User login

Trying to treat depression or anxiety in a midlife woman without asking how she’s sleeping may doom your treatment plan. Asking about sleep addresses issues that affect her quality of life and can provide valuable insight into effective interventions.

Psychiatric, psychosocial, and medical problems can disturb sleep during perimenopause.1 To help you diagnose and treat both mood disorders and insomnia, this article:

- describes how irregular hormone levels and psychosocial changes are linked to perimenopausal mood and sleep disorders

- offers evidence-based strategies for hormone replacement therapy (HRT), antidepressants, hypnotics, and psychotherapy.

DEPRESSION AND INSOMNIA AT MIDLIFE

Sixty-five percent of women seeking outpatient treatment for depression report disturbed sleep.2 Even mild anxiety and depression can undermine sleep quality, whereas insomnia can precede other symptoms of an evolving major depression.

Depressive disorders affect up to 29% of perimenopausal women (depending on the assessment tool used), compared with 8% to 12% of premenopausal women. Menopausal symptoms—hot flashes, poor sleep, memory problems—and not using HRT are associated with depression.3

Causes of midlife depression. Gonadal hormone changes have been implicated as a cause of increased depression in midlife women; declines in serum estradiol and testosterone are inversely associated with depression.4 The natural menopause transition (perimenopause) begins during the mid-40s, persists to the early 50s, and lasts an average 2 to 9 years. Estradiol produced by the ovary becomes erratic then decreases. Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) serum levels increase, then plateau and serve as laboratory markers of menopause.5

Sociodemographic factors also may contribute to depression, anxiety, and insomnia. A midlife woman may experience role transitions—such as children leaving home and aging parents needing care. She may be adapting to her or her spouse’s retirement or to the loss of her partner by divorce or death. She may be grappling with her own aging and questions about mortality and life purpose.

In the workup, consider medical factors that may worsen sleep problems, such as hot flashes, sleep apnea, thyroid disease, urinary frequency, chronic pain, restless leg syndrome, caffeine use, sedentary lifestyle, and primary insomnia. Some women lose sleep from a bed partner’s snoring or movement (“spousal arousal”). Stimulating drugs such as theophylline can also play a role.

SLEEP CHANGES AT PERIMENOPAUSE

Sleep changes are among the most common physical and psychological experiences healthy women describe during perimenopause:

- 100 consecutive women surveyed at a menopause clinic reported fatigue (91%), hot flashes (80%), insomnia and early awakenings (77%), and depression (65%).6

- Sleep problems were reported by >50% of 203 women interviewed for the Decisions at Menopause Study (DAMES).7

- Difficulty sleeping across 2 weeks was reported by 38% of a multiethnic population of 12,603 women ages 40 to 55.8

Sleep problems occur more often during perimenopause than earlier in life. In a clinic sample of 521 women, Owens et al1 found insomnia in 33% to 36% of those in premenopause and in 44% to 61% of women during perimenopause. In the total sample of healthy middle-aged women, 42% had sleep complaints, including:

- initial insomnia: 49%

- middle insomnia: 92%

- early morning awakening: 59%.

No association? Individuals experience sleep quality subjectively, and these assessments may not match those obtained objectively. The Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study,9 for example, found no association between menopause and diminished sleep quality in polysomnographic studies of 589 community-dwelling women. Even so, the peri- and postmenopausal women in the study reported less sleep satisfaction than premenopausal women did.

Most clinicians agree that a woman’s subjective experience of sleep is clinically relevant. Thus, rule out underlying sleep disorders before you attribute a midlife woman’s depressive signs and symptoms primarily to menopause.10

Treatment. Combination therapy may be useful, depending on the patient’s psychiatric and medical comorbidities (Algorithm).

TREATING PERIMENOPAUSAL DEPRESSION

HRT. Before the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI),10 guidelines recommended HRT for a first depressive episode during perimenopause and antidepressants for severe depressive symptoms and for women with a history of depression.11 This practice changed when the WHI found risks of thromboembolism, breast cancer, stroke, and coronary artery disease that increased over time with HRT.

HRT remains a short-term treatment option but is no longer considered the first or only approach to mood symptoms at perimenopause. Discuss with your patient potential benefits of short-term HRT for a first episode of depression—especially if she has vasomotor symptoms—versus potential risks.

Antidepressants can improve perimenopausal depression, but few studies have tested these agents’ effects on sleep. To reduce treatment-associated insomnia:

- select a relatively sedating antidepressant such as mirtazapine

- accept some insomnia for 3 to 4 weeks, until a stimulating antidepressant has had a full ffect on mood and its associated side effects would be expected to resolve

- or augment the antidepressant with a hypnotic such as zolpidem, zaleplon, eszopiclone, or trazodone.

When choosing therapy, consider patient factors and insomnia severity. For example, mirtazapine is typically associated with weight gain, so consider other options for overweight patients. Those with severe insomnia may prefer not to wait 3 to 4 weeks for improved sleep. With hypnotics, consider cost, any coexisting chemical dependency, and potential for morning hangover.

Psychotherapy can help perimenopausal patients accept aging, evaluate relationships, and examine their roles in the lives of more-dependent parents and less-dependent children.

HOT FLASHES AND INSOMNIA

Persistent hot flashes that disturb sleep may cause depression.12 They can wake a perimenopausal woman repeatedly (Figure 1). The awakenings may be brief—90% last <3 minutes—but a severely affected woman can lose an hour of sleep in a night.13 Even after a hot flash resolves, other factors such as anxiety may keep her awake.

Up to 85% of perimenopausal women experience hot flashes, especially during the first year after menses cease. Hot flashes persist for 5 years after menopause in 25% of women and indefinitely in a minority (Box ).14

Estrogen deficiency is thought to cause hot flashes via decreased serotonin synthesis and up-regulated 5HT2A receptors—the mediators of heat loss. As a result, a woman’s thermoregulatory zone narrows during perimenopause, reducing her tolerance for core body temperature changes. The thermoregulatory nucleus resides in the medial preoptic area of the anterior hypothalamus.

A hot flash begins with facial warmth when core temperatures exceed the thermoregulatory line. Heat spreads to the chest, often accompanied by flushing, diaphoresis, and headache. A woman may feel agitated, irritable, and distressed.

CNS noradrenergic activity may initiate hot flashes. Freedman et al13 compared the effects of IV clonidine (an alpha2 adrenergic agonist) plus yohimbine (an alpha2 adrenergic antagonist) or placebo in menopausal women with or without vasomotor symptoms. Among 9 symptomatic women, 6 experienced hot flashes when given yohimbine, and none did with placebo. No hot flashes occurred in asymptomatic women. Clonidine increased the duration of peripheral heating needed to trigger a hot flash and reduced the number of hot flashes in symptomatic women, compared with baseline.

Risk factors for nocturnal hot flashes include surgical menopause, Caucasian versus Asian ethnicity, lack of exercise, and nicotine use.8 Women suffering anxiety and stress also are at increased risk.15

HOT-FLASH THERAPIES

Placebo-controlled trials of hot flash therapies have found efficacies from 85% for HRT to 25% for placebo, vitamin E, black cohosh, soy, and behavioral therapy (Figure 2).16 Most trials were not designed to test the link between hot flashes and sleep, and many enrolled cancer patients not experiencing natural menopause. With the 25% placeboresponse rate, some therapies’ efficacy is unclear.

HRT can reduce nocturnal hot flash frequency. In a polysomnographic study,17 21 postmenopausal women received 6 months of conjugated estrogens, 0.625 mg/d, with medroxyprogesterone, 5 mg/d, or micronized progesterone, 200 mg/d. Sleep efficiency improved by 8% in women receiving micronized progesterone but was unchanged with medroxyprogesterone. Even so, both groups reported improved sleep quality and duration, with decreased awakenings.

The Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study9 found that HRT was not associated with improved sleep, as measured by polysomnography. Even so, the women in that study noted subjective sleep improvement with HRT.

Antidepressants. Venlafaxine, 75 mg/d, and fluoxetine, 20 mg/d, have shown benefit in reducing hot flashes,18 presumably by increasing CNS serotonin. As mentioned, however, many antidepressants can cause insomnia, and few studies have examined this problem.

Gabapentin has been effective for patients with hot flashes.19 This agent, which increases GABA levels and may modestly increase slow-wave sleep—can improve conditions that disrupt sleep, including restless legs syndrome and chronic pain. It is well-tolerated, even at 900 mg/d, and is more-sedating than most serotonergic antidepressants.

Hypnotics. Surprisingly little evidence addresses hypnotics’ role in managing insomnia caused by hot flashes. No data have been published on the role of benzodiazepines or the benzodiazepine receptor agonists (zolpidem, zaleplon, and eszopiclone). In my experience, benzodiazepine receptor agonists improve sleep quality compromised by multiple factors, including hot flashes.

Soy and black cohosh. Isoflavones in soy may be estrogen receptor modulators. Twelve randomized, controlled trials of soy or soy extracts have shown a modest benefit for hot flashes.20

Black cohosh extracts, 8 mg/d, were given to 80 postmenopausal women in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (RCT). Hot flashes in those receiving black cohosh decreased from 4.9 to 0.7 daily, compared with reductions of 5.2 to 3.2 in women receiving estrogen and 5.1 to 3.1 in those receiving placebo.21 As a result, the National Institutes of Health is funding a 12-month, RCT to determine whether black cohosh reduces hot flash frequency and intensity.

Alternative agents are widely used and warrant study. Those shown to be safe can be used alone or with other therapies, but advise the patient that these agents may not be effective. Relaxation and exercise may decrease hot flashes,22 although some outcomes have been similar to a placebo response.

SLEEP APNEA AT PERIMENOPAUSE

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), although more common in men than women, appears to increase during perimenopause. Women with untreated OSA are twice as likely as men to be treated for depression, less likely to report excessive daytime sleepiness and snoring, and more likely to present with depression, anxiety, and morning headache.

Bixler et al23 interviewed 12,219 women and 4,364 men ages 20 to 100 and conducted 1-night sleep studies in 1,000 women and 741 men. OSA rates were 3.9% in men, 0.6% in premenopausal women, 2.7% in postmenopausal women not taking HRT, and 0.5% in postmenopausal women taking HRT.

The risk of sleep-disordered breathing is lower during early menopause and peaks at approximately age 65. Declining hormones likely play a role; progesterone increases ventilatory drive, and estrogen increases ventilatory centers’ sensitivity to progesterone’s stimulant effect. In small studies, exogenous progesterone has shown a slight effect in improving OSA.24

OSA’s transient, repetitive upper airway collapse increases inspiratory effort and may cause hypoxemia. Repeated arousals can lead to prolonged awakenings and unrefreshing sleep. Snoring and increased body mass index are strongly associated factors, although the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study10 showed an increase in sleep apnea in perimenopausal women that was unrelated to increased body mass index.

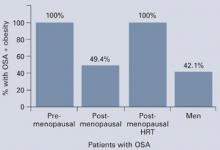

Obesity may not explain the increase in obstructive sleep apnea at perimenopause (Figure 3),28 although body fat distribution does change with aging. Women at perimenopause are likely to develop abdominal weight distribution.

Figure 3 Increased OSA in postmenopausal women is unrelated to obesity (BMI >32)

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in 1,000 women and 741 men was associated exclusively with obesity in premenopausal women and postmenopausal women using HRT, but nearly one-half of the postmenopausal women with OSA were not obese.

Source: Adapted from reference 23.Treatment. In the Sleep Heart Health Study25 of 2,852 women age 50 or older, HRT users had one-half the apnea prevalence of nonusers (6% vs 14%). HRT users were less likely to awaken at night and to get inadequate sleep. Snoring rates were similar (25% for HRT users, 23% for nonusers).

Nasal continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is the mainstay of apnea treatment, although some women appear to have difficulty accepting CPAP.26 Weight loss and moderate exercise can help manage weight and improve sleep quality by increasing slow-wave sleep. Regular exercise also may improve depressed mood.

Related resources

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. www.acog.org

- The North American Menopause Society. www.menopause.org

Drug brand names

- Conjugated estrogens • Premarin

- Eszopiclone • Lunesta

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Gabapentin • Neurontin

- Medroxyprogesterone • Provera

- Micronized progesterone • Prometrium

- Mirtazapine • Remeron

- Trazodone • Desyrel

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

- Zaleplon • Sonata

- Zolpidem • Ambien

Disclosures

Dr. Krahn reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Owens JF, Matthews KA. Sleep disturbance in healthy middle-aged women. Maturitas 1998;30:41-50.

2. Perlis ML, Giles DE, Buysse DJ, et al. Self-reported sleep disturbance as a prodromal symptom in recurrent depression. J Affect Disord 1997;42(2-3):209-12.

3. Bromberger JT, Assmann SF, Avis NE, et al. Persistent mood symptoms in a multiethnic community cohort of pre- and perimenopausal women. Am J Epidemiol 2003;158:347-56.

4. Sherwin BB. Changes in sexual behavior as a function of plasma sex steroid levels in post-menopausal women. Maturitas 1985;7(3):225-33.

5. Brizendine L. Minding menopause. Psychotropics vs estrogen: What you need to know now. Current Psychiatry 2003;2(10):12-31.

6. Anderson E, Hamburger S, Liu JH, Rebar RW. Characteristics of menopausal women seeking assistance. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1987;156(2):428-33.

7. Obermeyer CM, Reynolds RF, Price K, Abraham A. Therapeutic decisions for menopause: results of the DAMES project in central Massachusetts. Menopause 2004;11(4):456-65.

8. Kravitz HM, Ganz PA, Bromberger J, et al. Sleep difficulty in women at midlife: a community survey of sleep and the menopausal transition. Menopause 2003;10(1):19-28.

9. Young T, Rabago D, Zgierska A, et al. Objective and subjective sleep quality in premenopausal, perimenopausal, and postmenopausal women in the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study. Sleep 2003;26(6):667-72.

10. Wassertheil-Smoller S, Shumaker S, Ockene J, et al. Depression and cardiovascular sequelae in postmenopausal women. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:289-98.

11. Altshuler LL, Cohen LS, Moline ML, et al. The expert consensus guideline series. Treatment of depression in women. Postgrad Med 2001;March:1-107.

12. Krystal AD. Insomnia in women. Clin Cornerstone 2003;5(3):41-50.

13. Freedman RR. Physiology of hot flashes. Am J Hum Biol 2001;13(4):453-64.

14. Freedman RR, Woodward S, Sabharwal SC. A2-adrenergic mechanism in menopausal hot flushes. Obstet Gynecol 1990;76(4):573-8.

15. Miller AG, Li RM. Measuring hot flashes: summary of a NIH workshop. Mayo Clin Proc 2004;79:777-81.

16. Joffe H, Soares CN, Cohen LS. Assessment and treatment of hot flushes and menopausal mood disturbance. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2003 Sep;26(3):563-80.

17. Montplaisir J, Lorrain J, Denesle R, Petit D. Sleep in menopause: differential effects of two forms of hormone replacement therapy. Menopause 2001;8(1):10-16.

18. Loprinzi CL, Sloan JA, Perez EA, et al. Phase III evaluation of fluoxetine for treatment of hot flashes. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:1578-83.

19. Guttoso T, Jr, Kurlan R, McDermott MP, Kieburtz K. Gabapentin’s effects on hot flashes in postmenopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2003;101:337-45.

20. Kessel B, Kronenberg F. The role of complementary and alternative medicine in management of menopausal symptoms. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2004;33:717-39.

21. National Institutes of Health. National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Office of Dietary Supplements. Questions and answers about black cohosh and the symptoms of menopause. Available at: http://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/blackcohosh.asp. Accessed May 9, 2005.

22. Ivarsson T, Spetz AC, Hammar M. Physical exercise and vasomotor symptoms in postmenopausal women. Mauritas 1998;29:139-46.

23. Bixler EO, Vgontzas AN, Lin HM, et al. Prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in women: effects of gender. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;163:608-13.

24. Block AJ, Wynne JW, Boysen PG, et al. Menopause, medroxyprogesterone and breathing during sleep. Am J Med 1981;70:506-10.

25. Shahar E, Redline S, Young T, et al. Hormone replacement therapy and sleep-disordered breathing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;167:1186-92.

26. McArdle N, Devereux G, Heidarnejad H, et al. Long-term use of CPAP therapy for sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome. Am J Respir Crit. Care Med 1999;159:1108-14.

Trying to treat depression or anxiety in a midlife woman without asking how she’s sleeping may doom your treatment plan. Asking about sleep addresses issues that affect her quality of life and can provide valuable insight into effective interventions.

Psychiatric, psychosocial, and medical problems can disturb sleep during perimenopause.1 To help you diagnose and treat both mood disorders and insomnia, this article:

- describes how irregular hormone levels and psychosocial changes are linked to perimenopausal mood and sleep disorders

- offers evidence-based strategies for hormone replacement therapy (HRT), antidepressants, hypnotics, and psychotherapy.

DEPRESSION AND INSOMNIA AT MIDLIFE

Sixty-five percent of women seeking outpatient treatment for depression report disturbed sleep.2 Even mild anxiety and depression can undermine sleep quality, whereas insomnia can precede other symptoms of an evolving major depression.

Depressive disorders affect up to 29% of perimenopausal women (depending on the assessment tool used), compared with 8% to 12% of premenopausal women. Menopausal symptoms—hot flashes, poor sleep, memory problems—and not using HRT are associated with depression.3

Causes of midlife depression. Gonadal hormone changes have been implicated as a cause of increased depression in midlife women; declines in serum estradiol and testosterone are inversely associated with depression.4 The natural menopause transition (perimenopause) begins during the mid-40s, persists to the early 50s, and lasts an average 2 to 9 years. Estradiol produced by the ovary becomes erratic then decreases. Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) serum levels increase, then plateau and serve as laboratory markers of menopause.5

Sociodemographic factors also may contribute to depression, anxiety, and insomnia. A midlife woman may experience role transitions—such as children leaving home and aging parents needing care. She may be adapting to her or her spouse’s retirement or to the loss of her partner by divorce or death. She may be grappling with her own aging and questions about mortality and life purpose.

In the workup, consider medical factors that may worsen sleep problems, such as hot flashes, sleep apnea, thyroid disease, urinary frequency, chronic pain, restless leg syndrome, caffeine use, sedentary lifestyle, and primary insomnia. Some women lose sleep from a bed partner’s snoring or movement (“spousal arousal”). Stimulating drugs such as theophylline can also play a role.

SLEEP CHANGES AT PERIMENOPAUSE

Sleep changes are among the most common physical and psychological experiences healthy women describe during perimenopause:

- 100 consecutive women surveyed at a menopause clinic reported fatigue (91%), hot flashes (80%), insomnia and early awakenings (77%), and depression (65%).6

- Sleep problems were reported by >50% of 203 women interviewed for the Decisions at Menopause Study (DAMES).7

- Difficulty sleeping across 2 weeks was reported by 38% of a multiethnic population of 12,603 women ages 40 to 55.8

Sleep problems occur more often during perimenopause than earlier in life. In a clinic sample of 521 women, Owens et al1 found insomnia in 33% to 36% of those in premenopause and in 44% to 61% of women during perimenopause. In the total sample of healthy middle-aged women, 42% had sleep complaints, including:

- initial insomnia: 49%

- middle insomnia: 92%

- early morning awakening: 59%.

No association? Individuals experience sleep quality subjectively, and these assessments may not match those obtained objectively. The Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study,9 for example, found no association between menopause and diminished sleep quality in polysomnographic studies of 589 community-dwelling women. Even so, the peri- and postmenopausal women in the study reported less sleep satisfaction than premenopausal women did.

Most clinicians agree that a woman’s subjective experience of sleep is clinically relevant. Thus, rule out underlying sleep disorders before you attribute a midlife woman’s depressive signs and symptoms primarily to menopause.10

Treatment. Combination therapy may be useful, depending on the patient’s psychiatric and medical comorbidities (Algorithm).

TREATING PERIMENOPAUSAL DEPRESSION

HRT. Before the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI),10 guidelines recommended HRT for a first depressive episode during perimenopause and antidepressants for severe depressive symptoms and for women with a history of depression.11 This practice changed when the WHI found risks of thromboembolism, breast cancer, stroke, and coronary artery disease that increased over time with HRT.

HRT remains a short-term treatment option but is no longer considered the first or only approach to mood symptoms at perimenopause. Discuss with your patient potential benefits of short-term HRT for a first episode of depression—especially if she has vasomotor symptoms—versus potential risks.

Antidepressants can improve perimenopausal depression, but few studies have tested these agents’ effects on sleep. To reduce treatment-associated insomnia:

- select a relatively sedating antidepressant such as mirtazapine

- accept some insomnia for 3 to 4 weeks, until a stimulating antidepressant has had a full ffect on mood and its associated side effects would be expected to resolve

- or augment the antidepressant with a hypnotic such as zolpidem, zaleplon, eszopiclone, or trazodone.

When choosing therapy, consider patient factors and insomnia severity. For example, mirtazapine is typically associated with weight gain, so consider other options for overweight patients. Those with severe insomnia may prefer not to wait 3 to 4 weeks for improved sleep. With hypnotics, consider cost, any coexisting chemical dependency, and potential for morning hangover.

Psychotherapy can help perimenopausal patients accept aging, evaluate relationships, and examine their roles in the lives of more-dependent parents and less-dependent children.

HOT FLASHES AND INSOMNIA

Persistent hot flashes that disturb sleep may cause depression.12 They can wake a perimenopausal woman repeatedly (Figure 1). The awakenings may be brief—90% last <3 minutes—but a severely affected woman can lose an hour of sleep in a night.13 Even after a hot flash resolves, other factors such as anxiety may keep her awake.

Up to 85% of perimenopausal women experience hot flashes, especially during the first year after menses cease. Hot flashes persist for 5 years after menopause in 25% of women and indefinitely in a minority (Box ).14

Estrogen deficiency is thought to cause hot flashes via decreased serotonin synthesis and up-regulated 5HT2A receptors—the mediators of heat loss. As a result, a woman’s thermoregulatory zone narrows during perimenopause, reducing her tolerance for core body temperature changes. The thermoregulatory nucleus resides in the medial preoptic area of the anterior hypothalamus.

A hot flash begins with facial warmth when core temperatures exceed the thermoregulatory line. Heat spreads to the chest, often accompanied by flushing, diaphoresis, and headache. A woman may feel agitated, irritable, and distressed.

CNS noradrenergic activity may initiate hot flashes. Freedman et al13 compared the effects of IV clonidine (an alpha2 adrenergic agonist) plus yohimbine (an alpha2 adrenergic antagonist) or placebo in menopausal women with or without vasomotor symptoms. Among 9 symptomatic women, 6 experienced hot flashes when given yohimbine, and none did with placebo. No hot flashes occurred in asymptomatic women. Clonidine increased the duration of peripheral heating needed to trigger a hot flash and reduced the number of hot flashes in symptomatic women, compared with baseline.

Risk factors for nocturnal hot flashes include surgical menopause, Caucasian versus Asian ethnicity, lack of exercise, and nicotine use.8 Women suffering anxiety and stress also are at increased risk.15

HOT-FLASH THERAPIES

Placebo-controlled trials of hot flash therapies have found efficacies from 85% for HRT to 25% for placebo, vitamin E, black cohosh, soy, and behavioral therapy (Figure 2).16 Most trials were not designed to test the link between hot flashes and sleep, and many enrolled cancer patients not experiencing natural menopause. With the 25% placeboresponse rate, some therapies’ efficacy is unclear.

HRT can reduce nocturnal hot flash frequency. In a polysomnographic study,17 21 postmenopausal women received 6 months of conjugated estrogens, 0.625 mg/d, with medroxyprogesterone, 5 mg/d, or micronized progesterone, 200 mg/d. Sleep efficiency improved by 8% in women receiving micronized progesterone but was unchanged with medroxyprogesterone. Even so, both groups reported improved sleep quality and duration, with decreased awakenings.

The Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study9 found that HRT was not associated with improved sleep, as measured by polysomnography. Even so, the women in that study noted subjective sleep improvement with HRT.

Antidepressants. Venlafaxine, 75 mg/d, and fluoxetine, 20 mg/d, have shown benefit in reducing hot flashes,18 presumably by increasing CNS serotonin. As mentioned, however, many antidepressants can cause insomnia, and few studies have examined this problem.

Gabapentin has been effective for patients with hot flashes.19 This agent, which increases GABA levels and may modestly increase slow-wave sleep—can improve conditions that disrupt sleep, including restless legs syndrome and chronic pain. It is well-tolerated, even at 900 mg/d, and is more-sedating than most serotonergic antidepressants.

Hypnotics. Surprisingly little evidence addresses hypnotics’ role in managing insomnia caused by hot flashes. No data have been published on the role of benzodiazepines or the benzodiazepine receptor agonists (zolpidem, zaleplon, and eszopiclone). In my experience, benzodiazepine receptor agonists improve sleep quality compromised by multiple factors, including hot flashes.

Soy and black cohosh. Isoflavones in soy may be estrogen receptor modulators. Twelve randomized, controlled trials of soy or soy extracts have shown a modest benefit for hot flashes.20

Black cohosh extracts, 8 mg/d, were given to 80 postmenopausal women in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (RCT). Hot flashes in those receiving black cohosh decreased from 4.9 to 0.7 daily, compared with reductions of 5.2 to 3.2 in women receiving estrogen and 5.1 to 3.1 in those receiving placebo.21 As a result, the National Institutes of Health is funding a 12-month, RCT to determine whether black cohosh reduces hot flash frequency and intensity.

Alternative agents are widely used and warrant study. Those shown to be safe can be used alone or with other therapies, but advise the patient that these agents may not be effective. Relaxation and exercise may decrease hot flashes,22 although some outcomes have been similar to a placebo response.

SLEEP APNEA AT PERIMENOPAUSE

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), although more common in men than women, appears to increase during perimenopause. Women with untreated OSA are twice as likely as men to be treated for depression, less likely to report excessive daytime sleepiness and snoring, and more likely to present with depression, anxiety, and morning headache.

Bixler et al23 interviewed 12,219 women and 4,364 men ages 20 to 100 and conducted 1-night sleep studies in 1,000 women and 741 men. OSA rates were 3.9% in men, 0.6% in premenopausal women, 2.7% in postmenopausal women not taking HRT, and 0.5% in postmenopausal women taking HRT.

The risk of sleep-disordered breathing is lower during early menopause and peaks at approximately age 65. Declining hormones likely play a role; progesterone increases ventilatory drive, and estrogen increases ventilatory centers’ sensitivity to progesterone’s stimulant effect. In small studies, exogenous progesterone has shown a slight effect in improving OSA.24

OSA’s transient, repetitive upper airway collapse increases inspiratory effort and may cause hypoxemia. Repeated arousals can lead to prolonged awakenings and unrefreshing sleep. Snoring and increased body mass index are strongly associated factors, although the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study10 showed an increase in sleep apnea in perimenopausal women that was unrelated to increased body mass index.

Obesity may not explain the increase in obstructive sleep apnea at perimenopause (Figure 3),28 although body fat distribution does change with aging. Women at perimenopause are likely to develop abdominal weight distribution.

Figure 3 Increased OSA in postmenopausal women is unrelated to obesity (BMI >32)

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in 1,000 women and 741 men was associated exclusively with obesity in premenopausal women and postmenopausal women using HRT, but nearly one-half of the postmenopausal women with OSA were not obese.

Source: Adapted from reference 23.Treatment. In the Sleep Heart Health Study25 of 2,852 women age 50 or older, HRT users had one-half the apnea prevalence of nonusers (6% vs 14%). HRT users were less likely to awaken at night and to get inadequate sleep. Snoring rates were similar (25% for HRT users, 23% for nonusers).

Nasal continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is the mainstay of apnea treatment, although some women appear to have difficulty accepting CPAP.26 Weight loss and moderate exercise can help manage weight and improve sleep quality by increasing slow-wave sleep. Regular exercise also may improve depressed mood.

Related resources

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. www.acog.org

- The North American Menopause Society. www.menopause.org

Drug brand names

- Conjugated estrogens • Premarin

- Eszopiclone • Lunesta

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Gabapentin • Neurontin

- Medroxyprogesterone • Provera

- Micronized progesterone • Prometrium

- Mirtazapine • Remeron

- Trazodone • Desyrel

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

- Zaleplon • Sonata

- Zolpidem • Ambien

Disclosures

Dr. Krahn reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Trying to treat depression or anxiety in a midlife woman without asking how she’s sleeping may doom your treatment plan. Asking about sleep addresses issues that affect her quality of life and can provide valuable insight into effective interventions.

Psychiatric, psychosocial, and medical problems can disturb sleep during perimenopause.1 To help you diagnose and treat both mood disorders and insomnia, this article:

- describes how irregular hormone levels and psychosocial changes are linked to perimenopausal mood and sleep disorders

- offers evidence-based strategies for hormone replacement therapy (HRT), antidepressants, hypnotics, and psychotherapy.

DEPRESSION AND INSOMNIA AT MIDLIFE

Sixty-five percent of women seeking outpatient treatment for depression report disturbed sleep.2 Even mild anxiety and depression can undermine sleep quality, whereas insomnia can precede other symptoms of an evolving major depression.

Depressive disorders affect up to 29% of perimenopausal women (depending on the assessment tool used), compared with 8% to 12% of premenopausal women. Menopausal symptoms—hot flashes, poor sleep, memory problems—and not using HRT are associated with depression.3

Causes of midlife depression. Gonadal hormone changes have been implicated as a cause of increased depression in midlife women; declines in serum estradiol and testosterone are inversely associated with depression.4 The natural menopause transition (perimenopause) begins during the mid-40s, persists to the early 50s, and lasts an average 2 to 9 years. Estradiol produced by the ovary becomes erratic then decreases. Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) serum levels increase, then plateau and serve as laboratory markers of menopause.5

Sociodemographic factors also may contribute to depression, anxiety, and insomnia. A midlife woman may experience role transitions—such as children leaving home and aging parents needing care. She may be adapting to her or her spouse’s retirement or to the loss of her partner by divorce or death. She may be grappling with her own aging and questions about mortality and life purpose.

In the workup, consider medical factors that may worsen sleep problems, such as hot flashes, sleep apnea, thyroid disease, urinary frequency, chronic pain, restless leg syndrome, caffeine use, sedentary lifestyle, and primary insomnia. Some women lose sleep from a bed partner’s snoring or movement (“spousal arousal”). Stimulating drugs such as theophylline can also play a role.

SLEEP CHANGES AT PERIMENOPAUSE

Sleep changes are among the most common physical and psychological experiences healthy women describe during perimenopause:

- 100 consecutive women surveyed at a menopause clinic reported fatigue (91%), hot flashes (80%), insomnia and early awakenings (77%), and depression (65%).6

- Sleep problems were reported by >50% of 203 women interviewed for the Decisions at Menopause Study (DAMES).7

- Difficulty sleeping across 2 weeks was reported by 38% of a multiethnic population of 12,603 women ages 40 to 55.8

Sleep problems occur more often during perimenopause than earlier in life. In a clinic sample of 521 women, Owens et al1 found insomnia in 33% to 36% of those in premenopause and in 44% to 61% of women during perimenopause. In the total sample of healthy middle-aged women, 42% had sleep complaints, including:

- initial insomnia: 49%

- middle insomnia: 92%

- early morning awakening: 59%.

No association? Individuals experience sleep quality subjectively, and these assessments may not match those obtained objectively. The Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study,9 for example, found no association between menopause and diminished sleep quality in polysomnographic studies of 589 community-dwelling women. Even so, the peri- and postmenopausal women in the study reported less sleep satisfaction than premenopausal women did.

Most clinicians agree that a woman’s subjective experience of sleep is clinically relevant. Thus, rule out underlying sleep disorders before you attribute a midlife woman’s depressive signs and symptoms primarily to menopause.10

Treatment. Combination therapy may be useful, depending on the patient’s psychiatric and medical comorbidities (Algorithm).

TREATING PERIMENOPAUSAL DEPRESSION

HRT. Before the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI),10 guidelines recommended HRT for a first depressive episode during perimenopause and antidepressants for severe depressive symptoms and for women with a history of depression.11 This practice changed when the WHI found risks of thromboembolism, breast cancer, stroke, and coronary artery disease that increased over time with HRT.

HRT remains a short-term treatment option but is no longer considered the first or only approach to mood symptoms at perimenopause. Discuss with your patient potential benefits of short-term HRT for a first episode of depression—especially if she has vasomotor symptoms—versus potential risks.

Antidepressants can improve perimenopausal depression, but few studies have tested these agents’ effects on sleep. To reduce treatment-associated insomnia:

- select a relatively sedating antidepressant such as mirtazapine

- accept some insomnia for 3 to 4 weeks, until a stimulating antidepressant has had a full ffect on mood and its associated side effects would be expected to resolve

- or augment the antidepressant with a hypnotic such as zolpidem, zaleplon, eszopiclone, or trazodone.

When choosing therapy, consider patient factors and insomnia severity. For example, mirtazapine is typically associated with weight gain, so consider other options for overweight patients. Those with severe insomnia may prefer not to wait 3 to 4 weeks for improved sleep. With hypnotics, consider cost, any coexisting chemical dependency, and potential for morning hangover.

Psychotherapy can help perimenopausal patients accept aging, evaluate relationships, and examine their roles in the lives of more-dependent parents and less-dependent children.

HOT FLASHES AND INSOMNIA

Persistent hot flashes that disturb sleep may cause depression.12 They can wake a perimenopausal woman repeatedly (Figure 1). The awakenings may be brief—90% last <3 minutes—but a severely affected woman can lose an hour of sleep in a night.13 Even after a hot flash resolves, other factors such as anxiety may keep her awake.

Up to 85% of perimenopausal women experience hot flashes, especially during the first year after menses cease. Hot flashes persist for 5 years after menopause in 25% of women and indefinitely in a minority (Box ).14

Estrogen deficiency is thought to cause hot flashes via decreased serotonin synthesis and up-regulated 5HT2A receptors—the mediators of heat loss. As a result, a woman’s thermoregulatory zone narrows during perimenopause, reducing her tolerance for core body temperature changes. The thermoregulatory nucleus resides in the medial preoptic area of the anterior hypothalamus.

A hot flash begins with facial warmth when core temperatures exceed the thermoregulatory line. Heat spreads to the chest, often accompanied by flushing, diaphoresis, and headache. A woman may feel agitated, irritable, and distressed.

CNS noradrenergic activity may initiate hot flashes. Freedman et al13 compared the effects of IV clonidine (an alpha2 adrenergic agonist) plus yohimbine (an alpha2 adrenergic antagonist) or placebo in menopausal women with or without vasomotor symptoms. Among 9 symptomatic women, 6 experienced hot flashes when given yohimbine, and none did with placebo. No hot flashes occurred in asymptomatic women. Clonidine increased the duration of peripheral heating needed to trigger a hot flash and reduced the number of hot flashes in symptomatic women, compared with baseline.

Risk factors for nocturnal hot flashes include surgical menopause, Caucasian versus Asian ethnicity, lack of exercise, and nicotine use.8 Women suffering anxiety and stress also are at increased risk.15

HOT-FLASH THERAPIES

Placebo-controlled trials of hot flash therapies have found efficacies from 85% for HRT to 25% for placebo, vitamin E, black cohosh, soy, and behavioral therapy (Figure 2).16 Most trials were not designed to test the link between hot flashes and sleep, and many enrolled cancer patients not experiencing natural menopause. With the 25% placeboresponse rate, some therapies’ efficacy is unclear.

HRT can reduce nocturnal hot flash frequency. In a polysomnographic study,17 21 postmenopausal women received 6 months of conjugated estrogens, 0.625 mg/d, with medroxyprogesterone, 5 mg/d, or micronized progesterone, 200 mg/d. Sleep efficiency improved by 8% in women receiving micronized progesterone but was unchanged with medroxyprogesterone. Even so, both groups reported improved sleep quality and duration, with decreased awakenings.

The Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study9 found that HRT was not associated with improved sleep, as measured by polysomnography. Even so, the women in that study noted subjective sleep improvement with HRT.

Antidepressants. Venlafaxine, 75 mg/d, and fluoxetine, 20 mg/d, have shown benefit in reducing hot flashes,18 presumably by increasing CNS serotonin. As mentioned, however, many antidepressants can cause insomnia, and few studies have examined this problem.

Gabapentin has been effective for patients with hot flashes.19 This agent, which increases GABA levels and may modestly increase slow-wave sleep—can improve conditions that disrupt sleep, including restless legs syndrome and chronic pain. It is well-tolerated, even at 900 mg/d, and is more-sedating than most serotonergic antidepressants.

Hypnotics. Surprisingly little evidence addresses hypnotics’ role in managing insomnia caused by hot flashes. No data have been published on the role of benzodiazepines or the benzodiazepine receptor agonists (zolpidem, zaleplon, and eszopiclone). In my experience, benzodiazepine receptor agonists improve sleep quality compromised by multiple factors, including hot flashes.

Soy and black cohosh. Isoflavones in soy may be estrogen receptor modulators. Twelve randomized, controlled trials of soy or soy extracts have shown a modest benefit for hot flashes.20

Black cohosh extracts, 8 mg/d, were given to 80 postmenopausal women in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (RCT). Hot flashes in those receiving black cohosh decreased from 4.9 to 0.7 daily, compared with reductions of 5.2 to 3.2 in women receiving estrogen and 5.1 to 3.1 in those receiving placebo.21 As a result, the National Institutes of Health is funding a 12-month, RCT to determine whether black cohosh reduces hot flash frequency and intensity.

Alternative agents are widely used and warrant study. Those shown to be safe can be used alone or with other therapies, but advise the patient that these agents may not be effective. Relaxation and exercise may decrease hot flashes,22 although some outcomes have been similar to a placebo response.

SLEEP APNEA AT PERIMENOPAUSE

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), although more common in men than women, appears to increase during perimenopause. Women with untreated OSA are twice as likely as men to be treated for depression, less likely to report excessive daytime sleepiness and snoring, and more likely to present with depression, anxiety, and morning headache.

Bixler et al23 interviewed 12,219 women and 4,364 men ages 20 to 100 and conducted 1-night sleep studies in 1,000 women and 741 men. OSA rates were 3.9% in men, 0.6% in premenopausal women, 2.7% in postmenopausal women not taking HRT, and 0.5% in postmenopausal women taking HRT.

The risk of sleep-disordered breathing is lower during early menopause and peaks at approximately age 65. Declining hormones likely play a role; progesterone increases ventilatory drive, and estrogen increases ventilatory centers’ sensitivity to progesterone’s stimulant effect. In small studies, exogenous progesterone has shown a slight effect in improving OSA.24

OSA’s transient, repetitive upper airway collapse increases inspiratory effort and may cause hypoxemia. Repeated arousals can lead to prolonged awakenings and unrefreshing sleep. Snoring and increased body mass index are strongly associated factors, although the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study10 showed an increase in sleep apnea in perimenopausal women that was unrelated to increased body mass index.

Obesity may not explain the increase in obstructive sleep apnea at perimenopause (Figure 3),28 although body fat distribution does change with aging. Women at perimenopause are likely to develop abdominal weight distribution.

Figure 3 Increased OSA in postmenopausal women is unrelated to obesity (BMI >32)

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in 1,000 women and 741 men was associated exclusively with obesity in premenopausal women and postmenopausal women using HRT, but nearly one-half of the postmenopausal women with OSA were not obese.

Source: Adapted from reference 23.Treatment. In the Sleep Heart Health Study25 of 2,852 women age 50 or older, HRT users had one-half the apnea prevalence of nonusers (6% vs 14%). HRT users were less likely to awaken at night and to get inadequate sleep. Snoring rates were similar (25% for HRT users, 23% for nonusers).

Nasal continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is the mainstay of apnea treatment, although some women appear to have difficulty accepting CPAP.26 Weight loss and moderate exercise can help manage weight and improve sleep quality by increasing slow-wave sleep. Regular exercise also may improve depressed mood.

Related resources

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. www.acog.org

- The North American Menopause Society. www.menopause.org

Drug brand names

- Conjugated estrogens • Premarin

- Eszopiclone • Lunesta

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Gabapentin • Neurontin

- Medroxyprogesterone • Provera

- Micronized progesterone • Prometrium

- Mirtazapine • Remeron

- Trazodone • Desyrel

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

- Zaleplon • Sonata

- Zolpidem • Ambien

Disclosures

Dr. Krahn reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Owens JF, Matthews KA. Sleep disturbance in healthy middle-aged women. Maturitas 1998;30:41-50.

2. Perlis ML, Giles DE, Buysse DJ, et al. Self-reported sleep disturbance as a prodromal symptom in recurrent depression. J Affect Disord 1997;42(2-3):209-12.

3. Bromberger JT, Assmann SF, Avis NE, et al. Persistent mood symptoms in a multiethnic community cohort of pre- and perimenopausal women. Am J Epidemiol 2003;158:347-56.

4. Sherwin BB. Changes in sexual behavior as a function of plasma sex steroid levels in post-menopausal women. Maturitas 1985;7(3):225-33.

5. Brizendine L. Minding menopause. Psychotropics vs estrogen: What you need to know now. Current Psychiatry 2003;2(10):12-31.

6. Anderson E, Hamburger S, Liu JH, Rebar RW. Characteristics of menopausal women seeking assistance. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1987;156(2):428-33.

7. Obermeyer CM, Reynolds RF, Price K, Abraham A. Therapeutic decisions for menopause: results of the DAMES project in central Massachusetts. Menopause 2004;11(4):456-65.

8. Kravitz HM, Ganz PA, Bromberger J, et al. Sleep difficulty in women at midlife: a community survey of sleep and the menopausal transition. Menopause 2003;10(1):19-28.

9. Young T, Rabago D, Zgierska A, et al. Objective and subjective sleep quality in premenopausal, perimenopausal, and postmenopausal women in the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study. Sleep 2003;26(6):667-72.

10. Wassertheil-Smoller S, Shumaker S, Ockene J, et al. Depression and cardiovascular sequelae in postmenopausal women. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:289-98.

11. Altshuler LL, Cohen LS, Moline ML, et al. The expert consensus guideline series. Treatment of depression in women. Postgrad Med 2001;March:1-107.

12. Krystal AD. Insomnia in women. Clin Cornerstone 2003;5(3):41-50.

13. Freedman RR. Physiology of hot flashes. Am J Hum Biol 2001;13(4):453-64.

14. Freedman RR, Woodward S, Sabharwal SC. A2-adrenergic mechanism in menopausal hot flushes. Obstet Gynecol 1990;76(4):573-8.

15. Miller AG, Li RM. Measuring hot flashes: summary of a NIH workshop. Mayo Clin Proc 2004;79:777-81.

16. Joffe H, Soares CN, Cohen LS. Assessment and treatment of hot flushes and menopausal mood disturbance. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2003 Sep;26(3):563-80.

17. Montplaisir J, Lorrain J, Denesle R, Petit D. Sleep in menopause: differential effects of two forms of hormone replacement therapy. Menopause 2001;8(1):10-16.

18. Loprinzi CL, Sloan JA, Perez EA, et al. Phase III evaluation of fluoxetine for treatment of hot flashes. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:1578-83.

19. Guttoso T, Jr, Kurlan R, McDermott MP, Kieburtz K. Gabapentin’s effects on hot flashes in postmenopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2003;101:337-45.

20. Kessel B, Kronenberg F. The role of complementary and alternative medicine in management of menopausal symptoms. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2004;33:717-39.

21. National Institutes of Health. National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Office of Dietary Supplements. Questions and answers about black cohosh and the symptoms of menopause. Available at: http://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/blackcohosh.asp. Accessed May 9, 2005.

22. Ivarsson T, Spetz AC, Hammar M. Physical exercise and vasomotor symptoms in postmenopausal women. Mauritas 1998;29:139-46.

23. Bixler EO, Vgontzas AN, Lin HM, et al. Prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in women: effects of gender. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;163:608-13.

24. Block AJ, Wynne JW, Boysen PG, et al. Menopause, medroxyprogesterone and breathing during sleep. Am J Med 1981;70:506-10.

25. Shahar E, Redline S, Young T, et al. Hormone replacement therapy and sleep-disordered breathing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;167:1186-92.

26. McArdle N, Devereux G, Heidarnejad H, et al. Long-term use of CPAP therapy for sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome. Am J Respir Crit. Care Med 1999;159:1108-14.

1. Owens JF, Matthews KA. Sleep disturbance in healthy middle-aged women. Maturitas 1998;30:41-50.

2. Perlis ML, Giles DE, Buysse DJ, et al. Self-reported sleep disturbance as a prodromal symptom in recurrent depression. J Affect Disord 1997;42(2-3):209-12.

3. Bromberger JT, Assmann SF, Avis NE, et al. Persistent mood symptoms in a multiethnic community cohort of pre- and perimenopausal women. Am J Epidemiol 2003;158:347-56.

4. Sherwin BB. Changes in sexual behavior as a function of plasma sex steroid levels in post-menopausal women. Maturitas 1985;7(3):225-33.

5. Brizendine L. Minding menopause. Psychotropics vs estrogen: What you need to know now. Current Psychiatry 2003;2(10):12-31.

6. Anderson E, Hamburger S, Liu JH, Rebar RW. Characteristics of menopausal women seeking assistance. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1987;156(2):428-33.

7. Obermeyer CM, Reynolds RF, Price K, Abraham A. Therapeutic decisions for menopause: results of the DAMES project in central Massachusetts. Menopause 2004;11(4):456-65.

8. Kravitz HM, Ganz PA, Bromberger J, et al. Sleep difficulty in women at midlife: a community survey of sleep and the menopausal transition. Menopause 2003;10(1):19-28.

9. Young T, Rabago D, Zgierska A, et al. Objective and subjective sleep quality in premenopausal, perimenopausal, and postmenopausal women in the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study. Sleep 2003;26(6):667-72.

10. Wassertheil-Smoller S, Shumaker S, Ockene J, et al. Depression and cardiovascular sequelae in postmenopausal women. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:289-98.

11. Altshuler LL, Cohen LS, Moline ML, et al. The expert consensus guideline series. Treatment of depression in women. Postgrad Med 2001;March:1-107.

12. Krystal AD. Insomnia in women. Clin Cornerstone 2003;5(3):41-50.

13. Freedman RR. Physiology of hot flashes. Am J Hum Biol 2001;13(4):453-64.

14. Freedman RR, Woodward S, Sabharwal SC. A2-adrenergic mechanism in menopausal hot flushes. Obstet Gynecol 1990;76(4):573-8.

15. Miller AG, Li RM. Measuring hot flashes: summary of a NIH workshop. Mayo Clin Proc 2004;79:777-81.

16. Joffe H, Soares CN, Cohen LS. Assessment and treatment of hot flushes and menopausal mood disturbance. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2003 Sep;26(3):563-80.

17. Montplaisir J, Lorrain J, Denesle R, Petit D. Sleep in menopause: differential effects of two forms of hormone replacement therapy. Menopause 2001;8(1):10-16.

18. Loprinzi CL, Sloan JA, Perez EA, et al. Phase III evaluation of fluoxetine for treatment of hot flashes. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:1578-83.

19. Guttoso T, Jr, Kurlan R, McDermott MP, Kieburtz K. Gabapentin’s effects on hot flashes in postmenopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2003;101:337-45.

20. Kessel B, Kronenberg F. The role of complementary and alternative medicine in management of menopausal symptoms. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2004;33:717-39.

21. National Institutes of Health. National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Office of Dietary Supplements. Questions and answers about black cohosh and the symptoms of menopause. Available at: http://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/blackcohosh.asp. Accessed May 9, 2005.

22. Ivarsson T, Spetz AC, Hammar M. Physical exercise and vasomotor symptoms in postmenopausal women. Mauritas 1998;29:139-46.

23. Bixler EO, Vgontzas AN, Lin HM, et al. Prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in women: effects of gender. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;163:608-13.

24. Block AJ, Wynne JW, Boysen PG, et al. Menopause, medroxyprogesterone and breathing during sleep. Am J Med 1981;70:506-10.

25. Shahar E, Redline S, Young T, et al. Hormone replacement therapy and sleep-disordered breathing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;167:1186-92.

26. McArdle N, Devereux G, Heidarnejad H, et al. Long-term use of CPAP therapy for sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome. Am J Respir Crit. Care Med 1999;159:1108-14.