User login

Body sculpting, microneedling show strong growth

, according to a survey by the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery.

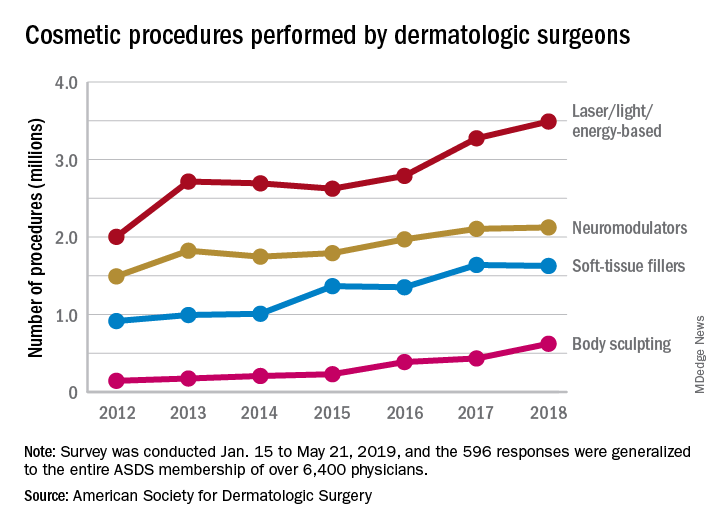

The society’s members performed an estimated 3.5 million laser/light/energy-based procedures and 2.1 million injectable neuromodulator procedures last year as the total volume of cosmetic treatments rose by more than 7% over 2017, the society reported. The total number of procedures in 2017 was 8.3 million, which represented an increase of 19% over 2016.

The largest percent increase in 2018 by type of procedure came in the body-sculpting sector, which jumped 43% from 2017 to 2018. In terms of the total number, however, body sculpting was well behind the other major categories of cosmetic treatments at 624,000 procedures performed. The most popular form of body sculpting last year was cryolipolysis (287,000 procedures), followed by radiofrequency (163,000), and deoxycholic acid (66,000), the ASDS reported.

“The coupling of scientific research and technology [is] driving innovative options for consumers seeking noninvasive cosmetic treatments,” said ASDS President Murad Alam, MD.

Among those newer options is microneedling, which was up by 45% over its 2017 total with almost 263,000 procedures in 2018. Another innovative treatment, thread lifts, in which temporary sutures visibly lift the skin around the face, appears to be gaining awareness as nearly 33,000 procedures were performed last year, according to the ASDS.

Year-over-year increases were smaller among the more established procedures: laser/light/energy-based procedures were up by 6.6%, injectable neuromodulators rose just 0.9%, injectable soft-tissue fillers were down 0.8%, and chemical peels increased by 2.4%, the society’s data show.

The survey was conducted among ASDS members from Jan. 15 to May 21, 2019, and the 596 responses were generalized to the entire ASDS membership of over 6,400 physicians.

, according to a survey by the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery.

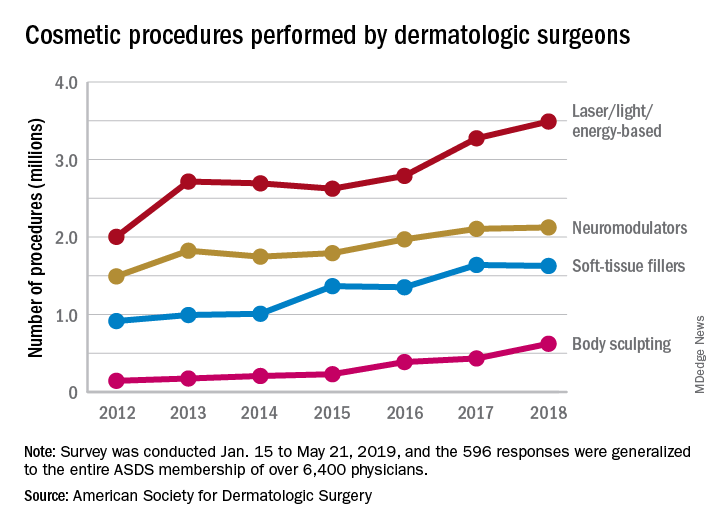

The society’s members performed an estimated 3.5 million laser/light/energy-based procedures and 2.1 million injectable neuromodulator procedures last year as the total volume of cosmetic treatments rose by more than 7% over 2017, the society reported. The total number of procedures in 2017 was 8.3 million, which represented an increase of 19% over 2016.

The largest percent increase in 2018 by type of procedure came in the body-sculpting sector, which jumped 43% from 2017 to 2018. In terms of the total number, however, body sculpting was well behind the other major categories of cosmetic treatments at 624,000 procedures performed. The most popular form of body sculpting last year was cryolipolysis (287,000 procedures), followed by radiofrequency (163,000), and deoxycholic acid (66,000), the ASDS reported.

“The coupling of scientific research and technology [is] driving innovative options for consumers seeking noninvasive cosmetic treatments,” said ASDS President Murad Alam, MD.

Among those newer options is microneedling, which was up by 45% over its 2017 total with almost 263,000 procedures in 2018. Another innovative treatment, thread lifts, in which temporary sutures visibly lift the skin around the face, appears to be gaining awareness as nearly 33,000 procedures were performed last year, according to the ASDS.

Year-over-year increases were smaller among the more established procedures: laser/light/energy-based procedures were up by 6.6%, injectable neuromodulators rose just 0.9%, injectable soft-tissue fillers were down 0.8%, and chemical peels increased by 2.4%, the society’s data show.

The survey was conducted among ASDS members from Jan. 15 to May 21, 2019, and the 596 responses were generalized to the entire ASDS membership of over 6,400 physicians.

, according to a survey by the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery.

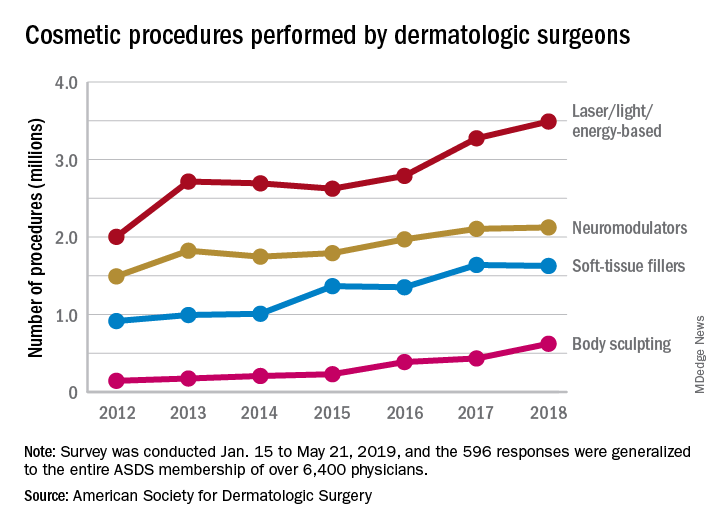

The society’s members performed an estimated 3.5 million laser/light/energy-based procedures and 2.1 million injectable neuromodulator procedures last year as the total volume of cosmetic treatments rose by more than 7% over 2017, the society reported. The total number of procedures in 2017 was 8.3 million, which represented an increase of 19% over 2016.

The largest percent increase in 2018 by type of procedure came in the body-sculpting sector, which jumped 43% from 2017 to 2018. In terms of the total number, however, body sculpting was well behind the other major categories of cosmetic treatments at 624,000 procedures performed. The most popular form of body sculpting last year was cryolipolysis (287,000 procedures), followed by radiofrequency (163,000), and deoxycholic acid (66,000), the ASDS reported.

“The coupling of scientific research and technology [is] driving innovative options for consumers seeking noninvasive cosmetic treatments,” said ASDS President Murad Alam, MD.

Among those newer options is microneedling, which was up by 45% over its 2017 total with almost 263,000 procedures in 2018. Another innovative treatment, thread lifts, in which temporary sutures visibly lift the skin around the face, appears to be gaining awareness as nearly 33,000 procedures were performed last year, according to the ASDS.

Year-over-year increases were smaller among the more established procedures: laser/light/energy-based procedures were up by 6.6%, injectable neuromodulators rose just 0.9%, injectable soft-tissue fillers were down 0.8%, and chemical peels increased by 2.4%, the society’s data show.

The survey was conducted among ASDS members from Jan. 15 to May 21, 2019, and the 596 responses were generalized to the entire ASDS membership of over 6,400 physicians.

Should you market your aesthetic services to the ‘Me Me Me Generation’?

SAN DIEGO – If the idea of marketing your aesthetic dermatology services to Millennials is an afterthought, Brian Biesman, MD, recommends that you reconsider that outlook. At the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium, Dr. Biesman told attendees that the age group dubbed as the “Me Me Me Generation” by Joel Stein of Time Magazine is slowly overtaking Baby Boomers as the largest shopping generation in history.

A large consumer survey conducted by Accenture found that by 2020, spending by Millennials will account for $1.4 trillion in U.S. retail sales. This segment of the population, which the Pew Research Center defines as those born from 1981 to 1996, also spends more online than any other generation. According to data from the consulting firm Bain & Company, 25% of luxury goods will be purchased online by 2025, up from 8% in 2016. “Millennials are going to be a huge economic driving force,” Dr. Biesman said.

Dr. Biesman, an oculofacial plastic surgeon who practices in Nashville, Tenn., said Millennials were born into a digital age. “They are very socially connected, sometimes to their detriment,” said Dr. Biesman, who is a past president of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “They’re definitely in debt ... but they’re comfortable with that and don’t mind spending. Their priorities are different. They tend to put off marriage and having kids, and they’re driven by social media.

They also hold a strong interest in appearance, said Dr, Biesman, who noted that the average Millennial woman is more likely to be aware of beauty issues by a factor of 10 years younger than her mother’s generation. “At age 25, Millennial women are getting interested in aesthetics, whereas the older generation didn’t start until about 35,” he said. Millennials “are educated, and they use the Internet to read up on procedures.” In his clinical experience, The most popular procedures include neuromodulators, fillers (especially in the lips and in the infraorbital hollow), minimally invasive laser hair removal, superficial laser resurfacing, and prescription skin care and cosmeceuticals.

According to a 2018 survey of 500 Millennials conducted by the aesthetics site Zalea, 32% were considering a cosmetic procedure and 6.6% had undergone one. Of the 149 Millennials who completed all of the survey questions, 65% indicated that they relied on Google search for information about cosmetic treatments, which was a higher proportion than for physicians (63%), friends and family (60%), and social networks such as Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter (25%). Dr. Biesman said that a paradigm shift is under way in aesthetic dermatology, in which the traditional means of achieving a strong reputation amongst patients by excellent training, publications, and research can be replaced by building a visible social media presence/personality.

“The social media influencer factor is a real phenomenon, and can carry tremendous weight due to their perceived relationship with their audience/followers,” Dr. Biesman said. “Some physicians are influencers, while others collaborate with influencers.” He emphasized that the decision to work with social media influencers depends on your preference, your comfort level/trust, the professionalism of the influencer, and your overall social media strategy. “The more you share about yourself, the more successful your social media account will be,” he said. “You need to determine your comfort zone, such as how much of your life you want to share.”

He advises aesthetic dermatologists to develop a strategy for reaching out to and incorporating Millennials into their practice. “Be deliberate in assessing the profile of your practice demographics, and determine which patient groups you want to serve, and to what extent,” he said. “If your practice is focused on minimally invasive aesthetics, it’s important to understand the Millennial mindset, because this is the largest group of consumers.”

Dr. Biesman reported having no relevant disclosures related to his presentation.

SAN DIEGO – If the idea of marketing your aesthetic dermatology services to Millennials is an afterthought, Brian Biesman, MD, recommends that you reconsider that outlook. At the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium, Dr. Biesman told attendees that the age group dubbed as the “Me Me Me Generation” by Joel Stein of Time Magazine is slowly overtaking Baby Boomers as the largest shopping generation in history.

A large consumer survey conducted by Accenture found that by 2020, spending by Millennials will account for $1.4 trillion in U.S. retail sales. This segment of the population, which the Pew Research Center defines as those born from 1981 to 1996, also spends more online than any other generation. According to data from the consulting firm Bain & Company, 25% of luxury goods will be purchased online by 2025, up from 8% in 2016. “Millennials are going to be a huge economic driving force,” Dr. Biesman said.

Dr. Biesman, an oculofacial plastic surgeon who practices in Nashville, Tenn., said Millennials were born into a digital age. “They are very socially connected, sometimes to their detriment,” said Dr. Biesman, who is a past president of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “They’re definitely in debt ... but they’re comfortable with that and don’t mind spending. Their priorities are different. They tend to put off marriage and having kids, and they’re driven by social media.

They also hold a strong interest in appearance, said Dr, Biesman, who noted that the average Millennial woman is more likely to be aware of beauty issues by a factor of 10 years younger than her mother’s generation. “At age 25, Millennial women are getting interested in aesthetics, whereas the older generation didn’t start until about 35,” he said. Millennials “are educated, and they use the Internet to read up on procedures.” In his clinical experience, The most popular procedures include neuromodulators, fillers (especially in the lips and in the infraorbital hollow), minimally invasive laser hair removal, superficial laser resurfacing, and prescription skin care and cosmeceuticals.

According to a 2018 survey of 500 Millennials conducted by the aesthetics site Zalea, 32% were considering a cosmetic procedure and 6.6% had undergone one. Of the 149 Millennials who completed all of the survey questions, 65% indicated that they relied on Google search for information about cosmetic treatments, which was a higher proportion than for physicians (63%), friends and family (60%), and social networks such as Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter (25%). Dr. Biesman said that a paradigm shift is under way in aesthetic dermatology, in which the traditional means of achieving a strong reputation amongst patients by excellent training, publications, and research can be replaced by building a visible social media presence/personality.

“The social media influencer factor is a real phenomenon, and can carry tremendous weight due to their perceived relationship with their audience/followers,” Dr. Biesman said. “Some physicians are influencers, while others collaborate with influencers.” He emphasized that the decision to work with social media influencers depends on your preference, your comfort level/trust, the professionalism of the influencer, and your overall social media strategy. “The more you share about yourself, the more successful your social media account will be,” he said. “You need to determine your comfort zone, such as how much of your life you want to share.”

He advises aesthetic dermatologists to develop a strategy for reaching out to and incorporating Millennials into their practice. “Be deliberate in assessing the profile of your practice demographics, and determine which patient groups you want to serve, and to what extent,” he said. “If your practice is focused on minimally invasive aesthetics, it’s important to understand the Millennial mindset, because this is the largest group of consumers.”

Dr. Biesman reported having no relevant disclosures related to his presentation.

SAN DIEGO – If the idea of marketing your aesthetic dermatology services to Millennials is an afterthought, Brian Biesman, MD, recommends that you reconsider that outlook. At the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium, Dr. Biesman told attendees that the age group dubbed as the “Me Me Me Generation” by Joel Stein of Time Magazine is slowly overtaking Baby Boomers as the largest shopping generation in history.

A large consumer survey conducted by Accenture found that by 2020, spending by Millennials will account for $1.4 trillion in U.S. retail sales. This segment of the population, which the Pew Research Center defines as those born from 1981 to 1996, also spends more online than any other generation. According to data from the consulting firm Bain & Company, 25% of luxury goods will be purchased online by 2025, up from 8% in 2016. “Millennials are going to be a huge economic driving force,” Dr. Biesman said.

Dr. Biesman, an oculofacial plastic surgeon who practices in Nashville, Tenn., said Millennials were born into a digital age. “They are very socially connected, sometimes to their detriment,” said Dr. Biesman, who is a past president of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “They’re definitely in debt ... but they’re comfortable with that and don’t mind spending. Their priorities are different. They tend to put off marriage and having kids, and they’re driven by social media.

They also hold a strong interest in appearance, said Dr, Biesman, who noted that the average Millennial woman is more likely to be aware of beauty issues by a factor of 10 years younger than her mother’s generation. “At age 25, Millennial women are getting interested in aesthetics, whereas the older generation didn’t start until about 35,” he said. Millennials “are educated, and they use the Internet to read up on procedures.” In his clinical experience, The most popular procedures include neuromodulators, fillers (especially in the lips and in the infraorbital hollow), minimally invasive laser hair removal, superficial laser resurfacing, and prescription skin care and cosmeceuticals.

According to a 2018 survey of 500 Millennials conducted by the aesthetics site Zalea, 32% were considering a cosmetic procedure and 6.6% had undergone one. Of the 149 Millennials who completed all of the survey questions, 65% indicated that they relied on Google search for information about cosmetic treatments, which was a higher proportion than for physicians (63%), friends and family (60%), and social networks such as Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter (25%). Dr. Biesman said that a paradigm shift is under way in aesthetic dermatology, in which the traditional means of achieving a strong reputation amongst patients by excellent training, publications, and research can be replaced by building a visible social media presence/personality.

“The social media influencer factor is a real phenomenon, and can carry tremendous weight due to their perceived relationship with their audience/followers,” Dr. Biesman said. “Some physicians are influencers, while others collaborate with influencers.” He emphasized that the decision to work with social media influencers depends on your preference, your comfort level/trust, the professionalism of the influencer, and your overall social media strategy. “The more you share about yourself, the more successful your social media account will be,” he said. “You need to determine your comfort zone, such as how much of your life you want to share.”

He advises aesthetic dermatologists to develop a strategy for reaching out to and incorporating Millennials into their practice. “Be deliberate in assessing the profile of your practice demographics, and determine which patient groups you want to serve, and to what extent,” he said. “If your practice is focused on minimally invasive aesthetics, it’s important to understand the Millennial mindset, because this is the largest group of consumers.”

Dr. Biesman reported having no relevant disclosures related to his presentation.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM MOAS 2019

Reunion

We were catching up during our 35th college reunion at our old fraternity house overlooking Cayuga Lake in Ithaca, N.Y. About 50 of us lived in the Tudor-style house, complete with secret basement room, and there was a ladder that allowed access to the relatively flat, painted aluminum roof. When the weather allowed, we climbed the ladder to sun ourselves on top of the house. We also flung water balloons at unsuspecting pedestrians with a sling shot device made by attaching rubber tubing to a funnel. The “funnelator” was very accurate to about 50 yards away. We were kids, and climbing that ladder meant fun, and we climbed it as often as we could.

Despite what many would have predicted when we graduated, my fraternity brothers became a very successful group of CEOs, vice presidents, doctors, lawyers, chairmen, and consultants. Our house was just off Cornell University’s campus at the top of Ithaca Falls, an idyllic setting on a beautiful June evening for my brothers to sit around, laugh about the old times, and philosophize about life. We recounted our life after college and reveled in each others’ accomplishments.

After climbing the roof ladder for fun, we had each climbed a different kind of ladder to success in our respective fields. We all really enjoyed the climb. I don’t think it is a coincidence that many of my brothers and I are now done climbing our ladders. Many of us are getting out of the rat race.

One of my friends is resigning as chairman of an academic ENT department. I remember his discipline in college, leaving the house after dinner every night to climb the hill where he studied in the quiet of Uris Library, which is attached to the iconic McGraw Tower. His hard work paid off with an acceptance to a prestigious medical school where he continued to excel. The author of more than 200 published manuscripts, with four senior-authored papers already this year, he is at the pinnacle of his academic success. Yet, he resigned.

Similarly, another of my fraternity brothers had recently resigned from his position as Senior Vice President and Chief Medical Officer for a large health care system. He would have been in line for the CEO position had he stayed. He has written well-received books on leadership and financial acumen for physicians. As a result, he is a frequent public speaker on similar topics. Yet, he resigned.

They were not the only ones resigning positions that others covet. I, too, resigned my position as Department Chairman earlier this year. None of us were fired, none of us were asked to leave, and none of us are burned out. So here we were, three accomplished physicians all resigning from powerful posts at the same time for what turns out to be similar reasons. Our priorities changed as our children moved out.

I would like to say that we all had the wisdom to know that our leadership skills were deteriorating and that we all wanted to get out while we are at the top of our game. Had Arthur Brooks written “Your Professional Decline Is Coming (Much) Sooner Than You Think” in The Atlantic (July 2019) before we made our decisions, I may have made that argument, but it would not have been true. All three of us feel like we have accomplished what we sought to achieve when we took our respective roles and now we wanted to leverage that experience into something different, if not better. None of us have settled into new roles yet, and all of us are still trying to define exactly what it is we want to do next, but all of us agree that we are no longer interested in driving ourselves to succeed at the expense of our family, friends, and relationships.

My fraternity brothers and I gushed with pride talking about our children and their success. Our progeny are starting their individual climbs up the ladder of opportunity in whatever field they have chosen. My friends and I, on the other hand, had already climbed a ladder and feel comfortable stopping. Or maybe we just want to start climbing a different ladder.

Dr. Kalaycio is editor in chief of Hematology News. He chairs the department of hematology and medical oncology at Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute. Contact him at kalaycm@ccf.org.

We were catching up during our 35th college reunion at our old fraternity house overlooking Cayuga Lake in Ithaca, N.Y. About 50 of us lived in the Tudor-style house, complete with secret basement room, and there was a ladder that allowed access to the relatively flat, painted aluminum roof. When the weather allowed, we climbed the ladder to sun ourselves on top of the house. We also flung water balloons at unsuspecting pedestrians with a sling shot device made by attaching rubber tubing to a funnel. The “funnelator” was very accurate to about 50 yards away. We were kids, and climbing that ladder meant fun, and we climbed it as often as we could.

Despite what many would have predicted when we graduated, my fraternity brothers became a very successful group of CEOs, vice presidents, doctors, lawyers, chairmen, and consultants. Our house was just off Cornell University’s campus at the top of Ithaca Falls, an idyllic setting on a beautiful June evening for my brothers to sit around, laugh about the old times, and philosophize about life. We recounted our life after college and reveled in each others’ accomplishments.

After climbing the roof ladder for fun, we had each climbed a different kind of ladder to success in our respective fields. We all really enjoyed the climb. I don’t think it is a coincidence that many of my brothers and I are now done climbing our ladders. Many of us are getting out of the rat race.

One of my friends is resigning as chairman of an academic ENT department. I remember his discipline in college, leaving the house after dinner every night to climb the hill where he studied in the quiet of Uris Library, which is attached to the iconic McGraw Tower. His hard work paid off with an acceptance to a prestigious medical school where he continued to excel. The author of more than 200 published manuscripts, with four senior-authored papers already this year, he is at the pinnacle of his academic success. Yet, he resigned.

Similarly, another of my fraternity brothers had recently resigned from his position as Senior Vice President and Chief Medical Officer for a large health care system. He would have been in line for the CEO position had he stayed. He has written well-received books on leadership and financial acumen for physicians. As a result, he is a frequent public speaker on similar topics. Yet, he resigned.

They were not the only ones resigning positions that others covet. I, too, resigned my position as Department Chairman earlier this year. None of us were fired, none of us were asked to leave, and none of us are burned out. So here we were, three accomplished physicians all resigning from powerful posts at the same time for what turns out to be similar reasons. Our priorities changed as our children moved out.

I would like to say that we all had the wisdom to know that our leadership skills were deteriorating and that we all wanted to get out while we are at the top of our game. Had Arthur Brooks written “Your Professional Decline Is Coming (Much) Sooner Than You Think” in The Atlantic (July 2019) before we made our decisions, I may have made that argument, but it would not have been true. All three of us feel like we have accomplished what we sought to achieve when we took our respective roles and now we wanted to leverage that experience into something different, if not better. None of us have settled into new roles yet, and all of us are still trying to define exactly what it is we want to do next, but all of us agree that we are no longer interested in driving ourselves to succeed at the expense of our family, friends, and relationships.

My fraternity brothers and I gushed with pride talking about our children and their success. Our progeny are starting their individual climbs up the ladder of opportunity in whatever field they have chosen. My friends and I, on the other hand, had already climbed a ladder and feel comfortable stopping. Or maybe we just want to start climbing a different ladder.

Dr. Kalaycio is editor in chief of Hematology News. He chairs the department of hematology and medical oncology at Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute. Contact him at kalaycm@ccf.org.

We were catching up during our 35th college reunion at our old fraternity house overlooking Cayuga Lake in Ithaca, N.Y. About 50 of us lived in the Tudor-style house, complete with secret basement room, and there was a ladder that allowed access to the relatively flat, painted aluminum roof. When the weather allowed, we climbed the ladder to sun ourselves on top of the house. We also flung water balloons at unsuspecting pedestrians with a sling shot device made by attaching rubber tubing to a funnel. The “funnelator” was very accurate to about 50 yards away. We were kids, and climbing that ladder meant fun, and we climbed it as often as we could.

Despite what many would have predicted when we graduated, my fraternity brothers became a very successful group of CEOs, vice presidents, doctors, lawyers, chairmen, and consultants. Our house was just off Cornell University’s campus at the top of Ithaca Falls, an idyllic setting on a beautiful June evening for my brothers to sit around, laugh about the old times, and philosophize about life. We recounted our life after college and reveled in each others’ accomplishments.

After climbing the roof ladder for fun, we had each climbed a different kind of ladder to success in our respective fields. We all really enjoyed the climb. I don’t think it is a coincidence that many of my brothers and I are now done climbing our ladders. Many of us are getting out of the rat race.

One of my friends is resigning as chairman of an academic ENT department. I remember his discipline in college, leaving the house after dinner every night to climb the hill where he studied in the quiet of Uris Library, which is attached to the iconic McGraw Tower. His hard work paid off with an acceptance to a prestigious medical school where he continued to excel. The author of more than 200 published manuscripts, with four senior-authored papers already this year, he is at the pinnacle of his academic success. Yet, he resigned.

Similarly, another of my fraternity brothers had recently resigned from his position as Senior Vice President and Chief Medical Officer for a large health care system. He would have been in line for the CEO position had he stayed. He has written well-received books on leadership and financial acumen for physicians. As a result, he is a frequent public speaker on similar topics. Yet, he resigned.

They were not the only ones resigning positions that others covet. I, too, resigned my position as Department Chairman earlier this year. None of us were fired, none of us were asked to leave, and none of us are burned out. So here we were, three accomplished physicians all resigning from powerful posts at the same time for what turns out to be similar reasons. Our priorities changed as our children moved out.

I would like to say that we all had the wisdom to know that our leadership skills were deteriorating and that we all wanted to get out while we are at the top of our game. Had Arthur Brooks written “Your Professional Decline Is Coming (Much) Sooner Than You Think” in The Atlantic (July 2019) before we made our decisions, I may have made that argument, but it would not have been true. All three of us feel like we have accomplished what we sought to achieve when we took our respective roles and now we wanted to leverage that experience into something different, if not better. None of us have settled into new roles yet, and all of us are still trying to define exactly what it is we want to do next, but all of us agree that we are no longer interested in driving ourselves to succeed at the expense of our family, friends, and relationships.

My fraternity brothers and I gushed with pride talking about our children and their success. Our progeny are starting their individual climbs up the ladder of opportunity in whatever field they have chosen. My friends and I, on the other hand, had already climbed a ladder and feel comfortable stopping. Or maybe we just want to start climbing a different ladder.

Dr. Kalaycio is editor in chief of Hematology News. He chairs the department of hematology and medical oncology at Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute. Contact him at kalaycm@ccf.org.

ABIM: Self-paced MOC pathway under development

Physician groups are praising a new option by the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) that will offer doctors a self-paced pathway for maintenance of certification (MOC) in place of the traditional long-form assessment route.

The new longitudinal assessment option, announced in late August, would enable physicians to acquire and demonstrate ongoing knowledge through shorter evaluations of specific content. The option, currently under development, also would provide doctors with immediate feedback about their answers and share links to educational material to address knowledge gaps, according to an announcement. While details are still being flushed out, a summary of the longitudinal assessment concept by the American Board of Medical Specialties explains that the approach draws on the principles of adult learning and modern technology “to promote learning, retention, and transfer of information.”

Developing a longitudinal assessment option is part of ABIM’s ongoing evolution, Marianne M. Green, MD, chair for ABIM’s board of directors and ABIM President Richard J. Baron, MD, wrote in a joint letter to internists posted on ABIM’s blog.

“We recognize that some physicians may prefer a more continuous process that easily integrates into their lives and allows them to engage seamlessly at their preferred pace, while being able to access the resources they use in practice,” the doctors wrote.

Douglas DeLong, MD, chair of the American College of Physician’s (ACP) board of regents said the option is a positive, first step that will support lifelong learning. He noted the new option is in line with recommendations by the American Board of Medical Specialties’ Continuing Board Certification: Vision for the Future Commission, which included ACP concerns.

“It’s pretty clear that some of the principles of adult learning – frequent information with quick feedback, repetition of material, and identifying gaps in knowledge – is really how people most effectively learn,” Dr. DeLong said in an interview. “Just cramming for an examination every decade hasn’t ever really been shown to affect long-term retention of knowledge or even patient care outcomes.”

Alan Lichtin, MD, chair of the MOC working group for the American Society of Hematology (ASH), said the self-paced pathway is a much-needed option, particularly the immediate feedback on test questions.

“For years, ASH has been advocating that ABIM move from the traditional sit-down testing to an alternative form of ‘formative’ assessment that has been adapted by other specialty boards,” Dr. Lichtin said in an interview. Anesthesiology and pediatrics have novel testing methods that fit into physicians’ schedules without being so disruptive and anxiety provoking. There is instantaneous feedback about whether the answers are correct or not. It is not useful to study hard for a time-intensive, comprehensive test only to get a summary of what was missed a long time after the test. By that point, the exam material is no longer fresh in one’s mind and therefore the feedback is no longer useful.”

The new pathway is still under development, and ABIM has not said when the option might be launched. In the meantime, the current MOC program and its traditional exam will remain in effect. The board is requesting feedback and comments from physicians about the option. Dr. Baron wrote that more information about the change will be forthcoming in the months ahead.

The ABIM announcement comes on the heels of an ongoing legal challenge levied at the board by a group of internists over its MOC process.

The lawsuit, filed Dec. 6, 2018, in Pennsylvania district court and later amended in 2019, claims that ABIM is charging inflated monopoly prices for maintaining certification, that the organization is forcing physicians to purchase MOC, and that ABIM is inducing employers and others to require ABIM certification. The four plaintiff-physicians are asking a judge to find ABIM in violation of federal antitrust law and to bar the board from continuing its MOC process. The suit is filed as a class action on behalf of all internists and subspecialists required by ABIM to purchase MOC to maintain their ABIM certifications. .

Two other lawsuits challenging MOC, one against the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology and another against the American Board of Radiology, are ongoing. A fourth lawsuit against the American Board of Medical Specialties, the American Board of Emergency Medicine, and the American Board of Anesthesiology was filed in February.

Attorneys for all three boards in the ABIM, American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology, and American Board of Radiology cases are seeking to dismiss the complaints. Judges have not yet ruled on the motions. In addition, a motion to consolidate all the cases was denied by the court.

A GoFundMe campaign launched by the Practicing Physicians of America to pay for plaintiffs’ costs associated with the class-action lawsuits has now garnered more than $300,000.

Physician groups are praising a new option by the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) that will offer doctors a self-paced pathway for maintenance of certification (MOC) in place of the traditional long-form assessment route.

The new longitudinal assessment option, announced in late August, would enable physicians to acquire and demonstrate ongoing knowledge through shorter evaluations of specific content. The option, currently under development, also would provide doctors with immediate feedback about their answers and share links to educational material to address knowledge gaps, according to an announcement. While details are still being flushed out, a summary of the longitudinal assessment concept by the American Board of Medical Specialties explains that the approach draws on the principles of adult learning and modern technology “to promote learning, retention, and transfer of information.”

Developing a longitudinal assessment option is part of ABIM’s ongoing evolution, Marianne M. Green, MD, chair for ABIM’s board of directors and ABIM President Richard J. Baron, MD, wrote in a joint letter to internists posted on ABIM’s blog.

“We recognize that some physicians may prefer a more continuous process that easily integrates into their lives and allows them to engage seamlessly at their preferred pace, while being able to access the resources they use in practice,” the doctors wrote.

Douglas DeLong, MD, chair of the American College of Physician’s (ACP) board of regents said the option is a positive, first step that will support lifelong learning. He noted the new option is in line with recommendations by the American Board of Medical Specialties’ Continuing Board Certification: Vision for the Future Commission, which included ACP concerns.

“It’s pretty clear that some of the principles of adult learning – frequent information with quick feedback, repetition of material, and identifying gaps in knowledge – is really how people most effectively learn,” Dr. DeLong said in an interview. “Just cramming for an examination every decade hasn’t ever really been shown to affect long-term retention of knowledge or even patient care outcomes.”

Alan Lichtin, MD, chair of the MOC working group for the American Society of Hematology (ASH), said the self-paced pathway is a much-needed option, particularly the immediate feedback on test questions.

“For years, ASH has been advocating that ABIM move from the traditional sit-down testing to an alternative form of ‘formative’ assessment that has been adapted by other specialty boards,” Dr. Lichtin said in an interview. Anesthesiology and pediatrics have novel testing methods that fit into physicians’ schedules without being so disruptive and anxiety provoking. There is instantaneous feedback about whether the answers are correct or not. It is not useful to study hard for a time-intensive, comprehensive test only to get a summary of what was missed a long time after the test. By that point, the exam material is no longer fresh in one’s mind and therefore the feedback is no longer useful.”

The new pathway is still under development, and ABIM has not said when the option might be launched. In the meantime, the current MOC program and its traditional exam will remain in effect. The board is requesting feedback and comments from physicians about the option. Dr. Baron wrote that more information about the change will be forthcoming in the months ahead.

The ABIM announcement comes on the heels of an ongoing legal challenge levied at the board by a group of internists over its MOC process.

The lawsuit, filed Dec. 6, 2018, in Pennsylvania district court and later amended in 2019, claims that ABIM is charging inflated monopoly prices for maintaining certification, that the organization is forcing physicians to purchase MOC, and that ABIM is inducing employers and others to require ABIM certification. The four plaintiff-physicians are asking a judge to find ABIM in violation of federal antitrust law and to bar the board from continuing its MOC process. The suit is filed as a class action on behalf of all internists and subspecialists required by ABIM to purchase MOC to maintain their ABIM certifications. .

Two other lawsuits challenging MOC, one against the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology and another against the American Board of Radiology, are ongoing. A fourth lawsuit against the American Board of Medical Specialties, the American Board of Emergency Medicine, and the American Board of Anesthesiology was filed in February.

Attorneys for all three boards in the ABIM, American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology, and American Board of Radiology cases are seeking to dismiss the complaints. Judges have not yet ruled on the motions. In addition, a motion to consolidate all the cases was denied by the court.

A GoFundMe campaign launched by the Practicing Physicians of America to pay for plaintiffs’ costs associated with the class-action lawsuits has now garnered more than $300,000.

Physician groups are praising a new option by the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) that will offer doctors a self-paced pathway for maintenance of certification (MOC) in place of the traditional long-form assessment route.

The new longitudinal assessment option, announced in late August, would enable physicians to acquire and demonstrate ongoing knowledge through shorter evaluations of specific content. The option, currently under development, also would provide doctors with immediate feedback about their answers and share links to educational material to address knowledge gaps, according to an announcement. While details are still being flushed out, a summary of the longitudinal assessment concept by the American Board of Medical Specialties explains that the approach draws on the principles of adult learning and modern technology “to promote learning, retention, and transfer of information.”

Developing a longitudinal assessment option is part of ABIM’s ongoing evolution, Marianne M. Green, MD, chair for ABIM’s board of directors and ABIM President Richard J. Baron, MD, wrote in a joint letter to internists posted on ABIM’s blog.

“We recognize that some physicians may prefer a more continuous process that easily integrates into their lives and allows them to engage seamlessly at their preferred pace, while being able to access the resources they use in practice,” the doctors wrote.

Douglas DeLong, MD, chair of the American College of Physician’s (ACP) board of regents said the option is a positive, first step that will support lifelong learning. He noted the new option is in line with recommendations by the American Board of Medical Specialties’ Continuing Board Certification: Vision for the Future Commission, which included ACP concerns.

“It’s pretty clear that some of the principles of adult learning – frequent information with quick feedback, repetition of material, and identifying gaps in knowledge – is really how people most effectively learn,” Dr. DeLong said in an interview. “Just cramming for an examination every decade hasn’t ever really been shown to affect long-term retention of knowledge or even patient care outcomes.”

Alan Lichtin, MD, chair of the MOC working group for the American Society of Hematology (ASH), said the self-paced pathway is a much-needed option, particularly the immediate feedback on test questions.

“For years, ASH has been advocating that ABIM move from the traditional sit-down testing to an alternative form of ‘formative’ assessment that has been adapted by other specialty boards,” Dr. Lichtin said in an interview. Anesthesiology and pediatrics have novel testing methods that fit into physicians’ schedules without being so disruptive and anxiety provoking. There is instantaneous feedback about whether the answers are correct or not. It is not useful to study hard for a time-intensive, comprehensive test only to get a summary of what was missed a long time after the test. By that point, the exam material is no longer fresh in one’s mind and therefore the feedback is no longer useful.”

The new pathway is still under development, and ABIM has not said when the option might be launched. In the meantime, the current MOC program and its traditional exam will remain in effect. The board is requesting feedback and comments from physicians about the option. Dr. Baron wrote that more information about the change will be forthcoming in the months ahead.

The ABIM announcement comes on the heels of an ongoing legal challenge levied at the board by a group of internists over its MOC process.

The lawsuit, filed Dec. 6, 2018, in Pennsylvania district court and later amended in 2019, claims that ABIM is charging inflated monopoly prices for maintaining certification, that the organization is forcing physicians to purchase MOC, and that ABIM is inducing employers and others to require ABIM certification. The four plaintiff-physicians are asking a judge to find ABIM in violation of federal antitrust law and to bar the board from continuing its MOC process. The suit is filed as a class action on behalf of all internists and subspecialists required by ABIM to purchase MOC to maintain their ABIM certifications. .

Two other lawsuits challenging MOC, one against the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology and another against the American Board of Radiology, are ongoing. A fourth lawsuit against the American Board of Medical Specialties, the American Board of Emergency Medicine, and the American Board of Anesthesiology was filed in February.

Attorneys for all three boards in the ABIM, American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology, and American Board of Radiology cases are seeking to dismiss the complaints. Judges have not yet ruled on the motions. In addition, a motion to consolidate all the cases was denied by the court.

A GoFundMe campaign launched by the Practicing Physicians of America to pay for plaintiffs’ costs associated with the class-action lawsuits has now garnered more than $300,000.

Time or money?

The authors of a recent study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine estimate that physician burnout is costing this country’s health care system $4.6 billion annually, using a conservative base-case model (Ann Intern Med. 2019;170[11]:784-90). I guess we shouldn’t be surprised at the magnitude of the drain on our economy caused by unhappy physicians. We all know colleagues who are showing signs of burnout. And, you may be feeling yourself that the challenges of work are taking too great a toll on your physical and mental health? Would you be happier if you had more time?

A study reported in Harvard Business Review has looked at recent college graduates to determine if how they prioritize time and money can predict their future happiness (“Are New Graduates Happier Making More Money or Having More Time?” July 25, 2019). The researchers at the Harvard Business School surveyed 1,000 college students in the 2015 and 2016 classes of the University of British Columbia, Vancouver. The students were asked to match themselves with descriptions of fictitious individuals to determine whether in general they prioritized time or money. The researchers then assessed the students’ level of happiness by asking them, “How satisfied are you with life overall?”

At a 2-year follow-up, the researchers found that, even taking into account the students’ level of happiness at the beginning of the study, “those who prioritized time were happier.” The authors also found that time-oriented people don’t necessarily work less or even earn more money, prompting their conclusion there is “strong evidence that valuing time puts people on a trajectory toward job satisfaction and well-being.”

Do the results of this study of Canadian college students provide any answers for our epidemic of physician burnout? One could argue that, if we wanted to minimize burnout, medical schools should include an assessment of each applicant’s level of happiness and how she or he prioritizes time and money using methods similar those used in this study? The problem is that some students are so heavily committed to becoming physicians that they would game the system and provide answers that will project the image that they are happy and prioritize time over money, when in reality they are ticking time bombs of discontent.

The bigger problem with interpreting the results of this study is that the subjects were Canadians who have significantly less educational debt than the medical students in this country. And as the authors observe, “people with objective financial constraints ... are more likely to focus on having more money.” Until we solve the problem of the high cost of medical education the system will continue to select for physicians whose decisions are too heavily influenced by their educational debt.

Finally, it is important to consider that time-oriented individuals don’t always work less, rather they make decisions that make it more likely that they will pursue activities they find enjoyable. For example, accepting a higher-paying job that requires an additional 3 hours of commute each day lays the foundation for a life in which a large portion of one’s day is expended in an activity that few of us find enjoyable. Choosing a long commute is a personal decision. Spending nearly 2 hours each day tethered to an EHR system was not something most physicians anticipated when they were choosing a career.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

The authors of a recent study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine estimate that physician burnout is costing this country’s health care system $4.6 billion annually, using a conservative base-case model (Ann Intern Med. 2019;170[11]:784-90). I guess we shouldn’t be surprised at the magnitude of the drain on our economy caused by unhappy physicians. We all know colleagues who are showing signs of burnout. And, you may be feeling yourself that the challenges of work are taking too great a toll on your physical and mental health? Would you be happier if you had more time?

A study reported in Harvard Business Review has looked at recent college graduates to determine if how they prioritize time and money can predict their future happiness (“Are New Graduates Happier Making More Money or Having More Time?” July 25, 2019). The researchers at the Harvard Business School surveyed 1,000 college students in the 2015 and 2016 classes of the University of British Columbia, Vancouver. The students were asked to match themselves with descriptions of fictitious individuals to determine whether in general they prioritized time or money. The researchers then assessed the students’ level of happiness by asking them, “How satisfied are you with life overall?”

At a 2-year follow-up, the researchers found that, even taking into account the students’ level of happiness at the beginning of the study, “those who prioritized time were happier.” The authors also found that time-oriented people don’t necessarily work less or even earn more money, prompting their conclusion there is “strong evidence that valuing time puts people on a trajectory toward job satisfaction and well-being.”

Do the results of this study of Canadian college students provide any answers for our epidemic of physician burnout? One could argue that, if we wanted to minimize burnout, medical schools should include an assessment of each applicant’s level of happiness and how she or he prioritizes time and money using methods similar those used in this study? The problem is that some students are so heavily committed to becoming physicians that they would game the system and provide answers that will project the image that they are happy and prioritize time over money, when in reality they are ticking time bombs of discontent.

The bigger problem with interpreting the results of this study is that the subjects were Canadians who have significantly less educational debt than the medical students in this country. And as the authors observe, “people with objective financial constraints ... are more likely to focus on having more money.” Until we solve the problem of the high cost of medical education the system will continue to select for physicians whose decisions are too heavily influenced by their educational debt.

Finally, it is important to consider that time-oriented individuals don’t always work less, rather they make decisions that make it more likely that they will pursue activities they find enjoyable. For example, accepting a higher-paying job that requires an additional 3 hours of commute each day lays the foundation for a life in which a large portion of one’s day is expended in an activity that few of us find enjoyable. Choosing a long commute is a personal decision. Spending nearly 2 hours each day tethered to an EHR system was not something most physicians anticipated when they were choosing a career.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

The authors of a recent study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine estimate that physician burnout is costing this country’s health care system $4.6 billion annually, using a conservative base-case model (Ann Intern Med. 2019;170[11]:784-90). I guess we shouldn’t be surprised at the magnitude of the drain on our economy caused by unhappy physicians. We all know colleagues who are showing signs of burnout. And, you may be feeling yourself that the challenges of work are taking too great a toll on your physical and mental health? Would you be happier if you had more time?

A study reported in Harvard Business Review has looked at recent college graduates to determine if how they prioritize time and money can predict their future happiness (“Are New Graduates Happier Making More Money or Having More Time?” July 25, 2019). The researchers at the Harvard Business School surveyed 1,000 college students in the 2015 and 2016 classes of the University of British Columbia, Vancouver. The students were asked to match themselves with descriptions of fictitious individuals to determine whether in general they prioritized time or money. The researchers then assessed the students’ level of happiness by asking them, “How satisfied are you with life overall?”

At a 2-year follow-up, the researchers found that, even taking into account the students’ level of happiness at the beginning of the study, “those who prioritized time were happier.” The authors also found that time-oriented people don’t necessarily work less or even earn more money, prompting their conclusion there is “strong evidence that valuing time puts people on a trajectory toward job satisfaction and well-being.”

Do the results of this study of Canadian college students provide any answers for our epidemic of physician burnout? One could argue that, if we wanted to minimize burnout, medical schools should include an assessment of each applicant’s level of happiness and how she or he prioritizes time and money using methods similar those used in this study? The problem is that some students are so heavily committed to becoming physicians that they would game the system and provide answers that will project the image that they are happy and prioritize time over money, when in reality they are ticking time bombs of discontent.

The bigger problem with interpreting the results of this study is that the subjects were Canadians who have significantly less educational debt than the medical students in this country. And as the authors observe, “people with objective financial constraints ... are more likely to focus on having more money.” Until we solve the problem of the high cost of medical education the system will continue to select for physicians whose decisions are too heavily influenced by their educational debt.

Finally, it is important to consider that time-oriented individuals don’t always work less, rather they make decisions that make it more likely that they will pursue activities they find enjoyable. For example, accepting a higher-paying job that requires an additional 3 hours of commute each day lays the foundation for a life in which a large portion of one’s day is expended in an activity that few of us find enjoyable. Choosing a long commute is a personal decision. Spending nearly 2 hours each day tethered to an EHR system was not something most physicians anticipated when they were choosing a career.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

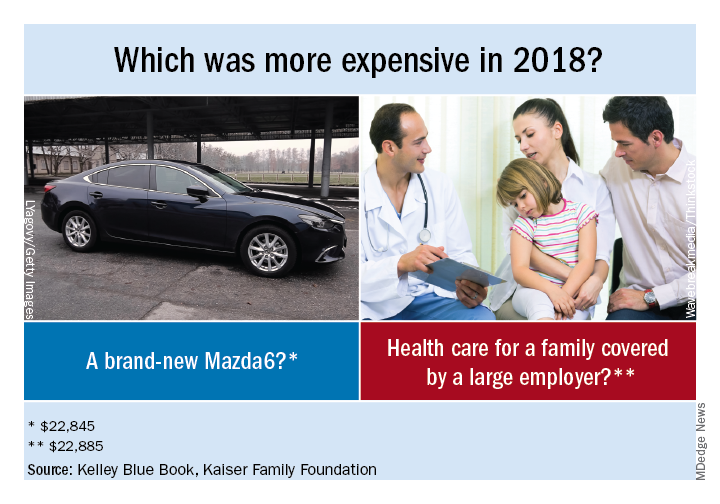

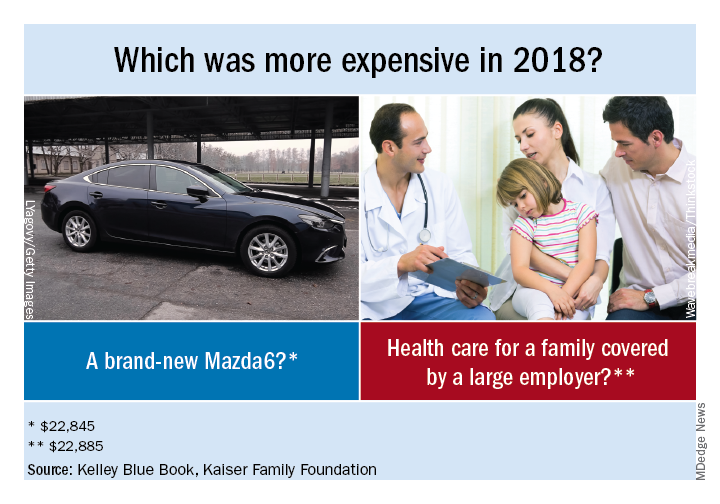

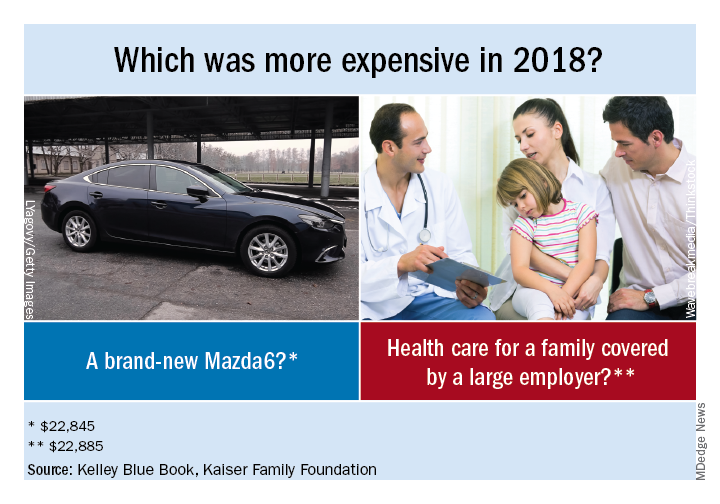

Health spending nears $23,000 per family

That average cost represents the employer’s contribution to the insurance premium ($15,159), along with the employee’s premium ($4,706) and the family’s out-of-pocket spending ($3,020), according to a KFF analysis of IBM MarketScan data and the 2018 KFF Employer Health Benefits Survey.

“Buying a new car every year would be a very impractical expense. It would also be cheaper than a year’s worth of health care for a family,” KFF President and CEO Drew Altman, PhD, wrote in his Axios column.

A little searching on the Kelley Blue Book Car Finder shows that the average family could have purchased a pretty nice new vehicle for the $22,885 that was spent on their health care in 2018:

- Mazda6 sedan: $22,845.

- Mini 2-door hatchback: $22,450.

- Jeep Renegade SUV: $21,040.

- Nissan Frontier king cab pickup: $20,035.

“The cost-shifting and complexity of health insurance can hide its high cost, which crowds out families’ other needs and depresses workers’ wages,” Dr. Altman said.

That average cost represents the employer’s contribution to the insurance premium ($15,159), along with the employee’s premium ($4,706) and the family’s out-of-pocket spending ($3,020), according to a KFF analysis of IBM MarketScan data and the 2018 KFF Employer Health Benefits Survey.

“Buying a new car every year would be a very impractical expense. It would also be cheaper than a year’s worth of health care for a family,” KFF President and CEO Drew Altman, PhD, wrote in his Axios column.

A little searching on the Kelley Blue Book Car Finder shows that the average family could have purchased a pretty nice new vehicle for the $22,885 that was spent on their health care in 2018:

- Mazda6 sedan: $22,845.

- Mini 2-door hatchback: $22,450.

- Jeep Renegade SUV: $21,040.

- Nissan Frontier king cab pickup: $20,035.

“The cost-shifting and complexity of health insurance can hide its high cost, which crowds out families’ other needs and depresses workers’ wages,” Dr. Altman said.

That average cost represents the employer’s contribution to the insurance premium ($15,159), along with the employee’s premium ($4,706) and the family’s out-of-pocket spending ($3,020), according to a KFF analysis of IBM MarketScan data and the 2018 KFF Employer Health Benefits Survey.

“Buying a new car every year would be a very impractical expense. It would also be cheaper than a year’s worth of health care for a family,” KFF President and CEO Drew Altman, PhD, wrote in his Axios column.

A little searching on the Kelley Blue Book Car Finder shows that the average family could have purchased a pretty nice new vehicle for the $22,885 that was spent on their health care in 2018:

- Mazda6 sedan: $22,845.

- Mini 2-door hatchback: $22,450.

- Jeep Renegade SUV: $21,040.

- Nissan Frontier king cab pickup: $20,035.

“The cost-shifting and complexity of health insurance can hide its high cost, which crowds out families’ other needs and depresses workers’ wages,” Dr. Altman said.

Before the die is cast

When asked about my decision to choose pediatrics over the other specialty opportunities I was being offered, I have always answered that my choice was primarily based on my desire to work with children. That affinity certainly didn’t stem from my experience with my sister who is 7 years my junior. By her own admission, she was a bratty little thing and a major annoyance during my journey through adolescence. However, during the summers of high school and college I worked as a lifeguard, and one of my duties was to teach swimming classes. The joy and reward of watching children overcome their fear of the water and become competent swimmers left a positive impression, which was in stark contrast to the few classes of adult nonswimmers my coworkers and I taught. Our success rate with adults was pretty close to zero.

If I was going to spend my time and effort becoming a physician, I decided I wanted to be working with patients with the high potential for positive change and ones who had yet to accumulate a several decades long list of bad health habits. I wanted to be practicing in situations well before the die had been cast.

With this background in mind, you can understand why I was drawn to a recent article in the Harvard Gazette titled “Social spending on kids yields the biggest bang for the buck,” by Clea Simon. The article describes a recent study by Opportunity Insights, a Harvard-based institute of policy analysts and social scientists (“A Unified Welfare Analysis of Government Policies” by Nathaniel Hendren, PhD, and Ben Sprung-Keyser). Using computer algorithms capable of mining large pools of data, the researchers looked at 133 government policy changes over the last 50 years and compared the long-term results of those changes by assessing dollars spent against those returned in the form of tax revenue.

The Harvard article quotes Dr. Hendren as saying, This association was most impressive for children who came from lower-income families. This was especially true for programs that aimed at improving child health and increasing educational attainment.

Of course, these observations don’t come as a surprise to those of us who have accepted the challenge of improving the health of children. But it’s always nice to hear some new data that warms our hearts and reinforces our commitment to building healthy communities by focusing our efforts on its youngest members.

However, the paper did provide a finding that disappointed me. This big data analysis revealed that programs aimed at encouraging young people to attend college produced higher future earnings than did those focused on job training. I guess this shouldn’t be much of a surprise, but I believe we have been overemphasizing college track programs when we should be destigmatizing a career path in one of the trades. It may be that job training has been poorly done or at least not flexible enough to meet the changing demands of industry.

The investigators were surprised that their analysis demonstrated that policy changes targeted at children through their middle and high school years and even into college yielded return on investment at least as great if not greater than some successful preschool programs. Dr. Hendren responded to this finding by observing that “it’s never too late.” However, I think his comment deserves the loud and clear caveat, “as long as we are still talking about children.”

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

When asked about my decision to choose pediatrics over the other specialty opportunities I was being offered, I have always answered that my choice was primarily based on my desire to work with children. That affinity certainly didn’t stem from my experience with my sister who is 7 years my junior. By her own admission, she was a bratty little thing and a major annoyance during my journey through adolescence. However, during the summers of high school and college I worked as a lifeguard, and one of my duties was to teach swimming classes. The joy and reward of watching children overcome their fear of the water and become competent swimmers left a positive impression, which was in stark contrast to the few classes of adult nonswimmers my coworkers and I taught. Our success rate with adults was pretty close to zero.

If I was going to spend my time and effort becoming a physician, I decided I wanted to be working with patients with the high potential for positive change and ones who had yet to accumulate a several decades long list of bad health habits. I wanted to be practicing in situations well before the die had been cast.

With this background in mind, you can understand why I was drawn to a recent article in the Harvard Gazette titled “Social spending on kids yields the biggest bang for the buck,” by Clea Simon. The article describes a recent study by Opportunity Insights, a Harvard-based institute of policy analysts and social scientists (“A Unified Welfare Analysis of Government Policies” by Nathaniel Hendren, PhD, and Ben Sprung-Keyser). Using computer algorithms capable of mining large pools of data, the researchers looked at 133 government policy changes over the last 50 years and compared the long-term results of those changes by assessing dollars spent against those returned in the form of tax revenue.

The Harvard article quotes Dr. Hendren as saying, This association was most impressive for children who came from lower-income families. This was especially true for programs that aimed at improving child health and increasing educational attainment.

Of course, these observations don’t come as a surprise to those of us who have accepted the challenge of improving the health of children. But it’s always nice to hear some new data that warms our hearts and reinforces our commitment to building healthy communities by focusing our efforts on its youngest members.

However, the paper did provide a finding that disappointed me. This big data analysis revealed that programs aimed at encouraging young people to attend college produced higher future earnings than did those focused on job training. I guess this shouldn’t be much of a surprise, but I believe we have been overemphasizing college track programs when we should be destigmatizing a career path in one of the trades. It may be that job training has been poorly done or at least not flexible enough to meet the changing demands of industry.

The investigators were surprised that their analysis demonstrated that policy changes targeted at children through their middle and high school years and even into college yielded return on investment at least as great if not greater than some successful preschool programs. Dr. Hendren responded to this finding by observing that “it’s never too late.” However, I think his comment deserves the loud and clear caveat, “as long as we are still talking about children.”

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

When asked about my decision to choose pediatrics over the other specialty opportunities I was being offered, I have always answered that my choice was primarily based on my desire to work with children. That affinity certainly didn’t stem from my experience with my sister who is 7 years my junior. By her own admission, she was a bratty little thing and a major annoyance during my journey through adolescence. However, during the summers of high school and college I worked as a lifeguard, and one of my duties was to teach swimming classes. The joy and reward of watching children overcome their fear of the water and become competent swimmers left a positive impression, which was in stark contrast to the few classes of adult nonswimmers my coworkers and I taught. Our success rate with adults was pretty close to zero.

If I was going to spend my time and effort becoming a physician, I decided I wanted to be working with patients with the high potential for positive change and ones who had yet to accumulate a several decades long list of bad health habits. I wanted to be practicing in situations well before the die had been cast.

With this background in mind, you can understand why I was drawn to a recent article in the Harvard Gazette titled “Social spending on kids yields the biggest bang for the buck,” by Clea Simon. The article describes a recent study by Opportunity Insights, a Harvard-based institute of policy analysts and social scientists (“A Unified Welfare Analysis of Government Policies” by Nathaniel Hendren, PhD, and Ben Sprung-Keyser). Using computer algorithms capable of mining large pools of data, the researchers looked at 133 government policy changes over the last 50 years and compared the long-term results of those changes by assessing dollars spent against those returned in the form of tax revenue.

The Harvard article quotes Dr. Hendren as saying, This association was most impressive for children who came from lower-income families. This was especially true for programs that aimed at improving child health and increasing educational attainment.

Of course, these observations don’t come as a surprise to those of us who have accepted the challenge of improving the health of children. But it’s always nice to hear some new data that warms our hearts and reinforces our commitment to building healthy communities by focusing our efforts on its youngest members.

However, the paper did provide a finding that disappointed me. This big data analysis revealed that programs aimed at encouraging young people to attend college produced higher future earnings than did those focused on job training. I guess this shouldn’t be much of a surprise, but I believe we have been overemphasizing college track programs when we should be destigmatizing a career path in one of the trades. It may be that job training has been poorly done or at least not flexible enough to meet the changing demands of industry.

The investigators were surprised that their analysis demonstrated that policy changes targeted at children through their middle and high school years and even into college yielded return on investment at least as great if not greater than some successful preschool programs. Dr. Hendren responded to this finding by observing that “it’s never too late.” However, I think his comment deserves the loud and clear caveat, “as long as we are still talking about children.”

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Ob.Gyn. News welcomes Dr. Krishna to the board

Dr. Krishna is an assistant professor of gynecology and obstetrics in the division of maternal-fetal medicine at Emory University in Atlanta.

She has published articles on topics such as low fetal fraction in noninvasive prenatal screening, breast cancer in pregnancy, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, obesity, diabetes, and chronic hypertension. She is currently involved in research on chronic hypertension during pregnancy.

Dr. Krishna serves on numerous committees at Emory for the department of gynecology and obstetrics, including the resident clinical competency committee and program evaluation committee, as well as similar committees for the maternal-fetal medicine fellowship program. She also is a member of the Emory University Hospital Midtown’s quality enhancement committee, ethics committee, and critical care committee.

Dr. Krishna received a Master of Public Health in epidemiology from Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine in New Orleans, and a medical degree from Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center in Shreveport. She completed her residency training in obstetrics and gynecology and fellowship training in maternal-fetal medicine at Emory, where she received awards for her clinical skills in obstetrics and completed a thesis research project on prenatal genetic screening. She also was recognized by her staff and colleagues as Outstanding Emory Faculty for her contributions to teaching and clinical service. Dr. Krishna is board certified in obstetrics and gynecology and in maternal-fetal medicine. She is a member of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine and a fellow of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Dr. Krishna is an assistant professor of gynecology and obstetrics in the division of maternal-fetal medicine at Emory University in Atlanta.

She has published articles on topics such as low fetal fraction in noninvasive prenatal screening, breast cancer in pregnancy, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, obesity, diabetes, and chronic hypertension. She is currently involved in research on chronic hypertension during pregnancy.

Dr. Krishna serves on numerous committees at Emory for the department of gynecology and obstetrics, including the resident clinical competency committee and program evaluation committee, as well as similar committees for the maternal-fetal medicine fellowship program. She also is a member of the Emory University Hospital Midtown’s quality enhancement committee, ethics committee, and critical care committee.

Dr. Krishna received a Master of Public Health in epidemiology from Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine in New Orleans, and a medical degree from Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center in Shreveport. She completed her residency training in obstetrics and gynecology and fellowship training in maternal-fetal medicine at Emory, where she received awards for her clinical skills in obstetrics and completed a thesis research project on prenatal genetic screening. She also was recognized by her staff and colleagues as Outstanding Emory Faculty for her contributions to teaching and clinical service. Dr. Krishna is board certified in obstetrics and gynecology and in maternal-fetal medicine. She is a member of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine and a fellow of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Dr. Krishna is an assistant professor of gynecology and obstetrics in the division of maternal-fetal medicine at Emory University in Atlanta.

She has published articles on topics such as low fetal fraction in noninvasive prenatal screening, breast cancer in pregnancy, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, obesity, diabetes, and chronic hypertension. She is currently involved in research on chronic hypertension during pregnancy.

Dr. Krishna serves on numerous committees at Emory for the department of gynecology and obstetrics, including the resident clinical competency committee and program evaluation committee, as well as similar committees for the maternal-fetal medicine fellowship program. She also is a member of the Emory University Hospital Midtown’s quality enhancement committee, ethics committee, and critical care committee.

Dr. Krishna received a Master of Public Health in epidemiology from Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine in New Orleans, and a medical degree from Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center in Shreveport. She completed her residency training in obstetrics and gynecology and fellowship training in maternal-fetal medicine at Emory, where she received awards for her clinical skills in obstetrics and completed a thesis research project on prenatal genetic screening. She also was recognized by her staff and colleagues as Outstanding Emory Faculty for her contributions to teaching and clinical service. Dr. Krishna is board certified in obstetrics and gynecology and in maternal-fetal medicine. She is a member of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine and a fellow of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Disputes over malpractice blame: Do allocations matter?

When the summons arrived, Nataly Minkina, MD, took one look at the lawsuit and fainted.

The Boston-area internist had treated the plaintiff just once while covering for the patient’s primary care physician. During a visit for an upper respiratory infection, the patient mentioned a lump in her breast, and Dr. Minkina confirmed a small thickening in the woman’s right breast. She sent the patient for a mammogram and ultrasound, the results of which the radiologist reported were normal, according to court documents.

Five years later, the patient claimed Dr. Minkina was one of several providers responsible for a missed breast cancer diagnosis.

Even worse than the lawsuit, however, was how her former insurer resolved the case, said Dr. Minkina, now an internist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Chestnut Hill, Mass. The claim was settled against the defendants for $500,000, and Dr. Minkina was alloted 30% of the liability. No fault was assigned to the other physicians named, while a nurse practitioner was alloted 10%, and the medical practice was alloted 60% liability, according to court documents.

“I was very upset,” Dr. Minkina said. “First of all, I was kept in the dark. Nobody ever talked to me. I did not get a single report or any document from my attorney in 12 months. When I asked why was I assigned the [30%] liability, they said the experts gave me bad evaluations, but they would not show reports to me. I was literally scapegoated.”

When the insurer refused to reconsider the allocation, Dr. Minkina took her complaint to court. The internist now has been embroiled in a legal challenge against Medical Professional Mutual Insurance Company (ProMutual) for 7 years. Dr. Minkina’s lawsuit alleges the insurer engaged in a bad faith allocation to serve its own economic interests by shifting fault for the claim from its insureds to its former client, Dr. Minkina. The insurance company contends the allocation was a careful and rational decision based on case evidence. In late July, the case went to trial in Dedham, Mass.

ProMutual declined comment on the case; the insurer also would not address general questions about its allocation policies.

“I started this fight because I felt violated and betrayed, not to make money,” Dr. Minkina said. “I am not rich by a long shot, and I wanted to clear my name because [a] good name is all I have. Additionally, having [a] record about malpractice payment in my physician profile makes me vulnerable.”

Liability experts say the case highlights the conflicts that can arise between physicians and insurers during malpractice lawsuits. The legal challenge also raises questions about allocations of liability by insurers, how the determinations are made, and what impact they have on doctors going forward.

The proportion of liability assigned after a settlement matters, said Jeffrey Segal, MD, JD, a neurosurgeon and founder of Medical Justice, a medicolegal consulting firm for physicians.