User login

Why and How ACOs Must Evolve

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) triumphantly announced in January 2016 that 121 new participants had joined 1 of its 3 accountable care organization (ACO) programs, and that the various ACOs had together saved the federal government $411 million in 2014 while improving on various quality metrics.[1] Yet even as the ACO model has gathered political momentum and shown promise in reducing payer spending in the short term, it is facing growing scrutiny that it may be insufficient to support meaningful care delivery transformation.

Different ACO models differ in their financial details, but the fundamental theme is the same: healthcare organizations earn bonuses, or shared savings, if they bill payers less than their projected fee‐for‐service revenue (known as the spending benchmark) and meet quality measures. In double‐sided ACO models, if fee‐for‐service revenue exceeds the benchmark, ACOs are also fined. In contrast with traditional fee‐for‐service, in which payments are tied directly to price and volume of services, ACOs were envisioned as a business model that would enable health systems to thrive by improving the care efficiency and clinical outcomes of their patient populations.

However, because health systems only earn shared savings bonuses if they reduce their fee‐for‐service revenue, ACOs do not have a clear business case for moving toward value‐oriented care. ThedaCare, the best performing Pioneer ACO in the first year of the program, reported that successful reduction of preventable hospital admissions led to shared savings payments. However, those payments did not cover the reduced fee‐for‐service revenue, leading to diminished overall financial performance.[2] Only 5% of the 434 Shared Savings Program ACOs have agreed to double‐sided contracts, suggesting discomfort with the structure of the model.[1] Although ACOs have continued to grow in overall number, the programs have experienced significant churn, with over two thirds of Pioneer ACOs leaving over the last 3 years. This suggests widespread commitment to the principle of population health but a struggle by health systems to make the specific models financially viable.[3]

How can payers reshape the ACO model to better support value‐oriented care delivery transformation while maintaining its key cost control elements? One strategy is for CMS to establish a pathway for adding care delivery interventions to the fee‐for‐service schedule for ACOs, a concept we call population health billing. Payers have shown some interest in supporting population health efforts via fee‐for‐service: for example, in 2015 CMS established the chronic care management fee, which pays a per patient per month fee for care coordination of Medicare beneficiaries with 2 or more chronic conditions, and the transitional care management fee, which reimburses a postdischarge office visit focused on managing a patient's transition out of the hospital.[4] UnitedHealthcare has begun reimbursing virtual physician visits for some self‐insured employers.[5]

These isolated efforts should be rolled up into a systematic pathway for population health interventions to become billable under fee‐for‐service for organizations in Medicare ACO contracts. CMS and institutional provider associations, whose technical committees generate the majority of billing codes, could together adopt a formal set of criteria to grade the evidence basis of population health interventions in terms of their impact on clinical outcomes, care quality, and care value, similar to the National Quality Forum's work with quality metrics, and establish a formal process by which interventions with demonstrated efficacy can be assigned billing values in a timely, rigorous, and transparent manner. Candidates for population health billing codes could include high‐risk case management, virtual visits, and home‐based primary care. ACOs would be free to determine which, if any, particular interventions to adopt.

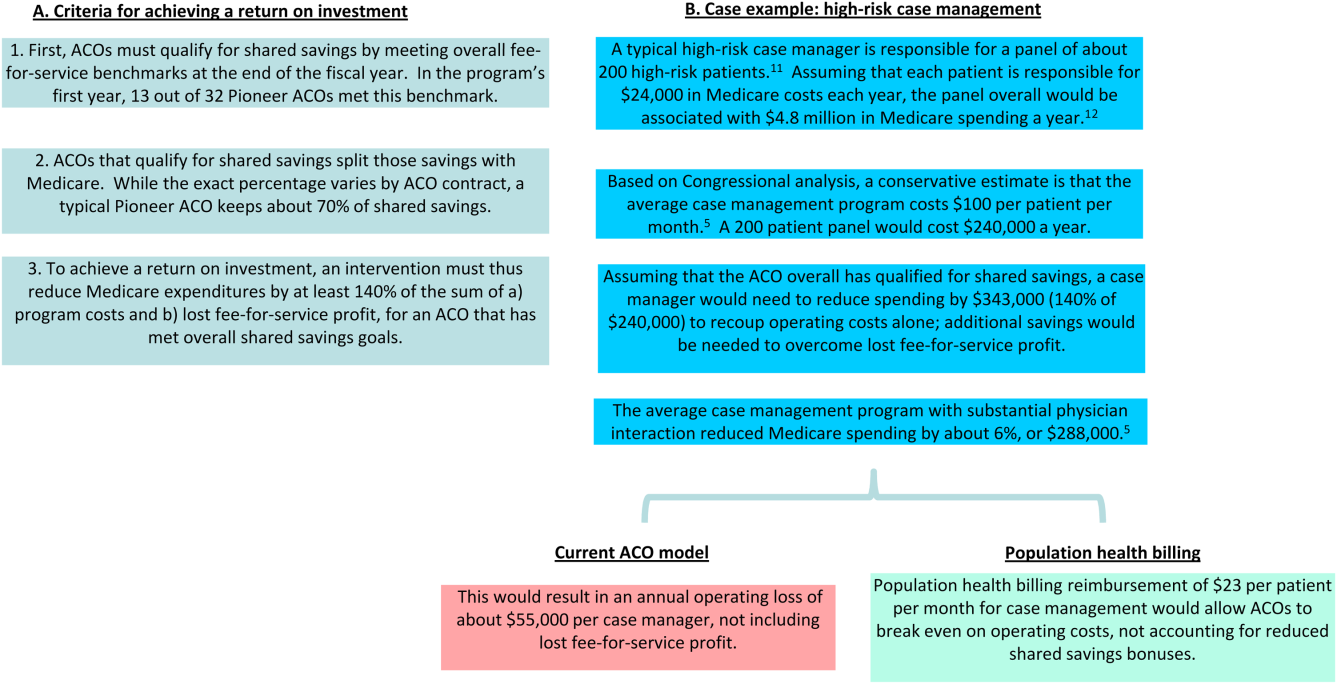

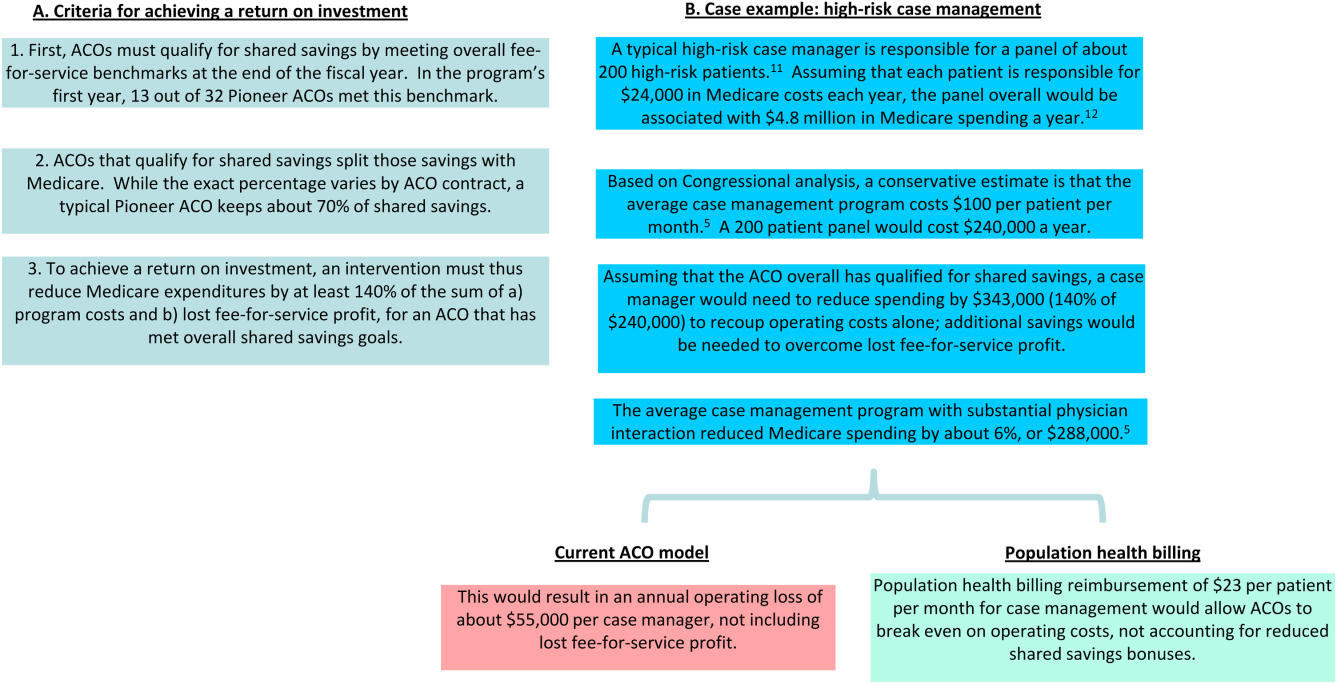

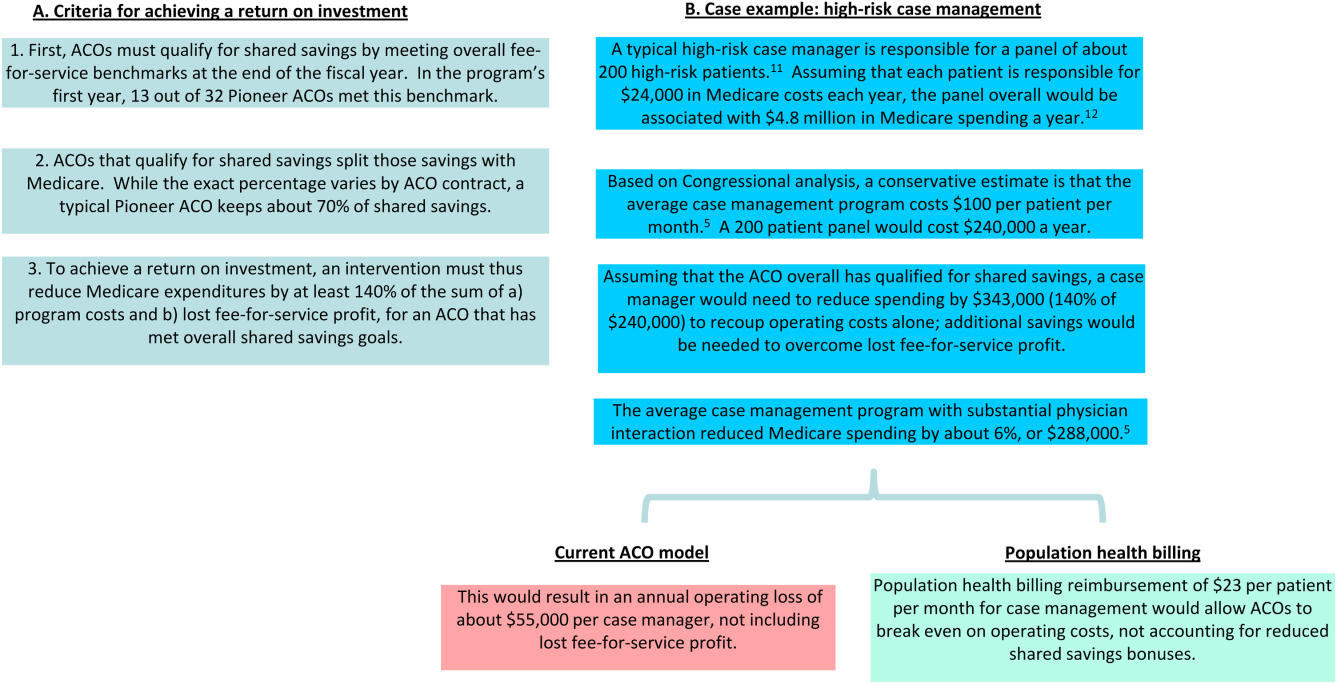

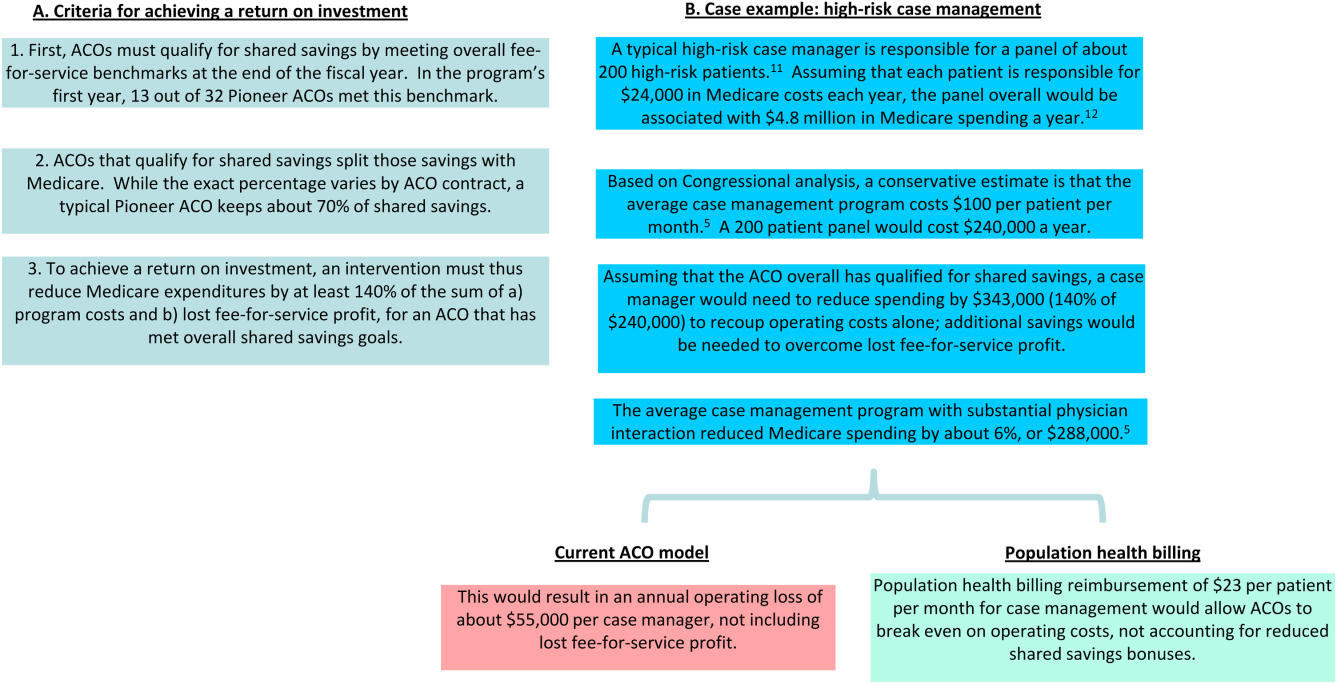

ACOs must currently invest in population health programs with out‐of‐pocket funds and bet that reductions in preventable healthcare utilization result in sufficient shared savings to compensate for both program costs and lost fee‐for‐service profit. Even clinically successful programs are often unable to reach this high threshold.[6] A recent New England Journal of Medicine article lamented a common theme among studies of population health interventions: clinical success, but financial unsustainability.[7] CMS' Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative, which provides about 500 primary care practices with case management fees to redesign their care delivery, resulted in a reduced volume of primary care visits and improved patient communication but no cost savings to Medicare after accounting for program fees (14). Congressional analysis found that although case management programs with substantial physician interaction reduced Medicare expenditures by an average of 6%, only 1 out of 34 programs achieved statistically significant savings to Medicare relative to their program fees alone.[8] E‐consults, when a specialist physician provides recommendations to a primary doctor by reviewing a patient's chart electronically, are associated with decreased wait times, high primary provider satisfaction, and lower costs compared to traditional care, yet adoption among ACOs has been limited by the opportunity cost of fee‐for‐service revenue.[9] In reducing Medicare costs and hence their own fee‐for‐service revenue by $300 million in their first year, Pioneer ACOs were only collectively granted bonuses of about $77 million against the significant operating and capital costs of population health.[10] The financial challenges of ACOs are a reflection of the difficulty in consistently developing a fiscally and clinically successful set of population health interventions under current ACO financial rules.

In Figure 1, we use high‐risk case management as an example to demonstrate how population billing could work. Population health billing could provide a per patient, per month fee‐for‐service payment to ACOs for high‐risk case management services. This payment would count against ACOs' spending benchmarks at the end of the year. By helping cover the operating costs of these programs, population health billing would make value‐oriented interventions significantly more sustainable compared to the current ACO models.

In providing fee‐for‐service revenue for population health interventions, population health billing would break the inherent tension between fee‐for‐service and shared savings bonuses. It would allow ACOs to transition ever‐greater portions of revenue from traditional transactional‐based sources toward shared savings, without requiring success in accountable care to mean fee‐for‐service losses. This is an important threshold for operational leaders who must integrate population health, which currently represent loss centers on balance sheets, within existing profitable fee‐for‐service business lines.

Some observers may argue that allowing billable care delivery interventions may encourage practices to roll out interventions that meet billing requirements but have little meaningful impact on population health; the efficacy of care delivery interventions is clearly dependent on the context of the health system and quality of execution. This concern is the same fundamental concern of fee‐for‐service reimbursement as a whole. However, because ACOs are paid bonuses for reducing fee‐for‐service revenue, they would have an incentive to only develop and bill for population health interventions they believe would have a meaningful return on investment in reducing healthcare costs. The fundamental incentives of ACOs would remain the same‐ to reduce healthcare spending by better managing the costs of their patient populations. Others may argue that population health billing would build upon our fee‐for‐service system that many have advocated we must move past. But ACO initiatives and bundled payments are similarly built upon a foundation of fee‐for‐service.

Whereas a greater number of billable services will likely reduce CMS' short‐term savings from ACO programs, the ACO model must offer a sustainable business case for care delivery reform to ultimately bend long‐term healthcare costs. Payers are not obligated to ensure that providers maintain historical income levels, but over the long term providers will not make the sizable infrastructure investments, such as integrated information technology platforms, data analytics, and risk management, required to deliver value‐based care without a sustainable business case. To limit the costs of population health billing, Medicare should restrict it to ACO contracts that allow for penalties. The fee‐for‐service reimbursement rates under population health billing could also be tied to performance on quality metrics, similar to how Medicare fee‐for‐service hospital reimbursement is linked to performance on value‐based metrics.[13]

In addition, this reduction in short‐term cost savings may actually improve the sustainability of the ACO model. Every year, each ACO's spending benchmark is re‐based, or recalculated based on the most recent spending data. This means that ACOs that successfully reduce their fee‐for‐service revenue below their spending benchmark will face an even lower benchmark the next year and have to reduce their costs even further, creating an unsustainable trend. Because population health billing would count against the spending benchmark, it would help slow down this race to the bottom while driving forward value‐oriented care delivery transformation.

ACOs have a number of other design problems, including high rates of patient churn, imperfect quality metrics that do not adequately capture the scope of population‐level health, and lags in data access.[14] The Next Generation ACO model addresses some of these concerns. For example, it allows ACOs to prospectively define their patient populations. Yet many challenges remain. Population health billing does not solve all of these problems, but it will improve the ability of health systems to meaningfully pivot toward a value‐oriented strategy.

As physicians and ACO operational leaders, we believe in the clinical and policy vision behind the ACO model but have also struggled with the limitations of the model to meaningfully support care delivery transformation. If CMS truly wants to meaningfully transform US healthcare from volume‐based to value‐based, it must invest in the needed care redesign even at the expense of short‐term cost savings.

Disclosures: Dr. Chen was formerly a consultant for Partners HealthCare, a Pioneer ACO, and a physician fellow on the Pioneer ACO Team at the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation. He currently serves on the advisory board of Radial Analytics and is a resident physician at Massachusetts General Hospital. Dr. Ackerly was formerly the associate medical director for Population Health and Continuing Care at Partners HealthCare and an Innovation Advisor to the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation. He currently serves as the Chief Clinical Officer of naviHealth. Dr. Gottlieb was formerly the President and Chief Executive Officer of Partners HealthCare and currently serves as the Chief Executive Officer of Partners In Health. The views represented here are those of the authors' and do not represent the views of Partners HealthCare, Massachusetts General Hospital, naviHealth, or Partners In Health.

- U.S. Department of Health 310:1341–1342.

- , , , . Performance differences in year 1 of the Pioneer accountable care organizations. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1927–1936.

- , , , , . Medicare chronic care management payments and financial returns to primary care practice: a modeling study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:580–588.

- UnitedHealthcare. UnitedHealthcare covers virtual care physician visits, expanding consumers' access to affordable health care options. Available at: http://www.uhc.com/news‐room/2015‐news‐release‐archive/unitedhealthcare‐covers‐virtual‐care‐physician‐visits. Published April 30, 2015. Accessed February 6, 2016.

- , , . Toward increased adoption of complex care management. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:491–493.

- , , . Asymmetric thinking about return on investment. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(7):606–608.

- . Lessons from Medicare's demonstration projects on disease management and care coordination. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Budget Office, Health and Human Resources Division, working paper 2012‐01, 2012. Available at: http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/WP2012‐01_Nelson_Medicare_DMCC_Demonstrations.pdf. Published January 2012. Accessed June 15, 2015.

- , , , . A safety‐net system gains efficiencies through ‘eReferrals’ to specialists. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29:969–971.

- Centers for Medicare MGH Medicare Demonstration Project for High-Cost Beneficiaries. Available at: http://www.massgeneral.org/News/assets/pdf/CMS_project_phase1FactSheet.pdf. Accessed April 2, 2016.

- , , , et al. Two-Year Costs and Quality in the Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative. N Engl J Med. 2016; DOI: 10.1056/NEJMsa1414953.

- , . Beyond ACOs and bundled payments: Medicare's shift toward accountability in fee‐for‐service. JAMA. 2014;311:673–674.

- , , , , . ACO model should encourage efficient care delivery. Healthc (Amst). 2015;3(3):150–152.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) triumphantly announced in January 2016 that 121 new participants had joined 1 of its 3 accountable care organization (ACO) programs, and that the various ACOs had together saved the federal government $411 million in 2014 while improving on various quality metrics.[1] Yet even as the ACO model has gathered political momentum and shown promise in reducing payer spending in the short term, it is facing growing scrutiny that it may be insufficient to support meaningful care delivery transformation.

Different ACO models differ in their financial details, but the fundamental theme is the same: healthcare organizations earn bonuses, or shared savings, if they bill payers less than their projected fee‐for‐service revenue (known as the spending benchmark) and meet quality measures. In double‐sided ACO models, if fee‐for‐service revenue exceeds the benchmark, ACOs are also fined. In contrast with traditional fee‐for‐service, in which payments are tied directly to price and volume of services, ACOs were envisioned as a business model that would enable health systems to thrive by improving the care efficiency and clinical outcomes of their patient populations.

However, because health systems only earn shared savings bonuses if they reduce their fee‐for‐service revenue, ACOs do not have a clear business case for moving toward value‐oriented care. ThedaCare, the best performing Pioneer ACO in the first year of the program, reported that successful reduction of preventable hospital admissions led to shared savings payments. However, those payments did not cover the reduced fee‐for‐service revenue, leading to diminished overall financial performance.[2] Only 5% of the 434 Shared Savings Program ACOs have agreed to double‐sided contracts, suggesting discomfort with the structure of the model.[1] Although ACOs have continued to grow in overall number, the programs have experienced significant churn, with over two thirds of Pioneer ACOs leaving over the last 3 years. This suggests widespread commitment to the principle of population health but a struggle by health systems to make the specific models financially viable.[3]

How can payers reshape the ACO model to better support value‐oriented care delivery transformation while maintaining its key cost control elements? One strategy is for CMS to establish a pathway for adding care delivery interventions to the fee‐for‐service schedule for ACOs, a concept we call population health billing. Payers have shown some interest in supporting population health efforts via fee‐for‐service: for example, in 2015 CMS established the chronic care management fee, which pays a per patient per month fee for care coordination of Medicare beneficiaries with 2 or more chronic conditions, and the transitional care management fee, which reimburses a postdischarge office visit focused on managing a patient's transition out of the hospital.[4] UnitedHealthcare has begun reimbursing virtual physician visits for some self‐insured employers.[5]

These isolated efforts should be rolled up into a systematic pathway for population health interventions to become billable under fee‐for‐service for organizations in Medicare ACO contracts. CMS and institutional provider associations, whose technical committees generate the majority of billing codes, could together adopt a formal set of criteria to grade the evidence basis of population health interventions in terms of their impact on clinical outcomes, care quality, and care value, similar to the National Quality Forum's work with quality metrics, and establish a formal process by which interventions with demonstrated efficacy can be assigned billing values in a timely, rigorous, and transparent manner. Candidates for population health billing codes could include high‐risk case management, virtual visits, and home‐based primary care. ACOs would be free to determine which, if any, particular interventions to adopt.

ACOs must currently invest in population health programs with out‐of‐pocket funds and bet that reductions in preventable healthcare utilization result in sufficient shared savings to compensate for both program costs and lost fee‐for‐service profit. Even clinically successful programs are often unable to reach this high threshold.[6] A recent New England Journal of Medicine article lamented a common theme among studies of population health interventions: clinical success, but financial unsustainability.[7] CMS' Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative, which provides about 500 primary care practices with case management fees to redesign their care delivery, resulted in a reduced volume of primary care visits and improved patient communication but no cost savings to Medicare after accounting for program fees (14). Congressional analysis found that although case management programs with substantial physician interaction reduced Medicare expenditures by an average of 6%, only 1 out of 34 programs achieved statistically significant savings to Medicare relative to their program fees alone.[8] E‐consults, when a specialist physician provides recommendations to a primary doctor by reviewing a patient's chart electronically, are associated with decreased wait times, high primary provider satisfaction, and lower costs compared to traditional care, yet adoption among ACOs has been limited by the opportunity cost of fee‐for‐service revenue.[9] In reducing Medicare costs and hence their own fee‐for‐service revenue by $300 million in their first year, Pioneer ACOs were only collectively granted bonuses of about $77 million against the significant operating and capital costs of population health.[10] The financial challenges of ACOs are a reflection of the difficulty in consistently developing a fiscally and clinically successful set of population health interventions under current ACO financial rules.

In Figure 1, we use high‐risk case management as an example to demonstrate how population billing could work. Population health billing could provide a per patient, per month fee‐for‐service payment to ACOs for high‐risk case management services. This payment would count against ACOs' spending benchmarks at the end of the year. By helping cover the operating costs of these programs, population health billing would make value‐oriented interventions significantly more sustainable compared to the current ACO models.

In providing fee‐for‐service revenue for population health interventions, population health billing would break the inherent tension between fee‐for‐service and shared savings bonuses. It would allow ACOs to transition ever‐greater portions of revenue from traditional transactional‐based sources toward shared savings, without requiring success in accountable care to mean fee‐for‐service losses. This is an important threshold for operational leaders who must integrate population health, which currently represent loss centers on balance sheets, within existing profitable fee‐for‐service business lines.

Some observers may argue that allowing billable care delivery interventions may encourage practices to roll out interventions that meet billing requirements but have little meaningful impact on population health; the efficacy of care delivery interventions is clearly dependent on the context of the health system and quality of execution. This concern is the same fundamental concern of fee‐for‐service reimbursement as a whole. However, because ACOs are paid bonuses for reducing fee‐for‐service revenue, they would have an incentive to only develop and bill for population health interventions they believe would have a meaningful return on investment in reducing healthcare costs. The fundamental incentives of ACOs would remain the same‐ to reduce healthcare spending by better managing the costs of their patient populations. Others may argue that population health billing would build upon our fee‐for‐service system that many have advocated we must move past. But ACO initiatives and bundled payments are similarly built upon a foundation of fee‐for‐service.

Whereas a greater number of billable services will likely reduce CMS' short‐term savings from ACO programs, the ACO model must offer a sustainable business case for care delivery reform to ultimately bend long‐term healthcare costs. Payers are not obligated to ensure that providers maintain historical income levels, but over the long term providers will not make the sizable infrastructure investments, such as integrated information technology platforms, data analytics, and risk management, required to deliver value‐based care without a sustainable business case. To limit the costs of population health billing, Medicare should restrict it to ACO contracts that allow for penalties. The fee‐for‐service reimbursement rates under population health billing could also be tied to performance on quality metrics, similar to how Medicare fee‐for‐service hospital reimbursement is linked to performance on value‐based metrics.[13]

In addition, this reduction in short‐term cost savings may actually improve the sustainability of the ACO model. Every year, each ACO's spending benchmark is re‐based, or recalculated based on the most recent spending data. This means that ACOs that successfully reduce their fee‐for‐service revenue below their spending benchmark will face an even lower benchmark the next year and have to reduce their costs even further, creating an unsustainable trend. Because population health billing would count against the spending benchmark, it would help slow down this race to the bottom while driving forward value‐oriented care delivery transformation.

ACOs have a number of other design problems, including high rates of patient churn, imperfect quality metrics that do not adequately capture the scope of population‐level health, and lags in data access.[14] The Next Generation ACO model addresses some of these concerns. For example, it allows ACOs to prospectively define their patient populations. Yet many challenges remain. Population health billing does not solve all of these problems, but it will improve the ability of health systems to meaningfully pivot toward a value‐oriented strategy.

As physicians and ACO operational leaders, we believe in the clinical and policy vision behind the ACO model but have also struggled with the limitations of the model to meaningfully support care delivery transformation. If CMS truly wants to meaningfully transform US healthcare from volume‐based to value‐based, it must invest in the needed care redesign even at the expense of short‐term cost savings.

Disclosures: Dr. Chen was formerly a consultant for Partners HealthCare, a Pioneer ACO, and a physician fellow on the Pioneer ACO Team at the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation. He currently serves on the advisory board of Radial Analytics and is a resident physician at Massachusetts General Hospital. Dr. Ackerly was formerly the associate medical director for Population Health and Continuing Care at Partners HealthCare and an Innovation Advisor to the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation. He currently serves as the Chief Clinical Officer of naviHealth. Dr. Gottlieb was formerly the President and Chief Executive Officer of Partners HealthCare and currently serves as the Chief Executive Officer of Partners In Health. The views represented here are those of the authors' and do not represent the views of Partners HealthCare, Massachusetts General Hospital, naviHealth, or Partners In Health.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) triumphantly announced in January 2016 that 121 new participants had joined 1 of its 3 accountable care organization (ACO) programs, and that the various ACOs had together saved the federal government $411 million in 2014 while improving on various quality metrics.[1] Yet even as the ACO model has gathered political momentum and shown promise in reducing payer spending in the short term, it is facing growing scrutiny that it may be insufficient to support meaningful care delivery transformation.

Different ACO models differ in their financial details, but the fundamental theme is the same: healthcare organizations earn bonuses, or shared savings, if they bill payers less than their projected fee‐for‐service revenue (known as the spending benchmark) and meet quality measures. In double‐sided ACO models, if fee‐for‐service revenue exceeds the benchmark, ACOs are also fined. In contrast with traditional fee‐for‐service, in which payments are tied directly to price and volume of services, ACOs were envisioned as a business model that would enable health systems to thrive by improving the care efficiency and clinical outcomes of their patient populations.

However, because health systems only earn shared savings bonuses if they reduce their fee‐for‐service revenue, ACOs do not have a clear business case for moving toward value‐oriented care. ThedaCare, the best performing Pioneer ACO in the first year of the program, reported that successful reduction of preventable hospital admissions led to shared savings payments. However, those payments did not cover the reduced fee‐for‐service revenue, leading to diminished overall financial performance.[2] Only 5% of the 434 Shared Savings Program ACOs have agreed to double‐sided contracts, suggesting discomfort with the structure of the model.[1] Although ACOs have continued to grow in overall number, the programs have experienced significant churn, with over two thirds of Pioneer ACOs leaving over the last 3 years. This suggests widespread commitment to the principle of population health but a struggle by health systems to make the specific models financially viable.[3]

How can payers reshape the ACO model to better support value‐oriented care delivery transformation while maintaining its key cost control elements? One strategy is for CMS to establish a pathway for adding care delivery interventions to the fee‐for‐service schedule for ACOs, a concept we call population health billing. Payers have shown some interest in supporting population health efforts via fee‐for‐service: for example, in 2015 CMS established the chronic care management fee, which pays a per patient per month fee for care coordination of Medicare beneficiaries with 2 or more chronic conditions, and the transitional care management fee, which reimburses a postdischarge office visit focused on managing a patient's transition out of the hospital.[4] UnitedHealthcare has begun reimbursing virtual physician visits for some self‐insured employers.[5]

These isolated efforts should be rolled up into a systematic pathway for population health interventions to become billable under fee‐for‐service for organizations in Medicare ACO contracts. CMS and institutional provider associations, whose technical committees generate the majority of billing codes, could together adopt a formal set of criteria to grade the evidence basis of population health interventions in terms of their impact on clinical outcomes, care quality, and care value, similar to the National Quality Forum's work with quality metrics, and establish a formal process by which interventions with demonstrated efficacy can be assigned billing values in a timely, rigorous, and transparent manner. Candidates for population health billing codes could include high‐risk case management, virtual visits, and home‐based primary care. ACOs would be free to determine which, if any, particular interventions to adopt.

ACOs must currently invest in population health programs with out‐of‐pocket funds and bet that reductions in preventable healthcare utilization result in sufficient shared savings to compensate for both program costs and lost fee‐for‐service profit. Even clinically successful programs are often unable to reach this high threshold.[6] A recent New England Journal of Medicine article lamented a common theme among studies of population health interventions: clinical success, but financial unsustainability.[7] CMS' Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative, which provides about 500 primary care practices with case management fees to redesign their care delivery, resulted in a reduced volume of primary care visits and improved patient communication but no cost savings to Medicare after accounting for program fees (14). Congressional analysis found that although case management programs with substantial physician interaction reduced Medicare expenditures by an average of 6%, only 1 out of 34 programs achieved statistically significant savings to Medicare relative to their program fees alone.[8] E‐consults, when a specialist physician provides recommendations to a primary doctor by reviewing a patient's chart electronically, are associated with decreased wait times, high primary provider satisfaction, and lower costs compared to traditional care, yet adoption among ACOs has been limited by the opportunity cost of fee‐for‐service revenue.[9] In reducing Medicare costs and hence their own fee‐for‐service revenue by $300 million in their first year, Pioneer ACOs were only collectively granted bonuses of about $77 million against the significant operating and capital costs of population health.[10] The financial challenges of ACOs are a reflection of the difficulty in consistently developing a fiscally and clinically successful set of population health interventions under current ACO financial rules.

In Figure 1, we use high‐risk case management as an example to demonstrate how population billing could work. Population health billing could provide a per patient, per month fee‐for‐service payment to ACOs for high‐risk case management services. This payment would count against ACOs' spending benchmarks at the end of the year. By helping cover the operating costs of these programs, population health billing would make value‐oriented interventions significantly more sustainable compared to the current ACO models.

In providing fee‐for‐service revenue for population health interventions, population health billing would break the inherent tension between fee‐for‐service and shared savings bonuses. It would allow ACOs to transition ever‐greater portions of revenue from traditional transactional‐based sources toward shared savings, without requiring success in accountable care to mean fee‐for‐service losses. This is an important threshold for operational leaders who must integrate population health, which currently represent loss centers on balance sheets, within existing profitable fee‐for‐service business lines.

Some observers may argue that allowing billable care delivery interventions may encourage practices to roll out interventions that meet billing requirements but have little meaningful impact on population health; the efficacy of care delivery interventions is clearly dependent on the context of the health system and quality of execution. This concern is the same fundamental concern of fee‐for‐service reimbursement as a whole. However, because ACOs are paid bonuses for reducing fee‐for‐service revenue, they would have an incentive to only develop and bill for population health interventions they believe would have a meaningful return on investment in reducing healthcare costs. The fundamental incentives of ACOs would remain the same‐ to reduce healthcare spending by better managing the costs of their patient populations. Others may argue that population health billing would build upon our fee‐for‐service system that many have advocated we must move past. But ACO initiatives and bundled payments are similarly built upon a foundation of fee‐for‐service.

Whereas a greater number of billable services will likely reduce CMS' short‐term savings from ACO programs, the ACO model must offer a sustainable business case for care delivery reform to ultimately bend long‐term healthcare costs. Payers are not obligated to ensure that providers maintain historical income levels, but over the long term providers will not make the sizable infrastructure investments, such as integrated information technology platforms, data analytics, and risk management, required to deliver value‐based care without a sustainable business case. To limit the costs of population health billing, Medicare should restrict it to ACO contracts that allow for penalties. The fee‐for‐service reimbursement rates under population health billing could also be tied to performance on quality metrics, similar to how Medicare fee‐for‐service hospital reimbursement is linked to performance on value‐based metrics.[13]

In addition, this reduction in short‐term cost savings may actually improve the sustainability of the ACO model. Every year, each ACO's spending benchmark is re‐based, or recalculated based on the most recent spending data. This means that ACOs that successfully reduce their fee‐for‐service revenue below their spending benchmark will face an even lower benchmark the next year and have to reduce their costs even further, creating an unsustainable trend. Because population health billing would count against the spending benchmark, it would help slow down this race to the bottom while driving forward value‐oriented care delivery transformation.

ACOs have a number of other design problems, including high rates of patient churn, imperfect quality metrics that do not adequately capture the scope of population‐level health, and lags in data access.[14] The Next Generation ACO model addresses some of these concerns. For example, it allows ACOs to prospectively define their patient populations. Yet many challenges remain. Population health billing does not solve all of these problems, but it will improve the ability of health systems to meaningfully pivot toward a value‐oriented strategy.

As physicians and ACO operational leaders, we believe in the clinical and policy vision behind the ACO model but have also struggled with the limitations of the model to meaningfully support care delivery transformation. If CMS truly wants to meaningfully transform US healthcare from volume‐based to value‐based, it must invest in the needed care redesign even at the expense of short‐term cost savings.

Disclosures: Dr. Chen was formerly a consultant for Partners HealthCare, a Pioneer ACO, and a physician fellow on the Pioneer ACO Team at the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation. He currently serves on the advisory board of Radial Analytics and is a resident physician at Massachusetts General Hospital. Dr. Ackerly was formerly the associate medical director for Population Health and Continuing Care at Partners HealthCare and an Innovation Advisor to the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation. He currently serves as the Chief Clinical Officer of naviHealth. Dr. Gottlieb was formerly the President and Chief Executive Officer of Partners HealthCare and currently serves as the Chief Executive Officer of Partners In Health. The views represented here are those of the authors' and do not represent the views of Partners HealthCare, Massachusetts General Hospital, naviHealth, or Partners In Health.

- U.S. Department of Health 310:1341–1342.

- , , , . Performance differences in year 1 of the Pioneer accountable care organizations. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1927–1936.

- , , , , . Medicare chronic care management payments and financial returns to primary care practice: a modeling study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:580–588.

- UnitedHealthcare. UnitedHealthcare covers virtual care physician visits, expanding consumers' access to affordable health care options. Available at: http://www.uhc.com/news‐room/2015‐news‐release‐archive/unitedhealthcare‐covers‐virtual‐care‐physician‐visits. Published April 30, 2015. Accessed February 6, 2016.

- , , . Toward increased adoption of complex care management. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:491–493.

- , , . Asymmetric thinking about return on investment. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(7):606–608.

- . Lessons from Medicare's demonstration projects on disease management and care coordination. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Budget Office, Health and Human Resources Division, working paper 2012‐01, 2012. Available at: http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/WP2012‐01_Nelson_Medicare_DMCC_Demonstrations.pdf. Published January 2012. Accessed June 15, 2015.

- , , , . A safety‐net system gains efficiencies through ‘eReferrals’ to specialists. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29:969–971.

- Centers for Medicare MGH Medicare Demonstration Project for High-Cost Beneficiaries. Available at: http://www.massgeneral.org/News/assets/pdf/CMS_project_phase1FactSheet.pdf. Accessed April 2, 2016.

- , , , et al. Two-Year Costs and Quality in the Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative. N Engl J Med. 2016; DOI: 10.1056/NEJMsa1414953.

- , . Beyond ACOs and bundled payments: Medicare's shift toward accountability in fee‐for‐service. JAMA. 2014;311:673–674.

- , , , , . ACO model should encourage efficient care delivery. Healthc (Amst). 2015;3(3):150–152.

- U.S. Department of Health 310:1341–1342.

- , , , . Performance differences in year 1 of the Pioneer accountable care organizations. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1927–1936.

- , , , , . Medicare chronic care management payments and financial returns to primary care practice: a modeling study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:580–588.

- UnitedHealthcare. UnitedHealthcare covers virtual care physician visits, expanding consumers' access to affordable health care options. Available at: http://www.uhc.com/news‐room/2015‐news‐release‐archive/unitedhealthcare‐covers‐virtual‐care‐physician‐visits. Published April 30, 2015. Accessed February 6, 2016.

- , , . Toward increased adoption of complex care management. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:491–493.

- , , . Asymmetric thinking about return on investment. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(7):606–608.

- . Lessons from Medicare's demonstration projects on disease management and care coordination. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Budget Office, Health and Human Resources Division, working paper 2012‐01, 2012. Available at: http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/WP2012‐01_Nelson_Medicare_DMCC_Demonstrations.pdf. Published January 2012. Accessed June 15, 2015.

- , , , . A safety‐net system gains efficiencies through ‘eReferrals’ to specialists. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29:969–971.

- Centers for Medicare MGH Medicare Demonstration Project for High-Cost Beneficiaries. Available at: http://www.massgeneral.org/News/assets/pdf/CMS_project_phase1FactSheet.pdf. Accessed April 2, 2016.

- , , , et al. Two-Year Costs and Quality in the Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative. N Engl J Med. 2016; DOI: 10.1056/NEJMsa1414953.

- , . Beyond ACOs and bundled payments: Medicare's shift toward accountability in fee‐for‐service. JAMA. 2014;311:673–674.

- , , , , . ACO model should encourage efficient care delivery. Healthc (Amst). 2015;3(3):150–152.