User login

Giant Solitary Synovial Chondromatosis Mimicking Chondrosarcoma: Report of a Rare Histologic Presentation and Literature Review

Synovial chondromatosis (SCM) is a relatively rare benign lesion of the synovium.1 Its pathogenesis has been thought to be a chondral metaplasia of the subintimal layer of the intra- or extra-articular synovium.2 However, evidence supporting a neoplastic cause of the disease is emerging.3 When intra-articular, any joint can be affected, though large joints are more prone to the disease; the knee, hip, and elbow are the most common locations.4 The synovial layer of tendons or bursae can be the origin of extra-articular SCM.5

Synovial chondrosarcoma (SCS), an even rarer pathology, can be caused by malignant transformation of SCM or can appear de novo on a synovial background.6 Histologic differentiation from SCM might be difficult because of the high incidence of hypercellularity, cellular atypia, and binucleated cells.6 Some features, such as presence of a very large mass or erosion of the surrounding bones, have been indicated as possible signs of malignancy.3 An unusual presentation of SCM, giant solitary synovial chondromatosis (GSSCM), can be hard to distinguish from SCS because of the large volume and possible aggressive radiologic findings.7 Some histologic features, such as presence of necrosis and mitotic cells, have been suggested as distinctive criteria for malignancy.8

In this article, we present a case of benign GSSCM with a histologic feature that has not been considered typical for benign SCM. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

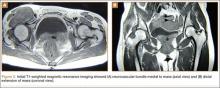

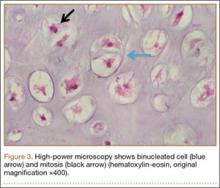

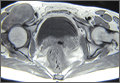

An 18-year-old woman presented with a large mass over the right hip. The mass had been growing slowly for 2 years. One year before presentation, a radiograph showed a large hip mass with fluffy calcification (Figure 1), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a large nonhomogeneous mass anterior to the hip capsule and extending into the hip joint back to the posterior part of the joint (Figures 2A, 2B). Open incisional biopsy was performed in a local hospital at the time, and the histologic analysis revealed presence of atypical binucleated cells and pleomorphism, in addition to some mitotic activity (0 to 1 per high-power field) (Figure 3). These findings suggested malignancy. The patient declined surgery up until the time she presented to our hospital, 1 year later.

Clinical examination findings on admission to our hospital were striking. The patient had a large mass in the groin region. It was fairly tender and firm to palpation, immobile, and close to the skin. Hip motion was mildly painful but obviously restricted.

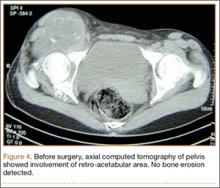

The mass was restaged. New radiographs and MRI did not show any significant changes since the previous year, computed tomography (CT) did not show any bone erosion (Figure 4), and chest radiograph, CT, and whole-body bone scan did not demonstrate any signs of metastasis.

Given the clinical presentation and previous histopathologic findings, a diagnosis of GSSCM with possible malignant transformation was made. The patient was scheduled for surgery. During surgery, the tumor was exposed through the Smith-Petersen approach. The mass was extruding under the fascia between the femoral neurovascular bundle medially and iliopsoas muscle laterally. There was no adhesion of the surrounding structures, including the femoral neurovascular bundle, to the mass. The muscle was sitting on the anterolateral surface of the mass, which was considered located in the iliopsoas bursa but extending to the joint. In the vertical plane, the mass extended down to the subtrochanteric area. The entire solid extra-articular mass was excised en bloc, and hip capsulotomy was performed inferior to the area of emergence of the mass. The joint was occupied by a single solid cartilaginous mass molding around the femoral neck, filling the piriformis fossa and propagating to the posterior joint space. Obtaining enough exposure to the back of the joint required surgical hip dislocation. The visualized acetabular fossa revealed chondral fragments, which were excised. Bone erosion or significant osteoarthritis was not detected in any part of the joint. A nearly total synovectomy was performed, leaving the ascending retinacular vessels intact. Meticulous technique was used to avoid contaminating the extra-articular tissues. The wound was closed in the routine way after hip relocation.

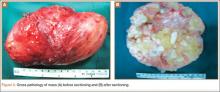

The 16×9.5×9-cm mass (Figure 5A) had a conglomerated internal structure (Figure 5B). Multiple specimens from the intra- and extra-articular portions of the mass were sent for histopathologic analysis, which revealed clusters of mature chondrocytes arranged in a lobular pattern and separated by thin fibrous bands. Areas of calcification and ossification were appreciated as well (Figures 6A-6C). No necrosis, mitosis, or bone permeation was detected. These findings were compatible with typical SCM. Given these pathologic findings and the lack of clinical deterioration over the previous year, a diagnosis of GSSCM with extension along the iliopsoas and obturator externus bursae was made. The already-performed marginal excision was deemed sufficient treatment. At most recent follow-up, 38 months after surgery, the patient was pain-free and had good hip range of motion and no indication of recurrence.

Discussion

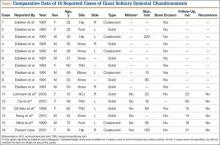

SCM is a benign disorder emerging from the synovium as a result of proliferative changes in the synovial membrane of the joints, tendon sheaths, or bursae, leading to the formation of numerous cartilaginous nodules, usually a few millimeters in diameter.8 In a rare presentation of the disease, the nodules may coalesce to form a large mass, or a single cartilaginous nodule may enlarge to form a mass. Edeiken and colleagues7 named this previously unrecognized SCM feature as GSSCM when there was a major single mass larger than 1 cm in diameter. There have been other SCM cases with multiple giant masses.9,10 In the English-language literature, we found 15 GSSCM cases, which include the first reported, by Edeiken and colleagues7 (Table). However, earlier SCM cases would be reclassified GSSCM according to their definition.11

The present case brings the total to 16. Nine of the 16 patients were male. Mean age at presentation was 41 years (range, 10-80 years). The knee was the most common GSSCM site (6 cases), followed by the temporomandibular and hip joints (3 each). Regarding gross pathology, 10 lesions were solid, and 6 (including the present one) were formed by conglomeration of the chondromatosis nodules. Lesions varied in size (16-200 mm), and 2 were primarily extra-articular (foot). One common issue with most of the cases was the initial diagnosis of chondrosarcoma. The exact surgical technique used was described for 6 cases (cases 11-16); the technique was marginal excision. In no case was recurrence 14 to 60 months after surgery reported.

This chondroproliferative process is potentially a diagnostic challenge, as distinguishing it from a chondrosarcoma, a more common lesion, could be difficult based on clinical and imaging findings, and, as is true for other chondral lesions, even histologic differentiation of the conditions might not be conclusive.12,13 Confusion in diagnosis was almost universal in this series of patients.

One important differentiating feature of benign and malignant skeletal lesions is the time course of the disease. Malignant tumors are expected to demonstrate rapid enlargement and local or systemic spread. Unfortunately, often SCS cannot be distinguished by this characteristic, as grade I or II chondrosarcoma is usually a slow-growing tumor and does not metastasize early.14 Although lack of recurrence is assuring, recurrence is not necessarily a sign of malignancy, as a considerable percentage of benign chondromatosis lesions recur.8

Radiologic differentiation between SCM and SCS is another challenge. Although bone erosion caused by a lesion not originating from bone is usually considered a sign of malignancy, GSSCM was reported as causing bone erosion in 5 of the 16 cases in our literature review.7,15 Our patient did not experience any bone erosion. However, lack of bone erosion is not a reliable criterion for excluding SCS, and bone erosion was noted in only 3 of the 9 SCS cases in the series reported by Bertoni and colleagues.6 Moreover, tumor size and propagation of tumor to surrounding tissue could be surprising in GSSCM. Large size (up to 20 cm) and extra-articular spread of a lesion originating in a joint are common findings.6,16 Our case was an obvious extension of a hip GSSCM to the iliopsoas and obturator externus bursa, which is the most common pattern of extracapsular spread of hip SCM.17 An interesting feature of the present case, however, was the relatively superficial location of the mass immediately under the fascia.

Calcified matrix is key in diagnosing a chondral lesion on imaging studies, but, in some cases, SCM does not demonstrate any radiographically detectable calcification at time of diagnosis.18 However, all the GSSCM cases reported to date had obvious calcified matrix.

The hypercellularity, cellular atypia, binucleated cells, and pleomorphism in the histologic examination of the present case are not features of malignancy in SCM.8 On the contrary, several other characteristics, including qualitative differences in the arrangement of chondrocytes (sheets rather than clusters), myxoid matrix, hypercellularity with crowding and spindling of the nuclei at the periphery, necrosis, and, most important, permeation of the trabecular bone with the filling up of marrow spaces, have been assumed to be indicative of malignancy.8 Furthermore, Davis and colleagues8 found no mitotic activity in the histopathologic investigation of 53 SCM cases. Even in 3 cases that developed malignant transformation to SCS, mitosis was not found in the initial biopsy specimens before transformation. This was compatible with the common opinion that SCM is not a neoplastic, but a metaplastic, process. Histopathologic data were available for only 8 of the previous 15 GSSCM cases. There were no reports of mitosis, and necrosis was found in only 1 case.16 In our patient’s case, however, the first biopsy did show remarkable mitotic activity. This was not the case for the second biopsy, when mature chondrocytes associated with marked calcification and ossification were prominent features (Figures 6A, 6B). We presume that, within a limited period during earlier stages of tissue maturation in SCM, mitotic activity might be a possible finding. Of note, none of the other aforementioned histologic criteria for malignancy was seen in the first or second biopsy in the present case (Figures 3, 6C).

The original idea that SCM originates from a metaplasia in the subintimal layer of the synovium, where the synovium is in direct contact with the articular cartilage, has been challenged. The high incidence of hypercellularity, binucleated cells, and cellular atypia was always an argument against a metaplastic origin for the disease. Evidence of clonal chromosomal changes, like translocation of chromosome 1218 and chromosome 5 and 6 abnormalities,19,20 in addition to other alterations,19,21 provide some evidence supporting a neoplastic rather than a metaplastic origin for SCM. Given the presence of mitosis in the present case, the lack of mitotic activity in SCM, as stated by other authors,22 is not a universal feature and cannot be used as an argument against a neoplastic origin for SCM.

Although mitotic activity is uncommon in SCM, the present case illustrates the possible presence of mitotic activity in GSSCM. The simple presence of mitotic activity, a common finding in some other chondral tumors,23,24 does not preclude the diagnosis of benign SCM, as suggested before,8 and correlation of the clinical and radiologic manifestations with histopathologic findings is crucial for a correct diagnosis.

1. Milgram JW. Synovial osteochondromatosis: a histopathological study of thirty cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59(6):792-801.

2. Trias A, Quintana O. Synovial chondrometaplasia: review of world literature and a study of 18 Canadian cases. Can J Surg. 1976;19(2):151-158.

3. Murphey MD, Vidal JA, Fanburg-Smith JC, Gajewski DA. Imaging of synovial chondromatosis with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2007;27(5):1465-1488.

4. Milgram JW. Synovial osteochondromatosis in association with Legg-Calve-Perthes disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1979;(145):179-182.

5. Sim FH, Dahlin DC, Ivins JC. Extra-articular synovial chondromatosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59(4):492-495.

6. Bertoni F, Unni KK, Beabout JW, Sim FH. Chondrosarcomas of the synovium. Cancer. 1991;67(1):155-162.

7. Edeiken J, Edeiken BS, Ayala AG, Raymond AK, Murray JA, Guo SQ. Giant solitary synovial chondromatosis. Skeletal Radiol. 1994;23(1):23-29.

8. Davis RI, Hamilton A, Biggart JD. Primary synovial chondromatosis: a clinicopathologic review and assessment of malignant potential. Hum Pathol. 1998;29(7):683-688.

9. Goel A, Cullen C, Paul AS, Freemont AJ. Multiple giant synovial chondromatosis of the knee. Knee. 2001;8(3):243-245.

10. Dogan A, Harman M, Uslu M, Bayram I, Akpinar F. Rocky form giant synovial chondromatosis: a case report. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14(5):465-468.

11. Eisenberg KS, Johnston JO. Synovial chondromatosis of the hip joint presenting as an intrapelvic mass: a case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972;54(1):176-178.

12. Lohmann CH, Köster G, Klinger HM, Kunze E. Giant synovial osteochondromatosis of the acromio-clavicular joint in a child. A case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2005;14(2):126-128.

13. Cai XY, Yang C, Chen MJ, Jiang B, Wang BL. Arthroscopically guided removal of large solitary synovial chondromatosis from the temporomandibular joint. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;39(12):1236-1239.

14. Gil-Salu JL, Lazaro R, Aldasoro J, Gonzalez-Darder JM. Giant solitary synovial chondromatosis of the temporomandibular joint with intracranial extension. Skull Base Surg. 1998;8(2):99-104.

15. Kang CH, Park JH, Lee DH, Kim CH, Park JM, Lee WS. Giant synovial chondromatosis of the knee mimicking a parosteal osteosarcoma: a case report. J Korean Bone Joint Tumor Soc. 2010;16(2):95-98.

16. Nihal A, Read CJ, Henderson DC, Malcolm AJ. Extra-articular giant solitary synovial chondromatosis of the foot: a case report and literature review. Foot Ankle Surg. 1999;5(1):29-32.

17. Robinson P, White LM, Kandel R, Bell RS, Wunder JS. Primary synovial osteochondromatosis of the hip: extracapsular patterns of spread. Skeletal Radiol. 2004;33(4):210-215.

18. Tallini G, Dorfman H, Brys P, et al. Correlation between clinicopathological features and karyotype in 100 cartilaginous and chordoid tumours. A report from the Chromosomes and Morphology (CHAMP) Collaborative Study Group. J Pathol. 2002;196(2):194-203.

19. Sah AP, Geller DS, Mankin HJ, et al. Malignant transformation of synovial chondromatosis of the shoulder to chondrosarcoma. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(6):1321-1328.

20. Buddingh EP, Krallman P, Neff JR, Nelson M, Liu J, Bridge JA. Chromosome 6 abnormalities are recurrent in synovial chondromatosis. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2003;140(1):18-22.

21. Rizzo M, Ghert MA, Harrelson JM, Scully SP. Chondrosarcoma of bone: analysis of 108 cases and evaluation for predictors of outcome. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;(391):224-233.

22. Davis RI, Foster H, Arthur K, Trewin S, Hamilton PW, Biggart DJ. Cell proliferation studies in primary synovial chondromatosis. J Pathol. 1998;184(1):18-23.

23. Ishikawa E, Tsuboi K, Onizawa K, et al. Chondroblastoma of the temporal base with high mitotic activity. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2002;42(11):516-520.

24. Kirin I, Jurisic D, Mokrovic H, Stanec Z, Stalekar H. Chondromyxoid fibroma of the second metacarpal bone—a case report. Coll Antropol. 2011;35(3):929-931.

Synovial chondromatosis (SCM) is a relatively rare benign lesion of the synovium.1 Its pathogenesis has been thought to be a chondral metaplasia of the subintimal layer of the intra- or extra-articular synovium.2 However, evidence supporting a neoplastic cause of the disease is emerging.3 When intra-articular, any joint can be affected, though large joints are more prone to the disease; the knee, hip, and elbow are the most common locations.4 The synovial layer of tendons or bursae can be the origin of extra-articular SCM.5

Synovial chondrosarcoma (SCS), an even rarer pathology, can be caused by malignant transformation of SCM or can appear de novo on a synovial background.6 Histologic differentiation from SCM might be difficult because of the high incidence of hypercellularity, cellular atypia, and binucleated cells.6 Some features, such as presence of a very large mass or erosion of the surrounding bones, have been indicated as possible signs of malignancy.3 An unusual presentation of SCM, giant solitary synovial chondromatosis (GSSCM), can be hard to distinguish from SCS because of the large volume and possible aggressive radiologic findings.7 Some histologic features, such as presence of necrosis and mitotic cells, have been suggested as distinctive criteria for malignancy.8

In this article, we present a case of benign GSSCM with a histologic feature that has not been considered typical for benign SCM. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

An 18-year-old woman presented with a large mass over the right hip. The mass had been growing slowly for 2 years. One year before presentation, a radiograph showed a large hip mass with fluffy calcification (Figure 1), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a large nonhomogeneous mass anterior to the hip capsule and extending into the hip joint back to the posterior part of the joint (Figures 2A, 2B). Open incisional biopsy was performed in a local hospital at the time, and the histologic analysis revealed presence of atypical binucleated cells and pleomorphism, in addition to some mitotic activity (0 to 1 per high-power field) (Figure 3). These findings suggested malignancy. The patient declined surgery up until the time she presented to our hospital, 1 year later.

Clinical examination findings on admission to our hospital were striking. The patient had a large mass in the groin region. It was fairly tender and firm to palpation, immobile, and close to the skin. Hip motion was mildly painful but obviously restricted.

The mass was restaged. New radiographs and MRI did not show any significant changes since the previous year, computed tomography (CT) did not show any bone erosion (Figure 4), and chest radiograph, CT, and whole-body bone scan did not demonstrate any signs of metastasis.

Given the clinical presentation and previous histopathologic findings, a diagnosis of GSSCM with possible malignant transformation was made. The patient was scheduled for surgery. During surgery, the tumor was exposed through the Smith-Petersen approach. The mass was extruding under the fascia between the femoral neurovascular bundle medially and iliopsoas muscle laterally. There was no adhesion of the surrounding structures, including the femoral neurovascular bundle, to the mass. The muscle was sitting on the anterolateral surface of the mass, which was considered located in the iliopsoas bursa but extending to the joint. In the vertical plane, the mass extended down to the subtrochanteric area. The entire solid extra-articular mass was excised en bloc, and hip capsulotomy was performed inferior to the area of emergence of the mass. The joint was occupied by a single solid cartilaginous mass molding around the femoral neck, filling the piriformis fossa and propagating to the posterior joint space. Obtaining enough exposure to the back of the joint required surgical hip dislocation. The visualized acetabular fossa revealed chondral fragments, which were excised. Bone erosion or significant osteoarthritis was not detected in any part of the joint. A nearly total synovectomy was performed, leaving the ascending retinacular vessels intact. Meticulous technique was used to avoid contaminating the extra-articular tissues. The wound was closed in the routine way after hip relocation.

The 16×9.5×9-cm mass (Figure 5A) had a conglomerated internal structure (Figure 5B). Multiple specimens from the intra- and extra-articular portions of the mass were sent for histopathologic analysis, which revealed clusters of mature chondrocytes arranged in a lobular pattern and separated by thin fibrous bands. Areas of calcification and ossification were appreciated as well (Figures 6A-6C). No necrosis, mitosis, or bone permeation was detected. These findings were compatible with typical SCM. Given these pathologic findings and the lack of clinical deterioration over the previous year, a diagnosis of GSSCM with extension along the iliopsoas and obturator externus bursae was made. The already-performed marginal excision was deemed sufficient treatment. At most recent follow-up, 38 months after surgery, the patient was pain-free and had good hip range of motion and no indication of recurrence.

Discussion

SCM is a benign disorder emerging from the synovium as a result of proliferative changes in the synovial membrane of the joints, tendon sheaths, or bursae, leading to the formation of numerous cartilaginous nodules, usually a few millimeters in diameter.8 In a rare presentation of the disease, the nodules may coalesce to form a large mass, or a single cartilaginous nodule may enlarge to form a mass. Edeiken and colleagues7 named this previously unrecognized SCM feature as GSSCM when there was a major single mass larger than 1 cm in diameter. There have been other SCM cases with multiple giant masses.9,10 In the English-language literature, we found 15 GSSCM cases, which include the first reported, by Edeiken and colleagues7 (Table). However, earlier SCM cases would be reclassified GSSCM according to their definition.11

The present case brings the total to 16. Nine of the 16 patients were male. Mean age at presentation was 41 years (range, 10-80 years). The knee was the most common GSSCM site (6 cases), followed by the temporomandibular and hip joints (3 each). Regarding gross pathology, 10 lesions were solid, and 6 (including the present one) were formed by conglomeration of the chondromatosis nodules. Lesions varied in size (16-200 mm), and 2 were primarily extra-articular (foot). One common issue with most of the cases was the initial diagnosis of chondrosarcoma. The exact surgical technique used was described for 6 cases (cases 11-16); the technique was marginal excision. In no case was recurrence 14 to 60 months after surgery reported.

This chondroproliferative process is potentially a diagnostic challenge, as distinguishing it from a chondrosarcoma, a more common lesion, could be difficult based on clinical and imaging findings, and, as is true for other chondral lesions, even histologic differentiation of the conditions might not be conclusive.12,13 Confusion in diagnosis was almost universal in this series of patients.

One important differentiating feature of benign and malignant skeletal lesions is the time course of the disease. Malignant tumors are expected to demonstrate rapid enlargement and local or systemic spread. Unfortunately, often SCS cannot be distinguished by this characteristic, as grade I or II chondrosarcoma is usually a slow-growing tumor and does not metastasize early.14 Although lack of recurrence is assuring, recurrence is not necessarily a sign of malignancy, as a considerable percentage of benign chondromatosis lesions recur.8

Radiologic differentiation between SCM and SCS is another challenge. Although bone erosion caused by a lesion not originating from bone is usually considered a sign of malignancy, GSSCM was reported as causing bone erosion in 5 of the 16 cases in our literature review.7,15 Our patient did not experience any bone erosion. However, lack of bone erosion is not a reliable criterion for excluding SCS, and bone erosion was noted in only 3 of the 9 SCS cases in the series reported by Bertoni and colleagues.6 Moreover, tumor size and propagation of tumor to surrounding tissue could be surprising in GSSCM. Large size (up to 20 cm) and extra-articular spread of a lesion originating in a joint are common findings.6,16 Our case was an obvious extension of a hip GSSCM to the iliopsoas and obturator externus bursa, which is the most common pattern of extracapsular spread of hip SCM.17 An interesting feature of the present case, however, was the relatively superficial location of the mass immediately under the fascia.

Calcified matrix is key in diagnosing a chondral lesion on imaging studies, but, in some cases, SCM does not demonstrate any radiographically detectable calcification at time of diagnosis.18 However, all the GSSCM cases reported to date had obvious calcified matrix.

The hypercellularity, cellular atypia, binucleated cells, and pleomorphism in the histologic examination of the present case are not features of malignancy in SCM.8 On the contrary, several other characteristics, including qualitative differences in the arrangement of chondrocytes (sheets rather than clusters), myxoid matrix, hypercellularity with crowding and spindling of the nuclei at the periphery, necrosis, and, most important, permeation of the trabecular bone with the filling up of marrow spaces, have been assumed to be indicative of malignancy.8 Furthermore, Davis and colleagues8 found no mitotic activity in the histopathologic investigation of 53 SCM cases. Even in 3 cases that developed malignant transformation to SCS, mitosis was not found in the initial biopsy specimens before transformation. This was compatible with the common opinion that SCM is not a neoplastic, but a metaplastic, process. Histopathologic data were available for only 8 of the previous 15 GSSCM cases. There were no reports of mitosis, and necrosis was found in only 1 case.16 In our patient’s case, however, the first biopsy did show remarkable mitotic activity. This was not the case for the second biopsy, when mature chondrocytes associated with marked calcification and ossification were prominent features (Figures 6A, 6B). We presume that, within a limited period during earlier stages of tissue maturation in SCM, mitotic activity might be a possible finding. Of note, none of the other aforementioned histologic criteria for malignancy was seen in the first or second biopsy in the present case (Figures 3, 6C).

The original idea that SCM originates from a metaplasia in the subintimal layer of the synovium, where the synovium is in direct contact with the articular cartilage, has been challenged. The high incidence of hypercellularity, binucleated cells, and cellular atypia was always an argument against a metaplastic origin for the disease. Evidence of clonal chromosomal changes, like translocation of chromosome 1218 and chromosome 5 and 6 abnormalities,19,20 in addition to other alterations,19,21 provide some evidence supporting a neoplastic rather than a metaplastic origin for SCM. Given the presence of mitosis in the present case, the lack of mitotic activity in SCM, as stated by other authors,22 is not a universal feature and cannot be used as an argument against a neoplastic origin for SCM.

Although mitotic activity is uncommon in SCM, the present case illustrates the possible presence of mitotic activity in GSSCM. The simple presence of mitotic activity, a common finding in some other chondral tumors,23,24 does not preclude the diagnosis of benign SCM, as suggested before,8 and correlation of the clinical and radiologic manifestations with histopathologic findings is crucial for a correct diagnosis.

Synovial chondromatosis (SCM) is a relatively rare benign lesion of the synovium.1 Its pathogenesis has been thought to be a chondral metaplasia of the subintimal layer of the intra- or extra-articular synovium.2 However, evidence supporting a neoplastic cause of the disease is emerging.3 When intra-articular, any joint can be affected, though large joints are more prone to the disease; the knee, hip, and elbow are the most common locations.4 The synovial layer of tendons or bursae can be the origin of extra-articular SCM.5

Synovial chondrosarcoma (SCS), an even rarer pathology, can be caused by malignant transformation of SCM or can appear de novo on a synovial background.6 Histologic differentiation from SCM might be difficult because of the high incidence of hypercellularity, cellular atypia, and binucleated cells.6 Some features, such as presence of a very large mass or erosion of the surrounding bones, have been indicated as possible signs of malignancy.3 An unusual presentation of SCM, giant solitary synovial chondromatosis (GSSCM), can be hard to distinguish from SCS because of the large volume and possible aggressive radiologic findings.7 Some histologic features, such as presence of necrosis and mitotic cells, have been suggested as distinctive criteria for malignancy.8

In this article, we present a case of benign GSSCM with a histologic feature that has not been considered typical for benign SCM. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

An 18-year-old woman presented with a large mass over the right hip. The mass had been growing slowly for 2 years. One year before presentation, a radiograph showed a large hip mass with fluffy calcification (Figure 1), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a large nonhomogeneous mass anterior to the hip capsule and extending into the hip joint back to the posterior part of the joint (Figures 2A, 2B). Open incisional biopsy was performed in a local hospital at the time, and the histologic analysis revealed presence of atypical binucleated cells and pleomorphism, in addition to some mitotic activity (0 to 1 per high-power field) (Figure 3). These findings suggested malignancy. The patient declined surgery up until the time she presented to our hospital, 1 year later.

Clinical examination findings on admission to our hospital were striking. The patient had a large mass in the groin region. It was fairly tender and firm to palpation, immobile, and close to the skin. Hip motion was mildly painful but obviously restricted.

The mass was restaged. New radiographs and MRI did not show any significant changes since the previous year, computed tomography (CT) did not show any bone erosion (Figure 4), and chest radiograph, CT, and whole-body bone scan did not demonstrate any signs of metastasis.

Given the clinical presentation and previous histopathologic findings, a diagnosis of GSSCM with possible malignant transformation was made. The patient was scheduled for surgery. During surgery, the tumor was exposed through the Smith-Petersen approach. The mass was extruding under the fascia between the femoral neurovascular bundle medially and iliopsoas muscle laterally. There was no adhesion of the surrounding structures, including the femoral neurovascular bundle, to the mass. The muscle was sitting on the anterolateral surface of the mass, which was considered located in the iliopsoas bursa but extending to the joint. In the vertical plane, the mass extended down to the subtrochanteric area. The entire solid extra-articular mass was excised en bloc, and hip capsulotomy was performed inferior to the area of emergence of the mass. The joint was occupied by a single solid cartilaginous mass molding around the femoral neck, filling the piriformis fossa and propagating to the posterior joint space. Obtaining enough exposure to the back of the joint required surgical hip dislocation. The visualized acetabular fossa revealed chondral fragments, which were excised. Bone erosion or significant osteoarthritis was not detected in any part of the joint. A nearly total synovectomy was performed, leaving the ascending retinacular vessels intact. Meticulous technique was used to avoid contaminating the extra-articular tissues. The wound was closed in the routine way after hip relocation.

The 16×9.5×9-cm mass (Figure 5A) had a conglomerated internal structure (Figure 5B). Multiple specimens from the intra- and extra-articular portions of the mass were sent for histopathologic analysis, which revealed clusters of mature chondrocytes arranged in a lobular pattern and separated by thin fibrous bands. Areas of calcification and ossification were appreciated as well (Figures 6A-6C). No necrosis, mitosis, or bone permeation was detected. These findings were compatible with typical SCM. Given these pathologic findings and the lack of clinical deterioration over the previous year, a diagnosis of GSSCM with extension along the iliopsoas and obturator externus bursae was made. The already-performed marginal excision was deemed sufficient treatment. At most recent follow-up, 38 months after surgery, the patient was pain-free and had good hip range of motion and no indication of recurrence.

Discussion

SCM is a benign disorder emerging from the synovium as a result of proliferative changes in the synovial membrane of the joints, tendon sheaths, or bursae, leading to the formation of numerous cartilaginous nodules, usually a few millimeters in diameter.8 In a rare presentation of the disease, the nodules may coalesce to form a large mass, or a single cartilaginous nodule may enlarge to form a mass. Edeiken and colleagues7 named this previously unrecognized SCM feature as GSSCM when there was a major single mass larger than 1 cm in diameter. There have been other SCM cases with multiple giant masses.9,10 In the English-language literature, we found 15 GSSCM cases, which include the first reported, by Edeiken and colleagues7 (Table). However, earlier SCM cases would be reclassified GSSCM according to their definition.11

The present case brings the total to 16. Nine of the 16 patients were male. Mean age at presentation was 41 years (range, 10-80 years). The knee was the most common GSSCM site (6 cases), followed by the temporomandibular and hip joints (3 each). Regarding gross pathology, 10 lesions were solid, and 6 (including the present one) were formed by conglomeration of the chondromatosis nodules. Lesions varied in size (16-200 mm), and 2 were primarily extra-articular (foot). One common issue with most of the cases was the initial diagnosis of chondrosarcoma. The exact surgical technique used was described for 6 cases (cases 11-16); the technique was marginal excision. In no case was recurrence 14 to 60 months after surgery reported.

This chondroproliferative process is potentially a diagnostic challenge, as distinguishing it from a chondrosarcoma, a more common lesion, could be difficult based on clinical and imaging findings, and, as is true for other chondral lesions, even histologic differentiation of the conditions might not be conclusive.12,13 Confusion in diagnosis was almost universal in this series of patients.

One important differentiating feature of benign and malignant skeletal lesions is the time course of the disease. Malignant tumors are expected to demonstrate rapid enlargement and local or systemic spread. Unfortunately, often SCS cannot be distinguished by this characteristic, as grade I or II chondrosarcoma is usually a slow-growing tumor and does not metastasize early.14 Although lack of recurrence is assuring, recurrence is not necessarily a sign of malignancy, as a considerable percentage of benign chondromatosis lesions recur.8

Radiologic differentiation between SCM and SCS is another challenge. Although bone erosion caused by a lesion not originating from bone is usually considered a sign of malignancy, GSSCM was reported as causing bone erosion in 5 of the 16 cases in our literature review.7,15 Our patient did not experience any bone erosion. However, lack of bone erosion is not a reliable criterion for excluding SCS, and bone erosion was noted in only 3 of the 9 SCS cases in the series reported by Bertoni and colleagues.6 Moreover, tumor size and propagation of tumor to surrounding tissue could be surprising in GSSCM. Large size (up to 20 cm) and extra-articular spread of a lesion originating in a joint are common findings.6,16 Our case was an obvious extension of a hip GSSCM to the iliopsoas and obturator externus bursa, which is the most common pattern of extracapsular spread of hip SCM.17 An interesting feature of the present case, however, was the relatively superficial location of the mass immediately under the fascia.

Calcified matrix is key in diagnosing a chondral lesion on imaging studies, but, in some cases, SCM does not demonstrate any radiographically detectable calcification at time of diagnosis.18 However, all the GSSCM cases reported to date had obvious calcified matrix.

The hypercellularity, cellular atypia, binucleated cells, and pleomorphism in the histologic examination of the present case are not features of malignancy in SCM.8 On the contrary, several other characteristics, including qualitative differences in the arrangement of chondrocytes (sheets rather than clusters), myxoid matrix, hypercellularity with crowding and spindling of the nuclei at the periphery, necrosis, and, most important, permeation of the trabecular bone with the filling up of marrow spaces, have been assumed to be indicative of malignancy.8 Furthermore, Davis and colleagues8 found no mitotic activity in the histopathologic investigation of 53 SCM cases. Even in 3 cases that developed malignant transformation to SCS, mitosis was not found in the initial biopsy specimens before transformation. This was compatible with the common opinion that SCM is not a neoplastic, but a metaplastic, process. Histopathologic data were available for only 8 of the previous 15 GSSCM cases. There were no reports of mitosis, and necrosis was found in only 1 case.16 In our patient’s case, however, the first biopsy did show remarkable mitotic activity. This was not the case for the second biopsy, when mature chondrocytes associated with marked calcification and ossification were prominent features (Figures 6A, 6B). We presume that, within a limited period during earlier stages of tissue maturation in SCM, mitotic activity might be a possible finding. Of note, none of the other aforementioned histologic criteria for malignancy was seen in the first or second biopsy in the present case (Figures 3, 6C).

The original idea that SCM originates from a metaplasia in the subintimal layer of the synovium, where the synovium is in direct contact with the articular cartilage, has been challenged. The high incidence of hypercellularity, binucleated cells, and cellular atypia was always an argument against a metaplastic origin for the disease. Evidence of clonal chromosomal changes, like translocation of chromosome 1218 and chromosome 5 and 6 abnormalities,19,20 in addition to other alterations,19,21 provide some evidence supporting a neoplastic rather than a metaplastic origin for SCM. Given the presence of mitosis in the present case, the lack of mitotic activity in SCM, as stated by other authors,22 is not a universal feature and cannot be used as an argument against a neoplastic origin for SCM.

Although mitotic activity is uncommon in SCM, the present case illustrates the possible presence of mitotic activity in GSSCM. The simple presence of mitotic activity, a common finding in some other chondral tumors,23,24 does not preclude the diagnosis of benign SCM, as suggested before,8 and correlation of the clinical and radiologic manifestations with histopathologic findings is crucial for a correct diagnosis.

1. Milgram JW. Synovial osteochondromatosis: a histopathological study of thirty cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59(6):792-801.

2. Trias A, Quintana O. Synovial chondrometaplasia: review of world literature and a study of 18 Canadian cases. Can J Surg. 1976;19(2):151-158.

3. Murphey MD, Vidal JA, Fanburg-Smith JC, Gajewski DA. Imaging of synovial chondromatosis with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2007;27(5):1465-1488.

4. Milgram JW. Synovial osteochondromatosis in association with Legg-Calve-Perthes disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1979;(145):179-182.

5. Sim FH, Dahlin DC, Ivins JC. Extra-articular synovial chondromatosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59(4):492-495.

6. Bertoni F, Unni KK, Beabout JW, Sim FH. Chondrosarcomas of the synovium. Cancer. 1991;67(1):155-162.

7. Edeiken J, Edeiken BS, Ayala AG, Raymond AK, Murray JA, Guo SQ. Giant solitary synovial chondromatosis. Skeletal Radiol. 1994;23(1):23-29.

8. Davis RI, Hamilton A, Biggart JD. Primary synovial chondromatosis: a clinicopathologic review and assessment of malignant potential. Hum Pathol. 1998;29(7):683-688.

9. Goel A, Cullen C, Paul AS, Freemont AJ. Multiple giant synovial chondromatosis of the knee. Knee. 2001;8(3):243-245.

10. Dogan A, Harman M, Uslu M, Bayram I, Akpinar F. Rocky form giant synovial chondromatosis: a case report. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14(5):465-468.

11. Eisenberg KS, Johnston JO. Synovial chondromatosis of the hip joint presenting as an intrapelvic mass: a case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972;54(1):176-178.

12. Lohmann CH, Köster G, Klinger HM, Kunze E. Giant synovial osteochondromatosis of the acromio-clavicular joint in a child. A case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2005;14(2):126-128.

13. Cai XY, Yang C, Chen MJ, Jiang B, Wang BL. Arthroscopically guided removal of large solitary synovial chondromatosis from the temporomandibular joint. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;39(12):1236-1239.

14. Gil-Salu JL, Lazaro R, Aldasoro J, Gonzalez-Darder JM. Giant solitary synovial chondromatosis of the temporomandibular joint with intracranial extension. Skull Base Surg. 1998;8(2):99-104.

15. Kang CH, Park JH, Lee DH, Kim CH, Park JM, Lee WS. Giant synovial chondromatosis of the knee mimicking a parosteal osteosarcoma: a case report. J Korean Bone Joint Tumor Soc. 2010;16(2):95-98.

16. Nihal A, Read CJ, Henderson DC, Malcolm AJ. Extra-articular giant solitary synovial chondromatosis of the foot: a case report and literature review. Foot Ankle Surg. 1999;5(1):29-32.

17. Robinson P, White LM, Kandel R, Bell RS, Wunder JS. Primary synovial osteochondromatosis of the hip: extracapsular patterns of spread. Skeletal Radiol. 2004;33(4):210-215.

18. Tallini G, Dorfman H, Brys P, et al. Correlation between clinicopathological features and karyotype in 100 cartilaginous and chordoid tumours. A report from the Chromosomes and Morphology (CHAMP) Collaborative Study Group. J Pathol. 2002;196(2):194-203.

19. Sah AP, Geller DS, Mankin HJ, et al. Malignant transformation of synovial chondromatosis of the shoulder to chondrosarcoma. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(6):1321-1328.

20. Buddingh EP, Krallman P, Neff JR, Nelson M, Liu J, Bridge JA. Chromosome 6 abnormalities are recurrent in synovial chondromatosis. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2003;140(1):18-22.

21. Rizzo M, Ghert MA, Harrelson JM, Scully SP. Chondrosarcoma of bone: analysis of 108 cases and evaluation for predictors of outcome. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;(391):224-233.

22. Davis RI, Foster H, Arthur K, Trewin S, Hamilton PW, Biggart DJ. Cell proliferation studies in primary synovial chondromatosis. J Pathol. 1998;184(1):18-23.

23. Ishikawa E, Tsuboi K, Onizawa K, et al. Chondroblastoma of the temporal base with high mitotic activity. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2002;42(11):516-520.

24. Kirin I, Jurisic D, Mokrovic H, Stanec Z, Stalekar H. Chondromyxoid fibroma of the second metacarpal bone—a case report. Coll Antropol. 2011;35(3):929-931.

1. Milgram JW. Synovial osteochondromatosis: a histopathological study of thirty cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59(6):792-801.

2. Trias A, Quintana O. Synovial chondrometaplasia: review of world literature and a study of 18 Canadian cases. Can J Surg. 1976;19(2):151-158.

3. Murphey MD, Vidal JA, Fanburg-Smith JC, Gajewski DA. Imaging of synovial chondromatosis with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2007;27(5):1465-1488.

4. Milgram JW. Synovial osteochondromatosis in association with Legg-Calve-Perthes disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1979;(145):179-182.

5. Sim FH, Dahlin DC, Ivins JC. Extra-articular synovial chondromatosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59(4):492-495.

6. Bertoni F, Unni KK, Beabout JW, Sim FH. Chondrosarcomas of the synovium. Cancer. 1991;67(1):155-162.

7. Edeiken J, Edeiken BS, Ayala AG, Raymond AK, Murray JA, Guo SQ. Giant solitary synovial chondromatosis. Skeletal Radiol. 1994;23(1):23-29.

8. Davis RI, Hamilton A, Biggart JD. Primary synovial chondromatosis: a clinicopathologic review and assessment of malignant potential. Hum Pathol. 1998;29(7):683-688.

9. Goel A, Cullen C, Paul AS, Freemont AJ. Multiple giant synovial chondromatosis of the knee. Knee. 2001;8(3):243-245.

10. Dogan A, Harman M, Uslu M, Bayram I, Akpinar F. Rocky form giant synovial chondromatosis: a case report. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14(5):465-468.

11. Eisenberg KS, Johnston JO. Synovial chondromatosis of the hip joint presenting as an intrapelvic mass: a case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972;54(1):176-178.

12. Lohmann CH, Köster G, Klinger HM, Kunze E. Giant synovial osteochondromatosis of the acromio-clavicular joint in a child. A case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2005;14(2):126-128.

13. Cai XY, Yang C, Chen MJ, Jiang B, Wang BL. Arthroscopically guided removal of large solitary synovial chondromatosis from the temporomandibular joint. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;39(12):1236-1239.

14. Gil-Salu JL, Lazaro R, Aldasoro J, Gonzalez-Darder JM. Giant solitary synovial chondromatosis of the temporomandibular joint with intracranial extension. Skull Base Surg. 1998;8(2):99-104.

15. Kang CH, Park JH, Lee DH, Kim CH, Park JM, Lee WS. Giant synovial chondromatosis of the knee mimicking a parosteal osteosarcoma: a case report. J Korean Bone Joint Tumor Soc. 2010;16(2):95-98.

16. Nihal A, Read CJ, Henderson DC, Malcolm AJ. Extra-articular giant solitary synovial chondromatosis of the foot: a case report and literature review. Foot Ankle Surg. 1999;5(1):29-32.

17. Robinson P, White LM, Kandel R, Bell RS, Wunder JS. Primary synovial osteochondromatosis of the hip: extracapsular patterns of spread. Skeletal Radiol. 2004;33(4):210-215.

18. Tallini G, Dorfman H, Brys P, et al. Correlation between clinicopathological features and karyotype in 100 cartilaginous and chordoid tumours. A report from the Chromosomes and Morphology (CHAMP) Collaborative Study Group. J Pathol. 2002;196(2):194-203.

19. Sah AP, Geller DS, Mankin HJ, et al. Malignant transformation of synovial chondromatosis of the shoulder to chondrosarcoma. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(6):1321-1328.

20. Buddingh EP, Krallman P, Neff JR, Nelson M, Liu J, Bridge JA. Chromosome 6 abnormalities are recurrent in synovial chondromatosis. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2003;140(1):18-22.

21. Rizzo M, Ghert MA, Harrelson JM, Scully SP. Chondrosarcoma of bone: analysis of 108 cases and evaluation for predictors of outcome. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;(391):224-233.

22. Davis RI, Foster H, Arthur K, Trewin S, Hamilton PW, Biggart DJ. Cell proliferation studies in primary synovial chondromatosis. J Pathol. 1998;184(1):18-23.

23. Ishikawa E, Tsuboi K, Onizawa K, et al. Chondroblastoma of the temporal base with high mitotic activity. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2002;42(11):516-520.

24. Kirin I, Jurisic D, Mokrovic H, Stanec Z, Stalekar H. Chondromyxoid fibroma of the second metacarpal bone—a case report. Coll Antropol. 2011;35(3):929-931.