User login

Resident Use of Handoff Information

Hospital communication failures are a leading cause of serious errors and adverse events in the United States.[1, 2, 3, 4] With the implementation of duty‐hour restrictions for resident physicians,[5] there has been particular focus on the transfer of information during handoffs at change of shift.[6, 7] Many residency programs have sought to improve the processes of written and verbal handoffs through various initiatives, including: (1) automated linkage of handoff forms to electronic medical records (EMRs)[8, 9, 10]; (2) introduction of oral communication curricula, handoff simulation, or mnemonics[11, 12, 13]; and (3) faculty oversight of housestaff handoffs.[14, 15] Underlying each initiative has been the assumption that improving written and verbal handoff processes will ensure the availability of optimal patient information for on‐call housestaff. There has been little investigation, however, into what clinical questions are actually being asked of on‐call trainees, as well as what sources of information they are using to provide answers.

The aim of our study was to examine the extent to which written and verbal handoffs are utilized by pediatric trainees to derive answers to questions posed during overnight shifts. We also sought to describe both the frequency and types of on‐call questions being asked of trainees. Our primary outcome was trainee use of written handoffs to answer on‐call questions. Secondary outcomes included trainee use of verbal handoffs, as well as their use of alternative information resources to answer on‐call questions, including other clinical staff (ie, attending physicians, senior residents, nursing staff), patients and their families, the medical record, or the Internet. We then examined a variety of trainee, patient, and question characteristics to assess potential predictors of written and verbal handoff use.

METHODS

Institutional approval was granted to prospectively observe pediatric interns at the start of their overnight on‐call shifts on 2 inpatient wards at Boston Children's Hospital during 3 winter months (November through January). Our study was conducted during the postintervention period of a larger study that was designed to examine the effectiveness of a new resident handoff bundle on resident workflow and patient safety.[13] Interns rotating on study ward 1 used a structured, nonautomated tool (Microsoft Word version 2003; Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA). Interns on study ward 2 used a handoff tool that was developed at the study hospital for use with the hospital's EMR, Cerner PowerChart version 2007.17 (Cerner Corp., Kansas City, MO). Interns on both wards received training on specific communication strategies, including verbal and written handoff processes.[13]

For our study, we recorded all questions being asked of on‐call interns by patients, parents, or other family members, as well as nurses or other clinical providers after completion of their evening handoff. We then directly observed all information resources used to derive answers to any questions asked pertaining to patients discussed in the evening handoff. We excluded any questions about new patient admissions or transfers, as well as nonpatient‐related questions.

Both study wards were staffed by separate day and night housestaff teams, who worked shifts of 12 to 14 hours in duration and had similar nursing schedules. The day team consisted of 3 interns and 1 senior resident per ward. The night team consisted of 1 intern on each ward, supervised by a senior resident covering both wards. Each day intern rotated for 1 week (Sunday through Thursday) during their month‐long ward rotation as part of the night team. We considered any intern on either of the 2 study wards to be eligible for enrollment in this study. Written consent was obtained from all participants.

The night intern received a verbal and written handoff at the shift change (usually performed between 5 and 7pm) from 1 of the departing day interns prior to the start of the observation period. This handoff was conducted face‐to‐face in a ward conference room typically with the on‐call night intern and supervising resident receiving the handoff together from the departing day intern/senior resident.

Observation Protocol

Data collection was conducted by an independent, board‐certified, pediatric physician observer on alternating weeknights immediately after the day‐to‐night evening handoff had taken place. A strict observation protocol was followed. When an eligible question was asked of the participating intern, the physician observer would record the question and the time. The question source, defined as a nurse, parent/patient, or other clinical staff (eg, pharmacist, consultant) was documented, as well as the mode of questioning, defined as face to face, text page, or phone call.

The observer would then note if and when the question was answered. Once the question was answered, the observer would ask the intern if he or she had used the written handoff to provide the answer (yes or no). Our primary outcome was reported use of the written handoff. In addition, the observer directly noted if the intern looked at the written handoff tool at any time when answering a question. The intern was also asked to name any and all additional information resources used, including verbal handoff, senior resident, nursing staff, other clinicians, a patient/parent or other family member, a patient's physical exam, the EMR, the Internet, or his or her own medical or clinical knowledge.

All question and answer information was tracked using a handheld, digital, time device. In addition, the following patient data were recorded for each patient involved in a recorded question: the patient's admitting service, transfer status, and length of stay.

Data Categorization and Analysis

Content of recorded questions were categorized according to whether they involved: (1) medications (including drug allergies or levels), (2) diet or fluids, (3) laboratory values or diagnostic testing/procedures, (4) physical exam findings (eg, a distended abdomen, blood pressure, height/weight), or (5) general care‐plan questions. We also categorized time used for generating an answer as immediate (<5 minutes), delayed (>5 minutes but <1.5 hours), or deferred (any question unanswered during the time of observation).

All data were entered into a database using SPSS 16.0 Data Builder software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL), and statistical analyses were performed with PASW 18 (SPSS Inc.) and SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) software. Observed questions were summarized according to content categories. We also described trainee and patient characteristics relevant to the questions being studied. To study risk factors for written handoff use, the outcome was dichotomized as reported use of written handoff by the intern as a resource to answer the question asked versus written handoff use was not reported by the intern as a resource to answer the question asked. We did not include observed use of the written handoff in these statistical analyses. To accommodate for patient‐ or provider‐induced correlations among observed questions, we used a generalized estimation equations approach (PROC GENMOD in SAS 9.2) to fit logistic regression models for written handoff use and permitted a nested correlation structure among the questions (ie, questions from the same patient were allowed to be correlated, and patients under the care of the same intern could have intern‐induced correlation). Univariate regression modeling was used to evaluate the effects of question, patient, and intern characteristics. Multivariate logistic regression models were used to identify independent risk factors for written handoff use. Any variable that had a P value 0.1 in univariate regression model was considered as a candidate variable in the multivariate regression model. We then used a backward elimination approach to obtain the final model, which only included variables remaining to be significant at a P<0.05 significance level. Our analysis for verbal handoff use was carried out in a similar fashion.

RESULTS

Twenty‐eight observation nights (equivalent to 77 hours and 6 minutes of total direct observation time), consisting of 13 sessions on study ward 1 and 15 sessions on study ward 2, were completed. A total of 15 first‐year pediatric interns (5 male, 33%; 10 female, 66.7%), with a median age of 27.5 years (interquartile range [IQR]: 2629 years) participated. Interns on the 2 study wards were comparable with regard to trainee week of service (P=0.43) and consecutive night of call at the time of observation (P=0.45). Each intern was observed for a mean of 2 sessions (range, 13 sessions), with a mean observation time per session of approximately 2 hours and 45 minutes ( 23 minutes).

Questions

A total of 260 questions (ward 1: 136 questions, ward 2: 124 questions) met inclusion criteria and involved 101 different patients, with a median of 2 questions/patient (IQR: 13) and a range of 1 to 14 questions/patient. Overall, interns were asked 2.6 questions/hour (IQR: 1.44.7), with a range of 0 to 7 questions per hour; the great majority of questions (210 [82%]) were posed face to face. Types of questions recorded included medications 28% (73), diet/fluids 15% (39), laboratory or diagnostic/procedural related 22% (57), physical exam or other measurements 8.5% (22), or other general medical or patient care‐plan questions 26.5% (69) (Table 1). Examples of recorded questions are provided in Table 2.

| No. (%) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Patients, n=101 | |

| Admitting services | |

| General pediatrics | 49 (48) |

| Pediatric subspecialty | 27 (27) |

| CCS* | 25 (25) |

| Patients transferred from critical care unit | |

| Yes | 21 (21) |

| No | 80 (79) |

| Questions, n=260 | |

| Patients' length of stay at time of recorded question* | |

| 2 days | 142 (55) |

| >2 days | 118 (45) |

| Intern consecutive night shift (15) | |

| 1st or 2nd night (early) | 86 (33) |

| 3rd through 5th night (late) | 174 (67) |

| Intern week of service during a 4‐week rotation | |

| Weeks 12 (early) | 119 (46) |

| Weeks 34 (late) | 141 (54) |

| Question sources | |

| Clinical provider | 167 (64) |

| Parent/patient or other family member | 93 (36) |

| Question categories | |

| Medications | 73 (28) |

| Diet and/or fluids | 39 (15) |

| Labs or diagnostic imaging/procedures | 57 (22) |

| Physical exam/vital signs/measurements | 22 (8.5) |

| Other general medical or patient care plan questions | 69 (26.5) |

| Answers, n=233 | |

| Resources reported | |

| Written sign‐out | 17 (7.3) |

| Verbal sign‐out (excluding any written sign‐out use) | 59 (25.3) |

| Other resources | 157 (67.4) |

| Question Categories |

|---|

|

| Medication questions (including medication allergy or drug level questions) |

| Could you clarify the lasix orders? |

| Pharmacy rejected the medication, what do you want to do? |

| Dietary and fluid questions |

| Do you want to continue NG feeds at 10 mL/hr and advance? |

| Is she going to need to be NPO for the biopsy in the AM? |

| Laboratory or diagnostic tests/procedure questions |

| Do you want blood cultures on this patient? |

| What was the result of her x‐ray? |

| Physical exam questions (including height/weight or vital sign measurements) |

| What do you think of my back (site of biopsy)? |

| Is my back okay, because it seems sore after the (renal) biopsy? |

| Other (patient related) general medical or care plan questions |

| Did you talk with urology about their recommendations? |

| Do you know the plan for tomorrow? |

Across the 2 study wards, 48% (49) of patients involved in questions were admitted to a general pediatric service; 27% (27) were admitted to a pediatric specialty service (including the genetics/metabolism, endocrinology, adolescent medicine, pulmonary, or toxicology admitting services); the remaining 25% (25) were admitted to a complex care service (CCS), specifically designed for patients with multisystem genetic, neurological, or congenital disorders (Table 1).[16, 17] Approximately 21% (21) of patients had been transferred to the floor from a critical care unit (Table 1).

Answers

Of the 260 recorded questions, 90% (233) had documented answers. For the 10% (27) of questions with undocumented answers, 21 were observed to be verbally deferred by the intern to the day team or another care provider (ie, other physician or nurse), and almost half (42.9% [9]) involved general care‐plan questions; the remainder involved medication (4), diet (2), diagnostic testing (5), or vital sign (1) questions. An additional 6 questions went unanswered during the observation period, and it is unknown if or when they were answered.

Of the answered questions, 90% (209) of answers were provided by trainees within 5 minutes and 9% (21) within 1.5 hours. In all, interns reported using 1 information resource to provide answers for 61% (142) of questions, at least 2 resources for 33% (76) questions, and 3 resources for 6% (15) questions.

Across both study wards, interns reported using information provided in written or verbal handoffs to answer 32.6% of questions. Interns reported using the written handoff, either alone or in combination with other information resources, to provide answers for 7.3% (17) of questions; verbal handoff, either alone or in combination with another resource (excluding written handoff), was reported as a resource for 25.3% (59) of questions. Of note, interns were directly observed to look at the written handoff when answering 21% (49) of questions.

A variety of other resources, including general medical/clinical knowledge, the EMR, and parents or other resources, were used to answer the remaining 67.4% (157) of questions. Intern general medical knowledge (ie, reports of simply knowing the answer to the question in their head[s]) was used to provide answers for 53.2% (124) of questions asked.

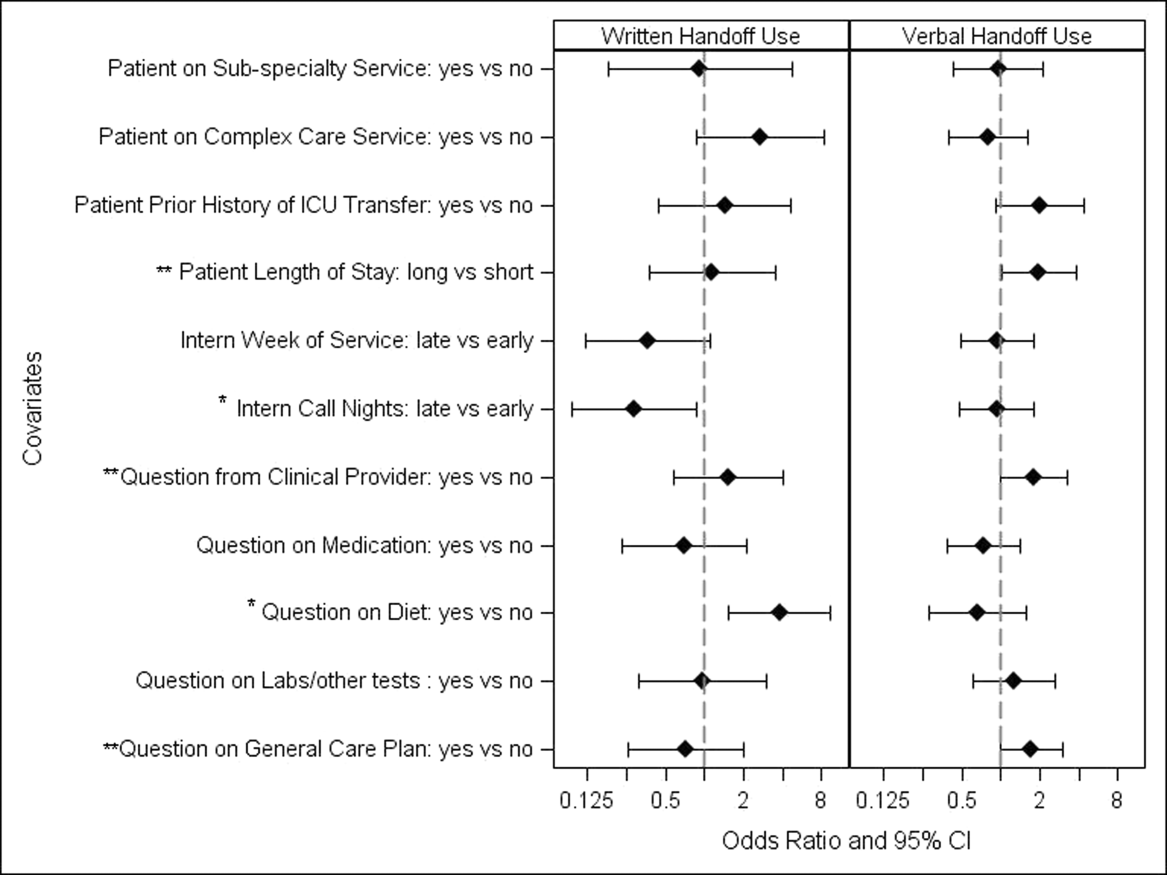

Unadjusted univariate regression analyses assessing predictors of written and verbal handoff use are shown in Figure 1. Multivariate logistic regression analyses showed that both dietary questions (odds ratio [OR]: 3.64, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.518.76; P=0.004) and interns' consecutive call night (OR: 0.29, 95% CI: 0.090.93; P=0.04) remained significant predictors of written handoff use. After adjusting for risk factors identified above, no differences in written handoff use were seen between the 2 wards.

Multivariate logistic regression for predictors of the verbal handoff use showed that questions regarding patients with longer lengths of stay (OR: 1.97, 95% CI: 1.023.8; P=0.04), those regarding general care plans (OR: 2.07, 95% CI: 1.133.78; P=0.02), as well as those asked by clinical staff (OR: 1.95, 95 CI: 1.043.66; P=0.04), remained significant predictors of reported verbal handoff use.

DISCUSSION

In light of the recent changes in duty hours implemented in July 2011, many pediatric training programs are having trainees work in day and night shifts.[18] Pediatric resident physicians frequently answer questions that pertain to patients handed off between day and night shifts. We found that on average, information provided in the verbal and written handoff was used almost once per hour. Housestaff in our study generally based their answers on information found in 1 or 2 resources, with almost one‐third of all questions involving some use of the written or verbal handoff. Prior research has documented widespread problems with resident handoff practices across programs and a high rate of medical errors due to miscommunications.[3, 4, 19, 20] Given how often information contained within the handoff was used as interns went about their nightly tasks, it is not difficult to understand how errors or omissions in the handoff process may potentially translate into frequent problems in direct patient care.

Trainees reported using written handoff tools to provide answers for 7.3% of questions. As we had suspected, they relied less frequently on their written handoffs as they completed more consecutive call nights. Interestingly, however, even when housestaff did not report using the written handoff, they were observed quite often to look at it before providing an answer. One explanation for this discrepancy between trainee reports and our observations is that the written handoff may serve as a memory tool, even if housestaff do not directly attribute their answers to its content. Our study also found that answers to questions concerning patients' diet and fluids were more likely to be ascribed to information contained in the written handoff. This finding supports the potential value of automated written handoff tools that are linked to the EMR, which can best ensure accuracy of this type of information.

Housestaff in our study also reported using information received during the verbal handoff to answer 1 out of every 4 on‐call questions. Although we did not specifically rate or monitor the quality of verbal handoffs, prior research has demonstrated that resident verbal handoff is often plagued with incomplete and inaccurate data.[3, 4, 19, 21] One investigation found that pediatric interns were prone to overestimating the effectiveness of their verbal handoffs, even as they failed to convey urgent information to their peers.[19] In light of such prior work, our finding that interns frequently rely on the verbal transfer of information supports specific residency training program handoff initiatives that target verbal exchanges.[11, 22, 23]

Although information obtained in the handoff was frequently required by on‐call housestaff, our study found that two‐thirds of all questions were answered using other resources, most often general medical or clinical knowledge. Clearly, background knowledge and experience is fundamental to trainees' ability to perform their jobs. Such reliance on general knowledge for problem solving may not be unique to interns. One recent observational study of senior pediatric cardiac subspecialists reported a high frequency of reliance on their own clinical experience, instinct, or prior training in making clinical decisions.[24] Further investigation may be useful to parse out the exact types of clinical knowledge being used, and may have important implications for how training programs plan for overnight supervision.[25, 26, 27]

Our study has several limitations. First, it was beyond the scope of this study to link housestaff answers to patient outcomes or medical errors. Given the frequency with which the handoff, a known source of vulnerability to medical error, was used by on‐call housestaff, our study suggests that future research evaluating the relationship between questions asked of on‐call housestaff, the answers provided, and downstream patient safety incidents may be merited. Second, our study was conducted in a single pediatric residency program with 1 physician observer midway through the first year of training and only in the early evening hours. This limits the generalizability of our findings, as the use of handoffs to answer on‐call questions may be different at other stages of the training process, within other specialties, or even at different times of the day. We also began our observations after the handoff had taken place; future studies may want to assess how variations in written and verbal handoff processes affect their use. As a final limitation, we note that although collecting information in real time using a direct observational method eliminated the problem of recall bias, there may have been attribution bias.

The results of our study demonstrate that on‐call pediatric housestaff are frequently asked a variety of clinical questions posed by hospital staff, patients, and their families. We found that trainees are apt to rely both on handoff information and other resources to provide answers. By better understanding what resources on‐call housestaff are accessing to answer questions overnight, we may be able to better target interventions needed to improve the availability of patient information, as well as the usefulness of written and verbal handoff tools.[11, 22, 23]

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Katharine Levinson, MD, and Melissa Atmadja, BA, for their help with the data review and guidance with database management. The authors also thank the housestaff from the Boston Combined Residency Program in Pediatrics for their participation in this study.

Disclosures: Maireade E. McSweeney, MD, as the responsible author certifies that all coauthors have seen and agree with the contents of this article, takes responsibility for the accuracy of these data, and certifies that this information is not under review by any other publication. All authors had no financial conflicts of interest or conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose. Dr. Landrigan is supported in part by the Children's Hospital Association for his work as an Executive Council member of the Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings network. In addition, he has received honoraria from the Committee of Interns and Residents as well as multiple academic medical centers for lectures delivered on handoffs, sleep deprivation, and patient safety, and he has served as an expert witness in cases regarding patient safety and sleep deprivation.

- Improving America's hospitals: The Joint Commission's annual report on quality and safety. 2007. Available at: http://www.jointcommission. org/Improving_Americas_Hospitals_The_Joint_Commissions_Annual_Report_on_Quality_and_Safety_‐_2007. Accessed October 3, 2011.

- US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General. Adverse events in hospitals: methods for identifying events. 2010. Available at: http://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei‐06‐08‐00221.pdf. Accessed October 3, 2011.

- , , , , . Communication failures in patient sign‐out and suggestions for improvement: a critical incident analysis. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14:401–407.

- , , , , . Consequences of inadequate sign‐out for patient care. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1755–1760.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Common program requirements. 2010. Available at: http://acgme‐2010standards.org/pdf/Common_Program_Requirements_07012011.pdf. Accessed January 25, 2011.

- , . Building physician work hour regulations from first principles and best evidence. JAMA. 2008;300:1197–1199.

- , , , , . Managing discontinuity in academic medical centers: strategies for a safe and effective resident sign‐out. J Hosp Med. 2006;1:257–266.

- , , , , . A randomized, controlled trial evaluating the impact of a computerized rounding and sign‐out system on continuity of care and resident work hours. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;200:538–545.

- , , , , , . Simple standardized patient handoff system that increases accuracy and completeness. J Surg Educ. 2008;65:476–485.

- , , , , . Review of computerized physician handoff tools for improving the quality of patient care [published online ahead of print November 20, 2012]. J Hosp Med. doi: 10.1002/jhm.1988.

- , , , . Establishing a multisite education and research project requires leadership, expertise, collaboration, and an important aim. Pediatrics. 2010;126:619–622.

- , , , et al. Hand‐off education and evaluation: piloting the observed simulated hand‐off experience (OSHE). J Gen Intern Med. 2009;25:129–134.

- , , , , , . I‐pass, a mnemonic to standardize verbal handoffs. Pediatrics. 2012;129:201–204.

- , , , et al. A structured handoff program for interns. Acad Med. 2009;84:347–352.

- , , , et al. Experience with faculty supervision of an electronic resident sign‐out system. Am J Med. 2010;123:376–381.

- , , , et al. Hospital utilization and characteristics of patients experiencing recurrent readmissions within children's hospitals. JAMA. 2011;305:682–690.

- , , , et al. Children with complex chronic conditions in inpatient hospital settings in the United States. Pediatrics. 2010;126:647–655.

- , , , . Effects of a night‐team system on resident sleep and work hours. Pediatrics. 2011;128:1142–1147.

- , , , . Interns overestimate the effectiveness of their hand‐off communication. Pediatrics. 2010;125:491–496.

- , , , . Patient handoffs: pediatric resident experiences and lessons learned. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2011;50:57–63.

- , , , . Adequacy of information transferred at resident sign‐out (in‐hospital handover of care): a prospective survey. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17:6–10.

- , . A model for building a standardized hand‐off protocol. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2006;32:646–655.

- , , . Development and implementation of an oral sign‐out skills curriculum. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1470–1474.

- , , , , . Deciding without data. Congenit Heart Dis. 2010;5:339–342.

- , , , et al. A systematic review: the effect of clinical supervision on patient and residency education outcomes. Acad Med. 2012;87:428–442.

- , , , , , . Effects of increased overnight supervision on resident education, decision‐making, and autonomy. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:606–610.

- , , , et al. Survey of overnight academic hospitalist supervision of trainees. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:521–523.

Hospital communication failures are a leading cause of serious errors and adverse events in the United States.[1, 2, 3, 4] With the implementation of duty‐hour restrictions for resident physicians,[5] there has been particular focus on the transfer of information during handoffs at change of shift.[6, 7] Many residency programs have sought to improve the processes of written and verbal handoffs through various initiatives, including: (1) automated linkage of handoff forms to electronic medical records (EMRs)[8, 9, 10]; (2) introduction of oral communication curricula, handoff simulation, or mnemonics[11, 12, 13]; and (3) faculty oversight of housestaff handoffs.[14, 15] Underlying each initiative has been the assumption that improving written and verbal handoff processes will ensure the availability of optimal patient information for on‐call housestaff. There has been little investigation, however, into what clinical questions are actually being asked of on‐call trainees, as well as what sources of information they are using to provide answers.

The aim of our study was to examine the extent to which written and verbal handoffs are utilized by pediatric trainees to derive answers to questions posed during overnight shifts. We also sought to describe both the frequency and types of on‐call questions being asked of trainees. Our primary outcome was trainee use of written handoffs to answer on‐call questions. Secondary outcomes included trainee use of verbal handoffs, as well as their use of alternative information resources to answer on‐call questions, including other clinical staff (ie, attending physicians, senior residents, nursing staff), patients and their families, the medical record, or the Internet. We then examined a variety of trainee, patient, and question characteristics to assess potential predictors of written and verbal handoff use.

METHODS

Institutional approval was granted to prospectively observe pediatric interns at the start of their overnight on‐call shifts on 2 inpatient wards at Boston Children's Hospital during 3 winter months (November through January). Our study was conducted during the postintervention period of a larger study that was designed to examine the effectiveness of a new resident handoff bundle on resident workflow and patient safety.[13] Interns rotating on study ward 1 used a structured, nonautomated tool (Microsoft Word version 2003; Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA). Interns on study ward 2 used a handoff tool that was developed at the study hospital for use with the hospital's EMR, Cerner PowerChart version 2007.17 (Cerner Corp., Kansas City, MO). Interns on both wards received training on specific communication strategies, including verbal and written handoff processes.[13]

For our study, we recorded all questions being asked of on‐call interns by patients, parents, or other family members, as well as nurses or other clinical providers after completion of their evening handoff. We then directly observed all information resources used to derive answers to any questions asked pertaining to patients discussed in the evening handoff. We excluded any questions about new patient admissions or transfers, as well as nonpatient‐related questions.

Both study wards were staffed by separate day and night housestaff teams, who worked shifts of 12 to 14 hours in duration and had similar nursing schedules. The day team consisted of 3 interns and 1 senior resident per ward. The night team consisted of 1 intern on each ward, supervised by a senior resident covering both wards. Each day intern rotated for 1 week (Sunday through Thursday) during their month‐long ward rotation as part of the night team. We considered any intern on either of the 2 study wards to be eligible for enrollment in this study. Written consent was obtained from all participants.

The night intern received a verbal and written handoff at the shift change (usually performed between 5 and 7pm) from 1 of the departing day interns prior to the start of the observation period. This handoff was conducted face‐to‐face in a ward conference room typically with the on‐call night intern and supervising resident receiving the handoff together from the departing day intern/senior resident.

Observation Protocol

Data collection was conducted by an independent, board‐certified, pediatric physician observer on alternating weeknights immediately after the day‐to‐night evening handoff had taken place. A strict observation protocol was followed. When an eligible question was asked of the participating intern, the physician observer would record the question and the time. The question source, defined as a nurse, parent/patient, or other clinical staff (eg, pharmacist, consultant) was documented, as well as the mode of questioning, defined as face to face, text page, or phone call.

The observer would then note if and when the question was answered. Once the question was answered, the observer would ask the intern if he or she had used the written handoff to provide the answer (yes or no). Our primary outcome was reported use of the written handoff. In addition, the observer directly noted if the intern looked at the written handoff tool at any time when answering a question. The intern was also asked to name any and all additional information resources used, including verbal handoff, senior resident, nursing staff, other clinicians, a patient/parent or other family member, a patient's physical exam, the EMR, the Internet, or his or her own medical or clinical knowledge.

All question and answer information was tracked using a handheld, digital, time device. In addition, the following patient data were recorded for each patient involved in a recorded question: the patient's admitting service, transfer status, and length of stay.

Data Categorization and Analysis

Content of recorded questions were categorized according to whether they involved: (1) medications (including drug allergies or levels), (2) diet or fluids, (3) laboratory values or diagnostic testing/procedures, (4) physical exam findings (eg, a distended abdomen, blood pressure, height/weight), or (5) general care‐plan questions. We also categorized time used for generating an answer as immediate (<5 minutes), delayed (>5 minutes but <1.5 hours), or deferred (any question unanswered during the time of observation).

All data were entered into a database using SPSS 16.0 Data Builder software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL), and statistical analyses were performed with PASW 18 (SPSS Inc.) and SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) software. Observed questions were summarized according to content categories. We also described trainee and patient characteristics relevant to the questions being studied. To study risk factors for written handoff use, the outcome was dichotomized as reported use of written handoff by the intern as a resource to answer the question asked versus written handoff use was not reported by the intern as a resource to answer the question asked. We did not include observed use of the written handoff in these statistical analyses. To accommodate for patient‐ or provider‐induced correlations among observed questions, we used a generalized estimation equations approach (PROC GENMOD in SAS 9.2) to fit logistic regression models for written handoff use and permitted a nested correlation structure among the questions (ie, questions from the same patient were allowed to be correlated, and patients under the care of the same intern could have intern‐induced correlation). Univariate regression modeling was used to evaluate the effects of question, patient, and intern characteristics. Multivariate logistic regression models were used to identify independent risk factors for written handoff use. Any variable that had a P value 0.1 in univariate regression model was considered as a candidate variable in the multivariate regression model. We then used a backward elimination approach to obtain the final model, which only included variables remaining to be significant at a P<0.05 significance level. Our analysis for verbal handoff use was carried out in a similar fashion.

RESULTS

Twenty‐eight observation nights (equivalent to 77 hours and 6 minutes of total direct observation time), consisting of 13 sessions on study ward 1 and 15 sessions on study ward 2, were completed. A total of 15 first‐year pediatric interns (5 male, 33%; 10 female, 66.7%), with a median age of 27.5 years (interquartile range [IQR]: 2629 years) participated. Interns on the 2 study wards were comparable with regard to trainee week of service (P=0.43) and consecutive night of call at the time of observation (P=0.45). Each intern was observed for a mean of 2 sessions (range, 13 sessions), with a mean observation time per session of approximately 2 hours and 45 minutes ( 23 minutes).

Questions

A total of 260 questions (ward 1: 136 questions, ward 2: 124 questions) met inclusion criteria and involved 101 different patients, with a median of 2 questions/patient (IQR: 13) and a range of 1 to 14 questions/patient. Overall, interns were asked 2.6 questions/hour (IQR: 1.44.7), with a range of 0 to 7 questions per hour; the great majority of questions (210 [82%]) were posed face to face. Types of questions recorded included medications 28% (73), diet/fluids 15% (39), laboratory or diagnostic/procedural related 22% (57), physical exam or other measurements 8.5% (22), or other general medical or patient care‐plan questions 26.5% (69) (Table 1). Examples of recorded questions are provided in Table 2.

| No. (%) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Patients, n=101 | |

| Admitting services | |

| General pediatrics | 49 (48) |

| Pediatric subspecialty | 27 (27) |

| CCS* | 25 (25) |

| Patients transferred from critical care unit | |

| Yes | 21 (21) |

| No | 80 (79) |

| Questions, n=260 | |

| Patients' length of stay at time of recorded question* | |

| 2 days | 142 (55) |

| >2 days | 118 (45) |

| Intern consecutive night shift (15) | |

| 1st or 2nd night (early) | 86 (33) |

| 3rd through 5th night (late) | 174 (67) |

| Intern week of service during a 4‐week rotation | |

| Weeks 12 (early) | 119 (46) |

| Weeks 34 (late) | 141 (54) |

| Question sources | |

| Clinical provider | 167 (64) |

| Parent/patient or other family member | 93 (36) |

| Question categories | |

| Medications | 73 (28) |

| Diet and/or fluids | 39 (15) |

| Labs or diagnostic imaging/procedures | 57 (22) |

| Physical exam/vital signs/measurements | 22 (8.5) |

| Other general medical or patient care plan questions | 69 (26.5) |

| Answers, n=233 | |

| Resources reported | |

| Written sign‐out | 17 (7.3) |

| Verbal sign‐out (excluding any written sign‐out use) | 59 (25.3) |

| Other resources | 157 (67.4) |

| Question Categories |

|---|

|

| Medication questions (including medication allergy or drug level questions) |

| Could you clarify the lasix orders? |

| Pharmacy rejected the medication, what do you want to do? |

| Dietary and fluid questions |

| Do you want to continue NG feeds at 10 mL/hr and advance? |

| Is she going to need to be NPO for the biopsy in the AM? |

| Laboratory or diagnostic tests/procedure questions |

| Do you want blood cultures on this patient? |

| What was the result of her x‐ray? |

| Physical exam questions (including height/weight or vital sign measurements) |

| What do you think of my back (site of biopsy)? |

| Is my back okay, because it seems sore after the (renal) biopsy? |

| Other (patient related) general medical or care plan questions |

| Did you talk with urology about their recommendations? |

| Do you know the plan for tomorrow? |

Across the 2 study wards, 48% (49) of patients involved in questions were admitted to a general pediatric service; 27% (27) were admitted to a pediatric specialty service (including the genetics/metabolism, endocrinology, adolescent medicine, pulmonary, or toxicology admitting services); the remaining 25% (25) were admitted to a complex care service (CCS), specifically designed for patients with multisystem genetic, neurological, or congenital disorders (Table 1).[16, 17] Approximately 21% (21) of patients had been transferred to the floor from a critical care unit (Table 1).

Answers

Of the 260 recorded questions, 90% (233) had documented answers. For the 10% (27) of questions with undocumented answers, 21 were observed to be verbally deferred by the intern to the day team or another care provider (ie, other physician or nurse), and almost half (42.9% [9]) involved general care‐plan questions; the remainder involved medication (4), diet (2), diagnostic testing (5), or vital sign (1) questions. An additional 6 questions went unanswered during the observation period, and it is unknown if or when they were answered.

Of the answered questions, 90% (209) of answers were provided by trainees within 5 minutes and 9% (21) within 1.5 hours. In all, interns reported using 1 information resource to provide answers for 61% (142) of questions, at least 2 resources for 33% (76) questions, and 3 resources for 6% (15) questions.

Across both study wards, interns reported using information provided in written or verbal handoffs to answer 32.6% of questions. Interns reported using the written handoff, either alone or in combination with other information resources, to provide answers for 7.3% (17) of questions; verbal handoff, either alone or in combination with another resource (excluding written handoff), was reported as a resource for 25.3% (59) of questions. Of note, interns were directly observed to look at the written handoff when answering 21% (49) of questions.

A variety of other resources, including general medical/clinical knowledge, the EMR, and parents or other resources, were used to answer the remaining 67.4% (157) of questions. Intern general medical knowledge (ie, reports of simply knowing the answer to the question in their head[s]) was used to provide answers for 53.2% (124) of questions asked.

Unadjusted univariate regression analyses assessing predictors of written and verbal handoff use are shown in Figure 1. Multivariate logistic regression analyses showed that both dietary questions (odds ratio [OR]: 3.64, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.518.76; P=0.004) and interns' consecutive call night (OR: 0.29, 95% CI: 0.090.93; P=0.04) remained significant predictors of written handoff use. After adjusting for risk factors identified above, no differences in written handoff use were seen between the 2 wards.

Multivariate logistic regression for predictors of the verbal handoff use showed that questions regarding patients with longer lengths of stay (OR: 1.97, 95% CI: 1.023.8; P=0.04), those regarding general care plans (OR: 2.07, 95% CI: 1.133.78; P=0.02), as well as those asked by clinical staff (OR: 1.95, 95 CI: 1.043.66; P=0.04), remained significant predictors of reported verbal handoff use.

DISCUSSION

In light of the recent changes in duty hours implemented in July 2011, many pediatric training programs are having trainees work in day and night shifts.[18] Pediatric resident physicians frequently answer questions that pertain to patients handed off between day and night shifts. We found that on average, information provided in the verbal and written handoff was used almost once per hour. Housestaff in our study generally based their answers on information found in 1 or 2 resources, with almost one‐third of all questions involving some use of the written or verbal handoff. Prior research has documented widespread problems with resident handoff practices across programs and a high rate of medical errors due to miscommunications.[3, 4, 19, 20] Given how often information contained within the handoff was used as interns went about their nightly tasks, it is not difficult to understand how errors or omissions in the handoff process may potentially translate into frequent problems in direct patient care.

Trainees reported using written handoff tools to provide answers for 7.3% of questions. As we had suspected, they relied less frequently on their written handoffs as they completed more consecutive call nights. Interestingly, however, even when housestaff did not report using the written handoff, they were observed quite often to look at it before providing an answer. One explanation for this discrepancy between trainee reports and our observations is that the written handoff may serve as a memory tool, even if housestaff do not directly attribute their answers to its content. Our study also found that answers to questions concerning patients' diet and fluids were more likely to be ascribed to information contained in the written handoff. This finding supports the potential value of automated written handoff tools that are linked to the EMR, which can best ensure accuracy of this type of information.

Housestaff in our study also reported using information received during the verbal handoff to answer 1 out of every 4 on‐call questions. Although we did not specifically rate or monitor the quality of verbal handoffs, prior research has demonstrated that resident verbal handoff is often plagued with incomplete and inaccurate data.[3, 4, 19, 21] One investigation found that pediatric interns were prone to overestimating the effectiveness of their verbal handoffs, even as they failed to convey urgent information to their peers.[19] In light of such prior work, our finding that interns frequently rely on the verbal transfer of information supports specific residency training program handoff initiatives that target verbal exchanges.[11, 22, 23]

Although information obtained in the handoff was frequently required by on‐call housestaff, our study found that two‐thirds of all questions were answered using other resources, most often general medical or clinical knowledge. Clearly, background knowledge and experience is fundamental to trainees' ability to perform their jobs. Such reliance on general knowledge for problem solving may not be unique to interns. One recent observational study of senior pediatric cardiac subspecialists reported a high frequency of reliance on their own clinical experience, instinct, or prior training in making clinical decisions.[24] Further investigation may be useful to parse out the exact types of clinical knowledge being used, and may have important implications for how training programs plan for overnight supervision.[25, 26, 27]

Our study has several limitations. First, it was beyond the scope of this study to link housestaff answers to patient outcomes or medical errors. Given the frequency with which the handoff, a known source of vulnerability to medical error, was used by on‐call housestaff, our study suggests that future research evaluating the relationship between questions asked of on‐call housestaff, the answers provided, and downstream patient safety incidents may be merited. Second, our study was conducted in a single pediatric residency program with 1 physician observer midway through the first year of training and only in the early evening hours. This limits the generalizability of our findings, as the use of handoffs to answer on‐call questions may be different at other stages of the training process, within other specialties, or even at different times of the day. We also began our observations after the handoff had taken place; future studies may want to assess how variations in written and verbal handoff processes affect their use. As a final limitation, we note that although collecting information in real time using a direct observational method eliminated the problem of recall bias, there may have been attribution bias.

The results of our study demonstrate that on‐call pediatric housestaff are frequently asked a variety of clinical questions posed by hospital staff, patients, and their families. We found that trainees are apt to rely both on handoff information and other resources to provide answers. By better understanding what resources on‐call housestaff are accessing to answer questions overnight, we may be able to better target interventions needed to improve the availability of patient information, as well as the usefulness of written and verbal handoff tools.[11, 22, 23]

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Katharine Levinson, MD, and Melissa Atmadja, BA, for their help with the data review and guidance with database management. The authors also thank the housestaff from the Boston Combined Residency Program in Pediatrics for their participation in this study.

Disclosures: Maireade E. McSweeney, MD, as the responsible author certifies that all coauthors have seen and agree with the contents of this article, takes responsibility for the accuracy of these data, and certifies that this information is not under review by any other publication. All authors had no financial conflicts of interest or conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose. Dr. Landrigan is supported in part by the Children's Hospital Association for his work as an Executive Council member of the Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings network. In addition, he has received honoraria from the Committee of Interns and Residents as well as multiple academic medical centers for lectures delivered on handoffs, sleep deprivation, and patient safety, and he has served as an expert witness in cases regarding patient safety and sleep deprivation.

Hospital communication failures are a leading cause of serious errors and adverse events in the United States.[1, 2, 3, 4] With the implementation of duty‐hour restrictions for resident physicians,[5] there has been particular focus on the transfer of information during handoffs at change of shift.[6, 7] Many residency programs have sought to improve the processes of written and verbal handoffs through various initiatives, including: (1) automated linkage of handoff forms to electronic medical records (EMRs)[8, 9, 10]; (2) introduction of oral communication curricula, handoff simulation, or mnemonics[11, 12, 13]; and (3) faculty oversight of housestaff handoffs.[14, 15] Underlying each initiative has been the assumption that improving written and verbal handoff processes will ensure the availability of optimal patient information for on‐call housestaff. There has been little investigation, however, into what clinical questions are actually being asked of on‐call trainees, as well as what sources of information they are using to provide answers.

The aim of our study was to examine the extent to which written and verbal handoffs are utilized by pediatric trainees to derive answers to questions posed during overnight shifts. We also sought to describe both the frequency and types of on‐call questions being asked of trainees. Our primary outcome was trainee use of written handoffs to answer on‐call questions. Secondary outcomes included trainee use of verbal handoffs, as well as their use of alternative information resources to answer on‐call questions, including other clinical staff (ie, attending physicians, senior residents, nursing staff), patients and their families, the medical record, or the Internet. We then examined a variety of trainee, patient, and question characteristics to assess potential predictors of written and verbal handoff use.

METHODS

Institutional approval was granted to prospectively observe pediatric interns at the start of their overnight on‐call shifts on 2 inpatient wards at Boston Children's Hospital during 3 winter months (November through January). Our study was conducted during the postintervention period of a larger study that was designed to examine the effectiveness of a new resident handoff bundle on resident workflow and patient safety.[13] Interns rotating on study ward 1 used a structured, nonautomated tool (Microsoft Word version 2003; Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA). Interns on study ward 2 used a handoff tool that was developed at the study hospital for use with the hospital's EMR, Cerner PowerChart version 2007.17 (Cerner Corp., Kansas City, MO). Interns on both wards received training on specific communication strategies, including verbal and written handoff processes.[13]

For our study, we recorded all questions being asked of on‐call interns by patients, parents, or other family members, as well as nurses or other clinical providers after completion of their evening handoff. We then directly observed all information resources used to derive answers to any questions asked pertaining to patients discussed in the evening handoff. We excluded any questions about new patient admissions or transfers, as well as nonpatient‐related questions.

Both study wards were staffed by separate day and night housestaff teams, who worked shifts of 12 to 14 hours in duration and had similar nursing schedules. The day team consisted of 3 interns and 1 senior resident per ward. The night team consisted of 1 intern on each ward, supervised by a senior resident covering both wards. Each day intern rotated for 1 week (Sunday through Thursday) during their month‐long ward rotation as part of the night team. We considered any intern on either of the 2 study wards to be eligible for enrollment in this study. Written consent was obtained from all participants.

The night intern received a verbal and written handoff at the shift change (usually performed between 5 and 7pm) from 1 of the departing day interns prior to the start of the observation period. This handoff was conducted face‐to‐face in a ward conference room typically with the on‐call night intern and supervising resident receiving the handoff together from the departing day intern/senior resident.

Observation Protocol

Data collection was conducted by an independent, board‐certified, pediatric physician observer on alternating weeknights immediately after the day‐to‐night evening handoff had taken place. A strict observation protocol was followed. When an eligible question was asked of the participating intern, the physician observer would record the question and the time. The question source, defined as a nurse, parent/patient, or other clinical staff (eg, pharmacist, consultant) was documented, as well as the mode of questioning, defined as face to face, text page, or phone call.

The observer would then note if and when the question was answered. Once the question was answered, the observer would ask the intern if he or she had used the written handoff to provide the answer (yes or no). Our primary outcome was reported use of the written handoff. In addition, the observer directly noted if the intern looked at the written handoff tool at any time when answering a question. The intern was also asked to name any and all additional information resources used, including verbal handoff, senior resident, nursing staff, other clinicians, a patient/parent or other family member, a patient's physical exam, the EMR, the Internet, or his or her own medical or clinical knowledge.

All question and answer information was tracked using a handheld, digital, time device. In addition, the following patient data were recorded for each patient involved in a recorded question: the patient's admitting service, transfer status, and length of stay.

Data Categorization and Analysis

Content of recorded questions were categorized according to whether they involved: (1) medications (including drug allergies or levels), (2) diet or fluids, (3) laboratory values or diagnostic testing/procedures, (4) physical exam findings (eg, a distended abdomen, blood pressure, height/weight), or (5) general care‐plan questions. We also categorized time used for generating an answer as immediate (<5 minutes), delayed (>5 minutes but <1.5 hours), or deferred (any question unanswered during the time of observation).

All data were entered into a database using SPSS 16.0 Data Builder software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL), and statistical analyses were performed with PASW 18 (SPSS Inc.) and SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) software. Observed questions were summarized according to content categories. We also described trainee and patient characteristics relevant to the questions being studied. To study risk factors for written handoff use, the outcome was dichotomized as reported use of written handoff by the intern as a resource to answer the question asked versus written handoff use was not reported by the intern as a resource to answer the question asked. We did not include observed use of the written handoff in these statistical analyses. To accommodate for patient‐ or provider‐induced correlations among observed questions, we used a generalized estimation equations approach (PROC GENMOD in SAS 9.2) to fit logistic regression models for written handoff use and permitted a nested correlation structure among the questions (ie, questions from the same patient were allowed to be correlated, and patients under the care of the same intern could have intern‐induced correlation). Univariate regression modeling was used to evaluate the effects of question, patient, and intern characteristics. Multivariate logistic regression models were used to identify independent risk factors for written handoff use. Any variable that had a P value 0.1 in univariate regression model was considered as a candidate variable in the multivariate regression model. We then used a backward elimination approach to obtain the final model, which only included variables remaining to be significant at a P<0.05 significance level. Our analysis for verbal handoff use was carried out in a similar fashion.

RESULTS

Twenty‐eight observation nights (equivalent to 77 hours and 6 minutes of total direct observation time), consisting of 13 sessions on study ward 1 and 15 sessions on study ward 2, were completed. A total of 15 first‐year pediatric interns (5 male, 33%; 10 female, 66.7%), with a median age of 27.5 years (interquartile range [IQR]: 2629 years) participated. Interns on the 2 study wards were comparable with regard to trainee week of service (P=0.43) and consecutive night of call at the time of observation (P=0.45). Each intern was observed for a mean of 2 sessions (range, 13 sessions), with a mean observation time per session of approximately 2 hours and 45 minutes ( 23 minutes).

Questions

A total of 260 questions (ward 1: 136 questions, ward 2: 124 questions) met inclusion criteria and involved 101 different patients, with a median of 2 questions/patient (IQR: 13) and a range of 1 to 14 questions/patient. Overall, interns were asked 2.6 questions/hour (IQR: 1.44.7), with a range of 0 to 7 questions per hour; the great majority of questions (210 [82%]) were posed face to face. Types of questions recorded included medications 28% (73), diet/fluids 15% (39), laboratory or diagnostic/procedural related 22% (57), physical exam or other measurements 8.5% (22), or other general medical or patient care‐plan questions 26.5% (69) (Table 1). Examples of recorded questions are provided in Table 2.

| No. (%) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Patients, n=101 | |

| Admitting services | |

| General pediatrics | 49 (48) |

| Pediatric subspecialty | 27 (27) |

| CCS* | 25 (25) |

| Patients transferred from critical care unit | |

| Yes | 21 (21) |

| No | 80 (79) |

| Questions, n=260 | |

| Patients' length of stay at time of recorded question* | |

| 2 days | 142 (55) |

| >2 days | 118 (45) |

| Intern consecutive night shift (15) | |

| 1st or 2nd night (early) | 86 (33) |

| 3rd through 5th night (late) | 174 (67) |

| Intern week of service during a 4‐week rotation | |

| Weeks 12 (early) | 119 (46) |

| Weeks 34 (late) | 141 (54) |

| Question sources | |

| Clinical provider | 167 (64) |

| Parent/patient or other family member | 93 (36) |

| Question categories | |

| Medications | 73 (28) |

| Diet and/or fluids | 39 (15) |

| Labs or diagnostic imaging/procedures | 57 (22) |

| Physical exam/vital signs/measurements | 22 (8.5) |

| Other general medical or patient care plan questions | 69 (26.5) |

| Answers, n=233 | |

| Resources reported | |

| Written sign‐out | 17 (7.3) |

| Verbal sign‐out (excluding any written sign‐out use) | 59 (25.3) |

| Other resources | 157 (67.4) |

| Question Categories |

|---|

|

| Medication questions (including medication allergy or drug level questions) |

| Could you clarify the lasix orders? |

| Pharmacy rejected the medication, what do you want to do? |

| Dietary and fluid questions |

| Do you want to continue NG feeds at 10 mL/hr and advance? |

| Is she going to need to be NPO for the biopsy in the AM? |

| Laboratory or diagnostic tests/procedure questions |

| Do you want blood cultures on this patient? |

| What was the result of her x‐ray? |

| Physical exam questions (including height/weight or vital sign measurements) |

| What do you think of my back (site of biopsy)? |

| Is my back okay, because it seems sore after the (renal) biopsy? |

| Other (patient related) general medical or care plan questions |

| Did you talk with urology about their recommendations? |

| Do you know the plan for tomorrow? |

Across the 2 study wards, 48% (49) of patients involved in questions were admitted to a general pediatric service; 27% (27) were admitted to a pediatric specialty service (including the genetics/metabolism, endocrinology, adolescent medicine, pulmonary, or toxicology admitting services); the remaining 25% (25) were admitted to a complex care service (CCS), specifically designed for patients with multisystem genetic, neurological, or congenital disorders (Table 1).[16, 17] Approximately 21% (21) of patients had been transferred to the floor from a critical care unit (Table 1).

Answers

Of the 260 recorded questions, 90% (233) had documented answers. For the 10% (27) of questions with undocumented answers, 21 were observed to be verbally deferred by the intern to the day team or another care provider (ie, other physician or nurse), and almost half (42.9% [9]) involved general care‐plan questions; the remainder involved medication (4), diet (2), diagnostic testing (5), or vital sign (1) questions. An additional 6 questions went unanswered during the observation period, and it is unknown if or when they were answered.

Of the answered questions, 90% (209) of answers were provided by trainees within 5 minutes and 9% (21) within 1.5 hours. In all, interns reported using 1 information resource to provide answers for 61% (142) of questions, at least 2 resources for 33% (76) questions, and 3 resources for 6% (15) questions.

Across both study wards, interns reported using information provided in written or verbal handoffs to answer 32.6% of questions. Interns reported using the written handoff, either alone or in combination with other information resources, to provide answers for 7.3% (17) of questions; verbal handoff, either alone or in combination with another resource (excluding written handoff), was reported as a resource for 25.3% (59) of questions. Of note, interns were directly observed to look at the written handoff when answering 21% (49) of questions.

A variety of other resources, including general medical/clinical knowledge, the EMR, and parents or other resources, were used to answer the remaining 67.4% (157) of questions. Intern general medical knowledge (ie, reports of simply knowing the answer to the question in their head[s]) was used to provide answers for 53.2% (124) of questions asked.

Unadjusted univariate regression analyses assessing predictors of written and verbal handoff use are shown in Figure 1. Multivariate logistic regression analyses showed that both dietary questions (odds ratio [OR]: 3.64, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.518.76; P=0.004) and interns' consecutive call night (OR: 0.29, 95% CI: 0.090.93; P=0.04) remained significant predictors of written handoff use. After adjusting for risk factors identified above, no differences in written handoff use were seen between the 2 wards.

Multivariate logistic regression for predictors of the verbal handoff use showed that questions regarding patients with longer lengths of stay (OR: 1.97, 95% CI: 1.023.8; P=0.04), those regarding general care plans (OR: 2.07, 95% CI: 1.133.78; P=0.02), as well as those asked by clinical staff (OR: 1.95, 95 CI: 1.043.66; P=0.04), remained significant predictors of reported verbal handoff use.

DISCUSSION

In light of the recent changes in duty hours implemented in July 2011, many pediatric training programs are having trainees work in day and night shifts.[18] Pediatric resident physicians frequently answer questions that pertain to patients handed off between day and night shifts. We found that on average, information provided in the verbal and written handoff was used almost once per hour. Housestaff in our study generally based their answers on information found in 1 or 2 resources, with almost one‐third of all questions involving some use of the written or verbal handoff. Prior research has documented widespread problems with resident handoff practices across programs and a high rate of medical errors due to miscommunications.[3, 4, 19, 20] Given how often information contained within the handoff was used as interns went about their nightly tasks, it is not difficult to understand how errors or omissions in the handoff process may potentially translate into frequent problems in direct patient care.

Trainees reported using written handoff tools to provide answers for 7.3% of questions. As we had suspected, they relied less frequently on their written handoffs as they completed more consecutive call nights. Interestingly, however, even when housestaff did not report using the written handoff, they were observed quite often to look at it before providing an answer. One explanation for this discrepancy between trainee reports and our observations is that the written handoff may serve as a memory tool, even if housestaff do not directly attribute their answers to its content. Our study also found that answers to questions concerning patients' diet and fluids were more likely to be ascribed to information contained in the written handoff. This finding supports the potential value of automated written handoff tools that are linked to the EMR, which can best ensure accuracy of this type of information.

Housestaff in our study also reported using information received during the verbal handoff to answer 1 out of every 4 on‐call questions. Although we did not specifically rate or monitor the quality of verbal handoffs, prior research has demonstrated that resident verbal handoff is often plagued with incomplete and inaccurate data.[3, 4, 19, 21] One investigation found that pediatric interns were prone to overestimating the effectiveness of their verbal handoffs, even as they failed to convey urgent information to their peers.[19] In light of such prior work, our finding that interns frequently rely on the verbal transfer of information supports specific residency training program handoff initiatives that target verbal exchanges.[11, 22, 23]

Although information obtained in the handoff was frequently required by on‐call housestaff, our study found that two‐thirds of all questions were answered using other resources, most often general medical or clinical knowledge. Clearly, background knowledge and experience is fundamental to trainees' ability to perform their jobs. Such reliance on general knowledge for problem solving may not be unique to interns. One recent observational study of senior pediatric cardiac subspecialists reported a high frequency of reliance on their own clinical experience, instinct, or prior training in making clinical decisions.[24] Further investigation may be useful to parse out the exact types of clinical knowledge being used, and may have important implications for how training programs plan for overnight supervision.[25, 26, 27]

Our study has several limitations. First, it was beyond the scope of this study to link housestaff answers to patient outcomes or medical errors. Given the frequency with which the handoff, a known source of vulnerability to medical error, was used by on‐call housestaff, our study suggests that future research evaluating the relationship between questions asked of on‐call housestaff, the answers provided, and downstream patient safety incidents may be merited. Second, our study was conducted in a single pediatric residency program with 1 physician observer midway through the first year of training and only in the early evening hours. This limits the generalizability of our findings, as the use of handoffs to answer on‐call questions may be different at other stages of the training process, within other specialties, or even at different times of the day. We also began our observations after the handoff had taken place; future studies may want to assess how variations in written and verbal handoff processes affect their use. As a final limitation, we note that although collecting information in real time using a direct observational method eliminated the problem of recall bias, there may have been attribution bias.

The results of our study demonstrate that on‐call pediatric housestaff are frequently asked a variety of clinical questions posed by hospital staff, patients, and their families. We found that trainees are apt to rely both on handoff information and other resources to provide answers. By better understanding what resources on‐call housestaff are accessing to answer questions overnight, we may be able to better target interventions needed to improve the availability of patient information, as well as the usefulness of written and verbal handoff tools.[11, 22, 23]

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Katharine Levinson, MD, and Melissa Atmadja, BA, for their help with the data review and guidance with database management. The authors also thank the housestaff from the Boston Combined Residency Program in Pediatrics for their participation in this study.

Disclosures: Maireade E. McSweeney, MD, as the responsible author certifies that all coauthors have seen and agree with the contents of this article, takes responsibility for the accuracy of these data, and certifies that this information is not under review by any other publication. All authors had no financial conflicts of interest or conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose. Dr. Landrigan is supported in part by the Children's Hospital Association for his work as an Executive Council member of the Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings network. In addition, he has received honoraria from the Committee of Interns and Residents as well as multiple academic medical centers for lectures delivered on handoffs, sleep deprivation, and patient safety, and he has served as an expert witness in cases regarding patient safety and sleep deprivation.

- Improving America's hospitals: The Joint Commission's annual report on quality and safety. 2007. Available at: http://www.jointcommission. org/Improving_Americas_Hospitals_The_Joint_Commissions_Annual_Report_on_Quality_and_Safety_‐_2007. Accessed October 3, 2011.

- US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General. Adverse events in hospitals: methods for identifying events. 2010. Available at: http://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei‐06‐08‐00221.pdf. Accessed October 3, 2011.

- , , , , . Communication failures in patient sign‐out and suggestions for improvement: a critical incident analysis. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14:401–407.

- , , , , . Consequences of inadequate sign‐out for patient care. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1755–1760.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Common program requirements. 2010. Available at: http://acgme‐2010standards.org/pdf/Common_Program_Requirements_07012011.pdf. Accessed January 25, 2011.

- , . Building physician work hour regulations from first principles and best evidence. JAMA. 2008;300:1197–1199.

- , , , , . Managing discontinuity in academic medical centers: strategies for a safe and effective resident sign‐out. J Hosp Med. 2006;1:257–266.

- , , , , . A randomized, controlled trial evaluating the impact of a computerized rounding and sign‐out system on continuity of care and resident work hours. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;200:538–545.

- , , , , , . Simple standardized patient handoff system that increases accuracy and completeness. J Surg Educ. 2008;65:476–485.

- , , , , . Review of computerized physician handoff tools for improving the quality of patient care [published online ahead of print November 20, 2012]. J Hosp Med. doi: 10.1002/jhm.1988.

- , , , . Establishing a multisite education and research project requires leadership, expertise, collaboration, and an important aim. Pediatrics. 2010;126:619–622.

- , , , et al. Hand‐off education and evaluation: piloting the observed simulated hand‐off experience (OSHE). J Gen Intern Med. 2009;25:129–134.

- , , , , , . I‐pass, a mnemonic to standardize verbal handoffs. Pediatrics. 2012;129:201–204.

- , , , et al. A structured handoff program for interns. Acad Med. 2009;84:347–352.

- , , , et al. Experience with faculty supervision of an electronic resident sign‐out system. Am J Med. 2010;123:376–381.

- , , , et al. Hospital utilization and characteristics of patients experiencing recurrent readmissions within children's hospitals. JAMA. 2011;305:682–690.

- , , , et al. Children with complex chronic conditions in inpatient hospital settings in the United States. Pediatrics. 2010;126:647–655.

- , , , . Effects of a night‐team system on resident sleep and work hours. Pediatrics. 2011;128:1142–1147.

- , , , . Interns overestimate the effectiveness of their hand‐off communication. Pediatrics. 2010;125:491–496.

- , , , . Patient handoffs: pediatric resident experiences and lessons learned. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2011;50:57–63.

- , , , . Adequacy of information transferred at resident sign‐out (in‐hospital handover of care): a prospective survey. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17:6–10.

- , . A model for building a standardized hand‐off protocol. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2006;32:646–655.

- , , . Development and implementation of an oral sign‐out skills curriculum. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1470–1474.

- , , , , . Deciding without data. Congenit Heart Dis. 2010;5:339–342.

- , , , et al. A systematic review: the effect of clinical supervision on patient and residency education outcomes. Acad Med. 2012;87:428–442.

- , , , , , . Effects of increased overnight supervision on resident education, decision‐making, and autonomy. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:606–610.

- , , , et al. Survey of overnight academic hospitalist supervision of trainees. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:521–523.

- Improving America's hospitals: The Joint Commission's annual report on quality and safety. 2007. Available at: http://www.jointcommission. org/Improving_Americas_Hospitals_The_Joint_Commissions_Annual_Report_on_Quality_and_Safety_‐_2007. Accessed October 3, 2011.

- US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General. Adverse events in hospitals: methods for identifying events. 2010. Available at: http://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei‐06‐08‐00221.pdf. Accessed October 3, 2011.

- , , , , . Communication failures in patient sign‐out and suggestions for improvement: a critical incident analysis. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14:401–407.

- , , , , . Consequences of inadequate sign‐out for patient care. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1755–1760.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Common program requirements. 2010. Available at: http://acgme‐2010standards.org/pdf/Common_Program_Requirements_07012011.pdf. Accessed January 25, 2011.

- , . Building physician work hour regulations from first principles and best evidence. JAMA. 2008;300:1197–1199.

- , , , , . Managing discontinuity in academic medical centers: strategies for a safe and effective resident sign‐out. J Hosp Med. 2006;1:257–266.

- , , , , . A randomized, controlled trial evaluating the impact of a computerized rounding and sign‐out system on continuity of care and resident work hours. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;200:538–545.

- , , , , , . Simple standardized patient handoff system that increases accuracy and completeness. J Surg Educ. 2008;65:476–485.

- , , , , . Review of computerized physician handoff tools for improving the quality of patient care [published online ahead of print November 20, 2012]. J Hosp Med. doi: 10.1002/jhm.1988.

- , , , . Establishing a multisite education and research project requires leadership, expertise, collaboration, and an important aim. Pediatrics. 2010;126:619–622.

- , , , et al. Hand‐off education and evaluation: piloting the observed simulated hand‐off experience (OSHE). J Gen Intern Med. 2009;25:129–134.

- , , , , , . I‐pass, a mnemonic to standardize verbal handoffs. Pediatrics. 2012;129:201–204.

- , , , et al. A structured handoff program for interns. Acad Med. 2009;84:347–352.

- , , , et al. Experience with faculty supervision of an electronic resident sign‐out system. Am J Med. 2010;123:376–381.

- , , , et al. Hospital utilization and characteristics of patients experiencing recurrent readmissions within children's hospitals. JAMA. 2011;305:682–690.

- , , , et al. Children with complex chronic conditions in inpatient hospital settings in the United States. Pediatrics. 2010;126:647–655.

- , , , . Effects of a night‐team system on resident sleep and work hours. Pediatrics. 2011;128:1142–1147.

- , , , . Interns overestimate the effectiveness of their hand‐off communication. Pediatrics. 2010;125:491–496.

- , , , . Patient handoffs: pediatric resident experiences and lessons learned. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2011;50:57–63.

- , , , . Adequacy of information transferred at resident sign‐out (in‐hospital handover of care): a prospective survey. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17:6–10.

- , . A model for building a standardized hand‐off protocol. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2006;32:646–655.

- , , . Development and implementation of an oral sign‐out skills curriculum. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1470–1474.

- , , , , . Deciding without data. Congenit Heart Dis. 2010;5:339–342.

- , , , et al. A systematic review: the effect of clinical supervision on patient and residency education outcomes. Acad Med. 2012;87:428–442.

- , , , , , . Effects of increased overnight supervision on resident education, decision‐making, and autonomy. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:606–610.

- , , , et al. Survey of overnight academic hospitalist supervision of trainees. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:521–523.

Copyright © 2013 Society of Hospital Medicine