User login

Process Improvement for Engaging With Trauma-Focused Evidence-Based Psychotherapy for PTSD

Process Improvement for Engaging With Trauma-Focused Evidence-Based Psychotherapy for PTSD

Trauma-focused evidence-based psychotherapies (TF-EBPs), including cognitive processing therapy (CPT) and prolonged exposure therapy (PE), are recommended treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in clinical practice guidelines.1-3 To increase initiation of these treatments, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) used a large-scale dissemination and implementation effort to improve access to TF-EBP.4,5 These efforts achieved modest success, increasing prevalence of TF-EBP from a handful of veterans in 2004 to an annual prevalence of 14.6% for CPT and 4.3% for PE in 2014.6

Throughout these efforts, qualitative studies have been used to better understand veterans’ perspectives on receiving TF-EBP care.7-18 Barriers to initiation of and engagement in TF-EBP and PTSD care have been identified from these qualitative studies. One identified barrier was lack of knowledge—particularly lack of knowledge about what is meant by a PTSD diagnosis and available treatments.7-10 Stigma (ie, automatic negative associations) toward mental health problems or seeking mental health care also has been identified as a barrier to initiation.7,10-14 Perceptions of poor alignment between treatment and veteran goals, including lack of buy-in for the rationale, served as barriers to initiation and engagement.8,15-18

Using prior qualitative work, numerous initiatives have been developed to reduce stigma, facilitate conversations about how treatment aligns with goals, and fill knowledge gaps, particularly through online resources and shared decision-making.19,20 To better inform the state of veterans’ experiences with TF-EBP, a qualitative investigation was conducted involving veterans who recently initiated TF-EBP. Themes directly related to transitions to TF-EBP were identified; however, all veterans interviewed also described their experiences with TFEBP engagement and mental health care. Consistent with recommendations for qualitative methods, this study extends prior work on transitions to TF-EBP by describing themes with a distinct focus on the experience of engaging with TF-EBP and mental health care.21,22

Methods

The experiences of veterans who were transitioning into TF-EBPs were collected in semistructured interviews and analyzed. The semistructured interview guide was developed and refined in consultation with both qualitative methods experts and PTSD treatment experts to ensure that 6 content domains were appropriately queried: PTSD treatment options, cultural sensitivity of treatment, PTSD treatment selection, transition criteria, beliefs about stabilization treatment, and treatment needs/preferences.

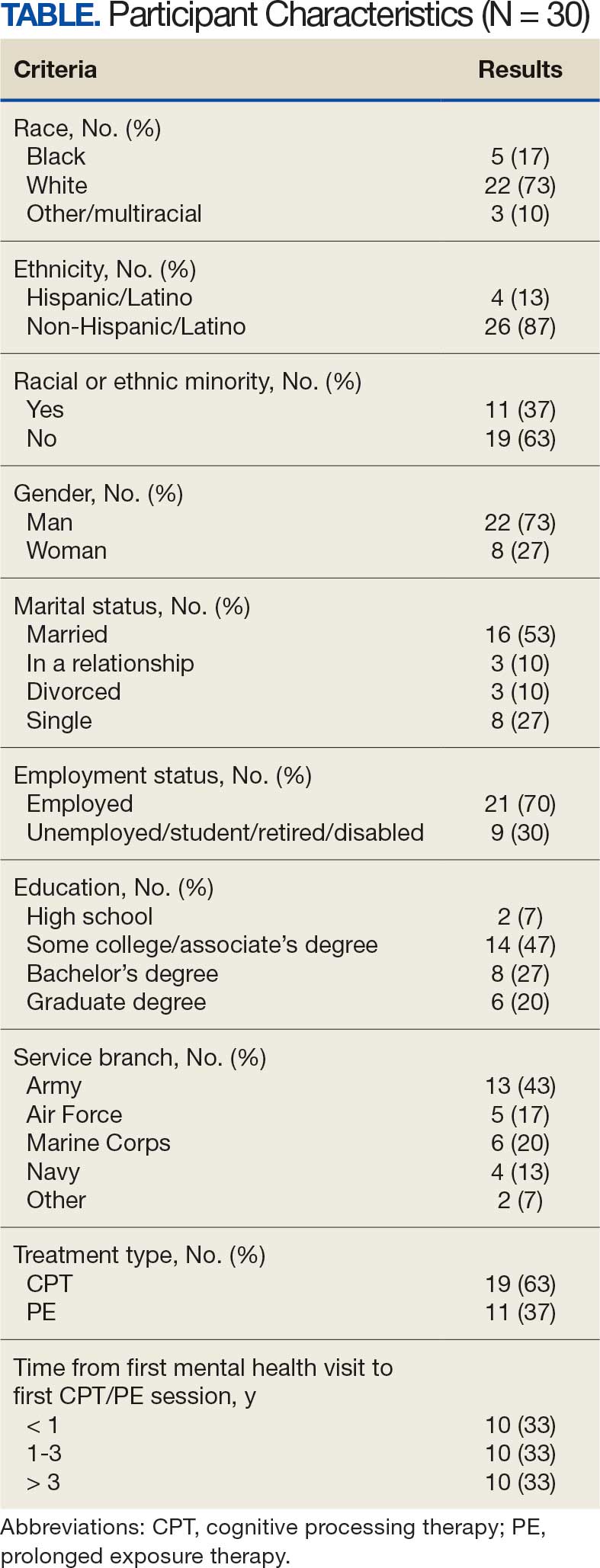

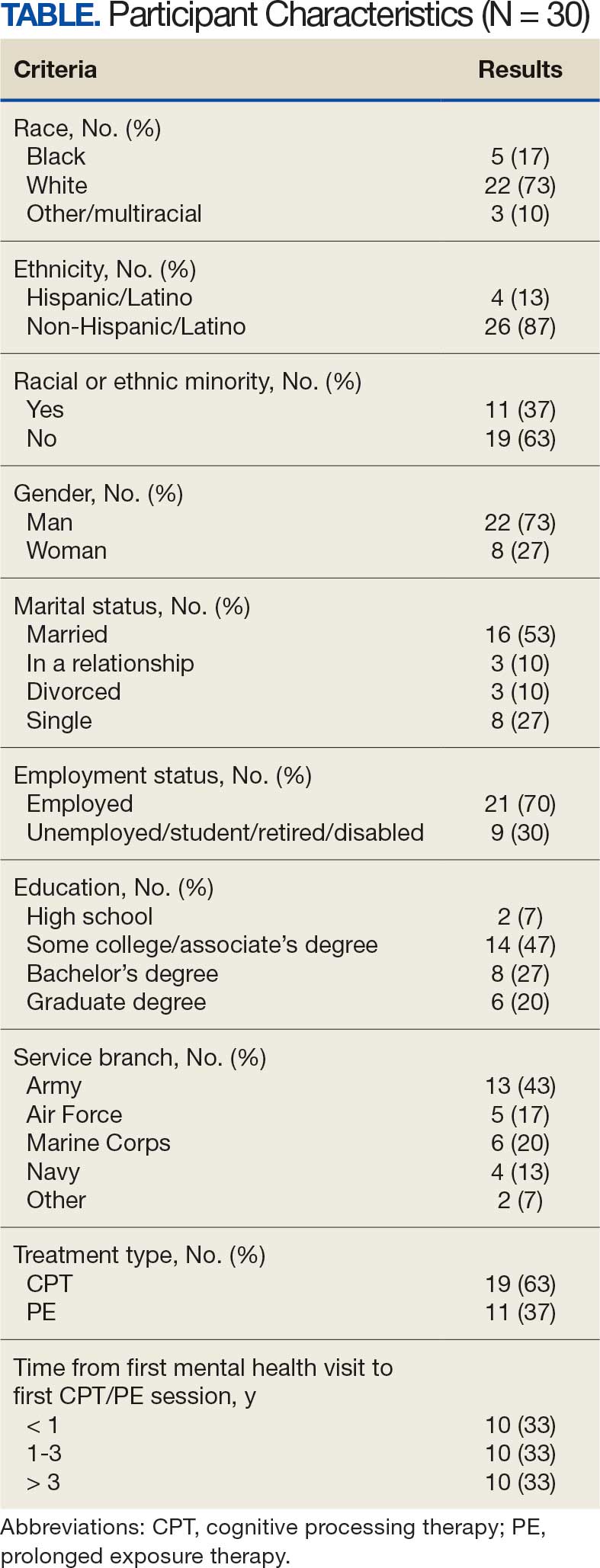

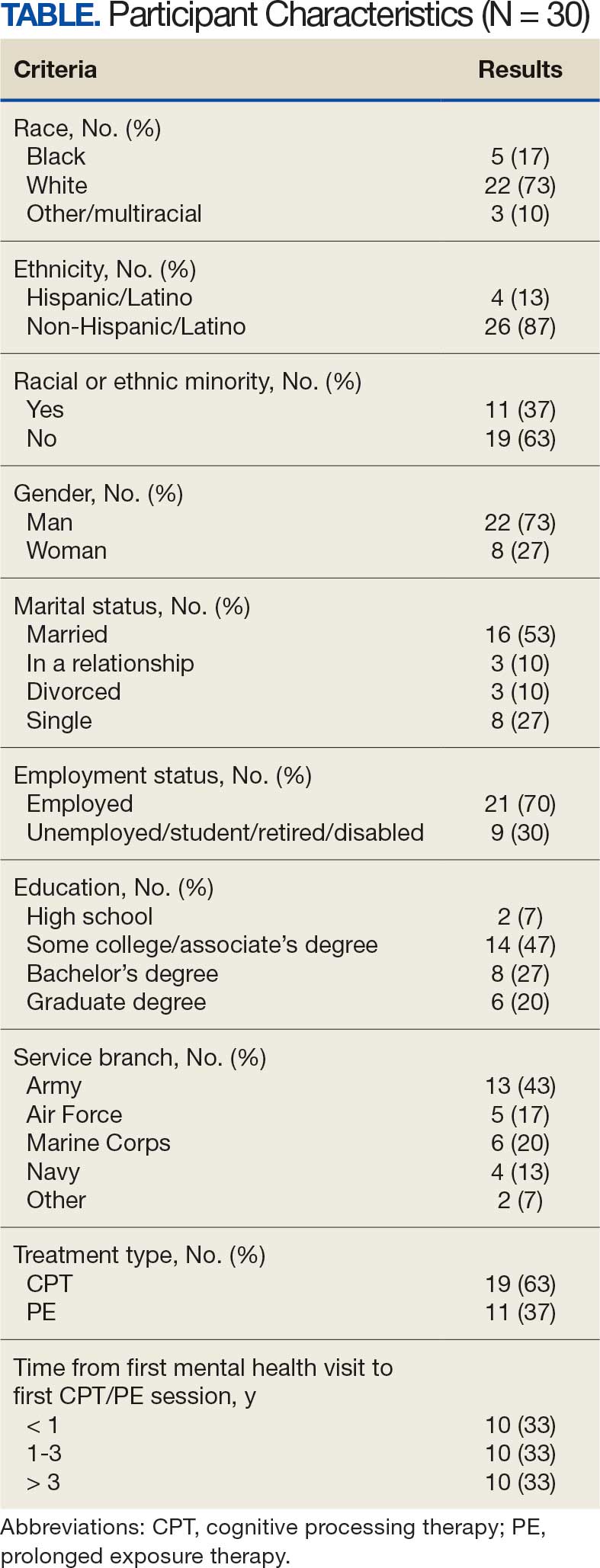

Participants were identified using the VA Corporate Data Warehouse and included post-9/11 veterans who had recently initiated CPT or PE for the first time between September 1, 2021, and September 1, 2022. More details of participant selection are available in Holder et al.21 From a population of 10,814 patients, stratified random sampling generated a recruitment pool of 200 veterans for further outreach. The strata were defined such that this recruitment pool had similar proportions of demographic characteristics (ie, gender, race, ethnicity) to the population of eligible veterans, equivalent distributions of time to CPT or PE initiation (ie, 33.3% < 1 year, 33.3% 1-3 years, and 33.3% > 3 years), and adequate variability in TF-EBP type (ie, 66.7% CPT, 33.3% PE). A manual chart review in the recruitment pool excluded 12 veterans who did not initiate CPT or PE, 1 veteran with evidence of current active psychosis and/or cognitive impairment that would likely preclude comprehension of study materials, and 1 who was deceased.

Eligible veterans from the recruitment pool were contacted in groups of 25. First, a recruitment letter with study information and instructions to opt-out of further contact was mailed or emailed to veterans. After 2 weeks, veterans who had not responded were contacted by phone up to 3 times. Veterans interested in participating were scheduled for a 1-time visit that included verbal consent and the qualitative interview. Metrics were established a priori to ensure an adequately diverse and inclusive sample. Specifically, a minimum number of racial and/or ethnic minority veterans (33%) and women veterans (20%) were sought. Equal distribution across the 3 categories of time from first mental health visit to CPT/PE initiation also was targeted. Throughout enrollment, recruitment efforts were adapted to meet these metrics in the emerging sample. While the goal was to generate a diverse and inclusive sample using these methods, the sample was not intended to be representative of the population.

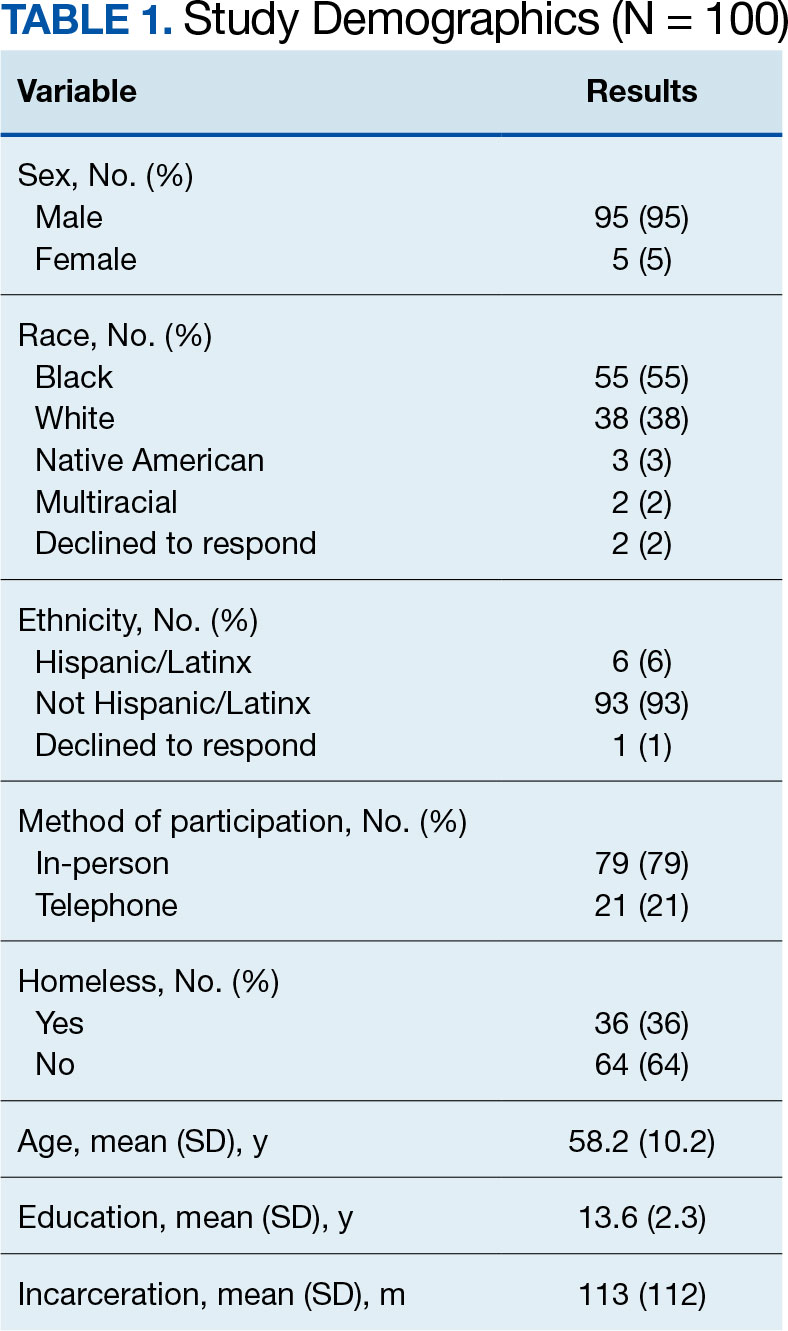

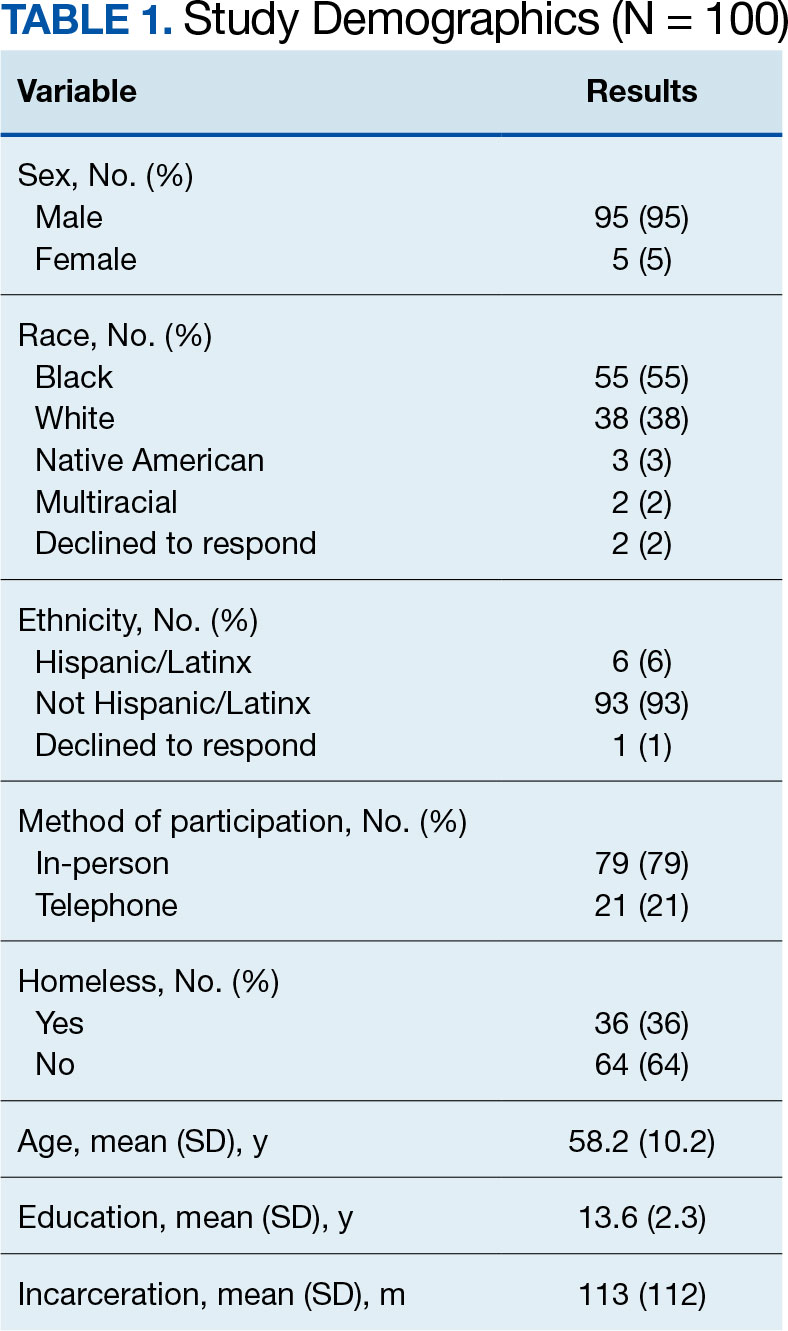

Of the 186 eligible participants, 21 declined participation and 26 could not be reached. The targeted sample was reached after exhausting contact for 47 veterans and contacting 80 veterans for a final response rate of 40% among fully contacted veterans and 27% among veterans with any contact. The final sample included 30 veterans who received CPT or PE in VA facilities (Table).

After veterans provided verbal consent for study participation, sociodemographic information was verbally reported, and a 30- to 60-minute semistructured qualitative phone interview was recorded and transcribed. Veterans received $40 for participation. All procedures were approved by the University of California San Francisco Institutional Review Board.

Qualitative Data Analysis

Rapid analysis procedures were used to analyze qualitative data. This approach is suitable for focused, moderately structured qualitative analyses in health services research and facilitates rapid dissemination to stakeholders.23 The qualitative analysts were 2 clinical psychologists with expertise in PTSD treatment (NH primary and RR secondary). Consistent with rapid analysis procedures, analysts prepared a templated summary (including relevant quotations) of each interview, organized by the prespecified content domains. Interviews were summarized independently, compared to ensure consistency, and discrepancies were resolved through review of the interview source materials. Individual summary templates were combined into a master analytic matrix to facilitate the identification of patterns and delineation of themes. Analysts routinely met to identify, discuss, and refine preliminary themes, revisiting source materials to reach consensus as needed.

Results

Fifteen themes were identified and organized into 2 distinct focus areas: themes directly related to the transition to TF-EBP (8 themes) and themes related to veterans’ experiences with TF-EBP and general mental health care with potential process-improvement implications (7 themes).21 Seven themes were identified related to experiences with TF-EBP engagement and VA mental health care. The 7 themes related to TF-EBP engagement and VA mental health care themes are summarized with exemplary quotations.

Veterans want a better understanding of psychotherapy and engaging with VA mental health. Veterans reported that they generally had a poor or “nebulous” understanding about the experience of psychotherapy. For example, veterans exhibited confusion about whether certain experiences were equivalent to participating in psychotherapy. They were sometimes unable to distinguish between interactions such as assessment, disability evaluations, peer support, and psychotherapy. One veteran described a conversation with a TFEBP therapist about prior treatment:

She [asked], have you ever been, or gone through a therapy to begin with? And I, I said, well I just chatted with somebody. And she said that’s not, that’s not therapy. So, I was like, oh, it’s not? That’s not what people do?

Veterans were surprised the VA offered a diverse range of psychotherapy interventions, rather than simply therapy. They did not realize there were different types of psychotherapy. As a result, veterans were not aware that some VA mental practitioners have specialty training and certification to provide treatment matched to specific diagnoses or needs. They thought that all clinicians could provide the same care. One veteran described their understanding:

I just figured all mental health people are mental health people. I didn’t have a better understanding of the system and all the different levels and how it plays out and specialties and things like that. Which, I guess, I should have because you have a primary care doctor, but then you have specialists in all these other different sectors that specialize in one particular area. I guess that should’ve been common sense, but it wasn’t.

Stigma was a barrier to seeking and engaging in mental health care. Veterans discovered they had to overcome stigma associated with seeking and engaging in mental health treatment. Military culture was often discussed as promoting stigma regarding mental health treatment. Specifically, veterans described that seeking treatment meant “either, I’m weak or I’m gonna be seen as weak.” In active-duty settings, the strategy for dealing with mental health symptoms was to “leave those feelings, you push ‘em aside,” an approach highly inconsistent with TF-EBP. In some cases, incorrect information about the VA and PTSD was presented as part of discharge from the military, leading to long-term skepticism of the VA and PTSD treatment. One veteran described his experience as part of a class on the VA compensation and pension assessment process for service-connected disabilities during his military discharge:

[A fellow discharging soldier asked] what about like PTSD, gettin’ rated for PTSD. I hear they take our weapons and stuff like we can’t own firearms and all that stuff. And [the instructor] was like, well, yes that’s a thing. He didn’t explain it like if you get compensated for PTSD you don’t lose your rights to carry a firearm or to have, to be able to go hunting.

Importantly, veterans often described how other identities (eg, race, ethnicity, gender, region of origin) interacted with military culture to enhance stigma. Hearing messaging from multiple sources reinforced beliefs that mental health treatment is inappropriate or is associated with weakness:

As a first-generation Italian, I was always taught keep your feelings to yourself. Never talk outside your family. Never bring up problems to other people and stuff like that. Same with the military. And then the old stigma working in [emergency medical services] and public safety, you’re weak if you get help.

The fundamentals of therapy, including rapport and flexibility, were important. Veterans valued nonspecific therapy factors, genuine empathy, building trust, being honest about treatment, personality, and rapport. These characteristics were almost universally described as particularly important:

I liked the fact that she made it personable and she cared. It wasn’t just like, here, we’re gonna start this. She explained it in the ways I could understand, not in medical terms, so to speak, but that’s what I liked about her. She really cared about what she did and helping me.

Flexibility was viewed as an asset, particularly when clinicians acknowledged veteran autonomy. A consistent example was when veterans were able to titrate trauma disclosure. One veteran described this flexible treatment experience: “She was right there in the room, she said, you know, at any time, you know, we could stop, we could debrief.”

Experiences of clinician flexibility and personalization of therapy were contrasted with experiences of overly rigid therapy. Overemphasis on protocols created barriers, often because treatment did not feel personalized. One veteran described how a clinician’s task-oriented approach interfered with their ability to engage in TF-EBP:

They listened, but it just didn’t seem like they were listening, because they really wanted to stay on task… So, I felt like if the person was more concerned, or more sympathetic to the things that was also going on in my life at that present time, I think I would’ve felt more comfortable talking about what was the PTSD part, too.

Veterans valued shared decision-making prior to TF-EBP initiation. Veterans typically described being involved in a shared decision-making process prior to initiating TF-EBP. During these sessions, clinicians discussed treatment options and provided veterans with a variety of materials describing treatments (eg, pamphlets, websites, videos, statistics). Most veterans appreciated being able to reflect on and discuss treatment options with their clinicians. Being given time in and out of session to review was viewed as valuable and increased confidence in treatment choice. One veteran described their experience:

I was given the information, you know, they gave me handouts, PDFs, whatever was available, and let me read over it. I didn’t have to choose anything right then and there, you know, they let me sleep on it. And I got back to them after some thought.

However, some veterans felt overwhelmed by being presented with too much information and did not believe they knew enough to make a final treatment decision. One veteran described being asked to contribute to the treatment decision:

I definitely asked [the clinician] to weigh in on maybe what he thought was best, because—I mean, I don’t know… I’m not necessarily sure I know what I think is best. I think we’re just lucky I’m here, so if you can give me a solid and help me out here by telling me just based on what I’ve said to you and the things that I’ve gone through, what do you think?

Veterans who perceived that their treatment preferences were respected had a positive outlook on TF-EBP. As part of the shared-decision making process, veterans typically described being given choices among PTSD treatments. One way that preferences were respected was through clinicians tailoring treatment descriptions to a veteran’s unique symptoms, experiences, and values. In these cases, clinicians observed specific concerns and clearly linked treatment principles to those concerns. For example, one veteran described their clinician’s recommendation for PE: “The hardest thing for me is to do the normal things like grocery store or getting on a train or anything like that. And so, he suggested that [PE] would be a good idea.”

In other cases, veterans wanted the highest quality of treatment rather than a match between treatment principles and the veteran’s presentation, goals, or strengths. These veterans wanted the best treatment available for PTSD and valued research support, recommendations from clinical practice guidelines, or clinician confidence in the effectiveness of the treatment. One veteran described this perspective:

I just wanted to be able to really tackle it in the best way possible and in the most like aggressive way possible. And it seemed like PE really was going to, they said that it’s a difficult type of therapy, but I really just wanted to kind of do the best that I could to eradicate some of the issues that I was having.

When veterans perceived a lack of respect for their preferences, they were hesitant about TF-EBP. For some veterans, a generic pitch for a TF-EBP was detrimental in the absence of the personal connection between the treatment and their own symptoms, goals, or strengths. These veterans did not question whether the treatment was effective in general but did question whether the treatment was best for them. One veteran described the contrast between their clinician’s perspective and their own.

I felt like they felt very comfortable, very confident in [CPT] being the program, because it was comfortable for them. Because they did it several times. And maybe they had a lot of success with other individuals... but they were very comfortable with that one, as a provider, more than: Is this the best fit for [me]?

Some veterans perceived little concern for their preferences and a lack of choice in available treatments, which tended to perpetuate negative perceptions of TFEBP. These veterans described their lack of choices with frustration. Alternatives to TFEBP were described by these veterans as so undesirable that they did not believe they had a real choice:

[CPT] was the only decision they had. There was nothing else for PTSD. They didn’t offer anything else. So, I mean it wasn’t a decision. It was either … take treatment or don’t take treatment at all… Actually, I need to correct myself. So, there were 2 options, group therapy or CPT. I forgot about that. I’m not a big group guy so I chose the CPT.

Another veteran was offered a choice between therapeutic approaches, but all were delivered via telehealth (consistent with the transition to virtual services during the COVID-19 pandemic). For this veteran, not only was the distinction between approaches unclear, but the choice between approaches was unimportant compared to the mode of delivery.

This happened during COVID-19 and VA stopped seeing anybody physically, face-to-face. So my only option for therapy was [telehealth]… There was like 3 of them, and I tried to figure out, you know, from the layperson’s perspective, like: I don’t know which one to go with.

Veterans wanted to be asked about their cultural identity. Veterans valued when clinicians asked questions about cultural identity as part of their mental health treatment and listened to their cultural context. Cultural identity factors extended beyond factors such as race, ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation to religion, military culture, and regionality. Veterans often described situations where they wished clinicians would ask the question or initiate conversations about culture. A veteran highlighted the importance of their faith but noted that it was a taboo topic. Their clinician did not say “we don’t go there,” but they “never dove into it either.” Another veteran expressed a desire for their clinician to ask questions about experiences in the National Guard and as an African American veteran:

If a provider was to say like: Oh, you know, it’s a stressful situation being a part of the military, being in the National Guard. You know, just asking questions about that. I think that would really go a long way… Being African American was difficult as well. And more so because of my region, I think… I felt like it would probably be an uncomfortable subject to speak on… I mean, it wasn’t anything that my providers necessarily did, it was more so just because it wasn’t brought up.

One common area of concern for veterans was a match between veteran and therapist demographics. When asked about how their cultural identity influenced treatment, several veterans described the relevance of therapist match. Much like questions about their own cultural identity, veterans valued being asked about identity preferences in clinicians (eg, gender or race matching), rather than having to bring up the preference themselves. One veteran described relief at this question being asked directly: “I was relieved when she had asked [whether I wanted a male or female clinician] primarily because I was going to ask that or bring that up somehow. But her asking that before me was a weight off my shoulders.”

Discussing cultural identity through treatment strengthened veterans’ engagement in therapy. Many veterans appreciated when analogies used in therapy were relevant to their cultural experiences and when clinicians understood their culture (eg, military culture, race, ethnicity, religious beliefs, sexual orientation). One veteran described how their clinician understood military culture and made connections between military culture and the rationale for TF-EBP, which strengthened the veteran’s buy-in for the treatment and alliance with the clinician:

At the beginning when she was explaining PTSD, and I remember she said that your brain needed to think this way when you were in the military because it was a way of protecting and surviving, so your brain was doing that in order for you to survive in whatever areas you were because there was danger. So, your brain had you thinking that way. But now, you’re not in those situations anymore. You’re not in danger. You’re not in the military, but your brain is still thinking you are, and that’s what PTSD generally does to you.

Specific elements of TF-EBP also provided opportunities to discuss and integrate important aspects of identity. This is accomplished in PE by assigning relevant in vivo exercises. In CPT, “connecting the dots” on how prior experiences influenced trauma-related stuck points achieved this element. One veteran described their experience with a clinician who was comfortable discussing the veteran’s sexual orientation and recognized the impacts of prior trauma on intimacy:

They’re very different, and there’s a lot of things that can be accepted in gay relationships that are not in straight ones. With all that said, I think [the PE therapist] did a fantastic job being not—like never once did she laugh or make an uncomfortable comment or say she didn’t wanna talk about something when like part of the reason I wanted to get into therapy is that my partner and I weren’t having sex unless I used alcohol.

Discussion

As part of a larger national qualitative investigation of the experiences of veterans who recently initiated TF-EBP, veterans discussed their experiences with therapy and mental health care that have important implications for continued process improvement.21 Three key areas for continued process improvement were identified: (1) providing information about the diverse range of mental health care services at the VA and the implications of this continuum of care; (2) consideration of veteran preferences in treatment decision-making, including the importance of perceived choice; and (3) incorporating cultural assessment and cultural responsiveness into case conceptualization and treatment.

One area of process improvement identified was increasing knowledge about different types of psychotherapy and the continuum of care available at the VA. Veterans in this study confused or conflated participating in psychotherapy with talking about mental health symptoms with a clinician (eg, assessment, disability evaluation). They were sometimes surprised that psychotherapy is an umbrella term referring to a variety of different modalities. The downstream impact of these misunderstandings was a perception of VA mental health care as nebulous. Veterans were surprised that all mental health practitioners were unable to provide the same care. Confusion may have been compounded by highly variable referral processes across VA.24 To address this, clinicians have developed local educational resources and handouts for both veterans and referring clinicians from nonmental health and general mental health specialties.25 Given the variability in referral processes both between and within VA medical centers, national dissemination of these educational materials may be more difficult compared to materials for TF-EBPs.24 The VA started to use behavioral health interdisciplinary program (BHIP) teams, which are designed to be clinical homes for veterans connected with a central clinician who can explain and coordinate their mental health care as well as bring more consistency to the referral process.26 The ongoing transition toward the BHIP model of mental health care at VA may provide the opportunity to consolidate and integrate knowledge about the VA approach to mental health care, potentially filling knowledge gaps.

A second area of process improvement focused on the shared decision-making process. Consistent with mental health initiatives, veterans generally believed they had received sufficient information about TF-EBP and engaged in shared decision-making with clinicians.20,27 Veterans were given educational materials to review and had the opportunity to discuss these materials with clinicians. However, veterans described variability in the success of shared decision-making. Although veterans valued receiving accurate, comprehensible information to support treatment decisions, some preferred to defer to clinicians’ expertise regarding which treatment to pursue. While these veterans valued information, they also valued the expertise of clinicians in explaining why specific treatments would be beneficial. A key contributor to veterans satisfaction was assessing how veterans wanted to engage in the decision-making process and respecting those preferences.28 Veterans approached shared decision-making differently, from making decisions independently after receiving information to relying solely on clinician recommendation. The process was most successful when clinicians articulated how their recommended treatment aligned with a veteran’s preferences, including recommendations based on specific values (eg, personalized match vs being the best). Another important consideration is ensuring veterans know they can receive a variety of different types of mental health services available in different modalities (eg, virtual vs in-person; group vs individual). When veterans did not perceive choice in treatment aspects important to them (typically despite having choices), they were less satisfied with their TF-EBP experience.

A final area of process improvement identified involves how therapists address important aspects of culture. Veterans often described mental health stigma coming from intersecting cultural identities and expressed appreciation when therapists helped them recognize the impact of these beliefs on treatment. Some veterans did not discuss important aspects of their identity with clinicians, including race/ethnicity, religion, and military culture. Veterans did not report negative interactions with clinicians or experiences suggesting it was inappropriate to discuss identity; however, they were reluctant to independently raise these identity factors. Strategies such as the ADDRESSING framework, a mnemonic acronym that describes a series of potentially relevant characteristics, can help clinicians comprehensively consider different aspects that may be relevant to veterans, modeling that discussion of relevant these characteristics is welcome in TF-EBP.29 Veterans reported that making culturally relevant connections enhanced the TF-EBP experience, most commonly with military culture. These data support that TF-EBP delivery with attention to culture should be an integrated part of treatment, supporting engagement and therapeutic alliance.30 The VA National Center for PTSD consultation program is a resource to support clinicians in assessing and incorporating relevant aspects of cultural identity.31 For example, the National Center for PTSD provides a guide for using case conceptualization to address patient reactions to race-based violence during PTSD treatment.32 Both manualized design and therapist certification training can reinforce that assessing and attending to case conceptualization (including identity factors) is an integral component of TF-EBP.33,34

Limitations

While the current study has numerous strengths (eg, national veteran sampling, robust qualitative methods), results should be considered within the context of study limitations. First, veteran participants all received TF-EBP, and the perspectives of veterans who never initiate TF-EBP may differ. Despite the strong sampling approach, the study design is not intended to be generalizable to all veterans receiving TF-EBP for PTSD. Qualitative analysis yielded 15 themes, described in this study and prior research, consistent with recommendations.21,22 This approach allows rich description of distinct focus areas that would not be possible in a single manuscript. Nonetheless, all veterans interviewed described their experiences in TF-EBP and general mental health care, the focus of the semistructured interview guide was on the experience of transitioning from other treatment to TF-EBP.

Conclusion

This study describes themes related to general mental health and TF-EBP process improvement as part of a larger study on transitions in PTSD care.21,22 Veterans valued the fundamentals of therapy, including rapport and flexibility. Treatment-specific rapport (eg, pointing out treatment progress and effort in completing treatment components) and flexibility within the context of fidelity (ie, personalizing treatment while maintaining core treatment elements) may be most effective at engaging veterans in recommended PTSD treatments.18,34 In addition to successes, themes suggest multiple opportunities for process improvement. Ongoing VA initiatives and priorities (ie, BHIP, shared decision-making, consultation services) aim to improve processes consistent with veteran recommendations. Future research is needed to evaluate the success of these and other programs to optimize access to and engagement in recommended PTSD treatments.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs; US Department of Defense. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of posttraumatic stress disorder and acute stress disorder. 2023. Updated August 20, 2025. Accessed October 17, 2025. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/ptsd/

- International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. ISTSS PTSD prevention and treatment guidelines: methodology and recommendations. Accessed August 13, 2025. http://www.istss.org/getattachment/Treating-Trauma/New-ISTSS-Prevention-and-TreatmentGuidelines/ISTSS_PreventionTreatmentGuidelines_FNL-March-19-2019.pdf.aspx

- American Psychological Association. Clinical practice guideline for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder in adults. Accessed August 13, 2025. https://www.apa.org/ptsd-guideline/ptsd.pdf

- Karlin BE, Cross G. From the laboratory to the therapy room: National dissemination and implementation of evidence- based psychotherapies in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Health Care System. Am Psychol. 2014;69:19-33. doi:10.1037/a0033888

- Rosen CS, Matthieu MM, Wiltsey Stirman S, et al. A review of studies on the system-wide implementation of evidencebased psychotherapies for posttraumatic stress disorder in the Veterans Health Administration. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2016;43:957-977. doi:10.1007/s10488-016-0755-0

- Maguen S, Holder N, Madden E, et al. Evidence-based psychotherapy trends among posttraumatic stress disorder patients in a national healthcare system, 2001-2014. Depress Anxiety. 2020;37:356-364. doi:10.1002/da.22983

- Cheney AM, Koenig CJ, Miller CJ, et al. Veteran-centered barriers to VA mental healthcare services use. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:591. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-3346-9

- Hundt NE, Mott JM, Miles SR, et al. Veterans’ perspectives on initiating evidence-based psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychol Trauma. 2015;7:539-546. doi:10.1037/tra0000035

- Hundt NE, Helm A, Smith TL, et al. Failure to engage: a qualitative study of veterans who decline evidence-based psychotherapies for PTSD. Psychol Serv. 2018;15:536- 542. doi:10.1037/ser0000212

- Sayer NA, Friedemann-Sanchez G, Spoont M, et al. A qualitative study of determinants of PTSD treatment initiation in veterans. Psychiatry. 2009;72:238-255. doi:10.1521/psyc.2009.72.3.238

- Mittal D, Drummond KL, Blevins D, et al. Stigma associated with PTSD: perceptions of treatment seeking combat veterans. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2013;36:86-92. doi:10.1037/h0094976

- Possemato K, Wray LO, Johnson E, et al. Facilitators and barriers to seeking mental health care among primary care veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress. 2018;31:742-752. doi:10.1002/jts.22327

- Silvestrini M, Chen JA. “It’s a sign of weakness”: Masculinity and help-seeking behaviors among male veterans accessing posttraumatic stress disorder care. Psychol Trauma. 2023;15:665-671. doi:10.1037/tra0001382

- Stecker T, Shiner B, Watts BV, et al. Treatment-seeking barriers for veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts who screen positive for PTSD. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64:280-283. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.001372012

- Etingen B, Grubbs KM, Harik JM. Drivers of preference for evidence-based PTSD treatment: a qualitative assessment. Mil Med. 2020;185:303-310. doi:10.1093/milmed/usz220

- Hundt NE, Ecker AH, Thompson K, et al. “It didn’t fit for me:” A qualitative examination of dropout from prolonged exposure and cognitive processing therapy in veterans. Psychol Serv. 2020;17:414-421. doi:10.1037/ser0000316

- Kehle-Forbes SM, Gerould H, Polusny MA, et al. “It leaves me very skeptical” messaging in marketing prolonged exposure and cognitive processing therapy to veterans with PTSD. Psychol Trauma. 2022;14:849-852. doi:10.1037/tra0000550

- Kehle-Forbes SM, Ackland PE, Spoont MR, et al. Divergent experiences of U.S. veterans who did and did not complete trauma-focused therapies for PTSD: a national qualitative study of treatment dropout. Behav Res Ther. 2022;154:104123. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2022.104123

- Hessinger JD, London MJ, Baer SM. Evaluation of a shared decision-making intervention on the utilization of evidence-based psychotherapy in a VA outpatient PTSD clinic. Psychol Serv. 2018;15:437-441. doi:10.1037/ser0000141

- Hamblen JL, Grubbs KM, Cole B, et al. “Will it work for me?” Developing patient-friendly graphical displays of posttraumatic stress disorder treatment effectiveness. J Trauma Stress. 2022;35:999-1010. doi:10.1002/jts.22808

- Holder N, Ranney RM, Delgado AK, et al. Transitioning into trauma-focused evidence-based psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder from other treatments: a qualitative investigation. Cogn Behav Ther. 2025;54:391-407. doi:10.1080/16506073.2024.2408386

- Levitt HM, Bamberg M, Creswell JW, et al. Journal article reporting standards for qualitative primary, qualitative meta-analytic, and mixed methods research in psychology: The APA Publications and Communications Board task force report. Am Psychol. 2018;73:26-46. doi:10.1037/amp0000151

- Palinkas LA, Mendon SJ, Hamilton AB. Innovations in mixed methods evaluations. Annu Rev Public Health. 2019;40:423- 442. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-044215

- Ranney RM, Cordova MJ, Maguen S. A review of the referral process for evidence-based psychotherapies for PTSD among veterans. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2022;53:276-285. doi:10.1037/pro0000463

- Holder N, Ranney RM, Delgado AK, et al. Transitions to trauma-focused evidence-based psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder from other treatment: a qualitative investigation of clinician’s perspectives. Cogn Behav Ther. 2025;1-19. doi:10.1080/16506073.2025.2481475

- Barry CN, Abraham KM, Weaver KR, et al. Innovating team-based outpatient mental health care in the Veterans Health Administration: staff-perceived benefits and challenges to pilot implementation of the Behavioral Health Interdisciplinary Program (BHIP). Psychol Serv. 2016;13:148-155. doi:10.1037/ser0000072

- Harik JM, Hundt NE, Bernardy NC, et al. Desired involvement in treatment decisions among adults with PTSD symptoms. J Trauma Stress. 2016;29:221-228. doi:10.1002/jts.22102

- Larsen SE, Hooyer K, Kehle-Forbes SM, et al. Patient experiences in making PTSD treatment decisions. Psychol Serv. 2024;21:529-537. doi:10.1037/ser0000817

- Hays PA. Four steps toward intersectionality in psychotherapy using the ADDRESSING framework. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2024;55:454-462. doi:10.1037/pro0000577

- Galovski TE, Nixon RDV, Kaysen D. Flexible Applications of Cognitive Processing Therapy: Evidence-Based Treatment Methods. Academic Press; 2020.

- Larsen SE, McKee T, Fielstein E, et al. The development of a posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) consultation program to support system-wide implementation of high-quality PTSD care for veterans. Psychol Serv. 2025;22:342-348. doi:10.1037/ser0000867

- Galovski T, Kaysen D, McClendon J, et al. Provider guide to addressing patient reactions to race-based violence during PTSD treatment. PTSD.va.gov. Accessed August 3, 2025. www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/treat/specific/patient_reactions_race_violence.asp

- Galovski TE, Nixon RDV, Kehle-Forbes S. Walking the line between fidelity and flexibility: a conceptual review of personalized approaches to manualized treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress. 2024;37:768-774. doi:10.1002/jts.23073

- Galovski TE, McSweeney LB, Nixon RDV, et al. Personalizing cognitive processing therapy with a case formulation approach to intentionally target impairment in psychosocial functioning associated with PTSD. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2024;42:101385. doi:10.1016/j.conctc.2024.101385

Trauma-focused evidence-based psychotherapies (TF-EBPs), including cognitive processing therapy (CPT) and prolonged exposure therapy (PE), are recommended treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in clinical practice guidelines.1-3 To increase initiation of these treatments, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) used a large-scale dissemination and implementation effort to improve access to TF-EBP.4,5 These efforts achieved modest success, increasing prevalence of TF-EBP from a handful of veterans in 2004 to an annual prevalence of 14.6% for CPT and 4.3% for PE in 2014.6

Throughout these efforts, qualitative studies have been used to better understand veterans’ perspectives on receiving TF-EBP care.7-18 Barriers to initiation of and engagement in TF-EBP and PTSD care have been identified from these qualitative studies. One identified barrier was lack of knowledge—particularly lack of knowledge about what is meant by a PTSD diagnosis and available treatments.7-10 Stigma (ie, automatic negative associations) toward mental health problems or seeking mental health care also has been identified as a barrier to initiation.7,10-14 Perceptions of poor alignment between treatment and veteran goals, including lack of buy-in for the rationale, served as barriers to initiation and engagement.8,15-18

Using prior qualitative work, numerous initiatives have been developed to reduce stigma, facilitate conversations about how treatment aligns with goals, and fill knowledge gaps, particularly through online resources and shared decision-making.19,20 To better inform the state of veterans’ experiences with TF-EBP, a qualitative investigation was conducted involving veterans who recently initiated TF-EBP. Themes directly related to transitions to TF-EBP were identified; however, all veterans interviewed also described their experiences with TFEBP engagement and mental health care. Consistent with recommendations for qualitative methods, this study extends prior work on transitions to TF-EBP by describing themes with a distinct focus on the experience of engaging with TF-EBP and mental health care.21,22

Methods

The experiences of veterans who were transitioning into TF-EBPs were collected in semistructured interviews and analyzed. The semistructured interview guide was developed and refined in consultation with both qualitative methods experts and PTSD treatment experts to ensure that 6 content domains were appropriately queried: PTSD treatment options, cultural sensitivity of treatment, PTSD treatment selection, transition criteria, beliefs about stabilization treatment, and treatment needs/preferences.

Participants were identified using the VA Corporate Data Warehouse and included post-9/11 veterans who had recently initiated CPT or PE for the first time between September 1, 2021, and September 1, 2022. More details of participant selection are available in Holder et al.21 From a population of 10,814 patients, stratified random sampling generated a recruitment pool of 200 veterans for further outreach. The strata were defined such that this recruitment pool had similar proportions of demographic characteristics (ie, gender, race, ethnicity) to the population of eligible veterans, equivalent distributions of time to CPT or PE initiation (ie, 33.3% < 1 year, 33.3% 1-3 years, and 33.3% > 3 years), and adequate variability in TF-EBP type (ie, 66.7% CPT, 33.3% PE). A manual chart review in the recruitment pool excluded 12 veterans who did not initiate CPT or PE, 1 veteran with evidence of current active psychosis and/or cognitive impairment that would likely preclude comprehension of study materials, and 1 who was deceased.

Eligible veterans from the recruitment pool were contacted in groups of 25. First, a recruitment letter with study information and instructions to opt-out of further contact was mailed or emailed to veterans. After 2 weeks, veterans who had not responded were contacted by phone up to 3 times. Veterans interested in participating were scheduled for a 1-time visit that included verbal consent and the qualitative interview. Metrics were established a priori to ensure an adequately diverse and inclusive sample. Specifically, a minimum number of racial and/or ethnic minority veterans (33%) and women veterans (20%) were sought. Equal distribution across the 3 categories of time from first mental health visit to CPT/PE initiation also was targeted. Throughout enrollment, recruitment efforts were adapted to meet these metrics in the emerging sample. While the goal was to generate a diverse and inclusive sample using these methods, the sample was not intended to be representative of the population.

Of the 186 eligible participants, 21 declined participation and 26 could not be reached. The targeted sample was reached after exhausting contact for 47 veterans and contacting 80 veterans for a final response rate of 40% among fully contacted veterans and 27% among veterans with any contact. The final sample included 30 veterans who received CPT or PE in VA facilities (Table).

After veterans provided verbal consent for study participation, sociodemographic information was verbally reported, and a 30- to 60-minute semistructured qualitative phone interview was recorded and transcribed. Veterans received $40 for participation. All procedures were approved by the University of California San Francisco Institutional Review Board.

Qualitative Data Analysis

Rapid analysis procedures were used to analyze qualitative data. This approach is suitable for focused, moderately structured qualitative analyses in health services research and facilitates rapid dissemination to stakeholders.23 The qualitative analysts were 2 clinical psychologists with expertise in PTSD treatment (NH primary and RR secondary). Consistent with rapid analysis procedures, analysts prepared a templated summary (including relevant quotations) of each interview, organized by the prespecified content domains. Interviews were summarized independently, compared to ensure consistency, and discrepancies were resolved through review of the interview source materials. Individual summary templates were combined into a master analytic matrix to facilitate the identification of patterns and delineation of themes. Analysts routinely met to identify, discuss, and refine preliminary themes, revisiting source materials to reach consensus as needed.

Results

Fifteen themes were identified and organized into 2 distinct focus areas: themes directly related to the transition to TF-EBP (8 themes) and themes related to veterans’ experiences with TF-EBP and general mental health care with potential process-improvement implications (7 themes).21 Seven themes were identified related to experiences with TF-EBP engagement and VA mental health care. The 7 themes related to TF-EBP engagement and VA mental health care themes are summarized with exemplary quotations.

Veterans want a better understanding of psychotherapy and engaging with VA mental health. Veterans reported that they generally had a poor or “nebulous” understanding about the experience of psychotherapy. For example, veterans exhibited confusion about whether certain experiences were equivalent to participating in psychotherapy. They were sometimes unable to distinguish between interactions such as assessment, disability evaluations, peer support, and psychotherapy. One veteran described a conversation with a TFEBP therapist about prior treatment:

She [asked], have you ever been, or gone through a therapy to begin with? And I, I said, well I just chatted with somebody. And she said that’s not, that’s not therapy. So, I was like, oh, it’s not? That’s not what people do?

Veterans were surprised the VA offered a diverse range of psychotherapy interventions, rather than simply therapy. They did not realize there were different types of psychotherapy. As a result, veterans were not aware that some VA mental practitioners have specialty training and certification to provide treatment matched to specific diagnoses or needs. They thought that all clinicians could provide the same care. One veteran described their understanding:

I just figured all mental health people are mental health people. I didn’t have a better understanding of the system and all the different levels and how it plays out and specialties and things like that. Which, I guess, I should have because you have a primary care doctor, but then you have specialists in all these other different sectors that specialize in one particular area. I guess that should’ve been common sense, but it wasn’t.

Stigma was a barrier to seeking and engaging in mental health care. Veterans discovered they had to overcome stigma associated with seeking and engaging in mental health treatment. Military culture was often discussed as promoting stigma regarding mental health treatment. Specifically, veterans described that seeking treatment meant “either, I’m weak or I’m gonna be seen as weak.” In active-duty settings, the strategy for dealing with mental health symptoms was to “leave those feelings, you push ‘em aside,” an approach highly inconsistent with TF-EBP. In some cases, incorrect information about the VA and PTSD was presented as part of discharge from the military, leading to long-term skepticism of the VA and PTSD treatment. One veteran described his experience as part of a class on the VA compensation and pension assessment process for service-connected disabilities during his military discharge:

[A fellow discharging soldier asked] what about like PTSD, gettin’ rated for PTSD. I hear they take our weapons and stuff like we can’t own firearms and all that stuff. And [the instructor] was like, well, yes that’s a thing. He didn’t explain it like if you get compensated for PTSD you don’t lose your rights to carry a firearm or to have, to be able to go hunting.

Importantly, veterans often described how other identities (eg, race, ethnicity, gender, region of origin) interacted with military culture to enhance stigma. Hearing messaging from multiple sources reinforced beliefs that mental health treatment is inappropriate or is associated with weakness:

As a first-generation Italian, I was always taught keep your feelings to yourself. Never talk outside your family. Never bring up problems to other people and stuff like that. Same with the military. And then the old stigma working in [emergency medical services] and public safety, you’re weak if you get help.

The fundamentals of therapy, including rapport and flexibility, were important. Veterans valued nonspecific therapy factors, genuine empathy, building trust, being honest about treatment, personality, and rapport. These characteristics were almost universally described as particularly important:

I liked the fact that she made it personable and she cared. It wasn’t just like, here, we’re gonna start this. She explained it in the ways I could understand, not in medical terms, so to speak, but that’s what I liked about her. She really cared about what she did and helping me.

Flexibility was viewed as an asset, particularly when clinicians acknowledged veteran autonomy. A consistent example was when veterans were able to titrate trauma disclosure. One veteran described this flexible treatment experience: “She was right there in the room, she said, you know, at any time, you know, we could stop, we could debrief.”

Experiences of clinician flexibility and personalization of therapy were contrasted with experiences of overly rigid therapy. Overemphasis on protocols created barriers, often because treatment did not feel personalized. One veteran described how a clinician’s task-oriented approach interfered with their ability to engage in TF-EBP:

They listened, but it just didn’t seem like they were listening, because they really wanted to stay on task… So, I felt like if the person was more concerned, or more sympathetic to the things that was also going on in my life at that present time, I think I would’ve felt more comfortable talking about what was the PTSD part, too.

Veterans valued shared decision-making prior to TF-EBP initiation. Veterans typically described being involved in a shared decision-making process prior to initiating TF-EBP. During these sessions, clinicians discussed treatment options and provided veterans with a variety of materials describing treatments (eg, pamphlets, websites, videos, statistics). Most veterans appreciated being able to reflect on and discuss treatment options with their clinicians. Being given time in and out of session to review was viewed as valuable and increased confidence in treatment choice. One veteran described their experience:

I was given the information, you know, they gave me handouts, PDFs, whatever was available, and let me read over it. I didn’t have to choose anything right then and there, you know, they let me sleep on it. And I got back to them after some thought.

However, some veterans felt overwhelmed by being presented with too much information and did not believe they knew enough to make a final treatment decision. One veteran described being asked to contribute to the treatment decision:

I definitely asked [the clinician] to weigh in on maybe what he thought was best, because—I mean, I don’t know… I’m not necessarily sure I know what I think is best. I think we’re just lucky I’m here, so if you can give me a solid and help me out here by telling me just based on what I’ve said to you and the things that I’ve gone through, what do you think?

Veterans who perceived that their treatment preferences were respected had a positive outlook on TF-EBP. As part of the shared-decision making process, veterans typically described being given choices among PTSD treatments. One way that preferences were respected was through clinicians tailoring treatment descriptions to a veteran’s unique symptoms, experiences, and values. In these cases, clinicians observed specific concerns and clearly linked treatment principles to those concerns. For example, one veteran described their clinician’s recommendation for PE: “The hardest thing for me is to do the normal things like grocery store or getting on a train or anything like that. And so, he suggested that [PE] would be a good idea.”

In other cases, veterans wanted the highest quality of treatment rather than a match between treatment principles and the veteran’s presentation, goals, or strengths. These veterans wanted the best treatment available for PTSD and valued research support, recommendations from clinical practice guidelines, or clinician confidence in the effectiveness of the treatment. One veteran described this perspective:

I just wanted to be able to really tackle it in the best way possible and in the most like aggressive way possible. And it seemed like PE really was going to, they said that it’s a difficult type of therapy, but I really just wanted to kind of do the best that I could to eradicate some of the issues that I was having.

When veterans perceived a lack of respect for their preferences, they were hesitant about TF-EBP. For some veterans, a generic pitch for a TF-EBP was detrimental in the absence of the personal connection between the treatment and their own symptoms, goals, or strengths. These veterans did not question whether the treatment was effective in general but did question whether the treatment was best for them. One veteran described the contrast between their clinician’s perspective and their own.

I felt like they felt very comfortable, very confident in [CPT] being the program, because it was comfortable for them. Because they did it several times. And maybe they had a lot of success with other individuals... but they were very comfortable with that one, as a provider, more than: Is this the best fit for [me]?

Some veterans perceived little concern for their preferences and a lack of choice in available treatments, which tended to perpetuate negative perceptions of TFEBP. These veterans described their lack of choices with frustration. Alternatives to TFEBP were described by these veterans as so undesirable that they did not believe they had a real choice:

[CPT] was the only decision they had. There was nothing else for PTSD. They didn’t offer anything else. So, I mean it wasn’t a decision. It was either … take treatment or don’t take treatment at all… Actually, I need to correct myself. So, there were 2 options, group therapy or CPT. I forgot about that. I’m not a big group guy so I chose the CPT.

Another veteran was offered a choice between therapeutic approaches, but all were delivered via telehealth (consistent with the transition to virtual services during the COVID-19 pandemic). For this veteran, not only was the distinction between approaches unclear, but the choice between approaches was unimportant compared to the mode of delivery.

This happened during COVID-19 and VA stopped seeing anybody physically, face-to-face. So my only option for therapy was [telehealth]… There was like 3 of them, and I tried to figure out, you know, from the layperson’s perspective, like: I don’t know which one to go with.

Veterans wanted to be asked about their cultural identity. Veterans valued when clinicians asked questions about cultural identity as part of their mental health treatment and listened to their cultural context. Cultural identity factors extended beyond factors such as race, ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation to religion, military culture, and regionality. Veterans often described situations where they wished clinicians would ask the question or initiate conversations about culture. A veteran highlighted the importance of their faith but noted that it was a taboo topic. Their clinician did not say “we don’t go there,” but they “never dove into it either.” Another veteran expressed a desire for their clinician to ask questions about experiences in the National Guard and as an African American veteran:

If a provider was to say like: Oh, you know, it’s a stressful situation being a part of the military, being in the National Guard. You know, just asking questions about that. I think that would really go a long way… Being African American was difficult as well. And more so because of my region, I think… I felt like it would probably be an uncomfortable subject to speak on… I mean, it wasn’t anything that my providers necessarily did, it was more so just because it wasn’t brought up.

One common area of concern for veterans was a match between veteran and therapist demographics. When asked about how their cultural identity influenced treatment, several veterans described the relevance of therapist match. Much like questions about their own cultural identity, veterans valued being asked about identity preferences in clinicians (eg, gender or race matching), rather than having to bring up the preference themselves. One veteran described relief at this question being asked directly: “I was relieved when she had asked [whether I wanted a male or female clinician] primarily because I was going to ask that or bring that up somehow. But her asking that before me was a weight off my shoulders.”

Discussing cultural identity through treatment strengthened veterans’ engagement in therapy. Many veterans appreciated when analogies used in therapy were relevant to their cultural experiences and when clinicians understood their culture (eg, military culture, race, ethnicity, religious beliefs, sexual orientation). One veteran described how their clinician understood military culture and made connections between military culture and the rationale for TF-EBP, which strengthened the veteran’s buy-in for the treatment and alliance with the clinician:

At the beginning when she was explaining PTSD, and I remember she said that your brain needed to think this way when you were in the military because it was a way of protecting and surviving, so your brain was doing that in order for you to survive in whatever areas you were because there was danger. So, your brain had you thinking that way. But now, you’re not in those situations anymore. You’re not in danger. You’re not in the military, but your brain is still thinking you are, and that’s what PTSD generally does to you.

Specific elements of TF-EBP also provided opportunities to discuss and integrate important aspects of identity. This is accomplished in PE by assigning relevant in vivo exercises. In CPT, “connecting the dots” on how prior experiences influenced trauma-related stuck points achieved this element. One veteran described their experience with a clinician who was comfortable discussing the veteran’s sexual orientation and recognized the impacts of prior trauma on intimacy:

They’re very different, and there’s a lot of things that can be accepted in gay relationships that are not in straight ones. With all that said, I think [the PE therapist] did a fantastic job being not—like never once did she laugh or make an uncomfortable comment or say she didn’t wanna talk about something when like part of the reason I wanted to get into therapy is that my partner and I weren’t having sex unless I used alcohol.

Discussion

As part of a larger national qualitative investigation of the experiences of veterans who recently initiated TF-EBP, veterans discussed their experiences with therapy and mental health care that have important implications for continued process improvement.21 Three key areas for continued process improvement were identified: (1) providing information about the diverse range of mental health care services at the VA and the implications of this continuum of care; (2) consideration of veteran preferences in treatment decision-making, including the importance of perceived choice; and (3) incorporating cultural assessment and cultural responsiveness into case conceptualization and treatment.

One area of process improvement identified was increasing knowledge about different types of psychotherapy and the continuum of care available at the VA. Veterans in this study confused or conflated participating in psychotherapy with talking about mental health symptoms with a clinician (eg, assessment, disability evaluation). They were sometimes surprised that psychotherapy is an umbrella term referring to a variety of different modalities. The downstream impact of these misunderstandings was a perception of VA mental health care as nebulous. Veterans were surprised that all mental health practitioners were unable to provide the same care. Confusion may have been compounded by highly variable referral processes across VA.24 To address this, clinicians have developed local educational resources and handouts for both veterans and referring clinicians from nonmental health and general mental health specialties.25 Given the variability in referral processes both between and within VA medical centers, national dissemination of these educational materials may be more difficult compared to materials for TF-EBPs.24 The VA started to use behavioral health interdisciplinary program (BHIP) teams, which are designed to be clinical homes for veterans connected with a central clinician who can explain and coordinate their mental health care as well as bring more consistency to the referral process.26 The ongoing transition toward the BHIP model of mental health care at VA may provide the opportunity to consolidate and integrate knowledge about the VA approach to mental health care, potentially filling knowledge gaps.

A second area of process improvement focused on the shared decision-making process. Consistent with mental health initiatives, veterans generally believed they had received sufficient information about TF-EBP and engaged in shared decision-making with clinicians.20,27 Veterans were given educational materials to review and had the opportunity to discuss these materials with clinicians. However, veterans described variability in the success of shared decision-making. Although veterans valued receiving accurate, comprehensible information to support treatment decisions, some preferred to defer to clinicians’ expertise regarding which treatment to pursue. While these veterans valued information, they also valued the expertise of clinicians in explaining why specific treatments would be beneficial. A key contributor to veterans satisfaction was assessing how veterans wanted to engage in the decision-making process and respecting those preferences.28 Veterans approached shared decision-making differently, from making decisions independently after receiving information to relying solely on clinician recommendation. The process was most successful when clinicians articulated how their recommended treatment aligned with a veteran’s preferences, including recommendations based on specific values (eg, personalized match vs being the best). Another important consideration is ensuring veterans know they can receive a variety of different types of mental health services available in different modalities (eg, virtual vs in-person; group vs individual). When veterans did not perceive choice in treatment aspects important to them (typically despite having choices), they were less satisfied with their TF-EBP experience.

A final area of process improvement identified involves how therapists address important aspects of culture. Veterans often described mental health stigma coming from intersecting cultural identities and expressed appreciation when therapists helped them recognize the impact of these beliefs on treatment. Some veterans did not discuss important aspects of their identity with clinicians, including race/ethnicity, religion, and military culture. Veterans did not report negative interactions with clinicians or experiences suggesting it was inappropriate to discuss identity; however, they were reluctant to independently raise these identity factors. Strategies such as the ADDRESSING framework, a mnemonic acronym that describes a series of potentially relevant characteristics, can help clinicians comprehensively consider different aspects that may be relevant to veterans, modeling that discussion of relevant these characteristics is welcome in TF-EBP.29 Veterans reported that making culturally relevant connections enhanced the TF-EBP experience, most commonly with military culture. These data support that TF-EBP delivery with attention to culture should be an integrated part of treatment, supporting engagement and therapeutic alliance.30 The VA National Center for PTSD consultation program is a resource to support clinicians in assessing and incorporating relevant aspects of cultural identity.31 For example, the National Center for PTSD provides a guide for using case conceptualization to address patient reactions to race-based violence during PTSD treatment.32 Both manualized design and therapist certification training can reinforce that assessing and attending to case conceptualization (including identity factors) is an integral component of TF-EBP.33,34

Limitations

While the current study has numerous strengths (eg, national veteran sampling, robust qualitative methods), results should be considered within the context of study limitations. First, veteran participants all received TF-EBP, and the perspectives of veterans who never initiate TF-EBP may differ. Despite the strong sampling approach, the study design is not intended to be generalizable to all veterans receiving TF-EBP for PTSD. Qualitative analysis yielded 15 themes, described in this study and prior research, consistent with recommendations.21,22 This approach allows rich description of distinct focus areas that would not be possible in a single manuscript. Nonetheless, all veterans interviewed described their experiences in TF-EBP and general mental health care, the focus of the semistructured interview guide was on the experience of transitioning from other treatment to TF-EBP.

Conclusion

This study describes themes related to general mental health and TF-EBP process improvement as part of a larger study on transitions in PTSD care.21,22 Veterans valued the fundamentals of therapy, including rapport and flexibility. Treatment-specific rapport (eg, pointing out treatment progress and effort in completing treatment components) and flexibility within the context of fidelity (ie, personalizing treatment while maintaining core treatment elements) may be most effective at engaging veterans in recommended PTSD treatments.18,34 In addition to successes, themes suggest multiple opportunities for process improvement. Ongoing VA initiatives and priorities (ie, BHIP, shared decision-making, consultation services) aim to improve processes consistent with veteran recommendations. Future research is needed to evaluate the success of these and other programs to optimize access to and engagement in recommended PTSD treatments.

Trauma-focused evidence-based psychotherapies (TF-EBPs), including cognitive processing therapy (CPT) and prolonged exposure therapy (PE), are recommended treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in clinical practice guidelines.1-3 To increase initiation of these treatments, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) used a large-scale dissemination and implementation effort to improve access to TF-EBP.4,5 These efforts achieved modest success, increasing prevalence of TF-EBP from a handful of veterans in 2004 to an annual prevalence of 14.6% for CPT and 4.3% for PE in 2014.6

Throughout these efforts, qualitative studies have been used to better understand veterans’ perspectives on receiving TF-EBP care.7-18 Barriers to initiation of and engagement in TF-EBP and PTSD care have been identified from these qualitative studies. One identified barrier was lack of knowledge—particularly lack of knowledge about what is meant by a PTSD diagnosis and available treatments.7-10 Stigma (ie, automatic negative associations) toward mental health problems or seeking mental health care also has been identified as a barrier to initiation.7,10-14 Perceptions of poor alignment between treatment and veteran goals, including lack of buy-in for the rationale, served as barriers to initiation and engagement.8,15-18

Using prior qualitative work, numerous initiatives have been developed to reduce stigma, facilitate conversations about how treatment aligns with goals, and fill knowledge gaps, particularly through online resources and shared decision-making.19,20 To better inform the state of veterans’ experiences with TF-EBP, a qualitative investigation was conducted involving veterans who recently initiated TF-EBP. Themes directly related to transitions to TF-EBP were identified; however, all veterans interviewed also described their experiences with TFEBP engagement and mental health care. Consistent with recommendations for qualitative methods, this study extends prior work on transitions to TF-EBP by describing themes with a distinct focus on the experience of engaging with TF-EBP and mental health care.21,22

Methods

The experiences of veterans who were transitioning into TF-EBPs were collected in semistructured interviews and analyzed. The semistructured interview guide was developed and refined in consultation with both qualitative methods experts and PTSD treatment experts to ensure that 6 content domains were appropriately queried: PTSD treatment options, cultural sensitivity of treatment, PTSD treatment selection, transition criteria, beliefs about stabilization treatment, and treatment needs/preferences.

Participants were identified using the VA Corporate Data Warehouse and included post-9/11 veterans who had recently initiated CPT or PE for the first time between September 1, 2021, and September 1, 2022. More details of participant selection are available in Holder et al.21 From a population of 10,814 patients, stratified random sampling generated a recruitment pool of 200 veterans for further outreach. The strata were defined such that this recruitment pool had similar proportions of demographic characteristics (ie, gender, race, ethnicity) to the population of eligible veterans, equivalent distributions of time to CPT or PE initiation (ie, 33.3% < 1 year, 33.3% 1-3 years, and 33.3% > 3 years), and adequate variability in TF-EBP type (ie, 66.7% CPT, 33.3% PE). A manual chart review in the recruitment pool excluded 12 veterans who did not initiate CPT or PE, 1 veteran with evidence of current active psychosis and/or cognitive impairment that would likely preclude comprehension of study materials, and 1 who was deceased.

Eligible veterans from the recruitment pool were contacted in groups of 25. First, a recruitment letter with study information and instructions to opt-out of further contact was mailed or emailed to veterans. After 2 weeks, veterans who had not responded were contacted by phone up to 3 times. Veterans interested in participating were scheduled for a 1-time visit that included verbal consent and the qualitative interview. Metrics were established a priori to ensure an adequately diverse and inclusive sample. Specifically, a minimum number of racial and/or ethnic minority veterans (33%) and women veterans (20%) were sought. Equal distribution across the 3 categories of time from first mental health visit to CPT/PE initiation also was targeted. Throughout enrollment, recruitment efforts were adapted to meet these metrics in the emerging sample. While the goal was to generate a diverse and inclusive sample using these methods, the sample was not intended to be representative of the population.

Of the 186 eligible participants, 21 declined participation and 26 could not be reached. The targeted sample was reached after exhausting contact for 47 veterans and contacting 80 veterans for a final response rate of 40% among fully contacted veterans and 27% among veterans with any contact. The final sample included 30 veterans who received CPT or PE in VA facilities (Table).

After veterans provided verbal consent for study participation, sociodemographic information was verbally reported, and a 30- to 60-minute semistructured qualitative phone interview was recorded and transcribed. Veterans received $40 for participation. All procedures were approved by the University of California San Francisco Institutional Review Board.

Qualitative Data Analysis

Rapid analysis procedures were used to analyze qualitative data. This approach is suitable for focused, moderately structured qualitative analyses in health services research and facilitates rapid dissemination to stakeholders.23 The qualitative analysts were 2 clinical psychologists with expertise in PTSD treatment (NH primary and RR secondary). Consistent with rapid analysis procedures, analysts prepared a templated summary (including relevant quotations) of each interview, organized by the prespecified content domains. Interviews were summarized independently, compared to ensure consistency, and discrepancies were resolved through review of the interview source materials. Individual summary templates were combined into a master analytic matrix to facilitate the identification of patterns and delineation of themes. Analysts routinely met to identify, discuss, and refine preliminary themes, revisiting source materials to reach consensus as needed.

Results

Fifteen themes were identified and organized into 2 distinct focus areas: themes directly related to the transition to TF-EBP (8 themes) and themes related to veterans’ experiences with TF-EBP and general mental health care with potential process-improvement implications (7 themes).21 Seven themes were identified related to experiences with TF-EBP engagement and VA mental health care. The 7 themes related to TF-EBP engagement and VA mental health care themes are summarized with exemplary quotations.

Veterans want a better understanding of psychotherapy and engaging with VA mental health. Veterans reported that they generally had a poor or “nebulous” understanding about the experience of psychotherapy. For example, veterans exhibited confusion about whether certain experiences were equivalent to participating in psychotherapy. They were sometimes unable to distinguish between interactions such as assessment, disability evaluations, peer support, and psychotherapy. One veteran described a conversation with a TFEBP therapist about prior treatment:

She [asked], have you ever been, or gone through a therapy to begin with? And I, I said, well I just chatted with somebody. And she said that’s not, that’s not therapy. So, I was like, oh, it’s not? That’s not what people do?

Veterans were surprised the VA offered a diverse range of psychotherapy interventions, rather than simply therapy. They did not realize there were different types of psychotherapy. As a result, veterans were not aware that some VA mental practitioners have specialty training and certification to provide treatment matched to specific diagnoses or needs. They thought that all clinicians could provide the same care. One veteran described their understanding:

I just figured all mental health people are mental health people. I didn’t have a better understanding of the system and all the different levels and how it plays out and specialties and things like that. Which, I guess, I should have because you have a primary care doctor, but then you have specialists in all these other different sectors that specialize in one particular area. I guess that should’ve been common sense, but it wasn’t.

Stigma was a barrier to seeking and engaging in mental health care. Veterans discovered they had to overcome stigma associated with seeking and engaging in mental health treatment. Military culture was often discussed as promoting stigma regarding mental health treatment. Specifically, veterans described that seeking treatment meant “either, I’m weak or I’m gonna be seen as weak.” In active-duty settings, the strategy for dealing with mental health symptoms was to “leave those feelings, you push ‘em aside,” an approach highly inconsistent with TF-EBP. In some cases, incorrect information about the VA and PTSD was presented as part of discharge from the military, leading to long-term skepticism of the VA and PTSD treatment. One veteran described his experience as part of a class on the VA compensation and pension assessment process for service-connected disabilities during his military discharge:

[A fellow discharging soldier asked] what about like PTSD, gettin’ rated for PTSD. I hear they take our weapons and stuff like we can’t own firearms and all that stuff. And [the instructor] was like, well, yes that’s a thing. He didn’t explain it like if you get compensated for PTSD you don’t lose your rights to carry a firearm or to have, to be able to go hunting.

Importantly, veterans often described how other identities (eg, race, ethnicity, gender, region of origin) interacted with military culture to enhance stigma. Hearing messaging from multiple sources reinforced beliefs that mental health treatment is inappropriate or is associated with weakness:

As a first-generation Italian, I was always taught keep your feelings to yourself. Never talk outside your family. Never bring up problems to other people and stuff like that. Same with the military. And then the old stigma working in [emergency medical services] and public safety, you’re weak if you get help.

The fundamentals of therapy, including rapport and flexibility, were important. Veterans valued nonspecific therapy factors, genuine empathy, building trust, being honest about treatment, personality, and rapport. These characteristics were almost universally described as particularly important:

I liked the fact that she made it personable and she cared. It wasn’t just like, here, we’re gonna start this. She explained it in the ways I could understand, not in medical terms, so to speak, but that’s what I liked about her. She really cared about what she did and helping me.

Flexibility was viewed as an asset, particularly when clinicians acknowledged veteran autonomy. A consistent example was when veterans were able to titrate trauma disclosure. One veteran described this flexible treatment experience: “She was right there in the room, she said, you know, at any time, you know, we could stop, we could debrief.”

Experiences of clinician flexibility and personalization of therapy were contrasted with experiences of overly rigid therapy. Overemphasis on protocols created barriers, often because treatment did not feel personalized. One veteran described how a clinician’s task-oriented approach interfered with their ability to engage in TF-EBP:

They listened, but it just didn’t seem like they were listening, because they really wanted to stay on task… So, I felt like if the person was more concerned, or more sympathetic to the things that was also going on in my life at that present time, I think I would’ve felt more comfortable talking about what was the PTSD part, too.

Veterans valued shared decision-making prior to TF-EBP initiation. Veterans typically described being involved in a shared decision-making process prior to initiating TF-EBP. During these sessions, clinicians discussed treatment options and provided veterans with a variety of materials describing treatments (eg, pamphlets, websites, videos, statistics). Most veterans appreciated being able to reflect on and discuss treatment options with their clinicians. Being given time in and out of session to review was viewed as valuable and increased confidence in treatment choice. One veteran described their experience:

I was given the information, you know, they gave me handouts, PDFs, whatever was available, and let me read over it. I didn’t have to choose anything right then and there, you know, they let me sleep on it. And I got back to them after some thought.

However, some veterans felt overwhelmed by being presented with too much information and did not believe they knew enough to make a final treatment decision. One veteran described being asked to contribute to the treatment decision: