User login

Losing a patient to suicide: Navigating the aftermath

At some point during their career, many mental health professionals will lose a patient to suicide, but few will be prepared for the experience and its aftermath. As I described in Part 1 of this article (

A chance for growth

Traumatic experiences such as a suicide loss can paradoxically present a multitude of opportunities for new growth and profound personal transformation.1 Such transformation is primarily fostered by social support in the aftermath of the trauma.2

Virtually all of the models of the clinician’s suicide grief trajectory I described in Part 1 not only assume the eventual resolution of the distressing reactions accompanying the original loss, but also suggest that mastery of these reactions can be a catalyst for both personal and professional growth. Clearly, not everyone who experiences such a loss will experience subsequent growth; there are many reports of clinicians leaving the field3 or becoming “burned out” after this occurs. Yet most clinicians who have described this loss in the literature and in discussion groups (including those I’ve conducted) have reported more positive eventual outcomes. It is difficult to establish whether this is due to a cohort effect—clinicians who are most likely to write about their experiences, be interviewed for research studies, and/or to seek out and participate in discussion/support groups may be more prone to find benefits in this experience, either by virtue of their nature or through the subsequent process of sharing these experiences in a supportive atmosphere.

The literature on patient suicide loss, as well as anecdotal reports, confirms that clinicians who experience optimal support are able to identify many retrospective benefits of their experience.4-6 Clinicians generally report that they are better able to identify potential risk and protective factors for suicide, and are more knowledgeable about optimal interventions with individuals who are suicidal. They also describe an increased sensitivity towards patients who are suicidal and those bereaved by suicide. In addition, clinicians report a reduction in therapeutic grandiosity/omnipotence, and more realistic appraisals and expectations in relation to their clinical competence. In their effort to understand the “whys” of their patient’s suicide, they are likely to retrospectively identify errors in treatment, “missed cues,” or things they might subsequently do differently,7 and to learn from these mistakes. Optimally, clinicians become more aware of their own therapeutic limitations, both in the short- and the long-term, and can use this knowledge to better determine how they will continue their clinical work. They also become much more aware of the issues involved in the aftermath of a patient suicide, including perceived gaps in the clinical and institutional systems that could optimally offer support to families and clinicians.

In addition to the positive changes related to knowledge and clinical skills, many clinicians also note deeper personal changes subsequent to their patient’s suicide, consistent with the literature on posttraumatic growth.1 Munson8 explored internal changes in clinicians following a patient suicide and found that in the aftermath, clinicians experienced both posttraumatic growth and compassion fatigue. He also found that the amount of time that elapsed since the patient’s suicide predicted posttraumatic growth, and the seemingly counterintuitive result that the number of years of clinical experience prior to the suicide was negatively correlated with posttraumatic growth.

Huhra et al4 described some of the existential issues that a clinician is likely to confront following a patient suicide. A clinician’s attempt to find a way to meaningfully understand the circumstances around this loss often prompts reflection on mortality, freedom, choice and personal autonomy, and the scope and limits of one’s responsibility toward others. The suicide challenges one’s previous conceptions and expectations around these professional issues, and the clinician must construct new paradigms that serve to integrate these new experiences and perspectives in a coherent way.

One of the most notable sequelae of this (and to other traumatic) experience is a subsequent desire to make use of the learning inherent in these experiences and to “give back.” Once they feel that they have resolved their own grief process, many clinicians express the desire to support others with similar experiences. Even when their experiences have been quite distressing, many clinicians are able to view the suicide as an opportunity to learn about ongoing limitations in the systems of support, and to work toward changing these in a way that ensures that future clinician-survivors will have more supportive experiences. Many view these new perspectives, and their consequent ability to be more helpful, as “unexpected gifts.” They often express gratitude toward the people and resources that have allowed them to make these transformations. Jones5 noted “the tragedy of patient suicide can also be an opportunity for us as therapists to grow in our skills at assessing and intervening in a suicidal crisis, to broaden and deepen the support we give and receive, to grow in our appreciation of the precious gift that life is, and to help each other live it more fully.”

Continue to: Guidelines for postvention

Guidelines for postvention

When a patient suicide occurs in the context of an agency setting, Grad9 recommends prompt responses on 4 levels:

- administrative

- institutional

- educational

- emotional.

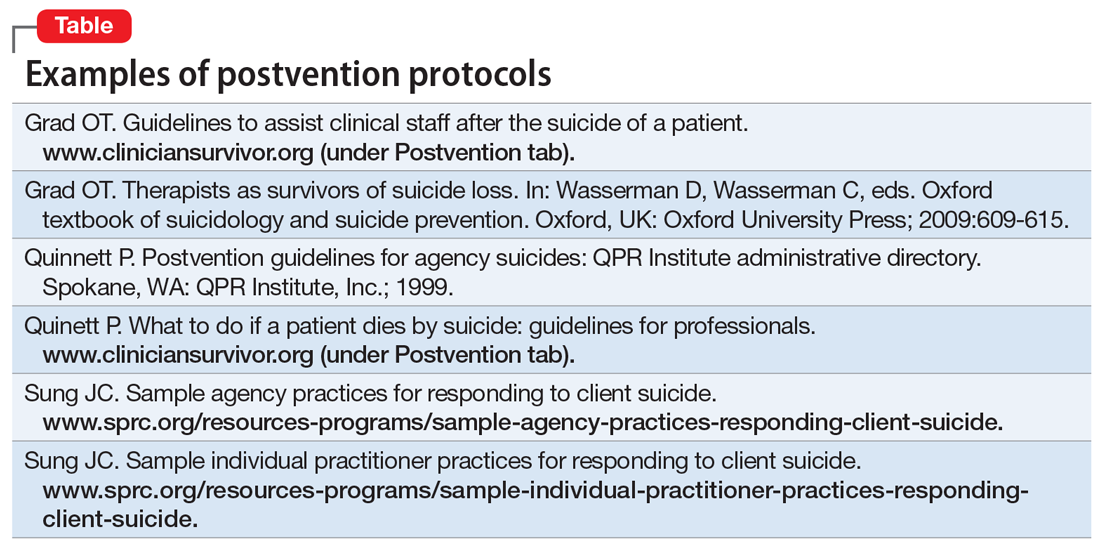

Numerous authors5,10-21 have developed suggestions, guidelines, and detailed postvention protocols to help agencies and clinicians in various mental health settings navigate the often-complicated sequelae to a patient’s suicide. The Table highlights a few of these. Most emphasize that information about suicide loss, including both its statistical likelihood and its potential aftermath, should integrated into clinicians’ general education and training. They also suggest that suicide postvention policies and protocols be in place from the outset, and that such information be incorporated into institutional policy and procedure manuals. In addition, they stress that legal, institutional, and administrative needs be balanced with the emotional needs of affected clinicians and staff, as well as those of the surviving family.

Institutional and administrative procedures

The following are some of the recommended procedures that should take place following a suicide loss. The postvention protocols listed in the Table provide more detailed recommendations.

Legal/ethical. It is essential to consult with a legal representative/risk management specialist associated with the affected agency (ideally, one with specific expertise in suicide litigation.). It is also crucial to clarify who holds privilege after a patient’s death (varies by state), what may and may not be shared under the restrictions of confidentiality and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) laws, and to clarify procedures for chart completion and review. It is also important to clarify the specific information to be shared both within and outside of the agency, and how to address the needs of current patients in the agency settings.

Case review. The optimal purpose of the case review (also known as a psychological autopsy) is to facilitate learning, identify gaps in agency procedures and training, improve pre- and postvention procedures, and help clinicians cope with the loss.22 Again, the legal and administrative needs of the agency need to be balanced with the attention to the emotional impact on the treating clinician.17 Ellis and Patel18 recommend delaying this procedure until the treating clinician is no longer in the “shock” phase of the loss, and is able to think and process events more objectively.

Continue to: Family contact

Family contact. Most authors have recommended that clinicians and/or agencies reach out to surviving families. Although some legal representatives will advise against this, experts in the field of suicide litigation have noted that compassionate family contact reduces liability and facilitates healing for both parties. In a personal communication (May 2008), Eric Harris, of the American Psychological Association Trust, recommended “compassion over caution” when considering these issues. Again, it is important to clarify who holds privilege after a patient’s death in determining when and with whom the patient’s confidential information may be shared. When confidentiality may be broken, clinical judgment should be used to determine how best to present the information to grieving family members.

Even if surviving family members do not hold privilege, there are many things that clinicians can do to be helpful.23 Inevitably, families will want any information that will help them make sense of the loss, and general psychoeducation about mental illness and suicide can be helpful in this regard. In addition, providing information about “Survivors After Suicide” support groups, reading materials, etc., can be helpful. Both support groups and survivor-related bibliographies are available on the web sites of the American Association of Suicidology (www.suicidology.org) and The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (www.afsp.org).

In addition, clinicians should ask the family if it would be helpful if they were to attend the funeral/memorial services, and how to introduce themselves if asked by other attendees.

Patients in clinics/hospitals. When a patient suicide occurs in a clinic or hospital setting, it is likely to impact other patients in that setting to the extent that they have heard, about the event, even from outside sources.According to Hodgkinson,24 in addition to being overwhelmed with intense feelings about the suicide loss (particularly if they had known the patient), affected patients are likely to be at increased risk for suicidal behaviors. This is consistent with the considerable literature on suicide contagion.

Thus, it is important to clarify information to be shared with patients; however, avoid describing details of the method, because this can foster contagion and “copycat” suicides. In addition, Kaye and Soreff22 noted that these patients may now be concerned about the staff’s ability to be helpful to them, because they were unable to help the deceased. In light of this, take extra care to attend to the impact of the suicide on current patients, and to monitor both pre-existing and new suicidality.

Continue to: Helping affected clinicians

Helping affected clinicians

Suggestions for optimally supporting affected clinicians include:

- clear communication about the nature of upcoming administrative procedures (including chart and institutional reviews)

- consultation from supervisors and/or colleagues that is supportive and reassuring, rather than blaming

- opportunities for the clinician to talk openly about the experience of the loss, either individually or in group settings, without fear of judgment or censure

- recognition that the loss is likely to impact clinical work, support in monitoring this impact, and the provision of medical leaves and/or modified caseloads (ie, fewer high-risk patients) as necessary.

Box 1

Frank Jones and Judy Meade founded the Clinical Survivor Task Force (CSTF) of the American Association of Suicidology (AAS) in 1987. As Jones noted, “clinicians who have lost patients to suicide need a place to acknowledge and carry forward their personal loss…to benefit both personally and professionally from the opportunity to talk with other therapists who have survived the loss of a patient through suicide.”7 Nina Gutin, PhD, and Vanessa McGann, PhD, have co-chaired the CSTF since 2003. It supports clinicians who have lost patients and/or loved ones, with the recognition that both types of losses carry implications within clinical and professional domains. The CSTF provides a listserve, opportunities to participate in video support groups, and a web site (www.cliniciansurvivor.org) that provides information about the clinician-survivor experience, the opportunity to read and post narratives about one’s experience with suicide loss, an updated bibliography maintained by John McIntosh, PhD, a list of clinical contacts, and links to several excellent postvention protocols. In addition, Drs. Gutin and McGann conduct clinician-survivor support activities at the annual AAS conference, and in their respective geographic areas.

Both researchers and clinician-survivors in my practice and support groups have noted that speaking with other clinicians who have experienced suicide loss can be particularly reassuring and validating. If none are available on staff, the listserve and online support groups of the American Association of Suicidology’s Clinician Survivor Task Force may be helpful (Box 17). In addition, the film “Collateral Damages: The Impact of Patient Suicide on the Physician” features physicians describing their experience of losing a patient to suicide (Box 2).

Box 2

“Collateral Damages: The Impact of Patient Suicide on the Physician” is a film that features several physicians speaking about their experience of losing a patient to suicide, as well as a group discussion. Psychiatrists in this educational film include Drs. Glen Gabbard, Sidney Zisook, and Jim Lomax. This resource can be used to facilitate an educational session for physicians, psychologists, residents, or other trainees. Please contact education@afsp.org to request a DVD of this film and a copy of a related article, Prabhakar D, Anzia JM, Balon R, et al. “Collateral damages”: preparing residents for coping with patient suicide. Acad Psychiatry. 2013;37(6):429-430.

Schultz14 offered suggestions for staff in supervisory positions, noting that they may bear at least some clinical and legal responsibility for the treatments that they supervise. She encouraged supervisors to take an active stance in advocating for trainees, to encourage colleagues to express their support, and to discourage rumors and other stigmatizing reactions. Schultz also urges supervisors to14:

- allow extra time for the clinician to engage in the normative exploration of the “whys” that are unique to suicide survivors

- use education about suicide to help the clinician gain a more realistic perspective on their relative culpability

- become aware of and provide education about normative grief reactions following a suicide.

Continue to: Because a suicide loss...

Because a suicide loss is likely to affect a clinician’s subsequent clinical activity, Schultz encourages supervisors to help clinicians monitor this impact on their work.14

A supportive environment is key

Losing a patient to suicide is a complicated, potentially traumatic process that many mental health clinicians will face. Yet with comprehensive and supportive postvention policies in place, clinicians who are impacted are more likely to experience healing and posttraumatic growth in both personal and professional domains.

Bottom Line

Although often traumatic, losing a patient to suicide presents clinicians with an opportunity for personal and professional growth. Following established postvention protocols can help ensure that legal, institutional, and administrative needs are balanced with the emotional needs of affected clinicians and staff, as well as those of the surviving family.

Related Resources

- American Association of Suicidology Clinician Survivor Task Force. www.cliniciansurvivor.org.

- Dotinga R. Coping when a patient commits suicide. July 21, 2017. www.mdedge.com/psychiatry/article/142975/depression/coping-when-patient-commits-suicide.

- Gutin N. Losing a patent to suicide: What we know. Part 1. 2019;18(10):14-16,19-22,30-32.

1. Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. Beyond the concept of recovery: Growth and the experience of loss. Death Stud. 2008;32(1):27-39.

2. Fuentes MA, Cruz D. Posttraumatic growth: positive psychological changes after trauma. Mental Health News. 2009;11(1):31,37.

3. Gitlin M. Aftermath of a tragedy: reaction of psychiatrists to patient suicides. Psychiatr Ann. 2007;37(10):684-687.

4. Huhra R, Hunka N, Rogers J, et al. Finding meaning: theoretical perspectives on patient suicide. Paper presented at: 2004 Annual Conference of the American Association of Suicidology; April 2004; Miami, FL.

5. Jones FA Jr. Therapists as survivors of patient suicide. In: Dunne EJ, McIntosh JL, Dunne-Maxim K, eds. Suicide and its aftermath: understanding and counseling the survivors. New York, NY: W.W. Norton; 1987;126-141.

6. Gutin N, McGann VM, Jordan JR. The impact of suicide on professional caregivers. In: Jordan J, McIntosh J, eds. Grief after suicide: understanding the consequences and caring for the survivors. New York, NY: Routledge; 2011:93-111.

7. Hendin H, Lipschitz A, Maltsberger JT, et al. Therapists’ reactions to patients’ suicides. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(12):2022-2027.

8. Munson JS. Impact of client suicide on practitioner posttraumatic growth [dissertation]. Gainesville, Florida: University of Florida; 2009.

9. Grad OT. Therapists as survivors of suicide loss. In: Wasserman D, Wasserman C, eds. Oxford textbook of suicidology and suicide prevention. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2009:609-615.

10. Douglas J, Brown HN. Suicide: understanding and responding: Harvard Medical School perspectives. Madison, CT: International Universities Press; 1989.

11. Farberow NL. The mental health professional as suicide survivor. Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2005;2(1):13-20.

12. Plakun EM, Tillman JG. Responding to clinicians after loss of a patient to suicide. Dir Psychiatry. 2005;25:301-310.

13. Quinnett P. QPR: for suicide prevention. QPR Institute, Inc. www.cliniciansurvivor.org (under Postvention tab). Published September 21, 2009. Accessed August 26, 2019.

14. Schultz, D. Suggestions for supervisors when a therapist experiences a client’s suicide. Women Ther. 2005;28(1):59-69.

15. Spiegelman JS Jr, Werth JL Jr. Don’t forget about me: the experiences of therapists-in-training after a patient has attempted or died by suicide. Women Ther. 2005;28(1):35-57.

16. American Association of Suicidology. Clinician Survivor Task Force. Clinicians as survivors of suicide: postvention information. http://cliniciansurvivor.org. Published May 16, 2016. Accessed January 13, 2019.

17. Whitmore CA, Cook J, Salg L. Supporting residents in the wake of patient suicide. The American Journal of Psychiatry Residents’ Journal. 2017;12(1):5-7.

18. Ellis TE, Patel AB. Client suicide: what now? Cogn Behav Pract. 2012;19(2):277-287.

19. Figueroa S, Dalack GW. Exploring the impact of suicide on clinicians: a multidisciplinary retreat model. J Psychiatr Pract. 2013;19(1):72-77.

20. Lerner U, Brooks, K, McNeil DE, et al. Coping with a patient’s suicide: a curriculum for psychiatry residency training programs. Acad Psychiatry. 2012;36(1):29-33.

21. Prabhakar D, Balon R, Anzia J, et al. Helping psychiatry residents cope with patient suicide. Acad Psychiatry. 2014;38(5):593-597.

22. Kaye NS, Soreff SM. The psychiatrist’s role, responses, and responsibilities when a patient commits suicide. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148(6):739-743.

23. McGann VL, Gutin N, Jordan JR. Guidelines for postvention care with survivor families after the suicide of a client. In: Jordan JR, McIntosh JL, eds. Grief after suicide: understanding the consequences and caring for the survivors. New York, NY: Routledge; 2011:133-155.

24. Hodgkinson PE. Responding to in-patient suicide. Br J Med Psychol. 1987;60(4):387-392.

At some point during their career, many mental health professionals will lose a patient to suicide, but few will be prepared for the experience and its aftermath. As I described in Part 1 of this article (

A chance for growth

Traumatic experiences such as a suicide loss can paradoxically present a multitude of opportunities for new growth and profound personal transformation.1 Such transformation is primarily fostered by social support in the aftermath of the trauma.2

Virtually all of the models of the clinician’s suicide grief trajectory I described in Part 1 not only assume the eventual resolution of the distressing reactions accompanying the original loss, but also suggest that mastery of these reactions can be a catalyst for both personal and professional growth. Clearly, not everyone who experiences such a loss will experience subsequent growth; there are many reports of clinicians leaving the field3 or becoming “burned out” after this occurs. Yet most clinicians who have described this loss in the literature and in discussion groups (including those I’ve conducted) have reported more positive eventual outcomes. It is difficult to establish whether this is due to a cohort effect—clinicians who are most likely to write about their experiences, be interviewed for research studies, and/or to seek out and participate in discussion/support groups may be more prone to find benefits in this experience, either by virtue of their nature or through the subsequent process of sharing these experiences in a supportive atmosphere.

The literature on patient suicide loss, as well as anecdotal reports, confirms that clinicians who experience optimal support are able to identify many retrospective benefits of their experience.4-6 Clinicians generally report that they are better able to identify potential risk and protective factors for suicide, and are more knowledgeable about optimal interventions with individuals who are suicidal. They also describe an increased sensitivity towards patients who are suicidal and those bereaved by suicide. In addition, clinicians report a reduction in therapeutic grandiosity/omnipotence, and more realistic appraisals and expectations in relation to their clinical competence. In their effort to understand the “whys” of their patient’s suicide, they are likely to retrospectively identify errors in treatment, “missed cues,” or things they might subsequently do differently,7 and to learn from these mistakes. Optimally, clinicians become more aware of their own therapeutic limitations, both in the short- and the long-term, and can use this knowledge to better determine how they will continue their clinical work. They also become much more aware of the issues involved in the aftermath of a patient suicide, including perceived gaps in the clinical and institutional systems that could optimally offer support to families and clinicians.

In addition to the positive changes related to knowledge and clinical skills, many clinicians also note deeper personal changes subsequent to their patient’s suicide, consistent with the literature on posttraumatic growth.1 Munson8 explored internal changes in clinicians following a patient suicide and found that in the aftermath, clinicians experienced both posttraumatic growth and compassion fatigue. He also found that the amount of time that elapsed since the patient’s suicide predicted posttraumatic growth, and the seemingly counterintuitive result that the number of years of clinical experience prior to the suicide was negatively correlated with posttraumatic growth.

Huhra et al4 described some of the existential issues that a clinician is likely to confront following a patient suicide. A clinician’s attempt to find a way to meaningfully understand the circumstances around this loss often prompts reflection on mortality, freedom, choice and personal autonomy, and the scope and limits of one’s responsibility toward others. The suicide challenges one’s previous conceptions and expectations around these professional issues, and the clinician must construct new paradigms that serve to integrate these new experiences and perspectives in a coherent way.

One of the most notable sequelae of this (and to other traumatic) experience is a subsequent desire to make use of the learning inherent in these experiences and to “give back.” Once they feel that they have resolved their own grief process, many clinicians express the desire to support others with similar experiences. Even when their experiences have been quite distressing, many clinicians are able to view the suicide as an opportunity to learn about ongoing limitations in the systems of support, and to work toward changing these in a way that ensures that future clinician-survivors will have more supportive experiences. Many view these new perspectives, and their consequent ability to be more helpful, as “unexpected gifts.” They often express gratitude toward the people and resources that have allowed them to make these transformations. Jones5 noted “the tragedy of patient suicide can also be an opportunity for us as therapists to grow in our skills at assessing and intervening in a suicidal crisis, to broaden and deepen the support we give and receive, to grow in our appreciation of the precious gift that life is, and to help each other live it more fully.”

Continue to: Guidelines for postvention

Guidelines for postvention

When a patient suicide occurs in the context of an agency setting, Grad9 recommends prompt responses on 4 levels:

- administrative

- institutional

- educational

- emotional.

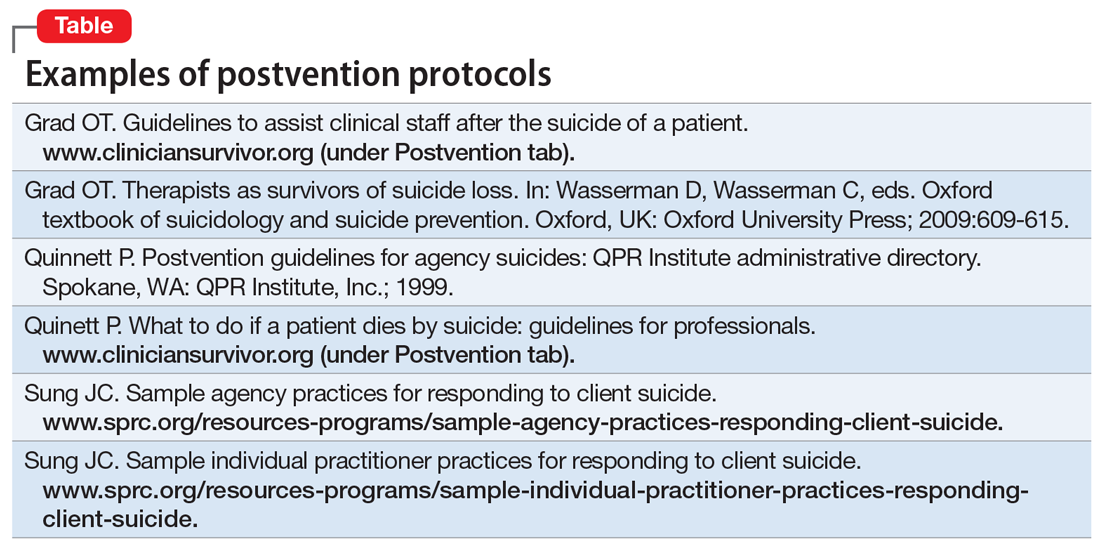

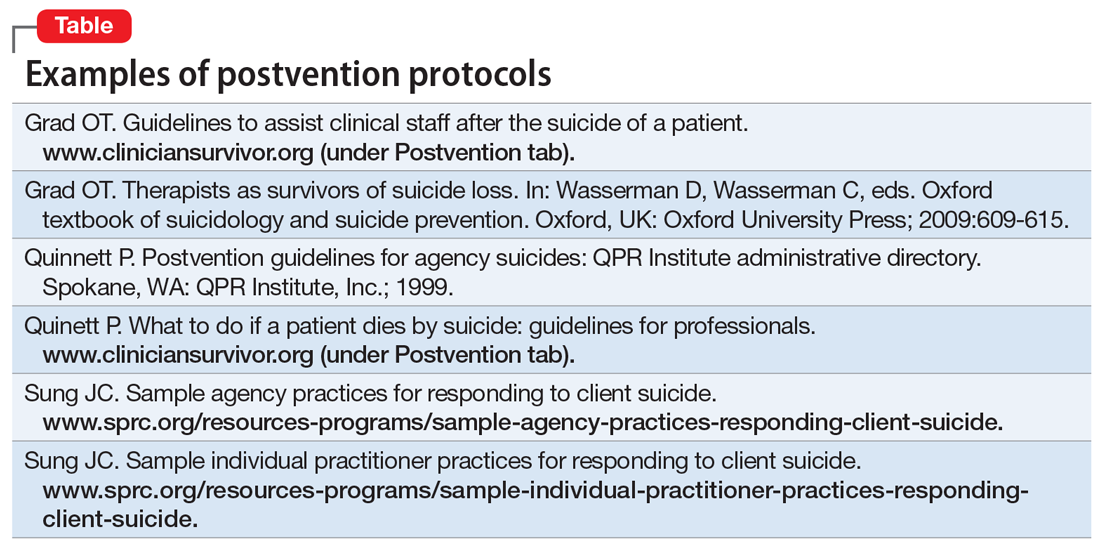

Numerous authors5,10-21 have developed suggestions, guidelines, and detailed postvention protocols to help agencies and clinicians in various mental health settings navigate the often-complicated sequelae to a patient’s suicide. The Table highlights a few of these. Most emphasize that information about suicide loss, including both its statistical likelihood and its potential aftermath, should integrated into clinicians’ general education and training. They also suggest that suicide postvention policies and protocols be in place from the outset, and that such information be incorporated into institutional policy and procedure manuals. In addition, they stress that legal, institutional, and administrative needs be balanced with the emotional needs of affected clinicians and staff, as well as those of the surviving family.

Institutional and administrative procedures

The following are some of the recommended procedures that should take place following a suicide loss. The postvention protocols listed in the Table provide more detailed recommendations.

Legal/ethical. It is essential to consult with a legal representative/risk management specialist associated with the affected agency (ideally, one with specific expertise in suicide litigation.). It is also crucial to clarify who holds privilege after a patient’s death (varies by state), what may and may not be shared under the restrictions of confidentiality and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) laws, and to clarify procedures for chart completion and review. It is also important to clarify the specific information to be shared both within and outside of the agency, and how to address the needs of current patients in the agency settings.

Case review. The optimal purpose of the case review (also known as a psychological autopsy) is to facilitate learning, identify gaps in agency procedures and training, improve pre- and postvention procedures, and help clinicians cope with the loss.22 Again, the legal and administrative needs of the agency need to be balanced with the attention to the emotional impact on the treating clinician.17 Ellis and Patel18 recommend delaying this procedure until the treating clinician is no longer in the “shock” phase of the loss, and is able to think and process events more objectively.

Continue to: Family contact

Family contact. Most authors have recommended that clinicians and/or agencies reach out to surviving families. Although some legal representatives will advise against this, experts in the field of suicide litigation have noted that compassionate family contact reduces liability and facilitates healing for both parties. In a personal communication (May 2008), Eric Harris, of the American Psychological Association Trust, recommended “compassion over caution” when considering these issues. Again, it is important to clarify who holds privilege after a patient’s death in determining when and with whom the patient’s confidential information may be shared. When confidentiality may be broken, clinical judgment should be used to determine how best to present the information to grieving family members.

Even if surviving family members do not hold privilege, there are many things that clinicians can do to be helpful.23 Inevitably, families will want any information that will help them make sense of the loss, and general psychoeducation about mental illness and suicide can be helpful in this regard. In addition, providing information about “Survivors After Suicide” support groups, reading materials, etc., can be helpful. Both support groups and survivor-related bibliographies are available on the web sites of the American Association of Suicidology (www.suicidology.org) and The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (www.afsp.org).

In addition, clinicians should ask the family if it would be helpful if they were to attend the funeral/memorial services, and how to introduce themselves if asked by other attendees.

Patients in clinics/hospitals. When a patient suicide occurs in a clinic or hospital setting, it is likely to impact other patients in that setting to the extent that they have heard, about the event, even from outside sources.According to Hodgkinson,24 in addition to being overwhelmed with intense feelings about the suicide loss (particularly if they had known the patient), affected patients are likely to be at increased risk for suicidal behaviors. This is consistent with the considerable literature on suicide contagion.

Thus, it is important to clarify information to be shared with patients; however, avoid describing details of the method, because this can foster contagion and “copycat” suicides. In addition, Kaye and Soreff22 noted that these patients may now be concerned about the staff’s ability to be helpful to them, because they were unable to help the deceased. In light of this, take extra care to attend to the impact of the suicide on current patients, and to monitor both pre-existing and new suicidality.

Continue to: Helping affected clinicians

Helping affected clinicians

Suggestions for optimally supporting affected clinicians include:

- clear communication about the nature of upcoming administrative procedures (including chart and institutional reviews)

- consultation from supervisors and/or colleagues that is supportive and reassuring, rather than blaming

- opportunities for the clinician to talk openly about the experience of the loss, either individually or in group settings, without fear of judgment or censure

- recognition that the loss is likely to impact clinical work, support in monitoring this impact, and the provision of medical leaves and/or modified caseloads (ie, fewer high-risk patients) as necessary.

Box 1

Frank Jones and Judy Meade founded the Clinical Survivor Task Force (CSTF) of the American Association of Suicidology (AAS) in 1987. As Jones noted, “clinicians who have lost patients to suicide need a place to acknowledge and carry forward their personal loss…to benefit both personally and professionally from the opportunity to talk with other therapists who have survived the loss of a patient through suicide.”7 Nina Gutin, PhD, and Vanessa McGann, PhD, have co-chaired the CSTF since 2003. It supports clinicians who have lost patients and/or loved ones, with the recognition that both types of losses carry implications within clinical and professional domains. The CSTF provides a listserve, opportunities to participate in video support groups, and a web site (www.cliniciansurvivor.org) that provides information about the clinician-survivor experience, the opportunity to read and post narratives about one’s experience with suicide loss, an updated bibliography maintained by John McIntosh, PhD, a list of clinical contacts, and links to several excellent postvention protocols. In addition, Drs. Gutin and McGann conduct clinician-survivor support activities at the annual AAS conference, and in their respective geographic areas.

Both researchers and clinician-survivors in my practice and support groups have noted that speaking with other clinicians who have experienced suicide loss can be particularly reassuring and validating. If none are available on staff, the listserve and online support groups of the American Association of Suicidology’s Clinician Survivor Task Force may be helpful (Box 17). In addition, the film “Collateral Damages: The Impact of Patient Suicide on the Physician” features physicians describing their experience of losing a patient to suicide (Box 2).

Box 2

“Collateral Damages: The Impact of Patient Suicide on the Physician” is a film that features several physicians speaking about their experience of losing a patient to suicide, as well as a group discussion. Psychiatrists in this educational film include Drs. Glen Gabbard, Sidney Zisook, and Jim Lomax. This resource can be used to facilitate an educational session for physicians, psychologists, residents, or other trainees. Please contact education@afsp.org to request a DVD of this film and a copy of a related article, Prabhakar D, Anzia JM, Balon R, et al. “Collateral damages”: preparing residents for coping with patient suicide. Acad Psychiatry. 2013;37(6):429-430.

Schultz14 offered suggestions for staff in supervisory positions, noting that they may bear at least some clinical and legal responsibility for the treatments that they supervise. She encouraged supervisors to take an active stance in advocating for trainees, to encourage colleagues to express their support, and to discourage rumors and other stigmatizing reactions. Schultz also urges supervisors to14:

- allow extra time for the clinician to engage in the normative exploration of the “whys” that are unique to suicide survivors

- use education about suicide to help the clinician gain a more realistic perspective on their relative culpability

- become aware of and provide education about normative grief reactions following a suicide.

Continue to: Because a suicide loss...

Because a suicide loss is likely to affect a clinician’s subsequent clinical activity, Schultz encourages supervisors to help clinicians monitor this impact on their work.14

A supportive environment is key

Losing a patient to suicide is a complicated, potentially traumatic process that many mental health clinicians will face. Yet with comprehensive and supportive postvention policies in place, clinicians who are impacted are more likely to experience healing and posttraumatic growth in both personal and professional domains.

Bottom Line

Although often traumatic, losing a patient to suicide presents clinicians with an opportunity for personal and professional growth. Following established postvention protocols can help ensure that legal, institutional, and administrative needs are balanced with the emotional needs of affected clinicians and staff, as well as those of the surviving family.

Related Resources

- American Association of Suicidology Clinician Survivor Task Force. www.cliniciansurvivor.org.

- Dotinga R. Coping when a patient commits suicide. July 21, 2017. www.mdedge.com/psychiatry/article/142975/depression/coping-when-patient-commits-suicide.

- Gutin N. Losing a patent to suicide: What we know. Part 1. 2019;18(10):14-16,19-22,30-32.

At some point during their career, many mental health professionals will lose a patient to suicide, but few will be prepared for the experience and its aftermath. As I described in Part 1 of this article (

A chance for growth

Traumatic experiences such as a suicide loss can paradoxically present a multitude of opportunities for new growth and profound personal transformation.1 Such transformation is primarily fostered by social support in the aftermath of the trauma.2

Virtually all of the models of the clinician’s suicide grief trajectory I described in Part 1 not only assume the eventual resolution of the distressing reactions accompanying the original loss, but also suggest that mastery of these reactions can be a catalyst for both personal and professional growth. Clearly, not everyone who experiences such a loss will experience subsequent growth; there are many reports of clinicians leaving the field3 or becoming “burned out” after this occurs. Yet most clinicians who have described this loss in the literature and in discussion groups (including those I’ve conducted) have reported more positive eventual outcomes. It is difficult to establish whether this is due to a cohort effect—clinicians who are most likely to write about their experiences, be interviewed for research studies, and/or to seek out and participate in discussion/support groups may be more prone to find benefits in this experience, either by virtue of their nature or through the subsequent process of sharing these experiences in a supportive atmosphere.

The literature on patient suicide loss, as well as anecdotal reports, confirms that clinicians who experience optimal support are able to identify many retrospective benefits of their experience.4-6 Clinicians generally report that they are better able to identify potential risk and protective factors for suicide, and are more knowledgeable about optimal interventions with individuals who are suicidal. They also describe an increased sensitivity towards patients who are suicidal and those bereaved by suicide. In addition, clinicians report a reduction in therapeutic grandiosity/omnipotence, and more realistic appraisals and expectations in relation to their clinical competence. In their effort to understand the “whys” of their patient’s suicide, they are likely to retrospectively identify errors in treatment, “missed cues,” or things they might subsequently do differently,7 and to learn from these mistakes. Optimally, clinicians become more aware of their own therapeutic limitations, both in the short- and the long-term, and can use this knowledge to better determine how they will continue their clinical work. They also become much more aware of the issues involved in the aftermath of a patient suicide, including perceived gaps in the clinical and institutional systems that could optimally offer support to families and clinicians.

In addition to the positive changes related to knowledge and clinical skills, many clinicians also note deeper personal changes subsequent to their patient’s suicide, consistent with the literature on posttraumatic growth.1 Munson8 explored internal changes in clinicians following a patient suicide and found that in the aftermath, clinicians experienced both posttraumatic growth and compassion fatigue. He also found that the amount of time that elapsed since the patient’s suicide predicted posttraumatic growth, and the seemingly counterintuitive result that the number of years of clinical experience prior to the suicide was negatively correlated with posttraumatic growth.

Huhra et al4 described some of the existential issues that a clinician is likely to confront following a patient suicide. A clinician’s attempt to find a way to meaningfully understand the circumstances around this loss often prompts reflection on mortality, freedom, choice and personal autonomy, and the scope and limits of one’s responsibility toward others. The suicide challenges one’s previous conceptions and expectations around these professional issues, and the clinician must construct new paradigms that serve to integrate these new experiences and perspectives in a coherent way.

One of the most notable sequelae of this (and to other traumatic) experience is a subsequent desire to make use of the learning inherent in these experiences and to “give back.” Once they feel that they have resolved their own grief process, many clinicians express the desire to support others with similar experiences. Even when their experiences have been quite distressing, many clinicians are able to view the suicide as an opportunity to learn about ongoing limitations in the systems of support, and to work toward changing these in a way that ensures that future clinician-survivors will have more supportive experiences. Many view these new perspectives, and their consequent ability to be more helpful, as “unexpected gifts.” They often express gratitude toward the people and resources that have allowed them to make these transformations. Jones5 noted “the tragedy of patient suicide can also be an opportunity for us as therapists to grow in our skills at assessing and intervening in a suicidal crisis, to broaden and deepen the support we give and receive, to grow in our appreciation of the precious gift that life is, and to help each other live it more fully.”

Continue to: Guidelines for postvention

Guidelines for postvention

When a patient suicide occurs in the context of an agency setting, Grad9 recommends prompt responses on 4 levels:

- administrative

- institutional

- educational

- emotional.

Numerous authors5,10-21 have developed suggestions, guidelines, and detailed postvention protocols to help agencies and clinicians in various mental health settings navigate the often-complicated sequelae to a patient’s suicide. The Table highlights a few of these. Most emphasize that information about suicide loss, including both its statistical likelihood and its potential aftermath, should integrated into clinicians’ general education and training. They also suggest that suicide postvention policies and protocols be in place from the outset, and that such information be incorporated into institutional policy and procedure manuals. In addition, they stress that legal, institutional, and administrative needs be balanced with the emotional needs of affected clinicians and staff, as well as those of the surviving family.

Institutional and administrative procedures

The following are some of the recommended procedures that should take place following a suicide loss. The postvention protocols listed in the Table provide more detailed recommendations.

Legal/ethical. It is essential to consult with a legal representative/risk management specialist associated with the affected agency (ideally, one with specific expertise in suicide litigation.). It is also crucial to clarify who holds privilege after a patient’s death (varies by state), what may and may not be shared under the restrictions of confidentiality and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) laws, and to clarify procedures for chart completion and review. It is also important to clarify the specific information to be shared both within and outside of the agency, and how to address the needs of current patients in the agency settings.

Case review. The optimal purpose of the case review (also known as a psychological autopsy) is to facilitate learning, identify gaps in agency procedures and training, improve pre- and postvention procedures, and help clinicians cope with the loss.22 Again, the legal and administrative needs of the agency need to be balanced with the attention to the emotional impact on the treating clinician.17 Ellis and Patel18 recommend delaying this procedure until the treating clinician is no longer in the “shock” phase of the loss, and is able to think and process events more objectively.

Continue to: Family contact

Family contact. Most authors have recommended that clinicians and/or agencies reach out to surviving families. Although some legal representatives will advise against this, experts in the field of suicide litigation have noted that compassionate family contact reduces liability and facilitates healing for both parties. In a personal communication (May 2008), Eric Harris, of the American Psychological Association Trust, recommended “compassion over caution” when considering these issues. Again, it is important to clarify who holds privilege after a patient’s death in determining when and with whom the patient’s confidential information may be shared. When confidentiality may be broken, clinical judgment should be used to determine how best to present the information to grieving family members.

Even if surviving family members do not hold privilege, there are many things that clinicians can do to be helpful.23 Inevitably, families will want any information that will help them make sense of the loss, and general psychoeducation about mental illness and suicide can be helpful in this regard. In addition, providing information about “Survivors After Suicide” support groups, reading materials, etc., can be helpful. Both support groups and survivor-related bibliographies are available on the web sites of the American Association of Suicidology (www.suicidology.org) and The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (www.afsp.org).

In addition, clinicians should ask the family if it would be helpful if they were to attend the funeral/memorial services, and how to introduce themselves if asked by other attendees.

Patients in clinics/hospitals. When a patient suicide occurs in a clinic or hospital setting, it is likely to impact other patients in that setting to the extent that they have heard, about the event, even from outside sources.According to Hodgkinson,24 in addition to being overwhelmed with intense feelings about the suicide loss (particularly if they had known the patient), affected patients are likely to be at increased risk for suicidal behaviors. This is consistent with the considerable literature on suicide contagion.

Thus, it is important to clarify information to be shared with patients; however, avoid describing details of the method, because this can foster contagion and “copycat” suicides. In addition, Kaye and Soreff22 noted that these patients may now be concerned about the staff’s ability to be helpful to them, because they were unable to help the deceased. In light of this, take extra care to attend to the impact of the suicide on current patients, and to monitor both pre-existing and new suicidality.

Continue to: Helping affected clinicians

Helping affected clinicians

Suggestions for optimally supporting affected clinicians include:

- clear communication about the nature of upcoming administrative procedures (including chart and institutional reviews)

- consultation from supervisors and/or colleagues that is supportive and reassuring, rather than blaming

- opportunities for the clinician to talk openly about the experience of the loss, either individually or in group settings, without fear of judgment or censure

- recognition that the loss is likely to impact clinical work, support in monitoring this impact, and the provision of medical leaves and/or modified caseloads (ie, fewer high-risk patients) as necessary.

Box 1

Frank Jones and Judy Meade founded the Clinical Survivor Task Force (CSTF) of the American Association of Suicidology (AAS) in 1987. As Jones noted, “clinicians who have lost patients to suicide need a place to acknowledge and carry forward their personal loss…to benefit both personally and professionally from the opportunity to talk with other therapists who have survived the loss of a patient through suicide.”7 Nina Gutin, PhD, and Vanessa McGann, PhD, have co-chaired the CSTF since 2003. It supports clinicians who have lost patients and/or loved ones, with the recognition that both types of losses carry implications within clinical and professional domains. The CSTF provides a listserve, opportunities to participate in video support groups, and a web site (www.cliniciansurvivor.org) that provides information about the clinician-survivor experience, the opportunity to read and post narratives about one’s experience with suicide loss, an updated bibliography maintained by John McIntosh, PhD, a list of clinical contacts, and links to several excellent postvention protocols. In addition, Drs. Gutin and McGann conduct clinician-survivor support activities at the annual AAS conference, and in their respective geographic areas.

Both researchers and clinician-survivors in my practice and support groups have noted that speaking with other clinicians who have experienced suicide loss can be particularly reassuring and validating. If none are available on staff, the listserve and online support groups of the American Association of Suicidology’s Clinician Survivor Task Force may be helpful (Box 17). In addition, the film “Collateral Damages: The Impact of Patient Suicide on the Physician” features physicians describing their experience of losing a patient to suicide (Box 2).

Box 2

“Collateral Damages: The Impact of Patient Suicide on the Physician” is a film that features several physicians speaking about their experience of losing a patient to suicide, as well as a group discussion. Psychiatrists in this educational film include Drs. Glen Gabbard, Sidney Zisook, and Jim Lomax. This resource can be used to facilitate an educational session for physicians, psychologists, residents, or other trainees. Please contact education@afsp.org to request a DVD of this film and a copy of a related article, Prabhakar D, Anzia JM, Balon R, et al. “Collateral damages”: preparing residents for coping with patient suicide. Acad Psychiatry. 2013;37(6):429-430.

Schultz14 offered suggestions for staff in supervisory positions, noting that they may bear at least some clinical and legal responsibility for the treatments that they supervise. She encouraged supervisors to take an active stance in advocating for trainees, to encourage colleagues to express their support, and to discourage rumors and other stigmatizing reactions. Schultz also urges supervisors to14:

- allow extra time for the clinician to engage in the normative exploration of the “whys” that are unique to suicide survivors

- use education about suicide to help the clinician gain a more realistic perspective on their relative culpability

- become aware of and provide education about normative grief reactions following a suicide.

Continue to: Because a suicide loss...

Because a suicide loss is likely to affect a clinician’s subsequent clinical activity, Schultz encourages supervisors to help clinicians monitor this impact on their work.14

A supportive environment is key

Losing a patient to suicide is a complicated, potentially traumatic process that many mental health clinicians will face. Yet with comprehensive and supportive postvention policies in place, clinicians who are impacted are more likely to experience healing and posttraumatic growth in both personal and professional domains.

Bottom Line

Although often traumatic, losing a patient to suicide presents clinicians with an opportunity for personal and professional growth. Following established postvention protocols can help ensure that legal, institutional, and administrative needs are balanced with the emotional needs of affected clinicians and staff, as well as those of the surviving family.

Related Resources

- American Association of Suicidology Clinician Survivor Task Force. www.cliniciansurvivor.org.

- Dotinga R. Coping when a patient commits suicide. July 21, 2017. www.mdedge.com/psychiatry/article/142975/depression/coping-when-patient-commits-suicide.

- Gutin N. Losing a patent to suicide: What we know. Part 1. 2019;18(10):14-16,19-22,30-32.

1. Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. Beyond the concept of recovery: Growth and the experience of loss. Death Stud. 2008;32(1):27-39.

2. Fuentes MA, Cruz D. Posttraumatic growth: positive psychological changes after trauma. Mental Health News. 2009;11(1):31,37.

3. Gitlin M. Aftermath of a tragedy: reaction of psychiatrists to patient suicides. Psychiatr Ann. 2007;37(10):684-687.

4. Huhra R, Hunka N, Rogers J, et al. Finding meaning: theoretical perspectives on patient suicide. Paper presented at: 2004 Annual Conference of the American Association of Suicidology; April 2004; Miami, FL.

5. Jones FA Jr. Therapists as survivors of patient suicide. In: Dunne EJ, McIntosh JL, Dunne-Maxim K, eds. Suicide and its aftermath: understanding and counseling the survivors. New York, NY: W.W. Norton; 1987;126-141.

6. Gutin N, McGann VM, Jordan JR. The impact of suicide on professional caregivers. In: Jordan J, McIntosh J, eds. Grief after suicide: understanding the consequences and caring for the survivors. New York, NY: Routledge; 2011:93-111.

7. Hendin H, Lipschitz A, Maltsberger JT, et al. Therapists’ reactions to patients’ suicides. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(12):2022-2027.

8. Munson JS. Impact of client suicide on practitioner posttraumatic growth [dissertation]. Gainesville, Florida: University of Florida; 2009.

9. Grad OT. Therapists as survivors of suicide loss. In: Wasserman D, Wasserman C, eds. Oxford textbook of suicidology and suicide prevention. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2009:609-615.

10. Douglas J, Brown HN. Suicide: understanding and responding: Harvard Medical School perspectives. Madison, CT: International Universities Press; 1989.

11. Farberow NL. The mental health professional as suicide survivor. Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2005;2(1):13-20.

12. Plakun EM, Tillman JG. Responding to clinicians after loss of a patient to suicide. Dir Psychiatry. 2005;25:301-310.

13. Quinnett P. QPR: for suicide prevention. QPR Institute, Inc. www.cliniciansurvivor.org (under Postvention tab). Published September 21, 2009. Accessed August 26, 2019.

14. Schultz, D. Suggestions for supervisors when a therapist experiences a client’s suicide. Women Ther. 2005;28(1):59-69.

15. Spiegelman JS Jr, Werth JL Jr. Don’t forget about me: the experiences of therapists-in-training after a patient has attempted or died by suicide. Women Ther. 2005;28(1):35-57.

16. American Association of Suicidology. Clinician Survivor Task Force. Clinicians as survivors of suicide: postvention information. http://cliniciansurvivor.org. Published May 16, 2016. Accessed January 13, 2019.

17. Whitmore CA, Cook J, Salg L. Supporting residents in the wake of patient suicide. The American Journal of Psychiatry Residents’ Journal. 2017;12(1):5-7.

18. Ellis TE, Patel AB. Client suicide: what now? Cogn Behav Pract. 2012;19(2):277-287.

19. Figueroa S, Dalack GW. Exploring the impact of suicide on clinicians: a multidisciplinary retreat model. J Psychiatr Pract. 2013;19(1):72-77.

20. Lerner U, Brooks, K, McNeil DE, et al. Coping with a patient’s suicide: a curriculum for psychiatry residency training programs. Acad Psychiatry. 2012;36(1):29-33.

21. Prabhakar D, Balon R, Anzia J, et al. Helping psychiatry residents cope with patient suicide. Acad Psychiatry. 2014;38(5):593-597.

22. Kaye NS, Soreff SM. The psychiatrist’s role, responses, and responsibilities when a patient commits suicide. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148(6):739-743.

23. McGann VL, Gutin N, Jordan JR. Guidelines for postvention care with survivor families after the suicide of a client. In: Jordan JR, McIntosh JL, eds. Grief after suicide: understanding the consequences and caring for the survivors. New York, NY: Routledge; 2011:133-155.

24. Hodgkinson PE. Responding to in-patient suicide. Br J Med Psychol. 1987;60(4):387-392.

1. Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. Beyond the concept of recovery: Growth and the experience of loss. Death Stud. 2008;32(1):27-39.

2. Fuentes MA, Cruz D. Posttraumatic growth: positive psychological changes after trauma. Mental Health News. 2009;11(1):31,37.

3. Gitlin M. Aftermath of a tragedy: reaction of psychiatrists to patient suicides. Psychiatr Ann. 2007;37(10):684-687.

4. Huhra R, Hunka N, Rogers J, et al. Finding meaning: theoretical perspectives on patient suicide. Paper presented at: 2004 Annual Conference of the American Association of Suicidology; April 2004; Miami, FL.

5. Jones FA Jr. Therapists as survivors of patient suicide. In: Dunne EJ, McIntosh JL, Dunne-Maxim K, eds. Suicide and its aftermath: understanding and counseling the survivors. New York, NY: W.W. Norton; 1987;126-141.

6. Gutin N, McGann VM, Jordan JR. The impact of suicide on professional caregivers. In: Jordan J, McIntosh J, eds. Grief after suicide: understanding the consequences and caring for the survivors. New York, NY: Routledge; 2011:93-111.

7. Hendin H, Lipschitz A, Maltsberger JT, et al. Therapists’ reactions to patients’ suicides. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(12):2022-2027.

8. Munson JS. Impact of client suicide on practitioner posttraumatic growth [dissertation]. Gainesville, Florida: University of Florida; 2009.

9. Grad OT. Therapists as survivors of suicide loss. In: Wasserman D, Wasserman C, eds. Oxford textbook of suicidology and suicide prevention. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2009:609-615.

10. Douglas J, Brown HN. Suicide: understanding and responding: Harvard Medical School perspectives. Madison, CT: International Universities Press; 1989.

11. Farberow NL. The mental health professional as suicide survivor. Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2005;2(1):13-20.

12. Plakun EM, Tillman JG. Responding to clinicians after loss of a patient to suicide. Dir Psychiatry. 2005;25:301-310.

13. Quinnett P. QPR: for suicide prevention. QPR Institute, Inc. www.cliniciansurvivor.org (under Postvention tab). Published September 21, 2009. Accessed August 26, 2019.

14. Schultz, D. Suggestions for supervisors when a therapist experiences a client’s suicide. Women Ther. 2005;28(1):59-69.

15. Spiegelman JS Jr, Werth JL Jr. Don’t forget about me: the experiences of therapists-in-training after a patient has attempted or died by suicide. Women Ther. 2005;28(1):35-57.

16. American Association of Suicidology. Clinician Survivor Task Force. Clinicians as survivors of suicide: postvention information. http://cliniciansurvivor.org. Published May 16, 2016. Accessed January 13, 2019.

17. Whitmore CA, Cook J, Salg L. Supporting residents in the wake of patient suicide. The American Journal of Psychiatry Residents’ Journal. 2017;12(1):5-7.

18. Ellis TE, Patel AB. Client suicide: what now? Cogn Behav Pract. 2012;19(2):277-287.

19. Figueroa S, Dalack GW. Exploring the impact of suicide on clinicians: a multidisciplinary retreat model. J Psychiatr Pract. 2013;19(1):72-77.

20. Lerner U, Brooks, K, McNeil DE, et al. Coping with a patient’s suicide: a curriculum for psychiatry residency training programs. Acad Psychiatry. 2012;36(1):29-33.

21. Prabhakar D, Balon R, Anzia J, et al. Helping psychiatry residents cope with patient suicide. Acad Psychiatry. 2014;38(5):593-597.

22. Kaye NS, Soreff SM. The psychiatrist’s role, responses, and responsibilities when a patient commits suicide. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148(6):739-743.

23. McGann VL, Gutin N, Jordan JR. Guidelines for postvention care with survivor families after the suicide of a client. In: Jordan JR, McIntosh JL, eds. Grief after suicide: understanding the consequences and caring for the survivors. New York, NY: Routledge; 2011:133-155.

24. Hodgkinson PE. Responding to in-patient suicide. Br J Med Psychol. 1987;60(4):387-392.

Losing a patient to suicide: What we know

Studies have found that 1 in 2 psychiatrists,1-4 and 1 in 5 psychologists, clinical social workers, and other mental health professionals,5 will lose a patient to suicide in the course of their career. This statistic suggests that losing a patient to suicide constitutes a clear occupational hazard.6,7 Despite this, most mental health professionals continue to view suicide loss as an aberration. Consequently, there is often a lack of preparedness for such an event when it does occur.

This 2-part article summarizes what is currently known about the unique personal and professional issues experienced by clinician-survivors (clinicians who have lost patients and/or loved ones to suicide). In Part 1, I cover:

- the impact of losing a patient to suicide

- confidentiality-related constraints on the ability to discuss and process the loss

- legal and ethical issues

- colleagues’ reactions and stigma

- the effects of a suicide loss on one’s clinical work.

Part 2 will discuss the opportunities for personal growth that can result from experiencing a suicide loss, guidelines for optimal postventions, and steps clinicians can take to help support colleagues who have lost a patient to suicide.

A neglected topic

For psychiatrists and other mental health professionals, the loss of a patient to suicide is certainly not uncommon.1-5 Despite this, coping with a patient’s suicide is a “neglected topic”8 in residency and general mental health training.

There are many published articles on clinicians experiencing suicide loss (for a comprehensive bibliography, see McIntosh9), and several authors10-19 have developed suggestions, guidelines, and detailed postvention protocols to help clinicians navigate the often-complicated sequelae to such a loss. However, these resources have generally not been integrated into clinical training, and tend to be poorly disseminated. In a national survey of chief residents, Melton and Coverdale20 found that only 25% of residency training programs covered topics related to postvention, and 72% of chief residents felt this topic needed more attention. Thus, despite the existence of guidelines for optimal postvention and support, clinicians are often left to cope with the consequences of this difficult loss on their own, and under less-than-optimal conditions.

A patient’s suicide typically affects clinicians on multiple levels, both personally and professionally. In this article, I highlight the range of normative responses, as well as the factors that may facilitate or inhibit subsequent healing and growth, with the hope that this knowledge may be utilized to help current and future generations of clinician-survivors obtain optimal support, and that institutions who treat potentially suicidal individuals will develop optimal postvention responses following a suicide loss. Many aspects of what this article discusses also apply to clinicians who have experienced a suicide loss in their personal or family life, as this also tends to “spill over” into one’s professional roles and identity.

Grief and other emotional effects

In many ways, clinicians’ responses after a patient’s suicide are similar to those of other survivors after the loss of a loved one to suicide.21 Chemtob et al2 found that approximately one-half of psychiatrists who lost a patient to suicide had scores on the Impact of an Event Scale that were comparable to those of a clinical population seeking treatment after the death of a parent.

Continue to: Jordan and McIntosh have detailed...

Jordan and McIntosh22 have detailed several elements and themes that differentiate suicide loss and its associated reactions from other types of loss and grief. In general, suicide loss is considered traumatic, and is often accompanied by intense confusion and existential questioning, reflecting a negative impact on one’s core beliefs and assumptive world. The subsequent need to address the myriad of “why” questions left in its wake are often tinted with what Jordan and Baugher23 term the “tyranny of hindsight,” and take the form of implicit guilt for “sins of omission or commission” in relation to the lost individual.

Responses to suicide loss typically include initial shock, denial and numbness, intense sadness, anxiety, anger, and intense distress. Consistent with the traumatic nature of the loss, survivors are also likely to experience posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms such as intrusive thoughts, avoidance, and dissociation. Survivors also commonly experience significant guilt and shame, and this is likely to be socially reinforced by the general stigma associated with suicide as well as the actual blaming and avoidance responses of others.24-27

Clinicians’ unique reactions

For clinicians, there are additional components that may further complicate or exacerbate these reactions and extend their duration. First and foremost, such a loss affects clinicians on both personal and professional levels, a phenomenon that Plakun and Tillman13 have termed a “twin bereavement.” Thus, in addition to the personal grief and trauma reactions entailed in losing a patient to suicide, this loss is likely to impact clinicians’ professional identities, their relationships with colleagues, and their clinical work.

Clinicians’ professional identities are often predicated on generally shared assumptions and beliefs that, as trained professionals, they should have the power, aptitude, and competence to heal, or at least improve, the lives of patients, to reduce their distress, and to provide safety. In addition, such assumptions about clinicians’ responsibility and ability to prevent suicide are often reinforced in the clinical literature.28,29

These assumptions are often challenged, if not shattered, when patients take their own lives. A clinician’s sense of professional responsibility, the guilt and self-blame that may accompany this, self-doubts about one’s skills and clinical competence, the fear of (and actual) blame of colleagues and family members, and the real or imagined threat of litigation may all greatly exacerbate a clinician’s distress.11

Continue to: Hendin et al found...

Hendin et al30 found that mental health therapists have described losing a patient as “the most profoundly disturbing event of their professional careers,” noting that one-third of these clinicians experienced severe distress that lasted at least 1 year beyond the initial loss. In a 2004 study, Ruskin et al4 similarly found that one-quarter of psychiatrists and psychiatric trainees noted that losing a patient had a “profound and enduring effect on them.” In her article on surviving a patient’s suicide, Rycroft31 describes a “professional void” following the loss of her patient, in which “the world had changed, nothing was predictable any more, and it was no longer safe to assume anything.” Additionally, many clinicians experience an “acute sense of aloneness and isolation” subsequent to the loss.32

Many clinicians have noted that they considered leaving the field after such a loss,33,34 and it is hypothesized that many may have done so.35-37 Others have noted that, at least temporarily, they stopped treating patients who were potentially suicidal.29,35

Box 1

Several authors have proposed general models for describing the suicide grief trajectories of clinicians after a suicide loss. Tillman38 identified distinct groups of responses to this event: traumatic, affective, those related to the treatment, those related to interactions with colleagues, liability concerns, and the impact on one’s professional philosophy. She also found that Erikson’s stages of identity39 provided an uncannily similar trajectory to the ways in which those who participated in her research—clinicians at a mental hospital—had attempted to cope with their patients’ deaths, noting that the “suicide of a patient may provoke a revisiting of Erikson’s psychosocial crises in a telescoped and accelerated fashion.”38

Maltsberger40 offered a detailed psychoanalytic analysis of the responses clinicians may manifest in relation to a suicide loss, including the initial narcissistic injury sustained in relation to their patient’s actions; the subsequent potential for melancholic, atonement, or avoidance reactions; and the eventual capacity for the resolution of these reactions.

Al-Mateen et al33 described 3 phases of the clinician’s reaction after losing a patient who was a child to suicide:

- initial, which includes trauma and shock

- turmoil, which includes emotional flooding and functional impairments

- new growth, in which clinicians are able to reflect on their experiences and implications for training and policy.

For each phase, they also described staff activities that would foster forward movement through the trajectory.

In a 1981 study, Bissell41 found that psychiatric nurses who had experienced patient completed suicides progressed through several developmental stages (naïveté, recognition, responsibility, individual choice) that enabled them to come to terms with their personal reactions and place the ultimate responsibility for the suicide with the patient.

After losing a patient to suicide, a clinician may experience grief that proceeds through specific stages (Box 133,38-41). Box 22-4,6,16,24,29,30,33,34,40,42-45 describes a wide range of factors that affect each clinician’s unique response to losing a patient to suicide.

Box 2

There are many factors that make the experience of losing a patient to suicide unique and variable for individual clinicians. These include the amount of a clinician’s professional training and experience, both in general and in working with potentially suicidal individuals. Chemtob et al2 found that trainees were more likely to experience patient suicide loss than more seasoned clinicians, and to experience more distress.4,30,42 Brown24 noted that many training programs were likely to assign the most “extraordinarily sick patients to inexperienced trainees.” He noted that because the skill level of trainees has not yet tempered their personal aspirations, they are likely to experience a patient’s suicide as a personal failure. However, in contrast to the findings of Kleespies,42 Hendin,30 Ruskin et al,4 and Brown24 suggested that the overall impact of a patient’s suicide may be greater for seasoned clinicians, when the “protective advantage” or “explanation” of being in training is no longer applicable. This appears consistent with Munson’s study,43 which found that a greater number of years of clinical experience prior to a suicide loss was negatively correlated with posttraumatic growth.

Other factors affecting a clinician’s grief response include the context in which the treatment occurred, such as inpatient, outpatient, clinic, private practice, etc.44; the presence and involvement of supportive mentors or supervisors16; the length and intensity of the clinical relationship6,29; countertransference issues40; whether the patient was a child33; and the time elapsed since the suicide occurred.

In addition, each clinician’s set of personal and life experiences can affect the way he/ she moves through the grieving process. Any previous trauma or losses, particularly prior exposure to suicide, will likely impact a clinician’s reaction to his/her current loss, as will any susceptibility to anxiety or depression. Gorkin45 has suggested that the degree of omnipotence in the clinician’s therapeutic strivings will affect his/her ability to accept the inherent ambiguity involved in suicide loss. Gender may also play a role: Henry et al34 found that female clinicians had higher levels of stress reactions, and Grad et al3 found that female clinicians felt more shame and guilt and professed more doubts about their professional competence than male clinicians, and were more than twice as likely as men to identify talking with colleagues as an effective coping strategy.

Continue to: Implications of confidentiality restrictions

Implications of confidentiality restrictions

Confidentiality issues, as well as advice from attorneys to limit the disclosure of information about a patient, are likely to preclude a clinician’s ability to talk freely about the patient, the therapeutic relationship, and his/her reactions to the loss, all of which are known to facilitate movement through the grief process.46

The development of trust and the sharing of pain are just 2 factors that can make the clinical encounter an intense emotional experience for both parties. Recent trends in the psychodynamic literature acknowledge the profundity and depth of the personal impact that patients have on the clinician, an impact that is neither pathological nor an indication of poor boundaries in the therapy dyad, but instead a recognition of how all aspects of the clinician’s person, whether consciously or not, are used within the context of a therapeutic relationship. Yet when clinicians lose a patient, confidentiality restrictions often leave them wondering if and where any aspects of their experiences can be shared. Legal counsel may advise a clinician against speaking to consultants or supervisors or even surviving family members for fear that these non-privileged communications are subject to discovery should any legal proceedings ensue. Furthermore, the usual grief rituals that facilitate the healing of loss and the processing of grief (eg, gathering with others who knew the deceased, sharing feelings and memories, attending memorials) are usually denied to the clinician, and are often compounded by the reactions of one’s professional colleagues, who tend not to view the therapist’s grief as “legitimate.” Thus, clinician-survivors, despite having experienced a profound and traumatic loss, have very few places where this may be processed or even validated. As one clinician in a clinician-survivors support group stated, “I felt like I was grieving in a vacuum, that I wasn’t allowed to talk about how much my patient meant to me or how I’m feeling about it.” The isolation of grieving alone is likely to be compounded by the general lack of resources for supporting clinicians after such a loss. In contrast to the general suicide “survivor” network of support groups for family members who have experienced a suicide loss, there is an almost complete lack of supportive resources for clinicians following such a loss, and most clinicians are not aware of the resources that are available, such as the Clinician Survivor Task Force of the American Association of Suicidology (Box 312).

Box 3

Frank Jones and Judy Meade founded the Clinician Survivor Task Force (CSTF) of the American Association of Suicidology (AAS) in 1987. As Jones noted, “clinicians who have lost patients to suicide need a place to acknowledge and carry forward their personal loss … to benefit both personally and professionally from the opportunity to talk with other therapists who have survived the loss of a patient through suicide.”12

Nina Gutin, PhD, and Vanessa McGann, PhD, have co-chaired the CSTF since 2003. It now supports clinicians who have lost patients and/or loved ones, with the recognition that both types of losses carry implications within clinical and professional domains. The CSTF provides a listserve, opportunities to participate in video support groups, and a web site (www. cliniciansurvivor.org) that provides information about the clinician-survivor experience, the opportunity to read and post narratives about one’s experience with suicide loss, an updated bibliography maintained by John McIntosh, PhD, a list of clinical contacts, and a link to several excellent postvention protocols. In addition, Drs. Gutin and McGann conduct clinician-survivor support activities at the annual AAS conference, and in their respective geographic areas.

Continue to: Doka has described...

Doka47 has described “disenfranchised grief” in which the bereaved person does not receive the type and quality of support accorded to other bereaved persons, and thus is likely to internalize the view that his/her grief is not legitimate, and to believe that sharing related distress is a shame-ridden liability. This clearly relates to the sense of profound isolation and distress often described by clinician-survivors.

Other legal/ethical issues

The clinician-survivor’s concern about litigation, or an actual lawsuit, is likely to produce intense anxiety. This common fear is both understandable and credible. According to Bongar,48 the most common malpractice lawsuits filed against clinicians are those that involve a patient’s suicide. Peterson et al49 found that 34% of surviving family members considered bringing a lawsuit against the clinician, and of these, 57% consulted a lawyer.

In addition, an institution’s concern about protecting itself from liability may compromise its ability to support the clinician or trainee who sustained the loss. As noted above, the potential prohibitions around discussing the case can compromise the grief process. Additionally, the fear of (or actual) legal reprisals against supervisors and the larger institution may engender angry and blaming responses toward the treating clinician. In a personal communication (April 2008), Quinnett described an incident in which a supervising psychologist stomped into the grieving therapist’s office unannounced and shouted, “Now look what you’ve done! You’re going to get me sued!”

Other studies29,50,51 note that clinician-survivors fear losing their job, and that their colleagues and supervisors will be reluctant to assign new patients to them. Spiegleman and Werth17 also note that trainees grapple with additional concerns over negative evaluations, suspension or termination from clinical sites or training programs, and a potential interruption of obtaining a degree. Such supervisory and institutional reactions are likely to intensify a clinician’s sense of shame and distress, and are antithetical to postvention responses that promote optimal personal and professional growth. Such negative reactions are also likely to contribute to a clinician or trainee’s subsequent reluctance to work with suicidal individuals, or their decision to discontinue their clinical work altogether. Lastly, other ethical issues, such as contact with the patient’s family following the suicide, attending the funeral, etc., are likely to be a source of additional anxiety and distress, particularly if the clinician needs to address these issues in isolation.

Professional relationships/colleagues’ reactions