User login

Larry Beresford is an Oakland, Calif.-based freelance medical journalist with a breadth of experience writing about the policy, financial, clinical, management and human aspects of hospice, palliative care, end-of-life care, death, and dying. He is a longtime contributor to The Hospitalist, for which he covers re-admissions, pain management, palliative care, physician stress and burnout, quality improvement, waste prevention, practice management, innovation, and technology. He also contributes to Medscape. Learn more about his work at www.larryberesford.com; follow him on Twitter @larryberesford.

99% of Medical-Device Monitoring Alerts Not Actionable

Nearly all medical-device monitoring alerts on regular hospital units were found not to be actionable, according to a study by pediatrician and researcher Chris Bonafide, MD, MSCE, at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, based on reviewing hours of video from patient rooms.1

Reference

- Bonafide CP, Lin R, Zander M, et al. Association between exposure to nonactionable physiologic monitor alarms and response time in a children’s hospital. J Hosp Med. 2015; 10(6):345–351.

Nearly all medical-device monitoring alerts on regular hospital units were found not to be actionable, according to a study by pediatrician and researcher Chris Bonafide, MD, MSCE, at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, based on reviewing hours of video from patient rooms.1

Reference

- Bonafide CP, Lin R, Zander M, et al. Association between exposure to nonactionable physiologic monitor alarms and response time in a children’s hospital. J Hosp Med. 2015; 10(6):345–351.

Nearly all medical-device monitoring alerts on regular hospital units were found not to be actionable, according to a study by pediatrician and researcher Chris Bonafide, MD, MSCE, at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, based on reviewing hours of video from patient rooms.1

Reference

- Bonafide CP, Lin R, Zander M, et al. Association between exposure to nonactionable physiologic monitor alarms and response time in a children’s hospital. J Hosp Med. 2015; 10(6):345–351.

Electronic Health Records Key Driver of Physician Burnout

Half of U.S. physicians are experiencing some of the symptoms of burnout, with even higher rates for general internists. Implementation of the electronic health record (EHR) has been cited as the biggest driver of physician job dissatisfaction, said Christine Sinsky, MD, a former hospitalist and currently vice president of professional satisfaction at the American Medical Association (AMA), to attendees at the 19th Management of the Hospitalized Patient Conference, presented by the University of California-San Francisco.1

Dr. Sinsky deemed physician discontent “the canary in the coal mine” for a dysfunctional healthcare system. After visiting 23 high-functioning medical teams, Dr. Sinsky said she had found that 70% to 80% of physician work output could be considered waste, defined as work that doesn’t need to be done and doesn’t add value to the patient. The AMA, she said, has made a commitment to addressing physicians’ dissatisfaction and burnout.

Dr. Sinsky offered a number of suggestions for physicians and the larger system. Among them was the idea of medical teams employing a documentation specialist, or scribe, to accompany physicians on patient rounds to help with the clerical tasks that divert physicians from patient care. She also cited David Reuben, MD, a gerontologist at UCLA whose JAMA Internal Medicine study documented his training of physician “practice partners,” often medical or nursing students, who help queue up orders in the EHR, and the improved patient satisfaction that resulted.2

“Be bold,” she advised hospitalists. “The patient care delivery modes of the future can’t be met with staffing models from the past.”

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Alameda, Calif.

References

- Friedberg M, Chen PG, Van Busum KR, et al. Factors affecting physician professional satisfaction and their implications for patient care, health systems, and health policy. 2013. Accessed November 3, 2015.

- Reuben DB, Knudsen J, Senelick W, Glazier E, Koretz BK. The effect of a physician partner program on physician efficiency and patient satisfaction. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(7):1190-1193.

Half of U.S. physicians are experiencing some of the symptoms of burnout, with even higher rates for general internists. Implementation of the electronic health record (EHR) has been cited as the biggest driver of physician job dissatisfaction, said Christine Sinsky, MD, a former hospitalist and currently vice president of professional satisfaction at the American Medical Association (AMA), to attendees at the 19th Management of the Hospitalized Patient Conference, presented by the University of California-San Francisco.1

Dr. Sinsky deemed physician discontent “the canary in the coal mine” for a dysfunctional healthcare system. After visiting 23 high-functioning medical teams, Dr. Sinsky said she had found that 70% to 80% of physician work output could be considered waste, defined as work that doesn’t need to be done and doesn’t add value to the patient. The AMA, she said, has made a commitment to addressing physicians’ dissatisfaction and burnout.

Dr. Sinsky offered a number of suggestions for physicians and the larger system. Among them was the idea of medical teams employing a documentation specialist, or scribe, to accompany physicians on patient rounds to help with the clerical tasks that divert physicians from patient care. She also cited David Reuben, MD, a gerontologist at UCLA whose JAMA Internal Medicine study documented his training of physician “practice partners,” often medical or nursing students, who help queue up orders in the EHR, and the improved patient satisfaction that resulted.2

“Be bold,” she advised hospitalists. “The patient care delivery modes of the future can’t be met with staffing models from the past.”

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Alameda, Calif.

References

- Friedberg M, Chen PG, Van Busum KR, et al. Factors affecting physician professional satisfaction and their implications for patient care, health systems, and health policy. 2013. Accessed November 3, 2015.

- Reuben DB, Knudsen J, Senelick W, Glazier E, Koretz BK. The effect of a physician partner program on physician efficiency and patient satisfaction. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(7):1190-1193.

Half of U.S. physicians are experiencing some of the symptoms of burnout, with even higher rates for general internists. Implementation of the electronic health record (EHR) has been cited as the biggest driver of physician job dissatisfaction, said Christine Sinsky, MD, a former hospitalist and currently vice president of professional satisfaction at the American Medical Association (AMA), to attendees at the 19th Management of the Hospitalized Patient Conference, presented by the University of California-San Francisco.1

Dr. Sinsky deemed physician discontent “the canary in the coal mine” for a dysfunctional healthcare system. After visiting 23 high-functioning medical teams, Dr. Sinsky said she had found that 70% to 80% of physician work output could be considered waste, defined as work that doesn’t need to be done and doesn’t add value to the patient. The AMA, she said, has made a commitment to addressing physicians’ dissatisfaction and burnout.

Dr. Sinsky offered a number of suggestions for physicians and the larger system. Among them was the idea of medical teams employing a documentation specialist, or scribe, to accompany physicians on patient rounds to help with the clerical tasks that divert physicians from patient care. She also cited David Reuben, MD, a gerontologist at UCLA whose JAMA Internal Medicine study documented his training of physician “practice partners,” often medical or nursing students, who help queue up orders in the EHR, and the improved patient satisfaction that resulted.2

“Be bold,” she advised hospitalists. “The patient care delivery modes of the future can’t be met with staffing models from the past.”

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Alameda, Calif.

References

- Friedberg M, Chen PG, Van Busum KR, et al. Factors affecting physician professional satisfaction and their implications for patient care, health systems, and health policy. 2013. Accessed November 3, 2015.

- Reuben DB, Knudsen J, Senelick W, Glazier E, Koretz BK. The effect of a physician partner program on physician efficiency and patient satisfaction. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(7):1190-1193.

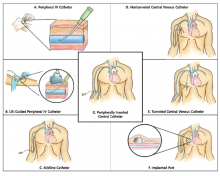

Guide Helps Hospitalists Choose Most Appropriate Catheter for Patients

The Michigan Appropriateness Guide for Intravenous Catheters (MAGIC) is a new resource designed to help clinicians select the safest and most appropriate peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) for individual patients.

“How do you decide which catheter is best for your patient? Until now there wasn’t a guide bringing together all of the best available evidence,” says the guide’s lead author Vineet Chopra, MD, MSc, FHM, a hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

“These are among the most commonly performed procedures on any hospitalized patient, and yet, the least studied,” he adds. “We as hospitalists are the physicians who order most of these devices, especially PICCs.”

The guide includes algorithms and color-coded pocket cards to help physicians determine which PICC to choose. The cards can be freely downloaded and printed from the Improve PICC website at the University of Michigan.

The project to develop the guide brought together 15 leading international experts on catheters and their infections and complications, including the authors of existing guidelines, to brainstorm more than 600 clinical scenarios and best evidence-based practice for catheter use using the Rand/UCLA Appropriateness Method. “We also had a patient on the panel, which was important to the clinicians because this patient had actually used many of the devices being discussed,” Dr. Chopra explains.

The guidelines “have the potential to change the game for hospitalists,” Dr. Chopra adds. “There has never before been guidance on using IV devices in hospitalized medical patients, despite the fact that we use these devices every day. Now, for the first time, we not only have guidance but also a tool to benchmark the quality of care provided by doctors when it comes to venous access.”

The Michigan Appropriateness Guide for Intravenous Catheters (MAGIC) is a new resource designed to help clinicians select the safest and most appropriate peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) for individual patients.

“How do you decide which catheter is best for your patient? Until now there wasn’t a guide bringing together all of the best available evidence,” says the guide’s lead author Vineet Chopra, MD, MSc, FHM, a hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

“These are among the most commonly performed procedures on any hospitalized patient, and yet, the least studied,” he adds. “We as hospitalists are the physicians who order most of these devices, especially PICCs.”

The guide includes algorithms and color-coded pocket cards to help physicians determine which PICC to choose. The cards can be freely downloaded and printed from the Improve PICC website at the University of Michigan.

The project to develop the guide brought together 15 leading international experts on catheters and their infections and complications, including the authors of existing guidelines, to brainstorm more than 600 clinical scenarios and best evidence-based practice for catheter use using the Rand/UCLA Appropriateness Method. “We also had a patient on the panel, which was important to the clinicians because this patient had actually used many of the devices being discussed,” Dr. Chopra explains.

The guidelines “have the potential to change the game for hospitalists,” Dr. Chopra adds. “There has never before been guidance on using IV devices in hospitalized medical patients, despite the fact that we use these devices every day. Now, for the first time, we not only have guidance but also a tool to benchmark the quality of care provided by doctors when it comes to venous access.”

The Michigan Appropriateness Guide for Intravenous Catheters (MAGIC) is a new resource designed to help clinicians select the safest and most appropriate peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) for individual patients.

“How do you decide which catheter is best for your patient? Until now there wasn’t a guide bringing together all of the best available evidence,” says the guide’s lead author Vineet Chopra, MD, MSc, FHM, a hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

“These are among the most commonly performed procedures on any hospitalized patient, and yet, the least studied,” he adds. “We as hospitalists are the physicians who order most of these devices, especially PICCs.”

The guide includes algorithms and color-coded pocket cards to help physicians determine which PICC to choose. The cards can be freely downloaded and printed from the Improve PICC website at the University of Michigan.

The project to develop the guide brought together 15 leading international experts on catheters and their infections and complications, including the authors of existing guidelines, to brainstorm more than 600 clinical scenarios and best evidence-based practice for catheter use using the Rand/UCLA Appropriateness Method. “We also had a patient on the panel, which was important to the clinicians because this patient had actually used many of the devices being discussed,” Dr. Chopra explains.

The guidelines “have the potential to change the game for hospitalists,” Dr. Chopra adds. “There has never before been guidance on using IV devices in hospitalized medical patients, despite the fact that we use these devices every day. Now, for the first time, we not only have guidance but also a tool to benchmark the quality of care provided by doctors when it comes to venous access.”

Institute of Medicine Report Examines Medical Misdiagnoses

Authors of the IOM’s “Improving Diagnosis in Health Care” report cite problems in communication and limitations in electronic health records behind inaccurate and delayed diagnoses, concluding that the problem of diagnostic errors generally has not been adequately studied.1

“This problem is significant and serious. Yet we don’t know for sure how often it occurs, how serious it is, or how much it costs,” said the IOM committee’s chair, John Ball, MD, of the American College of Physicians, in a prepared statement. The report concludes there is no easy fix for the problem of diagnostic errors, which are a leading cause of adverse events in hospitals and of malpractice lawsuits for hospitalists, but calls for a major reassessment of the diagnostic process.2

Hospitalist Mangla Gulati, MD, FACP, SFHM, assistant chief medical officer at the University of Maryland Medical Center in Baltimore, says hospitalists would be remiss if they failed to take a closer look at the IOM report. “Diagnostic error is something we haven’t much talked about in medicine,” Dr. Gulati says. “Part of the goal of this report is to actually include the patient in those conversations.” Patients who are rehospitalized, she says, may have been given an incorrect initial diagnosis that was never rectified, or there may have been a failure to communicate important information.

“How many tests do we order where results come back after a patient leaves the hospital?” asks Kedar Mate, MD, senior vice president at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement and a hospitalist at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City. “How many in-hospital diagnoses are made without all of the available information from outside providers?”

One simple intervention hospitalists could do immediately, he says, is to start tracking all important tests ordered for patients on a board in the medical team’s meeting room, only removing them from the board when results have been checked and communicated to the patient and outpatient provider.

References

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Improving Diagnosis in Health Care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. 2015.

- Saber Tehrani AS, Lee HW, Mathews SC, et al. 25-year summary of U.S. malpractice claims for diagnostic errors 1986–2010: An analysis from the National Practitioner Data Bank. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013 Aug; 22(8):672–680.

Authors of the IOM’s “Improving Diagnosis in Health Care” report cite problems in communication and limitations in electronic health records behind inaccurate and delayed diagnoses, concluding that the problem of diagnostic errors generally has not been adequately studied.1

“This problem is significant and serious. Yet we don’t know for sure how often it occurs, how serious it is, or how much it costs,” said the IOM committee’s chair, John Ball, MD, of the American College of Physicians, in a prepared statement. The report concludes there is no easy fix for the problem of diagnostic errors, which are a leading cause of adverse events in hospitals and of malpractice lawsuits for hospitalists, but calls for a major reassessment of the diagnostic process.2

Hospitalist Mangla Gulati, MD, FACP, SFHM, assistant chief medical officer at the University of Maryland Medical Center in Baltimore, says hospitalists would be remiss if they failed to take a closer look at the IOM report. “Diagnostic error is something we haven’t much talked about in medicine,” Dr. Gulati says. “Part of the goal of this report is to actually include the patient in those conversations.” Patients who are rehospitalized, she says, may have been given an incorrect initial diagnosis that was never rectified, or there may have been a failure to communicate important information.

“How many tests do we order where results come back after a patient leaves the hospital?” asks Kedar Mate, MD, senior vice president at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement and a hospitalist at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City. “How many in-hospital diagnoses are made without all of the available information from outside providers?”

One simple intervention hospitalists could do immediately, he says, is to start tracking all important tests ordered for patients on a board in the medical team’s meeting room, only removing them from the board when results have been checked and communicated to the patient and outpatient provider.

References

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Improving Diagnosis in Health Care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. 2015.

- Saber Tehrani AS, Lee HW, Mathews SC, et al. 25-year summary of U.S. malpractice claims for diagnostic errors 1986–2010: An analysis from the National Practitioner Data Bank. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013 Aug; 22(8):672–680.

Authors of the IOM’s “Improving Diagnosis in Health Care” report cite problems in communication and limitations in electronic health records behind inaccurate and delayed diagnoses, concluding that the problem of diagnostic errors generally has not been adequately studied.1

“This problem is significant and serious. Yet we don’t know for sure how often it occurs, how serious it is, or how much it costs,” said the IOM committee’s chair, John Ball, MD, of the American College of Physicians, in a prepared statement. The report concludes there is no easy fix for the problem of diagnostic errors, which are a leading cause of adverse events in hospitals and of malpractice lawsuits for hospitalists, but calls for a major reassessment of the diagnostic process.2

Hospitalist Mangla Gulati, MD, FACP, SFHM, assistant chief medical officer at the University of Maryland Medical Center in Baltimore, says hospitalists would be remiss if they failed to take a closer look at the IOM report. “Diagnostic error is something we haven’t much talked about in medicine,” Dr. Gulati says. “Part of the goal of this report is to actually include the patient in those conversations.” Patients who are rehospitalized, she says, may have been given an incorrect initial diagnosis that was never rectified, or there may have been a failure to communicate important information.

“How many tests do we order where results come back after a patient leaves the hospital?” asks Kedar Mate, MD, senior vice president at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement and a hospitalist at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City. “How many in-hospital diagnoses are made without all of the available information from outside providers?”

One simple intervention hospitalists could do immediately, he says, is to start tracking all important tests ordered for patients on a board in the medical team’s meeting room, only removing them from the board when results have been checked and communicated to the patient and outpatient provider.

References

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Improving Diagnosis in Health Care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. 2015.

- Saber Tehrani AS, Lee HW, Mathews SC, et al. 25-year summary of U.S. malpractice claims for diagnostic errors 1986–2010: An analysis from the National Practitioner Data Bank. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013 Aug; 22(8):672–680.

Quality Improvement Initiative Targets Sepsis

A quality improvement (QI) initiative at University Hospital in Salt Lake City aims to save lives and cut hospital costs by reducing inpatient sepsis mortality.

Program co-leaders, hospitalists Devin Horton, MD, and Kencee Graves, MD, of University Hospital, launched the initiative as a pilot program last October. They began by surveying hospital house staff and nurses on their ability to recognize and define six different sepsis syndromes from clinical vignettes. A total of 136 surveyed residents recognized the correct condition only 56% of the time, and 280 surveyed nurses only did so 17% of the time. The hospitalists determined that better education about sepsis was crucial.

“We developed a robust teaching program for nurses and residents using Septris, an online educational game from Stanford University,” Dr. Horton says. The team also developed technology that can recognize worsening vital signs in a patient and automatically trigger an alert to a charge nurse or rapid response team.

The team’s Modified Early Warning System (MEWS) for recognizing sepsis is similar to the Early Warning and Response System (EWRS) system used at the University of Pennsylvania Health System and the University of California San Diego, and draws on other hospitals’ sepsis systems. Dr. Horton says one difference in their system is the involvement of nursing aides who take vital signs, enter them real-time into electronic health records (EHR), and receive prompts from abnormal vital signs to retake all vitals and confirm abnormal results. It also incorporates EHR decision support tools, including links to pre-populated medical order panels, such as for the ordering of tests for lactate and blood cultures.

“Severe sepsis is often quoted as the number one cause of mortality among hospitalized patients, with a rate up to 10 times that of acute myocardial infarction,” Dr. Horton explains. “The one treatment that consistently decreases mortality is timely administration of antibiotics. But, in order for a patient to be given timely antibiotics, the nurse or resident must first recognize that the patient has sepsis.”

“This is one of the biggest and most far-reaching improvement initiatives that has been done at our institution,” says Robert Pendleton, MD, chief quality officer at University Hospital. Dr. Horton says he predicts the program will “save 50 lives and $1 million per year.”

For more information, contact him at: devin.horton@hsc.utah.edu.

A quality improvement (QI) initiative at University Hospital in Salt Lake City aims to save lives and cut hospital costs by reducing inpatient sepsis mortality.

Program co-leaders, hospitalists Devin Horton, MD, and Kencee Graves, MD, of University Hospital, launched the initiative as a pilot program last October. They began by surveying hospital house staff and nurses on their ability to recognize and define six different sepsis syndromes from clinical vignettes. A total of 136 surveyed residents recognized the correct condition only 56% of the time, and 280 surveyed nurses only did so 17% of the time. The hospitalists determined that better education about sepsis was crucial.

“We developed a robust teaching program for nurses and residents using Septris, an online educational game from Stanford University,” Dr. Horton says. The team also developed technology that can recognize worsening vital signs in a patient and automatically trigger an alert to a charge nurse or rapid response team.

The team’s Modified Early Warning System (MEWS) for recognizing sepsis is similar to the Early Warning and Response System (EWRS) system used at the University of Pennsylvania Health System and the University of California San Diego, and draws on other hospitals’ sepsis systems. Dr. Horton says one difference in their system is the involvement of nursing aides who take vital signs, enter them real-time into electronic health records (EHR), and receive prompts from abnormal vital signs to retake all vitals and confirm abnormal results. It also incorporates EHR decision support tools, including links to pre-populated medical order panels, such as for the ordering of tests for lactate and blood cultures.

“Severe sepsis is often quoted as the number one cause of mortality among hospitalized patients, with a rate up to 10 times that of acute myocardial infarction,” Dr. Horton explains. “The one treatment that consistently decreases mortality is timely administration of antibiotics. But, in order for a patient to be given timely antibiotics, the nurse or resident must first recognize that the patient has sepsis.”

“This is one of the biggest and most far-reaching improvement initiatives that has been done at our institution,” says Robert Pendleton, MD, chief quality officer at University Hospital. Dr. Horton says he predicts the program will “save 50 lives and $1 million per year.”

For more information, contact him at: devin.horton@hsc.utah.edu.

A quality improvement (QI) initiative at University Hospital in Salt Lake City aims to save lives and cut hospital costs by reducing inpatient sepsis mortality.

Program co-leaders, hospitalists Devin Horton, MD, and Kencee Graves, MD, of University Hospital, launched the initiative as a pilot program last October. They began by surveying hospital house staff and nurses on their ability to recognize and define six different sepsis syndromes from clinical vignettes. A total of 136 surveyed residents recognized the correct condition only 56% of the time, and 280 surveyed nurses only did so 17% of the time. The hospitalists determined that better education about sepsis was crucial.

“We developed a robust teaching program for nurses and residents using Septris, an online educational game from Stanford University,” Dr. Horton says. The team also developed technology that can recognize worsening vital signs in a patient and automatically trigger an alert to a charge nurse or rapid response team.

The team’s Modified Early Warning System (MEWS) for recognizing sepsis is similar to the Early Warning and Response System (EWRS) system used at the University of Pennsylvania Health System and the University of California San Diego, and draws on other hospitals’ sepsis systems. Dr. Horton says one difference in their system is the involvement of nursing aides who take vital signs, enter them real-time into electronic health records (EHR), and receive prompts from abnormal vital signs to retake all vitals and confirm abnormal results. It also incorporates EHR decision support tools, including links to pre-populated medical order panels, such as for the ordering of tests for lactate and blood cultures.

“Severe sepsis is often quoted as the number one cause of mortality among hospitalized patients, with a rate up to 10 times that of acute myocardial infarction,” Dr. Horton explains. “The one treatment that consistently decreases mortality is timely administration of antibiotics. But, in order for a patient to be given timely antibiotics, the nurse or resident must first recognize that the patient has sepsis.”

“This is one of the biggest and most far-reaching improvement initiatives that has been done at our institution,” says Robert Pendleton, MD, chief quality officer at University Hospital. Dr. Horton says he predicts the program will “save 50 lives and $1 million per year.”

For more information, contact him at: devin.horton@hsc.utah.edu.

Thombosis Management Demands Balanced Approach

The delicate balance involved in providing hospitalized patients with needed anticoagulant, anti-platelet, and thrombolytic therapies for stroke and possible cardiac complications, while minimizing bleed risks, was explored by several speakers at the University of California San Francisco’s annual Management of the Hospitalized Patient conference.

“These are dynamic issues and they’re moving all the time,” said Tracy Minichiello, MD, a former hospitalist who now runs Anticoagulation and Thrombosis Services at the San Francisco VA Medical Center. Dosing and monitoring choices for physicians have grown more complicated with the new oral anticoagulants (apixaban, dabigatran, and rivaroxaban), and Dr. Minichiello said another balancing act is emerging in hospitals trying to avoid unnecessary and wasteful treatments.

“There is interest on both sides of that question,” Dr. Minichiello said, adding that the stakes are high. “We don’t want to miss the diagnosis of pulmonary embolisms, which can be difficult to catch. But now there’s more discussion

of the other side of the issue—overdiagnosis and overtreatment—where we’re also trying to avoid, for example, overuse of CT scans.”

Another major thrust of Dr. Minichiello’s presentations involved bridging therapies, the application of a parenteral, short-acting anticoagulant therapy during the temporary interruption of warfarin anticoagulation for an invasive procedure. Bridging decreases stroke and embolism risk but comes with an increased risk for bleeding.

“Full intensity bridging therapy for anticoagulation potentially can do more harm than good,” she said, noting a dearth of data to support mortality benefits of bridging therapy.

Literature increasingly recommends that hospitalists be more selective about the use of bridging therapies that might have been employed reflexively in the past, Dr. Minichiello noted. “[Hospitalists] must be mindful of the risks and benefits,” she said. Physicians should also think twice about concomitant antiplatelet therapy, like aspirin with anticoagulants. “We need to work collaboratively with our cardiology colleagues when a patient is on two or three of these therapies,” she said. “Recommendations in this area are in evolution.”

Elise Bouchard, MD, an internist at Centre Maria-Chapdelaine in Dolbeau-Mistassini, Québec, attended Dr. Minichiello’s breakout session on challenging cases.

“I learned that we shouldn’t use aspirin with Coumadin or other anticoagulants, except for cases like acute coronary syndrome,”

Dr. Bouchard said. She also explained that a number of her patients with cancer, for example, need anticoagulation treatment and hate getting another injection, so she tries to offer the oral anticoagulants whenever possible.

Dr. Minichiello works with hospitalists at the San Francisco VA who seek consults around performing procedures, choosing anticoagulants, and determining when to restart treatments.

“Most hospitalists don’t have access to a service like ours, although they might be able to call on a hematology consult service [or pharmacist],” she said. She suggested that hospitalists trying to develop their own evidenced-based protocols use websites like the University of Washington’s Anticoagulation Services website, or the American Society of Health System Pharmacists’ Anticoagulation Resource Center.

The delicate balance involved in providing hospitalized patients with needed anticoagulant, anti-platelet, and thrombolytic therapies for stroke and possible cardiac complications, while minimizing bleed risks, was explored by several speakers at the University of California San Francisco’s annual Management of the Hospitalized Patient conference.

“These are dynamic issues and they’re moving all the time,” said Tracy Minichiello, MD, a former hospitalist who now runs Anticoagulation and Thrombosis Services at the San Francisco VA Medical Center. Dosing and monitoring choices for physicians have grown more complicated with the new oral anticoagulants (apixaban, dabigatran, and rivaroxaban), and Dr. Minichiello said another balancing act is emerging in hospitals trying to avoid unnecessary and wasteful treatments.

“There is interest on both sides of that question,” Dr. Minichiello said, adding that the stakes are high. “We don’t want to miss the diagnosis of pulmonary embolisms, which can be difficult to catch. But now there’s more discussion

of the other side of the issue—overdiagnosis and overtreatment—where we’re also trying to avoid, for example, overuse of CT scans.”

Another major thrust of Dr. Minichiello’s presentations involved bridging therapies, the application of a parenteral, short-acting anticoagulant therapy during the temporary interruption of warfarin anticoagulation for an invasive procedure. Bridging decreases stroke and embolism risk but comes with an increased risk for bleeding.

“Full intensity bridging therapy for anticoagulation potentially can do more harm than good,” she said, noting a dearth of data to support mortality benefits of bridging therapy.

Literature increasingly recommends that hospitalists be more selective about the use of bridging therapies that might have been employed reflexively in the past, Dr. Minichiello noted. “[Hospitalists] must be mindful of the risks and benefits,” she said. Physicians should also think twice about concomitant antiplatelet therapy, like aspirin with anticoagulants. “We need to work collaboratively with our cardiology colleagues when a patient is on two or three of these therapies,” she said. “Recommendations in this area are in evolution.”

Elise Bouchard, MD, an internist at Centre Maria-Chapdelaine in Dolbeau-Mistassini, Québec, attended Dr. Minichiello’s breakout session on challenging cases.

“I learned that we shouldn’t use aspirin with Coumadin or other anticoagulants, except for cases like acute coronary syndrome,”

Dr. Bouchard said. She also explained that a number of her patients with cancer, for example, need anticoagulation treatment and hate getting another injection, so she tries to offer the oral anticoagulants whenever possible.

Dr. Minichiello works with hospitalists at the San Francisco VA who seek consults around performing procedures, choosing anticoagulants, and determining when to restart treatments.

“Most hospitalists don’t have access to a service like ours, although they might be able to call on a hematology consult service [or pharmacist],” she said. She suggested that hospitalists trying to develop their own evidenced-based protocols use websites like the University of Washington’s Anticoagulation Services website, or the American Society of Health System Pharmacists’ Anticoagulation Resource Center.

The delicate balance involved in providing hospitalized patients with needed anticoagulant, anti-platelet, and thrombolytic therapies for stroke and possible cardiac complications, while minimizing bleed risks, was explored by several speakers at the University of California San Francisco’s annual Management of the Hospitalized Patient conference.

“These are dynamic issues and they’re moving all the time,” said Tracy Minichiello, MD, a former hospitalist who now runs Anticoagulation and Thrombosis Services at the San Francisco VA Medical Center. Dosing and monitoring choices for physicians have grown more complicated with the new oral anticoagulants (apixaban, dabigatran, and rivaroxaban), and Dr. Minichiello said another balancing act is emerging in hospitals trying to avoid unnecessary and wasteful treatments.

“There is interest on both sides of that question,” Dr. Minichiello said, adding that the stakes are high. “We don’t want to miss the diagnosis of pulmonary embolisms, which can be difficult to catch. But now there’s more discussion

of the other side of the issue—overdiagnosis and overtreatment—where we’re also trying to avoid, for example, overuse of CT scans.”

Another major thrust of Dr. Minichiello’s presentations involved bridging therapies, the application of a parenteral, short-acting anticoagulant therapy during the temporary interruption of warfarin anticoagulation for an invasive procedure. Bridging decreases stroke and embolism risk but comes with an increased risk for bleeding.

“Full intensity bridging therapy for anticoagulation potentially can do more harm than good,” she said, noting a dearth of data to support mortality benefits of bridging therapy.

Literature increasingly recommends that hospitalists be more selective about the use of bridging therapies that might have been employed reflexively in the past, Dr. Minichiello noted. “[Hospitalists] must be mindful of the risks and benefits,” she said. Physicians should also think twice about concomitant antiplatelet therapy, like aspirin with anticoagulants. “We need to work collaboratively with our cardiology colleagues when a patient is on two or three of these therapies,” she said. “Recommendations in this area are in evolution.”

Elise Bouchard, MD, an internist at Centre Maria-Chapdelaine in Dolbeau-Mistassini, Québec, attended Dr. Minichiello’s breakout session on challenging cases.

“I learned that we shouldn’t use aspirin with Coumadin or other anticoagulants, except for cases like acute coronary syndrome,”

Dr. Bouchard said. She also explained that a number of her patients with cancer, for example, need anticoagulation treatment and hate getting another injection, so she tries to offer the oral anticoagulants whenever possible.

Dr. Minichiello works with hospitalists at the San Francisco VA who seek consults around performing procedures, choosing anticoagulants, and determining when to restart treatments.

“Most hospitalists don’t have access to a service like ours, although they might be able to call on a hematology consult service [or pharmacist],” she said. She suggested that hospitalists trying to develop their own evidenced-based protocols use websites like the University of Washington’s Anticoagulation Services website, or the American Society of Health System Pharmacists’ Anticoagulation Resource Center.

Liver Transplant Only Cure for Some Inpatients with Cirrhosis

Bilal Hameed, MD, assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of California San Francisco, reviewed a wide range of serious and life-threatening medical complications resulting from cirrhosis during the annual UCSF Management of the Hospitalized Patient conference.

Recurring complications of cirrhosis can include ascites, acute variceal and portal hypertensive bleeds, hepatic encephalopathy, bacterial peritonitis, acute renal failure, sepsis, and a host of other infections. In many cases, options for treatment are limited, because the patient develops decompensated cirrhosis.

Poor prognosis makes it important to urge these patients to get on a liver transplantation list, sooner rather than later, Dr. Hameed told hospitalists attending his small group session.

“Liver transplantation has changed this field,” he said. “Call us to see if your patient might be a candidate.”

Unlike transplant lists for kidneys and some other organs, on which patients must wait for their turn, liver transplants are assigned based on need, as reflected in the patient’s Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score, an objective clinical scale derived from blood values.

“Patients do really well on transplants, with 60% survival at 10 years,” he said. He also noted that patients with advanced, decompensated disease who do not find a place on the transplant list might instead be candidates for palliative care or hospice referral.

Many conditions, such as infections, can still be managed with timely treatment, returning the patient back to baseline.

“The risk of infection is very high. Starting antibiotics early can help,” Dr. Hameed said.

And for conditions where fluid volume is an issue, including spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, hypernatremia, or intrinsic renal disease, albumin is recommended as the evidence-based treatment of choice. “Please don’t overtransfuse these patients,” he said.

Jeannie Yip, MD, a nocturnist at Kaiser Foundation Hospital in Oakland, Calif., said that she frequently admits these kinds of patients to her hospital. For her, Dr. Hameed’s albumin recommendation was the most important lesson.

“I was still using IV fluids in patients coming in with volume depletion, to rule out acute renal failure. It’s always a dilemma if you have a hypotensive patient with low sodium and low blood pressure who tells you, ‘I haven’t eaten for a week,’” she explained. “It’s been hard for me not to give them fluids. But after listening to this talk, I see that I should give albumin instead.”

Bilal Hameed, MD, assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of California San Francisco, reviewed a wide range of serious and life-threatening medical complications resulting from cirrhosis during the annual UCSF Management of the Hospitalized Patient conference.

Recurring complications of cirrhosis can include ascites, acute variceal and portal hypertensive bleeds, hepatic encephalopathy, bacterial peritonitis, acute renal failure, sepsis, and a host of other infections. In many cases, options for treatment are limited, because the patient develops decompensated cirrhosis.

Poor prognosis makes it important to urge these patients to get on a liver transplantation list, sooner rather than later, Dr. Hameed told hospitalists attending his small group session.

“Liver transplantation has changed this field,” he said. “Call us to see if your patient might be a candidate.”

Unlike transplant lists for kidneys and some other organs, on which patients must wait for their turn, liver transplants are assigned based on need, as reflected in the patient’s Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score, an objective clinical scale derived from blood values.

“Patients do really well on transplants, with 60% survival at 10 years,” he said. He also noted that patients with advanced, decompensated disease who do not find a place on the transplant list might instead be candidates for palliative care or hospice referral.

Many conditions, such as infections, can still be managed with timely treatment, returning the patient back to baseline.

“The risk of infection is very high. Starting antibiotics early can help,” Dr. Hameed said.

And for conditions where fluid volume is an issue, including spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, hypernatremia, or intrinsic renal disease, albumin is recommended as the evidence-based treatment of choice. “Please don’t overtransfuse these patients,” he said.

Jeannie Yip, MD, a nocturnist at Kaiser Foundation Hospital in Oakland, Calif., said that she frequently admits these kinds of patients to her hospital. For her, Dr. Hameed’s albumin recommendation was the most important lesson.

“I was still using IV fluids in patients coming in with volume depletion, to rule out acute renal failure. It’s always a dilemma if you have a hypotensive patient with low sodium and low blood pressure who tells you, ‘I haven’t eaten for a week,’” she explained. “It’s been hard for me not to give them fluids. But after listening to this talk, I see that I should give albumin instead.”

Bilal Hameed, MD, assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of California San Francisco, reviewed a wide range of serious and life-threatening medical complications resulting from cirrhosis during the annual UCSF Management of the Hospitalized Patient conference.

Recurring complications of cirrhosis can include ascites, acute variceal and portal hypertensive bleeds, hepatic encephalopathy, bacterial peritonitis, acute renal failure, sepsis, and a host of other infections. In many cases, options for treatment are limited, because the patient develops decompensated cirrhosis.

Poor prognosis makes it important to urge these patients to get on a liver transplantation list, sooner rather than later, Dr. Hameed told hospitalists attending his small group session.

“Liver transplantation has changed this field,” he said. “Call us to see if your patient might be a candidate.”

Unlike transplant lists for kidneys and some other organs, on which patients must wait for their turn, liver transplants are assigned based on need, as reflected in the patient’s Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score, an objective clinical scale derived from blood values.

“Patients do really well on transplants, with 60% survival at 10 years,” he said. He also noted that patients with advanced, decompensated disease who do not find a place on the transplant list might instead be candidates for palliative care or hospice referral.

Many conditions, such as infections, can still be managed with timely treatment, returning the patient back to baseline.

“The risk of infection is very high. Starting antibiotics early can help,” Dr. Hameed said.

And for conditions where fluid volume is an issue, including spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, hypernatremia, or intrinsic renal disease, albumin is recommended as the evidence-based treatment of choice. “Please don’t overtransfuse these patients,” he said.

Jeannie Yip, MD, a nocturnist at Kaiser Foundation Hospital in Oakland, Calif., said that she frequently admits these kinds of patients to her hospital. For her, Dr. Hameed’s albumin recommendation was the most important lesson.

“I was still using IV fluids in patients coming in with volume depletion, to rule out acute renal failure. It’s always a dilemma if you have a hypotensive patient with low sodium and low blood pressure who tells you, ‘I haven’t eaten for a week,’” she explained. “It’s been hard for me not to give them fluids. But after listening to this talk, I see that I should give albumin instead.”

Hospital Medicine Flourishing Around the World

Since last September, Anand Kartha, MD, MS, has headed the hospital medicine (HM) program at 600-bed Hamad General Hospital, the flagship facility for eight-hospital Hamad Medical Corporation in Doha, Qatar, a small nation of 1.8 million people located on the northeast corner of the Arabian Peninsula.

“Qatar has a world-class healthcare system,” he says. “But to me, it sometimes feels like 1999, with the beginnings of the hospitalist movement as a new model of care.”

Dr. Kartha, a native of India who trained at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Mercy and Boston University School of Medicine, was recruited by Hamad Medical Corporation to develop hospital medicine in response to the growing complexity of inpatient care—and of patients served.

“Hospital medicine, delivered 24/7 by attending physicians, is an important element of the Health Ministry’s strategy and vision,” he says. “They looked at Australian, British, and American health systems, trying to put together the best from each—adapted to local sensitivities.

“One reason I came here was to expand the hospitalist model and be part of its extraordinary growth and development.”

Dr. Kartha also participates in medical research and residency training. His group now employs 30 attending physicians, half of them recent hires from the U.S. and the U.K.

As in the U.S., international drivers for the hospitalist model of care include pressures to improve efficiency, throughput, and quality of care. Those drivers are especially in focus at Hamad General, which Dr. Kartha says has one of the busiest EDs in the world.

Hospital medicine programs are springing up in other parts of the world, too, often inspired by the success of the HM model in the U.S. Hospitalist pioneers from other countries pore over the published research and visit the U.S. to attend conferences like SHM’s annual meeting, with its programming for international members, or to complete fellowships or other trainings. U.S. hospitalists are invited to speak to groups in other countries. Some, like Dr. Kartha, are being tapped to build hospitalist programs around the globe.

Hospital medicine can be introduced from the top down as a strategy by the public health system or from the bottom up by pioneers and advocates at the grassroots level.

Ron Greeno, MD, MHM, FCCP, has been active in hospital medicine since before the term “hospitalist” was coined. Currently chief strategy officer with IPC Healthcare, Inc., he was a founder in 1993 of Cogent Healthcare, which recently merged with Sound Physicians in Tacoma, Wash. Dr. Greeno says he is fascinated by the growth in international hospital medicine.

“I have been impressed at the number of countries that are represented at SHM [meetings] and the enthusiasm they show as they talk about their experiences,” he says. “What I see in these young, enthusiastic physicians from around the world is they are not naïve, but they are very idealistic. Their descriptions of their struggles remind me of our early days in Southern California.

“The international representatives at SHM all recognize the need for data. Every one of them feels their hospitalist model has advantages for their health system. But everybody’s struggling with the need for more resources. That’s the same in the U.S.”

Similarities and Differences

Many aspects of the experience in Qatar have been surprisingly familiar for Dr. Kartha.

“We are a Joint Commission-accredited hospital,” he says. “Our residency program is accredited by the American College of Graduate Medical Education. We are the flagship hospital for Weill Cornell Medical College in Qatar.”

The workday of a hospitalist at Hamad General is strikingly similar to the one he knew as an academic hospitalist in Boston.

“Models we are introducing include extended hours coverage, evenings and weekends, proactive discharge planning, and co-management with specialists,” he says. The health system is also rolling out an electronic health record.

Still, his adaptation to a new medical system has generated many curiosities in the sports-mad, fully wired-for-Internet nation, which has the world’s highest per capita standard of living.

“Every now and then, I look around and think: ‘This isn’t Kansas anymore, Toto,’” Dr. Kartha says, adding that he has learned about important cultural and religious beliefs and traditions that affect patients’ attitudes toward health and healing.

Arpana Vidyarthi, MD, associate professor in the Duke-NUS Graduate Medical School in Singapore, previously worked as a hospitalist at the University of California-San Francisco (UCSF) before moving to Singapore in 2011. She thinks “pockets” of hospital medicine are being practiced all over the world “in response to local needs.”

“The model is manifest in a diverse fashion throughout the United States, yet it is agile enough to be adapted around the world and be truly relevant,” Dr. Vidyarthi says. “But local tradition and the way hospitals are structured will determine how the model is established.”

Traditionally, medical specialists, often without a central physician to coordinate care, manage inpatients in Singapore, according to Dr. Vidyarthi. At discharge, they are referred to numerous subspecialists and to a public health clinic. Half of hospital wards are staffed by “super-specialists,” the other half by general internists who see patients both in the clinic and in the hospital, she says.

“This is not hospital medicine as we know it in the United States,” she says, “but different models are evolving.”

Ten years ago, physicians from Singapore visited UCSF to observe how hospital medicine was practiced there. A family medicine hospitalist program was piloted in 2006 at Singapore General Hospital. The program helped reduce lengths of stay and costs of care without adversely affecting mortality or readmissions.1

Kheng-Hock Lee, MD, one of the researchers and president of the Singapore College of Family Physicians, says that defining a generalist role for hospital medicine in Singapore has been difficult.

“When I call myself a hospitalist here, there is a strong reaction from some who perceive it as profit driven,” Dr. Vidyarthi says. “Clearly, there is a need for a generalist physician at the center of the patient experience, to manage the complexity of the patient as a whole person, as well as the hospital system. That is where it’s emerging within internal medicine, whether it’s called hospital medicine or not.”

For the past year, Dr. Vidyarthi has been working at Singapore General.

“The concept of the academic hospitalist is new here. People are able to see when I’m on service that I do things differently. This is because of the hospitalist mindset I brought from the United States,” she says. “Because I have a systems lens, I organize my day differently than the other doctors. I teach concurrently with clinical care, delegate responsibilities and accountabilities, and focus on discharge from the first day of admission.

“In general, my team is happier and my patients have lower lengths of stay.”

Defining a Specialized Expertise

Whatever you call it, there is a need around the world for physicians to practice in hospitals—to help standardize care, improve quality and patient safety, and prevent waste. Peter Jamieson, MD, a family physician in Calgary, Alberta, Canada, and medical director of the Foothills Medical Centre, has worked as a hospitalist since 1997. He didn’t call himself a hospitalist at first, “but the concept is becoming better socialized and more widely recognized in Canada.”

The Canadian Society of Hospital Medicine, founded in 2001 and affiliated with SHM, has about 1,300 members.

“I’d say we’re more the same than different compared with the United States, with a similar focus on quality of care,” Dr. Jamieson says.

Interestingly, he says the moniker “hospitalist” is not helping the development—and recognition—of Canadians who practice hospital-based medicine. It’s a refrain echoed for years by many in the U.S.

“As leaders in hospital medicine in Canada, we’d prefer to move away from the term ‘hospitalist’ and toward ‘specialist’ or ‘expert in hospital medicine,’” he says. “That takes us more in the direction we want to go in defining the mission of hospital medicine.

“First of all, in Canada and other places, there’s a bit of baggage attached to the term ‘hospitalist.’ These other terms help us get away from some of the historical assumptions of what people thought a hospitalist was—based on educational background.”

In Canada, that has largely been family medicine. Hospital medicine advocates are now exploring the best preparation for practicing the specialty.

“We want to define the mission around competency, rather than board certification,” Dr. Jamieson explains.

Listen to Dr. Jamieson discuss the evolution of hospital medicine in Canada.

The days when the majority of Canadian primary care providers would join the staff of a hospital and continue to manage their patients’ care during the hospital stay are long gone, he adds. In smaller and rural hospitals, the family doctor may still be the physician of record, although the number of such hospitals is dwindling.

HM clinicians generally are not employed by the hospital but often are sole practitioners with independent corporations or organized into groups that associate for the sake of the practice, signing a common contract with the hospital. Depending on provincial law, most hospitalist groups have leaders appointed and compensated by the hospital for scheduling and coordination.

On top of billing fee-for-service to the provincial health authority, hospitalists may also receive a stipend from the hospital, collectively or individually.

“There is a recognition that the physician fee schedule has not kept pace with the demands of hospital medicine, and that stipend also covers other services performed in the hospital,” Dr. Jamieson says.

Vandad Yousefi, MD, CCFP, FHM, hospitalist at Vancouver General Hospital in British Columbia, Canada, and co-founder and CEO of Hospitalist Consulting Solutions, has researched the development of hospital medicine in Canada and says that, even more than in the U.S., it was driven by the withdrawal of PCPs from hospitals, which created a vacuum.2,3

“For a lot of programs I’ve consulted with, the crisis point happened when physicians resigned en masse from hospital staffs,” he says.

Another driver is an increase in “unattached” hospitalized patients, which in Canada means they don’t have a specific medical provider willing to supply their inpatient attending-level care. In his surveys of typologies of roles played by hospitalists, Dr. Yousefi has observed a lot of variation in program models—not just between academic centers, teaching hospitals, and rural hospitals, but also within each category.

“These differences in programs make it hard to benchmark,” he says.

Hospitalist—or House Officer?

The Netherlands also has “hospitalists,” although they also refer to themselves as “house officers,” says Marijke Timmermans, a doctoral student in epidemiology at the Scientific Institute for Quality of Healthcare at Radboud University Medical Center in Nijmegen. As part of a long-standing system of post-graduate, on-the-job training for doctors, Dutch hospitalists typically are medical residents who perform the medical care of hospitalized patients, but not as the physician of record.

Timmermans is studying the growing role of physician assistants (PAs) in managing hospitalized patients in response to demands for better continuity of care. Although the PA concept is little more than a decade old in the Netherlands, there are 1,000 PAs, with about half filling a hospitalist role under the supervision of a medical specialist. Timmermans’ research looks at the effectiveness and quality of care with PAs under a mixed model of PA and physician, compared with physician alone.4

In the Netherlands, the patient’s PCP does not assume medical management responsibility while the patient is hospitalized, although PCP visits might be made to reassure the patient and advise the hospital-based team. As in the U.S., the hospitalist will try to communicate with the primary care doctor at discharge and, if possible, schedule follow-up visits for the discharged patient at a clinic on the hospital campus.

A new experiment is underway in four Dutch hospitals. It’s a three-year medical education curriculum to train “hospital doctors” (ziekenhuisarts). The new medical specialty, with general medical training, will assume more responsibility for ward care in the hospital. Timmermans says it is not yet known how these professionals will relate to other professionals in the hospital.

Joseph Li, MD, SFHM, head of hospital medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston and past president of SHM, notes a key distinction between hospitalists as they are commonly understood in the U.S. and house officers: House officers don’t assume medical responsibility for the patient’s care.

“A house officer is not a hospitalist as we understand it—but even in this country, terminology varies and means different things in different hospitals,” Dr. Li says.

The Acute Medical Unit

In the U.K., a different model has emerged over the past two decades. It is called the acute medical unit [PDF] (AMU) and is staffed by dedicated consultants.5 The AMU fits functionally between the hospital’s ED, or front door admissions, and specialty care units within the hospital.

Patients generally are admitted to the AMU for a maximum of 72 hours for medical work-ups, with consultations as needed by specialists. They should be seen twice a day by the acute medical consultant, who is responsible for the delivery and direction of their care. Then they either go home or get transferred to a specialty unit within the hospital, with specialty care organized in a manner broadly similar to the U.S.

This frontloading of medical attention at admission allows patients to be worked up and turned around quickly, says Derek Bell, MD, head of acute medicine at Imperial College London and a founder in 2000 of the U.K.’s Society for Acute Medicine. Dr. Bell suggests that this system developed to ensure a safe haven for medical patients who are unstable or require ongoing investigation and treatment. A national “four-hour rule,” designed to reduce overcrowding in EDs, means that patients need to either go home or be admitted within four hours of presentation to the hospital.

U.K. hospitals also employ a registrar, a senior trainee who supervises junior and resident doctors. Hospital physicians are salaried and employed by “provider organizations,” which can be a single hospital or a collection of hospitals.

“My hospital admits about 30 to 35 medical patients per day, and we have two consultants working during the day just doing acute medicine, along with two registrars, one for emergency patients, two intermediate grade doctors, and two junior residents,” Dr. Bell says.

Acute medicine consultants generally do weekday shifts, with one consultant on call per night.

A few hospitals have embedded PCPs, who know the local system and can facilitate communication with the patient’s family doctor. “This model is well recognized but is not common,” Dr. Bell says.

What’s Happening Elsewhere?

In Australia, public hospitals in New South Wales generated positive results for a hospitalist pilot program in 2007, but also encountered some resistance from the Australian Medical Association and others concerned about its potential impact on such existing roles as career medical officer, PCP, and general physician, and on the provision of medical training in hospitals.6

Hospital medicine has grown since then, but slowly, with individual institutions successfully employing hospitalists at various levels. The fledgling specialty has yet to take off nationally, says Mary G.T. Webber, MBBS, a past president of the Australasian Society of Career Medical Officers. Dr. Webber practices hospital medicine at Ryde Hospital in suburban Sydney, where she has found the mix of clinical care, system development, and mentoring roles offered by the service personally rewarding. She has been frustrated with a lack of progress for the hospitalist movement overall in Australia.

“The concept of a rural generalist is already well accepted in Australia, and hospital medicine is the next logical iteration of the medical generalist,” Dr. Webber says. This need has been supported by the NSW Ministry of Health through a Hospital Skills Program, and, more recently, the successful implementation of a master’s degree for experienced nonspecialist doctors through the Senior Hospitalist Initiative at the University of Newcastle.

“Once you adopt a system view of patient care in hospitals, there is no going back,” says Dr. Webber, who was lead author of the hospital skills program curriculum in hospital medicine. “This is an idea whose time has come.”

A pioneering hospitalist program at National Taiwan University Hospital in Taipei (NTUH) was established by internists with diverse specializations in pulmonology, nephrology, infectious diseases, and family medicine and is led by Hung-Bin Tsai, MD, and Nin-Chieh Hsu, MD.7,8 Because of relatively low salaries for generalist physicians and a national health insurance program that incentivizes patient access to specialists, 95% of internal medicine doctors in Taiwan have chosen to subspecialize, Dr. Hsu says.

Other barriers to the dissemination of hospital medicine in Taiwan include a shortage of internal medicine residents and resident work-hour restrictions mandated by the country’s Ministry of Health, with resulting heavy work schedules for internal medicine attending physicians, who average 64 hours per week. Advocates believe the hospitalist model could help promote better work-life-salary balance for inpatient physicians.

“We are trying to persuade the Ministry of Health to pay a fair reimbursement for inpatient care,” Dr. Hsu says.

The pioneer hospitalist program at NTUH, developed in 2009 in a 36-bed, hospitalist-run ward, now 70 beds, has this year been joined by more than 20 other hospital medicine programs under an initiative of the Ministry of Health. Auspiciously, the chief of the pioneer hospitalist program at NTUH, Wen-je Ko, MD, PhD, was elected mayor of Taipei earlier this year. A Taiwanese Society of Hospital Medicine should be up and running by late 2015, says Dr. Tsai, who is its chief facilitator. When that happens, organizers expect hospital medicine to finally take off in Taiwan.

The Future Is Now

When Dr. Greeno talks to international hospitalists, he says, “If you’re doing a good job, that creates value for somebody. Find out who that is—that’s where you need to go to get your resources, financial or otherwise. Is it your individual hospital or your national health system? Everybody wants to deliver better care at lower cost. When you do that, that’s your driver for growth.”

Something about the hospitalist model, he adds, “just makes sense.”

“There are people virtually everywhere who are very enthusiastic about it. We in the United States can learn a lot from their enthusiasm,” he says. “It will evolve in different ways. The future is already here; it’s just unevenly distributed.”

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Alameda, Calif.

References

- Hock Lee K, Yang Y, Soong Yang K, Chi Ong B, Seong Ng H. Bringing generalists into the hospital: outcomes of a family medicine hospitalist model in Singapore. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(3):115-121.

- Yousefi V, Chong CAKY. Does implementation of a hospitalist program in a Canadian community hospital improve measures of quality of care and utilization? An observational comparative analysis of hospitalists vs. traditional care providers. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:204.

- Timmermans MJC, van Vught AJAH, Wensing M, Laurant MGH. The effectiveness of substitution of hospital ward care from medical doctors to physician assistants: a study protocol. BMC Health Serv Res.; 2014;14:43.

- Black C. Acute medicine: making it work for patients. Hosp Med. 2004;65(8):493-496.

- Australian Medical Association. AMA Position Statement: Hospitalists – 2008. October 21, 2008. Accessed October 5, 2015.

- Shu CC, Lin JW, Lin YF, Hsu NC, Ko WJ. Evaluating the performance of a hospitalist system in Taiwan: A pioneer study for nationwide health insurance in Asia. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(7):378-382.

- Shu CC, Hsu NC, Lin YF, Wang JY, Lin JW, Ko WJ. Integrated postdischarge transitional care in a hospitalist system to improve discharge outcome: an experimental study. BMC Med. 2011;9:96.

- Carmona-Torre F, Martinez-Urbistondo D, Landecho MF, Lucena JF. Surviving sepsis in an intermediate care unit. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(4):294-295.

- Lucena JF, Alegre F, Rodil R, et al. Results of a retrospective observational study of intermediate care staffed by hospitalists: impact on mortality, co-management, and teaching. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(5):411-415.

Since last September, Anand Kartha, MD, MS, has headed the hospital medicine (HM) program at 600-bed Hamad General Hospital, the flagship facility for eight-hospital Hamad Medical Corporation in Doha, Qatar, a small nation of 1.8 million people located on the northeast corner of the Arabian Peninsula.

“Qatar has a world-class healthcare system,” he says. “But to me, it sometimes feels like 1999, with the beginnings of the hospitalist movement as a new model of care.”

Dr. Kartha, a native of India who trained at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Mercy and Boston University School of Medicine, was recruited by Hamad Medical Corporation to develop hospital medicine in response to the growing complexity of inpatient care—and of patients served.

“Hospital medicine, delivered 24/7 by attending physicians, is an important element of the Health Ministry’s strategy and vision,” he says. “They looked at Australian, British, and American health systems, trying to put together the best from each—adapted to local sensitivities.

“One reason I came here was to expand the hospitalist model and be part of its extraordinary growth and development.”

Dr. Kartha also participates in medical research and residency training. His group now employs 30 attending physicians, half of them recent hires from the U.S. and the U.K.

As in the U.S., international drivers for the hospitalist model of care include pressures to improve efficiency, throughput, and quality of care. Those drivers are especially in focus at Hamad General, which Dr. Kartha says has one of the busiest EDs in the world.

Hospital medicine programs are springing up in other parts of the world, too, often inspired by the success of the HM model in the U.S. Hospitalist pioneers from other countries pore over the published research and visit the U.S. to attend conferences like SHM’s annual meeting, with its programming for international members, or to complete fellowships or other trainings. U.S. hospitalists are invited to speak to groups in other countries. Some, like Dr. Kartha, are being tapped to build hospitalist programs around the globe.

Hospital medicine can be introduced from the top down as a strategy by the public health system or from the bottom up by pioneers and advocates at the grassroots level.

Ron Greeno, MD, MHM, FCCP, has been active in hospital medicine since before the term “hospitalist” was coined. Currently chief strategy officer with IPC Healthcare, Inc., he was a founder in 1993 of Cogent Healthcare, which recently merged with Sound Physicians in Tacoma, Wash. Dr. Greeno says he is fascinated by the growth in international hospital medicine.

“I have been impressed at the number of countries that are represented at SHM [meetings] and the enthusiasm they show as they talk about their experiences,” he says. “What I see in these young, enthusiastic physicians from around the world is they are not naïve, but they are very idealistic. Their descriptions of their struggles remind me of our early days in Southern California.

“The international representatives at SHM all recognize the need for data. Every one of them feels their hospitalist model has advantages for their health system. But everybody’s struggling with the need for more resources. That’s the same in the U.S.”

Similarities and Differences

Many aspects of the experience in Qatar have been surprisingly familiar for Dr. Kartha.

“We are a Joint Commission-accredited hospital,” he says. “Our residency program is accredited by the American College of Graduate Medical Education. We are the flagship hospital for Weill Cornell Medical College in Qatar.”

The workday of a hospitalist at Hamad General is strikingly similar to the one he knew as an academic hospitalist in Boston.

“Models we are introducing include extended hours coverage, evenings and weekends, proactive discharge planning, and co-management with specialists,” he says. The health system is also rolling out an electronic health record.

Still, his adaptation to a new medical system has generated many curiosities in the sports-mad, fully wired-for-Internet nation, which has the world’s highest per capita standard of living.

“Every now and then, I look around and think: ‘This isn’t Kansas anymore, Toto,’” Dr. Kartha says, adding that he has learned about important cultural and religious beliefs and traditions that affect patients’ attitudes toward health and healing.

Arpana Vidyarthi, MD, associate professor in the Duke-NUS Graduate Medical School in Singapore, previously worked as a hospitalist at the University of California-San Francisco (UCSF) before moving to Singapore in 2011. She thinks “pockets” of hospital medicine are being practiced all over the world “in response to local needs.”

“The model is manifest in a diverse fashion throughout the United States, yet it is agile enough to be adapted around the world and be truly relevant,” Dr. Vidyarthi says. “But local tradition and the way hospitals are structured will determine how the model is established.”

Traditionally, medical specialists, often without a central physician to coordinate care, manage inpatients in Singapore, according to Dr. Vidyarthi. At discharge, they are referred to numerous subspecialists and to a public health clinic. Half of hospital wards are staffed by “super-specialists,” the other half by general internists who see patients both in the clinic and in the hospital, she says.

“This is not hospital medicine as we know it in the United States,” she says, “but different models are evolving.”

Ten years ago, physicians from Singapore visited UCSF to observe how hospital medicine was practiced there. A family medicine hospitalist program was piloted in 2006 at Singapore General Hospital. The program helped reduce lengths of stay and costs of care without adversely affecting mortality or readmissions.1

Kheng-Hock Lee, MD, one of the researchers and president of the Singapore College of Family Physicians, says that defining a generalist role for hospital medicine in Singapore has been difficult.

“When I call myself a hospitalist here, there is a strong reaction from some who perceive it as profit driven,” Dr. Vidyarthi says. “Clearly, there is a need for a generalist physician at the center of the patient experience, to manage the complexity of the patient as a whole person, as well as the hospital system. That is where it’s emerging within internal medicine, whether it’s called hospital medicine or not.”

For the past year, Dr. Vidyarthi has been working at Singapore General.

“The concept of the academic hospitalist is new here. People are able to see when I’m on service that I do things differently. This is because of the hospitalist mindset I brought from the United States,” she says. “Because I have a systems lens, I organize my day differently than the other doctors. I teach concurrently with clinical care, delegate responsibilities and accountabilities, and focus on discharge from the first day of admission.

“In general, my team is happier and my patients have lower lengths of stay.”

Defining a Specialized Expertise

Whatever you call it, there is a need around the world for physicians to practice in hospitals—to help standardize care, improve quality and patient safety, and prevent waste. Peter Jamieson, MD, a family physician in Calgary, Alberta, Canada, and medical director of the Foothills Medical Centre, has worked as a hospitalist since 1997. He didn’t call himself a hospitalist at first, “but the concept is becoming better socialized and more widely recognized in Canada.”

The Canadian Society of Hospital Medicine, founded in 2001 and affiliated with SHM, has about 1,300 members.

“I’d say we’re more the same than different compared with the United States, with a similar focus on quality of care,” Dr. Jamieson says.

Interestingly, he says the moniker “hospitalist” is not helping the development—and recognition—of Canadians who practice hospital-based medicine. It’s a refrain echoed for years by many in the U.S.

“As leaders in hospital medicine in Canada, we’d prefer to move away from the term ‘hospitalist’ and toward ‘specialist’ or ‘expert in hospital medicine,’” he says. “That takes us more in the direction we want to go in defining the mission of hospital medicine.

“First of all, in Canada and other places, there’s a bit of baggage attached to the term ‘hospitalist.’ These other terms help us get away from some of the historical assumptions of what people thought a hospitalist was—based on educational background.”

In Canada, that has largely been family medicine. Hospital medicine advocates are now exploring the best preparation for practicing the specialty.

“We want to define the mission around competency, rather than board certification,” Dr. Jamieson explains.

Listen to Dr. Jamieson discuss the evolution of hospital medicine in Canada.

The days when the majority of Canadian primary care providers would join the staff of a hospital and continue to manage their patients’ care during the hospital stay are long gone, he adds. In smaller and rural hospitals, the family doctor may still be the physician of record, although the number of such hospitals is dwindling.

HM clinicians generally are not employed by the hospital but often are sole practitioners with independent corporations or organized into groups that associate for the sake of the practice, signing a common contract with the hospital. Depending on provincial law, most hospitalist groups have leaders appointed and compensated by the hospital for scheduling and coordination.

On top of billing fee-for-service to the provincial health authority, hospitalists may also receive a stipend from the hospital, collectively or individually.

“There is a recognition that the physician fee schedule has not kept pace with the demands of hospital medicine, and that stipend also covers other services performed in the hospital,” Dr. Jamieson says.

Vandad Yousefi, MD, CCFP, FHM, hospitalist at Vancouver General Hospital in British Columbia, Canada, and co-founder and CEO of Hospitalist Consulting Solutions, has researched the development of hospital medicine in Canada and says that, even more than in the U.S., it was driven by the withdrawal of PCPs from hospitals, which created a vacuum.2,3

“For a lot of programs I’ve consulted with, the crisis point happened when physicians resigned en masse from hospital staffs,” he says.