User login

Effective surgical management of advanced pelvic organ prolapse (POP) depends on prolapse location and stage, presence of urinary incontinence, need for hysterectomy, the patient’s desire to maintain sexual function, type of surgery, and the surgeon’s skill and experience, among other factors. For these reasons, POP repair is not a one-size-fits all procedure.

In this article, experts in minimally invasive prolapse repair offer their perspectives on 3 surgical approaches: use of native tissue (Drs. White, Aguilar, and Rogers), abdominal sacrocolpopexy (Drs. Huber and Culligan), and transvaginal mesh (Drs. Lucente and Ton). They evaluate the evidence on these procedures and provide recommendations based on their experience of best practices for achieving surgical success and minimizing adverse events.

Using native tissue for vaginal anatomy repair

Amanda White, MD; Vivian Aguilar, MD; and Rebecca G. Rogers, MD

Dr. Rogers reports that she receives royalties from UpToDate. Drs. White and Aguilar report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Surgical therapy is the mainstay of treatment for POP, and 20% of US women will undergo prolapse and/or stress incontinence surgery by age 80.1 Prolapse surgery either restores the vaginal anatomy (reconstructive surgery) or obliterates the vaginal canal (obliterative surgery). Vaginal reconstruction can be performed using the patient's native tissue or mesh. Because of concerns associated with mesh use, native tissue repairs continue to be commonly performed.

Unfortunately, not all prolapse surgeries result in prolapse cure, and recurrent prolapse that necessitates repeat operation is not rare, regardless of whether or not mesh is used.2,3 Native tissue repairs are most commonly performed through the vaginal route, the first minimally invasive approach to prolapse surgery. Restoration of the vaginal apex has been identified as critically important in these surgeries. Apical native tissue repairs include reconstructive procedures, such as sacrospinous ligament suspension (SSLS) or uterosacral ligament suspension (USLS), and obliterative procedures, such as colpocleisis.

In this discussion, we present 2 case vignettes that highlight surgical decision making for repair of stage 3 or 4 pelvic organ prolapse utilizing these techniques.

- Native tissue repair offers a minimally invasive approach to prolapse repair.

- Sacrospinous and uterosacral ligament suspensions have equivalent success rates.

- Prophylactic midurethral slings reduce postoperative incontinence at the time of transvaginal native tissue repair.

- Hysterectomy at the time of colpocleisis should not be performed routinely.

CASE 1 Active woman with prolapse

A 65-year-old woman (G2P2) presents with stage 3 prolapse, with the anterior compartment at +3 and the cervix at the hymen with straining. She is sexually active and desires to retain coital function. A trial of pessary has failed.

What surgical options can be considered for this patient?

Reconstruction procedures for prolapse

This patient presents with a typical configuration of prolapse; the anterior and apical compartments are the most likely to prolapse.4 Importantly, conservative management of her prolapse has failed. While it is not required that women have a trial with pessary prior to undergoing surgery, all women should be offered conservative management of prolapse, according to the American Urogynecologic Society (AUGS) and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG).4,5

Apical suspension

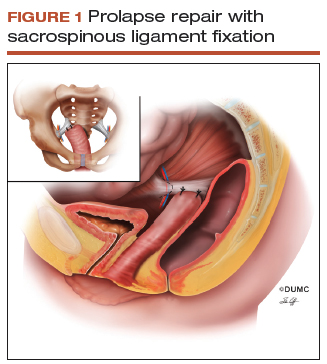

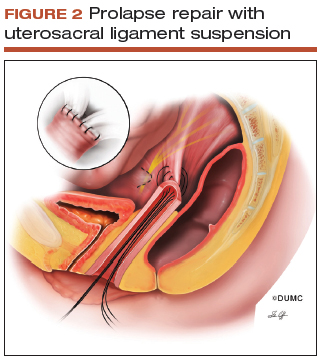

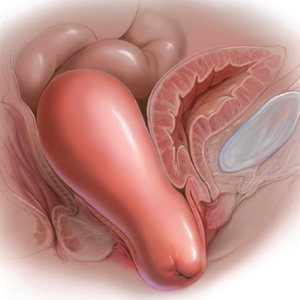

Since this patient desires to retain coital function, her gynecologist recommends a reconstructive procedure. The combination of apical and anterior vaginal wall prolapse will require an apical suspension procedure (FIGURES 1 and 2). If suspension of the apex does not correct the anterior wall prolapse, the patient also may require anterior compartment reconstruction.

The 2 most commonly performed native tissue apical suspension procedures, SSLS and USLS, have equivalent outcomes at 2 years, according to a multicenter randomized trial.6 Therefore, the choice of procedure is at the surgeon's discretion. USLS is most commonly performed at the time of hysterectomy via an intraperitoneal approach, while SSLS is often selected for posthysterectomy vault prolapse, given its extraperitoneal location.

Suture type. Whether to use permanent suture at the time of SSLS or USLS is controversial. Some data suggest that permanent suture provides greater long-term success compared with delayed absorbable suture.7 However, permanent suture has been reported to be associated with higher rates of suture complications--up to 44% in USLS and 36% in SSLS--compared with a 3.5% complication rate in a USLS cohort treated with absorbable suture.8-10

Hysterectomy versus hysteropexy. Considerable debate exists regarding whether a patient requires hysterectomy at the time of prolapse repair. In a randomized trial at 12 months' follow-up, uterine preservation by sacrospinous hysteropexy was noninferior to vaginal hysterectomy with suspension of the uterosacral ligaments for surgical failure of the apical compartment.11 A recent meta-analysis found that apical failure rates after sacrospinous hysteropexy versus vaginal hysterectomy were not different.12 Repeat surgery rates for prolapse also were not different between groups. The most significant disadvantage of uterine-preservation prolapse surgery, when compared with hysterectomy, is the lack of prevention and diagnosis of uterine malignancy.12 From 2002 to 2012, rates of hysteropexy significantly increased in the United States, although rates remain low.13

Sling procedure pros and cons. This case patient did not report urinary incontinence, but she may develop incontinence with reduction of the anterior wall prolapse. A large randomized controlled trial that included 337 women compared sling with no sling procedures among women with prolapse undergoing transvaginal prolapse repair.14 Management with a prophylactic sling resulted in less incontinence (27.3% and 43.0%, respectively, at 12 months postoperatively) but higher rates of urinary tract infection (31.0% vs 18.3%), major bleeding complications (3.1% vs 0%), and incomplete bladder emptying 6 weeks after surgery (3.7% vs 0%) (P≤.05 for all).14

CASE 1 Recommendations for this patient

For this case, we would offer the patient a transvaginal hysterectomy and USLS. At the time of repair, we would assess whether she needed an anterior repair as well. We would offer a prophylactic sling procedure and also would discuss the risks and benefits of concomitant versus interval incontinence procedures.

CASE 2 Elderly woman with severe prolapse

An 85-year-old woman (G3P3) presents with procidentia, or complete eversion of the vagina, with the cervix 10 cm outside of the hymen. She has difficulty voiding, and the prolapse is uncomfortable when walking. A trial of pessary has failed. The patient denies vaginal bleeding. She is not sexually active and does not desire to retain coital function.

What treatment options would be appropriate for this patient?

Obliterative surgery

This elderly patient presents with advanced pelvic organ prolapse, and conservative management has failed. She is not sexually active and does not desire coital function in the future, so an obliterative procedure is indicated. Colpocleisis is a minimally invasive procedure that has cure rates ranging from 91% to 100%.15 It is likely that this patient's voiding dysfunction will improve after surgery and that she will be highly satisfied with the surgery.16

The question of hysterectomy with colpocleisis

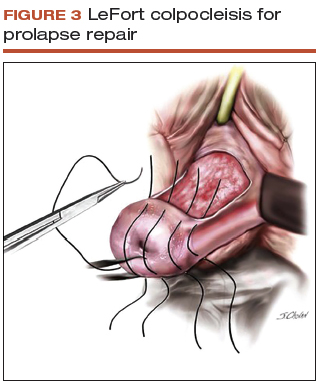

The role of hysterectomy at the time of colpocleisis is controversial. LeFort colpocleisis preserves the uterus, with the anterior and posterior vaginal walls sutured together (FIGURE 3). Hysterectomy at the time of vaginal closure increases the operative time and blood loss.15 On the other hand, closure without hysterectomy prohibits future endometrial or cervical cancer screening.

In a recent review using the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database, investigators compared women who underwent colopocleisis alone with those who underwent colpocleisis with hysterectomy.17 They found that the incidence of major complications was greater among women who underwent concomitant hysterectomy, and they concluded that hysterectomy should not be performed routinely at the time of colpocleisis.17

Among 322 urogynecologists who responded to a web-based survey, only 18% routinely performed hysterectomy at the time of colpocleisis.18 Further, in a decision analysis model, the utility for colpocleisis without hysterectomy was higher in women older than age 40, suggesting that hysterectomy should be performed only in special circumstances.19

Evaluating the endometrium. If the uterus remains in situ, should endometrial evaluation be performed? If so, should ultrasonography or endometrial biopsy be used? Authors of a decision analysis model found that among women at low risk for cancer and without abnormal uterine bleeding, endometrial biopsy was not favored until the probability of cancer reached 64%.20 Specifically, no evaluation or evaluation by transvaginal ultrasonography is adequate in the majority of cases.20 When screened by transvaginal ultrasonography, the high, 99% negative predictive value for endometrial disease, using a cutoff value of 5 mm for endometrial stripe width, will allow most patients to avoid unnecessary tissue sampling.

Stress incontinence. It is likely that this patient's voiding dysfunction will resolve with reduction of the prolapse, and she may develop stress incontinence symptoms. In up to 68% of women, occult stress incontinence will be revealed with reduction of stage 3 or stage 4 prolapse.21 If the patient demonstrates stress incontinence, a midurethral sling is likely to treat her incontinence effectively, with little added risk from the procedure.22 Even among women who have an elevated postvoid residual urine volume, the incidence of sling revision is low.15

CASE 2 Procedure recommendation for this patient

For this case, we would perform a LeFort colpocleisis and discuss whether or not the patient would prefer a midurethral sling if stress incontinence was demonstrated on examination. We would not perform endometrial evaluation in this patient, as she has not been bleeding and her risk for endometrial cancer is low.

Weighing the benefits of native tissue repair

Native tissue repair when performed transvaginally is a minimally invasive approach to prolapse repair. In a multicenter randomized trial, anatomic success was reported to be 64.5% at 2 years.6 Long-term follow up of patients undergoing mesh sacrocolpopexy shows a similar anatomic failure rate, with up to one-third of patients meeting the definition of composite failure.3 Unlike mesh-augmented repairs, however, adverse events, including bowel obstruction, mesh exposure, and thromboembolism, are more likely to occur in the mesh sacrocolpopexy group.23

Obliterative procedures have the highest success rates of all prolapse repairs and carry with them low morbidity. However, women must forego the ability for coitus in the future. For all native tissue vaginal repairs, the surgeon and patient must weigh the risks and benefits of concomitant anti-incontinence procedures.

Read about using abdominal sacrocolpopexy for apical prolapse repair.

Abdominal sacrocolpopexy: A tried-and-true approach for apical prolapse repair

Sarah Huber, MD, and Patrick Culligan, MD

Dr. Culligan reports that he is a shareholder in Oragami Surgical LLC and a consultant and speaker for Coloplast and Intuitive Surgical Inc. Dr. Huber reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

CASE Woman with advanced prolapse desires surgical repair

A 55-year-old woman (G2P2) presents to her gynecologist's office reporting a vaginal bulge and pressure that has been worsening for the past year. She describes a nontender ball of tissue the size of an orange protruding past the introitus that worsens with ambulating and lifting heavy objects. She reports some urinary urgency and increased frequency and at times feels as though her bladder does not empty completely with voiding. She denies any urinary incontinence. The patient has regular bowel movements but does report some difficulty with stool evacuation. She has a history of 2 vaginal deliveries and is sexually active. She is postmenopausal, with the last menses about 4 years ago. She is active and exercises regularly.

The patient's Pap smears, mammograms, and colonoscopy are up to date and test results have been normal. She has no significant medical or surgical history and no significant family history of cancer. On examination, her body mass index is normal, as is the cardiopulmonary exam. Her pelvic organ prolapse quantification system (POP-Q) score is Aa +3, Ba +3, C +4, GH 3, PB 3, TVL 10, Ap +2, Bp +2, and D +2. The patient is interested in surgical management.

What urodynamic tests would be appropriate for this patient, and what treatment options would you recommend?

- Robot-assisted laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy is a safe, effective, and durable treatment for advanced-stage pelvic organ prolapse.

- This procedure can completely correct stage 3 or 4 prolapse when the dissection of the anterior vaginal wall extends to the bladder neck and the dissection of the posterior vaginal wall extends to the perineal body.

- One can avoid the need for concomitant vaginal prolapse repair by gathering up stretched out vaginal epithelium while suturing to the mesh arms.

- Sacral attachment sutures should be placed in the anterior longitudinal ligament distal to the sacral promontory to avoid the L5-S1 disc.

- Unless contraindicated, lightweight macroporous polypropylene mesh is the current implant of choice.

Additional tests needed

Patients with advanced-stage pelvic organ prolapse are at an increased risk for stress urinary incontinence that may be masked by urethral "kinking" due to anatomic distortion of the periurethral support mechanism. Based on recommendations from the American Urological Association (AUA) and Society of Urodynamics, Female Pelvic Medicine and Urogenital Reconstruction (SUFU), we routinely perform a postvoid residual urine volume measurement, urinalysis, urine culture, and a prolapse reduction stress test.24 If the urinalysis is positive for blood, then a preoperative cystoscopy would be indicated.

If stress incontinence is confirmed by reduction stress testing, the patient should be offered an anti-incontinence procedure, such as a mesh midurethral sling.

This patient's overactive bladder symptoms warrant investigation via complex urodynamic testing to allow for comprehensive counseling about her postoperative expectations.

Counseling the patient on the sacrocolpopexy option

Abdominal sacrocolpopexy initially was described in 1962 by Lane as a technique to affix the vaginal apex to the sacral promontory using a graft. Although the procedure has been modified over the years, the principles of using an implanted strengthening material to permanently attach the apex to the anterior longitudinal ligament at the sacrum has proven to be a highly effective and safe treatment, establishing it as the gold standard for apical prolapse repair.25,26

Compared with other methods of apical prolapse repair, sacrocolpopexy via any approach is superior to vaginal surgery in terms of subjective and objective outcomes. In a recent systematic review comparing apical prolapse repairs, patients who underwent a vaginal approach were more likely to report awareness of their prolapse after surgery, undergo repeat surgery, have objective recurrent prolapse, and were at increased risk for postoperative stress urinary incontinence and dyspareunia.26 Prospective studies within our practice have shown 1-year composite subjective and objective cure rates of 94% to 95%.27,28

Selecting a route for sacrocolpopexy

Although sacrocolpopexy can be approached via laparotomy or conventional laparoscopy, we routinely use a robot-assisted approach, as it has been shown to be especially beneficial for complex situations, such as in patients with prior pelvic surgery, a foreshortened vagina, or obesity.29,30

Potential complications

Sacrocolpopexy complications are rare, especially when a minimally invasive approach is used.31 Reported complications of minimally invasive sacrocolpopexy include gastrointestinal or genitourinary injury, bowel obstruction or ileus, incisional hernia, vascular injury, discitis or osteomyelitis, conversion to open procedure, and mesh exposure.

Vaginal mesh exposure is rare following sacrocolpopexy, but it can occur at any time following surgery.31 Some risk factors include mesh material selection (specifically polytetrafluoroethylene [PTFE] mesh), concurrent total hysterectomy, vaginal atrophy, and smoking.32,33 As a result, recent recommendations have advised the use of polypropylene mesh with uterine preservation or supracervical hysterectomy at the time of sacrocolpopexy.34 In fact, supracervical hysterectomy alone appears to cut down or eliminate the risk of mesh exposure in laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy.35

In our practice, avoiding split-thickness vaginal dissection, employing supracervical hysterectomy techniques, and using ultralightweight mesh has resulted in mesh exposure rates approaching zero.28

For atrophic vaginal tissue, one can consider prescribing preoperative vaginal estrogen for 4 to 6 weeks, but this is not essential and should not routinely delay pelvic reconstructive surgery.

What type of implant material is best?

While various materials have been used as the fixation media in sacrocolpopexy, loosely knitted synthetic type I macroporous polypropylene mesh is the best choice due to its efficacy, availability, and low adverse effect profile. We recommend a lightweight mesh with a maximum weight of 25 g/m2. Two such products currently available are the UPsylon Y-Mesh (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, Massachusetts) and Restorelle Y mesh (Coloplast, Minneapolis, Minnesota). Lightweight mesh has been proven to maintain integrity, guaranteeing a successful outcome, while reducing the "mesh load" on the attached tissue.27,28

Comparative studies with fascia lata or cross-linked porcine dermal grafts demonstrated inferior outcomes versus synthetic mesh, and currently the only biologic material on the market indicated for prolapse repair augmentation, ACell Pelvic Floor Matrix (ACell, Columbia, Maryland), has not been extensively tested in sacrocolpopexy.36-38

Vaginal anatomy restored by sacrocolpopexy

Abdominal sacrocolpopexy, specifically via a minimally invasive approach, is an effective and long-lasting treatment that should be offered to women with advanced-stage prolapse.

Using the surgical techniques described below, including attachment of the mesh along the lengths of the anterior and posterior vaginal walls and gathering up excess tissue with mesh attachment, can provide women with adequate support for the entire vagina with restoration of normal vaginal anatomy and caliber.

Step-by-step tips for surgical efficiency

Robotic port placement

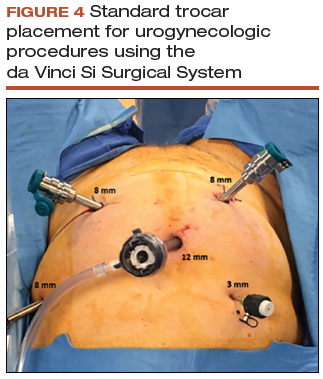

- Place the trocars in a "W" layout for the da Vinci Si Surgical System (FIGURE 4, VIDEO 1) or in a linear layout for the da Vinci Xi Surgical System (Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, California). Both Si and Xi port placement includes a 3- to 5-mm assistant port in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen.

Supracervical hysterectomy, if indicated

- Maneuver the uterus with the robotic tenaculum, which obviates the need for a uterine manipulator during the hysterectomy (VIDEO 2).

- Create the bladder flap just above the upper edge of the bladder to facilitate the upcoming anterior wall dissection. This helps to prevent the development of a split-thickness dissection plane.

- 1.5 to 2 cm of cervix should be left in place, and conization should be avoided.

Anterior vaginal wall dissection

- The key to a good full-thickness dissection is sustained tissue traction and countertraction. The bedside assistant pulls the anterior peritoneal cut edge anteriorly for "gross" traction, and further "fine" traction can be created by pulling the areolar tissue with robotic forceps. The cervix is grasped with the tenaculum, which applies a constant midline cephalad countertraction (VIDEO 3).

- Sharp dissection with cold scissors allows for creation of the dissection plane, while cautery is judiciously applied only for hemostasis. If bleeding is encountered, this usually indicates that a split thickness of the vaginal wall has been created, and the surgeon should correct to the proper dissection plane.

- Dissection is made easier by taking down the bladder pillars before advancing down toward the bladder neck.

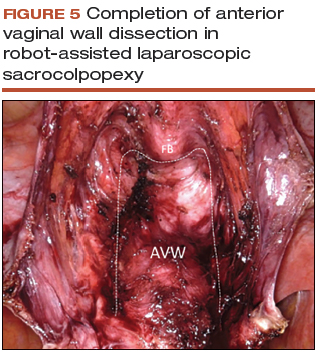

- The anterior dissection is always carried down to level of the trigone, confirmed by visualization of the Foley bulb (FIGURE 5).

Posterior vaginal wall dissection

- Begin dissection just above the rectal reflection, leaving peritoneum on the posterior cervix (VIDEO 4).

- Extend the incision bilaterally to the uterosacral ligaments only after the correct dissection plane is confirmed by visualization of the areolar tissue.

- Apply cervical traction using the tenaculum in a cephalad midline direction, and place traction on the cut edge of the posterior peritoneum using the bipolar forceps. The tenaculum wrist must be turned away from the working instruments to avoid internal clashing.

- Completely transect the right uterosacral ligament to better facilitate the creation of a contiguous peritoneal opening for burying the mesh. The remainder of the opening will be created later.

- While it is important to avoid split-thickness dissection, the vaginal plane must be "clean" (that is, without fat or adventitia) to allow for robust suturing.

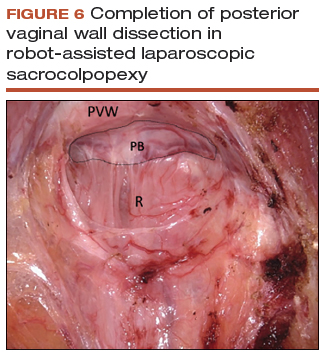

- Dissection at least halfway down the posterior vaginal wall is recommended but proceeding down to the perineal body provides the most optimal support (FIGURE 6).

Sacral dissection

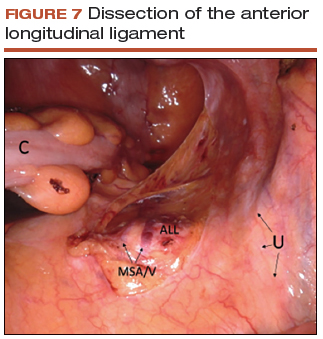

- Use a noncrushing instrument to laterally sweep the bowel to the left side, effectively "plastering" the peritoneum over the sacral promontory (FIGURE 7; VIDEO 5).

- Extend the superficial peritoneal incision down the right paracolic gutter halfway between the ureter and colon until it communicates with the incised posterior peritoneal edge created during the posterior dissection.

- Identify the middle sacral artery to avoid vascular injury, but there is no need to prophylactically coagulate it.

Vaginal mesh attachment

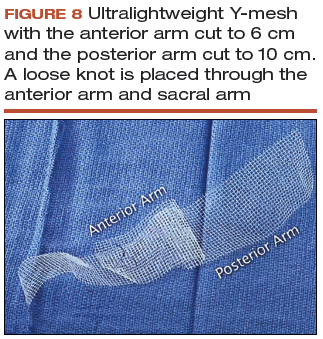

- Cut a lightweight Y-mesh to a length of 6 to 8 cm anteriorly and 8 to 11 cm posteriorly and place it into the surgical field (FIGURE 8; VIDEO 6). The length is determined based on the preoperative office examination and examination under anesthesia prior to starting the procedure.

- Attach the mesh securely and evenly to the anterior and posterior vaginal walls using multiple interrupted monofilament sutures. We aim to place sutures that provide mesh stability without excess vaginal wall incorporation to avoid "through-and-through" suturing.

- The posterior wall suturing is performed first, starting at the perineal body and continuing cephalad (VIDEO 7). We find it easiest to tie the knots between the mesh and the vagina in this space.

- Suture the crotch of the Y-mesh to the cervix so that no gap exists between tissue and mesh.

- For advanced-stage prolapse with significant anterior prolapse, the stretched out vaginal epithelium can be systematically gathered up to reconfigure the tissue to conform to the desired mesh dimensions (VIDEO 8). This tissue remodeling is evident even at the 2- to 4-week postoperative visit.

Peritoneal closure: Step 1

- Reapproximate the cut edges of peritoneum surrounding the vagina and cervix using a continuous purse-string suture of 0 Monocryl (poliglecaprone 25) on an SH needle (Ethicon, Somerville, New Jersey) with a fisherman's knot tied at the end (VIDEO 9). The needle passes are placed close together and close to the incised edge of the cut peritoneum.

- We typically start our peritoneal suture at the 5 o'clock position of the posterior peritoneum, extending in a clockwise direction and ultimately jumping anteriorly around the sacral arm of the mesh.

- Place the mesh within the paracolic peritoneal canal, and secure the needle for later use.

Sacral mesh attachment

- The mesh is tensioned so that a vaginal examination confirms adequate support of all the walls without excess tension or tissue banding. Some laxity of the anterior vaginal wall consistent with a mild cystocele is appropriate.

- Place 2 permanent PTFE sutures along the slope of the sacral promontory into the anterior longitudinal ligament (VIDEO 10). This avoids injury to the disc space that sits at the edge of the promontory. We do not advise the use of bone anchors as they increase the risk for discitis and osteomyelitis.

- Secure the mesh to the anterior longitudinal ligament without any tension. This is facilitated by creating mesh slack via cephalad pressure from a vaginal probe.

Peritoneal closure: Step 2

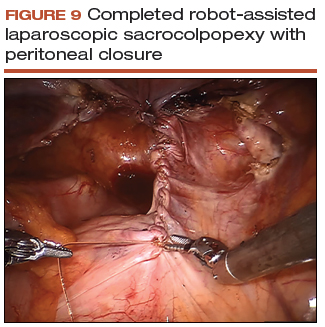

- Close the remaining paracolic peritoneal incision, completely burying the mesh within the created canal (FIGURE 9).

- At the end of the procedure, perform a repeat vaginal exam, rectal exam, and cystoscopy.

Technique with prior total hysterectomy

- In patients with a prior total hysterectomy, place a 13 x 3.5 cm Breisky vaginal retractor and/or coated nonconductive stent (Marina Medical, Sunrise, Florida) into the vagina to delineate the anterior and posterior walls at the vaginal apex during dissection.

- Some surgeons may opt to retrograde fill the bladder to better identify its location.

- We routinely leave a segment of peritoneum attached to the dome of the vaginal apex for added tissue integrity to prevent erosion.

Read about using transvaginal mesh for POP repair.

Transvaginal mesh: An effective, durable option for POP repair

Vincent R. Lucente, MD, MBA, and Jessica B. Ton, MD

Dr. Lucente reports that he has received grant or research support from Advanced Tactile Imaging, Boston Scientific, Coloplast, and Valencia; is a consultant to Coloplast; is a speaker for Allergan, Boston Scientific, Coloplast, and Shionogi; and serves as an expert witness for American Medical Systems and C.R. Bard. Dr. Ton reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

As baseline health in the elderly population continues to improve, the number of women in the United States with symptomatic POP will increase by approximately 50% by 2050.39 Unfortunately, after native tissue repair (NTR) the rate of prolapse recurrence is extremely high: approximately 40% regardless of approach, as demonstrated in the OPTIMAL (Operations and Pelvic Muscle Training in the Management of Apical Support Loss) trial by Barber and colleagues.6 The authors of that clinical trial recently revealed that at the 5-year follow-up, these failure rates progressed to 70% for sacrospinous ligament fixation and 61% for uterosacral ligament suspension (data presented at the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Annual Scientific Meeting 2018, Orlando, Florida). This establishes that NTR is not durable enough to meet the increasing physical demands of this age group and that mesh augmentation must be considered.

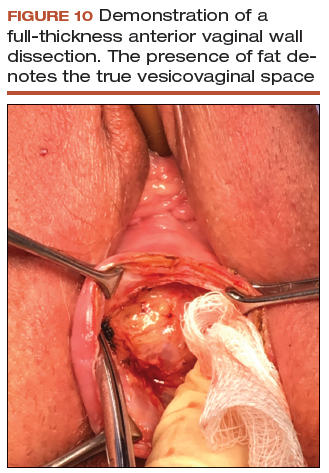

For patients at increased risk of prolapse recurrence, using transvaginal mesh (TVM) is the most minimally invasive approach and is an excellent option for mesh augmentation. Avoiding adverse events during placement of TVM depends largely on optimal surgical technique.40 (VIDEO: “Demonstration of an anterior vaginal wall dissection into the true vesicovaginal space”)

- Active advanced age requires a durable reconstructive pelvic surgery for pelvic organ prolapse, and native tissue repair does not meet that demand.

- Mesh augmentation reduces the risk of prolapse recurrence, and vaginal placement of mesh is the most minimally invasive approach.

- Rates of exposure with transvaginal mesh would be minimized with use of a full-thickness vaginal wall dissection.

- Optimal surgical technique could be highly reproducible with better surgical training.

The evidence on TVM versus NTR

Several studies have examined whether TVM has a measurable benefit over NTR.

A 2016 Cochrane review by Maher and colleagues included 37 randomized trials (4,023 women) that compared TVM and biologic grafts with NTR.41 Three primary outcomes were defined: awareness of prolapse, recurrence, and repeat surgery. Compared with women treated with NTR, those treated with synthetic nonabsorbable TVM exhibited a greater reduction in awareness of prolapse (risk ratio [RR], 0.66; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.54-0.81), decreased recurrence in the anterior compartment (RR, 0.33; 95% CI, 0.26-0.40), and decreased reoperation for prolapse (RR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.31-0.88). The overall calculated exposure rate was 12%, with a range of 3.2% to 20.8%.41 As we will discuss, this wide range most likely is attributed to a suboptimal, split-thickness dissection. There were no differences in other key secondary outcomes, including dyspareunia, operating time, and estimated blood loss.41

Longitudinal studies are emerging as almost 2 decades have passed since TVM was introduced. In a study of 5-year follow-up after TVM placement, Meyer and colleagues reported that patients had continued significant improvements in both subjective and objective outcomes.42 The mesh exposure rate was 6%, attributed to severe vaginal atrophy.42 A 10-year observational study by Weintraub and colleagues demonstrated a recurrence rate of only 2.6% in the anterior compartment, 7.6% in the posterior (nonaugmented) compartment, and no exposures or extrusions after anterior TVM placement.43

In contrast to the Cochrane review, in the 2017 multicenter PROSPECT (Prolapse surgery: Pragmatic evaluation and randomized controlled trials) trial, Glazener and colleagues found no difference in desired outcomes with TVM compared with NTR.44 There was an overall 6% to 7% exposure rate over 2 years.44 To reflect "real-world" practice, however, this study was intentionally designed without rigorous standardization of surgical technique. The authors reported that "appropriately experienced surgeons" performed the procedure, but it is unclear how experience was determined given that 20% of the cases were performed by "registrars," the equivalent of US residents or fellows.45

The PROSPECT study protocol described the TVM procedure as "a standard repair with a nonabsorbable mesh inlay to support the stitches," implying that there was no apical attachment of the mesh to the sacrospinous ligament.45 This is a suboptimal use of TVM because it does not address a detachment-type defect common in advanced prolapse. The PROSPECT study reinforces the need for better surgical training and standardization of the TVM procedure.44

How TVM compares with sacrocolpopexy

When comparing the use of TVM with sacrocolpopexy, our experience has been that TVM yields similar outcomes to sacrocolpopexy with additional benefits. We completed a 1-year retrospective cohort study comparing robot-assisted laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy (RALS) with TVM in a total of 86 patients, with both approaches performed by the same surgeon. Both treatment groups showed statistically significant improvements in nearly all functional and quality-of-life measures, including urinary symptoms, sexual function, and POP-Q scores.40 In particular, points Aa and Ba on the POP-Q score were significantly improved with TVM as compared to RALS. This suggests that TVM can achieve both lateral and apical support, where sacrocolpopexy addresses only the apex.40 This has clinical significance when considering DeLancey and colleagues' dynamic magnetic resonance imaging study, which demonstrated advanced prolapse results from both lateral and apical detachment.46 In addition, TVM placement also was considerably faster than RALS by approximately 96 minutes and could be performed using regional anesthesia. Only 1 mesh exposure in each study arm was reported.40

Finally, as with other vaginal procedures, patients who undergo TVM placement require minimal to no pain medication postoperatively and report faster return to daily activities. Almost none of our patients require narcotics, which is a significant benefit in the face of the ongoing national opioid crisis.

Gutman and colleagues compared laparoscopic mesh hysteropexy with TVM; they demonstrated comparable cure rates and, again, significantly longer operative times for the laparoscopic approach (174 vs 64 minutes; P<.0001).47 This multicenter study reported mesh exposure rates of 2.7% for laparoscopy and 6.6% for TVM,47 again likely due to a split-thickness dissection.

Safety of TVM depends on the surgeon factor

Because of the reported complications associated with TVM, in 2011 the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued an update on the safety and efficacy of TVM augmentation and mandated postmarket studies.48 While we do not dispute that the mesh exposure rates were accurate at the time the FDA document was issued, we recognize that exposure has been erroneously attributed to inherent properties of the mesh.

Mesh exposure rates reported in the literature vary widely, ranging from 0% to 30%, even when surgeons used identical mesh products.49 This clearly establishes that the main contributing variable is surgical technique. It is critically important to recognize the "surgeon factor" as a confounder in trials that compare surgical procedures.50 Studies on TVM have shown that low-volume surgeons had significantly higher reoperation rates, while high-volume surgeons achieved a 41% reduction in reoperations.51,52 When TVM is performed by expert surgeons, the reported mesh exposure rates for TVM are noticeably lower.40,42,43,53,54

Decreasing mesh exposure rates would reduce the most common adverse event associated with TVM, thus improving its safety. The critical step to successful TVM placement is the initial dissection. Gynecologists traditionally have performed a split-thickness, colporrhaphy-style dissection to place the mesh within the layers of the vaginal wall.55 Placement within these planes, however, is too superficial and increases the risk of exposure. By contrast, by consistently performing a full-thickness vaginal wall dissection (FIGURE 10) and placing the mesh in the true vesicovaginal space,56 we have achieved a TVM exposure rate as low as 0% to 3%.40,54 If we can standardize the dissection component across our subspecialty, the rate of mesh exposure undoubtedly will decrease.

The PROSPECT investigators readily admitted what the study was not: a trial conducted "exclusively by the most experienced surgeons in the highest volume centres¬with a highly protocolised technique."44 In reality, that is the kind of rigorous study on TVM that our subspecialty demands. We must hold ourselves accountable and ensure that only the most qualified surgeons are placing TVM.

Keep the mesh option available

We support the position of the American Urogynecologic Society in opposing an outright ban of TVM because such a restriction would deny our patients access to an effective, durable, and minimally invasive approach for prolapse repair.57

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Wu JM, Matthews CA, Conover MM, Pate V, Jonsson Funk M. Lifetime risk of stress urinary incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(6):1201-1206.

- Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, Colling JC, Clark AL. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89(4):501-506.

- Nygaard I, Brubaker L, Zyczynski HM, et al. Long-term outcomes following abdominal sacrocolpopexy for pelvic organ prolapse. JAMA. 2013;309(19):2016-2024.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, American Urogynecologic Society. Practice Bulletin No. 185 Summary: Pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(5):1170-1172.

- American Urogynecologic Society Best Practice Statement: Evaluation and counseling of patients with pelvic organ prolapse. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2017;23(5):281-287.

- Barber MD, Brubaker L, Burgio KL, et al; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Comparison of 2 transvaginal surgical approaches and perioperative behavioral therapy for apical vaginal prolapse: the OPTIMAL randomized trial. JAMA. 2014;311(10):1023-1034.

- Chung CP, Miskimins R, Kuehl TJ, Yandell PM, Shull BL. Permanent suture used in uterosacral ligament suspension offers better anatomical support than delayed absorbable suture. Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23(2):223-227.

- Yazdany T, Yip S, Bhatia NN, Nguyen JN. Suture complications in a teaching institution among patients undergoing uterosacral ligament suspension with permanent braided suture. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21(7):813-818.

- Toglia MR, Fagan MJ. Suture erosion rates and long-term surgical outcomes in patients undergoing sacrospinous ligament suspension with braided polyester suture. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(5):600.e1-e4.

- Wong MJ, Rezvan A, Bhatia NN, Yazdany T. Uterosacral ligament vaginal vault suspension using delayed absorbable monofilament suture. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22(11):1389-1394.

- Detollenaere RJ, den Boon J, Stekelenburg J, IntHout J, et al. Sacrospinous hysteropexy versus vaginal hysterectomy with suspension of the uterosacral ligaments in women with uterine prolapse stage 2 or higher: multicentre randomised non-inferiority trial. BMJ. 2015;351:h3717.

- Kapoor S, Sivanesan K, Robertson JA, Veerasingham M, Kapoor V. Sacrospinous hysteropexy: review and meta-analysis of outcomes. Int Urogynecol J. 2017;28(9):1285-1294.

- Madsen AM, Raker C, Sung VW. Trends in hysteropexy and apical support for uterovaginal prolapse in the United States from 2002 to 2012. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2017;23(6):365-371.

- Wei JT, Nygaard I, Richter HE, et al; Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. A midurethral sling to reduce incontinence after vaginal prolapse repair. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(25):2358-2367.

- Buchsbaum GM, Lee TG. Vaginal obliterative procedures for pelvic organ prolapse: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2017;72(3):175-183.

- Zebede S, Smith AL, Plowright LN, Hegde A, Aguilar VC, Davila GW. Obliterative LeFort colpocleisis in a large group of elderly women. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(2 pt 1):279-284.

- Bochenska K, Leader-Cramer A, Mueller M, Dave B, Alverdy A, Kenton K. Perioperative complications following colpocleisis with and without concomitant vaginal hysterectomy. Int Urogynecol J. 2017;28(11):1671-1675.

- Jones K, Wang G, Romano R, St Marie P, Harmanli O. Colpocleisis: a survey of current practice patterns. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2017;23(4):276-280.

- Jones KA, Zhuo Y, Solak S, Harmanli O. Hysterectomy at the time of colpocleisis: a decision analysis. Int Urogynecol J. 2016;27(5):805-810.

- Kandadai P, Flynn M, Zweizig S, Patterson D. Cost-utility of routine endometrial evaluation before le fort colpocleisis. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2014;20(3):168-173.

- Reena C, Kekre AN, Kekre N. Occult stress incontinence in women with pelvic organ prolapse. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2007;97(1):31-34.

- Oliphant SS, Shepherd JP, Lowder JL. Midurethral sling for treatment of occult stress urinary incontinence at the time of colpocleisis: a decision analysis. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2012;18(4):216-220.

- Siddiqui NY, Grimes CL, Casiano ER, et al; Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Systematic Review Group. Mesh sacrocolpopexy compared with native tissue vaginal repair: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(1):44-55.

- Winters JC, Dmochowski RR, Goldman HB, et al; American Urological Association; Society of Urodynamics, Female Pelvic Medicine and Urogenital Reconstruction. Urodynamic studies in adults: AUA/SUFU guideline. J Urol. 2012;188(6 suppl):2464-2472.

- Barber MD, Maher C. Apical prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24(11):1815-1833.

- Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, Christmann-Schmid C, Haya N, Brown J. Surgery for women with apical vaginal prolapse. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;10:CD012376.

- Salamon CG, Lewis C, Priestley J, Gurshumov E, Culligan PJ. Prospective study of an ultra-lightweight polypropylene Y mesh for robotic sacrocolpopexy. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24(8):1371-1375.

- Culligan PJ, Gurshumov E, Lewis C, et al. Subjective and objective results 1 year after robotic sacrocolpopexy using a lightweight Y-mesh. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25(6):731-735.

- Eddib A, Danakas A, Hughes S, et al. Influence of morbid obesity on surgical outcomes in robotic-assisted gynecologic surgery. J Gynecol Surg. 2014;30(2):81-86.

- Gallo T, Kashani S, Patel DA, Elsahwi K, Silasi D-A, Azodi M. Robotic-assisted laparoscopic hysterectomy: outcomes in obese and morbidly obese patients. JSLS. 2012;16(3):421-427.

- Serati M, Bogani G, Sorice P, et al. Robot-assisted sacrocolpopexy for pelvic organ prolapse: a systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. Eur Urol. 2014;66(2):303-318.

- Cundiff GW, Varner E, Visco AG, et al; Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Risk factors for mesh/suture erosion following sacral colpopexy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(6):688.e1-e5.

- Wu JM, Wells EC, Hundley AF, Connolly A, Williams KS, Visco AG. Mesh erosion in abdominal sacral colpopexy with and without concomitant hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(5):1418-1422.

- Costantini E, Brubaker L, Cervigni M, et al. Sacrocolpopexy for pelvic organ prolapse: evidence-based review and recommendations. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;205:60-65.

- Tan-Kim J, Menefee SA, Luber KM, Nager CW, Lukacz ES. Prevalence and risk factors for mesh erosion after laparoscopic-assisted sacrocolpopexy. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22:205-212.

- Culligan PJ, Salamon C, Priestley JL, Shariati A. Porcine dermis compared with polypropylene mesh for laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(1):143-151.

- Tate SB, Blackwell L, Lorenz DJ, Steptoe MM, Culligan PJ. Randomized trial of fascia lata and polypropylene mesh for abdominal sacrocolpopexy: 5-year follow-up. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22(2):137-143.

- Culligan PJ, Blackwell L, Goldsmith LJ, Graham CA, Rogers A, Heit MH. A randomized controlled trial comparing fascia lata and synthetic mesh for sacral colpopexy. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(1):29-37.

- ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology, American Urogynecologic Society. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 185: Pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(5):e234-e250.

- Jambusaria LH, Murphy M, Lucente VR. One-year functional and anatomic outcomes of robotic sacrocolpopexy versus vaginal extraperitoneal colpopexy with mesh. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2015;21(2):87-92.

- Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, Christmann-Schmid C, Haya N, Marjoribanks J. Transvaginal mesh or grafts compared with native tissue repair for vaginal prolapse. Cochrane Database System Rev. 2016:CD012079.

- Meyer I, McGwin G, Swain T, Alvarez MD, Ellington DR, Richter HE. Synthetic graft augmentation in vaginal prolapse surgery: long-term objective and subjective outcomes. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2016;23(4):614-621.

- Weintraub AY, Friedman T, Baumfeld Y, Neymeyer J, Neuman M, Krissi H. Long‐term functional outcomes following mesh‐augmented posterior vaginal prolapse repair. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2016;135(1):107-111.

- Glazener CM, Breeman S, Elders A, et al; PROSPECT Study Group. Mesh, graft, or standard repair for women having primary transvaginal anterior or posterior compartment prolapse surgery: two parallel-group, multicentre, randomised, controlled trials (PROSPECT). Lancet. 2017;389(10067):381-392.

- Clinical and cost-effectiveness of surgical options for the management of anterior and/or posterior vaginal wall prolapse: two randomized controlled trials within Comprehensive Cohort Study. PROSPECT study protocol. The National Institute for Health Research. https://www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/076018. Accessed January 17, 2018.

- Chen L, Lisse S, Larson K, Berger MB, Ashton-Miller JA, DeLancey JO. Structural failure sites in anterior vaginal wall prolapse: identification of a collinear triad. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(4):853-862.

- Gutman RE, Rardin CR, Sokol ER, et al. Vaginal and laparoscopic mesh hysteropexy for uterovaginal prolapse: a parallel cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(1):38.e1-e11.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Urogynecologic surgical mesh: update on the safety and effectiveness of transvaginal placement for pelvic organ prolapse. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/medicaldevices/safety/alertsandnotices/ucm262760.pdf. Published July 2011. Accessed January 9, 2017.

- Murphy M, Holzberg A, van Raalte H, et al; Pelvic Surgeons Network. Time to rethink: an evidence-based response from pelvic surgeons to the FDA Safety Communication: "Update on serious complications associated with transvaginal placement of surgical mesh for pelvic organ prolapse." Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23(1):5-9.

- Roman H, Marpeau L, Hulsey TC. Surgeons' experience and interaction effect in randomized controlled trials regarding new surgical procedures. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(2):108.e1-e6.

- Eilber KS, Alperin M, Khan A, et al. The role of the surgeon on outcomes of vaginal prolapse surgery with mesh. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2017;23 (5):293-296.

- Kelly EC, Winick-Ng J, Welk B. Surgeon experience and complications of transvaginal prolapse mesh. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(1):65-72.

- Altman D, Vayrynen T, Engh ME, Axelsen S, Falconer C; Nordic Transvaginal Mesh Group. Anterior colporrhaphy versus transvaginal mesh for pelvic-organ prolapse. N Engl J Med 2011;364(19):1826-1836.

- van Raalte HM, Lucente VR, Molden SM, Haff R, Murphy M. One-year anatomic and quality-of-life outcomes after the Prolift procedure for treatment of posthysterectomy prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008:199(6):694.e1-e6.

- Iyer S, Botros SM. Transvaginal mesh: a historical review and update of the current state of affairs in the United States. Int Urogynecol J. 2017;28(4):527-535.

- Ting M, Gonzalez A, Ephraim S, Murphy M, Lucente V. The importance of a full thickness vaginal wall dissection. Comment on "Transvaginal mesh: a historical review and update of the current state of affairs in the United States." Int Urogynecol J. 2017;28(10):1609-1610.

- American Urogynecologic Society. Position statement on restriction of surgical options for pelvic floor disorders. https://www.augs.org/assets/1/6/Position_Statement_Surgical_Options_for_PFDs.pdf. Published March 26, 2013. Accessed January 9, 2017.

Effective surgical management of advanced pelvic organ prolapse (POP) depends on prolapse location and stage, presence of urinary incontinence, need for hysterectomy, the patient’s desire to maintain sexual function, type of surgery, and the surgeon’s skill and experience, among other factors. For these reasons, POP repair is not a one-size-fits all procedure.

In this article, experts in minimally invasive prolapse repair offer their perspectives on 3 surgical approaches: use of native tissue (Drs. White, Aguilar, and Rogers), abdominal sacrocolpopexy (Drs. Huber and Culligan), and transvaginal mesh (Drs. Lucente and Ton). They evaluate the evidence on these procedures and provide recommendations based on their experience of best practices for achieving surgical success and minimizing adverse events.

Using native tissue for vaginal anatomy repair

Amanda White, MD; Vivian Aguilar, MD; and Rebecca G. Rogers, MD

Dr. Rogers reports that she receives royalties from UpToDate. Drs. White and Aguilar report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Surgical therapy is the mainstay of treatment for POP, and 20% of US women will undergo prolapse and/or stress incontinence surgery by age 80.1 Prolapse surgery either restores the vaginal anatomy (reconstructive surgery) or obliterates the vaginal canal (obliterative surgery). Vaginal reconstruction can be performed using the patient's native tissue or mesh. Because of concerns associated with mesh use, native tissue repairs continue to be commonly performed.

Unfortunately, not all prolapse surgeries result in prolapse cure, and recurrent prolapse that necessitates repeat operation is not rare, regardless of whether or not mesh is used.2,3 Native tissue repairs are most commonly performed through the vaginal route, the first minimally invasive approach to prolapse surgery. Restoration of the vaginal apex has been identified as critically important in these surgeries. Apical native tissue repairs include reconstructive procedures, such as sacrospinous ligament suspension (SSLS) or uterosacral ligament suspension (USLS), and obliterative procedures, such as colpocleisis.

In this discussion, we present 2 case vignettes that highlight surgical decision making for repair of stage 3 or 4 pelvic organ prolapse utilizing these techniques.

- Native tissue repair offers a minimally invasive approach to prolapse repair.

- Sacrospinous and uterosacral ligament suspensions have equivalent success rates.

- Prophylactic midurethral slings reduce postoperative incontinence at the time of transvaginal native tissue repair.

- Hysterectomy at the time of colpocleisis should not be performed routinely.

CASE 1 Active woman with prolapse

A 65-year-old woman (G2P2) presents with stage 3 prolapse, with the anterior compartment at +3 and the cervix at the hymen with straining. She is sexually active and desires to retain coital function. A trial of pessary has failed.

What surgical options can be considered for this patient?

Reconstruction procedures for prolapse

This patient presents with a typical configuration of prolapse; the anterior and apical compartments are the most likely to prolapse.4 Importantly, conservative management of her prolapse has failed. While it is not required that women have a trial with pessary prior to undergoing surgery, all women should be offered conservative management of prolapse, according to the American Urogynecologic Society (AUGS) and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG).4,5

Apical suspension

Since this patient desires to retain coital function, her gynecologist recommends a reconstructive procedure. The combination of apical and anterior vaginal wall prolapse will require an apical suspension procedure (FIGURES 1 and 2). If suspension of the apex does not correct the anterior wall prolapse, the patient also may require anterior compartment reconstruction.

The 2 most commonly performed native tissue apical suspension procedures, SSLS and USLS, have equivalent outcomes at 2 years, according to a multicenter randomized trial.6 Therefore, the choice of procedure is at the surgeon's discretion. USLS is most commonly performed at the time of hysterectomy via an intraperitoneal approach, while SSLS is often selected for posthysterectomy vault prolapse, given its extraperitoneal location.

Suture type. Whether to use permanent suture at the time of SSLS or USLS is controversial. Some data suggest that permanent suture provides greater long-term success compared with delayed absorbable suture.7 However, permanent suture has been reported to be associated with higher rates of suture complications--up to 44% in USLS and 36% in SSLS--compared with a 3.5% complication rate in a USLS cohort treated with absorbable suture.8-10

Hysterectomy versus hysteropexy. Considerable debate exists regarding whether a patient requires hysterectomy at the time of prolapse repair. In a randomized trial at 12 months' follow-up, uterine preservation by sacrospinous hysteropexy was noninferior to vaginal hysterectomy with suspension of the uterosacral ligaments for surgical failure of the apical compartment.11 A recent meta-analysis found that apical failure rates after sacrospinous hysteropexy versus vaginal hysterectomy were not different.12 Repeat surgery rates for prolapse also were not different between groups. The most significant disadvantage of uterine-preservation prolapse surgery, when compared with hysterectomy, is the lack of prevention and diagnosis of uterine malignancy.12 From 2002 to 2012, rates of hysteropexy significantly increased in the United States, although rates remain low.13

Sling procedure pros and cons. This case patient did not report urinary incontinence, but she may develop incontinence with reduction of the anterior wall prolapse. A large randomized controlled trial that included 337 women compared sling with no sling procedures among women with prolapse undergoing transvaginal prolapse repair.14 Management with a prophylactic sling resulted in less incontinence (27.3% and 43.0%, respectively, at 12 months postoperatively) but higher rates of urinary tract infection (31.0% vs 18.3%), major bleeding complications (3.1% vs 0%), and incomplete bladder emptying 6 weeks after surgery (3.7% vs 0%) (P≤.05 for all).14

CASE 1 Recommendations for this patient

For this case, we would offer the patient a transvaginal hysterectomy and USLS. At the time of repair, we would assess whether she needed an anterior repair as well. We would offer a prophylactic sling procedure and also would discuss the risks and benefits of concomitant versus interval incontinence procedures.

CASE 2 Elderly woman with severe prolapse

An 85-year-old woman (G3P3) presents with procidentia, or complete eversion of the vagina, with the cervix 10 cm outside of the hymen. She has difficulty voiding, and the prolapse is uncomfortable when walking. A trial of pessary has failed. The patient denies vaginal bleeding. She is not sexually active and does not desire to retain coital function.

What treatment options would be appropriate for this patient?

Obliterative surgery

This elderly patient presents with advanced pelvic organ prolapse, and conservative management has failed. She is not sexually active and does not desire coital function in the future, so an obliterative procedure is indicated. Colpocleisis is a minimally invasive procedure that has cure rates ranging from 91% to 100%.15 It is likely that this patient's voiding dysfunction will improve after surgery and that she will be highly satisfied with the surgery.16

The question of hysterectomy with colpocleisis

The role of hysterectomy at the time of colpocleisis is controversial. LeFort colpocleisis preserves the uterus, with the anterior and posterior vaginal walls sutured together (FIGURE 3). Hysterectomy at the time of vaginal closure increases the operative time and blood loss.15 On the other hand, closure without hysterectomy prohibits future endometrial or cervical cancer screening.

In a recent review using the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database, investigators compared women who underwent colopocleisis alone with those who underwent colpocleisis with hysterectomy.17 They found that the incidence of major complications was greater among women who underwent concomitant hysterectomy, and they concluded that hysterectomy should not be performed routinely at the time of colpocleisis.17

Among 322 urogynecologists who responded to a web-based survey, only 18% routinely performed hysterectomy at the time of colpocleisis.18 Further, in a decision analysis model, the utility for colpocleisis without hysterectomy was higher in women older than age 40, suggesting that hysterectomy should be performed only in special circumstances.19

Evaluating the endometrium. If the uterus remains in situ, should endometrial evaluation be performed? If so, should ultrasonography or endometrial biopsy be used? Authors of a decision analysis model found that among women at low risk for cancer and without abnormal uterine bleeding, endometrial biopsy was not favored until the probability of cancer reached 64%.20 Specifically, no evaluation or evaluation by transvaginal ultrasonography is adequate in the majority of cases.20 When screened by transvaginal ultrasonography, the high, 99% negative predictive value for endometrial disease, using a cutoff value of 5 mm for endometrial stripe width, will allow most patients to avoid unnecessary tissue sampling.

Stress incontinence. It is likely that this patient's voiding dysfunction will resolve with reduction of the prolapse, and she may develop stress incontinence symptoms. In up to 68% of women, occult stress incontinence will be revealed with reduction of stage 3 or stage 4 prolapse.21 If the patient demonstrates stress incontinence, a midurethral sling is likely to treat her incontinence effectively, with little added risk from the procedure.22 Even among women who have an elevated postvoid residual urine volume, the incidence of sling revision is low.15

CASE 2 Procedure recommendation for this patient

For this case, we would perform a LeFort colpocleisis and discuss whether or not the patient would prefer a midurethral sling if stress incontinence was demonstrated on examination. We would not perform endometrial evaluation in this patient, as she has not been bleeding and her risk for endometrial cancer is low.

Weighing the benefits of native tissue repair

Native tissue repair when performed transvaginally is a minimally invasive approach to prolapse repair. In a multicenter randomized trial, anatomic success was reported to be 64.5% at 2 years.6 Long-term follow up of patients undergoing mesh sacrocolpopexy shows a similar anatomic failure rate, with up to one-third of patients meeting the definition of composite failure.3 Unlike mesh-augmented repairs, however, adverse events, including bowel obstruction, mesh exposure, and thromboembolism, are more likely to occur in the mesh sacrocolpopexy group.23

Obliterative procedures have the highest success rates of all prolapse repairs and carry with them low morbidity. However, women must forego the ability for coitus in the future. For all native tissue vaginal repairs, the surgeon and patient must weigh the risks and benefits of concomitant anti-incontinence procedures.

Read about using abdominal sacrocolpopexy for apical prolapse repair.

Abdominal sacrocolpopexy: A tried-and-true approach for apical prolapse repair

Sarah Huber, MD, and Patrick Culligan, MD

Dr. Culligan reports that he is a shareholder in Oragami Surgical LLC and a consultant and speaker for Coloplast and Intuitive Surgical Inc. Dr. Huber reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

CASE Woman with advanced prolapse desires surgical repair

A 55-year-old woman (G2P2) presents to her gynecologist's office reporting a vaginal bulge and pressure that has been worsening for the past year. She describes a nontender ball of tissue the size of an orange protruding past the introitus that worsens with ambulating and lifting heavy objects. She reports some urinary urgency and increased frequency and at times feels as though her bladder does not empty completely with voiding. She denies any urinary incontinence. The patient has regular bowel movements but does report some difficulty with stool evacuation. She has a history of 2 vaginal deliveries and is sexually active. She is postmenopausal, with the last menses about 4 years ago. She is active and exercises regularly.

The patient's Pap smears, mammograms, and colonoscopy are up to date and test results have been normal. She has no significant medical or surgical history and no significant family history of cancer. On examination, her body mass index is normal, as is the cardiopulmonary exam. Her pelvic organ prolapse quantification system (POP-Q) score is Aa +3, Ba +3, C +4, GH 3, PB 3, TVL 10, Ap +2, Bp +2, and D +2. The patient is interested in surgical management.

What urodynamic tests would be appropriate for this patient, and what treatment options would you recommend?

- Robot-assisted laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy is a safe, effective, and durable treatment for advanced-stage pelvic organ prolapse.

- This procedure can completely correct stage 3 or 4 prolapse when the dissection of the anterior vaginal wall extends to the bladder neck and the dissection of the posterior vaginal wall extends to the perineal body.

- One can avoid the need for concomitant vaginal prolapse repair by gathering up stretched out vaginal epithelium while suturing to the mesh arms.

- Sacral attachment sutures should be placed in the anterior longitudinal ligament distal to the sacral promontory to avoid the L5-S1 disc.

- Unless contraindicated, lightweight macroporous polypropylene mesh is the current implant of choice.

Additional tests needed

Patients with advanced-stage pelvic organ prolapse are at an increased risk for stress urinary incontinence that may be masked by urethral "kinking" due to anatomic distortion of the periurethral support mechanism. Based on recommendations from the American Urological Association (AUA) and Society of Urodynamics, Female Pelvic Medicine and Urogenital Reconstruction (SUFU), we routinely perform a postvoid residual urine volume measurement, urinalysis, urine culture, and a prolapse reduction stress test.24 If the urinalysis is positive for blood, then a preoperative cystoscopy would be indicated.

If stress incontinence is confirmed by reduction stress testing, the patient should be offered an anti-incontinence procedure, such as a mesh midurethral sling.

This patient's overactive bladder symptoms warrant investigation via complex urodynamic testing to allow for comprehensive counseling about her postoperative expectations.

Counseling the patient on the sacrocolpopexy option

Abdominal sacrocolpopexy initially was described in 1962 by Lane as a technique to affix the vaginal apex to the sacral promontory using a graft. Although the procedure has been modified over the years, the principles of using an implanted strengthening material to permanently attach the apex to the anterior longitudinal ligament at the sacrum has proven to be a highly effective and safe treatment, establishing it as the gold standard for apical prolapse repair.25,26

Compared with other methods of apical prolapse repair, sacrocolpopexy via any approach is superior to vaginal surgery in terms of subjective and objective outcomes. In a recent systematic review comparing apical prolapse repairs, patients who underwent a vaginal approach were more likely to report awareness of their prolapse after surgery, undergo repeat surgery, have objective recurrent prolapse, and were at increased risk for postoperative stress urinary incontinence and dyspareunia.26 Prospective studies within our practice have shown 1-year composite subjective and objective cure rates of 94% to 95%.27,28

Selecting a route for sacrocolpopexy

Although sacrocolpopexy can be approached via laparotomy or conventional laparoscopy, we routinely use a robot-assisted approach, as it has been shown to be especially beneficial for complex situations, such as in patients with prior pelvic surgery, a foreshortened vagina, or obesity.29,30

Potential complications

Sacrocolpopexy complications are rare, especially when a minimally invasive approach is used.31 Reported complications of minimally invasive sacrocolpopexy include gastrointestinal or genitourinary injury, bowel obstruction or ileus, incisional hernia, vascular injury, discitis or osteomyelitis, conversion to open procedure, and mesh exposure.

Vaginal mesh exposure is rare following sacrocolpopexy, but it can occur at any time following surgery.31 Some risk factors include mesh material selection (specifically polytetrafluoroethylene [PTFE] mesh), concurrent total hysterectomy, vaginal atrophy, and smoking.32,33 As a result, recent recommendations have advised the use of polypropylene mesh with uterine preservation or supracervical hysterectomy at the time of sacrocolpopexy.34 In fact, supracervical hysterectomy alone appears to cut down or eliminate the risk of mesh exposure in laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy.35

In our practice, avoiding split-thickness vaginal dissection, employing supracervical hysterectomy techniques, and using ultralightweight mesh has resulted in mesh exposure rates approaching zero.28

For atrophic vaginal tissue, one can consider prescribing preoperative vaginal estrogen for 4 to 6 weeks, but this is not essential and should not routinely delay pelvic reconstructive surgery.

What type of implant material is best?

While various materials have been used as the fixation media in sacrocolpopexy, loosely knitted synthetic type I macroporous polypropylene mesh is the best choice due to its efficacy, availability, and low adverse effect profile. We recommend a lightweight mesh with a maximum weight of 25 g/m2. Two such products currently available are the UPsylon Y-Mesh (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, Massachusetts) and Restorelle Y mesh (Coloplast, Minneapolis, Minnesota). Lightweight mesh has been proven to maintain integrity, guaranteeing a successful outcome, while reducing the "mesh load" on the attached tissue.27,28

Comparative studies with fascia lata or cross-linked porcine dermal grafts demonstrated inferior outcomes versus synthetic mesh, and currently the only biologic material on the market indicated for prolapse repair augmentation, ACell Pelvic Floor Matrix (ACell, Columbia, Maryland), has not been extensively tested in sacrocolpopexy.36-38

Vaginal anatomy restored by sacrocolpopexy

Abdominal sacrocolpopexy, specifically via a minimally invasive approach, is an effective and long-lasting treatment that should be offered to women with advanced-stage prolapse.

Using the surgical techniques described below, including attachment of the mesh along the lengths of the anterior and posterior vaginal walls and gathering up excess tissue with mesh attachment, can provide women with adequate support for the entire vagina with restoration of normal vaginal anatomy and caliber.

Step-by-step tips for surgical efficiency

Robotic port placement

- Place the trocars in a "W" layout for the da Vinci Si Surgical System (FIGURE 4, VIDEO 1) or in a linear layout for the da Vinci Xi Surgical System (Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, California). Both Si and Xi port placement includes a 3- to 5-mm assistant port in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen.

Supracervical hysterectomy, if indicated

- Maneuver the uterus with the robotic tenaculum, which obviates the need for a uterine manipulator during the hysterectomy (VIDEO 2).

- Create the bladder flap just above the upper edge of the bladder to facilitate the upcoming anterior wall dissection. This helps to prevent the development of a split-thickness dissection plane.

- 1.5 to 2 cm of cervix should be left in place, and conization should be avoided.

Anterior vaginal wall dissection

- The key to a good full-thickness dissection is sustained tissue traction and countertraction. The bedside assistant pulls the anterior peritoneal cut edge anteriorly for "gross" traction, and further "fine" traction can be created by pulling the areolar tissue with robotic forceps. The cervix is grasped with the tenaculum, which applies a constant midline cephalad countertraction (VIDEO 3).

- Sharp dissection with cold scissors allows for creation of the dissection plane, while cautery is judiciously applied only for hemostasis. If bleeding is encountered, this usually indicates that a split thickness of the vaginal wall has been created, and the surgeon should correct to the proper dissection plane.

- Dissection is made easier by taking down the bladder pillars before advancing down toward the bladder neck.

- The anterior dissection is always carried down to level of the trigone, confirmed by visualization of the Foley bulb (FIGURE 5).

Posterior vaginal wall dissection

- Begin dissection just above the rectal reflection, leaving peritoneum on the posterior cervix (VIDEO 4).

- Extend the incision bilaterally to the uterosacral ligaments only after the correct dissection plane is confirmed by visualization of the areolar tissue.

- Apply cervical traction using the tenaculum in a cephalad midline direction, and place traction on the cut edge of the posterior peritoneum using the bipolar forceps. The tenaculum wrist must be turned away from the working instruments to avoid internal clashing.

- Completely transect the right uterosacral ligament to better facilitate the creation of a contiguous peritoneal opening for burying the mesh. The remainder of the opening will be created later.

- While it is important to avoid split-thickness dissection, the vaginal plane must be "clean" (that is, without fat or adventitia) to allow for robust suturing.

- Dissection at least halfway down the posterior vaginal wall is recommended but proceeding down to the perineal body provides the most optimal support (FIGURE 6).

Sacral dissection

- Use a noncrushing instrument to laterally sweep the bowel to the left side, effectively "plastering" the peritoneum over the sacral promontory (FIGURE 7; VIDEO 5).

- Extend the superficial peritoneal incision down the right paracolic gutter halfway between the ureter and colon until it communicates with the incised posterior peritoneal edge created during the posterior dissection.

- Identify the middle sacral artery to avoid vascular injury, but there is no need to prophylactically coagulate it.

Vaginal mesh attachment

- Cut a lightweight Y-mesh to a length of 6 to 8 cm anteriorly and 8 to 11 cm posteriorly and place it into the surgical field (FIGURE 8; VIDEO 6). The length is determined based on the preoperative office examination and examination under anesthesia prior to starting the procedure.

- Attach the mesh securely and evenly to the anterior and posterior vaginal walls using multiple interrupted monofilament sutures. We aim to place sutures that provide mesh stability without excess vaginal wall incorporation to avoid "through-and-through" suturing.

- The posterior wall suturing is performed first, starting at the perineal body and continuing cephalad (VIDEO 7). We find it easiest to tie the knots between the mesh and the vagina in this space.

- Suture the crotch of the Y-mesh to the cervix so that no gap exists between tissue and mesh.

- For advanced-stage prolapse with significant anterior prolapse, the stretched out vaginal epithelium can be systematically gathered up to reconfigure the tissue to conform to the desired mesh dimensions (VIDEO 8). This tissue remodeling is evident even at the 2- to 4-week postoperative visit.

Peritoneal closure: Step 1

- Reapproximate the cut edges of peritoneum surrounding the vagina and cervix using a continuous purse-string suture of 0 Monocryl (poliglecaprone 25) on an SH needle (Ethicon, Somerville, New Jersey) with a fisherman's knot tied at the end (VIDEO 9). The needle passes are placed close together and close to the incised edge of the cut peritoneum.

- We typically start our peritoneal suture at the 5 o'clock position of the posterior peritoneum, extending in a clockwise direction and ultimately jumping anteriorly around the sacral arm of the mesh.

- Place the mesh within the paracolic peritoneal canal, and secure the needle for later use.

Sacral mesh attachment

- The mesh is tensioned so that a vaginal examination confirms adequate support of all the walls without excess tension or tissue banding. Some laxity of the anterior vaginal wall consistent with a mild cystocele is appropriate.

- Place 2 permanent PTFE sutures along the slope of the sacral promontory into the anterior longitudinal ligament (VIDEO 10). This avoids injury to the disc space that sits at the edge of the promontory. We do not advise the use of bone anchors as they increase the risk for discitis and osteomyelitis.

- Secure the mesh to the anterior longitudinal ligament without any tension. This is facilitated by creating mesh slack via cephalad pressure from a vaginal probe.

Peritoneal closure: Step 2

- Close the remaining paracolic peritoneal incision, completely burying the mesh within the created canal (FIGURE 9).

- At the end of the procedure, perform a repeat vaginal exam, rectal exam, and cystoscopy.

Technique with prior total hysterectomy

- In patients with a prior total hysterectomy, place a 13 x 3.5 cm Breisky vaginal retractor and/or coated nonconductive stent (Marina Medical, Sunrise, Florida) into the vagina to delineate the anterior and posterior walls at the vaginal apex during dissection.

- Some surgeons may opt to retrograde fill the bladder to better identify its location.

- We routinely leave a segment of peritoneum attached to the dome of the vaginal apex for added tissue integrity to prevent erosion.

Read about using transvaginal mesh for POP repair.

Transvaginal mesh: An effective, durable option for POP repair

Vincent R. Lucente, MD, MBA, and Jessica B. Ton, MD

Dr. Lucente reports that he has received grant or research support from Advanced Tactile Imaging, Boston Scientific, Coloplast, and Valencia; is a consultant to Coloplast; is a speaker for Allergan, Boston Scientific, Coloplast, and Shionogi; and serves as an expert witness for American Medical Systems and C.R. Bard. Dr. Ton reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

As baseline health in the elderly population continues to improve, the number of women in the United States with symptomatic POP will increase by approximately 50% by 2050.39 Unfortunately, after native tissue repair (NTR) the rate of prolapse recurrence is extremely high: approximately 40% regardless of approach, as demonstrated in the OPTIMAL (Operations and Pelvic Muscle Training in the Management of Apical Support Loss) trial by Barber and colleagues.6 The authors of that clinical trial recently revealed that at the 5-year follow-up, these failure rates progressed to 70% for sacrospinous ligament fixation and 61% for uterosacral ligament suspension (data presented at the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Annual Scientific Meeting 2018, Orlando, Florida). This establishes that NTR is not durable enough to meet the increasing physical demands of this age group and that mesh augmentation must be considered.

For patients at increased risk of prolapse recurrence, using transvaginal mesh (TVM) is the most minimally invasive approach and is an excellent option for mesh augmentation. Avoiding adverse events during placement of TVM depends largely on optimal surgical technique.40 (VIDEO: “Demonstration of an anterior vaginal wall dissection into the true vesicovaginal space”)

- Active advanced age requires a durable reconstructive pelvic surgery for pelvic organ prolapse, and native tissue repair does not meet that demand.

- Mesh augmentation reduces the risk of prolapse recurrence, and vaginal placement of mesh is the most minimally invasive approach.

- Rates of exposure with transvaginal mesh would be minimized with use of a full-thickness vaginal wall dissection.

- Optimal surgical technique could be highly reproducible with better surgical training.

The evidence on TVM versus NTR

Several studies have examined whether TVM has a measurable benefit over NTR.

A 2016 Cochrane review by Maher and colleagues included 37 randomized trials (4,023 women) that compared TVM and biologic grafts with NTR.41 Three primary outcomes were defined: awareness of prolapse, recurrence, and repeat surgery. Compared with women treated with NTR, those treated with synthetic nonabsorbable TVM exhibited a greater reduction in awareness of prolapse (risk ratio [RR], 0.66; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.54-0.81), decreased recurrence in the anterior compartment (RR, 0.33; 95% CI, 0.26-0.40), and decreased reoperation for prolapse (RR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.31-0.88). The overall calculated exposure rate was 12%, with a range of 3.2% to 20.8%.41 As we will discuss, this wide range most likely is attributed to a suboptimal, split-thickness dissection. There were no differences in other key secondary outcomes, including dyspareunia, operating time, and estimated blood loss.41

Longitudinal studies are emerging as almost 2 decades have passed since TVM was introduced. In a study of 5-year follow-up after TVM placement, Meyer and colleagues reported that patients had continued significant improvements in both subjective and objective outcomes.42 The mesh exposure rate was 6%, attributed to severe vaginal atrophy.42 A 10-year observational study by Weintraub and colleagues demonstrated a recurrence rate of only 2.6% in the anterior compartment, 7.6% in the posterior (nonaugmented) compartment, and no exposures or extrusions after anterior TVM placement.43

In contrast to the Cochrane review, in the 2017 multicenter PROSPECT (Prolapse surgery: Pragmatic evaluation and randomized controlled trials) trial, Glazener and colleagues found no difference in desired outcomes with TVM compared with NTR.44 There was an overall 6% to 7% exposure rate over 2 years.44 To reflect "real-world" practice, however, this study was intentionally designed without rigorous standardization of surgical technique. The authors reported that "appropriately experienced surgeons" performed the procedure, but it is unclear how experience was determined given that 20% of the cases were performed by "registrars," the equivalent of US residents or fellows.45

The PROSPECT study protocol described the TVM procedure as "a standard repair with a nonabsorbable mesh inlay to support the stitches," implying that there was no apical attachment of the mesh to the sacrospinous ligament.45 This is a suboptimal use of TVM because it does not address a detachment-type defect common in advanced prolapse. The PROSPECT study reinforces the need for better surgical training and standardization of the TVM procedure.44

How TVM compares with sacrocolpopexy