User login

Evaluation of Glycemic Control and Cost Savings Associated With Liraglutide Dose Reduction at a Veterans Affairs Hospital

Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) are injectable incretin hormones approved for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). They are highly efficacious agents with hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) reduction potential of approximately 0.8 to 1.6% and mechanisms of action that result in an average weight loss of 1 to 3 kg.1,2 Published in 2016, The LEADER (Liraglutide Effect and Action in Diabetes: Evaluation of Cardiovascular Outcome Results) trial established cardiovascular benefits associated with liraglutide, making it a preferred GLP-1 RA.3

In addition to HbA1c reduction, weight loss, and cardiovascular benefits, liraglutide also has shown insulin-sparing effects when used in combination with insulin. A trial by Lane and colleagues revealed a 34% decrease in total daily insulin dose 6 months after the addition of liraglutide to insulin in patients with T2DM receiving > 100 units of insulin daily.4 When used in combination with basal insulin analogues (glargine or detemir) similar findings also were shown.5

The Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center (MEDVAMC) in Houston, Texas, selected liraglutide as its preferred GLP-1 RA because of its favorable glycemic and cardiovascular outcomes. In addition, as part of a cost-savings initiative for fiscal year 2018, liraglutide 6 mg/mL injection 2-count pen packs was selected as the preferred liraglutide product. Before the availability of the 2-count pen packs, veterans previously received 3-count pen packs, which allowed for up to a 30-day supply of liraglutide 1.8 mg daily dosing. However, the cost-efficient 2-count pen packs allow for up to 1.2 mg daily dose of liraglutide for a 30-day supply. Due to these changes, veterans at MEDVAMC were converted from liraglutide 1.8 mg daily to 1.2 mg daily between May 2018 and August 2018.

The primary objective of this study was to assess sustained glycemic control and cost savings that resulted from this change. The secondary objectives were to assess sustained weight loss and adverse effects (AEs).

Methods

This study was approved by the MEDVAMC Quality Assurance and Regulatory Affairs committee. In this single-center study, a retrospective chart review was conducted on veterans with T2DM who underwent a liraglutide dose reduction from 1.8 mg daily to 1.2 mg daily between May 2018 and August 2018. Patients were included if they were aged ≥ 18 years with an active prescription for liraglutide 1.8 mg daily and insulin (with or without other antihyperglycemic agents) at the time of conversion. In addition, patients must have had ≥ 1 HbA1c reading within 3 months of the dose conversion and a follow-up HbA1c within 6 months after the dose conversion. To assess the primary objective of glycemic control that resulted from the liraglutide dose reduction, mean change of HbA1c at time of dose conversion was compared with mean HbA1c 6 months postconversion. To assess savings, cost information was obtained from the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Drug Price Database and monthly and annual costs of liraglutide 6 mg/mL injection 2-count pen pack were compared with that of the 3-count pen pack. A chart review of patients’ electronic health records assessed secondary outcomes. The VA Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) was used to collect patient data.

Patients and Characteristics

The following patient information was obtained from patients’ records: age, sex, race/ethnicity, diabetic medications (at time of conversion and 6 months after conversion), cardiovascular history and risk factors (hypertension, coronary artery disease, heart failure, arrhythmias, peripheral artery disease, obesity, etc), prescriber type (physician, nurse practitioner/physician assistant, pharmacist, etc), weight (at baseline, at time of conversion, and 6 months after conversion), HbA1c (at baseline, at time of conversion, and 6 months after conversion), average blood glucose (at baseline, at time of conversion, and 6 months after conversion), insulin dose (at time of conversion and 6 months after conversion), and reported AEs.

Statistical Analysis

The 2-tailed, paired t test was used to assess changes in HbA1c, average blood glucose, and body weight. Demographic data and other outcomes were assessed using descriptive statistics.

Results

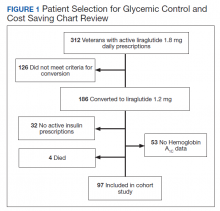

Prior to the dose reduction, 312 veterans had active prescriptions for liraglutide 1.8 mg daily. Due to lack of glycemic control benefit (failing to achieve a HbA1c reduction of at least 0.5% after at least 3 to 6 months following initiation of therapy) or nonadherence (assessed by medication refill history), 126 veterans did not meet the criteria for the dose conversion. As a result, liraglutide was discontinued, and veterans were sent patient letter notifications and health care providers were notified via medication review notes in the patient electronic health record “to make medication adjustments if warranted. A total of 186 veterans underwent a liraglutide dose reduction between May and August 2018. Thirty-two veterans were without active insulin prescriptions, 53 were without HbA1c results, and 4 veterans died; resulting in 97 veterans who were included in the study (Figure 1).

Most of the patients included in the study were male (90.7%) and White (63.9%) with an average (SD) age of 65.9 years (7.9) and a mean (SD) HbA1c at baseline of 8.4% (1.2). About 56.7% received concurrent T2DM treatment with metformin, and 8.3% received concurrent treatment with empagliflozin. The most common cardiovascular disease/risk factors included hypertension (93.8%), hyperlipidemia (85.6%), and obesity (85.6%) (Table 1).

Glycemic Control and Weight Loss

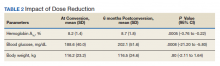

At the time of conversion, the average (SD) HbA1c was 8.2% (1.4) and increased to an average (SD) of 8.7% (1.8) (P =.0005) 6 months after the dose reduction (Table 2). The average (SD) body weight was 116.2 kg (23.2) at time of conversion and increased to 116.5 (24.6) 6 months following the dose reduction; however, the difference was not statistically significant (P = .8).

As a result of the HbA1c change, 41.2% of veterans underwent an insulin dose increase with dose increase of 5 to 200 units of total daily insulin during the 6-month period. Antihyperglycemic regimen remained unchanged for 40.2% of veterans, while additional glucose lowering agents were initiated in 6 veterans. Medications initiated included empagliflozin in 4 veterans and saxagliptin in 2 veterans.

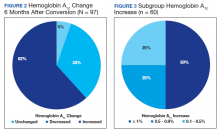

HbA1c reduction was noted in 33% of veterans (Figure 2) mostly due to improved diet and exercise habits. A majority of veterans, 62%, experienced an increase in HbA1c, whereas 5.2% of veterans maintained the same HbA1c. Of 60 veterans with HbA1c increases, 15 had an increase between 0.1% and 0.5%, another 15 with an increase between 0.5 to 0.9%, and half had HbA1c increases of at least 1% with a maximum increase of 5.1% (Figure 3).

Cost Savings

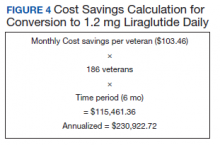

Cost information was obtained from the VA Drug Price Database. The estimated monthly cost savings per patient associated with the conversion from 3-count to 2-count injection pen packs of liraglutide 6 mg/mL was $103.46. With 186 veterans converted to the 2-count pen packs, MEDVAMC saved $115,461.36 in a 6-month period. The estimated annualized cost savings was estimated to be about $231,000 (Figure 4).

Adverse Effects During the 6-month period following the dose conversion, no major AEs associated with liraglutide were documented. Documented AEs included 3 cases of diarrhea, resulting in the discontinuation of metformin. Metformin also was discontinued in a veteran with worsened renal function and eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Discussion

According to previous clinical trials, when used in combination with insulin, 1.2 mg and 1.8 mg daily liraglutide showed significant improvement in glycemic control and body weight and was associated with decreased insulin requirements.4-6 However, subgroup analyses were not performed to show differences in benefit between the liraglutide 1.8 mg and 1.2 mg groups.4-6 Similarly, cardiovascular benefit was observed in patients receiving liraglutide 1.2 mg daily and liraglutide 1.8 mg daily in the LEADER trial with no subgroup analysis or distinction between treatment doses.3 With this information and approval by the Veterans Integrated Services Network, the pharmacoeconomics team at MEDVAMC made the decision to select a more cost-efficient preparation and, hence, lower dose of liraglutide.

To ensure that patients only taking liraglutide for glycemic control were captured, patients without insulin therapies at baseline were excluded. Due to concerns of potential off-label use of liraglutide for weight loss, patients without active prescriptions for insulin at baseline were excluded.

A mean HbA1c increase of 0.5% was observed over the 6-month period, supporting findings of a dose-dependent HbA1c decrease observed in clinical trials. In the LEAD-3 MONO trial when used as monotherapy, liraglutide 1.8 mg was associated with significantly greater HbA1c reduction than liraglutide 1.2 mg (–0·29%; –0·50 to –0.09, P = .005) after 52 weeks of treatment.7 Liraglutide 1.8 mg was also associated with higher rates of AEs; particularly gastrointestinal. 7 To minimize these AEs, it is recommended to initiate liraglutide at 0.6 mg daily for a week then increase to 1.2 mg daily. If tolerated, liraglutide can be further titrated to 1.8 mg daily to optimize glycemic control.8 Unsurprisingly, no major AEs were noted in this study, as AEs are typically noted with increased doses.

Despite the observed trend of increased HbA1c, no changes were made to glucoselowering agents in 39 veterans. This group of veterans consisted primarily of those whose HbA1c remained unchanged during the 6-month period, those whose HbA1c improved (with no documented hypoglycemia), and older veterans with less stringent HbA1c goals. As a result, doses of glucose lowering agents were maintained as appropriate.

No significant difference was noted in body weight during the 6-month period. The slight weight gain observed may have been due to several factors. Lack of exercise and dietary changes may have contributed to weight gain. In addition, insulin doses were increased in 40 veterans, which may have contributed to the observed weight gain.

As expected, significant cost savings were achieved as a result of the liraglutide dose reduction. Of note, liraglutide was discontinued in 126 veterans (prior to the dose reduction) due to nonadherence or inadequate response to therapy, which also resulted in additional savings. Although cost savings was achieved, the long-term benefit of this initiative still remains unknown. The worsened glycemic control that was detected may increase the risk of microvascular and macrovascular complications, thereby negating cost savings achieved. To assess this effect, longterm prospective studies are warranted.

Limitations

A number of issues limit these finding, including its retrospective data review, small sample size, additional factors contributing to HbA1c increase, and missing documentation in some patient records. Only 97 patients were included in the study, reflecting less than half of the charts reviewed (52% exclusion rate). In addition, several confounding factors may have contributed to the increased HbA1c observed. Medication changes and lifestyle factors may have contributed to the observed change in HbA1c levels. Exclusion of patients without active prescriptions for insulin may have contributed to a selection bias, as most patients included in the study were veterans with uncontrolled T2DM requiring insulin. Finally, as a retrospective study involving patient records, investigators relied heavily on information provided in patients’ charts (HbA1c, body weight, insulin doses, adverse effects, etc), which may not entirely be accurate and may have been missing other pertinent information.

Conclusions

The daily dose reduction of liraglutide from 1.8 mg to 1.2 mg due to a cost-savings initiative resulted in a HbA1c increase of 0.5% in a 6-month period. Due to HbA1c increases, 41.2% of veterans underwent an insulin dose increase, negating the insulin-sparing role of liraglutide. Although this study further confirms the dose-dependent HbA1c reduction with liraglutide that has been noted in previous trials, long-term prospective studies and cost-effectiveness analyses are warranted to assess the overall clinical significance and other benefits of the change, including its effects on cardiovascular outcomes.

1. American Diabetes Association. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(suppl 1):S90-S102. doi:10.2337/dc19-S009

2. Hinnen D. Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Spectr. 2017;30(3):202-210. doi:10.2337/ds16-0026

3. Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen K, et al. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(4):311-322. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1603827

4. Lane W, Weinrib S, Rappaport J, Hale C. The effect of addition of liraglutide to high-dose intensive insulin therapy: a randomized prospective trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2014;16(9):827-832. doi:10.1111/dom.12286

5. Ahmann A, Rodbard HW, Rosenstock J, et al. Efficacy and safety of liraglutide versus placebo added to basal insulin analogues (with or without metformin) in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;17(11):1056-1064. doi:10.1111/dom.12539

6. Lane W, Weinrib S, Rappaport J. The effect of liraglutide added to U-500 insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes and high insulin requirements. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2011;13(5):592-595. doi:10.1089/dia.2010.0221

7. Garber A, Henry R, Ratner R, et al. Liraglutide versus glimepiride monotherapy for type 2 diabetes (LEAD-3 Mono): a randomised, 52-week, phase III, double-blind, parallel-treatment trial. Lancet. 2009;373(9662):473-481. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61246-5.

8. Victoza [package insert]. Princeton: Novo Nordisk Inc; 2020.

Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) are injectable incretin hormones approved for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). They are highly efficacious agents with hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) reduction potential of approximately 0.8 to 1.6% and mechanisms of action that result in an average weight loss of 1 to 3 kg.1,2 Published in 2016, The LEADER (Liraglutide Effect and Action in Diabetes: Evaluation of Cardiovascular Outcome Results) trial established cardiovascular benefits associated with liraglutide, making it a preferred GLP-1 RA.3

In addition to HbA1c reduction, weight loss, and cardiovascular benefits, liraglutide also has shown insulin-sparing effects when used in combination with insulin. A trial by Lane and colleagues revealed a 34% decrease in total daily insulin dose 6 months after the addition of liraglutide to insulin in patients with T2DM receiving > 100 units of insulin daily.4 When used in combination with basal insulin analogues (glargine or detemir) similar findings also were shown.5

The Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center (MEDVAMC) in Houston, Texas, selected liraglutide as its preferred GLP-1 RA because of its favorable glycemic and cardiovascular outcomes. In addition, as part of a cost-savings initiative for fiscal year 2018, liraglutide 6 mg/mL injection 2-count pen packs was selected as the preferred liraglutide product. Before the availability of the 2-count pen packs, veterans previously received 3-count pen packs, which allowed for up to a 30-day supply of liraglutide 1.8 mg daily dosing. However, the cost-efficient 2-count pen packs allow for up to 1.2 mg daily dose of liraglutide for a 30-day supply. Due to these changes, veterans at MEDVAMC were converted from liraglutide 1.8 mg daily to 1.2 mg daily between May 2018 and August 2018.

The primary objective of this study was to assess sustained glycemic control and cost savings that resulted from this change. The secondary objectives were to assess sustained weight loss and adverse effects (AEs).

Methods

This study was approved by the MEDVAMC Quality Assurance and Regulatory Affairs committee. In this single-center study, a retrospective chart review was conducted on veterans with T2DM who underwent a liraglutide dose reduction from 1.8 mg daily to 1.2 mg daily between May 2018 and August 2018. Patients were included if they were aged ≥ 18 years with an active prescription for liraglutide 1.8 mg daily and insulin (with or without other antihyperglycemic agents) at the time of conversion. In addition, patients must have had ≥ 1 HbA1c reading within 3 months of the dose conversion and a follow-up HbA1c within 6 months after the dose conversion. To assess the primary objective of glycemic control that resulted from the liraglutide dose reduction, mean change of HbA1c at time of dose conversion was compared with mean HbA1c 6 months postconversion. To assess savings, cost information was obtained from the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Drug Price Database and monthly and annual costs of liraglutide 6 mg/mL injection 2-count pen pack were compared with that of the 3-count pen pack. A chart review of patients’ electronic health records assessed secondary outcomes. The VA Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) was used to collect patient data.

Patients and Characteristics

The following patient information was obtained from patients’ records: age, sex, race/ethnicity, diabetic medications (at time of conversion and 6 months after conversion), cardiovascular history and risk factors (hypertension, coronary artery disease, heart failure, arrhythmias, peripheral artery disease, obesity, etc), prescriber type (physician, nurse practitioner/physician assistant, pharmacist, etc), weight (at baseline, at time of conversion, and 6 months after conversion), HbA1c (at baseline, at time of conversion, and 6 months after conversion), average blood glucose (at baseline, at time of conversion, and 6 months after conversion), insulin dose (at time of conversion and 6 months after conversion), and reported AEs.

Statistical Analysis

The 2-tailed, paired t test was used to assess changes in HbA1c, average blood glucose, and body weight. Demographic data and other outcomes were assessed using descriptive statistics.

Results

Prior to the dose reduction, 312 veterans had active prescriptions for liraglutide 1.8 mg daily. Due to lack of glycemic control benefit (failing to achieve a HbA1c reduction of at least 0.5% after at least 3 to 6 months following initiation of therapy) or nonadherence (assessed by medication refill history), 126 veterans did not meet the criteria for the dose conversion. As a result, liraglutide was discontinued, and veterans were sent patient letter notifications and health care providers were notified via medication review notes in the patient electronic health record “to make medication adjustments if warranted. A total of 186 veterans underwent a liraglutide dose reduction between May and August 2018. Thirty-two veterans were without active insulin prescriptions, 53 were without HbA1c results, and 4 veterans died; resulting in 97 veterans who were included in the study (Figure 1).

Most of the patients included in the study were male (90.7%) and White (63.9%) with an average (SD) age of 65.9 years (7.9) and a mean (SD) HbA1c at baseline of 8.4% (1.2). About 56.7% received concurrent T2DM treatment with metformin, and 8.3% received concurrent treatment with empagliflozin. The most common cardiovascular disease/risk factors included hypertension (93.8%), hyperlipidemia (85.6%), and obesity (85.6%) (Table 1).

Glycemic Control and Weight Loss

At the time of conversion, the average (SD) HbA1c was 8.2% (1.4) and increased to an average (SD) of 8.7% (1.8) (P =.0005) 6 months after the dose reduction (Table 2). The average (SD) body weight was 116.2 kg (23.2) at time of conversion and increased to 116.5 (24.6) 6 months following the dose reduction; however, the difference was not statistically significant (P = .8).

As a result of the HbA1c change, 41.2% of veterans underwent an insulin dose increase with dose increase of 5 to 200 units of total daily insulin during the 6-month period. Antihyperglycemic regimen remained unchanged for 40.2% of veterans, while additional glucose lowering agents were initiated in 6 veterans. Medications initiated included empagliflozin in 4 veterans and saxagliptin in 2 veterans.

HbA1c reduction was noted in 33% of veterans (Figure 2) mostly due to improved diet and exercise habits. A majority of veterans, 62%, experienced an increase in HbA1c, whereas 5.2% of veterans maintained the same HbA1c. Of 60 veterans with HbA1c increases, 15 had an increase between 0.1% and 0.5%, another 15 with an increase between 0.5 to 0.9%, and half had HbA1c increases of at least 1% with a maximum increase of 5.1% (Figure 3).

Cost Savings

Cost information was obtained from the VA Drug Price Database. The estimated monthly cost savings per patient associated with the conversion from 3-count to 2-count injection pen packs of liraglutide 6 mg/mL was $103.46. With 186 veterans converted to the 2-count pen packs, MEDVAMC saved $115,461.36 in a 6-month period. The estimated annualized cost savings was estimated to be about $231,000 (Figure 4).

Adverse Effects During the 6-month period following the dose conversion, no major AEs associated with liraglutide were documented. Documented AEs included 3 cases of diarrhea, resulting in the discontinuation of metformin. Metformin also was discontinued in a veteran with worsened renal function and eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Discussion

According to previous clinical trials, when used in combination with insulin, 1.2 mg and 1.8 mg daily liraglutide showed significant improvement in glycemic control and body weight and was associated with decreased insulin requirements.4-6 However, subgroup analyses were not performed to show differences in benefit between the liraglutide 1.8 mg and 1.2 mg groups.4-6 Similarly, cardiovascular benefit was observed in patients receiving liraglutide 1.2 mg daily and liraglutide 1.8 mg daily in the LEADER trial with no subgroup analysis or distinction between treatment doses.3 With this information and approval by the Veterans Integrated Services Network, the pharmacoeconomics team at MEDVAMC made the decision to select a more cost-efficient preparation and, hence, lower dose of liraglutide.

To ensure that patients only taking liraglutide for glycemic control were captured, patients without insulin therapies at baseline were excluded. Due to concerns of potential off-label use of liraglutide for weight loss, patients without active prescriptions for insulin at baseline were excluded.

A mean HbA1c increase of 0.5% was observed over the 6-month period, supporting findings of a dose-dependent HbA1c decrease observed in clinical trials. In the LEAD-3 MONO trial when used as monotherapy, liraglutide 1.8 mg was associated with significantly greater HbA1c reduction than liraglutide 1.2 mg (–0·29%; –0·50 to –0.09, P = .005) after 52 weeks of treatment.7 Liraglutide 1.8 mg was also associated with higher rates of AEs; particularly gastrointestinal. 7 To minimize these AEs, it is recommended to initiate liraglutide at 0.6 mg daily for a week then increase to 1.2 mg daily. If tolerated, liraglutide can be further titrated to 1.8 mg daily to optimize glycemic control.8 Unsurprisingly, no major AEs were noted in this study, as AEs are typically noted with increased doses.

Despite the observed trend of increased HbA1c, no changes were made to glucoselowering agents in 39 veterans. This group of veterans consisted primarily of those whose HbA1c remained unchanged during the 6-month period, those whose HbA1c improved (with no documented hypoglycemia), and older veterans with less stringent HbA1c goals. As a result, doses of glucose lowering agents were maintained as appropriate.

No significant difference was noted in body weight during the 6-month period. The slight weight gain observed may have been due to several factors. Lack of exercise and dietary changes may have contributed to weight gain. In addition, insulin doses were increased in 40 veterans, which may have contributed to the observed weight gain.

As expected, significant cost savings were achieved as a result of the liraglutide dose reduction. Of note, liraglutide was discontinued in 126 veterans (prior to the dose reduction) due to nonadherence or inadequate response to therapy, which also resulted in additional savings. Although cost savings was achieved, the long-term benefit of this initiative still remains unknown. The worsened glycemic control that was detected may increase the risk of microvascular and macrovascular complications, thereby negating cost savings achieved. To assess this effect, longterm prospective studies are warranted.

Limitations

A number of issues limit these finding, including its retrospective data review, small sample size, additional factors contributing to HbA1c increase, and missing documentation in some patient records. Only 97 patients were included in the study, reflecting less than half of the charts reviewed (52% exclusion rate). In addition, several confounding factors may have contributed to the increased HbA1c observed. Medication changes and lifestyle factors may have contributed to the observed change in HbA1c levels. Exclusion of patients without active prescriptions for insulin may have contributed to a selection bias, as most patients included in the study were veterans with uncontrolled T2DM requiring insulin. Finally, as a retrospective study involving patient records, investigators relied heavily on information provided in patients’ charts (HbA1c, body weight, insulin doses, adverse effects, etc), which may not entirely be accurate and may have been missing other pertinent information.

Conclusions

The daily dose reduction of liraglutide from 1.8 mg to 1.2 mg due to a cost-savings initiative resulted in a HbA1c increase of 0.5% in a 6-month period. Due to HbA1c increases, 41.2% of veterans underwent an insulin dose increase, negating the insulin-sparing role of liraglutide. Although this study further confirms the dose-dependent HbA1c reduction with liraglutide that has been noted in previous trials, long-term prospective studies and cost-effectiveness analyses are warranted to assess the overall clinical significance and other benefits of the change, including its effects on cardiovascular outcomes.

Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) are injectable incretin hormones approved for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). They are highly efficacious agents with hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) reduction potential of approximately 0.8 to 1.6% and mechanisms of action that result in an average weight loss of 1 to 3 kg.1,2 Published in 2016, The LEADER (Liraglutide Effect and Action in Diabetes: Evaluation of Cardiovascular Outcome Results) trial established cardiovascular benefits associated with liraglutide, making it a preferred GLP-1 RA.3

In addition to HbA1c reduction, weight loss, and cardiovascular benefits, liraglutide also has shown insulin-sparing effects when used in combination with insulin. A trial by Lane and colleagues revealed a 34% decrease in total daily insulin dose 6 months after the addition of liraglutide to insulin in patients with T2DM receiving > 100 units of insulin daily.4 When used in combination with basal insulin analogues (glargine or detemir) similar findings also were shown.5

The Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center (MEDVAMC) in Houston, Texas, selected liraglutide as its preferred GLP-1 RA because of its favorable glycemic and cardiovascular outcomes. In addition, as part of a cost-savings initiative for fiscal year 2018, liraglutide 6 mg/mL injection 2-count pen packs was selected as the preferred liraglutide product. Before the availability of the 2-count pen packs, veterans previously received 3-count pen packs, which allowed for up to a 30-day supply of liraglutide 1.8 mg daily dosing. However, the cost-efficient 2-count pen packs allow for up to 1.2 mg daily dose of liraglutide for a 30-day supply. Due to these changes, veterans at MEDVAMC were converted from liraglutide 1.8 mg daily to 1.2 mg daily between May 2018 and August 2018.

The primary objective of this study was to assess sustained glycemic control and cost savings that resulted from this change. The secondary objectives were to assess sustained weight loss and adverse effects (AEs).

Methods

This study was approved by the MEDVAMC Quality Assurance and Regulatory Affairs committee. In this single-center study, a retrospective chart review was conducted on veterans with T2DM who underwent a liraglutide dose reduction from 1.8 mg daily to 1.2 mg daily between May 2018 and August 2018. Patients were included if they were aged ≥ 18 years with an active prescription for liraglutide 1.8 mg daily and insulin (with or without other antihyperglycemic agents) at the time of conversion. In addition, patients must have had ≥ 1 HbA1c reading within 3 months of the dose conversion and a follow-up HbA1c within 6 months after the dose conversion. To assess the primary objective of glycemic control that resulted from the liraglutide dose reduction, mean change of HbA1c at time of dose conversion was compared with mean HbA1c 6 months postconversion. To assess savings, cost information was obtained from the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Drug Price Database and monthly and annual costs of liraglutide 6 mg/mL injection 2-count pen pack were compared with that of the 3-count pen pack. A chart review of patients’ electronic health records assessed secondary outcomes. The VA Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) was used to collect patient data.

Patients and Characteristics

The following patient information was obtained from patients’ records: age, sex, race/ethnicity, diabetic medications (at time of conversion and 6 months after conversion), cardiovascular history and risk factors (hypertension, coronary artery disease, heart failure, arrhythmias, peripheral artery disease, obesity, etc), prescriber type (physician, nurse practitioner/physician assistant, pharmacist, etc), weight (at baseline, at time of conversion, and 6 months after conversion), HbA1c (at baseline, at time of conversion, and 6 months after conversion), average blood glucose (at baseline, at time of conversion, and 6 months after conversion), insulin dose (at time of conversion and 6 months after conversion), and reported AEs.

Statistical Analysis

The 2-tailed, paired t test was used to assess changes in HbA1c, average blood glucose, and body weight. Demographic data and other outcomes were assessed using descriptive statistics.

Results

Prior to the dose reduction, 312 veterans had active prescriptions for liraglutide 1.8 mg daily. Due to lack of glycemic control benefit (failing to achieve a HbA1c reduction of at least 0.5% after at least 3 to 6 months following initiation of therapy) or nonadherence (assessed by medication refill history), 126 veterans did not meet the criteria for the dose conversion. As a result, liraglutide was discontinued, and veterans were sent patient letter notifications and health care providers were notified via medication review notes in the patient electronic health record “to make medication adjustments if warranted. A total of 186 veterans underwent a liraglutide dose reduction between May and August 2018. Thirty-two veterans were without active insulin prescriptions, 53 were without HbA1c results, and 4 veterans died; resulting in 97 veterans who were included in the study (Figure 1).

Most of the patients included in the study were male (90.7%) and White (63.9%) with an average (SD) age of 65.9 years (7.9) and a mean (SD) HbA1c at baseline of 8.4% (1.2). About 56.7% received concurrent T2DM treatment with metformin, and 8.3% received concurrent treatment with empagliflozin. The most common cardiovascular disease/risk factors included hypertension (93.8%), hyperlipidemia (85.6%), and obesity (85.6%) (Table 1).

Glycemic Control and Weight Loss

At the time of conversion, the average (SD) HbA1c was 8.2% (1.4) and increased to an average (SD) of 8.7% (1.8) (P =.0005) 6 months after the dose reduction (Table 2). The average (SD) body weight was 116.2 kg (23.2) at time of conversion and increased to 116.5 (24.6) 6 months following the dose reduction; however, the difference was not statistically significant (P = .8).

As a result of the HbA1c change, 41.2% of veterans underwent an insulin dose increase with dose increase of 5 to 200 units of total daily insulin during the 6-month period. Antihyperglycemic regimen remained unchanged for 40.2% of veterans, while additional glucose lowering agents were initiated in 6 veterans. Medications initiated included empagliflozin in 4 veterans and saxagliptin in 2 veterans.

HbA1c reduction was noted in 33% of veterans (Figure 2) mostly due to improved diet and exercise habits. A majority of veterans, 62%, experienced an increase in HbA1c, whereas 5.2% of veterans maintained the same HbA1c. Of 60 veterans with HbA1c increases, 15 had an increase between 0.1% and 0.5%, another 15 with an increase between 0.5 to 0.9%, and half had HbA1c increases of at least 1% with a maximum increase of 5.1% (Figure 3).

Cost Savings

Cost information was obtained from the VA Drug Price Database. The estimated monthly cost savings per patient associated with the conversion from 3-count to 2-count injection pen packs of liraglutide 6 mg/mL was $103.46. With 186 veterans converted to the 2-count pen packs, MEDVAMC saved $115,461.36 in a 6-month period. The estimated annualized cost savings was estimated to be about $231,000 (Figure 4).

Adverse Effects During the 6-month period following the dose conversion, no major AEs associated with liraglutide were documented. Documented AEs included 3 cases of diarrhea, resulting in the discontinuation of metformin. Metformin also was discontinued in a veteran with worsened renal function and eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Discussion

According to previous clinical trials, when used in combination with insulin, 1.2 mg and 1.8 mg daily liraglutide showed significant improvement in glycemic control and body weight and was associated with decreased insulin requirements.4-6 However, subgroup analyses were not performed to show differences in benefit between the liraglutide 1.8 mg and 1.2 mg groups.4-6 Similarly, cardiovascular benefit was observed in patients receiving liraglutide 1.2 mg daily and liraglutide 1.8 mg daily in the LEADER trial with no subgroup analysis or distinction between treatment doses.3 With this information and approval by the Veterans Integrated Services Network, the pharmacoeconomics team at MEDVAMC made the decision to select a more cost-efficient preparation and, hence, lower dose of liraglutide.

To ensure that patients only taking liraglutide for glycemic control were captured, patients without insulin therapies at baseline were excluded. Due to concerns of potential off-label use of liraglutide for weight loss, patients without active prescriptions for insulin at baseline were excluded.

A mean HbA1c increase of 0.5% was observed over the 6-month period, supporting findings of a dose-dependent HbA1c decrease observed in clinical trials. In the LEAD-3 MONO trial when used as monotherapy, liraglutide 1.8 mg was associated with significantly greater HbA1c reduction than liraglutide 1.2 mg (–0·29%; –0·50 to –0.09, P = .005) after 52 weeks of treatment.7 Liraglutide 1.8 mg was also associated with higher rates of AEs; particularly gastrointestinal. 7 To minimize these AEs, it is recommended to initiate liraglutide at 0.6 mg daily for a week then increase to 1.2 mg daily. If tolerated, liraglutide can be further titrated to 1.8 mg daily to optimize glycemic control.8 Unsurprisingly, no major AEs were noted in this study, as AEs are typically noted with increased doses.

Despite the observed trend of increased HbA1c, no changes were made to glucoselowering agents in 39 veterans. This group of veterans consisted primarily of those whose HbA1c remained unchanged during the 6-month period, those whose HbA1c improved (with no documented hypoglycemia), and older veterans with less stringent HbA1c goals. As a result, doses of glucose lowering agents were maintained as appropriate.

No significant difference was noted in body weight during the 6-month period. The slight weight gain observed may have been due to several factors. Lack of exercise and dietary changes may have contributed to weight gain. In addition, insulin doses were increased in 40 veterans, which may have contributed to the observed weight gain.

As expected, significant cost savings were achieved as a result of the liraglutide dose reduction. Of note, liraglutide was discontinued in 126 veterans (prior to the dose reduction) due to nonadherence or inadequate response to therapy, which also resulted in additional savings. Although cost savings was achieved, the long-term benefit of this initiative still remains unknown. The worsened glycemic control that was detected may increase the risk of microvascular and macrovascular complications, thereby negating cost savings achieved. To assess this effect, longterm prospective studies are warranted.

Limitations

A number of issues limit these finding, including its retrospective data review, small sample size, additional factors contributing to HbA1c increase, and missing documentation in some patient records. Only 97 patients were included in the study, reflecting less than half of the charts reviewed (52% exclusion rate). In addition, several confounding factors may have contributed to the increased HbA1c observed. Medication changes and lifestyle factors may have contributed to the observed change in HbA1c levels. Exclusion of patients without active prescriptions for insulin may have contributed to a selection bias, as most patients included in the study were veterans with uncontrolled T2DM requiring insulin. Finally, as a retrospective study involving patient records, investigators relied heavily on information provided in patients’ charts (HbA1c, body weight, insulin doses, adverse effects, etc), which may not entirely be accurate and may have been missing other pertinent information.

Conclusions

The daily dose reduction of liraglutide from 1.8 mg to 1.2 mg due to a cost-savings initiative resulted in a HbA1c increase of 0.5% in a 6-month period. Due to HbA1c increases, 41.2% of veterans underwent an insulin dose increase, negating the insulin-sparing role of liraglutide. Although this study further confirms the dose-dependent HbA1c reduction with liraglutide that has been noted in previous trials, long-term prospective studies and cost-effectiveness analyses are warranted to assess the overall clinical significance and other benefits of the change, including its effects on cardiovascular outcomes.

1. American Diabetes Association. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(suppl 1):S90-S102. doi:10.2337/dc19-S009

2. Hinnen D. Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Spectr. 2017;30(3):202-210. doi:10.2337/ds16-0026

3. Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen K, et al. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(4):311-322. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1603827

4. Lane W, Weinrib S, Rappaport J, Hale C. The effect of addition of liraglutide to high-dose intensive insulin therapy: a randomized prospective trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2014;16(9):827-832. doi:10.1111/dom.12286

5. Ahmann A, Rodbard HW, Rosenstock J, et al. Efficacy and safety of liraglutide versus placebo added to basal insulin analogues (with or without metformin) in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;17(11):1056-1064. doi:10.1111/dom.12539

6. Lane W, Weinrib S, Rappaport J. The effect of liraglutide added to U-500 insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes and high insulin requirements. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2011;13(5):592-595. doi:10.1089/dia.2010.0221

7. Garber A, Henry R, Ratner R, et al. Liraglutide versus glimepiride monotherapy for type 2 diabetes (LEAD-3 Mono): a randomised, 52-week, phase III, double-blind, parallel-treatment trial. Lancet. 2009;373(9662):473-481. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61246-5.

8. Victoza [package insert]. Princeton: Novo Nordisk Inc; 2020.

1. American Diabetes Association. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(suppl 1):S90-S102. doi:10.2337/dc19-S009

2. Hinnen D. Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Spectr. 2017;30(3):202-210. doi:10.2337/ds16-0026

3. Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen K, et al. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(4):311-322. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1603827

4. Lane W, Weinrib S, Rappaport J, Hale C. The effect of addition of liraglutide to high-dose intensive insulin therapy: a randomized prospective trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2014;16(9):827-832. doi:10.1111/dom.12286

5. Ahmann A, Rodbard HW, Rosenstock J, et al. Efficacy and safety of liraglutide versus placebo added to basal insulin analogues (with or without metformin) in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;17(11):1056-1064. doi:10.1111/dom.12539

6. Lane W, Weinrib S, Rappaport J. The effect of liraglutide added to U-500 insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes and high insulin requirements. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2011;13(5):592-595. doi:10.1089/dia.2010.0221

7. Garber A, Henry R, Ratner R, et al. Liraglutide versus glimepiride monotherapy for type 2 diabetes (LEAD-3 Mono): a randomised, 52-week, phase III, double-blind, parallel-treatment trial. Lancet. 2009;373(9662):473-481. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61246-5.

8. Victoza [package insert]. Princeton: Novo Nordisk Inc; 2020.