User login

Problem with baby’s hearing? An intervention checklist

• Check hearing screening results for all newborns in your practice. B

• Refer all newborns who fail screening for audiologic and medical evaluation and diagnosis before 3 months of age. B

• Refer infants with diagnosed hearing loss for early intervention services no later than 6 months of age. B

• Educate families about services and resources available to them and their hearing-impaired child. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Congenital permanent hearing loss occurs in about 3 of every 1000 births.1 Undiagnosed hearing loss can result in speech-language, academic, social, and other developmental delays. Until about 20 years ago, most children with hearing loss were not diagnosed until about 3 years of age.2 By that age, opportunities for effective intervention to help these children develop communication skills were often delayed, and many children remained seriously disabled.

In this enlightened age, when newborn hearing screening is nearly universal (92%), the prospects for children with hearing impairments are brighter—but not as bright as they could be.3 That’s because more than half the newborns with positive screens are lost to follow-up.3 Too many remain “lost,” without a diagnosis or access to services, until they show up at school without the language skills they need to keep up, academically or socially, with their classmates.

The medical home can help

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the Health Resources Services Administration aggressively promote the concept of the medical home as the best locus for coordinating the care of children with special needs, and the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) has endorsed the medical home concept.2,4 According to the AAFP’s Joint Statement of Principles, the medical home is responsible for coordinating care across all elements of the health care system and the patient’s community.4 Most physicians in a recent survey believed the medical home should be responsible for coordinating services and guiding families in the development of intervention plans for children with hearing loss.5 Family physicians who provide a medical home for infants and young children are in an ideal position to ensure that children with hearing loss are not lost to follow-up and that they receive the services they need to lead healthy lives.

What follow-up entails

According to the 2007 Position Paper of the Joint Committee on Infant Hearing, a body composed of representatives from the AAP, the American Academy of Audiology, the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, and other professional organizations concerned with hearing loss, an effective program to mitigate the impact of hearing loss should follow this timetable6:

- By 1 month of age, all infants should receive hearing screening. (Of note: In 2008, the US Preventive Services Task Force issued a B recommendation for universal hearing screening of all newborns.7)

- By 3 months of age, hearing loss should be diagnosed.

- Within 1 month of diagnosis, hearing aids should be fitted for infants whose parents choose hearing aids.

- As soon as possible after diagnosis—but no later than 6 months of age—infants with confirmed, permanent hearing loss should receive early intervention services.6

Intervention services should include medical and surgical evaluation, evaluation for hearing aids, and then cochlear implants for those with severe-to-profound hearing loss who do not benefit from hearing aids. Communication assessment and therapy should also be considered. The goal of intervention is to help infants with hearing loss develop communication competence, social skills, emotional well-being, and positive self-esteem.6

The CLINICAL TOOL provides a detailed overview of the early hearing detection and intervention (EHDI) process outlined by the Joint Committee and a checklist of roles and responsibilities for physicians serving as medical homes for children with hearing loss and their families. Unfortunately, many primary caregivers report that their medical training did not prepare them to guide families through this process.8-10 This article is intended to provide the additional information caregivers have requested to help them meet these obligations.

CLINICAL TOOL

The early hearing detection and intervention process6

| Prenatal period | Birth – 1 month | By 3 months | No later than 6 months |

|---|---|---|---|

| Education for parents about the importance of newborn hearing screening and the distinction between screening and diagnosis | Hearing screening for all infants in hospital or at audiologist out-patient facility | Infants with positive screens are diagnosed by an audiologist with auditory brainstem response testing | Physician and parents monitor developmental milestones and experience with hearing aids |

| Auditory brainstem response screening for all NICU infants ≥5 days of age | Hearing loss is ruled out or confirmed | Meeting with family and early intervention personnel to develop an individualized family service plan | |

| Rescreening for all infants with risk factors who are hospitalized within 1 month of discharge | Audiologist shares results with family, medical home, and the early hearing detection and intervention coordinator | Individualized family service plan is in place, as mandated by federal law under the individuals with disabilities education Act | |

| Infants are linked to a medical home before discharge by the hospital | Families are counseled regarding diagnosis and follow-up and given educational materials | Early intervention services are instituted in accordance with the individualized family service plan | |

| Screening results are given to families and to the baby’s medical home | Audiologist recommends treatment in the medical home or referral to an ear, nose, and throat specialist for medical evaluation and treatment | Together, audiologist and family develop expectations for hearing aids | |

| Families are counseled about screening results and follow-up | Audiologist and/or physician provides referrals for genetic counseling and ophthalmologic consultation | If hearing aids are unsuccessful, families are counseled about cochlear implants | |

| Audiologist alerts parents and the medical home that child may need hearing aids and early intervention services | If family wishes, audiologist or medical home makes a referral to a cochlear implant team | ||

| Audiologist or physician counsels parents on the test results, treatments, and communication options: aural-oral, total communication, and sign language | Medical clearance and insurance authorizations are obtained for cochlear implants | ||

| Reports from all involved providers and agencies are transmitted to state early hearing detection and intervention coordinator | |||

| Checklist for family physicians | |||

| ____ Encourage all families to have their baby’s hearing screened | ____ Review screening results | ____ Review audiologic diagnostic evaluation results | ____ Coordinate early intervention services |

| ____ Explain screening procedures | ____ Make referrals for outpatient screening and audiologic diagnostic evaluation by an audiologist | ____ Ensure that an audiologic reevaluation has been completed | ____ Confer with audiologist on child’s progress with hearing aids and consideration of cochlear implants |

| ____ Assess for family history of hearing loss | ____ Ensure all infants hospitalized after discharge are rescreened | ____ Review findings from otolaryngology and audiologic consultations with family | ____ Provide families with basic information about cochlear implants |

| ____ Provide informational materials about newborn hearing screening | ____ Assess risk factors for hearing loss, including congenital and delayed-onset types | ____ Encourage family to comply with professionals’ recommendations and stress importance of keeping appointments | ____ Counsel families about the risks and benefits of cochlear implants |

| ____ Answer family’s questions about newborn screening or hearing loss | ____Ensure that screening results have been transmitted to state early hearing detection and intervention coordinator | ____ Refer for genetic counseling and ophthalmologic consultation | ____ Make referral to cochlear implant team |

| ____ Provide families with preliminary information on amplification and communication options | ____ Encourage families to comply with professionals’ recommendations | ||

| ____Confirm that families have received informational materials on screening and follow-up | ____ Make referral to audiologist for hearing aids | ____Ensure all reports are transmitted to state early hearing detection and intervention coordinator | |

| ____ Ensure hearing aids are fitted within 1 month of diagnosis | ____ Monitor developmental milestones | ||

| ____ Provide medical clearance, insurance authorization, and referral for hearing aids and early intervention services | |||

| ____ Ensure otolaryngology and audiologic results have been transmitted to state early hearing detection and intervention coordinator | |||

| NICU, neonatal intensive care unit. | |||

Getting an early start: Newborn screening

Ideally, intervention should begin before a child is born. When parents come in for prenatal visits, talk to them about the importance of newborn hearing screening. Tell them to expect that their baby will be screened at the birth hospital or at an outpatient audiology facility, and that this screening should be done by the time the baby is 1 month of age.

Tell parents their baby’s hearing will be tested with automated screening equipment that measures otoacoustic emissions from the baby’s ears or auditory brainstem response (ABR) to sound, both measurements that correlate with a child’s hearing and auditory behavior. Infants in well-baby nurseries can be screened by either technology. Infants in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) for more than 5 days should be screened with ABR technology, which is better able to pick up neural losses.6 NICU babies frequently are at higher risk for neural hearing loss including auditory neuropathy/dyssynchrony, a condition that may account for about 8% of pediatric hearing losses annually.3

Be sure to explain to expectant couples that a positive screen indicates only that a problem may exist. It is not equivalent to a diagnosis of hearing loss, which is usually made by an audiologist.

The medical home’s role. The medical home should make sure that infants who fail an initial or secondary hospital screening and those who were missed or born outside the hospital are referred for outpatient screening. Newborns who fail initial screening should have both ears rescreened before hospital discharge, even if only one ear had failed previously.6 Additionally, any infant readmitted to the hospital within the first month of life who has a condition associated with potential hearing loss should be rescreened before discharge, preferably with an ABR.6 Risk factors associated with permanent-congenital, delayed-onset, or progressive hearing loss in children are listed in the TABLE.

TABLE

Risk indicators associated with hearing loss in childhood

|

| *These indicators are of greater concern for delayed-onset hearing loss. Source: American Academy of Pediatrics, Joint Committee on Infant Hearing. Pediatrics. 2007.6 |

Reporting screening results

Screening results are useful only if they are transmitted to caregivers and families. Breakdowns in transmission are a persistent problem for the early hearing detection and intervention process.2 The process is facilitated when hospitals make sure that all babies and their families are linked to a medical home at the time of discharge.

Hospital personnel should also be responsible for providing screening results to families in a face-to-face meeting. Medical home providers should review screening results again with parents and answer any questions that might have arisen after the initial hospital stay. Screening results should be given to parents in a sensitive manner, and patient education materials should be provided in parents’ native language, written at an appropriate reading level. Because hospital staff may not be trained to do this properly, it is important that medical home providers oversee the process and address any parental concerns.2

Screening results should also be reported by the birth hospital to the state’s EHDI coordinator, part of the national tracking and surveillance system funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to ensure that all children with hearing loss achieve communication and social skills commensurate with their cognitive abilities. 11 You can find contact information for your state coordinator at www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/ehdi/documents/EHDI_contact.pdf.

Diagnosing hearing loss

When an infant who fails newborn screening testing arrives at the medical home, the urgent next step is to make sure he or she is referred to a pediatric audiologist for a complete audiologic diagnostic evaluation. Advising parents to “wait and see” is not appropriate; researchers have identified that response as a major obstacle to successful follow-up.2 The audiologic evaluation should be done by the time the baby is 3 months of age and should be performed by a pediatric audiologist specializing in diagnosis and management of young children with hearing loss.4-6

Tell parents that, with their approval, the audiologist may fit the baby with hearing aids as early as this visit, as amplification can help even very young infants hear all sounds in the environment, particularly spoken language.

Ongoing monitoring

Family practices serving as medical homes should continue to monitor children who pass their newborn screening but have high-risk factors for delayed-onset hearing loss. Those factors are listed in the TABLE. Refer children at higher risk for an audiologic diagnostic evaluation by 24 to 30 months of age.6 Follow-up on parental concerns about infant hearing or speech and monitor infants’ developmental milestones, auditory skills, and middle ear status using the AAP’s pediatric periodicity schedule.6 Conduct global developmental screenings at 9, 18, and 24 to 30 months of age, and refer for speech-language-hearing evaluations when appropriate.6

The medical home as central referral point

The medical home is a central referral point for the complex needs of children with hearing loss. The physician and all other providers involved in the child’s care should report results of diagnostic evaluations to state EHDI coordinators. The medical home’s continued involvement includes medical clearance for hearing aids, additional consultations, and screenings as necessary to help children receive needed services and keep them from being lost to the system.5,9

Referral for genetic consultation is important, because about half of all autosomal recessive sensorineural hearing losses that are not part of a syndrome are caused by mutations in the Connexin 26 GJB2 gene.12,13 Referral to a pediatric ophthalmologist is similarly important, to identify deficits in visual acuity that frequently co-occur with hearing loss, especially in preterm infants.6 Results of these consultations can assist the physician in guiding families through the intervention process.

Coordination of care among multiple providers is essential. When a family physician’s practice serves as a medical home for a child with hearing loss, the physician should oversee and coordinate the efforts of all stakeholders in the EHDI process; make referrals to, and receive reports from, all providers involved in diagnosis and treatment; and ensure that relevant information is shared. During all phases of the process, the role of the family physician is to encourage families to comply with professionals’ recommendations and to stress the importance of making and keeping scheduled appointments.

Making plans for intervention

Families with children who have any degree of permanent hearing loss in one or both ears are entitled to early intervention services.6 In most states, these services are provided by a multidisciplinary team at no or low cost through a federal grant program. Services can be home- or center-based. They may include, as needed, education for the affected child and family; physical, speech/language, and occupational therapy; and social work and psychotherapy services. The team works with the family to develop an individualized family service plan to document and guide the early intervention process.14

Families with a hearing-impaired child have a range of options to choose from in their search for an approach that is best for the child and most acceptable to them. Communication options span a continuum from emphasis on sign language as used by the deaf community to a variety of oral-aural approaches designed to lead to spoken language. Parental choices are influenced most heavily by the child’s success with hearing aids. Parents need unbiased, culturally sensitive counseling about all available communication options and hearing technologies, so they can make informed choices for their children.6

Answering parents’ questions

To ensure that parents have appropriate expectations for what auditory technology can do for their child, they need to receive information about traditional digital signal processing hearing aids, osseointegrated hearing implant systems (also known as bone-anchored hearing aids), and cochlear implants. They need to know that a trial period will probably be necessary to determine whether hearing aids are appropriate or if cochlear implantation should be considered. Cost of hearing aids and cochlear implants is a serious concern for parents, and for many, it presents a major barrier to obtaining optimal care.2

Many insurance plans cover cochlear implants, but require that children be at least 12 months of age, have bilateral profound sensorineural hearing loss (or severe-to-profound sensorineural hearing loss for those ≥24 months of age), receive minimal benefit from hearing aids, be enrolled in auditory rehabilitative therapy, and possess no medical contraindications.15 Hearing aids and cochlear implants may also be covered for children enrolled in Medicaid or the State Children’s Health Insurance Program.16 However, according to a recent evaluation of hearing screening programs nationwide, public and private insurance policies almost never provide adequate coverage for hearing services.2

As parents consider the options, be sure they are aware that some children younger than 12 months of age are receiving cochlear implants (sometimes in both ears), that stimulation of both ears is being recommended at earlier ages, and that it is also common for children to use a hearing aid in one ear and a cochlear implant in the other.17,18 Distinguishing among hearing loss types and knowing which treatment options are most effective helps physicians counsel families appropriately about making the best decisions for their children. Some physicians have expressed uncertainties about these issues and have requested additional information on this topic.19 Audiologists can help physicians obtain this information and help them to better counsel families about these options.

CORRESPONDENCE

Carole E. Johnson, PhD, AuD, 1199 Haley Center, Auburn University, Auburn, AL 36849; johns19@auburn.edu

1. Vartiainen E, Kemppinen P, Karjalainen S. Prevalence and etiology of bilateral sensorineural hearing impairment in a Finnish childhood population. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1997;41:175-185.

2. Shulman S, Besculides M, Saltzman A, et al. Evaluation of the universal newborn hearing screening and intervention program. Pediatrics. 2010;126(suppl 1):S19-S27.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Early hearing detection and intervention program. Summary of 2006 national EHDI data (version 4). October 2008. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/ncbdd/ehdi/documents/EHDI_Summ_2006_Web.pdf. Accessed December 23, 2010.

4. AAFP, AAP, ACP, AOA. Joint principles of the patient-centered medical home. February 2007. Available at: www.pcpcc.net/print/14. Accessed December 25, 2010.

5. Dorros C, Kurtzer-White E, Ahlgren M, et al. Medical home for children with hearing loss: physician perspectives and practices. Pediatrics. 2007;120:288-294.

6. American Academy of Pediatrics, Joint Committee on Infant Hearing. Year 2007 position statement: principles and guidelines for early hearing detection and intervention programs. Pediatrics. 2007;120:898-921.

7. US Preventive Services Task Force. Universal screening for hearing loss in newborns: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Pediatrics. 2008;122:143-148.

8. Brown NC, James K, Liu J, et al. Newborn hearing screening. An assessment of knowledge, attitudes, and practices among Minnesota physicians. Minn Med. 2006;89:50-54.

9. Moeller MP, White KR, Shisler L. Primary care physicians’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to newborn hearing screening. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1357-1370.

10. Johnson CE, Danhauer JL, Granali A, et al. Systematic review of physicians’ knowledge of, participation in, and attitudes toward newborn hearing screening programs. Semin Hear. 2009;30:149-164.

11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Early hearing detection and intervention (EHDI) national goals. Last updated September 17, 2010. Available at: www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/hearingloss/ehdi-goals.html. Accessed December 23, 2010.

12. Kenneson A, Van Naarden K, Boyle C. GJB2 (connexin 26) variants and nonsyndromic sensorineural hearing loss: A HuGe review. Genet Med. 2002;4:258-274.

13. Lerer I, Sagi M, Malamud E, et al. Contribution of connexin 26 mutations to nonsyndromic deafness in Ashkenazi patients and the variable phenotypic effect of the mutation 167delT. Am J Med Genet. 2000;95:53-56.

14. WrightsLaw. Early intervention (Part C of IDEA). Last updated August 16, 2010. Available at: www.wrightslaw.com/info/ei.index.htm. Accessed December 22, 2010.

15. Discolo DM, Hirose K. Pediatric cochlear implants. Am J Audiol. 2002;11:114-118.

16. McManus MA, Levtov R, White KR, et al. Medicaid reimbursement of hearing services for infants and young children. Pediatrics. 2010;126(suppl 1):S34-S42.

17. Papsin BC, Gordon KA. Bilateral cochlear implants should be the standard for children with bilateral sensorineural deafness. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;16:69-74.

18. Beijen JW, Mylanus EA, Leeuw AR, et al. Should a hearing aid in the contralateral ear be recommended for children with a unilateral cochlear implant? Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2008;117:397-403.

19. Carron JD, Moore RB, Dhaliwal AS. Perceptions of pediatric primary care physicians on congenital hearing loss and cochlear implantation. J Miss State Med Assoc. 2006;47:35-41.

• Check hearing screening results for all newborns in your practice. B

• Refer all newborns who fail screening for audiologic and medical evaluation and diagnosis before 3 months of age. B

• Refer infants with diagnosed hearing loss for early intervention services no later than 6 months of age. B

• Educate families about services and resources available to them and their hearing-impaired child. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Congenital permanent hearing loss occurs in about 3 of every 1000 births.1 Undiagnosed hearing loss can result in speech-language, academic, social, and other developmental delays. Until about 20 years ago, most children with hearing loss were not diagnosed until about 3 years of age.2 By that age, opportunities for effective intervention to help these children develop communication skills were often delayed, and many children remained seriously disabled.

In this enlightened age, when newborn hearing screening is nearly universal (92%), the prospects for children with hearing impairments are brighter—but not as bright as they could be.3 That’s because more than half the newborns with positive screens are lost to follow-up.3 Too many remain “lost,” without a diagnosis or access to services, until they show up at school without the language skills they need to keep up, academically or socially, with their classmates.

The medical home can help

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the Health Resources Services Administration aggressively promote the concept of the medical home as the best locus for coordinating the care of children with special needs, and the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) has endorsed the medical home concept.2,4 According to the AAFP’s Joint Statement of Principles, the medical home is responsible for coordinating care across all elements of the health care system and the patient’s community.4 Most physicians in a recent survey believed the medical home should be responsible for coordinating services and guiding families in the development of intervention plans for children with hearing loss.5 Family physicians who provide a medical home for infants and young children are in an ideal position to ensure that children with hearing loss are not lost to follow-up and that they receive the services they need to lead healthy lives.

What follow-up entails

According to the 2007 Position Paper of the Joint Committee on Infant Hearing, a body composed of representatives from the AAP, the American Academy of Audiology, the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, and other professional organizations concerned with hearing loss, an effective program to mitigate the impact of hearing loss should follow this timetable6:

- By 1 month of age, all infants should receive hearing screening. (Of note: In 2008, the US Preventive Services Task Force issued a B recommendation for universal hearing screening of all newborns.7)

- By 3 months of age, hearing loss should be diagnosed.

- Within 1 month of diagnosis, hearing aids should be fitted for infants whose parents choose hearing aids.

- As soon as possible after diagnosis—but no later than 6 months of age—infants with confirmed, permanent hearing loss should receive early intervention services.6

Intervention services should include medical and surgical evaluation, evaluation for hearing aids, and then cochlear implants for those with severe-to-profound hearing loss who do not benefit from hearing aids. Communication assessment and therapy should also be considered. The goal of intervention is to help infants with hearing loss develop communication competence, social skills, emotional well-being, and positive self-esteem.6

The CLINICAL TOOL provides a detailed overview of the early hearing detection and intervention (EHDI) process outlined by the Joint Committee and a checklist of roles and responsibilities for physicians serving as medical homes for children with hearing loss and their families. Unfortunately, many primary caregivers report that their medical training did not prepare them to guide families through this process.8-10 This article is intended to provide the additional information caregivers have requested to help them meet these obligations.

CLINICAL TOOL

The early hearing detection and intervention process6

| Prenatal period | Birth – 1 month | By 3 months | No later than 6 months |

|---|---|---|---|

| Education for parents about the importance of newborn hearing screening and the distinction between screening and diagnosis | Hearing screening for all infants in hospital or at audiologist out-patient facility | Infants with positive screens are diagnosed by an audiologist with auditory brainstem response testing | Physician and parents monitor developmental milestones and experience with hearing aids |

| Auditory brainstem response screening for all NICU infants ≥5 days of age | Hearing loss is ruled out or confirmed | Meeting with family and early intervention personnel to develop an individualized family service plan | |

| Rescreening for all infants with risk factors who are hospitalized within 1 month of discharge | Audiologist shares results with family, medical home, and the early hearing detection and intervention coordinator | Individualized family service plan is in place, as mandated by federal law under the individuals with disabilities education Act | |

| Infants are linked to a medical home before discharge by the hospital | Families are counseled regarding diagnosis and follow-up and given educational materials | Early intervention services are instituted in accordance with the individualized family service plan | |

| Screening results are given to families and to the baby’s medical home | Audiologist recommends treatment in the medical home or referral to an ear, nose, and throat specialist for medical evaluation and treatment | Together, audiologist and family develop expectations for hearing aids | |

| Families are counseled about screening results and follow-up | Audiologist and/or physician provides referrals for genetic counseling and ophthalmologic consultation | If hearing aids are unsuccessful, families are counseled about cochlear implants | |

| Audiologist alerts parents and the medical home that child may need hearing aids and early intervention services | If family wishes, audiologist or medical home makes a referral to a cochlear implant team | ||

| Audiologist or physician counsels parents on the test results, treatments, and communication options: aural-oral, total communication, and sign language | Medical clearance and insurance authorizations are obtained for cochlear implants | ||

| Reports from all involved providers and agencies are transmitted to state early hearing detection and intervention coordinator | |||

| Checklist for family physicians | |||

| ____ Encourage all families to have their baby’s hearing screened | ____ Review screening results | ____ Review audiologic diagnostic evaluation results | ____ Coordinate early intervention services |

| ____ Explain screening procedures | ____ Make referrals for outpatient screening and audiologic diagnostic evaluation by an audiologist | ____ Ensure that an audiologic reevaluation has been completed | ____ Confer with audiologist on child’s progress with hearing aids and consideration of cochlear implants |

| ____ Assess for family history of hearing loss | ____ Ensure all infants hospitalized after discharge are rescreened | ____ Review findings from otolaryngology and audiologic consultations with family | ____ Provide families with basic information about cochlear implants |

| ____ Provide informational materials about newborn hearing screening | ____ Assess risk factors for hearing loss, including congenital and delayed-onset types | ____ Encourage family to comply with professionals’ recommendations and stress importance of keeping appointments | ____ Counsel families about the risks and benefits of cochlear implants |

| ____ Answer family’s questions about newborn screening or hearing loss | ____Ensure that screening results have been transmitted to state early hearing detection and intervention coordinator | ____ Refer for genetic counseling and ophthalmologic consultation | ____ Make referral to cochlear implant team |

| ____ Provide families with preliminary information on amplification and communication options | ____ Encourage families to comply with professionals’ recommendations | ||

| ____Confirm that families have received informational materials on screening and follow-up | ____ Make referral to audiologist for hearing aids | ____Ensure all reports are transmitted to state early hearing detection and intervention coordinator | |

| ____ Ensure hearing aids are fitted within 1 month of diagnosis | ____ Monitor developmental milestones | ||

| ____ Provide medical clearance, insurance authorization, and referral for hearing aids and early intervention services | |||

| ____ Ensure otolaryngology and audiologic results have been transmitted to state early hearing detection and intervention coordinator | |||

| NICU, neonatal intensive care unit. | |||

Getting an early start: Newborn screening

Ideally, intervention should begin before a child is born. When parents come in for prenatal visits, talk to them about the importance of newborn hearing screening. Tell them to expect that their baby will be screened at the birth hospital or at an outpatient audiology facility, and that this screening should be done by the time the baby is 1 month of age.

Tell parents their baby’s hearing will be tested with automated screening equipment that measures otoacoustic emissions from the baby’s ears or auditory brainstem response (ABR) to sound, both measurements that correlate with a child’s hearing and auditory behavior. Infants in well-baby nurseries can be screened by either technology. Infants in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) for more than 5 days should be screened with ABR technology, which is better able to pick up neural losses.6 NICU babies frequently are at higher risk for neural hearing loss including auditory neuropathy/dyssynchrony, a condition that may account for about 8% of pediatric hearing losses annually.3

Be sure to explain to expectant couples that a positive screen indicates only that a problem may exist. It is not equivalent to a diagnosis of hearing loss, which is usually made by an audiologist.

The medical home’s role. The medical home should make sure that infants who fail an initial or secondary hospital screening and those who were missed or born outside the hospital are referred for outpatient screening. Newborns who fail initial screening should have both ears rescreened before hospital discharge, even if only one ear had failed previously.6 Additionally, any infant readmitted to the hospital within the first month of life who has a condition associated with potential hearing loss should be rescreened before discharge, preferably with an ABR.6 Risk factors associated with permanent-congenital, delayed-onset, or progressive hearing loss in children are listed in the TABLE.

TABLE

Risk indicators associated with hearing loss in childhood

|

| *These indicators are of greater concern for delayed-onset hearing loss. Source: American Academy of Pediatrics, Joint Committee on Infant Hearing. Pediatrics. 2007.6 |

Reporting screening results

Screening results are useful only if they are transmitted to caregivers and families. Breakdowns in transmission are a persistent problem for the early hearing detection and intervention process.2 The process is facilitated when hospitals make sure that all babies and their families are linked to a medical home at the time of discharge.

Hospital personnel should also be responsible for providing screening results to families in a face-to-face meeting. Medical home providers should review screening results again with parents and answer any questions that might have arisen after the initial hospital stay. Screening results should be given to parents in a sensitive manner, and patient education materials should be provided in parents’ native language, written at an appropriate reading level. Because hospital staff may not be trained to do this properly, it is important that medical home providers oversee the process and address any parental concerns.2

Screening results should also be reported by the birth hospital to the state’s EHDI coordinator, part of the national tracking and surveillance system funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to ensure that all children with hearing loss achieve communication and social skills commensurate with their cognitive abilities. 11 You can find contact information for your state coordinator at www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/ehdi/documents/EHDI_contact.pdf.

Diagnosing hearing loss

When an infant who fails newborn screening testing arrives at the medical home, the urgent next step is to make sure he or she is referred to a pediatric audiologist for a complete audiologic diagnostic evaluation. Advising parents to “wait and see” is not appropriate; researchers have identified that response as a major obstacle to successful follow-up.2 The audiologic evaluation should be done by the time the baby is 3 months of age and should be performed by a pediatric audiologist specializing in diagnosis and management of young children with hearing loss.4-6

Tell parents that, with their approval, the audiologist may fit the baby with hearing aids as early as this visit, as amplification can help even very young infants hear all sounds in the environment, particularly spoken language.

Ongoing monitoring

Family practices serving as medical homes should continue to monitor children who pass their newborn screening but have high-risk factors for delayed-onset hearing loss. Those factors are listed in the TABLE. Refer children at higher risk for an audiologic diagnostic evaluation by 24 to 30 months of age.6 Follow-up on parental concerns about infant hearing or speech and monitor infants’ developmental milestones, auditory skills, and middle ear status using the AAP’s pediatric periodicity schedule.6 Conduct global developmental screenings at 9, 18, and 24 to 30 months of age, and refer for speech-language-hearing evaluations when appropriate.6

The medical home as central referral point

The medical home is a central referral point for the complex needs of children with hearing loss. The physician and all other providers involved in the child’s care should report results of diagnostic evaluations to state EHDI coordinators. The medical home’s continued involvement includes medical clearance for hearing aids, additional consultations, and screenings as necessary to help children receive needed services and keep them from being lost to the system.5,9

Referral for genetic consultation is important, because about half of all autosomal recessive sensorineural hearing losses that are not part of a syndrome are caused by mutations in the Connexin 26 GJB2 gene.12,13 Referral to a pediatric ophthalmologist is similarly important, to identify deficits in visual acuity that frequently co-occur with hearing loss, especially in preterm infants.6 Results of these consultations can assist the physician in guiding families through the intervention process.

Coordination of care among multiple providers is essential. When a family physician’s practice serves as a medical home for a child with hearing loss, the physician should oversee and coordinate the efforts of all stakeholders in the EHDI process; make referrals to, and receive reports from, all providers involved in diagnosis and treatment; and ensure that relevant information is shared. During all phases of the process, the role of the family physician is to encourage families to comply with professionals’ recommendations and to stress the importance of making and keeping scheduled appointments.

Making plans for intervention

Families with children who have any degree of permanent hearing loss in one or both ears are entitled to early intervention services.6 In most states, these services are provided by a multidisciplinary team at no or low cost through a federal grant program. Services can be home- or center-based. They may include, as needed, education for the affected child and family; physical, speech/language, and occupational therapy; and social work and psychotherapy services. The team works with the family to develop an individualized family service plan to document and guide the early intervention process.14

Families with a hearing-impaired child have a range of options to choose from in their search for an approach that is best for the child and most acceptable to them. Communication options span a continuum from emphasis on sign language as used by the deaf community to a variety of oral-aural approaches designed to lead to spoken language. Parental choices are influenced most heavily by the child’s success with hearing aids. Parents need unbiased, culturally sensitive counseling about all available communication options and hearing technologies, so they can make informed choices for their children.6

Answering parents’ questions

To ensure that parents have appropriate expectations for what auditory technology can do for their child, they need to receive information about traditional digital signal processing hearing aids, osseointegrated hearing implant systems (also known as bone-anchored hearing aids), and cochlear implants. They need to know that a trial period will probably be necessary to determine whether hearing aids are appropriate or if cochlear implantation should be considered. Cost of hearing aids and cochlear implants is a serious concern for parents, and for many, it presents a major barrier to obtaining optimal care.2

Many insurance plans cover cochlear implants, but require that children be at least 12 months of age, have bilateral profound sensorineural hearing loss (or severe-to-profound sensorineural hearing loss for those ≥24 months of age), receive minimal benefit from hearing aids, be enrolled in auditory rehabilitative therapy, and possess no medical contraindications.15 Hearing aids and cochlear implants may also be covered for children enrolled in Medicaid or the State Children’s Health Insurance Program.16 However, according to a recent evaluation of hearing screening programs nationwide, public and private insurance policies almost never provide adequate coverage for hearing services.2

As parents consider the options, be sure they are aware that some children younger than 12 months of age are receiving cochlear implants (sometimes in both ears), that stimulation of both ears is being recommended at earlier ages, and that it is also common for children to use a hearing aid in one ear and a cochlear implant in the other.17,18 Distinguishing among hearing loss types and knowing which treatment options are most effective helps physicians counsel families appropriately about making the best decisions for their children. Some physicians have expressed uncertainties about these issues and have requested additional information on this topic.19 Audiologists can help physicians obtain this information and help them to better counsel families about these options.

CORRESPONDENCE

Carole E. Johnson, PhD, AuD, 1199 Haley Center, Auburn University, Auburn, AL 36849; johns19@auburn.edu

• Check hearing screening results for all newborns in your practice. B

• Refer all newborns who fail screening for audiologic and medical evaluation and diagnosis before 3 months of age. B

• Refer infants with diagnosed hearing loss for early intervention services no later than 6 months of age. B

• Educate families about services and resources available to them and their hearing-impaired child. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Congenital permanent hearing loss occurs in about 3 of every 1000 births.1 Undiagnosed hearing loss can result in speech-language, academic, social, and other developmental delays. Until about 20 years ago, most children with hearing loss were not diagnosed until about 3 years of age.2 By that age, opportunities for effective intervention to help these children develop communication skills were often delayed, and many children remained seriously disabled.

In this enlightened age, when newborn hearing screening is nearly universal (92%), the prospects for children with hearing impairments are brighter—but not as bright as they could be.3 That’s because more than half the newborns with positive screens are lost to follow-up.3 Too many remain “lost,” without a diagnosis or access to services, until they show up at school without the language skills they need to keep up, academically or socially, with their classmates.

The medical home can help

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the Health Resources Services Administration aggressively promote the concept of the medical home as the best locus for coordinating the care of children with special needs, and the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) has endorsed the medical home concept.2,4 According to the AAFP’s Joint Statement of Principles, the medical home is responsible for coordinating care across all elements of the health care system and the patient’s community.4 Most physicians in a recent survey believed the medical home should be responsible for coordinating services and guiding families in the development of intervention plans for children with hearing loss.5 Family physicians who provide a medical home for infants and young children are in an ideal position to ensure that children with hearing loss are not lost to follow-up and that they receive the services they need to lead healthy lives.

What follow-up entails

According to the 2007 Position Paper of the Joint Committee on Infant Hearing, a body composed of representatives from the AAP, the American Academy of Audiology, the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, and other professional organizations concerned with hearing loss, an effective program to mitigate the impact of hearing loss should follow this timetable6:

- By 1 month of age, all infants should receive hearing screening. (Of note: In 2008, the US Preventive Services Task Force issued a B recommendation for universal hearing screening of all newborns.7)

- By 3 months of age, hearing loss should be diagnosed.

- Within 1 month of diagnosis, hearing aids should be fitted for infants whose parents choose hearing aids.

- As soon as possible after diagnosis—but no later than 6 months of age—infants with confirmed, permanent hearing loss should receive early intervention services.6

Intervention services should include medical and surgical evaluation, evaluation for hearing aids, and then cochlear implants for those with severe-to-profound hearing loss who do not benefit from hearing aids. Communication assessment and therapy should also be considered. The goal of intervention is to help infants with hearing loss develop communication competence, social skills, emotional well-being, and positive self-esteem.6

The CLINICAL TOOL provides a detailed overview of the early hearing detection and intervention (EHDI) process outlined by the Joint Committee and a checklist of roles and responsibilities for physicians serving as medical homes for children with hearing loss and their families. Unfortunately, many primary caregivers report that their medical training did not prepare them to guide families through this process.8-10 This article is intended to provide the additional information caregivers have requested to help them meet these obligations.

CLINICAL TOOL

The early hearing detection and intervention process6

| Prenatal period | Birth – 1 month | By 3 months | No later than 6 months |

|---|---|---|---|

| Education for parents about the importance of newborn hearing screening and the distinction between screening and diagnosis | Hearing screening for all infants in hospital or at audiologist out-patient facility | Infants with positive screens are diagnosed by an audiologist with auditory brainstem response testing | Physician and parents monitor developmental milestones and experience with hearing aids |

| Auditory brainstem response screening for all NICU infants ≥5 days of age | Hearing loss is ruled out or confirmed | Meeting with family and early intervention personnel to develop an individualized family service plan | |

| Rescreening for all infants with risk factors who are hospitalized within 1 month of discharge | Audiologist shares results with family, medical home, and the early hearing detection and intervention coordinator | Individualized family service plan is in place, as mandated by federal law under the individuals with disabilities education Act | |

| Infants are linked to a medical home before discharge by the hospital | Families are counseled regarding diagnosis and follow-up and given educational materials | Early intervention services are instituted in accordance with the individualized family service plan | |

| Screening results are given to families and to the baby’s medical home | Audiologist recommends treatment in the medical home or referral to an ear, nose, and throat specialist for medical evaluation and treatment | Together, audiologist and family develop expectations for hearing aids | |

| Families are counseled about screening results and follow-up | Audiologist and/or physician provides referrals for genetic counseling and ophthalmologic consultation | If hearing aids are unsuccessful, families are counseled about cochlear implants | |

| Audiologist alerts parents and the medical home that child may need hearing aids and early intervention services | If family wishes, audiologist or medical home makes a referral to a cochlear implant team | ||

| Audiologist or physician counsels parents on the test results, treatments, and communication options: aural-oral, total communication, and sign language | Medical clearance and insurance authorizations are obtained for cochlear implants | ||

| Reports from all involved providers and agencies are transmitted to state early hearing detection and intervention coordinator | |||

| Checklist for family physicians | |||

| ____ Encourage all families to have their baby’s hearing screened | ____ Review screening results | ____ Review audiologic diagnostic evaluation results | ____ Coordinate early intervention services |

| ____ Explain screening procedures | ____ Make referrals for outpatient screening and audiologic diagnostic evaluation by an audiologist | ____ Ensure that an audiologic reevaluation has been completed | ____ Confer with audiologist on child’s progress with hearing aids and consideration of cochlear implants |

| ____ Assess for family history of hearing loss | ____ Ensure all infants hospitalized after discharge are rescreened | ____ Review findings from otolaryngology and audiologic consultations with family | ____ Provide families with basic information about cochlear implants |

| ____ Provide informational materials about newborn hearing screening | ____ Assess risk factors for hearing loss, including congenital and delayed-onset types | ____ Encourage family to comply with professionals’ recommendations and stress importance of keeping appointments | ____ Counsel families about the risks and benefits of cochlear implants |

| ____ Answer family’s questions about newborn screening or hearing loss | ____Ensure that screening results have been transmitted to state early hearing detection and intervention coordinator | ____ Refer for genetic counseling and ophthalmologic consultation | ____ Make referral to cochlear implant team |

| ____ Provide families with preliminary information on amplification and communication options | ____ Encourage families to comply with professionals’ recommendations | ||

| ____Confirm that families have received informational materials on screening and follow-up | ____ Make referral to audiologist for hearing aids | ____Ensure all reports are transmitted to state early hearing detection and intervention coordinator | |

| ____ Ensure hearing aids are fitted within 1 month of diagnosis | ____ Monitor developmental milestones | ||

| ____ Provide medical clearance, insurance authorization, and referral for hearing aids and early intervention services | |||

| ____ Ensure otolaryngology and audiologic results have been transmitted to state early hearing detection and intervention coordinator | |||

| NICU, neonatal intensive care unit. | |||

Getting an early start: Newborn screening

Ideally, intervention should begin before a child is born. When parents come in for prenatal visits, talk to them about the importance of newborn hearing screening. Tell them to expect that their baby will be screened at the birth hospital or at an outpatient audiology facility, and that this screening should be done by the time the baby is 1 month of age.

Tell parents their baby’s hearing will be tested with automated screening equipment that measures otoacoustic emissions from the baby’s ears or auditory brainstem response (ABR) to sound, both measurements that correlate with a child’s hearing and auditory behavior. Infants in well-baby nurseries can be screened by either technology. Infants in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) for more than 5 days should be screened with ABR technology, which is better able to pick up neural losses.6 NICU babies frequently are at higher risk for neural hearing loss including auditory neuropathy/dyssynchrony, a condition that may account for about 8% of pediatric hearing losses annually.3

Be sure to explain to expectant couples that a positive screen indicates only that a problem may exist. It is not equivalent to a diagnosis of hearing loss, which is usually made by an audiologist.

The medical home’s role. The medical home should make sure that infants who fail an initial or secondary hospital screening and those who were missed or born outside the hospital are referred for outpatient screening. Newborns who fail initial screening should have both ears rescreened before hospital discharge, even if only one ear had failed previously.6 Additionally, any infant readmitted to the hospital within the first month of life who has a condition associated with potential hearing loss should be rescreened before discharge, preferably with an ABR.6 Risk factors associated with permanent-congenital, delayed-onset, or progressive hearing loss in children are listed in the TABLE.

TABLE

Risk indicators associated with hearing loss in childhood

|

| *These indicators are of greater concern for delayed-onset hearing loss. Source: American Academy of Pediatrics, Joint Committee on Infant Hearing. Pediatrics. 2007.6 |

Reporting screening results

Screening results are useful only if they are transmitted to caregivers and families. Breakdowns in transmission are a persistent problem for the early hearing detection and intervention process.2 The process is facilitated when hospitals make sure that all babies and their families are linked to a medical home at the time of discharge.

Hospital personnel should also be responsible for providing screening results to families in a face-to-face meeting. Medical home providers should review screening results again with parents and answer any questions that might have arisen after the initial hospital stay. Screening results should be given to parents in a sensitive manner, and patient education materials should be provided in parents’ native language, written at an appropriate reading level. Because hospital staff may not be trained to do this properly, it is important that medical home providers oversee the process and address any parental concerns.2

Screening results should also be reported by the birth hospital to the state’s EHDI coordinator, part of the national tracking and surveillance system funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to ensure that all children with hearing loss achieve communication and social skills commensurate with their cognitive abilities. 11 You can find contact information for your state coordinator at www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/ehdi/documents/EHDI_contact.pdf.

Diagnosing hearing loss

When an infant who fails newborn screening testing arrives at the medical home, the urgent next step is to make sure he or she is referred to a pediatric audiologist for a complete audiologic diagnostic evaluation. Advising parents to “wait and see” is not appropriate; researchers have identified that response as a major obstacle to successful follow-up.2 The audiologic evaluation should be done by the time the baby is 3 months of age and should be performed by a pediatric audiologist specializing in diagnosis and management of young children with hearing loss.4-6

Tell parents that, with their approval, the audiologist may fit the baby with hearing aids as early as this visit, as amplification can help even very young infants hear all sounds in the environment, particularly spoken language.

Ongoing monitoring

Family practices serving as medical homes should continue to monitor children who pass their newborn screening but have high-risk factors for delayed-onset hearing loss. Those factors are listed in the TABLE. Refer children at higher risk for an audiologic diagnostic evaluation by 24 to 30 months of age.6 Follow-up on parental concerns about infant hearing or speech and monitor infants’ developmental milestones, auditory skills, and middle ear status using the AAP’s pediatric periodicity schedule.6 Conduct global developmental screenings at 9, 18, and 24 to 30 months of age, and refer for speech-language-hearing evaluations when appropriate.6

The medical home as central referral point

The medical home is a central referral point for the complex needs of children with hearing loss. The physician and all other providers involved in the child’s care should report results of diagnostic evaluations to state EHDI coordinators. The medical home’s continued involvement includes medical clearance for hearing aids, additional consultations, and screenings as necessary to help children receive needed services and keep them from being lost to the system.5,9

Referral for genetic consultation is important, because about half of all autosomal recessive sensorineural hearing losses that are not part of a syndrome are caused by mutations in the Connexin 26 GJB2 gene.12,13 Referral to a pediatric ophthalmologist is similarly important, to identify deficits in visual acuity that frequently co-occur with hearing loss, especially in preterm infants.6 Results of these consultations can assist the physician in guiding families through the intervention process.

Coordination of care among multiple providers is essential. When a family physician’s practice serves as a medical home for a child with hearing loss, the physician should oversee and coordinate the efforts of all stakeholders in the EHDI process; make referrals to, and receive reports from, all providers involved in diagnosis and treatment; and ensure that relevant information is shared. During all phases of the process, the role of the family physician is to encourage families to comply with professionals’ recommendations and to stress the importance of making and keeping scheduled appointments.

Making plans for intervention

Families with children who have any degree of permanent hearing loss in one or both ears are entitled to early intervention services.6 In most states, these services are provided by a multidisciplinary team at no or low cost through a federal grant program. Services can be home- or center-based. They may include, as needed, education for the affected child and family; physical, speech/language, and occupational therapy; and social work and psychotherapy services. The team works with the family to develop an individualized family service plan to document and guide the early intervention process.14

Families with a hearing-impaired child have a range of options to choose from in their search for an approach that is best for the child and most acceptable to them. Communication options span a continuum from emphasis on sign language as used by the deaf community to a variety of oral-aural approaches designed to lead to spoken language. Parental choices are influenced most heavily by the child’s success with hearing aids. Parents need unbiased, culturally sensitive counseling about all available communication options and hearing technologies, so they can make informed choices for their children.6

Answering parents’ questions

To ensure that parents have appropriate expectations for what auditory technology can do for their child, they need to receive information about traditional digital signal processing hearing aids, osseointegrated hearing implant systems (also known as bone-anchored hearing aids), and cochlear implants. They need to know that a trial period will probably be necessary to determine whether hearing aids are appropriate or if cochlear implantation should be considered. Cost of hearing aids and cochlear implants is a serious concern for parents, and for many, it presents a major barrier to obtaining optimal care.2

Many insurance plans cover cochlear implants, but require that children be at least 12 months of age, have bilateral profound sensorineural hearing loss (or severe-to-profound sensorineural hearing loss for those ≥24 months of age), receive minimal benefit from hearing aids, be enrolled in auditory rehabilitative therapy, and possess no medical contraindications.15 Hearing aids and cochlear implants may also be covered for children enrolled in Medicaid or the State Children’s Health Insurance Program.16 However, according to a recent evaluation of hearing screening programs nationwide, public and private insurance policies almost never provide adequate coverage for hearing services.2

As parents consider the options, be sure they are aware that some children younger than 12 months of age are receiving cochlear implants (sometimes in both ears), that stimulation of both ears is being recommended at earlier ages, and that it is also common for children to use a hearing aid in one ear and a cochlear implant in the other.17,18 Distinguishing among hearing loss types and knowing which treatment options are most effective helps physicians counsel families appropriately about making the best decisions for their children. Some physicians have expressed uncertainties about these issues and have requested additional information on this topic.19 Audiologists can help physicians obtain this information and help them to better counsel families about these options.

CORRESPONDENCE

Carole E. Johnson, PhD, AuD, 1199 Haley Center, Auburn University, Auburn, AL 36849; johns19@auburn.edu

1. Vartiainen E, Kemppinen P, Karjalainen S. Prevalence and etiology of bilateral sensorineural hearing impairment in a Finnish childhood population. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1997;41:175-185.

2. Shulman S, Besculides M, Saltzman A, et al. Evaluation of the universal newborn hearing screening and intervention program. Pediatrics. 2010;126(suppl 1):S19-S27.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Early hearing detection and intervention program. Summary of 2006 national EHDI data (version 4). October 2008. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/ncbdd/ehdi/documents/EHDI_Summ_2006_Web.pdf. Accessed December 23, 2010.

4. AAFP, AAP, ACP, AOA. Joint principles of the patient-centered medical home. February 2007. Available at: www.pcpcc.net/print/14. Accessed December 25, 2010.

5. Dorros C, Kurtzer-White E, Ahlgren M, et al. Medical home for children with hearing loss: physician perspectives and practices. Pediatrics. 2007;120:288-294.

6. American Academy of Pediatrics, Joint Committee on Infant Hearing. Year 2007 position statement: principles and guidelines for early hearing detection and intervention programs. Pediatrics. 2007;120:898-921.

7. US Preventive Services Task Force. Universal screening for hearing loss in newborns: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Pediatrics. 2008;122:143-148.

8. Brown NC, James K, Liu J, et al. Newborn hearing screening. An assessment of knowledge, attitudes, and practices among Minnesota physicians. Minn Med. 2006;89:50-54.

9. Moeller MP, White KR, Shisler L. Primary care physicians’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to newborn hearing screening. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1357-1370.

10. Johnson CE, Danhauer JL, Granali A, et al. Systematic review of physicians’ knowledge of, participation in, and attitudes toward newborn hearing screening programs. Semin Hear. 2009;30:149-164.

11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Early hearing detection and intervention (EHDI) national goals. Last updated September 17, 2010. Available at: www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/hearingloss/ehdi-goals.html. Accessed December 23, 2010.

12. Kenneson A, Van Naarden K, Boyle C. GJB2 (connexin 26) variants and nonsyndromic sensorineural hearing loss: A HuGe review. Genet Med. 2002;4:258-274.

13. Lerer I, Sagi M, Malamud E, et al. Contribution of connexin 26 mutations to nonsyndromic deafness in Ashkenazi patients and the variable phenotypic effect of the mutation 167delT. Am J Med Genet. 2000;95:53-56.

14. WrightsLaw. Early intervention (Part C of IDEA). Last updated August 16, 2010. Available at: www.wrightslaw.com/info/ei.index.htm. Accessed December 22, 2010.

15. Discolo DM, Hirose K. Pediatric cochlear implants. Am J Audiol. 2002;11:114-118.

16. McManus MA, Levtov R, White KR, et al. Medicaid reimbursement of hearing services for infants and young children. Pediatrics. 2010;126(suppl 1):S34-S42.

17. Papsin BC, Gordon KA. Bilateral cochlear implants should be the standard for children with bilateral sensorineural deafness. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;16:69-74.

18. Beijen JW, Mylanus EA, Leeuw AR, et al. Should a hearing aid in the contralateral ear be recommended for children with a unilateral cochlear implant? Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2008;117:397-403.

19. Carron JD, Moore RB, Dhaliwal AS. Perceptions of pediatric primary care physicians on congenital hearing loss and cochlear implantation. J Miss State Med Assoc. 2006;47:35-41.

1. Vartiainen E, Kemppinen P, Karjalainen S. Prevalence and etiology of bilateral sensorineural hearing impairment in a Finnish childhood population. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1997;41:175-185.

2. Shulman S, Besculides M, Saltzman A, et al. Evaluation of the universal newborn hearing screening and intervention program. Pediatrics. 2010;126(suppl 1):S19-S27.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Early hearing detection and intervention program. Summary of 2006 national EHDI data (version 4). October 2008. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/ncbdd/ehdi/documents/EHDI_Summ_2006_Web.pdf. Accessed December 23, 2010.

4. AAFP, AAP, ACP, AOA. Joint principles of the patient-centered medical home. February 2007. Available at: www.pcpcc.net/print/14. Accessed December 25, 2010.

5. Dorros C, Kurtzer-White E, Ahlgren M, et al. Medical home for children with hearing loss: physician perspectives and practices. Pediatrics. 2007;120:288-294.

6. American Academy of Pediatrics, Joint Committee on Infant Hearing. Year 2007 position statement: principles and guidelines for early hearing detection and intervention programs. Pediatrics. 2007;120:898-921.

7. US Preventive Services Task Force. Universal screening for hearing loss in newborns: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Pediatrics. 2008;122:143-148.

8. Brown NC, James K, Liu J, et al. Newborn hearing screening. An assessment of knowledge, attitudes, and practices among Minnesota physicians. Minn Med. 2006;89:50-54.

9. Moeller MP, White KR, Shisler L. Primary care physicians’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to newborn hearing screening. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1357-1370.

10. Johnson CE, Danhauer JL, Granali A, et al. Systematic review of physicians’ knowledge of, participation in, and attitudes toward newborn hearing screening programs. Semin Hear. 2009;30:149-164.

11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Early hearing detection and intervention (EHDI) national goals. Last updated September 17, 2010. Available at: www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/hearingloss/ehdi-goals.html. Accessed December 23, 2010.

12. Kenneson A, Van Naarden K, Boyle C. GJB2 (connexin 26) variants and nonsyndromic sensorineural hearing loss: A HuGe review. Genet Med. 2002;4:258-274.

13. Lerer I, Sagi M, Malamud E, et al. Contribution of connexin 26 mutations to nonsyndromic deafness in Ashkenazi patients and the variable phenotypic effect of the mutation 167delT. Am J Med Genet. 2000;95:53-56.

14. WrightsLaw. Early intervention (Part C of IDEA). Last updated August 16, 2010. Available at: www.wrightslaw.com/info/ei.index.htm. Accessed December 22, 2010.

15. Discolo DM, Hirose K. Pediatric cochlear implants. Am J Audiol. 2002;11:114-118.

16. McManus MA, Levtov R, White KR, et al. Medicaid reimbursement of hearing services for infants and young children. Pediatrics. 2010;126(suppl 1):S34-S42.

17. Papsin BC, Gordon KA. Bilateral cochlear implants should be the standard for children with bilateral sensorineural deafness. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;16:69-74.

18. Beijen JW, Mylanus EA, Leeuw AR, et al. Should a hearing aid in the contralateral ear be recommended for children with a unilateral cochlear implant? Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2008;117:397-403.

19. Carron JD, Moore RB, Dhaliwal AS. Perceptions of pediatric primary care physicians on congenital hearing loss and cochlear implantation. J Miss State Med Assoc. 2006;47:35-41.

EYE ON THE ELDERLY—Screening for hearing loss, risk of falls: A hassle-free approach

- Simply asking elderly patients whether they have trouble hearing is an effective start to screening for hearing loss (SOR: B).

- Refer elderly patients with suspected hearing impairment for audiologic diagnosis and nonmedical rehabilitation treatment, including hearing aids (SOR: B).

- To assess a patient’s risk of falling, review gait, balance disorders, weakness, environmental hazards, and medications (SOR: A).

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

- Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

- Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

- Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

“Do you have a hearing problem now? Have you fallen recently?” These 2 simple questions are the first step in assessing a patient’s hearing status and risk of falls—a screening opportunity too often overlooked. Although family physicians are well qualified to address hearing loss and the risk of falls, screening elderly patients for these problems often seems like a lower priority than evaluating for serious, or potentially life-threatening, conditions. In a recent national survey of primary care physicians, most said they had little time to screen for hearing loss or vestibular or balance disorders and did so only if patients broached the subject or showed clear evidence of risk.1

Screening for hearing impairment in patients 65 years of age and older, with referral to appropriate specialists, ranked 15th among services deemed effective by the US Preventive Services Task Force and the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices2,3—outranking screening for osteoporosis, cholesterol, and diabetes.

There is no evidence favoring any particular screening procedure. As a result, physicians have considerable leeway in assessing elderly patients’ functional ability and safety, including the risk of falls that may be precipitated by an impaired vestibular system and balance disorders.4

Screening for these problems need not be onerous. It can be accomplished as part of your continuity of care with longstanding patients or during the preventive care examination that Medicare offers newly enrolled patients. This review, and the screening tools and strategies that accompany it, will help you get started.

Hearing loss screening: Make it easier to do

Bilateral hearing impairment affects 1 in 3 adults over 65 years of age5 and is the third most common chronic condition among the elderly,6 trailing only arthritis and hypertension. Documented problems associated with hearing loss include social isolation, depression and anxiety, loneliness, diminished self-efficacy, and stressful relationships with family, friends, and coworkers who may experience frustration, impatience, anger, pity, or guilt in trying to communicate with a person who has a hearing loss.7-9

The mental, emotional, and social consequences of untreated hearing loss negatively affect patients’ health-related quality of life (HRQoL).8,10-15 Hearing loss also compromises patients’ ability to interact with you and to understand—and follow—your recommendations.

Simplify screening. A recent study assessed 2 hearing screening methods used with older adults who also underwent audiologic evaluation as part of the biennial examination for the Framingham Heart Study.16 It found that simply asking, “Do you have a hearing problem now?” effectively identified potential deficits. If you use the American Academy of Family Physicians’ (AAFP) Medicare Initial Preventive Physical Examination Encounter Form,17 consider replacing its entry for hearing loss with this simple question (See “Medicare preventive exam: Where the AAFP encounter form falls short”).

We recommend that you pose the question to elderly patients or their family members during regular office visits. If the answer is Yes, immediately assess the patient’s ability to understand conversational speech. If necessary, use an inexpensive amplification device to make it easier for you and your patient to communicate. Referral to an audiologist for a comprehensive evaluation may be indicated, as well.

The American Academy of Family Physicians’ (AAFP) Medicare Initial Preventive Physical Examination Encounter Form17 does not fully address hearing screening. Unlike the Depression Screen and Functional Ability/Safety Screen sections, which require Yes or No responses to questions, the section covering hearing merely presents the term “Hearing Evaluation,” followed by a space for recording information.

Although the form clearly states that a Yes response to any question about depression or function/safety should trigger further evaluation, there is no such recommendation for further evaluation of hearing. Thus, some practitioners short on time may overlook hearing screening entirely, and some elderly patients with sensorineural hearing loss may not receive appropriate education, counseling, or referral.

Furthermore, the second page of the AAFP form that is given to patients and makes recommendations for scheduled follow-up does not even mention hearing or the risk of falling. That’s why it’s important to remember to cover these areas with your elderly patients—and why you may want to ask the questions, “Do you have a hearing problem now?” and “Have you fallen recently?”

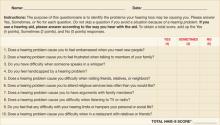

A time-saving suggestion. You can save precious consultation time by having elderly patients complete a standardized self-assessment questionnaire such as the Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly-Screening version (HHIE-S) (FIGURE 1) while they’re in the waiting room.18,19 When hearing loss is identified, counsel the patient as appropriate and strongly recommend further audiologic testing and management.20 The HHIE-S can help patients realize the social and emotional consequences of hearing loss, which may encourage them to seek assistance. But many won’t do so without your recommendation.

Let patients know something can be done. Evidence shows that nonmedical management of sensorineural hearing loss, including the fitting of hearing aids, is critical in helping older adults improve communication and reduce psychosocial problems.10,21

Recently, a task force of the American Academy of Audiology conducted a systematic review of the HRQoL benefits of amplification in adults.21 A meta-analysis revealed that hearing aids had at least a small effect on HRQoL, as measured by generic health instruments (eg, the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-36), and medium-to-large effects when disease-specific hearing outcome measures (eg, the HHIE) were used. Hearing aids, combined with auditory rehabilitation, changed patients’ perception of their handicap to a greater extent than amplification alone, particularly during the initial stage of adjusting to a device.22,23

Preprinted forms can help educate patients about hearing loss and the benefits of amplification. The PATIENT HANDOUT (ARE YOU HAVING HEARING PROBLEMS?) explains the causes and symptoms of sensorineural hearing loss, as well as diagnosis, frequency of audiologic evaluations, and treatments.

Sensorineural hearing loss occurs when sensory receptors (hair cells) in the inner ear (cochlea) or hearing nerve pathways to the brain are damaged. It is usually permanent and cannot be treated medically or surgically, but hearing aids almost always help.

Hearing loss most commonly results from age-related changes in the inner ear. Other possible causes are excessive noise exposure, drugs that are toxic to the auditory system, certain viruses or diseases, head trauma, and genetic or familial disorders.

If you think you may have a hearing loss or are having difficulty communicating, tell your doctor immediately.

What are the signs that I may be losing my hearing?

You may:

- complain that people are mumbling

- continually ask people to repeat themselves

- avoid noisy rooms, social occasions, or family gatherings

- prefer the TV or radio louder than other people do

- have difficulty understanding people when you can’t see their faces

- have trouble hearing at the movies or theater, your house of worship, or other public places

- have difficulty following conversations in a group

- become impatient, irritable, frustrated, or withdrawn.

Why can I hear people talk but not understand what they’re saying?

Hearing loss not only reduces your ability to hear normally audible sound, it interferes with your ability to detect particular sounds. High-pitched consonants (such as d, f, sh, s, t, and th) become harder to hear than low-pitched vowels. The high-pitched consonant sounds carry the meaning of words and help us understand speech, but in normal conversation, they’re softer than the less important low-pitched vowel sounds. So conversation may sound loud enough, but the words may not be clear.

How is hearing loss diagnosed?