User login

Patient Views of Discharge and a Novel e-Tool to Improve Transition from the Hospital

From the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN.

Abstract

- Objective: To elicit patient perceptions of a computer tablet (“e-Board”) used to display information relevant to hospital discharge and to gather patients’ expectations and perceptions regarding hospital discharge.

- Methods: Adult patients discharged from 1 of 3 medical-surgical, noncardiac monitored units of a 1265-bed, academic, tertiary care hospital were interviewed during patient focus groups. Reviewer pairs performed qualitative analysis of focus group transcripts and identified key themes, which were grouped into categories.

- Results: Patients felt a novel e-Board could help with the discharge process. They identified coordination of discharge, communication about discharge, ramifications of unexpected admissions, and interpersonal interactions during admission as the most significant issues around discharge.

- Conclusions: Focus groups elicit actionable information from patients about hospital discharge. Using this information, e-tools may help to design a patient-centered discharge process.

Key words: hospitals; patient satisfaction; focus groups; acute inpatient care.

Transition from the hospital to home represents a critical time for patients after acute illness, and support of patients and their care partners can help decrease consequences of poor care transitions, such as readmissions [1]. Focused discharge planning may improve outcomes and increase patient satisfaction [2], which is a key metric in hospital value-based purchasing programs, which tie Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Services (HCAHPS) survey scores to reimbursement. Although patient experience surveys explore several categories of patient satisfaction, HCAHPS may not reveal readily actionable opportunities that would allow clinicians to improve patient experience. Conducting focus groups and interviews can help discern patients’ perceptions and provide patient-centered opportunities to improve hospital discharge processes. Recent studies using these methodologies have revealed patients’ perceptions of barriers to inter-professional collaboration during discharge [3] and their desires and expectations of, as well as suggestions for improvement of, hospitalization [4].

Care transition bundles have been developed to facilitate the process of transitioning home [1,5], but none include e-health tools to help facilitate the discharge process. A study group leveraged available software at our institution to create a bedside “e-Board,” addressing opportunities that surfaced during previous patient focus groups regarding our institution’s discharge process. The software tools were loaded onto a tablet computer (Apple iPad; Cupertino, CA) and included displays of the patient’s physician and nurse, with estimated time of team bedside rounds; day and time of anticipated discharge; display of discharge medications; and a screening tool, I-MOVE, to assess mobility prior to return to independent living [6].

We conducted focus groups to gather patients’ insights for incorporation into a bedside e-health tool for discharge and into our hospital’s current discharge process. The primary objective of the current study was to elicit patient and family perceptions of a bedside e-Board, created to display information regarding discharge. Our secondary objective was to learn about patient expectations and perceptions regarding the hospital discharge process.

Methods

Setting

The study setting was 3 medical-surgical, non-cardiac monitored units of a 1265-bed, academic, tertiary care hospital in Rochester, MN. The study was considered a minimal risk study by the center’s institutional review board.

Participants

Patients aged 18 years or older discharged from 1 of the 3 study units during 2012–2013 were eligible to participate. Patients were excluded if they were not discharged home or to assisted living, were clinic employees, retirees or dependents of clinic employees, were hospitalized longer than 6 months prior to study entry, lived further than 60 miles from the town of Rochester, could not travel, or did not sign research consent.

There were 975 patients who met inclusion criteria. The institution’s survey research center randomly selected 300 eligible patients and contacted them by letter after discharge. The letter was followed up with a telephone call and verbal consent was obtained if the patient expressed interest in participation. Of the 17 patients who gave consent, 12 patients participated in focus group interviews.

E-Board Development

Prior focus group discussions facilitated by our institution’s marketing department (Mr. Kent Seltman, personal communication) explored patients’ perceptions of the discharge process from the institution’s primary hospital. The opportunities for improvement that surfaced during these focus groups included identifying the date of discharge, communication about the time of discharge, and discharging the patient at the identified time, not several hours later. The study group leveraged software available at our institution to create a bedside e-Board that could possibly mitigate these issues by improving communication about discharge. The software tools were loaded onto a tablet computer for patients to use as a resource during their admission. These tools included:

- A photo display of the patient’s nurse and physician, with estimated time of bedside rounds

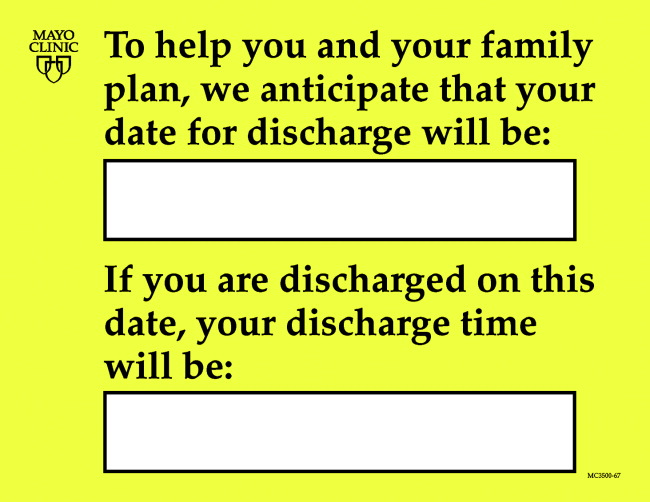

- A display of the day and time of anticipated discharge. Providing anticipated day and time of discharge has been found to be an achievable goal for internal medicine and surgical services [7].

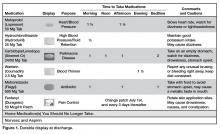

- A medication display, named the “Durable Display at Discharge,” previously found to improve patient understanding of prescribed medications [8]

- A display of a mobility tool, I-MOVE, designed to screen for debility that could prevent patients’ return to independent living [6].

Focus Groups

Facilitated interviews were conducted on 2 consecutive days in March 2014. Participants were divided into a focus group of 5 to 6 participants if they were functionally independent, or dyads of patient and care partner if they were functionally dependent. Interviews were both video- and audiotaped.

A trained facilitator led 1.5-hour sessions with each focus group. The sessions began with introductions and guidelines by which the focus groups were conducted, including explanations of the video and audio recording equipment, and a request for participants to speak one person at a time to facilitate recording. Discussions were carried out in 2 parts, guided by a facilitator script ( available from the authors). First, participants were asked to share their experiences regarding planning for discharge and the information they received leading up to their planned day and time of hospital discharge. Second, participants were shown a prototype of the e-Board. Participants were asked to reflect as to whether they had received similar information when they had been hospitalized, whether that information was helpful or useful, what information they did not receive that would have been helpful, how information was given, and whether information displayed via an e-Board would be better or worse than the ways they received information while in the hospital.

Data Analysis

Three teams, each comprised of 2 reviewers, met to analyze the video and audio recordings of each focus group. Unfortunately, the video files from the dyad interviews were not recoverable after the recorded sessions, and thus those groups were excluded from the study. Reviewers met prior to analyzing the focus group video and audio recordings to review the qualitative analysis protocol developed by the research team [9] (protocol available froom the authors). The teams then independently reviewed the video recordings and transcripts of the focus groups. The reviewer teams observed the focus group recordings and identified (1) themes regarding perceptions of the bedside e-Board and (2) experiences and perceptions around discharge. The protocol helped reviewer teams create a classification structure by identifying the key themes, which were then combined to create categories. The reviewer teams then compared their classification structures and by incorporating the most frequently identified categories, built a relational model of discharge perceptions.

Results

Eleven patients participated in 2 focus groups, one group of 5 patients and the other of 6 patients. Patient participants included 6 females and 5 males ranging in age from 22 to 84 years.

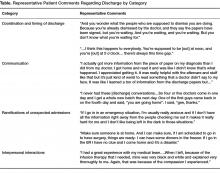

Using the qualitative analysis protocol, review teams grouped key themes from the focus group discussions about discharge into 4 categories. The categories, with themes listed below and representative patient comments in the Table, were

- Coordination and timing of discharge

- Giving patients the opportunity to prepare for discussion with clinician teams

- Communicating the specific time of discharge

- Internal collaboration of inter-professional teams

- Preparing for transition out of the hospital

2. Communication

- Patient inclusion in care discussions

- Discharge summary delay and/or completeness

- Education at the time of discharge

3. Ramifications of the unexpected and unknown

- Increased stress and frustration due to inability to plan, fear of the unknown, and lack of information

4. Interpersonal interactions

- Both favorable and unfavorable interactions caused an emotional response that impacts perceptions of hospitalization and discharge

The reviewers also analyzed patients’ comments regarding the bedside e-Board. The medication display (“Durable Display at Discharge,” Figure 1) was universally considered to be the most relevant and best-liked of the 4 elements tested. The visual display of medications and their purpose were commonly referenced as the most positive aspects of the display, and patients and caregivers were readily able to generate multiple potential uses for the display. Several mentioned that the information on the medication display were so desirable and necessary that if not supplied by the hospital, they hand-crafted such reminder displays at home.

The display of the care team and rounding time was perceived as helpful in allowing patients and family members to coordinate schedules with family members or care partners who may wish to be present during rounds. Patients also favorably reviewed the discharge day and time display, although multiple comments were made that this information is only helpful if it is accurate. Discussion around discharge time evoked the most emotions of topics discussed and patients expressed frustration with the inaccuracy of discharge time communicated to them on the day of discharge. Elaborating on this sentiment, a patient specified, “I prefer they don’t tell me a time at all until they know for sure”, and another shared that, “there is only going to be frustration with that if you say 4 pm and it ends up being 7 pm.”

It was difficult for patients to see how the I-MOVE assessment (Figure 2) would apply to their discharge planning. They perceived I-MOVE as a tool for clinicians. One exception was a patient who had on a previous admission undergone heart surgery. She explained to the other patients that in such debilitated conditions, mobility independence assessments were important and commonly done.

Patients voiced some skepticism and concerns regarding the e-Board, including expense, privacy, security, and cleanliness. One patient observed the tablet was “more current than a printed piece of paper. It’s more up to date.” Other patients, however, questioned the process required to update information and wondered how much electronic displays added compared to the dry-erase board already in each patient’s room with which they were more familiar. They also voiced concern that the tablet would replace face-to-face interactions with their care teams. A patient shared that, “if we don’t have the conversation and we just get it through this, then I would hate that…you want to be able to give your input.”

Discussion

In this study, we used available software to create a bedside e-Board that addressed opportunities for patient-centered improvement in our institution’s discharge process. Patients felt that 3 of 4 software tools on the tablet could enhance the discharge experience. Additionally, we explored patients’ expectations and perceptions of our hospital discharge process.

Key information to inform our current discharge process was divulged by our patients during focus groups. Patients conveyed that the only time that matters to them is the time they get to walk out the door of the hospital, and that general statements (eg, “You’ll probably be going home today.”) create anxiety and dissatisfaction. Since family and care partners need to manage hospital discharge in combination with regular activities of daily life (eg, work schedules, child care), un-communicated changes to the discharge time are very difficult to accommodate and should be discussed in advance. Further, acknowledging the disruption of hospital admission to patients’, their families’, and care partners’ daily lives, as well as being mindful of the impact of interpersonal interactions with patients, remind clinicians of the impact hospitalization has on patients.

Focus group discussions revealed that an ideal patient-centered discharge process would include active patient participation, clear communication regarding the discharge process, especially changes in the specific discharge date and time, and education regarding discharge summary instructions. Further, patients voiced that the unexpected nature of admissions can be very disruptive to patients’ lives and that interpersonal interactions during admission cause emotional responses in patients that influence their perceptions of hospitalization.

Comments regarding poor coordination and communication of internal processes, opportunities to improve collaboration within and across care teams, and need to improve communication with patients regarding timing of discharge and plan of care are consistent with recent studies that used focus groups to explore patient perceptions and expectations around discharge [3,4]. The ramifications of unexpected admissions and the emotional responses patients expressed regarding interpersonal interactions during admission have not been reported by others conducting patient focus groups.

The unexpected nature of many admissions, and the uncertainty of the day-to-day activities during hospitalization, caused patients anxiety and stress. These emotions perhaps heightened their response and memories of both favorable and unfavorable interpersonal interactions. These memories left lasting impressions on patients and care teams may help alleviate anxiety and stress by providing consistency and routine such as rounding at the same time daily, and communicating this time with patients. In this regard, the e-Board was helpful in communicating the patients’ care team and their planned rounding time.

Regarding the ability of e-tools to facilitate information sharing and planning for discharge, patients felt that the display of medications would have been most beneficial when thinking about post-discharge care. They perceived a display of discharge date and time estimate display as very useful to coordinate the activities around physically leaving the hospital, but based on their experiences did not find anticipated discharge times to be believable.

Patients’ perceptions of the tool were assessed after a recent hospitalization, and our data would have been strengthened had patients and their care partners used the e-Board during the actual admission. On the other hand, post-discharge, patients had time to reflect on opportunities for improving their recent admission and had insight into gaps in their discharge that the tool could potentially fill. Because we were unable to access video recordings from our dyad groups, which led us to exclude these participants, we lost care partners’ perceptions of the e-Board and discharge process. Care partners likely have different perceptions of discharge processes compared to patients, and their insight would have augmented our findings.

Several patients observed that the e-Board presented much of the same information that was filled out by care teams on the in-room dry erase boards and questioned whether the tablet was needed. These observations provide future opportunity for studies comparing display of discharge information on in-room dry-erase boards to an electronic tablet display. E-tools have shown some benefit when used for patient self-monitoring [10], to increase patient engagement [11,12], or to improve patient education [12]. Computer tablets may be most useful when used in these manners, compared to information display.

Focus groups provide patient-provided information that is readily actionable, and this work presents patient insight into discharge processes elicited through focus groups. Patients discussed their perceptions of an e-tool that might address patient-identified opportunities to improve the discharge process. Future work in this area will explore e-tools, and how best to leverage their functionality to design a patient-centered discharge process.

Acknowledgments: Our thanks to Mr. Thomas J. (Tripp) Welch for the original suggestion of this study design, and to Ms. Heidi Miller and Ms. Lizann Williams for their invaluable contributions to this work. A special thanks to our exceptional colleagues of the Mayo Clinic Department of Medicine Clinical Research Office Clinical Trials Unit for their efforts in executing this study, and to the study participants who participated in this research, without whom this project would not have been possible.

Corresponding author: Deanne Kashiwagi, MD, MS, 200 First Street SW, Rochester, MN 55902, kashiwagi.deanne@mayo.edu.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, et al. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1822–8.

2. Goncalves-Bradley DC, Lannin NA, Clemson LM, et al. Discharge planning from hospital. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;1:CD000313.

3. Pinelli V, Stuckey HL, Gonzalo JD. Exploring challenges in the patient’s discharge process from the internal medicine service: A qualitative study of patients’ and providers’ perceptions. J Interprof Care 2017:1–9.

4. Neeman, N, Quinn K, Shoeb M, et al. Postdischarge focus groups to improve the hospital experience. Am J Med Qual 2013;28:536–8.

5. Jack, BW, Chetty VK, Anthony D, et al. A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:178–87.

6. Manning, DM, Keller AS, Frank DL. Home alone: assessing mobility independence before discharge. J Hosp Med 2009;4:252–4.

7. Manning, DM, Tammel KJ, Blegen RN, et al. In-room display of day and time patient is anticipated to leave hospital: a “discharge appointment.” J Hosp Med 2007;2:13–6.

8. Manning, DM, O’Meara JG, Williams AR, et al. 3D: a tool for medication discharge education. Qual Saf Health Care 2007;16:71–6.

9. Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci 2013;15:398–405.

10. Kampmeijer, R, Pavlova M, Tambor M, et al. The use of e-health and m-health tools in health promotion and primary prevention among older adults: a systematic literature review. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16 Suppl 5:290.

11. Vawdrey, DK, Wilcox LG, Collins SA, et al. A tablet computer application for patients to participate in their hospital care. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2011:1428–35.

12. Greysen, SR, Khanna RR, Jacolbia R, et al. Tablet computers for hospitalized patients: a pilot study to improve inpatient engagement. J Hosp Med 2014;9:396–9.

From the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN.

Abstract

- Objective: To elicit patient perceptions of a computer tablet (“e-Board”) used to display information relevant to hospital discharge and to gather patients’ expectations and perceptions regarding hospital discharge.

- Methods: Adult patients discharged from 1 of 3 medical-surgical, noncardiac monitored units of a 1265-bed, academic, tertiary care hospital were interviewed during patient focus groups. Reviewer pairs performed qualitative analysis of focus group transcripts and identified key themes, which were grouped into categories.

- Results: Patients felt a novel e-Board could help with the discharge process. They identified coordination of discharge, communication about discharge, ramifications of unexpected admissions, and interpersonal interactions during admission as the most significant issues around discharge.

- Conclusions: Focus groups elicit actionable information from patients about hospital discharge. Using this information, e-tools may help to design a patient-centered discharge process.

Key words: hospitals; patient satisfaction; focus groups; acute inpatient care.

Transition from the hospital to home represents a critical time for patients after acute illness, and support of patients and their care partners can help decrease consequences of poor care transitions, such as readmissions [1]. Focused discharge planning may improve outcomes and increase patient satisfaction [2], which is a key metric in hospital value-based purchasing programs, which tie Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Services (HCAHPS) survey scores to reimbursement. Although patient experience surveys explore several categories of patient satisfaction, HCAHPS may not reveal readily actionable opportunities that would allow clinicians to improve patient experience. Conducting focus groups and interviews can help discern patients’ perceptions and provide patient-centered opportunities to improve hospital discharge processes. Recent studies using these methodologies have revealed patients’ perceptions of barriers to inter-professional collaboration during discharge [3] and their desires and expectations of, as well as suggestions for improvement of, hospitalization [4].

Care transition bundles have been developed to facilitate the process of transitioning home [1,5], but none include e-health tools to help facilitate the discharge process. A study group leveraged available software at our institution to create a bedside “e-Board,” addressing opportunities that surfaced during previous patient focus groups regarding our institution’s discharge process. The software tools were loaded onto a tablet computer (Apple iPad; Cupertino, CA) and included displays of the patient’s physician and nurse, with estimated time of team bedside rounds; day and time of anticipated discharge; display of discharge medications; and a screening tool, I-MOVE, to assess mobility prior to return to independent living [6].

We conducted focus groups to gather patients’ insights for incorporation into a bedside e-health tool for discharge and into our hospital’s current discharge process. The primary objective of the current study was to elicit patient and family perceptions of a bedside e-Board, created to display information regarding discharge. Our secondary objective was to learn about patient expectations and perceptions regarding the hospital discharge process.

Methods

Setting

The study setting was 3 medical-surgical, non-cardiac monitored units of a 1265-bed, academic, tertiary care hospital in Rochester, MN. The study was considered a minimal risk study by the center’s institutional review board.

Participants

Patients aged 18 years or older discharged from 1 of the 3 study units during 2012–2013 were eligible to participate. Patients were excluded if they were not discharged home or to assisted living, were clinic employees, retirees or dependents of clinic employees, were hospitalized longer than 6 months prior to study entry, lived further than 60 miles from the town of Rochester, could not travel, or did not sign research consent.

There were 975 patients who met inclusion criteria. The institution’s survey research center randomly selected 300 eligible patients and contacted them by letter after discharge. The letter was followed up with a telephone call and verbal consent was obtained if the patient expressed interest in participation. Of the 17 patients who gave consent, 12 patients participated in focus group interviews.

E-Board Development

Prior focus group discussions facilitated by our institution’s marketing department (Mr. Kent Seltman, personal communication) explored patients’ perceptions of the discharge process from the institution’s primary hospital. The opportunities for improvement that surfaced during these focus groups included identifying the date of discharge, communication about the time of discharge, and discharging the patient at the identified time, not several hours later. The study group leveraged software available at our institution to create a bedside e-Board that could possibly mitigate these issues by improving communication about discharge. The software tools were loaded onto a tablet computer for patients to use as a resource during their admission. These tools included:

- A photo display of the patient’s nurse and physician, with estimated time of bedside rounds

- A display of the day and time of anticipated discharge. Providing anticipated day and time of discharge has been found to be an achievable goal for internal medicine and surgical services [7].

- A medication display, named the “Durable Display at Discharge,” previously found to improve patient understanding of prescribed medications [8]

- A display of a mobility tool, I-MOVE, designed to screen for debility that could prevent patients’ return to independent living [6].

Focus Groups

Facilitated interviews were conducted on 2 consecutive days in March 2014. Participants were divided into a focus group of 5 to 6 participants if they were functionally independent, or dyads of patient and care partner if they were functionally dependent. Interviews were both video- and audiotaped.

A trained facilitator led 1.5-hour sessions with each focus group. The sessions began with introductions and guidelines by which the focus groups were conducted, including explanations of the video and audio recording equipment, and a request for participants to speak one person at a time to facilitate recording. Discussions were carried out in 2 parts, guided by a facilitator script ( available from the authors). First, participants were asked to share their experiences regarding planning for discharge and the information they received leading up to their planned day and time of hospital discharge. Second, participants were shown a prototype of the e-Board. Participants were asked to reflect as to whether they had received similar information when they had been hospitalized, whether that information was helpful or useful, what information they did not receive that would have been helpful, how information was given, and whether information displayed via an e-Board would be better or worse than the ways they received information while in the hospital.

Data Analysis

Three teams, each comprised of 2 reviewers, met to analyze the video and audio recordings of each focus group. Unfortunately, the video files from the dyad interviews were not recoverable after the recorded sessions, and thus those groups were excluded from the study. Reviewers met prior to analyzing the focus group video and audio recordings to review the qualitative analysis protocol developed by the research team [9] (protocol available froom the authors). The teams then independently reviewed the video recordings and transcripts of the focus groups. The reviewer teams observed the focus group recordings and identified (1) themes regarding perceptions of the bedside e-Board and (2) experiences and perceptions around discharge. The protocol helped reviewer teams create a classification structure by identifying the key themes, which were then combined to create categories. The reviewer teams then compared their classification structures and by incorporating the most frequently identified categories, built a relational model of discharge perceptions.

Results

Eleven patients participated in 2 focus groups, one group of 5 patients and the other of 6 patients. Patient participants included 6 females and 5 males ranging in age from 22 to 84 years.

Using the qualitative analysis protocol, review teams grouped key themes from the focus group discussions about discharge into 4 categories. The categories, with themes listed below and representative patient comments in the Table, were

- Coordination and timing of discharge

- Giving patients the opportunity to prepare for discussion with clinician teams

- Communicating the specific time of discharge

- Internal collaboration of inter-professional teams

- Preparing for transition out of the hospital

2. Communication

- Patient inclusion in care discussions

- Discharge summary delay and/or completeness

- Education at the time of discharge

3. Ramifications of the unexpected and unknown

- Increased stress and frustration due to inability to plan, fear of the unknown, and lack of information

4. Interpersonal interactions

- Both favorable and unfavorable interactions caused an emotional response that impacts perceptions of hospitalization and discharge

The reviewers also analyzed patients’ comments regarding the bedside e-Board. The medication display (“Durable Display at Discharge,” Figure 1) was universally considered to be the most relevant and best-liked of the 4 elements tested. The visual display of medications and their purpose were commonly referenced as the most positive aspects of the display, and patients and caregivers were readily able to generate multiple potential uses for the display. Several mentioned that the information on the medication display were so desirable and necessary that if not supplied by the hospital, they hand-crafted such reminder displays at home.

The display of the care team and rounding time was perceived as helpful in allowing patients and family members to coordinate schedules with family members or care partners who may wish to be present during rounds. Patients also favorably reviewed the discharge day and time display, although multiple comments were made that this information is only helpful if it is accurate. Discussion around discharge time evoked the most emotions of topics discussed and patients expressed frustration with the inaccuracy of discharge time communicated to them on the day of discharge. Elaborating on this sentiment, a patient specified, “I prefer they don’t tell me a time at all until they know for sure”, and another shared that, “there is only going to be frustration with that if you say 4 pm and it ends up being 7 pm.”

It was difficult for patients to see how the I-MOVE assessment (Figure 2) would apply to their discharge planning. They perceived I-MOVE as a tool for clinicians. One exception was a patient who had on a previous admission undergone heart surgery. She explained to the other patients that in such debilitated conditions, mobility independence assessments were important and commonly done.

Patients voiced some skepticism and concerns regarding the e-Board, including expense, privacy, security, and cleanliness. One patient observed the tablet was “more current than a printed piece of paper. It’s more up to date.” Other patients, however, questioned the process required to update information and wondered how much electronic displays added compared to the dry-erase board already in each patient’s room with which they were more familiar. They also voiced concern that the tablet would replace face-to-face interactions with their care teams. A patient shared that, “if we don’t have the conversation and we just get it through this, then I would hate that…you want to be able to give your input.”

Discussion

In this study, we used available software to create a bedside e-Board that addressed opportunities for patient-centered improvement in our institution’s discharge process. Patients felt that 3 of 4 software tools on the tablet could enhance the discharge experience. Additionally, we explored patients’ expectations and perceptions of our hospital discharge process.

Key information to inform our current discharge process was divulged by our patients during focus groups. Patients conveyed that the only time that matters to them is the time they get to walk out the door of the hospital, and that general statements (eg, “You’ll probably be going home today.”) create anxiety and dissatisfaction. Since family and care partners need to manage hospital discharge in combination with regular activities of daily life (eg, work schedules, child care), un-communicated changes to the discharge time are very difficult to accommodate and should be discussed in advance. Further, acknowledging the disruption of hospital admission to patients’, their families’, and care partners’ daily lives, as well as being mindful of the impact of interpersonal interactions with patients, remind clinicians of the impact hospitalization has on patients.

Focus group discussions revealed that an ideal patient-centered discharge process would include active patient participation, clear communication regarding the discharge process, especially changes in the specific discharge date and time, and education regarding discharge summary instructions. Further, patients voiced that the unexpected nature of admissions can be very disruptive to patients’ lives and that interpersonal interactions during admission cause emotional responses in patients that influence their perceptions of hospitalization.

Comments regarding poor coordination and communication of internal processes, opportunities to improve collaboration within and across care teams, and need to improve communication with patients regarding timing of discharge and plan of care are consistent with recent studies that used focus groups to explore patient perceptions and expectations around discharge [3,4]. The ramifications of unexpected admissions and the emotional responses patients expressed regarding interpersonal interactions during admission have not been reported by others conducting patient focus groups.

The unexpected nature of many admissions, and the uncertainty of the day-to-day activities during hospitalization, caused patients anxiety and stress. These emotions perhaps heightened their response and memories of both favorable and unfavorable interpersonal interactions. These memories left lasting impressions on patients and care teams may help alleviate anxiety and stress by providing consistency and routine such as rounding at the same time daily, and communicating this time with patients. In this regard, the e-Board was helpful in communicating the patients’ care team and their planned rounding time.

Regarding the ability of e-tools to facilitate information sharing and planning for discharge, patients felt that the display of medications would have been most beneficial when thinking about post-discharge care. They perceived a display of discharge date and time estimate display as very useful to coordinate the activities around physically leaving the hospital, but based on their experiences did not find anticipated discharge times to be believable.

Patients’ perceptions of the tool were assessed after a recent hospitalization, and our data would have been strengthened had patients and their care partners used the e-Board during the actual admission. On the other hand, post-discharge, patients had time to reflect on opportunities for improving their recent admission and had insight into gaps in their discharge that the tool could potentially fill. Because we were unable to access video recordings from our dyad groups, which led us to exclude these participants, we lost care partners’ perceptions of the e-Board and discharge process. Care partners likely have different perceptions of discharge processes compared to patients, and their insight would have augmented our findings.

Several patients observed that the e-Board presented much of the same information that was filled out by care teams on the in-room dry erase boards and questioned whether the tablet was needed. These observations provide future opportunity for studies comparing display of discharge information on in-room dry-erase boards to an electronic tablet display. E-tools have shown some benefit when used for patient self-monitoring [10], to increase patient engagement [11,12], or to improve patient education [12]. Computer tablets may be most useful when used in these manners, compared to information display.

Focus groups provide patient-provided information that is readily actionable, and this work presents patient insight into discharge processes elicited through focus groups. Patients discussed their perceptions of an e-tool that might address patient-identified opportunities to improve the discharge process. Future work in this area will explore e-tools, and how best to leverage their functionality to design a patient-centered discharge process.

Acknowledgments: Our thanks to Mr. Thomas J. (Tripp) Welch for the original suggestion of this study design, and to Ms. Heidi Miller and Ms. Lizann Williams for their invaluable contributions to this work. A special thanks to our exceptional colleagues of the Mayo Clinic Department of Medicine Clinical Research Office Clinical Trials Unit for their efforts in executing this study, and to the study participants who participated in this research, without whom this project would not have been possible.

Corresponding author: Deanne Kashiwagi, MD, MS, 200 First Street SW, Rochester, MN 55902, kashiwagi.deanne@mayo.edu.

Financial disclosures: None.

From the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN.

Abstract

- Objective: To elicit patient perceptions of a computer tablet (“e-Board”) used to display information relevant to hospital discharge and to gather patients’ expectations and perceptions regarding hospital discharge.

- Methods: Adult patients discharged from 1 of 3 medical-surgical, noncardiac monitored units of a 1265-bed, academic, tertiary care hospital were interviewed during patient focus groups. Reviewer pairs performed qualitative analysis of focus group transcripts and identified key themes, which were grouped into categories.

- Results: Patients felt a novel e-Board could help with the discharge process. They identified coordination of discharge, communication about discharge, ramifications of unexpected admissions, and interpersonal interactions during admission as the most significant issues around discharge.

- Conclusions: Focus groups elicit actionable information from patients about hospital discharge. Using this information, e-tools may help to design a patient-centered discharge process.

Key words: hospitals; patient satisfaction; focus groups; acute inpatient care.

Transition from the hospital to home represents a critical time for patients after acute illness, and support of patients and their care partners can help decrease consequences of poor care transitions, such as readmissions [1]. Focused discharge planning may improve outcomes and increase patient satisfaction [2], which is a key metric in hospital value-based purchasing programs, which tie Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Services (HCAHPS) survey scores to reimbursement. Although patient experience surveys explore several categories of patient satisfaction, HCAHPS may not reveal readily actionable opportunities that would allow clinicians to improve patient experience. Conducting focus groups and interviews can help discern patients’ perceptions and provide patient-centered opportunities to improve hospital discharge processes. Recent studies using these methodologies have revealed patients’ perceptions of barriers to inter-professional collaboration during discharge [3] and their desires and expectations of, as well as suggestions for improvement of, hospitalization [4].

Care transition bundles have been developed to facilitate the process of transitioning home [1,5], but none include e-health tools to help facilitate the discharge process. A study group leveraged available software at our institution to create a bedside “e-Board,” addressing opportunities that surfaced during previous patient focus groups regarding our institution’s discharge process. The software tools were loaded onto a tablet computer (Apple iPad; Cupertino, CA) and included displays of the patient’s physician and nurse, with estimated time of team bedside rounds; day and time of anticipated discharge; display of discharge medications; and a screening tool, I-MOVE, to assess mobility prior to return to independent living [6].

We conducted focus groups to gather patients’ insights for incorporation into a bedside e-health tool for discharge and into our hospital’s current discharge process. The primary objective of the current study was to elicit patient and family perceptions of a bedside e-Board, created to display information regarding discharge. Our secondary objective was to learn about patient expectations and perceptions regarding the hospital discharge process.

Methods

Setting

The study setting was 3 medical-surgical, non-cardiac monitored units of a 1265-bed, academic, tertiary care hospital in Rochester, MN. The study was considered a minimal risk study by the center’s institutional review board.

Participants

Patients aged 18 years or older discharged from 1 of the 3 study units during 2012–2013 were eligible to participate. Patients were excluded if they were not discharged home or to assisted living, were clinic employees, retirees or dependents of clinic employees, were hospitalized longer than 6 months prior to study entry, lived further than 60 miles from the town of Rochester, could not travel, or did not sign research consent.

There were 975 patients who met inclusion criteria. The institution’s survey research center randomly selected 300 eligible patients and contacted them by letter after discharge. The letter was followed up with a telephone call and verbal consent was obtained if the patient expressed interest in participation. Of the 17 patients who gave consent, 12 patients participated in focus group interviews.

E-Board Development

Prior focus group discussions facilitated by our institution’s marketing department (Mr. Kent Seltman, personal communication) explored patients’ perceptions of the discharge process from the institution’s primary hospital. The opportunities for improvement that surfaced during these focus groups included identifying the date of discharge, communication about the time of discharge, and discharging the patient at the identified time, not several hours later. The study group leveraged software available at our institution to create a bedside e-Board that could possibly mitigate these issues by improving communication about discharge. The software tools were loaded onto a tablet computer for patients to use as a resource during their admission. These tools included:

- A photo display of the patient’s nurse and physician, with estimated time of bedside rounds

- A display of the day and time of anticipated discharge. Providing anticipated day and time of discharge has been found to be an achievable goal for internal medicine and surgical services [7].

- A medication display, named the “Durable Display at Discharge,” previously found to improve patient understanding of prescribed medications [8]

- A display of a mobility tool, I-MOVE, designed to screen for debility that could prevent patients’ return to independent living [6].

Focus Groups

Facilitated interviews were conducted on 2 consecutive days in March 2014. Participants were divided into a focus group of 5 to 6 participants if they were functionally independent, or dyads of patient and care partner if they were functionally dependent. Interviews were both video- and audiotaped.

A trained facilitator led 1.5-hour sessions with each focus group. The sessions began with introductions and guidelines by which the focus groups were conducted, including explanations of the video and audio recording equipment, and a request for participants to speak one person at a time to facilitate recording. Discussions were carried out in 2 parts, guided by a facilitator script ( available from the authors). First, participants were asked to share their experiences regarding planning for discharge and the information they received leading up to their planned day and time of hospital discharge. Second, participants were shown a prototype of the e-Board. Participants were asked to reflect as to whether they had received similar information when they had been hospitalized, whether that information was helpful or useful, what information they did not receive that would have been helpful, how information was given, and whether information displayed via an e-Board would be better or worse than the ways they received information while in the hospital.

Data Analysis

Three teams, each comprised of 2 reviewers, met to analyze the video and audio recordings of each focus group. Unfortunately, the video files from the dyad interviews were not recoverable after the recorded sessions, and thus those groups were excluded from the study. Reviewers met prior to analyzing the focus group video and audio recordings to review the qualitative analysis protocol developed by the research team [9] (protocol available froom the authors). The teams then independently reviewed the video recordings and transcripts of the focus groups. The reviewer teams observed the focus group recordings and identified (1) themes regarding perceptions of the bedside e-Board and (2) experiences and perceptions around discharge. The protocol helped reviewer teams create a classification structure by identifying the key themes, which were then combined to create categories. The reviewer teams then compared their classification structures and by incorporating the most frequently identified categories, built a relational model of discharge perceptions.

Results

Eleven patients participated in 2 focus groups, one group of 5 patients and the other of 6 patients. Patient participants included 6 females and 5 males ranging in age from 22 to 84 years.

Using the qualitative analysis protocol, review teams grouped key themes from the focus group discussions about discharge into 4 categories. The categories, with themes listed below and representative patient comments in the Table, were

- Coordination and timing of discharge

- Giving patients the opportunity to prepare for discussion with clinician teams

- Communicating the specific time of discharge

- Internal collaboration of inter-professional teams

- Preparing for transition out of the hospital

2. Communication

- Patient inclusion in care discussions

- Discharge summary delay and/or completeness

- Education at the time of discharge

3. Ramifications of the unexpected and unknown

- Increased stress and frustration due to inability to plan, fear of the unknown, and lack of information

4. Interpersonal interactions

- Both favorable and unfavorable interactions caused an emotional response that impacts perceptions of hospitalization and discharge

The reviewers also analyzed patients’ comments regarding the bedside e-Board. The medication display (“Durable Display at Discharge,” Figure 1) was universally considered to be the most relevant and best-liked of the 4 elements tested. The visual display of medications and their purpose were commonly referenced as the most positive aspects of the display, and patients and caregivers were readily able to generate multiple potential uses for the display. Several mentioned that the information on the medication display were so desirable and necessary that if not supplied by the hospital, they hand-crafted such reminder displays at home.

The display of the care team and rounding time was perceived as helpful in allowing patients and family members to coordinate schedules with family members or care partners who may wish to be present during rounds. Patients also favorably reviewed the discharge day and time display, although multiple comments were made that this information is only helpful if it is accurate. Discussion around discharge time evoked the most emotions of topics discussed and patients expressed frustration with the inaccuracy of discharge time communicated to them on the day of discharge. Elaborating on this sentiment, a patient specified, “I prefer they don’t tell me a time at all until they know for sure”, and another shared that, “there is only going to be frustration with that if you say 4 pm and it ends up being 7 pm.”

It was difficult for patients to see how the I-MOVE assessment (Figure 2) would apply to their discharge planning. They perceived I-MOVE as a tool for clinicians. One exception was a patient who had on a previous admission undergone heart surgery. She explained to the other patients that in such debilitated conditions, mobility independence assessments were important and commonly done.

Patients voiced some skepticism and concerns regarding the e-Board, including expense, privacy, security, and cleanliness. One patient observed the tablet was “more current than a printed piece of paper. It’s more up to date.” Other patients, however, questioned the process required to update information and wondered how much electronic displays added compared to the dry-erase board already in each patient’s room with which they were more familiar. They also voiced concern that the tablet would replace face-to-face interactions with their care teams. A patient shared that, “if we don’t have the conversation and we just get it through this, then I would hate that…you want to be able to give your input.”

Discussion

In this study, we used available software to create a bedside e-Board that addressed opportunities for patient-centered improvement in our institution’s discharge process. Patients felt that 3 of 4 software tools on the tablet could enhance the discharge experience. Additionally, we explored patients’ expectations and perceptions of our hospital discharge process.

Key information to inform our current discharge process was divulged by our patients during focus groups. Patients conveyed that the only time that matters to them is the time they get to walk out the door of the hospital, and that general statements (eg, “You’ll probably be going home today.”) create anxiety and dissatisfaction. Since family and care partners need to manage hospital discharge in combination with regular activities of daily life (eg, work schedules, child care), un-communicated changes to the discharge time are very difficult to accommodate and should be discussed in advance. Further, acknowledging the disruption of hospital admission to patients’, their families’, and care partners’ daily lives, as well as being mindful of the impact of interpersonal interactions with patients, remind clinicians of the impact hospitalization has on patients.

Focus group discussions revealed that an ideal patient-centered discharge process would include active patient participation, clear communication regarding the discharge process, especially changes in the specific discharge date and time, and education regarding discharge summary instructions. Further, patients voiced that the unexpected nature of admissions can be very disruptive to patients’ lives and that interpersonal interactions during admission cause emotional responses in patients that influence their perceptions of hospitalization.

Comments regarding poor coordination and communication of internal processes, opportunities to improve collaboration within and across care teams, and need to improve communication with patients regarding timing of discharge and plan of care are consistent with recent studies that used focus groups to explore patient perceptions and expectations around discharge [3,4]. The ramifications of unexpected admissions and the emotional responses patients expressed regarding interpersonal interactions during admission have not been reported by others conducting patient focus groups.

The unexpected nature of many admissions, and the uncertainty of the day-to-day activities during hospitalization, caused patients anxiety and stress. These emotions perhaps heightened their response and memories of both favorable and unfavorable interpersonal interactions. These memories left lasting impressions on patients and care teams may help alleviate anxiety and stress by providing consistency and routine such as rounding at the same time daily, and communicating this time with patients. In this regard, the e-Board was helpful in communicating the patients’ care team and their planned rounding time.

Regarding the ability of e-tools to facilitate information sharing and planning for discharge, patients felt that the display of medications would have been most beneficial when thinking about post-discharge care. They perceived a display of discharge date and time estimate display as very useful to coordinate the activities around physically leaving the hospital, but based on their experiences did not find anticipated discharge times to be believable.

Patients’ perceptions of the tool were assessed after a recent hospitalization, and our data would have been strengthened had patients and their care partners used the e-Board during the actual admission. On the other hand, post-discharge, patients had time to reflect on opportunities for improving their recent admission and had insight into gaps in their discharge that the tool could potentially fill. Because we were unable to access video recordings from our dyad groups, which led us to exclude these participants, we lost care partners’ perceptions of the e-Board and discharge process. Care partners likely have different perceptions of discharge processes compared to patients, and their insight would have augmented our findings.

Several patients observed that the e-Board presented much of the same information that was filled out by care teams on the in-room dry erase boards and questioned whether the tablet was needed. These observations provide future opportunity for studies comparing display of discharge information on in-room dry-erase boards to an electronic tablet display. E-tools have shown some benefit when used for patient self-monitoring [10], to increase patient engagement [11,12], or to improve patient education [12]. Computer tablets may be most useful when used in these manners, compared to information display.

Focus groups provide patient-provided information that is readily actionable, and this work presents patient insight into discharge processes elicited through focus groups. Patients discussed their perceptions of an e-tool that might address patient-identified opportunities to improve the discharge process. Future work in this area will explore e-tools, and how best to leverage their functionality to design a patient-centered discharge process.

Acknowledgments: Our thanks to Mr. Thomas J. (Tripp) Welch for the original suggestion of this study design, and to Ms. Heidi Miller and Ms. Lizann Williams for their invaluable contributions to this work. A special thanks to our exceptional colleagues of the Mayo Clinic Department of Medicine Clinical Research Office Clinical Trials Unit for their efforts in executing this study, and to the study participants who participated in this research, without whom this project would not have been possible.

Corresponding author: Deanne Kashiwagi, MD, MS, 200 First Street SW, Rochester, MN 55902, kashiwagi.deanne@mayo.edu.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, et al. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1822–8.

2. Goncalves-Bradley DC, Lannin NA, Clemson LM, et al. Discharge planning from hospital. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;1:CD000313.

3. Pinelli V, Stuckey HL, Gonzalo JD. Exploring challenges in the patient’s discharge process from the internal medicine service: A qualitative study of patients’ and providers’ perceptions. J Interprof Care 2017:1–9.

4. Neeman, N, Quinn K, Shoeb M, et al. Postdischarge focus groups to improve the hospital experience. Am J Med Qual 2013;28:536–8.

5. Jack, BW, Chetty VK, Anthony D, et al. A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:178–87.

6. Manning, DM, Keller AS, Frank DL. Home alone: assessing mobility independence before discharge. J Hosp Med 2009;4:252–4.

7. Manning, DM, Tammel KJ, Blegen RN, et al. In-room display of day and time patient is anticipated to leave hospital: a “discharge appointment.” J Hosp Med 2007;2:13–6.

8. Manning, DM, O’Meara JG, Williams AR, et al. 3D: a tool for medication discharge education. Qual Saf Health Care 2007;16:71–6.

9. Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci 2013;15:398–405.

10. Kampmeijer, R, Pavlova M, Tambor M, et al. The use of e-health and m-health tools in health promotion and primary prevention among older adults: a systematic literature review. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16 Suppl 5:290.

11. Vawdrey, DK, Wilcox LG, Collins SA, et al. A tablet computer application for patients to participate in their hospital care. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2011:1428–35.

12. Greysen, SR, Khanna RR, Jacolbia R, et al. Tablet computers for hospitalized patients: a pilot study to improve inpatient engagement. J Hosp Med 2014;9:396–9.

1. Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, et al. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1822–8.

2. Goncalves-Bradley DC, Lannin NA, Clemson LM, et al. Discharge planning from hospital. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;1:CD000313.

3. Pinelli V, Stuckey HL, Gonzalo JD. Exploring challenges in the patient’s discharge process from the internal medicine service: A qualitative study of patients’ and providers’ perceptions. J Interprof Care 2017:1–9.

4. Neeman, N, Quinn K, Shoeb M, et al. Postdischarge focus groups to improve the hospital experience. Am J Med Qual 2013;28:536–8.

5. Jack, BW, Chetty VK, Anthony D, et al. A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:178–87.

6. Manning, DM, Keller AS, Frank DL. Home alone: assessing mobility independence before discharge. J Hosp Med 2009;4:252–4.

7. Manning, DM, Tammel KJ, Blegen RN, et al. In-room display of day and time patient is anticipated to leave hospital: a “discharge appointment.” J Hosp Med 2007;2:13–6.

8. Manning, DM, O’Meara JG, Williams AR, et al. 3D: a tool for medication discharge education. Qual Saf Health Care 2007;16:71–6.

9. Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci 2013;15:398–405.

10. Kampmeijer, R, Pavlova M, Tambor M, et al. The use of e-health and m-health tools in health promotion and primary prevention among older adults: a systematic literature review. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16 Suppl 5:290.

11. Vawdrey, DK, Wilcox LG, Collins SA, et al. A tablet computer application for patients to participate in their hospital care. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2011:1428–35.

12. Greysen, SR, Khanna RR, Jacolbia R, et al. Tablet computers for hospitalized patients: a pilot study to improve inpatient engagement. J Hosp Med 2014;9:396–9.

Discharge Appointments

Dicharge of a patient from the hospital is a complicated, interprofessional endeavor.1, 2 Several institutions report that discharge is one of the least satisfying elements of the patient's hospital experience.35 Recent evidence suggests that a poorly planned or disorganized discharge may compromise patient safety in the period soon after dismissal.6 Several initiatives have been aimed at improving patient satisfaction and safety related to discharge.710

In 2000 the Mayo Clinic (Rochester, Minnesota) Department of Internal Medicine leadership established a goal to improve patient satisfaction with the hospital dismissal process. Patient focus group data suggested that uncertainty about the anticipated date and time of discharge causes frustration to some patients and families.

We hypothesized that an appointment to leave the hospital might be practicable. We joined an Institute for Healthcare Improvement collaborative (Improving Flow Through Acute Care Settings, 1 of 6 Improvement Action Network [IMPACT] Learning and Innovation Communities) aimed at scheduling discharge appointments (DAs). The collaborating members deemed that, although the ideal DA is set at least a day in advance, a same‐day DA is also desirable for both patient satisfaction and staff task organization in pursuit of a high‐quality discharge.

METHODS

This project was approved by the Mayo Foundation Institutional Review Board. We tested the following hypotheses:

It is possible to make and display DAs in various care units.

Most DAs can be scheduled a day before dismissal.

Most DA patients depart on time.

Setting

Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, is a tertiary academic medical center with 2 hospitals (Saint Marys and Rochester Methodist) that house a total of 1951 licensed beds in 76 care units.

The preliminary study displaying DAs was carried out in the Innovation and Quality (IQ) Unit of Saint Marys Hospital, a 23‐bed general medical care unit that supports both resident and nonresident services. Traditionally, primary services usually consist of an attending physician and house officer physicians (junior and senior residents). Less commonly, primary services consist of an attending physician and either a nurse‐practitioner or a physician assistant.

The design pilot took place between August 2 and December 24, 2003. The subsequent, larger study of applicability took place across 8 care units (including the IQ Unit) between December 28, 2003, and April 25, 2004.

Preliminary Work: Design Pilot

We designed bedside dry‐erase wall displays and mounted them in the rooms in plain view of patients and their families and caregivers. Pilot testing of DA scheduling was done on a general medical care unit from August 2 to December 24, 2003. To optimize the process for scheduling a DA, our team developed 21 small tests to change the dismissal process through plan, do, study, and act cycles.11

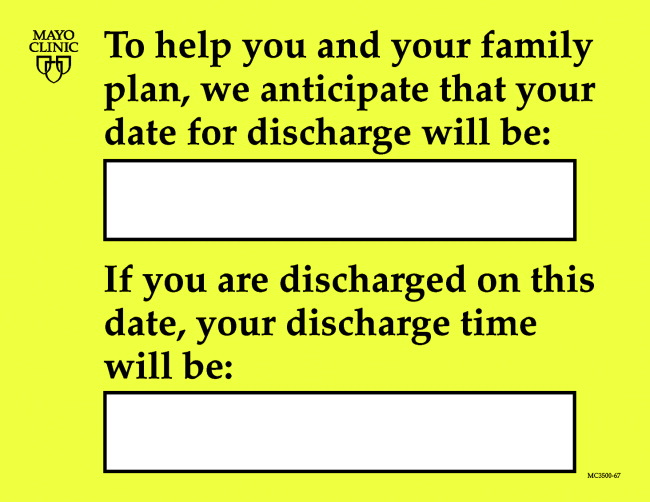

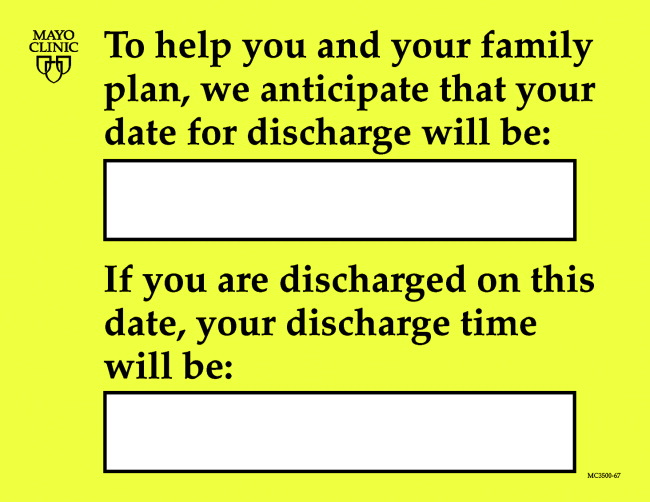

The recommended process was that as soon as an organized discharge could be reasonably envisioned, the primary service provider would discuss with the patient, family, and primary nurse (and a social service worker, if involved) the anticipated discharge day. A member of the primary service was to handwrite (with a marker) the anticipated day on the specially designed bedside dry‐erase board (Fig. 1) in view of the patient. The same primary service prescribers could amend this anticipated day (or time) by repeating the process of consultation and discussion as needed. The time of the DA could be written on the DA board (or amended) by either a member of the primary service or the primary care nurse.

Each morning, the primary care nurse transmitted the DA board data to the admission, discharge, and transfer log kept at the unit secretary desk (in which the actual discharge time has always been routinely recorded by the unit secretary).

Adoption of DA Scheduling in Other Care Units

Several meetings were held with 7 other patient care unit leaders about adopting the protocol. These units, both medical and surgical, were selected according to 3 criteria: (1) prior participation in unit‐level continuous improvement work, (2) current or recent work in any aspect of the discharge process, and (3) a reputation for having innovative nursing leadership and staff.

Data Acquisition and Analysis

Data were collected daily from each participating unit's admission, discharge, and transfer log: both the actual time of departure and the DA, if one had been scheduled. For each DA patient, the DA time was compared with the actual departure time.

RESULTS

During the 4‐month study of discharges across 8 care units, 1256 of 2046 patients (61%) received a DA; 576 of the DAs (46%) were scheduled at least 1 day in advance (Table 1). Among patients with a DA, 752 were discharged on time (60%), and only 240 (19%) were tardy.

| Unit | DAs | Departure time of patients compared with DA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Type of unit | No. of patients | Patients with DAs, n (%) | DAs scheduled ϵ 1 day ahead, n (%) | On time, n (%)a | Early, n (%) | Late, n (%) |

| |||||||

| 1 | Neurology/neurosurgery | 525 | 270 (51) | 0 (0) | 175 (65) | 44 (16) | 51 (19) |

| 2 | Surgery (mixed) | 481 | 325 (68) | 289 (89) | 166 (51) | 101 (31) | 58 (18) |

| 3 | General internal medicine (IQ Unit) | 466 | 243 (52) | 35 (14) | 132 (54) | 50 (21) | 61 (25) |

| 4 | Neurology/neurosurgery | 267 | 189 (71) | 40 (21) | 119 (63) | 41 (22) | 29 (15) |

| 5 | Vascular surgery | 201 | 127 (63) | 127 (100) | 90 (71) | 12 (9) | 25 (20) |

| 6 | Psychiatry | 46 | 42 (91) | 42 (100) | 28 (67) | 9 (21) | 5 (12) |

| 7 | Orthopedic surgeryelective | 38 | 38 (100) | 22 (58) | 24 (63) | 3 (8) | 11 (29) |

| 8 | Orthopedic surgerytrauma | 22 | 22 (100) | 21 (95) | 18 (82) | 4 (18) | 0 (0) |

| Total | 2046 | 1256 (61) | 576 (46) | 752 (60) | 264 (21) | 240 (19) | |

DISCUSSION

In response to patient focus group feedback, we designed a tool and a process by which a DA could be made and posted at bedside. Among 2046 patients discharged from 8 care units over 4 months, 61% (1256) had a posted, in‐room DA. Almost half the patients with DAs (46%) had a DA scheduled at least 1 calendar day ahead. Remarkably, among patients with a DA, fewer than 20% were discharged tardily. In‐room posting of DAs across a spectrum of care units appears to be practicable, even in the face of extant diagnostic or therapeutic uncertainty.

This was an initial test‐of‐concept project and an exploratory trial. The limitations are: (1) satisfaction (patient, family, nurse, and physician) was not tested with any validated survey instrument, (2) length of stay was not studied, (3) reasons for variable DA success among care units were not ascertained, and (4) resource use was not measured.

Anecdotal information from a postdischarge phone survey indicated that patients seemed appreciative of a DA. The survey data were not included in this article because the survey tool was not a validated instrument and the interviewer (a coauthor) was not blinded to the hypothesis and was therefore subject to bias. No negative comments were received through informal real‐time feedback from patients and family during the making and posting of DAs, and encouraging comments were common.

Physician participation in posting the DA appeared to be key, and the unavoidable dialogue about the clinical rationale for a chosen date seemed welcome. A telling anecdote came from a patient who did not have a DA board: I didn't get the same treatment as my roommate with the [DA] board. The other doctors talked with [him] more about discharge. I wish my team would have done this more with me.

We cannot be certain of the reasons for the care unit disparity in setting and meeting DAs. We speculate that the level of staff enthusiasm for DAs explains the variation rather than patient population characteristics. Further, we cannot explain why 39% of the patients did not receive a DA. Physician feedback was generally, but not uniformly, positive. Negative comments that might explain DA omissions include: (1) patients already are informed and awarethe tool is superfluous; (2) the day of discharge is unknowable in advance; and (3) patients or family members will hold us to it or be upset if the DA is changed.

We expected that diagnostic uncertainty might pose challenges to providing DAs. When primary service providers were reassured that DAs could be amended, this concern was reduced (but not eliminated). It seemed useful for providers to envision the earliest day of discharge by assuming that the results of a pending key test or consultation would be favorable. Frequency of DA modification was not studied. DAs were amended, however, and patients (to our knowledge) seemed unperturbedperhaps because of an almost unavoidable discussion of the clinical rationale because the act of posting the DA occurred in full view of (and in partnership with) the patient.

A trend toward discharge earlier in the day was observed (data not shown). Theoretically, such a trend offers the potential to improve inpatient flow, in part by discharging patients before morning surgical cases are completed.

Although we had many favorable comments about DAs from patients, family members, and nurses, satisfaction of patients, families, and staff members deserves formal study. Further, it is not known whether unused DA boards might contribute to patient dissatisfaction. Any effect that the display of DAs may have on the length of stay also may be a topic worthy of future study.

CONCLUSIONS

Patients and their families sometimes desire more communication about the anticipated day and time of hospital discharge. We designed a process for making a tentative DA and a tool by which the DA could be posted at the bedside. The results of this study suggest that (1) despite some uncertainty it is possible to schedule and post DAs in‐room in various care units and in various settings, (2) DAs were made at least a day ahead of time in almost half the DA discharges, and (3) most DA discharges were characterized by on‐time departure. In addition, patient, family, and nursing satisfaction (in relation to the DA) warrants further investigation.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the valuable insights and collaboration of our colleagues Deborah R. Fischer, Steven L. Bahnemann, Matthew Skelton, MD, Lauri J. Dahl, Pamela O. Johnson, MSN, Debra A. Hernke, MSN, Susan L. Stirn, MSN, Barbara R. Spurrier, Ryan R. Armbruster, Todd J. Bille, and Donna K. Lawson of the Mayo Clinic and Mayo Foundation.

- ,,, et al.Learning from patients: a discharge planning improvement project.Jt Comm J Qual Improv.1996;22:311–22.

- ,,,,,, et al.Payer‐hospital collaboration to improve patient satisfaction with hospital discharge.Jt Comm J Qual Improv.1996;22:336–344.

- ,,,,,.How was your hospital stay? Patients' reports about their care in Canadian hospitals.CMAJ.1994;150:1813–1822.

- .A hospitalization from hell: a patient's perspective on quality.Ann Intern Med.2003;138:33–39.

- ,,.Predictors of elder and family caregiver satisfaction with discharge planning.J Cardiovasc Nurs.2000;14:76–87.

- ,,,,.The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital.Ann Intern Med.2003;138:161–167.

- ,,, et al.Patient callback program: a quality improvement, customer service, and marketing tool.J Health Care Mark.1993;13:60–65.

- ,,,.Effects of a medical team coordinator on length of hospital stay.CMAJ.1992;146:511–515.

- ,.Discharge planning from hospital to home.Cochrane Database Syst Rev.2000;4:CD000313.

- ,,,.Continuity of care and patient outcomes after hospital discharge.J Gen Intern Med.2004;19:624–631.

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Cambridge, UK: Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Available from: http://www.ihi.org/IHI/Topics/Improvement/ImprovementMethods/HowToImprove/testingchanges.htm. Accessed July 28,2006.

Dicharge of a patient from the hospital is a complicated, interprofessional endeavor.1, 2 Several institutions report that discharge is one of the least satisfying elements of the patient's hospital experience.35 Recent evidence suggests that a poorly planned or disorganized discharge may compromise patient safety in the period soon after dismissal.6 Several initiatives have been aimed at improving patient satisfaction and safety related to discharge.710

In 2000 the Mayo Clinic (Rochester, Minnesota) Department of Internal Medicine leadership established a goal to improve patient satisfaction with the hospital dismissal process. Patient focus group data suggested that uncertainty about the anticipated date and time of discharge causes frustration to some patients and families.

We hypothesized that an appointment to leave the hospital might be practicable. We joined an Institute for Healthcare Improvement collaborative (Improving Flow Through Acute Care Settings, 1 of 6 Improvement Action Network [IMPACT] Learning and Innovation Communities) aimed at scheduling discharge appointments (DAs). The collaborating members deemed that, although the ideal DA is set at least a day in advance, a same‐day DA is also desirable for both patient satisfaction and staff task organization in pursuit of a high‐quality discharge.

METHODS

This project was approved by the Mayo Foundation Institutional Review Board. We tested the following hypotheses:

It is possible to make and display DAs in various care units.

Most DAs can be scheduled a day before dismissal.

Most DA patients depart on time.

Setting

Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, is a tertiary academic medical center with 2 hospitals (Saint Marys and Rochester Methodist) that house a total of 1951 licensed beds in 76 care units.

The preliminary study displaying DAs was carried out in the Innovation and Quality (IQ) Unit of Saint Marys Hospital, a 23‐bed general medical care unit that supports both resident and nonresident services. Traditionally, primary services usually consist of an attending physician and house officer physicians (junior and senior residents). Less commonly, primary services consist of an attending physician and either a nurse‐practitioner or a physician assistant.

The design pilot took place between August 2 and December 24, 2003. The subsequent, larger study of applicability took place across 8 care units (including the IQ Unit) between December 28, 2003, and April 25, 2004.

Preliminary Work: Design Pilot

We designed bedside dry‐erase wall displays and mounted them in the rooms in plain view of patients and their families and caregivers. Pilot testing of DA scheduling was done on a general medical care unit from August 2 to December 24, 2003. To optimize the process for scheduling a DA, our team developed 21 small tests to change the dismissal process through plan, do, study, and act cycles.11

The recommended process was that as soon as an organized discharge could be reasonably envisioned, the primary service provider would discuss with the patient, family, and primary nurse (and a social service worker, if involved) the anticipated discharge day. A member of the primary service was to handwrite (with a marker) the anticipated day on the specially designed bedside dry‐erase board (Fig. 1) in view of the patient. The same primary service prescribers could amend this anticipated day (or time) by repeating the process of consultation and discussion as needed. The time of the DA could be written on the DA board (or amended) by either a member of the primary service or the primary care nurse.

Each morning, the primary care nurse transmitted the DA board data to the admission, discharge, and transfer log kept at the unit secretary desk (in which the actual discharge time has always been routinely recorded by the unit secretary).

Adoption of DA Scheduling in Other Care Units

Several meetings were held with 7 other patient care unit leaders about adopting the protocol. These units, both medical and surgical, were selected according to 3 criteria: (1) prior participation in unit‐level continuous improvement work, (2) current or recent work in any aspect of the discharge process, and (3) a reputation for having innovative nursing leadership and staff.

Data Acquisition and Analysis

Data were collected daily from each participating unit's admission, discharge, and transfer log: both the actual time of departure and the DA, if one had been scheduled. For each DA patient, the DA time was compared with the actual departure time.

RESULTS

During the 4‐month study of discharges across 8 care units, 1256 of 2046 patients (61%) received a DA; 576 of the DAs (46%) were scheduled at least 1 day in advance (Table 1). Among patients with a DA, 752 were discharged on time (60%), and only 240 (19%) were tardy.

| Unit | DAs | Departure time of patients compared with DA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Type of unit | No. of patients | Patients with DAs, n (%) | DAs scheduled ϵ 1 day ahead, n (%) | On time, n (%)a | Early, n (%) | Late, n (%) |

| |||||||

| 1 | Neurology/neurosurgery | 525 | 270 (51) | 0 (0) | 175 (65) | 44 (16) | 51 (19) |

| 2 | Surgery (mixed) | 481 | 325 (68) | 289 (89) | 166 (51) | 101 (31) | 58 (18) |

| 3 | General internal medicine (IQ Unit) | 466 | 243 (52) | 35 (14) | 132 (54) | 50 (21) | 61 (25) |

| 4 | Neurology/neurosurgery | 267 | 189 (71) | 40 (21) | 119 (63) | 41 (22) | 29 (15) |

| 5 | Vascular surgery | 201 | 127 (63) | 127 (100) | 90 (71) | 12 (9) | 25 (20) |

| 6 | Psychiatry | 46 | 42 (91) | 42 (100) | 28 (67) | 9 (21) | 5 (12) |

| 7 | Orthopedic surgeryelective | 38 | 38 (100) | 22 (58) | 24 (63) | 3 (8) | 11 (29) |

| 8 | Orthopedic surgerytrauma | 22 | 22 (100) | 21 (95) | 18 (82) | 4 (18) | 0 (0) |

| Total | 2046 | 1256 (61) | 576 (46) | 752 (60) | 264 (21) | 240 (19) | |

DISCUSSION