User login

Palliative care is specialized medical care focused on providing relief from the symptoms, pain, and stress of a serious illness. The goal is to improve the quality of life for both the patient and the family. In all settings, palliative care has been found to improve patients’ quality of life,1,2 improve family satisfaction and well-being,3 reduce resource utilization and costs,4 and, in some studies, increase the length of life for seriously ill patients.5

Given the frequency with which seriously ill patients are hospitalized, hospitalists are well positioned to identify those who could benefit from palliative care interventions.6 Hospitalists routinely use primary palliative care skills, including pain and symptom management and skilled care planning conversations. For complex cases, such as patients with intractable symptoms or major family conflict, hospitalists may refer to specialist palliative care teams for consultation.

The Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) defines the key primary palliative care responsibilities for hospitalists as (1) leading discussions on the goals of care and advance care planning with patients and families, (2) screening and treating common physical symptoms, and (3) referring patients to community services to provide support postdischarge.7 According to data in the National Palliative Care Registry,8 48% of all palliative care referrals in 2015 came from hospitalists, which is more than double the percentage of referrals from any other specialty.9

In a recent survey conducted by SHM about serious illness communication, 53% of hospitalists reported concerns about a patient or family’s understanding of their prognosis, and 50% indicated that they do not feel confident managing family conflict.10

IMPROVING VALUE

Context

Patients with multiple serious chronic conditions are often forced to rely on emergency services when crises, such as uncontrolled pain or dyspnea exacerbation, occur after hours, resulting in the revolving-door hospitalizations that typically characterize their care.11 As the prevalence of serious illness rises and the shift to value-based payment accelerates, hospitals are under increasing pressure to deliver efficient and high-quality services that meet the needs of seriously ill patients. The integration of standardized palliative care screening and assessment enables hospitalists and other providers to identify high-need individuals and match services and delivery models to needs, whether it be respite care for an exhausted and overwhelmed family caregiver or a home protocol for managing recurrent dyspnea crises for a patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). This process improves the quality of care and quality of life, and in doing so, prevents the need for costly crisis care.

Reducing Readmissions

By identifying patients in need of extra symptom management support, or those at a turning point requiring discussion about achievable priorities for care, hospitalists can avert crises for patients earlier in the disease trajectory either by managing the patient’s palliative needs themselves or by connecting patients with specialty palliative care services as needed. This leads to a better quality of life (and survival in some studies) for both patients and their families1,3,5 and reduces unnecessary emergency department (ED) and hospital use.12 Hospitalists providing palliative care can also reduce readmissions by improving care coordination, including clinical communication and medication reconciliation after discharge.13

A 2015 Harvard Business Review study found that the quality of communication in the hospital is the strongest independent predictor of readmissions when combined with process-of-care improvements, such as standardized patient screening and assessment of family caregiver capacity.14 While medical education prepares physicians to deliver evidence-based medical care, it currently offers little to no training in communication skills, despite mounting evidence that this is a critical component of quality healthcare.

Cost Savings

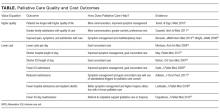

Hospital palliative care teams are associated with significant hospital cost savings that result from aligning care with patient priorities, leading, in turn, to reduced nonbeneficial hospital imaging, medications, procedures, and length of stay.15 See the table16,17 for examples of cost and quality outcomes of specialist palliative care provision and evidence supporting each outcome.18-25

Multiple studies consistently demonstrate that inpatient palliative care teams reduce hospital costs.26 One randomized controlled trial investigating the impact of an inpatient palliative care service found that patients who received care from the palliative care team reported greater satisfaction with their care, had fewer intensive care unit admissions, had more advanced directives at hospital discharge, longer hospice length of stay, and lower total healthcare costs (a net difference of $6766 per patient).23

Research shows that the earlier palliative care is provided, the greater the impact on the subsequent course of care,27 suggesting that hospitalists who provide frontline palliative care interventions as early as possible in a seriously ill patient’s stay will be able to provide higher quality care with lower overall costs. Notably, the majority of research on cost savings associated with palliative care has focused on the impact of specialist palliative care teams, and further research is needed to understand the economic impact of primary palliative care provision.

Improving Satisfaction

Shifting to value-based payment means that the patient and family experience determine an increasingly large percentage of hospital and provider reimbursement. Palliative care approaches, such as family caregiver assessment and support, access to 24/7 assistance after discharge, and person-centered care by an interdisciplinary team, improve performance in all of these measures. Communication skills training improves patient satisfaction scores, and skilled discussions about achievable priorities for care are associated with better quality of life, reduced nonbeneficial and burdensome treatments, and an increase in goal-concordant care.19 Communication skills training has also been shown to reduce burnout and improve empathy among physicians.28,29

SKILLS TRAINING OPPORTUNITIES

Though more evidence is needed to understand the impact of primary palliative care provision by hospitalists, the strong evidence on the benefits of specialty palliative care suggests that the skilled provision of primary palliative care by hospitalists will result in higher quality, higher value care. A number of training options exist for midcareer hospital medicine clinicians, including both in-person and online training in communication and other palliative care skills.

- The Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC) is a membership organization that offers online continuing education unit and continuing medical education courses on communication skills, pain and symptom management, caregiver support, and care coordination. CAPC also offers courses on palliative interventions for patients with dementia, COPD, and heart failure.

- SHM is actively invested in engaging hospitalists in palliative care skills training. SHM provides free toolkits on a variety of topics within the palliative care domain, including pain management, postacute care transitions, and opioid safety. The recently released Serious Illness Communication toolkit offers background on the role of hospitalists in palliative care provision, a pathway for fitting goals-of-care conversations into hospitalist workflow and recommended metrics and training resources. SHM also uses a mentored implementation model in which expert physicians mentor hospital team members on best practices in palliative care. SHM’s Palliative Care Task Force seeks to identify educational activities for hospitalists and create opportunities to integrate palliative care in hospital medicine.30

- The Serious Illness Care Program at Ariadne Labs in Boston aims to facilitate conversations between clinicians and seriously ill patients through its Serious Illness Conversation Guide, combined with technical assistance on workflow redesign to help clinicians conduct and document serious illness conversations.

- VitalTalk specializes in clinical communication education. Through online and in-person train-the-trainer programs, VitalTalk equips clinicians to lead communication training programs at their home institutions.

- The Education in Palliative and End-of-Life Care Program and End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium (ELNEC) uses a train-the-trainer approach to educate providers in palliative care clinical competencies and increase the reach of primary palliative care provision. ELNEC workshops are complemented by a curriculum of online clinical training modules.

CULTURE CHANGE

Though palliative care skills training is a necessary first step, hospitalists also cite lack of time, difficulty finding records of previous patient discussions, and frequent handoffs as among the barriers to integrating palliative care into their practice.10 Studies examining the process of palliative care and hospital culture change have found that barriers to palliative care integration include a culture of aggressive care in EDs, lack of standardized patient identification criteria, and limited knowledge about and staffing for palliative care.31 These data indicate the need for system changes that enable hospitalists to operationalize palliative care principles.

Health systems must implement systems and processes that routinize palliative care, making it part of the mainstream course of care for seriously ill patients and their caregivers. This includes developing systems for the identification of patients with palliative care needs, embedding palliative care assessment and referral into clinical workflows, and enabling standardized palliative care documentation in electronic medical records. While palliative care skills training is essential, investment in systems change is no less critical to embedding palliative care practices in clinical norms across specialties.

CONCLUSION

Hospitalists can use a palliative approach to improve care quality and quality of life for seriously ill patients while helping to avoid preventable and unnecessary 911 calls, ED visits, and hospitalizations. The shift towards value-based payment is a strong incentive for hospitals and hospitalists to direct resources toward practices that improve the quality of life and care for the highest-need patients and their families. When equipped with the tools they need to provide palliative care, either themselves or in collaboration with palliative care teams, hospitalists have the opportunity to profoundly redirect the experience of care for seriously ill patients and their families.

Disclosure

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

1. Casarett D, Pickard A, Bailey FA, et al. Do Palliative Consultations Improve Patient Outcomes? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(4):595-599. PubMed

2. Delgado-Guay MO, Parsons HA, Zhijun LM, Palmer LJ, Bruera E. Symptom distress, interventions, and outcomes of intensive care unit cancer patients referred to a palliative care consult team. Cancer. 2009;115(2):437-445. PubMed

3. Gelfman LP, Meier DE, Morrison SR. Does Palliative Care Improve Quality? A Survey of Bereaved Family Members. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;36(1):22-28. PubMed

4. Morrison SR, Dietrich J, Ladwig S, et al. Palliative Care Consultation Teams Cut Hospital Costs for Medicaid Beneficiaries. Health Aff. 2011;30:454-463. PubMed

5. Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non‐small‐cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733-742. PubMed

6. Lin RJ, Adelman RD, Diamond RR, Evans AT. The Sentinel Hospitalization and the Role of Palliative Care. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(5):320-323. PubMed

7. Palliative care. J Hosp Med. 2006;1:80-81. doi:10.1002/jhm.54.

8. Center to Advance Palliative Care. National palliative care registry. https://registry.capc.org/. Accessed May 26, 2017.

9. Rogers M, Dumanovsky T. How We Work: Trends and Insights in Hospital Palliative Care. New York: The Center to Advance Palliative Care and the National Palliative Care Research Center. https://registry.capc.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/How-We-Work-Trends-and-Insights-in-Hospital-Palliative-Care-2009-2015.pdf; 2017. Accessed May 26, 2017.

10. Rosenberg LB, Greenwald J, Caponi B, et al. Confidence with and Barriers to Serious Illness Communication: A National Survey of Hospitalists. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(9):1013-1019. PubMed

11. Aldridge MD, Kelley AS. The Myth Regarding the High Cost of End-of-Life Care. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(12):2411-2415. PubMed

12. Enguidanos S, Vesper E, Lorenz K. 30-Day Readmissions among Seriously Ill Older Adults. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(12):1356-1361. PubMed

13. Kripalani S, Theobald C, Anctil B, Vasilevskis E. Reducing Hospital Readmission Rates: Current Strategies and Future Directions. Annu Rev Med. 2014;65:471-485. PubMed

14. Senot C, Chandrasekaran A. What Has the Biggest Impact on Hospital Readmission Rates. Harvard Business Review. September 23, 2015. https://hbr.org/2015/09/what-has-the-biggest-impact-on-hospital-readmission-rates. Accessed March 29, 2017.

15. Morrison RS, Penrod JD, Cassel JB, et al. Cost Savings Associated with US Hospital Palliative Care Consultation Programs. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(16):1783-1790. PubMed

16. Cassel JB. Palliative Care’s Impact on Utilization and Costs: Implications for Health Services Research and Policy. In: Kelley AS, Meier DE, editors. Meeting the Needs of Older Adults with Serious Illness: Challenges and Opportunities in the Age of Health Care Reform. New York: Springer Science+Business Media; 2014:109-126.

17. Meier D, Silvers A. Serious Illness Strategies for Health Plans and Accountable Care Organizations. https://media.capc.org/filer_public/2c/69/2c69a0f0-c90f-43ac-893e-e90cd0438482/serious_illness_strategies_web.pdf. 2017. Accessed August 10, 2017.

18. Casarett D, Johnson M, Smith D, Richardson D. The Optimal Delivery of Palliative Care: A National Comparison of the Outcomes of Consultation Teams vs Inpatient Units. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(7):649-655. PubMed

19. Bernacki RE, Block SD. Communication About Serious Illness Care Goals: A Review and Synthesis of Best Practices. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(12):1994-2003. PubMed

20. Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations Between End-of-Life Discussions, Patient Mental Health, Medical Care Near Death, and Caregiver Bereavement Adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300(14):1665-1673. PubMed

21. May P, Garrido M, Cassel JB, et al. Cost Analysis of a Prospective Multi-Site Cohort Study of Palliative Care Consultation Teams for Adults with Advanced Cancer: Where Do Cost Savings Come From? Palliat Med. 2017;31(4):378-386. PubMed

22. Norton SA, Hogan LA, Holloway RG, et al. Proactive Palliative Care in the Medical Intensive Care Unit: Effects of Length of Stay for Selected High-Risk Patients. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(6):1530-1535. PubMed

23. Gade G, Venohr I, Conner D, et al. Impact of an Inpatient Palliative Care Team: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(2):180-201. PubMed

24. Adelson K, Paris J, Horton J, et al. Standardized Criteria for Palliative Care Consultation on a Solid Tumor Oncology Service Reduces Downstream Health Care use. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13(5):e431-e440. PubMed

25. Lustbader D, Mitchell M, Carole R, et al. The Impact of a Home-Based Palliative Care Program in an Accountable Care Organization. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(1):23-28. PubMed

26. May P, Normand C, Morrison R. Economic Impact of Hospital Inpatient Palliative Care Consultation: Review of Current Evidence and Directions for Future Research. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(9):1054-1063. PubMed

27. May P, Garrido MM, Bassel JB, et al. Prospective Cohort Study of Hospital Palliative Care Teams for Inpatients with Advanced Cancer: Earlier Consultation Is Associated with Larger Cost-Saving Effect. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(25):2745-2752. PubMed

28. Boissy A, Windover A, Bokar D, et al. Communication Skills Training for Physicians Improves Patient Satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(7):755-761. PubMed

29. Kirkland KB. Finding Joy in Practice Cocreation in Palliative Care. JAMA. 2017;317(20):2065-2066. PubMed

30. Whelan C. SHM Establishes Palliative Care Task Force. The Hospitalist. 2005;11. http://www.the-hospitalist.org/hospitalist/article/123027/hospice-palliative-medicine/shm-establishes-palliative-care-task-force. Accessed July 31, 2017.

31. Grudzen CR, Richardson LD, Major-Monfried H, et al. Hospital Administrators’ Views on Barriers and Opportunities to Delivering Palliative Care in the Emergency Department. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;61(6):654-660. PubMed

Palliative care is specialized medical care focused on providing relief from the symptoms, pain, and stress of a serious illness. The goal is to improve the quality of life for both the patient and the family. In all settings, palliative care has been found to improve patients’ quality of life,1,2 improve family satisfaction and well-being,3 reduce resource utilization and costs,4 and, in some studies, increase the length of life for seriously ill patients.5

Given the frequency with which seriously ill patients are hospitalized, hospitalists are well positioned to identify those who could benefit from palliative care interventions.6 Hospitalists routinely use primary palliative care skills, including pain and symptom management and skilled care planning conversations. For complex cases, such as patients with intractable symptoms or major family conflict, hospitalists may refer to specialist palliative care teams for consultation.

The Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) defines the key primary palliative care responsibilities for hospitalists as (1) leading discussions on the goals of care and advance care planning with patients and families, (2) screening and treating common physical symptoms, and (3) referring patients to community services to provide support postdischarge.7 According to data in the National Palliative Care Registry,8 48% of all palliative care referrals in 2015 came from hospitalists, which is more than double the percentage of referrals from any other specialty.9

In a recent survey conducted by SHM about serious illness communication, 53% of hospitalists reported concerns about a patient or family’s understanding of their prognosis, and 50% indicated that they do not feel confident managing family conflict.10

IMPROVING VALUE

Context

Patients with multiple serious chronic conditions are often forced to rely on emergency services when crises, such as uncontrolled pain or dyspnea exacerbation, occur after hours, resulting in the revolving-door hospitalizations that typically characterize their care.11 As the prevalence of serious illness rises and the shift to value-based payment accelerates, hospitals are under increasing pressure to deliver efficient and high-quality services that meet the needs of seriously ill patients. The integration of standardized palliative care screening and assessment enables hospitalists and other providers to identify high-need individuals and match services and delivery models to needs, whether it be respite care for an exhausted and overwhelmed family caregiver or a home protocol for managing recurrent dyspnea crises for a patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). This process improves the quality of care and quality of life, and in doing so, prevents the need for costly crisis care.

Reducing Readmissions

By identifying patients in need of extra symptom management support, or those at a turning point requiring discussion about achievable priorities for care, hospitalists can avert crises for patients earlier in the disease trajectory either by managing the patient’s palliative needs themselves or by connecting patients with specialty palliative care services as needed. This leads to a better quality of life (and survival in some studies) for both patients and their families1,3,5 and reduces unnecessary emergency department (ED) and hospital use.12 Hospitalists providing palliative care can also reduce readmissions by improving care coordination, including clinical communication and medication reconciliation after discharge.13

A 2015 Harvard Business Review study found that the quality of communication in the hospital is the strongest independent predictor of readmissions when combined with process-of-care improvements, such as standardized patient screening and assessment of family caregiver capacity.14 While medical education prepares physicians to deliver evidence-based medical care, it currently offers little to no training in communication skills, despite mounting evidence that this is a critical component of quality healthcare.

Cost Savings

Hospital palliative care teams are associated with significant hospital cost savings that result from aligning care with patient priorities, leading, in turn, to reduced nonbeneficial hospital imaging, medications, procedures, and length of stay.15 See the table16,17 for examples of cost and quality outcomes of specialist palliative care provision and evidence supporting each outcome.18-25

Multiple studies consistently demonstrate that inpatient palliative care teams reduce hospital costs.26 One randomized controlled trial investigating the impact of an inpatient palliative care service found that patients who received care from the palliative care team reported greater satisfaction with their care, had fewer intensive care unit admissions, had more advanced directives at hospital discharge, longer hospice length of stay, and lower total healthcare costs (a net difference of $6766 per patient).23

Research shows that the earlier palliative care is provided, the greater the impact on the subsequent course of care,27 suggesting that hospitalists who provide frontline palliative care interventions as early as possible in a seriously ill patient’s stay will be able to provide higher quality care with lower overall costs. Notably, the majority of research on cost savings associated with palliative care has focused on the impact of specialist palliative care teams, and further research is needed to understand the economic impact of primary palliative care provision.

Improving Satisfaction

Shifting to value-based payment means that the patient and family experience determine an increasingly large percentage of hospital and provider reimbursement. Palliative care approaches, such as family caregiver assessment and support, access to 24/7 assistance after discharge, and person-centered care by an interdisciplinary team, improve performance in all of these measures. Communication skills training improves patient satisfaction scores, and skilled discussions about achievable priorities for care are associated with better quality of life, reduced nonbeneficial and burdensome treatments, and an increase in goal-concordant care.19 Communication skills training has also been shown to reduce burnout and improve empathy among physicians.28,29

SKILLS TRAINING OPPORTUNITIES

Though more evidence is needed to understand the impact of primary palliative care provision by hospitalists, the strong evidence on the benefits of specialty palliative care suggests that the skilled provision of primary palliative care by hospitalists will result in higher quality, higher value care. A number of training options exist for midcareer hospital medicine clinicians, including both in-person and online training in communication and other palliative care skills.

- The Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC) is a membership organization that offers online continuing education unit and continuing medical education courses on communication skills, pain and symptom management, caregiver support, and care coordination. CAPC also offers courses on palliative interventions for patients with dementia, COPD, and heart failure.

- SHM is actively invested in engaging hospitalists in palliative care skills training. SHM provides free toolkits on a variety of topics within the palliative care domain, including pain management, postacute care transitions, and opioid safety. The recently released Serious Illness Communication toolkit offers background on the role of hospitalists in palliative care provision, a pathway for fitting goals-of-care conversations into hospitalist workflow and recommended metrics and training resources. SHM also uses a mentored implementation model in which expert physicians mentor hospital team members on best practices in palliative care. SHM’s Palliative Care Task Force seeks to identify educational activities for hospitalists and create opportunities to integrate palliative care in hospital medicine.30

- The Serious Illness Care Program at Ariadne Labs in Boston aims to facilitate conversations between clinicians and seriously ill patients through its Serious Illness Conversation Guide, combined with technical assistance on workflow redesign to help clinicians conduct and document serious illness conversations.

- VitalTalk specializes in clinical communication education. Through online and in-person train-the-trainer programs, VitalTalk equips clinicians to lead communication training programs at their home institutions.

- The Education in Palliative and End-of-Life Care Program and End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium (ELNEC) uses a train-the-trainer approach to educate providers in palliative care clinical competencies and increase the reach of primary palliative care provision. ELNEC workshops are complemented by a curriculum of online clinical training modules.

CULTURE CHANGE

Though palliative care skills training is a necessary first step, hospitalists also cite lack of time, difficulty finding records of previous patient discussions, and frequent handoffs as among the barriers to integrating palliative care into their practice.10 Studies examining the process of palliative care and hospital culture change have found that barriers to palliative care integration include a culture of aggressive care in EDs, lack of standardized patient identification criteria, and limited knowledge about and staffing for palliative care.31 These data indicate the need for system changes that enable hospitalists to operationalize palliative care principles.

Health systems must implement systems and processes that routinize palliative care, making it part of the mainstream course of care for seriously ill patients and their caregivers. This includes developing systems for the identification of patients with palliative care needs, embedding palliative care assessment and referral into clinical workflows, and enabling standardized palliative care documentation in electronic medical records. While palliative care skills training is essential, investment in systems change is no less critical to embedding palliative care practices in clinical norms across specialties.

CONCLUSION

Hospitalists can use a palliative approach to improve care quality and quality of life for seriously ill patients while helping to avoid preventable and unnecessary 911 calls, ED visits, and hospitalizations. The shift towards value-based payment is a strong incentive for hospitals and hospitalists to direct resources toward practices that improve the quality of life and care for the highest-need patients and their families. When equipped with the tools they need to provide palliative care, either themselves or in collaboration with palliative care teams, hospitalists have the opportunity to profoundly redirect the experience of care for seriously ill patients and their families.

Disclosure

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Palliative care is specialized medical care focused on providing relief from the symptoms, pain, and stress of a serious illness. The goal is to improve the quality of life for both the patient and the family. In all settings, palliative care has been found to improve patients’ quality of life,1,2 improve family satisfaction and well-being,3 reduce resource utilization and costs,4 and, in some studies, increase the length of life for seriously ill patients.5

Given the frequency with which seriously ill patients are hospitalized, hospitalists are well positioned to identify those who could benefit from palliative care interventions.6 Hospitalists routinely use primary palliative care skills, including pain and symptom management and skilled care planning conversations. For complex cases, such as patients with intractable symptoms or major family conflict, hospitalists may refer to specialist palliative care teams for consultation.

The Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) defines the key primary palliative care responsibilities for hospitalists as (1) leading discussions on the goals of care and advance care planning with patients and families, (2) screening and treating common physical symptoms, and (3) referring patients to community services to provide support postdischarge.7 According to data in the National Palliative Care Registry,8 48% of all palliative care referrals in 2015 came from hospitalists, which is more than double the percentage of referrals from any other specialty.9

In a recent survey conducted by SHM about serious illness communication, 53% of hospitalists reported concerns about a patient or family’s understanding of their prognosis, and 50% indicated that they do not feel confident managing family conflict.10

IMPROVING VALUE

Context

Patients with multiple serious chronic conditions are often forced to rely on emergency services when crises, such as uncontrolled pain or dyspnea exacerbation, occur after hours, resulting in the revolving-door hospitalizations that typically characterize their care.11 As the prevalence of serious illness rises and the shift to value-based payment accelerates, hospitals are under increasing pressure to deliver efficient and high-quality services that meet the needs of seriously ill patients. The integration of standardized palliative care screening and assessment enables hospitalists and other providers to identify high-need individuals and match services and delivery models to needs, whether it be respite care for an exhausted and overwhelmed family caregiver or a home protocol for managing recurrent dyspnea crises for a patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). This process improves the quality of care and quality of life, and in doing so, prevents the need for costly crisis care.

Reducing Readmissions

By identifying patients in need of extra symptom management support, or those at a turning point requiring discussion about achievable priorities for care, hospitalists can avert crises for patients earlier in the disease trajectory either by managing the patient’s palliative needs themselves or by connecting patients with specialty palliative care services as needed. This leads to a better quality of life (and survival in some studies) for both patients and their families1,3,5 and reduces unnecessary emergency department (ED) and hospital use.12 Hospitalists providing palliative care can also reduce readmissions by improving care coordination, including clinical communication and medication reconciliation after discharge.13

A 2015 Harvard Business Review study found that the quality of communication in the hospital is the strongest independent predictor of readmissions when combined with process-of-care improvements, such as standardized patient screening and assessment of family caregiver capacity.14 While medical education prepares physicians to deliver evidence-based medical care, it currently offers little to no training in communication skills, despite mounting evidence that this is a critical component of quality healthcare.

Cost Savings

Hospital palliative care teams are associated with significant hospital cost savings that result from aligning care with patient priorities, leading, in turn, to reduced nonbeneficial hospital imaging, medications, procedures, and length of stay.15 See the table16,17 for examples of cost and quality outcomes of specialist palliative care provision and evidence supporting each outcome.18-25

Multiple studies consistently demonstrate that inpatient palliative care teams reduce hospital costs.26 One randomized controlled trial investigating the impact of an inpatient palliative care service found that patients who received care from the palliative care team reported greater satisfaction with their care, had fewer intensive care unit admissions, had more advanced directives at hospital discharge, longer hospice length of stay, and lower total healthcare costs (a net difference of $6766 per patient).23

Research shows that the earlier palliative care is provided, the greater the impact on the subsequent course of care,27 suggesting that hospitalists who provide frontline palliative care interventions as early as possible in a seriously ill patient’s stay will be able to provide higher quality care with lower overall costs. Notably, the majority of research on cost savings associated with palliative care has focused on the impact of specialist palliative care teams, and further research is needed to understand the economic impact of primary palliative care provision.

Improving Satisfaction

Shifting to value-based payment means that the patient and family experience determine an increasingly large percentage of hospital and provider reimbursement. Palliative care approaches, such as family caregiver assessment and support, access to 24/7 assistance after discharge, and person-centered care by an interdisciplinary team, improve performance in all of these measures. Communication skills training improves patient satisfaction scores, and skilled discussions about achievable priorities for care are associated with better quality of life, reduced nonbeneficial and burdensome treatments, and an increase in goal-concordant care.19 Communication skills training has also been shown to reduce burnout and improve empathy among physicians.28,29

SKILLS TRAINING OPPORTUNITIES

Though more evidence is needed to understand the impact of primary palliative care provision by hospitalists, the strong evidence on the benefits of specialty palliative care suggests that the skilled provision of primary palliative care by hospitalists will result in higher quality, higher value care. A number of training options exist for midcareer hospital medicine clinicians, including both in-person and online training in communication and other palliative care skills.

- The Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC) is a membership organization that offers online continuing education unit and continuing medical education courses on communication skills, pain and symptom management, caregiver support, and care coordination. CAPC also offers courses on palliative interventions for patients with dementia, COPD, and heart failure.

- SHM is actively invested in engaging hospitalists in palliative care skills training. SHM provides free toolkits on a variety of topics within the palliative care domain, including pain management, postacute care transitions, and opioid safety. The recently released Serious Illness Communication toolkit offers background on the role of hospitalists in palliative care provision, a pathway for fitting goals-of-care conversations into hospitalist workflow and recommended metrics and training resources. SHM also uses a mentored implementation model in which expert physicians mentor hospital team members on best practices in palliative care. SHM’s Palliative Care Task Force seeks to identify educational activities for hospitalists and create opportunities to integrate palliative care in hospital medicine.30

- The Serious Illness Care Program at Ariadne Labs in Boston aims to facilitate conversations between clinicians and seriously ill patients through its Serious Illness Conversation Guide, combined with technical assistance on workflow redesign to help clinicians conduct and document serious illness conversations.

- VitalTalk specializes in clinical communication education. Through online and in-person train-the-trainer programs, VitalTalk equips clinicians to lead communication training programs at their home institutions.

- The Education in Palliative and End-of-Life Care Program and End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium (ELNEC) uses a train-the-trainer approach to educate providers in palliative care clinical competencies and increase the reach of primary palliative care provision. ELNEC workshops are complemented by a curriculum of online clinical training modules.

CULTURE CHANGE

Though palliative care skills training is a necessary first step, hospitalists also cite lack of time, difficulty finding records of previous patient discussions, and frequent handoffs as among the barriers to integrating palliative care into their practice.10 Studies examining the process of palliative care and hospital culture change have found that barriers to palliative care integration include a culture of aggressive care in EDs, lack of standardized patient identification criteria, and limited knowledge about and staffing for palliative care.31 These data indicate the need for system changes that enable hospitalists to operationalize palliative care principles.

Health systems must implement systems and processes that routinize palliative care, making it part of the mainstream course of care for seriously ill patients and their caregivers. This includes developing systems for the identification of patients with palliative care needs, embedding palliative care assessment and referral into clinical workflows, and enabling standardized palliative care documentation in electronic medical records. While palliative care skills training is essential, investment in systems change is no less critical to embedding palliative care practices in clinical norms across specialties.

CONCLUSION

Hospitalists can use a palliative approach to improve care quality and quality of life for seriously ill patients while helping to avoid preventable and unnecessary 911 calls, ED visits, and hospitalizations. The shift towards value-based payment is a strong incentive for hospitals and hospitalists to direct resources toward practices that improve the quality of life and care for the highest-need patients and their families. When equipped with the tools they need to provide palliative care, either themselves or in collaboration with palliative care teams, hospitalists have the opportunity to profoundly redirect the experience of care for seriously ill patients and their families.

Disclosure

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

1. Casarett D, Pickard A, Bailey FA, et al. Do Palliative Consultations Improve Patient Outcomes? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(4):595-599. PubMed

2. Delgado-Guay MO, Parsons HA, Zhijun LM, Palmer LJ, Bruera E. Symptom distress, interventions, and outcomes of intensive care unit cancer patients referred to a palliative care consult team. Cancer. 2009;115(2):437-445. PubMed

3. Gelfman LP, Meier DE, Morrison SR. Does Palliative Care Improve Quality? A Survey of Bereaved Family Members. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;36(1):22-28. PubMed

4. Morrison SR, Dietrich J, Ladwig S, et al. Palliative Care Consultation Teams Cut Hospital Costs for Medicaid Beneficiaries. Health Aff. 2011;30:454-463. PubMed

5. Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non‐small‐cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733-742. PubMed

6. Lin RJ, Adelman RD, Diamond RR, Evans AT. The Sentinel Hospitalization and the Role of Palliative Care. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(5):320-323. PubMed

7. Palliative care. J Hosp Med. 2006;1:80-81. doi:10.1002/jhm.54.

8. Center to Advance Palliative Care. National palliative care registry. https://registry.capc.org/. Accessed May 26, 2017.

9. Rogers M, Dumanovsky T. How We Work: Trends and Insights in Hospital Palliative Care. New York: The Center to Advance Palliative Care and the National Palliative Care Research Center. https://registry.capc.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/How-We-Work-Trends-and-Insights-in-Hospital-Palliative-Care-2009-2015.pdf; 2017. Accessed May 26, 2017.

10. Rosenberg LB, Greenwald J, Caponi B, et al. Confidence with and Barriers to Serious Illness Communication: A National Survey of Hospitalists. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(9):1013-1019. PubMed

11. Aldridge MD, Kelley AS. The Myth Regarding the High Cost of End-of-Life Care. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(12):2411-2415. PubMed

12. Enguidanos S, Vesper E, Lorenz K. 30-Day Readmissions among Seriously Ill Older Adults. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(12):1356-1361. PubMed

13. Kripalani S, Theobald C, Anctil B, Vasilevskis E. Reducing Hospital Readmission Rates: Current Strategies and Future Directions. Annu Rev Med. 2014;65:471-485. PubMed

14. Senot C, Chandrasekaran A. What Has the Biggest Impact on Hospital Readmission Rates. Harvard Business Review. September 23, 2015. https://hbr.org/2015/09/what-has-the-biggest-impact-on-hospital-readmission-rates. Accessed March 29, 2017.

15. Morrison RS, Penrod JD, Cassel JB, et al. Cost Savings Associated with US Hospital Palliative Care Consultation Programs. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(16):1783-1790. PubMed

16. Cassel JB. Palliative Care’s Impact on Utilization and Costs: Implications for Health Services Research and Policy. In: Kelley AS, Meier DE, editors. Meeting the Needs of Older Adults with Serious Illness: Challenges and Opportunities in the Age of Health Care Reform. New York: Springer Science+Business Media; 2014:109-126.

17. Meier D, Silvers A. Serious Illness Strategies for Health Plans and Accountable Care Organizations. https://media.capc.org/filer_public/2c/69/2c69a0f0-c90f-43ac-893e-e90cd0438482/serious_illness_strategies_web.pdf. 2017. Accessed August 10, 2017.

18. Casarett D, Johnson M, Smith D, Richardson D. The Optimal Delivery of Palliative Care: A National Comparison of the Outcomes of Consultation Teams vs Inpatient Units. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(7):649-655. PubMed

19. Bernacki RE, Block SD. Communication About Serious Illness Care Goals: A Review and Synthesis of Best Practices. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(12):1994-2003. PubMed

20. Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations Between End-of-Life Discussions, Patient Mental Health, Medical Care Near Death, and Caregiver Bereavement Adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300(14):1665-1673. PubMed

21. May P, Garrido M, Cassel JB, et al. Cost Analysis of a Prospective Multi-Site Cohort Study of Palliative Care Consultation Teams for Adults with Advanced Cancer: Where Do Cost Savings Come From? Palliat Med. 2017;31(4):378-386. PubMed

22. Norton SA, Hogan LA, Holloway RG, et al. Proactive Palliative Care in the Medical Intensive Care Unit: Effects of Length of Stay for Selected High-Risk Patients. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(6):1530-1535. PubMed

23. Gade G, Venohr I, Conner D, et al. Impact of an Inpatient Palliative Care Team: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(2):180-201. PubMed

24. Adelson K, Paris J, Horton J, et al. Standardized Criteria for Palliative Care Consultation on a Solid Tumor Oncology Service Reduces Downstream Health Care use. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13(5):e431-e440. PubMed

25. Lustbader D, Mitchell M, Carole R, et al. The Impact of a Home-Based Palliative Care Program in an Accountable Care Organization. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(1):23-28. PubMed

26. May P, Normand C, Morrison R. Economic Impact of Hospital Inpatient Palliative Care Consultation: Review of Current Evidence and Directions for Future Research. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(9):1054-1063. PubMed

27. May P, Garrido MM, Bassel JB, et al. Prospective Cohort Study of Hospital Palliative Care Teams for Inpatients with Advanced Cancer: Earlier Consultation Is Associated with Larger Cost-Saving Effect. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(25):2745-2752. PubMed

28. Boissy A, Windover A, Bokar D, et al. Communication Skills Training for Physicians Improves Patient Satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(7):755-761. PubMed

29. Kirkland KB. Finding Joy in Practice Cocreation in Palliative Care. JAMA. 2017;317(20):2065-2066. PubMed

30. Whelan C. SHM Establishes Palliative Care Task Force. The Hospitalist. 2005;11. http://www.the-hospitalist.org/hospitalist/article/123027/hospice-palliative-medicine/shm-establishes-palliative-care-task-force. Accessed July 31, 2017.

31. Grudzen CR, Richardson LD, Major-Monfried H, et al. Hospital Administrators’ Views on Barriers and Opportunities to Delivering Palliative Care in the Emergency Department. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;61(6):654-660. PubMed

1. Casarett D, Pickard A, Bailey FA, et al. Do Palliative Consultations Improve Patient Outcomes? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(4):595-599. PubMed

2. Delgado-Guay MO, Parsons HA, Zhijun LM, Palmer LJ, Bruera E. Symptom distress, interventions, and outcomes of intensive care unit cancer patients referred to a palliative care consult team. Cancer. 2009;115(2):437-445. PubMed

3. Gelfman LP, Meier DE, Morrison SR. Does Palliative Care Improve Quality? A Survey of Bereaved Family Members. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;36(1):22-28. PubMed

4. Morrison SR, Dietrich J, Ladwig S, et al. Palliative Care Consultation Teams Cut Hospital Costs for Medicaid Beneficiaries. Health Aff. 2011;30:454-463. PubMed

5. Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non‐small‐cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733-742. PubMed

6. Lin RJ, Adelman RD, Diamond RR, Evans AT. The Sentinel Hospitalization and the Role of Palliative Care. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(5):320-323. PubMed

7. Palliative care. J Hosp Med. 2006;1:80-81. doi:10.1002/jhm.54.

8. Center to Advance Palliative Care. National palliative care registry. https://registry.capc.org/. Accessed May 26, 2017.

9. Rogers M, Dumanovsky T. How We Work: Trends and Insights in Hospital Palliative Care. New York: The Center to Advance Palliative Care and the National Palliative Care Research Center. https://registry.capc.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/How-We-Work-Trends-and-Insights-in-Hospital-Palliative-Care-2009-2015.pdf; 2017. Accessed May 26, 2017.

10. Rosenberg LB, Greenwald J, Caponi B, et al. Confidence with and Barriers to Serious Illness Communication: A National Survey of Hospitalists. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(9):1013-1019. PubMed

11. Aldridge MD, Kelley AS. The Myth Regarding the High Cost of End-of-Life Care. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(12):2411-2415. PubMed

12. Enguidanos S, Vesper E, Lorenz K. 30-Day Readmissions among Seriously Ill Older Adults. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(12):1356-1361. PubMed

13. Kripalani S, Theobald C, Anctil B, Vasilevskis E. Reducing Hospital Readmission Rates: Current Strategies and Future Directions. Annu Rev Med. 2014;65:471-485. PubMed

14. Senot C, Chandrasekaran A. What Has the Biggest Impact on Hospital Readmission Rates. Harvard Business Review. September 23, 2015. https://hbr.org/2015/09/what-has-the-biggest-impact-on-hospital-readmission-rates. Accessed March 29, 2017.

15. Morrison RS, Penrod JD, Cassel JB, et al. Cost Savings Associated with US Hospital Palliative Care Consultation Programs. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(16):1783-1790. PubMed

16. Cassel JB. Palliative Care’s Impact on Utilization and Costs: Implications for Health Services Research and Policy. In: Kelley AS, Meier DE, editors. Meeting the Needs of Older Adults with Serious Illness: Challenges and Opportunities in the Age of Health Care Reform. New York: Springer Science+Business Media; 2014:109-126.

17. Meier D, Silvers A. Serious Illness Strategies for Health Plans and Accountable Care Organizations. https://media.capc.org/filer_public/2c/69/2c69a0f0-c90f-43ac-893e-e90cd0438482/serious_illness_strategies_web.pdf. 2017. Accessed August 10, 2017.

18. Casarett D, Johnson M, Smith D, Richardson D. The Optimal Delivery of Palliative Care: A National Comparison of the Outcomes of Consultation Teams vs Inpatient Units. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(7):649-655. PubMed

19. Bernacki RE, Block SD. Communication About Serious Illness Care Goals: A Review and Synthesis of Best Practices. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(12):1994-2003. PubMed

20. Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations Between End-of-Life Discussions, Patient Mental Health, Medical Care Near Death, and Caregiver Bereavement Adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300(14):1665-1673. PubMed

21. May P, Garrido M, Cassel JB, et al. Cost Analysis of a Prospective Multi-Site Cohort Study of Palliative Care Consultation Teams for Adults with Advanced Cancer: Where Do Cost Savings Come From? Palliat Med. 2017;31(4):378-386. PubMed

22. Norton SA, Hogan LA, Holloway RG, et al. Proactive Palliative Care in the Medical Intensive Care Unit: Effects of Length of Stay for Selected High-Risk Patients. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(6):1530-1535. PubMed

23. Gade G, Venohr I, Conner D, et al. Impact of an Inpatient Palliative Care Team: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(2):180-201. PubMed

24. Adelson K, Paris J, Horton J, et al. Standardized Criteria for Palliative Care Consultation on a Solid Tumor Oncology Service Reduces Downstream Health Care use. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13(5):e431-e440. PubMed

25. Lustbader D, Mitchell M, Carole R, et al. The Impact of a Home-Based Palliative Care Program in an Accountable Care Organization. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(1):23-28. PubMed

26. May P, Normand C, Morrison R. Economic Impact of Hospital Inpatient Palliative Care Consultation: Review of Current Evidence and Directions for Future Research. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(9):1054-1063. PubMed

27. May P, Garrido MM, Bassel JB, et al. Prospective Cohort Study of Hospital Palliative Care Teams for Inpatients with Advanced Cancer: Earlier Consultation Is Associated with Larger Cost-Saving Effect. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(25):2745-2752. PubMed

28. Boissy A, Windover A, Bokar D, et al. Communication Skills Training for Physicians Improves Patient Satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(7):755-761. PubMed

29. Kirkland KB. Finding Joy in Practice Cocreation in Palliative Care. JAMA. 2017;317(20):2065-2066. PubMed

30. Whelan C. SHM Establishes Palliative Care Task Force. The Hospitalist. 2005;11. http://www.the-hospitalist.org/hospitalist/article/123027/hospice-palliative-medicine/shm-establishes-palliative-care-task-force. Accessed July 31, 2017.

31. Grudzen CR, Richardson LD, Major-Monfried H, et al. Hospital Administrators’ Views on Barriers and Opportunities to Delivering Palliative Care in the Emergency Department. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;61(6):654-660. PubMed

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine