User login

New insulin preparations: A primer for the clinician

The first isolation and successful extraction of insulin in 1921 opened an important chapter in the management of diabetes, especially for patients with profound insulin deficiency. At that time, a 14-year-old patient who was dying from type 1 diabetes received the first insulin injection—a canine pancreatic extract. It was a lifesaving treatment. Within a few months of insulin administration, the patient regained weight and health and went on to live another 13 years before succumbing to pneumonia and chronic complications of hyperglycemia.

While the introduction of regular insulin from animal extracts provided lifesaving therapy for patients with type 1 diabetes, it was the introduction of protaminated insulin in 1946 that provided more extended “basal” coverage to taper some of the large glycemic fluctuations that occurred with the administration of regular insulin two to three times daily. The use of a split-mix approach with twice-daily administration of a combination of regular insulin plus either insulin neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH) or insulin lente provided overall better control with fewer episodes of hypoglycemia or severe hyperglycemia.

Insulin was the first protein to be sequenced (in 1955), and it became the first human protein to be manufactured through human recombinant technology. It was introduced into clinical practice in 1982 as synthetic “human” insulin, with the advantage of being less allergenic than animal insulin preparations. Human insulin eventually replaced all of the animal insulin preparations in the US market.

The pursuit of tight glycemic control as an effective strategy to prevent the chronic and devastating complications of the disease was confirmed in 1993 by publication of the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT), which undeniably established the relationship between normalization of glycemia and prevention of microvascular complications in patients with type 1 diabetes.1 The UK Prospective Diabetes Study, demonstrating a similar relationship in type 2 diabetes, was soon to follow.2 In both trials, the follow-up observation periods further underscored the importance of early glycemic control by showing both sustained reductions in microvascular complications (retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy) and statistically significant decreases in the risk of a cardiovascular event.3,4 Of note, it was the introduction in clinical practice of safer and more user-friendly insulin options that made these gains in glycemic control possible.

With the publication of the DCCT results,1 physiologic insulin replacement became the therapeutic standard in patients with advanced insulin deficiency, demonstrating that lowering hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) and mitigating glycemic variability translated into microvascular risk reduction. The use of longer-acting insulin preparations, such as ultralente insulin, and the delivery of the basal component through continuous subcutaneous (SC) insulin infusion using an insulin pump further facilitated achievement of near-normal glycemia.

Insulin products continue to be refined and new formulations and molecular entities developed (Table 1). The following sections review the current insulin products, their pharmacologic profiles, and their clinical roles in diabetes practice.

INSULIN ANALOGUES

In 1996, the first short-acting insulin analogue (or insulin-receptor ligand), lispro, was brought to market. In lispro, the penultimate lysine and proline amino acids on the end of the C-terminal of the beta-chain of human insulin are reversed, facilitating faster absorption of the insulin through the greater availability of insulin monomers following SC depot injection.

The three short-acting insulin analogues—lispro, aspart, and glulisine—have similar pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties, with earlier onset and peak of biologic action, and shorter duration of activity than regular insulin. Potentially, these characteristics should translate into greater administration flexibility (patients can inject anywhere from 20 minutes before to 20 minutes after the start of the meal), better control of postprandial hyperglycemia, and less risk of late prandial hypoglycemia (3 to 6 hours after the meal). In a meta-analysis comparing short-acting analogues with human regular insulin, the most relevant difference reported was a lower risk of severe hypoglycemia with the analogue preparations5 (Table 2). There might be an advantage with regards to bedtime and overnight hypoglycemia when using short-acting analogues, especially if a protaminated insulin is used for overnight basal coverage.6

While short-acting analogues have been approved for administration following a meal, postprandial control is clearly better if these preparations are injected prior to the meal, ideally 15 to 20 minutes before, to allow time to enter the circulation.7 Additionally, the pharmacokinetics and biologic activity of short-acting insulin analogues appear to be very different when administered to obese, insulin-resistant patients with type 2 diabetes, in whom the onset of action is delayed and the biologic activity considerably reduced.8

INHALED INSULIN

A recent entry into the short-acting insulin marketplace—Technosphere oral-inhaled insulin (Afrezza)—was US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved in 2014. Inhaled insulin has low bioavailability but is absorbed much more rapidly into the circulation than the current short-acting insulin analogues and has a shorter duration of biologic activity. However, the pharmacodynamics of inhaled insulin, when compared with insulin lispro, show only a slightly faster onset of action and a lower peak of biologic activity9 (Figure 1). Studies comparing the efficacy and safety of inhaled insulin with short-acting analogues or premix insulin have demonstrated equivalent or less effective blood glucose-lowering effect and equivalent or lower risk of hypoglycemia.10 For example, in trials of aspart insulin in patients with type 1 diabetes, inhaled insulin had statistically less reduction in HbA1c; in only one of the two trials did it show less hypoglycemia risk. Another trial comparing inhaled insulin plus basal insulin to premix aspart 70/30 showed equivalent HbA1c reductions, but less hypoglycemia with inhaled insulin.10

Inhaled insulin should not be used by smokers, patients with chronic lung disease (such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), and those with acute episodes of bronchospasm. In patients who have a history of or are at risk for lung cancer, the benefits of using inhaled insulin need to be carefully weighed against the potential risks, especially given the increase in lung cancer events in smokers that was observed with the prior inhaled-insulin preparation Exubera.11 Baseline and follow-up spirometry needs to be implemented for those using inhaled insulin to exclude clinically significant changes in forced expiratory volume in 1 second. Dosing of inhaled technosphere insulin is done via single-use cartridges of 4-, 8-, or 12-unit composition, making titration of smaller insulin increments more of a challenge. Patient reported outcomes in trials of inhaled insulin report variable effect (equivalent or favorable) on diabetes worries, health-related quality of life, or perceptions of insulin therapy, satisfaction, or preference.12,13

CONCENTRATED INSULIN

Concentrated insulin preparations have been available in clinical practice for many years and have been implemented with variable success. For example, Humulin R U-500 is a concentrated human regular insulin product (five times more concentrated than U-100) that has been used in patients requiring consistently high daily doses of insulin (usually > 200 U/day). Nonrandomized studies have shown significant improvement in glycemic control comparing pre- and post-intervention periods in patients switched from U-100 prandial insulin preparations to U-500 regular insulin.14 Given the slight differences in pharmacodynamic profiles between regular U-100 and U-500 insulin preparations,15 a randomized controlled trial comparing a U-500 insulin strategy with other currently available alternatives in very insulin-resistant patients will be needed to draw objective conclusions regarding the efficacy and safety of this concentrated insulin preparation.

For patients and providers who opt for a trial of regular U-500 insulin, a number of issues need to be considered to mitigate risks and optimize benefits of using this concentrated insulin. First and foremost is the frequent confusion in the communication between provider, pharmacy, and patient regarding the correct insulin dose to be administered. Because regular U-500 insulin is administered with U-100 insulin syringes, a 1-unit measure of U-500 corresponds to a 5-unit delivery of regular insulin.

To minimize confusion, regular U-500 prescriptions should be made out in volume rather than units, but this difference must be clearly explained to patients to avoid overdosing. For example, 0.01 mL of U-500 equates to 5 units of insulin, but it corresponds to the 1-unit mark of the standard U-100 insulin syringe. Newer concentrated insulin preparations on the market have avoided this confusion by providing measured doses in an insulin pen delivery system. For example, insulin lispro U-200 (Humalog U-200), a twofold concentration of insulin lispro U-100 with similar pharmacodynamics, is only available in a prefilled pen. Using insulin pen technology, a 1-unit dose of insulin actually corresponds to 1 unit of insulin, thereby removing any possible confusion regarding the prescription or administration of the correct insulin dose. Insulin lispro U-200 offers the convenience of holding more insulin per pen; it contains 600 units of insulin per pen compared with 300 units in the lispro U-100 pen.

BASAL INSULIN

Currently available basal insulin preparations include insulin NPH (Humulin N, Novolin N), insulin glargine U-100 (Lantus), insulin detemir (Levemir), and the 2015 FDA-approved formulations insulin glargine U-300 (Toujeo) and insulin degludec (Tresiba). The basal analogues introduced in the year 2000 with glargine U-100 were meant to fill the void left when the long-acting insulin ultralente animal preparations were pulled from the market in the early 1990s. The basal analogues have a longer duration of action than insulin NPH and, more importantly, have more stable and consistent biologic activity over a 24-hour period, resulting in more predictable glycemic levels and a lower risk of hypoglycemia.16–18

Three insulin analogue preparations—glargine U-300 and degludec (both FDA-approved) and pegylated lispro (currently in phase 3 trials)—have demonstrated longer protraction of biologic activity than glargine U-100, considered the current technical standard for basal insulin replacement. These three “second-generation” basal insulin analogues have pharmacodynamic activity that extends beyond 24 hours. When compared with glargine U-100 insulin, they exhibited fewer pronounced peaks of biologic activity and less pharmacokinetic variability, with similar glycemic control (as determined by HbA1c) but with an even lower risk of hypoglycemia, especially nocturnal hypoglycemia.19–21

The extended biologic activity raises concern for potential insulin stacking and subsequent hypoglycemia, which should be easily mitigated by restricting basal insulin dose adjustments to no more frequently than every 3 to 4 days, which corresponds to the time needed for these preparations to reach 90% or more of their effective steady state22 (Figure 2). Indeed, most of the clinical trials comparing these basal insulin preparations with glargine U-100 show a lower risk of hypoglycemia when basal dose adjustments are carried out weekly and no more frequently than every 3 days.23

Insulin glargine U-300 is essentially a threefold concentrated preparation of insulin glargine U-100 that results in a two-thirds volume reduction and a one-half reduction in depot surface following SC administration. The reduced depot surface area is presumed to account for much of the protracted absorption of glargine U-300 from the SC tissues. The metabolism and elimination of glargine U-300 is similar to that of the original compound, with formation of two active metabolites: M1 (the principal active moiety) and M2. Biologic steady state is achieved after 4 to 5 days of once-daily injections.24

When compared with glargine U-100 in patients with type 1 diabetes, insulin glargine U-300 at doses of 0.4 U/kg produced more stable insulin concentrations and glucose-lowering effect with a longer duration of action at steady state, as reflected by tight glucose control being maintained for about 5 hours longer (median of 30 hours).25 A meta-analysis of the EDITION I to III clinical trials in patients with type 2 diabetes at various stages of treatment found similar glucose-lowering effects for glargine U-300 compared with glargine U-100 but a lower rate of nonsevere hypoglycemia.20 Of note was the need for 10% to 15% more units of insulin for glargine U-300 in these clinical trials. Insulin glargine U-300 is available only in a 1.5 mL disposable prefilled pen, which contains 450 units of insulin. Because the dose counter on the pen window corresponds to the actual number of units of insulin to be injected, no dose recalculation is required by the patient or provider.

Insulin degludec is another ultra-long-acting basal insulin analogue with a half-life at steady state of greater than 25 hours.26 In comparison, the half-life of insulin glargine U-100 in that same study was reported as 12.1 hours. Further, insulin degludec exhibited flatter and more stable biologic activity, more evenly distributed over the course of a 24-hour period than insulin glargine U-100. The protraction mechanism is based on the formation of long strings of multihexamers, facilitated by a 16-carbon fatty acid chain linked via a glutamic acid spacer to the terminal end of the B-chain of the insulin molecule.27 In studies of patients with type 2 diabetes at various stages of treatment, insulin degludec also demonstrated lower risk of nonsevere hypoglycemia for an equivalent level of HbA1c control achieved.19

The flexibility of administration time for an ultra-long-acting insulin preparation such as degludec was tested by asking patients to alternate the injection of degludec between morning and evening, in effect creating administration intervals of up to 8 to 40 hours.28 Even within such drastic parameters, the efficacy and safety of insulin degludec were maintained when compared with insulin glargine U-100 injected at the same time of the day every day.

Because of an increase in major adverse cardiovascular events in phase 3 trials, degludec is undergoing a cardiovascular safety trial in patients with type 2 diabetes. The DEVOTE trial, which started in October 2013, will include 7,500 patients and will continue for up to 5 years. Interim results have recently been submitted to the FDA resulting in conditional approval of degludec in the US (Clinical Trials.gov Registration: NCT01959529). Degludec is available in disposable pen or cartridge format in U-100 and U-200 formulations.

COST

These new insulin preparations have introduced clinical options that have efficacy similar to that of available insulin products but, for the most part, have advantages of safety (less risk of nonsevere hypoglycemia) and patient convenience (flexibility in timing of insulin dose administration). While the latter is presumed to improve patient adherence, this has yet to be confirmed. Compared with synthetic human insulin preparations (regular insulin, NPH, and premix 70/30 insulin), which can be obtained in certain pharmacies at a discount (usually around 3 cents per unit of insulin), the currently available insulin analogues are considerably more expensive (around 16 to 27 cents per unit of insulin).

Within the guidelines for initiation and intensification of the insulin regimen using basal insulin formulations, the clinician will need to balance the potential benefits and current costs for the treatment of the individual patient. Clearly, as patients with diabetes are brought closer to their glycemic goals with insulin options, they stand to increasingly benefit from formulations that provide more consistent glycemic response and less risk of hypoglycemia. For those who are unable to afford the higher costs, especially if their glycemic control is far from the desired target, the use of synthetic human insulin formulations may be entirely appropriate. In this era of individualized care and prescriptions, clinicians have a range of insulin treatment options that will facilitate patients reaching appropriate goals.

- The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 1993; 329:977–986.

- UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lancet 1998; 352:837–853.

- Holman RR, Paul SK, Bethel MA, Matthews DR, Neil HA. 10-year follow-up of intensive glucose control in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2008; 359:1577–1589.

- Nathan DM, Cleary PA, Backlund JY, et al; Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (DCCT/EDIC) Study Research Group. Intensive diabetes treatment and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2005; 353:2643–2653.

- Siebenhofer A, Plank J, Berghold A, et al. Short acting insulin analogues versus regular human insulin in patients with diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; 19:CD003287.

- Gale EA. A randomized, controlled trial comparing insulin lispro with human soluble insulin in patients with type 1 diabetes on intensified insulin therapy. The UK Trial Group. Diabet Med 2000; 17:209–214.

- Cobry E, McFann K, Messer L, et al. Timing of meal insulin boluses to achieve optimal postprandial glycemic control in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther 2010; 12:173–177.

- Gagnon-Auger M, du Souich P, Baillargeon JP, et al. Dose-dependent delay of the hypoglycemic effect of short-acting insulin analogs in obese subjects with type 2 diabetes: a pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study. Diabetes Care 2010; 33:2502–2507.

- Afrezza (insulin human) inhalation powder [package insert]. Danbury, CT: MannKind Corp; 2014.

- Kugler AJ, Fabbio KL, Pham DQ, Nadeau DA. Inhaled technosphere insulin: a novel delivery system and formulation for the treatment of types 1 and 2 diabetes mellitus. Pharmacotherapy 2015; 35:298–314.

- Kling J. Inhaled insulin’s last gasp? Nat Biotechnol 2008; 26:479–480.

- Peyrot M, Rubin RR. Patient-reported outcomes in adults with type 2 diabetes using mealtime inhaled technosphere insulin and basal insulin versus premixed insulin. Diabetes Technol Ther 2011; 13:1201–1206.

- Testa MA, Simonson DC. Satisfaction and quality of life with premeal inhaled versus injected insulin in adolescents and adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2007; 30:1399–1405.

- Reutrakul S, Wroblewski K, Brown RL. Clinical use of U-500 regular insulin: review and meta-analysis. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2012; 6:412–420.

- de la Peña A, Riddle M, Morrow LA, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of high-dose human regular U-500 insulin versus human regular U-100 insulin in healthy obese subjects. Diabetes Care 2011; 34:2496–2501.

- Riddle MC, Rosenstock J, Gerich J; Insulin Glargine 4002 Study Investigators. The treat-to-target trial: randomized addition of glargine or human NPH insulin to oral therapy of type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 2003; 26:3080–3086.

- Heise T, Nosek L, Rønn BB, et al. Lower within-subject variability of insulin detemir in comparison to NPH insulin and insulin glargine in people with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 2004; 53:1614–1620.

- Philis-Tsimikas A, Charpentier G, Clauson P, Ravn GM, Roberts VL, Thorsteinsson B. Comparison of once-daily insulin detemir with NPH insulin added to a regimen of oral antidiabetic drugs in poorly controlled type 2 diabetes. Clin Ther 2006; 28:1569–1581.

- Einhorn D, Handelsman Y, Bode BW, Endahl LA, Mersebach H, King AB. Patients achieving good glycemic control (HbA1c <7%) experience a lower rate of hypoglycemia with insulin degludec than with insulin glargine: a meta-analysis of phase 3a trials. Endocr Pract 2015; 21:917–926.

- Ritzel R, Roussel R, Bolli GB, et al. Patient-level meta-analysis of the EDITION 1, 2 and 3 studies: glycaemic control and hypoglycaemia with new insulin glargine 300 U/ml versus glargine 100 U/ml in people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab 2015; 17:859–867.

- Bergenstal RM, Rosenstock J, Arakaki RF, et al. A randomized, controlled study of once-daily LY2605541, a novel long-acting basal insulin, versus insulin glargine in basal insulin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2012; 35:2140–2147.

- Heise T, Meneghini LF. Insulin stacking versus therapeutic accumulation: understanding the differences. Endocr Pract 2014; 20:75–83.

- Bolli GB, Riddle MC, Bergenstal RM, et al; on behalf of the EDITION 3 study investigators. New insulin glargine 300 U/ml compared with glargine 100 U/ml in insulin-naïve people with type 2 diabetes on oral glucose-lowering drugs: a randomized controlled trial (EDITION 3). Diabetes Obes Metab 2015; 17:386–394.

- Steinstraesser A, Schmidt R, Bergmann K, Dahmen R, Becker RH. Investigational new insulin glargine 300 U/ml has the same metabolism as insulin glargine 100 U/ml. Diabetes Obes Metab 2014; 16:873–876.

- Becker RH, Dahmen R, Bergmann K, Lehmann A, Jax T, Heise T. New insulin glargine 300 units⋅mL−1 provides a more even activity profile and prolonged glycemic control at steady state compared with insulin glargine 100 units·mL−1. Diabetes Care 2015; 38:637–643.

- Heise T, Hövelmann U, Nosek L, Hermanski L, Bøttcher SG, Haahr H. Comparison of the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles of insulin degludec and insulin glargine. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 2015; 11:1193–1201.

- Jonassen I, Havelund S, Hoeg-Jensen T, Steensgaard DB, Wahlund PO, Ribel U. Design of the novel protraction mechanism of insulin degludec, an ultra-long-acting basal insulin. Pharm Res 2012; 29:2104–2114.

- Meneghini L, Atkin SL, Gough SC, et al; NN1250-3668 (BEGIN FLEX) Trial Investigators. The efficacy and safety of insulin degludec given in variable once-daily dosing intervals compared with insulin glargine and insulin degludec dosed at the same time daily: a 26-week, randomized, open-label, parallel-group, treat-to-target trial in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2013; 36:858–864.

The first isolation and successful extraction of insulin in 1921 opened an important chapter in the management of diabetes, especially for patients with profound insulin deficiency. At that time, a 14-year-old patient who was dying from type 1 diabetes received the first insulin injection—a canine pancreatic extract. It was a lifesaving treatment. Within a few months of insulin administration, the patient regained weight and health and went on to live another 13 years before succumbing to pneumonia and chronic complications of hyperglycemia.

While the introduction of regular insulin from animal extracts provided lifesaving therapy for patients with type 1 diabetes, it was the introduction of protaminated insulin in 1946 that provided more extended “basal” coverage to taper some of the large glycemic fluctuations that occurred with the administration of regular insulin two to three times daily. The use of a split-mix approach with twice-daily administration of a combination of regular insulin plus either insulin neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH) or insulin lente provided overall better control with fewer episodes of hypoglycemia or severe hyperglycemia.

Insulin was the first protein to be sequenced (in 1955), and it became the first human protein to be manufactured through human recombinant technology. It was introduced into clinical practice in 1982 as synthetic “human” insulin, with the advantage of being less allergenic than animal insulin preparations. Human insulin eventually replaced all of the animal insulin preparations in the US market.

The pursuit of tight glycemic control as an effective strategy to prevent the chronic and devastating complications of the disease was confirmed in 1993 by publication of the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT), which undeniably established the relationship between normalization of glycemia and prevention of microvascular complications in patients with type 1 diabetes.1 The UK Prospective Diabetes Study, demonstrating a similar relationship in type 2 diabetes, was soon to follow.2 In both trials, the follow-up observation periods further underscored the importance of early glycemic control by showing both sustained reductions in microvascular complications (retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy) and statistically significant decreases in the risk of a cardiovascular event.3,4 Of note, it was the introduction in clinical practice of safer and more user-friendly insulin options that made these gains in glycemic control possible.

With the publication of the DCCT results,1 physiologic insulin replacement became the therapeutic standard in patients with advanced insulin deficiency, demonstrating that lowering hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) and mitigating glycemic variability translated into microvascular risk reduction. The use of longer-acting insulin preparations, such as ultralente insulin, and the delivery of the basal component through continuous subcutaneous (SC) insulin infusion using an insulin pump further facilitated achievement of near-normal glycemia.

Insulin products continue to be refined and new formulations and molecular entities developed (Table 1). The following sections review the current insulin products, their pharmacologic profiles, and their clinical roles in diabetes practice.

INSULIN ANALOGUES

In 1996, the first short-acting insulin analogue (or insulin-receptor ligand), lispro, was brought to market. In lispro, the penultimate lysine and proline amino acids on the end of the C-terminal of the beta-chain of human insulin are reversed, facilitating faster absorption of the insulin through the greater availability of insulin monomers following SC depot injection.

The three short-acting insulin analogues—lispro, aspart, and glulisine—have similar pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties, with earlier onset and peak of biologic action, and shorter duration of activity than regular insulin. Potentially, these characteristics should translate into greater administration flexibility (patients can inject anywhere from 20 minutes before to 20 minutes after the start of the meal), better control of postprandial hyperglycemia, and less risk of late prandial hypoglycemia (3 to 6 hours after the meal). In a meta-analysis comparing short-acting analogues with human regular insulin, the most relevant difference reported was a lower risk of severe hypoglycemia with the analogue preparations5 (Table 2). There might be an advantage with regards to bedtime and overnight hypoglycemia when using short-acting analogues, especially if a protaminated insulin is used for overnight basal coverage.6

While short-acting analogues have been approved for administration following a meal, postprandial control is clearly better if these preparations are injected prior to the meal, ideally 15 to 20 minutes before, to allow time to enter the circulation.7 Additionally, the pharmacokinetics and biologic activity of short-acting insulin analogues appear to be very different when administered to obese, insulin-resistant patients with type 2 diabetes, in whom the onset of action is delayed and the biologic activity considerably reduced.8

INHALED INSULIN

A recent entry into the short-acting insulin marketplace—Technosphere oral-inhaled insulin (Afrezza)—was US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved in 2014. Inhaled insulin has low bioavailability but is absorbed much more rapidly into the circulation than the current short-acting insulin analogues and has a shorter duration of biologic activity. However, the pharmacodynamics of inhaled insulin, when compared with insulin lispro, show only a slightly faster onset of action and a lower peak of biologic activity9 (Figure 1). Studies comparing the efficacy and safety of inhaled insulin with short-acting analogues or premix insulin have demonstrated equivalent or less effective blood glucose-lowering effect and equivalent or lower risk of hypoglycemia.10 For example, in trials of aspart insulin in patients with type 1 diabetes, inhaled insulin had statistically less reduction in HbA1c; in only one of the two trials did it show less hypoglycemia risk. Another trial comparing inhaled insulin plus basal insulin to premix aspart 70/30 showed equivalent HbA1c reductions, but less hypoglycemia with inhaled insulin.10

Inhaled insulin should not be used by smokers, patients with chronic lung disease (such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), and those with acute episodes of bronchospasm. In patients who have a history of or are at risk for lung cancer, the benefits of using inhaled insulin need to be carefully weighed against the potential risks, especially given the increase in lung cancer events in smokers that was observed with the prior inhaled-insulin preparation Exubera.11 Baseline and follow-up spirometry needs to be implemented for those using inhaled insulin to exclude clinically significant changes in forced expiratory volume in 1 second. Dosing of inhaled technosphere insulin is done via single-use cartridges of 4-, 8-, or 12-unit composition, making titration of smaller insulin increments more of a challenge. Patient reported outcomes in trials of inhaled insulin report variable effect (equivalent or favorable) on diabetes worries, health-related quality of life, or perceptions of insulin therapy, satisfaction, or preference.12,13

CONCENTRATED INSULIN

Concentrated insulin preparations have been available in clinical practice for many years and have been implemented with variable success. For example, Humulin R U-500 is a concentrated human regular insulin product (five times more concentrated than U-100) that has been used in patients requiring consistently high daily doses of insulin (usually > 200 U/day). Nonrandomized studies have shown significant improvement in glycemic control comparing pre- and post-intervention periods in patients switched from U-100 prandial insulin preparations to U-500 regular insulin.14 Given the slight differences in pharmacodynamic profiles between regular U-100 and U-500 insulin preparations,15 a randomized controlled trial comparing a U-500 insulin strategy with other currently available alternatives in very insulin-resistant patients will be needed to draw objective conclusions regarding the efficacy and safety of this concentrated insulin preparation.

For patients and providers who opt for a trial of regular U-500 insulin, a number of issues need to be considered to mitigate risks and optimize benefits of using this concentrated insulin. First and foremost is the frequent confusion in the communication between provider, pharmacy, and patient regarding the correct insulin dose to be administered. Because regular U-500 insulin is administered with U-100 insulin syringes, a 1-unit measure of U-500 corresponds to a 5-unit delivery of regular insulin.

To minimize confusion, regular U-500 prescriptions should be made out in volume rather than units, but this difference must be clearly explained to patients to avoid overdosing. For example, 0.01 mL of U-500 equates to 5 units of insulin, but it corresponds to the 1-unit mark of the standard U-100 insulin syringe. Newer concentrated insulin preparations on the market have avoided this confusion by providing measured doses in an insulin pen delivery system. For example, insulin lispro U-200 (Humalog U-200), a twofold concentration of insulin lispro U-100 with similar pharmacodynamics, is only available in a prefilled pen. Using insulin pen technology, a 1-unit dose of insulin actually corresponds to 1 unit of insulin, thereby removing any possible confusion regarding the prescription or administration of the correct insulin dose. Insulin lispro U-200 offers the convenience of holding more insulin per pen; it contains 600 units of insulin per pen compared with 300 units in the lispro U-100 pen.

BASAL INSULIN

Currently available basal insulin preparations include insulin NPH (Humulin N, Novolin N), insulin glargine U-100 (Lantus), insulin detemir (Levemir), and the 2015 FDA-approved formulations insulin glargine U-300 (Toujeo) and insulin degludec (Tresiba). The basal analogues introduced in the year 2000 with glargine U-100 were meant to fill the void left when the long-acting insulin ultralente animal preparations were pulled from the market in the early 1990s. The basal analogues have a longer duration of action than insulin NPH and, more importantly, have more stable and consistent biologic activity over a 24-hour period, resulting in more predictable glycemic levels and a lower risk of hypoglycemia.16–18

Three insulin analogue preparations—glargine U-300 and degludec (both FDA-approved) and pegylated lispro (currently in phase 3 trials)—have demonstrated longer protraction of biologic activity than glargine U-100, considered the current technical standard for basal insulin replacement. These three “second-generation” basal insulin analogues have pharmacodynamic activity that extends beyond 24 hours. When compared with glargine U-100 insulin, they exhibited fewer pronounced peaks of biologic activity and less pharmacokinetic variability, with similar glycemic control (as determined by HbA1c) but with an even lower risk of hypoglycemia, especially nocturnal hypoglycemia.19–21

The extended biologic activity raises concern for potential insulin stacking and subsequent hypoglycemia, which should be easily mitigated by restricting basal insulin dose adjustments to no more frequently than every 3 to 4 days, which corresponds to the time needed for these preparations to reach 90% or more of their effective steady state22 (Figure 2). Indeed, most of the clinical trials comparing these basal insulin preparations with glargine U-100 show a lower risk of hypoglycemia when basal dose adjustments are carried out weekly and no more frequently than every 3 days.23

Insulin glargine U-300 is essentially a threefold concentrated preparation of insulin glargine U-100 that results in a two-thirds volume reduction and a one-half reduction in depot surface following SC administration. The reduced depot surface area is presumed to account for much of the protracted absorption of glargine U-300 from the SC tissues. The metabolism and elimination of glargine U-300 is similar to that of the original compound, with formation of two active metabolites: M1 (the principal active moiety) and M2. Biologic steady state is achieved after 4 to 5 days of once-daily injections.24

When compared with glargine U-100 in patients with type 1 diabetes, insulin glargine U-300 at doses of 0.4 U/kg produced more stable insulin concentrations and glucose-lowering effect with a longer duration of action at steady state, as reflected by tight glucose control being maintained for about 5 hours longer (median of 30 hours).25 A meta-analysis of the EDITION I to III clinical trials in patients with type 2 diabetes at various stages of treatment found similar glucose-lowering effects for glargine U-300 compared with glargine U-100 but a lower rate of nonsevere hypoglycemia.20 Of note was the need for 10% to 15% more units of insulin for glargine U-300 in these clinical trials. Insulin glargine U-300 is available only in a 1.5 mL disposable prefilled pen, which contains 450 units of insulin. Because the dose counter on the pen window corresponds to the actual number of units of insulin to be injected, no dose recalculation is required by the patient or provider.

Insulin degludec is another ultra-long-acting basal insulin analogue with a half-life at steady state of greater than 25 hours.26 In comparison, the half-life of insulin glargine U-100 in that same study was reported as 12.1 hours. Further, insulin degludec exhibited flatter and more stable biologic activity, more evenly distributed over the course of a 24-hour period than insulin glargine U-100. The protraction mechanism is based on the formation of long strings of multihexamers, facilitated by a 16-carbon fatty acid chain linked via a glutamic acid spacer to the terminal end of the B-chain of the insulin molecule.27 In studies of patients with type 2 diabetes at various stages of treatment, insulin degludec also demonstrated lower risk of nonsevere hypoglycemia for an equivalent level of HbA1c control achieved.19

The flexibility of administration time for an ultra-long-acting insulin preparation such as degludec was tested by asking patients to alternate the injection of degludec between morning and evening, in effect creating administration intervals of up to 8 to 40 hours.28 Even within such drastic parameters, the efficacy and safety of insulin degludec were maintained when compared with insulin glargine U-100 injected at the same time of the day every day.

Because of an increase in major adverse cardiovascular events in phase 3 trials, degludec is undergoing a cardiovascular safety trial in patients with type 2 diabetes. The DEVOTE trial, which started in October 2013, will include 7,500 patients and will continue for up to 5 years. Interim results have recently been submitted to the FDA resulting in conditional approval of degludec in the US (Clinical Trials.gov Registration: NCT01959529). Degludec is available in disposable pen or cartridge format in U-100 and U-200 formulations.

COST

These new insulin preparations have introduced clinical options that have efficacy similar to that of available insulin products but, for the most part, have advantages of safety (less risk of nonsevere hypoglycemia) and patient convenience (flexibility in timing of insulin dose administration). While the latter is presumed to improve patient adherence, this has yet to be confirmed. Compared with synthetic human insulin preparations (regular insulin, NPH, and premix 70/30 insulin), which can be obtained in certain pharmacies at a discount (usually around 3 cents per unit of insulin), the currently available insulin analogues are considerably more expensive (around 16 to 27 cents per unit of insulin).

Within the guidelines for initiation and intensification of the insulin regimen using basal insulin formulations, the clinician will need to balance the potential benefits and current costs for the treatment of the individual patient. Clearly, as patients with diabetes are brought closer to their glycemic goals with insulin options, they stand to increasingly benefit from formulations that provide more consistent glycemic response and less risk of hypoglycemia. For those who are unable to afford the higher costs, especially if their glycemic control is far from the desired target, the use of synthetic human insulin formulations may be entirely appropriate. In this era of individualized care and prescriptions, clinicians have a range of insulin treatment options that will facilitate patients reaching appropriate goals.

The first isolation and successful extraction of insulin in 1921 opened an important chapter in the management of diabetes, especially for patients with profound insulin deficiency. At that time, a 14-year-old patient who was dying from type 1 diabetes received the first insulin injection—a canine pancreatic extract. It was a lifesaving treatment. Within a few months of insulin administration, the patient regained weight and health and went on to live another 13 years before succumbing to pneumonia and chronic complications of hyperglycemia.

While the introduction of regular insulin from animal extracts provided lifesaving therapy for patients with type 1 diabetes, it was the introduction of protaminated insulin in 1946 that provided more extended “basal” coverage to taper some of the large glycemic fluctuations that occurred with the administration of regular insulin two to three times daily. The use of a split-mix approach with twice-daily administration of a combination of regular insulin plus either insulin neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH) or insulin lente provided overall better control with fewer episodes of hypoglycemia or severe hyperglycemia.

Insulin was the first protein to be sequenced (in 1955), and it became the first human protein to be manufactured through human recombinant technology. It was introduced into clinical practice in 1982 as synthetic “human” insulin, with the advantage of being less allergenic than animal insulin preparations. Human insulin eventually replaced all of the animal insulin preparations in the US market.

The pursuit of tight glycemic control as an effective strategy to prevent the chronic and devastating complications of the disease was confirmed in 1993 by publication of the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT), which undeniably established the relationship between normalization of glycemia and prevention of microvascular complications in patients with type 1 diabetes.1 The UK Prospective Diabetes Study, demonstrating a similar relationship in type 2 diabetes, was soon to follow.2 In both trials, the follow-up observation periods further underscored the importance of early glycemic control by showing both sustained reductions in microvascular complications (retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy) and statistically significant decreases in the risk of a cardiovascular event.3,4 Of note, it was the introduction in clinical practice of safer and more user-friendly insulin options that made these gains in glycemic control possible.

With the publication of the DCCT results,1 physiologic insulin replacement became the therapeutic standard in patients with advanced insulin deficiency, demonstrating that lowering hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) and mitigating glycemic variability translated into microvascular risk reduction. The use of longer-acting insulin preparations, such as ultralente insulin, and the delivery of the basal component through continuous subcutaneous (SC) insulin infusion using an insulin pump further facilitated achievement of near-normal glycemia.

Insulin products continue to be refined and new formulations and molecular entities developed (Table 1). The following sections review the current insulin products, their pharmacologic profiles, and their clinical roles in diabetes practice.

INSULIN ANALOGUES

In 1996, the first short-acting insulin analogue (or insulin-receptor ligand), lispro, was brought to market. In lispro, the penultimate lysine and proline amino acids on the end of the C-terminal of the beta-chain of human insulin are reversed, facilitating faster absorption of the insulin through the greater availability of insulin monomers following SC depot injection.

The three short-acting insulin analogues—lispro, aspart, and glulisine—have similar pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties, with earlier onset and peak of biologic action, and shorter duration of activity than regular insulin. Potentially, these characteristics should translate into greater administration flexibility (patients can inject anywhere from 20 minutes before to 20 minutes after the start of the meal), better control of postprandial hyperglycemia, and less risk of late prandial hypoglycemia (3 to 6 hours after the meal). In a meta-analysis comparing short-acting analogues with human regular insulin, the most relevant difference reported was a lower risk of severe hypoglycemia with the analogue preparations5 (Table 2). There might be an advantage with regards to bedtime and overnight hypoglycemia when using short-acting analogues, especially if a protaminated insulin is used for overnight basal coverage.6

While short-acting analogues have been approved for administration following a meal, postprandial control is clearly better if these preparations are injected prior to the meal, ideally 15 to 20 minutes before, to allow time to enter the circulation.7 Additionally, the pharmacokinetics and biologic activity of short-acting insulin analogues appear to be very different when administered to obese, insulin-resistant patients with type 2 diabetes, in whom the onset of action is delayed and the biologic activity considerably reduced.8

INHALED INSULIN

A recent entry into the short-acting insulin marketplace—Technosphere oral-inhaled insulin (Afrezza)—was US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved in 2014. Inhaled insulin has low bioavailability but is absorbed much more rapidly into the circulation than the current short-acting insulin analogues and has a shorter duration of biologic activity. However, the pharmacodynamics of inhaled insulin, when compared with insulin lispro, show only a slightly faster onset of action and a lower peak of biologic activity9 (Figure 1). Studies comparing the efficacy and safety of inhaled insulin with short-acting analogues or premix insulin have demonstrated equivalent or less effective blood glucose-lowering effect and equivalent or lower risk of hypoglycemia.10 For example, in trials of aspart insulin in patients with type 1 diabetes, inhaled insulin had statistically less reduction in HbA1c; in only one of the two trials did it show less hypoglycemia risk. Another trial comparing inhaled insulin plus basal insulin to premix aspart 70/30 showed equivalent HbA1c reductions, but less hypoglycemia with inhaled insulin.10

Inhaled insulin should not be used by smokers, patients with chronic lung disease (such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), and those with acute episodes of bronchospasm. In patients who have a history of or are at risk for lung cancer, the benefits of using inhaled insulin need to be carefully weighed against the potential risks, especially given the increase in lung cancer events in smokers that was observed with the prior inhaled-insulin preparation Exubera.11 Baseline and follow-up spirometry needs to be implemented for those using inhaled insulin to exclude clinically significant changes in forced expiratory volume in 1 second. Dosing of inhaled technosphere insulin is done via single-use cartridges of 4-, 8-, or 12-unit composition, making titration of smaller insulin increments more of a challenge. Patient reported outcomes in trials of inhaled insulin report variable effect (equivalent or favorable) on diabetes worries, health-related quality of life, or perceptions of insulin therapy, satisfaction, or preference.12,13

CONCENTRATED INSULIN

Concentrated insulin preparations have been available in clinical practice for many years and have been implemented with variable success. For example, Humulin R U-500 is a concentrated human regular insulin product (five times more concentrated than U-100) that has been used in patients requiring consistently high daily doses of insulin (usually > 200 U/day). Nonrandomized studies have shown significant improvement in glycemic control comparing pre- and post-intervention periods in patients switched from U-100 prandial insulin preparations to U-500 regular insulin.14 Given the slight differences in pharmacodynamic profiles between regular U-100 and U-500 insulin preparations,15 a randomized controlled trial comparing a U-500 insulin strategy with other currently available alternatives in very insulin-resistant patients will be needed to draw objective conclusions regarding the efficacy and safety of this concentrated insulin preparation.

For patients and providers who opt for a trial of regular U-500 insulin, a number of issues need to be considered to mitigate risks and optimize benefits of using this concentrated insulin. First and foremost is the frequent confusion in the communication between provider, pharmacy, and patient regarding the correct insulin dose to be administered. Because regular U-500 insulin is administered with U-100 insulin syringes, a 1-unit measure of U-500 corresponds to a 5-unit delivery of regular insulin.

To minimize confusion, regular U-500 prescriptions should be made out in volume rather than units, but this difference must be clearly explained to patients to avoid overdosing. For example, 0.01 mL of U-500 equates to 5 units of insulin, but it corresponds to the 1-unit mark of the standard U-100 insulin syringe. Newer concentrated insulin preparations on the market have avoided this confusion by providing measured doses in an insulin pen delivery system. For example, insulin lispro U-200 (Humalog U-200), a twofold concentration of insulin lispro U-100 with similar pharmacodynamics, is only available in a prefilled pen. Using insulin pen technology, a 1-unit dose of insulin actually corresponds to 1 unit of insulin, thereby removing any possible confusion regarding the prescription or administration of the correct insulin dose. Insulin lispro U-200 offers the convenience of holding more insulin per pen; it contains 600 units of insulin per pen compared with 300 units in the lispro U-100 pen.

BASAL INSULIN

Currently available basal insulin preparations include insulin NPH (Humulin N, Novolin N), insulin glargine U-100 (Lantus), insulin detemir (Levemir), and the 2015 FDA-approved formulations insulin glargine U-300 (Toujeo) and insulin degludec (Tresiba). The basal analogues introduced in the year 2000 with glargine U-100 were meant to fill the void left when the long-acting insulin ultralente animal preparations were pulled from the market in the early 1990s. The basal analogues have a longer duration of action than insulin NPH and, more importantly, have more stable and consistent biologic activity over a 24-hour period, resulting in more predictable glycemic levels and a lower risk of hypoglycemia.16–18

Three insulin analogue preparations—glargine U-300 and degludec (both FDA-approved) and pegylated lispro (currently in phase 3 trials)—have demonstrated longer protraction of biologic activity than glargine U-100, considered the current technical standard for basal insulin replacement. These three “second-generation” basal insulin analogues have pharmacodynamic activity that extends beyond 24 hours. When compared with glargine U-100 insulin, they exhibited fewer pronounced peaks of biologic activity and less pharmacokinetic variability, with similar glycemic control (as determined by HbA1c) but with an even lower risk of hypoglycemia, especially nocturnal hypoglycemia.19–21

The extended biologic activity raises concern for potential insulin stacking and subsequent hypoglycemia, which should be easily mitigated by restricting basal insulin dose adjustments to no more frequently than every 3 to 4 days, which corresponds to the time needed for these preparations to reach 90% or more of their effective steady state22 (Figure 2). Indeed, most of the clinical trials comparing these basal insulin preparations with glargine U-100 show a lower risk of hypoglycemia when basal dose adjustments are carried out weekly and no more frequently than every 3 days.23

Insulin glargine U-300 is essentially a threefold concentrated preparation of insulin glargine U-100 that results in a two-thirds volume reduction and a one-half reduction in depot surface following SC administration. The reduced depot surface area is presumed to account for much of the protracted absorption of glargine U-300 from the SC tissues. The metabolism and elimination of glargine U-300 is similar to that of the original compound, with formation of two active metabolites: M1 (the principal active moiety) and M2. Biologic steady state is achieved after 4 to 5 days of once-daily injections.24

When compared with glargine U-100 in patients with type 1 diabetes, insulin glargine U-300 at doses of 0.4 U/kg produced more stable insulin concentrations and glucose-lowering effect with a longer duration of action at steady state, as reflected by tight glucose control being maintained for about 5 hours longer (median of 30 hours).25 A meta-analysis of the EDITION I to III clinical trials in patients with type 2 diabetes at various stages of treatment found similar glucose-lowering effects for glargine U-300 compared with glargine U-100 but a lower rate of nonsevere hypoglycemia.20 Of note was the need for 10% to 15% more units of insulin for glargine U-300 in these clinical trials. Insulin glargine U-300 is available only in a 1.5 mL disposable prefilled pen, which contains 450 units of insulin. Because the dose counter on the pen window corresponds to the actual number of units of insulin to be injected, no dose recalculation is required by the patient or provider.

Insulin degludec is another ultra-long-acting basal insulin analogue with a half-life at steady state of greater than 25 hours.26 In comparison, the half-life of insulin glargine U-100 in that same study was reported as 12.1 hours. Further, insulin degludec exhibited flatter and more stable biologic activity, more evenly distributed over the course of a 24-hour period than insulin glargine U-100. The protraction mechanism is based on the formation of long strings of multihexamers, facilitated by a 16-carbon fatty acid chain linked via a glutamic acid spacer to the terminal end of the B-chain of the insulin molecule.27 In studies of patients with type 2 diabetes at various stages of treatment, insulin degludec also demonstrated lower risk of nonsevere hypoglycemia for an equivalent level of HbA1c control achieved.19

The flexibility of administration time for an ultra-long-acting insulin preparation such as degludec was tested by asking patients to alternate the injection of degludec between morning and evening, in effect creating administration intervals of up to 8 to 40 hours.28 Even within such drastic parameters, the efficacy and safety of insulin degludec were maintained when compared with insulin glargine U-100 injected at the same time of the day every day.

Because of an increase in major adverse cardiovascular events in phase 3 trials, degludec is undergoing a cardiovascular safety trial in patients with type 2 diabetes. The DEVOTE trial, which started in October 2013, will include 7,500 patients and will continue for up to 5 years. Interim results have recently been submitted to the FDA resulting in conditional approval of degludec in the US (Clinical Trials.gov Registration: NCT01959529). Degludec is available in disposable pen or cartridge format in U-100 and U-200 formulations.

COST

These new insulin preparations have introduced clinical options that have efficacy similar to that of available insulin products but, for the most part, have advantages of safety (less risk of nonsevere hypoglycemia) and patient convenience (flexibility in timing of insulin dose administration). While the latter is presumed to improve patient adherence, this has yet to be confirmed. Compared with synthetic human insulin preparations (regular insulin, NPH, and premix 70/30 insulin), which can be obtained in certain pharmacies at a discount (usually around 3 cents per unit of insulin), the currently available insulin analogues are considerably more expensive (around 16 to 27 cents per unit of insulin).

Within the guidelines for initiation and intensification of the insulin regimen using basal insulin formulations, the clinician will need to balance the potential benefits and current costs for the treatment of the individual patient. Clearly, as patients with diabetes are brought closer to their glycemic goals with insulin options, they stand to increasingly benefit from formulations that provide more consistent glycemic response and less risk of hypoglycemia. For those who are unable to afford the higher costs, especially if their glycemic control is far from the desired target, the use of synthetic human insulin formulations may be entirely appropriate. In this era of individualized care and prescriptions, clinicians have a range of insulin treatment options that will facilitate patients reaching appropriate goals.

- The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 1993; 329:977–986.

- UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lancet 1998; 352:837–853.

- Holman RR, Paul SK, Bethel MA, Matthews DR, Neil HA. 10-year follow-up of intensive glucose control in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2008; 359:1577–1589.

- Nathan DM, Cleary PA, Backlund JY, et al; Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (DCCT/EDIC) Study Research Group. Intensive diabetes treatment and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2005; 353:2643–2653.

- Siebenhofer A, Plank J, Berghold A, et al. Short acting insulin analogues versus regular human insulin in patients with diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; 19:CD003287.

- Gale EA. A randomized, controlled trial comparing insulin lispro with human soluble insulin in patients with type 1 diabetes on intensified insulin therapy. The UK Trial Group. Diabet Med 2000; 17:209–214.

- Cobry E, McFann K, Messer L, et al. Timing of meal insulin boluses to achieve optimal postprandial glycemic control in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther 2010; 12:173–177.

- Gagnon-Auger M, du Souich P, Baillargeon JP, et al. Dose-dependent delay of the hypoglycemic effect of short-acting insulin analogs in obese subjects with type 2 diabetes: a pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study. Diabetes Care 2010; 33:2502–2507.

- Afrezza (insulin human) inhalation powder [package insert]. Danbury, CT: MannKind Corp; 2014.

- Kugler AJ, Fabbio KL, Pham DQ, Nadeau DA. Inhaled technosphere insulin: a novel delivery system and formulation for the treatment of types 1 and 2 diabetes mellitus. Pharmacotherapy 2015; 35:298–314.

- Kling J. Inhaled insulin’s last gasp? Nat Biotechnol 2008; 26:479–480.

- Peyrot M, Rubin RR. Patient-reported outcomes in adults with type 2 diabetes using mealtime inhaled technosphere insulin and basal insulin versus premixed insulin. Diabetes Technol Ther 2011; 13:1201–1206.

- Testa MA, Simonson DC. Satisfaction and quality of life with premeal inhaled versus injected insulin in adolescents and adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2007; 30:1399–1405.

- Reutrakul S, Wroblewski K, Brown RL. Clinical use of U-500 regular insulin: review and meta-analysis. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2012; 6:412–420.

- de la Peña A, Riddle M, Morrow LA, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of high-dose human regular U-500 insulin versus human regular U-100 insulin in healthy obese subjects. Diabetes Care 2011; 34:2496–2501.

- Riddle MC, Rosenstock J, Gerich J; Insulin Glargine 4002 Study Investigators. The treat-to-target trial: randomized addition of glargine or human NPH insulin to oral therapy of type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 2003; 26:3080–3086.

- Heise T, Nosek L, Rønn BB, et al. Lower within-subject variability of insulin detemir in comparison to NPH insulin and insulin glargine in people with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 2004; 53:1614–1620.

- Philis-Tsimikas A, Charpentier G, Clauson P, Ravn GM, Roberts VL, Thorsteinsson B. Comparison of once-daily insulin detemir with NPH insulin added to a regimen of oral antidiabetic drugs in poorly controlled type 2 diabetes. Clin Ther 2006; 28:1569–1581.

- Einhorn D, Handelsman Y, Bode BW, Endahl LA, Mersebach H, King AB. Patients achieving good glycemic control (HbA1c <7%) experience a lower rate of hypoglycemia with insulin degludec than with insulin glargine: a meta-analysis of phase 3a trials. Endocr Pract 2015; 21:917–926.

- Ritzel R, Roussel R, Bolli GB, et al. Patient-level meta-analysis of the EDITION 1, 2 and 3 studies: glycaemic control and hypoglycaemia with new insulin glargine 300 U/ml versus glargine 100 U/ml in people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab 2015; 17:859–867.

- Bergenstal RM, Rosenstock J, Arakaki RF, et al. A randomized, controlled study of once-daily LY2605541, a novel long-acting basal insulin, versus insulin glargine in basal insulin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2012; 35:2140–2147.

- Heise T, Meneghini LF. Insulin stacking versus therapeutic accumulation: understanding the differences. Endocr Pract 2014; 20:75–83.

- Bolli GB, Riddle MC, Bergenstal RM, et al; on behalf of the EDITION 3 study investigators. New insulin glargine 300 U/ml compared with glargine 100 U/ml in insulin-naïve people with type 2 diabetes on oral glucose-lowering drugs: a randomized controlled trial (EDITION 3). Diabetes Obes Metab 2015; 17:386–394.

- Steinstraesser A, Schmidt R, Bergmann K, Dahmen R, Becker RH. Investigational new insulin glargine 300 U/ml has the same metabolism as insulin glargine 100 U/ml. Diabetes Obes Metab 2014; 16:873–876.

- Becker RH, Dahmen R, Bergmann K, Lehmann A, Jax T, Heise T. New insulin glargine 300 units⋅mL−1 provides a more even activity profile and prolonged glycemic control at steady state compared with insulin glargine 100 units·mL−1. Diabetes Care 2015; 38:637–643.

- Heise T, Hövelmann U, Nosek L, Hermanski L, Bøttcher SG, Haahr H. Comparison of the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles of insulin degludec and insulin glargine. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 2015; 11:1193–1201.

- Jonassen I, Havelund S, Hoeg-Jensen T, Steensgaard DB, Wahlund PO, Ribel U. Design of the novel protraction mechanism of insulin degludec, an ultra-long-acting basal insulin. Pharm Res 2012; 29:2104–2114.

- Meneghini L, Atkin SL, Gough SC, et al; NN1250-3668 (BEGIN FLEX) Trial Investigators. The efficacy and safety of insulin degludec given in variable once-daily dosing intervals compared with insulin glargine and insulin degludec dosed at the same time daily: a 26-week, randomized, open-label, parallel-group, treat-to-target trial in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2013; 36:858–864.

- The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 1993; 329:977–986.

- UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lancet 1998; 352:837–853.

- Holman RR, Paul SK, Bethel MA, Matthews DR, Neil HA. 10-year follow-up of intensive glucose control in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2008; 359:1577–1589.

- Nathan DM, Cleary PA, Backlund JY, et al; Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (DCCT/EDIC) Study Research Group. Intensive diabetes treatment and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2005; 353:2643–2653.

- Siebenhofer A, Plank J, Berghold A, et al. Short acting insulin analogues versus regular human insulin in patients with diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; 19:CD003287.

- Gale EA. A randomized, controlled trial comparing insulin lispro with human soluble insulin in patients with type 1 diabetes on intensified insulin therapy. The UK Trial Group. Diabet Med 2000; 17:209–214.

- Cobry E, McFann K, Messer L, et al. Timing of meal insulin boluses to achieve optimal postprandial glycemic control in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther 2010; 12:173–177.

- Gagnon-Auger M, du Souich P, Baillargeon JP, et al. Dose-dependent delay of the hypoglycemic effect of short-acting insulin analogs in obese subjects with type 2 diabetes: a pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study. Diabetes Care 2010; 33:2502–2507.

- Afrezza (insulin human) inhalation powder [package insert]. Danbury, CT: MannKind Corp; 2014.

- Kugler AJ, Fabbio KL, Pham DQ, Nadeau DA. Inhaled technosphere insulin: a novel delivery system and formulation for the treatment of types 1 and 2 diabetes mellitus. Pharmacotherapy 2015; 35:298–314.

- Kling J. Inhaled insulin’s last gasp? Nat Biotechnol 2008; 26:479–480.

- Peyrot M, Rubin RR. Patient-reported outcomes in adults with type 2 diabetes using mealtime inhaled technosphere insulin and basal insulin versus premixed insulin. Diabetes Technol Ther 2011; 13:1201–1206.

- Testa MA, Simonson DC. Satisfaction and quality of life with premeal inhaled versus injected insulin in adolescents and adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2007; 30:1399–1405.

- Reutrakul S, Wroblewski K, Brown RL. Clinical use of U-500 regular insulin: review and meta-analysis. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2012; 6:412–420.

- de la Peña A, Riddle M, Morrow LA, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of high-dose human regular U-500 insulin versus human regular U-100 insulin in healthy obese subjects. Diabetes Care 2011; 34:2496–2501.

- Riddle MC, Rosenstock J, Gerich J; Insulin Glargine 4002 Study Investigators. The treat-to-target trial: randomized addition of glargine or human NPH insulin to oral therapy of type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 2003; 26:3080–3086.

- Heise T, Nosek L, Rønn BB, et al. Lower within-subject variability of insulin detemir in comparison to NPH insulin and insulin glargine in people with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 2004; 53:1614–1620.

- Philis-Tsimikas A, Charpentier G, Clauson P, Ravn GM, Roberts VL, Thorsteinsson B. Comparison of once-daily insulin detemir with NPH insulin added to a regimen of oral antidiabetic drugs in poorly controlled type 2 diabetes. Clin Ther 2006; 28:1569–1581.

- Einhorn D, Handelsman Y, Bode BW, Endahl LA, Mersebach H, King AB. Patients achieving good glycemic control (HbA1c <7%) experience a lower rate of hypoglycemia with insulin degludec than with insulin glargine: a meta-analysis of phase 3a trials. Endocr Pract 2015; 21:917–926.

- Ritzel R, Roussel R, Bolli GB, et al. Patient-level meta-analysis of the EDITION 1, 2 and 3 studies: glycaemic control and hypoglycaemia with new insulin glargine 300 U/ml versus glargine 100 U/ml in people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab 2015; 17:859–867.

- Bergenstal RM, Rosenstock J, Arakaki RF, et al. A randomized, controlled study of once-daily LY2605541, a novel long-acting basal insulin, versus insulin glargine in basal insulin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2012; 35:2140–2147.

- Heise T, Meneghini LF. Insulin stacking versus therapeutic accumulation: understanding the differences. Endocr Pract 2014; 20:75–83.

- Bolli GB, Riddle MC, Bergenstal RM, et al; on behalf of the EDITION 3 study investigators. New insulin glargine 300 U/ml compared with glargine 100 U/ml in insulin-naïve people with type 2 diabetes on oral glucose-lowering drugs: a randomized controlled trial (EDITION 3). Diabetes Obes Metab 2015; 17:386–394.

- Steinstraesser A, Schmidt R, Bergmann K, Dahmen R, Becker RH. Investigational new insulin glargine 300 U/ml has the same metabolism as insulin glargine 100 U/ml. Diabetes Obes Metab 2014; 16:873–876.

- Becker RH, Dahmen R, Bergmann K, Lehmann A, Jax T, Heise T. New insulin glargine 300 units⋅mL−1 provides a more even activity profile and prolonged glycemic control at steady state compared with insulin glargine 100 units·mL−1. Diabetes Care 2015; 38:637–643.

- Heise T, Hövelmann U, Nosek L, Hermanski L, Bøttcher SG, Haahr H. Comparison of the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles of insulin degludec and insulin glargine. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 2015; 11:1193–1201.

- Jonassen I, Havelund S, Hoeg-Jensen T, Steensgaard DB, Wahlund PO, Ribel U. Design of the novel protraction mechanism of insulin degludec, an ultra-long-acting basal insulin. Pharm Res 2012; 29:2104–2114.

- Meneghini L, Atkin SL, Gough SC, et al; NN1250-3668 (BEGIN FLEX) Trial Investigators. The efficacy and safety of insulin degludec given in variable once-daily dosing intervals compared with insulin glargine and insulin degludec dosed at the same time daily: a 26-week, randomized, open-label, parallel-group, treat-to-target trial in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2013; 36:858–864.

KEY POINTS

- Insulin extracted from an animal pancreas was first administered in 1921; the first insulin analogue was marketed in 1996.

- Insulin is considered the therapeutic standard in patients with advanced insulin deficiency.

- Types of available insulin products have differing onset, peak, and duration of action ranging from ultra-short-acting to ultra-long-acting.

- The US Food and Drug Administration approved an inhaled insulin product in 2014; all other products are administered subcutaneously.

- Concentrated insulin preparations provide an alternative for patients requiring consistently high daily doses of insulin.

Individualizing Insulin Therapy

The Evolution of Insulin Therapy in Diabetes Mellitus

The modern management of diabetes mellitus (DM) began with the discovery of insulin by Banting and Best in 1921 (see The Evolution of Insulin Therapy in Diabetes Mellitus in this supplement). Since that time, numerous additional classes of glucose-lowering agents have been introduced for the treatment of type 2 DM (T2DM). These medications primarily act by addressing 2 of the key defects of T2DM, insulin resistance and pancreatic β-cell dysfunction. T2DM is a progressive disease process that requires continued adjustment of therapy to maintain treatment goals. Most patients with T2DM will require insulin therapy at some point in their lives.

Role of Insulin in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Management

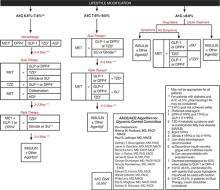

Consensus guidelines developed by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology (AACE/ACE) recommend initiating insulin when oral therapy fails to achieve glycemic control, A1C > 9.0% in treatment-naïve patients, or if the patient is symptomatic with glucose toxicity (polyuria, polydipsia, and weight loss) (FIGURE 1).1

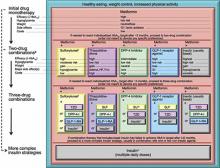

Similar consensus guidelines developed by the American Diabetes Association/European Association for the Study of Diabetes (ADA/EASD) advise the initiation of glucose-lowering therapy for most patients with T2DM with the combination of lifestyle modifications, diet, and metformin (FIGURE 2).2 For patients who do not achieve or maintain glycemic control over 3 months, or thereabouts, with metformin, a second oral agent should be added. Alternatives include a glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP-1R) agonist or basal insulin. Insulin should be strongly considered as initial therapy for a patient with significant symptoms of hyperglycemia and/or plasma glucose >300-350 mg/dL or A1C ≥10.0%.

The major role of insulin in the management of patients with T2DM stems from several important attributes. First, insulin is the only treatment that works in patients with advanced β-cell deficiency. It acts directly on tissues to regulate glucose homeostasis, unlike other glucose-lowering agents that require the presence of sufficient endogenous insulin to exert their effects as insulin sensitizers, secretagogues, incretin mimetics, amylin analogs, and other factors. This also means that the mechanism of action of insulin is complementary to those of other glucose-lowering agents. Second, there is less of a ceiling effect with insulin. That is, increasing the dose of insulin results in a progressive lowering of blood glucose in the majority of patients, with the major limitation being the risk for hypoglycemia. Third, the glucose-lowering efficacy of insulin is durable, unlike that of other glucose-lowering agents that depend on endogenous insulin secretion for continued effectiveness. Fourth, insulin improves the lipid profile, particularly triglyceride levels.2-5 Fifth, regarding the long-term safety and tolerability of insulin, it is well established that weight gain, likely mediated via reduction of glycosuria, and hypoglycemia are typically the most concerning adverse events encountered. Allergic reactions, which were a more common complication of animal-sourced insulins, are infrequent with the insulin analogs.6-17 Finally, the availability of insulin in different formulations allows for targeting fasting plasma glucose or postprandial glucose, and individualization of therapy (see The Evolution of Insulin Therapy in Diabetes Mellitus in this supplement.)

While both the AACE/ACE and ADA/EASD consensus guidelines provide treatment “algorithms,” both make it clear that these are suggested approaches suitable for the population with T2DM (FIGURE 1, FIGURE 2). The specific treatment approach must be individualized based on patient-specific factors such as age, comorbid conditions, and tolerance of hypoglycemia.

FIGURE 1

Role of insulin in the management of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus according to the AACE/ACE1

AACE, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists; ACE, American College of Endocrinology; AGI, α-glucosidase inhibitor; DPP4, dipeptidyl-peptidase-4 inhibitor; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; GLP-1, glucagon–like peptide-1 agonist; MET, metformin; PPG, postprandial glucose; SU, sulfonylurea; TZD, thiazolidinedione.

Reprinted from American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. AACE/ACE Diabetes Algorithm for Glycemic Control. Available at https://www.aace.com/sites/default/files/GlycemicControlAlgorithmPPT.pdf. Accessed April 4, 2012, with permission from the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

FIGURE 2

Role of insulin in the management of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus according to the ADA/EASD2

Moving from the top to the bottom of the figure, potential sequences of antihyperglycemic therapy. In most patients, begin with lifestyle changes; metformin monotherapy is added at, or soon after, diagnosis (unless there are explicit contraindications). If the HbA1c target is not achieved after ~3 months, consider 1 of the 5 treatment options combined with metformin: an SU, TZD, DPP-4-i, GLP-1-RA, or basal insulin. (The order in the chart is determined by historical introduction and route of administration and is not meant to denote any specific preference.) Choice is based on patient and drug characteristics, with the over-riding goal of improving glycemic control while minimizing side effects. Shared decision making with the patient may help in the selection of therapeutic options. The figure displays drugs commonly used both in the United States and/or Europe. Rapid-acting secretagogues (meglitinides) may be used in place of SUs. Other drugs not shown (α-glucosidase inhibitors, colesevelam, dopamine agonists, pramlintide) may be used where available in selected patients but have modest efficacy and/or limiting side effects. In patients intolerant of, or with contraindications for, metformin, select initial drug from other classes depicted and proceed accordingly. In this circumstance, while published trials are generally lacking, it is reasonable to consider 3-drug combinations other than metformin. Insulin is likely to be more effective than most other agents as a third-line therapy, especially when HbA1c is very high (eg, ≥ 9.0%). The therapeutic regimen should include some basal insulin before moving to more complex insulin strategies. Dashed arrow line on the left-hand side of the figure denotes the option of a more rapid progression from a 2-drug combination directly to multiple daily insulin doses, in those patients with severe hyperglycemia (eg, HbA1c, ≥ 10.0–12.0%).

DPP-4, dipeptidyl peptidase-4; DPP-4-i, DPP-4 inhibitor; Fx’s, bone fractures; GI, gastrointestinal; GLP-1, glucagon-like peptide 1; GLP-1-RA, GLP-1 receptor agonist; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; HF, heart failure; NPH, neutral protamine Hagedorn; SU, sulfonylurea; TZD, thiazolidinedione.

aConsider beginning at this stage in patients with very high HbA1c (eg, ≥ 9%); bConsider rapid-acting, non-SU secretagogues (meglitinides) in patients with irregular meal schedules or who develop late postprandial hypoglycemia on SUs; cUsually a basal insulin (NPH, glargine, detemir) in combination with noninsulin agents; dCertain noninsulin agents may be continued with insulin. Consider beginning at this stage if patient presents with severe hyperglycemia (≥ 16.7–19.4 mmol/L [≥ 300–350 mg/dL]; HbA1c≥ 10.0–12.0%) with or without catabolic features (weight loss, ketosis, etc).

Diabetes Care by American Diabetes Association. Copyright 2012. Reproduced with permission of AMERICAN DIABETES ASSOCIATION in the format Journal via Copyright Clearance Center.

Individualizing Therapy

The importance of individualizing therapy in a way that allows patients with T2DM to effectively self-manage their disease cannot be overstated. A study involving 1381 patients with T2DM cared for by 42 primary care physicians was conducted to estimate the magnitude of effect that physicians have on glycemic control.18 Hierarchical linear modeling showed that physician-related factors were associated with a statistically significant but modest variability in A1C change (2%) for the entire patient group. On the face of it, this finding might be discouraging. Further analysis showed, however, that for patients whose A1C did improve, physician-related factors accounted for 5% of the overall change in A1C (P = .005). On the other hand, physician-related factors had no impact on patients whose A1C did not improve or worsened. These results support the role that physicians play in affecting patient outcomes. The results also make it clear that without a physician’s influence, a patient’s glycemic outcomes may be difficult to change. The question is: How best can a physician influence patient outcomes?