User login

A long-acting, intramuscular (IM) naltrexone formulation—which at press time awaited FDA approval (Table)—could improve adherence to alcohol dependency pharmacotherapy.

Oral naltrexone can reduce alcohol consumption1 and relapse rates,1,2 but patients often stop taking it3 and increase their risk of relapse.2 Once-daily dosing, inconsistent motivation toward treatment, and cognitive impairment secondary to chronic alcohol dependence often thwart oral naltrexone therapy.

By contrast, IM naltrexone surmounts most compliance issues because you or a clinical assistant administer the drug. Short-term side effects—such as nausea for 2 days—are less likely to affect adherence because the medication keeps working weeks after side effects abate. This gives you time before the next dose to reassure the patient and gives the patient the benefits of continued treatment.

Table

IM naltrexone: Fast facts

| Drug brand name: Vivitrol |

| Class: Opioid antagonist |

| Prospective indication: Alcohol dependence |

| FDA action: Issued approvable letter Dec. 28, 2005 |

| Manufacturer: Alkermes |

| Dosing forms: 380 mg suspension via IM injection |

| Recommended dosage: 380 mg once monthly |

| Estimated date of availability: Spring 2006 |

How naltrexone works

Alcohol stimulates release of endogenous opioids, which in turn stimulate release of dopamine, which mediates reinforcement.4 Opioid receptor stimulation not associated with dopamine also reinforces alcohol use.5 Persons vulnerable to alcohol dependence generally have lower basal levels of opioid secretion and are stimulated at higher levels.6 Opioids also increase dopamine by inhibiting GABA neurons, which suppress dopamine release when uninhibited.

As an opioid antagonist, naltrexone prevents opioids from binding with μ-opioid receptors and modulates dopamine production. This may make drinking less “rewarding” and may reduce craving triggered by conditioned cues associated with alcohol use.

IM naltrexone is packaged in biodegradable microspheres that slowly release naltrexone for 1 month after injection. The microspheres are made of a polyactide-co-glycolide polymer used in other extended-release drugs and in absorbable sutures.

Pharmacokinetics

IM naltrexone plasma levels peak 2 to 3 days after injection, then decline gradually over 30 days. Oral naltrexone dosed at 50 mg/d for 30 days—a cumulative dose of 1,500 mg/month—produces daily peak plasma levels of approximately 10 ng/mL and troughs approaching zero. A once-monthly IM naltrexone injection results in a lower net dose but more-sustained naltrexone levels.

Efficacy

IM naltrexone significantly reduced heavy drinking among alcohol-dependent patients in a phase 3 randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial.7 Actively drinking adults who met DSM-IV criteria for alcohol dependence (N=624) received IM naltrexone, 190 or 380 mg, or placebo every 4 weeks for 6 months. Oral naltrexone lead-in doses were not given. All patients also received 12 sessions of standardized supportive psychosocial therapy during the study.

The primary efficacy measure was event rate of heavy drinking, defined as number of heavy drinking days (≥5 drinks/day for men, ≥4 drinks/day for women) divided by number of days in the study. An event rate ratio (treatment-group to placebo-group event rate) was then estimated over time, taking into account patients who discontinued the study.

After 6 months, event rate of heavy drinking fell 25% among patients receiving 380 mg of IM naltrexone and supportive therapy, compared with patients receiving placebo and supportive therapy (P=0.02). That rate decreased 17% among patients who received 190 mg of IM naltrexone compared with placebo, but the difference between the two treatment groups was not statistically significant (P=0.07).

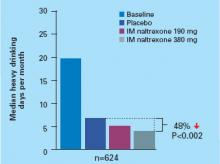

The median number of heavy drinking days per month decreased substantially across 6 months among all study groups. The decrease was more substantial among patients taking IM naltrexone, 380 mg, than among the placebo group (Figure).

Roughly 8% of patients abstained from drinking for 7 days before entering the study. Among patients who received 380 mg of IM naltrexone:

- those who were abstinent before the study had an 80% greater reduction in event rate of heavy drinking compared with placebo

- nonabstinent patients showed a 21% greater reduction in event rate of heavy drinking compared with placebo.

These findings suggest that IM naltrexone is more effective in persons abstaining from drinking but can also help actively drinking patients.

IM naltrexone also reduced heavy drinking among patients who entered a 1-year open-label extension study after completing the 6-month study.8 Drinking reductions were greater among patients who received 380 mg of naltrexone during both the 6-month and 1-year trials than among those who received placebo for 6 months and were switched to naltrexone, 380 mg, in the 1-year extension.

Figure Median heavy drinking days after 6 months of IM naltrexone or placebo

Source: Reference 7

Tolerability

IM naltrexone was well-tolerated in the phase 3 trial.7 Most-common adverse effects included

- nausea (reported by 33% of patients receiving 380 mg [n=205] and 25% of those receiving 190 mg [n=210])

- headache (22%, 16%)

- fatigue (20%, 16%).

At 380 mg, decreased appetite (13%), dizziness (13%), and injection site pain (12%) also differed significantly from placebo. Nausea was rated as mild or moderate in 95% of cases, usually occurred only after the first injection, and lasted 1 to 2 days on average.

Nine percent of patients taking naltrexone, 190 mg, or placebo also reported injection site pain. Approximately 1% of all patients dropped out because of injection site reactions.

Patients generally adhered to treatment, with 64% receiving 6 injections and 74% receiving at least 4. By comparison, a meta-analysis3 of oral naltrexone clinical trials showed an average 50% retention rate across studies, most of which lasted only 3 months. Study withdrawals because of adverse events were more prevalent among patients receiving IM naltrexone, 380 mg (14.1%), than among the placebo group (6.7%), but the number of serious adverse events differed little.7

Liver enzymes (AST and ALT) did not change significantly during the study. Gamma-glutamyltransferase decreased in all patients, consistent with reduced drinking.

Interactions between IM naltrexone and other medications are probably similar to those observed with oral naltrexone.

Contraindications

Although product labeling was not available when this article was written, IM naltrexone, like its oral form, will likely be contraindicated for patients who:

- are taking opioid analgesics

- are in acute opioid withdrawal

- test positive on urine screen for opioids

- have acute hepatitis or liver failure

- are taking maintenance methadone or buprenorphine or are opioid-dependent.

Patients should be opioid-free for 7 to 10 days before starting IM naltrexone to avoid acute withdrawal symptoms.

Before starting IM naltrexone in patients with a history of opioid abuse, give naloxone, 0.8 mg, to test for withdrawal. Do not start naltrexone if the patient shows signs of opioid withdrawal within 20 minutes of receiving naloxone.

Clinical implications

Long-acting IM naltrexone will make it easier to ensure treatment adherence, compared with oral naltrexone. Giving the drug during the office visit will change your practice patterns, but this increase in hands-on care could strengthen the therapeutic alliance. Compared with interpreting patient self-reports, you can also more accurately document adherence to IM naltrexone therapy.

All alcohol-dependence medications work best when combined with psychosocial treatment, and monthly medication visits alone will not provide patients the cognitive and skill-building work they need to recover. Patients early in recovery need to be seen much more often by you and/or another provider of recovery-oriented psychosocial treatment.

Which patients will be more receptive to in-office treatment is unclear. Patients who have relapsed because of nonadherence to oral medications may be more willing to try IM therapy after you explain its benefits. Similarly, IM naltrexone may be more beneficial to patients who:

- cannot adhere to oral medication because of cognitive problems or impulsivity

- face severe consequences—such as legal problems, loss of parental custody, or loss of employment—if treatment fails.

The optimal duration of IM naltrexone therapy is not known, but the injectable has shown efficacy after 6 months7 and 1 year.8 Some patients have taken it for more than 3 years.8 Before stopping IM naltrexone, consider whether the patient:

- has achieved sobriety

- has developed skills and external support to maintain sobriety

- has reduced craving intensity or time spent preoccupied with alcohol

- shows improved global psychosocial function as reflected in improved relationships, work performance, and general health.

Patients with family histories of alcohol dependence and who reduce days of heavy drinking but do not achieve sobriety on IM naltrexone are probably at higher risk of relapse to heavy drinking after stopping the medication.

Related resources

- Injectable naltrexone Web site. http://alkermes2005.ifactory.com/products/naltrexone.html.

Drug brand names

- IM naltrexone • Vivitrol

- Oral naltrexone • Depade

- Naloxone • Narcan

Disclosure

Dr. Rosenthal is a consultant for Forest Laboratories and Alkermes.

1. Anton RF, Moak DH, Waid LR, et al. Naltrexone and cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of outpatient alcoholics: results of a placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 1999;156:1758-64.

2. Pettinati HM, Volpicelli JR, Pierce JD, Jr, O’Brien CP. Improving naltrexone response: An intervention for medical practitioners toenhance medication compliance in alcohol dependent patients. J Addict Dis 2000;19:71-83.

3. Bouza C, Magro A, Munoz A, Amate J. Efficacy and safety of naltrexone and acamprosate in the treatment of alcohol dependence: a systematic review. Addiction 2004;99:811-28.

4. Weiss F, Lorang MT, Bloom FE, Koob GF. Oral alcohol self-administration stimulates dopamine release in the rat nucleus accumbens: genetic and motivational determinants. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1993;267:250-8.

5. Pettit HO, Ettenberg A, Bloom FE, Koob GF. Destruction of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens selectively attenuates cocaine but not heroin self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1984;84:167-73.

6. Gianoulakis C. Characterization of the effects of acute ethanol administration on the release of beta-endorphin peptides by the rat hypothalamus. Eur J Pharmacol 1990;180:21-9.

7. Garbutt JC, Kranzler HR, O’Malley SS, et al. Vivitrex Study Group. Efficacy and tolerability of long-acting injectable naltrexone for alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2005;293:1617-25.

8. Gastfriend DR, Dong Q, Loewy J, et al. Durability of effect of long-acting injectable naltrexone. Presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; 2005; Atlanta, GA.

A long-acting, intramuscular (IM) naltrexone formulation—which at press time awaited FDA approval (Table)—could improve adherence to alcohol dependency pharmacotherapy.

Oral naltrexone can reduce alcohol consumption1 and relapse rates,1,2 but patients often stop taking it3 and increase their risk of relapse.2 Once-daily dosing, inconsistent motivation toward treatment, and cognitive impairment secondary to chronic alcohol dependence often thwart oral naltrexone therapy.

By contrast, IM naltrexone surmounts most compliance issues because you or a clinical assistant administer the drug. Short-term side effects—such as nausea for 2 days—are less likely to affect adherence because the medication keeps working weeks after side effects abate. This gives you time before the next dose to reassure the patient and gives the patient the benefits of continued treatment.

Table

IM naltrexone: Fast facts

| Drug brand name: Vivitrol |

| Class: Opioid antagonist |

| Prospective indication: Alcohol dependence |

| FDA action: Issued approvable letter Dec. 28, 2005 |

| Manufacturer: Alkermes |

| Dosing forms: 380 mg suspension via IM injection |

| Recommended dosage: 380 mg once monthly |

| Estimated date of availability: Spring 2006 |

How naltrexone works

Alcohol stimulates release of endogenous opioids, which in turn stimulate release of dopamine, which mediates reinforcement.4 Opioid receptor stimulation not associated with dopamine also reinforces alcohol use.5 Persons vulnerable to alcohol dependence generally have lower basal levels of opioid secretion and are stimulated at higher levels.6 Opioids also increase dopamine by inhibiting GABA neurons, which suppress dopamine release when uninhibited.

As an opioid antagonist, naltrexone prevents opioids from binding with μ-opioid receptors and modulates dopamine production. This may make drinking less “rewarding” and may reduce craving triggered by conditioned cues associated with alcohol use.

IM naltrexone is packaged in biodegradable microspheres that slowly release naltrexone for 1 month after injection. The microspheres are made of a polyactide-co-glycolide polymer used in other extended-release drugs and in absorbable sutures.

Pharmacokinetics

IM naltrexone plasma levels peak 2 to 3 days after injection, then decline gradually over 30 days. Oral naltrexone dosed at 50 mg/d for 30 days—a cumulative dose of 1,500 mg/month—produces daily peak plasma levels of approximately 10 ng/mL and troughs approaching zero. A once-monthly IM naltrexone injection results in a lower net dose but more-sustained naltrexone levels.

Efficacy

IM naltrexone significantly reduced heavy drinking among alcohol-dependent patients in a phase 3 randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial.7 Actively drinking adults who met DSM-IV criteria for alcohol dependence (N=624) received IM naltrexone, 190 or 380 mg, or placebo every 4 weeks for 6 months. Oral naltrexone lead-in doses were not given. All patients also received 12 sessions of standardized supportive psychosocial therapy during the study.

The primary efficacy measure was event rate of heavy drinking, defined as number of heavy drinking days (≥5 drinks/day for men, ≥4 drinks/day for women) divided by number of days in the study. An event rate ratio (treatment-group to placebo-group event rate) was then estimated over time, taking into account patients who discontinued the study.

After 6 months, event rate of heavy drinking fell 25% among patients receiving 380 mg of IM naltrexone and supportive therapy, compared with patients receiving placebo and supportive therapy (P=0.02). That rate decreased 17% among patients who received 190 mg of IM naltrexone compared with placebo, but the difference between the two treatment groups was not statistically significant (P=0.07).

The median number of heavy drinking days per month decreased substantially across 6 months among all study groups. The decrease was more substantial among patients taking IM naltrexone, 380 mg, than among the placebo group (Figure).

Roughly 8% of patients abstained from drinking for 7 days before entering the study. Among patients who received 380 mg of IM naltrexone:

- those who were abstinent before the study had an 80% greater reduction in event rate of heavy drinking compared with placebo

- nonabstinent patients showed a 21% greater reduction in event rate of heavy drinking compared with placebo.

These findings suggest that IM naltrexone is more effective in persons abstaining from drinking but can also help actively drinking patients.

IM naltrexone also reduced heavy drinking among patients who entered a 1-year open-label extension study after completing the 6-month study.8 Drinking reductions were greater among patients who received 380 mg of naltrexone during both the 6-month and 1-year trials than among those who received placebo for 6 months and were switched to naltrexone, 380 mg, in the 1-year extension.

Figure Median heavy drinking days after 6 months of IM naltrexone or placebo

Source: Reference 7

Tolerability

IM naltrexone was well-tolerated in the phase 3 trial.7 Most-common adverse effects included

- nausea (reported by 33% of patients receiving 380 mg [n=205] and 25% of those receiving 190 mg [n=210])

- headache (22%, 16%)

- fatigue (20%, 16%).

At 380 mg, decreased appetite (13%), dizziness (13%), and injection site pain (12%) also differed significantly from placebo. Nausea was rated as mild or moderate in 95% of cases, usually occurred only after the first injection, and lasted 1 to 2 days on average.

Nine percent of patients taking naltrexone, 190 mg, or placebo also reported injection site pain. Approximately 1% of all patients dropped out because of injection site reactions.

Patients generally adhered to treatment, with 64% receiving 6 injections and 74% receiving at least 4. By comparison, a meta-analysis3 of oral naltrexone clinical trials showed an average 50% retention rate across studies, most of which lasted only 3 months. Study withdrawals because of adverse events were more prevalent among patients receiving IM naltrexone, 380 mg (14.1%), than among the placebo group (6.7%), but the number of serious adverse events differed little.7

Liver enzymes (AST and ALT) did not change significantly during the study. Gamma-glutamyltransferase decreased in all patients, consistent with reduced drinking.

Interactions between IM naltrexone and other medications are probably similar to those observed with oral naltrexone.

Contraindications

Although product labeling was not available when this article was written, IM naltrexone, like its oral form, will likely be contraindicated for patients who:

- are taking opioid analgesics

- are in acute opioid withdrawal

- test positive on urine screen for opioids

- have acute hepatitis or liver failure

- are taking maintenance methadone or buprenorphine or are opioid-dependent.

Patients should be opioid-free for 7 to 10 days before starting IM naltrexone to avoid acute withdrawal symptoms.

Before starting IM naltrexone in patients with a history of opioid abuse, give naloxone, 0.8 mg, to test for withdrawal. Do not start naltrexone if the patient shows signs of opioid withdrawal within 20 minutes of receiving naloxone.

Clinical implications

Long-acting IM naltrexone will make it easier to ensure treatment adherence, compared with oral naltrexone. Giving the drug during the office visit will change your practice patterns, but this increase in hands-on care could strengthen the therapeutic alliance. Compared with interpreting patient self-reports, you can also more accurately document adherence to IM naltrexone therapy.

All alcohol-dependence medications work best when combined with psychosocial treatment, and monthly medication visits alone will not provide patients the cognitive and skill-building work they need to recover. Patients early in recovery need to be seen much more often by you and/or another provider of recovery-oriented psychosocial treatment.

Which patients will be more receptive to in-office treatment is unclear. Patients who have relapsed because of nonadherence to oral medications may be more willing to try IM therapy after you explain its benefits. Similarly, IM naltrexone may be more beneficial to patients who:

- cannot adhere to oral medication because of cognitive problems or impulsivity

- face severe consequences—such as legal problems, loss of parental custody, or loss of employment—if treatment fails.

The optimal duration of IM naltrexone therapy is not known, but the injectable has shown efficacy after 6 months7 and 1 year.8 Some patients have taken it for more than 3 years.8 Before stopping IM naltrexone, consider whether the patient:

- has achieved sobriety

- has developed skills and external support to maintain sobriety

- has reduced craving intensity or time spent preoccupied with alcohol

- shows improved global psychosocial function as reflected in improved relationships, work performance, and general health.

Patients with family histories of alcohol dependence and who reduce days of heavy drinking but do not achieve sobriety on IM naltrexone are probably at higher risk of relapse to heavy drinking after stopping the medication.

Related resources

- Injectable naltrexone Web site. http://alkermes2005.ifactory.com/products/naltrexone.html.

Drug brand names

- IM naltrexone • Vivitrol

- Oral naltrexone • Depade

- Naloxone • Narcan

Disclosure

Dr. Rosenthal is a consultant for Forest Laboratories and Alkermes.

A long-acting, intramuscular (IM) naltrexone formulation—which at press time awaited FDA approval (Table)—could improve adherence to alcohol dependency pharmacotherapy.

Oral naltrexone can reduce alcohol consumption1 and relapse rates,1,2 but patients often stop taking it3 and increase their risk of relapse.2 Once-daily dosing, inconsistent motivation toward treatment, and cognitive impairment secondary to chronic alcohol dependence often thwart oral naltrexone therapy.

By contrast, IM naltrexone surmounts most compliance issues because you or a clinical assistant administer the drug. Short-term side effects—such as nausea for 2 days—are less likely to affect adherence because the medication keeps working weeks after side effects abate. This gives you time before the next dose to reassure the patient and gives the patient the benefits of continued treatment.

Table

IM naltrexone: Fast facts

| Drug brand name: Vivitrol |

| Class: Opioid antagonist |

| Prospective indication: Alcohol dependence |

| FDA action: Issued approvable letter Dec. 28, 2005 |

| Manufacturer: Alkermes |

| Dosing forms: 380 mg suspension via IM injection |

| Recommended dosage: 380 mg once monthly |

| Estimated date of availability: Spring 2006 |

How naltrexone works

Alcohol stimulates release of endogenous opioids, which in turn stimulate release of dopamine, which mediates reinforcement.4 Opioid receptor stimulation not associated with dopamine also reinforces alcohol use.5 Persons vulnerable to alcohol dependence generally have lower basal levels of opioid secretion and are stimulated at higher levels.6 Opioids also increase dopamine by inhibiting GABA neurons, which suppress dopamine release when uninhibited.

As an opioid antagonist, naltrexone prevents opioids from binding with μ-opioid receptors and modulates dopamine production. This may make drinking less “rewarding” and may reduce craving triggered by conditioned cues associated with alcohol use.

IM naltrexone is packaged in biodegradable microspheres that slowly release naltrexone for 1 month after injection. The microspheres are made of a polyactide-co-glycolide polymer used in other extended-release drugs and in absorbable sutures.

Pharmacokinetics

IM naltrexone plasma levels peak 2 to 3 days after injection, then decline gradually over 30 days. Oral naltrexone dosed at 50 mg/d for 30 days—a cumulative dose of 1,500 mg/month—produces daily peak plasma levels of approximately 10 ng/mL and troughs approaching zero. A once-monthly IM naltrexone injection results in a lower net dose but more-sustained naltrexone levels.

Efficacy

IM naltrexone significantly reduced heavy drinking among alcohol-dependent patients in a phase 3 randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial.7 Actively drinking adults who met DSM-IV criteria for alcohol dependence (N=624) received IM naltrexone, 190 or 380 mg, or placebo every 4 weeks for 6 months. Oral naltrexone lead-in doses were not given. All patients also received 12 sessions of standardized supportive psychosocial therapy during the study.

The primary efficacy measure was event rate of heavy drinking, defined as number of heavy drinking days (≥5 drinks/day for men, ≥4 drinks/day for women) divided by number of days in the study. An event rate ratio (treatment-group to placebo-group event rate) was then estimated over time, taking into account patients who discontinued the study.

After 6 months, event rate of heavy drinking fell 25% among patients receiving 380 mg of IM naltrexone and supportive therapy, compared with patients receiving placebo and supportive therapy (P=0.02). That rate decreased 17% among patients who received 190 mg of IM naltrexone compared with placebo, but the difference between the two treatment groups was not statistically significant (P=0.07).

The median number of heavy drinking days per month decreased substantially across 6 months among all study groups. The decrease was more substantial among patients taking IM naltrexone, 380 mg, than among the placebo group (Figure).

Roughly 8% of patients abstained from drinking for 7 days before entering the study. Among patients who received 380 mg of IM naltrexone:

- those who were abstinent before the study had an 80% greater reduction in event rate of heavy drinking compared with placebo

- nonabstinent patients showed a 21% greater reduction in event rate of heavy drinking compared with placebo.

These findings suggest that IM naltrexone is more effective in persons abstaining from drinking but can also help actively drinking patients.

IM naltrexone also reduced heavy drinking among patients who entered a 1-year open-label extension study after completing the 6-month study.8 Drinking reductions were greater among patients who received 380 mg of naltrexone during both the 6-month and 1-year trials than among those who received placebo for 6 months and were switched to naltrexone, 380 mg, in the 1-year extension.

Figure Median heavy drinking days after 6 months of IM naltrexone or placebo

Source: Reference 7

Tolerability

IM naltrexone was well-tolerated in the phase 3 trial.7 Most-common adverse effects included

- nausea (reported by 33% of patients receiving 380 mg [n=205] and 25% of those receiving 190 mg [n=210])

- headache (22%, 16%)

- fatigue (20%, 16%).

At 380 mg, decreased appetite (13%), dizziness (13%), and injection site pain (12%) also differed significantly from placebo. Nausea was rated as mild or moderate in 95% of cases, usually occurred only after the first injection, and lasted 1 to 2 days on average.

Nine percent of patients taking naltrexone, 190 mg, or placebo also reported injection site pain. Approximately 1% of all patients dropped out because of injection site reactions.

Patients generally adhered to treatment, with 64% receiving 6 injections and 74% receiving at least 4. By comparison, a meta-analysis3 of oral naltrexone clinical trials showed an average 50% retention rate across studies, most of which lasted only 3 months. Study withdrawals because of adverse events were more prevalent among patients receiving IM naltrexone, 380 mg (14.1%), than among the placebo group (6.7%), but the number of serious adverse events differed little.7

Liver enzymes (AST and ALT) did not change significantly during the study. Gamma-glutamyltransferase decreased in all patients, consistent with reduced drinking.

Interactions between IM naltrexone and other medications are probably similar to those observed with oral naltrexone.

Contraindications

Although product labeling was not available when this article was written, IM naltrexone, like its oral form, will likely be contraindicated for patients who:

- are taking opioid analgesics

- are in acute opioid withdrawal

- test positive on urine screen for opioids

- have acute hepatitis or liver failure

- are taking maintenance methadone or buprenorphine or are opioid-dependent.

Patients should be opioid-free for 7 to 10 days before starting IM naltrexone to avoid acute withdrawal symptoms.

Before starting IM naltrexone in patients with a history of opioid abuse, give naloxone, 0.8 mg, to test for withdrawal. Do not start naltrexone if the patient shows signs of opioid withdrawal within 20 minutes of receiving naloxone.

Clinical implications

Long-acting IM naltrexone will make it easier to ensure treatment adherence, compared with oral naltrexone. Giving the drug during the office visit will change your practice patterns, but this increase in hands-on care could strengthen the therapeutic alliance. Compared with interpreting patient self-reports, you can also more accurately document adherence to IM naltrexone therapy.

All alcohol-dependence medications work best when combined with psychosocial treatment, and monthly medication visits alone will not provide patients the cognitive and skill-building work they need to recover. Patients early in recovery need to be seen much more often by you and/or another provider of recovery-oriented psychosocial treatment.

Which patients will be more receptive to in-office treatment is unclear. Patients who have relapsed because of nonadherence to oral medications may be more willing to try IM therapy after you explain its benefits. Similarly, IM naltrexone may be more beneficial to patients who:

- cannot adhere to oral medication because of cognitive problems or impulsivity

- face severe consequences—such as legal problems, loss of parental custody, or loss of employment—if treatment fails.

The optimal duration of IM naltrexone therapy is not known, but the injectable has shown efficacy after 6 months7 and 1 year.8 Some patients have taken it for more than 3 years.8 Before stopping IM naltrexone, consider whether the patient:

- has achieved sobriety

- has developed skills and external support to maintain sobriety

- has reduced craving intensity or time spent preoccupied with alcohol

- shows improved global psychosocial function as reflected in improved relationships, work performance, and general health.

Patients with family histories of alcohol dependence and who reduce days of heavy drinking but do not achieve sobriety on IM naltrexone are probably at higher risk of relapse to heavy drinking after stopping the medication.

Related resources

- Injectable naltrexone Web site. http://alkermes2005.ifactory.com/products/naltrexone.html.

Drug brand names

- IM naltrexone • Vivitrol

- Oral naltrexone • Depade

- Naloxone • Narcan

Disclosure

Dr. Rosenthal is a consultant for Forest Laboratories and Alkermes.

1. Anton RF, Moak DH, Waid LR, et al. Naltrexone and cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of outpatient alcoholics: results of a placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 1999;156:1758-64.

2. Pettinati HM, Volpicelli JR, Pierce JD, Jr, O’Brien CP. Improving naltrexone response: An intervention for medical practitioners toenhance medication compliance in alcohol dependent patients. J Addict Dis 2000;19:71-83.

3. Bouza C, Magro A, Munoz A, Amate J. Efficacy and safety of naltrexone and acamprosate in the treatment of alcohol dependence: a systematic review. Addiction 2004;99:811-28.

4. Weiss F, Lorang MT, Bloom FE, Koob GF. Oral alcohol self-administration stimulates dopamine release in the rat nucleus accumbens: genetic and motivational determinants. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1993;267:250-8.

5. Pettit HO, Ettenberg A, Bloom FE, Koob GF. Destruction of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens selectively attenuates cocaine but not heroin self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1984;84:167-73.

6. Gianoulakis C. Characterization of the effects of acute ethanol administration on the release of beta-endorphin peptides by the rat hypothalamus. Eur J Pharmacol 1990;180:21-9.

7. Garbutt JC, Kranzler HR, O’Malley SS, et al. Vivitrex Study Group. Efficacy and tolerability of long-acting injectable naltrexone for alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2005;293:1617-25.

8. Gastfriend DR, Dong Q, Loewy J, et al. Durability of effect of long-acting injectable naltrexone. Presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; 2005; Atlanta, GA.

1. Anton RF, Moak DH, Waid LR, et al. Naltrexone and cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of outpatient alcoholics: results of a placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 1999;156:1758-64.

2. Pettinati HM, Volpicelli JR, Pierce JD, Jr, O’Brien CP. Improving naltrexone response: An intervention for medical practitioners toenhance medication compliance in alcohol dependent patients. J Addict Dis 2000;19:71-83.

3. Bouza C, Magro A, Munoz A, Amate J. Efficacy and safety of naltrexone and acamprosate in the treatment of alcohol dependence: a systematic review. Addiction 2004;99:811-28.

4. Weiss F, Lorang MT, Bloom FE, Koob GF. Oral alcohol self-administration stimulates dopamine release in the rat nucleus accumbens: genetic and motivational determinants. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1993;267:250-8.

5. Pettit HO, Ettenberg A, Bloom FE, Koob GF. Destruction of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens selectively attenuates cocaine but not heroin self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1984;84:167-73.

6. Gianoulakis C. Characterization of the effects of acute ethanol administration on the release of beta-endorphin peptides by the rat hypothalamus. Eur J Pharmacol 1990;180:21-9.

7. Garbutt JC, Kranzler HR, O’Malley SS, et al. Vivitrex Study Group. Efficacy and tolerability of long-acting injectable naltrexone for alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2005;293:1617-25.

8. Gastfriend DR, Dong Q, Loewy J, et al. Durability of effect of long-acting injectable naltrexone. Presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; 2005; Atlanta, GA.