User login

Bedside Swallow Examination Review

Dysphagia is a serious medical condition that can lead to aspiration pneumonia, malnutrition, and dehydration.[1] Dysphagia is the result of a variety of medical etiologies, including stroke, traumatic brain injury, progressive neurologic conditions, head and neck cancers, and general deconditioning. Prevalence estimates for dysphagia vary depending upon the etiology and patient age, but estimates as high as 38% for lifetime prevalence have been reported in those over age 65 years.[2]

To avoid adverse health outcomes, early detection of dysphagia is essential. In hospitalized patients, early detection has been associated with reduced risk of pneumonia, decreased length of hospital stay, and improved cost‐effectiveness resulting from a reduction in hospital days due to fewer cases of aspiration pneumonia.[3, 4, 5] Stroke guidelines in the United States recommend screening for dysphagia for all patients admitted with stroke.[6] Consequently, the majority of screening procedures have been designed for and tested in this population.[7, 8, 9, 10]

The videofluoroscopic swallow study (VFSS) is a commonly accepted, reference standard, instrumental evaluation technique for dysphagia, as it provides the most comprehensive information regarding anatomic and physiologic function for swallowing diagnosis and treatment. Flexible endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES) is also available, as are several less commonly used techniques (scintigraphy, manometry, and ultrasound). Due to availability, patient compliance, and expertise needed, it is not possible to perform instrumental examination on every patient with suspected dysphagia. Therefore, a number of minimally invasive bedside screening procedures for dysphagia have been developed.

The value of any diagnostic screening test centers on performance characteristics, which under ideal circumstances include a positive result for all those who have dysphagia (sensitivity) and negative result for all those who do not have dysphagia (specificity). Such an ideal screening procedure would reduce unnecessary referrals and testing, thus resulting in cost savings, more effective utilization of speech‐language pathology consultation services, and less unnecessary radiation exposure. In addition, an effective screen would detect all those at risk for aspiration pneumonia in need of intervention. However, most available bedside screening tools are lacking in some or all of these desirable attributes.[11, 12] We undertook a systematic review and meta‐analysis of bedside procedures to screen for dysphagia.

METHODS

Data Sources and Searches

We conducted a comprehensive search of 7 databases, including MEDLINE, Embase, and Scopus, from each database's earliest inception through June 9, 2014 for English‐language articles and abstracts. The search strategy was designed and conducted by an experienced librarian with input from 1 researcher (J.C.O.). Controlled vocabulary supplemented with keywords was used to search for comparative studies of bedside screening tests for predicting dysphagia (see Supporting Information, Appendix 1, in the online version of this article for the full strategy).

All abstracts were screened, and potentially relevant articles were identified for full‐text review. Those references were manually inspected to identify all relevant studies.

Study Selection

A study was eligible for inclusion if it tested a diagnostic swallow study of any variety against an acceptable reference standard (VFSS or flexible endoscopic evaluation of swallowing with sensory testing [FEEST]).

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

The primary outcome of the study was aspiration, as predicted by a bedside exam, compared to gold‐standard visualization of aspirated material entering below the vocal cords. From each study, data were abstracted based on the type of diagnostic method and reference standard study population and inclusion/exclusion characteristics, design, and prediction of aspiration. Prediction of aspiration was compared against the reference standard to yield true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives. Additional potential confounding variables were abstracted using a standard form based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analysis[13] (see Supporting Information, Appendix 2, in the online version of this article for the full abstraction template).

Data Synthesis and Analysis

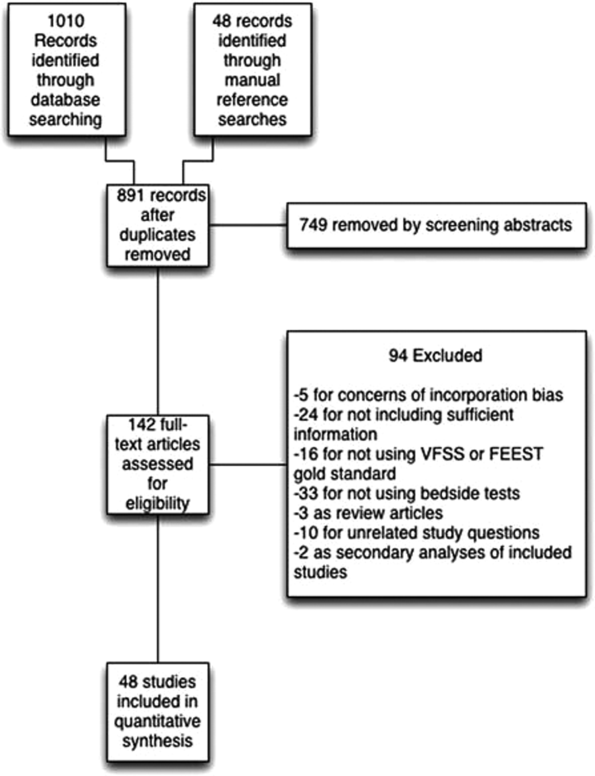

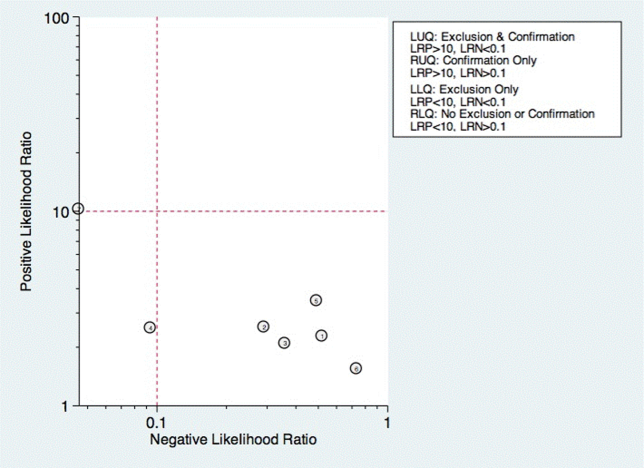

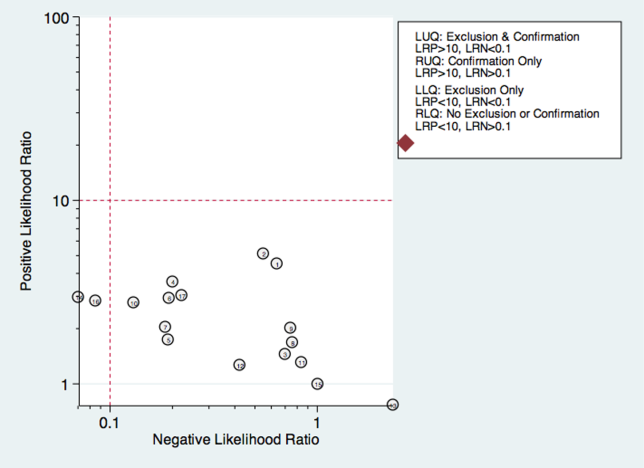

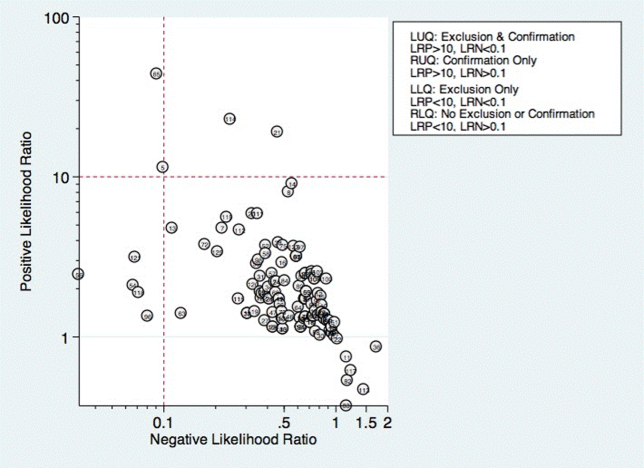

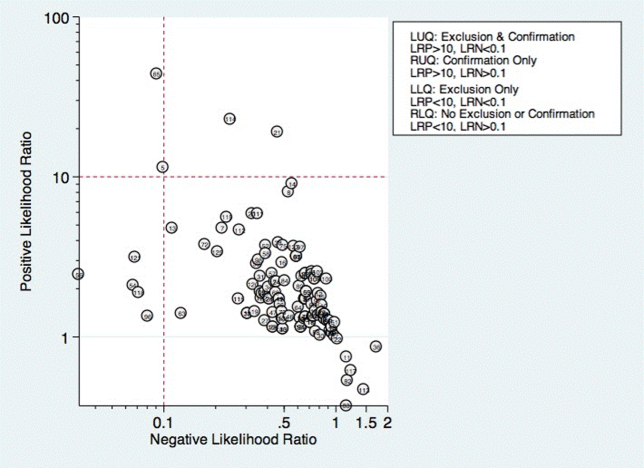

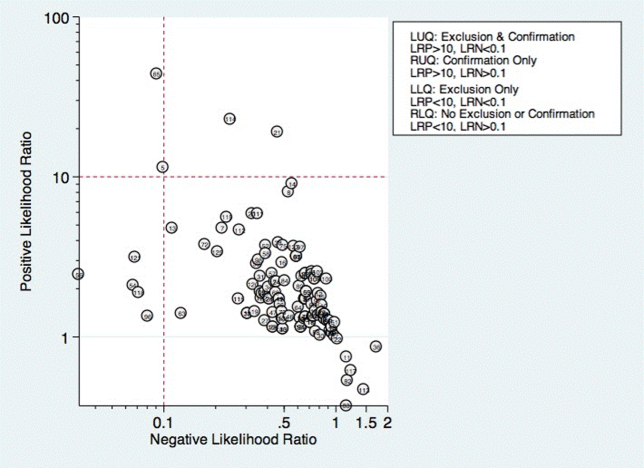

Sensitivity and specificity for each test that identified the presence of dysphagia was calculated for each study. These were used to generate positive and negative likelihood ratios (LRs), which were plotted on a likelihood matrix, a graphic depiction of the logarithm of the +LR on the ordinate versus the logarithm of the LR on the abscissa, dividing the graphic into quadrants such that the right upper quadrant is tests that can be used for confirmation, right lower quadrant neither confirmation nor exclusion, left lower quadrant exclusion only, and left upper quadrant an ideal test with both exclusionary and confirmatory properties.[14] A good screening test would thus be on the left half of the graphic to effectively rule out dysphagia, and the ideal test with both good sensitivity and specificity would be found in the left upper quadrant. Graphics were constructed using the Stata MIDAS package (Stata Corp., College Station, TX).[15]

RESULTS

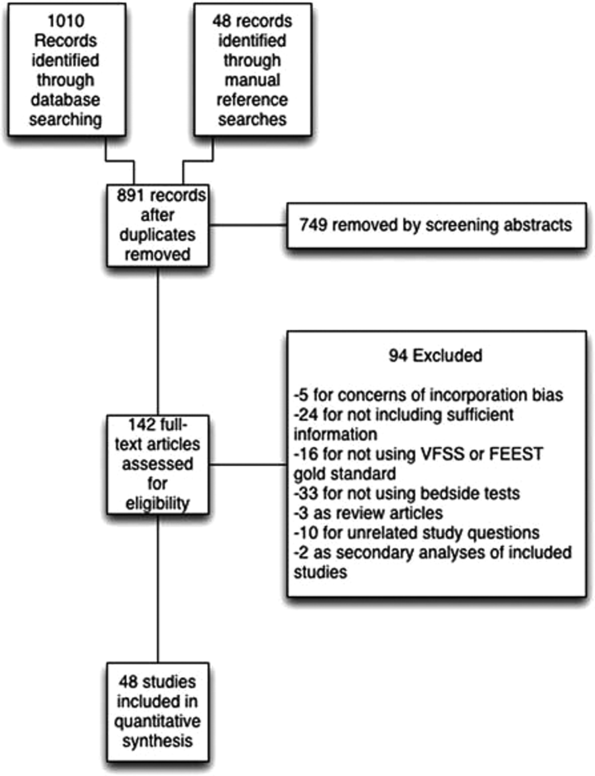

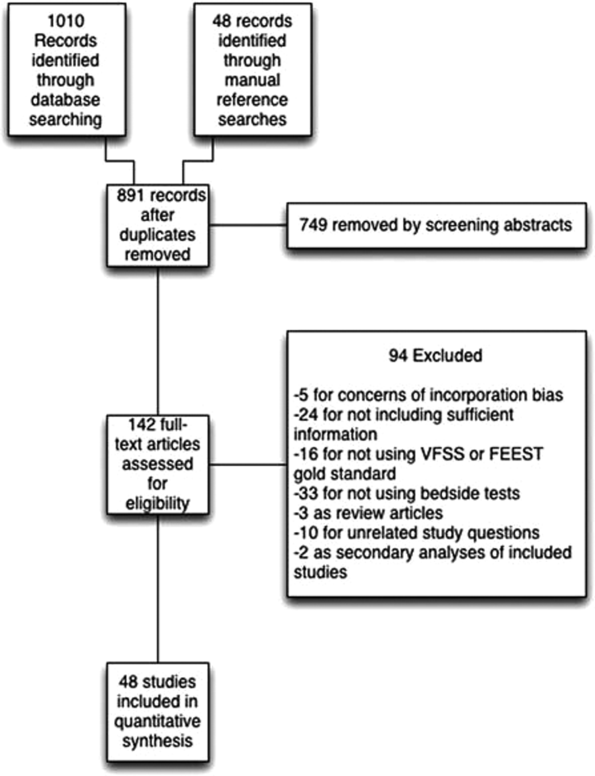

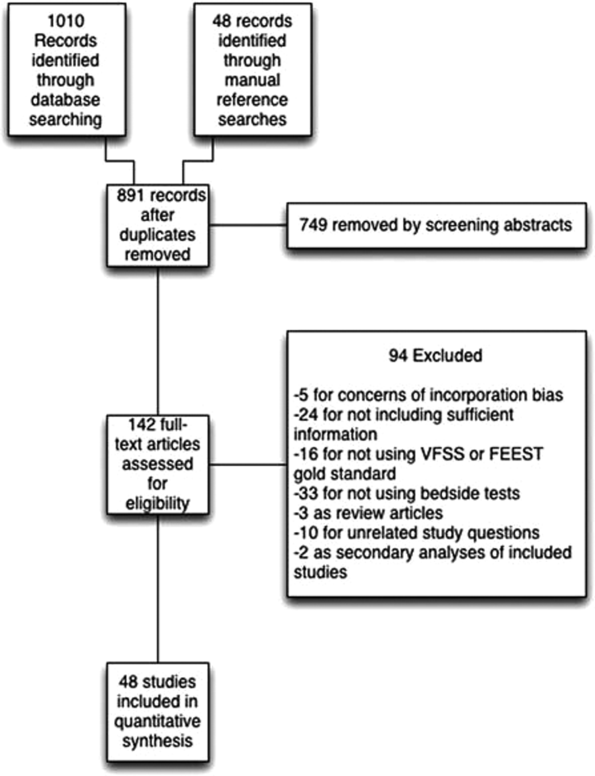

We identified 891 distinct articles. Of these, 749 were excluded based on abstract review. After reviewing the remaining 142 full‐text articles, 48 articles were determined to meet inclusion criteria, which included 10,437 observations across 7414 patients (Figure 1). We initially intended to conduct a meta‐analysis on each type, but heterogeneity in design and statistical heterogeneity in aggregate measures precluded pooling of results.

Characteristics of Included Studies

Of the 48 included studies, the majority (n=42) were prospective observational studies,[7, 8, 14, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53] whereas 2 were randomized trials,[9, 54] 2 studies were double‐blind observational,[9, 16] 1 was a case‐control design,[55] and 1 was a retrospective case series.[56] The majority of studies were exclusively inpatient,[7, 8, 9, 14, 17, 18, 19, 21, 22, 24, 25, 26, 31, 32, 33, 35, 36, 38, 41, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 49, 51, 52, 53, 55, 57] with 5 in mixed in and outpatient populations,[20, 27, 40, 55, 58] 2 in outpatient populations,[23, 41] and the remainder not reporting the setting from which they drew their study populations.

The indications for swallow evaluations fit broadly into 4 categories: stroke,[7, 8, 9, 14, 21, 22, 24, 25, 26, 31, 33, 34, 35, 38, 40, 41, 42, 43, 45, 48, 52, 56, 58] other neurologic disorders,[17, 18, 23, 28, 39, 47] all causes,[16, 20, 27, 29, 30, 36, 37, 44, 46, 49, 51, 52, 53, 54, 58] and postsurgical.[19, 32, 34] Most used VFSS as a reference standard,[7, 8, 9, 14, 16, 17, 18, 19, 21, 22, 23, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 34, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 56, 57, 58] with 8 using FEEST,[20, 24, 31, 32, 33, 35, 49, 55] and 1 accepting either videofluoroscopic evaluation of swallow or FEEST.[48]

Studies were placed into 1 or more of the following 4 categories: subjective bedside examination,[8, 9, 18, 19, 31, 34, 48] questionnaire‐based tools,[17, 23, 46, 53] protocolized multi‐item evaluations,[20, 21, 22, 25, 30, 33, 34, 37, 39, 44, 45, 52, 53, 57, 58] and single‐item exam maneuvers, symptoms, or signs.[7, 9, 14, 16, 24, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 56, 58, 59] The characteristics of all studies are detailed in Table 1.

| Study | Location | Design | Mean Age (SD) | Reason(s) for Dysphagia | Indx Test | Description | Reference Standard | Sample Size, No. of Patients | Sample Size, No. of Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Splaingard et al., 198844 | Milwaukee, WI, USA | Prospective observational study | NR | Multiple | Clinical bedside swallow exam | Combination of scored comprehensive physical exam, history, and observed swallow. | VFSS | 107 | 107 |

| DePippo et al., 199243 | White Plains, NY, USA | Prospective observational study | 71 (10) | Stroke | WST | Observation of swallow. | VFSS | 44 | |

| Horner et al., 199356 | Durham, NC, USA | Retrospective case series | 64* | Stroke | Clinical bedside swallow evaluation | VFSS | 38 | 114 | |

| Kidd et al., 199342 | Belfast, UK | Prospective observational study | 72 (10) | Stroke | Bedside 50‐mL swallow evaluation | Patient swallows 50 mL of water in 5‐mL aliquots, with therapist assessing for choking, coughing, or change in vocal quality after each swallow. | VFSS | 60 | 240 |

| Collins and Bakheit, 199741 | Southampton, UK | Prospective observational study | 65* | Stroke | Desaturation | Desaturation of at least 2% during videofluoroscopic study. | VFSS | 54 | 54 |

| Daniels et al., 199740 | New Orleans, LA, USA | Prospective observational study | 66 (11) | Stroke | Clinical bedside examination | 6 individual bedside assessments (dysphonia, dysphagia, cough before/after swallow, gag reflex and voice change) examined as predictors for aspiration risk. | VFSS | 59 | 354 |

| Mari et al., 199739 | Ancona, Italy | Prospective observational study | 60 (16) | Mixed neurologic diseases | Combined history and exam | Assessed symptoms of dysphagia, cough, and 3‐oz water swallow. | VFSS | 93 | 372 |

| Daniels et al., 19987 | New Orleans, LA, USA | Prospective observational study | 66 (11) | Stroke | Clinical bedside swallow evaluation | Describes sensitivity and specificity of several component physical exam maneuvers comprising the bedside exam. | VFSS | 55 | 330 |

| Smithard et al., 19988 | Ashford, UK | Prospective observational study | 79* | Stroke | Clinical bedside swallow evaluation | Not described. | VFSS | 83 | 249 |

| Addington et al., 199938 | Kansas City, MO, USA | Prospective observational study | 80* | Stroke | NR | Reflex cough. | VFSS | 40 | 40 |

| Logemann et al., 199937 | Evanston, IL, USA | Prospective observational study | 65 | Multiple | Northwestern Dysphagia Check Sheet | 28‐item screening procedure including history, observed swallow, and physical exam. | VFSS | 200 | 1400 |

| Smith et al., 20009 | Manchester, UK | Double blind observational | 69 | Stroke | Clinical bedside swallow evaluation, pulse oximetry evaluation | After eating/drinking, patient is evaluated for signs of aspiration including coughing, choking, or "wet voice." Procedure is repeated with several consistencies. Also evaluated if patient desaturates by at least 2% during evaluation. | VFSS | 53 | 53 |

| Warms et al., 200036 | Melbourne, Australia | Prospective observational study | 67 | Multiple | Wet voice | Voice was recorded and analyzed with Sony digital audio tape during videofluoroscopy. | VFSS | 23 | 708 |

| Lim et al., 200135 | Singapore, Singapore | Prospective observational study | NR | Stroke | Water swallow test, desaturation during swallow | 50‐mL swallow done in 5‐mL aliquots with assessment of phonation/choking afterward; desaturation >2% during swallow, | FEEST | 50 | 100 |

| McCullough et al., 200134 | Nashville, TN, USA | Prospective observational study | 60 (10) | Stroke | Clinical bedside swallow evaluation | 15‐item physical exam with observed swallow. | VFSS | 2040 | 60 |

| Rosen et al., 2001[74] | Newark, NJ, USA | Prospective observational study | 60 | Head and Neck cancer | Wet voice | Observation of swallow. | VFSS | 26 | 26 |

| Leder and Espinosa, 200233 | New Haven, CT, USA | Prospective observational study | 70* | Stroke | Clinical exam | Checklist evaluation of cough and voice change after swallow, volitional cough, dysphonia, dysarthria, and abnormal gag. | FEEST | 49 | 49 |

| Belafsky et al., 200332 | San Francisco, CA, USA | Prospective observational study | 65 (11) | Post‐tracheostomy patients | Modified Evans Blue Dye Test | 3 boluses of dye‐impregnated ice are given to patient. Tracheal secretions are suctioned, and evaluated for the presence of dye. | FEES | 30 | 30 |

| Chong et al., 200331 | Jalan Tan Tock Seng, Singapore | Prospective observational study | 75 (7) | Stroke | Water swallow test, desaturation during, clinical exam | Subjective exam, drinking 50 mL of water in 10‐mL aliquots, and evaluating for desaturation >2% during FEES. | FEEST | 50 | 150 |

| Tohara et al., 200330 | Tokyo, Japan | Prospective observational study | 63 (17) | Multiple | Food/water swallow tests, and a combination of the 2 | Protocolized observation of sequential food and water swallows with scored outcomes. | VFSS | 63 | 63 |

| Rosenbek et al., 200414 | Gainesville, FL, USA | Prospective observational study | 68* | Stroke | Clinical bedside swallow evaluation | Describes 5 parameters of voice quality and 15 physical examination maneuvers used. | VFSS | 60 | 1200 |

| Ryu et al., 200429 | Seoul, South Korea | Prospective observational study | 64 (14) | Multiple | Voice analysis parameters | Analysis of the/a/vowel sound with Visi‐Pitch II 3300. | VFSS | 93 | 372 |

| Shaw et al., 200428 | Sheffield, UK | Prospective observational study | 71 | Neurologic disease | Bronchial auscultation | Auscultation over the right main bronchus during trial feeding to listen for sounds of aspiration. | VFSS | 105 | 105 |

| Wu et al., 200427 | Taipei, Taiwan | Prospective observational study | 72 (11) | Multiple | 100‐mL swallow test | Patient lifts a glass of 100 mL of water and drinks as quickly as possible, and is assessed for signs of choking, coughing, or wet voice, and is timed for speed of drinking. | VFSS | 54 | 54 |

| Nishiwaki et al., 200526 | Shizuoaka, Japan | Prospective observational study | 70* | Stroke | Clinical bedside swallow evaluation | Describes sensitivity and specificity of several component physical exam maneuvers comprising the bedside exam. | VFSS | 31 | 248 |

| Wang et al., 200554 | Taipei, Taiwan | Prospective double‐blind study | 41* | Multiple | Desaturation | Desaturation of at least 2% during videofluoroscopic study. | VFSS | 60 | 60 |

| Ramsey et al., 200625 | Kent, UK | Prospective observational study | 71 (10) | Stroke | BSA | Assessment of lip seal, tongue movement, voice quality, cough, and observed 5‐mL swallow. | VFSS | 54 | 54 |

| Trapl et al., 200724 | Krems, Austria | Prospective observational study | 76 (2) | Stroke | Gugging Swallow Screen | Progressive observed swallow trials with saliva, then with 350 mL liquid, then dry bread. | FEEST | 49 | 49 |

| Suiter and Leder, 200849 | Several centers across the USA | Prospective observational study | 68.3 | Multiple | 3‐oz water swallow test | Observation of swallow. | FEEST | 3000 | 3000 |

| Wagasugi et al., 200850 | Tokyo, Japan | Prospective observational study | NR | Multiple | Cough test | Acoustic analysis of cough. | VFSS | 204 | 204 |

| Baylow et al., 200945 | New York, NY, USA | Prospective observational study | NR | Stroke | Northwestern Dysphagia Check Sheet | 28‐item screening procedure including history, observed swallow, and physical exam. | VFSS | 15 | 30 |

| Cox et al., 200923 | Leiden, the Netherlands | Prospective observational study | 68 (8) | Inclusion body myositis | Dysphagia questionnaire | Questionnaire assessing symptoms of dysphagia. | VFSS | 57 | 57 |

| Kagaya et al., 201051 | Tokyo, Japan | Prospective observational study | NR | Multiple | Simple Swallow Provocation Test | Injection of 1‐2 mL of water through nasal tube directed at the suprapharynx. | VFSS | 46 | 46 |

| Martino et al., 200957 | Toronto, Canada | Randomized trial | 69 (14) | Stroke | Toronto Bedside Swallow Screening Test | 4‐item physical assessment including Kidd water swallow test, pharyngeal sensation, tongue movement, and dysphonia (before and after water swallow). | VFSS | 59 | 59 |

| Santamato et al., 200955 | Bari, Italy | Case control | NR | Multiple | Acoustic analysis, postswallow apnea | Acoustic analysis of cough. | VFSS | 15 | 15 |

| Smith Hammond et al., 200948 | Durham, NC, USA | Prospective observational study | 67.7 (1.2) | Multiple | Cough, expiratory phase peak flow | Acoustic analysis of cough. | VFSS or FEES | 96 | 288 |

| Leigh et al., 201022 | Seoul, South Korea | Prospective observational study | NR | Stroke | Clinical bedside swallow evaluation | Not described. | VFSS | 167 | 167 |

| Pitts et al., 201047 | Gainesville, FL, USA | Prospective observational study | NR | Parkinson | Cough compression phase duration | Acoustic analysis of cough. | VFSS | 58 | 232 |

| Cohen and Manor, 201146 | Tel Aviv, Israel | Prospective observational Study | NR | Multiple | Swallow Disturbance Questionnaire | 15‐item questionnaire. | FEES | 100 | 100 |

| Edmiaston et al., 201121 | St. Louis, MO, USA | Prospective observational study | 63* | Stroke | SWALLOW‐3D Acute Stroke Dysphagia Screen | 5‐item screen including mental status; asymmetry or weakness of face, tongue, or palate; and subjective signs of aspiration when drinking 3 oz water. | VFSS | 225 | 225 |

| Mandysova et al., 201120 | Pardubice, Czech Republic | Prospective observational study | 69 (13) | Multiple | Brief Bedside Dysphagia Screening Test | 8‐item physician exam including ability to clench teeth; symmetry/strength of tongue, facial, and shoulder muscles; dysarthria; and choking, coughing, or dripping of food after taking thick liquid. | FEES | 87 | 87 |

| Steele et al., 201158 | Toronto, Canada | Double blind observational | 67 | Stroke | 4‐item bedside exam | Tongue lateralization, cough, throat clear, and voice quality. | VFSS | 400 | 40 |

| Yamamoto et al., 201117 | Kodaira, Japan | Prospective observational study | 67 (9) | Parkinson's Disease | Swallowing Disturbance Questionnaire | 15‐item questionnaire. | VFSS | 61 | 61 |

| Bhama et al., 201219 | Pittsburgh, PA, USA | Prospective observational study | 57 (14) | Post‐lung transplant | Clinical bedside swallow evaluation | Not described. | VFSS | 128 | 128 |

| Shem et al., 201218 | San Jose, CA, USA | Prospective observational study | 42 (17) | Spinal cord injuries resulting in tetraplegia | Clinical bedside swallow evaluation | After eating/drinking, patient is evaluated for signs of aspiration including coughing, choking, or "wet voice." Procedure is repeated with several consistencies. | VFSS | 26 | 26 |

| Steele et al., 201316 | Toronto, Canada | Prospective observational study | 67 (14) | Multiple | Dual‐axis accelerometry | Computed accelerometry of swallow. | VFSS | 37 | 37 |

| Edmiaston et al., 201452 | St. Louis, MO, USA | Prospective observational study | 63 (15) | Stroke | Barnes Jewish Stroke Dysphagia Screen | 5‐item screen including mental status; asymmetry or weakness of face, tongue, or palate; and subjective signs of aspiration when drinking 3 oz water. | VFSS | 225 | 225 |

| Rofes et al., 201453 | Barcelona, Spain | Prospective observational study | 74 (12) | Mixed | EAT‐10 questionnaire and variable viscosity swallow test | Symptom‐based questionnaire (EAT‐10) and repeated observations and measurements of swallow with different thickness liquids. | VFS | 134 | 134 |

Subjective Clinical Exam

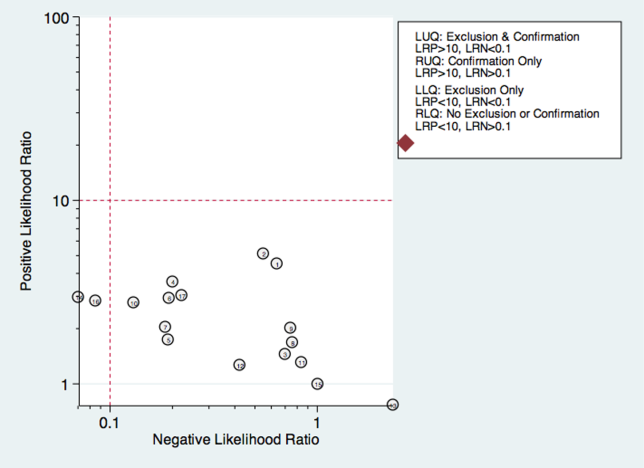

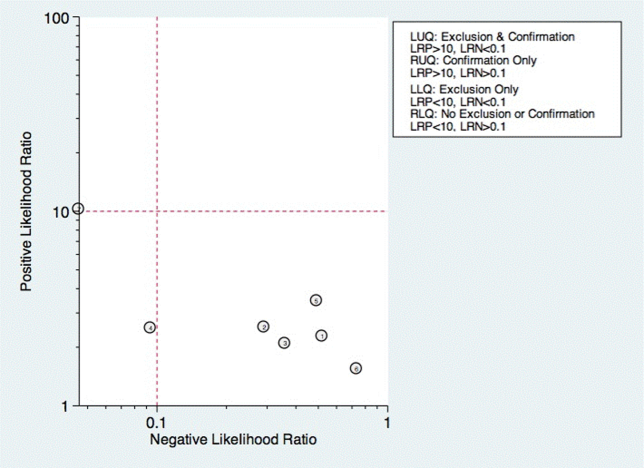

Seven studies reported the sensitivity and specificity of subjective assessments of nurses and speech‐language pathologists in observing swallowing and predicting aspiration.[8, 9, 18, 19, 31, 34, 48] The overall distribution of studies is summarized in the likelihood matrix in Figure 2. Two studies, Chong et al.[31] and Shem et al.,[18] were on the left side of the matrix, indicating a sensitive rule‐out test. However, both were small studies, and only Chong et al. reported reasonable sensitivity with incorporation bias from knowledge of a desaturation study outcome. Overall, subjective exams did not appear reliable in ruling out dysphagia.

Questionnaire‐Based Tools

Only 4 studies used questionnaire‐based tools filled out by the patient, asking about subjective assessment of dysphagia symptoms and frequency.[17, 23, 46, 53] Yamamoto et al. reported results of using the swallow dysphagia questionnaire in patients with Parkinson's disease.[17] Rofes et al. looked at the Eating Assessment Tool (EAT‐10) questionnaire among all referred patients and a small population of healthy volunteers.[53] Each was administered the questionnaire before undergoing a videofluoroscopic study. Overall, sensitivity and specificity were 77.8% and 84.6%, respectively. Cox et al. studied a different questionnaire in a group of patients with inclusion body myositis, finding 70% sensitivity and 44% specificity.[23] Cohen and Manor examined the swallow dysphagia questionnaire across several different causes of dysphagia, finding at optimum, the test is 78% specific and 73% sensitive.[46] Rofes et al. had an 86% sensitivity and 68% specificity for the EAT‐10 tool.[53]

Multi‐Item Exam Protocols

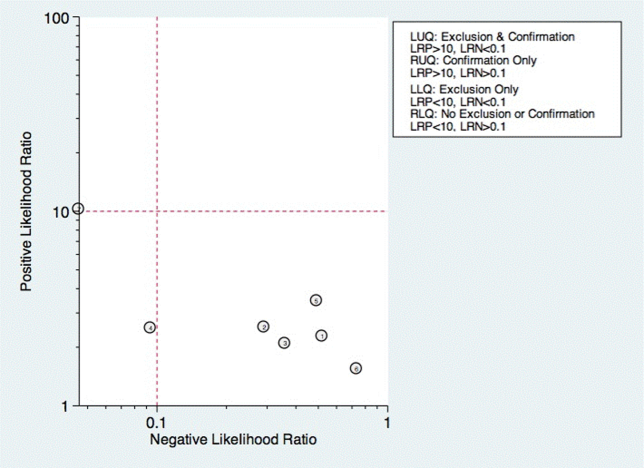

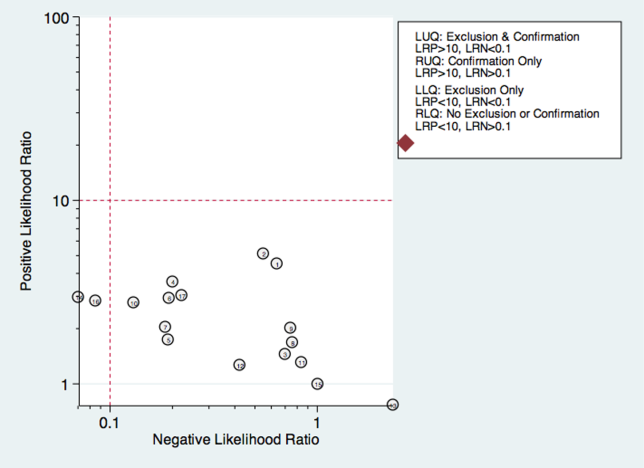

Sixteen studies reported multistep protocols for determining a patient's risk for aspiration.[9, 20, 21, 22, 25, 30, 33, 34, 37, 39, 44, 45, 52, 53, 57, 58] Each involved a combination of physical exam maneuvers and history elements, detailed in Table 1. This is shown in the likelihood matrix in Figure 3. Only 2 of these studies were in the left lower quadrant, Edmiaston et al. 201121 and 2014.[52] Both studies were restricted to stroke populations, but found reasonable sensitivity and specificity in identifying dysphagia.

Individual Exam Maneuvers

Thirty studies reported the diagnostic performance of individual exam maneuvers and signs.[7, 9, 14, 16, 24, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 54, 56, 58] Each is depicted in Figure 4 as a likelihood matrix demonstrating the +LR and LR for individual maneuvers as seen in the figure; most fall into the right lower quadrant, where they are not diagnostically useful tests. Studies in the left lower quadrant demonstrating the ability to exclude aspiration desirable in a screening test were dysphonia in McCullough et al.,[34] dual‐axis accelerometry in Steele et al.,[16] and the water swallow test in DePippo et al.[43] and Suiter and Leder.[49]

McCullough et al. found dysphonia to be the most discriminatory sign or symptom assessed, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.818. Dysphonia was judged by a sustained/a/and had 100% sensitivity but only 27% specificity. Wet voice within the same study was slightly less informative, with an AUC of 0.77 (sensitivity 50% and specificity 84%).[34]

Kidd et al. verified the diagnosis of stroke, and then assessed several neurologic parameters, including speech, muscle strength, and sensation. Pharyngeal sensation was assessed by touching each side of the pharyngeal wall and asking patients if they felt sensation that differed from each side. Patient report of abnormal sensation during this maneuver was 80% sensitive and 86% specific as a predictor of aspiration on VFSS.[42]

Steele et al. described the technique of dual axis accelerometry, where an accelerometer was placed at the midline of the neck over the cricoid cartilage during VFSS. The movement of the cricoid cartilage was captured for analysis in a computer algorithm to identify abnormal pharyngeal swallow behavior. Sensitivity was 100%, and specificity was 54%. Although the study was small (n=40), this novel method demonstrated good discrimination.[58]

DePippo et al. evaluated a 3‐oz water swallow in stroke patients. This protocol called for patients to drink the bolus of water without interruption, and be observed for 1 minute after for cough or wet‐hoarse voice. Presence of either sign was considered abnormal. Overall, sensitivity was 94% and specificity 30% looking for the presence of either sign.[43] Suiter and Leder used a similar protocol, with sensitivity of 97% and specificity of 49%.[49]

DISCUSSION

Our results show that most bedside swallow examinations lack the sensitivity to be used as a screening test for dysphagia across all patient populations examined. This is unfortunate as the ability to determine which patients require formal speech language pathology consultation or imaging as part of their diagnostic evaluation early in the hospital stay would lead to improved allocation of resources, cost reductions, and earlier implementation of effective therapy approaches. Furthermore, although radiation doses received during VFSS are not high when compared with other radiologic exams like computed tomography scans,[60] increasing awareness about the long‐term malignancy risks associated with medical imaging makes it desirable to reduce any test involving ionizing radiation.

There were several categories of screening procedures identified during this review process. Those classified as subjective bedside exams and protocolized multi‐item evaluations were found to have high heterogeneity in their sensitivity and specificity, though a few exam protocols did have a reasonable sensitivity and specificity.[21, 31, 52] The following individual exam maneuvers were found to demonstrate high sensitivity and an ability to exclude aspiration: a test for dysphonia through production of a sustained/a/34 and use of dual‐axis accelerometry.[16] Two other tests, the 3‐oz water swallow test[43] and testing of abnormal pharyngeal sensation,[42] were each found effective in a single study, with conflicting results from other studies.

Our results extend the findings from previous systematic reviews on this subject, most of which focused only on stroke patients.[5, 12, 61, 62] Martino and colleagues[5] conducted a review focused on screening for adults poststroke. From 13 identified articles, it was concluded that evidence to support inclusion or exclusion of screening was poor. Daniels et al. conducted a systematic review of swallowing screening tools specific to patients with acute or chronic stroke.[12] Based on 16 articles, the authors concluded that a combination of swallowing and nonswallowing features may be necessary for development of a valid screening tool. The generalizability of these reviews is limited given that all were conducted in patients poststroke, and therefore results and recommendations may not be generalizable to other patients.

Wilkinson et al.[62] conducted a recent systematic review that focused on screening techniques for inpatients 65 years or older that excluded patients with stroke or Parkinson's disease. The purpose of that review was to examine sensitivity and specificity of bedside screening tests as well as ability to accurately predict pneumonia. The authors concluded that existing evidence is not sufficient to recommend the use of bedside tests in a general older population.[62]

Specific screening tools identified by Martino and colleagues[5] to have good predictive value in detecting aspiration as a diagnostic marker of dysphagia were an abnormal test of pharyngeal sensation[42] and the 50‐mL water swallow test. Daniels et al. identified a water swallow test as an important component of a screen.[7] These results were consistent with those of this review in that the abnormal test of pharyngeal sensation[42] was identified for high levels of sensitivity. However, the 3‐oz water swallow test,[43, 49] rather than the 50‐mL water swallow test,[42] was identified in this review as the version of the water swallow test with the best predictive value in ruling out aspiration. Results of our review identified 2 additional individual items, dual‐axis accelerometry[16] and dysphonia,[34] that may be important to include in a comprehensive screening tool. In the absence of better tools, the 3 oz swallow test, properly executed, seems to be the best currently available tool validated in more than 1 study.

Several studies in the current review included an assessment of oral tongue movement that is not described thoroughly and varies between studies. Tongue movement as an individual item on a screening protocol was not found to yield high sensitivity or specificity. However, tongue movement or range of motion is only 1 aspect of oral tongue function; pressures produced by the tongue reflecting strength also may be important and warrant evaluation. Multiple studies have shown patients with dysphagia resulting from a variety of etiologies to produce lower than normal maximum isometric lingual pressures,[63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68] or pressures produced when the tongue is pushed as hard as possible against the hard palate. Tongue strengthening protocols that result in higher maximum isometric lingual pressures have been shown to carry over to positive changes in swallow function.[69, 70, 71, 72, 73] Inclusion of tongue pressure measurement in a comprehensive screening tool may help to improve predictive capabilities.

We believe our results have implications for practicing clinicians, and serve as a call to action for development of an easy‐to‐perform, accurate tool for dysphagia screening. Future prospective studies should focus on practical tools that can be deployed at the bedside, and correlate the results with not only gold‐standard VFSS and FEES, but with clinical outcomes such as pneumonia and aspiration events leading to prolonged length of stay.

There were several limitations to this review. High levels of heterogeneity were reported in the screening tests present in the literature, precluding meaningful meta‐analysis. In addition, the majority of studies included were in poststroke adults, which limits the generalizability of results.

In conclusion, no screening protocol has been shown to provide adequate predictive value for presence of aspiration. Several individual exam maneuvers demonstrate high sensitivity; however, the most effective combination of screening protocol components is unknown. There is a need for future research focused on the development of a comprehensive screening tool that can be applied across patient populations for accurate detection of dysphagia as well as prediction of other adverse health outcomes, including pneumonia.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Drs. Byun‐Mo Oh and Catrionia Steele for providing additional information in response to requests for unpublished information.

Disclosures: Nasia Safdar MD, is supported by a National Institutes of Health R03 GEMSSTAR award and a VA MERIT award. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , , , et al. Pathophysiology, relevance and natural history of oropharyngeal dysphagia among older people. Nestle Nutr Inst Workshop Ser. 2012;72:57–66.

- , , , Dysphagia in the elderly: preliminary evidence of prevalence, risk factors, and socioemotional effects. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2007;116(11):858–865.

- , , Formal dysphagia screening protocols prevent pneumonia. Stroke. 2006;37(3):765.

- , , Swallow management in patients on an acute stroke pathway: quality is cost effective. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1995;76(12):1130–1133.

- , , Screening for oropharyngeal dysphagia in stroke: insufficient evidence for guidelines. Dysphagia. 2000;15(1):19–30.

- , , , et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2013;44(3):870–947.

- , , , , , Aspiration in patients with acute stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;79(1):14–19.

- , , , et al. Can bedside assessment reliably exclude aspiration following acute stroke? Age Ageing. 1998;27(2):99–106.

- , , , The combination of bedside swallowing assessment and oxygen saturation monitoring of swallowing in acute stroke: a safe and humane screening tool. Age Ageing. 2000;29(6):495–499.

- , , , Validation of a dysphagia screening tool in acute stroke patients. Am J Crit Care. 2010;19(4):357–364.

- , Screening for dysphagia and aspiration in acute stroke: a systematic review. Dysphagia. 2001;16(1):7–18.

- , , Valid items for screening dysphagia risk in patients with stroke: a systematic review. Stroke. 2012;43(3):892–897.

- , , , , Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–269, W64.

- , , Is the information about a test important? Applying the methods of evidence‐based medicine to the clinical examination of swallowing. J Commun Disord. 2004;37(5):437–450.

- MIDAS: Stata module for meta‐analytical integration of diagnostic test accuracy studies. Statistical Software Components. S456880, Boston College Department of Economics, 2009.

- , , Noninvasive detection of thin‐liquid aspiration using dual‐axis swallowing accelerometry. Dysphagia. 2013;28(1):105–112.

- , , , , Validation of the Japanese translation of the Swallowing Disturbance Questionnaire in Parkinson's disease patients. Qual Life Res. 2012;21(7):1299–1303.

- , , , , , Diagnostic accuracy of bedside swallow evaluation versus videofluoroscopy to assess dysphagia in individuals with tetraplegia. PM R. 2012;4(4):283–289.

- , et al. 723 Aspiration after Lung Transplantation: Incidence, Risk Factors, and Accuracy of the Bedside Swallow Evaluation. The J Heart Lung Transplant. 2012;31(4 suppl 1):S247–S248.

- , , , Cerny M. Development of the brief bedside dysphagia screening test in the Czech Republic. Nurs Health Sci. 2011;13(4):388–395.

- , , SWALLOW‐3D, a simple 2‐minute bedside screening test, detects dysphagia in acute stroke patients with high sensitivity when validated against video‐fluoroscopy. Stroke. 2011;42(3):e352.

- , , , , Bedside screening and subacute reassessment of post‐stroke dysphagia: a prospective study. Int J Stroke. 2010;5:200.

- , , , , , Detecting dysphagia in inclusion body myositis. J Neurol. 2009;256(12):2009–2013.

- , , , et al. Dysphagia bedside screening for acute‐stroke patients: the Gugging Swallowing Screen. Stroke. 2007;38(11):2948–2952.

- , , Can pulse oximetry or a bedside swallowing assessment be used to detect aspiration after stroke? Stroke. 2006;37(12):2984–2988.

- , , , , , Identification of a simple screening tool for dysphagia in patients with stroke using factor analysis of multiple dysphagia variables. J Rehabil Med. 2005;37(4):247–251.

- , , , Evaluating swallowing dysfunction using a 100‐ml water swallowing test. Dysphagia. 2004;19(1):43–47.

- , , , et al. Bronchial auscultation: an effective adjunct to speech and language therapy bedside assessment when detecting dysphagia and aspiration? Dysphagia. 2004;19(4):211–218.

- , , Prediction of laryngeal aspiration using voice analysis. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;83(10):753–757.

- , , , , Three tests for predicting aspiration without videofluorography. Dysphagia. 2003;18(2):126–134.

- , , , , Bedside clinical methods useful as screening test for aspiration in elderly patients with recent and previous strokes. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2003;32(6):790–794.

- , , , The accuracy of the modified Evan's blue dye test in predicting aspiration. Laryngoscope. 2003;113(11):1969–1972.

- , Aspiration risk after acute stroke: comparison of clinical examination and fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing. Dysphagia. 2002;17(3):214–218.

- , , Sensitivity and specificity of clinical/bedside examination signs for detecting aspiration in adults subsequent to stroke. J Commun Disord. 2001;34(1‐2):55–72.

- , , , et al. Accuracy of bedside clinical methods compared with fiberoptic endoscopic examination of swallowing (FEES) in determining the risk of aspiration in acute stroke patients. Dysphagia. 2001;16(1):1–6.

- , “Wet Voice” as a predictor of penetration and aspiration in oropharyngeal dysphagia. Dysphagia. 2000;15(2):84–88.

- , , A screening procedure for oropharyngeal dysphagia. Dysphagia. 1999;14(1):44–51.

- , , , Assessing the laryngeal cough reflex and the risk of developing pneumonia after stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80(2):150–154.

- , , , , , Predictive value of clinical indices in detecting aspiration in patients with neurological disorders. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1997;63(4):456–460.

- , , , Clinical assessment of swallowing and prediction of dysphagia severity. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 1997;6(4):17–24.

- , Does pulse oximetry reliably detect aspiration in dysphagic stroke patients? Stroke. 1997;28(9):1773–1775.

- , , , Aspiration in acute stroke: a clinical study with videofluoroscopy. Q J Med. 1993;86(12):825–829.

- , , Validation of the 3‐oz water swallow test for aspiration following stroke. Arch Neurol. 1992;49(12):1259–1261.

- , , , Aspiration in rehabilitation patients: videofluoroscopy vs bedside clinical assessment. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1988;69(8):637–640.

- , , , Accuracy of clinical judgment of the chin‐down posture for dysphagia during the clinical/bedside assessment as corroborated by videofluoroscopy in adults with acute stroke. Dysphagia. 2009;24(4):423–433.

- , Swallowing disturbance questionnaire for detecting dysphagia. Laryngoscope. 2011;121(7):1383–1387.

- , , , , , . Using voluntary cough to detect penetration and aspiration during oropharyngeal swallowing in patients with Parkinson disease. Chest. 2010;138(6):1426–1431.

- , , , et al. Predicting aspiration in patients with ischemic stroke: comparison of clinical signs and aerodynamic measures of voluntary cough. Chest. 2009;135(3):769–777.

- , Clinical utility of the 3‐ounce water swallow test. Dysphagia. 2008;23(3):244–250.

- , , , et al. Screening test for silent aspiration at the bedside. Dysphagia. 2008;23(4):364–370.

- , , , , , Simple swallowing provocation test has limited applicability as a screening tool for detecting aspiration, silent aspiration, or penetration. Dysphagia. 2010;25(1):6–10.

- , , , A simple bedside stroke dysphagia screen, validated against videofluoroscopy, detects dysphagia and aspiration with high sensitivity. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;23 (4):712–716.

- , , , Sensitivity and specificity of the Eating Assessment Tool and the Volume‐Viscosity Swallow Test for clinical evaluation of oropharyngeal dysphagia. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;26(9):1256–1265.

- , , , Pulse oximetry does not reliably detect aspiration on videofluoroscopic swallowing study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(4):730–734.

- , , , et al. Acoustic analysis of swallowing sounds: a new technique for assessing dysphagia. J Rehabil Med. 2009;41(8):639–645.

- , , Aspiration in bilateral stroke patients: a validation study. Neurology. 1993;43(2):430–433.

- , , , et al. The Toronto Bedside Swallowing Screening Test (TOR‐BSST): development and validation of a dysphagia screening tool for patients with stroke. Stroke. 2009;40(2):555–561.

- , , , et al. Exploration of the utility of a brief swallow screening protocol with comparison to concurrent videofluoroscopy. Can J Speech Lang Pathol Audiol. 2011;35(3):228–242.

- , , , et al. Formal dysphagia screening protocols prevent pneumonia. Stroke. 2005;36(9):1972–1976.

- , , , et al. Radiation exposure time during MBSS: influence of swallowing impairment severity, medical diagnosis, clinician experience, and standardized protocol use. Dysphagia. 2013;28(1):77–85.

- Detection of eating difficulties after stroke: a systematic review. Int Nurs Rev. 2006;53(2):143–149.

- , , Aspiration in older patients without stroke: A systematic review of bedside diagnostic tests and predictors of pneumonia. Eur Geriatr Med. 2012;3(3):145–152.

- , , A tongue force measurement system for the assessment of oral‐phase swallowing disorders. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1991;72(1):38–42.

- , , Strength, Endurance, and stability of the tongue and hand in Parkinson disease. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2000;43(1):256–267.

- , , , et al. Effects of radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy on tongue strength and swallowing in patients with oral cancer. Head Neck. 2007;29(7):632–637.

- , , , , Tongue pressure against hard palate during swallowing in post‐stroke patients. Gerodontology. 2005;22(4):227–233.

- , Tongue measures in individuals with normal and impaired swallowing. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 2007;16(2):148–156.

- , , , et al. Tongue strength as a predictor of functional outcomes and quality of life after tongue cancer surgery. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2013;122(6):386–397.

- , , , Effects of two types of tongue strengthening exercises in young normals. Folia Phoniatr Logop. 2003;55(4):199–205.

- , , , , , The effects of lingual exercise on swallowing in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. S2005;53(9):1483–1489.

- , , , et al. The effects of lingual exercise in stroke patients with dysphagia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88(2):150–158.

- , , , , , Pretreatment swallowing exercises improve swallow function after chemoradiation. Laryngoscope. 2008;118(1):39–43.

- , , , Effects of directional exercise on lingual strength. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2009;52(4):1034–1047.

- , , et al. Prediction of aspiration in patients with newly diagnosed untreated advanced head and neck cancer. Archives of Otolaryngology – Head 127(8):975–979.

Dysphagia is a serious medical condition that can lead to aspiration pneumonia, malnutrition, and dehydration.[1] Dysphagia is the result of a variety of medical etiologies, including stroke, traumatic brain injury, progressive neurologic conditions, head and neck cancers, and general deconditioning. Prevalence estimates for dysphagia vary depending upon the etiology and patient age, but estimates as high as 38% for lifetime prevalence have been reported in those over age 65 years.[2]

To avoid adverse health outcomes, early detection of dysphagia is essential. In hospitalized patients, early detection has been associated with reduced risk of pneumonia, decreased length of hospital stay, and improved cost‐effectiveness resulting from a reduction in hospital days due to fewer cases of aspiration pneumonia.[3, 4, 5] Stroke guidelines in the United States recommend screening for dysphagia for all patients admitted with stroke.[6] Consequently, the majority of screening procedures have been designed for and tested in this population.[7, 8, 9, 10]

The videofluoroscopic swallow study (VFSS) is a commonly accepted, reference standard, instrumental evaluation technique for dysphagia, as it provides the most comprehensive information regarding anatomic and physiologic function for swallowing diagnosis and treatment. Flexible endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES) is also available, as are several less commonly used techniques (scintigraphy, manometry, and ultrasound). Due to availability, patient compliance, and expertise needed, it is not possible to perform instrumental examination on every patient with suspected dysphagia. Therefore, a number of minimally invasive bedside screening procedures for dysphagia have been developed.

The value of any diagnostic screening test centers on performance characteristics, which under ideal circumstances include a positive result for all those who have dysphagia (sensitivity) and negative result for all those who do not have dysphagia (specificity). Such an ideal screening procedure would reduce unnecessary referrals and testing, thus resulting in cost savings, more effective utilization of speech‐language pathology consultation services, and less unnecessary radiation exposure. In addition, an effective screen would detect all those at risk for aspiration pneumonia in need of intervention. However, most available bedside screening tools are lacking in some or all of these desirable attributes.[11, 12] We undertook a systematic review and meta‐analysis of bedside procedures to screen for dysphagia.

METHODS

Data Sources and Searches

We conducted a comprehensive search of 7 databases, including MEDLINE, Embase, and Scopus, from each database's earliest inception through June 9, 2014 for English‐language articles and abstracts. The search strategy was designed and conducted by an experienced librarian with input from 1 researcher (J.C.O.). Controlled vocabulary supplemented with keywords was used to search for comparative studies of bedside screening tests for predicting dysphagia (see Supporting Information, Appendix 1, in the online version of this article for the full strategy).

All abstracts were screened, and potentially relevant articles were identified for full‐text review. Those references were manually inspected to identify all relevant studies.

Study Selection

A study was eligible for inclusion if it tested a diagnostic swallow study of any variety against an acceptable reference standard (VFSS or flexible endoscopic evaluation of swallowing with sensory testing [FEEST]).

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

The primary outcome of the study was aspiration, as predicted by a bedside exam, compared to gold‐standard visualization of aspirated material entering below the vocal cords. From each study, data were abstracted based on the type of diagnostic method and reference standard study population and inclusion/exclusion characteristics, design, and prediction of aspiration. Prediction of aspiration was compared against the reference standard to yield true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives. Additional potential confounding variables were abstracted using a standard form based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analysis[13] (see Supporting Information, Appendix 2, in the online version of this article for the full abstraction template).

Data Synthesis and Analysis

Sensitivity and specificity for each test that identified the presence of dysphagia was calculated for each study. These were used to generate positive and negative likelihood ratios (LRs), which were plotted on a likelihood matrix, a graphic depiction of the logarithm of the +LR on the ordinate versus the logarithm of the LR on the abscissa, dividing the graphic into quadrants such that the right upper quadrant is tests that can be used for confirmation, right lower quadrant neither confirmation nor exclusion, left lower quadrant exclusion only, and left upper quadrant an ideal test with both exclusionary and confirmatory properties.[14] A good screening test would thus be on the left half of the graphic to effectively rule out dysphagia, and the ideal test with both good sensitivity and specificity would be found in the left upper quadrant. Graphics were constructed using the Stata MIDAS package (Stata Corp., College Station, TX).[15]

RESULTS

We identified 891 distinct articles. Of these, 749 were excluded based on abstract review. After reviewing the remaining 142 full‐text articles, 48 articles were determined to meet inclusion criteria, which included 10,437 observations across 7414 patients (Figure 1). We initially intended to conduct a meta‐analysis on each type, but heterogeneity in design and statistical heterogeneity in aggregate measures precluded pooling of results.

Characteristics of Included Studies

Of the 48 included studies, the majority (n=42) were prospective observational studies,[7, 8, 14, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53] whereas 2 were randomized trials,[9, 54] 2 studies were double‐blind observational,[9, 16] 1 was a case‐control design,[55] and 1 was a retrospective case series.[56] The majority of studies were exclusively inpatient,[7, 8, 9, 14, 17, 18, 19, 21, 22, 24, 25, 26, 31, 32, 33, 35, 36, 38, 41, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 49, 51, 52, 53, 55, 57] with 5 in mixed in and outpatient populations,[20, 27, 40, 55, 58] 2 in outpatient populations,[23, 41] and the remainder not reporting the setting from which they drew their study populations.

The indications for swallow evaluations fit broadly into 4 categories: stroke,[7, 8, 9, 14, 21, 22, 24, 25, 26, 31, 33, 34, 35, 38, 40, 41, 42, 43, 45, 48, 52, 56, 58] other neurologic disorders,[17, 18, 23, 28, 39, 47] all causes,[16, 20, 27, 29, 30, 36, 37, 44, 46, 49, 51, 52, 53, 54, 58] and postsurgical.[19, 32, 34] Most used VFSS as a reference standard,[7, 8, 9, 14, 16, 17, 18, 19, 21, 22, 23, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 34, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 56, 57, 58] with 8 using FEEST,[20, 24, 31, 32, 33, 35, 49, 55] and 1 accepting either videofluoroscopic evaluation of swallow or FEEST.[48]

Studies were placed into 1 or more of the following 4 categories: subjective bedside examination,[8, 9, 18, 19, 31, 34, 48] questionnaire‐based tools,[17, 23, 46, 53] protocolized multi‐item evaluations,[20, 21, 22, 25, 30, 33, 34, 37, 39, 44, 45, 52, 53, 57, 58] and single‐item exam maneuvers, symptoms, or signs.[7, 9, 14, 16, 24, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 56, 58, 59] The characteristics of all studies are detailed in Table 1.

| Study | Location | Design | Mean Age (SD) | Reason(s) for Dysphagia | Indx Test | Description | Reference Standard | Sample Size, No. of Patients | Sample Size, No. of Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Splaingard et al., 198844 | Milwaukee, WI, USA | Prospective observational study | NR | Multiple | Clinical bedside swallow exam | Combination of scored comprehensive physical exam, history, and observed swallow. | VFSS | 107 | 107 |

| DePippo et al., 199243 | White Plains, NY, USA | Prospective observational study | 71 (10) | Stroke | WST | Observation of swallow. | VFSS | 44 | |

| Horner et al., 199356 | Durham, NC, USA | Retrospective case series | 64* | Stroke | Clinical bedside swallow evaluation | VFSS | 38 | 114 | |

| Kidd et al., 199342 | Belfast, UK | Prospective observational study | 72 (10) | Stroke | Bedside 50‐mL swallow evaluation | Patient swallows 50 mL of water in 5‐mL aliquots, with therapist assessing for choking, coughing, or change in vocal quality after each swallow. | VFSS | 60 | 240 |

| Collins and Bakheit, 199741 | Southampton, UK | Prospective observational study | 65* | Stroke | Desaturation | Desaturation of at least 2% during videofluoroscopic study. | VFSS | 54 | 54 |

| Daniels et al., 199740 | New Orleans, LA, USA | Prospective observational study | 66 (11) | Stroke | Clinical bedside examination | 6 individual bedside assessments (dysphonia, dysphagia, cough before/after swallow, gag reflex and voice change) examined as predictors for aspiration risk. | VFSS | 59 | 354 |

| Mari et al., 199739 | Ancona, Italy | Prospective observational study | 60 (16) | Mixed neurologic diseases | Combined history and exam | Assessed symptoms of dysphagia, cough, and 3‐oz water swallow. | VFSS | 93 | 372 |

| Daniels et al., 19987 | New Orleans, LA, USA | Prospective observational study | 66 (11) | Stroke | Clinical bedside swallow evaluation | Describes sensitivity and specificity of several component physical exam maneuvers comprising the bedside exam. | VFSS | 55 | 330 |

| Smithard et al., 19988 | Ashford, UK | Prospective observational study | 79* | Stroke | Clinical bedside swallow evaluation | Not described. | VFSS | 83 | 249 |

| Addington et al., 199938 | Kansas City, MO, USA | Prospective observational study | 80* | Stroke | NR | Reflex cough. | VFSS | 40 | 40 |

| Logemann et al., 199937 | Evanston, IL, USA | Prospective observational study | 65 | Multiple | Northwestern Dysphagia Check Sheet | 28‐item screening procedure including history, observed swallow, and physical exam. | VFSS | 200 | 1400 |

| Smith et al., 20009 | Manchester, UK | Double blind observational | 69 | Stroke | Clinical bedside swallow evaluation, pulse oximetry evaluation | After eating/drinking, patient is evaluated for signs of aspiration including coughing, choking, or "wet voice." Procedure is repeated with several consistencies. Also evaluated if patient desaturates by at least 2% during evaluation. | VFSS | 53 | 53 |

| Warms et al., 200036 | Melbourne, Australia | Prospective observational study | 67 | Multiple | Wet voice | Voice was recorded and analyzed with Sony digital audio tape during videofluoroscopy. | VFSS | 23 | 708 |

| Lim et al., 200135 | Singapore, Singapore | Prospective observational study | NR | Stroke | Water swallow test, desaturation during swallow | 50‐mL swallow done in 5‐mL aliquots with assessment of phonation/choking afterward; desaturation >2% during swallow, | FEEST | 50 | 100 |

| McCullough et al., 200134 | Nashville, TN, USA | Prospective observational study | 60 (10) | Stroke | Clinical bedside swallow evaluation | 15‐item physical exam with observed swallow. | VFSS | 2040 | 60 |

| Rosen et al., 2001[74] | Newark, NJ, USA | Prospective observational study | 60 | Head and Neck cancer | Wet voice | Observation of swallow. | VFSS | 26 | 26 |

| Leder and Espinosa, 200233 | New Haven, CT, USA | Prospective observational study | 70* | Stroke | Clinical exam | Checklist evaluation of cough and voice change after swallow, volitional cough, dysphonia, dysarthria, and abnormal gag. | FEEST | 49 | 49 |

| Belafsky et al., 200332 | San Francisco, CA, USA | Prospective observational study | 65 (11) | Post‐tracheostomy patients | Modified Evans Blue Dye Test | 3 boluses of dye‐impregnated ice are given to patient. Tracheal secretions are suctioned, and evaluated for the presence of dye. | FEES | 30 | 30 |

| Chong et al., 200331 | Jalan Tan Tock Seng, Singapore | Prospective observational study | 75 (7) | Stroke | Water swallow test, desaturation during, clinical exam | Subjective exam, drinking 50 mL of water in 10‐mL aliquots, and evaluating for desaturation >2% during FEES. | FEEST | 50 | 150 |

| Tohara et al., 200330 | Tokyo, Japan | Prospective observational study | 63 (17) | Multiple | Food/water swallow tests, and a combination of the 2 | Protocolized observation of sequential food and water swallows with scored outcomes. | VFSS | 63 | 63 |

| Rosenbek et al., 200414 | Gainesville, FL, USA | Prospective observational study | 68* | Stroke | Clinical bedside swallow evaluation | Describes 5 parameters of voice quality and 15 physical examination maneuvers used. | VFSS | 60 | 1200 |

| Ryu et al., 200429 | Seoul, South Korea | Prospective observational study | 64 (14) | Multiple | Voice analysis parameters | Analysis of the/a/vowel sound with Visi‐Pitch II 3300. | VFSS | 93 | 372 |

| Shaw et al., 200428 | Sheffield, UK | Prospective observational study | 71 | Neurologic disease | Bronchial auscultation | Auscultation over the right main bronchus during trial feeding to listen for sounds of aspiration. | VFSS | 105 | 105 |

| Wu et al., 200427 | Taipei, Taiwan | Prospective observational study | 72 (11) | Multiple | 100‐mL swallow test | Patient lifts a glass of 100 mL of water and drinks as quickly as possible, and is assessed for signs of choking, coughing, or wet voice, and is timed for speed of drinking. | VFSS | 54 | 54 |

| Nishiwaki et al., 200526 | Shizuoaka, Japan | Prospective observational study | 70* | Stroke | Clinical bedside swallow evaluation | Describes sensitivity and specificity of several component physical exam maneuvers comprising the bedside exam. | VFSS | 31 | 248 |

| Wang et al., 200554 | Taipei, Taiwan | Prospective double‐blind study | 41* | Multiple | Desaturation | Desaturation of at least 2% during videofluoroscopic study. | VFSS | 60 | 60 |

| Ramsey et al., 200625 | Kent, UK | Prospective observational study | 71 (10) | Stroke | BSA | Assessment of lip seal, tongue movement, voice quality, cough, and observed 5‐mL swallow. | VFSS | 54 | 54 |

| Trapl et al., 200724 | Krems, Austria | Prospective observational study | 76 (2) | Stroke | Gugging Swallow Screen | Progressive observed swallow trials with saliva, then with 350 mL liquid, then dry bread. | FEEST | 49 | 49 |

| Suiter and Leder, 200849 | Several centers across the USA | Prospective observational study | 68.3 | Multiple | 3‐oz water swallow test | Observation of swallow. | FEEST | 3000 | 3000 |

| Wagasugi et al., 200850 | Tokyo, Japan | Prospective observational study | NR | Multiple | Cough test | Acoustic analysis of cough. | VFSS | 204 | 204 |

| Baylow et al., 200945 | New York, NY, USA | Prospective observational study | NR | Stroke | Northwestern Dysphagia Check Sheet | 28‐item screening procedure including history, observed swallow, and physical exam. | VFSS | 15 | 30 |

| Cox et al., 200923 | Leiden, the Netherlands | Prospective observational study | 68 (8) | Inclusion body myositis | Dysphagia questionnaire | Questionnaire assessing symptoms of dysphagia. | VFSS | 57 | 57 |

| Kagaya et al., 201051 | Tokyo, Japan | Prospective observational study | NR | Multiple | Simple Swallow Provocation Test | Injection of 1‐2 mL of water through nasal tube directed at the suprapharynx. | VFSS | 46 | 46 |

| Martino et al., 200957 | Toronto, Canada | Randomized trial | 69 (14) | Stroke | Toronto Bedside Swallow Screening Test | 4‐item physical assessment including Kidd water swallow test, pharyngeal sensation, tongue movement, and dysphonia (before and after water swallow). | VFSS | 59 | 59 |

| Santamato et al., 200955 | Bari, Italy | Case control | NR | Multiple | Acoustic analysis, postswallow apnea | Acoustic analysis of cough. | VFSS | 15 | 15 |

| Smith Hammond et al., 200948 | Durham, NC, USA | Prospective observational study | 67.7 (1.2) | Multiple | Cough, expiratory phase peak flow | Acoustic analysis of cough. | VFSS or FEES | 96 | 288 |

| Leigh et al., 201022 | Seoul, South Korea | Prospective observational study | NR | Stroke | Clinical bedside swallow evaluation | Not described. | VFSS | 167 | 167 |

| Pitts et al., 201047 | Gainesville, FL, USA | Prospective observational study | NR | Parkinson | Cough compression phase duration | Acoustic analysis of cough. | VFSS | 58 | 232 |

| Cohen and Manor, 201146 | Tel Aviv, Israel | Prospective observational Study | NR | Multiple | Swallow Disturbance Questionnaire | 15‐item questionnaire. | FEES | 100 | 100 |

| Edmiaston et al., 201121 | St. Louis, MO, USA | Prospective observational study | 63* | Stroke | SWALLOW‐3D Acute Stroke Dysphagia Screen | 5‐item screen including mental status; asymmetry or weakness of face, tongue, or palate; and subjective signs of aspiration when drinking 3 oz water. | VFSS | 225 | 225 |

| Mandysova et al., 201120 | Pardubice, Czech Republic | Prospective observational study | 69 (13) | Multiple | Brief Bedside Dysphagia Screening Test | 8‐item physician exam including ability to clench teeth; symmetry/strength of tongue, facial, and shoulder muscles; dysarthria; and choking, coughing, or dripping of food after taking thick liquid. | FEES | 87 | 87 |

| Steele et al., 201158 | Toronto, Canada | Double blind observational | 67 | Stroke | 4‐item bedside exam | Tongue lateralization, cough, throat clear, and voice quality. | VFSS | 400 | 40 |

| Yamamoto et al., 201117 | Kodaira, Japan | Prospective observational study | 67 (9) | Parkinson's Disease | Swallowing Disturbance Questionnaire | 15‐item questionnaire. | VFSS | 61 | 61 |

| Bhama et al., 201219 | Pittsburgh, PA, USA | Prospective observational study | 57 (14) | Post‐lung transplant | Clinical bedside swallow evaluation | Not described. | VFSS | 128 | 128 |

| Shem et al., 201218 | San Jose, CA, USA | Prospective observational study | 42 (17) | Spinal cord injuries resulting in tetraplegia | Clinical bedside swallow evaluation | After eating/drinking, patient is evaluated for signs of aspiration including coughing, choking, or "wet voice." Procedure is repeated with several consistencies. | VFSS | 26 | 26 |

| Steele et al., 201316 | Toronto, Canada | Prospective observational study | 67 (14) | Multiple | Dual‐axis accelerometry | Computed accelerometry of swallow. | VFSS | 37 | 37 |

| Edmiaston et al., 201452 | St. Louis, MO, USA | Prospective observational study | 63 (15) | Stroke | Barnes Jewish Stroke Dysphagia Screen | 5‐item screen including mental status; asymmetry or weakness of face, tongue, or palate; and subjective signs of aspiration when drinking 3 oz water. | VFSS | 225 | 225 |

| Rofes et al., 201453 | Barcelona, Spain | Prospective observational study | 74 (12) | Mixed | EAT‐10 questionnaire and variable viscosity swallow test | Symptom‐based questionnaire (EAT‐10) and repeated observations and measurements of swallow with different thickness liquids. | VFS | 134 | 134 |

Subjective Clinical Exam

Seven studies reported the sensitivity and specificity of subjective assessments of nurses and speech‐language pathologists in observing swallowing and predicting aspiration.[8, 9, 18, 19, 31, 34, 48] The overall distribution of studies is summarized in the likelihood matrix in Figure 2. Two studies, Chong et al.[31] and Shem et al.,[18] were on the left side of the matrix, indicating a sensitive rule‐out test. However, both were small studies, and only Chong et al. reported reasonable sensitivity with incorporation bias from knowledge of a desaturation study outcome. Overall, subjective exams did not appear reliable in ruling out dysphagia.

Questionnaire‐Based Tools

Only 4 studies used questionnaire‐based tools filled out by the patient, asking about subjective assessment of dysphagia symptoms and frequency.[17, 23, 46, 53] Yamamoto et al. reported results of using the swallow dysphagia questionnaire in patients with Parkinson's disease.[17] Rofes et al. looked at the Eating Assessment Tool (EAT‐10) questionnaire among all referred patients and a small population of healthy volunteers.[53] Each was administered the questionnaire before undergoing a videofluoroscopic study. Overall, sensitivity and specificity were 77.8% and 84.6%, respectively. Cox et al. studied a different questionnaire in a group of patients with inclusion body myositis, finding 70% sensitivity and 44% specificity.[23] Cohen and Manor examined the swallow dysphagia questionnaire across several different causes of dysphagia, finding at optimum, the test is 78% specific and 73% sensitive.[46] Rofes et al. had an 86% sensitivity and 68% specificity for the EAT‐10 tool.[53]

Multi‐Item Exam Protocols

Sixteen studies reported multistep protocols for determining a patient's risk for aspiration.[9, 20, 21, 22, 25, 30, 33, 34, 37, 39, 44, 45, 52, 53, 57, 58] Each involved a combination of physical exam maneuvers and history elements, detailed in Table 1. This is shown in the likelihood matrix in Figure 3. Only 2 of these studies were in the left lower quadrant, Edmiaston et al. 201121 and 2014.[52] Both studies were restricted to stroke populations, but found reasonable sensitivity and specificity in identifying dysphagia.

Individual Exam Maneuvers

Thirty studies reported the diagnostic performance of individual exam maneuvers and signs.[7, 9, 14, 16, 24, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 54, 56, 58] Each is depicted in Figure 4 as a likelihood matrix demonstrating the +LR and LR for individual maneuvers as seen in the figure; most fall into the right lower quadrant, where they are not diagnostically useful tests. Studies in the left lower quadrant demonstrating the ability to exclude aspiration desirable in a screening test were dysphonia in McCullough et al.,[34] dual‐axis accelerometry in Steele et al.,[16] and the water swallow test in DePippo et al.[43] and Suiter and Leder.[49]

McCullough et al. found dysphonia to be the most discriminatory sign or symptom assessed, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.818. Dysphonia was judged by a sustained/a/and had 100% sensitivity but only 27% specificity. Wet voice within the same study was slightly less informative, with an AUC of 0.77 (sensitivity 50% and specificity 84%).[34]

Kidd et al. verified the diagnosis of stroke, and then assessed several neurologic parameters, including speech, muscle strength, and sensation. Pharyngeal sensation was assessed by touching each side of the pharyngeal wall and asking patients if they felt sensation that differed from each side. Patient report of abnormal sensation during this maneuver was 80% sensitive and 86% specific as a predictor of aspiration on VFSS.[42]

Steele et al. described the technique of dual axis accelerometry, where an accelerometer was placed at the midline of the neck over the cricoid cartilage during VFSS. The movement of the cricoid cartilage was captured for analysis in a computer algorithm to identify abnormal pharyngeal swallow behavior. Sensitivity was 100%, and specificity was 54%. Although the study was small (n=40), this novel method demonstrated good discrimination.[58]

DePippo et al. evaluated a 3‐oz water swallow in stroke patients. This protocol called for patients to drink the bolus of water without interruption, and be observed for 1 minute after for cough or wet‐hoarse voice. Presence of either sign was considered abnormal. Overall, sensitivity was 94% and specificity 30% looking for the presence of either sign.[43] Suiter and Leder used a similar protocol, with sensitivity of 97% and specificity of 49%.[49]

DISCUSSION

Our results show that most bedside swallow examinations lack the sensitivity to be used as a screening test for dysphagia across all patient populations examined. This is unfortunate as the ability to determine which patients require formal speech language pathology consultation or imaging as part of their diagnostic evaluation early in the hospital stay would lead to improved allocation of resources, cost reductions, and earlier implementation of effective therapy approaches. Furthermore, although radiation doses received during VFSS are not high when compared with other radiologic exams like computed tomography scans,[60] increasing awareness about the long‐term malignancy risks associated with medical imaging makes it desirable to reduce any test involving ionizing radiation.

There were several categories of screening procedures identified during this review process. Those classified as subjective bedside exams and protocolized multi‐item evaluations were found to have high heterogeneity in their sensitivity and specificity, though a few exam protocols did have a reasonable sensitivity and specificity.[21, 31, 52] The following individual exam maneuvers were found to demonstrate high sensitivity and an ability to exclude aspiration: a test for dysphonia through production of a sustained/a/34 and use of dual‐axis accelerometry.[16] Two other tests, the 3‐oz water swallow test[43] and testing of abnormal pharyngeal sensation,[42] were each found effective in a single study, with conflicting results from other studies.

Our results extend the findings from previous systematic reviews on this subject, most of which focused only on stroke patients.[5, 12, 61, 62] Martino and colleagues[5] conducted a review focused on screening for adults poststroke. From 13 identified articles, it was concluded that evidence to support inclusion or exclusion of screening was poor. Daniels et al. conducted a systematic review of swallowing screening tools specific to patients with acute or chronic stroke.[12] Based on 16 articles, the authors concluded that a combination of swallowing and nonswallowing features may be necessary for development of a valid screening tool. The generalizability of these reviews is limited given that all were conducted in patients poststroke, and therefore results and recommendations may not be generalizable to other patients.

Wilkinson et al.[62] conducted a recent systematic review that focused on screening techniques for inpatients 65 years or older that excluded patients with stroke or Parkinson's disease. The purpose of that review was to examine sensitivity and specificity of bedside screening tests as well as ability to accurately predict pneumonia. The authors concluded that existing evidence is not sufficient to recommend the use of bedside tests in a general older population.[62]

Specific screening tools identified by Martino and colleagues[5] to have good predictive value in detecting aspiration as a diagnostic marker of dysphagia were an abnormal test of pharyngeal sensation[42] and the 50‐mL water swallow test. Daniels et al. identified a water swallow test as an important component of a screen.[7] These results were consistent with those of this review in that the abnormal test of pharyngeal sensation[42] was identified for high levels of sensitivity. However, the 3‐oz water swallow test,[43, 49] rather than the 50‐mL water swallow test,[42] was identified in this review as the version of the water swallow test with the best predictive value in ruling out aspiration. Results of our review identified 2 additional individual items, dual‐axis accelerometry[16] and dysphonia,[34] that may be important to include in a comprehensive screening tool. In the absence of better tools, the 3 oz swallow test, properly executed, seems to be the best currently available tool validated in more than 1 study.

Several studies in the current review included an assessment of oral tongue movement that is not described thoroughly and varies between studies. Tongue movement as an individual item on a screening protocol was not found to yield high sensitivity or specificity. However, tongue movement or range of motion is only 1 aspect of oral tongue function; pressures produced by the tongue reflecting strength also may be important and warrant evaluation. Multiple studies have shown patients with dysphagia resulting from a variety of etiologies to produce lower than normal maximum isometric lingual pressures,[63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68] or pressures produced when the tongue is pushed as hard as possible against the hard palate. Tongue strengthening protocols that result in higher maximum isometric lingual pressures have been shown to carry over to positive changes in swallow function.[69, 70, 71, 72, 73] Inclusion of tongue pressure measurement in a comprehensive screening tool may help to improve predictive capabilities.

We believe our results have implications for practicing clinicians, and serve as a call to action for development of an easy‐to‐perform, accurate tool for dysphagia screening. Future prospective studies should focus on practical tools that can be deployed at the bedside, and correlate the results with not only gold‐standard VFSS and FEES, but with clinical outcomes such as pneumonia and aspiration events leading to prolonged length of stay.

There were several limitations to this review. High levels of heterogeneity were reported in the screening tests present in the literature, precluding meaningful meta‐analysis. In addition, the majority of studies included were in poststroke adults, which limits the generalizability of results.

In conclusion, no screening protocol has been shown to provide adequate predictive value for presence of aspiration. Several individual exam maneuvers demonstrate high sensitivity; however, the most effective combination of screening protocol components is unknown. There is a need for future research focused on the development of a comprehensive screening tool that can be applied across patient populations for accurate detection of dysphagia as well as prediction of other adverse health outcomes, including pneumonia.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Drs. Byun‐Mo Oh and Catrionia Steele for providing additional information in response to requests for unpublished information.

Disclosures: Nasia Safdar MD, is supported by a National Institutes of Health R03 GEMSSTAR award and a VA MERIT award. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Dysphagia is a serious medical condition that can lead to aspiration pneumonia, malnutrition, and dehydration.[1] Dysphagia is the result of a variety of medical etiologies, including stroke, traumatic brain injury, progressive neurologic conditions, head and neck cancers, and general deconditioning. Prevalence estimates for dysphagia vary depending upon the etiology and patient age, but estimates as high as 38% for lifetime prevalence have been reported in those over age 65 years.[2]

To avoid adverse health outcomes, early detection of dysphagia is essential. In hospitalized patients, early detection has been associated with reduced risk of pneumonia, decreased length of hospital stay, and improved cost‐effectiveness resulting from a reduction in hospital days due to fewer cases of aspiration pneumonia.[3, 4, 5] Stroke guidelines in the United States recommend screening for dysphagia for all patients admitted with stroke.[6] Consequently, the majority of screening procedures have been designed for and tested in this population.[7, 8, 9, 10]

The videofluoroscopic swallow study (VFSS) is a commonly accepted, reference standard, instrumental evaluation technique for dysphagia, as it provides the most comprehensive information regarding anatomic and physiologic function for swallowing diagnosis and treatment. Flexible endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES) is also available, as are several less commonly used techniques (scintigraphy, manometry, and ultrasound). Due to availability, patient compliance, and expertise needed, it is not possible to perform instrumental examination on every patient with suspected dysphagia. Therefore, a number of minimally invasive bedside screening procedures for dysphagia have been developed.

The value of any diagnostic screening test centers on performance characteristics, which under ideal circumstances include a positive result for all those who have dysphagia (sensitivity) and negative result for all those who do not have dysphagia (specificity). Such an ideal screening procedure would reduce unnecessary referrals and testing, thus resulting in cost savings, more effective utilization of speech‐language pathology consultation services, and less unnecessary radiation exposure. In addition, an effective screen would detect all those at risk for aspiration pneumonia in need of intervention. However, most available bedside screening tools are lacking in some or all of these desirable attributes.[11, 12] We undertook a systematic review and meta‐analysis of bedside procedures to screen for dysphagia.

METHODS

Data Sources and Searches

We conducted a comprehensive search of 7 databases, including MEDLINE, Embase, and Scopus, from each database's earliest inception through June 9, 2014 for English‐language articles and abstracts. The search strategy was designed and conducted by an experienced librarian with input from 1 researcher (J.C.O.). Controlled vocabulary supplemented with keywords was used to search for comparative studies of bedside screening tests for predicting dysphagia (see Supporting Information, Appendix 1, in the online version of this article for the full strategy).

All abstracts were screened, and potentially relevant articles were identified for full‐text review. Those references were manually inspected to identify all relevant studies.

Study Selection

A study was eligible for inclusion if it tested a diagnostic swallow study of any variety against an acceptable reference standard (VFSS or flexible endoscopic evaluation of swallowing with sensory testing [FEEST]).

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

The primary outcome of the study was aspiration, as predicted by a bedside exam, compared to gold‐standard visualization of aspirated material entering below the vocal cords. From each study, data were abstracted based on the type of diagnostic method and reference standard study population and inclusion/exclusion characteristics, design, and prediction of aspiration. Prediction of aspiration was compared against the reference standard to yield true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives. Additional potential confounding variables were abstracted using a standard form based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analysis[13] (see Supporting Information, Appendix 2, in the online version of this article for the full abstraction template).

Data Synthesis and Analysis

Sensitivity and specificity for each test that identified the presence of dysphagia was calculated for each study. These were used to generate positive and negative likelihood ratios (LRs), which were plotted on a likelihood matrix, a graphic depiction of the logarithm of the +LR on the ordinate versus the logarithm of the LR on the abscissa, dividing the graphic into quadrants such that the right upper quadrant is tests that can be used for confirmation, right lower quadrant neither confirmation nor exclusion, left lower quadrant exclusion only, and left upper quadrant an ideal test with both exclusionary and confirmatory properties.[14] A good screening test would thus be on the left half of the graphic to effectively rule out dysphagia, and the ideal test with both good sensitivity and specificity would be found in the left upper quadrant. Graphics were constructed using the Stata MIDAS package (Stata Corp., College Station, TX).[15]

RESULTS

We identified 891 distinct articles. Of these, 749 were excluded based on abstract review. After reviewing the remaining 142 full‐text articles, 48 articles were determined to meet inclusion criteria, which included 10,437 observations across 7414 patients (Figure 1). We initially intended to conduct a meta‐analysis on each type, but heterogeneity in design and statistical heterogeneity in aggregate measures precluded pooling of results.

Characteristics of Included Studies

Of the 48 included studies, the majority (n=42) were prospective observational studies,[7, 8, 14, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53] whereas 2 were randomized trials,[9, 54] 2 studies were double‐blind observational,[9, 16] 1 was a case‐control design,[55] and 1 was a retrospective case series.[56] The majority of studies were exclusively inpatient,[7, 8, 9, 14, 17, 18, 19, 21, 22, 24, 25, 26, 31, 32, 33, 35, 36, 38, 41, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 49, 51, 52, 53, 55, 57] with 5 in mixed in and outpatient populations,[20, 27, 40, 55, 58] 2 in outpatient populations,[23, 41] and the remainder not reporting the setting from which they drew their study populations.