User login

A systematic approach to chronic abnormal uterine bleeding

Menstrual bleeding is considered normal when it occurs regularly (every 21-35 days), lasts 4 to 8 days, and is not associated with heavy bleeding.1 During the first few years after menarche, it is normal for girls to experience irregular menstrual cycles but, by the third year, 60% to 80% of girls have an adult pattern of menstrual bleeding.2

Menstrual flow without normal volume, duration, regularity, or frequency is considered abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB). The condition is considered acute if there is need for immediate intervention. In the absence of the need for immediate intervention, recurrent AUB is classified as chronic.3 Chronic AUB is the focus of this article.

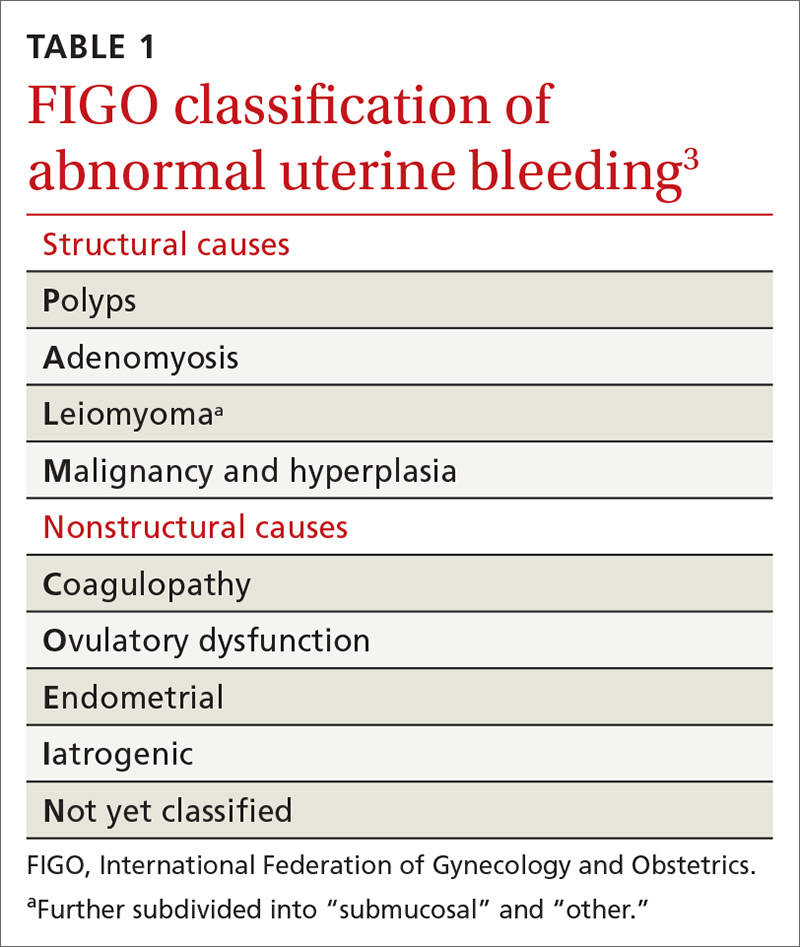

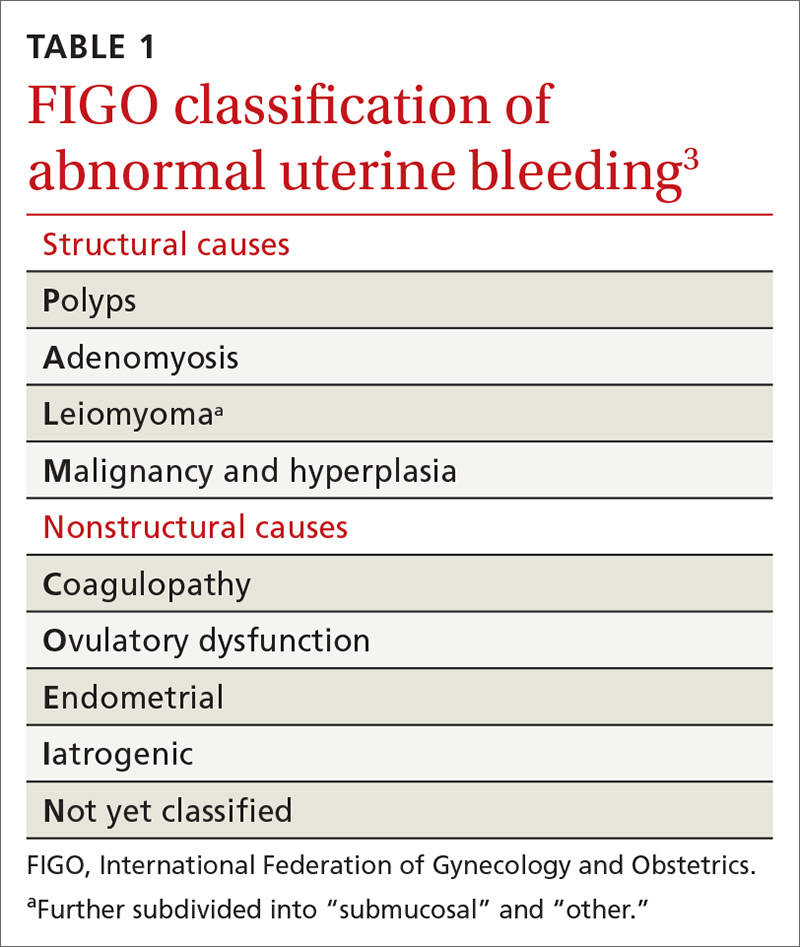

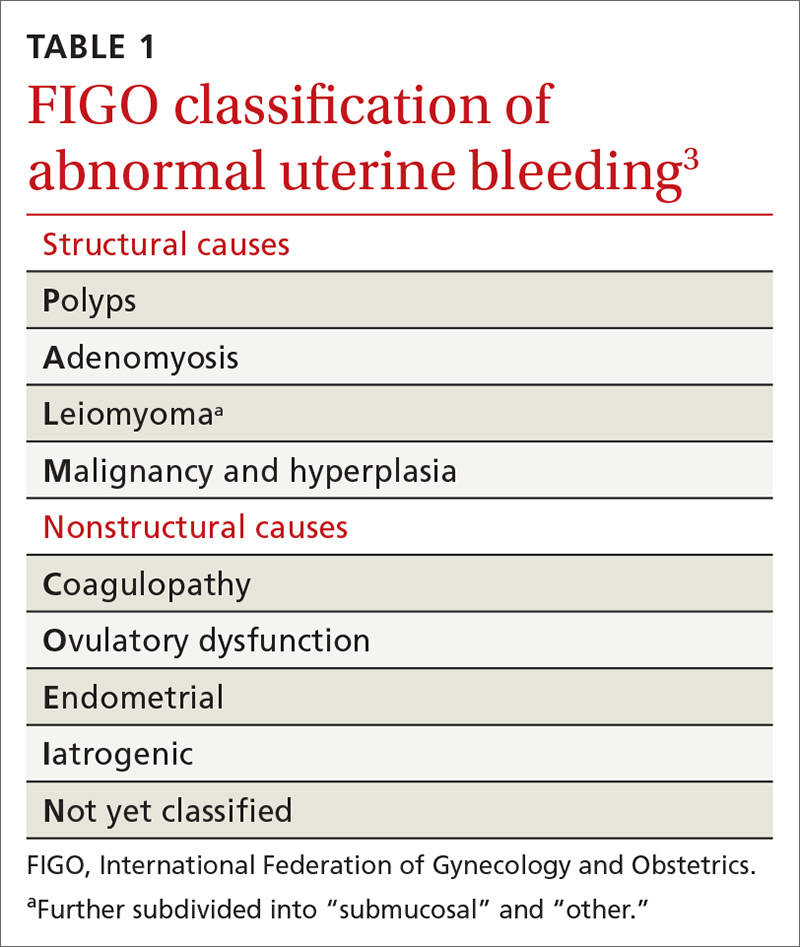

Invaluable tool: The FIGO classification

In 2011, the

- structural causes, recalled by “PALM” (Polyps, Adenomyosis, Leiomyoma, and Malignancy/hyperplasia)

- nonstructural causes, recalled by “COEIN” (Coagulopathy, Ovulatory dysfunction, Endometrial, Iatrogenic, and Not yet classified).

The PALM–COEIN system also uses descriptive terminology (heavy bleeding, intermenstrual bleeding) to characterize the bleeding pattern.3 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has adopted this classification system and recommends that such historically used terminology as “dysfunctional uterine bleeding,” “menorrhagia,” and “metrorrhagia” be abandoned.1

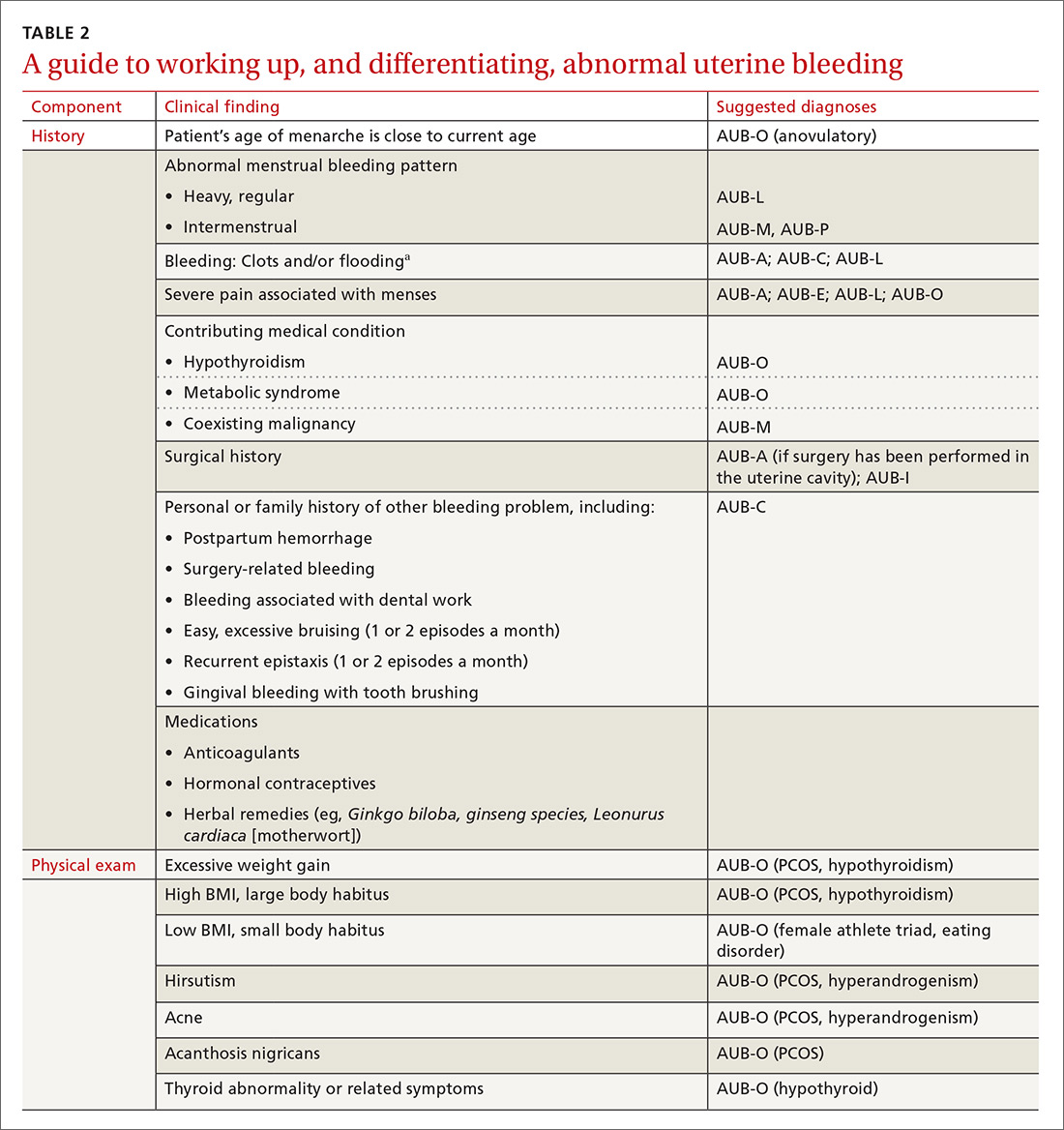

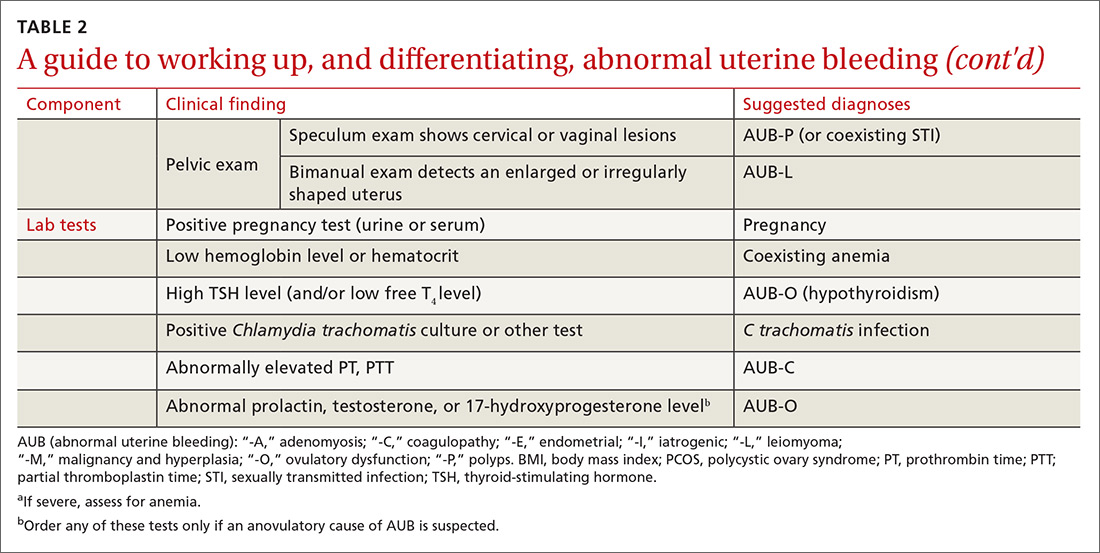

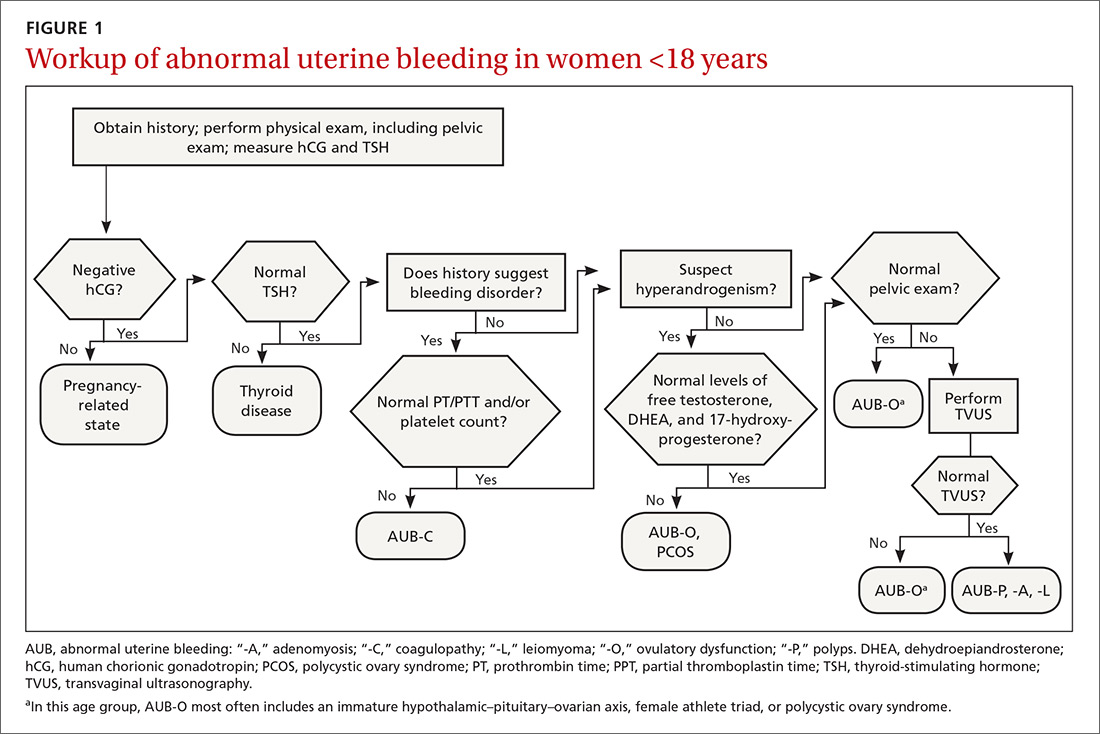

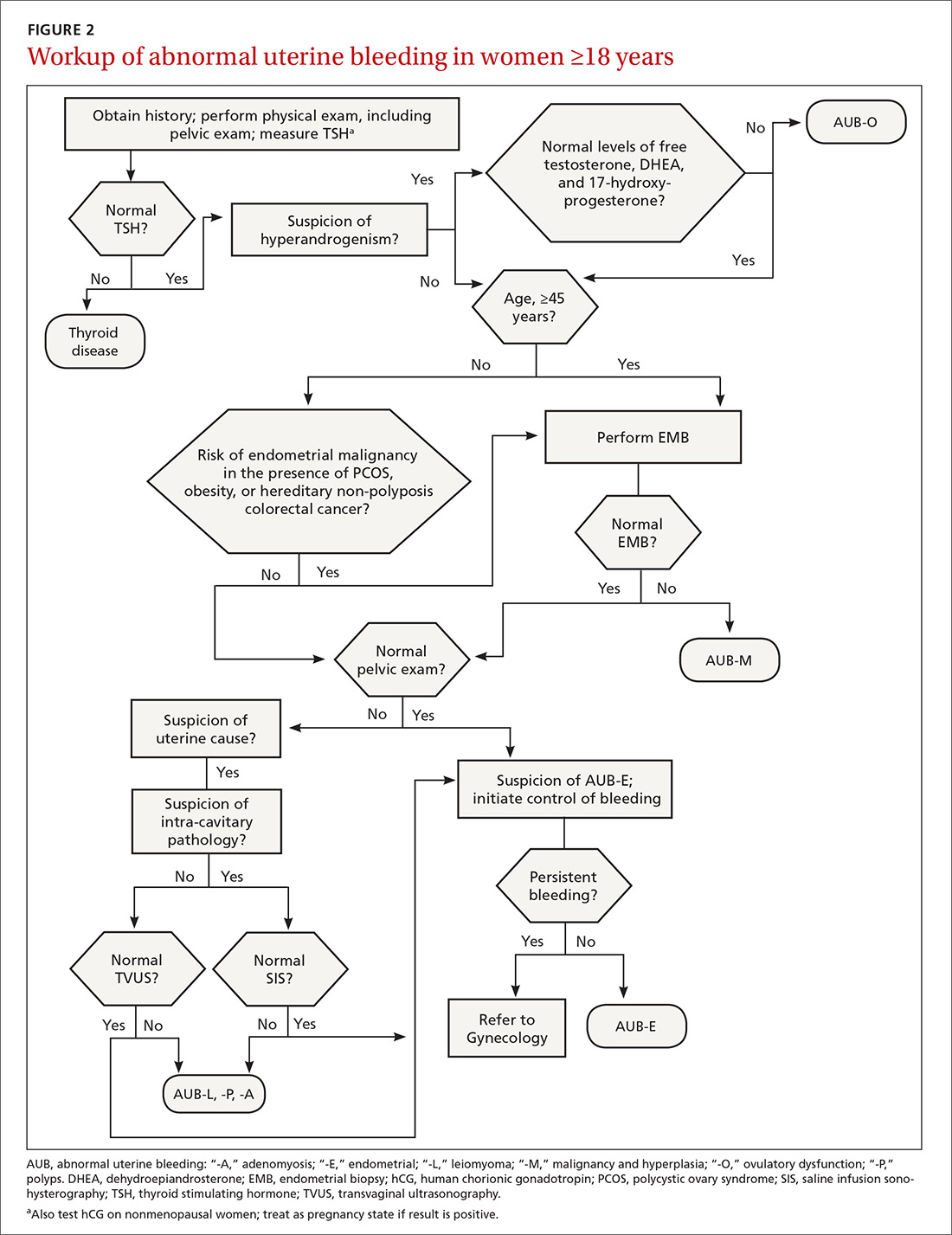

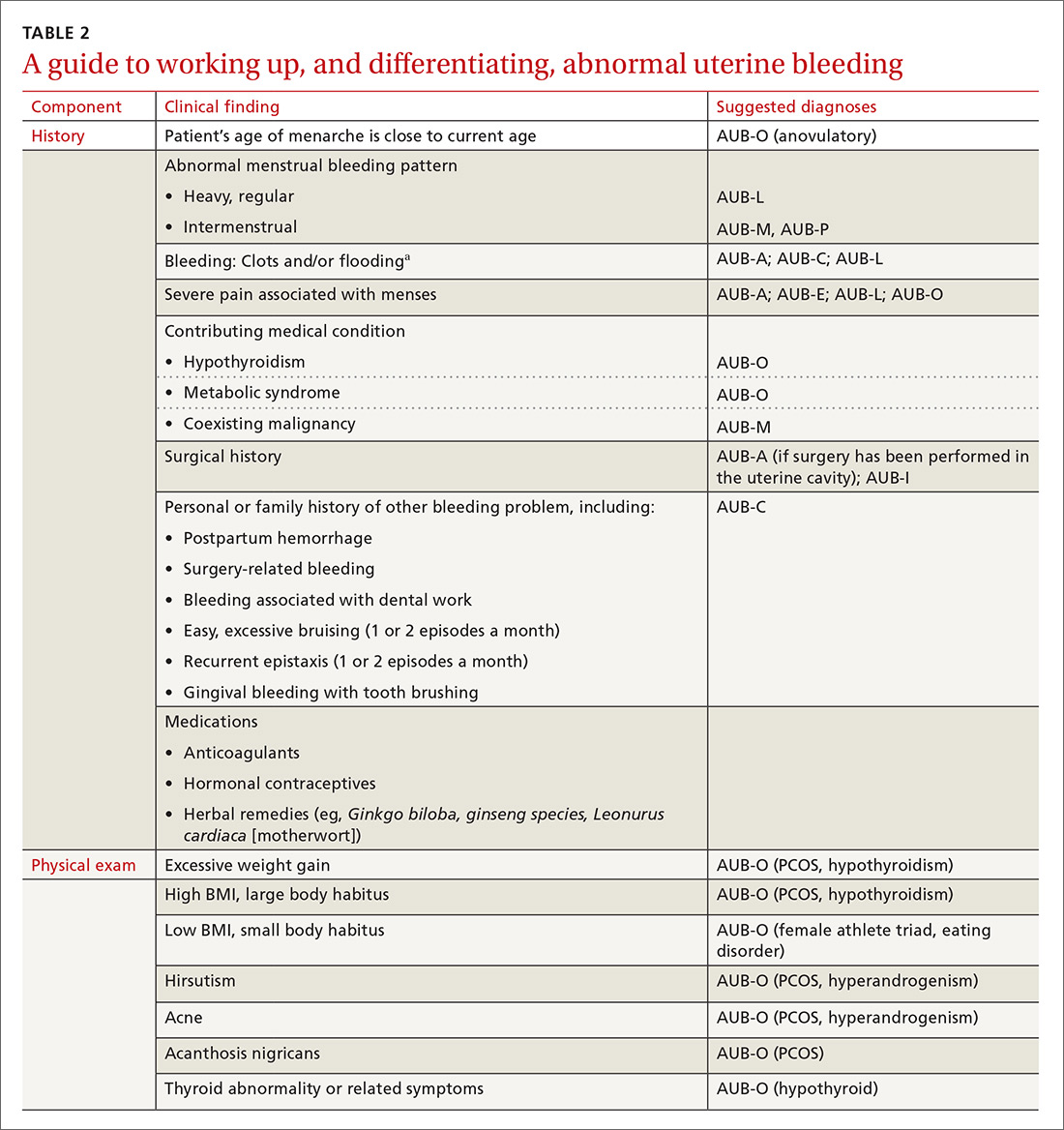

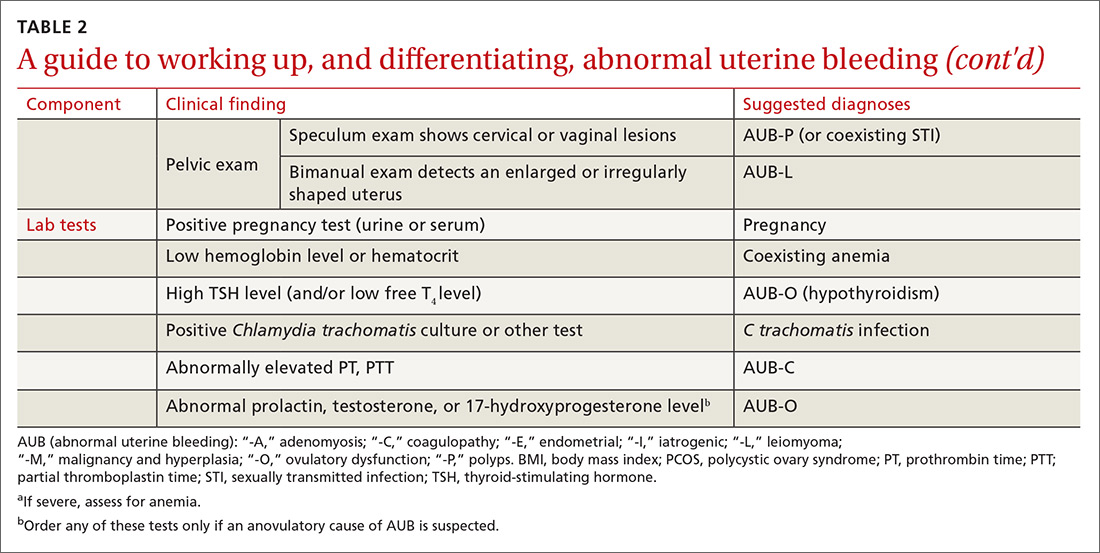

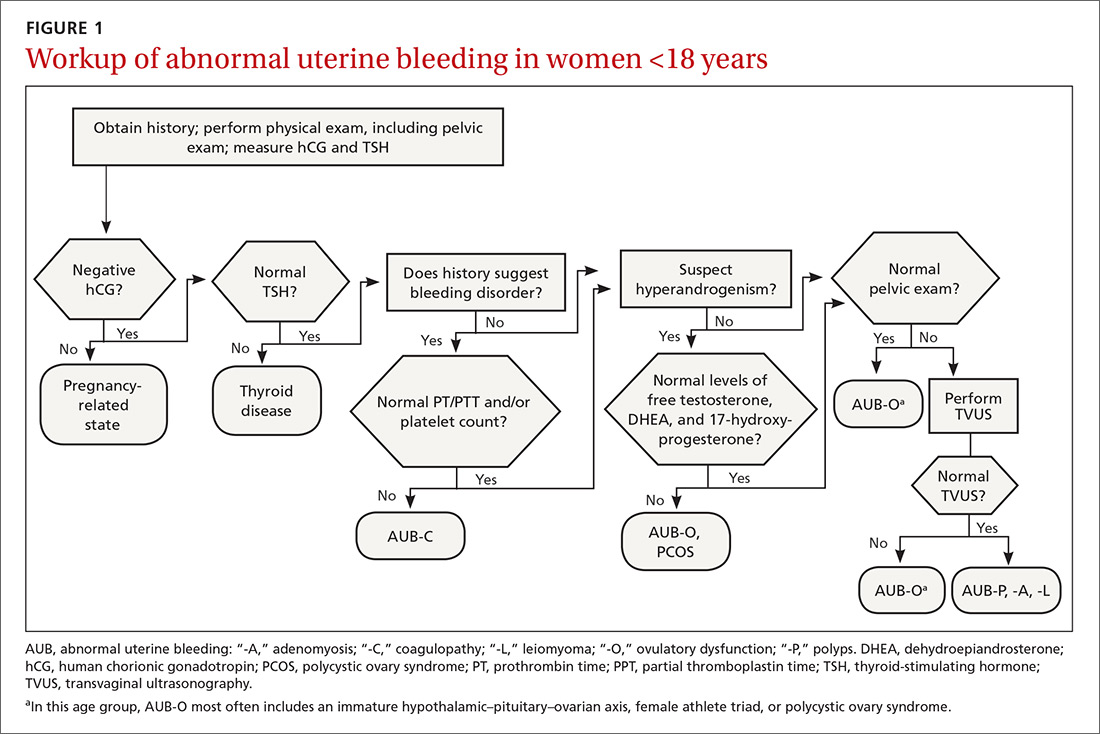

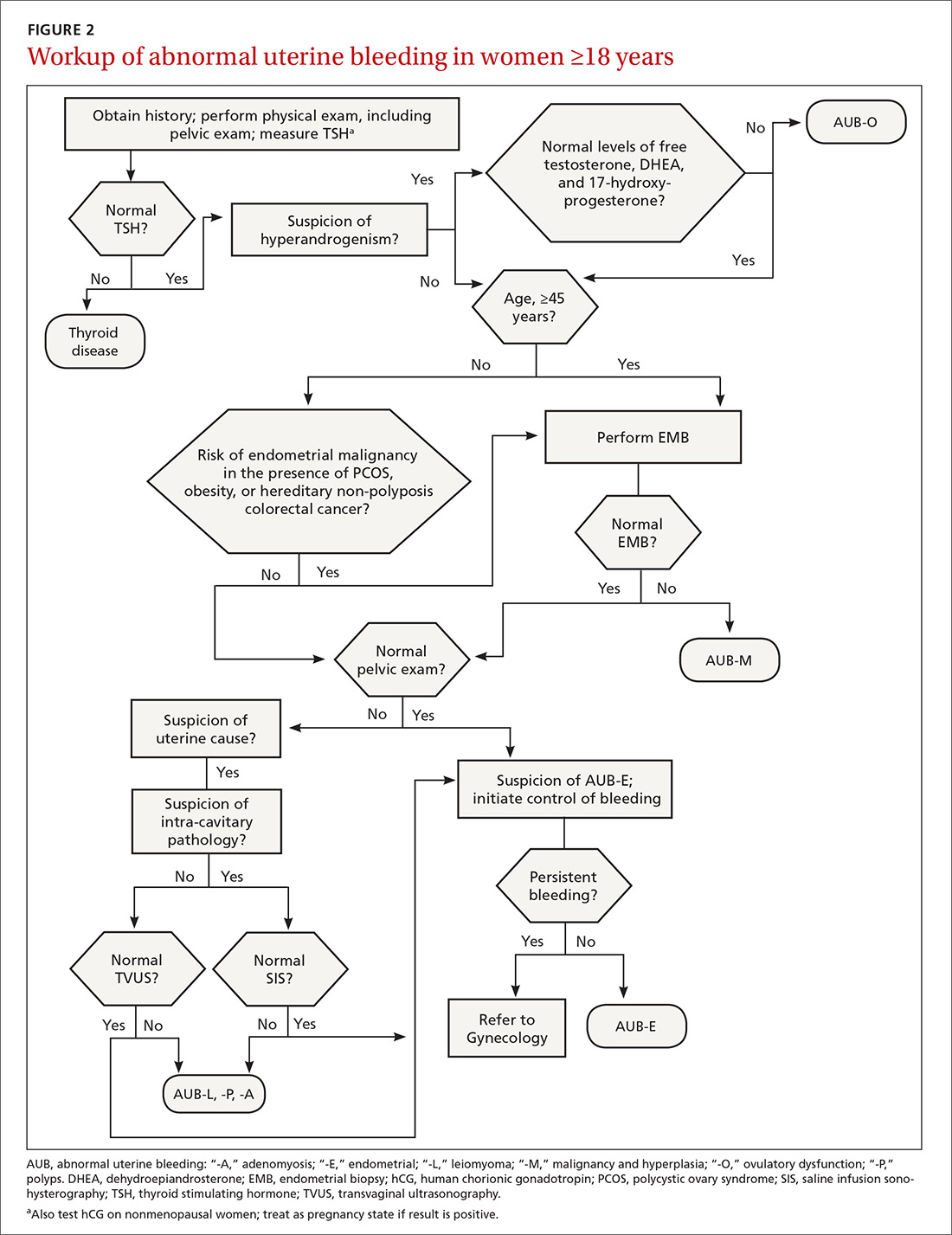

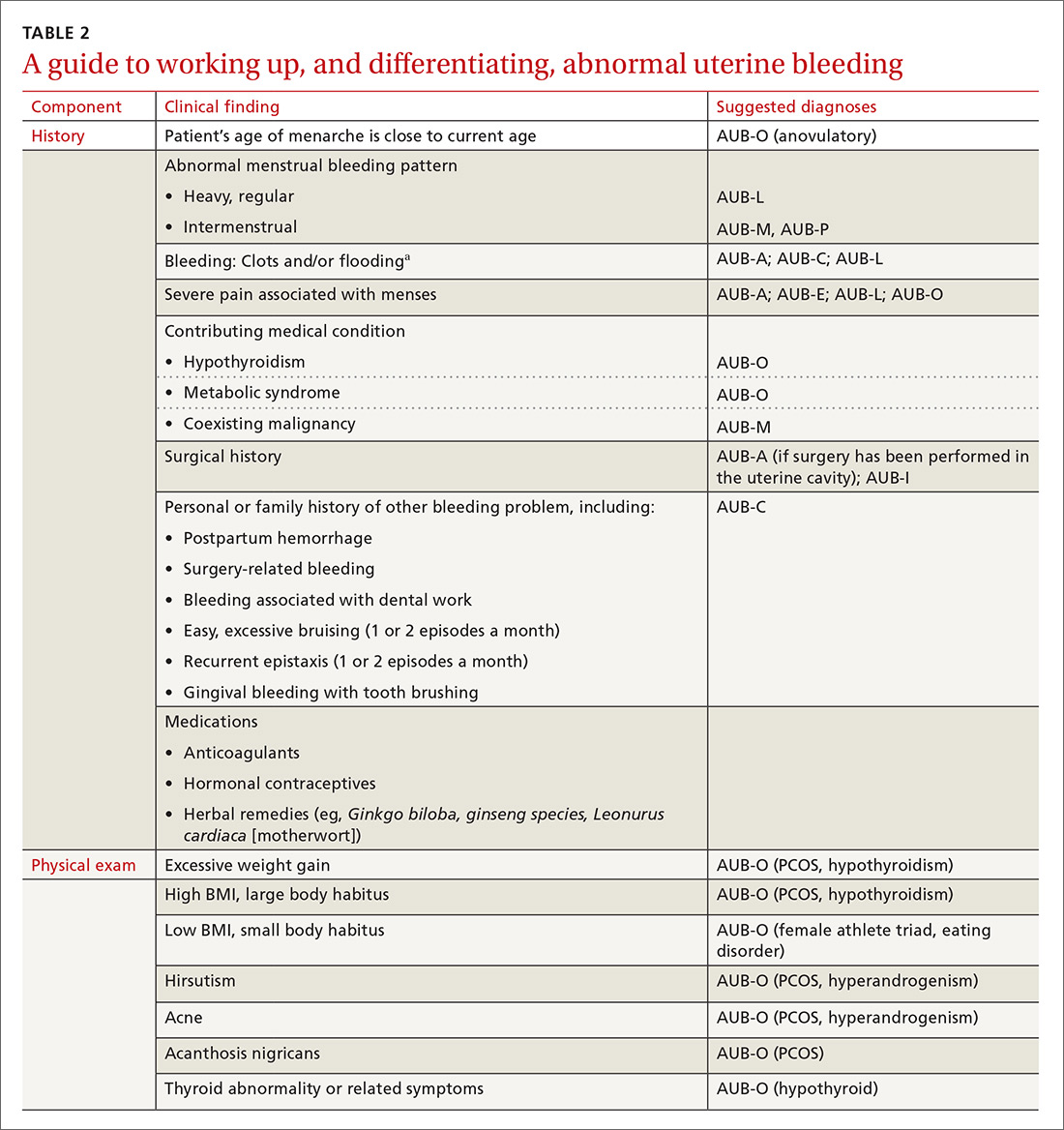

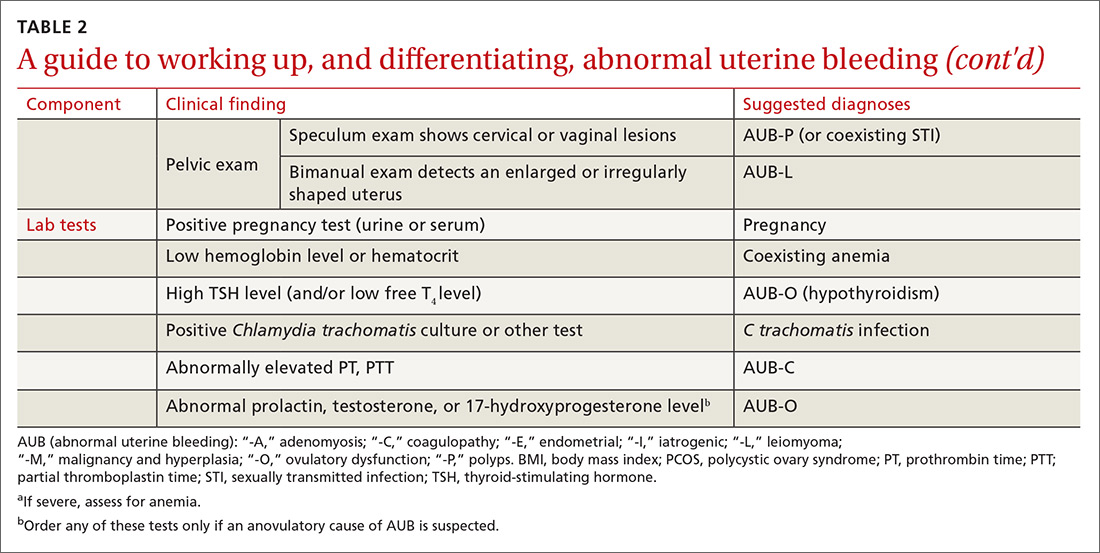

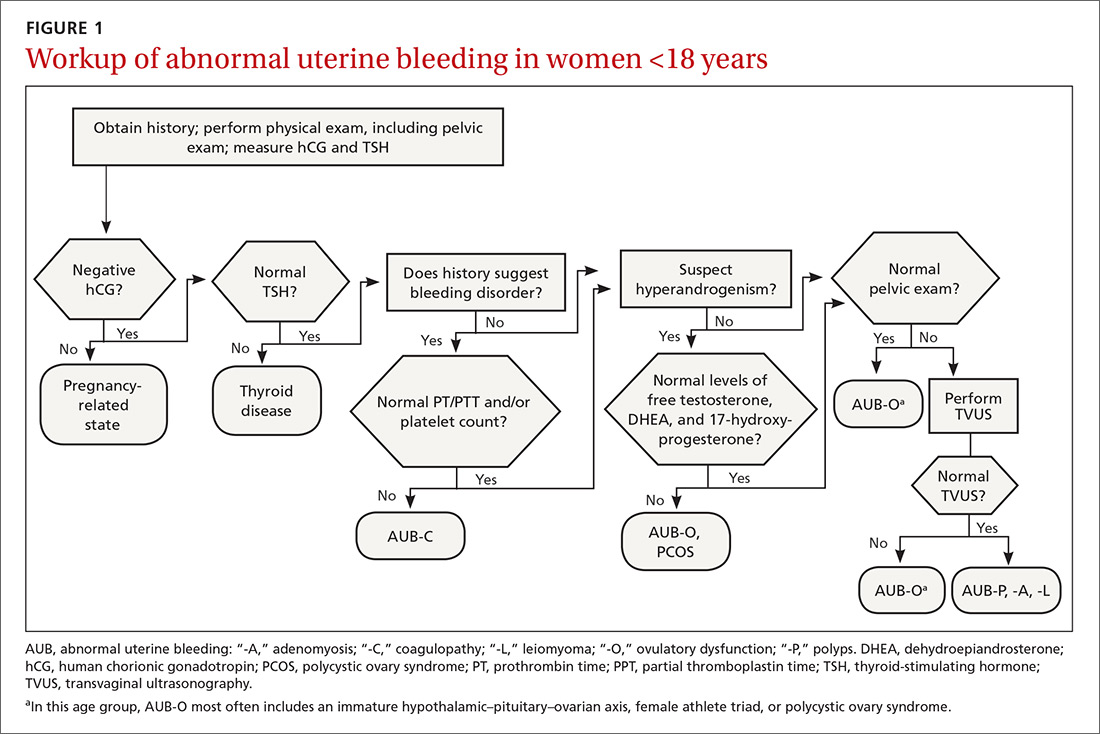

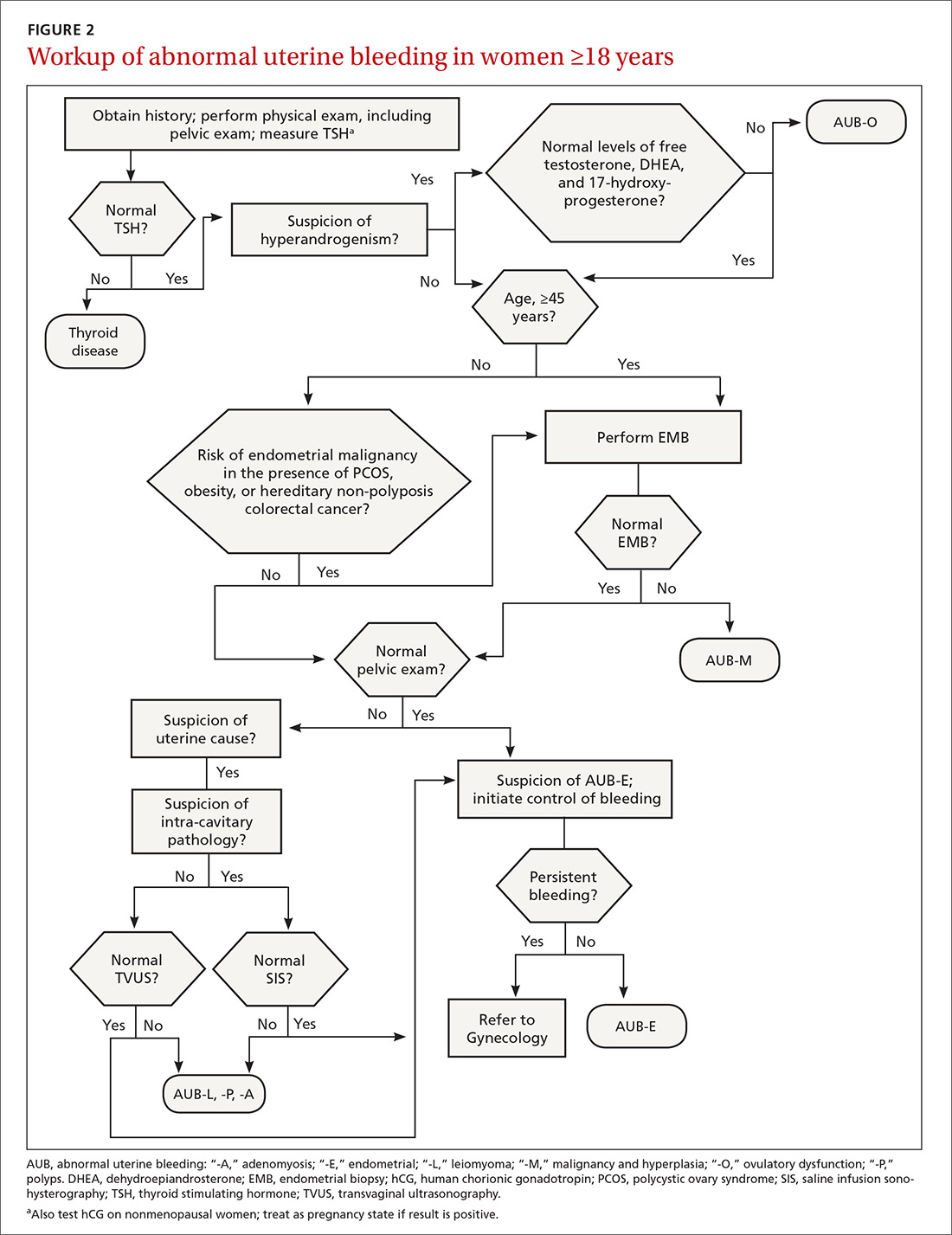

The initial workup of all causes of chronic uterine bleeding begins with a history; physical examination, including pelvic exam; and laboratory testing, including a urine pregnancy test, complete blood count, and a test of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TABLE 2). The need for additional laboratory testing, imaging, or endometrial biopsy depends on the suspected cause of AUB, detailed stepwise in FIGURE 1 (women <18 years) and FIGURE 2 (≥18 years).

We first briefly review the 9 categories of AUB in the PALM–COEIN system; discuss the most common causes in more detail; and review common treatment options (TABLE 3).

CASE 1

Marsha R, a 41-year-old-woman, complains of heavy menstrual bleeding for the past year that has become worse over the past 2 months. Her menstrual cycles have occurred every 28 days and last 10 days; she uses 10 to 12 pads a day.

Continue to: Recently, Ms. R reports...

Recently, Ms. R reports, she has been bleeding continuously for 14 days, with episodes of lighter bleeding followed by heavier bleeding. She also complains of fatigue.

Bimanual examination is notable for an enlarged uterus.

How would you proceed with the workup of this patient, to determine the cause of her bleeding and tailor management accordingly?

Structural AUB: The “PALM” mnemonic

A structural cause of AUB must be considered when you encounter an abnormality on physical exam (TABLE 1).3 In obese women or other patients in whom the physical exam is difficult, historical clues—including postcoital bleeding, intermenstrual bleeding, or pelvic pain or pressure—also suggest a structural abnormality.4

Transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) is the initial method of evaluation when a structural abnormality is suspected.1,4 However, although TVUS is excellent at visualizing the myometrium, lesions within the uterine cavity can be missed. If intracavitary pathology, such as submucosal fibroids or endometrial polyps, is suspected, additional imaging with saline infusion sonohysterography (SIS) should be performed. If a cavitary abnormality is confirmed, hysteroscopy is indicated.1 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is reserved for cases in which a uterine cavity abnormality is found on TVUS but cannot be further characterized by SIS or hysteroscopy.1

Continue to: Endometrial biopsy...

Endometrial biopsy (EMB) is indicated as part of the initial evaluation of AUB in all women >45 years and in younger women who have risk factors for endometrial cancer, including polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), obesity, and hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Such biopsy is necessary in these women whether or not another condition is the cause of the AUB and regardless of findings on TVUS.1-4 Endometrial biopsy should also be performed in women with AUB that persists despite medical management. If office EMB is nondiagnostic, hysteroscopy or SIS can be used to obtain tissue samples for further evaluation.5

Polyps. An endometrial polyp is a benign growth of endometrial tissue that is covered with epithelial cells. Polyps are often diagnosed by EMB or TVUS when these techniques are performed as part of the workup for AUB.6 Endometrial polyps are found more commonly in postmenopausal women, but should be considered as a cause of AUB in premenopausal women, too, especially those with intermenstrual bleeding or postcoital bleeding (or both) that is unresponsive to medical management.7 Risk factors for polyps include older age, obesity, and treatment with tamoxifen.7 The usual treatment for symptomatic endometrial polyps is removal by operative hysteroscopy.7

Adenomyosis. Ectopic endometrial tissue in the myometrium that leads to hypertrophy of the myometrium and uterine enlargement is known as adenomyosis. The disorder is most often diagnosed in women 40 to 50 years of age, who commonly complain of heavy uterine bleeding (40%-60% of cases) and dysmenorrhea (65%).8 Although definitive diagnosis is made histologically at hysterectomy, TVUS and MRI can be useful tools to help narrow the differential diagnosis in women with unexplained AUB.

According to a systematic review,9 the sensitivity and specificity of imaging in the diagnosis of adenomyosis is 72% and 81%, respectively, for TVUS and 77% and 89%, respectively, for MRI. Needle biopsy, performed hysteroscopically or laparoscopically, is less useful because the technique has low sensitivity (reported variously as 8%-56%) in diagnosing adenomyosis.8

Treatment options for adenomyosis are medical management with agents that reduce bleeding (eg, a combination oral contraceptive [OC], nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], the antifibrinolytic tranexamic acid, and, when there is no distortion of the uterine cavity, a levonorgestrel intrauterine device [LNG-IUD]); uterine artery embolization; and hysterectomy.8

Continue to: Leiomyoma

Leiomyoma. Uterine fibroids, or leiomyomas, are benign, fibromuscular solid tumors, thought to be hormone-dependent because many regress after menopause. In women of reproductive age, uterine fibroids are the most common cause of structural AUB, with a cumulative incidence of 70% to 80% among women in this age group.3,10 Fibroids are more common in African-American women, women who experienced early menarche, and women who are obese, have PCOS, or had a late first pregnancy.3-10

Many fibroids are asymptomatic, and are found incidentally on sonographic examination performed for other reasons; in one-third of affected patients, the fibroids result in heavy menstrual bleeding.10 Intermenstrual bleeding and postcoital bleeding can occur, but are not common symptoms with fibroids. Consider other causes of AUB, such as endometrial polyps, when these symptoms are present.

Treatment of fibroids is medical or surgical. Medical management is a reasonable first-line option, especially in women who have not completed childbearing and who have small (<3 cm in diameter) fibroids. Options include a combination OC, NSAIDs, tranexamic acid, and, when the uterine cavity is not distorted, an LNG-IUD.4,10,11

For women with larger fibroids, those for whom the aforementioned medical treatments are unsuccessful, and those who are seeking more definitive treatment, uterine artery embolization, myomectomy, or hysterectomy can be considered.

› Uterine artery embolization is performed by an interventional radiologist under local anesthesia and, if necessary, moderate sedation.12 After the procedure, fibroids decrease in size due to avascular necrosis, but the remainder of the myometrium is relatively unaffected because collateral blood supply develops.13,14 Patients might experience abdominal cramping for 2 or 3 days following the procedure, which can be managed with an oral NSAID.12 Approximately 90% of women treated with embolization note improvement in AUB by 3 months after the procedure.15 Uterine artery embolization is not recommended in women who have not completed childbearing.12,16,17

Continue to: Myomectomy

› Myomectomy (removal of the leiomyoma) is the surgical treatment of choice for women who want to maintain fertility. Depending on the size and location of the fibroid(s), myomectomy can be performed as an open surgical procedure, laparoscopically, or hysteroscopically. At the discretion of the surgeon, leuprolide acetate, a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist, can be prescribed for 3 months before myomectomy to reduce intraoperative blood loss by decreasing the vascularity of the fibroids.4,18 Reduction in bleeding is reported in 70% to 90% of patients who undergo myomectomy.19

› Hysterectomy, the definitive treatment for uterine fibroids, should be reserved for women who have completed childbearing and who have failed (or have a contraindication to) other treatment options.

Malignancy/hyperplasia. EMB should be performed when endometrial malignancy/hyperplasia is suspected. As noted, endometrial cancer should be considered as a diagnostic possibility in women >45 years, in younger women with risk factors, and in women who have failed to respond to medical treatment for other suspected causes of AUB.5

When hyperplasia without atypia is diagnosed, the LNG-IUD or oral progesterone is an acceptable treatment option; note that fewer women who have an LNG-IUD eventually require hysterectomy, compared to women who take oral hormone therapy for AUB.20 When hyperplasia with atypia is diagnosed, hysterectomy is the treatment of choice. If a woman wishes to maintain fertility, however, oral progesterone therapy can be offered.21

When the diagnosis is cancer, the patient should be referred to a gynecologic oncologist for staging and treatment. Treatment varies depending on stage, but generally requires hysterectomy including bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, with possible chemotherapy or radiation, or both.22

Continue to: CASE 1

CASE 1

Ms. R undergoes a sonogram that reveals a 4-cm fibroid in the uterine fundus that has not distorted the uterine cavity. Although she has completed childbearing, Ms. R is not interested in a surgical procedure at this time. You recommend insertion of an LNG-IUD; she accepts your advice.

CASE 2

Claire G, 27 years old, with a body mass index of 41,* complains of irregular menses for several months. Her menstrual cycle is irregular, as is the duration of menses and amount of bleeding. She has some mild fatigue without dizziness.

The physical exam is notable for mild hirsutism, without abnormalities on pelvic examination. Lab testing reveals iron-deficiency anemia; a pregnancy test is negative.

The questions that were raised by Ms. R’s case challenge you here, too: What is the appropriate workup of Ms. G’s bleeding? Once the cause is confirmed, how should you treat her?

Nonstructural AUB: The “COEIN” mnemonic

In the absence of abnormalities on a pelvic exam, and after excluding endometrial malignancy/hyperplasia in patients with the aforementioned risk factors, a nonstructural cause of AUB should be considered (TABLE 1).3 In women 20 to 40 years of age, the primary common cause of nonstructural uterine bleeding is ovulatory dysfunction, most often caused by PCOS or anovulatory bleeding.

Continue to: For nonstructual causes of AUB...

For nonstructural causes of AUB, the recommended laboratory workup varies with the suspected diagnosis. In addition, recently pregnant women should have a quantitative assay of β human chorionic gonadotropin to evaluate for trophoblastic disease.5,23

Imaging is not usually recommended when the cause of AUB is suspected to be nonstructural. However, when PCOS is suspected, TVUS can be used to confirm the presence of polycystic ovaries.23

As noted, EMB should be performed when AUB is present in women >45 years, in patients of any age group who fail to respond to medical therapy, and in those at increased risk for endometrial cancer.

Coagulopathy. When heavy bleeding has been present since the onset of menarche, inherited bleeding disorders must be considered, the most common of which is von Willebrand disease, a disorder of platelet adhesion.24 It is estimated that just under 50% of adolescents with abnormal uterine bleeding have a coagulopathy, most often a platelet function disorder.25 Additional clues to the presence of a coagulation disorder include a family history of bleeding disorder, a personal history of bleeding problems associated with surgery, and a history of iron-deficiency anemia.26 Abnormal uterine bleeding might resolve with treatment of the underlying coagulopathy; if it does not, consider consultation with a hematologist before prescribing an NSAID or an OC.

Heavy bleeding in patients taking an anticoagulant falls into the category of coagulopathy-related AUB. No further workup is generally needed for these women.3

Continue to: Ovulatory dysfunction

Ovulatory dysfunction. Abnormal uterine bleeding caused by ovulatory dysfunction is generally due to PCOS or anovulatory bleeding. Other causes, beyond the scope of this discussion, include hypothyroidism, hyperandrogenism, female athlete triad, stress, and hyperprolactinemia.

› Polycystic ovary syndrome. A diagnosis of PCOS is made using any of several recognized criteria. The commonly used Rotterdam 2003 criteria27 require that at least 2 of the following be present to make a diagnosis of PCOS:

- oligo-ovulation or anovulation

- hyperandrogenism

- polycystic ovaries seen on ultrasonography.

In addition, women with PCOS are frequently obese, show signs of insulin resistance (diabetes, prediabetes, acanthosis nigricans), or hyperandrogenism (hirsutism, acne). Even if these latter findings are not present at diagnosis, women with PCOS are at risk for a metabolic disorder. Once a diagnosis of PCOS has been established, therefore, screening tests for diabetes and cardiac risk factors (eg, dyslipidemia) should be performed.28.29

To evaluate for hyperandrogenism, free testosterone should be measured using a high-sensitivity immunoassay in all women in whom PCOS is suspected. Because of a higher prevalence of nonclassical (ie, late-onset) congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) in women of Ashkenazi Jewish (estimated prevalence, 3.7%), Hispanic (1.9%), Slavic (1.6%), and Italian (0.3%) descent, screening for CAH as a possible cause of hyperandrogenism is also recommended, by a test of a morning 17-hydroxyprogesterone level.23,29,30 (Note: The general Caucasian population has an estimated prevalence of nonclassical CAH of 0.1%.30)

Treatment of PCOS should be individualized, based on a patient’s symptoms and comorbidities. For overweight and obese women, weight loss, exercise, and metformin (1500-2000 mg/d) are the mainstays of therapy, and might reduce AUB.29,31 If these measures do not reduce AUB, other options include an OC, an LNG-IUD, and NSAIDs.

Continue to: Information on treating other PCOS-related symptoms...

Information on treating other PCOS-related symptoms (acne, hirsutism) is available from many sources29; these treatments do not typically help the patient’s AUB, however, and are therefore not addressed in this article.

› Anovulatory bleeding. In adolescence, the most common cause of AUB is anovulation resulting from immaturity of the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian axis. During anovulatory cycles, the imbalance of estrogen and progesterone creates a fragile endometrium, leading to unpredictable bleeding and irregular cycles. Other less common causes of AUB, such as ovarian or adrenal tumor, should be considered in adolescents who have hirsutism but do not meet the criteria for PCOS.5

When seeing an adolescent for evaluation of AUB, be aware that emotional barriers might be present that make it difficult for her to talk about menses and sexual activity. Be patient and normalize the patient’s symptoms when appropriate. Pelvic exam can be deferred, especially in adolescents who have not yet had vaginal intercourse. When AUB occurs in an adolescent and the cause is thought to be immaturity of the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian axis, there is no need for laboratory testing or imaging studies, other than excluding hypothyroidism and pregnancy as the cause.

Oral contraceptives, NSAIDs, tranexamic acid, and the LNG-IUD are all options for treating patients who have anovulatory bleeding4,5 (TABLE 3). An OC has a major advantage for adolescents because it alleviates other complaints related to adolescent hormonal changes, such as acne, and provides contraception when taken on a regular basis.

Alternatively, the LNG-IUD has the benefit of ease of use once inserted, while still providing the added benefit of contraception. In women who have not yet had vaginal intercourse, an intrauterine device might not be the first choice of treatment, however, and should be prescribed only after discussion with the patient. For both OCs and the LNG-IUD, myths surrounding the use of these medications must be addressed with the patient and, if she is a minor, her parents or guardian.32

Continue to: NSAIDS can be effective because...

NSAIDs can be effective because they reduce bleeding by causing vasoconstriction, but they provide the greatest benefit when started before menses, which can be difficult for a patient who has irregular cycles.

Endometrial causes of AUB should be suspected when a patient has heavy menstrual bleeding with regular menstrual cycles and no other causes can be identified. Endometrial dysfunction as the cause of AUB stems from aberrations in the biochemical pathways of endometrial hemostasis and repair, and therefore is difficult to confirm by laboratory analysis or histologic evaluation.3 Medical management focuses on alleviating heavy menstrual bleeding (TABLE 3).

Iatrogenic. The most common type of iatrogenic AUB is unscheduled bleeding, also known as breakthrough bleeding, that occurs during hormonal treatment with an OC or during the first few months after insertion of an LNG-IUD or contraceptive implant.3 In most cases, no specific treatment is required; bleeding resolves upon continued use of the contraceptive.

Not yet classified. This category is difficult to define; it was created for causes of AUB that have not yet been identified and remain unclear. For example, a condition known as chronic endometritis is under study as a possible cause of AUB, but has not been assigned to a PALM–COEIN category.3 As more data become available and understanding of pathophysiologic mechanisms lead to better definitions of disease, this and other poorly understood conditions will be moved to an appropriate category in the FIGO classification system.

CASE 2

Ms. G is given a diagnosis of PCOS, based on her history. You recommend weight loss and exercise; screen her for diabetes and dyslipidemia; and prescribe metformin.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Barry D. Weiss, MD, University of Arizona College of Medicine, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Tucson, assisted with the editing of this manuscript.

CORRESPONDENCE

Melody A. Jordahl-Iafrato, MD, Community Hospital East Family Medicine Residency, 10122 East 10th Street, Suite 100, Indianapolis, IN 46229; Mjordahl-iafrato@ecommunity.com.

1. Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Practice Bulletin Number 128, July 2012: Diagnosis of abnormal uterine bleeding in reproductive-aged women. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:197-206.

2. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee Opinion No. 651: Menstruation in girls and adolescents: using the menstrual cycle as a vital sign. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:e143-e146.

3. Munro MG, Critchley HO, Broder MS, et al; FIGO Working Group on Menstrual Disorders. FIGO classifcation system (PALM-COEIN) for causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in nongravid women of reproductive age. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;133:3-13.

4. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Heavy menstrual bleeding: assessment and management [NG88]. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng88. Accessed February 28, 2019.

5. Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Practice Bulletin Number 136, July 2013: Management of abnormal uterine bleeding associated with ovulatory dysfunction. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:176-185.

6. Hassa H, Tekin B, Senses T, et al. Are the site, diameter, and number of endometrial polyps related with symptomatology? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:718-721.

7. Salim S, Won H, Nesbitt-Hawes E, et al. Diagnosis and management of endometrial polyps: a critical review of the literature. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18:569-581.

8. Struble J, Reid S, Bedaiwy MA. Adenomyosis: A clinical review of a challenging gynecologic condition. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2016;23:164-185.

9. Champaneria R, Abedin P, Daniels J, et al. Ultrasound scan and magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of adenomyosis: systematic review comparing test accuracy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010;89:1374-1384.

10. Bartels CB, Cayton KC, Chuong FS, et al. An evidence-based approach to the medical management of fibroids: a systematic review. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2016;59:30-52.

11. Lethaby A, Cooke I, Rees MC. Progesterone or progestogen-releasing intrauterine systems for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(4):CD002126.

12. Spies JB. Current role of uterine artery embolization in the management of uterine fibroids. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2016;59:93-102.

13. Gupta JK, Sinha A, Lumsden MA, et al. Uterine artery embolization for symptomatic uterine fibroids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(12):CD005073.

14. Edwards RD, Moss JG, Lumsden MA, et al; Committee of the Randomized Trial of Embolization versus Surgical Treatment for Fibroids. Uterine artery embolization versus surgery for symptomatic uterine fibroids. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:360-370.

15. Pron G, Bennett J, Common A, et al; Ontario Uterine Fibroid Embolization Collaboration Group. The Ontario Uterine Fibroid Embolization Trial. Part 2. Uterine fibroid reduction and symptom relief after uterine artery embolization for fibroids. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:120-127.

16. Torre A, Fauconnier A, Kahn V, et al. Fertility after uterine artery embolization for symptomatic multiple fibroids with no other infertility factors. Eur Radiol. 2017;27:2850-2859.

17. Mara M, Maskova J, Fucikova Z, et al. Midterm clinical and first reproductive results of a randomized controlled trial comparing uterine fibroid embolization and myomectomy. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2008;31:73-85.

18. Lethaby A, Vollenhoven B, Sowter M. Pre-operative GnRH analogue therapy before hysterectomy or myomectomy for uterine fibroids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(2): CD000547.

19. Capmas P, Levaillant JM, Fernandez H. Surgical techniques and outcome in the management of submucous fibroids. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2013;25:332-338.

20. Abu Hashim H, Ghayaty E, El Rakhawy M. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system vs oral progestins for non-atypical endometrial hyperplasia: a systematic review and metaanalysis of randomized trials. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:469-478.

21. Reed SD, Voigt LF, Newton KM, et al. Weiss NS. Progestin therapy of complex endometrial hyperplasia with and without atypia. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113;655-662.

22. Morice P, Leary A, Creutzberg C, et al. Endometrial cancer. Lancet. 2016;387:1094-1108.

23. Goodman NF, Cobin RH, Futterweit W, et al; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE); American College of Endocrinology (ACE); Androgen Excess and PCOS Society (AES). American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, American College of Endocrinology, and Androgen Excess and PCOS Society disease state clinical review: guide to the best practices in the evaluation and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome—part 1. Endocr Pract. 2015;21:1291-1300.

24. Shankar M, Lee CA, Sabin CA, et al. von Willebrand disease in women with menorrhagia: a systematic review. BJOG. 2004;111:734-740.

25. Seravalli V, Linari S, Peruzzi E, et al. Prevalence of hemostatic disorders in adolescents with abnormal uterine bleeding. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2013;26:285-289.

26. Philipp CS, Faiz A, Dowling NF, et al. Development of a screening tool for identifying women with menorrhagia for hemostatic evaluation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:163.e1-e8.

27. The Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-sponsored PCOS consensus workshop group. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Hum Reprod. 2004;19:41-47.

28. Goodman NF, Cobin RH, Futterweit W, et al; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE); American College of Endocrinology (ACE); Androgen Excess and PCOS Society (AES). American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, American College of Endocrinology, and Androgen Excess and PCOS Society disease state clinical review: guide to the best practices in the evaluation and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome—part 2. Endocr Pract. 2015;21:1415-26.

29. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No 194: Polycystic ovary syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e157-e171.

30. Speiser PW, Dupont B, Rubinstein P, et al. High frequency of nonclassical steroid 21-hydroxylase deficiency. Am J Hum Genet. 1985;37:650-667.

31. Naderpoor N, Shorakae S, de Courten B, et al. Metformin and lifestyle modification in polycystic ovary syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2015;21:560-574.

32. Kolman KB, Hadley SK, Jordahl-Iafrato MA. Long-acting reversible contraception: who, what, when, and how. J Fam Pract. 2015;64:479-484.

Menstrual bleeding is considered normal when it occurs regularly (every 21-35 days), lasts 4 to 8 days, and is not associated with heavy bleeding.1 During the first few years after menarche, it is normal for girls to experience irregular menstrual cycles but, by the third year, 60% to 80% of girls have an adult pattern of menstrual bleeding.2

Menstrual flow without normal volume, duration, regularity, or frequency is considered abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB). The condition is considered acute if there is need for immediate intervention. In the absence of the need for immediate intervention, recurrent AUB is classified as chronic.3 Chronic AUB is the focus of this article.

Invaluable tool: The FIGO classification

In 2011, the

- structural causes, recalled by “PALM” (Polyps, Adenomyosis, Leiomyoma, and Malignancy/hyperplasia)

- nonstructural causes, recalled by “COEIN” (Coagulopathy, Ovulatory dysfunction, Endometrial, Iatrogenic, and Not yet classified).

The PALM–COEIN system also uses descriptive terminology (heavy bleeding, intermenstrual bleeding) to characterize the bleeding pattern.3 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has adopted this classification system and recommends that such historically used terminology as “dysfunctional uterine bleeding,” “menorrhagia,” and “metrorrhagia” be abandoned.1

The initial workup of all causes of chronic uterine bleeding begins with a history; physical examination, including pelvic exam; and laboratory testing, including a urine pregnancy test, complete blood count, and a test of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TABLE 2). The need for additional laboratory testing, imaging, or endometrial biopsy depends on the suspected cause of AUB, detailed stepwise in FIGURE 1 (women <18 years) and FIGURE 2 (≥18 years).

We first briefly review the 9 categories of AUB in the PALM–COEIN system; discuss the most common causes in more detail; and review common treatment options (TABLE 3).

CASE 1

Marsha R, a 41-year-old-woman, complains of heavy menstrual bleeding for the past year that has become worse over the past 2 months. Her menstrual cycles have occurred every 28 days and last 10 days; she uses 10 to 12 pads a day.

Continue to: Recently, Ms. R reports...

Recently, Ms. R reports, she has been bleeding continuously for 14 days, with episodes of lighter bleeding followed by heavier bleeding. She also complains of fatigue.

Bimanual examination is notable for an enlarged uterus.

How would you proceed with the workup of this patient, to determine the cause of her bleeding and tailor management accordingly?

Structural AUB: The “PALM” mnemonic

A structural cause of AUB must be considered when you encounter an abnormality on physical exam (TABLE 1).3 In obese women or other patients in whom the physical exam is difficult, historical clues—including postcoital bleeding, intermenstrual bleeding, or pelvic pain or pressure—also suggest a structural abnormality.4

Transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) is the initial method of evaluation when a structural abnormality is suspected.1,4 However, although TVUS is excellent at visualizing the myometrium, lesions within the uterine cavity can be missed. If intracavitary pathology, such as submucosal fibroids or endometrial polyps, is suspected, additional imaging with saline infusion sonohysterography (SIS) should be performed. If a cavitary abnormality is confirmed, hysteroscopy is indicated.1 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is reserved for cases in which a uterine cavity abnormality is found on TVUS but cannot be further characterized by SIS or hysteroscopy.1

Continue to: Endometrial biopsy...

Endometrial biopsy (EMB) is indicated as part of the initial evaluation of AUB in all women >45 years and in younger women who have risk factors for endometrial cancer, including polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), obesity, and hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Such biopsy is necessary in these women whether or not another condition is the cause of the AUB and regardless of findings on TVUS.1-4 Endometrial biopsy should also be performed in women with AUB that persists despite medical management. If office EMB is nondiagnostic, hysteroscopy or SIS can be used to obtain tissue samples for further evaluation.5

Polyps. An endometrial polyp is a benign growth of endometrial tissue that is covered with epithelial cells. Polyps are often diagnosed by EMB or TVUS when these techniques are performed as part of the workup for AUB.6 Endometrial polyps are found more commonly in postmenopausal women, but should be considered as a cause of AUB in premenopausal women, too, especially those with intermenstrual bleeding or postcoital bleeding (or both) that is unresponsive to medical management.7 Risk factors for polyps include older age, obesity, and treatment with tamoxifen.7 The usual treatment for symptomatic endometrial polyps is removal by operative hysteroscopy.7

Adenomyosis. Ectopic endometrial tissue in the myometrium that leads to hypertrophy of the myometrium and uterine enlargement is known as adenomyosis. The disorder is most often diagnosed in women 40 to 50 years of age, who commonly complain of heavy uterine bleeding (40%-60% of cases) and dysmenorrhea (65%).8 Although definitive diagnosis is made histologically at hysterectomy, TVUS and MRI can be useful tools to help narrow the differential diagnosis in women with unexplained AUB.

According to a systematic review,9 the sensitivity and specificity of imaging in the diagnosis of adenomyosis is 72% and 81%, respectively, for TVUS and 77% and 89%, respectively, for MRI. Needle biopsy, performed hysteroscopically or laparoscopically, is less useful because the technique has low sensitivity (reported variously as 8%-56%) in diagnosing adenomyosis.8

Treatment options for adenomyosis are medical management with agents that reduce bleeding (eg, a combination oral contraceptive [OC], nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], the antifibrinolytic tranexamic acid, and, when there is no distortion of the uterine cavity, a levonorgestrel intrauterine device [LNG-IUD]); uterine artery embolization; and hysterectomy.8

Continue to: Leiomyoma

Leiomyoma. Uterine fibroids, or leiomyomas, are benign, fibromuscular solid tumors, thought to be hormone-dependent because many regress after menopause. In women of reproductive age, uterine fibroids are the most common cause of structural AUB, with a cumulative incidence of 70% to 80% among women in this age group.3,10 Fibroids are more common in African-American women, women who experienced early menarche, and women who are obese, have PCOS, or had a late first pregnancy.3-10

Many fibroids are asymptomatic, and are found incidentally on sonographic examination performed for other reasons; in one-third of affected patients, the fibroids result in heavy menstrual bleeding.10 Intermenstrual bleeding and postcoital bleeding can occur, but are not common symptoms with fibroids. Consider other causes of AUB, such as endometrial polyps, when these symptoms are present.

Treatment of fibroids is medical or surgical. Medical management is a reasonable first-line option, especially in women who have not completed childbearing and who have small (<3 cm in diameter) fibroids. Options include a combination OC, NSAIDs, tranexamic acid, and, when the uterine cavity is not distorted, an LNG-IUD.4,10,11

For women with larger fibroids, those for whom the aforementioned medical treatments are unsuccessful, and those who are seeking more definitive treatment, uterine artery embolization, myomectomy, or hysterectomy can be considered.

› Uterine artery embolization is performed by an interventional radiologist under local anesthesia and, if necessary, moderate sedation.12 After the procedure, fibroids decrease in size due to avascular necrosis, but the remainder of the myometrium is relatively unaffected because collateral blood supply develops.13,14 Patients might experience abdominal cramping for 2 or 3 days following the procedure, which can be managed with an oral NSAID.12 Approximately 90% of women treated with embolization note improvement in AUB by 3 months after the procedure.15 Uterine artery embolization is not recommended in women who have not completed childbearing.12,16,17

Continue to: Myomectomy

› Myomectomy (removal of the leiomyoma) is the surgical treatment of choice for women who want to maintain fertility. Depending on the size and location of the fibroid(s), myomectomy can be performed as an open surgical procedure, laparoscopically, or hysteroscopically. At the discretion of the surgeon, leuprolide acetate, a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist, can be prescribed for 3 months before myomectomy to reduce intraoperative blood loss by decreasing the vascularity of the fibroids.4,18 Reduction in bleeding is reported in 70% to 90% of patients who undergo myomectomy.19

› Hysterectomy, the definitive treatment for uterine fibroids, should be reserved for women who have completed childbearing and who have failed (or have a contraindication to) other treatment options.

Malignancy/hyperplasia. EMB should be performed when endometrial malignancy/hyperplasia is suspected. As noted, endometrial cancer should be considered as a diagnostic possibility in women >45 years, in younger women with risk factors, and in women who have failed to respond to medical treatment for other suspected causes of AUB.5

When hyperplasia without atypia is diagnosed, the LNG-IUD or oral progesterone is an acceptable treatment option; note that fewer women who have an LNG-IUD eventually require hysterectomy, compared to women who take oral hormone therapy for AUB.20 When hyperplasia with atypia is diagnosed, hysterectomy is the treatment of choice. If a woman wishes to maintain fertility, however, oral progesterone therapy can be offered.21

When the diagnosis is cancer, the patient should be referred to a gynecologic oncologist for staging and treatment. Treatment varies depending on stage, but generally requires hysterectomy including bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, with possible chemotherapy or radiation, or both.22

Continue to: CASE 1

CASE 1

Ms. R undergoes a sonogram that reveals a 4-cm fibroid in the uterine fundus that has not distorted the uterine cavity. Although she has completed childbearing, Ms. R is not interested in a surgical procedure at this time. You recommend insertion of an LNG-IUD; she accepts your advice.

CASE 2

Claire G, 27 years old, with a body mass index of 41,* complains of irregular menses for several months. Her menstrual cycle is irregular, as is the duration of menses and amount of bleeding. She has some mild fatigue without dizziness.

The physical exam is notable for mild hirsutism, without abnormalities on pelvic examination. Lab testing reveals iron-deficiency anemia; a pregnancy test is negative.

The questions that were raised by Ms. R’s case challenge you here, too: What is the appropriate workup of Ms. G’s bleeding? Once the cause is confirmed, how should you treat her?

Nonstructural AUB: The “COEIN” mnemonic

In the absence of abnormalities on a pelvic exam, and after excluding endometrial malignancy/hyperplasia in patients with the aforementioned risk factors, a nonstructural cause of AUB should be considered (TABLE 1).3 In women 20 to 40 years of age, the primary common cause of nonstructural uterine bleeding is ovulatory dysfunction, most often caused by PCOS or anovulatory bleeding.

Continue to: For nonstructual causes of AUB...

For nonstructural causes of AUB, the recommended laboratory workup varies with the suspected diagnosis. In addition, recently pregnant women should have a quantitative assay of β human chorionic gonadotropin to evaluate for trophoblastic disease.5,23

Imaging is not usually recommended when the cause of AUB is suspected to be nonstructural. However, when PCOS is suspected, TVUS can be used to confirm the presence of polycystic ovaries.23

As noted, EMB should be performed when AUB is present in women >45 years, in patients of any age group who fail to respond to medical therapy, and in those at increased risk for endometrial cancer.

Coagulopathy. When heavy bleeding has been present since the onset of menarche, inherited bleeding disorders must be considered, the most common of which is von Willebrand disease, a disorder of platelet adhesion.24 It is estimated that just under 50% of adolescents with abnormal uterine bleeding have a coagulopathy, most often a platelet function disorder.25 Additional clues to the presence of a coagulation disorder include a family history of bleeding disorder, a personal history of bleeding problems associated with surgery, and a history of iron-deficiency anemia.26 Abnormal uterine bleeding might resolve with treatment of the underlying coagulopathy; if it does not, consider consultation with a hematologist before prescribing an NSAID or an OC.

Heavy bleeding in patients taking an anticoagulant falls into the category of coagulopathy-related AUB. No further workup is generally needed for these women.3

Continue to: Ovulatory dysfunction

Ovulatory dysfunction. Abnormal uterine bleeding caused by ovulatory dysfunction is generally due to PCOS or anovulatory bleeding. Other causes, beyond the scope of this discussion, include hypothyroidism, hyperandrogenism, female athlete triad, stress, and hyperprolactinemia.

› Polycystic ovary syndrome. A diagnosis of PCOS is made using any of several recognized criteria. The commonly used Rotterdam 2003 criteria27 require that at least 2 of the following be present to make a diagnosis of PCOS:

- oligo-ovulation or anovulation

- hyperandrogenism

- polycystic ovaries seen on ultrasonography.

In addition, women with PCOS are frequently obese, show signs of insulin resistance (diabetes, prediabetes, acanthosis nigricans), or hyperandrogenism (hirsutism, acne). Even if these latter findings are not present at diagnosis, women with PCOS are at risk for a metabolic disorder. Once a diagnosis of PCOS has been established, therefore, screening tests for diabetes and cardiac risk factors (eg, dyslipidemia) should be performed.28.29

To evaluate for hyperandrogenism, free testosterone should be measured using a high-sensitivity immunoassay in all women in whom PCOS is suspected. Because of a higher prevalence of nonclassical (ie, late-onset) congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) in women of Ashkenazi Jewish (estimated prevalence, 3.7%), Hispanic (1.9%), Slavic (1.6%), and Italian (0.3%) descent, screening for CAH as a possible cause of hyperandrogenism is also recommended, by a test of a morning 17-hydroxyprogesterone level.23,29,30 (Note: The general Caucasian population has an estimated prevalence of nonclassical CAH of 0.1%.30)

Treatment of PCOS should be individualized, based on a patient’s symptoms and comorbidities. For overweight and obese women, weight loss, exercise, and metformin (1500-2000 mg/d) are the mainstays of therapy, and might reduce AUB.29,31 If these measures do not reduce AUB, other options include an OC, an LNG-IUD, and NSAIDs.

Continue to: Information on treating other PCOS-related symptoms...

Information on treating other PCOS-related symptoms (acne, hirsutism) is available from many sources29; these treatments do not typically help the patient’s AUB, however, and are therefore not addressed in this article.

› Anovulatory bleeding. In adolescence, the most common cause of AUB is anovulation resulting from immaturity of the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian axis. During anovulatory cycles, the imbalance of estrogen and progesterone creates a fragile endometrium, leading to unpredictable bleeding and irregular cycles. Other less common causes of AUB, such as ovarian or adrenal tumor, should be considered in adolescents who have hirsutism but do not meet the criteria for PCOS.5

When seeing an adolescent for evaluation of AUB, be aware that emotional barriers might be present that make it difficult for her to talk about menses and sexual activity. Be patient and normalize the patient’s symptoms when appropriate. Pelvic exam can be deferred, especially in adolescents who have not yet had vaginal intercourse. When AUB occurs in an adolescent and the cause is thought to be immaturity of the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian axis, there is no need for laboratory testing or imaging studies, other than excluding hypothyroidism and pregnancy as the cause.

Oral contraceptives, NSAIDs, tranexamic acid, and the LNG-IUD are all options for treating patients who have anovulatory bleeding4,5 (TABLE 3). An OC has a major advantage for adolescents because it alleviates other complaints related to adolescent hormonal changes, such as acne, and provides contraception when taken on a regular basis.

Alternatively, the LNG-IUD has the benefit of ease of use once inserted, while still providing the added benefit of contraception. In women who have not yet had vaginal intercourse, an intrauterine device might not be the first choice of treatment, however, and should be prescribed only after discussion with the patient. For both OCs and the LNG-IUD, myths surrounding the use of these medications must be addressed with the patient and, if she is a minor, her parents or guardian.32

Continue to: NSAIDS can be effective because...

NSAIDs can be effective because they reduce bleeding by causing vasoconstriction, but they provide the greatest benefit when started before menses, which can be difficult for a patient who has irregular cycles.

Endometrial causes of AUB should be suspected when a patient has heavy menstrual bleeding with regular menstrual cycles and no other causes can be identified. Endometrial dysfunction as the cause of AUB stems from aberrations in the biochemical pathways of endometrial hemostasis and repair, and therefore is difficult to confirm by laboratory analysis or histologic evaluation.3 Medical management focuses on alleviating heavy menstrual bleeding (TABLE 3).

Iatrogenic. The most common type of iatrogenic AUB is unscheduled bleeding, also known as breakthrough bleeding, that occurs during hormonal treatment with an OC or during the first few months after insertion of an LNG-IUD or contraceptive implant.3 In most cases, no specific treatment is required; bleeding resolves upon continued use of the contraceptive.

Not yet classified. This category is difficult to define; it was created for causes of AUB that have not yet been identified and remain unclear. For example, a condition known as chronic endometritis is under study as a possible cause of AUB, but has not been assigned to a PALM–COEIN category.3 As more data become available and understanding of pathophysiologic mechanisms lead to better definitions of disease, this and other poorly understood conditions will be moved to an appropriate category in the FIGO classification system.

CASE 2

Ms. G is given a diagnosis of PCOS, based on her history. You recommend weight loss and exercise; screen her for diabetes and dyslipidemia; and prescribe metformin.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Barry D. Weiss, MD, University of Arizona College of Medicine, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Tucson, assisted with the editing of this manuscript.

CORRESPONDENCE

Melody A. Jordahl-Iafrato, MD, Community Hospital East Family Medicine Residency, 10122 East 10th Street, Suite 100, Indianapolis, IN 46229; Mjordahl-iafrato@ecommunity.com.

Menstrual bleeding is considered normal when it occurs regularly (every 21-35 days), lasts 4 to 8 days, and is not associated with heavy bleeding.1 During the first few years after menarche, it is normal for girls to experience irregular menstrual cycles but, by the third year, 60% to 80% of girls have an adult pattern of menstrual bleeding.2

Menstrual flow without normal volume, duration, regularity, or frequency is considered abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB). The condition is considered acute if there is need for immediate intervention. In the absence of the need for immediate intervention, recurrent AUB is classified as chronic.3 Chronic AUB is the focus of this article.

Invaluable tool: The FIGO classification

In 2011, the

- structural causes, recalled by “PALM” (Polyps, Adenomyosis, Leiomyoma, and Malignancy/hyperplasia)

- nonstructural causes, recalled by “COEIN” (Coagulopathy, Ovulatory dysfunction, Endometrial, Iatrogenic, and Not yet classified).

The PALM–COEIN system also uses descriptive terminology (heavy bleeding, intermenstrual bleeding) to characterize the bleeding pattern.3 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has adopted this classification system and recommends that such historically used terminology as “dysfunctional uterine bleeding,” “menorrhagia,” and “metrorrhagia” be abandoned.1

The initial workup of all causes of chronic uterine bleeding begins with a history; physical examination, including pelvic exam; and laboratory testing, including a urine pregnancy test, complete blood count, and a test of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TABLE 2). The need for additional laboratory testing, imaging, or endometrial biopsy depends on the suspected cause of AUB, detailed stepwise in FIGURE 1 (women <18 years) and FIGURE 2 (≥18 years).

We first briefly review the 9 categories of AUB in the PALM–COEIN system; discuss the most common causes in more detail; and review common treatment options (TABLE 3).

CASE 1

Marsha R, a 41-year-old-woman, complains of heavy menstrual bleeding for the past year that has become worse over the past 2 months. Her menstrual cycles have occurred every 28 days and last 10 days; she uses 10 to 12 pads a day.

Continue to: Recently, Ms. R reports...

Recently, Ms. R reports, she has been bleeding continuously for 14 days, with episodes of lighter bleeding followed by heavier bleeding. She also complains of fatigue.

Bimanual examination is notable for an enlarged uterus.

How would you proceed with the workup of this patient, to determine the cause of her bleeding and tailor management accordingly?

Structural AUB: The “PALM” mnemonic

A structural cause of AUB must be considered when you encounter an abnormality on physical exam (TABLE 1).3 In obese women or other patients in whom the physical exam is difficult, historical clues—including postcoital bleeding, intermenstrual bleeding, or pelvic pain or pressure—also suggest a structural abnormality.4

Transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) is the initial method of evaluation when a structural abnormality is suspected.1,4 However, although TVUS is excellent at visualizing the myometrium, lesions within the uterine cavity can be missed. If intracavitary pathology, such as submucosal fibroids or endometrial polyps, is suspected, additional imaging with saline infusion sonohysterography (SIS) should be performed. If a cavitary abnormality is confirmed, hysteroscopy is indicated.1 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is reserved for cases in which a uterine cavity abnormality is found on TVUS but cannot be further characterized by SIS or hysteroscopy.1

Continue to: Endometrial biopsy...

Endometrial biopsy (EMB) is indicated as part of the initial evaluation of AUB in all women >45 years and in younger women who have risk factors for endometrial cancer, including polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), obesity, and hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Such biopsy is necessary in these women whether or not another condition is the cause of the AUB and regardless of findings on TVUS.1-4 Endometrial biopsy should also be performed in women with AUB that persists despite medical management. If office EMB is nondiagnostic, hysteroscopy or SIS can be used to obtain tissue samples for further evaluation.5

Polyps. An endometrial polyp is a benign growth of endometrial tissue that is covered with epithelial cells. Polyps are often diagnosed by EMB or TVUS when these techniques are performed as part of the workup for AUB.6 Endometrial polyps are found more commonly in postmenopausal women, but should be considered as a cause of AUB in premenopausal women, too, especially those with intermenstrual bleeding or postcoital bleeding (or both) that is unresponsive to medical management.7 Risk factors for polyps include older age, obesity, and treatment with tamoxifen.7 The usual treatment for symptomatic endometrial polyps is removal by operative hysteroscopy.7

Adenomyosis. Ectopic endometrial tissue in the myometrium that leads to hypertrophy of the myometrium and uterine enlargement is known as adenomyosis. The disorder is most often diagnosed in women 40 to 50 years of age, who commonly complain of heavy uterine bleeding (40%-60% of cases) and dysmenorrhea (65%).8 Although definitive diagnosis is made histologically at hysterectomy, TVUS and MRI can be useful tools to help narrow the differential diagnosis in women with unexplained AUB.

According to a systematic review,9 the sensitivity and specificity of imaging in the diagnosis of adenomyosis is 72% and 81%, respectively, for TVUS and 77% and 89%, respectively, for MRI. Needle biopsy, performed hysteroscopically or laparoscopically, is less useful because the technique has low sensitivity (reported variously as 8%-56%) in diagnosing adenomyosis.8

Treatment options for adenomyosis are medical management with agents that reduce bleeding (eg, a combination oral contraceptive [OC], nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], the antifibrinolytic tranexamic acid, and, when there is no distortion of the uterine cavity, a levonorgestrel intrauterine device [LNG-IUD]); uterine artery embolization; and hysterectomy.8

Continue to: Leiomyoma

Leiomyoma. Uterine fibroids, or leiomyomas, are benign, fibromuscular solid tumors, thought to be hormone-dependent because many regress after menopause. In women of reproductive age, uterine fibroids are the most common cause of structural AUB, with a cumulative incidence of 70% to 80% among women in this age group.3,10 Fibroids are more common in African-American women, women who experienced early menarche, and women who are obese, have PCOS, or had a late first pregnancy.3-10

Many fibroids are asymptomatic, and are found incidentally on sonographic examination performed for other reasons; in one-third of affected patients, the fibroids result in heavy menstrual bleeding.10 Intermenstrual bleeding and postcoital bleeding can occur, but are not common symptoms with fibroids. Consider other causes of AUB, such as endometrial polyps, when these symptoms are present.

Treatment of fibroids is medical or surgical. Medical management is a reasonable first-line option, especially in women who have not completed childbearing and who have small (<3 cm in diameter) fibroids. Options include a combination OC, NSAIDs, tranexamic acid, and, when the uterine cavity is not distorted, an LNG-IUD.4,10,11

For women with larger fibroids, those for whom the aforementioned medical treatments are unsuccessful, and those who are seeking more definitive treatment, uterine artery embolization, myomectomy, or hysterectomy can be considered.

› Uterine artery embolization is performed by an interventional radiologist under local anesthesia and, if necessary, moderate sedation.12 After the procedure, fibroids decrease in size due to avascular necrosis, but the remainder of the myometrium is relatively unaffected because collateral blood supply develops.13,14 Patients might experience abdominal cramping for 2 or 3 days following the procedure, which can be managed with an oral NSAID.12 Approximately 90% of women treated with embolization note improvement in AUB by 3 months after the procedure.15 Uterine artery embolization is not recommended in women who have not completed childbearing.12,16,17

Continue to: Myomectomy

› Myomectomy (removal of the leiomyoma) is the surgical treatment of choice for women who want to maintain fertility. Depending on the size and location of the fibroid(s), myomectomy can be performed as an open surgical procedure, laparoscopically, or hysteroscopically. At the discretion of the surgeon, leuprolide acetate, a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist, can be prescribed for 3 months before myomectomy to reduce intraoperative blood loss by decreasing the vascularity of the fibroids.4,18 Reduction in bleeding is reported in 70% to 90% of patients who undergo myomectomy.19

› Hysterectomy, the definitive treatment for uterine fibroids, should be reserved for women who have completed childbearing and who have failed (or have a contraindication to) other treatment options.

Malignancy/hyperplasia. EMB should be performed when endometrial malignancy/hyperplasia is suspected. As noted, endometrial cancer should be considered as a diagnostic possibility in women >45 years, in younger women with risk factors, and in women who have failed to respond to medical treatment for other suspected causes of AUB.5

When hyperplasia without atypia is diagnosed, the LNG-IUD or oral progesterone is an acceptable treatment option; note that fewer women who have an LNG-IUD eventually require hysterectomy, compared to women who take oral hormone therapy for AUB.20 When hyperplasia with atypia is diagnosed, hysterectomy is the treatment of choice. If a woman wishes to maintain fertility, however, oral progesterone therapy can be offered.21

When the diagnosis is cancer, the patient should be referred to a gynecologic oncologist for staging and treatment. Treatment varies depending on stage, but generally requires hysterectomy including bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, with possible chemotherapy or radiation, or both.22

Continue to: CASE 1

CASE 1

Ms. R undergoes a sonogram that reveals a 4-cm fibroid in the uterine fundus that has not distorted the uterine cavity. Although she has completed childbearing, Ms. R is not interested in a surgical procedure at this time. You recommend insertion of an LNG-IUD; she accepts your advice.

CASE 2

Claire G, 27 years old, with a body mass index of 41,* complains of irregular menses for several months. Her menstrual cycle is irregular, as is the duration of menses and amount of bleeding. She has some mild fatigue without dizziness.

The physical exam is notable for mild hirsutism, without abnormalities on pelvic examination. Lab testing reveals iron-deficiency anemia; a pregnancy test is negative.

The questions that were raised by Ms. R’s case challenge you here, too: What is the appropriate workup of Ms. G’s bleeding? Once the cause is confirmed, how should you treat her?

Nonstructural AUB: The “COEIN” mnemonic

In the absence of abnormalities on a pelvic exam, and after excluding endometrial malignancy/hyperplasia in patients with the aforementioned risk factors, a nonstructural cause of AUB should be considered (TABLE 1).3 In women 20 to 40 years of age, the primary common cause of nonstructural uterine bleeding is ovulatory dysfunction, most often caused by PCOS or anovulatory bleeding.

Continue to: For nonstructual causes of AUB...

For nonstructural causes of AUB, the recommended laboratory workup varies with the suspected diagnosis. In addition, recently pregnant women should have a quantitative assay of β human chorionic gonadotropin to evaluate for trophoblastic disease.5,23

Imaging is not usually recommended when the cause of AUB is suspected to be nonstructural. However, when PCOS is suspected, TVUS can be used to confirm the presence of polycystic ovaries.23

As noted, EMB should be performed when AUB is present in women >45 years, in patients of any age group who fail to respond to medical therapy, and in those at increased risk for endometrial cancer.

Coagulopathy. When heavy bleeding has been present since the onset of menarche, inherited bleeding disorders must be considered, the most common of which is von Willebrand disease, a disorder of platelet adhesion.24 It is estimated that just under 50% of adolescents with abnormal uterine bleeding have a coagulopathy, most often a platelet function disorder.25 Additional clues to the presence of a coagulation disorder include a family history of bleeding disorder, a personal history of bleeding problems associated with surgery, and a history of iron-deficiency anemia.26 Abnormal uterine bleeding might resolve with treatment of the underlying coagulopathy; if it does not, consider consultation with a hematologist before prescribing an NSAID or an OC.

Heavy bleeding in patients taking an anticoagulant falls into the category of coagulopathy-related AUB. No further workup is generally needed for these women.3

Continue to: Ovulatory dysfunction

Ovulatory dysfunction. Abnormal uterine bleeding caused by ovulatory dysfunction is generally due to PCOS or anovulatory bleeding. Other causes, beyond the scope of this discussion, include hypothyroidism, hyperandrogenism, female athlete triad, stress, and hyperprolactinemia.

› Polycystic ovary syndrome. A diagnosis of PCOS is made using any of several recognized criteria. The commonly used Rotterdam 2003 criteria27 require that at least 2 of the following be present to make a diagnosis of PCOS:

- oligo-ovulation or anovulation

- hyperandrogenism

- polycystic ovaries seen on ultrasonography.

In addition, women with PCOS are frequently obese, show signs of insulin resistance (diabetes, prediabetes, acanthosis nigricans), or hyperandrogenism (hirsutism, acne). Even if these latter findings are not present at diagnosis, women with PCOS are at risk for a metabolic disorder. Once a diagnosis of PCOS has been established, therefore, screening tests for diabetes and cardiac risk factors (eg, dyslipidemia) should be performed.28.29

To evaluate for hyperandrogenism, free testosterone should be measured using a high-sensitivity immunoassay in all women in whom PCOS is suspected. Because of a higher prevalence of nonclassical (ie, late-onset) congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) in women of Ashkenazi Jewish (estimated prevalence, 3.7%), Hispanic (1.9%), Slavic (1.6%), and Italian (0.3%) descent, screening for CAH as a possible cause of hyperandrogenism is also recommended, by a test of a morning 17-hydroxyprogesterone level.23,29,30 (Note: The general Caucasian population has an estimated prevalence of nonclassical CAH of 0.1%.30)

Treatment of PCOS should be individualized, based on a patient’s symptoms and comorbidities. For overweight and obese women, weight loss, exercise, and metformin (1500-2000 mg/d) are the mainstays of therapy, and might reduce AUB.29,31 If these measures do not reduce AUB, other options include an OC, an LNG-IUD, and NSAIDs.

Continue to: Information on treating other PCOS-related symptoms...

Information on treating other PCOS-related symptoms (acne, hirsutism) is available from many sources29; these treatments do not typically help the patient’s AUB, however, and are therefore not addressed in this article.

› Anovulatory bleeding. In adolescence, the most common cause of AUB is anovulation resulting from immaturity of the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian axis. During anovulatory cycles, the imbalance of estrogen and progesterone creates a fragile endometrium, leading to unpredictable bleeding and irregular cycles. Other less common causes of AUB, such as ovarian or adrenal tumor, should be considered in adolescents who have hirsutism but do not meet the criteria for PCOS.5

When seeing an adolescent for evaluation of AUB, be aware that emotional barriers might be present that make it difficult for her to talk about menses and sexual activity. Be patient and normalize the patient’s symptoms when appropriate. Pelvic exam can be deferred, especially in adolescents who have not yet had vaginal intercourse. When AUB occurs in an adolescent and the cause is thought to be immaturity of the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian axis, there is no need for laboratory testing or imaging studies, other than excluding hypothyroidism and pregnancy as the cause.

Oral contraceptives, NSAIDs, tranexamic acid, and the LNG-IUD are all options for treating patients who have anovulatory bleeding4,5 (TABLE 3). An OC has a major advantage for adolescents because it alleviates other complaints related to adolescent hormonal changes, such as acne, and provides contraception when taken on a regular basis.

Alternatively, the LNG-IUD has the benefit of ease of use once inserted, while still providing the added benefit of contraception. In women who have not yet had vaginal intercourse, an intrauterine device might not be the first choice of treatment, however, and should be prescribed only after discussion with the patient. For both OCs and the LNG-IUD, myths surrounding the use of these medications must be addressed with the patient and, if she is a minor, her parents or guardian.32

Continue to: NSAIDS can be effective because...

NSAIDs can be effective because they reduce bleeding by causing vasoconstriction, but they provide the greatest benefit when started before menses, which can be difficult for a patient who has irregular cycles.

Endometrial causes of AUB should be suspected when a patient has heavy menstrual bleeding with regular menstrual cycles and no other causes can be identified. Endometrial dysfunction as the cause of AUB stems from aberrations in the biochemical pathways of endometrial hemostasis and repair, and therefore is difficult to confirm by laboratory analysis or histologic evaluation.3 Medical management focuses on alleviating heavy menstrual bleeding (TABLE 3).

Iatrogenic. The most common type of iatrogenic AUB is unscheduled bleeding, also known as breakthrough bleeding, that occurs during hormonal treatment with an OC or during the first few months after insertion of an LNG-IUD or contraceptive implant.3 In most cases, no specific treatment is required; bleeding resolves upon continued use of the contraceptive.

Not yet classified. This category is difficult to define; it was created for causes of AUB that have not yet been identified and remain unclear. For example, a condition known as chronic endometritis is under study as a possible cause of AUB, but has not been assigned to a PALM–COEIN category.3 As more data become available and understanding of pathophysiologic mechanisms lead to better definitions of disease, this and other poorly understood conditions will be moved to an appropriate category in the FIGO classification system.

CASE 2

Ms. G is given a diagnosis of PCOS, based on her history. You recommend weight loss and exercise; screen her for diabetes and dyslipidemia; and prescribe metformin.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Barry D. Weiss, MD, University of Arizona College of Medicine, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Tucson, assisted with the editing of this manuscript.

CORRESPONDENCE

Melody A. Jordahl-Iafrato, MD, Community Hospital East Family Medicine Residency, 10122 East 10th Street, Suite 100, Indianapolis, IN 46229; Mjordahl-iafrato@ecommunity.com.

1. Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Practice Bulletin Number 128, July 2012: Diagnosis of abnormal uterine bleeding in reproductive-aged women. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:197-206.

2. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee Opinion No. 651: Menstruation in girls and adolescents: using the menstrual cycle as a vital sign. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:e143-e146.

3. Munro MG, Critchley HO, Broder MS, et al; FIGO Working Group on Menstrual Disorders. FIGO classifcation system (PALM-COEIN) for causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in nongravid women of reproductive age. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;133:3-13.

4. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Heavy menstrual bleeding: assessment and management [NG88]. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng88. Accessed February 28, 2019.

5. Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Practice Bulletin Number 136, July 2013: Management of abnormal uterine bleeding associated with ovulatory dysfunction. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:176-185.

6. Hassa H, Tekin B, Senses T, et al. Are the site, diameter, and number of endometrial polyps related with symptomatology? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:718-721.

7. Salim S, Won H, Nesbitt-Hawes E, et al. Diagnosis and management of endometrial polyps: a critical review of the literature. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18:569-581.

8. Struble J, Reid S, Bedaiwy MA. Adenomyosis: A clinical review of a challenging gynecologic condition. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2016;23:164-185.

9. Champaneria R, Abedin P, Daniels J, et al. Ultrasound scan and magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of adenomyosis: systematic review comparing test accuracy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010;89:1374-1384.

10. Bartels CB, Cayton KC, Chuong FS, et al. An evidence-based approach to the medical management of fibroids: a systematic review. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2016;59:30-52.

11. Lethaby A, Cooke I, Rees MC. Progesterone or progestogen-releasing intrauterine systems for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(4):CD002126.

12. Spies JB. Current role of uterine artery embolization in the management of uterine fibroids. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2016;59:93-102.

13. Gupta JK, Sinha A, Lumsden MA, et al. Uterine artery embolization for symptomatic uterine fibroids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(12):CD005073.

14. Edwards RD, Moss JG, Lumsden MA, et al; Committee of the Randomized Trial of Embolization versus Surgical Treatment for Fibroids. Uterine artery embolization versus surgery for symptomatic uterine fibroids. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:360-370.

15. Pron G, Bennett J, Common A, et al; Ontario Uterine Fibroid Embolization Collaboration Group. The Ontario Uterine Fibroid Embolization Trial. Part 2. Uterine fibroid reduction and symptom relief after uterine artery embolization for fibroids. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:120-127.

16. Torre A, Fauconnier A, Kahn V, et al. Fertility after uterine artery embolization for symptomatic multiple fibroids with no other infertility factors. Eur Radiol. 2017;27:2850-2859.

17. Mara M, Maskova J, Fucikova Z, et al. Midterm clinical and first reproductive results of a randomized controlled trial comparing uterine fibroid embolization and myomectomy. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2008;31:73-85.

18. Lethaby A, Vollenhoven B, Sowter M. Pre-operative GnRH analogue therapy before hysterectomy or myomectomy for uterine fibroids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(2): CD000547.

19. Capmas P, Levaillant JM, Fernandez H. Surgical techniques and outcome in the management of submucous fibroids. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2013;25:332-338.

20. Abu Hashim H, Ghayaty E, El Rakhawy M. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system vs oral progestins for non-atypical endometrial hyperplasia: a systematic review and metaanalysis of randomized trials. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:469-478.

21. Reed SD, Voigt LF, Newton KM, et al. Weiss NS. Progestin therapy of complex endometrial hyperplasia with and without atypia. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113;655-662.

22. Morice P, Leary A, Creutzberg C, et al. Endometrial cancer. Lancet. 2016;387:1094-1108.

23. Goodman NF, Cobin RH, Futterweit W, et al; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE); American College of Endocrinology (ACE); Androgen Excess and PCOS Society (AES). American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, American College of Endocrinology, and Androgen Excess and PCOS Society disease state clinical review: guide to the best practices in the evaluation and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome—part 1. Endocr Pract. 2015;21:1291-1300.

24. Shankar M, Lee CA, Sabin CA, et al. von Willebrand disease in women with menorrhagia: a systematic review. BJOG. 2004;111:734-740.

25. Seravalli V, Linari S, Peruzzi E, et al. Prevalence of hemostatic disorders in adolescents with abnormal uterine bleeding. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2013;26:285-289.

26. Philipp CS, Faiz A, Dowling NF, et al. Development of a screening tool for identifying women with menorrhagia for hemostatic evaluation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:163.e1-e8.

27. The Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-sponsored PCOS consensus workshop group. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Hum Reprod. 2004;19:41-47.

28. Goodman NF, Cobin RH, Futterweit W, et al; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE); American College of Endocrinology (ACE); Androgen Excess and PCOS Society (AES). American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, American College of Endocrinology, and Androgen Excess and PCOS Society disease state clinical review: guide to the best practices in the evaluation and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome—part 2. Endocr Pract. 2015;21:1415-26.

29. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No 194: Polycystic ovary syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e157-e171.

30. Speiser PW, Dupont B, Rubinstein P, et al. High frequency of nonclassical steroid 21-hydroxylase deficiency. Am J Hum Genet. 1985;37:650-667.

31. Naderpoor N, Shorakae S, de Courten B, et al. Metformin and lifestyle modification in polycystic ovary syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2015;21:560-574.

32. Kolman KB, Hadley SK, Jordahl-Iafrato MA. Long-acting reversible contraception: who, what, when, and how. J Fam Pract. 2015;64:479-484.

1. Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Practice Bulletin Number 128, July 2012: Diagnosis of abnormal uterine bleeding in reproductive-aged women. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:197-206.

2. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee Opinion No. 651: Menstruation in girls and adolescents: using the menstrual cycle as a vital sign. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:e143-e146.

3. Munro MG, Critchley HO, Broder MS, et al; FIGO Working Group on Menstrual Disorders. FIGO classifcation system (PALM-COEIN) for causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in nongravid women of reproductive age. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;133:3-13.

4. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Heavy menstrual bleeding: assessment and management [NG88]. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng88. Accessed February 28, 2019.

5. Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Practice Bulletin Number 136, July 2013: Management of abnormal uterine bleeding associated with ovulatory dysfunction. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:176-185.

6. Hassa H, Tekin B, Senses T, et al. Are the site, diameter, and number of endometrial polyps related with symptomatology? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:718-721.

7. Salim S, Won H, Nesbitt-Hawes E, et al. Diagnosis and management of endometrial polyps: a critical review of the literature. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18:569-581.

8. Struble J, Reid S, Bedaiwy MA. Adenomyosis: A clinical review of a challenging gynecologic condition. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2016;23:164-185.

9. Champaneria R, Abedin P, Daniels J, et al. Ultrasound scan and magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of adenomyosis: systematic review comparing test accuracy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010;89:1374-1384.

10. Bartels CB, Cayton KC, Chuong FS, et al. An evidence-based approach to the medical management of fibroids: a systematic review. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2016;59:30-52.

11. Lethaby A, Cooke I, Rees MC. Progesterone or progestogen-releasing intrauterine systems for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(4):CD002126.

12. Spies JB. Current role of uterine artery embolization in the management of uterine fibroids. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2016;59:93-102.

13. Gupta JK, Sinha A, Lumsden MA, et al. Uterine artery embolization for symptomatic uterine fibroids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(12):CD005073.

14. Edwards RD, Moss JG, Lumsden MA, et al; Committee of the Randomized Trial of Embolization versus Surgical Treatment for Fibroids. Uterine artery embolization versus surgery for symptomatic uterine fibroids. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:360-370.

15. Pron G, Bennett J, Common A, et al; Ontario Uterine Fibroid Embolization Collaboration Group. The Ontario Uterine Fibroid Embolization Trial. Part 2. Uterine fibroid reduction and symptom relief after uterine artery embolization for fibroids. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:120-127.

16. Torre A, Fauconnier A, Kahn V, et al. Fertility after uterine artery embolization for symptomatic multiple fibroids with no other infertility factors. Eur Radiol. 2017;27:2850-2859.

17. Mara M, Maskova J, Fucikova Z, et al. Midterm clinical and first reproductive results of a randomized controlled trial comparing uterine fibroid embolization and myomectomy. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2008;31:73-85.

18. Lethaby A, Vollenhoven B, Sowter M. Pre-operative GnRH analogue therapy before hysterectomy or myomectomy for uterine fibroids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(2): CD000547.

19. Capmas P, Levaillant JM, Fernandez H. Surgical techniques and outcome in the management of submucous fibroids. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2013;25:332-338.

20. Abu Hashim H, Ghayaty E, El Rakhawy M. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system vs oral progestins for non-atypical endometrial hyperplasia: a systematic review and metaanalysis of randomized trials. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:469-478.

21. Reed SD, Voigt LF, Newton KM, et al. Weiss NS. Progestin therapy of complex endometrial hyperplasia with and without atypia. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113;655-662.

22. Morice P, Leary A, Creutzberg C, et al. Endometrial cancer. Lancet. 2016;387:1094-1108.

23. Goodman NF, Cobin RH, Futterweit W, et al; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE); American College of Endocrinology (ACE); Androgen Excess and PCOS Society (AES). American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, American College of Endocrinology, and Androgen Excess and PCOS Society disease state clinical review: guide to the best practices in the evaluation and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome—part 1. Endocr Pract. 2015;21:1291-1300.

24. Shankar M, Lee CA, Sabin CA, et al. von Willebrand disease in women with menorrhagia: a systematic review. BJOG. 2004;111:734-740.

25. Seravalli V, Linari S, Peruzzi E, et al. Prevalence of hemostatic disorders in adolescents with abnormal uterine bleeding. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2013;26:285-289.

26. Philipp CS, Faiz A, Dowling NF, et al. Development of a screening tool for identifying women with menorrhagia for hemostatic evaluation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:163.e1-e8.

27. The Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-sponsored PCOS consensus workshop group. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Hum Reprod. 2004;19:41-47.

28. Goodman NF, Cobin RH, Futterweit W, et al; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE); American College of Endocrinology (ACE); Androgen Excess and PCOS Society (AES). American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, American College of Endocrinology, and Androgen Excess and PCOS Society disease state clinical review: guide to the best practices in the evaluation and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome—part 2. Endocr Pract. 2015;21:1415-26.

29. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No 194: Polycystic ovary syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e157-e171.

30. Speiser PW, Dupont B, Rubinstein P, et al. High frequency of nonclassical steroid 21-hydroxylase deficiency. Am J Hum Genet. 1985;37:650-667.

31. Naderpoor N, Shorakae S, de Courten B, et al. Metformin and lifestyle modification in polycystic ovary syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2015;21:560-574.

32. Kolman KB, Hadley SK, Jordahl-Iafrato MA. Long-acting reversible contraception: who, what, when, and how. J Fam Pract. 2015;64:479-484.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Perform endometrial biopsy on all women who have abnormal uterine bleeding and risk factors for endometrial cancer and on all women ≥45 years, regardless of risk. C

› Initiate a workup for a coagulation disorder in women who are close to the onset of menarche and have a history of heavy menstrual bleeding. C

› Promote lifestyle changes and weight loss as primary treatments for polycystic ovary syndrome. B