User login

Subcutaneous Nodule on the Postauricular Neck

The Diagnosis: Pleomorphic Lipoma

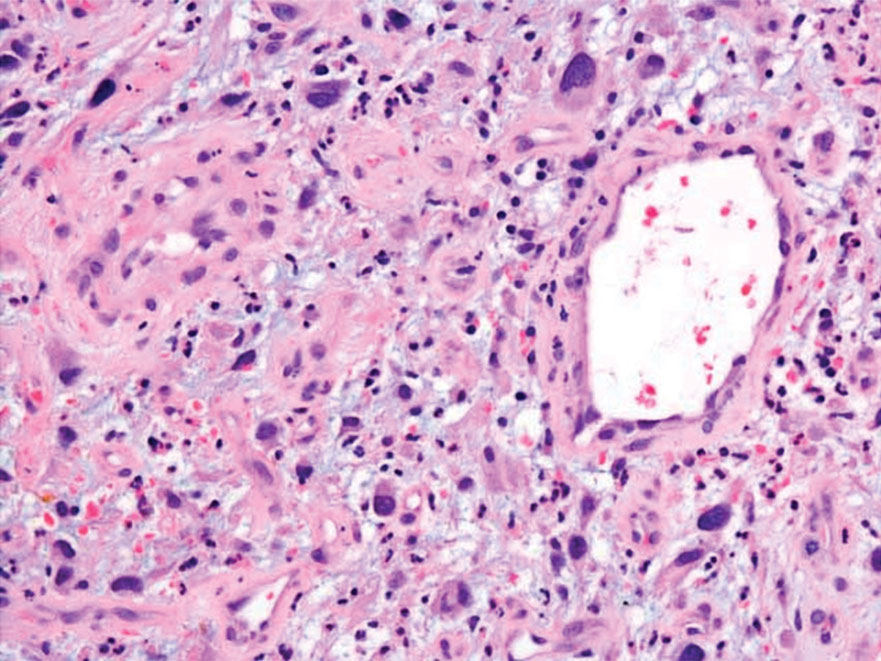

Pleomorphic lipoma is a rare, benign, adipocytic neoplasm that presents in the subcutaneous tissues of the upper shoulder, back, or neck. It predominantly affects men aged 50 to 70 years. Most lesions are situated in the subcutaneous tissues; few cases of intramuscular and retroperitoneal tumors have been reported.1 Clinically, pleomorphic lipomas present as painless, well-circumscribed lesions of the subcutaneous tissue that often resemble a lipoma or occasionally may be mistaken for liposarcoma. Histopathologic examination of ordinary lipomas reveals uniform mature adipocytes. However, pleomorphic lipomas consist of a mixture of multinucleated floretlike giant cells, variable-sized adipocytes, and fibrous tissue (ropy collagen bundles) with some myxoid and spindled areas.1,2 The most characteristic histologic feature of pleomorphic lipoma is multinucleated floretlike giant cells. The nuclei of these giant cells appear hyperchromatic, enlarged, and disposed to the periphery of the cell in a circular pattern. Additionally, tumors frequently contain excess mature dense collagen bundles that are strongly refractile in polarized light. Numerous mast cells are present. Atypical lipoblasts and capillary networks commonly are not visible in pleomorphic lipoma.3 The spindle cells express CD34 on immunohistochemistry. Loss of Rb-1 expression is typical.4

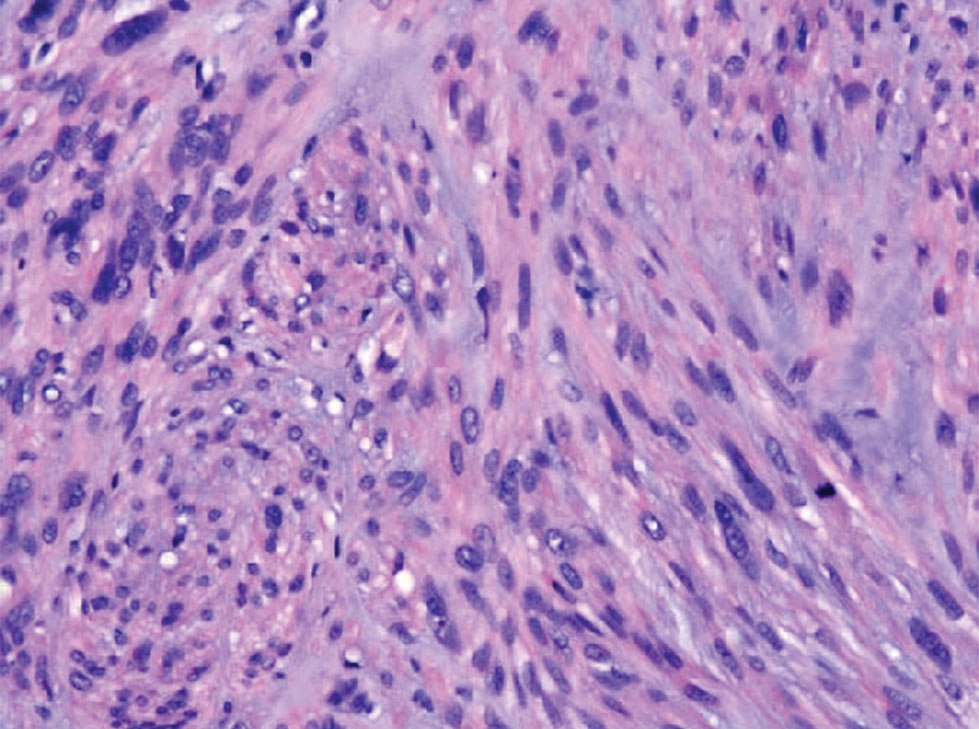

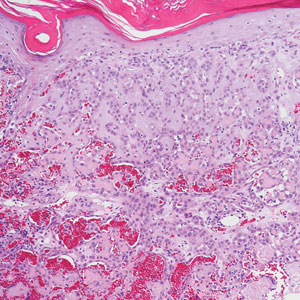

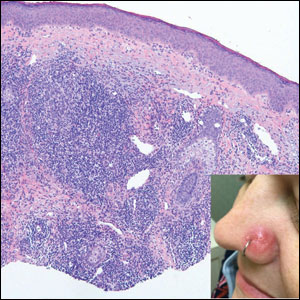

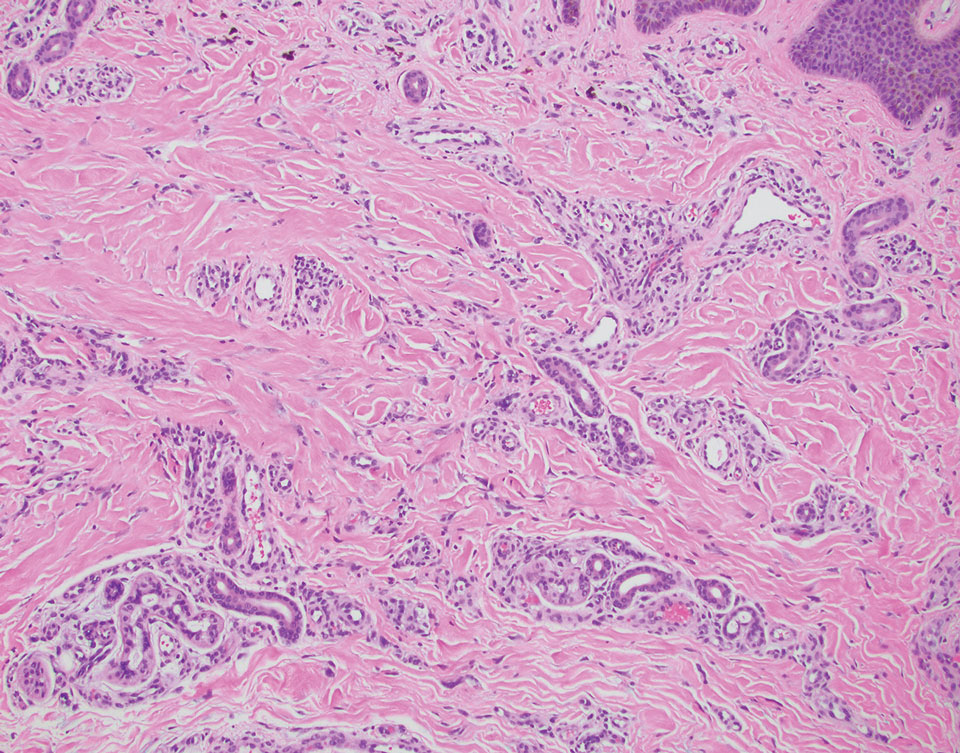

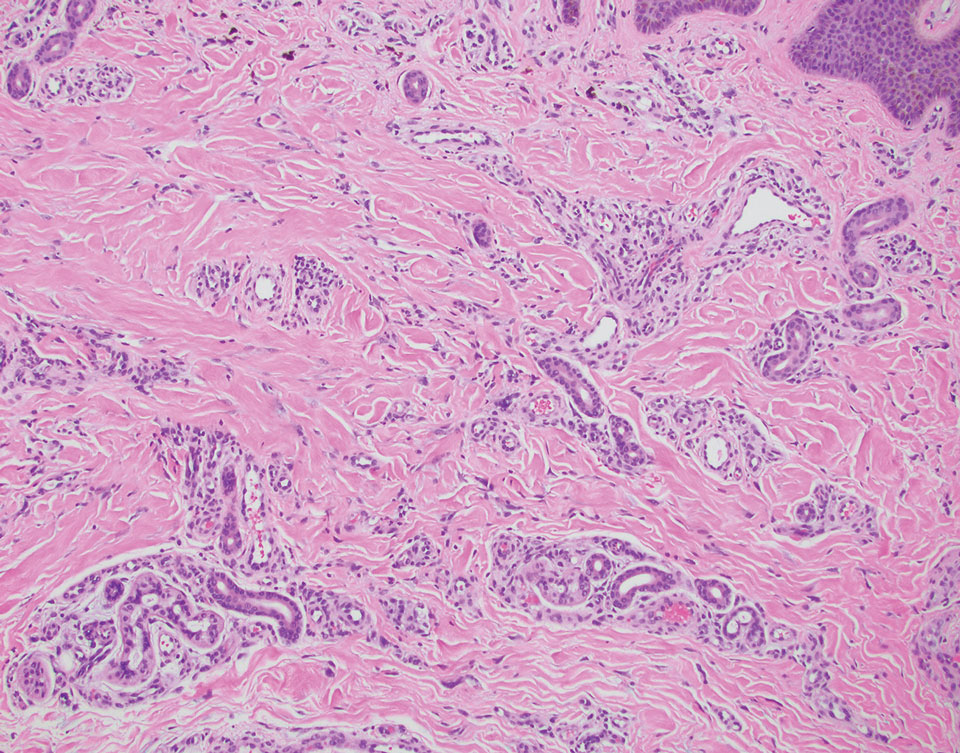

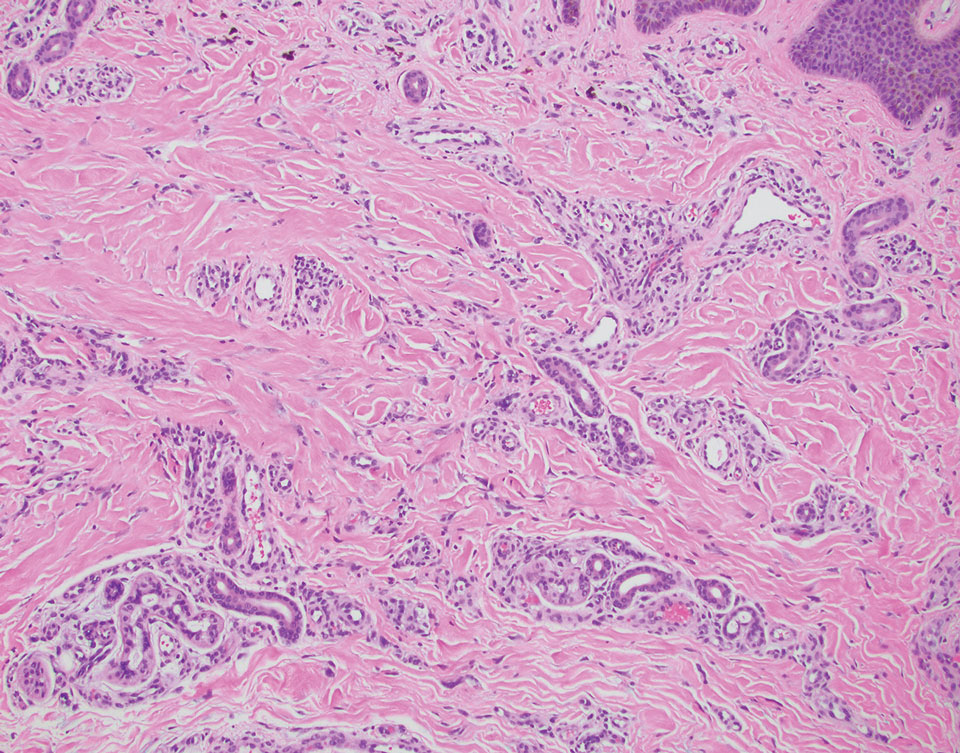

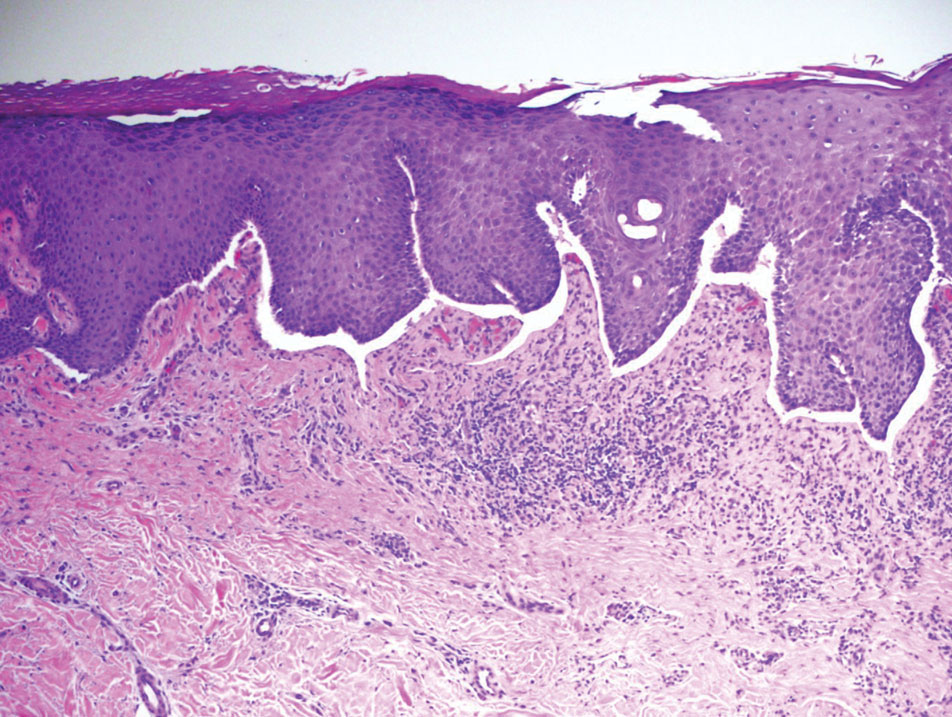

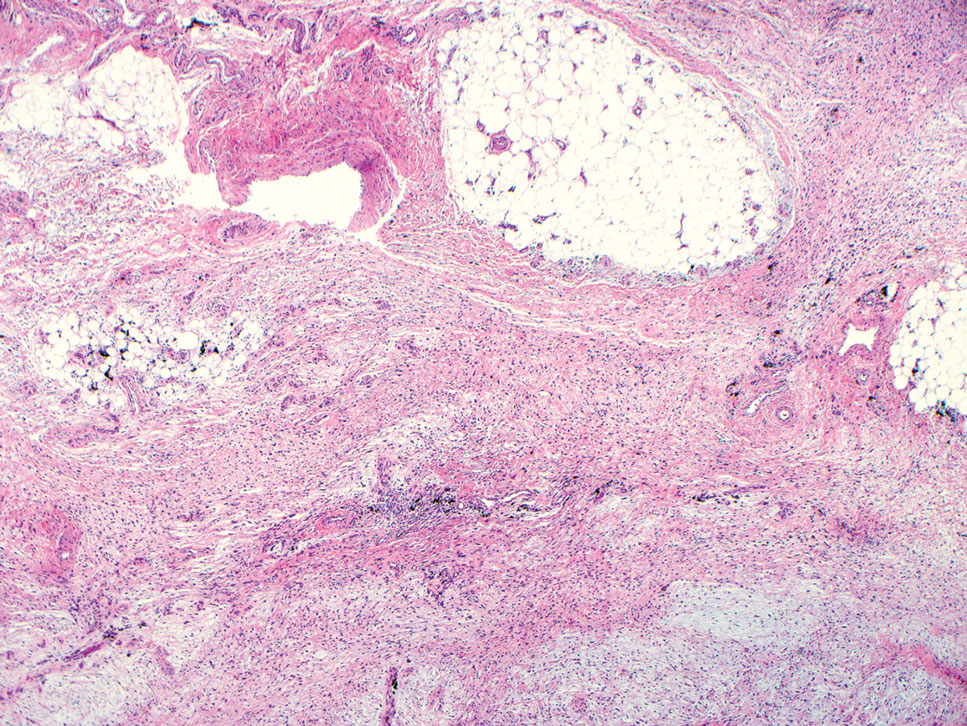

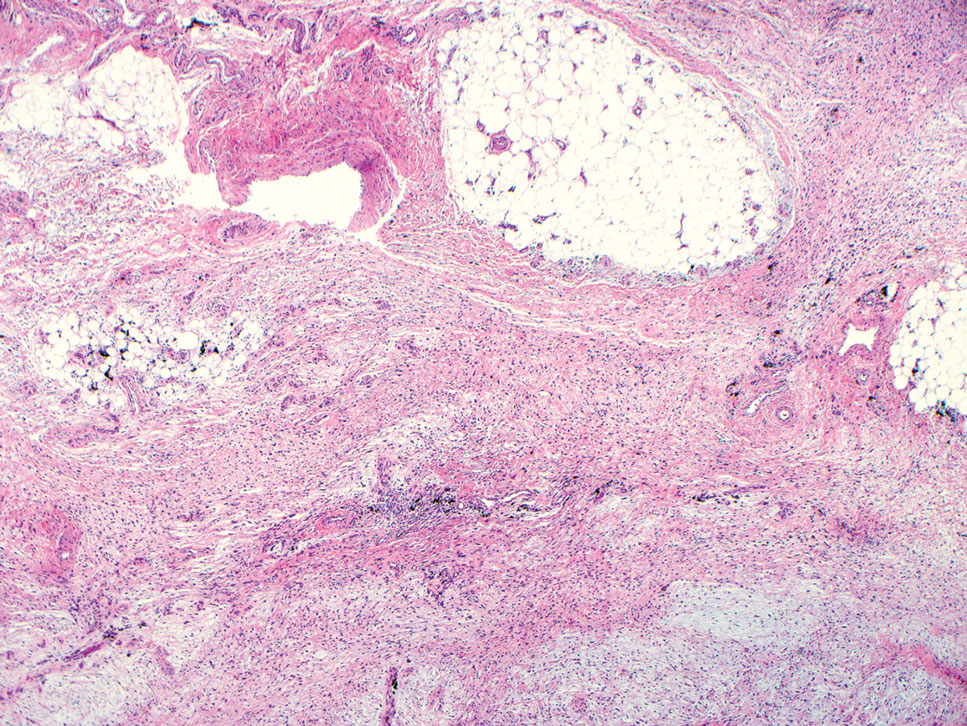

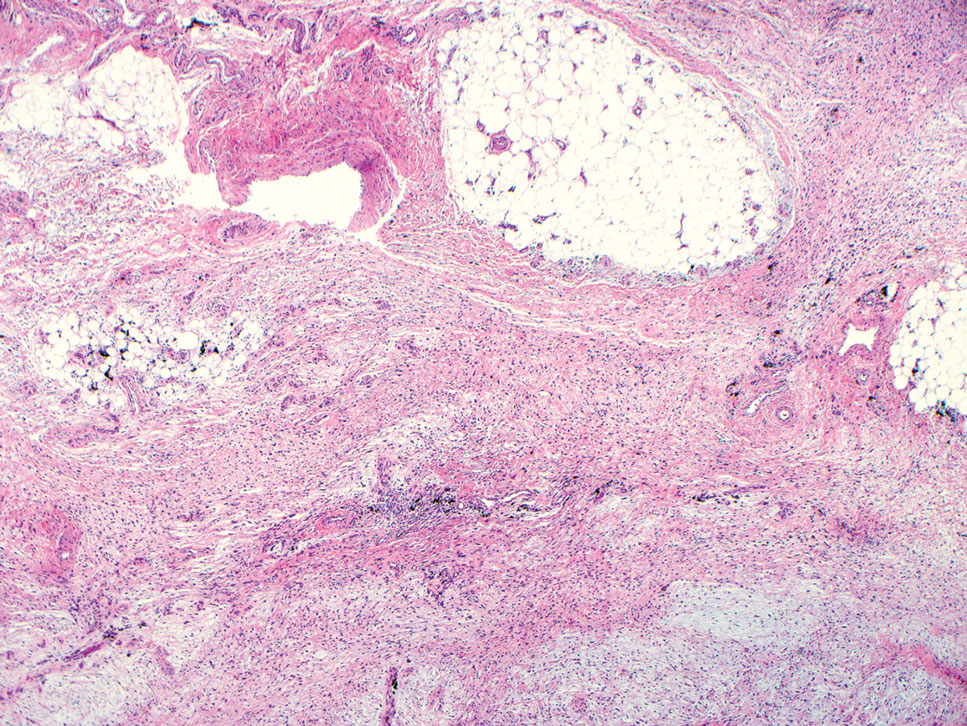

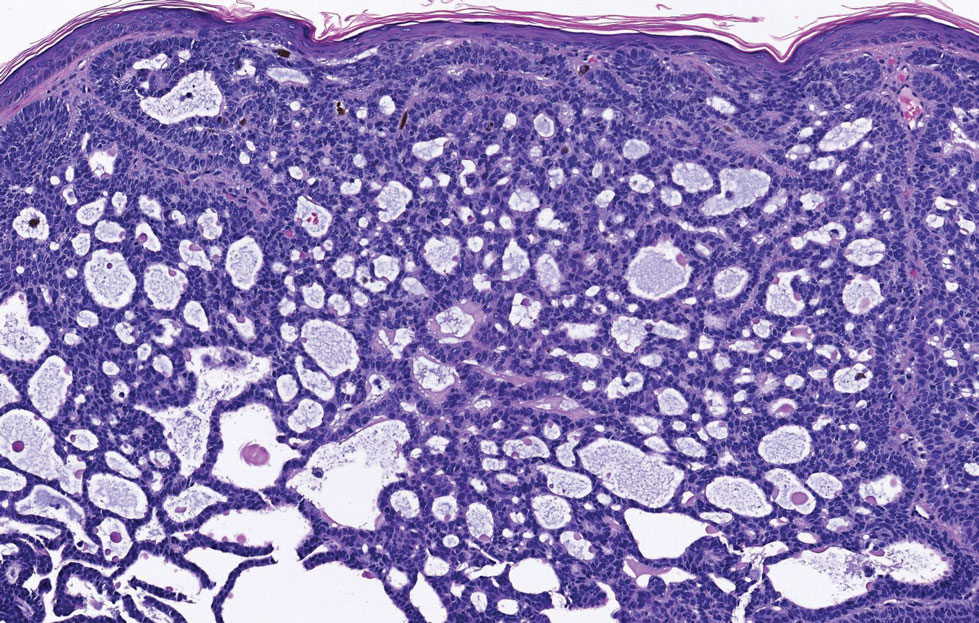

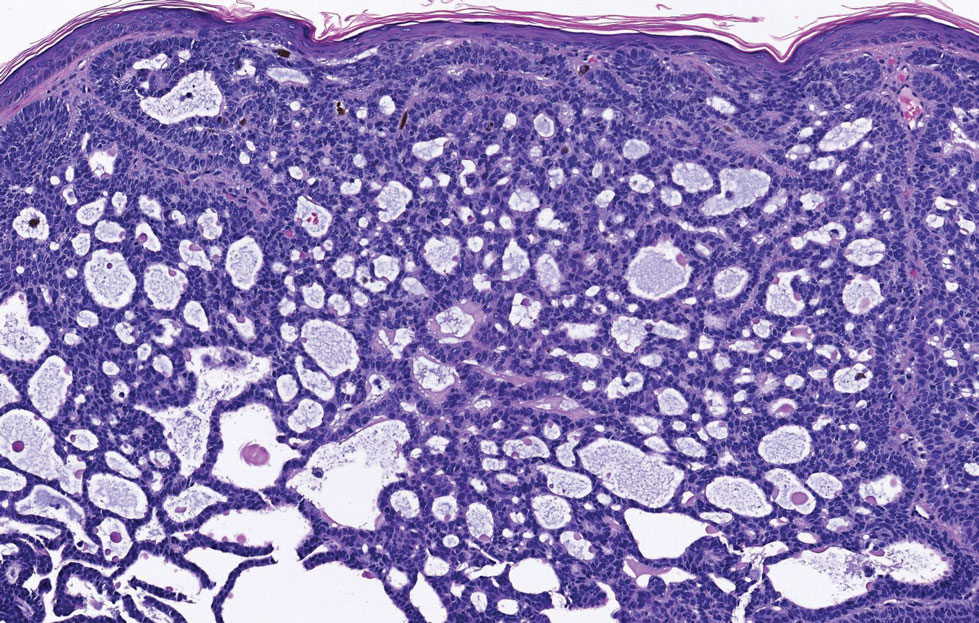

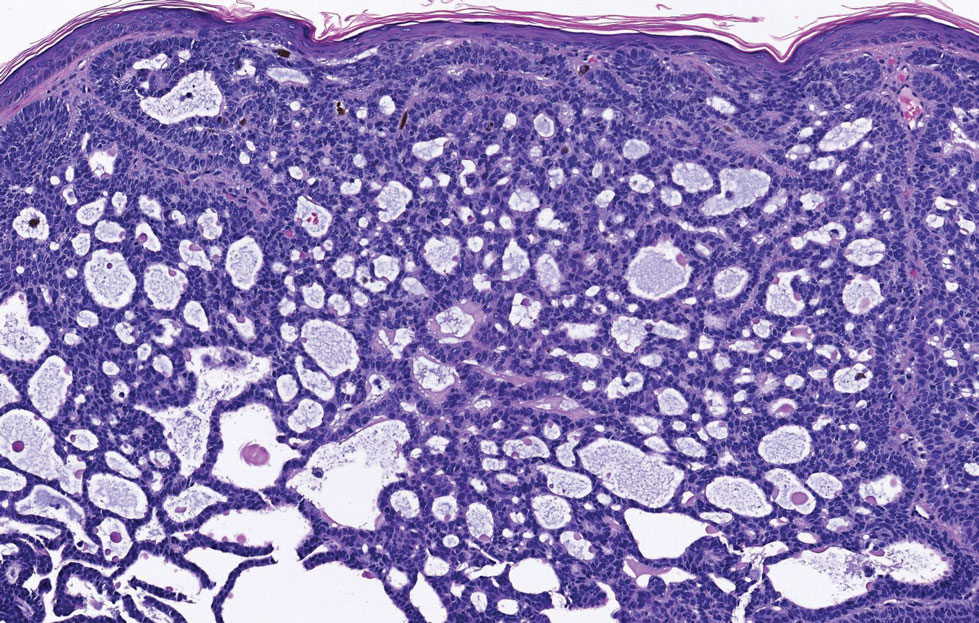

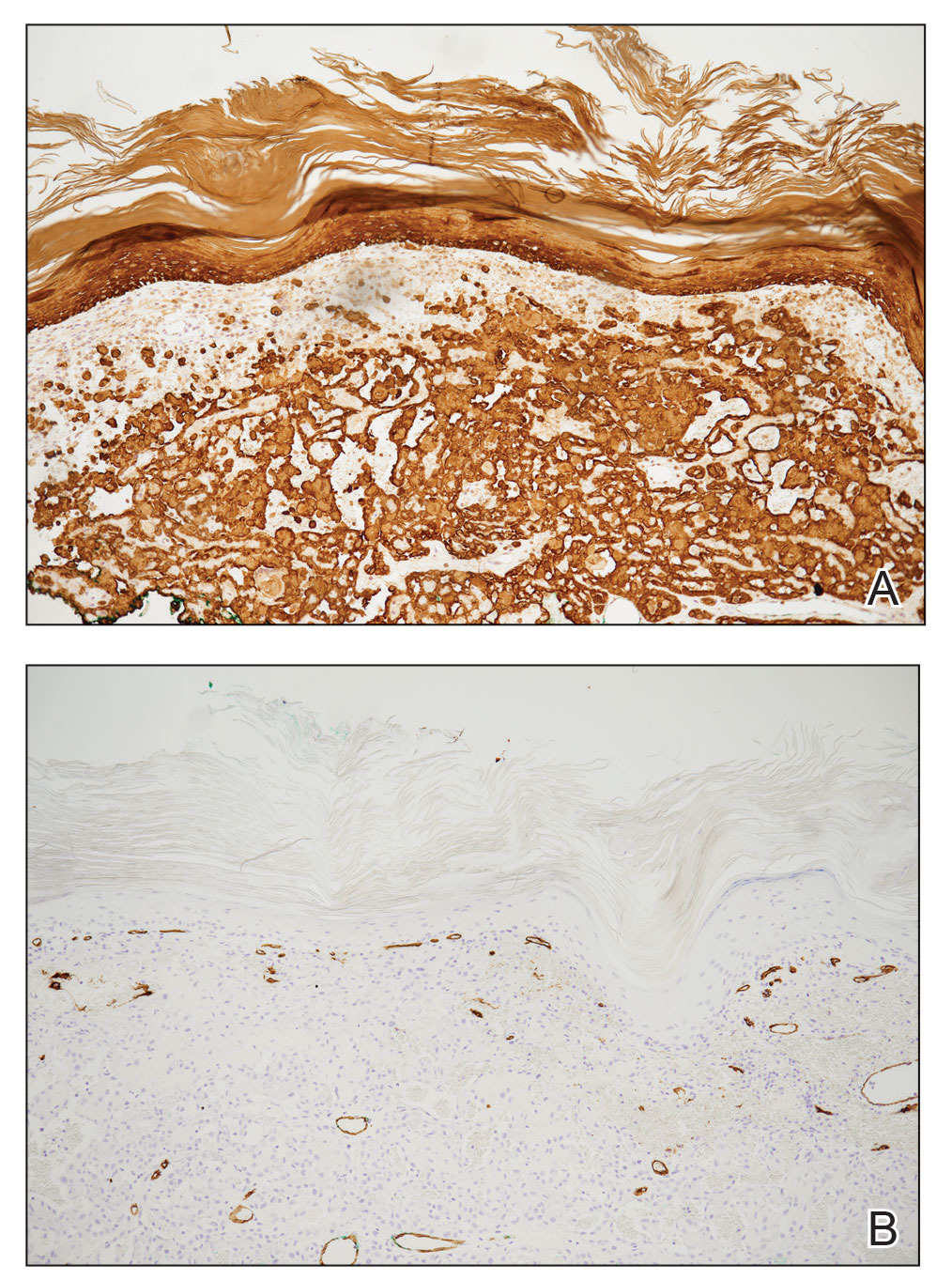

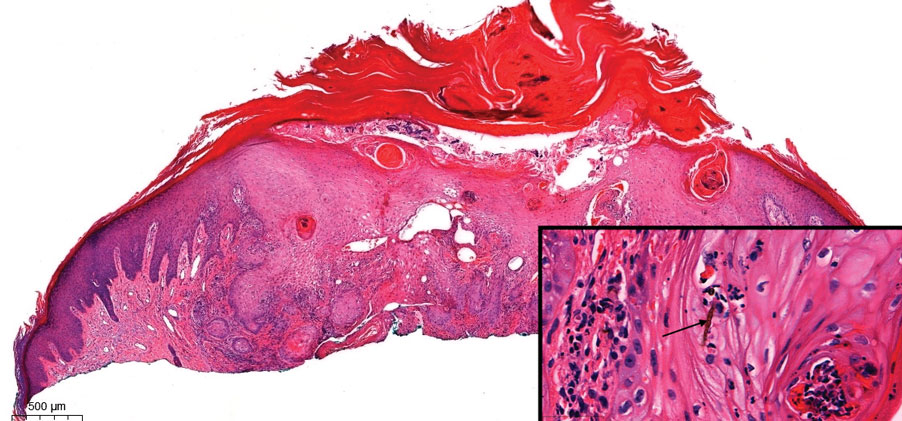

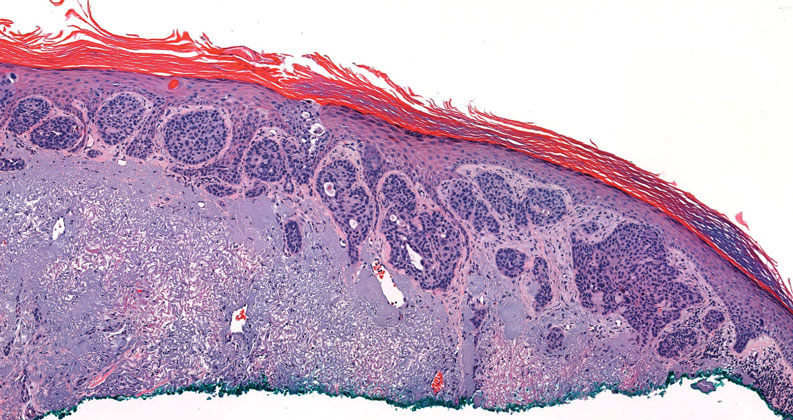

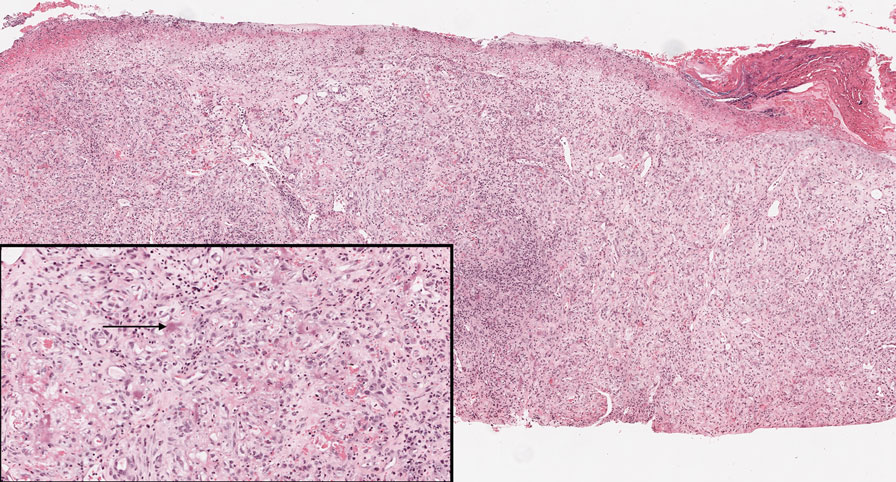

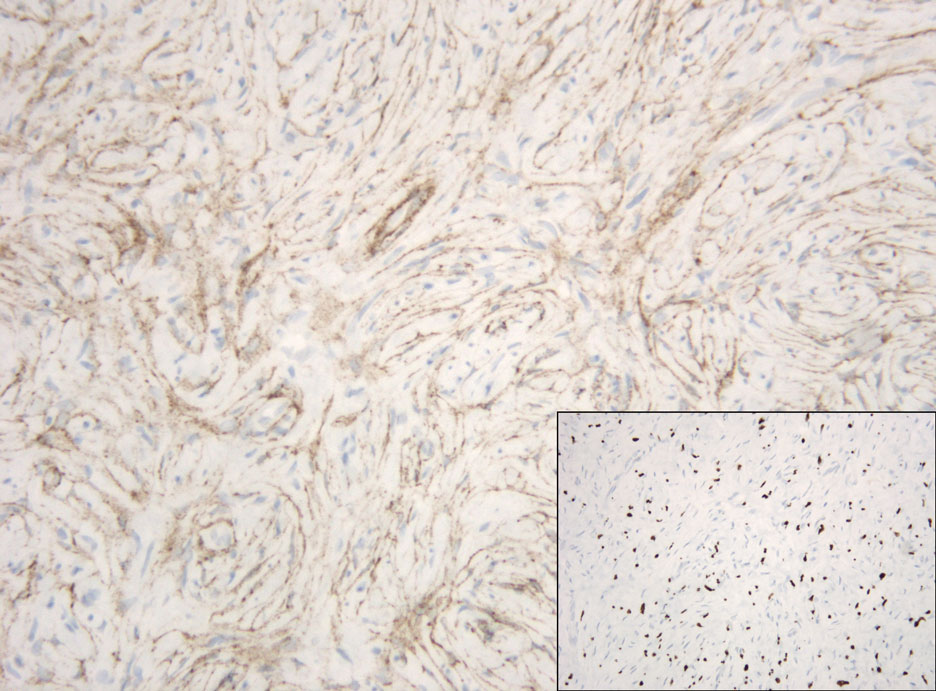

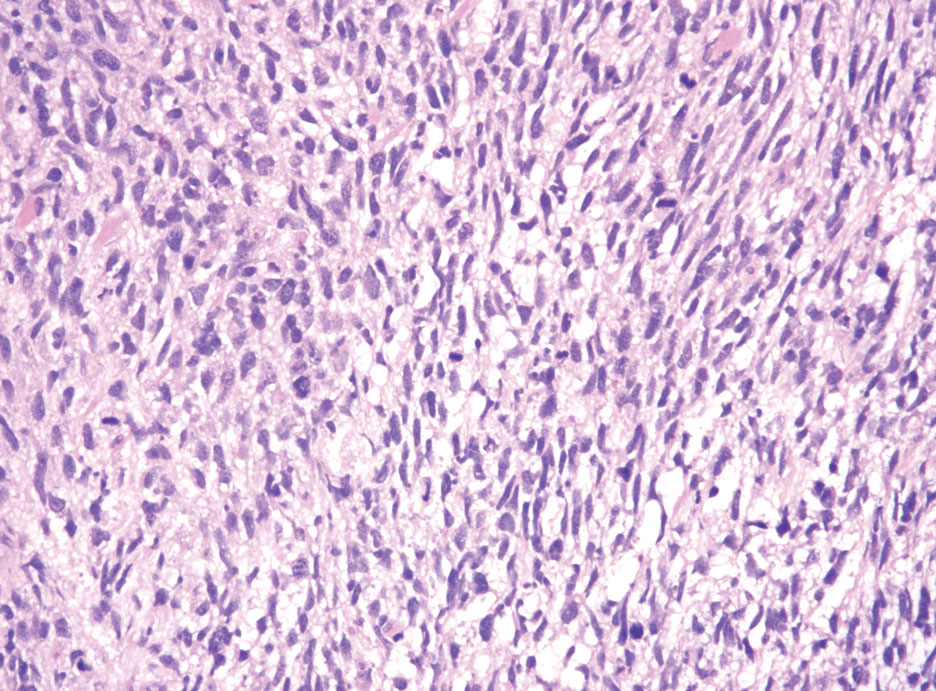

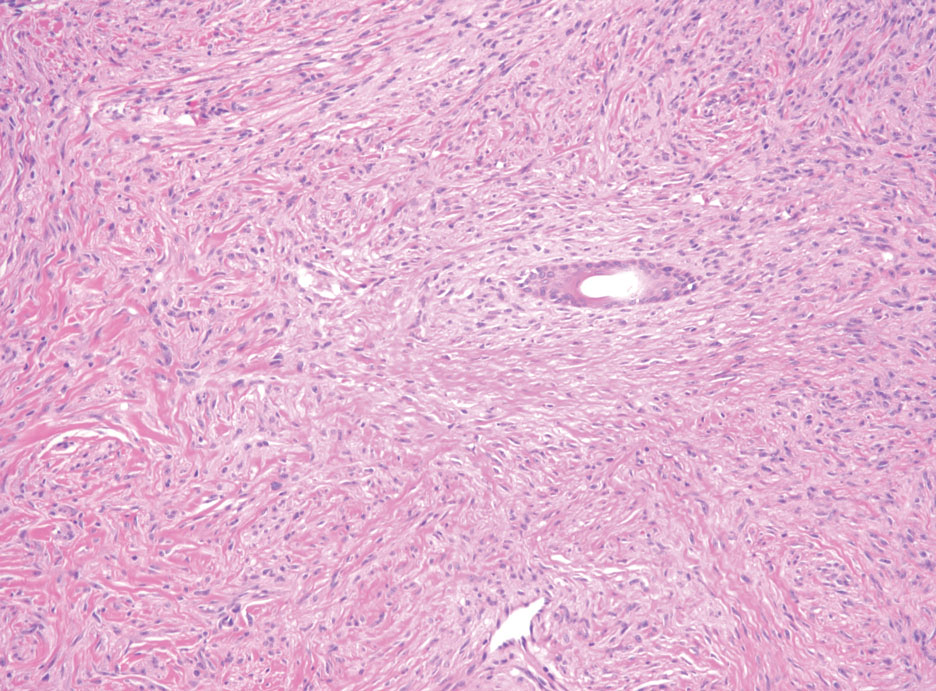

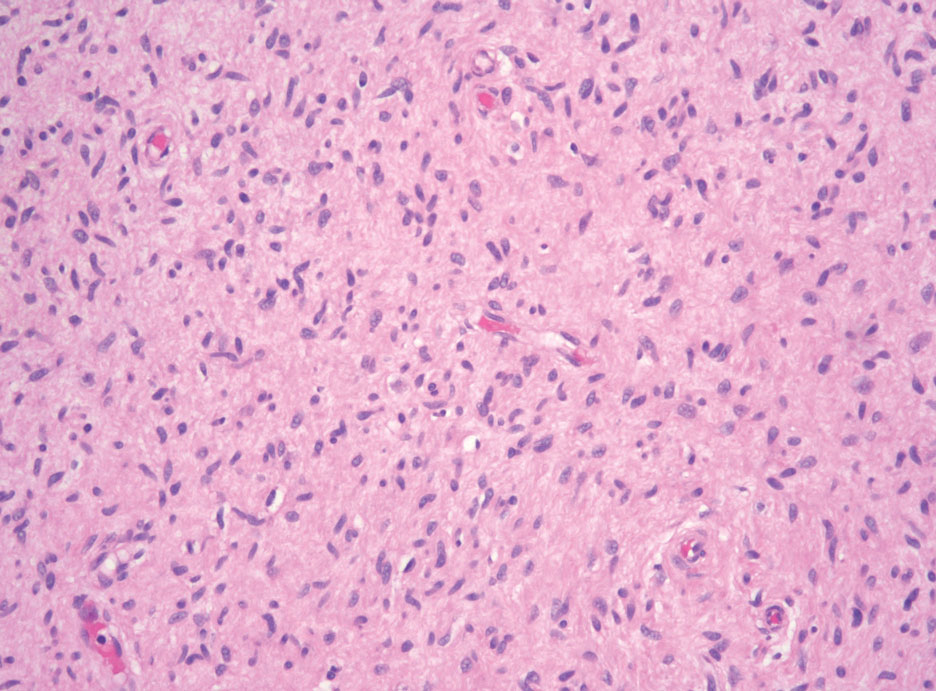

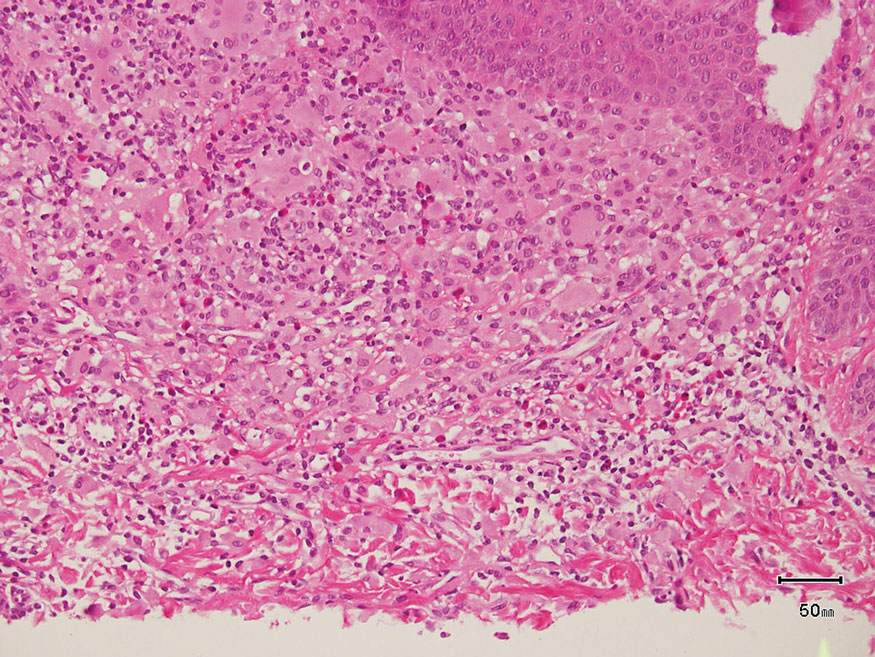

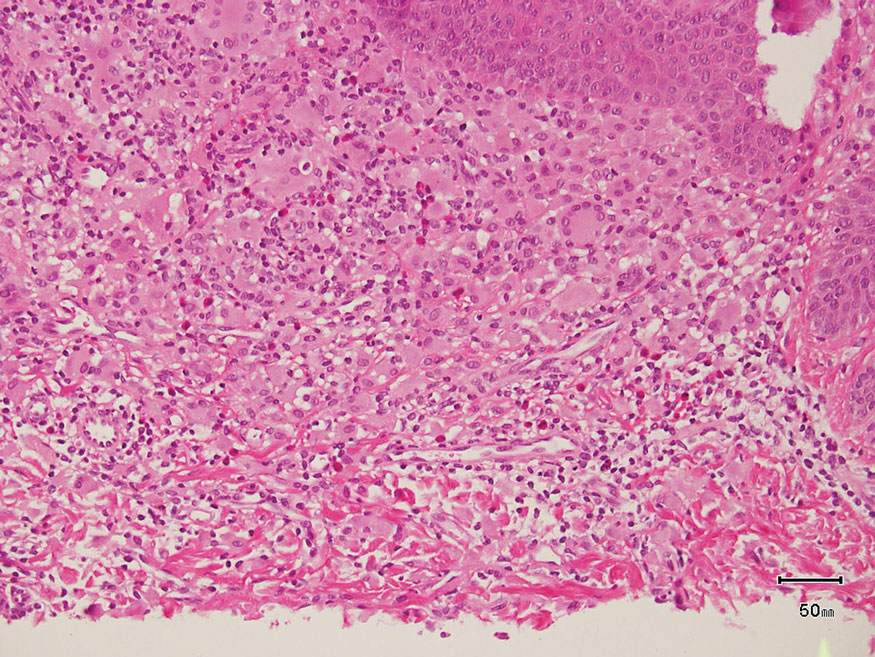

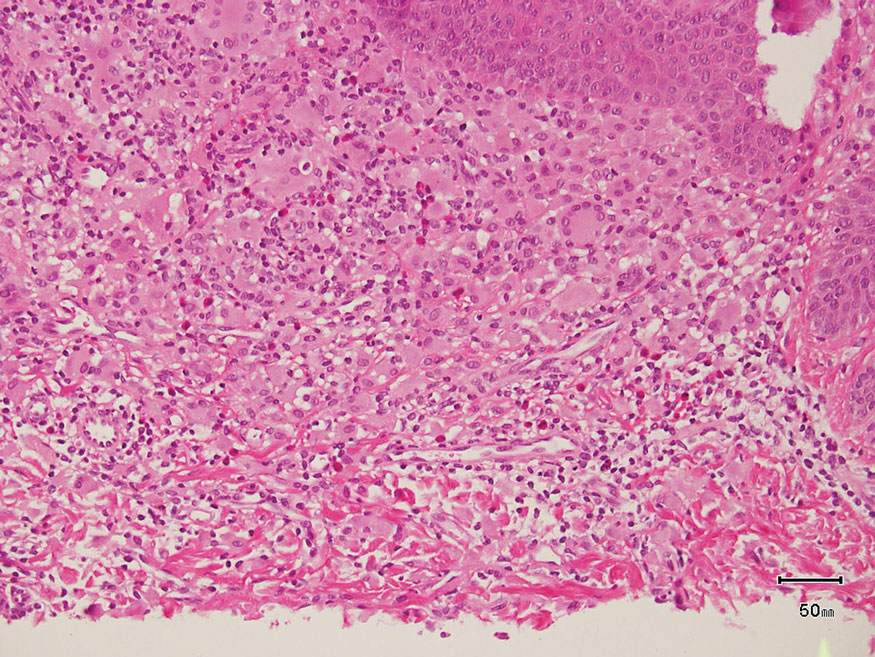

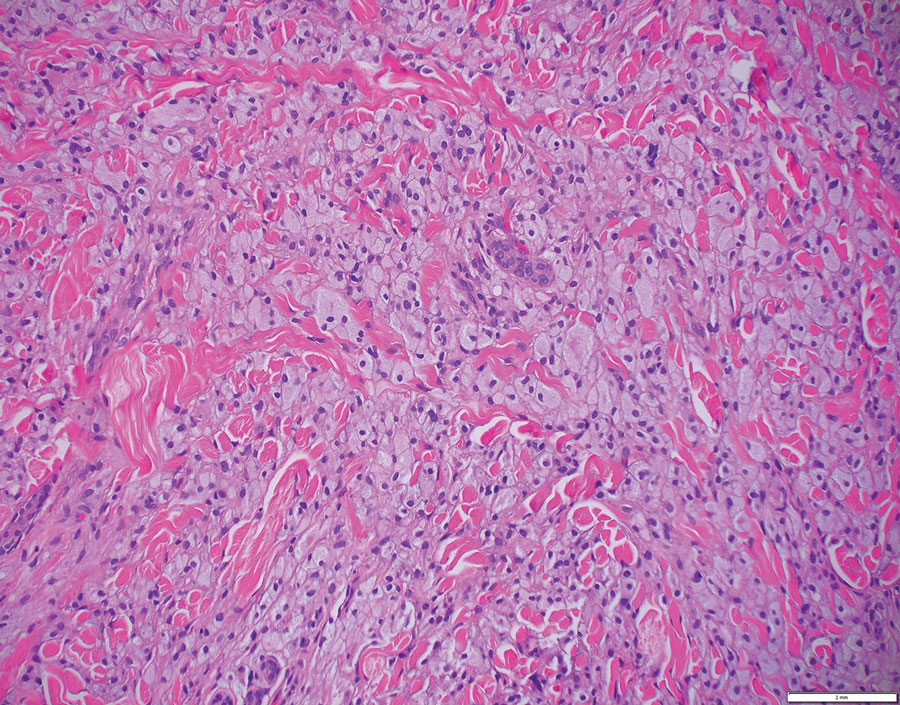

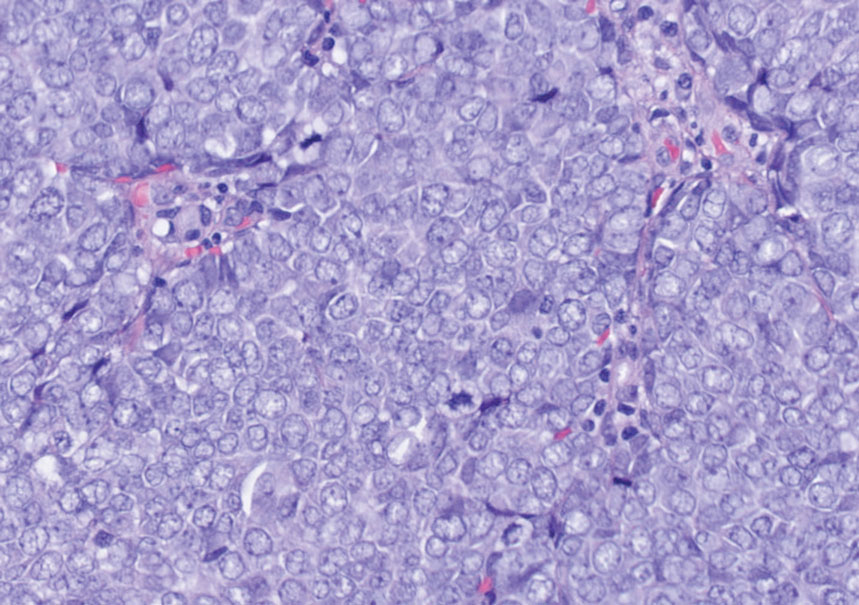

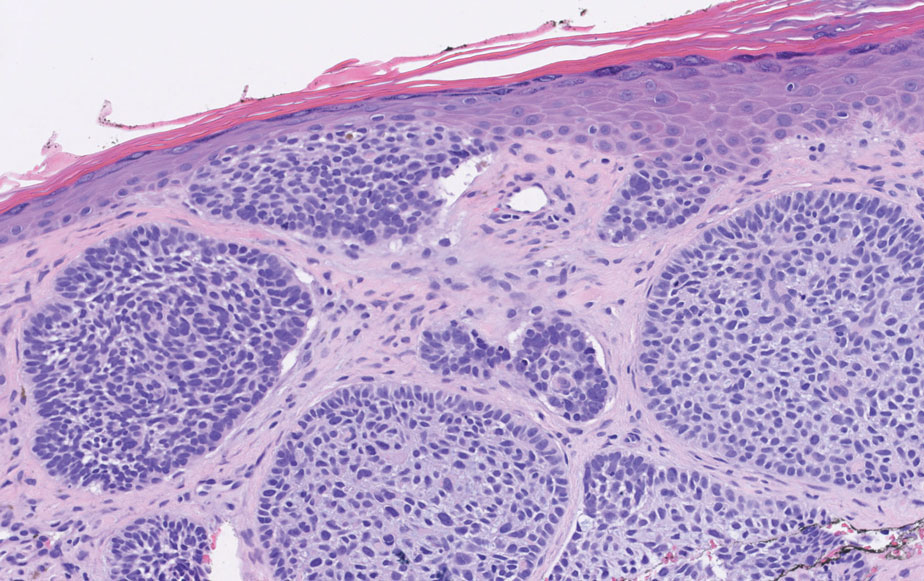

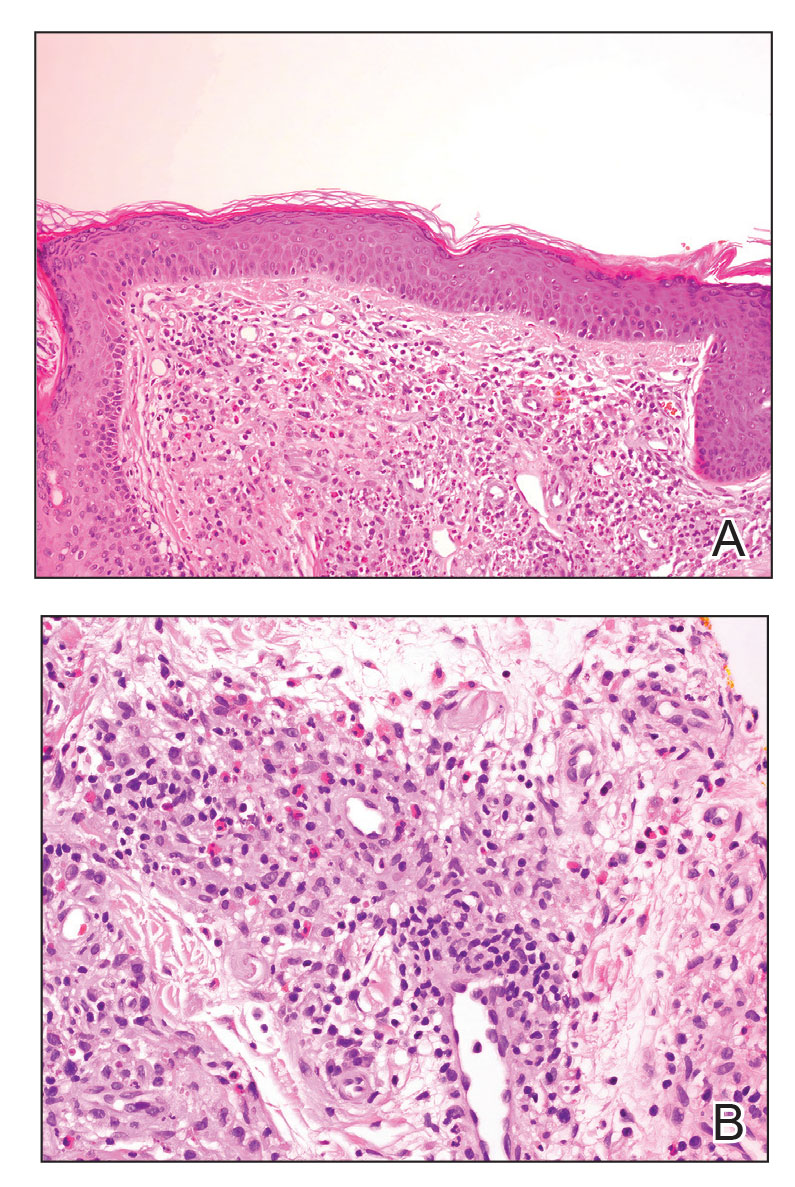

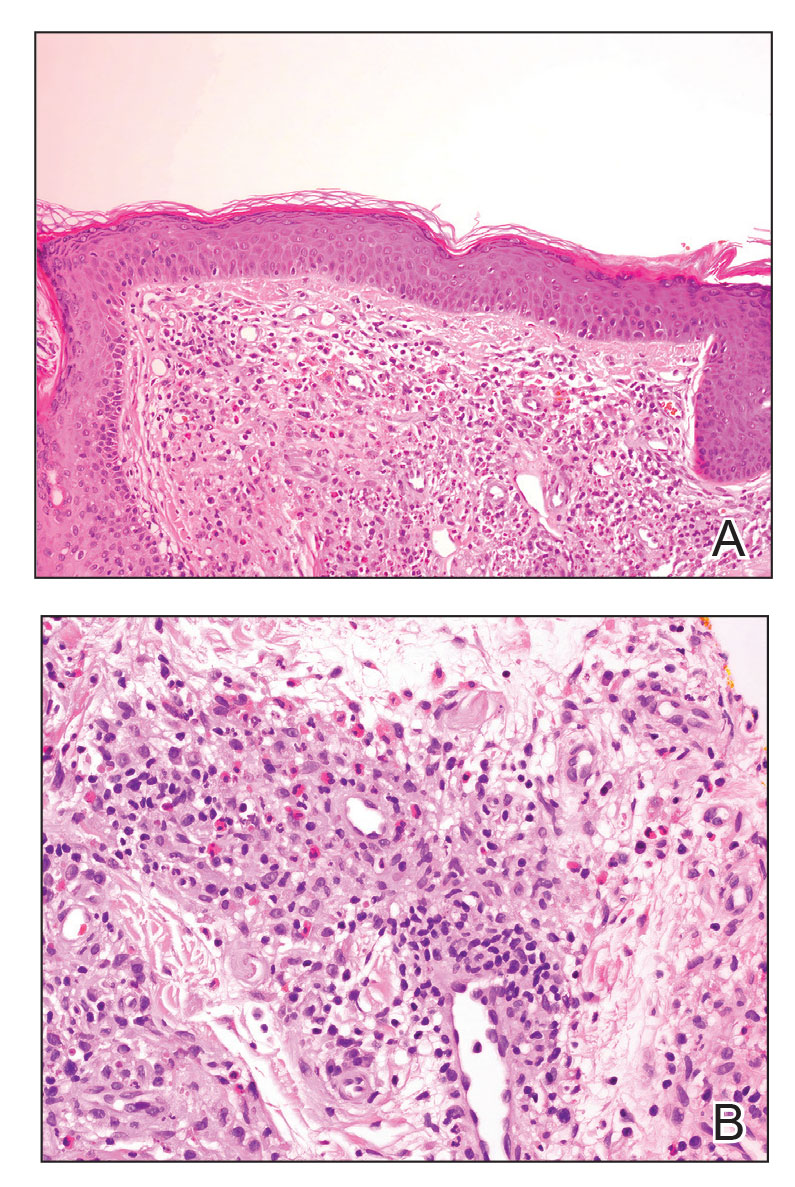

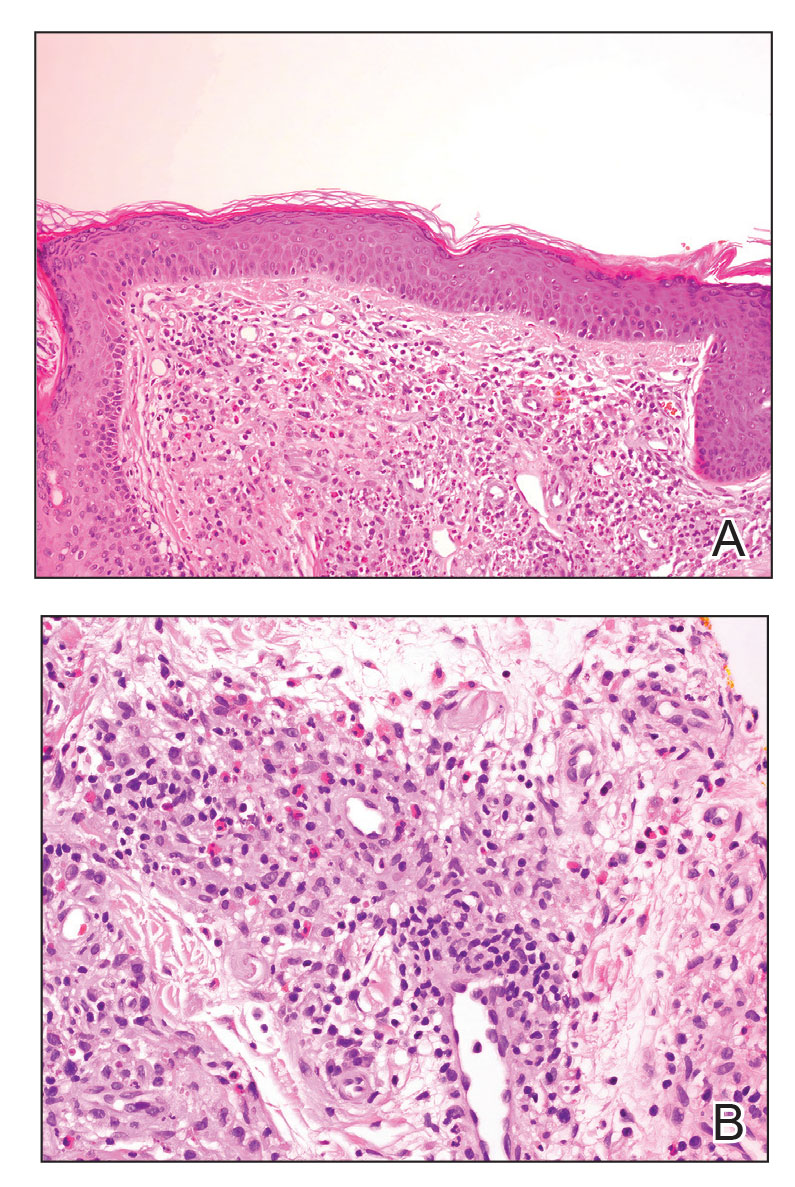

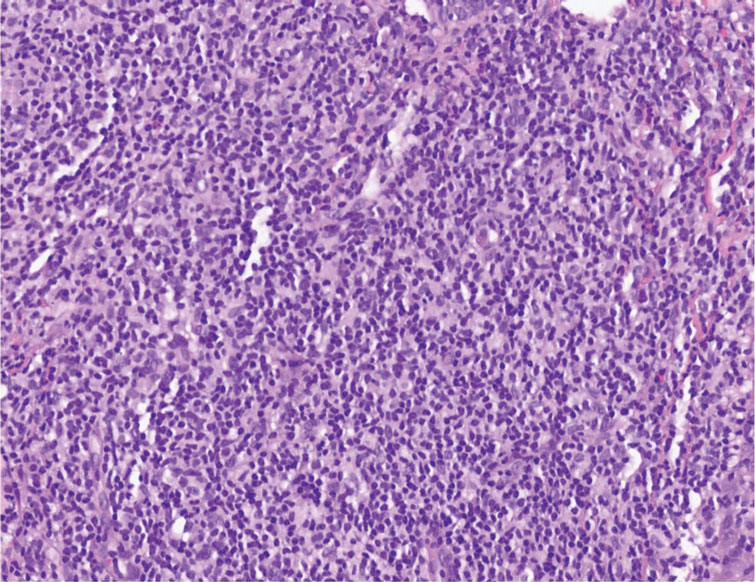

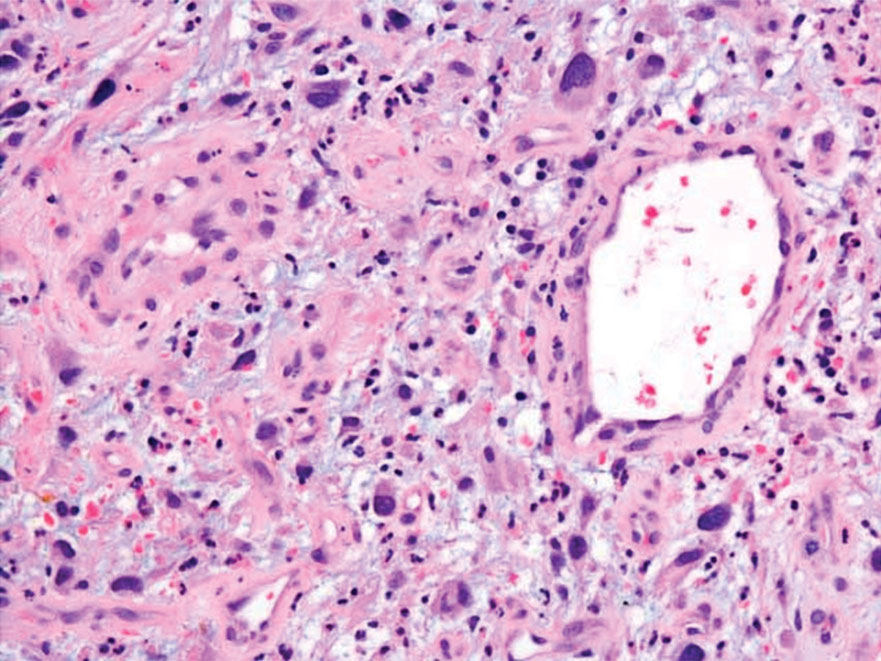

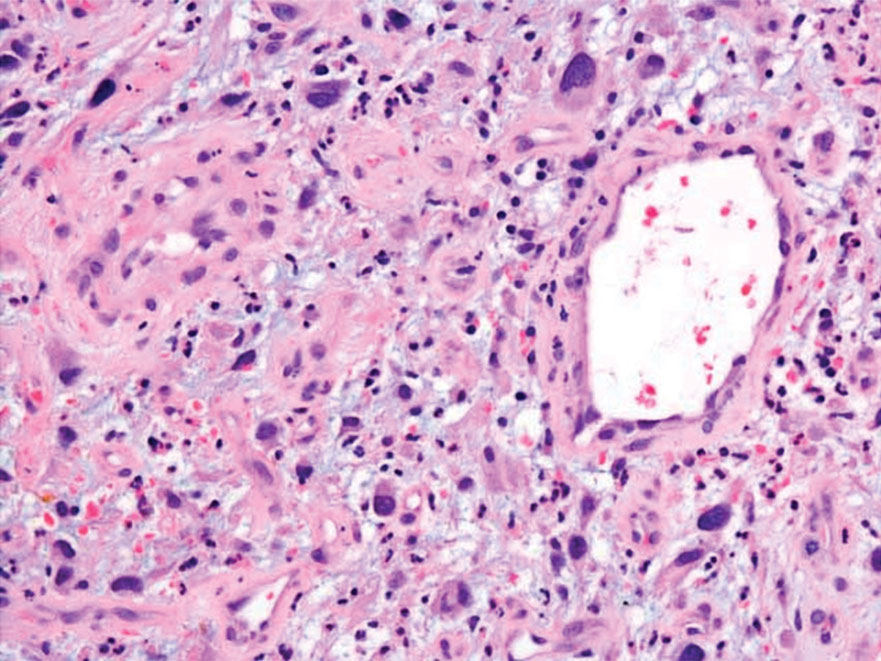

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a slow-growing soft tissue sarcoma that commonly begins as a pink or violet plaque on the trunk or upper limbs. Involvement of the head or neck accounts for only 10% to 15% of cases.5 This tumor has low metastatic potential but is highly infiltrative of surrounding tissues. It is associated with a translocation between chromosomes 22 and 17, leading to the fusion of the platelet-derived growth factor subunit β, PDGFB, and collagen type 1α1, COL1A1, genes.5 Clinically, patients often report that the lesion was present for several years prior to presentation with general stability in size and shape. Eventually, untreated lesions progress to become nodules or tumors and may even bleed or ulcerate. Histology reveals a storiform spindle cell proliferation throughout the dermis with infiltration into subcutaneous fat, commonly appearing in a honeycomblike pattern (Figure 1). Numerous histologic variants exist, including myxoid, sclerosing, pigmented (Bednar tumor), myoid, atrophic, or fibrosarcomatous dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, as well as a giant cell fibroblastoma variant.6 These tumor subtypes can exist independently or in association with one another, creating hybrid lesions that can closely mimic other entities such as pleomorphic lipoma. The spindle cells stain positively for CD34. Treatment of these tumors involves complete surgical excision or Mohs micrographic surgery; however, recurrence is common for tumors involving the head or neck.5

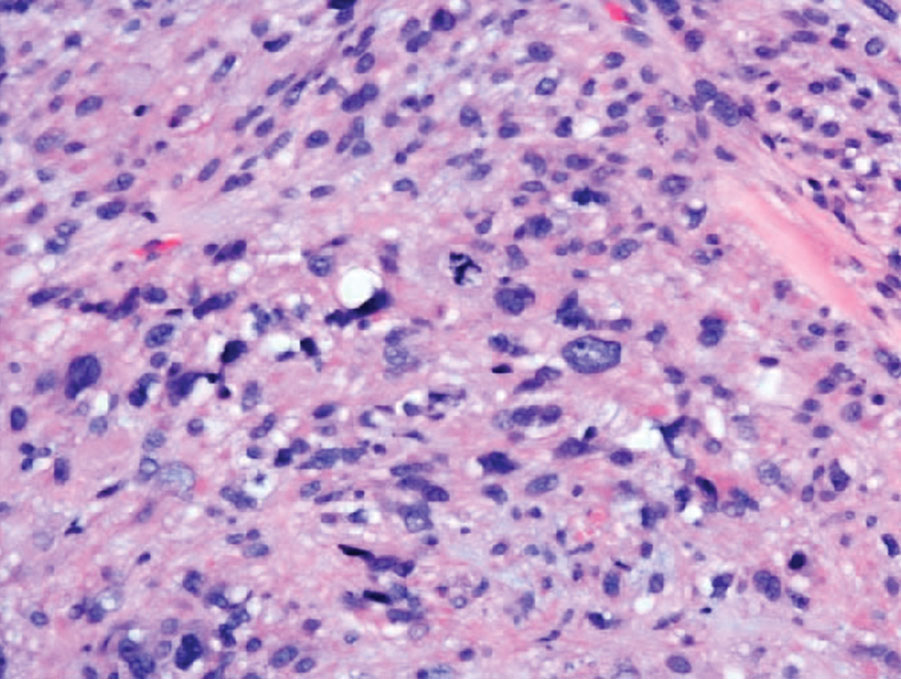

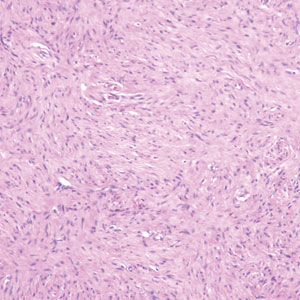

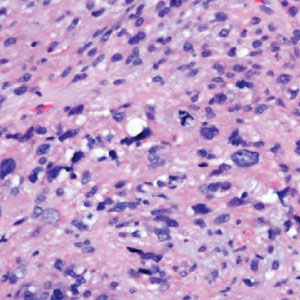

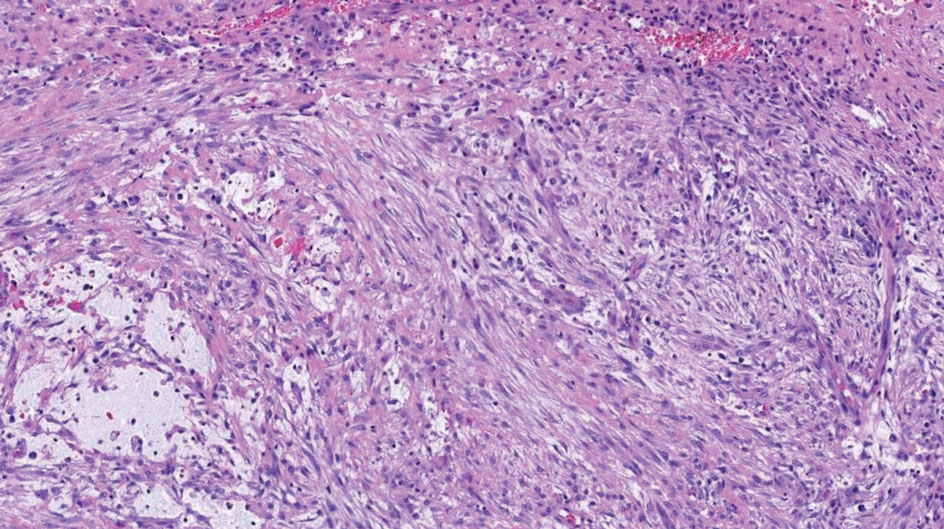

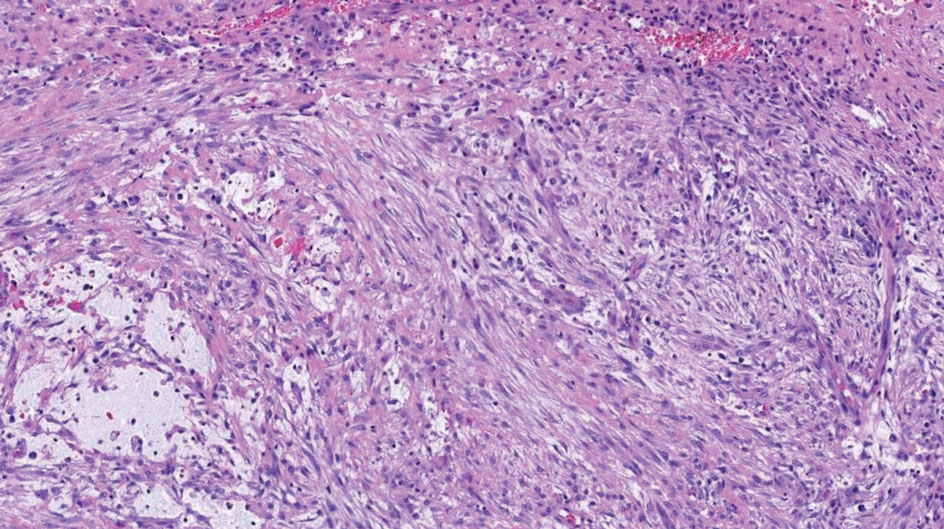

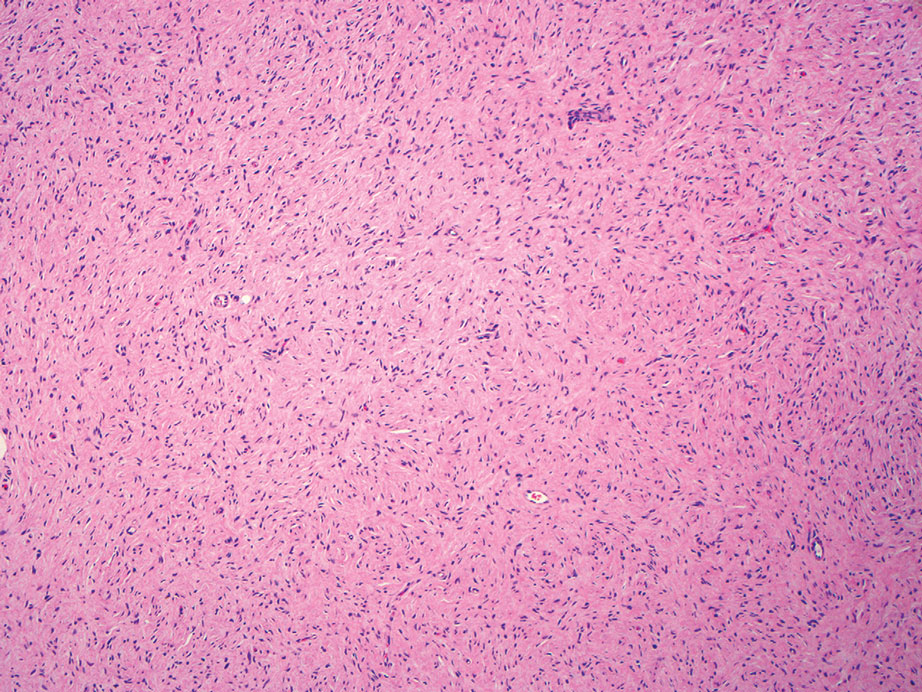

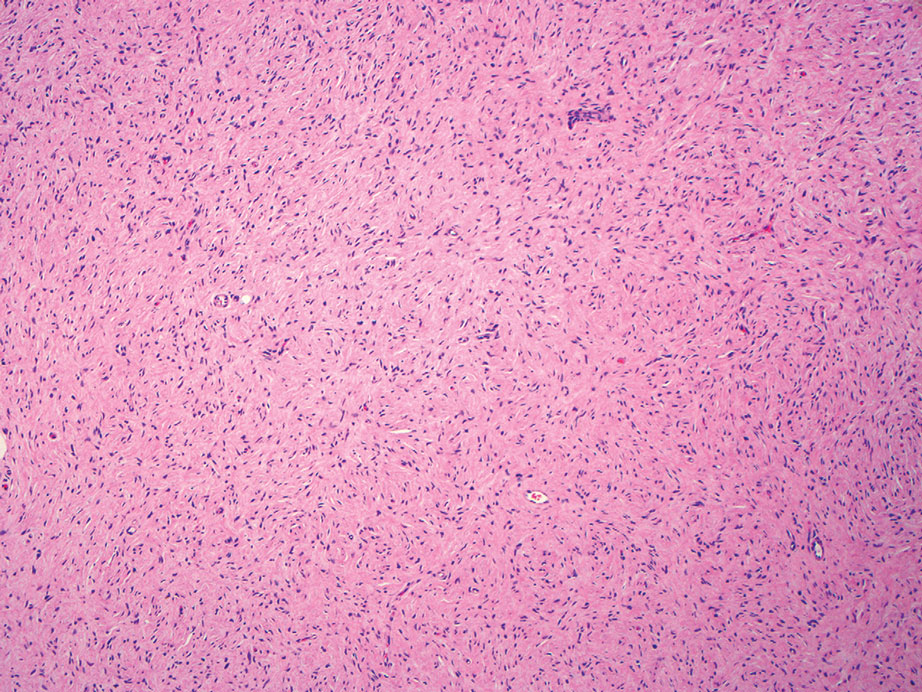

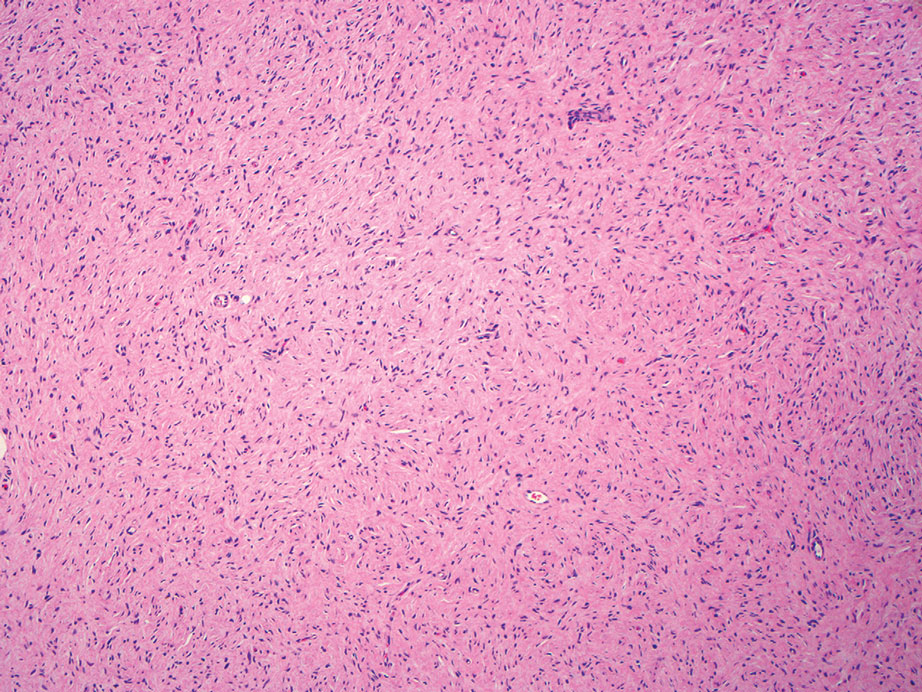

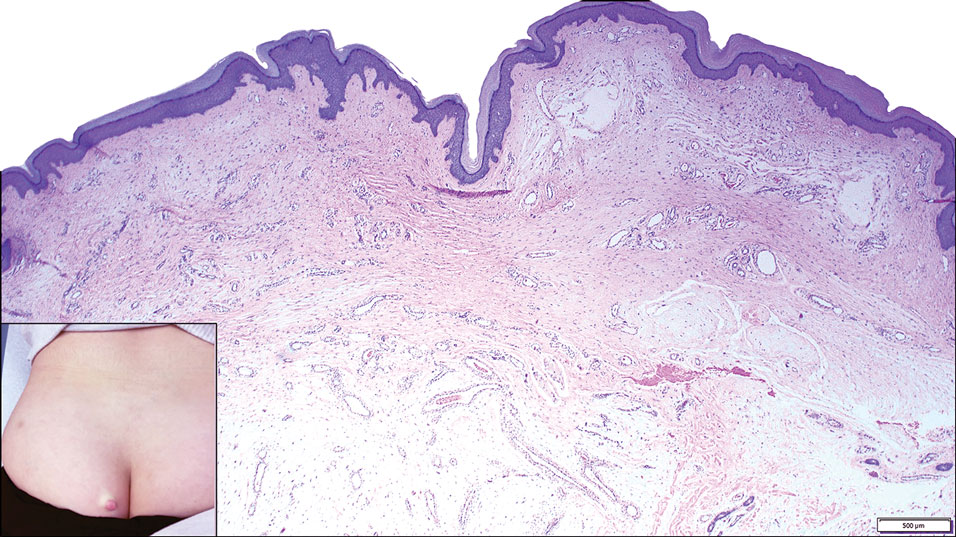

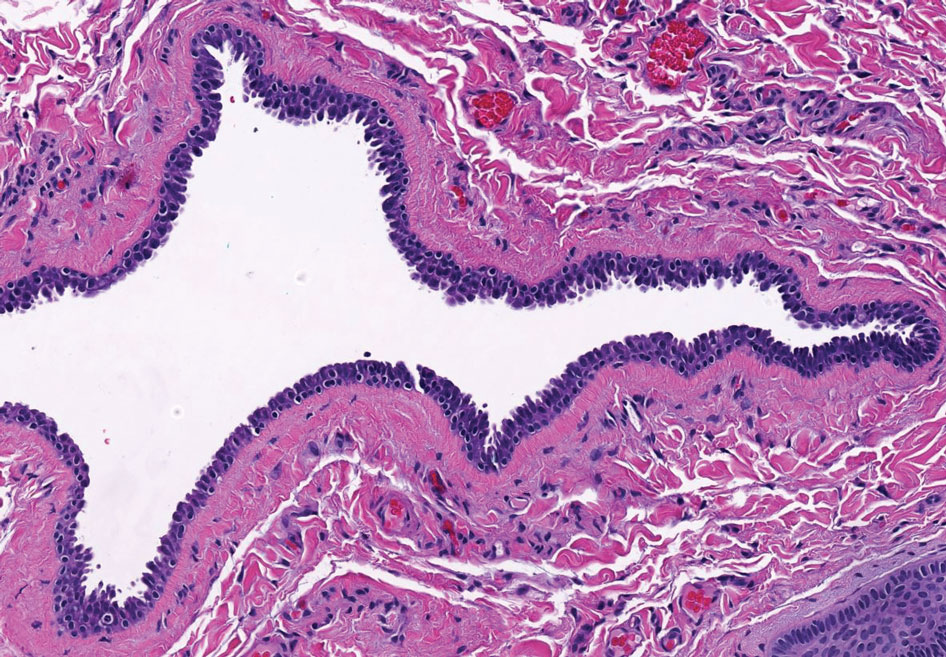

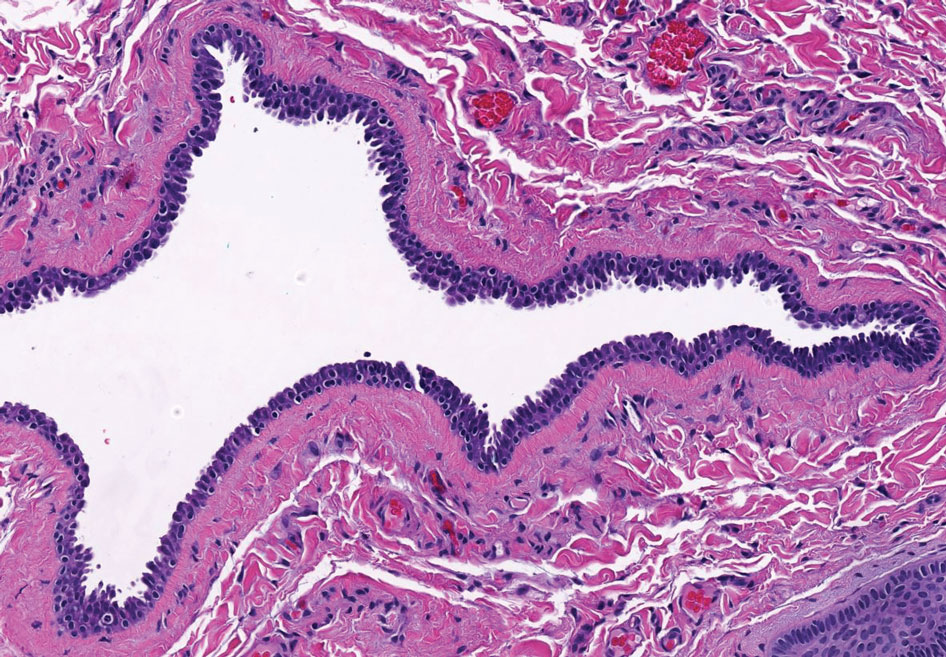

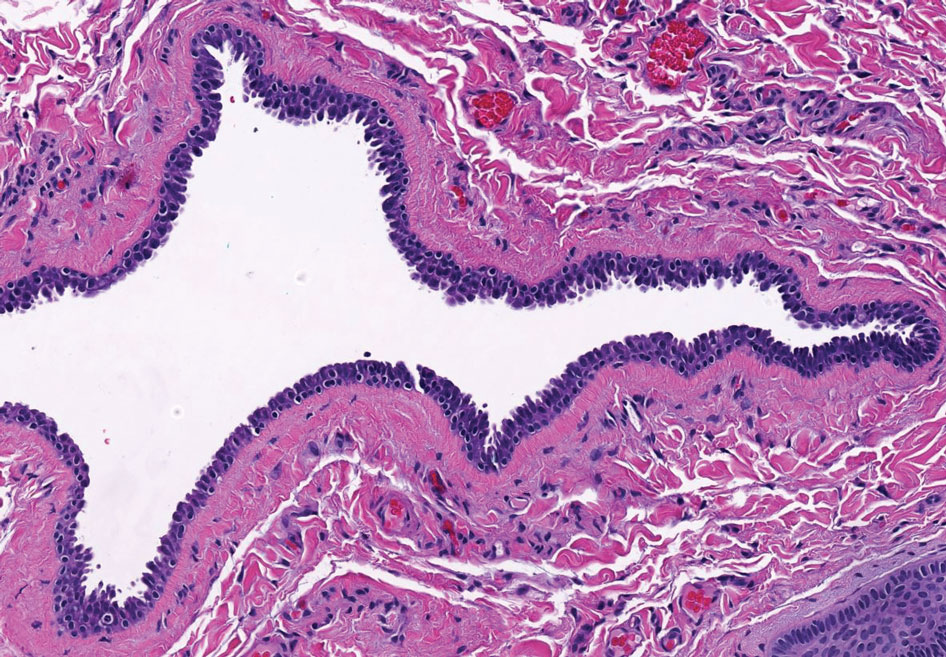

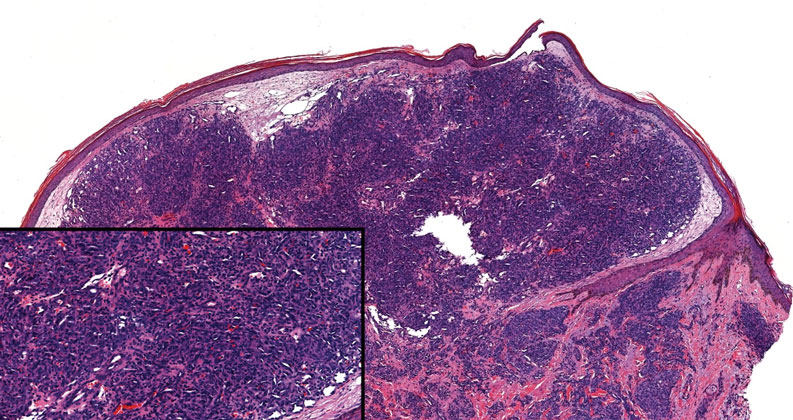

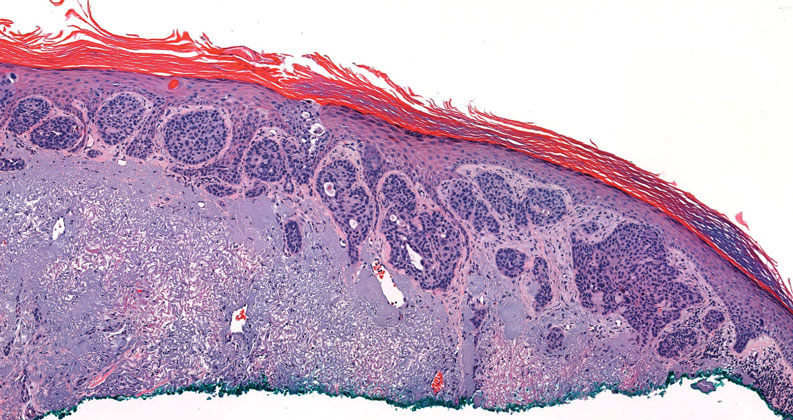

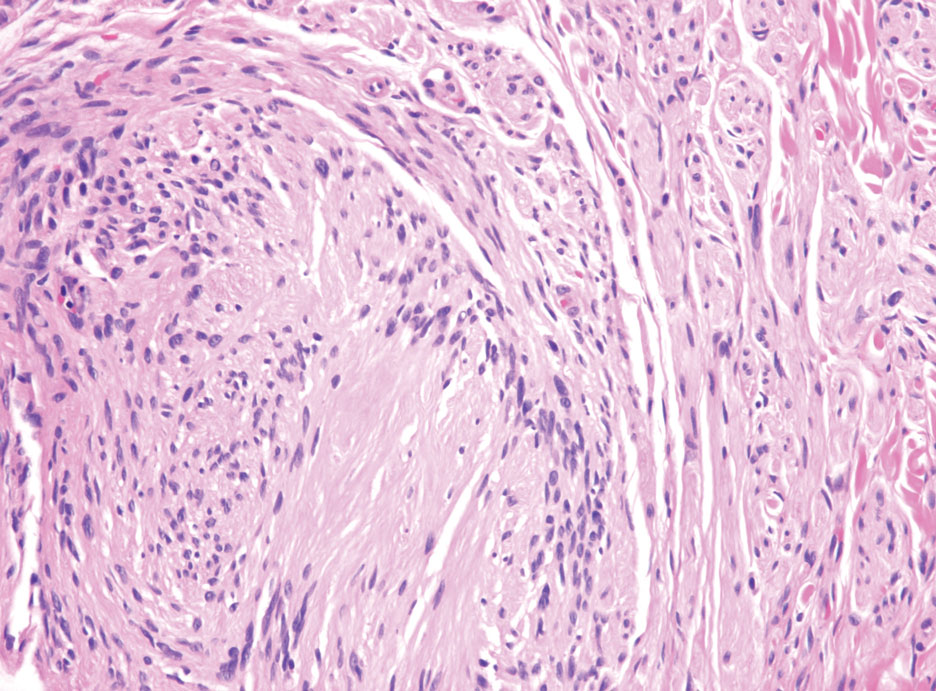

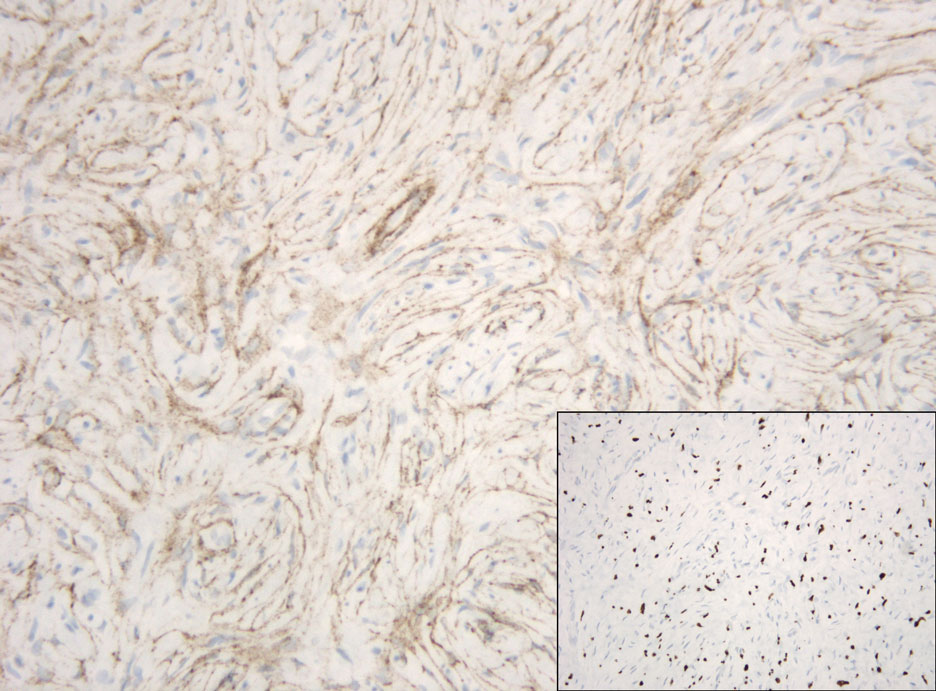

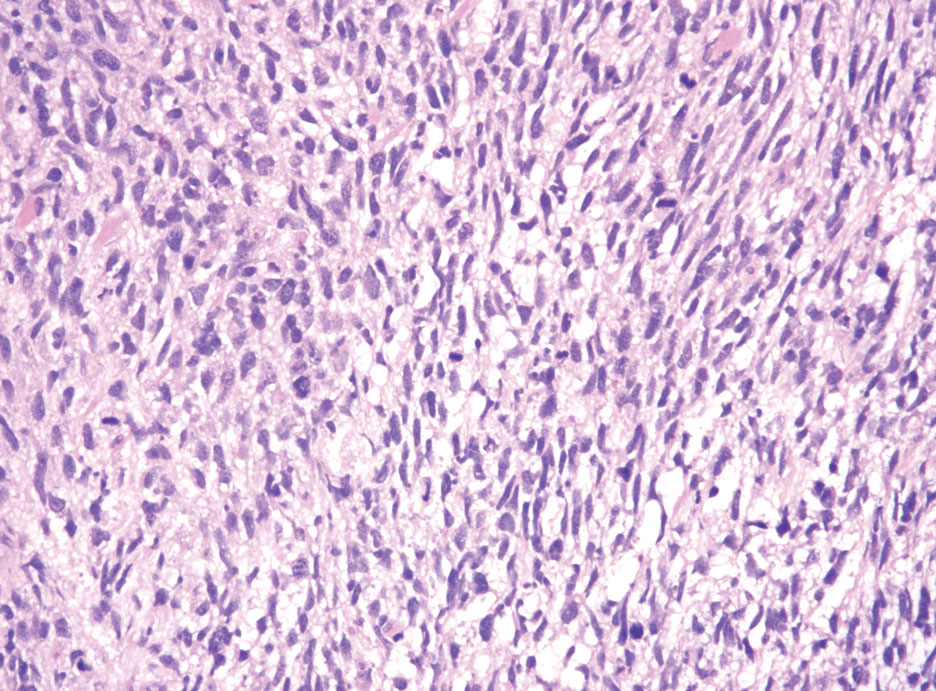

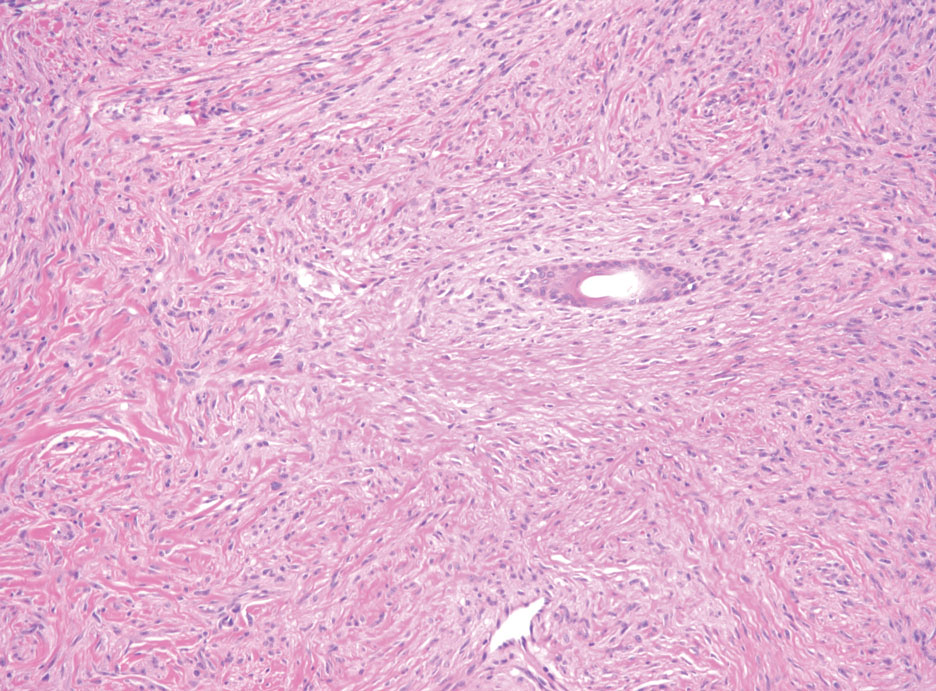

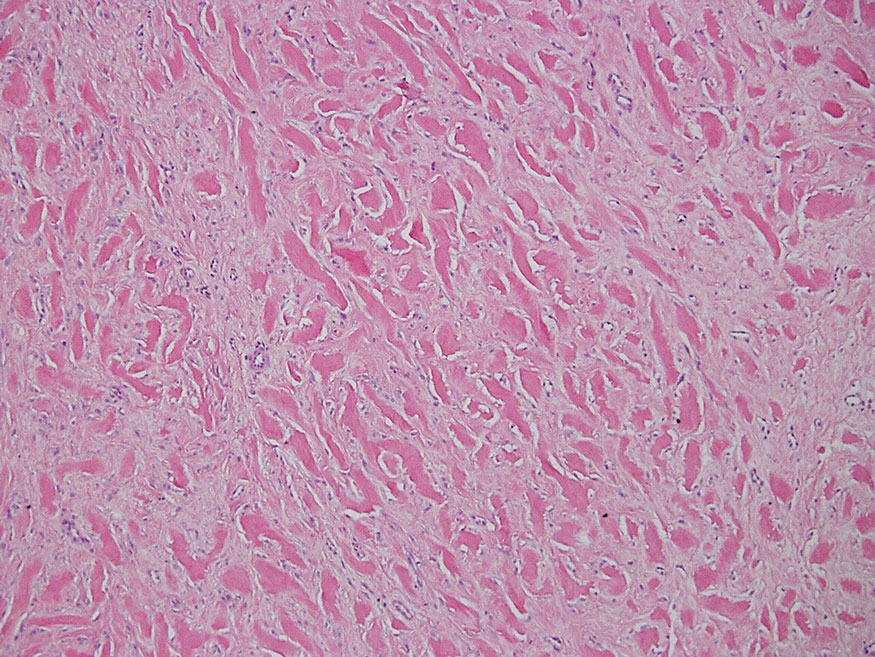

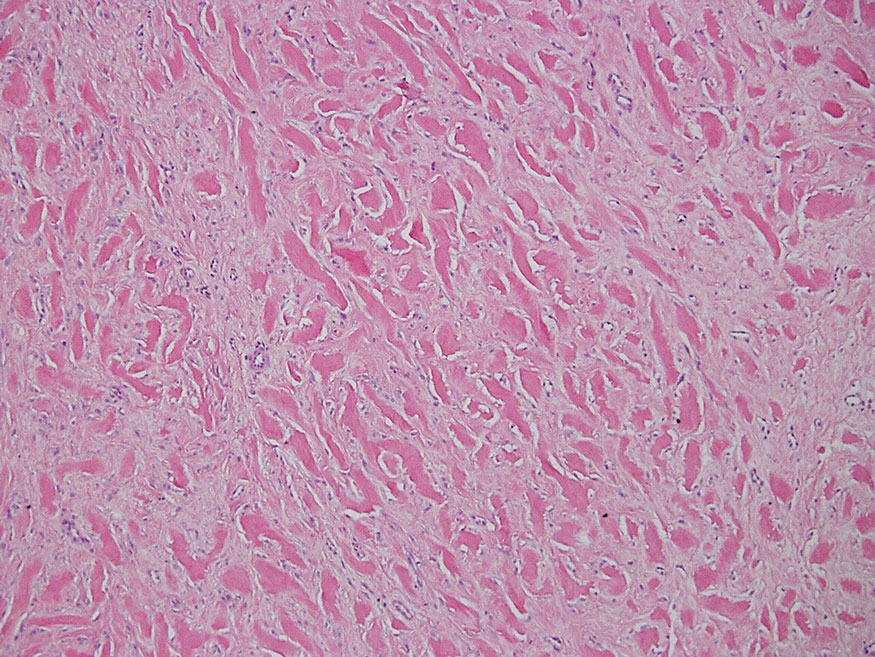

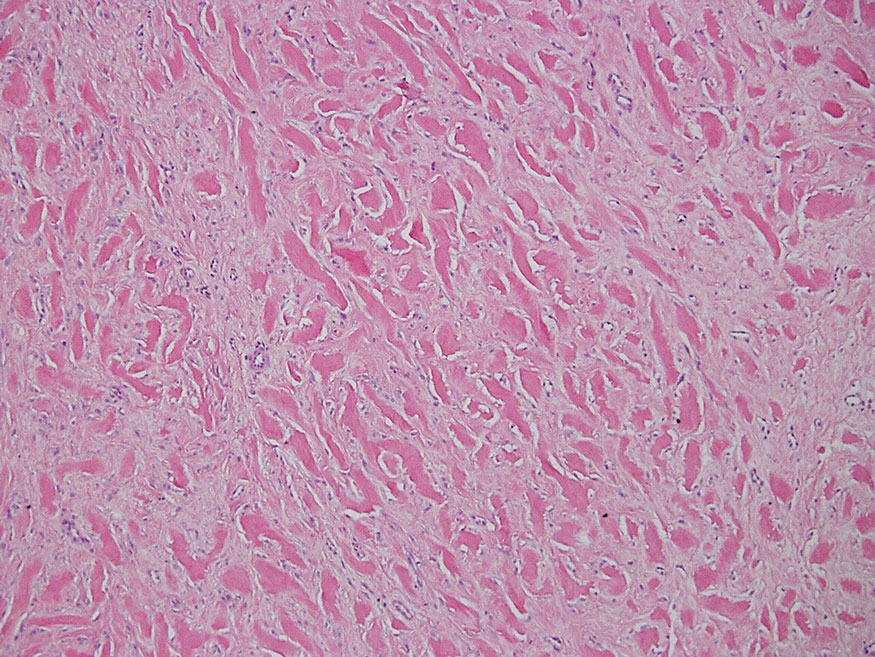

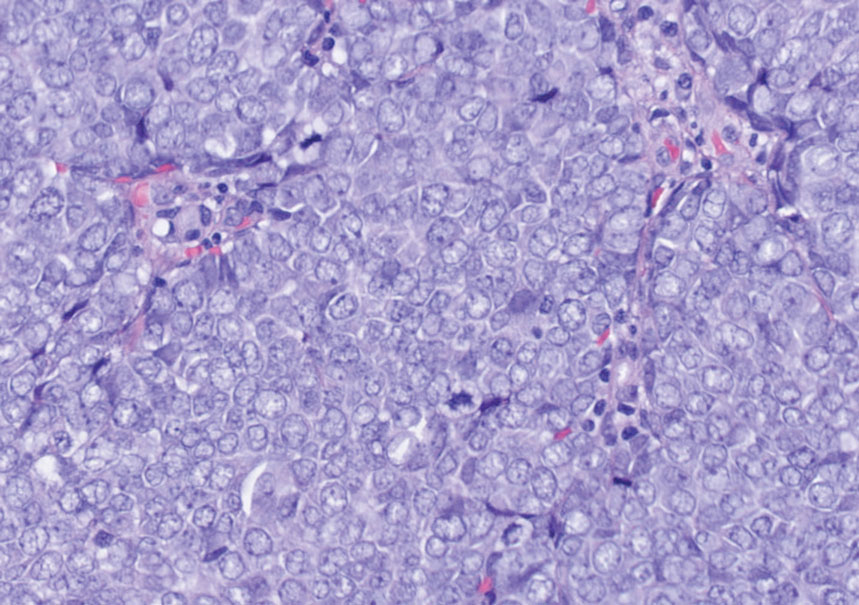

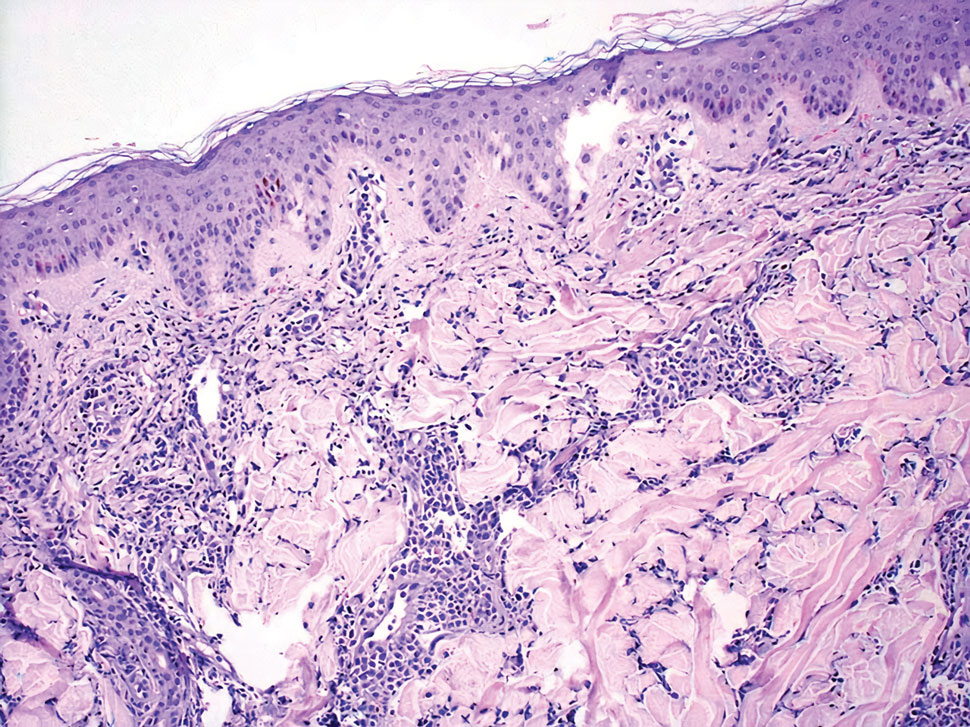

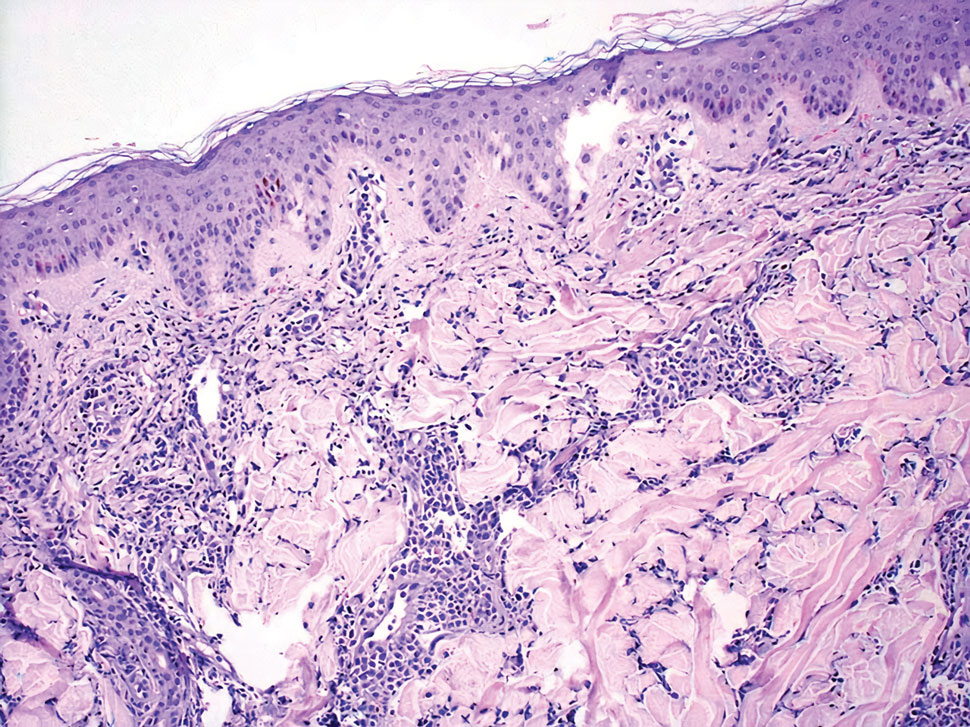

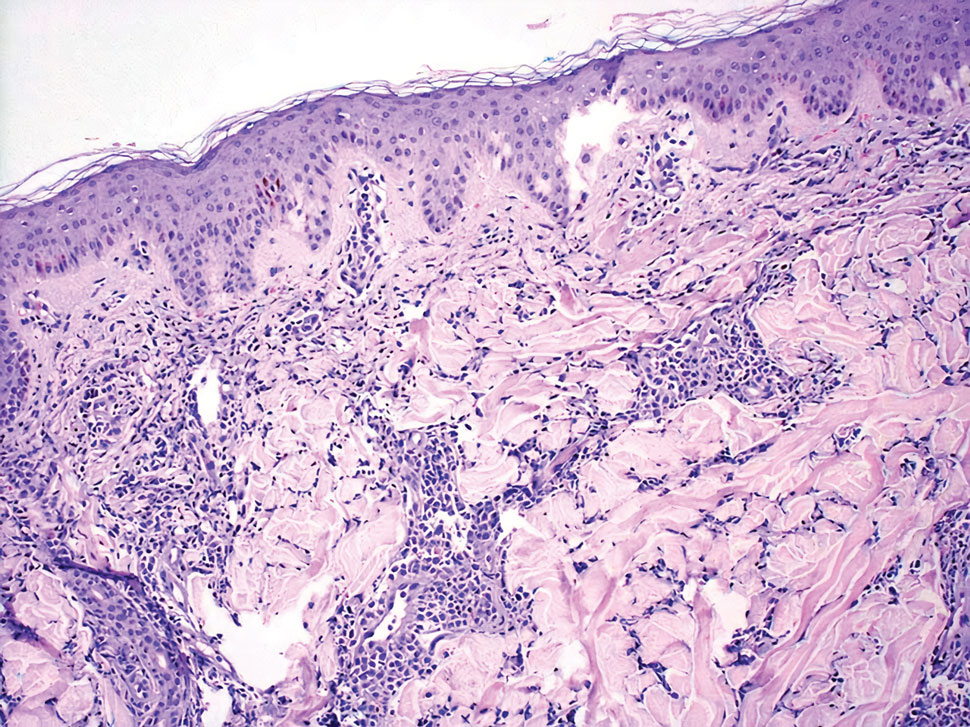

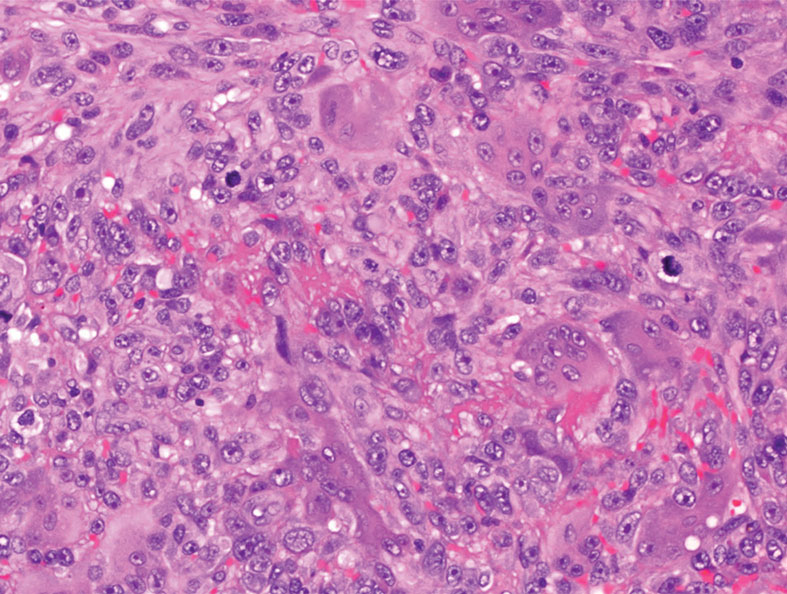

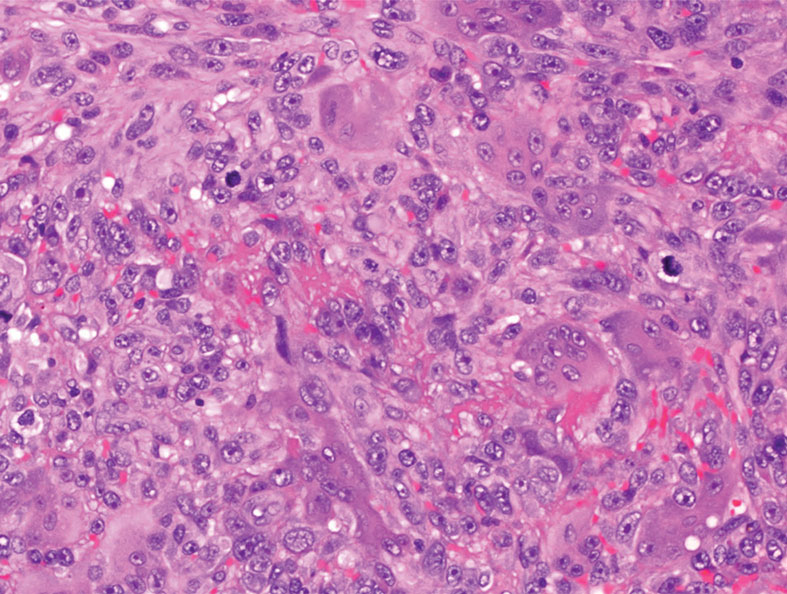

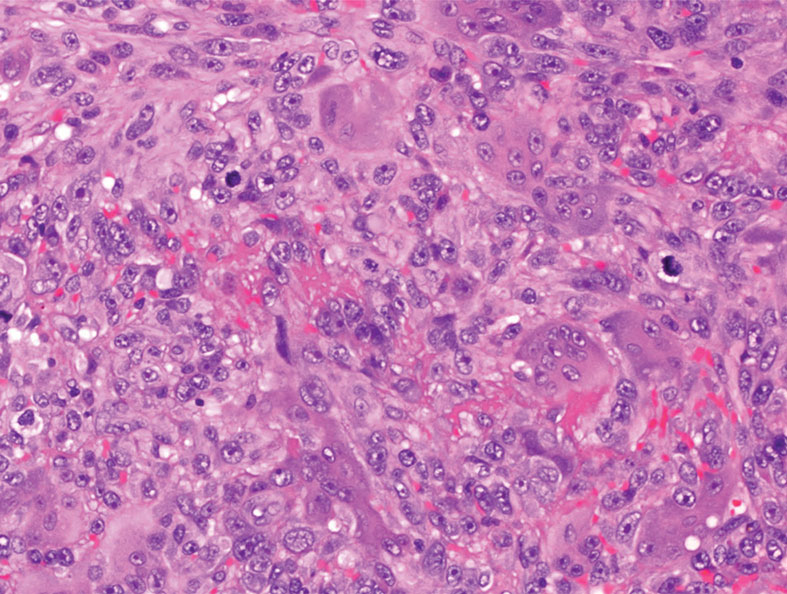

Superficial angiomyxoma is a slow-growing papule that most commonly appears on the trunk, head, or neck in middle-aged adults. Occasionally, patients with Carney complex also can develop lesions on the external ear or breast.7 Histologically, superficial angiomyxoma is a hypocellular tumor characterized by abundant myxoid stroma, thin blood vessels, and small spindled and stellate cells with minimal cytoplasm (Figure 2).8 Superficial angiomyxoma and pleomorphic lipoma present differently on histology; superficial angiomyxoma is not associated with nuclear atypia or pleomorphism, whereas pleomorphic lipoma characteristically contains multinucleated floretlike giant cells and pleomorphism. Frequently, there also is loss of normal PRKAR1A gene expression, which is responsible for protein kinase A regulatory subunit 1-alpha expression.8

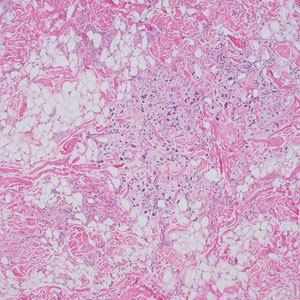

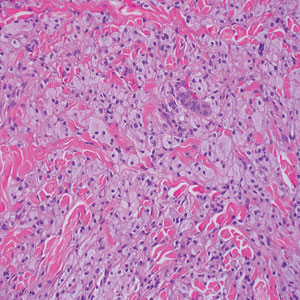

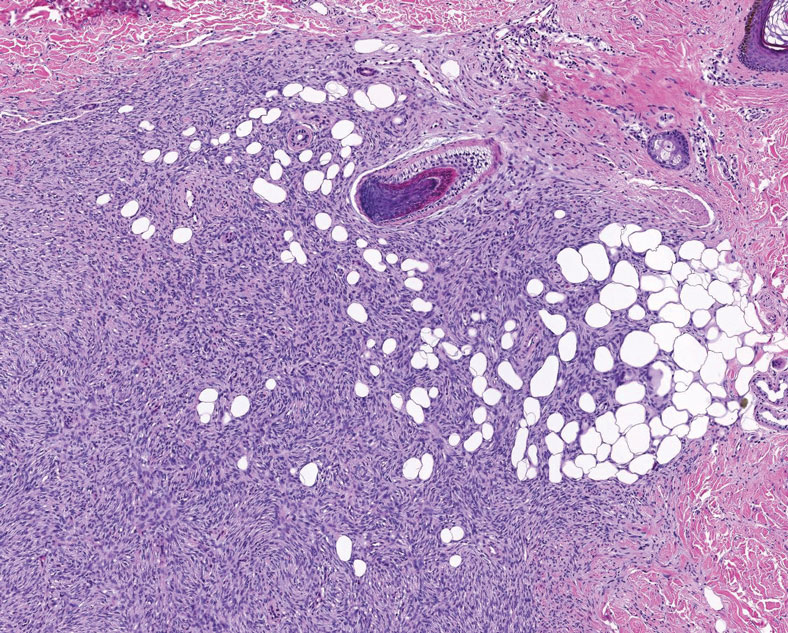

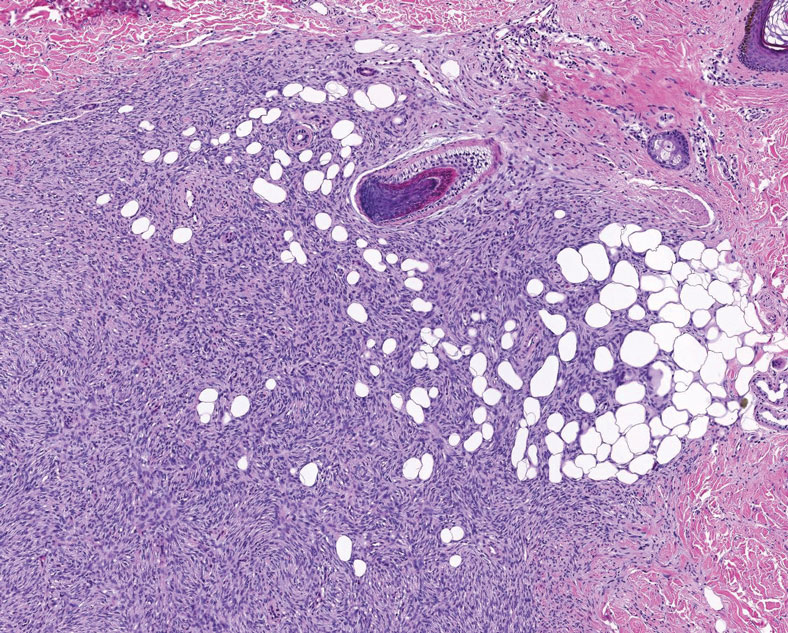

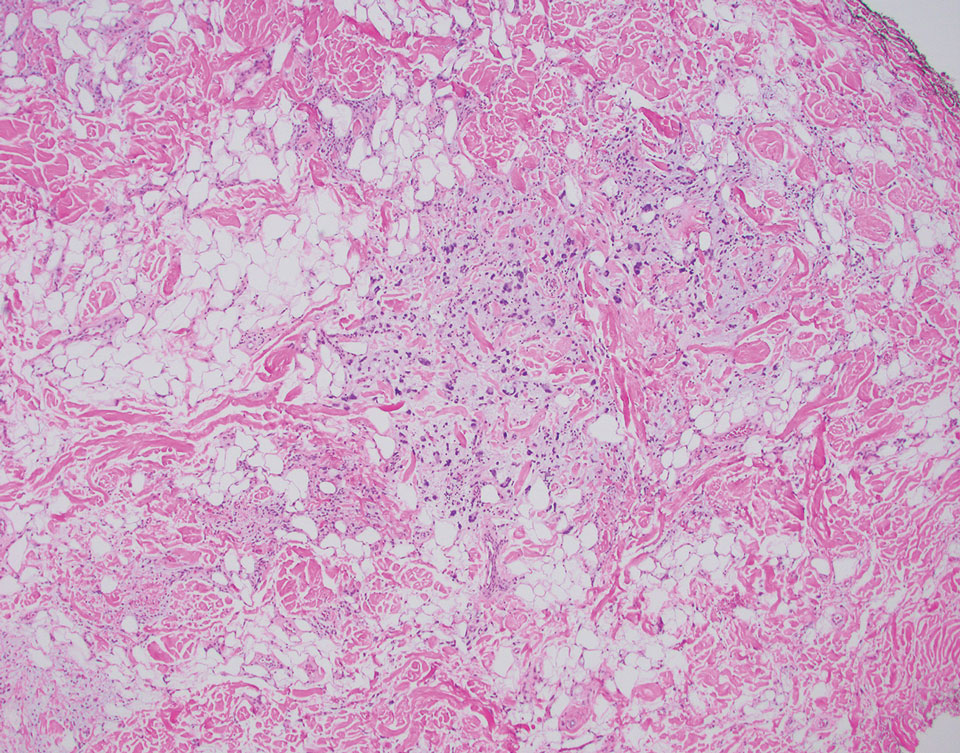

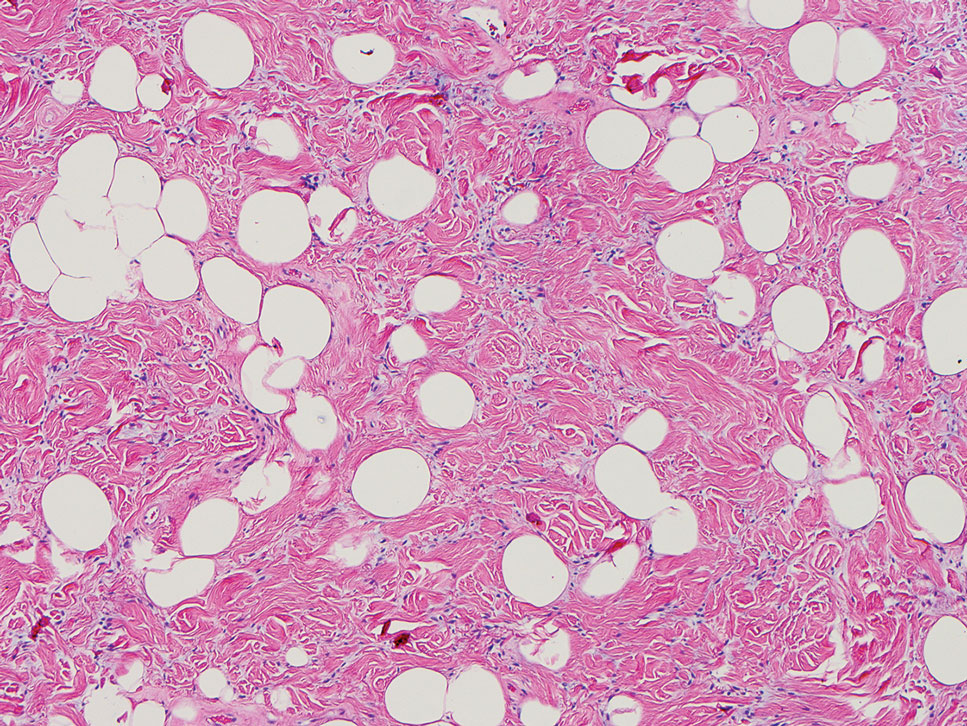

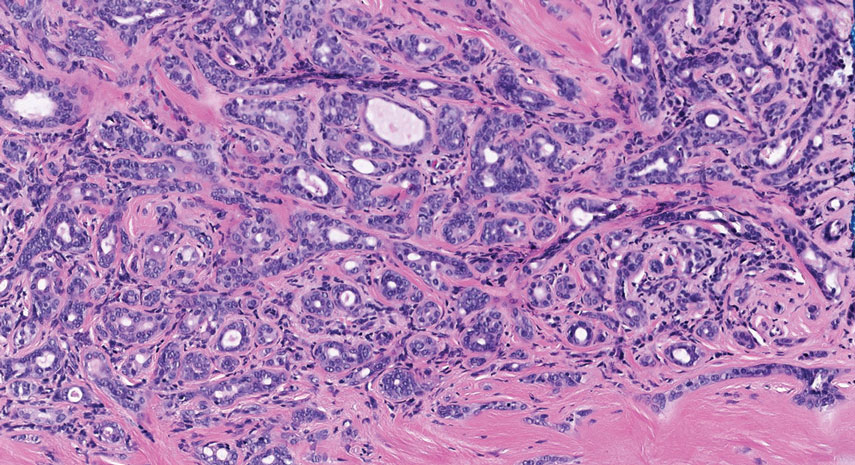

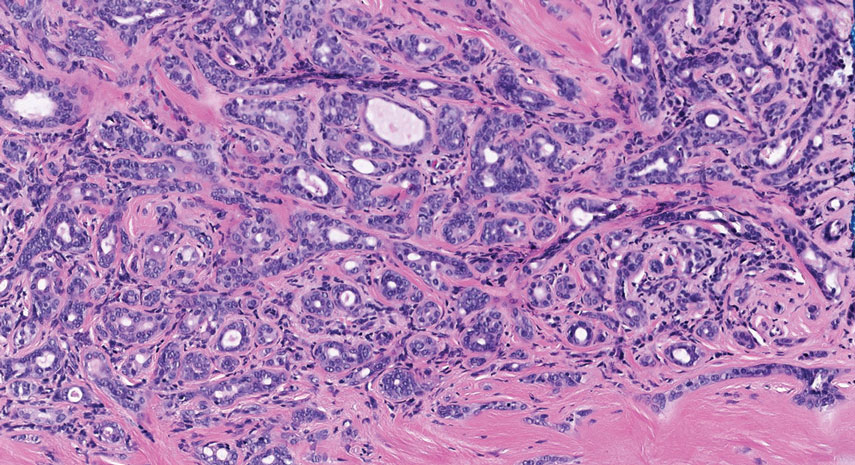

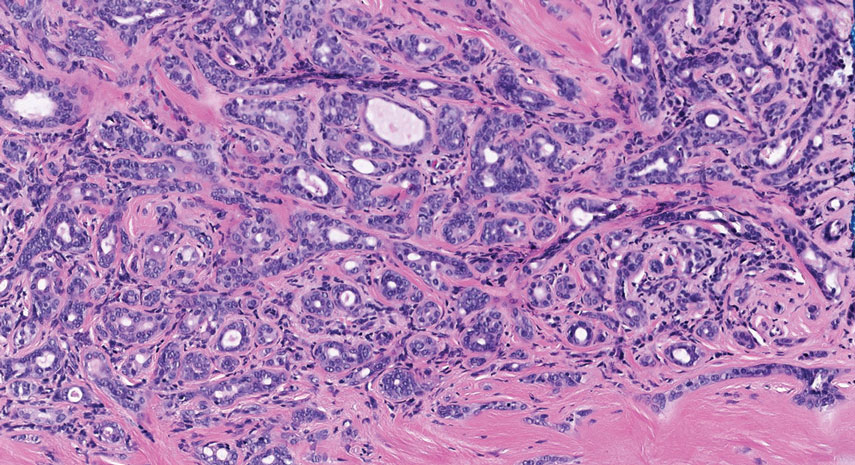

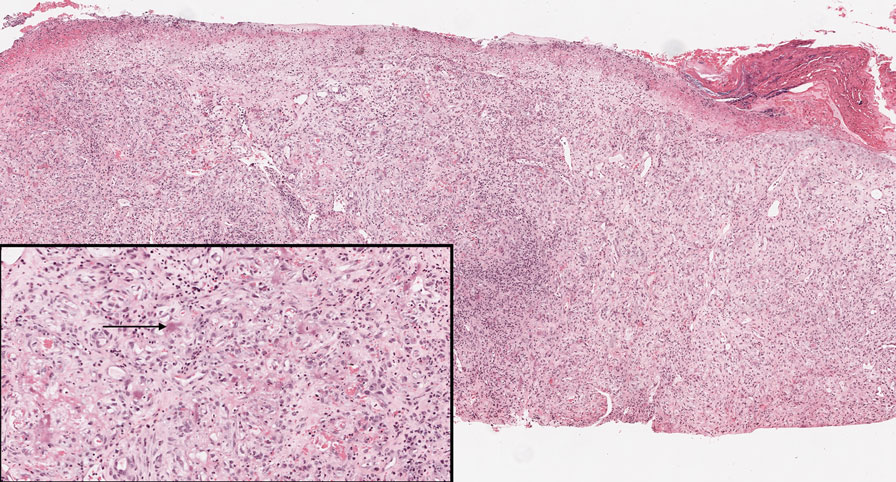

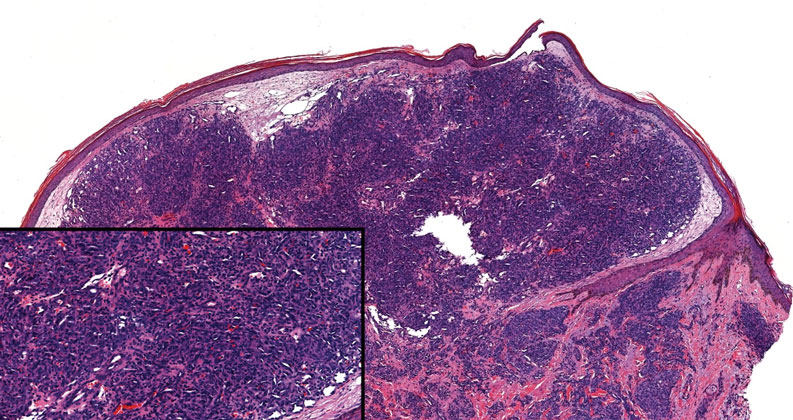

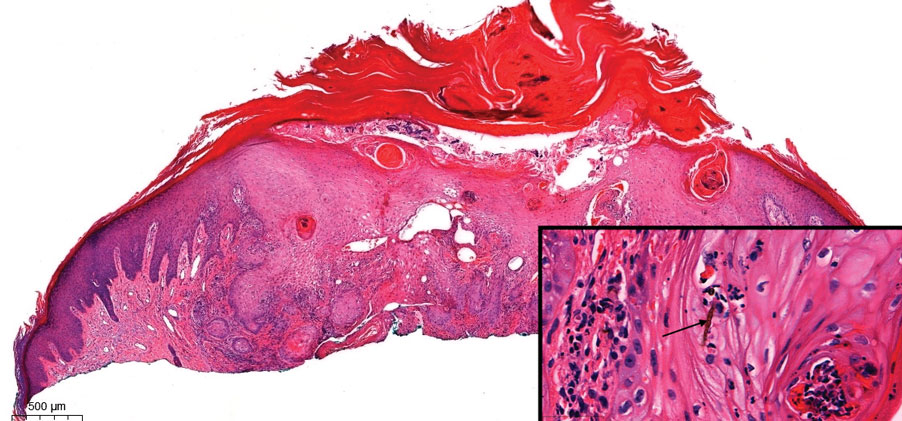

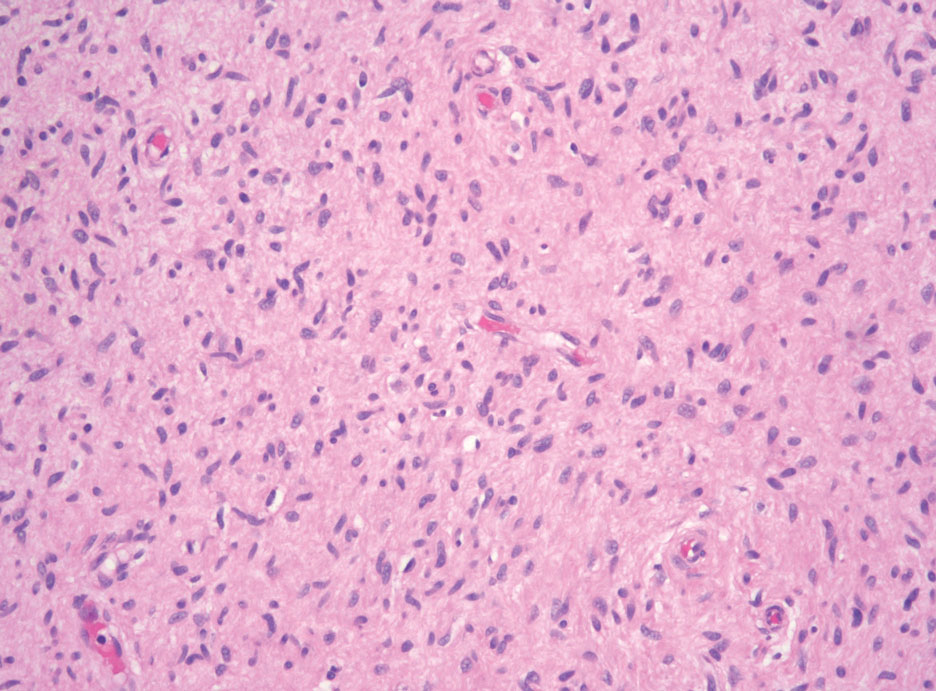

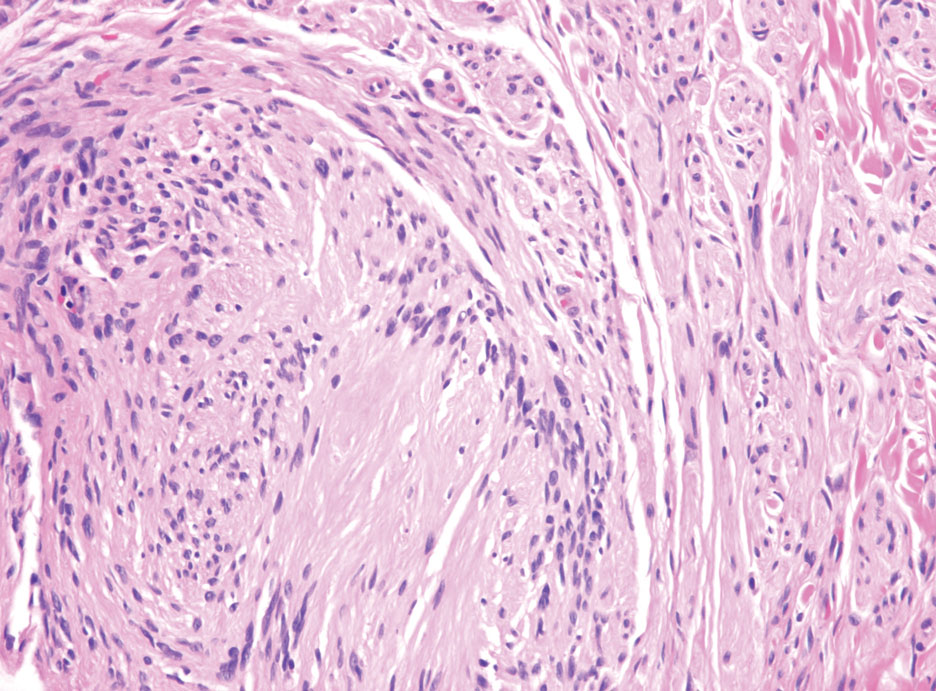

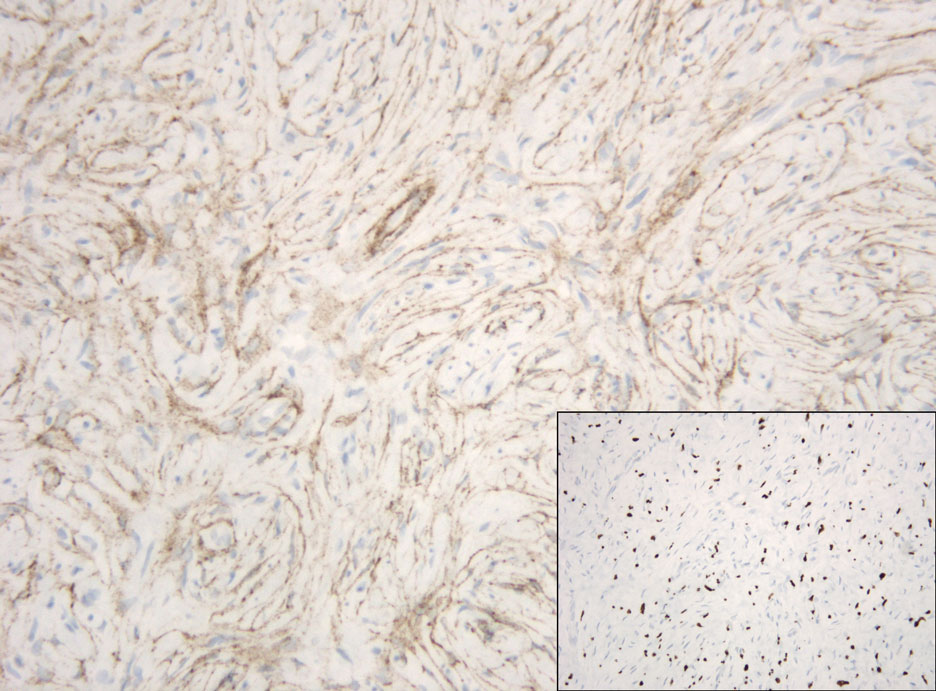

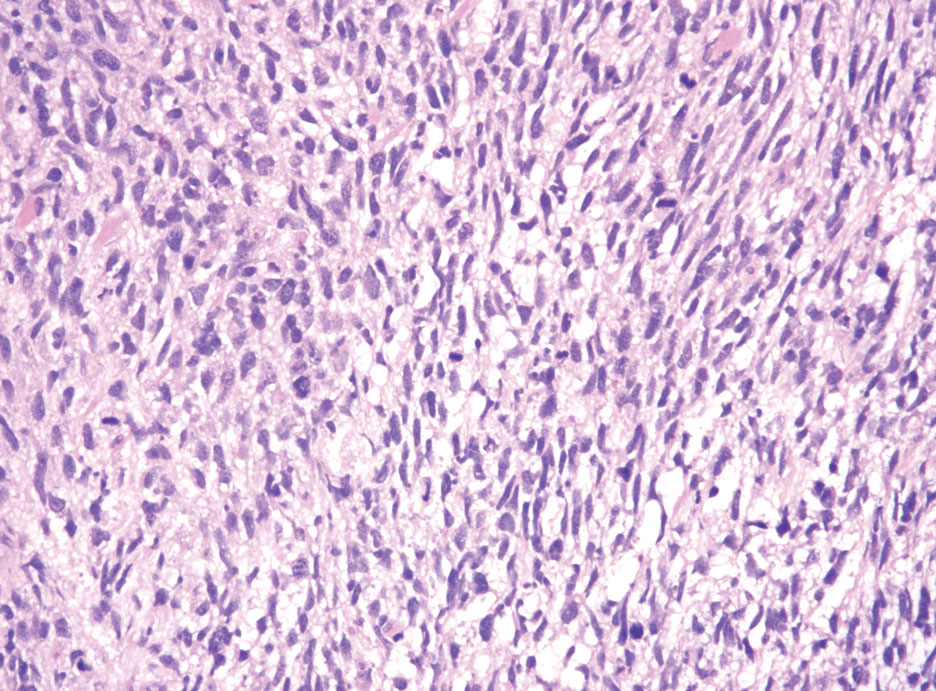

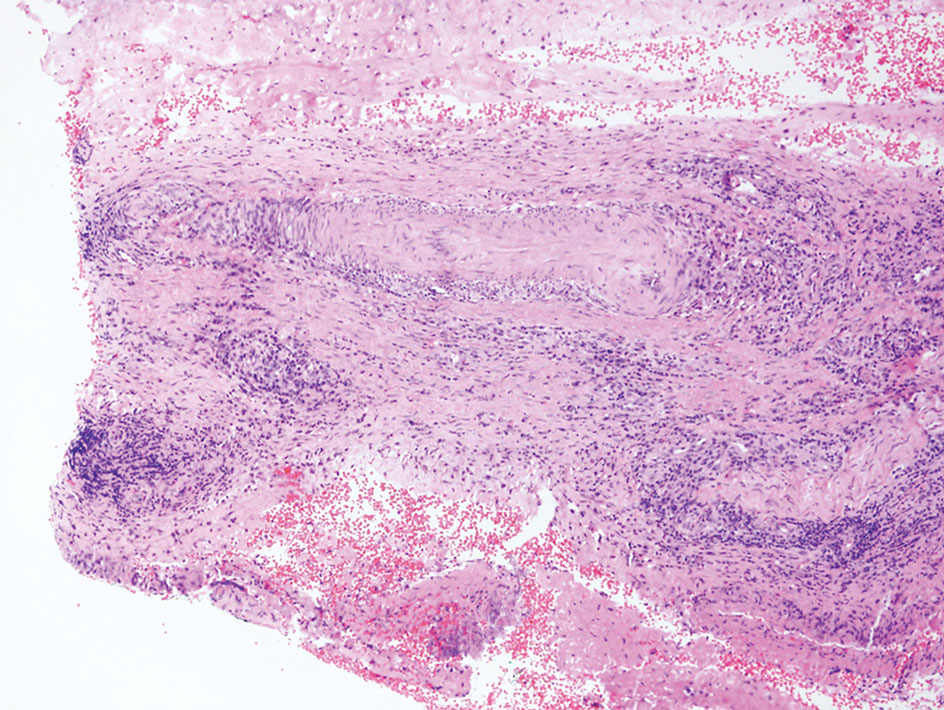

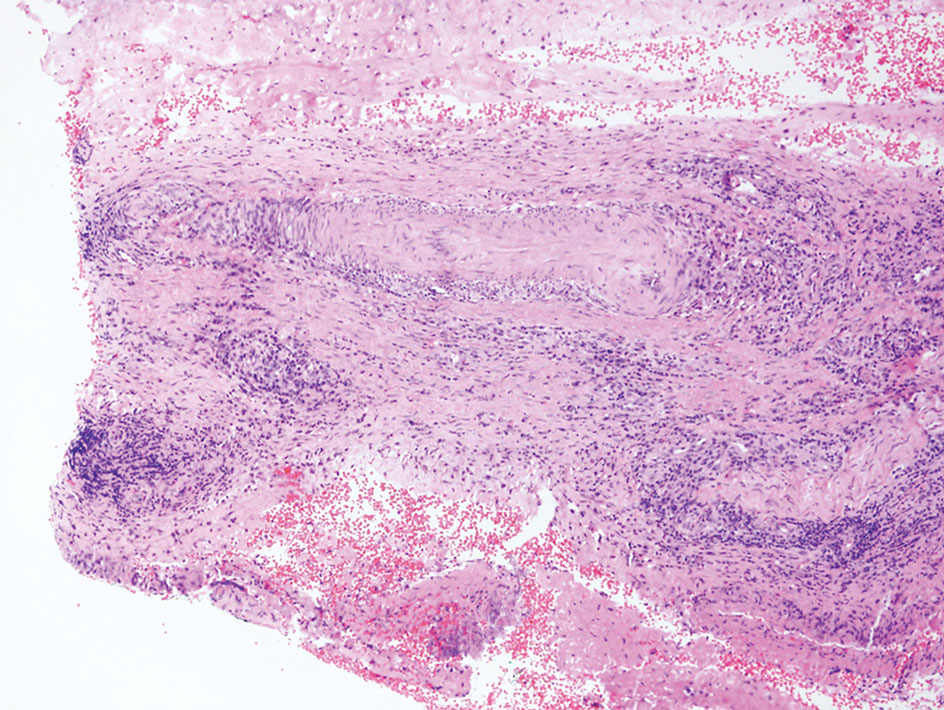

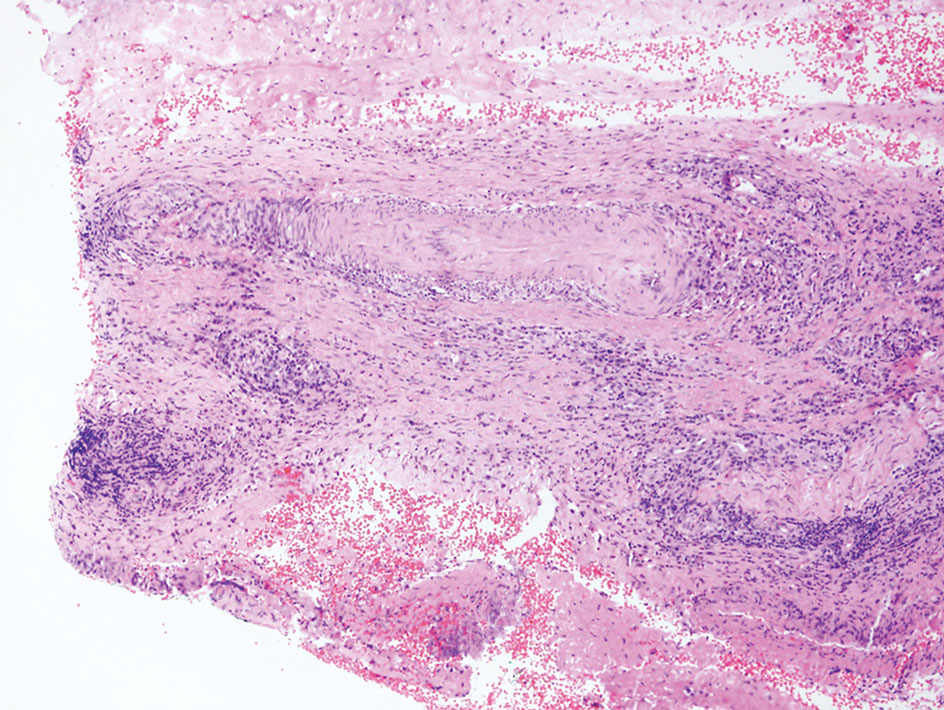

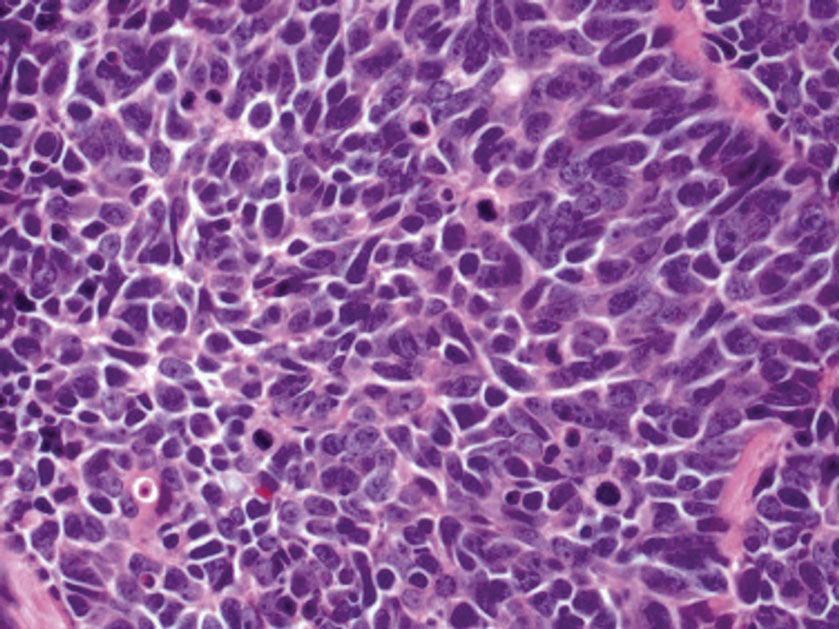

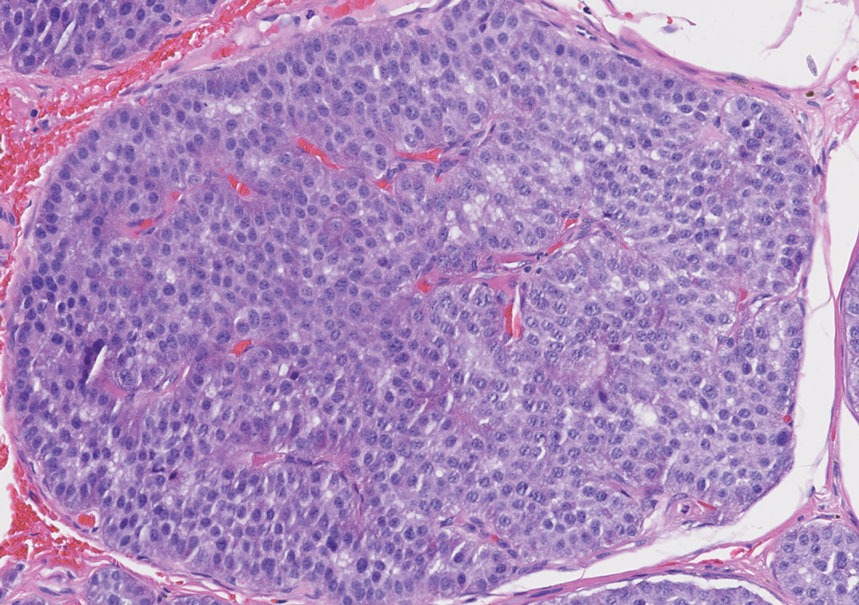

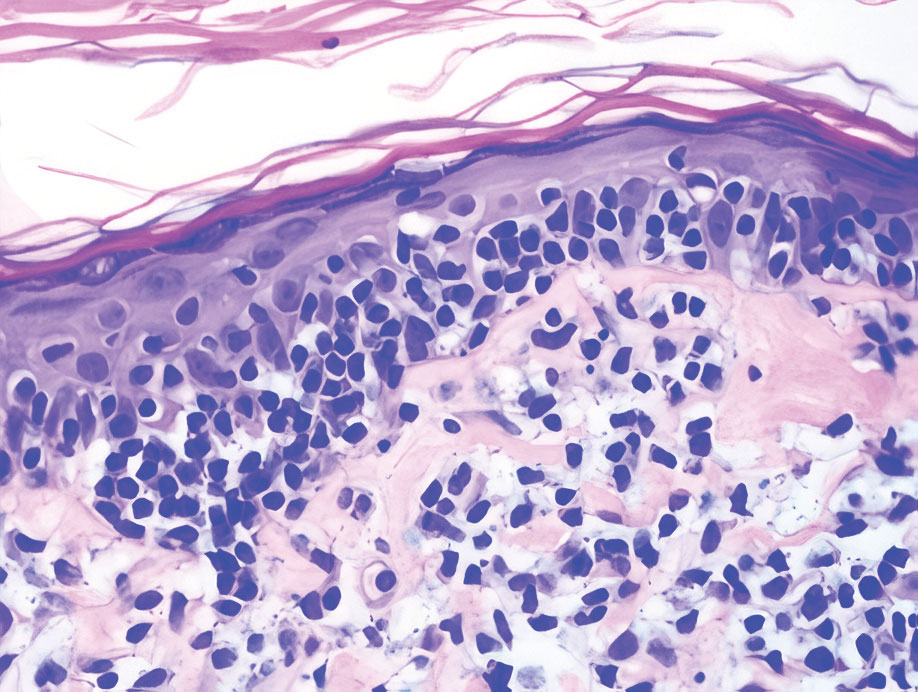

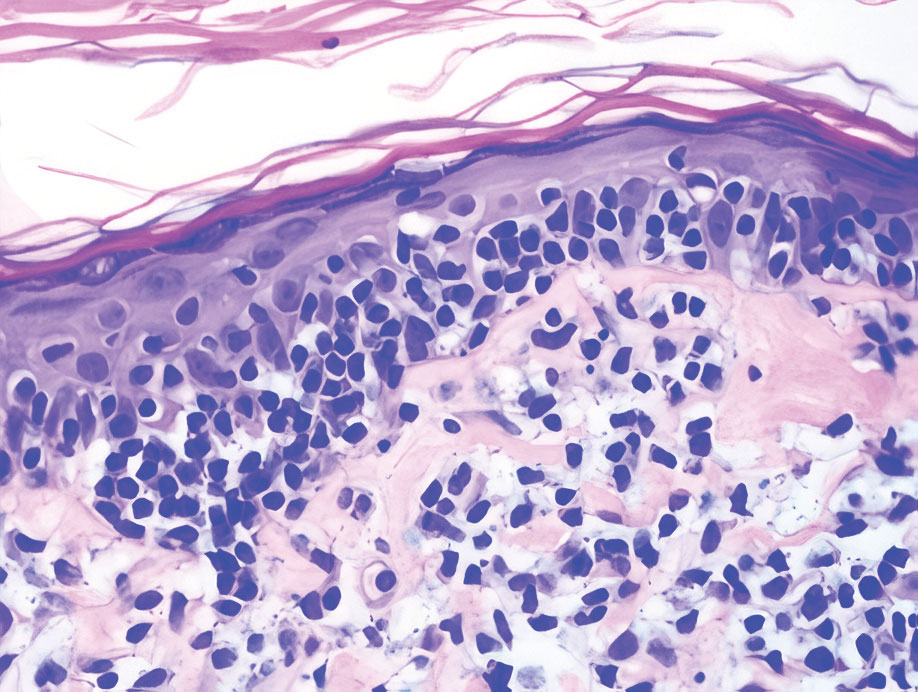

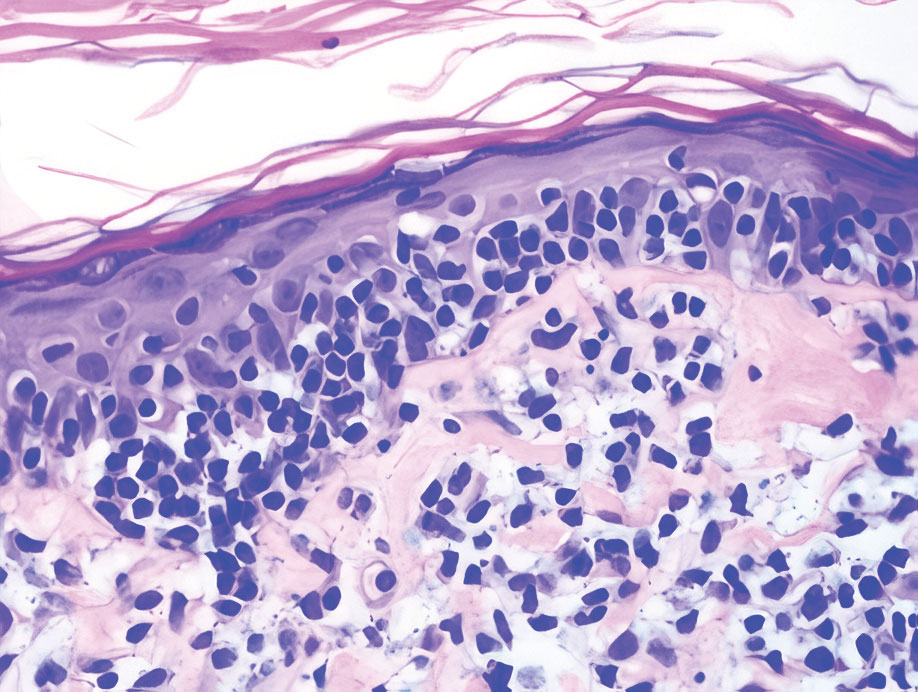

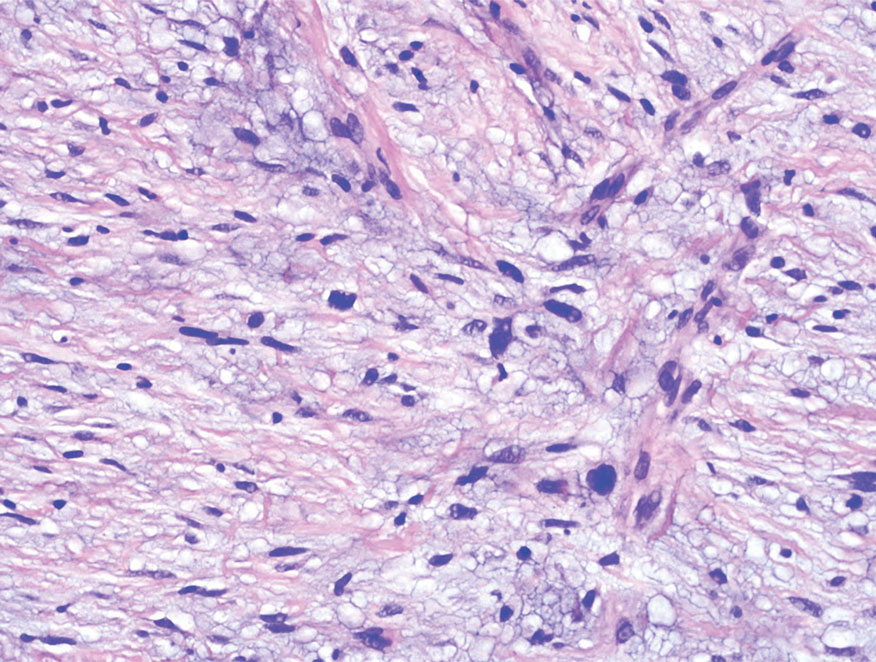

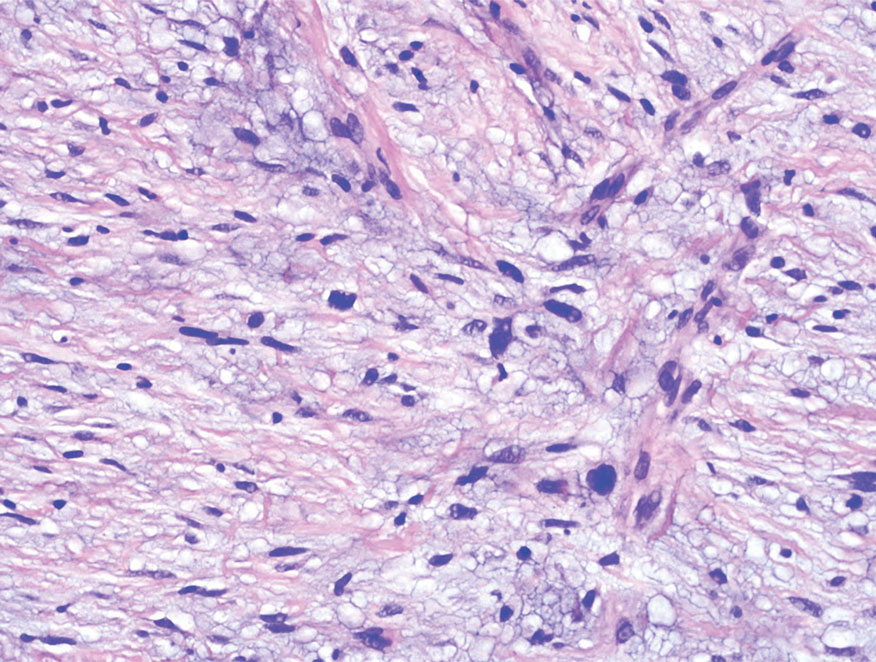

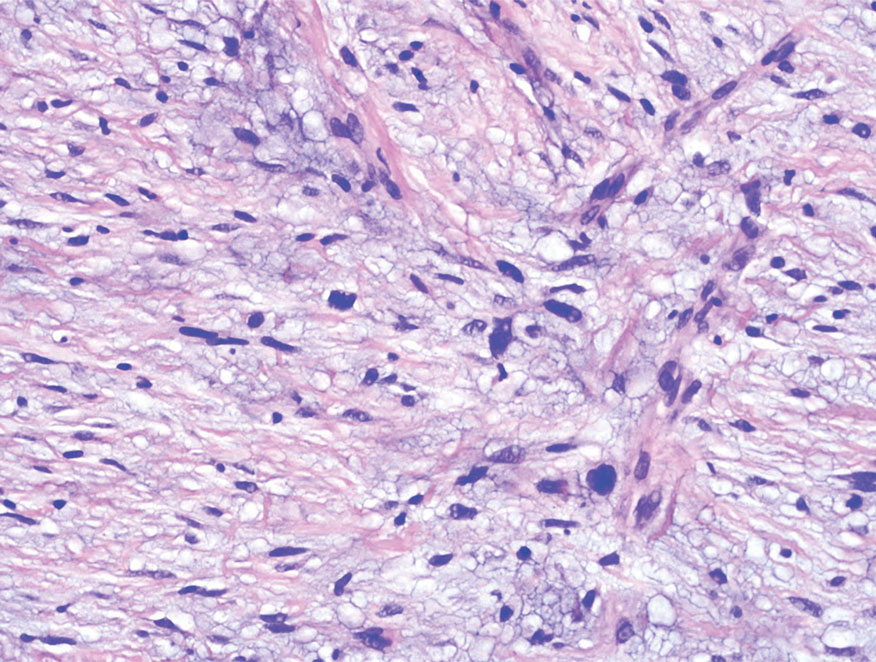

Multinucleate cell angiohistiocytoma is a rare benign proliferation that presents with numerous red-violet asymptomatic papules that commonly appear on the upper and lower extremities of women aged 40 to 70 years. Lesions feature both a fibrohistiocytic and vascular component.9 Histologic examination commonly shows multinucleated cells with angular outlining in the superficial dermis accompanied by fibrosis and ectatic small-caliber vessels (Figure 3). Although both pleomorphic lipoma and multinucleate cell angiohistiocytoma have similar-appearing multinucleated giant cells, the latter has a proliferation of narrow vessels in thick collagen bundles and lacks an adipocytic component, which distinguishes it from the former.10 Multinucleate cell angiohistiocytoma also is characterized by a substantial number of factor XIIIa–positive fibrohistiocytic interstitial cells and vascular hyperplasia.9

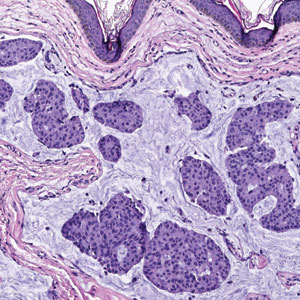

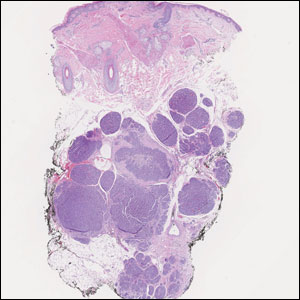

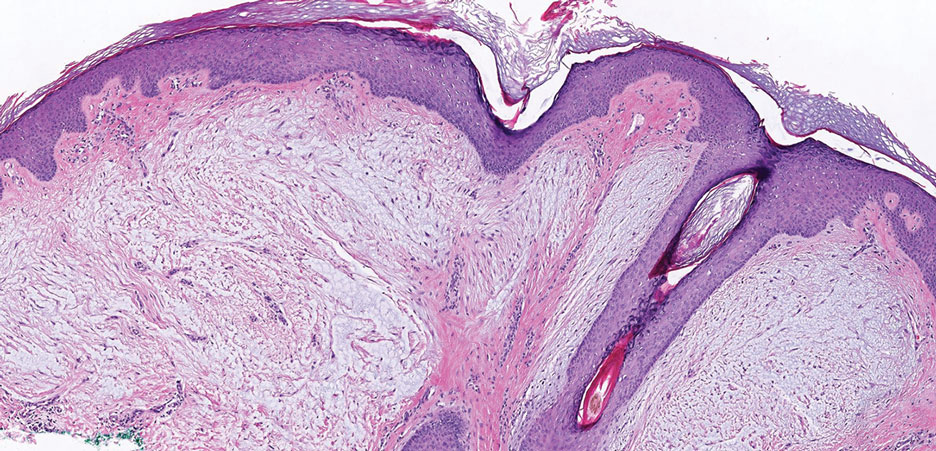

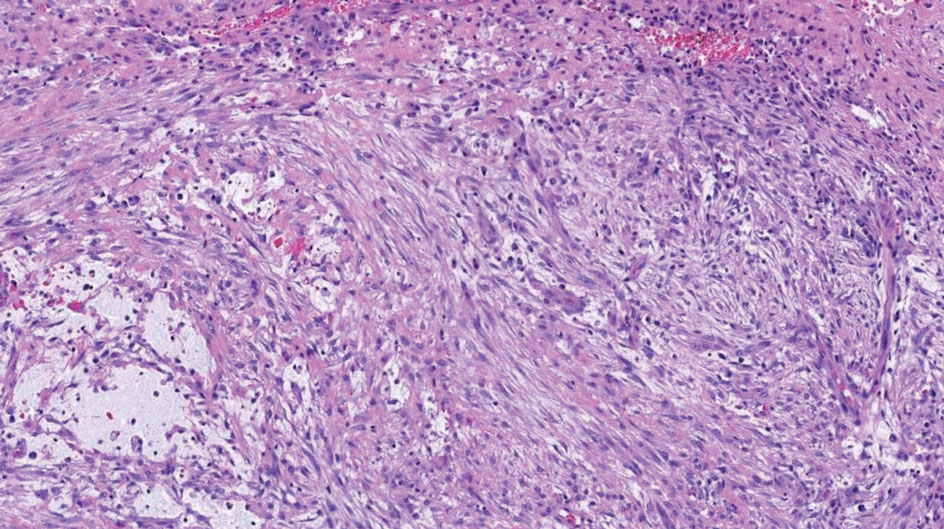

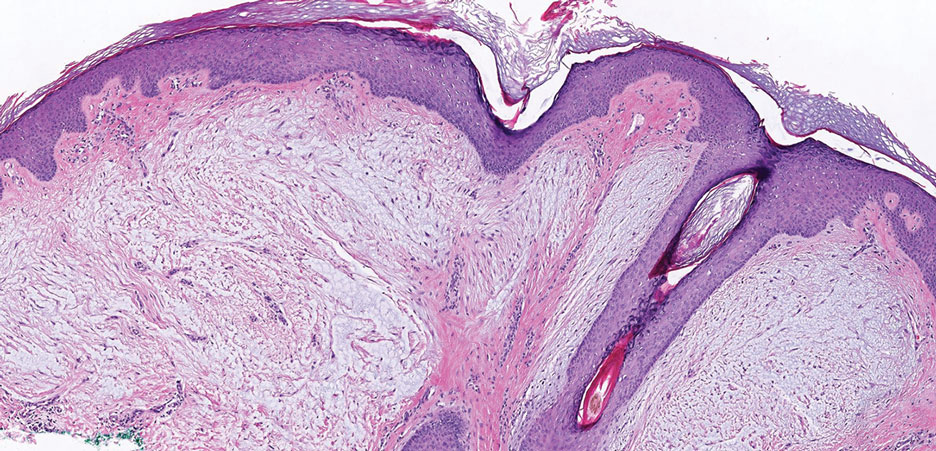

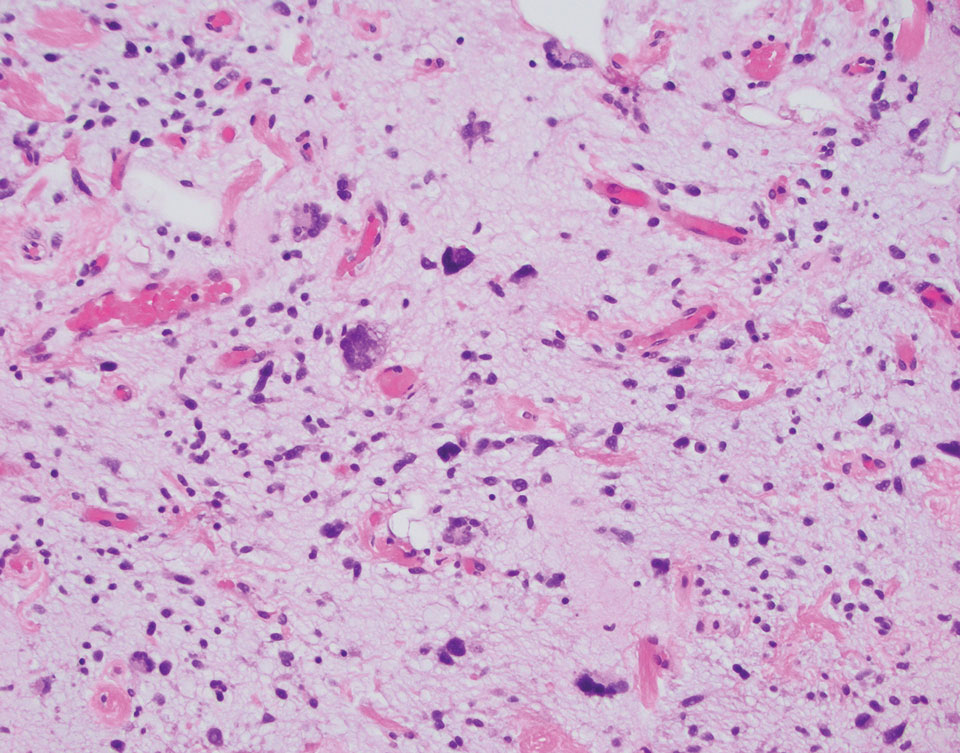

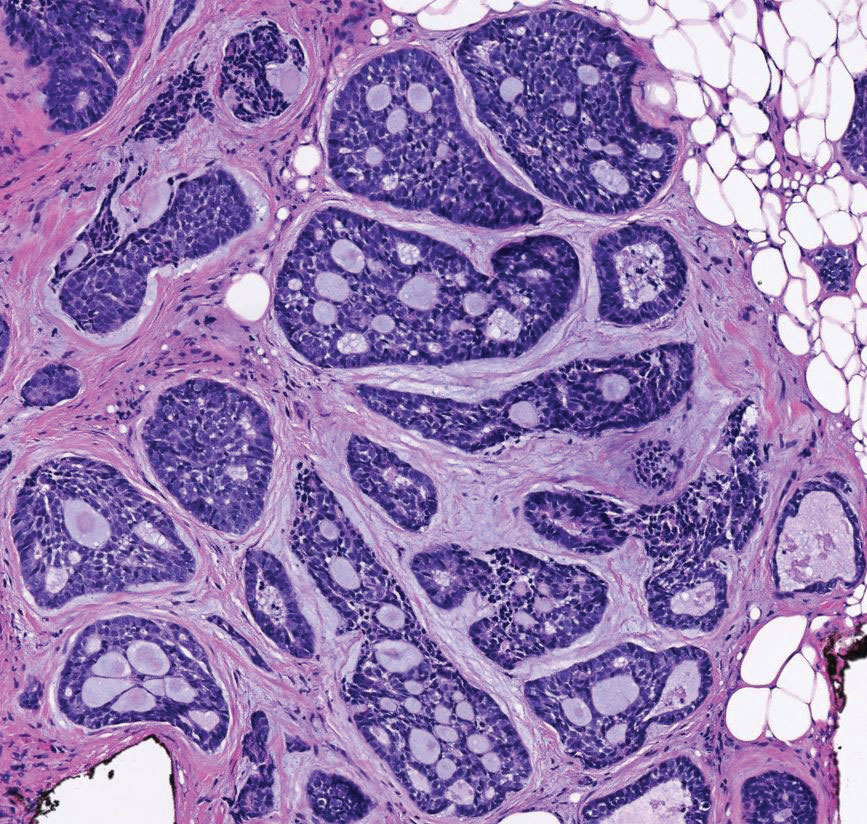

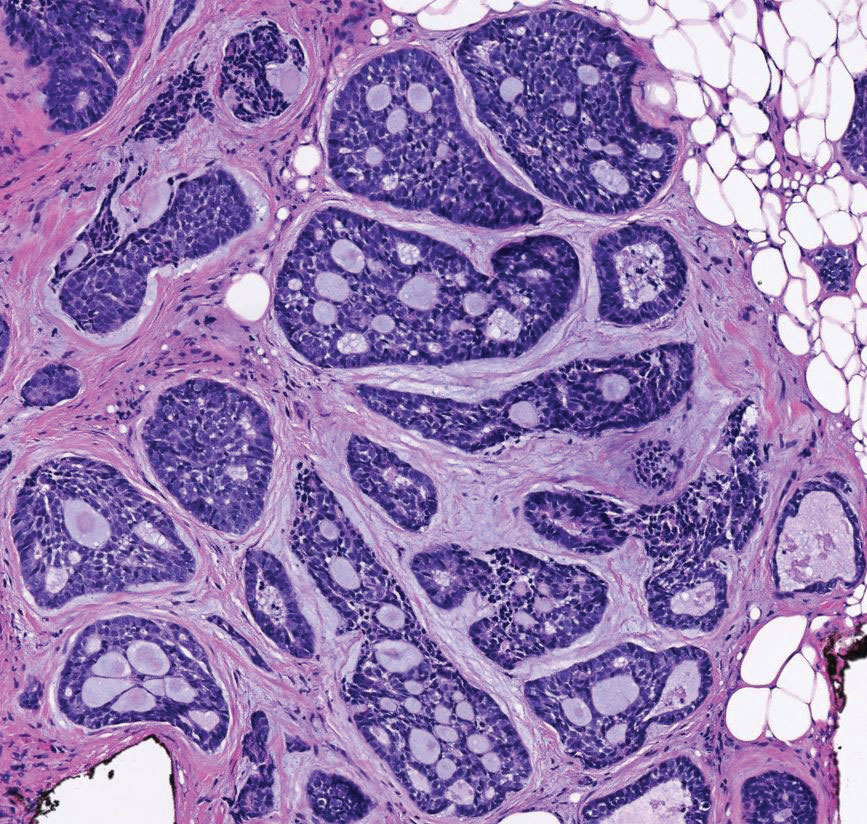

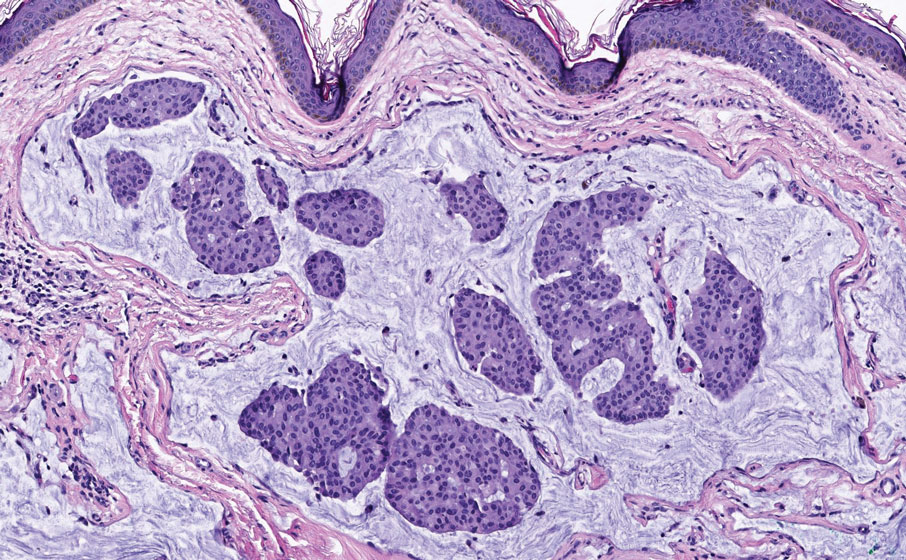

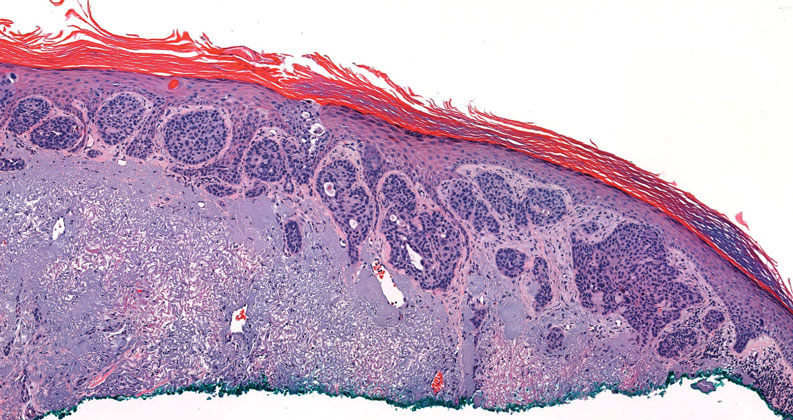

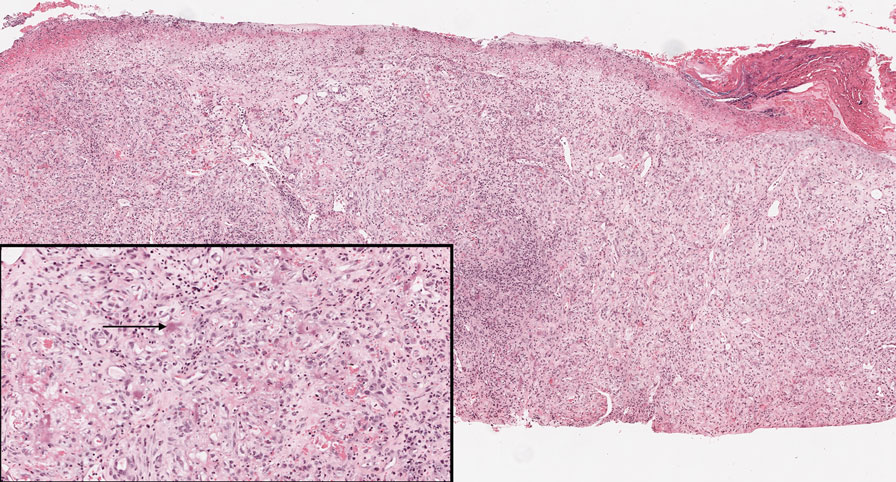

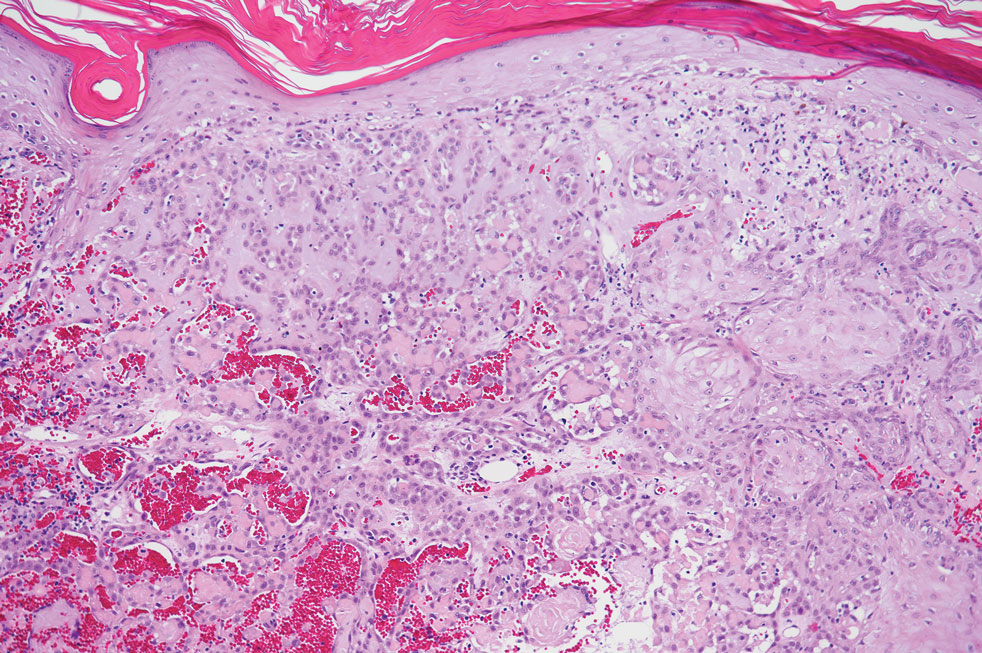

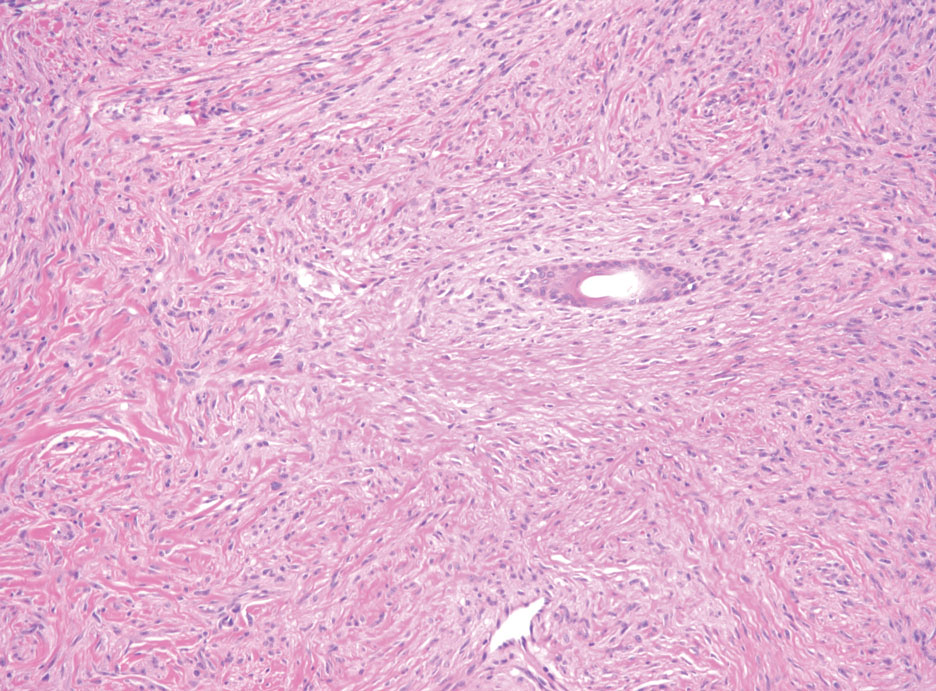

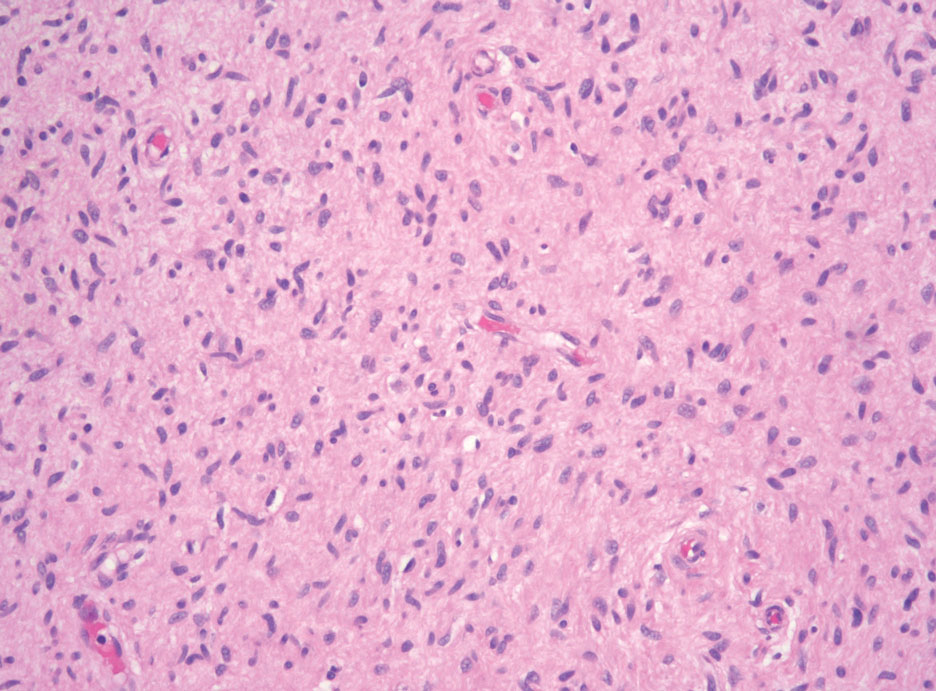

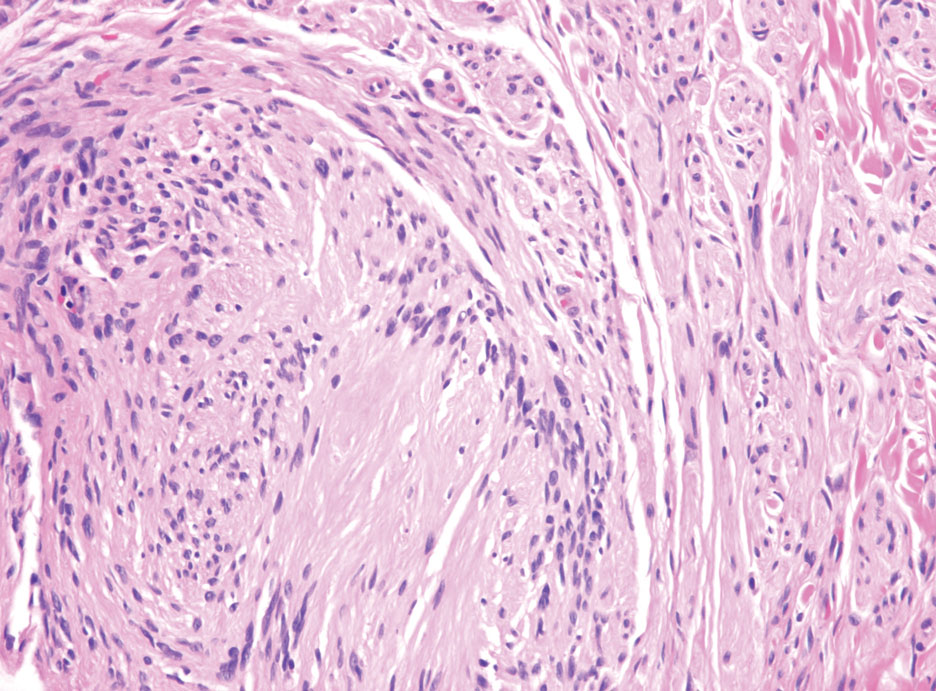

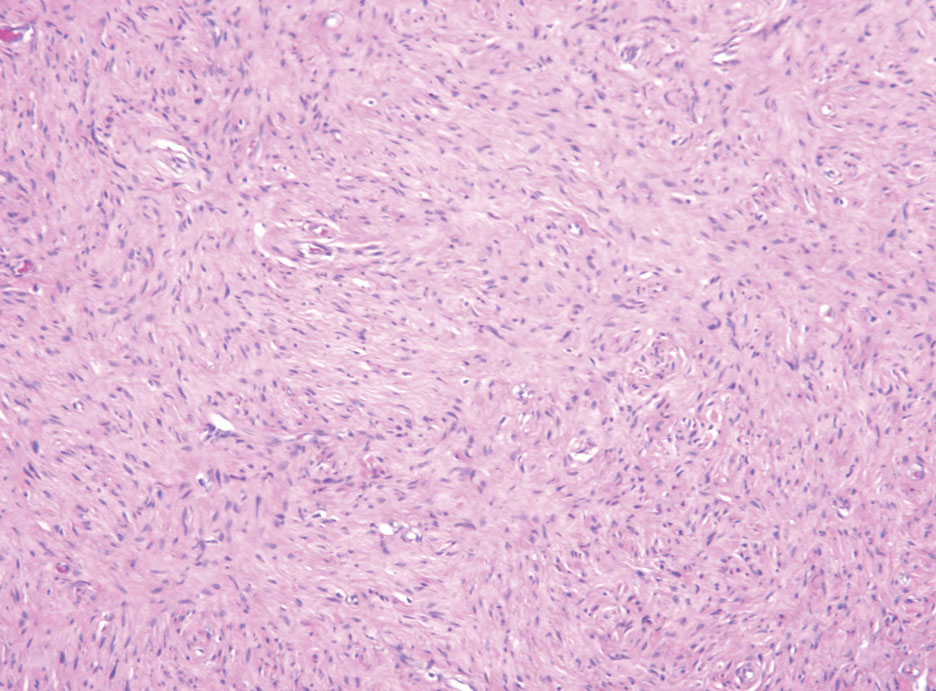

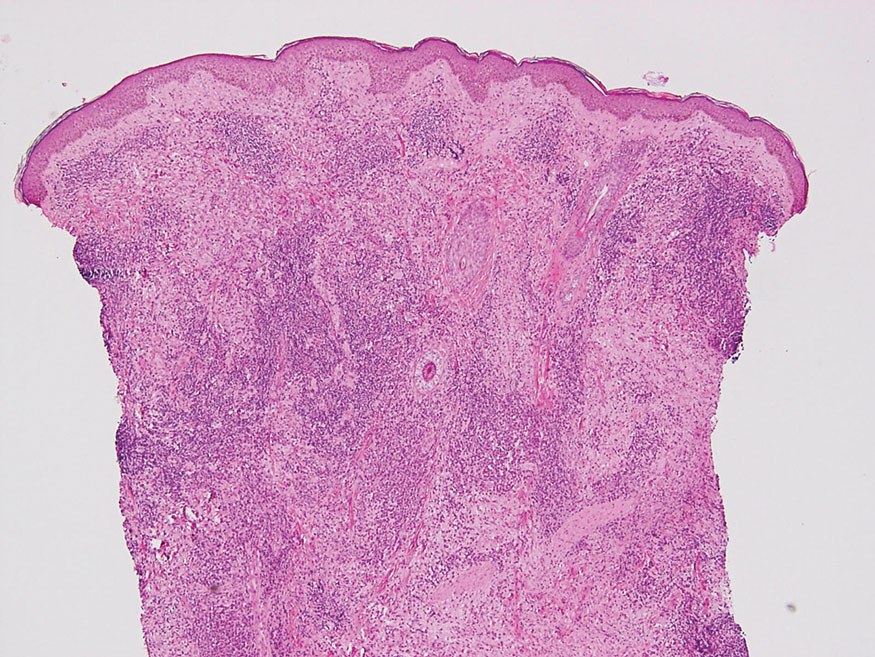

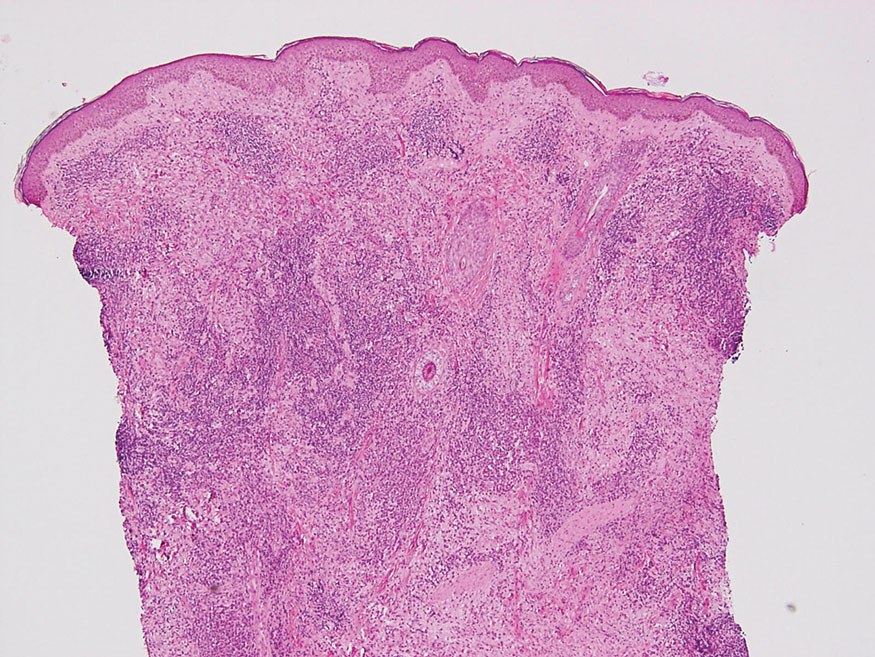

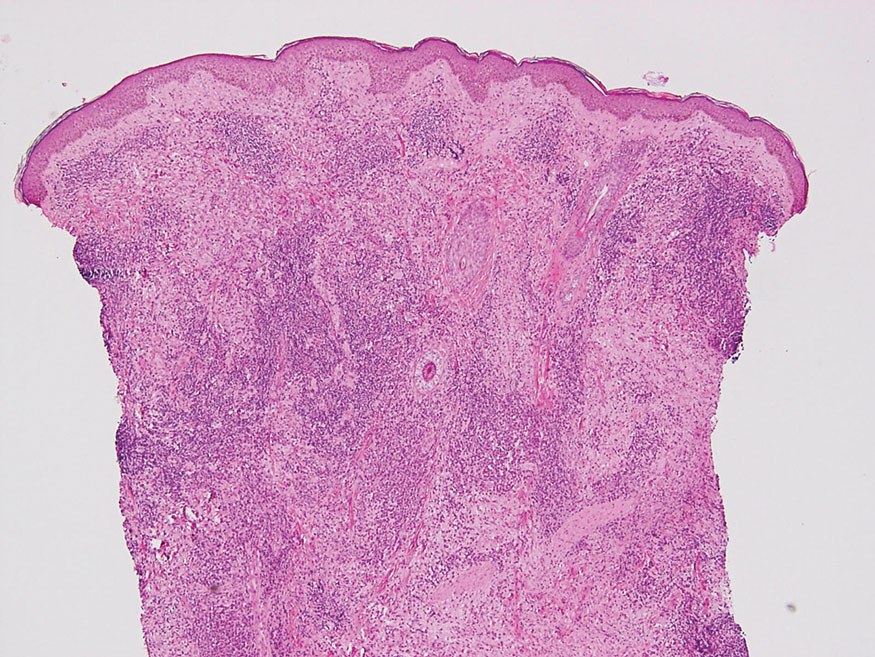

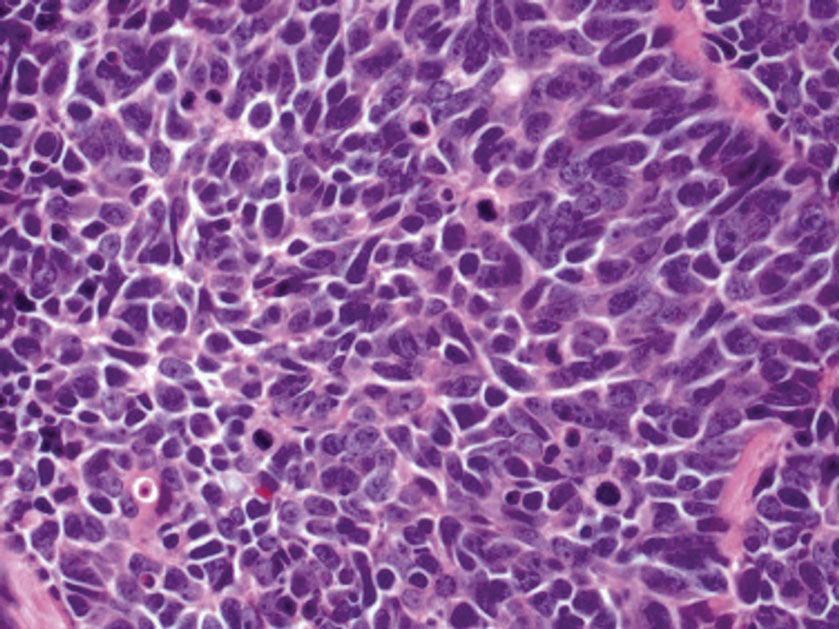

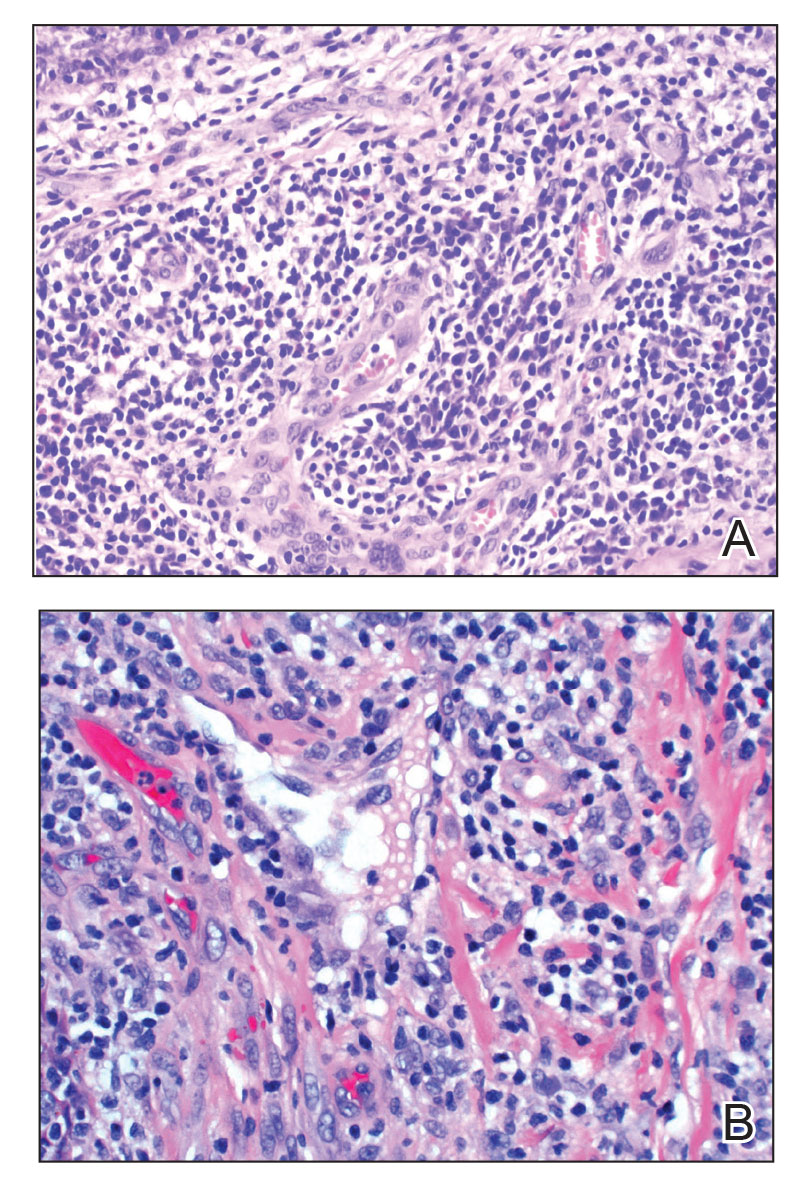

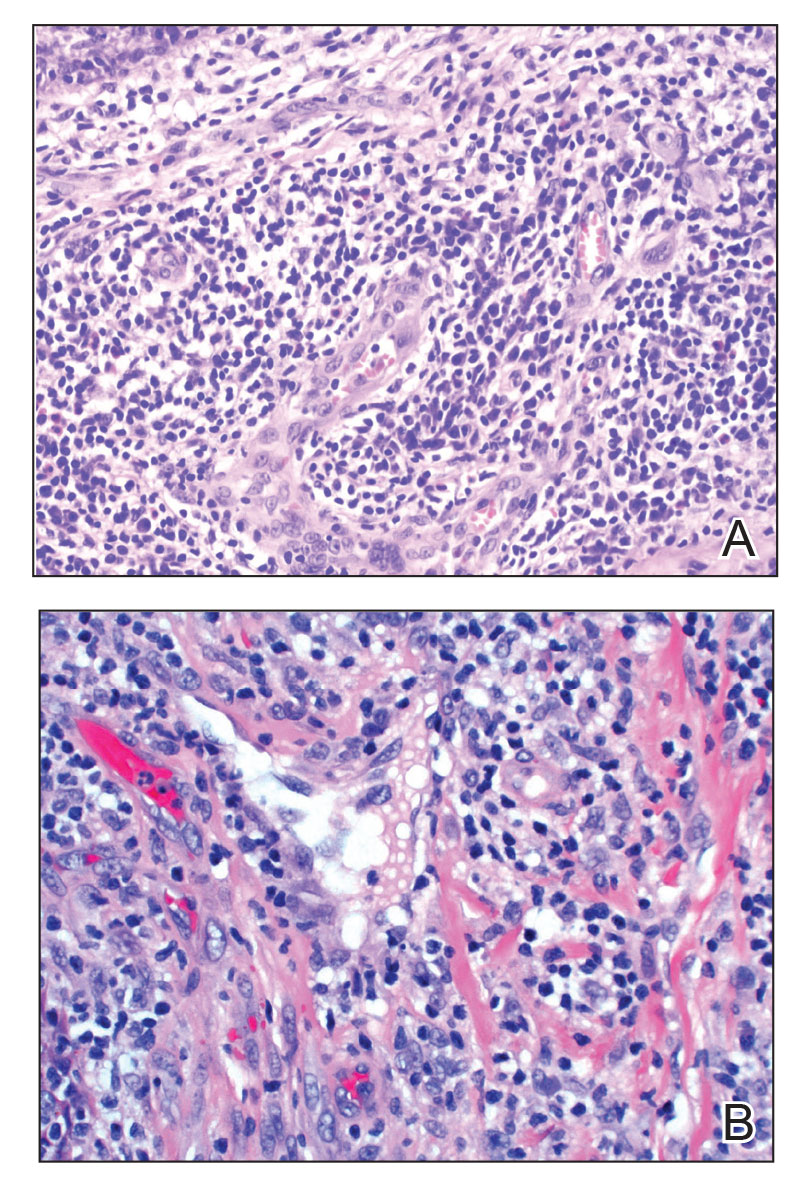

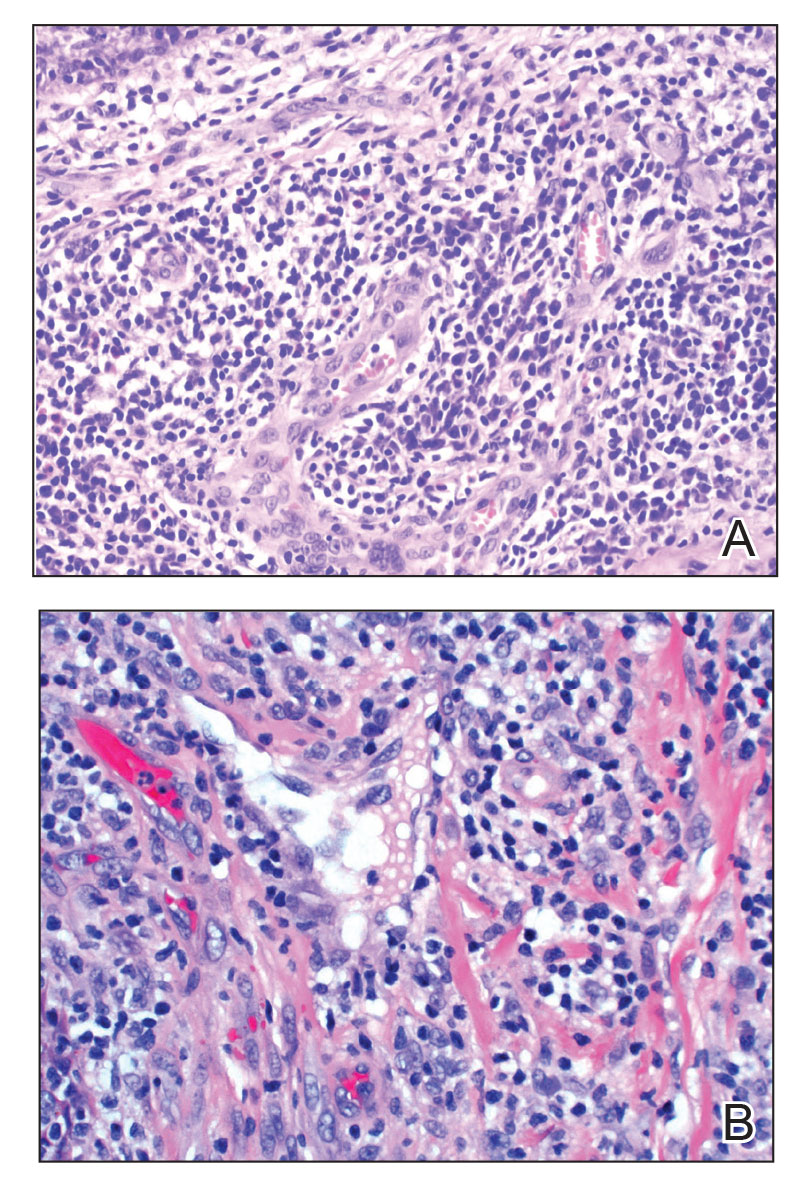

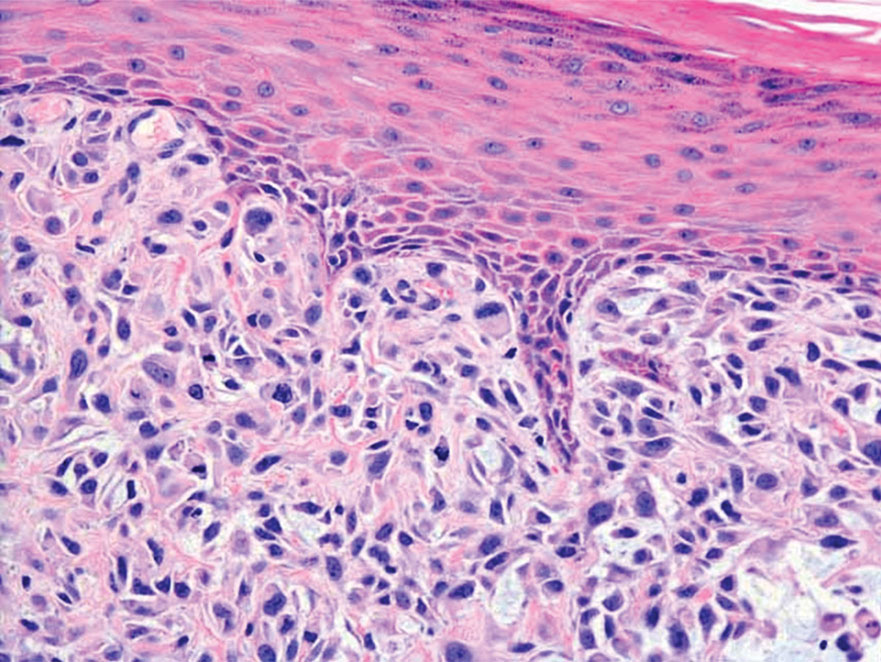

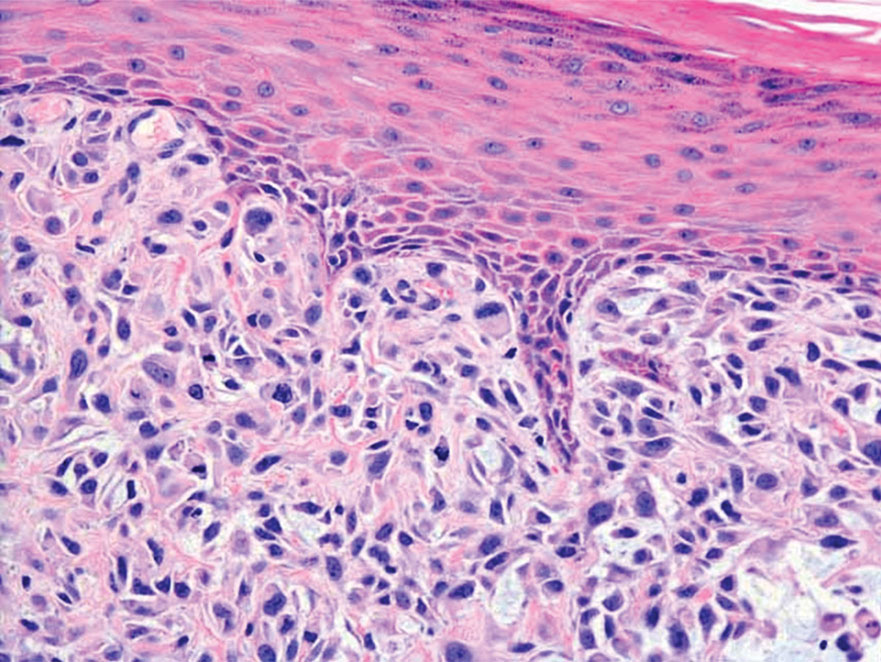

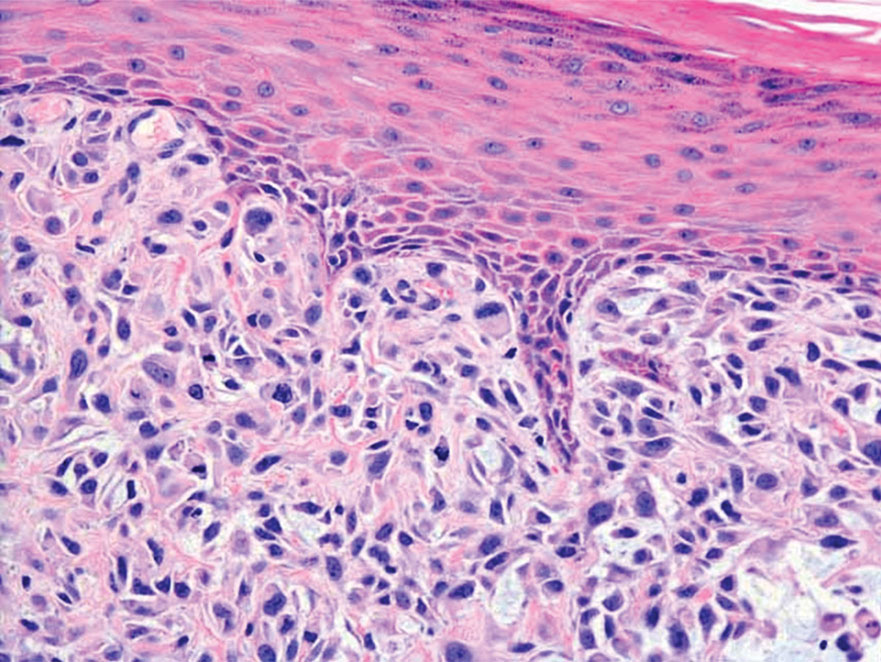

Nodular fasciitis is a benign lesion involving the rapid proliferation of myofibroblasts and fibroblasts in the subcutaneous tissue and most commonly is encountered on the extremities or head and neck regions. Many cases appear at sites of prior trauma, especially in patients aged 20 to 40 years. However, in infants and children the lesions typically are found in the head and neck regions.11 Clinically, lesions present as subcutaneous nodules. Histology reveals an infiltrative and poorly circumscribed proliferation of spindled myofibroblasts associated with myxoid stroma and dense collagen depositions. The spindled cells are loosely associated, rendering a tissue culture–like appearance (Figure 4). It also is common to see erythrocyte extravasation adjacent to myxoid stroma.11 Positive stains include vimentin, smooth muscle actin, and CD68, though immunohistochemistry often is not necessary for diagnosis.12 There often is abundant mitotic activity in nodular fasciitis, especially in early lesions, and the differential diagnosis includes sarcoma. Although nodular fasciitis is mitotically active, it does not show atypical mitotic figures. Nodular fasciitis commonly harbors a gene translocation of the MYH9 gene’s promoter region to the USP6 gene’s coding region.13

- Sakhadeo U, Mundhe R, DeSouza MA, et al. Pleomorphic lipoma: a gentle giant of pathology. J Cytol. 2015;32:201-203. doi:10.4103 /0970-9371.168904

- Shmookler BM, Enzinger FM. Pleomorphic lipoma: a benign tumor simulating liposarcoma. a clinicopathologic analysis of 48 cases. Cancer. 1981;47:126-133.

- Azzopardi JG, Iocco J, Salm R. Pleomorphic lipoma: a tumour simulating liposarcoma. Histopathology. 1983;7:511-523. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2559.1983.tb02264.x

- Jäger M, Winkelmann R, Eichler K, et al. Pleomorphic lipoma. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018;16:208-210. doi:10.1111/ddg.13422

- Allen A, Ahn C, Sangüeza OP. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:483-488. doi:10.1016/j.det.2019.05.006

- Socoliuc C, Zurac S, Andrei R, et al. Multiple histological subtypes of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans occurring in the same tumor. Rom J Intern Med. 2015;53:79-88. doi:10.1515/rjim-2015-0011

- Abarzúa-Araya A, Lallas A, Piana S, et al. Superficial angiomyxoma of the skin. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2016;6:47-49. doi:10.5826 /dpc.0603a09

- Hornick J. Practical Soft Tissue Pathology A Diagnostic Approach. 2nd ed. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2017.

- Rato M, Monteiro AF, Parente J, et al. Case for diagnosis. multinucleated cell angiohistiocytoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:291-293. doi:10.1590 /abd1806-4841.20186821

- Grgurich E, Quinn K, Oram C, et al. Multinucleate cell angiohistiocytoma: case report and literature review. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:59-61. doi:10.1111/cup.13361

- Zuber TJ, Finley JL. Nodular fasciitis. South Med J. 1994;87:842-844. doi:10.1097/00007611-199408000-00020

- Yver CM, Husson MA, Friedman O. Pathology clinic: nodular fasciitis involving the external ear [published online March 18, 2021]. Ear Nose Throat J. doi:10.1177/01455613211001958

- Erickson-Johnson M, Chou M, Evers B, et al. Nodular fasciitis: a novel model of transient neoplasia induced by MYH9-USP6 gene fusion. Lab Invest. 2011;91:1427-1433. https://doi.org/10.1038 /labinvest.2011.118

The Diagnosis: Pleomorphic Lipoma

Pleomorphic lipoma is a rare, benign, adipocytic neoplasm that presents in the subcutaneous tissues of the upper shoulder, back, or neck. It predominantly affects men aged 50 to 70 years. Most lesions are situated in the subcutaneous tissues; few cases of intramuscular and retroperitoneal tumors have been reported.1 Clinically, pleomorphic lipomas present as painless, well-circumscribed lesions of the subcutaneous tissue that often resemble a lipoma or occasionally may be mistaken for liposarcoma. Histopathologic examination of ordinary lipomas reveals uniform mature adipocytes. However, pleomorphic lipomas consist of a mixture of multinucleated floretlike giant cells, variable-sized adipocytes, and fibrous tissue (ropy collagen bundles) with some myxoid and spindled areas.1,2 The most characteristic histologic feature of pleomorphic lipoma is multinucleated floretlike giant cells. The nuclei of these giant cells appear hyperchromatic, enlarged, and disposed to the periphery of the cell in a circular pattern. Additionally, tumors frequently contain excess mature dense collagen bundles that are strongly refractile in polarized light. Numerous mast cells are present. Atypical lipoblasts and capillary networks commonly are not visible in pleomorphic lipoma.3 The spindle cells express CD34 on immunohistochemistry. Loss of Rb-1 expression is typical.4

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a slow-growing soft tissue sarcoma that commonly begins as a pink or violet plaque on the trunk or upper limbs. Involvement of the head or neck accounts for only 10% to 15% of cases.5 This tumor has low metastatic potential but is highly infiltrative of surrounding tissues. It is associated with a translocation between chromosomes 22 and 17, leading to the fusion of the platelet-derived growth factor subunit β, PDGFB, and collagen type 1α1, COL1A1, genes.5 Clinically, patients often report that the lesion was present for several years prior to presentation with general stability in size and shape. Eventually, untreated lesions progress to become nodules or tumors and may even bleed or ulcerate. Histology reveals a storiform spindle cell proliferation throughout the dermis with infiltration into subcutaneous fat, commonly appearing in a honeycomblike pattern (Figure 1). Numerous histologic variants exist, including myxoid, sclerosing, pigmented (Bednar tumor), myoid, atrophic, or fibrosarcomatous dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, as well as a giant cell fibroblastoma variant.6 These tumor subtypes can exist independently or in association with one another, creating hybrid lesions that can closely mimic other entities such as pleomorphic lipoma. The spindle cells stain positively for CD34. Treatment of these tumors involves complete surgical excision or Mohs micrographic surgery; however, recurrence is common for tumors involving the head or neck.5

Superficial angiomyxoma is a slow-growing papule that most commonly appears on the trunk, head, or neck in middle-aged adults. Occasionally, patients with Carney complex also can develop lesions on the external ear or breast.7 Histologically, superficial angiomyxoma is a hypocellular tumor characterized by abundant myxoid stroma, thin blood vessels, and small spindled and stellate cells with minimal cytoplasm (Figure 2).8 Superficial angiomyxoma and pleomorphic lipoma present differently on histology; superficial angiomyxoma is not associated with nuclear atypia or pleomorphism, whereas pleomorphic lipoma characteristically contains multinucleated floretlike giant cells and pleomorphism. Frequently, there also is loss of normal PRKAR1A gene expression, which is responsible for protein kinase A regulatory subunit 1-alpha expression.8

Multinucleate cell angiohistiocytoma is a rare benign proliferation that presents with numerous red-violet asymptomatic papules that commonly appear on the upper and lower extremities of women aged 40 to 70 years. Lesions feature both a fibrohistiocytic and vascular component.9 Histologic examination commonly shows multinucleated cells with angular outlining in the superficial dermis accompanied by fibrosis and ectatic small-caliber vessels (Figure 3). Although both pleomorphic lipoma and multinucleate cell angiohistiocytoma have similar-appearing multinucleated giant cells, the latter has a proliferation of narrow vessels in thick collagen bundles and lacks an adipocytic component, which distinguishes it from the former.10 Multinucleate cell angiohistiocytoma also is characterized by a substantial number of factor XIIIa–positive fibrohistiocytic interstitial cells and vascular hyperplasia.9

Nodular fasciitis is a benign lesion involving the rapid proliferation of myofibroblasts and fibroblasts in the subcutaneous tissue and most commonly is encountered on the extremities or head and neck regions. Many cases appear at sites of prior trauma, especially in patients aged 20 to 40 years. However, in infants and children the lesions typically are found in the head and neck regions.11 Clinically, lesions present as subcutaneous nodules. Histology reveals an infiltrative and poorly circumscribed proliferation of spindled myofibroblasts associated with myxoid stroma and dense collagen depositions. The spindled cells are loosely associated, rendering a tissue culture–like appearance (Figure 4). It also is common to see erythrocyte extravasation adjacent to myxoid stroma.11 Positive stains include vimentin, smooth muscle actin, and CD68, though immunohistochemistry often is not necessary for diagnosis.12 There often is abundant mitotic activity in nodular fasciitis, especially in early lesions, and the differential diagnosis includes sarcoma. Although nodular fasciitis is mitotically active, it does not show atypical mitotic figures. Nodular fasciitis commonly harbors a gene translocation of the MYH9 gene’s promoter region to the USP6 gene’s coding region.13

The Diagnosis: Pleomorphic Lipoma

Pleomorphic lipoma is a rare, benign, adipocytic neoplasm that presents in the subcutaneous tissues of the upper shoulder, back, or neck. It predominantly affects men aged 50 to 70 years. Most lesions are situated in the subcutaneous tissues; few cases of intramuscular and retroperitoneal tumors have been reported.1 Clinically, pleomorphic lipomas present as painless, well-circumscribed lesions of the subcutaneous tissue that often resemble a lipoma or occasionally may be mistaken for liposarcoma. Histopathologic examination of ordinary lipomas reveals uniform mature adipocytes. However, pleomorphic lipomas consist of a mixture of multinucleated floretlike giant cells, variable-sized adipocytes, and fibrous tissue (ropy collagen bundles) with some myxoid and spindled areas.1,2 The most characteristic histologic feature of pleomorphic lipoma is multinucleated floretlike giant cells. The nuclei of these giant cells appear hyperchromatic, enlarged, and disposed to the periphery of the cell in a circular pattern. Additionally, tumors frequently contain excess mature dense collagen bundles that are strongly refractile in polarized light. Numerous mast cells are present. Atypical lipoblasts and capillary networks commonly are not visible in pleomorphic lipoma.3 The spindle cells express CD34 on immunohistochemistry. Loss of Rb-1 expression is typical.4

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a slow-growing soft tissue sarcoma that commonly begins as a pink or violet plaque on the trunk or upper limbs. Involvement of the head or neck accounts for only 10% to 15% of cases.5 This tumor has low metastatic potential but is highly infiltrative of surrounding tissues. It is associated with a translocation between chromosomes 22 and 17, leading to the fusion of the platelet-derived growth factor subunit β, PDGFB, and collagen type 1α1, COL1A1, genes.5 Clinically, patients often report that the lesion was present for several years prior to presentation with general stability in size and shape. Eventually, untreated lesions progress to become nodules or tumors and may even bleed or ulcerate. Histology reveals a storiform spindle cell proliferation throughout the dermis with infiltration into subcutaneous fat, commonly appearing in a honeycomblike pattern (Figure 1). Numerous histologic variants exist, including myxoid, sclerosing, pigmented (Bednar tumor), myoid, atrophic, or fibrosarcomatous dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, as well as a giant cell fibroblastoma variant.6 These tumor subtypes can exist independently or in association with one another, creating hybrid lesions that can closely mimic other entities such as pleomorphic lipoma. The spindle cells stain positively for CD34. Treatment of these tumors involves complete surgical excision or Mohs micrographic surgery; however, recurrence is common for tumors involving the head or neck.5

Superficial angiomyxoma is a slow-growing papule that most commonly appears on the trunk, head, or neck in middle-aged adults. Occasionally, patients with Carney complex also can develop lesions on the external ear or breast.7 Histologically, superficial angiomyxoma is a hypocellular tumor characterized by abundant myxoid stroma, thin blood vessels, and small spindled and stellate cells with minimal cytoplasm (Figure 2).8 Superficial angiomyxoma and pleomorphic lipoma present differently on histology; superficial angiomyxoma is not associated with nuclear atypia or pleomorphism, whereas pleomorphic lipoma characteristically contains multinucleated floretlike giant cells and pleomorphism. Frequently, there also is loss of normal PRKAR1A gene expression, which is responsible for protein kinase A regulatory subunit 1-alpha expression.8

Multinucleate cell angiohistiocytoma is a rare benign proliferation that presents with numerous red-violet asymptomatic papules that commonly appear on the upper and lower extremities of women aged 40 to 70 years. Lesions feature both a fibrohistiocytic and vascular component.9 Histologic examination commonly shows multinucleated cells with angular outlining in the superficial dermis accompanied by fibrosis and ectatic small-caliber vessels (Figure 3). Although both pleomorphic lipoma and multinucleate cell angiohistiocytoma have similar-appearing multinucleated giant cells, the latter has a proliferation of narrow vessels in thick collagen bundles and lacks an adipocytic component, which distinguishes it from the former.10 Multinucleate cell angiohistiocytoma also is characterized by a substantial number of factor XIIIa–positive fibrohistiocytic interstitial cells and vascular hyperplasia.9

Nodular fasciitis is a benign lesion involving the rapid proliferation of myofibroblasts and fibroblasts in the subcutaneous tissue and most commonly is encountered on the extremities or head and neck regions. Many cases appear at sites of prior trauma, especially in patients aged 20 to 40 years. However, in infants and children the lesions typically are found in the head and neck regions.11 Clinically, lesions present as subcutaneous nodules. Histology reveals an infiltrative and poorly circumscribed proliferation of spindled myofibroblasts associated with myxoid stroma and dense collagen depositions. The spindled cells are loosely associated, rendering a tissue culture–like appearance (Figure 4). It also is common to see erythrocyte extravasation adjacent to myxoid stroma.11 Positive stains include vimentin, smooth muscle actin, and CD68, though immunohistochemistry often is not necessary for diagnosis.12 There often is abundant mitotic activity in nodular fasciitis, especially in early lesions, and the differential diagnosis includes sarcoma. Although nodular fasciitis is mitotically active, it does not show atypical mitotic figures. Nodular fasciitis commonly harbors a gene translocation of the MYH9 gene’s promoter region to the USP6 gene’s coding region.13

- Sakhadeo U, Mundhe R, DeSouza MA, et al. Pleomorphic lipoma: a gentle giant of pathology. J Cytol. 2015;32:201-203. doi:10.4103 /0970-9371.168904

- Shmookler BM, Enzinger FM. Pleomorphic lipoma: a benign tumor simulating liposarcoma. a clinicopathologic analysis of 48 cases. Cancer. 1981;47:126-133.

- Azzopardi JG, Iocco J, Salm R. Pleomorphic lipoma: a tumour simulating liposarcoma. Histopathology. 1983;7:511-523. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2559.1983.tb02264.x

- Jäger M, Winkelmann R, Eichler K, et al. Pleomorphic lipoma. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018;16:208-210. doi:10.1111/ddg.13422

- Allen A, Ahn C, Sangüeza OP. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:483-488. doi:10.1016/j.det.2019.05.006

- Socoliuc C, Zurac S, Andrei R, et al. Multiple histological subtypes of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans occurring in the same tumor. Rom J Intern Med. 2015;53:79-88. doi:10.1515/rjim-2015-0011

- Abarzúa-Araya A, Lallas A, Piana S, et al. Superficial angiomyxoma of the skin. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2016;6:47-49. doi:10.5826 /dpc.0603a09

- Hornick J. Practical Soft Tissue Pathology A Diagnostic Approach. 2nd ed. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2017.

- Rato M, Monteiro AF, Parente J, et al. Case for diagnosis. multinucleated cell angiohistiocytoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:291-293. doi:10.1590 /abd1806-4841.20186821

- Grgurich E, Quinn K, Oram C, et al. Multinucleate cell angiohistiocytoma: case report and literature review. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:59-61. doi:10.1111/cup.13361

- Zuber TJ, Finley JL. Nodular fasciitis. South Med J. 1994;87:842-844. doi:10.1097/00007611-199408000-00020

- Yver CM, Husson MA, Friedman O. Pathology clinic: nodular fasciitis involving the external ear [published online March 18, 2021]. Ear Nose Throat J. doi:10.1177/01455613211001958

- Erickson-Johnson M, Chou M, Evers B, et al. Nodular fasciitis: a novel model of transient neoplasia induced by MYH9-USP6 gene fusion. Lab Invest. 2011;91:1427-1433. https://doi.org/10.1038 /labinvest.2011.118

- Sakhadeo U, Mundhe R, DeSouza MA, et al. Pleomorphic lipoma: a gentle giant of pathology. J Cytol. 2015;32:201-203. doi:10.4103 /0970-9371.168904

- Shmookler BM, Enzinger FM. Pleomorphic lipoma: a benign tumor simulating liposarcoma. a clinicopathologic analysis of 48 cases. Cancer. 1981;47:126-133.

- Azzopardi JG, Iocco J, Salm R. Pleomorphic lipoma: a tumour simulating liposarcoma. Histopathology. 1983;7:511-523. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2559.1983.tb02264.x

- Jäger M, Winkelmann R, Eichler K, et al. Pleomorphic lipoma. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018;16:208-210. doi:10.1111/ddg.13422

- Allen A, Ahn C, Sangüeza OP. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:483-488. doi:10.1016/j.det.2019.05.006

- Socoliuc C, Zurac S, Andrei R, et al. Multiple histological subtypes of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans occurring in the same tumor. Rom J Intern Med. 2015;53:79-88. doi:10.1515/rjim-2015-0011

- Abarzúa-Araya A, Lallas A, Piana S, et al. Superficial angiomyxoma of the skin. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2016;6:47-49. doi:10.5826 /dpc.0603a09

- Hornick J. Practical Soft Tissue Pathology A Diagnostic Approach. 2nd ed. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2017.

- Rato M, Monteiro AF, Parente J, et al. Case for diagnosis. multinucleated cell angiohistiocytoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:291-293. doi:10.1590 /abd1806-4841.20186821

- Grgurich E, Quinn K, Oram C, et al. Multinucleate cell angiohistiocytoma: case report and literature review. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:59-61. doi:10.1111/cup.13361

- Zuber TJ, Finley JL. Nodular fasciitis. South Med J. 1994;87:842-844. doi:10.1097/00007611-199408000-00020

- Yver CM, Husson MA, Friedman O. Pathology clinic: nodular fasciitis involving the external ear [published online March 18, 2021]. Ear Nose Throat J. doi:10.1177/01455613211001958

- Erickson-Johnson M, Chou M, Evers B, et al. Nodular fasciitis: a novel model of transient neoplasia induced by MYH9-USP6 gene fusion. Lab Invest. 2011;91:1427-1433. https://doi.org/10.1038 /labinvest.2011.118

An otherwise healthy 56-year-old man with a family history of lymphoma presented with a raised lesion on the postauricular neck. He first noticed the nodule 3 months prior and was unsure if it was still getting larger. It was predominantly asymptomatic. Physical examination revealed a 1.5×1.5-cm, mobile, subcutaneous nodule. An incisional biopsy was performed and submitted for histologic evaluation.

Recurrent Oral and Gluteal Cleft Erosions

The Diagnosis: Lichen Planus Pemphigoides

Lichen planus pemphigoides (LPP) is a rare acquired autoimmune blistering disorder with an estimated worldwide prevalence of approximately 1 in 1,000,000 individuals.1 It often manifests with overlapping features of both LP and bullous pemphigoid (BP). The condition usually presents in the fifth decade of life and has a slight female predominance.2 Although primarily idiopathic, it has been associated with certain medications and treatments, such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, programmed cell death protein 1 inhibitors, programmed cell death ligand 1 inhibitors, labetalol, narrowband UVB, and psoralen plus UVA.3,4

Patients initially present with lesions of classic lichen planus (LP) with pink-purple, flat-topped, pruritic, polygonal papules and plaques.5 After weeks to months, tense vesicles and bullae usually develop on the sites of LP as well as on uninvolved skin. One study found a mean lag time of about 8.3 months for blistering to present after LP,5 but concurrent presentations of both have been reported.1 In addition, oral mucosal involvement has been seen in 36% of cases. The most commonly affected sites are the extremities; however, involvement can be widespread.2

The pathogenesis of LPP currently is unknown. It has been proposed that in LP, injury of basal keratinocytes exposes hidden basement membrane and hemidesmosome antigens including BP180, a 180 kDa transmembrane protein of the basement membrane zone (BMZ),6 which triggers an immune response where T cells recognize the extracellular portion of BP180 and antibodies are formed against the likely autoantigen.1 One study has suggested that the autoantigen in LPP is the MCW-4 epitope within the C-terminal end of the NC16A domain of BP180.7

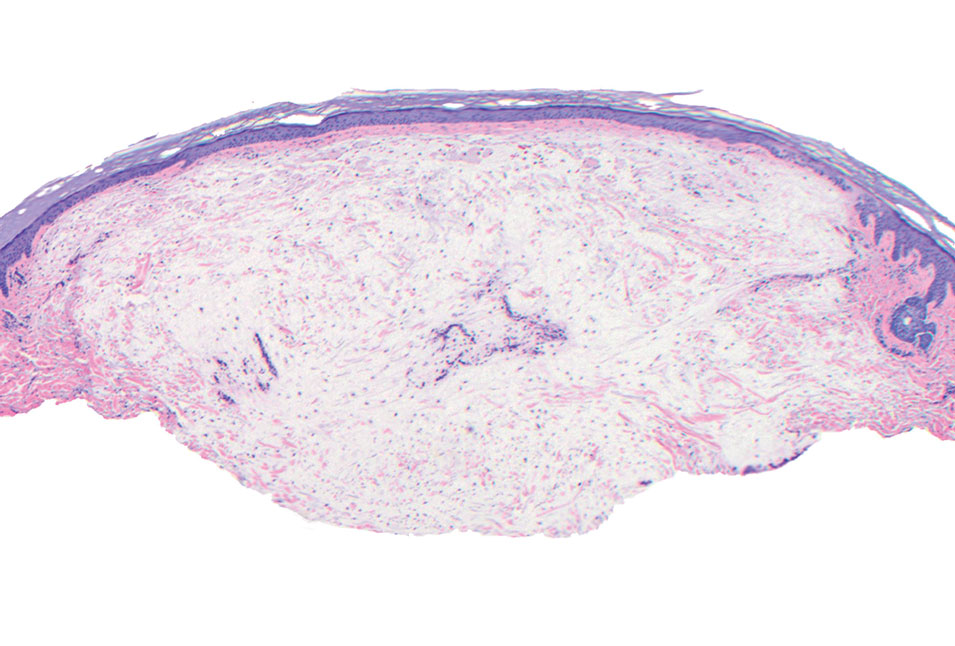

Histopathology of LPP reveals characteristics of both LP as well as BP. Typical features of LP on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining include lichenoid lymphocytic interface dermatitis, sawtooth rete ridges, wedge-shaped hypergranulosis, and colloid bodies, as demonstrated from the biopsy of our patient’s gluteal cleft lesion (quiz image 1), while the predominant feature of BP on H&E staining includes a subepidermal bulla with eosinophils.2 Typically, direct immunofluorescence (DIF) shows linear deposits of IgG and/or C3 along the BMZ. Indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) often reveals IgG against the roof of the BMZ in a human split-skin substrate.1 Antibodies against BP180 or uncommonly BP230 often are detected on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). For our patient, IIF and ELISA tests were positive. Given the clinical presentation with recurrent oral and gluteal cleft erosions, histologic findings, and the results of our patient’s immunological testing, the diagnosis of LPP was made.

Topical steroids often are used to treat localized disease of LPP.8 Oral prednisone also may be given for widespread or unresponsive disease.9 Other treatments include azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, hydroxychloroquine, dapsone, tetracycline in combination with nicotinamide, acitretin, ustekinumab, baricitinib, and rituximab with intravenous immunoglobulin.3,8,10-12 Any potential medication culprits should be discontinued.9 Patients with oral involvement may require a soft diet to avoid further mucosal insult.10 Additionally, providers should consider dentistry, ophthalmology, and/or otolaryngology referrals depending on disease severity.

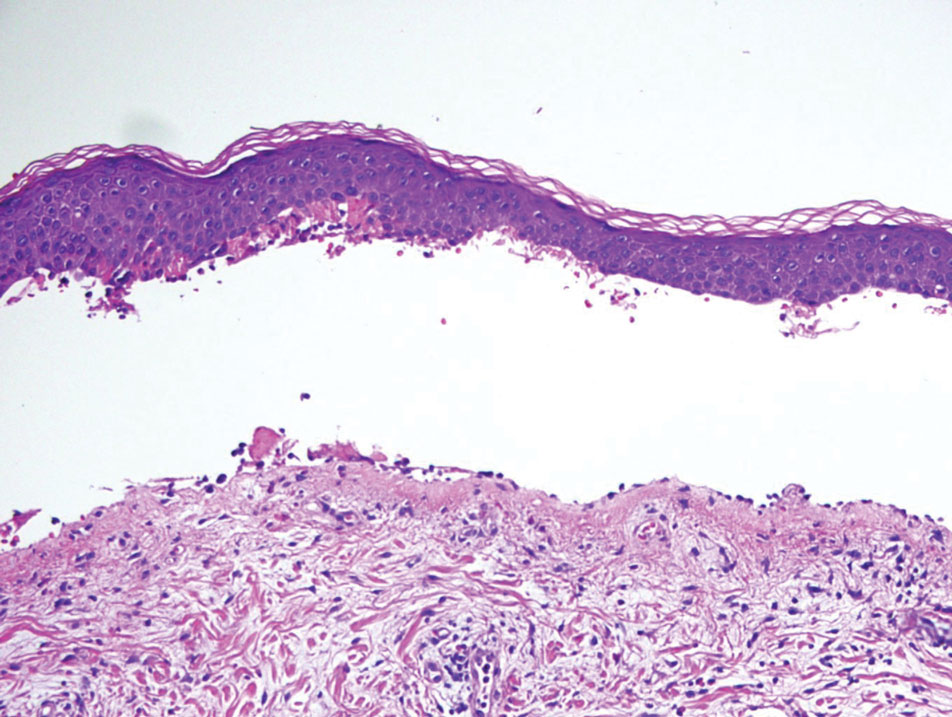

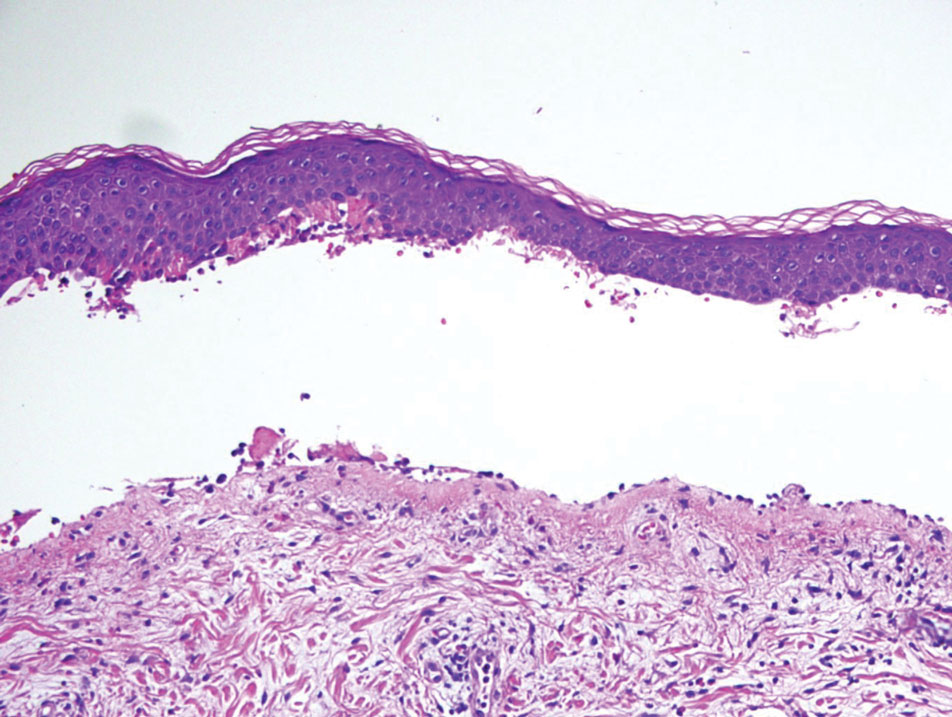

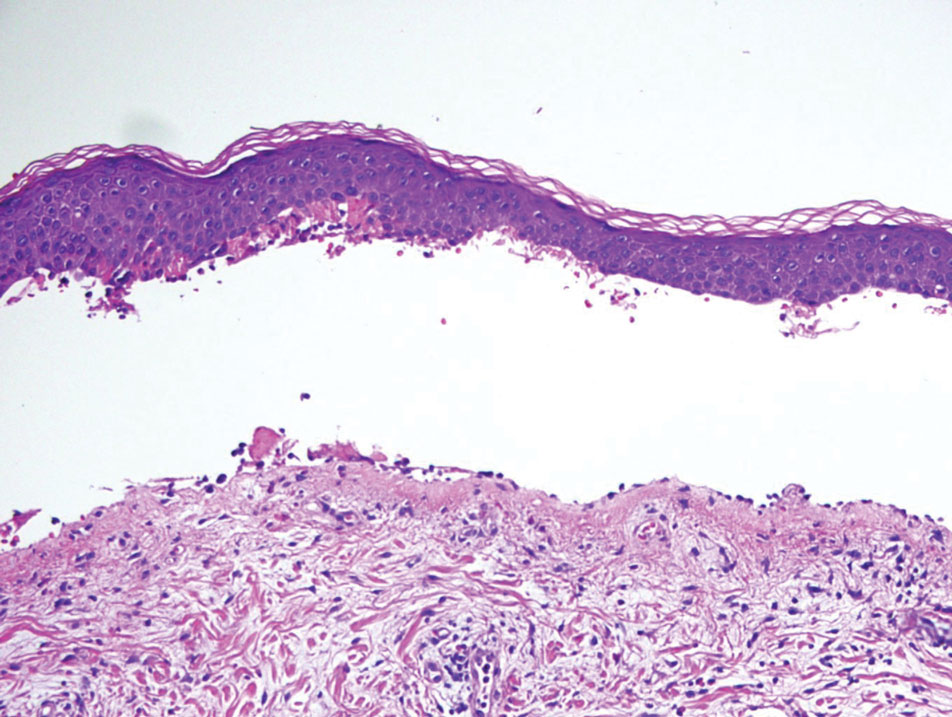

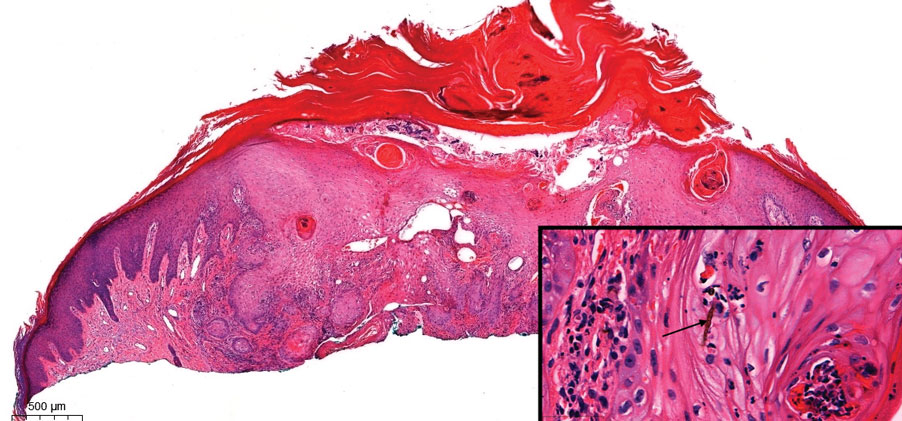

Bullous pemphigoid, the most common autoimmune blistering disease, has an estimated incidence of 10 to 43 per million individuals per year.2 Classically, it presents with tense bullae on the skin of the lower abdomen, thighs, groin, forearms, and axillae. Circulating antibodies against 2 BMZ proteins—BP180 and BP230—are important factors in BP pathogenesis.2 Diagnosis of BP is based on clinical features, histologic findings, and immunological studies including DIF, IIF, and ELISA. An eosinophil-rich subepidermal split typically is seen on H&E staining (Figure 1).

Direct immunofluorescence displays linear IgG and/ or C3 staining at the BMZ. Indirect immunofluorescence on a human salt-split skin substrate commonly shows linear BMZ deposition on the roof of the blister.2 Indirect immunofluorescence for IgG deposition on monkey esophagus substrate shows linear BMZ deposition. Antibodies against the NC16A domain of BP180 (NC16A-BP180) are dominant, but BP230 antibodies against BP230 also are detected with ELISA.2 Further studies have indicated that the NC16A epitopes of BP180 that are targeted in BP are MCW-0-3,2 different from the autoantigen MCW-4 that is targeted in LPP.7

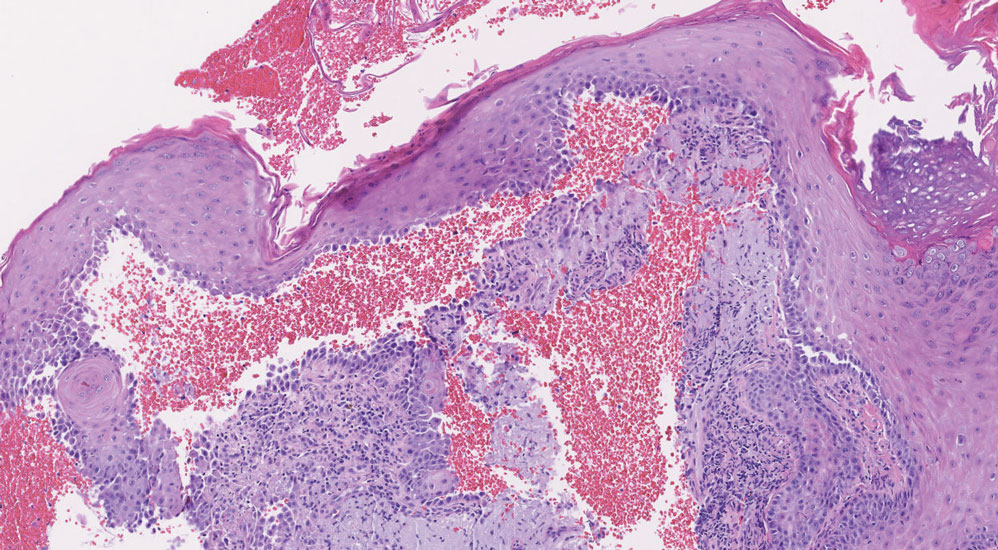

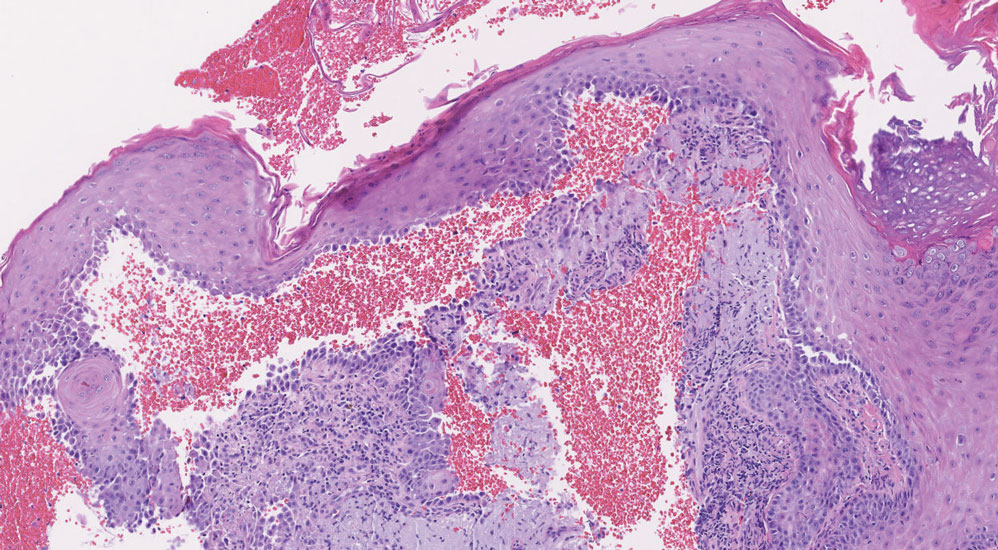

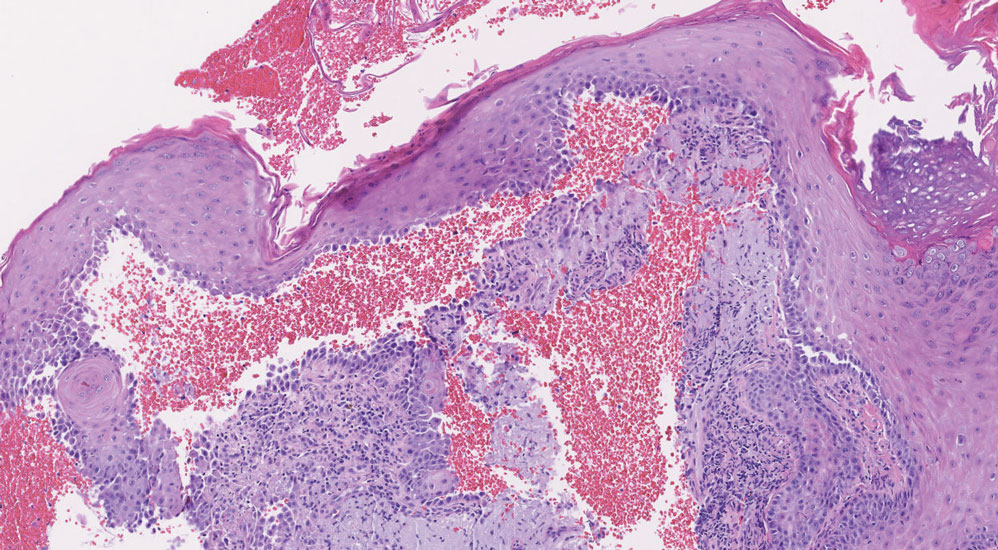

Paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP) is another diagnosis to consider. Patients with PNP initially present with oral findings—most commonly chronic, erosive, and painful mucositis—followed by cutaneous involvement, which varies from the development of bullae to the formation of plaques similar to those of LP.13 The latter, in combination with oral erosions, may appear clinically similar to LPP. The results of DIF in conjugation with IIF and ELISA may help to further differentiate these disorders. Direct immunofluorescence in PNP typically reveals positive intercellular and/or BMZ IgG and C3, while DIF in LPP reveals depositions along the BMZ alone. Indirect immunofluorescence performed on rat bladder epithelium is particularly useful, as binding of IgG to rat bladder epithelium is characteristic of PNP and not seen in other disorders.14 Lastly, patients with PNP may develop IgG antibodies to various antigens such as desmoplakin I, desmoplakin II, envoplakin, periplakin, BP230, desmoglein 1, and desmoglein 3, which would not be expected in LPP patients.15 Hematoxylin and eosin staining differs from LPP, primarily with the location of the blister being intraepidermal. Acantholysis with hemorrhagic bullae can be seen (Figure 2).

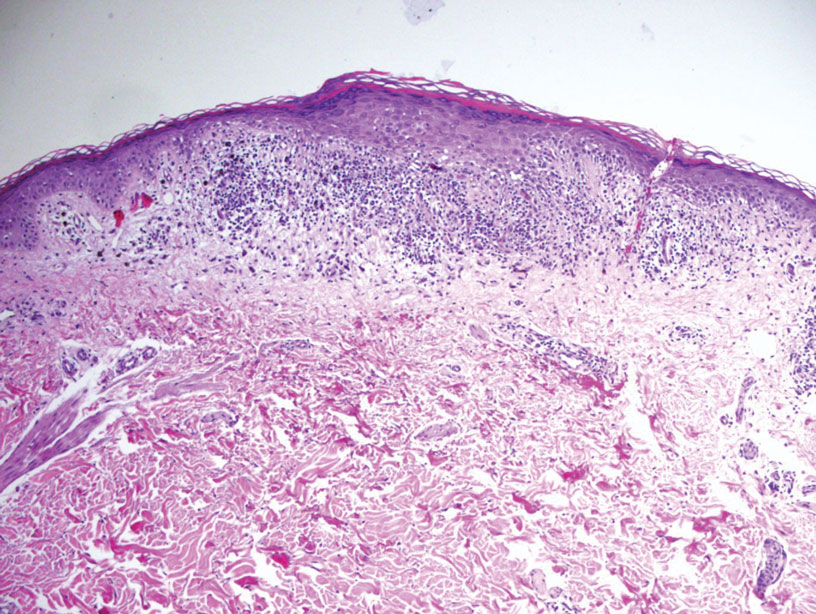

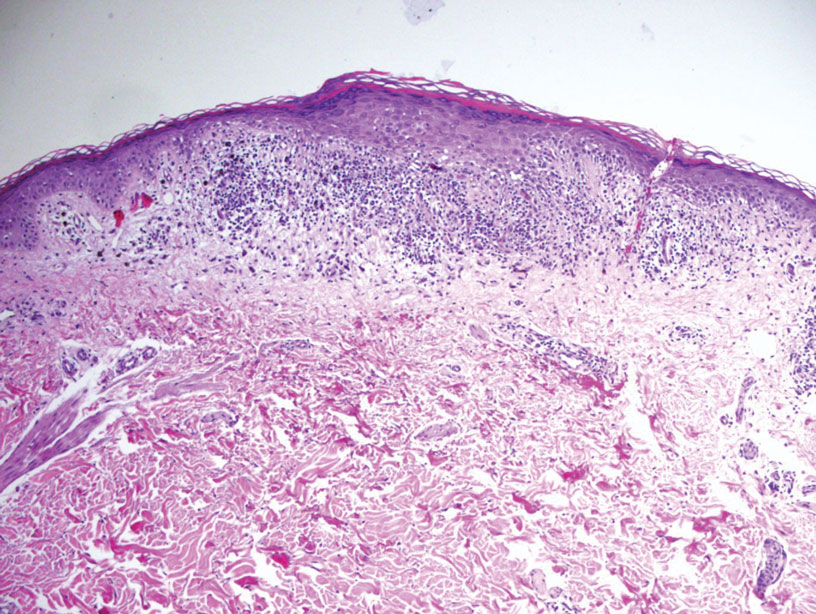

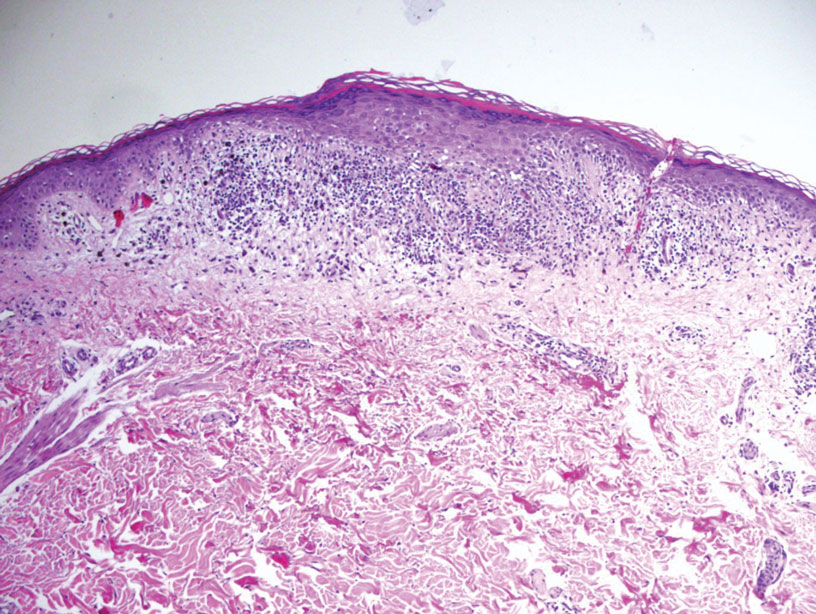

Classic LP is an inflammatory disorder that mainly affects adults, with an estimated incidence of less than 1%.16 The classic form presents with purple, flat-topped, pruritic, polygonal papules and plaques of varying size that often are characterized by Wickham striae. Lichen planus possesses a broad spectrum of subtypes involving different locations, though skin lesions usually are localized to the extremities. Despite an unknown etiology, activated T cells and T helper type 1 cytokines are considered key in keratinocyte injury. Compact orthokeratosis, wedge-shaped hypergranulosis, focal dyskeratosis, and colloid bodies typically are found on H&E staining, along with a dense bandlike lymphohistiocytic infiltrate at the dermoepidermal junction (DEJ)(Figure 3). Direct immunofluorescence typically shows a shaggy band of fibrinogen along the DEJ in addition to colloid bodies that stain with various autoantibodies including IgM, IgG, IgA, and C3.16

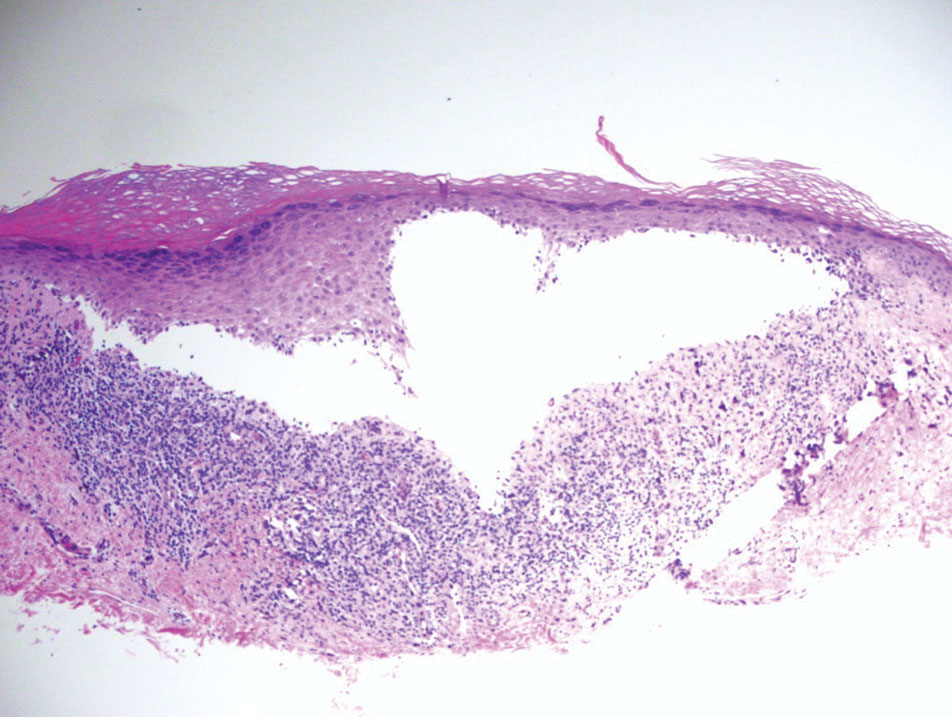

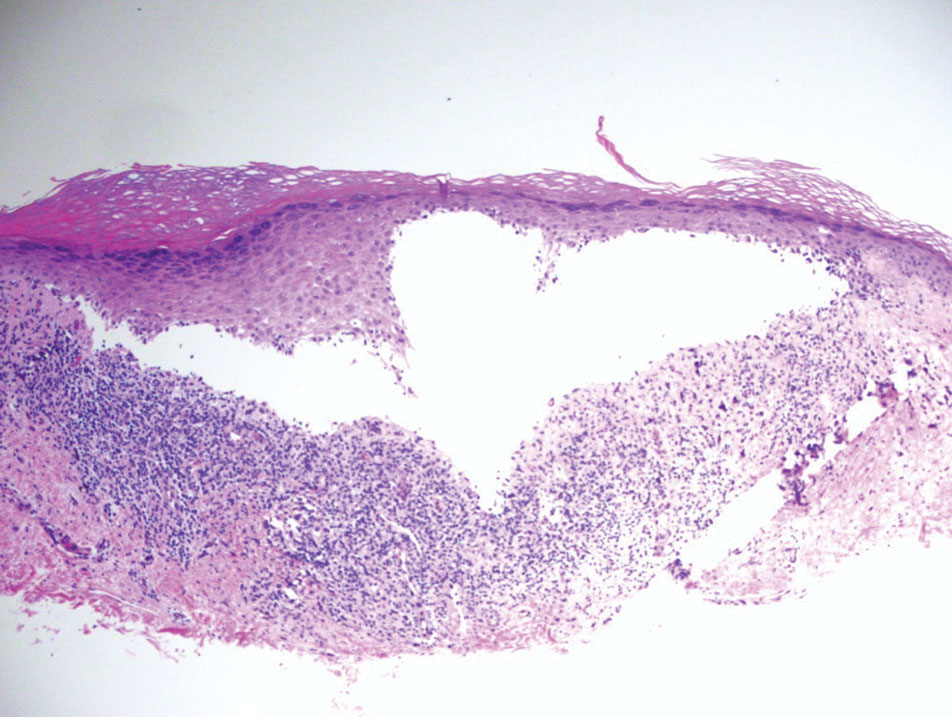

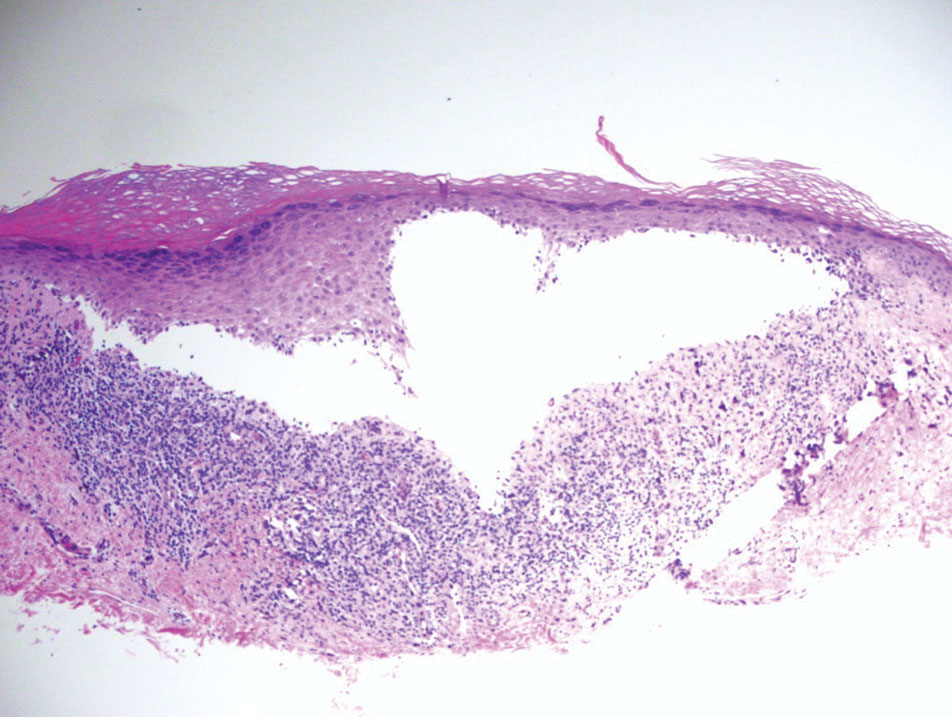

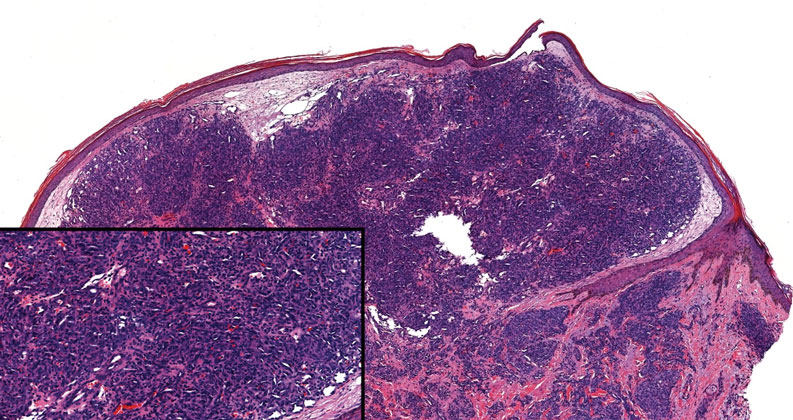

Bullous LP is a rare variant of LP that commonly develops on the oral mucosa and the legs, with blisters confined on pre-existing LP lesions.9 The pathogenesis is related to an epidermal inflammatory infiltrate that leads to basal layer destruction followed by dermal-epidermal separations that cause blistering.17 Bullous LP does not have positive DIF, IIF, or ELISA because the pathophysiology does not involve autoantibody production. Histopathology typically displays an extensive inflammatory infiltrate and degeneration of the basal keratinocytes, resulting in large dermal-epidermal separations called Max-Joseph spaces (Figure 4).17 Colloid bodies are prominent in bullous LP but rarely are seen in LPP; eosinophils also are much more prominent in LPP compared to bullous LP.18 Unlike in LPP, DIF usually is negative in bullous LP, though lichenoid lesions may exhibit globular deposition of IgM, IgG, and IgA in the colloid bodies of the lower epidermis and/or papillary dermis. Similar to LP, DIF of the biopsy specimen shows linear or shaggy deposits of fibrinogen at the DEJ.17

- Hübner F, Langan EA, Recke A. Lichen planus pemphigoides: from lichenoid inflammation to autoantibody-mediated blistering. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1389.

- Montagnon CM, Tolkachjov SN, Murrell DF, et al. Subepithelial autoimmune blistering dermatoses: clinical features and diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1-14.

- Hackländer K, Lehmann P, Hofmann SC. Successful treatment of lichen planus pemphigoides using acitretin as monotherapy. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2014;12:818-819.

- Boyle M, Ashi S, Puiu T, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides associated with PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors: a case series and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2022;44:360-367.

- Zaraa I, Mahfoudh A, Sellami MK, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides: four new cases and a review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:406-412.

- Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018.

- Zillikens D, Caux F, Mascaru JM Jr, et al. Autoantibodies in lichen planus pemphigoides react with a novel epitope within the C-terminal NC16A domain of BP180. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:117-121.

- Knisley RR, Petropolis AA, Mackey VT. Lichen planus pemphigoides treated with ustekinumab. Cutis. 2017;100:415-418.

- Liakopoulou A, Rallis E. Bullous lichen planus—a review. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2017;11:1-4.

- Weston G, Payette M. Update on lichen planus and its clinical variants. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015;1:140-149.

- Moussa A, Colla TG, Asfour L, et al. Effective treatment of refractory lichen planus pemphigoides with a Janus kinase-1/2 inhibitor. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:2040-2041.

- Brennan M, Baldissano M, King L, et al. Successful use of rituximab and intravenous gamma globulin to treat checkpoint inhibitor-induced severe lichen planus pemphigoides. Skinmed. 2020;18:246-249.

- Kim JH, Kim SC. Paraneoplastic pemphigus: paraneoplastic autoimmune disease of the skin and mucosa. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1259.

- Stevens SR, Griffiths CE, Anhalt GJ, et al. Paraneoplastic pemphigus presenting as a lichen planus pemphigoides-like eruption. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:866-869.

- Ohzono A, Sogame R, Li X, et al. Clinical and immunological findings in 104 cases of paraneoplastic pemphigus. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:1447-1452.

- Tziotzios C, Lee JYW, Brier T, et al. Lichen planus and lichenoid dermatoses: clinical overview and molecular basis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:789-804.

- Papara C, Danescu S, Sitaru C, et al. Challenges and pitfalls between lichen planus pemphigoides and bullous lichen planus. Australas J Dermatol. 2022;63:165-171.

- Tripathy DM, Vashisht D, Rathore G, et al. Bullous lichen planus vs lichen planus pemphigoides: a diagnostic dilemma. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2022;13:282-284.

The Diagnosis: Lichen Planus Pemphigoides

Lichen planus pemphigoides (LPP) is a rare acquired autoimmune blistering disorder with an estimated worldwide prevalence of approximately 1 in 1,000,000 individuals.1 It often manifests with overlapping features of both LP and bullous pemphigoid (BP). The condition usually presents in the fifth decade of life and has a slight female predominance.2 Although primarily idiopathic, it has been associated with certain medications and treatments, such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, programmed cell death protein 1 inhibitors, programmed cell death ligand 1 inhibitors, labetalol, narrowband UVB, and psoralen plus UVA.3,4

Patients initially present with lesions of classic lichen planus (LP) with pink-purple, flat-topped, pruritic, polygonal papules and plaques.5 After weeks to months, tense vesicles and bullae usually develop on the sites of LP as well as on uninvolved skin. One study found a mean lag time of about 8.3 months for blistering to present after LP,5 but concurrent presentations of both have been reported.1 In addition, oral mucosal involvement has been seen in 36% of cases. The most commonly affected sites are the extremities; however, involvement can be widespread.2

The pathogenesis of LPP currently is unknown. It has been proposed that in LP, injury of basal keratinocytes exposes hidden basement membrane and hemidesmosome antigens including BP180, a 180 kDa transmembrane protein of the basement membrane zone (BMZ),6 which triggers an immune response where T cells recognize the extracellular portion of BP180 and antibodies are formed against the likely autoantigen.1 One study has suggested that the autoantigen in LPP is the MCW-4 epitope within the C-terminal end of the NC16A domain of BP180.7

Histopathology of LPP reveals characteristics of both LP as well as BP. Typical features of LP on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining include lichenoid lymphocytic interface dermatitis, sawtooth rete ridges, wedge-shaped hypergranulosis, and colloid bodies, as demonstrated from the biopsy of our patient’s gluteal cleft lesion (quiz image 1), while the predominant feature of BP on H&E staining includes a subepidermal bulla with eosinophils.2 Typically, direct immunofluorescence (DIF) shows linear deposits of IgG and/or C3 along the BMZ. Indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) often reveals IgG against the roof of the BMZ in a human split-skin substrate.1 Antibodies against BP180 or uncommonly BP230 often are detected on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). For our patient, IIF and ELISA tests were positive. Given the clinical presentation with recurrent oral and gluteal cleft erosions, histologic findings, and the results of our patient’s immunological testing, the diagnosis of LPP was made.

Topical steroids often are used to treat localized disease of LPP.8 Oral prednisone also may be given for widespread or unresponsive disease.9 Other treatments include azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, hydroxychloroquine, dapsone, tetracycline in combination with nicotinamide, acitretin, ustekinumab, baricitinib, and rituximab with intravenous immunoglobulin.3,8,10-12 Any potential medication culprits should be discontinued.9 Patients with oral involvement may require a soft diet to avoid further mucosal insult.10 Additionally, providers should consider dentistry, ophthalmology, and/or otolaryngology referrals depending on disease severity.

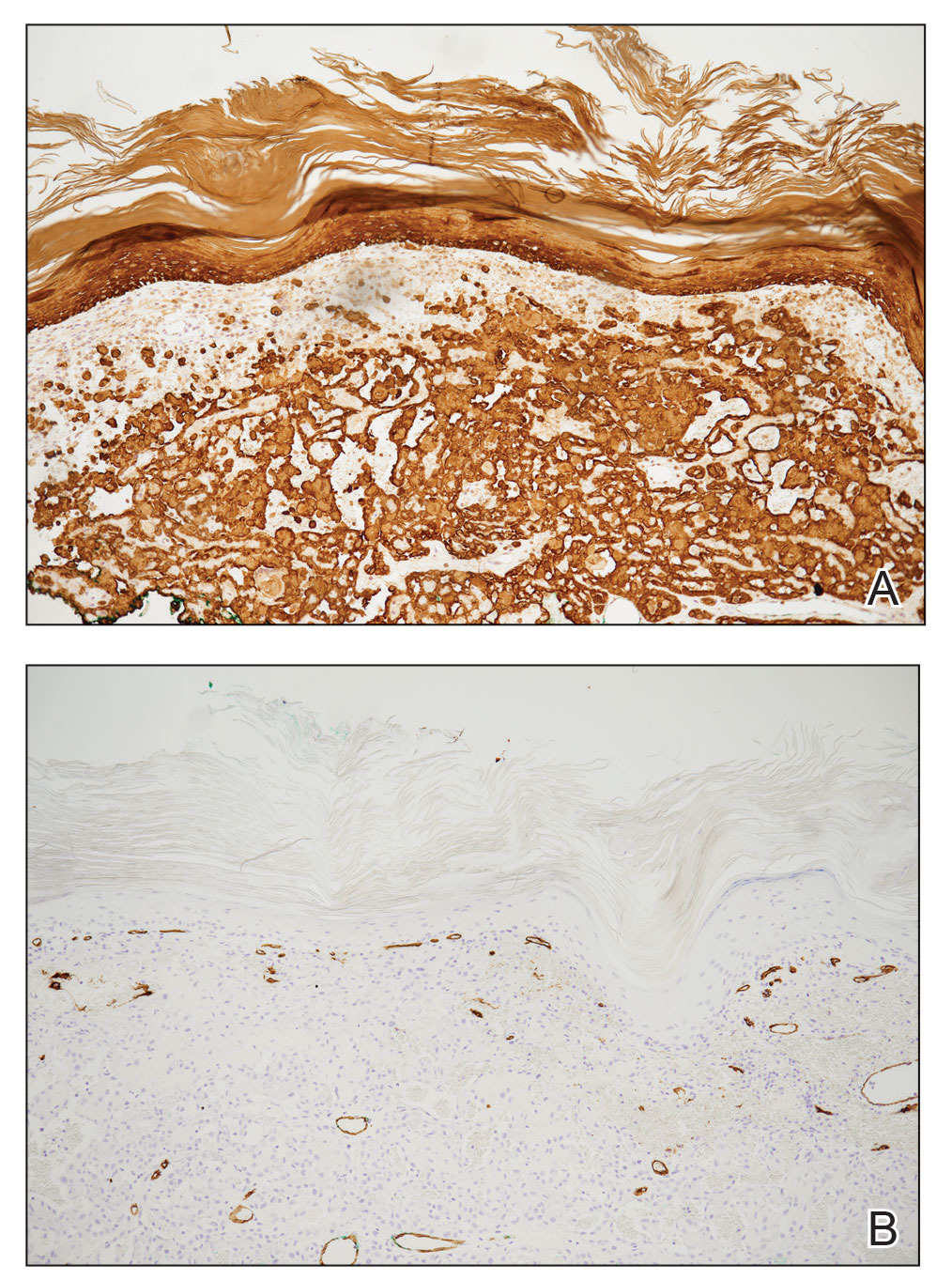

Bullous pemphigoid, the most common autoimmune blistering disease, has an estimated incidence of 10 to 43 per million individuals per year.2 Classically, it presents with tense bullae on the skin of the lower abdomen, thighs, groin, forearms, and axillae. Circulating antibodies against 2 BMZ proteins—BP180 and BP230—are important factors in BP pathogenesis.2 Diagnosis of BP is based on clinical features, histologic findings, and immunological studies including DIF, IIF, and ELISA. An eosinophil-rich subepidermal split typically is seen on H&E staining (Figure 1).

Direct immunofluorescence displays linear IgG and/ or C3 staining at the BMZ. Indirect immunofluorescence on a human salt-split skin substrate commonly shows linear BMZ deposition on the roof of the blister.2 Indirect immunofluorescence for IgG deposition on monkey esophagus substrate shows linear BMZ deposition. Antibodies against the NC16A domain of BP180 (NC16A-BP180) are dominant, but BP230 antibodies against BP230 also are detected with ELISA.2 Further studies have indicated that the NC16A epitopes of BP180 that are targeted in BP are MCW-0-3,2 different from the autoantigen MCW-4 that is targeted in LPP.7

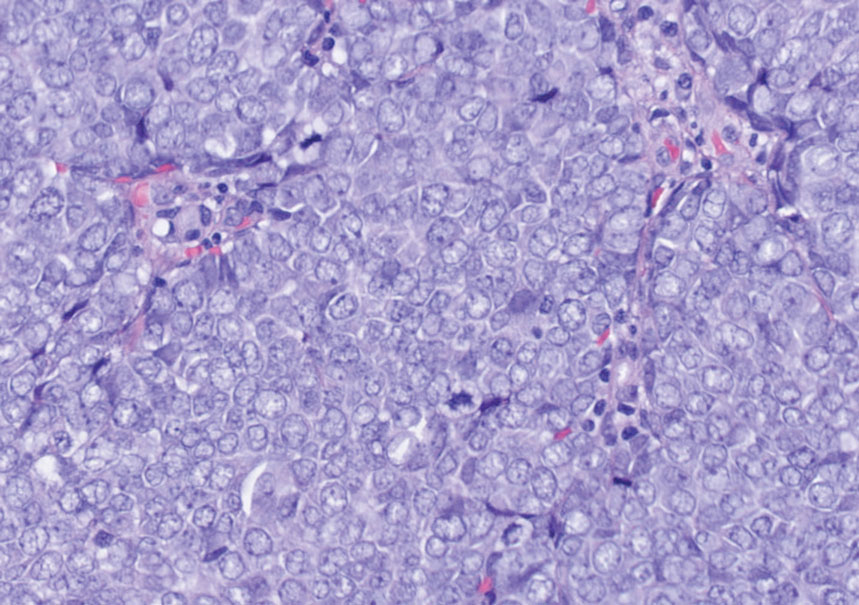

Paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP) is another diagnosis to consider. Patients with PNP initially present with oral findings—most commonly chronic, erosive, and painful mucositis—followed by cutaneous involvement, which varies from the development of bullae to the formation of plaques similar to those of LP.13 The latter, in combination with oral erosions, may appear clinically similar to LPP. The results of DIF in conjugation with IIF and ELISA may help to further differentiate these disorders. Direct immunofluorescence in PNP typically reveals positive intercellular and/or BMZ IgG and C3, while DIF in LPP reveals depositions along the BMZ alone. Indirect immunofluorescence performed on rat bladder epithelium is particularly useful, as binding of IgG to rat bladder epithelium is characteristic of PNP and not seen in other disorders.14 Lastly, patients with PNP may develop IgG antibodies to various antigens such as desmoplakin I, desmoplakin II, envoplakin, periplakin, BP230, desmoglein 1, and desmoglein 3, which would not be expected in LPP patients.15 Hematoxylin and eosin staining differs from LPP, primarily with the location of the blister being intraepidermal. Acantholysis with hemorrhagic bullae can be seen (Figure 2).

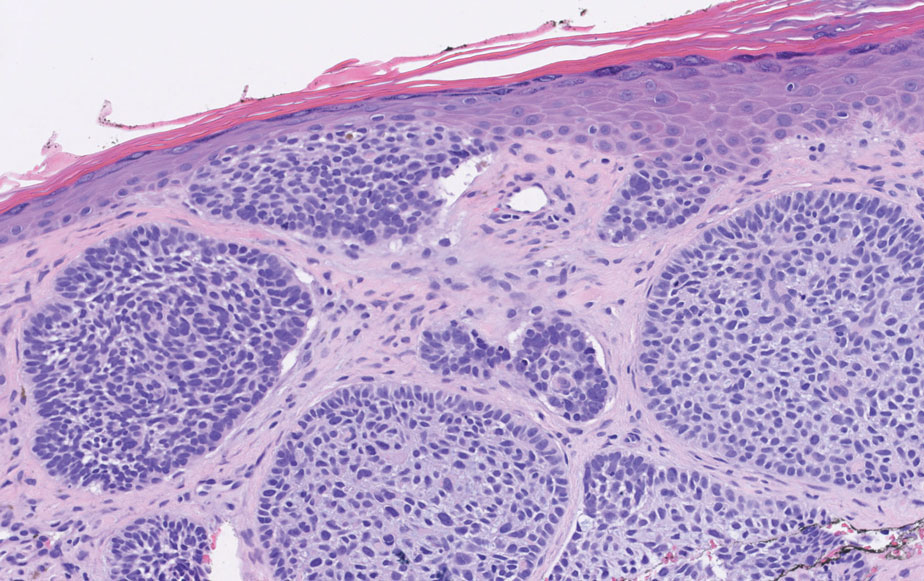

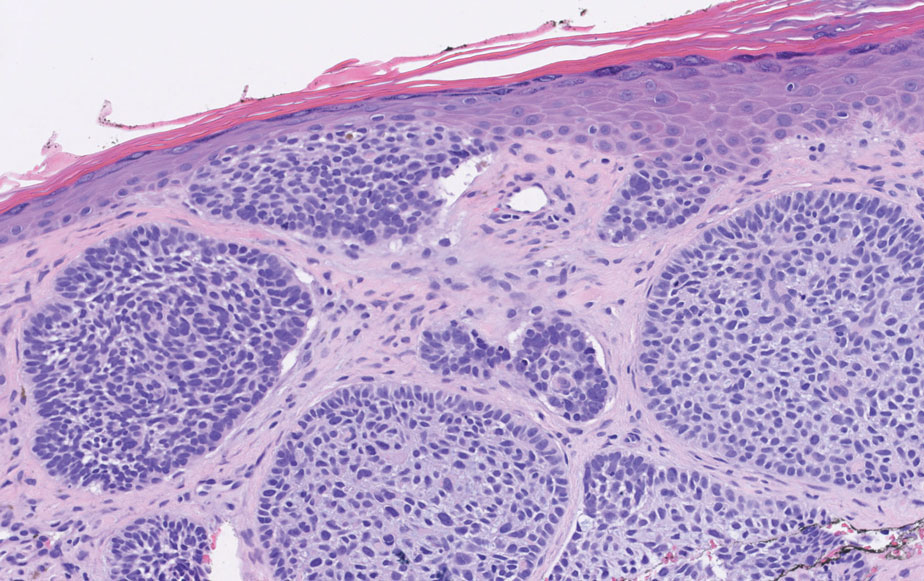

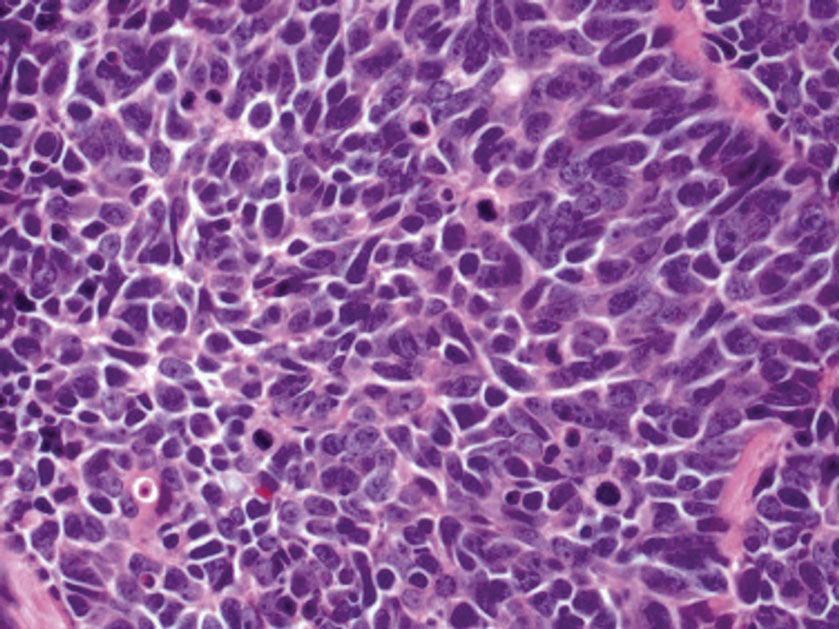

Classic LP is an inflammatory disorder that mainly affects adults, with an estimated incidence of less than 1%.16 The classic form presents with purple, flat-topped, pruritic, polygonal papules and plaques of varying size that often are characterized by Wickham striae. Lichen planus possesses a broad spectrum of subtypes involving different locations, though skin lesions usually are localized to the extremities. Despite an unknown etiology, activated T cells and T helper type 1 cytokines are considered key in keratinocyte injury. Compact orthokeratosis, wedge-shaped hypergranulosis, focal dyskeratosis, and colloid bodies typically are found on H&E staining, along with a dense bandlike lymphohistiocytic infiltrate at the dermoepidermal junction (DEJ)(Figure 3). Direct immunofluorescence typically shows a shaggy band of fibrinogen along the DEJ in addition to colloid bodies that stain with various autoantibodies including IgM, IgG, IgA, and C3.16

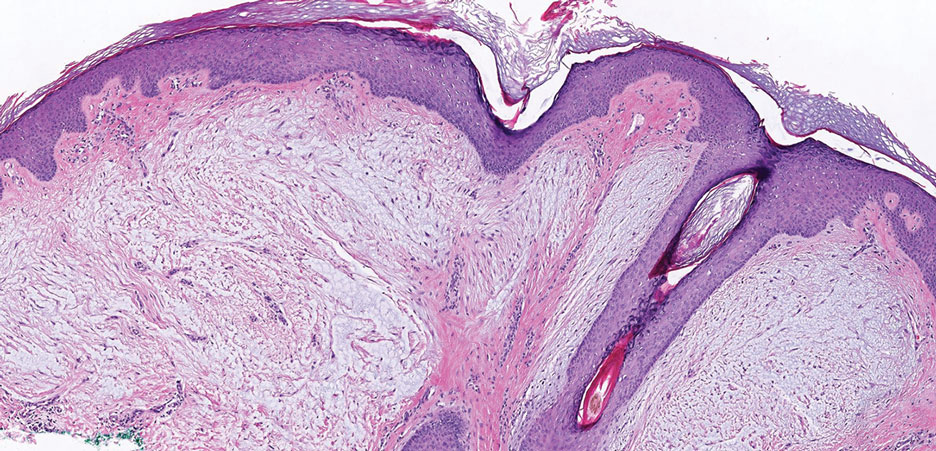

Bullous LP is a rare variant of LP that commonly develops on the oral mucosa and the legs, with blisters confined on pre-existing LP lesions.9 The pathogenesis is related to an epidermal inflammatory infiltrate that leads to basal layer destruction followed by dermal-epidermal separations that cause blistering.17 Bullous LP does not have positive DIF, IIF, or ELISA because the pathophysiology does not involve autoantibody production. Histopathology typically displays an extensive inflammatory infiltrate and degeneration of the basal keratinocytes, resulting in large dermal-epidermal separations called Max-Joseph spaces (Figure 4).17 Colloid bodies are prominent in bullous LP but rarely are seen in LPP; eosinophils also are much more prominent in LPP compared to bullous LP.18 Unlike in LPP, DIF usually is negative in bullous LP, though lichenoid lesions may exhibit globular deposition of IgM, IgG, and IgA in the colloid bodies of the lower epidermis and/or papillary dermis. Similar to LP, DIF of the biopsy specimen shows linear or shaggy deposits of fibrinogen at the DEJ.17

The Diagnosis: Lichen Planus Pemphigoides

Lichen planus pemphigoides (LPP) is a rare acquired autoimmune blistering disorder with an estimated worldwide prevalence of approximately 1 in 1,000,000 individuals.1 It often manifests with overlapping features of both LP and bullous pemphigoid (BP). The condition usually presents in the fifth decade of life and has a slight female predominance.2 Although primarily idiopathic, it has been associated with certain medications and treatments, such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, programmed cell death protein 1 inhibitors, programmed cell death ligand 1 inhibitors, labetalol, narrowband UVB, and psoralen plus UVA.3,4

Patients initially present with lesions of classic lichen planus (LP) with pink-purple, flat-topped, pruritic, polygonal papules and plaques.5 After weeks to months, tense vesicles and bullae usually develop on the sites of LP as well as on uninvolved skin. One study found a mean lag time of about 8.3 months for blistering to present after LP,5 but concurrent presentations of both have been reported.1 In addition, oral mucosal involvement has been seen in 36% of cases. The most commonly affected sites are the extremities; however, involvement can be widespread.2

The pathogenesis of LPP currently is unknown. It has been proposed that in LP, injury of basal keratinocytes exposes hidden basement membrane and hemidesmosome antigens including BP180, a 180 kDa transmembrane protein of the basement membrane zone (BMZ),6 which triggers an immune response where T cells recognize the extracellular portion of BP180 and antibodies are formed against the likely autoantigen.1 One study has suggested that the autoantigen in LPP is the MCW-4 epitope within the C-terminal end of the NC16A domain of BP180.7

Histopathology of LPP reveals characteristics of both LP as well as BP. Typical features of LP on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining include lichenoid lymphocytic interface dermatitis, sawtooth rete ridges, wedge-shaped hypergranulosis, and colloid bodies, as demonstrated from the biopsy of our patient’s gluteal cleft lesion (quiz image 1), while the predominant feature of BP on H&E staining includes a subepidermal bulla with eosinophils.2 Typically, direct immunofluorescence (DIF) shows linear deposits of IgG and/or C3 along the BMZ. Indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) often reveals IgG against the roof of the BMZ in a human split-skin substrate.1 Antibodies against BP180 or uncommonly BP230 often are detected on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). For our patient, IIF and ELISA tests were positive. Given the clinical presentation with recurrent oral and gluteal cleft erosions, histologic findings, and the results of our patient’s immunological testing, the diagnosis of LPP was made.

Topical steroids often are used to treat localized disease of LPP.8 Oral prednisone also may be given for widespread or unresponsive disease.9 Other treatments include azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, hydroxychloroquine, dapsone, tetracycline in combination with nicotinamide, acitretin, ustekinumab, baricitinib, and rituximab with intravenous immunoglobulin.3,8,10-12 Any potential medication culprits should be discontinued.9 Patients with oral involvement may require a soft diet to avoid further mucosal insult.10 Additionally, providers should consider dentistry, ophthalmology, and/or otolaryngology referrals depending on disease severity.

Bullous pemphigoid, the most common autoimmune blistering disease, has an estimated incidence of 10 to 43 per million individuals per year.2 Classically, it presents with tense bullae on the skin of the lower abdomen, thighs, groin, forearms, and axillae. Circulating antibodies against 2 BMZ proteins—BP180 and BP230—are important factors in BP pathogenesis.2 Diagnosis of BP is based on clinical features, histologic findings, and immunological studies including DIF, IIF, and ELISA. An eosinophil-rich subepidermal split typically is seen on H&E staining (Figure 1).

Direct immunofluorescence displays linear IgG and/ or C3 staining at the BMZ. Indirect immunofluorescence on a human salt-split skin substrate commonly shows linear BMZ deposition on the roof of the blister.2 Indirect immunofluorescence for IgG deposition on monkey esophagus substrate shows linear BMZ deposition. Antibodies against the NC16A domain of BP180 (NC16A-BP180) are dominant, but BP230 antibodies against BP230 also are detected with ELISA.2 Further studies have indicated that the NC16A epitopes of BP180 that are targeted in BP are MCW-0-3,2 different from the autoantigen MCW-4 that is targeted in LPP.7

Paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP) is another diagnosis to consider. Patients with PNP initially present with oral findings—most commonly chronic, erosive, and painful mucositis—followed by cutaneous involvement, which varies from the development of bullae to the formation of plaques similar to those of LP.13 The latter, in combination with oral erosions, may appear clinically similar to LPP. The results of DIF in conjugation with IIF and ELISA may help to further differentiate these disorders. Direct immunofluorescence in PNP typically reveals positive intercellular and/or BMZ IgG and C3, while DIF in LPP reveals depositions along the BMZ alone. Indirect immunofluorescence performed on rat bladder epithelium is particularly useful, as binding of IgG to rat bladder epithelium is characteristic of PNP and not seen in other disorders.14 Lastly, patients with PNP may develop IgG antibodies to various antigens such as desmoplakin I, desmoplakin II, envoplakin, periplakin, BP230, desmoglein 1, and desmoglein 3, which would not be expected in LPP patients.15 Hematoxylin and eosin staining differs from LPP, primarily with the location of the blister being intraepidermal. Acantholysis with hemorrhagic bullae can be seen (Figure 2).

Classic LP is an inflammatory disorder that mainly affects adults, with an estimated incidence of less than 1%.16 The classic form presents with purple, flat-topped, pruritic, polygonal papules and plaques of varying size that often are characterized by Wickham striae. Lichen planus possesses a broad spectrum of subtypes involving different locations, though skin lesions usually are localized to the extremities. Despite an unknown etiology, activated T cells and T helper type 1 cytokines are considered key in keratinocyte injury. Compact orthokeratosis, wedge-shaped hypergranulosis, focal dyskeratosis, and colloid bodies typically are found on H&E staining, along with a dense bandlike lymphohistiocytic infiltrate at the dermoepidermal junction (DEJ)(Figure 3). Direct immunofluorescence typically shows a shaggy band of fibrinogen along the DEJ in addition to colloid bodies that stain with various autoantibodies including IgM, IgG, IgA, and C3.16

Bullous LP is a rare variant of LP that commonly develops on the oral mucosa and the legs, with blisters confined on pre-existing LP lesions.9 The pathogenesis is related to an epidermal inflammatory infiltrate that leads to basal layer destruction followed by dermal-epidermal separations that cause blistering.17 Bullous LP does not have positive DIF, IIF, or ELISA because the pathophysiology does not involve autoantibody production. Histopathology typically displays an extensive inflammatory infiltrate and degeneration of the basal keratinocytes, resulting in large dermal-epidermal separations called Max-Joseph spaces (Figure 4).17 Colloid bodies are prominent in bullous LP but rarely are seen in LPP; eosinophils also are much more prominent in LPP compared to bullous LP.18 Unlike in LPP, DIF usually is negative in bullous LP, though lichenoid lesions may exhibit globular deposition of IgM, IgG, and IgA in the colloid bodies of the lower epidermis and/or papillary dermis. Similar to LP, DIF of the biopsy specimen shows linear or shaggy deposits of fibrinogen at the DEJ.17

- Hübner F, Langan EA, Recke A. Lichen planus pemphigoides: from lichenoid inflammation to autoantibody-mediated blistering. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1389.

- Montagnon CM, Tolkachjov SN, Murrell DF, et al. Subepithelial autoimmune blistering dermatoses: clinical features and diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1-14.

- Hackländer K, Lehmann P, Hofmann SC. Successful treatment of lichen planus pemphigoides using acitretin as monotherapy. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2014;12:818-819.

- Boyle M, Ashi S, Puiu T, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides associated with PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors: a case series and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2022;44:360-367.

- Zaraa I, Mahfoudh A, Sellami MK, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides: four new cases and a review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:406-412.

- Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018.

- Zillikens D, Caux F, Mascaru JM Jr, et al. Autoantibodies in lichen planus pemphigoides react with a novel epitope within the C-terminal NC16A domain of BP180. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:117-121.

- Knisley RR, Petropolis AA, Mackey VT. Lichen planus pemphigoides treated with ustekinumab. Cutis. 2017;100:415-418.

- Liakopoulou A, Rallis E. Bullous lichen planus—a review. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2017;11:1-4.

- Weston G, Payette M. Update on lichen planus and its clinical variants. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015;1:140-149.

- Moussa A, Colla TG, Asfour L, et al. Effective treatment of refractory lichen planus pemphigoides with a Janus kinase-1/2 inhibitor. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:2040-2041.

- Brennan M, Baldissano M, King L, et al. Successful use of rituximab and intravenous gamma globulin to treat checkpoint inhibitor-induced severe lichen planus pemphigoides. Skinmed. 2020;18:246-249.

- Kim JH, Kim SC. Paraneoplastic pemphigus: paraneoplastic autoimmune disease of the skin and mucosa. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1259.

- Stevens SR, Griffiths CE, Anhalt GJ, et al. Paraneoplastic pemphigus presenting as a lichen planus pemphigoides-like eruption. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:866-869.

- Ohzono A, Sogame R, Li X, et al. Clinical and immunological findings in 104 cases of paraneoplastic pemphigus. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:1447-1452.

- Tziotzios C, Lee JYW, Brier T, et al. Lichen planus and lichenoid dermatoses: clinical overview and molecular basis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:789-804.

- Papara C, Danescu S, Sitaru C, et al. Challenges and pitfalls between lichen planus pemphigoides and bullous lichen planus. Australas J Dermatol. 2022;63:165-171.

- Tripathy DM, Vashisht D, Rathore G, et al. Bullous lichen planus vs lichen planus pemphigoides: a diagnostic dilemma. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2022;13:282-284.

- Hübner F, Langan EA, Recke A. Lichen planus pemphigoides: from lichenoid inflammation to autoantibody-mediated blistering. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1389.

- Montagnon CM, Tolkachjov SN, Murrell DF, et al. Subepithelial autoimmune blistering dermatoses: clinical features and diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1-14.

- Hackländer K, Lehmann P, Hofmann SC. Successful treatment of lichen planus pemphigoides using acitretin as monotherapy. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2014;12:818-819.

- Boyle M, Ashi S, Puiu T, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides associated with PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors: a case series and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2022;44:360-367.

- Zaraa I, Mahfoudh A, Sellami MK, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides: four new cases and a review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:406-412.

- Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018.

- Zillikens D, Caux F, Mascaru JM Jr, et al. Autoantibodies in lichen planus pemphigoides react with a novel epitope within the C-terminal NC16A domain of BP180. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:117-121.

- Knisley RR, Petropolis AA, Mackey VT. Lichen planus pemphigoides treated with ustekinumab. Cutis. 2017;100:415-418.

- Liakopoulou A, Rallis E. Bullous lichen planus—a review. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2017;11:1-4.

- Weston G, Payette M. Update on lichen planus and its clinical variants. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015;1:140-149.

- Moussa A, Colla TG, Asfour L, et al. Effective treatment of refractory lichen planus pemphigoides with a Janus kinase-1/2 inhibitor. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:2040-2041.

- Brennan M, Baldissano M, King L, et al. Successful use of rituximab and intravenous gamma globulin to treat checkpoint inhibitor-induced severe lichen planus pemphigoides. Skinmed. 2020;18:246-249.

- Kim JH, Kim SC. Paraneoplastic pemphigus: paraneoplastic autoimmune disease of the skin and mucosa. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1259.

- Stevens SR, Griffiths CE, Anhalt GJ, et al. Paraneoplastic pemphigus presenting as a lichen planus pemphigoides-like eruption. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:866-869.

- Ohzono A, Sogame R, Li X, et al. Clinical and immunological findings in 104 cases of paraneoplastic pemphigus. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:1447-1452.

- Tziotzios C, Lee JYW, Brier T, et al. Lichen planus and lichenoid dermatoses: clinical overview and molecular basis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:789-804.

- Papara C, Danescu S, Sitaru C, et al. Challenges and pitfalls between lichen planus pemphigoides and bullous lichen planus. Australas J Dermatol. 2022;63:165-171.

- Tripathy DM, Vashisht D, Rathore G, et al. Bullous lichen planus vs lichen planus pemphigoides: a diagnostic dilemma. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2022;13:282-284.

A 71-year-old woman with no relevant medical history presented with recurrent painful erosions on the gingivae and gluteal cleft of 1 year’s duration. She previously was diagnosed by her periodontist with erosive lichen planus and was prescribed topical and oral steroids with minimal improvement. She denied fever, chills, weakness, fatigue, vision changes, eye pain, and sore throat. Dermatologic examination revealed edematous and erythematous upper and lower gingivae with mild erosions, as well as thin, eroded, erythematous plaques within the gluteal cleft. Indirect immunofluorescence revealed IgG with epidermal localization in a human split-skin substrate, and an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay revealed positive IgG to bullous pemphigoid (BP) 180 and negative IgG to BP230. A 4-mm punch biopsy of the gluteal cleft was performed.

Protuberant, Pink, Irritated Growth on the Buttocks

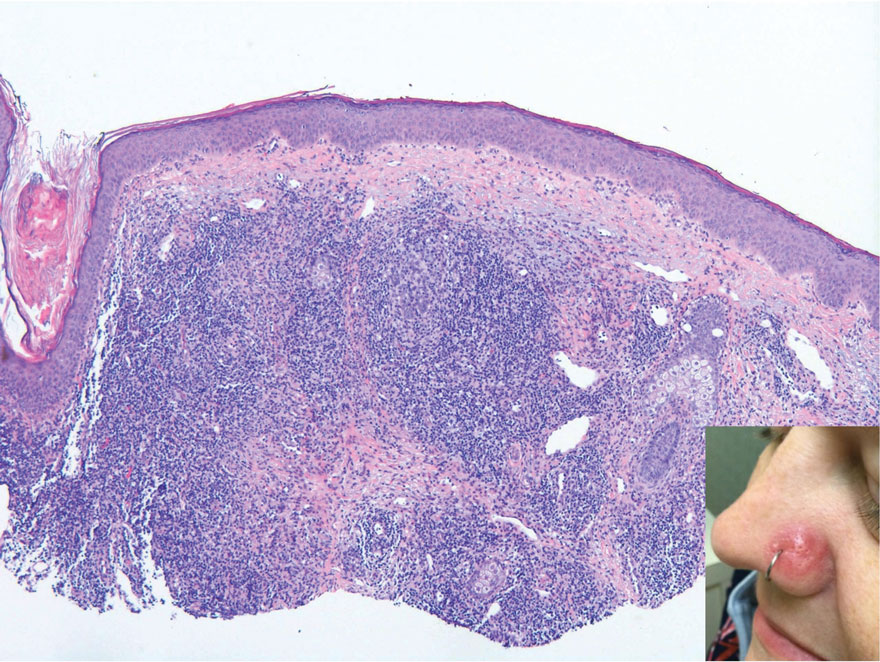

The Diagnosis: Superficial Angiomyxoma

Superficial angiomyxoma is a rare, benign, cutaneous tumor of a myxoid matrix and blood vessels that was first described in association with Carney complex.1 Tumors may be solitary or multiple. A recent review of cases in the literature revealed a roughly equal distribution of superficial angiomyxomas in males and females occurring most frequently on the head and neck, extremities, and trunk or back. The peak incidence is between the fourth and fifth decades of life.2 Superficial angiomyxomas can occur sporadically or in association with Carney complex, an autosomal-dominant condition with germline inactivating mutations in protein kinase A, PRKAR1A. Interestingly, sporadic cases of superficial angiomyxoma also have shown loss of PRKAR1A expression on immunohistochemistry (IHC).3

Common histologic mimics of superficial angiomyxoma include aggressive angiomyxoma and angiomyofibroblastoma.4 It is thought that these 3 distinct tumor entities may arise from a common pluripotent cell of origin located near connective tissue vasculature, which may contribute to the similarities observed between them.5 For example, aggressive angiomyxomas and angiomyofibroblastomas also demonstrate a similar myxoid background and vascular proliferation that can closely mimic superficial angiomyxomas clinically. However, the vessels of superficial angiomyxomas tend to be long and thin walled, while aggressive angiomyxomas are characterized by large and thick-walled vessels and angiomyofibroblastomas by abundant smaller vessels. Additionally, unlike superficial angiomyxomas, both aggressive angiomyxomas and angiomyofibroblastomas typically occur in the genital tract of young to middle-aged women.6

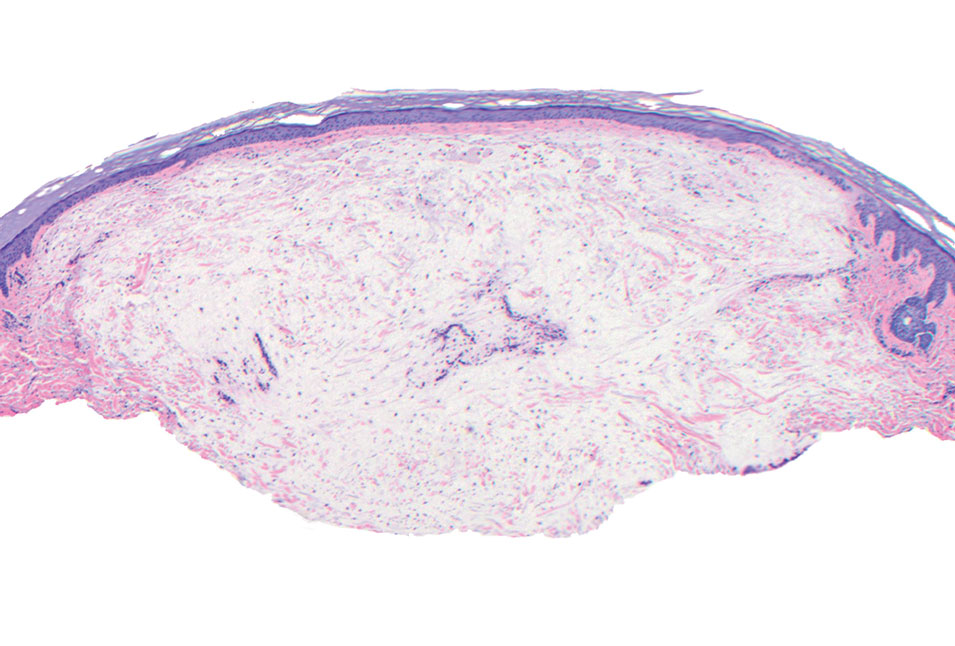

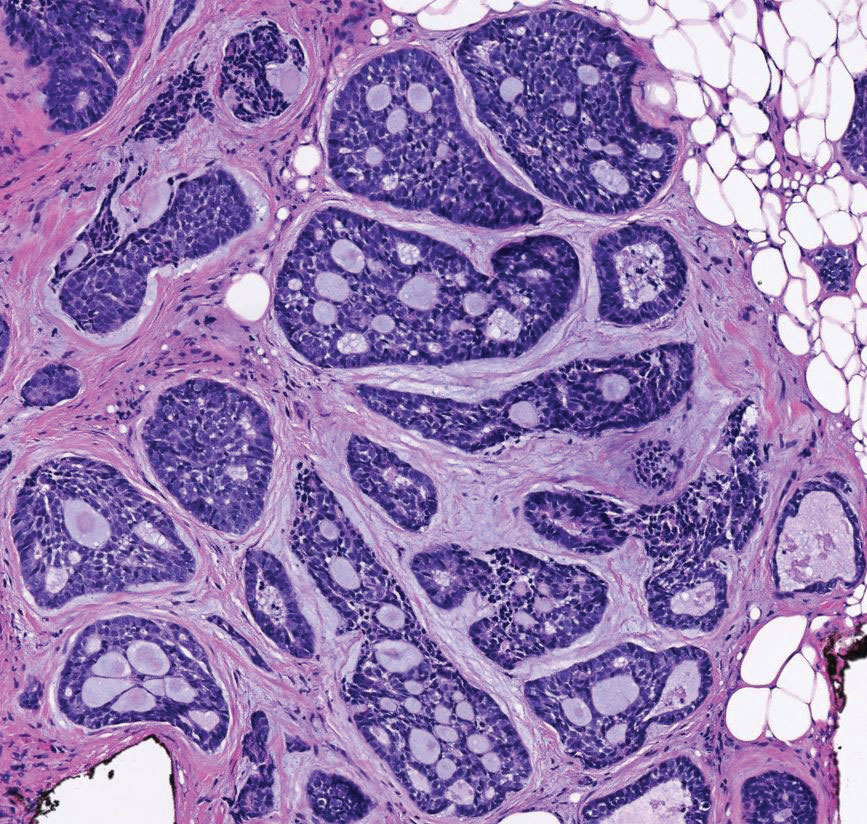

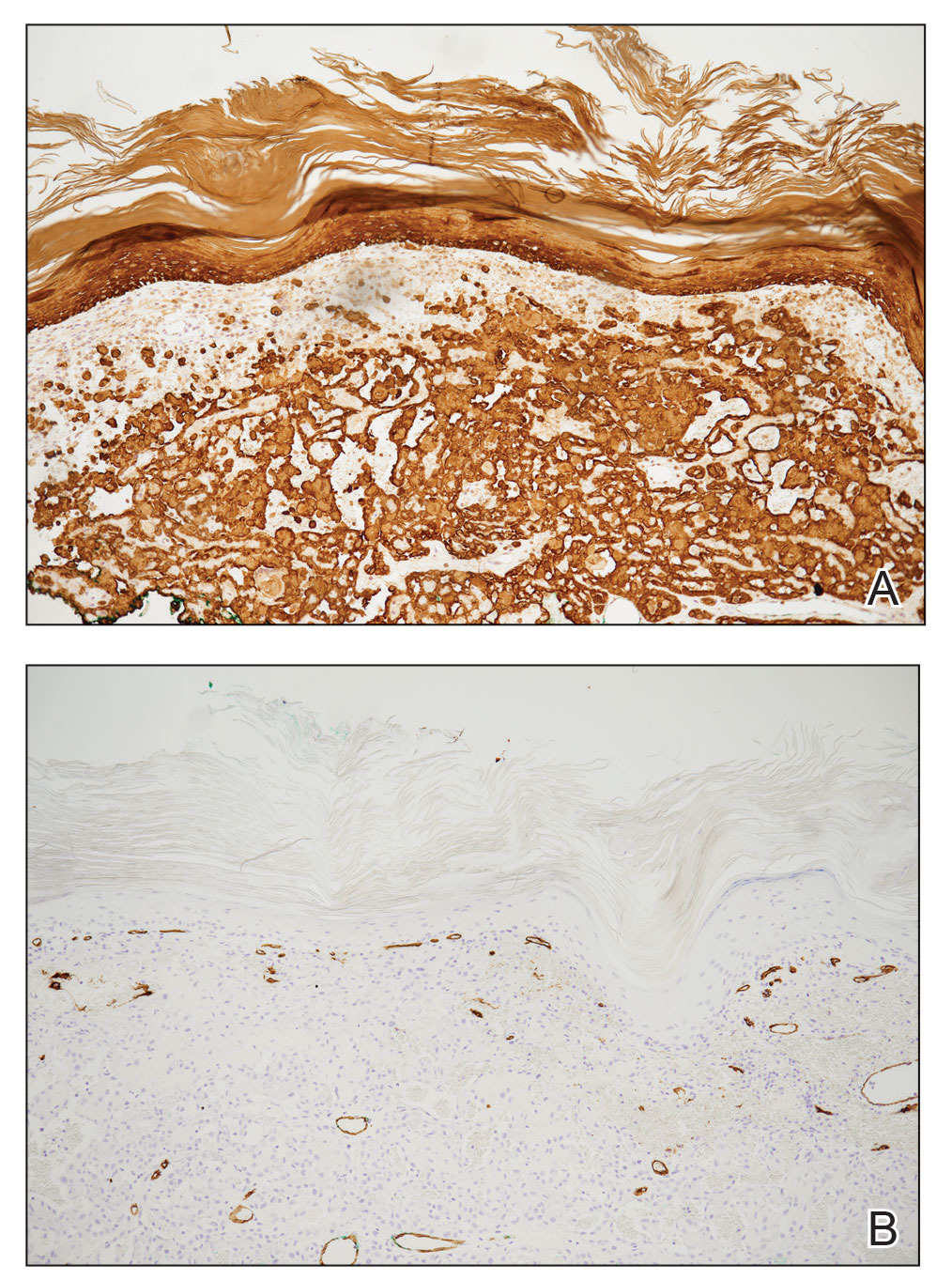

Histopathologic examination is imperative for differentiating between superficial angiomyxoma and more aggressive histologic mimics. Superficial angiomyxomas typically consist of a rich myxoid stroma, thin-walled or arborizing blood vessels, and spindled to stellate fibroblastlike cells (quiz image 2).3 Although not prominent in our case, superficial angiomyxomas also frequently present with stromal neutrophils and epithelial components, including keratinous cysts, basaloid buds, and strands of squamous epithelium.7 Minimal cellular atypia, mitotic activity, and nuclear pleomorphism often are seen, with IHC negative for desmin, estrogen receptor, and progesterone receptor; positive for CD34 and smooth muscle actin; and variable for S-100 and muscle-specific actin. Although IHC has limited utility in the diagnosis of superficial angiomyxomas, it may be useful to rule out other differential diagnoses.2,3 Superficial angiomyxomas usually show fibroblastic stromal cells, proteoglycan matrix, and collagen fibers on electron microscopy.8 Importantly, histopathologic examination of aggressive angiomyxoma will comparatively present with more invasive, infiltrative, and less well-circumscribed tumors.9 Other differential diagnoses on histology may include neurofibroma, focal cutaneous mucinosis, spindle cell lipoma, and myxofibrosarcoma. Additional considerations include fibroepithelial polyp, nevus lipomatosis, angiomyxolipoma, and anetoderma.

An important differential diagnosis in the evaluation of superficial angiomyxoma is neurofibroma, a benign peripheral nerve sheath tumor that presents as a smooth, flesh-colored, and painless papule or nodule commonly associated with the buttonhole sign. Histopathology of neurofibroma features elongated spindle cells with comma-shaped or buckled wavy nuclei and variably sized collagen bundles described as “shredded carrots” (Figure 1).10 Occasional mast cells also can be seen. Immunohistochemistry targeting elements of peripheral nerve sheaths may assist in the diagnosis of neurofibromas, including positive S-100 and SOX10 in Schwann cells, epithelial membrane antigen in perineural cells, and fingerprint positivity for CD34 in fibroblasts.10

Cutaneous mucinoses encompass a diverse group of connective tissue disorders characterized by accumulation of mucin in the skin. Solitary focal cutaneous mucinoses (FCMs) are individual isolated lesions of mucin deposits that are unassociated with systemic conditions.11 Conversely, multiple FCMs presenting with multiple cutaneous lesions also have been described in association with systemic diseases such as scleroderma, systemic lupus erythematosus, and thyroid disease.12 Solitary FCM typically presents as an asymptomatic, flesh-colored papule or nodule on the extremities. It often arises in mid to late adulthood with a slightly increased frequency among males.12 Histopathology of solitary FCM commonly demonstrates a dome-shaped pool of basophilic mucin in the upper dermis sparing involvement of the underlying subcutaneous tissue (Figure 2).13 Notably, FCM often lacks the vascularity as well as stromal neutrophils and epithelial elements that are seen in superficial angiomyxomas. Although hematoxylin and eosin stains can be sufficient for diagnosis of solitary FCM, additional stains for mucin such as Alcian blue, colloidal iron, or toluidine blue also may be considered to support the diagnosis.12

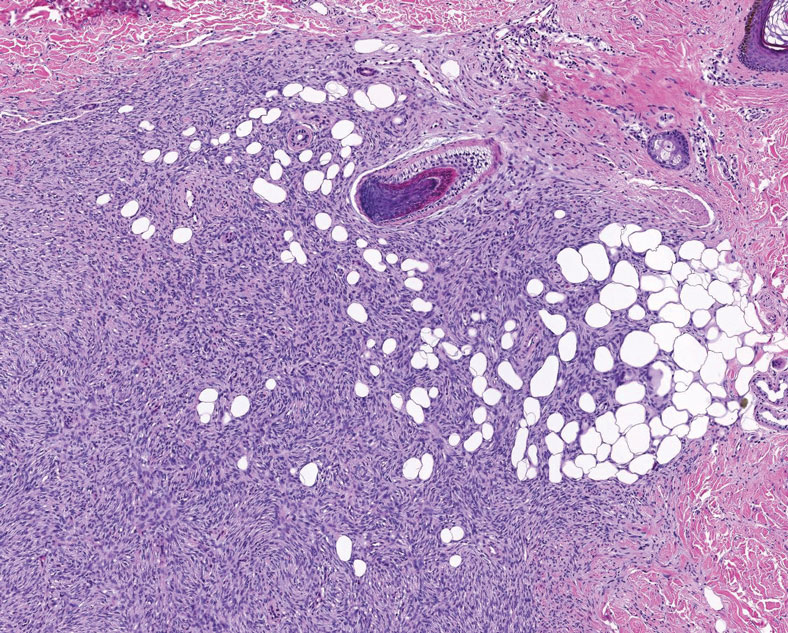

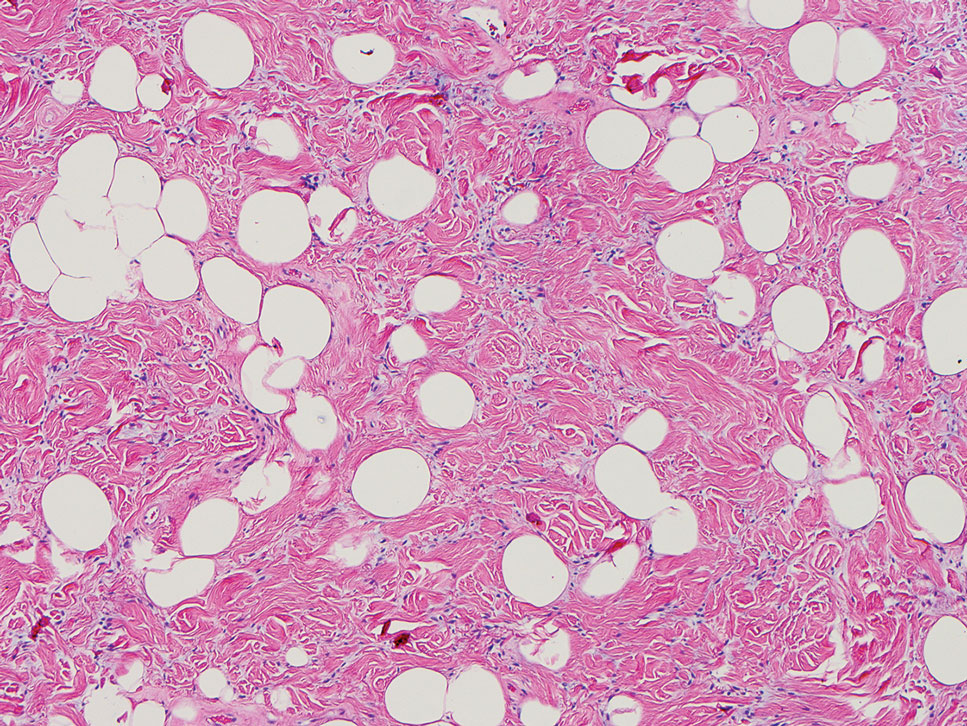

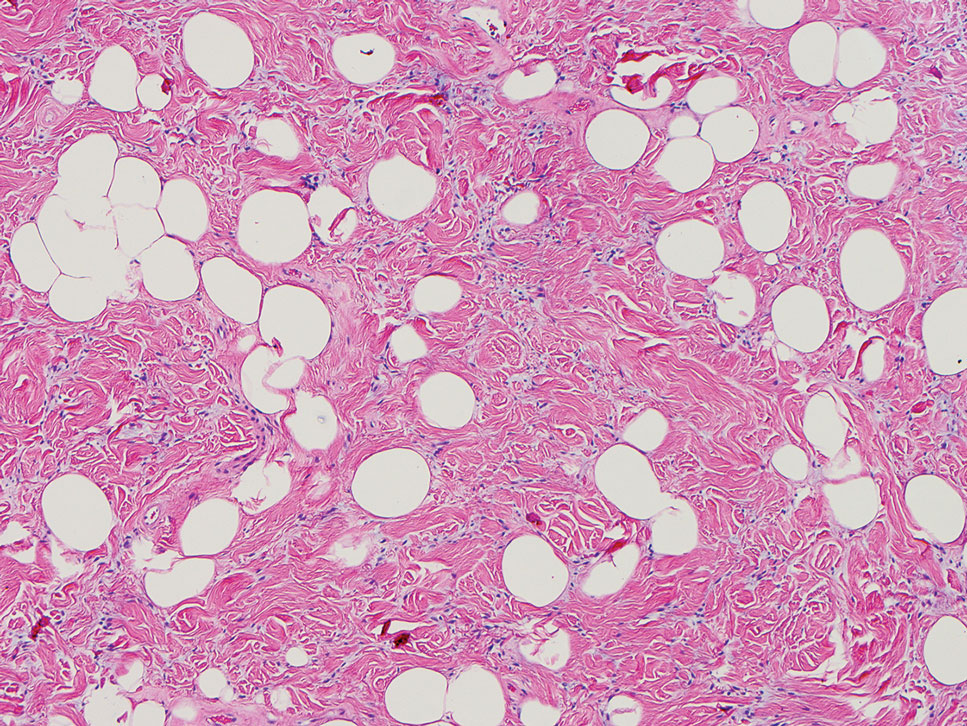

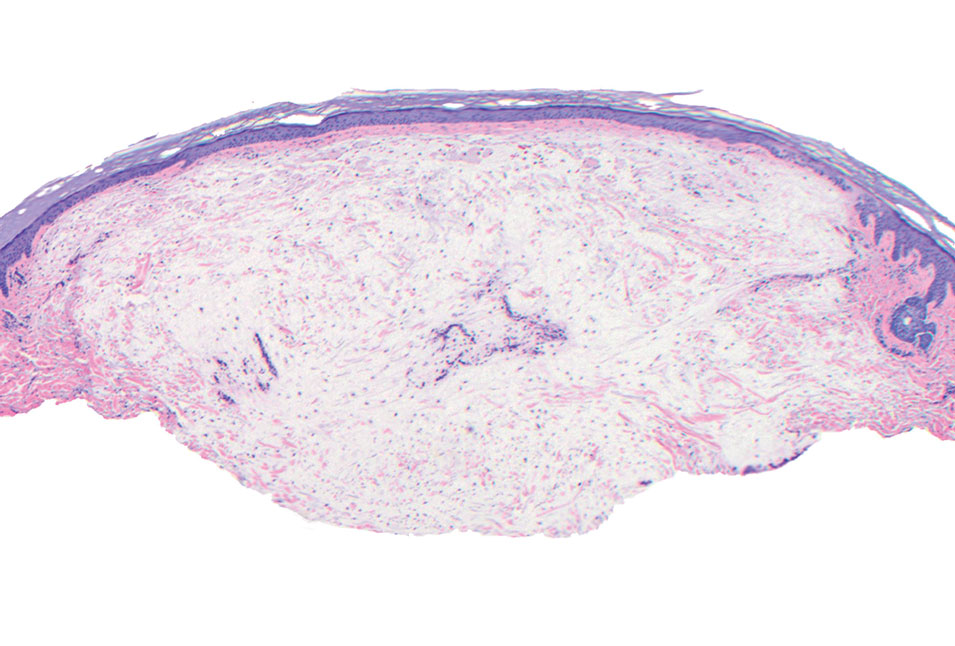

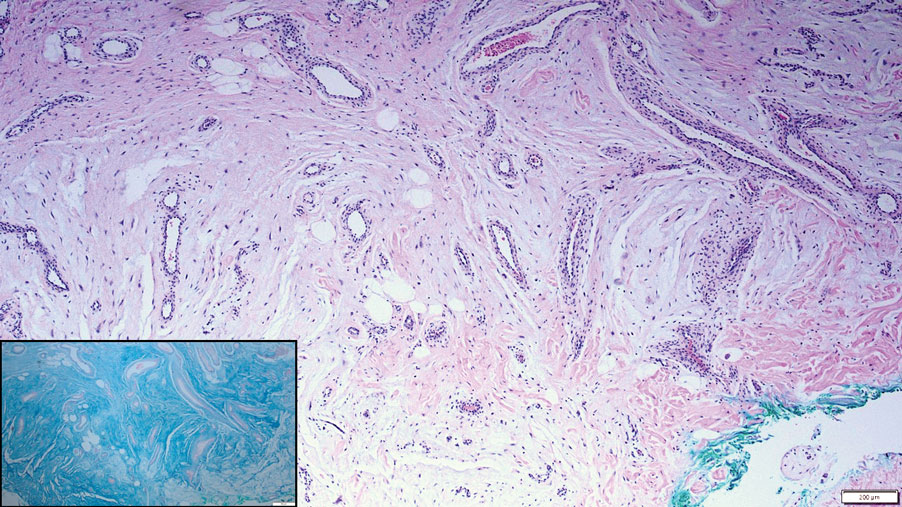

Spindle cell lipomas (SCLs) are rare, benign, subcutaneous, adipocytic tumors that arise on the upper back, posterior neck, or shoulders of middle-aged or elderly adult males.14 The clinical presentation often is an asymptomatic, well-circumscribed, mobile subcutaneous mass that is firmer than a common lipoma. Histologically, SCLs are characterized by mature adipocytes, spindle cells, and wire or ropelike collagen fibers in a myxoid background (Figure 3). The spindle cells usually are bland with a notable bipolar shape and blunted ends. Infiltrative growth patterns or mitotic figures are uncommon. Diagnosis can be supported by IHC, as SCLs stain diffusely positive for CD34 with loss of the retinoblastoma protein.7

Another important differential diagnosis to consider is myxofibrosarcoma, a rare and malignant myxoid cutaneous tumor. Clinically, it presents asymptomatically as an indolent, slow-growing nodule on the limbs and limb girdles.7 Histopathologic features demonstrate a multilobular tumor composed of a mixture of hypocellular and hypercellular regions with incomplete fibrous septae (Figure 4). The presence of curvilinear vasculature is characteristic. Multinucleated giant cells and cellular atypia with nuclear pleomorphism also can be seen. Although IHC findings generally are not specific, they can be used to rule out other potential diagnoses. Myxofibrosarcomas stain positive for vimentin and occasionally smooth muscle actin, muscle-specific actin, and CD34.7

Superficial angiomyxomas are benign; however, excision is recommended to distinguish between mimics. Local recurrence after excision is common in 30% to 40% of patients.15 Mohs micrographic surgery has been considered, especially if the following are present: tumor characteristics (eg, poorly circumscribed), location (eg, head and neck or other cosmetically or functionally sensitive areas), and likelihood of recurrence (high for superficial angiomyxomas). 16 This case otherwise highlights a rare example of superficial angiomyxomas involving the buttocks.

- Allen PW, Dymock RB, MacCormac LB. Superficial angiomyxomas with and without epithelial components. report of 30 tumors in 28 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 1988;12:519-530. doi:10.1097 /00000478-198807000-00003

- Sharma A, Khaitan N, Ko JS, et al. A clinicopathologic analysis of 54 cases of cutaneous myxoma. Hum Pathol. 2021:S0046-8177(21) 00201-X. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2021.12.003

- Hafeez F, Krakowski AC, Lian CG, et al. Sporadic superficial angiomyxomas demonstrate loss of PRKAR1A expression [published online March 17, 2022]. Histopathology. 2022;80:1001-1003. doi:10.1111/his.14568

- Mehrotra K, Bhandari M, Khullar G, et al. Large superficial angiomyxoma of the vulva: report of two cases with varied clinical presentation. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2021;12:605-607. doi:10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_489_20

- Alameda F, Munné A, Baró T, et al. Vulvar angiomyxoma, aggressive angiomyxoma, and angiomyofibroblastoma: an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. Ultrastruct Pathol. 2006;30:193-205. doi:10.1080/01913120500520911

- Haroon S, Irshad L, Zia S, et al. Aggressive angiomyxoma, angiomyofibroblastoma, and cellular angiofibroma of the lower female genital tract: related entities with different outcomes. Cureus. 2022;14:E29250. doi:10.7759/cureus.29250

- Zou Y, Billings SD. Myxoid cutaneous tumors: a review. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:903-918. doi:10.1111/cup.12749

- Allen PW. Myxoma is not a single entity: a review of the concept of myxoma. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2000;4:99-123. doi:10.1016 /s1092-9134(00)90019-4

- Lee C-C, Chen Y-L, Liau J-Y, et al. Superficial angiomyxoma on the vulva of an adolescent. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;53:104-106. doi:10.1016/j.tjog.2013.08.001

- Magro G, Amico P, Vecchio GM, et al. Multinucleated floret-like giant cells in sporadic and NF1-associated neurofibromas: a clinicopathologic study of 94 cases. Virchows Arch. 2010;456:71-76. doi:10.1007/s00428-009-0859-y

- Kuo KL, Lee LY, Kuo TT. Solitary cutaneous focal mucinosis: a clinicopathological study of 11 cases of soft fibroma-like cutaneous mucinous lesions. J Dermatol. 2017;44:335-338. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.13523

- Gutierrez N, Erickson C, Calame A, et al. Solitary cutaneous focal mucinosis. Cureus. 2021;13:E18618. doi:10.7759/cureus.18618

- Biondo G, Sola S, Pastorino C, et al. Clinical, dermoscopic, and histologic aspects of two cases of cutaneous focal mucinosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:334-336. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20198381

- Chen S, Huang H, He S, et al. Spindle cell lipoma: clinicopathologic characterization of 40 cases. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2019;12:2613-2621.

- Bembem K, Jaiswal A, Singh M, et al. Cyto-histo correlation of a very rare tumor: superficial angiomyxoma. J Cytol. 2017;34:230-232. doi:10.4103/0970-9371.216119

- Aberdein G, Veitch D, Perrett C. Mohs micrographic surgery for the treatment of superficial angiomyxoma. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42: 1014-1016. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000782

The Diagnosis: Superficial Angiomyxoma

Superficial angiomyxoma is a rare, benign, cutaneous tumor of a myxoid matrix and blood vessels that was first described in association with Carney complex.1 Tumors may be solitary or multiple. A recent review of cases in the literature revealed a roughly equal distribution of superficial angiomyxomas in males and females occurring most frequently on the head and neck, extremities, and trunk or back. The peak incidence is between the fourth and fifth decades of life.2 Superficial angiomyxomas can occur sporadically or in association with Carney complex, an autosomal-dominant condition with germline inactivating mutations in protein kinase A, PRKAR1A. Interestingly, sporadic cases of superficial angiomyxoma also have shown loss of PRKAR1A expression on immunohistochemistry (IHC).3

Common histologic mimics of superficial angiomyxoma include aggressive angiomyxoma and angiomyofibroblastoma.4 It is thought that these 3 distinct tumor entities may arise from a common pluripotent cell of origin located near connective tissue vasculature, which may contribute to the similarities observed between them.5 For example, aggressive angiomyxomas and angiomyofibroblastomas also demonstrate a similar myxoid background and vascular proliferation that can closely mimic superficial angiomyxomas clinically. However, the vessels of superficial angiomyxomas tend to be long and thin walled, while aggressive angiomyxomas are characterized by large and thick-walled vessels and angiomyofibroblastomas by abundant smaller vessels. Additionally, unlike superficial angiomyxomas, both aggressive angiomyxomas and angiomyofibroblastomas typically occur in the genital tract of young to middle-aged women.6

Histopathologic examination is imperative for differentiating between superficial angiomyxoma and more aggressive histologic mimics. Superficial angiomyxomas typically consist of a rich myxoid stroma, thin-walled or arborizing blood vessels, and spindled to stellate fibroblastlike cells (quiz image 2).3 Although not prominent in our case, superficial angiomyxomas also frequently present with stromal neutrophils and epithelial components, including keratinous cysts, basaloid buds, and strands of squamous epithelium.7 Minimal cellular atypia, mitotic activity, and nuclear pleomorphism often are seen, with IHC negative for desmin, estrogen receptor, and progesterone receptor; positive for CD34 and smooth muscle actin; and variable for S-100 and muscle-specific actin. Although IHC has limited utility in the diagnosis of superficial angiomyxomas, it may be useful to rule out other differential diagnoses.2,3 Superficial angiomyxomas usually show fibroblastic stromal cells, proteoglycan matrix, and collagen fibers on electron microscopy.8 Importantly, histopathologic examination of aggressive angiomyxoma will comparatively present with more invasive, infiltrative, and less well-circumscribed tumors.9 Other differential diagnoses on histology may include neurofibroma, focal cutaneous mucinosis, spindle cell lipoma, and myxofibrosarcoma. Additional considerations include fibroepithelial polyp, nevus lipomatosis, angiomyxolipoma, and anetoderma.

An important differential diagnosis in the evaluation of superficial angiomyxoma is neurofibroma, a benign peripheral nerve sheath tumor that presents as a smooth, flesh-colored, and painless papule or nodule commonly associated with the buttonhole sign. Histopathology of neurofibroma features elongated spindle cells with comma-shaped or buckled wavy nuclei and variably sized collagen bundles described as “shredded carrots” (Figure 1).10 Occasional mast cells also can be seen. Immunohistochemistry targeting elements of peripheral nerve sheaths may assist in the diagnosis of neurofibromas, including positive S-100 and SOX10 in Schwann cells, epithelial membrane antigen in perineural cells, and fingerprint positivity for CD34 in fibroblasts.10

Cutaneous mucinoses encompass a diverse group of connective tissue disorders characterized by accumulation of mucin in the skin. Solitary focal cutaneous mucinoses (FCMs) are individual isolated lesions of mucin deposits that are unassociated with systemic conditions.11 Conversely, multiple FCMs presenting with multiple cutaneous lesions also have been described in association with systemic diseases such as scleroderma, systemic lupus erythematosus, and thyroid disease.12 Solitary FCM typically presents as an asymptomatic, flesh-colored papule or nodule on the extremities. It often arises in mid to late adulthood with a slightly increased frequency among males.12 Histopathology of solitary FCM commonly demonstrates a dome-shaped pool of basophilic mucin in the upper dermis sparing involvement of the underlying subcutaneous tissue (Figure 2).13 Notably, FCM often lacks the vascularity as well as stromal neutrophils and epithelial elements that are seen in superficial angiomyxomas. Although hematoxylin and eosin stains can be sufficient for diagnosis of solitary FCM, additional stains for mucin such as Alcian blue, colloidal iron, or toluidine blue also may be considered to support the diagnosis.12

Spindle cell lipomas (SCLs) are rare, benign, subcutaneous, adipocytic tumors that arise on the upper back, posterior neck, or shoulders of middle-aged or elderly adult males.14 The clinical presentation often is an asymptomatic, well-circumscribed, mobile subcutaneous mass that is firmer than a common lipoma. Histologically, SCLs are characterized by mature adipocytes, spindle cells, and wire or ropelike collagen fibers in a myxoid background (Figure 3). The spindle cells usually are bland with a notable bipolar shape and blunted ends. Infiltrative growth patterns or mitotic figures are uncommon. Diagnosis can be supported by IHC, as SCLs stain diffusely positive for CD34 with loss of the retinoblastoma protein.7

Another important differential diagnosis to consider is myxofibrosarcoma, a rare and malignant myxoid cutaneous tumor. Clinically, it presents asymptomatically as an indolent, slow-growing nodule on the limbs and limb girdles.7 Histopathologic features demonstrate a multilobular tumor composed of a mixture of hypocellular and hypercellular regions with incomplete fibrous septae (Figure 4). The presence of curvilinear vasculature is characteristic. Multinucleated giant cells and cellular atypia with nuclear pleomorphism also can be seen. Although IHC findings generally are not specific, they can be used to rule out other potential diagnoses. Myxofibrosarcomas stain positive for vimentin and occasionally smooth muscle actin, muscle-specific actin, and CD34.7

Superficial angiomyxomas are benign; however, excision is recommended to distinguish between mimics. Local recurrence after excision is common in 30% to 40% of patients.15 Mohs micrographic surgery has been considered, especially if the following are present: tumor characteristics (eg, poorly circumscribed), location (eg, head and neck or other cosmetically or functionally sensitive areas), and likelihood of recurrence (high for superficial angiomyxomas). 16 This case otherwise highlights a rare example of superficial angiomyxomas involving the buttocks.

The Diagnosis: Superficial Angiomyxoma

Superficial angiomyxoma is a rare, benign, cutaneous tumor of a myxoid matrix and blood vessels that was first described in association with Carney complex.1 Tumors may be solitary or multiple. A recent review of cases in the literature revealed a roughly equal distribution of superficial angiomyxomas in males and females occurring most frequently on the head and neck, extremities, and trunk or back. The peak incidence is between the fourth and fifth decades of life.2 Superficial angiomyxomas can occur sporadically or in association with Carney complex, an autosomal-dominant condition with germline inactivating mutations in protein kinase A, PRKAR1A. Interestingly, sporadic cases of superficial angiomyxoma also have shown loss of PRKAR1A expression on immunohistochemistry (IHC).3

Common histologic mimics of superficial angiomyxoma include aggressive angiomyxoma and angiomyofibroblastoma.4 It is thought that these 3 distinct tumor entities may arise from a common pluripotent cell of origin located near connective tissue vasculature, which may contribute to the similarities observed between them.5 For example, aggressive angiomyxomas and angiomyofibroblastomas also demonstrate a similar myxoid background and vascular proliferation that can closely mimic superficial angiomyxomas clinically. However, the vessels of superficial angiomyxomas tend to be long and thin walled, while aggressive angiomyxomas are characterized by large and thick-walled vessels and angiomyofibroblastomas by abundant smaller vessels. Additionally, unlike superficial angiomyxomas, both aggressive angiomyxomas and angiomyofibroblastomas typically occur in the genital tract of young to middle-aged women.6

Histopathologic examination is imperative for differentiating between superficial angiomyxoma and more aggressive histologic mimics. Superficial angiomyxomas typically consist of a rich myxoid stroma, thin-walled or arborizing blood vessels, and spindled to stellate fibroblastlike cells (quiz image 2).3 Although not prominent in our case, superficial angiomyxomas also frequently present with stromal neutrophils and epithelial components, including keratinous cysts, basaloid buds, and strands of squamous epithelium.7 Minimal cellular atypia, mitotic activity, and nuclear pleomorphism often are seen, with IHC negative for desmin, estrogen receptor, and progesterone receptor; positive for CD34 and smooth muscle actin; and variable for S-100 and muscle-specific actin. Although IHC has limited utility in the diagnosis of superficial angiomyxomas, it may be useful to rule out other differential diagnoses.2,3 Superficial angiomyxomas usually show fibroblastic stromal cells, proteoglycan matrix, and collagen fibers on electron microscopy.8 Importantly, histopathologic examination of aggressive angiomyxoma will comparatively present with more invasive, infiltrative, and less well-circumscribed tumors.9 Other differential diagnoses on histology may include neurofibroma, focal cutaneous mucinosis, spindle cell lipoma, and myxofibrosarcoma. Additional considerations include fibroepithelial polyp, nevus lipomatosis, angiomyxolipoma, and anetoderma.

An important differential diagnosis in the evaluation of superficial angiomyxoma is neurofibroma, a benign peripheral nerve sheath tumor that presents as a smooth, flesh-colored, and painless papule or nodule commonly associated with the buttonhole sign. Histopathology of neurofibroma features elongated spindle cells with comma-shaped or buckled wavy nuclei and variably sized collagen bundles described as “shredded carrots” (Figure 1).10 Occasional mast cells also can be seen. Immunohistochemistry targeting elements of peripheral nerve sheaths may assist in the diagnosis of neurofibromas, including positive S-100 and SOX10 in Schwann cells, epithelial membrane antigen in perineural cells, and fingerprint positivity for CD34 in fibroblasts.10