User login

For heavy menstrual bleeding, are long-term outcomes similar for treatment with the LNG-IUS and radiofrequency endometrial ablation?

Beelen P, van den Brink MJ, Herman MC, et al. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system versus endometrial ablation for heavy menstrual bleeding. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;224:187.e1-187.e10.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

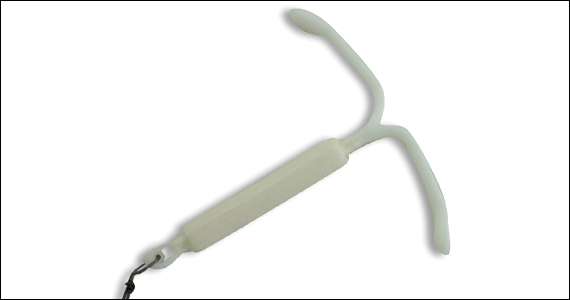

Counseling patients regarding treatment of HMB requires a realistic discussion about the risks of intervention and the expected outcomes. In addition to decreasing menstrual blood loss, treatment benefits of the LNG-IUS include a reversible form of intervention, minimal discomfort with placement in an office environment with an awake patient, and a reliable form of contraception. Abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) and progesterone-related adverse effects historically have been associated with LNG-IUS use and can lead to patient desires for device removal or additional intervention.

Similarly, in addition to endometrial ablation (EA) decreasing menstrual blood loss, its benefits include avoiding a hysterectomy with an outpatient procedure. Endometrial ablation does require a desire for no future pregnancies while using a reliable form of contraception. Risks of EA include failure to improve HMB or worsening pelvic pain that requires additional intervention, such as hysterectomy. Historically, clinical data suggest failure is more likely for women less than 40 years of age or with adenomyosis at the time of ablation.

Results of a long-term RCT by Beelen and colleagues may aid gynecologists in counseling patients on the risks and benefits of these 2 treatment options.

Details of the study

Performed between 2012 and 2016, this multicenter RCT evaluated primary intervention of the LNG-IUS in 132 women versus EA in 138 women. The women were older than age 34, did not want a future pregnancy, and had other etiologies of AUB eliminated.

The primary outcome was blood loss after 24 months as assessed with a Pictorial Blood Loss Assessment Chart (PBAC) score.

Secondary outcomes included controlled bleeding, defined as a PBAC score not exceeding 75 points; complications and reinterventions within 24 months; amenorrhea; spotting; dysmenorrhea; presence of clots; duration of blood loss; satisfaction with treatment; QoL; and sexual function.

The statistical null hypothesis of the trial was noninferiority of LNG-IUS treatment compared with EA treatment.

Results. Regarding the primary outcome, the mean PBAC score at 2 years was 64.8 for the LNG-IUS treatment group and 14.2 for the EA group. Importantly, however, the authors could not demonstrate noninferiority of the LNG-IUS compared with EA as a primary intervention for HMB.

For the secondary outcomes, there was no significant difference between groups, with both groups having a significant decrease in HMB at 3 months with PBAC scores that did not exceed 75 points: 60% in the LNG-IUS group and 83% in the EA group. In the LNG-IUS group, 35% of women received additional medical or surgical intervention versus 20% in the EA group.

Study strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study include its multicenter design, with 26 hospitals, and the long-term follow-up of 24 months. During the follow-up period, women were allowed to receive a reintervention as clinically indicated; thus, outcomes reflect results that are not from only a single designated intervention. For example, of the women in the LNG-IUS group, 34 received a surgical intervention, 31 (24%) underwent EA, and 9 (7%) underwent a hysterectomy. However, 6 of the 9 who underwent hysterectomy had a preceding EA, and these 6 women are not reported as surgical intervention of EA since the original designation for intervention was the LNG-IUS.

Notably, the patients and physicians were not blinded to the intervention, and the study excluded patients who wanted a future pregnancy. ●

Counseling patients regarding the LNG-IUS and EA for management of HMB requires a discussion balanced by information regarding the risks and the foreseeable benefits of these interventions. This study suggests that long-term primary and secondary outcomes are similar. Therefore, in choosing between the 2, a patient may rely more on her values, her age, and her consideration of future pregnancy and uterine preservation.

AMY L. GARCIA, MD

Beelen P, van den Brink MJ, Herman MC, et al. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system versus endometrial ablation for heavy menstrual bleeding. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;224:187.e1-187.e10.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Counseling patients regarding treatment of HMB requires a realistic discussion about the risks of intervention and the expected outcomes. In addition to decreasing menstrual blood loss, treatment benefits of the LNG-IUS include a reversible form of intervention, minimal discomfort with placement in an office environment with an awake patient, and a reliable form of contraception. Abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) and progesterone-related adverse effects historically have been associated with LNG-IUS use and can lead to patient desires for device removal or additional intervention.

Similarly, in addition to endometrial ablation (EA) decreasing menstrual blood loss, its benefits include avoiding a hysterectomy with an outpatient procedure. Endometrial ablation does require a desire for no future pregnancies while using a reliable form of contraception. Risks of EA include failure to improve HMB or worsening pelvic pain that requires additional intervention, such as hysterectomy. Historically, clinical data suggest failure is more likely for women less than 40 years of age or with adenomyosis at the time of ablation.

Results of a long-term RCT by Beelen and colleagues may aid gynecologists in counseling patients on the risks and benefits of these 2 treatment options.

Details of the study

Performed between 2012 and 2016, this multicenter RCT evaluated primary intervention of the LNG-IUS in 132 women versus EA in 138 women. The women were older than age 34, did not want a future pregnancy, and had other etiologies of AUB eliminated.

The primary outcome was blood loss after 24 months as assessed with a Pictorial Blood Loss Assessment Chart (PBAC) score.

Secondary outcomes included controlled bleeding, defined as a PBAC score not exceeding 75 points; complications and reinterventions within 24 months; amenorrhea; spotting; dysmenorrhea; presence of clots; duration of blood loss; satisfaction with treatment; QoL; and sexual function.

The statistical null hypothesis of the trial was noninferiority of LNG-IUS treatment compared with EA treatment.

Results. Regarding the primary outcome, the mean PBAC score at 2 years was 64.8 for the LNG-IUS treatment group and 14.2 for the EA group. Importantly, however, the authors could not demonstrate noninferiority of the LNG-IUS compared with EA as a primary intervention for HMB.

For the secondary outcomes, there was no significant difference between groups, with both groups having a significant decrease in HMB at 3 months with PBAC scores that did not exceed 75 points: 60% in the LNG-IUS group and 83% in the EA group. In the LNG-IUS group, 35% of women received additional medical or surgical intervention versus 20% in the EA group.

Study strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study include its multicenter design, with 26 hospitals, and the long-term follow-up of 24 months. During the follow-up period, women were allowed to receive a reintervention as clinically indicated; thus, outcomes reflect results that are not from only a single designated intervention. For example, of the women in the LNG-IUS group, 34 received a surgical intervention, 31 (24%) underwent EA, and 9 (7%) underwent a hysterectomy. However, 6 of the 9 who underwent hysterectomy had a preceding EA, and these 6 women are not reported as surgical intervention of EA since the original designation for intervention was the LNG-IUS.

Notably, the patients and physicians were not blinded to the intervention, and the study excluded patients who wanted a future pregnancy. ●

Counseling patients regarding the LNG-IUS and EA for management of HMB requires a discussion balanced by information regarding the risks and the foreseeable benefits of these interventions. This study suggests that long-term primary and secondary outcomes are similar. Therefore, in choosing between the 2, a patient may rely more on her values, her age, and her consideration of future pregnancy and uterine preservation.

AMY L. GARCIA, MD

Beelen P, van den Brink MJ, Herman MC, et al. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system versus endometrial ablation for heavy menstrual bleeding. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;224:187.e1-187.e10.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Counseling patients regarding treatment of HMB requires a realistic discussion about the risks of intervention and the expected outcomes. In addition to decreasing menstrual blood loss, treatment benefits of the LNG-IUS include a reversible form of intervention, minimal discomfort with placement in an office environment with an awake patient, and a reliable form of contraception. Abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) and progesterone-related adverse effects historically have been associated with LNG-IUS use and can lead to patient desires for device removal or additional intervention.

Similarly, in addition to endometrial ablation (EA) decreasing menstrual blood loss, its benefits include avoiding a hysterectomy with an outpatient procedure. Endometrial ablation does require a desire for no future pregnancies while using a reliable form of contraception. Risks of EA include failure to improve HMB or worsening pelvic pain that requires additional intervention, such as hysterectomy. Historically, clinical data suggest failure is more likely for women less than 40 years of age or with adenomyosis at the time of ablation.

Results of a long-term RCT by Beelen and colleagues may aid gynecologists in counseling patients on the risks and benefits of these 2 treatment options.

Details of the study

Performed between 2012 and 2016, this multicenter RCT evaluated primary intervention of the LNG-IUS in 132 women versus EA in 138 women. The women were older than age 34, did not want a future pregnancy, and had other etiologies of AUB eliminated.

The primary outcome was blood loss after 24 months as assessed with a Pictorial Blood Loss Assessment Chart (PBAC) score.

Secondary outcomes included controlled bleeding, defined as a PBAC score not exceeding 75 points; complications and reinterventions within 24 months; amenorrhea; spotting; dysmenorrhea; presence of clots; duration of blood loss; satisfaction with treatment; QoL; and sexual function.

The statistical null hypothesis of the trial was noninferiority of LNG-IUS treatment compared with EA treatment.

Results. Regarding the primary outcome, the mean PBAC score at 2 years was 64.8 for the LNG-IUS treatment group and 14.2 for the EA group. Importantly, however, the authors could not demonstrate noninferiority of the LNG-IUS compared with EA as a primary intervention for HMB.

For the secondary outcomes, there was no significant difference between groups, with both groups having a significant decrease in HMB at 3 months with PBAC scores that did not exceed 75 points: 60% in the LNG-IUS group and 83% in the EA group. In the LNG-IUS group, 35% of women received additional medical or surgical intervention versus 20% in the EA group.

Study strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study include its multicenter design, with 26 hospitals, and the long-term follow-up of 24 months. During the follow-up period, women were allowed to receive a reintervention as clinically indicated; thus, outcomes reflect results that are not from only a single designated intervention. For example, of the women in the LNG-IUS group, 34 received a surgical intervention, 31 (24%) underwent EA, and 9 (7%) underwent a hysterectomy. However, 6 of the 9 who underwent hysterectomy had a preceding EA, and these 6 women are not reported as surgical intervention of EA since the original designation for intervention was the LNG-IUS.

Notably, the patients and physicians were not blinded to the intervention, and the study excluded patients who wanted a future pregnancy. ●

Counseling patients regarding the LNG-IUS and EA for management of HMB requires a discussion balanced by information regarding the risks and the foreseeable benefits of these interventions. This study suggests that long-term primary and secondary outcomes are similar. Therefore, in choosing between the 2, a patient may rely more on her values, her age, and her consideration of future pregnancy and uterine preservation.

AMY L. GARCIA, MD

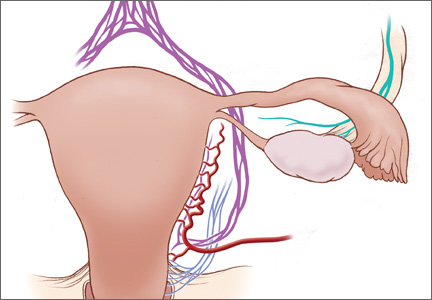

The role of hysteroscopy in diagnosing endometrial cancer

For more than 45 years, gynecologists have used hysteroscopy to diagnose endometrial carcinoma and to associate morphologic descriptive terms with visual findings.1 Today, considerably more clinical evidence supports visual pattern recognition to assess the risk for and presence of endometrial carcinoma, improving observer-dependent biopsy of the most suspect lesions (VIDEO 1).

In this article, I discuss the clinical evolution of hysteroscopic pattern recognition of endometrial disease and review the visual findings that correlate with the likelihood of endometrial carcinoma. In addition, I have provided 9 short videos that show hysteroscopic views of various endometrial pathologies in the online version of this article at https://www.mdedge.com/obgyn.

Video 1. Endometrial carcinoma and visually directed biopsy

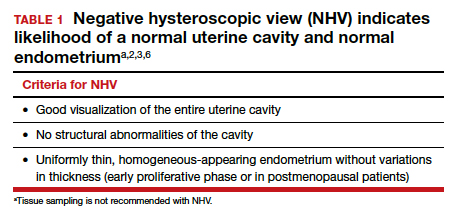

The negative hysteroscopic view defined

In 1989, Dr. Frank Loffer confirmed the diagnostic superiority of visually directed biopsy. He demonstrated the advantages of using hysteroscopy and directed biopsy in the evaluation of abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) to obtain a more accurate diagnosis compared with dilation and curettage (D&C) alone (sensitivity, 98% vs 65%, respectively).2

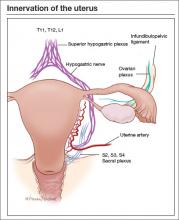

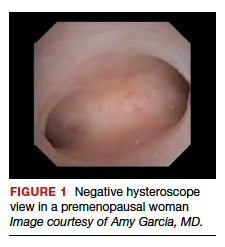

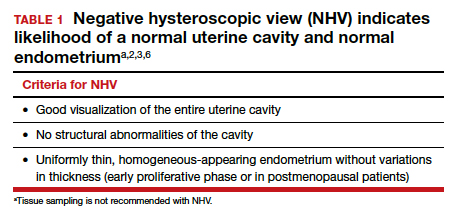

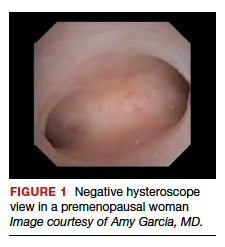

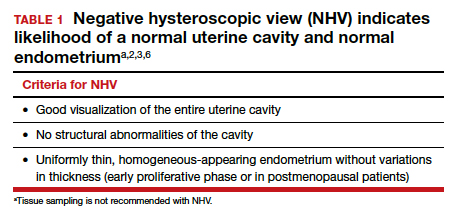

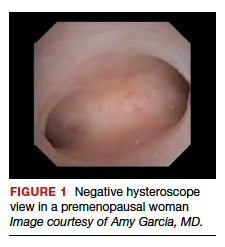

Also derived from this work is the clinical application of the “negative hysteroscopic view” (NHV). Loffer used the following criteria to define the NHV: good visualization of the entire uterine cavity, no structural abnormalities of the cavity, and a uniformly thin, homogeneous-appearing endometrium without variations in thickness (TABLE 1). The last criterion can be expected to occur only in the early proliferative phase or in postmenopausal women.

Use of hysteroscopy therefore can predict accurately the absence of intrauterine and endometrial pathology when visual findings are negative and tissue sampling is not warranted (FIGURE 1, VIDEO 2).

Video 2. Negative hysteroscopic view

Efforts in hysteroscopic classification of endometrial carcinoma

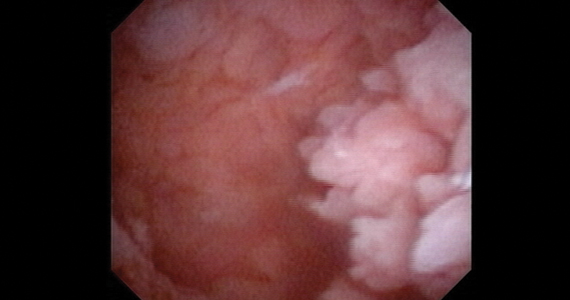

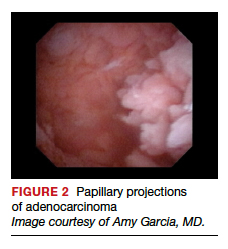

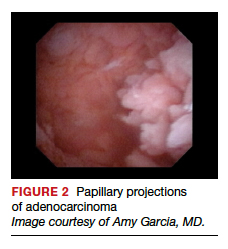

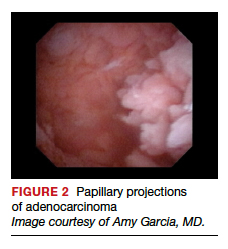

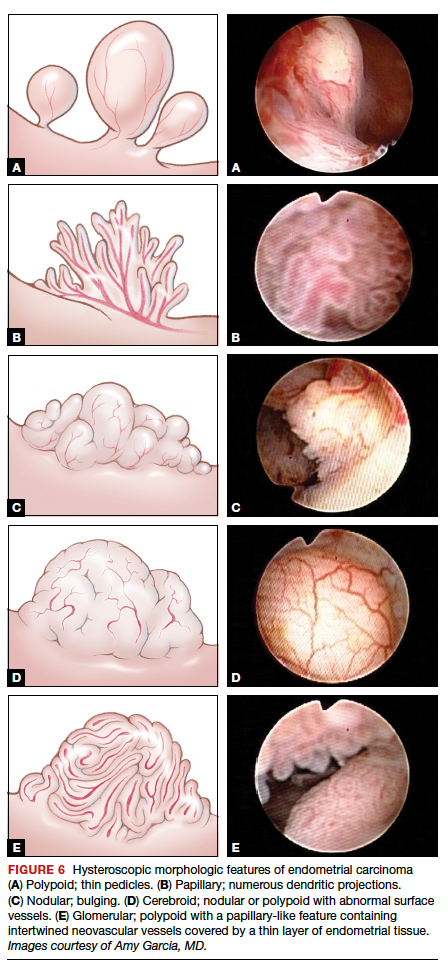

Lesion morphologic characteristics. Sugimoto was among the first to describe the hysteroscopic identification of visual morphologic features that are most likely to be associated with endometrial carcinoma.1 Patients with AUB were evaluated with hysteroscopy as first-line management to describe lesion morphology and confirm biopsy with histopathology. Sugimoto classified endometrial carcinoma as circumscribed or exophytic with distinct forms, such as polypoid, nodular, papillary, and ulcerated (FIGURE 2). Diffuse or endophytic carcinoma is defined by an ulcerated type of lesion that indicates necrosis; this is most likely to represent an undifferentiated tumor. Sugimoto also described abnormal vascularity that often is associated with carcinoma.1

Endometrial features. Valli and Zupi created a nomenclature and classification for hysteroscopic endometrial lesions by prospectively grading 4 features: thickness, surface, vascularization, and color.3 Features were scored based on the degree of abnormality and could be considered to be of low or high risk for the presence of carcinoma. High-risk hysteroscopic features included endometrial thickness greater than 10 mm, polymorphous surface, irregular vascularization, and white-grayish color. The sensitivity for accurately diagnosing endometrial lesions was 86.9% for mild lesions and 96% for severe lesions.3 Also, these investigators confirmed the clinical value of the NHV and associated overall risk of precancer or cancer of the endometrium.

Continue to: Amount of endometrial involvement...

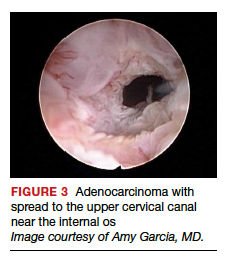

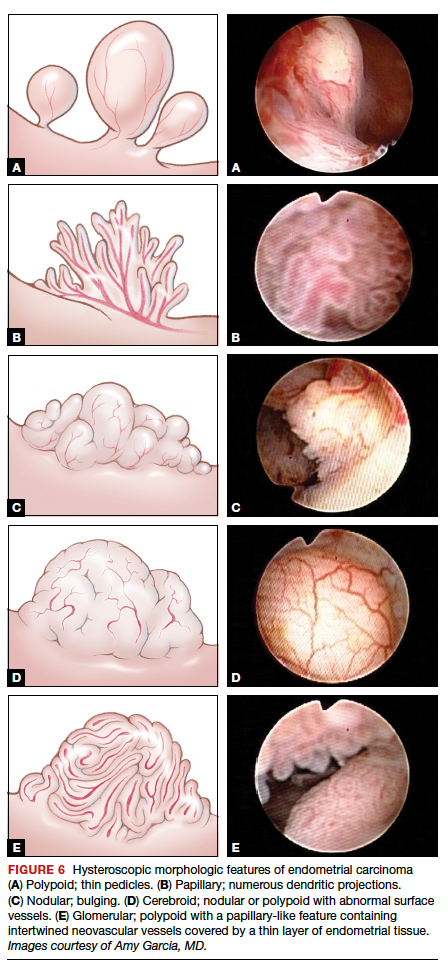

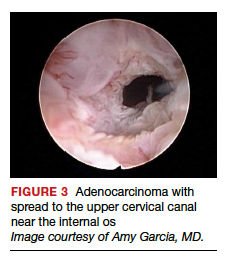

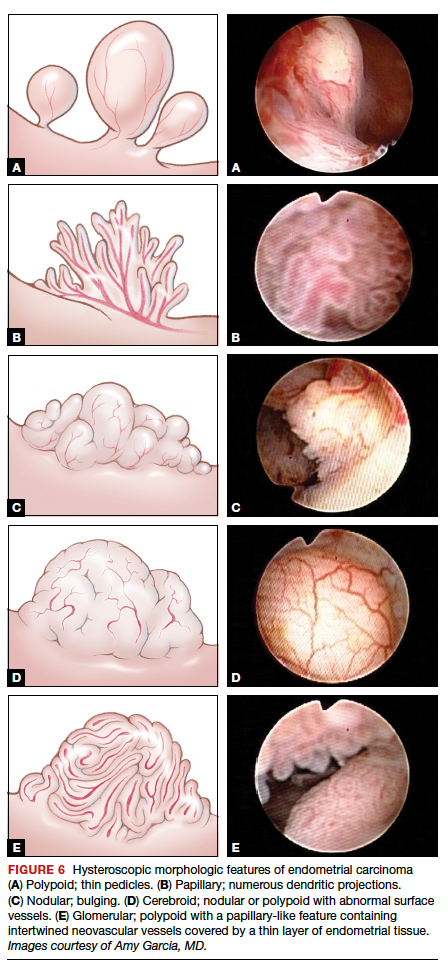

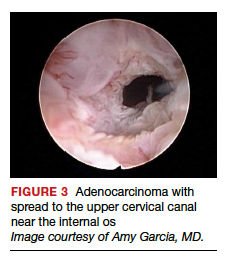

Amount of endometrial involvement. A few years later, Garuti and colleagues retrospectively related the hysteroscopic tumor features of known endometrial adenocarcinoma to stage, grade, and overall survival.4 In this system, they focused on classification of tumor morphology as nodular (bulging), polypoid (thin pedicles), or papillary (numerous dendritic projections), as well as whether the amount of abnormal tissue present was less than or more than half of the endometrium and if the lesion involved the cervix.

Several important findings associated with this system may improve visual diagnosis. First, hysteroscopic evaluation had a 100% negative predictive value for the cervical spread of disease (FIGURE 3, VIDEO 3). Second, the hysteroscopic morphologic tumor type did not relate to surgical stage or pathologic grade. Third, when less than half of the endometrium was involved, stage I disease was found (97%, 33 of 34). Last, when more than half of the endometrium was involved, advanced disease beyond stage I was found (9 of 26, 6 of whom had poorly differentiated disease).4

Video 3. Cervical spread of adenocarcinoma and visually directed biopsy

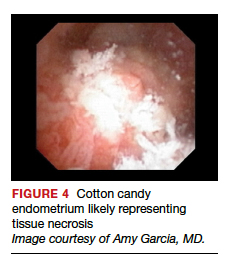

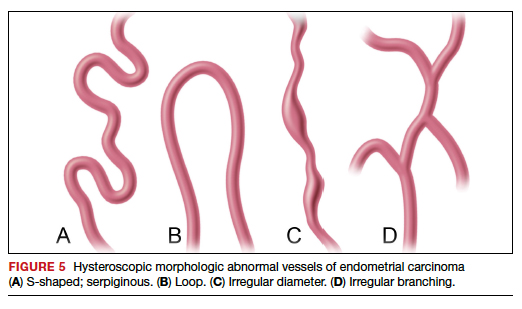

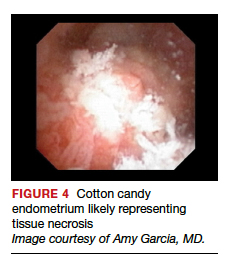

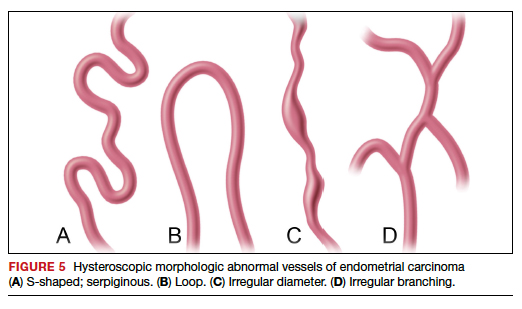

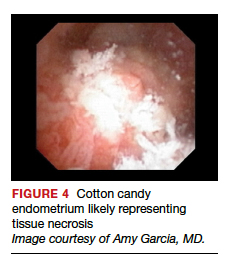

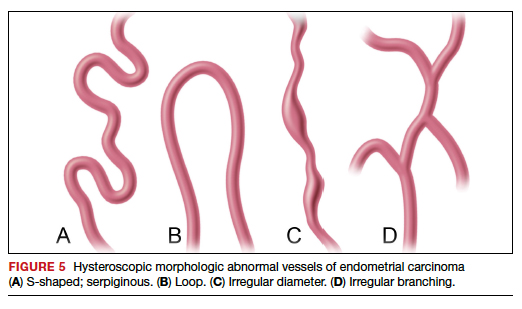

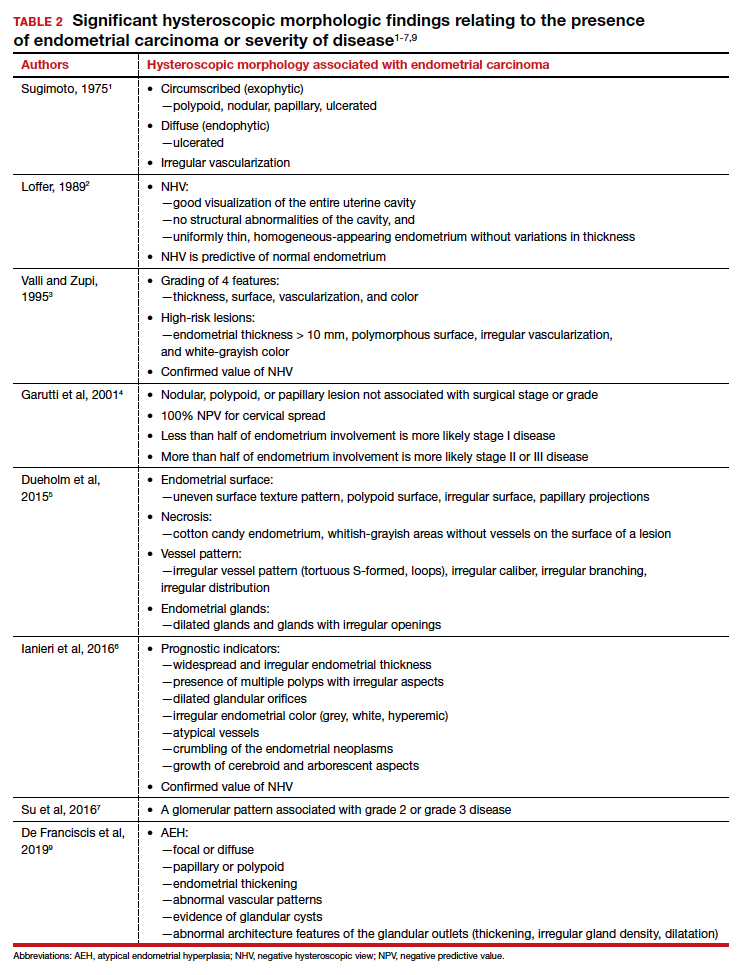

Structured pattern analysis. Recently, Dueholm and co-investigators published a prospective evaluation of women with postmenopausal bleeding and an endometrial thickness of 5 mm or greater.5 They used a structured system of visual pattern analysis during hysteroscopy that they termed the hysteroscopic cancer (HYCA) scoring system. The HYCA scoring system is based on surface outline (uneven, polypoid, and papillary projections), necrosis (cotton candy endometrium [FIGURE 4], whitish-grayish areas without vessels on the surface), and vessel pattern (tortuous S-shaped, loops, irregular caliber, irregular branching, and irregular distribution [FIGURE 5]). Structured pattern analysis predicted cancer with higher accuracy than subjective evaluation.5

Morphologic variables as indicators. In 2016, Ianieri and colleagues published a retrospective study on a risk scoring system for diagnosing endometrial hyperplasia and adenocarcinoma via hysteroscopy.6 They created a statistical risk model for development of the scoring system. A number of morphologic variables were prognostic indicators of atypical endometrial hyperplasia (AEH) and adenocarcinoma. These included widespread and irregular endometrial thickness, presence of multiple polyps with irregular aspects, dilated glandular orifices, irregular endometrial color (grey, white, or hyperemic), atypical vessels, crumbling of the endometrial neoplasms, and growth of cerebroid and arborescent aspects (VIDEO 4).

Video 4. Endometrial adenocarcinoma

The scoring system for endometrial adenocarcinoma correctly classified 42 of 44 cancers (sensitivity, 95.4%; specificity, 98.2%), and AEH had a sensitivity of 63.3% and a specificity of 90.4%.6 These investigators also showed a high negative predictive value of 99.5% for endometrial adenocarcinoma associated with a negative view at hysteroscopy. Similar to the Dueholm data, Ianieri and colleagues’ morphologic pattern analysis predicted cancer with high accuracy.

Glomerular pattern association. Su and colleagues also showed that pattern recognition could aid in the accurate hysteroscopic diagnosis of endometrial adenocarcinoma.7 They used the hysteroscopic presence of a glomerular pattern to predict the association with endometrial adenocarcinoma. A glomerular pattern was described as polypoid endometrium with a papillary-like feature, containing an abnormal neovascularization feature with “intertwined neovascular vessels covered by a thin layer of endometrial tissue” (FIGURE 6). The presence of a glomerular pattern indicated grade 2 or grade 3 disease in 25 of 26 women (96%; sensitivity, 84.6%, specificity, 81.8%)7 (see video 4).

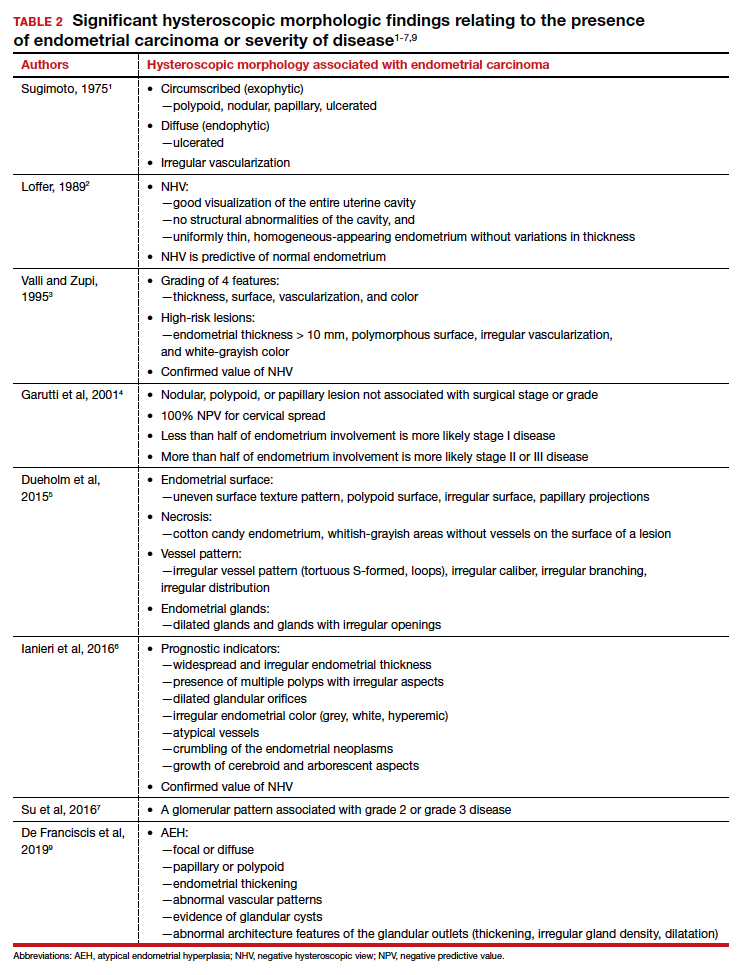

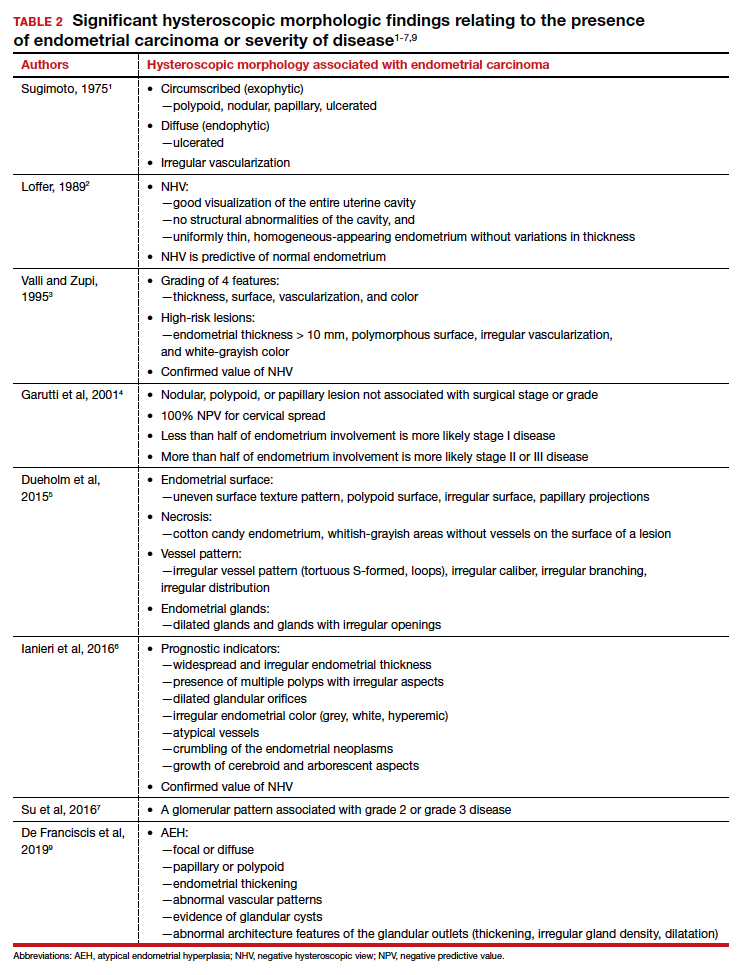

TABLE 2 summarizes significant morphologic findings relating to the presences of endometrial carcinoma.

Continue to: Atypical endometrial hyperplasia: A difficult diagnosis...

Atypical endometrial hyperplasia: A difficult diagnosis

The most common type of endometrial cancer is endometrioid adenocarcinoma (type 1 endometrial carcinoma), and it accounts for approximately 75% to 80% of endometrial cancer diagnoses.8 Risk factors include prolonged unopposed estrogen exposure, obesity, diabetes, and age. Type 1 endometrial carcinoma follows a progressive continuum of histopathologic change: from endometrial hyperplasia without atypia to endometrial hyperplasia with atypia (AEH) to well-differentiated endometrial cancer. Therefore, it is possible for endometrial carcinoma to be present simultaneously with AEH. The reported prevalence of concurrent endometrial carcinoma among patients with AEH on biopsy is between 17% and 52%.8 Thus, the clinical consideration is for hysterectomy, especially in the postmenopausal patient with a diagnosis of AEH.

Hysteroscopic diagnosis of AEH, however, is more difficult than identification of endometrial carcinoma because a range of morphologic characteristics exist that resemble normal endometrium as well as more progressive disease (VIDEO 5). De Franciscis and colleagues based a hysteroscopic diagnosis of hyperplasia on one or more of the following findings: focal or diffuse, papillary or polypoid, endometrial thickening; abnormal vascular patterns; evidence of glandular cysts; and abnormal architecture features of the glandular outlets (thickening, irregular gland density, or dilatation)9 (VIDEO 6).

Video 5. Endometrial polyp and atypical hyperplasia

Additional studies, including that from Ianieri and colleagues, also have determined that AEH is difficult to discern visually from normal endometrium and other endometrial pathologies.6 In another investigation, Lasmar and coauthors reported a retrospective analysis of 4,054 hysteroscopic procedures with directed biopsies evaluating for concordance between the hysteroscopic view and histopathology.10 Agreement was 56.3% for AEH versus 94% for endometrial carcinoma. Among those with a histologic diagnosis of AEH, in 35.4% benign disease was suspected; in 2.1%, endometrial carcinoma was suspected; and in 6%, normal findings were presumed.10

Video 6. Nodular, polypoid atypical hyperplasia

Because of the similarities in morphologic features between AEH and endometrial carcinoma, tissue biopsy under direct visualization is warranted to assure sampling of the most significantly abnormal tissue and to confirm visual interpretation of findings.

Techniques for hysteroscopic-directed biopsy

Using a visual assessment of endometrial abnormalities allows the surgeon to examine the entire uterine cavity and to biopsy the most suspicious and concerning lesions. The directed biopsy technique can involve a simple grasping maneuver: With the jaws of a small grasper open, push slightly forward to accumulate tissue within the jaw, close the jaw, and remove the tissue carefully through the cervix (VIDEO 7). The size of the sample may be limited, and multiple samples may be needed, depending on the quantity of the tissue retrieved.

Video 7. Visually directed endometrial biopsy

Another technique involves first creating a plane of tissue to be removed with scissors and subsequently grasping and removing the tissue (see video 1 and video 3). This particular technique will yield more tissue with one pass of the hysteroscope into the cavity. Careful removal of tissue through the cervix is facilitated by withdrawing the sample in the grasper and the hysteroscope together at the same time, without pulling the sample through the operative channel of the hysteroscope. Also, by turning off the inflow port, the stream of saline does not wash the sample off the grasper at hysteroscope removal from the cervix.

Blind biopsy. If visual inspection reveals a diffuse process within the uterine cavity such that no normal endometrium is noted and the abnormality is of equal degree throughout the endometrial surface, a decision can be made to replace directed biopsy with a blind biopsy. In this scenario, the blind biopsy is certain to sample the representative disease process and not potentially miss significant lesions (see video 4 and video 6). Otherwise, the hysteroscope-directed biopsy would be preferable.

Continue to: Potential for intraperitoneal dissemination of endometrial cancer...

Potential for intraperitoneal dissemination of endometrial cancer

There is some concern about intraperitoneal dissemination of endometrial carcinoma at the time of hysteroscopy and effect on disease prognosis. Chang and colleagues conducted a large meta-analysis and found that hysteroscopy performed in the presence of type 1 endometrial carcinoma statistically significantly increased the likelihood of positive intraperitoneal cytology.11 In the included studies that reported survival rates (6 of 19), positive cytology did not alter the clinical outcome. The investigators recommended that hysteroscopy not be avoided for this reason, as it helps in the diagnosis of endometrial carcinoma, especially in the early stages of disease.11

In a recent retrospective analysis, Namazov and colleagues included only stage I endometrial carcinoma (to exclude the adverse effect of advanced stage on survival) and evaluated the assumed isolated effect of hysteroscopy on survival.12 They compared women in whom stage I endometrial carcinoma was diagnosed: 355 by hysteroscopy and 969 by a nonhysteroscopy method (D&C or office endometrial biopsy). Tumors were classified and grouped as low grade (endometrioid grade 1-2 and villoglandular) and high grade, consisting of endometrioid grade 3 and type 2 endometrial carcinoma (serous carcinoma, clear cell carcinoma, and carcinosarcoma) (VIDEOS 8 and 9). Positive intraperitoneal cytology at the time of surgery was 2.3% and 2.1% (P = .832), with an average interval from diagnosis to surgery of 34.6 days (range, 7–43 days).

Video 8. Carcinosarcoma

The authors proposed several explanations for the low rate of intraperitoneal cytology with hysteroscopy. One possibility is having lower mean intrauterine pressure below 100 mm Hg for saline uterine distension, although this was not standardized for all surgeons in the study but rather was a custom of the institution. In addition, the length of time between hysteroscopy and surgery may allow the immune-reactive peritoneum to respond to the cellular insult, thus decreasing the biologic burden at the time of surgery. The median follow-up was 52 months (range, 12–120 months), and there were no differences between the hysteroscopy and the nonhysteroscopy groups in the 5-year recurrence-free survival (90.2% vs 88.2%; P = .53), disease-specific survival (93.4% vs 91.7%; P = .5), and overall survival (86.2% vs 80.6%; P = .22). The authors concluded that hysteroscopy does not compromise the survival of patients with early-stage endometrial cancer.12

Video 9. Carcinosarcoma

Retrospective data from Chen and colleagues regarding type 2 endometrial carcinoma indicated a statistically significant increase in positive intraperitoneal cytology for carcinomas evaluated by hysteroscopy versus D&C (30% vs 12%; P = .008).13 Among the patients who died, there was no difference in disease-specific survival (53 months for hysteroscopy and 63.5 months for D&C; P = .34), and there was no difference in overall recurrence rates.13 Compared with type 1 endometrial carcinoma, type 2 endometrial carcinoma behaves more aggressively, with a higher incidence of extrauterine disease and an increased propensity for recurrence and poor outcome even in the early stages of the disease. This makes it difficult to determine the role of hysteroscopy in the prognosis of these carcinomas, especially in this study where most patients were diagnosed at a later stage.

Key takeaways

Hysteroscopy and directed biopsy are highly effective for visual and histopathologic diagnosis of atypical endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial carcinoma, and they are recommended in the evaluation of AUB, especially in the postmenopausal woman. When the hysteroscopic view is negative, there is a high correlation with the absence of uterine cavity and endometrial pathology. Hysteroscopic diagnostic accuracy is improved with structured use of visual grading scales, well-defined descriptors of endometrial pathology, and hysteroscopist experience.

Low operating intrauterine pressure may decrease the intraperitoneal spread of carcinoma cells during hysteroscopy, and current evidence suggests that there is no change in type 1 endometrial carcinoma prognosis and overall outcomes. Type 2 endometrial carcinoma is more aggressive and is associated with poor outcomes even in early stages, and the effect on disease progression by intraperitoneal spread of carcinoma cells at hysteroscopy is not yet known. Hysteroscopic evaluation of the uterine cavity and directed biopsy is easily and safely performed in the office and adds significantly to the evaluation and management of endometrial carcinoma.

Access them in the article online at mdedge.com/obgyn

Video 1. Endometrial carcinoma and visually directed biopsy

Nodular endometrioid adenocarcinoma grade 1 (type 1 endometrial carcinoma), benign endometrial polyps, and endometrial atrophy in a postmenopausal woman with bleeding. This video demonstrates visually directed biopsy to assure sampling of the most significant lesion.

Video 2. Negative hysteroscopic view

Digital flexible diagnostic hysteroscopy showing a negative hysteroscopic view in a premenopausal woman.

Video 3. Cervical spread of adenocarcinoma and visually directed biopsy

Diffuse endometrioid adenocarcinoma spread to the upper cervical canal near the internal cervical os. Hysteroscopic directed biopsy is performed.

Video 4. Endometrial adenocarcinoma

Fiberoptic flexible diagnostic hysteroscopy demonstrating diffuse endometrioid adenocarcinoma grade 3 with multiple morphologic features: polypoid, nodular, papillary, and glomerular with areas of necrosis.

Video 5. Endometrial polyp and atypical hyperplasia

Large benign endometrial polyp in an asymptomatic postmenopausal woman with enlarged endometrial stripe on pelvic ultrasound. The endometrium is atrophic except for a small whitish area on the anterior wall, which is atypical hyperplasia. This video highlights the need for visually directed biopsy to assure sampling of the most significant lesion.

Video 6. Nodular, polypoid atypical hyperplasia

Fiberoptic flexible diagnostic hysteroscopy showing diffuse nodular and polypoid atypical hyperplasia with abnormal glandular openings in a postmenopausal woman. Hysterectomy was performed secondary to the significant likelihood of concomitant endometrial carcinoma.

Video 7. Visually directed endometrial biopsy

Hysteroscopic-directed biopsy showing the technique of grasping and removing tissue of a benign adenomyosis cyst and proliferative endometrium.

Video 8. Carcinosarcoma

Carcinosarcoma (type 2 endometrial carcinoma) presents as a large intracavitary mass with soft, polypoid-like tissue in a symptomatic postmenopausal woman with bleeding.

Video 9. Carcinosarcoma

Carcinosarcoma (type 2 endometrial carcinoma) presents as a dense mass in a symptomatic postmenopausal woman with bleeding. This video shows the mass is nodular. These cancers typically grow into a spherical mass within the cavity

- Sugimoto O. Hysteroscopic diagnosis of endometrial carcinoma. A report of fifty-three cases examined at the Women’s Clinic of Kyoto University Hospital. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1975;121:105-113.

- Loffer FD. Hysteroscopy with selective endometrial sampling compared with D&C for abnormal uterine bleeding: the value of a negative hysteroscopic view. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;73:16-20.

- Valli E, Zupi E. A new hysteroscopic classification of and nomenclature for endometrial lesions. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1995;2:279-283.

- Garuti G, De Giorgi O, Sambruni I, et al. Prognostic significance of hysteroscopic imaging in endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;81: 408-413.

- Dueholm M, Hjorth IMD, Secher P, et al. Structured hysteroscopic evaluation of endometrium in women with postmenopausal bleeding. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22:1215-1224.

- Ianieri MM, Staniscia T, Pontrelli G, et al. A new hysteroscopic risk scoring system for diagnosing endometrial hyperplasia and adenocarcinoma. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2016;23: 712-718.

- Su H, Pandey D, Liu L-Y, et al. Pattern recognition to prognosticate endometrial cancer: the science behind the art of office hysteroscopy—a retrospective study. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2016;26:705-710.

- Trimble CL, Kauderer J, Zaino R, et al. Concurrent endometrial carcinoma in women with a biopsy diagnosis of atypical endometrial hyperplasia: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Cancer. 2006;106:812-819.

- De Franciscis P, Riemma G, Schiattarella A, et al. Concordance between the hysteroscopic diagnosis of endometrial hyperplasia and histopathological examination. Diagnostics (Basel). 2019;9(4).

- Lasmar RB, Barrozo PRM, de Oliveira MAP, et al. Validation of hysteroscopic view in cases of endometrial hyperplasia and cancer in patients with abnormal uterine bleeding. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2006;13:409-412.

- Chang Y-N, Zhang Y, Wang Y-J, et al. Effect of hysteroscopy on the peritoneal dissemination of endometrial cancer cells: a meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2011;96:957-961.

- Namazov A, Gemer O, Helpman L, et al. The oncological safety of hysteroscopy in the diagnosis of early-stage endometrial cancer: an Israel Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2019;243:120-124.

- Chen J, Clark LH, Kong W-M, et al. Does hysteroscopy worsen prognosis in women with type II endometrial carcinoma? PLoS One. 2017;12(3):e0174226.

For more than 45 years, gynecologists have used hysteroscopy to diagnose endometrial carcinoma and to associate morphologic descriptive terms with visual findings.1 Today, considerably more clinical evidence supports visual pattern recognition to assess the risk for and presence of endometrial carcinoma, improving observer-dependent biopsy of the most suspect lesions (VIDEO 1).

In this article, I discuss the clinical evolution of hysteroscopic pattern recognition of endometrial disease and review the visual findings that correlate with the likelihood of endometrial carcinoma. In addition, I have provided 9 short videos that show hysteroscopic views of various endometrial pathologies in the online version of this article at https://www.mdedge.com/obgyn.

Video 1. Endometrial carcinoma and visually directed biopsy

The negative hysteroscopic view defined

In 1989, Dr. Frank Loffer confirmed the diagnostic superiority of visually directed biopsy. He demonstrated the advantages of using hysteroscopy and directed biopsy in the evaluation of abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) to obtain a more accurate diagnosis compared with dilation and curettage (D&C) alone (sensitivity, 98% vs 65%, respectively).2

Also derived from this work is the clinical application of the “negative hysteroscopic view” (NHV). Loffer used the following criteria to define the NHV: good visualization of the entire uterine cavity, no structural abnormalities of the cavity, and a uniformly thin, homogeneous-appearing endometrium without variations in thickness (TABLE 1). The last criterion can be expected to occur only in the early proliferative phase or in postmenopausal women.

Use of hysteroscopy therefore can predict accurately the absence of intrauterine and endometrial pathology when visual findings are negative and tissue sampling is not warranted (FIGURE 1, VIDEO 2).

Video 2. Negative hysteroscopic view

Efforts in hysteroscopic classification of endometrial carcinoma

Lesion morphologic characteristics. Sugimoto was among the first to describe the hysteroscopic identification of visual morphologic features that are most likely to be associated with endometrial carcinoma.1 Patients with AUB were evaluated with hysteroscopy as first-line management to describe lesion morphology and confirm biopsy with histopathology. Sugimoto classified endometrial carcinoma as circumscribed or exophytic with distinct forms, such as polypoid, nodular, papillary, and ulcerated (FIGURE 2). Diffuse or endophytic carcinoma is defined by an ulcerated type of lesion that indicates necrosis; this is most likely to represent an undifferentiated tumor. Sugimoto also described abnormal vascularity that often is associated with carcinoma.1

Endometrial features. Valli and Zupi created a nomenclature and classification for hysteroscopic endometrial lesions by prospectively grading 4 features: thickness, surface, vascularization, and color.3 Features were scored based on the degree of abnormality and could be considered to be of low or high risk for the presence of carcinoma. High-risk hysteroscopic features included endometrial thickness greater than 10 mm, polymorphous surface, irregular vascularization, and white-grayish color. The sensitivity for accurately diagnosing endometrial lesions was 86.9% for mild lesions and 96% for severe lesions.3 Also, these investigators confirmed the clinical value of the NHV and associated overall risk of precancer or cancer of the endometrium.

Continue to: Amount of endometrial involvement...

Amount of endometrial involvement. A few years later, Garuti and colleagues retrospectively related the hysteroscopic tumor features of known endometrial adenocarcinoma to stage, grade, and overall survival.4 In this system, they focused on classification of tumor morphology as nodular (bulging), polypoid (thin pedicles), or papillary (numerous dendritic projections), as well as whether the amount of abnormal tissue present was less than or more than half of the endometrium and if the lesion involved the cervix.

Several important findings associated with this system may improve visual diagnosis. First, hysteroscopic evaluation had a 100% negative predictive value for the cervical spread of disease (FIGURE 3, VIDEO 3). Second, the hysteroscopic morphologic tumor type did not relate to surgical stage or pathologic grade. Third, when less than half of the endometrium was involved, stage I disease was found (97%, 33 of 34). Last, when more than half of the endometrium was involved, advanced disease beyond stage I was found (9 of 26, 6 of whom had poorly differentiated disease).4

Video 3. Cervical spread of adenocarcinoma and visually directed biopsy

Structured pattern analysis. Recently, Dueholm and co-investigators published a prospective evaluation of women with postmenopausal bleeding and an endometrial thickness of 5 mm or greater.5 They used a structured system of visual pattern analysis during hysteroscopy that they termed the hysteroscopic cancer (HYCA) scoring system. The HYCA scoring system is based on surface outline (uneven, polypoid, and papillary projections), necrosis (cotton candy endometrium [FIGURE 4], whitish-grayish areas without vessels on the surface), and vessel pattern (tortuous S-shaped, loops, irregular caliber, irregular branching, and irregular distribution [FIGURE 5]). Structured pattern analysis predicted cancer with higher accuracy than subjective evaluation.5

Morphologic variables as indicators. In 2016, Ianieri and colleagues published a retrospective study on a risk scoring system for diagnosing endometrial hyperplasia and adenocarcinoma via hysteroscopy.6 They created a statistical risk model for development of the scoring system. A number of morphologic variables were prognostic indicators of atypical endometrial hyperplasia (AEH) and adenocarcinoma. These included widespread and irregular endometrial thickness, presence of multiple polyps with irregular aspects, dilated glandular orifices, irregular endometrial color (grey, white, or hyperemic), atypical vessels, crumbling of the endometrial neoplasms, and growth of cerebroid and arborescent aspects (VIDEO 4).

Video 4. Endometrial adenocarcinoma

The scoring system for endometrial adenocarcinoma correctly classified 42 of 44 cancers (sensitivity, 95.4%; specificity, 98.2%), and AEH had a sensitivity of 63.3% and a specificity of 90.4%.6 These investigators also showed a high negative predictive value of 99.5% for endometrial adenocarcinoma associated with a negative view at hysteroscopy. Similar to the Dueholm data, Ianieri and colleagues’ morphologic pattern analysis predicted cancer with high accuracy.

Glomerular pattern association. Su and colleagues also showed that pattern recognition could aid in the accurate hysteroscopic diagnosis of endometrial adenocarcinoma.7 They used the hysteroscopic presence of a glomerular pattern to predict the association with endometrial adenocarcinoma. A glomerular pattern was described as polypoid endometrium with a papillary-like feature, containing an abnormal neovascularization feature with “intertwined neovascular vessels covered by a thin layer of endometrial tissue” (FIGURE 6). The presence of a glomerular pattern indicated grade 2 or grade 3 disease in 25 of 26 women (96%; sensitivity, 84.6%, specificity, 81.8%)7 (see video 4).

TABLE 2 summarizes significant morphologic findings relating to the presences of endometrial carcinoma.

Continue to: Atypical endometrial hyperplasia: A difficult diagnosis...

Atypical endometrial hyperplasia: A difficult diagnosis

The most common type of endometrial cancer is endometrioid adenocarcinoma (type 1 endometrial carcinoma), and it accounts for approximately 75% to 80% of endometrial cancer diagnoses.8 Risk factors include prolonged unopposed estrogen exposure, obesity, diabetes, and age. Type 1 endometrial carcinoma follows a progressive continuum of histopathologic change: from endometrial hyperplasia without atypia to endometrial hyperplasia with atypia (AEH) to well-differentiated endometrial cancer. Therefore, it is possible for endometrial carcinoma to be present simultaneously with AEH. The reported prevalence of concurrent endometrial carcinoma among patients with AEH on biopsy is between 17% and 52%.8 Thus, the clinical consideration is for hysterectomy, especially in the postmenopausal patient with a diagnosis of AEH.

Hysteroscopic diagnosis of AEH, however, is more difficult than identification of endometrial carcinoma because a range of morphologic characteristics exist that resemble normal endometrium as well as more progressive disease (VIDEO 5). De Franciscis and colleagues based a hysteroscopic diagnosis of hyperplasia on one or more of the following findings: focal or diffuse, papillary or polypoid, endometrial thickening; abnormal vascular patterns; evidence of glandular cysts; and abnormal architecture features of the glandular outlets (thickening, irregular gland density, or dilatation)9 (VIDEO 6).

Video 5. Endometrial polyp and atypical hyperplasia

Additional studies, including that from Ianieri and colleagues, also have determined that AEH is difficult to discern visually from normal endometrium and other endometrial pathologies.6 In another investigation, Lasmar and coauthors reported a retrospective analysis of 4,054 hysteroscopic procedures with directed biopsies evaluating for concordance between the hysteroscopic view and histopathology.10 Agreement was 56.3% for AEH versus 94% for endometrial carcinoma. Among those with a histologic diagnosis of AEH, in 35.4% benign disease was suspected; in 2.1%, endometrial carcinoma was suspected; and in 6%, normal findings were presumed.10

Video 6. Nodular, polypoid atypical hyperplasia

Because of the similarities in morphologic features between AEH and endometrial carcinoma, tissue biopsy under direct visualization is warranted to assure sampling of the most significantly abnormal tissue and to confirm visual interpretation of findings.

Techniques for hysteroscopic-directed biopsy

Using a visual assessment of endometrial abnormalities allows the surgeon to examine the entire uterine cavity and to biopsy the most suspicious and concerning lesions. The directed biopsy technique can involve a simple grasping maneuver: With the jaws of a small grasper open, push slightly forward to accumulate tissue within the jaw, close the jaw, and remove the tissue carefully through the cervix (VIDEO 7). The size of the sample may be limited, and multiple samples may be needed, depending on the quantity of the tissue retrieved.

Video 7. Visually directed endometrial biopsy

Another technique involves first creating a plane of tissue to be removed with scissors and subsequently grasping and removing the tissue (see video 1 and video 3). This particular technique will yield more tissue with one pass of the hysteroscope into the cavity. Careful removal of tissue through the cervix is facilitated by withdrawing the sample in the grasper and the hysteroscope together at the same time, without pulling the sample through the operative channel of the hysteroscope. Also, by turning off the inflow port, the stream of saline does not wash the sample off the grasper at hysteroscope removal from the cervix.

Blind biopsy. If visual inspection reveals a diffuse process within the uterine cavity such that no normal endometrium is noted and the abnormality is of equal degree throughout the endometrial surface, a decision can be made to replace directed biopsy with a blind biopsy. In this scenario, the blind biopsy is certain to sample the representative disease process and not potentially miss significant lesions (see video 4 and video 6). Otherwise, the hysteroscope-directed biopsy would be preferable.

Continue to: Potential for intraperitoneal dissemination of endometrial cancer...

Potential for intraperitoneal dissemination of endometrial cancer

There is some concern about intraperitoneal dissemination of endometrial carcinoma at the time of hysteroscopy and effect on disease prognosis. Chang and colleagues conducted a large meta-analysis and found that hysteroscopy performed in the presence of type 1 endometrial carcinoma statistically significantly increased the likelihood of positive intraperitoneal cytology.11 In the included studies that reported survival rates (6 of 19), positive cytology did not alter the clinical outcome. The investigators recommended that hysteroscopy not be avoided for this reason, as it helps in the diagnosis of endometrial carcinoma, especially in the early stages of disease.11

In a recent retrospective analysis, Namazov and colleagues included only stage I endometrial carcinoma (to exclude the adverse effect of advanced stage on survival) and evaluated the assumed isolated effect of hysteroscopy on survival.12 They compared women in whom stage I endometrial carcinoma was diagnosed: 355 by hysteroscopy and 969 by a nonhysteroscopy method (D&C or office endometrial biopsy). Tumors were classified and grouped as low grade (endometrioid grade 1-2 and villoglandular) and high grade, consisting of endometrioid grade 3 and type 2 endometrial carcinoma (serous carcinoma, clear cell carcinoma, and carcinosarcoma) (VIDEOS 8 and 9). Positive intraperitoneal cytology at the time of surgery was 2.3% and 2.1% (P = .832), with an average interval from diagnosis to surgery of 34.6 days (range, 7–43 days).

Video 8. Carcinosarcoma

The authors proposed several explanations for the low rate of intraperitoneal cytology with hysteroscopy. One possibility is having lower mean intrauterine pressure below 100 mm Hg for saline uterine distension, although this was not standardized for all surgeons in the study but rather was a custom of the institution. In addition, the length of time between hysteroscopy and surgery may allow the immune-reactive peritoneum to respond to the cellular insult, thus decreasing the biologic burden at the time of surgery. The median follow-up was 52 months (range, 12–120 months), and there were no differences between the hysteroscopy and the nonhysteroscopy groups in the 5-year recurrence-free survival (90.2% vs 88.2%; P = .53), disease-specific survival (93.4% vs 91.7%; P = .5), and overall survival (86.2% vs 80.6%; P = .22). The authors concluded that hysteroscopy does not compromise the survival of patients with early-stage endometrial cancer.12

Video 9. Carcinosarcoma

Retrospective data from Chen and colleagues regarding type 2 endometrial carcinoma indicated a statistically significant increase in positive intraperitoneal cytology for carcinomas evaluated by hysteroscopy versus D&C (30% vs 12%; P = .008).13 Among the patients who died, there was no difference in disease-specific survival (53 months for hysteroscopy and 63.5 months for D&C; P = .34), and there was no difference in overall recurrence rates.13 Compared with type 1 endometrial carcinoma, type 2 endometrial carcinoma behaves more aggressively, with a higher incidence of extrauterine disease and an increased propensity for recurrence and poor outcome even in the early stages of the disease. This makes it difficult to determine the role of hysteroscopy in the prognosis of these carcinomas, especially in this study where most patients were diagnosed at a later stage.

Key takeaways

Hysteroscopy and directed biopsy are highly effective for visual and histopathologic diagnosis of atypical endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial carcinoma, and they are recommended in the evaluation of AUB, especially in the postmenopausal woman. When the hysteroscopic view is negative, there is a high correlation with the absence of uterine cavity and endometrial pathology. Hysteroscopic diagnostic accuracy is improved with structured use of visual grading scales, well-defined descriptors of endometrial pathology, and hysteroscopist experience.

Low operating intrauterine pressure may decrease the intraperitoneal spread of carcinoma cells during hysteroscopy, and current evidence suggests that there is no change in type 1 endometrial carcinoma prognosis and overall outcomes. Type 2 endometrial carcinoma is more aggressive and is associated with poor outcomes even in early stages, and the effect on disease progression by intraperitoneal spread of carcinoma cells at hysteroscopy is not yet known. Hysteroscopic evaluation of the uterine cavity and directed biopsy is easily and safely performed in the office and adds significantly to the evaluation and management of endometrial carcinoma.

Access them in the article online at mdedge.com/obgyn

Video 1. Endometrial carcinoma and visually directed biopsy

Nodular endometrioid adenocarcinoma grade 1 (type 1 endometrial carcinoma), benign endometrial polyps, and endometrial atrophy in a postmenopausal woman with bleeding. This video demonstrates visually directed biopsy to assure sampling of the most significant lesion.

Video 2. Negative hysteroscopic view

Digital flexible diagnostic hysteroscopy showing a negative hysteroscopic view in a premenopausal woman.

Video 3. Cervical spread of adenocarcinoma and visually directed biopsy

Diffuse endometrioid adenocarcinoma spread to the upper cervical canal near the internal cervical os. Hysteroscopic directed biopsy is performed.

Video 4. Endometrial adenocarcinoma

Fiberoptic flexible diagnostic hysteroscopy demonstrating diffuse endometrioid adenocarcinoma grade 3 with multiple morphologic features: polypoid, nodular, papillary, and glomerular with areas of necrosis.

Video 5. Endometrial polyp and atypical hyperplasia

Large benign endometrial polyp in an asymptomatic postmenopausal woman with enlarged endometrial stripe on pelvic ultrasound. The endometrium is atrophic except for a small whitish area on the anterior wall, which is atypical hyperplasia. This video highlights the need for visually directed biopsy to assure sampling of the most significant lesion.

Video 6. Nodular, polypoid atypical hyperplasia

Fiberoptic flexible diagnostic hysteroscopy showing diffuse nodular and polypoid atypical hyperplasia with abnormal glandular openings in a postmenopausal woman. Hysterectomy was performed secondary to the significant likelihood of concomitant endometrial carcinoma.

Video 7. Visually directed endometrial biopsy

Hysteroscopic-directed biopsy showing the technique of grasping and removing tissue of a benign adenomyosis cyst and proliferative endometrium.

Video 8. Carcinosarcoma

Carcinosarcoma (type 2 endometrial carcinoma) presents as a large intracavitary mass with soft, polypoid-like tissue in a symptomatic postmenopausal woman with bleeding.

Video 9. Carcinosarcoma

Carcinosarcoma (type 2 endometrial carcinoma) presents as a dense mass in a symptomatic postmenopausal woman with bleeding. This video shows the mass is nodular. These cancers typically grow into a spherical mass within the cavity

For more than 45 years, gynecologists have used hysteroscopy to diagnose endometrial carcinoma and to associate morphologic descriptive terms with visual findings.1 Today, considerably more clinical evidence supports visual pattern recognition to assess the risk for and presence of endometrial carcinoma, improving observer-dependent biopsy of the most suspect lesions (VIDEO 1).

In this article, I discuss the clinical evolution of hysteroscopic pattern recognition of endometrial disease and review the visual findings that correlate with the likelihood of endometrial carcinoma. In addition, I have provided 9 short videos that show hysteroscopic views of various endometrial pathologies in the online version of this article at https://www.mdedge.com/obgyn.

Video 1. Endometrial carcinoma and visually directed biopsy

The negative hysteroscopic view defined

In 1989, Dr. Frank Loffer confirmed the diagnostic superiority of visually directed biopsy. He demonstrated the advantages of using hysteroscopy and directed biopsy in the evaluation of abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) to obtain a more accurate diagnosis compared with dilation and curettage (D&C) alone (sensitivity, 98% vs 65%, respectively).2

Also derived from this work is the clinical application of the “negative hysteroscopic view” (NHV). Loffer used the following criteria to define the NHV: good visualization of the entire uterine cavity, no structural abnormalities of the cavity, and a uniformly thin, homogeneous-appearing endometrium without variations in thickness (TABLE 1). The last criterion can be expected to occur only in the early proliferative phase or in postmenopausal women.

Use of hysteroscopy therefore can predict accurately the absence of intrauterine and endometrial pathology when visual findings are negative and tissue sampling is not warranted (FIGURE 1, VIDEO 2).

Video 2. Negative hysteroscopic view

Efforts in hysteroscopic classification of endometrial carcinoma

Lesion morphologic characteristics. Sugimoto was among the first to describe the hysteroscopic identification of visual morphologic features that are most likely to be associated with endometrial carcinoma.1 Patients with AUB were evaluated with hysteroscopy as first-line management to describe lesion morphology and confirm biopsy with histopathology. Sugimoto classified endometrial carcinoma as circumscribed or exophytic with distinct forms, such as polypoid, nodular, papillary, and ulcerated (FIGURE 2). Diffuse or endophytic carcinoma is defined by an ulcerated type of lesion that indicates necrosis; this is most likely to represent an undifferentiated tumor. Sugimoto also described abnormal vascularity that often is associated with carcinoma.1

Endometrial features. Valli and Zupi created a nomenclature and classification for hysteroscopic endometrial lesions by prospectively grading 4 features: thickness, surface, vascularization, and color.3 Features were scored based on the degree of abnormality and could be considered to be of low or high risk for the presence of carcinoma. High-risk hysteroscopic features included endometrial thickness greater than 10 mm, polymorphous surface, irregular vascularization, and white-grayish color. The sensitivity for accurately diagnosing endometrial lesions was 86.9% for mild lesions and 96% for severe lesions.3 Also, these investigators confirmed the clinical value of the NHV and associated overall risk of precancer or cancer of the endometrium.

Continue to: Amount of endometrial involvement...

Amount of endometrial involvement. A few years later, Garuti and colleagues retrospectively related the hysteroscopic tumor features of known endometrial adenocarcinoma to stage, grade, and overall survival.4 In this system, they focused on classification of tumor morphology as nodular (bulging), polypoid (thin pedicles), or papillary (numerous dendritic projections), as well as whether the amount of abnormal tissue present was less than or more than half of the endometrium and if the lesion involved the cervix.

Several important findings associated with this system may improve visual diagnosis. First, hysteroscopic evaluation had a 100% negative predictive value for the cervical spread of disease (FIGURE 3, VIDEO 3). Second, the hysteroscopic morphologic tumor type did not relate to surgical stage or pathologic grade. Third, when less than half of the endometrium was involved, stage I disease was found (97%, 33 of 34). Last, when more than half of the endometrium was involved, advanced disease beyond stage I was found (9 of 26, 6 of whom had poorly differentiated disease).4

Video 3. Cervical spread of adenocarcinoma and visually directed biopsy

Structured pattern analysis. Recently, Dueholm and co-investigators published a prospective evaluation of women with postmenopausal bleeding and an endometrial thickness of 5 mm or greater.5 They used a structured system of visual pattern analysis during hysteroscopy that they termed the hysteroscopic cancer (HYCA) scoring system. The HYCA scoring system is based on surface outline (uneven, polypoid, and papillary projections), necrosis (cotton candy endometrium [FIGURE 4], whitish-grayish areas without vessels on the surface), and vessel pattern (tortuous S-shaped, loops, irregular caliber, irregular branching, and irregular distribution [FIGURE 5]). Structured pattern analysis predicted cancer with higher accuracy than subjective evaluation.5

Morphologic variables as indicators. In 2016, Ianieri and colleagues published a retrospective study on a risk scoring system for diagnosing endometrial hyperplasia and adenocarcinoma via hysteroscopy.6 They created a statistical risk model for development of the scoring system. A number of morphologic variables were prognostic indicators of atypical endometrial hyperplasia (AEH) and adenocarcinoma. These included widespread and irregular endometrial thickness, presence of multiple polyps with irregular aspects, dilated glandular orifices, irregular endometrial color (grey, white, or hyperemic), atypical vessels, crumbling of the endometrial neoplasms, and growth of cerebroid and arborescent aspects (VIDEO 4).

Video 4. Endometrial adenocarcinoma

The scoring system for endometrial adenocarcinoma correctly classified 42 of 44 cancers (sensitivity, 95.4%; specificity, 98.2%), and AEH had a sensitivity of 63.3% and a specificity of 90.4%.6 These investigators also showed a high negative predictive value of 99.5% for endometrial adenocarcinoma associated with a negative view at hysteroscopy. Similar to the Dueholm data, Ianieri and colleagues’ morphologic pattern analysis predicted cancer with high accuracy.

Glomerular pattern association. Su and colleagues also showed that pattern recognition could aid in the accurate hysteroscopic diagnosis of endometrial adenocarcinoma.7 They used the hysteroscopic presence of a glomerular pattern to predict the association with endometrial adenocarcinoma. A glomerular pattern was described as polypoid endometrium with a papillary-like feature, containing an abnormal neovascularization feature with “intertwined neovascular vessels covered by a thin layer of endometrial tissue” (FIGURE 6). The presence of a glomerular pattern indicated grade 2 or grade 3 disease in 25 of 26 women (96%; sensitivity, 84.6%, specificity, 81.8%)7 (see video 4).

TABLE 2 summarizes significant morphologic findings relating to the presences of endometrial carcinoma.

Continue to: Atypical endometrial hyperplasia: A difficult diagnosis...

Atypical endometrial hyperplasia: A difficult diagnosis

The most common type of endometrial cancer is endometrioid adenocarcinoma (type 1 endometrial carcinoma), and it accounts for approximately 75% to 80% of endometrial cancer diagnoses.8 Risk factors include prolonged unopposed estrogen exposure, obesity, diabetes, and age. Type 1 endometrial carcinoma follows a progressive continuum of histopathologic change: from endometrial hyperplasia without atypia to endometrial hyperplasia with atypia (AEH) to well-differentiated endometrial cancer. Therefore, it is possible for endometrial carcinoma to be present simultaneously with AEH. The reported prevalence of concurrent endometrial carcinoma among patients with AEH on biopsy is between 17% and 52%.8 Thus, the clinical consideration is for hysterectomy, especially in the postmenopausal patient with a diagnosis of AEH.

Hysteroscopic diagnosis of AEH, however, is more difficult than identification of endometrial carcinoma because a range of morphologic characteristics exist that resemble normal endometrium as well as more progressive disease (VIDEO 5). De Franciscis and colleagues based a hysteroscopic diagnosis of hyperplasia on one or more of the following findings: focal or diffuse, papillary or polypoid, endometrial thickening; abnormal vascular patterns; evidence of glandular cysts; and abnormal architecture features of the glandular outlets (thickening, irregular gland density, or dilatation)9 (VIDEO 6).

Video 5. Endometrial polyp and atypical hyperplasia

Additional studies, including that from Ianieri and colleagues, also have determined that AEH is difficult to discern visually from normal endometrium and other endometrial pathologies.6 In another investigation, Lasmar and coauthors reported a retrospective analysis of 4,054 hysteroscopic procedures with directed biopsies evaluating for concordance between the hysteroscopic view and histopathology.10 Agreement was 56.3% for AEH versus 94% for endometrial carcinoma. Among those with a histologic diagnosis of AEH, in 35.4% benign disease was suspected; in 2.1%, endometrial carcinoma was suspected; and in 6%, normal findings were presumed.10

Video 6. Nodular, polypoid atypical hyperplasia

Because of the similarities in morphologic features between AEH and endometrial carcinoma, tissue biopsy under direct visualization is warranted to assure sampling of the most significantly abnormal tissue and to confirm visual interpretation of findings.

Techniques for hysteroscopic-directed biopsy

Using a visual assessment of endometrial abnormalities allows the surgeon to examine the entire uterine cavity and to biopsy the most suspicious and concerning lesions. The directed biopsy technique can involve a simple grasping maneuver: With the jaws of a small grasper open, push slightly forward to accumulate tissue within the jaw, close the jaw, and remove the tissue carefully through the cervix (VIDEO 7). The size of the sample may be limited, and multiple samples may be needed, depending on the quantity of the tissue retrieved.

Video 7. Visually directed endometrial biopsy

Another technique involves first creating a plane of tissue to be removed with scissors and subsequently grasping and removing the tissue (see video 1 and video 3). This particular technique will yield more tissue with one pass of the hysteroscope into the cavity. Careful removal of tissue through the cervix is facilitated by withdrawing the sample in the grasper and the hysteroscope together at the same time, without pulling the sample through the operative channel of the hysteroscope. Also, by turning off the inflow port, the stream of saline does not wash the sample off the grasper at hysteroscope removal from the cervix.

Blind biopsy. If visual inspection reveals a diffuse process within the uterine cavity such that no normal endometrium is noted and the abnormality is of equal degree throughout the endometrial surface, a decision can be made to replace directed biopsy with a blind biopsy. In this scenario, the blind biopsy is certain to sample the representative disease process and not potentially miss significant lesions (see video 4 and video 6). Otherwise, the hysteroscope-directed biopsy would be preferable.

Continue to: Potential for intraperitoneal dissemination of endometrial cancer...

Potential for intraperitoneal dissemination of endometrial cancer

There is some concern about intraperitoneal dissemination of endometrial carcinoma at the time of hysteroscopy and effect on disease prognosis. Chang and colleagues conducted a large meta-analysis and found that hysteroscopy performed in the presence of type 1 endometrial carcinoma statistically significantly increased the likelihood of positive intraperitoneal cytology.11 In the included studies that reported survival rates (6 of 19), positive cytology did not alter the clinical outcome. The investigators recommended that hysteroscopy not be avoided for this reason, as it helps in the diagnosis of endometrial carcinoma, especially in the early stages of disease.11

In a recent retrospective analysis, Namazov and colleagues included only stage I endometrial carcinoma (to exclude the adverse effect of advanced stage on survival) and evaluated the assumed isolated effect of hysteroscopy on survival.12 They compared women in whom stage I endometrial carcinoma was diagnosed: 355 by hysteroscopy and 969 by a nonhysteroscopy method (D&C or office endometrial biopsy). Tumors were classified and grouped as low grade (endometrioid grade 1-2 and villoglandular) and high grade, consisting of endometrioid grade 3 and type 2 endometrial carcinoma (serous carcinoma, clear cell carcinoma, and carcinosarcoma) (VIDEOS 8 and 9). Positive intraperitoneal cytology at the time of surgery was 2.3% and 2.1% (P = .832), with an average interval from diagnosis to surgery of 34.6 days (range, 7–43 days).

Video 8. Carcinosarcoma

The authors proposed several explanations for the low rate of intraperitoneal cytology with hysteroscopy. One possibility is having lower mean intrauterine pressure below 100 mm Hg for saline uterine distension, although this was not standardized for all surgeons in the study but rather was a custom of the institution. In addition, the length of time between hysteroscopy and surgery may allow the immune-reactive peritoneum to respond to the cellular insult, thus decreasing the biologic burden at the time of surgery. The median follow-up was 52 months (range, 12–120 months), and there were no differences between the hysteroscopy and the nonhysteroscopy groups in the 5-year recurrence-free survival (90.2% vs 88.2%; P = .53), disease-specific survival (93.4% vs 91.7%; P = .5), and overall survival (86.2% vs 80.6%; P = .22). The authors concluded that hysteroscopy does not compromise the survival of patients with early-stage endometrial cancer.12

Video 9. Carcinosarcoma

Retrospective data from Chen and colleagues regarding type 2 endometrial carcinoma indicated a statistically significant increase in positive intraperitoneal cytology for carcinomas evaluated by hysteroscopy versus D&C (30% vs 12%; P = .008).13 Among the patients who died, there was no difference in disease-specific survival (53 months for hysteroscopy and 63.5 months for D&C; P = .34), and there was no difference in overall recurrence rates.13 Compared with type 1 endometrial carcinoma, type 2 endometrial carcinoma behaves more aggressively, with a higher incidence of extrauterine disease and an increased propensity for recurrence and poor outcome even in the early stages of the disease. This makes it difficult to determine the role of hysteroscopy in the prognosis of these carcinomas, especially in this study where most patients were diagnosed at a later stage.

Key takeaways

Hysteroscopy and directed biopsy are highly effective for visual and histopathologic diagnosis of atypical endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial carcinoma, and they are recommended in the evaluation of AUB, especially in the postmenopausal woman. When the hysteroscopic view is negative, there is a high correlation with the absence of uterine cavity and endometrial pathology. Hysteroscopic diagnostic accuracy is improved with structured use of visual grading scales, well-defined descriptors of endometrial pathology, and hysteroscopist experience.

Low operating intrauterine pressure may decrease the intraperitoneal spread of carcinoma cells during hysteroscopy, and current evidence suggests that there is no change in type 1 endometrial carcinoma prognosis and overall outcomes. Type 2 endometrial carcinoma is more aggressive and is associated with poor outcomes even in early stages, and the effect on disease progression by intraperitoneal spread of carcinoma cells at hysteroscopy is not yet known. Hysteroscopic evaluation of the uterine cavity and directed biopsy is easily and safely performed in the office and adds significantly to the evaluation and management of endometrial carcinoma.

Access them in the article online at mdedge.com/obgyn

Video 1. Endometrial carcinoma and visually directed biopsy

Nodular endometrioid adenocarcinoma grade 1 (type 1 endometrial carcinoma), benign endometrial polyps, and endometrial atrophy in a postmenopausal woman with bleeding. This video demonstrates visually directed biopsy to assure sampling of the most significant lesion.

Video 2. Negative hysteroscopic view

Digital flexible diagnostic hysteroscopy showing a negative hysteroscopic view in a premenopausal woman.

Video 3. Cervical spread of adenocarcinoma and visually directed biopsy

Diffuse endometrioid adenocarcinoma spread to the upper cervical canal near the internal cervical os. Hysteroscopic directed biopsy is performed.

Video 4. Endometrial adenocarcinoma

Fiberoptic flexible diagnostic hysteroscopy demonstrating diffuse endometrioid adenocarcinoma grade 3 with multiple morphologic features: polypoid, nodular, papillary, and glomerular with areas of necrosis.

Video 5. Endometrial polyp and atypical hyperplasia

Large benign endometrial polyp in an asymptomatic postmenopausal woman with enlarged endometrial stripe on pelvic ultrasound. The endometrium is atrophic except for a small whitish area on the anterior wall, which is atypical hyperplasia. This video highlights the need for visually directed biopsy to assure sampling of the most significant lesion.

Video 6. Nodular, polypoid atypical hyperplasia

Fiberoptic flexible diagnostic hysteroscopy showing diffuse nodular and polypoid atypical hyperplasia with abnormal glandular openings in a postmenopausal woman. Hysterectomy was performed secondary to the significant likelihood of concomitant endometrial carcinoma.

Video 7. Visually directed endometrial biopsy

Hysteroscopic-directed biopsy showing the technique of grasping and removing tissue of a benign adenomyosis cyst and proliferative endometrium.

Video 8. Carcinosarcoma

Carcinosarcoma (type 2 endometrial carcinoma) presents as a large intracavitary mass with soft, polypoid-like tissue in a symptomatic postmenopausal woman with bleeding.

Video 9. Carcinosarcoma

Carcinosarcoma (type 2 endometrial carcinoma) presents as a dense mass in a symptomatic postmenopausal woman with bleeding. This video shows the mass is nodular. These cancers typically grow into a spherical mass within the cavity

- Sugimoto O. Hysteroscopic diagnosis of endometrial carcinoma. A report of fifty-three cases examined at the Women’s Clinic of Kyoto University Hospital. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1975;121:105-113.

- Loffer FD. Hysteroscopy with selective endometrial sampling compared with D&C for abnormal uterine bleeding: the value of a negative hysteroscopic view. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;73:16-20.

- Valli E, Zupi E. A new hysteroscopic classification of and nomenclature for endometrial lesions. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1995;2:279-283.

- Garuti G, De Giorgi O, Sambruni I, et al. Prognostic significance of hysteroscopic imaging in endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;81: 408-413.

- Dueholm M, Hjorth IMD, Secher P, et al. Structured hysteroscopic evaluation of endometrium in women with postmenopausal bleeding. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22:1215-1224.

- Ianieri MM, Staniscia T, Pontrelli G, et al. A new hysteroscopic risk scoring system for diagnosing endometrial hyperplasia and adenocarcinoma. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2016;23: 712-718.

- Su H, Pandey D, Liu L-Y, et al. Pattern recognition to prognosticate endometrial cancer: the science behind the art of office hysteroscopy—a retrospective study. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2016;26:705-710.

- Trimble CL, Kauderer J, Zaino R, et al. Concurrent endometrial carcinoma in women with a biopsy diagnosis of atypical endometrial hyperplasia: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Cancer. 2006;106:812-819.

- De Franciscis P, Riemma G, Schiattarella A, et al. Concordance between the hysteroscopic diagnosis of endometrial hyperplasia and histopathological examination. Diagnostics (Basel). 2019;9(4).

- Lasmar RB, Barrozo PRM, de Oliveira MAP, et al. Validation of hysteroscopic view in cases of endometrial hyperplasia and cancer in patients with abnormal uterine bleeding. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2006;13:409-412.

- Chang Y-N, Zhang Y, Wang Y-J, et al. Effect of hysteroscopy on the peritoneal dissemination of endometrial cancer cells: a meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2011;96:957-961.

- Namazov A, Gemer O, Helpman L, et al. The oncological safety of hysteroscopy in the diagnosis of early-stage endometrial cancer: an Israel Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2019;243:120-124.

- Chen J, Clark LH, Kong W-M, et al. Does hysteroscopy worsen prognosis in women with type II endometrial carcinoma? PLoS One. 2017;12(3):e0174226.

- Sugimoto O. Hysteroscopic diagnosis of endometrial carcinoma. A report of fifty-three cases examined at the Women’s Clinic of Kyoto University Hospital. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1975;121:105-113.

- Loffer FD. Hysteroscopy with selective endometrial sampling compared with D&C for abnormal uterine bleeding: the value of a negative hysteroscopic view. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;73:16-20.

- Valli E, Zupi E. A new hysteroscopic classification of and nomenclature for endometrial lesions. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1995;2:279-283.

- Garuti G, De Giorgi O, Sambruni I, et al. Prognostic significance of hysteroscopic imaging in endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;81: 408-413.

- Dueholm M, Hjorth IMD, Secher P, et al. Structured hysteroscopic evaluation of endometrium in women with postmenopausal bleeding. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22:1215-1224.

- Ianieri MM, Staniscia T, Pontrelli G, et al. A new hysteroscopic risk scoring system for diagnosing endometrial hyperplasia and adenocarcinoma. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2016;23: 712-718.

- Su H, Pandey D, Liu L-Y, et al. Pattern recognition to prognosticate endometrial cancer: the science behind the art of office hysteroscopy—a retrospective study. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2016;26:705-710.

- Trimble CL, Kauderer J, Zaino R, et al. Concurrent endometrial carcinoma in women with a biopsy diagnosis of atypical endometrial hyperplasia: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Cancer. 2006;106:812-819.

- De Franciscis P, Riemma G, Schiattarella A, et al. Concordance between the hysteroscopic diagnosis of endometrial hyperplasia and histopathological examination. Diagnostics (Basel). 2019;9(4).

- Lasmar RB, Barrozo PRM, de Oliveira MAP, et al. Validation of hysteroscopic view in cases of endometrial hyperplasia and cancer in patients with abnormal uterine bleeding. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2006;13:409-412.

- Chang Y-N, Zhang Y, Wang Y-J, et al. Effect of hysteroscopy on the peritoneal dissemination of endometrial cancer cells: a meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2011;96:957-961.

- Namazov A, Gemer O, Helpman L, et al. The oncological safety of hysteroscopy in the diagnosis of early-stage endometrial cancer: an Israel Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2019;243:120-124.

- Chen J, Clark LH, Kong W-M, et al. Does hysteroscopy worsen prognosis in women with type II endometrial carcinoma? PLoS One. 2017;12(3):e0174226.

2015 Update on minimally invasive gynecologic surgery

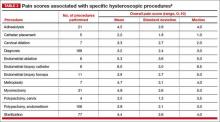

Office hysteroscopy offers many benefits and is becoming more acceptable among patients and gynecologists for both diagnostic and operative procedures (TABLE 1). Despite its clear advantages, however, many gynecologists remain hesitant to perform in-office procedures out of fear that the patient, who is generally awake, will experience significant discomfort.

Certainly, pain and low patient tolerance of discomfort have been the primary limitations to widespread use of office hysteroscopy without anesthesia.1 Data on the use of anesthesia for office hysteroscopy—especially diagnostic procedures—historically have been inconsistent in regard to the reduction of patient discomfort.2

Bettocchi and Selvaggi first reported a vaginoscopic approach to diagnostic hysteroscopy to reduce the discomfort of the procedure, compared with the conventional approach. They did not place a vaginal speculum or tenaculum and, therefore, avoided placing local anesthetic into the cervix.3

A randomized controlled trial by Sagiv and colleagues found reduced pain during diagnostic hysteroscopy with vaginoscopy (VIDEO).4