User login

Patients with mood disorders may have altered microbiome

Discuss dietary interventions, such as probiotics, as ‘supplemental therapeutic options’

CRYSTAL CITY, VA. – Individuals with mood disorders might have an altered microbiome, but more information is needed to understand how the microorganisms that make up the microbiome affect patients’ health, an expert said at Focus on Neuropsychiatry presented by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists.

“An increased understanding of the neurobiology of the microbiome is required so that the benefit that these microorganisms serve to human health can be fully harnessed,” said Emily G. Severance, PhD, assistant professor of pediatrics at John Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Diseases that involve the microbiome include those with a single identifiable infectious agent that produces persistent inflammation, central nervous system diseases with mucosal surface involvement, and diseases with “variable response to antibiotic and anti-inflammatory agents.”

“It’s becoming clear that [the microbiome is] integral for the modulation of the central nervous system,” which occurs through neurotransmitter production, Dr. Severance said at the meeting presented by Global Academy for Medical Education.

“We have an extensive enteric nervous system that has the very same receptors that the brain does,” she said. “If you have those receptors activated in the gut or [are] having the neurotransmitters produced in the gut, and if there’s a way for those neurotransmitters to reach the brain, that’s a very powerful mechanism to illustrate the gut-brain axis.”

In addition to neuropsychiatric diseases, the microbiome also can be involved in inflammatory gastrointestinal, systemic rheumatoid and autoimmune, chronic inflammatory lung, and periodontal diseases, as well as immune-mediated skin disorders. Mood disorders in particular have evidence for dysbiosis in low-level inflammation and leaky gut pathology, which is present in patients with depression, Dr. Severance said. “All these data suggest that We can do that because gut bacteria are easily accessed and can be altered through probiotics, prebiotics, diet, and fecal transplant, and in patients, Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium combinations may improve mood, reduce anxiety, and enhance cognitive function.”

In addition, epidemiological studies show that antibiotic exposure can be a risk factor for developing mood disorders. One recent study found that anti-infective agents, particularly antibiotics, increased the risk of schizophrenia (hazard rate ratio, 2.05; 95% confidence interval, 1.77-2.38) and affective disorders (HRR, 2.59; 95% CI, 2.31-2.89), which the researchers attributed to brain inflammation, the microbiome, and environmental factors (Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016 Nov 21. doi: 10.1111/acps.12671). In mice, other researchers found that those that received a fecal transplant with a “depression microbiota” showed symptoms of major depressive disorder, compared with mice that received a “healthy microbiota.” Those results suggest that change in microbiota can induce mood disorders (Mol Psychiatry. 2016 Apr 12. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.44).

The evidence for probiotics is mixed, primarily because the study population in trials are so heterogeneous, but there is evidence for its efficacy in patients with mood disorders, Dr. Severance said. Probiotics have been shown to prevent rehospitalization for patients in mania. For example, one study showed reduced rehospitalization in patients with mania (8 of 33 patients) who received probiotics, compared with placebo (24 of 33 patients). Also, probiotic use was associated with fewer days of rehospitalization (Bipolar Disord. 2018 Apr 25. doi: 10. 1111/bdi.12652).

Meanwhile, a pilot study analyzing patients with irritable bowel syndrome and mild to moderate anxiety and/or depression found use of B. longum in this population reduced depression scores, but not anxiety or irritable bowel syndrome symptoms, compared with placebo (Gastroenterology. 2017 May 5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.05.003).

Probiotic efficacy can be variable for patients with mood disorders, but the intervention is a “relatively low-risk, potentially high reward” option for these patients, Dr. Severance said. “Clinicians should inquire about patient GI conditions and overall GI health. Dietary interventions and the use of probiotics and their limitations should be discussed as supplemental therapeutic options.”

Dr. Severance reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Discuss dietary interventions, such as probiotics, as ‘supplemental therapeutic options’

Discuss dietary interventions, such as probiotics, as ‘supplemental therapeutic options’

CRYSTAL CITY, VA. – Individuals with mood disorders might have an altered microbiome, but more information is needed to understand how the microorganisms that make up the microbiome affect patients’ health, an expert said at Focus on Neuropsychiatry presented by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists.

“An increased understanding of the neurobiology of the microbiome is required so that the benefit that these microorganisms serve to human health can be fully harnessed,” said Emily G. Severance, PhD, assistant professor of pediatrics at John Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Diseases that involve the microbiome include those with a single identifiable infectious agent that produces persistent inflammation, central nervous system diseases with mucosal surface involvement, and diseases with “variable response to antibiotic and anti-inflammatory agents.”

“It’s becoming clear that [the microbiome is] integral for the modulation of the central nervous system,” which occurs through neurotransmitter production, Dr. Severance said at the meeting presented by Global Academy for Medical Education.

“We have an extensive enteric nervous system that has the very same receptors that the brain does,” she said. “If you have those receptors activated in the gut or [are] having the neurotransmitters produced in the gut, and if there’s a way for those neurotransmitters to reach the brain, that’s a very powerful mechanism to illustrate the gut-brain axis.”

In addition to neuropsychiatric diseases, the microbiome also can be involved in inflammatory gastrointestinal, systemic rheumatoid and autoimmune, chronic inflammatory lung, and periodontal diseases, as well as immune-mediated skin disorders. Mood disorders in particular have evidence for dysbiosis in low-level inflammation and leaky gut pathology, which is present in patients with depression, Dr. Severance said. “All these data suggest that We can do that because gut bacteria are easily accessed and can be altered through probiotics, prebiotics, diet, and fecal transplant, and in patients, Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium combinations may improve mood, reduce anxiety, and enhance cognitive function.”

In addition, epidemiological studies show that antibiotic exposure can be a risk factor for developing mood disorders. One recent study found that anti-infective agents, particularly antibiotics, increased the risk of schizophrenia (hazard rate ratio, 2.05; 95% confidence interval, 1.77-2.38) and affective disorders (HRR, 2.59; 95% CI, 2.31-2.89), which the researchers attributed to brain inflammation, the microbiome, and environmental factors (Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016 Nov 21. doi: 10.1111/acps.12671). In mice, other researchers found that those that received a fecal transplant with a “depression microbiota” showed symptoms of major depressive disorder, compared with mice that received a “healthy microbiota.” Those results suggest that change in microbiota can induce mood disorders (Mol Psychiatry. 2016 Apr 12. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.44).

The evidence for probiotics is mixed, primarily because the study population in trials are so heterogeneous, but there is evidence for its efficacy in patients with mood disorders, Dr. Severance said. Probiotics have been shown to prevent rehospitalization for patients in mania. For example, one study showed reduced rehospitalization in patients with mania (8 of 33 patients) who received probiotics, compared with placebo (24 of 33 patients). Also, probiotic use was associated with fewer days of rehospitalization (Bipolar Disord. 2018 Apr 25. doi: 10. 1111/bdi.12652).

Meanwhile, a pilot study analyzing patients with irritable bowel syndrome and mild to moderate anxiety and/or depression found use of B. longum in this population reduced depression scores, but not anxiety or irritable bowel syndrome symptoms, compared with placebo (Gastroenterology. 2017 May 5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.05.003).

Probiotic efficacy can be variable for patients with mood disorders, but the intervention is a “relatively low-risk, potentially high reward” option for these patients, Dr. Severance said. “Clinicians should inquire about patient GI conditions and overall GI health. Dietary interventions and the use of probiotics and their limitations should be discussed as supplemental therapeutic options.”

Dr. Severance reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

CRYSTAL CITY, VA. – Individuals with mood disorders might have an altered microbiome, but more information is needed to understand how the microorganisms that make up the microbiome affect patients’ health, an expert said at Focus on Neuropsychiatry presented by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists.

“An increased understanding of the neurobiology of the microbiome is required so that the benefit that these microorganisms serve to human health can be fully harnessed,” said Emily G. Severance, PhD, assistant professor of pediatrics at John Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Diseases that involve the microbiome include those with a single identifiable infectious agent that produces persistent inflammation, central nervous system diseases with mucosal surface involvement, and diseases with “variable response to antibiotic and anti-inflammatory agents.”

“It’s becoming clear that [the microbiome is] integral for the modulation of the central nervous system,” which occurs through neurotransmitter production, Dr. Severance said at the meeting presented by Global Academy for Medical Education.

“We have an extensive enteric nervous system that has the very same receptors that the brain does,” she said. “If you have those receptors activated in the gut or [are] having the neurotransmitters produced in the gut, and if there’s a way for those neurotransmitters to reach the brain, that’s a very powerful mechanism to illustrate the gut-brain axis.”

In addition to neuropsychiatric diseases, the microbiome also can be involved in inflammatory gastrointestinal, systemic rheumatoid and autoimmune, chronic inflammatory lung, and periodontal diseases, as well as immune-mediated skin disorders. Mood disorders in particular have evidence for dysbiosis in low-level inflammation and leaky gut pathology, which is present in patients with depression, Dr. Severance said. “All these data suggest that We can do that because gut bacteria are easily accessed and can be altered through probiotics, prebiotics, diet, and fecal transplant, and in patients, Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium combinations may improve mood, reduce anxiety, and enhance cognitive function.”

In addition, epidemiological studies show that antibiotic exposure can be a risk factor for developing mood disorders. One recent study found that anti-infective agents, particularly antibiotics, increased the risk of schizophrenia (hazard rate ratio, 2.05; 95% confidence interval, 1.77-2.38) and affective disorders (HRR, 2.59; 95% CI, 2.31-2.89), which the researchers attributed to brain inflammation, the microbiome, and environmental factors (Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016 Nov 21. doi: 10.1111/acps.12671). In mice, other researchers found that those that received a fecal transplant with a “depression microbiota” showed symptoms of major depressive disorder, compared with mice that received a “healthy microbiota.” Those results suggest that change in microbiota can induce mood disorders (Mol Psychiatry. 2016 Apr 12. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.44).

The evidence for probiotics is mixed, primarily because the study population in trials are so heterogeneous, but there is evidence for its efficacy in patients with mood disorders, Dr. Severance said. Probiotics have been shown to prevent rehospitalization for patients in mania. For example, one study showed reduced rehospitalization in patients with mania (8 of 33 patients) who received probiotics, compared with placebo (24 of 33 patients). Also, probiotic use was associated with fewer days of rehospitalization (Bipolar Disord. 2018 Apr 25. doi: 10. 1111/bdi.12652).

Meanwhile, a pilot study analyzing patients with irritable bowel syndrome and mild to moderate anxiety and/or depression found use of B. longum in this population reduced depression scores, but not anxiety or irritable bowel syndrome symptoms, compared with placebo (Gastroenterology. 2017 May 5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.05.003).

Probiotic efficacy can be variable for patients with mood disorders, but the intervention is a “relatively low-risk, potentially high reward” option for these patients, Dr. Severance said. “Clinicians should inquire about patient GI conditions and overall GI health. Dietary interventions and the use of probiotics and their limitations should be discussed as supplemental therapeutic options.”

Dr. Severance reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM FOCUS ON NEUROPSYCHIATRY 2019

Suicide rates rise in U.S. adolescents and young adults

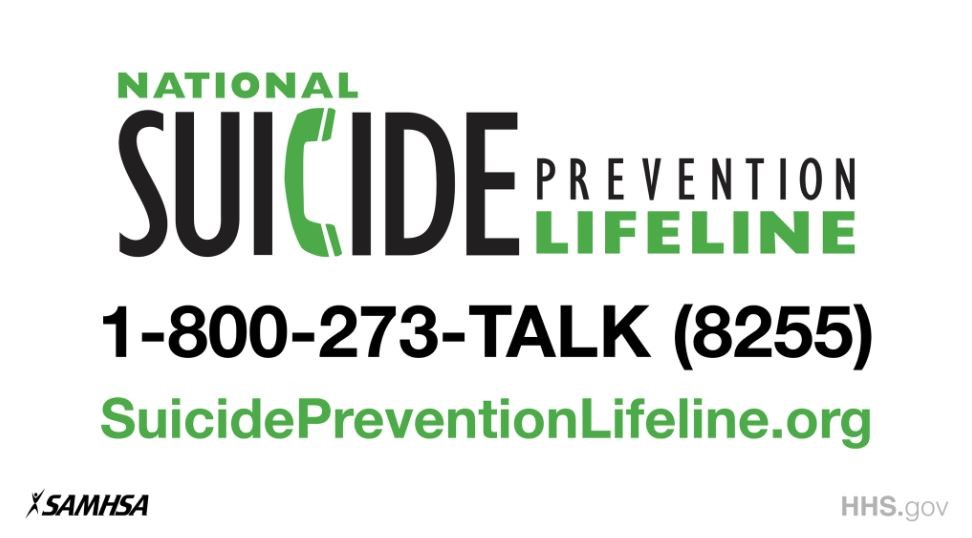

Suicides in teens and young adults reached 6,241 in 2017, the highest since 2000, according to data from a review of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Underlying Cause of Death database.

The suicide rate overall was 12 per 100,000 in 2017 for 15-19 year olds.

Although suicide rates have increased across all age groups in the United States since 2000, “adolescents are of particular concern, with increases in social media use, anxiety, depression, and self-inflicted injuries,” wrote Oren Miron of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues.

In a research letter published in JAMA, the researchers analyzed trends in teen and young adult suicides from 2000 to 2017. The combined suicide rate for males and females aged 15-19 years in 2000 was 8 per 100,000 with no significant changes until 2007, followed by an annual percentage change (APC) of 3% from 2007 to 2014 and 10% from 2014 to 2017.

When the data were broken out by gender, Of note, these young men showed a decreasing trend in APC of –2% from 2000 to 2007 before increasing.

Among females aged 15-19 years, no increase was noted until 2010, then researchers identified an APC of 8% from 2010 to 2017.

For ages 20-24 years, the combined suicide rate for males and females was 13 per 100,000 in 2000, which rose to 17 per 100,000 in 2017. The APC in the older group was 1% from 2000 to 2013 and 6% from 2013 to 2017. Increasing trends were observed for both males and females over the study period.

The study was limited by the potential inaccuracy in cause of death listed on death certificates, such as mistaking a suicide for an accidental overdose, and the increased suicide rate could reflect more accurate reporting, the researchers noted.

Nonetheless, the results support the need for more studies of contributing factors to teen and young adult suicides to help develop prevention strategies and analysis of factors that may have contributed to declines in suicide rates in the past, they said.

Coauthor Dr. Yu was supported by the Harvard Data Science Fellowship. The researchers had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Miron O et al. JAMA. 2019 Jun 28;321:2362-4.

Suicides in teens and young adults reached 6,241 in 2017, the highest since 2000, according to data from a review of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Underlying Cause of Death database.

The suicide rate overall was 12 per 100,000 in 2017 for 15-19 year olds.

Although suicide rates have increased across all age groups in the United States since 2000, “adolescents are of particular concern, with increases in social media use, anxiety, depression, and self-inflicted injuries,” wrote Oren Miron of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues.

In a research letter published in JAMA, the researchers analyzed trends in teen and young adult suicides from 2000 to 2017. The combined suicide rate for males and females aged 15-19 years in 2000 was 8 per 100,000 with no significant changes until 2007, followed by an annual percentage change (APC) of 3% from 2007 to 2014 and 10% from 2014 to 2017.

When the data were broken out by gender, Of note, these young men showed a decreasing trend in APC of –2% from 2000 to 2007 before increasing.

Among females aged 15-19 years, no increase was noted until 2010, then researchers identified an APC of 8% from 2010 to 2017.

For ages 20-24 years, the combined suicide rate for males and females was 13 per 100,000 in 2000, which rose to 17 per 100,000 in 2017. The APC in the older group was 1% from 2000 to 2013 and 6% from 2013 to 2017. Increasing trends were observed for both males and females over the study period.

The study was limited by the potential inaccuracy in cause of death listed on death certificates, such as mistaking a suicide for an accidental overdose, and the increased suicide rate could reflect more accurate reporting, the researchers noted.

Nonetheless, the results support the need for more studies of contributing factors to teen and young adult suicides to help develop prevention strategies and analysis of factors that may have contributed to declines in suicide rates in the past, they said.

Coauthor Dr. Yu was supported by the Harvard Data Science Fellowship. The researchers had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Miron O et al. JAMA. 2019 Jun 28;321:2362-4.

Suicides in teens and young adults reached 6,241 in 2017, the highest since 2000, according to data from a review of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Underlying Cause of Death database.

The suicide rate overall was 12 per 100,000 in 2017 for 15-19 year olds.

Although suicide rates have increased across all age groups in the United States since 2000, “adolescents are of particular concern, with increases in social media use, anxiety, depression, and self-inflicted injuries,” wrote Oren Miron of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues.

In a research letter published in JAMA, the researchers analyzed trends in teen and young adult suicides from 2000 to 2017. The combined suicide rate for males and females aged 15-19 years in 2000 was 8 per 100,000 with no significant changes until 2007, followed by an annual percentage change (APC) of 3% from 2007 to 2014 and 10% from 2014 to 2017.

When the data were broken out by gender, Of note, these young men showed a decreasing trend in APC of –2% from 2000 to 2007 before increasing.

Among females aged 15-19 years, no increase was noted until 2010, then researchers identified an APC of 8% from 2010 to 2017.

For ages 20-24 years, the combined suicide rate for males and females was 13 per 100,000 in 2000, which rose to 17 per 100,000 in 2017. The APC in the older group was 1% from 2000 to 2013 and 6% from 2013 to 2017. Increasing trends were observed for both males and females over the study period.

The study was limited by the potential inaccuracy in cause of death listed on death certificates, such as mistaking a suicide for an accidental overdose, and the increased suicide rate could reflect more accurate reporting, the researchers noted.

Nonetheless, the results support the need for more studies of contributing factors to teen and young adult suicides to help develop prevention strategies and analysis of factors that may have contributed to declines in suicide rates in the past, they said.

Coauthor Dr. Yu was supported by the Harvard Data Science Fellowship. The researchers had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Miron O et al. JAMA. 2019 Jun 28;321:2362-4.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: Suicide rates in U.S. adolescents and young adults have increased since 2000.

Major finding: The combined suicide rate for males and females aged 15-19 years underwent an annual percentage change of 3% from 2007 to 2014 and 10% from 2014 to 2017.

Study details: The data come from the CDC Underlying Cause of Death database.

Disclosures: Coauthor Dr. Yu was supported by the Harvard Data Science Fellowship. The researchers had no relevant financial disclosures.

Source: Miron O et al. JAMA. 2019 Jun 28;321:2362-4.

Ask patients about worst example of suicidal ideation

CRYSTAL CITY, VA. – Some patients experience consistent suicidal ideation – but most do not, an expert said at Focus on Neuropsychiatry presented by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists.

“In most patients, the ideation tends to go up and down – which means you ask the patient about the most severe example of suicidal ideation … in the last week or 2,” J. John Mann, MD, said. Getting a handle on patients’ worst suicidal ideation also can provide clues into the range of suicidal behavior they might be subject to, he added.

U.S. suicide rates have increased dramatically since 2000, and most people who die by suicide had depression, said Dr. Mann, the Paul Janssen Professor of Translational Neuroscience (in psychiatry and in radiology) at Columbia University, New York. However, those patients who are depressed tend to attempt suicide early in their depression.

“Most people with a major depressive episode never attempt suicide,” said Dr. Mann, who also is affiliated with the New York State Psychiatric Institute. “Suicidal behavior is not a ‘wear and tear’ phenomenon.”

When assessing risk of suicide clinically, patients most at risk include those with past history of suicide attempts, a family history of suicide, and those who have the worst suicidal ideation.

About half of the predisposition to suicidal behavior is genetic and independent of genetic risk associated with major psychiatric disorders. This genetic risk affects the diathesis each patient has for suicidal behavior. In the stress-diathesis model for suicidal behavior, stress from major depressive episodes and life events contributes to the patient’s perception of stress, which in turn contributes to that patient’s response to stress. Rather than depression itself being a suicidal trigger, these stressors in the form of adverse life events appear to be the trigger for suicide attempts, Dr. Mann noted.

“All of the risk is pretty much accounted for by whether the patient was in or out of an episode of major depression,” said Dr. Mann. “If they were in an episode of major depression, all the risk was accounted for by the major depression, and the stressors counted for enough. When they’re out of an episode of major depression, the risk fell right away and the stressors didn’t matter much.”

In the stress-diathesis model, trait components of suicidal behavior include mood and emotion dysregulation and perception; misreading social signals; reactive or impulsive aggressive traits of decision making or delayed discounting; and altered learning, memory, and problem solving. However, clinicians should look to the patients for whom depression appears more painful in subjective scores, because going by these trait components alone will not distinguish between patients at risk for suicide and those who will not make an attempt.

According to the Columbia Classification Algorithm of Suicide Assessment, suicide is distinguished by whether a patient wished to die, if an attempt is stopped by themselves or another person before harm has begun, and whether a patient prepared for the act beyond verbalizing or thinking of suicide but before harm has begun.

In addition to prescribing antidepressants, treatments with evidence for preventing suicide include means restriction and cognitive-behavioral therapy. For patients with borderline personality disorder, dialectical behavior therapy has proven effective. School interventions that educate students about mental health also have shown effectiveness. Other strategies include educating reporters about media guidelines on writing about suicide. Internet outreach interventions are promising, he said, but more evidence is needed to determine whether they work.

Among antidepressant options for patients with suicidal ideation, fluoxetine appears best for adolescents, and data show that venlafaxine is effective in adults. The Food and Drug Administration originally put a black box warning on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in 2004; however, recent data have shown that the increased risk of suicidal ideation brought on by those medications tapers off after the first week on the medication. Meanwhile, in the case of ketamine, there is “rapid and robust improvement” in depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation, which targets the diathesis, Dr. Mann said at the meeting presented by Global Academy for Medical Education.

“We need to identify rapidly acting antisuicidal medications, and we now see there’s a clear path forward to do that” with treatments like ketamine, he said.

Dr. Mann’s presentation was based on research funded by the National Institute of Mental Health and the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation. He reported receiving royalties from the Research Foundation for Mental Hygiene for commercial use of the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale.

Global Academy for Medical Education, Current Psychiatry, and this publication are owned by the same company.

CRYSTAL CITY, VA. – Some patients experience consistent suicidal ideation – but most do not, an expert said at Focus on Neuropsychiatry presented by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists.

“In most patients, the ideation tends to go up and down – which means you ask the patient about the most severe example of suicidal ideation … in the last week or 2,” J. John Mann, MD, said. Getting a handle on patients’ worst suicidal ideation also can provide clues into the range of suicidal behavior they might be subject to, he added.

U.S. suicide rates have increased dramatically since 2000, and most people who die by suicide had depression, said Dr. Mann, the Paul Janssen Professor of Translational Neuroscience (in psychiatry and in radiology) at Columbia University, New York. However, those patients who are depressed tend to attempt suicide early in their depression.

“Most people with a major depressive episode never attempt suicide,” said Dr. Mann, who also is affiliated with the New York State Psychiatric Institute. “Suicidal behavior is not a ‘wear and tear’ phenomenon.”

When assessing risk of suicide clinically, patients most at risk include those with past history of suicide attempts, a family history of suicide, and those who have the worst suicidal ideation.

About half of the predisposition to suicidal behavior is genetic and independent of genetic risk associated with major psychiatric disorders. This genetic risk affects the diathesis each patient has for suicidal behavior. In the stress-diathesis model for suicidal behavior, stress from major depressive episodes and life events contributes to the patient’s perception of stress, which in turn contributes to that patient’s response to stress. Rather than depression itself being a suicidal trigger, these stressors in the form of adverse life events appear to be the trigger for suicide attempts, Dr. Mann noted.

“All of the risk is pretty much accounted for by whether the patient was in or out of an episode of major depression,” said Dr. Mann. “If they were in an episode of major depression, all the risk was accounted for by the major depression, and the stressors counted for enough. When they’re out of an episode of major depression, the risk fell right away and the stressors didn’t matter much.”

In the stress-diathesis model, trait components of suicidal behavior include mood and emotion dysregulation and perception; misreading social signals; reactive or impulsive aggressive traits of decision making or delayed discounting; and altered learning, memory, and problem solving. However, clinicians should look to the patients for whom depression appears more painful in subjective scores, because going by these trait components alone will not distinguish between patients at risk for suicide and those who will not make an attempt.

According to the Columbia Classification Algorithm of Suicide Assessment, suicide is distinguished by whether a patient wished to die, if an attempt is stopped by themselves or another person before harm has begun, and whether a patient prepared for the act beyond verbalizing or thinking of suicide but before harm has begun.

In addition to prescribing antidepressants, treatments with evidence for preventing suicide include means restriction and cognitive-behavioral therapy. For patients with borderline personality disorder, dialectical behavior therapy has proven effective. School interventions that educate students about mental health also have shown effectiveness. Other strategies include educating reporters about media guidelines on writing about suicide. Internet outreach interventions are promising, he said, but more evidence is needed to determine whether they work.

Among antidepressant options for patients with suicidal ideation, fluoxetine appears best for adolescents, and data show that venlafaxine is effective in adults. The Food and Drug Administration originally put a black box warning on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in 2004; however, recent data have shown that the increased risk of suicidal ideation brought on by those medications tapers off after the first week on the medication. Meanwhile, in the case of ketamine, there is “rapid and robust improvement” in depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation, which targets the diathesis, Dr. Mann said at the meeting presented by Global Academy for Medical Education.

“We need to identify rapidly acting antisuicidal medications, and we now see there’s a clear path forward to do that” with treatments like ketamine, he said.

Dr. Mann’s presentation was based on research funded by the National Institute of Mental Health and the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation. He reported receiving royalties from the Research Foundation for Mental Hygiene for commercial use of the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale.

Global Academy for Medical Education, Current Psychiatry, and this publication are owned by the same company.

CRYSTAL CITY, VA. – Some patients experience consistent suicidal ideation – but most do not, an expert said at Focus on Neuropsychiatry presented by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists.

“In most patients, the ideation tends to go up and down – which means you ask the patient about the most severe example of suicidal ideation … in the last week or 2,” J. John Mann, MD, said. Getting a handle on patients’ worst suicidal ideation also can provide clues into the range of suicidal behavior they might be subject to, he added.

U.S. suicide rates have increased dramatically since 2000, and most people who die by suicide had depression, said Dr. Mann, the Paul Janssen Professor of Translational Neuroscience (in psychiatry and in radiology) at Columbia University, New York. However, those patients who are depressed tend to attempt suicide early in their depression.

“Most people with a major depressive episode never attempt suicide,” said Dr. Mann, who also is affiliated with the New York State Psychiatric Institute. “Suicidal behavior is not a ‘wear and tear’ phenomenon.”

When assessing risk of suicide clinically, patients most at risk include those with past history of suicide attempts, a family history of suicide, and those who have the worst suicidal ideation.

About half of the predisposition to suicidal behavior is genetic and independent of genetic risk associated with major psychiatric disorders. This genetic risk affects the diathesis each patient has for suicidal behavior. In the stress-diathesis model for suicidal behavior, stress from major depressive episodes and life events contributes to the patient’s perception of stress, which in turn contributes to that patient’s response to stress. Rather than depression itself being a suicidal trigger, these stressors in the form of adverse life events appear to be the trigger for suicide attempts, Dr. Mann noted.

“All of the risk is pretty much accounted for by whether the patient was in or out of an episode of major depression,” said Dr. Mann. “If they were in an episode of major depression, all the risk was accounted for by the major depression, and the stressors counted for enough. When they’re out of an episode of major depression, the risk fell right away and the stressors didn’t matter much.”

In the stress-diathesis model, trait components of suicidal behavior include mood and emotion dysregulation and perception; misreading social signals; reactive or impulsive aggressive traits of decision making or delayed discounting; and altered learning, memory, and problem solving. However, clinicians should look to the patients for whom depression appears more painful in subjective scores, because going by these trait components alone will not distinguish between patients at risk for suicide and those who will not make an attempt.

According to the Columbia Classification Algorithm of Suicide Assessment, suicide is distinguished by whether a patient wished to die, if an attempt is stopped by themselves or another person before harm has begun, and whether a patient prepared for the act beyond verbalizing or thinking of suicide but before harm has begun.

In addition to prescribing antidepressants, treatments with evidence for preventing suicide include means restriction and cognitive-behavioral therapy. For patients with borderline personality disorder, dialectical behavior therapy has proven effective. School interventions that educate students about mental health also have shown effectiveness. Other strategies include educating reporters about media guidelines on writing about suicide. Internet outreach interventions are promising, he said, but more evidence is needed to determine whether they work.

Among antidepressant options for patients with suicidal ideation, fluoxetine appears best for adolescents, and data show that venlafaxine is effective in adults. The Food and Drug Administration originally put a black box warning on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in 2004; however, recent data have shown that the increased risk of suicidal ideation brought on by those medications tapers off after the first week on the medication. Meanwhile, in the case of ketamine, there is “rapid and robust improvement” in depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation, which targets the diathesis, Dr. Mann said at the meeting presented by Global Academy for Medical Education.

“We need to identify rapidly acting antisuicidal medications, and we now see there’s a clear path forward to do that” with treatments like ketamine, he said.

Dr. Mann’s presentation was based on research funded by the National Institute of Mental Health and the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation. He reported receiving royalties from the Research Foundation for Mental Hygiene for commercial use of the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale.

Global Academy for Medical Education, Current Psychiatry, and this publication are owned by the same company.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM FOCUS ON NEUROPSYCHIATRY 2019

LTC-associated suicide among older adults more common than previously thought

The rate of suicide associated with residential long-term care (LTC) in adults aged 55 years and older may be significantly higher than the injury location coding of the National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS) suggests, according to new research.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that there are about 16,000 nursing homes and 31,000 assisted living facilities in the United States and they currently house about 25% of all Medicare beneficiaries. “As such, residential LTC may be a potential location for identifying individuals at high risk of self-harm and for implementing interventions to reduce suicide risk, wrote Briana Mezuk, PhD, and associates from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. The study was published in JAMA Network Open.

Dr. Mezuk and colleagues conducted a cross-sectional, epidemiologic study using a natural language–processing algorithm to analyze restricted-access data from the NVDRS between 2003 and 2015. A total of 47,759 suicides and undetermined deaths in adults aged 55 years and older from 27 states were included in the analysis (median age, 64 years; 77.6% male; 90.0% non-Hispanic white).

The algorithm identified 1,037 (2.2% of the total) suicide deaths associated with LTC, with 428 occurring in adults living in LTC, 449 occurring during the transition into or out of LTC, and 160 otherwise associated with LTC. Decedents in this group had a median age of 79 years, were 73.8% male, and were 94.3% non-Hispanic white. The number of suicide deaths varied widely from year to year, but no trend was found in the change over the study period.

Deaths while living in LTC were more likely among women, which the investigators noted is to be expected because LTC residents are disproportionately women. Death while transitioning into or out of LTC was more likely among adults who previously had expressed suicide ideation and had a physical health problem cited as a contributing circumstance. Death otherwise associated with LTC was more likely in adults who were married or in a relationship, had a depressed mood, and had a recent crisis cited as a contributing factor.

“Living in LTC or transitioning to LTC is also correlated with a host of characteristics that are established risk factors for suicide,” the investigators noted.

In further analysis, the investigators compared the number of suicide deaths the algorithm identified as occurring within an LTC facility (n = 428) with the injury location code SRF (supervised residential facility; n = 263) and the death location code LTC/nursing home (n = 567) within the NVDRS. Of the 263 SRF injuries, 106 were identified as occurring within a LTC facility by the algorithm. The agreement between the algorithm and the SRF coding was poor (kappa statistic, 0.30; 95% confidence interval, 0.26-0.35).

“Leaders in the field have continued to call for a shift away from a medicalized paradigm of residential LTC toward institutional practices that instead focus on fostering meaningful interactions between residents, promote engagement in care, and enhance quality of life. In addition, existing, scalable programs that support older adults living in the community offer the potential to promote quality of life for older adults who may be considering transitioning into or out of residential LTC,” the investigators concluded. “These findings emphasize the importance of such efforts for the mental health of older adults.”

The study was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health. The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mezuk B et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Jun 14. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.5627.

Filling the gap in knowledge about the consequences of transitioning into long-term care is sorely needed, wrote Yoram Barak, MD, MHA, and Chris Gale, MB,ChB, MPH, given that fewer than 20 studies on the subject have been published in the past 30 years. A 2015 systematic review of nursing home suicides included only eight studies and 101 suicide deaths.

Despite the limits of an epidemiologic study on long-term care in elderly adults, such as the significant differences between elderly populations in America and other countries, this study by Mezuk et al. provides useful information on a longer period of time than would be possible with case-control studies and at a more granular level than data that would be available from national case registers, Dr. Barak and Dr. Gale wrote.

Dr. Barak and Dr. Gale are with the department of psychological medicine at the University of Otago in Dunedin, New Zealand. They made these comments in an editorial published in JAMA Network Open (2019 Jun 14. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.5634). They did not report any conflicts of interest.

Filling the gap in knowledge about the consequences of transitioning into long-term care is sorely needed, wrote Yoram Barak, MD, MHA, and Chris Gale, MB,ChB, MPH, given that fewer than 20 studies on the subject have been published in the past 30 years. A 2015 systematic review of nursing home suicides included only eight studies and 101 suicide deaths.

Despite the limits of an epidemiologic study on long-term care in elderly adults, such as the significant differences between elderly populations in America and other countries, this study by Mezuk et al. provides useful information on a longer period of time than would be possible with case-control studies and at a more granular level than data that would be available from national case registers, Dr. Barak and Dr. Gale wrote.

Dr. Barak and Dr. Gale are with the department of psychological medicine at the University of Otago in Dunedin, New Zealand. They made these comments in an editorial published in JAMA Network Open (2019 Jun 14. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.5634). They did not report any conflicts of interest.

Filling the gap in knowledge about the consequences of transitioning into long-term care is sorely needed, wrote Yoram Barak, MD, MHA, and Chris Gale, MB,ChB, MPH, given that fewer than 20 studies on the subject have been published in the past 30 years. A 2015 systematic review of nursing home suicides included only eight studies and 101 suicide deaths.

Despite the limits of an epidemiologic study on long-term care in elderly adults, such as the significant differences between elderly populations in America and other countries, this study by Mezuk et al. provides useful information on a longer period of time than would be possible with case-control studies and at a more granular level than data that would be available from national case registers, Dr. Barak and Dr. Gale wrote.

Dr. Barak and Dr. Gale are with the department of psychological medicine at the University of Otago in Dunedin, New Zealand. They made these comments in an editorial published in JAMA Network Open (2019 Jun 14. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.5634). They did not report any conflicts of interest.

The rate of suicide associated with residential long-term care (LTC) in adults aged 55 years and older may be significantly higher than the injury location coding of the National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS) suggests, according to new research.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that there are about 16,000 nursing homes and 31,000 assisted living facilities in the United States and they currently house about 25% of all Medicare beneficiaries. “As such, residential LTC may be a potential location for identifying individuals at high risk of self-harm and for implementing interventions to reduce suicide risk, wrote Briana Mezuk, PhD, and associates from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. The study was published in JAMA Network Open.

Dr. Mezuk and colleagues conducted a cross-sectional, epidemiologic study using a natural language–processing algorithm to analyze restricted-access data from the NVDRS between 2003 and 2015. A total of 47,759 suicides and undetermined deaths in adults aged 55 years and older from 27 states were included in the analysis (median age, 64 years; 77.6% male; 90.0% non-Hispanic white).

The algorithm identified 1,037 (2.2% of the total) suicide deaths associated with LTC, with 428 occurring in adults living in LTC, 449 occurring during the transition into or out of LTC, and 160 otherwise associated with LTC. Decedents in this group had a median age of 79 years, were 73.8% male, and were 94.3% non-Hispanic white. The number of suicide deaths varied widely from year to year, but no trend was found in the change over the study period.

Deaths while living in LTC were more likely among women, which the investigators noted is to be expected because LTC residents are disproportionately women. Death while transitioning into or out of LTC was more likely among adults who previously had expressed suicide ideation and had a physical health problem cited as a contributing circumstance. Death otherwise associated with LTC was more likely in adults who were married or in a relationship, had a depressed mood, and had a recent crisis cited as a contributing factor.

“Living in LTC or transitioning to LTC is also correlated with a host of characteristics that are established risk factors for suicide,” the investigators noted.

In further analysis, the investigators compared the number of suicide deaths the algorithm identified as occurring within an LTC facility (n = 428) with the injury location code SRF (supervised residential facility; n = 263) and the death location code LTC/nursing home (n = 567) within the NVDRS. Of the 263 SRF injuries, 106 were identified as occurring within a LTC facility by the algorithm. The agreement between the algorithm and the SRF coding was poor (kappa statistic, 0.30; 95% confidence interval, 0.26-0.35).

“Leaders in the field have continued to call for a shift away from a medicalized paradigm of residential LTC toward institutional practices that instead focus on fostering meaningful interactions between residents, promote engagement in care, and enhance quality of life. In addition, existing, scalable programs that support older adults living in the community offer the potential to promote quality of life for older adults who may be considering transitioning into or out of residential LTC,” the investigators concluded. “These findings emphasize the importance of such efforts for the mental health of older adults.”

The study was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health. The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mezuk B et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Jun 14. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.5627.

The rate of suicide associated with residential long-term care (LTC) in adults aged 55 years and older may be significantly higher than the injury location coding of the National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS) suggests, according to new research.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that there are about 16,000 nursing homes and 31,000 assisted living facilities in the United States and they currently house about 25% of all Medicare beneficiaries. “As such, residential LTC may be a potential location for identifying individuals at high risk of self-harm and for implementing interventions to reduce suicide risk, wrote Briana Mezuk, PhD, and associates from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. The study was published in JAMA Network Open.

Dr. Mezuk and colleagues conducted a cross-sectional, epidemiologic study using a natural language–processing algorithm to analyze restricted-access data from the NVDRS between 2003 and 2015. A total of 47,759 suicides and undetermined deaths in adults aged 55 years and older from 27 states were included in the analysis (median age, 64 years; 77.6% male; 90.0% non-Hispanic white).

The algorithm identified 1,037 (2.2% of the total) suicide deaths associated with LTC, with 428 occurring in adults living in LTC, 449 occurring during the transition into or out of LTC, and 160 otherwise associated with LTC. Decedents in this group had a median age of 79 years, were 73.8% male, and were 94.3% non-Hispanic white. The number of suicide deaths varied widely from year to year, but no trend was found in the change over the study period.

Deaths while living in LTC were more likely among women, which the investigators noted is to be expected because LTC residents are disproportionately women. Death while transitioning into or out of LTC was more likely among adults who previously had expressed suicide ideation and had a physical health problem cited as a contributing circumstance. Death otherwise associated with LTC was more likely in adults who were married or in a relationship, had a depressed mood, and had a recent crisis cited as a contributing factor.

“Living in LTC or transitioning to LTC is also correlated with a host of characteristics that are established risk factors for suicide,” the investigators noted.

In further analysis, the investigators compared the number of suicide deaths the algorithm identified as occurring within an LTC facility (n = 428) with the injury location code SRF (supervised residential facility; n = 263) and the death location code LTC/nursing home (n = 567) within the NVDRS. Of the 263 SRF injuries, 106 were identified as occurring within a LTC facility by the algorithm. The agreement between the algorithm and the SRF coding was poor (kappa statistic, 0.30; 95% confidence interval, 0.26-0.35).

“Leaders in the field have continued to call for a shift away from a medicalized paradigm of residential LTC toward institutional practices that instead focus on fostering meaningful interactions between residents, promote engagement in care, and enhance quality of life. In addition, existing, scalable programs that support older adults living in the community offer the potential to promote quality of life for older adults who may be considering transitioning into or out of residential LTC,” the investigators concluded. “These findings emphasize the importance of such efforts for the mental health of older adults.”

The study was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health. The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mezuk B et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Jun 14. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.5627.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Key clinical point: Suicide associated with long-term care may be more common than previous data have indicated.

Major finding: About 2.2% of the suicide deaths reported to the National Violent Death Reporting System occurred or were associated with long-term care.

Study details: An analysis of 47,759 suicides and undetermined deaths in adults aged at least 55 years with data included in the National Violent Death Reporting System.Disclosures: The study was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health. The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Mezuk B et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Jun 14. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.5627.

FDA overlooked red flags in esketamine testing

For some patients, it also has dwelled in the shadows of conventional medicine as a depression treatment – prescribed by their doctors, but not approved for that purpose by the federal agency responsible for determining which treatments are “safe and effective.”

That effectively changed in March, when the Food and Drug Administration approved a ketamine cousin called esketamine, taken as a nasal spray, for patients with intractable depression. With that, the esketamine nasal spray, under the brand name Spravato, was introduced as a miracle drug – announced in press releases, celebrated on the evening news, and embraced by major health care providers like the Department of Veterans Affairs.

The problem, critics say, is that the drug’s manufacturer, Janssen, provided the FDA with at best modest evidence it worked and then only in limited trials. It presented no information about the safety of Spravato for long-term use beyond 60 weeks. And three patients who received the drug died by suicide during clinical trials, compared with none in the control group, which raised red flags Janssen and the FDA dismissed.

The FDA, under political pressure to rapidly green-light drugs that treat life-threatening conditions, approved it anyway. And, though Spravato’s appearance on the market was greeted with public applause, some deep misgivings were expressed at its day-long review meeting and in the agency’s own briefing materials, according to public recordings, documents, and interviews with participants, KHN found.

Jess Fiedorowicz, MD, director of the Mood Disorders Center at the University of Iowa, Iowa City, and a member of the FDA advisory committee that reviewed the drug, described its benefit as “almost certainly exaggerated” after hearing the evidence.

Dr. Fiedorowicz said he expected at least a split decision by the committee. “And then it went strongly in favor, which surprised me,” he said in an interview.

Esketamine’s trajectory to approval shows – step by step – how drugmakers can take advantage of shortcuts in the FDA process with the agency’s blessing and maneuver through safety and efficacy reviews to bring a lucrative drug to market.

Step 1: In late 2013, Janssen got the FDA to designate esketamine a “breakthrough therapy” because it showed the potential to reverse depression rapidly — a holy grail for suicidal patients, such as those in an emergency room. That potential was based on a 2-day study during which 30 patients were given esketamine intravenously.

“Breakthrough therapy” status puts drugs on a fast track to approval, with more frequent input from the FDA.

Step 2: But discussions between regulators and drug manufacturers can affect the amount and quality of evidence required by the agency. In the case of Spravato, they involved questions like “How many drugs must fail before a patient’s depression is considered intractable or ‘treatment resistant’?” and “How many successful clinical trials are necessary for FDA approval?”

Step 3: Any prior agreements can leave the FDA’s expert advisory committees hamstrung in reaching a verdict. Dr. Fiedorowicz abstained on Spravato because, though he considered Janssen’s study design flawed, the FDA had approved it.

The expert panel cleared the drug according to the evidence that the agency and Janssen had determined was sufficient. Matthew Rudorfer, MD, an associate director at the National Institute of Mental Health, concluded that the “benefits outweighed the risks.” Explaining his “yes” vote, he said, “I think we’re all agreeing on the very important, and sometimes life-or-death, risk of inadequately treated depression that factored into my equation.”

But others who also voted “yes” were more explicit in their qualms. “I don’t think that we really understand what happens when you take this week after week for weeks and months and years,” said Steven Meisel, PharmD, system director of medication safety for Fairview Health Services based in Minneapolis.

A Nasal Spray Offers A Path To A Patent

Spravato is available only under supervision at a certified facility where patients must be monitored for at least two hours after taking the drug to watch for side effects like dizziness, detachment from reality, and increased blood pressure, as well as to reduce the risk of abuse. Patients must take it with an oral antidepressant.

Despite those requirements, Janssen, part of Johnson & Johnson, defended its new offering. “Until the recent FDA approval of Spravato, health care providers haven’t had any new medication options,” Kristina Chang, a Janssen spokeswoman, wrote in an emailed statement.

Esketamine is the first new type of drug approved to treat severe depression in about three decades.

Although ketamine has been used off-label for years to treat depression and posttraumatic stress disorder, drugmakers saw little profit in doing the studies to prove to the FDA that it worked for that purpose. But a nasal spray of esketamine, which is derived from ketamine and is (in some studies) more potent, could be patented as a new drug.

Although Spravato costs more than $4,700 for the first month of treatment (not including the cost of monitoring or the oral antidepressant), insurers are more likely to reimburse for Spravato than for ketamine, since the latter is not approved for depression.

Shortly before the committee began voting, a study participant identifying herself only as “Patient 20015525” said, “I am offering real-world proof of efficacy, and that is I am both alive and here today.”

The drug did not work “for the majority of people who took it,” Dr. Meisel, the medication safety expert, said in an interview. “But for a subset of those for whom it did work, it was dramatic.”

Concerns About Testing Precedents

Those considerations apparently helped outweigh several scientific red flags that committee members called out during the hearing.

Although the drug had gotten breakthrough status because of its potential for results within 24 hours, the trials were not persuasive enough for the FDA to label it “rapid acting.”

The FDA typically requires that applicants provide at least two clinical trials demonstrating the drug’s efficacy, “each convincing on its own.” Janssen provided just one successful short-term, double-blind trial of esketamine. Two other trials it ran to test efficacy fell short.

To reach the two-trial threshold, the FDA broke its precedent for psychiatric drugs and allowed the company to count a trial conducted to study a different topic: relapse and remission trends. But, by definition, every patient in the trial had already taken and seen improvement from esketamine.

What’s more, that single positive efficacy trial showed just a 4-point improvement in depression symptoms, compared with the placebo treatment, on a 60-point scale some clinicians use to measure depression severity. Some committee members noted the trial wasn’t really blind since participants could recognize they were getting the drug from side effects like a temporary out-of-body sensation.

Finally, the FDA lowered the bar for “treatment-resistant depression.” Initially, for inclusion, trial participants would have had to have failed two classes of oral antidepressants.

Less than 2 years later, the FDA loosened that definition, saying a patient needed only to have taken two different pills, no matter the class.

Forty-nine of the 227 people who participated in Janssen’s only successful efficacy trial had failed just one class of oral antidepressants. “They weeded out the true treatment-resistant patients,” said Erick Turner, MD, a former FDA reviewer who serves on the committee but did not attend the meeting.

Six participants died during the studies, three by suicide. Janssen and the FDA dismissed the deaths as unrelated to the drug, noting the low number and lack of a pattern among hundreds of participants. They also pointed out that suicidal behavior is associated with severe depression – even though those who had suicidal ideation with some intent to act in the previous 6 months, or a history of suicidal behavior in the previous year, were excluded from the studies.

In a recent commentary in the American Journal of Psychiatry, Alan Schatzberg, MD, a Stanford (Calif.) University researcher who has studied ketamine, suggested there might be a link caused by “a protracted withdrawal reaction, as has been reported with opioids,” since ketamine appears to interact with the brain’s opioid receptors (Am J Psych. 2019. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19040423).

Kim Witczak, the committee’s consumer representative, found Janssen’s conclusion about the suicides unsatisfying. “I just feel like it was kind of a quick brush-over,” Ms. Witczak said in an interview. She voted against the drug.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

For some patients, it also has dwelled in the shadows of conventional medicine as a depression treatment – prescribed by their doctors, but not approved for that purpose by the federal agency responsible for determining which treatments are “safe and effective.”

That effectively changed in March, when the Food and Drug Administration approved a ketamine cousin called esketamine, taken as a nasal spray, for patients with intractable depression. With that, the esketamine nasal spray, under the brand name Spravato, was introduced as a miracle drug – announced in press releases, celebrated on the evening news, and embraced by major health care providers like the Department of Veterans Affairs.

The problem, critics say, is that the drug’s manufacturer, Janssen, provided the FDA with at best modest evidence it worked and then only in limited trials. It presented no information about the safety of Spravato for long-term use beyond 60 weeks. And three patients who received the drug died by suicide during clinical trials, compared with none in the control group, which raised red flags Janssen and the FDA dismissed.

The FDA, under political pressure to rapidly green-light drugs that treat life-threatening conditions, approved it anyway. And, though Spravato’s appearance on the market was greeted with public applause, some deep misgivings were expressed at its day-long review meeting and in the agency’s own briefing materials, according to public recordings, documents, and interviews with participants, KHN found.

Jess Fiedorowicz, MD, director of the Mood Disorders Center at the University of Iowa, Iowa City, and a member of the FDA advisory committee that reviewed the drug, described its benefit as “almost certainly exaggerated” after hearing the evidence.

Dr. Fiedorowicz said he expected at least a split decision by the committee. “And then it went strongly in favor, which surprised me,” he said in an interview.

Esketamine’s trajectory to approval shows – step by step – how drugmakers can take advantage of shortcuts in the FDA process with the agency’s blessing and maneuver through safety and efficacy reviews to bring a lucrative drug to market.

Step 1: In late 2013, Janssen got the FDA to designate esketamine a “breakthrough therapy” because it showed the potential to reverse depression rapidly — a holy grail for suicidal patients, such as those in an emergency room. That potential was based on a 2-day study during which 30 patients were given esketamine intravenously.

“Breakthrough therapy” status puts drugs on a fast track to approval, with more frequent input from the FDA.

Step 2: But discussions between regulators and drug manufacturers can affect the amount and quality of evidence required by the agency. In the case of Spravato, they involved questions like “How many drugs must fail before a patient’s depression is considered intractable or ‘treatment resistant’?” and “How many successful clinical trials are necessary for FDA approval?”

Step 3: Any prior agreements can leave the FDA’s expert advisory committees hamstrung in reaching a verdict. Dr. Fiedorowicz abstained on Spravato because, though he considered Janssen’s study design flawed, the FDA had approved it.

The expert panel cleared the drug according to the evidence that the agency and Janssen had determined was sufficient. Matthew Rudorfer, MD, an associate director at the National Institute of Mental Health, concluded that the “benefits outweighed the risks.” Explaining his “yes” vote, he said, “I think we’re all agreeing on the very important, and sometimes life-or-death, risk of inadequately treated depression that factored into my equation.”

But others who also voted “yes” were more explicit in their qualms. “I don’t think that we really understand what happens when you take this week after week for weeks and months and years,” said Steven Meisel, PharmD, system director of medication safety for Fairview Health Services based in Minneapolis.

A Nasal Spray Offers A Path To A Patent

Spravato is available only under supervision at a certified facility where patients must be monitored for at least two hours after taking the drug to watch for side effects like dizziness, detachment from reality, and increased blood pressure, as well as to reduce the risk of abuse. Patients must take it with an oral antidepressant.

Despite those requirements, Janssen, part of Johnson & Johnson, defended its new offering. “Until the recent FDA approval of Spravato, health care providers haven’t had any new medication options,” Kristina Chang, a Janssen spokeswoman, wrote in an emailed statement.

Esketamine is the first new type of drug approved to treat severe depression in about three decades.

Although ketamine has been used off-label for years to treat depression and posttraumatic stress disorder, drugmakers saw little profit in doing the studies to prove to the FDA that it worked for that purpose. But a nasal spray of esketamine, which is derived from ketamine and is (in some studies) more potent, could be patented as a new drug.

Although Spravato costs more than $4,700 for the first month of treatment (not including the cost of monitoring or the oral antidepressant), insurers are more likely to reimburse for Spravato than for ketamine, since the latter is not approved for depression.

Shortly before the committee began voting, a study participant identifying herself only as “Patient 20015525” said, “I am offering real-world proof of efficacy, and that is I am both alive and here today.”

The drug did not work “for the majority of people who took it,” Dr. Meisel, the medication safety expert, said in an interview. “But for a subset of those for whom it did work, it was dramatic.”

Concerns About Testing Precedents

Those considerations apparently helped outweigh several scientific red flags that committee members called out during the hearing.

Although the drug had gotten breakthrough status because of its potential for results within 24 hours, the trials were not persuasive enough for the FDA to label it “rapid acting.”

The FDA typically requires that applicants provide at least two clinical trials demonstrating the drug’s efficacy, “each convincing on its own.” Janssen provided just one successful short-term, double-blind trial of esketamine. Two other trials it ran to test efficacy fell short.

To reach the two-trial threshold, the FDA broke its precedent for psychiatric drugs and allowed the company to count a trial conducted to study a different topic: relapse and remission trends. But, by definition, every patient in the trial had already taken and seen improvement from esketamine.

What’s more, that single positive efficacy trial showed just a 4-point improvement in depression symptoms, compared with the placebo treatment, on a 60-point scale some clinicians use to measure depression severity. Some committee members noted the trial wasn’t really blind since participants could recognize they were getting the drug from side effects like a temporary out-of-body sensation.

Finally, the FDA lowered the bar for “treatment-resistant depression.” Initially, for inclusion, trial participants would have had to have failed two classes of oral antidepressants.

Less than 2 years later, the FDA loosened that definition, saying a patient needed only to have taken two different pills, no matter the class.

Forty-nine of the 227 people who participated in Janssen’s only successful efficacy trial had failed just one class of oral antidepressants. “They weeded out the true treatment-resistant patients,” said Erick Turner, MD, a former FDA reviewer who serves on the committee but did not attend the meeting.

Six participants died during the studies, three by suicide. Janssen and the FDA dismissed the deaths as unrelated to the drug, noting the low number and lack of a pattern among hundreds of participants. They also pointed out that suicidal behavior is associated with severe depression – even though those who had suicidal ideation with some intent to act in the previous 6 months, or a history of suicidal behavior in the previous year, were excluded from the studies.

In a recent commentary in the American Journal of Psychiatry, Alan Schatzberg, MD, a Stanford (Calif.) University researcher who has studied ketamine, suggested there might be a link caused by “a protracted withdrawal reaction, as has been reported with opioids,” since ketamine appears to interact with the brain’s opioid receptors (Am J Psych. 2019. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19040423).

Kim Witczak, the committee’s consumer representative, found Janssen’s conclusion about the suicides unsatisfying. “I just feel like it was kind of a quick brush-over,” Ms. Witczak said in an interview. She voted against the drug.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

For some patients, it also has dwelled in the shadows of conventional medicine as a depression treatment – prescribed by their doctors, but not approved for that purpose by the federal agency responsible for determining which treatments are “safe and effective.”

That effectively changed in March, when the Food and Drug Administration approved a ketamine cousin called esketamine, taken as a nasal spray, for patients with intractable depression. With that, the esketamine nasal spray, under the brand name Spravato, was introduced as a miracle drug – announced in press releases, celebrated on the evening news, and embraced by major health care providers like the Department of Veterans Affairs.

The problem, critics say, is that the drug’s manufacturer, Janssen, provided the FDA with at best modest evidence it worked and then only in limited trials. It presented no information about the safety of Spravato for long-term use beyond 60 weeks. And three patients who received the drug died by suicide during clinical trials, compared with none in the control group, which raised red flags Janssen and the FDA dismissed.

The FDA, under political pressure to rapidly green-light drugs that treat life-threatening conditions, approved it anyway. And, though Spravato’s appearance on the market was greeted with public applause, some deep misgivings were expressed at its day-long review meeting and in the agency’s own briefing materials, according to public recordings, documents, and interviews with participants, KHN found.

Jess Fiedorowicz, MD, director of the Mood Disorders Center at the University of Iowa, Iowa City, and a member of the FDA advisory committee that reviewed the drug, described its benefit as “almost certainly exaggerated” after hearing the evidence.

Dr. Fiedorowicz said he expected at least a split decision by the committee. “And then it went strongly in favor, which surprised me,” he said in an interview.

Esketamine’s trajectory to approval shows – step by step – how drugmakers can take advantage of shortcuts in the FDA process with the agency’s blessing and maneuver through safety and efficacy reviews to bring a lucrative drug to market.

Step 1: In late 2013, Janssen got the FDA to designate esketamine a “breakthrough therapy” because it showed the potential to reverse depression rapidly — a holy grail for suicidal patients, such as those in an emergency room. That potential was based on a 2-day study during which 30 patients were given esketamine intravenously.

“Breakthrough therapy” status puts drugs on a fast track to approval, with more frequent input from the FDA.

Step 2: But discussions between regulators and drug manufacturers can affect the amount and quality of evidence required by the agency. In the case of Spravato, they involved questions like “How many drugs must fail before a patient’s depression is considered intractable or ‘treatment resistant’?” and “How many successful clinical trials are necessary for FDA approval?”

Step 3: Any prior agreements can leave the FDA’s expert advisory committees hamstrung in reaching a verdict. Dr. Fiedorowicz abstained on Spravato because, though he considered Janssen’s study design flawed, the FDA had approved it.

The expert panel cleared the drug according to the evidence that the agency and Janssen had determined was sufficient. Matthew Rudorfer, MD, an associate director at the National Institute of Mental Health, concluded that the “benefits outweighed the risks.” Explaining his “yes” vote, he said, “I think we’re all agreeing on the very important, and sometimes life-or-death, risk of inadequately treated depression that factored into my equation.”

But others who also voted “yes” were more explicit in their qualms. “I don’t think that we really understand what happens when you take this week after week for weeks and months and years,” said Steven Meisel, PharmD, system director of medication safety for Fairview Health Services based in Minneapolis.

A Nasal Spray Offers A Path To A Patent

Spravato is available only under supervision at a certified facility where patients must be monitored for at least two hours after taking the drug to watch for side effects like dizziness, detachment from reality, and increased blood pressure, as well as to reduce the risk of abuse. Patients must take it with an oral antidepressant.

Despite those requirements, Janssen, part of Johnson & Johnson, defended its new offering. “Until the recent FDA approval of Spravato, health care providers haven’t had any new medication options,” Kristina Chang, a Janssen spokeswoman, wrote in an emailed statement.

Esketamine is the first new type of drug approved to treat severe depression in about three decades.

Although ketamine has been used off-label for years to treat depression and posttraumatic stress disorder, drugmakers saw little profit in doing the studies to prove to the FDA that it worked for that purpose. But a nasal spray of esketamine, which is derived from ketamine and is (in some studies) more potent, could be patented as a new drug.

Although Spravato costs more than $4,700 for the first month of treatment (not including the cost of monitoring or the oral antidepressant), insurers are more likely to reimburse for Spravato than for ketamine, since the latter is not approved for depression.

Shortly before the committee began voting, a study participant identifying herself only as “Patient 20015525” said, “I am offering real-world proof of efficacy, and that is I am both alive and here today.”

The drug did not work “for the majority of people who took it,” Dr. Meisel, the medication safety expert, said in an interview. “But for a subset of those for whom it did work, it was dramatic.”

Concerns About Testing Precedents

Those considerations apparently helped outweigh several scientific red flags that committee members called out during the hearing.

Although the drug had gotten breakthrough status because of its potential for results within 24 hours, the trials were not persuasive enough for the FDA to label it “rapid acting.”

The FDA typically requires that applicants provide at least two clinical trials demonstrating the drug’s efficacy, “each convincing on its own.” Janssen provided just one successful short-term, double-blind trial of esketamine. Two other trials it ran to test efficacy fell short.

To reach the two-trial threshold, the FDA broke its precedent for psychiatric drugs and allowed the company to count a trial conducted to study a different topic: relapse and remission trends. But, by definition, every patient in the trial had already taken and seen improvement from esketamine.

What’s more, that single positive efficacy trial showed just a 4-point improvement in depression symptoms, compared with the placebo treatment, on a 60-point scale some clinicians use to measure depression severity. Some committee members noted the trial wasn’t really blind since participants could recognize they were getting the drug from side effects like a temporary out-of-body sensation.

Finally, the FDA lowered the bar for “treatment-resistant depression.” Initially, for inclusion, trial participants would have had to have failed two classes of oral antidepressants.

Less than 2 years later, the FDA loosened that definition, saying a patient needed only to have taken two different pills, no matter the class.

Forty-nine of the 227 people who participated in Janssen’s only successful efficacy trial had failed just one class of oral antidepressants. “They weeded out the true treatment-resistant patients,” said Erick Turner, MD, a former FDA reviewer who serves on the committee but did not attend the meeting.

Six participants died during the studies, three by suicide. Janssen and the FDA dismissed the deaths as unrelated to the drug, noting the low number and lack of a pattern among hundreds of participants. They also pointed out that suicidal behavior is associated with severe depression – even though those who had suicidal ideation with some intent to act in the previous 6 months, or a history of suicidal behavior in the previous year, were excluded from the studies.

In a recent commentary in the American Journal of Psychiatry, Alan Schatzberg, MD, a Stanford (Calif.) University researcher who has studied ketamine, suggested there might be a link caused by “a protracted withdrawal reaction, as has been reported with opioids,” since ketamine appears to interact with the brain’s opioid receptors (Am J Psych. 2019. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19040423).

Kim Witczak, the committee’s consumer representative, found Janssen’s conclusion about the suicides unsatisfying. “I just feel like it was kind of a quick brush-over,” Ms. Witczak said in an interview. She voted against the drug.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Intranasal esketamine plus antidepressant deflects relapse

Esketamine nasal spray used with an oral antidepressant was significantly more effective at delaying a relapse of depression compared with placebo, based on data from 297 adults in remission.

Patients with treatment-resistant depression are more likely to relapse, wrote Ella J. Daly, MD, of Janssen Research and Development, Titusville, N.J., and colleagues.