User login

Pessaries for POP and SUI: Their fitting, care, and effectiveness in various disorders

In Part 1 of this article in the December 2020 issue of OBG Management, I discussed the reasons that pessaries are an effective treatment option for many women with pelvic organ prolapse (POP) and stress urinary incontinence (SUI) and provided details on the types of pessaries available.

In this article, I highlight the steps in fitting a pessary, pessary aftercare, and potential complications associated with pessary use. In addition, I discuss the effectiveness of pessary treatment for POP and SUI as well as for preterm labor prevention and defecatory disorders.

The pessary fitting process

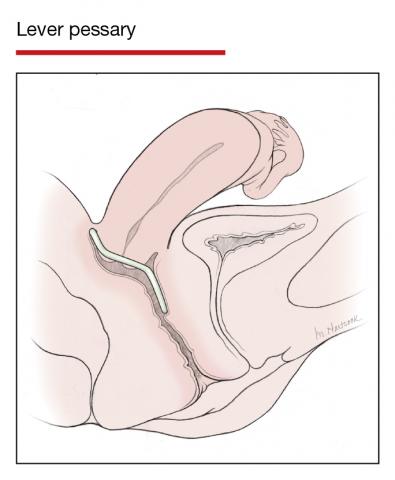

For a given patient, the best size pessary is the smallest one that will not fall out. The only “rule” for fitting a pessary is that a woman’s internal vaginal caliber should be wider than her introitus.

When fitting a pessary, goals include that the selected pessary:

- should be comfortable for the patient to wear

- is not easily expelled

- does not interfere with urination or defecation

- does not cause vaginal irritation.

The presence or absence of a cervix or uterus does not affect pessary choice.

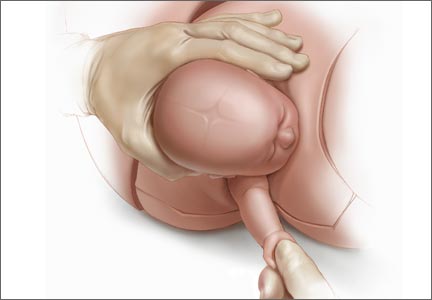

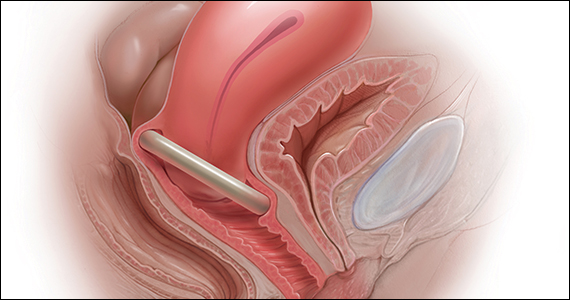

Most experts agree that the process for fitting the right size pessary is one of trial and error. As with fitting a contraceptive diaphragm, the clinician should perform a manual examination to estimate the integrity and width of the perineum and the depth of the vagina to roughly approximate the pessary size that might best fit. Using a set of “fitting pessaries,” a pessary of the estimated size should be placed into the vagina and the fit evaluated as to whether the device is too big, too small, or appropriate. If the pessary is easily expelled, larger sizes should be tried until the pessary remains in place or the patient is uncomfortable. Once the pessary is in place, the clinician should be able to run his or her finger around the entire pessary; if this is not possible, the pessary is too tight. In addition, the pessary should remain more than one finger breadth above the introitus when the patient is standing or bearing down.

Since many patients who require a pessary are elderly, their perineal skin and vaginal mucosa may be atrophic and fragile. Inserting a pessary can be uncomfortable and can cause abrasions or tears. Successfully fitting a pessary may require extra care under these circumstances. The following steps may help alleviate these difficulties:

- Explain the fitting process to the patient in detail.

- Employ lubrication liberally.

- Enlarge the introitus by applying gentle digital pressure on the posterior fourchette.

- Apply 2% lidocaine ointment several minutes prior to pessary fitting to help decrease patient discomfort.

- Treat the patient for several weeks with vaginal estrogen cream before attempting to fit a pessary if severe vulvovaginal atrophy is present.

Once the type and size of the pessary are selected and a pessary is inserted, evaluate the patient with the pessary in place. Assess for the following:

Discomfort. Ask the patient if she feels discomfort with the pessary in position. A patient with a properly fitting pessary should not feel that it is in place. If she does feel discomfort initially, the discomfort will only increase with time and the issue should be addressed at that time.

Expulsion. Test to make certain that the pessary is not easily expelled from the vagina. Have the patient walk, cough, squat, and even jump if possible.

Urination. Have the patient urinate with the pessary in place. This tests for her ability to void while wearing the pessary and shows whether the contraction of pelvic muscles during voiding results in expulsion of the pessary. (Experience shows that it is best to do this with a plastic “hat” over the toilet so that if the pessary is expelled, it does not drop into the bowl.)

Re-examination. After these provocative tests, examine the patient again to ensure that the pessary has not slid out of place.

Depending on whether or not your office stocks pessaries, at this point the patient is either given the correct type and size of pessary or it is ordered for her. If the former, the patient should try placing it herself; if she is unable to, the clinician should place it for her. In either event, its position should be checked. If the pessary has to be ordered, the patient must schedule an appointment to return for pessary insertion.

Whether the pessary is supplied by the office or ordered, instruct the patient on how to insert and remove the pessary, how frequently to remove it for cleansing (see below), and signs to watch for, such as vaginal bleeding, inability to void or defecate, or pelvic pain.

It is advisable to schedule a subsequent visit for 2 to 3 weeks after initial pessary placement to assess how the patient is doing and to address any issues that have developed.

Continue to: Special circumstances...

Special circumstances

It is safe for a patient with a pessary in place to undergo magnetic resonance imaging.1 Patients should be informed, however, that full body scans, such as at airports, will detect pessaries. Patients may need to obtain a physician’s note to document that the pessary is a medical device.

Finally, several factors may prevent successful pessary fitting. These include prior pelvic surgery, obesity, short vaginal length (less than 6–7 cm), and a vaginal introitus width of greater than 4 finger breadths.

Necessary pessary aftercare

Once a pessary is in place and the patient is comfortable with it, the only maintenance necessary is the pessary’s intermittent removal for cleansing and for evaluation of the vaginal mucosa for erosion and ulcerations. How frequently this should be done varies based on the type of pessary, the amount of discharge that a woman produces, whether or not an odor develops after prolonged wearing of the pessary, and whether or not the patient’s vaginal mucosa has been abraded.

The question of timing for pessary cleaning

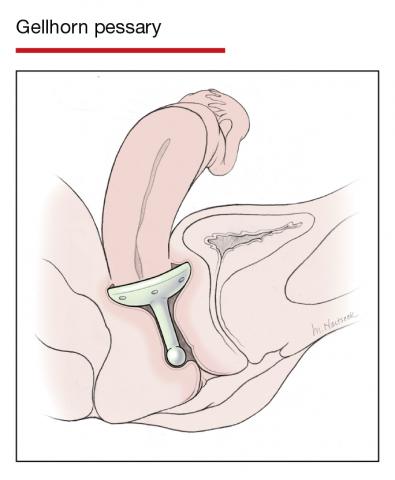

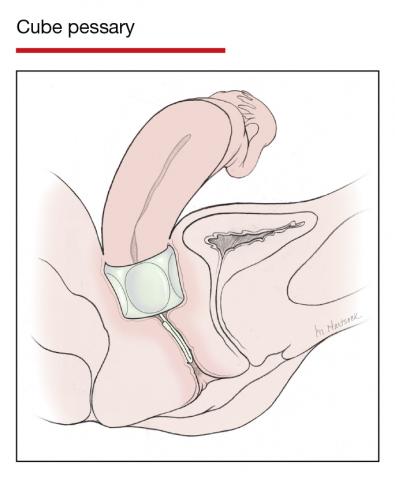

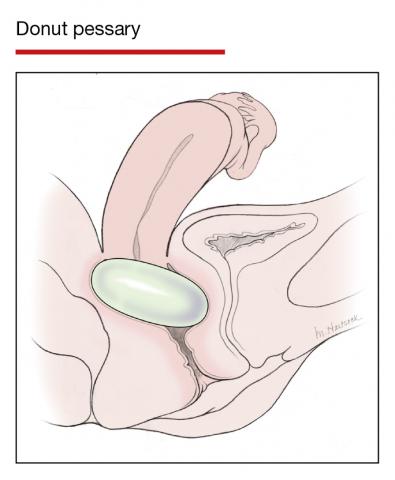

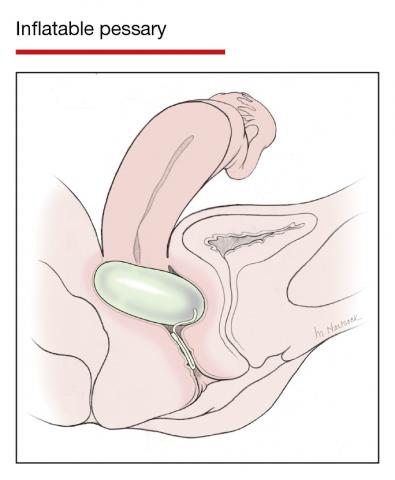

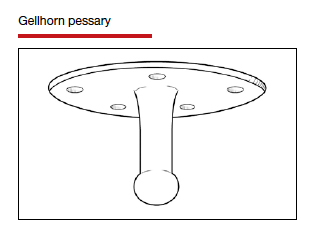

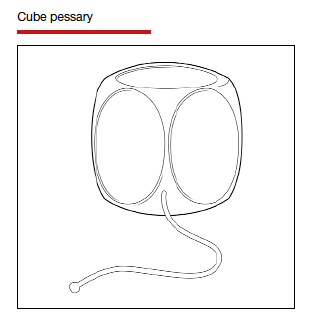

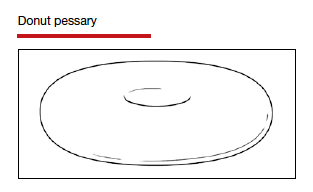

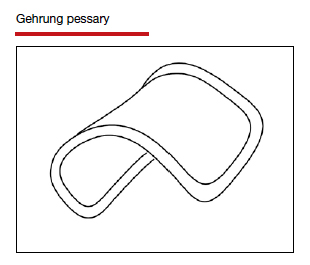

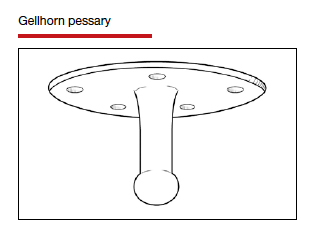

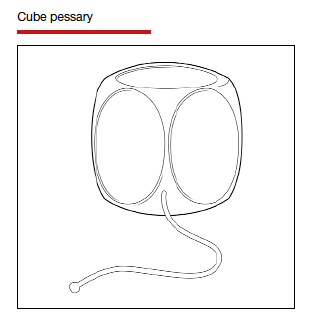

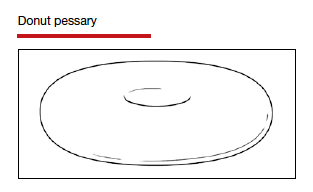

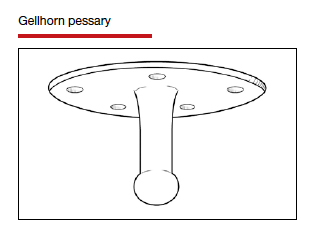

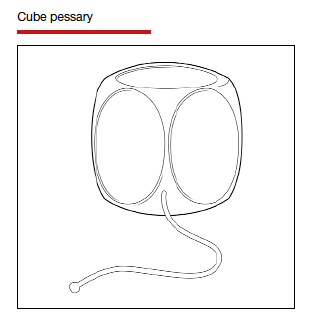

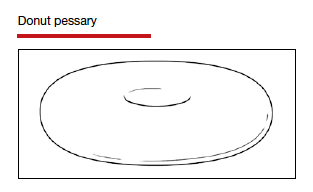

Although there are many opinions about how often pessaries should be removed and cleaned, no data in the literature support any specific interval. Pessaries that are easily removed by women themselves can be cleaned as frequently as desired, often on a weekly basis. The patient simply removes the pessary, washes it with soap and water, and reinserts it. For pessaries that are difficult to remove (such as the Gellhorn, cube, or donut) or for women who are physically unable to remove their own ring pessary, the clinician should remove and clean the pessary in the office every 3 to 6 months. It has been shown that there is no difference in complications from pessary use with either of these intervals.2

Prior to any vaginal surgical procedure, patients must be instructed to remove their pessary 10 to 14 days beforehand so that the surgeon can see the full extent of prolapse when making decisions about reconstruction and so that any vaginal mucosal erosions or abrasions have time to heal.

Office visits for follow-up care

The pessary “cleaning visit” has several goals, including to:

- see if the pessary is meeting the patient’s needs in terms of resolving symptoms of prolapse and/or restoring urinary continence

- discuss with the patient any problems she may be having, such as pelvic discomfort or pressure, difficulty voiding or defecating, excessive vaginal discharge, or vaginal odor

- check for vaginal mucosal erosion or ulceration; such vaginal lesions often can be prevented by the prophylactic use of either estrogen vaginal cream twice weekly or the continuous use of an estradiol vaginal ring in addition to the pessary

- evaluate the condition of the pessary itself and clean it with soap and water.

Continue to: Potential complications of pessary use...

Potential complications of pessary use

The most common complications experienced by pessary users are:

Odor or excessive discharge. Bacterial vaginosis (BV) occurs more frequently in women who use pessaries. The symptoms of BV can be minimized—but unfortunately not totally eliminated—by the prophylactic use of antiseptic vaginal creams or gels, such as metronidazole, clindamycin, Trimo-San (oxyquinoline sulfate and sodium lauryl sulfate), and others. Inserting the gel vaginally once a week can significantly reduce discharge and odor.3

Vaginal mucosal erosion and ulceration. These are treated by removing the pessary for 2 weeks during which time estrogen cream is applied daily or an estradiol vaginal ring is put in place. If no resolution occurs after 2 weeks, the nonhealing vaginal mucosa should be biopsied.

Pressure on the rectum or bladder. If the pessary causes significant discomfort or interferes with voiding function, then either a different size or a different type pessary should be tried

Patients may discontinue pessary use for a variety of reasons. Among these are:

- discomfort

- inadequate improvement of POP or incontinence symptoms

- expulsion of the pessary during daily activities

- the patient’s desire for surgery instead

- worsening of urine leakage

- difficulty inserting or removing the pessary

- damage to the vaginal mucosa

- pain during removal of the pessary in the office.

Pessary effectiveness for POP and SUI symptoms

As might be expected with a device that is available in so many forms and is used to treat varied types of POP and SUI, the data concerning the success rates of pessary use vary considerably. These rates depend on the definition of success, that is, complete or partial control of prolapse and/or incontinence; which devices are being evaluated; and the nature and severity of the POP and/or SUI being treated.

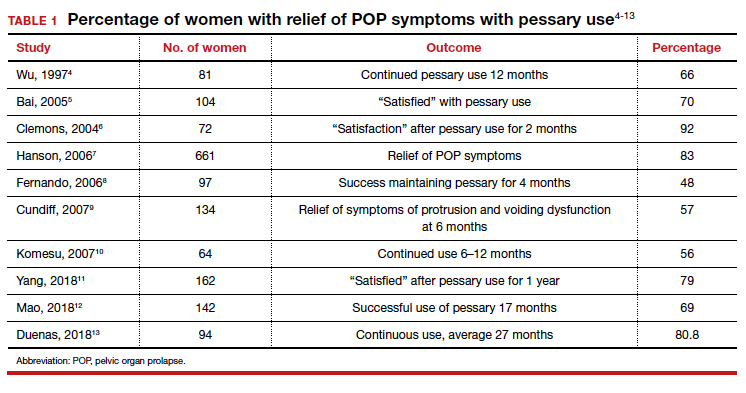

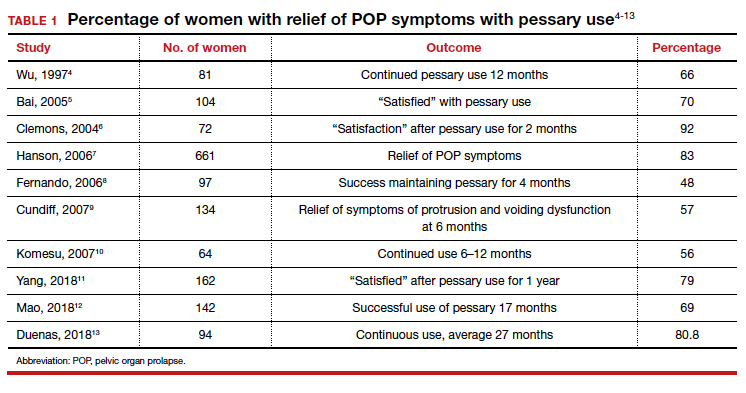

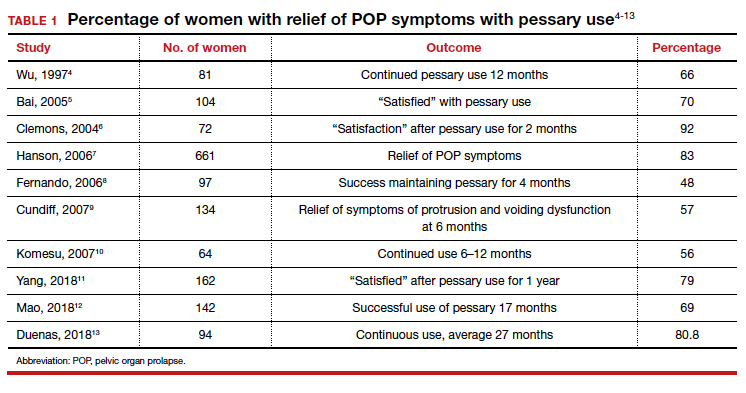

That being said, a review of the literature reveals that the rates of prolapse symptom relief vary from 48% to 92% (TABLE 1).4-13

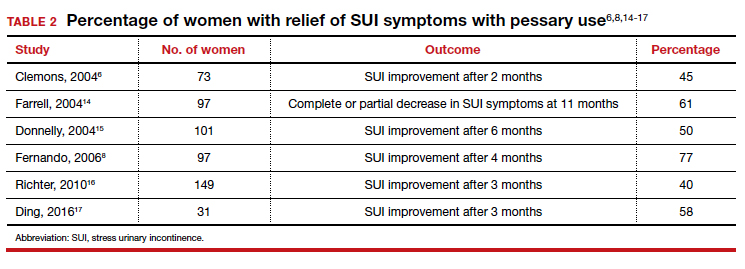

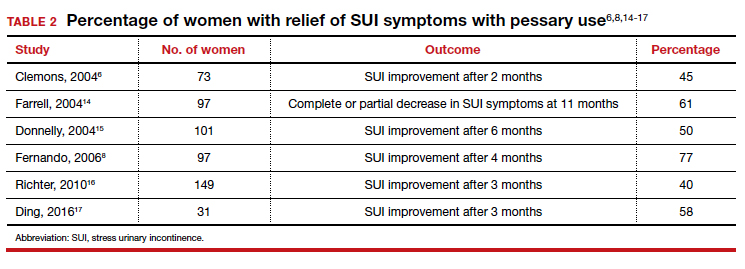

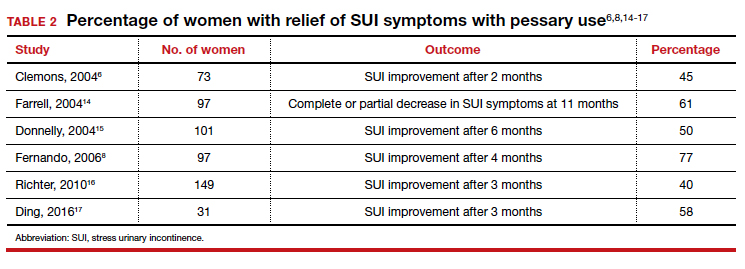

As for success in relieving symptoms of incontinence, studies show improvements in from 40% to 77% of patients (TABLE 2).6,8,14-17

In addition, some studies show a 50% improvement in bowel symptoms (urgency, obstruction, and anal incontinence) with the use of a pessary.9,18

How pessaries compare with surgery

While surgery has the advantage of being a one-time fix with a very high rate of initial success in correcting both POP and incontinence, surgery also has potential drawbacks:

- It is an invasive procedure with the discomfort and risk of complications any surgery entails.

- There is a relatively high rate of prolapse recurrence.

- It exposes the patient to the possibility of mesh erosion if mesh is employed either for POP support or incontinence treatment.

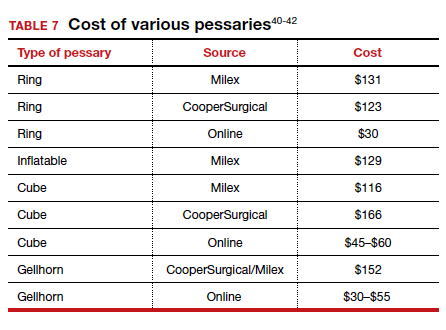

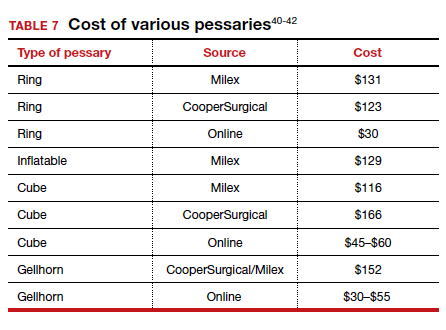

Pessaries, on the other hand, are inexpensive, nonsurgical, removable, and allow for immediate correction of symptoms. Moreover, if the pessary is tried and is found to be unsatisfactory, surgery always can be performed subsequently.

Drawbacks of pessary treatment compared with surgery include the:

- ongoing need to wear an artificial internal device

- need for intermittent pessary removal and cleansing

- inability to have sexual intercourse with certain kinds of pessaries in place

- possible accumulation of vaginal discharge and odor.

Sexual activity and pessaries

Studies by Fernando, Meriwether, and Kuhn concur that for a substantial number of pessary users who are sexually active, both frequency and satisfaction with sexual intercourse are increased.8,19,20 Kuhn further showed that desire, orgasm, and lubrication improved with the use of pessaries.20 While some types of pessaries do require removal for intercourse, Clemons reported that issues involving sexual activity are not associated with pessary discontinuation.21

Using a pessary to predict a surgical outcome

Because a pessary elevates the pelvic organs, supports the vaginal walls, and lifts the bladder and urethra into a position that simulates the results of surgical repair, trial placement of a pessary can be used as a fairly accurate predictive tool to model what pelvic support and continence status will be after a proposed surgical procedure.22,23 This is especially important because a significant number of patients with POP will have their occult stress incontinence unmasked following a reparative procedure.24 A brief pessary trial prior to surgery, therefore, can be a useful tool for both patient and surgeon.

Continue to: Pessaries for prevention of preterm labor...

Pessaries for prevention of preterm labor

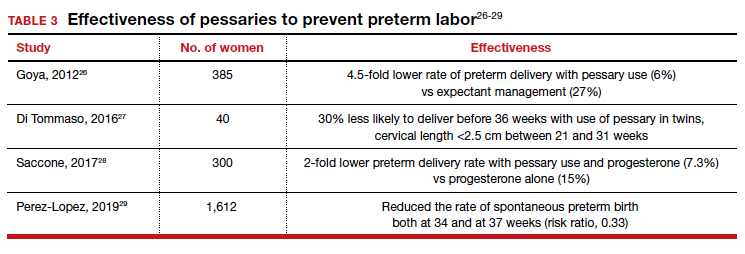

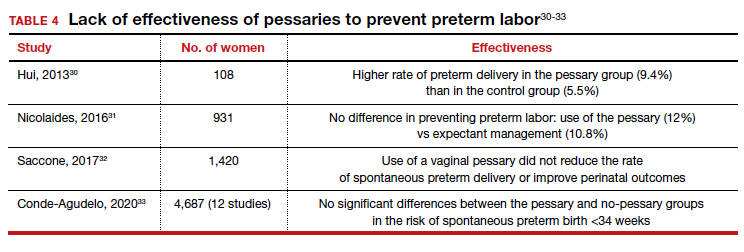

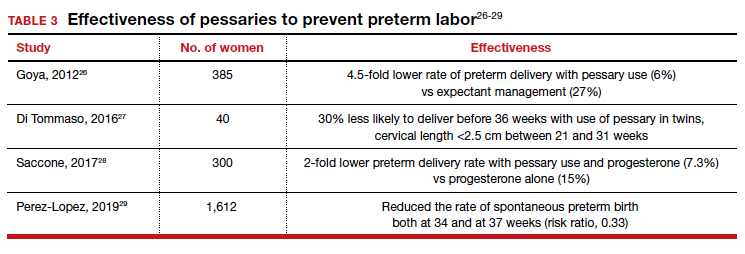

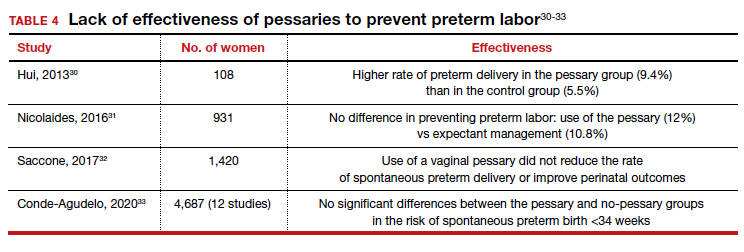

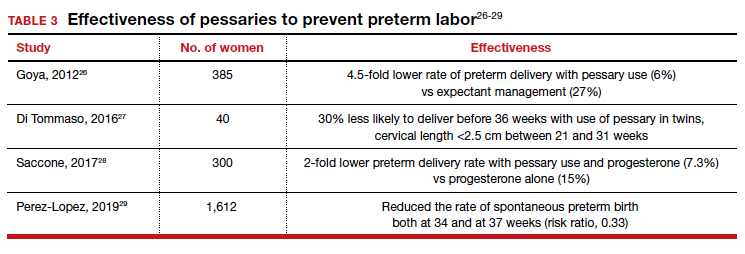

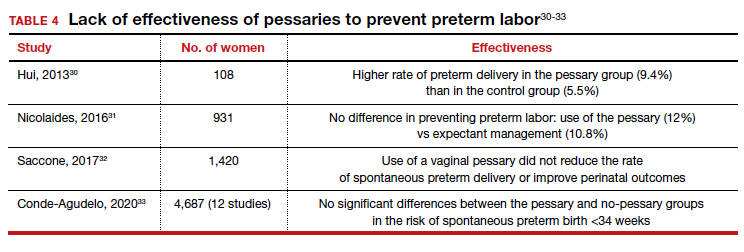

Almost 1 in 10 births in the United States occurs before 37 completed weeks of gestation.25 Obstetricians have long thought that in women at risk for preterm delivery, the use of a pessary might help reduce the pressure of the growing uterus on the cervix and thus help prevent premature cervical dilation. It also has been thought that use of a pessary would be a safer and less invasive alternative to cervical cerclage. Many studies have evaluated the use of pessaries for the prevention of preterm labor with a mixture of positive (TABLE 3)26-29 and negative results (TABLE 4).30-33

From these data, it is reasonable to conclude that:

- The final answer concerning the effectiveness or lack thereof of pessary use in preventing preterm delivery is not yet in.

- Any advantage there might be to using pessaries to prevent preterm delivery cannot be too significant if multiple studies show as many negative outcomes as positive ones.

Pessary effectiveness in defecatory disorders

Vaginal birth has the potential to create multiple anatomic injuries in the anus, lower pelvis, and perineum that can affect defecation and bowel control. Tears of the anal sphincter, whether obvious or occult, may heal incompletely or be repaired inadequately.34 Nerve innervation of the perianal and perineal areas can be interrupted or damaged by stretching, tearing, or prolonged compression. Of healthy parous adult women, 7% to 16% admit incontinence of gas or feces.35,36

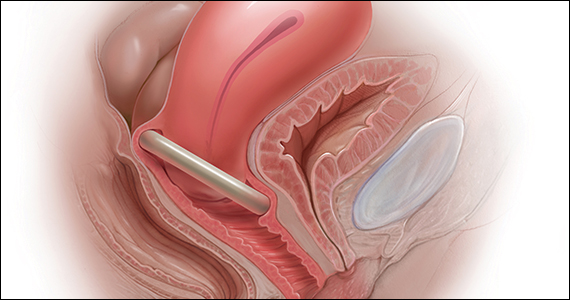

In addition, when a rectocele is present, stool in the lower rectum may cause bulging of the anterior rectal wall into the vagina, preventing stool from passing out of the anus. This sometimes requires women to digitally press their posterior vaginal walls during defecation to evacuate stool successfully. The question thus arises as to whether or not pessary placement and subsequent relief of rectoceles might facilitate bowel movements and decrease or eliminate defecatory dysfunction.

As with the issue of pessary use for prevention of preterm delivery, the answer is mixed. For instance, while Brazell18 showed that there was an overall improvement in bowel symptoms in pessary users, a study by Komesu10 did not demonstrate improvement.

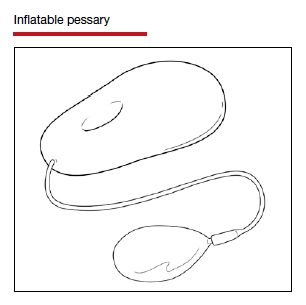

There is, however, a relatively new device specifically designed to control defecatory problems: the vaginal bowel control system (Eclipse; Pelvalon). The silicon device is placed intravaginally as one does a pessary. After insertion, it is inflated via a valve and syringe. It works by putting pressure on and reversibly closing the lower rectum, thus blocking the uncontrolled passage of stool and gas. It can be worn continuously or intermittently, but it does need to be deflated for normal bowel movements. One trial of this device demonstrated a 50% reduction in incontinence episodes with a patient satisfaction rate of 84% at 3 months.37 This device may well prove to be a valuable nonsurgical approach to the treatment of fecal incontinence. Unfortunately, the device is relatively expensive and usually is not covered by insurance as third-party payers do not consider it to be a pessary (which generally is covered).

Practice management particulars

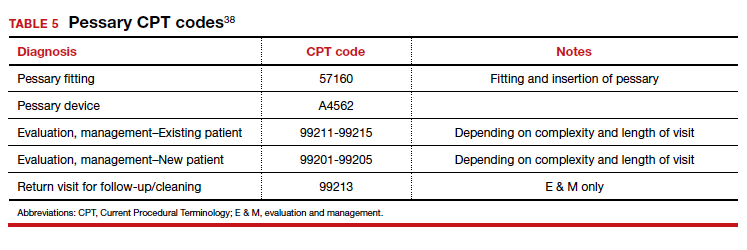

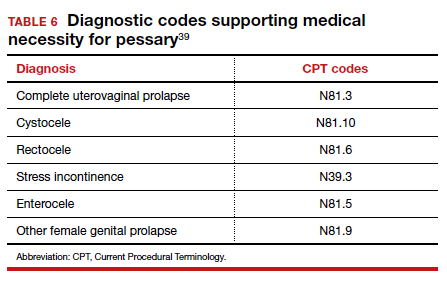

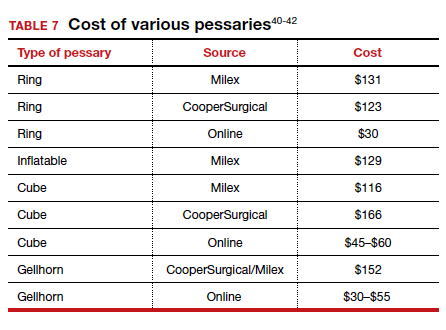

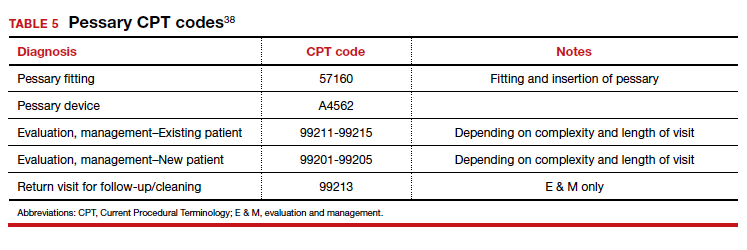

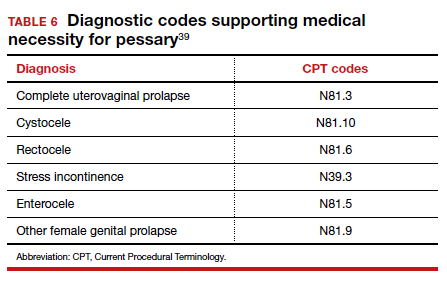

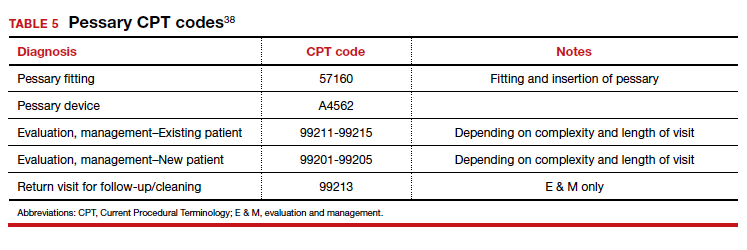

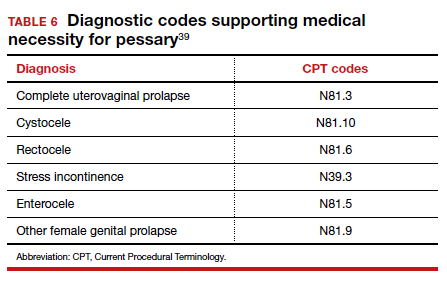

Useful information on Current Procedural Terminology codes for pessaries, diagnostic codes, and the cost of various pessaries is provided in TABLE 5,38TABLE 6,39 and TABLE 7.40-42

A contemporary device used since antiquity

Pessaries, considered “old-fashioned” by many gynecologists, are actually a very cost-effective and useful tool for the correction of POP and SUI. It behooves all who provide medical care to women to be familiar with them, to know when they might be useful, and to know how to fit and prescribe them. ●

- O’Dell K, Atnip S. Pessary care: follow up and management of complications. Urol Nurs. 2012;32:126-136, 145.

- Gorti M, Hudelist G, Simons A. Evaluation of vaginal pessary management: a UK-based survey. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;29:129-131.

- Meriwether KV, Rogers RG, Craig E, et al. The effect of hydroxyquinoline-based gel on pessary-associated bacterial vaginosis: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:729.e1-9.

- Wu V, Farrell SA, Baskett TF, et al. A simplified protocol for pessary management. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:990-994.

- Bai SW, Yoon BS, Kwon JY, et al. Survey of the characteristics and satisfaction degree of the patients using a pessary. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2005;16:182-186.

- Clemons JL, Aguilar VC, Tillinghast TA, et al. Patient satisfaction and changes in prolapse and urinary symptoms in women who were fitted successfully with a pessary for pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:1025-1029.

- Hanson LM, Schulz JA, Flood CG, et al. Vaginal pessaries in managing women with pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence: patient characteristics and factors contributing to success. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006;17: 155-159.

- Fernando RJ, Thakar R, Sultan AH, et al. Effect of vaginal pessaries on symptoms associated with pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:93-99.

- Cundiff GW, Amundsen CL, Bent AE, et al. The PESSRI study: symptom relief outcomes of a randomized crossover trial of the ring and Gellhorn pessaries. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:405.e1-405e.8.

- Komesu YM Rogers RG, Rode MA, et al. Pelvic floor symptom changes in pessary users. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197: 620.e1-6.

- Yang J, Han J, Zhu F, et al. Ring and Gellhorn pessaries used inpatients with pelvic organ prolapse: a retrospective study of 8 years. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2018;298:623-629.

- Mao M, Ai F, Zhang Y, et al. Changes in the symptoms and quality of life of women with symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse fitted with a ring with support pessary. Maturitas. 2018;117:51-56.

- Duenas JL, Miceli A. Effectiveness of a continuous-use ringshaped vaginal pessary without support for advanced pelvic organ prolapse in postmenopausal women. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29:1629-1636.

- Farrell S, Singh B, Aldakhil L. Continence pessaries in the management of urinary incontinence in women. J Obstet Gynaecol Canada. 2004;26:113-117.

- Donnelly MJ, Powell-Morgan SP, Olsen AL, et al. Vaginal pessaries for the management of stress and mixed urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2004;15:302-307.

- Richter HE, Burgio KL, Brubaker L, et al; Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Continence pessary compared with behavioral therapy or combined therapy for stress incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:609-617.

- Ding J, Chen C, Song XC, et al. Changes in prolapse and urinary symptoms after successful fitting of a ring pessary with support in women with advanced pelvic organ prolapse: a prospective study. Urology. 2016;87:70-75.

- Brazell HD, Patel M, O’Sullivan DM, et al. The impact of pessary use on bowel symptoms: one-year outcomes. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2014;20:95-98.

- Meriwether KV, Komesu YM, Craig C, et al. Sexual function and pessary management among women using a pessary for pelvic floor disorders. J Sex Med. 2015;12:2339-2349.

- Kuhn A, Bapst D, Stadlmayr W, et al. Sexual and organ function in patients with symptomatic prolapse: are pessaries helpful? Fertil Steril. 2009;91:1914-1918.

- Clemons JL, Aguilar VC, Sokol ER, et al. Patient characteristics that are associated with continued pessary use versus surgery after 1 year. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:159-164.

- Liang CC, Chang YL, Chang SD, et al. Pessary test to predict postoperative urinary incontinence in women undergoing hysterectomy for prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:795-800.

- Liapis A, Bakas P, Georgantopoulou C, et al. The use of the pessary test in preoperative assessment of women with severe genital prolapse. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011; 155:110-113.

- Wei JT, Nygaard I, Richter HE, et al; Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. A midurethral sling to reduce incontinence after vaginal prolapse repair. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2358-2367.

- March of Dimes. Quick facts: preterm birth. https://www .marchofdimes.org/Peristats/ViewTopic.aspx?reg=99 &top=3&lev=0&slev=1&gclid=EAIaIQobChMI4r. Accessed December 10, 2020.

- Goya M, Pratcorona L, Merced C, et al; PECEP Trial Group. Cervical pessary in pregnant women with a short cervix (PECEP): an open-label randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;379:1800-1806.

- Di Tommaso M, Seravalli V, Arduino S, et al. Arabin cervical pessary to prevent preterm birth in twin pregnancies with short cervix. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;36:715-718.

- Saccone G, Maruotti GM, Giudicepietro A, et al; Italian Preterm Birth Prevention (IPP) Working Group. Effect of cervical pessary on spontaneous preterm birth in women with singleton pregnancies and short cervical length: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318:2317-2324.

- Perez-Lopez FR, Chedraui P, Perez-Roncero GR, et al; Health Outcomes and Systematic Analyses (HOUSSAY) Project. Effectiveness of the cervical pessary for the prevention of preterm birth in singleton pregnancies with a short cervix: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2019;299:1215-1231.

- Hui SYA, Chor CM, Lau TK, et al. Cerclage pessary for preventing preterm birth in women with a singleton pregnancy and a short cervix at 20 to 24 weeks: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Perinatol. 2013;30:283-288.

- Nicolaides KH, Syngelaki A, Poon LC, et al. A randomized trial of a cervical pessary to prevent preterm singleton birth. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1044-1052.

- Saccone G, Ciardulli A, Xodo S, et al. Cervical pessary for preventing preterm birth in singleton pregnancies with short cervical length: a systematic review and meta-analyses. J Ultrasound Med. 2017;36:1535-1543.

- Conde-Agudelo A, Romero R, Nicolaides KH. Cervical pessary to prevent preterm birth in asymptomatic high-risk women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:42-65.e2.

- Sultan AH, Kamm MA, Hudson CN, et al. Anal-sphincter disruption during vaginal delivery. N Engl J Med. 1993;329: 1905-1911.

- Talley NJ, O’Keefe EA, Zinsmeister AR, et al. Prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms in the elderly: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:895-901.

- Denis P, Bercoff E, Bizien MF, et al. Prevalence of anal incontinence in adults [in French]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1992;16:344-350.

- Richter HE, Matthew CA, Muir T, et al. A vaginal bowel-control system for the treatment of fecal incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:540-547.

- 2019 Current Procedural Coding Expert. Optum360; 2018.

- ICD-10-CM Expert for Physicians. Optum360; 2019.

- MDS Medical Department Store website. http://www .medicaldepartmentstore.com/Pessary-Vaginal -Pessaries-/3788.htm?gclid=CjwKCAiAlNf-BRB _EiwA2osbxdqln8fQg-AxOUEMphM9aYlTIft Skwy0xXLT0PrcpIZnb5gBhiLc1RoCsbMQAvD_BwE. Accessed December 15, 2020.

- Monarch Medical Products website. https://www .monarchmedicalproducts.com/index.php?route=product /category&path=99_67. Accessed December 15, 2020.

- CooperSurgical Medical Devices website. https://www .coopersurgical.com/our-brands/milex/. Accessed December 15, 2020.

In Part 1 of this article in the December 2020 issue of OBG Management, I discussed the reasons that pessaries are an effective treatment option for many women with pelvic organ prolapse (POP) and stress urinary incontinence (SUI) and provided details on the types of pessaries available.

In this article, I highlight the steps in fitting a pessary, pessary aftercare, and potential complications associated with pessary use. In addition, I discuss the effectiveness of pessary treatment for POP and SUI as well as for preterm labor prevention and defecatory disorders.

The pessary fitting process

For a given patient, the best size pessary is the smallest one that will not fall out. The only “rule” for fitting a pessary is that a woman’s internal vaginal caliber should be wider than her introitus.

When fitting a pessary, goals include that the selected pessary:

- should be comfortable for the patient to wear

- is not easily expelled

- does not interfere with urination or defecation

- does not cause vaginal irritation.

The presence or absence of a cervix or uterus does not affect pessary choice.

Most experts agree that the process for fitting the right size pessary is one of trial and error. As with fitting a contraceptive diaphragm, the clinician should perform a manual examination to estimate the integrity and width of the perineum and the depth of the vagina to roughly approximate the pessary size that might best fit. Using a set of “fitting pessaries,” a pessary of the estimated size should be placed into the vagina and the fit evaluated as to whether the device is too big, too small, or appropriate. If the pessary is easily expelled, larger sizes should be tried until the pessary remains in place or the patient is uncomfortable. Once the pessary is in place, the clinician should be able to run his or her finger around the entire pessary; if this is not possible, the pessary is too tight. In addition, the pessary should remain more than one finger breadth above the introitus when the patient is standing or bearing down.

Since many patients who require a pessary are elderly, their perineal skin and vaginal mucosa may be atrophic and fragile. Inserting a pessary can be uncomfortable and can cause abrasions or tears. Successfully fitting a pessary may require extra care under these circumstances. The following steps may help alleviate these difficulties:

- Explain the fitting process to the patient in detail.

- Employ lubrication liberally.

- Enlarge the introitus by applying gentle digital pressure on the posterior fourchette.

- Apply 2% lidocaine ointment several minutes prior to pessary fitting to help decrease patient discomfort.

- Treat the patient for several weeks with vaginal estrogen cream before attempting to fit a pessary if severe vulvovaginal atrophy is present.

Once the type and size of the pessary are selected and a pessary is inserted, evaluate the patient with the pessary in place. Assess for the following:

Discomfort. Ask the patient if she feels discomfort with the pessary in position. A patient with a properly fitting pessary should not feel that it is in place. If she does feel discomfort initially, the discomfort will only increase with time and the issue should be addressed at that time.

Expulsion. Test to make certain that the pessary is not easily expelled from the vagina. Have the patient walk, cough, squat, and even jump if possible.

Urination. Have the patient urinate with the pessary in place. This tests for her ability to void while wearing the pessary and shows whether the contraction of pelvic muscles during voiding results in expulsion of the pessary. (Experience shows that it is best to do this with a plastic “hat” over the toilet so that if the pessary is expelled, it does not drop into the bowl.)

Re-examination. After these provocative tests, examine the patient again to ensure that the pessary has not slid out of place.

Depending on whether or not your office stocks pessaries, at this point the patient is either given the correct type and size of pessary or it is ordered for her. If the former, the patient should try placing it herself; if she is unable to, the clinician should place it for her. In either event, its position should be checked. If the pessary has to be ordered, the patient must schedule an appointment to return for pessary insertion.

Whether the pessary is supplied by the office or ordered, instruct the patient on how to insert and remove the pessary, how frequently to remove it for cleansing (see below), and signs to watch for, such as vaginal bleeding, inability to void or defecate, or pelvic pain.

It is advisable to schedule a subsequent visit for 2 to 3 weeks after initial pessary placement to assess how the patient is doing and to address any issues that have developed.

Continue to: Special circumstances...

Special circumstances

It is safe for a patient with a pessary in place to undergo magnetic resonance imaging.1 Patients should be informed, however, that full body scans, such as at airports, will detect pessaries. Patients may need to obtain a physician’s note to document that the pessary is a medical device.

Finally, several factors may prevent successful pessary fitting. These include prior pelvic surgery, obesity, short vaginal length (less than 6–7 cm), and a vaginal introitus width of greater than 4 finger breadths.

Necessary pessary aftercare

Once a pessary is in place and the patient is comfortable with it, the only maintenance necessary is the pessary’s intermittent removal for cleansing and for evaluation of the vaginal mucosa for erosion and ulcerations. How frequently this should be done varies based on the type of pessary, the amount of discharge that a woman produces, whether or not an odor develops after prolonged wearing of the pessary, and whether or not the patient’s vaginal mucosa has been abraded.

The question of timing for pessary cleaning

Although there are many opinions about how often pessaries should be removed and cleaned, no data in the literature support any specific interval. Pessaries that are easily removed by women themselves can be cleaned as frequently as desired, often on a weekly basis. The patient simply removes the pessary, washes it with soap and water, and reinserts it. For pessaries that are difficult to remove (such as the Gellhorn, cube, or donut) or for women who are physically unable to remove their own ring pessary, the clinician should remove and clean the pessary in the office every 3 to 6 months. It has been shown that there is no difference in complications from pessary use with either of these intervals.2

Prior to any vaginal surgical procedure, patients must be instructed to remove their pessary 10 to 14 days beforehand so that the surgeon can see the full extent of prolapse when making decisions about reconstruction and so that any vaginal mucosal erosions or abrasions have time to heal.

Office visits for follow-up care

The pessary “cleaning visit” has several goals, including to:

- see if the pessary is meeting the patient’s needs in terms of resolving symptoms of prolapse and/or restoring urinary continence

- discuss with the patient any problems she may be having, such as pelvic discomfort or pressure, difficulty voiding or defecating, excessive vaginal discharge, or vaginal odor

- check for vaginal mucosal erosion or ulceration; such vaginal lesions often can be prevented by the prophylactic use of either estrogen vaginal cream twice weekly or the continuous use of an estradiol vaginal ring in addition to the pessary

- evaluate the condition of the pessary itself and clean it with soap and water.

Continue to: Potential complications of pessary use...

Potential complications of pessary use

The most common complications experienced by pessary users are:

Odor or excessive discharge. Bacterial vaginosis (BV) occurs more frequently in women who use pessaries. The symptoms of BV can be minimized—but unfortunately not totally eliminated—by the prophylactic use of antiseptic vaginal creams or gels, such as metronidazole, clindamycin, Trimo-San (oxyquinoline sulfate and sodium lauryl sulfate), and others. Inserting the gel vaginally once a week can significantly reduce discharge and odor.3

Vaginal mucosal erosion and ulceration. These are treated by removing the pessary for 2 weeks during which time estrogen cream is applied daily or an estradiol vaginal ring is put in place. If no resolution occurs after 2 weeks, the nonhealing vaginal mucosa should be biopsied.

Pressure on the rectum or bladder. If the pessary causes significant discomfort or interferes with voiding function, then either a different size or a different type pessary should be tried

Patients may discontinue pessary use for a variety of reasons. Among these are:

- discomfort

- inadequate improvement of POP or incontinence symptoms

- expulsion of the pessary during daily activities

- the patient’s desire for surgery instead

- worsening of urine leakage

- difficulty inserting or removing the pessary

- damage to the vaginal mucosa

- pain during removal of the pessary in the office.

Pessary effectiveness for POP and SUI symptoms

As might be expected with a device that is available in so many forms and is used to treat varied types of POP and SUI, the data concerning the success rates of pessary use vary considerably. These rates depend on the definition of success, that is, complete or partial control of prolapse and/or incontinence; which devices are being evaluated; and the nature and severity of the POP and/or SUI being treated.

That being said, a review of the literature reveals that the rates of prolapse symptom relief vary from 48% to 92% (TABLE 1).4-13

As for success in relieving symptoms of incontinence, studies show improvements in from 40% to 77% of patients (TABLE 2).6,8,14-17

In addition, some studies show a 50% improvement in bowel symptoms (urgency, obstruction, and anal incontinence) with the use of a pessary.9,18

How pessaries compare with surgery

While surgery has the advantage of being a one-time fix with a very high rate of initial success in correcting both POP and incontinence, surgery also has potential drawbacks:

- It is an invasive procedure with the discomfort and risk of complications any surgery entails.

- There is a relatively high rate of prolapse recurrence.

- It exposes the patient to the possibility of mesh erosion if mesh is employed either for POP support or incontinence treatment.

Pessaries, on the other hand, are inexpensive, nonsurgical, removable, and allow for immediate correction of symptoms. Moreover, if the pessary is tried and is found to be unsatisfactory, surgery always can be performed subsequently.

Drawbacks of pessary treatment compared with surgery include the:

- ongoing need to wear an artificial internal device

- need for intermittent pessary removal and cleansing

- inability to have sexual intercourse with certain kinds of pessaries in place

- possible accumulation of vaginal discharge and odor.

Sexual activity and pessaries

Studies by Fernando, Meriwether, and Kuhn concur that for a substantial number of pessary users who are sexually active, both frequency and satisfaction with sexual intercourse are increased.8,19,20 Kuhn further showed that desire, orgasm, and lubrication improved with the use of pessaries.20 While some types of pessaries do require removal for intercourse, Clemons reported that issues involving sexual activity are not associated with pessary discontinuation.21

Using a pessary to predict a surgical outcome

Because a pessary elevates the pelvic organs, supports the vaginal walls, and lifts the bladder and urethra into a position that simulates the results of surgical repair, trial placement of a pessary can be used as a fairly accurate predictive tool to model what pelvic support and continence status will be after a proposed surgical procedure.22,23 This is especially important because a significant number of patients with POP will have their occult stress incontinence unmasked following a reparative procedure.24 A brief pessary trial prior to surgery, therefore, can be a useful tool for both patient and surgeon.

Continue to: Pessaries for prevention of preterm labor...

Pessaries for prevention of preterm labor

Almost 1 in 10 births in the United States occurs before 37 completed weeks of gestation.25 Obstetricians have long thought that in women at risk for preterm delivery, the use of a pessary might help reduce the pressure of the growing uterus on the cervix and thus help prevent premature cervical dilation. It also has been thought that use of a pessary would be a safer and less invasive alternative to cervical cerclage. Many studies have evaluated the use of pessaries for the prevention of preterm labor with a mixture of positive (TABLE 3)26-29 and negative results (TABLE 4).30-33

From these data, it is reasonable to conclude that:

- The final answer concerning the effectiveness or lack thereof of pessary use in preventing preterm delivery is not yet in.

- Any advantage there might be to using pessaries to prevent preterm delivery cannot be too significant if multiple studies show as many negative outcomes as positive ones.

Pessary effectiveness in defecatory disorders

Vaginal birth has the potential to create multiple anatomic injuries in the anus, lower pelvis, and perineum that can affect defecation and bowel control. Tears of the anal sphincter, whether obvious or occult, may heal incompletely or be repaired inadequately.34 Nerve innervation of the perianal and perineal areas can be interrupted or damaged by stretching, tearing, or prolonged compression. Of healthy parous adult women, 7% to 16% admit incontinence of gas or feces.35,36

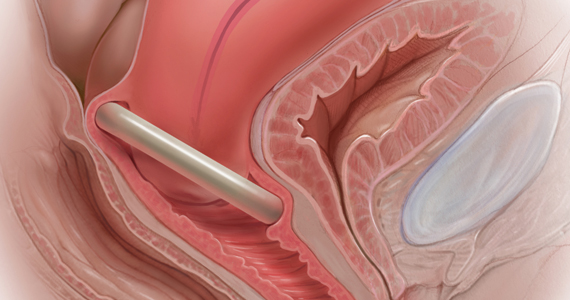

In addition, when a rectocele is present, stool in the lower rectum may cause bulging of the anterior rectal wall into the vagina, preventing stool from passing out of the anus. This sometimes requires women to digitally press their posterior vaginal walls during defecation to evacuate stool successfully. The question thus arises as to whether or not pessary placement and subsequent relief of rectoceles might facilitate bowel movements and decrease or eliminate defecatory dysfunction.

As with the issue of pessary use for prevention of preterm delivery, the answer is mixed. For instance, while Brazell18 showed that there was an overall improvement in bowel symptoms in pessary users, a study by Komesu10 did not demonstrate improvement.

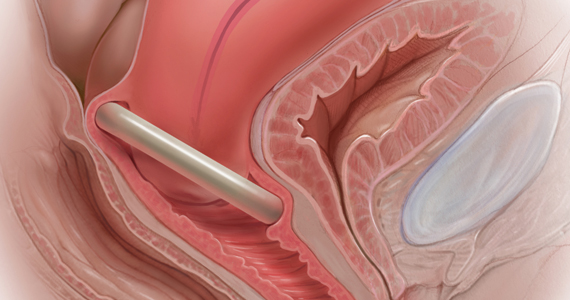

There is, however, a relatively new device specifically designed to control defecatory problems: the vaginal bowel control system (Eclipse; Pelvalon). The silicon device is placed intravaginally as one does a pessary. After insertion, it is inflated via a valve and syringe. It works by putting pressure on and reversibly closing the lower rectum, thus blocking the uncontrolled passage of stool and gas. It can be worn continuously or intermittently, but it does need to be deflated for normal bowel movements. One trial of this device demonstrated a 50% reduction in incontinence episodes with a patient satisfaction rate of 84% at 3 months.37 This device may well prove to be a valuable nonsurgical approach to the treatment of fecal incontinence. Unfortunately, the device is relatively expensive and usually is not covered by insurance as third-party payers do not consider it to be a pessary (which generally is covered).

Practice management particulars

Useful information on Current Procedural Terminology codes for pessaries, diagnostic codes, and the cost of various pessaries is provided in TABLE 5,38TABLE 6,39 and TABLE 7.40-42

A contemporary device used since antiquity

Pessaries, considered “old-fashioned” by many gynecologists, are actually a very cost-effective and useful tool for the correction of POP and SUI. It behooves all who provide medical care to women to be familiar with them, to know when they might be useful, and to know how to fit and prescribe them. ●

In Part 1 of this article in the December 2020 issue of OBG Management, I discussed the reasons that pessaries are an effective treatment option for many women with pelvic organ prolapse (POP) and stress urinary incontinence (SUI) and provided details on the types of pessaries available.

In this article, I highlight the steps in fitting a pessary, pessary aftercare, and potential complications associated with pessary use. In addition, I discuss the effectiveness of pessary treatment for POP and SUI as well as for preterm labor prevention and defecatory disorders.

The pessary fitting process

For a given patient, the best size pessary is the smallest one that will not fall out. The only “rule” for fitting a pessary is that a woman’s internal vaginal caliber should be wider than her introitus.

When fitting a pessary, goals include that the selected pessary:

- should be comfortable for the patient to wear

- is not easily expelled

- does not interfere with urination or defecation

- does not cause vaginal irritation.

The presence or absence of a cervix or uterus does not affect pessary choice.

Most experts agree that the process for fitting the right size pessary is one of trial and error. As with fitting a contraceptive diaphragm, the clinician should perform a manual examination to estimate the integrity and width of the perineum and the depth of the vagina to roughly approximate the pessary size that might best fit. Using a set of “fitting pessaries,” a pessary of the estimated size should be placed into the vagina and the fit evaluated as to whether the device is too big, too small, or appropriate. If the pessary is easily expelled, larger sizes should be tried until the pessary remains in place or the patient is uncomfortable. Once the pessary is in place, the clinician should be able to run his or her finger around the entire pessary; if this is not possible, the pessary is too tight. In addition, the pessary should remain more than one finger breadth above the introitus when the patient is standing or bearing down.

Since many patients who require a pessary are elderly, their perineal skin and vaginal mucosa may be atrophic and fragile. Inserting a pessary can be uncomfortable and can cause abrasions or tears. Successfully fitting a pessary may require extra care under these circumstances. The following steps may help alleviate these difficulties:

- Explain the fitting process to the patient in detail.

- Employ lubrication liberally.

- Enlarge the introitus by applying gentle digital pressure on the posterior fourchette.

- Apply 2% lidocaine ointment several minutes prior to pessary fitting to help decrease patient discomfort.

- Treat the patient for several weeks with vaginal estrogen cream before attempting to fit a pessary if severe vulvovaginal atrophy is present.

Once the type and size of the pessary are selected and a pessary is inserted, evaluate the patient with the pessary in place. Assess for the following:

Discomfort. Ask the patient if she feels discomfort with the pessary in position. A patient with a properly fitting pessary should not feel that it is in place. If she does feel discomfort initially, the discomfort will only increase with time and the issue should be addressed at that time.

Expulsion. Test to make certain that the pessary is not easily expelled from the vagina. Have the patient walk, cough, squat, and even jump if possible.

Urination. Have the patient urinate with the pessary in place. This tests for her ability to void while wearing the pessary and shows whether the contraction of pelvic muscles during voiding results in expulsion of the pessary. (Experience shows that it is best to do this with a plastic “hat” over the toilet so that if the pessary is expelled, it does not drop into the bowl.)

Re-examination. After these provocative tests, examine the patient again to ensure that the pessary has not slid out of place.

Depending on whether or not your office stocks pessaries, at this point the patient is either given the correct type and size of pessary or it is ordered for her. If the former, the patient should try placing it herself; if she is unable to, the clinician should place it for her. In either event, its position should be checked. If the pessary has to be ordered, the patient must schedule an appointment to return for pessary insertion.

Whether the pessary is supplied by the office or ordered, instruct the patient on how to insert and remove the pessary, how frequently to remove it for cleansing (see below), and signs to watch for, such as vaginal bleeding, inability to void or defecate, or pelvic pain.

It is advisable to schedule a subsequent visit for 2 to 3 weeks after initial pessary placement to assess how the patient is doing and to address any issues that have developed.

Continue to: Special circumstances...

Special circumstances

It is safe for a patient with a pessary in place to undergo magnetic resonance imaging.1 Patients should be informed, however, that full body scans, such as at airports, will detect pessaries. Patients may need to obtain a physician’s note to document that the pessary is a medical device.

Finally, several factors may prevent successful pessary fitting. These include prior pelvic surgery, obesity, short vaginal length (less than 6–7 cm), and a vaginal introitus width of greater than 4 finger breadths.

Necessary pessary aftercare

Once a pessary is in place and the patient is comfortable with it, the only maintenance necessary is the pessary’s intermittent removal for cleansing and for evaluation of the vaginal mucosa for erosion and ulcerations. How frequently this should be done varies based on the type of pessary, the amount of discharge that a woman produces, whether or not an odor develops after prolonged wearing of the pessary, and whether or not the patient’s vaginal mucosa has been abraded.

The question of timing for pessary cleaning

Although there are many opinions about how often pessaries should be removed and cleaned, no data in the literature support any specific interval. Pessaries that are easily removed by women themselves can be cleaned as frequently as desired, often on a weekly basis. The patient simply removes the pessary, washes it with soap and water, and reinserts it. For pessaries that are difficult to remove (such as the Gellhorn, cube, or donut) or for women who are physically unable to remove their own ring pessary, the clinician should remove and clean the pessary in the office every 3 to 6 months. It has been shown that there is no difference in complications from pessary use with either of these intervals.2

Prior to any vaginal surgical procedure, patients must be instructed to remove their pessary 10 to 14 days beforehand so that the surgeon can see the full extent of prolapse when making decisions about reconstruction and so that any vaginal mucosal erosions or abrasions have time to heal.

Office visits for follow-up care

The pessary “cleaning visit” has several goals, including to:

- see if the pessary is meeting the patient’s needs in terms of resolving symptoms of prolapse and/or restoring urinary continence

- discuss with the patient any problems she may be having, such as pelvic discomfort or pressure, difficulty voiding or defecating, excessive vaginal discharge, or vaginal odor

- check for vaginal mucosal erosion or ulceration; such vaginal lesions often can be prevented by the prophylactic use of either estrogen vaginal cream twice weekly or the continuous use of an estradiol vaginal ring in addition to the pessary

- evaluate the condition of the pessary itself and clean it with soap and water.

Continue to: Potential complications of pessary use...

Potential complications of pessary use

The most common complications experienced by pessary users are:

Odor or excessive discharge. Bacterial vaginosis (BV) occurs more frequently in women who use pessaries. The symptoms of BV can be minimized—but unfortunately not totally eliminated—by the prophylactic use of antiseptic vaginal creams or gels, such as metronidazole, clindamycin, Trimo-San (oxyquinoline sulfate and sodium lauryl sulfate), and others. Inserting the gel vaginally once a week can significantly reduce discharge and odor.3

Vaginal mucosal erosion and ulceration. These are treated by removing the pessary for 2 weeks during which time estrogen cream is applied daily or an estradiol vaginal ring is put in place. If no resolution occurs after 2 weeks, the nonhealing vaginal mucosa should be biopsied.

Pressure on the rectum or bladder. If the pessary causes significant discomfort or interferes with voiding function, then either a different size or a different type pessary should be tried

Patients may discontinue pessary use for a variety of reasons. Among these are:

- discomfort

- inadequate improvement of POP or incontinence symptoms

- expulsion of the pessary during daily activities

- the patient’s desire for surgery instead

- worsening of urine leakage

- difficulty inserting or removing the pessary

- damage to the vaginal mucosa

- pain during removal of the pessary in the office.

Pessary effectiveness for POP and SUI symptoms

As might be expected with a device that is available in so many forms and is used to treat varied types of POP and SUI, the data concerning the success rates of pessary use vary considerably. These rates depend on the definition of success, that is, complete or partial control of prolapse and/or incontinence; which devices are being evaluated; and the nature and severity of the POP and/or SUI being treated.

That being said, a review of the literature reveals that the rates of prolapse symptom relief vary from 48% to 92% (TABLE 1).4-13

As for success in relieving symptoms of incontinence, studies show improvements in from 40% to 77% of patients (TABLE 2).6,8,14-17

In addition, some studies show a 50% improvement in bowel symptoms (urgency, obstruction, and anal incontinence) with the use of a pessary.9,18

How pessaries compare with surgery

While surgery has the advantage of being a one-time fix with a very high rate of initial success in correcting both POP and incontinence, surgery also has potential drawbacks:

- It is an invasive procedure with the discomfort and risk of complications any surgery entails.

- There is a relatively high rate of prolapse recurrence.

- It exposes the patient to the possibility of mesh erosion if mesh is employed either for POP support or incontinence treatment.

Pessaries, on the other hand, are inexpensive, nonsurgical, removable, and allow for immediate correction of symptoms. Moreover, if the pessary is tried and is found to be unsatisfactory, surgery always can be performed subsequently.

Drawbacks of pessary treatment compared with surgery include the:

- ongoing need to wear an artificial internal device

- need for intermittent pessary removal and cleansing

- inability to have sexual intercourse with certain kinds of pessaries in place

- possible accumulation of vaginal discharge and odor.

Sexual activity and pessaries

Studies by Fernando, Meriwether, and Kuhn concur that for a substantial number of pessary users who are sexually active, both frequency and satisfaction with sexual intercourse are increased.8,19,20 Kuhn further showed that desire, orgasm, and lubrication improved with the use of pessaries.20 While some types of pessaries do require removal for intercourse, Clemons reported that issues involving sexual activity are not associated with pessary discontinuation.21

Using a pessary to predict a surgical outcome

Because a pessary elevates the pelvic organs, supports the vaginal walls, and lifts the bladder and urethra into a position that simulates the results of surgical repair, trial placement of a pessary can be used as a fairly accurate predictive tool to model what pelvic support and continence status will be after a proposed surgical procedure.22,23 This is especially important because a significant number of patients with POP will have their occult stress incontinence unmasked following a reparative procedure.24 A brief pessary trial prior to surgery, therefore, can be a useful tool for both patient and surgeon.

Continue to: Pessaries for prevention of preterm labor...

Pessaries for prevention of preterm labor

Almost 1 in 10 births in the United States occurs before 37 completed weeks of gestation.25 Obstetricians have long thought that in women at risk for preterm delivery, the use of a pessary might help reduce the pressure of the growing uterus on the cervix and thus help prevent premature cervical dilation. It also has been thought that use of a pessary would be a safer and less invasive alternative to cervical cerclage. Many studies have evaluated the use of pessaries for the prevention of preterm labor with a mixture of positive (TABLE 3)26-29 and negative results (TABLE 4).30-33

From these data, it is reasonable to conclude that:

- The final answer concerning the effectiveness or lack thereof of pessary use in preventing preterm delivery is not yet in.

- Any advantage there might be to using pessaries to prevent preterm delivery cannot be too significant if multiple studies show as many negative outcomes as positive ones.

Pessary effectiveness in defecatory disorders

Vaginal birth has the potential to create multiple anatomic injuries in the anus, lower pelvis, and perineum that can affect defecation and bowel control. Tears of the anal sphincter, whether obvious or occult, may heal incompletely or be repaired inadequately.34 Nerve innervation of the perianal and perineal areas can be interrupted or damaged by stretching, tearing, or prolonged compression. Of healthy parous adult women, 7% to 16% admit incontinence of gas or feces.35,36

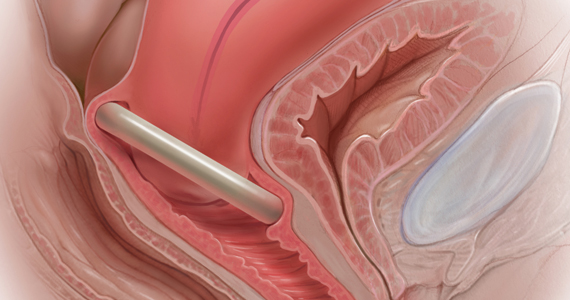

In addition, when a rectocele is present, stool in the lower rectum may cause bulging of the anterior rectal wall into the vagina, preventing stool from passing out of the anus. This sometimes requires women to digitally press their posterior vaginal walls during defecation to evacuate stool successfully. The question thus arises as to whether or not pessary placement and subsequent relief of rectoceles might facilitate bowel movements and decrease or eliminate defecatory dysfunction.

As with the issue of pessary use for prevention of preterm delivery, the answer is mixed. For instance, while Brazell18 showed that there was an overall improvement in bowel symptoms in pessary users, a study by Komesu10 did not demonstrate improvement.

There is, however, a relatively new device specifically designed to control defecatory problems: the vaginal bowel control system (Eclipse; Pelvalon). The silicon device is placed intravaginally as one does a pessary. After insertion, it is inflated via a valve and syringe. It works by putting pressure on and reversibly closing the lower rectum, thus blocking the uncontrolled passage of stool and gas. It can be worn continuously or intermittently, but it does need to be deflated for normal bowel movements. One trial of this device demonstrated a 50% reduction in incontinence episodes with a patient satisfaction rate of 84% at 3 months.37 This device may well prove to be a valuable nonsurgical approach to the treatment of fecal incontinence. Unfortunately, the device is relatively expensive and usually is not covered by insurance as third-party payers do not consider it to be a pessary (which generally is covered).

Practice management particulars

Useful information on Current Procedural Terminology codes for pessaries, diagnostic codes, and the cost of various pessaries is provided in TABLE 5,38TABLE 6,39 and TABLE 7.40-42

A contemporary device used since antiquity

Pessaries, considered “old-fashioned” by many gynecologists, are actually a very cost-effective and useful tool for the correction of POP and SUI. It behooves all who provide medical care to women to be familiar with them, to know when they might be useful, and to know how to fit and prescribe them. ●

- O’Dell K, Atnip S. Pessary care: follow up and management of complications. Urol Nurs. 2012;32:126-136, 145.

- Gorti M, Hudelist G, Simons A. Evaluation of vaginal pessary management: a UK-based survey. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;29:129-131.

- Meriwether KV, Rogers RG, Craig E, et al. The effect of hydroxyquinoline-based gel on pessary-associated bacterial vaginosis: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:729.e1-9.

- Wu V, Farrell SA, Baskett TF, et al. A simplified protocol for pessary management. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:990-994.

- Bai SW, Yoon BS, Kwon JY, et al. Survey of the characteristics and satisfaction degree of the patients using a pessary. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2005;16:182-186.

- Clemons JL, Aguilar VC, Tillinghast TA, et al. Patient satisfaction and changes in prolapse and urinary symptoms in women who were fitted successfully with a pessary for pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:1025-1029.

- Hanson LM, Schulz JA, Flood CG, et al. Vaginal pessaries in managing women with pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence: patient characteristics and factors contributing to success. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006;17: 155-159.

- Fernando RJ, Thakar R, Sultan AH, et al. Effect of vaginal pessaries on symptoms associated with pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:93-99.

- Cundiff GW, Amundsen CL, Bent AE, et al. The PESSRI study: symptom relief outcomes of a randomized crossover trial of the ring and Gellhorn pessaries. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:405.e1-405e.8.

- Komesu YM Rogers RG, Rode MA, et al. Pelvic floor symptom changes in pessary users. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197: 620.e1-6.

- Yang J, Han J, Zhu F, et al. Ring and Gellhorn pessaries used inpatients with pelvic organ prolapse: a retrospective study of 8 years. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2018;298:623-629.

- Mao M, Ai F, Zhang Y, et al. Changes in the symptoms and quality of life of women with symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse fitted with a ring with support pessary. Maturitas. 2018;117:51-56.

- Duenas JL, Miceli A. Effectiveness of a continuous-use ringshaped vaginal pessary without support for advanced pelvic organ prolapse in postmenopausal women. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29:1629-1636.

- Farrell S, Singh B, Aldakhil L. Continence pessaries in the management of urinary incontinence in women. J Obstet Gynaecol Canada. 2004;26:113-117.

- Donnelly MJ, Powell-Morgan SP, Olsen AL, et al. Vaginal pessaries for the management of stress and mixed urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2004;15:302-307.

- Richter HE, Burgio KL, Brubaker L, et al; Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Continence pessary compared with behavioral therapy or combined therapy for stress incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:609-617.

- Ding J, Chen C, Song XC, et al. Changes in prolapse and urinary symptoms after successful fitting of a ring pessary with support in women with advanced pelvic organ prolapse: a prospective study. Urology. 2016;87:70-75.

- Brazell HD, Patel M, O’Sullivan DM, et al. The impact of pessary use on bowel symptoms: one-year outcomes. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2014;20:95-98.

- Meriwether KV, Komesu YM, Craig C, et al. Sexual function and pessary management among women using a pessary for pelvic floor disorders. J Sex Med. 2015;12:2339-2349.

- Kuhn A, Bapst D, Stadlmayr W, et al. Sexual and organ function in patients with symptomatic prolapse: are pessaries helpful? Fertil Steril. 2009;91:1914-1918.

- Clemons JL, Aguilar VC, Sokol ER, et al. Patient characteristics that are associated with continued pessary use versus surgery after 1 year. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:159-164.

- Liang CC, Chang YL, Chang SD, et al. Pessary test to predict postoperative urinary incontinence in women undergoing hysterectomy for prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:795-800.

- Liapis A, Bakas P, Georgantopoulou C, et al. The use of the pessary test in preoperative assessment of women with severe genital prolapse. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011; 155:110-113.

- Wei JT, Nygaard I, Richter HE, et al; Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. A midurethral sling to reduce incontinence after vaginal prolapse repair. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2358-2367.

- March of Dimes. Quick facts: preterm birth. https://www .marchofdimes.org/Peristats/ViewTopic.aspx?reg=99 &top=3&lev=0&slev=1&gclid=EAIaIQobChMI4r. Accessed December 10, 2020.

- Goya M, Pratcorona L, Merced C, et al; PECEP Trial Group. Cervical pessary in pregnant women with a short cervix (PECEP): an open-label randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;379:1800-1806.

- Di Tommaso M, Seravalli V, Arduino S, et al. Arabin cervical pessary to prevent preterm birth in twin pregnancies with short cervix. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;36:715-718.

- Saccone G, Maruotti GM, Giudicepietro A, et al; Italian Preterm Birth Prevention (IPP) Working Group. Effect of cervical pessary on spontaneous preterm birth in women with singleton pregnancies and short cervical length: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318:2317-2324.

- Perez-Lopez FR, Chedraui P, Perez-Roncero GR, et al; Health Outcomes and Systematic Analyses (HOUSSAY) Project. Effectiveness of the cervical pessary for the prevention of preterm birth in singleton pregnancies with a short cervix: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2019;299:1215-1231.

- Hui SYA, Chor CM, Lau TK, et al. Cerclage pessary for preventing preterm birth in women with a singleton pregnancy and a short cervix at 20 to 24 weeks: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Perinatol. 2013;30:283-288.

- Nicolaides KH, Syngelaki A, Poon LC, et al. A randomized trial of a cervical pessary to prevent preterm singleton birth. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1044-1052.

- Saccone G, Ciardulli A, Xodo S, et al. Cervical pessary for preventing preterm birth in singleton pregnancies with short cervical length: a systematic review and meta-analyses. J Ultrasound Med. 2017;36:1535-1543.

- Conde-Agudelo A, Romero R, Nicolaides KH. Cervical pessary to prevent preterm birth in asymptomatic high-risk women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:42-65.e2.

- Sultan AH, Kamm MA, Hudson CN, et al. Anal-sphincter disruption during vaginal delivery. N Engl J Med. 1993;329: 1905-1911.

- Talley NJ, O’Keefe EA, Zinsmeister AR, et al. Prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms in the elderly: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:895-901.

- Denis P, Bercoff E, Bizien MF, et al. Prevalence of anal incontinence in adults [in French]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1992;16:344-350.

- Richter HE, Matthew CA, Muir T, et al. A vaginal bowel-control system for the treatment of fecal incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:540-547.

- 2019 Current Procedural Coding Expert. Optum360; 2018.

- ICD-10-CM Expert for Physicians. Optum360; 2019.

- MDS Medical Department Store website. http://www .medicaldepartmentstore.com/Pessary-Vaginal -Pessaries-/3788.htm?gclid=CjwKCAiAlNf-BRB _EiwA2osbxdqln8fQg-AxOUEMphM9aYlTIft Skwy0xXLT0PrcpIZnb5gBhiLc1RoCsbMQAvD_BwE. Accessed December 15, 2020.

- Monarch Medical Products website. https://www .monarchmedicalproducts.com/index.php?route=product /category&path=99_67. Accessed December 15, 2020.

- CooperSurgical Medical Devices website. https://www .coopersurgical.com/our-brands/milex/. Accessed December 15, 2020.

- O’Dell K, Atnip S. Pessary care: follow up and management of complications. Urol Nurs. 2012;32:126-136, 145.

- Gorti M, Hudelist G, Simons A. Evaluation of vaginal pessary management: a UK-based survey. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;29:129-131.

- Meriwether KV, Rogers RG, Craig E, et al. The effect of hydroxyquinoline-based gel on pessary-associated bacterial vaginosis: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:729.e1-9.

- Wu V, Farrell SA, Baskett TF, et al. A simplified protocol for pessary management. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:990-994.

- Bai SW, Yoon BS, Kwon JY, et al. Survey of the characteristics and satisfaction degree of the patients using a pessary. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2005;16:182-186.

- Clemons JL, Aguilar VC, Tillinghast TA, et al. Patient satisfaction and changes in prolapse and urinary symptoms in women who were fitted successfully with a pessary for pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:1025-1029.

- Hanson LM, Schulz JA, Flood CG, et al. Vaginal pessaries in managing women with pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence: patient characteristics and factors contributing to success. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006;17: 155-159.

- Fernando RJ, Thakar R, Sultan AH, et al. Effect of vaginal pessaries on symptoms associated with pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:93-99.

- Cundiff GW, Amundsen CL, Bent AE, et al. The PESSRI study: symptom relief outcomes of a randomized crossover trial of the ring and Gellhorn pessaries. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:405.e1-405e.8.

- Komesu YM Rogers RG, Rode MA, et al. Pelvic floor symptom changes in pessary users. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197: 620.e1-6.

- Yang J, Han J, Zhu F, et al. Ring and Gellhorn pessaries used inpatients with pelvic organ prolapse: a retrospective study of 8 years. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2018;298:623-629.

- Mao M, Ai F, Zhang Y, et al. Changes in the symptoms and quality of life of women with symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse fitted with a ring with support pessary. Maturitas. 2018;117:51-56.

- Duenas JL, Miceli A. Effectiveness of a continuous-use ringshaped vaginal pessary without support for advanced pelvic organ prolapse in postmenopausal women. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29:1629-1636.

- Farrell S, Singh B, Aldakhil L. Continence pessaries in the management of urinary incontinence in women. J Obstet Gynaecol Canada. 2004;26:113-117.

- Donnelly MJ, Powell-Morgan SP, Olsen AL, et al. Vaginal pessaries for the management of stress and mixed urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2004;15:302-307.

- Richter HE, Burgio KL, Brubaker L, et al; Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Continence pessary compared with behavioral therapy or combined therapy for stress incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:609-617.

- Ding J, Chen C, Song XC, et al. Changes in prolapse and urinary symptoms after successful fitting of a ring pessary with support in women with advanced pelvic organ prolapse: a prospective study. Urology. 2016;87:70-75.

- Brazell HD, Patel M, O’Sullivan DM, et al. The impact of pessary use on bowel symptoms: one-year outcomes. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2014;20:95-98.

- Meriwether KV, Komesu YM, Craig C, et al. Sexual function and pessary management among women using a pessary for pelvic floor disorders. J Sex Med. 2015;12:2339-2349.

- Kuhn A, Bapst D, Stadlmayr W, et al. Sexual and organ function in patients with symptomatic prolapse: are pessaries helpful? Fertil Steril. 2009;91:1914-1918.

- Clemons JL, Aguilar VC, Sokol ER, et al. Patient characteristics that are associated with continued pessary use versus surgery after 1 year. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:159-164.

- Liang CC, Chang YL, Chang SD, et al. Pessary test to predict postoperative urinary incontinence in women undergoing hysterectomy for prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:795-800.

- Liapis A, Bakas P, Georgantopoulou C, et al. The use of the pessary test in preoperative assessment of women with severe genital prolapse. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011; 155:110-113.

- Wei JT, Nygaard I, Richter HE, et al; Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. A midurethral sling to reduce incontinence after vaginal prolapse repair. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2358-2367.

- March of Dimes. Quick facts: preterm birth. https://www .marchofdimes.org/Peristats/ViewTopic.aspx?reg=99 &top=3&lev=0&slev=1&gclid=EAIaIQobChMI4r. Accessed December 10, 2020.

- Goya M, Pratcorona L, Merced C, et al; PECEP Trial Group. Cervical pessary in pregnant women with a short cervix (PECEP): an open-label randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;379:1800-1806.

- Di Tommaso M, Seravalli V, Arduino S, et al. Arabin cervical pessary to prevent preterm birth in twin pregnancies with short cervix. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;36:715-718.

- Saccone G, Maruotti GM, Giudicepietro A, et al; Italian Preterm Birth Prevention (IPP) Working Group. Effect of cervical pessary on spontaneous preterm birth in women with singleton pregnancies and short cervical length: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318:2317-2324.

- Perez-Lopez FR, Chedraui P, Perez-Roncero GR, et al; Health Outcomes and Systematic Analyses (HOUSSAY) Project. Effectiveness of the cervical pessary for the prevention of preterm birth in singleton pregnancies with a short cervix: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2019;299:1215-1231.

- Hui SYA, Chor CM, Lau TK, et al. Cerclage pessary for preventing preterm birth in women with a singleton pregnancy and a short cervix at 20 to 24 weeks: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Perinatol. 2013;30:283-288.

- Nicolaides KH, Syngelaki A, Poon LC, et al. A randomized trial of a cervical pessary to prevent preterm singleton birth. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1044-1052.

- Saccone G, Ciardulli A, Xodo S, et al. Cervical pessary for preventing preterm birth in singleton pregnancies with short cervical length: a systematic review and meta-analyses. J Ultrasound Med. 2017;36:1535-1543.

- Conde-Agudelo A, Romero R, Nicolaides KH. Cervical pessary to prevent preterm birth in asymptomatic high-risk women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:42-65.e2.

- Sultan AH, Kamm MA, Hudson CN, et al. Anal-sphincter disruption during vaginal delivery. N Engl J Med. 1993;329: 1905-1911.

- Talley NJ, O’Keefe EA, Zinsmeister AR, et al. Prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms in the elderly: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:895-901.

- Denis P, Bercoff E, Bizien MF, et al. Prevalence of anal incontinence in adults [in French]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1992;16:344-350.

- Richter HE, Matthew CA, Muir T, et al. A vaginal bowel-control system for the treatment of fecal incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:540-547.

- 2019 Current Procedural Coding Expert. Optum360; 2018.

- ICD-10-CM Expert for Physicians. Optum360; 2019.

- MDS Medical Department Store website. http://www .medicaldepartmentstore.com/Pessary-Vaginal -Pessaries-/3788.htm?gclid=CjwKCAiAlNf-BRB _EiwA2osbxdqln8fQg-AxOUEMphM9aYlTIft Skwy0xXLT0PrcpIZnb5gBhiLc1RoCsbMQAvD_BwE. Accessed December 15, 2020.

- Monarch Medical Products website. https://www .monarchmedicalproducts.com/index.php?route=product /category&path=99_67. Accessed December 15, 2020.

- CooperSurgical Medical Devices website. https://www .coopersurgical.com/our-brands/milex/. Accessed December 15, 2020.

Pessaries for POP and SUI: Your options and guidance on use

Over the last 30 years, surgical correction of the common condition pelvic organ prolapse (POP) and stress urinary incontinence (SUI) has become so routine and straightforward that many gynecologists and urogynecologists choose surgery as their first choice for treating these conditions, withholding it only from the riskiest patients or from those who, for a variety of reasons, do not choose surgery. Moreover, as generalist gynecologists increasingly refer patients with POP or incontinence to their urogynecologist colleagues, they increasingly lack the skills, or have not been trained, to use conservative treatment strategies for these disorders. Thus, pessaries—devices constructed of inert plastic, silicone, or latex and placed inside the vagina to support prolapsed pelvic structures—frequently are not part of the general gynecologist’s armamentarium.

When properly selected, however, pessaries used for indicated purposes and correctly fitted are an excellent, inexpensive, low-risk, and noninvasive tool that can provide immediate relief not only of POP but also of SUI and defecatory difficulties. As an alternative to surgery, pessaries are especially valuable, because the other major nonsurgical modality for treatment of POP and incontinence—pelvic floor muscle training—often is not covered by insurance (making it expensive for patients), takes many weekly sessions to complete (which can make access challenging), and frequently is not readily available.1

POP is very common. An estimated 15% to 30% of women in North America have some degree of prolapse, and more than 500,000 surgeries for this condition are performed in the United States each year.2 Risk factors for POP include:

- vaginal childbirth, especially higher parity

- advancing age

- high body mass index (BMI)

- prior hysterectomy

- raised intra-abdominal pressure, such as from obesity, chronic cough, or heavy lifting.

In addition to the discomfort caused by the herniation of pelvic and vaginal structures, POP also is associated with urinary incontinence (73%), urinary urgency and frequency (86%), and fecal incontinence (31%).3

Moreover, according to the US Census Bureau, the number of American women aged 65 or older will double to more than 40 million by 2030.4 This will greatly increase the population of women at risk for POP who may be candidates for pessary use. It therefore behooves gynecologists to become familiar with the correct usage, fitting, and maintenance of this effective, nonsurgical mode of treatment for POP.

In this article, I discuss why pessaries are a good option for many patients with POP, review the types of pessaries available, and offer guidance on how to choose the right pessary for an individual patient’s needs. In addition, the box at the end of this article provides an interesting timeline of pessary history dating back to antiquity.

Next month in Part 2 of this article, I cover how to fit a pessary; device aftercare; potential complications of use; and effectiveness of pessaries for POP, SUI, preterm labor prevention, and defecatory disorders.

Continue to: Potential candidates for pessary use...

Potential candidates for pessary use

Almost all women with POP—and in many cases accompanying SUI—are potential candidates for a pessary. In fact, many urogynecologists believe that a trial of pessary usage should be the first treatment modality offered for POP.5 Women who cannot use a pessary include those with an extremely short vagina (<6 cm) and those who have severely eroded vaginal mucosa. In the latter situation, the mucosa can be treated with estrogen cream for several weeks and, once the tissue has healed, a pessary can be fitted.

Given that surgical repair is generally a straightforward, one-time procedure that obviates the need for long-term use of an artificial device worn internally, why might a patient or her physician opt for a pessary instead?

Some of the many reasons include:

- Many patients prefer to avoid surgery.

- Many patients are not appropriate candidates for surgery because they have significant comorbid risk factors or high BMI.

- Patients may have recurrent prolapse or incontinence and wish to avoid repeat surgery.

- Patients with SUI may have heard of the occurrence of mesh erosion and wish to avoid that possibility.

- Women who live in low-resource environments or countries where elective surgical care is relatively unavailable may not have the option of surgery.

A clinician might also recommend pessary use:

- as a diagnostic tool to attempt to assess the potential results of vaginal repair surgery

- to estimate the potential effectiveness of a midurethral sling procedure; several investigators have found this to be approximately as accurate as urodynamic testing6,7

- as prophylaxis for pregnant women with either a history of preterm cervical dilation or a short cervix detected on ultrasonography

- for pregnant women with POP that is worsening and becoming increasingly uncomfortable

- for women with POP who wish to have more children

- for short-term use while a patient is delaying or awaiting POP surgery or to allow time for other medical issues to resolve

- for patients who wish only intermittent, temporary support while exercising or engaging in sports.

Patient acceptance may be contingent on counseling

Numerous studies show that women who choose pessaries to treat POP are generally older than women who elect surgery. Still, patient acceptance of a trial of pessary use depends much on the counseling and information she receives. Properly informed, many patients with POP will opt for a trial of pessary placement. One study showed that, of women with untreated POP, 36% preferred pessary placement to surgery.8 Other investigators reported that when women with symptomatic POP had the benefits of a pessary versus surgery explained to them, nearly two-thirds opted for a pessary as their mode of treatment.9

Exceptions to pessary use

Fortunately, there are relatively few contraindications to pessary use. These are vaginal or pelvic infection and an exposed foreign body in the vagina, such as eroded vaginal mesh. In addition, patients at risk for nonadherence with follow-up care are poor candidates, as it could lead to missing such problems as mucosal erosion, ulceration, or even (extremely rarely) fistula formation. Pessaries may be inappropriate for sexually active women who on their own are unable to remove and reinsert pessary types that do not allow for intercourse while in place (see below).

Continue to: Types of pessaries...

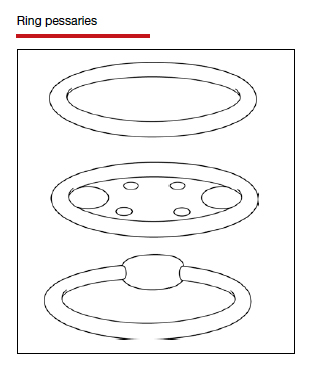

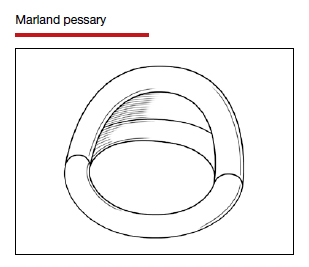

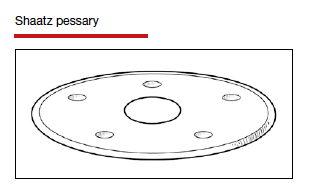

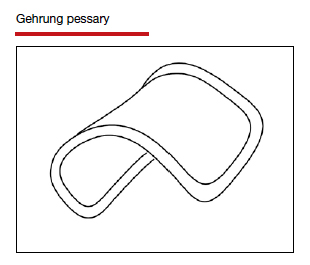

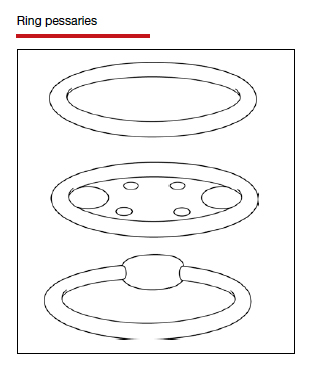

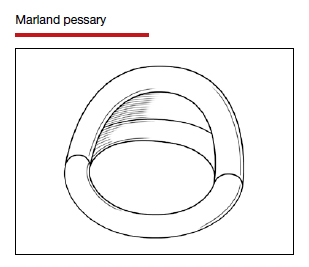

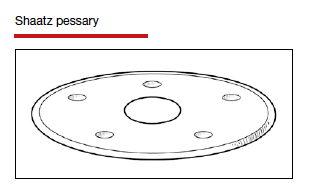

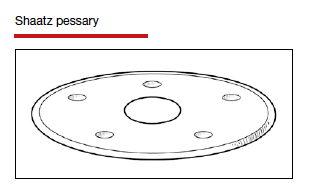

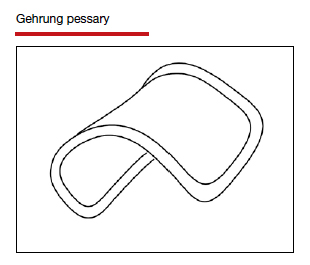

Types of pessaries

The numerous kinds of pessaries available fall into 3 general categories: support, space filling, and lever, and devices within each group have modifications and variations. As with most areas of prescribing and treatment in medicine, it is best to become very familiar with just a few kinds of pessaries, know their indications, and use them when appropriate.

Most pessaries are constructed of inert silicone which, unlike earlier rubber pessaries, does not absorb odor or discharge. They are easy to clean, long lasting, and are autoclavable and hypoallergenic.