User login

After treatment, cancer patients transition to a survivorship phase, often with little information or support. Cancer survivors are at increased risk of recurrence, secondary cancers, comorbid conditions, and late treatment effects.1,2 However, many remain unaware of these risks and the options for managing them3 and face numerous unmet medical, psychosocial, and informational needs that can be addressed through survivorship care programs.4 Anxiety may increase as they lose their treatment team’s support while attempting to reestablish their lives.2 Patients need to know the long-term risks of cancer treatments, probabilities of recurrence and second cancers, effectiveness of surveillance and interventions for managing late effects and psychosocial concerns, and benefits of healthy lifestyles.2

Due to sociocultural and economic factors, Spanish-speaking Latina breast cancer survivors (SSBCS) suffer worse posttreatment health-related quality of life and more pain, fatigue, depressive symptoms, body image issues, and distress than their white counterparts.5-7 However, they are less likely to receive necessary cancer treatment, symptom management, and surveillance. For example, compared with whites, Latina breast cancer survivors receive less guideline-adherent treatment8 and follow-up care, including survivorship information.3,9 SSBCS, in particular have less access to survivorship information.10 Consequently, SSBCS are more likely to report unmet symptom management needs.11

Several breast cancer survivorship program trials have included Latinas,12,13 but their effectiveness has been demonstrated only for depressive symptoms or health worry. A comprehensive assessment of the posttreatment needs of SSBCS would provide a foundation for designing tailored survivorship interventions for this vulnerable group. This study aimed to identify the symptom management, psychosocial, and informational needs of SSBCS during the transition to survivorship from the perspectives of SSBCS and their cancer support providers and cancer physicians.

Methods

We sampled respondents within a 5-county area in Northern California to obtain multiple perspectives of the survivorship care needs of SSBCS using structured and in-depth methods: a telephone survey of SSBCS; semistructured interviews with SSBCS; semistructured interviews with cancer support providers serving SSBCS; and semistructured interviews with physicians providing cancer care for SSBCS. The study protocol was approved by the University of California San Francisco Committee on Human Research.

Sample and procedures

Structured telephone survey with SSBCS. The sample was drawn evenly from San Francisco General Hospital-University of California San Francisco primary care practices and SSBCS from a previous study who agreed to be re-contacted.14 The inclusion criteria were: completed active treatment (except adjuvant hormonal therapy) for nonmetastatic breast cancer within 10 years; living in one of the five counties; primarily Spanish-speaking; and self-identified as Latina. The exclusion criteria were: previous cancer except nonmelanoma skin cancer; terminal illness; or metastatic breast cancer. Study staff mailed potential participants a bilingual letter and information sheet, and bilingual opt-out postcard (6th grade reading level assessed by Flesch-Kincaid grade level statistic). Female bilingual-bicultural research associates conducted interviews of 20-30 minutes in Spanish after obtaining verbal consent. Participants were mailed $20. Surveys were conducted during March-November 2014.

Semistructured in-person interviews with SSBCS. Four community-based organizations (CBOs) in the targeted area providing cancer support services to Latinos agreed to recruit SSBCS for interviews. Inclusion criteria were identical to the survey. Patient navigators or support providers from CBOs contacted women by phone or in-person to invite them to an interview to assess their cancer survivorship needs. Women could choose a focus group or individual interview. With permission, names and contact information were given to study interviewers who called, explained the study, screened for eligibility, and scheduled an interview.

Recruitment was stratified by age (under or over age 50). We sampled women until saturation was achieved (no new themes emerged). Focus groups (90 minutes) were conducted at the CBOs. Individual interviews (45 minutes) were conducted in participants’ homes. Written informed consent was obtained. Participants were paid $50. Interviews were conducted during August-November, 2014, audiotaped, and transcribed.

Semistructured in-person interviews with cancer support providers and physicians. Investigators invited five cancer support providers (three patient navigators from three county hospitals, and two CBO directors of cancer psychosocial support services) and four physicians (three oncologists and one breast cancer surgeon from three county hospitals) to an in-person interview to identify SSBCS’ survivorship care needs. All agreed to participate. No further candidates were approached because saturation was achieved. We obtained written informed consent and 30-minute interviews were conducted in participants’ offices during August-October, 2014. Interviews were audiotaped and transcribed. Participants were paid $50.

Ethical approval. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Measures

Structured telephone survey. Based on cancer survivor needs assessments,15 we assessed: physical and emotional symptoms; problems with sleep and memory/concentration; concerns about mortality, family, social isolation, intimacy, appearance; and healthy lifestyles. Items were adapted and translated into Spanish if needed, using forward/backward translation with team reconciliation. These questions used the introduction, “Now I am going to ask you if you have had any problems because of your cancer. In the past month, how much have you been bothered by …” with responses rated on a scale of 1-5 (1, Not at all; 5, A lot). For example, we asked, “In the past month, how much have you been bothered by fatigue?”

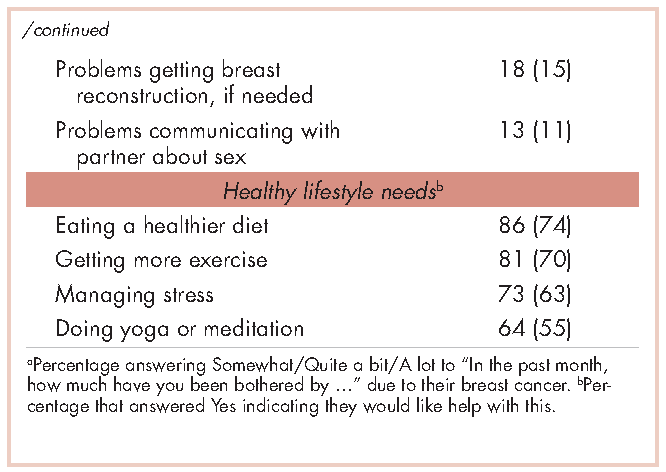

Regarding healthy lifestyles, we used the introduction, “Here are some changes women sometimes want to make after cancer. Would you like help with …?” For example, we asked, “Would you like help with getting more exercise?” We asked if they wanted help getting more exercise, eating healthier, managing stress, and doing meditation or yoga (Yes/No).

Semistructured interview guide for SSBCS. Participants were asked about their emotional and physical concerns when treatment ended, current cancer needs, symptoms or late effects, and issues related to relationships, family, employment, insurance, financial hardships, barriers to follow-up care, health behaviors, and survivorship program content. Sample questions are, “Have you had any symptoms or side effects related to your cancer or treatment?” and “What kinds of information do you feel you need now about your cancer or treatment?” A brief questionnaire assessed demographics.

Semistructured interview guide for cancer support providers and physicians. Support providers and physicians were asked about informational, psychosocial, and symptom management needs of SSBCS and recommended self-management content and formats. Sample questions are, “What kinds of information and support do you wish was available to help Spanish-speaking women take care of their health after treatment ends?” and “What do you think are the most pressing emotional needs of Spanish-speaking women after breast cancer treatment ends?” A brief questionnaire assessed demographics.

Analysis

Frequencies are reported for survey items. For questions about symptoms/concerns, we report the frequency of responding that they were bothered Somewhat/Quite a bit/A lot. For healthy lifestyles, we present the frequency answering Yes.

Verbatim semistructured interview transcripts were verified against audiotapes. Using QSR NVIVO software, transcripts were coded independently by two bilingual-bicultural investigators using a constant comparative method to generate coding categories for cancer survivorship needs.16 Coders started with themes specified by the interview guides, expanded them to represent the data, and discussed and reconciled coding discrepancies. Coding was compared by type of interview participant (survivor, support provider, or physician). Triangulation of survey and semistructured interviews occurred through team discussions to verify codes, themes, and implications for interventions.

Results

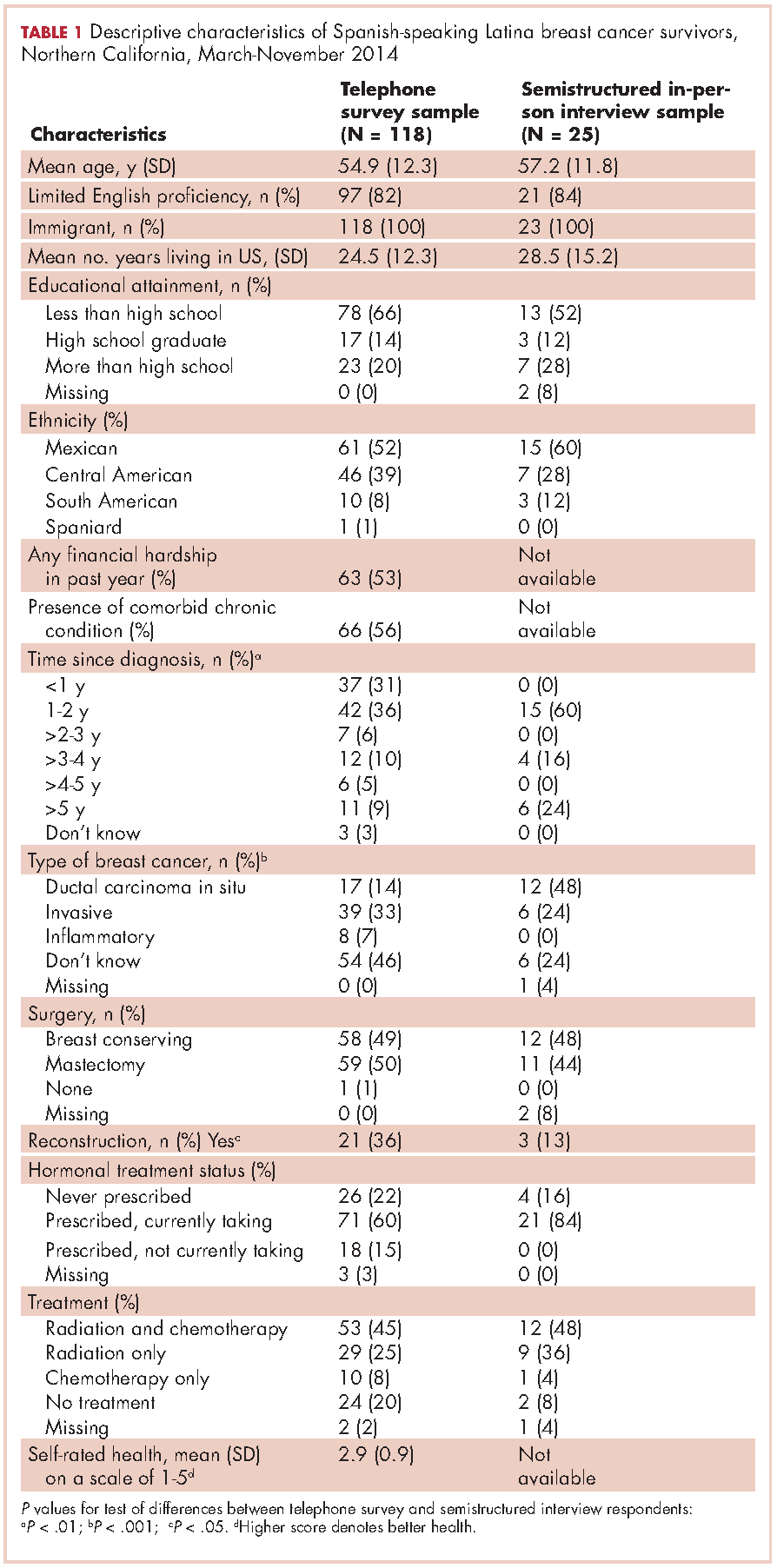

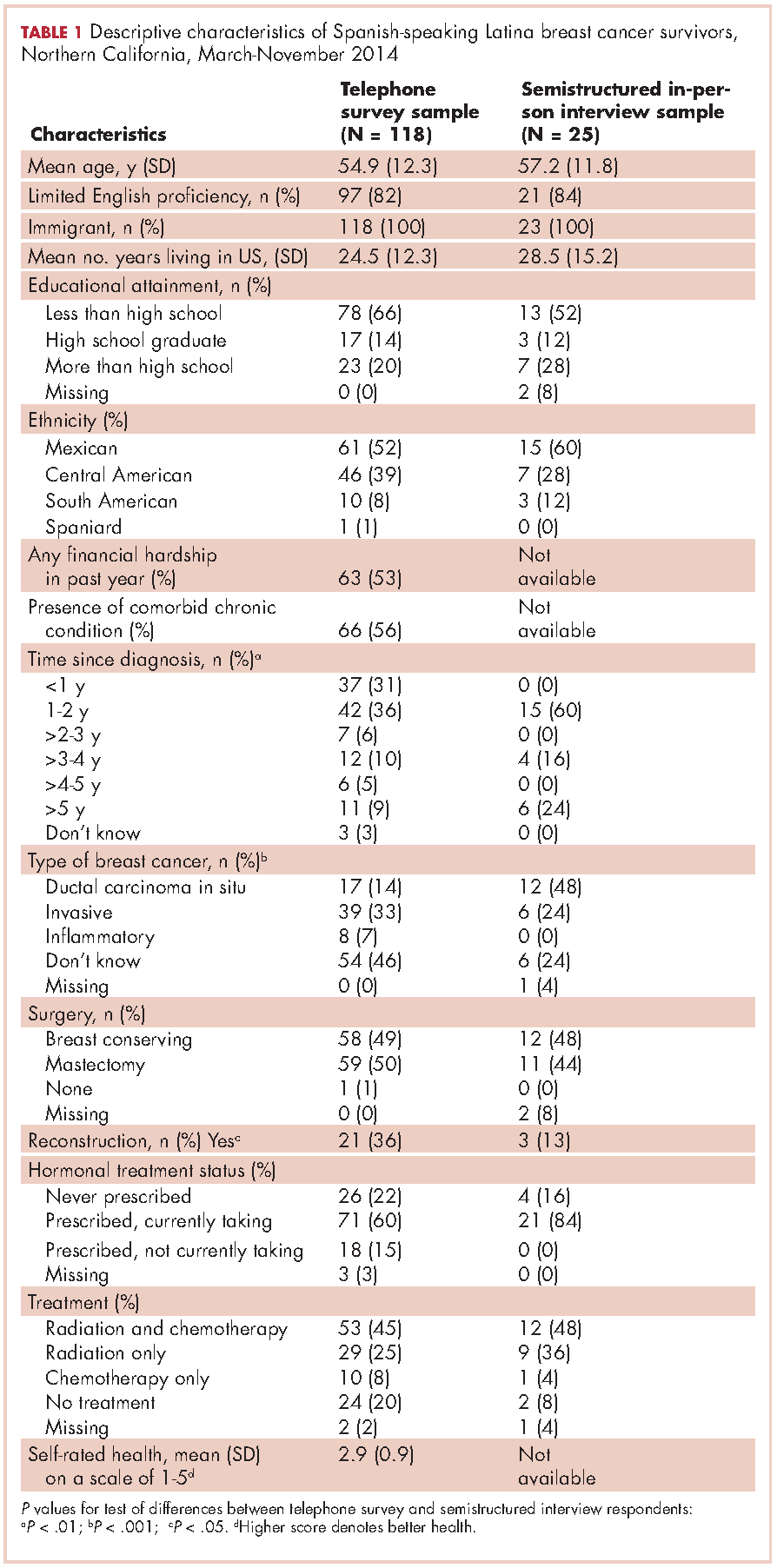

Telephone survey of SSBCS

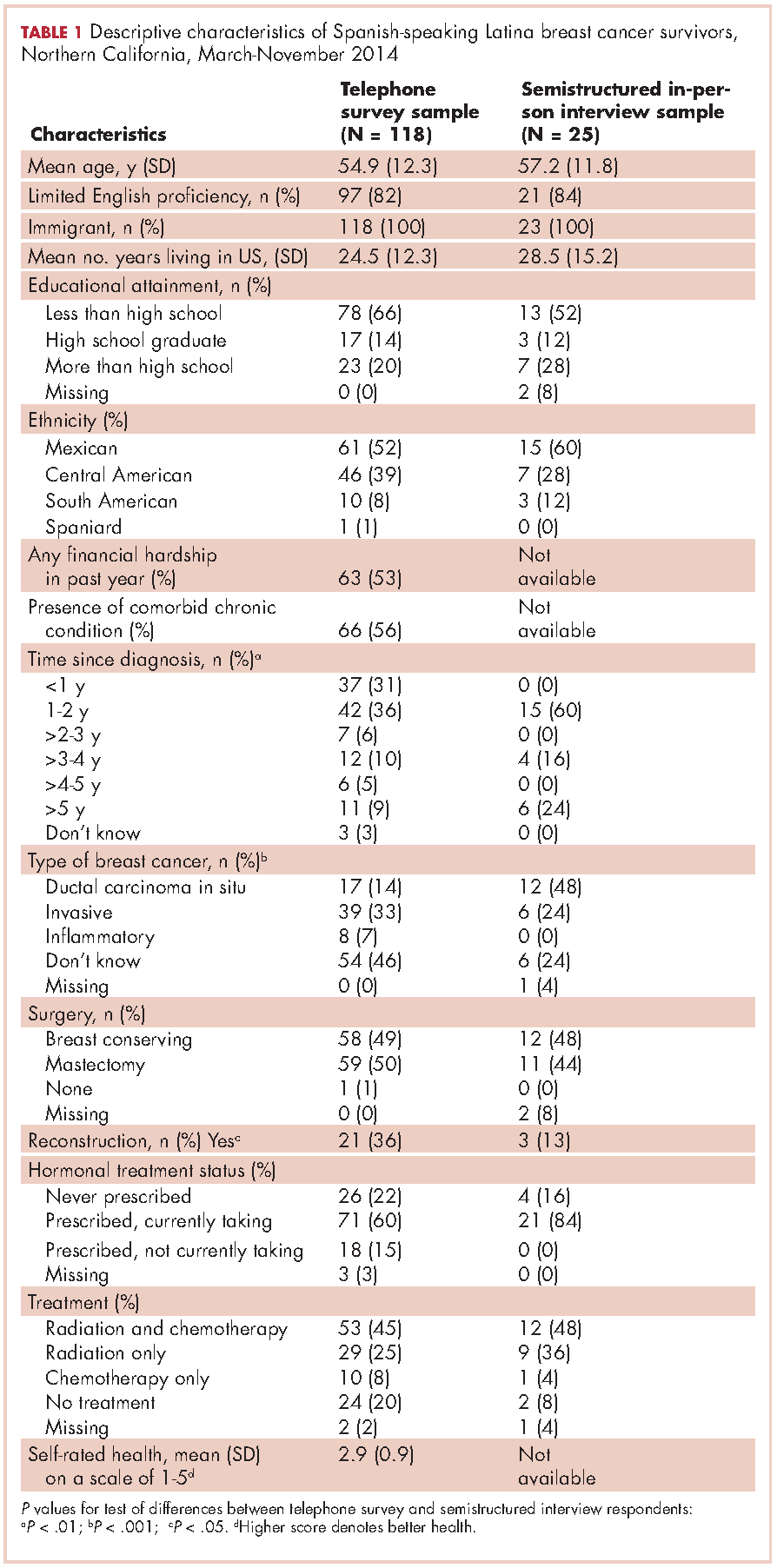

Of the telephone survey sampling frame (N = 231), 118 individuals (51%) completed the interview, 37 (16%) were ineligible, 31 (13%) could not be reached, 22 (10%) had incorrect contact information, 19 (8%) refused to participate, and 4 (2%) were deceased. Mean age of the participants was 54.9 years (SD, 12.3); all were foreign-born, with more than half of Mexican origin; and most had less than a high-school education (Table 1). All had completed active treatment, and most (68%) were within 2 years of diagnosis.

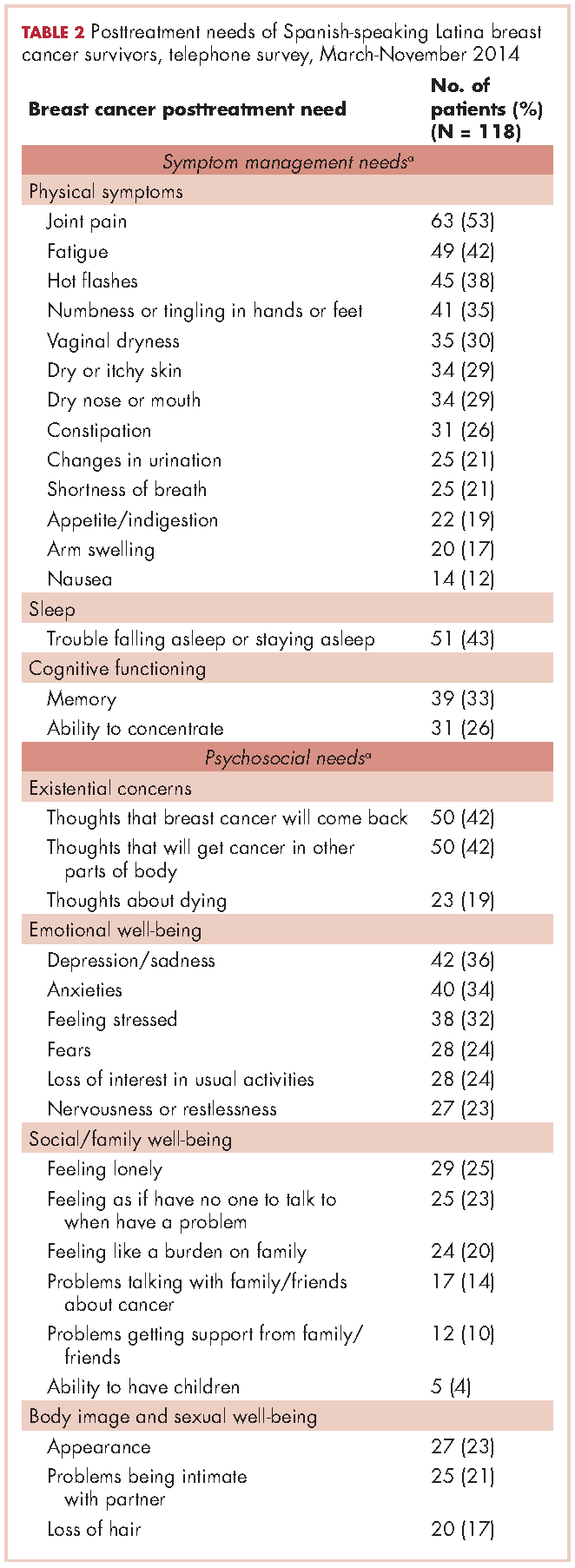

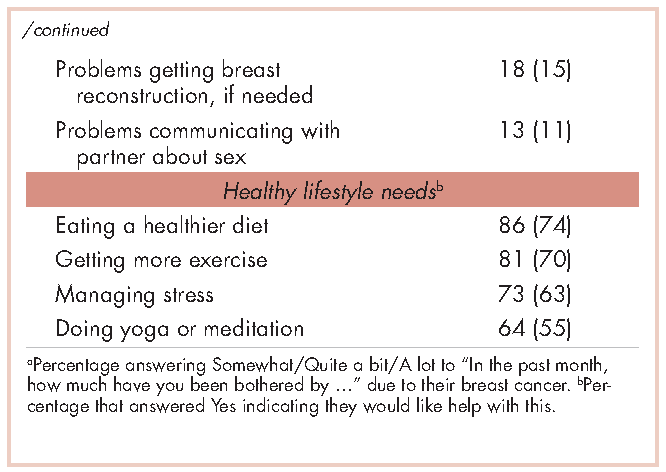

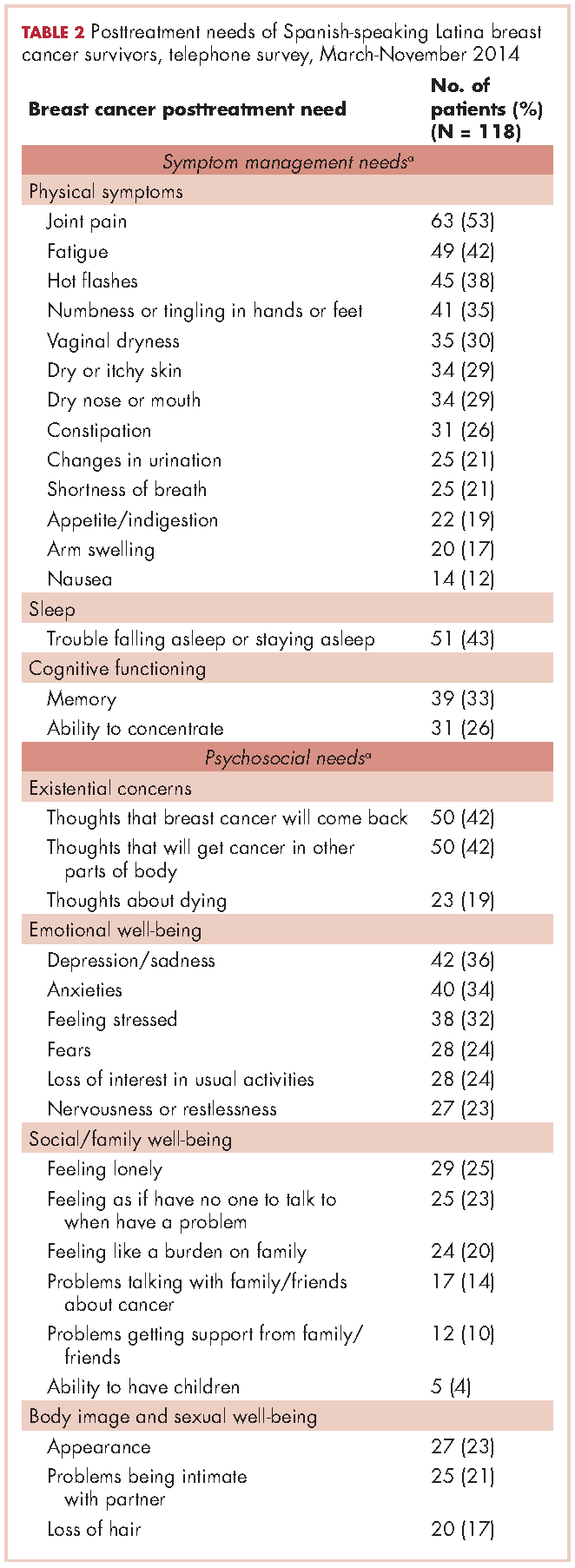

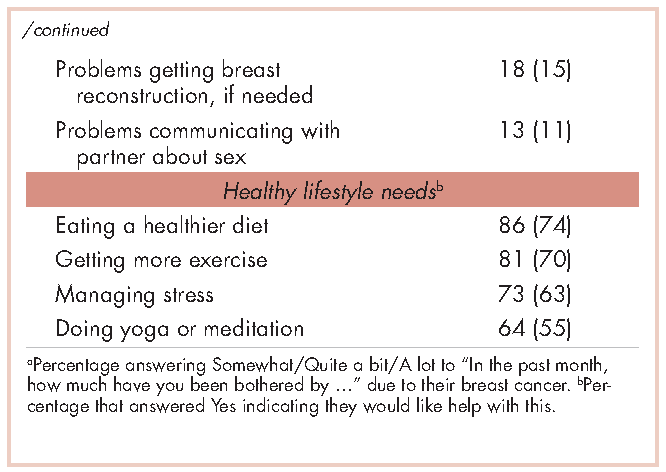

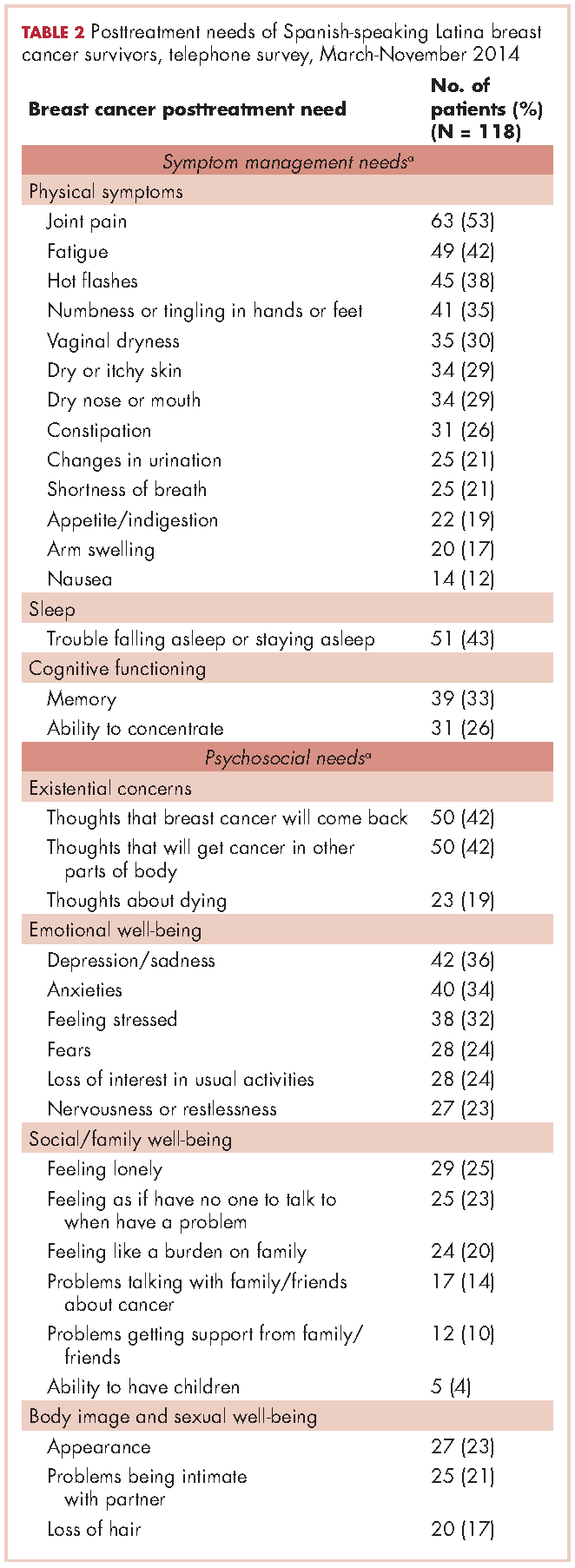

For symptom management needs (Table 2), the most prevalent (bothersome) symptoms (reported by more than 30%, in rank order) were joint pain, sleep problems, fatigue, hot flashes, numbness/tingling of extremities, and memory. Next most prevalent (reported by 20%-30%) were vaginal dryness, dry/itchy skin, dry nose/mouth, inability to concentrate, constipation, changes in urination, and shortness of breath.

For psychosocial needs, fears of recurrence or new cancers were reported by 42%. Emotional symptoms reported by more than 30% were depression/sadness, anxieties, and feeling stressed. Next most prevalent (20%-30%) were fears, loss of interest in usual activities, and nervousness/restlessness. Social well-being concerns reported by 20%-30% of survivors were loneliness, having no one to talk to, and being a burden to their families. Body image and sexual problems reported by 20%-30% of survivors included appearance and problems being intimate with partners.

Regarding lifestyle, most of the participants said they wanted help with eating a healthier diet (74%), getting more exercise (69%), managing stress (63%), and doing yoga or meditation (55%).

Semistructured interviews

Twenty-five SSBCS completed semistructured interviews, 10 in individual interviews and 15 in one of two focus groups (one of 9 women older than 50 years; one of 6 women younger than 50). The telephone survey respondents were similar to semistructured interview respondents on all sociodemographic characteristics, but differed slightly on some clinical characteristics (Table 1). The telephone survey women had been more recently diagnosed (P < .01), were less likely to have ductal carcinoma in situ (P < .001), and more likely to have had reconstructive surgery

(P < .05).

Five cancer support providers and 4 physicians were interviewed. All support providers were Spanish-speaking Latinas with at least some college education. Cancer physicians were board certified. Two were men; two were white and two Asian; one was a breast surgeon and three were hematologists/oncologists; three spoke Spanish poorly/not at all and one spoke it fairly well.

Seven themes emerged from interviews: unmet physical symptom management needs; social support often ends when treatment ends; challenges resuming roles; sense of abandonment by health care system when treatment ends; need for formal transition from active treatment to follow-up care; fear of recurrence especially when obtaining follow-up care; and desire for information on late effects of initial treatments and side effects of hormonal treatments. We summarize results according to these themes.

Unmet physical symptom management needs. The main physical symptoms reported by survivors and physicians in interviews were arthralgia, menopausal symptoms, and neuropathy. Fatigue was reported only by survivors. Many survivors and several support providers expressed that symptoms were poorly managed and often ignored. One stated,

I have a lot of pain where I had surgery, it burns. I worry a lot about my arm because I have sacs of fluid. My doctor only says, ‘They will dissolve over the years.’ So, I don’t feel any support. (FocGrp1#6)

Survivors reported side effects of hormonal therapies, and felt that physicians downplayed these to prevent them from discontinuing medications.

Social support from family and friends often ends when treatment ends. Many survivors described a loss of support from family and friends who expected them to get back to “normal” once treatment ended. One said,

My sisters have told me to my face that there’s nothing wrong with me. So now when people ask me, I say, ‘I’m fine, thank God, I have nothing,’ even though I’m dying of pain and have all these pills to take. (Survivor#1025)

A support provider related,

The client was telling me that as she was getting closer to finishing her treatment, her husband was upset because he felt like all she was doing was focusing on the cancer. I think caregivers, family, spouses, and children out of their own sort of selfishness want this person to be well. (SuppProv#104)

A few survivors said that family bonds were strengthened after cancer and several reported lacking support because their families were in their home countries.

Challenges resuming roles, especially returning to work. Survivors, support providers, and physicians described challenges and few resources as women transition back to their normal roles. Survivors questioned their ability to return to work due to physically demanding occupations. One stated,

I would like information on how to take care of myself, how working can affect this side if I don’t take care of it. I clean houses and I need both hands. (Survivor#3012)

Survivors described how changes in memory affected daily chores and work performance. Support providers and physicians described the need for resources to aid with return to work and household responsibilities. One physician noted,

There are usually questions about how to go ahead and live their lives from that point forward. It’s a sort of reverse shock: going back to life as they know it. (Physician#004)

Support providers and physicians mentioned that women needed help with resuming intimate partner relations.

Sense of abandonment by health care system once active treatment ends. Survivors, support providers, and physicians reported a loss of support and sense of abandonment by the patients’ oncology team at the end of active treatment. One survivor stated,

Once they tell you to stop the pills, ‘You’re cured, there’s nothing wrong with you,’ the truth is that one feels, ‘Now what do I do? I have no one to help me.’ I felt very abandoned. (FocGrp1#5)

A provider said,

The support system falls apart once women complete treatment. They lose their entire support system at the medical level. They no longer have nurses checking in about symptoms and addressing anything that’s come up. They won’t have access to doctors unless they’re doing their screening. (SuppProv#101)

An oncologist, noting that this loss of support occurs when women face pressures of transitioning back to work or family obligations, commented,

So here’s a woman whose marriage is in turmoil, whose husband may even have left her during this, and now her clinic is leaving her and she’s on her own … that must be scary as hell because there’s nobody out there to support her. (Physician#002)

Need for formal transition from active treatment to follow-up care. Two themes emerged about transitioning from active treatment: transferring care from oncologists to primary care physicians (PCP); and issues of follow-up care (with oncologists or PCPs). Survivors felt lost in transitioning from specialty to primary care, or expressed apprehension seeing a PCP rather than a cancer specialist. One stated,

I have my doctor but she is not a specialist. She does what I tell her to and orders a mammogram every year. But, I don’t go to the oncologist anymore, and so I worry. With the specialists, I feel protected. (FocGrp1#5)

Physicians acknowledged the lack of a formal transition to primary care such as a survivorship care program.

Follow-up care issues were common. Physicians stressed that women needed to know how often to return for follow-up once active treatment ends and about recommended examinations and tests, especially when receiving hormonal therapy. Physicians indicated the need for patient education materials specific to patients’ treatments, for example, elevated risk of heart disease with certain chemotherapy agents. An oncologist expressed concern that PCPs are not prepared adequately about late effects and hormonal treatment side effects, and suggested providing summary notes for PCPs detailing these.

Survivors identified several barriers to follow-up care: lacking information on which symptoms merited a call to physicians; financial burden/limited health insurance; lacking appointment reminders; fear of examinations; and limited English proficiency. A survivor stated,

If you have insurance, you can make your appointment, see the doctor, and have your mammogram. I stopped taking my pills because I didn’t have insurance. I tried to get them again but they told me they would cost me a thousand dollars. (FocGrp1#5)

One oncologist suggested scheduling a follow-up appointment before patients leave treatment and calling patients who miss appointments.

Facilitators of regular follow-up care identified by survivors were physicians informing them about symptom monitoring and reporting, having a clinic contact person/navigator, being given a follow-up appointment, being assertive about one’s care, and physicians’ reinforcement of adherence to hormonal treatment and follow-up. According to support providers, a key facilitator was having a clinic contact person/navigator. Once treatment ended, support providers often served as the liaison between the patient and the physician, making them the first point of contact for symptom reporting.

Fear of recurrence especially when obtaining follow-up care. Fear of recurrence dominated survivor interviews. This fear was heightened at the time of follow-up examinations or when they experienced unusual pain. A survivor commented,

Every time I’m due for my mammogram, I can’t sleep, worrying. I lose sleep until I get the letter with my results. Then I feel at peace again. (FocGrp1#9)

Support providers discussed the need to provide reassurance to SSBCS to help them cope with fears of recurrence. Physicians expressed challenges in allaying fears of recurrence among SSBCS, requiring a lot of time when recommending follow-up mammograms.

Desire for information on late effects of treatments and side effects of hormonal therapies. All survivors expressed receiving insufficient information on potential symptoms and side effects. One stated,

Doctors only have five minutes. There has never been someone who gave me guidance like, ‘From now on you have to do this or you might get these symptoms now or in the future. (Survivor#6019)

They indicated uncertainty about what symptoms were “normal” and when symptoms merited a call to the physician. Several survivors reported being unaware that fatigue, arthralgia and neuropathy were side effects of breast cancer treatments until they reported these to physicians.

Physicians stressed the importance of women knowing about the elevated risk of future cancers, symptoms of recurrence, and seeking follow-up care if they experience symptoms that are out of the ordinary. Support providers felt that it was important to provide SSBCS with information on signs of recurrence and when to report these. However, providers expressed concern that giving women too much information might elevate their anxiety. A physician suggested,

It’s probably better to have a symptom list that’s short and relevant for the most common and catastrophic things, same thing with side effects … short to avoid overwhelming the patient. (Physician#001)

Hormonal treatments were of special concern. Survivors expressed a need for information on hormonal treatments and support providers stressed that this information is needed in simple Spanish. Several survivors indicated they stopped taking hormonal treatments due to side effects. One woman experienced severe headaches and heart palpitations, stopped taking the hormonal medication, felt better, and did not inform her physician until her next appointment. A support provider stated,

What I hear from a lot of women is that if side effects are too uncomfortable, they just stop it (hormonal treatment) without saying anything to the doctor. So more information about why they have to take it and that there is a good chance of recurrence is really important. (SuppProv#101)

Likewise, physicians indicated that SSBCS’ lack of information on hormonal treatments often resulted in nonadherence, emphasizing the need to reinforce adherence to prevent recurrence.

Conceptual framework of interventions

Based on triangulation of survey and interview results, we compiled a conceptual framework that includes needs identified, suggested components of a survivorship care intervention to address these needs, potential mediators by which such interventions could improve outcomes, and relevant outcomes (Figure). Survivorship care needs fell into four categories: symptom management, psychosocial, sense of abandonment by health care team, and healthy lifestyles. Survivorship care programs would provide skills training in symptom and stress management, and communicating with providers, family, friends, and coworkers. Mediators include increased self-efficacy, knowledge and perceived social support, ultimately leading to reduced distress (anxiety and depressive symptoms) and stress, and improved health-related quality of life.

Conclusions

Our study aimed to identify the most critical needs of SSBCS in the posttreatment survivorship phase to facilitate the design of survivorship interventions for this vulnerable group. SSBCS, cancer support providers, and cancer physicians reported substantial symptom management, psychosocial, and informational needs among this population. Results from surveys and open-ended interviews were remarkably consistent. Survivors, physicians, and support providers viewed transition out of active treatment as a time of increased psychosocial need and heightened vulnerability.

Our findings are consistent with needs assessments conducted in other breast cancer survivors. Similar to a study of rural white women with breast cancer, fear of recurrence was among the most common psychosocial concerns.17 Results of two studies that included white, African American and Latina breast cancer survivors were consistent with ours in finding that pain and fatigue were among the most persistent symptoms; in both studies, Latinas were more likely to report pain and a higher number of symptoms.7,18 The prevalence of sleep problems in our sample was identical to that reported in a sample of African American breast cancer survivors.19 Our findings of a high need for symptom management information and support, social support from family and friends, and self-management resources were similar to studies of other vulnerable breast cancer survivors.18,20

Our results suggest that it is critical for health care professionals to provide assistance with managing side effects and information to alleviate fears, and reinforce behaviors of symptom monitoring and reporting, and adherence to follow-up care and hormonal therapies. Yet this information is not being conveyed effectively and is complicated by the need to balance women’s need for information with minimizing anxiety when providing such information.

A limitation of our study is that most of our sample was Mexican origin and may not reflect experiences of Spanish-speaking Latinas of other national origin groups or outside of Northern California. Another limitation is the lack of an English-speaking comparison group, which would have permitted the identification of similarities and differences across language groups. Finally, we did not interview radiation oncologists who may have had opinions that are not represented here.

Survivorship care programs offer great promise for meeting patients’ informational and symptom management needs and improving well-being and communication with clinicians.21 Due to limited access to survivorship care information, financial hardships, and pressures from their families to resume their social roles, concerted efforts are needed to develop appropriate survivorship programs for SSBCS.22 Unique language, cultural and socioeconomic factors of Spanish-speaking Latinas require tailoring of cancer survivorship programs to best meet their needs.23 These programs need to provide psychosocial stress and symptom management assistance, simple information on recommended follow-up care, and healthy lifestyle and role reintegration strategies that account for their unique sociocultural contexts.

1. Danese MD, O’Malley C, Lindquist K, Gleeson M, Griffiths RI. An observational study of the prevalence and incidence of comorbid conditions in older women with breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(7):1756-1765.

2. Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E, eds. From cancer patient to cancer survivor: lost in transition. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences; 2006.

3. Beckjord EB, Arora NK, McLaughlin W, Oakley-Girvan I, Hamilton AS, Hesse BW. Health-related information needs in a large and diverse sample of adult cancer survivors: implications for cancer care. J Cancer Surviv. 2008;2(3):179-189.

4. Hewitt ME, Bamundo A, Day R, Harvey C. Perspectives on posttreatment cancer care: qualitative research with survivors, nurses, and physicians. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(16):2270-2273.

5. Ashing-Giwa KT, Tejero JS, Kim J, Padilla GV, Hellemann G. Examining predictive models of HRQOL in a population-based, multiethnic sample of women with breast carcinoma. Qual Life Res. 2007;16(3):413-428.

6. Clauser SB, Arora NK, Bellizzi KM, Haffer SC, Topor M, Hays RD. Disparities in HRQOL of cancer survivors and non-cancer managed care enrollees. Health Care Financ Rev. 2008;29(4):23-40.

7. Eversley R, Estrin D, Dibble S, Wardlaw L, Pedrosa M, Favila-Penney W. Posttreatment symptoms among ethnic minority breast cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2005;32(2):250-256.

8. Bickell NA, Wang JJ, Oluwole S, et al. Missed opportunities: racial disparities in adjuvant breast cancer treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(9):1357-1362.

9. Arora NK, Reeve BB, Hays RD, Clauser SB, Oakley-Girvan I. Assessment of quality of cancer-related follow-up care from the cancer survivor’s perspective. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(10):1280-1289.

10. Janz NK, Mujahid MS, Hawley ST, Griggs JJ, Hamilton AS, Katz SJ. Racial/ethnic differences in adequacy of information and support for women with breast cancer. Cancer. 2008;113(5):1058-1067.

11. Yoon J, Malin JL, Tisnado DM, et al. Symptom management after breast cancer treatment: is it influenced by patient characteristics? Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;108(1):69-77.

12. Ashing K, Rosales M. A telephonic-based trial to reduce depressive symptoms among Latina breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2014;23(5):507-515.

13. Hershman DL, Greenlee H, Awad D, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a clinic-based survivorship intervention following adjuvant therapy in breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;138(3):795-806.

14. Napoles AM, Ortiz C, Santoyo-Olsson J, et al. Nuevo Amanecer: results of a randomized controlled trial of a community-based, peer-delivered stress management intervention to improve quality of life in Latinas with breast cancer. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(suppl 3):e55-63.

15. Rechis R, Reynolds KA, Beckjord EB, Nutt S, Burns RM, Schaefer JS. ‘I learned to live with it’ is not good enough: challenges reported by posttreatment cancer survivors in the Livestrong surveys. Austin, TX: Livestrong;2011.

16. Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. Hawthorne: Aldine Publishing Company; 1967.

17. Befort CA, Klemp J. Sequelae of breast cancer and the influence of menopausal status at diagnosis among rural breast cancer survivors. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2011;20(9):1307-1313.

18. Fu OS, Crew KD, Jacobson JS, et al. Ethnicity and persistent symptom burden in breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2009;3(4):241-250.

19. Taylor TR, Huntley ED, Makambi K, et al. Understanding sleep disturbances in African-American breast cancer survivors: a pilot study. Psychooncology. 2012;21(8):896-902.

20. Adams N, Gisiger-Camata S, Hardy CM, Thomas TF, Jukkala A, Meneses K. Evaluating survivorship experiences and needs among rural African American breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Educ. October 24, 2015 [Epub ahead of print].

21. Blinder VS, Patil S, Thind A, et al. Return to work in low-income Latina and non-Latina white breast cancer survivors: a 3-year longitudinal study. Cancer. 2012;118(6):1664-1674.

22. Lopez-Class M, Perret-Gentil M, Kreling B, Caicedo L, Mandelblatt J, Graves KD. Quality of life among immigrant Latina breast cancer survivors: realities of culture and enhancing cancer care. J Cancer Educ. 2011;26(4):724-733.

23. Napoles-Springer AM, Ortiz C, O’Brien H, Diaz-Mendez M. Developing a culturally competent peer support intervention for Spanish-speaking Latinas with breast cancer. J Immigr Minor Health. 2009;11(4):268-280

After treatment, cancer patients transition to a survivorship phase, often with little information or support. Cancer survivors are at increased risk of recurrence, secondary cancers, comorbid conditions, and late treatment effects.1,2 However, many remain unaware of these risks and the options for managing them3 and face numerous unmet medical, psychosocial, and informational needs that can be addressed through survivorship care programs.4 Anxiety may increase as they lose their treatment team’s support while attempting to reestablish their lives.2 Patients need to know the long-term risks of cancer treatments, probabilities of recurrence and second cancers, effectiveness of surveillance and interventions for managing late effects and psychosocial concerns, and benefits of healthy lifestyles.2

Due to sociocultural and economic factors, Spanish-speaking Latina breast cancer survivors (SSBCS) suffer worse posttreatment health-related quality of life and more pain, fatigue, depressive symptoms, body image issues, and distress than their white counterparts.5-7 However, they are less likely to receive necessary cancer treatment, symptom management, and surveillance. For example, compared with whites, Latina breast cancer survivors receive less guideline-adherent treatment8 and follow-up care, including survivorship information.3,9 SSBCS, in particular have less access to survivorship information.10 Consequently, SSBCS are more likely to report unmet symptom management needs.11

Several breast cancer survivorship program trials have included Latinas,12,13 but their effectiveness has been demonstrated only for depressive symptoms or health worry. A comprehensive assessment of the posttreatment needs of SSBCS would provide a foundation for designing tailored survivorship interventions for this vulnerable group. This study aimed to identify the symptom management, psychosocial, and informational needs of SSBCS during the transition to survivorship from the perspectives of SSBCS and their cancer support providers and cancer physicians.

Methods

We sampled respondents within a 5-county area in Northern California to obtain multiple perspectives of the survivorship care needs of SSBCS using structured and in-depth methods: a telephone survey of SSBCS; semistructured interviews with SSBCS; semistructured interviews with cancer support providers serving SSBCS; and semistructured interviews with physicians providing cancer care for SSBCS. The study protocol was approved by the University of California San Francisco Committee on Human Research.

Sample and procedures

Structured telephone survey with SSBCS. The sample was drawn evenly from San Francisco General Hospital-University of California San Francisco primary care practices and SSBCS from a previous study who agreed to be re-contacted.14 The inclusion criteria were: completed active treatment (except adjuvant hormonal therapy) for nonmetastatic breast cancer within 10 years; living in one of the five counties; primarily Spanish-speaking; and self-identified as Latina. The exclusion criteria were: previous cancer except nonmelanoma skin cancer; terminal illness; or metastatic breast cancer. Study staff mailed potential participants a bilingual letter and information sheet, and bilingual opt-out postcard (6th grade reading level assessed by Flesch-Kincaid grade level statistic). Female bilingual-bicultural research associates conducted interviews of 20-30 minutes in Spanish after obtaining verbal consent. Participants were mailed $20. Surveys were conducted during March-November 2014.

Semistructured in-person interviews with SSBCS. Four community-based organizations (CBOs) in the targeted area providing cancer support services to Latinos agreed to recruit SSBCS for interviews. Inclusion criteria were identical to the survey. Patient navigators or support providers from CBOs contacted women by phone or in-person to invite them to an interview to assess their cancer survivorship needs. Women could choose a focus group or individual interview. With permission, names and contact information were given to study interviewers who called, explained the study, screened for eligibility, and scheduled an interview.

Recruitment was stratified by age (under or over age 50). We sampled women until saturation was achieved (no new themes emerged). Focus groups (90 minutes) were conducted at the CBOs. Individual interviews (45 minutes) were conducted in participants’ homes. Written informed consent was obtained. Participants were paid $50. Interviews were conducted during August-November, 2014, audiotaped, and transcribed.

Semistructured in-person interviews with cancer support providers and physicians. Investigators invited five cancer support providers (three patient navigators from three county hospitals, and two CBO directors of cancer psychosocial support services) and four physicians (three oncologists and one breast cancer surgeon from three county hospitals) to an in-person interview to identify SSBCS’ survivorship care needs. All agreed to participate. No further candidates were approached because saturation was achieved. We obtained written informed consent and 30-minute interviews were conducted in participants’ offices during August-October, 2014. Interviews were audiotaped and transcribed. Participants were paid $50.

Ethical approval. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Measures

Structured telephone survey. Based on cancer survivor needs assessments,15 we assessed: physical and emotional symptoms; problems with sleep and memory/concentration; concerns about mortality, family, social isolation, intimacy, appearance; and healthy lifestyles. Items were adapted and translated into Spanish if needed, using forward/backward translation with team reconciliation. These questions used the introduction, “Now I am going to ask you if you have had any problems because of your cancer. In the past month, how much have you been bothered by …” with responses rated on a scale of 1-5 (1, Not at all; 5, A lot). For example, we asked, “In the past month, how much have you been bothered by fatigue?”

Regarding healthy lifestyles, we used the introduction, “Here are some changes women sometimes want to make after cancer. Would you like help with …?” For example, we asked, “Would you like help with getting more exercise?” We asked if they wanted help getting more exercise, eating healthier, managing stress, and doing meditation or yoga (Yes/No).

Semistructured interview guide for SSBCS. Participants were asked about their emotional and physical concerns when treatment ended, current cancer needs, symptoms or late effects, and issues related to relationships, family, employment, insurance, financial hardships, barriers to follow-up care, health behaviors, and survivorship program content. Sample questions are, “Have you had any symptoms or side effects related to your cancer or treatment?” and “What kinds of information do you feel you need now about your cancer or treatment?” A brief questionnaire assessed demographics.

Semistructured interview guide for cancer support providers and physicians. Support providers and physicians were asked about informational, psychosocial, and symptom management needs of SSBCS and recommended self-management content and formats. Sample questions are, “What kinds of information and support do you wish was available to help Spanish-speaking women take care of their health after treatment ends?” and “What do you think are the most pressing emotional needs of Spanish-speaking women after breast cancer treatment ends?” A brief questionnaire assessed demographics.

Analysis

Frequencies are reported for survey items. For questions about symptoms/concerns, we report the frequency of responding that they were bothered Somewhat/Quite a bit/A lot. For healthy lifestyles, we present the frequency answering Yes.

Verbatim semistructured interview transcripts were verified against audiotapes. Using QSR NVIVO software, transcripts were coded independently by two bilingual-bicultural investigators using a constant comparative method to generate coding categories for cancer survivorship needs.16 Coders started with themes specified by the interview guides, expanded them to represent the data, and discussed and reconciled coding discrepancies. Coding was compared by type of interview participant (survivor, support provider, or physician). Triangulation of survey and semistructured interviews occurred through team discussions to verify codes, themes, and implications for interventions.

Results

Telephone survey of SSBCS

Of the telephone survey sampling frame (N = 231), 118 individuals (51%) completed the interview, 37 (16%) were ineligible, 31 (13%) could not be reached, 22 (10%) had incorrect contact information, 19 (8%) refused to participate, and 4 (2%) were deceased. Mean age of the participants was 54.9 years (SD, 12.3); all were foreign-born, with more than half of Mexican origin; and most had less than a high-school education (Table 1). All had completed active treatment, and most (68%) were within 2 years of diagnosis.

For symptom management needs (Table 2), the most prevalent (bothersome) symptoms (reported by more than 30%, in rank order) were joint pain, sleep problems, fatigue, hot flashes, numbness/tingling of extremities, and memory. Next most prevalent (reported by 20%-30%) were vaginal dryness, dry/itchy skin, dry nose/mouth, inability to concentrate, constipation, changes in urination, and shortness of breath.

For psychosocial needs, fears of recurrence or new cancers were reported by 42%. Emotional symptoms reported by more than 30% were depression/sadness, anxieties, and feeling stressed. Next most prevalent (20%-30%) were fears, loss of interest in usual activities, and nervousness/restlessness. Social well-being concerns reported by 20%-30% of survivors were loneliness, having no one to talk to, and being a burden to their families. Body image and sexual problems reported by 20%-30% of survivors included appearance and problems being intimate with partners.

Regarding lifestyle, most of the participants said they wanted help with eating a healthier diet (74%), getting more exercise (69%), managing stress (63%), and doing yoga or meditation (55%).

Semistructured interviews

Twenty-five SSBCS completed semistructured interviews, 10 in individual interviews and 15 in one of two focus groups (one of 9 women older than 50 years; one of 6 women younger than 50). The telephone survey respondents were similar to semistructured interview respondents on all sociodemographic characteristics, but differed slightly on some clinical characteristics (Table 1). The telephone survey women had been more recently diagnosed (P < .01), were less likely to have ductal carcinoma in situ (P < .001), and more likely to have had reconstructive surgery

(P < .05).

Five cancer support providers and 4 physicians were interviewed. All support providers were Spanish-speaking Latinas with at least some college education. Cancer physicians were board certified. Two were men; two were white and two Asian; one was a breast surgeon and three were hematologists/oncologists; three spoke Spanish poorly/not at all and one spoke it fairly well.

Seven themes emerged from interviews: unmet physical symptom management needs; social support often ends when treatment ends; challenges resuming roles; sense of abandonment by health care system when treatment ends; need for formal transition from active treatment to follow-up care; fear of recurrence especially when obtaining follow-up care; and desire for information on late effects of initial treatments and side effects of hormonal treatments. We summarize results according to these themes.

Unmet physical symptom management needs. The main physical symptoms reported by survivors and physicians in interviews were arthralgia, menopausal symptoms, and neuropathy. Fatigue was reported only by survivors. Many survivors and several support providers expressed that symptoms were poorly managed and often ignored. One stated,

I have a lot of pain where I had surgery, it burns. I worry a lot about my arm because I have sacs of fluid. My doctor only says, ‘They will dissolve over the years.’ So, I don’t feel any support. (FocGrp1#6)

Survivors reported side effects of hormonal therapies, and felt that physicians downplayed these to prevent them from discontinuing medications.

Social support from family and friends often ends when treatment ends. Many survivors described a loss of support from family and friends who expected them to get back to “normal” once treatment ended. One said,

My sisters have told me to my face that there’s nothing wrong with me. So now when people ask me, I say, ‘I’m fine, thank God, I have nothing,’ even though I’m dying of pain and have all these pills to take. (Survivor#1025)

A support provider related,

The client was telling me that as she was getting closer to finishing her treatment, her husband was upset because he felt like all she was doing was focusing on the cancer. I think caregivers, family, spouses, and children out of their own sort of selfishness want this person to be well. (SuppProv#104)

A few survivors said that family bonds were strengthened after cancer and several reported lacking support because their families were in their home countries.

Challenges resuming roles, especially returning to work. Survivors, support providers, and physicians described challenges and few resources as women transition back to their normal roles. Survivors questioned their ability to return to work due to physically demanding occupations. One stated,

I would like information on how to take care of myself, how working can affect this side if I don’t take care of it. I clean houses and I need both hands. (Survivor#3012)

Survivors described how changes in memory affected daily chores and work performance. Support providers and physicians described the need for resources to aid with return to work and household responsibilities. One physician noted,

There are usually questions about how to go ahead and live their lives from that point forward. It’s a sort of reverse shock: going back to life as they know it. (Physician#004)

Support providers and physicians mentioned that women needed help with resuming intimate partner relations.

Sense of abandonment by health care system once active treatment ends. Survivors, support providers, and physicians reported a loss of support and sense of abandonment by the patients’ oncology team at the end of active treatment. One survivor stated,

Once they tell you to stop the pills, ‘You’re cured, there’s nothing wrong with you,’ the truth is that one feels, ‘Now what do I do? I have no one to help me.’ I felt very abandoned. (FocGrp1#5)

A provider said,

The support system falls apart once women complete treatment. They lose their entire support system at the medical level. They no longer have nurses checking in about symptoms and addressing anything that’s come up. They won’t have access to doctors unless they’re doing their screening. (SuppProv#101)

An oncologist, noting that this loss of support occurs when women face pressures of transitioning back to work or family obligations, commented,

So here’s a woman whose marriage is in turmoil, whose husband may even have left her during this, and now her clinic is leaving her and she’s on her own … that must be scary as hell because there’s nobody out there to support her. (Physician#002)

Need for formal transition from active treatment to follow-up care. Two themes emerged about transitioning from active treatment: transferring care from oncologists to primary care physicians (PCP); and issues of follow-up care (with oncologists or PCPs). Survivors felt lost in transitioning from specialty to primary care, or expressed apprehension seeing a PCP rather than a cancer specialist. One stated,

I have my doctor but she is not a specialist. She does what I tell her to and orders a mammogram every year. But, I don’t go to the oncologist anymore, and so I worry. With the specialists, I feel protected. (FocGrp1#5)

Physicians acknowledged the lack of a formal transition to primary care such as a survivorship care program.

Follow-up care issues were common. Physicians stressed that women needed to know how often to return for follow-up once active treatment ends and about recommended examinations and tests, especially when receiving hormonal therapy. Physicians indicated the need for patient education materials specific to patients’ treatments, for example, elevated risk of heart disease with certain chemotherapy agents. An oncologist expressed concern that PCPs are not prepared adequately about late effects and hormonal treatment side effects, and suggested providing summary notes for PCPs detailing these.

Survivors identified several barriers to follow-up care: lacking information on which symptoms merited a call to physicians; financial burden/limited health insurance; lacking appointment reminders; fear of examinations; and limited English proficiency. A survivor stated,

If you have insurance, you can make your appointment, see the doctor, and have your mammogram. I stopped taking my pills because I didn’t have insurance. I tried to get them again but they told me they would cost me a thousand dollars. (FocGrp1#5)

One oncologist suggested scheduling a follow-up appointment before patients leave treatment and calling patients who miss appointments.

Facilitators of regular follow-up care identified by survivors were physicians informing them about symptom monitoring and reporting, having a clinic contact person/navigator, being given a follow-up appointment, being assertive about one’s care, and physicians’ reinforcement of adherence to hormonal treatment and follow-up. According to support providers, a key facilitator was having a clinic contact person/navigator. Once treatment ended, support providers often served as the liaison between the patient and the physician, making them the first point of contact for symptom reporting.

Fear of recurrence especially when obtaining follow-up care. Fear of recurrence dominated survivor interviews. This fear was heightened at the time of follow-up examinations or when they experienced unusual pain. A survivor commented,

Every time I’m due for my mammogram, I can’t sleep, worrying. I lose sleep until I get the letter with my results. Then I feel at peace again. (FocGrp1#9)

Support providers discussed the need to provide reassurance to SSBCS to help them cope with fears of recurrence. Physicians expressed challenges in allaying fears of recurrence among SSBCS, requiring a lot of time when recommending follow-up mammograms.

Desire for information on late effects of treatments and side effects of hormonal therapies. All survivors expressed receiving insufficient information on potential symptoms and side effects. One stated,

Doctors only have five minutes. There has never been someone who gave me guidance like, ‘From now on you have to do this or you might get these symptoms now or in the future. (Survivor#6019)

They indicated uncertainty about what symptoms were “normal” and when symptoms merited a call to the physician. Several survivors reported being unaware that fatigue, arthralgia and neuropathy were side effects of breast cancer treatments until they reported these to physicians.

Physicians stressed the importance of women knowing about the elevated risk of future cancers, symptoms of recurrence, and seeking follow-up care if they experience symptoms that are out of the ordinary. Support providers felt that it was important to provide SSBCS with information on signs of recurrence and when to report these. However, providers expressed concern that giving women too much information might elevate their anxiety. A physician suggested,

It’s probably better to have a symptom list that’s short and relevant for the most common and catastrophic things, same thing with side effects … short to avoid overwhelming the patient. (Physician#001)

Hormonal treatments were of special concern. Survivors expressed a need for information on hormonal treatments and support providers stressed that this information is needed in simple Spanish. Several survivors indicated they stopped taking hormonal treatments due to side effects. One woman experienced severe headaches and heart palpitations, stopped taking the hormonal medication, felt better, and did not inform her physician until her next appointment. A support provider stated,

What I hear from a lot of women is that if side effects are too uncomfortable, they just stop it (hormonal treatment) without saying anything to the doctor. So more information about why they have to take it and that there is a good chance of recurrence is really important. (SuppProv#101)

Likewise, physicians indicated that SSBCS’ lack of information on hormonal treatments often resulted in nonadherence, emphasizing the need to reinforce adherence to prevent recurrence.

Conceptual framework of interventions

Based on triangulation of survey and interview results, we compiled a conceptual framework that includes needs identified, suggested components of a survivorship care intervention to address these needs, potential mediators by which such interventions could improve outcomes, and relevant outcomes (Figure). Survivorship care needs fell into four categories: symptom management, psychosocial, sense of abandonment by health care team, and healthy lifestyles. Survivorship care programs would provide skills training in symptom and stress management, and communicating with providers, family, friends, and coworkers. Mediators include increased self-efficacy, knowledge and perceived social support, ultimately leading to reduced distress (anxiety and depressive symptoms) and stress, and improved health-related quality of life.

Conclusions

Our study aimed to identify the most critical needs of SSBCS in the posttreatment survivorship phase to facilitate the design of survivorship interventions for this vulnerable group. SSBCS, cancer support providers, and cancer physicians reported substantial symptom management, psychosocial, and informational needs among this population. Results from surveys and open-ended interviews were remarkably consistent. Survivors, physicians, and support providers viewed transition out of active treatment as a time of increased psychosocial need and heightened vulnerability.

Our findings are consistent with needs assessments conducted in other breast cancer survivors. Similar to a study of rural white women with breast cancer, fear of recurrence was among the most common psychosocial concerns.17 Results of two studies that included white, African American and Latina breast cancer survivors were consistent with ours in finding that pain and fatigue were among the most persistent symptoms; in both studies, Latinas were more likely to report pain and a higher number of symptoms.7,18 The prevalence of sleep problems in our sample was identical to that reported in a sample of African American breast cancer survivors.19 Our findings of a high need for symptom management information and support, social support from family and friends, and self-management resources were similar to studies of other vulnerable breast cancer survivors.18,20

Our results suggest that it is critical for health care professionals to provide assistance with managing side effects and information to alleviate fears, and reinforce behaviors of symptom monitoring and reporting, and adherence to follow-up care and hormonal therapies. Yet this information is not being conveyed effectively and is complicated by the need to balance women’s need for information with minimizing anxiety when providing such information.

A limitation of our study is that most of our sample was Mexican origin and may not reflect experiences of Spanish-speaking Latinas of other national origin groups or outside of Northern California. Another limitation is the lack of an English-speaking comparison group, which would have permitted the identification of similarities and differences across language groups. Finally, we did not interview radiation oncologists who may have had opinions that are not represented here.

Survivorship care programs offer great promise for meeting patients’ informational and symptom management needs and improving well-being and communication with clinicians.21 Due to limited access to survivorship care information, financial hardships, and pressures from their families to resume their social roles, concerted efforts are needed to develop appropriate survivorship programs for SSBCS.22 Unique language, cultural and socioeconomic factors of Spanish-speaking Latinas require tailoring of cancer survivorship programs to best meet their needs.23 These programs need to provide psychosocial stress and symptom management assistance, simple information on recommended follow-up care, and healthy lifestyle and role reintegration strategies that account for their unique sociocultural contexts.

After treatment, cancer patients transition to a survivorship phase, often with little information or support. Cancer survivors are at increased risk of recurrence, secondary cancers, comorbid conditions, and late treatment effects.1,2 However, many remain unaware of these risks and the options for managing them3 and face numerous unmet medical, psychosocial, and informational needs that can be addressed through survivorship care programs.4 Anxiety may increase as they lose their treatment team’s support while attempting to reestablish their lives.2 Patients need to know the long-term risks of cancer treatments, probabilities of recurrence and second cancers, effectiveness of surveillance and interventions for managing late effects and psychosocial concerns, and benefits of healthy lifestyles.2

Due to sociocultural and economic factors, Spanish-speaking Latina breast cancer survivors (SSBCS) suffer worse posttreatment health-related quality of life and more pain, fatigue, depressive symptoms, body image issues, and distress than their white counterparts.5-7 However, they are less likely to receive necessary cancer treatment, symptom management, and surveillance. For example, compared with whites, Latina breast cancer survivors receive less guideline-adherent treatment8 and follow-up care, including survivorship information.3,9 SSBCS, in particular have less access to survivorship information.10 Consequently, SSBCS are more likely to report unmet symptom management needs.11

Several breast cancer survivorship program trials have included Latinas,12,13 but their effectiveness has been demonstrated only for depressive symptoms or health worry. A comprehensive assessment of the posttreatment needs of SSBCS would provide a foundation for designing tailored survivorship interventions for this vulnerable group. This study aimed to identify the symptom management, psychosocial, and informational needs of SSBCS during the transition to survivorship from the perspectives of SSBCS and their cancer support providers and cancer physicians.

Methods

We sampled respondents within a 5-county area in Northern California to obtain multiple perspectives of the survivorship care needs of SSBCS using structured and in-depth methods: a telephone survey of SSBCS; semistructured interviews with SSBCS; semistructured interviews with cancer support providers serving SSBCS; and semistructured interviews with physicians providing cancer care for SSBCS. The study protocol was approved by the University of California San Francisco Committee on Human Research.

Sample and procedures

Structured telephone survey with SSBCS. The sample was drawn evenly from San Francisco General Hospital-University of California San Francisco primary care practices and SSBCS from a previous study who agreed to be re-contacted.14 The inclusion criteria were: completed active treatment (except adjuvant hormonal therapy) for nonmetastatic breast cancer within 10 years; living in one of the five counties; primarily Spanish-speaking; and self-identified as Latina. The exclusion criteria were: previous cancer except nonmelanoma skin cancer; terminal illness; or metastatic breast cancer. Study staff mailed potential participants a bilingual letter and information sheet, and bilingual opt-out postcard (6th grade reading level assessed by Flesch-Kincaid grade level statistic). Female bilingual-bicultural research associates conducted interviews of 20-30 minutes in Spanish after obtaining verbal consent. Participants were mailed $20. Surveys were conducted during March-November 2014.

Semistructured in-person interviews with SSBCS. Four community-based organizations (CBOs) in the targeted area providing cancer support services to Latinos agreed to recruit SSBCS for interviews. Inclusion criteria were identical to the survey. Patient navigators or support providers from CBOs contacted women by phone or in-person to invite them to an interview to assess their cancer survivorship needs. Women could choose a focus group or individual interview. With permission, names and contact information were given to study interviewers who called, explained the study, screened for eligibility, and scheduled an interview.

Recruitment was stratified by age (under or over age 50). We sampled women until saturation was achieved (no new themes emerged). Focus groups (90 minutes) were conducted at the CBOs. Individual interviews (45 minutes) were conducted in participants’ homes. Written informed consent was obtained. Participants were paid $50. Interviews were conducted during August-November, 2014, audiotaped, and transcribed.

Semistructured in-person interviews with cancer support providers and physicians. Investigators invited five cancer support providers (three patient navigators from three county hospitals, and two CBO directors of cancer psychosocial support services) and four physicians (three oncologists and one breast cancer surgeon from three county hospitals) to an in-person interview to identify SSBCS’ survivorship care needs. All agreed to participate. No further candidates were approached because saturation was achieved. We obtained written informed consent and 30-minute interviews were conducted in participants’ offices during August-October, 2014. Interviews were audiotaped and transcribed. Participants were paid $50.

Ethical approval. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Measures

Structured telephone survey. Based on cancer survivor needs assessments,15 we assessed: physical and emotional symptoms; problems with sleep and memory/concentration; concerns about mortality, family, social isolation, intimacy, appearance; and healthy lifestyles. Items were adapted and translated into Spanish if needed, using forward/backward translation with team reconciliation. These questions used the introduction, “Now I am going to ask you if you have had any problems because of your cancer. In the past month, how much have you been bothered by …” with responses rated on a scale of 1-5 (1, Not at all; 5, A lot). For example, we asked, “In the past month, how much have you been bothered by fatigue?”

Regarding healthy lifestyles, we used the introduction, “Here are some changes women sometimes want to make after cancer. Would you like help with …?” For example, we asked, “Would you like help with getting more exercise?” We asked if they wanted help getting more exercise, eating healthier, managing stress, and doing meditation or yoga (Yes/No).

Semistructured interview guide for SSBCS. Participants were asked about their emotional and physical concerns when treatment ended, current cancer needs, symptoms or late effects, and issues related to relationships, family, employment, insurance, financial hardships, barriers to follow-up care, health behaviors, and survivorship program content. Sample questions are, “Have you had any symptoms or side effects related to your cancer or treatment?” and “What kinds of information do you feel you need now about your cancer or treatment?” A brief questionnaire assessed demographics.

Semistructured interview guide for cancer support providers and physicians. Support providers and physicians were asked about informational, psychosocial, and symptom management needs of SSBCS and recommended self-management content and formats. Sample questions are, “What kinds of information and support do you wish was available to help Spanish-speaking women take care of their health after treatment ends?” and “What do you think are the most pressing emotional needs of Spanish-speaking women after breast cancer treatment ends?” A brief questionnaire assessed demographics.

Analysis

Frequencies are reported for survey items. For questions about symptoms/concerns, we report the frequency of responding that they were bothered Somewhat/Quite a bit/A lot. For healthy lifestyles, we present the frequency answering Yes.

Verbatim semistructured interview transcripts were verified against audiotapes. Using QSR NVIVO software, transcripts were coded independently by two bilingual-bicultural investigators using a constant comparative method to generate coding categories for cancer survivorship needs.16 Coders started with themes specified by the interview guides, expanded them to represent the data, and discussed and reconciled coding discrepancies. Coding was compared by type of interview participant (survivor, support provider, or physician). Triangulation of survey and semistructured interviews occurred through team discussions to verify codes, themes, and implications for interventions.

Results

Telephone survey of SSBCS

Of the telephone survey sampling frame (N = 231), 118 individuals (51%) completed the interview, 37 (16%) were ineligible, 31 (13%) could not be reached, 22 (10%) had incorrect contact information, 19 (8%) refused to participate, and 4 (2%) were deceased. Mean age of the participants was 54.9 years (SD, 12.3); all were foreign-born, with more than half of Mexican origin; and most had less than a high-school education (Table 1). All had completed active treatment, and most (68%) were within 2 years of diagnosis.

For symptom management needs (Table 2), the most prevalent (bothersome) symptoms (reported by more than 30%, in rank order) were joint pain, sleep problems, fatigue, hot flashes, numbness/tingling of extremities, and memory. Next most prevalent (reported by 20%-30%) were vaginal dryness, dry/itchy skin, dry nose/mouth, inability to concentrate, constipation, changes in urination, and shortness of breath.

For psychosocial needs, fears of recurrence or new cancers were reported by 42%. Emotional symptoms reported by more than 30% were depression/sadness, anxieties, and feeling stressed. Next most prevalent (20%-30%) were fears, loss of interest in usual activities, and nervousness/restlessness. Social well-being concerns reported by 20%-30% of survivors were loneliness, having no one to talk to, and being a burden to their families. Body image and sexual problems reported by 20%-30% of survivors included appearance and problems being intimate with partners.

Regarding lifestyle, most of the participants said they wanted help with eating a healthier diet (74%), getting more exercise (69%), managing stress (63%), and doing yoga or meditation (55%).

Semistructured interviews

Twenty-five SSBCS completed semistructured interviews, 10 in individual interviews and 15 in one of two focus groups (one of 9 women older than 50 years; one of 6 women younger than 50). The telephone survey respondents were similar to semistructured interview respondents on all sociodemographic characteristics, but differed slightly on some clinical characteristics (Table 1). The telephone survey women had been more recently diagnosed (P < .01), were less likely to have ductal carcinoma in situ (P < .001), and more likely to have had reconstructive surgery

(P < .05).

Five cancer support providers and 4 physicians were interviewed. All support providers were Spanish-speaking Latinas with at least some college education. Cancer physicians were board certified. Two were men; two were white and two Asian; one was a breast surgeon and three were hematologists/oncologists; three spoke Spanish poorly/not at all and one spoke it fairly well.

Seven themes emerged from interviews: unmet physical symptom management needs; social support often ends when treatment ends; challenges resuming roles; sense of abandonment by health care system when treatment ends; need for formal transition from active treatment to follow-up care; fear of recurrence especially when obtaining follow-up care; and desire for information on late effects of initial treatments and side effects of hormonal treatments. We summarize results according to these themes.

Unmet physical symptom management needs. The main physical symptoms reported by survivors and physicians in interviews were arthralgia, menopausal symptoms, and neuropathy. Fatigue was reported only by survivors. Many survivors and several support providers expressed that symptoms were poorly managed and often ignored. One stated,

I have a lot of pain where I had surgery, it burns. I worry a lot about my arm because I have sacs of fluid. My doctor only says, ‘They will dissolve over the years.’ So, I don’t feel any support. (FocGrp1#6)

Survivors reported side effects of hormonal therapies, and felt that physicians downplayed these to prevent them from discontinuing medications.

Social support from family and friends often ends when treatment ends. Many survivors described a loss of support from family and friends who expected them to get back to “normal” once treatment ended. One said,

My sisters have told me to my face that there’s nothing wrong with me. So now when people ask me, I say, ‘I’m fine, thank God, I have nothing,’ even though I’m dying of pain and have all these pills to take. (Survivor#1025)

A support provider related,

The client was telling me that as she was getting closer to finishing her treatment, her husband was upset because he felt like all she was doing was focusing on the cancer. I think caregivers, family, spouses, and children out of their own sort of selfishness want this person to be well. (SuppProv#104)

A few survivors said that family bonds were strengthened after cancer and several reported lacking support because their families were in their home countries.

Challenges resuming roles, especially returning to work. Survivors, support providers, and physicians described challenges and few resources as women transition back to their normal roles. Survivors questioned their ability to return to work due to physically demanding occupations. One stated,

I would like information on how to take care of myself, how working can affect this side if I don’t take care of it. I clean houses and I need both hands. (Survivor#3012)

Survivors described how changes in memory affected daily chores and work performance. Support providers and physicians described the need for resources to aid with return to work and household responsibilities. One physician noted,

There are usually questions about how to go ahead and live their lives from that point forward. It’s a sort of reverse shock: going back to life as they know it. (Physician#004)

Support providers and physicians mentioned that women needed help with resuming intimate partner relations.

Sense of abandonment by health care system once active treatment ends. Survivors, support providers, and physicians reported a loss of support and sense of abandonment by the patients’ oncology team at the end of active treatment. One survivor stated,

Once they tell you to stop the pills, ‘You’re cured, there’s nothing wrong with you,’ the truth is that one feels, ‘Now what do I do? I have no one to help me.’ I felt very abandoned. (FocGrp1#5)

A provider said,

The support system falls apart once women complete treatment. They lose their entire support system at the medical level. They no longer have nurses checking in about symptoms and addressing anything that’s come up. They won’t have access to doctors unless they’re doing their screening. (SuppProv#101)

An oncologist, noting that this loss of support occurs when women face pressures of transitioning back to work or family obligations, commented,

So here’s a woman whose marriage is in turmoil, whose husband may even have left her during this, and now her clinic is leaving her and she’s on her own … that must be scary as hell because there’s nobody out there to support her. (Physician#002)

Need for formal transition from active treatment to follow-up care. Two themes emerged about transitioning from active treatment: transferring care from oncologists to primary care physicians (PCP); and issues of follow-up care (with oncologists or PCPs). Survivors felt lost in transitioning from specialty to primary care, or expressed apprehension seeing a PCP rather than a cancer specialist. One stated,

I have my doctor but she is not a specialist. She does what I tell her to and orders a mammogram every year. But, I don’t go to the oncologist anymore, and so I worry. With the specialists, I feel protected. (FocGrp1#5)

Physicians acknowledged the lack of a formal transition to primary care such as a survivorship care program.

Follow-up care issues were common. Physicians stressed that women needed to know how often to return for follow-up once active treatment ends and about recommended examinations and tests, especially when receiving hormonal therapy. Physicians indicated the need for patient education materials specific to patients’ treatments, for example, elevated risk of heart disease with certain chemotherapy agents. An oncologist expressed concern that PCPs are not prepared adequately about late effects and hormonal treatment side effects, and suggested providing summary notes for PCPs detailing these.

Survivors identified several barriers to follow-up care: lacking information on which symptoms merited a call to physicians; financial burden/limited health insurance; lacking appointment reminders; fear of examinations; and limited English proficiency. A survivor stated,

If you have insurance, you can make your appointment, see the doctor, and have your mammogram. I stopped taking my pills because I didn’t have insurance. I tried to get them again but they told me they would cost me a thousand dollars. (FocGrp1#5)

One oncologist suggested scheduling a follow-up appointment before patients leave treatment and calling patients who miss appointments.

Facilitators of regular follow-up care identified by survivors were physicians informing them about symptom monitoring and reporting, having a clinic contact person/navigator, being given a follow-up appointment, being assertive about one’s care, and physicians’ reinforcement of adherence to hormonal treatment and follow-up. According to support providers, a key facilitator was having a clinic contact person/navigator. Once treatment ended, support providers often served as the liaison between the patient and the physician, making them the first point of contact for symptom reporting.

Fear of recurrence especially when obtaining follow-up care. Fear of recurrence dominated survivor interviews. This fear was heightened at the time of follow-up examinations or when they experienced unusual pain. A survivor commented,

Every time I’m due for my mammogram, I can’t sleep, worrying. I lose sleep until I get the letter with my results. Then I feel at peace again. (FocGrp1#9)

Support providers discussed the need to provide reassurance to SSBCS to help them cope with fears of recurrence. Physicians expressed challenges in allaying fears of recurrence among SSBCS, requiring a lot of time when recommending follow-up mammograms.

Desire for information on late effects of treatments and side effects of hormonal therapies. All survivors expressed receiving insufficient information on potential symptoms and side effects. One stated,

Doctors only have five minutes. There has never been someone who gave me guidance like, ‘From now on you have to do this or you might get these symptoms now or in the future. (Survivor#6019)

They indicated uncertainty about what symptoms were “normal” and when symptoms merited a call to the physician. Several survivors reported being unaware that fatigue, arthralgia and neuropathy were side effects of breast cancer treatments until they reported these to physicians.

Physicians stressed the importance of women knowing about the elevated risk of future cancers, symptoms of recurrence, and seeking follow-up care if they experience symptoms that are out of the ordinary. Support providers felt that it was important to provide SSBCS with information on signs of recurrence and when to report these. However, providers expressed concern that giving women too much information might elevate their anxiety. A physician suggested,

It’s probably better to have a symptom list that’s short and relevant for the most common and catastrophic things, same thing with side effects … short to avoid overwhelming the patient. (Physician#001)

Hormonal treatments were of special concern. Survivors expressed a need for information on hormonal treatments and support providers stressed that this information is needed in simple Spanish. Several survivors indicated they stopped taking hormonal treatments due to side effects. One woman experienced severe headaches and heart palpitations, stopped taking the hormonal medication, felt better, and did not inform her physician until her next appointment. A support provider stated,

What I hear from a lot of women is that if side effects are too uncomfortable, they just stop it (hormonal treatment) without saying anything to the doctor. So more information about why they have to take it and that there is a good chance of recurrence is really important. (SuppProv#101)

Likewise, physicians indicated that SSBCS’ lack of information on hormonal treatments often resulted in nonadherence, emphasizing the need to reinforce adherence to prevent recurrence.

Conceptual framework of interventions

Based on triangulation of survey and interview results, we compiled a conceptual framework that includes needs identified, suggested components of a survivorship care intervention to address these needs, potential mediators by which such interventions could improve outcomes, and relevant outcomes (Figure). Survivorship care needs fell into four categories: symptom management, psychosocial, sense of abandonment by health care team, and healthy lifestyles. Survivorship care programs would provide skills training in symptom and stress management, and communicating with providers, family, friends, and coworkers. Mediators include increased self-efficacy, knowledge and perceived social support, ultimately leading to reduced distress (anxiety and depressive symptoms) and stress, and improved health-related quality of life.

Conclusions

Our study aimed to identify the most critical needs of SSBCS in the posttreatment survivorship phase to facilitate the design of survivorship interventions for this vulnerable group. SSBCS, cancer support providers, and cancer physicians reported substantial symptom management, psychosocial, and informational needs among this population. Results from surveys and open-ended interviews were remarkably consistent. Survivors, physicians, and support providers viewed transition out of active treatment as a time of increased psychosocial need and heightened vulnerability.