User login

Elusive Edema: A Case of Nephrotic Syndrome Mimicking Decompensated Cirrhosis

Elusive Edema: A Case of Nephrotic Syndrome Mimicking Decompensated Cirrhosis

Histology is the gold standard for cirrhosis diagnosis. However, a combination of clinical history, physical examination findings, and supportive laboratory and radiographic features is generally sufficient to make the diagnosis. Routine ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) imaging often identifies a nodular liver contour with sequelae of portal hypertension, including splenomegaly, varices, and ascites, which can suggest cirrhosis when supported by laboratory parameters and clinical features. As a result, the diagnosis is typically made clinically.1 Many patients with compensated cirrhosis go undetected. The presence of a decompensation event (ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, variceal hemorrhage, or hepatic encephalopathy) often leads to index diagnosis when patients were previously compensated. When a patient presents with suspected decompensated cirrhosis, it is important to consider other diagnoses with similar presentations and ensure that multiple disease processes are not contributing to the symptoms.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 64-year-old male with a history of intravenous (IV) methamphetamine use and prior incarceration presented with a 3-week history of progressively worsening generalized swelling. Prior to the onset of his symptoms, the patient injured his right lower extremity (RLE) in a bicycle accident, resulting in edema that progressed to bilateral lower extremity (BLE) edema and worsening fatigue, despite resolution of the initial injury. The patient gained weight though he could not quantify the amount. He experienced progressive hunger, thirst, and fatigue as well as increased sleep. Additionally, the patient experienced worsening dyspnea on exertion and orthopnea. He started using 2 pillows instead of 1 pillow at night.

The patient reported no fevers, chills, sputum production, chest pain, or paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea. He had no known history of sexually transmitted infections, no significant history of alcohol use, and occasional tobacco and marijuana use. He had been incarcerated > 10 years before and last used IV methamphetamine 3 years before. He did not regularly take any medications.

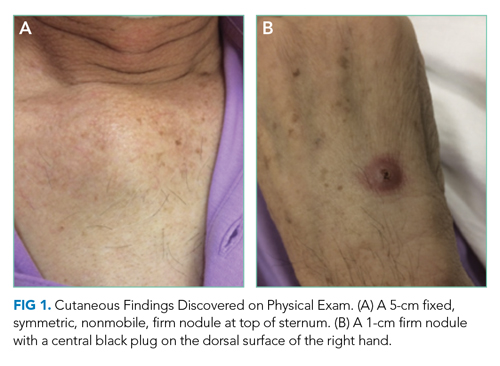

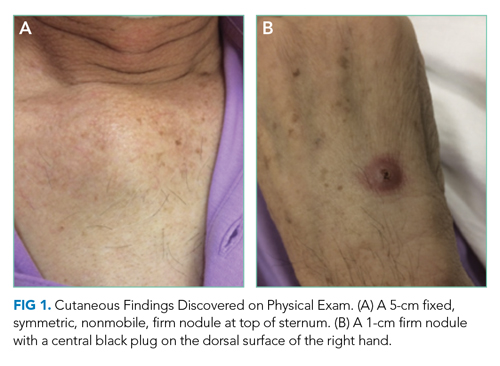

The patient’s vital signs included a temperature of 98.2 °F; 78/min heart rate; 15/min respiratory rate; 159/109 mm Hg blood pressure; and 98% oxygen saturation on room air. He had gained 20 lbs in the past 4 months. He had pitting edema in both legs and arms, as well as periorbital swelling, but no jugular venous distention, abnormal heart sounds, or murmurs. Breath sounds were distant but clear to auscultation. His abdomen was distended with normal bowel sounds and no fluid wave; mild epigastric tenderness was present, but no intra-abdominal masses were palpated. He had spider angiomata on the upper chest but no other stigmata of cirrhosis, such as caput medusae or jaundice. Tattoos were noted.

Laboratory test results showed a platelet count of 178 x 103/μL (reference range, 140- 440 ~ 103μL).Creatinine was 0.80 mg/dL (reference range, < 1.28 mg/dL), with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 99 mL/min/1.73 m2 using the Chronic Kidney Disease-Epidemiology equation (reference range, > 60 mL/min/1.73 m2), (reference range, > 60 mL/min/1.73 m2), and Cystatin C was 1.14 mg/L (reference range, < 1.15 mg/L). His electrolytes and complete blood count were within normal limits, including sodium, 134 mmol/L; potassium, 4.4 mmol/L; chloride, 108 mmol/L; and carbon dioxide, 22.5 mmol/L.

Additional test results included alkaline phosphatase, 126 U/L (reference range, < 94 U/L); alanine transaminase, 41 U/L (reference range, < 45 U/L); aspartate aminotransferase, 70 U/L (reference range, < 35 U/L); total bilirubin, 0.6 mg/dL (reference range, < 1 mg/dL); albumin, 1.8 g/dL (reference range, 3.2-4.8 g/dL); and total protein, 6.3 g/dL (reference range, 5.9-8.3 g/dL). The patient’s international normalized ratio was 0.96 (reference range, 0.8-1.1), and brain natriuretic peptide was normal at 56 pg/mL. No prior laboratory results were available for comparison.

Urine toxicology was positive for amphetamines. Urinalysis demonstrated large occult blood, with a red blood cell count of 26/ HPF (reference range, 0/HPF) and proteinuria (100 mg/dL; reference range, negative), without bacteria, nitrites, or leukocyte esterase. Urine white blood cell count was 10/ HPF (reference range, 0/HPF), and fine granular casts and hyaline casts were present.

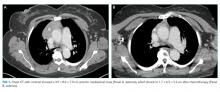

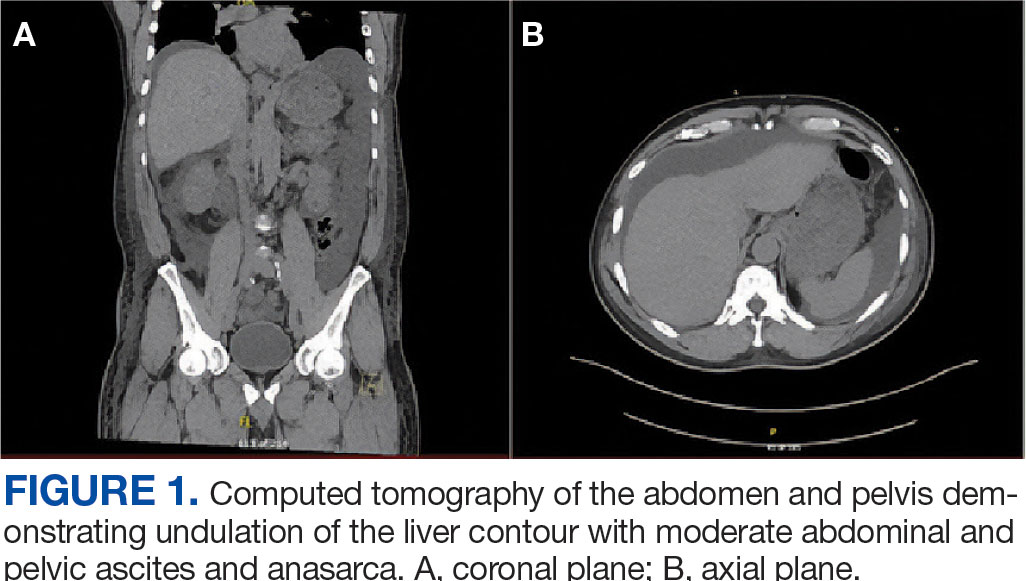

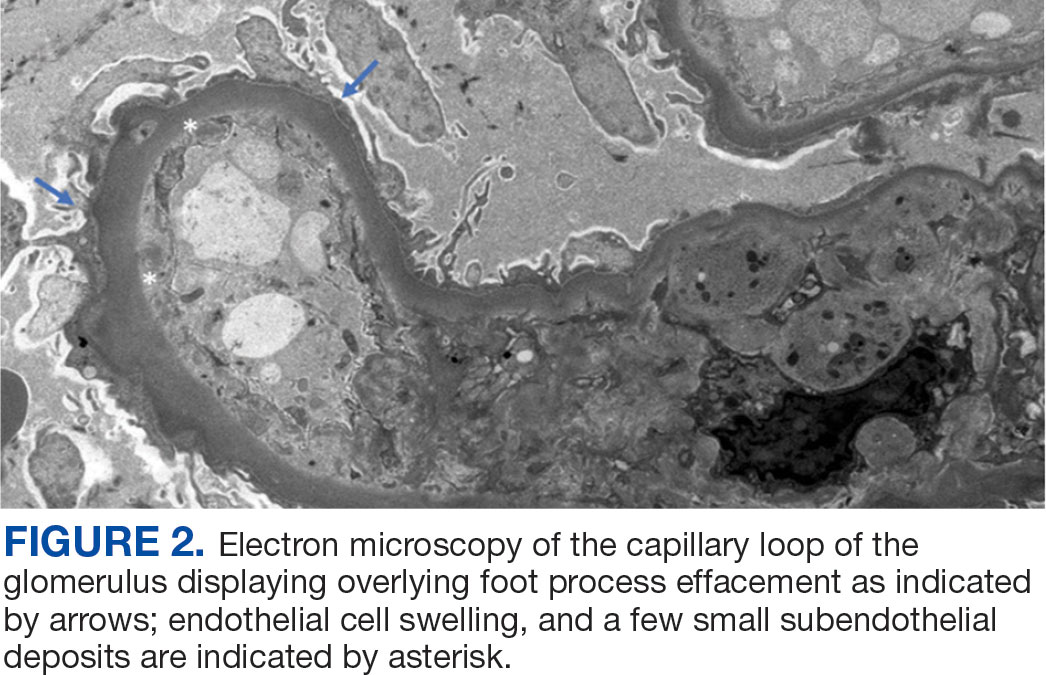

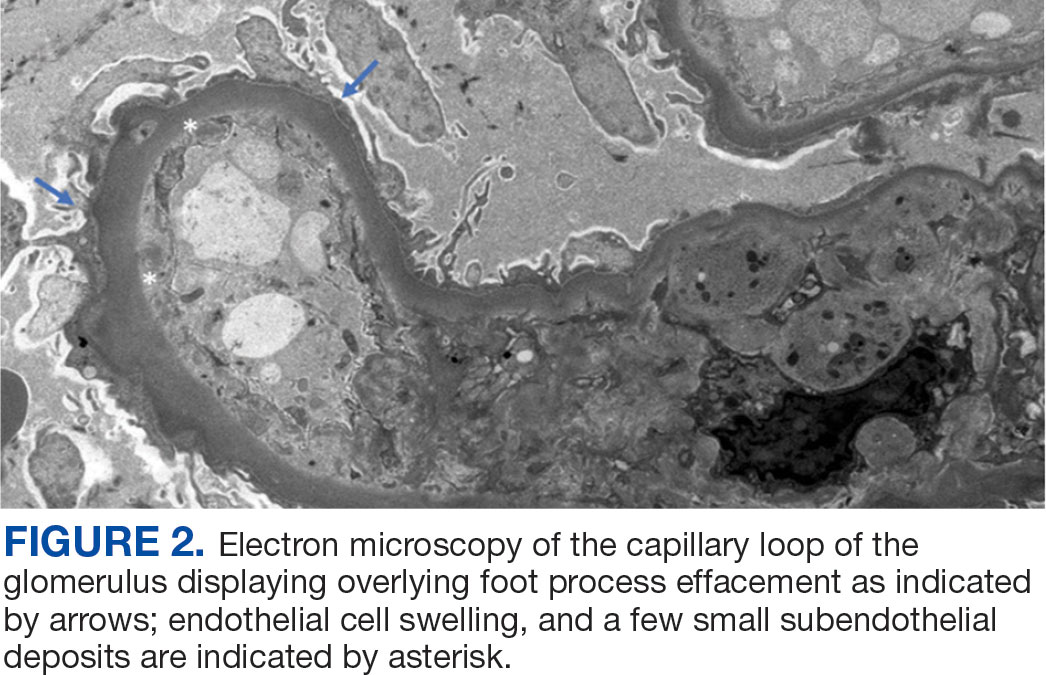

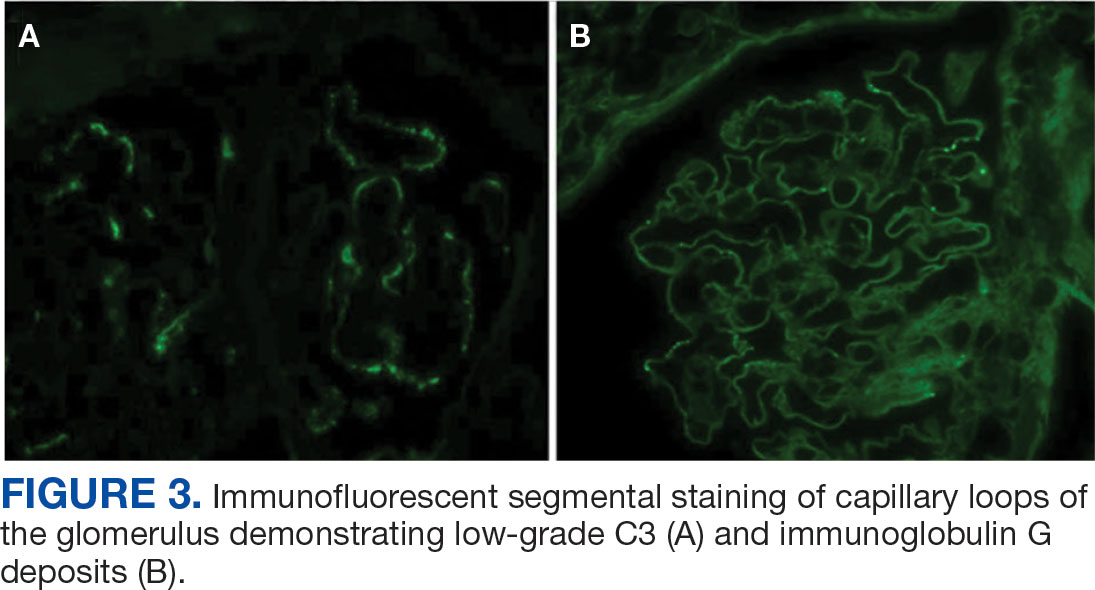

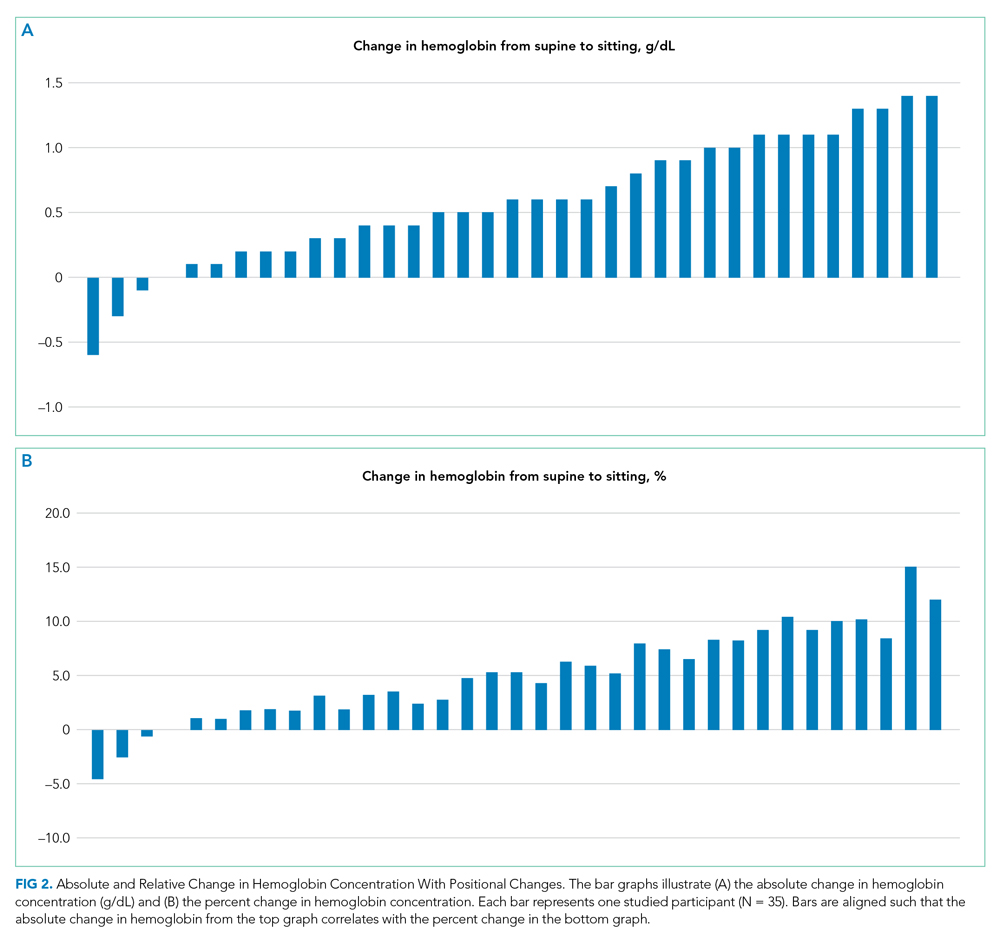

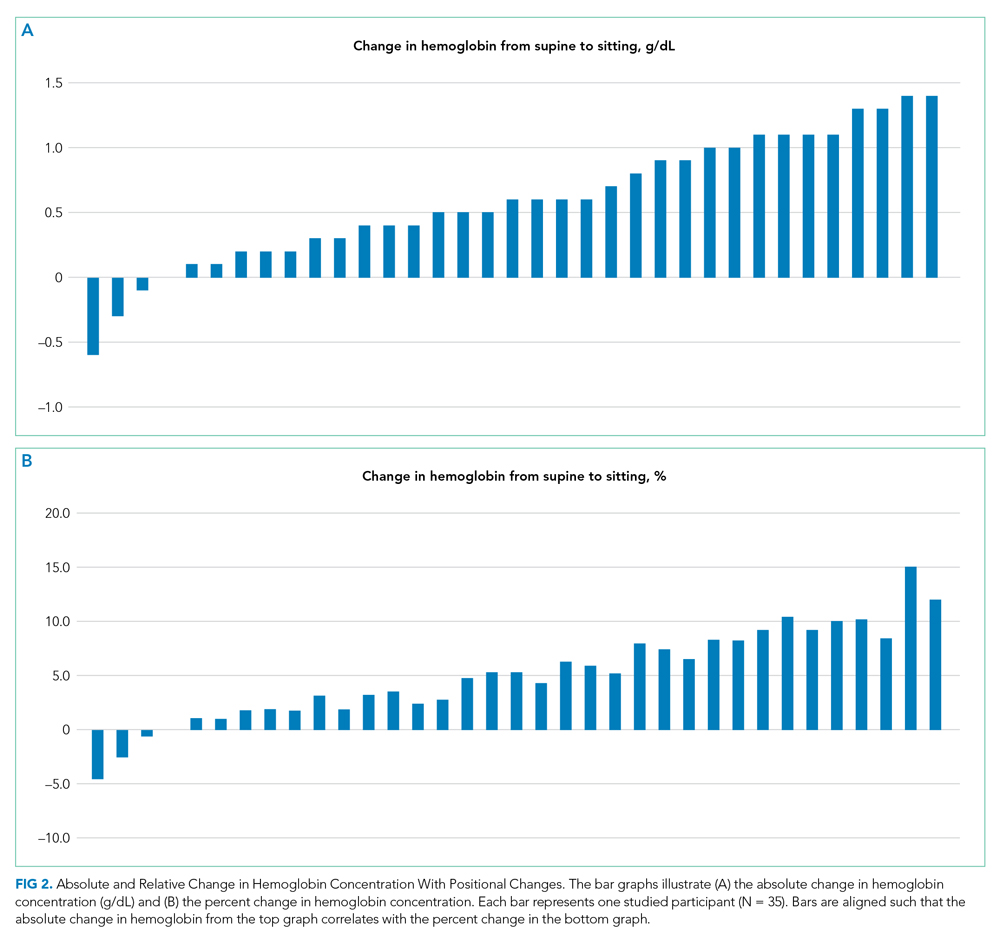

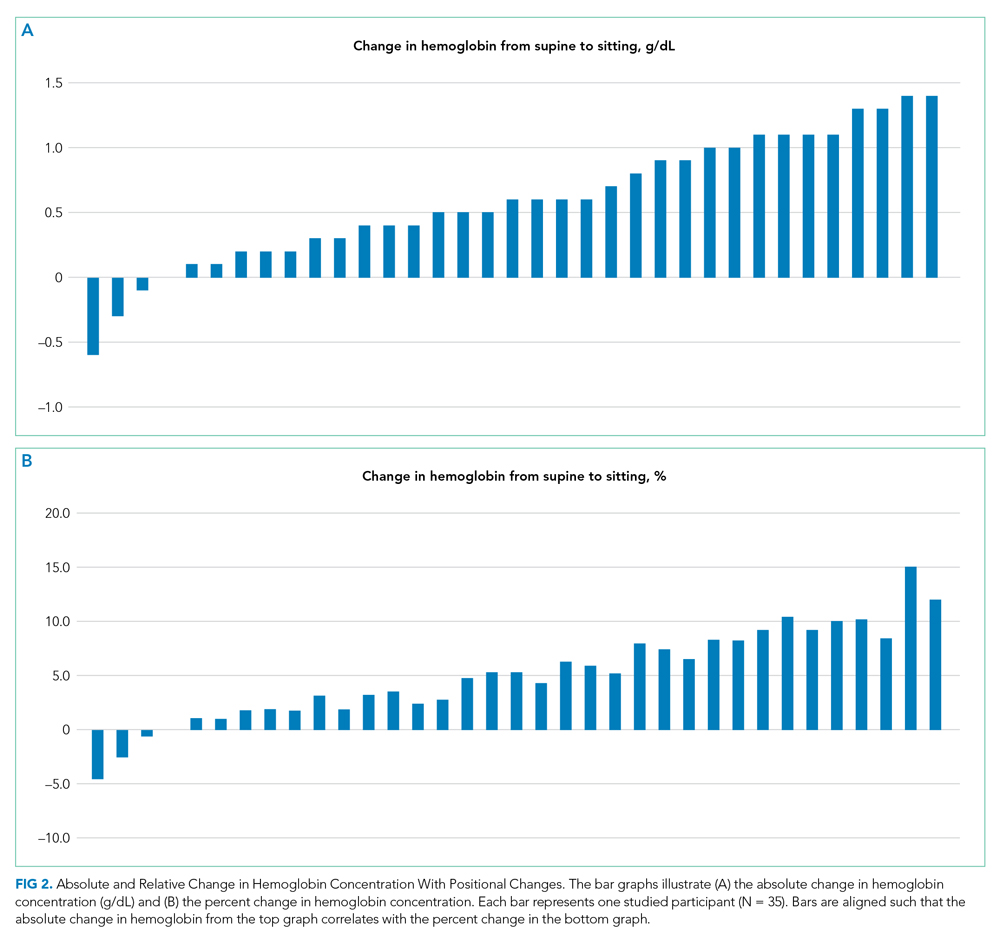

A noncontrast CT of the abdomen and pelvis in the emergency department showed an irregular liver contour with diffuse nodularity, multiple portosystemic collaterals, moderate abdominal and pelvic ascites, small bilateral pleural effusions with associated atelectasis, and anasarca consistent with cirrhosis (Figure 1). The patient was admitted to the internal medicine service for workup and management of newly diagnosed cirrhosis.

Paracentesis revealed straw-colored fluid with an ascitic fluid neutrophil count of 17/μL, a protein level of < 3 g/dL and albumin level of < 1.5 g/dL. Gram stain of the ascitic fluid showed a moderate white blood cell count with no organisms. Fluid culture showed no microbial growth.

Initial workup for cirrhosis demonstrated a positive total hepatitis A antibody. The patient had a nonreactive hepatitis B surface antigen and surface antibody, but a reactive hepatitis B core antibody; a hepatitis B DNA level was not ordered. He had a reactive hepatitis C antibody with a viral load of 4,490,000 II/mL (genotype 1a). The patient’s iron level was 120 μg/dL, with a calculated total iron-binding capacity (TIBC) of 126.2 μg/dL. His transferrin saturation (TSAT) (serum iron divided by TIBC) was 95%. The patient had nonreactive antinuclear antibody and antimitochondrial antibody tests and a positive antismooth muscle antibody test with a titer of 1:40. His α-fetoprotein (AFP) level was 505 ng/mL (reference range, < 8 ng/mL).

Follow-up MRI of the abdomen and pelvis showed cirrhotic morphology with large volume ascites and portosystemic collaterals, consistent with portal hypertension. Additionally, it showed multiple scattered peripheral sub centimeter hyperenhancing foci, most likely representing benign lesions.

The patient's spot urine protein-creatinine ratio was 3.76. To better quantify proteinuria, a 24-hour urine collection was performed and revealed 12.8 g/d of urine protein (reference range, 0-0.17 g/d). His serum triglyceride level was 175 mg/dL (reference range, 40-60 mg/dL); total cholesterol was 177 mg/ dL (reference range, ≤ 200 mg/dL); low density lipoprotein cholesterol was 98 mg/ dL (reference range, ≤ 130 mg/dL); and highdensity lipoprotein cholesterol was 43.8 mg/ dL (reference range, ≥ 40 mg/dL); C3 complement level was 71 mg/dL (reference range, 82-185 mg/dL); and C4 complement level was 22 mg/dL (reference range, 15-53 mg/ dL). His rheumatoid factor was < 14 IU/mL. Tests for rapid plasma reagin and HIV antigen- antibody were nonreactive, and the phospholipase A2 receptor antibody test was negative. The patient tested positive for QuantiFERON-TB Gold and qualitative cryoglobulin, which indicated a cryocrit of 1%.

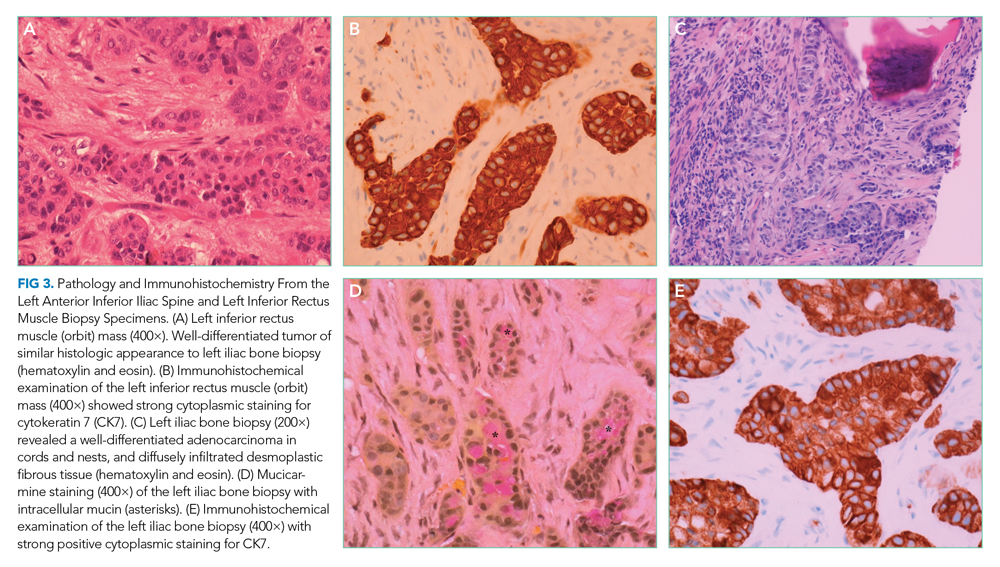

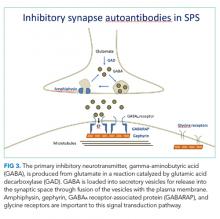

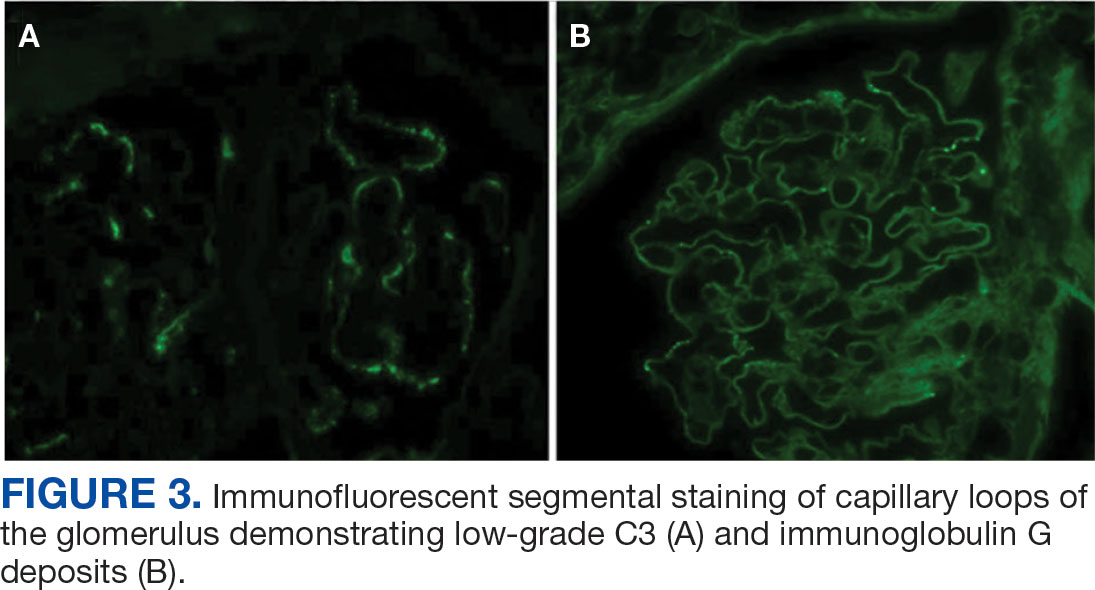

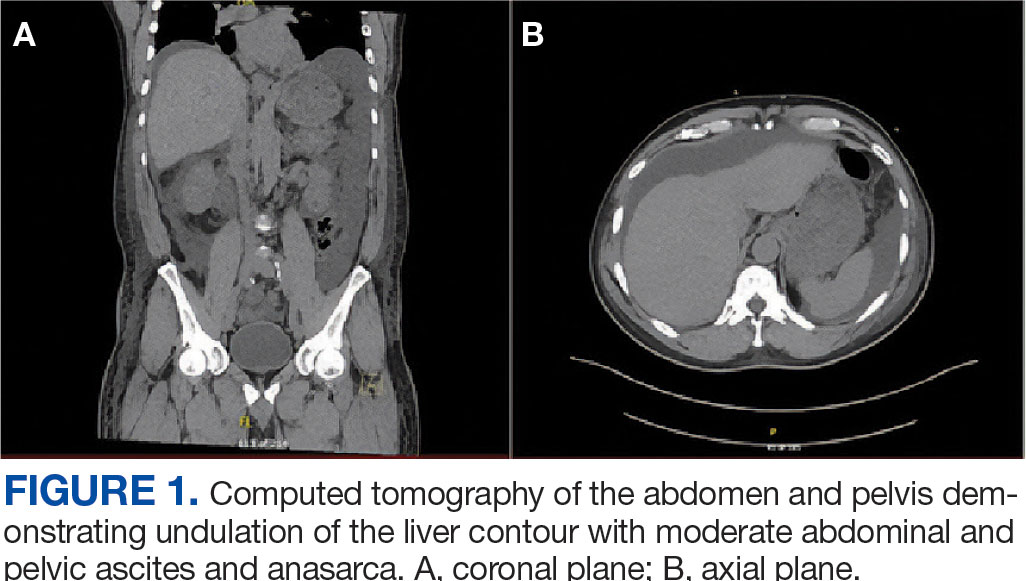

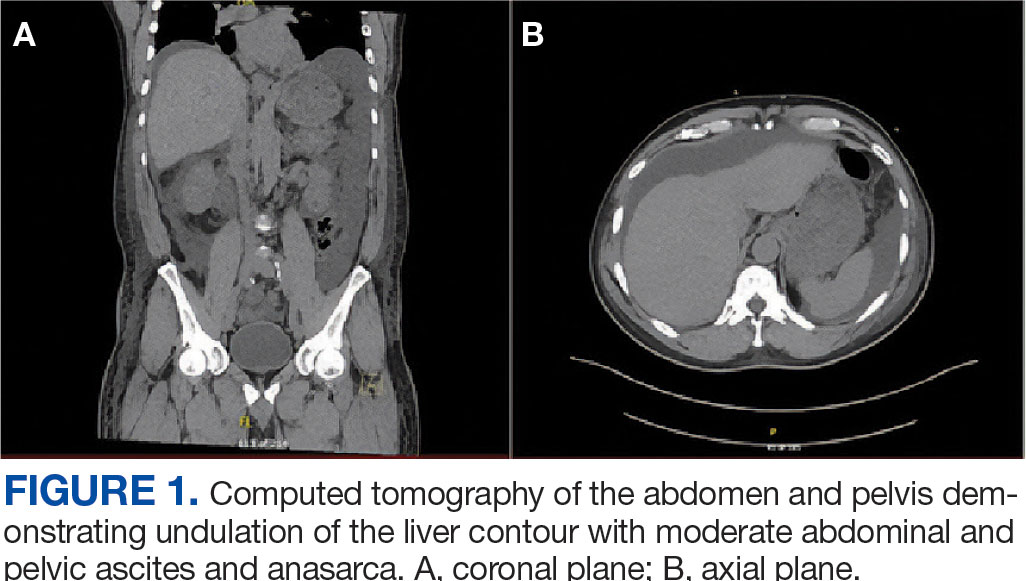

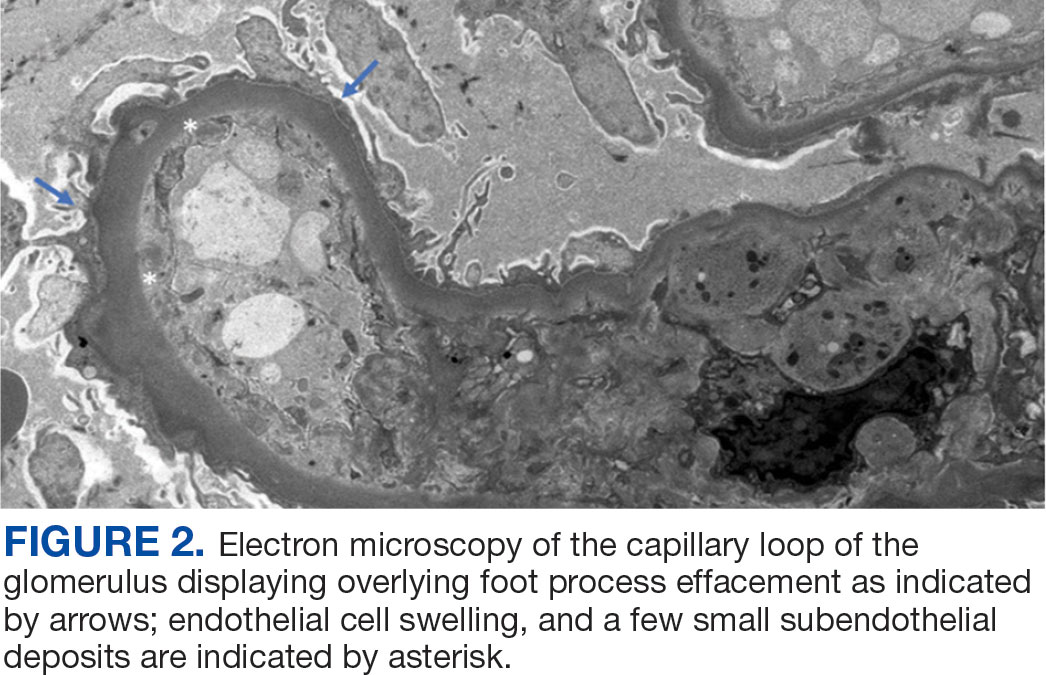

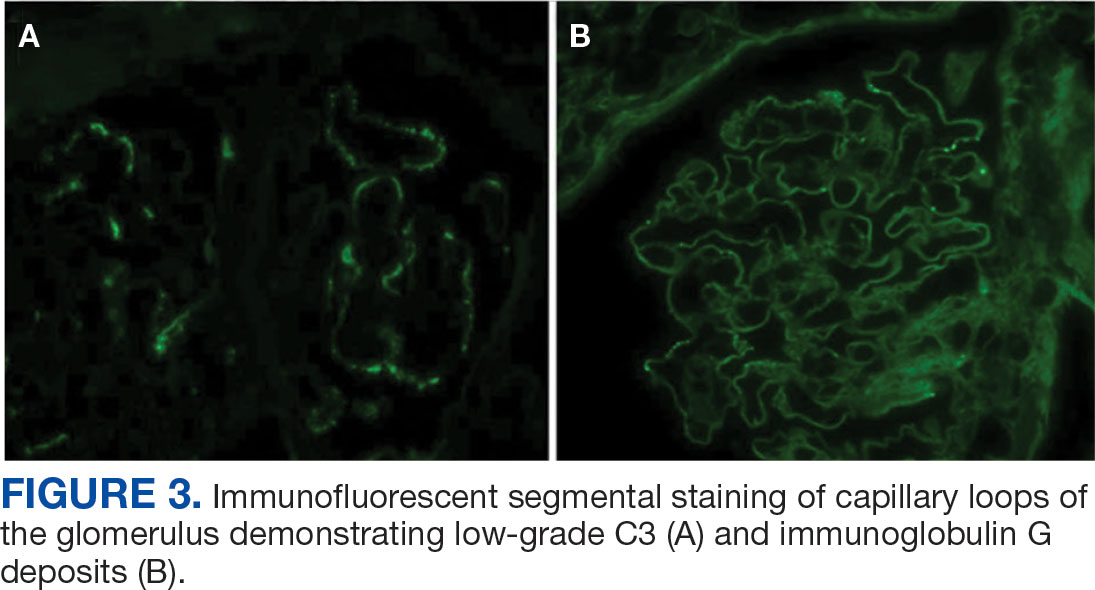

A renal biopsy was performed, revealing diffuse podocyte foot process effacement and glomerulonephritis with low-grade C3 and immunoglobulin (Ig) G deposits, consistent with early membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN) (Figures 2 and 3).

The patient was initially diuresed with IV furosemide without significant urine output. He was then diuresed with IV 25% albumin (total, 25 g), followed by IV furosemide 40 mg twice daily, which led to significant urine output and resolution of his anasarca. Given the patient’s hypoalbuminemic state, IV albumin was necessary to deliver furosemide to the proximal tubule. He was started on lisinopril for renal protection and discharged with spironolactone and furosemide for fluid management in the context of cirrhosis.

The patient was evaluated by the Liver Nodule Clinic, which includes specialists from hepatology, medical oncology, radiation oncology, interventional radiology, and diagnostic radiology. The team considered the patient’s medical history and characteristics of the nodules on imaging. Notable aspects of the patient’s history included hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and an elevated AFP level, although imaging showed no lesion concerning for malignancy. Given these findings, the patient was scheduled for a liver biopsy to establish a tissue diagnosis of cirrhosis. Hepatology, nephrology, and infectious disease specialists coordinated to plan the management and treatment of latent tuberculosis (TB), chronic HCV, MPGN, compensated cirrhosis, and suspicious liver lesions.

The patient chose to handle management and treatment as an outpatient. He was discharged with furosemide and spironolactone for anasarca management, and amlodipine and lisinopril for his hypertension and MPGN. Follow-up appointments were scheduled with infectious disease for management of latent TB and HCV, nephrology for MPGN, gastroenterology for cirrhosis, and interventional radiology for liver biopsy. Unfortunately, the patient was unhoused with limited access to transportation, which prevented timely follow-up. Given these social factors, immunosuppression was not started. Additionally, he did not start on HCV therapy because the viral load was still pending at time of discharge.

DISCUSSION

The diagnosis of decompensated cirrhosis was prematurely established, resulting in a diagnostic delay, a form of diagnostic error. However, on hospital day 2, the initial hypothesis of decompensated cirrhosis as the sole driver of the patient’s presentation was reconsidered due to the disconnect between the severity of hypoalbuminemia and diffuse edema (anasarca), and the absence of laboratory evidence of hepatic decompensation (normal international normalized ratio, bilirubin, and low but normal platelet count). Although image findings supported cirrhosis, laboratory markers did not indicate hepatic decompensation. The severity of hypoalbuminemia and anasarca, along with an indeterminate Serum-Ascites Albumin Gradient, prompted the patient’s care team to consider other causes, specifically, nephrotic syndrome.

The patien’s spot protein-to-creatinine ratio was 3.76 (reference range < 0.2 mg/mg creatinine), but a 24-hour urine protein collection was 12.8 g/day (reference range < 150 mg/day). While most spot urine protein- to-creatinine ratios (UPCR) correlate with a 24-hour urine collection, discrepancies can occur, as in this case. It is important to recognize that the spot UPCR assumes that patients are excreting 1000 mg of creatinine daily in their urine, which is not always the case. In addition, changes in urine osmolality can lead to different values. The gold standard for proteinuria is a 24-hour urine collection for protein and creatinine.

The patient’s nephrotic-range proteinuria and severe hypoalbuminemia are not solely explained by cirrhosis. In addition, the patient’s lower extremity edema pointed to nephrotic syndrome. The differential diagnosis for nephrotic syndrome includes both primary and secondary forms of membranous nephropathy, minimal change disease, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, and MPGN, a histopathological diagnosis that requires distinguishing between immune complex-mediated and complement-mediated forms. Other causes of nephrotic syndrome that do not fit in any of these buckets include amyloidosis, IgA nephropathy, and diabetes mellitus (DM). Despite DM being a common cause of nephrotic range proteinuria, it rarely leads to full nephrotic syndrome.

When considering the diagnosis, we reframed the patient’s clinical syndrome as compensated cirrhosis plus nephrotic syndrome. This approach prioritized identifying a cause that could explain both cirrhosis (from any cause) leading to IgA nephropathy or injection drug use serving as a risk factor for cirrhosis and nephrotic syndrome through HCV or AA amyloidosis, respectively. This problem representation guided us to the correct diagnosis. There are multiple renal diseases associated with HCV infection, including MPGN, membranous nephropathy, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, and IgA nephropathy.2 MPGN and mixed cryoglobulinemia are the most common. In the past, MPGN was classified as type I, II, and III.

The patient’s urine toxicology revealed recent amphetamine use, which can also lead to acute kidney injury through rhabdomyolysis or acute interstitial nephritis (AIN).3 In the cases of rhabdomyolysis, urinalysis would show positive heme without any red blood cell on microscopic analysis, which was not present in this case. AIN commonly manifests as acute kidney injury, pyuria, and proteinuria but without a decrease in complement levels.4 While the patient’s urine sediment included white blood cell (10/high-power field), the presence of microscopic hematuria, decreased complement levels, and proteinuria in the context of HCV positivity makes MPGN more likely than AIN.

Recently, there has been greater emphasis on using immunofluorescence for kidney biopsies. MPGN is now classified into 2 main categories: MPGN with mesangial immunoglobulins and C3 deposits in the capillary walls, and MPGN with C3 deposits but without Ig.5 MPGN with Ig-complement deposits is seen in autoimmune diseases and infections and is associated with dysproteinemias.

The renal biopsy in this patient was consistent with MPGN with immunofluorescence, a common finding in patients with infection. By synthesizing these data, we concluded that the patient represented a case of chronic HCV infection that led to MPGN with cryoglobulinemia. The normal C4 and negative RF do not suggest cryoglobulinemic crisis. Compensated cirrhosis was seen on imaging, pending liver biopsy.

Treatment

The management of MPGN secondary to HCV infection relies on the treatment of the underlying infection and clearance of viral load. Direct-acting antivirals have been used successfully in the treatment of HCV-associated MPGN. When cryoglobulinemia is present, immunosuppressive therapy is recommended. These regimens commonly include rituximab and steroids.5 Rituximab is also used for nephrotic syndrome associated with MPGN, as recommended in the 2018 Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes guidelines.6

When initiating rituximab therapy in a patient who tests positive for hepatitis B (HBcAb positive or HBsAb positive), it is recommended to follow the established guidelines, which include treating them with entecavir for prophylaxis to prevent reactivation or a flare of hepatitis B.7 The patient in this case needed close follow-up in the nephrology and hepatology clinic. Immunosuppressive therapy was not pursued while the patient was admitted to the hospital due to instability with housing, transportation, and difficulty in ensuring close follow-up.

CONCLUSIONS

Clinicians should maintain a broad differential even in the face of confirmatory imaging and other objective findings. In the case of anasarca, nephrotic syndrome should be considered. Key causes of nephrotic syndromes include MPGN, membranous nephropathy, minimal change disease, and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. MPGN is a histopathological diagnosis, and it is essential to identify if it is secondary to immune complexes or only complement mediated because Ig-complement deposits are seen in autoimmune disease and infection. The management of MPGN due to HCV infection relies on antiviral therapy. In the presence of cryoglobulinemia, immunosuppressive therapy is recommended.

- Tapper EB, Parikh ND. Diagnosis and management of cirrhosis and its complications: a review. JAMA. 2023;329(18):1589–1602. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.5997

- Ozkok A, Yildiz A. Hepatitis C virus associated glomerulopathies. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(24):7544-7554. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i24.7544

- Foley RJ, Kapatkin K, Vrani R, Weinman EJ. Amphetamineinduced acute renal failure. South Med J. 1984;77(2):258- 260. doi:10.1097/00007611-198402000-00035

- Rossert J. Drug - induced acute interstitial nephritis. Kidney Int. 2001;60(2):804-817. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.060002804.x

- Sethi S, Fervenza FC. Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis: pathogenetic heterogeneity and proposal for a new classification. Semin Nephrol. 2011;31(4):341-348. doi:10.1016/j.semnephrol.2011.06.005

- Jadoul M, Berenguer MC, Doss W, et al. Executive summary of the 2018 KDIGO hepatitis C in CKD guideline: welcoming advances in evaluation and management. Kidney Int. 2018;94(4):663-673. doi:10.1016/j.kint.2018.06.011

- Myint A, Tong MJ, Beaven SW. Reactivation of hepatitis b virus: a review of clinical guidelines. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2020;15(4):162-167. doi:10.1002/cld.883

Histology is the gold standard for cirrhosis diagnosis. However, a combination of clinical history, physical examination findings, and supportive laboratory and radiographic features is generally sufficient to make the diagnosis. Routine ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) imaging often identifies a nodular liver contour with sequelae of portal hypertension, including splenomegaly, varices, and ascites, which can suggest cirrhosis when supported by laboratory parameters and clinical features. As a result, the diagnosis is typically made clinically.1 Many patients with compensated cirrhosis go undetected. The presence of a decompensation event (ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, variceal hemorrhage, or hepatic encephalopathy) often leads to index diagnosis when patients were previously compensated. When a patient presents with suspected decompensated cirrhosis, it is important to consider other diagnoses with similar presentations and ensure that multiple disease processes are not contributing to the symptoms.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 64-year-old male with a history of intravenous (IV) methamphetamine use and prior incarceration presented with a 3-week history of progressively worsening generalized swelling. Prior to the onset of his symptoms, the patient injured his right lower extremity (RLE) in a bicycle accident, resulting in edema that progressed to bilateral lower extremity (BLE) edema and worsening fatigue, despite resolution of the initial injury. The patient gained weight though he could not quantify the amount. He experienced progressive hunger, thirst, and fatigue as well as increased sleep. Additionally, the patient experienced worsening dyspnea on exertion and orthopnea. He started using 2 pillows instead of 1 pillow at night.

The patient reported no fevers, chills, sputum production, chest pain, or paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea. He had no known history of sexually transmitted infections, no significant history of alcohol use, and occasional tobacco and marijuana use. He had been incarcerated > 10 years before and last used IV methamphetamine 3 years before. He did not regularly take any medications.

The patient’s vital signs included a temperature of 98.2 °F; 78/min heart rate; 15/min respiratory rate; 159/109 mm Hg blood pressure; and 98% oxygen saturation on room air. He had gained 20 lbs in the past 4 months. He had pitting edema in both legs and arms, as well as periorbital swelling, but no jugular venous distention, abnormal heart sounds, or murmurs. Breath sounds were distant but clear to auscultation. His abdomen was distended with normal bowel sounds and no fluid wave; mild epigastric tenderness was present, but no intra-abdominal masses were palpated. He had spider angiomata on the upper chest but no other stigmata of cirrhosis, such as caput medusae or jaundice. Tattoos were noted.

Laboratory test results showed a platelet count of 178 x 103/μL (reference range, 140- 440 ~ 103μL).Creatinine was 0.80 mg/dL (reference range, < 1.28 mg/dL), with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 99 mL/min/1.73 m2 using the Chronic Kidney Disease-Epidemiology equation (reference range, > 60 mL/min/1.73 m2), (reference range, > 60 mL/min/1.73 m2), and Cystatin C was 1.14 mg/L (reference range, < 1.15 mg/L). His electrolytes and complete blood count were within normal limits, including sodium, 134 mmol/L; potassium, 4.4 mmol/L; chloride, 108 mmol/L; and carbon dioxide, 22.5 mmol/L.

Additional test results included alkaline phosphatase, 126 U/L (reference range, < 94 U/L); alanine transaminase, 41 U/L (reference range, < 45 U/L); aspartate aminotransferase, 70 U/L (reference range, < 35 U/L); total bilirubin, 0.6 mg/dL (reference range, < 1 mg/dL); albumin, 1.8 g/dL (reference range, 3.2-4.8 g/dL); and total protein, 6.3 g/dL (reference range, 5.9-8.3 g/dL). The patient’s international normalized ratio was 0.96 (reference range, 0.8-1.1), and brain natriuretic peptide was normal at 56 pg/mL. No prior laboratory results were available for comparison.

Urine toxicology was positive for amphetamines. Urinalysis demonstrated large occult blood, with a red blood cell count of 26/ HPF (reference range, 0/HPF) and proteinuria (100 mg/dL; reference range, negative), without bacteria, nitrites, or leukocyte esterase. Urine white blood cell count was 10/ HPF (reference range, 0/HPF), and fine granular casts and hyaline casts were present.

A noncontrast CT of the abdomen and pelvis in the emergency department showed an irregular liver contour with diffuse nodularity, multiple portosystemic collaterals, moderate abdominal and pelvic ascites, small bilateral pleural effusions with associated atelectasis, and anasarca consistent with cirrhosis (Figure 1). The patient was admitted to the internal medicine service for workup and management of newly diagnosed cirrhosis.

Paracentesis revealed straw-colored fluid with an ascitic fluid neutrophil count of 17/μL, a protein level of < 3 g/dL and albumin level of < 1.5 g/dL. Gram stain of the ascitic fluid showed a moderate white blood cell count with no organisms. Fluid culture showed no microbial growth.

Initial workup for cirrhosis demonstrated a positive total hepatitis A antibody. The patient had a nonreactive hepatitis B surface antigen and surface antibody, but a reactive hepatitis B core antibody; a hepatitis B DNA level was not ordered. He had a reactive hepatitis C antibody with a viral load of 4,490,000 II/mL (genotype 1a). The patient’s iron level was 120 μg/dL, with a calculated total iron-binding capacity (TIBC) of 126.2 μg/dL. His transferrin saturation (TSAT) (serum iron divided by TIBC) was 95%. The patient had nonreactive antinuclear antibody and antimitochondrial antibody tests and a positive antismooth muscle antibody test with a titer of 1:40. His α-fetoprotein (AFP) level was 505 ng/mL (reference range, < 8 ng/mL).

Follow-up MRI of the abdomen and pelvis showed cirrhotic morphology with large volume ascites and portosystemic collaterals, consistent with portal hypertension. Additionally, it showed multiple scattered peripheral sub centimeter hyperenhancing foci, most likely representing benign lesions.

The patient's spot urine protein-creatinine ratio was 3.76. To better quantify proteinuria, a 24-hour urine collection was performed and revealed 12.8 g/d of urine protein (reference range, 0-0.17 g/d). His serum triglyceride level was 175 mg/dL (reference range, 40-60 mg/dL); total cholesterol was 177 mg/ dL (reference range, ≤ 200 mg/dL); low density lipoprotein cholesterol was 98 mg/ dL (reference range, ≤ 130 mg/dL); and highdensity lipoprotein cholesterol was 43.8 mg/ dL (reference range, ≥ 40 mg/dL); C3 complement level was 71 mg/dL (reference range, 82-185 mg/dL); and C4 complement level was 22 mg/dL (reference range, 15-53 mg/ dL). His rheumatoid factor was < 14 IU/mL. Tests for rapid plasma reagin and HIV antigen- antibody were nonreactive, and the phospholipase A2 receptor antibody test was negative. The patient tested positive for QuantiFERON-TB Gold and qualitative cryoglobulin, which indicated a cryocrit of 1%.

A renal biopsy was performed, revealing diffuse podocyte foot process effacement and glomerulonephritis with low-grade C3 and immunoglobulin (Ig) G deposits, consistent with early membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN) (Figures 2 and 3).

The patient was initially diuresed with IV furosemide without significant urine output. He was then diuresed with IV 25% albumin (total, 25 g), followed by IV furosemide 40 mg twice daily, which led to significant urine output and resolution of his anasarca. Given the patient’s hypoalbuminemic state, IV albumin was necessary to deliver furosemide to the proximal tubule. He was started on lisinopril for renal protection and discharged with spironolactone and furosemide for fluid management in the context of cirrhosis.

The patient was evaluated by the Liver Nodule Clinic, which includes specialists from hepatology, medical oncology, radiation oncology, interventional radiology, and diagnostic radiology. The team considered the patient’s medical history and characteristics of the nodules on imaging. Notable aspects of the patient’s history included hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and an elevated AFP level, although imaging showed no lesion concerning for malignancy. Given these findings, the patient was scheduled for a liver biopsy to establish a tissue diagnosis of cirrhosis. Hepatology, nephrology, and infectious disease specialists coordinated to plan the management and treatment of latent tuberculosis (TB), chronic HCV, MPGN, compensated cirrhosis, and suspicious liver lesions.

The patient chose to handle management and treatment as an outpatient. He was discharged with furosemide and spironolactone for anasarca management, and amlodipine and lisinopril for his hypertension and MPGN. Follow-up appointments were scheduled with infectious disease for management of latent TB and HCV, nephrology for MPGN, gastroenterology for cirrhosis, and interventional radiology for liver biopsy. Unfortunately, the patient was unhoused with limited access to transportation, which prevented timely follow-up. Given these social factors, immunosuppression was not started. Additionally, he did not start on HCV therapy because the viral load was still pending at time of discharge.

DISCUSSION

The diagnosis of decompensated cirrhosis was prematurely established, resulting in a diagnostic delay, a form of diagnostic error. However, on hospital day 2, the initial hypothesis of decompensated cirrhosis as the sole driver of the patient’s presentation was reconsidered due to the disconnect between the severity of hypoalbuminemia and diffuse edema (anasarca), and the absence of laboratory evidence of hepatic decompensation (normal international normalized ratio, bilirubin, and low but normal platelet count). Although image findings supported cirrhosis, laboratory markers did not indicate hepatic decompensation. The severity of hypoalbuminemia and anasarca, along with an indeterminate Serum-Ascites Albumin Gradient, prompted the patient’s care team to consider other causes, specifically, nephrotic syndrome.

The patien’s spot protein-to-creatinine ratio was 3.76 (reference range < 0.2 mg/mg creatinine), but a 24-hour urine protein collection was 12.8 g/day (reference range < 150 mg/day). While most spot urine protein- to-creatinine ratios (UPCR) correlate with a 24-hour urine collection, discrepancies can occur, as in this case. It is important to recognize that the spot UPCR assumes that patients are excreting 1000 mg of creatinine daily in their urine, which is not always the case. In addition, changes in urine osmolality can lead to different values. The gold standard for proteinuria is a 24-hour urine collection for protein and creatinine.

The patient’s nephrotic-range proteinuria and severe hypoalbuminemia are not solely explained by cirrhosis. In addition, the patient’s lower extremity edema pointed to nephrotic syndrome. The differential diagnosis for nephrotic syndrome includes both primary and secondary forms of membranous nephropathy, minimal change disease, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, and MPGN, a histopathological diagnosis that requires distinguishing between immune complex-mediated and complement-mediated forms. Other causes of nephrotic syndrome that do not fit in any of these buckets include amyloidosis, IgA nephropathy, and diabetes mellitus (DM). Despite DM being a common cause of nephrotic range proteinuria, it rarely leads to full nephrotic syndrome.

When considering the diagnosis, we reframed the patient’s clinical syndrome as compensated cirrhosis plus nephrotic syndrome. This approach prioritized identifying a cause that could explain both cirrhosis (from any cause) leading to IgA nephropathy or injection drug use serving as a risk factor for cirrhosis and nephrotic syndrome through HCV or AA amyloidosis, respectively. This problem representation guided us to the correct diagnosis. There are multiple renal diseases associated with HCV infection, including MPGN, membranous nephropathy, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, and IgA nephropathy.2 MPGN and mixed cryoglobulinemia are the most common. In the past, MPGN was classified as type I, II, and III.

The patient’s urine toxicology revealed recent amphetamine use, which can also lead to acute kidney injury through rhabdomyolysis or acute interstitial nephritis (AIN).3 In the cases of rhabdomyolysis, urinalysis would show positive heme without any red blood cell on microscopic analysis, which was not present in this case. AIN commonly manifests as acute kidney injury, pyuria, and proteinuria but without a decrease in complement levels.4 While the patient’s urine sediment included white blood cell (10/high-power field), the presence of microscopic hematuria, decreased complement levels, and proteinuria in the context of HCV positivity makes MPGN more likely than AIN.

Recently, there has been greater emphasis on using immunofluorescence for kidney biopsies. MPGN is now classified into 2 main categories: MPGN with mesangial immunoglobulins and C3 deposits in the capillary walls, and MPGN with C3 deposits but without Ig.5 MPGN with Ig-complement deposits is seen in autoimmune diseases and infections and is associated with dysproteinemias.

The renal biopsy in this patient was consistent with MPGN with immunofluorescence, a common finding in patients with infection. By synthesizing these data, we concluded that the patient represented a case of chronic HCV infection that led to MPGN with cryoglobulinemia. The normal C4 and negative RF do not suggest cryoglobulinemic crisis. Compensated cirrhosis was seen on imaging, pending liver biopsy.

Treatment

The management of MPGN secondary to HCV infection relies on the treatment of the underlying infection and clearance of viral load. Direct-acting antivirals have been used successfully in the treatment of HCV-associated MPGN. When cryoglobulinemia is present, immunosuppressive therapy is recommended. These regimens commonly include rituximab and steroids.5 Rituximab is also used for nephrotic syndrome associated with MPGN, as recommended in the 2018 Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes guidelines.6

When initiating rituximab therapy in a patient who tests positive for hepatitis B (HBcAb positive or HBsAb positive), it is recommended to follow the established guidelines, which include treating them with entecavir for prophylaxis to prevent reactivation or a flare of hepatitis B.7 The patient in this case needed close follow-up in the nephrology and hepatology clinic. Immunosuppressive therapy was not pursued while the patient was admitted to the hospital due to instability with housing, transportation, and difficulty in ensuring close follow-up.

CONCLUSIONS

Clinicians should maintain a broad differential even in the face of confirmatory imaging and other objective findings. In the case of anasarca, nephrotic syndrome should be considered. Key causes of nephrotic syndromes include MPGN, membranous nephropathy, minimal change disease, and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. MPGN is a histopathological diagnosis, and it is essential to identify if it is secondary to immune complexes or only complement mediated because Ig-complement deposits are seen in autoimmune disease and infection. The management of MPGN due to HCV infection relies on antiviral therapy. In the presence of cryoglobulinemia, immunosuppressive therapy is recommended.

Histology is the gold standard for cirrhosis diagnosis. However, a combination of clinical history, physical examination findings, and supportive laboratory and radiographic features is generally sufficient to make the diagnosis. Routine ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) imaging often identifies a nodular liver contour with sequelae of portal hypertension, including splenomegaly, varices, and ascites, which can suggest cirrhosis when supported by laboratory parameters and clinical features. As a result, the diagnosis is typically made clinically.1 Many patients with compensated cirrhosis go undetected. The presence of a decompensation event (ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, variceal hemorrhage, or hepatic encephalopathy) often leads to index diagnosis when patients were previously compensated. When a patient presents with suspected decompensated cirrhosis, it is important to consider other diagnoses with similar presentations and ensure that multiple disease processes are not contributing to the symptoms.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 64-year-old male with a history of intravenous (IV) methamphetamine use and prior incarceration presented with a 3-week history of progressively worsening generalized swelling. Prior to the onset of his symptoms, the patient injured his right lower extremity (RLE) in a bicycle accident, resulting in edema that progressed to bilateral lower extremity (BLE) edema and worsening fatigue, despite resolution of the initial injury. The patient gained weight though he could not quantify the amount. He experienced progressive hunger, thirst, and fatigue as well as increased sleep. Additionally, the patient experienced worsening dyspnea on exertion and orthopnea. He started using 2 pillows instead of 1 pillow at night.

The patient reported no fevers, chills, sputum production, chest pain, or paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea. He had no known history of sexually transmitted infections, no significant history of alcohol use, and occasional tobacco and marijuana use. He had been incarcerated > 10 years before and last used IV methamphetamine 3 years before. He did not regularly take any medications.

The patient’s vital signs included a temperature of 98.2 °F; 78/min heart rate; 15/min respiratory rate; 159/109 mm Hg blood pressure; and 98% oxygen saturation on room air. He had gained 20 lbs in the past 4 months. He had pitting edema in both legs and arms, as well as periorbital swelling, but no jugular venous distention, abnormal heart sounds, or murmurs. Breath sounds were distant but clear to auscultation. His abdomen was distended with normal bowel sounds and no fluid wave; mild epigastric tenderness was present, but no intra-abdominal masses were palpated. He had spider angiomata on the upper chest but no other stigmata of cirrhosis, such as caput medusae or jaundice. Tattoos were noted.

Laboratory test results showed a platelet count of 178 x 103/μL (reference range, 140- 440 ~ 103μL).Creatinine was 0.80 mg/dL (reference range, < 1.28 mg/dL), with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 99 mL/min/1.73 m2 using the Chronic Kidney Disease-Epidemiology equation (reference range, > 60 mL/min/1.73 m2), (reference range, > 60 mL/min/1.73 m2), and Cystatin C was 1.14 mg/L (reference range, < 1.15 mg/L). His electrolytes and complete blood count were within normal limits, including sodium, 134 mmol/L; potassium, 4.4 mmol/L; chloride, 108 mmol/L; and carbon dioxide, 22.5 mmol/L.

Additional test results included alkaline phosphatase, 126 U/L (reference range, < 94 U/L); alanine transaminase, 41 U/L (reference range, < 45 U/L); aspartate aminotransferase, 70 U/L (reference range, < 35 U/L); total bilirubin, 0.6 mg/dL (reference range, < 1 mg/dL); albumin, 1.8 g/dL (reference range, 3.2-4.8 g/dL); and total protein, 6.3 g/dL (reference range, 5.9-8.3 g/dL). The patient’s international normalized ratio was 0.96 (reference range, 0.8-1.1), and brain natriuretic peptide was normal at 56 pg/mL. No prior laboratory results were available for comparison.

Urine toxicology was positive for amphetamines. Urinalysis demonstrated large occult blood, with a red blood cell count of 26/ HPF (reference range, 0/HPF) and proteinuria (100 mg/dL; reference range, negative), without bacteria, nitrites, or leukocyte esterase. Urine white blood cell count was 10/ HPF (reference range, 0/HPF), and fine granular casts and hyaline casts were present.

A noncontrast CT of the abdomen and pelvis in the emergency department showed an irregular liver contour with diffuse nodularity, multiple portosystemic collaterals, moderate abdominal and pelvic ascites, small bilateral pleural effusions with associated atelectasis, and anasarca consistent with cirrhosis (Figure 1). The patient was admitted to the internal medicine service for workup and management of newly diagnosed cirrhosis.

Paracentesis revealed straw-colored fluid with an ascitic fluid neutrophil count of 17/μL, a protein level of < 3 g/dL and albumin level of < 1.5 g/dL. Gram stain of the ascitic fluid showed a moderate white blood cell count with no organisms. Fluid culture showed no microbial growth.

Initial workup for cirrhosis demonstrated a positive total hepatitis A antibody. The patient had a nonreactive hepatitis B surface antigen and surface antibody, but a reactive hepatitis B core antibody; a hepatitis B DNA level was not ordered. He had a reactive hepatitis C antibody with a viral load of 4,490,000 II/mL (genotype 1a). The patient’s iron level was 120 μg/dL, with a calculated total iron-binding capacity (TIBC) of 126.2 μg/dL. His transferrin saturation (TSAT) (serum iron divided by TIBC) was 95%. The patient had nonreactive antinuclear antibody and antimitochondrial antibody tests and a positive antismooth muscle antibody test with a titer of 1:40. His α-fetoprotein (AFP) level was 505 ng/mL (reference range, < 8 ng/mL).

Follow-up MRI of the abdomen and pelvis showed cirrhotic morphology with large volume ascites and portosystemic collaterals, consistent with portal hypertension. Additionally, it showed multiple scattered peripheral sub centimeter hyperenhancing foci, most likely representing benign lesions.

The patient's spot urine protein-creatinine ratio was 3.76. To better quantify proteinuria, a 24-hour urine collection was performed and revealed 12.8 g/d of urine protein (reference range, 0-0.17 g/d). His serum triglyceride level was 175 mg/dL (reference range, 40-60 mg/dL); total cholesterol was 177 mg/ dL (reference range, ≤ 200 mg/dL); low density lipoprotein cholesterol was 98 mg/ dL (reference range, ≤ 130 mg/dL); and highdensity lipoprotein cholesterol was 43.8 mg/ dL (reference range, ≥ 40 mg/dL); C3 complement level was 71 mg/dL (reference range, 82-185 mg/dL); and C4 complement level was 22 mg/dL (reference range, 15-53 mg/ dL). His rheumatoid factor was < 14 IU/mL. Tests for rapid plasma reagin and HIV antigen- antibody were nonreactive, and the phospholipase A2 receptor antibody test was negative. The patient tested positive for QuantiFERON-TB Gold and qualitative cryoglobulin, which indicated a cryocrit of 1%.

A renal biopsy was performed, revealing diffuse podocyte foot process effacement and glomerulonephritis with low-grade C3 and immunoglobulin (Ig) G deposits, consistent with early membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN) (Figures 2 and 3).

The patient was initially diuresed with IV furosemide without significant urine output. He was then diuresed with IV 25% albumin (total, 25 g), followed by IV furosemide 40 mg twice daily, which led to significant urine output and resolution of his anasarca. Given the patient’s hypoalbuminemic state, IV albumin was necessary to deliver furosemide to the proximal tubule. He was started on lisinopril for renal protection and discharged with spironolactone and furosemide for fluid management in the context of cirrhosis.

The patient was evaluated by the Liver Nodule Clinic, which includes specialists from hepatology, medical oncology, radiation oncology, interventional radiology, and diagnostic radiology. The team considered the patient’s medical history and characteristics of the nodules on imaging. Notable aspects of the patient’s history included hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and an elevated AFP level, although imaging showed no lesion concerning for malignancy. Given these findings, the patient was scheduled for a liver biopsy to establish a tissue diagnosis of cirrhosis. Hepatology, nephrology, and infectious disease specialists coordinated to plan the management and treatment of latent tuberculosis (TB), chronic HCV, MPGN, compensated cirrhosis, and suspicious liver lesions.

The patient chose to handle management and treatment as an outpatient. He was discharged with furosemide and spironolactone for anasarca management, and amlodipine and lisinopril for his hypertension and MPGN. Follow-up appointments were scheduled with infectious disease for management of latent TB and HCV, nephrology for MPGN, gastroenterology for cirrhosis, and interventional radiology for liver biopsy. Unfortunately, the patient was unhoused with limited access to transportation, which prevented timely follow-up. Given these social factors, immunosuppression was not started. Additionally, he did not start on HCV therapy because the viral load was still pending at time of discharge.

DISCUSSION

The diagnosis of decompensated cirrhosis was prematurely established, resulting in a diagnostic delay, a form of diagnostic error. However, on hospital day 2, the initial hypothesis of decompensated cirrhosis as the sole driver of the patient’s presentation was reconsidered due to the disconnect between the severity of hypoalbuminemia and diffuse edema (anasarca), and the absence of laboratory evidence of hepatic decompensation (normal international normalized ratio, bilirubin, and low but normal platelet count). Although image findings supported cirrhosis, laboratory markers did not indicate hepatic decompensation. The severity of hypoalbuminemia and anasarca, along with an indeterminate Serum-Ascites Albumin Gradient, prompted the patient’s care team to consider other causes, specifically, nephrotic syndrome.

The patien’s spot protein-to-creatinine ratio was 3.76 (reference range < 0.2 mg/mg creatinine), but a 24-hour urine protein collection was 12.8 g/day (reference range < 150 mg/day). While most spot urine protein- to-creatinine ratios (UPCR) correlate with a 24-hour urine collection, discrepancies can occur, as in this case. It is important to recognize that the spot UPCR assumes that patients are excreting 1000 mg of creatinine daily in their urine, which is not always the case. In addition, changes in urine osmolality can lead to different values. The gold standard for proteinuria is a 24-hour urine collection for protein and creatinine.

The patient’s nephrotic-range proteinuria and severe hypoalbuminemia are not solely explained by cirrhosis. In addition, the patient’s lower extremity edema pointed to nephrotic syndrome. The differential diagnosis for nephrotic syndrome includes both primary and secondary forms of membranous nephropathy, minimal change disease, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, and MPGN, a histopathological diagnosis that requires distinguishing between immune complex-mediated and complement-mediated forms. Other causes of nephrotic syndrome that do not fit in any of these buckets include amyloidosis, IgA nephropathy, and diabetes mellitus (DM). Despite DM being a common cause of nephrotic range proteinuria, it rarely leads to full nephrotic syndrome.

When considering the diagnosis, we reframed the patient’s clinical syndrome as compensated cirrhosis plus nephrotic syndrome. This approach prioritized identifying a cause that could explain both cirrhosis (from any cause) leading to IgA nephropathy or injection drug use serving as a risk factor for cirrhosis and nephrotic syndrome through HCV or AA amyloidosis, respectively. This problem representation guided us to the correct diagnosis. There are multiple renal diseases associated with HCV infection, including MPGN, membranous nephropathy, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, and IgA nephropathy.2 MPGN and mixed cryoglobulinemia are the most common. In the past, MPGN was classified as type I, II, and III.

The patient’s urine toxicology revealed recent amphetamine use, which can also lead to acute kidney injury through rhabdomyolysis or acute interstitial nephritis (AIN).3 In the cases of rhabdomyolysis, urinalysis would show positive heme without any red blood cell on microscopic analysis, which was not present in this case. AIN commonly manifests as acute kidney injury, pyuria, and proteinuria but without a decrease in complement levels.4 While the patient’s urine sediment included white blood cell (10/high-power field), the presence of microscopic hematuria, decreased complement levels, and proteinuria in the context of HCV positivity makes MPGN more likely than AIN.

Recently, there has been greater emphasis on using immunofluorescence for kidney biopsies. MPGN is now classified into 2 main categories: MPGN with mesangial immunoglobulins and C3 deposits in the capillary walls, and MPGN with C3 deposits but without Ig.5 MPGN with Ig-complement deposits is seen in autoimmune diseases and infections and is associated with dysproteinemias.

The renal biopsy in this patient was consistent with MPGN with immunofluorescence, a common finding in patients with infection. By synthesizing these data, we concluded that the patient represented a case of chronic HCV infection that led to MPGN with cryoglobulinemia. The normal C4 and negative RF do not suggest cryoglobulinemic crisis. Compensated cirrhosis was seen on imaging, pending liver biopsy.

Treatment

The management of MPGN secondary to HCV infection relies on the treatment of the underlying infection and clearance of viral load. Direct-acting antivirals have been used successfully in the treatment of HCV-associated MPGN. When cryoglobulinemia is present, immunosuppressive therapy is recommended. These regimens commonly include rituximab and steroids.5 Rituximab is also used for nephrotic syndrome associated with MPGN, as recommended in the 2018 Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes guidelines.6

When initiating rituximab therapy in a patient who tests positive for hepatitis B (HBcAb positive or HBsAb positive), it is recommended to follow the established guidelines, which include treating them with entecavir for prophylaxis to prevent reactivation or a flare of hepatitis B.7 The patient in this case needed close follow-up in the nephrology and hepatology clinic. Immunosuppressive therapy was not pursued while the patient was admitted to the hospital due to instability with housing, transportation, and difficulty in ensuring close follow-up.

CONCLUSIONS

Clinicians should maintain a broad differential even in the face of confirmatory imaging and other objective findings. In the case of anasarca, nephrotic syndrome should be considered. Key causes of nephrotic syndromes include MPGN, membranous nephropathy, minimal change disease, and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. MPGN is a histopathological diagnosis, and it is essential to identify if it is secondary to immune complexes or only complement mediated because Ig-complement deposits are seen in autoimmune disease and infection. The management of MPGN due to HCV infection relies on antiviral therapy. In the presence of cryoglobulinemia, immunosuppressive therapy is recommended.

- Tapper EB, Parikh ND. Diagnosis and management of cirrhosis and its complications: a review. JAMA. 2023;329(18):1589–1602. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.5997

- Ozkok A, Yildiz A. Hepatitis C virus associated glomerulopathies. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(24):7544-7554. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i24.7544

- Foley RJ, Kapatkin K, Vrani R, Weinman EJ. Amphetamineinduced acute renal failure. South Med J. 1984;77(2):258- 260. doi:10.1097/00007611-198402000-00035

- Rossert J. Drug - induced acute interstitial nephritis. Kidney Int. 2001;60(2):804-817. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.060002804.x

- Sethi S, Fervenza FC. Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis: pathogenetic heterogeneity and proposal for a new classification. Semin Nephrol. 2011;31(4):341-348. doi:10.1016/j.semnephrol.2011.06.005

- Jadoul M, Berenguer MC, Doss W, et al. Executive summary of the 2018 KDIGO hepatitis C in CKD guideline: welcoming advances in evaluation and management. Kidney Int. 2018;94(4):663-673. doi:10.1016/j.kint.2018.06.011

- Myint A, Tong MJ, Beaven SW. Reactivation of hepatitis b virus: a review of clinical guidelines. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2020;15(4):162-167. doi:10.1002/cld.883

- Tapper EB, Parikh ND. Diagnosis and management of cirrhosis and its complications: a review. JAMA. 2023;329(18):1589–1602. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.5997

- Ozkok A, Yildiz A. Hepatitis C virus associated glomerulopathies. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(24):7544-7554. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i24.7544

- Foley RJ, Kapatkin K, Vrani R, Weinman EJ. Amphetamineinduced acute renal failure. South Med J. 1984;77(2):258- 260. doi:10.1097/00007611-198402000-00035

- Rossert J. Drug - induced acute interstitial nephritis. Kidney Int. 2001;60(2):804-817. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.060002804.x

- Sethi S, Fervenza FC. Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis: pathogenetic heterogeneity and proposal for a new classification. Semin Nephrol. 2011;31(4):341-348. doi:10.1016/j.semnephrol.2011.06.005

- Jadoul M, Berenguer MC, Doss W, et al. Executive summary of the 2018 KDIGO hepatitis C in CKD guideline: welcoming advances in evaluation and management. Kidney Int. 2018;94(4):663-673. doi:10.1016/j.kint.2018.06.011

- Myint A, Tong MJ, Beaven SW. Reactivation of hepatitis b virus: a review of clinical guidelines. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2020;15(4):162-167. doi:10.1002/cld.883

Elusive Edema: A Case of Nephrotic Syndrome Mimicking Decompensated Cirrhosis

Elusive Edema: A Case of Nephrotic Syndrome Mimicking Decompensated Cirrhosis

Buried Deep

This icon represents the patient’s case. Each paragraph that follows represents the discussant’s thoughts.

A 56-year-old-woman with a history of HIV and locally invasive ductal carcinoma recently treated with mastectomy and adjuvant doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide, now on paclitaxel, was transferred from another hospital with worsening nausea, epigastric pain, and dyspnea. She had been admitted multiple times to both this hospital and another hospital and had extensive workup over the previous 2 months for gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding and progressive dyspnea with orthopnea and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea in the setting of a documented 43-lb weight loss.

Her past medical history was otherwise significant only for the events of the previous few months. Eight months earlier, she was diagnosed with grade 3 triple-negative (estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2) invasive ductal carcinoma and underwent mastectomy with negative sentinel lymph node biopsy. She completed four cycles of adjuvant doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide and most recently completed cycle three of paclitaxel chemotherapy.

Her HIV disease was controlled with an antiretroviral regimen of dolutegravir/rilpivirine. She had an undetectable viral load for 20 years (CD4, 239 cells/μL 2 weeks prior to transfer).

Her social history included a 1-pack-year smoking history. She denied alcohol or illicit drug use. Family history included pancreatic cancer in her father and endometrial cancer in her paternal grandmother. She was originally from Mexico but moved to Illinois 27 years earlier.

Work-up for her dyspnea was initiated 7 weeks earlier: noncontrast CT of the chest showed extensive diffuse interstitial thickening and ground-glass opacities bilaterally. Bronchoscopy showed no gross abnormalities, and bronchial washings were negative for bacteria, fungi, Pneumocystis jirovecii , acid-fast bacilli, and cancer. She also had a TTE, which showed an ejection fraction of 65% to 70% and was only significant for a pulmonary artery systolic pressure of 45 mm Hg . She was diagnosed with paclitaxel-induced pneumonitis and was discharged home with prednisone 50 mg daily, dapsone, pantoprazole, and 2 L oxygen via nasal cannula.

Two weeks later, she was admitted for coffee-ground emesis and epigastric pain. Her hemoglobin was 5.9 g/dL, for which she was transfused 3 units of packed red blood cells. EGD showed bleeding from diffuse duodenitis, which was treated with argon plasma coagulation. She was also found to have bilateral pulmonary emboli and lower-extremity deep venous thromboses. An inferior vena cava filter was placed, and she was discharged. One week later, she was readmitted with melena, and repeat EGD showed multiple duodenal ulcers with no active bleeding. Colonoscopy was normal. She was continued on prednisone 40 mg daily, as any attempts at tapering the dose resulted in hypotension.

At the time of transfer, she had presented to the outside hospital with worsening nausea and epigastric pain, increasing postprandial abdominal pain, ongoing weight loss, worsening dyspnea on exertion, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, and orthopnea. She denied symptoms of GI bleeding at that time.

Her imaging is consistent with, albeit not specific for, paclitaxel-induced acute pneumonitis. Her persistent dyspnea may be due to worsening of this pneumonitis.

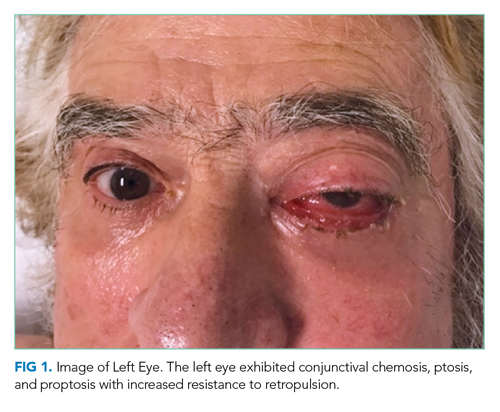

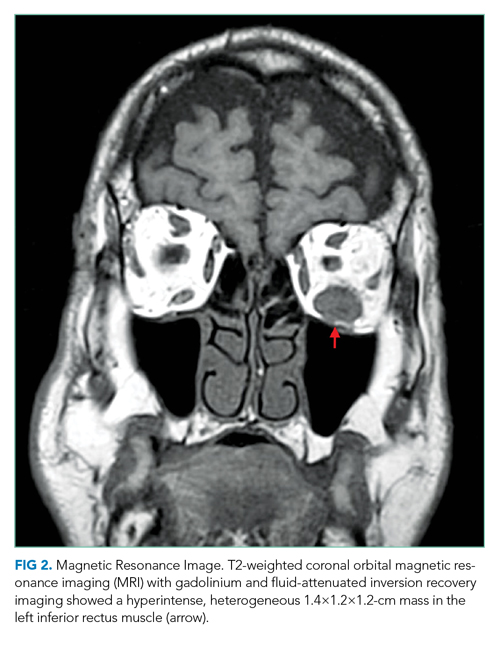

Upon arrival on physical exam, her temperature was 35.4° C, heart rate 112 beats per minute, blood pressure 135/96 mm Hg, respiratory rate 34 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation 97% on room air. She was ill- appearing and in mild respiratory distress with severe muscle wasting. Cervical and supraclavicular lymphadenopathy were not detected. Heart sounds were normal without murmurs. Her jugular venous pressure was approximately 7 cm H2O. She had no lower-extremity edema. On lung exam, diffuse rhonchi were audible bilaterally with no crackles or wheezing. There was no accessory muscle use. No clubbing was present. Her abdomen was soft and mildly tender in the epigastrium with normal bowel sounds.

Her labs revealed a white blood cell (WBC) count of 5,050/μL (neutrophils, 3,600/μL; lymphocytes, 560/μL; eosinophils, 560/μL; hemoglobin, 8.7 g/dL; mean corpuscular volume, 89.3 fL; and platelets, 402,000/μL). Her CD4 count was 235 cells/μL. Her comprehensive metabolic panel demonstrated a sodium of 127 mmol/L; potassium, 4.0 mmol/L; albumin, 2.0 g/dL; calcium, 8.6 mg/dL; creatinine, 0.41 mg/dL; aspartate aminotransferase (AST), 11 U/L; alanine aminotransferase (ALT), 17 U/L; and serum osmolarity, 258 mOs/kg. Her lipase was 30 U/L, and lactate was 0.8 mmol/L. Urine studies showed creatinine 41 mg/dL, osmolality 503 mOs/kg, and sodium 53 mmol/L.

At this point, the patient has been diagnosed with multiple pulmonary emboli and recurrent GI bleeding from duodenal ulcers with chest imaging suggestive of taxane-induced pulmonary toxicity. She now presents with worsening dyspnea and upper-GI symptoms.

Her dyspnea may represent worsening of her taxane-induced lung disease. However, she may have developed a superimposed infection, heart failure, or further pulmonary emboli

On exam, she is in respiratory distress, almost mildly hypothermic and tachycardic with rhonchi on auscultation. This combination of findings could reflect worsening of her pulmonary disease and/or infection on the background of her cachectic state. Her epigastric tenderness, upper-GI symptoms, and anemia have continued to cause concern for persistent duodenal ulcers

Her anemia could represent ongoing blood loss since her last EGD or an inflammatory state due to infection. Also of concern is her use of dapsone, which can lead to hemolysis with or without glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency (G6PD), and this should be excluded.

She has hypotonic hyponatremia and apparent euvolemia with a high urine sodium and osmolality; this suggests syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion, which may be due to her ongoing pulmonary disease process.

On day 3 of her hospitalization, her abdominal pain became more diffuse and colicky, with two episodes of associated nonbloody bilious vomiting. During the next 48 hours, her abdominal pain and tenderness worsened diffusely but without rigidity or peritoneal signs. She developed mild abdominal distention. An abdominal X-ray showed moderate to large stool burden and increased bowel dilation concerning for small bowel obstruction. A nasogastric tube was placed, with initial improvement of her abdominal pain and distention. On the morning of day six of hospitalization, she had approximately 100 mL of hematemesis. She immediately became hypotensive to the 50s/20s, and roughly 400 mL of sanguineous fluid was suctioned from her nasogastric tube. She was promptly given intravenous (IV) fluids and 2 units of cross-matched packed red blood cells with normalization of her blood pressure and was transferred to the medical intensive care unit (MICU).

Later that day, she had an EGD that showed copious clots and a severely friable duodenum with duodenal narrowing. Duodenal biopsies were taken.

The duodenal ulcers have led to a complication of stricture formation and obstruction resulting in some degree of small bowel obstruction. EGD with biopsies can shed light on the etiology of these ulcers and can specifically exclude viral, fungal, protozoal, or mycobacterial infection; infiltrative diseases (lymphoma, sarcoidosis, amyloidosis); cancer; and inflammatory noninfectious diseases such as vasculitis/connective tissue disorder. Biopsy specimens should undergo light and electron microscopy (for protozoa-like Cryptosporidium); stains for fungal infections such as histoplasmosis, Candida, and Cryptococcus; and stains for mycobacterium. Immunohistochemistry and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing can identify CMV, HIV, HSV, and EBV within the duodenal tissue.

She remained on methylprednisolone 30 mg IV because of her known history of pneumonitis and concern for adrenal insufficiency in the setting of acute illness. Over the next 3 days, she remained normotensive with a stable hemoglobin and had no further episodes of hematemesis. She was transferred to the general medical floor.

One day later, she required an additional unit of cross-matched red blood cells because of a hemoglobin decrease to 6.4 g/dL. The next day, she developed acute-onset respiratory distress and was intubated for hypoxemic respiratory failure and readmitted to the MICU.

Her drop in hemoglobin may reflect ongoing bleeding from the duodenum or may be due to diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH) complicating her pneumonitis. The deterioration in the patient’s respiratory status could represent worsening of her taxane pneumonitis (possibly complicated by DAH or acute respiratory distress syndrome), as fatalities have been reported despite steroid treatment. However, as stated earlier, it is prudent to exclude superimposed pulmonary infection or recurrent pulmonary embolism. Broad-spectrum antibiotics should be provided to cover hospital-acquired pneumonia. Transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI) as a cause of her respiratory distress is much less likely given onset after 24 hours from transfusion. Symptoms of TRALI almost always develop within 1 to 2 hours of starting a transfusion, with most starting within minutes. The timing of respiratory distress after 24 hours of transfusion also makes transfusion-associated circulatory overload unlikely, as this presents within 6 to 12 hours of a transfusion being completed and generally in patients receiving large transfusion volumes who have underlying cardiac or renal disease.

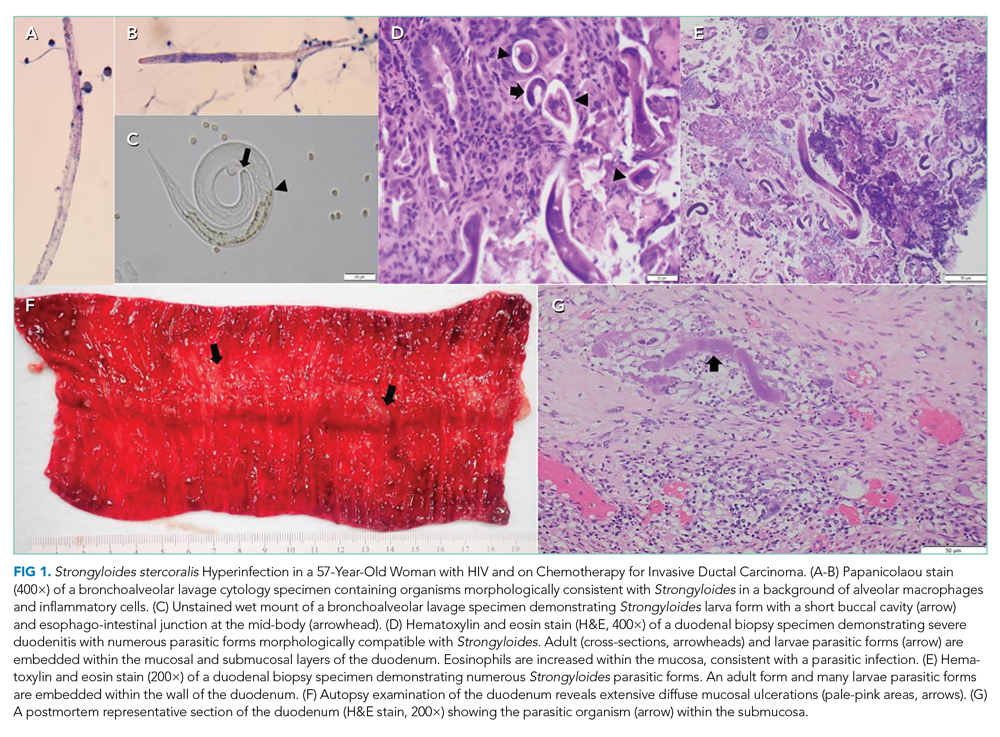

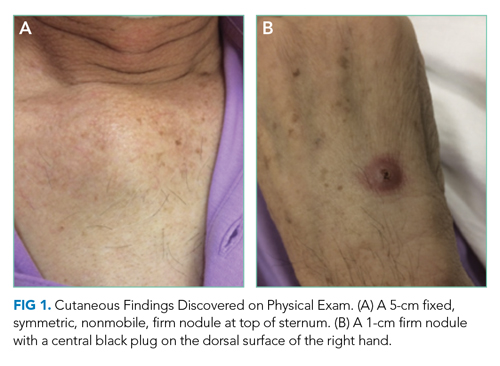

Her duodenal pathology revealed Strongyloides stercoralis infection (Figure 1), and she was placed on ivermectin. Steroids were continued due to concern for adrenal insufficiency in the setting of critical illness and later septic shock. Bronchoscopy was also performed, and a specimen grew S stercoralis. She developed septic shock from disseminated S stercoralis infection that required vasopressors. Her sanguineous orogastric output increased, and her abdominal distension worsened, concerning for an intra-abdominal bleed or possible duodenal perforation. As attempts were made to stabilize the patient, ultimately, she experienced cardiac arrest and died.

The patient succumbed to hyperinfection/dissemination of strongyloidiasis. Her risk factors for superinfection included chemotherapy and high-dose steroids, which led to an unchecked autoinfection.

A high index of suspicion remains the most effective overall diagnostic tool for superinfection, which carries a mortality rate of up to 85% even with treatment. Therefore, prevention is the best treatment. Asymptomatic patients with epidemiological exposure or from endemic areas should be evaluated for empiric treatment of S stercoralis prior to initiation of immunosuppressive treatment.

COMMENTARY

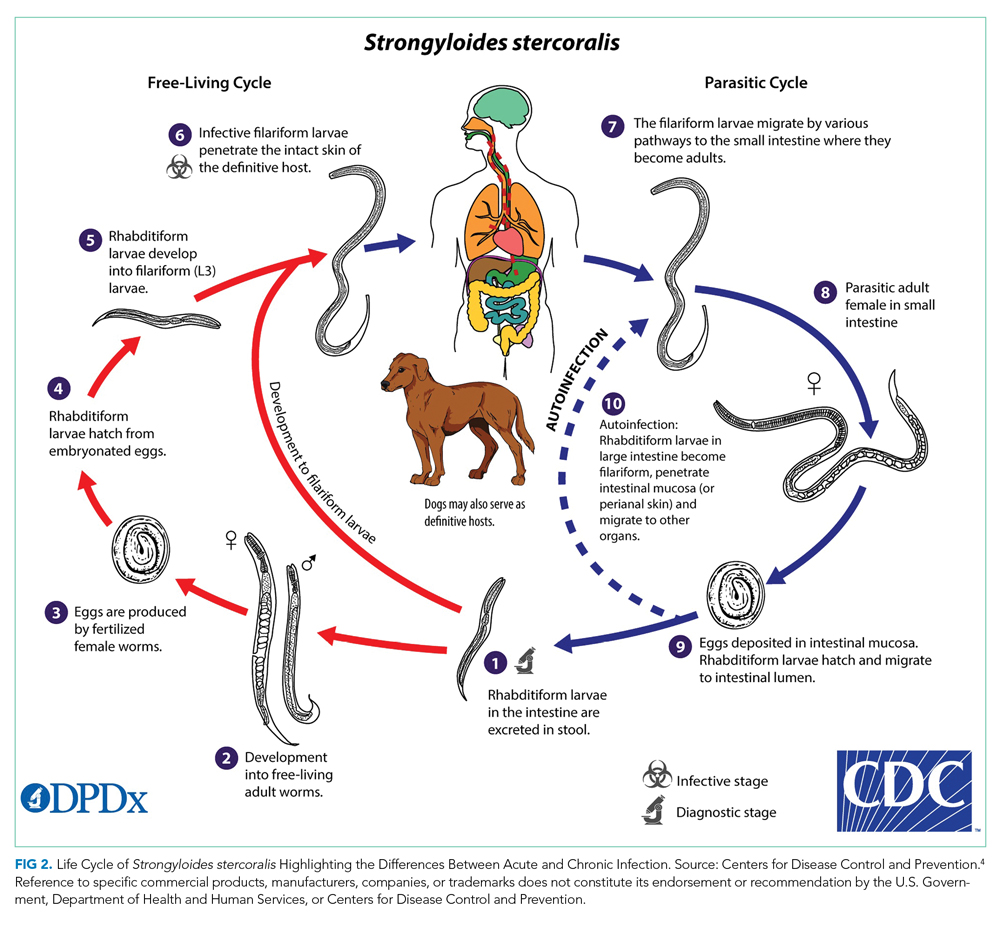

Strongyloides stercoralis is a helminth responsible for one of the most overlooked tropical diseases worldwide.1 It is estimated that 370 million individuals are infected with S stercoralis globally, and prevalence in the endemic tropics and subtropics is 10% to 40%.2,3Strongyloides stercoralis infection is characterized by typically nonspecific cutaneous, pulmonary, and GI symptoms, and chronic infection can often be asymptomatic. Once the infection is established, the entirety of the S stercoralis unique life cycle can occur inside the human host, forming a cycle of endogenous autoinfection that can keep the host chronically infected and infectious for decades (Figure 24). While our patient was likely chronically infected for 27 years, cases of patients being infected for up to 75 years have been reported.5 Though mostly identified in societies where fecal contamination of soil and poor sanitation are common, S stercoralis should be considered among populations who have traveled to endemic areas and are immunocompromised.

Most chronic S stercoralis infections are asymptomatic, but infection can progress to the life-threatening hyperinfection phase, which has a mortality rate of approximately 85%.6 Hyperinfection and disseminated disease occur when there is a rapid proliferation of larvae within the pulmonary and GI tracts, but in the case of disseminated disease, may travel to the liver, brain, and kidneys.7,8 Typically, this is caused by decreased cellular immunity, often due to preexisting conditions such as human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) or medications that allow larvae proliferation to go unchecked.6,7 One common class of medications known to increase risk of progression to hyperinfection is corticosteroids, which are thought to both depress immunity and directly increase larvae population growth.6,9 Our patient had been on a prolonged course of steroids for her pulmonary symptoms, with increased doses during her acute illness because of concern for adrenal insufficiency; this likely further contributed to her progression to hyperinfection syndrome. Furthermore, the patient was also immunocompromised from chemotherapy. In addition, she had HIV, which has a controversial association with S stercoralis infection. While previously an AIDS-defining illness, prevalence data indicate a significant co-infection rate between S stercoralis and HIV, but it is unlikely that HIV increases progression to hyperinfection.3

Diagnosing chronic S stercoralis infection is difficult given the lack of a widely accepted gold standard for diagnosis. Traditionally, diagnosis relied on direct visualization of larvae with stool microscopy studies. However, to obtain adequate sensitivity from this method, up to seven serial stool samples must be examined, which is impractical from patient, cost, and efficiency standpoints.10 While other stool-based techniques, such as enriching the stool sample, stool agar plate culture, or PCR-based stool analysis, improve sensitivity, all stool-based studies are limited by intermittent larvae shedding and low worm burden associated with chronic infection.11 Conversely, serologic studies have higher sensitivity, but concerns exist about lower specificity due to potential cross-reactions with other helminths and the persistence of antibodies even after larvae eradication.11,12 Patients with suspected S stercoralis infection and pulmonary infiltrates on imaging may have larvae visible on sputum cultures. A final diagnostic method is direct visualization via biopsy during endoscopy or bronchoscopy, which is typically recommended in cases where suspicion is high yet stool studies have been negative.13 Our patient’s diagnosis was made by duodenal biopsy after her stool study was negative for S stercoralis.

Deciding who to test is difficult given the nonspecific nature of the symptoms but critically important because of the potential for mortality if the disease progresses to hyperinfection. Diagnosis should be suspected in a patient who has spent time in an endemic area and presents with any combination of pulmonary, dermatologic, or GI symptoms. If suspicion for infection is high in a patient being assessed for solid organ transplant or high-dose steroids, prophylactic treatment with ivermectin should be considered. Given the difficulty in diagnosis, some have suggested using eosinophilia as a key diagnostic element, but this has poor predictive value, particularly if the patient is on corticosteroids.7 This patient did not manifest with significant eosinophilia throughout her hospitalization.

This case highlights the difficulties of S stercoralis diagnosis given the nonspecific and variable symptoms, limitations in testing, and potential for remote travel history to endemic regions. It further underscores the need for provider vigilance when starting patients on immunosuppression, even with steroids, given the potential to accelerate chronic infections that were previously buried deep in the mucosa into a lethal hyperinfectious state.

TEACHING POINTS

- The cycle of autoinfection by S stercoralis allows it to persist for decades even while asymptomatic. This means patients can present with infection years after travel to endemic regions.

- Because progression to hyperinfection syndrome carries a high mortality rate and is associated with immunosuppressants, particularly corticosteroids, screening patients from or who have spent time in endemic regions for chronic S stercoralis infection is recommended prior to beginning immunosuppression.

- Diagnosing chronic S stercoralis infection is difficult given the lack of a highly accurate, gold-standard test. Therefore, if suspicion for infection is high yet low-sensitivity stool studies have been negative, direct visualization with a biopsy is a diagnostic option.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Dr Nicholas Moore, microbiologist at Rush University Medical Center, for his assistance in obtaining and preparing the histology images.

1. Olsen A, van Lieshout L, Marti H, et al. Strongyloidiasis--the most neglected of the neglected tropical diseases? Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009;103(10):967-972. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trstmh.2009.02.013

2. Bisoffi Z, Buonfrate D, Montresor A, et al. Strongyloides stercoralis: a plea for action. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7(5):e2214. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0002214

3. Schär F, Trostdorf U, Giardina F, et al. Strongyloides stercoralis: global distribution and risk factors. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7(7):e2288. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0002288

4. Silva AJ, Moser M. Life cycle of Strongyloides stercoralis. Accessed June 5, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/strongyloides/biology.html

5. Prendki V, Fenaux P, Durand R, Thellier M, Bouchaud O. Strongyloidiasis in man 75 years after initial exposure. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17(5):931-932. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1705.100490

6. Nutman TB. Human infection with Strongyloides stercoralis and other related Strongyloides species. Parasitology. 2017;144(3):263-273. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182016000834

7. Naidu P, Yanow SK, Kowalewska-Grochowska KT. Eosinophilia: a poor predictor of Strongyloides infection in refugees. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2013;24(2):93-96. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/290814

8. Kassalik M, Mönkemüller K. Strongyloides stercoralis hyperinfection syndrome and disseminated disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2011;7(11):766-768.

9. Genta RM. Dysregulation of strongyloidiasis: a new hypothesis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1992;5(4):345-355. https://doi.org/10.1128/cmr.5.4.345

10. Siddiqui AA, Berk SL. Diagnosis of Strongyloides stercoralis infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33(7):1040-1047. https://doi.org/10.1086/322707

11. Buonfrate D, Requena-Mendez A, Angheben A, et al. Accuracy of molecular biology techniques for the diagnosis of Strongyloides stercoralis infection—a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12(2):e0006229. dohttps://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0006229

12. Arifin N, Hanafiah KM, Ahmad H, Noordin R. Serodiagnosis and early detection of Strongyloides stercoralis infection. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2019;52(3):371-378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmii.2018.10.001

13. Lowe RC, Chu JN, Pierce TT, Weil AA, Branda JA. Case 3-2020: a 44-year-old man with weight loss, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(4):365-374. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMcpc1913473

This icon represents the patient’s case. Each paragraph that follows represents the discussant’s thoughts.

A 56-year-old-woman with a history of HIV and locally invasive ductal carcinoma recently treated with mastectomy and adjuvant doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide, now on paclitaxel, was transferred from another hospital with worsening nausea, epigastric pain, and dyspnea. She had been admitted multiple times to both this hospital and another hospital and had extensive workup over the previous 2 months for gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding and progressive dyspnea with orthopnea and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea in the setting of a documented 43-lb weight loss.

Her past medical history was otherwise significant only for the events of the previous few months. Eight months earlier, she was diagnosed with grade 3 triple-negative (estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2) invasive ductal carcinoma and underwent mastectomy with negative sentinel lymph node biopsy. She completed four cycles of adjuvant doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide and most recently completed cycle three of paclitaxel chemotherapy.

Her HIV disease was controlled with an antiretroviral regimen of dolutegravir/rilpivirine. She had an undetectable viral load for 20 years (CD4, 239 cells/μL 2 weeks prior to transfer).

Her social history included a 1-pack-year smoking history. She denied alcohol or illicit drug use. Family history included pancreatic cancer in her father and endometrial cancer in her paternal grandmother. She was originally from Mexico but moved to Illinois 27 years earlier.

Work-up for her dyspnea was initiated 7 weeks earlier: noncontrast CT of the chest showed extensive diffuse interstitial thickening and ground-glass opacities bilaterally. Bronchoscopy showed no gross abnormalities, and bronchial washings were negative for bacteria, fungi, Pneumocystis jirovecii , acid-fast bacilli, and cancer. She also had a TTE, which showed an ejection fraction of 65% to 70% and was only significant for a pulmonary artery systolic pressure of 45 mm Hg . She was diagnosed with paclitaxel-induced pneumonitis and was discharged home with prednisone 50 mg daily, dapsone, pantoprazole, and 2 L oxygen via nasal cannula.

Two weeks later, she was admitted for coffee-ground emesis and epigastric pain. Her hemoglobin was 5.9 g/dL, for which she was transfused 3 units of packed red blood cells. EGD showed bleeding from diffuse duodenitis, which was treated with argon plasma coagulation. She was also found to have bilateral pulmonary emboli and lower-extremity deep venous thromboses. An inferior vena cava filter was placed, and she was discharged. One week later, she was readmitted with melena, and repeat EGD showed multiple duodenal ulcers with no active bleeding. Colonoscopy was normal. She was continued on prednisone 40 mg daily, as any attempts at tapering the dose resulted in hypotension.

At the time of transfer, she had presented to the outside hospital with worsening nausea and epigastric pain, increasing postprandial abdominal pain, ongoing weight loss, worsening dyspnea on exertion, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, and orthopnea. She denied symptoms of GI bleeding at that time.

Her imaging is consistent with, albeit not specific for, paclitaxel-induced acute pneumonitis. Her persistent dyspnea may be due to worsening of this pneumonitis.

Upon arrival on physical exam, her temperature was 35.4° C, heart rate 112 beats per minute, blood pressure 135/96 mm Hg, respiratory rate 34 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation 97% on room air. She was ill- appearing and in mild respiratory distress with severe muscle wasting. Cervical and supraclavicular lymphadenopathy were not detected. Heart sounds were normal without murmurs. Her jugular venous pressure was approximately 7 cm H2O. She had no lower-extremity edema. On lung exam, diffuse rhonchi were audible bilaterally with no crackles or wheezing. There was no accessory muscle use. No clubbing was present. Her abdomen was soft and mildly tender in the epigastrium with normal bowel sounds.

Her labs revealed a white blood cell (WBC) count of 5,050/μL (neutrophils, 3,600/μL; lymphocytes, 560/μL; eosinophils, 560/μL; hemoglobin, 8.7 g/dL; mean corpuscular volume, 89.3 fL; and platelets, 402,000/μL). Her CD4 count was 235 cells/μL. Her comprehensive metabolic panel demonstrated a sodium of 127 mmol/L; potassium, 4.0 mmol/L; albumin, 2.0 g/dL; calcium, 8.6 mg/dL; creatinine, 0.41 mg/dL; aspartate aminotransferase (AST), 11 U/L; alanine aminotransferase (ALT), 17 U/L; and serum osmolarity, 258 mOs/kg. Her lipase was 30 U/L, and lactate was 0.8 mmol/L. Urine studies showed creatinine 41 mg/dL, osmolality 503 mOs/kg, and sodium 53 mmol/L.

At this point, the patient has been diagnosed with multiple pulmonary emboli and recurrent GI bleeding from duodenal ulcers with chest imaging suggestive of taxane-induced pulmonary toxicity. She now presents with worsening dyspnea and upper-GI symptoms.

Her dyspnea may represent worsening of her taxane-induced lung disease. However, she may have developed a superimposed infection, heart failure, or further pulmonary emboli

On exam, she is in respiratory distress, almost mildly hypothermic and tachycardic with rhonchi on auscultation. This combination of findings could reflect worsening of her pulmonary disease and/or infection on the background of her cachectic state. Her epigastric tenderness, upper-GI symptoms, and anemia have continued to cause concern for persistent duodenal ulcers

Her anemia could represent ongoing blood loss since her last EGD or an inflammatory state due to infection. Also of concern is her use of dapsone, which can lead to hemolysis with or without glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency (G6PD), and this should be excluded.

She has hypotonic hyponatremia and apparent euvolemia with a high urine sodium and osmolality; this suggests syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion, which may be due to her ongoing pulmonary disease process.

On day 3 of her hospitalization, her abdominal pain became more diffuse and colicky, with two episodes of associated nonbloody bilious vomiting. During the next 48 hours, her abdominal pain and tenderness worsened diffusely but without rigidity or peritoneal signs. She developed mild abdominal distention. An abdominal X-ray showed moderate to large stool burden and increased bowel dilation concerning for small bowel obstruction. A nasogastric tube was placed, with initial improvement of her abdominal pain and distention. On the morning of day six of hospitalization, she had approximately 100 mL of hematemesis. She immediately became hypotensive to the 50s/20s, and roughly 400 mL of sanguineous fluid was suctioned from her nasogastric tube. She was promptly given intravenous (IV) fluids and 2 units of cross-matched packed red blood cells with normalization of her blood pressure and was transferred to the medical intensive care unit (MICU).

Later that day, she had an EGD that showed copious clots and a severely friable duodenum with duodenal narrowing. Duodenal biopsies were taken.

The duodenal ulcers have led to a complication of stricture formation and obstruction resulting in some degree of small bowel obstruction. EGD with biopsies can shed light on the etiology of these ulcers and can specifically exclude viral, fungal, protozoal, or mycobacterial infection; infiltrative diseases (lymphoma, sarcoidosis, amyloidosis); cancer; and inflammatory noninfectious diseases such as vasculitis/connective tissue disorder. Biopsy specimens should undergo light and electron microscopy (for protozoa-like Cryptosporidium); stains for fungal infections such as histoplasmosis, Candida, and Cryptococcus; and stains for mycobacterium. Immunohistochemistry and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing can identify CMV, HIV, HSV, and EBV within the duodenal tissue.

She remained on methylprednisolone 30 mg IV because of her known history of pneumonitis and concern for adrenal insufficiency in the setting of acute illness. Over the next 3 days, she remained normotensive with a stable hemoglobin and had no further episodes of hematemesis. She was transferred to the general medical floor.

One day later, she required an additional unit of cross-matched red blood cells because of a hemoglobin decrease to 6.4 g/dL. The next day, she developed acute-onset respiratory distress and was intubated for hypoxemic respiratory failure and readmitted to the MICU.