User login

Larry Beresford is an Oakland, Calif.-based freelance medical journalist with a breadth of experience writing about the policy, financial, clinical, management and human aspects of hospice, palliative care, end-of-life care, death, and dying. He is a longtime contributor to The Hospitalist, for which he covers re-admissions, pain management, palliative care, physician stress and burnout, quality improvement, waste prevention, practice management, innovation, and technology. He also contributes to Medscape. Learn more about his work at www.larryberesford.com; follow him on Twitter @larryberesford.

The state of hospital medicine in 2018

Productivity, pay, and roles remain center stage

In a national health care environment undergoing unprecedented transformation, the specialty of hospital medicine appears to be an island of relative stability, a conclusion that is supported by the principal findings from SHM’s 2018 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) report.

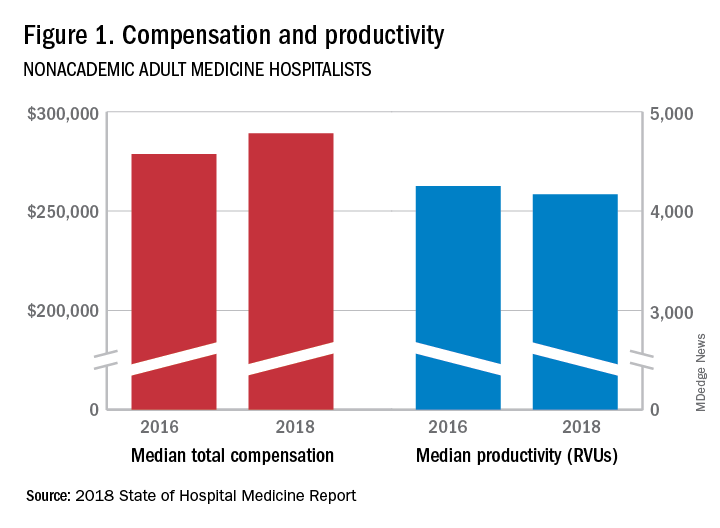

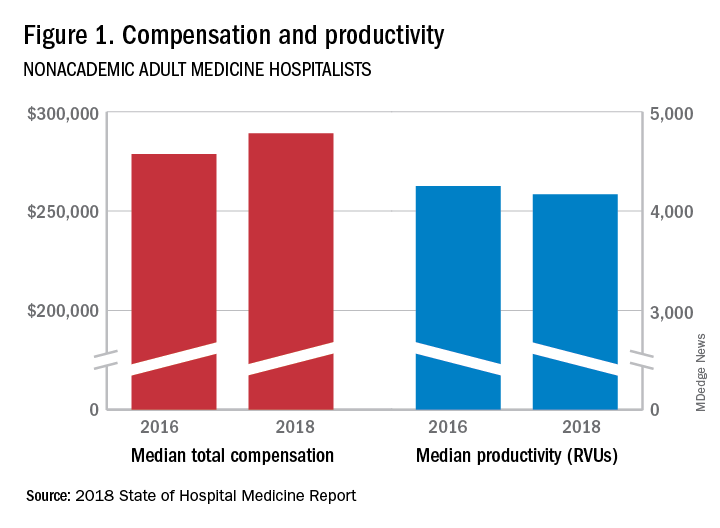

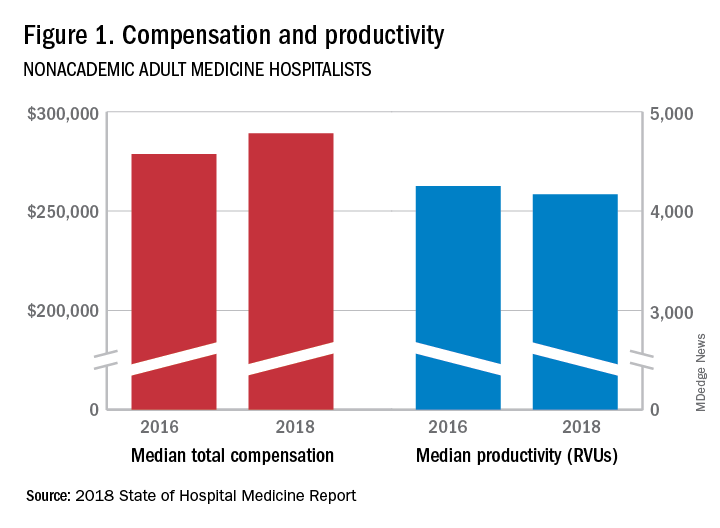

The report of hospitalist group practice characteristics, as well as other key data defining the field’s current status, that the Society of Hospital Medicine puts out every 2 years reveals that overall salaries for hospitalist physicians are up by 3.8% since 2016. Although productivity, as measured by work relative value units (RVUs), remained largely flat over the same period, financial support per full-time equivalent (FTE) physician position to hospitalist groups from their hospitals and health systems is up significantly.

Total support per FTE averaged $176,657 in 2018, 12% higher than in 2016, noted Leslie Flores, MHA, SFHM, of Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants, and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee, which oversees the biennial survey. Compensation and productivity data were collected by the Medical Group Management Association and licensed by SHM for inclusion in its report.

These findings – particularly the flat productivity – raise questions about long-term sustainability, Ms. Flores said. “What is going on? Do hospital administrators still recognize the value hospitalists bring to the operations and the quality of their hospitals? Or is paying the subsidy just a cost of doing business – a necessity for most hospitals in a setting where demand for hospitalist positions remains high?”

Andrew White, MD, FACP, SFHM, chair of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee and director of the hospital medicine service at the University of Washington Medical Center, Seattle, said basic market forces dictate that it is “pretty much inconceivable” to run a modern hospital of any size without hospitalists.

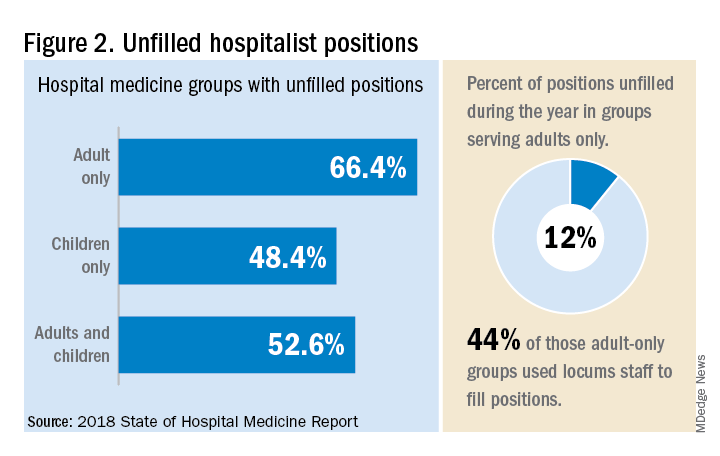

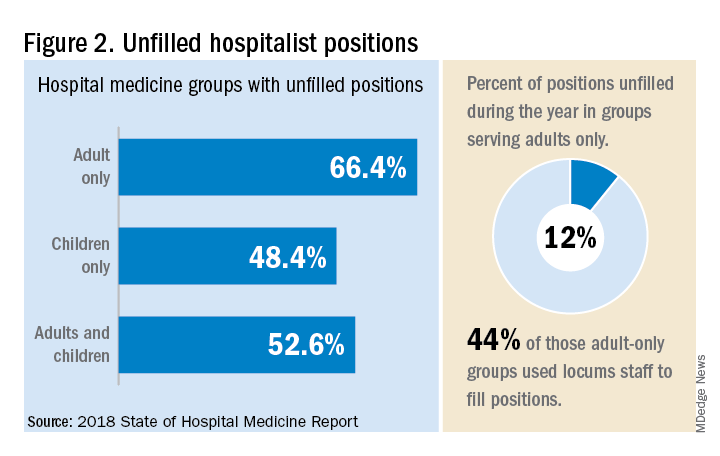

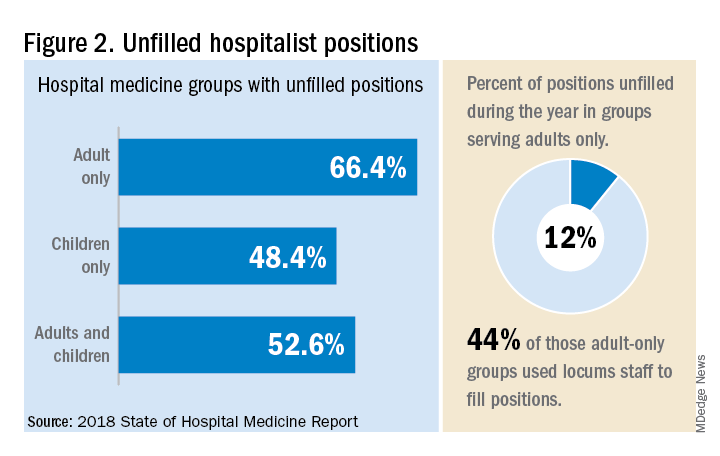

“Clearly, demand outstrips supply, which drives up salaries and support, whether CEOs feel that the hospitalist group is earning that support or not,” Dr. White said. “The unfilled hospitalist positions we identified speak to ongoing projected greater demand than supply. That said, hospitalists and group leaders can’t be complacent and must collaborate effectively with hospitals to provide highly valuable services.” Turnover of hospitalist positions was up slightly, he noted, at 7.4% in 2018, from 6.9% in 2016, reversing a trend of previous years.

But will these trends continue at a time when hospitals face continued pressure to cut costs, as the hospital medicine subsidy may represent one of their largest cost centers? Because the size of hospitalist groups continues to grow, hospitals’ total subsidy for hospital medicine is going up faster than the percentage increase in support per FTE.

How do hospitalists use the SoHM report?

Dr. White called the 2018 SoHM report the “most representative and balanced sample to date” of hospitalist group practices, with some of the highest quality data, thanks to more robust participation in the survey by pediatric groups and improved distribution among hospitalist management companies and academic programs.

“Not that past reports had major flaws, but this version is more authoritative, reflecting an intentional effort by our Practice Analysis Committee to bring in more participants from key groups,” he said.

The biennial report has been around long enough to achieve brand recognition in the field as the most authoritative source of information regarding hospitalist practice, he added. “We worked hard this year to balance the participants, with more of our responses than in the past coming from multi-hospital groups, whether 4 to 5 sites, or 20 to 30.”

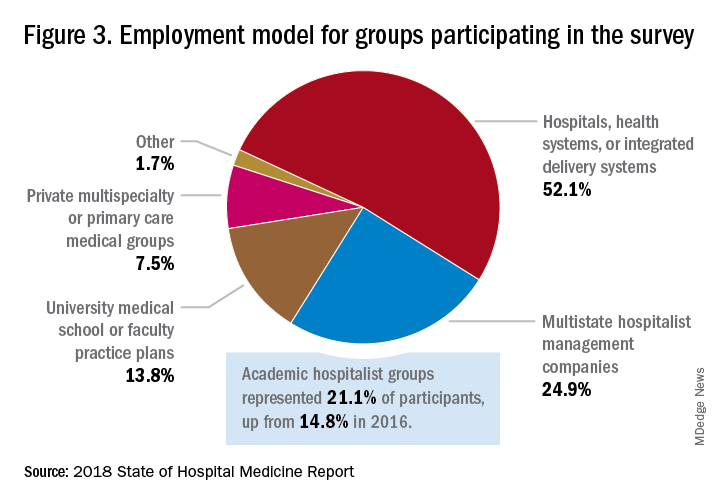

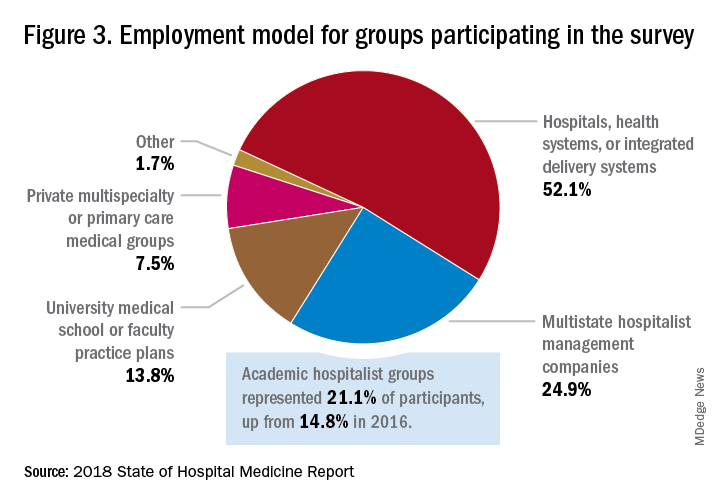

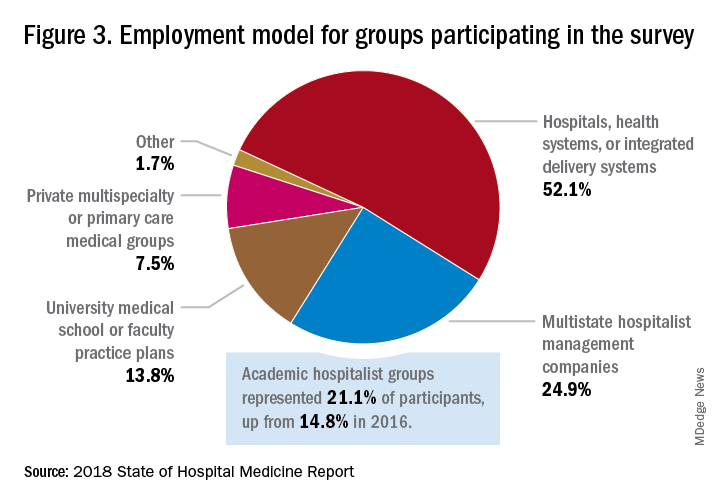

Surveys were conducted online in January and February of 2018 in response to invitations mailed and emailed to targeted hospital medicine group leaders. A total of 569 groups completed the survey, representing 8,889 hospitalist FTEs, approximately 16% of the total hospitalist workforce. Responses were presented in several categories, including by size of program, region and employment model. Groups that care for adults only represented 87.9% of the surveys, while groups that care for children only were 6.7% and groups that care for both adults and children were 5.4%.

“This survey doesn’t tell us what should be best practice in hospital medicine,” Dr. White said, only what is actual current practice. He uses it in his own health system to not only contextualize and justify his group’s performance metrics for hospital administrators – relative to national and categorical averages – but also to see if the direction his group is following is consistent with what’s going on in the larger field.

“These data offer a very powerful resource regarding the trends in hospital medicine,” said Romil Chadha, MD, MPH, FACP, SFHM, associate division chief for operations in the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky and UK Healthcare, Lexington. “It is my repository of data to go before my administrators for decisions that need to be made or to pilot new programs.”

Dr. Chadha also uses the data to help answer compensation, scheduling, and support questions from his group’s members.

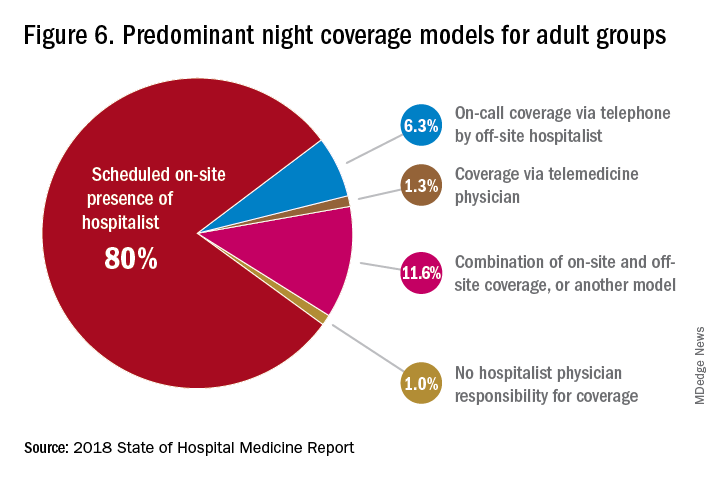

Thomas McIlraith, MD, immediate past chairman of the hospital medicine department at Mercy Medical Group, Sacramento, Calif., said the report’s value is that it allows comparisons of salaries in different settings, and to see, for example, how night staffing is structured. “A lot of leaders I spoke to at SHM’s 2018 Leadership Academy in Vancouver were saying they didn’t feel up to parity with the national standards. You can use the report to look at the state of hospital medicine nationally and make comparisons,” he said.

Calls for more productivity

Roberta Himebaugh, MBA, SFHM, senior vice president of acute care services for the national hospitalist management company TeamHealth, and cochair of the SHM Practice Administrators Special Interest Group, said her company’s clients have traditionally asked for greater productivity from their hospitalist contracts as a way to decrease overall costs. Some markets are starting to see a change in that approach, she noted.

“Recently there’s been an increased focus on paying hospitalists to focus on quality rather than just productivity. Some of our clients are willing to pay for that, and we are trying to assign value to this non-billable time or adjust our productivity standards appropriately. I think hospitals definitely understand the value of non-billable services from hospitalists, but still will push us on the productivity targets,” Ms. Himebaugh said.

“I don’t believe hospital medicine can be sustainable long term on flat productivity or flat RVUs,” she added. “Yet the costs of burnout associated with pushing higher productivity are not sustainable, either.” So what are the answers? She said many inefficiencies are involved in responding to inquiries on the floor that could have been addressed another way, or waiting for the turnaround of diagnostic tests.

“Maybe we don’t need physicians to be in the hospital 24/7 if we have access to telehealth, or a partnership with the emergency department, or greater use of advanced care practice providers,” Ms. Himebaugh said. “Our hospitals are examining those options, and we have to look at how we can become more efficient and less costly. At TeamHealth, we are trying to staff for value – looking at patient flow patterns and adjusting our schedules accordingly. Is there a bolus of admissions tied to emergency department shift changes, or to certain days of the week? How can we move from the 12-hour shift that begins at 7 a.m. and ends at 7 p.m., and instead provide coverage for when the patients are there?”

Mark Williams, MD, MHM, chief of the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky, Lexington, said he appreciates the volume of data in the report but wishes for even more survey participants, which could make the breakouts for subgroups such as academic hospitalists more robust. Other current sources of hospitalist salary data include the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), which produces compensation reports to help medical schools and teaching hospitals with benchmarking, and the Faculty Practice Solution Center developed jointly by AAMC and Vizient to provide faculty practice plans with analytic tools. The Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) is another valuable source of information, some of which was licensed for inclusion in the SoHM report.

“There is no source of absolute truth that hospitalists can point to,” Dr. Williams said. “I will present my data and my administrators will reply: ‘We have our own data.’ Our institution has consistently ranked first or second nationwide for the sickest patients. We take more Medicaid and dually eligible patients, who have a lot of social issues. They take a lot of time to manage medically and the RVUs don’t reflect that. And yet I’m still judged by my RVUs generated per hospitalist. Hospital administrators understandably want to get the most productivity, and they are looking for their own data for average productivity numbers.”

Ryan Brown, MD, specialty medical director for hospital medicine with Atrium Health in Charlotte, N.C., said that hospital medicine’s flat productivity trends would be difficult to sustain in the business world. But there aren’t easy or obvious ways to increase hospitalists’ productivity. The SoHM report also shows that as productivity increases, total compensation increases but at a lower rate, resulting in a gradual decrease in compensation per RVU.

Pressures to increase productivity can be a double-edged sword, Dr. Williams added. Demanding that doctors make more billable visits faster to generate more RVUs can be a recipe for burnout and turnover, with huge costs associated with recruiting replacements.

“If there was recent turnover of hospitalists at the hospital, with the need to find replacements, there may be institutional memory about that,” he said. “But where are hospitals spending their money? Bottom line, we still need to learn to cut our costs.”

How is hospitalist practice evolving?

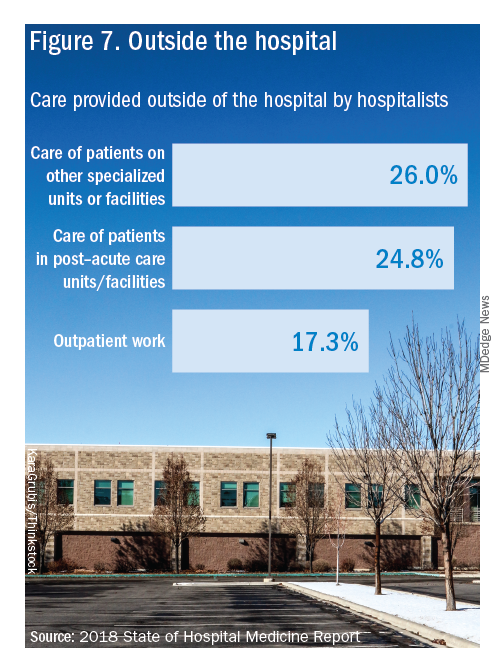

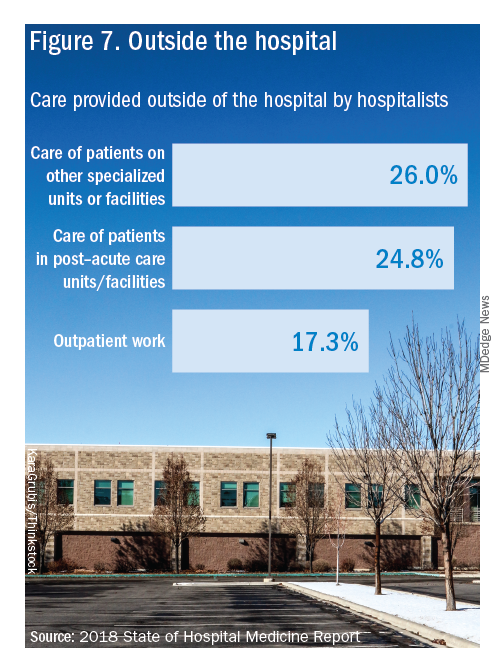

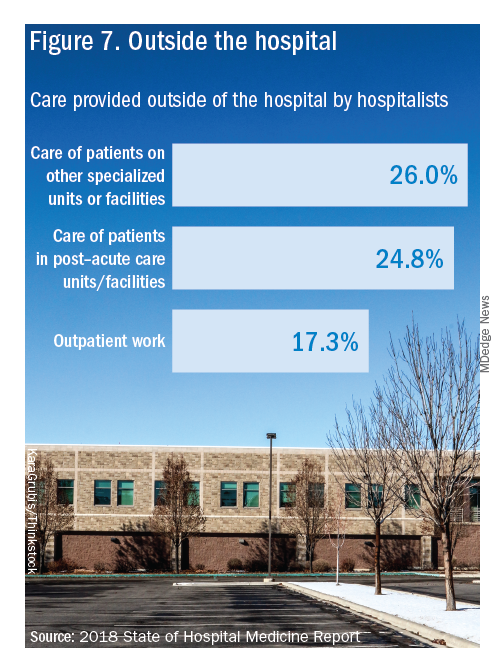

In addition to payment and productivity data, the SoHM report provides a current picture of the evolving state of hospitalist group practices. A key thread is how the work hospitalists are doing, and the way they do it, is changing, with new information about comanagement roles, dedicated admitters, night coverage, geographic rounding, and the like.

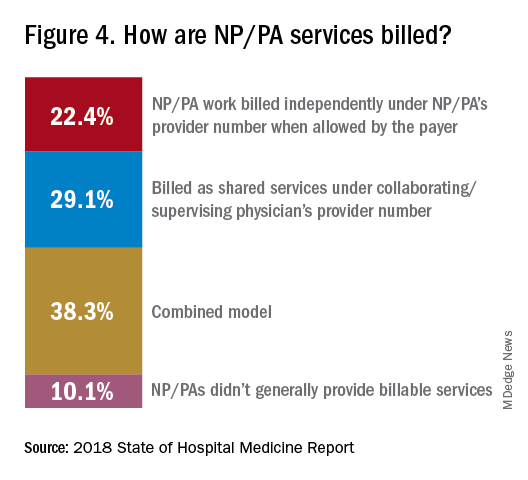

Making greater use of nurse practitioners and physician assistants (NPs/PAs), may be one way to change the flat productivity trends, Dr. Brown said. With a cost per RVU that’s roughly half that of a doctor’s, NPs/PAs could contribute to the bottom line. But he sees surprisingly large variation in how hospitalist groups are using them. Typically, they are deployed at a ratio of four doctors to one NP/PA, but that ratio could be two to one or even one to one, he said.

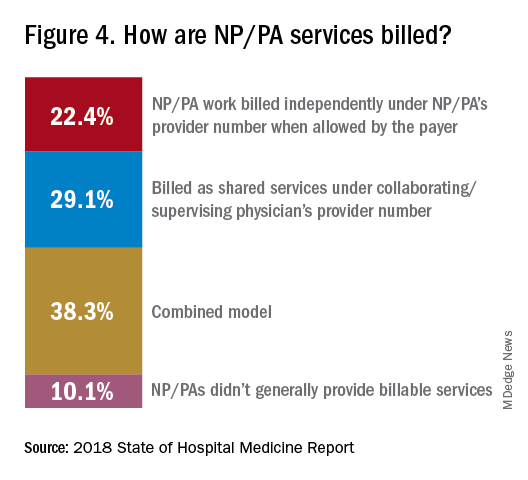

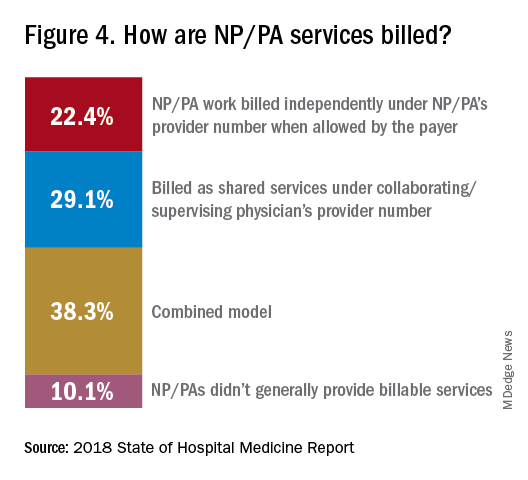

Use of NPs/PAs by academic hospitalist groups is up, from 52.1% in 2016 to 75.7% in 2018. For adult-only groups, 76.8% had NPs/PAs, with higher rates in hospitals and health systems and lower rates in the West region. But a lot of groups are using these practitioners for nonproductive work, and some are failing to generate any billing income, Dr. Brown said.

“The rate at which NPs/PAs performed billable services was higher in physician-owned practices, resulting in a lower cost per RVU, suggesting that many practices may be underutilizing their NPs/PAs or not sharing the work.” Not every NP or PA wants to or is able to care for very complex patients, Dr. Brown said, “but you want a system where the NP and PA can work at the highest level permitted by state law.”

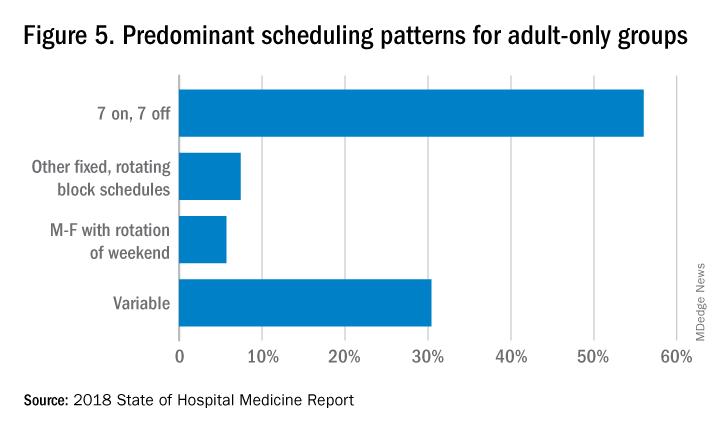

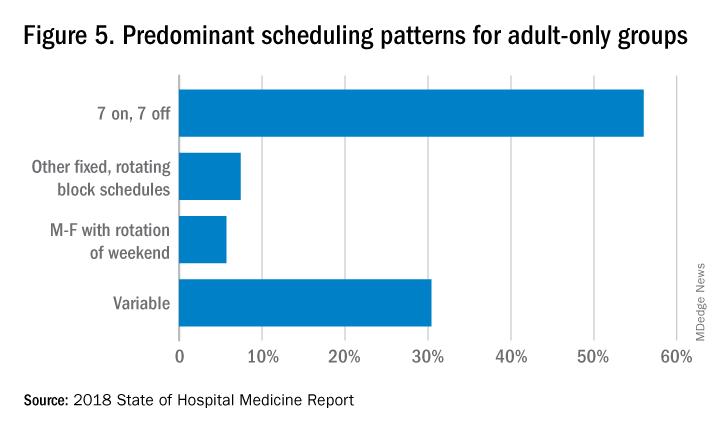

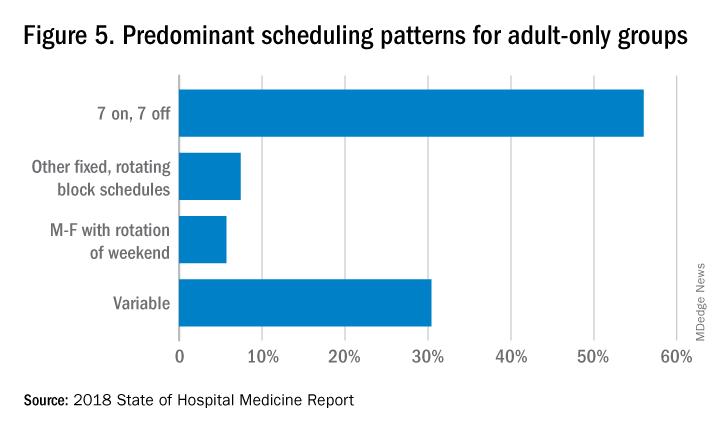

The predominant scheduling model of hospital medicine, 7 days on duty followed by 7 days off, has diminished somewhat in recent years. There appears to be some fluctuation and a gradual move away from 7 on/7 off toward some kind of variable approach, since the former may not be physically sustainable for the doctor over the long haul, Dr. Brown said. Some groups are experimenting with a combined approach.

“I think balancing workload with manpower has always been a challenge for our field. Maybe we should be working shorter shifts or fewer days and making sure our hospitalists aren’t ever sitting around idle,” he said. “And could we come in on nonclinical days to do administrative tasks? I think the solution is out there, but we haven’t created the algorithms to define that yet. If you could somehow use the data for volume, number of beds, nurse staffing, etc., by year and seasonally, you might be able to reliably predict census. This is about applying data hospitals already have in their electronic health records, but utilizing the data in ways that are more helpful.”

Dr. McIlraith added that a big driver of the future of hospital medicine will be the evolution of the EHR and the digitalization of health care, as hospitals learn how to leverage more of what’s in their EHRs. “The impact will grow for hospitalists through the creation and maturation of big data systems – and the learning that can be extracted from what’s contained in the electronic health record.”

Another important question for hospitalist groups is their model of backup scheduling, to make sure there is a replacement available if a scheduled doctor calls in sick or if demand is unexpectedly high.

“In today’s world, this is how we have traditionally managed unpredictability,” Dr. Brown said. “You don’t know when you will need it, but if you need it, you want it immediately. So how do you pay for it – only when the doctor comes in, or also an amount just for being on call?” Some groups pay for both, he said, others for neither.

“We are a group of 70 hospitalists, and if someone is sick you can’t just shut down the service,” said Dr. Chadha. “We are one of the few to use incentives for both, which could include a 1-week decrease in clinical shifts in exchange for 2 weeks of backup. We have times with 25% usage of backup number 1, and 10% usage of backup number 2,” he noted. “But the goal is for our hospitalists to have assurances that there is a backup system and that it works.”

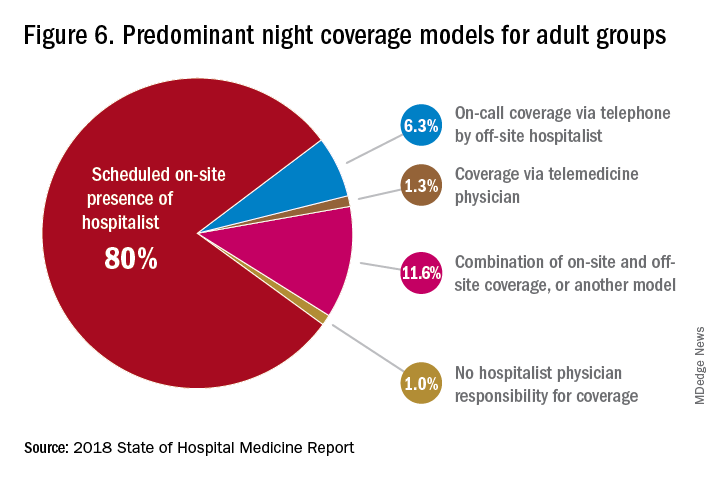

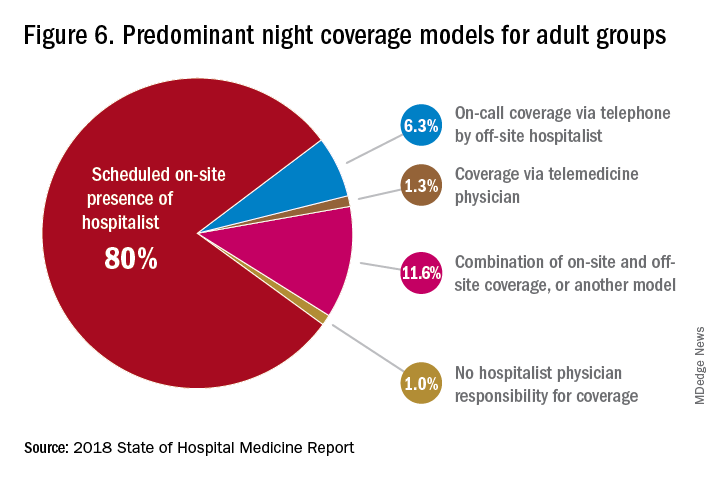

The presence of nocturnists in hospitals continues to rise, with 76.1% of adults-only groups having nocturnists, 27.6% of children-only groups, and 68.2% of adults and children groups. Geographic or unit-based hospital assignments have grown to 36.4% of adult-only groups.

What are hospitalists’ other new roles?

“We have a large group of 50 doctors, with about 40 FTEs, and we are evolving from the traditional generalist role toward more subspecialty comanagement,” said Bryan Huang, MD, physician adviser and associate clinical professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of California–San Diego. “Our hospitalists are asking what it means to be an academic hospitalist as our teaching roles have shrunk.”

Dr. Huang recently took on a new role as physician adviser for his hospital in such areas as utilization review, patient flow, and length of stay. “I’m spearheading a work group to address quality issues – all of which involve collaboration with other professionals. We also developed an admitting role here for a hospitalist whose sole role for the day is to admit patients.” Nationally up to 51.2% of hospitalist groups utilize a dedicated daytime admitter.

The report found that hospital services for which hospitalists are more likely to be attendings than consultants include GI/liver, 78.4%; palliative care, 77.3%; neurology/stroke, 73.6%; oncology, 67.8%; cardiology, 56.9%; and critical care, 50.7%. Conditions where hospitalists are more likely to consult rather than admit and attend include neurosurgery, orthopedics, general surgery, cardiovascular surgery, and other surgical subspecialties.

Other hospital services routinely provided by adult-only hospitalists include care of patients in an ICU setting (62.7%); primary responsibility for observation units (54.6%); primary clinical responsibility for rapid response teams (48.8%); primary responsibility for code blue or cardiac arrest teams (43.8%); nighttime admissions or tuck-in services (33.9%); and medical procedures (31.5%). For pediatric hospital medicine groups, care of healthy newborns and medical procedures were among the most common services provided, while for hospitalists serving adults and children, rapid response teams, ICUs, and specialty units were most common.

New models of payment for health care

As the larger health care system is being transformed by new payment models and benefit structures, including accountable care organizations (ACOs), value-based purchasing, bundled payments, and other forms of population-based coverage – which is described as a volume-to-value shift in health care – how are these new models affecting hospitalists?

Observers say penetration of these new models varies widely by locality but they haven’t had much direct impact on hospitalists’ practices – at least not yet. However, as hospitals and health systems find themselves needing to learn new ways to invest their resources differently in response to these trends, what matters to the hospital should be of great importance to the hospitalist group.

“I haven’t seen a lot of dramatic changes in how hospitalists engage with value-based purchasing,” Dr. White said. “If we know that someone is part of an ACO, the instinctual – and right – response is to treat them like any other patient. But we still need to be committed to not waste resources.”

Hospitalists are the best people to understand the intricacies of how the health care system works under value-based approaches, Dr. Huang said. “That’s why so many hospitalists have taken leadership positions in their hospitals. I think all of this translates to the practical, day-to-day work of hospitalists, reflected in our focus on readmissions and length of stay.”

Dr. Williams said the health care system still hasn’t turned the corner from fee-for-service to value-based purchasing. “It still represents a tiny fraction of the income of hospitalists. Hospitals still have to focus on the bottom line, as fee-for-service reimbursement for hospitalized patients continues to get squeezed, and ACOs aren’t exactly paying premium rates either. Ask almost any hospital CEO what drives their bottom line today and the answer is volume – along with optimizing productivity. Pretty much every place I look, the future does not look terribly rosy for hospitals.”

Ms. Himebaugh said she is bullish on hospital medicine, in the sense that it’s unlikely to go away anytime soon. “Hospitalists are needed and provide value. But I don’t think we have devised the right model yet. I’m not sure our current model is sustainable. We need to find new models we can afford that don’t require squeezing our providers.”

For more information about the 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report, contact SHM’s Practice Management Department at: survey@hospitalmedicine.org or call 800-843-3360. See also: https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/practice-management/shms-state-of-hospital-medicine/.

Productivity, pay, and roles remain center stage

Productivity, pay, and roles remain center stage

In a national health care environment undergoing unprecedented transformation, the specialty of hospital medicine appears to be an island of relative stability, a conclusion that is supported by the principal findings from SHM’s 2018 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) report.

The report of hospitalist group practice characteristics, as well as other key data defining the field’s current status, that the Society of Hospital Medicine puts out every 2 years reveals that overall salaries for hospitalist physicians are up by 3.8% since 2016. Although productivity, as measured by work relative value units (RVUs), remained largely flat over the same period, financial support per full-time equivalent (FTE) physician position to hospitalist groups from their hospitals and health systems is up significantly.

Total support per FTE averaged $176,657 in 2018, 12% higher than in 2016, noted Leslie Flores, MHA, SFHM, of Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants, and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee, which oversees the biennial survey. Compensation and productivity data were collected by the Medical Group Management Association and licensed by SHM for inclusion in its report.

These findings – particularly the flat productivity – raise questions about long-term sustainability, Ms. Flores said. “What is going on? Do hospital administrators still recognize the value hospitalists bring to the operations and the quality of their hospitals? Or is paying the subsidy just a cost of doing business – a necessity for most hospitals in a setting where demand for hospitalist positions remains high?”

Andrew White, MD, FACP, SFHM, chair of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee and director of the hospital medicine service at the University of Washington Medical Center, Seattle, said basic market forces dictate that it is “pretty much inconceivable” to run a modern hospital of any size without hospitalists.

“Clearly, demand outstrips supply, which drives up salaries and support, whether CEOs feel that the hospitalist group is earning that support or not,” Dr. White said. “The unfilled hospitalist positions we identified speak to ongoing projected greater demand than supply. That said, hospitalists and group leaders can’t be complacent and must collaborate effectively with hospitals to provide highly valuable services.” Turnover of hospitalist positions was up slightly, he noted, at 7.4% in 2018, from 6.9% in 2016, reversing a trend of previous years.

But will these trends continue at a time when hospitals face continued pressure to cut costs, as the hospital medicine subsidy may represent one of their largest cost centers? Because the size of hospitalist groups continues to grow, hospitals’ total subsidy for hospital medicine is going up faster than the percentage increase in support per FTE.

How do hospitalists use the SoHM report?

Dr. White called the 2018 SoHM report the “most representative and balanced sample to date” of hospitalist group practices, with some of the highest quality data, thanks to more robust participation in the survey by pediatric groups and improved distribution among hospitalist management companies and academic programs.

“Not that past reports had major flaws, but this version is more authoritative, reflecting an intentional effort by our Practice Analysis Committee to bring in more participants from key groups,” he said.

The biennial report has been around long enough to achieve brand recognition in the field as the most authoritative source of information regarding hospitalist practice, he added. “We worked hard this year to balance the participants, with more of our responses than in the past coming from multi-hospital groups, whether 4 to 5 sites, or 20 to 30.”

Surveys were conducted online in January and February of 2018 in response to invitations mailed and emailed to targeted hospital medicine group leaders. A total of 569 groups completed the survey, representing 8,889 hospitalist FTEs, approximately 16% of the total hospitalist workforce. Responses were presented in several categories, including by size of program, region and employment model. Groups that care for adults only represented 87.9% of the surveys, while groups that care for children only were 6.7% and groups that care for both adults and children were 5.4%.

“This survey doesn’t tell us what should be best practice in hospital medicine,” Dr. White said, only what is actual current practice. He uses it in his own health system to not only contextualize and justify his group’s performance metrics for hospital administrators – relative to national and categorical averages – but also to see if the direction his group is following is consistent with what’s going on in the larger field.

“These data offer a very powerful resource regarding the trends in hospital medicine,” said Romil Chadha, MD, MPH, FACP, SFHM, associate division chief for operations in the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky and UK Healthcare, Lexington. “It is my repository of data to go before my administrators for decisions that need to be made or to pilot new programs.”

Dr. Chadha also uses the data to help answer compensation, scheduling, and support questions from his group’s members.

Thomas McIlraith, MD, immediate past chairman of the hospital medicine department at Mercy Medical Group, Sacramento, Calif., said the report’s value is that it allows comparisons of salaries in different settings, and to see, for example, how night staffing is structured. “A lot of leaders I spoke to at SHM’s 2018 Leadership Academy in Vancouver were saying they didn’t feel up to parity with the national standards. You can use the report to look at the state of hospital medicine nationally and make comparisons,” he said.

Calls for more productivity

Roberta Himebaugh, MBA, SFHM, senior vice president of acute care services for the national hospitalist management company TeamHealth, and cochair of the SHM Practice Administrators Special Interest Group, said her company’s clients have traditionally asked for greater productivity from their hospitalist contracts as a way to decrease overall costs. Some markets are starting to see a change in that approach, she noted.

“Recently there’s been an increased focus on paying hospitalists to focus on quality rather than just productivity. Some of our clients are willing to pay for that, and we are trying to assign value to this non-billable time or adjust our productivity standards appropriately. I think hospitals definitely understand the value of non-billable services from hospitalists, but still will push us on the productivity targets,” Ms. Himebaugh said.

“I don’t believe hospital medicine can be sustainable long term on flat productivity or flat RVUs,” she added. “Yet the costs of burnout associated with pushing higher productivity are not sustainable, either.” So what are the answers? She said many inefficiencies are involved in responding to inquiries on the floor that could have been addressed another way, or waiting for the turnaround of diagnostic tests.

“Maybe we don’t need physicians to be in the hospital 24/7 if we have access to telehealth, or a partnership with the emergency department, or greater use of advanced care practice providers,” Ms. Himebaugh said. “Our hospitals are examining those options, and we have to look at how we can become more efficient and less costly. At TeamHealth, we are trying to staff for value – looking at patient flow patterns and adjusting our schedules accordingly. Is there a bolus of admissions tied to emergency department shift changes, or to certain days of the week? How can we move from the 12-hour shift that begins at 7 a.m. and ends at 7 p.m., and instead provide coverage for when the patients are there?”

Mark Williams, MD, MHM, chief of the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky, Lexington, said he appreciates the volume of data in the report but wishes for even more survey participants, which could make the breakouts for subgroups such as academic hospitalists more robust. Other current sources of hospitalist salary data include the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), which produces compensation reports to help medical schools and teaching hospitals with benchmarking, and the Faculty Practice Solution Center developed jointly by AAMC and Vizient to provide faculty practice plans with analytic tools. The Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) is another valuable source of information, some of which was licensed for inclusion in the SoHM report.

“There is no source of absolute truth that hospitalists can point to,” Dr. Williams said. “I will present my data and my administrators will reply: ‘We have our own data.’ Our institution has consistently ranked first or second nationwide for the sickest patients. We take more Medicaid and dually eligible patients, who have a lot of social issues. They take a lot of time to manage medically and the RVUs don’t reflect that. And yet I’m still judged by my RVUs generated per hospitalist. Hospital administrators understandably want to get the most productivity, and they are looking for their own data for average productivity numbers.”

Ryan Brown, MD, specialty medical director for hospital medicine with Atrium Health in Charlotte, N.C., said that hospital medicine’s flat productivity trends would be difficult to sustain in the business world. But there aren’t easy or obvious ways to increase hospitalists’ productivity. The SoHM report also shows that as productivity increases, total compensation increases but at a lower rate, resulting in a gradual decrease in compensation per RVU.

Pressures to increase productivity can be a double-edged sword, Dr. Williams added. Demanding that doctors make more billable visits faster to generate more RVUs can be a recipe for burnout and turnover, with huge costs associated with recruiting replacements.

“If there was recent turnover of hospitalists at the hospital, with the need to find replacements, there may be institutional memory about that,” he said. “But where are hospitals spending their money? Bottom line, we still need to learn to cut our costs.”

How is hospitalist practice evolving?

In addition to payment and productivity data, the SoHM report provides a current picture of the evolving state of hospitalist group practices. A key thread is how the work hospitalists are doing, and the way they do it, is changing, with new information about comanagement roles, dedicated admitters, night coverage, geographic rounding, and the like.

Making greater use of nurse practitioners and physician assistants (NPs/PAs), may be one way to change the flat productivity trends, Dr. Brown said. With a cost per RVU that’s roughly half that of a doctor’s, NPs/PAs could contribute to the bottom line. But he sees surprisingly large variation in how hospitalist groups are using them. Typically, they are deployed at a ratio of four doctors to one NP/PA, but that ratio could be two to one or even one to one, he said.

Use of NPs/PAs by academic hospitalist groups is up, from 52.1% in 2016 to 75.7% in 2018. For adult-only groups, 76.8% had NPs/PAs, with higher rates in hospitals and health systems and lower rates in the West region. But a lot of groups are using these practitioners for nonproductive work, and some are failing to generate any billing income, Dr. Brown said.

“The rate at which NPs/PAs performed billable services was higher in physician-owned practices, resulting in a lower cost per RVU, suggesting that many practices may be underutilizing their NPs/PAs or not sharing the work.” Not every NP or PA wants to or is able to care for very complex patients, Dr. Brown said, “but you want a system where the NP and PA can work at the highest level permitted by state law.”

The predominant scheduling model of hospital medicine, 7 days on duty followed by 7 days off, has diminished somewhat in recent years. There appears to be some fluctuation and a gradual move away from 7 on/7 off toward some kind of variable approach, since the former may not be physically sustainable for the doctor over the long haul, Dr. Brown said. Some groups are experimenting with a combined approach.

“I think balancing workload with manpower has always been a challenge for our field. Maybe we should be working shorter shifts or fewer days and making sure our hospitalists aren’t ever sitting around idle,” he said. “And could we come in on nonclinical days to do administrative tasks? I think the solution is out there, but we haven’t created the algorithms to define that yet. If you could somehow use the data for volume, number of beds, nurse staffing, etc., by year and seasonally, you might be able to reliably predict census. This is about applying data hospitals already have in their electronic health records, but utilizing the data in ways that are more helpful.”

Dr. McIlraith added that a big driver of the future of hospital medicine will be the evolution of the EHR and the digitalization of health care, as hospitals learn how to leverage more of what’s in their EHRs. “The impact will grow for hospitalists through the creation and maturation of big data systems – and the learning that can be extracted from what’s contained in the electronic health record.”

Another important question for hospitalist groups is their model of backup scheduling, to make sure there is a replacement available if a scheduled doctor calls in sick or if demand is unexpectedly high.

“In today’s world, this is how we have traditionally managed unpredictability,” Dr. Brown said. “You don’t know when you will need it, but if you need it, you want it immediately. So how do you pay for it – only when the doctor comes in, or also an amount just for being on call?” Some groups pay for both, he said, others for neither.

“We are a group of 70 hospitalists, and if someone is sick you can’t just shut down the service,” said Dr. Chadha. “We are one of the few to use incentives for both, which could include a 1-week decrease in clinical shifts in exchange for 2 weeks of backup. We have times with 25% usage of backup number 1, and 10% usage of backup number 2,” he noted. “But the goal is for our hospitalists to have assurances that there is a backup system and that it works.”

The presence of nocturnists in hospitals continues to rise, with 76.1% of adults-only groups having nocturnists, 27.6% of children-only groups, and 68.2% of adults and children groups. Geographic or unit-based hospital assignments have grown to 36.4% of adult-only groups.

What are hospitalists’ other new roles?

“We have a large group of 50 doctors, with about 40 FTEs, and we are evolving from the traditional generalist role toward more subspecialty comanagement,” said Bryan Huang, MD, physician adviser and associate clinical professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of California–San Diego. “Our hospitalists are asking what it means to be an academic hospitalist as our teaching roles have shrunk.”

Dr. Huang recently took on a new role as physician adviser for his hospital in such areas as utilization review, patient flow, and length of stay. “I’m spearheading a work group to address quality issues – all of which involve collaboration with other professionals. We also developed an admitting role here for a hospitalist whose sole role for the day is to admit patients.” Nationally up to 51.2% of hospitalist groups utilize a dedicated daytime admitter.

The report found that hospital services for which hospitalists are more likely to be attendings than consultants include GI/liver, 78.4%; palliative care, 77.3%; neurology/stroke, 73.6%; oncology, 67.8%; cardiology, 56.9%; and critical care, 50.7%. Conditions where hospitalists are more likely to consult rather than admit and attend include neurosurgery, orthopedics, general surgery, cardiovascular surgery, and other surgical subspecialties.

Other hospital services routinely provided by adult-only hospitalists include care of patients in an ICU setting (62.7%); primary responsibility for observation units (54.6%); primary clinical responsibility for rapid response teams (48.8%); primary responsibility for code blue or cardiac arrest teams (43.8%); nighttime admissions or tuck-in services (33.9%); and medical procedures (31.5%). For pediatric hospital medicine groups, care of healthy newborns and medical procedures were among the most common services provided, while for hospitalists serving adults and children, rapid response teams, ICUs, and specialty units were most common.

New models of payment for health care

As the larger health care system is being transformed by new payment models and benefit structures, including accountable care organizations (ACOs), value-based purchasing, bundled payments, and other forms of population-based coverage – which is described as a volume-to-value shift in health care – how are these new models affecting hospitalists?

Observers say penetration of these new models varies widely by locality but they haven’t had much direct impact on hospitalists’ practices – at least not yet. However, as hospitals and health systems find themselves needing to learn new ways to invest their resources differently in response to these trends, what matters to the hospital should be of great importance to the hospitalist group.

“I haven’t seen a lot of dramatic changes in how hospitalists engage with value-based purchasing,” Dr. White said. “If we know that someone is part of an ACO, the instinctual – and right – response is to treat them like any other patient. But we still need to be committed to not waste resources.”

Hospitalists are the best people to understand the intricacies of how the health care system works under value-based approaches, Dr. Huang said. “That’s why so many hospitalists have taken leadership positions in their hospitals. I think all of this translates to the practical, day-to-day work of hospitalists, reflected in our focus on readmissions and length of stay.”

Dr. Williams said the health care system still hasn’t turned the corner from fee-for-service to value-based purchasing. “It still represents a tiny fraction of the income of hospitalists. Hospitals still have to focus on the bottom line, as fee-for-service reimbursement for hospitalized patients continues to get squeezed, and ACOs aren’t exactly paying premium rates either. Ask almost any hospital CEO what drives their bottom line today and the answer is volume – along with optimizing productivity. Pretty much every place I look, the future does not look terribly rosy for hospitals.”

Ms. Himebaugh said she is bullish on hospital medicine, in the sense that it’s unlikely to go away anytime soon. “Hospitalists are needed and provide value. But I don’t think we have devised the right model yet. I’m not sure our current model is sustainable. We need to find new models we can afford that don’t require squeezing our providers.”

For more information about the 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report, contact SHM’s Practice Management Department at: survey@hospitalmedicine.org or call 800-843-3360. See also: https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/practice-management/shms-state-of-hospital-medicine/.

In a national health care environment undergoing unprecedented transformation, the specialty of hospital medicine appears to be an island of relative stability, a conclusion that is supported by the principal findings from SHM’s 2018 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) report.

The report of hospitalist group practice characteristics, as well as other key data defining the field’s current status, that the Society of Hospital Medicine puts out every 2 years reveals that overall salaries for hospitalist physicians are up by 3.8% since 2016. Although productivity, as measured by work relative value units (RVUs), remained largely flat over the same period, financial support per full-time equivalent (FTE) physician position to hospitalist groups from their hospitals and health systems is up significantly.

Total support per FTE averaged $176,657 in 2018, 12% higher than in 2016, noted Leslie Flores, MHA, SFHM, of Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants, and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee, which oversees the biennial survey. Compensation and productivity data were collected by the Medical Group Management Association and licensed by SHM for inclusion in its report.

These findings – particularly the flat productivity – raise questions about long-term sustainability, Ms. Flores said. “What is going on? Do hospital administrators still recognize the value hospitalists bring to the operations and the quality of their hospitals? Or is paying the subsidy just a cost of doing business – a necessity for most hospitals in a setting where demand for hospitalist positions remains high?”

Andrew White, MD, FACP, SFHM, chair of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee and director of the hospital medicine service at the University of Washington Medical Center, Seattle, said basic market forces dictate that it is “pretty much inconceivable” to run a modern hospital of any size without hospitalists.

“Clearly, demand outstrips supply, which drives up salaries and support, whether CEOs feel that the hospitalist group is earning that support or not,” Dr. White said. “The unfilled hospitalist positions we identified speak to ongoing projected greater demand than supply. That said, hospitalists and group leaders can’t be complacent and must collaborate effectively with hospitals to provide highly valuable services.” Turnover of hospitalist positions was up slightly, he noted, at 7.4% in 2018, from 6.9% in 2016, reversing a trend of previous years.

But will these trends continue at a time when hospitals face continued pressure to cut costs, as the hospital medicine subsidy may represent one of their largest cost centers? Because the size of hospitalist groups continues to grow, hospitals’ total subsidy for hospital medicine is going up faster than the percentage increase in support per FTE.

How do hospitalists use the SoHM report?

Dr. White called the 2018 SoHM report the “most representative and balanced sample to date” of hospitalist group practices, with some of the highest quality data, thanks to more robust participation in the survey by pediatric groups and improved distribution among hospitalist management companies and academic programs.

“Not that past reports had major flaws, but this version is more authoritative, reflecting an intentional effort by our Practice Analysis Committee to bring in more participants from key groups,” he said.

The biennial report has been around long enough to achieve brand recognition in the field as the most authoritative source of information regarding hospitalist practice, he added. “We worked hard this year to balance the participants, with more of our responses than in the past coming from multi-hospital groups, whether 4 to 5 sites, or 20 to 30.”

Surveys were conducted online in January and February of 2018 in response to invitations mailed and emailed to targeted hospital medicine group leaders. A total of 569 groups completed the survey, representing 8,889 hospitalist FTEs, approximately 16% of the total hospitalist workforce. Responses were presented in several categories, including by size of program, region and employment model. Groups that care for adults only represented 87.9% of the surveys, while groups that care for children only were 6.7% and groups that care for both adults and children were 5.4%.

“This survey doesn’t tell us what should be best practice in hospital medicine,” Dr. White said, only what is actual current practice. He uses it in his own health system to not only contextualize and justify his group’s performance metrics for hospital administrators – relative to national and categorical averages – but also to see if the direction his group is following is consistent with what’s going on in the larger field.

“These data offer a very powerful resource regarding the trends in hospital medicine,” said Romil Chadha, MD, MPH, FACP, SFHM, associate division chief for operations in the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky and UK Healthcare, Lexington. “It is my repository of data to go before my administrators for decisions that need to be made or to pilot new programs.”

Dr. Chadha also uses the data to help answer compensation, scheduling, and support questions from his group’s members.

Thomas McIlraith, MD, immediate past chairman of the hospital medicine department at Mercy Medical Group, Sacramento, Calif., said the report’s value is that it allows comparisons of salaries in different settings, and to see, for example, how night staffing is structured. “A lot of leaders I spoke to at SHM’s 2018 Leadership Academy in Vancouver were saying they didn’t feel up to parity with the national standards. You can use the report to look at the state of hospital medicine nationally and make comparisons,” he said.

Calls for more productivity

Roberta Himebaugh, MBA, SFHM, senior vice president of acute care services for the national hospitalist management company TeamHealth, and cochair of the SHM Practice Administrators Special Interest Group, said her company’s clients have traditionally asked for greater productivity from their hospitalist contracts as a way to decrease overall costs. Some markets are starting to see a change in that approach, she noted.

“Recently there’s been an increased focus on paying hospitalists to focus on quality rather than just productivity. Some of our clients are willing to pay for that, and we are trying to assign value to this non-billable time or adjust our productivity standards appropriately. I think hospitals definitely understand the value of non-billable services from hospitalists, but still will push us on the productivity targets,” Ms. Himebaugh said.

“I don’t believe hospital medicine can be sustainable long term on flat productivity or flat RVUs,” she added. “Yet the costs of burnout associated with pushing higher productivity are not sustainable, either.” So what are the answers? She said many inefficiencies are involved in responding to inquiries on the floor that could have been addressed another way, or waiting for the turnaround of diagnostic tests.

“Maybe we don’t need physicians to be in the hospital 24/7 if we have access to telehealth, or a partnership with the emergency department, or greater use of advanced care practice providers,” Ms. Himebaugh said. “Our hospitals are examining those options, and we have to look at how we can become more efficient and less costly. At TeamHealth, we are trying to staff for value – looking at patient flow patterns and adjusting our schedules accordingly. Is there a bolus of admissions tied to emergency department shift changes, or to certain days of the week? How can we move from the 12-hour shift that begins at 7 a.m. and ends at 7 p.m., and instead provide coverage for when the patients are there?”

Mark Williams, MD, MHM, chief of the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky, Lexington, said he appreciates the volume of data in the report but wishes for even more survey participants, which could make the breakouts for subgroups such as academic hospitalists more robust. Other current sources of hospitalist salary data include the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), which produces compensation reports to help medical schools and teaching hospitals with benchmarking, and the Faculty Practice Solution Center developed jointly by AAMC and Vizient to provide faculty practice plans with analytic tools. The Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) is another valuable source of information, some of which was licensed for inclusion in the SoHM report.

“There is no source of absolute truth that hospitalists can point to,” Dr. Williams said. “I will present my data and my administrators will reply: ‘We have our own data.’ Our institution has consistently ranked first or second nationwide for the sickest patients. We take more Medicaid and dually eligible patients, who have a lot of social issues. They take a lot of time to manage medically and the RVUs don’t reflect that. And yet I’m still judged by my RVUs generated per hospitalist. Hospital administrators understandably want to get the most productivity, and they are looking for their own data for average productivity numbers.”

Ryan Brown, MD, specialty medical director for hospital medicine with Atrium Health in Charlotte, N.C., said that hospital medicine’s flat productivity trends would be difficult to sustain in the business world. But there aren’t easy or obvious ways to increase hospitalists’ productivity. The SoHM report also shows that as productivity increases, total compensation increases but at a lower rate, resulting in a gradual decrease in compensation per RVU.

Pressures to increase productivity can be a double-edged sword, Dr. Williams added. Demanding that doctors make more billable visits faster to generate more RVUs can be a recipe for burnout and turnover, with huge costs associated with recruiting replacements.

“If there was recent turnover of hospitalists at the hospital, with the need to find replacements, there may be institutional memory about that,” he said. “But where are hospitals spending their money? Bottom line, we still need to learn to cut our costs.”

How is hospitalist practice evolving?

In addition to payment and productivity data, the SoHM report provides a current picture of the evolving state of hospitalist group practices. A key thread is how the work hospitalists are doing, and the way they do it, is changing, with new information about comanagement roles, dedicated admitters, night coverage, geographic rounding, and the like.

Making greater use of nurse practitioners and physician assistants (NPs/PAs), may be one way to change the flat productivity trends, Dr. Brown said. With a cost per RVU that’s roughly half that of a doctor’s, NPs/PAs could contribute to the bottom line. But he sees surprisingly large variation in how hospitalist groups are using them. Typically, they are deployed at a ratio of four doctors to one NP/PA, but that ratio could be two to one or even one to one, he said.

Use of NPs/PAs by academic hospitalist groups is up, from 52.1% in 2016 to 75.7% in 2018. For adult-only groups, 76.8% had NPs/PAs, with higher rates in hospitals and health systems and lower rates in the West region. But a lot of groups are using these practitioners for nonproductive work, and some are failing to generate any billing income, Dr. Brown said.

“The rate at which NPs/PAs performed billable services was higher in physician-owned practices, resulting in a lower cost per RVU, suggesting that many practices may be underutilizing their NPs/PAs or not sharing the work.” Not every NP or PA wants to or is able to care for very complex patients, Dr. Brown said, “but you want a system where the NP and PA can work at the highest level permitted by state law.”

The predominant scheduling model of hospital medicine, 7 days on duty followed by 7 days off, has diminished somewhat in recent years. There appears to be some fluctuation and a gradual move away from 7 on/7 off toward some kind of variable approach, since the former may not be physically sustainable for the doctor over the long haul, Dr. Brown said. Some groups are experimenting with a combined approach.

“I think balancing workload with manpower has always been a challenge for our field. Maybe we should be working shorter shifts or fewer days and making sure our hospitalists aren’t ever sitting around idle,” he said. “And could we come in on nonclinical days to do administrative tasks? I think the solution is out there, but we haven’t created the algorithms to define that yet. If you could somehow use the data for volume, number of beds, nurse staffing, etc., by year and seasonally, you might be able to reliably predict census. This is about applying data hospitals already have in their electronic health records, but utilizing the data in ways that are more helpful.”

Dr. McIlraith added that a big driver of the future of hospital medicine will be the evolution of the EHR and the digitalization of health care, as hospitals learn how to leverage more of what’s in their EHRs. “The impact will grow for hospitalists through the creation and maturation of big data systems – and the learning that can be extracted from what’s contained in the electronic health record.”

Another important question for hospitalist groups is their model of backup scheduling, to make sure there is a replacement available if a scheduled doctor calls in sick or if demand is unexpectedly high.

“In today’s world, this is how we have traditionally managed unpredictability,” Dr. Brown said. “You don’t know when you will need it, but if you need it, you want it immediately. So how do you pay for it – only when the doctor comes in, or also an amount just for being on call?” Some groups pay for both, he said, others for neither.

“We are a group of 70 hospitalists, and if someone is sick you can’t just shut down the service,” said Dr. Chadha. “We are one of the few to use incentives for both, which could include a 1-week decrease in clinical shifts in exchange for 2 weeks of backup. We have times with 25% usage of backup number 1, and 10% usage of backup number 2,” he noted. “But the goal is for our hospitalists to have assurances that there is a backup system and that it works.”

The presence of nocturnists in hospitals continues to rise, with 76.1% of adults-only groups having nocturnists, 27.6% of children-only groups, and 68.2% of adults and children groups. Geographic or unit-based hospital assignments have grown to 36.4% of adult-only groups.

What are hospitalists’ other new roles?

“We have a large group of 50 doctors, with about 40 FTEs, and we are evolving from the traditional generalist role toward more subspecialty comanagement,” said Bryan Huang, MD, physician adviser and associate clinical professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of California–San Diego. “Our hospitalists are asking what it means to be an academic hospitalist as our teaching roles have shrunk.”

Dr. Huang recently took on a new role as physician adviser for his hospital in such areas as utilization review, patient flow, and length of stay. “I’m spearheading a work group to address quality issues – all of which involve collaboration with other professionals. We also developed an admitting role here for a hospitalist whose sole role for the day is to admit patients.” Nationally up to 51.2% of hospitalist groups utilize a dedicated daytime admitter.

The report found that hospital services for which hospitalists are more likely to be attendings than consultants include GI/liver, 78.4%; palliative care, 77.3%; neurology/stroke, 73.6%; oncology, 67.8%; cardiology, 56.9%; and critical care, 50.7%. Conditions where hospitalists are more likely to consult rather than admit and attend include neurosurgery, orthopedics, general surgery, cardiovascular surgery, and other surgical subspecialties.

Other hospital services routinely provided by adult-only hospitalists include care of patients in an ICU setting (62.7%); primary responsibility for observation units (54.6%); primary clinical responsibility for rapid response teams (48.8%); primary responsibility for code blue or cardiac arrest teams (43.8%); nighttime admissions or tuck-in services (33.9%); and medical procedures (31.5%). For pediatric hospital medicine groups, care of healthy newborns and medical procedures were among the most common services provided, while for hospitalists serving adults and children, rapid response teams, ICUs, and specialty units were most common.

New models of payment for health care

As the larger health care system is being transformed by new payment models and benefit structures, including accountable care organizations (ACOs), value-based purchasing, bundled payments, and other forms of population-based coverage – which is described as a volume-to-value shift in health care – how are these new models affecting hospitalists?

Observers say penetration of these new models varies widely by locality but they haven’t had much direct impact on hospitalists’ practices – at least not yet. However, as hospitals and health systems find themselves needing to learn new ways to invest their resources differently in response to these trends, what matters to the hospital should be of great importance to the hospitalist group.

“I haven’t seen a lot of dramatic changes in how hospitalists engage with value-based purchasing,” Dr. White said. “If we know that someone is part of an ACO, the instinctual – and right – response is to treat them like any other patient. But we still need to be committed to not waste resources.”

Hospitalists are the best people to understand the intricacies of how the health care system works under value-based approaches, Dr. Huang said. “That’s why so many hospitalists have taken leadership positions in their hospitals. I think all of this translates to the practical, day-to-day work of hospitalists, reflected in our focus on readmissions and length of stay.”

Dr. Williams said the health care system still hasn’t turned the corner from fee-for-service to value-based purchasing. “It still represents a tiny fraction of the income of hospitalists. Hospitals still have to focus on the bottom line, as fee-for-service reimbursement for hospitalized patients continues to get squeezed, and ACOs aren’t exactly paying premium rates either. Ask almost any hospital CEO what drives their bottom line today and the answer is volume – along with optimizing productivity. Pretty much every place I look, the future does not look terribly rosy for hospitals.”

Ms. Himebaugh said she is bullish on hospital medicine, in the sense that it’s unlikely to go away anytime soon. “Hospitalists are needed and provide value. But I don’t think we have devised the right model yet. I’m not sure our current model is sustainable. We need to find new models we can afford that don’t require squeezing our providers.”

For more information about the 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report, contact SHM’s Practice Management Department at: survey@hospitalmedicine.org or call 800-843-3360. See also: https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/practice-management/shms-state-of-hospital-medicine/.

A deep commitment to veterans’ medical needs

VA hospitalist Dr. Mel Anderson loves his work

Mel C. Anderson, MD, FACP, section chief of hospital medicine for the Veterans Administration of Eastern Colorado, and his hospitalist colleagues share a mission to care for the men and women who served their country in the armed forces and are now being served by the VA.

“That mission binds us together in a deep and impactful way,” he said. “One of the greatest joys of my life has been to dedicate, with the teams I lead, our hearts and minds to serving this population of veterans.”

Approximately 400 hospitalists work nationwide in the VA, the country’s largest integrated health system, typically in groups of about a dozen. Not every VA medical center employs hospitalists; this depends on local tradition and size of the facility. Dr. Anderson was for several years the lone hospitalist at the VA Medical Center in Denver, starting in 2005, and now he heads a group of 17. The Denver facility employs five inpatient teams plus nocturnists, supported by residents, interns, and medical students in training from the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, to deliver all of its inpatient medical care.

“We also have an open ICU here. Hospitalists are able to follow their patients across the hospital, and we can make the decision to move them to the ICU,” Dr. Anderson said. The Denver group also established a hospitalist-staffed postdischarge clinic, where patients can reconnect with their hospital team. “It’s not to supplant primary care but to help promote safe transit as the patient moves back to the community,” he said. “We’ve also developed a surgery consult service for orthopedics and other surgical subspecialties.”

The VA’s integrated electronic medical record facilitates communication between hospitalists and primary care physicians, with instant messaging for updating the PCPs on the patient’s hospital stay.

The Denver VA hospitalists value their collegial culture, Dr. Anderson said. “We are invested in our group and in one another and in life-long learning. I often ask my group for their feedback. It’s one of the singular joys of my career to lead such a wonderful group, which has been built up person by person. I hired every single member. As much as their clinical skills and the achievements on their curriculum vitae were important, I also paid attention to their interpersonal communication skills.”

Members of the Denver hospitalist group also share an academic focus and commitment to scholarship and research. Dr. Anderson’s academic emphasis is on how to promote teaching and faculty development through organized bedside rounding and how to orient students to teaching as a potential career path. He is associate program director for medicine residencies at the University of Colorado and leads its Clinician/Educator Pathway.

The VA hospital’s interdisciplinary bedside rounding initiative involves the medicine team – students, residents, attending – and pharmacist, plus the patient’s bedside nurse and nurse care coordinator. “We have worked on fostering an interdisciplinary culture, and we’re very proud of the rounding model we developed here. We all round together at the bedside, and typically that might include 7 or 8 people,” Dr. Anderson explained.

“In planning this program, we used a Rapid Performance Improvement Project team with a nurse, pharmacist, and physical therapist helping us envision how to redesign rounds to overcome the time constraints,” he said. “We altered nurses’ work flow to permit them to join the rounding for their patients, and we moved morning medication administration to 7 a.m., so it wouldn’t get in the way of the rounding. We now audit rates of physician-to-nurse communication on rounds and how often we successfully achieve the nurse’s participation.”1 This approach has also cut rates of phone pages from nurses to house staff, and substantially increased job satisfaction.

What’s different in the VA?

The work of hospitalists in the VA is mostly similar to other hospital settings, but perhaps with more intensity, Dr. Anderson said. There are comorbidities such as higher rates of PTSD, alcohol use disorder, substance abuse, and mental health issues – all of which have an effect over time on patients. But veterans also have different attitudes about, for example, pain.

“When patients are asked to rate their pain on a scale of 0 to 10, for a veteran of a foreign war, 2 out of 10 is not the same as someone else’s 2 out of 10. How do we compensate for that difference?” he said. “And while awareness of PTSD and efforts to mitigate its impact have made incredible gains over the past 15 years, we still see a lot of these issues and their manifestations in social challenges such as homelessness. We are fortunate to have VA outpatient services and homeless veteran programs to help with these issues.”

There is a different paradigm for care at the VA, Dr. Anderson said. “We are a not-for-profit institution with the welfare of veterans as our primary aim. Beyond their health and wellness, that means supporting them in other ways and reaching out into the community. As doctors and nurses we feel a kinship around that mission, although we also have to be stewards of taxpayer dollars. We recognize that the VA is a large and complicated, somewhat inertia-laden organization in which making changes can be very challenging. But there are also opportunities as a national organization to effect changes on a national scale.”

Dr. Anderson chairs the VA’s Hospitalist Field Advisory Committee (HFAC), a group of about eight hospitalists empaneled to advise the system’s Office of Specialty Care Services on clinical policy and program development. They serve 3-year terms and meet monthly by phone and annually in Washington. The HFAC’s last annual meeting occurred in mid-September 2018 in Washington with a focus on developing a hospital medicine annual survey and needs assessment, revisiting strategic goals, and convening multilateral meetings with the chiefs of medicine and emergency medicine FACs.

“Our biggest emphasis is clinical – this includes clinical pathways, best practices for managing PTSD or acute coronary syndrome, and the like. We also share management issues, such as how to configure medical records or arrange night coverage. This is a national conversation to share what some sites have already experienced and learned,” Dr. Anderson said.

“We also have a VA Academic Hospitalist Subcommittee, working together on multisite research studies and on resident education protocols. Because we’re a large system, we’re able to connect with one another and leverage what we’ve learned. I get emails almost every day about research topics from colleagues across the country,” he said. A collaborative website and email distribution list allows doctors to post questions to their peers nationwide.

A calling for hospital medicine

Before moving to Denver, Dr. Anderson served as a major in the Air Force Medical Corps and was based at the David Grant US Air Force Medical Center on Travis Air Force Base in California – which is where he did his residency. In the course of a “traditionalist” internal medical training, including 4-month stints on hospital wards in addition to outpatient services, he realized he had a calling for hospital medicine.

In a job at the Providence (R.I.) VA Medical Center, he exclusively practiced outpatient care, but he found that he missed key aspects of inpatient work, such as the intensity of the clinical issues and teaching encounters. “I cold-called the hospital’s chief of medicine and volunteered to start mentoring inpatient residents,” Dr. Anderson said. “That was 17 years ago.”

Another abiding interest derived from Dr. Anderson’s military service is travel medicine. While a physician in the Air Force, he was deployed to Haiti in 1995 and to Nicaragua in 2000, where he treated thousands of patients – both U.S. service personnel and local populations.

“In Haiti, our primary mission was for U.S. troops who were still based there following the 1994 Operation Uphold Democracy intervention, but there were a lot fewer of them, so we mostly kept busy providing care to Haitian nationals,” he said. “That work was eye opening, to say the least,” and led to a professional interest in tropical illnesses. “Since then, I’ve been a visiting professor for the University of Colorado posted to the University of Zimbabwe in Harare in 2012 and 2016.”

What gives Dr. Anderson such joy and enthusiasm for his VA work? “I am a curious lifelong learner. Every day, there are 10 new things I need to learn, whether clinically or operationally in a big hospital system or just the day-to-day realities of leading a group of physicians. I never feel like I’m treading water,” he said. He is also energized by teaching – seeing “the light bulb go on” for the students he is instructing – and by serving as a role model for doctors in training.

“As I contemplate all the simultaneous balls I have in the air, including our recent move into a new hospital building, sometimes I think it is kind of crazy to be doing as much as I do,” he said. “But I also take time away, balancing work versus nonwork.” He spends quality time with his wife of 21 years, 17-year-old daughter, other relatives, and friends, as well as on physical activity, reading books about philosophy, and his hobby of rebuilding motorcycles, which he says offers a kind of meditative calm.

“I also feel a deep sense of service – to patients, colleagues, students, and to the mission of the VA,” Dr. Anderson said. “There is truly something special about caring for the veteran. It’s hard to articulate, but it really keeps us coming back for more. I’ve had vets sing to me, tell jokes, do magic tricks, share their war stories. I’ve had patients open up to me in ways that were both profound and humbling.”

References

1. Young E et al. Impact of altered medication administration time on interdisciplinary bedside rounds on academic medical ward. J Nurs Care Qual. 2017 Jul/Sep;32(3):218-225.

VA hospitalist Dr. Mel Anderson loves his work

VA hospitalist Dr. Mel Anderson loves his work

Mel C. Anderson, MD, FACP, section chief of hospital medicine for the Veterans Administration of Eastern Colorado, and his hospitalist colleagues share a mission to care for the men and women who served their country in the armed forces and are now being served by the VA.

“That mission binds us together in a deep and impactful way,” he said. “One of the greatest joys of my life has been to dedicate, with the teams I lead, our hearts and minds to serving this population of veterans.”

Approximately 400 hospitalists work nationwide in the VA, the country’s largest integrated health system, typically in groups of about a dozen. Not every VA medical center employs hospitalists; this depends on local tradition and size of the facility. Dr. Anderson was for several years the lone hospitalist at the VA Medical Center in Denver, starting in 2005, and now he heads a group of 17. The Denver facility employs five inpatient teams plus nocturnists, supported by residents, interns, and medical students in training from the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, to deliver all of its inpatient medical care.

“We also have an open ICU here. Hospitalists are able to follow their patients across the hospital, and we can make the decision to move them to the ICU,” Dr. Anderson said. The Denver group also established a hospitalist-staffed postdischarge clinic, where patients can reconnect with their hospital team. “It’s not to supplant primary care but to help promote safe transit as the patient moves back to the community,” he said. “We’ve also developed a surgery consult service for orthopedics and other surgical subspecialties.”

The VA’s integrated electronic medical record facilitates communication between hospitalists and primary care physicians, with instant messaging for updating the PCPs on the patient’s hospital stay.

The Denver VA hospitalists value their collegial culture, Dr. Anderson said. “We are invested in our group and in one another and in life-long learning. I often ask my group for their feedback. It’s one of the singular joys of my career to lead such a wonderful group, which has been built up person by person. I hired every single member. As much as their clinical skills and the achievements on their curriculum vitae were important, I also paid attention to their interpersonal communication skills.”

Members of the Denver hospitalist group also share an academic focus and commitment to scholarship and research. Dr. Anderson’s academic emphasis is on how to promote teaching and faculty development through organized bedside rounding and how to orient students to teaching as a potential career path. He is associate program director for medicine residencies at the University of Colorado and leads its Clinician/Educator Pathway.

The VA hospital’s interdisciplinary bedside rounding initiative involves the medicine team – students, residents, attending – and pharmacist, plus the patient’s bedside nurse and nurse care coordinator. “We have worked on fostering an interdisciplinary culture, and we’re very proud of the rounding model we developed here. We all round together at the bedside, and typically that might include 7 or 8 people,” Dr. Anderson explained.

“In planning this program, we used a Rapid Performance Improvement Project team with a nurse, pharmacist, and physical therapist helping us envision how to redesign rounds to overcome the time constraints,” he said. “We altered nurses’ work flow to permit them to join the rounding for their patients, and we moved morning medication administration to 7 a.m., so it wouldn’t get in the way of the rounding. We now audit rates of physician-to-nurse communication on rounds and how often we successfully achieve the nurse’s participation.”1 This approach has also cut rates of phone pages from nurses to house staff, and substantially increased job satisfaction.

What’s different in the VA?

The work of hospitalists in the VA is mostly similar to other hospital settings, but perhaps with more intensity, Dr. Anderson said. There are comorbidities such as higher rates of PTSD, alcohol use disorder, substance abuse, and mental health issues – all of which have an effect over time on patients. But veterans also have different attitudes about, for example, pain.

“When patients are asked to rate their pain on a scale of 0 to 10, for a veteran of a foreign war, 2 out of 10 is not the same as someone else’s 2 out of 10. How do we compensate for that difference?” he said. “And while awareness of PTSD and efforts to mitigate its impact have made incredible gains over the past 15 years, we still see a lot of these issues and their manifestations in social challenges such as homelessness. We are fortunate to have VA outpatient services and homeless veteran programs to help with these issues.”

There is a different paradigm for care at the VA, Dr. Anderson said. “We are a not-for-profit institution with the welfare of veterans as our primary aim. Beyond their health and wellness, that means supporting them in other ways and reaching out into the community. As doctors and nurses we feel a kinship around that mission, although we also have to be stewards of taxpayer dollars. We recognize that the VA is a large and complicated, somewhat inertia-laden organization in which making changes can be very challenging. But there are also opportunities as a national organization to effect changes on a national scale.”

Dr. Anderson chairs the VA’s Hospitalist Field Advisory Committee (HFAC), a group of about eight hospitalists empaneled to advise the system’s Office of Specialty Care Services on clinical policy and program development. They serve 3-year terms and meet monthly by phone and annually in Washington. The HFAC’s last annual meeting occurred in mid-September 2018 in Washington with a focus on developing a hospital medicine annual survey and needs assessment, revisiting strategic goals, and convening multilateral meetings with the chiefs of medicine and emergency medicine FACs.

“Our biggest emphasis is clinical – this includes clinical pathways, best practices for managing PTSD or acute coronary syndrome, and the like. We also share management issues, such as how to configure medical records or arrange night coverage. This is a national conversation to share what some sites have already experienced and learned,” Dr. Anderson said.

“We also have a VA Academic Hospitalist Subcommittee, working together on multisite research studies and on resident education protocols. Because we’re a large system, we’re able to connect with one another and leverage what we’ve learned. I get emails almost every day about research topics from colleagues across the country,” he said. A collaborative website and email distribution list allows doctors to post questions to their peers nationwide.

A calling for hospital medicine

Before moving to Denver, Dr. Anderson served as a major in the Air Force Medical Corps and was based at the David Grant US Air Force Medical Center on Travis Air Force Base in California – which is where he did his residency. In the course of a “traditionalist” internal medical training, including 4-month stints on hospital wards in addition to outpatient services, he realized he had a calling for hospital medicine.

In a job at the Providence (R.I.) VA Medical Center, he exclusively practiced outpatient care, but he found that he missed key aspects of inpatient work, such as the intensity of the clinical issues and teaching encounters. “I cold-called the hospital’s chief of medicine and volunteered to start mentoring inpatient residents,” Dr. Anderson said. “That was 17 years ago.”

Another abiding interest derived from Dr. Anderson’s military service is travel medicine. While a physician in the Air Force, he was deployed to Haiti in 1995 and to Nicaragua in 2000, where he treated thousands of patients – both U.S. service personnel and local populations.

“In Haiti, our primary mission was for U.S. troops who were still based there following the 1994 Operation Uphold Democracy intervention, but there were a lot fewer of them, so we mostly kept busy providing care to Haitian nationals,” he said. “That work was eye opening, to say the least,” and led to a professional interest in tropical illnesses. “Since then, I’ve been a visiting professor for the University of Colorado posted to the University of Zimbabwe in Harare in 2012 and 2016.”

What gives Dr. Anderson such joy and enthusiasm for his VA work? “I am a curious lifelong learner. Every day, there are 10 new things I need to learn, whether clinically or operationally in a big hospital system or just the day-to-day realities of leading a group of physicians. I never feel like I’m treading water,” he said. He is also energized by teaching – seeing “the light bulb go on” for the students he is instructing – and by serving as a role model for doctors in training.

“As I contemplate all the simultaneous balls I have in the air, including our recent move into a new hospital building, sometimes I think it is kind of crazy to be doing as much as I do,” he said. “But I also take time away, balancing work versus nonwork.” He spends quality time with his wife of 21 years, 17-year-old daughter, other relatives, and friends, as well as on physical activity, reading books about philosophy, and his hobby of rebuilding motorcycles, which he says offers a kind of meditative calm.

“I also feel a deep sense of service – to patients, colleagues, students, and to the mission of the VA,” Dr. Anderson said. “There is truly something special about caring for the veteran. It’s hard to articulate, but it really keeps us coming back for more. I’ve had vets sing to me, tell jokes, do magic tricks, share their war stories. I’ve had patients open up to me in ways that were both profound and humbling.”

References

1. Young E et al. Impact of altered medication administration time on interdisciplinary bedside rounds on academic medical ward. J Nurs Care Qual. 2017 Jul/Sep;32(3):218-225.