User login

Is your patient’s cannabis use problematic?

CASE

Jessica F is a new 23-year-old patient at your clinic who is seeing you to discuss her severe anxiety. She also has asthma and reports during your exploration of her family history that her father has been diagnosed with schizophrenia. She has been using 3 cartridges of cannabis vape daily to help “calm her mind” but has never tried other psychotropic medications and has never been referred to a psychiatrist.

How would you proceed with this patient?

Despite emerging evidence of the harmful effects of cannabis consumption, public perception of harm has steadily declined over the past 10 years.1,2 More adults are using cannabis than before and using it more frequently. Among primary care patients who consume cannabis recreationally, about half report less than monthly consumption; 15% use it weekly, and 20% daily.3 The potency of cannabis products has also increased. In the past 2 decades, the average tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) content of recreational cannabis rose from 3% to 19%, and high-THC content delivery modalities such as vaporizer pens (“vapes”) were introduced.4,5

Health hazards of cannabis use include gastrointestinal dysfunction (eg, cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome), acute psychosis or exacerbation of an existing mood, anxiety, or psychotic disorder, and cardiovascular sequelae such as myocardial infarction or dysrhythmia.6 Potential long-term effects include neurocognitive impairment among adolescents who use cannabis,7-9 worse outcomes in anxiety and mood disorders,10 schizophrenia,11 cardiovascular sequelae,12 chronic bronchitis,13 negative impact on reproductive function,14 and poor birth outcomes.15-17

Hidden in plain sight. Many patients who use cannabis report that their primary care physicians are unaware of their cannabis consumption.18 Inadequate screening for cannabis can be attributed to time constraints, inconsistent definitions for problematic or risky cannabis use, and lack of guidance.19,20 This article offers a more inclusive definition of “problematic cannabis use,” presents an up-to-date framework for evaluating it in the outpatient setting, and outlines potential interventions.

Your patient doesn’t meetthe DSM criteria, but …

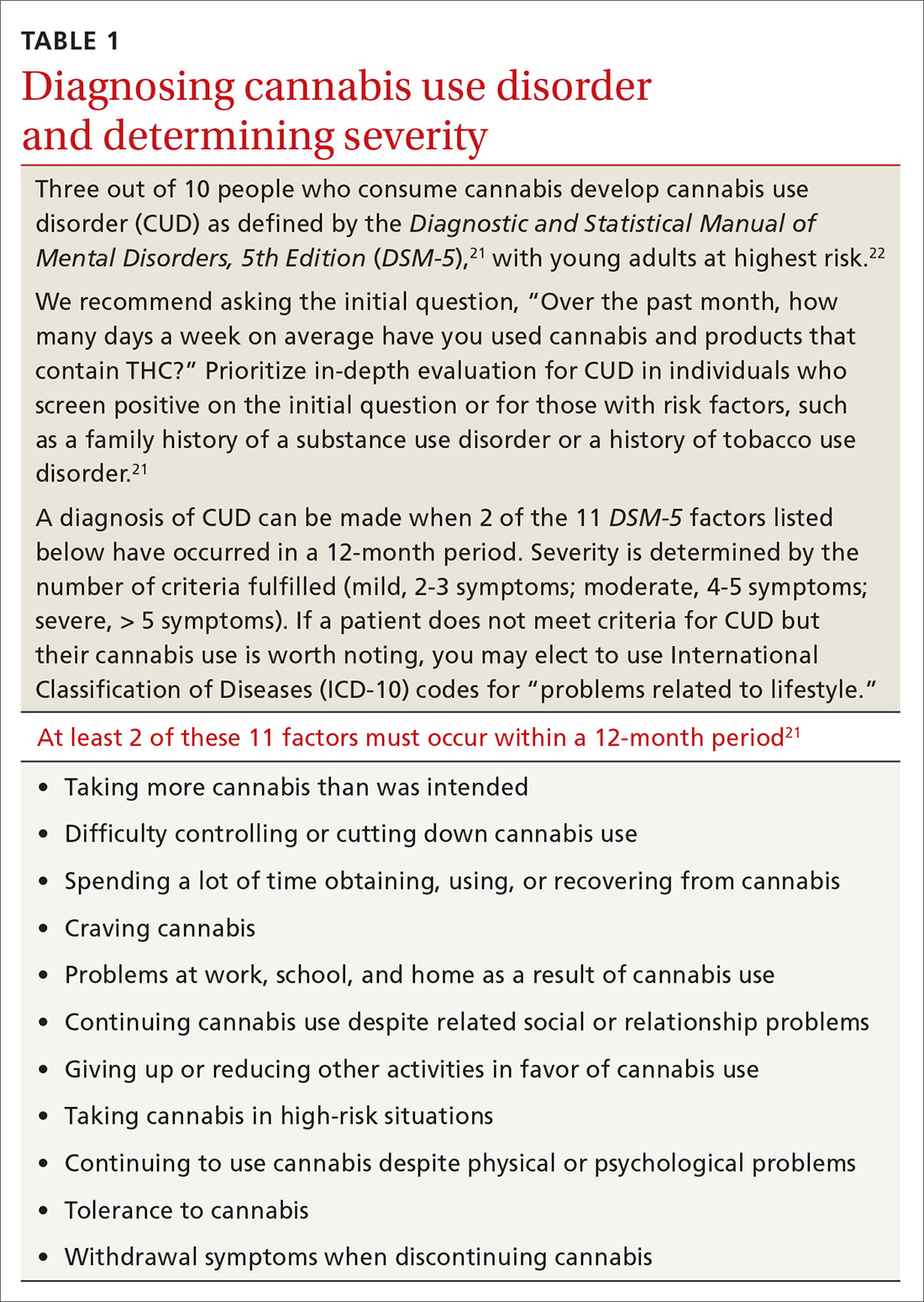

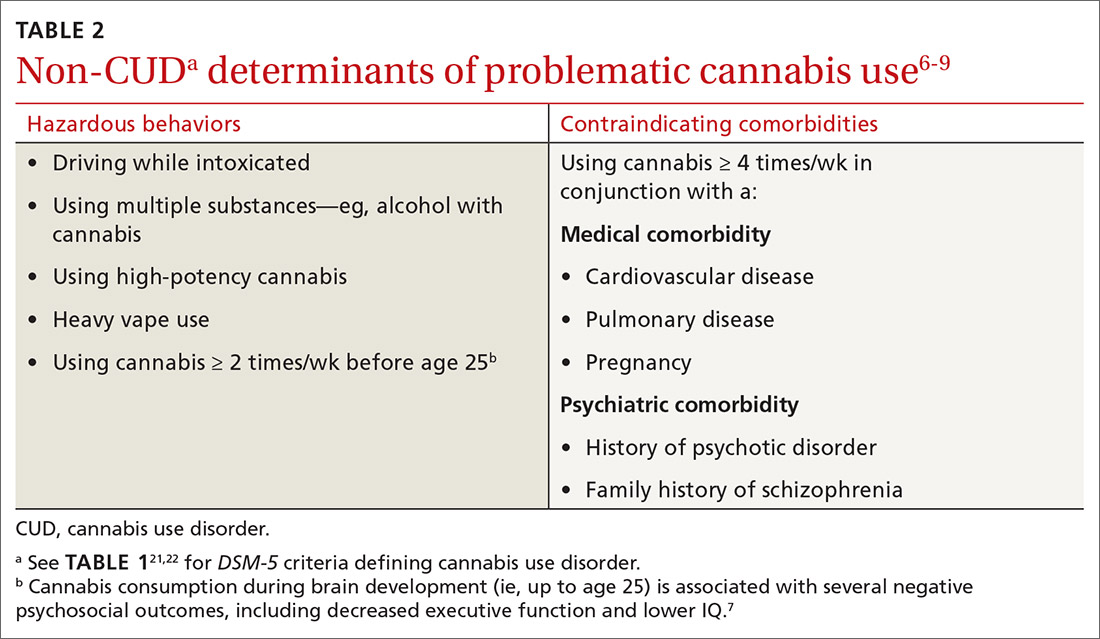

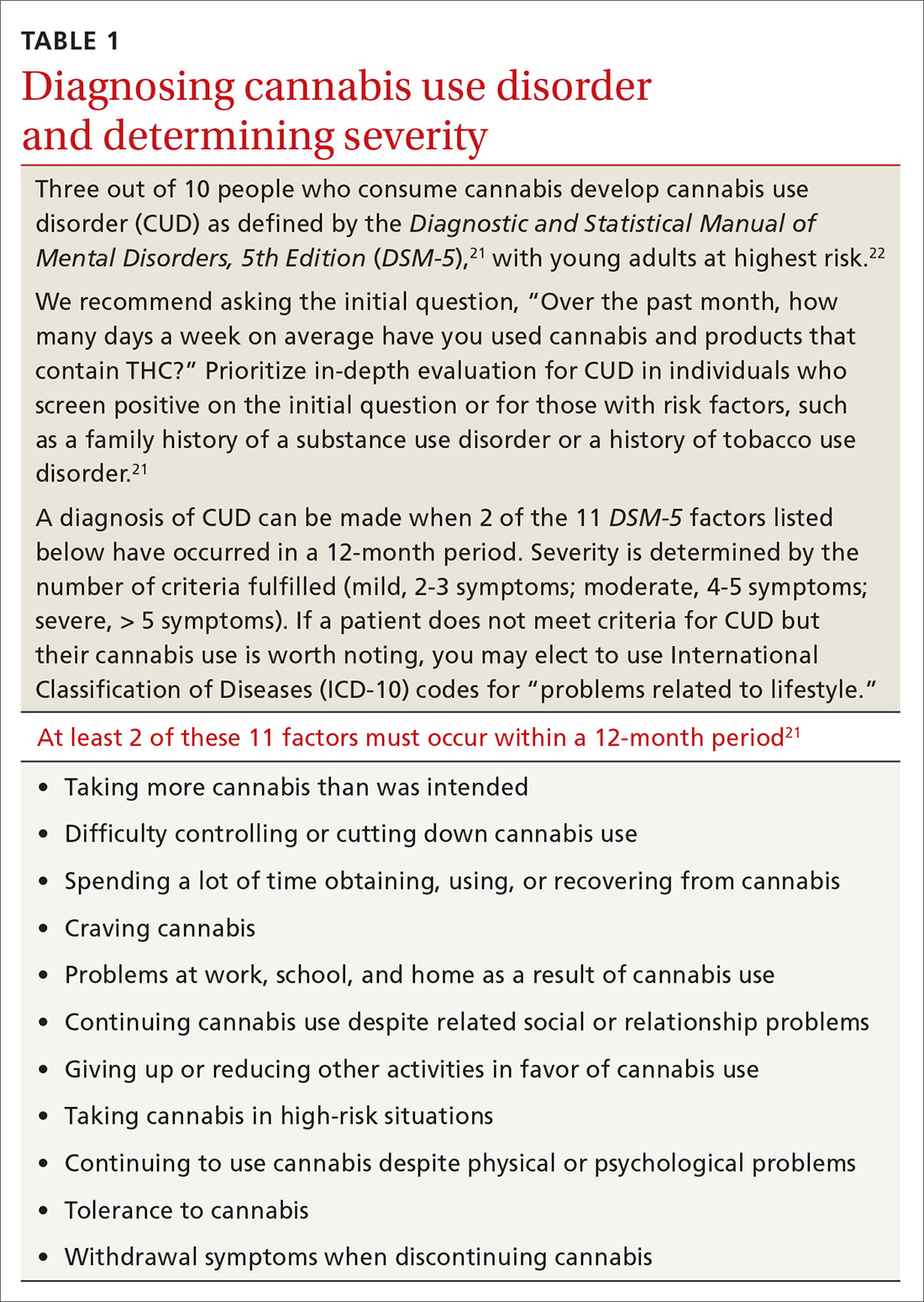

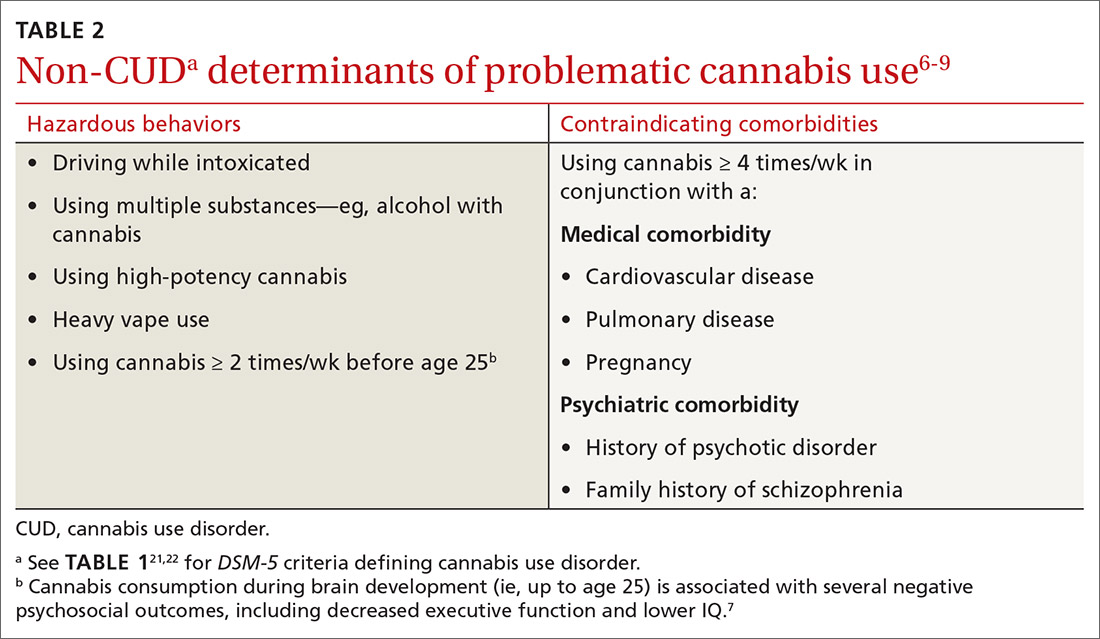

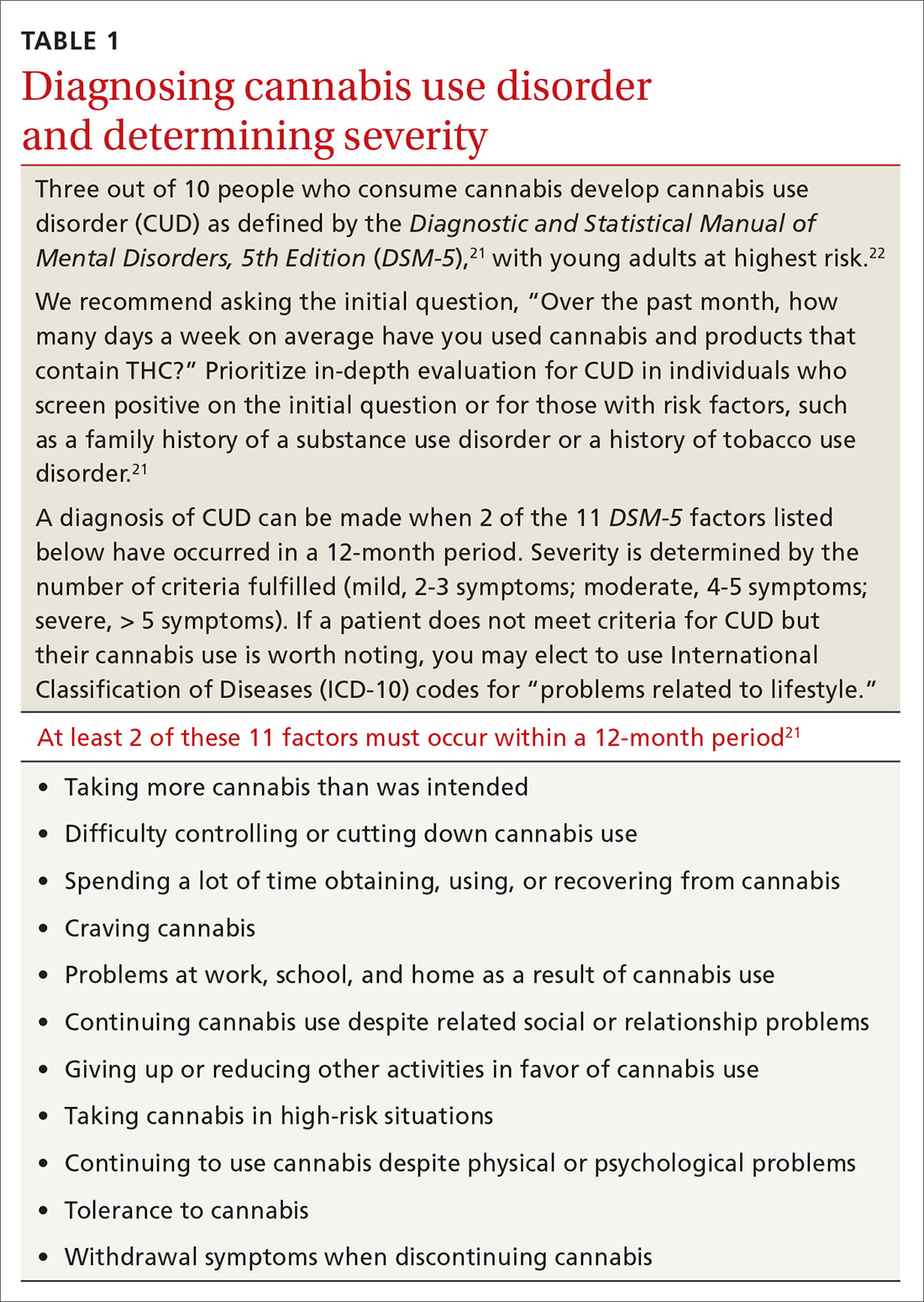

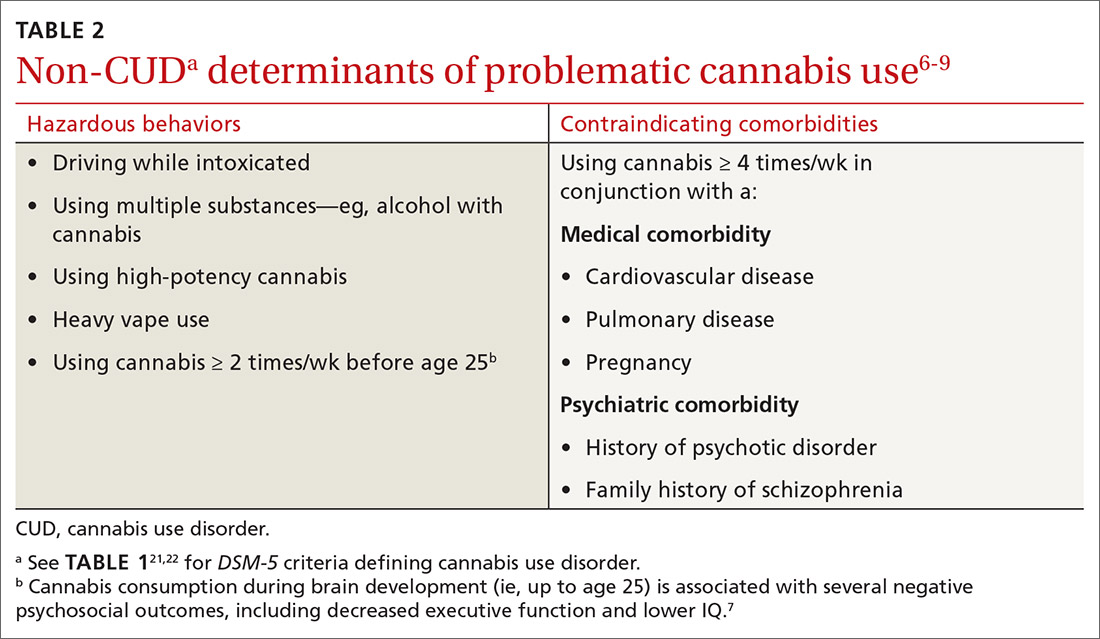

Although it is important to identify cannabis use disorder (CUD) as defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5; TABLE 121,22), consider also the immediate and long-term consequences of cannabis use for individuals who do not meet criteria for CUD. “Problematic cannabis use,” as we define it, may also involve (a) high-risk behaviors or (b) contraindicating medical or psychiatric comorbidities (TABLE 26-9).

CASE

The patient in our case exhibited

Continue to: Guidelines for screening and evaluation

Guidelines for screening and evaluation

All primary care patients should be screened for problematic cannabis use, but especially teenagers, young adults, pregnant women, and patients with a mental health or substance use history. A variation of the single question used to screen for alcohol use disorder can be applied to cannabis use.23 We recommend asking the initial question, “Over the past month, how many days a week on average have you used cannabis and products that contain THC?” Although some guidelines emphasize frequency of cannabis use when identifying problematic consumption,24,25 duration of behavior and content of THC are also important indicators.19 Inquire about cannabis consumption over 1 month to differentiate sporadic use from longstanding persistent use.

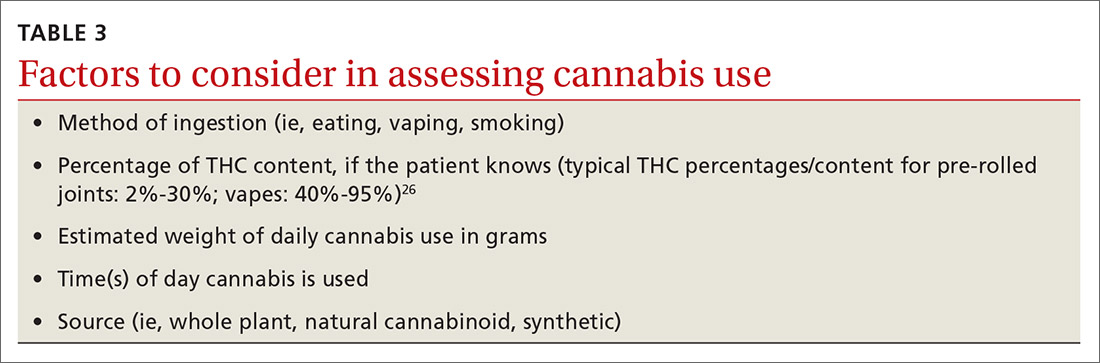

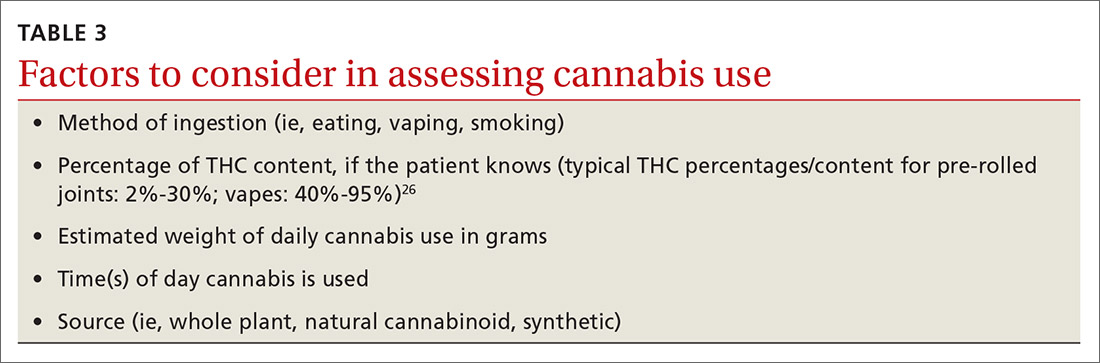

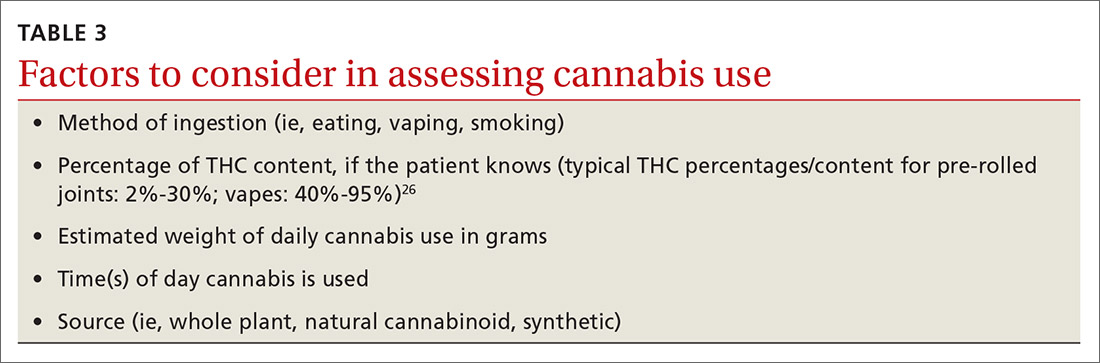

Explore what types of cannabis the patient is ingesting and whether the patient uses cannabis heavily (4 or more times a week on average). Also determine the method of ingestion (eg, eating, vaping, smoking), THC-content (%, if known), and estimated weight of daily cannabis use in grams (TABLE 326). Although patients may not always be able to provide accurate answers, you can gain a sense of the quantity and forms of cannabis a patient is ingesting to inform future conversations on risk and harm reduction.27

Assess a patient’s risk for harm

Cannabis use has the potential to cause immediate harm (linked to a single event of problematic cannabis use) and long-term harm (linked to a recurring pattern of problematic consumption). Cannabis can be especially harmful for patients with the following medical comorbidities or psychosocial factors, and should be avoided.

Cardiovascular disease. Cannabis is associated with an elevated risk for acute coronary syndrome and cardiovascular disease.28 Long-term cannabis use is linked to increased frequency of anginal events, development of cardiac arrhythmias, peripheral arteritis, coronary vasospasms, and problems with platelet aggregation.29,30 Strongly caution against cannabis use with patients who have a history of cardiovascular disease, orthostatic hypotension, tachyarrhythmia, or hypertension.

Pulmonary disease. Patients with pulmonary disease such as asthma may find cannabis helpful as a short-term bronchodilator.31 However, for patients with underlying pulmonary disease who also smoke cigarettes, strongly discourage the smoking of cannabis or hashish, as that may worsen asthma symptoms,32 increase risk of chronic bronchitis,33 and increase cough, sputum production, and wheezing.31 There is currently insufficient evidence to suggest a positive association between cannabis use and the development of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.34

Continue to: Family history of psychotic disorders

Family history of psychotic disorders. Cannabis is associated with a dose-dependent risk of schizophrenia, which is especially pronounced in patients with a family history of schizophrenia.35 Among patients with a history of psychosis, heavy cannabis use has been associated with increased hospitalizations, increased positive symptoms, and more frequent relapses.36-38

Pregnancy, current or planned. Some women turn to cannabis during pregnancy due to its antiemetic properties. However, perinatal exposure to cannabis is associated with significant risk to the offspring. Maternal cannabis use during the first and second trimesters of pregnancy is associated with decreased performance of the child on measures of function at 3 years of age.39 In addition, cannabis consumption during pregnancy is linked to increased frequency of childhood behavioral issues, inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity.40 Peripartum cannabis exposure can affect birth outcomes and is correlated with lower birth weight, incidence of preterm labor, and neonatal intensive care unit admission.15-17,41 Of note, the THC concentration in breast milk peaks at 1 hour after the nursing mother inhales cannabis and typically dissipates after 4 hours.42

Age < 25 years. Chronic heavy use of cannabis in those younger than 25 is associated with higher likelihood of developing CUD, lower IQ,9 lower level of educational attainment, lower income,43 and decreased executive function.8

Substance use disorder history. Recreational cannabis use can hinder recovery from other substance use disorders.44

Consider these 5 interventions

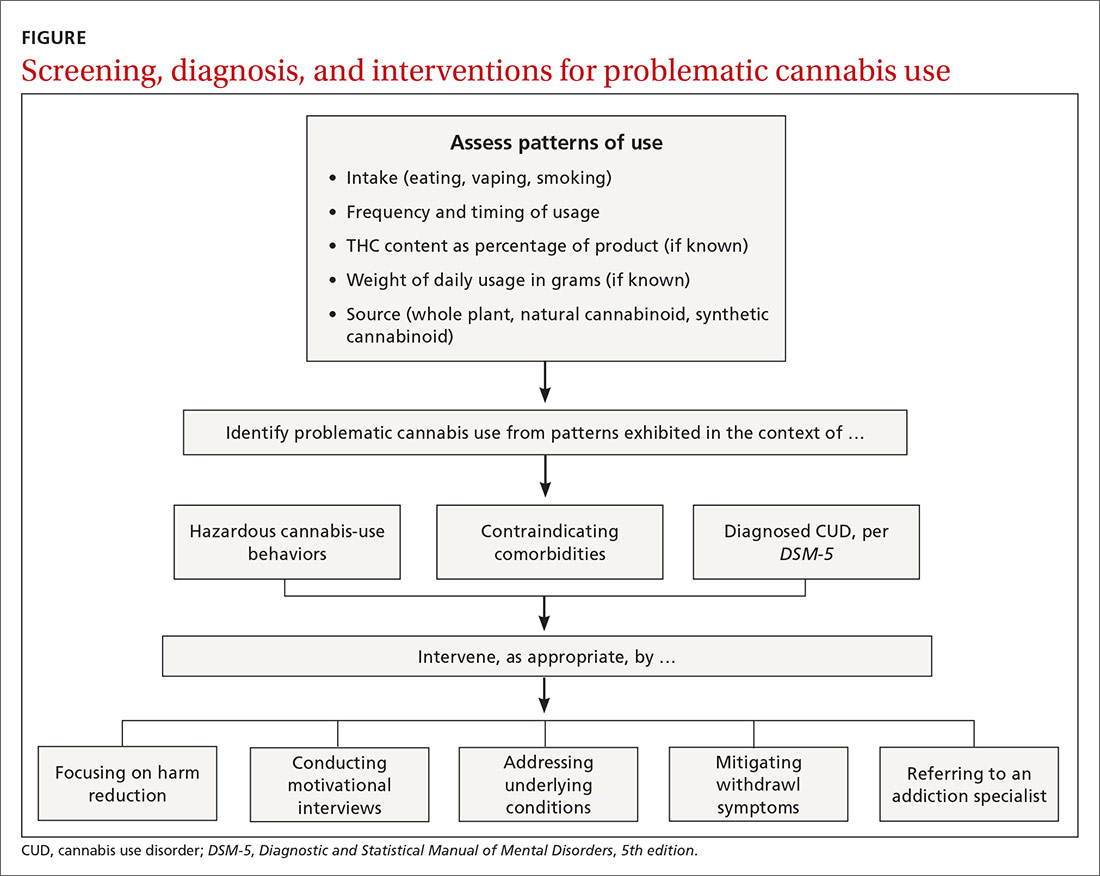

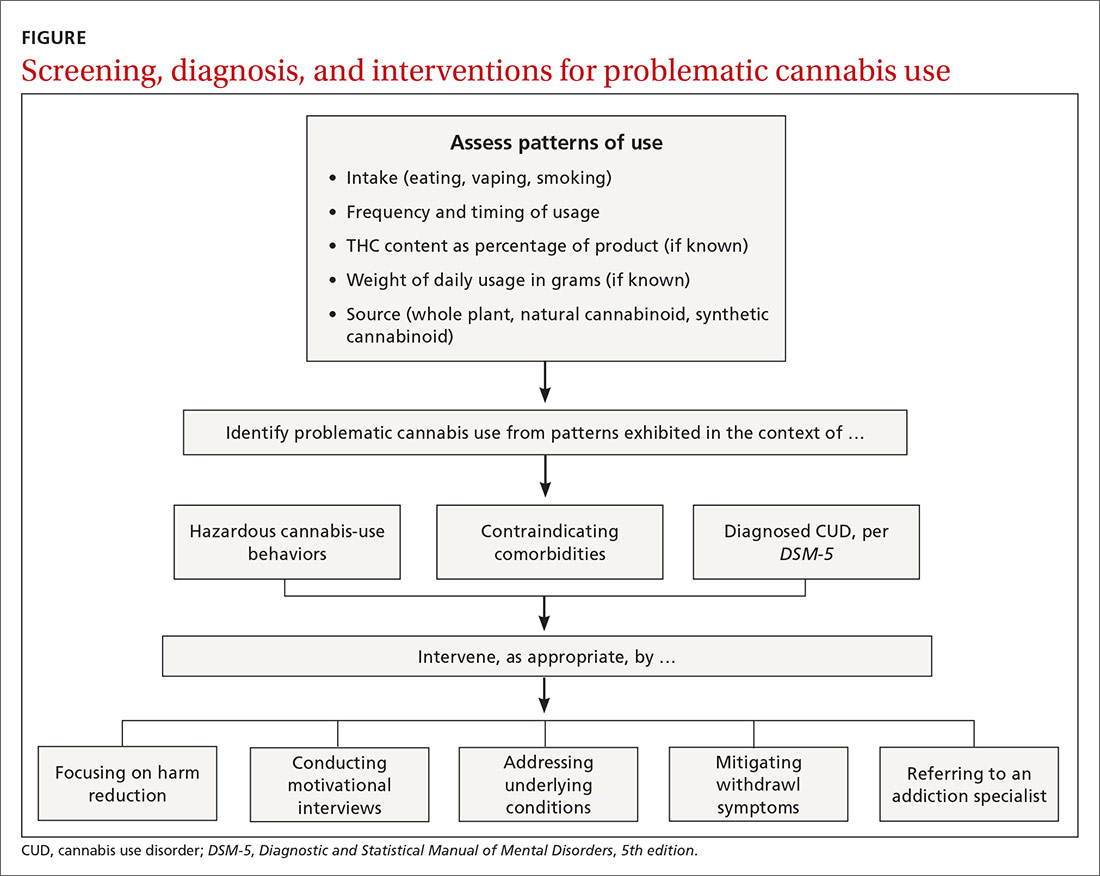

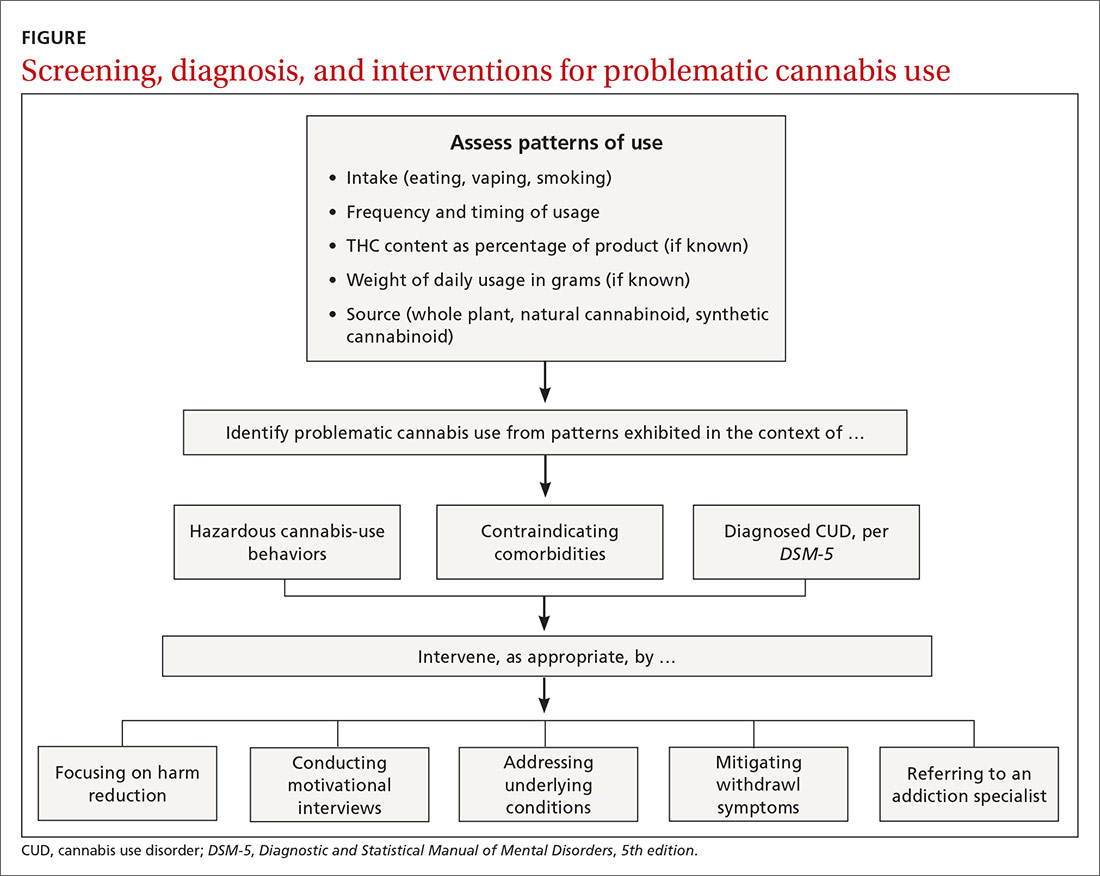

Physicians can address problematic cannabis use with a 5-pronged approach: (1) harm reduction, (2) motivational interviewing, (3) addressing underlying conditions, (4) mitigating withdrawal symptoms, and (5) referring to an addiction specialist (FIGURE).

Continue to: Harm reduction

Harm reduction

Harm reduction applies to all individuals who use cannabis but especially to problematic cannabis users. Ask users to abstain from cannabis for limited periods of time to see how such abstinence affects other areas of their life. While abstinence is a goal, be prepared to perform non-abstinence-based interventions. The goal of harm reduction is to encourage behaviors that minimize health risks to which cannabis users are exposed. Encourage patients to:

Abstain from driving while intoxicated. Cannabis use while driving slows reaction time,45 impairs road tracking (driving with correct road position),46 increases weaving,47 and causes a loss of anticipatory reactions learned in driving practice.48 Risk of crashing is significantly increased with elevated levels of THC, and driving within 1 hour of cannabis ingestion nearly doubles the risk of a crash.49-51

Abstain from vaping THC-containing products. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that patients minimize the use of THC-containing e-cigarette or vaping products in light of the thousands of reports in the United States of product-associated lung injury, which in some cases have led to death.52

Clarify serving sizes and recognize delayed effects. Inexperienced cannabis users often are confused by recommended serving sizes for edible cannabis products. A typical cannabis-infused brownie may contain 100 mg of THC when the recommended serving size typically is 10 mg. THC content is included on the label of cannabis edibles purchased in state-regulated stores; these products are tested regularly in laboratories designated by the state.

Due to the delayed onset of THC’s effect, there have been numerous cases of patients taking a higher-than-intended dose of edible cannabis that caused acute intoxication and psychomedical sequelae leading to emergency hospital visits and, in some cases, death.6,53 Individuals should start at a low dose and gradually work up to a higher dose as tolerated. Patients naïve to cannabis should be especially cautious when ingesting edible products.

Continue to: Abstain from cannabis with high THC content

Abstain from cannabis with high THC content. High-potency cannabis (> 10% THC) is associated with earlier onset of first-episode psychosis.54,55

Motivational interviewing

Motivational interviewing (MI) is a psychosocial approach that emphasizes a patient’s self-efficacy and an interviewer’s positive feedback to collaboratively address substance use.56 MI can be performed in short, discrete sessions. Such interventions can reduce the average number of days of cannabis use. One large-scale Cochrane review found that cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), motivational enhancement therapy, or the 2 therapies combined most consistently reduced the frequency of cannabis use reported by patients at early follow-up.57

Address underlying conditions

Some patients use cannabis to self-medicate for pain, insomnia, nausea, and anxiety. Identify these conditions and address them with first-line pharmacologic or psychotherapeutic interventions when possible. This is especially important for conditions in which long-term cannabis use may adversely impact outcomes, such as in posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and mood disorders.58-60 Little evidence exists for the use of cannabis as treatment of any primary psychiatric disorder.61,62 Family physicians who are uncomfortable treating a specific underlying condition can consult specialists in pain management, sleep medicine, psychiatry, and neurology.

Mitigate withdrawal symptoms

Discontinuation of cannabis use may lead to withdrawal symptoms such as waxing and waning irritability, restlessness, sweating, aggression, anxiety, depressed mood, sleep disturbance, or changes in appetite.63,64 These symptoms typically emerge within the first couple days of abstinence and can last up to 28 days.63,64 Although the US Food and Drug Administration has not approved any medications for CUD treatment, and there are no established protocols for detoxification, there is evidence that CBT or medications such as gabapentin or zolpidem can reduce the intensity of withdrawal symptoms.65,66

Refer to an addiction specialist

Consider referring patients with problematic cannabis use to an addiction specialist with expertise in psychopharmacologic and psychotherapeutic approaches to managing substance use.

Continue to: CASE

CASE

You renew Ms. F’s asthma medications, discuss her cannabis use, start her on a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, and refer her to an outpatient psychiatrist. Over the next few weeks, you and the outpatient psychiatrist employ brief motivational interviewing around cannabis use, and you provide psychoeducation around potential harms of use when driving and in light of the patient’s asthma.

The patient’s anxiety symptoms decrease with up-titration of the SSRI by the outpatient psychiatrist and with enrollment in individual CBT. She is slowly able to taper off cannabis vaping with continued motivational interviewing and encouragement, despite withdrawal-induced anxiety and sleep disturbance.

CORRESPONDENCE

Michael Hsu, MD, Brigham & Women’s Hospital, 75 Francis Street, Boston, MA 02215; mhsu7@partners.org.

1. Sarvet AL, Wall MM, Keyes KM, et al. Recent rapid decrease in adolescents’ perception that marijuana is harmful, but no concurrent increase in use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;186:68-74.

2. Compton WM, Han B, Jones CM, Blanco C, Hughes A. Marijuana use and use disorders in adults in the USA, 2002-14: analysis of annual cross-sectional surveys. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:954-964.

3. Lapham GT, Lee AK, Caldeiro RM, et al. Frequency of cannabis use among primary care patients in Washington state. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30:795‐805.

4. Chandra S, Radwan MM, Majumdar CG, et al. New trends in cannabis potency in USA and Europe during the last decade (2008-2017). Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2019;269:5-15.

5. Sevigny EL, Pacula RL, Heaton P. The effects of medical marijuana laws on potency. Int J Drug Policy. 2014;25:308-319.

6. Monte AA, Shelton SK, Mills E, et al. Acute illness associated with cannabis use, by route of exposure: an observational study. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170:531-537.

7. Scott JC, Slomiak ST, Jones JD, et al. Association of cannabis with cognitive functioning in adolescents and young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75:585-595.

8. Gruber SA, Sagar KA, Dahlgren MK, et al. Age of onset of marijuana use and executive function. Psychol Addict Behav. 2012;26:496-506.

9. Meier MH, Caspi A, Ambler A, et al. Persistent cannabis users show neuropsychological decline from childhood to midlife. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:E2657-E2664.

10. Mammen G, Rueda S, Roerecke M, et al. Association of cannabis with long-term clinical symptoms in anxiety and mood disorders: a systematic review of prospective studies. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79:17r11839.

11. Gage SH, Hickman M, Zammit S. Association between cannabis and psychosis: epidemiologic evidence. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79:549-556.

12. Singh A, Saluja S, Kumar A, et al. Cardiovascular complications of marijuana and related substances: a review. Cardiol Ther. 2018;7:45-59.

13. Volkow ND, Compton WM, Weiss SR. Adverse health effects of marijuana use. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2219-2227.

14. Bari M, Battista N, Pirazzi V, et al. The manifold actions of endocannabinoids on female and male reproductive events. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 2011;16:498-516.

15. Hayatbakhsh MR, Flenady VJ, Gibbons KS, et al. Birth outcomes associated with cannabis use before and during pregnancy. Pediatr Res. 2012;71:215-219.

16. Saurel-Cubizolles M-J, Prunet C, Blondel B. Cannabis use during pregnancy in France in 2010. BJOG. 2014;121:971-977.

17. Prunet C, Delnord M, Saurel-Cubizolles M-J, et al. Risk factors of preterm birth in France in 2010 and changes since 1995: results from the French national perinatal surveys. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2017;46:19-28.

18. Kondrad EC, Reed AJ, Simpson MJ, et al. Lack of communication about medical marijuana use between doctors and their patients. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31:805-808.

19. Casajuana C, López-Pelayo H, Balcells MM, et al. Definitions of risky and problematic cannabis use: a systematic review. Subst Use Misuse. 2016;51:1760-1770.

20. Norberg MM, Gates P, Dillon P, et al. Screening and managing cannabis use: comparing GP’s and nurses’ knowledge, beliefs, and behavior. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2012;7:31.

21. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington DC: APA Publishing; 2013:509-516.

22. Hasin DS, Saha TD, Kerridge BT, et al. Prevalence of marijuana use disorders in the United States between 2001-2002 and 2012-2013. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:1235-1242.

23. Smith PC, Schmidt SM, Allensworth-Davies D, et al. A single-question screening test for drug use in primary care. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1155-1160.

24. Fischer B, Jones W, Shuper P, et al. 12-month follow-up of an exploratory ‘brief intervention’ for high-frequency cannabis users among Canadian university students. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2012;7:15.

25. Turner SD, Spithoff S, Kahan M. Approach to cannabis use disorder in primary care: focus on youth and other high-risk users. Can Fam Physician. 2014;60:801-808.

26. Smart R, Caulkins JP, Kilmer B, et al. Variation in cannabis potency & prices in a newly-legal market: evidence from 30 million cannabis sales in Washington State. Addiction. 2017;112:2167-2177.

27. Bonn-Miller MO, Loflin MJE, Thomas BF, et al. Labeling accuracy of cannabidiol extracts sold online. JAMA. 2017;318:1708-1709.

28. Richards JR, Bing ML, Moulin AK, et al. Cannabis use and acute coronary syndrome. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2019;57:831-841.

29. Subramaniam VN, Menezes AR, DeSchutter A, et al. The cardiovascular effects of marijuana: are the potential adverse effects worth the high? Mo Med. 2019;116:146-153.

30. Jones RT. Cardiovascular system effects of marijuana. J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;42:58S-63S.

31. Tetrault JM, Crothers K, Moore BA, et al. Effects of marijuana smoking on pulmonary function and respiratory complications: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:221-228.

32. Bramness JG, von Soest T. A longitudinal study of cannabis use increasing the use of asthma medication in young Norwegian adults. BMC Pulm Med. 2019;19:52.

33. Moore BA, Augustson EM, Moser RP, et al. Respiratory effects of marijuana and tobacco use in a U.S. sample. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:33-37.

34. Tashkin DP. Does marijuana pose risks for chronic airflow obstruction? Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12:235-236.

35. McGuire PK, Jones P, Harvey I, et al. Morbid risk of schizophrenia for relatives of patients with cannabis-associated psychosis. Schizophr Res. 1995;15:277-281.

36. Hall W, Degenhardt L. Cannabis use and the risk of developing a psychotic disorder. World Psychiatry. 2008;7:68-71.

37. Gerlach J, Koret B, Gereš N, et al. Clinical challenges in patients with first episode psychosis and cannabis use: mini-review and a case study. Psychiatr Danub. 2019;31(suppl 2):162-170.

38. Patel R, Wilson R, Jackson R, et al. Association of cannabis use with hospital admission and antipsychotic treatment failure in first episode psychosis: an observational study. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e009888.

39. Day NL, Richardson GA, Goldschmidt L, et al. Effect of prenatal marijuana exposure on the cognitive development of offspring at age three. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1994;16:169-175.

40. Goldschmidt L, Day NL, Richardson GA. Effects of prenatal marijuana exposure on child behavior problems at age 10. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2000;22:325-336.

41. Corsi DJ, Walsh L, Weiss D, et al. Association between self-reported prenatal cannabis use and maternal, perinatal, and neonatal outcomes. JAMA. 2019;322:145-152.

42. Baker T, Datta P, Rewers-Felkins K, et al. Transfer of inhaled cannabis into human breast milk. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:783-788.

43. Thompson K, Leadbeater B, Ames M, et al. Associations between marijuana use trajectories and educational and occupational success in young adulthood. Prev Sci. 2019;20:257-269.

44. Yuan M, Kanellopoulos T, Kotbi N. Cannabis use and psychiatric illness in the context of medical marijuana legalization: a clinical perspective. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2019;61:82-83.

45. Ronen A, Gershon P, Drobiner H, et al. Effects of THC on driving performance, physiological state and subjective feelings relative to alcohol. Accid Anal Prev. 2008;40:926-934.

46. Robbe H. Marijuana’s impairing effects on driving are moderate when taken alone but severe when combined with alcohol. Hum Psychopharmacol Clin Exp. 1998;13(suppl 2):S70-S78.

47. Lenné MG, Dietze PM, Triggs TJ, et al. The effects of cannabis and alcohol on simulated arterial driving: influences of driving experience and task demand. Accid Anal Prev. 2010;42:859-866.

48. Anderson BM, Rizzo M, Block RI, et al. Sex differences in the effects of marijuana on simulated driving performance. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2010;42:19-30.

49. Laumon B, Gadegbeku B, Martin J-L, Biecheler M-B. Cannabis intoxication and fatal road crashes in France: population based case-control study. BMJ. 2005;331:1371.

50. Asbridge M, Poulin C, Donato A. Motor vehicle collision risk and driving under the influence of cannabis: evidence from adolescents in Atlantic Canada. Accid Anal Prev. 2005;37:1025-1034.

51. Mann RE, Adlaf E, Zhao J, et al. Cannabis use and self-reported collisions in a representative sample of adult drivers. J Safety Res. 2007;38:669-674.

52. Taylor J, Wiens T, Peterson J, et al. Characteristics of e-cigarette, or vaping, products used by patients with associated lung injury and products seized by law enforcement—Minnesota, 2018 and 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:1096-1100.

53. Hancock-Allen JB, Barker L, VanDyke M, et al. Notes from the field: death following ingestion of an edible marijuana product—Colorado, March 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:771-772.

54. Murray RM, Quigley H, Quattrone D, et al. Traditional marijuana, high-potency cannabis and synthetic cannabinoids: increasing risk for psychosis. World Psychiatry. 2016;15:195-204.

55. Di Forti MD, Sallis H, Allegri F, et al. Daily use, especially of high-potency cannabis, drives the earlier onset of psychosis in cannabis users. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40:1509-1517.

56. Miller WR. Motivational interviewing: research, practice, and puzzles. Addict Behav. 1996;21:835-842.

57. Gates PJ, Sabioni P, Copeland J, et al. Psychosocial interventions for cannabis use disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(5):CD005336.

58. Wilkinson ST, Stefanovics E, Rosenheck RA. Marijuana use is associated with worse outcomes in symptom severity and violent behavior in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76:1174-1180.

59. Cougle JR, Bonn-Miller MO, Vujanovic AA, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and cannabis use in a nationally representative sample. Psychol Addict Behav. 2011;25:554-558.

60. Johnson MJ, Pierce JD, Mavandadi S, et al. Mental health symptom severity in cannabis using and non-using veterans with probable PTSD. J Affect Disord. 2016;190:439-442.

61. Wilkinson ST, Radhakrishnan R, D’Souza DC. A systematic review of the evidence for medical marijuana in psychiatric indications. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77:1050-1064.

62. Black N, Stockings E, Campbell G, et al. Cannabinoids for the treatment of mental disorders and symptoms of mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6:995-1010.

63. Bonnet U, Preuss U. The cannabis withdrawal syndrome: current insights. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2017;8:9-37.

64. Vandrey R, Smith MT, McCann UD, et al. Sleep disturbance and the effects of extended-release zolpidem during cannabis withdrawal. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;117:38-44.

65. Mason BJ, Crean R, Goodell V, et al. A proof-of-concept randomized controlled study of gabapentin: effects on cannabis use, withdrawal and executive function deficits in cannabis-dependent adults. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:1689-1698.

66. Weinstein A, Miller H, Tal E, et al. Treatment of cannabis withdrawal syndrome using cognitive-behavioral therapy and relapse prevention for cannabis dependence. J Groups Addict Recover. 2010;5:240-263.

CASE

Jessica F is a new 23-year-old patient at your clinic who is seeing you to discuss her severe anxiety. She also has asthma and reports during your exploration of her family history that her father has been diagnosed with schizophrenia. She has been using 3 cartridges of cannabis vape daily to help “calm her mind” but has never tried other psychotropic medications and has never been referred to a psychiatrist.

How would you proceed with this patient?

Despite emerging evidence of the harmful effects of cannabis consumption, public perception of harm has steadily declined over the past 10 years.1,2 More adults are using cannabis than before and using it more frequently. Among primary care patients who consume cannabis recreationally, about half report less than monthly consumption; 15% use it weekly, and 20% daily.3 The potency of cannabis products has also increased. In the past 2 decades, the average tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) content of recreational cannabis rose from 3% to 19%, and high-THC content delivery modalities such as vaporizer pens (“vapes”) were introduced.4,5

Health hazards of cannabis use include gastrointestinal dysfunction (eg, cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome), acute psychosis or exacerbation of an existing mood, anxiety, or psychotic disorder, and cardiovascular sequelae such as myocardial infarction or dysrhythmia.6 Potential long-term effects include neurocognitive impairment among adolescents who use cannabis,7-9 worse outcomes in anxiety and mood disorders,10 schizophrenia,11 cardiovascular sequelae,12 chronic bronchitis,13 negative impact on reproductive function,14 and poor birth outcomes.15-17

Hidden in plain sight. Many patients who use cannabis report that their primary care physicians are unaware of their cannabis consumption.18 Inadequate screening for cannabis can be attributed to time constraints, inconsistent definitions for problematic or risky cannabis use, and lack of guidance.19,20 This article offers a more inclusive definition of “problematic cannabis use,” presents an up-to-date framework for evaluating it in the outpatient setting, and outlines potential interventions.

Your patient doesn’t meetthe DSM criteria, but …

Although it is important to identify cannabis use disorder (CUD) as defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5; TABLE 121,22), consider also the immediate and long-term consequences of cannabis use for individuals who do not meet criteria for CUD. “Problematic cannabis use,” as we define it, may also involve (a) high-risk behaviors or (b) contraindicating medical or psychiatric comorbidities (TABLE 26-9).

CASE

The patient in our case exhibited

Continue to: Guidelines for screening and evaluation

Guidelines for screening and evaluation

All primary care patients should be screened for problematic cannabis use, but especially teenagers, young adults, pregnant women, and patients with a mental health or substance use history. A variation of the single question used to screen for alcohol use disorder can be applied to cannabis use.23 We recommend asking the initial question, “Over the past month, how many days a week on average have you used cannabis and products that contain THC?” Although some guidelines emphasize frequency of cannabis use when identifying problematic consumption,24,25 duration of behavior and content of THC are also important indicators.19 Inquire about cannabis consumption over 1 month to differentiate sporadic use from longstanding persistent use.

Explore what types of cannabis the patient is ingesting and whether the patient uses cannabis heavily (4 or more times a week on average). Also determine the method of ingestion (eg, eating, vaping, smoking), THC-content (%, if known), and estimated weight of daily cannabis use in grams (TABLE 326). Although patients may not always be able to provide accurate answers, you can gain a sense of the quantity and forms of cannabis a patient is ingesting to inform future conversations on risk and harm reduction.27

Assess a patient’s risk for harm

Cannabis use has the potential to cause immediate harm (linked to a single event of problematic cannabis use) and long-term harm (linked to a recurring pattern of problematic consumption). Cannabis can be especially harmful for patients with the following medical comorbidities or psychosocial factors, and should be avoided.

Cardiovascular disease. Cannabis is associated with an elevated risk for acute coronary syndrome and cardiovascular disease.28 Long-term cannabis use is linked to increased frequency of anginal events, development of cardiac arrhythmias, peripheral arteritis, coronary vasospasms, and problems with platelet aggregation.29,30 Strongly caution against cannabis use with patients who have a history of cardiovascular disease, orthostatic hypotension, tachyarrhythmia, or hypertension.

Pulmonary disease. Patients with pulmonary disease such as asthma may find cannabis helpful as a short-term bronchodilator.31 However, for patients with underlying pulmonary disease who also smoke cigarettes, strongly discourage the smoking of cannabis or hashish, as that may worsen asthma symptoms,32 increase risk of chronic bronchitis,33 and increase cough, sputum production, and wheezing.31 There is currently insufficient evidence to suggest a positive association between cannabis use and the development of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.34

Continue to: Family history of psychotic disorders

Family history of psychotic disorders. Cannabis is associated with a dose-dependent risk of schizophrenia, which is especially pronounced in patients with a family history of schizophrenia.35 Among patients with a history of psychosis, heavy cannabis use has been associated with increased hospitalizations, increased positive symptoms, and more frequent relapses.36-38

Pregnancy, current or planned. Some women turn to cannabis during pregnancy due to its antiemetic properties. However, perinatal exposure to cannabis is associated with significant risk to the offspring. Maternal cannabis use during the first and second trimesters of pregnancy is associated with decreased performance of the child on measures of function at 3 years of age.39 In addition, cannabis consumption during pregnancy is linked to increased frequency of childhood behavioral issues, inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity.40 Peripartum cannabis exposure can affect birth outcomes and is correlated with lower birth weight, incidence of preterm labor, and neonatal intensive care unit admission.15-17,41 Of note, the THC concentration in breast milk peaks at 1 hour after the nursing mother inhales cannabis and typically dissipates after 4 hours.42

Age < 25 years. Chronic heavy use of cannabis in those younger than 25 is associated with higher likelihood of developing CUD, lower IQ,9 lower level of educational attainment, lower income,43 and decreased executive function.8

Substance use disorder history. Recreational cannabis use can hinder recovery from other substance use disorders.44

Consider these 5 interventions

Physicians can address problematic cannabis use with a 5-pronged approach: (1) harm reduction, (2) motivational interviewing, (3) addressing underlying conditions, (4) mitigating withdrawal symptoms, and (5) referring to an addiction specialist (FIGURE).

Continue to: Harm reduction

Harm reduction

Harm reduction applies to all individuals who use cannabis but especially to problematic cannabis users. Ask users to abstain from cannabis for limited periods of time to see how such abstinence affects other areas of their life. While abstinence is a goal, be prepared to perform non-abstinence-based interventions. The goal of harm reduction is to encourage behaviors that minimize health risks to which cannabis users are exposed. Encourage patients to:

Abstain from driving while intoxicated. Cannabis use while driving slows reaction time,45 impairs road tracking (driving with correct road position),46 increases weaving,47 and causes a loss of anticipatory reactions learned in driving practice.48 Risk of crashing is significantly increased with elevated levels of THC, and driving within 1 hour of cannabis ingestion nearly doubles the risk of a crash.49-51

Abstain from vaping THC-containing products. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that patients minimize the use of THC-containing e-cigarette or vaping products in light of the thousands of reports in the United States of product-associated lung injury, which in some cases have led to death.52

Clarify serving sizes and recognize delayed effects. Inexperienced cannabis users often are confused by recommended serving sizes for edible cannabis products. A typical cannabis-infused brownie may contain 100 mg of THC when the recommended serving size typically is 10 mg. THC content is included on the label of cannabis edibles purchased in state-regulated stores; these products are tested regularly in laboratories designated by the state.

Due to the delayed onset of THC’s effect, there have been numerous cases of patients taking a higher-than-intended dose of edible cannabis that caused acute intoxication and psychomedical sequelae leading to emergency hospital visits and, in some cases, death.6,53 Individuals should start at a low dose and gradually work up to a higher dose as tolerated. Patients naïve to cannabis should be especially cautious when ingesting edible products.

Continue to: Abstain from cannabis with high THC content

Abstain from cannabis with high THC content. High-potency cannabis (> 10% THC) is associated with earlier onset of first-episode psychosis.54,55

Motivational interviewing

Motivational interviewing (MI) is a psychosocial approach that emphasizes a patient’s self-efficacy and an interviewer’s positive feedback to collaboratively address substance use.56 MI can be performed in short, discrete sessions. Such interventions can reduce the average number of days of cannabis use. One large-scale Cochrane review found that cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), motivational enhancement therapy, or the 2 therapies combined most consistently reduced the frequency of cannabis use reported by patients at early follow-up.57

Address underlying conditions

Some patients use cannabis to self-medicate for pain, insomnia, nausea, and anxiety. Identify these conditions and address them with first-line pharmacologic or psychotherapeutic interventions when possible. This is especially important for conditions in which long-term cannabis use may adversely impact outcomes, such as in posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and mood disorders.58-60 Little evidence exists for the use of cannabis as treatment of any primary psychiatric disorder.61,62 Family physicians who are uncomfortable treating a specific underlying condition can consult specialists in pain management, sleep medicine, psychiatry, and neurology.

Mitigate withdrawal symptoms

Discontinuation of cannabis use may lead to withdrawal symptoms such as waxing and waning irritability, restlessness, sweating, aggression, anxiety, depressed mood, sleep disturbance, or changes in appetite.63,64 These symptoms typically emerge within the first couple days of abstinence and can last up to 28 days.63,64 Although the US Food and Drug Administration has not approved any medications for CUD treatment, and there are no established protocols for detoxification, there is evidence that CBT or medications such as gabapentin or zolpidem can reduce the intensity of withdrawal symptoms.65,66

Refer to an addiction specialist

Consider referring patients with problematic cannabis use to an addiction specialist with expertise in psychopharmacologic and psychotherapeutic approaches to managing substance use.

Continue to: CASE

CASE

You renew Ms. F’s asthma medications, discuss her cannabis use, start her on a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, and refer her to an outpatient psychiatrist. Over the next few weeks, you and the outpatient psychiatrist employ brief motivational interviewing around cannabis use, and you provide psychoeducation around potential harms of use when driving and in light of the patient’s asthma.

The patient’s anxiety symptoms decrease with up-titration of the SSRI by the outpatient psychiatrist and with enrollment in individual CBT. She is slowly able to taper off cannabis vaping with continued motivational interviewing and encouragement, despite withdrawal-induced anxiety and sleep disturbance.

CORRESPONDENCE

Michael Hsu, MD, Brigham & Women’s Hospital, 75 Francis Street, Boston, MA 02215; mhsu7@partners.org.

CASE

Jessica F is a new 23-year-old patient at your clinic who is seeing you to discuss her severe anxiety. She also has asthma and reports during your exploration of her family history that her father has been diagnosed with schizophrenia. She has been using 3 cartridges of cannabis vape daily to help “calm her mind” but has never tried other psychotropic medications and has never been referred to a psychiatrist.

How would you proceed with this patient?

Despite emerging evidence of the harmful effects of cannabis consumption, public perception of harm has steadily declined over the past 10 years.1,2 More adults are using cannabis than before and using it more frequently. Among primary care patients who consume cannabis recreationally, about half report less than monthly consumption; 15% use it weekly, and 20% daily.3 The potency of cannabis products has also increased. In the past 2 decades, the average tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) content of recreational cannabis rose from 3% to 19%, and high-THC content delivery modalities such as vaporizer pens (“vapes”) were introduced.4,5

Health hazards of cannabis use include gastrointestinal dysfunction (eg, cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome), acute psychosis or exacerbation of an existing mood, anxiety, or psychotic disorder, and cardiovascular sequelae such as myocardial infarction or dysrhythmia.6 Potential long-term effects include neurocognitive impairment among adolescents who use cannabis,7-9 worse outcomes in anxiety and mood disorders,10 schizophrenia,11 cardiovascular sequelae,12 chronic bronchitis,13 negative impact on reproductive function,14 and poor birth outcomes.15-17

Hidden in plain sight. Many patients who use cannabis report that their primary care physicians are unaware of their cannabis consumption.18 Inadequate screening for cannabis can be attributed to time constraints, inconsistent definitions for problematic or risky cannabis use, and lack of guidance.19,20 This article offers a more inclusive definition of “problematic cannabis use,” presents an up-to-date framework for evaluating it in the outpatient setting, and outlines potential interventions.

Your patient doesn’t meetthe DSM criteria, but …

Although it is important to identify cannabis use disorder (CUD) as defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5; TABLE 121,22), consider also the immediate and long-term consequences of cannabis use for individuals who do not meet criteria for CUD. “Problematic cannabis use,” as we define it, may also involve (a) high-risk behaviors or (b) contraindicating medical or psychiatric comorbidities (TABLE 26-9).

CASE

The patient in our case exhibited

Continue to: Guidelines for screening and evaluation

Guidelines for screening and evaluation

All primary care patients should be screened for problematic cannabis use, but especially teenagers, young adults, pregnant women, and patients with a mental health or substance use history. A variation of the single question used to screen for alcohol use disorder can be applied to cannabis use.23 We recommend asking the initial question, “Over the past month, how many days a week on average have you used cannabis and products that contain THC?” Although some guidelines emphasize frequency of cannabis use when identifying problematic consumption,24,25 duration of behavior and content of THC are also important indicators.19 Inquire about cannabis consumption over 1 month to differentiate sporadic use from longstanding persistent use.

Explore what types of cannabis the patient is ingesting and whether the patient uses cannabis heavily (4 or more times a week on average). Also determine the method of ingestion (eg, eating, vaping, smoking), THC-content (%, if known), and estimated weight of daily cannabis use in grams (TABLE 326). Although patients may not always be able to provide accurate answers, you can gain a sense of the quantity and forms of cannabis a patient is ingesting to inform future conversations on risk and harm reduction.27

Assess a patient’s risk for harm

Cannabis use has the potential to cause immediate harm (linked to a single event of problematic cannabis use) and long-term harm (linked to a recurring pattern of problematic consumption). Cannabis can be especially harmful for patients with the following medical comorbidities or psychosocial factors, and should be avoided.

Cardiovascular disease. Cannabis is associated with an elevated risk for acute coronary syndrome and cardiovascular disease.28 Long-term cannabis use is linked to increased frequency of anginal events, development of cardiac arrhythmias, peripheral arteritis, coronary vasospasms, and problems with platelet aggregation.29,30 Strongly caution against cannabis use with patients who have a history of cardiovascular disease, orthostatic hypotension, tachyarrhythmia, or hypertension.

Pulmonary disease. Patients with pulmonary disease such as asthma may find cannabis helpful as a short-term bronchodilator.31 However, for patients with underlying pulmonary disease who also smoke cigarettes, strongly discourage the smoking of cannabis or hashish, as that may worsen asthma symptoms,32 increase risk of chronic bronchitis,33 and increase cough, sputum production, and wheezing.31 There is currently insufficient evidence to suggest a positive association between cannabis use and the development of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.34

Continue to: Family history of psychotic disorders

Family history of psychotic disorders. Cannabis is associated with a dose-dependent risk of schizophrenia, which is especially pronounced in patients with a family history of schizophrenia.35 Among patients with a history of psychosis, heavy cannabis use has been associated with increased hospitalizations, increased positive symptoms, and more frequent relapses.36-38

Pregnancy, current or planned. Some women turn to cannabis during pregnancy due to its antiemetic properties. However, perinatal exposure to cannabis is associated with significant risk to the offspring. Maternal cannabis use during the first and second trimesters of pregnancy is associated with decreased performance of the child on measures of function at 3 years of age.39 In addition, cannabis consumption during pregnancy is linked to increased frequency of childhood behavioral issues, inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity.40 Peripartum cannabis exposure can affect birth outcomes and is correlated with lower birth weight, incidence of preterm labor, and neonatal intensive care unit admission.15-17,41 Of note, the THC concentration in breast milk peaks at 1 hour after the nursing mother inhales cannabis and typically dissipates after 4 hours.42

Age < 25 years. Chronic heavy use of cannabis in those younger than 25 is associated with higher likelihood of developing CUD, lower IQ,9 lower level of educational attainment, lower income,43 and decreased executive function.8

Substance use disorder history. Recreational cannabis use can hinder recovery from other substance use disorders.44

Consider these 5 interventions

Physicians can address problematic cannabis use with a 5-pronged approach: (1) harm reduction, (2) motivational interviewing, (3) addressing underlying conditions, (4) mitigating withdrawal symptoms, and (5) referring to an addiction specialist (FIGURE).

Continue to: Harm reduction

Harm reduction

Harm reduction applies to all individuals who use cannabis but especially to problematic cannabis users. Ask users to abstain from cannabis for limited periods of time to see how such abstinence affects other areas of their life. While abstinence is a goal, be prepared to perform non-abstinence-based interventions. The goal of harm reduction is to encourage behaviors that minimize health risks to which cannabis users are exposed. Encourage patients to:

Abstain from driving while intoxicated. Cannabis use while driving slows reaction time,45 impairs road tracking (driving with correct road position),46 increases weaving,47 and causes a loss of anticipatory reactions learned in driving practice.48 Risk of crashing is significantly increased with elevated levels of THC, and driving within 1 hour of cannabis ingestion nearly doubles the risk of a crash.49-51

Abstain from vaping THC-containing products. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that patients minimize the use of THC-containing e-cigarette or vaping products in light of the thousands of reports in the United States of product-associated lung injury, which in some cases have led to death.52

Clarify serving sizes and recognize delayed effects. Inexperienced cannabis users often are confused by recommended serving sizes for edible cannabis products. A typical cannabis-infused brownie may contain 100 mg of THC when the recommended serving size typically is 10 mg. THC content is included on the label of cannabis edibles purchased in state-regulated stores; these products are tested regularly in laboratories designated by the state.

Due to the delayed onset of THC’s effect, there have been numerous cases of patients taking a higher-than-intended dose of edible cannabis that caused acute intoxication and psychomedical sequelae leading to emergency hospital visits and, in some cases, death.6,53 Individuals should start at a low dose and gradually work up to a higher dose as tolerated. Patients naïve to cannabis should be especially cautious when ingesting edible products.

Continue to: Abstain from cannabis with high THC content

Abstain from cannabis with high THC content. High-potency cannabis (> 10% THC) is associated with earlier onset of first-episode psychosis.54,55

Motivational interviewing

Motivational interviewing (MI) is a psychosocial approach that emphasizes a patient’s self-efficacy and an interviewer’s positive feedback to collaboratively address substance use.56 MI can be performed in short, discrete sessions. Such interventions can reduce the average number of days of cannabis use. One large-scale Cochrane review found that cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), motivational enhancement therapy, or the 2 therapies combined most consistently reduced the frequency of cannabis use reported by patients at early follow-up.57

Address underlying conditions

Some patients use cannabis to self-medicate for pain, insomnia, nausea, and anxiety. Identify these conditions and address them with first-line pharmacologic or psychotherapeutic interventions when possible. This is especially important for conditions in which long-term cannabis use may adversely impact outcomes, such as in posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and mood disorders.58-60 Little evidence exists for the use of cannabis as treatment of any primary psychiatric disorder.61,62 Family physicians who are uncomfortable treating a specific underlying condition can consult specialists in pain management, sleep medicine, psychiatry, and neurology.

Mitigate withdrawal symptoms

Discontinuation of cannabis use may lead to withdrawal symptoms such as waxing and waning irritability, restlessness, sweating, aggression, anxiety, depressed mood, sleep disturbance, or changes in appetite.63,64 These symptoms typically emerge within the first couple days of abstinence and can last up to 28 days.63,64 Although the US Food and Drug Administration has not approved any medications for CUD treatment, and there are no established protocols for detoxification, there is evidence that CBT or medications such as gabapentin or zolpidem can reduce the intensity of withdrawal symptoms.65,66

Refer to an addiction specialist

Consider referring patients with problematic cannabis use to an addiction specialist with expertise in psychopharmacologic and psychotherapeutic approaches to managing substance use.

Continue to: CASE

CASE

You renew Ms. F’s asthma medications, discuss her cannabis use, start her on a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, and refer her to an outpatient psychiatrist. Over the next few weeks, you and the outpatient psychiatrist employ brief motivational interviewing around cannabis use, and you provide psychoeducation around potential harms of use when driving and in light of the patient’s asthma.

The patient’s anxiety symptoms decrease with up-titration of the SSRI by the outpatient psychiatrist and with enrollment in individual CBT. She is slowly able to taper off cannabis vaping with continued motivational interviewing and encouragement, despite withdrawal-induced anxiety and sleep disturbance.

CORRESPONDENCE

Michael Hsu, MD, Brigham & Women’s Hospital, 75 Francis Street, Boston, MA 02215; mhsu7@partners.org.

1. Sarvet AL, Wall MM, Keyes KM, et al. Recent rapid decrease in adolescents’ perception that marijuana is harmful, but no concurrent increase in use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;186:68-74.

2. Compton WM, Han B, Jones CM, Blanco C, Hughes A. Marijuana use and use disorders in adults in the USA, 2002-14: analysis of annual cross-sectional surveys. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:954-964.

3. Lapham GT, Lee AK, Caldeiro RM, et al. Frequency of cannabis use among primary care patients in Washington state. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30:795‐805.

4. Chandra S, Radwan MM, Majumdar CG, et al. New trends in cannabis potency in USA and Europe during the last decade (2008-2017). Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2019;269:5-15.

5. Sevigny EL, Pacula RL, Heaton P. The effects of medical marijuana laws on potency. Int J Drug Policy. 2014;25:308-319.

6. Monte AA, Shelton SK, Mills E, et al. Acute illness associated with cannabis use, by route of exposure: an observational study. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170:531-537.

7. Scott JC, Slomiak ST, Jones JD, et al. Association of cannabis with cognitive functioning in adolescents and young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75:585-595.

8. Gruber SA, Sagar KA, Dahlgren MK, et al. Age of onset of marijuana use and executive function. Psychol Addict Behav. 2012;26:496-506.

9. Meier MH, Caspi A, Ambler A, et al. Persistent cannabis users show neuropsychological decline from childhood to midlife. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:E2657-E2664.

10. Mammen G, Rueda S, Roerecke M, et al. Association of cannabis with long-term clinical symptoms in anxiety and mood disorders: a systematic review of prospective studies. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79:17r11839.

11. Gage SH, Hickman M, Zammit S. Association between cannabis and psychosis: epidemiologic evidence. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79:549-556.

12. Singh A, Saluja S, Kumar A, et al. Cardiovascular complications of marijuana and related substances: a review. Cardiol Ther. 2018;7:45-59.

13. Volkow ND, Compton WM, Weiss SR. Adverse health effects of marijuana use. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2219-2227.

14. Bari M, Battista N, Pirazzi V, et al. The manifold actions of endocannabinoids on female and male reproductive events. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 2011;16:498-516.

15. Hayatbakhsh MR, Flenady VJ, Gibbons KS, et al. Birth outcomes associated with cannabis use before and during pregnancy. Pediatr Res. 2012;71:215-219.

16. Saurel-Cubizolles M-J, Prunet C, Blondel B. Cannabis use during pregnancy in France in 2010. BJOG. 2014;121:971-977.

17. Prunet C, Delnord M, Saurel-Cubizolles M-J, et al. Risk factors of preterm birth in France in 2010 and changes since 1995: results from the French national perinatal surveys. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2017;46:19-28.

18. Kondrad EC, Reed AJ, Simpson MJ, et al. Lack of communication about medical marijuana use between doctors and their patients. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31:805-808.

19. Casajuana C, López-Pelayo H, Balcells MM, et al. Definitions of risky and problematic cannabis use: a systematic review. Subst Use Misuse. 2016;51:1760-1770.

20. Norberg MM, Gates P, Dillon P, et al. Screening and managing cannabis use: comparing GP’s and nurses’ knowledge, beliefs, and behavior. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2012;7:31.

21. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington DC: APA Publishing; 2013:509-516.

22. Hasin DS, Saha TD, Kerridge BT, et al. Prevalence of marijuana use disorders in the United States between 2001-2002 and 2012-2013. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:1235-1242.

23. Smith PC, Schmidt SM, Allensworth-Davies D, et al. A single-question screening test for drug use in primary care. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1155-1160.

24. Fischer B, Jones W, Shuper P, et al. 12-month follow-up of an exploratory ‘brief intervention’ for high-frequency cannabis users among Canadian university students. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2012;7:15.

25. Turner SD, Spithoff S, Kahan M. Approach to cannabis use disorder in primary care: focus on youth and other high-risk users. Can Fam Physician. 2014;60:801-808.

26. Smart R, Caulkins JP, Kilmer B, et al. Variation in cannabis potency & prices in a newly-legal market: evidence from 30 million cannabis sales in Washington State. Addiction. 2017;112:2167-2177.

27. Bonn-Miller MO, Loflin MJE, Thomas BF, et al. Labeling accuracy of cannabidiol extracts sold online. JAMA. 2017;318:1708-1709.

28. Richards JR, Bing ML, Moulin AK, et al. Cannabis use and acute coronary syndrome. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2019;57:831-841.

29. Subramaniam VN, Menezes AR, DeSchutter A, et al. The cardiovascular effects of marijuana: are the potential adverse effects worth the high? Mo Med. 2019;116:146-153.

30. Jones RT. Cardiovascular system effects of marijuana. J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;42:58S-63S.

31. Tetrault JM, Crothers K, Moore BA, et al. Effects of marijuana smoking on pulmonary function and respiratory complications: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:221-228.

32. Bramness JG, von Soest T. A longitudinal study of cannabis use increasing the use of asthma medication in young Norwegian adults. BMC Pulm Med. 2019;19:52.

33. Moore BA, Augustson EM, Moser RP, et al. Respiratory effects of marijuana and tobacco use in a U.S. sample. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:33-37.

34. Tashkin DP. Does marijuana pose risks for chronic airflow obstruction? Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12:235-236.

35. McGuire PK, Jones P, Harvey I, et al. Morbid risk of schizophrenia for relatives of patients with cannabis-associated psychosis. Schizophr Res. 1995;15:277-281.

36. Hall W, Degenhardt L. Cannabis use and the risk of developing a psychotic disorder. World Psychiatry. 2008;7:68-71.

37. Gerlach J, Koret B, Gereš N, et al. Clinical challenges in patients with first episode psychosis and cannabis use: mini-review and a case study. Psychiatr Danub. 2019;31(suppl 2):162-170.

38. Patel R, Wilson R, Jackson R, et al. Association of cannabis use with hospital admission and antipsychotic treatment failure in first episode psychosis: an observational study. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e009888.

39. Day NL, Richardson GA, Goldschmidt L, et al. Effect of prenatal marijuana exposure on the cognitive development of offspring at age three. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1994;16:169-175.

40. Goldschmidt L, Day NL, Richardson GA. Effects of prenatal marijuana exposure on child behavior problems at age 10. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2000;22:325-336.

41. Corsi DJ, Walsh L, Weiss D, et al. Association between self-reported prenatal cannabis use and maternal, perinatal, and neonatal outcomes. JAMA. 2019;322:145-152.

42. Baker T, Datta P, Rewers-Felkins K, et al. Transfer of inhaled cannabis into human breast milk. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:783-788.

43. Thompson K, Leadbeater B, Ames M, et al. Associations between marijuana use trajectories and educational and occupational success in young adulthood. Prev Sci. 2019;20:257-269.

44. Yuan M, Kanellopoulos T, Kotbi N. Cannabis use and psychiatric illness in the context of medical marijuana legalization: a clinical perspective. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2019;61:82-83.

45. Ronen A, Gershon P, Drobiner H, et al. Effects of THC on driving performance, physiological state and subjective feelings relative to alcohol. Accid Anal Prev. 2008;40:926-934.

46. Robbe H. Marijuana’s impairing effects on driving are moderate when taken alone but severe when combined with alcohol. Hum Psychopharmacol Clin Exp. 1998;13(suppl 2):S70-S78.

47. Lenné MG, Dietze PM, Triggs TJ, et al. The effects of cannabis and alcohol on simulated arterial driving: influences of driving experience and task demand. Accid Anal Prev. 2010;42:859-866.

48. Anderson BM, Rizzo M, Block RI, et al. Sex differences in the effects of marijuana on simulated driving performance. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2010;42:19-30.

49. Laumon B, Gadegbeku B, Martin J-L, Biecheler M-B. Cannabis intoxication and fatal road crashes in France: population based case-control study. BMJ. 2005;331:1371.

50. Asbridge M, Poulin C, Donato A. Motor vehicle collision risk and driving under the influence of cannabis: evidence from adolescents in Atlantic Canada. Accid Anal Prev. 2005;37:1025-1034.

51. Mann RE, Adlaf E, Zhao J, et al. Cannabis use and self-reported collisions in a representative sample of adult drivers. J Safety Res. 2007;38:669-674.

52. Taylor J, Wiens T, Peterson J, et al. Characteristics of e-cigarette, or vaping, products used by patients with associated lung injury and products seized by law enforcement—Minnesota, 2018 and 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:1096-1100.

53. Hancock-Allen JB, Barker L, VanDyke M, et al. Notes from the field: death following ingestion of an edible marijuana product—Colorado, March 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:771-772.

54. Murray RM, Quigley H, Quattrone D, et al. Traditional marijuana, high-potency cannabis and synthetic cannabinoids: increasing risk for psychosis. World Psychiatry. 2016;15:195-204.

55. Di Forti MD, Sallis H, Allegri F, et al. Daily use, especially of high-potency cannabis, drives the earlier onset of psychosis in cannabis users. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40:1509-1517.

56. Miller WR. Motivational interviewing: research, practice, and puzzles. Addict Behav. 1996;21:835-842.

57. Gates PJ, Sabioni P, Copeland J, et al. Psychosocial interventions for cannabis use disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(5):CD005336.

58. Wilkinson ST, Stefanovics E, Rosenheck RA. Marijuana use is associated with worse outcomes in symptom severity and violent behavior in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76:1174-1180.

59. Cougle JR, Bonn-Miller MO, Vujanovic AA, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and cannabis use in a nationally representative sample. Psychol Addict Behav. 2011;25:554-558.

60. Johnson MJ, Pierce JD, Mavandadi S, et al. Mental health symptom severity in cannabis using and non-using veterans with probable PTSD. J Affect Disord. 2016;190:439-442.

61. Wilkinson ST, Radhakrishnan R, D’Souza DC. A systematic review of the evidence for medical marijuana in psychiatric indications. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77:1050-1064.

62. Black N, Stockings E, Campbell G, et al. Cannabinoids for the treatment of mental disorders and symptoms of mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6:995-1010.

63. Bonnet U, Preuss U. The cannabis withdrawal syndrome: current insights. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2017;8:9-37.

64. Vandrey R, Smith MT, McCann UD, et al. Sleep disturbance and the effects of extended-release zolpidem during cannabis withdrawal. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;117:38-44.

65. Mason BJ, Crean R, Goodell V, et al. A proof-of-concept randomized controlled study of gabapentin: effects on cannabis use, withdrawal and executive function deficits in cannabis-dependent adults. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:1689-1698.

66. Weinstein A, Miller H, Tal E, et al. Treatment of cannabis withdrawal syndrome using cognitive-behavioral therapy and relapse prevention for cannabis dependence. J Groups Addict Recover. 2010;5:240-263.

1. Sarvet AL, Wall MM, Keyes KM, et al. Recent rapid decrease in adolescents’ perception that marijuana is harmful, but no concurrent increase in use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;186:68-74.

2. Compton WM, Han B, Jones CM, Blanco C, Hughes A. Marijuana use and use disorders in adults in the USA, 2002-14: analysis of annual cross-sectional surveys. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:954-964.

3. Lapham GT, Lee AK, Caldeiro RM, et al. Frequency of cannabis use among primary care patients in Washington state. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30:795‐805.

4. Chandra S, Radwan MM, Majumdar CG, et al. New trends in cannabis potency in USA and Europe during the last decade (2008-2017). Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2019;269:5-15.

5. Sevigny EL, Pacula RL, Heaton P. The effects of medical marijuana laws on potency. Int J Drug Policy. 2014;25:308-319.

6. Monte AA, Shelton SK, Mills E, et al. Acute illness associated with cannabis use, by route of exposure: an observational study. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170:531-537.

7. Scott JC, Slomiak ST, Jones JD, et al. Association of cannabis with cognitive functioning in adolescents and young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75:585-595.

8. Gruber SA, Sagar KA, Dahlgren MK, et al. Age of onset of marijuana use and executive function. Psychol Addict Behav. 2012;26:496-506.

9. Meier MH, Caspi A, Ambler A, et al. Persistent cannabis users show neuropsychological decline from childhood to midlife. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:E2657-E2664.

10. Mammen G, Rueda S, Roerecke M, et al. Association of cannabis with long-term clinical symptoms in anxiety and mood disorders: a systematic review of prospective studies. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79:17r11839.

11. Gage SH, Hickman M, Zammit S. Association between cannabis and psychosis: epidemiologic evidence. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79:549-556.

12. Singh A, Saluja S, Kumar A, et al. Cardiovascular complications of marijuana and related substances: a review. Cardiol Ther. 2018;7:45-59.

13. Volkow ND, Compton WM, Weiss SR. Adverse health effects of marijuana use. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2219-2227.

14. Bari M, Battista N, Pirazzi V, et al. The manifold actions of endocannabinoids on female and male reproductive events. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 2011;16:498-516.

15. Hayatbakhsh MR, Flenady VJ, Gibbons KS, et al. Birth outcomes associated with cannabis use before and during pregnancy. Pediatr Res. 2012;71:215-219.

16. Saurel-Cubizolles M-J, Prunet C, Blondel B. Cannabis use during pregnancy in France in 2010. BJOG. 2014;121:971-977.

17. Prunet C, Delnord M, Saurel-Cubizolles M-J, et al. Risk factors of preterm birth in France in 2010 and changes since 1995: results from the French national perinatal surveys. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2017;46:19-28.

18. Kondrad EC, Reed AJ, Simpson MJ, et al. Lack of communication about medical marijuana use between doctors and their patients. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31:805-808.

19. Casajuana C, López-Pelayo H, Balcells MM, et al. Definitions of risky and problematic cannabis use: a systematic review. Subst Use Misuse. 2016;51:1760-1770.

20. Norberg MM, Gates P, Dillon P, et al. Screening and managing cannabis use: comparing GP’s and nurses’ knowledge, beliefs, and behavior. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2012;7:31.

21. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington DC: APA Publishing; 2013:509-516.

22. Hasin DS, Saha TD, Kerridge BT, et al. Prevalence of marijuana use disorders in the United States between 2001-2002 and 2012-2013. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:1235-1242.

23. Smith PC, Schmidt SM, Allensworth-Davies D, et al. A single-question screening test for drug use in primary care. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1155-1160.

24. Fischer B, Jones W, Shuper P, et al. 12-month follow-up of an exploratory ‘brief intervention’ for high-frequency cannabis users among Canadian university students. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2012;7:15.

25. Turner SD, Spithoff S, Kahan M. Approach to cannabis use disorder in primary care: focus on youth and other high-risk users. Can Fam Physician. 2014;60:801-808.

26. Smart R, Caulkins JP, Kilmer B, et al. Variation in cannabis potency & prices in a newly-legal market: evidence from 30 million cannabis sales in Washington State. Addiction. 2017;112:2167-2177.

27. Bonn-Miller MO, Loflin MJE, Thomas BF, et al. Labeling accuracy of cannabidiol extracts sold online. JAMA. 2017;318:1708-1709.

28. Richards JR, Bing ML, Moulin AK, et al. Cannabis use and acute coronary syndrome. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2019;57:831-841.

29. Subramaniam VN, Menezes AR, DeSchutter A, et al. The cardiovascular effects of marijuana: are the potential adverse effects worth the high? Mo Med. 2019;116:146-153.

30. Jones RT. Cardiovascular system effects of marijuana. J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;42:58S-63S.

31. Tetrault JM, Crothers K, Moore BA, et al. Effects of marijuana smoking on pulmonary function and respiratory complications: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:221-228.

32. Bramness JG, von Soest T. A longitudinal study of cannabis use increasing the use of asthma medication in young Norwegian adults. BMC Pulm Med. 2019;19:52.

33. Moore BA, Augustson EM, Moser RP, et al. Respiratory effects of marijuana and tobacco use in a U.S. sample. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:33-37.

34. Tashkin DP. Does marijuana pose risks for chronic airflow obstruction? Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12:235-236.

35. McGuire PK, Jones P, Harvey I, et al. Morbid risk of schizophrenia for relatives of patients with cannabis-associated psychosis. Schizophr Res. 1995;15:277-281.

36. Hall W, Degenhardt L. Cannabis use and the risk of developing a psychotic disorder. World Psychiatry. 2008;7:68-71.

37. Gerlach J, Koret B, Gereš N, et al. Clinical challenges in patients with first episode psychosis and cannabis use: mini-review and a case study. Psychiatr Danub. 2019;31(suppl 2):162-170.

38. Patel R, Wilson R, Jackson R, et al. Association of cannabis use with hospital admission and antipsychotic treatment failure in first episode psychosis: an observational study. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e009888.

39. Day NL, Richardson GA, Goldschmidt L, et al. Effect of prenatal marijuana exposure on the cognitive development of offspring at age three. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1994;16:169-175.

40. Goldschmidt L, Day NL, Richardson GA. Effects of prenatal marijuana exposure on child behavior problems at age 10. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2000;22:325-336.

41. Corsi DJ, Walsh L, Weiss D, et al. Association between self-reported prenatal cannabis use and maternal, perinatal, and neonatal outcomes. JAMA. 2019;322:145-152.

42. Baker T, Datta P, Rewers-Felkins K, et al. Transfer of inhaled cannabis into human breast milk. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:783-788.

43. Thompson K, Leadbeater B, Ames M, et al. Associations between marijuana use trajectories and educational and occupational success in young adulthood. Prev Sci. 2019;20:257-269.

44. Yuan M, Kanellopoulos T, Kotbi N. Cannabis use and psychiatric illness in the context of medical marijuana legalization: a clinical perspective. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2019;61:82-83.

45. Ronen A, Gershon P, Drobiner H, et al. Effects of THC on driving performance, physiological state and subjective feelings relative to alcohol. Accid Anal Prev. 2008;40:926-934.

46. Robbe H. Marijuana’s impairing effects on driving are moderate when taken alone but severe when combined with alcohol. Hum Psychopharmacol Clin Exp. 1998;13(suppl 2):S70-S78.

47. Lenné MG, Dietze PM, Triggs TJ, et al. The effects of cannabis and alcohol on simulated arterial driving: influences of driving experience and task demand. Accid Anal Prev. 2010;42:859-866.

48. Anderson BM, Rizzo M, Block RI, et al. Sex differences in the effects of marijuana on simulated driving performance. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2010;42:19-30.

49. Laumon B, Gadegbeku B, Martin J-L, Biecheler M-B. Cannabis intoxication and fatal road crashes in France: population based case-control study. BMJ. 2005;331:1371.

50. Asbridge M, Poulin C, Donato A. Motor vehicle collision risk and driving under the influence of cannabis: evidence from adolescents in Atlantic Canada. Accid Anal Prev. 2005;37:1025-1034.

51. Mann RE, Adlaf E, Zhao J, et al. Cannabis use and self-reported collisions in a representative sample of adult drivers. J Safety Res. 2007;38:669-674.

52. Taylor J, Wiens T, Peterson J, et al. Characteristics of e-cigarette, or vaping, products used by patients with associated lung injury and products seized by law enforcement—Minnesota, 2018 and 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:1096-1100.

53. Hancock-Allen JB, Barker L, VanDyke M, et al. Notes from the field: death following ingestion of an edible marijuana product—Colorado, March 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:771-772.

54. Murray RM, Quigley H, Quattrone D, et al. Traditional marijuana, high-potency cannabis and synthetic cannabinoids: increasing risk for psychosis. World Psychiatry. 2016;15:195-204.

55. Di Forti MD, Sallis H, Allegri F, et al. Daily use, especially of high-potency cannabis, drives the earlier onset of psychosis in cannabis users. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40:1509-1517.

56. Miller WR. Motivational interviewing: research, practice, and puzzles. Addict Behav. 1996;21:835-842.

57. Gates PJ, Sabioni P, Copeland J, et al. Psychosocial interventions for cannabis use disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(5):CD005336.

58. Wilkinson ST, Stefanovics E, Rosenheck RA. Marijuana use is associated with worse outcomes in symptom severity and violent behavior in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76:1174-1180.

59. Cougle JR, Bonn-Miller MO, Vujanovic AA, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and cannabis use in a nationally representative sample. Psychol Addict Behav. 2011;25:554-558.

60. Johnson MJ, Pierce JD, Mavandadi S, et al. Mental health symptom severity in cannabis using and non-using veterans with probable PTSD. J Affect Disord. 2016;190:439-442.

61. Wilkinson ST, Radhakrishnan R, D’Souza DC. A systematic review of the evidence for medical marijuana in psychiatric indications. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77:1050-1064.

62. Black N, Stockings E, Campbell G, et al. Cannabinoids for the treatment of mental disorders and symptoms of mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6:995-1010.

63. Bonnet U, Preuss U. The cannabis withdrawal syndrome: current insights. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2017;8:9-37.

64. Vandrey R, Smith MT, McCann UD, et al. Sleep disturbance and the effects of extended-release zolpidem during cannabis withdrawal. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;117:38-44.

65. Mason BJ, Crean R, Goodell V, et al. A proof-of-concept randomized controlled study of gabapentin: effects on cannabis use, withdrawal and executive function deficits in cannabis-dependent adults. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:1689-1698.

66. Weinstein A, Miller H, Tal E, et al. Treatment of cannabis withdrawal syndrome using cognitive-behavioral therapy and relapse prevention for cannabis dependence. J Groups Addict Recover. 2010;5:240-263.

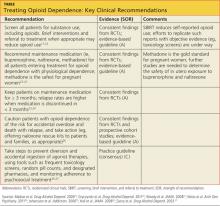

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Address underlying conditions for which patients use recreational cannabis to manage symptoms. B

› Consider discrete, in-office sessions of motivational interviewing and referral for cognitive behavioral therapy for patients with problematic cannabis use. B

› Provide counseling around harm reduction for all patients—especially those with problematic cannabis use. C

› Consider referral to an addiction specialist for patients with cannabis use disorder or other problematic cannabis use. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Cannabis use disorder

Diagnosing and Treating Opioid Dependence

CASE Sam M., age 48, is in your office for the first time in more than two years. He has gained a considerable amount of weight and appears a bit sluggish, and you wonder whether he's depressed. As you take a history, Sam reminds you that he was laid off 16 months ago and had been caring for his wife, who sustained a debilitating back injury. When you saw her recently, she told you she's back to work and pain-free. So you're taken aback when Sam asks you to refill his wife's oxycodone prescription for lingering pain that often keeps her up at night.

If Sam were your patient, would you suspect opioid dependence?

Dependence on opioid analgesics and the adverse consequences associated with it have steadily increased during the past decade. Consider the following:

• Between 2004 and 2008, the number of emergency department visits related to nonmedical prescription opioid use more than doubled, rising by 111%.1

• The increasing prevalence of opioid abuse has led to a recent spike in unintentional deaths,2 with the number of lives lost to opioid analgesic overdose now exceeding that of heroin or cocaine.3

• More than 75% of opioids used for nonmedical purposes were prescribed for someone else.4

The course of opioid use is highly variable. Some people start with a legitimate medical prescription for an opioid analgesic, then continue taking it after the pain subsides. Others experiment briefly with nonmedical prescription opioids or use them intermittently without adverse effect. Some progress from prescription opioids to heroin, despite its dangers.5 Still others experience a catastrophic outcome, such as an overdose or severe accident, the first time they use opioids.6 Rapid progression from misuse of opioids to dependence is most likely to occur in vulnerable populations, such as those with concurrent mental illness, other substance use disorders, or increased sensitivity to pain.7

Understanding the terms. Before we continue, a word about terminology is in order. Misuse generally refers to the use of a medication in a manner (ie, purpose, dose, or frequency) other than its intended use, whereas drug addiction is the repeated use of a drug despite resulting harm. Here we will use opioid dependence to mean a pattern of increasing use characterized by significant impairment and distress and an inability to stop, and opioid withdrawal to reflect a constellation of symptoms, such as insomnia, nausea, diarrhea, and muscle aches, that can follow physiological dependence (though not necessarily opioid dependence). Our definitions of these terms are consistent with those of the American Psychiatric Association (APA).8 Worth noting, however, is the fact that as the APA prepares for the publication of the 5th edition of its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, its Substance Disorder Work Group has proposed replacing the term opioid dependence with opioid use disorder to reduce the confusion associated with these definitions.9

Assessing Illicit Opioid Use: Start With a Targeted Question

Most patients who are opioid dependent do not seek treatment for it10 and are typically free of medical sequelae associated with drug addiction when they see family practitioners. The absence of self-reporting and obvious physical signs and symptoms, coupled with the increase in illicit use of prescription opioids, underscores the need for clinicians to identify patients who are abusing opioids and ensure that they get the help they need.

Screening tools. There are a number of screening tools you can use for this purpose—eg, CAGE-Adapted to Include Drugs (CAGE-AID) and Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST)11,12—but they have not been found to be significantly better than a careful substance abuse history.13

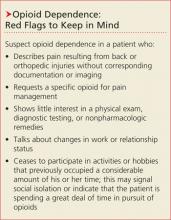

Straightforward questions. You can start by asking, "Do you take any medications for pain?" If the answer is Yes, get the name of the drug and inquire about the frequency of use and the route, the amount typically taken, and the duration of the current use pattern. Ask specifically about opioids when taking a substance abuse history. After a question about alcohol use, you can say, "Do you use any other drugs in a serious way? Marijuana? Opioids, like Percocet, Vicodin, or Oxycontin?" Although it can be very difficult to detect opioid dependence if the patient is not forthcoming, other likely indicators of drug-seeking behavior should trigger additional questions. (See "Opioid dependence: Red Flags to Keep in Mind."14-16)

"Brief" protocols. Recent studies of Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) programs have found that the simple, time-limited interventions they offer (visit www.samhsa.gov/prevention/sbirt/SBIRTwhitepaper.pdf to learn more) lead to a reduction in self-reported illicit opioid use.17,18 Clinicians can readily incorporate SBIRT protocols into routine practice, as an evidence-based and often reimbursable approach to substance abuse.17

Additional Steps Before Initiating Treatment

After screening and diagnostic evaluation provide evidence that a patient is opioid dependent, you can take several steps to guide him or her to the appropriate treatment.

A thorough biopsychosocial assessment covering co-occurring psychiatric illnesses, pain, psychosocial stressors contributing to opioid use, and infectious disease screening is required to gain a clear picture of the patient's situation. In every case, acute emergencies such as suicidal ideation require immediate intervention, which may include hospitalization.19