User login

The Hospitalist only

CHAMP: A Real Winner at Teaching Geriatrics

The elderly constitute the fastest-growing segment of the U.S. population. According to one estimate, nearly one in five Americans will be 65 years old or older by 2050.1 Geriatric medicine has produced a plethora of information regarding older patients’ special needs, but when it comes to teaching medical students and residents, most curricular materials focus on the care and management of older outpatients, rather than inpatients. In an effort to fill this gap, faculty at the University of Chicago School of Medicine developed the Curriculum for the Hospitalized Aging Medical Patient (CHAMP). It is designed to help instructors teach the management of elderly inpatients. In this month’s issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, lead author Paula Podrazik, MD, associate professor in the section of geriatrics, department of medicine, University of Chicago, and her co-authors explain CHAMP as it was perceived by a targeted group of faculty learners.

—Paula Podrazik, MD, associate professor in the section of geriatrics, department of medicine, University of Chicago

CHAMP incorporates knowledge gleaned from first-hand experience and a review of the literature and existing models of care. “Our goal was to improve patient care and systems of hospital care through education by faculty development,” Dr. Podrazik tells The Hospitalist. The CHAMP program emphasizes issues of particular importance in geriatric hospital medicine, including frailty, avoiding hazards of hospitalization, palliation, and care transitions.

For example, “hospitalists need to know certain aspects of dementia care, such as how to recognize it and screen for it,” she explains. “They have to determine whether a particular patient is able to make decisions, and they have to understand what it is about this condition that puts these patients at higher risk in the hospital.” Another example includes medication review and “communicating medication changes when transitioning the patient to a skilled nursing facility, home, or a rehabilitation center.”

Dr. Podrazik and her colleagues hope CHAMP might entice more medical students and residents to consider entering geriatric medicine. “Half of the [hospital] beds in the U.S. are filled with patients who are at least 65 years old. Many students and residents base their career decisions on what they see during their hospital rotation, so this was a great opportunity for us, as geriatricians, to influence that decision.”

The program consists of learning modules presented in 12, four-hour sessions. The modules address four basic themes:

- Identification of the frail or vulnerable elderly patient;

- Recognition and avoidance of hospitalization hazards, such as falls and dementia;

- Palliative care and end-of-life issues; and

- Improving transitions of care.

Each module has specific learning objectives and an evaluation process based on the standard precepts of curriculum design. The first part of each session covers topics on geriatric inpatient medicine, such as high-risk medications, medication reconciliation, restraint use, care transitions, and other aspects of mandates from The Joint Commission, which have particular relevance to the care of elderly people. Faculty participants listen to 30- to 90-minute lectures on each topic, with an emphasis on applying the content during bedside teaching rounds.

Modules presented in the second half of the session cover teaching techniques, such as the Stanford Faculty Development Program for Medical Teachers, which uses case scenarios and practice sessions to polish participants’ teaching skills. Another component specifically developed for CHAMP is a mini-course called “Teaching on Today’s Wards.” It is designed to help non-geriatric faculty put more geriatrics content in their bedside rounds, and to improve bedside teaching techniques in the inpatient wards.

The CHAMP curriculum also addresses the core competencies designated by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), namely professionalism, communication, systems-based practice, and practice-based learning and improvement.

The basic principles of geriatric care already exist, Dr. Podrazik says. “It was our job to pull it all together,” she explains. “A program of this size and magnitude couldn’t have been done without the participation of people in a multitude of areas, including hospitalists, geriatricians, internists, and PhD educators. We had multiple champions who took different areas and just ran with them.”

With eight faculty scholars volunteering to serve as guinea pigs, Dr. Podrazik and her colleagues pilot-tested the program in the spring of 2004. By 2006, another 21 faculty members had participated in CHAMP, including nearly half of the university’s general medicine faculty and most of its hospitalists. The response was enthusiastic, she says, with learners praising the presentation of geriatric issues and concrete suggestions for incorporating the information in their own teaching sessions. Upon completion of the CHAMP series, participants reported feeling significantly more knowledgeable about geriatric content, had more positive attitudes toward older patients, and felt more confident in their ability to care for older patients and teach geriatric medicine.

A major challenge was “providing enough ongoing support to reinforce learning with an eye on the greater goal of changing teaching behaviors and clinical outcomes,” the authors wrote. To solve this problem, they added objective structural teaching evaluations (OSTEs), so participants could test their teaching skills and mastery of geriatric content. Practice-oriented games, exercises, and tutorials, and ongoing contact with CHAMP alumnae and faculty are provided, as well as access to support materials online. Efforts are under way to incorporate core CHAMP faculty members into hospitalist and general medicine lecture series. Also being considered is having a CHAMP core faculty member attend during inpatient ward rounds.

It appears as though CHAMP is starting to pay off, in terms of patient care, Dr. Podrazik says. Although she cautioned the findings are “really preliminary,” and data analysis is ongoing, clinical data “do show a beneficial effect on a number of patient care outcomes.” TH

Norra MacReady is a medical writer based in California.

Reference

1. Passel JS, Cohn D. U.S. population projections: 2005-2050. Pew Research Center. http://pewhispanic.org/reports/report.php?ReportID=85. Published February 11, 2008. Accessed Thursday, October 23, 2008.

The elderly constitute the fastest-growing segment of the U.S. population. According to one estimate, nearly one in five Americans will be 65 years old or older by 2050.1 Geriatric medicine has produced a plethora of information regarding older patients’ special needs, but when it comes to teaching medical students and residents, most curricular materials focus on the care and management of older outpatients, rather than inpatients. In an effort to fill this gap, faculty at the University of Chicago School of Medicine developed the Curriculum for the Hospitalized Aging Medical Patient (CHAMP). It is designed to help instructors teach the management of elderly inpatients. In this month’s issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, lead author Paula Podrazik, MD, associate professor in the section of geriatrics, department of medicine, University of Chicago, and her co-authors explain CHAMP as it was perceived by a targeted group of faculty learners.

—Paula Podrazik, MD, associate professor in the section of geriatrics, department of medicine, University of Chicago

CHAMP incorporates knowledge gleaned from first-hand experience and a review of the literature and existing models of care. “Our goal was to improve patient care and systems of hospital care through education by faculty development,” Dr. Podrazik tells The Hospitalist. The CHAMP program emphasizes issues of particular importance in geriatric hospital medicine, including frailty, avoiding hazards of hospitalization, palliation, and care transitions.

For example, “hospitalists need to know certain aspects of dementia care, such as how to recognize it and screen for it,” she explains. “They have to determine whether a particular patient is able to make decisions, and they have to understand what it is about this condition that puts these patients at higher risk in the hospital.” Another example includes medication review and “communicating medication changes when transitioning the patient to a skilled nursing facility, home, or a rehabilitation center.”

Dr. Podrazik and her colleagues hope CHAMP might entice more medical students and residents to consider entering geriatric medicine. “Half of the [hospital] beds in the U.S. are filled with patients who are at least 65 years old. Many students and residents base their career decisions on what they see during their hospital rotation, so this was a great opportunity for us, as geriatricians, to influence that decision.”

The program consists of learning modules presented in 12, four-hour sessions. The modules address four basic themes:

- Identification of the frail or vulnerable elderly patient;

- Recognition and avoidance of hospitalization hazards, such as falls and dementia;

- Palliative care and end-of-life issues; and

- Improving transitions of care.

Each module has specific learning objectives and an evaluation process based on the standard precepts of curriculum design. The first part of each session covers topics on geriatric inpatient medicine, such as high-risk medications, medication reconciliation, restraint use, care transitions, and other aspects of mandates from The Joint Commission, which have particular relevance to the care of elderly people. Faculty participants listen to 30- to 90-minute lectures on each topic, with an emphasis on applying the content during bedside teaching rounds.

Modules presented in the second half of the session cover teaching techniques, such as the Stanford Faculty Development Program for Medical Teachers, which uses case scenarios and practice sessions to polish participants’ teaching skills. Another component specifically developed for CHAMP is a mini-course called “Teaching on Today’s Wards.” It is designed to help non-geriatric faculty put more geriatrics content in their bedside rounds, and to improve bedside teaching techniques in the inpatient wards.

The CHAMP curriculum also addresses the core competencies designated by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), namely professionalism, communication, systems-based practice, and practice-based learning and improvement.

The basic principles of geriatric care already exist, Dr. Podrazik says. “It was our job to pull it all together,” she explains. “A program of this size and magnitude couldn’t have been done without the participation of people in a multitude of areas, including hospitalists, geriatricians, internists, and PhD educators. We had multiple champions who took different areas and just ran with them.”

With eight faculty scholars volunteering to serve as guinea pigs, Dr. Podrazik and her colleagues pilot-tested the program in the spring of 2004. By 2006, another 21 faculty members had participated in CHAMP, including nearly half of the university’s general medicine faculty and most of its hospitalists. The response was enthusiastic, she says, with learners praising the presentation of geriatric issues and concrete suggestions for incorporating the information in their own teaching sessions. Upon completion of the CHAMP series, participants reported feeling significantly more knowledgeable about geriatric content, had more positive attitudes toward older patients, and felt more confident in their ability to care for older patients and teach geriatric medicine.

A major challenge was “providing enough ongoing support to reinforce learning with an eye on the greater goal of changing teaching behaviors and clinical outcomes,” the authors wrote. To solve this problem, they added objective structural teaching evaluations (OSTEs), so participants could test their teaching skills and mastery of geriatric content. Practice-oriented games, exercises, and tutorials, and ongoing contact with CHAMP alumnae and faculty are provided, as well as access to support materials online. Efforts are under way to incorporate core CHAMP faculty members into hospitalist and general medicine lecture series. Also being considered is having a CHAMP core faculty member attend during inpatient ward rounds.

It appears as though CHAMP is starting to pay off, in terms of patient care, Dr. Podrazik says. Although she cautioned the findings are “really preliminary,” and data analysis is ongoing, clinical data “do show a beneficial effect on a number of patient care outcomes.” TH

Norra MacReady is a medical writer based in California.

Reference

1. Passel JS, Cohn D. U.S. population projections: 2005-2050. Pew Research Center. http://pewhispanic.org/reports/report.php?ReportID=85. Published February 11, 2008. Accessed Thursday, October 23, 2008.

The elderly constitute the fastest-growing segment of the U.S. population. According to one estimate, nearly one in five Americans will be 65 years old or older by 2050.1 Geriatric medicine has produced a plethora of information regarding older patients’ special needs, but when it comes to teaching medical students and residents, most curricular materials focus on the care and management of older outpatients, rather than inpatients. In an effort to fill this gap, faculty at the University of Chicago School of Medicine developed the Curriculum for the Hospitalized Aging Medical Patient (CHAMP). It is designed to help instructors teach the management of elderly inpatients. In this month’s issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, lead author Paula Podrazik, MD, associate professor in the section of geriatrics, department of medicine, University of Chicago, and her co-authors explain CHAMP as it was perceived by a targeted group of faculty learners.

—Paula Podrazik, MD, associate professor in the section of geriatrics, department of medicine, University of Chicago

CHAMP incorporates knowledge gleaned from first-hand experience and a review of the literature and existing models of care. “Our goal was to improve patient care and systems of hospital care through education by faculty development,” Dr. Podrazik tells The Hospitalist. The CHAMP program emphasizes issues of particular importance in geriatric hospital medicine, including frailty, avoiding hazards of hospitalization, palliation, and care transitions.

For example, “hospitalists need to know certain aspects of dementia care, such as how to recognize it and screen for it,” she explains. “They have to determine whether a particular patient is able to make decisions, and they have to understand what it is about this condition that puts these patients at higher risk in the hospital.” Another example includes medication review and “communicating medication changes when transitioning the patient to a skilled nursing facility, home, or a rehabilitation center.”

Dr. Podrazik and her colleagues hope CHAMP might entice more medical students and residents to consider entering geriatric medicine. “Half of the [hospital] beds in the U.S. are filled with patients who are at least 65 years old. Many students and residents base their career decisions on what they see during their hospital rotation, so this was a great opportunity for us, as geriatricians, to influence that decision.”

The program consists of learning modules presented in 12, four-hour sessions. The modules address four basic themes:

- Identification of the frail or vulnerable elderly patient;

- Recognition and avoidance of hospitalization hazards, such as falls and dementia;

- Palliative care and end-of-life issues; and

- Improving transitions of care.

Each module has specific learning objectives and an evaluation process based on the standard precepts of curriculum design. The first part of each session covers topics on geriatric inpatient medicine, such as high-risk medications, medication reconciliation, restraint use, care transitions, and other aspects of mandates from The Joint Commission, which have particular relevance to the care of elderly people. Faculty participants listen to 30- to 90-minute lectures on each topic, with an emphasis on applying the content during bedside teaching rounds.

Modules presented in the second half of the session cover teaching techniques, such as the Stanford Faculty Development Program for Medical Teachers, which uses case scenarios and practice sessions to polish participants’ teaching skills. Another component specifically developed for CHAMP is a mini-course called “Teaching on Today’s Wards.” It is designed to help non-geriatric faculty put more geriatrics content in their bedside rounds, and to improve bedside teaching techniques in the inpatient wards.

The CHAMP curriculum also addresses the core competencies designated by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), namely professionalism, communication, systems-based practice, and practice-based learning and improvement.

The basic principles of geriatric care already exist, Dr. Podrazik says. “It was our job to pull it all together,” she explains. “A program of this size and magnitude couldn’t have been done without the participation of people in a multitude of areas, including hospitalists, geriatricians, internists, and PhD educators. We had multiple champions who took different areas and just ran with them.”

With eight faculty scholars volunteering to serve as guinea pigs, Dr. Podrazik and her colleagues pilot-tested the program in the spring of 2004. By 2006, another 21 faculty members had participated in CHAMP, including nearly half of the university’s general medicine faculty and most of its hospitalists. The response was enthusiastic, she says, with learners praising the presentation of geriatric issues and concrete suggestions for incorporating the information in their own teaching sessions. Upon completion of the CHAMP series, participants reported feeling significantly more knowledgeable about geriatric content, had more positive attitudes toward older patients, and felt more confident in their ability to care for older patients and teach geriatric medicine.

A major challenge was “providing enough ongoing support to reinforce learning with an eye on the greater goal of changing teaching behaviors and clinical outcomes,” the authors wrote. To solve this problem, they added objective structural teaching evaluations (OSTEs), so participants could test their teaching skills and mastery of geriatric content. Practice-oriented games, exercises, and tutorials, and ongoing contact with CHAMP alumnae and faculty are provided, as well as access to support materials online. Efforts are under way to incorporate core CHAMP faculty members into hospitalist and general medicine lecture series. Also being considered is having a CHAMP core faculty member attend during inpatient ward rounds.

It appears as though CHAMP is starting to pay off, in terms of patient care, Dr. Podrazik says. Although she cautioned the findings are “really preliminary,” and data analysis is ongoing, clinical data “do show a beneficial effect on a number of patient care outcomes.” TH

Norra MacReady is a medical writer based in California.

Reference

1. Passel JS, Cohn D. U.S. population projections: 2005-2050. Pew Research Center. http://pewhispanic.org/reports/report.php?ReportID=85. Published February 11, 2008. Accessed Thursday, October 23, 2008.

End of '08 Drug Update

The FDA has approved the first nucleic acid HBV viral DNA test for measuring HBV viral load from a patient’s blood. Via HBV viral load assessment, healthcare professionals now have a highly sensitive method for gauging antiviral therapy progress in patients with chronic HBV infections.

The test is known as the COBAS TaqMan HBV Test (Roche Diagnostic Division). It is used to measure HBV levels before beginning treatment, and then follow-up levels during treatment to assess therapy response. It is estimated that approximately 1.25 million people in the U.S. are infected with HBV, with approximately 60,000 becoming infected each year. About 5,000 people die from HBV-related complications each year.8

New Warnings

In October 2007, the Federal Drug and Food Administration (FDA) issued information for healthcare professionals regarding the subcutaneous use of exenatide (Byetta, Amylin Pharmaceuti-cals).9 Since then, the FDA has received at least six additional case reports of necrotizing or pancreatitis in patients taking exenatide.

Of these six cases, all patients needed hospitalization, two patients died, and four were recovering at the time of the reporting. Exenatide was discontinued in all of these patients.

If pancreatitis is suspected, exenatide and other potentially suspect drugs should be discontinued. There are no signs or symptoms distinguishing acute hemorrhagic or necrotizing pancreatitis associated with exenatide from less severe forms of pancreatitis. If pancreatitis is confirmed, appropriate treatment should be initiated and patients should be carefully monitored until they fully recover. Exenatide should not be restarted. The FDA is working with Amylin Pharmaceuticals to add stronger and more prominent warnings to the product label regarding the noted risks.

Since the last warning of natalizumab injection (Tysabri, Biogen IDEC), the FDA has informed healthcare professionals of two new cases of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) in European patients receiving it for more than a year as monotherapy for multiple sclerosis (MS).10

The agent currently is FDA approved to treat multiple sclerosis and Crohn’s disease. Approximately 39,000 patients have received treatment worldwide, with approximately 12,000 patients receiving treatment for at least a year. No new cases have been reported in the U.S., where approximately 7,500 patients have received the drug for more than a year and approximately 3,300 have received the drug for more than 18 months.

The FDA still believes natalizumab monotherapy may confer a lower risk of PML than usage with other immunomodulatory medications. Prescribing information for natalizumab has been revised to reflect this new information. TH

Michele B. Kaufman, PharmD, BSc, RPh, is a registered pharmacist based in New York City.

References:

1. Peck P. IV calcium channel blocker wins FDA okay. www.medpagetoday.com/ProductAlert/Prescriptions/10431. Published August 5, 2008. Accessed October 28, 2008.

2. Riley K. www.fda.gov. FDA approves first bone marrow stimulator to treat immune-related low platelet counts. www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/NEWS/2008/NEW01876.html Published August 22, 2008. Accessed October 28, 2008.

4. Waknine Y. www.fda.org. FDA approvals: stavzor, cardene IV, eovist. www.medscape.com/viewarticle/ 579068. Published August 14, 2008. Accessed October 28, 2008.

5. Eisai Pharmaceutical Company. www.eisai.com. FDA approves ALOXI® (palonosetron HCl) capsules for prevention of acute chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. www.eisai.com/view_press_ release.asp? ID=147&press=195. Published August 23, 2008. Accessed October 28, 2008.

6. Monthly Prescribing Reference. www. prescribingreference.com. FDA approves viread for hepatitis B. www. prescribingreference.com/news/showNews/ which/FDAApprovesVireadForHepatitisB8123/. Published August 12, 2008. Accessed October 28, 2008.

7. Nainggolan L. theheart.org. First ARB/CCB combo approved for initial therapy. www.theheart.org/ article/886011.do. Published August 5, 2008. Accessed October 28. 2008.

8. Long P. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. www.fda.org. FDA approves DNA test to measure hepatitis B virus levels. www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/ NEWS/2008/NEW01880.html. Published September 4, 2008. Accessed October 28, 2008.

9. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. www.fda.org. 2007 safety alerts for human medical products—Byetta (exenatide). www.fda.gov/medwatch/safety/2007 /safety07.htm#Byetta. Published August 18, 2008. Accessed October 28, 2008.

10. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. www.fda.org. 2008 safety alerts for human medical products–Tysabri (natalizumab). www.fda.gov/medwatch/ safety/2008/safety08.htm#Tysabri2. Published August 25, 2008. Accessed October 28, 2008.

The FDA has approved the first nucleic acid HBV viral DNA test for measuring HBV viral load from a patient’s blood. Via HBV viral load assessment, healthcare professionals now have a highly sensitive method for gauging antiviral therapy progress in patients with chronic HBV infections.

The test is known as the COBAS TaqMan HBV Test (Roche Diagnostic Division). It is used to measure HBV levels before beginning treatment, and then follow-up levels during treatment to assess therapy response. It is estimated that approximately 1.25 million people in the U.S. are infected with HBV, with approximately 60,000 becoming infected each year. About 5,000 people die from HBV-related complications each year.8

New Warnings

In October 2007, the Federal Drug and Food Administration (FDA) issued information for healthcare professionals regarding the subcutaneous use of exenatide (Byetta, Amylin Pharmaceuti-cals).9 Since then, the FDA has received at least six additional case reports of necrotizing or pancreatitis in patients taking exenatide.

Of these six cases, all patients needed hospitalization, two patients died, and four were recovering at the time of the reporting. Exenatide was discontinued in all of these patients.

If pancreatitis is suspected, exenatide and other potentially suspect drugs should be discontinued. There are no signs or symptoms distinguishing acute hemorrhagic or necrotizing pancreatitis associated with exenatide from less severe forms of pancreatitis. If pancreatitis is confirmed, appropriate treatment should be initiated and patients should be carefully monitored until they fully recover. Exenatide should not be restarted. The FDA is working with Amylin Pharmaceuticals to add stronger and more prominent warnings to the product label regarding the noted risks.

Since the last warning of natalizumab injection (Tysabri, Biogen IDEC), the FDA has informed healthcare professionals of two new cases of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) in European patients receiving it for more than a year as monotherapy for multiple sclerosis (MS).10

The agent currently is FDA approved to treat multiple sclerosis and Crohn’s disease. Approximately 39,000 patients have received treatment worldwide, with approximately 12,000 patients receiving treatment for at least a year. No new cases have been reported in the U.S., where approximately 7,500 patients have received the drug for more than a year and approximately 3,300 have received the drug for more than 18 months.

The FDA still believes natalizumab monotherapy may confer a lower risk of PML than usage with other immunomodulatory medications. Prescribing information for natalizumab has been revised to reflect this new information. TH

Michele B. Kaufman, PharmD, BSc, RPh, is a registered pharmacist based in New York City.

References:

1. Peck P. IV calcium channel blocker wins FDA okay. www.medpagetoday.com/ProductAlert/Prescriptions/10431. Published August 5, 2008. Accessed October 28, 2008.

2. Riley K. www.fda.gov. FDA approves first bone marrow stimulator to treat immune-related low platelet counts. www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/NEWS/2008/NEW01876.html Published August 22, 2008. Accessed October 28, 2008.

4. Waknine Y. www.fda.org. FDA approvals: stavzor, cardene IV, eovist. www.medscape.com/viewarticle/ 579068. Published August 14, 2008. Accessed October 28, 2008.

5. Eisai Pharmaceutical Company. www.eisai.com. FDA approves ALOXI® (palonosetron HCl) capsules for prevention of acute chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. www.eisai.com/view_press_ release.asp? ID=147&press=195. Published August 23, 2008. Accessed October 28, 2008.

6. Monthly Prescribing Reference. www. prescribingreference.com. FDA approves viread for hepatitis B. www. prescribingreference.com/news/showNews/ which/FDAApprovesVireadForHepatitisB8123/. Published August 12, 2008. Accessed October 28, 2008.

7. Nainggolan L. theheart.org. First ARB/CCB combo approved for initial therapy. www.theheart.org/ article/886011.do. Published August 5, 2008. Accessed October 28. 2008.

8. Long P. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. www.fda.org. FDA approves DNA test to measure hepatitis B virus levels. www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/ NEWS/2008/NEW01880.html. Published September 4, 2008. Accessed October 28, 2008.

9. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. www.fda.org. 2007 safety alerts for human medical products—Byetta (exenatide). www.fda.gov/medwatch/safety/2007 /safety07.htm#Byetta. Published August 18, 2008. Accessed October 28, 2008.

10. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. www.fda.org. 2008 safety alerts for human medical products–Tysabri (natalizumab). www.fda.gov/medwatch/ safety/2008/safety08.htm#Tysabri2. Published August 25, 2008. Accessed October 28, 2008.

The FDA has approved the first nucleic acid HBV viral DNA test for measuring HBV viral load from a patient’s blood. Via HBV viral load assessment, healthcare professionals now have a highly sensitive method for gauging antiviral therapy progress in patients with chronic HBV infections.

The test is known as the COBAS TaqMan HBV Test (Roche Diagnostic Division). It is used to measure HBV levels before beginning treatment, and then follow-up levels during treatment to assess therapy response. It is estimated that approximately 1.25 million people in the U.S. are infected with HBV, with approximately 60,000 becoming infected each year. About 5,000 people die from HBV-related complications each year.8

New Warnings

In October 2007, the Federal Drug and Food Administration (FDA) issued information for healthcare professionals regarding the subcutaneous use of exenatide (Byetta, Amylin Pharmaceuti-cals).9 Since then, the FDA has received at least six additional case reports of necrotizing or pancreatitis in patients taking exenatide.

Of these six cases, all patients needed hospitalization, two patients died, and four were recovering at the time of the reporting. Exenatide was discontinued in all of these patients.

If pancreatitis is suspected, exenatide and other potentially suspect drugs should be discontinued. There are no signs or symptoms distinguishing acute hemorrhagic or necrotizing pancreatitis associated with exenatide from less severe forms of pancreatitis. If pancreatitis is confirmed, appropriate treatment should be initiated and patients should be carefully monitored until they fully recover. Exenatide should not be restarted. The FDA is working with Amylin Pharmaceuticals to add stronger and more prominent warnings to the product label regarding the noted risks.

Since the last warning of natalizumab injection (Tysabri, Biogen IDEC), the FDA has informed healthcare professionals of two new cases of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) in European patients receiving it for more than a year as monotherapy for multiple sclerosis (MS).10

The agent currently is FDA approved to treat multiple sclerosis and Crohn’s disease. Approximately 39,000 patients have received treatment worldwide, with approximately 12,000 patients receiving treatment for at least a year. No new cases have been reported in the U.S., where approximately 7,500 patients have received the drug for more than a year and approximately 3,300 have received the drug for more than 18 months.

The FDA still believes natalizumab monotherapy may confer a lower risk of PML than usage with other immunomodulatory medications. Prescribing information for natalizumab has been revised to reflect this new information. TH

Michele B. Kaufman, PharmD, BSc, RPh, is a registered pharmacist based in New York City.

References:

1. Peck P. IV calcium channel blocker wins FDA okay. www.medpagetoday.com/ProductAlert/Prescriptions/10431. Published August 5, 2008. Accessed October 28, 2008.

2. Riley K. www.fda.gov. FDA approves first bone marrow stimulator to treat immune-related low platelet counts. www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/NEWS/2008/NEW01876.html Published August 22, 2008. Accessed October 28, 2008.

4. Waknine Y. www.fda.org. FDA approvals: stavzor, cardene IV, eovist. www.medscape.com/viewarticle/ 579068. Published August 14, 2008. Accessed October 28, 2008.

5. Eisai Pharmaceutical Company. www.eisai.com. FDA approves ALOXI® (palonosetron HCl) capsules for prevention of acute chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. www.eisai.com/view_press_ release.asp? ID=147&press=195. Published August 23, 2008. Accessed October 28, 2008.

6. Monthly Prescribing Reference. www. prescribingreference.com. FDA approves viread for hepatitis B. www. prescribingreference.com/news/showNews/ which/FDAApprovesVireadForHepatitisB8123/. Published August 12, 2008. Accessed October 28, 2008.

7. Nainggolan L. theheart.org. First ARB/CCB combo approved for initial therapy. www.theheart.org/ article/886011.do. Published August 5, 2008. Accessed October 28. 2008.

8. Long P. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. www.fda.org. FDA approves DNA test to measure hepatitis B virus levels. www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/ NEWS/2008/NEW01880.html. Published September 4, 2008. Accessed October 28, 2008.

9. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. www.fda.org. 2007 safety alerts for human medical products—Byetta (exenatide). www.fda.gov/medwatch/safety/2007 /safety07.htm#Byetta. Published August 18, 2008. Accessed October 28, 2008.

10. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. www.fda.org. 2008 safety alerts for human medical products–Tysabri (natalizumab). www.fda.gov/medwatch/ safety/2008/safety08.htm#Tysabri2. Published August 25, 2008. Accessed October 28, 2008.

When should lipid-lowering therapy be started in the hospitalized patient?

Case

A 52-year-old man with no medical history other than a transient ischemic attack (TIA) three months ago presents to the emergency department (ED) following multiple episodes of substernal (ST) chest pressure. He takes no medication. His electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed lateral ST segment depressions, and his cardiac biomarkers were elevated. He underwent cardiac catheterization, and a single drug-eluting stent was successfully placed to a culprit left circumflex lesion. He is now stable less than 24 hours following his initial presentation, without any evidence of heart failure. His providers prescribe aspirin, clopidogrel, metoprolol, and lisinopril. His fasting LDL level is 92 mg/dL.

What, if any, is the role for lipid-lowering therapy at this time?

Overview

Long-term therapy with HMG CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) has been shown through several large, randomized, controlled trials to reduce the risk for death, myocardial infarction (MI), and stroke in patients with established coronary disease. The most significant effects were evident after approximately two years of treatment.1,2,3,4

Subsequent trials have shown earlier and more significant reductions in the rates of recurrent ischemic cardiovascular events following acute coronary syndromes (ACS) when statins are administered early—within days of the initial event. This is a window of time in which most patients still are hospitalized.4,5,6,7

In addition to this data regarding statin use following ACS, a large, randomized, controlled trial demonstrated similar reductions in the incidence of strokes and cardiovascular events when high-dose atorvastatin was administered within one to six months following TIA or stroke in patients without established coronary disease.8 There is growing data supporting the hypothesis that statins have pleiotropic (non cholesterol-lowering), neuroprotective, properties that may improve patient outcomes following cerebrovascular events.9,10,11 There are ongoing trials investing the role of statins in the acute management of stroke.12,13

Hospitalists frequently manage patients in the stages immediately following ACS and stroke. Based on the large and evolving volume of data regarding the use of statins following these events, when and how should a statin be started in the hospital?

Review of the Data

Following Acute Coronary Syndrome: Death and recurrent ischemic events following ACS are most likely to occur in the early phase of recovery. Based on this observation and evidence supporting the early (in some cases within hours of administration) ‘pleiotropic’ or non-cholesterol lowering effects of statins, including improvement in endothelial function and decreases in platelet aggregation, thrombus deposition, and vascular inflammation, the MIRACL study was designed to answer the question of whether the initiation of treatment with a statin within 24 to 96 hours following ACS would reduce the occurrence of death and recurrent ischemia.4,7,14 Investigators randomized 3,086 patients within 24-96 hours (mean 63 hours) following admission for non-ST segment myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) or unstable angina (UA) to receive either atorvastatin 80 mg/d or placebo.

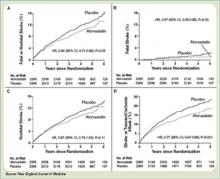

Investigators monitored patients for the primary end points of ischemic events (death, non-fatal MI, cardiac arrest with resuscitation, symptomatic myocardial ischemia with objective evidence) during a 16-week period. In the treatment arm, the risk of the primary combined end point was significantly reduced—relative risk (RR) 0.84; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.70-1.00; p=0.048. (See Figure 1, pg. 39)

No significant differences were found between atorvastatin and placebo in the risk of death, non-fatal MI, or cardiac arrest with resuscitation. There was, however, a significantly lower risk of recurrent symptomatic myocardial ischemia with objective evidence requiring emergent re-hospitalization in the treatment arm (RR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.57-0.95; p=0.02). The mean baseline LDL level in the treatment arm was 124 mg/dL, a value that may represent, in part, suppression of the LDL level in the setting of acute ACS. This is a phenomenon previously described in an analysis of the LUNAR trial.15

Suppression of LDL level after ACS appeared to be minimal, however, and is unlikely to be clinically significant. The benefits of atorvastatin in the MIRACL trial did not appear to depend on baseline LDL level—suggesting the decision to initiate statin therapy after ACS should not be influenced by LDL level at the time of the event.

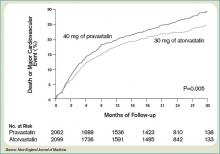

Only one dose of statin was used in the MIRACL trial, and the investigators commented they were unable to determine if a lower dose of atorvastatin or a gradual dose titration to a predetermined LDL target would have achieved similar benefits. The PROVE IT-TIMI 22 trial was designed to compare the reductions in death and major cardiovascular events following ACS between LDL lowering to approximately 100 mg/dL using 40 mg/d of pravastatin, and more intensive LDL lowering to approximately 70 mg/dL using 80 mg/d of atorvastatin.5 Investigators enrolled 4,162 patients for a median of seven days following ACS (STEMI, NSTEMI, or UA) to the two treatment arms. Investigators observed patients for a period of 18 to 36 months for the primary end points of death, MI, UA, revascularization, and stroke. The median LDL level at the time of enrollment was 106 mg/dL in both treatment arms. During follow up, the median LDL levels achieved were 95 mg/dL in the pravastatin group and 62 mg/dL in the atorvastatin group. After two years, a 16% reduction in the hazard ratio for any primary end point was seen favoring 80 mg/d of atorvastatin—p=0.005; 95% CI=5-26%. (See Figure 2, pg. 39) The benefit of high-dose atorvastatin was seen as early as 30 days after randomization and was sustained throughout the trial.

While the PROVE IT-TIMI 22 trial supported a specified dosing strategy for statin use following ACS, Phase Z of the A-to-Z trial was designed to evaluate the early initiation of intensive lipid lowering following ACS, as compared to a delayed and less-intensive strategy.5,6 Investigators randomized 4,497 patients (a mean of 3.7 days following either NSTEMI or STEMI) to receive either placebo for four months followed by simvastatin 20 mg/d or simvastatin 40 mg/d for one month followed by simvastatin 80 mg/d. They followed patients for 24 months for the primary end points of cardiovascular death, MI, readmission for ACS, or stroke. The primary end point occurred in 16.7% of the delayed, lower-intensity treatment group and in 14.4% of the early, higher-intensity treatment group (95% CI 0.76-1.04; p=0.14). Despite the lack of a significant difference in the composite primary end point between the two treatment arms, a significant reduction in the secondary end points of cardiovascular mortality (absolute risk reduction (ARR 1.3%; P=0.05) and congestive heart failure (ARR 1.3%; P=0.04) was evident favoring the early, intensive treatment strategy. These differences were not evident until at least four months after randomization. The A-to-Z trial investigators offered several possible explanations for the delay in evident clinical benefits in their trial when compared against the strong trend toward clinical benefit seen with 30 days following the early initiation of high-dose atorvastatin following ACS in the PROVE IT-TIMI 22 trial. In the PROVE IT trial, patients were enrolled an average of seven days after their index event, and as a result, 69% had undergone revascularization by this time. In the A-to-Z trial, patients were enrolled an average of three to four days earlier, and, therefore, were less likely to have undergone a revascularization procedure by the time of enrollment—and may have continued on with active thrombotic processes relatively less responsive to statin therapy.6 Another notable difference between PROVE IT and A-to-Z subjects was the C-reactive protein (CRP) concentrations in the A-to-Z subjects did not differ between treatment groups within 30 days despite significant differences in their LDL levels.16 This lack of a concurrent, pleiotropic, anti-inflammatory effect in the A-to-Z trial aggressive treatment arm may also have contributed to the delayed treatment effect.

In conclusion, the A-to-Z investigators suggest more intensive statin therapy (than the 40 mg Simvastatin in their intensive treatment arm) may be required to derive the most rapid and maximal clinical benefits during the highest risk period immediately following ACS.

Following stroke: Although there is more robust data supporting the benefits of early, intensive, statin therapy following ACS, there also is established and emerging data supporting similar treatment approaches following stroke.

The Stroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels (SPARCL) trial was designed to determine whether or not atorvastatin 80 mg daily would reduce the risk of stroke in patients without known coronary heart disease who had suffered a TIA or stroke within the preceding six months.8 Patients who experienced a hemorrhagic or ischemic TIA or stroke between one to six months before study entry were randomized to receive either atorvastatin 80 mg/d or placebo.

Investigators followed patients for a mean period of 4.9 years for the primary end point of time to non-fatal or fatal stroke. Secondary composite end points included stroke or TIA, and any coronary or peripheral arterial event, including death from cardiac causes, non-fatal MI, ACS, revascularization (coronary, carotid, peripheral), and death from any cause. No difference in mean baseline LDL levels was witnessed between the treatment and placebo arms (132.7 and 133.7 mg/dL, respectively). Atorvastatin was associated with a 16% relative reduction in the risk of stroke—hazard ratio, 0.84; 95% CI 0.71–0.99; p=0.03. This was found despite an increase in hemorrhagic stroke in the atorvastatin group—a finding that supports an epidemiologic association between low cholesterol levels and brain hemorrhage. The risk of cardiovascular events also was significantly reduced, however, no significant difference in overall mortality was observed between the two groups.

In conclusion, the authors recommend the initiation of high-dose atorvastatin “soon” after stroke or TIA. One can only conclude, based on these data, statin therapy should be initiated within six months of TIA or stroke, in accordance with the study design. There is retrospective data suggesting benefit to statin therapy initiated within four weeks following ischemic stroke, and there are prospective trials in process evaluating the potential benefits of statins initiated within 24 hours following ischemic stroke, however, no large, randomized, controlled trial can demonstrate the effect of statins when used as acute stroke therapy.9,12,13,17

Back to the Case

The patient described in our case has a history of TIA and experienced an acute coronary syndrome (NSTEMI) within the preceding 24 hours. He underwent a revascularization procedure (PCI with stent), and is on appropriate therapy, including dual anti-platelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel, a beta-blocker, and an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor. Based on the data and conclusions of the MIRACL, PROVE IT-TIMI 22, and SPARCL trials, high-dose statin therapy with atorvastatin 80 mg/d should be initiated immediately in the patient in order to significantly reduce his risk of recurrent ischemic cardiovascular events and stroke following his acute coronary syndrome and TIA.

Bottom Line

Following ACS, high-dose statin therapy with 80 mg of atorvastatin per day should be initiated when the patient is still in the hospital, irrespective of baseline LDL level. Statin therapy should also strongly be considered for secondary stroke prevention in most patients with a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack. TH

Caleb Hale, MD, is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. Joseph Ming Wah Li is director of the hospital medicine program and associate chief, division of general medicine and primary care at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, and assistant professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School.

References

1. Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study Group. Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S). Lancet 1994;344:1383-1389.

2. Sacks RM, Pfeffer MA, Moye LA, et al. The effect of pravastatin on coronary events after myocardial infarction in patients with average cholesterol levels. N Engl J Med 1996;335:1001-1009.

3. The Long-Term Intervention with Pravastatin in Ischaemic Disease (LIPID) Study Group. Prevention of cardiovascular events and death with pravastatin in patients with coronary heart disease and a broad range of initial cholesterol levels. N Engl J Med 1998;339:1349-1357.

4. Schwartz GG, Olsson AG, Ezekowitz MD, et al. Effects of atorvastatin on early recurrent ischemic events in acute coronary syndromes. The MIRACL study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;285:1711-1718.

5. Cannon CP, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, et al. Intensive versus moderate lipid lowering with statins after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1495-1504.

6. Lemos JA, Blazing MA, Wiviott SD, et al. Early intensive vs. a delayed conservative simvastatin strategy in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Phase Z of the A to Z trial. JAMA. 2004;292:1307-1316.

7. Waters D, Schwartz GG, Olsson AG. The myocardial ischemia reduction with acute cholesterol lowering (MIRACL) trial: a new frontier for statins? Curr Control Trials Cardiovasc Med. 2001;2;111-114.

8. The Stroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels (SPARCL) Investigators. High-dose atorvastatin after stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:549-559.

9. Moonis M, Kane K, Schwiderski U, Sandage BW, Fisher M. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors improve acute ischemic stroke outcome. Stroke. 2005;36:1298-1300.

10. Elkind MS, Flint AC, Sciacca RR, Sacco RL. Lipid-lowering agent use at ischemic stroke onset is associated with decreased mortality. Neurology. 2005;65:253-258.

11. Vaughan CJ, Delanty N. Neuroprotective properties of statins in cerebral ischemia and stroke. Stroke. 1999;30:1969-1973.

12. Elkind MS, Sacco RL, MacArthur RB, et al. The neuroprotection with statin therapy for acute recovery trial (NeuSTART): an adaptive design phase I dose-escalation study of high-dose lovastatin in acute ischemic stroke. Int J Stroke. 2008;3:210-218.

13. Montaner J, Chacon P, Krupinski J, et al. Simvastatin in the acute phase of ischemic stroke: a safety and efficacy pilot trial. Eur J of Neurol. 2008;15:82-90.

14. Ridker PM, Cannon CP, Morrow D, et al. C-reactive protein levels and outcomes after statin therapy. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:20-28.

15. Pitt B, Loscalzo J, Ycas J, Raichlen JS. Lipid levels after acute coronary syndromes. JACC. 2008;51:1440-1445.

16. Wiviott SD, de Lemos JA, Cannon CP, et al. A tale of two trials: a comparison of the post-acute coronary syndrome lipid-lowering trials of A to Z and PROVE IT-TIMI 22. Circulation. 2006;113:1406-1414.

17. Elking MS. Statins as acute-stroke treatment. Int J Stroke. 2006;1:224-225.

Case

A 52-year-old man with no medical history other than a transient ischemic attack (TIA) three months ago presents to the emergency department (ED) following multiple episodes of substernal (ST) chest pressure. He takes no medication. His electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed lateral ST segment depressions, and his cardiac biomarkers were elevated. He underwent cardiac catheterization, and a single drug-eluting stent was successfully placed to a culprit left circumflex lesion. He is now stable less than 24 hours following his initial presentation, without any evidence of heart failure. His providers prescribe aspirin, clopidogrel, metoprolol, and lisinopril. His fasting LDL level is 92 mg/dL.

What, if any, is the role for lipid-lowering therapy at this time?

Overview

Long-term therapy with HMG CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) has been shown through several large, randomized, controlled trials to reduce the risk for death, myocardial infarction (MI), and stroke in patients with established coronary disease. The most significant effects were evident after approximately two years of treatment.1,2,3,4

Subsequent trials have shown earlier and more significant reductions in the rates of recurrent ischemic cardiovascular events following acute coronary syndromes (ACS) when statins are administered early—within days of the initial event. This is a window of time in which most patients still are hospitalized.4,5,6,7

In addition to this data regarding statin use following ACS, a large, randomized, controlled trial demonstrated similar reductions in the incidence of strokes and cardiovascular events when high-dose atorvastatin was administered within one to six months following TIA or stroke in patients without established coronary disease.8 There is growing data supporting the hypothesis that statins have pleiotropic (non cholesterol-lowering), neuroprotective, properties that may improve patient outcomes following cerebrovascular events.9,10,11 There are ongoing trials investing the role of statins in the acute management of stroke.12,13

Hospitalists frequently manage patients in the stages immediately following ACS and stroke. Based on the large and evolving volume of data regarding the use of statins following these events, when and how should a statin be started in the hospital?

Review of the Data

Following Acute Coronary Syndrome: Death and recurrent ischemic events following ACS are most likely to occur in the early phase of recovery. Based on this observation and evidence supporting the early (in some cases within hours of administration) ‘pleiotropic’ or non-cholesterol lowering effects of statins, including improvement in endothelial function and decreases in platelet aggregation, thrombus deposition, and vascular inflammation, the MIRACL study was designed to answer the question of whether the initiation of treatment with a statin within 24 to 96 hours following ACS would reduce the occurrence of death and recurrent ischemia.4,7,14 Investigators randomized 3,086 patients within 24-96 hours (mean 63 hours) following admission for non-ST segment myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) or unstable angina (UA) to receive either atorvastatin 80 mg/d or placebo.

Investigators monitored patients for the primary end points of ischemic events (death, non-fatal MI, cardiac arrest with resuscitation, symptomatic myocardial ischemia with objective evidence) during a 16-week period. In the treatment arm, the risk of the primary combined end point was significantly reduced—relative risk (RR) 0.84; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.70-1.00; p=0.048. (See Figure 1, pg. 39)

No significant differences were found between atorvastatin and placebo in the risk of death, non-fatal MI, or cardiac arrest with resuscitation. There was, however, a significantly lower risk of recurrent symptomatic myocardial ischemia with objective evidence requiring emergent re-hospitalization in the treatment arm (RR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.57-0.95; p=0.02). The mean baseline LDL level in the treatment arm was 124 mg/dL, a value that may represent, in part, suppression of the LDL level in the setting of acute ACS. This is a phenomenon previously described in an analysis of the LUNAR trial.15

Suppression of LDL level after ACS appeared to be minimal, however, and is unlikely to be clinically significant. The benefits of atorvastatin in the MIRACL trial did not appear to depend on baseline LDL level—suggesting the decision to initiate statin therapy after ACS should not be influenced by LDL level at the time of the event.

Only one dose of statin was used in the MIRACL trial, and the investigators commented they were unable to determine if a lower dose of atorvastatin or a gradual dose titration to a predetermined LDL target would have achieved similar benefits. The PROVE IT-TIMI 22 trial was designed to compare the reductions in death and major cardiovascular events following ACS between LDL lowering to approximately 100 mg/dL using 40 mg/d of pravastatin, and more intensive LDL lowering to approximately 70 mg/dL using 80 mg/d of atorvastatin.5 Investigators enrolled 4,162 patients for a median of seven days following ACS (STEMI, NSTEMI, or UA) to the two treatment arms. Investigators observed patients for a period of 18 to 36 months for the primary end points of death, MI, UA, revascularization, and stroke. The median LDL level at the time of enrollment was 106 mg/dL in both treatment arms. During follow up, the median LDL levels achieved were 95 mg/dL in the pravastatin group and 62 mg/dL in the atorvastatin group. After two years, a 16% reduction in the hazard ratio for any primary end point was seen favoring 80 mg/d of atorvastatin—p=0.005; 95% CI=5-26%. (See Figure 2, pg. 39) The benefit of high-dose atorvastatin was seen as early as 30 days after randomization and was sustained throughout the trial.

While the PROVE IT-TIMI 22 trial supported a specified dosing strategy for statin use following ACS, Phase Z of the A-to-Z trial was designed to evaluate the early initiation of intensive lipid lowering following ACS, as compared to a delayed and less-intensive strategy.5,6 Investigators randomized 4,497 patients (a mean of 3.7 days following either NSTEMI or STEMI) to receive either placebo for four months followed by simvastatin 20 mg/d or simvastatin 40 mg/d for one month followed by simvastatin 80 mg/d. They followed patients for 24 months for the primary end points of cardiovascular death, MI, readmission for ACS, or stroke. The primary end point occurred in 16.7% of the delayed, lower-intensity treatment group and in 14.4% of the early, higher-intensity treatment group (95% CI 0.76-1.04; p=0.14). Despite the lack of a significant difference in the composite primary end point between the two treatment arms, a significant reduction in the secondary end points of cardiovascular mortality (absolute risk reduction (ARR 1.3%; P=0.05) and congestive heart failure (ARR 1.3%; P=0.04) was evident favoring the early, intensive treatment strategy. These differences were not evident until at least four months after randomization. The A-to-Z trial investigators offered several possible explanations for the delay in evident clinical benefits in their trial when compared against the strong trend toward clinical benefit seen with 30 days following the early initiation of high-dose atorvastatin following ACS in the PROVE IT-TIMI 22 trial. In the PROVE IT trial, patients were enrolled an average of seven days after their index event, and as a result, 69% had undergone revascularization by this time. In the A-to-Z trial, patients were enrolled an average of three to four days earlier, and, therefore, were less likely to have undergone a revascularization procedure by the time of enrollment—and may have continued on with active thrombotic processes relatively less responsive to statin therapy.6 Another notable difference between PROVE IT and A-to-Z subjects was the C-reactive protein (CRP) concentrations in the A-to-Z subjects did not differ between treatment groups within 30 days despite significant differences in their LDL levels.16 This lack of a concurrent, pleiotropic, anti-inflammatory effect in the A-to-Z trial aggressive treatment arm may also have contributed to the delayed treatment effect.

In conclusion, the A-to-Z investigators suggest more intensive statin therapy (than the 40 mg Simvastatin in their intensive treatment arm) may be required to derive the most rapid and maximal clinical benefits during the highest risk period immediately following ACS.

Following stroke: Although there is more robust data supporting the benefits of early, intensive, statin therapy following ACS, there also is established and emerging data supporting similar treatment approaches following stroke.

The Stroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels (SPARCL) trial was designed to determine whether or not atorvastatin 80 mg daily would reduce the risk of stroke in patients without known coronary heart disease who had suffered a TIA or stroke within the preceding six months.8 Patients who experienced a hemorrhagic or ischemic TIA or stroke between one to six months before study entry were randomized to receive either atorvastatin 80 mg/d or placebo.

Investigators followed patients for a mean period of 4.9 years for the primary end point of time to non-fatal or fatal stroke. Secondary composite end points included stroke or TIA, and any coronary or peripheral arterial event, including death from cardiac causes, non-fatal MI, ACS, revascularization (coronary, carotid, peripheral), and death from any cause. No difference in mean baseline LDL levels was witnessed between the treatment and placebo arms (132.7 and 133.7 mg/dL, respectively). Atorvastatin was associated with a 16% relative reduction in the risk of stroke—hazard ratio, 0.84; 95% CI 0.71–0.99; p=0.03. This was found despite an increase in hemorrhagic stroke in the atorvastatin group—a finding that supports an epidemiologic association between low cholesterol levels and brain hemorrhage. The risk of cardiovascular events also was significantly reduced, however, no significant difference in overall mortality was observed between the two groups.

In conclusion, the authors recommend the initiation of high-dose atorvastatin “soon” after stroke or TIA. One can only conclude, based on these data, statin therapy should be initiated within six months of TIA or stroke, in accordance with the study design. There is retrospective data suggesting benefit to statin therapy initiated within four weeks following ischemic stroke, and there are prospective trials in process evaluating the potential benefits of statins initiated within 24 hours following ischemic stroke, however, no large, randomized, controlled trial can demonstrate the effect of statins when used as acute stroke therapy.9,12,13,17

Back to the Case

The patient described in our case has a history of TIA and experienced an acute coronary syndrome (NSTEMI) within the preceding 24 hours. He underwent a revascularization procedure (PCI with stent), and is on appropriate therapy, including dual anti-platelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel, a beta-blocker, and an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor. Based on the data and conclusions of the MIRACL, PROVE IT-TIMI 22, and SPARCL trials, high-dose statin therapy with atorvastatin 80 mg/d should be initiated immediately in the patient in order to significantly reduce his risk of recurrent ischemic cardiovascular events and stroke following his acute coronary syndrome and TIA.

Bottom Line

Following ACS, high-dose statin therapy with 80 mg of atorvastatin per day should be initiated when the patient is still in the hospital, irrespective of baseline LDL level. Statin therapy should also strongly be considered for secondary stroke prevention in most patients with a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack. TH

Caleb Hale, MD, is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. Joseph Ming Wah Li is director of the hospital medicine program and associate chief, division of general medicine and primary care at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, and assistant professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School.

References

1. Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study Group. Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S). Lancet 1994;344:1383-1389.

2. Sacks RM, Pfeffer MA, Moye LA, et al. The effect of pravastatin on coronary events after myocardial infarction in patients with average cholesterol levels. N Engl J Med 1996;335:1001-1009.

3. The Long-Term Intervention with Pravastatin in Ischaemic Disease (LIPID) Study Group. Prevention of cardiovascular events and death with pravastatin in patients with coronary heart disease and a broad range of initial cholesterol levels. N Engl J Med 1998;339:1349-1357.

4. Schwartz GG, Olsson AG, Ezekowitz MD, et al. Effects of atorvastatin on early recurrent ischemic events in acute coronary syndromes. The MIRACL study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;285:1711-1718.

5. Cannon CP, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, et al. Intensive versus moderate lipid lowering with statins after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1495-1504.

6. Lemos JA, Blazing MA, Wiviott SD, et al. Early intensive vs. a delayed conservative simvastatin strategy in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Phase Z of the A to Z trial. JAMA. 2004;292:1307-1316.

7. Waters D, Schwartz GG, Olsson AG. The myocardial ischemia reduction with acute cholesterol lowering (MIRACL) trial: a new frontier for statins? Curr Control Trials Cardiovasc Med. 2001;2;111-114.

8. The Stroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels (SPARCL) Investigators. High-dose atorvastatin after stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:549-559.

9. Moonis M, Kane K, Schwiderski U, Sandage BW, Fisher M. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors improve acute ischemic stroke outcome. Stroke. 2005;36:1298-1300.

10. Elkind MS, Flint AC, Sciacca RR, Sacco RL. Lipid-lowering agent use at ischemic stroke onset is associated with decreased mortality. Neurology. 2005;65:253-258.

11. Vaughan CJ, Delanty N. Neuroprotective properties of statins in cerebral ischemia and stroke. Stroke. 1999;30:1969-1973.

12. Elkind MS, Sacco RL, MacArthur RB, et al. The neuroprotection with statin therapy for acute recovery trial (NeuSTART): an adaptive design phase I dose-escalation study of high-dose lovastatin in acute ischemic stroke. Int J Stroke. 2008;3:210-218.

13. Montaner J, Chacon P, Krupinski J, et al. Simvastatin in the acute phase of ischemic stroke: a safety and efficacy pilot trial. Eur J of Neurol. 2008;15:82-90.

14. Ridker PM, Cannon CP, Morrow D, et al. C-reactive protein levels and outcomes after statin therapy. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:20-28.

15. Pitt B, Loscalzo J, Ycas J, Raichlen JS. Lipid levels after acute coronary syndromes. JACC. 2008;51:1440-1445.

16. Wiviott SD, de Lemos JA, Cannon CP, et al. A tale of two trials: a comparison of the post-acute coronary syndrome lipid-lowering trials of A to Z and PROVE IT-TIMI 22. Circulation. 2006;113:1406-1414.

17. Elking MS. Statins as acute-stroke treatment. Int J Stroke. 2006;1:224-225.

Case

A 52-year-old man with no medical history other than a transient ischemic attack (TIA) three months ago presents to the emergency department (ED) following multiple episodes of substernal (ST) chest pressure. He takes no medication. His electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed lateral ST segment depressions, and his cardiac biomarkers were elevated. He underwent cardiac catheterization, and a single drug-eluting stent was successfully placed to a culprit left circumflex lesion. He is now stable less than 24 hours following his initial presentation, without any evidence of heart failure. His providers prescribe aspirin, clopidogrel, metoprolol, and lisinopril. His fasting LDL level is 92 mg/dL.

What, if any, is the role for lipid-lowering therapy at this time?

Overview

Long-term therapy with HMG CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) has been shown through several large, randomized, controlled trials to reduce the risk for death, myocardial infarction (MI), and stroke in patients with established coronary disease. The most significant effects were evident after approximately two years of treatment.1,2,3,4

Subsequent trials have shown earlier and more significant reductions in the rates of recurrent ischemic cardiovascular events following acute coronary syndromes (ACS) when statins are administered early—within days of the initial event. This is a window of time in which most patients still are hospitalized.4,5,6,7

In addition to this data regarding statin use following ACS, a large, randomized, controlled trial demonstrated similar reductions in the incidence of strokes and cardiovascular events when high-dose atorvastatin was administered within one to six months following TIA or stroke in patients without established coronary disease.8 There is growing data supporting the hypothesis that statins have pleiotropic (non cholesterol-lowering), neuroprotective, properties that may improve patient outcomes following cerebrovascular events.9,10,11 There are ongoing trials investing the role of statins in the acute management of stroke.12,13

Hospitalists frequently manage patients in the stages immediately following ACS and stroke. Based on the large and evolving volume of data regarding the use of statins following these events, when and how should a statin be started in the hospital?

Review of the Data

Following Acute Coronary Syndrome: Death and recurrent ischemic events following ACS are most likely to occur in the early phase of recovery. Based on this observation and evidence supporting the early (in some cases within hours of administration) ‘pleiotropic’ or non-cholesterol lowering effects of statins, including improvement in endothelial function and decreases in platelet aggregation, thrombus deposition, and vascular inflammation, the MIRACL study was designed to answer the question of whether the initiation of treatment with a statin within 24 to 96 hours following ACS would reduce the occurrence of death and recurrent ischemia.4,7,14 Investigators randomized 3,086 patients within 24-96 hours (mean 63 hours) following admission for non-ST segment myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) or unstable angina (UA) to receive either atorvastatin 80 mg/d or placebo.

Investigators monitored patients for the primary end points of ischemic events (death, non-fatal MI, cardiac arrest with resuscitation, symptomatic myocardial ischemia with objective evidence) during a 16-week period. In the treatment arm, the risk of the primary combined end point was significantly reduced—relative risk (RR) 0.84; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.70-1.00; p=0.048. (See Figure 1, pg. 39)

No significant differences were found between atorvastatin and placebo in the risk of death, non-fatal MI, or cardiac arrest with resuscitation. There was, however, a significantly lower risk of recurrent symptomatic myocardial ischemia with objective evidence requiring emergent re-hospitalization in the treatment arm (RR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.57-0.95; p=0.02). The mean baseline LDL level in the treatment arm was 124 mg/dL, a value that may represent, in part, suppression of the LDL level in the setting of acute ACS. This is a phenomenon previously described in an analysis of the LUNAR trial.15

Suppression of LDL level after ACS appeared to be minimal, however, and is unlikely to be clinically significant. The benefits of atorvastatin in the MIRACL trial did not appear to depend on baseline LDL level—suggesting the decision to initiate statin therapy after ACS should not be influenced by LDL level at the time of the event.

Only one dose of statin was used in the MIRACL trial, and the investigators commented they were unable to determine if a lower dose of atorvastatin or a gradual dose titration to a predetermined LDL target would have achieved similar benefits. The PROVE IT-TIMI 22 trial was designed to compare the reductions in death and major cardiovascular events following ACS between LDL lowering to approximately 100 mg/dL using 40 mg/d of pravastatin, and more intensive LDL lowering to approximately 70 mg/dL using 80 mg/d of atorvastatin.5 Investigators enrolled 4,162 patients for a median of seven days following ACS (STEMI, NSTEMI, or UA) to the two treatment arms. Investigators observed patients for a period of 18 to 36 months for the primary end points of death, MI, UA, revascularization, and stroke. The median LDL level at the time of enrollment was 106 mg/dL in both treatment arms. During follow up, the median LDL levels achieved were 95 mg/dL in the pravastatin group and 62 mg/dL in the atorvastatin group. After two years, a 16% reduction in the hazard ratio for any primary end point was seen favoring 80 mg/d of atorvastatin—p=0.005; 95% CI=5-26%. (See Figure 2, pg. 39) The benefit of high-dose atorvastatin was seen as early as 30 days after randomization and was sustained throughout the trial.

While the PROVE IT-TIMI 22 trial supported a specified dosing strategy for statin use following ACS, Phase Z of the A-to-Z trial was designed to evaluate the early initiation of intensive lipid lowering following ACS, as compared to a delayed and less-intensive strategy.5,6 Investigators randomized 4,497 patients (a mean of 3.7 days following either NSTEMI or STEMI) to receive either placebo for four months followed by simvastatin 20 mg/d or simvastatin 40 mg/d for one month followed by simvastatin 80 mg/d. They followed patients for 24 months for the primary end points of cardiovascular death, MI, readmission for ACS, or stroke. The primary end point occurred in 16.7% of the delayed, lower-intensity treatment group and in 14.4% of the early, higher-intensity treatment group (95% CI 0.76-1.04; p=0.14). Despite the lack of a significant difference in the composite primary end point between the two treatment arms, a significant reduction in the secondary end points of cardiovascular mortality (absolute risk reduction (ARR 1.3%; P=0.05) and congestive heart failure (ARR 1.3%; P=0.04) was evident favoring the early, intensive treatment strategy. These differences were not evident until at least four months after randomization. The A-to-Z trial investigators offered several possible explanations for the delay in evident clinical benefits in their trial when compared against the strong trend toward clinical benefit seen with 30 days following the early initiation of high-dose atorvastatin following ACS in the PROVE IT-TIMI 22 trial. In the PROVE IT trial, patients were enrolled an average of seven days after their index event, and as a result, 69% had undergone revascularization by this time. In the A-to-Z trial, patients were enrolled an average of three to four days earlier, and, therefore, were less likely to have undergone a revascularization procedure by the time of enrollment—and may have continued on with active thrombotic processes relatively less responsive to statin therapy.6 Another notable difference between PROVE IT and A-to-Z subjects was the C-reactive protein (CRP) concentrations in the A-to-Z subjects did not differ between treatment groups within 30 days despite significant differences in their LDL levels.16 This lack of a concurrent, pleiotropic, anti-inflammatory effect in the A-to-Z trial aggressive treatment arm may also have contributed to the delayed treatment effect.

In conclusion, the A-to-Z investigators suggest more intensive statin therapy (than the 40 mg Simvastatin in their intensive treatment arm) may be required to derive the most rapid and maximal clinical benefits during the highest risk period immediately following ACS.

Following stroke: Although there is more robust data supporting the benefits of early, intensive, statin therapy following ACS, there also is established and emerging data supporting similar treatment approaches following stroke.

The Stroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels (SPARCL) trial was designed to determine whether or not atorvastatin 80 mg daily would reduce the risk of stroke in patients without known coronary heart disease who had suffered a TIA or stroke within the preceding six months.8 Patients who experienced a hemorrhagic or ischemic TIA or stroke between one to six months before study entry were randomized to receive either atorvastatin 80 mg/d or placebo.

Investigators followed patients for a mean period of 4.9 years for the primary end point of time to non-fatal or fatal stroke. Secondary composite end points included stroke or TIA, and any coronary or peripheral arterial event, including death from cardiac causes, non-fatal MI, ACS, revascularization (coronary, carotid, peripheral), and death from any cause. No difference in mean baseline LDL levels was witnessed between the treatment and placebo arms (132.7 and 133.7 mg/dL, respectively). Atorvastatin was associated with a 16% relative reduction in the risk of stroke—hazard ratio, 0.84; 95% CI 0.71–0.99; p=0.03. This was found despite an increase in hemorrhagic stroke in the atorvastatin group—a finding that supports an epidemiologic association between low cholesterol levels and brain hemorrhage. The risk of cardiovascular events also was significantly reduced, however, no significant difference in overall mortality was observed between the two groups.

In conclusion, the authors recommend the initiation of high-dose atorvastatin “soon” after stroke or TIA. One can only conclude, based on these data, statin therapy should be initiated within six months of TIA or stroke, in accordance with the study design. There is retrospective data suggesting benefit to statin therapy initiated within four weeks following ischemic stroke, and there are prospective trials in process evaluating the potential benefits of statins initiated within 24 hours following ischemic stroke, however, no large, randomized, controlled trial can demonstrate the effect of statins when used as acute stroke therapy.9,12,13,17

Back to the Case

The patient described in our case has a history of TIA and experienced an acute coronary syndrome (NSTEMI) within the preceding 24 hours. He underwent a revascularization procedure (PCI with stent), and is on appropriate therapy, including dual anti-platelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel, a beta-blocker, and an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor. Based on the data and conclusions of the MIRACL, PROVE IT-TIMI 22, and SPARCL trials, high-dose statin therapy with atorvastatin 80 mg/d should be initiated immediately in the patient in order to significantly reduce his risk of recurrent ischemic cardiovascular events and stroke following his acute coronary syndrome and TIA.

Bottom Line

Following ACS, high-dose statin therapy with 80 mg of atorvastatin per day should be initiated when the patient is still in the hospital, irrespective of baseline LDL level. Statin therapy should also strongly be considered for secondary stroke prevention in most patients with a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack. TH

Caleb Hale, MD, is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. Joseph Ming Wah Li is director of the hospital medicine program and associate chief, division of general medicine and primary care at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, and assistant professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School.

References

1. Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study Group. Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S). Lancet 1994;344:1383-1389.

2. Sacks RM, Pfeffer MA, Moye LA, et al. The effect of pravastatin on coronary events after myocardial infarction in patients with average cholesterol levels. N Engl J Med 1996;335:1001-1009.

3. The Long-Term Intervention with Pravastatin in Ischaemic Disease (LIPID) Study Group. Prevention of cardiovascular events and death with pravastatin in patients with coronary heart disease and a broad range of initial cholesterol levels. N Engl J Med 1998;339:1349-1357.

4. Schwartz GG, Olsson AG, Ezekowitz MD, et al. Effects of atorvastatin on early recurrent ischemic events in acute coronary syndromes. The MIRACL study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;285:1711-1718.

5. Cannon CP, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, et al. Intensive versus moderate lipid lowering with statins after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1495-1504.

6. Lemos JA, Blazing MA, Wiviott SD, et al. Early intensive vs. a delayed conservative simvastatin strategy in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Phase Z of the A to Z trial. JAMA. 2004;292:1307-1316.

7. Waters D, Schwartz GG, Olsson AG. The myocardial ischemia reduction with acute cholesterol lowering (MIRACL) trial: a new frontier for statins? Curr Control Trials Cardiovasc Med. 2001;2;111-114.

8. The Stroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels (SPARCL) Investigators. High-dose atorvastatin after stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:549-559.