User login

Spontaneous Retroperitoneal Hematoma

A 56‐year‐old male presented to the emergency department with a 2‐week history of increasing abdominal girth, nausea, vomiting, and lower extremity edema. His girlfriend had also noted a yellow tinge to his skin and eyes. His past medical history was significant for bipolar disorder, alcohol‐related seizures, and pneumonia. He had no allergies and denied medications prior to admission. Family history was negative for liver disease and social history was notable for ongoing tobacco use and alcohol dependence. He was afebrile with stable vital signs. Physical examination demonstrated an alert gentleman whose answers to questions required occasional factual correction by his partner. His abdomen was distended and nontender with prominent vasculature and shifting dullness. Lower extremity edema was symmetric and bilateral, rated as 2+. Scattered spider angiomata and a fine bilateral hand tremor without asterixis were also noted. Initial laboratory data demonstrated a white blood cell count of 13,900/L, hematocrit 37%, and platelet count 176,000/L. His sodium was 130 mg/dL, blood urea nitrogen (BUN) 1 mg/dL, and creatinine 0.7 mg/dL. International normalized ratio (INR) was 1.8, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) was 117 U/L, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 33 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 191 U/L, total bilirubin 9.2 mg/dL, total protein 7.0 g/dL, and albumin 1.9 g/dL. Abdominal ultrasound revealed a diffusely hyperechoic liver with a large amount of ascites.

The patient was admitted with the diagnoses of presumed alcoholic hepatitis and end‐stage liver disease. Model for End‐Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score was 21 and discriminant function 16.8. Paracentesis demonstrated a serum‐ascites albumin gradient of >1.1 and no evidence of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Diuresis was initiated. He was placed on unfractionated heparin at a dose of 5000 units every 8 hours for deep venous thrombosis (DVT) prophylaxis. By hospital day 3, the patient's laboratory values had improved, yet his stay was prolonged by alcohol withdrawal requiring benzodiazepines, altered mental status presumed secondary to hepatic encephalopathy, acute renal failure, aspiration pneumonia, and persistent unexplained leukocytosis. He required medical restraints during this time given confusion and propensity to ambulate without assistance, yet sustained no falls or other known trauma in care delivered during this time.

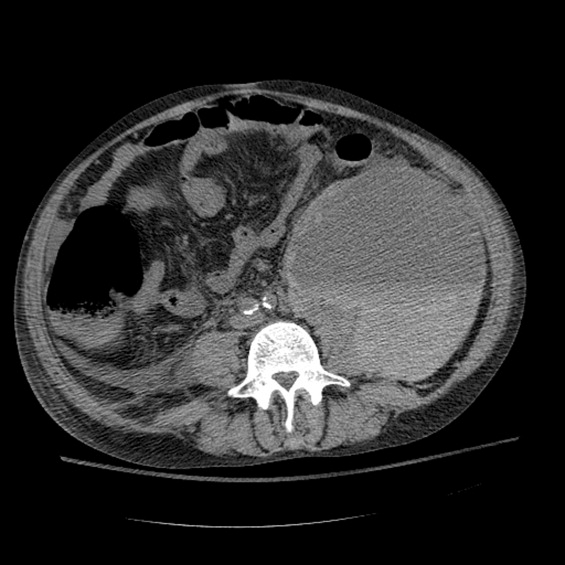

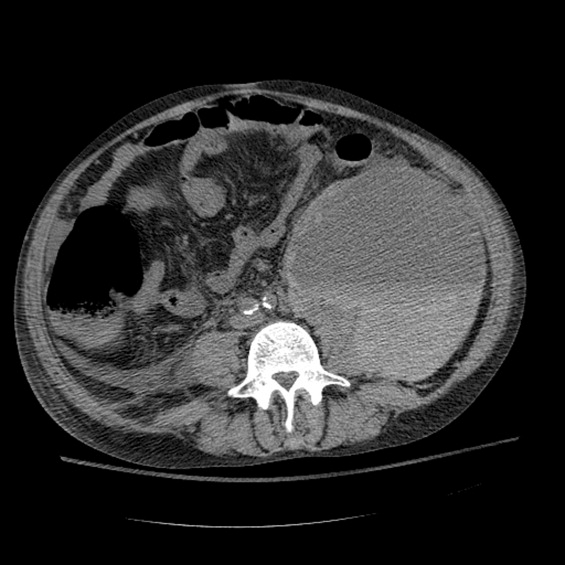

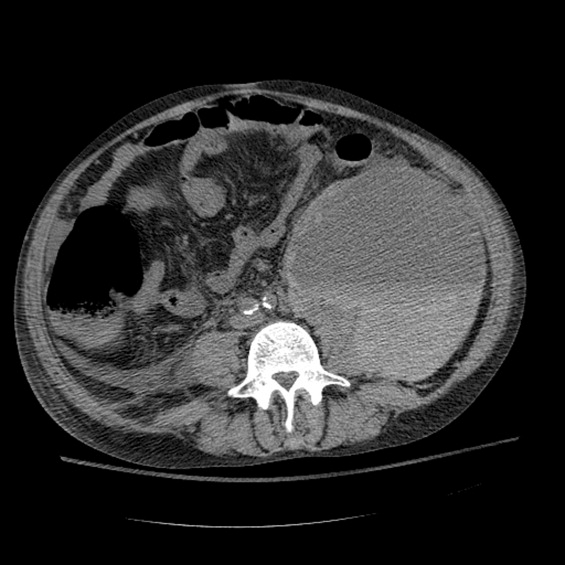

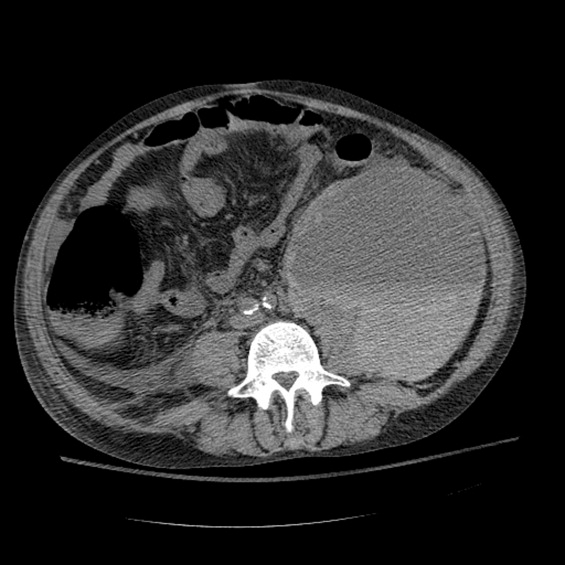

Between days 14 and 17, the patient's hematocrit fell from 36% to 30%; vital signs remained stable. He underwent an uncomplicated, ultrasound‐guided therapeutic paracentesis, which yielded 1.4 L of straw‐colored fluid on the afternoon of day 17; the procedure was attempted only on the right side. On the morning of day 18, the patient's blood pressure dropped to 78/55 mmHg with a pulse of 123 beats per minute; he became pale and unresponsive. Physical examination was notable for somnolence and a tender, warm left flank mass, contralateral to his paracentesis site. No flank or periumbilical ecchymoses were identified. Complete blood count demonstrated a white blood count (WBC) of 22,970/L, hematocrit 16%, and platelet count 104,000/L. INR was 2.0, unchanged from the last check on day 10. Partial thromboplastin time was 41 seconds and fibrinogen was 293 mg/dL (normal 150‐400 mg/dL). Peripheral blood smear was negative for red cell fragments. Blood chemistries revealed a sodium of 134 mg/dL, bicarbonate 20 mEq/L, anion gap 7, BUN 24 mg/dL, and creatinine 1.6 mg/dL (up from 1.0 mg/dL the previous day). His venous lactate level was 4.6 mmol/L and arterial blood gas sampling on room air demonstrated a pH of 7.35, partial pressure of carbon dioxide (pCO2) 29 mmHg, partial pressure of oxygen (pCO2) 54 mmHg, and bicarbonate 15 mEq/L. A femoral introducer was placed for volume resuscitation and the patient was urgently transfused with packed red blood cells (PRBCs) and fresh‐frozen plasma (FFP) to correct his coagulopathy. Computed tomography of the abdomen revealed a large left retroperitoneal hematoma measuring 15 15 22 cm3 (Figure 1). Despite transfusion, his hematocrit continued to fall. Urgent angiography was performed, upon which he was found to have active bleeding from the left L3‐L5 lumbar arteries. These were successfully embolized. He required PRBCs and FFP transfusion only once following this procedure. Given a transient decrease in his urine output, his bladder pressures were followed closely for evidence of abdominal compartment syndrome, which did not develop. He was transferred from the intensive care unit (ICU) to the floor on day 20, where his physical exam and hematocrit remained stable and his delirium slowly cleared. He was ultimately discharged to a skilled nursing facility on day 33.

Discussion

Spontaneous retroperitoneal hematoma is a well‐recognized entity that may present with the classic triad of abdominal or groin pain, palpable abdominal or flank mass, and shock or lower extremity motor or sensory changes due to femoral nerve compression.1 Although classically described as skin findings associated with retroperitoneal hemorrhage, Cullen and Grey‐Turner signs are relatively late findings that may not develop in all patients.

Retroperitoneal hemorrhage is well‐recognized as a result of iatrogenic anticoagulation,1 but has been reported less commonly as a result of coagulopathy related to cirrhosis. Di Bisceglie and Richart2 describe 2 patients with MELD scores of 29 and 25, respectively, who developed spontaneous retroperitoneal and rectus muscle hemorrhage. Both had evidence of associated disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) and died. Even less common is spontaneous lumbar artery rupture, occurring rarely in the absence of trauma or instrumentation. One reported bleed developed in the context of systemic anticoagulation for a mechanical valve.3 Halak et al.4 relate a case in which the only known risk factor was chronic renal disease. Hama et al.5 describe a patient with a history of alcoholic liver cirrhosis and INR of 2.3 whose lumbar artery rupture was successfully managed with transcatheter arterial embolization.

It is difficult to ascertain the effect of prophylactic anticoagulation in development of this particular hemorrhage. Retroperitoneal bleeding is a very rare complication of pharmacologic prophylaxis for DVT reported with both low‐molecular weight and unfractionated heparins.6 There may be additive risk of prophylaxis in a cirrhotic patient with baseline elevated INR and thrombocytopenia, particularly in the context of renal failure.

Options in the management of spontaneous retroperitoneal hematoma include transarterial embolization, percutaneous decompression, and open surgery. Nonoperative management of these bleeds when possible may be preferable in cirrhotic patients, as their baseline liver disease renders them higher‐risk candidates for surgery. There are no randomized trials comparing these approaches.1

In summary, we report the case of a 56‐year‐old man with end‐stage liver disease and associated coagulopathy without evidence of DIC who survived to discharge with intravascular management of a spontaneous retroperitoneal hemorrhage from the lumbar arteries. To our knowledge, this is the second reported case of spontaneous retroperitoneal hemorrhage in a cirrhotic in which the lumbar arteries were implicated and the first in which multiple arteries were found to be bleeding simultaneously. Any hospitalized patient who develops abdominal pain, flank pain, or hemodynamic instability in the context of coagulopathy, regardless of cause, warrants evaluation for retroperitoneal bleed. Appropriate early management includes immediate resuscitation, intensive monitoring, urgent imaging, and surgical and interventional radiology consultation in order to prevent a fatal outcome.

- ,,,.Management of spontaneous and iatrogenic retroperitoneal haemorrhage: conservative management, endovascular intervention or open surgery?Int J Clin Pract.2007;62:1604–1613.

- ,.Spontaneous retroperitoneal and rectus muscle hemorrhage as a potentially lethal complication of cirrhosis.Liver Int.2006;26:1291–1293.

- ,,.Spontaneous rupture of a lumbar artery. A rare etiology of retroperitoneal hematoma.Urologe A.2003;42:840–844.

- ,,,,.Spontaneous ruptured lumbar artery in a chronic renal failure patient.Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg.2001;21:569–571.

- ,,.Spontaneous rupture of the lumbar artery.Intern Med.2004;43:759.

- ,,.The rate of bleeding complications after pharmacologic deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis.Arch Surg.2006;141:790–799.

A 56‐year‐old male presented to the emergency department with a 2‐week history of increasing abdominal girth, nausea, vomiting, and lower extremity edema. His girlfriend had also noted a yellow tinge to his skin and eyes. His past medical history was significant for bipolar disorder, alcohol‐related seizures, and pneumonia. He had no allergies and denied medications prior to admission. Family history was negative for liver disease and social history was notable for ongoing tobacco use and alcohol dependence. He was afebrile with stable vital signs. Physical examination demonstrated an alert gentleman whose answers to questions required occasional factual correction by his partner. His abdomen was distended and nontender with prominent vasculature and shifting dullness. Lower extremity edema was symmetric and bilateral, rated as 2+. Scattered spider angiomata and a fine bilateral hand tremor without asterixis were also noted. Initial laboratory data demonstrated a white blood cell count of 13,900/L, hematocrit 37%, and platelet count 176,000/L. His sodium was 130 mg/dL, blood urea nitrogen (BUN) 1 mg/dL, and creatinine 0.7 mg/dL. International normalized ratio (INR) was 1.8, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) was 117 U/L, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 33 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 191 U/L, total bilirubin 9.2 mg/dL, total protein 7.0 g/dL, and albumin 1.9 g/dL. Abdominal ultrasound revealed a diffusely hyperechoic liver with a large amount of ascites.

The patient was admitted with the diagnoses of presumed alcoholic hepatitis and end‐stage liver disease. Model for End‐Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score was 21 and discriminant function 16.8. Paracentesis demonstrated a serum‐ascites albumin gradient of >1.1 and no evidence of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Diuresis was initiated. He was placed on unfractionated heparin at a dose of 5000 units every 8 hours for deep venous thrombosis (DVT) prophylaxis. By hospital day 3, the patient's laboratory values had improved, yet his stay was prolonged by alcohol withdrawal requiring benzodiazepines, altered mental status presumed secondary to hepatic encephalopathy, acute renal failure, aspiration pneumonia, and persistent unexplained leukocytosis. He required medical restraints during this time given confusion and propensity to ambulate without assistance, yet sustained no falls or other known trauma in care delivered during this time.

Between days 14 and 17, the patient's hematocrit fell from 36% to 30%; vital signs remained stable. He underwent an uncomplicated, ultrasound‐guided therapeutic paracentesis, which yielded 1.4 L of straw‐colored fluid on the afternoon of day 17; the procedure was attempted only on the right side. On the morning of day 18, the patient's blood pressure dropped to 78/55 mmHg with a pulse of 123 beats per minute; he became pale and unresponsive. Physical examination was notable for somnolence and a tender, warm left flank mass, contralateral to his paracentesis site. No flank or periumbilical ecchymoses were identified. Complete blood count demonstrated a white blood count (WBC) of 22,970/L, hematocrit 16%, and platelet count 104,000/L. INR was 2.0, unchanged from the last check on day 10. Partial thromboplastin time was 41 seconds and fibrinogen was 293 mg/dL (normal 150‐400 mg/dL). Peripheral blood smear was negative for red cell fragments. Blood chemistries revealed a sodium of 134 mg/dL, bicarbonate 20 mEq/L, anion gap 7, BUN 24 mg/dL, and creatinine 1.6 mg/dL (up from 1.0 mg/dL the previous day). His venous lactate level was 4.6 mmol/L and arterial blood gas sampling on room air demonstrated a pH of 7.35, partial pressure of carbon dioxide (pCO2) 29 mmHg, partial pressure of oxygen (pCO2) 54 mmHg, and bicarbonate 15 mEq/L. A femoral introducer was placed for volume resuscitation and the patient was urgently transfused with packed red blood cells (PRBCs) and fresh‐frozen plasma (FFP) to correct his coagulopathy. Computed tomography of the abdomen revealed a large left retroperitoneal hematoma measuring 15 15 22 cm3 (Figure 1). Despite transfusion, his hematocrit continued to fall. Urgent angiography was performed, upon which he was found to have active bleeding from the left L3‐L5 lumbar arteries. These were successfully embolized. He required PRBCs and FFP transfusion only once following this procedure. Given a transient decrease in his urine output, his bladder pressures were followed closely for evidence of abdominal compartment syndrome, which did not develop. He was transferred from the intensive care unit (ICU) to the floor on day 20, where his physical exam and hematocrit remained stable and his delirium slowly cleared. He was ultimately discharged to a skilled nursing facility on day 33.

Discussion

Spontaneous retroperitoneal hematoma is a well‐recognized entity that may present with the classic triad of abdominal or groin pain, palpable abdominal or flank mass, and shock or lower extremity motor or sensory changes due to femoral nerve compression.1 Although classically described as skin findings associated with retroperitoneal hemorrhage, Cullen and Grey‐Turner signs are relatively late findings that may not develop in all patients.

Retroperitoneal hemorrhage is well‐recognized as a result of iatrogenic anticoagulation,1 but has been reported less commonly as a result of coagulopathy related to cirrhosis. Di Bisceglie and Richart2 describe 2 patients with MELD scores of 29 and 25, respectively, who developed spontaneous retroperitoneal and rectus muscle hemorrhage. Both had evidence of associated disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) and died. Even less common is spontaneous lumbar artery rupture, occurring rarely in the absence of trauma or instrumentation. One reported bleed developed in the context of systemic anticoagulation for a mechanical valve.3 Halak et al.4 relate a case in which the only known risk factor was chronic renal disease. Hama et al.5 describe a patient with a history of alcoholic liver cirrhosis and INR of 2.3 whose lumbar artery rupture was successfully managed with transcatheter arterial embolization.

It is difficult to ascertain the effect of prophylactic anticoagulation in development of this particular hemorrhage. Retroperitoneal bleeding is a very rare complication of pharmacologic prophylaxis for DVT reported with both low‐molecular weight and unfractionated heparins.6 There may be additive risk of prophylaxis in a cirrhotic patient with baseline elevated INR and thrombocytopenia, particularly in the context of renal failure.

Options in the management of spontaneous retroperitoneal hematoma include transarterial embolization, percutaneous decompression, and open surgery. Nonoperative management of these bleeds when possible may be preferable in cirrhotic patients, as their baseline liver disease renders them higher‐risk candidates for surgery. There are no randomized trials comparing these approaches.1

In summary, we report the case of a 56‐year‐old man with end‐stage liver disease and associated coagulopathy without evidence of DIC who survived to discharge with intravascular management of a spontaneous retroperitoneal hemorrhage from the lumbar arteries. To our knowledge, this is the second reported case of spontaneous retroperitoneal hemorrhage in a cirrhotic in which the lumbar arteries were implicated and the first in which multiple arteries were found to be bleeding simultaneously. Any hospitalized patient who develops abdominal pain, flank pain, or hemodynamic instability in the context of coagulopathy, regardless of cause, warrants evaluation for retroperitoneal bleed. Appropriate early management includes immediate resuscitation, intensive monitoring, urgent imaging, and surgical and interventional radiology consultation in order to prevent a fatal outcome.

A 56‐year‐old male presented to the emergency department with a 2‐week history of increasing abdominal girth, nausea, vomiting, and lower extremity edema. His girlfriend had also noted a yellow tinge to his skin and eyes. His past medical history was significant for bipolar disorder, alcohol‐related seizures, and pneumonia. He had no allergies and denied medications prior to admission. Family history was negative for liver disease and social history was notable for ongoing tobacco use and alcohol dependence. He was afebrile with stable vital signs. Physical examination demonstrated an alert gentleman whose answers to questions required occasional factual correction by his partner. His abdomen was distended and nontender with prominent vasculature and shifting dullness. Lower extremity edema was symmetric and bilateral, rated as 2+. Scattered spider angiomata and a fine bilateral hand tremor without asterixis were also noted. Initial laboratory data demonstrated a white blood cell count of 13,900/L, hematocrit 37%, and platelet count 176,000/L. His sodium was 130 mg/dL, blood urea nitrogen (BUN) 1 mg/dL, and creatinine 0.7 mg/dL. International normalized ratio (INR) was 1.8, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) was 117 U/L, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 33 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 191 U/L, total bilirubin 9.2 mg/dL, total protein 7.0 g/dL, and albumin 1.9 g/dL. Abdominal ultrasound revealed a diffusely hyperechoic liver with a large amount of ascites.

The patient was admitted with the diagnoses of presumed alcoholic hepatitis and end‐stage liver disease. Model for End‐Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score was 21 and discriminant function 16.8. Paracentesis demonstrated a serum‐ascites albumin gradient of >1.1 and no evidence of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Diuresis was initiated. He was placed on unfractionated heparin at a dose of 5000 units every 8 hours for deep venous thrombosis (DVT) prophylaxis. By hospital day 3, the patient's laboratory values had improved, yet his stay was prolonged by alcohol withdrawal requiring benzodiazepines, altered mental status presumed secondary to hepatic encephalopathy, acute renal failure, aspiration pneumonia, and persistent unexplained leukocytosis. He required medical restraints during this time given confusion and propensity to ambulate without assistance, yet sustained no falls or other known trauma in care delivered during this time.

Between days 14 and 17, the patient's hematocrit fell from 36% to 30%; vital signs remained stable. He underwent an uncomplicated, ultrasound‐guided therapeutic paracentesis, which yielded 1.4 L of straw‐colored fluid on the afternoon of day 17; the procedure was attempted only on the right side. On the morning of day 18, the patient's blood pressure dropped to 78/55 mmHg with a pulse of 123 beats per minute; he became pale and unresponsive. Physical examination was notable for somnolence and a tender, warm left flank mass, contralateral to his paracentesis site. No flank or periumbilical ecchymoses were identified. Complete blood count demonstrated a white blood count (WBC) of 22,970/L, hematocrit 16%, and platelet count 104,000/L. INR was 2.0, unchanged from the last check on day 10. Partial thromboplastin time was 41 seconds and fibrinogen was 293 mg/dL (normal 150‐400 mg/dL). Peripheral blood smear was negative for red cell fragments. Blood chemistries revealed a sodium of 134 mg/dL, bicarbonate 20 mEq/L, anion gap 7, BUN 24 mg/dL, and creatinine 1.6 mg/dL (up from 1.0 mg/dL the previous day). His venous lactate level was 4.6 mmol/L and arterial blood gas sampling on room air demonstrated a pH of 7.35, partial pressure of carbon dioxide (pCO2) 29 mmHg, partial pressure of oxygen (pCO2) 54 mmHg, and bicarbonate 15 mEq/L. A femoral introducer was placed for volume resuscitation and the patient was urgently transfused with packed red blood cells (PRBCs) and fresh‐frozen plasma (FFP) to correct his coagulopathy. Computed tomography of the abdomen revealed a large left retroperitoneal hematoma measuring 15 15 22 cm3 (Figure 1). Despite transfusion, his hematocrit continued to fall. Urgent angiography was performed, upon which he was found to have active bleeding from the left L3‐L5 lumbar arteries. These were successfully embolized. He required PRBCs and FFP transfusion only once following this procedure. Given a transient decrease in his urine output, his bladder pressures were followed closely for evidence of abdominal compartment syndrome, which did not develop. He was transferred from the intensive care unit (ICU) to the floor on day 20, where his physical exam and hematocrit remained stable and his delirium slowly cleared. He was ultimately discharged to a skilled nursing facility on day 33.

Discussion

Spontaneous retroperitoneal hematoma is a well‐recognized entity that may present with the classic triad of abdominal or groin pain, palpable abdominal or flank mass, and shock or lower extremity motor or sensory changes due to femoral nerve compression.1 Although classically described as skin findings associated with retroperitoneal hemorrhage, Cullen and Grey‐Turner signs are relatively late findings that may not develop in all patients.

Retroperitoneal hemorrhage is well‐recognized as a result of iatrogenic anticoagulation,1 but has been reported less commonly as a result of coagulopathy related to cirrhosis. Di Bisceglie and Richart2 describe 2 patients with MELD scores of 29 and 25, respectively, who developed spontaneous retroperitoneal and rectus muscle hemorrhage. Both had evidence of associated disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) and died. Even less common is spontaneous lumbar artery rupture, occurring rarely in the absence of trauma or instrumentation. One reported bleed developed in the context of systemic anticoagulation for a mechanical valve.3 Halak et al.4 relate a case in which the only known risk factor was chronic renal disease. Hama et al.5 describe a patient with a history of alcoholic liver cirrhosis and INR of 2.3 whose lumbar artery rupture was successfully managed with transcatheter arterial embolization.

It is difficult to ascertain the effect of prophylactic anticoagulation in development of this particular hemorrhage. Retroperitoneal bleeding is a very rare complication of pharmacologic prophylaxis for DVT reported with both low‐molecular weight and unfractionated heparins.6 There may be additive risk of prophylaxis in a cirrhotic patient with baseline elevated INR and thrombocytopenia, particularly in the context of renal failure.

Options in the management of spontaneous retroperitoneal hematoma include transarterial embolization, percutaneous decompression, and open surgery. Nonoperative management of these bleeds when possible may be preferable in cirrhotic patients, as their baseline liver disease renders them higher‐risk candidates for surgery. There are no randomized trials comparing these approaches.1

In summary, we report the case of a 56‐year‐old man with end‐stage liver disease and associated coagulopathy without evidence of DIC who survived to discharge with intravascular management of a spontaneous retroperitoneal hemorrhage from the lumbar arteries. To our knowledge, this is the second reported case of spontaneous retroperitoneal hemorrhage in a cirrhotic in which the lumbar arteries were implicated and the first in which multiple arteries were found to be bleeding simultaneously. Any hospitalized patient who develops abdominal pain, flank pain, or hemodynamic instability in the context of coagulopathy, regardless of cause, warrants evaluation for retroperitoneal bleed. Appropriate early management includes immediate resuscitation, intensive monitoring, urgent imaging, and surgical and interventional radiology consultation in order to prevent a fatal outcome.

- ,,,.Management of spontaneous and iatrogenic retroperitoneal haemorrhage: conservative management, endovascular intervention or open surgery?Int J Clin Pract.2007;62:1604–1613.

- ,.Spontaneous retroperitoneal and rectus muscle hemorrhage as a potentially lethal complication of cirrhosis.Liver Int.2006;26:1291–1293.

- ,,.Spontaneous rupture of a lumbar artery. A rare etiology of retroperitoneal hematoma.Urologe A.2003;42:840–844.

- ,,,,.Spontaneous ruptured lumbar artery in a chronic renal failure patient.Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg.2001;21:569–571.

- ,,.Spontaneous rupture of the lumbar artery.Intern Med.2004;43:759.

- ,,.The rate of bleeding complications after pharmacologic deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis.Arch Surg.2006;141:790–799.

- ,,,.Management of spontaneous and iatrogenic retroperitoneal haemorrhage: conservative management, endovascular intervention or open surgery?Int J Clin Pract.2007;62:1604–1613.

- ,.Spontaneous retroperitoneal and rectus muscle hemorrhage as a potentially lethal complication of cirrhosis.Liver Int.2006;26:1291–1293.

- ,,.Spontaneous rupture of a lumbar artery. A rare etiology of retroperitoneal hematoma.Urologe A.2003;42:840–844.

- ,,,,.Spontaneous ruptured lumbar artery in a chronic renal failure patient.Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg.2001;21:569–571.

- ,,.Spontaneous rupture of the lumbar artery.Intern Med.2004;43:759.

- ,,.The rate of bleeding complications after pharmacologic deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis.Arch Surg.2006;141:790–799.

Incisional Iliac Hernia

A 61‐year‐old woman presented with 1 month of abdominal pain and bowel irregularity. Physical examination was normal. Computed tomography of the abdomen demonstrated a nonincarcerated hernia of the ascending colon through a 25‐mm bony defect in the superior aspect of the right iliac crest (Figure 1)a defect created 16 years prior when iliac crest bone graft harvest was performed during subtalar fusion. An open surgical approach was employed to reduce the hernia and close the defect with mesh. Her postoperative course was unremarkable. Her symptoms resolved entirely.

The iliac crest is the site utilized most frequently in orthopedic surgery for bone graft harvest. The literature suggests that up to 5% of these procedures may be complicated by symptomatic herniation of abdominal contents.1 Other procedural complications include: donor site pain, nerve injury (commonly the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, manifesting as meralgia paresthetica), vascular disruption (including superior gluteal and lumbar arteries), hematoma, visible deformity, abnormal gait, and stress fracture.2, 3 Advanced age, obesity, muscular weakness, larger defect size, and full‐thickness harvest have been identified as risk factors.4 The hernia often presents as a soft‐tissue mass originating at the defect site, which may become more pronounced with cough. Auscultation over the area may reveal bowel sounds. The spectrum of associated abdominal symptoms ranges from mild discomfort to colicky pain and distention;3 up to 16% of patients present with acute signs of intestinal obstruction.1 Iliac herniation may be prevented by harvest of a partial thickness graft, whenever possible. Selective removal of bone from the anterior or posterior crest, rather than the middle, may also decrease the risk.4 Clinicians caring for patients with a history of iliac crest bone graft harvest should be familiar with this complication and consider prompt radiologic imaging when investigating new or unexplained abdominal symptoms.

- ,,,.Hernia through iliac crest defects.Int Orthop.1995;19:367–369.

- ,,.Harvesting autogenous iliac bone grafts: a review of complications and techniques.Spine.1989;14:1324–1331.

- ,,,.Hernia through an iliac crest bone graft site: report of a case and review of the literature.Bull Hosp Jt Dis.2006;63:166–168.

- ,.Incisional hernia through iliac crest defects.Arch Orthop Trauma Surg.1989;108:383–385.

A 61‐year‐old woman presented with 1 month of abdominal pain and bowel irregularity. Physical examination was normal. Computed tomography of the abdomen demonstrated a nonincarcerated hernia of the ascending colon through a 25‐mm bony defect in the superior aspect of the right iliac crest (Figure 1)a defect created 16 years prior when iliac crest bone graft harvest was performed during subtalar fusion. An open surgical approach was employed to reduce the hernia and close the defect with mesh. Her postoperative course was unremarkable. Her symptoms resolved entirely.

The iliac crest is the site utilized most frequently in orthopedic surgery for bone graft harvest. The literature suggests that up to 5% of these procedures may be complicated by symptomatic herniation of abdominal contents.1 Other procedural complications include: donor site pain, nerve injury (commonly the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, manifesting as meralgia paresthetica), vascular disruption (including superior gluteal and lumbar arteries), hematoma, visible deformity, abnormal gait, and stress fracture.2, 3 Advanced age, obesity, muscular weakness, larger defect size, and full‐thickness harvest have been identified as risk factors.4 The hernia often presents as a soft‐tissue mass originating at the defect site, which may become more pronounced with cough. Auscultation over the area may reveal bowel sounds. The spectrum of associated abdominal symptoms ranges from mild discomfort to colicky pain and distention;3 up to 16% of patients present with acute signs of intestinal obstruction.1 Iliac herniation may be prevented by harvest of a partial thickness graft, whenever possible. Selective removal of bone from the anterior or posterior crest, rather than the middle, may also decrease the risk.4 Clinicians caring for patients with a history of iliac crest bone graft harvest should be familiar with this complication and consider prompt radiologic imaging when investigating new or unexplained abdominal symptoms.

A 61‐year‐old woman presented with 1 month of abdominal pain and bowel irregularity. Physical examination was normal. Computed tomography of the abdomen demonstrated a nonincarcerated hernia of the ascending colon through a 25‐mm bony defect in the superior aspect of the right iliac crest (Figure 1)a defect created 16 years prior when iliac crest bone graft harvest was performed during subtalar fusion. An open surgical approach was employed to reduce the hernia and close the defect with mesh. Her postoperative course was unremarkable. Her symptoms resolved entirely.

The iliac crest is the site utilized most frequently in orthopedic surgery for bone graft harvest. The literature suggests that up to 5% of these procedures may be complicated by symptomatic herniation of abdominal contents.1 Other procedural complications include: donor site pain, nerve injury (commonly the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, manifesting as meralgia paresthetica), vascular disruption (including superior gluteal and lumbar arteries), hematoma, visible deformity, abnormal gait, and stress fracture.2, 3 Advanced age, obesity, muscular weakness, larger defect size, and full‐thickness harvest have been identified as risk factors.4 The hernia often presents as a soft‐tissue mass originating at the defect site, which may become more pronounced with cough. Auscultation over the area may reveal bowel sounds. The spectrum of associated abdominal symptoms ranges from mild discomfort to colicky pain and distention;3 up to 16% of patients present with acute signs of intestinal obstruction.1 Iliac herniation may be prevented by harvest of a partial thickness graft, whenever possible. Selective removal of bone from the anterior or posterior crest, rather than the middle, may also decrease the risk.4 Clinicians caring for patients with a history of iliac crest bone graft harvest should be familiar with this complication and consider prompt radiologic imaging when investigating new or unexplained abdominal symptoms.

- ,,,.Hernia through iliac crest defects.Int Orthop.1995;19:367–369.

- ,,.Harvesting autogenous iliac bone grafts: a review of complications and techniques.Spine.1989;14:1324–1331.

- ,,,.Hernia through an iliac crest bone graft site: report of a case and review of the literature.Bull Hosp Jt Dis.2006;63:166–168.

- ,.Incisional hernia through iliac crest defects.Arch Orthop Trauma Surg.1989;108:383–385.

- ,,,.Hernia through iliac crest defects.Int Orthop.1995;19:367–369.

- ,,.Harvesting autogenous iliac bone grafts: a review of complications and techniques.Spine.1989;14:1324–1331.

- ,,,.Hernia through an iliac crest bone graft site: report of a case and review of the literature.Bull Hosp Jt Dis.2006;63:166–168.

- ,.Incisional hernia through iliac crest defects.Arch Orthop Trauma Surg.1989;108:383–385.

A SAFE DC

Homeless patients are admitted to the hospital more frequently for both medical and psychiatric conditions as compared with domiciled but otherwise similar patients.13 They are also more likely to be hospitalized for conditions usually managed in the outpatient setting, such as cellulitis and respiratory infections.35 Physicians have reported a lower threshold for admission of patients whose conditions will worsen on the streets.4 Homeless inpatients are typically younger and may be hospitalized for longer than comparable patients with housing, often at higher cost.4, 5 These patients suffer from an average of 8 to 9 active medical problems6 and markedly increased mortality,710 with an average life expectancy of 45 years.7 Many homeless patients are uninsured or underinsured11, 12 and receive no ambulatory medical care.11 These patients are often cared for by hospitalists.

A general understanding of the unique needs of the homeless population is paramount for the hospitalist who strives to provide high‐quality care. The most commonly referenced definition of homelessness from the McKinney‐Vento Homeless Assistance Act defines a homeless person as an individual who lacks a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence or a person who resides in a shelter, welfare hotel, transitional program, or place not ordinarily used as regular sleeping accommodations, such as streets, cars, movie theaters, abandoned buildings, or on the streets.13 This definition is often extended to include those who are occasionally but unstably housed with family or friends.14 Undomiciled and unstably housed patients face many barriers in obtaining healthcare, including cognitive or developmental impairment, cultural or linguistic issues, unreliable means of transportation, inability to pay for medications and supplies, and addiction and substance abuse. Systemic barriers include inadequate health insurance, limited access to health services, and provider bias or ignorance toward the issues of homelessness.

A hospitalist working with homeless patients may be discouraged by perceived inability to arrange reliable follow‐up or may be frustrated by hospital readmission resulting from patient noncompliance. Commonly, crisis management takes precedence over addressing the fundamental issues of homelessness.15, 16 Managing transitions of care at discharge, a vulnerable time for all hospitalized patients,17 is often particularly difficult when a patient has no place to go. We present here a review of selected literature that may inform care of the hospitalized homeless inpatient, providing background information on burden of disease, and supplementing this with evidence‐based and consensus‐based recommendations for adaptations of care. Additionally, we propose a simple mnemonic checklist, A SAFE DC, and discuss systems‐based approaches to the challenges of providing care to this population.

A SAFE DC: A Conceptual Framework for Care of the Homeless Inpatient

The mnemonic checklist A SAFE DC is an acronym for the 7 parts of a conceptual framework for care of the homeless inpatient (Table 1).

| A = assess housing status |

| S = screening and prevention |

| A = address primary care issues |

| F = follow‐up care |

| E = end of life discussions |

| D = discharge instructions, simple and realistic |

| C = communication method after discharge |

A: Assess Housing Situation

Hospitals are not required to collect homelessness data. Where such data are collected, they are often inaccurate and internally inconsistent. In 1 survey of inpatients at a public hospital, over 25% of inpatients met strict criteria for homelessness.18 Effective discharge planning begins on admission.15 Hospitalists should ask specifically about housing status at the onset of hospitalization.19 This should be done in a direct, yet sensitive, manner. Given the recent economic downturn, increasing numbers of individuals and families are marginally housed; these patients may not show outward signs of homelessness and may not volunteer this information during the initial encounter. Be aware that some patients may become homeless during hospitalization,18 often as a result of inability to work or attend to financial matters during an inpatient stay. Resultant medical debt is a common cause of personal bankruptcy and homelessness following discharge.

Although it is accepted that a patient should be medically stable prior to discharge and that the decision to discharge should be based on medical, not financial considerations,20, 21 other standards for discharge vary from provider to provider. Hospitalists may be more cautious in discharging a patient without a stable home,4 yet facilitating outpatient follow‐up care or arranging transfer to a sheltered, structured environment can lengthen the hospital stay. Many cities offer formal medical respite care in a number of forms well described in the literature, including free‐standing2225 or shelter‐based units,25, 26 or skilled nursing facilities that contract directly with hospitals for short stays. One innovative model is the hoptel, or hospital hotel,27 a temporary housing facility proximate to the hospital to which self‐sufficient homeless patients may be discharged for recuperation. Some hospitals distribute motel vouchers at discharge.22, 25 All of these options provide opportunities for rest and recovery. Some facilities are staffed with a nurse who can check vital signs and provide wound care. Respite discharge may decrease early readmission and death rates23 and decrease repeat hospitalizations,24 particularly in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) patients.

The National Health Care for the Homeless Council (NHCHC) maintains a national map and directory of respite care programs and services (see Table 2). Hospital providers should develop familiarity with all programs offered in a given geographic area and work closely with case managers and social workers to ensure that a homeless patient is considered for all programs for which he or she is eligible.

|

| NHCHC ( |

| Clinical Practice Guidelines ( |

| Cardiovascular disease |

| HIV/AIDS |

| Otitis media |

| Asthma |

| Chlamydial and gonococcal infections |

| Reproductive healthcare |

| Diabetes mellitus (wallet‐sized personal health history available for homeless patients) |

| Clinical Practice Resources ( |

| Shelter Health Fact Sheets for patients (in English and Spanish) ( |

| NHCHC Clinicians' Network ( |

| Respite resources, including Introduction to Medical Respite Care ( |

| Discharge Planning resources ( |

| National Coalition for the Homeless ( |

| Directory of local homeless service organizations by state ( |

| National housing database for the homeless and low‐income ( |

| Homeless Health Care Los Angeles ( |

| Representative programs: Hospital Discharge Planning Training seminar ( |

S: Screening and Prevention

In addition to treating the presenting condition, a hospitalist should evaluate homeless patients for disease processes common in indigence. A full physical examination, preferably unclothed, is also recommended.28 Homelessness markedly increases an individual's risk of chronic medical conditions. Reactive airway disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) occur at higher rates as a result of tobacco and inhalational drug abuse. Diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and chronic liver and renal disease may remain undetected for years, with end‐organ effects commonly seen at presentation. Peripheral vascular disease is 10 to 15 times more frequent than in the general population.16, 28, 29 Tuberculosis, with prevalence rates greater than 30 times the national average,30 and other communicable diseases, including HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C,16 are exceedingly prevalent and in some cases endemic.12 Infestations are also common. One out of 5 Health Care for the Homeless clients has an infectious or communicable disease.16 Up to two‐thirds of homeless individuals are HIV‐positive, with younger, Hispanic, and black populations at highest risk.29 Systemic infections may be traced to poor dentition, common in this population. Poor vision and skin conditions, also rampant,30 are easily overlooked in acute care encounters. The rate of drug and alcohol abuse in the homeless population may be as high as 8 times that of the general population.31 In 1 survey of homeless adults, the majority identified substance abuse as a major factor in ongoing homelessness.32 Mental illness prevalence in the may be as high as 80% to 95%33 and street violence is commonplace; more than 50% of homeless women have been sexually assaulted.11

There is a paucity of data on the effectiveness of inpatient health interventions for the homeless. In a 2005 systematic review of 45 studies evaluating the impact of various programs on homeless health, only 1 targeted an inpatient population.34 Furthermore, the literature suggests that street‐based or shelter‐based delivery of preventative services is most effective for undomiciled patients.35 Understanding these limitations, inpatient admission remains an opportunity to offer services that may decrease morbidity.

Evidence‐based preventative measures (Table 3) include vaccination against hepatitis A and hepatitis B in the intravenous drugusing homeless population. An accelerated hepatitis B vaccine administration schedule, with doses at 0, 7, and 21 days and a booster at 12 months, has been shown to increase completion rates.36 Drug users should be advised to utilize needle exchange programs and avoid sharing equipment. Sexually active homeless patients should be counseled regarding safe sexual practices and condom use. Consider tuberculosis screening with purified protein derivative (PPD) testing and spot sputum check, which have been shown in a shelter‐based intervention to detect an infection rate of 3.1%.37 Notably, within that cohort, symptom‐based screening was not found to be helpful. Influenza, diphtheria, tetanus, and pneumococcal vaccinations are also recommended, but have not been studied in regard to secondary decrease of infection rates in the homeless.

|

| Vaccines: hepatitis A and B, influenza, Pneumococcus, Td |

| Tobacco abuse: cessation counseling and resources |

| Substance abuse: information regarding needle exchange programs, social work consultation for treatment options |

| Tuberculosis: consider screening with PPD (spot sputum for AFB) |

| Sexual behavior: counseling on safer sex practices and STD risk |

| Domestic and street violence: social work consultation for counseling and resources |

| Mental health: depression screening, MMSE |

Admission to the hospital should be considered a treatable moment for substance abuse. In focus groups of homeless smokers, 76% of participants expressed intention to quit within 6 months and all were interested in using pharmacotherapy and behavioral treatments.38 In another study comparing admitted homeless vs. domiciled substance‐using adults, a higher percentage of the homeless patients were found to be in the action stage of change, as compared with the precontemplative or contemplative stage.39 When ongoing use is likely, recommended strategies include advocating for safer routes or patterns or use and praising small successes on the continuum to abstinence.40 Where such services are available, the hospitalist should coordinate with primary care providers (PCPs) and social workers to refer patients for drug treatment and rehabilitation. Likewise, mental health follow‐up should be confirmed and ongoing care coordinated with the patient's mental health case worker, if one exists.

A: Address Primary Care Issues

The inpatient setting is often a homeless patient's only ongoing source of medical care, but may not meet all of his or her healthcare needs. During an admission for congestive heart failure (CHF), for example, he or she may receive diuresis and afterload reduction but not outpatient interventions such lipid and blood pressure management. Chronic diagnoses, such as malignancy, may be viewed as secondary and remain unaddressed. Questions about extent of a hospitalist's obligations to provide primary care arise in cases where a patient has failed to establish (and the system failed to provide) an outpatient medical home.

Just as emergency department physicians have become de facto primary care providers for underserved patients, hospitalists can expect to provide routine care for patients facing homelessness. Some interventions traditionally considered outpatient services, such as pneumococcal vaccination or counseling regarding smoking cessation, are now identified as inpatient core quality measures. Whether sexually transmitted disease or colon cancer screening or evaluation of cardiac risk status, for example, should become inpatient services for medically indigent patients is open for debate. Whenever possible, our goal is to facilitate screening and specialty consultations in the inpatient setting when this will not unnecessarily prolong hospitalization.

F: Follow‐Up Care

Ideally, transfer of care occurs smoothly between the hospitalist and a PCP or specialist who will provide a patient's ongoing medical care. Because many homeless patients lack or cannot identify a consistent outpatient provider, they may require additional assistance to ensure they receive medical care after discharge. If the patient has a PCP, the hospitalist should initiate contact with this individual at admission and discharge, forwarding relevant records in a timely fashion, including a faxed or electronic discharge summary. We often provide patients with a hard copy of the discharge summary and ask them to hand‐carry it to any follow‐up appointments. When a patient has no PCP, the hospitalist should attempt to expedite establishment of primary care. Unfortunately, many communities have limited primary care availability for patients who lack health insurance, posing challenges for hospital providers and patients.

At our institution, follow‐up appointments are often made by a clerk or nurse who later relays the appointment date and time to the patient. Some clinics collect contact information and call the patient themselves. There are frequent lapses in this scheduling system; some patients never receive a follow‐up appointment because they have no means of contact. Providing a scheduled follow‐up date and time prior to discharge may circumvent this problem.41

It is also optimal if some options for follow‐up care do not require a previously scheduled appointment. At our institution, a postdischarge aftercare clinic fills this need for patients without an established PCP, until such a relationship can be established. Aftercare appointments are designed to address specific, time‐critical, clinical issues (eg, assessing response to antibiotics, follow‐up creatinine in patient on diuretics, etc). To the degree that it is possible, selecting a site for follow‐up care that minimizes transportation (eg, a shelter‐based clinic) may improve the likelihood of follow‐up. It is wise to ask the patient when and where he or she would prefer to be seen. Consider that evening appointments may be best for day workers.28 Some authors have advocated that providers consider dispensing fewer numbers of medications at any given time, in order to enhance compliance with the follow‐up appointments,28 even if this may not reflect optimal medical management.

Careful consideration should be given before ordering tests for which results may not be available prior to anticipated discharge. These may include microbiological cultures, pathology reports, or sexually transmitted disease screening, including HIV testing. Note that even when a patient does have an established PCP, the hospitalist's liability for medical care may persist after hospital discharge. Emergency room physicians, for example, have been found liable for lack of postdischarge communication of radiologic findings.42

Timely and thorough documentation is critical. In many cases, a hospitalist is the only physician aware of a homeless patient's active medical issues. On admission, records should be thoroughly reviewed to ensure that pressing concerns, even those not traditionally requiring hospitalization, are addressed in a timely fashion. Detailed discharge documentation helps to ensure that ongoing issues are not lost during follow‐up. It may be useful to provide a given patient with a portable summary of his or her medical history for self‐reference and facilitation of ongoing care, particularly for those with a history of seeking healthcare at multiple facilities.28

E: End‐of‐Life Discussions

Given the increased mortality and decreased life expectancy of the homeless population, an acute care hospitalization provides an excellent opportunity to discuss end‐of‐life preferences, particularly if the patient does not have an established PCP. Focus groups have noted little difference in the range of end‐of‐life preferences of the homeless as compared with the general population, yet a common fear among the homeless is that of an anonymous death, or a life without remembrance.43 Many homeless patients believe that physicians would use deceit in withdrawing life‐sustaining support or that their body might be disposed of without consent. They identify advance directives as a way to regain control over their lives.44 It is important to obtain and update emergency contacts for friends and family on each admission. Notably, homeless people often designate an unrelated friend or associate as their decision maker, rather than family, and express that it is less important to have family present at their death as it is to be cared for compassionately and respectfully by those who are present.44

D: Discharge Instructions Simple and Realistic

Health illiteracy profoundly affects homeless patients. In the predischarge narratives of 21 low‐income urban medical inpatients, almost one‐half believed it would be impossible to follow medical advice at discharge.45 Healthcare providers may overestimate a patient's ability to understand discharge instructions46 and to provide self‐care at the time of discharge.47 Homeless patients are at high risk for disease relapse following discharge, given chaotic living conditions and lack of social support.1 The presence of community support has been shown to decrease the likelihood of rehospitalization.48

Medication compliance poses a particular challenge. In 1 study, one‐third of homeless patients reported inability to comply with medications.2 Cost, storage capability, and complexity of regimen are common obstacles. Side effects should be considered when medications are selected, since common side effects like gastrointestinal upset or diarrhea, or desired effects like diuresis, may be intolerable if a patient cannot reliably access a restroom. Physicians should also weigh the possibility that discharge medications and supplies may be abused or stolen on the streets. Difficulty accessing routine meals can be particularly problematic in homeless patients with diabetes, who must eat on a regular schedule in order to avoid hypoglycemia. Diabetic goals may be adjusted accordingly to minimize risk. Diet may also be an issue if a patient must take a medication with food, as with some antiretrovirals. The physician must anticipate an erratic diet and, whenever possible, dose medications accordingly. Directly observed therapy for diseases such as tuberculosis is optimal if the ability to comply is in question.28 The NHCHC has developed guidelines for adaptations of care in homeless patients with a variety of clinical conditions, including diabetes mellitus, HIV, cardiovascular disease, and asthma; these are available for reference and download on their website (Table 2).

Illiteracy and low educational level also impact compliance. In 1 sample of indigent psychiatric patients, 76% read at or below the seventh grade level.49 Aftercare instructions should be easy to understand by those with lower levels of education (fourth grade level or less), written down in simple language, and reviewed verbally by nurse, pharmacist, and physician. Consider initiating projects within your hospital to streamline discharge instruction forms.50 The use of pictorial or video‐assisted discharge instructions for common diagnoses is an area of promise.17, 51, 52

Of note, there is no body of literature addressing the extent to which hospitalists or other inpatient physicians alter treatment goals at the time of discharge for homeless patients, but this may be a common occurrence and warrants further study.

C: Communication Methods After Discharge

Before discharge, clarify how a patient can be contacted for additional test results or information regarding follow‐up appointments. Although some homeless patients maintain mobile phones, telephone‐based methods used by some hospitalists for postdischarge follow‐up53, 54 may be unreliable in this population. Some shelters or respite facilities will accept messages for clients who reside there; others will provide clients with access to voicemail or e‐mail. For those patients who are technologically savvy, free e‐mail accounts can readily be obtained and accessed at public facilities, such as the public library. Contact information for a case manager can also be very useful. We occasionally ask patients to return to the hospital to retrieve test results or a message from their physician at a predetermined time and place. Where safe and appropriate, providing patients with direct physician contact information (rather than general hospital information) may minimize communication barriers.

The Big Picture: Systems‐Based Approaches to the Discharge of Homeless Patients

The discharge of homeless patients is suited to a comprehensive, interdisciplinary approach. There are many challenges to effective discharge planning: lack of time, lack of process ownership at the institutional level, financial constraints, and perhaps most significantly, lack of consensus regarding best practices.19 There is growing acknowledgement of the need to develop policies and standardize practice in this area. Hospitalists are uniquely situated to contribute to the development of new initiatives at the institutional, local, and national level.

Interventions (Table 4) may be as simple as the identification of a dedicated social worker for all homeless discharges15, 21, 55 or creation of a hospital‐wide discharge planning committee or inpatient homeless consultation service.15, 21 The distribution of discharge planning guides for patients and resource lists to providers is also gaining in popularity.21, 56 Some innovations specifically target clinicians, such as training seminars that teach communication skills and motivational interviewing and build familiarity with safety‐net services within the community.21, 57 Community‐based programs include medical respite care services, previously discussed, and the facilitation of preferred provider relationships directed by hospitals toward skilled nursing facilities willing to accept homeless and other challenging clients.15

|

| Discharge planning training seminars for the clinician |

| SWAT team for difficult discharges |

| Hospital‐wide discharge planning committee |

| Inpatient homeless consult service |

| Dedicated social worker for homeless discharges |

| Preferred provider status for skilled nursing facilities |

| Medical respite care |

| Discharge planning guide or resource list for homeless patients |

Homelessness has also been identified as an area of focus by state governments, with many states funding initiatives to improve training and assistance to homeless providers, policies for discharge planning from public institutions, and homeless needs assessments. Some states have gone so far as to determine that discharge to an emergency shelter is not appropriate.19 On the national level, large advocacy organizations such as the NHCHC and National Coalition for the Homeless have spearheaded Housing First efforts on behalf of homeless patients and providers throughout the country. Such programs have been shown to decrease healthcare expenditures, emergency department visits, and hospitalizations in certain homeless populations.58, 59 Check the NHCHC website for consolidated discharge planning program development resources for healthcare institutions (

Commentary

Homeless patients frequently require more energy and services at the time of service in order to achieve standard medical care. Optimally, a patient assumes full responsibility for his or her health, but there may be limits to this responsibility for selected patients,60 especially in light of limited access to primary care. Understandably, homeless patients may focus more on immediate physical needs (eg, food, shelter, safety) than on chronic medical problems. In addition, they may experience a sense of unwelcomeness from healthcare providers that they perceive as discrimination; this may dissuade them from seeking care.61 The inpatient physician should aim to build trust with each encounter. As suggested by 1 author, it is important to promise only what can be delivered and deliver what is promised.62 Involving the patient in care and decision‐making is the most important first step in accomplishing this goal.

It is important in caring for homeless patients to reframe one's notion of a successful outcome.16 Ideally, on resolution of his or her acute medical issues, a homeless patient would be discharged to permanent housing with substance abuse and mental health treatment. This scenario is unfortunately rare. The hospitalist often has little ability to arrange stable, on‐demand housing at discharge. He or she is best advised to focus on optimizing acute care delivery at the point of care and maximize opportunities for future health.

It has been suggested that the discontinuity inherent in the hospitalist model may confer a special obligation on hospital medicine providers to abide by a more rigorous standard of care42; one might argue that this obligation becomes even more compelling when applied to this vulnerable population. In 1 study, a disturbing 27% of an American cohort of homeless adults had no healthcare contacts in the year prior to death, underscoring this group's underutilization of health services. Armed with this knowledge, hospitalists should seize every healthcare interaction as an opportunity to offer therapies with potential for longer‐term benefit.

- ,,,,.Mental health and social characteristics of the homeless: a survey of mission users.Am J Public Health.1986;76:519–524.

- ,,.Factors associated with the health care utilization of homeless persons.JAMA.2001;285(2):200–206.

- ,,,,,.Hospitalization in an urban homeless population: the Honolulu urban homeless project.Ann Int Med.1992:116:299–303.

- ,,,,.Hospitalization costs associated with homelessness in New York City.N Engl J Med.1997;338:1734–1740.

- ,.Homelessness; health service use and related costs.Med Care.1998;38:1256–1264.

- ,,, et al.Health and mental problems of homeless men and women in Baltimore.JAMA.1989;262:1352–1357.

- ,,, et al.Mortality in a cohort of homeless adults in Philadelphia.N Engl J Med.1994;331:304–309.

- . Utilization and costs of medical services by homeless persons: a review of the literature and implications for the future. National Health Care for the Homeless Council website. Published April 1999. Available at: http://www.nhchc.org/Publications/utilization.htm. Accessed Month Year.

- ,,,,.Causes of death in homeless adults in Boston.Ann Intern Med.1997;126:625–628.

- ,.Risk of death among homeless women; a cohort study and review of the literature.CMAJ.2004;170(8):1243–1237.

- ,.Health care for homeless persons.N Engl J Med.2004;350:2329–2332.

- .Homelessness and health.CMAJ.2001;164:229–233.

- U.S. Congress..McKinney Homeless Assistance Act. Publ. No. 100–77, 101 Stat. 484.Washington, DC:U.S. Congress;1987.

- ,.How can health services effectively meet the health needs of homeless people?Br J Gen Pract.2006;56:286–293.

- Homeless Health Care Los Angeles. Homelessness: An Overview and Effective Strategies for Discharge Planning of Homeless Patients. Available at: http://www.nhchc.org/Publications/utilizations.html. Accessed Month Year.

- ,,. Balancing act: clinical practices that respond to the needs of homeless people. 1998 National Symposium on Homelessness Research. U.S. Health and Human Services. Available at: http://aspe.hhs.gov/ProgSys/homeless/symposium/8‐Clinical.htm. Accessed June2009.

- ,,,.Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists.J Hosp Med.2007;2:314–323.

- ,,,.Identifying homelessness at an urban public hospital: a moving target?J Health Care Poor Underserved.2005;16:297–307.

- ,,.The role of effective discharge planning in preventing homelessness.J Prim Prev.2007;28:229–243.

- ,.Saying goodbye: ethical issues in the stewardship of bed spaces.J Clin Ethics.2005;16:170–175.

- National Health Care for the Homeless Council.Tools to help clinicians achieve effective discharge planning.Healing Hands2008;12:1–6. Available at: http://www.nhchc.org/Network/HealingHands/2008/Oct2008Healing Hands.pdf. Accessed Juneyear="2009"2009.

- ,,, et al.It takes a village: a multidisciplinary model of the acute illness aftercare of individuals experiencing homelessness.J Health Care Poor Underserved.2005;16:257–272.

- ,,, et al. Hospital discharge to a homeless medical respite program prevents readmission [Abstract]. Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program. Published 2005. Available at: http://www.nhchc.org/Respite/RespiteResearcUpdateSept05.ppt. Accessed June2009.

- ,,,.The effects of respite care for homeless patients: a cohort study.Am J Public Health.2006:96:1278–1281.

- . Medical Respite Services for Homeless People: Practical Models. National Health Care for the Homeless Council. Published 1999. Available at: http://www.nhchc.org/Publications/MedicalRespiteServices.pdf. Accessed June2009.

- ,,,.Shelter‐based convalescence for homeless adults.Can J Public Health.2006;97:379–383.

- ,.Hoptel equalizes length of stay for homeless and domiciled inpatients.Med Care.2000;38:1003–1010.

- .The homeless in America: adapting your practice.Am Fam Physician.2006;74:1132–1138.

- . A Preliminary Review of Literature: Chronic Medical Illness and Homeless Individuals, Nashville, TN. National Health Care for the Homeless Council. Published April 2002. Available at: http://www.nhchc.org/Publications/literaturereview_chronicillness.pdf. Accessed June2009.

- ,.Diagnostic patterns in hospital use by an urban homeless population.West J Med.1989;151:472–478.

- ,,.Drug use disorders and treatment contact among homeless adults in Alameda County, California.Am J Public Health.1997;87:221–228.

- ,,,,,.Self‐reported changes in drug and alcohol use after becoming homeless.Am J Public Health.2004;94:830–835.

- .A review of physical and mental health in homeless persons.Public Health Rev.2001;29:13–33.

- ,,,.Interventions to improve the health of the homeless; a systematic review.Am J Prev Med.2005;29:311–319.

- ,,.Preventing and controlling emerging and reemerging transmissible diseases in the homeless.Emerg Infect Dis.2008;14:1353–1359.

- ,,.Comparison of conventional and accelerated hepatitis B immunisation schedules for homeless drug users.Commun Dis Public Health.2002;5:324–326.

- ,,,,,.Spot sputum screening: evaluation of an intervention in two homeless shelters.Int J Tuberc Lung Dis.1999;3:613–619.

- ,,, et al.Homelessness and smoking cessation: insights from focus groups.Nicotine Tob Res.2006;8:287–296.

- ,,,.The health encounter as a treatable moment for homeless substance‐using adults: the role of homelessness, health‐seeking behavior, readiness for behavior change and motivation for treatment.Addict Behav.2008;33:1239–1243.

- ,. To dance with grace: outreach and engagement to persons on the street. 1998 National Symposium on Homelessness Research. U.S. Health and Human Services. Available at: http://aspe.hhs.gov/ProgSys/homeless/symposium/6‐Outreach.htm. Accessed June2009.

- .The best way to improve emergency department follow‐up is actually to give the patient a specific appointment.J Gen Intern Med.2006;21:398.

- .Key legal principles for hospitalists.Am J Med.2001;11:5s–9s.

- ,,.Attitudes, experiences and beliefs affecting end of life decision‐making among homeless individuals.J Palliat Med.2005;8:36–48.

- ,,,,,.Dying on the streets; homeless person's concerns and desires about end of life care.J Gen Intern Med.2007;22:435–441.

- ,,.Understanding rehospitalization risk: can hospital discharge be modified to reduce recurrent hospitalization.J Hosp Med.2007:2:297–304.

- ,,, et al.Patient‐physician communication at hospital discharge and patients' understanding of the postdischarge treatment plan.Arch Intern Med.1997;157:1026–1030.

- ,,,,,.Discharge planning: comparison of patients and nurses' perceptions of patients following hospital discharge.Image J Nurs Sch.1996;28:143–147.

- ,,,.Predicting health services utilization among homeless adults: a prospective analysis.J Health Care Poor Underserved.2000:11:212–230.

- ,.The prevalence of low literacy in an indigent psychiatric population.Psychiatr Serv.1999;50:262–263.

- Majority of emergency patients don't understand discharge instructions.ED Manag.2008;20:97–98.

- ,.Communicating information to patients: the use of cartoon illustrations to improve comprehension of instructions.Acad Emerg Med.1996;3:264–270.

- ,,,.The effectiveness of mobile discharge instruction videos (MDIVs) in communicating discharge instructions to patients with lacerations or sprains.South Med J.2009;102:239–247.

- .The importance of postdischarge telephone follow up from hospitalists: a view from the trenches.Am J Med.2001;111:43s–44s.

- ,.Using an interactive voice response system to improve patient safety following hospital discharge.Eval Clin Pract.2007;13:346–351.

- Resource Guide for Service Providers. Homeless Health Care Los Angeles. Available at: http://www.hhcla.org/training/pdf‐docs/2007%20RESOURCE%20GUIDE.pdf. Accessed June2009.

- Hospital Discharge Planning Training Workshop. Homeless Health Care Los Angeles. Available at: http://www.hhcla.org/discharge.htm. Accessed June2009.

- ,,, et al.Health care and public service use and costs before and after provision of housing for chronically homeless persons with severe alcohol problems.JAMA.2009;301:1349–1357.

- ,,,.Effect of a housing and case management program on emergency department visits and hospitalizations among chronically ill homeless adults.JAMA.2009;301:1771–1778.

- .Limits on patient responsibility.J Med Phil.2005;30:189–206.

- ,,.Homeless people's perceptions of welcomeness and unwelcomeness in healthcare encounters.J Gen Intern Med.2007;22:1011–1017.

- .Increasing competency in the care of homeless patients [Teaching Tips].J Contin Educ Nurs.2008;39:153–154.

- ,,, et al.Health care utilization among homeless adults prior to death.J Health Care Poor Underserved.1999;12:50–58.

Homeless patients are admitted to the hospital more frequently for both medical and psychiatric conditions as compared with domiciled but otherwise similar patients.13 They are also more likely to be hospitalized for conditions usually managed in the outpatient setting, such as cellulitis and respiratory infections.35 Physicians have reported a lower threshold for admission of patients whose conditions will worsen on the streets.4 Homeless inpatients are typically younger and may be hospitalized for longer than comparable patients with housing, often at higher cost.4, 5 These patients suffer from an average of 8 to 9 active medical problems6 and markedly increased mortality,710 with an average life expectancy of 45 years.7 Many homeless patients are uninsured or underinsured11, 12 and receive no ambulatory medical care.11 These patients are often cared for by hospitalists.

A general understanding of the unique needs of the homeless population is paramount for the hospitalist who strives to provide high‐quality care. The most commonly referenced definition of homelessness from the McKinney‐Vento Homeless Assistance Act defines a homeless person as an individual who lacks a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence or a person who resides in a shelter, welfare hotel, transitional program, or place not ordinarily used as regular sleeping accommodations, such as streets, cars, movie theaters, abandoned buildings, or on the streets.13 This definition is often extended to include those who are occasionally but unstably housed with family or friends.14 Undomiciled and unstably housed patients face many barriers in obtaining healthcare, including cognitive or developmental impairment, cultural or linguistic issues, unreliable means of transportation, inability to pay for medications and supplies, and addiction and substance abuse. Systemic barriers include inadequate health insurance, limited access to health services, and provider bias or ignorance toward the issues of homelessness.

A hospitalist working with homeless patients may be discouraged by perceived inability to arrange reliable follow‐up or may be frustrated by hospital readmission resulting from patient noncompliance. Commonly, crisis management takes precedence over addressing the fundamental issues of homelessness.15, 16 Managing transitions of care at discharge, a vulnerable time for all hospitalized patients,17 is often particularly difficult when a patient has no place to go. We present here a review of selected literature that may inform care of the hospitalized homeless inpatient, providing background information on burden of disease, and supplementing this with evidence‐based and consensus‐based recommendations for adaptations of care. Additionally, we propose a simple mnemonic checklist, A SAFE DC, and discuss systems‐based approaches to the challenges of providing care to this population.

A SAFE DC: A Conceptual Framework for Care of the Homeless Inpatient

The mnemonic checklist A SAFE DC is an acronym for the 7 parts of a conceptual framework for care of the homeless inpatient (Table 1).

| A = assess housing status |

| S = screening and prevention |

| A = address primary care issues |

| F = follow‐up care |

| E = end of life discussions |

| D = discharge instructions, simple and realistic |

| C = communication method after discharge |

A: Assess Housing Situation

Hospitals are not required to collect homelessness data. Where such data are collected, they are often inaccurate and internally inconsistent. In 1 survey of inpatients at a public hospital, over 25% of inpatients met strict criteria for homelessness.18 Effective discharge planning begins on admission.15 Hospitalists should ask specifically about housing status at the onset of hospitalization.19 This should be done in a direct, yet sensitive, manner. Given the recent economic downturn, increasing numbers of individuals and families are marginally housed; these patients may not show outward signs of homelessness and may not volunteer this information during the initial encounter. Be aware that some patients may become homeless during hospitalization,18 often as a result of inability to work or attend to financial matters during an inpatient stay. Resultant medical debt is a common cause of personal bankruptcy and homelessness following discharge.

Although it is accepted that a patient should be medically stable prior to discharge and that the decision to discharge should be based on medical, not financial considerations,20, 21 other standards for discharge vary from provider to provider. Hospitalists may be more cautious in discharging a patient without a stable home,4 yet facilitating outpatient follow‐up care or arranging transfer to a sheltered, structured environment can lengthen the hospital stay. Many cities offer formal medical respite care in a number of forms well described in the literature, including free‐standing2225 or shelter‐based units,25, 26 or skilled nursing facilities that contract directly with hospitals for short stays. One innovative model is the hoptel, or hospital hotel,27 a temporary housing facility proximate to the hospital to which self‐sufficient homeless patients may be discharged for recuperation. Some hospitals distribute motel vouchers at discharge.22, 25 All of these options provide opportunities for rest and recovery. Some facilities are staffed with a nurse who can check vital signs and provide wound care. Respite discharge may decrease early readmission and death rates23 and decrease repeat hospitalizations,24 particularly in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) patients.

The National Health Care for the Homeless Council (NHCHC) maintains a national map and directory of respite care programs and services (see Table 2). Hospital providers should develop familiarity with all programs offered in a given geographic area and work closely with case managers and social workers to ensure that a homeless patient is considered for all programs for which he or she is eligible.

|

| NHCHC ( |

| Clinical Practice Guidelines ( |

| Cardiovascular disease |

| HIV/AIDS |

| Otitis media |

| Asthma |

| Chlamydial and gonococcal infections |

| Reproductive healthcare |

| Diabetes mellitus (wallet‐sized personal health history available for homeless patients) |

| Clinical Practice Resources ( |

| Shelter Health Fact Sheets for patients (in English and Spanish) ( |

| NHCHC Clinicians' Network ( |

| Respite resources, including Introduction to Medical Respite Care ( |

| Discharge Planning resources ( |

| National Coalition for the Homeless ( |

| Directory of local homeless service organizations by state ( |

| National housing database for the homeless and low‐income ( |

| Homeless Health Care Los Angeles ( |

| Representative programs: Hospital Discharge Planning Training seminar ( |

S: Screening and Prevention

In addition to treating the presenting condition, a hospitalist should evaluate homeless patients for disease processes common in indigence. A full physical examination, preferably unclothed, is also recommended.28 Homelessness markedly increases an individual's risk of chronic medical conditions. Reactive airway disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) occur at higher rates as a result of tobacco and inhalational drug abuse. Diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and chronic liver and renal disease may remain undetected for years, with end‐organ effects commonly seen at presentation. Peripheral vascular disease is 10 to 15 times more frequent than in the general population.16, 28, 29 Tuberculosis, with prevalence rates greater than 30 times the national average,30 and other communicable diseases, including HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C,16 are exceedingly prevalent and in some cases endemic.12 Infestations are also common. One out of 5 Health Care for the Homeless clients has an infectious or communicable disease.16 Up to two‐thirds of homeless individuals are HIV‐positive, with younger, Hispanic, and black populations at highest risk.29 Systemic infections may be traced to poor dentition, common in this population. Poor vision and skin conditions, also rampant,30 are easily overlooked in acute care encounters. The rate of drug and alcohol abuse in the homeless population may be as high as 8 times that of the general population.31 In 1 survey of homeless adults, the majority identified substance abuse as a major factor in ongoing homelessness.32 Mental illness prevalence in the may be as high as 80% to 95%33 and street violence is commonplace; more than 50% of homeless women have been sexually assaulted.11

There is a paucity of data on the effectiveness of inpatient health interventions for the homeless. In a 2005 systematic review of 45 studies evaluating the impact of various programs on homeless health, only 1 targeted an inpatient population.34 Furthermore, the literature suggests that street‐based or shelter‐based delivery of preventative services is most effective for undomiciled patients.35 Understanding these limitations, inpatient admission remains an opportunity to offer services that may decrease morbidity.

Evidence‐based preventative measures (Table 3) include vaccination against hepatitis A and hepatitis B in the intravenous drugusing homeless population. An accelerated hepatitis B vaccine administration schedule, with doses at 0, 7, and 21 days and a booster at 12 months, has been shown to increase completion rates.36 Drug users should be advised to utilize needle exchange programs and avoid sharing equipment. Sexually active homeless patients should be counseled regarding safe sexual practices and condom use. Consider tuberculosis screening with purified protein derivative (PPD) testing and spot sputum check, which have been shown in a shelter‐based intervention to detect an infection rate of 3.1%.37 Notably, within that cohort, symptom‐based screening was not found to be helpful. Influenza, diphtheria, tetanus, and pneumococcal vaccinations are also recommended, but have not been studied in regard to secondary decrease of infection rates in the homeless.

|

| Vaccines: hepatitis A and B, influenza, Pneumococcus, Td |

| Tobacco abuse: cessation counseling and resources |