User login

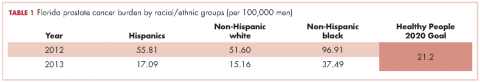

As of 2016, Florida ranks second among all states in the United States in estimated new cases of prostate cancer and second in estimated deaths from prostate cancer.1 Disparities in diagnosis, mortality rates, and access to cancer care also continue to be a major problem in Florida, especially for black men. For example, black men were the only racial/ethnic group that did not meet the Healthy People (HP) 2010 objective to reduce the prostate cancer death rate to 28.2 per 100,000 men and that has not met the HP 2020 objective to reduce the prostate cancer death rate to 21.2 per 100,000 men (Table 1). Based on the 2013 prostate cancer mortality rates for Florida,2 the death rate for black men is almost twice the HP 2020 goal (37.49 per 100,000).

A diagnosis of prostate cancer is a life changing event for a man. In particular, there is limited research on the experiences and coping mechanisms of black men at diagnosis. This limited body of research indicates that black men’s reactions to their initial diagnoses varied, from being shocked when notified of their initial diagnosis of prostate cancer,3 to perceiving that they had received a “death sentence”.4 In regard to having to make decisions about their treatment options, some black men indicated that the information about treatment that they received from physicians decreased their anxiety,5 whereas others noted that they had not been given adequate information by a physician to make a decision.6 Patients have also reported that they felt as though they were not knowledgeable enough to ask questions concerning treatment options and preferred for the physician to make the treatment choice for them.6 Decisional regret is now a common observation among men who are not involved in making decisions about their treatment.3

According to the American Cancer Society, about 30,000 black men were diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2016.7 It is important to understand these men’s needs and help them cope effectively as they navigate the survivorship continuum. In line with our research program’s goal of ensuring quality cancer care for black men, the primary objective of this study was to explore the experiences and needs of black men at the point of prostate cancer diagnosis (PPCD). Specifically, we developed an interpretative framework for black men’s experiences at the PPCD, focusing on United States or native-born black men (NBBM) and Caribbean-born black men (CBBM). African-born black men were not included in this study because of the low sample size for that ethnicity. This study is part of a large-scale study that focuses on developing a model of prostate cancer care and survivorship (CaPCaS model) using grounded theory to study black, ethnically diverse prostate cancer survivors.

Methods

The study aims to close the prostate health disparity gap for black men in Florida through community engaged research in partnership with survivors of prostate cancer and their advocates. The current study was a prospective, grounded theory study that involved one-on-one, in-depth interviews with 31 prostate cancer patients about their care and survivorship experiences. Specifically, 17 NBBM and 14 CBBM were enrolled in the project. Appropriate human subjects review and approval were obtained from the University of Florida, the Florida Department of Health, and the Department of Defense.

Research design

This is a qualitative research study. Based on the principles of community engaged research and using a rigorous qualitative research methodology, we recruited NBBM and CBBM with a personal history of prostate cancer. Guided by open-ended questions developed by the team, one-on-one in-depth interviews were conducted with each participant in their home or at a convenient location in the community. Our primary focus was on the participants’ care and survivorship experiences, with primary focus on their prostate cancer diagnosis. Qualitative research was our methodology of choice because little is known about the PPCD experiences of black men.8 With qualitative research, we were able to get our participants to “relive” their experiences in the presence of a culturally competent, well-trained interviewer and elicit the information about their care and survivorship experiences based on their interpretation. In addition, we were able to capture the dynamic processes associated with their experiences, documenting sequential patterns and change through both verbal and nonverbal communications, because the participants were interviewed twice.

Research population and recruitment

The study setting was Florida. The inclusion criteria were: black men, personal history of prostate cancer, ability to complete two separate interviews with each one expected to last 2-3 hours, and flexibility to meet interviewers at a convenient community site for the interviews. Participants were identified through the Florida Cancer Data System (FCDS)9 database. At the time of the study, the most recent FCDS database was for 2010. The FCDS has collected the number of new cancer cancers diagnosed in the state of Florida annually since 1981. It is a comprehensive incidence-only registry and does not extract data on patients with a death certificate. All investigators are bounded by the confidential pledge required for the use of the FCDS data.

We used the Florida Department of Health’s (DoH’s) Bureau of Epidemiology standard procedure for the FCDS9 to recruit participants. Our recruitment strategies included: initial patient contact by written correspondence; second mailing that included a telephone opt-out card after 3 weeks for nonrespondents (the telephone opt-out card explained to the patient that if no response was received, the study investigator would attempt a telephone call to introduce the study); and a telephone call by a study staff to introduce the study for nonrespondents. As per the Florida DoH standard procedure, we did not disclose on the cover of the study mailings that the patient was being contacted for a study specific to cancer. Efforts to recruit a patient stopped immediately if a patient indicated that he did not wish to participate. All of the study staff making participant contact were extensively trained to provide a clear and accurate description of cancer registration in Florida. In addition, to assist the study staff in providing clear and accurate responses, responses to frequently asked questions were made available to the study staff. During the participant recruitment phase, anyone who seemed to be upset when contacted was reported immediately (within 24 hours) to the DoH cancer epidemiologist. In addition, the name of anyone who stated that he did not wish to be contacted again was given to the DoH so that the person would not be re-contacted.

Prescreening of participants for eligibility

All eligible participants who agreed to participate in the study comprised the pool of potential study participants. For those who agreed to participate, the following information was obtained by telephone interview using REDCap software:10 name and contact information, country of birth, age, marital status, and education level. The demographic information facilitated a purposeful systematic selection of black men of diverse age groups (younger than 50 years or older than 50 years), marital status (single, including divorced or separated, or married/in a relationship), and educational level (college degree or not college educated). An incentive of a $5 gift card was provided to all the men who participated in the screening phase. Using systematic sampling to ensure demographically diverse participants, 40 participants (20 NBBM, 20 CBBM) were selected from the initial pool of participants to participate in the study.

Data collection

The data collection was conducted by a trained Community Health Worker (CHW) using semi-structured interview process. The interview guide was constructed by the research team and the study community advisory board members to ensure language appropriateness, understanding and cultural sensitivity. For this study, the interview questions focused on participants’ background information and diagnosis history, including: participants’ personal story of diagnosis, feelings, emotions, reactions, regrets and level of personal/family/physician involvement in diagnosis. For the CBBM, we also obtained information on the age at which they immigrated to the United States. The CHW interviewer was trained to question participants and encourage them to elaborate on areas of importance to their experience.

A total time of about 5-6 hours was scheduled for the data collection per participant, which is sufficient for gathering in-depth perspectives. We scheduled two interviews lasting not more than 3 hours at a time so as not to create burden for study participants. Participants had the choice to have the interviews completed in a single session or spread out over 2 days. The interviews were audio-recorded to provide ease of transcription and back-up of data. At the end of the interviews, participants were compensated for participating in the study.

Data management and analyses

The study dataset included interview transcripts and field notes of the CHW interviewer describing his insights about the interviews. The data analyses included preparing and verifying the narrative data, coding data, and developing an interpretative framework for black men’s experiences at the PPCD. Interviews were transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription service that has policies in place for protected health information. Each transcript was then verified for accuracy by the CHW interviewer. The interview transcripts were imported directly into NVivo 11, a computer-assisted data analysis software that allows coding and modeling of complex narrative data. The data coding was conducted by our interdisciplinary team of clinicians, behavioral scientists, and social scientists. It is important to note that the NVivo 11 software was not used to analyze the data per se. However, it provided a sophisticated and systematic way to manage the following tasks for the analyses: organizing large quantities of narrative data, coding text, retrieving text by codes, querying the data, comparing sets of data interpretation between NBBM and CBBM; and developing analytic models. The study team members coded the data in weekly team meetings. The coding consisted of reading the data and identifying major themes, then assigning labels to and defining emerging categories.

Two levels of coding were used. The first, open coding, refers to an approach to data with no preconceived ideas about what will be found; and the second, focused or axial coding, refers to reviewing data for the purpose of more richly coding on a particular theme.11 We used dimensional analysis to ensure that each emerging concept was carefully defined. The study team went back and forth between the data and the emerging analytic framework, using constant comparison of new data with already coded data and new categories with previously analyzed text.12

To ensure trustworthiness and credibility,13 the study team maintained an audit trail that documented how and when analytic decisions were made. In addition, peer debriefing was conducted to ensure credibility, including the presentation of findings to the study community advisory board members as part of the community engaged research approach.

Results

Description of participants

The FCDS provided a database of 1,813 participants identified as black men diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2010. Because the FCDS does not extract data on patients with a death certificate, we found out during the pre-screening phase that a few of the men were deceased. In addition, there were a significant number of incorrect addresses. We obtained a total of 212 completed responses by phone during the prescreening phase. The majority of the participants were aged 60-69 years (48.2%), had a high school diploma only (26.1%), and were currently married (65.3%). Relative to ethnicity, 67% of participants classified themselves NBBM, 24% as CBBM, 3.5% as black men born in Africa, and 5.5% as Other/Don’t know/Refused. For the CBBM, the most common countries of birth were Jamaica, Haiti, and Guyana, respectively.

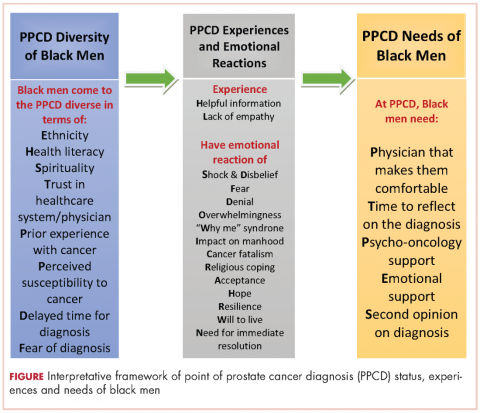

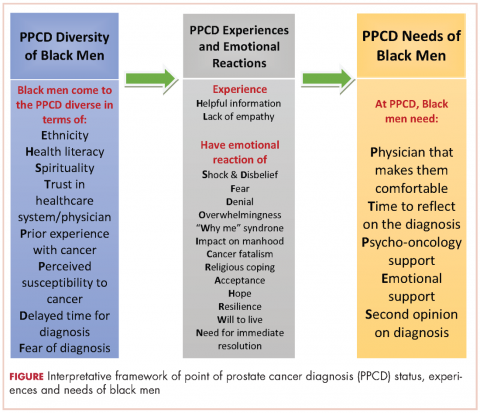

In all, 40 participants (20 NBBM and 20 CBBM) were selected from the 212 participants to participate in the study. Selection was conducted systematically to ensure representation in terms of age, marital status, education, and geographical location. Data saturation was achieved with 17 NBBM and 14 CBBM, after which we ended data collection (Table 2). Data saturation is the standard for deciding that we are not finding anything different from the interviews first coded and last coded. Although we were specifically looking for differences between the two groups (NBBM and CBBM), no between-group differences emerged. Each man’s experience was unique to him with some common themes emerging described hereinafter (Figure).

Moderating factors and experiences at PPCD

Some of the moderating factors that the study participants identified as affecting their reactions to the PPCD included health literacy, insurance status, spirituality, mistrust, prior experience with cancer, perceived susceptibility to cancer, and delay in diagnosis (Table 3). Health literacy, defined as personal, cognitive, and social skills that determine the ability of individuals to gain access to, understand, and use information to promote and maintain good health, was one of the moderating factors found in this study.13 Some of the black men came to the PPCD with a low level of health literacy, which had an impact on their understanding of the treatment options. For example, in the interview, participant 798 (NBBM) was confused about what tests had been done and was not able to accurately describe the treatments offered to him. Participant 1263 (CBBM) struggled to express the purpose and procedures associated with diagnostic biopsy. However, there were participants with a high level of health literacy (eg, participant 449 [NBBM]), who decided to research the disease.

Another factor to consider is the insurance status of participants at the PPCD. The majority of the participants had good insurance coverage, but some were affected by poor insurance coverage. Participant 1881(NBBM) made his treatment decision primarily on the basis of the pending lapse of his insurance coverage rather than the best clinical option for him. Participant 1979 (CBBM) described both his confusion on the screening tests and the impact of not having insurance coverage. Upon obtaining insurance coverage, he sought treatment for his prostate cancer with an urgency that he did not experience when he was first diagnosed when uninsured.

The spirituality of black men was another moderating factor at the PPCD. Participant 827 (NBBM) noted that he was unaffected when he received his diagnosis because he was a true believer. Some of the black men also came to the PPCD with lack of trust in the physician and/or the health care system and perceived a sense of contempt from the physician. Participant 1594 (NBBM) described mistrust based on the history of medical exploitation of black men as well as a perception of current discriminatory practices.

Another important PPCD status to note for black men is prior experience with cancer, including prior personal cancer history and/or prior cancer history of a family member. Participant 2024 (CBBM) described the meaning of cancer to him, while participant 798 (NBBM) echoed the despair of the cancer diagnosis based on experience with other cancers in the family. Sometimes there were multiple cancers in the family or even among the significant others of the participant, as was the case with Participant 1936 (CBBM).

Of greatest concern were men who delayed their diagnosis or treatment, perhaps resulting in their cancer being at a more advanced stage when they eventually did return for care. Finally, some of the men came to the PPCD appointment with a low expectation of receiving a diagnosis of prostate cancer, whereas others came to the PPCD fearful of the results of their testing.

In describing their experiences, participants expressed both positive and negative experiences: on the positive side, they found the information provided by the physician to be helpful; but on the negative side, the sterile or medically focused encounter was perceived as a lack empathy on the part of the physician.

Cognitive, emotional, and behavioral coping experiences

As expected, there were ranges of emotions, including shock, disbelief and denial (Table 4). Some of the men questioned why this (the cancer) was happening to them when they had done “nothing” to deserve it. Doing nothing in this case meant that they had lived a healthy lifestyle with no obvious apparent cause to have the cancer. Fear and cancer fatalism were experienced by a significant number of the men, with their thoughts immediately turning to death and dying. This was especially the case for men who had lost a loved one to cancer. Conversely, some of the men wanted immediate resolution, focusing instead on ways to beat the cancer and with a strong will to live.

Reliance on faith was a big part of coping at the PPCD. Some of the men drew strength from their faith to get them through their cancer journey. Others found a way to accept the diagnosis – one participant accepted the diagnosis and the fact that this could mean dying (after living a good life), whereas another participant accepted the diagnosis with the hope that he would find a cure. Hope was more realistic with the knowledge that other men had survived prostate cancer.

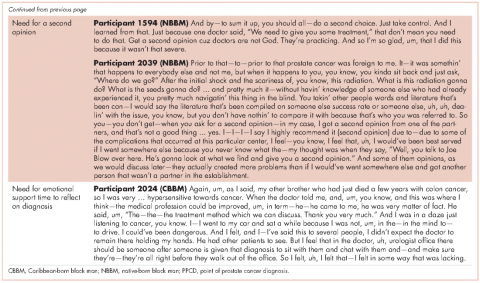

Reflecting back on their experiences, the men also identified clear needs at the PPCD. One of the needs they identified was having a physician they were comfortable with to discuss their diagnosis. Another need was for a second opinion. Participant 1594 (NBBM) advised that it was important for black men to take control by requesting a second opinion. Participant 2039 (NBBM) described a feeling of navigating blindly and trying to find answers that would be helpful to him in his cancer journey. However, his experience with a second opinion was not helpful because the second physician was at the same clinic as his primary physician. His recommendation was to get a second opinion at a different clinic or center. Another important need was emotional support at the PPCD. Participant 2024 (CBBM) made a strong case for emotional support, especially for men who are not accompanied during diagnosis. In addition, Participant 2024’s (CBBM) reflections underscore the fact that the PPCD may not be an ideal place or time to discuss treatment options. With the range of emotions that the men go through at the PPCD, it is difficult to comprehend any follow-up discussions after hearing the words “you have prostate cancer.” Participant 2024 (CBBM) also strongly expressed that men need time to deal with the diagnosis at the PPCD.

Discussion

The primary goal of this study was to develop an interpretative framework of black men’s experiences at the PPCD. The Figure provides a pictorial summary of the framework. Study results indicated that black men come to the PPCD with different emotions and different experiences. Although the majority of the men were NBBM, there is a significantly increasing number of foreign-born black men receiving a diagnosis of prostate cancer in the United States. Given that black men carry a disproportionate burden of the disease, with a significantly higher incidence compared with any other racial group, it is important that tailored services are provided to black men at the PPCD.

We also found that black men came to the PPCD diverse in terms of their ethnicity, health literacy, spirituality, trust in health care system/physician, prior experience with cancer, perceived susceptibility to cancer, delayed time for diagnosis, and fear of diagnosis. Of importance for physicians is that the black race is not homogeneous. There is a significant number of foreign-born blacks at the PPCD, and they often have different cultural beliefs and values compared with NBBM. In addition, some of the foreign-born black men may not have English proficiency and may need a medical interpreter during the PPCD consultation. In addition, a patient’s pre-existing lack of trust in the health care system may have a negative impact on the PPCD consultation. It is thus important that the physician takes the time to instill trust and make the men comfortable during the PPCD consultation.

For some of the men who had fear of a prostate cancer diagnosis and/or prior experience with cancer, cancer fatalism was experienced at the PPCD. Cancer fatalism, defined as an individual’s belief that death is bound to happen when diagnosed with cancer, has been documented as a major barrier to cancer detection and control.15 For example, fatalistic perspectives have been reported to affect cervical cancer,16 breast cancer,17,18 colorectal cancer,19 and prostate cancer20,21 among blacks. It is thus important to effectively address fatalistic beliefs when a man is diagnosed with prostate cancer.

Other emotions at the PPCD that may affect effective treatment decision making also need to be addressed immediately. For example, the emotions of fear, denial, and feeling overwhelmed are potential barriers to timely treatment decision making. Psycho-oncology interventions to appropriately deal with these emotions at PPCD or right after the diagnosis may be crucial for the men. In particular, a group-based psychosocial intervention focusing on: provision of education about treatment options for prostate cancer and their acute and late effects; negotiating treatment and treatment side effects; enhancing communication with treatment providers; managing distress; and engaging positive family- and community-based social support to optimize emotional, behavioral, social, and physical outcomes in black men with prostate cancer.

In addition to having physicians make them comfortable at PPCD, the PPCD needs expressed by participants included having time to come to terms with the diagnosis and receiving psycho-oncology/emotional support. Anyone who has just received a diagnosis of cancer cannot be expected to immediately continue to function as he did before the PPCD. This is especially difficult for men who are alone at the PPCD. Nevertheless, it is expected that they will listen attentively and understand subsequent consultation by the physician, then leave the consultation room almost immediately, and be able drive home or back to work right after the diagnosis. There seems to be a support gap that needs to be closed at the PPCD. Providing the men with immediate support to cope with the diagnosis may make a significant difference in effective treatment choices and eliminating treatment decisional regrets.

Methodological rigor was established through purposeful sampling, extended time with participants, standardized procedures for data collection, management and analysis, multidisciplinary interpretation, and validation of results with the community advisory board. Because the research participants were purposefully selected from a statewide database of black men diagnosed with CaP, generalizability of findings to the two target groups of NBBM and CBBM can be assumed, with the caveat that men with different experiences may have chosen not to respond to recruitment efforts or refused participation. Black men who were not sufficiently fluent in English to be interviewed were also excluded and are not represented in these findings. Black men of other nativity (including African-born black men) and residing outside of Florida were also not represented.

In conclusion, the PPCD interpretative framework developed in this study, describes the status of black men at the PPCD, their experiences during the PPCD, and their needs at the PPCD. The framework provides information that can be used by physicians to prepare for their PPCD consultation with black men as well as develop a support system for black men at the PPCD.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the men who participated in the CaPCaS study. They also thank the CaPCaS project community advisory board chairs (Mr Jim West, Dr Angela Adams, and Prince Oladapo Odedina) and all the CaPCaS project community advisory board members for their effort throughout the project. Finally, they rxecognize the effort of additional CaPCaS scientific team, especially the primary interviewer, Mr Kenneth Stokes. Weekly meeting support for this study was provided by the University of Florida MiCaRT Center, which is funded by the NIH-National Cancer Institute Award # 1P20CA192990-02. REDCaP software was supported by the UF Clinical and Translational Science Institute, which is funded in part by the NIH Clinical and Translational Science Award program (grants UL1TR001427, KL2TR001429 and TL1TR001428).

1. American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2016. http://www.cancer.org/research/cancerfactsstatistics/cancerfactsfigures2016/. Published 2016. Accessed January 10, 2017.

2. Florida Cancer Data System. Florida Statewide Population-Based Cancer Registry. https://fcds.med.miami.edu/scripts/fcdspubrates/production/doSelection.aspx?election=map. Processed February 16, 2016.

3. Sinfield P, Baker R, Camosso-Stefinovic J, et al. Men’s and carers’ experiences of care for prostate cancer: a narrative literature review. Health Expect. 2009;12:301-312.

4. Maliski SL, Connor SE, Williams L, Litwin MS. Faith among low-income, African American/ black men treated for prostate cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2010;33(6):470-478.

5. Jones RA, Wenzel J, Hinton I, et el. Exploring cancer support needs for older African-American men with prostate cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19(9):1411-1419.

6. Sinfield P, Baker R, Agarwal S, Tarrant C. Patient-centred care: what are the experiences of prostate cancer patients and their partners? Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73(1):91-96.

7. American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures for African Americans 2016-2018. http://www.cancer.org/research/cancerfactsstatistics/cancer-facts-figures-for-african-americans. Published 2016. Accessed January 10, 2017.

8. Patton MQ. Qualitative research & evaluation methods. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2001.

9. Florida Department of Health, Bureau of Epidemiology. Procedure guide for studies that utilize patient identifiable data from the Florida Cancer Data System. http://www.fcds.med.miami.edu/downloads/datarequest/Procedure%20Guide_Revised%20

October%202007.pdf. Accessed July 24, 2010.

10. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381.

11. Strauss A. Qualitative analysis for social scientists. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1987.

12. Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. Chicago, IL: Aldine; 1967.

13. Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1994.

14. Nutbeam, D. Health literacy as a public health goal: a challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promot Int. 2000;15(3):259-267.

15. Powe BD, Finnie R. Cancer fatalism: the state of the science. Cancer Nurs. 2003;26:454-467.

16. Powe BD. Fatalism among elderly African Americans: effects on colorectal cancer screening. Cancer Nurs. 1995;18:285-392.

17. Powe BD. Cancer fatalism among elderly Caucasians and African Americans. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1995;22(9):1355-1359.

18. Thoresen CE. Spirituality, health, and science: the coming revival? In: Roth RS, Kurpius SR, eds. The emerging role of counseling psychology in health care. New York, NY: WW Norton; 1998.

19. Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK. Assessing coping strategies: a theoretically based approach. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;56:267-283.

21. Odedina FT, Yu D, Akinremi TO, Reams RR, Freedman ML, Kumar N. Prostate cancer cognitive-behavioral factors in a West African population. J Immigr Minor Health. 2009;11(4):258-267.

22. Odedina FT, Scrivens JJ Jr, Larose-Pierre M, et al. Modifiable prostate cancer risk reduction and early detection behaviors in black men. Am J Health Behav. 2011;35(4):470-484.

As of 2016, Florida ranks second among all states in the United States in estimated new cases of prostate cancer and second in estimated deaths from prostate cancer.1 Disparities in diagnosis, mortality rates, and access to cancer care also continue to be a major problem in Florida, especially for black men. For example, black men were the only racial/ethnic group that did not meet the Healthy People (HP) 2010 objective to reduce the prostate cancer death rate to 28.2 per 100,000 men and that has not met the HP 2020 objective to reduce the prostate cancer death rate to 21.2 per 100,000 men (Table 1). Based on the 2013 prostate cancer mortality rates for Florida,2 the death rate for black men is almost twice the HP 2020 goal (37.49 per 100,000).

A diagnosis of prostate cancer is a life changing event for a man. In particular, there is limited research on the experiences and coping mechanisms of black men at diagnosis. This limited body of research indicates that black men’s reactions to their initial diagnoses varied, from being shocked when notified of their initial diagnosis of prostate cancer,3 to perceiving that they had received a “death sentence”.4 In regard to having to make decisions about their treatment options, some black men indicated that the information about treatment that they received from physicians decreased their anxiety,5 whereas others noted that they had not been given adequate information by a physician to make a decision.6 Patients have also reported that they felt as though they were not knowledgeable enough to ask questions concerning treatment options and preferred for the physician to make the treatment choice for them.6 Decisional regret is now a common observation among men who are not involved in making decisions about their treatment.3

According to the American Cancer Society, about 30,000 black men were diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2016.7 It is important to understand these men’s needs and help them cope effectively as they navigate the survivorship continuum. In line with our research program’s goal of ensuring quality cancer care for black men, the primary objective of this study was to explore the experiences and needs of black men at the point of prostate cancer diagnosis (PPCD). Specifically, we developed an interpretative framework for black men’s experiences at the PPCD, focusing on United States or native-born black men (NBBM) and Caribbean-born black men (CBBM). African-born black men were not included in this study because of the low sample size for that ethnicity. This study is part of a large-scale study that focuses on developing a model of prostate cancer care and survivorship (CaPCaS model) using grounded theory to study black, ethnically diverse prostate cancer survivors.

Methods

The study aims to close the prostate health disparity gap for black men in Florida through community engaged research in partnership with survivors of prostate cancer and their advocates. The current study was a prospective, grounded theory study that involved one-on-one, in-depth interviews with 31 prostate cancer patients about their care and survivorship experiences. Specifically, 17 NBBM and 14 CBBM were enrolled in the project. Appropriate human subjects review and approval were obtained from the University of Florida, the Florida Department of Health, and the Department of Defense.

Research design

This is a qualitative research study. Based on the principles of community engaged research and using a rigorous qualitative research methodology, we recruited NBBM and CBBM with a personal history of prostate cancer. Guided by open-ended questions developed by the team, one-on-one in-depth interviews were conducted with each participant in their home or at a convenient location in the community. Our primary focus was on the participants’ care and survivorship experiences, with primary focus on their prostate cancer diagnosis. Qualitative research was our methodology of choice because little is known about the PPCD experiences of black men.8 With qualitative research, we were able to get our participants to “relive” their experiences in the presence of a culturally competent, well-trained interviewer and elicit the information about their care and survivorship experiences based on their interpretation. In addition, we were able to capture the dynamic processes associated with their experiences, documenting sequential patterns and change through both verbal and nonverbal communications, because the participants were interviewed twice.

Research population and recruitment

The study setting was Florida. The inclusion criteria were: black men, personal history of prostate cancer, ability to complete two separate interviews with each one expected to last 2-3 hours, and flexibility to meet interviewers at a convenient community site for the interviews. Participants were identified through the Florida Cancer Data System (FCDS)9 database. At the time of the study, the most recent FCDS database was for 2010. The FCDS has collected the number of new cancer cancers diagnosed in the state of Florida annually since 1981. It is a comprehensive incidence-only registry and does not extract data on patients with a death certificate. All investigators are bounded by the confidential pledge required for the use of the FCDS data.

We used the Florida Department of Health’s (DoH’s) Bureau of Epidemiology standard procedure for the FCDS9 to recruit participants. Our recruitment strategies included: initial patient contact by written correspondence; second mailing that included a telephone opt-out card after 3 weeks for nonrespondents (the telephone opt-out card explained to the patient that if no response was received, the study investigator would attempt a telephone call to introduce the study); and a telephone call by a study staff to introduce the study for nonrespondents. As per the Florida DoH standard procedure, we did not disclose on the cover of the study mailings that the patient was being contacted for a study specific to cancer. Efforts to recruit a patient stopped immediately if a patient indicated that he did not wish to participate. All of the study staff making participant contact were extensively trained to provide a clear and accurate description of cancer registration in Florida. In addition, to assist the study staff in providing clear and accurate responses, responses to frequently asked questions were made available to the study staff. During the participant recruitment phase, anyone who seemed to be upset when contacted was reported immediately (within 24 hours) to the DoH cancer epidemiologist. In addition, the name of anyone who stated that he did not wish to be contacted again was given to the DoH so that the person would not be re-contacted.

Prescreening of participants for eligibility

All eligible participants who agreed to participate in the study comprised the pool of potential study participants. For those who agreed to participate, the following information was obtained by telephone interview using REDCap software:10 name and contact information, country of birth, age, marital status, and education level. The demographic information facilitated a purposeful systematic selection of black men of diverse age groups (younger than 50 years or older than 50 years), marital status (single, including divorced or separated, or married/in a relationship), and educational level (college degree or not college educated). An incentive of a $5 gift card was provided to all the men who participated in the screening phase. Using systematic sampling to ensure demographically diverse participants, 40 participants (20 NBBM, 20 CBBM) were selected from the initial pool of participants to participate in the study.

Data collection

The data collection was conducted by a trained Community Health Worker (CHW) using semi-structured interview process. The interview guide was constructed by the research team and the study community advisory board members to ensure language appropriateness, understanding and cultural sensitivity. For this study, the interview questions focused on participants’ background information and diagnosis history, including: participants’ personal story of diagnosis, feelings, emotions, reactions, regrets and level of personal/family/physician involvement in diagnosis. For the CBBM, we also obtained information on the age at which they immigrated to the United States. The CHW interviewer was trained to question participants and encourage them to elaborate on areas of importance to their experience.

A total time of about 5-6 hours was scheduled for the data collection per participant, which is sufficient for gathering in-depth perspectives. We scheduled two interviews lasting not more than 3 hours at a time so as not to create burden for study participants. Participants had the choice to have the interviews completed in a single session or spread out over 2 days. The interviews were audio-recorded to provide ease of transcription and back-up of data. At the end of the interviews, participants were compensated for participating in the study.

Data management and analyses

The study dataset included interview transcripts and field notes of the CHW interviewer describing his insights about the interviews. The data analyses included preparing and verifying the narrative data, coding data, and developing an interpretative framework for black men’s experiences at the PPCD. Interviews were transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription service that has policies in place for protected health information. Each transcript was then verified for accuracy by the CHW interviewer. The interview transcripts were imported directly into NVivo 11, a computer-assisted data analysis software that allows coding and modeling of complex narrative data. The data coding was conducted by our interdisciplinary team of clinicians, behavioral scientists, and social scientists. It is important to note that the NVivo 11 software was not used to analyze the data per se. However, it provided a sophisticated and systematic way to manage the following tasks for the analyses: organizing large quantities of narrative data, coding text, retrieving text by codes, querying the data, comparing sets of data interpretation between NBBM and CBBM; and developing analytic models. The study team members coded the data in weekly team meetings. The coding consisted of reading the data and identifying major themes, then assigning labels to and defining emerging categories.

Two levels of coding were used. The first, open coding, refers to an approach to data with no preconceived ideas about what will be found; and the second, focused or axial coding, refers to reviewing data for the purpose of more richly coding on a particular theme.11 We used dimensional analysis to ensure that each emerging concept was carefully defined. The study team went back and forth between the data and the emerging analytic framework, using constant comparison of new data with already coded data and new categories with previously analyzed text.12

To ensure trustworthiness and credibility,13 the study team maintained an audit trail that documented how and when analytic decisions were made. In addition, peer debriefing was conducted to ensure credibility, including the presentation of findings to the study community advisory board members as part of the community engaged research approach.

Results

Description of participants

The FCDS provided a database of 1,813 participants identified as black men diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2010. Because the FCDS does not extract data on patients with a death certificate, we found out during the pre-screening phase that a few of the men were deceased. In addition, there were a significant number of incorrect addresses. We obtained a total of 212 completed responses by phone during the prescreening phase. The majority of the participants were aged 60-69 years (48.2%), had a high school diploma only (26.1%), and were currently married (65.3%). Relative to ethnicity, 67% of participants classified themselves NBBM, 24% as CBBM, 3.5% as black men born in Africa, and 5.5% as Other/Don’t know/Refused. For the CBBM, the most common countries of birth were Jamaica, Haiti, and Guyana, respectively.

In all, 40 participants (20 NBBM and 20 CBBM) were selected from the 212 participants to participate in the study. Selection was conducted systematically to ensure representation in terms of age, marital status, education, and geographical location. Data saturation was achieved with 17 NBBM and 14 CBBM, after which we ended data collection (Table 2). Data saturation is the standard for deciding that we are not finding anything different from the interviews first coded and last coded. Although we were specifically looking for differences between the two groups (NBBM and CBBM), no between-group differences emerged. Each man’s experience was unique to him with some common themes emerging described hereinafter (Figure).

Moderating factors and experiences at PPCD

Some of the moderating factors that the study participants identified as affecting their reactions to the PPCD included health literacy, insurance status, spirituality, mistrust, prior experience with cancer, perceived susceptibility to cancer, and delay in diagnosis (Table 3). Health literacy, defined as personal, cognitive, and social skills that determine the ability of individuals to gain access to, understand, and use information to promote and maintain good health, was one of the moderating factors found in this study.13 Some of the black men came to the PPCD with a low level of health literacy, which had an impact on their understanding of the treatment options. For example, in the interview, participant 798 (NBBM) was confused about what tests had been done and was not able to accurately describe the treatments offered to him. Participant 1263 (CBBM) struggled to express the purpose and procedures associated with diagnostic biopsy. However, there were participants with a high level of health literacy (eg, participant 449 [NBBM]), who decided to research the disease.

Another factor to consider is the insurance status of participants at the PPCD. The majority of the participants had good insurance coverage, but some were affected by poor insurance coverage. Participant 1881(NBBM) made his treatment decision primarily on the basis of the pending lapse of his insurance coverage rather than the best clinical option for him. Participant 1979 (CBBM) described both his confusion on the screening tests and the impact of not having insurance coverage. Upon obtaining insurance coverage, he sought treatment for his prostate cancer with an urgency that he did not experience when he was first diagnosed when uninsured.

The spirituality of black men was another moderating factor at the PPCD. Participant 827 (NBBM) noted that he was unaffected when he received his diagnosis because he was a true believer. Some of the black men also came to the PPCD with lack of trust in the physician and/or the health care system and perceived a sense of contempt from the physician. Participant 1594 (NBBM) described mistrust based on the history of medical exploitation of black men as well as a perception of current discriminatory practices.

Another important PPCD status to note for black men is prior experience with cancer, including prior personal cancer history and/or prior cancer history of a family member. Participant 2024 (CBBM) described the meaning of cancer to him, while participant 798 (NBBM) echoed the despair of the cancer diagnosis based on experience with other cancers in the family. Sometimes there were multiple cancers in the family or even among the significant others of the participant, as was the case with Participant 1936 (CBBM).

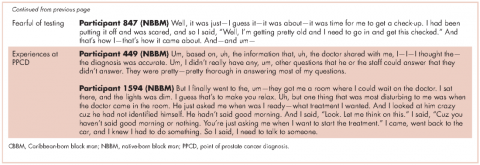

Of greatest concern were men who delayed their diagnosis or treatment, perhaps resulting in their cancer being at a more advanced stage when they eventually did return for care. Finally, some of the men came to the PPCD appointment with a low expectation of receiving a diagnosis of prostate cancer, whereas others came to the PPCD fearful of the results of their testing.

In describing their experiences, participants expressed both positive and negative experiences: on the positive side, they found the information provided by the physician to be helpful; but on the negative side, the sterile or medically focused encounter was perceived as a lack empathy on the part of the physician.

Cognitive, emotional, and behavioral coping experiences

As expected, there were ranges of emotions, including shock, disbelief and denial (Table 4). Some of the men questioned why this (the cancer) was happening to them when they had done “nothing” to deserve it. Doing nothing in this case meant that they had lived a healthy lifestyle with no obvious apparent cause to have the cancer. Fear and cancer fatalism were experienced by a significant number of the men, with their thoughts immediately turning to death and dying. This was especially the case for men who had lost a loved one to cancer. Conversely, some of the men wanted immediate resolution, focusing instead on ways to beat the cancer and with a strong will to live.

Reliance on faith was a big part of coping at the PPCD. Some of the men drew strength from their faith to get them through their cancer journey. Others found a way to accept the diagnosis – one participant accepted the diagnosis and the fact that this could mean dying (after living a good life), whereas another participant accepted the diagnosis with the hope that he would find a cure. Hope was more realistic with the knowledge that other men had survived prostate cancer.

Reflecting back on their experiences, the men also identified clear needs at the PPCD. One of the needs they identified was having a physician they were comfortable with to discuss their diagnosis. Another need was for a second opinion. Participant 1594 (NBBM) advised that it was important for black men to take control by requesting a second opinion. Participant 2039 (NBBM) described a feeling of navigating blindly and trying to find answers that would be helpful to him in his cancer journey. However, his experience with a second opinion was not helpful because the second physician was at the same clinic as his primary physician. His recommendation was to get a second opinion at a different clinic or center. Another important need was emotional support at the PPCD. Participant 2024 (CBBM) made a strong case for emotional support, especially for men who are not accompanied during diagnosis. In addition, Participant 2024’s (CBBM) reflections underscore the fact that the PPCD may not be an ideal place or time to discuss treatment options. With the range of emotions that the men go through at the PPCD, it is difficult to comprehend any follow-up discussions after hearing the words “you have prostate cancer.” Participant 2024 (CBBM) also strongly expressed that men need time to deal with the diagnosis at the PPCD.

Discussion

The primary goal of this study was to develop an interpretative framework of black men’s experiences at the PPCD. The Figure provides a pictorial summary of the framework. Study results indicated that black men come to the PPCD with different emotions and different experiences. Although the majority of the men were NBBM, there is a significantly increasing number of foreign-born black men receiving a diagnosis of prostate cancer in the United States. Given that black men carry a disproportionate burden of the disease, with a significantly higher incidence compared with any other racial group, it is important that tailored services are provided to black men at the PPCD.

We also found that black men came to the PPCD diverse in terms of their ethnicity, health literacy, spirituality, trust in health care system/physician, prior experience with cancer, perceived susceptibility to cancer, delayed time for diagnosis, and fear of diagnosis. Of importance for physicians is that the black race is not homogeneous. There is a significant number of foreign-born blacks at the PPCD, and they often have different cultural beliefs and values compared with NBBM. In addition, some of the foreign-born black men may not have English proficiency and may need a medical interpreter during the PPCD consultation. In addition, a patient’s pre-existing lack of trust in the health care system may have a negative impact on the PPCD consultation. It is thus important that the physician takes the time to instill trust and make the men comfortable during the PPCD consultation.

For some of the men who had fear of a prostate cancer diagnosis and/or prior experience with cancer, cancer fatalism was experienced at the PPCD. Cancer fatalism, defined as an individual’s belief that death is bound to happen when diagnosed with cancer, has been documented as a major barrier to cancer detection and control.15 For example, fatalistic perspectives have been reported to affect cervical cancer,16 breast cancer,17,18 colorectal cancer,19 and prostate cancer20,21 among blacks. It is thus important to effectively address fatalistic beliefs when a man is diagnosed with prostate cancer.

Other emotions at the PPCD that may affect effective treatment decision making also need to be addressed immediately. For example, the emotions of fear, denial, and feeling overwhelmed are potential barriers to timely treatment decision making. Psycho-oncology interventions to appropriately deal with these emotions at PPCD or right after the diagnosis may be crucial for the men. In particular, a group-based psychosocial intervention focusing on: provision of education about treatment options for prostate cancer and their acute and late effects; negotiating treatment and treatment side effects; enhancing communication with treatment providers; managing distress; and engaging positive family- and community-based social support to optimize emotional, behavioral, social, and physical outcomes in black men with prostate cancer.

In addition to having physicians make them comfortable at PPCD, the PPCD needs expressed by participants included having time to come to terms with the diagnosis and receiving psycho-oncology/emotional support. Anyone who has just received a diagnosis of cancer cannot be expected to immediately continue to function as he did before the PPCD. This is especially difficult for men who are alone at the PPCD. Nevertheless, it is expected that they will listen attentively and understand subsequent consultation by the physician, then leave the consultation room almost immediately, and be able drive home or back to work right after the diagnosis. There seems to be a support gap that needs to be closed at the PPCD. Providing the men with immediate support to cope with the diagnosis may make a significant difference in effective treatment choices and eliminating treatment decisional regrets.

Methodological rigor was established through purposeful sampling, extended time with participants, standardized procedures for data collection, management and analysis, multidisciplinary interpretation, and validation of results with the community advisory board. Because the research participants were purposefully selected from a statewide database of black men diagnosed with CaP, generalizability of findings to the two target groups of NBBM and CBBM can be assumed, with the caveat that men with different experiences may have chosen not to respond to recruitment efforts or refused participation. Black men who were not sufficiently fluent in English to be interviewed were also excluded and are not represented in these findings. Black men of other nativity (including African-born black men) and residing outside of Florida were also not represented.

In conclusion, the PPCD interpretative framework developed in this study, describes the status of black men at the PPCD, their experiences during the PPCD, and their needs at the PPCD. The framework provides information that can be used by physicians to prepare for their PPCD consultation with black men as well as develop a support system for black men at the PPCD.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the men who participated in the CaPCaS study. They also thank the CaPCaS project community advisory board chairs (Mr Jim West, Dr Angela Adams, and Prince Oladapo Odedina) and all the CaPCaS project community advisory board members for their effort throughout the project. Finally, they rxecognize the effort of additional CaPCaS scientific team, especially the primary interviewer, Mr Kenneth Stokes. Weekly meeting support for this study was provided by the University of Florida MiCaRT Center, which is funded by the NIH-National Cancer Institute Award # 1P20CA192990-02. REDCaP software was supported by the UF Clinical and Translational Science Institute, which is funded in part by the NIH Clinical and Translational Science Award program (grants UL1TR001427, KL2TR001429 and TL1TR001428).

As of 2016, Florida ranks second among all states in the United States in estimated new cases of prostate cancer and second in estimated deaths from prostate cancer.1 Disparities in diagnosis, mortality rates, and access to cancer care also continue to be a major problem in Florida, especially for black men. For example, black men were the only racial/ethnic group that did not meet the Healthy People (HP) 2010 objective to reduce the prostate cancer death rate to 28.2 per 100,000 men and that has not met the HP 2020 objective to reduce the prostate cancer death rate to 21.2 per 100,000 men (Table 1). Based on the 2013 prostate cancer mortality rates for Florida,2 the death rate for black men is almost twice the HP 2020 goal (37.49 per 100,000).

A diagnosis of prostate cancer is a life changing event for a man. In particular, there is limited research on the experiences and coping mechanisms of black men at diagnosis. This limited body of research indicates that black men’s reactions to their initial diagnoses varied, from being shocked when notified of their initial diagnosis of prostate cancer,3 to perceiving that they had received a “death sentence”.4 In regard to having to make decisions about their treatment options, some black men indicated that the information about treatment that they received from physicians decreased their anxiety,5 whereas others noted that they had not been given adequate information by a physician to make a decision.6 Patients have also reported that they felt as though they were not knowledgeable enough to ask questions concerning treatment options and preferred for the physician to make the treatment choice for them.6 Decisional regret is now a common observation among men who are not involved in making decisions about their treatment.3

According to the American Cancer Society, about 30,000 black men were diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2016.7 It is important to understand these men’s needs and help them cope effectively as they navigate the survivorship continuum. In line with our research program’s goal of ensuring quality cancer care for black men, the primary objective of this study was to explore the experiences and needs of black men at the point of prostate cancer diagnosis (PPCD). Specifically, we developed an interpretative framework for black men’s experiences at the PPCD, focusing on United States or native-born black men (NBBM) and Caribbean-born black men (CBBM). African-born black men were not included in this study because of the low sample size for that ethnicity. This study is part of a large-scale study that focuses on developing a model of prostate cancer care and survivorship (CaPCaS model) using grounded theory to study black, ethnically diverse prostate cancer survivors.

Methods

The study aims to close the prostate health disparity gap for black men in Florida through community engaged research in partnership with survivors of prostate cancer and their advocates. The current study was a prospective, grounded theory study that involved one-on-one, in-depth interviews with 31 prostate cancer patients about their care and survivorship experiences. Specifically, 17 NBBM and 14 CBBM were enrolled in the project. Appropriate human subjects review and approval were obtained from the University of Florida, the Florida Department of Health, and the Department of Defense.

Research design

This is a qualitative research study. Based on the principles of community engaged research and using a rigorous qualitative research methodology, we recruited NBBM and CBBM with a personal history of prostate cancer. Guided by open-ended questions developed by the team, one-on-one in-depth interviews were conducted with each participant in their home or at a convenient location in the community. Our primary focus was on the participants’ care and survivorship experiences, with primary focus on their prostate cancer diagnosis. Qualitative research was our methodology of choice because little is known about the PPCD experiences of black men.8 With qualitative research, we were able to get our participants to “relive” their experiences in the presence of a culturally competent, well-trained interviewer and elicit the information about their care and survivorship experiences based on their interpretation. In addition, we were able to capture the dynamic processes associated with their experiences, documenting sequential patterns and change through both verbal and nonverbal communications, because the participants were interviewed twice.

Research population and recruitment

The study setting was Florida. The inclusion criteria were: black men, personal history of prostate cancer, ability to complete two separate interviews with each one expected to last 2-3 hours, and flexibility to meet interviewers at a convenient community site for the interviews. Participants were identified through the Florida Cancer Data System (FCDS)9 database. At the time of the study, the most recent FCDS database was for 2010. The FCDS has collected the number of new cancer cancers diagnosed in the state of Florida annually since 1981. It is a comprehensive incidence-only registry and does not extract data on patients with a death certificate. All investigators are bounded by the confidential pledge required for the use of the FCDS data.

We used the Florida Department of Health’s (DoH’s) Bureau of Epidemiology standard procedure for the FCDS9 to recruit participants. Our recruitment strategies included: initial patient contact by written correspondence; second mailing that included a telephone opt-out card after 3 weeks for nonrespondents (the telephone opt-out card explained to the patient that if no response was received, the study investigator would attempt a telephone call to introduce the study); and a telephone call by a study staff to introduce the study for nonrespondents. As per the Florida DoH standard procedure, we did not disclose on the cover of the study mailings that the patient was being contacted for a study specific to cancer. Efforts to recruit a patient stopped immediately if a patient indicated that he did not wish to participate. All of the study staff making participant contact were extensively trained to provide a clear and accurate description of cancer registration in Florida. In addition, to assist the study staff in providing clear and accurate responses, responses to frequently asked questions were made available to the study staff. During the participant recruitment phase, anyone who seemed to be upset when contacted was reported immediately (within 24 hours) to the DoH cancer epidemiologist. In addition, the name of anyone who stated that he did not wish to be contacted again was given to the DoH so that the person would not be re-contacted.

Prescreening of participants for eligibility

All eligible participants who agreed to participate in the study comprised the pool of potential study participants. For those who agreed to participate, the following information was obtained by telephone interview using REDCap software:10 name and contact information, country of birth, age, marital status, and education level. The demographic information facilitated a purposeful systematic selection of black men of diverse age groups (younger than 50 years or older than 50 years), marital status (single, including divorced or separated, or married/in a relationship), and educational level (college degree or not college educated). An incentive of a $5 gift card was provided to all the men who participated in the screening phase. Using systematic sampling to ensure demographically diverse participants, 40 participants (20 NBBM, 20 CBBM) were selected from the initial pool of participants to participate in the study.

Data collection

The data collection was conducted by a trained Community Health Worker (CHW) using semi-structured interview process. The interview guide was constructed by the research team and the study community advisory board members to ensure language appropriateness, understanding and cultural sensitivity. For this study, the interview questions focused on participants’ background information and diagnosis history, including: participants’ personal story of diagnosis, feelings, emotions, reactions, regrets and level of personal/family/physician involvement in diagnosis. For the CBBM, we also obtained information on the age at which they immigrated to the United States. The CHW interviewer was trained to question participants and encourage them to elaborate on areas of importance to their experience.

A total time of about 5-6 hours was scheduled for the data collection per participant, which is sufficient for gathering in-depth perspectives. We scheduled two interviews lasting not more than 3 hours at a time so as not to create burden for study participants. Participants had the choice to have the interviews completed in a single session or spread out over 2 days. The interviews were audio-recorded to provide ease of transcription and back-up of data. At the end of the interviews, participants were compensated for participating in the study.

Data management and analyses

The study dataset included interview transcripts and field notes of the CHW interviewer describing his insights about the interviews. The data analyses included preparing and verifying the narrative data, coding data, and developing an interpretative framework for black men’s experiences at the PPCD. Interviews were transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription service that has policies in place for protected health information. Each transcript was then verified for accuracy by the CHW interviewer. The interview transcripts were imported directly into NVivo 11, a computer-assisted data analysis software that allows coding and modeling of complex narrative data. The data coding was conducted by our interdisciplinary team of clinicians, behavioral scientists, and social scientists. It is important to note that the NVivo 11 software was not used to analyze the data per se. However, it provided a sophisticated and systematic way to manage the following tasks for the analyses: organizing large quantities of narrative data, coding text, retrieving text by codes, querying the data, comparing sets of data interpretation between NBBM and CBBM; and developing analytic models. The study team members coded the data in weekly team meetings. The coding consisted of reading the data and identifying major themes, then assigning labels to and defining emerging categories.

Two levels of coding were used. The first, open coding, refers to an approach to data with no preconceived ideas about what will be found; and the second, focused or axial coding, refers to reviewing data for the purpose of more richly coding on a particular theme.11 We used dimensional analysis to ensure that each emerging concept was carefully defined. The study team went back and forth between the data and the emerging analytic framework, using constant comparison of new data with already coded data and new categories with previously analyzed text.12

To ensure trustworthiness and credibility,13 the study team maintained an audit trail that documented how and when analytic decisions were made. In addition, peer debriefing was conducted to ensure credibility, including the presentation of findings to the study community advisory board members as part of the community engaged research approach.

Results

Description of participants

The FCDS provided a database of 1,813 participants identified as black men diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2010. Because the FCDS does not extract data on patients with a death certificate, we found out during the pre-screening phase that a few of the men were deceased. In addition, there were a significant number of incorrect addresses. We obtained a total of 212 completed responses by phone during the prescreening phase. The majority of the participants were aged 60-69 years (48.2%), had a high school diploma only (26.1%), and were currently married (65.3%). Relative to ethnicity, 67% of participants classified themselves NBBM, 24% as CBBM, 3.5% as black men born in Africa, and 5.5% as Other/Don’t know/Refused. For the CBBM, the most common countries of birth were Jamaica, Haiti, and Guyana, respectively.

In all, 40 participants (20 NBBM and 20 CBBM) were selected from the 212 participants to participate in the study. Selection was conducted systematically to ensure representation in terms of age, marital status, education, and geographical location. Data saturation was achieved with 17 NBBM and 14 CBBM, after which we ended data collection (Table 2). Data saturation is the standard for deciding that we are not finding anything different from the interviews first coded and last coded. Although we were specifically looking for differences between the two groups (NBBM and CBBM), no between-group differences emerged. Each man’s experience was unique to him with some common themes emerging described hereinafter (Figure).

Moderating factors and experiences at PPCD

Some of the moderating factors that the study participants identified as affecting their reactions to the PPCD included health literacy, insurance status, spirituality, mistrust, prior experience with cancer, perceived susceptibility to cancer, and delay in diagnosis (Table 3). Health literacy, defined as personal, cognitive, and social skills that determine the ability of individuals to gain access to, understand, and use information to promote and maintain good health, was one of the moderating factors found in this study.13 Some of the black men came to the PPCD with a low level of health literacy, which had an impact on their understanding of the treatment options. For example, in the interview, participant 798 (NBBM) was confused about what tests had been done and was not able to accurately describe the treatments offered to him. Participant 1263 (CBBM) struggled to express the purpose and procedures associated with diagnostic biopsy. However, there were participants with a high level of health literacy (eg, participant 449 [NBBM]), who decided to research the disease.

Another factor to consider is the insurance status of participants at the PPCD. The majority of the participants had good insurance coverage, but some were affected by poor insurance coverage. Participant 1881(NBBM) made his treatment decision primarily on the basis of the pending lapse of his insurance coverage rather than the best clinical option for him. Participant 1979 (CBBM) described both his confusion on the screening tests and the impact of not having insurance coverage. Upon obtaining insurance coverage, he sought treatment for his prostate cancer with an urgency that he did not experience when he was first diagnosed when uninsured.

The spirituality of black men was another moderating factor at the PPCD. Participant 827 (NBBM) noted that he was unaffected when he received his diagnosis because he was a true believer. Some of the black men also came to the PPCD with lack of trust in the physician and/or the health care system and perceived a sense of contempt from the physician. Participant 1594 (NBBM) described mistrust based on the history of medical exploitation of black men as well as a perception of current discriminatory practices.

Another important PPCD status to note for black men is prior experience with cancer, including prior personal cancer history and/or prior cancer history of a family member. Participant 2024 (CBBM) described the meaning of cancer to him, while participant 798 (NBBM) echoed the despair of the cancer diagnosis based on experience with other cancers in the family. Sometimes there were multiple cancers in the family or even among the significant others of the participant, as was the case with Participant 1936 (CBBM).

Of greatest concern were men who delayed their diagnosis or treatment, perhaps resulting in their cancer being at a more advanced stage when they eventually did return for care. Finally, some of the men came to the PPCD appointment with a low expectation of receiving a diagnosis of prostate cancer, whereas others came to the PPCD fearful of the results of their testing.

In describing their experiences, participants expressed both positive and negative experiences: on the positive side, they found the information provided by the physician to be helpful; but on the negative side, the sterile or medically focused encounter was perceived as a lack empathy on the part of the physician.

Cognitive, emotional, and behavioral coping experiences

As expected, there were ranges of emotions, including shock, disbelief and denial (Table 4). Some of the men questioned why this (the cancer) was happening to them when they had done “nothing” to deserve it. Doing nothing in this case meant that they had lived a healthy lifestyle with no obvious apparent cause to have the cancer. Fear and cancer fatalism were experienced by a significant number of the men, with their thoughts immediately turning to death and dying. This was especially the case for men who had lost a loved one to cancer. Conversely, some of the men wanted immediate resolution, focusing instead on ways to beat the cancer and with a strong will to live.

Reliance on faith was a big part of coping at the PPCD. Some of the men drew strength from their faith to get them through their cancer journey. Others found a way to accept the diagnosis – one participant accepted the diagnosis and the fact that this could mean dying (after living a good life), whereas another participant accepted the diagnosis with the hope that he would find a cure. Hope was more realistic with the knowledge that other men had survived prostate cancer.

Reflecting back on their experiences, the men also identified clear needs at the PPCD. One of the needs they identified was having a physician they were comfortable with to discuss their diagnosis. Another need was for a second opinion. Participant 1594 (NBBM) advised that it was important for black men to take control by requesting a second opinion. Participant 2039 (NBBM) described a feeling of navigating blindly and trying to find answers that would be helpful to him in his cancer journey. However, his experience with a second opinion was not helpful because the second physician was at the same clinic as his primary physician. His recommendation was to get a second opinion at a different clinic or center. Another important need was emotional support at the PPCD. Participant 2024 (CBBM) made a strong case for emotional support, especially for men who are not accompanied during diagnosis. In addition, Participant 2024’s (CBBM) reflections underscore the fact that the PPCD may not be an ideal place or time to discuss treatment options. With the range of emotions that the men go through at the PPCD, it is difficult to comprehend any follow-up discussions after hearing the words “you have prostate cancer.” Participant 2024 (CBBM) also strongly expressed that men need time to deal with the diagnosis at the PPCD.

Discussion

The primary goal of this study was to develop an interpretative framework of black men’s experiences at the PPCD. The Figure provides a pictorial summary of the framework. Study results indicated that black men come to the PPCD with different emotions and different experiences. Although the majority of the men were NBBM, there is a significantly increasing number of foreign-born black men receiving a diagnosis of prostate cancer in the United States. Given that black men carry a disproportionate burden of the disease, with a significantly higher incidence compared with any other racial group, it is important that tailored services are provided to black men at the PPCD.

We also found that black men came to the PPCD diverse in terms of their ethnicity, health literacy, spirituality, trust in health care system/physician, prior experience with cancer, perceived susceptibility to cancer, delayed time for diagnosis, and fear of diagnosis. Of importance for physicians is that the black race is not homogeneous. There is a significant number of foreign-born blacks at the PPCD, and they often have different cultural beliefs and values compared with NBBM. In addition, some of the foreign-born black men may not have English proficiency and may need a medical interpreter during the PPCD consultation. In addition, a patient’s pre-existing lack of trust in the health care system may have a negative impact on the PPCD consultation. It is thus important that the physician takes the time to instill trust and make the men comfortable during the PPCD consultation.

For some of the men who had fear of a prostate cancer diagnosis and/or prior experience with cancer, cancer fatalism was experienced at the PPCD. Cancer fatalism, defined as an individual’s belief that death is bound to happen when diagnosed with cancer, has been documented as a major barrier to cancer detection and control.15 For example, fatalistic perspectives have been reported to affect cervical cancer,16 breast cancer,17,18 colorectal cancer,19 and prostate cancer20,21 among blacks. It is thus important to effectively address fatalistic beliefs when a man is diagnosed with prostate cancer.

Other emotions at the PPCD that may affect effective treatment decision making also need to be addressed immediately. For example, the emotions of fear, denial, and feeling overwhelmed are potential barriers to timely treatment decision making. Psycho-oncology interventions to appropriately deal with these emotions at PPCD or right after the diagnosis may be crucial for the men. In particular, a group-based psychosocial intervention focusing on: provision of education about treatment options for prostate cancer and their acute and late effects; negotiating treatment and treatment side effects; enhancing communication with treatment providers; managing distress; and engaging positive family- and community-based social support to optimize emotional, behavioral, social, and physical outcomes in black men with prostate cancer.

In addition to having physicians make them comfortable at PPCD, the PPCD needs expressed by participants included having time to come to terms with the diagnosis and receiving psycho-oncology/emotional support. Anyone who has just received a diagnosis of cancer cannot be expected to immediately continue to function as he did before the PPCD. This is especially difficult for men who are alone at the PPCD. Nevertheless, it is expected that they will listen attentively and understand subsequent consultation by the physician, then leave the consultation room almost immediately, and be able drive home or back to work right after the diagnosis. There seems to be a support gap that needs to be closed at the PPCD. Providing the men with immediate support to cope with the diagnosis may make a significant difference in effective treatment choices and eliminating treatment decisional regrets.

Methodological rigor was established through purposeful sampling, extended time with participants, standardized procedures for data collection, management and analysis, multidisciplinary interpretation, and validation of results with the community advisory board. Because the research participants were purposefully selected from a statewide database of black men diagnosed with CaP, generalizability of findings to the two target groups of NBBM and CBBM can be assumed, with the caveat that men with different experiences may have chosen not to respond to recruitment efforts or refused participation. Black men who were not sufficiently fluent in English to be interviewed were also excluded and are not represented in these findings. Black men of other nativity (including African-born black men) and residing outside of Florida were also not represented.

In conclusion, the PPCD interpretative framework developed in this study, describes the status of black men at the PPCD, their experiences during the PPCD, and their needs at the PPCD. The framework provides information that can be used by physicians to prepare for their PPCD consultation with black men as well as develop a support system for black men at the PPCD.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the men who participated in the CaPCaS study. They also thank the CaPCaS project community advisory board chairs (Mr Jim West, Dr Angela Adams, and Prince Oladapo Odedina) and all the CaPCaS project community advisory board members for their effort throughout the project. Finally, they rxecognize the effort of additional CaPCaS scientific team, especially the primary interviewer, Mr Kenneth Stokes. Weekly meeting support for this study was provided by the University of Florida MiCaRT Center, which is funded by the NIH-National Cancer Institute Award # 1P20CA192990-02. REDCaP software was supported by the UF Clinical and Translational Science Institute, which is funded in part by the NIH Clinical and Translational Science Award program (grants UL1TR001427, KL2TR001429 and TL1TR001428).

1. American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2016. http://www.cancer.org/research/cancerfactsstatistics/cancerfactsfigures2016/. Published 2016. Accessed January 10, 2017.

2. Florida Cancer Data System. Florida Statewide Population-Based Cancer Registry. https://fcds.med.miami.edu/scripts/fcdspubrates/production/doSelection.aspx?election=map. Processed February 16, 2016.