User login

Dust in the Wind

A 52-year-old woman presented with a 4-day history of progressive dyspnea, nonproductive cough, pleuritic chest pain, and subjective fevers. She described dyspnea at rest, which worsened with exertion. She reported no chills, night sweats, weight change, wheezing, hemoptysis, orthopnea, lower extremity edema, or nasal congestion. She also denied myalgia, arthralgia, or joint swelling. She reported no rash, itching, or peripheral lymphadenopathy. She had no seasonal allergies. She was treated for presumed bronchitis with azithromycin by her primary care provider 4 days prior to presentation but experienced progressive dyspnea.

The constellation of dry cough, fever, and dyspnea is often infectious in origin, with the nonproductive, dry cough more suggestive of a viral than bacterial syndrome. Atypical organisms such as Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Legionella pneumophila, and Chlamydia pneumoniae may also present with these symptoms. Noninfectious etiologies should also be considered, including pulmonary embolism, systemic lupus erythematosus, asbestosis, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, sarcoidosis, and lung cancer. The dyspnea at rest stands out as a worrisome feature, as it implies hypoxia; therefore, an oxygen saturation is necessary to quickly determine her peripheral oxygen saturation.

Her past medical history was notable for lung adenocarcinoma, for which she had undergone right upper lobectomy, without chemotherapy or radiation, 13 years ago without recurrence. She had no history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, or pneumonia, nor a family history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, pneumonia, or lung cancer. Her only medication was azithromycin. She drank alcohol on occasion and denied illicit drug use. Three weeks prior to admission, she began smoking 4 to 5 cigarettes per day after 13 years of abstinence. Her smoking history prior to abstinence was 1 pack per day for 20 years. She worked as a department store remodeler; she had no exposure to asbestos, mold, or water-damaged wood. She reported no recent travel, sick contacts, or exposure to animals.

A primary lung neoplasm with a pleural effusion could cause her shortness of breath and pleuritic chest pain. Her history of lung cancer at age 39 raises the possibility of recurrence. For cigarette smokers, a second lung cancer may occur many years after the first diagnosis and treatment, even if they have quit smoking. A review of her original cancer records is essential to confirm the diagnosis of pulmonary adenocarcinoma. What is now being described as pulmonary adenocarcinoma may have been a metastatic lesion arising from outside the lung. Although unlikely, a primary adenocarcinoma may remain active.

Infectious etiologies continue to merit consideration. A parapneumonic effusion from a pneumonia or an empyema are consistent with her symptoms. Systemic lupus erythematosus can cause lung disease with pleural effusions. She does exhibit dyspnea and pleurisy, which are consistent with autoimmune disease, but does not exhibit some of the more typical autoimmune symptoms such as arthralgias, joint swelling, and rash. Pneumothorax could also produce her symptoms; however, pneumothorax usually occurs spontaneously in younger patients or after trauma or a procedure. Remote right upper lobectomy would not be a cause of pneumothorax now. Her reported history makes lung disease or pneumoconiosis due to occupational exposure to mold or aspergillosis a possibility. Legionellosis, histoplasmosis, or coccidioidomycosis should be considered if she lives in or has visited a high-risk area. Pulmonary embolism remains a concern for all patients with new-onset shortness of breath. Decision support tools, such as the Wells criteria, are valuable, but the gestalt of the physician does not lag far behind in accuracy.

Cardiac disease is also in the differential. Bibasilar crackles, third heart sound gallop, and jugular vein distension would suggest heart failure. A pericardial friction rub would be highly suggestive of pericarditis. A paradoxical pulse would raise concern for pericardial tamponade. Pleurisy may be associated with a pericardial effusion, making viral pericarditis and myocarditis possibilities.

She was in moderate distress with tachypnea and increased work of breathing. Her temperature was 36.7°C, heart rate 104 beats per minute, respiratory rate 24 breaths per minute, oxygen saturation was 88% on room air, 94% on 3 liters of oxygen, and blood pressure was 147/61 mmHg. Auscultation of the lungs revealed bibasilar crackles and decreased breath sounds at the bases. She was tachycardic, with a regular rhythm and no appreciable murmurs, rubs, or gallops. There was no jugular venous distention or lower extremity edema. Her thyroid was palpable, without appreciation of nodules. Skin and musculoskeletal examinations were normal.

Unless she is immunocompromised, infection has become lower in the differential, as she is afebrile. Decreased breath sounds at the bases and bibasilar crackles may be due to pleural effusions. Congestive heart failure is a possibility, especially given her dyspnea and bibasilar crackles. Volume overload from renal failure is possible, but she does not have other signs of volume overload such as lower extremity edema or jugular venous distension. It is important to note that crackles may be due to other etiologies, including atelectasis, fibrosis, or pneumonia. Pulmonary embolism may cause hypoxia, tachycardia, and pleural effusions. Additional diseases may present similarly, including human immunodeficiency virus with Pneumocystis jirovecii, causing dyspnea, tachypnea, and tachycardia; hematologic malignancy with anemia, causing dyspnea and tachycardia; and thyrotoxic states with thyromegaly, causing dyspnea and tachycardia. Thyroid storm patients appear in distress, are tachycardic, and may have thyromegaly.

Moderate distress, increased work of breathing, tachycardia, tachypnea, and hypoxia are all worrisome signs. Her temperature is subnormal, although this may not be accurate, as oral temperatures may register lower in patients with increased respiratory rates because of increased air flow across the thermometer. Bibasilar crackles with decreased bibasilar sounds require further investigation. A complete blood count, complete metabolic profile, troponin, arterial blood gas (ABG), electrocardiogram (ECG), and chest radiograph are warranted.

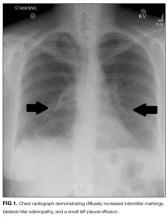

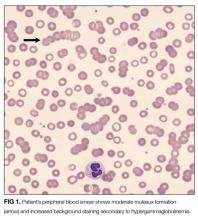

Laboratory studies revealed a white blood cell count of 8600 per mm3 with 11% bands and 7.3% eosinophils, and a hemoglobin count of 15 gm/dL. Basic metabolic panel, liver function tests, coagulation panel, and urinalysis were within normal limits, including serum creatinine 0.7 mg/dL, sodium 143 mmoL/L, chloride 104 mmoL/L, bicarbonate 30 mEq/L, anion gap 9 mmoL/L, and blood urea nitrogen 12 mg/dL. Chest radiograph disclosed diffusely increased interstitial markings and a small left pleural effusion (Figure 1).

Her bandemia suggests infection. Stress can cause a leukocytosis by demargination of mature white blood cells; however, stress does not often cause immature cells such as bands to appear. Her chest radiograph with diffuse interstitial markings is consistent with a community-acquired pneumonia. Empiric antibiotic therapy should be initiated because of the possibility of community-acquired pneumonia. Recent studies demonstrate that steroids decrease mortality, the need for mechanical ventilation, and the length of stay for patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia; therefore, this patient should also be treated with steroids.

Eosinophilia may be seen in drug reactions, allergies, pulmonary emboli, pleural effusions, and occasionally in malignancy. Eosinophilic pneumonia typically has the “reverse pulmonary edema” picture, with infiltrates in the periphery and not centrally, as in congestive heart failure.

A serum bicarbonate of 30 mEq/L suggests a metabolic compensation for a chronic respiratory acidosis as renal compensation, and rise in bicarbonate generally takes 3 days. She may have been hypoxic longer than her symptoms suggest.

An ABG should be ordered to determine the degree of hypoxia and whether a higher level of care is indicated. The abnormal chest radiograph, along with her hypoxia, merits a closer look at her lung parenchyma with chest computed tomography (CT). A D-dimer would be beneficial to rule out pulmonary embolism. If the D-dimer is positive, chest CT with contrast is indicated to determine if a pulmonary embolism is present. A brain natriuretic peptide would assist in the diagnosis of congestive heart failure. A sputum culture and Gram stain and respiratory viral panel may establish a pathogen for pneumonia. An ECG and troponin to rule out myocardial infarction should be performed as well.

The presence of hilar and subcarinal lymph nodes expands the differential. Stage IV pulmonary sarcoid may present with diffuse infiltrates and nodes, although the acuity in this case makes it less likely. A very aggressive malignancy such as Burkitt lymphoma may have these findings. Acute viral and atypical pneumonias remain possible. Right middle lobe syndrome may cause partial collapse of the right middle lobe. Tuberculosis can be associated with right middle lobe syndrome; however, in this day and age an obstructing mass is more likely the cause. Pulmonary disease, such as cryptogenic organizing pneumonia, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, and interstitial lung disease, should be considered in patients with pneumonia unresponsive to antibiotics. Lung biopsy and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) would help make the diagnosis and should be the next step, unless her degree of hypoxia is prohibitive. Similarly, thoracentesis with analysis of the pleural fluid for cell count, Gram stain, and culture may help make the diagnosis. Thoracentesis should be done with fluoroscopic guidance, given the risk of pneumothorax, which would further compromise her tenuous respiratory status.

Thoracentesis was attempted, but the pleural effusion was too small to provide a sample. Subsequent serum blood counts with differential showed an increased eosinophilia to 20% and resolved bandemia. Upon further questioning, she recalled several months of extensive, daily, fine-dust exposure from demolition during the remodeling of a new building.

Hypereosinophilia and pulmonary infiltrates narrow the differential considerably to include asthma; parasitic infection, such as the pulmonary phase of ascariasis; exposure, such as to dust, cigarettes, or asbestosis; or hypereosinophilic syndromes characterized by peripheral eosinophilia, along with a tissue eosinophilia, causing organ dysfunction. Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome, a hypereosinophilic syndrome of unknown etiology despite extensive diagnostic testing, is rare, and eosinophilic leukemia even rarer. Her history strongly suggests exposure. Many eosinophilic diseases respond rapidly to steroids, and response to treatment would help narrow the diagnosis. If she does not respond to steroids, a lung and/or bone marrow biopsy would be the next step.

A BAL of the right middle lobe revealed 51% eosinophils, 3% neutrophils, 15% macrophages, and 28% lymphocytes. Gram stain, as well as cultures for bacteria, acid fast bacilli, fungus, herpes simplex virus, and cytomegalovirus cultures, were negative. Transbronchial lung biopsy revealed focal interstitial fibrosis and inflammation, without evidence of infection.

Eosinophils are primarily located in tissues; therefore, peripheral blood eosinophil counts often underestimate the degree of infiltration into end organs such as the lung. With 50% eosinophils, her BAL reflects this. Mold, fungus, chemical, and particle exposure could produce an eosinophilic BAL. She does not appear to be at risk for parasitic exposure. Eosinophilic granulomatosis (previously known as Churg-Strauss) is a consideration, but the lack of signs of vasculitis and wheezing make this less likely. A negative antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody may provide reassurance. “Fine dust exposure” is consistent with environmental exposure but not a specific antigen. Steroids provide a brisk eosinophil reduction and are appropriate for this patient. There is the possibility of missing infectious or parasitic etiologies; therefore, a culture of BAL fluid should be sent.

Eosinophilic infiltration may lead to fibrosis, as was found on the lung biopsy. She should be counseled to avoid “fine dust exposure” in the future. Follow-up lung imaging and pulmonary function tests (PFTs) should be performed once her acute illness resolves. She should be strongly urged not to smoke tobacco. Interestingly, there are reports that ex-smokers who restart smoking have an increased risk of eosinophilic pneumonia, but in this case dust exposure is the more likely etiology.

She was diagnosed with acute eosinophilic pneumonia (AEP). Antibiotics were discontinued, and oral prednisone was initiated at 40 mg daily, with a brisk response and resolution of her dyspnea. She was discharged with a 6-week prednisone taper. She had no cough, dyspnea, chest pain, or fevers at her follow-up 14 days after discharge. On a 6-week, postdischarge phone call, she continued to report no symptoms, and she maintained abstinence from cigarette smoking.

This case highlights that the very best test in any medical situation is a thorough, detailed history and physical examination. A comprehensive history with physical examination is noninvasive, safe, and cheap. Had the history of fine-dust exposure been known, it is likely that a great deal of testing and money would have been saved. The patient would have been diagnosed and treated earlier, and suffered less.

COMMENTARY

First described in 1989,1,2 AEP is an uncommon cause of acute respiratory failure. Cases have been reported throughout the world, including in the United States, Belgium, Japan, and Iraq.2,3 AEP is an acute febrile illness with cough, chest pain, and dyspnea for fewer than 7 days, diffuse pulmonary infiltrates on chest radiograph, hypoxemia, no history of asthma or atopic disease, no infection, and greater than 25% eosinophils on a BAL.1,3 Physical examination typically reveals fever, tachypnea, and crackles on auscultation.1 Peripheral blood eosinophilia is inconsistently seen at presentation but generally observed as the disease progresses.1 Peripheral eosinophilia at presentation is positively correlated with a milder course of AEP, including higher oxygen saturation and fewer intensive care admissions.4 Acute respiratory failure in AEP progresses rapidly, often within hours.1 Delayed recognition of AEP may lead to respiratory failure, requiring intubation, and even to death.1

Reticular markings with Kerley-B lines, mixed reticular and alveolar infiltrates, and pleural effusions are usually found on chest radiography.1 Bilateral areas of ground-glass attenuation, interlobular septal thickening, bronchovascular bundle thickening, and pleural effusions are seen on chest CT.5 Marked eosinophilic infiltration of the interstitium and alveolar spaces, as well as diffuse alveolar damage with hyaline membrane fibroblast proliferation and inflammatory cells, are present on lung biopsy.1 Restriction with impaired diffusion capacity is found on PFTs. However, PFTs return to normal after recovery.1

AEP is distinguished from other pulmonary diseases by BAL, lung biopsy, symptoms, symptom course, and/or radiographically. AEP is often misdiagnosed as severe community-acquired pneumonia and/or acute respiratory distress syndrome, as AEP tends to occur in previously healthy individuals who have diffuse infiltrates on chest radiograph, fevers, and acute, often severe, respiratory symptoms.1-3 Other eosinophilic lung diseases to rule out include simple pulmonary eosinophilia, chronic eosinophilic pneumonia, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangitis (Churg-Strauss), idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome, infection, and drug reactions.1,3,5 Simple eosinophilic pneumonia is characterized by no symptoms or very mild pulmonary symptoms and transient patchy infiltrates on radiography.3,5 Patients with simple pulmonary eosinophilia do not have interlobular septal thickening, thickening of the bronchovascular bundles, or pleural effusions radiographically, as seen with AEP.5 Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia is subacute, with respiratory symptoms of more than 3 months in duration, in contrast with the 7 days of respiratory symptoms for AEP, and is also not associated with interlobular septal thickening, thickening of the bronchovascular bundles, or pleural effusions on radiography.3,5 Unlike AEP, chronic eosinophilic pneumonia often recurs after the course of steroids has ended.3 In contrast with AEP, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangitis is associated with concomitant asthma and the involvement of nonpulmonary organs.3 Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome is characterized by extremely high peripheral eosinophilia and by eosinophilic involvement of multiple organs, and it requires chronic steroid use.3 Patients with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA), in contrast with AEP, typically have steroid-dependent asthma and chronic respiratory symptoms.3 ABPA also differs from AEP in that radiographic infiltrates are localized and transient, and the syndrome may relapse after steroid treatment.3 Other infectious etiologies that may present similarly to AEP include invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, pulmonary coccidiodomycosis, Pneumocystis jioveri pneumonia, pulmonary toxocariasis, pulmonary filariasis, paragonimiasis, and Loeffler syndrome (pneumonia due to Strongyloides, Ascaris, or hookworms), highlighting the importance of a thorough travel and exposure history.1,3 Several drugs may cause eosinophilic lung disease, including nitrofurantoin, tetracyclines, phenytoin, L-tryptophan, acetaminophen, ampicillin, heroin, and cocaine, which necessitates a thorough review of medication and illegal drug use.3

Steroids and supportive care are the treatment of choice for AEP, although spontaneous resolution has been seen.1,3 Significant clinical improvement occurs within 24 to 48 hours of steroid initiation.1,3 Optimal dose and duration of therapy have not been determined; however, methylprednisolone 125 mg intravenously every 6 hours until improvement is an often-used option.1 Tapers vary from 2 to 12 weeks with no difference in outcome.1-3 AEP does not recur after appropriate treatment with steroids.1,3

Little is known about the etiology of AEP. It usually occurs in young, healthy individuals and is presumed to be an unusual, acute hypersensitivity reaction to an inhaled allergen.1 A report of 18 US soldiers deployed in or near Iraq proposed dust exposure and cigarette or cigar smoking as a cause of AEP.2 Similar to our patient’s fine-dust exposure and recent onset of cigarette smoking, the soldiers were exposed to the dusty, arid environment for at least 1 day and had been smoking for at least 1 month.2 The authors proposed that small dust particles irritate alveoli, stimulating eosinophils, which are exacerbated by the onset of smoking. Alternatively, cigarette smoke may prime the lung such that dust triggers an inflammatory cascade, resulting in AEP.

TEACHING POINTS

- With the potential for the rapid progression of respiratory failure, it is imperative that the diagnosis of AEP be considered for a patient with diffuse infiltrates on a chest radiograph and acute respiratory failure of unknown cause.

- A thorough history of exposure is key to including AEP in the differential of acute pulmonary disease, with recent-onset cigarette smoking and dust exposure.

- The rapid initiation of steroids leads to a full recovery without recurrence and may be life-saving in AEP.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

1. Allen J. Acute eosinophilic pneumonia. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;27:142-147. PubMed

2. Shorr AF, Scoville SL, Cersovsky SB, et al. Acute eosinophilic pneumonia among US military personnel deployed in or near Iraq. JAMA. 2004;292:2997-3005. PubMed

3. Pope-Harman AL, Davis WB, Allen ED, Christoforidis AJ, Allen JN. Acute eosinophilic pneumonia. A summary of 15 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1996;75(6):334-342. PubMed

4. Jhun BW, Kim SJ, Kim K, Lee JE. Clinical implications of initial peripheral eosinophilia in acute eosinophilic pneumonia. Respirology. 2014;19:1059-1065. PubMed

5. Daimon T, Johkoh T, Sumikawa H, et al. Acute eosinophilic pneumonia: Thin-section CT findings in 29 patients. Eur J Radiol. 2008;65:462-467. PubMed

A 52-year-old woman presented with a 4-day history of progressive dyspnea, nonproductive cough, pleuritic chest pain, and subjective fevers. She described dyspnea at rest, which worsened with exertion. She reported no chills, night sweats, weight change, wheezing, hemoptysis, orthopnea, lower extremity edema, or nasal congestion. She also denied myalgia, arthralgia, or joint swelling. She reported no rash, itching, or peripheral lymphadenopathy. She had no seasonal allergies. She was treated for presumed bronchitis with azithromycin by her primary care provider 4 days prior to presentation but experienced progressive dyspnea.

The constellation of dry cough, fever, and dyspnea is often infectious in origin, with the nonproductive, dry cough more suggestive of a viral than bacterial syndrome. Atypical organisms such as Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Legionella pneumophila, and Chlamydia pneumoniae may also present with these symptoms. Noninfectious etiologies should also be considered, including pulmonary embolism, systemic lupus erythematosus, asbestosis, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, sarcoidosis, and lung cancer. The dyspnea at rest stands out as a worrisome feature, as it implies hypoxia; therefore, an oxygen saturation is necessary to quickly determine her peripheral oxygen saturation.

Her past medical history was notable for lung adenocarcinoma, for which she had undergone right upper lobectomy, without chemotherapy or radiation, 13 years ago without recurrence. She had no history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, or pneumonia, nor a family history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, pneumonia, or lung cancer. Her only medication was azithromycin. She drank alcohol on occasion and denied illicit drug use. Three weeks prior to admission, she began smoking 4 to 5 cigarettes per day after 13 years of abstinence. Her smoking history prior to abstinence was 1 pack per day for 20 years. She worked as a department store remodeler; she had no exposure to asbestos, mold, or water-damaged wood. She reported no recent travel, sick contacts, or exposure to animals.

A primary lung neoplasm with a pleural effusion could cause her shortness of breath and pleuritic chest pain. Her history of lung cancer at age 39 raises the possibility of recurrence. For cigarette smokers, a second lung cancer may occur many years after the first diagnosis and treatment, even if they have quit smoking. A review of her original cancer records is essential to confirm the diagnosis of pulmonary adenocarcinoma. What is now being described as pulmonary adenocarcinoma may have been a metastatic lesion arising from outside the lung. Although unlikely, a primary adenocarcinoma may remain active.

Infectious etiologies continue to merit consideration. A parapneumonic effusion from a pneumonia or an empyema are consistent with her symptoms. Systemic lupus erythematosus can cause lung disease with pleural effusions. She does exhibit dyspnea and pleurisy, which are consistent with autoimmune disease, but does not exhibit some of the more typical autoimmune symptoms such as arthralgias, joint swelling, and rash. Pneumothorax could also produce her symptoms; however, pneumothorax usually occurs spontaneously in younger patients or after trauma or a procedure. Remote right upper lobectomy would not be a cause of pneumothorax now. Her reported history makes lung disease or pneumoconiosis due to occupational exposure to mold or aspergillosis a possibility. Legionellosis, histoplasmosis, or coccidioidomycosis should be considered if she lives in or has visited a high-risk area. Pulmonary embolism remains a concern for all patients with new-onset shortness of breath. Decision support tools, such as the Wells criteria, are valuable, but the gestalt of the physician does not lag far behind in accuracy.

Cardiac disease is also in the differential. Bibasilar crackles, third heart sound gallop, and jugular vein distension would suggest heart failure. A pericardial friction rub would be highly suggestive of pericarditis. A paradoxical pulse would raise concern for pericardial tamponade. Pleurisy may be associated with a pericardial effusion, making viral pericarditis and myocarditis possibilities.

She was in moderate distress with tachypnea and increased work of breathing. Her temperature was 36.7°C, heart rate 104 beats per minute, respiratory rate 24 breaths per minute, oxygen saturation was 88% on room air, 94% on 3 liters of oxygen, and blood pressure was 147/61 mmHg. Auscultation of the lungs revealed bibasilar crackles and decreased breath sounds at the bases. She was tachycardic, with a regular rhythm and no appreciable murmurs, rubs, or gallops. There was no jugular venous distention or lower extremity edema. Her thyroid was palpable, without appreciation of nodules. Skin and musculoskeletal examinations were normal.

Unless she is immunocompromised, infection has become lower in the differential, as she is afebrile. Decreased breath sounds at the bases and bibasilar crackles may be due to pleural effusions. Congestive heart failure is a possibility, especially given her dyspnea and bibasilar crackles. Volume overload from renal failure is possible, but she does not have other signs of volume overload such as lower extremity edema or jugular venous distension. It is important to note that crackles may be due to other etiologies, including atelectasis, fibrosis, or pneumonia. Pulmonary embolism may cause hypoxia, tachycardia, and pleural effusions. Additional diseases may present similarly, including human immunodeficiency virus with Pneumocystis jirovecii, causing dyspnea, tachypnea, and tachycardia; hematologic malignancy with anemia, causing dyspnea and tachycardia; and thyrotoxic states with thyromegaly, causing dyspnea and tachycardia. Thyroid storm patients appear in distress, are tachycardic, and may have thyromegaly.

Moderate distress, increased work of breathing, tachycardia, tachypnea, and hypoxia are all worrisome signs. Her temperature is subnormal, although this may not be accurate, as oral temperatures may register lower in patients with increased respiratory rates because of increased air flow across the thermometer. Bibasilar crackles with decreased bibasilar sounds require further investigation. A complete blood count, complete metabolic profile, troponin, arterial blood gas (ABG), electrocardiogram (ECG), and chest radiograph are warranted.

Laboratory studies revealed a white blood cell count of 8600 per mm3 with 11% bands and 7.3% eosinophils, and a hemoglobin count of 15 gm/dL. Basic metabolic panel, liver function tests, coagulation panel, and urinalysis were within normal limits, including serum creatinine 0.7 mg/dL, sodium 143 mmoL/L, chloride 104 mmoL/L, bicarbonate 30 mEq/L, anion gap 9 mmoL/L, and blood urea nitrogen 12 mg/dL. Chest radiograph disclosed diffusely increased interstitial markings and a small left pleural effusion (Figure 1).

Her bandemia suggests infection. Stress can cause a leukocytosis by demargination of mature white blood cells; however, stress does not often cause immature cells such as bands to appear. Her chest radiograph with diffuse interstitial markings is consistent with a community-acquired pneumonia. Empiric antibiotic therapy should be initiated because of the possibility of community-acquired pneumonia. Recent studies demonstrate that steroids decrease mortality, the need for mechanical ventilation, and the length of stay for patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia; therefore, this patient should also be treated with steroids.

Eosinophilia may be seen in drug reactions, allergies, pulmonary emboli, pleural effusions, and occasionally in malignancy. Eosinophilic pneumonia typically has the “reverse pulmonary edema” picture, with infiltrates in the periphery and not centrally, as in congestive heart failure.

A serum bicarbonate of 30 mEq/L suggests a metabolic compensation for a chronic respiratory acidosis as renal compensation, and rise in bicarbonate generally takes 3 days. She may have been hypoxic longer than her symptoms suggest.

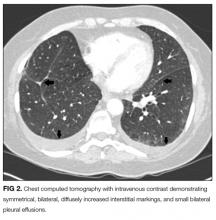

An ABG should be ordered to determine the degree of hypoxia and whether a higher level of care is indicated. The abnormal chest radiograph, along with her hypoxia, merits a closer look at her lung parenchyma with chest computed tomography (CT). A D-dimer would be beneficial to rule out pulmonary embolism. If the D-dimer is positive, chest CT with contrast is indicated to determine if a pulmonary embolism is present. A brain natriuretic peptide would assist in the diagnosis of congestive heart failure. A sputum culture and Gram stain and respiratory viral panel may establish a pathogen for pneumonia. An ECG and troponin to rule out myocardial infarction should be performed as well.

The presence of hilar and subcarinal lymph nodes expands the differential. Stage IV pulmonary sarcoid may present with diffuse infiltrates and nodes, although the acuity in this case makes it less likely. A very aggressive malignancy such as Burkitt lymphoma may have these findings. Acute viral and atypical pneumonias remain possible. Right middle lobe syndrome may cause partial collapse of the right middle lobe. Tuberculosis can be associated with right middle lobe syndrome; however, in this day and age an obstructing mass is more likely the cause. Pulmonary disease, such as cryptogenic organizing pneumonia, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, and interstitial lung disease, should be considered in patients with pneumonia unresponsive to antibiotics. Lung biopsy and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) would help make the diagnosis and should be the next step, unless her degree of hypoxia is prohibitive. Similarly, thoracentesis with analysis of the pleural fluid for cell count, Gram stain, and culture may help make the diagnosis. Thoracentesis should be done with fluoroscopic guidance, given the risk of pneumothorax, which would further compromise her tenuous respiratory status.

Thoracentesis was attempted, but the pleural effusion was too small to provide a sample. Subsequent serum blood counts with differential showed an increased eosinophilia to 20% and resolved bandemia. Upon further questioning, she recalled several months of extensive, daily, fine-dust exposure from demolition during the remodeling of a new building.

Hypereosinophilia and pulmonary infiltrates narrow the differential considerably to include asthma; parasitic infection, such as the pulmonary phase of ascariasis; exposure, such as to dust, cigarettes, or asbestosis; or hypereosinophilic syndromes characterized by peripheral eosinophilia, along with a tissue eosinophilia, causing organ dysfunction. Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome, a hypereosinophilic syndrome of unknown etiology despite extensive diagnostic testing, is rare, and eosinophilic leukemia even rarer. Her history strongly suggests exposure. Many eosinophilic diseases respond rapidly to steroids, and response to treatment would help narrow the diagnosis. If she does not respond to steroids, a lung and/or bone marrow biopsy would be the next step.

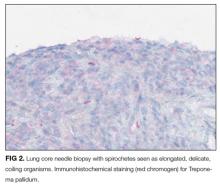

A BAL of the right middle lobe revealed 51% eosinophils, 3% neutrophils, 15% macrophages, and 28% lymphocytes. Gram stain, as well as cultures for bacteria, acid fast bacilli, fungus, herpes simplex virus, and cytomegalovirus cultures, were negative. Transbronchial lung biopsy revealed focal interstitial fibrosis and inflammation, without evidence of infection.

Eosinophils are primarily located in tissues; therefore, peripheral blood eosinophil counts often underestimate the degree of infiltration into end organs such as the lung. With 50% eosinophils, her BAL reflects this. Mold, fungus, chemical, and particle exposure could produce an eosinophilic BAL. She does not appear to be at risk for parasitic exposure. Eosinophilic granulomatosis (previously known as Churg-Strauss) is a consideration, but the lack of signs of vasculitis and wheezing make this less likely. A negative antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody may provide reassurance. “Fine dust exposure” is consistent with environmental exposure but not a specific antigen. Steroids provide a brisk eosinophil reduction and are appropriate for this patient. There is the possibility of missing infectious or parasitic etiologies; therefore, a culture of BAL fluid should be sent.

Eosinophilic infiltration may lead to fibrosis, as was found on the lung biopsy. She should be counseled to avoid “fine dust exposure” in the future. Follow-up lung imaging and pulmonary function tests (PFTs) should be performed once her acute illness resolves. She should be strongly urged not to smoke tobacco. Interestingly, there are reports that ex-smokers who restart smoking have an increased risk of eosinophilic pneumonia, but in this case dust exposure is the more likely etiology.

She was diagnosed with acute eosinophilic pneumonia (AEP). Antibiotics were discontinued, and oral prednisone was initiated at 40 mg daily, with a brisk response and resolution of her dyspnea. She was discharged with a 6-week prednisone taper. She had no cough, dyspnea, chest pain, or fevers at her follow-up 14 days after discharge. On a 6-week, postdischarge phone call, she continued to report no symptoms, and she maintained abstinence from cigarette smoking.

This case highlights that the very best test in any medical situation is a thorough, detailed history and physical examination. A comprehensive history with physical examination is noninvasive, safe, and cheap. Had the history of fine-dust exposure been known, it is likely that a great deal of testing and money would have been saved. The patient would have been diagnosed and treated earlier, and suffered less.

COMMENTARY

First described in 1989,1,2 AEP is an uncommon cause of acute respiratory failure. Cases have been reported throughout the world, including in the United States, Belgium, Japan, and Iraq.2,3 AEP is an acute febrile illness with cough, chest pain, and dyspnea for fewer than 7 days, diffuse pulmonary infiltrates on chest radiograph, hypoxemia, no history of asthma or atopic disease, no infection, and greater than 25% eosinophils on a BAL.1,3 Physical examination typically reveals fever, tachypnea, and crackles on auscultation.1 Peripheral blood eosinophilia is inconsistently seen at presentation but generally observed as the disease progresses.1 Peripheral eosinophilia at presentation is positively correlated with a milder course of AEP, including higher oxygen saturation and fewer intensive care admissions.4 Acute respiratory failure in AEP progresses rapidly, often within hours.1 Delayed recognition of AEP may lead to respiratory failure, requiring intubation, and even to death.1

Reticular markings with Kerley-B lines, mixed reticular and alveolar infiltrates, and pleural effusions are usually found on chest radiography.1 Bilateral areas of ground-glass attenuation, interlobular septal thickening, bronchovascular bundle thickening, and pleural effusions are seen on chest CT.5 Marked eosinophilic infiltration of the interstitium and alveolar spaces, as well as diffuse alveolar damage with hyaline membrane fibroblast proliferation and inflammatory cells, are present on lung biopsy.1 Restriction with impaired diffusion capacity is found on PFTs. However, PFTs return to normal after recovery.1

AEP is distinguished from other pulmonary diseases by BAL, lung biopsy, symptoms, symptom course, and/or radiographically. AEP is often misdiagnosed as severe community-acquired pneumonia and/or acute respiratory distress syndrome, as AEP tends to occur in previously healthy individuals who have diffuse infiltrates on chest radiograph, fevers, and acute, often severe, respiratory symptoms.1-3 Other eosinophilic lung diseases to rule out include simple pulmonary eosinophilia, chronic eosinophilic pneumonia, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangitis (Churg-Strauss), idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome, infection, and drug reactions.1,3,5 Simple eosinophilic pneumonia is characterized by no symptoms or very mild pulmonary symptoms and transient patchy infiltrates on radiography.3,5 Patients with simple pulmonary eosinophilia do not have interlobular septal thickening, thickening of the bronchovascular bundles, or pleural effusions radiographically, as seen with AEP.5 Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia is subacute, with respiratory symptoms of more than 3 months in duration, in contrast with the 7 days of respiratory symptoms for AEP, and is also not associated with interlobular septal thickening, thickening of the bronchovascular bundles, or pleural effusions on radiography.3,5 Unlike AEP, chronic eosinophilic pneumonia often recurs after the course of steroids has ended.3 In contrast with AEP, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangitis is associated with concomitant asthma and the involvement of nonpulmonary organs.3 Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome is characterized by extremely high peripheral eosinophilia and by eosinophilic involvement of multiple organs, and it requires chronic steroid use.3 Patients with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA), in contrast with AEP, typically have steroid-dependent asthma and chronic respiratory symptoms.3 ABPA also differs from AEP in that radiographic infiltrates are localized and transient, and the syndrome may relapse after steroid treatment.3 Other infectious etiologies that may present similarly to AEP include invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, pulmonary coccidiodomycosis, Pneumocystis jioveri pneumonia, pulmonary toxocariasis, pulmonary filariasis, paragonimiasis, and Loeffler syndrome (pneumonia due to Strongyloides, Ascaris, or hookworms), highlighting the importance of a thorough travel and exposure history.1,3 Several drugs may cause eosinophilic lung disease, including nitrofurantoin, tetracyclines, phenytoin, L-tryptophan, acetaminophen, ampicillin, heroin, and cocaine, which necessitates a thorough review of medication and illegal drug use.3

Steroids and supportive care are the treatment of choice for AEP, although spontaneous resolution has been seen.1,3 Significant clinical improvement occurs within 24 to 48 hours of steroid initiation.1,3 Optimal dose and duration of therapy have not been determined; however, methylprednisolone 125 mg intravenously every 6 hours until improvement is an often-used option.1 Tapers vary from 2 to 12 weeks with no difference in outcome.1-3 AEP does not recur after appropriate treatment with steroids.1,3

Little is known about the etiology of AEP. It usually occurs in young, healthy individuals and is presumed to be an unusual, acute hypersensitivity reaction to an inhaled allergen.1 A report of 18 US soldiers deployed in or near Iraq proposed dust exposure and cigarette or cigar smoking as a cause of AEP.2 Similar to our patient’s fine-dust exposure and recent onset of cigarette smoking, the soldiers were exposed to the dusty, arid environment for at least 1 day and had been smoking for at least 1 month.2 The authors proposed that small dust particles irritate alveoli, stimulating eosinophils, which are exacerbated by the onset of smoking. Alternatively, cigarette smoke may prime the lung such that dust triggers an inflammatory cascade, resulting in AEP.

TEACHING POINTS

- With the potential for the rapid progression of respiratory failure, it is imperative that the diagnosis of AEP be considered for a patient with diffuse infiltrates on a chest radiograph and acute respiratory failure of unknown cause.

- A thorough history of exposure is key to including AEP in the differential of acute pulmonary disease, with recent-onset cigarette smoking and dust exposure.

- The rapid initiation of steroids leads to a full recovery without recurrence and may be life-saving in AEP.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

A 52-year-old woman presented with a 4-day history of progressive dyspnea, nonproductive cough, pleuritic chest pain, and subjective fevers. She described dyspnea at rest, which worsened with exertion. She reported no chills, night sweats, weight change, wheezing, hemoptysis, orthopnea, lower extremity edema, or nasal congestion. She also denied myalgia, arthralgia, or joint swelling. She reported no rash, itching, or peripheral lymphadenopathy. She had no seasonal allergies. She was treated for presumed bronchitis with azithromycin by her primary care provider 4 days prior to presentation but experienced progressive dyspnea.

The constellation of dry cough, fever, and dyspnea is often infectious in origin, with the nonproductive, dry cough more suggestive of a viral than bacterial syndrome. Atypical organisms such as Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Legionella pneumophila, and Chlamydia pneumoniae may also present with these symptoms. Noninfectious etiologies should also be considered, including pulmonary embolism, systemic lupus erythematosus, asbestosis, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, sarcoidosis, and lung cancer. The dyspnea at rest stands out as a worrisome feature, as it implies hypoxia; therefore, an oxygen saturation is necessary to quickly determine her peripheral oxygen saturation.

Her past medical history was notable for lung adenocarcinoma, for which she had undergone right upper lobectomy, without chemotherapy or radiation, 13 years ago without recurrence. She had no history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, or pneumonia, nor a family history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, pneumonia, or lung cancer. Her only medication was azithromycin. She drank alcohol on occasion and denied illicit drug use. Three weeks prior to admission, she began smoking 4 to 5 cigarettes per day after 13 years of abstinence. Her smoking history prior to abstinence was 1 pack per day for 20 years. She worked as a department store remodeler; she had no exposure to asbestos, mold, or water-damaged wood. She reported no recent travel, sick contacts, or exposure to animals.

A primary lung neoplasm with a pleural effusion could cause her shortness of breath and pleuritic chest pain. Her history of lung cancer at age 39 raises the possibility of recurrence. For cigarette smokers, a second lung cancer may occur many years after the first diagnosis and treatment, even if they have quit smoking. A review of her original cancer records is essential to confirm the diagnosis of pulmonary adenocarcinoma. What is now being described as pulmonary adenocarcinoma may have been a metastatic lesion arising from outside the lung. Although unlikely, a primary adenocarcinoma may remain active.

Infectious etiologies continue to merit consideration. A parapneumonic effusion from a pneumonia or an empyema are consistent with her symptoms. Systemic lupus erythematosus can cause lung disease with pleural effusions. She does exhibit dyspnea and pleurisy, which are consistent with autoimmune disease, but does not exhibit some of the more typical autoimmune symptoms such as arthralgias, joint swelling, and rash. Pneumothorax could also produce her symptoms; however, pneumothorax usually occurs spontaneously in younger patients or after trauma or a procedure. Remote right upper lobectomy would not be a cause of pneumothorax now. Her reported history makes lung disease or pneumoconiosis due to occupational exposure to mold or aspergillosis a possibility. Legionellosis, histoplasmosis, or coccidioidomycosis should be considered if she lives in or has visited a high-risk area. Pulmonary embolism remains a concern for all patients with new-onset shortness of breath. Decision support tools, such as the Wells criteria, are valuable, but the gestalt of the physician does not lag far behind in accuracy.

Cardiac disease is also in the differential. Bibasilar crackles, third heart sound gallop, and jugular vein distension would suggest heart failure. A pericardial friction rub would be highly suggestive of pericarditis. A paradoxical pulse would raise concern for pericardial tamponade. Pleurisy may be associated with a pericardial effusion, making viral pericarditis and myocarditis possibilities.

She was in moderate distress with tachypnea and increased work of breathing. Her temperature was 36.7°C, heart rate 104 beats per minute, respiratory rate 24 breaths per minute, oxygen saturation was 88% on room air, 94% on 3 liters of oxygen, and blood pressure was 147/61 mmHg. Auscultation of the lungs revealed bibasilar crackles and decreased breath sounds at the bases. She was tachycardic, with a regular rhythm and no appreciable murmurs, rubs, or gallops. There was no jugular venous distention or lower extremity edema. Her thyroid was palpable, without appreciation of nodules. Skin and musculoskeletal examinations were normal.

Unless she is immunocompromised, infection has become lower in the differential, as she is afebrile. Decreased breath sounds at the bases and bibasilar crackles may be due to pleural effusions. Congestive heart failure is a possibility, especially given her dyspnea and bibasilar crackles. Volume overload from renal failure is possible, but she does not have other signs of volume overload such as lower extremity edema or jugular venous distension. It is important to note that crackles may be due to other etiologies, including atelectasis, fibrosis, or pneumonia. Pulmonary embolism may cause hypoxia, tachycardia, and pleural effusions. Additional diseases may present similarly, including human immunodeficiency virus with Pneumocystis jirovecii, causing dyspnea, tachypnea, and tachycardia; hematologic malignancy with anemia, causing dyspnea and tachycardia; and thyrotoxic states with thyromegaly, causing dyspnea and tachycardia. Thyroid storm patients appear in distress, are tachycardic, and may have thyromegaly.

Moderate distress, increased work of breathing, tachycardia, tachypnea, and hypoxia are all worrisome signs. Her temperature is subnormal, although this may not be accurate, as oral temperatures may register lower in patients with increased respiratory rates because of increased air flow across the thermometer. Bibasilar crackles with decreased bibasilar sounds require further investigation. A complete blood count, complete metabolic profile, troponin, arterial blood gas (ABG), electrocardiogram (ECG), and chest radiograph are warranted.

Laboratory studies revealed a white blood cell count of 8600 per mm3 with 11% bands and 7.3% eosinophils, and a hemoglobin count of 15 gm/dL. Basic metabolic panel, liver function tests, coagulation panel, and urinalysis were within normal limits, including serum creatinine 0.7 mg/dL, sodium 143 mmoL/L, chloride 104 mmoL/L, bicarbonate 30 mEq/L, anion gap 9 mmoL/L, and blood urea nitrogen 12 mg/dL. Chest radiograph disclosed diffusely increased interstitial markings and a small left pleural effusion (Figure 1).

Her bandemia suggests infection. Stress can cause a leukocytosis by demargination of mature white blood cells; however, stress does not often cause immature cells such as bands to appear. Her chest radiograph with diffuse interstitial markings is consistent with a community-acquired pneumonia. Empiric antibiotic therapy should be initiated because of the possibility of community-acquired pneumonia. Recent studies demonstrate that steroids decrease mortality, the need for mechanical ventilation, and the length of stay for patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia; therefore, this patient should also be treated with steroids.

Eosinophilia may be seen in drug reactions, allergies, pulmonary emboli, pleural effusions, and occasionally in malignancy. Eosinophilic pneumonia typically has the “reverse pulmonary edema” picture, with infiltrates in the periphery and not centrally, as in congestive heart failure.

A serum bicarbonate of 30 mEq/L suggests a metabolic compensation for a chronic respiratory acidosis as renal compensation, and rise in bicarbonate generally takes 3 days. She may have been hypoxic longer than her symptoms suggest.

An ABG should be ordered to determine the degree of hypoxia and whether a higher level of care is indicated. The abnormal chest radiograph, along with her hypoxia, merits a closer look at her lung parenchyma with chest computed tomography (CT). A D-dimer would be beneficial to rule out pulmonary embolism. If the D-dimer is positive, chest CT with contrast is indicated to determine if a pulmonary embolism is present. A brain natriuretic peptide would assist in the diagnosis of congestive heart failure. A sputum culture and Gram stain and respiratory viral panel may establish a pathogen for pneumonia. An ECG and troponin to rule out myocardial infarction should be performed as well.

The presence of hilar and subcarinal lymph nodes expands the differential. Stage IV pulmonary sarcoid may present with diffuse infiltrates and nodes, although the acuity in this case makes it less likely. A very aggressive malignancy such as Burkitt lymphoma may have these findings. Acute viral and atypical pneumonias remain possible. Right middle lobe syndrome may cause partial collapse of the right middle lobe. Tuberculosis can be associated with right middle lobe syndrome; however, in this day and age an obstructing mass is more likely the cause. Pulmonary disease, such as cryptogenic organizing pneumonia, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, and interstitial lung disease, should be considered in patients with pneumonia unresponsive to antibiotics. Lung biopsy and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) would help make the diagnosis and should be the next step, unless her degree of hypoxia is prohibitive. Similarly, thoracentesis with analysis of the pleural fluid for cell count, Gram stain, and culture may help make the diagnosis. Thoracentesis should be done with fluoroscopic guidance, given the risk of pneumothorax, which would further compromise her tenuous respiratory status.

Thoracentesis was attempted, but the pleural effusion was too small to provide a sample. Subsequent serum blood counts with differential showed an increased eosinophilia to 20% and resolved bandemia. Upon further questioning, she recalled several months of extensive, daily, fine-dust exposure from demolition during the remodeling of a new building.

Hypereosinophilia and pulmonary infiltrates narrow the differential considerably to include asthma; parasitic infection, such as the pulmonary phase of ascariasis; exposure, such as to dust, cigarettes, or asbestosis; or hypereosinophilic syndromes characterized by peripheral eosinophilia, along with a tissue eosinophilia, causing organ dysfunction. Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome, a hypereosinophilic syndrome of unknown etiology despite extensive diagnostic testing, is rare, and eosinophilic leukemia even rarer. Her history strongly suggests exposure. Many eosinophilic diseases respond rapidly to steroids, and response to treatment would help narrow the diagnosis. If she does not respond to steroids, a lung and/or bone marrow biopsy would be the next step.

A BAL of the right middle lobe revealed 51% eosinophils, 3% neutrophils, 15% macrophages, and 28% lymphocytes. Gram stain, as well as cultures for bacteria, acid fast bacilli, fungus, herpes simplex virus, and cytomegalovirus cultures, were negative. Transbronchial lung biopsy revealed focal interstitial fibrosis and inflammation, without evidence of infection.

Eosinophils are primarily located in tissues; therefore, peripheral blood eosinophil counts often underestimate the degree of infiltration into end organs such as the lung. With 50% eosinophils, her BAL reflects this. Mold, fungus, chemical, and particle exposure could produce an eosinophilic BAL. She does not appear to be at risk for parasitic exposure. Eosinophilic granulomatosis (previously known as Churg-Strauss) is a consideration, but the lack of signs of vasculitis and wheezing make this less likely. A negative antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody may provide reassurance. “Fine dust exposure” is consistent with environmental exposure but not a specific antigen. Steroids provide a brisk eosinophil reduction and are appropriate for this patient. There is the possibility of missing infectious or parasitic etiologies; therefore, a culture of BAL fluid should be sent.

Eosinophilic infiltration may lead to fibrosis, as was found on the lung biopsy. She should be counseled to avoid “fine dust exposure” in the future. Follow-up lung imaging and pulmonary function tests (PFTs) should be performed once her acute illness resolves. She should be strongly urged not to smoke tobacco. Interestingly, there are reports that ex-smokers who restart smoking have an increased risk of eosinophilic pneumonia, but in this case dust exposure is the more likely etiology.

She was diagnosed with acute eosinophilic pneumonia (AEP). Antibiotics were discontinued, and oral prednisone was initiated at 40 mg daily, with a brisk response and resolution of her dyspnea. She was discharged with a 6-week prednisone taper. She had no cough, dyspnea, chest pain, or fevers at her follow-up 14 days after discharge. On a 6-week, postdischarge phone call, she continued to report no symptoms, and she maintained abstinence from cigarette smoking.

This case highlights that the very best test in any medical situation is a thorough, detailed history and physical examination. A comprehensive history with physical examination is noninvasive, safe, and cheap. Had the history of fine-dust exposure been known, it is likely that a great deal of testing and money would have been saved. The patient would have been diagnosed and treated earlier, and suffered less.

COMMENTARY

First described in 1989,1,2 AEP is an uncommon cause of acute respiratory failure. Cases have been reported throughout the world, including in the United States, Belgium, Japan, and Iraq.2,3 AEP is an acute febrile illness with cough, chest pain, and dyspnea for fewer than 7 days, diffuse pulmonary infiltrates on chest radiograph, hypoxemia, no history of asthma or atopic disease, no infection, and greater than 25% eosinophils on a BAL.1,3 Physical examination typically reveals fever, tachypnea, and crackles on auscultation.1 Peripheral blood eosinophilia is inconsistently seen at presentation but generally observed as the disease progresses.1 Peripheral eosinophilia at presentation is positively correlated with a milder course of AEP, including higher oxygen saturation and fewer intensive care admissions.4 Acute respiratory failure in AEP progresses rapidly, often within hours.1 Delayed recognition of AEP may lead to respiratory failure, requiring intubation, and even to death.1

Reticular markings with Kerley-B lines, mixed reticular and alveolar infiltrates, and pleural effusions are usually found on chest radiography.1 Bilateral areas of ground-glass attenuation, interlobular septal thickening, bronchovascular bundle thickening, and pleural effusions are seen on chest CT.5 Marked eosinophilic infiltration of the interstitium and alveolar spaces, as well as diffuse alveolar damage with hyaline membrane fibroblast proliferation and inflammatory cells, are present on lung biopsy.1 Restriction with impaired diffusion capacity is found on PFTs. However, PFTs return to normal after recovery.1

AEP is distinguished from other pulmonary diseases by BAL, lung biopsy, symptoms, symptom course, and/or radiographically. AEP is often misdiagnosed as severe community-acquired pneumonia and/or acute respiratory distress syndrome, as AEP tends to occur in previously healthy individuals who have diffuse infiltrates on chest radiograph, fevers, and acute, often severe, respiratory symptoms.1-3 Other eosinophilic lung diseases to rule out include simple pulmonary eosinophilia, chronic eosinophilic pneumonia, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangitis (Churg-Strauss), idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome, infection, and drug reactions.1,3,5 Simple eosinophilic pneumonia is characterized by no symptoms or very mild pulmonary symptoms and transient patchy infiltrates on radiography.3,5 Patients with simple pulmonary eosinophilia do not have interlobular septal thickening, thickening of the bronchovascular bundles, or pleural effusions radiographically, as seen with AEP.5 Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia is subacute, with respiratory symptoms of more than 3 months in duration, in contrast with the 7 days of respiratory symptoms for AEP, and is also not associated with interlobular septal thickening, thickening of the bronchovascular bundles, or pleural effusions on radiography.3,5 Unlike AEP, chronic eosinophilic pneumonia often recurs after the course of steroids has ended.3 In contrast with AEP, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangitis is associated with concomitant asthma and the involvement of nonpulmonary organs.3 Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome is characterized by extremely high peripheral eosinophilia and by eosinophilic involvement of multiple organs, and it requires chronic steroid use.3 Patients with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA), in contrast with AEP, typically have steroid-dependent asthma and chronic respiratory symptoms.3 ABPA also differs from AEP in that radiographic infiltrates are localized and transient, and the syndrome may relapse after steroid treatment.3 Other infectious etiologies that may present similarly to AEP include invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, pulmonary coccidiodomycosis, Pneumocystis jioveri pneumonia, pulmonary toxocariasis, pulmonary filariasis, paragonimiasis, and Loeffler syndrome (pneumonia due to Strongyloides, Ascaris, or hookworms), highlighting the importance of a thorough travel and exposure history.1,3 Several drugs may cause eosinophilic lung disease, including nitrofurantoin, tetracyclines, phenytoin, L-tryptophan, acetaminophen, ampicillin, heroin, and cocaine, which necessitates a thorough review of medication and illegal drug use.3

Steroids and supportive care are the treatment of choice for AEP, although spontaneous resolution has been seen.1,3 Significant clinical improvement occurs within 24 to 48 hours of steroid initiation.1,3 Optimal dose and duration of therapy have not been determined; however, methylprednisolone 125 mg intravenously every 6 hours until improvement is an often-used option.1 Tapers vary from 2 to 12 weeks with no difference in outcome.1-3 AEP does not recur after appropriate treatment with steroids.1,3

Little is known about the etiology of AEP. It usually occurs in young, healthy individuals and is presumed to be an unusual, acute hypersensitivity reaction to an inhaled allergen.1 A report of 18 US soldiers deployed in or near Iraq proposed dust exposure and cigarette or cigar smoking as a cause of AEP.2 Similar to our patient’s fine-dust exposure and recent onset of cigarette smoking, the soldiers were exposed to the dusty, arid environment for at least 1 day and had been smoking for at least 1 month.2 The authors proposed that small dust particles irritate alveoli, stimulating eosinophils, which are exacerbated by the onset of smoking. Alternatively, cigarette smoke may prime the lung such that dust triggers an inflammatory cascade, resulting in AEP.

TEACHING POINTS

- With the potential for the rapid progression of respiratory failure, it is imperative that the diagnosis of AEP be considered for a patient with diffuse infiltrates on a chest radiograph and acute respiratory failure of unknown cause.

- A thorough history of exposure is key to including AEP in the differential of acute pulmonary disease, with recent-onset cigarette smoking and dust exposure.

- The rapid initiation of steroids leads to a full recovery without recurrence and may be life-saving in AEP.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

1. Allen J. Acute eosinophilic pneumonia. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;27:142-147. PubMed

2. Shorr AF, Scoville SL, Cersovsky SB, et al. Acute eosinophilic pneumonia among US military personnel deployed in or near Iraq. JAMA. 2004;292:2997-3005. PubMed

3. Pope-Harman AL, Davis WB, Allen ED, Christoforidis AJ, Allen JN. Acute eosinophilic pneumonia. A summary of 15 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1996;75(6):334-342. PubMed

4. Jhun BW, Kim SJ, Kim K, Lee JE. Clinical implications of initial peripheral eosinophilia in acute eosinophilic pneumonia. Respirology. 2014;19:1059-1065. PubMed

5. Daimon T, Johkoh T, Sumikawa H, et al. Acute eosinophilic pneumonia: Thin-section CT findings in 29 patients. Eur J Radiol. 2008;65:462-467. PubMed

1. Allen J. Acute eosinophilic pneumonia. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;27:142-147. PubMed

2. Shorr AF, Scoville SL, Cersovsky SB, et al. Acute eosinophilic pneumonia among US military personnel deployed in or near Iraq. JAMA. 2004;292:2997-3005. PubMed

3. Pope-Harman AL, Davis WB, Allen ED, Christoforidis AJ, Allen JN. Acute eosinophilic pneumonia. A summary of 15 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1996;75(6):334-342. PubMed

4. Jhun BW, Kim SJ, Kim K, Lee JE. Clinical implications of initial peripheral eosinophilia in acute eosinophilic pneumonia. Respirology. 2014;19:1059-1065. PubMed

5. Daimon T, Johkoh T, Sumikawa H, et al. Acute eosinophilic pneumonia: Thin-section CT findings in 29 patients. Eur J Radiol. 2008;65:462-467. PubMed

Morbo Serpentino

A 58-year-old Danish man presented to an urgent care center due to several months of gradually worsening fatigue, weight loss, abdominal pain, and changes in vision . His abdominal pain was diffuse, constant, and moderate in severity. There was no association with meals, and he reported no nausea, vomiting, or change in bowel movements. He also said his vision in both eyes was blurry, but denied diplopia and said the blurring did not improve when either eye w as closed. He denied dysphagia, headache, focal weakness, or sensitivity to bright lights.

Fatigue and weight loss in a middle-aged man are nonspecific complaints that mainly help to alert the clinician that there may be a serious, systemic process lurking. Constant abdominal pain without nausea, vomiting, or change in bowel movements makes intestinal obstruction or a motility disorder less likely. Given that the pain is diffuse, it raises the possibility of an intraperitoneal process or a process within an organ that is irritating the peritoneum.

Worsening of vision can result from disorders anywhere along the visual pathway, including the cornea (keratitis or corneal edema from glaucoma), anterior chamber (uveitis or hyphema), lens (cataracts, dislocations, hyperglycemia), vitreous humor (uveitis), retina (infections, ischemia, detachment, diabetic retinopathy), macula (degenerative disease), optic nerve (optic neuritis), optic chiasm, and the visual projections through the hemispheres to the occipital lobes. To narrow the differential diagnosis, it would be important to inquire about prior eye problems, to measure visual acuity and intraocular pressure, to perform fundoscopic and slit-lamp exams to detect retinal and anterior chamber disorders, respectively, and to assess visual fields. An afferent pupillary defect would suggest optic nerve pathology.

Disorders that could unify the constitutional, abdominal, and visual symptoms include systemic inflammatory diseases, such as sarcoidosis (which has an increased incidence among Northern Europeans), tuberculosis, or cancer. While diabetes mellitus could explain his visual problems, weight loss, and fatigue, the absence of polyuria, polydipsia, or polyphagia argues against this possibility.

The patient had hypercholesterolemia and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Medications were metformin, atorvastatin, and glimepiride. He was a former smoker with 23 pack-years and had quit over 5 years prior. He had not traveled outside of Denmark in 2 years and had no pets at home. He reported being monogamous with his same-sex partner for the past 25 years. He had no significant family history, and he worked at a local hospital as a nurse. He denied any previous ocular history.

On examination, the pulse was 67 beats per minute, temperature was 36.7 degrees Celsius, respiratory rate was 16 breaths per minute, oxygen saturation was 99% while breathing ambient air, and blood pressure was 132/78. Oropharynx demonstrated no thrush or other lesions. The heart rhythm was regular and there were no murmurs. Lungs were clear to auscultation bilaterally. Abdominal exam was normal except for mild tenderness upon palpation in all quadrants, but no masses, organomegaly, rigidity, or rebound tenderness were present. Skin examination revealed several subcutaneous nodules measuring up to 0.5 cm in diameter overlying the right and left posterolateral chest walls. T he nodules were rubbery, pink, nontender, and not warm nor fluctuant. Visual acuity was reduced in both eyes. Extraocular movements were intact, and the pupils reacted to light and accommodated appropriately. The sclerae were injected bilaterally. The remainder of the cranial nerves and neurologic exam were normal. Due to the vision loss , the patient was referred to an ophthalmologist who diagnosed bilateral anterior uveitis.

Though monogamous with his male partner for many years, it is mandatory to consider complications of human immunodeficiency virus infection (HIV ). The absence of oral lesions indicative of a low CD4 count, such as oral hairy leukoplakia or thrush, does not rule out HIV disease. Additional history about his work as a nurse might shed light on his risk of infection, such as airborne exposure to tuberculosis or acquisition of blood-borne pathogens through a needle stick injury. His unremarkable vital signs support the chronicity of his medical condition.

Uveitis can result from numerous causes. When confined to the eye, uncommon hereditary and acquired causes are less likely . In many patients, uveitis arises in the setting of systemic infection or inflammation. The numerous infectious causes of uveitis include syphilis, tuberculosis, toxoplasmosis, cat scratch disease, and viruses such as HIV, West Nile, and Ebola. Among the inflammatory diseases that can cause uveitis are sarcoidosis, inflammatory bowel disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, Behçet disease, and Sjogren syndrome.

Several of these conditions, including tuberculosis and syphilis, may also cause subcutaneous nodules. Both tuberculosis and syphilis can cause skin and gastrointestinal disease. Sarcoidosis could involve the skin, peritoneum, and uvea, and is a possibility in this patient. The dermatologic conditions associated with sarcoidosis are protean and include granulomatous inflammation and nongranulomatous processes such as erythema nodosum. Usually the nodules of erythema nodosum are tender, red or purple, and located on the lower extremities. The lack of tenderness points away from erythema nodosum in this patient. Metastatic cancer can disseminate to the subcutaneous tissue, and the patient’s smoking history and age mandate we consider malignancy. However, skin metastases tend to be hard, not rubbery.

A cost-effective evaluation at this point would include syphilis serologies, HIV testing, testing for tuberculosis with either a purified protein derivative test or interferon gamma release assay, chest radiography, and biopsy of 1 of the lesions on his back.

Laboratory data showed 12,400 white blood cells per cubic milliliter (64% neutrophils, 24% lymphocytes, 9% monocytes, 2% eosinophils, 1% basophils), hemoglobin 7.9 g/dL, mean corpuscular volume 85 fL, platelets 476,000 per cubic milliliter , C-reactive protein 43 mg/ d L (normal < 8 mg/L), gamma-glutamyl-transferase 554 IU/L (normal range 0-45), alkaline phosphatase 865 U/L (normal range 60-200), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) 71 mm per hour. International normalized ratio was 1.0, albumin was 3.0 mg/dL, activated partial thromboplastin time was 32 seconds (normal 22 to 35 seconds), and bilirubin was 0.3 mg/dL. Antibodies to HIV , hepatitis C, and hepatitis B surface antigen were not detectable. Electrocardiography ( ECG ) was normal. Plain radiograph of the chest demonstrated multiple nodular lesions bilaterally measuring up to 1 cm with no cavitation. There was a left pleural effusion.

The history and exam findings indicate a serious inflammatory condition affecting his lungs, pleura, eyes, skin, liver, and possibly his peritoneum. In this context, the elevated C-reactive protein and ESR are not helpful in differentiating inflammatory from infectious causes. The constellation of uveitis, pulmonary and cutaneous nodules, and marked abnormalities of liver tests in a middle-aged man of Northern European origin points us toward sarcoidosis. Pleural effusions are not common with sarcoidosis but may occur. However, to avoid premature closure, it is important to consider other possibilities.

Metastatic cancer, including lymphoma, could cause pulmonary and cutaneous nodules and liver involvement, but the chronic time course and uveitis are not consistent with malignancy. Tuberculosis is still a consideration, though one would have expected him to report fevers, night sweats, and, perhaps, exposure to patients with pulmonary tuberculosis in his job as a nurse. Multiple solid pulmonary nodules are also uncommon with pulmonary tuberculosis. Fungal infections such as histoplasmosis can cause skin lesions and pulmonary nodules but do not fit well with uveitis.

At this point, “ tissue is the issue.” A skin nodule would be the easiest site to biopsy. If skin biopsy was not diagnostic, computed tomography (CT) of his chest and abdomen should be performed to identify the next most accessible site for biopsy.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and colonoscopy showed normal findings, and random biopsies from the stomach and colon were normal. CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis performed with the administration of intravenous contrast showed multiple solid opacities in both lung fields up to 1 cm, with enlarged mediastinal and retroperitoneal lymph nodes measuring 1 to 3 cm in diameter, a left pleural effusion, wall thickening in the right colon, and several nonspecific hypodensities in the liver. A punch biopsy taken from the right chest wall lesion demonstrated chronic inflammation without granulomas. The patient underwent CT-guided biopsy of 1 of the right-sided lung nodules, which revealed noncaseating granulomatous inflammation, fibrosis, and necrosis. Neither biopsy contained malignant cells, and additional stains revealed no bacteria, fungi, or acid fast bacilli.

The retroperitoneal and mediastinal adenopathy are indicative of a widely disseminated inflammatory process. Lymphoma continues to be a concern, though uveitis as an initial presenting problem would very unusual. Although biopsy of the chest wall lesion failed to demonstrate granulomatous inflammation, the most parsimonious explanation is that the skin and lung nodules are both related to a single systemic process.

Granulomas form in an attempt to wall off offending agents, whether foreign antigens (talc, certain medications), infectious agents, or self-antigens. Review of histopathology and microbiologic studies are useful first steps. Stains for bacteria, fungi, or acid-fast organisms may diagnose an infectious cause, such as tuberculosis, leprosy, syphilis, fungi, or cat scratch disease. Granulomas in association with vascular inflammation would indicate vasculitis. Other autoimmune considerations include sarcoidosis and Crohn disease. Noncaseating granulomas are typically found in sarcoidosis, cat scratch disease, syphilis, leprosy, or Crohn disease, but do not entirely exclude tuberculosis.

The negative infectious studies and lack of classic features of Crohn disease or other autoimmune diseases further point to sarcoidosis as the etiology of this patient’s illness. A Norwegian dermatologist first described the pathology of sarcoidosis based upon specimens taken from skin nodules. He thought the lesions were sarcoma and described them as, “ multiple benign sarcoid of the skin,” which is where the name “ sarcoidosis” originated.

Diagnosing sarcoidosis requires excluding other mimickers. Additional testing should include syphilis serologies, rheumatoid factor, and antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibodies. The latter is associated with granulomatosis with polyangiitis and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, either of which may produce granulomatous inflammation of the lungs, skin, and uvea.

At this juncture, PET-CT represents a costly and unnecessary test that does not narrow our diagnostic possibilities sufficiently to justify its use. Osteolytic lesions would be unusual in sarcoidosis and more likely in lymphoma or infectious processes such as tuberculosis. Tests for syphilis and tuberculosis are required, and are a fraction of the cost of a PET-CT.

With the biopsy revealing spirochetes, and the positive results of a nontreponemal test (RPR) and confirmatory treponemal results, the diagnosis of syphilis is firmly established. Uveitis indicates neurosyphilis and warrants a longer course of intravenous penicillin. Lumbar puncture should be performed.

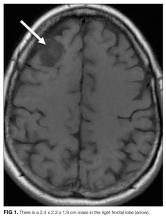

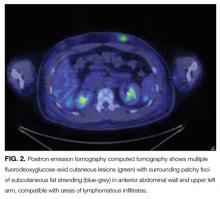

A lumbar puncture was performed. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) contained 9 white blood cells and 73 red blood cells per cubic milliliter; protein concentration was 73 mg/dL, and glucose was 116 mg/dL. Polymerase chain reaction for T. pallidum was negative. Transthoracic ECG and magnetic resonance imaging of the brain were normal. The patient was treated with intravenous penicillin G at 5 million units 4 times daily for 15 days. A PET-CT scan 3 months later revealed complete resolution of the subcutaneous, pulmonary, liver lesions, lymphadenopathy, and uveitis. Repeat treponemal serologies demonstrated a greater than 4-fold decline in titers.

DISCUSSION

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted disease with increasing incidence worldwide. Untreated infection progresses through 3 stages. The primary stage is characterized by the appearance of a painless chancre after an incubation period of 2 to 3 weeks. Four to 8 weeks later, the secondary stage emerges as a systemic infection, often heralded by a maculopapular rash with desquamation, frequently involving the soles and palms. Hepatitis, iridocyclitis, and early neurosyphilis may also be seen at this stage. Subsequently, syphilis becomes latent. One-third of patients with untreated latent syphilis will develop tertiary syphilis, typified by late neurosyphilis (tabes dorsalis and general paresis), cardiovascular disease (aortitis), or gummatous disease. 1

Gummas are destructive granulomatous lesions that typically present indolently, may occur singly or multiply, and may involve almost any organ. It has been suggested that gummas are the immune system’s defense to slow the bacteria after attempts to kill it have failed. Histologically, gummas are hyalinized nodules with surrounding granulomatous infiltrate of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and multinucleated giant cells with or without necrosis . In the preantibiotic era, gummas were seen in approximately 15% of infected patients, with a latency of 1 to 46 years after primary infection. 2 Penicillin led to a drastic reduction in gummas until the HIV epidemic, which led to the resurgence of gummas at a drastically shortened interval following primary syphilis. 3

Most commonly, gummas affect the skin and bones. In the skin , lesions may be superficial or deep and may progress into ulcerative nodules. In the bones, destructive gummas have a characteristic “moth-eaten” appearance. Less common sequelae of gummas incude gummatous hepatitis, perforated nasal septum (saddle nose deformity), or hard palate erosions. 2,4 R arely, syphilis involves the lungs, appearing as nodules, infiltrates, or pleural effusion. 5

Ocular manifestations occur in approximately 5% of patients with syphilis, more often in secondary and tertiary stages, and are strongly associated with a spread to the central nervous system. Syphilis may affect any structure of the eye, with anterior uveitis as the most frequent manifestation. Partial or complete vision loss is identified in approximately half of the patients with ocular syphilis and may be completely reversed by appropriate treatment. Ophthalmologic findings such as optic neuritis and papilledema imply advanced illness , as do Argyll-Robertson pupils (small pupils that are poorly reactive to light , but with preserved accommodation and convergence). 6,7 The treatment of ocular syphilis is identical to that of neurosyphilis. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends CSF analysis in any patient with ocular syphilis. Abnormal results should prompt repeat lumbar puncture every 3 to 6 months following treatment until the CSF results normalize. 8

The diagnosis of syphilis relies on indirect serologic tests. T. pallidum cannot be cultured in vitro, and techniques to identify spirochetes directly by using darkfield microscopy or DNA amplification via polymerase chain reaction are limited by availability or by poor sensitivity in advanced syphilis. 1 Imaging modalities including PET cannot reliably differentiate syphilis from other infectious and noninfectious mimickers. 9 F ortunately, syphilis infection can be diagnosed accurately based on reactive treponemal and nontreponemal serum tests. Nontreponemal tests, such as the RPR and Venereal Disease Research Laboratory, have traditionally been utilized as first-line evaluation, followed by a confirmatory treponemal test. However, nontreponemal tests may be nonreactive in a few settings: very early or very late in infection, and in individuals previously treated for syphilis. Thus, newer “reverse testing” algorithms utilize more sensitive and less expensive treponemal tests as the first test, followed by nontreponemal tests if the initial treponemal test is reactive. 8 Regardless of the testing sequence, in patients with no prior history of syphilis, reactive results on both treponemal and nontreponemal assays firmly establish a diagnosis of syphilis, obviating the need for more invasive and costly testing.