might influence the accuracy of their reports. Other professionals, such as occupational therapists, can provide useful information as reference points for treatment planning.

Consider treatments aimed at increasing introspective accuracy, such as structured training and exposure to self-assessment situations,6 and interventions aimed at increasing organization and skills performance. Cognitive remediation therapies, although not widely available, have potential to improve functioning, with excellent persistence over time.21

Related Resources

• Harvey PD, ed. Cognitive impairment in schizophrenia: characteristics, assessment and treatment. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2013.

• Gould F, McGuire LS, Durand D, et al. Self-assessment in schizophrenia: accuracy of assessment of cognition and everyday functioning [published online February 2, 2015]. Neuropsychology.

• Dunning D. Self-insight: detours and roadblocks on the path to knowing thyself. New York, NY: Psychology Press; 2012.

Acknowledgment

This paper was supported by Grants MH078775 to Dr. Harvey and MH093432 to Drs. Harvey and Pinkham from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Disclosures

Dr. Harvey has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Forum Pharmaceuticals, Genentech, Otsuka America Pharmaceuticals, Roche, Sanofi, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Pinkham has served as a consultant for Otsuka America Pharmaceuticals.

1. Amador XF, Flaum M, Andreasen NC, et al. Awareness of illness in schizophrenia and schizoaffective and mood disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(10):826-836.

2. Medalia A, Thysen J. A comparison of insight into clinical symptoms versus insight into neuro-cognitive symptoms in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2010;118(1-3):134-139.

3. Beck AT, Baruch E, Balter JM, et al. A new instrument for measuring insight: the Beck Cognitive Insight Scale. Schizophr Res. 2004;68(2-3):319-329.

4. Kruger J, Dunning D. Unskilled and unaware of it: how difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;77(6):1121-1134.

5. Lysaker P, Vohs J, Ballard R, et al. Metacognition, self-reflection and recovery in schizophrenia. Future Neurology. 2013;8(1):103-115.

6. Lysaker PH, Dimaggio G. Metacognitive capacities for reflection in schizophrenia: implications for developing treatments. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40(3):487-491.

7. Koren D, Seidman LJ, Goldsmith M, et al. Real-world cognitive—and metacognitive—dysfunction in schizophrenia: a new approach for measuring (and remediating) more “right stuff.” Schizophr Bull. 2006;32(2):310-326.

8. McKibbin C, Patterson TL, Jeste DV. Assessing disability in older patients with schizophrenia: results from the WHODAS-II. J Ner Men Dis. 2004;192(6):405-413.

9. Sabbag S, Twamley EW, Vella L, et al. Assessing everyday functioning in schizophrenia: not all informants seem equally informative. Schizophr Res. 2011;131(1-3):250-255.

10. Gould F, Sabbag S, Durand D, et al. Self-assessment of functional ability in schizophrenia: milestone achievement and its relationship to accuracy of self-evaluation. Psychiatry Res. 2013;207(1-2):19-24.

11. Keefe RS, Poe M, Walker TM, et al. The Schizophrenia Cognition Rating Scale: an interview-based assessment and its relationship to cognition, real-world functioning, and functional capacity. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(3):426-432.

12. Durand D, Strassnig M, Sabbag S, et al. Factors influencing self-assessment of cognition and functioning in schizophrenia: implications for treatment studies [published online July 25, 2014]. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2014.07.008.

13. McClure MM, Bowie CR, Patterson TL, et al. Correlations of functional capacity and neuropsychological performance in older patients with schizophrenia: evidence for specificity of relationships? Schizophr Res. 2007;89(1-3):330-338.

14. Köther U, Veckenstedt R, Vitzthum F, et al. “Don’t give me that look” - overconfidence in false mental state perception in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2012;196(1):1-8.

15. Demily C, Weiss T, Desmurget M, et al Recognition of self-generated facial emotions is impaired in schizophrenia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;23(2):189-193.

16. Moritz S, Woznica A, Andreou C, et al. Response confidence for emotion perception in schizophrenia using a Continuous Facial Sequence Task. Psychiatry Res. 2012;200(2-3):202-207.

17. Langdon R, Connors MH, Connaughton E. Social cognition and social judgment in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research: Cognition. 2014;1(4):171-174.

18. Gould F, McGuire LS, Durand D, et al. Self-assessment in schizophrenia: accuracy of evaluation of cognition and everyday functioning [published online February 2, 2015]. Neuropsychology.

19. Bowie CR, Twamley EW, Anderson H, et al. Self-assessment of functional status in schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res. 2007;41(12):1012-1018.

20. Sabbag S, Twamley EW, Vella L, et al. Predictors of the accuracy of self-assessment of everyday functioning in people with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2012;137(1- 3):190-195.

21. McGurk SR, Mueser KT, Feldman K, et al. Cognitive training for supported employment: 2-3 year outcomes of a randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(3):437-441.

1. Amador XF, Flaum M, Andreasen NC, et al. Awareness of illness in schizophrenia and schizoaffective and mood disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(10):826-836.

2. Medalia A, Thysen J. A comparison of insight into clinical symptoms versus insight into neuro-cognitive symptoms in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2010;118(1-3):134-139.

3. Beck AT, Baruch E, Balter JM, et al. A new instrument for measuring insight: the Beck Cognitive Insight Scale. Schizophr Res. 2004;68(2-3):319-329.

4. Kruger J, Dunning D. Unskilled and unaware of it: how difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;77(6):1121-1134.

5. Lysaker P, Vohs J, Ballard R, et al. Metacognition, self-reflection and recovery in schizophrenia. Future Neurology. 2013;8(1):103-115.

6. Lysaker PH, Dimaggio G. Metacognitive capacities for reflection in schizophrenia: implications for developing treatments. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40(3):487-491.

7. Koren D, Seidman LJ, Goldsmith M, et al. Real-world cognitive—and metacognitive—dysfunction in schizophrenia: a new approach for measuring (and remediating) more “right stuff.” Schizophr Bull. 2006;32(2):310-326.

8. McKibbin C, Patterson TL, Jeste DV. Assessing disability in older patients with schizophrenia: results from the WHODAS-II. J Ner Men Dis. 2004;192(6):405-413.

9. Sabbag S, Twamley EW, Vella L, et al. Assessing everyday functioning in schizophrenia: not all informants seem equally informative. Schizophr Res. 2011;131(1-3):250-255.

10. Gould F, Sabbag S, Durand D, et al. Self-assessment of functional ability in schizophrenia: milestone achievement and its relationship to accuracy of self-evaluation. Psychiatry Res. 2013;207(1-2):19-24.

11. Keefe RS, Poe M, Walker TM, et al. The Schizophrenia Cognition Rating Scale: an interview-based assessment and its relationship to cognition, real-world functioning, and functional capacity. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(3):426-432.

12. Durand D, Strassnig M, Sabbag S, et al. Factors influencing self-assessment of cognition and functioning in schizophrenia: implications for treatment studies [published online July 25, 2014]. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2014.07.008.

13. McClure MM, Bowie CR, Patterson TL, et al. Correlations of functional capacity and neuropsychological performance in older patients with schizophrenia: evidence for specificity of relationships? Schizophr Res. 2007;89(1-3):330-338.

14. Köther U, Veckenstedt R, Vitzthum F, et al. “Don’t give me that look” - overconfidence in false mental state perception in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2012;196(1):1-8.

15. Demily C, Weiss T, Desmurget M, et al Recognition of self-generated facial emotions is impaired in schizophrenia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;23(2):189-193.

16. Moritz S, Woznica A, Andreou C, et al. Response confidence for emotion perception in schizophrenia using a Continuous Facial Sequence Task. Psychiatry Res. 2012;200(2-3):202-207.

17. Langdon R, Connors MH, Connaughton E. Social cognition and social judgment in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research: Cognition. 2014;1(4):171-174.

18. Gould F, McGuire LS, Durand D, et al. Self-assessment in schizophrenia: accuracy of evaluation of cognition and everyday functioning [published online February 2, 2015]. Neuropsychology.

19. Bowie CR, Twamley EW, Anderson H, et al. Self-assessment of functional status in schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res. 2007;41(12):1012-1018.

20. Sabbag S, Twamley EW, Vella L, et al. Predictors of the accuracy of self-assessment of everyday functioning in people with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2012;137(1- 3):190-195.

21. McGurk SR, Mueser KT, Feldman K, et al. Cognitive training for supported employment: 2-3 year outcomes of a randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(3):437-441.