User login

Attitudes of Physicians in Training Regarding Reporting of Patient Safety Events

From the Department of Internal Medicine, Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, IL.

Abstract

- Objective: To understand the attitudes and experiences of physicians in training with regard to patient safety event reporting.

- Methods: Residents and fellows in the department of internal medicine were surveyed using a questionnaire containing 5 closed-ended items. These items examined trainees’ attitudes, experiences and knowledge about safety event reporting and barriers to their reporting.

- Results: 61% of 80 eligible trainees responded. The majority of residents understood that it is their responsibility to report safety events. Identified barriers to reporting were the complexity of the reporting system, lack of feedback after reporting safety events to gain knowledge of system advances, and reporting was not a priority in clinical workflow.

- Conclusion: An inpatient safety and quality committee intends to develop solutions to the challenges faced by trainees’ in reporting patient safety events.

Nationwide, graduate medical education programs are changing to include a greater focus on quality improvement and patient safety [1,2]. This has been recognized as a priority by the Institute of Medicine, the Joint Commission, and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) [3–6]. Hospital safety event reporting systems have been implemented to improve patient safety. Despite national expectations and demonstrated benefits of reporting adverse events, most resident and attending physicians fail to understand the value, lack the skills to report, and do not participate in incident reporting [7–9].

Past attempts to increase awareness about patient safety reporting have resulted in minimal participation [10,11]. In relation to other health care providers, attending and resident physicians have the lowest rate of patient safety reporting [12]. Interventions aiming to improve reporting have had mixed results, with sustained improvement being a major challenge [13,14]. To advance our efforts to improve reporting of patient safety events as a means toward improving patient safety, we sought to understand the attitudes and beliefs of our physicians in training with regard to patient safety event reporting.

Methods

Setting

Our institution, a community teaching hospital located in Park Ridge, IL, began patient safety event reporting in 2006 by remote data entry using the Midas information management system (MidasPlus, Xerox, Tucson, AZ). In 2012, as part of the system-based practice ACGME competency, we asked residents enter at least 1 patient safety event for each rotation block. The events could be entered with identifying information or anonymously.

Quality Improvement Project

Given the national focus on patient safety and quality improvement, as well as our organizational goal of zero patient safety events by 2020, in 2014 we formed an inpatient safety and quality committee. This committee includes the medical director of patient safety, internal medicine program director, associate program director, chief resident, fellows, residents and attending physicians. The committee was formed with the long-term objective of advancing patient safety and quality improvement efforts and to decrease preventable errors. As physicians in training are key frontline personnel, the committee decided to focus its initial short-term efforts on this group.

Questionnaire

To understand the magnitude and context of resident reporting behavior, we surveyed the residents and fellows in the department of internal medicine. The fellowships were in cardiology, gastroenterology, and hematology/oncology. The questionnaire we used contained 5 closed-ended items that examined trainees attitudes, experiences, and knowledge about incident reporting. The survey was distributed to the residents and fellows via SurveyMonkeyduring August 2014.

Results

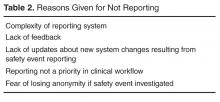

When asked to outline reasons for not reporting incidents, participating residents and fellows identified the complexity of reporting system, lack of feedback, lack of updates about new system changes resulting from safety event reporting,

Discussion

This pilot study demonstrated that resident and fellow physicians in the department of internal medicine at our institution understand the necessity of reporting and that it is their responsibility; however, it is not a priority during the busy clinical workflow on the wards. Other investigators have observed similar attitudes/behaviors among physicians across teaching hospitals in the United States [10,12]. In a study by Boike et al [15], despite positive attitudes among internal medicine residents regarding reporting, increased reporting could not be sustained after the initial increase.

Our finding that 71.4% felt it was useful to discuss safety events is similar to Kaldjian et al’s [16] finding that 70% of generalist physicians in teaching hospitals believed that discussing mistakes strengthens professional relationships. The physicians in that study indicated that they usually discuss their errors with colleagues.

Prior to the development of the inpatient safety committee, the institution had a basic resource in place for reporting events, but there were minimal contributions from resident and fellow physicians. It is likely that the higher rates of reporting by nursing, laboratory, and pharmacy services (data not presented) that were seen are due to a required reporting protocol that is part of the workflow.

Since the inception of the inpatient safety committee, we have started several projects to build upon the foundation of positive resident and fellow physician attitudes. Based on the input of resident and fellow physicians, who are the front-line agents of process improvement, the existing patient safety reporting method was revised and reorganized. Previously, an online standardized patient safety event form was accessible after several click throughs on the institution’s homepage. This form was confusing and laborious to complete by residents and fellows, who were already operating on thin margins of spare time. The online reporting form was moved to the homepage for easy access and a free text option was enabled.

Another barrier to reporting was access to available computers. As such, the committee instituted a phone hotline reporting system. Instead of residents entering events using the Midas information management system, they now are able to call an in-house line and leave an anonymous voicemail to report safety events. Both the online and phone hotline reporting systems are integrated into a central database.

Lastly, resident and fellow physician education curricula were developed to instruct on the need to report patient safety events. Time is allotted at every monthly resident business meeting to discuss reportable patient safety events and offer feedback about concerns. In addition, the director of patient safety sends weekly safety updates, which are emailed to all faculty, residents, and fellows. These include de-identified safety event reports and any organizational and system improvements made in response to these events. Additionally, a mock root analysis takes place each quarter in which the patient safety director reviews a mock case with trainees to identify root causes and system failures. The committee has committed to transparency of reporting patient safety events as means to track the results of our efforts and interventions [17].

We plan to resurvey the resident and fellow physicians to reassess stability or changes in attitudes as a result of these physician-focused improvements. A more systematic analysis of temporal trends in reporting and comparisons across residency programs within our health system is being designed.

Conclusion

Reporting patient safety events should not be seen as a cumbersome task in an already busy clinical workday. We intend to develop scalable solutions that take into account the challenges faced by physicians in training. As the institution strives to become a high-reliability organization with a goal of zero serious patient safety events by 2020, we hope to share the lessons from our quality improvement efforts with other learning organizations.

Acknowledgements: The authors thank Suela Sulo, PhD, for manuscript review and editing.

Corresponding author: Jill Patton, DO, Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, 1775 Dempster St., Park Ridge, IL 60068, jill.patton@advocatehealth.com.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Boonyasai RT, Windish DM, Chakraborti C, et al. Effectiveness of teaching quality improvement to clinicians: a systematic review. JAMA 2007;298:1023–37.

2. Wong BM, Etchells EE, Kuper A, et al. Teaching quality improvement and patient safety to trainees: a systematic review. Acad Med 2010;85:1425–39.

3. Leape LL, Berwick DM. Five years after To Err Is Human: what have we learned? JAMA. 2005;293:2384–90.

4. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS. To err is human: Building a safer health system. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1999.

5. Swing SR. The ACGME outcome project: retrospective and prospective. Med Teach 2007;29:648–54.

6. ACGME. Common program requirements. Available at www.acgme.org.

7. Kaldjian LC, Jones EW, Wu BJ, et al. Reporting medical errors to improve patient safety: a survey of physicians in teaching hospitals. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:40–6.

8. Kaldjian LC, Jones EW, Rosenthal GE, et al. An empirically derived taxonomy of factors affecting physicians’ willingness to disclose medical errors. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21:942–8.

9. White AA, Gallagher TH, Krauss MJ, et al. The attitudes and experiences of trainees regarding disclosing medical errors to patients. Acad Med 2008;83:250–6.

10. Farley DO, Haviland A, Champagne S, et al. Adverse-event-reporting practices by US hospitals: results of a national survey. Qual Saf Health Care 2008;17:416–23.

11. Schectman JM, Plews-Ogan ML. Physician perception of hospital safety and barriers to incident reporting. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2006;32:337–43.

12. Milch CE, Salem DN, Pauker SG, et al. Voluntary electronic reporting of medical errors and adverse events. An analysis of 92,547 reports from 26 acute care hospitals. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21:165–70.

13. Madigosky WS, Headrick LA, Nelson K, et al. Changing and sustaining medical students’ knowledge, skills, and attitudes about patient safety and medical fallibility. Acad Med 2006;81:94–101.

14. Jericho BG, Tassone RF, Centomani NM, et al. An assessment of an educational intervention on resident physician attitudes, knowledge, and skills related to adverse event reporting. J Grad Med Educ 2010;2:188–94.

15. Boike JR, Bortman JS, Radosta JM, et al. Patient safety event reporting expectation: does it influence residents’ attitudes and reporting behaviors? J Patient Saf 2013;9:59–67.

16.Kaldjian LC, Forman-Hoffman VL, Jones EW, et al. Do faculty and resident physicians discuss their medical errors? J Med Ethics 2008;34:717–22.

17. Willeumier D. Advocate health care: a systemwide approach to quality and safety. Jt Comm J Qual Saf 2004;30:559–66.

From the Department of Internal Medicine, Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, IL.

Abstract

- Objective: To understand the attitudes and experiences of physicians in training with regard to patient safety event reporting.

- Methods: Residents and fellows in the department of internal medicine were surveyed using a questionnaire containing 5 closed-ended items. These items examined trainees’ attitudes, experiences and knowledge about safety event reporting and barriers to their reporting.

- Results: 61% of 80 eligible trainees responded. The majority of residents understood that it is their responsibility to report safety events. Identified barriers to reporting were the complexity of the reporting system, lack of feedback after reporting safety events to gain knowledge of system advances, and reporting was not a priority in clinical workflow.

- Conclusion: An inpatient safety and quality committee intends to develop solutions to the challenges faced by trainees’ in reporting patient safety events.

Nationwide, graduate medical education programs are changing to include a greater focus on quality improvement and patient safety [1,2]. This has been recognized as a priority by the Institute of Medicine, the Joint Commission, and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) [3–6]. Hospital safety event reporting systems have been implemented to improve patient safety. Despite national expectations and demonstrated benefits of reporting adverse events, most resident and attending physicians fail to understand the value, lack the skills to report, and do not participate in incident reporting [7–9].

Past attempts to increase awareness about patient safety reporting have resulted in minimal participation [10,11]. In relation to other health care providers, attending and resident physicians have the lowest rate of patient safety reporting [12]. Interventions aiming to improve reporting have had mixed results, with sustained improvement being a major challenge [13,14]. To advance our efforts to improve reporting of patient safety events as a means toward improving patient safety, we sought to understand the attitudes and beliefs of our physicians in training with regard to patient safety event reporting.

Methods

Setting

Our institution, a community teaching hospital located in Park Ridge, IL, began patient safety event reporting in 2006 by remote data entry using the Midas information management system (MidasPlus, Xerox, Tucson, AZ). In 2012, as part of the system-based practice ACGME competency, we asked residents enter at least 1 patient safety event for each rotation block. The events could be entered with identifying information or anonymously.

Quality Improvement Project

Given the national focus on patient safety and quality improvement, as well as our organizational goal of zero patient safety events by 2020, in 2014 we formed an inpatient safety and quality committee. This committee includes the medical director of patient safety, internal medicine program director, associate program director, chief resident, fellows, residents and attending physicians. The committee was formed with the long-term objective of advancing patient safety and quality improvement efforts and to decrease preventable errors. As physicians in training are key frontline personnel, the committee decided to focus its initial short-term efforts on this group.

Questionnaire

To understand the magnitude and context of resident reporting behavior, we surveyed the residents and fellows in the department of internal medicine. The fellowships were in cardiology, gastroenterology, and hematology/oncology. The questionnaire we used contained 5 closed-ended items that examined trainees attitudes, experiences, and knowledge about incident reporting. The survey was distributed to the residents and fellows via SurveyMonkeyduring August 2014.

Results

When asked to outline reasons for not reporting incidents, participating residents and fellows identified the complexity of reporting system, lack of feedback, lack of updates about new system changes resulting from safety event reporting,

Discussion

This pilot study demonstrated that resident and fellow physicians in the department of internal medicine at our institution understand the necessity of reporting and that it is their responsibility; however, it is not a priority during the busy clinical workflow on the wards. Other investigators have observed similar attitudes/behaviors among physicians across teaching hospitals in the United States [10,12]. In a study by Boike et al [15], despite positive attitudes among internal medicine residents regarding reporting, increased reporting could not be sustained after the initial increase.

Our finding that 71.4% felt it was useful to discuss safety events is similar to Kaldjian et al’s [16] finding that 70% of generalist physicians in teaching hospitals believed that discussing mistakes strengthens professional relationships. The physicians in that study indicated that they usually discuss their errors with colleagues.

Prior to the development of the inpatient safety committee, the institution had a basic resource in place for reporting events, but there were minimal contributions from resident and fellow physicians. It is likely that the higher rates of reporting by nursing, laboratory, and pharmacy services (data not presented) that were seen are due to a required reporting protocol that is part of the workflow.

Since the inception of the inpatient safety committee, we have started several projects to build upon the foundation of positive resident and fellow physician attitudes. Based on the input of resident and fellow physicians, who are the front-line agents of process improvement, the existing patient safety reporting method was revised and reorganized. Previously, an online standardized patient safety event form was accessible after several click throughs on the institution’s homepage. This form was confusing and laborious to complete by residents and fellows, who were already operating on thin margins of spare time. The online reporting form was moved to the homepage for easy access and a free text option was enabled.

Another barrier to reporting was access to available computers. As such, the committee instituted a phone hotline reporting system. Instead of residents entering events using the Midas information management system, they now are able to call an in-house line and leave an anonymous voicemail to report safety events. Both the online and phone hotline reporting systems are integrated into a central database.

Lastly, resident and fellow physician education curricula were developed to instruct on the need to report patient safety events. Time is allotted at every monthly resident business meeting to discuss reportable patient safety events and offer feedback about concerns. In addition, the director of patient safety sends weekly safety updates, which are emailed to all faculty, residents, and fellows. These include de-identified safety event reports and any organizational and system improvements made in response to these events. Additionally, a mock root analysis takes place each quarter in which the patient safety director reviews a mock case with trainees to identify root causes and system failures. The committee has committed to transparency of reporting patient safety events as means to track the results of our efforts and interventions [17].

We plan to resurvey the resident and fellow physicians to reassess stability or changes in attitudes as a result of these physician-focused improvements. A more systematic analysis of temporal trends in reporting and comparisons across residency programs within our health system is being designed.

Conclusion

Reporting patient safety events should not be seen as a cumbersome task in an already busy clinical workday. We intend to develop scalable solutions that take into account the challenges faced by physicians in training. As the institution strives to become a high-reliability organization with a goal of zero serious patient safety events by 2020, we hope to share the lessons from our quality improvement efforts with other learning organizations.

Acknowledgements: The authors thank Suela Sulo, PhD, for manuscript review and editing.

Corresponding author: Jill Patton, DO, Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, 1775 Dempster St., Park Ridge, IL 60068, jill.patton@advocatehealth.com.

Financial disclosures: None.

From the Department of Internal Medicine, Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, IL.

Abstract

- Objective: To understand the attitudes and experiences of physicians in training with regard to patient safety event reporting.

- Methods: Residents and fellows in the department of internal medicine were surveyed using a questionnaire containing 5 closed-ended items. These items examined trainees’ attitudes, experiences and knowledge about safety event reporting and barriers to their reporting.

- Results: 61% of 80 eligible trainees responded. The majority of residents understood that it is their responsibility to report safety events. Identified barriers to reporting were the complexity of the reporting system, lack of feedback after reporting safety events to gain knowledge of system advances, and reporting was not a priority in clinical workflow.

- Conclusion: An inpatient safety and quality committee intends to develop solutions to the challenges faced by trainees’ in reporting patient safety events.

Nationwide, graduate medical education programs are changing to include a greater focus on quality improvement and patient safety [1,2]. This has been recognized as a priority by the Institute of Medicine, the Joint Commission, and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) [3–6]. Hospital safety event reporting systems have been implemented to improve patient safety. Despite national expectations and demonstrated benefits of reporting adverse events, most resident and attending physicians fail to understand the value, lack the skills to report, and do not participate in incident reporting [7–9].

Past attempts to increase awareness about patient safety reporting have resulted in minimal participation [10,11]. In relation to other health care providers, attending and resident physicians have the lowest rate of patient safety reporting [12]. Interventions aiming to improve reporting have had mixed results, with sustained improvement being a major challenge [13,14]. To advance our efforts to improve reporting of patient safety events as a means toward improving patient safety, we sought to understand the attitudes and beliefs of our physicians in training with regard to patient safety event reporting.

Methods

Setting

Our institution, a community teaching hospital located in Park Ridge, IL, began patient safety event reporting in 2006 by remote data entry using the Midas information management system (MidasPlus, Xerox, Tucson, AZ). In 2012, as part of the system-based practice ACGME competency, we asked residents enter at least 1 patient safety event for each rotation block. The events could be entered with identifying information or anonymously.

Quality Improvement Project

Given the national focus on patient safety and quality improvement, as well as our organizational goal of zero patient safety events by 2020, in 2014 we formed an inpatient safety and quality committee. This committee includes the medical director of patient safety, internal medicine program director, associate program director, chief resident, fellows, residents and attending physicians. The committee was formed with the long-term objective of advancing patient safety and quality improvement efforts and to decrease preventable errors. As physicians in training are key frontline personnel, the committee decided to focus its initial short-term efforts on this group.

Questionnaire

To understand the magnitude and context of resident reporting behavior, we surveyed the residents and fellows in the department of internal medicine. The fellowships were in cardiology, gastroenterology, and hematology/oncology. The questionnaire we used contained 5 closed-ended items that examined trainees attitudes, experiences, and knowledge about incident reporting. The survey was distributed to the residents and fellows via SurveyMonkeyduring August 2014.

Results

When asked to outline reasons for not reporting incidents, participating residents and fellows identified the complexity of reporting system, lack of feedback, lack of updates about new system changes resulting from safety event reporting,

Discussion

This pilot study demonstrated that resident and fellow physicians in the department of internal medicine at our institution understand the necessity of reporting and that it is their responsibility; however, it is not a priority during the busy clinical workflow on the wards. Other investigators have observed similar attitudes/behaviors among physicians across teaching hospitals in the United States [10,12]. In a study by Boike et al [15], despite positive attitudes among internal medicine residents regarding reporting, increased reporting could not be sustained after the initial increase.

Our finding that 71.4% felt it was useful to discuss safety events is similar to Kaldjian et al’s [16] finding that 70% of generalist physicians in teaching hospitals believed that discussing mistakes strengthens professional relationships. The physicians in that study indicated that they usually discuss their errors with colleagues.

Prior to the development of the inpatient safety committee, the institution had a basic resource in place for reporting events, but there were minimal contributions from resident and fellow physicians. It is likely that the higher rates of reporting by nursing, laboratory, and pharmacy services (data not presented) that were seen are due to a required reporting protocol that is part of the workflow.

Since the inception of the inpatient safety committee, we have started several projects to build upon the foundation of positive resident and fellow physician attitudes. Based on the input of resident and fellow physicians, who are the front-line agents of process improvement, the existing patient safety reporting method was revised and reorganized. Previously, an online standardized patient safety event form was accessible after several click throughs on the institution’s homepage. This form was confusing and laborious to complete by residents and fellows, who were already operating on thin margins of spare time. The online reporting form was moved to the homepage for easy access and a free text option was enabled.

Another barrier to reporting was access to available computers. As such, the committee instituted a phone hotline reporting system. Instead of residents entering events using the Midas information management system, they now are able to call an in-house line and leave an anonymous voicemail to report safety events. Both the online and phone hotline reporting systems are integrated into a central database.

Lastly, resident and fellow physician education curricula were developed to instruct on the need to report patient safety events. Time is allotted at every monthly resident business meeting to discuss reportable patient safety events and offer feedback about concerns. In addition, the director of patient safety sends weekly safety updates, which are emailed to all faculty, residents, and fellows. These include de-identified safety event reports and any organizational and system improvements made in response to these events. Additionally, a mock root analysis takes place each quarter in which the patient safety director reviews a mock case with trainees to identify root causes and system failures. The committee has committed to transparency of reporting patient safety events as means to track the results of our efforts and interventions [17].

We plan to resurvey the resident and fellow physicians to reassess stability or changes in attitudes as a result of these physician-focused improvements. A more systematic analysis of temporal trends in reporting and comparisons across residency programs within our health system is being designed.

Conclusion

Reporting patient safety events should not be seen as a cumbersome task in an already busy clinical workday. We intend to develop scalable solutions that take into account the challenges faced by physicians in training. As the institution strives to become a high-reliability organization with a goal of zero serious patient safety events by 2020, we hope to share the lessons from our quality improvement efforts with other learning organizations.

Acknowledgements: The authors thank Suela Sulo, PhD, for manuscript review and editing.

Corresponding author: Jill Patton, DO, Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, 1775 Dempster St., Park Ridge, IL 60068, jill.patton@advocatehealth.com.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Boonyasai RT, Windish DM, Chakraborti C, et al. Effectiveness of teaching quality improvement to clinicians: a systematic review. JAMA 2007;298:1023–37.

2. Wong BM, Etchells EE, Kuper A, et al. Teaching quality improvement and patient safety to trainees: a systematic review. Acad Med 2010;85:1425–39.

3. Leape LL, Berwick DM. Five years after To Err Is Human: what have we learned? JAMA. 2005;293:2384–90.

4. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS. To err is human: Building a safer health system. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1999.

5. Swing SR. The ACGME outcome project: retrospective and prospective. Med Teach 2007;29:648–54.

6. ACGME. Common program requirements. Available at www.acgme.org.

7. Kaldjian LC, Jones EW, Wu BJ, et al. Reporting medical errors to improve patient safety: a survey of physicians in teaching hospitals. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:40–6.

8. Kaldjian LC, Jones EW, Rosenthal GE, et al. An empirically derived taxonomy of factors affecting physicians’ willingness to disclose medical errors. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21:942–8.

9. White AA, Gallagher TH, Krauss MJ, et al. The attitudes and experiences of trainees regarding disclosing medical errors to patients. Acad Med 2008;83:250–6.

10. Farley DO, Haviland A, Champagne S, et al. Adverse-event-reporting practices by US hospitals: results of a national survey. Qual Saf Health Care 2008;17:416–23.

11. Schectman JM, Plews-Ogan ML. Physician perception of hospital safety and barriers to incident reporting. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2006;32:337–43.

12. Milch CE, Salem DN, Pauker SG, et al. Voluntary electronic reporting of medical errors and adverse events. An analysis of 92,547 reports from 26 acute care hospitals. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21:165–70.

13. Madigosky WS, Headrick LA, Nelson K, et al. Changing and sustaining medical students’ knowledge, skills, and attitudes about patient safety and medical fallibility. Acad Med 2006;81:94–101.

14. Jericho BG, Tassone RF, Centomani NM, et al. An assessment of an educational intervention on resident physician attitudes, knowledge, and skills related to adverse event reporting. J Grad Med Educ 2010;2:188–94.

15. Boike JR, Bortman JS, Radosta JM, et al. Patient safety event reporting expectation: does it influence residents’ attitudes and reporting behaviors? J Patient Saf 2013;9:59–67.

16.Kaldjian LC, Forman-Hoffman VL, Jones EW, et al. Do faculty and resident physicians discuss their medical errors? J Med Ethics 2008;34:717–22.

17. Willeumier D. Advocate health care: a systemwide approach to quality and safety. Jt Comm J Qual Saf 2004;30:559–66.

1. Boonyasai RT, Windish DM, Chakraborti C, et al. Effectiveness of teaching quality improvement to clinicians: a systematic review. JAMA 2007;298:1023–37.

2. Wong BM, Etchells EE, Kuper A, et al. Teaching quality improvement and patient safety to trainees: a systematic review. Acad Med 2010;85:1425–39.

3. Leape LL, Berwick DM. Five years after To Err Is Human: what have we learned? JAMA. 2005;293:2384–90.

4. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS. To err is human: Building a safer health system. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1999.

5. Swing SR. The ACGME outcome project: retrospective and prospective. Med Teach 2007;29:648–54.

6. ACGME. Common program requirements. Available at www.acgme.org.

7. Kaldjian LC, Jones EW, Wu BJ, et al. Reporting medical errors to improve patient safety: a survey of physicians in teaching hospitals. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:40–6.

8. Kaldjian LC, Jones EW, Rosenthal GE, et al. An empirically derived taxonomy of factors affecting physicians’ willingness to disclose medical errors. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21:942–8.

9. White AA, Gallagher TH, Krauss MJ, et al. The attitudes and experiences of trainees regarding disclosing medical errors to patients. Acad Med 2008;83:250–6.

10. Farley DO, Haviland A, Champagne S, et al. Adverse-event-reporting practices by US hospitals: results of a national survey. Qual Saf Health Care 2008;17:416–23.

11. Schectman JM, Plews-Ogan ML. Physician perception of hospital safety and barriers to incident reporting. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2006;32:337–43.

12. Milch CE, Salem DN, Pauker SG, et al. Voluntary electronic reporting of medical errors and adverse events. An analysis of 92,547 reports from 26 acute care hospitals. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21:165–70.

13. Madigosky WS, Headrick LA, Nelson K, et al. Changing and sustaining medical students’ knowledge, skills, and attitudes about patient safety and medical fallibility. Acad Med 2006;81:94–101.

14. Jericho BG, Tassone RF, Centomani NM, et al. An assessment of an educational intervention on resident physician attitudes, knowledge, and skills related to adverse event reporting. J Grad Med Educ 2010;2:188–94.

15. Boike JR, Bortman JS, Radosta JM, et al. Patient safety event reporting expectation: does it influence residents’ attitudes and reporting behaviors? J Patient Saf 2013;9:59–67.

16.Kaldjian LC, Forman-Hoffman VL, Jones EW, et al. Do faculty and resident physicians discuss their medical errors? J Med Ethics 2008;34:717–22.

17. Willeumier D. Advocate health care: a systemwide approach to quality and safety. Jt Comm J Qual Saf 2004;30:559–66.