User login

The Hospitalist only

Behind the Scenes

In the last year, SHM has made great strides in improving the user experience at www. hospitalmedicine.org. Now it’s easier than ever to keep up with the latest news from the fastest-growing specialty in the history of modern healthcare. In an effort to bring as much energy as possible to this cutting-edge specialty, SHM strives to expand our online tools by offering our members the latest resources in education, events and publications over the newest mediums available. Like hospital medicine, Web 2.0 is a trend on the rise. From blogs to podcasts to our new RSS feeds, you will notice many new applications throughout SHM’s site.

hospitalmedicine.org: New and Improved

The first step in setting this new approach into motion was a complete overhaul of SHM’s Web site. This major renovation set the stage for a variety of new features, including seven resource rooms focused on Quality Improvement and supplemental clinical tools, as well as the introduction of online discussion forums and the SHM Career Center.

New Event Sites

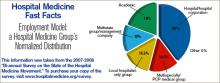

Following our Web site expansion, we introduced several specialty sites for our most popular products, including SHM’s “2007-2008 State of the Hospital Medicine Movement” survey, as well as SHM’s Leadership Academy, Annual Meeting, and (coming soon) SHM’s One Day University.

These sites offer inside information about product news, meeting topics, curricula, and exclusive member offers. This year’s Hospital Medicine 2009 (HM09) site features more than 40 presentations from Hospital Medicine 2008 (HM08) for users to view such topics as quality improvement, operations, and clinical. With year-round access to resources, information from past meetings isn’t lost. It can be retrieved daily for practicing hospitalists.

Blogs

SHM first introduced blogs to our members in 2007 with the launch of “Wachter’s World” (www.wachtersworld.org), as well as the HM07 blog, which featured an inside look at the goings-on at the annual meeting. Blogs create an interactive forum to discuss relevant issues on a daily basis and introduce readers to the perspectives of some of the most reputable hospitalists in the specialty today.

This year, we expanded our blogs to reflect on past events, offering participants a chance to share highlights and feedback from our annual meetings. Not only does this help our members keep current on hospital medicine news, but it also provides an outlet to voice opinions and help influence the direction of the society.

Podcasts

For those of you who enjoy auditory learning, you will find podcasts attached to event pages and CME listings. Our podcast library features guests, such as featured keynote speakers, industry specialists, SHM board members, and event attendees. Be on the lookout for SHM team members at upcoming events, as you may have the opportunity for a podcast interview of your own!

RSS Feeds

In June 2008 SHM created its own RSS feed, offering biweekly updates. Subscribers to SHM’s RSS feed receive up-to-the minute news streaming to their e-mail/PDAs, with updates ranging from SHM’s organizational growth and development to relative changes in legislation/public policy and anything relating to hospital medicine. Subscribe today so that you don’t miss the most current updates to hospitalmedicine.org.

Social Networking

Networking always has been one of the most important benefits of SHM membership. From communicating with local hospitalists at chapter meetings, to national and international colleagues at our annual meeting, there is a sense of community among those in the hospital medicine field. SHM recognizes the importance of building this community and has taken networking to a new level through participation in social networking sites such as Facebook and LinkedIn. If you currently are a user of these sites, join the SHM group and get connected!

All of these resources are at your fingertips. Visit us online at www.hospitalmedicine.org to try out one or all of these new features and upgrade your SHM experience. TH

In the last year, SHM has made great strides in improving the user experience at www. hospitalmedicine.org. Now it’s easier than ever to keep up with the latest news from the fastest-growing specialty in the history of modern healthcare. In an effort to bring as much energy as possible to this cutting-edge specialty, SHM strives to expand our online tools by offering our members the latest resources in education, events and publications over the newest mediums available. Like hospital medicine, Web 2.0 is a trend on the rise. From blogs to podcasts to our new RSS feeds, you will notice many new applications throughout SHM’s site.

hospitalmedicine.org: New and Improved

The first step in setting this new approach into motion was a complete overhaul of SHM’s Web site. This major renovation set the stage for a variety of new features, including seven resource rooms focused on Quality Improvement and supplemental clinical tools, as well as the introduction of online discussion forums and the SHM Career Center.

New Event Sites

Following our Web site expansion, we introduced several specialty sites for our most popular products, including SHM’s “2007-2008 State of the Hospital Medicine Movement” survey, as well as SHM’s Leadership Academy, Annual Meeting, and (coming soon) SHM’s One Day University.

These sites offer inside information about product news, meeting topics, curricula, and exclusive member offers. This year’s Hospital Medicine 2009 (HM09) site features more than 40 presentations from Hospital Medicine 2008 (HM08) for users to view such topics as quality improvement, operations, and clinical. With year-round access to resources, information from past meetings isn’t lost. It can be retrieved daily for practicing hospitalists.

Blogs

SHM first introduced blogs to our members in 2007 with the launch of “Wachter’s World” (www.wachtersworld.org), as well as the HM07 blog, which featured an inside look at the goings-on at the annual meeting. Blogs create an interactive forum to discuss relevant issues on a daily basis and introduce readers to the perspectives of some of the most reputable hospitalists in the specialty today.

This year, we expanded our blogs to reflect on past events, offering participants a chance to share highlights and feedback from our annual meetings. Not only does this help our members keep current on hospital medicine news, but it also provides an outlet to voice opinions and help influence the direction of the society.

Podcasts

For those of you who enjoy auditory learning, you will find podcasts attached to event pages and CME listings. Our podcast library features guests, such as featured keynote speakers, industry specialists, SHM board members, and event attendees. Be on the lookout for SHM team members at upcoming events, as you may have the opportunity for a podcast interview of your own!

RSS Feeds

In June 2008 SHM created its own RSS feed, offering biweekly updates. Subscribers to SHM’s RSS feed receive up-to-the minute news streaming to their e-mail/PDAs, with updates ranging from SHM’s organizational growth and development to relative changes in legislation/public policy and anything relating to hospital medicine. Subscribe today so that you don’t miss the most current updates to hospitalmedicine.org.

Social Networking

Networking always has been one of the most important benefits of SHM membership. From communicating with local hospitalists at chapter meetings, to national and international colleagues at our annual meeting, there is a sense of community among those in the hospital medicine field. SHM recognizes the importance of building this community and has taken networking to a new level through participation in social networking sites such as Facebook and LinkedIn. If you currently are a user of these sites, join the SHM group and get connected!

All of these resources are at your fingertips. Visit us online at www.hospitalmedicine.org to try out one or all of these new features and upgrade your SHM experience. TH

In the last year, SHM has made great strides in improving the user experience at www. hospitalmedicine.org. Now it’s easier than ever to keep up with the latest news from the fastest-growing specialty in the history of modern healthcare. In an effort to bring as much energy as possible to this cutting-edge specialty, SHM strives to expand our online tools by offering our members the latest resources in education, events and publications over the newest mediums available. Like hospital medicine, Web 2.0 is a trend on the rise. From blogs to podcasts to our new RSS feeds, you will notice many new applications throughout SHM’s site.

hospitalmedicine.org: New and Improved

The first step in setting this new approach into motion was a complete overhaul of SHM’s Web site. This major renovation set the stage for a variety of new features, including seven resource rooms focused on Quality Improvement and supplemental clinical tools, as well as the introduction of online discussion forums and the SHM Career Center.

New Event Sites

Following our Web site expansion, we introduced several specialty sites for our most popular products, including SHM’s “2007-2008 State of the Hospital Medicine Movement” survey, as well as SHM’s Leadership Academy, Annual Meeting, and (coming soon) SHM’s One Day University.

These sites offer inside information about product news, meeting topics, curricula, and exclusive member offers. This year’s Hospital Medicine 2009 (HM09) site features more than 40 presentations from Hospital Medicine 2008 (HM08) for users to view such topics as quality improvement, operations, and clinical. With year-round access to resources, information from past meetings isn’t lost. It can be retrieved daily for practicing hospitalists.

Blogs

SHM first introduced blogs to our members in 2007 with the launch of “Wachter’s World” (www.wachtersworld.org), as well as the HM07 blog, which featured an inside look at the goings-on at the annual meeting. Blogs create an interactive forum to discuss relevant issues on a daily basis and introduce readers to the perspectives of some of the most reputable hospitalists in the specialty today.

This year, we expanded our blogs to reflect on past events, offering participants a chance to share highlights and feedback from our annual meetings. Not only does this help our members keep current on hospital medicine news, but it also provides an outlet to voice opinions and help influence the direction of the society.

Podcasts

For those of you who enjoy auditory learning, you will find podcasts attached to event pages and CME listings. Our podcast library features guests, such as featured keynote speakers, industry specialists, SHM board members, and event attendees. Be on the lookout for SHM team members at upcoming events, as you may have the opportunity for a podcast interview of your own!

RSS Feeds

In June 2008 SHM created its own RSS feed, offering biweekly updates. Subscribers to SHM’s RSS feed receive up-to-the minute news streaming to their e-mail/PDAs, with updates ranging from SHM’s organizational growth and development to relative changes in legislation/public policy and anything relating to hospital medicine. Subscribe today so that you don’t miss the most current updates to hospitalmedicine.org.

Social Networking

Networking always has been one of the most important benefits of SHM membership. From communicating with local hospitalists at chapter meetings, to national and international colleagues at our annual meeting, there is a sense of community among those in the hospital medicine field. SHM recognizes the importance of building this community and has taken networking to a new level through participation in social networking sites such as Facebook and LinkedIn. If you currently are a user of these sites, join the SHM group and get connected!

All of these resources are at your fingertips. Visit us online at www.hospitalmedicine.org to try out one or all of these new features and upgrade your SHM experience. TH

Mixed Messages Called Out

I am a hospitalist outsider. A traditional internist, I cared for my patients in and out of the hospital, provided ICU and unassigned ED call, and later transitioned to hospital-only work. Our group developed a hospitalist program and has, hopefully, run an above-average system growing with our community. Even performing full-time hospital work, it took me a year to get over being referred to as a “hospitalist.” It seemed a confining label.

I also feel like an outsider while reading hospitalist literature’s divergent messages to hospitalists. On one hand, I hear great things about how hospitalists will revolutionize healthcare, spearheading improvements in safety, efficiency, and satisfaction, and filling administrative roles. I then see articles about negotiating out of working nights and weekends, about how the productivity of hospitalists remains stagnant but subsidy demands increase, and about how to limit caseloads. I see articles about hospitalist groups becoming privately held corporations, sending revenue that physicians generate (and hospitals subsidize) into the pockets of private investors.

There are two growing hospitalist camps. The first is filled with strategic thinkers driven to fix inefficient hospital care and save each of those 100,000 Institute of Medicine lives. These are the chief residents of yesterday, academically oriented problem solvers with IT savvy and a propensity for coffee-fueled all-nighters. You know them within your hospitalist groups and medical staffs.

The second camp consists of the lifestyle hospitalists; those for whom salary and 16 shifts a month are the goals that supersede professional loyalty to any particular group. These are the physicians who can help meet various metrics but want nothing to do with designing them.

These two groups read the literature with different eyes and career aspirations. As this division spreads, I strain to hear a drowning voice regarding another physician role: our responsibility to our patients. Drowning because both camps are swimming away from the patient, one toward a desk job, the other to a defined shift schedule.

Caring for patients is why we are in medicine in the first place. Most hospitalists came from primary care residencies, so the rewards of lifestyle and money must have been less important than direct patient contact. Primary care graduates entered traditional practices, promptly encountering the headaches of running a practice. Then suddenly a plum job with higher compensation and limited work hours was born, and, unsurprisingly, the primary care fields lost physicians to the hospitalist movement.

For new hospitalists exiting residency, there is no institutional knowledge of the old ways, and while they are not perfect, there are some noble qualities. Dedication to the profession is one, as is an enduring responsibility to one’s patient. Medicine required an occasional need to interrupt personal interests to help a sick human being—a patient—through a difficult time. For those physicians with traditional experience, can you recall articles suggesting negotiating for no nights and weekends? I’m not sure who we expect to provide this care to our patients if we can negotiate out of working.

There are certainly drawbacks to the traditional system: strained family relationships, substance abuse, and poor work-life balance—but don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater. These values elevated medicine to the position it holds today: a respected and well-compensated profession. I fear this young hospitalist specialty may not live up to its hype or responsibilities if hospitalists are motivated to focus on their “job” rather that their duties as the “doctor.” So what to do?

I think this can be a specialty that identifies members as physicians first and hospitalists second through the expectations of our peers in our own groups, medical staffs, and physician societies. We need to grow our groups with physicians dedicated not just to their partners, but the physician community at large; with those who want to improve care not just by meeting myocardial infarction guidelines, but with those who work with other physicians to help the patient manage their heart disease for 30 years; with physicians who ask about quality, teamwork, and the local community during the job interview and don’t begin with salary, patient caps, and weekend limitations.

Hospitalist group leaders need to expect these traits from their physicians. Otherwise practicing hospitalists will forever remain glorified residents and not leaders.

SHM needs to promote and recognize the values of being a physician in this field, instead of patting itself on the back for how trailblazing hospitalists could be while simultaneously ignoring what we are. TH

Edward Norman, MD, Internist/Hospitalist, Loveland, Colo.

I am a hospitalist outsider. A traditional internist, I cared for my patients in and out of the hospital, provided ICU and unassigned ED call, and later transitioned to hospital-only work. Our group developed a hospitalist program and has, hopefully, run an above-average system growing with our community. Even performing full-time hospital work, it took me a year to get over being referred to as a “hospitalist.” It seemed a confining label.

I also feel like an outsider while reading hospitalist literature’s divergent messages to hospitalists. On one hand, I hear great things about how hospitalists will revolutionize healthcare, spearheading improvements in safety, efficiency, and satisfaction, and filling administrative roles. I then see articles about negotiating out of working nights and weekends, about how the productivity of hospitalists remains stagnant but subsidy demands increase, and about how to limit caseloads. I see articles about hospitalist groups becoming privately held corporations, sending revenue that physicians generate (and hospitals subsidize) into the pockets of private investors.

There are two growing hospitalist camps. The first is filled with strategic thinkers driven to fix inefficient hospital care and save each of those 100,000 Institute of Medicine lives. These are the chief residents of yesterday, academically oriented problem solvers with IT savvy and a propensity for coffee-fueled all-nighters. You know them within your hospitalist groups and medical staffs.

The second camp consists of the lifestyle hospitalists; those for whom salary and 16 shifts a month are the goals that supersede professional loyalty to any particular group. These are the physicians who can help meet various metrics but want nothing to do with designing them.

These two groups read the literature with different eyes and career aspirations. As this division spreads, I strain to hear a drowning voice regarding another physician role: our responsibility to our patients. Drowning because both camps are swimming away from the patient, one toward a desk job, the other to a defined shift schedule.

Caring for patients is why we are in medicine in the first place. Most hospitalists came from primary care residencies, so the rewards of lifestyle and money must have been less important than direct patient contact. Primary care graduates entered traditional practices, promptly encountering the headaches of running a practice. Then suddenly a plum job with higher compensation and limited work hours was born, and, unsurprisingly, the primary care fields lost physicians to the hospitalist movement.

For new hospitalists exiting residency, there is no institutional knowledge of the old ways, and while they are not perfect, there are some noble qualities. Dedication to the profession is one, as is an enduring responsibility to one’s patient. Medicine required an occasional need to interrupt personal interests to help a sick human being—a patient—through a difficult time. For those physicians with traditional experience, can you recall articles suggesting negotiating for no nights and weekends? I’m not sure who we expect to provide this care to our patients if we can negotiate out of working.

There are certainly drawbacks to the traditional system: strained family relationships, substance abuse, and poor work-life balance—but don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater. These values elevated medicine to the position it holds today: a respected and well-compensated profession. I fear this young hospitalist specialty may not live up to its hype or responsibilities if hospitalists are motivated to focus on their “job” rather that their duties as the “doctor.” So what to do?

I think this can be a specialty that identifies members as physicians first and hospitalists second through the expectations of our peers in our own groups, medical staffs, and physician societies. We need to grow our groups with physicians dedicated not just to their partners, but the physician community at large; with those who want to improve care not just by meeting myocardial infarction guidelines, but with those who work with other physicians to help the patient manage their heart disease for 30 years; with physicians who ask about quality, teamwork, and the local community during the job interview and don’t begin with salary, patient caps, and weekend limitations.

Hospitalist group leaders need to expect these traits from their physicians. Otherwise practicing hospitalists will forever remain glorified residents and not leaders.

SHM needs to promote and recognize the values of being a physician in this field, instead of patting itself on the back for how trailblazing hospitalists could be while simultaneously ignoring what we are. TH

Edward Norman, MD, Internist/Hospitalist, Loveland, Colo.

I am a hospitalist outsider. A traditional internist, I cared for my patients in and out of the hospital, provided ICU and unassigned ED call, and later transitioned to hospital-only work. Our group developed a hospitalist program and has, hopefully, run an above-average system growing with our community. Even performing full-time hospital work, it took me a year to get over being referred to as a “hospitalist.” It seemed a confining label.

I also feel like an outsider while reading hospitalist literature’s divergent messages to hospitalists. On one hand, I hear great things about how hospitalists will revolutionize healthcare, spearheading improvements in safety, efficiency, and satisfaction, and filling administrative roles. I then see articles about negotiating out of working nights and weekends, about how the productivity of hospitalists remains stagnant but subsidy demands increase, and about how to limit caseloads. I see articles about hospitalist groups becoming privately held corporations, sending revenue that physicians generate (and hospitals subsidize) into the pockets of private investors.

There are two growing hospitalist camps. The first is filled with strategic thinkers driven to fix inefficient hospital care and save each of those 100,000 Institute of Medicine lives. These are the chief residents of yesterday, academically oriented problem solvers with IT savvy and a propensity for coffee-fueled all-nighters. You know them within your hospitalist groups and medical staffs.

The second camp consists of the lifestyle hospitalists; those for whom salary and 16 shifts a month are the goals that supersede professional loyalty to any particular group. These are the physicians who can help meet various metrics but want nothing to do with designing them.

These two groups read the literature with different eyes and career aspirations. As this division spreads, I strain to hear a drowning voice regarding another physician role: our responsibility to our patients. Drowning because both camps are swimming away from the patient, one toward a desk job, the other to a defined shift schedule.

Caring for patients is why we are in medicine in the first place. Most hospitalists came from primary care residencies, so the rewards of lifestyle and money must have been less important than direct patient contact. Primary care graduates entered traditional practices, promptly encountering the headaches of running a practice. Then suddenly a plum job with higher compensation and limited work hours was born, and, unsurprisingly, the primary care fields lost physicians to the hospitalist movement.

For new hospitalists exiting residency, there is no institutional knowledge of the old ways, and while they are not perfect, there are some noble qualities. Dedication to the profession is one, as is an enduring responsibility to one’s patient. Medicine required an occasional need to interrupt personal interests to help a sick human being—a patient—through a difficult time. For those physicians with traditional experience, can you recall articles suggesting negotiating for no nights and weekends? I’m not sure who we expect to provide this care to our patients if we can negotiate out of working.

There are certainly drawbacks to the traditional system: strained family relationships, substance abuse, and poor work-life balance—but don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater. These values elevated medicine to the position it holds today: a respected and well-compensated profession. I fear this young hospitalist specialty may not live up to its hype or responsibilities if hospitalists are motivated to focus on their “job” rather that their duties as the “doctor.” So what to do?

I think this can be a specialty that identifies members as physicians first and hospitalists second through the expectations of our peers in our own groups, medical staffs, and physician societies. We need to grow our groups with physicians dedicated not just to their partners, but the physician community at large; with those who want to improve care not just by meeting myocardial infarction guidelines, but with those who work with other physicians to help the patient manage their heart disease for 30 years; with physicians who ask about quality, teamwork, and the local community during the job interview and don’t begin with salary, patient caps, and weekend limitations.

Hospitalist group leaders need to expect these traits from their physicians. Otherwise practicing hospitalists will forever remain glorified residents and not leaders.

SHM needs to promote and recognize the values of being a physician in this field, instead of patting itself on the back for how trailblazing hospitalists could be while simultaneously ignoring what we are. TH

Edward Norman, MD, Internist/Hospitalist, Loveland, Colo.

Do post-discharge telephone calls to patients reduce the rate of complications?

Case

A 75-year-old male with history of diabetes and heart disease is discharged from the hospital after treatment for pneumonia. He has eight medications on his discharge list and is given two new prescriptions at discharge. He has a primary care provider but will not be able to see her until three weeks after discharge. Will a follow-up call decrease potential complications?

Overview

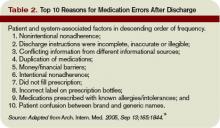

Medication errors are prevalent, especially during the transition period from discharge to follow-up with primary care physicians. There are more than 700,000 emergency department (ED) visits each year for adverse drug events with nearly 120,000 of these episodes resulting in hospitalization.1

The likelihood of an adverse drug event increases in patients using more than five medications and when there is a lack of understanding of how and why they are taking certain medications, scenarios common on hospital discharge.2 Studies evaluating effective means to reduce medication errors during transitions out of the hospital offer few solutions. One effective method, however, appears to be follow-up telephone calls.

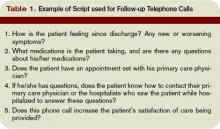

Telephone calls have been looked at in multiple studies and usually are performed in the studies by nurses, nurse practitioners, or pharmacists and occur within days of discharge from the hospital. These calls offer a mechanism to provide answers to questions about their medical condition or medications.

Review of the Data

There is a wide range of studies evaluating the benefit of a post-discharge telephone call. Unfortunately, most of the data are of low methodological quality with low patient numbers and high risk of bias.3

Much of the data are divided into subgroups of patients, including ED patients, cardiac patients, surgical patients, medicine patients, and other small groups. The end points also vary and examine areas such as patient satisfaction, reduction in medication errors, and effect on readmissions or repeat ED visits. The bulk of studies used a standardized script. These calls lasted only minutes, which could make it user-friendly, especially for a busy hospitalist’s schedule. Unfortunately, the effect of these interventions is mixed.

With ED patients, phone calls have been shown to be an effective means of communication between patients and physicians. In a study of 297 patients, the authors were only able to reach half the patients but still were able to identify medical problems needing referral or further intervention in 37% of the patients contacted.4 Another two studies revealed similar results with approximately 40% of the contacted patients requiring further clarification on their discharge instructions.5,6

Importantly, 95% of these patients felt the call was beneficial. Thus, more than one-third of patients discharged from an ED are likely to have problems and a follow-up telephone call offers an opportunity to intervene on these potential problems. Another ED study evaluated patients older than 75 and found a nurse liaison could effectively assess the complexity of a patient’s questions and appropriately advise them over the phone or triage them to the correct care provider for further care.7

Post-discharge follow-up telephone calls also can benefit patients discharged from the hospital. A recent paper reported that approximately 12% of patients develop new or worsening symptoms within a few days post-discharge and adverse drug events can occur in between 23% to 49% of people during this transition period.8-10

Another study evaluating resource use in heart failure patients found follow-up telephone calls significantly decreased the average number of hospital days over six months time and readmission rate at six months in the call group, as well as increased patient satisfaction.11

A randomized placebo-controlled trial evaluating follow-up calls from pharmacists to discharged medical patients found the call group patients were more satisfied with their post-discharge care. Additionally, there were less ED visits within 30 days of discharge in the call group compared to placebo or standard care.12

On the other hand, several studies have questioned the utility of follow-up telephone calls for improving transitions of care. A Stanford University group divided medical and surgical patients into three groups with one receiving routine follow-up calls, another requiring a patient-initiated call and a final group without any intervention and found there was no difference between these groups in regards to patient satisfaction or 30-day readmission rates.13

An outpatient trial completed at a South Dakota Veterans Affairs clinic also determined telephone calls had little effect on decreasing resources or hospital admissions.14

Although this study did not include inpatients, it demonstrates the fact that follow-up telephone calls may not be as helpful as shown in other trials and that more thorough and well-designed trials are needed to more definitively answer this question.

Back to the Case

The hospitalist makes a call to the patient to follow-up after he is discharged, and he says he is glad she called. He had questions about one of his medications that was discontinued while he was hospitalized and wants to know if he should restart it. He also says he is having low-grade fevers again and is not sure if he should come back in for evaluation.

The hospitalist is able to answer his questions about his medication list and instructs him to restart the metformin they had stopped while he was an inpatient. The hospitalist also is able to better explain what symptoms to be aware of and when the patient should come in for re-evaluation. The patient appreciates the five-minute call, and the hospitalist is glad she cleared up the patient’s confusion regarding his medications before a serious error or unnecessary readmission to the hospital occurred. TH

Dr. Moulds is a third-year internal medicine resident at the University of Colorado Denver. Dr. Epstein is director of medical affairs and clinical research at IPC-The Hospitalist Company.

References

- www.cdc.gov.

- Epstein K, Juarez E, Loya K, Gorman MJ, Singer A. Frequency of new or worsening symptoms in the post-hospitalization period. J Hosp Med. 2007 Mar;2(2):58-68.

- Mistiaen P, Poot E. Telephone follow-up, initiated by a hospital-based health professional, for post-discharge problems in patients discharged from hospital to home. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006, Issue 4. Art. No.: CD004510. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD004510.pub3.

- Shesser R, Smith M, Adams S, Walls R, Paxton M. The effectiveness of an organized follow-up system. Ann Emerg Med. 1986 Aug;15(8):911-915.

- Jones J, Clark W, Bradford J, Dougherty J. Efficacy of a telephone follow-up system in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 1988 May-June;6(3):249-254.

- Jones JS, Young MS, LaFleur RA, Brown MD. Effectiveness of an organized follow-up system for elder patients released from the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 1997 Dec;4(12):1147-1152.

- Poncia HD, Ryan J, Carver M. Next day telephone follow up of the elderly: a needs assessment and critical incident monitoring tool for the accident and emergency department. J Accid Emerg Med. 2000 Sep;17(5):337-340.

- Kripalani S, Price M, Vigil V, Epstein K. Frequency and predictors of prescription-related issues after hospital discharge. J Hosp Med. 2008 Jan/Feb;3(1):12-19.

- Forster A, Murff H, Peterson J, Gandhi T, Bates D. Adverse drug events occurring following hospital discharge. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:317-323.

- Forster A, Murff H, Peterson J, Gandhi T, Bates D. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:161-167.

- Riegel B, Carlson B, Kopp Z, LePetri B, Glaser D, Unger A. Effect of a standardized nurse case-management telephone intervention on resource use in patients with chronic heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 2002 Mar 25;162(6):705-712.

- Dudas V, Bookwalter T, Kerr KM, Pantilat SZ. The impact of follow-up telephone calls to patients after hospitalization. Am J Med. 2001 Dec 21;111(9B):26S-30S.

- Bostrom J, Caldwell J, McGuire K, Everson D. Telephone follow-up after discharge from the hospital: does it make a difference? Appl Nurs Res. 1996 May;9(2):47-52.

- Welch HG, Johnson DJ, Edson R. Telephone care as an adjunct to routine medical follow-up. A negative randomized trial. Eff Clin Pract. 2000 May-June;3(3):123-130.

- Coleman E, Smith J, Raha D, Min S. Posthospital medication discrepancies. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1842-1847.

Case

A 75-year-old male with history of diabetes and heart disease is discharged from the hospital after treatment for pneumonia. He has eight medications on his discharge list and is given two new prescriptions at discharge. He has a primary care provider but will not be able to see her until three weeks after discharge. Will a follow-up call decrease potential complications?

Overview

Medication errors are prevalent, especially during the transition period from discharge to follow-up with primary care physicians. There are more than 700,000 emergency department (ED) visits each year for adverse drug events with nearly 120,000 of these episodes resulting in hospitalization.1

The likelihood of an adverse drug event increases in patients using more than five medications and when there is a lack of understanding of how and why they are taking certain medications, scenarios common on hospital discharge.2 Studies evaluating effective means to reduce medication errors during transitions out of the hospital offer few solutions. One effective method, however, appears to be follow-up telephone calls.

Telephone calls have been looked at in multiple studies and usually are performed in the studies by nurses, nurse practitioners, or pharmacists and occur within days of discharge from the hospital. These calls offer a mechanism to provide answers to questions about their medical condition or medications.

Review of the Data

There is a wide range of studies evaluating the benefit of a post-discharge telephone call. Unfortunately, most of the data are of low methodological quality with low patient numbers and high risk of bias.3

Much of the data are divided into subgroups of patients, including ED patients, cardiac patients, surgical patients, medicine patients, and other small groups. The end points also vary and examine areas such as patient satisfaction, reduction in medication errors, and effect on readmissions or repeat ED visits. The bulk of studies used a standardized script. These calls lasted only minutes, which could make it user-friendly, especially for a busy hospitalist’s schedule. Unfortunately, the effect of these interventions is mixed.

With ED patients, phone calls have been shown to be an effective means of communication between patients and physicians. In a study of 297 patients, the authors were only able to reach half the patients but still were able to identify medical problems needing referral or further intervention in 37% of the patients contacted.4 Another two studies revealed similar results with approximately 40% of the contacted patients requiring further clarification on their discharge instructions.5,6

Importantly, 95% of these patients felt the call was beneficial. Thus, more than one-third of patients discharged from an ED are likely to have problems and a follow-up telephone call offers an opportunity to intervene on these potential problems. Another ED study evaluated patients older than 75 and found a nurse liaison could effectively assess the complexity of a patient’s questions and appropriately advise them over the phone or triage them to the correct care provider for further care.7

Post-discharge follow-up telephone calls also can benefit patients discharged from the hospital. A recent paper reported that approximately 12% of patients develop new or worsening symptoms within a few days post-discharge and adverse drug events can occur in between 23% to 49% of people during this transition period.8-10

Another study evaluating resource use in heart failure patients found follow-up telephone calls significantly decreased the average number of hospital days over six months time and readmission rate at six months in the call group, as well as increased patient satisfaction.11

A randomized placebo-controlled trial evaluating follow-up calls from pharmacists to discharged medical patients found the call group patients were more satisfied with their post-discharge care. Additionally, there were less ED visits within 30 days of discharge in the call group compared to placebo or standard care.12

On the other hand, several studies have questioned the utility of follow-up telephone calls for improving transitions of care. A Stanford University group divided medical and surgical patients into three groups with one receiving routine follow-up calls, another requiring a patient-initiated call and a final group without any intervention and found there was no difference between these groups in regards to patient satisfaction or 30-day readmission rates.13

An outpatient trial completed at a South Dakota Veterans Affairs clinic also determined telephone calls had little effect on decreasing resources or hospital admissions.14

Although this study did not include inpatients, it demonstrates the fact that follow-up telephone calls may not be as helpful as shown in other trials and that more thorough and well-designed trials are needed to more definitively answer this question.

Back to the Case

The hospitalist makes a call to the patient to follow-up after he is discharged, and he says he is glad she called. He had questions about one of his medications that was discontinued while he was hospitalized and wants to know if he should restart it. He also says he is having low-grade fevers again and is not sure if he should come back in for evaluation.

The hospitalist is able to answer his questions about his medication list and instructs him to restart the metformin they had stopped while he was an inpatient. The hospitalist also is able to better explain what symptoms to be aware of and when the patient should come in for re-evaluation. The patient appreciates the five-minute call, and the hospitalist is glad she cleared up the patient’s confusion regarding his medications before a serious error or unnecessary readmission to the hospital occurred. TH

Dr. Moulds is a third-year internal medicine resident at the University of Colorado Denver. Dr. Epstein is director of medical affairs and clinical research at IPC-The Hospitalist Company.

References

- www.cdc.gov.

- Epstein K, Juarez E, Loya K, Gorman MJ, Singer A. Frequency of new or worsening symptoms in the post-hospitalization period. J Hosp Med. 2007 Mar;2(2):58-68.

- Mistiaen P, Poot E. Telephone follow-up, initiated by a hospital-based health professional, for post-discharge problems in patients discharged from hospital to home. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006, Issue 4. Art. No.: CD004510. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD004510.pub3.

- Shesser R, Smith M, Adams S, Walls R, Paxton M. The effectiveness of an organized follow-up system. Ann Emerg Med. 1986 Aug;15(8):911-915.

- Jones J, Clark W, Bradford J, Dougherty J. Efficacy of a telephone follow-up system in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 1988 May-June;6(3):249-254.

- Jones JS, Young MS, LaFleur RA, Brown MD. Effectiveness of an organized follow-up system for elder patients released from the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 1997 Dec;4(12):1147-1152.

- Poncia HD, Ryan J, Carver M. Next day telephone follow up of the elderly: a needs assessment and critical incident monitoring tool for the accident and emergency department. J Accid Emerg Med. 2000 Sep;17(5):337-340.

- Kripalani S, Price M, Vigil V, Epstein K. Frequency and predictors of prescription-related issues after hospital discharge. J Hosp Med. 2008 Jan/Feb;3(1):12-19.

- Forster A, Murff H, Peterson J, Gandhi T, Bates D. Adverse drug events occurring following hospital discharge. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:317-323.

- Forster A, Murff H, Peterson J, Gandhi T, Bates D. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:161-167.

- Riegel B, Carlson B, Kopp Z, LePetri B, Glaser D, Unger A. Effect of a standardized nurse case-management telephone intervention on resource use in patients with chronic heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 2002 Mar 25;162(6):705-712.

- Dudas V, Bookwalter T, Kerr KM, Pantilat SZ. The impact of follow-up telephone calls to patients after hospitalization. Am J Med. 2001 Dec 21;111(9B):26S-30S.

- Bostrom J, Caldwell J, McGuire K, Everson D. Telephone follow-up after discharge from the hospital: does it make a difference? Appl Nurs Res. 1996 May;9(2):47-52.

- Welch HG, Johnson DJ, Edson R. Telephone care as an adjunct to routine medical follow-up. A negative randomized trial. Eff Clin Pract. 2000 May-June;3(3):123-130.

- Coleman E, Smith J, Raha D, Min S. Posthospital medication discrepancies. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1842-1847.

Case

A 75-year-old male with history of diabetes and heart disease is discharged from the hospital after treatment for pneumonia. He has eight medications on his discharge list and is given two new prescriptions at discharge. He has a primary care provider but will not be able to see her until three weeks after discharge. Will a follow-up call decrease potential complications?

Overview

Medication errors are prevalent, especially during the transition period from discharge to follow-up with primary care physicians. There are more than 700,000 emergency department (ED) visits each year for adverse drug events with nearly 120,000 of these episodes resulting in hospitalization.1

The likelihood of an adverse drug event increases in patients using more than five medications and when there is a lack of understanding of how and why they are taking certain medications, scenarios common on hospital discharge.2 Studies evaluating effective means to reduce medication errors during transitions out of the hospital offer few solutions. One effective method, however, appears to be follow-up telephone calls.

Telephone calls have been looked at in multiple studies and usually are performed in the studies by nurses, nurse practitioners, or pharmacists and occur within days of discharge from the hospital. These calls offer a mechanism to provide answers to questions about their medical condition or medications.

Review of the Data

There is a wide range of studies evaluating the benefit of a post-discharge telephone call. Unfortunately, most of the data are of low methodological quality with low patient numbers and high risk of bias.3

Much of the data are divided into subgroups of patients, including ED patients, cardiac patients, surgical patients, medicine patients, and other small groups. The end points also vary and examine areas such as patient satisfaction, reduction in medication errors, and effect on readmissions or repeat ED visits. The bulk of studies used a standardized script. These calls lasted only minutes, which could make it user-friendly, especially for a busy hospitalist’s schedule. Unfortunately, the effect of these interventions is mixed.

With ED patients, phone calls have been shown to be an effective means of communication between patients and physicians. In a study of 297 patients, the authors were only able to reach half the patients but still were able to identify medical problems needing referral or further intervention in 37% of the patients contacted.4 Another two studies revealed similar results with approximately 40% of the contacted patients requiring further clarification on their discharge instructions.5,6

Importantly, 95% of these patients felt the call was beneficial. Thus, more than one-third of patients discharged from an ED are likely to have problems and a follow-up telephone call offers an opportunity to intervene on these potential problems. Another ED study evaluated patients older than 75 and found a nurse liaison could effectively assess the complexity of a patient’s questions and appropriately advise them over the phone or triage them to the correct care provider for further care.7

Post-discharge follow-up telephone calls also can benefit patients discharged from the hospital. A recent paper reported that approximately 12% of patients develop new or worsening symptoms within a few days post-discharge and adverse drug events can occur in between 23% to 49% of people during this transition period.8-10

Another study evaluating resource use in heart failure patients found follow-up telephone calls significantly decreased the average number of hospital days over six months time and readmission rate at six months in the call group, as well as increased patient satisfaction.11

A randomized placebo-controlled trial evaluating follow-up calls from pharmacists to discharged medical patients found the call group patients were more satisfied with their post-discharge care. Additionally, there were less ED visits within 30 days of discharge in the call group compared to placebo or standard care.12

On the other hand, several studies have questioned the utility of follow-up telephone calls for improving transitions of care. A Stanford University group divided medical and surgical patients into three groups with one receiving routine follow-up calls, another requiring a patient-initiated call and a final group without any intervention and found there was no difference between these groups in regards to patient satisfaction or 30-day readmission rates.13

An outpatient trial completed at a South Dakota Veterans Affairs clinic also determined telephone calls had little effect on decreasing resources or hospital admissions.14

Although this study did not include inpatients, it demonstrates the fact that follow-up telephone calls may not be as helpful as shown in other trials and that more thorough and well-designed trials are needed to more definitively answer this question.

Back to the Case

The hospitalist makes a call to the patient to follow-up after he is discharged, and he says he is glad she called. He had questions about one of his medications that was discontinued while he was hospitalized and wants to know if he should restart it. He also says he is having low-grade fevers again and is not sure if he should come back in for evaluation.

The hospitalist is able to answer his questions about his medication list and instructs him to restart the metformin they had stopped while he was an inpatient. The hospitalist also is able to better explain what symptoms to be aware of and when the patient should come in for re-evaluation. The patient appreciates the five-minute call, and the hospitalist is glad she cleared up the patient’s confusion regarding his medications before a serious error or unnecessary readmission to the hospital occurred. TH

Dr. Moulds is a third-year internal medicine resident at the University of Colorado Denver. Dr. Epstein is director of medical affairs and clinical research at IPC-The Hospitalist Company.

References

- www.cdc.gov.

- Epstein K, Juarez E, Loya K, Gorman MJ, Singer A. Frequency of new or worsening symptoms in the post-hospitalization period. J Hosp Med. 2007 Mar;2(2):58-68.

- Mistiaen P, Poot E. Telephone follow-up, initiated by a hospital-based health professional, for post-discharge problems in patients discharged from hospital to home. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006, Issue 4. Art. No.: CD004510. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD004510.pub3.

- Shesser R, Smith M, Adams S, Walls R, Paxton M. The effectiveness of an organized follow-up system. Ann Emerg Med. 1986 Aug;15(8):911-915.

- Jones J, Clark W, Bradford J, Dougherty J. Efficacy of a telephone follow-up system in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 1988 May-June;6(3):249-254.

- Jones JS, Young MS, LaFleur RA, Brown MD. Effectiveness of an organized follow-up system for elder patients released from the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 1997 Dec;4(12):1147-1152.

- Poncia HD, Ryan J, Carver M. Next day telephone follow up of the elderly: a needs assessment and critical incident monitoring tool for the accident and emergency department. J Accid Emerg Med. 2000 Sep;17(5):337-340.

- Kripalani S, Price M, Vigil V, Epstein K. Frequency and predictors of prescription-related issues after hospital discharge. J Hosp Med. 2008 Jan/Feb;3(1):12-19.

- Forster A, Murff H, Peterson J, Gandhi T, Bates D. Adverse drug events occurring following hospital discharge. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:317-323.

- Forster A, Murff H, Peterson J, Gandhi T, Bates D. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:161-167.

- Riegel B, Carlson B, Kopp Z, LePetri B, Glaser D, Unger A. Effect of a standardized nurse case-management telephone intervention on resource use in patients with chronic heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 2002 Mar 25;162(6):705-712.

- Dudas V, Bookwalter T, Kerr KM, Pantilat SZ. The impact of follow-up telephone calls to patients after hospitalization. Am J Med. 2001 Dec 21;111(9B):26S-30S.

- Bostrom J, Caldwell J, McGuire K, Everson D. Telephone follow-up after discharge from the hospital: does it make a difference? Appl Nurs Res. 1996 May;9(2):47-52.

- Welch HG, Johnson DJ, Edson R. Telephone care as an adjunct to routine medical follow-up. A negative randomized trial. Eff Clin Pract. 2000 May-June;3(3):123-130.

- Coleman E, Smith J, Raha D, Min S. Posthospital medication discrepancies. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1842-1847.

Seek Work Wisely

Hospital medicine has come a long way since the term hospitalist was coined slightly more than a decade ago. SHM estimates the need for 30,000 practicing hospitalists within the next decade.

Filling an available hospitalist position is a two-way process that involves considerations and negotiations at various levels. When looking for the suitable hospitalist job, it is critical that you think both about what your potential employer needs and what you expect from the role you seek. The following insights provide a gauge of what an employer is looking for in a hospitalist applicant.

1) Clinical and procedural skills. Good clinical acumen is fundamental to being a successful hospitalist. As you complete residency training, your professional references are a reliable means for others to judge clinical skills. It’s important that your references comment on your clinical proficiency in their letters. Procedural skills always are welcome but by no means mandatory.

In larger facilities, where residents in training or specialists do many procedures, the program may not insist on procedural skills. On the other hand, some hospital medicine programs may require a proficiency in ICU procedures, which include intubations, central line placement, and A-line placements to mention a few. The SHM publication The Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine: A Framework for Curriculum Development is a great resource for understanding the knowledge and skills expected of a hospitalist physician.

2) Professionalism and teamwork. There are an extraordinary number of healthcare providers a hospitalist needs to work with. In addition to establishing a courteous rapport with patients and their families, good communication with primary care physicians, specialists, nursing staff, case managers, midlevel providers, and administrative and secretarial staff is essential. With this diversity of interactions, professionalism and teamwork are highly regarded and go a long way in establishing you as proficient hospitalist. An applicant’s professionalism is not only judged during the interview period but also confirmed by references. An unwavering positive attitude and commitment to a healthy work environment also are attributes that are recognized by a potential employer.

3) Quality improvement focus. Quality improvement activities and participation in such programs have rightly received unprecedented attention. SHM data indicate that 86% of hospitalist groups are active in quality improvement initiatives. Many hospital medicine programs participate in some form of Medicare pay-for-performance initiatives in order to ensure evidence-based patient care, better health outcomes, and reduce preventable complications.

A commitment to and active interest in quality improvement is highly desirable. Prior participation in and/or research for programs such as venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis, inpatient glycemic control, fall preventions, CHF optimization, medicine reconciliation pathways, and other evidence-based measures are a definite plus. In addition, specific training in areas such as perioperative care, improving safety of transitions of care, and stroke management are beneficial. Elaborating on any systems enhancement projects undertaken especially during hospital medicine clinical rotations/electives and/or fellowships will be invaluable.

4) Leadership skills. Nonclinical and administrative responsibilities are an important element of many hospitalist programs. Interest in various committees and an ability to assume leadership roles reflect favorably on your application. A good hospital medicine program will often encourage your interest in fostering the program and invite your involvement in initiatives to promote good patient care and facilitate fiscal strength.

An applicant should inquire about opportunities to participate in organizational committees and develop leadership skills, as this will be important for your professional growth. Take the time to point out any previous committee involvement in national healthcare organizations such as SHM.

5) Workflow efficiency. The ability to multitask and be organized are great skills to have as a hospitalist. Hospitalist work often involves managing several things during a short time span (i.e., rounding, admitting, teaching, holding family conferences, answering pages, and running codes). Successfully completing these responsibilities involves patience, structure, and resourcefulness during the course of any given day.

6) Teaching and research skills. In academic hospital medicine programs, good teaching and research skills can be very desirable. Chief residency or assistant chief residency experience is a good sign of teaching experience. Participation in research projects will boost your chances when looking for an academic hospitalist job. In non-academic practices, the employer may not focus much on these skills. Nevertheless, it is of significant value when the practice also hires midlevel practitioners like nurse practitioners or physician’s assistants or is thinking about how to evaluate the effects of a new program or intervention.

7) Local ties and durability. In view of the significant demand for hospitalists, recruiting can be challenging for any program. Another important aspect an employer looks at is whether you have any local ties or other compelling reasons to stay in the area for a long time. If you do have some geographic attachments or other reasons to be in the area for an extended duration, it will make the program more receptive toward you. Also, obtaining or applying for state licensure will save significant time and put you ahead of the curve.

8) Board certification. Most programs require you to be board certified or eligible when hired. Many programs expect you to obtain board certification within one to two years of starting your job. The sooner this is accomplished the more beneficial for the applicant.

Other Considerations

The diversity of hospital medicine programs provides an array of opportunities to choose from. Broadly speaking, the practice type could be academic or community based. The choice would depend upon your interest and proficiency in teaching.

In terms of schedules offered, several models exist. Many hospitalist programs are increasingly becoming 24/7, and it may be expected that you work different shifts. Also look into the licensure requirements of the state where you want to practice and be prepared with the required documentation, as some states may take longer to issue the license.

Above all, always remember: As much as it is important for you to find a befitting job, it is similarly essential for hospital medicine programs to hire worthy and valuable physicians. TH

Dr. Asudani is assistant clinical professor of medicine and a hospitalist at Baystate Medical Center, Tufts School of Medicine. Dr. Gandla is program medical director, Cogent Healthcare, High Point Regional Health System.

Hospital medicine has come a long way since the term hospitalist was coined slightly more than a decade ago. SHM estimates the need for 30,000 practicing hospitalists within the next decade.

Filling an available hospitalist position is a two-way process that involves considerations and negotiations at various levels. When looking for the suitable hospitalist job, it is critical that you think both about what your potential employer needs and what you expect from the role you seek. The following insights provide a gauge of what an employer is looking for in a hospitalist applicant.

1) Clinical and procedural skills. Good clinical acumen is fundamental to being a successful hospitalist. As you complete residency training, your professional references are a reliable means for others to judge clinical skills. It’s important that your references comment on your clinical proficiency in their letters. Procedural skills always are welcome but by no means mandatory.

In larger facilities, where residents in training or specialists do many procedures, the program may not insist on procedural skills. On the other hand, some hospital medicine programs may require a proficiency in ICU procedures, which include intubations, central line placement, and A-line placements to mention a few. The SHM publication The Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine: A Framework for Curriculum Development is a great resource for understanding the knowledge and skills expected of a hospitalist physician.

2) Professionalism and teamwork. There are an extraordinary number of healthcare providers a hospitalist needs to work with. In addition to establishing a courteous rapport with patients and their families, good communication with primary care physicians, specialists, nursing staff, case managers, midlevel providers, and administrative and secretarial staff is essential. With this diversity of interactions, professionalism and teamwork are highly regarded and go a long way in establishing you as proficient hospitalist. An applicant’s professionalism is not only judged during the interview period but also confirmed by references. An unwavering positive attitude and commitment to a healthy work environment also are attributes that are recognized by a potential employer.

3) Quality improvement focus. Quality improvement activities and participation in such programs have rightly received unprecedented attention. SHM data indicate that 86% of hospitalist groups are active in quality improvement initiatives. Many hospital medicine programs participate in some form of Medicare pay-for-performance initiatives in order to ensure evidence-based patient care, better health outcomes, and reduce preventable complications.

A commitment to and active interest in quality improvement is highly desirable. Prior participation in and/or research for programs such as venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis, inpatient glycemic control, fall preventions, CHF optimization, medicine reconciliation pathways, and other evidence-based measures are a definite plus. In addition, specific training in areas such as perioperative care, improving safety of transitions of care, and stroke management are beneficial. Elaborating on any systems enhancement projects undertaken especially during hospital medicine clinical rotations/electives and/or fellowships will be invaluable.

4) Leadership skills. Nonclinical and administrative responsibilities are an important element of many hospitalist programs. Interest in various committees and an ability to assume leadership roles reflect favorably on your application. A good hospital medicine program will often encourage your interest in fostering the program and invite your involvement in initiatives to promote good patient care and facilitate fiscal strength.

An applicant should inquire about opportunities to participate in organizational committees and develop leadership skills, as this will be important for your professional growth. Take the time to point out any previous committee involvement in national healthcare organizations such as SHM.

5) Workflow efficiency. The ability to multitask and be organized are great skills to have as a hospitalist. Hospitalist work often involves managing several things during a short time span (i.e., rounding, admitting, teaching, holding family conferences, answering pages, and running codes). Successfully completing these responsibilities involves patience, structure, and resourcefulness during the course of any given day.

6) Teaching and research skills. In academic hospital medicine programs, good teaching and research skills can be very desirable. Chief residency or assistant chief residency experience is a good sign of teaching experience. Participation in research projects will boost your chances when looking for an academic hospitalist job. In non-academic practices, the employer may not focus much on these skills. Nevertheless, it is of significant value when the practice also hires midlevel practitioners like nurse practitioners or physician’s assistants or is thinking about how to evaluate the effects of a new program or intervention.

7) Local ties and durability. In view of the significant demand for hospitalists, recruiting can be challenging for any program. Another important aspect an employer looks at is whether you have any local ties or other compelling reasons to stay in the area for a long time. If you do have some geographic attachments or other reasons to be in the area for an extended duration, it will make the program more receptive toward you. Also, obtaining or applying for state licensure will save significant time and put you ahead of the curve.

8) Board certification. Most programs require you to be board certified or eligible when hired. Many programs expect you to obtain board certification within one to two years of starting your job. The sooner this is accomplished the more beneficial for the applicant.

Other Considerations

The diversity of hospital medicine programs provides an array of opportunities to choose from. Broadly speaking, the practice type could be academic or community based. The choice would depend upon your interest and proficiency in teaching.

In terms of schedules offered, several models exist. Many hospitalist programs are increasingly becoming 24/7, and it may be expected that you work different shifts. Also look into the licensure requirements of the state where you want to practice and be prepared with the required documentation, as some states may take longer to issue the license.

Above all, always remember: As much as it is important for you to find a befitting job, it is similarly essential for hospital medicine programs to hire worthy and valuable physicians. TH

Dr. Asudani is assistant clinical professor of medicine and a hospitalist at Baystate Medical Center, Tufts School of Medicine. Dr. Gandla is program medical director, Cogent Healthcare, High Point Regional Health System.

Hospital medicine has come a long way since the term hospitalist was coined slightly more than a decade ago. SHM estimates the need for 30,000 practicing hospitalists within the next decade.

Filling an available hospitalist position is a two-way process that involves considerations and negotiations at various levels. When looking for the suitable hospitalist job, it is critical that you think both about what your potential employer needs and what you expect from the role you seek. The following insights provide a gauge of what an employer is looking for in a hospitalist applicant.

1) Clinical and procedural skills. Good clinical acumen is fundamental to being a successful hospitalist. As you complete residency training, your professional references are a reliable means for others to judge clinical skills. It’s important that your references comment on your clinical proficiency in their letters. Procedural skills always are welcome but by no means mandatory.

In larger facilities, where residents in training or specialists do many procedures, the program may not insist on procedural skills. On the other hand, some hospital medicine programs may require a proficiency in ICU procedures, which include intubations, central line placement, and A-line placements to mention a few. The SHM publication The Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine: A Framework for Curriculum Development is a great resource for understanding the knowledge and skills expected of a hospitalist physician.

2) Professionalism and teamwork. There are an extraordinary number of healthcare providers a hospitalist needs to work with. In addition to establishing a courteous rapport with patients and their families, good communication with primary care physicians, specialists, nursing staff, case managers, midlevel providers, and administrative and secretarial staff is essential. With this diversity of interactions, professionalism and teamwork are highly regarded and go a long way in establishing you as proficient hospitalist. An applicant’s professionalism is not only judged during the interview period but also confirmed by references. An unwavering positive attitude and commitment to a healthy work environment also are attributes that are recognized by a potential employer.

3) Quality improvement focus. Quality improvement activities and participation in such programs have rightly received unprecedented attention. SHM data indicate that 86% of hospitalist groups are active in quality improvement initiatives. Many hospital medicine programs participate in some form of Medicare pay-for-performance initiatives in order to ensure evidence-based patient care, better health outcomes, and reduce preventable complications.

A commitment to and active interest in quality improvement is highly desirable. Prior participation in and/or research for programs such as venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis, inpatient glycemic control, fall preventions, CHF optimization, medicine reconciliation pathways, and other evidence-based measures are a definite plus. In addition, specific training in areas such as perioperative care, improving safety of transitions of care, and stroke management are beneficial. Elaborating on any systems enhancement projects undertaken especially during hospital medicine clinical rotations/electives and/or fellowships will be invaluable.

4) Leadership skills. Nonclinical and administrative responsibilities are an important element of many hospitalist programs. Interest in various committees and an ability to assume leadership roles reflect favorably on your application. A good hospital medicine program will often encourage your interest in fostering the program and invite your involvement in initiatives to promote good patient care and facilitate fiscal strength.

An applicant should inquire about opportunities to participate in organizational committees and develop leadership skills, as this will be important for your professional growth. Take the time to point out any previous committee involvement in national healthcare organizations such as SHM.

5) Workflow efficiency. The ability to multitask and be organized are great skills to have as a hospitalist. Hospitalist work often involves managing several things during a short time span (i.e., rounding, admitting, teaching, holding family conferences, answering pages, and running codes). Successfully completing these responsibilities involves patience, structure, and resourcefulness during the course of any given day.

6) Teaching and research skills. In academic hospital medicine programs, good teaching and research skills can be very desirable. Chief residency or assistant chief residency experience is a good sign of teaching experience. Participation in research projects will boost your chances when looking for an academic hospitalist job. In non-academic practices, the employer may not focus much on these skills. Nevertheless, it is of significant value when the practice also hires midlevel practitioners like nurse practitioners or physician’s assistants or is thinking about how to evaluate the effects of a new program or intervention.

7) Local ties and durability. In view of the significant demand for hospitalists, recruiting can be challenging for any program. Another important aspect an employer looks at is whether you have any local ties or other compelling reasons to stay in the area for a long time. If you do have some geographic attachments or other reasons to be in the area for an extended duration, it will make the program more receptive toward you. Also, obtaining or applying for state licensure will save significant time and put you ahead of the curve.

8) Board certification. Most programs require you to be board certified or eligible when hired. Many programs expect you to obtain board certification within one to two years of starting your job. The sooner this is accomplished the more beneficial for the applicant.

Other Considerations

The diversity of hospital medicine programs provides an array of opportunities to choose from. Broadly speaking, the practice type could be academic or community based. The choice would depend upon your interest and proficiency in teaching.

In terms of schedules offered, several models exist. Many hospitalist programs are increasingly becoming 24/7, and it may be expected that you work different shifts. Also look into the licensure requirements of the state where you want to practice and be prepared with the required documentation, as some states may take longer to issue the license.

Above all, always remember: As much as it is important for you to find a befitting job, it is similarly essential for hospital medicine programs to hire worthy and valuable physicians. TH

Dr. Asudani is assistant clinical professor of medicine and a hospitalist at Baystate Medical Center, Tufts School of Medicine. Dr. Gandla is program medical director, Cogent Healthcare, High Point Regional Health System.

Medical Board Maneuvers

There are a few pieces of mail that bring an instant feeling of dread—an audit letter from the IRS, a credit card bill after a Las Vegas vacation, and a letter from the medical board. We have no good solutions for the first two pieces of correspondence, but we have a few suggestions when communicating with the medical board.

1) Understand the medical board’s purpose. Every state regulates the practice of medicine for the same reason: Medicine requires highly specialized knowledge, and the average patient does not have the knowledge or experience to determine which physicians are qualified to practice.

Think of the harm that could result if incompetent physicians could practice medicine without oversight. Even worse, think of the harm that could result if non-physicians could provide medical services without proper education and training. That’s why, in every state, the legislatures have passed laws to regulate and control the practice of medicine so people can be properly protected against the unauthorized, unqualified, and improper practice of medicine. Almost everyone agrees regulation of this nature serves a legitimate public purpose.

Consequently, whenever a physician deals with a medical board, they are best served by remembering that the medical board exists to protect the public from the unauthorized, unqualified and improper practice of medicine. The physician’s ultimate goal is to reassure that medical board that their practice is authorized, well-grounded in medicine, and within the standards of professional care. Even if the patient has complained because of a questionable motive, such as attempting to gain an advantage in a billing dispute, a physician cannot use the patient’s motive as grounds for defending poor medical care. Medical boards often distrust physicians who try to shift the focus from the adequacy of their medical care to a patient’s shortcomings.

2) Do I need a lawyer? In most states, the medical board will ask a physician to respond to every patient complaint—even if the complaint is outlandish. Rather than judging the complaint when it arrives, the medical board is more interested in assessing the physician’s response to the complaint. An unhappy patient may lack the acumen to explain the course of treatment and the specifics of their condition, so the medical board relies upon the physician to describe their conduct and the course of care.

Unless the patient’s complaint is in the category of “the doctor placed transmitters in my brain and now the aliens won’t leave me alone,” we always recommend a physician review the complaint and the proposed response with an attorney. In every state, there are attorneys who specialize in representing physicians before medical boards.

Because they’ve dealt with the medical board in many cases throughout a number of years, these attorneys have a good idea of what the medical board expects to see in a response, and, more importantly, what the medical board does not want to see in a response. Investing in an attorney’s services at the outset is money well spent.

Far too often, we see physicians who tried to save a couple of hundred dollars by responding to the medical board, but their response was ineffective. The physician is then faced with spending several thousand dollars defending a disciplinary proceeding. Even worse, if the physician has made a sufficiently serious mistake in the initial response, the physician is going to be stuck with that mistake, severely limiting the attorney’s ability to defend the disciplinary proceeding. Some medical malpractice insurers reimburse physicians for attorney’s fees incurred in responding to a medical board complaint, so check your policy.

3) Candor is your friend. Undoubtedly, there are occasions when a patient complains about medical care without justification. Patients have unrealistic expectations and often fail to understand that each patient’s condition presents a unique challenge. Conversely, some complaints absolutely are legitimate. Every physician makes mistakes, and the medical board will react negatively to a physician who defends an unreasonable course of care. In fact, the medical board will view the physician’s defense of unreasonable care as evidence the mistake is not an aberration in the physician’s practice.

When confronted with one of those instances where the patient’s complaint is legitimate, we doubly recommend you confer with an attorney about your response. At a minimum, however, a physician must be able to explain:

- Why a mistake occurred;

- What steps the physician took to minimize the consequences of the mistake for the patient;

- Why the mistake represents an aberration, not a reason for continued concern; and

- What changes the physician has implemented to ensure the mistake will not reoccur.

In preparing a response to the medical board, we’ve recommended physicians take continuing education in the areas of the patients’ complaints. By taking this remedial measure voluntarily, a physician reduces the likelihood the medical board will impose it as a remedial sanction.