User login

Strategies for managing hot flashes

• Use hormone therapy (HT) at the lowest effective dose and for the shortest duration possible (preferably ≤5 years) in women for whom the potential benefits outweigh the potential risks. A

• Counsel patients that the effectiveness of phytoestrogens (soy), exercise routines, yoga, acupuncture, vitamin E, evening primrose oil, and other herbal preparations has not been established. B

• When HT is refused or contraindicated by a patient’s risk profile, consider antidepressants (selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors), gabapentin, or clonidine. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Hot flashes are the most prevalent and most bothersome symptoms of the menopausal transition and the leading cause for seeking medical attention during that period of a woman’s life.1 They may last for a few seconds or for several minutes and may occur as frequently as every hour to several times per week. On average, women experience hot flashes for a period of 6 months to 2 years, but the symptoms may last up to 10 years or more.2,3

Hot flashes have been reported by up to 70% of women undergoing natural menopause, and by almost all women undergoing surgical menopause.4 For many women, these symptoms are mild and can be managed with reassurance and counseling. For others, the symptoms are severe, overwhelming, last for many years, and impair the quality of life.

According to a community-based survey of 16,000 women, hot flashes occur most often in late perimenopause and among those with a body mass index ≥27. Hot flashes are also more common among African Americans and women who are less physically active and have a lower income.5

Since the publication of the Women’s Health Initiative study in 2002 raised concerns about the long-term safety of hormone therapy (HT), nonhormonal remedies have emerged as potential alternative treatments.6,7 A wealth of evidence has accumulated on the efficacy and safety of these, and various other approaches to the management of hot flashes. This review will summarize that evidence to help you provide optimal care and assist patients in making informed choices about their treatment.

Hormone replacement therapy

HT, given as estrogen alone in women without a uterus or estrogen plus progestin in women with a uterus, is the most studied and most effective therapy for vasomotor symptoms attributable to menopause. Data from one Cochrane review showed a significant reduction in the frequency of weekly hot flashes for oral estrogen compared with placebo, with a weighted mean difference (WMD) of -17.92 (95% confidence interval [CI], -22.86 to -12.99).8 This was equivalent to a 75% reduction in frequency (95% CI, 64.3-82.3) for HT relative to placebo. Results were similar for both opposed and unopposed estrogen regimens.8

Transdermal vs oral therapy. Another review compared oral estradiol, transdermal estradiol, and placebo in terms of reduction of hot flash frequency or severity, or both.9 The review revealed a pooled WMD in hot flashes of -16.8 per week (95% CI, -23.4 to -10.2) for oral estradiol and -22.4 per week (95% CI, -35.9 to -10.4) for transdermal estradiol. Results were similar for opposed and unopposed estrogen regimens.9

Transdermal delivery of estrogen as patches, gels, and sprays delivers unmetabolized estradiol directly to the blood stream, so that lower doses can achieve similar efficacy to doses administered orally.10 Thus, the transdermal route would be in keeping with current guidelines to prescribe the lowest effective dose that relieves symptoms. Emerging research should provide more insight regarding safety and the potential for fewer health risks with transdermal HT compared with oral therapy.

Best way to discontinue? When HT is discontinued, hot flashes may return—sometimes immediately, sometimes after a few months. No evidence-based guidelines exist on the best way to discontinue HT with the least recurrence and severity of hot flashes. No optimal tapering regimen (either by dose or number of days per week that HT is taken) has yet been described in any studies, nor have any randomized controlled trials (RCTs)revealed a significant difference between tapered or abrupt discontinuation.11,12

The breast cancer connection. The relationship between HT and breast cancer has generated considerable controversy. In the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) trial, which included participants on estrogen-only and estrogen plus progesterone regimens, an overall increased risk (hazard ratio [HR]=1.26; 95% CI, 1.00-1.59) was reported. The increased risk fell short of statistical significance, and varied with the duration of exposure.6

In subsequent studies, the magnitude of the associated risk was substantially greater for the estrogen-progestogen preparation, and also higher for longer-term exposure.13 Additionally, a meta-analysis of 8 studies of the risk of breast cancer with combination HT resulted in an odds ratio (OR) of 1.39 (95% CI, 1.12-1.72). Estimates were higher for more than 5 years of use (OR=1.63; 95% CI, 1.22-2.18) when compared with estimates for less than 5 years of use (OR=1.35; CI, 1.16-1.57).14 Recent studies have reported a decline in the incidence of breast cancer in the United States, which has been attributed to a parallel reduction in HT use.15

In contrast to the findings for women taking combination HT, the estrogen-only arm of the WHI study showed a decrease in the overall risk of breast cancer.16 A new analysis of data on participants in the estrogen-only arm of the study shows that, 10 years after the intervention ended, a decreased risk of breast cancer persists. In addition, the increased risk of stroke and deep vein thrombosis found in the original study had dissipated, and the decreased risk of hip fracture was not maintained.

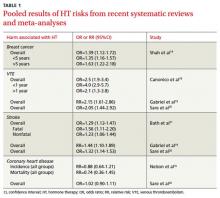

Age matters. Health outcomes in this new analysis were more favorable for younger women for coronary heart disease, heart attack, colorectal cancer, total mortality, and a global index of chronic diseases.17 Pooled results of systematic reviews and meta-analyses on HT risks are available in TABLE 1.14,16,18-21

Progestins

Progesterone in the form of injections (Depo-Provera 150 mg, for example) or oral medroxyprogesterone acetate 20 mg daily has shown a significant reduction in hot flashes compared with placebo.22 However, associated side effects (withdrawal bleeding and weight gain) and concerns about breast cancer often limit the use of this medication.23 Because of the paucity of evidence, transdermal progesterone creams should not be recommended.24

Tibolone

Tibolone is a synthetic steroid that is structurally related to 19-nortestosterone derivatives. It has weak estrogenic, progestogenic, and androgenic properties and has shown significant reduction in hot flashes and night sweating compared with placebo.25 Tibolone has also been shown to enhance mood and sexual function.26 However, evidence of its safety on outcomes such as breast cancer and cardiovascular events is obscure and has shown conflicting results, especially for breast cancer.25,26

A recent double-blinded trial on women with breast cancer found that although tibolone significantly improved vasomotor symptoms, it was associated with an increased risk of breast cancer recurrence (HR=1.40; 95% CI, 1.14-1.70]; P=.001).27 Tibolone is not approved for sale in the United States.

Nonhormonal options

Lifestyle modifications

According to recent reviews, exercise is less effective than HT in relieving hot flashes, but does seems to have beneficial effects on mood, sleep, and overall quality of life.28,29 Other lifestyle modifications such as smoking cessation and weight loss may also be of use.5

Antidepressants

Data from one meta-analysis showed that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) were significantly more effective than placebo in reducing daily frequency of hot flashes (WMD=-1.13; 95% CI, -1.70 to -0.57).30 Efficacy varied for individual drugs.

Venlafaxine, an SNRI, has been shown to be more effective than placebo in managing hot flashes.31 The effect on hot flashes was noticed after 4 weeks of treatment with the 75- and 150-mg doses, but the higher dosage was associated with more adverse effects such as dry mouth, sleeplessness, and decreased appetite.32 Even so, 93% of the participants in the venlafaxine group chose to continue treatment, because the reduction in hot flashes had significantly improved their daily lives.31 Desvenlafaxine, a metabolite of venlafaxine, has been shown to reduce the number of hot flashes by almost 65% from baseline at Weeks 4 and 12, with dosages of 100 and 150 mg/d.33

The SSRIs fluoxetine, citalopram, and paroxetine in 10-, 20-, and 30-mg doses and paroxetine CR (12.5 and 25 mg) have been studied in many RCTs. All have demonstrated a significant decrease in hot flashes compared with placebo with various dosages used. SSRIs reduce hot flashes by as much as 50% to 60%, compared with 80% for estrogen.34 The duration of treatment ranged from 4 weeks to 6 months.

Gabapentin

Gabapentin is approved by the FDA for the treatment of partial seizures and postherpetic neuralgia.35 A meta-analysis of multiple studies published in 2006 showed that gabapentin reduced the mean number of daily hot flashes by 2.05 (95% CI, -2.80 to -1.30).30 Two recent reviews evaluated the efficacy and safety of gabapentin in the treatment of hot flashes in menopausal women and reported that gabapentin in daily doses ranging from 900 to 2400 mg and titration periods lasting 3 to12 days was well tolerated and effective.35,36

A meta-analysis published in 2009 that included 4 RCTs reported significant heterogeneity from one study to another, but comparisons of gabapentin and placebo showed reductions of 20% to 30% in the frequency and severity of hot flashes with gabapentin.36 The most commonly reported adverse effects included somnolence, dizziness, ataxia, fatigue, nystagmus, and peripheral edema.

Clonidine

Clonidine has been studied in oral and transdermal forms for the treatment of hot flashes in menopausal women, especially in women with breast cancer.37-39 Data from one meta-analysis revealed significant reductions in daily hot flashes in the clonidine group compared with placebo at 4 weeks (mean difference [MD]=-0.95; 95% CI, -1.44 to -0.47) and at 8 weeks (MD=-1.63; 95% CI, -2.76 to -0.50).30 Adverse effects included dry mouth, drowsiness, and dizziness. The transdermal route may avoid some of these side effects.40

Alternative remedies

Phytoestrogen and isoflavones. Phytoestrogens are sterol molecules produced by plants. They are similar in structure to human estrogens and have been shown to have estrogen-like activity.40 They are available as dietary soy, soy extract, and red clover extracts. Isoflavones are a type of phytoestrogen.

Comparing trials of effects of soy or isoflavone is difficult, as various formulations and amounts of these products have been used. Combining the data from these trials yielded nonsignificant results for Promensil, a red clover extract (WMD=-0.6; 95% CI, -1.8 to 0.6), and inconsistent results (sometimes favoring the intervention, other times the placebo) for soy food and soy extracts.41-43

There is no evidence of estrogenic stimulation of the endometrium with phytoestrogens used for up to 2 years.41 Nevertheless, in the absence of evidence on the safety of long-term use, women with a personal or strong family history of hormone-dependent cancers (breast, uterine, or ovarian) or thromboembolic events should be cautious about using soy-based therapies.42 Long-term safety of these products has to be established before any evidence-based recommendations can be made.

Black cohosh. Actaea racemosa (formerly Cimicifuga racemosa) is the most studied and perhaps the most widely used herbal remedy for hot flashes. It is commonly known as black cohosh and has been used traditionally by Native Americans for the treatment of various medical conditions, including amenorrhea and menopause.44,45

Remifemin is an available standardized extract. Evidence for effectiveness is limited and contradictory. Data from a recent meta-analysis showed that although there was significant heterogeneity between included trials, preparations containing black cohosh improved vasomotor symptoms overall by 26% (95% CI, 11%-40%).45

A recent well-conducted RCT concluded that neither black cohosh nor red clover significantly reduced the frequency of symptoms compared with placebo.46 The same study found that both botanicals were safe as administered for a 12-month period. Some case reports have identified serious adverse events including acute hepatocellular damage, which warrants further investigation, although no causal relationship has been established.47

Evidence for safety and efficacy of antidepressants, gabapentin, clonidine, isoflavones, black cohosh, yoga, acupuncture, and herbal remedies is summarized in TABLE 2.30,36,41,47-55

For more on the treatment of hot flashes, see “Clinical approach to managing hot flashes”.40

Start with a detailed history: Ask about the nature of your patient’s symptoms, her past gynecologic and medical history, and her family history. Take a baseline blood pressure, measure body mass index (BMI), and order a lipid profile. Exclude other possible causes of hot flashes: hyperthyroidism, panic disorder, diabetes, and medications such as antiestrogens or selective estrogen receptor modulators.

Assess the severity of hot flashes and explain their typical clinical course. Discuss lifestyle modifications that may help: losing weight, quitting smoking, wearing lighter clothing, and cutting down on caffeine intake, alcohol, and spicy foods. Tell your patient that hormone therapy (HT) has been shown to be the most effective treatment for women without contraindications. These include current, past, or suspected breast cancer, other estrogen-sensitive malignant conditions, undiagnosed genital bleeding, untreated endometrial hyperplasia, venous thromboembolism, angina, myocardial infarction, uncontrolled hypertension, liver disease, porphyria cutanea tarda (absolute contraindication), or hypersensitivity to the active substances of HT.40

If contraindications can be ruled out, find out whether she is receptive to HT or would prefer alternatives. If she is interested in HT, discuss the risks and benefits involved and the different dosages and routes of administration that are available. If she prefers to explore nonhormonal remedies, discuss the various options and present the evidence for their safety and efficacy. Tell her that the safety of some herbal remedies that contain estrogenic compounds has not been established.

What the future holds

The selective estrogen receptor agonist MF-101, which can induce tissue-specific estrogen-like effects, has been shown to be effective in reducing menopausal hot flashes compared with placebo in a phase II trial.56 A larger phase III trial is in progress.

Lower and ultra-lower doses of systemic estrogen are now available and approved by the FDA, and were found effective in relieving vasomotor symptoms.57-59 The drawback of these preparations is that they may take longer than standard-dose estrogen to achieve maximum relief of symptoms (8-12 weeks vs 4 weeks, respectively). The lower doses have been associated with fewer adverse effects (such as vaginal bleeding and breast tenderness) compared with the standard doses.58,59 Their long-term effects on the cardiovascular system, bone, and breast are still being tested and need to be established.

Newer selective estrogen receptor modulators, especially in combination with estrogen, are another approach to menopausal symptoms currently in testing.60

CORRESPONDENCE

Ghufran A. Jassim, MD, ABMS, MSc, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland-Medical University of Bahrain, PO Box 15503, Adliya, Bahrain; gjassim@rcsi-mub.com

1. Williams RE, Kalilani L, DiBenedetti DB. Healthcare seeking and treatment for menopausal symptoms in the US. Maturitas. 2007;58:348-358.

2. North American Menopause Society. Estrogen and progestogen use in postmenopausal women: 2010 position statement of the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2010;17:242-256.

3. National Institutes of Health. NIH state-of-the-science conference statement: management of menopause-related symptoms. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(12 pt 2):1003-1013.

4. Berecki-Gisolf J, Begum N, Dobson AJ. Symptoms reported by women in midlife: menopausal transition or aging? Menopause. 2009;16:1021-1029.

5. Gold EB, Sternfeld B, Kelsey JL. Relation of demographic and lifestyle factors to symptoms in a multi-racial/ethnic population of women 40-55 years of age. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152:463-473.

6. Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al. Writing group for the Women’s Health Initiative investigators. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women. JAMA. 2002;288:321-333.

7. Lukes A. Evolving issues in the clinical and managed care settings on the management of menopause following the Women’s Health Initiative. J Manag Care Pharm. 2008;14(3 suppl):7-13.

8. MacLennan AH, Broadbent JL, Lester W, et al. Oral oestrogen and combined oestrogen/progestogen therapy versus placebo for hot flushes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(4):CD002978.-

9. Nelson HD. Commonly used types of postmenopausal estrogen for treatment of hot flashes: scientific review. JAMA. 2004;291:1610-1620.

10. Carroll N. A review of transdermal nonpatch estrogen therapy for the management of menopausal symptoms. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2010;19:47-55.

11. Suffoletto JA, Hess R. Tapering vs cold turkey: symptoms versus successful discontinuation of menopausal hormone therapy. Menopause. 2009;16:436-437.

12. Lindh-Astrand L, Bixo M, Hirschberg AL, et al. A randomized controlled study of taper-down or abrupt discontinuation of hormone therapy in women treated for vasomotor symptoms. Menopause. 2010;17:72-29.

13. Banks E, Canfell K, Reeves G. HRT and breast cancer. Womens Health. 2008;4:427-431.

14. Shah NR, Borenstein J, Dubois RW. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and breast cancer. Menopause. 2005;12:668-678.

15. Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD. Decline in US breast cancer rates after the Women’s Health Initiative. Am J Public Health. 2010;100 (suppl 1):S132-S139.

16. Nelson HD, Humphrey LL, Nygren P, et al. Postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy: scientific review. JAMA. 2002;288:872-881.

17. LaCroix AZ, Chiebowski RT, Manson JE, et al. Health outcomes after stopping conjugated equine estrogens among postmenopausal women with prior hysterectomy. JAMA. 2011;305:1305-1314.

18. Canonico M, Plu-Bureau G, Lowe GD, et al. Hormone replacement therapy and risk of venous thromboembolism in postmenopausal women. BMJ. 2008;336:1227-1231.

19. Gabriel SR, Carmona L, Roque M, et al. Hormone replacement therapy for preventing cardiovascular disease in post-menopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(2):CD002229.-

20. Sare GM, Gray LJ, Bath PM. Association between hormone replacement therapy and subsequent arterial and venous vascular events: a meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2031-2041.

21. Bath PM, Gray LJ. Association between hormone replacement therapy and subsequent stroke. BMJ. 2005;330:342.-

22. Boothby LA, Doering PL, Kipersztok S. Bioidentical hormone therapy: a review. Menopause. 2004;11:356-367.

23. Pasqualini JR. Progestins and breast cancer. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2007;23(suppl 1):32-41.

24. Wren BG. Transdermal progesterone creams for postmenopausal women. Med J Aust. 2005;182:237-225.

25. Kenemans P, Speroff L. Tibolone: clinical recommendations and practical guidelines: a report of the International Tibolone Consensus Group. Maturitas. 2005;51:21-28.

26. Wang PH, Cheng MH, Chao HT, et al. Effects of tibolone on the breast of postmenopausal women. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;46:121-126.

27. Kenemans P, Bundred NJ, Foidart JM, et al. Safety and efficacy of tibolone in breast-cancer patients with vasomotor symptoms. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:135-146.

28. Daley A, Stokes-Lampard HJ, Macarthur C. Exercise to reduce vasomotor and other menopausal symptoms: a review. Maturitas. 2009;63:176-180.

29. Daley A, MacArthur C, Mutrie N, et al. Exercise for vasomotor menopausal symptoms. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD006108.-

30. Nelson HD, Vesco KK, Haney E, et al. Nonhormonal therapies for menopausal hot flashes. JAMA. 2006;295:2057-2072.

31. Evans ML, Pritts E, Vittinghof E, et al. Management of postmenopausal hot flushes with venlafaxine hydrochloride. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:161-166.

32. Barton D, La Vasseur B, Loprinzi C, et al. Venlafaxine for the control of hot flashes. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2002;29:33-40.

33. Lilue M, Palacios S. Non-hormonal treatment for vasomotor symptoms during menopause: role of desvenlafaxine. Ginecol Obstet Mex. 2009;77:475-481.

34. Albertazzi P. Non-estrogenic approaches for the treatment of climacteric symptoms. Climacteric. 2007;10(suppl 2):115-120.

35. Brown JN, Wright BR. Use of gabapentin in patients experiencing hot flashes. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29:74-81.

36. Toulis KA, Tzellas T, Kouvelas D, et al. Gabapentin for the treatment of hot flashes in women with natural or tamoxifen-induced menopause: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Ther. 2009;31:221-235.

37. Pandya KJ, Raubertas AF, Flynn PJ, et al. Oral clonidine in postmenopausal patients with breast cancer experiencing tamoxifen-induced hot flashes. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:788-793.

38. Goldberg RM, Loprinzi CL, O’Fallon JR. Transdermal clonidine for ameliorating tamoxifen-induced hot flashes. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:155-158.

39. Buijs C, Mom CH, Willemse PH, et al. Venlafaxine versus clonidine for the treatment of hot flashes in breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;115:573-580.

40. Cobin RH, Futterweit W, Ginzburg SB, et al. AACE Menopause Guidelines Revision Task Force. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists medical guidelines for clinical practice for the diagnosis and treatment of menopause. Endocr Pract. 2006;12:315-337.

41. Lethaby AE, Brown J, Marjoribanks J. Phytoestrogens for vasomotor menopausal symptoms. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD001395.-

42. Tempfer CB, Bentz EH, Leodolter S, et al. Phytoestrogens in clinical practice. Fertil Steril. 2007;87:1243-1249.

43. Krebs EE, Ensrud KE, MacDonald R, et al. Phytoestrogens for treatment of menopausal symptoms: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:824-836.

44. McKenna DJ, Jones K, Humphrey S, et al. Black cohosh. Altern Ther Health Med. 2001;7:93-100.

45. Shams T, Setia MS, Hemmings R, et al. Efficacy of black cohosh-containing preparations on menopausal symptoms: a meta-analysis. Altern Ther Health Med. 2010;16:36-44.

46. Geller SE, Shulman LP, van Breeman RB, et al. Safety and efficacy of black cohosh and red clover for the management of vasomotor symptoms. Menopause. 2009;16:1156-1166.

47. Borrelli F, Ernst E. Black cohosh (Cimicifuga racemosa): a systematic review of adverse events. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199:455-466.

48. Nelson HD. Menopause. Lancet. 2008;371:760-770.

49. Borrelli F, Ernst E. Black cohosh (Cimicifuga racemosa) for menopausal symptoms. Pharmacol Res. 2008;58:8-14.

50. Huntley A, Ernst E. A systematic review of the safety of black cohosh. Menopause. 2003;10:58-64.

51. Kanadys WM, Leszczynska-Gorselak B, Oleszczuk J. Efficacy and safety of black cohosh in the treatment of vasomotor symptoms. Ginekol Pol. 2008;79:287-296.

52. Huntley AL, Ernst E. A systematic review of herbal medicinal products for the treatment of menopausal symptoms. Menopause. 2003;10:465-476.

53. Lee MS, Shin BC, Ernst E. Acupuncture for treating menopausal hot flushes: a systematic review. Climacteric. 2009;12:16-25.

54. Lee MS, Kim JI, Ha JY, et al. Yoga for menopausal symptoms: a systematic review. Menopause. 2009;16:602-608.

55. Cho SH, Whang WW. Acupuncture for vasomotor menopausal symptoms. Menopause. 2009;16:1065-1073.

56. Stovall DW, Pinkerton JV. MF-101, an estrogen receptor beta agonist for the treatment of vasomotor symptoms in peri- and postmenopausal women. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;10:365-371.

57. Peeyananjarassri K, Baber R. Effects of low-dose hormone therapy on menopausal symptoms, bone mineral density, endometrium, and the cardiovascular system. Climacteric. 2004;8:13-23.

58. Ettinger B. Vasomotor symptom relief versus unwanted effects: role of estrogen dosage. Am J Med. 2005;118(suppl 12B):74-78.

59. Ettinger B. Rationale for use of lower estrogen doses for postmenopausal hormone therapy. Maturitas. 2007;57:81-84.

60. Jain N, Xu J, Kanojia RM, et al. Identification and structure-activity relationships of chromene-derived selective estrogen receptor modulators for treatment of postmenopausal symptoms. J Med Chem. 2009;52:7544-7569.

• Use hormone therapy (HT) at the lowest effective dose and for the shortest duration possible (preferably ≤5 years) in women for whom the potential benefits outweigh the potential risks. A

• Counsel patients that the effectiveness of phytoestrogens (soy), exercise routines, yoga, acupuncture, vitamin E, evening primrose oil, and other herbal preparations has not been established. B

• When HT is refused or contraindicated by a patient’s risk profile, consider antidepressants (selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors), gabapentin, or clonidine. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Hot flashes are the most prevalent and most bothersome symptoms of the menopausal transition and the leading cause for seeking medical attention during that period of a woman’s life.1 They may last for a few seconds or for several minutes and may occur as frequently as every hour to several times per week. On average, women experience hot flashes for a period of 6 months to 2 years, but the symptoms may last up to 10 years or more.2,3

Hot flashes have been reported by up to 70% of women undergoing natural menopause, and by almost all women undergoing surgical menopause.4 For many women, these symptoms are mild and can be managed with reassurance and counseling. For others, the symptoms are severe, overwhelming, last for many years, and impair the quality of life.

According to a community-based survey of 16,000 women, hot flashes occur most often in late perimenopause and among those with a body mass index ≥27. Hot flashes are also more common among African Americans and women who are less physically active and have a lower income.5

Since the publication of the Women’s Health Initiative study in 2002 raised concerns about the long-term safety of hormone therapy (HT), nonhormonal remedies have emerged as potential alternative treatments.6,7 A wealth of evidence has accumulated on the efficacy and safety of these, and various other approaches to the management of hot flashes. This review will summarize that evidence to help you provide optimal care and assist patients in making informed choices about their treatment.

Hormone replacement therapy

HT, given as estrogen alone in women without a uterus or estrogen plus progestin in women with a uterus, is the most studied and most effective therapy for vasomotor symptoms attributable to menopause. Data from one Cochrane review showed a significant reduction in the frequency of weekly hot flashes for oral estrogen compared with placebo, with a weighted mean difference (WMD) of -17.92 (95% confidence interval [CI], -22.86 to -12.99).8 This was equivalent to a 75% reduction in frequency (95% CI, 64.3-82.3) for HT relative to placebo. Results were similar for both opposed and unopposed estrogen regimens.8

Transdermal vs oral therapy. Another review compared oral estradiol, transdermal estradiol, and placebo in terms of reduction of hot flash frequency or severity, or both.9 The review revealed a pooled WMD in hot flashes of -16.8 per week (95% CI, -23.4 to -10.2) for oral estradiol and -22.4 per week (95% CI, -35.9 to -10.4) for transdermal estradiol. Results were similar for opposed and unopposed estrogen regimens.9

Transdermal delivery of estrogen as patches, gels, and sprays delivers unmetabolized estradiol directly to the blood stream, so that lower doses can achieve similar efficacy to doses administered orally.10 Thus, the transdermal route would be in keeping with current guidelines to prescribe the lowest effective dose that relieves symptoms. Emerging research should provide more insight regarding safety and the potential for fewer health risks with transdermal HT compared with oral therapy.

Best way to discontinue? When HT is discontinued, hot flashes may return—sometimes immediately, sometimes after a few months. No evidence-based guidelines exist on the best way to discontinue HT with the least recurrence and severity of hot flashes. No optimal tapering regimen (either by dose or number of days per week that HT is taken) has yet been described in any studies, nor have any randomized controlled trials (RCTs)revealed a significant difference between tapered or abrupt discontinuation.11,12

The breast cancer connection. The relationship between HT and breast cancer has generated considerable controversy. In the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) trial, which included participants on estrogen-only and estrogen plus progesterone regimens, an overall increased risk (hazard ratio [HR]=1.26; 95% CI, 1.00-1.59) was reported. The increased risk fell short of statistical significance, and varied with the duration of exposure.6

In subsequent studies, the magnitude of the associated risk was substantially greater for the estrogen-progestogen preparation, and also higher for longer-term exposure.13 Additionally, a meta-analysis of 8 studies of the risk of breast cancer with combination HT resulted in an odds ratio (OR) of 1.39 (95% CI, 1.12-1.72). Estimates were higher for more than 5 years of use (OR=1.63; 95% CI, 1.22-2.18) when compared with estimates for less than 5 years of use (OR=1.35; CI, 1.16-1.57).14 Recent studies have reported a decline in the incidence of breast cancer in the United States, which has been attributed to a parallel reduction in HT use.15

In contrast to the findings for women taking combination HT, the estrogen-only arm of the WHI study showed a decrease in the overall risk of breast cancer.16 A new analysis of data on participants in the estrogen-only arm of the study shows that, 10 years after the intervention ended, a decreased risk of breast cancer persists. In addition, the increased risk of stroke and deep vein thrombosis found in the original study had dissipated, and the decreased risk of hip fracture was not maintained.

Age matters. Health outcomes in this new analysis were more favorable for younger women for coronary heart disease, heart attack, colorectal cancer, total mortality, and a global index of chronic diseases.17 Pooled results of systematic reviews and meta-analyses on HT risks are available in TABLE 1.14,16,18-21

Progestins

Progesterone in the form of injections (Depo-Provera 150 mg, for example) or oral medroxyprogesterone acetate 20 mg daily has shown a significant reduction in hot flashes compared with placebo.22 However, associated side effects (withdrawal bleeding and weight gain) and concerns about breast cancer often limit the use of this medication.23 Because of the paucity of evidence, transdermal progesterone creams should not be recommended.24

Tibolone

Tibolone is a synthetic steroid that is structurally related to 19-nortestosterone derivatives. It has weak estrogenic, progestogenic, and androgenic properties and has shown significant reduction in hot flashes and night sweating compared with placebo.25 Tibolone has also been shown to enhance mood and sexual function.26 However, evidence of its safety on outcomes such as breast cancer and cardiovascular events is obscure and has shown conflicting results, especially for breast cancer.25,26

A recent double-blinded trial on women with breast cancer found that although tibolone significantly improved vasomotor symptoms, it was associated with an increased risk of breast cancer recurrence (HR=1.40; 95% CI, 1.14-1.70]; P=.001).27 Tibolone is not approved for sale in the United States.

Nonhormonal options

Lifestyle modifications

According to recent reviews, exercise is less effective than HT in relieving hot flashes, but does seems to have beneficial effects on mood, sleep, and overall quality of life.28,29 Other lifestyle modifications such as smoking cessation and weight loss may also be of use.5

Antidepressants

Data from one meta-analysis showed that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) were significantly more effective than placebo in reducing daily frequency of hot flashes (WMD=-1.13; 95% CI, -1.70 to -0.57).30 Efficacy varied for individual drugs.

Venlafaxine, an SNRI, has been shown to be more effective than placebo in managing hot flashes.31 The effect on hot flashes was noticed after 4 weeks of treatment with the 75- and 150-mg doses, but the higher dosage was associated with more adverse effects such as dry mouth, sleeplessness, and decreased appetite.32 Even so, 93% of the participants in the venlafaxine group chose to continue treatment, because the reduction in hot flashes had significantly improved their daily lives.31 Desvenlafaxine, a metabolite of venlafaxine, has been shown to reduce the number of hot flashes by almost 65% from baseline at Weeks 4 and 12, with dosages of 100 and 150 mg/d.33

The SSRIs fluoxetine, citalopram, and paroxetine in 10-, 20-, and 30-mg doses and paroxetine CR (12.5 and 25 mg) have been studied in many RCTs. All have demonstrated a significant decrease in hot flashes compared with placebo with various dosages used. SSRIs reduce hot flashes by as much as 50% to 60%, compared with 80% for estrogen.34 The duration of treatment ranged from 4 weeks to 6 months.

Gabapentin

Gabapentin is approved by the FDA for the treatment of partial seizures and postherpetic neuralgia.35 A meta-analysis of multiple studies published in 2006 showed that gabapentin reduced the mean number of daily hot flashes by 2.05 (95% CI, -2.80 to -1.30).30 Two recent reviews evaluated the efficacy and safety of gabapentin in the treatment of hot flashes in menopausal women and reported that gabapentin in daily doses ranging from 900 to 2400 mg and titration periods lasting 3 to12 days was well tolerated and effective.35,36

A meta-analysis published in 2009 that included 4 RCTs reported significant heterogeneity from one study to another, but comparisons of gabapentin and placebo showed reductions of 20% to 30% in the frequency and severity of hot flashes with gabapentin.36 The most commonly reported adverse effects included somnolence, dizziness, ataxia, fatigue, nystagmus, and peripheral edema.

Clonidine

Clonidine has been studied in oral and transdermal forms for the treatment of hot flashes in menopausal women, especially in women with breast cancer.37-39 Data from one meta-analysis revealed significant reductions in daily hot flashes in the clonidine group compared with placebo at 4 weeks (mean difference [MD]=-0.95; 95% CI, -1.44 to -0.47) and at 8 weeks (MD=-1.63; 95% CI, -2.76 to -0.50).30 Adverse effects included dry mouth, drowsiness, and dizziness. The transdermal route may avoid some of these side effects.40

Alternative remedies

Phytoestrogen and isoflavones. Phytoestrogens are sterol molecules produced by plants. They are similar in structure to human estrogens and have been shown to have estrogen-like activity.40 They are available as dietary soy, soy extract, and red clover extracts. Isoflavones are a type of phytoestrogen.

Comparing trials of effects of soy or isoflavone is difficult, as various formulations and amounts of these products have been used. Combining the data from these trials yielded nonsignificant results for Promensil, a red clover extract (WMD=-0.6; 95% CI, -1.8 to 0.6), and inconsistent results (sometimes favoring the intervention, other times the placebo) for soy food and soy extracts.41-43

There is no evidence of estrogenic stimulation of the endometrium with phytoestrogens used for up to 2 years.41 Nevertheless, in the absence of evidence on the safety of long-term use, women with a personal or strong family history of hormone-dependent cancers (breast, uterine, or ovarian) or thromboembolic events should be cautious about using soy-based therapies.42 Long-term safety of these products has to be established before any evidence-based recommendations can be made.

Black cohosh. Actaea racemosa (formerly Cimicifuga racemosa) is the most studied and perhaps the most widely used herbal remedy for hot flashes. It is commonly known as black cohosh and has been used traditionally by Native Americans for the treatment of various medical conditions, including amenorrhea and menopause.44,45

Remifemin is an available standardized extract. Evidence for effectiveness is limited and contradictory. Data from a recent meta-analysis showed that although there was significant heterogeneity between included trials, preparations containing black cohosh improved vasomotor symptoms overall by 26% (95% CI, 11%-40%).45

A recent well-conducted RCT concluded that neither black cohosh nor red clover significantly reduced the frequency of symptoms compared with placebo.46 The same study found that both botanicals were safe as administered for a 12-month period. Some case reports have identified serious adverse events including acute hepatocellular damage, which warrants further investigation, although no causal relationship has been established.47

Evidence for safety and efficacy of antidepressants, gabapentin, clonidine, isoflavones, black cohosh, yoga, acupuncture, and herbal remedies is summarized in TABLE 2.30,36,41,47-55

For more on the treatment of hot flashes, see “Clinical approach to managing hot flashes”.40

Start with a detailed history: Ask about the nature of your patient’s symptoms, her past gynecologic and medical history, and her family history. Take a baseline blood pressure, measure body mass index (BMI), and order a lipid profile. Exclude other possible causes of hot flashes: hyperthyroidism, panic disorder, diabetes, and medications such as antiestrogens or selective estrogen receptor modulators.

Assess the severity of hot flashes and explain their typical clinical course. Discuss lifestyle modifications that may help: losing weight, quitting smoking, wearing lighter clothing, and cutting down on caffeine intake, alcohol, and spicy foods. Tell your patient that hormone therapy (HT) has been shown to be the most effective treatment for women without contraindications. These include current, past, or suspected breast cancer, other estrogen-sensitive malignant conditions, undiagnosed genital bleeding, untreated endometrial hyperplasia, venous thromboembolism, angina, myocardial infarction, uncontrolled hypertension, liver disease, porphyria cutanea tarda (absolute contraindication), or hypersensitivity to the active substances of HT.40

If contraindications can be ruled out, find out whether she is receptive to HT or would prefer alternatives. If she is interested in HT, discuss the risks and benefits involved and the different dosages and routes of administration that are available. If she prefers to explore nonhormonal remedies, discuss the various options and present the evidence for their safety and efficacy. Tell her that the safety of some herbal remedies that contain estrogenic compounds has not been established.

What the future holds

The selective estrogen receptor agonist MF-101, which can induce tissue-specific estrogen-like effects, has been shown to be effective in reducing menopausal hot flashes compared with placebo in a phase II trial.56 A larger phase III trial is in progress.

Lower and ultra-lower doses of systemic estrogen are now available and approved by the FDA, and were found effective in relieving vasomotor symptoms.57-59 The drawback of these preparations is that they may take longer than standard-dose estrogen to achieve maximum relief of symptoms (8-12 weeks vs 4 weeks, respectively). The lower doses have been associated with fewer adverse effects (such as vaginal bleeding and breast tenderness) compared with the standard doses.58,59 Their long-term effects on the cardiovascular system, bone, and breast are still being tested and need to be established.

Newer selective estrogen receptor modulators, especially in combination with estrogen, are another approach to menopausal symptoms currently in testing.60

CORRESPONDENCE

Ghufran A. Jassim, MD, ABMS, MSc, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland-Medical University of Bahrain, PO Box 15503, Adliya, Bahrain; gjassim@rcsi-mub.com

• Use hormone therapy (HT) at the lowest effective dose and for the shortest duration possible (preferably ≤5 years) in women for whom the potential benefits outweigh the potential risks. A

• Counsel patients that the effectiveness of phytoestrogens (soy), exercise routines, yoga, acupuncture, vitamin E, evening primrose oil, and other herbal preparations has not been established. B

• When HT is refused or contraindicated by a patient’s risk profile, consider antidepressants (selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors), gabapentin, or clonidine. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Hot flashes are the most prevalent and most bothersome symptoms of the menopausal transition and the leading cause for seeking medical attention during that period of a woman’s life.1 They may last for a few seconds or for several minutes and may occur as frequently as every hour to several times per week. On average, women experience hot flashes for a period of 6 months to 2 years, but the symptoms may last up to 10 years or more.2,3

Hot flashes have been reported by up to 70% of women undergoing natural menopause, and by almost all women undergoing surgical menopause.4 For many women, these symptoms are mild and can be managed with reassurance and counseling. For others, the symptoms are severe, overwhelming, last for many years, and impair the quality of life.

According to a community-based survey of 16,000 women, hot flashes occur most often in late perimenopause and among those with a body mass index ≥27. Hot flashes are also more common among African Americans and women who are less physically active and have a lower income.5

Since the publication of the Women’s Health Initiative study in 2002 raised concerns about the long-term safety of hormone therapy (HT), nonhormonal remedies have emerged as potential alternative treatments.6,7 A wealth of evidence has accumulated on the efficacy and safety of these, and various other approaches to the management of hot flashes. This review will summarize that evidence to help you provide optimal care and assist patients in making informed choices about their treatment.

Hormone replacement therapy

HT, given as estrogen alone in women without a uterus or estrogen plus progestin in women with a uterus, is the most studied and most effective therapy for vasomotor symptoms attributable to menopause. Data from one Cochrane review showed a significant reduction in the frequency of weekly hot flashes for oral estrogen compared with placebo, with a weighted mean difference (WMD) of -17.92 (95% confidence interval [CI], -22.86 to -12.99).8 This was equivalent to a 75% reduction in frequency (95% CI, 64.3-82.3) for HT relative to placebo. Results were similar for both opposed and unopposed estrogen regimens.8

Transdermal vs oral therapy. Another review compared oral estradiol, transdermal estradiol, and placebo in terms of reduction of hot flash frequency or severity, or both.9 The review revealed a pooled WMD in hot flashes of -16.8 per week (95% CI, -23.4 to -10.2) for oral estradiol and -22.4 per week (95% CI, -35.9 to -10.4) for transdermal estradiol. Results were similar for opposed and unopposed estrogen regimens.9

Transdermal delivery of estrogen as patches, gels, and sprays delivers unmetabolized estradiol directly to the blood stream, so that lower doses can achieve similar efficacy to doses administered orally.10 Thus, the transdermal route would be in keeping with current guidelines to prescribe the lowest effective dose that relieves symptoms. Emerging research should provide more insight regarding safety and the potential for fewer health risks with transdermal HT compared with oral therapy.

Best way to discontinue? When HT is discontinued, hot flashes may return—sometimes immediately, sometimes after a few months. No evidence-based guidelines exist on the best way to discontinue HT with the least recurrence and severity of hot flashes. No optimal tapering regimen (either by dose or number of days per week that HT is taken) has yet been described in any studies, nor have any randomized controlled trials (RCTs)revealed a significant difference between tapered or abrupt discontinuation.11,12

The breast cancer connection. The relationship between HT and breast cancer has generated considerable controversy. In the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) trial, which included participants on estrogen-only and estrogen plus progesterone regimens, an overall increased risk (hazard ratio [HR]=1.26; 95% CI, 1.00-1.59) was reported. The increased risk fell short of statistical significance, and varied with the duration of exposure.6

In subsequent studies, the magnitude of the associated risk was substantially greater for the estrogen-progestogen preparation, and also higher for longer-term exposure.13 Additionally, a meta-analysis of 8 studies of the risk of breast cancer with combination HT resulted in an odds ratio (OR) of 1.39 (95% CI, 1.12-1.72). Estimates were higher for more than 5 years of use (OR=1.63; 95% CI, 1.22-2.18) when compared with estimates for less than 5 years of use (OR=1.35; CI, 1.16-1.57).14 Recent studies have reported a decline in the incidence of breast cancer in the United States, which has been attributed to a parallel reduction in HT use.15

In contrast to the findings for women taking combination HT, the estrogen-only arm of the WHI study showed a decrease in the overall risk of breast cancer.16 A new analysis of data on participants in the estrogen-only arm of the study shows that, 10 years after the intervention ended, a decreased risk of breast cancer persists. In addition, the increased risk of stroke and deep vein thrombosis found in the original study had dissipated, and the decreased risk of hip fracture was not maintained.

Age matters. Health outcomes in this new analysis were more favorable for younger women for coronary heart disease, heart attack, colorectal cancer, total mortality, and a global index of chronic diseases.17 Pooled results of systematic reviews and meta-analyses on HT risks are available in TABLE 1.14,16,18-21

Progestins

Progesterone in the form of injections (Depo-Provera 150 mg, for example) or oral medroxyprogesterone acetate 20 mg daily has shown a significant reduction in hot flashes compared with placebo.22 However, associated side effects (withdrawal bleeding and weight gain) and concerns about breast cancer often limit the use of this medication.23 Because of the paucity of evidence, transdermal progesterone creams should not be recommended.24

Tibolone

Tibolone is a synthetic steroid that is structurally related to 19-nortestosterone derivatives. It has weak estrogenic, progestogenic, and androgenic properties and has shown significant reduction in hot flashes and night sweating compared with placebo.25 Tibolone has also been shown to enhance mood and sexual function.26 However, evidence of its safety on outcomes such as breast cancer and cardiovascular events is obscure and has shown conflicting results, especially for breast cancer.25,26

A recent double-blinded trial on women with breast cancer found that although tibolone significantly improved vasomotor symptoms, it was associated with an increased risk of breast cancer recurrence (HR=1.40; 95% CI, 1.14-1.70]; P=.001).27 Tibolone is not approved for sale in the United States.

Nonhormonal options

Lifestyle modifications

According to recent reviews, exercise is less effective than HT in relieving hot flashes, but does seems to have beneficial effects on mood, sleep, and overall quality of life.28,29 Other lifestyle modifications such as smoking cessation and weight loss may also be of use.5

Antidepressants

Data from one meta-analysis showed that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) were significantly more effective than placebo in reducing daily frequency of hot flashes (WMD=-1.13; 95% CI, -1.70 to -0.57).30 Efficacy varied for individual drugs.

Venlafaxine, an SNRI, has been shown to be more effective than placebo in managing hot flashes.31 The effect on hot flashes was noticed after 4 weeks of treatment with the 75- and 150-mg doses, but the higher dosage was associated with more adverse effects such as dry mouth, sleeplessness, and decreased appetite.32 Even so, 93% of the participants in the venlafaxine group chose to continue treatment, because the reduction in hot flashes had significantly improved their daily lives.31 Desvenlafaxine, a metabolite of venlafaxine, has been shown to reduce the number of hot flashes by almost 65% from baseline at Weeks 4 and 12, with dosages of 100 and 150 mg/d.33

The SSRIs fluoxetine, citalopram, and paroxetine in 10-, 20-, and 30-mg doses and paroxetine CR (12.5 and 25 mg) have been studied in many RCTs. All have demonstrated a significant decrease in hot flashes compared with placebo with various dosages used. SSRIs reduce hot flashes by as much as 50% to 60%, compared with 80% for estrogen.34 The duration of treatment ranged from 4 weeks to 6 months.

Gabapentin

Gabapentin is approved by the FDA for the treatment of partial seizures and postherpetic neuralgia.35 A meta-analysis of multiple studies published in 2006 showed that gabapentin reduced the mean number of daily hot flashes by 2.05 (95% CI, -2.80 to -1.30).30 Two recent reviews evaluated the efficacy and safety of gabapentin in the treatment of hot flashes in menopausal women and reported that gabapentin in daily doses ranging from 900 to 2400 mg and titration periods lasting 3 to12 days was well tolerated and effective.35,36

A meta-analysis published in 2009 that included 4 RCTs reported significant heterogeneity from one study to another, but comparisons of gabapentin and placebo showed reductions of 20% to 30% in the frequency and severity of hot flashes with gabapentin.36 The most commonly reported adverse effects included somnolence, dizziness, ataxia, fatigue, nystagmus, and peripheral edema.

Clonidine

Clonidine has been studied in oral and transdermal forms for the treatment of hot flashes in menopausal women, especially in women with breast cancer.37-39 Data from one meta-analysis revealed significant reductions in daily hot flashes in the clonidine group compared with placebo at 4 weeks (mean difference [MD]=-0.95; 95% CI, -1.44 to -0.47) and at 8 weeks (MD=-1.63; 95% CI, -2.76 to -0.50).30 Adverse effects included dry mouth, drowsiness, and dizziness. The transdermal route may avoid some of these side effects.40

Alternative remedies

Phytoestrogen and isoflavones. Phytoestrogens are sterol molecules produced by plants. They are similar in structure to human estrogens and have been shown to have estrogen-like activity.40 They are available as dietary soy, soy extract, and red clover extracts. Isoflavones are a type of phytoestrogen.

Comparing trials of effects of soy or isoflavone is difficult, as various formulations and amounts of these products have been used. Combining the data from these trials yielded nonsignificant results for Promensil, a red clover extract (WMD=-0.6; 95% CI, -1.8 to 0.6), and inconsistent results (sometimes favoring the intervention, other times the placebo) for soy food and soy extracts.41-43

There is no evidence of estrogenic stimulation of the endometrium with phytoestrogens used for up to 2 years.41 Nevertheless, in the absence of evidence on the safety of long-term use, women with a personal or strong family history of hormone-dependent cancers (breast, uterine, or ovarian) or thromboembolic events should be cautious about using soy-based therapies.42 Long-term safety of these products has to be established before any evidence-based recommendations can be made.

Black cohosh. Actaea racemosa (formerly Cimicifuga racemosa) is the most studied and perhaps the most widely used herbal remedy for hot flashes. It is commonly known as black cohosh and has been used traditionally by Native Americans for the treatment of various medical conditions, including amenorrhea and menopause.44,45

Remifemin is an available standardized extract. Evidence for effectiveness is limited and contradictory. Data from a recent meta-analysis showed that although there was significant heterogeneity between included trials, preparations containing black cohosh improved vasomotor symptoms overall by 26% (95% CI, 11%-40%).45

A recent well-conducted RCT concluded that neither black cohosh nor red clover significantly reduced the frequency of symptoms compared with placebo.46 The same study found that both botanicals were safe as administered for a 12-month period. Some case reports have identified serious adverse events including acute hepatocellular damage, which warrants further investigation, although no causal relationship has been established.47

Evidence for safety and efficacy of antidepressants, gabapentin, clonidine, isoflavones, black cohosh, yoga, acupuncture, and herbal remedies is summarized in TABLE 2.30,36,41,47-55

For more on the treatment of hot flashes, see “Clinical approach to managing hot flashes”.40

Start with a detailed history: Ask about the nature of your patient’s symptoms, her past gynecologic and medical history, and her family history. Take a baseline blood pressure, measure body mass index (BMI), and order a lipid profile. Exclude other possible causes of hot flashes: hyperthyroidism, panic disorder, diabetes, and medications such as antiestrogens or selective estrogen receptor modulators.

Assess the severity of hot flashes and explain their typical clinical course. Discuss lifestyle modifications that may help: losing weight, quitting smoking, wearing lighter clothing, and cutting down on caffeine intake, alcohol, and spicy foods. Tell your patient that hormone therapy (HT) has been shown to be the most effective treatment for women without contraindications. These include current, past, or suspected breast cancer, other estrogen-sensitive malignant conditions, undiagnosed genital bleeding, untreated endometrial hyperplasia, venous thromboembolism, angina, myocardial infarction, uncontrolled hypertension, liver disease, porphyria cutanea tarda (absolute contraindication), or hypersensitivity to the active substances of HT.40

If contraindications can be ruled out, find out whether she is receptive to HT or would prefer alternatives. If she is interested in HT, discuss the risks and benefits involved and the different dosages and routes of administration that are available. If she prefers to explore nonhormonal remedies, discuss the various options and present the evidence for their safety and efficacy. Tell her that the safety of some herbal remedies that contain estrogenic compounds has not been established.

What the future holds

The selective estrogen receptor agonist MF-101, which can induce tissue-specific estrogen-like effects, has been shown to be effective in reducing menopausal hot flashes compared with placebo in a phase II trial.56 A larger phase III trial is in progress.

Lower and ultra-lower doses of systemic estrogen are now available and approved by the FDA, and were found effective in relieving vasomotor symptoms.57-59 The drawback of these preparations is that they may take longer than standard-dose estrogen to achieve maximum relief of symptoms (8-12 weeks vs 4 weeks, respectively). The lower doses have been associated with fewer adverse effects (such as vaginal bleeding and breast tenderness) compared with the standard doses.58,59 Their long-term effects on the cardiovascular system, bone, and breast are still being tested and need to be established.

Newer selective estrogen receptor modulators, especially in combination with estrogen, are another approach to menopausal symptoms currently in testing.60

CORRESPONDENCE

Ghufran A. Jassim, MD, ABMS, MSc, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland-Medical University of Bahrain, PO Box 15503, Adliya, Bahrain; gjassim@rcsi-mub.com

1. Williams RE, Kalilani L, DiBenedetti DB. Healthcare seeking and treatment for menopausal symptoms in the US. Maturitas. 2007;58:348-358.

2. North American Menopause Society. Estrogen and progestogen use in postmenopausal women: 2010 position statement of the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2010;17:242-256.

3. National Institutes of Health. NIH state-of-the-science conference statement: management of menopause-related symptoms. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(12 pt 2):1003-1013.

4. Berecki-Gisolf J, Begum N, Dobson AJ. Symptoms reported by women in midlife: menopausal transition or aging? Menopause. 2009;16:1021-1029.

5. Gold EB, Sternfeld B, Kelsey JL. Relation of demographic and lifestyle factors to symptoms in a multi-racial/ethnic population of women 40-55 years of age. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152:463-473.

6. Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al. Writing group for the Women’s Health Initiative investigators. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women. JAMA. 2002;288:321-333.

7. Lukes A. Evolving issues in the clinical and managed care settings on the management of menopause following the Women’s Health Initiative. J Manag Care Pharm. 2008;14(3 suppl):7-13.

8. MacLennan AH, Broadbent JL, Lester W, et al. Oral oestrogen and combined oestrogen/progestogen therapy versus placebo for hot flushes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(4):CD002978.-

9. Nelson HD. Commonly used types of postmenopausal estrogen for treatment of hot flashes: scientific review. JAMA. 2004;291:1610-1620.

10. Carroll N. A review of transdermal nonpatch estrogen therapy for the management of menopausal symptoms. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2010;19:47-55.

11. Suffoletto JA, Hess R. Tapering vs cold turkey: symptoms versus successful discontinuation of menopausal hormone therapy. Menopause. 2009;16:436-437.

12. Lindh-Astrand L, Bixo M, Hirschberg AL, et al. A randomized controlled study of taper-down or abrupt discontinuation of hormone therapy in women treated for vasomotor symptoms. Menopause. 2010;17:72-29.

13. Banks E, Canfell K, Reeves G. HRT and breast cancer. Womens Health. 2008;4:427-431.

14. Shah NR, Borenstein J, Dubois RW. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and breast cancer. Menopause. 2005;12:668-678.

15. Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD. Decline in US breast cancer rates after the Women’s Health Initiative. Am J Public Health. 2010;100 (suppl 1):S132-S139.

16. Nelson HD, Humphrey LL, Nygren P, et al. Postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy: scientific review. JAMA. 2002;288:872-881.

17. LaCroix AZ, Chiebowski RT, Manson JE, et al. Health outcomes after stopping conjugated equine estrogens among postmenopausal women with prior hysterectomy. JAMA. 2011;305:1305-1314.

18. Canonico M, Plu-Bureau G, Lowe GD, et al. Hormone replacement therapy and risk of venous thromboembolism in postmenopausal women. BMJ. 2008;336:1227-1231.

19. Gabriel SR, Carmona L, Roque M, et al. Hormone replacement therapy for preventing cardiovascular disease in post-menopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(2):CD002229.-

20. Sare GM, Gray LJ, Bath PM. Association between hormone replacement therapy and subsequent arterial and venous vascular events: a meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2031-2041.

21. Bath PM, Gray LJ. Association between hormone replacement therapy and subsequent stroke. BMJ. 2005;330:342.-

22. Boothby LA, Doering PL, Kipersztok S. Bioidentical hormone therapy: a review. Menopause. 2004;11:356-367.

23. Pasqualini JR. Progestins and breast cancer. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2007;23(suppl 1):32-41.

24. Wren BG. Transdermal progesterone creams for postmenopausal women. Med J Aust. 2005;182:237-225.

25. Kenemans P, Speroff L. Tibolone: clinical recommendations and practical guidelines: a report of the International Tibolone Consensus Group. Maturitas. 2005;51:21-28.

26. Wang PH, Cheng MH, Chao HT, et al. Effects of tibolone on the breast of postmenopausal women. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;46:121-126.

27. Kenemans P, Bundred NJ, Foidart JM, et al. Safety and efficacy of tibolone in breast-cancer patients with vasomotor symptoms. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:135-146.

28. Daley A, Stokes-Lampard HJ, Macarthur C. Exercise to reduce vasomotor and other menopausal symptoms: a review. Maturitas. 2009;63:176-180.

29. Daley A, MacArthur C, Mutrie N, et al. Exercise for vasomotor menopausal symptoms. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD006108.-

30. Nelson HD, Vesco KK, Haney E, et al. Nonhormonal therapies for menopausal hot flashes. JAMA. 2006;295:2057-2072.

31. Evans ML, Pritts E, Vittinghof E, et al. Management of postmenopausal hot flushes with venlafaxine hydrochloride. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:161-166.

32. Barton D, La Vasseur B, Loprinzi C, et al. Venlafaxine for the control of hot flashes. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2002;29:33-40.

33. Lilue M, Palacios S. Non-hormonal treatment for vasomotor symptoms during menopause: role of desvenlafaxine. Ginecol Obstet Mex. 2009;77:475-481.

34. Albertazzi P. Non-estrogenic approaches for the treatment of climacteric symptoms. Climacteric. 2007;10(suppl 2):115-120.

35. Brown JN, Wright BR. Use of gabapentin in patients experiencing hot flashes. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29:74-81.

36. Toulis KA, Tzellas T, Kouvelas D, et al. Gabapentin for the treatment of hot flashes in women with natural or tamoxifen-induced menopause: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Ther. 2009;31:221-235.

37. Pandya KJ, Raubertas AF, Flynn PJ, et al. Oral clonidine in postmenopausal patients with breast cancer experiencing tamoxifen-induced hot flashes. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:788-793.

38. Goldberg RM, Loprinzi CL, O’Fallon JR. Transdermal clonidine for ameliorating tamoxifen-induced hot flashes. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:155-158.

39. Buijs C, Mom CH, Willemse PH, et al. Venlafaxine versus clonidine for the treatment of hot flashes in breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;115:573-580.

40. Cobin RH, Futterweit W, Ginzburg SB, et al. AACE Menopause Guidelines Revision Task Force. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists medical guidelines for clinical practice for the diagnosis and treatment of menopause. Endocr Pract. 2006;12:315-337.

41. Lethaby AE, Brown J, Marjoribanks J. Phytoestrogens for vasomotor menopausal symptoms. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD001395.-

42. Tempfer CB, Bentz EH, Leodolter S, et al. Phytoestrogens in clinical practice. Fertil Steril. 2007;87:1243-1249.

43. Krebs EE, Ensrud KE, MacDonald R, et al. Phytoestrogens for treatment of menopausal symptoms: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:824-836.

44. McKenna DJ, Jones K, Humphrey S, et al. Black cohosh. Altern Ther Health Med. 2001;7:93-100.

45. Shams T, Setia MS, Hemmings R, et al. Efficacy of black cohosh-containing preparations on menopausal symptoms: a meta-analysis. Altern Ther Health Med. 2010;16:36-44.

46. Geller SE, Shulman LP, van Breeman RB, et al. Safety and efficacy of black cohosh and red clover for the management of vasomotor symptoms. Menopause. 2009;16:1156-1166.

47. Borrelli F, Ernst E. Black cohosh (Cimicifuga racemosa): a systematic review of adverse events. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199:455-466.

48. Nelson HD. Menopause. Lancet. 2008;371:760-770.

49. Borrelli F, Ernst E. Black cohosh (Cimicifuga racemosa) for menopausal symptoms. Pharmacol Res. 2008;58:8-14.

50. Huntley A, Ernst E. A systematic review of the safety of black cohosh. Menopause. 2003;10:58-64.

51. Kanadys WM, Leszczynska-Gorselak B, Oleszczuk J. Efficacy and safety of black cohosh in the treatment of vasomotor symptoms. Ginekol Pol. 2008;79:287-296.

52. Huntley AL, Ernst E. A systematic review of herbal medicinal products for the treatment of menopausal symptoms. Menopause. 2003;10:465-476.

53. Lee MS, Shin BC, Ernst E. Acupuncture for treating menopausal hot flushes: a systematic review. Climacteric. 2009;12:16-25.

54. Lee MS, Kim JI, Ha JY, et al. Yoga for menopausal symptoms: a systematic review. Menopause. 2009;16:602-608.

55. Cho SH, Whang WW. Acupuncture for vasomotor menopausal symptoms. Menopause. 2009;16:1065-1073.

56. Stovall DW, Pinkerton JV. MF-101, an estrogen receptor beta agonist for the treatment of vasomotor symptoms in peri- and postmenopausal women. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;10:365-371.

57. Peeyananjarassri K, Baber R. Effects of low-dose hormone therapy on menopausal symptoms, bone mineral density, endometrium, and the cardiovascular system. Climacteric. 2004;8:13-23.

58. Ettinger B. Vasomotor symptom relief versus unwanted effects: role of estrogen dosage. Am J Med. 2005;118(suppl 12B):74-78.

59. Ettinger B. Rationale for use of lower estrogen doses for postmenopausal hormone therapy. Maturitas. 2007;57:81-84.

60. Jain N, Xu J, Kanojia RM, et al. Identification and structure-activity relationships of chromene-derived selective estrogen receptor modulators for treatment of postmenopausal symptoms. J Med Chem. 2009;52:7544-7569.

1. Williams RE, Kalilani L, DiBenedetti DB. Healthcare seeking and treatment for menopausal symptoms in the US. Maturitas. 2007;58:348-358.

2. North American Menopause Society. Estrogen and progestogen use in postmenopausal women: 2010 position statement of the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2010;17:242-256.

3. National Institutes of Health. NIH state-of-the-science conference statement: management of menopause-related symptoms. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(12 pt 2):1003-1013.

4. Berecki-Gisolf J, Begum N, Dobson AJ. Symptoms reported by women in midlife: menopausal transition or aging? Menopause. 2009;16:1021-1029.

5. Gold EB, Sternfeld B, Kelsey JL. Relation of demographic and lifestyle factors to symptoms in a multi-racial/ethnic population of women 40-55 years of age. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152:463-473.

6. Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al. Writing group for the Women’s Health Initiative investigators. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women. JAMA. 2002;288:321-333.

7. Lukes A. Evolving issues in the clinical and managed care settings on the management of menopause following the Women’s Health Initiative. J Manag Care Pharm. 2008;14(3 suppl):7-13.

8. MacLennan AH, Broadbent JL, Lester W, et al. Oral oestrogen and combined oestrogen/progestogen therapy versus placebo for hot flushes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(4):CD002978.-

9. Nelson HD. Commonly used types of postmenopausal estrogen for treatment of hot flashes: scientific review. JAMA. 2004;291:1610-1620.

10. Carroll N. A review of transdermal nonpatch estrogen therapy for the management of menopausal symptoms. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2010;19:47-55.

11. Suffoletto JA, Hess R. Tapering vs cold turkey: symptoms versus successful discontinuation of menopausal hormone therapy. Menopause. 2009;16:436-437.

12. Lindh-Astrand L, Bixo M, Hirschberg AL, et al. A randomized controlled study of taper-down or abrupt discontinuation of hormone therapy in women treated for vasomotor symptoms. Menopause. 2010;17:72-29.

13. Banks E, Canfell K, Reeves G. HRT and breast cancer. Womens Health. 2008;4:427-431.

14. Shah NR, Borenstein J, Dubois RW. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and breast cancer. Menopause. 2005;12:668-678.

15. Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD. Decline in US breast cancer rates after the Women’s Health Initiative. Am J Public Health. 2010;100 (suppl 1):S132-S139.

16. Nelson HD, Humphrey LL, Nygren P, et al. Postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy: scientific review. JAMA. 2002;288:872-881.

17. LaCroix AZ, Chiebowski RT, Manson JE, et al. Health outcomes after stopping conjugated equine estrogens among postmenopausal women with prior hysterectomy. JAMA. 2011;305:1305-1314.

18. Canonico M, Plu-Bureau G, Lowe GD, et al. Hormone replacement therapy and risk of venous thromboembolism in postmenopausal women. BMJ. 2008;336:1227-1231.

19. Gabriel SR, Carmona L, Roque M, et al. Hormone replacement therapy for preventing cardiovascular disease in post-menopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(2):CD002229.-

20. Sare GM, Gray LJ, Bath PM. Association between hormone replacement therapy and subsequent arterial and venous vascular events: a meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2031-2041.

21. Bath PM, Gray LJ. Association between hormone replacement therapy and subsequent stroke. BMJ. 2005;330:342.-

22. Boothby LA, Doering PL, Kipersztok S. Bioidentical hormone therapy: a review. Menopause. 2004;11:356-367.

23. Pasqualini JR. Progestins and breast cancer. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2007;23(suppl 1):32-41.

24. Wren BG. Transdermal progesterone creams for postmenopausal women. Med J Aust. 2005;182:237-225.

25. Kenemans P, Speroff L. Tibolone: clinical recommendations and practical guidelines: a report of the International Tibolone Consensus Group. Maturitas. 2005;51:21-28.

26. Wang PH, Cheng MH, Chao HT, et al. Effects of tibolone on the breast of postmenopausal women. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;46:121-126.

27. Kenemans P, Bundred NJ, Foidart JM, et al. Safety and efficacy of tibolone in breast-cancer patients with vasomotor symptoms. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:135-146.

28. Daley A, Stokes-Lampard HJ, Macarthur C. Exercise to reduce vasomotor and other menopausal symptoms: a review. Maturitas. 2009;63:176-180.

29. Daley A, MacArthur C, Mutrie N, et al. Exercise for vasomotor menopausal symptoms. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD006108.-

30. Nelson HD, Vesco KK, Haney E, et al. Nonhormonal therapies for menopausal hot flashes. JAMA. 2006;295:2057-2072.

31. Evans ML, Pritts E, Vittinghof E, et al. Management of postmenopausal hot flushes with venlafaxine hydrochloride. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:161-166.

32. Barton D, La Vasseur B, Loprinzi C, et al. Venlafaxine for the control of hot flashes. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2002;29:33-40.

33. Lilue M, Palacios S. Non-hormonal treatment for vasomotor symptoms during menopause: role of desvenlafaxine. Ginecol Obstet Mex. 2009;77:475-481.

34. Albertazzi P. Non-estrogenic approaches for the treatment of climacteric symptoms. Climacteric. 2007;10(suppl 2):115-120.

35. Brown JN, Wright BR. Use of gabapentin in patients experiencing hot flashes. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29:74-81.

36. Toulis KA, Tzellas T, Kouvelas D, et al. Gabapentin for the treatment of hot flashes in women with natural or tamoxifen-induced menopause: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Ther. 2009;31:221-235.

37. Pandya KJ, Raubertas AF, Flynn PJ, et al. Oral clonidine in postmenopausal patients with breast cancer experiencing tamoxifen-induced hot flashes. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:788-793.

38. Goldberg RM, Loprinzi CL, O’Fallon JR. Transdermal clonidine for ameliorating tamoxifen-induced hot flashes. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:155-158.

39. Buijs C, Mom CH, Willemse PH, et al. Venlafaxine versus clonidine for the treatment of hot flashes in breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;115:573-580.

40. Cobin RH, Futterweit W, Ginzburg SB, et al. AACE Menopause Guidelines Revision Task Force. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists medical guidelines for clinical practice for the diagnosis and treatment of menopause. Endocr Pract. 2006;12:315-337.

41. Lethaby AE, Brown J, Marjoribanks J. Phytoestrogens for vasomotor menopausal symptoms. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD001395.-

42. Tempfer CB, Bentz EH, Leodolter S, et al. Phytoestrogens in clinical practice. Fertil Steril. 2007;87:1243-1249.

43. Krebs EE, Ensrud KE, MacDonald R, et al. Phytoestrogens for treatment of menopausal symptoms: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:824-836.

44. McKenna DJ, Jones K, Humphrey S, et al. Black cohosh. Altern Ther Health Med. 2001;7:93-100.

45. Shams T, Setia MS, Hemmings R, et al. Efficacy of black cohosh-containing preparations on menopausal symptoms: a meta-analysis. Altern Ther Health Med. 2010;16:36-44.

46. Geller SE, Shulman LP, van Breeman RB, et al. Safety and efficacy of black cohosh and red clover for the management of vasomotor symptoms. Menopause. 2009;16:1156-1166.

47. Borrelli F, Ernst E. Black cohosh (Cimicifuga racemosa): a systematic review of adverse events. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199:455-466.

48. Nelson HD. Menopause. Lancet. 2008;371:760-770.

49. Borrelli F, Ernst E. Black cohosh (Cimicifuga racemosa) for menopausal symptoms. Pharmacol Res. 2008;58:8-14.

50. Huntley A, Ernst E. A systematic review of the safety of black cohosh. Menopause. 2003;10:58-64.

51. Kanadys WM, Leszczynska-Gorselak B, Oleszczuk J. Efficacy and safety of black cohosh in the treatment of vasomotor symptoms. Ginekol Pol. 2008;79:287-296.

52. Huntley AL, Ernst E. A systematic review of herbal medicinal products for the treatment of menopausal symptoms. Menopause. 2003;10:465-476.

53. Lee MS, Shin BC, Ernst E. Acupuncture for treating menopausal hot flushes: a systematic review. Climacteric. 2009;12:16-25.

54. Lee MS, Kim JI, Ha JY, et al. Yoga for menopausal symptoms: a systematic review. Menopause. 2009;16:602-608.

55. Cho SH, Whang WW. Acupuncture for vasomotor menopausal symptoms. Menopause. 2009;16:1065-1073.

56. Stovall DW, Pinkerton JV. MF-101, an estrogen receptor beta agonist for the treatment of vasomotor symptoms in peri- and postmenopausal women. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;10:365-371.

57. Peeyananjarassri K, Baber R. Effects of low-dose hormone therapy on menopausal symptoms, bone mineral density, endometrium, and the cardiovascular system. Climacteric. 2004;8:13-23.

58. Ettinger B. Vasomotor symptom relief versus unwanted effects: role of estrogen dosage. Am J Med. 2005;118(suppl 12B):74-78.

59. Ettinger B. Rationale for use of lower estrogen doses for postmenopausal hormone therapy. Maturitas. 2007;57:81-84.

60. Jain N, Xu J, Kanojia RM, et al. Identification and structure-activity relationships of chromene-derived selective estrogen receptor modulators for treatment of postmenopausal symptoms. J Med Chem. 2009;52:7544-7569.