User login

Your 15-year-old patient requests an IUD without parental knowledge

CASE Adolescent seeks care without parent

A 15-year-old patient (G0) presents to the gynecology clinic requesting birth control. She reports being sexually active over the past 6 months and having several male partners over the past 2 years. She and her current male partner use condoms inconsistently. She reports being active in school sports, and her academic performance has been noteworthy. Her peers have encouraged her to seek out birth control; one of her good friends recently became pregnant and dropped out of school. She states that her best friend went to a similar clinic and received a “gynecologic encounter” that included information regarding safe sex and contraception, with no pelvic exam required for her to receive birth control pills.

The patient insists that her parents are not to know of her request for contraception due to sexual activity or that she is a patient at the clinic. The gynecologist covering the clinic is aware of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Adolescent Health Care and their many publications. The patient is counseled regarding human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination and screened for sexually transmitted infections. In addition, the gynecologist discusses contraceptive options with the patient, ranging from oral contraceptives, vaginal rings, subdermal implants, depomedroxyprogesterone acetate, as well as intrauterine devices (IUDs). The gynecologist emphasizes safe sex and advises that her partner consider use of condoms independent of her method of birth control. The patient asks for oral contraceptives and is given information about their use and risks, and she indicates that she understands.

A few months later the patient requests an IUD, as she would like to have lighter menses and not have to remember to take a pill every day. The provider obtains informed consent for the insertion procedure; the patient signs the appropriate forms.

The IUD is inserted, with difficulty, by a resident physician in the clinic. The patient experiences severe pelvic pain during and immediately following the insertion. She is sent home and told to contact the clinic or another health care provider or proceed to the local emergency department should pain persist or if fever develops.

The patient returns 72 hours later in pain. Pelvic ultrasonography shows the IUD out of place and at risk of perforating the fundus of the uterus. Later that day the patient’s mother calls the clinic, saying that she found a statement of service with the clinic’s number on it in her daughter’s bedroom. She wants to know if her daughter is there, what is going on, and what services have been or are being provided. In passing she remarks that she has no intention of paying (or allowing her insurance to pay for) any care that was provided.

What are the provider’s obligations at this point, both medically and legally?

Medical and legal considerations

One of the most difficult and important health law questions in adolescent medicine is the ability of minors to consent to treatment and to control the health care information resulting from treatment. (“Minor” describes a child or adolescent who has not obtained the age of legal consent, generally 18 years old, to lawfully enter into a legal transaction.)

Continue to: The consent of minor patients...

The consent of minor patients

The traditional legal rule is that parents or guardians (“parent” refers to both) must consent to medical treatment for minor children. There is an exception for emergency situations but generally minors do not provide consent for medical care, a parent does.1 The parent typically is obliged to provide payment (often through insurance) for those services.

This traditional rule has some exceptions—the emergency exception already noted and the case of emancipated minors, notably an adolescent who is living almost entirely independent of her parents (for example, she is married or not relying on parents in a meaningful way). In recent times there has been increasing authority for “mature minors” to make some medical decisions.2 A mature minor is one who has sufficient understanding and judgment to appreciate the consequences, benefits, and risks of accepting proposed medical intervention.

No circumstance involving adolescent treatment has been more contentious than services related to abortion and, to a lesser degree, contraception.3 Both the law of consent to services and the rights of parents to obtain information about contraceptive and abortion services have been a matter of strong, continuing debate. The law in these areas varies greatly from state-to-state, and includes a mix of state law (statutes and court decisions) with an overlay of federal constitutional law related to reproduction-related decisions of adolescents. In addition, the law in this area of consent and information changes relatively frequently.4 Clinicians, of course, must focus on the consent laws of the state in which they practice.

STI counseling and treatment

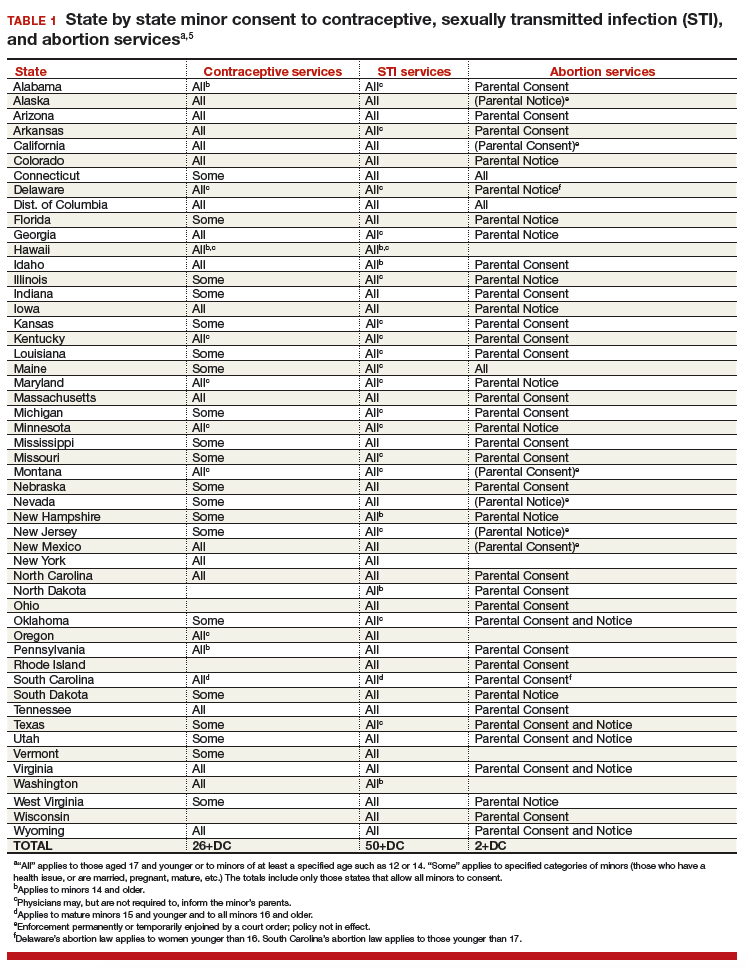

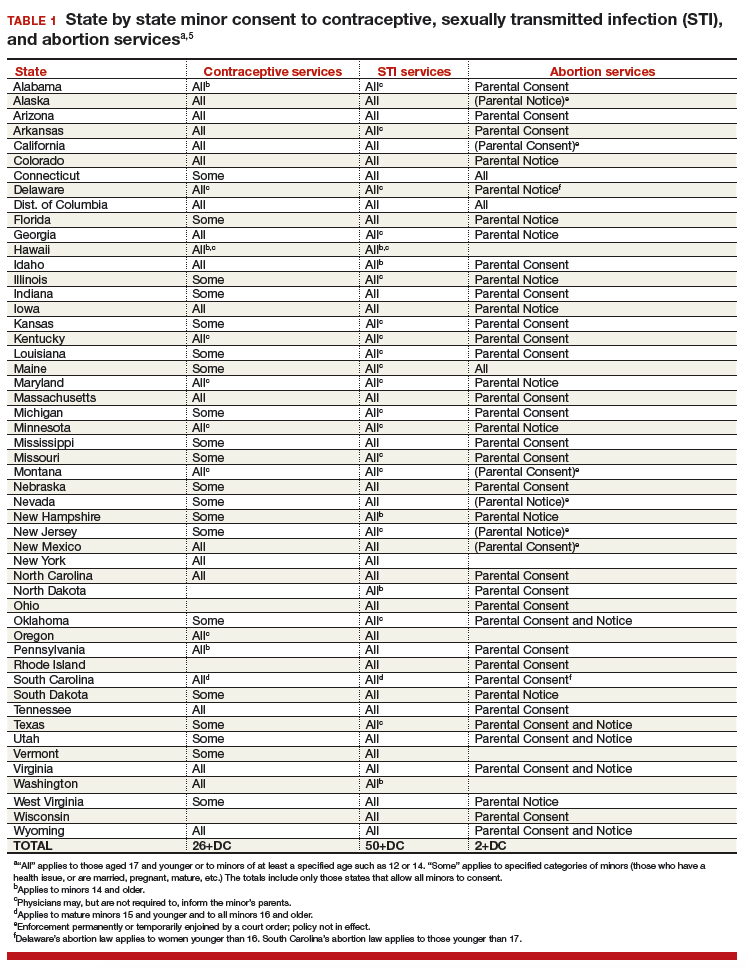

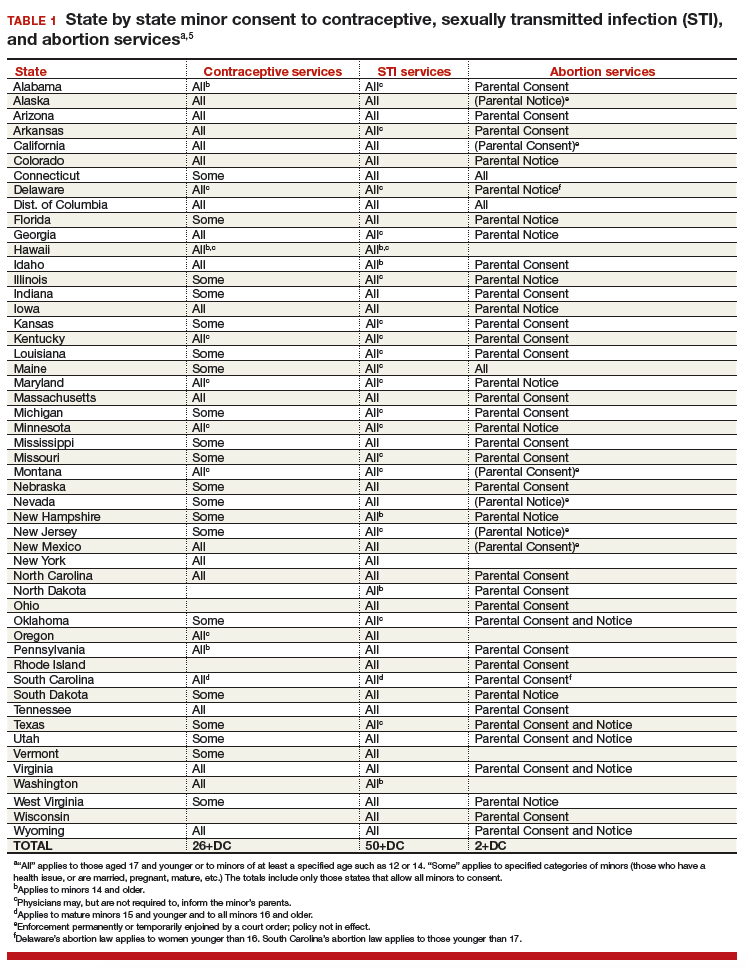

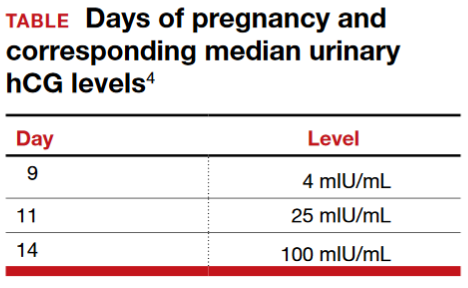

All states permit a minor patient to consent to treatment for an STI (TABLE 1).5 A number of states expressly permit, but do not require, health care providers to inform parents of treatment when a physician determines it would be in the best interest of the minor. Thus, the clinic would not be required to provide proactively the information to our case patient’s mother (regarding any STI issues) when she called.6

Contraception

Consent for contraception is more complicated. About half the states allow minors who have reached a certain age (12, 14, or 16 years) to consent to contraception. About 20 other states allow some minors to consent to contraceptive services, but the “allowed group” may be fairly narrow (eg, be married, have a health issue, or be “mature”). In 4 states there is currently no clear legal authority to provide contraceptive services to minors, yet those states do not specifically prohibit it. The US Supreme Court has held that a state cannot completely prohibit the availability of contraception to minors.7 The reach of that decision, however, is not clear and may not extend beyond what the states currently permit.

The ability of minors to consent to contraception services does not mean that there is a right to consent to all contraceptive options. As contraception becomes more irreversible, permanent, or risky, it is more problematic. For example, consent to sterilization would not ordinarily be within a minor’s recognized ability to consent. Standard, low risk, reversible contraception generally is covered by these state laws.8

In our case here, the patient likely was able to consent to contraception—initially to the oral contraception and later to the IUD. The risks and reversibility of both are probably within her ability to consent.9,10 Of course, if the care was provided in a state that does not include the patient within the groups that can give consent to contraception, it is possible that she might not have the legal authority to consent.

Continue to: General requirements of consent...

General requirements of consent

Even when adolescent consent is permitted for treatment, including in cases of contraception, it is essential that all of the legal and ethical requirements related to informed consent are met.

1. The adolescent has the capacity to consent. This means not only that the state-mandated requirements are met (age, for example) but also that the patient can and does understand the various elements of consent, and can make a sensible, informed decision.

The bottom line is “adolescent capacity is a complex process dependent upon the development of maturity of the adolescent, degree of intervention, expected benefit of the medical procedure, and the sociocultural context surrounding the decision.”11 Other items of interest include the “evolving capacity” of the child,12 which is the concept of increasing ability of the teen to process information and provide more appropriate informed consent. Central nervous system (CNS) maturation allows the adolescent to become increasingly more capable of decision making and has awareness of consequences of such decisions. Abstract thinking capabilities is a reflection of this CNS maturing process. If this competency is not established, the adolescent patient cannot give legitimate consent.

2. The patient must be given appropriate information (be “informed”). The discussion should include information relevant to the condition being treated (and the disease process if relevant). In addition, information about the treatment or intervention proposed and its risks and alternatives must be provided to the patient and in a way that is understandable.

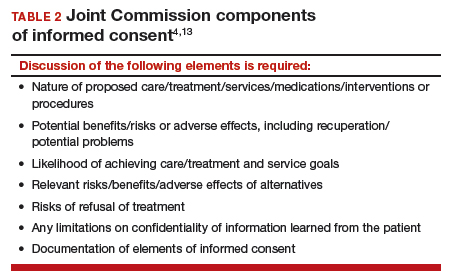

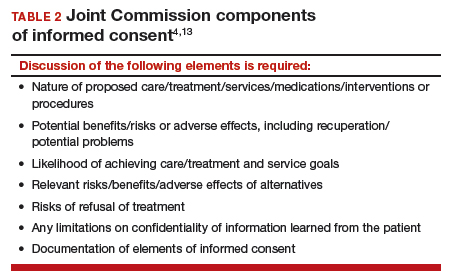

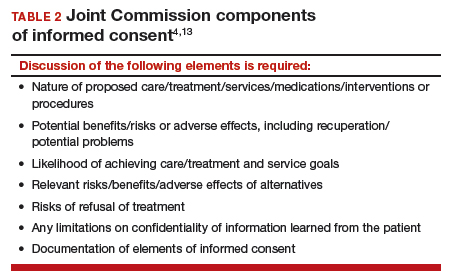

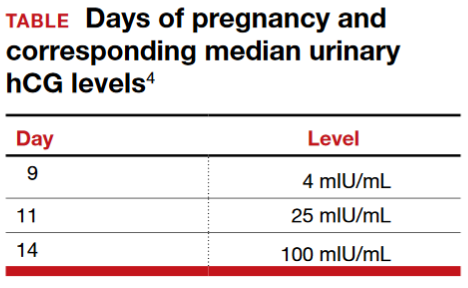

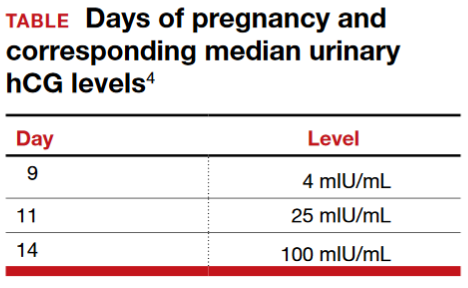

3. As with all patients, consent must be voluntary and free of coercion or manipulation. These elements of informed consent are expanded on by the Joint Commission, which has established a number of components of informed consent (TABLE 2).4,13

Confidentiality and release of information to parents and others

Similar to consent, parents historically have had the authority to obtain medical information about their minor children. This right generally continues today, with some limitations. The right to give consent generally carries with it the right to medical information. There are some times when parents may access medical information even if they have not given consent.

This right adds complexity to minor consent and is an important treatment issue and legal consideration because confidentiality for adolescents affects quality of care. Adolescents report that “confidentiality is an important factor in their decision to seek [medical] care.”14 Many parents are under the assumption that the health care provider will automatically inform them independent of whether or not the adolescent expressed precise instruction not to inform.15,16

Of course if a minor patient authorizes the physician to provide information to her parents, that is consent and the health care provider may then provide the information. If the patient instructs the provider to convey the information, the practitioner would ordinarily be expected to be proactive in providing the information to the parent. The issue of “voluntariness” of the waiver of confidentiality can be a question, and the physician may discuss that question with the patient. Ordinarily, however, once a minor has authorized disclosure to the parent, the clinician has the authority to disclose the information to the parent, but not to others.

All of the usual considerations of confidentiality in health care apply to adolescent ObGyn services and care. This includes the general obligation not to disclose information without consent and to ensure that health care information is protected from accidental release as required by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and other health information privacy laws.17

It is important to emphasize that the issues of consent to abortion are much different than those for contraception and sexually transmitted infections. As our case presentation does not deal with abortion, we will address this complex but important discussion in the future--as there are an estimated 90,000 abortions in adolescent girls annually.1

Given that abortion consent and notification laws are often complex, any physician providing abortion services to any minor should have sound legal advice on the requirements of the pertinent state law. In earlier publications of this section in OBG Management we have discussed the importance of practitioners having an ongoing relationship with a health law attorney. We make this point again, as this person can provide advice on consent and the rights of parents to have information about their minor children.

Reference

- Henshaw SK. U.S. teenage pregnancy statistics with comparative statistics for women age 20-24. New York, New York: Alan Guttmacher Institute; May 2003.

Continue to: How and when to protect minor confidentiality...

How and when to protect minor confidentiality

A clinician cannot assure minors of absolute confidentiality and should not agree to do so or imply that they are doing so.18 In our hypothetical case, when the patient told the physician that her parents were not to know of any of her treatment or communications, the provider should not have acquiesced by silence. He/she might have responded along these lines: “I have a strong commitment to confidentiality of your information, and we take many steps to protect that information. The law also allows some special protection of health care information. Despite the commitment to privacy, there are circumstances in which the law requires disclosure of information—and that might even be to parents. In addition, if you want any of your care covered by insurance, we would have to disclose that. While I expect that we can do as you ask about maintaining your confidentiality, no health care provider can absolutely guarantee it.”

Proactive vs reactive disclosure. There is “proactive” disclosure of information and “reactive” disclosure. Proactive is when the provider (without being asked) contacts a parent or others and provides information. Some states require proactive information about specific kinds of treatment (especially abortion services). For the most part, in states where a minor can legally consent to treatment, health care providers are not required to proactively disclose information.19

Clinicians may be required to respond to parental requests for information, which is reactive disclosure and is reflected in our case presentation. Even in such circumstances, however, the individual providing care may seek to avoid disclosure. In many states, the law would not require the release of this information (but would permit it if it is in the best interest of the patient). In addition, there are practical ways of avoiding the release of information. For example, the health care provider might acknowledge the interest and desire of the parent to have the information, but might humbly explain that in the experience of many clinicians protecting the confidentiality of patients is very important to successful treatment and it is the policy of the office/clinic not to breach the expectation of patient confidentiality except where that is clearly in the best interest of the patient or required by law.

In response to the likely question, “Well, isn’t that required by law?” the clinician can honestly reply, “I don’t know. There are many complex factors in the law regarding disclosure of medical information and as I am not an attorney I do not know how they all apply in this instance.” In some cases the parent may push the matter or take some kind of legal action. It is in this type of situation that an attorney familiar with health law and the clinician’s practice can be invaluable.

When parents are involved in the minor’s treatment (bringing the patient to the office/clinic, for example), there is an opportunity for an understanding, or agreement, among the patient, provider, and parent about what information the parent will receive. Ordinarily the agreement should not create the expectation of detailed information for the parent. Perhaps, for example, the physician will provide information only when he or she believes that doing so will be in the best interest of the patient. Even with parental agreement, complete confidentiality cannot be assured for minor patients. There may, for example, be another parent who will not feel bound by the established understanding, and the law requires some disclosures (in the case of child abuse or a court order).20

Continue to: Accidental disclosure...

Accidental disclosure. Health care providers also should make sure that office procedures do not unnecessarily or accidentally disclose information about patients. For example, routinely gathering information about insurance coverage may well trigger the release of information to the policy holder (often a parent). Thus, there should be clear understandings about billing, insurance, and related issues before information is divulged by the patient. This should be part of the process of obtaining informed consent to treatment. It should be up front and honest. Developing a clear understanding of the legal requirements of the state is essential, so that assurance of confidentiality is on legal, solid ground.

As the pediatric and adolescent segment of gynecologic care continues to evolve, it is noteworthy that the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology recently has established a "Focused Practice" designation in pediatric adolescent gynecology. This allows ObGyns to have an ongoing level of professional education in this specialized area. Additional information can be obtained at www.abog.org or info@abog.org.

More resources for adolescent contraceptive care include:

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) "Birth Control (Especially for Teens)" frequently asked questions information series (https://www.acog.org/Patients/FAQs/Birth-Control-Especially-for-Teens)

- ACOG's Adolescent Healthcare Committee Opinions address adolescent pregnancy, contraception, and sexual activity (https://www.acog.org/-/media/List-of-Titles/COListOfTitles.pdf)

- ACOG statement on teen pregnancy and contraception, April 7, 2015 (https://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/News-Room/Statements/2015/ACOG-Statement-on-Teen-Pregnancy-and-Contraception?IsMobileSet=false)

- North American Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology resources for patients (https://www.naspag.org/page/patienttools)

- Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine statement regarding contraceptive access policies (https://www.adolescenthealth.org)

- The Guttmacher Institute's overview of state laws relevant to minor consent, as of January 1, 2019 (https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/overview-minors-consent-law). It is updated frequently.

Abuse reporting obligations

All states have mandatory child abuse reporting laws. These laws require medical professionals (and others) to report known, and often suspected, abuse of children. Abuse includes physical, sexual, or emotional, and generally also includes neglect that is harming a child. When there is apparent sexual or physical abuse, the health care provider is obligated to report it to designated state authorities, generally child protective services. Reporting laws vary from state to state based on the relationship between the suspected abuser and the minor, the nature of the harm, and how strong the suspicion of abuse needs to be. The failure to make required reports is a crime in most states and also may result in civil liability or licensure discipline. Criminal charges seldom result from the failure to report, but in some cases the failure to report may have serious consequences for the professional.

An ObGyn example of the complexity of reporting laws, and variation from state to state, is in the area of “statutory rape” reporting. Those state laws, which define serious criminal offenses, set out the age below which an individual is not legally capable of consenting to sexual activity. It varies among states, but may be an absolute age of consent, the age differential between the parties, or some combination of age and age differential.21 The question of reporting is further complicated by the issue of when statutory rape must be reported—for example, the circumstances when the harm to the underage person is sufficient to require reporting.22

Laws are complex, as is practice navigation

It is apparent that navigating these issues makes it essential for an ObGyn practice to have clear policies and practices regarding reporting, yet the overall complexity is also why it is so difficult to develop those policies in the first place. Of course, they must be tailored to the state in which the practice resides. Once again, the need is clear for health care professionals to have an ongoing relationship with a health attorney who can help navigate ongoing questions.

- Benjamin L, Ishimine P, Joseph M, et al. Evaluation and treatment of minors. Ann Emerg Med. 2018;71(2):225-232.

- Coleman D, Rosoff P. The legal authority of mature minors to consent to general medical treatment. Pediatrics. 2013;13:786-793.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 699. Adolescent pregnancy, contraception, and sexual activity. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:e142-e149.

- Tillett J. Adolescents and informed consent. J Perinat Neonat Nurs. 2005;19:112-121.

- An overview of minor's consent law. Guttmacher Institute's website. https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/overview-minors-consent-law. Accessed February 14, 2019.

- Chelmow D, Karjane N, Ricciotti HA, et al, eds. A 16-year-old adolescent requesting confidential treatment for chlamydia exposure (understanding state laws regarding minors and resources). Office Gynecology: A Case-Based Approach. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; January 31, 2019:39.

- Carey v Population Services, 431 US 678 (1977).

- Williams RL, Meredith AH, Ott MA. Expanding adolescent access to hormonal contraception: an update on over-the-counter, pharmacist prescribing, and web-based telehealth approaches. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2018;30:458-464.

- McClellan K, Temples H, Miller L. The latest in teen pregnancy prevention: long-acting reversible contraception. J Pediatr Health Care. 2018;32:e91-e97.

- Behmer Hansen RT, Arora KS. Consenting to invasive contraceptives: an ethical analysis of adolescent decision-making authority for long-acting reversible contraception. J Med Ethics. 2018;44:585-588.

- Robertson D. Opinions in pediatric and adolescent gynecology. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2008:21:47-51.

- Lansdown G. The evolving capacities of the child. Florence, Italy: UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre, Innocenti Insight; 2005. https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/384-the-evolving-capacities-of-the-child.html. Accessed February 15, 2019.

- Clapp JT, Fleisher LA. What is the realistic scope of informed consent? Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2018;44(6):341-342.

- Berlan E, Bravender T. Confidentiality, consent and caring for the adolescent. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2009;21:450-456.

- Schantz K. Who Needs to Know? Confidentiality in Adolescent Sexual Health Care. Act for Youth website. http://www.actforyouth.net/resources/rf/rf_confidentiality_1118.pdf. Accessed February 14, 2019.

- Lynn A, Kodish E, Lazebnik R, et al. Understanding confidentiality: perspectives of African American adolescents and their parents. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39:261-265.

- English A, Ford CA. The HIPAA privacy rule and adolescents: legal questions and clinical challenges. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2004;36:80-86.

- Schapiro NA, Mejia J. Adolescent confidentiality and women's health: history, rationale, and current threats. Nurs Clin North Am. 2018;53:145-156.

- Scott NL, Alderman EM, 2018. Case of a girl with a secret. In: Adolescent Gynecology: A Clinical Casebook. New York, New York: Springer International; 2017:3-11.

- Cullitan CM. Please don't tell my mom--a minor's right to informational privacy. JL & Educ. 2011;40:417-460.

- Bierie DM, Budd KM. Romeo, Juliet, and statutory rape. Sex Abuse. 2018;30:296-321.

- Mathews B. A taxonomy of duties to report child sexual abuse: legal developments offer new ways to facilitate disclosure. Child Abuse Negl. 2019;88:337-347.

CASE Adolescent seeks care without parent

A 15-year-old patient (G0) presents to the gynecology clinic requesting birth control. She reports being sexually active over the past 6 months and having several male partners over the past 2 years. She and her current male partner use condoms inconsistently. She reports being active in school sports, and her academic performance has been noteworthy. Her peers have encouraged her to seek out birth control; one of her good friends recently became pregnant and dropped out of school. She states that her best friend went to a similar clinic and received a “gynecologic encounter” that included information regarding safe sex and contraception, with no pelvic exam required for her to receive birth control pills.

The patient insists that her parents are not to know of her request for contraception due to sexual activity or that she is a patient at the clinic. The gynecologist covering the clinic is aware of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Adolescent Health Care and their many publications. The patient is counseled regarding human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination and screened for sexually transmitted infections. In addition, the gynecologist discusses contraceptive options with the patient, ranging from oral contraceptives, vaginal rings, subdermal implants, depomedroxyprogesterone acetate, as well as intrauterine devices (IUDs). The gynecologist emphasizes safe sex and advises that her partner consider use of condoms independent of her method of birth control. The patient asks for oral contraceptives and is given information about their use and risks, and she indicates that she understands.

A few months later the patient requests an IUD, as she would like to have lighter menses and not have to remember to take a pill every day. The provider obtains informed consent for the insertion procedure; the patient signs the appropriate forms.

The IUD is inserted, with difficulty, by a resident physician in the clinic. The patient experiences severe pelvic pain during and immediately following the insertion. She is sent home and told to contact the clinic or another health care provider or proceed to the local emergency department should pain persist or if fever develops.

The patient returns 72 hours later in pain. Pelvic ultrasonography shows the IUD out of place and at risk of perforating the fundus of the uterus. Later that day the patient’s mother calls the clinic, saying that she found a statement of service with the clinic’s number on it in her daughter’s bedroom. She wants to know if her daughter is there, what is going on, and what services have been or are being provided. In passing she remarks that she has no intention of paying (or allowing her insurance to pay for) any care that was provided.

What are the provider’s obligations at this point, both medically and legally?

Medical and legal considerations

One of the most difficult and important health law questions in adolescent medicine is the ability of minors to consent to treatment and to control the health care information resulting from treatment. (“Minor” describes a child or adolescent who has not obtained the age of legal consent, generally 18 years old, to lawfully enter into a legal transaction.)

Continue to: The consent of minor patients...

The consent of minor patients

The traditional legal rule is that parents or guardians (“parent” refers to both) must consent to medical treatment for minor children. There is an exception for emergency situations but generally minors do not provide consent for medical care, a parent does.1 The parent typically is obliged to provide payment (often through insurance) for those services.

This traditional rule has some exceptions—the emergency exception already noted and the case of emancipated minors, notably an adolescent who is living almost entirely independent of her parents (for example, she is married or not relying on parents in a meaningful way). In recent times there has been increasing authority for “mature minors” to make some medical decisions.2 A mature minor is one who has sufficient understanding and judgment to appreciate the consequences, benefits, and risks of accepting proposed medical intervention.

No circumstance involving adolescent treatment has been more contentious than services related to abortion and, to a lesser degree, contraception.3 Both the law of consent to services and the rights of parents to obtain information about contraceptive and abortion services have been a matter of strong, continuing debate. The law in these areas varies greatly from state-to-state, and includes a mix of state law (statutes and court decisions) with an overlay of federal constitutional law related to reproduction-related decisions of adolescents. In addition, the law in this area of consent and information changes relatively frequently.4 Clinicians, of course, must focus on the consent laws of the state in which they practice.

STI counseling and treatment

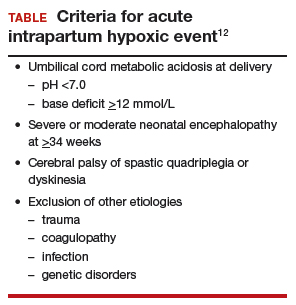

All states permit a minor patient to consent to treatment for an STI (TABLE 1).5 A number of states expressly permit, but do not require, health care providers to inform parents of treatment when a physician determines it would be in the best interest of the minor. Thus, the clinic would not be required to provide proactively the information to our case patient’s mother (regarding any STI issues) when she called.6

Contraception

Consent for contraception is more complicated. About half the states allow minors who have reached a certain age (12, 14, or 16 years) to consent to contraception. About 20 other states allow some minors to consent to contraceptive services, but the “allowed group” may be fairly narrow (eg, be married, have a health issue, or be “mature”). In 4 states there is currently no clear legal authority to provide contraceptive services to minors, yet those states do not specifically prohibit it. The US Supreme Court has held that a state cannot completely prohibit the availability of contraception to minors.7 The reach of that decision, however, is not clear and may not extend beyond what the states currently permit.

The ability of minors to consent to contraception services does not mean that there is a right to consent to all contraceptive options. As contraception becomes more irreversible, permanent, or risky, it is more problematic. For example, consent to sterilization would not ordinarily be within a minor’s recognized ability to consent. Standard, low risk, reversible contraception generally is covered by these state laws.8

In our case here, the patient likely was able to consent to contraception—initially to the oral contraception and later to the IUD. The risks and reversibility of both are probably within her ability to consent.9,10 Of course, if the care was provided in a state that does not include the patient within the groups that can give consent to contraception, it is possible that she might not have the legal authority to consent.

Continue to: General requirements of consent...

General requirements of consent

Even when adolescent consent is permitted for treatment, including in cases of contraception, it is essential that all of the legal and ethical requirements related to informed consent are met.

1. The adolescent has the capacity to consent. This means not only that the state-mandated requirements are met (age, for example) but also that the patient can and does understand the various elements of consent, and can make a sensible, informed decision.

The bottom line is “adolescent capacity is a complex process dependent upon the development of maturity of the adolescent, degree of intervention, expected benefit of the medical procedure, and the sociocultural context surrounding the decision.”11 Other items of interest include the “evolving capacity” of the child,12 which is the concept of increasing ability of the teen to process information and provide more appropriate informed consent. Central nervous system (CNS) maturation allows the adolescent to become increasingly more capable of decision making and has awareness of consequences of such decisions. Abstract thinking capabilities is a reflection of this CNS maturing process. If this competency is not established, the adolescent patient cannot give legitimate consent.

2. The patient must be given appropriate information (be “informed”). The discussion should include information relevant to the condition being treated (and the disease process if relevant). In addition, information about the treatment or intervention proposed and its risks and alternatives must be provided to the patient and in a way that is understandable.

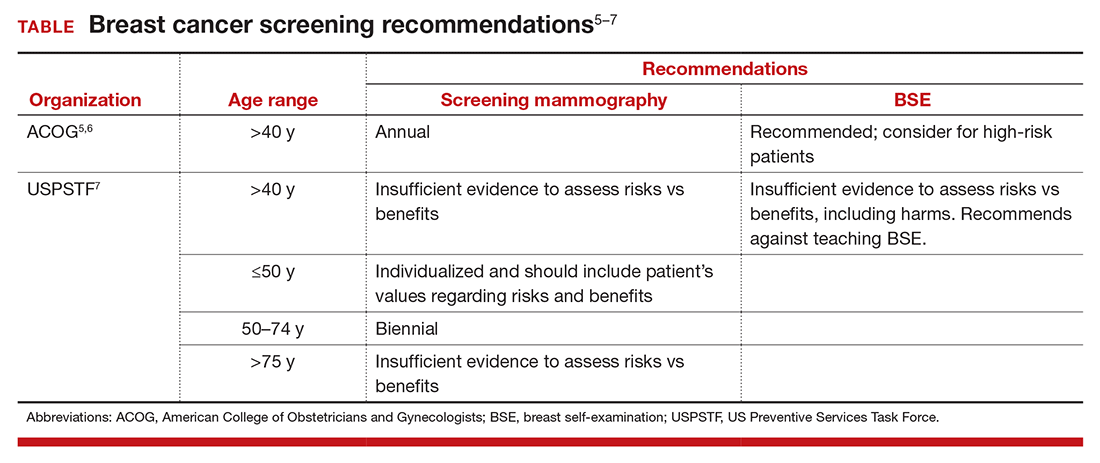

3. As with all patients, consent must be voluntary and free of coercion or manipulation. These elements of informed consent are expanded on by the Joint Commission, which has established a number of components of informed consent (TABLE 2).4,13

Confidentiality and release of information to parents and others

Similar to consent, parents historically have had the authority to obtain medical information about their minor children. This right generally continues today, with some limitations. The right to give consent generally carries with it the right to medical information. There are some times when parents may access medical information even if they have not given consent.

This right adds complexity to minor consent and is an important treatment issue and legal consideration because confidentiality for adolescents affects quality of care. Adolescents report that “confidentiality is an important factor in their decision to seek [medical] care.”14 Many parents are under the assumption that the health care provider will automatically inform them independent of whether or not the adolescent expressed precise instruction not to inform.15,16

Of course if a minor patient authorizes the physician to provide information to her parents, that is consent and the health care provider may then provide the information. If the patient instructs the provider to convey the information, the practitioner would ordinarily be expected to be proactive in providing the information to the parent. The issue of “voluntariness” of the waiver of confidentiality can be a question, and the physician may discuss that question with the patient. Ordinarily, however, once a minor has authorized disclosure to the parent, the clinician has the authority to disclose the information to the parent, but not to others.

All of the usual considerations of confidentiality in health care apply to adolescent ObGyn services and care. This includes the general obligation not to disclose information without consent and to ensure that health care information is protected from accidental release as required by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and other health information privacy laws.17

It is important to emphasize that the issues of consent to abortion are much different than those for contraception and sexually transmitted infections. As our case presentation does not deal with abortion, we will address this complex but important discussion in the future--as there are an estimated 90,000 abortions in adolescent girls annually.1

Given that abortion consent and notification laws are often complex, any physician providing abortion services to any minor should have sound legal advice on the requirements of the pertinent state law. In earlier publications of this section in OBG Management we have discussed the importance of practitioners having an ongoing relationship with a health law attorney. We make this point again, as this person can provide advice on consent and the rights of parents to have information about their minor children.

Reference

- Henshaw SK. U.S. teenage pregnancy statistics with comparative statistics for women age 20-24. New York, New York: Alan Guttmacher Institute; May 2003.

Continue to: How and when to protect minor confidentiality...

How and when to protect minor confidentiality

A clinician cannot assure minors of absolute confidentiality and should not agree to do so or imply that they are doing so.18 In our hypothetical case, when the patient told the physician that her parents were not to know of any of her treatment or communications, the provider should not have acquiesced by silence. He/she might have responded along these lines: “I have a strong commitment to confidentiality of your information, and we take many steps to protect that information. The law also allows some special protection of health care information. Despite the commitment to privacy, there are circumstances in which the law requires disclosure of information—and that might even be to parents. In addition, if you want any of your care covered by insurance, we would have to disclose that. While I expect that we can do as you ask about maintaining your confidentiality, no health care provider can absolutely guarantee it.”

Proactive vs reactive disclosure. There is “proactive” disclosure of information and “reactive” disclosure. Proactive is when the provider (without being asked) contacts a parent or others and provides information. Some states require proactive information about specific kinds of treatment (especially abortion services). For the most part, in states where a minor can legally consent to treatment, health care providers are not required to proactively disclose information.19

Clinicians may be required to respond to parental requests for information, which is reactive disclosure and is reflected in our case presentation. Even in such circumstances, however, the individual providing care may seek to avoid disclosure. In many states, the law would not require the release of this information (but would permit it if it is in the best interest of the patient). In addition, there are practical ways of avoiding the release of information. For example, the health care provider might acknowledge the interest and desire of the parent to have the information, but might humbly explain that in the experience of many clinicians protecting the confidentiality of patients is very important to successful treatment and it is the policy of the office/clinic not to breach the expectation of patient confidentiality except where that is clearly in the best interest of the patient or required by law.

In response to the likely question, “Well, isn’t that required by law?” the clinician can honestly reply, “I don’t know. There are many complex factors in the law regarding disclosure of medical information and as I am not an attorney I do not know how they all apply in this instance.” In some cases the parent may push the matter or take some kind of legal action. It is in this type of situation that an attorney familiar with health law and the clinician’s practice can be invaluable.

When parents are involved in the minor’s treatment (bringing the patient to the office/clinic, for example), there is an opportunity for an understanding, or agreement, among the patient, provider, and parent about what information the parent will receive. Ordinarily the agreement should not create the expectation of detailed information for the parent. Perhaps, for example, the physician will provide information only when he or she believes that doing so will be in the best interest of the patient. Even with parental agreement, complete confidentiality cannot be assured for minor patients. There may, for example, be another parent who will not feel bound by the established understanding, and the law requires some disclosures (in the case of child abuse or a court order).20

Continue to: Accidental disclosure...

Accidental disclosure. Health care providers also should make sure that office procedures do not unnecessarily or accidentally disclose information about patients. For example, routinely gathering information about insurance coverage may well trigger the release of information to the policy holder (often a parent). Thus, there should be clear understandings about billing, insurance, and related issues before information is divulged by the patient. This should be part of the process of obtaining informed consent to treatment. It should be up front and honest. Developing a clear understanding of the legal requirements of the state is essential, so that assurance of confidentiality is on legal, solid ground.

As the pediatric and adolescent segment of gynecologic care continues to evolve, it is noteworthy that the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology recently has established a "Focused Practice" designation in pediatric adolescent gynecology. This allows ObGyns to have an ongoing level of professional education in this specialized area. Additional information can be obtained at www.abog.org or info@abog.org.

More resources for adolescent contraceptive care include:

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) "Birth Control (Especially for Teens)" frequently asked questions information series (https://www.acog.org/Patients/FAQs/Birth-Control-Especially-for-Teens)

- ACOG's Adolescent Healthcare Committee Opinions address adolescent pregnancy, contraception, and sexual activity (https://www.acog.org/-/media/List-of-Titles/COListOfTitles.pdf)

- ACOG statement on teen pregnancy and contraception, April 7, 2015 (https://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/News-Room/Statements/2015/ACOG-Statement-on-Teen-Pregnancy-and-Contraception?IsMobileSet=false)

- North American Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology resources for patients (https://www.naspag.org/page/patienttools)

- Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine statement regarding contraceptive access policies (https://www.adolescenthealth.org)

- The Guttmacher Institute's overview of state laws relevant to minor consent, as of January 1, 2019 (https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/overview-minors-consent-law). It is updated frequently.

Abuse reporting obligations

All states have mandatory child abuse reporting laws. These laws require medical professionals (and others) to report known, and often suspected, abuse of children. Abuse includes physical, sexual, or emotional, and generally also includes neglect that is harming a child. When there is apparent sexual or physical abuse, the health care provider is obligated to report it to designated state authorities, generally child protective services. Reporting laws vary from state to state based on the relationship between the suspected abuser and the minor, the nature of the harm, and how strong the suspicion of abuse needs to be. The failure to make required reports is a crime in most states and also may result in civil liability or licensure discipline. Criminal charges seldom result from the failure to report, but in some cases the failure to report may have serious consequences for the professional.

An ObGyn example of the complexity of reporting laws, and variation from state to state, is in the area of “statutory rape” reporting. Those state laws, which define serious criminal offenses, set out the age below which an individual is not legally capable of consenting to sexual activity. It varies among states, but may be an absolute age of consent, the age differential between the parties, or some combination of age and age differential.21 The question of reporting is further complicated by the issue of when statutory rape must be reported—for example, the circumstances when the harm to the underage person is sufficient to require reporting.22

Laws are complex, as is practice navigation

It is apparent that navigating these issues makes it essential for an ObGyn practice to have clear policies and practices regarding reporting, yet the overall complexity is also why it is so difficult to develop those policies in the first place. Of course, they must be tailored to the state in which the practice resides. Once again, the need is clear for health care professionals to have an ongoing relationship with a health attorney who can help navigate ongoing questions.

CASE Adolescent seeks care without parent

A 15-year-old patient (G0) presents to the gynecology clinic requesting birth control. She reports being sexually active over the past 6 months and having several male partners over the past 2 years. She and her current male partner use condoms inconsistently. She reports being active in school sports, and her academic performance has been noteworthy. Her peers have encouraged her to seek out birth control; one of her good friends recently became pregnant and dropped out of school. She states that her best friend went to a similar clinic and received a “gynecologic encounter” that included information regarding safe sex and contraception, with no pelvic exam required for her to receive birth control pills.

The patient insists that her parents are not to know of her request for contraception due to sexual activity or that she is a patient at the clinic. The gynecologist covering the clinic is aware of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Adolescent Health Care and their many publications. The patient is counseled regarding human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination and screened for sexually transmitted infections. In addition, the gynecologist discusses contraceptive options with the patient, ranging from oral contraceptives, vaginal rings, subdermal implants, depomedroxyprogesterone acetate, as well as intrauterine devices (IUDs). The gynecologist emphasizes safe sex and advises that her partner consider use of condoms independent of her method of birth control. The patient asks for oral contraceptives and is given information about their use and risks, and she indicates that she understands.

A few months later the patient requests an IUD, as she would like to have lighter menses and not have to remember to take a pill every day. The provider obtains informed consent for the insertion procedure; the patient signs the appropriate forms.

The IUD is inserted, with difficulty, by a resident physician in the clinic. The patient experiences severe pelvic pain during and immediately following the insertion. She is sent home and told to contact the clinic or another health care provider or proceed to the local emergency department should pain persist or if fever develops.

The patient returns 72 hours later in pain. Pelvic ultrasonography shows the IUD out of place and at risk of perforating the fundus of the uterus. Later that day the patient’s mother calls the clinic, saying that she found a statement of service with the clinic’s number on it in her daughter’s bedroom. She wants to know if her daughter is there, what is going on, and what services have been or are being provided. In passing she remarks that she has no intention of paying (or allowing her insurance to pay for) any care that was provided.

What are the provider’s obligations at this point, both medically and legally?

Medical and legal considerations

One of the most difficult and important health law questions in adolescent medicine is the ability of minors to consent to treatment and to control the health care information resulting from treatment. (“Minor” describes a child or adolescent who has not obtained the age of legal consent, generally 18 years old, to lawfully enter into a legal transaction.)

Continue to: The consent of minor patients...

The consent of minor patients

The traditional legal rule is that parents or guardians (“parent” refers to both) must consent to medical treatment for minor children. There is an exception for emergency situations but generally minors do not provide consent for medical care, a parent does.1 The parent typically is obliged to provide payment (often through insurance) for those services.

This traditional rule has some exceptions—the emergency exception already noted and the case of emancipated minors, notably an adolescent who is living almost entirely independent of her parents (for example, she is married or not relying on parents in a meaningful way). In recent times there has been increasing authority for “mature minors” to make some medical decisions.2 A mature minor is one who has sufficient understanding and judgment to appreciate the consequences, benefits, and risks of accepting proposed medical intervention.

No circumstance involving adolescent treatment has been more contentious than services related to abortion and, to a lesser degree, contraception.3 Both the law of consent to services and the rights of parents to obtain information about contraceptive and abortion services have been a matter of strong, continuing debate. The law in these areas varies greatly from state-to-state, and includes a mix of state law (statutes and court decisions) with an overlay of federal constitutional law related to reproduction-related decisions of adolescents. In addition, the law in this area of consent and information changes relatively frequently.4 Clinicians, of course, must focus on the consent laws of the state in which they practice.

STI counseling and treatment

All states permit a minor patient to consent to treatment for an STI (TABLE 1).5 A number of states expressly permit, but do not require, health care providers to inform parents of treatment when a physician determines it would be in the best interest of the minor. Thus, the clinic would not be required to provide proactively the information to our case patient’s mother (regarding any STI issues) when she called.6

Contraception

Consent for contraception is more complicated. About half the states allow minors who have reached a certain age (12, 14, or 16 years) to consent to contraception. About 20 other states allow some minors to consent to contraceptive services, but the “allowed group” may be fairly narrow (eg, be married, have a health issue, or be “mature”). In 4 states there is currently no clear legal authority to provide contraceptive services to minors, yet those states do not specifically prohibit it. The US Supreme Court has held that a state cannot completely prohibit the availability of contraception to minors.7 The reach of that decision, however, is not clear and may not extend beyond what the states currently permit.

The ability of minors to consent to contraception services does not mean that there is a right to consent to all contraceptive options. As contraception becomes more irreversible, permanent, or risky, it is more problematic. For example, consent to sterilization would not ordinarily be within a minor’s recognized ability to consent. Standard, low risk, reversible contraception generally is covered by these state laws.8

In our case here, the patient likely was able to consent to contraception—initially to the oral contraception and later to the IUD. The risks and reversibility of both are probably within her ability to consent.9,10 Of course, if the care was provided in a state that does not include the patient within the groups that can give consent to contraception, it is possible that she might not have the legal authority to consent.

Continue to: General requirements of consent...

General requirements of consent

Even when adolescent consent is permitted for treatment, including in cases of contraception, it is essential that all of the legal and ethical requirements related to informed consent are met.

1. The adolescent has the capacity to consent. This means not only that the state-mandated requirements are met (age, for example) but also that the patient can and does understand the various elements of consent, and can make a sensible, informed decision.

The bottom line is “adolescent capacity is a complex process dependent upon the development of maturity of the adolescent, degree of intervention, expected benefit of the medical procedure, and the sociocultural context surrounding the decision.”11 Other items of interest include the “evolving capacity” of the child,12 which is the concept of increasing ability of the teen to process information and provide more appropriate informed consent. Central nervous system (CNS) maturation allows the adolescent to become increasingly more capable of decision making and has awareness of consequences of such decisions. Abstract thinking capabilities is a reflection of this CNS maturing process. If this competency is not established, the adolescent patient cannot give legitimate consent.

2. The patient must be given appropriate information (be “informed”). The discussion should include information relevant to the condition being treated (and the disease process if relevant). In addition, information about the treatment or intervention proposed and its risks and alternatives must be provided to the patient and in a way that is understandable.

3. As with all patients, consent must be voluntary and free of coercion or manipulation. These elements of informed consent are expanded on by the Joint Commission, which has established a number of components of informed consent (TABLE 2).4,13

Confidentiality and release of information to parents and others

Similar to consent, parents historically have had the authority to obtain medical information about their minor children. This right generally continues today, with some limitations. The right to give consent generally carries with it the right to medical information. There are some times when parents may access medical information even if they have not given consent.

This right adds complexity to minor consent and is an important treatment issue and legal consideration because confidentiality for adolescents affects quality of care. Adolescents report that “confidentiality is an important factor in their decision to seek [medical] care.”14 Many parents are under the assumption that the health care provider will automatically inform them independent of whether or not the adolescent expressed precise instruction not to inform.15,16

Of course if a minor patient authorizes the physician to provide information to her parents, that is consent and the health care provider may then provide the information. If the patient instructs the provider to convey the information, the practitioner would ordinarily be expected to be proactive in providing the information to the parent. The issue of “voluntariness” of the waiver of confidentiality can be a question, and the physician may discuss that question with the patient. Ordinarily, however, once a minor has authorized disclosure to the parent, the clinician has the authority to disclose the information to the parent, but not to others.

All of the usual considerations of confidentiality in health care apply to adolescent ObGyn services and care. This includes the general obligation not to disclose information without consent and to ensure that health care information is protected from accidental release as required by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and other health information privacy laws.17

It is important to emphasize that the issues of consent to abortion are much different than those for contraception and sexually transmitted infections. As our case presentation does not deal with abortion, we will address this complex but important discussion in the future--as there are an estimated 90,000 abortions in adolescent girls annually.1

Given that abortion consent and notification laws are often complex, any physician providing abortion services to any minor should have sound legal advice on the requirements of the pertinent state law. In earlier publications of this section in OBG Management we have discussed the importance of practitioners having an ongoing relationship with a health law attorney. We make this point again, as this person can provide advice on consent and the rights of parents to have information about their minor children.

Reference

- Henshaw SK. U.S. teenage pregnancy statistics with comparative statistics for women age 20-24. New York, New York: Alan Guttmacher Institute; May 2003.

Continue to: How and when to protect minor confidentiality...

How and when to protect minor confidentiality

A clinician cannot assure minors of absolute confidentiality and should not agree to do so or imply that they are doing so.18 In our hypothetical case, when the patient told the physician that her parents were not to know of any of her treatment or communications, the provider should not have acquiesced by silence. He/she might have responded along these lines: “I have a strong commitment to confidentiality of your information, and we take many steps to protect that information. The law also allows some special protection of health care information. Despite the commitment to privacy, there are circumstances in which the law requires disclosure of information—and that might even be to parents. In addition, if you want any of your care covered by insurance, we would have to disclose that. While I expect that we can do as you ask about maintaining your confidentiality, no health care provider can absolutely guarantee it.”

Proactive vs reactive disclosure. There is “proactive” disclosure of information and “reactive” disclosure. Proactive is when the provider (without being asked) contacts a parent or others and provides information. Some states require proactive information about specific kinds of treatment (especially abortion services). For the most part, in states where a minor can legally consent to treatment, health care providers are not required to proactively disclose information.19

Clinicians may be required to respond to parental requests for information, which is reactive disclosure and is reflected in our case presentation. Even in such circumstances, however, the individual providing care may seek to avoid disclosure. In many states, the law would not require the release of this information (but would permit it if it is in the best interest of the patient). In addition, there are practical ways of avoiding the release of information. For example, the health care provider might acknowledge the interest and desire of the parent to have the information, but might humbly explain that in the experience of many clinicians protecting the confidentiality of patients is very important to successful treatment and it is the policy of the office/clinic not to breach the expectation of patient confidentiality except where that is clearly in the best interest of the patient or required by law.

In response to the likely question, “Well, isn’t that required by law?” the clinician can honestly reply, “I don’t know. There are many complex factors in the law regarding disclosure of medical information and as I am not an attorney I do not know how they all apply in this instance.” In some cases the parent may push the matter or take some kind of legal action. It is in this type of situation that an attorney familiar with health law and the clinician’s practice can be invaluable.

When parents are involved in the minor’s treatment (bringing the patient to the office/clinic, for example), there is an opportunity for an understanding, or agreement, among the patient, provider, and parent about what information the parent will receive. Ordinarily the agreement should not create the expectation of detailed information for the parent. Perhaps, for example, the physician will provide information only when he or she believes that doing so will be in the best interest of the patient. Even with parental agreement, complete confidentiality cannot be assured for minor patients. There may, for example, be another parent who will not feel bound by the established understanding, and the law requires some disclosures (in the case of child abuse or a court order).20

Continue to: Accidental disclosure...

Accidental disclosure. Health care providers also should make sure that office procedures do not unnecessarily or accidentally disclose information about patients. For example, routinely gathering information about insurance coverage may well trigger the release of information to the policy holder (often a parent). Thus, there should be clear understandings about billing, insurance, and related issues before information is divulged by the patient. This should be part of the process of obtaining informed consent to treatment. It should be up front and honest. Developing a clear understanding of the legal requirements of the state is essential, so that assurance of confidentiality is on legal, solid ground.

As the pediatric and adolescent segment of gynecologic care continues to evolve, it is noteworthy that the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology recently has established a "Focused Practice" designation in pediatric adolescent gynecology. This allows ObGyns to have an ongoing level of professional education in this specialized area. Additional information can be obtained at www.abog.org or info@abog.org.

More resources for adolescent contraceptive care include:

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) "Birth Control (Especially for Teens)" frequently asked questions information series (https://www.acog.org/Patients/FAQs/Birth-Control-Especially-for-Teens)

- ACOG's Adolescent Healthcare Committee Opinions address adolescent pregnancy, contraception, and sexual activity (https://www.acog.org/-/media/List-of-Titles/COListOfTitles.pdf)

- ACOG statement on teen pregnancy and contraception, April 7, 2015 (https://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/News-Room/Statements/2015/ACOG-Statement-on-Teen-Pregnancy-and-Contraception?IsMobileSet=false)

- North American Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology resources for patients (https://www.naspag.org/page/patienttools)

- Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine statement regarding contraceptive access policies (https://www.adolescenthealth.org)

- The Guttmacher Institute's overview of state laws relevant to minor consent, as of January 1, 2019 (https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/overview-minors-consent-law). It is updated frequently.

Abuse reporting obligations

All states have mandatory child abuse reporting laws. These laws require medical professionals (and others) to report known, and often suspected, abuse of children. Abuse includes physical, sexual, or emotional, and generally also includes neglect that is harming a child. When there is apparent sexual or physical abuse, the health care provider is obligated to report it to designated state authorities, generally child protective services. Reporting laws vary from state to state based on the relationship between the suspected abuser and the minor, the nature of the harm, and how strong the suspicion of abuse needs to be. The failure to make required reports is a crime in most states and also may result in civil liability or licensure discipline. Criminal charges seldom result from the failure to report, but in some cases the failure to report may have serious consequences for the professional.

An ObGyn example of the complexity of reporting laws, and variation from state to state, is in the area of “statutory rape” reporting. Those state laws, which define serious criminal offenses, set out the age below which an individual is not legally capable of consenting to sexual activity. It varies among states, but may be an absolute age of consent, the age differential between the parties, or some combination of age and age differential.21 The question of reporting is further complicated by the issue of when statutory rape must be reported—for example, the circumstances when the harm to the underage person is sufficient to require reporting.22

Laws are complex, as is practice navigation

It is apparent that navigating these issues makes it essential for an ObGyn practice to have clear policies and practices regarding reporting, yet the overall complexity is also why it is so difficult to develop those policies in the first place. Of course, they must be tailored to the state in which the practice resides. Once again, the need is clear for health care professionals to have an ongoing relationship with a health attorney who can help navigate ongoing questions.

- Benjamin L, Ishimine P, Joseph M, et al. Evaluation and treatment of minors. Ann Emerg Med. 2018;71(2):225-232.

- Coleman D, Rosoff P. The legal authority of mature minors to consent to general medical treatment. Pediatrics. 2013;13:786-793.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 699. Adolescent pregnancy, contraception, and sexual activity. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:e142-e149.

- Tillett J. Adolescents and informed consent. J Perinat Neonat Nurs. 2005;19:112-121.

- An overview of minor's consent law. Guttmacher Institute's website. https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/overview-minors-consent-law. Accessed February 14, 2019.

- Chelmow D, Karjane N, Ricciotti HA, et al, eds. A 16-year-old adolescent requesting confidential treatment for chlamydia exposure (understanding state laws regarding minors and resources). Office Gynecology: A Case-Based Approach. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; January 31, 2019:39.

- Carey v Population Services, 431 US 678 (1977).

- Williams RL, Meredith AH, Ott MA. Expanding adolescent access to hormonal contraception: an update on over-the-counter, pharmacist prescribing, and web-based telehealth approaches. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2018;30:458-464.

- McClellan K, Temples H, Miller L. The latest in teen pregnancy prevention: long-acting reversible contraception. J Pediatr Health Care. 2018;32:e91-e97.

- Behmer Hansen RT, Arora KS. Consenting to invasive contraceptives: an ethical analysis of adolescent decision-making authority for long-acting reversible contraception. J Med Ethics. 2018;44:585-588.

- Robertson D. Opinions in pediatric and adolescent gynecology. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2008:21:47-51.

- Lansdown G. The evolving capacities of the child. Florence, Italy: UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre, Innocenti Insight; 2005. https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/384-the-evolving-capacities-of-the-child.html. Accessed February 15, 2019.

- Clapp JT, Fleisher LA. What is the realistic scope of informed consent? Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2018;44(6):341-342.

- Berlan E, Bravender T. Confidentiality, consent and caring for the adolescent. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2009;21:450-456.

- Schantz K. Who Needs to Know? Confidentiality in Adolescent Sexual Health Care. Act for Youth website. http://www.actforyouth.net/resources/rf/rf_confidentiality_1118.pdf. Accessed February 14, 2019.

- Lynn A, Kodish E, Lazebnik R, et al. Understanding confidentiality: perspectives of African American adolescents and their parents. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39:261-265.

- English A, Ford CA. The HIPAA privacy rule and adolescents: legal questions and clinical challenges. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2004;36:80-86.

- Schapiro NA, Mejia J. Adolescent confidentiality and women's health: history, rationale, and current threats. Nurs Clin North Am. 2018;53:145-156.

- Scott NL, Alderman EM, 2018. Case of a girl with a secret. In: Adolescent Gynecology: A Clinical Casebook. New York, New York: Springer International; 2017:3-11.

- Cullitan CM. Please don't tell my mom--a minor's right to informational privacy. JL & Educ. 2011;40:417-460.

- Bierie DM, Budd KM. Romeo, Juliet, and statutory rape. Sex Abuse. 2018;30:296-321.

- Mathews B. A taxonomy of duties to report child sexual abuse: legal developments offer new ways to facilitate disclosure. Child Abuse Negl. 2019;88:337-347.

- Benjamin L, Ishimine P, Joseph M, et al. Evaluation and treatment of minors. Ann Emerg Med. 2018;71(2):225-232.

- Coleman D, Rosoff P. The legal authority of mature minors to consent to general medical treatment. Pediatrics. 2013;13:786-793.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 699. Adolescent pregnancy, contraception, and sexual activity. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:e142-e149.

- Tillett J. Adolescents and informed consent. J Perinat Neonat Nurs. 2005;19:112-121.

- An overview of minor's consent law. Guttmacher Institute's website. https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/overview-minors-consent-law. Accessed February 14, 2019.

- Chelmow D, Karjane N, Ricciotti HA, et al, eds. A 16-year-old adolescent requesting confidential treatment for chlamydia exposure (understanding state laws regarding minors and resources). Office Gynecology: A Case-Based Approach. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; January 31, 2019:39.

- Carey v Population Services, 431 US 678 (1977).

- Williams RL, Meredith AH, Ott MA. Expanding adolescent access to hormonal contraception: an update on over-the-counter, pharmacist prescribing, and web-based telehealth approaches. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2018;30:458-464.

- McClellan K, Temples H, Miller L. The latest in teen pregnancy prevention: long-acting reversible contraception. J Pediatr Health Care. 2018;32:e91-e97.

- Behmer Hansen RT, Arora KS. Consenting to invasive contraceptives: an ethical analysis of adolescent decision-making authority for long-acting reversible contraception. J Med Ethics. 2018;44:585-588.

- Robertson D. Opinions in pediatric and adolescent gynecology. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2008:21:47-51.

- Lansdown G. The evolving capacities of the child. Florence, Italy: UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre, Innocenti Insight; 2005. https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/384-the-evolving-capacities-of-the-child.html. Accessed February 15, 2019.

- Clapp JT, Fleisher LA. What is the realistic scope of informed consent? Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2018;44(6):341-342.

- Berlan E, Bravender T. Confidentiality, consent and caring for the adolescent. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2009;21:450-456.

- Schantz K. Who Needs to Know? Confidentiality in Adolescent Sexual Health Care. Act for Youth website. http://www.actforyouth.net/resources/rf/rf_confidentiality_1118.pdf. Accessed February 14, 2019.

- Lynn A, Kodish E, Lazebnik R, et al. Understanding confidentiality: perspectives of African American adolescents and their parents. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39:261-265.

- English A, Ford CA. The HIPAA privacy rule and adolescents: legal questions and clinical challenges. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2004;36:80-86.

- Schapiro NA, Mejia J. Adolescent confidentiality and women's health: history, rationale, and current threats. Nurs Clin North Am. 2018;53:145-156.

- Scott NL, Alderman EM, 2018. Case of a girl with a secret. In: Adolescent Gynecology: A Clinical Casebook. New York, New York: Springer International; 2017:3-11.

- Cullitan CM. Please don't tell my mom--a minor's right to informational privacy. JL & Educ. 2011;40:417-460.

- Bierie DM, Budd KM. Romeo, Juliet, and statutory rape. Sex Abuse. 2018;30:296-321.

- Mathews B. A taxonomy of duties to report child sexual abuse: legal developments offer new ways to facilitate disclosure. Child Abuse Negl. 2019;88:337-347.

Cost-conscious minimally invasive hysterectomy: A case illustration

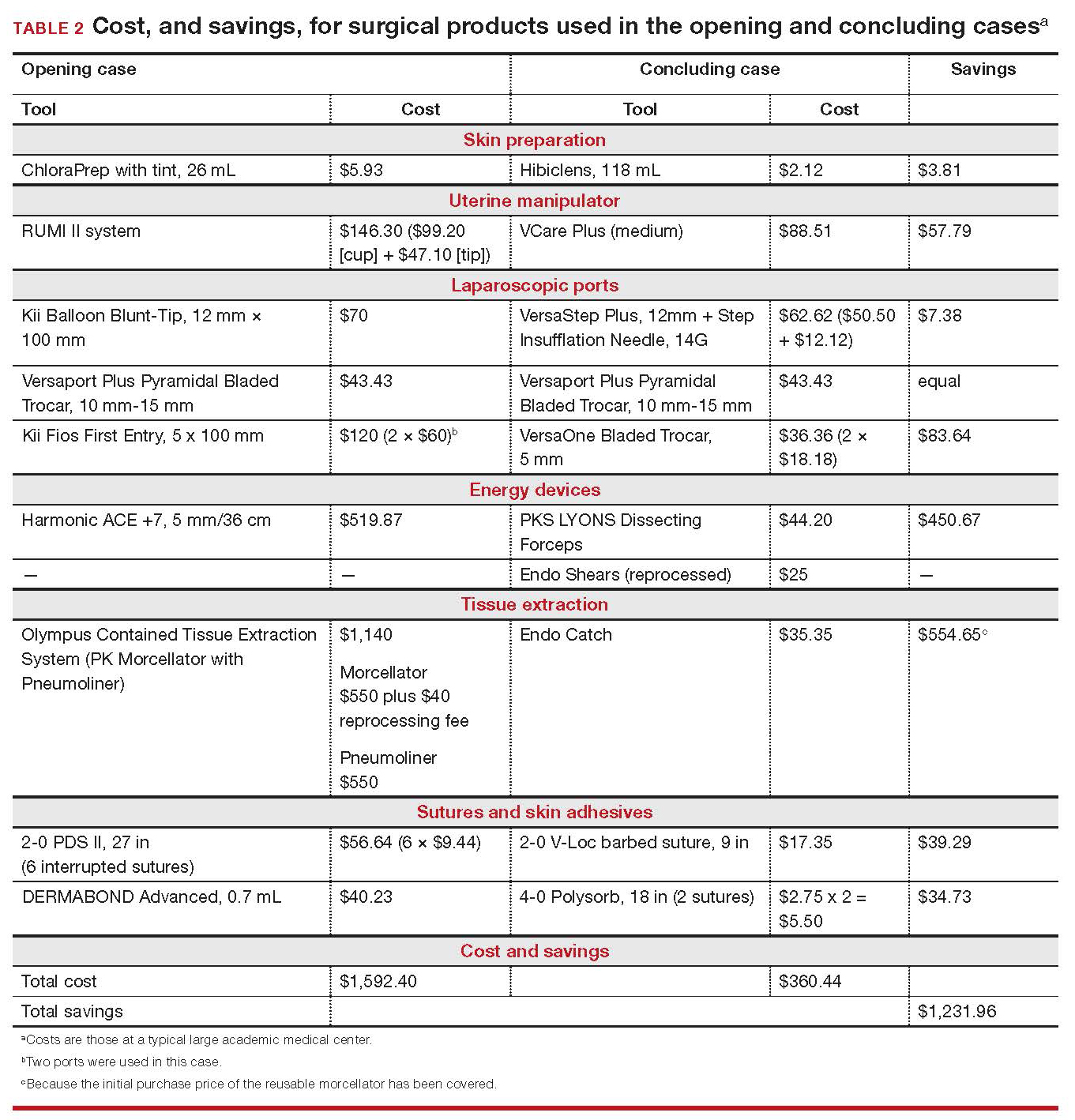

CASE Cost-conscious benign laparoscopic hysterectomy

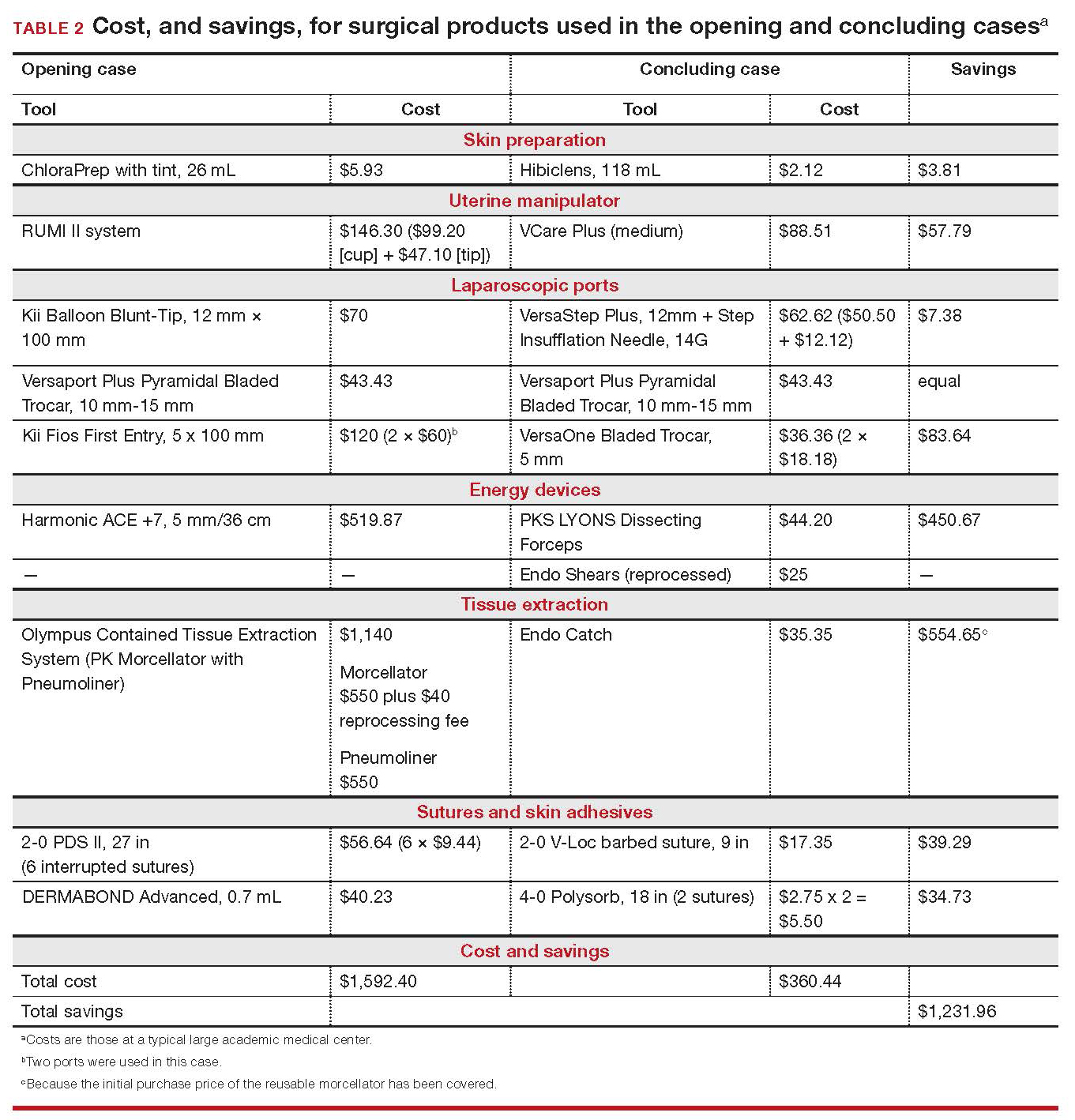

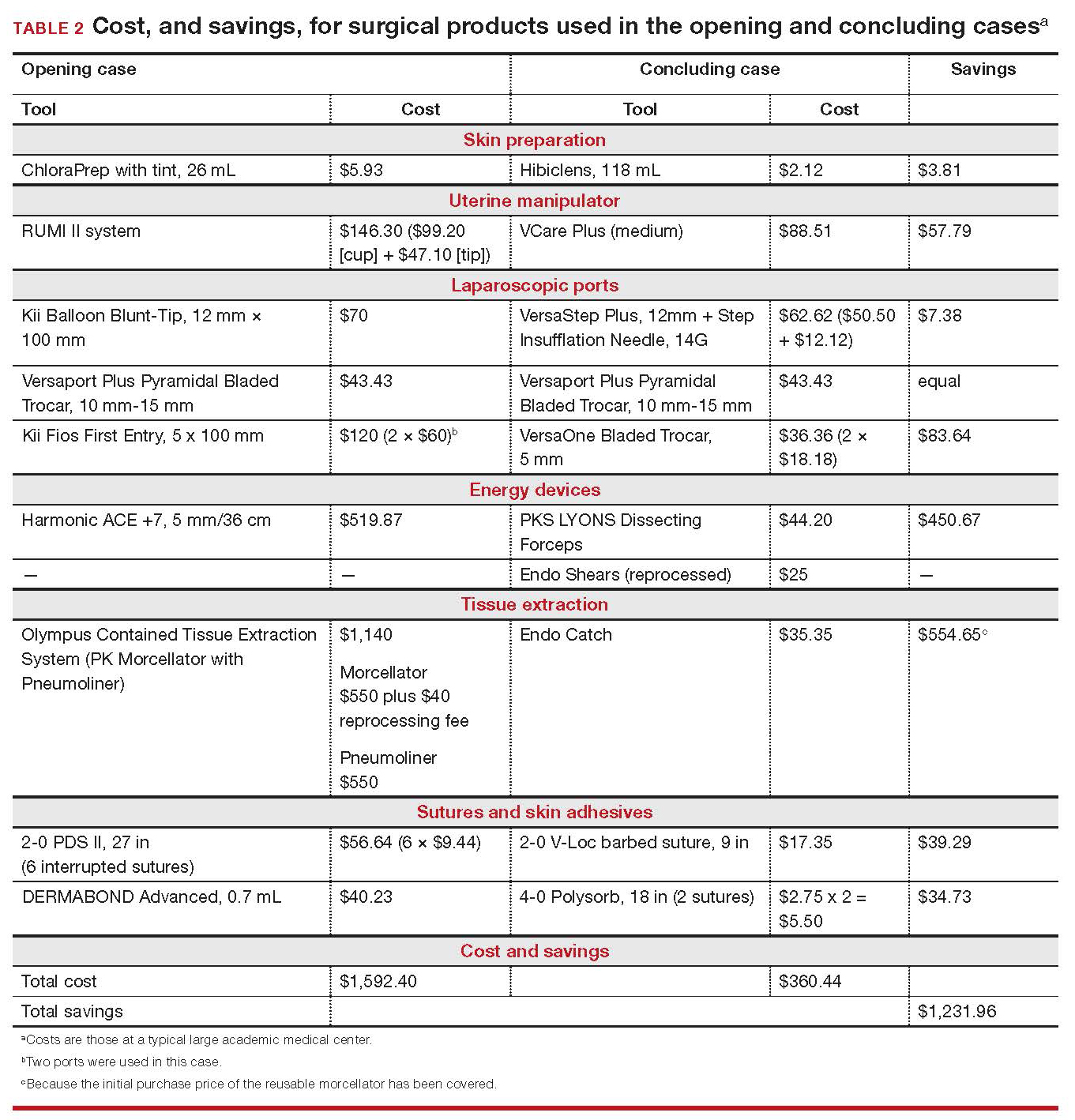

A 43-year-old woman undergoes laparoscopic hysterectomy for treatment of presumed benign uterine fibroids and menorrhagia. Once she is prepped with ChloraPrep with tint, a RUMI II uterine manipulator is placed. Laparoscopic ports include a Kii Balloon Blunt Tip system, a Versaport Plus Pyramidal Bladed Trocar, and 2 Kii Fios First Entry trocars.

The surgeon uses the Harmonic ACE +7 device (a purely ultrasonic device) to perform most of the procedure. The uterus is morcellated and removed using the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved Olympus Contained Tissue Extraction System, and the vaginal cuff is closed using a series of 2-0 PDS II sutures. Skin incisions are closed using Dermabond skin adhesive.

Total cost of the products used in this case: $1,592.40. Could different product choices have reduced this figure?

Health-care costs continue to rise faster than inflation: Total health-care expenditures account for approximately 18% of gross domestic product in the United States. Physicians therefore face increasing pressure to take cost into account in their care of patients.1 Cost-effectiveness and outcome quality continue to increase in importance as measures in many clinical trials that compare standard and alternative therapies. And women’s health—specifically, minimally invasive gynecologic surgery—invites such comparisons.

Overall, conventional laparoscopic gynecologic procedures tend to cost less than laparotomy, a consequence of shorter hospital stays, faster recovery, and fewer complications.2-5 What is not fully appreciated, however, is how choice of laparoscopic instrumentation and associated products affects surgical costs. In this article, which revisits and updates a 2013 OBG Management examination of cost-consciousness in the selection of equipment and supplies for minimally invasive gynecologic surgery,6 we review these costs in 2018. Our goal is to raise awareness of the role of cost in care among minimally invasive gynecologic surgeons.

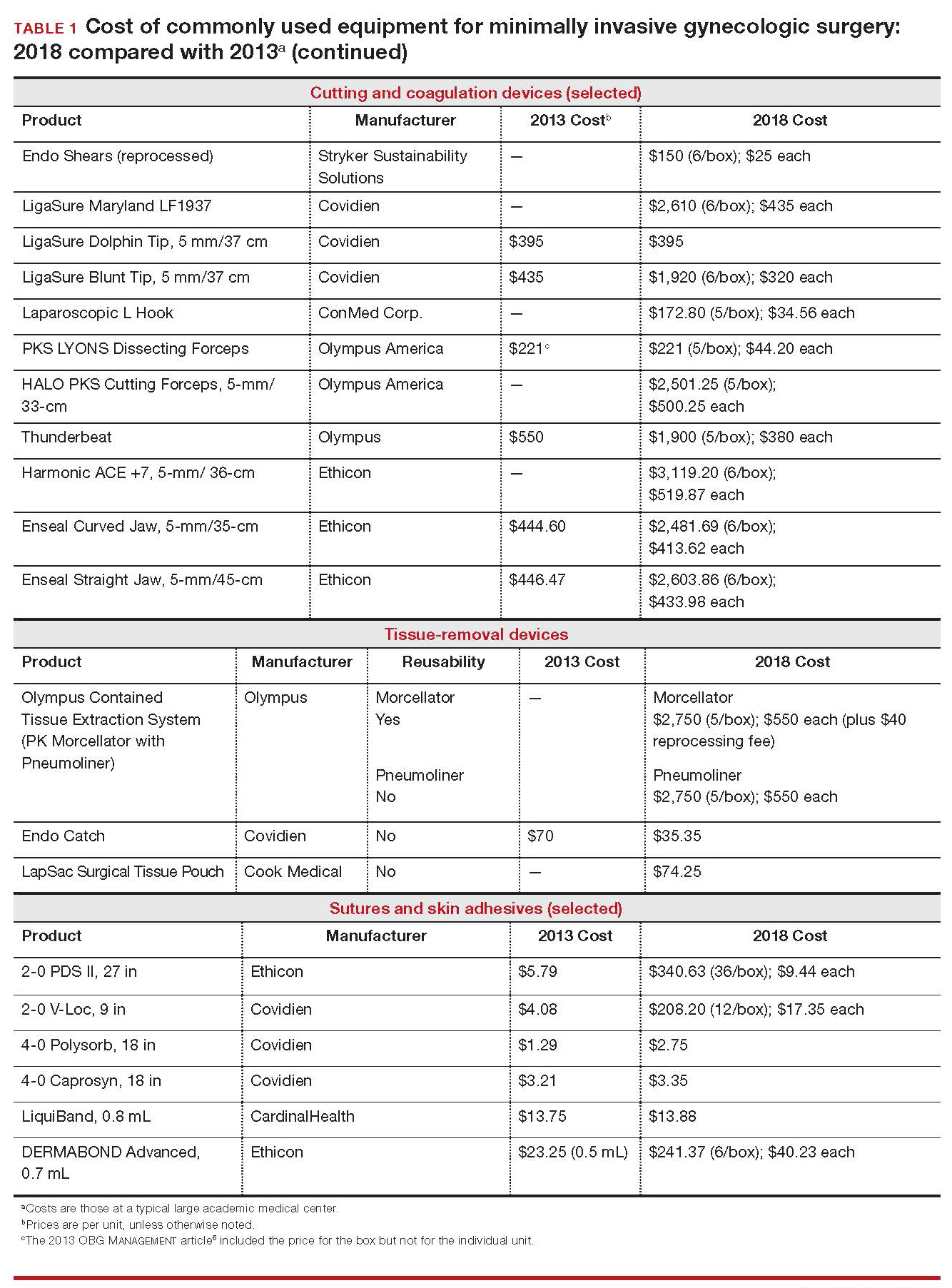

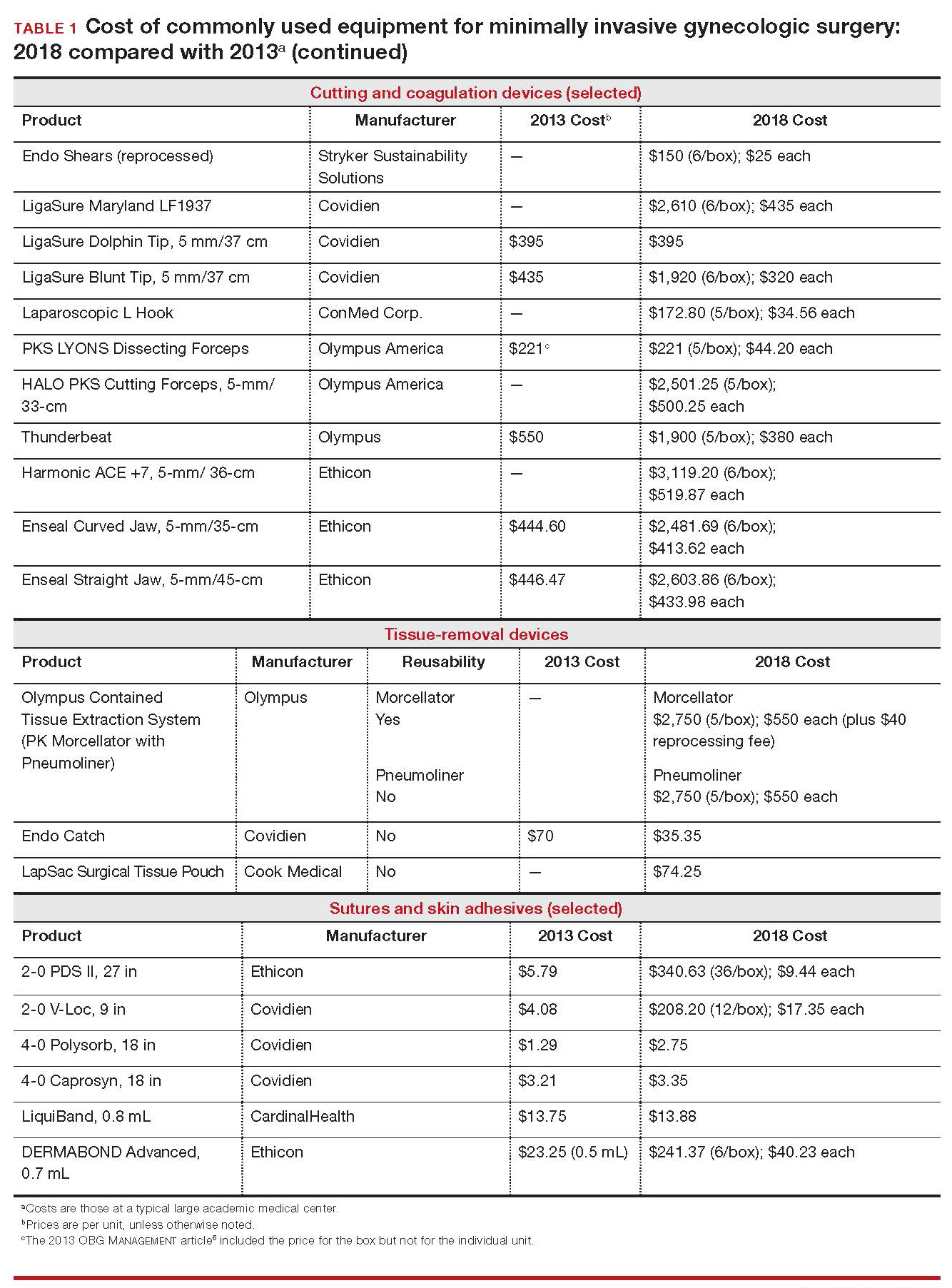

In the sections that follow, we highlight several aspects of laparoscopic gynecologic surgery that can affect your selection of instruments and products, describing differences in cost as well as some distinctive characteristics of products. Note that our comparisons focus solely on cost—not on ease of utility, effectiveness, surgical technique, risk of complications, or any other assessment. Note also that numerous other instruments and devices are commercially available besides those we list.

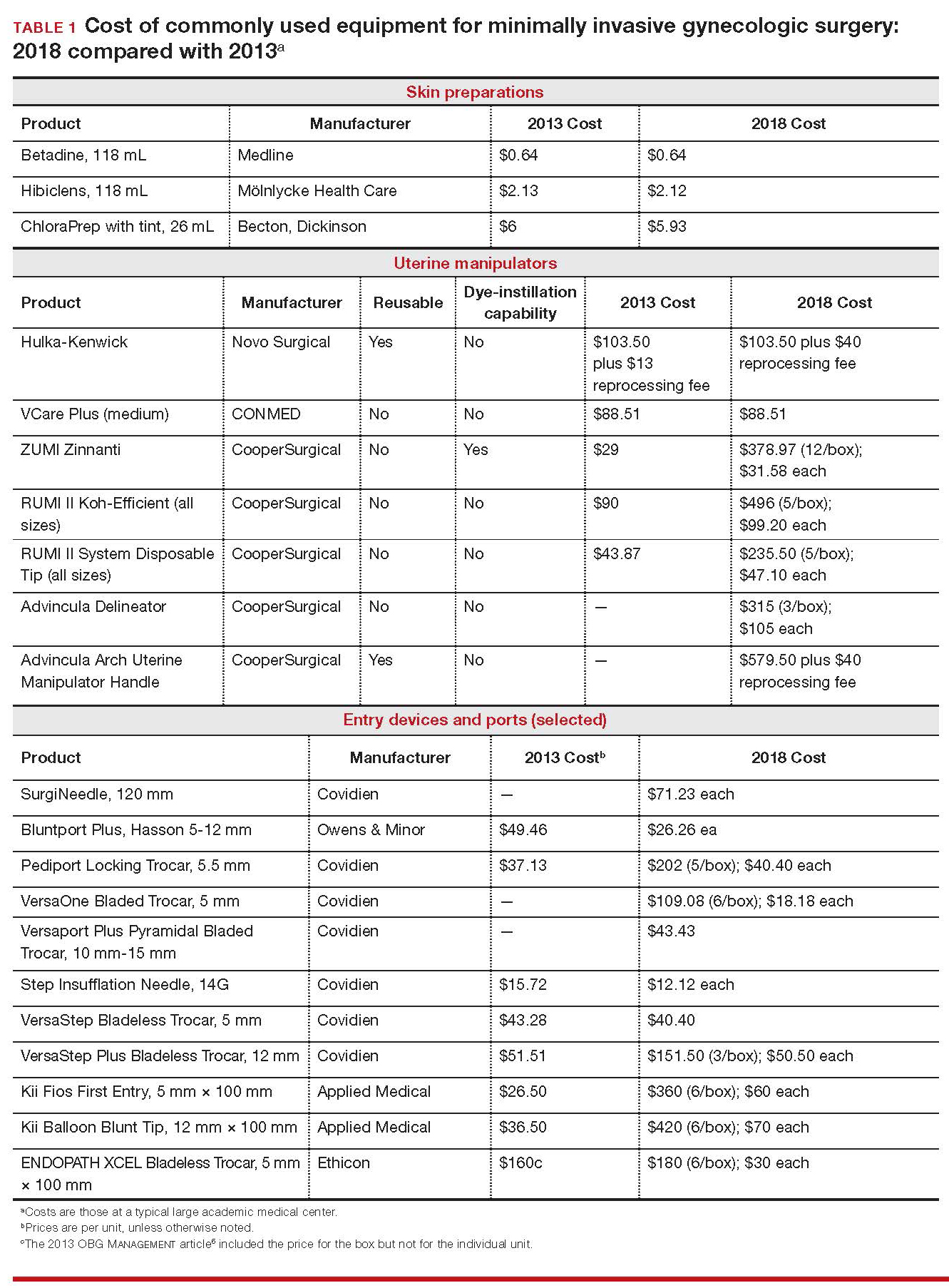

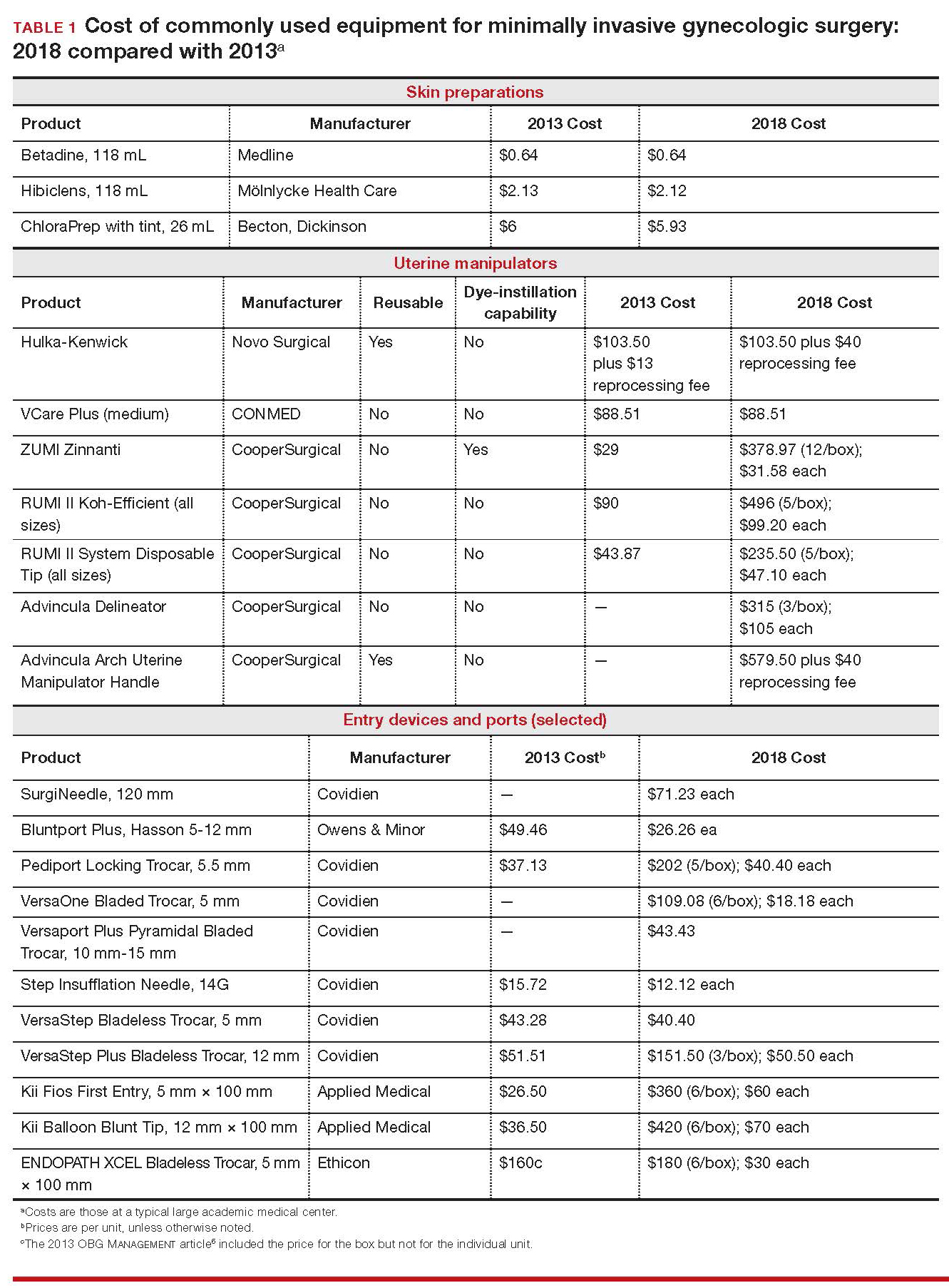

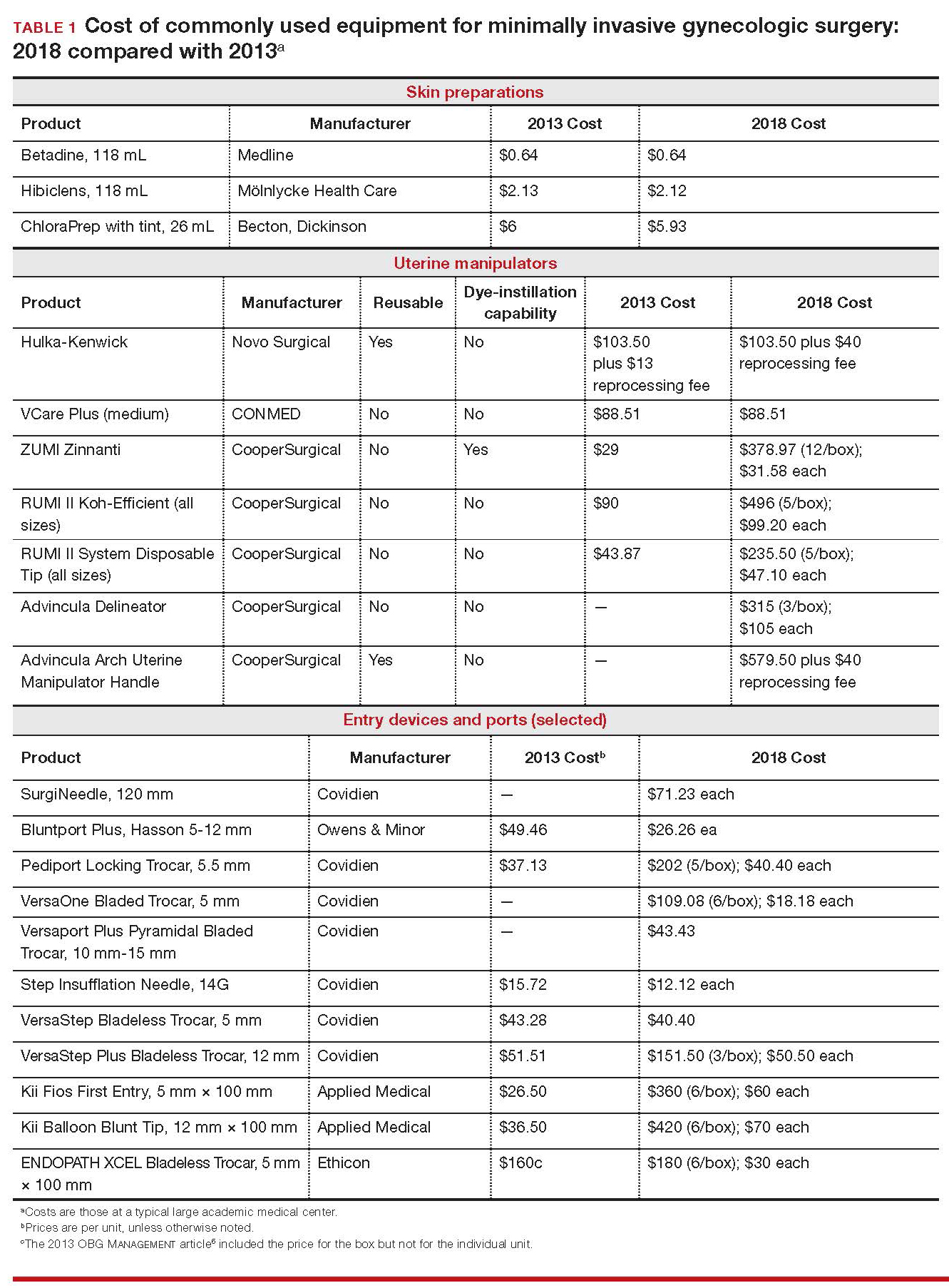

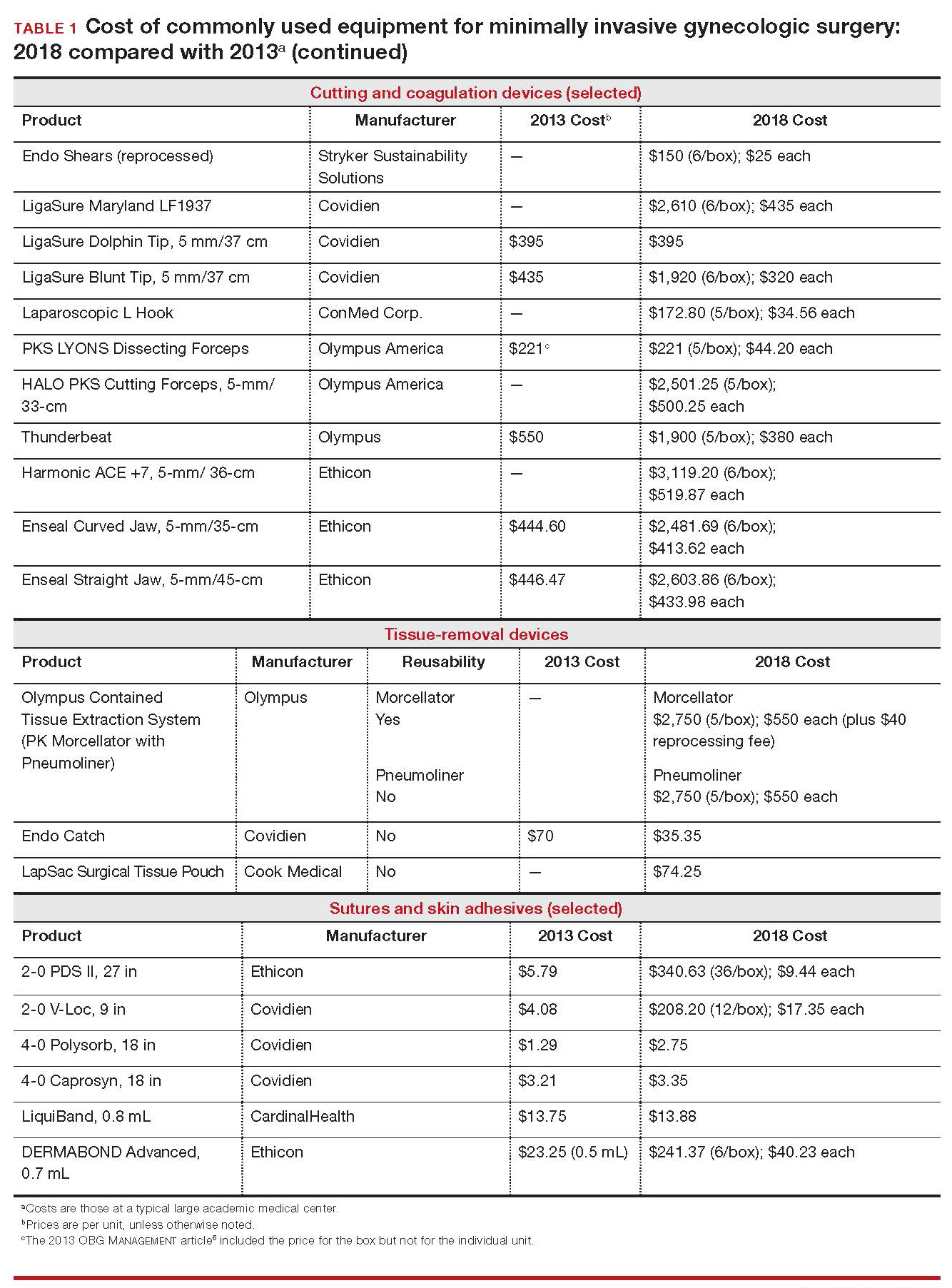

Importantly, 2013 and 2018 costs are included in TABLE 1. Unless otherwise noted, costs are per unit. Changes in manufacturers and material costs and technologic advances have contributed to some, but not all, of the changes in cost between 2013 and 2018.

Continue to: Variables to keep in mind

Variables to keep in mind

Even when taking cost into consideration, tailor your selection of instruments and supplies to your capabilities and comfort, as well as to the particular characteristics of the patient and the planned procedure. Also, remember that your institution might have arrangements with companies that supply minimally invasive instruments, and that such arrangements might limit your options, to some degree. Last, be aware that reprocessed ports and instruments are now available at a reduced cost. In short, we believe that it is crucial for surgeons to be cognizant of all products available to them prior to attending a surgical case.

Skin preparation and other preop considerations

Multiple preoperative skin preparations are available (TABLE 1). Traditionally, a povidone–iodine topical antiseptic, such as Betadine, has been used for skin and vaginal preparation prior to gynecologic surgery. Hibiclens and ChloraPrep are different combinations of chlorhexidine gluconate and isopropyl alcohol that act as broad-spectrum antiseptics.

ChloraPrep is applied with a wand-like applicator and contains a much higher concentration of isopropyl alcohol than Hibiclens (70% and 4%, respectively), rendering it more flammable. It also requires longer drying time before surgery can be started. Clear and tinted ChloraPrep formulations are available.

Continue to: Uterine manipulators

Uterine manipulators

Cannulation of the cervical canal allows for uterine manipulation, increasing intraoperative traction and exposure as well as visualization of the adnexae and peritoneal surfaces.

The Hulka-Kenwick is a reusable uterine manipulator that is fairly standard and easy to apply. Specialized, single-use manipulators also are available, including the Advincula Delineator and VCare Plus uterine manipulator/elevator. The VCare Plus manipulator consists of 2 opposing cups: one cup (available in 4 sizes, small to extra-large) fits around the cervix and defines the site for colpotomy; the other helps maintain pneumoperitoneum once a colpotomy is created.

The ZUMI (Zinnanti Uterine Manipulator Injector) is a rigid, curved shaft with an intrauterine balloon to help prevent expulsion. It also has an integrated injection channel to allow for intraoperative chromotubation.

The RUMI II System fits individual patient anatomy with various tip lengths and colpotomy cup sizes. The Advincula Arch Uterine Manipulator Handle is a reusable alternative to the articulating RUMI II and works with the RUMI II System Disposable Tip (TABLE 1).

Continue to: Entry style and ports

Entry style and ports

The peritoneal cavity can be entered using either a closed (Veress needle) or open (Hasson) technique.7,8 Closed entry might allow for quicker access to the peritoneal cavity. A 2015 Cochrane review of 46 randomized, controlled trials of 7,389 patients undergoing laparoscopy compared outcomes between laparoscopic entry techniques and found no difference in major vascular or visceral injury between closed and open techniques at the umbilicus.9 However, open entry was associated with a greater likelihood of successful entry into the peritoneal cavity.9

Left upper-quadrant (Palmer’s point) entry is another option when adhesions are anticipated or abnormal anatomy is encountered at the umbilicus.

In general, complications related to laparoscopic entry are rare in gynecologic surgery, ranging from 0.18% to 0.5% of cases in studies.8,10,11 A minimally invasive surgeon might prefer one entry technique over another but should be able to perform both methods competently and recognize when a particular technique is warranted.

--

Choosing a port

Laparoscopic ports usually range from 5 mm to 12 mm and can be fixed or variable in size.

The primary port, usually placed through the umbilicus, can be a standard, blunt, 10-mm (Bluntport Plus Hasson) port, or it can be specialized to ease entry of the port or stabilize the port once it is introduced through the skin incision.

Optical trocars have a transparent tip that allows the surgeon to visualize the abdominal wall entry layer by layer using a 0° laparoscope, sometimes after pneumoperitoneum is created with a Veress needle. Other specialized ports include those that have balloons or foam collars, or both, to secure the port without traditional stay sutures on the fascia and to minimize leakage of pneumoperitoneum.

Continue to: Accessory ports

Accessory ports

When choosing an accessory port type and size, it is important to anticipate which instruments and devices, such as an Endo Catch bag, suture, or needle, will need to pass through it. Also, know whether 5-mm and 10-mm laparoscopes are available, and anticipate whether a second port with insufflation capabilities will be required.

The Pediport Locking Trocar is a user-friendly, 5-mm bladed port that deploys a mushroom-shaped stabilizer to prevent dislodgement. The Versaport bladed trocar has a spring-loaded entry shield, which slides over the blade to protect it once the peritoneal cavity is entered.