User login

Geriatric Train‐The‐Trainer Program

Nearly half of the hospital beds in the United States are occupied by the elderly,1 whose numbers are increasing.2 The odds of a hospitalized Medicare patient being cared for by a hospitalist are increasing by nearly 30% per year.3 Hospitalists require competence in geriatrics to serve their patients and to teach trainees. Train‐the‐Trainer (TTT) programs both educate health care providers and provide educational materials, information, and skills for teaching others.4 This model has been successfully used in geriatrics to impact knowledge, attitudes, and self‐efficacy among health care workers.46

A prominent example of a geriatrics TTT program is the University of Chicago Curriculum for the Hospitalized Aging Medical Patient (CHAMP),7 which requires 48 hours of instruction over 12 sessions. To create a less time‐intensive learning format for busy hospitalists, the University of Chicago developed Mini‐CHAMP, a streamlined 2‐day workshop with web‐based components for hospitalist clinicians, but not necessarily hospitalist educators.7

We created The Donald W. Reynolds Program for Advancing Geriatrics Education (PAGE) at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), in light of the time intensity of CHAMP, to integrate geriatric TTT sessions within preexisting hospitalist faculty meetings. This model is consistent with current practices in faculty development.8 This paper describes the evaluation of the PAGE Model, which sought answers to 3 research questions: (1) Does PAGE increase faculty confidence in teaching geriatrics?, (2) Does PAGE increase the frequency of hospitalist teaching geriatrics topics?, and (3) Does PAGE increase residents' practice of geriatrics skills?

Methods

The PAGE Model

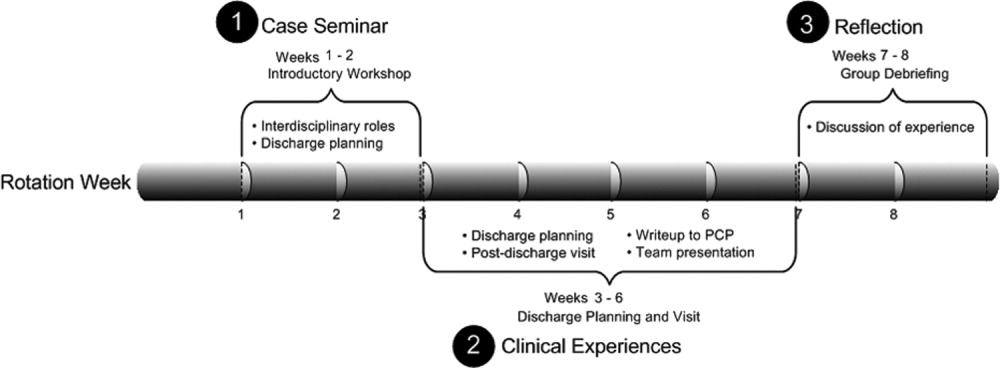

The PAGE Model comprises 10 hour‐long monthly seminars held at UCSF from January through December 2008 to teach specific geriatrics principles and clinical skills relevant to providing competent care to a hospitalized older adult. The aims of the PAGE are to:

Give hospitalist physicians knowledge and skills to teach geriatric topics to trainees in a time‐limited environment

Provide exportable teaching modules on geriatric topics for inpatient teaching

Increase teaching about geriatrics received by internal medicine residents

Increase resident use of 15 specific geriatric skills

Create a collaborative environment between the Geriatrics and Hospital Medicine Divisions at UCSF

The PAGE Development Group, which included 2 hospitalists, 2 geriatricians, and an analyst funded by the Donald W. Reynolds Foundation, reviewed American Geriatrics Society core competencies,9 national guidelines and mandates,10, 11 and existing published geriatric curricula.7, 1214 In late 2007, an email‐based needs assessment listing 38 possible topics, drawn from the resources above, was emailed to the 31 hospitalists at UCSF. Each hospitalist identified, in no particular order, 5 topics considered most useful to improve his/her geriatric teaching skills, with write‐in space for additional topic suggestions. The needs assessment also queried what format of teaching tools would be most useful and efficient, such as PowerPoint slides or pocket cards, and interest in session coteaching.

The topics most commonly selected by the respondents (n = 14, response rate 45%) included: home/community resources (64%), delirium/dementia (57%), minimizing medication problems (50%), using prognostic indices to make decisions (43%), and general approach to older inpatients (43%). The Development Group identified less popular topics (falls, pressure ulcers, indwelling catheters/emncontinence) that were gaining significant national attention.15 Finally, a topic suggested by many hospitalists, pain management, was added. Each topic session was mapped to 1 or more of the 15 geriatrics skills in the CHAMP model7 for residents to acquire. The requested and selected topics were then modified to create distinct sessions grouped around a theme, shown in Table 1. For example home and community resources was addressed in the session on Framework on Transitions in Care.

| Topics | Geriatric Skills Addressed for Hospitalized Older Patients |

|---|---|

| |

| 1. Approach to the vulnerable older patient; assessing function; goals of care | Conduct functional status assessmentMobilize early to prevent deconditioning |

| 2. Minimizing medication problems | Reduce polypharmacy and use of high risk/low benefit drugs |

| 3. Framework for transitions in care (including home and community resources) | Develop a safe and appropriate discharge plan, involving communication with other team members, family members and primary care physicians |

| 4. Using prognostics to guide treatment decisions | Give bad news |

| Document advance directives and DNR orders | |

| Discuss hospice care | |

| 5. Falls & immobility | Identify risk factors of hospital falls, including conventional and unconventional types of restraints |

| 6. Delirium | Assess risk and prevent delirium |

| 7. Dementia & depression | Conduct cognitive assessmentScreen for depression |

| Routinely assess pain at bedside in persons with dementia | |

| 8. Pain assessment in the elderly | Routinely assess pain at bedside in persons with dementia |

| Manage pain using the WHO 3‐step ladder and opiate conversion table and manage side effects of opiates | |

| 9. Foley catheters and incontinence | Determine appropriateness for urinary catheter use, discontinuing when inappropriate |

| 10. Pressure ulcers and wound care | Routinely perform a complete skin exam |

Most respondents (86%) wanted teaching materials in a format suitable for attending rounds; 64% preferred teaching cases, 29% PowerPoint presentations, and 29% quality improvement resources. The Development Group, with approval of the Chief of Hospital Medicine, planned 10, 1‐hour monthly sessions during weekly hospitalist meetings to optimize participation. Nine hospitalists agreed to lead sessions with geriatricians; 1 session was co‐led by a hospitalist and urologist.

The Development Group encouraged session leaders to create case‐based PowerPoint teaching modules that could be used during attending rounds, highlighting teaching triggers or teachable moments that modify or reinforce skills.1618 A Development Group hospitalist/geriatrician team cotaught the first session, which modeled the structure and style recommended. A teaching team typically met at least once to define goals and outline their teaching hour; most met repeatedly to refine their presentations. An example of a 1 PAGE session can be found online.19

Evaluation

Evaluation involved data from hospitalist faculty trainees, hospitalist and geriatrician session leaders, and internal medicine residents. The institutional review board approved this study. Self‐report rating scales were used for data collection, which were reviewed by experts in medical education at UCSF and piloted on nonparticipant faculty, or had been previously used by the CHAMP study.7

Hospitalist Trainees' Program Perceptions and Self‐Efficacy

Hospitalist trainees (n = 36) completed paper questionnaires after each session to assess perceived likelihood to use the teaching tools that were presented (1: not at all likely, 5: highly likely), whether they would recommend the program to colleagues (1: do not recommend, 5: highly recommend), and the utility of the PAGE program (Was this experience useful? and Prior to the sessions, did you think it would be useful? 1: definitely not, 5: definitely yes). Change in trainees' perceived self‐efficacy20 to teach geriatrics skills was assessed at the end of the PAGE program, using a posttest and retrospective pretest format with a 12‐items (1: low, 5: high) that was used in the CHAMP study.7 This format was used to avoid response shift bias, or the program‐produced change in a participant's understanding of the construct being measured.21

Faculty Session Leaders' Program Perceptions

After PAGE completion, all faculty session leaders (n = 15) completed an online questionnaire assessing teaching satisfaction (Likert‐type 5‐point scales), experience with coteaching, and years of faculty teaching experience.

Medical Residents

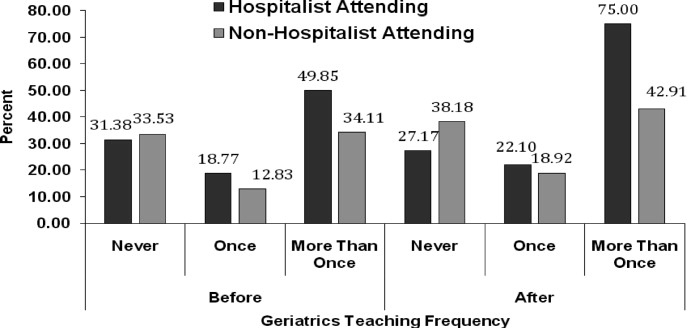

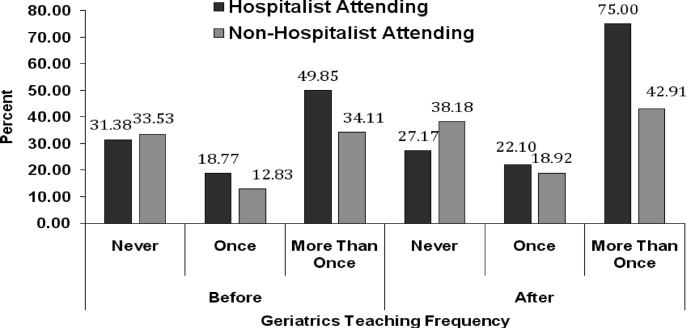

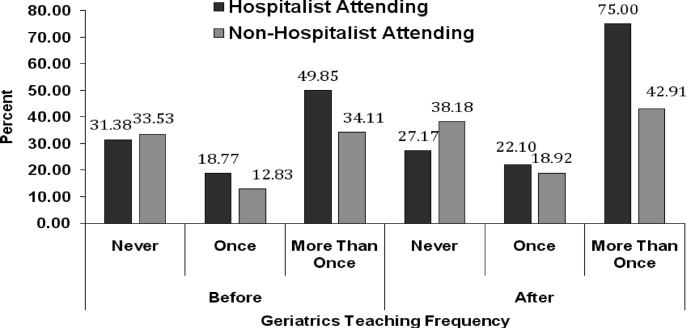

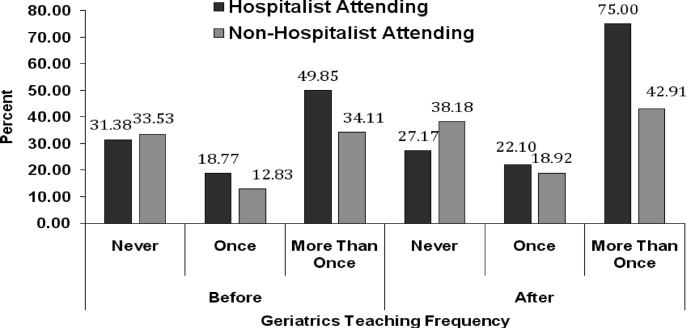

To assess change in hospitalists' teaching about geriatrics and residents' practice of geriatric clinical skills, residents (n = 56; post‐graduate year (PGY)1 = 29, PGY2 = 27) who would not complete residency before the end of PAGE received an online questionnaire, modified from the CHAMP study,7 prior to and after the completion of PAGE. Respondents received monetary gift cards as incentives. Residents gave separate ratings for their inpatient teaching attendings who were hospitalists (80% of inpatient ward attendings) and nonhospitalists (20%, mostly generalists) regarding frequency over the past year of being taught each of 15 geriatric clinical skills. A 3‐point scale was used: (1) never, (2) once, and (3) more than once. Residents also reported the frequency of practicing those skills themselves, using a questionnaire from the CHAMP study,7 with a scale of (1) never to (5) always.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were computed for all measures. Scale means were constructed from all individual items for the retrospective pretest and posttest measures. Wilcoxon matched‐pairs signed ranks‐tests were used to compare teaching differences between hospitalist and other attendings. For the unmatched pre‐post data on frequency of teaching, Wilcoxon‐Mann‐Whitney tests were used to determine significant differences in instruction, conducting separate tests for hospitalists and nonhospitalist attendings. Effect size22 was calculated using Cohen's d23 to determine the magnitude of increase in self‐efficacy to teach geriatrics; an effect size exceeding 0.8 is considered large. Statistics were performed using PASW Statistics 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

The hospitalist group grew from 31 to 36 members in June of 2008. On average, 14 hospitalists (M = 14.40, standard deviation [SD] = 2.41, range 1119) attended each session, with all hospitalists (n = 36) attending 1 session (M = 3.83, SD = 2.35, range 19). At each session, an average of 72% completed a post‐session evaluation form. Overall, faculty were likely to use the PAGE teaching tools (M = 4.61, SD = 0.53) and would recommend PAGE to other hospitalists (M = 4.63, SD = 0.51).

Thirteen hospitalist trainees of 36 (36%) completed a post‐PAGE online questionnaire. Respondents taught on faculty for an average of 5 years (mean (M) = 5.08, SD = 3.52). Faculty perceived self‐efficacy at teaching residents about geriatrics improved significantly with a large effect size (pretest M = 3.05, SD = .60; posttest M = 3.96, SD = .36, d = 1.52; P < 0.001). Session attendance was positively correlated with the increase in geriatrics teaching self‐efficacy (r = .62, P < 0.05), while teaching experience was not (r = 0.05, P = 0.88). Hospitalist trainees found the PAGE model more useful after participating (M = 4.62, SD = 0.65), than they had expected (M = 3.92, SD = 0.76; P < 0.05).

All session leaders (n = 15) completed the questionnaire after PAGE (9 hospitalists, 5 geriatricians, 1 urologist). Two‐thirds had 5 years on faculty; eight had no prior experience as a faculty development trainer. Over 80% indicated that they found their coteaching experience, enjoyable, useful and collaborative. Only 1 participant did not commit to interdisciplinary teaching again. Most hospitalist session leaders reported that coteaching with a geriatrician enhanced their knowledge; they were more likely to consult a geriatrician regarding patients. All but 2 session leaders felt that the model fostered a collaborative environment between their 2 divisions.

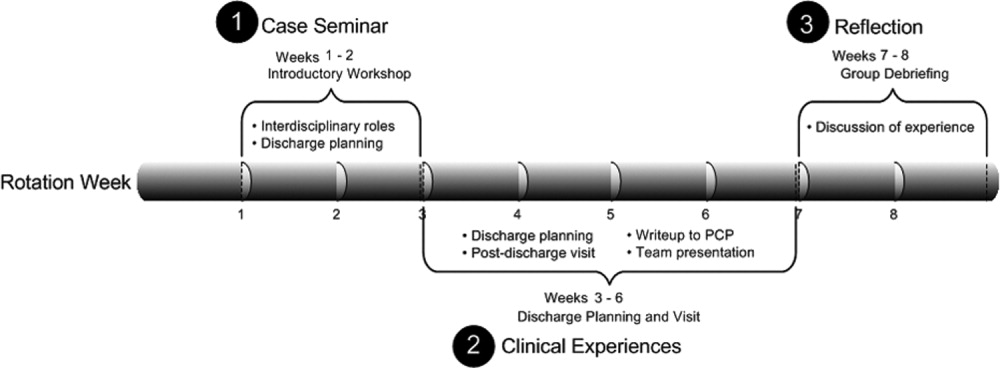

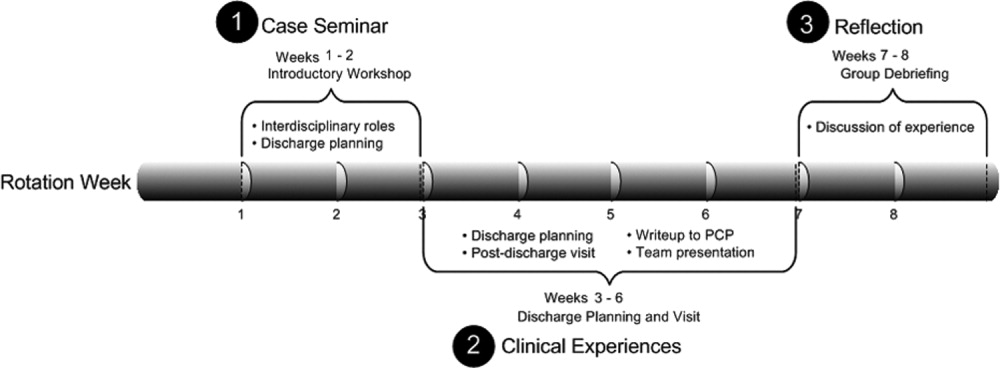

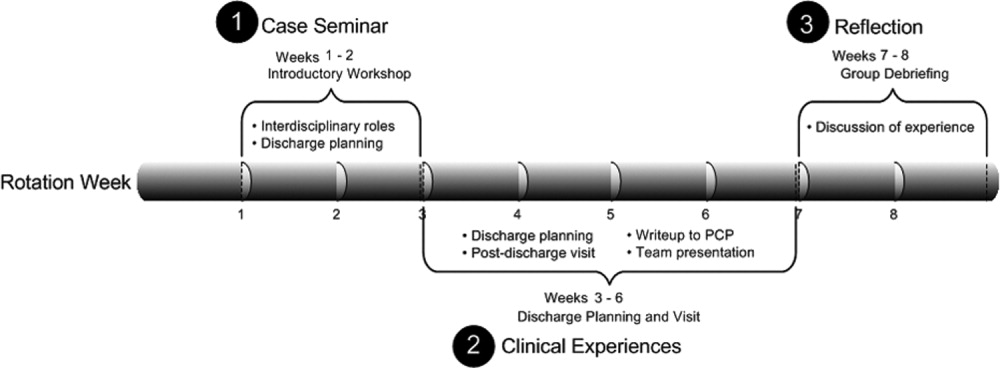

Of the 56 residents, 41% (16 PGY1, 7 PGY2) completed a pretest; 43% (15 PGY1, 9 PGY2) completed a posttest. Residents reported receiving inpatient teaching on geriatrics skills significantly more frequently from hospitalists vs. nonhospitalist attendings both before PAGE (hospitalists M = 2.18, SD = 0.37; nonhospitalists M = 2.00, SD = 0.53, P < 0.05), and after (hospitalists M = 2.39, SD = 0.46; nonhospitalists M = 2.05, SD = 0.57, P < 0.05; see Fig. 1). Although hospitalists taught more frequently about geriatrics than nonhospitalists before PAGE, our findings suggest that they increased their teaching by a greater magnitude than nonhospitalists (P < 0.01, P > 0.05, respectively). Residents reported increased geriatric skill practice after PAGE with a medium effect size (pretest M = 2.92, SD = 0.55, posttest M = 3.28, SD = 0.66, P = 0.052, d = 0.66). There was greater mean reported practice for all skills with the exception of hospice care, which already was being performed between often and very often before PAGE. The largest increases in skill practice were (descending order, most increased first): assessing polypharmacy, performing skin exams, prognostication, performing functional assessments and examining Foley catheter use.

Discussion

Our aging population and a shortage of geriatricians necessitates new, feasible models for geriatric training. Similar to the CHAMP model,7 PAGE had a favorable impact on faculty perceived behavioral change; after the PAGE sessions, faculty reported significantly greater self‐efficacy of teaching geriatrics. However, this study also examined the impact of the PAGE Model on 2 groups not previously reported in the literature: faculty session leaders and medicine residents.

To our knowledge, this is the first study about a hospitalist TTT program codeveloped with nonhospitalists aimed at teaching geriatrics skills to residents, though smaller scale programs for medical students exist.24 We believe codevelopment was important in our model for many reasons. First, using hospitalist peers and local geriatricians likely increased trust in the educational curricula and allowed for strong communication channels between instructors.25, 26 Second, coteaching allowed for hospitalist mentorship. Hospitalists acknowledged their coleaders as mentors and several hospitalists subsequently engaged in new geriatric projects. Third, coteaching was felt to enhance patient care and increase geriatrician consultations. Coteaching may have applicability to other hospitalist faculty development such as intensive care and palliative care, and hospitalist programs may benefit from creating faculty development programs internally with their colleagues, rather than using online resources.

Another important finding of this study is that training hospitalists to teach about geriatrics seems to result in an increase in both the geriatric teaching that residents receive and residents' practice of geriatric skills. This outcome has not been previously demonstrated with geriatric TTT activities.27 This trickle‐down effect to residents likely results from both the increased teaching efficacy of hospitalists after the PAGE Model and the exportable nature of the teaching tools.

Several continuing medical education best practices were used which we believe contributed to the success of PAGE. First, we conducted a needs assessment, which improves knowledge outcomes.28, 29 Second, sessions included cases, lectures, and discussions. Use of multiple educational techniques yields greater knowledge and behavioral change as compared to a single method, such as lecture alone.24, 25, 30, 31 Finally, sessions were sequenced over a year, rather than clustered in short, intensive activity. Sequenced, or learn‐work‐learn opportunities allow education to be translated to practice and reinforced.8, 27, 30, 32

We believe that the PAGE Model is transportable to other hospitalist programs due to its cost and flexible nature. In economically‐lean times, hospitalist divisions can create a program similar to the PAGE Model essentially at no cost, except for donated faculty preparation time. In contrast, CHAMP was expensive, costing nearly $72,000 for 12 faculty to participate in the 48‐hour curriculum,7, 33 and volunteering physicians were compensated for their time. Though Mini‐CHAMP is a streamlined 2‐day workshop that offers free online lectures and slide sets, there may be some benefit to producing a faculty development program internally, as we stated above, and PAGE included additional topics (urinary catheters and decubitus ulcers/wound care) not covered in mini‐CHAMP.

There were several limitations to this study. First, some outcomes of the PAGE Model were assessed by retrospective self‐report, which may allow for recall bias. Although self‐report may or may not correlate with actual behavior,34 faculty and resident perspectives of their teaching and learning experiences are themselves important. Furthermore, a retrospective presurvey allows for content of an educational program or intervention to be explained prior to a survey, so that participants first assess their new level of understanding or skill on the post test, then reflectively assess the level of understanding or skill they had prior to the workshop. This avoids response shift bias and can improve internal validity.21, 35

Second, the small numbers of session leaders, hospitalist trainees, and residents restricted statistical power to detect small effects. The fact that we found significant improvements enhances the likelihood that the differences observed were not due to chance.

Third, the low response rates from the hospitalist trainee post‐intervention questionnaire and the residents' questionnaires may affect the validity of our results. For the resident survey, the subjects were not matched, and we cannot state that an individual's geriatric skill practice changed due to PAGE, though the results suggest the residency program as a whole improved the frequency of geriatric skill practice.

Finally, the residents were required to report the frequency of teaching on and practice of geriatric skills practice over the prior year and accuracy of recall may be an issue. However, frequencies were queried both pre and post intervention and favorable change was noted. Furthermore, because the high end of the 3‐point teaching scale was limited to more than once, the true amount of teaching may have been underestimated if more than once actually represented high frequencies.

Future studies are needed to replicate these findings at other institutions to confirm generalizability. It would be beneficial to measure patient outcomes to determine whether increased teaching and skill practice benefits patients using measures such as reduction in catheter related urinary tract infections, falls, and inadequate pain management. Further investigations of cotaught faculty development programs between hospitalists and other specialists help emphasize why internally created TTT programs are of greater value than online resources.

Conclusions

This time‐sensitive adaptation of a hospitalist geriatric TTT program was successfully implemented at an academic medical center and suggests improved hospitalist faculty self‐efficacy at teaching geriatric skills, increased frequency of inpatient geriatric teaching by hospitalists and increased resident geriatric skill practice. Confidence to care for geriatric patients and a strong skill set to assess risks and manage them appropriately will equip hospitalists and trainees to provide care that reduces geriatric patients' in‐hospital morbidity and costs of care. As hospitalists increasingly care for older adults, the need for time‐efficient methods of teaching geriatrics will continue to grow. The PAGE Model, and other new models of geriatric training for hospitalists, demonstrates that we are beginning to address this urgent need.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Joan Abrams, MA, MPA, and Patricia O'Sullivan, EdD, whose work was key to the success of this program and this manuscript. They also thank the Donald W. Reynolds Foundation for support of this project.

- ,.2005 National Hospital Discharge Survey.Adv Data.2007;385:1–19.

- ,,,. In:U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Reports, 65+ in the United States: 2005,Washington, D.C.:U.S. Government Printing Office;2005:23–209.

- ,,,.Growth in the care of older patients by hospitalists in the United States.N Engl J Med.2009;360(11):1102–1112.

- ,,,.Providing dementia outreach education to rural communities: lessons learned from a train‐the‐trainer program.J Appl Gerontol.2002;21:294–313.

- .Gerontologizing health care: a train‐the‐trainer program for nurses.Gerontol Geriatr Educ.1999;19:47–56.

- ,,.A statewide model detection and prevention program for geriatric alcoholism and alcohol abuse: increased knowledge among service providers.Community Ment Health J.2000;36:137–148.

- ,,, et al.The curriculum for the hospitalized aging medical patient program: a collaborative faculty development program for hospitalists, general internists, and geriatricians.J Hosp Med.2008;3(5):384–393.

- Reframing professional development through understanding authentic professional learning.Rev Educ Res.2009;79:702–739.

- The Education Committee Writing Group of the American Geriatrics Society.Core competencies for the care of older patients: recommendations of the American Geriatrics Society.Acad Med.2000;75:252–255.

- ,,, et al.American Geriatrics Society Task Force on the future of geriatric medicine.J Am Geriatr Soc.2005;53 (6 Suppl):S245–S256.

- Nadzam, Deborah. Preventing patient falls. Joint Commission Resources. Available at: http://www.jcrinc.com/Preventing‐Patient‐Falls. Accessed April2010.

- ,.Curricular recommendations for resident training in nursing home care. A collaborative effort of the Society of General Internal Medicine Task Force on Geriatric Medicine, the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Geriatrics Task Force, the American Medical Directors Association, and the American Geriatrics Society Education Committee.J Am Geriatr Soc.1994;42:1200–1201.

- ,,,,.Curriculum recommendations for resident training in geriatrics interdisciplinary team care.J Am Geriatr Soc.1999;47:1145–1148.

- ,.ACGME requirements for geriatrics medicine curricula in medical specialties: Progress made and progress needed.Acad Med.2005;80:279–285.

- CMS Office of Public Affairs. CMS Improves Patient Safety for Medicare and Medicaid by Addressing Never Events, August 04, 2008. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/apps/media/press/factsheet.asp?Counter=322434(5):337–343.

- ,.The changing paradigm for continuing medical education: impact of information on the teachable moment.Bull Med Libr Assoc.1990;78(2):173–179.

- ,.Creating the teachable moment.J Nurs Educ.1998;37(6):278–280.

- Society of Hospital Medicine, BOOSTing Care Transitions Resource Room. Mazotti L, Johnston CB. Faculty development: Teaching triggers for transitional care. “A train‐the‐trainer model.” Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/ResourceRoomRedesign/RR_CareTransitions/PDFs/Mazotti_UCSF_Transitions.PPT. Accessed April2010.

- .Self‐efficacy: The Exercise of Control.New York:W.H. Freeman and Company;1997.

- .Internal invalidity in pretest‐posttest self‐report evaluations and a re‐evaluation of retrospective pretests.Applied Psychological Measurement.1979;3:1–23.

- ,.A visitor's guide to effect sizes.Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract.2004;9:241–249.

- .Statistical Power Analyses for the Behavioral Sciences.2nd ed.Hillsdale, NJ:Lawrence Erlbaum Associates;1988.

- ,,,.Hazards of hospitalization: Hospitalists and geriatricians educating medical students about delirium and falls in geriatric patients.Gerontol Geriatr Educ.2008;28(4):94–104.

- ,,, et al.Continuing medical education, continuing professional development, and knowledge translation: Improving care of older patients by practicing physicians.J Am Geriatr Soc.2006:54(10):1610–1618.

- ,,, et al.Practicing physician education in geriatrics: Lessons learned from a train‐the‐trainer model.J Am Geriatr Soc.2007:55(8):1281–1286.

- ,.CHAMP trains champions: hospitalist‐educators develop new ways to teach care for older patients.J Hosp Med.2008;3(5):357–360.

- ,,,,,.Impact of formal continuing medical education: Do conferences, workshops, rounds, and other traditional continuing education activities change physician behavior or health care outcomes?JAMA.1999;282(9):867–874.

- ,.Association for the Study of Medical Education Booklet: The effectiveness of continuing professional development.Edinburgh, Scotland:Association for the Study of Medical Education;2000.

- ,,, et al.Effectiveness of continuing medical education.Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep).2007;149:1–69.

- ,,, et al.Continuing education meetings and workshops: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes.Cochrane Database Syst Rev.2009;(2):CD003030.

- ,.Continuing medical education and the physician as learner: guide to the evidence.JAMA.2002;288(9):1057–1060.

- .Care of hospitalized older patients: opportunities for hospital‐based physicians.J Hosp Med.2006;1:42–47.

- ,.What we say and what we do: self‐reported teaching behavior versus performances in written simulations among medical school faculty.Acad Med.1992;67(8):522–527.

- ,.The retrospective pretest and the role of pretest information in evaluation studies.Psychol Rep.1992;70:699–704.

Nearly half of the hospital beds in the United States are occupied by the elderly,1 whose numbers are increasing.2 The odds of a hospitalized Medicare patient being cared for by a hospitalist are increasing by nearly 30% per year.3 Hospitalists require competence in geriatrics to serve their patients and to teach trainees. Train‐the‐Trainer (TTT) programs both educate health care providers and provide educational materials, information, and skills for teaching others.4 This model has been successfully used in geriatrics to impact knowledge, attitudes, and self‐efficacy among health care workers.46

A prominent example of a geriatrics TTT program is the University of Chicago Curriculum for the Hospitalized Aging Medical Patient (CHAMP),7 which requires 48 hours of instruction over 12 sessions. To create a less time‐intensive learning format for busy hospitalists, the University of Chicago developed Mini‐CHAMP, a streamlined 2‐day workshop with web‐based components for hospitalist clinicians, but not necessarily hospitalist educators.7

We created The Donald W. Reynolds Program for Advancing Geriatrics Education (PAGE) at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), in light of the time intensity of CHAMP, to integrate geriatric TTT sessions within preexisting hospitalist faculty meetings. This model is consistent with current practices in faculty development.8 This paper describes the evaluation of the PAGE Model, which sought answers to 3 research questions: (1) Does PAGE increase faculty confidence in teaching geriatrics?, (2) Does PAGE increase the frequency of hospitalist teaching geriatrics topics?, and (3) Does PAGE increase residents' practice of geriatrics skills?

Methods

The PAGE Model

The PAGE Model comprises 10 hour‐long monthly seminars held at UCSF from January through December 2008 to teach specific geriatrics principles and clinical skills relevant to providing competent care to a hospitalized older adult. The aims of the PAGE are to:

Give hospitalist physicians knowledge and skills to teach geriatric topics to trainees in a time‐limited environment

Provide exportable teaching modules on geriatric topics for inpatient teaching

Increase teaching about geriatrics received by internal medicine residents

Increase resident use of 15 specific geriatric skills

Create a collaborative environment between the Geriatrics and Hospital Medicine Divisions at UCSF

The PAGE Development Group, which included 2 hospitalists, 2 geriatricians, and an analyst funded by the Donald W. Reynolds Foundation, reviewed American Geriatrics Society core competencies,9 national guidelines and mandates,10, 11 and existing published geriatric curricula.7, 1214 In late 2007, an email‐based needs assessment listing 38 possible topics, drawn from the resources above, was emailed to the 31 hospitalists at UCSF. Each hospitalist identified, in no particular order, 5 topics considered most useful to improve his/her geriatric teaching skills, with write‐in space for additional topic suggestions. The needs assessment also queried what format of teaching tools would be most useful and efficient, such as PowerPoint slides or pocket cards, and interest in session coteaching.

The topics most commonly selected by the respondents (n = 14, response rate 45%) included: home/community resources (64%), delirium/dementia (57%), minimizing medication problems (50%), using prognostic indices to make decisions (43%), and general approach to older inpatients (43%). The Development Group identified less popular topics (falls, pressure ulcers, indwelling catheters/emncontinence) that were gaining significant national attention.15 Finally, a topic suggested by many hospitalists, pain management, was added. Each topic session was mapped to 1 or more of the 15 geriatrics skills in the CHAMP model7 for residents to acquire. The requested and selected topics were then modified to create distinct sessions grouped around a theme, shown in Table 1. For example home and community resources was addressed in the session on Framework on Transitions in Care.

| Topics | Geriatric Skills Addressed for Hospitalized Older Patients |

|---|---|

| |

| 1. Approach to the vulnerable older patient; assessing function; goals of care | Conduct functional status assessmentMobilize early to prevent deconditioning |

| 2. Minimizing medication problems | Reduce polypharmacy and use of high risk/low benefit drugs |

| 3. Framework for transitions in care (including home and community resources) | Develop a safe and appropriate discharge plan, involving communication with other team members, family members and primary care physicians |

| 4. Using prognostics to guide treatment decisions | Give bad news |

| Document advance directives and DNR orders | |

| Discuss hospice care | |

| 5. Falls & immobility | Identify risk factors of hospital falls, including conventional and unconventional types of restraints |

| 6. Delirium | Assess risk and prevent delirium |

| 7. Dementia & depression | Conduct cognitive assessmentScreen for depression |

| Routinely assess pain at bedside in persons with dementia | |

| 8. Pain assessment in the elderly | Routinely assess pain at bedside in persons with dementia |

| Manage pain using the WHO 3‐step ladder and opiate conversion table and manage side effects of opiates | |

| 9. Foley catheters and incontinence | Determine appropriateness for urinary catheter use, discontinuing when inappropriate |

| 10. Pressure ulcers and wound care | Routinely perform a complete skin exam |

Most respondents (86%) wanted teaching materials in a format suitable for attending rounds; 64% preferred teaching cases, 29% PowerPoint presentations, and 29% quality improvement resources. The Development Group, with approval of the Chief of Hospital Medicine, planned 10, 1‐hour monthly sessions during weekly hospitalist meetings to optimize participation. Nine hospitalists agreed to lead sessions with geriatricians; 1 session was co‐led by a hospitalist and urologist.

The Development Group encouraged session leaders to create case‐based PowerPoint teaching modules that could be used during attending rounds, highlighting teaching triggers or teachable moments that modify or reinforce skills.1618 A Development Group hospitalist/geriatrician team cotaught the first session, which modeled the structure and style recommended. A teaching team typically met at least once to define goals and outline their teaching hour; most met repeatedly to refine their presentations. An example of a 1 PAGE session can be found online.19

Evaluation

Evaluation involved data from hospitalist faculty trainees, hospitalist and geriatrician session leaders, and internal medicine residents. The institutional review board approved this study. Self‐report rating scales were used for data collection, which were reviewed by experts in medical education at UCSF and piloted on nonparticipant faculty, or had been previously used by the CHAMP study.7

Hospitalist Trainees' Program Perceptions and Self‐Efficacy

Hospitalist trainees (n = 36) completed paper questionnaires after each session to assess perceived likelihood to use the teaching tools that were presented (1: not at all likely, 5: highly likely), whether they would recommend the program to colleagues (1: do not recommend, 5: highly recommend), and the utility of the PAGE program (Was this experience useful? and Prior to the sessions, did you think it would be useful? 1: definitely not, 5: definitely yes). Change in trainees' perceived self‐efficacy20 to teach geriatrics skills was assessed at the end of the PAGE program, using a posttest and retrospective pretest format with a 12‐items (1: low, 5: high) that was used in the CHAMP study.7 This format was used to avoid response shift bias, or the program‐produced change in a participant's understanding of the construct being measured.21

Faculty Session Leaders' Program Perceptions

After PAGE completion, all faculty session leaders (n = 15) completed an online questionnaire assessing teaching satisfaction (Likert‐type 5‐point scales), experience with coteaching, and years of faculty teaching experience.

Medical Residents

To assess change in hospitalists' teaching about geriatrics and residents' practice of geriatric clinical skills, residents (n = 56; post‐graduate year (PGY)1 = 29, PGY2 = 27) who would not complete residency before the end of PAGE received an online questionnaire, modified from the CHAMP study,7 prior to and after the completion of PAGE. Respondents received monetary gift cards as incentives. Residents gave separate ratings for their inpatient teaching attendings who were hospitalists (80% of inpatient ward attendings) and nonhospitalists (20%, mostly generalists) regarding frequency over the past year of being taught each of 15 geriatric clinical skills. A 3‐point scale was used: (1) never, (2) once, and (3) more than once. Residents also reported the frequency of practicing those skills themselves, using a questionnaire from the CHAMP study,7 with a scale of (1) never to (5) always.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were computed for all measures. Scale means were constructed from all individual items for the retrospective pretest and posttest measures. Wilcoxon matched‐pairs signed ranks‐tests were used to compare teaching differences between hospitalist and other attendings. For the unmatched pre‐post data on frequency of teaching, Wilcoxon‐Mann‐Whitney tests were used to determine significant differences in instruction, conducting separate tests for hospitalists and nonhospitalist attendings. Effect size22 was calculated using Cohen's d23 to determine the magnitude of increase in self‐efficacy to teach geriatrics; an effect size exceeding 0.8 is considered large. Statistics were performed using PASW Statistics 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

The hospitalist group grew from 31 to 36 members in June of 2008. On average, 14 hospitalists (M = 14.40, standard deviation [SD] = 2.41, range 1119) attended each session, with all hospitalists (n = 36) attending 1 session (M = 3.83, SD = 2.35, range 19). At each session, an average of 72% completed a post‐session evaluation form. Overall, faculty were likely to use the PAGE teaching tools (M = 4.61, SD = 0.53) and would recommend PAGE to other hospitalists (M = 4.63, SD = 0.51).

Thirteen hospitalist trainees of 36 (36%) completed a post‐PAGE online questionnaire. Respondents taught on faculty for an average of 5 years (mean (M) = 5.08, SD = 3.52). Faculty perceived self‐efficacy at teaching residents about geriatrics improved significantly with a large effect size (pretest M = 3.05, SD = .60; posttest M = 3.96, SD = .36, d = 1.52; P < 0.001). Session attendance was positively correlated with the increase in geriatrics teaching self‐efficacy (r = .62, P < 0.05), while teaching experience was not (r = 0.05, P = 0.88). Hospitalist trainees found the PAGE model more useful after participating (M = 4.62, SD = 0.65), than they had expected (M = 3.92, SD = 0.76; P < 0.05).

All session leaders (n = 15) completed the questionnaire after PAGE (9 hospitalists, 5 geriatricians, 1 urologist). Two‐thirds had 5 years on faculty; eight had no prior experience as a faculty development trainer. Over 80% indicated that they found their coteaching experience, enjoyable, useful and collaborative. Only 1 participant did not commit to interdisciplinary teaching again. Most hospitalist session leaders reported that coteaching with a geriatrician enhanced their knowledge; they were more likely to consult a geriatrician regarding patients. All but 2 session leaders felt that the model fostered a collaborative environment between their 2 divisions.

Of the 56 residents, 41% (16 PGY1, 7 PGY2) completed a pretest; 43% (15 PGY1, 9 PGY2) completed a posttest. Residents reported receiving inpatient teaching on geriatrics skills significantly more frequently from hospitalists vs. nonhospitalist attendings both before PAGE (hospitalists M = 2.18, SD = 0.37; nonhospitalists M = 2.00, SD = 0.53, P < 0.05), and after (hospitalists M = 2.39, SD = 0.46; nonhospitalists M = 2.05, SD = 0.57, P < 0.05; see Fig. 1). Although hospitalists taught more frequently about geriatrics than nonhospitalists before PAGE, our findings suggest that they increased their teaching by a greater magnitude than nonhospitalists (P < 0.01, P > 0.05, respectively). Residents reported increased geriatric skill practice after PAGE with a medium effect size (pretest M = 2.92, SD = 0.55, posttest M = 3.28, SD = 0.66, P = 0.052, d = 0.66). There was greater mean reported practice for all skills with the exception of hospice care, which already was being performed between often and very often before PAGE. The largest increases in skill practice were (descending order, most increased first): assessing polypharmacy, performing skin exams, prognostication, performing functional assessments and examining Foley catheter use.

Discussion

Our aging population and a shortage of geriatricians necessitates new, feasible models for geriatric training. Similar to the CHAMP model,7 PAGE had a favorable impact on faculty perceived behavioral change; after the PAGE sessions, faculty reported significantly greater self‐efficacy of teaching geriatrics. However, this study also examined the impact of the PAGE Model on 2 groups not previously reported in the literature: faculty session leaders and medicine residents.

To our knowledge, this is the first study about a hospitalist TTT program codeveloped with nonhospitalists aimed at teaching geriatrics skills to residents, though smaller scale programs for medical students exist.24 We believe codevelopment was important in our model for many reasons. First, using hospitalist peers and local geriatricians likely increased trust in the educational curricula and allowed for strong communication channels between instructors.25, 26 Second, coteaching allowed for hospitalist mentorship. Hospitalists acknowledged their coleaders as mentors and several hospitalists subsequently engaged in new geriatric projects. Third, coteaching was felt to enhance patient care and increase geriatrician consultations. Coteaching may have applicability to other hospitalist faculty development such as intensive care and palliative care, and hospitalist programs may benefit from creating faculty development programs internally with their colleagues, rather than using online resources.

Another important finding of this study is that training hospitalists to teach about geriatrics seems to result in an increase in both the geriatric teaching that residents receive and residents' practice of geriatric skills. This outcome has not been previously demonstrated with geriatric TTT activities.27 This trickle‐down effect to residents likely results from both the increased teaching efficacy of hospitalists after the PAGE Model and the exportable nature of the teaching tools.

Several continuing medical education best practices were used which we believe contributed to the success of PAGE. First, we conducted a needs assessment, which improves knowledge outcomes.28, 29 Second, sessions included cases, lectures, and discussions. Use of multiple educational techniques yields greater knowledge and behavioral change as compared to a single method, such as lecture alone.24, 25, 30, 31 Finally, sessions were sequenced over a year, rather than clustered in short, intensive activity. Sequenced, or learn‐work‐learn opportunities allow education to be translated to practice and reinforced.8, 27, 30, 32

We believe that the PAGE Model is transportable to other hospitalist programs due to its cost and flexible nature. In economically‐lean times, hospitalist divisions can create a program similar to the PAGE Model essentially at no cost, except for donated faculty preparation time. In contrast, CHAMP was expensive, costing nearly $72,000 for 12 faculty to participate in the 48‐hour curriculum,7, 33 and volunteering physicians were compensated for their time. Though Mini‐CHAMP is a streamlined 2‐day workshop that offers free online lectures and slide sets, there may be some benefit to producing a faculty development program internally, as we stated above, and PAGE included additional topics (urinary catheters and decubitus ulcers/wound care) not covered in mini‐CHAMP.

There were several limitations to this study. First, some outcomes of the PAGE Model were assessed by retrospective self‐report, which may allow for recall bias. Although self‐report may or may not correlate with actual behavior,34 faculty and resident perspectives of their teaching and learning experiences are themselves important. Furthermore, a retrospective presurvey allows for content of an educational program or intervention to be explained prior to a survey, so that participants first assess their new level of understanding or skill on the post test, then reflectively assess the level of understanding or skill they had prior to the workshop. This avoids response shift bias and can improve internal validity.21, 35

Second, the small numbers of session leaders, hospitalist trainees, and residents restricted statistical power to detect small effects. The fact that we found significant improvements enhances the likelihood that the differences observed were not due to chance.

Third, the low response rates from the hospitalist trainee post‐intervention questionnaire and the residents' questionnaires may affect the validity of our results. For the resident survey, the subjects were not matched, and we cannot state that an individual's geriatric skill practice changed due to PAGE, though the results suggest the residency program as a whole improved the frequency of geriatric skill practice.

Finally, the residents were required to report the frequency of teaching on and practice of geriatric skills practice over the prior year and accuracy of recall may be an issue. However, frequencies were queried both pre and post intervention and favorable change was noted. Furthermore, because the high end of the 3‐point teaching scale was limited to more than once, the true amount of teaching may have been underestimated if more than once actually represented high frequencies.

Future studies are needed to replicate these findings at other institutions to confirm generalizability. It would be beneficial to measure patient outcomes to determine whether increased teaching and skill practice benefits patients using measures such as reduction in catheter related urinary tract infections, falls, and inadequate pain management. Further investigations of cotaught faculty development programs between hospitalists and other specialists help emphasize why internally created TTT programs are of greater value than online resources.

Conclusions

This time‐sensitive adaptation of a hospitalist geriatric TTT program was successfully implemented at an academic medical center and suggests improved hospitalist faculty self‐efficacy at teaching geriatric skills, increased frequency of inpatient geriatric teaching by hospitalists and increased resident geriatric skill practice. Confidence to care for geriatric patients and a strong skill set to assess risks and manage them appropriately will equip hospitalists and trainees to provide care that reduces geriatric patients' in‐hospital morbidity and costs of care. As hospitalists increasingly care for older adults, the need for time‐efficient methods of teaching geriatrics will continue to grow. The PAGE Model, and other new models of geriatric training for hospitalists, demonstrates that we are beginning to address this urgent need.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Joan Abrams, MA, MPA, and Patricia O'Sullivan, EdD, whose work was key to the success of this program and this manuscript. They also thank the Donald W. Reynolds Foundation for support of this project.

Nearly half of the hospital beds in the United States are occupied by the elderly,1 whose numbers are increasing.2 The odds of a hospitalized Medicare patient being cared for by a hospitalist are increasing by nearly 30% per year.3 Hospitalists require competence in geriatrics to serve their patients and to teach trainees. Train‐the‐Trainer (TTT) programs both educate health care providers and provide educational materials, information, and skills for teaching others.4 This model has been successfully used in geriatrics to impact knowledge, attitudes, and self‐efficacy among health care workers.46

A prominent example of a geriatrics TTT program is the University of Chicago Curriculum for the Hospitalized Aging Medical Patient (CHAMP),7 which requires 48 hours of instruction over 12 sessions. To create a less time‐intensive learning format for busy hospitalists, the University of Chicago developed Mini‐CHAMP, a streamlined 2‐day workshop with web‐based components for hospitalist clinicians, but not necessarily hospitalist educators.7

We created The Donald W. Reynolds Program for Advancing Geriatrics Education (PAGE) at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), in light of the time intensity of CHAMP, to integrate geriatric TTT sessions within preexisting hospitalist faculty meetings. This model is consistent with current practices in faculty development.8 This paper describes the evaluation of the PAGE Model, which sought answers to 3 research questions: (1) Does PAGE increase faculty confidence in teaching geriatrics?, (2) Does PAGE increase the frequency of hospitalist teaching geriatrics topics?, and (3) Does PAGE increase residents' practice of geriatrics skills?

Methods

The PAGE Model

The PAGE Model comprises 10 hour‐long monthly seminars held at UCSF from January through December 2008 to teach specific geriatrics principles and clinical skills relevant to providing competent care to a hospitalized older adult. The aims of the PAGE are to:

Give hospitalist physicians knowledge and skills to teach geriatric topics to trainees in a time‐limited environment

Provide exportable teaching modules on geriatric topics for inpatient teaching

Increase teaching about geriatrics received by internal medicine residents

Increase resident use of 15 specific geriatric skills

Create a collaborative environment between the Geriatrics and Hospital Medicine Divisions at UCSF

The PAGE Development Group, which included 2 hospitalists, 2 geriatricians, and an analyst funded by the Donald W. Reynolds Foundation, reviewed American Geriatrics Society core competencies,9 national guidelines and mandates,10, 11 and existing published geriatric curricula.7, 1214 In late 2007, an email‐based needs assessment listing 38 possible topics, drawn from the resources above, was emailed to the 31 hospitalists at UCSF. Each hospitalist identified, in no particular order, 5 topics considered most useful to improve his/her geriatric teaching skills, with write‐in space for additional topic suggestions. The needs assessment also queried what format of teaching tools would be most useful and efficient, such as PowerPoint slides or pocket cards, and interest in session coteaching.

The topics most commonly selected by the respondents (n = 14, response rate 45%) included: home/community resources (64%), delirium/dementia (57%), minimizing medication problems (50%), using prognostic indices to make decisions (43%), and general approach to older inpatients (43%). The Development Group identified less popular topics (falls, pressure ulcers, indwelling catheters/emncontinence) that were gaining significant national attention.15 Finally, a topic suggested by many hospitalists, pain management, was added. Each topic session was mapped to 1 or more of the 15 geriatrics skills in the CHAMP model7 for residents to acquire. The requested and selected topics were then modified to create distinct sessions grouped around a theme, shown in Table 1. For example home and community resources was addressed in the session on Framework on Transitions in Care.

| Topics | Geriatric Skills Addressed for Hospitalized Older Patients |

|---|---|

| |

| 1. Approach to the vulnerable older patient; assessing function; goals of care | Conduct functional status assessmentMobilize early to prevent deconditioning |

| 2. Minimizing medication problems | Reduce polypharmacy and use of high risk/low benefit drugs |

| 3. Framework for transitions in care (including home and community resources) | Develop a safe and appropriate discharge plan, involving communication with other team members, family members and primary care physicians |

| 4. Using prognostics to guide treatment decisions | Give bad news |

| Document advance directives and DNR orders | |

| Discuss hospice care | |

| 5. Falls & immobility | Identify risk factors of hospital falls, including conventional and unconventional types of restraints |

| 6. Delirium | Assess risk and prevent delirium |

| 7. Dementia & depression | Conduct cognitive assessmentScreen for depression |

| Routinely assess pain at bedside in persons with dementia | |

| 8. Pain assessment in the elderly | Routinely assess pain at bedside in persons with dementia |

| Manage pain using the WHO 3‐step ladder and opiate conversion table and manage side effects of opiates | |

| 9. Foley catheters and incontinence | Determine appropriateness for urinary catheter use, discontinuing when inappropriate |

| 10. Pressure ulcers and wound care | Routinely perform a complete skin exam |

Most respondents (86%) wanted teaching materials in a format suitable for attending rounds; 64% preferred teaching cases, 29% PowerPoint presentations, and 29% quality improvement resources. The Development Group, with approval of the Chief of Hospital Medicine, planned 10, 1‐hour monthly sessions during weekly hospitalist meetings to optimize participation. Nine hospitalists agreed to lead sessions with geriatricians; 1 session was co‐led by a hospitalist and urologist.

The Development Group encouraged session leaders to create case‐based PowerPoint teaching modules that could be used during attending rounds, highlighting teaching triggers or teachable moments that modify or reinforce skills.1618 A Development Group hospitalist/geriatrician team cotaught the first session, which modeled the structure and style recommended. A teaching team typically met at least once to define goals and outline their teaching hour; most met repeatedly to refine their presentations. An example of a 1 PAGE session can be found online.19

Evaluation

Evaluation involved data from hospitalist faculty trainees, hospitalist and geriatrician session leaders, and internal medicine residents. The institutional review board approved this study. Self‐report rating scales were used for data collection, which were reviewed by experts in medical education at UCSF and piloted on nonparticipant faculty, or had been previously used by the CHAMP study.7

Hospitalist Trainees' Program Perceptions and Self‐Efficacy

Hospitalist trainees (n = 36) completed paper questionnaires after each session to assess perceived likelihood to use the teaching tools that were presented (1: not at all likely, 5: highly likely), whether they would recommend the program to colleagues (1: do not recommend, 5: highly recommend), and the utility of the PAGE program (Was this experience useful? and Prior to the sessions, did you think it would be useful? 1: definitely not, 5: definitely yes). Change in trainees' perceived self‐efficacy20 to teach geriatrics skills was assessed at the end of the PAGE program, using a posttest and retrospective pretest format with a 12‐items (1: low, 5: high) that was used in the CHAMP study.7 This format was used to avoid response shift bias, or the program‐produced change in a participant's understanding of the construct being measured.21

Faculty Session Leaders' Program Perceptions

After PAGE completion, all faculty session leaders (n = 15) completed an online questionnaire assessing teaching satisfaction (Likert‐type 5‐point scales), experience with coteaching, and years of faculty teaching experience.

Medical Residents

To assess change in hospitalists' teaching about geriatrics and residents' practice of geriatric clinical skills, residents (n = 56; post‐graduate year (PGY)1 = 29, PGY2 = 27) who would not complete residency before the end of PAGE received an online questionnaire, modified from the CHAMP study,7 prior to and after the completion of PAGE. Respondents received monetary gift cards as incentives. Residents gave separate ratings for their inpatient teaching attendings who were hospitalists (80% of inpatient ward attendings) and nonhospitalists (20%, mostly generalists) regarding frequency over the past year of being taught each of 15 geriatric clinical skills. A 3‐point scale was used: (1) never, (2) once, and (3) more than once. Residents also reported the frequency of practicing those skills themselves, using a questionnaire from the CHAMP study,7 with a scale of (1) never to (5) always.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were computed for all measures. Scale means were constructed from all individual items for the retrospective pretest and posttest measures. Wilcoxon matched‐pairs signed ranks‐tests were used to compare teaching differences between hospitalist and other attendings. For the unmatched pre‐post data on frequency of teaching, Wilcoxon‐Mann‐Whitney tests were used to determine significant differences in instruction, conducting separate tests for hospitalists and nonhospitalist attendings. Effect size22 was calculated using Cohen's d23 to determine the magnitude of increase in self‐efficacy to teach geriatrics; an effect size exceeding 0.8 is considered large. Statistics were performed using PASW Statistics 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

The hospitalist group grew from 31 to 36 members in June of 2008. On average, 14 hospitalists (M = 14.40, standard deviation [SD] = 2.41, range 1119) attended each session, with all hospitalists (n = 36) attending 1 session (M = 3.83, SD = 2.35, range 19). At each session, an average of 72% completed a post‐session evaluation form. Overall, faculty were likely to use the PAGE teaching tools (M = 4.61, SD = 0.53) and would recommend PAGE to other hospitalists (M = 4.63, SD = 0.51).

Thirteen hospitalist trainees of 36 (36%) completed a post‐PAGE online questionnaire. Respondents taught on faculty for an average of 5 years (mean (M) = 5.08, SD = 3.52). Faculty perceived self‐efficacy at teaching residents about geriatrics improved significantly with a large effect size (pretest M = 3.05, SD = .60; posttest M = 3.96, SD = .36, d = 1.52; P < 0.001). Session attendance was positively correlated with the increase in geriatrics teaching self‐efficacy (r = .62, P < 0.05), while teaching experience was not (r = 0.05, P = 0.88). Hospitalist trainees found the PAGE model more useful after participating (M = 4.62, SD = 0.65), than they had expected (M = 3.92, SD = 0.76; P < 0.05).

All session leaders (n = 15) completed the questionnaire after PAGE (9 hospitalists, 5 geriatricians, 1 urologist). Two‐thirds had 5 years on faculty; eight had no prior experience as a faculty development trainer. Over 80% indicated that they found their coteaching experience, enjoyable, useful and collaborative. Only 1 participant did not commit to interdisciplinary teaching again. Most hospitalist session leaders reported that coteaching with a geriatrician enhanced their knowledge; they were more likely to consult a geriatrician regarding patients. All but 2 session leaders felt that the model fostered a collaborative environment between their 2 divisions.

Of the 56 residents, 41% (16 PGY1, 7 PGY2) completed a pretest; 43% (15 PGY1, 9 PGY2) completed a posttest. Residents reported receiving inpatient teaching on geriatrics skills significantly more frequently from hospitalists vs. nonhospitalist attendings both before PAGE (hospitalists M = 2.18, SD = 0.37; nonhospitalists M = 2.00, SD = 0.53, P < 0.05), and after (hospitalists M = 2.39, SD = 0.46; nonhospitalists M = 2.05, SD = 0.57, P < 0.05; see Fig. 1). Although hospitalists taught more frequently about geriatrics than nonhospitalists before PAGE, our findings suggest that they increased their teaching by a greater magnitude than nonhospitalists (P < 0.01, P > 0.05, respectively). Residents reported increased geriatric skill practice after PAGE with a medium effect size (pretest M = 2.92, SD = 0.55, posttest M = 3.28, SD = 0.66, P = 0.052, d = 0.66). There was greater mean reported practice for all skills with the exception of hospice care, which already was being performed between often and very often before PAGE. The largest increases in skill practice were (descending order, most increased first): assessing polypharmacy, performing skin exams, prognostication, performing functional assessments and examining Foley catheter use.

Discussion

Our aging population and a shortage of geriatricians necessitates new, feasible models for geriatric training. Similar to the CHAMP model,7 PAGE had a favorable impact on faculty perceived behavioral change; after the PAGE sessions, faculty reported significantly greater self‐efficacy of teaching geriatrics. However, this study also examined the impact of the PAGE Model on 2 groups not previously reported in the literature: faculty session leaders and medicine residents.

To our knowledge, this is the first study about a hospitalist TTT program codeveloped with nonhospitalists aimed at teaching geriatrics skills to residents, though smaller scale programs for medical students exist.24 We believe codevelopment was important in our model for many reasons. First, using hospitalist peers and local geriatricians likely increased trust in the educational curricula and allowed for strong communication channels between instructors.25, 26 Second, coteaching allowed for hospitalist mentorship. Hospitalists acknowledged their coleaders as mentors and several hospitalists subsequently engaged in new geriatric projects. Third, coteaching was felt to enhance patient care and increase geriatrician consultations. Coteaching may have applicability to other hospitalist faculty development such as intensive care and palliative care, and hospitalist programs may benefit from creating faculty development programs internally with their colleagues, rather than using online resources.

Another important finding of this study is that training hospitalists to teach about geriatrics seems to result in an increase in both the geriatric teaching that residents receive and residents' practice of geriatric skills. This outcome has not been previously demonstrated with geriatric TTT activities.27 This trickle‐down effect to residents likely results from both the increased teaching efficacy of hospitalists after the PAGE Model and the exportable nature of the teaching tools.

Several continuing medical education best practices were used which we believe contributed to the success of PAGE. First, we conducted a needs assessment, which improves knowledge outcomes.28, 29 Second, sessions included cases, lectures, and discussions. Use of multiple educational techniques yields greater knowledge and behavioral change as compared to a single method, such as lecture alone.24, 25, 30, 31 Finally, sessions were sequenced over a year, rather than clustered in short, intensive activity. Sequenced, or learn‐work‐learn opportunities allow education to be translated to practice and reinforced.8, 27, 30, 32

We believe that the PAGE Model is transportable to other hospitalist programs due to its cost and flexible nature. In economically‐lean times, hospitalist divisions can create a program similar to the PAGE Model essentially at no cost, except for donated faculty preparation time. In contrast, CHAMP was expensive, costing nearly $72,000 for 12 faculty to participate in the 48‐hour curriculum,7, 33 and volunteering physicians were compensated for their time. Though Mini‐CHAMP is a streamlined 2‐day workshop that offers free online lectures and slide sets, there may be some benefit to producing a faculty development program internally, as we stated above, and PAGE included additional topics (urinary catheters and decubitus ulcers/wound care) not covered in mini‐CHAMP.

There were several limitations to this study. First, some outcomes of the PAGE Model were assessed by retrospective self‐report, which may allow for recall bias. Although self‐report may or may not correlate with actual behavior,34 faculty and resident perspectives of their teaching and learning experiences are themselves important. Furthermore, a retrospective presurvey allows for content of an educational program or intervention to be explained prior to a survey, so that participants first assess their new level of understanding or skill on the post test, then reflectively assess the level of understanding or skill they had prior to the workshop. This avoids response shift bias and can improve internal validity.21, 35

Second, the small numbers of session leaders, hospitalist trainees, and residents restricted statistical power to detect small effects. The fact that we found significant improvements enhances the likelihood that the differences observed were not due to chance.

Third, the low response rates from the hospitalist trainee post‐intervention questionnaire and the residents' questionnaires may affect the validity of our results. For the resident survey, the subjects were not matched, and we cannot state that an individual's geriatric skill practice changed due to PAGE, though the results suggest the residency program as a whole improved the frequency of geriatric skill practice.

Finally, the residents were required to report the frequency of teaching on and practice of geriatric skills practice over the prior year and accuracy of recall may be an issue. However, frequencies were queried both pre and post intervention and favorable change was noted. Furthermore, because the high end of the 3‐point teaching scale was limited to more than once, the true amount of teaching may have been underestimated if more than once actually represented high frequencies.

Future studies are needed to replicate these findings at other institutions to confirm generalizability. It would be beneficial to measure patient outcomes to determine whether increased teaching and skill practice benefits patients using measures such as reduction in catheter related urinary tract infections, falls, and inadequate pain management. Further investigations of cotaught faculty development programs between hospitalists and other specialists help emphasize why internally created TTT programs are of greater value than online resources.

Conclusions

This time‐sensitive adaptation of a hospitalist geriatric TTT program was successfully implemented at an academic medical center and suggests improved hospitalist faculty self‐efficacy at teaching geriatric skills, increased frequency of inpatient geriatric teaching by hospitalists and increased resident geriatric skill practice. Confidence to care for geriatric patients and a strong skill set to assess risks and manage them appropriately will equip hospitalists and trainees to provide care that reduces geriatric patients' in‐hospital morbidity and costs of care. As hospitalists increasingly care for older adults, the need for time‐efficient methods of teaching geriatrics will continue to grow. The PAGE Model, and other new models of geriatric training for hospitalists, demonstrates that we are beginning to address this urgent need.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Joan Abrams, MA, MPA, and Patricia O'Sullivan, EdD, whose work was key to the success of this program and this manuscript. They also thank the Donald W. Reynolds Foundation for support of this project.

- ,.2005 National Hospital Discharge Survey.Adv Data.2007;385:1–19.

- ,,,. In:U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Reports, 65+ in the United States: 2005,Washington, D.C.:U.S. Government Printing Office;2005:23–209.

- ,,,.Growth in the care of older patients by hospitalists in the United States.N Engl J Med.2009;360(11):1102–1112.

- ,,,.Providing dementia outreach education to rural communities: lessons learned from a train‐the‐trainer program.J Appl Gerontol.2002;21:294–313.

- .Gerontologizing health care: a train‐the‐trainer program for nurses.Gerontol Geriatr Educ.1999;19:47–56.

- ,,.A statewide model detection and prevention program for geriatric alcoholism and alcohol abuse: increased knowledge among service providers.Community Ment Health J.2000;36:137–148.

- ,,, et al.The curriculum for the hospitalized aging medical patient program: a collaborative faculty development program for hospitalists, general internists, and geriatricians.J Hosp Med.2008;3(5):384–393.

- Reframing professional development through understanding authentic professional learning.Rev Educ Res.2009;79:702–739.

- The Education Committee Writing Group of the American Geriatrics Society.Core competencies for the care of older patients: recommendations of the American Geriatrics Society.Acad Med.2000;75:252–255.

- ,,, et al.American Geriatrics Society Task Force on the future of geriatric medicine.J Am Geriatr Soc.2005;53 (6 Suppl):S245–S256.

- Nadzam, Deborah. Preventing patient falls. Joint Commission Resources. Available at: http://www.jcrinc.com/Preventing‐Patient‐Falls. Accessed April2010.

- ,.Curricular recommendations for resident training in nursing home care. A collaborative effort of the Society of General Internal Medicine Task Force on Geriatric Medicine, the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Geriatrics Task Force, the American Medical Directors Association, and the American Geriatrics Society Education Committee.J Am Geriatr Soc.1994;42:1200–1201.

- ,,,,.Curriculum recommendations for resident training in geriatrics interdisciplinary team care.J Am Geriatr Soc.1999;47:1145–1148.

- ,.ACGME requirements for geriatrics medicine curricula in medical specialties: Progress made and progress needed.Acad Med.2005;80:279–285.

- CMS Office of Public Affairs. CMS Improves Patient Safety for Medicare and Medicaid by Addressing Never Events, August 04, 2008. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/apps/media/press/factsheet.asp?Counter=322434(5):337–343.

- ,.The changing paradigm for continuing medical education: impact of information on the teachable moment.Bull Med Libr Assoc.1990;78(2):173–179.

- ,.Creating the teachable moment.J Nurs Educ.1998;37(6):278–280.

- Society of Hospital Medicine, BOOSTing Care Transitions Resource Room. Mazotti L, Johnston CB. Faculty development: Teaching triggers for transitional care. “A train‐the‐trainer model.” Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/ResourceRoomRedesign/RR_CareTransitions/PDFs/Mazotti_UCSF_Transitions.PPT. Accessed April2010.

- .Self‐efficacy: The Exercise of Control.New York:W.H. Freeman and Company;1997.

- .Internal invalidity in pretest‐posttest self‐report evaluations and a re‐evaluation of retrospective pretests.Applied Psychological Measurement.1979;3:1–23.

- ,.A visitor's guide to effect sizes.Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract.2004;9:241–249.

- .Statistical Power Analyses for the Behavioral Sciences.2nd ed.Hillsdale, NJ:Lawrence Erlbaum Associates;1988.

- ,,,.Hazards of hospitalization: Hospitalists and geriatricians educating medical students about delirium and falls in geriatric patients.Gerontol Geriatr Educ.2008;28(4):94–104.

- ,,, et al.Continuing medical education, continuing professional development, and knowledge translation: Improving care of older patients by practicing physicians.J Am Geriatr Soc.2006:54(10):1610–1618.

- ,,, et al.Practicing physician education in geriatrics: Lessons learned from a train‐the‐trainer model.J Am Geriatr Soc.2007:55(8):1281–1286.

- ,.CHAMP trains champions: hospitalist‐educators develop new ways to teach care for older patients.J Hosp Med.2008;3(5):357–360.

- ,,,,,.Impact of formal continuing medical education: Do conferences, workshops, rounds, and other traditional continuing education activities change physician behavior or health care outcomes?JAMA.1999;282(9):867–874.

- ,.Association for the Study of Medical Education Booklet: The effectiveness of continuing professional development.Edinburgh, Scotland:Association for the Study of Medical Education;2000.

- ,,, et al.Effectiveness of continuing medical education.Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep).2007;149:1–69.

- ,,, et al.Continuing education meetings and workshops: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes.Cochrane Database Syst Rev.2009;(2):CD003030.

- ,.Continuing medical education and the physician as learner: guide to the evidence.JAMA.2002;288(9):1057–1060.

- .Care of hospitalized older patients: opportunities for hospital‐based physicians.J Hosp Med.2006;1:42–47.

- ,.What we say and what we do: self‐reported teaching behavior versus performances in written simulations among medical school faculty.Acad Med.1992;67(8):522–527.

- ,.The retrospective pretest and the role of pretest information in evaluation studies.Psychol Rep.1992;70:699–704.

- ,.2005 National Hospital Discharge Survey.Adv Data.2007;385:1–19.

- ,,,. In:U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Reports, 65+ in the United States: 2005,Washington, D.C.:U.S. Government Printing Office;2005:23–209.

- ,,,.Growth in the care of older patients by hospitalists in the United States.N Engl J Med.2009;360(11):1102–1112.

- ,,,.Providing dementia outreach education to rural communities: lessons learned from a train‐the‐trainer program.J Appl Gerontol.2002;21:294–313.

- .Gerontologizing health care: a train‐the‐trainer program for nurses.Gerontol Geriatr Educ.1999;19:47–56.

- ,,.A statewide model detection and prevention program for geriatric alcoholism and alcohol abuse: increased knowledge among service providers.Community Ment Health J.2000;36:137–148.

- ,,, et al.The curriculum for the hospitalized aging medical patient program: a collaborative faculty development program for hospitalists, general internists, and geriatricians.J Hosp Med.2008;3(5):384–393.

- Reframing professional development through understanding authentic professional learning.Rev Educ Res.2009;79:702–739.

- The Education Committee Writing Group of the American Geriatrics Society.Core competencies for the care of older patients: recommendations of the American Geriatrics Society.Acad Med.2000;75:252–255.

- ,,, et al.American Geriatrics Society Task Force on the future of geriatric medicine.J Am Geriatr Soc.2005;53 (6 Suppl):S245–S256.

- Nadzam, Deborah. Preventing patient falls. Joint Commission Resources. Available at: http://www.jcrinc.com/Preventing‐Patient‐Falls. Accessed April2010.

- ,.Curricular recommendations for resident training in nursing home care. A collaborative effort of the Society of General Internal Medicine Task Force on Geriatric Medicine, the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Geriatrics Task Force, the American Medical Directors Association, and the American Geriatrics Society Education Committee.J Am Geriatr Soc.1994;42:1200–1201.

- ,,,,.Curriculum recommendations for resident training in geriatrics interdisciplinary team care.J Am Geriatr Soc.1999;47:1145–1148.

- ,.ACGME requirements for geriatrics medicine curricula in medical specialties: Progress made and progress needed.Acad Med.2005;80:279–285.

- CMS Office of Public Affairs. CMS Improves Patient Safety for Medicare and Medicaid by Addressing Never Events, August 04, 2008. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/apps/media/press/factsheet.asp?Counter=322434(5):337–343.

- ,.The changing paradigm for continuing medical education: impact of information on the teachable moment.Bull Med Libr Assoc.1990;78(2):173–179.

- ,.Creating the teachable moment.J Nurs Educ.1998;37(6):278–280.

- Society of Hospital Medicine, BOOSTing Care Transitions Resource Room. Mazotti L, Johnston CB. Faculty development: Teaching triggers for transitional care. “A train‐the‐trainer model.” Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/ResourceRoomRedesign/RR_CareTransitions/PDFs/Mazotti_UCSF_Transitions.PPT. Accessed April2010.

- .Self‐efficacy: The Exercise of Control.New York:W.H. Freeman and Company;1997.

- .Internal invalidity in pretest‐posttest self‐report evaluations and a re‐evaluation of retrospective pretests.Applied Psychological Measurement.1979;3:1–23.

- ,.A visitor's guide to effect sizes.Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract.2004;9:241–249.

- .Statistical Power Analyses for the Behavioral Sciences.2nd ed.Hillsdale, NJ:Lawrence Erlbaum Associates;1988.

- ,,,.Hazards of hospitalization: Hospitalists and geriatricians educating medical students about delirium and falls in geriatric patients.Gerontol Geriatr Educ.2008;28(4):94–104.

- ,,, et al.Continuing medical education, continuing professional development, and knowledge translation: Improving care of older patients by practicing physicians.J Am Geriatr Soc.2006:54(10):1610–1618.

- ,,, et al.Practicing physician education in geriatrics: Lessons learned from a train‐the‐trainer model.J Am Geriatr Soc.2007:55(8):1281–1286.

- ,.CHAMP trains champions: hospitalist‐educators develop new ways to teach care for older patients.J Hosp Med.2008;3(5):357–360.

- ,,,,,.Impact of formal continuing medical education: Do conferences, workshops, rounds, and other traditional continuing education activities change physician behavior or health care outcomes?JAMA.1999;282(9):867–874.

- ,.Association for the Study of Medical Education Booklet: The effectiveness of continuing professional development.Edinburgh, Scotland:Association for the Study of Medical Education;2000.

- ,,, et al.Effectiveness of continuing medical education.Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep).2007;149:1–69.

- ,,, et al.Continuing education meetings and workshops: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes.Cochrane Database Syst Rev.2009;(2):CD003030.

- ,.Continuing medical education and the physician as learner: guide to the evidence.JAMA.2002;288(9):1057–1060.

- .Care of hospitalized older patients: opportunities for hospital‐based physicians.J Hosp Med.2006;1:42–47.

- ,.What we say and what we do: self‐reported teaching behavior versus performances in written simulations among medical school faculty.Acad Med.1992;67(8):522–527.

- ,.The retrospective pretest and the role of pretest information in evaluation studies.Psychol Rep.1992;70:699–704.

Copyright © 2010 Society of Hospital Medicine

Hospitalist Attendings: Systematic Review

Wachter and Goldman1 described the hospitalist model for inpatient care more than a decade ago. The Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) defines hospitalists as physicians whose primary professional focus is the general medical care of hospitalized patients. Their activities include patient care, teaching, research, and leadership related to hospital medicine.2 This care delivery model has enjoyed exponential growth, with approximately 20,000 hospitalists in the United States, and an estimated 30,000 by the end of the decade.35 Currently, 29% of hospitals, including 55% with at least 200 beds, employ hospitalists to coordinate inpatient care.6 Data suggests that hospitalists promote cost containment and decrease length of stay without negatively affecting rates of death, readmission, or patient satisfaction.715

In academic settings, hospitalists also provide a substantial amount of teaching to trainees,1618 and the hospitalist model represents a fundamental change in inpatient education delivery. Traditional ward attendings typically consisted of a heterogeneous group of subspecialists, laboratory‐based clinician scientists, and general internists, many of whom attended and taught relatively infrequently. By virtue of focusing purely on inpatient care, hospitalists are more intimately involved with inpatient care systems, as well as teaching challenges (and opportunities) in the inpatient setting. The theoretical educational benefits of hospitalists include greater availability, more expertise in hospital medicine, and more emphasis on cost‐effective care.7, 18, 19 Concerns that trainees would have diminished autonomy and less exposure to subspecialist care have not been borne out.16, 20, 21

The purpose of this study was to examine the role of hospitalists on inpatient trainee education. We systematically reviewed the literature to determine the impact of hospitalists compared to nonhospitalist attendings on medical students' and residents' education.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

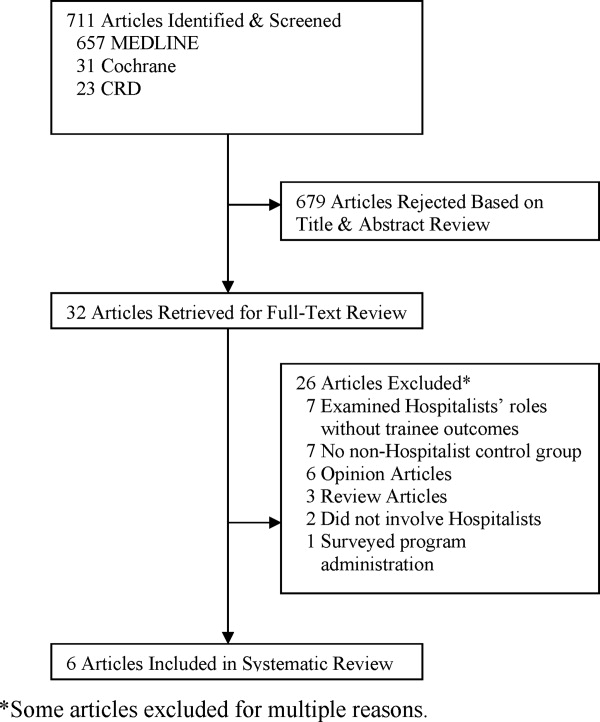

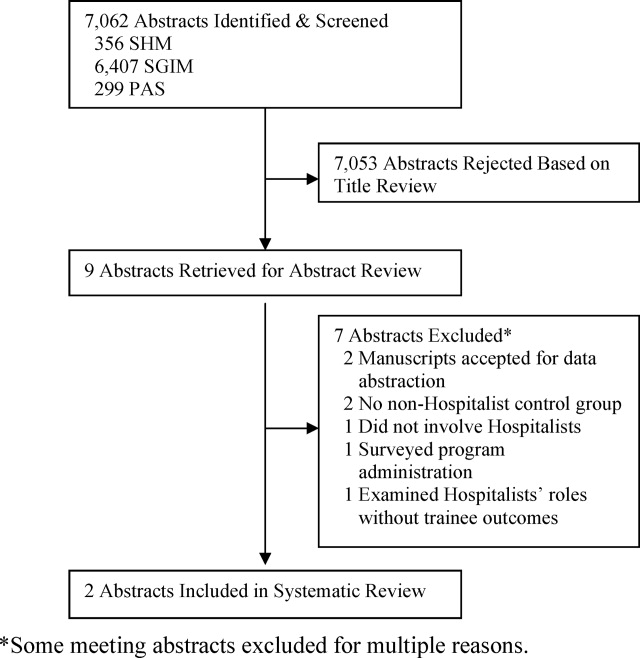

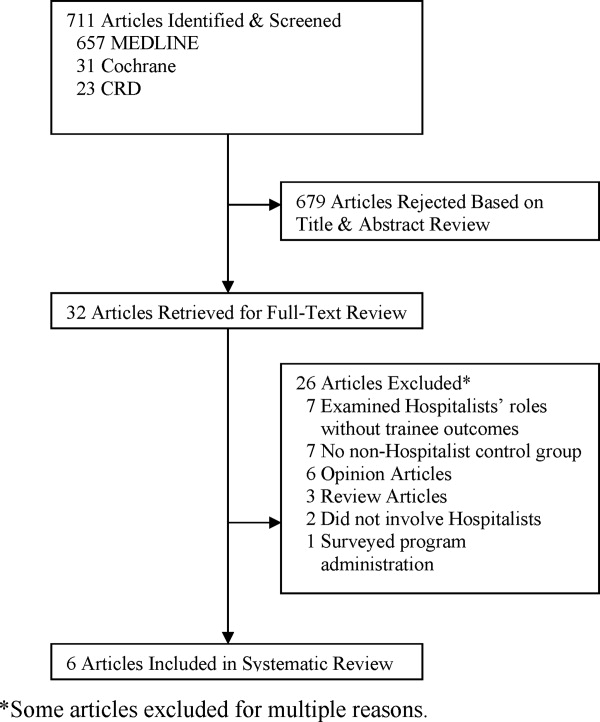

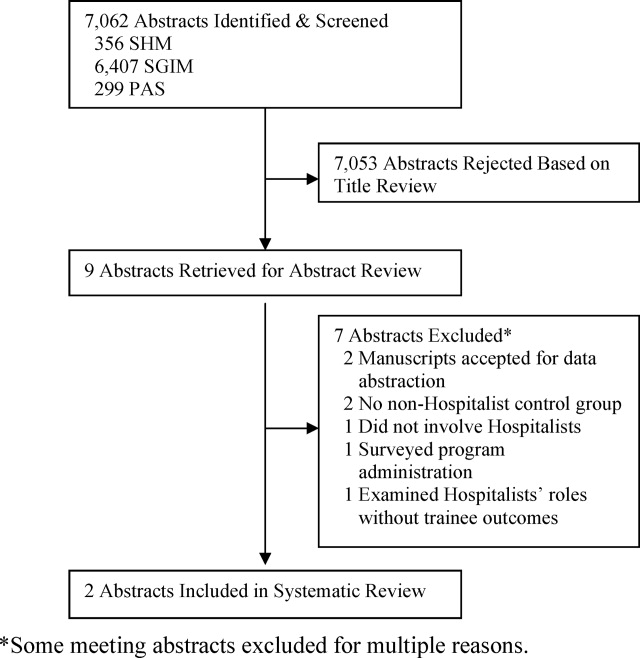

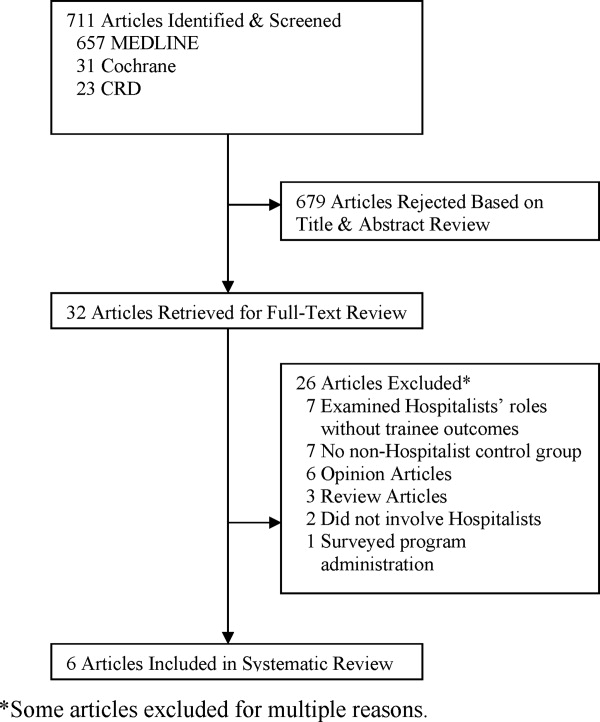

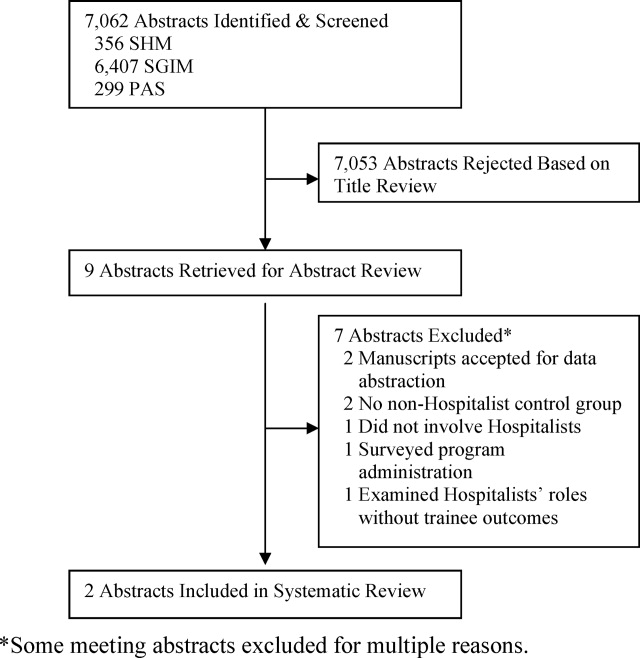

Data Sources