User login

Hospitalists and Hip Fractures

Because the incidence of hip fracture increases dramatically with age and the elderly are the fastest‐growing portion of the United States population, the number of hip fractures is expected to triple by 2040.1 With the associated increase in postoperative morbidity and mortality, the costs will likely exceed $16‐$20 billion annually.15 Already by 2002, the number of patients with hip fractures exceeded 340,000 in this country, resulting in $8.6 billion in health care expenditures from in‐hospital and posthospital costs.68 This makes hip fracture a serious public health concern and triggers a need to devise an efficient means of caring for these patients. We previously reported that a hospitalist service can decrease time to surgery and shorten length of stay without affecting the number of inpatient deaths or 30‐day readmissions of patients undergoing hip fracture surgery.9 However, one concern with reducing length of stay and time to surgery in the high‐risk hip fracture patient population is the effect on long‐term mortality because the death rate following hip fracture repair may be as high as 43% after 1 year.10 To evaluate this important issue, we assessed mortality over a 1‐year period in the same cohort of patients previously described.9 We also identified predictors associated with mortality. We hypothesized that the expedited surgical treatment and decreased length of stay of a hospitalist‐managed group would not have an adverse effect on 1‐year mortality.

METHODS

Patient Selection

Following approval by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board, we used the Mayo Clinic Surgical Index to identify patients admitted between July 1, 2000, and June 30, 2002, who matched International Classification of Diseases (9th Edition) hip fracture codes.11 These patients were cross‐referenced with those having a primary surgical indication of hip fracture. Patients transferred to our facility more than 72 hours after fracture were excluded from our study. Study patients provided authorization to use their medical records for the purposes of research.

A cohort of 466 patients was identified. For purposes of comparison, patients admitted between July 1, 2000, and June 30, 2001, were deemed to belong to the standard care service, and patients admitted between July 1, 2001, and June 30, 2002, were deemed part of the hospitalist service.

Intervention

Prior to July 2001, Mayo Clinic patients aged 65 and older having surgical repair of a hip fracture were triaged directly to a surgical orthopedic or general medical teaching service. Patients with multiple medical diagnoses were managed initially on a medical teaching service prior to transfer to the operating room. The primary team (medical or surgical) was responsible for the postoperative care of the patient and any orders or consultations required.

After July 1, 2001, these patients were admitted by the orthopedic surgery service and medically comanaged by a hospitalist service, which consisted of a hospitalist physician and 2 allied‐health practitioners. Twelve hospitalists and 12 allied health care professionals cared for patients during the study period. All preoperative and postoperative evaluations, inpatient management decisions, and coordination of outpatient care were performed by the hospitalists. This model of care is similar to one previously studied and published elsewhere.12 A census cap of 20 patients limited the number of patients managed by the hospitalist service. Any overflow of hip fracture patients was triaged directly to a non‐hospitalist‐based primary medical or surgical service as before. Thus, 23 hip fracture patients (10%) admitted after July 1, 2001, were not managed by the hospitalists but are included in this group for an intent‐to‐treat analysis.

Data Collection

Study nurses abstracted all data including admitting diagnoses, demographic features, type and mechanism of hip fracture, admission date and time, American Society of Anesthesia (ASA) class, comorbid medical conditions, medications, all clinical data, and readmission rates. Date of last follow‐up was confirmed using the Mayo Clinic medical record, whereas date and cause of death were obtained from death certificates obtained from state and national sources. Length of stay was defined as the number of days between admission and discharge. Time to surgery was defined in hours as the time from hospital admission to the start of the surgery. Finally, time from surgery to dismissal was defined as the number of days from the initiation of the surgical procedure to the time of dismissal. Thirty‐day readmission was defined as readmission to our hospital within 30 days of discharge date.

Statistical Considerations

Power

The power analysis was based on the end point of survival following surgical repair of hip fracture and primary comparison of patients in the standard care group with those in the hospitalist group. With 236 patients in the standard care group, 230 in the hospitalist group, and 274 observed deaths during the follow‐up period, there was 80% power to detect a hazard ratio of 1.4 or greater as being statistically significant (alpha = 0.05, beta = 0.2).

Analysis

The analysis focused on the end point of survival following surgical repair of hip fracture. In addition to the hospitalist versus standard care service, demographic, baseline clinical, and in‐hospital data were evaluated as potential predictors of survival. Survival rates were estimated using the method of Kaplan and Meier, and relative differences in survival were evaluated using the Cox proportional hazards regression models.13, 14 Potential predictors were analyzed both univariately and in a multivariable model. For the multivariable model, initial variable selection was accomplished using stepwise selection, backward elimination, and recursive partitioning.15 Each method yielded similar results. Bootstrap resampling was then used to confirm the variables selected for each model.16, 17 The threshold of statistical significance was set at P = .05 for all tests. All analyses were conducted in SAS version 8.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and Splus version 6.2.1 (Insightful Corporation, Seattle, WA).

RESULTS

There were 236 patients with hip fractures (50.6%) admitted to the standard care service, and 230 patients (49.4%) admitted to the hospitalist service. As shown in Table 1, the baseline characteristics of the patients admitted to the 2 services did not differ significantly except that a greater proportion of patients with hypoxia were admitted to the hospitalist service (11.3% vs. 5.5%; P = .02). However, time to surgery, postsurgery stay, and overall length of hospitalization of the hospitalist‐treated patients were all significantly shorter.

| Patient characteristic | Standard care n = 236 | Hospitalist care n = 230 | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Age (years) | 82 | 83 | .34 | ||

| Female sex | 171 | 72.5% | 163 | 70.9% | .70 |

| Comorbidity | |||||

| Coronary artery disease | 69 | 29.2% | 77 | 33.5% | .32 |

| Congestive heart failure | 41 | 17.4% | 49 | 21.3% | .28 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 36 | 15.3% | 38 | 16.5% | .71 |

| Cerebral vascular accident or transient ischemic attack | 36 | 15.3% | 50 | 21.7% | .07 |

| Dementia | 54 | 22.9% | 62 | 27.0% | .31 |

| Diabetes | 45 | 19.1% | 46 | 20.0% | .80 |

| Renal insufficiency | 17 | 7.2% | 17 | 7.4% | .94 |

| Residence at time of admission | .07 | ||||

| Home | 149 | 63.1% | 138 | 60.0% | |

| Assisted living | 32 | 13.6% | 42 | 18.3% | |

| Nursing home | 55 | 23.3% | 50 | 21.7% | |

| Ambulatory status at time of admission | .14 | ||||

| Independent | 114 | 48.3% | 89 | 38.7% | |

| Assistive device | 99 | 41.9% | 115 | 50.0% | |

| Personal help | 9 | 3.8% | 16 | 7.0% | |

| Transfer to bed or chair | 9 | 3.8% | 7 | 3.0% | |

| Nonambulatory | 5 | 2.1% | 3 | 1.3% | |

| Signs at time of admission | |||||

| Hypotension | 4 | 1.7% | 3 | 1.3% | > .99 |

| Hypoxia | 13 | 5.5% | 26 | 11.3% | .02 |

| Pulmonary edema | 37 | 15.7% | 29 | 12.6% | .34 |

| Tachycardia | 19 | 8.1% | 25 | 10.9% | .3 |

| Fracture type | .78 | ||||

| Femoral neck | 118 | 50.0% | 118 | 51.3% | |

| Intertrochanteric | 118 | 50.0% | 112 | 48.7% | |

| Mechanism of fracture | .82 | ||||

| Fall | 219 | 92.8% | 212 | 92.2% | |

| Trauma | 1 | 0.4% | 3 | 1.3% | |

| Pathologic | 7 | 3.0% | 6 | 2.6% | |

| Unknown | 9 | 3.8% | 7 | 3.0% | |

| ASA* class | .38 | ||||

| I or II | 33 | 14.0% | 23 | 10.0% | |

| III | 166 | 70.3% | 166 | 72.2% | |

| IV | 37 | 15.7% | 41 | 17.8% | |

| Location discharged to | .07 | ||||

| Home or assisted living | 24 | 10.5% | 13 | 5.9% | |

| Nursing home | 196 | 86.0% | 192 | 87.3% | |

| Another hospital or hospice | 8 | 3.5% | 15 | 6.8% | |

| Time to surgery (hours) | 38 | 25 | .001 | ||

| Time from surgery to discharge (days) | 9 | 7 | .04 | ||

| Length of stay | 10.6 | 8.4 | < .00 | ||

| Readmission rate | 25 | 10.6% | 20 | 8.7% | .49 |

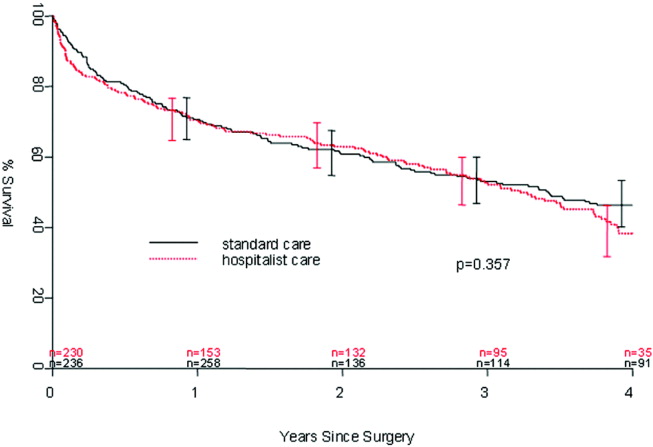

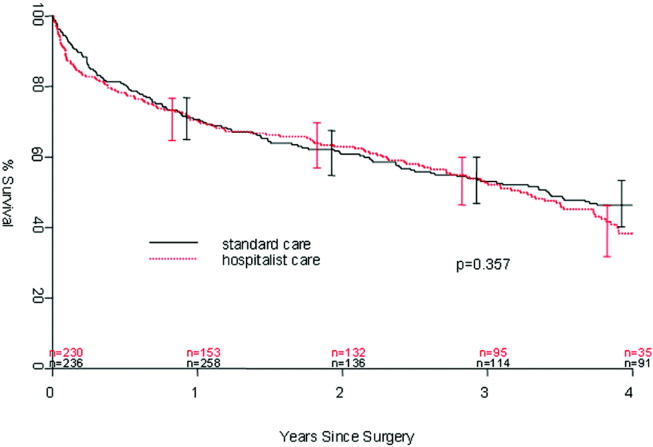

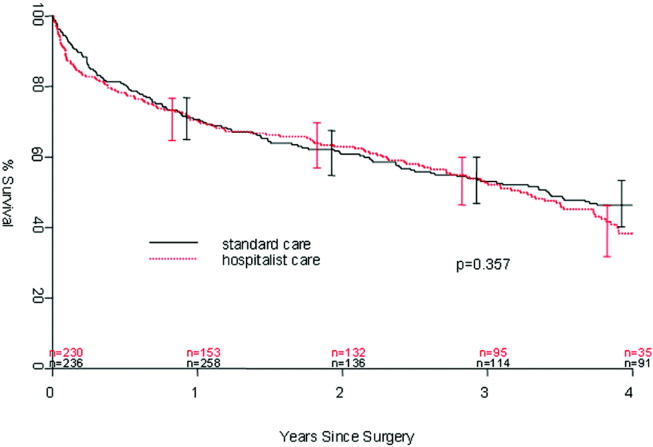

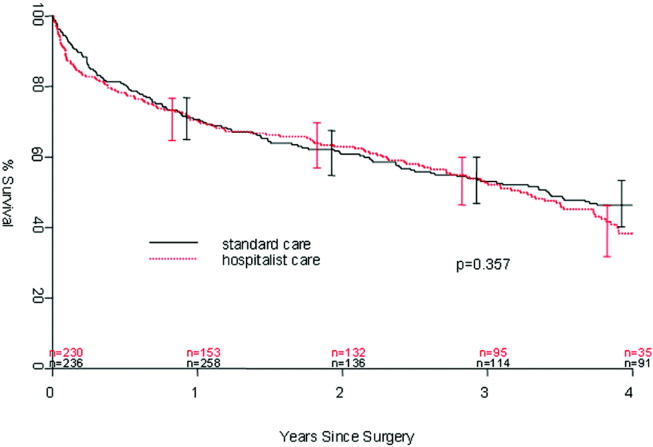

Patients were followed for a median of 4.0 years (range 5 days to 5.6 years), and 192 patients were still alive at the end of follow‐up (April 2006). As illustrated in Figure 1, survival did not differ between the 2 treatment groups (P = .36). Overall survival at 1 year was 70.6% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 66.5%, 74.9%). Survival at 1 year in the standard care group was 70.6% (95% CI: 64.9%, 76.8%), whereas in the hospitalist group, it was 70.5% (95% CI: 64.8%, 76.7%). As delineated in Table 2, cardiovascular causes accounted for 34 deaths (25.6%), with 14 of these in the standard care group and 20 in the hospitalist group; 29 deaths (21.8%) had respiratory causes, 20 in the standard care group and 9 in the hospitalist group; and 17 (12.8%) were due to cancer, with 7 and 10 in the standard care and hospitalist groups, respectively. Unknown causes accounted for 21 cases, or 15.8% of total deaths.

| Standard care | Hospitalist care | Total No. of deaths | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer | 7 | 10 | 17 | 12.8% |

| Cardiovascular | 14 | 20 | 34 | 25.6% |

| Infectious | 5 | 4 | 9 | 6.8% |

| Neurological | 5 | 10 | 15 | 11.3% |

| Other | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1.5% |

| Renal | 4 | 2 | 6 | 4.5% |

| Respiratory | 20 | 9 | 29 | 21.8% |

| Unknown | 11 | 10 | 21 | 15.8% |

| Total | 66 | 67 | 133 | 100.0% |

In the univariate analysis, we found 29 variables that were significant predictors of survival (Table 3). A hospitalist model of care was not significantly associated with patient survival, despite the shorter length of stay (8.4 days vs. 10.6 days; P < .001) or expedited time to surgery (25 vs. 38 hours; P < .001), when compared with the standard care group, as previously reported by Phy et al.9 In the multivariable analysis (Table 4), however, the independent predictors of mortality were ASA class III or IV versus class II (hazard ratio [HR] 4.20; 95% CI: 2.21, 7.99), admission from a nursing home versus from home or assisted living (HR 2.24; 95% CI: 1.73, 2.90), and inpatient complications, which included patients requiring admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) and those who had a myocardial infarction or acute renal failure as an inpatient (HR 1.85; 95% CI: 1.45, 2.35). Even after adjusting for these factors, survival following hip fracture did not differ significantly between the hospitalist care patients and the standard care patients (HR 1.16; 95% CI: 0.91, 1.48).

| Variable | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Age on admission per 10 years | 1.41 (1.20, 1.65) | < .001 |

| ASA* II | 1.0 (referent) | |

| ASA* III | 5.27 (2.79, 9.96) | < .001 |

| ASA* IV | 11.7 (5.97, 22.9) | < .001 |

| History of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1.82 (1.35, 2.43) | < .001 |

| History of renal insufficiency | 2.40 (1.62,3.55) | < .001 |

| History of stroke/transient ischemic attack | 1.46 (1.10, 1.95) | .01 |

| History of diabetes | 1.70 (1.29,2.25) | < .001 |

| History of congestive heart failure | 2.26 (1.73, 2.96) | < .001 |

| History of coronary artery disease | 1.53 (1.20, 1.97) | < .001 |

| History of dementia | 2.02 (1.57, 2.59) | < .001 |

| Admission from home | 1.0 (referent) | |

| Admission from assisted living | 1.47 (1.06, 2.04) | .02 |

| Admission from nursing home | 3.04 (2.33, 3.98) | < .001 |

| Independent | 1.0 (referent) | |

| Use of assistive device | 1.81 (1.39, 2.36) | < .001 |

| Personal help | 3.49 (2.16, 5.64) | < .001 |

| Nonambulatory | 3.96 (2.47, 6.35) | < .001 |

| Crackles on admission | 2.03 (1.50, 2.74) | < .001 |

| Hypoxia on admission | 1.56 (1.04, 2.32) | .03 |

| Hypotension on admission | 6.21 (2.72, 14.2) | < .001 |

| Tachycardia on admission | 1.66 (1.15, 2.41) | .007 |

| Coumadin on admission | 1.57 (1.13, 2.18) | .007 |

| Confusion/unconsciousness on admission | 2.23 (1.74, 2.87) | < .001 |

| Fever on admission | 1.98 (1.16, 3.40) | .01 |

| Tachypnea on admission | 1.95 (1.39, 2.72) | < .001 |

| Inpatient myocardial Infarction | 3.59 (2.35, 5.48) | < .001 |

| Inpatient atrial fibrillation | 2.00 (1.37, 2.92) | < .001 |

| Inpatient congestive heart failure | 2.62 (1.79, 3.84) | < .0001 |

| Inpatient delirium | 1.46 (1.13, 1.90) | < .005 |

| Inpatient lung infection | 2.52 (1.85, 3.42) | < .001 |

| Inpatient respiratory failure | 2.76 (1.64, 4.66) | < .001 |

| Inpatient mechanical ventilation | 2.56 (1.43, 4.57) | .002 |

| Inpatient renal failure | 3.60 (1.97, 6.61) | < .001 |

| Days from admission to surgery | 1.06 (1.005, 1.12) | .03 |

| Intensive care unit stay | 1.93 (1.51, 2.47) | < .001 |

| Variable | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Age on admission per 10 years | 1.17 (0.99, 1.38) | .07 |

| ASA* class III or IV | 4.20 (2.21, 7.99) | < .001 |

| ASA* class II | 1.0 (referent) | |

| Admission from nursing home | 2.24 (1.73, 2.90) | < .001 |

| Admission from home or assisted living | 1.0 (referent) | |

| Inpatient myocardial infarction, inpatient acute renal failure, or intensive care unit stay | 1.85 (1.45, 2.35) | < .001 |

| No inpatient myocardial infarction, no inpatient acute renal failure, and no intensive care unit stay | 1.0 (referent) | |

DISCUSSION

In our previous study, length of stay and time to surgery were significantly lower in a hospitalist care model.9 The present study shows that neither the reduced length of stay nor the shortened time to surgery of patients managed by the hospitalist group was associated with a difference in mortality compared with a standard care group, despite significantly improved efficiency and processes of care. Thus, our results refute initial concerns of increased mortality in a hospitalist model of care.

Delivery of perioperative medical care to hip fracture patients by hospitalists is associated with significant decreases in time to surgery and length of stay compared with standard care, with no differences in short‐term mortality.9, 18 Although there have been conflicting reports on the impact of length of stay and time to surgery on long‐term outcomes, our findings support previous results that decreased time to surgery was not associated with an observable effect on mortality.1923 A recent study by Orosz et al. that evaluated 1178 patients showed that earlier hip fracture surgery (performed less than 24 hours after admission) was not associated with reduced mortality, although it was associated with shorter length of stay.19 Our study also corroborates the results of an examination of 8383 hip fracture patients by Grimes et al., who found that time to surgery between 24 and 48 hours after admission had no effect on either 30‐day or long‐term mortality compared with that of those who underwent surgery between 48 and 72 hours, between 72 and 96 hours, or more than 96 hours after admission.20 However, both these results and our own are contrary to those of Gdalevich, whose study of 651 patients found that 1‐year mortality was 1.6‐fold higher for those whose hip fracture repair was postponed more than 48 hours.21 However, time to surgery in both the standard care and hospitalist model in our study was well below the 48‐hour cutoff, suggesting that operating anywhere within the normally accepted 48‐hour time frame may not influence long‐term mortality.

Because of the small number of events in both groups, we were unable to specifically compare whether a hospitalist model of care has any specific impact on long‐term cause of death. Although causes of death of patients with hip fracture were consistent with those of previous studies,10, 24 our death rate at 1 year, 29.4%, was higher than that seen among similar population groups at tertiary referral centers.19, 20, 2429 This is most likely a result of the cohort having a high proportion of nursing home patients (22%)19, 24, 26 transferred for evaluation to St. Mary's Hospital, which serves most of Olmsted County, Minnesota. This hospital also has some characteristics of a community‐based hospital, as it is where greater than 95% of all county patients receive care for surgical repair of hip fracture. Mortality rates are often higher at these types of hospitals.30 Previous studies using patients from Olmsted County indicate results can also be extrapolated to a large part of the U.S. population.31 In Pitto et al.'s study, the risk of death was 31% lower in those admitted from home than for those admitted from a nursing home.32 The latter patients normally have a higher number of comorbid conditions and tend to be less ambulatory than those in a community home‐dwelling setting. Our study also demonstrated that admission from a nursing home was a strong predictor of mortality for up to 1 year in the geriatric population. This may reflect the inherent decreased survival in this patient group, which is in agreement with the findings of other studies that showed inactivity and decreased ambulation prior to fracture were associated with increased mortality.3335

Multiple comorbidities, commonly seen in a geriatric population, translate into a higher ASA class and an increased risk of significant in‐hospital complications. Our study confirmed the findings of previous studies that a higher ASA class is a strong predictor of mortality,21, 26, 30, 3537 independent of decreased time to surgery.38 We also noted that significant in‐hospital complications, including renal failure, respiratory failure, and myocardial infarction, are documented predictors of mortality after hip fracture.27 Although mortality may vary depending on fracture type (femoral neck vs. intertrochanteric),3941 these differences were not observed in our study, in line with the results of previous published studies.37, 42 Controlling for age and comorbidities may be why an association was not found between fracture type and mortality. Finally, in a model containing comorbidity, ASA class, and nursing home residence prior to fracture, age was not a significant predictor of mortality.

Our study had a number of limitations. First, this was a retrospective cohort study based on chart review, so some data may have been subject to recording bias, and this might have differed between the serial models. Because of the retrospective nature of the study and referral of some of the patients from outside the community, our 1‐year follow‐up was not complete, but approached a respectable 93%. Other studies have described the benefits derived by a hospitalist practice only following the first year of its implementation, likely because of the hospitalist learning curve.43, 44 This may be why there was no difference in mortality between the standard care and hospitalist groups, as the latter was only in its first year of existence. Additional longitudinal study is required to find out if mortality differences emerge between the treatment groups. Furthermore, although in‐hospital care may influence short‐term outcomes, its effect on long‐term mortality has been unclear. Our data demonstrate that even though a hospitalist service can shorten length of stay and time to surgery, there were no appreciable intermediate differences in mortality at 1 year. Further prospective studies are needed to determine whether this medical‐surgical partnership in caring for these patients provides more favorable outcomes of reducing mortality and intercurrent complications.

Acknowledgements

We thank Donna K. Lawson for her assistance in data collection and management.

- ,,.The future of hip fractures in the United States. Numbers, costs, and potential effects of postmenopausal estrogen.Clin Orthop Relat Res1990 (252):163–166.

- ,,.Hip fractures in the elderly: a world‐wide projection.Osteoporos Int.1992;2:285–289.

- ,,,.The economic cost of hip fractures among elderly women. A one‐year, prospective, observational cohort study with matched‐pair analysis.Belgian Hip Fracture Study Group.J Bone Joint Surg Am.2001;83‐A:493–500.

- ,,.Estimating hip fracture morbidity, mortality and costs.J Am Geriatr Soc.2003;51:364–370.

- ,.The aging of America. Impact on health care costs.JAMA.1990;263:2335–2340.

- ,,,.Medical expenditures for the treatment of osteoporotic fractures in the United States in 1995: report from the National Osteoporosis Foundation.J Bone Miner Res.1997;12(1):24–35.

- US Department of Health and Human Services.Surveillance for selected public health indicators affecting older adults —United States.MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep1999;48:33–34.

- ,.Epidemiology and outcomes of osteoporotic fractures.Lancet.2002;359:1761–1767.

- ,,, et al.Effects of a hospitalist model on elderly patients with hip fracture.Arch Intern Med.2005;165:796–801.

- ,,.Hip fractures in Finland and Great Britain—a comparison of patient characteristics and outcomes.Int Orthop.2001;25:349–354.

- WHO.International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision (ICD‐9).Geneva, Switzerland:World Health Organization;1977.

- ,,, et al.Medical and surgical comanagement after elective hip and knee arthroplasty: a randomized, controlled trial.Ann Intern Med.2004;141(1):28–38.

- .Regression models and life‐tables (with discussion).J R Stat Soc Ser B.1972;34:187–220.

- ,.Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations.J Am Statistical Assoc.1958;53:457–481.

- ,.An Introduction to Recursive Partitioning using the RPART Routines: Section of Biostatistics, Mayo Clinic;1997.

- .Computer Intensive Statistical Methods, Validation, Model Selection, and Bootstrap.London:Chapman and Hall;1994.

- ,.A bootstrap resampling procedure for model building: application to the Cox regression model.Stat Med.1992;11:2093–2109.

- ,,.Associations between the hospitalist model of care and quality‐of‐care‐related outcomes in patients undergoing hip fracture surgery.Mayo Clin Proc.2006;81(1):28–31.

- ,,, et al.Association of timing of surgery for hip fracture and patient outcomes.JAMA.2004;291:1738–1743.

- ,,,,.The effects of time‐to‐surgery on mortality and morbidity in patients following hip fracture.Am J Med.2002;112:702–709.

- ,,,.Morbidity and mortality after hip fracture: the impact of operative delay.Arch Orthop Trauma Surg.2004;124:334–340.

- ,,.Delay to surgery prolongs hospital stay in patients with fractures of the proximal femur.J Bone Joint Surg Br.2005;87:1123–1126.

- ,.The timing of surgery for proximal femoral fractures.J Bone Joint Surg Br.1992;74(2):203–205.

- ,,, et al.Hospital readmissions after hospital discharge for hip fracture: surgical and nonsurgical causes and effect on outcomes.J Am Geriatr Soc.2003;51:399–403.

- ,.Mortality after hip fractures.Acta Orthop Scand1979;50(2):161–167.

- ,,,,.Medical complications and outcomes after hip fracture repair.Arch Intern Med.2002;162:2053–2057.

- ,,, et al.Development and initial validation of a risk score for predicting in‐hospital and 1‐year mortality in patients with hip fractures.J Bone Miner Res.2005;20:494–500.

- ,,,,.Outcome after hip fracture in individuals ninety years of age and older.J Orthop Trauma.2001;15(1):34–39.

- ,,,.Hip fractures in the elderly: predictors of one year mortality.J Orthop Trauma.1997;11(3):162–165.

- ,,,.The effect of hospital type and surgical delay on mortality after surgery for hip fracture.J Bone Joint Surg Br.2005;87:361–366.

- .History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project.Mayo Clin Proc.1996;71:266–274.

- .The mortality and social prognosis of hip fractures. A prospective multifactorial study.Int Orthop.1994;18(2):109–113.

- ,.Functional outcome after hip fracture. A 1‐year prospective outcome study of 275 patients.Injury.2003;34:529–532.

- ,,.Rate of mortality for elderly patients after fracture of the hip in the 1980's.J Bone Joint Surg Am.1987;69:1335–1340.

- ,,,.Hip fractures in the elderly. Mortality, functional results and social readaptation.Int Surg.1989;74(3):191–194.

- ,,.Blood transfusion requirements in femoral neck fracture.Injury.2000;31(1):7–10.

- ,,.Mortality and causes of death after hip fractures in The Netherlands.Neth J Med.1992;41(1–2):4–10.

- ,,.Influence of preoperative medical status and delay to surgery on death following a hip fracture.ANZ J Surg.2002;72:405–407.

- ,,,Predictors of mortality and institutionalization after hip fracture: the New Haven EPESE cohort. Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly.Am J Public Health.1994;84:1807–1812.

- ,,,.Mortality risk after hip fracture.J Orthop Trauma.2003;17(1):53–56.

- ,,.Thirty‐day mortality following hip arthroplasty for acute fracture.J Bone Joint Surg Am.2004;86‐A:1983–1988.

- ,,,,.Functional outcomes and mortality vary among different types of hip fractures: a function of patient characteristics.Clin Orthop Relat Res.2004:64–71.

- ,,,,,.Implementation of a voluntary hospitalist service at a community teaching hospital: improved clinical efficiency and patient outcomes.Ann Intern Med.2002;137:859–865.

- ,,, et al.Effects of physician experience on costs and outcomes on an academic general medicine service: results of a trial of hospitalists.Ann Intern Med.2002;137:866–874.

Because the incidence of hip fracture increases dramatically with age and the elderly are the fastest‐growing portion of the United States population, the number of hip fractures is expected to triple by 2040.1 With the associated increase in postoperative morbidity and mortality, the costs will likely exceed $16‐$20 billion annually.15 Already by 2002, the number of patients with hip fractures exceeded 340,000 in this country, resulting in $8.6 billion in health care expenditures from in‐hospital and posthospital costs.68 This makes hip fracture a serious public health concern and triggers a need to devise an efficient means of caring for these patients. We previously reported that a hospitalist service can decrease time to surgery and shorten length of stay without affecting the number of inpatient deaths or 30‐day readmissions of patients undergoing hip fracture surgery.9 However, one concern with reducing length of stay and time to surgery in the high‐risk hip fracture patient population is the effect on long‐term mortality because the death rate following hip fracture repair may be as high as 43% after 1 year.10 To evaluate this important issue, we assessed mortality over a 1‐year period in the same cohort of patients previously described.9 We also identified predictors associated with mortality. We hypothesized that the expedited surgical treatment and decreased length of stay of a hospitalist‐managed group would not have an adverse effect on 1‐year mortality.

METHODS

Patient Selection

Following approval by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board, we used the Mayo Clinic Surgical Index to identify patients admitted between July 1, 2000, and June 30, 2002, who matched International Classification of Diseases (9th Edition) hip fracture codes.11 These patients were cross‐referenced with those having a primary surgical indication of hip fracture. Patients transferred to our facility more than 72 hours after fracture were excluded from our study. Study patients provided authorization to use their medical records for the purposes of research.

A cohort of 466 patients was identified. For purposes of comparison, patients admitted between July 1, 2000, and June 30, 2001, were deemed to belong to the standard care service, and patients admitted between July 1, 2001, and June 30, 2002, were deemed part of the hospitalist service.

Intervention

Prior to July 2001, Mayo Clinic patients aged 65 and older having surgical repair of a hip fracture were triaged directly to a surgical orthopedic or general medical teaching service. Patients with multiple medical diagnoses were managed initially on a medical teaching service prior to transfer to the operating room. The primary team (medical or surgical) was responsible for the postoperative care of the patient and any orders or consultations required.

After July 1, 2001, these patients were admitted by the orthopedic surgery service and medically comanaged by a hospitalist service, which consisted of a hospitalist physician and 2 allied‐health practitioners. Twelve hospitalists and 12 allied health care professionals cared for patients during the study period. All preoperative and postoperative evaluations, inpatient management decisions, and coordination of outpatient care were performed by the hospitalists. This model of care is similar to one previously studied and published elsewhere.12 A census cap of 20 patients limited the number of patients managed by the hospitalist service. Any overflow of hip fracture patients was triaged directly to a non‐hospitalist‐based primary medical or surgical service as before. Thus, 23 hip fracture patients (10%) admitted after July 1, 2001, were not managed by the hospitalists but are included in this group for an intent‐to‐treat analysis.

Data Collection

Study nurses abstracted all data including admitting diagnoses, demographic features, type and mechanism of hip fracture, admission date and time, American Society of Anesthesia (ASA) class, comorbid medical conditions, medications, all clinical data, and readmission rates. Date of last follow‐up was confirmed using the Mayo Clinic medical record, whereas date and cause of death were obtained from death certificates obtained from state and national sources. Length of stay was defined as the number of days between admission and discharge. Time to surgery was defined in hours as the time from hospital admission to the start of the surgery. Finally, time from surgery to dismissal was defined as the number of days from the initiation of the surgical procedure to the time of dismissal. Thirty‐day readmission was defined as readmission to our hospital within 30 days of discharge date.

Statistical Considerations

Power

The power analysis was based on the end point of survival following surgical repair of hip fracture and primary comparison of patients in the standard care group with those in the hospitalist group. With 236 patients in the standard care group, 230 in the hospitalist group, and 274 observed deaths during the follow‐up period, there was 80% power to detect a hazard ratio of 1.4 or greater as being statistically significant (alpha = 0.05, beta = 0.2).

Analysis

The analysis focused on the end point of survival following surgical repair of hip fracture. In addition to the hospitalist versus standard care service, demographic, baseline clinical, and in‐hospital data were evaluated as potential predictors of survival. Survival rates were estimated using the method of Kaplan and Meier, and relative differences in survival were evaluated using the Cox proportional hazards regression models.13, 14 Potential predictors were analyzed both univariately and in a multivariable model. For the multivariable model, initial variable selection was accomplished using stepwise selection, backward elimination, and recursive partitioning.15 Each method yielded similar results. Bootstrap resampling was then used to confirm the variables selected for each model.16, 17 The threshold of statistical significance was set at P = .05 for all tests. All analyses were conducted in SAS version 8.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and Splus version 6.2.1 (Insightful Corporation, Seattle, WA).

RESULTS

There were 236 patients with hip fractures (50.6%) admitted to the standard care service, and 230 patients (49.4%) admitted to the hospitalist service. As shown in Table 1, the baseline characteristics of the patients admitted to the 2 services did not differ significantly except that a greater proportion of patients with hypoxia were admitted to the hospitalist service (11.3% vs. 5.5%; P = .02). However, time to surgery, postsurgery stay, and overall length of hospitalization of the hospitalist‐treated patients were all significantly shorter.

| Patient characteristic | Standard care n = 236 | Hospitalist care n = 230 | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Age (years) | 82 | 83 | .34 | ||

| Female sex | 171 | 72.5% | 163 | 70.9% | .70 |

| Comorbidity | |||||

| Coronary artery disease | 69 | 29.2% | 77 | 33.5% | .32 |

| Congestive heart failure | 41 | 17.4% | 49 | 21.3% | .28 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 36 | 15.3% | 38 | 16.5% | .71 |

| Cerebral vascular accident or transient ischemic attack | 36 | 15.3% | 50 | 21.7% | .07 |

| Dementia | 54 | 22.9% | 62 | 27.0% | .31 |

| Diabetes | 45 | 19.1% | 46 | 20.0% | .80 |

| Renal insufficiency | 17 | 7.2% | 17 | 7.4% | .94 |

| Residence at time of admission | .07 | ||||

| Home | 149 | 63.1% | 138 | 60.0% | |

| Assisted living | 32 | 13.6% | 42 | 18.3% | |

| Nursing home | 55 | 23.3% | 50 | 21.7% | |

| Ambulatory status at time of admission | .14 | ||||

| Independent | 114 | 48.3% | 89 | 38.7% | |

| Assistive device | 99 | 41.9% | 115 | 50.0% | |

| Personal help | 9 | 3.8% | 16 | 7.0% | |

| Transfer to bed or chair | 9 | 3.8% | 7 | 3.0% | |

| Nonambulatory | 5 | 2.1% | 3 | 1.3% | |

| Signs at time of admission | |||||

| Hypotension | 4 | 1.7% | 3 | 1.3% | > .99 |

| Hypoxia | 13 | 5.5% | 26 | 11.3% | .02 |

| Pulmonary edema | 37 | 15.7% | 29 | 12.6% | .34 |

| Tachycardia | 19 | 8.1% | 25 | 10.9% | .3 |

| Fracture type | .78 | ||||

| Femoral neck | 118 | 50.0% | 118 | 51.3% | |

| Intertrochanteric | 118 | 50.0% | 112 | 48.7% | |

| Mechanism of fracture | .82 | ||||

| Fall | 219 | 92.8% | 212 | 92.2% | |

| Trauma | 1 | 0.4% | 3 | 1.3% | |

| Pathologic | 7 | 3.0% | 6 | 2.6% | |

| Unknown | 9 | 3.8% | 7 | 3.0% | |

| ASA* class | .38 | ||||

| I or II | 33 | 14.0% | 23 | 10.0% | |

| III | 166 | 70.3% | 166 | 72.2% | |

| IV | 37 | 15.7% | 41 | 17.8% | |

| Location discharged to | .07 | ||||

| Home or assisted living | 24 | 10.5% | 13 | 5.9% | |

| Nursing home | 196 | 86.0% | 192 | 87.3% | |

| Another hospital or hospice | 8 | 3.5% | 15 | 6.8% | |

| Time to surgery (hours) | 38 | 25 | .001 | ||

| Time from surgery to discharge (days) | 9 | 7 | .04 | ||

| Length of stay | 10.6 | 8.4 | < .00 | ||

| Readmission rate | 25 | 10.6% | 20 | 8.7% | .49 |

Patients were followed for a median of 4.0 years (range 5 days to 5.6 years), and 192 patients were still alive at the end of follow‐up (April 2006). As illustrated in Figure 1, survival did not differ between the 2 treatment groups (P = .36). Overall survival at 1 year was 70.6% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 66.5%, 74.9%). Survival at 1 year in the standard care group was 70.6% (95% CI: 64.9%, 76.8%), whereas in the hospitalist group, it was 70.5% (95% CI: 64.8%, 76.7%). As delineated in Table 2, cardiovascular causes accounted for 34 deaths (25.6%), with 14 of these in the standard care group and 20 in the hospitalist group; 29 deaths (21.8%) had respiratory causes, 20 in the standard care group and 9 in the hospitalist group; and 17 (12.8%) were due to cancer, with 7 and 10 in the standard care and hospitalist groups, respectively. Unknown causes accounted for 21 cases, or 15.8% of total deaths.

| Standard care | Hospitalist care | Total No. of deaths | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer | 7 | 10 | 17 | 12.8% |

| Cardiovascular | 14 | 20 | 34 | 25.6% |

| Infectious | 5 | 4 | 9 | 6.8% |

| Neurological | 5 | 10 | 15 | 11.3% |

| Other | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1.5% |

| Renal | 4 | 2 | 6 | 4.5% |

| Respiratory | 20 | 9 | 29 | 21.8% |

| Unknown | 11 | 10 | 21 | 15.8% |

| Total | 66 | 67 | 133 | 100.0% |

In the univariate analysis, we found 29 variables that were significant predictors of survival (Table 3). A hospitalist model of care was not significantly associated with patient survival, despite the shorter length of stay (8.4 days vs. 10.6 days; P < .001) or expedited time to surgery (25 vs. 38 hours; P < .001), when compared with the standard care group, as previously reported by Phy et al.9 In the multivariable analysis (Table 4), however, the independent predictors of mortality were ASA class III or IV versus class II (hazard ratio [HR] 4.20; 95% CI: 2.21, 7.99), admission from a nursing home versus from home or assisted living (HR 2.24; 95% CI: 1.73, 2.90), and inpatient complications, which included patients requiring admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) and those who had a myocardial infarction or acute renal failure as an inpatient (HR 1.85; 95% CI: 1.45, 2.35). Even after adjusting for these factors, survival following hip fracture did not differ significantly between the hospitalist care patients and the standard care patients (HR 1.16; 95% CI: 0.91, 1.48).

| Variable | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Age on admission per 10 years | 1.41 (1.20, 1.65) | < .001 |

| ASA* II | 1.0 (referent) | |

| ASA* III | 5.27 (2.79, 9.96) | < .001 |

| ASA* IV | 11.7 (5.97, 22.9) | < .001 |

| History of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1.82 (1.35, 2.43) | < .001 |

| History of renal insufficiency | 2.40 (1.62,3.55) | < .001 |

| History of stroke/transient ischemic attack | 1.46 (1.10, 1.95) | .01 |

| History of diabetes | 1.70 (1.29,2.25) | < .001 |

| History of congestive heart failure | 2.26 (1.73, 2.96) | < .001 |

| History of coronary artery disease | 1.53 (1.20, 1.97) | < .001 |

| History of dementia | 2.02 (1.57, 2.59) | < .001 |

| Admission from home | 1.0 (referent) | |

| Admission from assisted living | 1.47 (1.06, 2.04) | .02 |

| Admission from nursing home | 3.04 (2.33, 3.98) | < .001 |

| Independent | 1.0 (referent) | |

| Use of assistive device | 1.81 (1.39, 2.36) | < .001 |

| Personal help | 3.49 (2.16, 5.64) | < .001 |

| Nonambulatory | 3.96 (2.47, 6.35) | < .001 |

| Crackles on admission | 2.03 (1.50, 2.74) | < .001 |

| Hypoxia on admission | 1.56 (1.04, 2.32) | .03 |

| Hypotension on admission | 6.21 (2.72, 14.2) | < .001 |

| Tachycardia on admission | 1.66 (1.15, 2.41) | .007 |

| Coumadin on admission | 1.57 (1.13, 2.18) | .007 |

| Confusion/unconsciousness on admission | 2.23 (1.74, 2.87) | < .001 |

| Fever on admission | 1.98 (1.16, 3.40) | .01 |

| Tachypnea on admission | 1.95 (1.39, 2.72) | < .001 |

| Inpatient myocardial Infarction | 3.59 (2.35, 5.48) | < .001 |

| Inpatient atrial fibrillation | 2.00 (1.37, 2.92) | < .001 |

| Inpatient congestive heart failure | 2.62 (1.79, 3.84) | < .0001 |

| Inpatient delirium | 1.46 (1.13, 1.90) | < .005 |

| Inpatient lung infection | 2.52 (1.85, 3.42) | < .001 |

| Inpatient respiratory failure | 2.76 (1.64, 4.66) | < .001 |

| Inpatient mechanical ventilation | 2.56 (1.43, 4.57) | .002 |

| Inpatient renal failure | 3.60 (1.97, 6.61) | < .001 |

| Days from admission to surgery | 1.06 (1.005, 1.12) | .03 |

| Intensive care unit stay | 1.93 (1.51, 2.47) | < .001 |

| Variable | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Age on admission per 10 years | 1.17 (0.99, 1.38) | .07 |

| ASA* class III or IV | 4.20 (2.21, 7.99) | < .001 |

| ASA* class II | 1.0 (referent) | |

| Admission from nursing home | 2.24 (1.73, 2.90) | < .001 |

| Admission from home or assisted living | 1.0 (referent) | |

| Inpatient myocardial infarction, inpatient acute renal failure, or intensive care unit stay | 1.85 (1.45, 2.35) | < .001 |

| No inpatient myocardial infarction, no inpatient acute renal failure, and no intensive care unit stay | 1.0 (referent) | |

DISCUSSION

In our previous study, length of stay and time to surgery were significantly lower in a hospitalist care model.9 The present study shows that neither the reduced length of stay nor the shortened time to surgery of patients managed by the hospitalist group was associated with a difference in mortality compared with a standard care group, despite significantly improved efficiency and processes of care. Thus, our results refute initial concerns of increased mortality in a hospitalist model of care.

Delivery of perioperative medical care to hip fracture patients by hospitalists is associated with significant decreases in time to surgery and length of stay compared with standard care, with no differences in short‐term mortality.9, 18 Although there have been conflicting reports on the impact of length of stay and time to surgery on long‐term outcomes, our findings support previous results that decreased time to surgery was not associated with an observable effect on mortality.1923 A recent study by Orosz et al. that evaluated 1178 patients showed that earlier hip fracture surgery (performed less than 24 hours after admission) was not associated with reduced mortality, although it was associated with shorter length of stay.19 Our study also corroborates the results of an examination of 8383 hip fracture patients by Grimes et al., who found that time to surgery between 24 and 48 hours after admission had no effect on either 30‐day or long‐term mortality compared with that of those who underwent surgery between 48 and 72 hours, between 72 and 96 hours, or more than 96 hours after admission.20 However, both these results and our own are contrary to those of Gdalevich, whose study of 651 patients found that 1‐year mortality was 1.6‐fold higher for those whose hip fracture repair was postponed more than 48 hours.21 However, time to surgery in both the standard care and hospitalist model in our study was well below the 48‐hour cutoff, suggesting that operating anywhere within the normally accepted 48‐hour time frame may not influence long‐term mortality.

Because of the small number of events in both groups, we were unable to specifically compare whether a hospitalist model of care has any specific impact on long‐term cause of death. Although causes of death of patients with hip fracture were consistent with those of previous studies,10, 24 our death rate at 1 year, 29.4%, was higher than that seen among similar population groups at tertiary referral centers.19, 20, 2429 This is most likely a result of the cohort having a high proportion of nursing home patients (22%)19, 24, 26 transferred for evaluation to St. Mary's Hospital, which serves most of Olmsted County, Minnesota. This hospital also has some characteristics of a community‐based hospital, as it is where greater than 95% of all county patients receive care for surgical repair of hip fracture. Mortality rates are often higher at these types of hospitals.30 Previous studies using patients from Olmsted County indicate results can also be extrapolated to a large part of the U.S. population.31 In Pitto et al.'s study, the risk of death was 31% lower in those admitted from home than for those admitted from a nursing home.32 The latter patients normally have a higher number of comorbid conditions and tend to be less ambulatory than those in a community home‐dwelling setting. Our study also demonstrated that admission from a nursing home was a strong predictor of mortality for up to 1 year in the geriatric population. This may reflect the inherent decreased survival in this patient group, which is in agreement with the findings of other studies that showed inactivity and decreased ambulation prior to fracture were associated with increased mortality.3335

Multiple comorbidities, commonly seen in a geriatric population, translate into a higher ASA class and an increased risk of significant in‐hospital complications. Our study confirmed the findings of previous studies that a higher ASA class is a strong predictor of mortality,21, 26, 30, 3537 independent of decreased time to surgery.38 We also noted that significant in‐hospital complications, including renal failure, respiratory failure, and myocardial infarction, are documented predictors of mortality after hip fracture.27 Although mortality may vary depending on fracture type (femoral neck vs. intertrochanteric),3941 these differences were not observed in our study, in line with the results of previous published studies.37, 42 Controlling for age and comorbidities may be why an association was not found between fracture type and mortality. Finally, in a model containing comorbidity, ASA class, and nursing home residence prior to fracture, age was not a significant predictor of mortality.

Our study had a number of limitations. First, this was a retrospective cohort study based on chart review, so some data may have been subject to recording bias, and this might have differed between the serial models. Because of the retrospective nature of the study and referral of some of the patients from outside the community, our 1‐year follow‐up was not complete, but approached a respectable 93%. Other studies have described the benefits derived by a hospitalist practice only following the first year of its implementation, likely because of the hospitalist learning curve.43, 44 This may be why there was no difference in mortality between the standard care and hospitalist groups, as the latter was only in its first year of existence. Additional longitudinal study is required to find out if mortality differences emerge between the treatment groups. Furthermore, although in‐hospital care may influence short‐term outcomes, its effect on long‐term mortality has been unclear. Our data demonstrate that even though a hospitalist service can shorten length of stay and time to surgery, there were no appreciable intermediate differences in mortality at 1 year. Further prospective studies are needed to determine whether this medical‐surgical partnership in caring for these patients provides more favorable outcomes of reducing mortality and intercurrent complications.

Acknowledgements

We thank Donna K. Lawson for her assistance in data collection and management.

Because the incidence of hip fracture increases dramatically with age and the elderly are the fastest‐growing portion of the United States population, the number of hip fractures is expected to triple by 2040.1 With the associated increase in postoperative morbidity and mortality, the costs will likely exceed $16‐$20 billion annually.15 Already by 2002, the number of patients with hip fractures exceeded 340,000 in this country, resulting in $8.6 billion in health care expenditures from in‐hospital and posthospital costs.68 This makes hip fracture a serious public health concern and triggers a need to devise an efficient means of caring for these patients. We previously reported that a hospitalist service can decrease time to surgery and shorten length of stay without affecting the number of inpatient deaths or 30‐day readmissions of patients undergoing hip fracture surgery.9 However, one concern with reducing length of stay and time to surgery in the high‐risk hip fracture patient population is the effect on long‐term mortality because the death rate following hip fracture repair may be as high as 43% after 1 year.10 To evaluate this important issue, we assessed mortality over a 1‐year period in the same cohort of patients previously described.9 We also identified predictors associated with mortality. We hypothesized that the expedited surgical treatment and decreased length of stay of a hospitalist‐managed group would not have an adverse effect on 1‐year mortality.

METHODS

Patient Selection

Following approval by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board, we used the Mayo Clinic Surgical Index to identify patients admitted between July 1, 2000, and June 30, 2002, who matched International Classification of Diseases (9th Edition) hip fracture codes.11 These patients were cross‐referenced with those having a primary surgical indication of hip fracture. Patients transferred to our facility more than 72 hours after fracture were excluded from our study. Study patients provided authorization to use their medical records for the purposes of research.

A cohort of 466 patients was identified. For purposes of comparison, patients admitted between July 1, 2000, and June 30, 2001, were deemed to belong to the standard care service, and patients admitted between July 1, 2001, and June 30, 2002, were deemed part of the hospitalist service.

Intervention

Prior to July 2001, Mayo Clinic patients aged 65 and older having surgical repair of a hip fracture were triaged directly to a surgical orthopedic or general medical teaching service. Patients with multiple medical diagnoses were managed initially on a medical teaching service prior to transfer to the operating room. The primary team (medical or surgical) was responsible for the postoperative care of the patient and any orders or consultations required.

After July 1, 2001, these patients were admitted by the orthopedic surgery service and medically comanaged by a hospitalist service, which consisted of a hospitalist physician and 2 allied‐health practitioners. Twelve hospitalists and 12 allied health care professionals cared for patients during the study period. All preoperative and postoperative evaluations, inpatient management decisions, and coordination of outpatient care were performed by the hospitalists. This model of care is similar to one previously studied and published elsewhere.12 A census cap of 20 patients limited the number of patients managed by the hospitalist service. Any overflow of hip fracture patients was triaged directly to a non‐hospitalist‐based primary medical or surgical service as before. Thus, 23 hip fracture patients (10%) admitted after July 1, 2001, were not managed by the hospitalists but are included in this group for an intent‐to‐treat analysis.

Data Collection

Study nurses abstracted all data including admitting diagnoses, demographic features, type and mechanism of hip fracture, admission date and time, American Society of Anesthesia (ASA) class, comorbid medical conditions, medications, all clinical data, and readmission rates. Date of last follow‐up was confirmed using the Mayo Clinic medical record, whereas date and cause of death were obtained from death certificates obtained from state and national sources. Length of stay was defined as the number of days between admission and discharge. Time to surgery was defined in hours as the time from hospital admission to the start of the surgery. Finally, time from surgery to dismissal was defined as the number of days from the initiation of the surgical procedure to the time of dismissal. Thirty‐day readmission was defined as readmission to our hospital within 30 days of discharge date.

Statistical Considerations

Power

The power analysis was based on the end point of survival following surgical repair of hip fracture and primary comparison of patients in the standard care group with those in the hospitalist group. With 236 patients in the standard care group, 230 in the hospitalist group, and 274 observed deaths during the follow‐up period, there was 80% power to detect a hazard ratio of 1.4 or greater as being statistically significant (alpha = 0.05, beta = 0.2).

Analysis

The analysis focused on the end point of survival following surgical repair of hip fracture. In addition to the hospitalist versus standard care service, demographic, baseline clinical, and in‐hospital data were evaluated as potential predictors of survival. Survival rates were estimated using the method of Kaplan and Meier, and relative differences in survival were evaluated using the Cox proportional hazards regression models.13, 14 Potential predictors were analyzed both univariately and in a multivariable model. For the multivariable model, initial variable selection was accomplished using stepwise selection, backward elimination, and recursive partitioning.15 Each method yielded similar results. Bootstrap resampling was then used to confirm the variables selected for each model.16, 17 The threshold of statistical significance was set at P = .05 for all tests. All analyses were conducted in SAS version 8.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and Splus version 6.2.1 (Insightful Corporation, Seattle, WA).

RESULTS

There were 236 patients with hip fractures (50.6%) admitted to the standard care service, and 230 patients (49.4%) admitted to the hospitalist service. As shown in Table 1, the baseline characteristics of the patients admitted to the 2 services did not differ significantly except that a greater proportion of patients with hypoxia were admitted to the hospitalist service (11.3% vs. 5.5%; P = .02). However, time to surgery, postsurgery stay, and overall length of hospitalization of the hospitalist‐treated patients were all significantly shorter.

| Patient characteristic | Standard care n = 236 | Hospitalist care n = 230 | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Age (years) | 82 | 83 | .34 | ||

| Female sex | 171 | 72.5% | 163 | 70.9% | .70 |

| Comorbidity | |||||

| Coronary artery disease | 69 | 29.2% | 77 | 33.5% | .32 |

| Congestive heart failure | 41 | 17.4% | 49 | 21.3% | .28 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 36 | 15.3% | 38 | 16.5% | .71 |

| Cerebral vascular accident or transient ischemic attack | 36 | 15.3% | 50 | 21.7% | .07 |

| Dementia | 54 | 22.9% | 62 | 27.0% | .31 |

| Diabetes | 45 | 19.1% | 46 | 20.0% | .80 |

| Renal insufficiency | 17 | 7.2% | 17 | 7.4% | .94 |

| Residence at time of admission | .07 | ||||

| Home | 149 | 63.1% | 138 | 60.0% | |

| Assisted living | 32 | 13.6% | 42 | 18.3% | |

| Nursing home | 55 | 23.3% | 50 | 21.7% | |

| Ambulatory status at time of admission | .14 | ||||

| Independent | 114 | 48.3% | 89 | 38.7% | |

| Assistive device | 99 | 41.9% | 115 | 50.0% | |

| Personal help | 9 | 3.8% | 16 | 7.0% | |

| Transfer to bed or chair | 9 | 3.8% | 7 | 3.0% | |

| Nonambulatory | 5 | 2.1% | 3 | 1.3% | |

| Signs at time of admission | |||||

| Hypotension | 4 | 1.7% | 3 | 1.3% | > .99 |

| Hypoxia | 13 | 5.5% | 26 | 11.3% | .02 |

| Pulmonary edema | 37 | 15.7% | 29 | 12.6% | .34 |

| Tachycardia | 19 | 8.1% | 25 | 10.9% | .3 |

| Fracture type | .78 | ||||

| Femoral neck | 118 | 50.0% | 118 | 51.3% | |

| Intertrochanteric | 118 | 50.0% | 112 | 48.7% | |

| Mechanism of fracture | .82 | ||||

| Fall | 219 | 92.8% | 212 | 92.2% | |

| Trauma | 1 | 0.4% | 3 | 1.3% | |

| Pathologic | 7 | 3.0% | 6 | 2.6% | |

| Unknown | 9 | 3.8% | 7 | 3.0% | |

| ASA* class | .38 | ||||

| I or II | 33 | 14.0% | 23 | 10.0% | |

| III | 166 | 70.3% | 166 | 72.2% | |

| IV | 37 | 15.7% | 41 | 17.8% | |

| Location discharged to | .07 | ||||

| Home or assisted living | 24 | 10.5% | 13 | 5.9% | |

| Nursing home | 196 | 86.0% | 192 | 87.3% | |

| Another hospital or hospice | 8 | 3.5% | 15 | 6.8% | |

| Time to surgery (hours) | 38 | 25 | .001 | ||

| Time from surgery to discharge (days) | 9 | 7 | .04 | ||

| Length of stay | 10.6 | 8.4 | < .00 | ||

| Readmission rate | 25 | 10.6% | 20 | 8.7% | .49 |

Patients were followed for a median of 4.0 years (range 5 days to 5.6 years), and 192 patients were still alive at the end of follow‐up (April 2006). As illustrated in Figure 1, survival did not differ between the 2 treatment groups (P = .36). Overall survival at 1 year was 70.6% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 66.5%, 74.9%). Survival at 1 year in the standard care group was 70.6% (95% CI: 64.9%, 76.8%), whereas in the hospitalist group, it was 70.5% (95% CI: 64.8%, 76.7%). As delineated in Table 2, cardiovascular causes accounted for 34 deaths (25.6%), with 14 of these in the standard care group and 20 in the hospitalist group; 29 deaths (21.8%) had respiratory causes, 20 in the standard care group and 9 in the hospitalist group; and 17 (12.8%) were due to cancer, with 7 and 10 in the standard care and hospitalist groups, respectively. Unknown causes accounted for 21 cases, or 15.8% of total deaths.

| Standard care | Hospitalist care | Total No. of deaths | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer | 7 | 10 | 17 | 12.8% |

| Cardiovascular | 14 | 20 | 34 | 25.6% |

| Infectious | 5 | 4 | 9 | 6.8% |

| Neurological | 5 | 10 | 15 | 11.3% |

| Other | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1.5% |

| Renal | 4 | 2 | 6 | 4.5% |

| Respiratory | 20 | 9 | 29 | 21.8% |

| Unknown | 11 | 10 | 21 | 15.8% |

| Total | 66 | 67 | 133 | 100.0% |

In the univariate analysis, we found 29 variables that were significant predictors of survival (Table 3). A hospitalist model of care was not significantly associated with patient survival, despite the shorter length of stay (8.4 days vs. 10.6 days; P < .001) or expedited time to surgery (25 vs. 38 hours; P < .001), when compared with the standard care group, as previously reported by Phy et al.9 In the multivariable analysis (Table 4), however, the independent predictors of mortality were ASA class III or IV versus class II (hazard ratio [HR] 4.20; 95% CI: 2.21, 7.99), admission from a nursing home versus from home or assisted living (HR 2.24; 95% CI: 1.73, 2.90), and inpatient complications, which included patients requiring admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) and those who had a myocardial infarction or acute renal failure as an inpatient (HR 1.85; 95% CI: 1.45, 2.35). Even after adjusting for these factors, survival following hip fracture did not differ significantly between the hospitalist care patients and the standard care patients (HR 1.16; 95% CI: 0.91, 1.48).

| Variable | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Age on admission per 10 years | 1.41 (1.20, 1.65) | < .001 |

| ASA* II | 1.0 (referent) | |

| ASA* III | 5.27 (2.79, 9.96) | < .001 |

| ASA* IV | 11.7 (5.97, 22.9) | < .001 |

| History of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1.82 (1.35, 2.43) | < .001 |

| History of renal insufficiency | 2.40 (1.62,3.55) | < .001 |

| History of stroke/transient ischemic attack | 1.46 (1.10, 1.95) | .01 |

| History of diabetes | 1.70 (1.29,2.25) | < .001 |

| History of congestive heart failure | 2.26 (1.73, 2.96) | < .001 |

| History of coronary artery disease | 1.53 (1.20, 1.97) | < .001 |

| History of dementia | 2.02 (1.57, 2.59) | < .001 |

| Admission from home | 1.0 (referent) | |

| Admission from assisted living | 1.47 (1.06, 2.04) | .02 |

| Admission from nursing home | 3.04 (2.33, 3.98) | < .001 |

| Independent | 1.0 (referent) | |

| Use of assistive device | 1.81 (1.39, 2.36) | < .001 |

| Personal help | 3.49 (2.16, 5.64) | < .001 |

| Nonambulatory | 3.96 (2.47, 6.35) | < .001 |

| Crackles on admission | 2.03 (1.50, 2.74) | < .001 |

| Hypoxia on admission | 1.56 (1.04, 2.32) | .03 |

| Hypotension on admission | 6.21 (2.72, 14.2) | < .001 |

| Tachycardia on admission | 1.66 (1.15, 2.41) | .007 |

| Coumadin on admission | 1.57 (1.13, 2.18) | .007 |

| Confusion/unconsciousness on admission | 2.23 (1.74, 2.87) | < .001 |

| Fever on admission | 1.98 (1.16, 3.40) | .01 |

| Tachypnea on admission | 1.95 (1.39, 2.72) | < .001 |

| Inpatient myocardial Infarction | 3.59 (2.35, 5.48) | < .001 |

| Inpatient atrial fibrillation | 2.00 (1.37, 2.92) | < .001 |

| Inpatient congestive heart failure | 2.62 (1.79, 3.84) | < .0001 |

| Inpatient delirium | 1.46 (1.13, 1.90) | < .005 |

| Inpatient lung infection | 2.52 (1.85, 3.42) | < .001 |

| Inpatient respiratory failure | 2.76 (1.64, 4.66) | < .001 |

| Inpatient mechanical ventilation | 2.56 (1.43, 4.57) | .002 |

| Inpatient renal failure | 3.60 (1.97, 6.61) | < .001 |

| Days from admission to surgery | 1.06 (1.005, 1.12) | .03 |

| Intensive care unit stay | 1.93 (1.51, 2.47) | < .001 |

| Variable | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Age on admission per 10 years | 1.17 (0.99, 1.38) | .07 |

| ASA* class III or IV | 4.20 (2.21, 7.99) | < .001 |

| ASA* class II | 1.0 (referent) | |

| Admission from nursing home | 2.24 (1.73, 2.90) | < .001 |

| Admission from home or assisted living | 1.0 (referent) | |

| Inpatient myocardial infarction, inpatient acute renal failure, or intensive care unit stay | 1.85 (1.45, 2.35) | < .001 |

| No inpatient myocardial infarction, no inpatient acute renal failure, and no intensive care unit stay | 1.0 (referent) | |

DISCUSSION

In our previous study, length of stay and time to surgery were significantly lower in a hospitalist care model.9 The present study shows that neither the reduced length of stay nor the shortened time to surgery of patients managed by the hospitalist group was associated with a difference in mortality compared with a standard care group, despite significantly improved efficiency and processes of care. Thus, our results refute initial concerns of increased mortality in a hospitalist model of care.

Delivery of perioperative medical care to hip fracture patients by hospitalists is associated with significant decreases in time to surgery and length of stay compared with standard care, with no differences in short‐term mortality.9, 18 Although there have been conflicting reports on the impact of length of stay and time to surgery on long‐term outcomes, our findings support previous results that decreased time to surgery was not associated with an observable effect on mortality.1923 A recent study by Orosz et al. that evaluated 1178 patients showed that earlier hip fracture surgery (performed less than 24 hours after admission) was not associated with reduced mortality, although it was associated with shorter length of stay.19 Our study also corroborates the results of an examination of 8383 hip fracture patients by Grimes et al., who found that time to surgery between 24 and 48 hours after admission had no effect on either 30‐day or long‐term mortality compared with that of those who underwent surgery between 48 and 72 hours, between 72 and 96 hours, or more than 96 hours after admission.20 However, both these results and our own are contrary to those of Gdalevich, whose study of 651 patients found that 1‐year mortality was 1.6‐fold higher for those whose hip fracture repair was postponed more than 48 hours.21 However, time to surgery in both the standard care and hospitalist model in our study was well below the 48‐hour cutoff, suggesting that operating anywhere within the normally accepted 48‐hour time frame may not influence long‐term mortality.

Because of the small number of events in both groups, we were unable to specifically compare whether a hospitalist model of care has any specific impact on long‐term cause of death. Although causes of death of patients with hip fracture were consistent with those of previous studies,10, 24 our death rate at 1 year, 29.4%, was higher than that seen among similar population groups at tertiary referral centers.19, 20, 2429 This is most likely a result of the cohort having a high proportion of nursing home patients (22%)19, 24, 26 transferred for evaluation to St. Mary's Hospital, which serves most of Olmsted County, Minnesota. This hospital also has some characteristics of a community‐based hospital, as it is where greater than 95% of all county patients receive care for surgical repair of hip fracture. Mortality rates are often higher at these types of hospitals.30 Previous studies using patients from Olmsted County indicate results can also be extrapolated to a large part of the U.S. population.31 In Pitto et al.'s study, the risk of death was 31% lower in those admitted from home than for those admitted from a nursing home.32 The latter patients normally have a higher number of comorbid conditions and tend to be less ambulatory than those in a community home‐dwelling setting. Our study also demonstrated that admission from a nursing home was a strong predictor of mortality for up to 1 year in the geriatric population. This may reflect the inherent decreased survival in this patient group, which is in agreement with the findings of other studies that showed inactivity and decreased ambulation prior to fracture were associated with increased mortality.3335

Multiple comorbidities, commonly seen in a geriatric population, translate into a higher ASA class and an increased risk of significant in‐hospital complications. Our study confirmed the findings of previous studies that a higher ASA class is a strong predictor of mortality,21, 26, 30, 3537 independent of decreased time to surgery.38 We also noted that significant in‐hospital complications, including renal failure, respiratory failure, and myocardial infarction, are documented predictors of mortality after hip fracture.27 Although mortality may vary depending on fracture type (femoral neck vs. intertrochanteric),3941 these differences were not observed in our study, in line with the results of previous published studies.37, 42 Controlling for age and comorbidities may be why an association was not found between fracture type and mortality. Finally, in a model containing comorbidity, ASA class, and nursing home residence prior to fracture, age was not a significant predictor of mortality.

Our study had a number of limitations. First, this was a retrospective cohort study based on chart review, so some data may have been subject to recording bias, and this might have differed between the serial models. Because of the retrospective nature of the study and referral of some of the patients from outside the community, our 1‐year follow‐up was not complete, but approached a respectable 93%. Other studies have described the benefits derived by a hospitalist practice only following the first year of its implementation, likely because of the hospitalist learning curve.43, 44 This may be why there was no difference in mortality between the standard care and hospitalist groups, as the latter was only in its first year of existence. Additional longitudinal study is required to find out if mortality differences emerge between the treatment groups. Furthermore, although in‐hospital care may influence short‐term outcomes, its effect on long‐term mortality has been unclear. Our data demonstrate that even though a hospitalist service can shorten length of stay and time to surgery, there were no appreciable intermediate differences in mortality at 1 year. Further prospective studies are needed to determine whether this medical‐surgical partnership in caring for these patients provides more favorable outcomes of reducing mortality and intercurrent complications.

Acknowledgements

We thank Donna K. Lawson for her assistance in data collection and management.

- ,,.The future of hip fractures in the United States. Numbers, costs, and potential effects of postmenopausal estrogen.Clin Orthop Relat Res1990 (252):163–166.

- ,,.Hip fractures in the elderly: a world‐wide projection.Osteoporos Int.1992;2:285–289.

- ,,,.The economic cost of hip fractures among elderly women. A one‐year, prospective, observational cohort study with matched‐pair analysis.Belgian Hip Fracture Study Group.J Bone Joint Surg Am.2001;83‐A:493–500.

- ,,.Estimating hip fracture morbidity, mortality and costs.J Am Geriatr Soc.2003;51:364–370.

- ,.The aging of America. Impact on health care costs.JAMA.1990;263:2335–2340.

- ,,,.Medical expenditures for the treatment of osteoporotic fractures in the United States in 1995: report from the National Osteoporosis Foundation.J Bone Miner Res.1997;12(1):24–35.

- US Department of Health and Human Services.Surveillance for selected public health indicators affecting older adults —United States.MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep1999;48:33–34.

- ,.Epidemiology and outcomes of osteoporotic fractures.Lancet.2002;359:1761–1767.

- ,,, et al.Effects of a hospitalist model on elderly patients with hip fracture.Arch Intern Med.2005;165:796–801.

- ,,.Hip fractures in Finland and Great Britain—a comparison of patient characteristics and outcomes.Int Orthop.2001;25:349–354.

- WHO.International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision (ICD‐9).Geneva, Switzerland:World Health Organization;1977.

- ,,, et al.Medical and surgical comanagement after elective hip and knee arthroplasty: a randomized, controlled trial.Ann Intern Med.2004;141(1):28–38.

- .Regression models and life‐tables (with discussion).J R Stat Soc Ser B.1972;34:187–220.

- ,.Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations.J Am Statistical Assoc.1958;53:457–481.

- ,.An Introduction to Recursive Partitioning using the RPART Routines: Section of Biostatistics, Mayo Clinic;1997.

- .Computer Intensive Statistical Methods, Validation, Model Selection, and Bootstrap.London:Chapman and Hall;1994.

- ,.A bootstrap resampling procedure for model building: application to the Cox regression model.Stat Med.1992;11:2093–2109.

- ,,.Associations between the hospitalist model of care and quality‐of‐care‐related outcomes in patients undergoing hip fracture surgery.Mayo Clin Proc.2006;81(1):28–31.

- ,,, et al.Association of timing of surgery for hip fracture and patient outcomes.JAMA.2004;291:1738–1743.

- ,,,,.The effects of time‐to‐surgery on mortality and morbidity in patients following hip fracture.Am J Med.2002;112:702–709.

- ,,,.Morbidity and mortality after hip fracture: the impact of operative delay.Arch Orthop Trauma Surg.2004;124:334–340.

- ,,.Delay to surgery prolongs hospital stay in patients with fractures of the proximal femur.J Bone Joint Surg Br.2005;87:1123–1126.

- ,.The timing of surgery for proximal femoral fractures.J Bone Joint Surg Br.1992;74(2):203–205.

- ,,, et al.Hospital readmissions after hospital discharge for hip fracture: surgical and nonsurgical causes and effect on outcomes.J Am Geriatr Soc.2003;51:399–403.

- ,.Mortality after hip fractures.Acta Orthop Scand1979;50(2):161–167.

- ,,,,.Medical complications and outcomes after hip fracture repair.Arch Intern Med.2002;162:2053–2057.

- ,,, et al.Development and initial validation of a risk score for predicting in‐hospital and 1‐year mortality in patients with hip fractures.J Bone Miner Res.2005;20:494–500.

- ,,,,.Outcome after hip fracture in individuals ninety years of age and older.J Orthop Trauma.2001;15(1):34–39.

- ,,,.Hip fractures in the elderly: predictors of one year mortality.J Orthop Trauma.1997;11(3):162–165.

- ,,,.The effect of hospital type and surgical delay on mortality after surgery for hip fracture.J Bone Joint Surg Br.2005;87:361–366.

- .History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project.Mayo Clin Proc.1996;71:266–274.

- .The mortality and social prognosis of hip fractures. A prospective multifactorial study.Int Orthop.1994;18(2):109–113.

- ,.Functional outcome after hip fracture. A 1‐year prospective outcome study of 275 patients.Injury.2003;34:529–532.

- ,,.Rate of mortality for elderly patients after fracture of the hip in the 1980's.J Bone Joint Surg Am.1987;69:1335–1340.

- ,,,.Hip fractures in the elderly. Mortality, functional results and social readaptation.Int Surg.1989;74(3):191–194.

- ,,.Blood transfusion requirements in femoral neck fracture.Injury.2000;31(1):7–10.

- ,,.Mortality and causes of death after hip fractures in The Netherlands.Neth J Med.1992;41(1–2):4–10.

- ,,.Influence of preoperative medical status and delay to surgery on death following a hip fracture.ANZ J Surg.2002;72:405–407.

- ,,,Predictors of mortality and institutionalization after hip fracture: the New Haven EPESE cohort. Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly.Am J Public Health.1994;84:1807–1812.

- ,,,.Mortality risk after hip fracture.J Orthop Trauma.2003;17(1):53–56.

- ,,.Thirty‐day mortality following hip arthroplasty for acute fracture.J Bone Joint Surg Am.2004;86‐A:1983–1988.

- ,,,,.Functional outcomes and mortality vary among different types of hip fractures: a function of patient characteristics.Clin Orthop Relat Res.2004:64–71.

- ,,,,,.Implementation of a voluntary hospitalist service at a community teaching hospital: improved clinical efficiency and patient outcomes.Ann Intern Med.2002;137:859–865.

- ,,, et al.Effects of physician experience on costs and outcomes on an academic general medicine service: results of a trial of hospitalists.Ann Intern Med.2002;137:866–874.

- ,,.The future of hip fractures in the United States. Numbers, costs, and potential effects of postmenopausal estrogen.Clin Orthop Relat Res1990 (252):163–166.

- ,,.Hip fractures in the elderly: a world‐wide projection.Osteoporos Int.1992;2:285–289.

- ,,,.The economic cost of hip fractures among elderly women. A one‐year, prospective, observational cohort study with matched‐pair analysis.Belgian Hip Fracture Study Group.J Bone Joint Surg Am.2001;83‐A:493–500.

- ,,.Estimating hip fracture morbidity, mortality and costs.J Am Geriatr Soc.2003;51:364–370.

- ,.The aging of America. Impact on health care costs.JAMA.1990;263:2335–2340.

- ,,,.Medical expenditures for the treatment of osteoporotic fractures in the United States in 1995: report from the National Osteoporosis Foundation.J Bone Miner Res.1997;12(1):24–35.

- US Department of Health and Human Services.Surveillance for selected public health indicators affecting older adults —United States.MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep1999;48:33–34.

- ,.Epidemiology and outcomes of osteoporotic fractures.Lancet.2002;359:1761–1767.

- ,,, et al.Effects of a hospitalist model on elderly patients with hip fracture.Arch Intern Med.2005;165:796–801.

- ,,.Hip fractures in Finland and Great Britain—a comparison of patient characteristics and outcomes.Int Orthop.2001;25:349–354.

- WHO.International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision (ICD‐9).Geneva, Switzerland:World Health Organization;1977.

- ,,, et al.Medical and surgical comanagement after elective hip and knee arthroplasty: a randomized, controlled trial.Ann Intern Med.2004;141(1):28–38.

- .Regression models and life‐tables (with discussion).J R Stat Soc Ser B.1972;34:187–220.

- ,.Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations.J Am Statistical Assoc.1958;53:457–481.

- ,.An Introduction to Recursive Partitioning using the RPART Routines: Section of Biostatistics, Mayo Clinic;1997.

- .Computer Intensive Statistical Methods, Validation, Model Selection, and Bootstrap.London:Chapman and Hall;1994.

- ,.A bootstrap resampling procedure for model building: application to the Cox regression model.Stat Med.1992;11:2093–2109.

- ,,.Associations between the hospitalist model of care and quality‐of‐care‐related outcomes in patients undergoing hip fracture surgery.Mayo Clin Proc.2006;81(1):28–31.

- ,,, et al.Association of timing of surgery for hip fracture and patient outcomes.JAMA.2004;291:1738–1743.

- ,,,,.The effects of time‐to‐surgery on mortality and morbidity in patients following hip fracture.Am J Med.2002;112:702–709.

- ,,,.Morbidity and mortality after hip fracture: the impact of operative delay.Arch Orthop Trauma Surg.2004;124:334–340.

- ,,.Delay to surgery prolongs hospital stay in patients with fractures of the proximal femur.J Bone Joint Surg Br.2005;87:1123–1126.

- ,.The timing of surgery for proximal femoral fractures.J Bone Joint Surg Br.1992;74(2):203–205.

- ,,, et al.Hospital readmissions after hospital discharge for hip fracture: surgical and nonsurgical causes and effect on outcomes.J Am Geriatr Soc.2003;51:399–403.

- ,.Mortality after hip fractures.Acta Orthop Scand1979;50(2):161–167.

- ,,,,.Medical complications and outcomes after hip fracture repair.Arch Intern Med.2002;162:2053–2057.

- ,,, et al.Development and initial validation of a risk score for predicting in‐hospital and 1‐year mortality in patients with hip fractures.J Bone Miner Res.2005;20:494–500.

- ,,,,.Outcome after hip fracture in individuals ninety years of age and older.J Orthop Trauma.2001;15(1):34–39.

- ,,,.Hip fractures in the elderly: predictors of one year mortality.J Orthop Trauma.1997;11(3):162–165.

- ,,,.The effect of hospital type and surgical delay on mortality after surgery for hip fracture.J Bone Joint Surg Br.2005;87:361–366.

- .History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project.Mayo Clin Proc.1996;71:266–274.

- .The mortality and social prognosis of hip fractures. A prospective multifactorial study.Int Orthop.1994;18(2):109–113.

- ,.Functional outcome after hip fracture. A 1‐year prospective outcome study of 275 patients.Injury.2003;34:529–532.

- ,,.Rate of mortality for elderly patients after fracture of the hip in the 1980's.J Bone Joint Surg Am.1987;69:1335–1340.

- ,,,.Hip fractures in the elderly. Mortality, functional results and social readaptation.Int Surg.1989;74(3):191–194.

- ,,.Blood transfusion requirements in femoral neck fracture.Injury.2000;31(1):7–10.

- ,,.Mortality and causes of death after hip fractures in The Netherlands.Neth J Med.1992;41(1–2):4–10.

- ,,.Influence of preoperative medical status and delay to surgery on death following a hip fracture.ANZ J Surg.2002;72:405–407.