User login

Dr. David Lieberman: A Groundbreaking Career in Gastroenterology

David Lieberman, MD, AGAF, spent much of his long career asking questions about everyday clinical practice in GI medicine and then researching ways to answer those questions.

“The answer to one question often leads to further questions. And I think that’s what makes this research so exciting and dynamic,” said Lieberman, professor emeritus with Oregon Health and Science University, where he served as chief of the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology for 24 years.

He was also instrumental in creating a blood and tissue repository for colorectal cancer (CRC) research, and a national endoscopic database.

His groundbreaking GI research in colorectal cancer screening earned him AGA’s Julius Friedenwald Medal, a top career honor. “We started off with some questions about the role of specific screening tests like colonoscopy and stool-based tests for screening,” he said. This led to the first large study about the value of screening with colonoscopy, which set the stage for current screening guidelines. Assessing more than 3,000 asymptomatic adults, Lieberman and colleagues determined that colonoscopy was more effective than sigmoidoscopy in detecting advanced colonic neoplasms.

The next phase of research focused on how well GI doctors were performing colonoscopy, asking questions about the quality of the colonoscopies being performed, and what course of action to take in polyp discovery. “We did some work related to polyp surveillance, what happens after we take out polyps and some recommendations for the appropriate length of follow up afterwards,” he summarized.

Most recently, Lieberman has centered his research on program effectiveness. “If you’re doing high quality colonoscopy and you’re doing appropriate surveillance, how effective is that? And what are the potential problems that might impair effectiveness?”

Adherence and participation remain significant challenges, he said. “If people don’t get the tests done, then they’re not going to be effective. Or if they get part of it done, there can be issues.”

In an interview, Lieberman discussed the reasons why people resist CRC screening, and the new technologies and research underway to make screening options more palatable for reluctant patients.

What do you think are the biggest deterrents to getting screened for CRC?

Dr. Lieberman: The whole idea of dealing with a stool sample is not appealing to patients. The second issue, and this has been shown in many studies, is patients who are referred for colonoscopy may resist because they have heard stories about bowel preps and about colonoscopy itself. But there are many other reasons. I mean, there are issues with access to care that are important. What if you have a positive stool test and you need to get a colonoscopy? How do you get a colonoscopy? There are barriers in moving from one test to the other in a different setting. There are issues with having to take a day off work that’s potentially a financial hardship for some patients. If you’re taking care of elderly relatives or children or if you need transportation, that’s an issue for people.

So, there are many potential barriers, and we’ve been trying to work at a national level to try to understand these barriers and then develop tools to mitigate these problems and improve the overall participation in screening.

How has the field of GI changed since you started practicing medicine?

Dr. Lieberman: I think there have been many exciting changes in technology. The endoscopes we used when I started my career were called fiberoptic scopes. These were scopes that contained tiny glass fibers that ran the length of the scope, and they were good, but not great in terms of imaging, and sometimes they would break down. We now have digital imaging that far surpasses the quality there. We’ve come a long way in terms of things like CT scans, for example, and MRI imaging. The other big technology change has been the development of minimally invasive treatments. For example, if you have a gallstone that’s in your bile duct, we now have ways to remove that without sending the patient to surgery.

The second big change has been the assessment of quality. When I started my career in gastroenterology, we were doing a lot of things, but we didn’t necessarily know if we were doing them well. Most of us thought we were doing them well, of course, but nobody was really measuring quality. There were no quality benchmarks. And so if you don’t measure it, you don’t know. Where we are today in gastroenterology is we’re intensively concerned about quality and measuring quality in various aspects of what we do. And I think that’s a positive development.

What key achievements came out of the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer?

Dr. Lieberman: This panel evolved because back in the early 2000s, each of the GI organizations were producing guidelines related to colon cancer screening and follow-up. And they were slightly different. This was an attempt to bring all the relevant groups together and try to align the guidelines and recommendations among the GI organizations so that there wouldn’t be a confusing message.

Over the history of this task force, which started around 2002, it’s been remarkably productive. The task force has really examined all aspects of colorectal cancer, including things like the bowel prep, quality of exams, high risk management, hereditary syndromes that can lead to the higher likelihood of developing colon cancer, polypectomy and polypectomy techniques, and screening and surveillance recommendations, which have evolved over time. It’s been, in my opinion, a remarkably productive task force and continues to this day. I’m so very proud of that group.

Could you give a status update on the blood and tissue repository you created for CRC research?

Dr. Lieberman: Our initial studies were part of a Veterans Affairs cooperative study, which is a mechanism of funding within the VA that allows us to work with multiple VA centers to collect data and information. At the very outset of this study, we were performing screening colonoscopies in individuals, and we decided to create a bio-repository that included blood samples, polyp tissue, and normal rectal tissue. The thinking was at some point we might be able to do some genomic studies that might help us predict which patients are most likely to develop colon polyps and colon cancer. All that happened in the 1990s. It was supported by the National Cancer Institute. We created this repository, which sat for a long period of time while we were waiting for the technology to develop and so that we could perform genomic studies in a cost-effective way.

We’re now at that point, which is really exciting. We’re beginning to look at this tissue and perform some genomic studies. Some of this data has been presented at national meetings. This was a precursor to creating a similar type of bio-repository in a larger VA cooperative study. CSP #577 Colonoscopy vs. Fecal Immunochemical Test in Reducing Mortality from Colorectal Cancer (CONFIRM) is a randomized study comparing two forms of screening, a fecal immunochemical test versus a colonoscopy. We’re in the process of enrolling 50,000 patients in that study. We have also created a blood and tissue repository, which we hope will be useful for future studies.

You lead the AGA CRC Task Force, which advances research and policy initiatives to improve screening rates and patient outcomes. What would you like to see in future GI research, particularly in colorectal cancer?

Dr. Lieberman: We have new blood tests coming along that are going to be very attractive to both patients and physicians. You can obtain a blood sample at a point of service and patients won’t have to deal with stool samples. We need to understand how those tests perform in clinical practice. If the test is abnormal, indicating a patient has a higher risk of colon cancer and should get a colonoscopy, are they getting that colonoscopy or not? And what are the barriers? And if it’s normal, then that patient should have a repeat test at an appropriate interval.

We know that the effectiveness of screening really depends on the participation of individuals in terms of completing the steps. We’ve published some work already on trying to understand the role of these blood tests. We expect that these tests will continue to improve over time.

We’re also working on trying to develop these risk stratification tools that could be used in clinical practice to help figure out the most appropriate test for a particular individual.

Let’s say you go to your doctor for colon cancer screening, and if we could determine that you are a low-risk individual, you may benefit best from having a non-invasive test, like a blood test or a stool test. Whereas if you’re a higher risk individual, you may need to have a more invasive screening test like colonoscopy.

This falls into a concept of personalized medicine where we’re trying to use all the information we have from the medical history, and maybe genomic information that I mentioned earlier, to try to determine who needs the most intensive screening and who might benefit from less intensive screening.

I think the most recent work is really focused on these gaps in screening. And the biggest gap are patients that get a non-invasive test, like a stool test, but do not get a colonoscopy that renders the program ineffective if they don’t get the colonoscopy. We’re trying to highlight that for primary care providers and make sure that everyone understands the importance of this follow-up. And then, trying to develop tools to help the primary care provider navigate that patient to a colonoscopy.

What do you think is the biggest misconception about your specialty?

Dr. Lieberman: If there’s a misconception, it’s that GI physicians are focused on procedures. I think a good GI provider should be holistic, and I think many are. What I mean by holistic is that many GI symptoms could be due to stress, medications, diet, or other aspects of behavior, and the remedy is not necessarily a procedure. I think that many GI physicians are really skilled at obtaining this information and trying to help guide the patient through some uncomfortable symptoms.

It means being more like an internist, spending time with the patient to take a detailed history and delve into many different possibilities that might be going on.

David Lieberman, MD, AGAF, spent much of his long career asking questions about everyday clinical practice in GI medicine and then researching ways to answer those questions.

“The answer to one question often leads to further questions. And I think that’s what makes this research so exciting and dynamic,” said Lieberman, professor emeritus with Oregon Health and Science University, where he served as chief of the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology for 24 years.

He was also instrumental in creating a blood and tissue repository for colorectal cancer (CRC) research, and a national endoscopic database.

His groundbreaking GI research in colorectal cancer screening earned him AGA’s Julius Friedenwald Medal, a top career honor. “We started off with some questions about the role of specific screening tests like colonoscopy and stool-based tests for screening,” he said. This led to the first large study about the value of screening with colonoscopy, which set the stage for current screening guidelines. Assessing more than 3,000 asymptomatic adults, Lieberman and colleagues determined that colonoscopy was more effective than sigmoidoscopy in detecting advanced colonic neoplasms.

The next phase of research focused on how well GI doctors were performing colonoscopy, asking questions about the quality of the colonoscopies being performed, and what course of action to take in polyp discovery. “We did some work related to polyp surveillance, what happens after we take out polyps and some recommendations for the appropriate length of follow up afterwards,” he summarized.

Most recently, Lieberman has centered his research on program effectiveness. “If you’re doing high quality colonoscopy and you’re doing appropriate surveillance, how effective is that? And what are the potential problems that might impair effectiveness?”

Adherence and participation remain significant challenges, he said. “If people don’t get the tests done, then they’re not going to be effective. Or if they get part of it done, there can be issues.”

In an interview, Lieberman discussed the reasons why people resist CRC screening, and the new technologies and research underway to make screening options more palatable for reluctant patients.

What do you think are the biggest deterrents to getting screened for CRC?

Dr. Lieberman: The whole idea of dealing with a stool sample is not appealing to patients. The second issue, and this has been shown in many studies, is patients who are referred for colonoscopy may resist because they have heard stories about bowel preps and about colonoscopy itself. But there are many other reasons. I mean, there are issues with access to care that are important. What if you have a positive stool test and you need to get a colonoscopy? How do you get a colonoscopy? There are barriers in moving from one test to the other in a different setting. There are issues with having to take a day off work that’s potentially a financial hardship for some patients. If you’re taking care of elderly relatives or children or if you need transportation, that’s an issue for people.

So, there are many potential barriers, and we’ve been trying to work at a national level to try to understand these barriers and then develop tools to mitigate these problems and improve the overall participation in screening.

How has the field of GI changed since you started practicing medicine?

Dr. Lieberman: I think there have been many exciting changes in technology. The endoscopes we used when I started my career were called fiberoptic scopes. These were scopes that contained tiny glass fibers that ran the length of the scope, and they were good, but not great in terms of imaging, and sometimes they would break down. We now have digital imaging that far surpasses the quality there. We’ve come a long way in terms of things like CT scans, for example, and MRI imaging. The other big technology change has been the development of minimally invasive treatments. For example, if you have a gallstone that’s in your bile duct, we now have ways to remove that without sending the patient to surgery.

The second big change has been the assessment of quality. When I started my career in gastroenterology, we were doing a lot of things, but we didn’t necessarily know if we were doing them well. Most of us thought we were doing them well, of course, but nobody was really measuring quality. There were no quality benchmarks. And so if you don’t measure it, you don’t know. Where we are today in gastroenterology is we’re intensively concerned about quality and measuring quality in various aspects of what we do. And I think that’s a positive development.

What key achievements came out of the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer?

Dr. Lieberman: This panel evolved because back in the early 2000s, each of the GI organizations were producing guidelines related to colon cancer screening and follow-up. And they were slightly different. This was an attempt to bring all the relevant groups together and try to align the guidelines and recommendations among the GI organizations so that there wouldn’t be a confusing message.

Over the history of this task force, which started around 2002, it’s been remarkably productive. The task force has really examined all aspects of colorectal cancer, including things like the bowel prep, quality of exams, high risk management, hereditary syndromes that can lead to the higher likelihood of developing colon cancer, polypectomy and polypectomy techniques, and screening and surveillance recommendations, which have evolved over time. It’s been, in my opinion, a remarkably productive task force and continues to this day. I’m so very proud of that group.

Could you give a status update on the blood and tissue repository you created for CRC research?

Dr. Lieberman: Our initial studies were part of a Veterans Affairs cooperative study, which is a mechanism of funding within the VA that allows us to work with multiple VA centers to collect data and information. At the very outset of this study, we were performing screening colonoscopies in individuals, and we decided to create a bio-repository that included blood samples, polyp tissue, and normal rectal tissue. The thinking was at some point we might be able to do some genomic studies that might help us predict which patients are most likely to develop colon polyps and colon cancer. All that happened in the 1990s. It was supported by the National Cancer Institute. We created this repository, which sat for a long period of time while we were waiting for the technology to develop and so that we could perform genomic studies in a cost-effective way.

We’re now at that point, which is really exciting. We’re beginning to look at this tissue and perform some genomic studies. Some of this data has been presented at national meetings. This was a precursor to creating a similar type of bio-repository in a larger VA cooperative study. CSP #577 Colonoscopy vs. Fecal Immunochemical Test in Reducing Mortality from Colorectal Cancer (CONFIRM) is a randomized study comparing two forms of screening, a fecal immunochemical test versus a colonoscopy. We’re in the process of enrolling 50,000 patients in that study. We have also created a blood and tissue repository, which we hope will be useful for future studies.

You lead the AGA CRC Task Force, which advances research and policy initiatives to improve screening rates and patient outcomes. What would you like to see in future GI research, particularly in colorectal cancer?

Dr. Lieberman: We have new blood tests coming along that are going to be very attractive to both patients and physicians. You can obtain a blood sample at a point of service and patients won’t have to deal with stool samples. We need to understand how those tests perform in clinical practice. If the test is abnormal, indicating a patient has a higher risk of colon cancer and should get a colonoscopy, are they getting that colonoscopy or not? And what are the barriers? And if it’s normal, then that patient should have a repeat test at an appropriate interval.

We know that the effectiveness of screening really depends on the participation of individuals in terms of completing the steps. We’ve published some work already on trying to understand the role of these blood tests. We expect that these tests will continue to improve over time.

We’re also working on trying to develop these risk stratification tools that could be used in clinical practice to help figure out the most appropriate test for a particular individual.

Let’s say you go to your doctor for colon cancer screening, and if we could determine that you are a low-risk individual, you may benefit best from having a non-invasive test, like a blood test or a stool test. Whereas if you’re a higher risk individual, you may need to have a more invasive screening test like colonoscopy.

This falls into a concept of personalized medicine where we’re trying to use all the information we have from the medical history, and maybe genomic information that I mentioned earlier, to try to determine who needs the most intensive screening and who might benefit from less intensive screening.

I think the most recent work is really focused on these gaps in screening. And the biggest gap are patients that get a non-invasive test, like a stool test, but do not get a colonoscopy that renders the program ineffective if they don’t get the colonoscopy. We’re trying to highlight that for primary care providers and make sure that everyone understands the importance of this follow-up. And then, trying to develop tools to help the primary care provider navigate that patient to a colonoscopy.

What do you think is the biggest misconception about your specialty?

Dr. Lieberman: If there’s a misconception, it’s that GI physicians are focused on procedures. I think a good GI provider should be holistic, and I think many are. What I mean by holistic is that many GI symptoms could be due to stress, medications, diet, or other aspects of behavior, and the remedy is not necessarily a procedure. I think that many GI physicians are really skilled at obtaining this information and trying to help guide the patient through some uncomfortable symptoms.

It means being more like an internist, spending time with the patient to take a detailed history and delve into many different possibilities that might be going on.

David Lieberman, MD, AGAF, spent much of his long career asking questions about everyday clinical practice in GI medicine and then researching ways to answer those questions.

“The answer to one question often leads to further questions. And I think that’s what makes this research so exciting and dynamic,” said Lieberman, professor emeritus with Oregon Health and Science University, where he served as chief of the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology for 24 years.

He was also instrumental in creating a blood and tissue repository for colorectal cancer (CRC) research, and a national endoscopic database.

His groundbreaking GI research in colorectal cancer screening earned him AGA’s Julius Friedenwald Medal, a top career honor. “We started off with some questions about the role of specific screening tests like colonoscopy and stool-based tests for screening,” he said. This led to the first large study about the value of screening with colonoscopy, which set the stage for current screening guidelines. Assessing more than 3,000 asymptomatic adults, Lieberman and colleagues determined that colonoscopy was more effective than sigmoidoscopy in detecting advanced colonic neoplasms.

The next phase of research focused on how well GI doctors were performing colonoscopy, asking questions about the quality of the colonoscopies being performed, and what course of action to take in polyp discovery. “We did some work related to polyp surveillance, what happens after we take out polyps and some recommendations for the appropriate length of follow up afterwards,” he summarized.

Most recently, Lieberman has centered his research on program effectiveness. “If you’re doing high quality colonoscopy and you’re doing appropriate surveillance, how effective is that? And what are the potential problems that might impair effectiveness?”

Adherence and participation remain significant challenges, he said. “If people don’t get the tests done, then they’re not going to be effective. Or if they get part of it done, there can be issues.”

In an interview, Lieberman discussed the reasons why people resist CRC screening, and the new technologies and research underway to make screening options more palatable for reluctant patients.

What do you think are the biggest deterrents to getting screened for CRC?

Dr. Lieberman: The whole idea of dealing with a stool sample is not appealing to patients. The second issue, and this has been shown in many studies, is patients who are referred for colonoscopy may resist because they have heard stories about bowel preps and about colonoscopy itself. But there are many other reasons. I mean, there are issues with access to care that are important. What if you have a positive stool test and you need to get a colonoscopy? How do you get a colonoscopy? There are barriers in moving from one test to the other in a different setting. There are issues with having to take a day off work that’s potentially a financial hardship for some patients. If you’re taking care of elderly relatives or children or if you need transportation, that’s an issue for people.

So, there are many potential barriers, and we’ve been trying to work at a national level to try to understand these barriers and then develop tools to mitigate these problems and improve the overall participation in screening.

How has the field of GI changed since you started practicing medicine?

Dr. Lieberman: I think there have been many exciting changes in technology. The endoscopes we used when I started my career were called fiberoptic scopes. These were scopes that contained tiny glass fibers that ran the length of the scope, and they were good, but not great in terms of imaging, and sometimes they would break down. We now have digital imaging that far surpasses the quality there. We’ve come a long way in terms of things like CT scans, for example, and MRI imaging. The other big technology change has been the development of minimally invasive treatments. For example, if you have a gallstone that’s in your bile duct, we now have ways to remove that without sending the patient to surgery.

The second big change has been the assessment of quality. When I started my career in gastroenterology, we were doing a lot of things, but we didn’t necessarily know if we were doing them well. Most of us thought we were doing them well, of course, but nobody was really measuring quality. There were no quality benchmarks. And so if you don’t measure it, you don’t know. Where we are today in gastroenterology is we’re intensively concerned about quality and measuring quality in various aspects of what we do. And I think that’s a positive development.

What key achievements came out of the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer?

Dr. Lieberman: This panel evolved because back in the early 2000s, each of the GI organizations were producing guidelines related to colon cancer screening and follow-up. And they were slightly different. This was an attempt to bring all the relevant groups together and try to align the guidelines and recommendations among the GI organizations so that there wouldn’t be a confusing message.

Over the history of this task force, which started around 2002, it’s been remarkably productive. The task force has really examined all aspects of colorectal cancer, including things like the bowel prep, quality of exams, high risk management, hereditary syndromes that can lead to the higher likelihood of developing colon cancer, polypectomy and polypectomy techniques, and screening and surveillance recommendations, which have evolved over time. It’s been, in my opinion, a remarkably productive task force and continues to this day. I’m so very proud of that group.

Could you give a status update on the blood and tissue repository you created for CRC research?

Dr. Lieberman: Our initial studies were part of a Veterans Affairs cooperative study, which is a mechanism of funding within the VA that allows us to work with multiple VA centers to collect data and information. At the very outset of this study, we were performing screening colonoscopies in individuals, and we decided to create a bio-repository that included blood samples, polyp tissue, and normal rectal tissue. The thinking was at some point we might be able to do some genomic studies that might help us predict which patients are most likely to develop colon polyps and colon cancer. All that happened in the 1990s. It was supported by the National Cancer Institute. We created this repository, which sat for a long period of time while we were waiting for the technology to develop and so that we could perform genomic studies in a cost-effective way.

We’re now at that point, which is really exciting. We’re beginning to look at this tissue and perform some genomic studies. Some of this data has been presented at national meetings. This was a precursor to creating a similar type of bio-repository in a larger VA cooperative study. CSP #577 Colonoscopy vs. Fecal Immunochemical Test in Reducing Mortality from Colorectal Cancer (CONFIRM) is a randomized study comparing two forms of screening, a fecal immunochemical test versus a colonoscopy. We’re in the process of enrolling 50,000 patients in that study. We have also created a blood and tissue repository, which we hope will be useful for future studies.

You lead the AGA CRC Task Force, which advances research and policy initiatives to improve screening rates and patient outcomes. What would you like to see in future GI research, particularly in colorectal cancer?

Dr. Lieberman: We have new blood tests coming along that are going to be very attractive to both patients and physicians. You can obtain a blood sample at a point of service and patients won’t have to deal with stool samples. We need to understand how those tests perform in clinical practice. If the test is abnormal, indicating a patient has a higher risk of colon cancer and should get a colonoscopy, are they getting that colonoscopy or not? And what are the barriers? And if it’s normal, then that patient should have a repeat test at an appropriate interval.

We know that the effectiveness of screening really depends on the participation of individuals in terms of completing the steps. We’ve published some work already on trying to understand the role of these blood tests. We expect that these tests will continue to improve over time.

We’re also working on trying to develop these risk stratification tools that could be used in clinical practice to help figure out the most appropriate test for a particular individual.

Let’s say you go to your doctor for colon cancer screening, and if we could determine that you are a low-risk individual, you may benefit best from having a non-invasive test, like a blood test or a stool test. Whereas if you’re a higher risk individual, you may need to have a more invasive screening test like colonoscopy.

This falls into a concept of personalized medicine where we’re trying to use all the information we have from the medical history, and maybe genomic information that I mentioned earlier, to try to determine who needs the most intensive screening and who might benefit from less intensive screening.

I think the most recent work is really focused on these gaps in screening. And the biggest gap are patients that get a non-invasive test, like a stool test, but do not get a colonoscopy that renders the program ineffective if they don’t get the colonoscopy. We’re trying to highlight that for primary care providers and make sure that everyone understands the importance of this follow-up. And then, trying to develop tools to help the primary care provider navigate that patient to a colonoscopy.

What do you think is the biggest misconception about your specialty?

Dr. Lieberman: If there’s a misconception, it’s that GI physicians are focused on procedures. I think a good GI provider should be holistic, and I think many are. What I mean by holistic is that many GI symptoms could be due to stress, medications, diet, or other aspects of behavior, and the remedy is not necessarily a procedure. I think that many GI physicians are really skilled at obtaining this information and trying to help guide the patient through some uncomfortable symptoms.

It means being more like an internist, spending time with the patient to take a detailed history and delve into many different possibilities that might be going on.

Approach to Weight Management in GI Practice

Introduction

The majority of patients in the United States are now overweight or obese, and as gastroenterologists we treat a number of conditions that are caused or worsened by obesity.1 Cirrhosis related to metabolic associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) is now a leading indication for liver transplantation in the US2 and obesity is a clear risk factor for all major malignancies of the GI tract, including esophageal, gastric cardia, pancreatic, liver, gallbladder, colon, and rectum.3 Obesity is associated with dysbiosis and impacts barrier function: increasing permeability, abnormal gut bacterial translocation, and inflammation.4 It is more common than malnutrition in our patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), where it impacts response to biologic drugs, increases the technical difficulty of surgeries, such as IPAA, and is associated with worse surgical outcomes.5 Furthermore, patients with obesity may be less likely to undergo preventative cancer screenings and are at increased risk related to sedation for endoscopic procedures.6 With over 40% of Americans suffering from obesity, and increasingly effective treatments available,

Understanding the Mechanisms of Obesity

There are complex orexigenic and anorexigenic brain pathways in the hypothalamus which control global energy balance.7 Obesity results when energy intake exceeds energy expenditure. While overeating and a sedentary lifestyle are commonly blamed, there are a number of elements that contribute, including genetics, medical conditions, medications, psychosocial factors, and environmental components. For example, sleep loss contributes to weight gain by several mechanisms including increasing ghrelin and decreasing leptin levels, thereby increasing hunger and appetite, as well as by decreasing insulin sensitivity and increasing cortisol. Subjects exposed to sleep deprivation in research settings take in 550 kcal more the following day.8 Medications used commonly in GI practice including corticosteroids, antihistamines, propranolol, and amitriptyline, are obesogenic9 and cannabis can impact hypothalamic pathways to stimulate hunger.10

When patients diet or exercise to lose weight, as we have traditionally advised, there are strong hormonal changes and metabolic adaptations that occur to preserve the defended fat mass or “set point.” Loss of adipose tissue results in decreased production of leptin, a hormone that stimulates satiety pathways and inhibits orexigenic pathways, greatly increasing hunger and cravings. Increases in ghrelin production by the stomach decreases perceptions of fullness. With weight loss, energy requirements decrease, and muscles become more efficient, meaning fewer kcal are needed to maintain bodily processes.11 Eventually a plateau is reached, while motivation to diet and restraint around food wane, and hedonistic (reward) pathways are activated. These powerful factors result in the regain of lost weight within one year in the majority of patients.

Implementing Weight Management into GI Practice

Given the stigma and bias around obesity, patients often feel shame and vulnerability around the condition. It is important to have empathy in your approach, asking permission to discuss weight and using patient-first language (e.g. “patient with obesity” not “obese patient”). While BMI is predictive of health outcomes, it does not measure body fat percentage and may be misleading, such as in muscular individuals. Other measures of adiposity including waist circumference and body composition testing, such as with DEXA, may provide additional data. A BMI of 30 or above defines obesity, though newer definitions incorporate related symptoms, organ disfunction, and metabolic abnormalities into the term “clinical obesity.”12 Asian patients experience metabolic complications at a lower BMI, and therefore the definition of obese is 27.5kg/m2 in this population.

Begin by taking a weight history. Has this been a lifelong struggle or is there a particular life circumstance, such as working a third shift or recent pregnancy which precipitated weight gain? Patients should be asked about binge eating or eating late into the evening or waking at night to eat, as these disordered eating behaviors are managed with specific medications and behavioral therapies. Inquire about sleep duration and quality and refer for a sleep study if there is suspicion for obstructive sleep apnea. Other weight-related comorbidities including hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and MAFLD should be considered and merit a more aggressive approach, as does more severe obesity (class III, BMI ≥40). Questions about marijuana and alcohol use as well as review of the medication list for obesogenic medications can provide further insight into modifiable contributing factors.

Pillars of Weight Management

The internet is awash with trendy diet recommendations, and widespread misconceptions about obesity management are even ingrained into how physicians approach the disease. It is critical to remember that this is not a consequence of bad choices or lack of self-control. Exercise alone is insufficient to result in significant weight loss.13 Furthermore, whether it is through low fat, low carb, or intermittent fasting, weight loss will occur with calorie deficit.14 Evidence-based diet and lifestyle recommendations to lay the groundwork for success should be discussed at each visit (see Table 1). The Mediterranean diet is recommended for weight loss as well as for several GI disorders (i.e., MAFLD and IBD) and is the optimal eating strategy for cardiovascular health.15 Patients should be advised to engage in 150 minutes of moderate exercise per week, such as brisk walking, and should incorporate resistance training to build muscle and maintain bone density.

Anti-obesity Medications

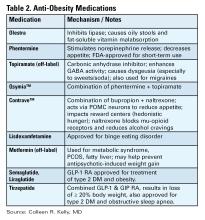

There are a number of medications, either FDA approved or used off label, for treatment of obesity (see Table 2).16 All are indicated for patients with a BMI of ≥ 30 kg/m2 or for those with a BMI between 27-29 kg/m2 with weight-related comorbidities and should be used in combination with diet and lifestyle interventions. None are approved or safe in pregnancy. Mechanisms of action vary by type and include decreased appetite, increased energy expenditure, improved insulin sensitivity, and interfere with absorption.

The newest and most effective anti-obesity medications (AOM), the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RA) are derived from gut hormones secreted in the distal small bowel and colon in response to a meal, which function to delay gastric emptying, increase insulin release from the pancreas, and reduce hepatic gluconeogenesis. Central nervous system effects are not yet entirely understood, but function to decrease appetite and increase satiety. Initially developed for treatment of T2DM, observed weight reduction in patients treated with GLP-1 RA led to clinical trials for treatment of obesity. Semaglutide treatment resulted in weight reduction of 16.9% of total body weight (TBW), and one third of subjects lost ≥ 20% of TBW.17 Tirzepatide combines GLP-1 RA and a gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP) receptor agonist, which also has an incretin effect and functions to slow gastric emptying. In the pivotal SURMOUNT trial, approximately 58% of patients achieved ≥20% loss of TBW18 with 15mg weekly dosing of tirzepatide. This class of drugs is a logical choice in patients with T2DM and obesity. Long-term treatment appears necessary, as patients typically regain two-thirds of lost weight within a year after GLP-1 RA are stopped.

Based on tumors observed in rodents, GLP-1 RA are contraindicated in patients with a personal or family history of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 (MEN II) or medullary thyroid cancer. These tumors have not been observed in humans treated with GLP-1 RA. They should be used with caution in patients with history of pancreatitis, gastroparesis, or diabetic retinopathy, though a recent systematic review and meta-analysis suggests showed little to no increased risk for biliary events from GLP-1 RA.19 Side effects are most commonly gastrointestinal in nature (nausea, reflux, constipation or diarrhea) and are typically most severe with initiation of the drug and with dose escalation. Side effects can be mitigated by initiating these drugs at lowest doses and gradually titrating up (every four weeks) based on effectiveness and tolerability. Antisecretory, antiemetic, and laxative medications can also be used to help manage GLP-1 RA related side effects.

There is no reason to escalate to highest doses if patients are experiencing weight loss and reduction in food cravings at lower doses. Both semaglutide and tirzepatide are administered subcutaneously every seven days. Once patients have reached goal weight, they can either continue maintenance therapy at that same dose/interval, or if motivated to do so, may gradually reduce the weekly dose in a stepwise approach to determine the minimally effective dose to maintain weight loss. There are not yet published maintenance studies to guide this process. Currently the price of GLP-1 RA and inconsistent insurance coverage make them inaccessible to many patients. The manufacturers of both semaglutide and tirzepatide offer direct to consumer pricing and home delivery.

Bariatric Surgery

In patients with higher BMI (≥35kg/m2) or those with BMI ≥30kg/m2 and obesity-related metabolic disease and the desire to avoid lifelong medications or who fail or are intolerant of AOM, bariatric options should be considered.20 Sleeve gastrectomy has become the most performed surgery for treatment of obesity. It is a restrictive procedure, removing 80% of the stomach, but a drop in circulating levels of ghrelin afterwards also leads to decreased feelings of hunger. It results in weight loss of 25-30% TBW loss. It is not a good choice for patients who suffer from severe GERD, as this typically worsens afterwards; furthermore, de novo Barrett’s has been observed in nearly 6% of patients who undergo sleeve gastrectomy.21

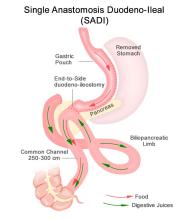

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass is a restrictive and malabsorptive procedure, resulting in 30-35% TBW loss. It has beneficial and immediate metabolic effects, including increased release of endogenous GLP-1, which leads to improvements in weight-related T2DM. The newer single anastomosis duodenal-ileal bypass with sleeve gastrectomy (SADI-S) starts with a sleeve gastrectomy, making a smaller tube-shaped stomach. The duodenum is divided just after the stomach and then a loop of ileum is brought up and connected to the stomach (see Figure 1). This procedure is highly effective, with patients losing 75-95% of excess body weight and is becoming a preferred option for patients with greater BMI (≥50kg/m2). It is also an option for patients who have already had a sleeve gastrectomy and are seeking further weight loss. Because there is only one anastomosis, perioperative complications, such as anastomotic leaks, are reduced. The risk of micronutrient deficiencies is present with all malabsorptive procedures, and these patients must supplement with multivitamins, iron, vitamin D, and calcium.

Endoscopic Therapies

Endoscopic bariatric and metabolic therapies (EBMTs) have been increasingly studied and utilized, and this less invasive option may be more appropriate for or attractive to many patients. Intragastric balloons, which reduce meal volume and delay gastric emptying, can be used short term only (six months) resulting in loss of about 6.9% of total body weight (TBW) greater than lifestyle modification (LM) alone, and may be considered in limited situations, such as need for pre-operative weight loss to reduce risks in very obese individuals.22

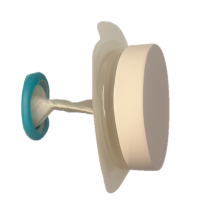

Endoscopic gastric remodeling (EGR), also known as endoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (ESG), is a purely restrictive procedure in which the stomach is cinched to resize and reshape using an endoscopic suturing device (see Figure 2).23 It is an option for patients with class 1 or 2 obesity, with data from a randomized controlled trial in this population demonstrating mean percentage of TBW loss of 13.6% at 52 weeks compared to 0.8% in those treated with LM alone.24 A recent meta-analysis of 21 observational studies, including patients with higher BMIs (32.5 to 49.9 kg/m2) showed pooled average weight loss of 17.3% TBW at 12 months with EGR.22 This procedure has potential advantages of fewer complications, quicker recovery, and much less new-onset GERD compared to laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Furthermore, it may be utilized in combination with AOMs to achieve optimum weight loss and metabolic outcomes.25,26 Potential adverse events include abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting (which may be severe), as well as rare instances of intra/extra luminal bleeding or abdominal abscess requiring drainage.22

Recent joint American/European Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guidelines suggest the use of EBMTs plus lifestyle modification in patients with a BMI of ≥ 30 kg/m2, or with a BMI of 27.0-29.9 kg/m2 with at least 1 obesity-related comorbidity.22 Small bowel interventions including duodenal-jejunal bypass liner and duodenal mucosal resurfacing are being investigated for patients with obesity and type 2 diabetes but not yet commercially available.

Conclusion

Given the overlap of obesity with many GI disorders, it is entirely appropriate for gastroenterologists to consider it worthy of aggressive treatment, particularly in patients with MAFLD and other serious weight related comorbidities. With a compassionate and empathetic approach, and a number of highly effective medical, endoscopic, and surgical therapies now available, weight management has the potential to be extremely rewarding when implemented in GI practice.

Dr. Kelly is based in the Department of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, Massachusetts. She serves on the clinical advisory board for OpenBiome (unpaid) and has served on an advisory board for Eli Lilly and Company.

References

1. Hales CM, et al. Prevalence of Obesity and Severe Obesity Among Adults: United States, 2017-2018. NCHS Data Brief 2020 Feb:(360):1–8.

2. Pais R, et al. NAFLD and liver transplantation: Current burden and expected challenges. J Hepatol. 2016 Dec. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.07.033.

3. Lauby-Secretan B, et al. Body Fatness and Cancer--Viewpoint of the IARC Working Group. N Engl J Med. 2016 Aug. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1606602.

4. Kim A. Dysbiosis: A Review Highlighting Obesity and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015 Nov-Dec. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000356.

5. Singh S, et al. Obesity in IBD: epidemiology, pathogenesis, disease course and treatment outcomes. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017 Feb. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.181.

6. Sundararaman L, Goudra B. Sedation for GI Endoscopy in the Morbidly Obese: Challenges and Possible Solutions. J Clin Med. 2024 Aug. doi: 10.3390/jcm13164635.

7. Bombassaro B, et al. The hypothalamus as the central regulator of energy balance and its impact on current and future obesity treatments. Arch Endocrinol Metab. 2024 Nov. doi: 10.20945/2359-4292-2024-0082.

8. Beccuti G, Pannain S. Sleep and obesity. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2011 Jul. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e3283479109.

9. Desalermos A, et al. Effect of Obesogenic Medications on Weight-Loss Outcomes in a Behavioral Weight-Management Program. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2019 May. doi: 10.1002/oby.22444.

10. Lord MN, Noble EE. Hypothalamic cannabinoid signaling: Consequences for eating behavior. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2024 Oct. doi: 10.1002/prp2.1251.

11. Farhana A, Rehman A. Metabolic Consequences of Weight Reduction. [Updated 2023 Jul 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK572145/.

12. Rubino F, et al. Definition and diagnostic criteria of clinical obesity. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2025 Mar. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(24)00316-4.

13. Cox CE. Role of Physical Activity for Weight Loss and Weight Maintenance. Diabetes Spectr. 2017 Aug. doi: 10.2337/ds17-0013.

14. Chaput JP, et al. Widespread misconceptions about obesity. Can Fam Physician. 2014 Nov. PMID: 25392431.

15. Muscogiuri G, et al. Mediterranean Diet and Obesity-related Disorders: What is the Evidence? Curr Obes Rep. 2022 Dec. doi: 10.1007/s13679-022-00481-1.

16. Gudzune KA, Kushner RF. Medications for Obesity: A Review. JAMA. 2024 Aug. doi: 10.1001/jama.2024.10816.

17. Wilding JPH, et al. Once-Weekly Semaglutide in Adults with Overweight or Obesity. N Engl J Med. 2021 Feb. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2032183.

18. Jastreboff AM, et al. Tirzepatide Once Weekly for the Treatment of Obesity. N Engl J Med. 2022 Jun. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2206038.

19. Chiang CH, et al. Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists and Gastrointestinal Adverse Events: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology. 2025 Nov. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2025.06.003.

20. Aderinto N, et al. Recent advances in bariatric surgery: a narrative review of weight loss procedures. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2023 Nov. doi: 10.1097/MS9.0000000000001472.

21. Chandan S, et al. Risk of De Novo Barrett’s Esophagus Post Sleeve Gastrectomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Studies With Long-Term Follow-Up. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025 Jan. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2024.06.041.

22. Jirapinyo P, et al. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy-European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guideline on primary endoscopic bariatric and metabolic therapies for adults with obesity. Gastrointest Endosc. 2024 Jun. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2023.12.004.

23. Nduma BN, et al. Endoscopic Gastric Sleeve: A Review of Literature. Cureus. 2023 Mar. doi: 10.7759/cureus.36353.

24. Abu Dayyeh BK, et al. Endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty for treatment of class 1 and 2 obesity (MERIT): a prospective, multicentre, randomised trial. Lancet. 2022 Aug. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01280-6.

25. Gala K, et al. Outcomes of concomitant antiobesity medication use with endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty in clinical US settings. Obes Pillars. 2024 May. doi: 10.1016/j.obpill.2024.100112.

26. Chung CS, et al. Endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty combined with anti-obesity medication for better control of weight and diabetes. Clin Endosc. 2025 May. doi: 10.5946/ce.2024.274.

Introduction

The majority of patients in the United States are now overweight or obese, and as gastroenterologists we treat a number of conditions that are caused or worsened by obesity.1 Cirrhosis related to metabolic associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) is now a leading indication for liver transplantation in the US2 and obesity is a clear risk factor for all major malignancies of the GI tract, including esophageal, gastric cardia, pancreatic, liver, gallbladder, colon, and rectum.3 Obesity is associated with dysbiosis and impacts barrier function: increasing permeability, abnormal gut bacterial translocation, and inflammation.4 It is more common than malnutrition in our patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), where it impacts response to biologic drugs, increases the technical difficulty of surgeries, such as IPAA, and is associated with worse surgical outcomes.5 Furthermore, patients with obesity may be less likely to undergo preventative cancer screenings and are at increased risk related to sedation for endoscopic procedures.6 With over 40% of Americans suffering from obesity, and increasingly effective treatments available,

Understanding the Mechanisms of Obesity

There are complex orexigenic and anorexigenic brain pathways in the hypothalamus which control global energy balance.7 Obesity results when energy intake exceeds energy expenditure. While overeating and a sedentary lifestyle are commonly blamed, there are a number of elements that contribute, including genetics, medical conditions, medications, psychosocial factors, and environmental components. For example, sleep loss contributes to weight gain by several mechanisms including increasing ghrelin and decreasing leptin levels, thereby increasing hunger and appetite, as well as by decreasing insulin sensitivity and increasing cortisol. Subjects exposed to sleep deprivation in research settings take in 550 kcal more the following day.8 Medications used commonly in GI practice including corticosteroids, antihistamines, propranolol, and amitriptyline, are obesogenic9 and cannabis can impact hypothalamic pathways to stimulate hunger.10

When patients diet or exercise to lose weight, as we have traditionally advised, there are strong hormonal changes and metabolic adaptations that occur to preserve the defended fat mass or “set point.” Loss of adipose tissue results in decreased production of leptin, a hormone that stimulates satiety pathways and inhibits orexigenic pathways, greatly increasing hunger and cravings. Increases in ghrelin production by the stomach decreases perceptions of fullness. With weight loss, energy requirements decrease, and muscles become more efficient, meaning fewer kcal are needed to maintain bodily processes.11 Eventually a plateau is reached, while motivation to diet and restraint around food wane, and hedonistic (reward) pathways are activated. These powerful factors result in the regain of lost weight within one year in the majority of patients.

Implementing Weight Management into GI Practice

Given the stigma and bias around obesity, patients often feel shame and vulnerability around the condition. It is important to have empathy in your approach, asking permission to discuss weight and using patient-first language (e.g. “patient with obesity” not “obese patient”). While BMI is predictive of health outcomes, it does not measure body fat percentage and may be misleading, such as in muscular individuals. Other measures of adiposity including waist circumference and body composition testing, such as with DEXA, may provide additional data. A BMI of 30 or above defines obesity, though newer definitions incorporate related symptoms, organ disfunction, and metabolic abnormalities into the term “clinical obesity.”12 Asian patients experience metabolic complications at a lower BMI, and therefore the definition of obese is 27.5kg/m2 in this population.

Begin by taking a weight history. Has this been a lifelong struggle or is there a particular life circumstance, such as working a third shift or recent pregnancy which precipitated weight gain? Patients should be asked about binge eating or eating late into the evening or waking at night to eat, as these disordered eating behaviors are managed with specific medications and behavioral therapies. Inquire about sleep duration and quality and refer for a sleep study if there is suspicion for obstructive sleep apnea. Other weight-related comorbidities including hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and MAFLD should be considered and merit a more aggressive approach, as does more severe obesity (class III, BMI ≥40). Questions about marijuana and alcohol use as well as review of the medication list for obesogenic medications can provide further insight into modifiable contributing factors.

Pillars of Weight Management

The internet is awash with trendy diet recommendations, and widespread misconceptions about obesity management are even ingrained into how physicians approach the disease. It is critical to remember that this is not a consequence of bad choices or lack of self-control. Exercise alone is insufficient to result in significant weight loss.13 Furthermore, whether it is through low fat, low carb, or intermittent fasting, weight loss will occur with calorie deficit.14 Evidence-based diet and lifestyle recommendations to lay the groundwork for success should be discussed at each visit (see Table 1). The Mediterranean diet is recommended for weight loss as well as for several GI disorders (i.e., MAFLD and IBD) and is the optimal eating strategy for cardiovascular health.15 Patients should be advised to engage in 150 minutes of moderate exercise per week, such as brisk walking, and should incorporate resistance training to build muscle and maintain bone density.

Anti-obesity Medications

There are a number of medications, either FDA approved or used off label, for treatment of obesity (see Table 2).16 All are indicated for patients with a BMI of ≥ 30 kg/m2 or for those with a BMI between 27-29 kg/m2 with weight-related comorbidities and should be used in combination with diet and lifestyle interventions. None are approved or safe in pregnancy. Mechanisms of action vary by type and include decreased appetite, increased energy expenditure, improved insulin sensitivity, and interfere with absorption.

The newest and most effective anti-obesity medications (AOM), the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RA) are derived from gut hormones secreted in the distal small bowel and colon in response to a meal, which function to delay gastric emptying, increase insulin release from the pancreas, and reduce hepatic gluconeogenesis. Central nervous system effects are not yet entirely understood, but function to decrease appetite and increase satiety. Initially developed for treatment of T2DM, observed weight reduction in patients treated with GLP-1 RA led to clinical trials for treatment of obesity. Semaglutide treatment resulted in weight reduction of 16.9% of total body weight (TBW), and one third of subjects lost ≥ 20% of TBW.17 Tirzepatide combines GLP-1 RA and a gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP) receptor agonist, which also has an incretin effect and functions to slow gastric emptying. In the pivotal SURMOUNT trial, approximately 58% of patients achieved ≥20% loss of TBW18 with 15mg weekly dosing of tirzepatide. This class of drugs is a logical choice in patients with T2DM and obesity. Long-term treatment appears necessary, as patients typically regain two-thirds of lost weight within a year after GLP-1 RA are stopped.

Based on tumors observed in rodents, GLP-1 RA are contraindicated in patients with a personal or family history of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 (MEN II) or medullary thyroid cancer. These tumors have not been observed in humans treated with GLP-1 RA. They should be used with caution in patients with history of pancreatitis, gastroparesis, or diabetic retinopathy, though a recent systematic review and meta-analysis suggests showed little to no increased risk for biliary events from GLP-1 RA.19 Side effects are most commonly gastrointestinal in nature (nausea, reflux, constipation or diarrhea) and are typically most severe with initiation of the drug and with dose escalation. Side effects can be mitigated by initiating these drugs at lowest doses and gradually titrating up (every four weeks) based on effectiveness and tolerability. Antisecretory, antiemetic, and laxative medications can also be used to help manage GLP-1 RA related side effects.

There is no reason to escalate to highest doses if patients are experiencing weight loss and reduction in food cravings at lower doses. Both semaglutide and tirzepatide are administered subcutaneously every seven days. Once patients have reached goal weight, they can either continue maintenance therapy at that same dose/interval, or if motivated to do so, may gradually reduce the weekly dose in a stepwise approach to determine the minimally effective dose to maintain weight loss. There are not yet published maintenance studies to guide this process. Currently the price of GLP-1 RA and inconsistent insurance coverage make them inaccessible to many patients. The manufacturers of both semaglutide and tirzepatide offer direct to consumer pricing and home delivery.

Bariatric Surgery

In patients with higher BMI (≥35kg/m2) or those with BMI ≥30kg/m2 and obesity-related metabolic disease and the desire to avoid lifelong medications or who fail or are intolerant of AOM, bariatric options should be considered.20 Sleeve gastrectomy has become the most performed surgery for treatment of obesity. It is a restrictive procedure, removing 80% of the stomach, but a drop in circulating levels of ghrelin afterwards also leads to decreased feelings of hunger. It results in weight loss of 25-30% TBW loss. It is not a good choice for patients who suffer from severe GERD, as this typically worsens afterwards; furthermore, de novo Barrett’s has been observed in nearly 6% of patients who undergo sleeve gastrectomy.21

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass is a restrictive and malabsorptive procedure, resulting in 30-35% TBW loss. It has beneficial and immediate metabolic effects, including increased release of endogenous GLP-1, which leads to improvements in weight-related T2DM. The newer single anastomosis duodenal-ileal bypass with sleeve gastrectomy (SADI-S) starts with a sleeve gastrectomy, making a smaller tube-shaped stomach. The duodenum is divided just after the stomach and then a loop of ileum is brought up and connected to the stomach (see Figure 1). This procedure is highly effective, with patients losing 75-95% of excess body weight and is becoming a preferred option for patients with greater BMI (≥50kg/m2). It is also an option for patients who have already had a sleeve gastrectomy and are seeking further weight loss. Because there is only one anastomosis, perioperative complications, such as anastomotic leaks, are reduced. The risk of micronutrient deficiencies is present with all malabsorptive procedures, and these patients must supplement with multivitamins, iron, vitamin D, and calcium.

Endoscopic Therapies

Endoscopic bariatric and metabolic therapies (EBMTs) have been increasingly studied and utilized, and this less invasive option may be more appropriate for or attractive to many patients. Intragastric balloons, which reduce meal volume and delay gastric emptying, can be used short term only (six months) resulting in loss of about 6.9% of total body weight (TBW) greater than lifestyle modification (LM) alone, and may be considered in limited situations, such as need for pre-operative weight loss to reduce risks in very obese individuals.22

Endoscopic gastric remodeling (EGR), also known as endoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (ESG), is a purely restrictive procedure in which the stomach is cinched to resize and reshape using an endoscopic suturing device (see Figure 2).23 It is an option for patients with class 1 or 2 obesity, with data from a randomized controlled trial in this population demonstrating mean percentage of TBW loss of 13.6% at 52 weeks compared to 0.8% in those treated with LM alone.24 A recent meta-analysis of 21 observational studies, including patients with higher BMIs (32.5 to 49.9 kg/m2) showed pooled average weight loss of 17.3% TBW at 12 months with EGR.22 This procedure has potential advantages of fewer complications, quicker recovery, and much less new-onset GERD compared to laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Furthermore, it may be utilized in combination with AOMs to achieve optimum weight loss and metabolic outcomes.25,26 Potential adverse events include abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting (which may be severe), as well as rare instances of intra/extra luminal bleeding or abdominal abscess requiring drainage.22

Recent joint American/European Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guidelines suggest the use of EBMTs plus lifestyle modification in patients with a BMI of ≥ 30 kg/m2, or with a BMI of 27.0-29.9 kg/m2 with at least 1 obesity-related comorbidity.22 Small bowel interventions including duodenal-jejunal bypass liner and duodenal mucosal resurfacing are being investigated for patients with obesity and type 2 diabetes but not yet commercially available.

Conclusion

Given the overlap of obesity with many GI disorders, it is entirely appropriate for gastroenterologists to consider it worthy of aggressive treatment, particularly in patients with MAFLD and other serious weight related comorbidities. With a compassionate and empathetic approach, and a number of highly effective medical, endoscopic, and surgical therapies now available, weight management has the potential to be extremely rewarding when implemented in GI practice.

Dr. Kelly is based in the Department of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, Massachusetts. She serves on the clinical advisory board for OpenBiome (unpaid) and has served on an advisory board for Eli Lilly and Company.

References

1. Hales CM, et al. Prevalence of Obesity and Severe Obesity Among Adults: United States, 2017-2018. NCHS Data Brief 2020 Feb:(360):1–8.

2. Pais R, et al. NAFLD and liver transplantation: Current burden and expected challenges. J Hepatol. 2016 Dec. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.07.033.

3. Lauby-Secretan B, et al. Body Fatness and Cancer--Viewpoint of the IARC Working Group. N Engl J Med. 2016 Aug. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1606602.

4. Kim A. Dysbiosis: A Review Highlighting Obesity and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015 Nov-Dec. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000356.

5. Singh S, et al. Obesity in IBD: epidemiology, pathogenesis, disease course and treatment outcomes. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017 Feb. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.181.

6. Sundararaman L, Goudra B. Sedation for GI Endoscopy in the Morbidly Obese: Challenges and Possible Solutions. J Clin Med. 2024 Aug. doi: 10.3390/jcm13164635.

7. Bombassaro B, et al. The hypothalamus as the central regulator of energy balance and its impact on current and future obesity treatments. Arch Endocrinol Metab. 2024 Nov. doi: 10.20945/2359-4292-2024-0082.

8. Beccuti G, Pannain S. Sleep and obesity. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2011 Jul. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e3283479109.

9. Desalermos A, et al. Effect of Obesogenic Medications on Weight-Loss Outcomes in a Behavioral Weight-Management Program. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2019 May. doi: 10.1002/oby.22444.

10. Lord MN, Noble EE. Hypothalamic cannabinoid signaling: Consequences for eating behavior. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2024 Oct. doi: 10.1002/prp2.1251.

11. Farhana A, Rehman A. Metabolic Consequences of Weight Reduction. [Updated 2023 Jul 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK572145/.

12. Rubino F, et al. Definition and diagnostic criteria of clinical obesity. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2025 Mar. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(24)00316-4.

13. Cox CE. Role of Physical Activity for Weight Loss and Weight Maintenance. Diabetes Spectr. 2017 Aug. doi: 10.2337/ds17-0013.

14. Chaput JP, et al. Widespread misconceptions about obesity. Can Fam Physician. 2014 Nov. PMID: 25392431.

15. Muscogiuri G, et al. Mediterranean Diet and Obesity-related Disorders: What is the Evidence? Curr Obes Rep. 2022 Dec. doi: 10.1007/s13679-022-00481-1.

16. Gudzune KA, Kushner RF. Medications for Obesity: A Review. JAMA. 2024 Aug. doi: 10.1001/jama.2024.10816.

17. Wilding JPH, et al. Once-Weekly Semaglutide in Adults with Overweight or Obesity. N Engl J Med. 2021 Feb. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2032183.

18. Jastreboff AM, et al. Tirzepatide Once Weekly for the Treatment of Obesity. N Engl J Med. 2022 Jun. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2206038.

19. Chiang CH, et al. Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists and Gastrointestinal Adverse Events: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology. 2025 Nov. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2025.06.003.

20. Aderinto N, et al. Recent advances in bariatric surgery: a narrative review of weight loss procedures. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2023 Nov. doi: 10.1097/MS9.0000000000001472.

21. Chandan S, et al. Risk of De Novo Barrett’s Esophagus Post Sleeve Gastrectomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Studies With Long-Term Follow-Up. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025 Jan. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2024.06.041.

22. Jirapinyo P, et al. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy-European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guideline on primary endoscopic bariatric and metabolic therapies for adults with obesity. Gastrointest Endosc. 2024 Jun. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2023.12.004.

23. Nduma BN, et al. Endoscopic Gastric Sleeve: A Review of Literature. Cureus. 2023 Mar. doi: 10.7759/cureus.36353.

24. Abu Dayyeh BK, et al. Endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty for treatment of class 1 and 2 obesity (MERIT): a prospective, multicentre, randomised trial. Lancet. 2022 Aug. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01280-6.

25. Gala K, et al. Outcomes of concomitant antiobesity medication use with endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty in clinical US settings. Obes Pillars. 2024 May. doi: 10.1016/j.obpill.2024.100112.

26. Chung CS, et al. Endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty combined with anti-obesity medication for better control of weight and diabetes. Clin Endosc. 2025 May. doi: 10.5946/ce.2024.274.

Introduction

The majority of patients in the United States are now overweight or obese, and as gastroenterologists we treat a number of conditions that are caused or worsened by obesity.1 Cirrhosis related to metabolic associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) is now a leading indication for liver transplantation in the US2 and obesity is a clear risk factor for all major malignancies of the GI tract, including esophageal, gastric cardia, pancreatic, liver, gallbladder, colon, and rectum.3 Obesity is associated with dysbiosis and impacts barrier function: increasing permeability, abnormal gut bacterial translocation, and inflammation.4 It is more common than malnutrition in our patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), where it impacts response to biologic drugs, increases the technical difficulty of surgeries, such as IPAA, and is associated with worse surgical outcomes.5 Furthermore, patients with obesity may be less likely to undergo preventative cancer screenings and are at increased risk related to sedation for endoscopic procedures.6 With over 40% of Americans suffering from obesity, and increasingly effective treatments available,

Understanding the Mechanisms of Obesity

There are complex orexigenic and anorexigenic brain pathways in the hypothalamus which control global energy balance.7 Obesity results when energy intake exceeds energy expenditure. While overeating and a sedentary lifestyle are commonly blamed, there are a number of elements that contribute, including genetics, medical conditions, medications, psychosocial factors, and environmental components. For example, sleep loss contributes to weight gain by several mechanisms including increasing ghrelin and decreasing leptin levels, thereby increasing hunger and appetite, as well as by decreasing insulin sensitivity and increasing cortisol. Subjects exposed to sleep deprivation in research settings take in 550 kcal more the following day.8 Medications used commonly in GI practice including corticosteroids, antihistamines, propranolol, and amitriptyline, are obesogenic9 and cannabis can impact hypothalamic pathways to stimulate hunger.10

When patients diet or exercise to lose weight, as we have traditionally advised, there are strong hormonal changes and metabolic adaptations that occur to preserve the defended fat mass or “set point.” Loss of adipose tissue results in decreased production of leptin, a hormone that stimulates satiety pathways and inhibits orexigenic pathways, greatly increasing hunger and cravings. Increases in ghrelin production by the stomach decreases perceptions of fullness. With weight loss, energy requirements decrease, and muscles become more efficient, meaning fewer kcal are needed to maintain bodily processes.11 Eventually a plateau is reached, while motivation to diet and restraint around food wane, and hedonistic (reward) pathways are activated. These powerful factors result in the regain of lost weight within one year in the majority of patients.

Implementing Weight Management into GI Practice

Given the stigma and bias around obesity, patients often feel shame and vulnerability around the condition. It is important to have empathy in your approach, asking permission to discuss weight and using patient-first language (e.g. “patient with obesity” not “obese patient”). While BMI is predictive of health outcomes, it does not measure body fat percentage and may be misleading, such as in muscular individuals. Other measures of adiposity including waist circumference and body composition testing, such as with DEXA, may provide additional data. A BMI of 30 or above defines obesity, though newer definitions incorporate related symptoms, organ disfunction, and metabolic abnormalities into the term “clinical obesity.”12 Asian patients experience metabolic complications at a lower BMI, and therefore the definition of obese is 27.5kg/m2 in this population.

Begin by taking a weight history. Has this been a lifelong struggle or is there a particular life circumstance, such as working a third shift or recent pregnancy which precipitated weight gain? Patients should be asked about binge eating or eating late into the evening or waking at night to eat, as these disordered eating behaviors are managed with specific medications and behavioral therapies. Inquire about sleep duration and quality and refer for a sleep study if there is suspicion for obstructive sleep apnea. Other weight-related comorbidities including hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and MAFLD should be considered and merit a more aggressive approach, as does more severe obesity (class III, BMI ≥40). Questions about marijuana and alcohol use as well as review of the medication list for obesogenic medications can provide further insight into modifiable contributing factors.

Pillars of Weight Management

The internet is awash with trendy diet recommendations, and widespread misconceptions about obesity management are even ingrained into how physicians approach the disease. It is critical to remember that this is not a consequence of bad choices or lack of self-control. Exercise alone is insufficient to result in significant weight loss.13 Furthermore, whether it is through low fat, low carb, or intermittent fasting, weight loss will occur with calorie deficit.14 Evidence-based diet and lifestyle recommendations to lay the groundwork for success should be discussed at each visit (see Table 1). The Mediterranean diet is recommended for weight loss as well as for several GI disorders (i.e., MAFLD and IBD) and is the optimal eating strategy for cardiovascular health.15 Patients should be advised to engage in 150 minutes of moderate exercise per week, such as brisk walking, and should incorporate resistance training to build muscle and maintain bone density.

Anti-obesity Medications

There are a number of medications, either FDA approved or used off label, for treatment of obesity (see Table 2).16 All are indicated for patients with a BMI of ≥ 30 kg/m2 or for those with a BMI between 27-29 kg/m2 with weight-related comorbidities and should be used in combination with diet and lifestyle interventions. None are approved or safe in pregnancy. Mechanisms of action vary by type and include decreased appetite, increased energy expenditure, improved insulin sensitivity, and interfere with absorption.

The newest and most effective anti-obesity medications (AOM), the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RA) are derived from gut hormones secreted in the distal small bowel and colon in response to a meal, which function to delay gastric emptying, increase insulin release from the pancreas, and reduce hepatic gluconeogenesis. Central nervous system effects are not yet entirely understood, but function to decrease appetite and increase satiety. Initially developed for treatment of T2DM, observed weight reduction in patients treated with GLP-1 RA led to clinical trials for treatment of obesity. Semaglutide treatment resulted in weight reduction of 16.9% of total body weight (TBW), and one third of subjects lost ≥ 20% of TBW.17 Tirzepatide combines GLP-1 RA and a gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP) receptor agonist, which also has an incretin effect and functions to slow gastric emptying. In the pivotal SURMOUNT trial, approximately 58% of patients achieved ≥20% loss of TBW18 with 15mg weekly dosing of tirzepatide. This class of drugs is a logical choice in patients with T2DM and obesity. Long-term treatment appears necessary, as patients typically regain two-thirds of lost weight within a year after GLP-1 RA are stopped.

Based on tumors observed in rodents, GLP-1 RA are contraindicated in patients with a personal or family history of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 (MEN II) or medullary thyroid cancer. These tumors have not been observed in humans treated with GLP-1 RA. They should be used with caution in patients with history of pancreatitis, gastroparesis, or diabetic retinopathy, though a recent systematic review and meta-analysis suggests showed little to no increased risk for biliary events from GLP-1 RA.19 Side effects are most commonly gastrointestinal in nature (nausea, reflux, constipation or diarrhea) and are typically most severe with initiation of the drug and with dose escalation. Side effects can be mitigated by initiating these drugs at lowest doses and gradually titrating up (every four weeks) based on effectiveness and tolerability. Antisecretory, antiemetic, and laxative medications can also be used to help manage GLP-1 RA related side effects.

There is no reason to escalate to highest doses if patients are experiencing weight loss and reduction in food cravings at lower doses. Both semaglutide and tirzepatide are administered subcutaneously every seven days. Once patients have reached goal weight, they can either continue maintenance therapy at that same dose/interval, or if motivated to do so, may gradually reduce the weekly dose in a stepwise approach to determine the minimally effective dose to maintain weight loss. There are not yet published maintenance studies to guide this process. Currently the price of GLP-1 RA and inconsistent insurance coverage make them inaccessible to many patients. The manufacturers of both semaglutide and tirzepatide offer direct to consumer pricing and home delivery.

Bariatric Surgery

In patients with higher BMI (≥35kg/m2) or those with BMI ≥30kg/m2 and obesity-related metabolic disease and the desire to avoid lifelong medications or who fail or are intolerant of AOM, bariatric options should be considered.20 Sleeve gastrectomy has become the most performed surgery for treatment of obesity. It is a restrictive procedure, removing 80% of the stomach, but a drop in circulating levels of ghrelin afterwards also leads to decreased feelings of hunger. It results in weight loss of 25-30% TBW loss. It is not a good choice for patients who suffer from severe GERD, as this typically worsens afterwards; furthermore, de novo Barrett’s has been observed in nearly 6% of patients who undergo sleeve gastrectomy.21