User login

Seniors with COVID-19 show unusual symptoms, doctors say

complicating efforts to ensure they get timely and appropriate treatment, according to physicians.

COVID-19 is typically signaled by three symptoms: a fever, an insistent cough, and shortness of breath. But older adults – the age group most at risk of severe complications or death from this condition – may have none of these characteristics.

Instead, seniors may seem “off” – not acting like themselves – early on after being infected by the coronavirus. They may sleep more than usual or stop eating. They may seem unusually apathetic or confused, losing orientation to their surroundings. They may become dizzy and fall. Sometimes, seniors stop speaking or simply collapse.

“With a lot of conditions, older adults don’t present in a typical way, and we’re seeing that with COVID-19 as well,” said Camille Vaughan, MD, section chief of geriatrics and gerontology at Emory University, Atlanta.

The reason has to do with how older bodies respond to illness and infection.

At advanced ages, “someone’s immune response may be blunted and their ability to regulate temperature may be altered,” said Dr. Joseph Ouslander, a professor of geriatric medicine at Florida Atlantic University in Boca Raton.

“Underlying chronic illnesses can mask or interfere with signs of infection,” he said. “Some older people, whether from age-related changes or previous neurologic issues such as a stroke, may have altered cough reflexes. Others with cognitive impairment may not be able to communicate their symptoms.”

Recognizing danger signs is important: If early signs of COVID-19 are missed, seniors may deteriorate before getting needed care. And people may go in and out of their homes without adequate protective measures, risking the spread of infection.

Quratulain Syed, MD, an Atlanta geriatrician, describes a man in his 80s whom she treated in mid-March. Over a period of days, this patient, who had heart disease, diabetes and moderate cognitive impairment, stopped walking and became incontinent and profoundly lethargic. But he didn’t have a fever or a cough. His only respiratory symptom: sneezing off and on.

The man’s elderly spouse called 911 twice. Both times, paramedics checked his vital signs and declared he was OK. After another worried call from the overwhelmed spouse, Dr. Syed insisted the patient be taken to the hospital, where he tested positive for COVID-19.

“I was quite concerned about the paramedics and health aides who’d been in the house and who hadn’t used PPE [personal protective equipment],” Dr. Syed said.

Dr. Sam Torbati, medical director of the emergency department at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, describes treating seniors who initially appear to be trauma patients but are found to have COVID-19.

“They get weak and dehydrated,” he said, “and when they stand to walk, they collapse and injure themselves badly.”

Dr. Torbati has seen older adults who are profoundly disoriented and unable to speak and who appear at first to have suffered strokes.

“When we test them, we discover that what’s producing these changes is a central nervous system effect of coronavirus,” he said.

Laura Perry, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, saw a patient like this several weeks ago. The woman, in her 80s, had what seemed to be a cold before becoming very confused. In the hospital, she couldn’t identify where she was or stay awake during an examination. Dr. Perry diagnosed hypoactive delirium, an altered mental state in which people become inactive and drowsy. The patient tested positive for coronavirus and is still in the ICU.

Anthony Perry, MD, of the department of geriatric medicine at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, tells of an 81-year-old woman with nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea who tested positive for COVID-19 in the emergency room. After receiving intravenous fluids, oxygen, and medication for her intestinal upset, she returned home after 2 days and is doing well.

Another 80-year-old Rush patient with similar symptoms – nausea and vomiting, but no cough, fever, or shortness of breath – is in intensive care after getting a positive COVID-19 test and due to be put on a ventilator. The difference? This patient is frail with “a lot of cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Perry said. Other than that, it’s not yet clear why some older patients do well while others do not.

So far, reports of cases like these have been anecdotal. But a few physicians are trying to gather more systematic information.

In Switzerland, Sylvain Nguyen, MD, a geriatrician at the University of Lausanne Hospital Center, put together a list of typical and atypical symptoms in older COVID-19 patients for a paper to be published in the Revue Médicale Suisse. Included on the atypical list are changes in a patient’s usual status, delirium, falls, fatigue, lethargy, low blood pressure, painful swallowing, fainting, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and the loss of smell and taste.

Data come from hospitals and nursing homes in Switzerland, Italy, and France, Dr. Nguyen said in an email.

On the front lines, physicians need to make sure they carefully assess an older patient’s symptoms.

“While we have to have a high suspicion of COVID-19 because it’s so dangerous in the older population, there are many other things to consider,” said Kathleen Unroe, MD, a geriatrician at Indiana University, Indianapolis.

Seniors may also do poorly because their routines have changed. In nursing homes and most assisted living centers, activities have stopped and “residents are going to get weaker and more deconditioned because they’re not walking to and from the dining hall,” she said.

At home, isolated seniors may not be getting as much help with medication management or other essential needs from family members who are keeping their distance, other experts suggested. Or they may have become apathetic or depressed.

“I’d want to know ‘What’s the potential this person has had an exposure [to the coronavirus], especially in the last 2 weeks?’ ” said Dr. Vaughan of Emory. “Do they have home health personnel coming in? Have they gotten together with other family members? Are chronic conditions being controlled? Is there another diagnosis that seems more likely?”

“Someone may be just having a bad day. But if they’re not themselves for a couple of days, absolutely reach out to a primary care doctor or a local health system hotline to see if they meet the threshold for [coronavirus] testing,” Dr. Vaughan advised. “Be persistent. If you get a ‘no’ the first time and things aren’t improving, call back and ask again.”

Kaiser Health News (khn.org) is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

complicating efforts to ensure they get timely and appropriate treatment, according to physicians.

COVID-19 is typically signaled by three symptoms: a fever, an insistent cough, and shortness of breath. But older adults – the age group most at risk of severe complications or death from this condition – may have none of these characteristics.

Instead, seniors may seem “off” – not acting like themselves – early on after being infected by the coronavirus. They may sleep more than usual or stop eating. They may seem unusually apathetic or confused, losing orientation to their surroundings. They may become dizzy and fall. Sometimes, seniors stop speaking or simply collapse.

“With a lot of conditions, older adults don’t present in a typical way, and we’re seeing that with COVID-19 as well,” said Camille Vaughan, MD, section chief of geriatrics and gerontology at Emory University, Atlanta.

The reason has to do with how older bodies respond to illness and infection.

At advanced ages, “someone’s immune response may be blunted and their ability to regulate temperature may be altered,” said Dr. Joseph Ouslander, a professor of geriatric medicine at Florida Atlantic University in Boca Raton.

“Underlying chronic illnesses can mask or interfere with signs of infection,” he said. “Some older people, whether from age-related changes or previous neurologic issues such as a stroke, may have altered cough reflexes. Others with cognitive impairment may not be able to communicate their symptoms.”

Recognizing danger signs is important: If early signs of COVID-19 are missed, seniors may deteriorate before getting needed care. And people may go in and out of their homes without adequate protective measures, risking the spread of infection.

Quratulain Syed, MD, an Atlanta geriatrician, describes a man in his 80s whom she treated in mid-March. Over a period of days, this patient, who had heart disease, diabetes and moderate cognitive impairment, stopped walking and became incontinent and profoundly lethargic. But he didn’t have a fever or a cough. His only respiratory symptom: sneezing off and on.

The man’s elderly spouse called 911 twice. Both times, paramedics checked his vital signs and declared he was OK. After another worried call from the overwhelmed spouse, Dr. Syed insisted the patient be taken to the hospital, where he tested positive for COVID-19.

“I was quite concerned about the paramedics and health aides who’d been in the house and who hadn’t used PPE [personal protective equipment],” Dr. Syed said.

Dr. Sam Torbati, medical director of the emergency department at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, describes treating seniors who initially appear to be trauma patients but are found to have COVID-19.

“They get weak and dehydrated,” he said, “and when they stand to walk, they collapse and injure themselves badly.”

Dr. Torbati has seen older adults who are profoundly disoriented and unable to speak and who appear at first to have suffered strokes.

“When we test them, we discover that what’s producing these changes is a central nervous system effect of coronavirus,” he said.

Laura Perry, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, saw a patient like this several weeks ago. The woman, in her 80s, had what seemed to be a cold before becoming very confused. In the hospital, she couldn’t identify where she was or stay awake during an examination. Dr. Perry diagnosed hypoactive delirium, an altered mental state in which people become inactive and drowsy. The patient tested positive for coronavirus and is still in the ICU.

Anthony Perry, MD, of the department of geriatric medicine at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, tells of an 81-year-old woman with nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea who tested positive for COVID-19 in the emergency room. After receiving intravenous fluids, oxygen, and medication for her intestinal upset, she returned home after 2 days and is doing well.

Another 80-year-old Rush patient with similar symptoms – nausea and vomiting, but no cough, fever, or shortness of breath – is in intensive care after getting a positive COVID-19 test and due to be put on a ventilator. The difference? This patient is frail with “a lot of cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Perry said. Other than that, it’s not yet clear why some older patients do well while others do not.

So far, reports of cases like these have been anecdotal. But a few physicians are trying to gather more systematic information.

In Switzerland, Sylvain Nguyen, MD, a geriatrician at the University of Lausanne Hospital Center, put together a list of typical and atypical symptoms in older COVID-19 patients for a paper to be published in the Revue Médicale Suisse. Included on the atypical list are changes in a patient’s usual status, delirium, falls, fatigue, lethargy, low blood pressure, painful swallowing, fainting, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and the loss of smell and taste.

Data come from hospitals and nursing homes in Switzerland, Italy, and France, Dr. Nguyen said in an email.

On the front lines, physicians need to make sure they carefully assess an older patient’s symptoms.

“While we have to have a high suspicion of COVID-19 because it’s so dangerous in the older population, there are many other things to consider,” said Kathleen Unroe, MD, a geriatrician at Indiana University, Indianapolis.

Seniors may also do poorly because their routines have changed. In nursing homes and most assisted living centers, activities have stopped and “residents are going to get weaker and more deconditioned because they’re not walking to and from the dining hall,” she said.

At home, isolated seniors may not be getting as much help with medication management or other essential needs from family members who are keeping their distance, other experts suggested. Or they may have become apathetic or depressed.

“I’d want to know ‘What’s the potential this person has had an exposure [to the coronavirus], especially in the last 2 weeks?’ ” said Dr. Vaughan of Emory. “Do they have home health personnel coming in? Have they gotten together with other family members? Are chronic conditions being controlled? Is there another diagnosis that seems more likely?”

“Someone may be just having a bad day. But if they’re not themselves for a couple of days, absolutely reach out to a primary care doctor or a local health system hotline to see if they meet the threshold for [coronavirus] testing,” Dr. Vaughan advised. “Be persistent. If you get a ‘no’ the first time and things aren’t improving, call back and ask again.”

Kaiser Health News (khn.org) is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

complicating efforts to ensure they get timely and appropriate treatment, according to physicians.

COVID-19 is typically signaled by three symptoms: a fever, an insistent cough, and shortness of breath. But older adults – the age group most at risk of severe complications or death from this condition – may have none of these characteristics.

Instead, seniors may seem “off” – not acting like themselves – early on after being infected by the coronavirus. They may sleep more than usual or stop eating. They may seem unusually apathetic or confused, losing orientation to their surroundings. They may become dizzy and fall. Sometimes, seniors stop speaking or simply collapse.

“With a lot of conditions, older adults don’t present in a typical way, and we’re seeing that with COVID-19 as well,” said Camille Vaughan, MD, section chief of geriatrics and gerontology at Emory University, Atlanta.

The reason has to do with how older bodies respond to illness and infection.

At advanced ages, “someone’s immune response may be blunted and their ability to regulate temperature may be altered,” said Dr. Joseph Ouslander, a professor of geriatric medicine at Florida Atlantic University in Boca Raton.

“Underlying chronic illnesses can mask or interfere with signs of infection,” he said. “Some older people, whether from age-related changes or previous neurologic issues such as a stroke, may have altered cough reflexes. Others with cognitive impairment may not be able to communicate their symptoms.”

Recognizing danger signs is important: If early signs of COVID-19 are missed, seniors may deteriorate before getting needed care. And people may go in and out of their homes without adequate protective measures, risking the spread of infection.

Quratulain Syed, MD, an Atlanta geriatrician, describes a man in his 80s whom she treated in mid-March. Over a period of days, this patient, who had heart disease, diabetes and moderate cognitive impairment, stopped walking and became incontinent and profoundly lethargic. But he didn’t have a fever or a cough. His only respiratory symptom: sneezing off and on.

The man’s elderly spouse called 911 twice. Both times, paramedics checked his vital signs and declared he was OK. After another worried call from the overwhelmed spouse, Dr. Syed insisted the patient be taken to the hospital, where he tested positive for COVID-19.

“I was quite concerned about the paramedics and health aides who’d been in the house and who hadn’t used PPE [personal protective equipment],” Dr. Syed said.

Dr. Sam Torbati, medical director of the emergency department at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, describes treating seniors who initially appear to be trauma patients but are found to have COVID-19.

“They get weak and dehydrated,” he said, “and when they stand to walk, they collapse and injure themselves badly.”

Dr. Torbati has seen older adults who are profoundly disoriented and unable to speak and who appear at first to have suffered strokes.

“When we test them, we discover that what’s producing these changes is a central nervous system effect of coronavirus,” he said.

Laura Perry, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, saw a patient like this several weeks ago. The woman, in her 80s, had what seemed to be a cold before becoming very confused. In the hospital, she couldn’t identify where she was or stay awake during an examination. Dr. Perry diagnosed hypoactive delirium, an altered mental state in which people become inactive and drowsy. The patient tested positive for coronavirus and is still in the ICU.

Anthony Perry, MD, of the department of geriatric medicine at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, tells of an 81-year-old woman with nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea who tested positive for COVID-19 in the emergency room. After receiving intravenous fluids, oxygen, and medication for her intestinal upset, she returned home after 2 days and is doing well.

Another 80-year-old Rush patient with similar symptoms – nausea and vomiting, but no cough, fever, or shortness of breath – is in intensive care after getting a positive COVID-19 test and due to be put on a ventilator. The difference? This patient is frail with “a lot of cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Perry said. Other than that, it’s not yet clear why some older patients do well while others do not.

So far, reports of cases like these have been anecdotal. But a few physicians are trying to gather more systematic information.

In Switzerland, Sylvain Nguyen, MD, a geriatrician at the University of Lausanne Hospital Center, put together a list of typical and atypical symptoms in older COVID-19 patients for a paper to be published in the Revue Médicale Suisse. Included on the atypical list are changes in a patient’s usual status, delirium, falls, fatigue, lethargy, low blood pressure, painful swallowing, fainting, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and the loss of smell and taste.

Data come from hospitals and nursing homes in Switzerland, Italy, and France, Dr. Nguyen said in an email.

On the front lines, physicians need to make sure they carefully assess an older patient’s symptoms.

“While we have to have a high suspicion of COVID-19 because it’s so dangerous in the older population, there are many other things to consider,” said Kathleen Unroe, MD, a geriatrician at Indiana University, Indianapolis.

Seniors may also do poorly because their routines have changed. In nursing homes and most assisted living centers, activities have stopped and “residents are going to get weaker and more deconditioned because they’re not walking to and from the dining hall,” she said.

At home, isolated seniors may not be getting as much help with medication management or other essential needs from family members who are keeping their distance, other experts suggested. Or they may have become apathetic or depressed.

“I’d want to know ‘What’s the potential this person has had an exposure [to the coronavirus], especially in the last 2 weeks?’ ” said Dr. Vaughan of Emory. “Do they have home health personnel coming in? Have they gotten together with other family members? Are chronic conditions being controlled? Is there another diagnosis that seems more likely?”

“Someone may be just having a bad day. But if they’re not themselves for a couple of days, absolutely reach out to a primary care doctor or a local health system hotline to see if they meet the threshold for [coronavirus] testing,” Dr. Vaughan advised. “Be persistent. If you get a ‘no’ the first time and things aren’t improving, call back and ask again.”

Kaiser Health News (khn.org) is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

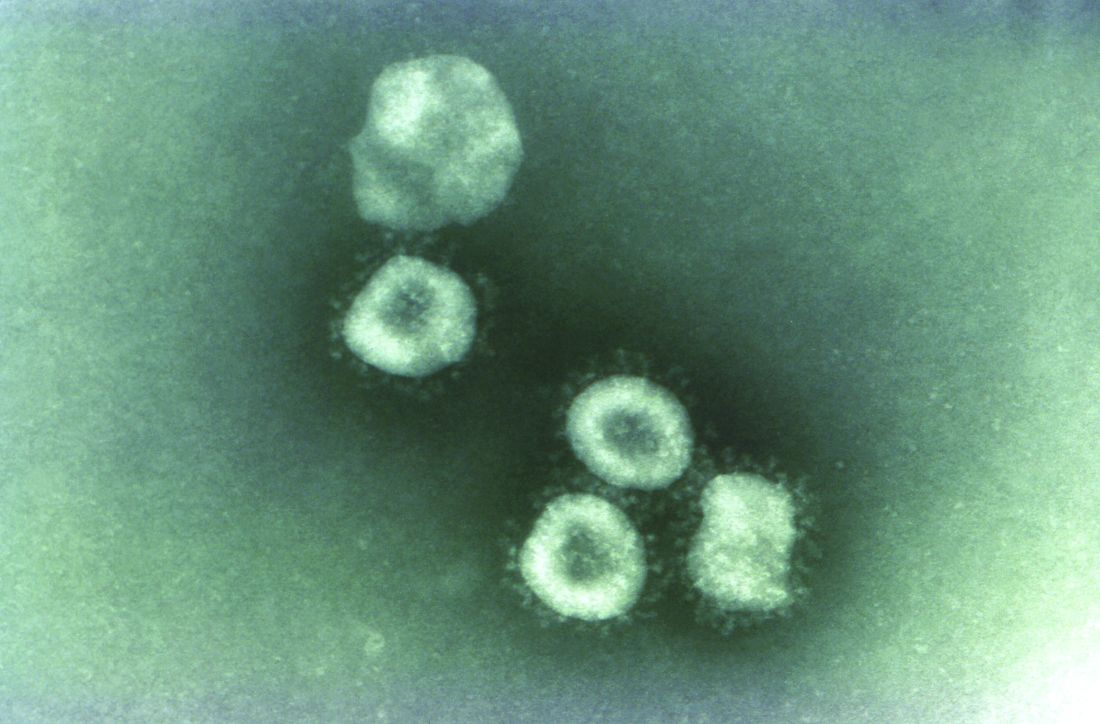

SARS-CoV-2 present significantly longer in stool than in respiratory, serum samples

A study from China showed that the presence of SARS-CoV-2 lasts significantly longer in stool samples from COVID-19 patients than in respiratory and serum samples.

However, the virus also persists longer with higher loads and later peaks in the respiratory tissue of patients with severe disease than in those with mild disease, according to an analysis of 96 consecutively admitted patients with laboratory confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The retrospective study cohort data were collected from Jan. 19 to March 20 at a designated hospital for patients with COVID-19 in Zhejiang province. Among the patients, 22 had mild disease, and 74 had severe disease, according to the researchers.

Infection was confirmed in all patients by testing sputum and saliva samples. Viral RNA was detected in the stool of 59% of the patients and in the serum of 41% of patients. Only one of the patients had a positive urine sample. The median duration of virus in stool (22 days) was significantly longer than in respiratory (18 days; P = .002) and serum samples (16 days; P < .001).

In addition, the median duration of virus in the respiratory samples of patients with severe disease (21 days) was significantly longer than in patients with mild disease (14 days; P = .04).

“In the mild group, the viral loads peaked in respiratory samples in the second week from disease onset, whereas viral load continued to be high during the third week in the severe group,” the authors stated.

Virus duration was also longer in patients older than 60 years and in men.

The longer duration of SARS-CoV-2 in stool samples highlights the need to strengthen the management of stool samples in the prevention and control of the epidemic, especially for patients in the later stages of the disease, the authors advised.

“Compared with patients with mild disease, those with severe disease showed longer duration of SARS-CoV-2 in respiratory samples, higher viral load, and a later shedding peak. These findings suggest that reducing viral loads through clinical means and strengthening management during each stage of severe disease should help to prevent the spread of the virus,” the researchers concluded.

The study was funded by the China National Mega-Projects for Infectious Diseases and the National Natural Science Foundation of China. The authors reported they had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Zheng S et al. BMJ. 2020;369:m1443.

A study from China showed that the presence of SARS-CoV-2 lasts significantly longer in stool samples from COVID-19 patients than in respiratory and serum samples.

However, the virus also persists longer with higher loads and later peaks in the respiratory tissue of patients with severe disease than in those with mild disease, according to an analysis of 96 consecutively admitted patients with laboratory confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The retrospective study cohort data were collected from Jan. 19 to March 20 at a designated hospital for patients with COVID-19 in Zhejiang province. Among the patients, 22 had mild disease, and 74 had severe disease, according to the researchers.

Infection was confirmed in all patients by testing sputum and saliva samples. Viral RNA was detected in the stool of 59% of the patients and in the serum of 41% of patients. Only one of the patients had a positive urine sample. The median duration of virus in stool (22 days) was significantly longer than in respiratory (18 days; P = .002) and serum samples (16 days; P < .001).

In addition, the median duration of virus in the respiratory samples of patients with severe disease (21 days) was significantly longer than in patients with mild disease (14 days; P = .04).

“In the mild group, the viral loads peaked in respiratory samples in the second week from disease onset, whereas viral load continued to be high during the third week in the severe group,” the authors stated.

Virus duration was also longer in patients older than 60 years and in men.

The longer duration of SARS-CoV-2 in stool samples highlights the need to strengthen the management of stool samples in the prevention and control of the epidemic, especially for patients in the later stages of the disease, the authors advised.

“Compared with patients with mild disease, those with severe disease showed longer duration of SARS-CoV-2 in respiratory samples, higher viral load, and a later shedding peak. These findings suggest that reducing viral loads through clinical means and strengthening management during each stage of severe disease should help to prevent the spread of the virus,” the researchers concluded.

The study was funded by the China National Mega-Projects for Infectious Diseases and the National Natural Science Foundation of China. The authors reported they had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Zheng S et al. BMJ. 2020;369:m1443.

A study from China showed that the presence of SARS-CoV-2 lasts significantly longer in stool samples from COVID-19 patients than in respiratory and serum samples.

However, the virus also persists longer with higher loads and later peaks in the respiratory tissue of patients with severe disease than in those with mild disease, according to an analysis of 96 consecutively admitted patients with laboratory confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The retrospective study cohort data were collected from Jan. 19 to March 20 at a designated hospital for patients with COVID-19 in Zhejiang province. Among the patients, 22 had mild disease, and 74 had severe disease, according to the researchers.

Infection was confirmed in all patients by testing sputum and saliva samples. Viral RNA was detected in the stool of 59% of the patients and in the serum of 41% of patients. Only one of the patients had a positive urine sample. The median duration of virus in stool (22 days) was significantly longer than in respiratory (18 days; P = .002) and serum samples (16 days; P < .001).

In addition, the median duration of virus in the respiratory samples of patients with severe disease (21 days) was significantly longer than in patients with mild disease (14 days; P = .04).

“In the mild group, the viral loads peaked in respiratory samples in the second week from disease onset, whereas viral load continued to be high during the third week in the severe group,” the authors stated.

Virus duration was also longer in patients older than 60 years and in men.

The longer duration of SARS-CoV-2 in stool samples highlights the need to strengthen the management of stool samples in the prevention and control of the epidemic, especially for patients in the later stages of the disease, the authors advised.

“Compared with patients with mild disease, those with severe disease showed longer duration of SARS-CoV-2 in respiratory samples, higher viral load, and a later shedding peak. These findings suggest that reducing viral loads through clinical means and strengthening management during each stage of severe disease should help to prevent the spread of the virus,” the researchers concluded.

The study was funded by the China National Mega-Projects for Infectious Diseases and the National Natural Science Foundation of China. The authors reported they had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Zheng S et al. BMJ. 2020;369:m1443.

FROM THE BRITISH MEDICAL JOURNAL

COVID-19 linked to large vessel stroke in young adults

In a rapid communication to be published online April 29 in the New England Journal of Medicine, investigators led by Thomas Oxley, MD, PhD, of the department of neurosurgery at Mount Sinai Health System, reported five cases of large vessel stroke over a 2-week period in COVID-19 patients under age 50 years. This represents a sevenfold increase in what would normally be expected.

The five cases had either no, or mild, COVID-19 symptoms.

“It’s been surprising to learn that the virus appears to cause disease through a process of blood clotting,” Dr. Oxley said in an interview.

The message for neurologists and other physicians is “we’re learning that this can disproportionally affect large vessels more than small vessels in terms of presentation of stroke,” he said.

Inflammation in the blood vessel walls may be driving thrombosis formation, Dr. Oxley added. This report joins other research pointing to this emerging phenomenon.

Recently, investigators in the Netherlands found a “remarkably high” 31% rate of thrombotic complications among 184 critical care patients with COVID-19 pneumonia.

Dr. Oxley and colleagues also suggested that, since the onset of the pandemic, fewer patients may be calling emergency services when they experience signs of a stroke. The physicians noted that two of the five cases in the report delayed calling an ambulance.

“I understand why people do not want to leave the household. I think people are more willing to ignore other [non–COVID-19] symptoms in this environment,” he said.

As previously reported, physicians in hospitals across the United States and elsewhere have reported a significant drop in stroke patients since the COVID-19 pandemic took hold, which suggests that patients may indeed be foregoing emergency care.

The observations from Dr. Oxley and colleagues call for greater awareness of the association between COVID-19 and large vessel strokes in this age group, they add.

One patient in the case series died, one remains hospitalized, two are undergoing rehabilitation, and one was discharged home as of April 24.

Dr. Oxley and colleagues dedicated their report to “our inspiring colleague Gary Sclar, MD, a stroke physician who succumbed to COVID-19 while caring for his patients.”

Dr. Oxley has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

In a rapid communication to be published online April 29 in the New England Journal of Medicine, investigators led by Thomas Oxley, MD, PhD, of the department of neurosurgery at Mount Sinai Health System, reported five cases of large vessel stroke over a 2-week period in COVID-19 patients under age 50 years. This represents a sevenfold increase in what would normally be expected.

The five cases had either no, or mild, COVID-19 symptoms.

“It’s been surprising to learn that the virus appears to cause disease through a process of blood clotting,” Dr. Oxley said in an interview.

The message for neurologists and other physicians is “we’re learning that this can disproportionally affect large vessels more than small vessels in terms of presentation of stroke,” he said.

Inflammation in the blood vessel walls may be driving thrombosis formation, Dr. Oxley added. This report joins other research pointing to this emerging phenomenon.

Recently, investigators in the Netherlands found a “remarkably high” 31% rate of thrombotic complications among 184 critical care patients with COVID-19 pneumonia.

Dr. Oxley and colleagues also suggested that, since the onset of the pandemic, fewer patients may be calling emergency services when they experience signs of a stroke. The physicians noted that two of the five cases in the report delayed calling an ambulance.

“I understand why people do not want to leave the household. I think people are more willing to ignore other [non–COVID-19] symptoms in this environment,” he said.

As previously reported, physicians in hospitals across the United States and elsewhere have reported a significant drop in stroke patients since the COVID-19 pandemic took hold, which suggests that patients may indeed be foregoing emergency care.

The observations from Dr. Oxley and colleagues call for greater awareness of the association between COVID-19 and large vessel strokes in this age group, they add.

One patient in the case series died, one remains hospitalized, two are undergoing rehabilitation, and one was discharged home as of April 24.

Dr. Oxley and colleagues dedicated their report to “our inspiring colleague Gary Sclar, MD, a stroke physician who succumbed to COVID-19 while caring for his patients.”

Dr. Oxley has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

In a rapid communication to be published online April 29 in the New England Journal of Medicine, investigators led by Thomas Oxley, MD, PhD, of the department of neurosurgery at Mount Sinai Health System, reported five cases of large vessel stroke over a 2-week period in COVID-19 patients under age 50 years. This represents a sevenfold increase in what would normally be expected.

The five cases had either no, or mild, COVID-19 symptoms.

“It’s been surprising to learn that the virus appears to cause disease through a process of blood clotting,” Dr. Oxley said in an interview.

The message for neurologists and other physicians is “we’re learning that this can disproportionally affect large vessels more than small vessels in terms of presentation of stroke,” he said.

Inflammation in the blood vessel walls may be driving thrombosis formation, Dr. Oxley added. This report joins other research pointing to this emerging phenomenon.

Recently, investigators in the Netherlands found a “remarkably high” 31% rate of thrombotic complications among 184 critical care patients with COVID-19 pneumonia.

Dr. Oxley and colleagues also suggested that, since the onset of the pandemic, fewer patients may be calling emergency services when they experience signs of a stroke. The physicians noted that two of the five cases in the report delayed calling an ambulance.

“I understand why people do not want to leave the household. I think people are more willing to ignore other [non–COVID-19] symptoms in this environment,” he said.

As previously reported, physicians in hospitals across the United States and elsewhere have reported a significant drop in stroke patients since the COVID-19 pandemic took hold, which suggests that patients may indeed be foregoing emergency care.

The observations from Dr. Oxley and colleagues call for greater awareness of the association between COVID-19 and large vessel strokes in this age group, they add.

One patient in the case series died, one remains hospitalized, two are undergoing rehabilitation, and one was discharged home as of April 24.

Dr. Oxley and colleagues dedicated their report to “our inspiring colleague Gary Sclar, MD, a stroke physician who succumbed to COVID-19 while caring for his patients.”

Dr. Oxley has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA reiterates hydroxychloroquine limitations for COVID-19

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration reinforced its March guidance on when it’s permissible to use hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine to treat COVID-19 patients and on the multiple risks these drugs pose in a Safety Communication on April 24.

The new communication reiterated the agency’s position from the Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) it granted on March 28 to allow hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine treatment of COVID-19 patients only when they are hospitalized and participation in a clinical trial is “not available,” or “not feasible.” The April 24 update to the EUA noted that “the FDA is aware of reports of serious heart rhythm problems in patients with COVID-19 treated with hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine, often in combination with azithromycin and other QT-prolonging medicines. We are also aware of increased use of these medicines through outpatient prescriptions.”

In addition to reiterating the prior limitations on permissible patients for these treatment the agency also said in the new communication that “close supervision is strongly recommended, “ specifying that “we recommend initial evaluation and monitoring when using hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine under the EUA or in clinical trials that investigate these medicines for the treatment or prevention of COVID-19. Monitoring may include baseline ECG, electrolytes, renal function, and hepatic tests.” The communication also highlighted several potential serious adverse effects from hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine that include QT prolongation with increased risk in patients with renal insufficiency or failure, increased insulin levels and insulin action causing increased risk of severe hypoglycemia, hemolysis in selected patients, and interaction with other medicines that cause QT prolongation.

“If a healthcare professional is considering use of hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine to treat or prevent COVID-19, FDA recommends checking www.clinicaltrials.gov for a suitable clinical trial and consider enrolling the patient,” the statement added.

The FDA’s Safety Communication came a day after the European Medicines Agency issued a similar reminder about the risk for serious adverse effects from treatment with hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine, the need for adverse effect monitoring, and the unproven status of purported benefits from these agents.

The statement came after ongoing promotion by the Trump administration of hydroxychloroquine, in particular, for COVID-19 despite a lack of evidence.

The FDA’s communication cited recent case reports sent to the FDA, as well as published findings, and reports to the National Poison Data System that have described serious, heart-related adverse events and death in COVID-19 patients who received hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine, alone or in combination with azithromycin or another QT-prolonging drug. One recent, notable but not peer-reviewed report on 368 patients treated at any of several U.S. VA medical centers showed no apparent benefit to hospitalized COVID-19 patients treated with hydroxychloroquine and a signal for increased mortality among certain patients on this drug (medRxiv. 2020 Apr 23; doi: 10.1101/2020.04.16.20065920). Several cardiology societies have also highlighted the cardiac considerations for using these drugs in patients with COVID-19, including a summary coauthored by the presidents of the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association, and the Heart Rhythm Society (Circulation. 2020 Apr 8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047521), and in guidance from the European Society of Cardiology.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration reinforced its March guidance on when it’s permissible to use hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine to treat COVID-19 patients and on the multiple risks these drugs pose in a Safety Communication on April 24.

The new communication reiterated the agency’s position from the Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) it granted on March 28 to allow hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine treatment of COVID-19 patients only when they are hospitalized and participation in a clinical trial is “not available,” or “not feasible.” The April 24 update to the EUA noted that “the FDA is aware of reports of serious heart rhythm problems in patients with COVID-19 treated with hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine, often in combination with azithromycin and other QT-prolonging medicines. We are also aware of increased use of these medicines through outpatient prescriptions.”

In addition to reiterating the prior limitations on permissible patients for these treatment the agency also said in the new communication that “close supervision is strongly recommended, “ specifying that “we recommend initial evaluation and monitoring when using hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine under the EUA or in clinical trials that investigate these medicines for the treatment or prevention of COVID-19. Monitoring may include baseline ECG, electrolytes, renal function, and hepatic tests.” The communication also highlighted several potential serious adverse effects from hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine that include QT prolongation with increased risk in patients with renal insufficiency or failure, increased insulin levels and insulin action causing increased risk of severe hypoglycemia, hemolysis in selected patients, and interaction with other medicines that cause QT prolongation.

“If a healthcare professional is considering use of hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine to treat or prevent COVID-19, FDA recommends checking www.clinicaltrials.gov for a suitable clinical trial and consider enrolling the patient,” the statement added.

The FDA’s Safety Communication came a day after the European Medicines Agency issued a similar reminder about the risk for serious adverse effects from treatment with hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine, the need for adverse effect monitoring, and the unproven status of purported benefits from these agents.

The statement came after ongoing promotion by the Trump administration of hydroxychloroquine, in particular, for COVID-19 despite a lack of evidence.

The FDA’s communication cited recent case reports sent to the FDA, as well as published findings, and reports to the National Poison Data System that have described serious, heart-related adverse events and death in COVID-19 patients who received hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine, alone or in combination with azithromycin or another QT-prolonging drug. One recent, notable but not peer-reviewed report on 368 patients treated at any of several U.S. VA medical centers showed no apparent benefit to hospitalized COVID-19 patients treated with hydroxychloroquine and a signal for increased mortality among certain patients on this drug (medRxiv. 2020 Apr 23; doi: 10.1101/2020.04.16.20065920). Several cardiology societies have also highlighted the cardiac considerations for using these drugs in patients with COVID-19, including a summary coauthored by the presidents of the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association, and the Heart Rhythm Society (Circulation. 2020 Apr 8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047521), and in guidance from the European Society of Cardiology.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration reinforced its March guidance on when it’s permissible to use hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine to treat COVID-19 patients and on the multiple risks these drugs pose in a Safety Communication on April 24.

The new communication reiterated the agency’s position from the Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) it granted on March 28 to allow hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine treatment of COVID-19 patients only when they are hospitalized and participation in a clinical trial is “not available,” or “not feasible.” The April 24 update to the EUA noted that “the FDA is aware of reports of serious heart rhythm problems in patients with COVID-19 treated with hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine, often in combination with azithromycin and other QT-prolonging medicines. We are also aware of increased use of these medicines through outpatient prescriptions.”

In addition to reiterating the prior limitations on permissible patients for these treatment the agency also said in the new communication that “close supervision is strongly recommended, “ specifying that “we recommend initial evaluation and monitoring when using hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine under the EUA or in clinical trials that investigate these medicines for the treatment or prevention of COVID-19. Monitoring may include baseline ECG, electrolytes, renal function, and hepatic tests.” The communication also highlighted several potential serious adverse effects from hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine that include QT prolongation with increased risk in patients with renal insufficiency or failure, increased insulin levels and insulin action causing increased risk of severe hypoglycemia, hemolysis in selected patients, and interaction with other medicines that cause QT prolongation.

“If a healthcare professional is considering use of hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine to treat or prevent COVID-19, FDA recommends checking www.clinicaltrials.gov for a suitable clinical trial and consider enrolling the patient,” the statement added.

The FDA’s Safety Communication came a day after the European Medicines Agency issued a similar reminder about the risk for serious adverse effects from treatment with hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine, the need for adverse effect monitoring, and the unproven status of purported benefits from these agents.

The statement came after ongoing promotion by the Trump administration of hydroxychloroquine, in particular, for COVID-19 despite a lack of evidence.

The FDA’s communication cited recent case reports sent to the FDA, as well as published findings, and reports to the National Poison Data System that have described serious, heart-related adverse events and death in COVID-19 patients who received hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine, alone or in combination with azithromycin or another QT-prolonging drug. One recent, notable but not peer-reviewed report on 368 patients treated at any of several U.S. VA medical centers showed no apparent benefit to hospitalized COVID-19 patients treated with hydroxychloroquine and a signal for increased mortality among certain patients on this drug (medRxiv. 2020 Apr 23; doi: 10.1101/2020.04.16.20065920). Several cardiology societies have also highlighted the cardiac considerations for using these drugs in patients with COVID-19, including a summary coauthored by the presidents of the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association, and the Heart Rhythm Society (Circulation. 2020 Apr 8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047521), and in guidance from the European Society of Cardiology.

FROM THE FDA

COVID-19: Experts call for ‘urgent’ global action to prevent suicide

A global group of suicide experts is urging governments around the world to take action to prevent a possible jump in suicide rates because of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

In a commentary published online April 21 in Lancet Psychiatry, members of the International COVID-19 Suicide Prevention Research Collaboration warned that suicide rates are likely to rise as the pandemic spreads and its ensuing long-term effects on the general population, economy, and vulnerable groups emerge.

“Preventing suicide therefore needs urgent consideration. The response must capitalize on, but extend beyond, general mental health policies and practices,” the experts wrote.

The COVID-19 collaboration was started by David Gunnell, MBChB, PhD, University of Bristol, England, and includes 42 members with suicide expertise from around the world.

“We’re an ad hoc grouping of international suicide prevention researchers, research leaders, and members of larger international suicide prevention organizations. We include specialists in public health, psychiatry, psychology, and other clinical disciplines,” Dr. Gunnell said in an interview.

“Through this comment piece we hope to share our ideas and experiences about best practice, and ask others working in the field of suicide prevention at a regional, national, and international level to share our intervention and surveillance/data collection recommendations with relevant policy makers,” he added.

Lessons from the past

During times of crisis, people with existing mental health disorders may suffer worsening symptoms, whereas others may develop new mental health problems, especially depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), the group notes.

There is some evidence that suicide increased in the United States during the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918 and among older people in Hong Kong during the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak.

An increase in suicide related to COVID-19 is not inevitable provided preventive action is prompt, the group notes.

In their article, the group offered several potential public health responses to mitigate suicide risk associated with the COVID-19 pandemic.

These include:

- Clear care pathways for those who are suicidal.

- Remote or digital assessments for patients currently under the care of a mental health professional.

- Staff training to support new ways of working.

- Increased support for mental health helplines.

- Providing easily accessible grief counseling for those who have lost a loved one to the virus.

- Financial safety nets and labor market programs.

- Dissemination of evidence-based online interventions.

Public health responses must also ensure that those facing domestic violence have access to support and a place to go during times of crisis, they suggested.

“These are unprecedented times. The pandemic will cause distress and leave many vulnerable. Mental health consequences are likely to be present for longer and peak later than the actual pandemic. However, research evidence and the experience of national strategies provide a strong basis for suicide prevention,” the group wrote.

Dr. Gunnell said it’s hard to predict what impact the pandemic will have on suicide rates, “but given the range of concerns, it is important to be prepared and take steps to mitigate risk as much as possible.”

Concerning spike in gun sales

Eric Fleegler, MD, MPH, and colleagues from Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, agreed.

“The time to act is now. Both population and individual approaches are needed to reduce the risk for suicide in the coming months,” they wrote in a commentary published online April 22 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Dr. Fleegler and colleagues are particularly concerned about a potential increase in gun-related suicides, as gun sales in the United States have “skyrocketed” during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In March, more than 2.5 million firearms were sold, including 1.5 million handguns. That’s an 85% increase in gun sales compared with March 2019 and the highest firearm sales ever recorded in the United States, they reported.

In addition, research has shown that individuals who buy handguns have a 22-fold higher rate of firearm-related suicide within the first year vs. those who don’t purchase a handgun.

“In the best of times, increased gun ownership is associated with a heightened risk for firearm-related suicide. These are not the best of times,” the authors wrote.

Dr. Fleegler and colleagues said From 2006 to 2018, firearm-related suicide rates increased by more than 25%, according to the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. In 2018 alone, there were 24,432 firearm-related suicides in the United States.

“The United States should take policy and clinical action to avoid a potential epidemic of firearm-related suicide in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic,” they concluded.

This research had no specific funding. Dr. Gunnell and Dr. Fleegler disclosed no relevant financial relationships .

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

A global group of suicide experts is urging governments around the world to take action to prevent a possible jump in suicide rates because of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

In a commentary published online April 21 in Lancet Psychiatry, members of the International COVID-19 Suicide Prevention Research Collaboration warned that suicide rates are likely to rise as the pandemic spreads and its ensuing long-term effects on the general population, economy, and vulnerable groups emerge.

“Preventing suicide therefore needs urgent consideration. The response must capitalize on, but extend beyond, general mental health policies and practices,” the experts wrote.

The COVID-19 collaboration was started by David Gunnell, MBChB, PhD, University of Bristol, England, and includes 42 members with suicide expertise from around the world.

“We’re an ad hoc grouping of international suicide prevention researchers, research leaders, and members of larger international suicide prevention organizations. We include specialists in public health, psychiatry, psychology, and other clinical disciplines,” Dr. Gunnell said in an interview.

“Through this comment piece we hope to share our ideas and experiences about best practice, and ask others working in the field of suicide prevention at a regional, national, and international level to share our intervention and surveillance/data collection recommendations with relevant policy makers,” he added.

Lessons from the past

During times of crisis, people with existing mental health disorders may suffer worsening symptoms, whereas others may develop new mental health problems, especially depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), the group notes.

There is some evidence that suicide increased in the United States during the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918 and among older people in Hong Kong during the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak.

An increase in suicide related to COVID-19 is not inevitable provided preventive action is prompt, the group notes.

In their article, the group offered several potential public health responses to mitigate suicide risk associated with the COVID-19 pandemic.

These include:

- Clear care pathways for those who are suicidal.

- Remote or digital assessments for patients currently under the care of a mental health professional.

- Staff training to support new ways of working.

- Increased support for mental health helplines.

- Providing easily accessible grief counseling for those who have lost a loved one to the virus.

- Financial safety nets and labor market programs.

- Dissemination of evidence-based online interventions.

Public health responses must also ensure that those facing domestic violence have access to support and a place to go during times of crisis, they suggested.

“These are unprecedented times. The pandemic will cause distress and leave many vulnerable. Mental health consequences are likely to be present for longer and peak later than the actual pandemic. However, research evidence and the experience of national strategies provide a strong basis for suicide prevention,” the group wrote.

Dr. Gunnell said it’s hard to predict what impact the pandemic will have on suicide rates, “but given the range of concerns, it is important to be prepared and take steps to mitigate risk as much as possible.”

Concerning spike in gun sales

Eric Fleegler, MD, MPH, and colleagues from Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, agreed.

“The time to act is now. Both population and individual approaches are needed to reduce the risk for suicide in the coming months,” they wrote in a commentary published online April 22 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Dr. Fleegler and colleagues are particularly concerned about a potential increase in gun-related suicides, as gun sales in the United States have “skyrocketed” during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In March, more than 2.5 million firearms were sold, including 1.5 million handguns. That’s an 85% increase in gun sales compared with March 2019 and the highest firearm sales ever recorded in the United States, they reported.

In addition, research has shown that individuals who buy handguns have a 22-fold higher rate of firearm-related suicide within the first year vs. those who don’t purchase a handgun.

“In the best of times, increased gun ownership is associated with a heightened risk for firearm-related suicide. These are not the best of times,” the authors wrote.

Dr. Fleegler and colleagues said From 2006 to 2018, firearm-related suicide rates increased by more than 25%, according to the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. In 2018 alone, there were 24,432 firearm-related suicides in the United States.

“The United States should take policy and clinical action to avoid a potential epidemic of firearm-related suicide in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic,” they concluded.

This research had no specific funding. Dr. Gunnell and Dr. Fleegler disclosed no relevant financial relationships .

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

A global group of suicide experts is urging governments around the world to take action to prevent a possible jump in suicide rates because of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

In a commentary published online April 21 in Lancet Psychiatry, members of the International COVID-19 Suicide Prevention Research Collaboration warned that suicide rates are likely to rise as the pandemic spreads and its ensuing long-term effects on the general population, economy, and vulnerable groups emerge.

“Preventing suicide therefore needs urgent consideration. The response must capitalize on, but extend beyond, general mental health policies and practices,” the experts wrote.

The COVID-19 collaboration was started by David Gunnell, MBChB, PhD, University of Bristol, England, and includes 42 members with suicide expertise from around the world.

“We’re an ad hoc grouping of international suicide prevention researchers, research leaders, and members of larger international suicide prevention organizations. We include specialists in public health, psychiatry, psychology, and other clinical disciplines,” Dr. Gunnell said in an interview.

“Through this comment piece we hope to share our ideas and experiences about best practice, and ask others working in the field of suicide prevention at a regional, national, and international level to share our intervention and surveillance/data collection recommendations with relevant policy makers,” he added.

Lessons from the past

During times of crisis, people with existing mental health disorders may suffer worsening symptoms, whereas others may develop new mental health problems, especially depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), the group notes.

There is some evidence that suicide increased in the United States during the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918 and among older people in Hong Kong during the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak.

An increase in suicide related to COVID-19 is not inevitable provided preventive action is prompt, the group notes.

In their article, the group offered several potential public health responses to mitigate suicide risk associated with the COVID-19 pandemic.

These include:

- Clear care pathways for those who are suicidal.

- Remote or digital assessments for patients currently under the care of a mental health professional.

- Staff training to support new ways of working.

- Increased support for mental health helplines.

- Providing easily accessible grief counseling for those who have lost a loved one to the virus.

- Financial safety nets and labor market programs.

- Dissemination of evidence-based online interventions.

Public health responses must also ensure that those facing domestic violence have access to support and a place to go during times of crisis, they suggested.

“These are unprecedented times. The pandemic will cause distress and leave many vulnerable. Mental health consequences are likely to be present for longer and peak later than the actual pandemic. However, research evidence and the experience of national strategies provide a strong basis for suicide prevention,” the group wrote.

Dr. Gunnell said it’s hard to predict what impact the pandemic will have on suicide rates, “but given the range of concerns, it is important to be prepared and take steps to mitigate risk as much as possible.”

Concerning spike in gun sales

Eric Fleegler, MD, MPH, and colleagues from Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, agreed.

“The time to act is now. Both population and individual approaches are needed to reduce the risk for suicide in the coming months,” they wrote in a commentary published online April 22 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Dr. Fleegler and colleagues are particularly concerned about a potential increase in gun-related suicides, as gun sales in the United States have “skyrocketed” during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In March, more than 2.5 million firearms were sold, including 1.5 million handguns. That’s an 85% increase in gun sales compared with March 2019 and the highest firearm sales ever recorded in the United States, they reported.

In addition, research has shown that individuals who buy handguns have a 22-fold higher rate of firearm-related suicide within the first year vs. those who don’t purchase a handgun.

“In the best of times, increased gun ownership is associated with a heightened risk for firearm-related suicide. These are not the best of times,” the authors wrote.

Dr. Fleegler and colleagues said From 2006 to 2018, firearm-related suicide rates increased by more than 25%, according to the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. In 2018 alone, there were 24,432 firearm-related suicides in the United States.

“The United States should take policy and clinical action to avoid a potential epidemic of firearm-related suicide in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic,” they concluded.

This research had no specific funding. Dr. Gunnell and Dr. Fleegler disclosed no relevant financial relationships .

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

What will pediatrics look like in 2022?

In 1966 I was struggling with the decision of whether to become an art historian or go to medical school. I decided corporate ladder climbs and tenure chases were not for me. I wanted to be my own boss. I reckoned that medicine would offer me rock-solid job security and a comfortable income that I could adjust to my needs simply by working harder. In my Norman Rockwell–influenced view of the world, there would always be sick children. There would never be a quiet week or even a day when I would have to worry about not having an income.

So it was an idyllic existence for decades, tarnished only slightly when corporate entities began gobbling up owner-operator practices. But I never envisioned a pandemic that would turn the world – including its pediatricians – upside down. For the last several weeks as I pedal past my old office, I am dumbstruck by the empty parking lot. For the present I appear to be buffered by my retirement, but know that many of you are under serious financial pressure as a result of the pandemic.

We are all yearning to return to business as usual, but we know that it isn’t going to happen because everything has changed. The usual has yet to be defined. When you finally reopen your offices, you will be walking into a strange and eerie new normal. Initially you may struggle to make it feel like nothing has changed, but very quickly the full force of the postpandemic tsunami will hit us all broadside. In 2 years, the ship may still be rocking but what will clinical pediatrics look like in the late spring of 2022?

Will the patient mix have shifted even more toward behavioral and mental health complaints as a ripple effect of the pandemic’s emotional turmoil? Will your waiting room have become a maze of plexiglass barriers to separate the sick from the well? Has the hospital invested hundreds of thousands of dollars in a ventilation system in hopes of minimizing contagion in your exam rooms? Maybe you will have instituted an appointment schedule with sick visits in the morning and well checks in the afternoon. Or you may no longer have a waiting room because patients are queuing in their cars in the parking lot. Your support staff may be rollerskating around like carhops at a drive-in recording histories and taking vital signs.

Telemedicine will hopefully have gone mainstream with more robust guidelines for billing and quality control. Medical schools may be devoting more attention to teaching student how to assess remotely. Parents may now be equipped with a tool kit of remote sensors so that you can assess their child’s tympanic membranes, pulse rate, oxygen saturation, and blood pressure on your office computer screen.

Will the EHR finally have begun to emerge from its awkward and at times painful adolescence into an easily accessible and transportable nationwide data bank that includes immunization records for all ages? Patients may have been asked or ordered to allow their cell phones to be used as tracking devices for serious communicable diseases. How many vaccine-resistant people will have responded to the pandemic by deciding that immunizations are worth the minimal risks? I fear not many.

How many of your colleagues will have left pediatrics and heeded the call for more epidemiologists? Will you be required to take a CME course in ventilation management? The good news may be that to keep the pediatric workforce robust the government has decided to forgive your student loans.

None of these changes may have come to pass because we have notoriously short memories. But I am sure that we will all still bear the deep scars of this world changing event.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

In 1966 I was struggling with the decision of whether to become an art historian or go to medical school. I decided corporate ladder climbs and tenure chases were not for me. I wanted to be my own boss. I reckoned that medicine would offer me rock-solid job security and a comfortable income that I could adjust to my needs simply by working harder. In my Norman Rockwell–influenced view of the world, there would always be sick children. There would never be a quiet week or even a day when I would have to worry about not having an income.

So it was an idyllic existence for decades, tarnished only slightly when corporate entities began gobbling up owner-operator practices. But I never envisioned a pandemic that would turn the world – including its pediatricians – upside down. For the last several weeks as I pedal past my old office, I am dumbstruck by the empty parking lot. For the present I appear to be buffered by my retirement, but know that many of you are under serious financial pressure as a result of the pandemic.

We are all yearning to return to business as usual, but we know that it isn’t going to happen because everything has changed. The usual has yet to be defined. When you finally reopen your offices, you will be walking into a strange and eerie new normal. Initially you may struggle to make it feel like nothing has changed, but very quickly the full force of the postpandemic tsunami will hit us all broadside. In 2 years, the ship may still be rocking but what will clinical pediatrics look like in the late spring of 2022?

Will the patient mix have shifted even more toward behavioral and mental health complaints as a ripple effect of the pandemic’s emotional turmoil? Will your waiting room have become a maze of plexiglass barriers to separate the sick from the well? Has the hospital invested hundreds of thousands of dollars in a ventilation system in hopes of minimizing contagion in your exam rooms? Maybe you will have instituted an appointment schedule with sick visits in the morning and well checks in the afternoon. Or you may no longer have a waiting room because patients are queuing in their cars in the parking lot. Your support staff may be rollerskating around like carhops at a drive-in recording histories and taking vital signs.

Telemedicine will hopefully have gone mainstream with more robust guidelines for billing and quality control. Medical schools may be devoting more attention to teaching student how to assess remotely. Parents may now be equipped with a tool kit of remote sensors so that you can assess their child’s tympanic membranes, pulse rate, oxygen saturation, and blood pressure on your office computer screen.

Will the EHR finally have begun to emerge from its awkward and at times painful adolescence into an easily accessible and transportable nationwide data bank that includes immunization records for all ages? Patients may have been asked or ordered to allow their cell phones to be used as tracking devices for serious communicable diseases. How many vaccine-resistant people will have responded to the pandemic by deciding that immunizations are worth the minimal risks? I fear not many.

How many of your colleagues will have left pediatrics and heeded the call for more epidemiologists? Will you be required to take a CME course in ventilation management? The good news may be that to keep the pediatric workforce robust the government has decided to forgive your student loans.

None of these changes may have come to pass because we have notoriously short memories. But I am sure that we will all still bear the deep scars of this world changing event.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

In 1966 I was struggling with the decision of whether to become an art historian or go to medical school. I decided corporate ladder climbs and tenure chases were not for me. I wanted to be my own boss. I reckoned that medicine would offer me rock-solid job security and a comfortable income that I could adjust to my needs simply by working harder. In my Norman Rockwell–influenced view of the world, there would always be sick children. There would never be a quiet week or even a day when I would have to worry about not having an income.

So it was an idyllic existence for decades, tarnished only slightly when corporate entities began gobbling up owner-operator practices. But I never envisioned a pandemic that would turn the world – including its pediatricians – upside down. For the last several weeks as I pedal past my old office, I am dumbstruck by the empty parking lot. For the present I appear to be buffered by my retirement, but know that many of you are under serious financial pressure as a result of the pandemic.

We are all yearning to return to business as usual, but we know that it isn’t going to happen because everything has changed. The usual has yet to be defined. When you finally reopen your offices, you will be walking into a strange and eerie new normal. Initially you may struggle to make it feel like nothing has changed, but very quickly the full force of the postpandemic tsunami will hit us all broadside. In 2 years, the ship may still be rocking but what will clinical pediatrics look like in the late spring of 2022?

Will the patient mix have shifted even more toward behavioral and mental health complaints as a ripple effect of the pandemic’s emotional turmoil? Will your waiting room have become a maze of plexiglass barriers to separate the sick from the well? Has the hospital invested hundreds of thousands of dollars in a ventilation system in hopes of minimizing contagion in your exam rooms? Maybe you will have instituted an appointment schedule with sick visits in the morning and well checks in the afternoon. Or you may no longer have a waiting room because patients are queuing in their cars in the parking lot. Your support staff may be rollerskating around like carhops at a drive-in recording histories and taking vital signs.

Telemedicine will hopefully have gone mainstream with more robust guidelines for billing and quality control. Medical schools may be devoting more attention to teaching student how to assess remotely. Parents may now be equipped with a tool kit of remote sensors so that you can assess their child’s tympanic membranes, pulse rate, oxygen saturation, and blood pressure on your office computer screen.

Will the EHR finally have begun to emerge from its awkward and at times painful adolescence into an easily accessible and transportable nationwide data bank that includes immunization records for all ages? Patients may have been asked or ordered to allow their cell phones to be used as tracking devices for serious communicable diseases. How many vaccine-resistant people will have responded to the pandemic by deciding that immunizations are worth the minimal risks? I fear not many.

How many of your colleagues will have left pediatrics and heeded the call for more epidemiologists? Will you be required to take a CME course in ventilation management? The good news may be that to keep the pediatric workforce robust the government has decided to forgive your student loans.

None of these changes may have come to pass because we have notoriously short memories. But I am sure that we will all still bear the deep scars of this world changing event.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Prioritizing ambulatory gynecology care during COVID-19: The latest guidance

What exactly constitutes appropriate ambulatory gynecology during this time of social distancing?

On March 30, 2020, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) weighed in, releasing COVID-19 FAQs for Obstetrician-Gynecologists. These recommendations, which include information about obstetric and gynecologic surgery, are available to everyone, including the general public. They are intended to supplement guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, as well as previously released ACOG guidance.

The recommendations include examples of patients needing in-person appointments, telehealth visits, or visits that should be deferred.

In-person appointments. Examples of patients for whom in-person appointments are appropriate include those with suspected ectopic pregnancy or profuse vaginal bleeding. With respect to contraceptive services, ACOG suggests that placement of IUDs and implants should continue whenever possible. If placement of the contraceptive device is deferred, use of self-administered hormonal contraceptives (including subcutaneous injections, oral, transdermal patch, and vaginal ring) should be encouraged as a bridge to later initiation of long-acting methods.

Telehealth visits. Video or telephone visits are advised for women desiring counseling and prescribing for contraception or menopausal symptoms.

Deferred. Deferral of office visits until after COVID-19 lockdowns is advised for average-risk women wishing routine well-woman visits. Other situations in which deferral should be considered include the following:

- For patients with abnormal cervical cancer screening results, ACOG suggests that colposcopy with cervical biopsies could be deferred for 6-12 months for patients with low-grade test results. In contrast, for patients with high-grade results, ACOG recommends that evaluation be performed within 3 months.

- For women who wish to discontinue their contraceptive, ACOG advises that removal of IUDs and implants be postponed when possible. These women should be counseled regarding extended use of these devices.

ACOG emphasizes that decisions regarding ambulatory gynecology should be individualized and take into consideration such issues as availability of local and regional resources, staffing, personal protective equipment, and the local prevalence of COVID-19.

As a gynecologist focused on ambulatory care, I believe that many clinicians will welcome this guidance from ACOG, which helps us provide optimal care during these challenging times.

Dr. Kaunitz is professor and associate chairman in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Florida, Jacksonville. He has disclosed receiving royalties from UpToDate, serving on the safety monitoring board for Femasys, and serving as a consultant for AMAG Pharmaceuticals, Merck & Co, Mithra, and Pfizer. His institution has received funding from pharmaceutical companies and nonprofits.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

What exactly constitutes appropriate ambulatory gynecology during this time of social distancing?

On March 30, 2020, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) weighed in, releasing COVID-19 FAQs for Obstetrician-Gynecologists. These recommendations, which include information about obstetric and gynecologic surgery, are available to everyone, including the general public. They are intended to supplement guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, as well as previously released ACOG guidance.

The recommendations include examples of patients needing in-person appointments, telehealth visits, or visits that should be deferred.

In-person appointments. Examples of patients for whom in-person appointments are appropriate include those with suspected ectopic pregnancy or profuse vaginal bleeding. With respect to contraceptive services, ACOG suggests that placement of IUDs and implants should continue whenever possible. If placement of the contraceptive device is deferred, use of self-administered hormonal contraceptives (including subcutaneous injections, oral, transdermal patch, and vaginal ring) should be encouraged as a bridge to later initiation of long-acting methods.

Telehealth visits. Video or telephone visits are advised for women desiring counseling and prescribing for contraception or menopausal symptoms.

Deferred. Deferral of office visits until after COVID-19 lockdowns is advised for average-risk women wishing routine well-woman visits. Other situations in which deferral should be considered include the following:

- For patients with abnormal cervical cancer screening results, ACOG suggests that colposcopy with cervical biopsies could be deferred for 6-12 months for patients with low-grade test results. In contrast, for patients with high-grade results, ACOG recommends that evaluation be performed within 3 months.

- For women who wish to discontinue their contraceptive, ACOG advises that removal of IUDs and implants be postponed when possible. These women should be counseled regarding extended use of these devices.