User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

OTX015 dose for lymphoma narrowed in phase 1 study

As a single agent for use in patients with lymphoma, an acceptable once-daily dose of OTX015 appears to be 80 mg on a 14 days on, 7 days off schedule, the results of a phase 1 study indicate.

The small-molecule inhibitor, which inhibits binding of bromodomain and exterminal proteins to acetylated histones, was associated with acceptable toxicity and efficacy in this regimen. The investigational drug is now being tested in expansion cohorts on a schedule of 14 days every 3 weeks, a regimen projected to allow for recovery from the drug’s toxic effects, Dr. Sandy Amorin of Hôpital Saint Louis, Paris, and associates reported.

The drug also is being evaluated in patients with acute leukemias.

Adults with nonleukemia hematologic malignancies that progressed on standard therapies participated in the open-label study, which was conducted at seven university hospital centers in Europe. Oral OTX015 was given once a day at one of five doses (10 mg, 20 mg, 40 mg, 80 mg, and 120 mg). The 3 + 3 study design permitted evaluation of alternative administration schedules. The primary endpoint was dose-limiting toxicity in the first treatment cycle (21 days). Secondary objectives were to evaluate safety, pharmacokinetics, and preliminary clinical activity of OTX015. The study is ongoing and is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT01713582.

The study included 33 patients with lymphoma and 12 with myeloma; patients’ median age was 66 years, and they had received a median of four lines of prior therapy. No dose-limiting toxicities were seen in three patients given doses as high as 80 mg once a day. However, grade 4 thrombocytopenia occurred in five of six patients on a 21-day schedule of 40 mg twice a day. No patient tolerated various schedules of 120 mg once a day (Lancet Haematol. 2016;3[4]:e196-204).

The researchers then examined the 80 mg once a day dose on a continuous basis in four patients, two of whom developed grade 4 thrombocytopenia. In light of these and other toxicities, a regimen was proposed of 80 mg once a day on a schedule of 14 days on, 7 days off.

Thrombocytopenia affected 43 of 45 patients, and 26 of them had grade 3-4 events. Other grade 3-4 events were infrequent. Anemia was seen in 41, and neutropenia in 23.

Of three patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, two had complete responses at 120 mg once a day, and one had a partial response at 80 mg once a day. Six additional patients, two with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and four with indolent lymphomas, had evidence of clinical activity, but did not meet the criteria for an objective response.

The study was funded by the developers of OTX015, Oncoethix GmbH, a wholly owned subsidiary of Merck Sharp & Dohme.

On Twitter @maryjodales

As a single agent for use in patients with lymphoma, an acceptable once-daily dose of OTX015 appears to be 80 mg on a 14 days on, 7 days off schedule, the results of a phase 1 study indicate.

The small-molecule inhibitor, which inhibits binding of bromodomain and exterminal proteins to acetylated histones, was associated with acceptable toxicity and efficacy in this regimen. The investigational drug is now being tested in expansion cohorts on a schedule of 14 days every 3 weeks, a regimen projected to allow for recovery from the drug’s toxic effects, Dr. Sandy Amorin of Hôpital Saint Louis, Paris, and associates reported.

The drug also is being evaluated in patients with acute leukemias.

Adults with nonleukemia hematologic malignancies that progressed on standard therapies participated in the open-label study, which was conducted at seven university hospital centers in Europe. Oral OTX015 was given once a day at one of five doses (10 mg, 20 mg, 40 mg, 80 mg, and 120 mg). The 3 + 3 study design permitted evaluation of alternative administration schedules. The primary endpoint was dose-limiting toxicity in the first treatment cycle (21 days). Secondary objectives were to evaluate safety, pharmacokinetics, and preliminary clinical activity of OTX015. The study is ongoing and is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT01713582.

The study included 33 patients with lymphoma and 12 with myeloma; patients’ median age was 66 years, and they had received a median of four lines of prior therapy. No dose-limiting toxicities were seen in three patients given doses as high as 80 mg once a day. However, grade 4 thrombocytopenia occurred in five of six patients on a 21-day schedule of 40 mg twice a day. No patient tolerated various schedules of 120 mg once a day (Lancet Haematol. 2016;3[4]:e196-204).

The researchers then examined the 80 mg once a day dose on a continuous basis in four patients, two of whom developed grade 4 thrombocytopenia. In light of these and other toxicities, a regimen was proposed of 80 mg once a day on a schedule of 14 days on, 7 days off.

Thrombocytopenia affected 43 of 45 patients, and 26 of them had grade 3-4 events. Other grade 3-4 events were infrequent. Anemia was seen in 41, and neutropenia in 23.

Of three patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, two had complete responses at 120 mg once a day, and one had a partial response at 80 mg once a day. Six additional patients, two with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and four with indolent lymphomas, had evidence of clinical activity, but did not meet the criteria for an objective response.

The study was funded by the developers of OTX015, Oncoethix GmbH, a wholly owned subsidiary of Merck Sharp & Dohme.

On Twitter @maryjodales

As a single agent for use in patients with lymphoma, an acceptable once-daily dose of OTX015 appears to be 80 mg on a 14 days on, 7 days off schedule, the results of a phase 1 study indicate.

The small-molecule inhibitor, which inhibits binding of bromodomain and exterminal proteins to acetylated histones, was associated with acceptable toxicity and efficacy in this regimen. The investigational drug is now being tested in expansion cohorts on a schedule of 14 days every 3 weeks, a regimen projected to allow for recovery from the drug’s toxic effects, Dr. Sandy Amorin of Hôpital Saint Louis, Paris, and associates reported.

The drug also is being evaluated in patients with acute leukemias.

Adults with nonleukemia hematologic malignancies that progressed on standard therapies participated in the open-label study, which was conducted at seven university hospital centers in Europe. Oral OTX015 was given once a day at one of five doses (10 mg, 20 mg, 40 mg, 80 mg, and 120 mg). The 3 + 3 study design permitted evaluation of alternative administration schedules. The primary endpoint was dose-limiting toxicity in the first treatment cycle (21 days). Secondary objectives were to evaluate safety, pharmacokinetics, and preliminary clinical activity of OTX015. The study is ongoing and is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT01713582.

The study included 33 patients with lymphoma and 12 with myeloma; patients’ median age was 66 years, and they had received a median of four lines of prior therapy. No dose-limiting toxicities were seen in three patients given doses as high as 80 mg once a day. However, grade 4 thrombocytopenia occurred in five of six patients on a 21-day schedule of 40 mg twice a day. No patient tolerated various schedules of 120 mg once a day (Lancet Haematol. 2016;3[4]:e196-204).

The researchers then examined the 80 mg once a day dose on a continuous basis in four patients, two of whom developed grade 4 thrombocytopenia. In light of these and other toxicities, a regimen was proposed of 80 mg once a day on a schedule of 14 days on, 7 days off.

Thrombocytopenia affected 43 of 45 patients, and 26 of them had grade 3-4 events. Other grade 3-4 events were infrequent. Anemia was seen in 41, and neutropenia in 23.

Of three patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, two had complete responses at 120 mg once a day, and one had a partial response at 80 mg once a day. Six additional patients, two with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and four with indolent lymphomas, had evidence of clinical activity, but did not meet the criteria for an objective response.

The study was funded by the developers of OTX015, Oncoethix GmbH, a wholly owned subsidiary of Merck Sharp & Dohme.

On Twitter @maryjodales

FROM THE LANCET HAEMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: For lymphoma patients, a regimen has been determined for the small-molecule inhibitor OTX015 that was associated with acceptable toxicity and efficacy.

Major finding: On a regimen of 80 mg once a day on a schedule of 14 days on, 7 days off, thrombocytopenia affected 43 of 45 patients, and 26 of them had grade 3-4 events. However, other grade 3-4 events were infrequent.

Data source: The open-label study NCT01713582 was conducted at seven university hospital centers in Europe.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the developers of OTX015, Oncoethix GmbH, a wholly owned subsidiary of Merck Sharp & Dohme.

Feds advance cancer moonshot with expert panel, outline of goals

Federal officials took the next step in their moonshot to end cancer by announcing on April 4 a blue ribbon panel to guide the effort.

A total of 28 leading researchers, clinicians, and patient advocates have been named to the panel charged with informing the scientific direction and goals of the National Cancer Moonshot Initiative, led by Vice President Joe Biden.

“This Blue Ribbon Panel will ensure that, as [the National Institutes of Health] allocates new resources through the Moonshot, decisions will be grounded in the best science,” Vice President Biden said in a statement. “I look forward to working with this panel and many others involved with the Moonshot to make unprecedented improvements in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of cancer.”

The key goals of the initiative were set out simultaneously in a perspective from Dr. Francis S. Collins, NIH director, and Dr. Douglas R. Lowy, director of the National Cancer Institute. The editorial was published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Fueled by an additional $680 million in the proposed fiscal year 2017 budget for the NIH, plus additional resources for the Food and Drug Administration, the initiative will aim to accelerate progress toward the next generation of interventions that we hope will substantially reduce cancer incidence and dramatically improve patient outcomes,” Dr. Collins and Dr. Lowy wrote. “The NIH’s most compelling opportunities for progress will be set forth by late summer 2016 in a research plan informed by the deliberations of a blue-ribbon panel of experts, which will provide scientific input to the National Cancer Advisory Board. Some possible opportunities include vaccine development, early-detection technology, single-cell genomic analysis, immunotherapy, a focus on pediatric cancer, and enhanced data sharing.”

To read the full editorial, click here.

On Twitter @denisefulton

Federal officials took the next step in their moonshot to end cancer by announcing on April 4 a blue ribbon panel to guide the effort.

A total of 28 leading researchers, clinicians, and patient advocates have been named to the panel charged with informing the scientific direction and goals of the National Cancer Moonshot Initiative, led by Vice President Joe Biden.

“This Blue Ribbon Panel will ensure that, as [the National Institutes of Health] allocates new resources through the Moonshot, decisions will be grounded in the best science,” Vice President Biden said in a statement. “I look forward to working with this panel and many others involved with the Moonshot to make unprecedented improvements in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of cancer.”

The key goals of the initiative were set out simultaneously in a perspective from Dr. Francis S. Collins, NIH director, and Dr. Douglas R. Lowy, director of the National Cancer Institute. The editorial was published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Fueled by an additional $680 million in the proposed fiscal year 2017 budget for the NIH, plus additional resources for the Food and Drug Administration, the initiative will aim to accelerate progress toward the next generation of interventions that we hope will substantially reduce cancer incidence and dramatically improve patient outcomes,” Dr. Collins and Dr. Lowy wrote. “The NIH’s most compelling opportunities for progress will be set forth by late summer 2016 in a research plan informed by the deliberations of a blue-ribbon panel of experts, which will provide scientific input to the National Cancer Advisory Board. Some possible opportunities include vaccine development, early-detection technology, single-cell genomic analysis, immunotherapy, a focus on pediatric cancer, and enhanced data sharing.”

To read the full editorial, click here.

On Twitter @denisefulton

Federal officials took the next step in their moonshot to end cancer by announcing on April 4 a blue ribbon panel to guide the effort.

A total of 28 leading researchers, clinicians, and patient advocates have been named to the panel charged with informing the scientific direction and goals of the National Cancer Moonshot Initiative, led by Vice President Joe Biden.

“This Blue Ribbon Panel will ensure that, as [the National Institutes of Health] allocates new resources through the Moonshot, decisions will be grounded in the best science,” Vice President Biden said in a statement. “I look forward to working with this panel and many others involved with the Moonshot to make unprecedented improvements in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of cancer.”

The key goals of the initiative were set out simultaneously in a perspective from Dr. Francis S. Collins, NIH director, and Dr. Douglas R. Lowy, director of the National Cancer Institute. The editorial was published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Fueled by an additional $680 million in the proposed fiscal year 2017 budget for the NIH, plus additional resources for the Food and Drug Administration, the initiative will aim to accelerate progress toward the next generation of interventions that we hope will substantially reduce cancer incidence and dramatically improve patient outcomes,” Dr. Collins and Dr. Lowy wrote. “The NIH’s most compelling opportunities for progress will be set forth by late summer 2016 in a research plan informed by the deliberations of a blue-ribbon panel of experts, which will provide scientific input to the National Cancer Advisory Board. Some possible opportunities include vaccine development, early-detection technology, single-cell genomic analysis, immunotherapy, a focus on pediatric cancer, and enhanced data sharing.”

To read the full editorial, click here.

On Twitter @denisefulton

FROM NEJM

Idelalisib use halted in six combo therapy trials, FDA announces

An increased rate of adverse events, including deaths, have been reported in clinical trials with idelalisib (Zydelig) in combination with other cancer medicines, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration announced.

Gilead Sciences, Inc. has confirmed that they are stopping six clinical trials in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia, small lymphocytic lymphoma and indolent non-Hodgkin lymphomas. The FDA is reviewing the findings of the clinical trials and will communicate new information as necessary, according to the FDA press release.

Idelalisib is not approved for previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia. It is approved by the FDA for the treatment of:

• Relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia, in combination with rituximab, in patients for whom rituximab alone would be considered appropriate therapy due to other co-morbidities.

• Relapsed follicular B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma in patients who have received at least two prior systemic therapies.

• Relapsed small lymphocytic lymphoma in patients who have received at least two prior systemic therapies.

Adverse events involving idelalisib should be reported to the FDA MedWatch program, the release advised.

On Twitter @maryjodales

An increased rate of adverse events, including deaths, have been reported in clinical trials with idelalisib (Zydelig) in combination with other cancer medicines, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration announced.

Gilead Sciences, Inc. has confirmed that they are stopping six clinical trials in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia, small lymphocytic lymphoma and indolent non-Hodgkin lymphomas. The FDA is reviewing the findings of the clinical trials and will communicate new information as necessary, according to the FDA press release.

Idelalisib is not approved for previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia. It is approved by the FDA for the treatment of:

• Relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia, in combination with rituximab, in patients for whom rituximab alone would be considered appropriate therapy due to other co-morbidities.

• Relapsed follicular B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma in patients who have received at least two prior systemic therapies.

• Relapsed small lymphocytic lymphoma in patients who have received at least two prior systemic therapies.

Adverse events involving idelalisib should be reported to the FDA MedWatch program, the release advised.

On Twitter @maryjodales

An increased rate of adverse events, including deaths, have been reported in clinical trials with idelalisib (Zydelig) in combination with other cancer medicines, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration announced.

Gilead Sciences, Inc. has confirmed that they are stopping six clinical trials in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia, small lymphocytic lymphoma and indolent non-Hodgkin lymphomas. The FDA is reviewing the findings of the clinical trials and will communicate new information as necessary, according to the FDA press release.

Idelalisib is not approved for previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia. It is approved by the FDA for the treatment of:

• Relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia, in combination with rituximab, in patients for whom rituximab alone would be considered appropriate therapy due to other co-morbidities.

• Relapsed follicular B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma in patients who have received at least two prior systemic therapies.

• Relapsed small lymphocytic lymphoma in patients who have received at least two prior systemic therapies.

Adverse events involving idelalisib should be reported to the FDA MedWatch program, the release advised.

On Twitter @maryjodales

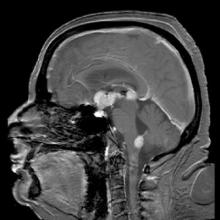

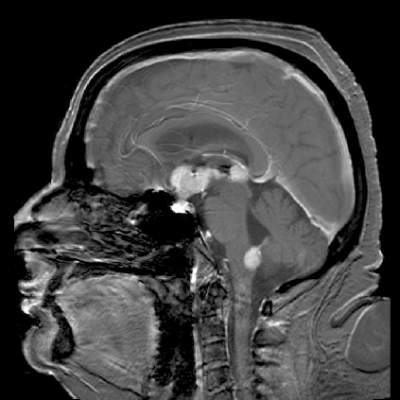

Temsirolimus results in good but short-duration responses in primary CNS lymphoma

Single-agent therapy with temsirolimus was active in patients with relapsed/refractory primary central nervous system lymphoma, but most of the responses were short lived, results of a phase II trial show.

Among 37 patients with primary CNS lymphoma (PCNSL) for whom firstline therapy had failed, there were five complete responses (CR), three CR unconfirmed, and 12 partial responses (PR), for an overall response rate (ORR) of 54%, reported Dr. Agnieszka Korfel from Charité University Medicine Berlin (Germany) and colleagues.

The median progression-free survival (PFS), however, was just 2.1 months, although 1 patient had PFS of 15.8 months duration, and another had a response lasting for more than 44 months, the investigators noted in a study published online in the Journal of Clinical Oncology (doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.9897).

The rationale for trying temsirolimus (Torisel), an inhibitor of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), came from studies showing the drug’s efficacy against relapsed/refractory mantle-cell lymphoma and against other, more aggressive forms of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Patients with relapsed/refractory aggressive lymphomas tolerate temsirolimus relatively well, and the drug has the ability to penetrate brain tumor tissue, the authors noted.

They enrolled 37 patients with a median age of 70 years and a median time since their last treatment of 3.9 months into an open-label trial. The patients were all immuncompetent with histologically confirmed primary central nervous system lymphoma for whom high-dose methotrexate-based chemotherapy had failed and for whom high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplant had either failed or was not an option.

The first six patients were treated with temsirolimus 25 mg intravenously once weekly, and the remaining 31 were treated with 75 mg IV once weekly until disease progression, intolerable toxicity, patient or physician decision to terminate, or death.

As noted before, ORR, the primary endpoint, was 54%. Median overall survival (OS), a secondary endpoint, was 3.7 months, and 1-year and 2-year OS were 19% and 16.2%, respectively.

The most frequently occurring toxicities include hyperglycemia, myelosuppression, pneumonias and other infections, and fatigue. A total of 28 severe adverse events occurred in 21 patients, including infectious episodes, hospitalizations because of disease progression, deep-vein thromboses, hyperglycemia, and one case each of seizures, grade 4 thrombocytopenia, drug fever, hyponatremia, renal insufficiency, and atrial fibrillation.

“Although most responses were short lived, some patients achieved long-term control. Thus, further evaluation in combination with other drugs seems reasonable. However, one has to be aware of the risk of hematotoxicity and infections necessitating primary antibiotic prophylaxis. Definition of biomarkers allowing identification of potential responders and those who are at particular risk for toxicity would be highly desirable,” the investigators concluded.

Single-agent therapy with temsirolimus was active in patients with relapsed/refractory primary central nervous system lymphoma, but most of the responses were short lived, results of a phase II trial show.

Among 37 patients with primary CNS lymphoma (PCNSL) for whom firstline therapy had failed, there were five complete responses (CR), three CR unconfirmed, and 12 partial responses (PR), for an overall response rate (ORR) of 54%, reported Dr. Agnieszka Korfel from Charité University Medicine Berlin (Germany) and colleagues.

The median progression-free survival (PFS), however, was just 2.1 months, although 1 patient had PFS of 15.8 months duration, and another had a response lasting for more than 44 months, the investigators noted in a study published online in the Journal of Clinical Oncology (doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.9897).

The rationale for trying temsirolimus (Torisel), an inhibitor of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), came from studies showing the drug’s efficacy against relapsed/refractory mantle-cell lymphoma and against other, more aggressive forms of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Patients with relapsed/refractory aggressive lymphomas tolerate temsirolimus relatively well, and the drug has the ability to penetrate brain tumor tissue, the authors noted.

They enrolled 37 patients with a median age of 70 years and a median time since their last treatment of 3.9 months into an open-label trial. The patients were all immuncompetent with histologically confirmed primary central nervous system lymphoma for whom high-dose methotrexate-based chemotherapy had failed and for whom high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplant had either failed or was not an option.

The first six patients were treated with temsirolimus 25 mg intravenously once weekly, and the remaining 31 were treated with 75 mg IV once weekly until disease progression, intolerable toxicity, patient or physician decision to terminate, or death.

As noted before, ORR, the primary endpoint, was 54%. Median overall survival (OS), a secondary endpoint, was 3.7 months, and 1-year and 2-year OS were 19% and 16.2%, respectively.

The most frequently occurring toxicities include hyperglycemia, myelosuppression, pneumonias and other infections, and fatigue. A total of 28 severe adverse events occurred in 21 patients, including infectious episodes, hospitalizations because of disease progression, deep-vein thromboses, hyperglycemia, and one case each of seizures, grade 4 thrombocytopenia, drug fever, hyponatremia, renal insufficiency, and atrial fibrillation.

“Although most responses were short lived, some patients achieved long-term control. Thus, further evaluation in combination with other drugs seems reasonable. However, one has to be aware of the risk of hematotoxicity and infections necessitating primary antibiotic prophylaxis. Definition of biomarkers allowing identification of potential responders and those who are at particular risk for toxicity would be highly desirable,” the investigators concluded.

Single-agent therapy with temsirolimus was active in patients with relapsed/refractory primary central nervous system lymphoma, but most of the responses were short lived, results of a phase II trial show.

Among 37 patients with primary CNS lymphoma (PCNSL) for whom firstline therapy had failed, there were five complete responses (CR), three CR unconfirmed, and 12 partial responses (PR), for an overall response rate (ORR) of 54%, reported Dr. Agnieszka Korfel from Charité University Medicine Berlin (Germany) and colleagues.

The median progression-free survival (PFS), however, was just 2.1 months, although 1 patient had PFS of 15.8 months duration, and another had a response lasting for more than 44 months, the investigators noted in a study published online in the Journal of Clinical Oncology (doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.9897).

The rationale for trying temsirolimus (Torisel), an inhibitor of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), came from studies showing the drug’s efficacy against relapsed/refractory mantle-cell lymphoma and against other, more aggressive forms of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Patients with relapsed/refractory aggressive lymphomas tolerate temsirolimus relatively well, and the drug has the ability to penetrate brain tumor tissue, the authors noted.

They enrolled 37 patients with a median age of 70 years and a median time since their last treatment of 3.9 months into an open-label trial. The patients were all immuncompetent with histologically confirmed primary central nervous system lymphoma for whom high-dose methotrexate-based chemotherapy had failed and for whom high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplant had either failed or was not an option.

The first six patients were treated with temsirolimus 25 mg intravenously once weekly, and the remaining 31 were treated with 75 mg IV once weekly until disease progression, intolerable toxicity, patient or physician decision to terminate, or death.

As noted before, ORR, the primary endpoint, was 54%. Median overall survival (OS), a secondary endpoint, was 3.7 months, and 1-year and 2-year OS were 19% and 16.2%, respectively.

The most frequently occurring toxicities include hyperglycemia, myelosuppression, pneumonias and other infections, and fatigue. A total of 28 severe adverse events occurred in 21 patients, including infectious episodes, hospitalizations because of disease progression, deep-vein thromboses, hyperglycemia, and one case each of seizures, grade 4 thrombocytopenia, drug fever, hyponatremia, renal insufficiency, and atrial fibrillation.

“Although most responses were short lived, some patients achieved long-term control. Thus, further evaluation in combination with other drugs seems reasonable. However, one has to be aware of the risk of hematotoxicity and infections necessitating primary antibiotic prophylaxis. Definition of biomarkers allowing identification of potential responders and those who are at particular risk for toxicity would be highly desirable,” the investigators concluded.

FROM JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Relapsed/refractory primary CNS lymphoma has a poor prognosis and no standard treatment option.

Major finding: The overall response rate to once-weekly temsirolimus was 54%; most responses were short lived.

Data source: Open-label phase 2 study in 37 adults with relapsed/refractory primary CNS lymphoma.

Disclosures: The study was supported by Pfizer Germany. Dr. Korfel and several colleagues disclosed research support from or consulting/advising for the company.

Follicular lymphoma: Quantitative PET/CT measures for detecting bone marrow involvement

Quantifying bone marrow uptake of FDG (18fluorodeoxyglucose) improved the diagnostic accuracy of PET/CT for predicting bone marrow involvement in patients with follicular lymphoma, based on the results of a retrospective study.

Visual evidence of focal increased uptake on PET/CT indicates marrow involvement in follicular lymphoma; however, diffuse uptake is a nonspecific finding. Measuring the mean bone marrow standardized uptake value (BM SUV mean) improves PET/CT diagnostic accuracy, Dr. Chava Perry and his colleagues at Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center reported in Medicine [(Baltimore). 2016 Mar;95(9):e2910].

The researchers evaluated 68 consecutive patients with follicular lymphoma; 16 had bone marrow involvement – 13 had biopsy-proven involvement and 3 had a negative biopsy with increased medullary uptake that normalized after treatment. BM FDG uptake was diffuse in 8 of them and focal in the other 8.

While focal increased uptake is indicative of bone marrow involvement, diffuse uptake can be associated with false-positive results, as it was in the case of 17 patients (32.7% of those with diffuse uptake). Overall, visual assessment of scan results had a negative predictive value of 100% and a positive predictive value (PPV) of 48.5%.

On a quantitative assessment, however, BM SUV mean was significantly higher in patients with bone marrow involvement (SUV mean of 3.7 [1.7-6] vs. 1.4 [0.4-2.65]; P less than .001). On the receiver operator curve (ROC) analysis, a BM SUV mean exceeding 2.7 had a positive predictive value of 100% for bone marrow involvement (sensitivity of 68%). A BM SUV mean less than 1.7 had an negative predictive value of 100% (specificity of 73%).

A mean standardized uptake value (BM SUV mean) below 1.7 may spare the need for bone marrow biopsy while a BM SUV mean above 2.7 is compatible with bone marrow involvement, although biopsy may still be recommended to exclude large cell transformation, the researchers concluded.

On Twitter @maryjodales

Quantifying bone marrow uptake of FDG (18fluorodeoxyglucose) improved the diagnostic accuracy of PET/CT for predicting bone marrow involvement in patients with follicular lymphoma, based on the results of a retrospective study.

Visual evidence of focal increased uptake on PET/CT indicates marrow involvement in follicular lymphoma; however, diffuse uptake is a nonspecific finding. Measuring the mean bone marrow standardized uptake value (BM SUV mean) improves PET/CT diagnostic accuracy, Dr. Chava Perry and his colleagues at Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center reported in Medicine [(Baltimore). 2016 Mar;95(9):e2910].

The researchers evaluated 68 consecutive patients with follicular lymphoma; 16 had bone marrow involvement – 13 had biopsy-proven involvement and 3 had a negative biopsy with increased medullary uptake that normalized after treatment. BM FDG uptake was diffuse in 8 of them and focal in the other 8.

While focal increased uptake is indicative of bone marrow involvement, diffuse uptake can be associated with false-positive results, as it was in the case of 17 patients (32.7% of those with diffuse uptake). Overall, visual assessment of scan results had a negative predictive value of 100% and a positive predictive value (PPV) of 48.5%.

On a quantitative assessment, however, BM SUV mean was significantly higher in patients with bone marrow involvement (SUV mean of 3.7 [1.7-6] vs. 1.4 [0.4-2.65]; P less than .001). On the receiver operator curve (ROC) analysis, a BM SUV mean exceeding 2.7 had a positive predictive value of 100% for bone marrow involvement (sensitivity of 68%). A BM SUV mean less than 1.7 had an negative predictive value of 100% (specificity of 73%).

A mean standardized uptake value (BM SUV mean) below 1.7 may spare the need for bone marrow biopsy while a BM SUV mean above 2.7 is compatible with bone marrow involvement, although biopsy may still be recommended to exclude large cell transformation, the researchers concluded.

On Twitter @maryjodales

Quantifying bone marrow uptake of FDG (18fluorodeoxyglucose) improved the diagnostic accuracy of PET/CT for predicting bone marrow involvement in patients with follicular lymphoma, based on the results of a retrospective study.

Visual evidence of focal increased uptake on PET/CT indicates marrow involvement in follicular lymphoma; however, diffuse uptake is a nonspecific finding. Measuring the mean bone marrow standardized uptake value (BM SUV mean) improves PET/CT diagnostic accuracy, Dr. Chava Perry and his colleagues at Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center reported in Medicine [(Baltimore). 2016 Mar;95(9):e2910].

The researchers evaluated 68 consecutive patients with follicular lymphoma; 16 had bone marrow involvement – 13 had biopsy-proven involvement and 3 had a negative biopsy with increased medullary uptake that normalized after treatment. BM FDG uptake was diffuse in 8 of them and focal in the other 8.

While focal increased uptake is indicative of bone marrow involvement, diffuse uptake can be associated with false-positive results, as it was in the case of 17 patients (32.7% of those with diffuse uptake). Overall, visual assessment of scan results had a negative predictive value of 100% and a positive predictive value (PPV) of 48.5%.

On a quantitative assessment, however, BM SUV mean was significantly higher in patients with bone marrow involvement (SUV mean of 3.7 [1.7-6] vs. 1.4 [0.4-2.65]; P less than .001). On the receiver operator curve (ROC) analysis, a BM SUV mean exceeding 2.7 had a positive predictive value of 100% for bone marrow involvement (sensitivity of 68%). A BM SUV mean less than 1.7 had an negative predictive value of 100% (specificity of 73%).

A mean standardized uptake value (BM SUV mean) below 1.7 may spare the need for bone marrow biopsy while a BM SUV mean above 2.7 is compatible with bone marrow involvement, although biopsy may still be recommended to exclude large cell transformation, the researchers concluded.

On Twitter @maryjodales

FROM MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Measuring the mean standardized uptake value of 18fluorodeoxyglucose in the bone marrow of patients with follicular lymphoma improves the diagnostic accuracy of PET/CT.

Major finding: In this study, diffuse uptake was associated with 17 (32.7%) false positive cases.

Data source: Retrospective study of 68 consecutive patients with follicular lymphoma.

Disclosures: The authors had no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

Pregnancy did not increase Hodgkin lymphoma relapse rate

Women who become pregnant while in remission from Hodgkin lymphoma were not at increased risk for cancer relapse, according to an analysis of data from Swedish health care registries combined with medical records.

Of 449 women who were diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma between 1992 and 2009, 144 (32%) became pregnant during follow-up, which started 6 months after diagnosis, when the disease was assumed to be in remission. Only one of these women experienced a pregnancy-associated relapse, which was defined as a relapse occurring during pregnancy or within 5 years of delivery. Of the women who did not become pregnant, 46 had a relapse.

The effect of pregnancy on relapse has been a concern of patients and clinicians, but “our findings suggest that the risk of pregnancy-associated relapse does not need to be taken into account in family planning for women whose Hodgkin lymphoma is in remission,” said Caroline E. Weibull of Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, and her associates.

The researchers used the nationwide “Swedish Cancer Register” to identify all cases of Hodgkin lymphoma (reporting is mandatory) and merged this data with clinical information from other registries and medical records.

The pregnancy rates were similar among women who had limited- and advanced-stage disease and among women with and without B symptoms at diagnosis – a finding that negates consideration of a so-called “healthy mother effect” in protecting against relapse, they wrote (J Clin Onc. 2015 Dec. 14 [doi:10.1200/JCO.2015.63.3446]).

The researchers also found that the absolute risk for relapse was highest in the first 2-3 years after diagnosis, which suggests that women should be advised, “if possible, to wait 2 years after cessation of treatment before becoming pregnant.” Additionally, the relapse rate more than doubled in women aged 30 years or older at diagnosis, compared with women aged 18-24 years at diagnosis – a finding consistent with previous research, they noted.

Women in the study were aged 18-40 at diagnosis. Follow-up ended on the date of relapse, the date of death, or at the end of 2010, whichever came first.

Women who become pregnant while in remission from Hodgkin lymphoma were not at increased risk for cancer relapse, according to an analysis of data from Swedish health care registries combined with medical records.

Of 449 women who were diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma between 1992 and 2009, 144 (32%) became pregnant during follow-up, which started 6 months after diagnosis, when the disease was assumed to be in remission. Only one of these women experienced a pregnancy-associated relapse, which was defined as a relapse occurring during pregnancy or within 5 years of delivery. Of the women who did not become pregnant, 46 had a relapse.

The effect of pregnancy on relapse has been a concern of patients and clinicians, but “our findings suggest that the risk of pregnancy-associated relapse does not need to be taken into account in family planning for women whose Hodgkin lymphoma is in remission,” said Caroline E. Weibull of Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, and her associates.

The researchers used the nationwide “Swedish Cancer Register” to identify all cases of Hodgkin lymphoma (reporting is mandatory) and merged this data with clinical information from other registries and medical records.

The pregnancy rates were similar among women who had limited- and advanced-stage disease and among women with and without B symptoms at diagnosis – a finding that negates consideration of a so-called “healthy mother effect” in protecting against relapse, they wrote (J Clin Onc. 2015 Dec. 14 [doi:10.1200/JCO.2015.63.3446]).

The researchers also found that the absolute risk for relapse was highest in the first 2-3 years after diagnosis, which suggests that women should be advised, “if possible, to wait 2 years after cessation of treatment before becoming pregnant.” Additionally, the relapse rate more than doubled in women aged 30 years or older at diagnosis, compared with women aged 18-24 years at diagnosis – a finding consistent with previous research, they noted.

Women in the study were aged 18-40 at diagnosis. Follow-up ended on the date of relapse, the date of death, or at the end of 2010, whichever came first.

Women who become pregnant while in remission from Hodgkin lymphoma were not at increased risk for cancer relapse, according to an analysis of data from Swedish health care registries combined with medical records.

Of 449 women who were diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma between 1992 and 2009, 144 (32%) became pregnant during follow-up, which started 6 months after diagnosis, when the disease was assumed to be in remission. Only one of these women experienced a pregnancy-associated relapse, which was defined as a relapse occurring during pregnancy or within 5 years of delivery. Of the women who did not become pregnant, 46 had a relapse.

The effect of pregnancy on relapse has been a concern of patients and clinicians, but “our findings suggest that the risk of pregnancy-associated relapse does not need to be taken into account in family planning for women whose Hodgkin lymphoma is in remission,” said Caroline E. Weibull of Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, and her associates.

The researchers used the nationwide “Swedish Cancer Register” to identify all cases of Hodgkin lymphoma (reporting is mandatory) and merged this data with clinical information from other registries and medical records.

The pregnancy rates were similar among women who had limited- and advanced-stage disease and among women with and without B symptoms at diagnosis – a finding that negates consideration of a so-called “healthy mother effect” in protecting against relapse, they wrote (J Clin Onc. 2015 Dec. 14 [doi:10.1200/JCO.2015.63.3446]).

The researchers also found that the absolute risk for relapse was highest in the first 2-3 years after diagnosis, which suggests that women should be advised, “if possible, to wait 2 years after cessation of treatment before becoming pregnant.” Additionally, the relapse rate more than doubled in women aged 30 years or older at diagnosis, compared with women aged 18-24 years at diagnosis – a finding consistent with previous research, they noted.

Women in the study were aged 18-40 at diagnosis. Follow-up ended on the date of relapse, the date of death, or at the end of 2010, whichever came first.

FROM JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Pregnancy did not increase the risk of relapse of Hodgkin lymphoma in a population-based study.

Major finding: Of 144 women who became pregnant 6 months or longer after diagnosis of Hodgkin lymphoma, 1 experienced a pregnancy-associated relapse.

Data source: Population-based study utilizing Swedish health care registries and medical records, in which 449 women with Hodgkin lymphoma diagnoses, and 47 relapses, were identified.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Swedish Cancer Society, the Strategic Research Program in Epidemiology at Karolinska Institutet, the Swedish Society for Medicine, and the Swedish Society for Medical Research.

Expert panel issues guidelines for treatment of hematologic cancers in pregnancy

Consensus guidelines for the perinatal management of hematologic malignancies detected during pregnancy have been issued by a panel of international experts.

The guidelines, published online in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, aim to ensure that timely treatment of the cancers is not delayed in pregnant women (doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.4445).

While rare, hematologic malignancies in pregnancy introduce clinical, social, ethical, and moral dilemmas. Evidence-based data are scarce, according to the researchers, who note the International Network on Cancer, Infertility and Pregnancy registers all cancers occurring during gestation.

“Patient accrual is ongoing and essential, because registration of new cases and long-term follow-up will improve clinical knowledge and increase the level of evidence,” Dr. Michael Lishner of Tel Aviv University and Meir Medical Center, Kfar Saba, Israel, and his fellow panelists wrote.

Hodgkin lymphoma

The researchers note that Hodgkin lymphoma is the most common hematologic cancer in pregnancy, and the prognosis for these patients is excellent. When diagnosed during the first trimester, a regimen based on vinblastine monotherapy has been used. ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine) therapy can be used postpartum and has been used in cases of progression during pregnancy, the panelists wrote.

“The limited data available suggest that ABVD may be administered safely and effectively during the latter phases of pregnancy,” the panel wrote. “Although it may be associated with prematurity and lower birth weights, studies have not reported significant disadvantages.”

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

The second most common cancer in pregnancy is non-Hodgkin lymphoma. In the case of indolent disease, watchful waiting is possible, with the intent to treat with monoclonal antibodies – with or without chemotherapy – if symptoms or evidence of disease progression are noted. Steroids can be administered during the first trimester as a bridge to the second trimester, when chemotherapy can be used with relatively greater safety, the panelists noted.

Aggressive lymphomas diagnosed before 20 weeks’ gestation warrant pregnancy termination and treatment, they recommend. When diagnosed after 20 weeks, therapy should be comparable to that given a nonpregnant woman, including monoclonal antibodies (R-CHOP).

Chronic myeloid leukemia

Chronic myeloid leukemia occurs in approximately 1 in 100,000 pregnancies and is typically diagnosed during routine blood testing in an asymptomatic patient. As a result, treatment may not be needed until the patient’s white count or platelet count have risen to levels associated with the onset of symptoms. An approximate guideline is a white cell count greater than 100 X 109/L and a platelet count greater than 500 X 109/L.

Therapeutic approaches in pregnancy include interferon-a (INF-a), which does not inhibit DNA synthesis or readily cross the placenta, and leukapheresis, which is frequently required two to three times per week during the first and second trimesters. Counts tend to drop during the third trimester, allowing less frequent intervention.

Consideration should be given to adding aspirin or low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) when the platelet count exceeds 1,000 X 109/L.

Myeloproliferative neoplasms

The most common myeloproliferative neoplasm seen in women of childbearing age is essential thrombocytosis.

“A large meta-analysis of pregnant women with essential thrombocytosis reported a live birth rate of 50%-70%, first trimester loss in 25%-40%, late pregnancy loss in 10%, placental abruption in 3.6%, and intrauterine growth restriction in 4.5%. Maternal morbidity is rare, but stroke has been reported,” according to the panelists.

Limited literature suggests similar outcomes for pregnant women with polycythemia vera and primary myelofibrosis.

In low-risk pregnancies, aspirin (75 mg/day) should be offered unless clearly contraindicated. For women with polycythemia vera, venesection may be continued when tolerated to maintain the hematocrit within the gestation-appropriate range.

Fetal ultrasound scans should be performed at 20, 26, and 34 weeks of gestation and uterine artery Doppler should be performed at 20 weeks’ gestation. If the mean pulsatility index exceeds 1.4, the pregnancy may be considered high risk, and treatment and monitoring should be increased.

In high-risk pregnancies, additional treatment includes cytoreductive therapy with or without LMWH. If cytoreductive therapy is required, INF-a should be titrated to maintain a platelet count of less than 400 X 109/L and hematocrit within appropriate range.

Local protocols regarding interruption of LMWH should be adhered to during labor, and dehydration should be avoided. Platelet count and hematocrit may increase postpartum, requiring cytoreductive therapy. Thromboprophylaxis should be considered at 6 weeks’ postpartum because of the increased risk of thrombosis, the guidelines note.

Acute leukemia

“The remarkable anemia, thrombocytopenia, and neutropenia that characterize acute myeloid and lymphoblastic leukemia” require prompt treatment. Leukapheresis in the presence of clinically significant evidence of leukostasis can be considered, regardless of gestational stage. When patients are diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia during the first trimester, pregnancy termination followed by conventional induction therapy (cytarabine/anthracycline) is recommended.

Those diagnosed later in pregnancy can receive conventional induction therapy, although this seems to be associated with increased risk of fetal growth restriction and even fetal loss. “Notably, neonates rarely experience neutropenia and cardiac impairment unless exposed to lipophilic idarubicin, which should not be used,” the panelists wrote.

When acute promyelocytic leukemia is diagnosed in the first trimester, pregnancy termination is recommended before initiating conventional ATRA-anthracycline therapy. Later in pregnancy, the regimen demonstrates low teratogenicity and can be used in women diagnosed after that stage. Arsenic treatment is highly teratogenic and is prohibited throughout gestation.

Acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) requires prophylactic CNS therapy, including methotrexate and L-asparaginase, which are fetotoxic. Methotrexate interferes with organogenesis and is prohibited before week 20 of gestation. L-asparaginase may increase the high risk for thromboembolic events attributed to the combination of pregnancy and malignancy.

Notably, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, essential for patients with Philadelphia chromosome–positive ALL, are teratogenic. Given these limitations, women diagnosed with ALL before 20 weeks’ gestation should undergo termination of the pregnancy and start conventional treatment. After week 20, conventional chemotherapy can be administered during pregnancy. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors can be initiated postpartum.

The guidelines also contain recommendations on diagnostic testing and radiotherapy, maternal supportive care, and perinatal and pediatric aspects of hematologic malignancies in pregnancy. An online appendix offers recommendations on the treatment of rare hematologic malignancies, including hairy cell leukemia, multiple myeloma, and myelodysplastic syndromes.

Dr. Lishner and nine of his coauthors had no financial relationships to disclose. Three coauthors received honoraria and research funding or are consultants to a wide variety of drug makers.

On Twitter @maryjodales

Consensus guidelines for the perinatal management of hematologic malignancies detected during pregnancy have been issued by a panel of international experts.

The guidelines, published online in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, aim to ensure that timely treatment of the cancers is not delayed in pregnant women (doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.4445).

While rare, hematologic malignancies in pregnancy introduce clinical, social, ethical, and moral dilemmas. Evidence-based data are scarce, according to the researchers, who note the International Network on Cancer, Infertility and Pregnancy registers all cancers occurring during gestation.

“Patient accrual is ongoing and essential, because registration of new cases and long-term follow-up will improve clinical knowledge and increase the level of evidence,” Dr. Michael Lishner of Tel Aviv University and Meir Medical Center, Kfar Saba, Israel, and his fellow panelists wrote.

Hodgkin lymphoma

The researchers note that Hodgkin lymphoma is the most common hematologic cancer in pregnancy, and the prognosis for these patients is excellent. When diagnosed during the first trimester, a regimen based on vinblastine monotherapy has been used. ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine) therapy can be used postpartum and has been used in cases of progression during pregnancy, the panelists wrote.

“The limited data available suggest that ABVD may be administered safely and effectively during the latter phases of pregnancy,” the panel wrote. “Although it may be associated with prematurity and lower birth weights, studies have not reported significant disadvantages.”

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

The second most common cancer in pregnancy is non-Hodgkin lymphoma. In the case of indolent disease, watchful waiting is possible, with the intent to treat with monoclonal antibodies – with or without chemotherapy – if symptoms or evidence of disease progression are noted. Steroids can be administered during the first trimester as a bridge to the second trimester, when chemotherapy can be used with relatively greater safety, the panelists noted.

Aggressive lymphomas diagnosed before 20 weeks’ gestation warrant pregnancy termination and treatment, they recommend. When diagnosed after 20 weeks, therapy should be comparable to that given a nonpregnant woman, including monoclonal antibodies (R-CHOP).

Chronic myeloid leukemia

Chronic myeloid leukemia occurs in approximately 1 in 100,000 pregnancies and is typically diagnosed during routine blood testing in an asymptomatic patient. As a result, treatment may not be needed until the patient’s white count or platelet count have risen to levels associated with the onset of symptoms. An approximate guideline is a white cell count greater than 100 X 109/L and a platelet count greater than 500 X 109/L.

Therapeutic approaches in pregnancy include interferon-a (INF-a), which does not inhibit DNA synthesis or readily cross the placenta, and leukapheresis, which is frequently required two to three times per week during the first and second trimesters. Counts tend to drop during the third trimester, allowing less frequent intervention.

Consideration should be given to adding aspirin or low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) when the platelet count exceeds 1,000 X 109/L.

Myeloproliferative neoplasms

The most common myeloproliferative neoplasm seen in women of childbearing age is essential thrombocytosis.

“A large meta-analysis of pregnant women with essential thrombocytosis reported a live birth rate of 50%-70%, first trimester loss in 25%-40%, late pregnancy loss in 10%, placental abruption in 3.6%, and intrauterine growth restriction in 4.5%. Maternal morbidity is rare, but stroke has been reported,” according to the panelists.

Limited literature suggests similar outcomes for pregnant women with polycythemia vera and primary myelofibrosis.

In low-risk pregnancies, aspirin (75 mg/day) should be offered unless clearly contraindicated. For women with polycythemia vera, venesection may be continued when tolerated to maintain the hematocrit within the gestation-appropriate range.

Fetal ultrasound scans should be performed at 20, 26, and 34 weeks of gestation and uterine artery Doppler should be performed at 20 weeks’ gestation. If the mean pulsatility index exceeds 1.4, the pregnancy may be considered high risk, and treatment and monitoring should be increased.

In high-risk pregnancies, additional treatment includes cytoreductive therapy with or without LMWH. If cytoreductive therapy is required, INF-a should be titrated to maintain a platelet count of less than 400 X 109/L and hematocrit within appropriate range.

Local protocols regarding interruption of LMWH should be adhered to during labor, and dehydration should be avoided. Platelet count and hematocrit may increase postpartum, requiring cytoreductive therapy. Thromboprophylaxis should be considered at 6 weeks’ postpartum because of the increased risk of thrombosis, the guidelines note.

Acute leukemia

“The remarkable anemia, thrombocytopenia, and neutropenia that characterize acute myeloid and lymphoblastic leukemia” require prompt treatment. Leukapheresis in the presence of clinically significant evidence of leukostasis can be considered, regardless of gestational stage. When patients are diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia during the first trimester, pregnancy termination followed by conventional induction therapy (cytarabine/anthracycline) is recommended.

Those diagnosed later in pregnancy can receive conventional induction therapy, although this seems to be associated with increased risk of fetal growth restriction and even fetal loss. “Notably, neonates rarely experience neutropenia and cardiac impairment unless exposed to lipophilic idarubicin, which should not be used,” the panelists wrote.

When acute promyelocytic leukemia is diagnosed in the first trimester, pregnancy termination is recommended before initiating conventional ATRA-anthracycline therapy. Later in pregnancy, the regimen demonstrates low teratogenicity and can be used in women diagnosed after that stage. Arsenic treatment is highly teratogenic and is prohibited throughout gestation.

Acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) requires prophylactic CNS therapy, including methotrexate and L-asparaginase, which are fetotoxic. Methotrexate interferes with organogenesis and is prohibited before week 20 of gestation. L-asparaginase may increase the high risk for thromboembolic events attributed to the combination of pregnancy and malignancy.

Notably, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, essential for patients with Philadelphia chromosome–positive ALL, are teratogenic. Given these limitations, women diagnosed with ALL before 20 weeks’ gestation should undergo termination of the pregnancy and start conventional treatment. After week 20, conventional chemotherapy can be administered during pregnancy. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors can be initiated postpartum.

The guidelines also contain recommendations on diagnostic testing and radiotherapy, maternal supportive care, and perinatal and pediatric aspects of hematologic malignancies in pregnancy. An online appendix offers recommendations on the treatment of rare hematologic malignancies, including hairy cell leukemia, multiple myeloma, and myelodysplastic syndromes.

Dr. Lishner and nine of his coauthors had no financial relationships to disclose. Three coauthors received honoraria and research funding or are consultants to a wide variety of drug makers.

On Twitter @maryjodales

Consensus guidelines for the perinatal management of hematologic malignancies detected during pregnancy have been issued by a panel of international experts.

The guidelines, published online in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, aim to ensure that timely treatment of the cancers is not delayed in pregnant women (doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.4445).

While rare, hematologic malignancies in pregnancy introduce clinical, social, ethical, and moral dilemmas. Evidence-based data are scarce, according to the researchers, who note the International Network on Cancer, Infertility and Pregnancy registers all cancers occurring during gestation.

“Patient accrual is ongoing and essential, because registration of new cases and long-term follow-up will improve clinical knowledge and increase the level of evidence,” Dr. Michael Lishner of Tel Aviv University and Meir Medical Center, Kfar Saba, Israel, and his fellow panelists wrote.

Hodgkin lymphoma

The researchers note that Hodgkin lymphoma is the most common hematologic cancer in pregnancy, and the prognosis for these patients is excellent. When diagnosed during the first trimester, a regimen based on vinblastine monotherapy has been used. ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine) therapy can be used postpartum and has been used in cases of progression during pregnancy, the panelists wrote.

“The limited data available suggest that ABVD may be administered safely and effectively during the latter phases of pregnancy,” the panel wrote. “Although it may be associated with prematurity and lower birth weights, studies have not reported significant disadvantages.”

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

The second most common cancer in pregnancy is non-Hodgkin lymphoma. In the case of indolent disease, watchful waiting is possible, with the intent to treat with monoclonal antibodies – with or without chemotherapy – if symptoms or evidence of disease progression are noted. Steroids can be administered during the first trimester as a bridge to the second trimester, when chemotherapy can be used with relatively greater safety, the panelists noted.

Aggressive lymphomas diagnosed before 20 weeks’ gestation warrant pregnancy termination and treatment, they recommend. When diagnosed after 20 weeks, therapy should be comparable to that given a nonpregnant woman, including monoclonal antibodies (R-CHOP).

Chronic myeloid leukemia

Chronic myeloid leukemia occurs in approximately 1 in 100,000 pregnancies and is typically diagnosed during routine blood testing in an asymptomatic patient. As a result, treatment may not be needed until the patient’s white count or platelet count have risen to levels associated with the onset of symptoms. An approximate guideline is a white cell count greater than 100 X 109/L and a platelet count greater than 500 X 109/L.

Therapeutic approaches in pregnancy include interferon-a (INF-a), which does not inhibit DNA synthesis or readily cross the placenta, and leukapheresis, which is frequently required two to three times per week during the first and second trimesters. Counts tend to drop during the third trimester, allowing less frequent intervention.

Consideration should be given to adding aspirin or low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) when the platelet count exceeds 1,000 X 109/L.

Myeloproliferative neoplasms

The most common myeloproliferative neoplasm seen in women of childbearing age is essential thrombocytosis.

“A large meta-analysis of pregnant women with essential thrombocytosis reported a live birth rate of 50%-70%, first trimester loss in 25%-40%, late pregnancy loss in 10%, placental abruption in 3.6%, and intrauterine growth restriction in 4.5%. Maternal morbidity is rare, but stroke has been reported,” according to the panelists.

Limited literature suggests similar outcomes for pregnant women with polycythemia vera and primary myelofibrosis.

In low-risk pregnancies, aspirin (75 mg/day) should be offered unless clearly contraindicated. For women with polycythemia vera, venesection may be continued when tolerated to maintain the hematocrit within the gestation-appropriate range.

Fetal ultrasound scans should be performed at 20, 26, and 34 weeks of gestation and uterine artery Doppler should be performed at 20 weeks’ gestation. If the mean pulsatility index exceeds 1.4, the pregnancy may be considered high risk, and treatment and monitoring should be increased.

In high-risk pregnancies, additional treatment includes cytoreductive therapy with or without LMWH. If cytoreductive therapy is required, INF-a should be titrated to maintain a platelet count of less than 400 X 109/L and hematocrit within appropriate range.

Local protocols regarding interruption of LMWH should be adhered to during labor, and dehydration should be avoided. Platelet count and hematocrit may increase postpartum, requiring cytoreductive therapy. Thromboprophylaxis should be considered at 6 weeks’ postpartum because of the increased risk of thrombosis, the guidelines note.

Acute leukemia

“The remarkable anemia, thrombocytopenia, and neutropenia that characterize acute myeloid and lymphoblastic leukemia” require prompt treatment. Leukapheresis in the presence of clinically significant evidence of leukostasis can be considered, regardless of gestational stage. When patients are diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia during the first trimester, pregnancy termination followed by conventional induction therapy (cytarabine/anthracycline) is recommended.

Those diagnosed later in pregnancy can receive conventional induction therapy, although this seems to be associated with increased risk of fetal growth restriction and even fetal loss. “Notably, neonates rarely experience neutropenia and cardiac impairment unless exposed to lipophilic idarubicin, which should not be used,” the panelists wrote.

When acute promyelocytic leukemia is diagnosed in the first trimester, pregnancy termination is recommended before initiating conventional ATRA-anthracycline therapy. Later in pregnancy, the regimen demonstrates low teratogenicity and can be used in women diagnosed after that stage. Arsenic treatment is highly teratogenic and is prohibited throughout gestation.

Acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) requires prophylactic CNS therapy, including methotrexate and L-asparaginase, which are fetotoxic. Methotrexate interferes with organogenesis and is prohibited before week 20 of gestation. L-asparaginase may increase the high risk for thromboembolic events attributed to the combination of pregnancy and malignancy.

Notably, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, essential for patients with Philadelphia chromosome–positive ALL, are teratogenic. Given these limitations, women diagnosed with ALL before 20 weeks’ gestation should undergo termination of the pregnancy and start conventional treatment. After week 20, conventional chemotherapy can be administered during pregnancy. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors can be initiated postpartum.

The guidelines also contain recommendations on diagnostic testing and radiotherapy, maternal supportive care, and perinatal and pediatric aspects of hematologic malignancies in pregnancy. An online appendix offers recommendations on the treatment of rare hematologic malignancies, including hairy cell leukemia, multiple myeloma, and myelodysplastic syndromes.

Dr. Lishner and nine of his coauthors had no financial relationships to disclose. Three coauthors received honoraria and research funding or are consultants to a wide variety of drug makers.

On Twitter @maryjodales

FROM JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Medical Roundtable: Pediatric Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma (NHL) Classification Guidelines - International Pediatric NHL Staging System (IPNHLSS)

Moderator: Catherine Bollard, MD, FRACP, FRCPA1

Discussants: Mitchell S. Cairo, MD2; Eric J. Lowe, MD3; Thomas G. Gross, MD, PhD4

Address for correspondence: Catherine Bollard, MD, FRACP, FRCPA, 111 Michigan Avenue, NW, 5th Floor Main, Suite 5225, Washington, DC 20010

E-mail: cbollard@cnmc.org

Biographical sketch: From The George Washington University, School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Washington, DC1; Westchester Medical Center, New York Medical College, Valhalla, NY2; Children’s Hospital of the King’s Daughters, Norfolk, VA3; Center for Global Health at the National Cancer Institute, Rockville, MD

DR. BOLLARD: My name is Dr. Catherine Bollard. I'm Chief of the Division of Allergy and Immunology at Children's National Health System and the Chair of the NHL Committee of the Children's Oncology Group. I hope that today we can provide some clarity and give you some of our first-hand expertise and experience regarding some of the challenges and controversies of treating pediatric patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). Here with me are Drs. Mitchell Cairo, Chief of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology and Stem Cell Transplantation at New York Medical College in the Maria Fareri Children's Hospital, Westchester Medical Center; Eric Lowe, Division Director for Pediatric Hematology/Oncology at the Children's Hospital of the King's Daughters; and Thomas Gross, Deputy Director for Science at the Center for Global Health at the National Cancer Institute.

I'd like to start the questioning, firstly to Dr. Cairo, who recently published with a group of leaders in the pediatric lymphoma field, new staging and response classifications. Dr. Cairo, I’d like you to highlight how these are different from the current classifications, and what you see are the strengths and the limitations at this time.

DR. CAIRO: Thank you, Cath. The original staging classification was developed in the late 1970s by Dr. Murphy while she was at St. Jude's hospital, and either goes by the name the Murphy Staging Classification or the St. Jude's Classification. That classification I think was quite useful at that time when we recognized really only a couple subtypes of NHL, as well as the capabilities we had in those days both imaging as well as further molecular identification as well as trying to identify sites of spread. As some 35 years have evolved, new pathological entities have been identified, much more precise imaging techniques, new methods of detecting more evidence of minimal disease, and also identifying new organ sites of involvement, allowed the creation of a multidisciplinary international task force to look at how we could enhance the original observations by the St. Jude's group.

As Dr. Bollard pointed out, we eventually, over 9 years of evidence-based review, came up with an enhanced staging classification called the International Pediatric NHL Staging System (IPNHLSS).1 In this new system we account for new histological subtypes, allow for different organ distributions, improve on the new imaging techniques to identify areas of involvement, and also to more molecularly identify extent of disease. I think the advantages are stated above. The disadvantage is that like all staging systems it's a breathing document. It will require international collaboration. As time evolves, this staging system will of course need to be updated as we gain new experience.

Briefly, in terms of the response classification that also came out of the same international multidisciplinary task force that was led by Dr. Sandlund at St. Jude's2; there had never been a response criteria that had been focused entirely in childhood and adolescent NHL. The previous response criteria had been developed by adult NHL investigators, and there was a need to develop the first response criteria for pediatric NHL because of different histologies, different sites of sanctuary disease, and now obviously enhanced imaging capabilities. That also now has been named the International Pediatric Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Response Criteria (IPNHLRC)—hopefully for harmonizing a response across new studies, but also a breathing document that is going to be limited as we gain new knowledge into how we can better assess response as new techniques are developed.

DR. BOLLARD: I thank you very much for your detailed response. My next question is actually to Dr. Gross, who is currently chairing the international study for upfront diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and Burkitt lymphoma in pediatric young adults. I would like you to speak to a couple of issues, and you can put it in the context of the current randomized trial, looking at rituximab vs no rituximab for this disease. I think firstly it would be useful for you to speak to the implications of this new classification system as we go forward with choosing new therapeutic strategies for these patients, and in particular I'd like to focus on the newly diagnosed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients who are in that adolescent/young adult range.

I would also be interested in your opinion regarding how you would manage a patient who is 17 years old but is going to turn 18 tomorrow, and he comes to you with newly diagnosed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. As you know, the adult oncologists treat diffuse large B-cell lymphoma different to Burkitt lymphoma, and in pediatrics we generally treat these diseases the same. Do you tell this patient that you will treat him today on a pediatric regimen, or do you tell him to go tomorrow, when he's 18, to be treated by an adult oncologist? I would like you to justify your answer please.

DR. GROSS: First to discuss the implications of the new staging as it applies to the current international trial. As Dr. Cairo pointed out, this was developed through a literature review and evidence based analyses, but like any new staging system, the value of staging is to provide us with information that can try to help us to identify patients to improve their outcome. Essentially, staging is to help direct therapy or provide prognosis for outcome, and the only way to do that is to test new systems or classifications in a prospective fashion. Indeed, that is what we are trying to do with this international effort.

This international effort, just as an aside, illustrates one of the challenges of all rare cancers, but particularly pediatrics. In pediatric mature B-cell NHL, both large-cell and Burkitt, we are now at a cure rate of about 90%. To make advances, we don't have enough patients seen in North America and Australia, and it requires international collaboration. This trial, to get 600 patients randomized, it will take 7 years with 14 countries participating—that is one of the challenges, certainly, we have with pediatric NHL. Also, we want to try to gain as much information as possible, not just to the effect of rituximab as Dr. Bollard said, but also to test other questions such as the role or the value in validating this new staging system.

To talk about the controversy of treatment, certainly we know that there is a very different approach in pediatrics. For many years, we have treated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma just like Burkitt. This is a very important delineation when you're seen by a medical oncologist because the treatment for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is outpatient therapy, ie rituximab, cyclophosphamide, adriamycin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP). Treatment for Burkitt is inpatient with high doses of methotrexate, but other higher doses of the same agents used to treat diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. The question is, do we really need to treat all the pediatric diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with these aggressive Burkitt regimens? I think one of the things that is encouraging to me as a pediatric oncologist is that we are beginning to learn that the biology is very different. Though the disease looks the same under the microscope or by flow cytometry, when you look at it genetically it's quite different. We know now that the younger the patient is with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, even though it looks for all intents and purposes like the same disease as seen in adults, when you look at the genetics, many times, as high as 30% of the time, it will be genetically the same as a Burkitt lymphoma. I think when you're talking about young patients we can easily justify treating them both the same because the biology would suggest that a good number of patients would need Burkitt therapy to be cured.

Now, that changes over time, so that it appears that sometime in young adulthood, maybe somewhere between 25 and 35 years of age, you don't see the genetic disease that looks like diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, but is genetically Burkitt lymphoma. As for the 18-year-old patient that Dr. Bollard was posing to me, I've had several patients like this. I go through the pluses and minuses of the therapy, inpatient vs outpatient, but also the potential long-term side effects. The outpatient therapy has potentially more long-term side effects as far as potential infertility and potential heart damage. Every time I have given the choice to the family and the patient, the teenager has always chosen the outpatient therapy that you would get as an adult, and the parents always say they would rather have the inpatient therapy, and that spending a couple of days in the hospital to try to reduce the chance of long-term damage is their choice. It's a very interesting dynamic and I think sometimes the issues that go into choice of treatment are quite variable. My personal opinion is that hopefully in the future we will be able to have a better understanding of biology, so that when we see these patients, be they 18 or 25 years old, we're not looking at what it looks like under the microscope or who they see, and what they're used to giving, but the biology will determine which therapy is more likely to cure them. Right now we don't have that ability in most of the patients.

DR. BOLLARD: Thank you, Dr. Gross. Again, another very comprehensive answer to a difficult question. I'm actually going to push this back to Dr. Cairo and then impose the same soon to be 18-year-old patient to you. This time, he's coming to you with relapsed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. What are you going to tell him? Are you going to treat him today on pediatric protocols, or will you wait until tomorrow when he could have access to adult protocols?

DR. CAIRO: I think the results are relatively similar, but, in part, the answer to the question is of course based on what their original therapy was. If the original therapy was the pediatric-inspired type of treatment, I think there's a world of experience of what are some of the best pediatric-inspired regimens to use for retrieval. If, however, the original therapy was an adult-inspired regimen, then I think the options are open because the disease may not be as resistant in that setting; therefore, one would want to consider all the adult type of retrieval regimens in that case, because that group of patients—at least in the adult experience—tend to have disease that may be more responsive because they're not as resistant to the higher dose and multi-agent therapy that a pediatric-inspired regimen would have given them had they been treated that way.

DR. BOLLARD: I was also trying to ask you to speak to the access that an 18-year-old might have to novel therapies that a 17-year-old might not. How do you address that issue?

DR. CAIRO: That's an excellent question. I think that for first relapse or first induction failure most of the retrieval regimens, the first line regimens, that are available, either pediatric inspired or adult inspired, probably don't require an investigational agent that an 18-year-old might have access to if he was being treated on an adult type of regimen. However, I would strongly encourage an 18-year-old who failed one retrieval regimen to consider experimental therapy. There I think the access to new agents—if you're 18 or over—are so much greater that I would encourage them to be treated on an adult retrieval regimen, where some of the newer agents may be investigational, are not available to a pediatric program.

DR. BOLLARD: Thank you very much, Dr. Cairo. I have one last question on the B-cell diseases before I move to Dr. Lowe, and the last question goes to Dr. Gross. Would you recommend that a patient with relapsed Burkitt lymphoma—now increasingly rare—be treated with salvage chemotherapy and then autologous transplant or allogeneic stem cell transplant?

DR. GROSS: As the others on this discussion know, we performed an analysis from data in the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR), and the problem is that Burkitt lymphoma tends to reoccur so rapidly after transplant. The median time to relapse is 3 months after transplant. We could not find a difference in the outcome between autografts and allografts because of its early reoccurrence. That said, my personal opinion is, since we know that Burkitt lymphoma is a hematologically spread disease, that I always prefer a donor source where I know they're not going to have tumor cells in them, which is an allogeneic donor. I always prefer an allogeneic donor, because I know it's tumor-free, but also it gives us an opportunity, if the disease will stay under control long enough, to potentially get an immune response against any residual tumor. For that reason, I recommend an allogeneic donor if it can be found readily.